Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. XX, No. 983, October 29, 1898

Author: Various

Release date: August 6, 2015 [eBook #49642]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner, Chris Curnow, Pamela Patten and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

| Vol. XX.—No. 983.] | OCTOBER 29, 1898. | [Price One Penny. |

[Transcriber's Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

WHERE SWALLOWS BUILD.

OUR PUZZLE POEM REPORT: A SHORT STORY IN VERSE.

GIRLS AS I HAVE KNOWN THEM.

"OUR HERO."

ABOUT PEGGY SAVILLE.

FROCKS FOR TO-MORROW.

TO OUR EDITOR.

THE RULES OF SOCIETY.

FROM LONDON TO DAMASCUS.

THE GIRL'S OWN QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS COMPETITION.

OUR NEW PUZZLE POEM.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

OUR SUPPLEMENT STORY COMPETITIONS.

SPECIAL NOTICE TO OUR READERS.

By SARAH DOUDNEY.

All rights reserved.]

CHAPTER III.

The next day was Sunday. Cardigan, who had learnt from his young hostess all that she could tell of her dressmaker, looked eagerly for Alice's face in the village church. But he could not find her there. She had gone away over the hills to a smaller church, to which the Monteagles never went, and was not to be seen with the Bowers in the seat allotted to the tenants of Swallow's Nest.

He was restless, and longed to secure a little time to himself in the afternoon. Somehow, without being observed, he contrived to slip away, out of the Hall, through the gardens, and then up to that high ground from whence he had first looked down upon the old farm.

There it lay in the still sunshine, asleep in a Sunday peace. He waited there, and watched until he saw the slender, upright figure of a young woman come out of the porch. She went down the little garden-path, opened the wicket, and then sauntered slowly across the grass to the lane.

She was in a very thoughtful mood as she paced deliberately under the shade of the old oaks. The sun, now getting low, burnished the brown hair, wound so simply around her uncovered head. Once she paused to reach a spray of late honeysuckle growing on the top of the hedge, and then stood still to tuck it into the front of her dress. When she moved again and lifted her eyes, she saw Cardigan standing before her under a tree.

"Miss Harper," he said, rather awkwardly, "it is a great pleasure to see you again. You have been hidden away so long!"

"I wanted to be hidden," she answered, as she gave him her hand. "Is it not very natural that I should hide myself, Mr. Cardigan? My life was darkened; it was best to live it all alone."

"I don't know if it was best," said he, reddening to the roots of his hair with the endeavour to speak his thought. "There were those who would have helped you to live it, if you would have let them."

"Ah, but I could not." Her face softly reflected the glow on his. "But, by the way," she added more lightly, "you have come to spoil the life I am leading here. I am told that you have bought Swallow's Nest, and mean to pull the old house down. Have you, by chance, given just a passing thought to those who are living under its roof?"

He flushed again.

"I confess I didn't," he said penitently. "But——"

"Oh, you rich men!" she interrupted, with a weary sigh. "With you to see is to desire, to desire is to have, to have is to leave others lacking. Shall I tell you what you were going to do?"

"Tell me anything you please," he answered eagerly.

"It is always much easier to pull down than to build up," she went on. "The old home yonder has been years in making. More than a century ago, when it was fresh and new, a young couple began there the serious business of life. They were poor in money, but very rich in love and faith. Their prayers are built into the walls; their angels have hallowed every humble room with holy ministry; their souls passed gently from that earthly dwelling to the Father's house on high. Children and children's children have filled the places that they left vacant, living just the same simple, God-fearing life. The old house is still sound and strong; there are no cracks anywhere; it keeps out the rough weather. But a rich man has decided that it is old-fashioned and ugly, therefore it must be pulled down."

Cardigan had grown pale. Her words had gone down right to the deeps of his heart, and moved him painfully.

"It shall not be pulled down!" he cried. "Miss Harper, I have been a stupid, selfish man. But it is not too late to begin again?"

"No, it is not too late," she said, with a very bright face. "And you will really let the house stand? Well, so much the better for us and the swallows. Dear birds, they are just going away. I wonder what they would have felt if they had come back to find their old nest in ruins. Mr. Cardigan, I think it is a good thing that I met you to-day. Now I must go back quickly and set some troubled hearts at rest."

"Do not go yet," he pleaded. "No one has ever given me such a straight talking to before. My money was making a selfish brute of me very fast. Hit me as hard as you can, Miss Harper. Every blow knocks some of the evil out."

She gave a soft little laugh.

"Why, it seems that I have found a new vocation," said she.

"I wish you had found it sooner!" he cried. "Can you not leave the nest to the swallows, and take me in hand? Is it too much to ask?"

There was a silence which only lasted for a moment, and yet seemed half a lifetime. The bright look faded from her face; she was perplexed and troubled.

"Mr. Cardigan," she said gravely, "you must take yourself in hand."

"That means that a man should not ask a woman to do for him what he ought to do for himself," said he, in a saddened tone. "Well, you are right. I have not given any proof of amendment."

"You have given a very plain proof of a kind heart," she said, with an earnestness that made her eyes glisten. "I thank you for it. But I must go now and carry the good news indoors."

He did not try to detain her again; but, just as she was turning away, he made a last request.

"Miss Harper, will you let me see you once more before I go away? Will you meet me here again, in this spot, next Sunday afternoon?"

"I will," she said quietly. And there was a very sweet look on her face as she made the promise.

Robert Cardigan went back across the fields with a great hunger in his heart.

He knew now that he loved her. He had begun to love her unconsciously when she was a girl in Park Lane, looking at life with serious eyes, and talking of the things that she would do some day.

How strange it was that wealth had been taken out of her hands, and put into his. Life is full of riddles like this. Strong, tender spirits are left to work hard for a pittance, suffering the heart-thrill of those who have nothing to give but prayers and love. Lazy men and women have their hands crammed with gold, and look round constantly for some new pleasure to buy for themselves. And yet there is One who is mindful of His own.

It was a very long week. Alice, busy with her work, was conscious of a dull ache when she called up a vision of Cardigan's face. The Bowers rejoiced with a great joy. They did not ask how it was that she knew Mr. Cardigan, and they promised not to speak of the matter. But they wondered silently why she, who had brought them gladness, should be sad herself.

Quite alone, in the stillness of another golden Sunday, Alice slowly took her way to the quiet lane. She knew that she should find him waiting there; and she knew, too, the answer that she would give him. Yet, in her innermost self, there was a deep regret that she could not give a different answer. A man must work out his own salvation, she thought. He must not put the tools into a woman's hand, and say, "Shape and fashion my life according to your will."

"So you have come. It is kind of you," he said.

Her face was a little paler than it had been last Sunday, and her lips slightly quivered.

"You have made us all so happy," she said, in a soft, hurried voice. "The Bowers are good people, and the old place feels like a home to me."

"Do you want to stay there always?" he asked with an impatient sigh.

"I have not lived there long," she said evasively. "You cannot realise what a rest it is. For two years I worked hard in London, learning my business; and I used to pine for fresh air, and the sight of fields and trees, as only working girls can. It was Miss de Vigny who found this home for me."

"She would not tell me anything about you," said he. "Do you know what I feel when I hear of all your sorrows and struggles? I feel mad to think that I have got so much money. It seems as if Providence were playing with us both. Don't look shocked. I have a bad habit of saying odd things when I am wrought upon."

She stood still. Her face was beautiful, but very pale.

"But I didn't bring you here to listen to my ravings," he went on. "I want to ask if you can give me any hope? Will there ever be a time when we shall work together? Only tell me this!"

She turned her face away that he might not see the tears gathering in her eyes.

"How can I answer?" asked she, sadly. "I do not know. We have seen so little of each other. You are under the spell of strong feeling; but feeling only changes a man for a little while. It alters the surface of his nature, but leaves the inmost self untouched."

"Ah," he said bitterly, "you could not say that if you, too, were under the spell!"

"That is the truth." She looked up at him with a face that seemed to apologise for her words; it was so tender, as well as so true. "I am free from the spell. Because I am free, I would leave you so also. You think, just now, that you could do all the things and make all the sacrifices which I feel right. But, if we were together always, that mood of yours might not last."

"Does not love last?" he asked impatiently.

She shook her head, with a sad little smile.

"Miss Harper," he cried, "where did you learn this bitter wisdom? Why has God given us these feelings which you seem to mistrust?"

"I mistrust them only till I see what they will lead to," she said gently. "They are the beginnings of love, but not love itself. That which you call love is not lasting; it is a blossom that the wind blows away."

