![[Image of the cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: German Atrocities: A Record of Shameless Deeds

Author: William Le Queux

Release date: May 16, 2016 [eBook #52082]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

![[Image of the cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

The Leading Illustrated Authority

on the War is

Navy AND Army

6D. ILLUSTRATED 6D.

. WEEKLY .

THIS magnificent publication is a complete pictorial history of the war week by week. It is, moreover, the only journal that provides interesting and authoritative articles on the ships, the weapons, and the men engaged in the war.

SUPERB ILLUSTRATIONS

MAGNIFICENT

PHOTOGRAVURE

PORTRAITS

OF

LORD KITCHENER

AND

ADMIRAL JELLICOE

are offered to the readers of

this book at the special price of

2/6 the pair, packed in strong tube, carriage paid.

These two Portraits should occupy an

honoured place in every British home, and

as the supply is limited, you should write at

once and make sure of securing them.

| 2/6 THE PAIR. | 16 ins. by 22 ins. Splendid Portraits |

——

GEORGE NEWNES, Ltd. (Dept. G),

8-11, Southampton Street, Strand, London, W.C.

England Invaded

The Invasion

Obtainable at all Railway Bookstalls and Booksellers’.

Price 6d., paper cover, or bound in cloth, 7d.;

or may be had direct (2d. extra for postage) from

GEORGE NEWNES, LTD.,

8-11, Southampton Street, Strand,

London, W.C.

England Triumphant

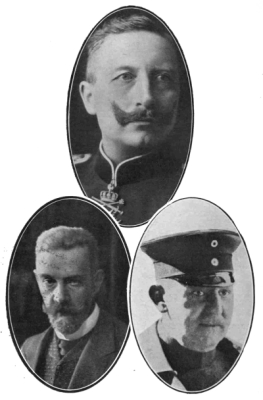

| THE KAISER. Photo, Stanley and Co. | ||

| CHANCELLOR VON BETHMANN-HOLLWEG. Photo, Stanley and Co. | GENERAL VON MOLTKE. Photo, Record Press. | |

| Face title-page. | ||

A R E C O R D OF

SHAMELESS DEEDS

BY

WILLIAM LE QUEUX

![[Image of the colophon unavailable.]](images/colophon.jpg)

GEORGE NEWNES, LIMITED

LONDON

THIS fearful and disgraceful record of a Nation’s shame and of an Emperor’s complicity in atrocious crimes against God and man is no work of fiction, but a plain unvarnished statement of the grim and terrible work of the Kaiser’s Huns of Attila which I have considered it a duty to lay before the British public.

Modern Germany, frothing with military Nietzschism, seems to have returned to a primitive barbarism. Belgium, a peaceful modern nation, has been swept by fire and sword, and its honest, pious inhabitants tortured and massacred, not because the German soldiery desired to wreak such vengeance upon a people with whom they could have no quarrel, but because they had been encouraged “to act with unrelenting severity, to create examples which by their frightfulness would be a warning to the whole country.”

The wild orgies of blood and debauchery, the atrocious outrages, murders, and mutilations, the ruthless violation and killing of defenceless women, girls, and children of tender age, have been, it is now admitted by the Germans themselves, carried out with their full knowledge, and even as part of the actual plan of campaign of their War-Lords.

Germany, though boasting of her culture, her refinement, her honest home-life, and the peaceful efforts of her Emperor, has for ever lost her place among civilized nations. It now stands revealed that when her diplomatic methods of base chicanery and lying fail then she does not hesitate to resort to acts so dastardly and inhuman as to have no parallel. Not only has she broken her most solemn treaties and moral engagements, but all the rules of civilized warfare to which she was a signatory at The Hague she has also violated, merely regarding them as “a scrap of paper.”

Not content with resorting to every act of savagery and every refinement of cruelty which degenerated minds, filled with the{6} blood-lust of war, could conceive, her troops, by order of her generals, have made a practice all along the line of placing before them innocent women and children to act as a living screen, in the hope that the Allies would not, from motives of humanity, fire upon them.

One cannot read a single page of this awful record—the German Black Book—without being thrilled with horror at unspeakable acts of civilized troops, who, at the behest of their Kaiser, and the exposed yet still ruling camarilla at Berlin, have become simply as the Huns of Attila.

The contents of this book are no hearsay stories, but hard facts officially recorded in dossiers in the French and Belgian Ministries of War, most of them, indeed, sworn statements taken before burgomasters, mayors, prefects, and magistrates. Even our brave fellows wounded in the Kaiser’s savage attack upon Europe have brought back from the front similar narratives of the most appalling crimes. Evidence of German trickery and savagery we have, too, in our midst, for trains, sentries, and policemen have been shot at under cover of darkness by men who mean to emulate the methods of their compatriots.

The frightful deeds which have been done over the face of Belgium and in France are, no doubt, intended to be repeated in Great Britain, and, if it were possible, the Red Hand of Destruction would certainly be laid very heavy upon us—more heavily, perhaps, because we, by our honesty of purpose, have incurred the hatred of Kaiserdom.

I would bid all sufferers in Belgium and France to remember that when Attila of old came to Chalons, full of ostentation as the great War-Lord, he came to his own undoing, and his dominion at once disappeared to the winds. There is One with Whom vengeance lies for wrongs, and most assuredly will He mete out the same dread Fate of death and obscurity to the unblushing War-Lord of Germany, who, daily, with his blasphemous impiety, lifts his bloodstained hands and thanks his Maker for his shameful “successes.”

WILLIAM LE QUEUX.

| PAGE | |||

| Preface | 5 | ||

| What the Kaiser Said | 8 | ||

| Foreword | 9 | ||

| Author’s Note | 10 | ||

| Introduction | 11 | ||

| Chapter | I. | Article XXIII. of The Hague Convention | 19 |

| “ | II. | My Interview with Belgian Ministers of State | 21 |

| “ | III. | The British Press Bureau Statement | 26 |

| “ | IV. | Second Report of the Belgian Committee of Inquiry | 34 |

| “ | V. | Can these Things be True? | 44 |

| “ | VI. | Wanton Brutality | 47 |

| “ | VII. | 300 Men Shot in Cold Blood | 52 |

| “ | VIII. | The Inferno at Visé | 54 |

| “ | IX. | The Maiden Tribute | 58 |

| “ | X. | Atrocities Round Liége | 66 |

| “ | XI. | The Crime of Louvain | 73 |

| “ | XII. | French Protest to the Powers | 91 |

| “ | XIII. | The Desecration of Churches | 101 |

| “ | XIV. | Treatment of English Travellers | 105 |

| “ | XV. | What Our Soldiers Say | 109 |

| “ | XVI. | The Antwerp Outrage | 117 |

| “ | XVII. | “The Hussar-like Stroke” | 124 |

| The Day | 127 | ||

WHAT THE KAISER SAID:

“When you meet the foe you will defeat him. No quarter will be given, no prisoners will be taken. Let all who fall into your hands be at your mercy. Gain a reputation like the Huns under Attila.”

This quotation from an address of the Kaiser to German troops, before they were dispatched to Peking in 1900, was circulated on post cards throughout Germany.

WHO WERE

THE HUNS OF ATTILA?

