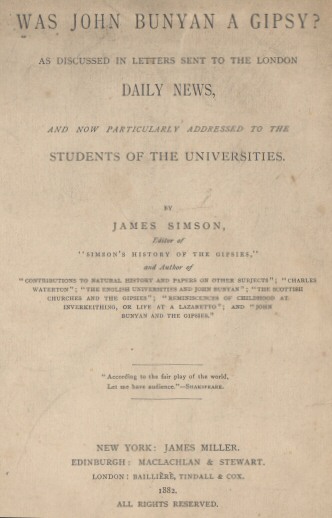

Title: Was John Bunyan a Gipsy?

Author: James Simson

Release date: March 14, 2016 [eBook #51456]

Language: English

Credits: Transcribed from the 1882 Maclachlan & Stewart edition by David Price

Transcribed from the 1882 Maclachlan & Stewart edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

AS DISCUSSED

IN LETTERS SENT TO THE LONDON

DAILY NEWS,

AND NOW PARTICULARLY ADDRESSED TO THE

STUDENTS OF THE UNIVERSITIES.

BY

JAMES SIMSON,

Editor of

“SIMSON’S HISTORY OF THE GIPSIES,”

and Author of

“CONTRIBUTIONS TO NATURAL HISTORY

AND PAPERS ON OTHER SUBJECTS”; “CHARLES

WATERTON”; “THE ENGLISH

UNIVERSITIES AND JOHN BUNYAN”; “THE

SCOTTISH

CHURCHES AND THE GIPSIES”;

“REMINISCENCES OF CHILDHOOD AT

INVERKEITHING, OR LIFE AT A

LAZARETTO”; AND “JOHN

BUNYAN AND THE GIPSIES.”

“According to the fair play of the world,

Let me have audience.”—Shakspeare.

NEW YORK: JAMES MILLER.

EDINBURGH: MACLACHLAN & STEWART.

LONDON: BAILLIÈRÈ, TINDALL

& COX.

1882.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The title-page of this little publication states that it is “particularly addressed to the students of the universities.” It is based on a History of the Gipsies, published in 1865, in a prefatory note to which it was said that this subject,

“When thus comprehensively treated, forms a study for the most advanced and cultivated mind, as well as for the youth whose intellectual and literary character is still to be formed; and furnishes, among other things, a system of science not too abstract in its nature, and having for its subject-matter the strongest of human feelings and sympathies.”

This race entered Great Britain before the year 1506, and sooner or later became legally and socially proscribed. It has been my endeavour for some years back to have the social proscription removed (the legal one having ceased to exist), so that at least the name and blood of this people should be acknowledged by the rest of the world, and each member of the race as such treated according to his personal merits. The great difficulty I have encountered in this matter is the general impression that this race is confined to a few wandering people of swarthy appearance, who live in tents, or are popularly known as Gipsies; and that these “cease to be Gipsies” when they in any way “fall into the ranks,” and dress and live, more or less, like other people. Unfortunately many have so publicly committed themselves to this view of the subject that it is hardly possible to get them to revise their opinion, and admit the leading fact of the question, viz.: that the Gipsies do not “cease to be Gipsies” by any change in their style of life or character, and that the same holds good with their descendants. Taking the race or blood in itself, and especially when mixed with native, it has every reason to call itself, in one sense at least, English, from having been nearly four hundred years in England. The race has been a very hardy and prolific one, and (with the exception of a few families, about which there it no certainty) has got very much mixed with native blood, which so greatly modified the appearance of that part of it that it was enabled to steal into society, and escape the observation of the native race, and their prejudice against everything Gipsy, so far as they understood the subject.

It is a long stretch for a native family to trace its descent to people living in the time of Henry VIII., but a very short one for a semi-barbarous tribe as such, having so singular an origin as a p. 4tent, as applicable to all descending from it, however much part of their blood may be of the ordinary race; the origin of which is generally unknown to them. Thus they have no other sense of origin than a Gipsy one, and that “theirs is a Gipsy family,” of an arrival in England like that of yesterday, with words and signs, and a cast of mind peculiar to themselves, leading, by their associations and sympathies of race, to them generally, if not almost invariably, marrying among themselves, and perpetuating the race, as something distinct from the rest of the world, and scattered over its surface, in various stages of civilization and purity of blood.

Leaving out the tented or more primitive Gipsies, there is hardly anything about this people, when their blood has been mixed and their habits changed, to attract the eye of the world; hence it becomes the subject of a mental inquiry, so far as its nature is concerned. And the human faculties being so limited in their powers, even when trained from early youth, it will be, at the best, a difficult matter to get the subject of the Gipsies understood; while it appears to be a desperate effort to get people beyond a certain age, or of a peculiar mind or training, to make anything of it, or even to listen to the mention of it, which almost seems to be offensive to them. On this account, if the subject of the Gipsy race, in all its mixtures of blood and aspects of meaning, can ever become one of interest, or even known, to the rest of the human family, it must be taken up, for the most part, by young people whose minds are open to receive information, as illustrated by what I wrote in connexion with Scotch university students:—

“At their time of life they are more easily impressed with the truth of what can be demonstrated, than after having acquired modes of thought and feeling in regard to it, which have to be modified or got rid of, after more or less trouble and sometimes pain.”

This subject does not in any way clash with what is generally held in dispute among men, but touches many traits of their common humanity. Its investigation illustrates the laws of evidence on whatever subject to which evidence may be applicable—that all questions should be settled by facts, and not by suppositions; and that no one has a right to maintain capriciously that anything is a truth until it is proved to be an untruth. As regards John Bunyan, it is not in dispute that he was an English man, but whether he was of the native English race, or of the Gipsy English one, or of both, and holding by the Gipsy connexion. What is necessary to be done is not merely to correct, but to create, and permanently establish a knowledge that has now no existence with people generally, in consequence of the habits of the original Gipsies leading to their legal and social proscription, and the naturally secretive nature of the race, which has been intensified by the way in which they were everywhere treated or regarded.

Apart from this subject in itself, it may be said to be one of those side questions which it is always advisable for a student to have p. 5on hand, as a mental relief after severe studies, and to liberalize or expand his mind generally.

The question of John Bunyan having been of the Gipsy race, discussed in the following pages, is merely an incidental part of the subject of the Gipsies. What I have said there about the Rev. John Brown, of Bedford, makes it unnecessary for me to add much here, except to say that, as he has no standing in the discussion of the Gipsy question as applicable to Bunyan, he would not be listened to but for his being minister of Bunyan’s Church, and setting forth theories as to his nationality that meet the preconceived opinions and ardent wishes of others. His discovery of Bunyan’s descent is of great interest; but for it to be of any use, he should have taken it to such as were able to interpret it, instead of proclaiming that he had thereby done away with the idea of Bunyan having been of the Gipsy race, to the apparent welcome of those who will have it so. He had previously “done away with” the same idea by discovering that the name of Bunyan existed in England before the Gipsies arrived in it! As the occupant of Bunyan’s pulpit, it was clearly his sacred duty to carefully scrutinize the information left by Bunyan as to “what he said he was and was not, and his calling and surroundings,” for these exclusively constitute the question at issue, and as carefully study everything bearing on the subject. Had he done so, he would have found that the family of the illustrious dreamer did not enter England from Normandy with William the Conqueror (whatever might have been the blood of William and Thomas Bonyon in 1542), or were native English vagabonds, as some have thought, but Gipsies whose blood was mixed; so that John Bunyan doubtless spoke the language of the race in great purity, and was capable, after a little effort, to have written it. In England to-day there are many such men as Bunyan, barring his piety and genius, following his original calling, that speak the Gipsy language with more or less purity, saying nothing of others in much higher positions in life. Of the former especially I have met and conversed in America with a number, who had no doubt of John Bunyan having been one of their race.

Whatever the future may bring forth, I have no reason to change what I wrote in Contributions to Natural History, etc., in 1871, in regard to the only bar in the way of receiving Bunyan as a Gipsy being the prejudice of caste against the name:—

“Even in the United States I find intelligent and liberal-minded Scotchmen, twenty years absent from their native country, saying, ‘I would not like it to be said,’ and others, ‘I would not have it said,’ that Bunyan was a Gipsy” (p. 158).