There was a silence so deep that they could hear the rustle of a falling leaf. Cardigan broke the pause with a voice full of pain.

"Once more," he said, "I ask if you will give me a hope? To-morrow I am going away. May I come back again?"

"Yes," she answered, with a sudden bright look. "Come back when the swallows build. They owe it to your kindness that they will find the old place just the same. Mr. Cardigan, I am not as hard-hearted as you suppose. But a man must put himself to the test."

The fall of the year brought a quantity of work to the industrious fingers at the farm. Miss Harper's fame was spreading far and wide. Letty Monteagle's tea-gown was the forerunner of a great many orders from her and her friends. The squire's young wife{67} would have been more sociable if Alice had not persisted in keeping her at a distance. More than once, when Letty tried to begin a conversation she felt herself very gently, but very firmly, checked. She had never found out that Cardigan had seen Alice before he went away.

All through the short, sharp winter, and into the early spring, the busy fingers toiled on. There was a pause when Alice paid a flying visit to a famous drapery house in London. She went for patterns and goods, but found time to see Mary de Vigny.

"Have you heard that Robert Cardigan is making himself useful?" the little lady asked. "Really useful, I mean. He came to me for advice, and I gave him some. It does not do to plunge into amateur philanthropy unaided, you see. Well, my dear, the country seems to agree with you. I never saw you looking so well, and yet you are as grave as a nun."

"Oh, that is the result of constant work," Alice replied.

In June a son and heir was born at the Hall. And then Miss Harper broke through her usual reserve, and sent an exquisite cover for the baby's cradle. The young mother wrote a cordial note, so full of genuine feeling and happiness that Alice was gladdened herself, and went out into the porch to watch the swallows. They darted round and round the old house, and the sunlight shone upon the rapid wings.

"They are building," Milly said, a little later, when the sun was pouring down upon the fields. "See, they are making their nest in the old spot!"

On the evening of the same day the farmer came indoors with a grave face. There had been an accident, he said. The squire's new groom had gone to the station with the dog-cart to meet a gentleman. It was a mistake to trust a young fellow with that flighty chestnut; in Bower's opinion the groom was as bad a whip as he had ever seen. On the way back the mare had bolted; both the men were flung out, but it was the gentleman who was hurt—very badly hurt, it was feared. They had got him to bed at the Hall, and the doctor would stay with him far into the night.

A woman, pale and sorrowful, knelt alone in her room, with her face uplifted to the stars. "If it had not been for me, he would not have come back! Oh, God, spare his life," she prayed. "Spare him, and let the way be made clear for my feet!"

Days came and went—brilliant days, full of summer sweetness and bloom, but Cardigan lay crushed and helpless at the squire's house. He was a lonely man. There was neither mother nor sister to share the nurse's watch in the sick room; but when the news of the disaster came to Mary de Vigny's ears, she wrote to the Monteagles and said that she was coming. She arrived, quiet and self-possessed as ever; and with her presence came a gleam of hope and light. The patient began to rally. Very slowly, very feebly, he seemed to feel his way back into life.

One evening Mary de Vigny sent a note to Swallow's Nest. The squire himself was the bearer. He drove to the gate in his wife's pony-cart, and waited till Miss Harper was ready to go up to the Hall.

Cardigan, propped up on his pillows, motionless and pale, brightened wonderfully when she entered the room.

"Ah, I knew you would come," he said. "I could not lie here any longer without seeing you, and hearing your voice. Do you believe in me yet, Alice? Is there any more hope for me now than there was last year?"

"Hush," she said gently. "You are not well enough to talk about these things."

"I shall never get well till I have talked about them! Alice, I want to tell you that I made my will after I saw you last. I left you Swallow's Nest, and everything else besides. Perhaps I had better die, for you will know what to do with the money. A man's life, after all, is a little thing, and I never was good enough for you. If I die——"

"Hush," she said again. "If you die, I will never marry anyone else as long as I live. But you mustn't die."

She burst into tears; and then his hand stole along the coverlet until it found hers, and held it fast.

[THE END.]

A Short Story in Verse.

Twelve Shillings and Sixpence Each.

Five Shillings Each.

Very Highly Commended.

Eliza Acworth, Maud L. Ansell, Ethel C. Burlingham, M. J. Champneys, Helen M. Coulthard, S. Dewhirst, Lily Dickin, Mabel Dickin, Edith E. Grundy, Alice E. Johnson, Rev. V. Odom, Ada Rickards, Mrs. G. W. Smith, Gertrude Smith, Isabel Snell, S. Southall, Ellen Thurtell, May Tutte.

Highly Commended.

N. Campbell, M. Christie, Mabel E. Davis, Ethel Dobell, A. and F. Fooks, E. F. Franks, Eva Florence Gammage, Nelly I. Hobday, Eva Hooley, D. A. Leslie, Nellie Meikle, E. M. Rudge, Jas. J. Slade, Constance Taylor, C. E. Thompson.

Honourable Mention.

Maud Allen, Mrs. Astbury, Agnes Beale, Isabel Borrow, Leonard Duncan, Annie K. Edwards, Dorothy Fulford, Peter Kelly, E. M. Le Mottée, Fred. Lindley, Marian E. Messenger, J. D. Musgrave, E. Cunliffe Owen, Alfred Scott, Miss Sharp, M. Short, Winifred Skelton, Ellen R. Smith, C. E. Thurger, Ethel Tomlinson, Edward Tweed, E. Watherstow.

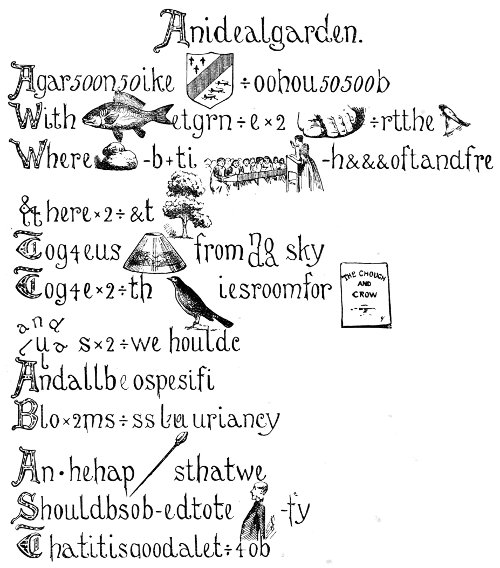

The title is not "A Small Conservative in Verse." Apart from its absurdity there is an objection against it which appears to have escaped the notice of many competitors. Concerning the rest of the puzzle, there is little to say, it is so simple. The chief value of it lies in the instruction, afforded by the solution, on the use of quotation marks in verse. These should be placed at the beginning of the quotation, at the beginning of every line of quotation, and at the end of the whole quotation.

The solutions of the 1st prize winners were perfect; those of the 2nd prize winners only failed to give the form of the verse correctly. The solutions very highly commended placed the quotation marks wrongly but gave the form properly; those highly commended were incorrect in both respects, while those in the last list contained trifling errors in other ways.

"Wisely" and "rightly" often took the place of sagely in line 11. The picture represents a sage, and though sages are often wise there was no necessity to go so deeply into the matter to obtain a good reading. "Rightly" is altogether wrong.

To Violet and others. The "O" in the solution of Fluctuations should have been Oh.

By ELSA D'ESTERRE KEELING, Author of "Old Maids and Young."

THE SENTIMENTAL GIRL.

This is the girl who has "dear five hundred friends," to borrow a phrase from Cowper, and whose friendship divided among so many yields so small a part to each that Coleridge will not call it friendship, but calls it "a feminine friendism."

This is the girl who kisses other girls with an indiscriminateness which made a man say lately, "It makes men envious." To which—alack and alas!—the answer made was, "It's meant to do that!"

This is the girl who uses words of the kind that Oliver Wendell Holmes called "highly oxygenated," but which are, if the plain truth be said of them, the weak expression of weak feeling.

This is the girl who, even when she is least impious, may forget that only the Divinity should be adored; who is never without what a witty woman writer has called "a gentle sorrow"; whose favourite words are "so" and "oh"; and who writes at an early age a novel the heroine of which—I quote from a manuscript beside me—has "hair of the colour of Aventurine glass, of a lovely brownish-red tint with golden flashes in it," which hair turns white with fright in a single night.

This is the girl who sometimes lays herself open to the terrible charge levelled by a writer on the emotions at Sterne and Byron and others of the school of literature to which they belonged. Says Professor Bain, "Some of the sentimental writers, such as Sterne and Byron, seem to have had their capacities of tenderness excited only by ideal objects, and to have been very hard-hearted towards real persons."