The Kaiser, we read, has exhorted his soldiers to make themselves as much dreaded as the Huns of Attila. It is worth while to recall the methods of this savage, for he was nothing better. In one expedition across Greece and in another across Italy he reduced seventy of the finest cities to smoking ruins and to shambles. The inhabitants were either slaughtered on the spot or marched away in chains to end their lives as slaves. Men, women, children, babies—all came alike to this black demon of outrage and destruction. Briefly, the Monarch of the Huns may be best described as the worthy leader of one vast gang of Jack-the-Rippers.

And this is the blood-guilty ruffian whom the Kaiser now holds up as his exemplar! Judging by Louvain, he is no unworthy follower of his Master.{10}

In addition to the sworn facts and statements supplied officially to me by the Belgian Government, I have here included some others which have been recounted by wounded men who have returned from the front, by doctors who have attended them, and by the special correspondents of Reuter’s, the Central News, and other news agencies, and of the London and provincial newspapers.{11}

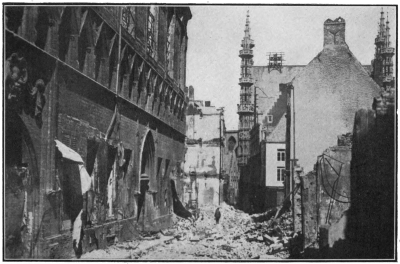

Mr. Asquith has described the sacking of Louvain as “the greatest crime committed against civilization and culture since the Thirty Years’ War. With its buildings, its pictures, its unique library, its unrivalled associations, a shameless holocaust of irreparable treasures lit up by blind barbarian vengeance.”

IT was a little over a month after the declaration of war that reports of great events began to crowd in upon us. Much had happened in that short space of time. The enormous forces of the Kaiser had forced back the line of the Allies well into France. We admired the huge machine at work. From a military point of view the rapidity of the advance of such an enormous body of men was something unique in warfare. It was not this wonderful achievement of the German army, however, it was not the equally wonderful resistance made by the Allies against overwhelming numbers, it was not the glorious record of Belgian,{12} French, and British heroism—which resulted in practically nothing being gained by their adversary—it was none of these things that aroused and amazed the nations of the civilized world. It was something very different which arrested their horrified wonder, something which, in the words of the Times, “will turn the hand of every civilized nation in the world against them” (the German nation).

The atrocious acts committed by the troops of the Kaiser have staggered the civilized world, and it must now be plain to the meanest intelligence that these atrocities and acts of inhuman barbarity were not the doings of soldiers intoxicated with the excitement of success in battle, or maddened to the point of avenging defeat, or to be ascribed to an unbridled license of irresponsible troops out of hand. There is no longer any doubt, even in minds slow to believe them, that deeds which bring the blush of shame to the cheek as we read of them have been perpetrated; there is as little doubt where the responsibility for them rests. It is with the Kaiser and the men around him.

“Until now we have maintained an attitude of deliberate reserve upon the innumerable stories of German atrocities which have reached us,” says the Times. “We published without comment the unanswerable list of shocking excesses committed by the German troops, which was sent to England by the Belgian authorities.{13} When a German Zeppelin cast bombs upon ill-fated women asleep in their beds at Antwerp, we did no more than explain the bearings of international law upon conduct which has met with universal reprobation in Europe and America. But now the real object of German savagery is self-revealed, not only by the effacement of Louvain, but by the shameful admissions sent forth from the wireless station at Berlin. On Thursday night the following official notification regarding Belgium came vibrating through the air:—

“ ‘The only means of preventing surprise attacks from the civil population has been to interfere with unrelenting severity and to create examples which by their frightfulness would be a warning to the whole country.’

“Such is the cynical nature of the German apologia for the destruction of Louvain. Such is the character of the warfare of the modern Huns. They seek to strike terror into the hearts of their foes by methods which belong to the days of the old barbaric hosts, who were thought to have vanished from the world for ever.

“There must be no mistake about the apportionment of blame for this and numberless other crimes. We have listened too long to the bleatings of professors bemused by the false glamour of a philosophy which the Germans themselves have thrust aside. The Kaiser and his people are alike responsible for the acts of their Government and their troops, and there can be no differentiation when the day of reckoning comes.{14}

“The Kaiser could stop these things with a word. Instead, he pronounces impious benedictions upon them. Daily he appeals for the blessing of God upon the dreadful deeds which are staining the face of Western Europe—the ravaged villages, the hapless non-combatants hanged or shot, the women and children torn from their beds by cowards and made to walk before them under fire, all the infamies which have eternally disgraced German ‘valour.’ We are no longer dependent upon hearsay for these stories. Our own men are bringing them back from the front. Let there be no mistake as to where the responsibility rests.”

It was the Kaiser (addressing his troops in June, 1900, on their setting out for Peking) who said:—

“When you meet the foe you will defeat him. No quarter will be given, no prisoners will be taken. Let all who fall into your hands be at your mercy. Gain a reputation like the Huns under Attila.”

And Who Was Attila?

It is worth while to recall the methods of this savage, for he was nothing better. In one expedition across Greece and in another across Italy he reduced seventy of the finest cities to smoking ruins and to shambles. The inhabitants were either slaughtered on the spot or marched away in chains to end their lives as slaves. Men, women, children, babies—all{15} came alike to this black demon of outrage and destruction. Briefly, the Monarch of the Huns may be best described as the worthy leader of one vast gang of Jack the Rippers.

And this is the blood-guilty ruffian whom the Kaiser now holds up as his exemplar! Judging by Louvain, he is no unworthy follower of his Master.

Then was it not Bismarck who said:—

“You must leave the people through whom you march only their eyes to weep with.”

It was also the Kaiser who said, addressing his soldiers, “You must only have one will, and it is mine; there is only one law, and it is mine.”

And then again, I repeat, it was a Berlin wireless that flashed the official message:—

“The only means of preventing surprise attacks from the civil population has been to interfere with unrelenting severity and to create examples which by their frightfulness would be a warning to the whole country.”

Need we seek further to fix the responsibility?

What are the rights of nations in a state of war? There are first of all the unwritten laws of nations and humanity which need, or should need, no defining amongst civilized peoples. There are also the definite and specific Acts laid down at The Hague Convention,{16} which it was declared by the signatories would not be legitimate in war between civilized nations. Germany was a signatory to The Hague Convention. At this Convention the Powers limited the rights of belligerents in the means to be adopted of injuring the enemy. Here are some of them:—

By Article XXIII. it was especially forbidden:—

“To kill or wound treacherously individuals belonging to the hostile nation or army.

“To kill or wound an enemy who, having laid down his arms, or having no longer means of defence, has surrendered at discretion.

“To declare that no quarter will be given.

“To employ arms, projectiles, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering.

“To make improper use of a flag of truce, of the national flag, or of the military insignia and uniform of the enemy, as well as the distinctive badges of the Geneva Convention.

“To destroy or seize the enemy’s property, unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war.”

The law of civilized warfare was further made plain as follows:—

Article XXV.: “The attack or bombardment, by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings which are undefended, is prohibited.”{17}

Article XXVI.: “The officer in command of an attacking force must, before commencing a bombardment, except in cases of assault, do all in his power to warn the authority.”

Article XXVII.: “In sieges and bombardments all necessary steps must be taken to spare as far as possible buildings dedicated to religion, art, science, or charitable purposes, historic monuments, hospitals, and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not being used at the time for military purposes. It is the duty of the besieged to indicate the presence of such buildings or places by distinctive and visible signs which shall be notified to the enemy beforehand.”

