Title: Strange Survivals: Some Chapters in the History of Man

Author: S. Baring-Gould

Release date: May 9, 2016 [eBook #52024]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Elisa and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive).

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

Old Country Life. Large Crown 8vo, 10s. 6d.

Historic Oddities and Strange Events. Crown 8vo, 6s.

Freaks of Fanaticism. Crown 8vo, 6s.

Songs of the West: Traditional Ballads and Songs of the West of England, with their Traditional Melodies. Parts I., II., and III., 3s. each; Part IV., 5s. Complete in one Vol., French Morocco, gilt edges, 15s.

Yorkshire Oddities and Strange Events. Crown 8vo, 6s.

In the Roar Of the Sea: A Tale of the Cornish Coast. Crown 8vo, 6s.

Jacquetta, and other Stories. Crown 8vo, 3s. 6d. Boards, 2s.

Arminell: A Social Romance. Crown 8vo, 3s. 6d. Boards, 2s.

Urith: A Story of Dartmoor. Crown 8vo, 3s. 6d.

Margery Of Quether, and other Stories. Crown 8vo, 3s. 6d.

The Tragedy of the Cæsars: The Emperors of the Julian and Claudian Lines. 2 Vols., Royal 8vo.

[In the Press.

RIDGE TILE, TOTNES.

Frontispiece.

STRANGE SURVIVALS

Some Chapters in the History of Man

BY

S. BARING-GOULD, M.A.

AUTHOR OF “MEHALAH,” “OLD COUNTRY LIFE,” “URITH,”

“IN THE ROAR OF THE SEA.”

Methuen & Co.

18 BURY STREET, LONDON, W.C.

1892.

Printed by Cowan & Co., Limited, Perth.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. | On Foundations | 1 |

| II. | On Gables | 36 |

| III. | Ovens | 62 |

| IV. | Beds | 84 |

| V. | Striking a Light | 110 |

| VI. | Umbrellas | 129 |

| VII. | Dolls | 139 |

| VIII. | Revivals | 149 |

| IX. | Broadside Ballads | 180 |

| X. | Riddles | 220 |

| XI. | The Gallows | 238 |

| XII. | Holes | 252 |

| XIII. | Raising the Hat | 282 |

STRANGE SURVIVALS:

SOME CHAPTERS IN THE HISTORY OF MAN.

When the writer was a parson in Yorkshire, he had in his parish a blacksmith blessed, or afflicted—which shall we say?—with seven daughters and not a son. Now the parish was a newly constituted one, and it had a temporary licensed service room; but during the week before the newly erected church was to be consecrated, the blacksmith’s wife presented her husband with a boy—his first boy. Then the blacksmith came to the parson, and the following conversation ensued:—

Blacksmith: “Please, sir, I’ve gotten a little lad at last, and I want to have him baptised on Sunday.”

Parson: “Why, Joseph, put it off till Thursday, when the new church will be consecrated; then your little man will be the first child christened in the new font in the new church.”

Blacksmith (shuffling with his feet, hitching his shoulders, looking down): “Please, sir, folks say that[2] t’ fust child as is baptised i’ a new church is bound to dee (die). T’ old un (the devil) claims it. Now, sir, I’ve seven little lasses, and but one lad. If this were a lass again ’twouldn’t ’a’ mattered; but as it’s a lad—well, sir, I won’t risk it.”

A curious instance this of a very widespread and very ancient superstition, the origin of which we shall arrive at presently.

In the first place, let us see the several forms it takes.

All over the north of Europe the greatest aversion is felt to be the first to enter a new building, or to go over a newly erected bridge. If to do this is not everywhere and in all cases thought to entail death, it is considered supremely unlucky. Several German legends are connected with this superstition. The reader, if he has been to Aix-la-Chapelle, has doubtless had the rift in the great door pointed out to him, and has been told how it came there. The devil and the architect made a compact that the first should draw the plans, and the second gain the Kudos; and the devil’s wage was to be that he should receive the first who crossed the threshold of the church when completed. When the building was finished, the architect’s conscience smote him, and he confessed the compact to the bishop. “We’ll do him,” said the prelate; that is to say, he said something to this effect in terms more appropriate to the century in which he lived, and to his high ecclesiastical office.

When the procession formed to enter the minster for the consecration, the devil lurked in ambush behind[3] a pillar, and fixed his wicked eye on a fine fat and succulent little chorister as his destined prey. But alas for his hopes! this fat little boy had been given his instructions, and, as he neared the great door, loosed the chain of a wolf and sent it through. The evil one uttered a howl of rage, snatched up the wolf and rushed away, giving the door a kick, as he passed it, that split the solid oak.

The castle of Gleichberg, near Rönskild, was erected by the devil in one night. The Baron of Gleichberg was threatened by his foes, and he promised to give the devil his daughter if he erected the castle before cockcrow. The nurse overheard the compact, and, just as the castle was finished, set fire to a stack of corn. The cock, seeing the light, thought morning had come, and crowed before the last stone was added to the walls. The devil in a rage carried off the old baron—and served him right—instead of the maiden. We shall see presently how this story works into our subject.

At Frankfort may be seen, on the Sachsenhäuser Bridge, an iron rod with a gilt cock on the top. This is the reason: An architect undertook to build the bridge within a fixed time, but three days before that on which he had contracted to complete it, the bridge was only half finished. In his distress he invoked the devil, who undertook the job if he might receive the first who crossed the bridge. The work was done by the appointed day, and then the architect drove a cock over the bridge. The devil, who had reckoned on getting a human being, was furious; he tore the poor cock in two, and flung it with such[4] violence at the bridge that he knocked two holes in it, which to the present day cannot be closed, for if stones are put in by day they are torn out by night. In memorial of the event, the image of the cock was set up on the bridge.

Sometimes the owner of a house or barn calls in the devil, and forfeits his life or his soul by so doing, which falls to the devil when the building is complete.

And now, without further quotation of examples, what do they mean? They mean this—that in remote times a sacrifice of some sort was offered at the completion of a building; but not only at the completion—the foundation of a house, a castle, a bridge, a town, even of a church, was laid in blood. In heathen times a sacrifice was offered to the god under whose protection the building was placed; in Christian times, wherever much of old Paganism lingered on, the sacrifice continued, but was given another signification. It was said that no edifice would stand firmly unless the foundations were laid in blood. Some animal was placed under the corner-stone—a dog, a sow, a wolf, a black cock, a goat, sometimes the body of a malefactor who had been executed for his crimes.

Here is a ghastly story, given by Thiele in his “Danish Folk-tales.” Many years ago, when the ramparts were being raised round Copenhagen, the wall always sank, so that it was not possible to get it to stand firm. They, therefore, took a little innocent girl, placed her in a chair by a table, and gave her playthings and sweetmeats. While she thus sat enjoying herself, twelve masons built an arch over her,[5] which, when completed, they covered with earth to the sound of drums and trumpets. By this process the walls were made solid.

When, a few years ago, the Bridge Gate of the Bremen city walls was demolished, the skeleton of a child was actually found embedded in the foundations.

Heinrich Heine says on this subject: “In the Middle Ages the opinion prevailed that when any building was to be erected something living must be killed, in the blood of which the foundation had to be laid, by which process the building would be secured from falling; and in ballads and traditions the remembrance is still preserved how children and animals were slaughtered for the purpose of strengthening large buildings with their blood.”

The story of the walls of Copenhagen comes to us only as a tradition, but the horrible truth must be told that in all probability it is no invention of the fancy, but a fact.

Throughout Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and North Germany, tradition associates some animal with every church, and it goes by the name of Kirk-Grim. These Kirk-Grims are the goblin apparitions of the beasts that were buried under the foundation-stones of the churches. It is the same in Devonshire—the writer will not say at the present day, but certainly forty or fifty years ago. Indeed, when he was a boy he drew up a list of the Kirk-Grims that haunted all the neighbouring parishes. To the church of the parish in which he lived, belonged two white sows yoked together with a silver chain; to another, a black dog; to a third, a ghostly calf; to a fourth, a white lamb.

Afzelius, in his collection of Swedish folk-tales, says: “Heathen superstition did not fail to show itself in the construction of Christian churches. In laying the foundations, the people retained something of their former religion, and sacrificed to their old deities, whom they could not forget, some animal, which they buried alive, either under the foundation or without the wall. The spectre of this animal is said to wander about the churchyard at night, and is called the Kirk-Grim. A tradition has also been preserved that under the altar of the first Christian churches, a lamb was usually buried, which imparted security and duration to the edifice. This is an emblem of the true Church Lamb—the Saviour, who is the Corner-Stone of His Church. When anyone enters a church at a time when there is no service, he may chance to see a little lamb spring across the quire and vanish. This is the church-lamb. When it appears to a person in the churchyard, particularly to the grave-digger, it is said to forbode the death of a child.”

Thiele, in his “Danish Folk-tales,” says much the same of the churches in Denmark. He assures us that every church there has its Kirk-Grim, which dwells either in the tower, or in some other place of concealment.

What lies at the base of all stories of haunted houses is the same idea. All old mansions had their foundations laid in blood. This fact is, indeed, forgotten, but it is not forgotten that a ghostly guard watches the house, who is accounted for in various ways, and very often a crime is attributed to one of the former inhabitants to account for the walking of the[7] ghost. By no means infrequently the crime, which, in the popular mind, accounts for the ghost, can be demonstrated historically not to have taken place. Again, in a great number of cases, the spectre attached to a building is not that of a human being at all, but of some animal, and then tradition is completely at a loss to explain this phenomenon.

The proverb says that there is a skeleton in every man’s house, and the proverb is a statement of what at one time was a fact. Every house had its skeleton, and every house was intended to have its skeleton; and what was more, every house was designed to have not only its skeleton, but its ghost.

