Title: Birds and Nature, Vol. 12 No. 2 [July 1902]

Author: Various

Editor: William Kerr Higley

Release date: January 5, 2015 [eBook #47882]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Stephen Hutcheson,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

BIRDS AND NATURE. | ||

| ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vol. XII. | SEPTEMBER, 1902. | No. 2. |

O golden month! How high thy gold is heaped!

The yellow birch-leaves shine like bright coins strung

On wands; the chestnut’s yellow pennons tongue

To every wind its harvest challenge. Steeped

In yellow, still lie fields where wheat was reaped;

And yellow still the corn sheaves, stacked among

The yellow gourds, which from the earth have wrung

Her utmost gold. To highest boughs have leaped

The purple grape,—last thing to ripen, late

By very reason of its precious cost.

O Heart, remember, vintages are lost

If grapes do not for freezing night-dews wait.

Think, while thou sunnest thyself in Joy’s estate,

Mayhap thou canst not ripen without frost!

—Helen Hunt Jackson.

Graceful tossing plume of gold,

Waving lowly on the rocky ledge;

Leaning seaward, lovely to behold,

Clinging to the high cliff’s ragged edge;

Burning in the pure September day,

Spike of gold against the stainless blue,

Do you watch the vessels drifting by?

Does the quiet day seem long to you?

—Celia Thaxter, in “Seaside Goldenrod.”

Then tiny warblers flit and sing,

With golden spots on crest and wing,

Or, decked with scarlet epaulette

Above each dusky winglet set,

They hunt the blossoms for their prey

And pipe their fairy roundelay.

—Rose Terry Cooke, “My Apple Tree.”

There are two varieties of this species, the Palm or Red-poll Warbler, and the yellow palm or yellow red-poll warbler. The latter is a native of the Atlantic States and breeds from Maine northward to Hudson Bay. The former frequents the interior of the United States and migrates northward as far as the Great Slave Lake. It is seldom seen in the Atlantic States except during its migrations.

In this connection the account of Mr. William Dutcher, regarding the first observation of the Palm Warbler in Long Island, is of interest. It is the more interesting because it partially answers the question so often asked, “Where do the birds die?” Mr. Dutcher says, “During the night of the twenty-third of September, 1887, a great bird wave was rolling southward along the Atlantic coast. Mr. E. J. Udall, of the Fire Island Light, wrote me that the air was full of birds. Very many of the little travellers met with an untimely fate, for Mr. Udall picked up at the foot of the light house tower, and shipped to me, no less than five hundred and ninety-five victims. Twenty-five species were included in the number, all of them being land birds, very nearly half of which were Wood Warblers. Among them I found one Palm Warbler.”

Both varieties winter in the Southern States that border the Atlantic ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, in Mexico and in the islands of the West Indies. While both birds are often seen in the same flock during the winter, the Palm Warbler is much more common in Florida than is the eastern cousin. When together the two forms may be readily distinguished by the brighter yellow of the yellow palm warbler.

Three of the large family of Wood Warblers may be called the vagabonds of the family, for they do not love the forest. These are the Palm, the yellow Palm and the Prairie Warblers.

Dr. Ridgway says of the Palm Warbler, “During the spring migration this is one of the most abundant of the warblers,” in Illinois, “and for a brief season may be seen along the fences, or the borders of fields, usually near the ground, walking in a graceful, gliding manner, the body tilting and the tail oscillating at each step. For this reason it is sometimes, and not inappropriately called Wag-Tail Warbler.” The observer is reminded of the titlarks as he watches the nervous activity of this Warbler as it constantly jerks its tail while it flutters about the hedges and scattered shrubbery, or when running on the ground among the weeds of old fields. It may even frequent dusty roadsides. Wherever it is, it frequently utters its low “tsip,” a note that is very similar to that of many of its sister warblers.

Dr. Brewer says, “They have no other song than a few simple and feeble notes, so thin and weak that they might almost be mistaken for the sound made by the common grasshopper.”

The Palm Warbler’s nest is a trim structure, usually placed upon the ground and never far above it. The walls consist of interwoven dry grasses, stems of the smaller herbaceous plants, bark fibres and various mosses. It is lined with very fine grasses, vegetable down and feathers. Though this home is placed in quite open places, a retired spot is usually selected. Here are laid the white or buffy white eggs, more or less distinctly marked with a brownish color, and a family of four or five of these peculiar Warblers is raised.

PALM WARBLER.

(Dendroica palmarum).

Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

While in our camp on the shore of Gloucester harbor, many were our adventures first and last, some of our own choosing, some not. In the mouth of Rafe’s Chasm is a big oblong seamed rock, considerably lower than either wall at that point, with perpendicular sides and top slanting to the lower wall, which is the west, and the natural approach. At low tide the boys made a point of leaping the western channel and climbing up across the narrower eastern one, and where the boys went, the younger girls expected to follow. (How was it, I wonder, that girls began to be “tomboys” just then? They have kept it up ever since, but it is no longer a matter of reproach.) The first girl who did this held the championship for some time, but the smaller ones qualified in the end. We were there one day at half tide when a good deal of surf was running, so we established ourselves well up on the rocks, but our Newfoundland dog elected to go down and enter the water at the western corner of the chasm. He was immediately swept out, and out started somebody’s eyes! “You’ve lost your dog!” But even as we gazed in consternation, the wave—walked back and returned him! A strange sight it was—that black dog advancing as in a vehicle, standing unconcernedly in a tall green wave and, when it arrived, walking calmly out and shaking himself! No suction, no struggle, his feet just on a level with the flat ledge; out he walked and was hugged, dripping, as soon as we could lay hold of him.

The Magnolia Swamp stretches far toward Essex and Manchester, and with the surrounding heath and forest forms a wilderness which a wild animal might range for miles, crossing now and then a lonely road; and in the summer of 1884 two of us saw a very odd wild animal in the old road. Descending suddenly from the hill above, we saw a dingy white creature jogging slowly along in the middle of the road a short stone’s throw ahead. It was clumsily made, and its gait was awkward and lumbering. It had short legs, very round hind-quarters, no perceptible tail, and long, slightly wavy white hair, exactly the same all over, without mark, spot or difference. We mended our pace and gained on it, when the creature did the same without looking round and plunged into a dense cover of brier with the heavy rolling gait of an elephant and at such an angle that we never saw its head, nor could we trace its line of retreat in the underbrush.

Now what was that? Please don’t say poodle or woodchuck or skunk or raccoon. It bore no resemblance to either, except, in size and color, to the poodle. The only thing I ever saw at all like it was a stuffed lynx in a New Hampshire town. In color, length of hair, and absence of tail they were exactly alike. The stuffed specimen was twice as big as the live animal and long-limbed in proportion, while the latter was thick-set and clumsy like a cub.

One September day at sunset I was sitting on a low rock platform trying to paint a great green wave which reappeared at regular intervals, gathering under the rock with a growl and falling on the shore like lead. (The effort looked like a tin wave, and an artist said it should not have been attempted. The opposite headland was better, fresh from one ducking and expecting another from the pale green border surging up out of the gray, away from the eye.) At last the sole companionship of this sulky wave became oppressive, and turning landward, I looked up into an uncanny sky—a wild red afterglow barring the slate with flame-color—and smelt a 54 skunk, and felt far from home. And there on the top of the ridge, the highest point in that great amphitheater of wooded hills, the only habitation in sight, it stood out black against those flaming bars, amid the silhouettes of dying pines.

The dog would have been a support, but he wasn’t there. After some experience of sketching-parties, he had given up attending. Collies are particular, and this one hated to sit with the wind in his face. When we first had him, he dogged every footstep for fear of being left behind, but at this stage of his development he would not stir a step with sketching material or a gardening hat; he knew too well that such accessories led to nothing. Yet his polished behavior in other respects had so impressed a small visitor in long Greenaway robe and cap, that when she made her series of curtsies to the family semicircle on leaving, she curtsied with equal gravity to the dog as he lay chin to the floor, half under the table. And that was quite right. Doubtless we all bow to persons far less deserving than this forgiving dog who always hastened to console you when you trod on him.

However, on this occasion I had to get home alone and dodge skunks unsupported under that awesome sky. The best part of a mile away and all the way up-hill, the last pitch abominably steep and rough, the choice of site would have done credit to a robber baron, but the land falls away gently to the Manchester road on the other side. It took months with a derrick and oxen to forge the connecting link, however; and one section, which rounds a hill and crosses a gully, looked like the bed of a mountain torrent for weeks. The camp of 1865 led to the choice of 1883, as many a camp has done from Roman days on. The Pequot war settled central Massachusetts as the Revolution filled up New Hampshire and Vermont. It was not so much that the land stood empty as that men went out and saw the land, that it was good. Behold a by-product of war.