This is the girl who said dolefully the other day, "Oh, yes, one meets heaps of men, but they don't propose!" Concerning which speech one can only say that it might with advantage have been left unmade.

This, finally, is the girl whose letters show up the untenability of Miss Bingley's rule, as set forth in Jane Austen's novel Pride and Prejudice.

"It is a rule with me"—so said Miss Bingley—"that a person who can write a long letter with ease cannot write ill."

The average sentimental girl can write a long letter with ease, and can write ill. In a long letter by such a girl which has been placed at my disposal, she constitutes herself petitioner for a poor family, of which she writes, "They are getting into despair as to how to meet their rent, much less food. It is a fearful idea of people in one's own class wanting for food." The sentiment of that is rather narrow, and the wording of it is execrable.

Tact is not always but is sometimes denied to the young sentimental letter-writer. "I have been reading"—so wrote some little time ago a girl to a novelist—"your last book, and have fallen in love with you, and now the thought has come into my head, 'Could not I collect together my feeble attempts at writing and publish them?'"

The writer who is informed that his work has suggested the collecting together of feeble attempts and publishing them is made the recipient of a dubious compliment.

Very often the inducement to do a thing as set forth by the girl-sentimentalist is of a kind not calculated to weigh strongly with persons less sentimental.

A lady of high accomplishments and keen relish of social intercourse asserts that while on the staff of a London High School she suffered for years from the invitations of young girls who, in imploring her to accept their family's hospitality, never failed to emphasise the fact that there would be "nobody else invited."

There is a very general idea that the girl-sentimentalist totally ignores the practical side of life. That is not so.

"I have a short wait here," so writes a girl from the Welsh border. "This letter is the last I shall write on English soil, and I want it to be to you. In spite of good resolutions, I have cried without ceasing since I left —— Not even the evident amusement of a small boy, my vis-a-vie" (spelling is not a strong point with this writer) "could dry up those tears. Dignity doesn't help one to forget an aching heart. I must fly now to see to my luggage."

The heart in a girl like that is balanced by the head, and the same thing is true of the girl-writer of the next letter-extract:

"I look often at his picture upon my table, and wonder why it is there. I am so exquisitely happy, and yet so keenly aware of my own shortcomings. This great new thing that has come into my life makes me feel my own unworthiness. Tell me of all my misspellings, please."

The misspellings of the average girl-sentimentalist are legion; in fact, I have heard a schoolmistress say—the speech having been addressed by her to a younger schoolmistress—"Put down sentimentality; it leads to misspelling."

From this schoolmistress I have it that the girl who can spell "parallel," "ridiculous," and "predilection," is rarely an incurable sentimentalist.

My own experience has been that it is the sentimental girl who writes—and says—"rearly" and "warfted," and the following curiosities in spelling are culled from the—unpublished—works of girl-novelists:

"He had suffered the yolk of tyranny."

"She carried a little book, with guilt edges, a prayer-book."

The girl who describes a prayer-book as a book with "guilt" edges is almost guilty of profanation. Tell her this, and so far is this sort of girl from being a hardened sinner that the strong likelihood is that she will never again commit this error. An appeal to her heart is always better than an appeal to her head. This fact was realised by the Israelite who said to a young maiden of this type who had written "sinagog" for "synagogue," "You must not spell the name of our temple like that. It is not only incorrect, but very unkind spelling."

"I will never spell so again," was the young maiden's answer.

Sometimes the defence of her spelling put forward by the girl of sentimental rather than logical bias is very remarkable. "'Court-material,'" said recently a young English damsel who had written "court-material" for "court-martial," "makes quite as much sense to me as 'court-martial.'"

The objection to this form is, of course, that it does not make quite as much sense to other people.

It may be asked now, Does the non-sentimental girl experience no difficulties in connection with spelling? Certainly she does. She was heard the other day saying that the word assassination had been a standing difficulty to her until another girl told her that it began with "two asses" as thus, ass-ass-ination. The non-sentimental girl has also been known to say, looking up from a book—

"Hullo, here's 'wobble' spelt not with an 'o' but with an 'a'—'wabble.' Now I wonder which is the right spelling."

This is perhaps the place in which to say that there is nothing more difficult than to determine what forms the line of demarcation between the sentimental and the non-sentimental girl. There are persons who assert that a girl who uses the interjection Hullo! may be safely termed non-sentimental, but that is so far from being true that among the girl-readers of this paper there will be one with whom Hullo! is a favourite expletive, and who said, this summer, as a full-blown rose which she was presenting to a person greatly loved by her fell in a shower of petals to the ground, "Even the roses fall at your feet."

That was surely the language of sentiment.

Others assert that girls who wear men's collars with men's neckties may safely be dubbed non-sentimental, but it was a girl in boy's attire to the waist whom the writer of this paper heard say in reference to a beautiful woman to whom she gave the whole homage of the girl's heart that beat under the boyish garb that she favoured, "She is ordered by her doctor to Buxton to drink the waters. Happy waters!"

That was surely the language of sentiment.

If there be aught in a name, it is to be regretted that Angelina is no longer a name much given in baptism, and that no poet of this day follows him who sang in praise of "the dear Amanda." Not that Angelina or Amanda is the best possible name for a{69} sentimental girl. No; such a girl should be called Delia. Mr. Henley has given the reason why—

"Sentiment hallows the vowels in Delia."

To return to the sentimental girl as writer. Misspellings, it has been stated, are legion with her. Of other marks by which you shall know her a leading one is that she has a tendency to write all abstract nouns, starting with "love," with capital initials; she writes impassioned postcards, favours such obscure phrasing as "farewell, but not good-bye," has been known to bring a letter to a close with the words, "Ever yours always lovingly," and to send "much best love."

To sum up, however, the sentimental girl must not be too harshly condemned. To one and other of us she has signed herself "Yours ever" and has been ours for a day; this has made us feel bitter. To one and other of us she has said, using words which are used by Shakespeare, who, one feels quite certain, heard them from a girl-sentimentalist, "I love thee best, oh, most best, believe it," and, having said that to us, has been heard by us saying that to another; this has made us feel jealous. In bitterness and in jealousy we are apt to misjudge the girl-sentimentalist, thinking hard thoughts of her, saying harsh things of her, instead of being right happy to be of those to whom she makes her Shakespearian protestations. Shakespeare is very good in print, but he is very much better from young lips.

Some people are greatly alarmed by the spectacle of a girl who appears to be without sentiment. This girl's heart is wrapped in a cool outer shell, like the world, but, like the world, it has, be sure, a hot nucleus. One could not be a girl, worth the name of girl, and this thing be different. To have a heart full of love in one's body is not to be sentimental. To be sentimental is to have a heart full of loves and likes, and to wear it on one's sleeve.

(To be continued.)

A TALE OF THE FRANCO-ENGLISH WAR NINETY YEARS AGO.

By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of "Sun, Moon and Stars," "The Girl at the Dower House," etc.

A MILITARY NURSE.

Colonel Baron might not confess the fact in so many words, but before he had been three days in Paris, he was sorely regretting his own action in taking Roy across the Channel.

Had he admitted that it really was his wife's persistency, overbearing his better judgment, which had settled the matter, he might have been tempted to blame her. But even to himself he did not admit this. Rather than confess that he had been managed by a woman, he preferred to look upon the mistake as entirely his own. Moreover, he was too devoted a husband to condemn openly any fault in his wife. She was, of course, a woman, and as such he would have counted it infra dig. on his part to have been controlled by her; but she was also in his eyes the fairest and most charming woman that ever had lived; and the one thing on earth before which the Colonel's courage failed was the sight of tears in his Harriette's large grey eyes.

That they should return home, as at first proposed, by the end of a fortnight, unless they were willing to leave the boy behind, was impossible; and neither of them would for a moment contemplate that idea. No matter how well Roy might get on, he would be a prisoner beyond the fortnight. Small-pox is a disease which "gangs its ain gait," and makes haste for no man's convenience. Even after actual recovery, there would still be need for quarantine.

Had Roy remained at home, he would probably have sickened at the same date, if, as was supposed, he had taken the infection from one of his schoolfellows. But then he would have been safe in England, and his parents could any day have returned to him. Now he seemed likely to keep them abroad, at a time when war-clouds hovered unpleasantly near.