We are going back to heathen times, when we say that at the foundation-stone laying of every house, castle, or bridge, provision was made to give to each its presiding, haunting, protecting spirit. The idea, indeed, of providing every building with its spectre, as its spiritual guard, was not the primary idea, it grew later, out of the original one, the characteristically Pagan idea, of a sacrifice associated with the beginning of every work of importance.

When the primeval savage lived in a hut of poles over which he stretched skins, he thought little of his house, which could be carried from place to place with ease, but directly he began to build of stone, or raise earthworks as fortifications, he considered himself engaged on a serious undertaking. He was disturbing the face of Mother Earth, he was securing to himself in permanency a portion of that surface which had been given by her to all her children in common. Partly with the notion of offering a propitiatory sacrifice[8] to the earth, and partly also with the idea of securing to himself for ever a portion of soil by some sacramental act, the old Pagan laid the foundations of his house and fortress in blood.

Every great work was initiated with sacrifice. If a man started on a journey, he first made an offering. A warlike expedition was not undertaken till an oblation had been made, and the recollection of this lingered on in an altered form of superstition, viz., that that side would win the day which was the first to shed blood, a belief alluded to in the “Lady of the Lake.” A ship could not be launched without a sacrifice, and the baptism of a vessel nowadays with a bottle of wine is a relic of the breaking of the neck of a human victim and the suffusion of the prow with blood, just as the burial of a bottle with coins at the present day under a foundation stone is the faded reminiscence of the immuring of a human victim.

Building, in early ages, was not so lightly taken in hand as at present, and the principles of architectural construction were ill understood. If the walls showed tokens of settlement, the reason supposed was that the earth had not been sufficiently propitiated, and that she refused to bear the superimposed burden.

Plutarch says that when Romulus was about to found the Eternal City, by the advice of Etruscan Augurs, he opened a deep pit, and cast into it the “first fruits of everything that is reckoned good by use, or necessary by nature,” and before it was closed by a great stone, Faustulus and Quinctilius were killed and laid under it. This place was the[9] Comitium, and from it as a centre, Romulus described the circuit of the walls.[1] The legend of Romulus slaying Remus because he leaned over the low walls is probably a confused recollection of the sacrifice of the brothers who were laid under the bounding wall. According to Pomponius Mela, the brothers Philæni were buried alive at the Carthaginian frontier. A dispute having arisen between the Carthaginians and Cyrenæans about their boundaries, it was agreed that deputies should start at a fixed time from each of the cities, and that the place of their meeting should thenceforth form the limit of demarcation. The Philæni departed from Carthage, and advanced much farther than the Cyrenæans. The latter accused them of having set out before the time agreed upon, but at length consented to accept the spot which they had reached as a boundary line, if the Philæni would submit to be buried alive there. To this the brothers consented. Here the story is astray of the truth. Really, the Philæni were buried at the confines of the Punic territory, to be the ghostly guardians of the frontier. There can be little doubt that elsewhere burials took place at boundaries, and it is possible that the whipping of boys on gang-days or Rogations may have been a mediæval and Christian mitigation of an old sacrifice. Certainly there are many legends of spectres that haunt and[10] watch frontiers, and these legends point to some such practice. But let us return to foundations.

In the ballad of the “Cout of Keeldar,” in the minstrelsy of the Border, it is said,

In a note, Sir Walter Scott alludes to the tradition that the foundation stones of Pictish raths were bathed in human gore.

A curious incident occurs in the legend of St. Columba, founder of Iona, which shows how deep a hold the old custom had taken. The original idea of a sacrifice to propitiate the earth was gone, but the idea that appropriation of a site was not possible without one took its place. The Saint is said to have buried one of his monks, Oran by name, alive, under the foundations of his new abbey, because, as fast as he built, the spirits of the soil demolished by night what he raised by day. In the life of the Saint by O’Donnell (Trias Thaumat.) the horrible truth is disguised. The story is told thus:—On arriving at Hy (Iona), St. Columba said, that whoever willed to die first would ratify the right of the community to the island by taking corporal possession of it. Then, for the good of the community, Oran consented to die. That is all told, the dismal sequel, the immuring of the living monk, is passed over. More recent legend, unable to understand the burial alive of a monk, explains[11] it in another way. Columba interred him because he denied the resurrection.

It is certain that the usage remained in practice long after Europe had become nominally Christian; how late it continued we shall be able to show presently.

Grimm, in his “German Mythology,” says: “It was often considered necessary to build living animals, even human beings, into the foundations on which any edifice was reared, as an oblation to the earth to induce her to bear the superincumbent weight it was proposed to lay on her. By this horrible practice it was supposed that the stability of the structure was assured, as well as other advantages gained.” Good weather is still thought, in parts of Germany, to be secured by building a live cock into a wall, and cattle are prevented from straying by burying a living blind dog under the threshold of a stable. The animal is, of course, a substitute for a human victim, just as the bottle and coins are the modern substitute for the live beast.

In France, among the peasantry, a new farmhouse is not entered on till a cock has been killed, and its blood sprinkled in the rooms. In Poitou, the explanation given is that if the living are to dwell in the house, the dead must have first passed through it. And in Germany, after the interment of a living being under a foundation was abandoned, it was customary till comparatively recently to place an empty coffin under the foundations of a house.

This custom was by no means confined to Pagan Europe. We find traces of it elsewhere. It is alluded[12] to by Joshua in his curse on Jericho which he had destroyed, “Cursed be the man before the Lord, that riseth up, and buildeth this city Jericho: he shall lay the foundation thereof in his firstborn, and in his youngest son shall he set up the gates of it.” (Josh. vi. 26.)

The idea of a sacrifice faded out with the spread of Christianity, and when tenure of soil and of buildings became fixed and usual, the notion of securing it by blood disappeared; but in its place rose the notion of securing a spiritual protector to a building, sacred or profane, and until quite late, the belief remained that weak foundations could be strengthened and be made to stand by burying a living being, generally human, under them. The thought of a sacrifice to the Earth goddess was quite lost, but not the conviction that by a sacrifice the cracking walls could be secured.

The vast bulk of the clergy in the early Middle Ages were imbued with the superstitions of the race and age to which they belonged. They were of the people. They were not reared in seminaries, and so cut off from the influences of ignorant and superstitious surroundings. They were a little ahead of their fellows in culture, but only a little. The mediæval priest allowed the old Pagan customs to continue unrebuked, he half believed in them himself. One curious and profane incident of the close of the fifteenth century may be quoted to show to how late a date heathenism lingered mixed up with Christian ideas. An Italian contemporary historian says, that when Sessa was besieged by the King of Naples, and ran short of water, the inhabitants put a consecrated host[13] in the mouth of an ass, and buried the ass alive in the porch of the church. Scarcely was this horrible ceremony completed, before the windows of heaven were opened, and the rain poured down.[2]

In 1885, Holsworthy parish church was restored, and in the course of restoration the south-west angle wall of the church was taken down. In it, embedded in the mortar and stone, was found a skeleton. The wall of this portion of the church was faulty, and had settled. According to the account given by the masons who found the ghastly remains, there was no trace of a tomb, but every appearance of the person having been buried alive, and hurriedly. A mass of mortar was over the mouth, and the stones were huddled about the corpse as though hastily heaped about it, then the wall was leisurely proceeded with.

The parish church of Kirkcudbright was partially taken down in 1838, when, in removing the lintel of the west doorhead, a skull of a man was found built into the wall above the doorway. This parish church was only erected in 1730, so that this seems to show a dim reminiscence, at a comparatively recent date, of the obligation to place some relic of a man in the wall to insure its stability.

In the walls of the ancient castle of Henneberg, the seat of a line of powerful counts, is a relieving arch, and the story goes that a mason engaged on the castle was induced by the offer of a sum of money to yield his child to be built into it. The child was given a cake, and the father stood on a[14] ladder superintending the building. When the last stone was put in, the child screamed in the wall, and the man, overwhelmed with self-reproach, lost his hold, fell from the ladder, and broke his neck. A similar story is told of the castle of Liebenstein. A mother sold her child for the purpose. As the wall rose about the little creature, it cried out, “Mother, I still see you!” then, later, “Mother, I can hardly see you!” and lastly, “Mother, I see you no more!” In the castle of Reichenfels, also, a child was immured, and the superstitious conviction of the neighbourhood is, that were the stones that enclose it removed, the castle would fall.

In the Eifel district, rising out of a gorge is a ridge on which stand the ruins of two extensive castles, Ober and Nieder Manderscheid. According to popular tradition, a young damsel was built into the wall of Nieder Manderscheid, yet with an opening left, through which she was fed as long as she was able to eat. In 1844 the wall at this point was broken through, and a cavity was discovered in the depth of the wall, in which a human skeleton actually was discovered.

The Baron of Winneburg, in the Eifel, ordered a master mason to erect a strong tower whilst he was absent. On his return he found that the tower had not been built, and he threatened to dismiss the mason. That night someone came to the man and said to him: “I will help you to complete the tower in a few days, if you will build your little daughter into the foundations.” The master consented, and at midnight the child was laid in the wall, and the[15] stones built over her. That is why the tower of Winneburg is so strong that it cannot be overthrown.

When the church of Blex, in Oldenburg, was building, the foundations gave way, being laid in sand. Accordingly, the authorities of the village crossed the Weser, and bought a child from a poor mother at Bremerleke, and built it alive into the foundations. Two children were thus immured in the basement of the wall of Sandel, one in that of Ganderkesee. At Butjadeirgen, a portion of the dyke gave way, therefore a boy named Hugo was sunk alive in the foundations of the dam. In 1615 Count Anthony Günther of Oldenburg, on visiting a dyke in process of construction, found the workmen about to bury an infant under it. The count interfered, saved the child, reprimanded the dam-builders, and imprisoned the mother who had sold her babe for the purpose. Singularly enough, this same count is declared by tradition to have buried a living child in the foundations of his castle at Oldenburg.