In other further Articles it was laid down that a belligerent is forbidden to force the inhabitants of territory occupied by him to furnish information about the army of the other belligerent, or about its means of defence. It was forbidden to confiscate private property, and also laid down that family honour and rights, the lives of persons, and private property, as well as religious convictions and practice, must be respected. Pillage was forbidden, and prisoners must be humanely treated.

Stories of German brutality and ruthless disregard of these rules of civilized warfare as set out above were, from the opening of the war, continually reaching England. At first the public were sceptical about such{18} tales of horror. Unfortunately, however, it was too clearly seen that the Germans made war in a manner which was very far from being civilized. Atrocities were being committed with a definite object—an object which was self-revealed, not only by the effacement of Louvain, “a shameless holocaust of irreparable treasures lit up by blind barbarian vengeance,” but by the disgraceful admissions sent forth from the German wireless station which I have already quoted.

The character of the warfare of these modern Huns was to terrorize the inhabitants of a hostile country, so that the invader might proceed on his way without fear of molestation. Therefore, the unspeakable crimes of the Kaiser’s forces have not even the excuse of being outbursts of national savagery. The shameful record contained in these pages are the cold and calculated brutalities of a nation who boasted of its “culture,” whose prayerful Emperor held up his hands to his Maker invoking success for his horde of ruthless barbarians, but who has shown that in war he respects no law of God, and regards the solemn treaties of nations as “scraps of paper.”

“We can only pray for a hastening of the day when all that is best in the German people will reassert itself as of old, and when the long reign of an arrogant and ruthless military caste will be looked back to by the countrymen of Schiller and Goethe as a nightmare that never can return.”

—From the American Nation.

Article XXIII. of The Hague Convention forbids:—“To kill or wound treacherously individuals belonging to the hostile nation or army.”

From almost the first day of the war this undertaking, given by Germany along with the other Great Powers, has been treated by her as a “scrap of paper.”

The fearful deeds of horror which have besmirched the name of Germany form a terrible page of history. They have been proved by captured Germans themselves to have been deliberate, and to have been actually ordered by officers as high in rank as colonels and majors, and to be part of the Kaiser’s preconceived plan. The murder of unarmed, inoffensive citizens, the hussar-like stroke of sowing neutral waters with death, the destruction of unfortified towns and the massacre of their inhabitants, the violation of women and young girls, the forcing of men, women, and children to march as shields in front of their troops, the murder of the wounded, the wholesale slaughter of non-combatants, the tortures, the mutilations, and the vile outrages are surely sins against humanity, and are bound to meet with an awful and just retribution. The blood of those martyred innocents cries aloud to God for vengeance, and such vengeance must surely come upon the Kaiser and the inhuman monsters surrounding him who have so deliberately urged on their wild assassins{20} to commit the unspeakable crimes reported during the first month of the war.

It must be remembered, in reading of these terrible atrocities, that while they were being committed on the defenceless on every hand, yet the Kaiser sent a telegram to the King of Würtemberg actually thanking the Almighty for the success of his marauders in their murderous campaign against women and children. The text of the Kaiser’s message was: “With God’s gracious assistance, Duke Albrecht and his splendid army have gained a glorious victory. You will join me in thanking the Almighty. I have bestowed on Albrecht the Iron Cross of the First and Second Class.—Wilhelm.” God’s gracious assistance!

The ruthless and utterly inexcusable barbarities committed by the German army were surely without parallel in the whole history of the world. The spectacle of racial degeneration which Germany displayed staggered civilization, and this awful story of murder, cruelty, and debauchery will surely remain for all time as a record of infamies which have eternally disgraced the German nation. About the apportionment of blame there must be no mistake. The Kaiser could have prevented it by a single word. But, condemned by his own speech, he and his people are alike responsible for the acts of the troops, and no differentiation can be made by right-thinking people.{21}

My Interview with Belgian Ministers of State.

In order that the civilized world should be acquainted with the terrible atrocities committed in Belgium, the King of the Belgians, who had served in the trenches with his men, disguised as a private soldier, appointed a Mission to proceed to the President of the United States and lay the case before him. The members of the Mission were:—

M. Carton de Wiart, Chief of the Mission, who is the Belgian Minister of Justice;

M. de Sadeleer, Leader of the Conservative Party;

M. Pau Hemans, Leader of the Liberal Party;

M. Emile Van der Velde, Leader of the Socialist Party.

All these men are Belgian Ministers of State, and were accompanied by Count de Lichtervelde, who acted as Secretary to the Mission.

The members of this Mission first came to London to present an Address to the King. On the evening of the day these gentlemen were received by His Majesty, and later by Sir Edward Grey, I had the privilege of a private interview with them.

I had a long talk with M. Carton de Wiart, during which he unfolded to me many frightful details, and{22}

“These abominable crimes against humanity and civilization call for condign reprobation in the face of the civilized world.... Let us hear no more whining about German ‘culture.’ But let us make it known that we will make the world ring with our sense of horror.”—Frederic Harrison.

explained the reason for the appointment of a committee of inquiry. He described to me scenes he himself had witnessed. He laid stress upon the bombardment and destruction of open towns—that is, towns unprotected and undefended by any military works—such as Malines and Louvain; while Antwerp, being a fortified place, ought to have had twenty-four hours’ notice given to its inhabitants before it was attacked with bombs, yet no such notice was given. On the contrary, attacks by Zeppelins had been made without warning in the dead of night. He also described to me the atrocities committed by the Germans in the bombardment and setting fire to small villages without any military reason or necessity whatever. He related harrowing details of the massacre of perfectly innocent people, non-combatants, men, women, and children.

He showed me a letter from a person of repute in Belgium who had motored from Brussels to Louvain by the Tervueren road, in which I read: “After I got to a village named Veerde St. George I saw only burning villages; peasants beside themselves with terror threw up their arms in sign of submission on my approach.{23} When I got to Louvain I found the whole town in ruins, and soldiers were still piling straw against buildings which had escaped the flames and igniting them.”

The mass of documents which the Mission were carrying to America, he informed me, were all signed statements of persons who had been eye-witnesses of the atrocities, as well as those of many who had suffered.

In a chat I also had with M. Emile Van der Velde, another member of the Delegation and the leader of the Belgian Socialists, he said: “I went to Malines after the fighting, in order to investigate the state of affairs. I found only eight Belgian people in the town, but even then the Germans were bombarding the deserted houses, apparently with the sole object of destroying them. The whole object of the Germans,” he added, “had been to create such a reign of terror that the whole population of Belgium should flee into Antwerp, and so render it impossible for the people congregated there to be fed. I myself examined the bodies of a peasant and his son which had been cut to pieces by bayonet thrusts.”

Another member of the Delegation told me that he had learned from several wounded persons how a druggist living near Tirlemont, on refusing to act as guide to the Uhlans, was shot three times and then bayoneted; and further, in the same hospital, wounded soldiers had told him how that while lying upon the battlefield many had been bayoneted or shot.{24}

The Delegation had, earlier in the day on which I had this interview with them, presented an Address to His Majesty at Buckingham Palace, the text of which has been published. It ran:—

“Sire,—Belgium, having had to choose between the sacrifice of her honour and the peril of war, did not hesitate. She opposed the brutal aggression committed by a Power which was one of the guarantors of her neutrality.