When Roy first fell ill, the doctor who was hastily called in at once pronounced him to be sickening for that fell disease, which held the world in a thraldom of terror. Not without good reason. It was reckoned that in those days nearly half a million of people died in Europe every year of small-pox; about forty-five millions being swept away in a century; while tens of thousands were rendered hideous for life, and large numbers were hopelessly blinded. We, who know small-pox mainly in the very modified form which sometimes occurs in vaccinated people, can scarcely even imagine what the ravages of the disease were in those years of its fullest and most unchecked sway.

Mrs. Baron was a fond and tender mother; yet when first that dread word left the doctor's lips, even she fled in horror from the sick room, agonised, not only at the thought of losing her child, but of parting also with her own attractive looks. From infancy she had been used to admiration; and she knew only too well to what a mere mockery of the human face many a lovelier countenance than hers was reduced. Though a most winning woman, she was hardly of a strong nature; and even her mother-love failed for the moment under that fearful test. The Colonel, kind but helpless, was left alone by his boy's bedside.

Soon, ashamed of herself, Mrs. Baron rallied and would have returned; but at the door she was met by the Colonel, who sternly prohibited re-entrance. She bowed to his decision, trembling, as she did not always bow when her wishes were crossed.

The people of the hotel, no whit less dismayed, insisted on Roy's instant removal. The question was, where could he go?

Then it was that Denham Ivor came to the rescue. He had had small-pox; he had nursed a friend through it; he was, therefore, not only safe but also experienced. He would undertake the boy himself, allowing no other to enter the room. Neither Mrs. Baron nor Colonel Baron might again approach Roy, until all danger of infection was over. His steady manner and cheerful face brought comfort to everybody.

He consulted with the hotel people, and heard of a certain Monsieur and Madame de Bertrand, members of the lesser noblesse of past days, who lived in a street near, and who might be willing to take in him and Roy. Three years earlier they had both been inoculated, and had had the complaint. Their servant, too, was safe; and, since they had lost heavily in Revolution times, and were badly off, they might be glad thus to make a little money.

Colonel Baron hastened to the house, ready to offer anything, and he was met kindly, matters being speedily arranged. Roy was then conveyed thither, wrapped in blankets, already much too ill to care what might be done with him. Colonel and Mrs. Baron remained at the hotel, to endure a long agony of suspense. The Colonel was, indeed, almost overcome with terror, not only for Roy, but also for his wife, lest she should already have caught the infection.

As days passed this dread was proved to be groundless, and Roy was found to have the complaint on the whole mildly, though thoroughly. It was not a case of the awful "confluent" small-pox, of which fully half the number attacked generally died, but of the simple "discrete" kind. Though he had much of the eruption on his body, few pustules appeared on his face. There was a good deal of fever, and at times he wandered, calling for "Molly," and complaining that she was cross and{70} would not answer him. More often he was dull and stupefied, saying little.

No one who had seen Denham Ivor only on parade or in society, would have singled him out as likely to be an especially good nurse; but Roy soon learnt this side of the man. A modern hospital nurse would doubtless have found a great deal to complain of in his methods, and not a little to arouse her laughter. Many of his arrangements were highly masculine. The room was seldom in anything like order; and whatever he used he commonly plumped down afterwards in the most unlikely places. But his patience and attention never failed; he never forgot essentials; he never seemed to think of himself, or to require rest. Day after day he remained in that upstairs room with the invalid, only once in the twenty-four hours going out of the house for half-an-hour's turn, that he might report Roy's condition to Colonel Baron, meeting him and standing a few yards distant.

The usual nine days of full eruption, following upon forty-eight hours of fever, were gone through, with, of course, abundance of discomfort and restlessness. Despite the comparatively mild nature of his illness, Roy fell away fast in flesh and strength, while Ivor managed with a minimum of repose. If Roy were able to get a short sleep, Denham used that opportunity to do the same himself, but in some mysterious way he always contrived to be awake before Roy woke up. His handsome bronzed face grew less bronzed with the confinement and lack of exercise.

So far as he knew how to guard against the spread of infection, he did his best. No one beside himself and the doctor entered the sick room, except a wizened old Frenchwoman, herself frightful from the effects of the same dire disease, who was hired to come in each morning for half-an-hour, while Ivor went out, that she might put the room into something like order. For the rest, the gallant young Guardsman, sweet Polly's lover, undertook the whole.

Then tokens of improvement began; and Colonel Baron sent a letter home which cheered Molly's sore heart; and, just when all promised well for a quick recovery, violent inflammation of one ear set in. For days and nights the boy suffered tortures, and sleep was impossible for him, therefore for his nurse. Roy, in his weakened state, sometimes broke down and cried bitterly with the pain, imploring Ivor never to let Molly know that he had cried.

"She'd think me so girlish," he said, while tears rolled down his thin cheeks, marked by half-a-dozen red pits. "Please don't ever tell her!"

In the midst of this trouble a most unexpected blow fell upon Ivor, in the shape of a stern official notice, desiring him to consider himself a prisoner of war, and at once to render his parole. Ivor was a calm-mannered man generally, with the composure which means only the determined holding-down of a far from placid nature, but some fierce and angry words broke from him that day. He was compelled to go out to give his parole, infection or no infection, leaving the old woman in charge for as brief a space as might be; and indignant utterances were exchanged between himself and Colonel Baron, whom he chanced to meet, bent on the same errand. Then he had to hasten back to the boy, with a heavy weight at his heart. It meant to Ivor, not only indefinite separation from Polly, but also a complete deadlock in his military career. He was passionately in love with her; he was hardly less passionately in love with his profession. Had imprisonment come in the ordinary way, through reverse or capture in actual warfare, he would have borne it more easily; but the sense of injustice rankled here. Also at once he foresaw the complications likely to arise, and the probability that an exchange of prisoners would be impossible. As he patiently tended the boy, doing all that he could to bring relief, his brain went round at the thought of his position, and that of Colonel Baron.

(To be continued.)

By JESSIE MANSERGH (Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey), Author of "A Girl in Springtime," "Sisters Three," etc.

For four long days had Mariquita Saville dwelt beneath Mr. Asplin's roof, and her companions still gazed upon her with fear and trembling, as a mysterious and extraordinary creature, whom they altogether failed to understand. She talked like a book, she behaved like a well-conducted old lady of seventy, and she sat with folded hands gazing around, with a curious, dancing light in her hazel eyes, which seemed to imply that there was some tremendous joke on hand, the secret of which was known only to herself. Esther and Mellicent had confided their impressions to their mother, but in Mrs. Asplin's presence, Peggy was just a quiet, modest girl, a trifle shy and retiring, as was natural under the circumstances, but with no marked peculiarity of any kind. She answered to the name of "Peggy," to which address she was persistently deaf at other times, and sat with eyelids lowered, and neat little feet crossed before her, the picture of a demure, well-behaved, young schoolgirl. The sisters assured their mother that Mariquita was a very different person in the schoolroom, but when she inquired as to the nature of the difference, it was not so easy to explain.

"She talked so grandly, and used such great, big words."

A good thing, too, Mrs. Asplin averred. She wished the rest would follow her example, and not use so much foolish, meaningless slang.——Her eyes looked so bright and mocking, as if she were laughing at something all the time. Poor, dear child! could she not talk as she liked? It was a great blessing she could be bright, poor lamb, with such a parting before her!——She was so—so—grown-up, and patronising, and superior! Tut! tut! Nonsense! Peggy had come from a large boarding-school, and her ways were different from theirs—that was all. They must not take stupid notions, but be kind and friendly and make the poor girl feel at home.

Fraulein on her side reported that her new pupil was docile and obedient, and anxious to get on with her studies, though not so far advanced as might have been expected. Esther was far ahead of her in most subjects, and Mellicent learned with pained surprise that she knew nothing whatever about decimal fractions.

"Circumstances, dear," she explained, "circumstances over which I had no control, prevented an acquaintance, but no doubt I shall soon know all about them, and then I shall be pleased to give you the promised help," and Mellicent found herself saying, "Thank you," in a meek and submissive manner, instead of indulging in a well-merited rebuke.

No amount of ignorance seemed to daunt Mariquita, or to shake her belief in herself. When Maxwell came to grief in a Latin essay, she looked up, and said, "Can I assist you?" And when Robert read out a passage from Carlyle, she laid her head on one side and said, "Now, do you know, I am not altogether sure that I am with him on that point!" with an assurance which paralysed the hearers.