If the merry greenwood was as our native heath, so too was the water. It was about a third of a mile off the Rock that he of the rifle once had a difference with a shark. He was out alone in a dory when the shark happened along and thought, being there, he might as well see if he couldn’t upset the boat. So he came swarming up on the oar until the youth got tired of it, and standing up, balanced himself not to overreach in case the shark proved slippery and thrust the butt as hard as he dared between the eyes, which were about a foot apart. But the shark was not slippery. He felt rough, and as hard and solid as a ledge, while the youth felt as if he had hit that same. However, his Honor seems not to have enjoyed it either, for he soon settled in the water, and circling lower and lower two or three times, disappeared.

Some years before that, this boy was out with another when the harbor was full of herring, and a whale appeared which had followed the schools in. And he popped up so frequently and blew in such unexpected places that the boys deemed it best to make for the nearest land. Meantime the whale rose in their wake with his jaws wide open in the middle of a school of herring, and they saw a lot of the fish flipping dry in his throat; and the boat came in and all the passengers stood on deck looking at him, and then he got excited and ran aground, the tide being low, on some shoals in behind the Island, and thrashed about so, they thought he must have hurt himself. It was a thrilling afternoon.

The dory is a proved little craft for serious business in rough water, while none can be better for ladies about rocks and beaches; because it has a flat bottom and there is no keel to catch and leave you tipping about with the lap of the water running ever so far inside. Moreover, the dory has so much shear that very little of the bottom touches at one time; and if it hangs anywhere, you can take it by the nose and work it off quite easily. We fully appreciated the merits of a build which permitted crossing the harbor in good gowns to make a call we did not wish to spend a whole evening on, landing perhaps on a lonely bit of shingle with a sharp little sea thrashing in, “firing” all along the tops of the waves. We often went out to 55 supper in dories, taking a small charcoal furnace, a griddle and a pitcher of batter, and rowing down to some great flat sheets of rock made for the purpose on the Point. There we pulled up the boats, set up housekeeping and fried our flapjacks, first waiting to enjoy the sunset over the western shore reflected in the harbor. (If you stay in the house the sun always sets while you are at supper, if you notice; and this is nature’s revenge on you for eating indoors instead of out-of-doors, like Christians.) Then we rowed home by moonlight or perhaps by starlight, pausing to amuse ourselves by stamping on the bottom of the boat, startling the fish under us and making them dart, leaving a phosphorescent wake far below.

If a thunder-shower surprised us, we rolled the boats over and crept under, the valued shear allowed plenty of air. It is true, if the shower lasted too long, the water was apt to run down the rock and leave somebody in a puddle, while it might become painful to take too perfect an impression of the pattern of the rock on one elbow, but it’s worth getting wet to cross the harbor in the rain with the drops hissing in the water and turning to pale fire wherever they strike.

The dory is a stiff little craft, too, not easily upset, as some of our party proved at the beach one day. Half-a-dozen of them embarked in bathing dresses and when beyond their depth stood up on the seats and rocked with all their might; but this not effecting their purpose, the girls jumped out and the two or three men left danced on the gunwale and finally overturned it.

One starlight evening two of us, escaping from the heat in town, were floating close inshore somewhere down near Black Bess, when suddenly out of the darkness arose the sound of a sailboat bearing down on us full tilt. We sprang up in dismay, though it was dead calm and we knew no boat could come where we were. We peered into the darkness, but nothing came and the sound died as it sprung into being, full grown, without crescendo and without diminuendo. There was no splashing, either; just the full, steady rip of the cutwater at speed. It lasted perhaps a minute, and was a startling affair. Experienced persons say they never heard anything like it, and suggest sharks. People always suggest that—what can you expect after Lyell said shark to our family pet, “the sea-serpent,” which our own grandparents saw in 1817 from such a coign of vantage that if it had been a shark, one would think they would have known it. We all know the place where they were driving “along the edge of a cliff—when he saw the sea-serpent at the base—on the white beach where there was not more than six or seven feet of water; and giving the reins to his wife, looked down upon the creature, and made up his mind that it was ninety feet long. He then took his wife to the spot, and she said it was as long as their wharf, and this measured one hundred feet. While they were looking down on it, the creature appeared to be alarmed, and started off.” (Lyell’s Diary.) This is an incredulous world.

Does anyone ever read “The Toilers of the Sea” nowadays, or remember the finale? Having purposely allowed the tide to catch him, the hero sits in a niche in the cliff awaiting death, with his eye on the ship which bears away his beloved, who has married the wrong man. And as the ship drops behind the horizon, the water covers his eyes—when we read that, with one accord we made for the beach, and as soon as the tide served round a big ledge, we practiced that scene, and found it unimpressive. As we expected, you float off: you can’t stay there! and we thought Victor Hugo should really have practiced it himself.

Helen Mansfield.

Alive in this world of beautiful forms,

No form is alien to men, or apart,

Each morning sunbeam our being warms,

Each tree is a kinsman of friendly heart.

We love the clear bird songs that fill our ear

With melody ringing for us alone.

The cricket’s chirp is for us, and we hear

A human voice in the rivulet’s tone.

Each lovely thing of nature finds room

In our heart of hearts—our lover and mate,

The star and the dew and the vine’s sweet bloom

Are fitted to us, and our spirit innate.

They are kinsmen—each century blazing star!

Each snowclad summit, each rose-flushed peak

Have most subtle oneness with us, for afar

Of things sublime and eternal they speak.

With all beautiful things that live, we are one.

We are kin to the circle of nature’s whole.

So, O beautiful trees that stand in the sun,

Your beauty entrancing slips into the soul.

For the children of one great Kinsman above

Are the myriad forms of nature and we.

Kinsman, Creator, He fits our love

To the star and the flower, the bird and the tree.

—Mrs. Merrill E. Gates.

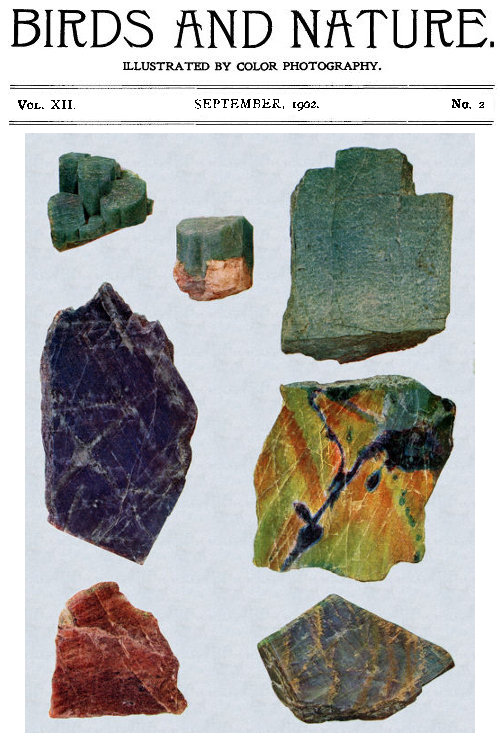

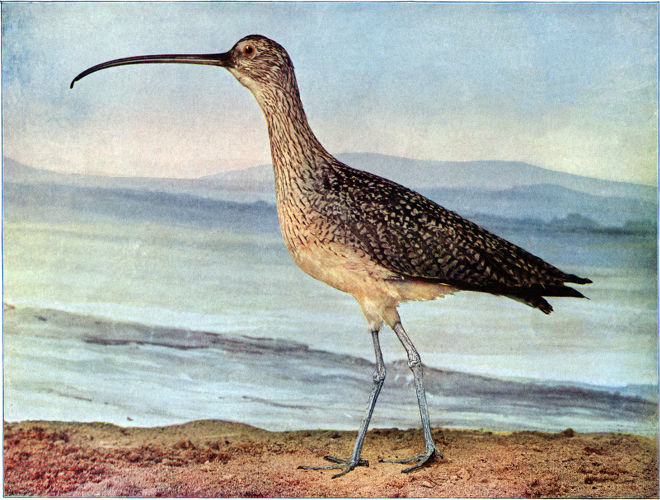

LONG-BILLED CURLEW.

(Numenius longirostris).