“In this critical situation it was for our country an inestimable tower of strength to see coming forth the resolute and immediate intervention by great and powerful England.

“Commissioned by His Majesty the King of the Belgians with a Mission to the President of the United States, we have considered it to be our duty to make a stay in the capital of the British Empire to convey to your Majesty the respectful and ardent expression of gratitude of the Belgian nation....

“Our adversary, after invading our territory, has decimated the civil population, massacred women and children, carried into captivity inoffensive peasants, put to death wounded, destroyed undefended towns, burned churches, historical monuments, and the famous library of the University of Louvain. All these facts are established by authenticated documents. Each we shall have the{25} honour of submitting to the Government of your Majesty.

“In spite of all this suffering in Belgium, which has been made the personification of outraged right, the country is resolute in fulfilling to the utmost her duties towards Europe. Whatever may happen, she must defend her existence, her honour, and her liberty.”

The King, in reply, said that he would support Belgium, and expressed his horror at the shocking report of German brutality.

The delegation was subsequently received by Sir Edward Grey at the Foreign Office, where they outlined some of the violations of international law and of humanity committed by Germany, viz.:—

1. Violation of Belgium’s neutrality.

2. Taking of several millions of francs from the private National Bank at Liége and Hasselt.

3. Bombardment of the open towns of Louvain and Malines and the bombardment of Antwerp at night by airship without the twenty-four hours’ notice due in international law to the inhabitants of a fortified town.

4. Bombardment and burning of villages and the massacre of non-combatant inhabitants, including women and children.

Our own Press Bureau issued on the 25th August the following statement to the English Press:—

“The Belgian Minister has made the following statement:—

“In spite of solemn assurances of good will and long-standing treaty obligations, Germany has made a sudden savage and utterly unwarranted attack on Belgium.

“However sorely pressed she may be, Belgium will never fight unfairly and never stoop to infringe the laws and customs of legitimate warfare. She is putting up a brave fight against overwhelming odds; she may be beaten, she may be crushed, but, to quote our noble King’s words, ‘She will never be enslaved.’

“When German troops invaded our country, the Belgian Government issued public statements, which were placarded in every town, village, and hamlet, warning all civilians to abstain scrupulously from hostile acts against the enemy’s troops. The Belgian Press daily published similar notices broadcast through the land. Nevertheless, the German authorities have issued lately statements containing grave imputations against the attitude of the Belgian civilian population, threatening us at the same time with dire reprisals. These imputations{27} are contrary to the real facts of the case, and as to threats of further vengeance, no menace of odious reprisals on the part of the German troops will deter the Belgian Government from protesting before the civilized world against the fearful and atrocious crimes committed wilfully and deliberately by the invading hosts against helpless non-combatants, old men, women, and children.

“Long is the list of outrages committed by the German troops and appalling the details of atrocities, as vouched for by the Committee of Inquiry recently formed by the Belgian Minister of Justice and presided over by him. This committee comprises the highest judicial and University authorities of Belgium, such as Chief Justice Van Iseghem, Judge Nys, Professors Cottier, Wodon, etc.

“The following instances and particulars have been established by careful investigations, based in each case on the evidence of reliable eye-witnesses:—

“German cavalry occupying the village of Linsmeau were attacked by some Belgian infantry and two gendarmes. A German officer was killed by our troops during the fight and subsequently buried at the request of the Belgian officer in command. No one of the civilian population took part in the fighting at Linsmeau. Nevertheless, the village was invaded at dusk on August 10th by a strong force of German cavalry, artillery, and machine guns.{28}

“In spite of the formal assurances given by the Burgomaster of Linsmeau that none of the peasants had taken part in the previous fight, two farms and six outlying houses were destroyed by gun fire and burnt. All the male inhabitants were then compelled to come forward and hand over whatever arms they possessed. No recently discharged firearms were found.

“Nevertheless, the invaders divided these peasants into three groups; those in one group were bound, and eleven of them placed in a ditch, where they were afterwards found dead, their skulls fractured by the butts of German rifles.

“During the night of August 10th German cavalry entered Velm in great numbers. The inhabitants were asleep. The Germans, without provocation, fired on M. Deglimme Gevers’ house, broke into it, destroyed furniture, looted money, burnt barns, hay and corn stacks, farm implements, six oxen, and the contents of the farmyard. They carried off Mrs. Deglimme, half naked, to a place two miles away. She was then let go, and was fired upon as she fled, without being hit. Her husband was carried away in another direction and fired upon. He is dying. The same troops sacked and burned the house of a railway watchman.

“Farmer Jef Dierick, of Neerhespen, bears witness to the following acts of cruelty committed by German{29} cavalry at Orsmael and Neerhespen on August 10th, 11th, and 12th:—

“An old man of the latter village had his arm sliced in three longitudinal cuts; he was then hanged head downwards and burned alive. Young girls have been raped and little children outraged at Orsmael, where several inhabitants suffered mutilations too horrible to describe. A Belgian soldier belonging to a battalion of cyclist carabiniers, who had been wounded and made prisoner, was hanged; whilst another, who was tending his comrade, was bound to a telegraph pole on the St. Trond road and shot.

“On Wednesday, August 12th, after an engagement at Haelen, Commandant Van Damme, so severely wounded that he was lying prone on his back, was finally murdered by German infantrymen firing their revolvers into his mouth.

“On Monday, August 10th, at Orsmael, the Germans picked up Commandant Knapen, very seriously wounded, propped him up against a tree, and shot him. Finally they hacked his corpse with swords.

“In different places, notably at Hollogue sur Geer, Barchon, Pontisse, Haelen, and Zelck, German troops have fired on doctors, ambulance bearers, ambulances, and ambulance wagons carrying the Red Cross.

“At Boncelles a body of German troops marched into battle carrying a Belgian flag.{30}

WHY THE GERMANS COMMIT ATROCITIES.

“True strategy consists in hitting your enemy, and hitting him hard. Above all you must inflict on the inhabitants of invaded towns the maximum of suffering, so that they may become sick of the struggle and may bring pressure to bear on their Government to discontinue it. You must leave the people through whom you march only their eyes to weep with.

“In every case the principle which guided our general was that war must be made terrible to the civil population, so that it may sue for peace.”

BISMARCK.

“On Thursday, August 6th, before a fort at Liége, German soldiers continued to fire on a party of Belgian soldiers (who were unarmed, and had been surrounded while digging a trench) after these had hoisted the white flag.

“On the same day, at Vottem, near the fort of Loncin, a group of German infantry hoisted the white flag. When Belgian soldiers approached to take them prisoners the Germans suddenly opened fire on them at close range.

“Harrowing reports of German savagery at Aerschot have reached the Belgian Government at Antwerp from official local sources. Thus on Tuesday, August 18th, the Belgian troops occupying a position in front of Aerschot received orders to retire without engaging the enemy. A small force was left behind to cover the retreat. This force resisted valiantly against overwhelming{31} German forces, and inflicted serious losses on them. Meanwhile, practically the whole civilian population of Aerschot, terrorized by the atrocities committed by the Germans in the neighbouring villages, had fled from the town.