When Detinetz was built on the Danube, the Slavonic settlers sent out into the neighbourhood to capture the first child encountered. A boy was taken, and walled into the foundations of their town. Thence the city takes its name, dijete is the Slavonic for boy.

In the life of Merlin, as given by Nennius and by Geoffrey of Monmouth, we are told that Vortigern tried to build a castle, but that the walls gave way as fast as he erected them. He consulted the wise men, and they told him that his foundations could only be[16] made to stand if smeared with the blood of a fatherless boy. Thus we get the same superstition among Celts, Slaves, Teutons, and Northmen.

Count Floris III. of Holland, who married Ada, daughter of Henry, the son of David, King of Scotland, visited the island of Walcheren in 1157, to receive the homage of the islanders. On his return to Holland he despatched a number of experienced workmen to repair the sea-walls which were in a dilapidated condition. In one place where the dam crossed a quicksand, they were unable to make it stand till they had sunk a live dog in the quicksand. The dyke is called Hontsdamm to this day. Usually a live horse was buried in such places, and this horse haunts the sea-walls; if an incautious person mounts it, the spectre beast plunges into the sea and dissolves into foam.

The dog or horse is the substitute for a child. A few centuries earlier the dyke builders would have reared it over an infant buried alive. The trace of the substitution remains in some folk-tales. An architect promises the devil the soul of the first person who crosses the threshold of the house, or church, or goes over the bridge he has built with the devil’s aid. The evil one expects a human victim, and is put off with a wolf, or a dog, or a cock. At Aix-la-Chapelle, as we have seen, a wolf took the place of a human victim: at Frankfort a cock.

In Yorkshire, the Kirk-Grim is usually a huge black dog with eyes like saucers, and is called a padfoot. It generally frequents the church lanes; and he who sees it knows that he must die within the[17] year. And now—to somewhat relieve this ghastly subject—I may tell an odd incident connected with it, to which the writer contributed something.

On a stormy night in November, he was out holding over his head a big umbrella, that had a handle of white bone. A sudden gust—and the umbrella was whisked out of his hand, and carried away into infinite darkness and mist of rain.

That same night a friend of his was walking down a very lonely church lane, between hedges and fields, without a house near. In the loneliest, most haunted portion of this lane, his feet, his pulsation and his breath were suddenly arrested by the sight of a great black creature, occupying the middle of the way, shaking itself impatiently, moving forward, then bounding on one side, then running to the other. No saucer eyes, it is true, were visible, but it had a white nose that, to the horrified traveller, seemed lit with a supernatural phosphoric radiance. Being a man of intelligence, he would not admit to himself that he was confronted by the padfoot; he argued with himself that what he saw was a huge Newfoundland dog. So he addressed it in broad Yorkshire: “Sith’ere, lass, don’t be troublesome. There’s a bonny dog, let me pass. I’ve no stick. I wi’nt hurt thee. Come, lass, come, let me by.”

At that moment a blast rushed along the lane. The black dog, monster, padfoot, made a leap upon the terrified man, who screamed with fear. He felt claws in him, and he grasped—an umbrella. Mine!

That this idea of human victims being required to ensure the stability of a structure is by no means[18] extinct, and that it constitutes a difficulty that has to be met and overcome in the East, will be seen from the following interesting extract from a recent number of the London and China Telegraph. The writer says:—“Ever and anon the idea gets abroad that a certain number of human bodies are wanted, in connection with laying the foundation of some building that is in progress; and a senseless panic ensues, and everyone fears to venture out after nightfall. The fact that not only is no proof forthcoming of anyone having been kidnapped, but that, on the contrary, the circle of friends and acquaintances is complete, quite fails to allay it. But is there ever any reasoning with superstition? The idea has somehow got started; it is a familiar one, and it finds ready credence. Nor is the belief confined either to race, creed, or locality. We find it cropping up in India and Korea, in China and Malaysia, and we have a strong impression of having read somewhere of its appearance in Persia. Like the notions of celibacy and retreat in religion, it is common property—the outcome, apparently, of a certain course of thought rather than of any peculiar surroundings. The description of the island of Solovetsk in Mr. Hepworth Dixon’s ‘Free Russia’ might serve, mutatis mutandis, for a description of Pootoo; and so a report of one of these building scares in China would serve equally well for the Straits. When the last mail left, an idea had got abroad among the Coolie population that a number of heads were required in laying the foundations of some Government works at Singapore; and so there was a general fear[19] of venturing out after nightfall, lest the adventurer should be pounced on and decapitated. One might have thought the ways of the Singapore Government were better understood! That such ideas should get abroad about the requirements of Government even in China or Annam is curious enough; but the British Government of the Straits above all others! Yet there it is; the natives had got it into their heads that the Government stood in need of 960 human heads to ensure the safe completion of certain public works, and that 480 of the number were still wanting. Old residents in Shanghai will remember the outbreak of a very similar panic at Shanghai, in connection with the building of the cathedral. The idea got abroad that the Municipal Council wanted a certain number of human bodies to bury beneath the foundation of that edifice, and a general dread of venturing out after nightfall—especially of going past the cathedral compound—prevailed for weeks, with all kinds of variations and details. A similar notion was said to be at the bottom of the riots which broke out last autumn at Söul. Foreigners—the missionaries for choice—were accused of wanting children for some mysterious purpose, and the mob seized and decapitated in the public streets nine Korean officials who were said to have been parties to kidnapping victims to supply the want. This, however, seems more akin to the curious desire for infantile victims which was charged against missionaries in the famous Honan proclamation which preceded the Tientsin massacre, and which was one of the items in the indictment against[20] the Roman Catholics on the occasion of that outbreak. Sometimes children’s brains are wanted for medicine, sometimes their eyes are wanted to compound material for photography. But these, although cognate, are not precisely similar superstitions to the one which now has bestirred the population of Singapore. A case came to us, however, last autumn, from Calcutta, which is so exactly on all fours with this latest manifestation, that it would almost seem as if the idea had travelled like an epidemic and broken out afresh in a congenial atmosphere. Four villagers of the Dinagepore district were convicted, last September, of causing the death of two Cabulis and injuring a third, for the precise reason that they had been kidnapping children to be sacrificed in connection with the building of a railway bridge over the Mahanuddi. A rumour had got abroad that such proceedings were in contemplation, and when these Cabulis came to trade with the villagers they were denounced as kidnappers and mobbed. Two were killed outright, their bodies being flung into the river; while the third, after being severely handled, escaped by hiding himself. We are not aware whether the origin of this curious fancy has ever been investigated and explained, for it may be taken for granted that, like other superstitions, it has its origin in some forgotten custom or faded belief of which a burlesque tradition only remains. This is not the place to go into a disquisition on the origin of human sacrifice; but it is not difficult to believe that, to people who believe in its efficacy, the idea of offering up human beings to[21] propitiate the deity, when laying the foundations of a public edifice, would be natural enough. Whether the notion which crops up now and again, all over Asia, really represents the tradition of a practice—whether certain monarchs ever did bury human bodies, as we bury newspapers and coins, beneath the foundations of their palaces and temples, is a question we must leave others to answer. It is conceivable that they may have done so, as an extravagant form of sacrifice; and it is also conceivable that the abounding capacity of man for distorting superstitious imagery, may have come to transmute the idea of sacrificing human beings as a measure of propitiation, into that of employing human bodies as actual elements in the foundation itself. It is possible that the inhabitants of Dinagepore conserve the more ideal and spiritual view, which the practical Chinese mind has materialised, as in the recent instance at Singapore. Anyhow, the idea is sufficiently wide-spread and curious to deserve a word of examination as well as of passing record.”

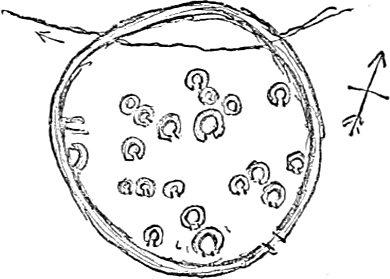

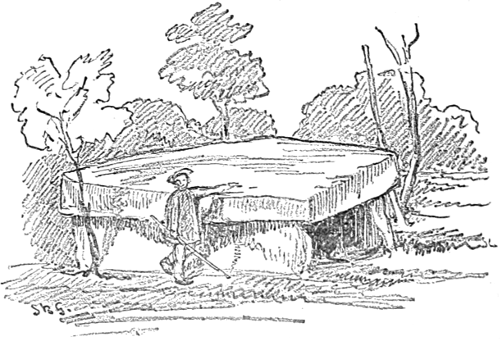

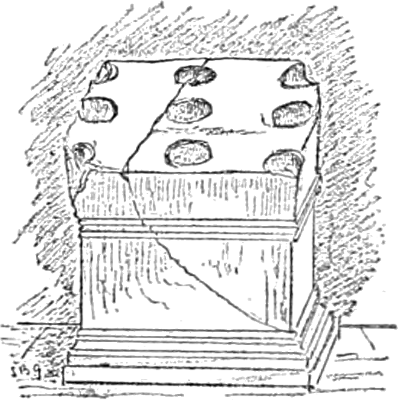

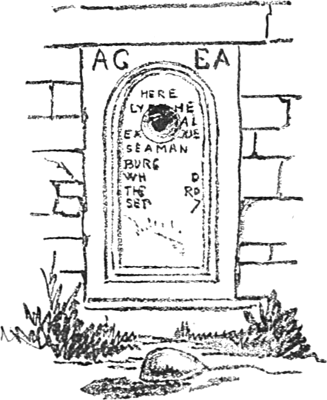

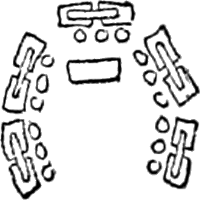

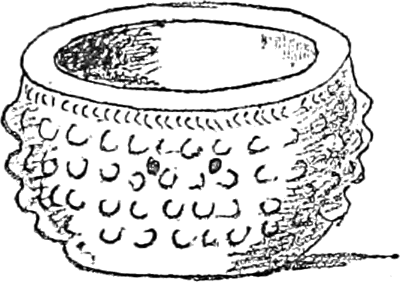

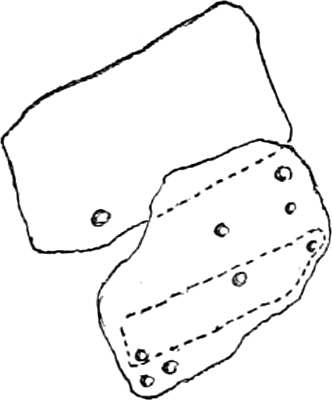

Fig. 1.—FIGURE FOUND UNDER THE FOUNDATIONS AT STINVEZAND.