⅓ Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

Each day are heard, and almost every hour,

New notes to swell the music of the groves,

And soon the latest of the feathered train

At evening twilight come;—the lonely snipe,

O’er marshy fields, high in the dusky air,

Invisible, but, with faint, tremulous tones,

Hovering or playing o’er the listener’s head.

—Carlos Wilcox, “The Age of Benevolence.”

The Long-billed Curlew is the largest of the American curlews and has a wide range covering nearly the whole of temperate North America. It is not a bird of high altitudes and in winter it seeks the milder climate of the Southern States, Mexico, Guatemala, Cuba and Jamaica. During the breeding season, which is passed in the South Atlantic States or in the interior of North America as far north as Manitoba, it is not a social bird. While migrating, however, and in winter, it enjoys the society of its fellows and is generally observed in flocks of a greater or less number.

Mr. Wilson has well described its flight during migration or when passing from one feeding ground to another. He says, “The Curlews fly high, generally in a wedge-like form, somewhat resembling certain ducks, occasionally uttering their loud, whistling note, by a dexterous imitation of which a whole flock may sometimes be enticed within gunshot, while the cries of the wounded are sure to detain them until the gunner has made repeated shots and great havoc among them.”

Though the natural home of the curlews is the muddy shores and grassy lowlands adjacent to bodies of water the Long-billed species also frequents drier places at a distance from water, and even breeds in the uplands. Here their food consists of worms, insects and berries. When fattened with such food their flesh is tender and lacks the stronger flavor that is present when they have fed exclusively on the animal food of the marshes of the sea shore. It is interesting to watch the Curlew upon the beach as it gracefully moves from point to point in search of food. Now and then it thrusts its long sensitive bill into the soft soil and usually draws forth some form of animal food—a larva of some insect, a crab, a snail or a worm. Frequently it will explore the holes of crawfish and it is often rewarded with a dainty morsel of curlew food.

The Curlew’s bill is very characteristic and especially adapted to the bird’s habit of probing for food. It is very variable in length and not infrequently grows to a length of seven or eight inches, and it has been known to reach a length of nearly nine inches. The upper mandible is somewhat longer than the under and is provided with a knob at the tip. The bill is much curved, a characteristic which has given the bird the names Sickle-bill and Sickle-billed Curlew or Snipe. It was the curved bill that suggested to Linnaeus the generic name Numenius for the curlews. It is a Greek word meaning the new moon. The long bill also suggested to Wilson the specific name longirostris or long-snouted.

Dr. Coues says, “Its voice is sonorous and not at all musical. During the breeding season, in particular, its harsh cries of alarm resound when the safety of its nest or young is threatened.”

The Long-billed Curlew spends but little time in home building. Its nest consists of a layer of grass placed in any suitable saucer shaped hollow on the ground.

The downy young resemble the adult bird but little. In color they are a pale brownish yellow modified by a trace of sulphur yellow, the under parts being somewhat darker. The upper parts are irregularly mottled with coarse black spots. At this period in the life of this Curlew, the bill is straight and about one and one-half inches in length.

There are few or none who fail to delight in the beauty of the butterfly, while to the thinker its different stages of existence are rich with lessons in which the analogy-loving soul of man can revel to fullest gratification. Flitting about above the things of earth it seems to descend for rest only, or to sip the sweets of some nectar-bearing flower. In the sunshine all day long, chasing at will through field or woodland, and with no more care than the so-called “butterflies of fashion” (not as much, for it needs to give no thought to the fashion or fit of its garb), it basks till nightfall in the delights that go to make up its ethereal existence.

But whenever we thus watch the brilliant little creature we should remember that it has come up through many changes and tribulations to this its last and perfect stage. Weeks, months, or—as in the case of one or two species—three years before, a tiny egg was deposited in some safe, secluded spot, the parent butterflies dying soon after because of their mission being then accomplished.

The egg is the first stage of the butterfly, as it is also of the moth. The eggs of the different species vary greatly in size and shape, and are deposited in as many different kinds of places. Some are placed on the under side of leaves, others on the outside of the cocoon; some are glued together in rings around the smaller branches of fruit trees, others on the interior of bee-hives. In this stage they remain for periods varying from a few weeks to three years, when the larva or caterpillar state is entered upon. The larvæ are very greedy, beginning to eat as soon as hatched and devouring the leaves, spreading themselves over the web prepared for them by the parent, ravaging the fruit trees, or routing the bees from their rightful possessions. A number of changes of skin take place during the larval stage, ranging from five to ten. Some are smooth-skinned and are used by insectivorous animals for food, while others are hairy and on this account are rejected as food, the hair having the power of stinging much the same as nettles.

Having attained its full growth the instincts of the caterpillar undergo a change. It ceases to eat and begins to weave a couch or cocoon round about itself by which it is finally more or less enclosed. It then throws off the caterpillar or larval skin and appears in the third stage.

This state of its existence seems to me the most mysterious and therefore the most interesting. More than one of these cocoons have I found attached to walls, fences, limbs and in similar places, looking as though they were but the dried-up remains of some species of insect life. But there was life within them, a germ which sooner or later would spring forth in all the wonderful beauty of the moth or the butterfly.

This third period is termed the pupa, nymph or chrysalis state. Its duration varies from a few weeks to several months, according to the time of year at which it enters this stage. The common Cabbage Butterfly, which rears two broods during the season, is quickest to make the change, only a few weeks of the pupa form being necessary. Some remain in the chrysalis a month or more, appearing in the butterfly form at the close of the summer. Those becoming encased in autumn are like the hibernating animals in many respects, lying dormant the winter through. The only sign of life ever discovered in the pupa is a convulsive twitching when irritated, and for this reason those who know nothing of the hidden beauties of butterfly life miss a great deal of pleasure in not being able to study the seemingly lifeless chrysalis.

When mature the pupa case cracks 61 toward the anterior end, and the butterfly or moth crawls forth with wings which, though at first small and crumpled up, in a few hours attain their full size. As soon as they are strong enough the new creature mounts upon them and, if it be a butterfly, flies out into the sunlight; while the moth hies away to some dark corner until nightfall, then for the first time in its existence it rises upon wings to enjoy the summer zephyrs.

I remember having watched one butterfly leave the chrysalis and, though but a child at the time, I shall never outlive the impressions which that rare pleasure left with me. It was one of the large-winged, black-white-and-yellow fellows which every one admires so much, and which species is regarded as a treasure here in these Central States. Little by little the ugly casing opened, and when I first saw the baby butterfly he was like a tiny mass of mingled colors, with neither life nor shape to give me an idea of the sort of creature into which he would develop. Soon he began to move uneasily, like a child awaking out of a long sleep; then he stretched his wings leisurely as though proud to have found them at last. Next he drew himself up and finished bursting his paper-like shell, gained a foothold on the plank on which we had placed him and looked about with a, seemingly, very much surprised though gratified air. Meanwhile he kept working his wings and stretching them anon, very impatient because of their, to him, slow growth. At last he gained the confidence to try them, and within an hour from the time we first saw him he had arisen and flown away into the sunshine to seek his place in the world.

Butterflies and moths are widely distributed all over the globe, occurring, however, in greatest variety and abundance in tropical lands. They are found as far north as Spitzbergen, on the Alps to the height of 9,000 feet, and to double that height on the Andes. In Great Britain there are sixty-six species, while in all Europe only three hundred and ninety have been enumerated. In Brazil there are about seven hundred, and the total number of species of moths is about two thousand. Among the butterflies are to be found some exceedingly beautiful insects, some of them very large, especially in the tropical belt.

The butterflies are to insects what the humming-birds are to the feathered tribes, the analogy holding good not only in the brilliant colors and manner of flight, but also in the nature of their nutriment—the honeyed juices of flowers. Both seem destined to brighten and beautify the way for man, while the lesson of immortality gathered from the life of the ethereal butterfly, like that conveyed by the beautiful and ever-wandering Psyche of Greek mythology, is so easy of comprehension that we can but stop and wonder at the exquisite simplicity with which the all-wise Creator has clothed so important a truth.

Claudia May Ferrin.

Oh! the bonny, bonny dell, whaur the primroses won,

Luikin’ oot o’ their leaves like wee sons o’ the sun;

Whaur the wild roses hing like flickers o’ flame,

And fa’ at the touch wi’ a dainty shame;

Whaur the bee swings ower the white clovery sod,

And the butterfly flits like a stray thoucht o’ God.

—MacDonald.

High in mid-air the sailing hawk is pois’d.

—Isaac McLellan, “Nature’s Invitation.”