“Next day, Wednesday, August 19th, German troops entered Aerschot, without a shot having been fired from the town and without any resistance whatever having been made. The few inhabitants that remained had closed their doors and windows in compliance with the general orders issued by the Belgian Government. Nevertheless, the Germans broke into the houses and told the inhabitants to quit.

“In one single street the first six male inhabitants who crossed their thresholds were seized and shot at once, under the very eyes of their wives and children.

“The German troops then retired for the day, only to return in greater numbers on the next day, Thursday, August 20th.

“They then compelled the inhabitants to leave their houses and marched them to a place two hundred yards from the town. There, without more ado, they shot M. Thielemans, the Burgomaster, his fifteen-year-old son, the clerk of the local judicial board, and ten prominent citizens. They then set fire to the town and destroyed it.

“The following statement was made by Commandant{32} Georges Gilson, of the 9th Infantry of the Line, now lying in hospital at Antwerp:—

“I was told to cover the retreat of our troops in front of Aerschot. During the action fought there on Wednesday, August 19th, between six and eight o’clock in the morning, suddenly I saw on the high road, between the German and Belgian forces, which were fighting at close range, a group of four women, with babies in their arms, and two little girls clinging to their skirts. Our men stopped firing till the women got through our lines, but the German machine guns went on firing all the time, and one of the women was wounded in the arm.

“These women could not have got through the neighbouring German lines and been on the high road unless with the consent of the enemy.

“All the evidence and circumstances seem to point to the fact that these women had been deliberately pushed forward by the Germans to act as a shield for their advance guard, and in the hope that the Belgians would cease firing for fear of killing the women and children.

“This statement was made and duly certified in the Antwerp hospital on August 22nd by Commandant Gilson in the presence of the Chevalier Ernst N. Bunswyck, Chief Secretary to the Belgian Minister of Justice, and M. de Cartier de Marchienne, Belgian Minister to China.{33}

“Further German atrocities were continuously being brought to notice and made the subject of official and expert inquiry by the proper authorities.

“In publishing the above statements the only comment the Press Bureau can offer is, that these atrocities appear to be committed in villages and throughout the countryside with the deliberate intention of terrorizing the people, and so making it unnecessary to leave troops in occupation of small places, or to protect lines of communication. In larger places, like Brussels, where the diplomatic representatives of neutral Powers are eye-witnesses, there appear to have been no excesses.”

Such was the document issued by the Press Bureau. I have quoted it word for word (emphasizing only in italics or in heavy type certain passages).

PRIMITIVE SAVAGERY.

“Their utter contempt for the established usages of international intercourse, and even for the ordinary decencies of life, was displayed in their brutal treatment of the French and Russian Ambassadors, in the stripping naked of the wives of Russian officials, in the atrocities they have since committed in Belgium, in their seizure of hostages, in their homicidal mine-laying in the North Sea. In all these matters one seems to discern a sudden lapse into primitive savagery.”

—Dr. Dillon in the Contemporary Review.

The following is the second report issued by the Belgian Commission of Inquiry, and which was published by the British Official Press Bureau on September 15th, 1914.

To M. Carton de Wiart, Minister of Justice, Antwerp.

Sir,—The Commission of Inquiry has the honour to make the following report on acts of which the town of Louvain, the neighbourhood, and the district of Malines have been the scene.

The German Army entered Louvain on Wednesday, August 19th, after having burned down the villages through which it had passed.

As soon as they had entered the town of Louvain the Germans requisitioned food and lodging for their troops. They went to all the banks of the town and took possession of the cash in hand. German soldiers burst open the doors of houses which had been abandoned by their inhabitants, pillaged them, and committed other excesses.

The German authorities took as hostages the mayor of the city, Senator Van der Kelen, the Vice-Rector of the Catholic University, and the senior priest of the city,{35} besides certain magistrates and aldermen. All the weapons possessed by the inhabitants, even fencing swords, had already been given up to the municipal authorities and placed by them in the Church of St. Pierre.

In a neighbouring village, Corbeek Loo, on Wednesday, August 19th, a young woman, aged twenty-two, whose husband was with the Army, and some of her relations, were surprised by a band of German soldiers. The persons who were with her were locked up in a deserted house, while she herself was dragged into another cottage, where she was assaulted by five soldiers.

Fate of 16-year-old Girl.

In the same village on Thursday, August 20, German soldiers fetched from their house a young girl, about sixteen years old, and her parents. They conducted them to a small deserted country house, and while some of them held back the father and mother, others entered the house, and, finding the cellar open, forced the girl to drink. They then brought her on to the lawn in front of the house and assaulted her. Finally they stabbed her in the breast with their bayonets.

When this young girl had been abandoned by them after these abominable deeds, she was brought back to her parents’ house, and the following day, in view of the gravity of her condition, she received extreme unction{36} from the parish priest and was taken to the hospital of Louvain, as her life was despaired of.

On August 24 and 25 Belgian troops made a sortie from the entrenched camp of Antwerp and attacked the German army before Malines. The Germans were thrown back on Louvain and Vilvorde.

On entering the villages which had been occupied by the enemy the Belgian army found them devastated. The Germans, as they retired, had pillaged and burnt the villages, taking with them the male inhabitants, whom they forced to march in front of them.

Belgian soldiers entering Hofstade on August 25 found the body of an old woman who had been killed by bayonet thrusts. She still held in her hand the needle with which she was sewing when she was killed. A woman and her fifteen or sixteen year old son lay on the ground, pierced by bayonets. A man had been hanged.

At Sempst, a neighbouring village, were found the bodies of two men partially carbonised. One of them had his legs cut off at the knees; the other had the arms and legs cut off. A workman, whose burnt body has been seen by several witnesses, had been struck several times with bayonets, and then, while still alive, the Germans had poured petroleum over him and thrown him into a house to which they set fire. A woman who came out of her house was killed in the same way.

A witness, whose evidence has been taken by a reliable{37} British subject, declares that he saw, on August 26, not far from Malines, during the last Belgian attack, an old man tied by the arms to one of the rafters in the ceiling of his farm. The body was completely carbonised, but the head, arms, and feet were unburnt. Further on, a child of about fifteen was tied up, the hands behind the back, and the body was completely torn open with bayonet wounds. Numerous corpses of peasants lay on the ground in positions of supplication, their arms lifted and their hands clasped.

Facts about Louvain.

At nightfall on August 26 the German troops, repulsed by our soldiers, entered Louvain panic-stricken. Several witnesses affirm that the German garrison which occupied Louvain was erroneously informed that the enemy were entering the town. Men of the garrison immediately marched to the station, shooting haphazard the while, and there met the German troops who had been repulsed by the Belgians, the latter having just ceased the pursuit.

Everything tends to prove that the German regiments fired on one another. At once the Germans began bombarding the town, pretending that civilians had fired on the troops, a suggestion which is contradicted by all the witnesses, and could scarcely have been possible, because the inhabitants of Louvain had had to give up their arms to the municipal authorities several days before.{38}

The bombardment lasted till about ten o’clock at night. The Germans then set fire to the town. Wherever the fire had not spread, the German soldiers entered the houses and threw fire grenades, with which some of them seemed to be provided. The greater part of the town of Louvain was thus a prey to the flames, particularly the quarters of the upper town, comprising the modern buildings, the ancient Cathedral of St. Pierre, the university buildings, together with the university library, its manuscripts and collections, and the municipal theatre.