When the north wall of the parish church of Chulmleigh in North Devon was taken down a few years ago—a wall of Perpendicular date—in it was found laid a very early carved figure of Christ crucified to a vine, or interlacing tree, such as is seen in so-called Runic monuments. The north wall having been falling in the fifteenth century, had been re-erected, and this figure was laid in it, and the wall erected over it, just as, in the same county, about the same time, the wall of Holsworthy Church was built over a human being. At Chulmleigh there was an advance in civilisation.[22] The image was laid over the wall in place of the living victim.

When, in 1842, the remains of a Romano-Batavian temple were explored at Stinvezand, near Rysbergen, a singular mummy-like object was found under the foundation. This was doubtless a substitute for the human victim.

The stubborn prejudice which still exists in all parts against a first burial in a new cemetery or churchyard is due to the fact that in Pagan times the first to be buried was the victim, and in mediæval times was held to be the perquisite of the devil, who stepped into the place of the Pagan deity.

Every so-called Devil’s Bridge has some story associated with it pointing to sacrifice, and sometimes to the substitution of an animal for the human victim. The almost invariable story is that the devil had been invoked and promised his aid, if given the first life that passed over the bridge. On the completion of the structure a goat, or a dog, or a rabbit is driven over, and is torn to pieces by the devil. At Pont-la-Ville, near Courbières, is a four-arched Devil’s Bridge, where six mice, then six rats, and lastly six cats, were driven across, according to the popular story, in place of the eighteen human souls demanded by the Evil One.

At Cahors, in Ouercy, is a singularly fine bridge over the Lot, with three towers on it. The lower side of the middle tower could never be finished, it always[23] gave way at one angle. The story goes that the devil was defrauded of his due—the soul of the architect—when he helped to build the bridge, and so declared that the bridge never should be finished. Of late years the tower has been completed, and in token that modern skill has triumphed, the Evil One has been represented on the angle, carved in stone. The legend shows that the vulgar thought that the bridge should have been laid in blood, and as it was not so, concluded that the faulty tower was due to the neglect of the Pagan usage.

The black dog that haunts Peel Castle, and the bloodhound of Launceston Castle, are the spectres of the animals buried under their walls, and so the White Ladies and luminous children, who are rumoured to appear in certain old mansions, are the faded recollections of the unfortunate sacrifices offered when these houses were first reared, not, perhaps, the present buildings, but the original manor-halls before the Conquest.

At Coatham, in Yorkshire, is a house where a little child is seen occasionally—it vanishes when pursued. In some German castles the apparition of a child is called the “Still child;” it is deadly pale, white-clothed, with a wreath on the head. At Falkenstein, near Erfurth, the appearance is that of a little maiden of ten, white as a sheet, with long double plaits of hair. A white baby haunts Lünisberg, near Aerzen. I have heard of a house in the West of England, where on a pane of glass, every cold morning, is found the scribbling of little fingers. However often the glass be cleaned, the marks of the ghostly fingers[24] return. The Cauld Lad of Hilton Castle in the valley of Wear is well known. He is said to wail at night:

At Guilsland, in Cumberland, is another Cauld Lad; he is deadly white, and appears ever shivering with cold, and his teeth chattering.

An allied apparition is that of the Radiant Boy. Lord Castlereagh is said to have seen one, a spectre, which the owner of the castle where he saw it admitted had been visible to many others. Dr. Kerner mentions a very similar story, wherein an advocate and his wife were awakened by a noise and a light, and saw a beautiful child enveloped in a sort of glory. I have heard of a similar appearance in a Lincolnshire house. A story was told me, second-hand, the other day, of a house where such a child was seen, which always disappeared at the hearth, and sometimes, instead of the child, little white hands were observed held up appealingly above the hearthstone. The stone was taken up, quite recently, and some bones found under it, which were submitted to an eminent comparative anatomist, who pronounced them to be those of a child.

Mrs. Crowe, in her “Night Side of Nature,” gives[25] an account of such an apparition from an eye-witness, dated 1824. “Soon after we went to bed, we fell asleep: it might be between one and two in the morning when I awoke. I observed that the fire was totally extinguished; but, although that was the case, and we had no light, I saw a glimmer in the centre of the room, which suddenly increased to a bright flame. I looked out, apprehending that something had caught fire, when, to my amazement, I beheld a beautiful boy standing by my bedside, in which position he remained some minutes, fixing his eyes upon me with a mild and benevolent expression. He then glided gently away towards the side of the chimney, where it is obvious there is no possible egress, and entirely disappeared. I found myself in total darkness, and all remained quiet until the usual hour of rising. I declare this to be a true account of what I saw at C—— Castle, upon my word as a clergyman.”

When we consider that the hearth is the centre and sacred spot of a house, and that the chimney above it is the highest portion built, and the most difficult to rear, it is by no means improbable that the victim was buried under the hearthstone or jamb of the chimney. The case already mentioned of a child’s bones having been found in this position is by no means an isolated one.

It would be impossible to give a tithe of the stories of White Ladies and Black Ladies and Brown Ladies who haunt old houses and castles.

The latest instance of a human being having been immured alive, of which a record remains and which is well authenticated, is that of Geronimo of Oran, in[26] the wall of the fort near the gate Bab-el-oved, of Algiers, in 1569. The fort is composed of blocks of pise, a concrete made of stones, lime, and sand, mixed in certain proportions, trodden down and rammed hard into a mould, and exposed to dry in the sun. When thoroughly baked and solid it is turned out of the mould, and is then ready for use. Geronimo was a Christian, who had served in a Spanish regiment; he was taken by pirates and made over to the Dey of Algiers. When the fort was in construction, Geronimo was put into one of the moulds, and the concrete rammed round him (18th Sept., 1569), and then the block was put into the walls. Don Diego de Haedo, the contemporary author of the “Topography of Algiers,” says, “On examining with attention the blocks of pise which form the walls of the fort, a block will be observed in the north wall of which the surface has sunk in, and looks as if it had been disturbed; for the body in decaying left a hollow in the block, which has caused the sinkage.”

On December 27, 1853, the block was extracted. The old fort was demolished to make room for the modern “Fort des vingt-quatre-heures,” under the direction of Captain Susoni, when a petard which had been placed beneath two or three courses of pise near the ground, exploded, and exposed a cavity containing a human skeleton, the whole of which was visible, from the neck to the knees, in a perfect state of preservation. The remains, the cast of the head, and the broken block of pise, are now in the Cathedral of Algiers.

The walls of Scutari are said also to contain the body of a victim; in this case of a woman, who was built in, but an opening was left through which her infant might be passed in to be suckled by her as long as life remained in the poor creature, after which the hole was closed.

At Arta also, in the vilajet of Janina, a woman was walled into the foundation of the bridge. The gravelly soil gave way, and it was decided that the only means by which the substructure could be solidified was by a human life. One of the mason’s wives brought her husband a bowl with his dinner, when he dropped his ring into the hole dug for the pier, and asked her to search for it. When she descended into the pit, the masons threw in lime and stones upon her, and buried her.

The following story is told of several churches in Europe. The masons could not get the walls to stand, and they resolved among themselves to bury under them the first woman or child that came to their works. They took oath to this effect. The first to arrive was the wife of the master-mason, who came with the dinner. The men at once fell on her and walled her into the foundations. One version of the story is less gruesome. The masons had provided meat for their work, and the wife of the master had dealt so carelessly with the provision, that it ran out before the building was much advanced. She accordingly put the remaining bones into a cauldron, and made a soup of vegetables. When she brought it to the mason, he flew into a rage, and built the cauldron and bones into the wall, as a perpetual[28] caution to improvident wives. This is the story told of the church of Notre Dame at Bruges, where the cauldron and bones are supposed to be still seen in the wall. At Tuckebrande are two basins built into the wall, and various legends not agreeing with one another are told to account for their presence. Perhaps these cauldrons contained the blood of victims of some sort immured to secure the stability of the edifice.[3]

A very curious usage prevails in Roumania and Transylvania to the present day, which is a reminiscence of the old interment in the foundations of a house. When masons are engaged on the erection of a new dwelling, they endeavour to catch the shadow of a stranger passing by and wall it in, and throw in stones and mortar whilst his shadow rests on the walls. If no one goes by to cast his shade on the stones, the masons go in quest of a woman or child, who does not belong to the place, and, unperceived by the person, apply a reed to the shadow, and this reed is then immured; and it is believed that when this is done, the woman or child thus measured will languish and die, but luck attaches to the house. In this we see the survival of the old confusion between soul and shade. The Manes are the shadows of the dead. In some places it is said that a man who has sold his soul to the devil is shadowless,[29] because soul and shadow are one. But there are other instances of substitution hardly less curious. In Holland have been found immured in foundations curious objects like ninepins, but which are really rude imitations of babes in their swaddling-bands. When it became unlawful to bury a child, an image representing it was laid in the wall in its place. Another usage was to immure an egg. The egg had in it life, but undeveloped life, so that by walling it in the principle of sacrificing a life was maintained without any shock to human feelings. Another form of substitution was that of a candle. From an early period the candle was burnt in place of the sacrifice of a human victim. At Heliopolis, till the reign of Amasis, three men were daily sacrificed; but when Amasis expelled the Hyksos kings, he abolished these human offerings, and ordered that in their place three candles should be burned daily on the altar. In Italy, wax figures, sometimes figures of straw, were burnt in the place of the former bloody sacrifices.