Esther and Mellicent discussed seriously together as to whether they liked, or disliked, this extraordinary creature, and had great difficulty in coming to a conclusion. She teased, puzzled, aggravated, and provoked them; therefore, if they had any claim to be logical, they should dislike her cordially, yet somehow or other they could not bring themselves to say that they disliked Mariquita. There were moments when they came perilously near loving the aggravating creature.{71} Already it gave them quite a shock to look back upon the time when there was no Peggy Saville to occupy their thoughts, and life without the interest of her presence would have seemed unspeakably flat and uninteresting. She was a bundle of mystery. Even her looks seemed to exercise an uncanny fascination. On the evening of her arrival the unanimous opinion had been that she was decidedly plain, but there was something about the pale little face which always seemed to invite a second glance, and the more closely you gazed, the more complete was the feeling of satisfaction.

"Her face is so neat," Mellicent said to herself, and the adjective was not inappropriate, for Peggy's small features looked as though they had been modelled by the hand of a fastidious artist, and the air of dainty finish extended to her hands and feet, and slight graceful figure.

The subject came up for discussion on the third evening after Peggy's arrival, when she had been called out of the room to speak to Mrs. Asplin for a few minutes. Esther gazed after her as she walked across the floor with her slow, dignified tread, and when the door was safely closed, she said slowly—

"I don't think Mariquita is as plain now, as I did at first, do you, Oswald?"

"N—no! I don't think I do. I should not call her exactly plain. She is a funny, little thing, but there's something nice about her face."

"Very nice."

"Last night in the pink dress she looked almost pretty."

"Y—es!"

"Quite pretty!"

"Y—es! really quite pretty."

"We shall think her lovely in another week," said Mellicent tragically. "Those awful Savilles! They are all alike—there is something Indian about them. Indian people have a lot of secrets that we know nothing about, they use spells, and poisons, and incantations that no English person can understand, and they can charm snakes. I've read about it in books. Arthur and Peggy were born in India, and it's my opinion that they are bewitched. Perhaps the ayahs did it when they were in their cradles. I don't say it is their own fault, but they are not like other people, and they use their charms on us, as there are no snakes in England. Look at Arthur! He was the naughtiest boy, always hurting himself, and spilling things, and getting into trouble, and yet everyone in the house bowed down before him and did what he wanted. Now mark my word, Peggy will be the same!"

Mellicent's companions were not in the habit of "marking her words," but on this occasion they looked thoughtful, for there was no denying that they were always more or less under the spell of the remorseless stranger.

On the afternoon of the fourth day Miss Peggy came down to tea with her pig-tail smoother and more glossy than ever, and the light of war shining in her eyes. She drew her chair to the table and looked blandly at each of her companions in turn.

"I have been thinking," she said sweetly, and the listeners quaked at the thought of what was coming. "The thought has been weighing on my mind that we neglect many valuable and precious opportunities. This hour, which is given to us for our own use, might be turned to profit and advantage, instead of being idly frittered away. 'In work, in work, in work alway, let my young days be spent.' It was the estimable Dr. Watts, I think, who wrote those immortal lines! I think it would be a desirable thing to carry on all conversation at this table in the French language for the future. Passez-moi le beurre, s'il vous plait, Mellicent, ma très chère. J'aime beaucoup le beurre, quand il est frais. Est-ce que vous aimez le beurre plus de la—I forget at the moment how you translate jam. Il fait très beau, ce après-midi, n'est pas?"

She was so absolutely, imperturbably, grave that no one dared to laugh. Mellicent, who took everything in deadly earnest, summoned up courage to give a mild little squeak of a reply. "Wee—mais hier soir, il pleut;" and in the silence that followed, Robert was visited with a mischievous inspiration. He had had French nursery governesses in his childhood, and had, moreover, spent two years abroad, so that French came as naturally to him as his own mother tongue. The temptation to discompose Miss Peggy was too strong to be resisted. He raised his dark, square-chinned face, looked straight into her eyes, and rattled out a long, breathless sentence, to the effect that there was nothing so necessary as conversation if one wished to master a foreign language; that he had talked French in the nursery; and that the same Marie who had nursed him as a baby, was still in his father's service, and acted as maid to his only sister. She was getting old now, but was a most faithful creature, devoted to the family, though she had never overcome her prejudices against England, and English ways. He rattled on until he was fairly out of breath, and Peggy leant her little chin on her hand, and stared at him with an expression of absorbing attention. Esther felt convinced that she did not understand a word of what was being said, but the moment that Robert stopped, she threw back her head, clasped her hands together, and exclaimed—

"Mais certainement, avec pleasure!" with such vivacity and Frenchiness of manner, that she was forced into unwilling admiration.

"Has no one else a remark to make?" continued this terrible girl, collapsing suddenly into English, and looking inquiringly round the table. "Perhaps there is some other language which you would prefer to French. It is all the same to me. I think we ought to strive to become proficient in foreign tongues. At the school where I was at Brighton there was a little girl in the fourth form who could speak and even write Greek quite admirably. It impressed me very much, for I myself knew so little of the language. And she was only six——"

"Six!" The boys straightened themselves at that, roused into eager protest. "Six years old! And spoke Greek! And wrote Greek! Impossible!"

"I have heard her talking for half-an-hour at a time. I have known the girls in the first form ask her to help them with their exercises. She knew more than anyone in the school."

"Then she is a human prodigy. She ought to be exhibited. Six years old! Oh, I say—that child ought to turn out something great when she grows up. What did you say her name was, by the by?"

Peggy lowered her eyelids, and pursed up her lips. "Andromeda Michaelides," she said slowly. "She was six last Christmas. Her father is Greek consul in Manchester."

There was a pause of stunned surprise; and then, suddenly, an extraordinary thing happened. Mariquita bounded from her seat, and began flying wildly round and round the table. Her pigtail flew out behind her; her arms waved like the sails of a windmill, and as she raced along, she seized upon every loose article which she could reach, and tossed it upon the floor. Cushions from chairs and sofa went flying into the window; books were knocked off the table with one rapid sweep of the hand; magazines went tossing up in the air, and were kicked about like so many footballs. Round and round she went, faster and faster, while the five beholders gasped and stared, with visions of madhouses, strait-jackets, and padded rooms, rushing through their bewildered brains. Her pale cheeks glowed with colour; her eyes shone; she gave a wild shriek of laughter, and threw herself, panting and gasping, into a chair by the fireside.

"Three cheers for Mariquita! Ho! Ho! Ho! Didn't I do it well? If you could have seen your faces!"

"P—P—P—eggy! Do you mean to say you have been pretending all this time? What do you mean? Have you been putting on all those airs and graces for a joke?" asked Esther, severely, and Peggy gave a feeble splutter of laughter.

"W—wanted to see what you were like! Oh, my heart! Ho! Ho! Ho! wasn't it lovely? Can't keep it up any longer! Good-bye, Mariquita! I'm Peggy now, my dears. Some more tea!"

(To be continued.)

By "THE LADY DRESSMAKER."

If the French craze for plaids and tartans be followed in England, it will be as well to remind everyone that there are certain people to whom they are quite forbidden. I refer to the very stout and the very thin. And it is to be hoped that these two classes may be wise in season and avoid them. For the rest, the new plaids are, some of them, pretty and in quiet hues, though I noticed, when in Paris, that people liked them more vivid as to colouring, and one consequently saw some very lively-looking ones in scarlet and bright red. These plaids are more used as skirts than as entire dresses; in fact, the newest departure in coats and skirts is to have the skirt of plaid and the coat of a plain cloth which suits it in colour. For this purpose a sacque coat is always used, and this is a fortunate thing, for they suit all figures, thin and stout, equally well; but they, more than any other description of jacket, require a good cut, as they are so easily made to hitch up or to droop at the back by an inexperienced cutter. And the oddest part of it is that no alteration seems to do any good, for the trouble appears to lie deeper than that, in the very foundation of the jacket.

The few notes that I have collected together on the subject of furs I will use at the beginning of my article. Fur trimmings of all{73} kinds are very much worn, and so many of the winter gowns are decorated with fur bands, that the fashion seems like a uniform. The peculiarity of this form of trimming is that this season it must be accompanied by bands of brightly-coloured velvet and generally with braid. Seal and sable are constant favourites, and they will be used in combination for the fitted-back jackets or sacque-backed ones, which are the two shapes for fur jackets at present. Skunk and bear, which were last year so popular, have fallen out of favour; but caracul is much used, and has not been freshly named this year. So far as I can see, white satin seems to be the popular lining for all fur jackets and capes, though I have seen one or two lined with gold colour and pale blue. The capes of fur follow the fashion of those in cloth and are flounced just as they were last year, many of them; but this year the flounces are wider and more visible to the eye. The collars of all fur garments are very high. And, lastly, I must mention that long fur boas are expected to take the place of the feather ones to which we have been so faithful.