The Everglade Kite or Snail Hawk, as it is sometimes called, has a very small range within the borders of the United States, where it is limited to the swamps and marshes of Southern Florida. It also frequents Eastern Mexico, Central America, Cuba and the eastern portion of South America as far southward as the Argentine Republic.

Its habits are very interesting. Peaceable and sociable at all times, other birds do not fear them. “The name of the Sociable Marsh Hawk is very appropriate, for they invariably live in flocks of from twenty to a hundred individuals and migrate and even breed in company. In Buenos Ayres they appear in September and resort to marshes and streams abounding in large water snails, on which they feed exclusively.” They spend much of the time flying, and when soaring will frequently remain poised in the air for a considerable time without apparent motion, except that the tail is constantly and nervously moved in nearly every direction.

An authority, writing of these birds in Florida, says, “Their favorite nesting sites are swamps overgrown with low willow bushes, the nests usually being placed about four feet from the ground. They frequent the borders of open ponds and feed their young entirely on snails. According to my observations the female does not assist in the building of the nest. I have watched these birds for hours. She sits in the immediate vicinity of the nest and watches while the male builds it. The male will bring a few twigs and alternate this work at the same time by supplying his mate with snails, until the structure is completed. They feed and care for their young longer than any other birds I know of, until you can scarcely distinguish them from the adults.”

The nest is a flat structure, the cavity being rarely more than two or three inches in depth, and the whole structure is about twelve or sixteen inches in diameter and about one-half as high. It is usually placed in low shrubs or fastened to the rank growth of saw grass sufficiently low to be secure from observation. The materials used in its construction are generally dry twigs and sticks loosely woven together. The cavity may be bare or lined with small vines, leaves or dry saw grass.

Dr. A. K. Fisher says, “Its food, as far as known, consists exclusively of fresh-water univalve mollusks, which it finds among the water plants at the edges of shallow lakes and rivers or the overflowed portions of the everglades. When the bird has captured one of these mollusks it flies to the nearest perch and removes the meat from the shell with apparent ease and without injuring the latter. While collecting food it will often secure five or six before returning to the nest, keeping in its gullet the parts it has extracted for the young.”

EVERGLADE KITE.

(Rostrhamus sociabilis).

⅖ Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

Once upon a time—for this is a fairy story—all the beasts and birds and bugs gathered in a solemn convention. The object of their meeting was explained by the dog, who—because of his intelligence and his intimacy with men and their ways—had been elected chairman of the convention.

He spoke thus:

“My friends, we have gathered here to discuss an important question, namely, ‘Our dealings with men, and men’s dealings with us.’ It is a sad fact that although we are the benefactors of mankind, and positively necessary to their well-being and even to their lives, they do not appreciate us as they should. If you will pardon my egotism, I will illustrate this assertion by my own experience. I may say modestly—for I am only quoting men’s words—that I am considered the most intelligent of beasts, and am chosen as the companion, the playmate, the assistant, yea, the protector of man. I cheer hours of his loneliness from the cradle to the grave, and am ever ready to assist him in a thousand different ways. Yet how am I treated? A hard crust, a dry bone, kicks and curses and harsh words, a bed on a hard plank or on the cold ground, wherever I can find it. These are too often the inventory of my rewards; while the torments inflicted by small boys, and the indignity and torture of tin cans tied to my tail, fill the full record of my tale of woe. No doubt the rest of you have grievances many and various.

“We will be pleased to hear from any of you who desire to speak, and will be glad of any suggestion, or plan for the general good which may present itself to you. The meeting is now open for remarks.”

He sat down on his tail and assumed his most dignified and intelligent expression, while he looked about the miscellaneous assembly. In an instant the horse walked forward, and was duly recognized by the chairman.

“The words of our chairman have struck a responsive chord in my heart,” he said gravely. “I have pondered on this subject many times when suffering from the abuse of men. Sometimes I am driven at my utmost speed for hours at a time, while my head is held unnaturally high and my graceful neck cramped and stiffened by the cruel check-rain; my body exposed to the torments of flies because my beautiful tail has been docked; and then, when weary and sore and over-heated, I am tied up in some chilling draught of wind while my feet are obliged to stand in a wet gutter, and I am stiffened and ruined for life by some person’s ignorance or foolishness.

“It does seem a pity, to me, that some more rational creature than man had not been chosen as ‘The lord of creation’ in the beginning. Why, he cannot govern himself. Then how can he be capable of governing us who follow unerring instincts with unfailing faithfulness? The question is wide as the world and deep as the sea. As I have said, I have pondered it many times in all its aspects, but as yet have reached no definite conclusion which might suggest a remedy.

“Therefore, let me urge upon you all to give us your wisest thoughts upon this subject, which is of vital importance to us all.”

He returned to his place and waited anxiously for the next speaker.

The cat took the floor with a graceful step and a gentle expression which caught the favor of the assembly.

“I am small among beasts, but my grievances are many and great. I am chosen by men as a playmate for their children, so that the mothers may be free to attend to what they call their ‘necessary work’ in peace and without interruption. How am I rewarded?

“The children whom I strive to amuse drag me ceaselessly around, pull my tail and pinch my ears, blow in my face and jerk my sensitive whiskers; and if I remonstrate with voice or teeth or claws, I am beaten and kicked and tossed out of doors without even the privilege of trial by jury.

“I catch the rats and mice which infest men’s houses, and then when they forget to give me milk which is so necessary to prevent the ill effects which follow a diet of meat and I help myself delicately to a few laps of cream, I am abused as if I had committed a mighty and unpardonable sin.

“They call me a necessity, yet they drown my beautiful kittens, or carry them off in bags and cast them helpless and forlorn upon the mercy of a cold and cruel world. And then men presume to say that they are made after the image of God, and have been divinely appointed masters of the world! What blasphemy! What blind stupidity! Words fail me in view of these appalling facts.”

Half the assembly was in tears before poor pussy had finished her category of woes.

A fly buzzed forward with impulsive haste, and spoke with a little rasping voice:

“We flies are small; but we are mighty. We remove mountains of dirt for uncleanly men, and how do they reward us? They catch us in traps and drown us with boiling water. They snare our feet with treacherous fly-papers, and after laughing at our struggles to get free, burn us without mercy. Small boys torture us with pins, or pull off legs and wings for what they call ‘fun.’ If they do not want us about them, why do they make the filth which necessitates our presence? That is a conundrum beyond my solving. I leave it for this wise assembly to answer.”

The fly buzzed back to a sunny spot, and an unwieldy hog ambled forward.

“‘As greedy as a hog.’ ‘As lazy as a pig.’ ‘As fat as a pig.’ ‘No more sense than a hog.’ Have you never heard such expressions as these fall from the lips of men? They shut us up in little dirty pens where we must needs be lazy, since we cannot run about. They continually tempt us with food, and the more we eat the better they like it, since it produces the fat which they afterwards deride. If we weary of dry corn or thin slop, and break through some convenient hole which their own carelessness has left, and help ourselves to the tender cabbages and peas of their gardens, they chase us with yells and sticks and stones, and send their dogs to make devilled ham of us before we are dead.”

His pun so amused the assembly that they were convulsed with laughter. After vainly waiting several minutes for silence the hog returned calmly to his place, convinced that he had at least presented his grievances in a striking manner.

A handsome black Spanish rooster strutted forward to the platform, and stretching his neck, called the audience to order with his clear-toned

“How-do-you-do? I am the ‘Cock-o’-the-walk,’” he explained, “a term which men are pleased to borrow and apply to themselves. They rely upon me to give them warning of the approach of day, and then grumble because I disturb their slumbers. How can they expect to wake up without having their slumbers disturbed? That’s what I would like to know. They rely upon me to eat the worms and bugs and grasshoppers that destroy their gardens, and then chase me with stones and dogs when they find me in their gardens doing my duty.

“They pen me up, often for days at a time, with insufficient food and water, and do not even deign an apology for their neglect.

“My wives supply numerous eggs for men’s food, yet they wring our necks without mercy if we venture to eat an egg ourselves when they have forgotten to feed us. ‘As full as an egg is of meat,’ is a comparison which might properly be balanced with ‘As full as a man is of inconsistency.’

“If men would attend to their business and scratch for a living as I do, the world would be a far better place than it is today.”

He ended amid prolonged applause, and walked proudly to a conspicuous perch in the sunshine.

By this time there was much excitement among the audience, who all signified a desire to speak at once. While the 67 chairman was busy quieting them with most vigorous barks, a monkey with much agility made his way over the heads of the audience, and leaped to the platform, where he was ready to make his profoundest bows to the assembly the moment quiet reigned.