In the classic tale, at the birth of Meleager, the three fates were present; Atropos foretold that he would live as long as the brand then burning on the hearth remained unconsumed; thereupon his mother, Althæa, snatched it from the fire, and concealed it in a chest. When, in after years, Meleager slew one of his mother’s brothers, she, in a paroxysm of rage and vengeance, drew forth the brand, and burnt it, whereupon Meleager died.

In Norse mythology a similar tale is found. The Norns wandered over the earth, and were one night[30] given shelter by the father of Nornagest; the child lay in a cradle, with two candles burning at the head. The first two of the Norns bestowed luck and wealth on the child; but the third and youngest, having been thrust from her stool in the crush, uttered the curse, “The child shall live no longer than these candles burn.” Instantly the eldest of the fateful sisters snatched the candles up, extinguished them, and gave them to the mother, with a warning to take good heed of them.

A story found in Ireland, and Cornwall, and elsewhere, is to this effect. A man has sold himself to the devil. When the time comes for him to die, he is in great alarm; then his wife, or a priest, persuades the devil to let him live as long as a candle is unconsumed. At once the candle is extinguished, and hidden where it can never be found. It is said that a candle is immured in the chancel wall of Bridgerule Church, no one knows exactly where. A few years ago, in a tower of St. Osyth’s Priory, Essex, a tallow candle was discovered built in.

As the ancients associated shadow and soul, so does the superstitious mind nowadays connect soul with flame. The corpse-candle which comes from a churchyard and goes to the house where one is to die, and hovers on the doorstep, is one form of this idea. In a family in the West of England the elder of two children had died. On the night of the funeral the parents saw a little flame come in through the key-hole and run up to the side of the cradle where the baby lay. It hovered about it, and presently two[31] little flames went back through the key-hole. The baby was then found to be dead.

In the Arabic metaphysical romance of “Yokkdan,” the hero, who is brought up by a she-goat on a solitary island, seeks to discover the principle of life. He finds that the soul is a whitish luminous vapour in one of the cavities of the heart, and it burns his finger when he touches it.

In the German household tale of “Godfather Death,” a daring man enters a cave, where he finds a number of candles burning; each represents a man, and when the light expires, that man whom it represents dies. “Jack o’ lanterns” are the spirits of men who have removed landmarks. One of Hebel’s charming Allemanic poems has reference to this superstition.

The extinguished torch represents the departed life, and in Yorkshire it was at one time customary to bury a candle in a coffin, the modern explanation being that the deceased needed it to light him on his road to Paradise; but in reality it represented an extinguished life, and probably was a substitute for the human sacrifice which in Pagan times accompanied a burial. In almost all the old vaults opened in Woodbury Church, Devon, candles have been found affixed to the walls. The lamps set in graves in Italy and Greece were due to the same idea. The candle took the place of a life, as a dog or sow in other places was killed instead of a child.

It is curious and significant that great works of art and architecture should be associated with tragedies. The Roslyn pillar, the Amiens rose window, the[32] Strassburg clock, many spires, and churches. The architect of Cologne sold himself to the devil to obtain the plan. A master and an apprentice carve pillars or construct windows, and because the apprentice’s work is best, his master murders him. The mechanician of a clock is blinded, some say killed, to prevent him from making another like it. Perdix, for inventing the compass, was cast down a tower by Daedalus.

It will be remembered that the architect of Cologne Cathedral, according to the legend, sold himself to the devil for the plan, and forfeited his life when the building was in progress. This really means that the man voluntarily gave himself up to death, probably to be laid under the tower or at the foundation of the choir, to ensure the stability of the enormous superstructure, which he supposed could not be held up in any other way.

An inspector of dams on the Elbe, in 1813, in his “Praxis,” relates that, as he was engaged on a peculiarly difficult dyke, an old peasant advised him to get a child, and sink it under the foundations.

As an instance of even later date to which the belief in the necessity of a sacrifice lingered, I may mention that, in 1843, a new bridge was about to be built at Halle, in Germany. The people insisted to the architect and masons that their attempt to make the piers secure was useless, unless they first immured a living child in the basement. We may be very confident that if only fifty years ago people could be found so ignorant and so superstitious as to desire to commit such an atrocious crime, they[33] would not have been restrained in the Middle Ages from carrying their purpose into execution.

I have already said that originally the sacrifice was offered to the Earth goddess, to propitiate her, and obtain her consent to the appropriation of the soil and to bearing the burden imposed on it. But the sacrifice had a further meaning. The world itself, the universe, was a vast fabric, and in almost all cosmogonies the foundations of the world are laid in blood. Creation rises out of death. The Norsemen held that the giant Ymir was slain, that out of his body the world might be built up. His bones formed the rocks, his flesh the soil, his blood the rivers, and his hair the trees and herbage. So among the Greeks Dionysos Zagreus was the Earth deity, slain by the Titans, and from his torn flesh sprang corn and the vine, the grapes were inflated with his blood, and the earth, his flesh, transubstantiated into bread. In India, Brahma gave himself to form the universe. “Purusha is this All; his head is heaven, the sun is fashioned out of his eyes, the moon out of his heart, fire comes from his mouth, the winds are his breath, from his navel is the atmosphere, from his ears the quarters of the world, and the earth is trodden out of his feet” (“Rig. Veda” viii. c. 4, hymn 17-19).

So, in Persia, the Divine Ox, Ahidad, was slain that the world might be fashioned out of him; and the Mithraic figures represent this myth. If we put ourselves back in thought to the period when the Gospel was proclaimed, we shall understand better some of its allusions; with this notion of sacrifice[34] underlying all great undertakings, all constructive work, we shall see how some of the illustrations used by the first preachers would come home to those who heard them. We can see exactly how suitable was the description given of Christ as the Lamb that was slain from the foundation of the world. As the World-Lamb, He was the sustainer of the great building, He secured its stability; and just as the sacrifice haunts the building reared on it, so was the idea of Christ to enter into and haunt all history, all mythology, all religion.

We see, moreover, the appropriateness of the symbol of Christ as the chief Corner-stone, and of the Apostles as foundation stones of the Church; they are, as it were, the pise blocks, living stones, on whom the whole superstructure of the spiritual city is reared.

With extraordinary vividness, moreover, does the full significance of the old ecclesiastical hymn for the Dedication of a Church come out when we remember this wide-spread, deeply-rooted, almost ineradicable belief.

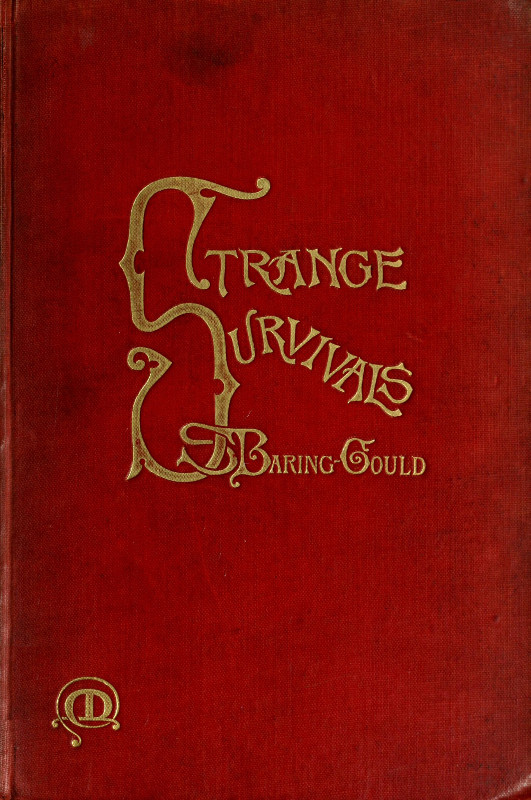

The tourist on the Rhine, as a matter of duty, visits in Cologne three points of interest, in addition to providing himself with a little box of the world-famous Eau, at the real original Maria Farina’s factory. After he has “done” the Cathedral, and the bones of the Eleven Thousand Virgins, he feels it incumbent on him to pay a visit to the horses’ heads in the market-place, looking out of an attic window.