This feeling cannot be changed in a day, however involuntary it frequently is, or however much it may be repudiated in public.

The Gipsy, whatever his position in life, and however much his blood may be mixed, is exceedingly proud of the romance of his descent. The following extracts are taken from the Disquisition on the Gipsies on that subject:—

p. 6“He pictures to himself these men [John Faw, Towla Bailyow, and others, in 1540], as so many swarthy, slashing heroes, dressed in scarlet and green, armed with pistols and broad-swords, mounted on blood-horses, with hawks and hounds in their train. True to nature, every Gipsy is delighted with his descent, no matter what other people, in their ignorance of the subject, may think of it, or what their prejudices may be in regard to it” (p. 500).—“If we refer to the treaty between John Faw and James V., in 1540, we will very readily conclude that, three centuries ago, the leaders of the Gipsies were very superior men in their way; cunning, astute, and slippery Oriental barbarians, with the experience of upwards of a century in European society generally; well up to the ways of the world and the general ways of Church and State, and, in a sense, at home with kings, popes, cardinals, nobility, and gentry. That was the character of a superior Gipsy in 1540. In 1840 we find the race represented by as fine a man as ever graced the Church of Scotland” (p. 465).—“Scottish Gipsies are British subjects as much as either Highland or Lowland Scots; their being of foreign origin does not alter the case; and they are entitled to have that justice meted out to them that has been accorded to the ordinary natives. They are not a heaven-born race, but they certainly found their way into the country as if they had dropped into it out of the clouds. As a race, they have that much mystery, originality, and antiquity about them, and that inextinguishable sensation of being a branch of the same tribe everywhere, that ought to cover a multitude of failings connected with their past history. Indeed, what we do know of their earliest history is not nearly so barbarous as that of our own; for we must contemplate our own ancestors at one time as painted and skin-clad barbarians. What we do know for certainty of the earliest history of the Scottish Gipsies is contained more particularly in the Act of 1540; and we would naturally say that, for a people in a barbarous state, such is the dignity and majesty, with all the roguishness displayed in the conduct of the Gipsies of that period, one could hardly have a better, certainly not a more romantic descent; provided the person whose descent it is, is to be found amid the ranks of Scots, with talents, a character, and a position equal to those of others around him. For this reason, it must be said of the race, that whenever it shakes itself clear of objectionable habits, and follows any kind of ordinary industry, the cause of every prejudice against it is gone, or ought to disappear; for then, as I have already said, the Gipsies become ordinary citizens of the Gipsy clan. It then follows, that in passing a fair judgment upon the Gipsy race, we ought to establish a principle of progression, and set our minds upon the best specimens of it, as well as the worst, and not judge of it solely from the poorest, the most ignorant, or the most barbarous part of it” (p. 479).

Satisfied with, even proud of, their descent, the Gipsies hide it from the rest of the world, for reasons that are obvious, however much I have explained them on previous occasions. And thus, as I wrote in Contributions to Natural History, etc.,

“It unfortunately happens that, owing to the peculiarity of their origin, and the prejudice of the rest of the population, the race hide the fact of their being Gipsies from the rest of the world, as they acquire settled habits, or even leave the tent, so that they never get the credit of any good that may spring from them as a people” (158). And this may have been going on from the time of their arrival in England.

With reference to this phenomenon, I wrote thus in the Disquisition on the Gipsies:—

“Now, since John Bunyan has become so famous throughout the world, and so honoured by all sects and parties, what an inimitable instrument Providence has placed in our hands wherewith to raise up the name of Gipsy! Through him we can touch the heart of Christendom!” (p. 530).

p. 7It would be a sad thing to have the century close without the Gipsy race being acknowledged by the rest of the world, in some form or other, or that that should be deemed unworthy of our boasted civilization! To get this subject completely before the British public would resemble the recovery of a lost art, or the discovery of a new one. People taking it up there would require to show a high degree of courage, candour, and courtesy, and all the better qualities of their nature.

On the 8th September I wrote thus to the editor of the Daily News:—“I intend printing the articles sent you as the bulk of a pamphlet, . . . so that I am in hopes you will have previously printed them in the Daily News,” which he does not seem to have done.

New York, 2d October, 1882.

The first notice of my pamphlet, under the title of John Bunyan and the Gipsies, that has come under my observation I found in the Daily News of the 15th August. In the preface to it I said:—“This little publication is intended, in the first place, for the British Press,” as an appeal for a hearing on the subjects discussed in it. The time that elapsed between receiving the pamphlet and writing the notice of it was too short to enable almost any one to do justice to it, for that required time to think over it as having reference to my previous writings, to which the two letters to an English clergyman contained in it were merely an allusion.

The writer is hardly correct when he speaks of the “long debated question of whether the illustrious author of the Pilgrim’s Progress was of Gipsy race.” This question has not been even once “debated” in England, so far as I, living in America, am aware of. I stated it fully in Notes and Queries on the 12th December, 1857, and more fully in the History of the Gipsies, published by Sampson, Low & Co. in 1865; again in Notes and Queries on the 27th March, 1875, with reference to the “fairish appearance” of Bunyan, and the existence of his surname (variously spelt) in England before the Gipsies arrived in it; then in Contributions to Natural History and Papers on Other Subjects, and The English Universities and John Bunyan, and The Encyclopædia Britannica and the Gipsies; then in The Scottish Churches and the Gipsies; and, finally, in the pamphlet alluded to. So that, instead of having “nothing to say” to the “fairish appearance” and the surname of Bunyan, I fully anticipated these questions, and disposed of them as they were brought forward by people at a venture, who seemed to know nothing of the subject they were treating. Much as I have published on this question, I am not aware that any one has ever attempted to set aside my facts, arguments, and proof that John Bunyan was of the Gipsy race. My “opponents” (so called) assume that he was of the ordinary English race, and therefore was, and must be held to have been, such till it is proved that he was not that, but of the Gipsy race, or something else; a most unreasonable position for any one to take up. So far from people stating the kind of proof they want, they simply pass over everything I have written on the subject, and repeat their untenable, meaningless, and oft-refuted assertions. Thus the Rev. John Brown, of Bunyan Church, Bedford, apparently knowing nothing of the Gipsy subject, and disregarding everything printed on it, and looking neither to the right nor the left, makes out from the surname that the illustrious dreamer’s family was a broken-down branch of the English aristocracy, instead of, as Bunyan himself told us, “the meanest and most despised of all the families in the land,” and “not of the Israelites,” that is, not Jews, but tinkers, that is, Gipsies of more or less mixed blood; so that his having been a tinker was in itself amply sufficient to prove Bunyan to p. 10have been of the Gipsy race; while it illustrated and confirmed his admission about “his father’s house” having been of the Gipsy tribe.

Having written so frequently, and at such length, on this subject, it would be impossible, at least unreasonable, to repeat in a newspaper article what I have done, and I must refer the reader to the various publications mentioned. I may allude to the scepticism of Blackwood, who will not believe that Bunyan was of the Gipsy race because he did not say so plainly, in the face of the legal and social responsibility; [10a] and to that of Mr. Groome, the writer on the Gipsies in the Encyclopædia Britannica, because he alluded to a Gipsy woman carrying off a child, and because his children did not bear the old-fashioned Gipsy Christian names which were adopted by the race after their arrival in Europe. I disposed of these trifling and meaningless objections in their proper places, and need not reproduce them here. [10b] The strangest thing advanced about Bunyan is the assertion that it is impossible he could have been a Gipsy, because the name existed in England before the race arrived in it. From this it would follow that there can be no Gipsies in England, or anywhere else, because they bear surnames common to the natives of the soil. The circumstances under which they adopted these, and how Gipsies of mixed blood are found of all colours, I have on previous occasions elaborately explained. Hence it can be said that the writer in the Daily News is not strictly correct when, in allusion to the two letters to an English clergyman, contained in the pamphlet, he says that I “have nothing to say to all this;” and that “this is really all the evidence, as well as all the argument, forthcoming on the subject.” This subject has no standing if we do not admit of the existence of a “ferocious prejudice of caste against the name of Gipsy”; and that in regard to the nationality of John Bunyan, “the question at issue is really not one of evidence, but of an unfortunate feeling of caste that bars the way against all investigation and proof.”