The Commission considers it its duty to insist, in the midst of all these horrors, on the crime committed against civilisation by the deliberate destruction of an academic library which was one of the treasures of Europe.

The corpses of many civilians encumbered the streets and squares. On the road from Tirlemont to Louvain alone a witness counted more than fifty. On the doorsteps of houses could be seen carbonised bodies of inhabitants, who, hiding in their cellars, were driven out by the fire, tried to escape, and fell into the flames. The suburbs of Louvain suffered the same fate.

We can affirm that the houses in all the districts between Louvain and Malines, and most of the suburbs of Louvain itself, have practically been destroyed.

Thousands Sent to Germany.

On Wednesday morning, August 26th, the Germans brought to the station squares of Louvain a group of{39} more than seventy-five persons, including several prominent citizens of the town, among whom were Father Coloboet and another Spanish priest, and also an American priest.

The men were brutally separated from their wives and children, and after having been subjected to the most abominable treatment by the Germans, who several times threatened to shoot them, they were forced to march to the village of Campenhout in front of the German troops. They were shut up in the village church, where they passed the night.

About four o’clock the next morning a German officer told them they had better go to confession, as they would be shot half an hour later. About half-past four they were liberated. Shortly afterwards they were again arrested by a German brigade, which forced them to march before them in the direction of Malines. In reply to a question of one of the prisoners, a German officer said they were going to give them a taste of the Belgian quickfirers before Antwerp. They were at last released on the Thursday afternoon at the gates of Malines.

It appears from other witnesses that several thousand male inhabitants of Louvain, who had escaped the shooting and the fire, were sent to Germany for a purpose which is still unknown to us.

Eye-Witness’s Account.

The fire at Louvain burnt for several days. An eye-witness who left Louvain on August 30th gave the{40} following description of the town at that time:—“Leaving Weert St. George’s, I only saw burnt-down villages and half-crazy peasants, who on meeting anyone held up their hands as a sign of submission. Before every house, even those burnt down, hung a white flag, and the burnt rags of them could be seen among the ruins.

“At Weert St. George’s I questioned the inhabitants on the causes of the German reprisals, and they affirmed most positively that no inhabitant had fired a shot, that in any case the arms had been previously collected, but that the Germans had taken vengeance on the population because a Belgian soldier belonging to the gendarmerie had killed an Uhlan.

“The population still remaining in Louvain have taken refuge in the suburb of Héverlé, where they are extremely crowded. They have been cleared out of the town by the troops and the fire.

“The fire started a little beyond the American College, and the town is entirely destroyed, except for the town hall and the station. Furthermore, the fire was still burning to-day, and the Germans, far from taking any steps to stop it, seemed to feed it with straw, an instance of which I observed in the street adjoining the town hall.

“The cathedral and the theatre are destroyed and have fallen in, as also the library; in short, the town has{41} the appearance of an ancient ruined city, in the midst of which only a few drunken soldiers move about, carrying bottles of wine and liqueurs, while the officers themselves, seated in arm-chairs round the tables, drink like their men.”

The Commission has not yet been able to obtain information about the fate of the Mayor of Louvain and of the other notables who were taken as hostages.

The Commission is able to draw the following conclusions from the facts which have so far been brought to its notice:—

In this war, the occupation of any place is systematically accompanied and followed, sometimes even preceded, by acts of violence towards the civil population, which acts are contrary both to the usages of war and to the most elementary principles of humanity.

Brutality Everywhere.

The German procedure is everywhere the same. They advance along a road, shooting inoffensive passers-by—particularly bicyclists—as well as peasants working in the fields.

In the towns or villages where they stop they begin by requisitioning food and drink, which they consume till intoxicated.

Sometimes from the interior of deserted houses they let off their rifles at random and declare that it was the inhabitants who fired. Then the scenes of fire, murder,{42} and especially pillage begin, accompanied by acts of deliberate cruelty, without respect to sex or age. Even where they pretend to know the actual person guilty of the acts they allege, they do not content themselves with executing him summarily, but they seize the opportunity to decimate the population, pillage the houses, and then set them on fire.

After a preliminary attack and massacre they shut up the men in the church, and then order the women to return to their houses and to leave their doors open all night.

From several places the male population has been sent to Germany, there to be forced, it appears, to work at the harvest, as in the old days of slavery. There are many cases of the inhabitants being forced to act as guides and to dig trenches and entrenchments for the Germans. Numerous witnesses assert that during their marches, and even when attacking, the Germans place civilians, men and women, in their front ranks, in order to prevent our soldiers firing.

The evidence of Belgian officers and soldiers shows that German detachments do not hesitate to display either the white flag or the Red Cross flag in order to approach our troops with impunity. On the other hand, they fire on our ambulances and maltreat the ambulance men. They maltreat and even kill the wounded. The clergy seem to be particularly chosen as subjects for their brutality.{43}

Finally, we have in our possession expanding bullets which had been abandoned by the enemy at Werchter, and we possess doctors’ certificates showing that wounds must have been inflicted by bullets of this kind.

The documents and evidence on which these conclusions rest will be published in due course.

(Signed)

The President, Cooreman.

Members of the Commission, Count Goblet d’Alviella, Ryckmans, Strauss, Van Cutsem.

Secretaries, Chev. Ernst de Bunswyck, Orts.

“The report of the Belgian Commission of Inquiry into the German atrocities in Belgium is perhaps the most appalling document that has ever been submitted to civilised man. It reveals a cruelty more perverse than that of the Boxer or Bashi-Bazuk, and it covers the reputation of the German soldiery with eternal shame.... They themselves have transgressed every law of God and man.”

—From the Daily Mail.

Can These Things Be True?

Can these cold-blooded deeds of atrocity be true? Is it a fact that they have been proved to the satisfaction of the most exacting critics? Is this “welter of fire, blood, and destruction” to be written finally on the pages of history?

I can only say this:

1. These stories came to us first from responsible correspondents of all our leading newspapers, who took them down for the most part at first hand from eye-witnesses and from the poor victims themselves.

2. A committee of eminent lawyers, assisted by the Belgian Minister of Justice, made a searching inquiry, sifting vague reports from actual facts.

3. The evidence of the atrocities thus collected was formulated in an Official Report to be presented to the President of the United States by the Belgian Delegation of Ministers of State, now on their way to America.

4. The British Official Press Bureau issued, on the 25th August, a statement of the representations made to them, which I have already quoted.

5. The Report of the Belgian Government was confirmed by the French protest against German atrocities{45} which was addressed on September 2nd to the Powers by the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

6. Mr. Richard Harding Davis, an eminent American author and correspondent in Belgium of the New York Tribune, has entirely confirmed, in cables sent to this leading American journal, things he has seen with his own eyes.

7. I have narrated the information given to me verbally by M. Van der Velde himself. “I myself examined the bodies of a peasant and his son which have been cut to pieces by bayonet thrusts.”

8. While at first the reports of these atrocities were received in this country with some reserve, the accumulated and overwhelming evidence, aggravated from day to day since the very commencement of the war, has provoked the public men of England, and every responsible newspaper in the country, as well as all our leading weeklies like the Spectator, the Saturday Review, the Nation, the British Weekly, and others, into a passionate protest against the inhuman and barbarous methods of warfare that have stained the name of Germany for ever.