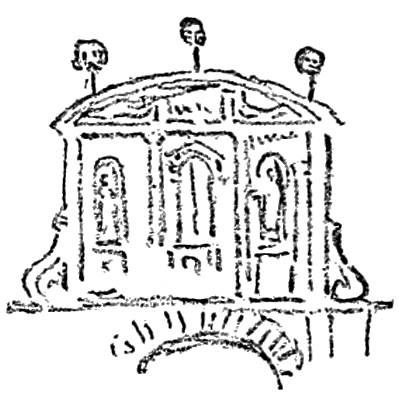

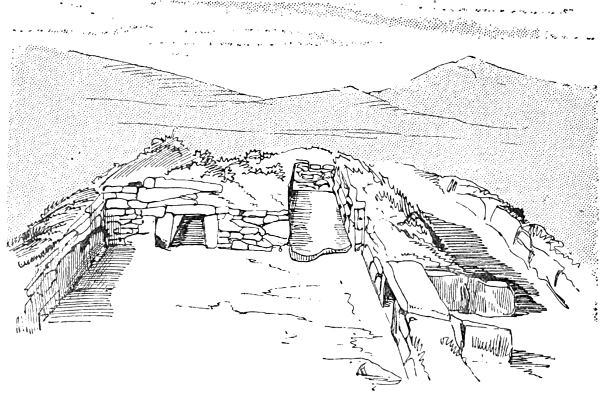

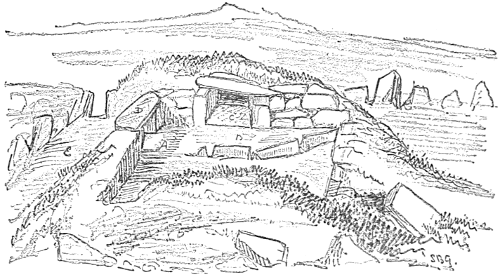

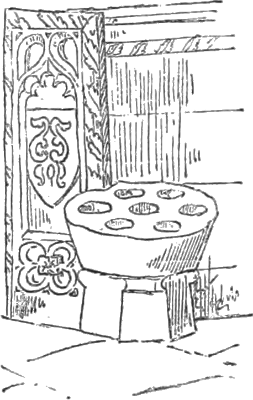

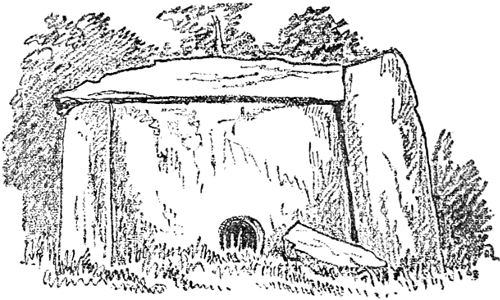

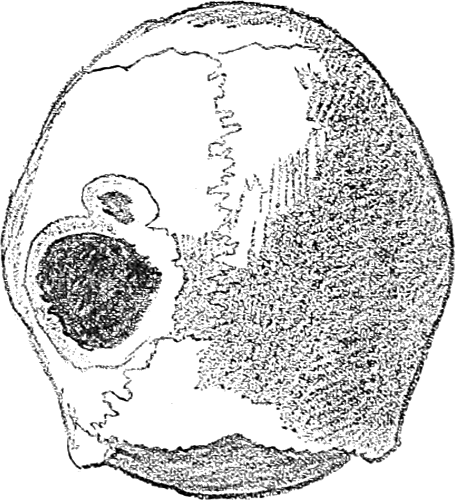

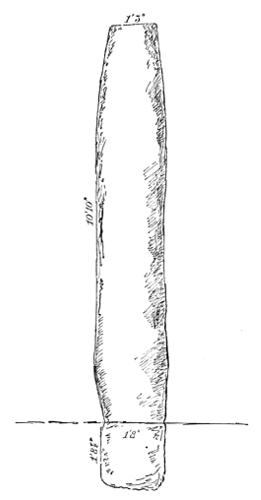

Fig. 2.—THE HORSES’ HEADS, COLOGNE.

Myths attach equally to the Minster, the Ursuline relics, and to the horses’ heads. The devil is said to have prophesied that the cathedral would never be completed, yet lo! it is finished to the last stone of the spires! The bones of the eleven thousand virgins have been proved to have come from an old neglected cemetery, broken into when the mediæval walls of Cologne were erected. It will be shown that the heads of the two grey mares[37] near the Church of the Apostles have a very curious and instructive history attaching to them, and that, though the story that accounts for their presence on top of a house is fabulous, their presence is of extreme interest to the antiquary.

The legend told of these particular heads is shortly this:[4] Richmod of Adocht was a wealthy citizen’s wife at Cologne. She died in 1357, and was buried with her jewelry about her. At night the sexton opened her grave, and, because he could not remove the rings, cut her finger. The blood began to flow, and she awoke from her cataleptic fit. The sexton fled panic-stricken. She then walked home, and knocked at her door, and called up the apprentice, who, without admitting her, ran upstairs to his master, to tell him that his wife stood without. “Pshaw!” said the widower, “as well make me believe that my pair of greys are looking out of the attic window.” Hardly were the words spoken, than, tramp—tramp—and his horses ascended the staircase, passed his door, and entered the garret. Next day every passer-by saw their heads peering from the window. The greatest difficulty was experienced in getting the brutes downstairs again. As a remembrance of this marvel, the horses were stuffed, and placed where they are now to be seen.

Such is the story as we take it from an account[38] published in 1816. I had an opportunity a little while ago of examining the heads. They are of painted wood.

The story of the resuscitation of the lady is a very common one, and we are not concerned with this part of the myth. That which occupies us is the presence of the horses’ heads in the window. Now, singularly enough, precisely the same story is told of other horses’ heads occupying precisely similar positions in other parts of Germany. We know of at least a dozen.[5] It seems therefore probable that the story is of later origin, and grew up to account for the presence of the heads, which the popular mind could not otherwise explain. This conjecture becomes a certainty when we find that pairs of horses’ heads were at one time a very general adornment of gable ends, and that they are so still in many places.

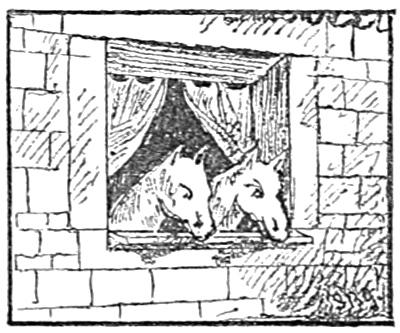

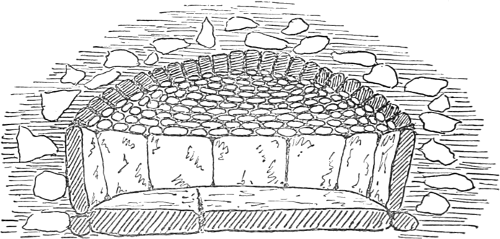

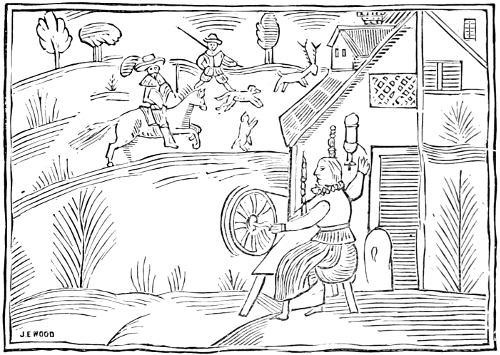

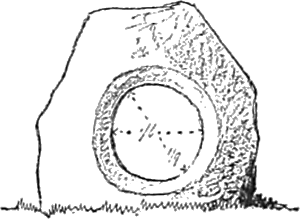

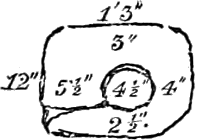

Fig. 3.—GABLE OF A FARM-HOUSE IN MECKLENBURG.

In Mecklenburg, Pomerania, Luneburg, Holstein, it is still customary to affix carved wooden horse-heads to the apex of the principal gable of the house. There are usually two of these, back to back, the heads pointed in opposite directions. In Tyrol, the heads of chamois occupy similar positions. The writer of this article was recently in Silesia, and sketched similar heads on the[39] gables of wooden houses of modern construction in the “Giant Mountains.” They are also found in Russia.

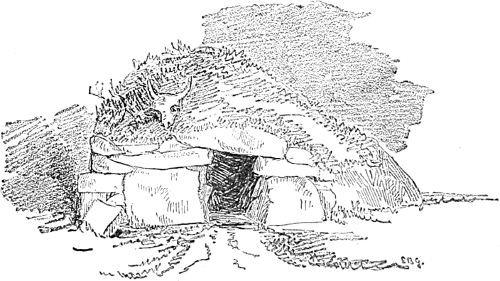

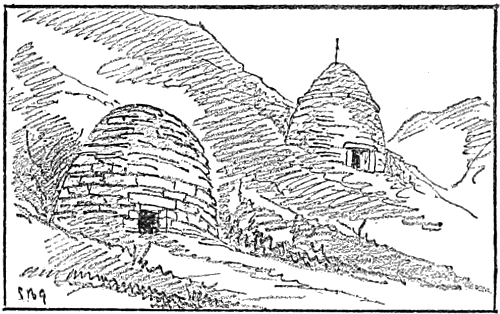

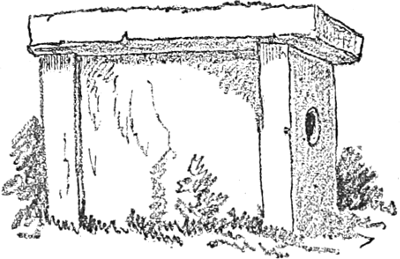

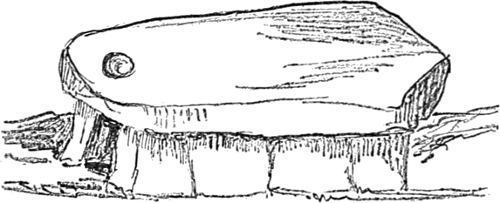

Fig. 4.—ANCIENT GERMAN HOUSE.