Apart from John Bunyan personally, the subject of the race to which he belonged has a very important bearing on the “social emancipation of the Gipsies” in the British Isles. There cannot be less than several hundred thousand of these in various positions in life—many, perhaps most of them, differing in no other way from the “ordinary natives” but that in respect to that part of their blood which is Gipsy, they have sprung, really or representatively, from the tent—the hive from which the whole of the Gipsy tribe have swarmed. Notwithstanding that, this fact carries certain mental peculiarities with it, which should be admitted as a preliminary step to a full social equality, should the incognito Gipsy element in society present itself for that purpose.

Since the above was written I have read with great interest the letter from “Thomas Bunyan, chief warder, Tower of London, and born in Roxburghshire,” in the Daily News of the 17th. The origin which he gives of the name is apparently the correct one, viz.: that “the first Bunyan was an Italian mason, who came to Melrose, and was at the building of p. 11that famous abbey in the year 1136;” and that “the oldest gravestone in the graveyard around Melrose Abbey has on it the name of Bunyan.” In my Disquisition on the Gipsies, published in 1865, I said:—“The name Bunyan would seem to be of foreign origin” (p. 519). It does not necessarily follow that the blood of the Italian mason flowed in John Bunyan’s veins, except by it having in some way got mixed with and merged in that of the Gipsy race. [11a]

The following letter, which I addressed to-day to a clergyman of the Church of England, applies so well to the Rev. John Brown of Bunyan Church, Bedford, that it may be considered as the first part of my reply to his letter in the Daily News of the 22d August. The remainder will follow soon.

I have to thank you for your letter of the 22d August containing a newspaper slip. You say that the idea of Bunyan having been of the Gipsy race; “from absolute want of evidence is totally incapable of proof,” and “from beginning to end is no better than a conjecture”; and that as proof to the contrary is “the fact that before the birth of Bunyan his ancestors are known to have resided in Bedfordshire for many generations, some of them having been landed proprietors.” Now read what Bunyan said of himself:—

“For my descent, it was, as is well known to many, of a low and inconsiderable generation, my father’s house being of that rank that is meanest and most despised of all the families in the land.”

This descent, he said, was “well known to many.” Was not that a fact? If it was then “well known to many,” how has the knowledge of it died out in his Church and neighbourhood? A fact like that could not have been forgotten within two centuries, during which time Banyan’s memory, with all relating to it, has been cherished more and more, unless it had been, at some time, wilfully or tacitly suppressed; and an attempt made to connect him even with the aristocracy of the country! I have never seen or heard of an allusion to any of his relations, although the great probability is that there was an “extensive ramification” of them. The reason I have assigned for that is that “very probably his being a tinker was, with friends and enemies, a circumstance so altogether discreditable as to render any investigation of the kind perfectly superfluous” (Dis. p. 517). [11c] p. 12“A low and inconsiderable generation.” What did that phrase mean? And as if that were not sufficient, he added that “his father’s house” was “of that rank that is meanest and most despised of all the families in land”; and still not satisfied with that, he continued:—

“Another thought came into my mind, and that was, whether we [his family and relations] were of the Israelites or no? For finding in the Scriptures that they were once the peculiar people of God, thought I, if I were one of this race [how significant is the expression!] my soul must needs be happy. Now again, I found within me a great longing to be resolved about this question, but could not tell how I should. At last I asked my father of it, who told me, No, we [his father included] were not.”

In my Disquisition on the Gipsies I said:—

“Such a question is entertained by the Gipsies even at the present day, for they naturally think of the Jews, and wonder whether, after all, their race may not, at some time, have been connected with them. I have heard the same question put by Gipsy lads to their parent (a very much mixed Gipsy), and it was answered thus:—‘We must have been among the Jews, for some of our ceremonies are like theirs.’” (p. 511).

I presume that no one will question the assertions that Bunyan was a tinker, and that English “tinkers” are simply Gipsies of more or less mixed blood. Put together these three ideas—his description of his “father’s house,” and their not being Jews, but tinkers, that is, Gipsies of mixed blood—and you have the evidence or proof that John Bunyan was of the Gipsy race. If people are hanged on circumstantial evidence, cannot the same kind of proof be used to explain the language which Bunyan used to remind the world who and what he was, at a time when it was death by law for being a Gipsy, and “felony without benefit of clergy” for associating with them, and odious to the rest of the population? From all that we know of Bunyan, we could safely conclude that he was not the man to leave the world in doubt as to who and what he was. He even reminded it of what it knew well; but with his usual discretion he abstained from using a word that was banned by the law of the land and the more despotic decree of society, and concluded that it perfectly understood what he meant, although there was no necessity, or even occasion, for him to do what he did. [12]

Why then say that there is an “absolute want of evidence” in regard to Bunyan having been of the Gipsy race, and that it is “totally incapable of proof”; and assert that it is a fact that his ancestors were “landed proprietors,” and that there might be better grounds for holding p. 13that Bunyan was of Norman origin than of Gipsy descent?

Bunyan was either of the Gipsy race (of mixed blood) or of the native one. I have given the proof of the former—proof which, I think, is sufficient to hang a man. Where is the proof of his having been something else than of the Gipsy race? And if there is no proof of that, why assert it? What Bunyan said of his family was proof that he was not of the native race. Asserting as a fact that, from the surname, his ancestors were ordinary natives of England, and landed proprietors at that, is nearly as unreasonable as to maintain that every English Gipsy of the name of Stanley is nearly related to the Earl of Derby because his name is Stanley.

Like any one charged with an offense unbecoming Englishmen, almost any of them will protest that he has no prejudice against the name of Gipsy, and that “he would not have the smallest objection to believe that Bunyan was one of the race if the fact was only proved by sufficient evidence”; while at the same time he will retain and manifest his prejudices, and entirely ignore the evidence, or refuse to say in what respect it is deficient, and believe the opposite, or something entirely different from it, without a particle of proof in its favour, or entirely disproved by Bunyan’s admission in regard to his “father’s house.”

The Gipsy subject will not always remain in its present position. It will sooner or later have a resurrection, when some one will see who were the “goats” on the occasion. Bunyan will occupy a very important position in what is now represented by the following extract from my Disquisition on the Gipsies, published in London in 1865:—

“It is beyond doubt that there cannot be less than a quarter of a million of Gipsies in the British Isles, who are living under a grinding despotism of caste; a despotism so absolute and odious that the people upon whom it bears, cannot, as in Scotland, were it almost to save their lives, even say who they are!” (p. 440).

The main thing to be considered in regard to Mr. Brown is to ascertain his motive for investigating the question whether or not John Bunyan was of the Gipsy race, and the steps he took to that end. I am satisfied that his only motive, from first to last, has been to get rid, under any circumstances, of what he considers a stigma cast on Bunyan’s memory. He is apparently entirely ignorant of the subject of the Gipsies, and will listen to nothing that bears on Bunyan’s nationality. How then does it happen that he should step out into the world and say so positively that Bunyan was not of the Gipsy race? His first “proof” was the discovery that the name of Bunyan existed in England before the Gipsies arrived in it, so that on that account John Bunyan’s family could not have been Gipsies, but a broken-down branch of an aristocratic family! That “proof” proving worthless, he has recourse to what he finds to have been Bunyan’s ancestor, apparently on the “native side of the house,” viz.: Thomas Bonyon, who succeeded his father, William Bonyon, in 1542, to the property of “Bunyan’s End,” that is, a cottage and nine acres of land, about a mile from Elstow Church. This Thomas is described as “a labourer, and his wife as a brewer of beer and ‘a baker p. 14of human bread.’” In my Disquisition on the Gipsies I said in regard to John Bunyan:—