“You may consider me an alien, since I hail from a far country, yet I am truly American—for even South America reveres the Stars and Stripes,” he said, and his words were applauded by the very ones who had but a moment previous frowned at his audacity.

“I hold myself the superior of mankind since many of their scientists assert that the human race are but highly developed monkeys. To be sure, a few haughty fellows have lately declared that monkeys are but the offspring of degenerate men, but we monkeys resent such assertions as uncalled-for insults. Why, it is bad enough to have to endure the thought that possibly—mind you, I say possibly, not probably—possibly men have descended from our race. There is no monkey but what lives up to the best of his God-given instincts, whereas, on the other hand, there is no man that does at all times the very best that he knows. Therefore, by all the rules of logic, the monkey is superior to the man, and must be thus considered by all fair-minded judges.

“This, however, is but a prologue to my more serious remarks. I have only been presenting my credentials to this court.

“May I now proceed to disclose my plan for calling the attention of ungrateful men to the benefactions we are daily bestowing upon them?” He paused and bowed respectfully to the chairman and then to the audience.

A thunder of applause greeted his proposition, and the hall resounded with cries of “Good! good!” “Go on!” “Three cheers for Brother Monkey.”

When quiet was restored, the monkey continued rapidly:

“Since my time is necessarily spent in intimate association with men, I have taken note of many of their schemes for self-aggrandizement. The most popular at the present time, is the Fair, where everyone seeks to outdo his neighbor and to proclaim his own superiority to the whole world, while he exhibits his own abilities and his own genius by a display of his productions.

“Now, what I propose is this: Let us secure a convenient enclosure, and let each family of birds and beasts and reptiles erect a booth in which to display the gifts which they are daily bestowing upon mankind. Perhaps in this way the hearts of men will be drawn to honor us, and they will—after the ruling passion of men—seek to advance their own interests by favoring ours. Does my plan meet with approval? If so, your humble servant feels highly honored.” He placed his hand upon his heart and bowed deeply to his audience, then, with customary dexterity, returned to his place as he had come, while the hall resounded with prolonged applause.

The meeting was at once declared a “Committee of the Whole,” and vigorous plans were laid for the carrying out of the monkey’s scheme.

Because of his familiarity with such places of resort, the monkey was elected President of the Fair, an office which he accepted with many expressions of humility, and equally numerous feelings of self-complacency.

Other officers and directors were speedily appointed, the place for holding the Fair selected, and the time set. Being unacquainted with the red tape and appropriation-grabbing customs of men, the animals thus speedily brought their business affairs to the working point, and in the utmost harmony adjourned to begin their preparations without delay.

Mary McCrae Culter.

Belonging to our household was a tiny creature, Nixie, who from his gilded cage between the lace curtains observed and commented on all our actions. His door was left open occasionally, and his gregariousness moved him to go where he could take part in conversations and see people. He desired company even at his bath; he had never heard of fear, and won our hearts by his perfect trust. Morning and evening we gave him first salutation, and allowed him to pick our fingers by way of shaking hands. Messages came to him from over sea; gifts fell to him at Christmas; in all our life he had a part. And even the mouse made its bow.

Our hearts had been softened toward the “wee, cow’rin, timrous beasties” by a tender little tale of a parsonage mouse, and we made friends with a gray visitor that showed itself, now in the den at the back of our house, now in the sitting room in front. Because we took our meals out, Monsieur Mousie’s crumbs were uncertain; but he investigated thoroughly and managed to find a livelihood. In our quiet rooms we often heard him at his hunting, and smiled at thought of his daring and industry. Twice he was emptied out of the carpet-sweeper (he must have fallen on very hard times at those periods), but seemed none the worse for the adventure, although the manipulator of the sweeper was herself much disturbed. The waste paper basket finally became his cupboard, and peanut shells his favorite fare. Often as we sat, my brother smoking and I reading, we would hear bits of paper rustling and would know bright eyes were watching us while sharp teeth nibbled the husks we had saved for them. Daily, for a month or two, the small thing came for his share.

Alone in the room one Sunday evening, I was lying on the couch reading when I saw a little gray shadow steal out and creep toward the waste paper basket. I knew there was nothing in it, and lazily felt for Mousie’s disappointment. The gray shadow stole back, halted by the lace curtains, floated up them half way, and stopped near Nixie’s cage. I held my breath. What next? Was he after bird seed? Was this the explanation of Nixie’s empty cup that had perplexed me the last week? But a peculiar, quick chirp made me wonder if the bird were afraid, if the mouse could get at and hurt him. I raised my head and saw the gray thing sitting on the seed cup eating like one starved. Nixie was looking at it, his wings wide spread, eyes flashing, mouth wide open in protest, body poised for attack. But the feast went quietly on. Nixie gave a few sharp questions and then settled down to study his visitor.

It was too good to keep to myself; I called my mother and brother and whistled up the tube for neighbors to join us in watching the strange scene. By the time the audience was gathered the actors were ready to play their parts. Nixie went close to the seed dish and chirped a welcome to his guest, then, hopping backward, selected a station and sang a sweet song for him. The mouse seemed to like it. He left off his eating and crept along outside the floor of the cage, which extended a couple of inches from the bars. Nixie within and Mousie without promenaded together around the four sides; and close together, too, Nixie all the time gayly gossiping and chattering. We say they kept it up for half an hour, but that is a pretty long time. At any rate it was several minutes.

How the acquaintance might have ended I cannot say. The next day the curtains were taken down and Mousie, sadly disappointed, had no ladder by which to climb. And later in the week Nixie went out of town for the summer. We wanted to take the mouse, too, but the noise the packers and movers made probably frightened him to such an extent that he dared not show himself. We do not know what his future was, but we trust it was crowned with the success due pluck and gentleness.

Katharine Pope.

GRASSHOPPER SPARROW.

(Ammodramus savannarum passerinus).

Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

Of all the bird voices of the meadow, for its interesting originality and its effect in ensemble, we can least spare that of the little Grasshopper Sparrow.—R. M. Silloway, in “Sketches of Some Common Birds.”

This little bird of the meadow and hayfield is quite easily identified by the marked yellow color at the shoulders of the wings, the yellowish color of the lesser wing coverts, the buff colored breast and the orange colored line before the eyes. Its home is on the ground, where its retiring habits lead it to seek the protecting cover of tall grass and other herbage. As it is not often seen except when flushed or when it rises to the rail of a fence or to the top of a tall spear of grass to utter its peculiar song, it is often considered rare. It is, however, a common bird in many localities of its range, which covers the whole of eastern North America, where it builds, upon the ground, its nest of grass lined with hair and a few feathers. It nests as far north as Massachusetts and Minnesota and winters in the southern states and the adjacent islands.

This bird was given the name Grasshopper Sparrow from the fancied resemblance of its weak cherup—“a peculiar monotonous song”—to the shrilling produced by the long-horned grasshopper. However, the song often begins and ends with a faint warble. Mr. Chapman says that these notes “may be written pit túck zee-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e.”

Mr. Silloway writes at length and enthusiastically of the Grasshopper Sparrow. He says, “To the sympathetic ear the voice of the humble Grasshopper Sparrow is as necessary to the harmony of the meadow overture as the clear piping of the meadow lark or the jingling triangle of the bobolink. The leading instruments of the orchestra usually receive our attention, yet the accompanying pieces are chiefly responsible for the resulting harmony. Taken alone, the notes of the minor parts are harsh and unmelodious, but sounded in time and accord with the cornet, the first violin, and the double bass, they assist in producing an effect delightful and harmonious. Thus it is with the voices of our little accompanist in the mottled brown coat. Heard alone at close station, it is seemingly shrill and unmusical; but in the midst of expanded verdure, following the lead of the meadow voices, its noonday crooning produces a dreamy harmony perfectly in accord with the thoughts of the listener.”

The name of this little bird is not only appropriate because of its song but also on account of its food. In the examination of one hundred and seventy stomachs, Dr. Sylvester D. Judd found that the contents contained sixty-three per cent of animal matter, twenty-three per cent of which consisted of the remains of grasshoppers. His investigations covered a period of eight months. Thus during that period these insects formed nearly one-fourth of the total diet of the birds examined. He also discovered that during the month of June, the greatest number of grasshoppers was eaten and formed about sixty per cent of the stomach contents.

In rural districts it is seldom called a sparrow and is more commonly called Grass-bird, Ground-bird or Grasshopper-bird. Another appropriate name is Yellow-winged Sparrow. All these names well portray its habits and characteristics. Its flights are short and rapid, but “on the ground or in the grass it runs like meadow mice to elude the presence and notice of intruders.”