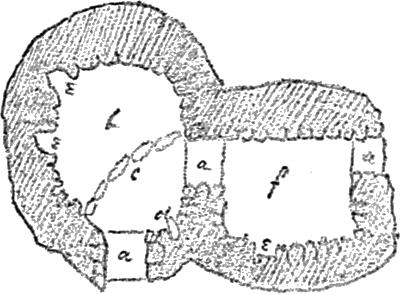

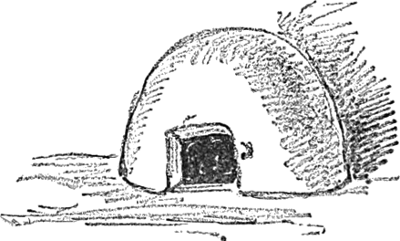

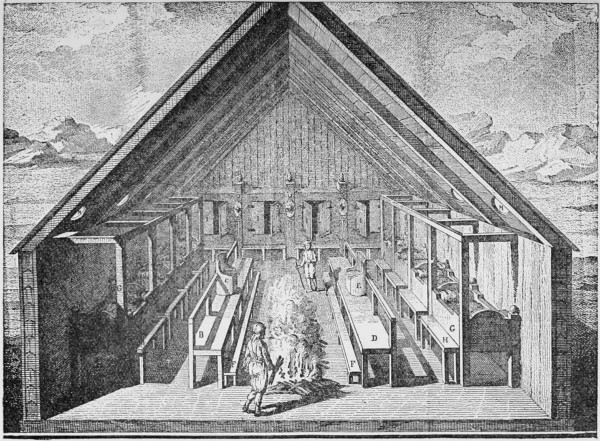

Originally, in Germany, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and indeed England, all houses were built of timber, and those which were not of circular form, with bee-hive roofs, had gables. Unfortunately, we have but one very early representation of a Teutonic village, and that is on the Antonine column at Rome. One of the bas-reliefs there shows us the attack by Romans on a German village. The houses are figured as built of wattled sides, and thatched over. Most are of bee-hive shape, but one, that of the chief, is oblong and gabled. The soldiers are applying torches to the roofs, and, provokingly enough, we cannot see the gable of the quadrangular house, because it is obscured by the figure of a German warrior who is being killed by a Roman soldier. Though this representation does not help us much, still there is abundance of evidence to show that the old German houses—at least, those of the chiefs—were like the dwellings of the Scandinavian Bonders, with oblong walls with gables, and with but a single main front and gable a-piece. The Icelandic farmhouses perpetuate the type to the present day, with some modifications. These dwellings have lateral walls of stone and turf scarcely six feet high, and from six to ten feet thick, to bank out the cold. On these low[40] parallel walls rest the principals of the roof, which is turf-covered. The face of the house is to the south, it is the only face that shows; the back is banked up like the sides, so that from every quarter but one a house looks like a grassy mound. The front consists of two or more wooden gables, and is all of wood, often painted red. Originally, we know, there was but a single gable. At present the subsidiary gable is low, comparatively insignificant, and contains the door. Now the old Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and German houses of the chiefs were all originally constructed on the same principle, and the timber and plaster gable fronts of our old houses, the splendid stone and brick-gabled faces of the halls of the trade guilds in the market-place at Brussels, and the wonderful stepped and convoluted house-fronts throughout Holland and Germany, are direct descendants of the old rude oblong house of our common forefathers.

We come now to another point, the gable apex.

A gable, of course, is and must be an inverted v, ![]() ;

but there are just three ways in which the apex can

be treated. When the principals are first erected

they form an x,

;

but there are just three ways in which the apex can

be treated. When the principals are first erected

they form an x, ![]() , the upper limbs shorter than the

lower. Sometimes they are so left. But sometimes

they are sawn off, and are held together by mortices

into an upright piece of timber. Then the gable

represents an inverted

, the upper limbs shorter than the

lower. Sometimes they are so left. But sometimes

they are sawn off, and are held together by mortices

into an upright piece of timber. Then the gable

represents an inverted ![]() . If the ends are sawn

off, and there be no such upright, then there remains

an inverted v, but, to prevent the rotting of the ends

at the apex, a crease like a small v is put over the

juncture,

. If the ends are sawn

off, and there be no such upright, then there remains

an inverted v, but, to prevent the rotting of the ends

at the apex, a crease like a small v is put over the

juncture, ![]() . These are the only three variations conceivable.

The last is the latest, and dates from the[41]

introduction of lead, or of tile ridges. By far the

earliest type is the simplest, the leaving of the protruding

ends of the principals forming

. These are the only three variations conceivable.

The last is the latest, and dates from the[41]

introduction of lead, or of tile ridges. By far the

earliest type is the simplest, the leaving of the protruding

ends of the principals forming ![]() . Then, to

protect these ends from the weather, to prevent the

water from entering the grain, and rotting them, they

were covered with horse-skulls, and thus two horse-skulls

looking in opposite directions became an usual

ornament of the gable of a house. Precisely the same

thing was done with the tie-beams that protruded

under the eaves. These also were exposed with the

grain to the weather, though not to the same extent

as the principals. They also were protected by skulls

being fastened over their ends, and these skulls at the

end of the tie-beams are the prototypes of the corbel-heads

round old Norman churches.

. Then, to

protect these ends from the weather, to prevent the

water from entering the grain, and rotting them, they

were covered with horse-skulls, and thus two horse-skulls

looking in opposite directions became an usual

ornament of the gable of a house. Precisely the same

thing was done with the tie-beams that protruded

under the eaves. These also were exposed with the

grain to the weather, though not to the same extent

as the principals. They also were protected by skulls

being fastened over their ends, and these skulls at the

end of the tie-beams are the prototypes of the corbel-heads

round old Norman churches.

Among the Anglo-Saxons the ![]() gable was soon displaced

by that shaped like

gable was soon displaced

by that shaped like ![]() , if we may judge by early

illustrations, but the more archaic and simple construction

prevailed in North Germany and in Scandinavia.

To the present day the carved heads are affixed to

the ends of the principals, and these

heads take the place of the original

skulls. The gable of the Horn

Church in Essex has got an ox’s

head with horns on it.

, if we may judge by early

illustrations, but the more archaic and simple construction

prevailed in North Germany and in Scandinavia.

To the present day the carved heads are affixed to

the ends of the principals, and these

heads take the place of the original

skulls. The gable of the Horn

Church in Essex has got an ox’s

head with horns on it.

HORNED HEAD ON CHURCH

GABLE OF CHURCH, HORN-CHURCH.—Fig. 5.

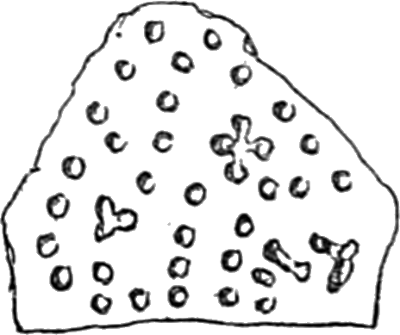

In one Anglo-Saxon miniature representing a nobleman’s house, a stag’s head is at the apex. The old Norwegian wooden church of Wang of the twelfth century, which was bought and transported to the flanks of the Schnee-Koppe in Silesia by Frederick William IV. in 1842, is adorned with two heads of sea-snakes or[42] dragons, one at each end of the gable. In the Rhætian Alps the gables of old timber houses have on them the fore-parts of horses, carved out of the ends of the intersecting principals.

But the horse’s head, sometimes even a human skull, was also affixed to the upright leg of the inverted y—the hipknob,[6] as architects term it—partly, no doubt, as a protection of the cross-cut end from rain and rotting. But though there was a practical reason for putting skulls on these exposed timber-ends, their use was not only practical, they were there affixed for religious reasons also, and indeed principally for these.

As a sacrifice was offered when the foundations of a house were laid, so was a sacrifice offered when the roof was completed. The roof was especially subject to the assaults of the wind, and the wind was among the Northmen and Germans, Odin, Woden, or Wuotan. Moreover, in high buildings, there was a liability to their being struck by lightning, and the thunder-god Thorr had to be propitiated to stave off a fire. The farmhouses in the Black Forest to the present day are protected from lightning by poles with bunches of flowers and leaves on the top, that have been carried to church on Palm Sunday, and are then taken home and affixed to the gable, where they stand throughout the year. The bunch represents[43] the old oblation offered annually to the God of the Storm.[7] Horses were especially regarded as sacred animals by the Germans, the Norsemen, and by the Slaves. Tacitus tells us that white horses were kept by the ancient Germans in groves sacred to the gods; and gave auguries by neighing. The Icelandic sagas contain many allusions to the old dedication of horses to the gods. Among the Slaves, horses were likewise esteemed sacred animals; swords were planted in the ground, and a horse was led over them. Auguries were taken by the way in which he went, whether avoiding or touching the blades. In like manner the fate of prisoners was determined by the actions of an oracular horse. When a horse was killed at a sacrifice, its flesh was eaten. St. Jerome speaks of the Vandals and other Germanic races as horse-eaters, and St. Boniface forbade his Thuringian converts to eat horse-flesh.

The eating of this sort of meat was a sacramental token of allegiance to Odin. When Hakon, Athelstan’s foster-son, who had been baptised in England, refused to partake of the sacrificial banquet of horse-flesh at the annual Council in Norway, the Bonders threatened to kill him. A compromise was arrived at, so odd that it deserves giving in the words of the saga: “The Bonders pressed the King strongly to eat horse-flesh; and as he would not do so, they wanted him to drink the soup; as he declined, they insisted that he should taste the gravy; and on his refusal, were about to lay hands on him.[44] Earl Sigurd made peace by inducing the King to hold his mouth over the handle of the kettle upon which the fat steam of the boiled horse-flesh had settled; and the King laid a linen cloth over the handle, and then gaped above it, and so returned to his throne; but neither party was satisfied with this.” This was at the harvest gathering. At Yule, discontent became so threatening, that King Hakon was forced to appease the ferment by eating some bits of horse’s liver.

Giraldus Cambrensis says of the Irish that in Ulster a king is thus created: “A white mare is led into the midst of the people, is killed, cut to pieces and boiled; then a bath is prepared of the broth. Into this the King gets, and sitting in it, he eats of the flesh, the people also standing round partake of it. He is also required to drink of the broth in which he has bathed, lapping it with his mouth.” (“Topography of Ireland,” c. xxv.) This is, perhaps, the origin of the Irish expression, “a broth of a boy.”