“Beyond being a Gipsy it is impossible to say what his pedigree really was. His grandfather might have been an ordinary native, even of fair birth, who, in a thoughtless moment, might have ‘gone off with the Gipsies;’ or his ancestor on the native side of the house might have been one of the ‘many English loiterers’ who joined the Gipsies on their arrival in England, when they were ‘esteemed and held in great admiration’” (p. 518). And, “Let a Gipsy once be grafted upon a native family and she rises with it; leavens the little circle of which she is the centre, and leaves it and its descendants for all time coming Gipsies” (p. 412). [14a]

Thomas Bonyon seems to have been born about 1502, [14b] and was apparently of the native race, as was probably his wife; but between him and Thomas (John’s grandfather), whose will was dated in 1641, there were doubtless several generations. Without asking with whom each generation of this family married, Mr. Brown says:—“Here, then, we have a family living certainly in the same cottage and cultivating the same land from 1542 to 1641, and probably much earlier, a fact which seems to me utterly fatal to the theory of Gipsy blood”—assuming that the blood of the family through marriage was native English all the way down; and that they cultivated the nine acres of land, and did not rent or sell it, for Thomas Bunyan by his will, dated in 1641, leaves “the cottage or tenement wherein I doe now dwell.” This Thomas could not have been less than the grandson of the first-mentioned Thomas, and described himself in his will, dated November 20th, 1641, as a “pettie chapman”—a calling that is very common with Gipsies of mixed blood. The will of his son Thomas (John’s father) is dated May 28th, 1675, in which he describes himself as a “braseyer”—which is a favourite word with the Gipsies, and sounds better than tinker, and is frequently put on their tombstones. Mr. Brown says:—“From this it appears that Bunyan’s father was the first tinker in the family.” Instead of that, he should have said that it was the first one found in a will. Again he says that he has discovered from the annual returns of the parishes in Bedfordshire between 1603 and 1650, that “the families both of Bunyan’s father and of his mother, Margaret Bentley, were living there all this time as steadily as any of the other village families, and as unlike a Gipsy encampment as can well be conceived.” He found no such information in “annual parish returns,” but perhaps merely the fact of Bunyan’s father having had his legal and general residence at the cottage, while he followed his calling of tinkering all over the neighbourhood, as regulated by the chief of the tinkers or Gipsies for the district. Beyond the cottage being the residence of Thomas, we know nothing of his movements, nor of the company coming to his house; and if p. 15Mr. Brown had known anything of the subject of the Gipsies, or been willing to learn it from others, he would not have concluded that the Bunyans were not of that race, merely because they might not (as they probably did not) use a tent. It would appear that Mr. Brown has not mastered even the first principle of this subject, so as to be able to define what is meant by it being said that Bunyan was or was not of the Gipsy race.

Thomas Bonyon, in 1542, called a “labourer” in a legal document or record, and his wife a “brewer and baker,” appear to have kept a little wayside public-house, which would be frequented by the Gipsies, especially when they were “esteemed and held in great admiration.” And here it is likely that the native English Bunyans were changed into English Gipsy Bunyans by the male heir of Thomas marrying a Gipsy, whose son or grandson was Thomas, the “pettie chapman”; and whose son Thomas, the “braseyer,” was the father of John. All these would doubtless marry early, but perhaps not so early as John, who married before he was nineteen, so far as is known.

In my communication of the 6th September, I think I said enough on the question of proof as to Bunyan having been of the Gipsy race. Even with the limited knowledge about the race generally, and especially about the mixture of its blood, before I published a history of the Gipsies, Sir Walter Scott (an excellent judge), with reference to the rank of his father’s house, and not being Jews, but tinkers, said that Bunyan was “most probably a Gipsy reclaimed.” Mr. Offor, an editor of Bunyan’s works, said that “his father must have been a Gipsy.” Mr. Leland’s investigation and decision is that he “was a Gipsy,” even apparently on the sole ground of his having been a tinker. In regard to myself, Mr. Brown says that I have “really nothing to go upon but Bunyan’s own words, in which he says that his father’s house was ‘of that rank that is meanest and most despised of all the families of [in] the land,’ which might simply mean that his father was a poor man in a village”(!) According to Mr. Brown, Bunyan’s admission, or rather reminder, had no bearing on his nationality, while others think it conclusive, apart from his having been a tinker. But Mr. Brown did not give all of Bunyan’s language, for he left out the most important part of it, which was that of his descent, which was well known to many to have been of a low and inconsiderable generation, which had no reference to his “father being a poor man in a village.” He also omitted Bunyan’s question as to his “father’s house” being or not being Jews, using the word we in both instances; a discussion that could not have taken place between a father and a son of any of the ordinary race of Englishmen. In this way Mr. Brown gets rid of the proof that proceeded from Bunyan himself, by simply brushing it aside. When I saw him in New York, I alluded to all of Bunyan’s admissions, when he replied, “Oh, that can be easily explained.” [15a] And when I said that “one cannot say in England that Bunyan was a Gipsy, for society would not allow it,” he made no reply, so far as I noticed, but appeared to wince at the remark. I had some hesitation in giving Mr. Brown an interview, for I was satisfied that he did not wish to have the truth about Bunyan admitted; but I concluded that, having sent him some pamphlets, it would have been rude to refuse him one. [15b] It lasted only about p. 16five minutes, at the entrance of a banking-house in Broadway, and ended with some remarks about his having found the wills of the Bunyans; not one word of which was to the point in question. His only motive for an interview seemed to be to gratify his curiosity and behold the person who would dare to “cast a stigma on Bunyan’s memory.” Now he says that there is no “ferocious prejudice of caste against the name of Gipsy,” and that “none of Bunyan’s admirers would object to his being shown to be a Gipsy, if only sufficient proof were adduced”; while he has ignored everything that bears upon the subject, even what came out of Bunyan’s mouth. [16a] In place of being influenced by evidence, he put forth the fanciful idea that he could not have been a Gipsy because the name of Bunyan existed in England before the Gipsies arrived there. And now he maintains that Bunyan could not have been a Gipsy, because he owed his descent “on the native side of the house” to Thomas Bonyon, a labourer or publican or both, born about 1502, without regard to the “marriages and movements” of perhaps five or six generations till the birth of the immortal dreamer, who was baptized on the 30th November, 1628.

But for the limited space at my disposal I would put a long string of questions to Mr. Brown, and suggest a course of action for him to undo the injury he has done to Bunyan and the Gipsy race generally, particularly owing to his remarks about the illustrious pilgrim having been credited and circulated by the press in Great Britain, which complicates the question in all its bearings. [16b] We p. 17have heard much of the American John Brown in connexion with the emancipation of the Negroes in the United States, while the English John Brown seems to be doing his best, directly or indirectly, to rivet the fetters of a social despotism on a large body of his fellow-creatures in the British Islands.

I have said above that Thomas Bonyon and his wife, living in 1542, were apparently of the native English race, and made my remarks to correspond with that idea. But there was more than a possibility of them having been part of the original Gipsy stock, of mixed blood, that arrived in Great Britain before 1506, and, like their race generally, assumed the surname of a “good family in the land,” as I will illustrate at some length in my next communication, which will make its appearance in due time.