9. Germany herself has admitted her wanton deeds, and sought to excuse them in a way that makes her guilt all the more deplorable. We are told that these barbarian atrocities against the civil population and unoffending peasants, the sacking, looting, and burning of towns and villages, are part of the general plan of attack, and that they are accomplished in cold blood for{46} purely strategical considerations. Unfortunately they are not merely the riotous and isolated outbursts of marauding and buccaneering soldiers.

“The only means of preventing surprise attacks from the civil population has been to interfere with unrelenting severity and to create examples which by their frightfulness would be a warning to the whole country.” To prevent “surprise attacks” tortures were inflicted on helpless old men, women, and children, peaceful villagers were hanged, innocent children were savagely sabred by German officers, wounded soldiers and officers shot and mutilated. There was the burning of Visé and the terrible massacre at Seraing, the sacking and plundering of many another harmless village, the bombardment of Malines, and the crowning sacrilege of all, the burning and sacking of Louvain, the torture and massacre of its defenceless people. Abler pens than mine have told the story of these blood-guilty ruffians, and abler historians will yet chronicle for future generations the record of the modern Huns of Attila. “For every vile deed wrought under the impious benedictions of the monarch who is ravaging Europe ample reparation will be exacted.... The memory of them will burn in the heart and mind of every Englishman.” So said the Times. I affirm this is the feeling of every true Britisher.{47}

It is specially forbidden “To kill or wound an enemy who, having laid down his arms, or having no longer means of defence, has surrendered at discretion. To make improper use of a flag of truce, of the national flag, or of the military insignia and uniform of the enemy.”—Hague Convention, Article XXIII.

Wanton Brutality.

I have made it plain from the official documents I have quoted that the German troops violated every item of this article. But in addition to cases of brutality already cited in the official document, the Belgian Mission, while in London, gave me the following:—

On August 19th Aerschot, in North Brabant, with about five thousand inhabitants, was, as already reported, destroyed. It appears that during the three days the German soldiery massacred and pillaged the town, which had not resisted, although there was no military force there whatever.

In the neighbouring village of Diest many of the inhabitants were put to the sword. The wife of Francis Luyckx, aged forty-five, and her daughter, twelve years of age, had, in their terror, taken refuge in a sewer. They were discovered, dragged out, and shot.

The little daughter of Jean Oyyen, a pretty child of nine, was shot, and a man named Andre Willem, aged{48} twenty-three, the village sexton, was bound to a tree and burned alive.

In the village of Schaffen, near Diest, two men, named Lodts and Marken, both aged forty, were captured and entombed. When exhumed, it was found that they had been buried alive, head downwards. These occurrences—which are only a few of a very long list—had been fully inquired into, and confirmed by the committee of investigation, which was composed of the highest magistrates of Belgium and the chief professors of the Universities.

Statements were made that aged villagers in many places on the Franco-German frontier were hanged to trees; others, after being killed, had their eyes gouged out. In one place fifteen bodies were found mutilated in a heap, and along the whole frontier from Luxemburg to Basle outrages were committed on women, girls, and children.

Mlle. Marie Malet, the daughter of a judicial official in Brussels, who had been sent to London with a party of Belgian girls for safety, stated that she had seen a little girl, a friend of hers, aged ten, savagely sabred by a German officer, merely because she made a remark that the Germans were bullies. The child died an hour afterwards. Mlle. Malet stated that she had been sent from near Brussels with her sister, owing to the insults to which Belgian girls were subjected by German soldiers. Her mother had been wounded and her home looted of food and valuables.{49}

The record of German atrocities in Belgium, indeed, rivals that of Alva in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century. The worst Balkan methods were being pursued by the army of the pious Kaiser. At Pontillac, between Liége and Namur, the Burgomaster officially reported that the men of the 17th Hussars from Mecklenburg entered the place, met with no resistance, and demanded food, which the inhabitants at once gave them. After eating and drinking to their full, to the surprise of everyone they rode wildly through the streets emptying their carbines at the windows of the houses. Two Belgian soldiers who were secreted in the village returned their fire. A hot fusillade ensued, and then the Germans deliberately shot down all the villagers they could find. They also seized a M. Lahaye, a member of the Communal Council, and dragged him through the streets with a rope round his neck.

Drunken German Soldiers.

Further details regarding the wild savagery at Aerschot reached the Belgian Government after the issuing of the official report printed in the foregoing pages. It seems that the population of the Belgian provinces overrun by the Germans suffered, not only from the outrages of the troops acting under the orders of their officers, but also from atrocities due to drunken soldiers.

In one town some of them fired their rifles openly into the air and afterwards declared that the inhabitants had{50} fired on them. On this pretext the people were dragged from their houses, which were then set on fire, and in many cases women and girls were outraged and the men shot. At Aerschot the troops—upon whom the Kaiser and the Austrian Emperor were beseeching God’s blessing—stabled their horses in the church, one of the most beautiful in Belgium, while the troops were set to work to destroy the pictures and fittings in the noble edifice. The Germans accused the son of the Burgomaster of killing the son of a German colonel. This was denied by the Burgomaster’s son, who only fired to defend his mother and sister from gross insults by the soldiery.

“For every evil and unwarrantable act committed in the Western theatre, ample vengeance will be exacted at the other end.”—Times.

The Germans, however, surrounded the town. The inhabitants were then dragged from their homes and the women separated from the men. The latter were divided into batches and forced to run towards the river, the troops laughing at them and firing at them as they ran. One man who escaped by feigning death afterwards returned and counted forty-one bodies of his friends. Many of them had been stabbed by bayonets after being wounded. About one hundred and fifty of the male inhabitants of this place were compelled to watch the German troops shoot the Burgomaster, his son, and the Burgomaster’s brother.{51}

Women Mutilated.

Mr. Adolph Coussmaekrs, a well-known resident of Antwerp, wrote giving nine cases of atrocities committed by the Germans in the districts of Orsmael and Barchon.

I do not reproduce here the nine cases instanced by this gentleman. The wanton mutilation on women and children is revolting and seems incredible.

In addition, there were criminal assaults on women which I cannot dwell upon in these pages; they have been narrated by unimpeachable persons. Mothers had their daughters dragged away from them by shameless officers to a fate that must have driven them to despair. Women and young children were injured by bayonet-thrusts and revolver-shots, and were still suffering from their wounds.

“In no war of modern times has an enemy so distinguished himself by war on civilians as in this. The brutality of the methods employed by the Prussian apostles of ‘culture’ is only equalled by its futility.”—Daily Telegraph.

300 Men Shot in Cold Blood.

A terrible story of the holocaust at Liége was told to the correspondent of the Daily Mail by a wealthy Dutch cigarette manufacturer who had lived for a long time in Belgium, and was married to a Belgium woman. He stated that on the day of their entry the Germans posted an order on the streets that all arms in possession of private persons must be immediately delivered, under the threat of being shot. The inhabitants complied with the order. Among others, collections of old arms were brought, valued sometimes at hundreds of pounds. The new vandals destroyed all these pitilessly.