The Grasshopper Sparrow is an adept in leading an intruder from the vicinity of its nest. The male seldom utters its song close by its brooding mate, and 72 either bird when disturbed in the vicinity of their home will skulk through the grass for some distance and, if necessity of refuge requires flight, will rise from a point sufficiently far away to mislead the intruder.

Both sexes bear the responsibilities of brooding and their home life seems to be one round of contentment. “Although the male seeks to win the affections of his lady love by persistently shrilling near her the story of his passion he generally represses his love trills near the home which his mistress has established. * * * Cheer her he must, however, and so he trills throughout the day from fancied situations within her hearing, yet safely removed from the guarded spot.”

“Papa” is now the name of our college rooster, his hereditary name, however, having been the “Duke of Wellington,” since he always claimed that he descended from renowned English stock. Be all that as it may, he is a handsome bird of portly proportions and of deep orange and golden plumage. He sports a superb mural crown and has brilliant eyes ever on the watch for the welfare of his numerous family of wives and children. Altogether he is a domestic hero and steps as proudly as ever Hector trod the plains of ancient Troy, while his clarion voice wakes the morning echoes for miles around.

Now, the reason why our big rooster is called Papa springs from quite a novel circumstance all his own and which has been for some time the town talk among the Four Hundred of our poultry social circles. The curious affair was strictly in this wise: Late last fall, or, to be more definite, about the middle of November, one of our little hens, “Biddy the Bantam,” stole her nest, as old housewives would put it, in the adjoining thicket, and in the fullness of time brought off an even dozen as bright, cherry chicks as ever gladdened the heart of a mother partlet.

As soon as the chickens could nimbly walk the provident hen led them to the rear of the college kitchen to be properly fed.

Now it may suffice to enhance the interest of our story and perhaps make several points more clearly understood by the casual reader to say, or rather to delicately intimate, sub rosa, of course, that Biddy the Bantam was not the real mother pure and simple of all the chickens she had so industriously hatched and brought off her fern embowered nest. As it often happens in the best regulated poultry yards, several other and bigger hens had smuggled their own eggs into Biddy’s nest; a fact which would certainly have been a foregone conclusion in a few days from the difference in size of the chickens if for no other reason. I am sorry to say, however, that when the truth leaked out it was an every day scandal from one end of the poultry yard to the other. But Biddy the Bantam, like the brave little mother she was, pondered these things in her heart, lived down the wicked calumny and raised her family despite the alleged illegitimacy of three or four of the longer legged youngsters.

It was determined by the college authorities that everything should be done for the comfort of the rather untimely brood notwithstanding the lateness of the season and the threatened cold weather. To this end mother and chicks were put into a nice warm dry goods box with plenty of soft hay for a bed, and the whole establishment placed under the south veranda of our main building.

Well, with plenty of food the chickens grew, Biddy the Bantam was happy, and 73 all went along nicely till quite lately, when the chickens, having become about a quarter grown, it was discovered that Biddy could not cover them all at the same time, exert herself as best she might. Hence on each frosty morning it was evident that the chickens had suffered a good deal during the night. Their cries could be heard late at night and early in the morning as they crowded each other out into the bitter cold, the stronger ones striving to secure the warmest place under mamma’s soft feather coverlet.

Now a dire emergency had come and something had to be done, and done it was in a most mysterious manner; and herein, also, is contained the gist of our story. The grievous complaint of the chickens came to a sudden discontinuation. Did the little hen mother in her deep affliction appeal to Sir Duke, the big rooster, for advice and succor? The sequel would certainly argue in favor of such a conclusion, for now he comes regularly every evening at early candle light, squeezes his bulky form through the bars of the coop, sits down by the side of Biddy the Bantam and spreads his broad wings over more than half of the chickens. Peace, indeed, has returned and there are no more family jars in that little household.

It is a pleasant pastime to take a lantern and make a social evening call at the coop after Papa and Biddy have put their children to sleep. The most amusing thing of all is to hear the old rooster talk to the chickens. Thus, if anything goes wrong, any naughty crowding or some little foot trodden upon so as to cause an outcry, Papa slowly rises, shakes out his feathers, readjusts his great spreading toes, pokes in with his beak any little protruding head and then settles down again, all the while talking and saying in plain chicken lingo, “There, little dears, now nestle down and go to sleep.”

In conclusion I will say to the readers of Birds and Nature that this little story is no fancy sketch but a true recital of events that took place at Vashon College while I was a member of the faculty of that institution. The chanticleer of every farmyard is a noble bird and a hero in his own sovereign right.

L. Philo Venen.

This is a small insect—that is it is smaller than some of the dragon flies, to which order—Odonata—it belongs. It is of more gentle habits and not so swift of wing as the dragon fly. It was the French writers who gave it the name it bears, while some English authorities placed it along with the dragons. Howard says they are seldom found far from the stream or pond where they are born, yet I have two or three varieties that I caught on the prairie some miles from any water. Their wings are not held horizontally, but are folded parallel with their bodies. This facilitates the backing down the stem of a plant or reed when the female wishes to deposit her eggs below the surface of the water, which is usually the place for incubation. The wings are gauze like, some nearly black, others with a beautiful metallic luster. They are not so savage as the dragons, although one I took last summer held on to the threads of the net until it nearly severed them, and bit at my fingers in a most savage manner.

Alvin M. Hendee.

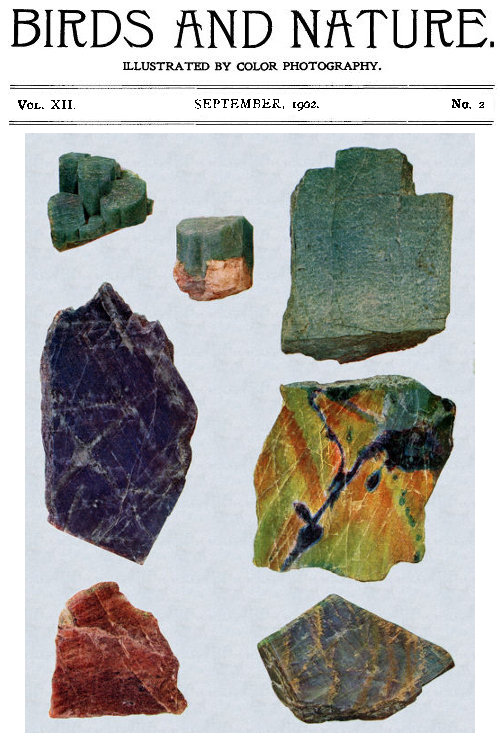

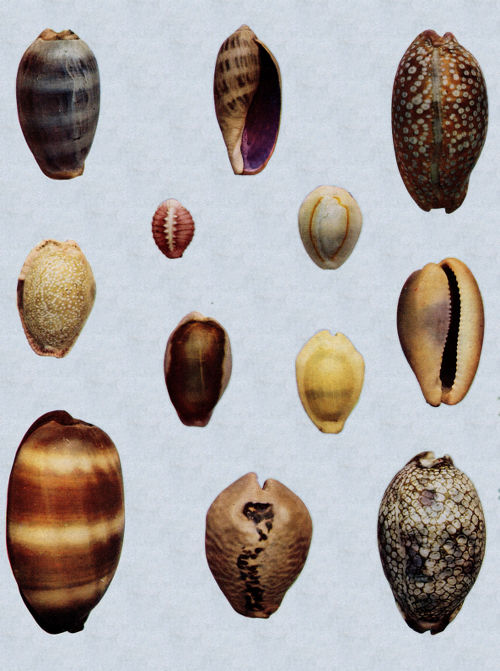

Feldspar is the family name of several minerals closely related and indeed grading into each other, but distinguished by mineralogists by separate specific terms. These minerals are all silicates of aluminum, with some alkali or alkali earth, having a hardness of about 6 in the scale in which quartz is 7 and a specific gravity varying from 2.5 to 2.7. They are fusible with difficulty before the blowpipe, crystallize in the monoclinic or triclinic system and cleave in two well-marked directions nearly or quite at right angles to each other. It is this latter property, probably, which led to the grouping of these minerals as spar, since this term is applied in common language to any minerals which break with bright crystalline surfaces. Thus calc spar is a common name for calcite, heavy spar for barite, needle spar for aragonite, and so on. The term field spar, of which Feldspar is probably a corruption, was perhaps given the minerals of this group because of their widespread occurrence. The English spelling of the word is Felspar. The Feldspars form an essential part of nearly all eruptive rocks and by their decomposition produce clays and other soils which may harden into great areas of sedimentary rocks. They are thus of great geological importance and interest. Usually the white crystals to be seen in an eruptive rock in contrast to the dark green or black of the pyroxene or hornblende, or the glassy, nearly colorless quartz, are Feldspar. The Feldspar may, however, contain more or less iron and then take on a flesh color or become even darker. Feldspar crystals can best be recognized by their prominent cleavage, which appears as numerous bright flat surfaces extending in any given crystal in the same direction. The crystals, while they may be of so minute dimensions as to be visible only with the microscope, may on the other hand reach in veins in coarse-grained granites a length of a foot or more.