I said in my communication of the 8th that there was more than a possibility of Thomas Bonyon and his wife, in 1542, having been of the original stock of Gipsies, of mixed blood, that assumed the surname of a “good family in the land.” As illustrative of this question, we have a writ of the Scots’ parliament, of the 8th April, 1554, pardoning thirteen Gipsies for the slaughter of Ninian Small, their names being the following:—“Andro Faw, captain of the Egyptians, George Faw, Robert Faw, and Anthony Faw, his sons, Johnne Faw, Andrew George Nichoah, George Sebastiane Colyne, George Colyne, Julie Colyne, Johnne Colyne, James Haw, Johnne Browne, and George Browne, Egyptians.” There being thus Gipsies of the name of Brown (and, oddly enough, one called John Brown), in Scotland before 1554, we should have no difficulty in believing that there were, or might have been, some in England of the name of Bonyon in 1542. The only native name assumed by the tribe in Scotland before 1540, when they were noticed officially, was Bailyow, or Baillie. And how did we have Gipsies in Scotland of the name of Brown (apparently the only native name, except Baillie), in a public document before 1554? Between 1506 and 1579 was the “golden age” of the Gipsies in Scotland, excepting (nominally, at least) the year 1541–2, for, on the 6th June, 1541, they were ordered to leave the realm within thirty days, on pain of death, owing to an attack made by them on James V. while roaming over the country in disguise. “But the king, whom, according to tradition, they had personally so deeply offended, dying in the following year (1542), a new reign brought new prospects to the denounced wanderers” (His., p. 107). There is a tradition that the Gipsies were in Scotland before 1460, for McLellan of Bombie happening to kill a chief of some “Saracens or Gipsies from Ireland,” was reinstated in the Barony of Bombie, and took for his crest a Moor’s head, and “Think on” for his motto. And it is a tradition amongst all the Scottish Gipsies that their ancestors came by way of Ireland into Scotland. How, then, were there Gipsies described, in a writ of the Scots’ parliament, by the names of John and George Brown in 1554? In no other apparent way, during their “golden age,” than that a native p. 18or natives of that name had married into the tribe, and that the two Browns, perhaps brothers, mentioned were the issue, and grown-up men at that; so that the marriage could not have taken place later than 1533, and probably considerably earlier. There was little chance of a Scotch lawyer describing these two Browns as “Egyptians” unless they had been the children of a native father, or had previously assumed the surname of Brown; the first being the most probable. [18]

If we can imagine that William Bonyon, the first of the name mentioned by Mr. Brown, had been a native of England, and, like the Scotch Brown, had married a Gipsy, we would have found Thomas, in 1542, a member of the tribe. It was not necessary that he should have been 40 years old in 1542, or that the property of “Bunyan’s End” “had probably been in the possession of the family long before 1542”; or that William had not died in middle life, leaving Thomas a young man, born of a Gipsy mother. Even William might have been one of the original Gipsies, of mixed blood, that is, “such a ‘foreign tinker’ as is alluded to in the Spanish Gipsy edicts, and in the Act of Queen Elizabeth, in which mention is made of ‘strangers,’ as distinguished from natural-born subjects, being with the Gipsies . . . It is therefore very likely that there was not a drop of common English blood in Bunyan’s veins. John Bunyan belongs to the world at large, and England is only entitled to the credit of the formation of his character” (p. 518). He might have assumed the name of Bonyon and bought “Bunyan’s End,” when the severe law was passed by Henry VIII. against the race about 1530. Thomas might have been an ordinary native of England and married a Gipsy who was a “brewer and baker,” possibly of the second generation of the race born in England. She seems to have been a “lawless lass” of some kind, for Mr. Brown says that it is on record that “between 1542 and 1550 she was fined six or eight times for breaking the assize of beer and bread.” On this head I said in the Disquisition on the Gipsies:—“Considering what is popularly understood to be the natural disposition and capacity of the Gipsies, we would readily conclude that to turn innkeepers would be the most unlikely of all their employments; yet that is very common” (p. 467), all over Europe from almost the day of their arrival in it. It is no uncommon thing for English Gipsies who have the means to buy a small house with a little ground attached on landing in America, even should they not always occupy it personally. I have been informed of several such p. 19purchases, and knew the owner of one “homestead” intimately, and was often in his house. And this seems to have been a trait in the character of the superior Gipsies of mixed blood in Great Britain, perhaps from the time of their arrival.

With regard to the pedigree of John Bunyan, the most probable one seems to be the following:—William Bonyon and his wife were apparently ordinary English people, which would make Thomas of the same race. [19] His wife—the “lawless brewer and baker”—was either of the native race or of a superior class of mixed Gipsies, perhaps of the second generation born in England. If she was the former, the male heir of Thomas married a Gipsy while he kept his little wayside public-house, leading to their issue being turned into the Gipsy current in society. Thus the little property of “Bunyan’s End” (at least the cottage) would remain in the family, leading to a will being made to bequeath it from generation to generation. “Petty chapmen and tinkers” (using brazier instead of tinker) are the happiest words that could be used to describe many Gipsies of mixed blood in England to-day.

A remark in the Graphic for the 26th August, in adopting Mr. Brown’s theory that all that sprung from Thomas Bonyon, in 1542, were ordinary natives of England, makes it very plain what is the motive for not having it said that Bunyan was of the Gipsy race, viz.: to show that his were “positively respectable” people, and not “tinkering Gipsies.” Petty chapmen and tinkers, if of the native race, would be “positively respectable,” but not if they had had a “dash” of Gipsy blood in their veins (which might have improved them,) p. 20and held by the Gipsy connexion, if for no other reason than that the white blood would have disowned them if they had known of its existence. In this way they would be cut off from the native race, or would mix with it no further than was unavoidable; living thus as Gipsies incog., or as outcasts, for that is the right word to use till the Gipsy blood becomes acknowledged by the rest of the world. The Graphic “let the cat out of the bag,” and somewhat illustrated what I meant when I spoke of the “ferocious prejudice of caste against the name of Gipsy.”

I refer to the Disquisition on the Gipsies and my subsequent writings on John Bunyan and the Gipsies, and add a few extracts from the Disquisition; all of which should have been studied by Mr. Brown before “putting his foot into” the subject in the way he has done, for that is of too sacred a nature to be treated factiously or capriciously.

“The world generally has never even thought about this subject. When I have spoken to people promiscuously in regard to it, they have replied, ‘We suppose that the Gipsies as they have settled in life have got lost among the general population’; than which nothing can be more unfounded as a matter of fact, or ridiculous as a matter of theory” (p. 454).—“What difficulty can there therefore be in understanding how a man can be a Gipsy whose blood is mixed, even ‘dreadfully mixed,’ as the English Gipsies express it? Gipsies are Gipsies, let their blood be mixed as much as it may, whether the introduction of the native blood may have come into the family through the male or the female line. In the descent of . . . the Gipsy race, the thing to be transmitted is not merely a question of family, but a race distinct from any particular family” (p. 451).—“The principle of progression, the passing through one phase of history into another, while the race maintains its identity, holds good with the Gipsies as well as with any other people” (p. 414).—“Take a Gipsy from any country in the world you may, and the feeling of his being a Gipsy comes as naturally to him as does the nationality of a Jew to a Jew; although we will naturally give him a more definite name to distinguish him, such as an English, Welsh, Scotch, or Irish Gipsy, or by whatever country of which the Gipsy happens to be a native” (p. 447).—“But it is impossible for any one to give an account of the Gipsies in Scotland from the year 1506 down to the present time. This much, however, can be said of them, that they are as much Gipsies now as ever they were; that is, the Gipsies of to-day are the representatives of the race as it appeared in Scotland three centuries and a half ago, and hold themselves to be Gipsies now, as indeed they always will do” (p. 466).—“The admission of the good man alluded to casts a flood of light upon the history of the Scottish Gipsy race, shrouded as it is from the eye of the general population; but the information given by him was apt to fall flat upon the ear of the ordinary native unless it was accompanied by some such exposition of the subject as is given in this work. Still, we can gather from it where Gipsies are to be found, what a Scottish Gipsy is, and what the race is capable of, and what might be expected of it, if the prejudice of their fellow-creatures was withdrawn from the race, as distinguished from the various classes into which it may be divided, or, I should rather say, the personal conduct of each Gipsy individually” (p. 415).—“It is a subject, however, which I have found some difficulty in getting people to understand. One cannot see how a person can be a Gipsy ‘because his father was a respectable man’; another, ‘because his father was an old soldier’; and another cannot see ‘how it necessarily follows that a person is a Gipsy for the reason that his parents were Gipsies’” (p. 505).