As I look round trying to satisfy myself as to the fashionable colours for the autumn, I find myself in a decided difficulty. There is a new shade of lavender or hyacinth-blue, which is very pretty, but needs to be toned down with white or black, and I am sure others will have noticed that there is a perfect run on lavender-blue hats, which are prepared for the winter in every shade of this hue. Then there is a deep-hued tomato-red, which is very handsome in velvet, and a new blue known as "old Japanese." Dark brown cloth, with reliefs of orange velvet and satin; grey face cloth, with reliefs of turquoise blue; and red with black cordings, are all fashionable winter mixtures. Pink, ranging from a pale coral to a very deep du Barry rose hue, is quite as much worn as ever, and from what I see, orange-colour is the same.

Both for day and night the hair is now dressed quite low on the nape of the neck, in a coil of twists, and on the head and over the ears it is waved in wide undulations, the front hair being cut short and curled over the forehead. For the evening a rose fastened in by a diamond pin behind the left ear is said to be the latest idea.

The reason of this change in the style of dressing the hair appears to lie in the change in the style of the hats and bonnets of the season. There is no doubt that, to the majority of Englishwomen, the hair dressed in this manner is more becoming than in any other style.

In the way of new skirts we find several in which there are neither pleats nor gathers at the back; but the most popular have two box-pleats, on which there are placed (in some skirts at least) a row or two of rather large buttons, from the waist to the hem. Dresses are, I am sorry to say, being made very much longer in the skirt. They touch the ground at the front and sides, and lie on it completely at the back, while for evening use the long train is universally adopted. I think the Princess-gown will be the favourite one for evening use, and here sleeves seem to be banished entirely, a velvet ribbon or a flower being considered a sufficient substitute for them. For walking-skirts in thick materials, however, the sensible ones are to be left a choice, so we shall probably see as many short skirts worn as long ones. After all, the bicycle-skirt has to be considered, and many of us wear that in the country nearly all day long.

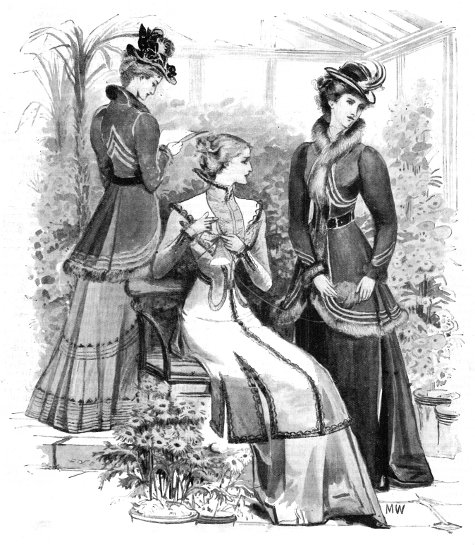

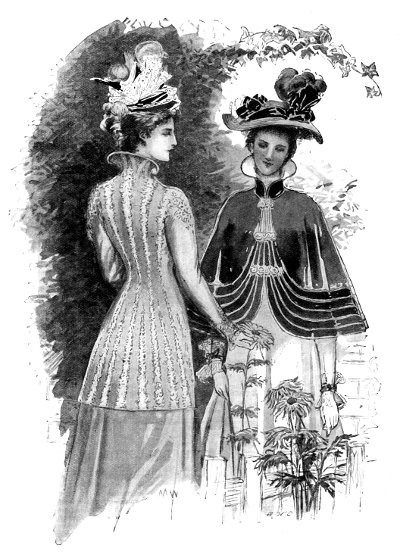

Our first illustration shows two of the reigning winter and autumn styles, namely, the three-quarter jacket, and the strapped cape, with bands of cloth piped with scarlet silk. The figure on the left wears a tailor-made and beautifully-fitting jacket of grey cloth, which is braided with a darker grey braid over bands of paler grey cloth, the lines running longitudinally from the top of the collar to the edge of the jacket. The skirt is of plain cloth of the same tone of grey as the jacket. The latter is lined with orange silk. The toque is of orange velvet, with cream-coloured lace, and feathers and wings of orange and black.

The second figure in the illustration wears a black cloth cape, lined with scarlet silk, and piped with the same at each side of the wide cloth bands, which make the decoration of the cape. These bands are tapered gradually round the fronts and up the sides, where they are crossed with ornamental straps which fasten the cape in front. The collar is high, and is piped and lined with scarlet. The hat is of straw, with scarlet and black velvet, and black feathers at one side, and scarlet and black rosettes below the brim at the back and sides.

The next illustration consists of a single figure only, who wears one of the new jackets of the winter, the material of which is dark green cloth, braided in black, and edged with caracul fur. The new feature in this jacket is the flounce of cloth of about eight inches in depth, which is placed round the edge, and which is also trimmed with fur. The hat is of white felt, with trimmings of green velvet, and green feathers; and the dress worn is of green cashmere, with green velvet trimmings.

The group of three figures fully displays one of the most stylish of the season's confections,{74} two views being given of it, a front and a back one, on the figures which stand on the right and left. This jacket is of cloth, tight-fitting, and of three-quarter length, with the fronts rounded to the bands at the waist. It is trimmed with bands of fur, and with cloth bands of a lighter colour, which taper towards the waist in front, and on the bodice are arranged so as to simulate an Eton jacket. The seated figure shows one of the new tunics. The material is of dark blue cloth, and the tunic is cut to reach a little below the knee. The bodice is open in front to show a vest of apricot-coloured velvet which has white lace motifs on it. The tunic and the revers of the bodice are edged with bands of astrachan, which is laid on apricot velvet, edged and overlaid with fancy braiding in black. There is a large collar high at the back, which is bordered in the same manner, and lined with black velvet. The edge of the skirt is trimmed with bands of astrachan, which are put on to match the battlements of the tunic.

The very smart coats of the autumn are all made of a thick satin merveilleux, which was used for the same purpose some years ago, and seems to have returned to favour. Other coats are of black velvet, on one of which a great deal of Irish crochet lace has been lavished as decoration; but all of them are of the same three-quarter length, and aspire to great perfection of cut and fit. One sees by these coats how desirable it is to be slight in figure, for most of these fashions are only suitable for the thin. Pipings are the predominant ornament; and, indeed, this form of decoration is more popular than anything else.

Mittens are coming into use, and, for the evening, will perhaps supersede gloves; the late tropical heat has rendered the most careful people quite careless of their gloves, and it has been nothing remarkable to meet well-dressed women in the street carrying their gloves in their hands. The ribbon bands round the neck, which have been so much used this year, are now being replaced by velvet ones, tied in the same manner—in a bow at the back. It is rumoured that wide strings of ribbon for bonnets are coming in again, but I do not think it likely, as they add much to the look of age on the face.

Hats turned up in front were an introduction of the later summer season; but they have taken immensely, and will be worn during the winter, and it is well to remember, nevertheless, that they require a plump face, for thin cheeks stand no chance at all, in their very uncompromising lack of shadow.

The following is sent by an anonymous reader in response to the address on our Prospectus.—Ed.

From his "Garden of Girls."

By LADY WILLIAM LENNOX.

The following remarks upon the "Rules of Society" are made for the benefit of those who from one cause or another feel a little uncertain with respect to the small observances which, although not to be counted among the weightier matters in life, yet hold no unimportant place therein, if our daily comfort and well-being are to be considered; but are, indeed, like oil on the wheels, not absolutely essential to movement, but making all the difference as regards smoothness or the reverse.

Life would go on certainly though we were all as rude and uncultivated as could be—sitting on the ground and tearing our food with our hands preparatory to gnawing the bones, and speaking the most terrible home truths to each other without any veil whatever—but it would not be so pleasant. And as civilisation has progressed, so by degrees a sort of code of rules—unwritten in some particulars, but none the less binding—has been evolved very much to the advantage of us all in the way of preventing roughness in manner and making the great machine called Society—which is but another name for an assemblage of human beings—run easily and without friction.

More especially perhaps is an acquaintance with the "code" necessary to women for their own happiness, sensitive and keen by nature as they are and painfully aware of the slightest awkwardness; for, akin to the feeling of discomfort—I may almost say general disorganisation—produced by the consciousness of having on a badly-fitting gown, a hideous hat, or a shoe whose beauties are things of the past, just when there is urgent reason for wishing to look well, is the sensation of nervous depression brought on by suddenly awakening to the fact that one does not know quite "how to behave" or "what to do" in the circumstances of the moment.