As ornamental stones only certain varieties of Feldspar are valued and their value depends on accidents of color or structure. The first of the Feldspars which may be mentioned as being prized as an ornamental stone is amazonstone or green Feldspar. This in composition is what is called a potash Feldspar, potash being the alkali which in combination with alumina and silica goes to make up the mineral. The percentages of each in a pure amazonstone are silica 64.7, alumina 18.4 and potash 16.9. The mineralogical name of the species is micro-cline, meaning small inclination, and refers to the fact that the angle between the two cleavages of the mineral is not quite a right angle. The common color of microcline is white to pale yellow, but occasionally green and red occur.

It is only to the green variety that the name of amazonstone is applied, a name meaning stone from the Amazon river. It first referred probably to jade or some such green stone from that locality and then came to include green Feldspar. No occurrence of green Feldspar in that region is now known.

Practically all the amazonstone now used for ornamental purposes comes from three localities. These are the vicinity of Miask in the Ural Mountains, Pike’s Peak, Colorado, and Amelia Court House, Virginia. In all these places the amazonstone occurs in coarse-grained granite and is closely accompanied by quartz and Feldspar. All gradations are found in color from the deep green to white, only the bright green being prized for ornamental purposes. The Feldspar is usually well crystallized and crystals of several pounds weight may be found. A crystal will rarely be of a uniform color, streaks of paler green or white being commonly present. Only the uniformly colored portions are prized for ornamental purposes. The green often takes on a bluish tone and blue sometimes even predominates. The color is doubtless due to some organic matter, as it disappears, leaving the stone white, on heating. The stone is always opaque. Its use is not extensive, its sale being greater to tourists in the vicinity of the regions where it is found than to gem cutters. Several other localities in the United States besides those mentioned afford the mineral, though not in large quantities. It occurs in two or three localities in North Carolina; in Paris, Maine; Mount Desert, Maine; Rockport, Massachusetts; and Delaware county, Pennsylvania. The finest comes from the Pike’s Peak locality. Mr. G. F. Kunz states in regard to these crystals that when they were first exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 they were a great surprise to Russian dealers who had brought over some amazonstone from the Urals, expecting to sell it at what would now be considered fabulously high prices.

FELDSPAR.

LOANED BY FOOTE MINERAL CO.

The second species of Feldspar which may be mentioned as of use as an ornamental stone is labradorite. This differs in composition from amazonstone in containing soda and lime in place of potash, the percentages in a typical labradorite being, silica 53.7, alumina 29.6, lime 11.8 and soda 4.8. Labradorite has the typical cleavage of Feldspar and cleavage surfaces in the direction of easiest cleavage are usually marked by rows of parallel striae. These show that the mass is made up of a series of crystal twins in parallel position and afford an excellent criterion for determining a triclinic Feldspar. Labradorite is a common rock-forming mineral, especially in the older rocks. It is only, however, when it occurs in large pieces which exhibit a play of colors that it is prized as an ornamental stone. The labradorite exhibiting the latter property in the most remarkable degree and hence most valued is that found on the coast of Labrador near Nain and the adjacent island of St. Paul. It was first found here by a Moravian missionary named Wolfe and brought to Europe in the year 1775. It occurs together with the form of pyroxene known as hypersthene, in a coarse-grained granite, or perhaps a gneiss. From these it is weathered out by wave and atmospheric action and occurs as beach pebbles. It is also mined from veins. Labradorite of pleasing color and opalescence occurs in a few other localities in Canada, and in Essex county, New York, in the United States. Two localities occur in Russia, one near St. Petersburg and the other in the region of Kiew. The labradorite of the latter locality is the better, its occurrence being in a coarse-grained gabbro. The Labrador occurrence exceeds all others, however, in abundance and beauty and by far the larger quantity used in the arts comes from there. The play of colors which gives labradorite its attractiveness is rarely seen to advantage except upon a polished surface, but whether polished or unpolished it only appears when the surface is held at a particular angle with reference to the eye. Emerson thus describes it in his essay on Experience as illustrating the limitations of the individual: “A man is like a bit of Labrador spar, which has no lustre as you turn it in your hand until you come to a particular angle; then it shows deep and beautiful colors.”

The play of colors seen in labradorite is not like that of the opal, which presents to the eye fragments of different colors varying in different positions, but appears as broad surfaces of a single color. It is only rarely that these colors change with a change of position. Bauer remarks that the appearance is similar to that seen on the wings of some tropical butterflies. The colors over any given surface are not necessarily alike, but more than two or three tints are rare. Each tint is uniform where it occurs. A surface may be interspersed with many spots exhibiting no sheen. Both colored and uncolored portions have only vague outlines and merge into each other at the edges. Bauer mentions a labradorite from Russia the colored portions of which formed a striking likeness of Louis XVI, the head being a beautiful blue against a gold green background, while above appeared a beautiful garnet red crown. Excellent effects are sometimes produced in labradorite by cutting it in the form of cameos so as to make the base of different color from the figure in relief. Of the different colors shown by labradorite blue and 78 green are the most common, yellow and red least so. These colors are regarded by Vogelsang as of different origin, the blue being, in his opinion, a polarization phenomenon due to the lamellar structure of the Feldspar, and the yellows and reds the result of the reflection of light from minute included crystals of magnetite, hematite and ilmenite. These lying in parallel position in great numbers in the labradorite give the colors.

The gems known as moonstone and sunstone owe the play of colors which gives them their respective names to similar causes. These gems are generally some form of Feldspar, although any mineral giving a similar sheen of color might be included under them. The moonstone of commerce comes chiefly from Ceylon, where it occurs in large pieces the size of a fist in a clay resulting from the decomposition of a porphyritic rock. Pieces of these when polished exhibit the beautiful pale blue light coming from within which makes the stone prized as a gem. The cause of this light is undoubtedly minute tabular crystals lying in parallel position through the stone.

The stone varies from translucent to opaque, and from colorless to white, the essential feature being the blue opalescent light or chatoyancy exhibited from a polished surface. Good moonstones are worth from three to five dollars a carat.

The Ceylon moonstone is sometimes known as Ceylon opal, but it is the variety of Feldspar known as orthoclase, which is a potash Feldspar, differing from the microcline just described in being monoclinic in crystallization and in having two cleavages meeting at right angles. Another species of Feldspar used as moonstone is albite. This is a soda Feldspar and is triclinic, but exhibits the color characteristic of moonstone. One variety is known as peristerite, from the Greek word for pigeon, and is applied on account of the resemblance of the sheen to that of a pigeon’s neck. It is found at Macomb, St. Lawrence county, New York. Albite found at Mineral Hill, Pennsylvania, also exhibits the chatoyancy of moonstone. Amelia Court House, Virginia, is another locality whence come pieces either of orthoclase or oligoclase exhibiting this property. Like most of the more or less opaque gems, moonstone is cut chiefly in the rounded form known as en cabochon. It is of late, however, cut in the form of balls, which are quite popular, the bringing of good luck being attributed to them. The brilliancy of moonstone is considerably increased by mounting it against black.

Sunstone is the term by which those kinds of Feldspar are known which reflect a spangled yellow light. The appearance comes from minute crystals of iron oxide, hematite or gothite, which are included in the stone and both reflect the light and give it a reddish color. Like labradorite the sheen is visible only when the stone is held at a certain angle. Some specimens of the mineral carnallite, which is a chloride of potassium and magnesium, exhibit a similar sheen, and being soluble in water the crystals of hematite can be separated out. They are then seen to be perfect little hexagons of a blood-red color. The sheen of sunstone is best visible when the stone is held in the sunlight or strong artificial light. The variety of Feldspar to which the sunstone most in use at the present time belongs is oligoclase, a soda-lime triclinic Feldspar. Like labradorite it usually exhibits on the surface of easiest cleavage parallel striations due to twinning structure. The best sunstone at the present time comes from Tvedestrand, in southern Norway, where it occurs in compact masses together with white quartz, in veins, in gneiss. Some also comes from Hittero, Norway. In Werchne Udinsk, Siberia, another occurrence was discovered in 1831. Previous to this Bauer states that all the sunstone known came from the Island of Sattel in the White Sea, and was very costly, although of a quality which would not now be deemed desirable. At the present time, although stones of fine quality can be obtained, sunstone is little used in jewelry, and its market value is very low. Statesville, North Carolina, and Delaware county, Pennsylvania, are two localities in the United States where good sunstone has been obtained.