Apart from the prejudice of caste now existing against the Gipsies, and the novelty of the light in which the race is now presented, there should be no difficulty in understanding the subject in all its bearings. Every other race entering England has had justice done to it; and the same should not be withheld from people who claim to be “members of the Gipsy tribe,” although their blood, perhaps in the most of instances, is more of the ordinary than of the Gipsy race.

p. 21Ever since entering Great Britain, about the year 1506, the Gipsies have been drawing into their body the blood of the ordinary inhabitants and conforming to their ways; and so prolific has the race been, that there cannot be less than 250,000 Gipsies of all castes, colours, characters, occupations, degrees of education, culture, and position in life, in the British Isles alone, and possibly double that number. There are many of the same race in the United States of America. Indeed, there have been Gipsies in America from nearly the first day of its settlement; for many of the race were banished to the plantations, often for very trifling offences, and sometimes merely for being by “habit and repute Egyptians.” But as the Gipsy race leaves the tent, and rises to civilization, it hides its nationality from the rest of the world, so great is the prejudice against the name of Gipsy. In Europe and America together, there cannot be less than 4,000,000 Gipsies in existence. John Bunyan, the author of the celebrated Pilgrim’s Progress, was one of this singular people, as will be conclusively shown in the present work. The philosophy of the existence of the Jews, since the dispersion, will also be discussed and established in it.

When the “wonderful story” of the Gipsies is told, as it ought to be told, it constitutes a work of interest to many classes of readers, being a subject unique, distinct from, and unknown to, the rest of the human family. In the present work, the race has been treated of so fully and elaborately, in all its aspects, as in a great measure to fill and satisfy the mind, instead of being, as heretofore, little better than a myth to the understanding of the most intelligent person.

The history of the Gipsies, when thus comprehensively treated, forms a study for the most advanced and cultivated mind, as well as for the youth whose intellectual and literary character is still to be formed; and furnishes, among other things, a system of science not too abstract in its nature, and having for its subject-matter the strongest of human feelings and sympathies. The work also seeks to raise the name of Gipsy out of the dust, where it now lies; while it has a very important bearing on the conversion of the Jews, the advancement of Christianity generally, and the development of historical and moral science.

London, October 10th, 1865.

SIMSON’S HISTORY OF THE GIPSIES.

575 Pages. Crown 8vo. Price, $2.00.

NOTICES OF THE AMERICAN PRESS.

National Quarterly Review.—“The title of this work gives a correct idea of its character; the matter fully justifies it. Even in its original form it was the most interesting and reliable history of the Gipsies with which we were acquainted. But it is now much enlarged, and brought down to the present time. The disquisition on the past, present, and future of that singular race, added by the editor, greatly enhances the value of the work, for it embodies the results of extensive research and careful investigation.” “The chapter on the Gipsy language should be read by all who take any interest either in comparative philology or ethnology; for it is much more curious and instructive than most people would expect from the nature of the subject. The volume is well printed and neatly bound, and has the advantage of a copious alphabetical index.”

Congregational Review. (Beaton.)—“The senior partner in the authorship of this book was a Scotchman who made it his life-long pleasure to go a ‘Gipsy hunting,’ to use his own phrase. He was a personal friend of Sir Walter Scott. . . . His enthusiasm was genuine, his diligence great, his sagacity remarkable, and his discoveries rewarding.” “The book is undoubtedly the fullest and most reliable which our language contains on the subject.” “This volume is valuable for its instruction, and exceedingly amusing anecdotically. It overruns with the humorous.” “The subject in its present form is novel, and we freely add, very sensational.” “Indeed, the book assures us that our country is full of this people, mixed up as they have become, by marriage, with all the European stocks during the last three centuries. The amalgamation has done much to merge them in the general current of modern education and civilization; yet they retain their language with closest tenacity, as a sort of Freemason medium of intercommunion; and while they never are willing to own their origin among outsiders, they are very proud of it among themselves.” “We had regarded them as entitled to considerable antiquity, but we now find that they were none other than the ‘mixed multitude’ which accompanied the Hebrew exode (Ex. XII 38) under Moses—straggling or disaffected Egyptians, who went along to ventilate their discontent, or to improve their fortunes. . . . We are not prepared to take issue with these authors on any of the points raised by them.”

Methodist Quarterly Review.—“Have we Gipsies among us! Yea, verily, if Mr. Simson is to be believed, they swarm our country in secret legions. There is no place on the four quarters of the globe where some of them have not penetrated. Even in New England a sly Gipsy girl will enter the factory as employe, will by her allurements win a young Jonathan to marry her, and in due season, the ’cute gentleman will find himself the father of a young brood of intense Gipsies. The mother will have opened to her young progeny the mystery and p. 23the romance of its lineage, will have disclosed its birth-right connection with a secret brotherhood, whose profounder Freemasonry is based on blood, historically extending itself into the most dim antiquity, and geographically spreading over most of the earth. The fascinations of this mystic tie are wonderful. Afraid or ashamed to reveal the secret to the outside world, the young Gipsy is inwardly intensely proud of his unique nobility, and is very likely to despise his alien father, who is of course glad to keep the late discovered secret from the world. Hence dear reader, you know not but your next neighbour is a Gipsy.” “The volume before us possesses a rare interest, both from the unique character of the subject, and from the absence of nearly any other source of full information. It is the result of observation from real life.” The language “is spoken with varying dialects in different countries, but with standard purity in Hungary. It is the precious inheritance and proud peculiarity of the Gipsy, which he will never forget and seldom reveal. The varied and skillful manœuvres of Mr. Simeon to purloin or wheedle out a small vocabulary, with the various effects of the operation on the minds and actions of the Gipsies, furnish many an amusing narrative in these pages.” “Persecutions of the most cruel character have embittered and barbarized them. . . . Even now . . . they do not realize the kindly feeling of enlightened minds toward them, and view with fierce suspicion every approach designed to draw from them the secrets of their history, habits, laws and language.” “The age of racial caste is passing away. Modern Christianity will refuse to tolerate the spirit of hostility and oppression based on feature, colour, or lineage.” The “book is an intended first step for the improvement of the race that forms its subject, and every magnanimous spirit must wish that it may prove not the last. We heartily commend the work to our readers as not only full of fascinating details, but abounding with points of interest to the benevolent Christian heart.” “The general spirit of the work is eminently enlightened, liberal, and humane.”

Evangelical Quarterly Review.—“The Gipsies, their race and language have always excited a more than ordinary interest. The work before us, apparently the result of careful research, is a comprehensive history of this singular people, abounding in marvelous incidents and curious information. It is highly instructive, and there is appended a full and most careful index—so important in every work.”

National Freemason.—“We feel confident that our readers will relish the following concerning the Gipsies, from the British Masonic Organ: That an article on Gipsyism is not out of place in this Magazine will be admitted by every one who knows anything of the history, manners, and customs of these strange wanderers among the nations of the earth. The Freemasons have a language, words, and signs peculiar to themselves; so have the Gipsies. A Freemason has in every country a friend, and in every climate a home, secured to him by the mystic influence of that worldwide association to which he belongs; similar are the privileges of the Gipsy. But here, of course, the analogy ceases. Freemasonry is an Order banded together for purposes of the highest benevolence. Gipsyism, we fear, has been a source of constant trouble and inconvenience to European nations. The interest, therefore, which as Masons we may evince in the Gipsies arises principally, we may say wholly, from the fact of their being a secret society, and also from the fact that many of them are enrolled in our lodges. . . . There are p. 24in the United Kingdom a vast multitude of mixed Gipsies, differing very little in outward appearance, manners, and customs from ordinary Britons; but in heart thorough Gipsies, as carefully and jealously guarding their language and secrets, as we do the secrets of the Masonic Order.” “Mr. Simson makes masterly establishment of the fact that John Bunyan, the world-renowned author of the ‘Pilgrim’s Progress,’ was descended from Gipsy blood.”

New York Independent.—“Such a book is the History of the Gipsies. Every one who has a fondness for the acquisition of out-of-the-way knowledge, chiefly for the pleasure afforded by its possession, will like this book. It contains a mass of facts, of stories, and of legends connected with the Gipsies; a variety of theories as to their origin . . . and various interesting incidents of adventures among these modern Ishmaelites. There is a great deal of curious information to be obtained from this history, nearly all of which will be new to Americans.” “It is singular that so little attention has been heretofore given to this particular topic; but it is probably owing to the fact that Gipsies are so careful to keep outsiders from a knowledge of their language that they even deny its existence.” “The history is just the book with which to occupy one’s idle moments; for, whatever else it lacks, it certainly is not wanting in interest.”