I ought, I think, to begin by offering an apology to the many readers of The Girl's Own Paper who have no need of any instruction or hints on the matter for choosing a subject which always provokes a smile—either good-natured or cynical—when mentioned, on account doubtless of its being among those things which everybody is supposed to know. But there is no occasion for the already enlightened to wade through this paper. The heading will warn them off, and they can simply skip it all.

Leaving the majority therefore out of the question as in no way concerned, I address myself to the comparatively few; and, on the principle of taking the first step before{75} attempting the second, I begin at the beginning and will try to answer queries which present themselves to my imagination as likely to be asked if people had the opportunity of asking them.

We will consider at starting the very ordinary occurrence of a dinner party about to be given; the invitations being sent out. These may be formal cards—"Mr. and Mrs. A. request the honour"—or the pleasure—"of Mr. and Mrs. B's company at dinner on Tuesday, the 8th of June, at 8 o'clock"—or merely notes—"Dear Mrs. A., will you and Mr. A. give us the pleasure of your company at dinner on," etc.

In either case the answer must be couched in the same terms as the invitation, except when, as sometimes happens, the inviter is a near relative or very intimate friend of the invited, in which event the formality may be disregarded in favour of a note. "Dear Mrs. B."—or the Christian name only—"we have great pleasure in accepting your kind invitation," or "We shall have great pleasure in dining with you," etc.

And here please be careful to notice the difference in the wording, and avoid a mistake constantly made in letters of this sort. People write, "I shall have much pleasure in accepting," not considering that the acceptance refers to the present, and consequently there is no "shall" about it. But if the phrase runs, "I shall have much pleasure in dining with you," it is correct because it refers to the dinner which is in the future.

The date fixed for the party arrives, and you make your appearance in your host's drawing-room, followed by your daughter—if she was asked—and then your husband. Never, on any account, go in arm-in-arm. It is a mistake very seldom made; but, as I have seen it happen occasionally, it must be mentioned. The old-fashioned arm-in-arm is, indeed, pretty nearly obsolete, except when actually going down to dinner or supper, or just through the hall to a carriage. At no other time, unless in some frightful crowd as a protection, is such a thing ever witnessed now.

Dinner is announced and you take your seats. With regard to the mode of eating, it may be roughly laid down that a knife is not to be used when spoon and fork will do, and a spoon should not be employed if a fork alone is sufficient. In the case of fish, silver knives are usually provided, and when they are not it is advisable to use two forks if one will not quite answer the purpose. Curry, properly cooked, requires no knife, only spoon and fork. Quails and cutlets, of course, must have a knife, but many entrées can be perfectly well managed with a fork alone.

It is hardly necessary, perhaps, to say that under no circumstances whatever, whether when eating vegetables, cheese, or any other thing, must a knife approach the mouth. Such an unbecoming as well as dangerous habit would at once mark the person indulging in it as standing in need of some little teaching.

On the other hand, we know that "fingers were made before knives and forks," and custom ordains the exemplification of this adage on certain occasions. Asparagus is eaten in the primitive manner, and requires some dexterity in conveying the end of a rather limp stalk to the mouth. Green artichokes are pulled to pieces leaf by leaf until the "choke" is reached, when fork and spoon come into requisition, and uncooked celery, after the thick end has been cut off, is taken up by the fingers. The fragile pencil-like things called "cheese-straws" must be eaten in the same manner, for they break if touched by any implement, and I well remember watching the dire confusion of a woman who vainly tried to catch some of the straws by pursuing them round and round her plate with a fork, the only result being a collection of unattainable splinters.

Some dishes are easy enough to help oneself to, but there are others which demand cool determination to attack, and care lest a portion land upon the tablecloth instead of in the plate. We are not all gifted with the self-possession of Theodore Hook, who, when carving a tough goose one day let it by chance slip bodily into the lap of his neighbour, and, turning to the unlucky victim, said severely, "Madam, I will trouble you for that goose!"

Fortunately for us, the days of carving at table are over, and we have only to avoid catastrophes with extra hard vol-au-vents, infirm jellies, and pyramids of strawberries.

A story is told of a man who, hopelessly in difficulties as to what he ought to do, pulled some grapes off their stalks and tried to cut each berry with a knife. It puts one's teeth on edge to think of the pips on that occasion, and indeed the idea of steel blades and fruit in juxtaposition is terrible, except in the case of oranges, when silver knives create a feeling not far short of desperation.

As regards wine, persons who have come to years of discretion can observe that discretion as seems good to them; but to those girls who allow themselves wine, I would advise a small quantity of one kind. It does not look well to have odds and ends of wine standing in the various glasses by the side of a girl, neither is it attractive to see her finish up with liqueur at the end of dinner.

In the matter of introductions there is but little of that now, though, of course, unless previously acquainted, the man who takes you down to dinner is first presented to you, and you may be introduced to some one or other of the guests during the evening; but, especially if the party be large, it is by no means certain that you will be. In the act of introduction the name of the person highest in rank—or, if there is no difference in that respect, then the elder of the two—should be mentioned first, as "Lady A.—Mrs. B.," not vice versâ; and when a man is presented to a woman there is generally the proviso, "Mrs. B., may I introduce Mr. C.?" A woman is not taken up to be introduced to a man; always he to her, except in the case of royalty, and then the royal personage has intimated his wish that she should be presented to him.

A fault very common is not being sufficiently careful to pronounce clearly the names of individuals when introducing them, and it is a great oversight, as it prevents the landmarks—if I may so style them—being visible, which are so necessary in this land, where relationships run closely through every stratum of society, and it is almost impossible to go anywhere without finding people either nearly or distantly connected with each other. We cannot be a sort of Bradshaw's Guide through the network of lines of kinship, but the more we understand about it the better, and to know exactly whom one is speaking to is an undoubted help in that direction, enabling us to avoid mistakes in conversation which may plant a sting unremovable by any after-excuse or apology. The only safe course to follow in the absence of such information is to say nothing but what is favourable about people or even nations, lest you should wound the feelings of your neighbour, and oblige him to say hurriedly, "she is my sister" or "perhaps I had better mention my name," to show that he belongs to the country about which you have been holding forth in not over-pleasant terms.

One of the best indeed among the "rules of society" is that which makes it incumbent on everybody not only to furnish his or her quantum of wit, humour, general agreeability, or what not, for the amusement and gratification of the company, but also, by a skilful word or two, to try and turn the conversation away from any topic likely to cause violent discussion or uncomfortable feeling; and nothing marks ignorance of what ought to be done more distinctly than the tactless introduction or continuation of a subject which, like a hedgehog, is covered with prickles and sure to hurt somebody.

A word before concluding this paper to those who now and then give dinners. Not the great banquets in big houses, which are part of the routine of life, and being perfect in every detail go like clockwork; but the modest entertainments in small abodes where the infrequency of "parties" causes some excitement and extra work in the household. The first thing to be remembered when such an event occurs is not to attempt more than can be done properly as regards the number of guests or dishes, and secondly, having settled the quantity and quality of both, and arranged all things to the best of your ability, to leave it alone. That is to say, do not let your mind worry and bother about it, for of all fatal obstacles to the success of a dinner-party, the irrelevant answers and wandering eye of the hostess, due to her thoughts being fixed upon the delay in handing the vegetables, or the non-appearance of a sauce, are the greatest, and moreover call attention to shortcomings which otherwise might pass unobserved. Therefore "assume the virtue" of coolness "if you have it not," and never allow your neighbour to see that while he is trying to interest you and make himself agreeable your mind is elsewhere, and that you have not heard a word of what was said. Remember also that your business at the time is to be hostess, not cook, footman, or parlour-maid, and that the more you attend to your own duties, and do not, to use an expressive word, "fluster" the servants, the more likely are they to get through their part creditably; and finally do not forget that an important rule of society forbids the exhibition of personal annoyances and domestic grievances to our acquaintances or friends.

(To be continued.)

I suppose most girl-readers will understand the thrill of surprise and delight with which I read the following sentences from a friend's letter one February morning.

"My uncle thinks I need a change, and suggests my going abroad. Will you go with me to Palestine for two or three months? We ought to get off before the warm season begins there. Do you think we could leave England at the end of this month?" Two or three times I read the words in a dazed sort of way, and then astonished my hostess (a well-known contributor to the G.O.P.) by quietly remarking—

"Would you be greatly surprised if I started for the Holy Land in a few days? Elizabeth N. has asked me to go with her."

"The Holy Land!" echoed Mrs. B. "Do you really mean it?"