Tacitus tells us that after a defeat of the Chatti, their conquerors sacrificed horses, ate their flesh, and hung up their heads in trees, or affixed them to poles, as offerings to Wuotan. So, after the defeat of Varus and his legions, when Cæcina visited the scene of the disaster, he found the heads of the horses affixed to the branches and trunks of the trees. Gregory the Great, in a letter to Queen Brunehild, exhorted her not to suffer the Franks thus to expose the heads of animals offered in sacrifice. At the beginning of the fifth century, St. Germanus, who was addicted to the chase before he was made[45] Bishop of Auxerre, was wont to hang up the heads and antlers of the game killed in hunting in a huge pear-tree in the midst of Auxerre, as an oblation to Odin, regardless of the reproof of his bishop, Amator, who, to put an end to this continuance of a heathenish ceremony, cut down the tree.

Adam of Bremen tells of the custom of hanging men, horses, and dogs at Upsala; and a Christian who visited the place counted seventy-two bodies. In Zeeland, in the eleventh century, every ninth year, men, horses, dogs, and cocks were thus sacrificed, as Dietmar (Bishop of Merseburg) tells us. Saxo, the grammarian, at the end of the twelfth century, describes how horses’ heads were set up on poles, with pieces of wood stuck in their jaws to keep them open. The object was to produce terror in the minds of enemies, and to drive away evil spirits and the pestilence. For this reason it was, in addition to the practical one already adduced, that the heads of horses, men, and other creatures which had been sacrificed to Odin were fastened to the gables of houses. The creature offered to the god became, so to speak, incorporate in the god, partook of the Divine power, and its skull acted as a protection to the house, because that skull in some sort represented the god.

In the Egil’s saga, an old Icelandic chief is said to have taken a post, fixed a horse’s head on the top, and to have recited an incantation over it which carried a curse on Norway and the King and Queen; when he turned the head inland, it made all the guardian spirits of the land to fly. This post he fixed[46] into the side of a mountain, with the open jaws turned towards Norway.[8] Another Icelander took a pole, carved a human head at the top, then killed a mare, slit up the body, inserted the post and set it up with the head looking towards the residence of an enemy.[9]

These figures were called Nith-stangs, and their original force and significance became obscured. The nith-stang primarily was the head of the victim offered in sacrifice, lifted up with an invocation to the god to look on the sacrifice, and in return carry evil to the houses of all those who wished ill to the sacrificer. The figure-head of a war-ship was designed in like manner, to strike terror into the opponents, and scare away their guardian spirits. The last trace of the nith-stang as a vehicle of doing ill was at Basle, where the inhabitants of Great and Little Basle set up figures at their several ends of the bridge over the Rhine to outrage each other.

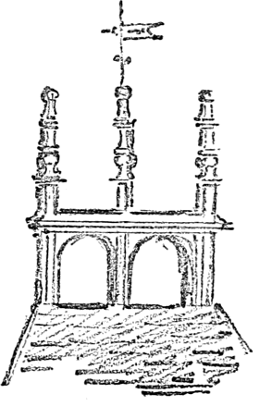

Fig. 6.—A GABLE, GUILDFORD.

In Ireland we meet with similar ideas. On the death of Laeghaire (King Lear), his body was carried to Tara and interred with his arms and cuirass, and with his face turned towards his enemies, as if still threatening them. Eoghan, King of Connaught, was so buried in Sligo, and as long as his dead head looked towards Ulster, the Connaught men were victorious; so the Ulster men disinterred him and buried him face downwards, and then gained the[47] victory. According to Welsh tradition, the head of Bran was buried with the face to France, so that no invasion could come from thence. A Welsh story says that the son of Lear bade his companions cut off his head, take it to the White Hill in London, and bury it there, with the face directed towards France. The head of man and beast, when cut off, was thought to be gifted with oracular powers, and the piping of the wind in the skulls over the house gables was interpreted—as he who consulted it desired.

In an account we have of the Wends in the fifteenth century, we are told that they set up the heads of horses and cows on stakes above their stables to drive away disease from their cattle, and they put the skull of a horse under the fodder in the manger to scare away the hobgoblins who ride horses at night. In Holland, horses’ heads are hung up over pigstyes, and in Mecklenburg they are placed under the pillows of the sick to drive away fever. It must be remembered that pest or fever was formerly, and is still among the superstitious Slaves, held to be a female deity or spirit of evil.

Now we can understand whence came the headless horses, so common in superstition, as premonitions of death. Sometimes a horse is heard galloping along a road or through a street. It is seen to be headless. It stops before a door, or it strikes the door with its hoof. That is a sure death token. The reader may recall Albert Dürer’s engraving of the white horse at a door, waiting for the dead soul to mount it, that it may bear him away to the doleful realms of Hæla. In Denmark and North Germany[48] the “Hell-horse” is well known. It has three legs, and is not necessarily headless. It looks in at a window and neighs for a soul to mount it. The image of Death on the Pale Horse in the Apocalypse was not unfamiliar to the Norse and German races. They knew all about Odin’s white horse that conveyed souls to the drear abode.

Properly, every village, every house had its own hell-horse. Indeed, it was not unusual to bury a live horse in a churchyard, to serve the purpose of conveying souls. A vault was recently opened in a church at Görlitz, which was found to contain a skeleton of a horse only, and this church and yard had long been believed to be haunted by a hell-horse. The horse whose head was set up over the gable of a house was the domestic spirit of the family, retained to carry the souls away.

The child’s hobby-horse is the degraded hell-horse. The grey or white hobby was one of the essential performers in old May Day mummings, and this represents the pale horse of Odin, as Robin Hood represents Odin himself.[10] We see in the hobby-horse the long beam of the principal with the head at the end. It was copied therefrom, and the copy remains long after the original has disappeared from among us.

A man was on his way at night from Oldenburg to Heiligenhafen. When he came near the gallows-hill he saw a white horse standing under it. He was tired, and jumped on its back. The horse went on with him, but became larger and larger at every step,[49] and whither that ghostly beast would have carried him no one can say; but, fortunately, the man flung himself off the back. In Sweden the village of Hästveda is said to take its name from häst-hvith, a white horse which haunts the churchyard and village.

In Bürger’s ballad of Leonore, the dead lover comes riding at night to the door of the maiden, and persuades her to mount behind him. Then the horse dashes off.

They dash past a graveyard in which is a mourning train with a coffin. But the funeral is interrupted; the dead man must follow horse and rider.

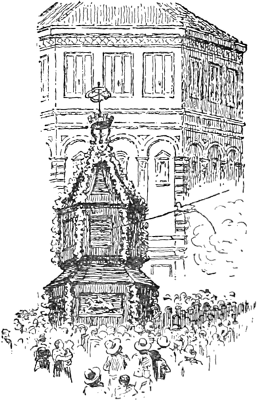

Fig. 7.—OLD TEMPLE BAR, WITH TRAITORS’ HEADS.

They pass a gallows, round which a ghostly crew are hovering. The hanging men and the spectral dance must follow.

The rider carries his bride to a churchyard, and plunges down with her into a vault.

Bürger has utilised for his ballad a tradition of Woden as the God of the Dead, carrying off the souls on his hell-horse. The story is found in many places; amongst others in Iceland, and variously modified.

The nightmare is the same horse coming in and trampling on the sleeper’s chest. The reader will remember Fuseli’s picture of the head of the spectre[50] horse peering in at the sleeper between the curtains of her bed, whilst an imp sits on and oppresses her bosom.

But the horse is not always ridden. Modern ideas, modern luxury, have invaded the phantom world, and now—we hear of death-coaches drawn by headless horses. These are black, like mourning carriages, and the horses are sable; a driver sits on the box; he is in black, but he has no weeper to his hat, because he has not a hat. He has not a hat, because he is without a head. The death-coach is sometimes not seen, but heard. At others it is seen, not heard. It rolls silently as a shadow along the road.

But, indeed, Woden had a black horse as well as one that was white. Rime-locks (Hrimfaxi) was his sable steed, and Shining-locks (Skinfaxi) his white one. The first is the night horse, from whose mane falls the dew; the second is the day horse, whose mane is the morning light. One of the legends of St. Nicholas refers to these two horses, which have been transferred to him when Woden was displaced. The saint was travelling with a black and a white steed, when some evil-minded man cut off their heads at an inn where they were spending the night. When St. Nicholas heard what had been done, he sent his servant to put on the heads again. This the man did; but so hurriedly and carelessly, that he put the black head on the white trunk, and vice versâ. In the morning St. Nicholas saw, when too late, what had been done. The horses were alive and running. This legend refers to the morning and the evening twilights, part night and part day. The morning[51] twilight has the body dark and the head light; and the evening twilight has the white trunk and the black head.

St. Nicholas has taken Odin’s place in other ways. As Saint Klaus he appears to children at Yule. The very name is a predicate of the god of the dead. He is represented as the patron of ships; indeed, St. Nicholas is a puzzle to ecclesiastical historians—his history and his symbols and cult have so little in common. The reason is, that he has taken to him the symbols, and myths, and functions of the Northern god. His ship is Odin’s death-ship, constructed out of dead men’s finger and toe-nails.

Fig. 8.—A GABLE, CHARTRES.

In Denmark, a shovelful of oats is thrown out at Yule for Saint Klaus’s horse; if this be neglected, death enters the house and claims a soul. When a person is convalescent after a dangerous illness, he is said to have “given a feed to Death’s Horse.” The identification is complete. Formerly, the last bundle of oats in a field was cast into the air by the reapers “for Odin at Yule to feed his horse.” And in the writer’s recollection it was customary in Devon for the last sheaf to be raised in the air with the cry, “A neck Weeday!” That is to “Nickar Woden.”

The sheaf of corn, which is fastened in Norway and Denmark to the gable of a house, is now supposed to be an offering to the birds; originally, it was a feed for the pale horse of the death-god Woden. And now we see the origin of the bush which is set up when a roof is completed, and also of the floral hip-knobs of Gothic buildings. Both are relics of the oblation affixed to the gable made to the horse of[52] Woden,—corn, or hay, or grass; and this is also the origin of the “palms,” poles with bouquets at the top, erected in the Black Forest to keep off lightning.