New York Observer.—“Among the peoples of the world, the Gipsies are the most mysterious and romantic. Their origin, modes of life, and habits have been, until quite recently, rather conjectural than known. Mr. Walter Simson, after years of investigation and study, produced a history of this remarkable people which is unrivalled for the amount of information which it conveys in a manner adapted to excite the deepest interest.” “We are glad that Mr. James Simson has not felt the same timidity, but has given the book to the public, having enriched it with many notes, an able introduction, and a disquisition upon the past, present, and future of the Gipsy race.” “Of the Gipsies in Spain we have already learned much from the work of Borrow, but this is a more thorough and elaborate treatise upon Gipsy life in general, though largely devoted to the tribe as it appeared in England and Scotland.” “Such are some views and opinions respecting a curious people, of whose history and customs Mr. Simson has given a deeply interesting delineation.”

New York Methodist.—“The Gipsies present one of the most remarkable anomalies in the history of the human race. Though they have lived among European nations for centuries, forming in some districts a prominent element in the population, they have succeeded in keeping themselves separate in social relations, customs, language, and in a measure, in government, and excluding strangers from real knowledge of the character of their communities and organizations. Scarcely more is known of them by the world in general than was know when they first made their appearance among civilized nations.” “Another curious thing advanced by Mr. Simson is that of the perpetuity of the race . . . He thinks that it never dies out, and that Gipsies, however much they may intermarry with the world’s people, and adopt the habits of civilisation, remain Gipsies, preserve the language, the Gipsy mode of thought, and loyalty to the race and its traditions to remote generations. His work turns, in fact, upon these two theories, and the incidents, p. 25facts, and citations from history with which it abounds, are all skillfully used in support of them.” “There are some facts of interest in relation to the Gipsies in Scotland and America, which are brought out quite fully in Mr. Simson’s book,” which “abounds in novel and interesting matter . . . and will well repay perusal.” “Pertinent anecdotes, illustrating the habits and craft of the Gipsies, may be picked up at random in any part of the book.”

New York Evening Post.—“The editor corrects some popular notions in regard to the habits of the Gipsies. They are not now, in the main, the wanderers they used to be. Through intermarriage with other people, and from other causes, they have adopted more stationary modes of life, and have assimilated to the manners of the countries in which they live. As the editor of this volume says: ‘They carry the language, the associations, and the sympathies of their race, and their peculiar feelings toward the community with them; and, as residents of towns, have greater facilities, from others of their race residing near them, for perpetuating their language, than when strolling over the country.’” “We have no space for such full extracts as we should like to give.”

New York Journal of Commerce.—“We have seldom found a more readable book than Simson’s History of the Gipsies. A large part of the volume is necessarily devoted to the local histories of families in England (Scotland), but these go to form part of one of the most interesting chapters of human history.” “We commend the book as very readable, and giving much instruction on a curious subject.”

New York Times.—“Mr. . . . has done good service to the American public by reproducing here this very interesting and valuable volume.” “The work is more interesting than a romance, and that it is full of facts is very easily seen by a glance at the index, which is very minute, and adds greatly to the value of the book.”

New York Albion.—“An extremely curious work is a History of the Gipsies.” “The wildest scenes in ‘Lavengro,’ as for instance the fight with the Flaming Tinman, are comparatively tame beside some of the incidents narrated here.”

Hours at Home (now Scribner’s Monthly).—“Years ago we read, with an interest we shall never forget, Borrow’s book on the Gipsies of Spain. We have now a history of this mysterious race as it exists in the British Islands, which, though written before Borrow’s, has just been published. It is the result of much time and patient labor, and is a valuable contribution toward a complete history of this extraordinary people. The Gipsy race and the Gipsy language are subjects of much interest, socially and ethnologically.” “He estimates the number of Gipsies in Great Britain at 250,000, and the whole number in Europe and America at 4,000,000.” “The work is what it professes to be, a veritable history—a history in which Gipsy life has been stripped of everything pertaining to fiction, so that the reader will see depicted in their true character this strange people . . . And yet, these pages of sober history are crowded with facts and incidents stranger and more thrilling than the wildest imaginings of the romantic school.”

NEW YORK: JAMES MILLER.

“In this pamphlet Mr. James Simson again does battle in support of his contention that Bunyan was a Gipsy—a thesis first promulgated by him in an elaborate work on the Gipsies, published in 1865. He is indignant at Mr. Froude for ignoring the discussion of the question in his recent biography of Bunyan, and he comments in strong terms on the dicta of Mr. Francis H. Groome, in the article ‘Gipsies,’ in the new edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, that John Bunyan does not appear to have had one drop of Gipsy blood.’” “Mr. Simson’s tractate will be perused with deep interest by all students of the customs and history of the Gipsies.”—Edinburgh Courant, November 3, 1880.

“In this pamphlet Mr. James Simson, editor of Simson’s History of the Gipsies, states his grounds for believing that John Bunyan was a Gipsy, and invokes the assistance of the Universities to investigate the matter and put it beyond the possibility of doubt. It may not matter much whether or not the ‘immortal dreamer’ was a Gipsy and we do not think Mr. Simson attaches any great importance to the circumstance per se. What he aims at, we believe, is to stir up some interest in the Gipsy race, and this he thinks may be done were the public to have their sympathies awakened by the fact that John Bunyan was a descendant of it. By way of supplement, Mr. Simson criticises some statements made in an article in the Encyclopædia Britannica, on the Gipsies. The curious in the subject of Gipsy lore will doubtless find in the pamphlet matter that will interest them.”—Perthshire Advertiser, October 28, 1880.

“Mr. Simson suggests, and supports, on arguments that have the highest bearing on anthropological questions, the theory that John Bunyan was a Gipsy. The great secret that civilised Europe has even now amongst it a few individuals who are descended from a Hindoo race, and are capable, by reason of the fact that they have a particularly original soul of their own, to reconcile some of the difficulties between the eastern and the western schools of thought, may be the real future fact of modern anthropology. The difficulty is, of course, where and how to find the Gipsies. We have been much pleased with Mr. Simson’s pamphlet. It is not every writer who has treated the subject in his philosophical manner; and we are glad to perceive that he strongly accents the fact that a person may be a Gipsy and yet be entirely ignorant [not absolutely so] of the Gipsy language. Evidently Mr. Simson has studied anthropological problems at first hand, and apart from the speculators who have regarded language as the first key to the science of man.”—Public Opinion, October 15, 1880.

“That Mr. Simson had a duty—to himself as well as to the public—to perform in justifying his previous remarks about Charles Waterton, by writing this monograph, is unquestionable. Although it is a somewhat difficult task unsparingly to point out the mistakes and shortcomings of a man, when he can no longer defend himself, without seeming to be guilty of an offence against the old rule—Nil nisi bonum de mortuis—Mr. Simson may fairly claim credit for having adhered to the Shakespearian advice in regard to fault-finding; for, if he has extenuated nothing, he has set down naught in malice. The example of Charles Waterton, country gentleman and naturalist, may serve as a useful warning to students of natural history, by teaching them that only the most patient investigation and careful reflection can produce results that will be of real and permanent value to science. They have here the example of a man who had most excellent opportunities for such investigations, as well as the strongest taste for their pursuit, and who, by an exact and systematic method of study, might have made most important additions to our knowledge of natural history. But by inaccurate observation, by a certain looseness of statement, and by taking things for granted instead of personally verifying them, he has greatly diminished the value of his labours. Mr. Simson, though his task is to set right the unduly high estimate in which the squire of Walton Hall has been held as a man of science, shows an appreciation of the strong points of his character that completely takes away any appearance of censoriousness; and his work incidentally affords an interesting study of the man himself, who, in his personal life and his enthusiastic devotion to natural history, showed a strong individuality that is quite refreshing in this age of conventionalities.”—Aberdeen Journal, August 30, 1880.

210 Pages, Octavo, Cloth. Price, $1.25.

CONTRIBUTIONS TO NATURAL

HISTORY,

AND PAPERS ON OTHER SUBJECTS.

BY JAMES SIMSON,

EDITOR OF SIMSON’S “HISTORY OF

THE GIPSIES.”