Both sunstone and moonstone can be accurately imitated in glass and the distinction of the artificial from the real by 79 ocular examination alone would be almost impossible. Glass, however, lacks the cleavage of Feldspar and is somewhat heavier and softer. The discovery of the method of making artificial sunstone is said to have been accidental, and was made at Murano, near Venice, when a quantity of brass filings by chance fell into a pot of melted glass. The product was for a long time and is still used in the arts under the name of goldstone. Sunstone is sometimes known as aventurine Feldspar, in distinction from aventurine quartz, which presents a similar appearance, owing to the inclusion of scales of mica. The term aventurine is from the Italian avventura, meaning chance, and refers to the chance discovery above referred to.

Gems are occasionally cut from other forms of Feldspar than those here described, which are transparent and colorless and valued for their lustre. The varieties chiefly employed in this manner are adularia, a variety of orthoclase which is often transparent, the best specimens being obtained in Switzerland, and oligoclase, in the transparent form in which it is found near Bakersville, North Carolina.

Oliver Cummings Farrington.

Who knows the dim, least-traveled way

Where wood-folk keep their holiday;

Who knows the paths of little care

Whereon the thicket-dwellers fare,

Let him be heedful, lest he wake

Unfriendly echoes in the brake,

Or dare, with alien thought, to find

His way among the timid kind.

Let him beware, then, for they know

The subtle footsteps of a foe.

But all the wee wood-fellows spare

Such welcome as they ever share

To him who finds in dale and dell

That undefined, familiar spell

That greets the faith prepared to meet

A faith as beautiful and sweet.

—Frank Walcott Hutt.

It was my good fortune to spend some months in a cozy little cottage in a suburban district, the natural surroundings of which were such as to at once appeal to a naturalist, aside from furnishing ample opportunity for rest and quiet. The large lawn belonging to the property, with its abundance of shade trees, fronted on the main avenue of a populous corporate town, while in the rear was a strip of woodland, which in turn was bordered by a clearing covered mainly by briars and thick low bushes, its whole length being intersected by a winding brook.

Birds in the locality were quite numerous and some of them showed remarkable tameness. During the hours of night time, giving voice as it were to the weird lights and shadows around the house, we could hear the mournful ditty of a screech owl whose home was in a nearby hickory tree, while the first gray streak of each returning dawn was heralded by the sweet songs of the robins. Flickers were frequently seen hopping around in the grass near the roots of various trees; the notes of the yellow-billed cuckoo were also heard in the thick foliage of the maples: redeyed vireos kept up a continual warbling all day long and doubtless had a nest in the vicinity, as we observed the mother bird feeding two very young ones; the latter being perched in a low bush in the yard. The happy song of the house wrens was always in evidence and three nests were built under the porch roof. I personally observed one of the broods leaving the nest and was surprised to see two of their number climb up the straight trunk of a wild cherry tree—genuine woodpecker fashion—for a distance of twelve or fifteen feet, where the limbs began to branch out. However, they arrived at the top safely and remained there for the balance of the day.

Humming birds often came and hovered over the many beautiful flowers in the yard, and sometimes consented to alight for a few minutes for our benefit. On one of these occasions a party of five (including my baby daughter) approached to within three feet of the flower stalk upon which our little visitor was perched; still it sat there, turning its wee head this way and that, looking at us with fearless unconcern. At last it gave a sharp chirp, flew, and was soon lost to sight. On one occasion in the early morning, we were greeted with the familiar call “Bob White,” which seemed to come from the woods in the rear of the yard. The call was repeated several times, but we were unable to discover the author of it. A tree of fine red cherries proved a great attraction for cat birds and other feathered fruit lovers. But what we considered the greatest privilege, and one which was exceedingly enjoyed, was the daily greeting of the wood thrushes during the breakfast hour. What could be more charming than to sit leisurely eating the morning meal and all the while listening to the sweet, clear strains of the loveliest bird songs pouring from the throats of the russet-brown vocalists just outside the kitchen window, peal after peal, in endless volume and variation. In addition to the birds already mentioned we sometimes heard the shrill scream of the blue jay, also the notes of the king birds and crested flycatchers, while from the distance, floating to us from across some field or meadow, came the morning praises of a meadow lark or the well known call of the kildeer. The crows also added their deep caw-caw-caw to the chorus of woodland voices. The clearing above referred to proved to be the home of two or three species of the warbler family, and a walk through the vicinity the following winter revealed a number of nests. They were all placed low, and one of them showed every indication of having been built and occupied by an oven bird.

The usual wild flowers of the season were abundant and the surrounding country at large was admirably suited for exploration and research; hence our sojourn at the “Cottage” was one of great pleasure and instruction.

Berton Mercer.

SILVER-SPOT BUTTERFLY.

(Argynnis nitocris nigra-caerulea).

Life-size.

FROM COL. MRS WILMATTE PORTER COCKERELL.

The butterfly to which I want to introduce you is a rare beauty! It is called Argynnis nitocris nigrocaerulea by scientists, but the young people of our school call it the blue-black silver spot or the Sapello Fritillary. They wanted very much to name it after the Territory, but unfortunately there is a butterfly of this genus that bears the name of New Mexico Silver-spot.

Every member of the genus Argynnis is beautiful and it is a great treat to see the glint of the silver dotted wings of these butterflies as they hover about the gaily colored flowers in some mountain canyon or alpine meadow. But no member of the genus will compare in beauty with the female of the nigrocaerulea, and I should find difficulty in forgetting the pleasure I felt in seeing two of these lovely creatures sucking the nectar from a large bright colored Rudbeckia.

The nigrocaerulea is very much like a silver-spot that is found in the mountains of Arizona; both belong to the species nitocris and there is still a third form found in the mountains of Mexico. It is very likely that these forms were the same years ago, but the mountains in this arid region are like islands, and are separated by dry expanses upon which an Argynnis could not live. It follows, therefore, that in the isolated mountain regions many forms of the same species may be found, and when the country has been more carefully explored we shall very probably find other varieties of nitocris.

The nigrocaerulea was discovered in August, 1900, in the Sapello Canyon, a beautiful canyon in the Rocky Mountains near Las Vegas, New Mexico. The male is reddish-fulvous on the upper surface, with well defined markings consisting of waved transverse lines and crescent shaped spots. On the under side the design of the fore wings is somewhat indistinctly repeated, and the base is colored with a most exquisite reddish pink. The under surface of the hind wings is a rich brown with a wide yellow border, and is profusely marked with spots of glistening silver. The female on the upper side is bluish black, well marked near the margin by large spots of yellow suffused with blue. The under surface is very like that of the male, though the colors are more pronounced, the brown in the hind wing merging into black. The Sapello Fritillary flies during the month of August. Though the caterpillar is not known, it is supposed to feed upon the leaves of violets, which grow very abundantly in the Sapello Canyon. Diligent search will be made for it, and I am sure all will be interested if at some future time I can give the history and picture of the chrysalis of this beautiful Silver-spot.

Wilmatte Porter Cockerell.

Lo, the bright train their radiant wings unfold!

With silver fringed, and freckled o’er with gold:

On the gay bosom of some fragrant flower

They, idly fluttering, live their little hour;

Their life all pleasure, and their task all play,

All spring their age, and sunshine all their day.

—Mrs. Barbauld.

Butterfly, on golden wings,

Tell us of your wanderings!

Tell us of aerial spaces,

Where, in pleasant sunshine places,

You go sailing high and low,

Wheresoever you would go!

Leisure, freedom, grace, is yours;

Earth and air to you ensures

Findings for your utmost need,

Be it blossom, dewdrop, seed;

And you roam the fields of air,

Happy, and without a care.

When the sudden storm comes down,

And the sun flees at its frown,

You with folded wings will hide

’Neath a leaf, and safely bide

Till the tempest flashes through,

And the sky is blue for you.

Thus on rested wings you sail

In the wake of every gale,