For answer, I handed her my letter, and greatly enjoyed the sensation it created at the breakfast-table.

"How lovely," said kind Mrs. B., "to visit the sacred spots where our Lord began and ended his ministry. How I wish I was strong enough to go with you!"

"Shall we order the camels to come round to the front door?" exclaimed a lively and irreverent member of the family. "I can already picture you, dear E., riding over the trackless desert (composing poetry under an umbrella), living in Bedouin tents, and finally being carried off by a wild Arab chief, on a wild Arab steed, while we at home mourn and frantically petition the Home Secretary or somebody to institute a search for the missing English lady."

We all laughed at this ridiculous, unpunctuated speech, and then fell to discussing the possibilities of eastern travel.

The next post carried my answer to Elizabeth's letter, and in a few days we were in London making our final arrangements. We decided from motives of economy to go by long sea, and selected the North German Lloyd line of steamers because of their excellent second-class accommodation. We booked our passage to Port Said in the Prinz Heinrich, sailing from Southampton on February 28th.

Our remaining days were fully occupied with business, in the intervals of which we packed our small portmanteaux (not omitting warm wraps), got our passports viséd at the Turkish Consulate, and attended to the hundred and one trifles which seemed to crop up at the last moment. It was not till we were safely on board the steamer and waving our good-byes to the friends who had come to see us off, and who were now returning to shore, that we felt our eastern travels were to become a reality.

Fair indeed looked the green slopes of the Isle of Wight on that glorious morning, and as we passed the Needles, many eyes filled with tears, for the ship was bound for distant China and Japan, and few of her passengers could hope to look upon Old England again for many long years. As for us, our hearts were light, and we were eager to go forward. Not even the unknown terrors of the Bay of Biscay appalled us. Fortunately it proved most kind. We passed Gibraltar at midnight, on March 3rd, the wonderful old rock looking awful and mysterious in the moonlight. Genoa was reached on the 6th, but, alas! heavy rain and cold winds set in, and the "superb" city did not look tempting enough to draw us from our comfortable ship for the forty-eight hours we were tied up in her harbour. There was a general murmur of satisfaction when the last cargo had been shipped and we were on the move again. As we entered the bewitching Bay of Naples the weather cleared, and the sun shone warm and bright. Here we had to wait until the evening for the mails, and everybody seized this opportunity of going on shore. How well I remember my sensations of delight as we wandered about the old streets, admiring the queer, tall, gaily-painted houses and the quaint bits of picturesque Neapolitan life which we came upon in our long climb to the top of the old ramparts which overlooked the busy city. From this height we gazed our fill on the pretty picture. The lemon trees with the golden fruit shining through the glistening leaves threw a shade on the irregularly-built houses. Beyond glittered the glorious bay, dotted with stately vessels and other smaller craft, while above loomed the giant Vesuvius, his sullen frowns adding a touch of melancholy to the scene. All too swiftly that dream-like day passed, and once again we were sailing Eastward Ho!

Wickedly did the fair Mediterranean behave for the next four days, and wildly did our good ship pitch and toss on those treacherous blue waves! Those days were days of intense bitterness of spirit, when to most of us past sorrows and future hopes were forgotten in the agonising longing for immediate annihilation. But even sea-sickness yields to time and smooth water, and we had begun to take a more cheerful view of life when we dropped anchor in Port Said on Sunday the 13th. Our curiosity was strongly excited, and though we were truly sorry to say good-bye to our travelling-companions, whose lives had touched ours for a brief space in pleasant intercourse, we were eager to get our first glimpse of eastern life. We smiled in quite a superior manner when an old gentleman, noticing our impatience, remarked cynically—

"Well, young ladies, if you can find anything pleasing in that hole"—indicating the town—"I should say your capacity for enjoyment must be abnormal."

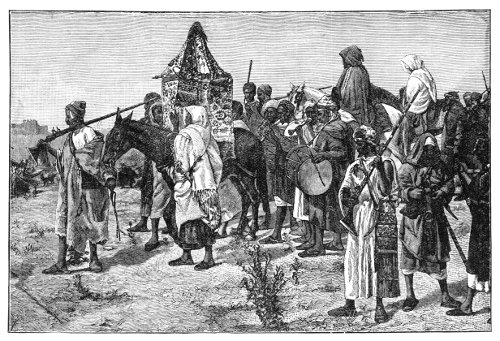

Summoning a boat, whose boatmen bore on their scarlet jerseys the legend "New Continental Hotel," Elizabeth and I stepped into it and waved adieu to the good ship Prinz Heinrich. We were quickly rowed ashore, where the hotel guide took our passports, showed them, and us, to the Turkish official, who courteously handed us over to the customs-house officers. These gentlemen proved to be equally civil, evidently seeing nothing suspicious either in us or our modest luggage. Our formal introduction to Egypt being thus agreeably made, we walked to the hotel, and were soon seated under the cool verandah, discussing delicious tea and bread and butter. We ascertained that the steamer going to Jaffa did not leave before Tuesday evening, so that we had ample time to become acquainted with Port Said. What an un-Sabbath-like appearance our novel surroundings presented! Noisy donkey-boys, with bold inventiveness, were loudly urging the new arrivals to mount Queen Victoria, Lord Salisbury, Prince Bismarck, Mrs. Langtry, Mrs. Cornwallis West, etc., for these high-sounding names were tacked on to the wretched little donkeys. Bare-legged shoe-blacks, with most engaging smiles, seized your feet and began operations without even a "By your leave." Importunate blind beggars, whose picturesque garments were indescribably dirty, demanded backsheesh, and according to the response, poured out a choice selection of blessings or curses in Arabic, which would have astonished the most accomplished Irish professor of the same craft. Shrewd, hook-nosed Jewish money-changers sat in the highway, each before his glass box, which contained a wire tray covered with a tempting store of bank-notes and coins. These had doubtless been exchanged at an exorbitant rate of interest for Turkish money. Black men, white men, brown men, yellow men in their native dress, sat drinking coffee and playing backgammon and dominoes in the open street, or walked leisurely along the road. It was a strange, fascinating scene, unlike anything we had witnessed before, and the ubiquitous bicycle as it flashed by with its British rider failed to break the charm.

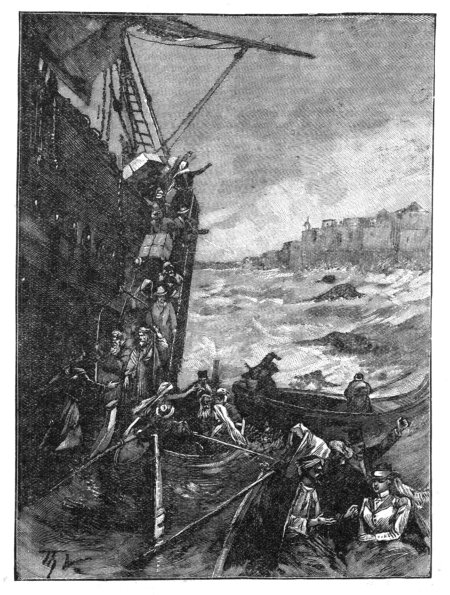

Towards evening we strolled into the town, where we discovered an English "Sailors' Rest." We opened the door, and following the sound of voices, boldly walked upstairs. In an upper room knelt twenty Jack Tars, who had come in from one of her Majesty's ships lying in the harbour. Very hearty and refreshing were the simple prayers uttered by the men. Only too well they knew the dangers and temptations of a shore life. We heard afterwards from the gentle lady who presided at this gathering how that bright little room, with its books and pictures, and, above all, the presence of kindly friends, had proved a haven of peace to many of our British sailors, for whom the perils of the ports are more terrible than the perils of the deep. On our return we found letters from our friends in Jaffa, telling of unprecedented storms visiting the coast, and reminding us, that unless the present wind went down, we should find it impossible to land. In the event of this happening, the only other alternative was to go on to Beyrout, and from thence to Damascus by rail. This plan did not commend itself to us in the least, for we particularly wished to begin our Palestine wanderings from Jaffa, and also we desired to consult our friends there as to the best routes, and other important items relating to our tour. It was no use grumbling, however, and as we could not arrange the weather to our liking, we wisely agreed to let it alone, hoped that all would be well, and that we should yet enter Jaffa with a fair breeze and in smooth water.

Two days served to satisfy our curiosity and exhaust for us the delights of Port Said; therefore we were not sorry when Tuesday night arrived, and we were once more on board a ship, which we trusted would bring us in a few hours to our desired haven.