NOTICES OF THE BRITISH PRESS.

Dublin University Magazine, July, 1875.

“The principal articles in this volume that have reference to natural history originally appeared in Land and Water, and are, in many respects, highly interesting. Concerning vipers and snakes, we are presented with a good deal of information that is instructive, not only as regards their habits generally, but also with respect to points that are in dispute among naturalists.” “For instance, it is a vexed question whether, under any circumstances, the young retreat into the stomach [inside] of the mother snake. A great authority, [?] Mr. Frank Buckland, affirms that they do not; while our author is as positive that they do. And he certainly, with reason, contends that the question is entirely one of evidence, and, therefore, should be settled ‘as a fact is proved in a court of justice; difficulties, suppositions, or theories not being allowed to form part of the testimony.’” “In support of his own views, Mr. Simson has collected a large body of evidence that undoubtedly appears authentic and conclusive.” “Of the miscellaneous papers in this volume, the best is a critical study of the late John Stuart Mill. Taken altogether, the volume is very entertaining, and affords pleasing and instructive reading.”

Evening Standard, June 8, 1875.

“It is with real pleasure we see these Contributions to Land and Water no longer limited to the columns of a newspaper, whatever may be its circulation. For the excellence and charm of these papers we must refer the reader to the volume before us, which cannot fail to interest and instruct its readers. Their variety and range may be gathered from the subjects treated:—Snakes, Vipers, English Snakes, Waterton as a Naturalist, John Stuart Mill, History of the Gipsies, and the Duke of Argyll on the Preservation of the Jews.”

London Courier, June, 1875.

“The Natural History Contributions, which are very interesting, though partaking largely of a controversial nature, deal chiefly with questions affecting snakes and vipers. Of the other Contributions, the most attractive and readable is the one which contests some of Mr. Borrow’s conclusions in his well-known account of the Gipsies. Mr. John Stuart Mill forms the subject of a slashing dissertation, which is not likely to find much favour with the friends of the departed philosopher.”

Rochdale Observer, June 19, 1875.

“The study of natural history has a peculiar charm for most people, but for Lancashire folk it seems to have a special interest. Perhaps the most striking feature of the book at the head of this notice is the variety of topics touched upon, p. 28topics which, although apparently incompatible and incongruous, are, nevertheless, both curious and interesting. The author certainly brings a large amount of special knowledge to the discussion of the questions he introduces, and the essays are undoubtedly well written. Our readers will see that the work is full of controversial matter, embracing natural history, theology, and biography, and consequently will suit the taste of those who like to enter into discussions which excite the feelings, and in which abundance of energy and ability is displayed. The book is certainly ably written, and the author shows himself to be a man of large accomplishments.”

Liverpool Albion, June 18, 1875.

“The articles are written in a very readable manner, and will be found interesting even by those who have no special knowledge of natural history or interest in it. The Gipsies are competitors with the snakes for Mr. Simson’s regards, and several papers are devoted to these mysterious nomadic tribes. Perhaps the most curious paper in the volume is written to prove that John Bunyan was a Gipsy, and a very fair case is certainly made out, principally from Bunyan’s own autobiographical statements. With the exception of the papers on John Stuart Mill, to which we have already alluded, and which are far worse than worthless, the book is one which we can recommend.”

Newcastle Courant, June 11, 1875.

“The bulk of these Contributions appeared in Land and Water. We think the author has done well to give them to the public in the more enduring form of a well got up volume. The book contains, also, a critical sketch of the career of John Stuart Mill; some gossip about Gipsies; and the Duke of Argyll’s notions about the preservation of the Jews. Altogether, the book is very readable.”

Northern Whig, June 17, 1875.

“This volume consists of Contributions to Land and Water by a writer well-known as the author [editor] of a standard book on the Gipsies, and is evidently the production of a clear, intelligent, and most observant mind. Mr. Simson adds a number of miscellaneous papers, including a masterly, though severe, criticism of John Stuart Mill—‘his religion, his education, a crisis in his history, his wife, Mill and son,’—as well as several desultory papers on the Gipsies, elicited, for the most part, by criticisms on his work on that singular race.”

Western Times, June 29, 1875.

“The preface to this volume is dated from New York, and the contents bear marks of the free, racy style of transatlantic writers. The volume closes with a paper on the ‘Preservation of the Jews.’ The writer deals with his several subjects with marked ability, and his essays form a volume which will pay for reading, and therefore pay for purchasing.”

Daily Review, June 11, 1875.

“We need only mention the other subjects—Waterton as a Naturalist, Romanism, John Stuart Mill, Simson’s History of the Gipsies, Borrow on the Gipsies, the Scottish Churches and the Gipsies, Was John Bunyan a Gipsy? and, of course, the literary ubiquitous Duke of Argyll on the Preservation of the Jews. The only paper we have not ventured to look at is the last, in the dread that on this question the versatile Duke might be found, as in the matter of the Scottish Church, verifying the French proverb—Il va chercher midi à quatorze heures—a work in which the author of this volume is an adept in quiet, quaint, and clever ways, however, which make it interesting.”

NEW YORK: JAMES MILLER.

|

PAGE |

|

Vipers and Snakes generally |

7 |

|

White of Selborne on the Viper |

10 |

|

White of Selborne on Snakes |

17 |

|

Snakes swallowing their young |

23 |

|

Snakes swallowing their young |

25 |

|

Snakes charming birds |

30 |

|

Mr. Frank Buckland on English Snakes |

31 |

|

Mr. Gosse on the Jamaica Boa swallowing her young |

33 |

|

American Snakes |

36 |

|

American Science Convention on Snakes |

36 |

|

Charles Waterton as a Naturalist |

39 |

|

Romanism |

49 |

|

John Stuart Mill: a Study. |

||

|

His Religion |

69 |

|

His Education |

82 |

|

A Crisis in his History |

90 |

|

His Wife |

97 |

|

Mill and Son |

105 |

Simson’s History of the Gipsies |

111 |

|

Mr. Borrow on the Gipsies |

112 |

|

The Scottish Churches and the Social Emancipation of the Gipsies |

150 |

|

Was John Bunyan a Gipsy? |

157 |

|

The Duke of Argyll on the Preservation of the Jews |

161 |

|

Index |

171 |

|

Appendix. |

||

I. |

John Bunyan and the Gipsies |

183 |

II. |

Mr. Frank Buckland and White of Selborne |

187 |

III. |

Mr. Frank Buckland on the Viper |

192 |

IV. |

The Endowment of Research |

199 |

[9] Dated 30th August, 1882.

[10a] Contributions to Natural History, etc., p. 158.

[10b] I have commented on the assertion of Mr. Groome, that “John Bunyan, from parish registers, does not appear to have had one drop of Gipsy blood,” as if that could have been ascertained from parish registers! I did not expect to find such a loose idea as that in the Encyclopædia Britannica, taken from a casual or stray contributor to Notes and Queries. But I find an English journal quoting it as a proof that Bunyan was not of the Gipsy race; and supporting it by Mr. Froude’s ignoring the question in his highly conventional work on Bunyan.—The Scottish Churches and the Gipsies, pp. 11, 52 and 59.

[11a] Mr. Brown objects to its being said that the English Bunyans could have sprung from Bunyans that left Scotland fifty years before 1548, for the reason that he finds men of that name in England, in 1219, 1257 and 1310. Thomas Bunyan, if he is correct in his information, says that the Italian mason of the name of Bunyan was at Melrose in 1136. The name might have had its origin in foreign masons called Bunyan, as there would be families of that craft, continued from generation to generation, during the middle ages, employed in church architecture all over Europe, including England as well as Scotland. I have not seen Mr. Thomas Bunyan’s information, as quoted above, called in question by any one.

[11b] Dated 6th September, 1882.

[11c] In an article in Notes and Queries, for the 27th March, 1875, I said:—“In addition to the investigations made in church registers, I would suggest that the records of the different criminal courts in Bedfordshire (if they still exist) should be examined, to find if people of the name of Bunyan (and how designated) are found to have been on trial, and for what offences.”—Contributions, etc., p. 186.