“During the first days the Germans paid for everything they took. But later on soldiers produced valueless pieces of paper, on which something had been scribbled which could hardly be read. On Sunday, August 23rd, at midnight, the inhabitants were suddenly awakened by soldiers knocking at the doors. ‘We need immediately two hundred and fifty mattresses, two hundred pounds of coffee, two hundred and fifty loaves of bread, and five hundred eggs,’ they said. ‘If these are not delivered in an hour’s time your hostages will be shot.’ Everybody rushed to the market-place, many people in their night clothes. There stood the mayor, half-dressed.

“After the inhabitants had brought in everything which was demanded they were informed that the whole was a mistake and that they could go to bed. The old{53} mayor, however, was detained the whole night in the street.

“One day when the soldiers sat down to dinner, an alarm was suddenly beaten in the streets. Soldiers from all the houses were summoned to their regiments. Immediately after, the bombardment of the houses began. The informant took refuge with his wife and children in a cellar, which was constantly filled with smoke from the neighbouring houses, which had caught fire. On Wednesday morning the bombardment ceased and they ventured to the station.

“Here, notwithstanding his protests, and proposals to produce papers, showing that he was a Dutch subject, the cigarette manufacturer was separated from his family, of whom he has since lost sight. He was surrounded by soldiers, who bound his hands behind his back, and with other refugees he was kept at the station many hours. During this time he saw a party of three hundred Belgian civilians, among whom were old men and lads of fourteen or fifteen, driven at the point of the bayonet to a remote spot near the station, where they were all shot before his eyes.

“After a terrible night, he and his group of seventy-six men were set free. They had had nothing to eat or drink for thirty-six hours. All streets and roads in and round Liége were strewn, according to the witness, with bodies of men, women, and children. Among those shot were the mayor, two aldermen, the rector of the University, two deans, and many police inspectors.”{54}

“Our German people will be the grand block on which the good God may complete His work of civilizing the world.”

From a speech of The Kaiser’s.

The Inferno at Visé.

A correspondent of the Handelsblad was an eye-witness of the scenes in Visé, near Liége, when it was burned, and told a tale of German barbarity, and of the murder and torture of its helpless inhabitants, of a nature to make one’s blood run cold. As summarized in the Daily News the story is as follows:—

“It was an awful sight. Every house was a mass of flames, through which the streets were hardly visible.

“At the entrance of the Grand Hotel were three disarmed soldiers bound hand and foot. Entering the hotel, I found the floor covered with dead bodies. In that hall of the dead several soldiers stood guard. From this awful, nauseating scene I hurried back to the blinding glare and suffocating heat of the burning villages.

“The correspondent describes how a colleague supported an aged lady found lying near her blazing house. She pleaded, ‘Let me die.’ Poor, unhappy creature, bereft of home and even of adequate clothing, the aged{55}

and defenceless victim of the Kaiser’s gallant army! He adds: ‘We fled from the scene that must for ever blur the scutcheon of the Kaiser, and I pray as long as I live it will never be my task to see such an inferno again.’

“Absolutely incredible was the picture of incidents connected with the burning of Visé by the Germans and the shooting given in private letters which arrived from Eysden, on the Dutch frontier, and seen by the Telegraaf. According to these letters, the Germans alleged that the citizens had fired on the troops. All the inhabitants were then hunted out of their houses to spend the night in the square watching the burning. Men were taken prisoners, and possibly shot, and the rest were driven out of the town, which was given to the flames. Eysden is filled with refugees—one hundred and fifty in one canteen and two hundred and fifty in the Protestant Church, while four hundred have been sent to Maastricht.

“Two trainloads of refugees came into Brussels from the Tirlemont district. The scenes I have witnessed,” telegraphs a Press Association correspondent, “and the stories told by these poor people would melt a heart of stone. Removal from the face of the earth—a phrase of the German papers themselves—continues to be the invader’s idea of how best to deal with unarmed, unoffending villages, the only crime of whose people is that they have fallen in his path.

“The Germans entered Tirlemont, in the vicinity of{56} which they have been for some days. They were in strong force, mostly cavalry and artillery. The big guns shelled the place, and the cavalry played at war by attacking the flying and panic-stricken populace, shooting and stabbing them at random.

“Never have I seen such a picture of woe as a peasant woman and five children who stood bewildered in the Place de la Gare here, all crying as if their hearts would break. It was a terrible story the woman had to tell. ‘They shot my husband before my eyes,’ she said, ‘and trampled two of my children to death.’

“A German knocked at the door of the house of the Burgomaster at Venne, near the Dutch frontier, and when the Burgomaster’s wife opened the door she was knocked down and killed with the butt end of a rifle.

“A solicitor, who was a member of the Belgian Chamber, and who was staying in the house, rushed to the front door, and he also was instantly knocked down and killed with a bayonet thrust. On hearing of these atrocities the population fled in terror.”

Lancer’s Fiendish Act.

M. Isadore Felix Cruls, a Belgian refugee who arrived in London, had a tragic story to tell. He carried on a prosperous printing business at Saint Jossé, a suburb of Brussels. When hostilities broke out he was called up for service in the Civil Guard, and stationed on the Chaussée de Louvain, the road between Louvain and{57} Brussels. As reported in the Daily Telegraph, he stated:—

“At midnight on August 19th-20th I was on duty on the Chaussée de Louvain watching the refugees come in from the various towns and villages. The road was blocked when I got near. I saw that a party of German Lancers were at the rear of the procession of refugees. I saw one of the Lancers prodding a woman, who had four or five children walking by her side.

“There was an old woman, evidently the mother of the young woman, walking with them. One of the Lancers was amusing himself by pricking this old woman with his lance in order to make her walk along more quickly. The young woman turned round and shouted something at the Lancer, either by way of remonstrance or insult. I was not near enough to hear what she said. The Lancer took up his lance and ran it through one of the little girls who was walking along, clutching the hand of her mother. She was a fair-haired girl of about seven or eight years of age. When the crowd saw this they became infuriated, and a panic ensued. The Lancers bore down upon the people, scattering them in all directions. What became of these people I do not know.”{58}

The Maiden Tribute.

Another story M. Cruls related was told to him by the mother herself. At a village called Leau a squadron of about five hundred Uhlans was marching through the town when they declared that someone had fired at them. On going round to all the houses, searching for firearms, they came to one where the family circle consisted of a grandfather, the father, mother, and a girl of seventeen or eighteen, and a young boy, who, upon seeing the approach of the German soldiers, fled and hid himself. The soldiers came in, and without any questioning fired at and killed the father. They were going to shoot the grandfather when the mother and daughter fell on their knees and begged the soldiers to spare the life of the old man. The officer, or under-officer, of the party then said, “Yes, we won’t trouble about the old people,” and touching the cheek of the young girl with his fingers, he added, with a significant laugh, “Pretty youth is better.” The sequel need not be written here, although the mother of the girl has told it.

A Governess Hanged.

A well-known family in Brussels were staying at their villa at Genck, about six kilometres from the capital. On arrival of the Germans there they entered the villa,{59} smashed everything they could, and stole whatever was of value, “even taking away the wedding-ring that the husband wore on his finger.” They took away the men first, and nobody knows what has become of them. A member of the family and two servants fled from the house in terror, but returned when they saw the German soldiers going.

This is what they saw: “The body of an old lady of seventy years of age lying on the floor with her throat cut. A governess, about thirty years of age—I cannot tell you her nationality—was found hanging from a tree, stark naked and mutilated.”

Although this happened within six kilometres of Brussels, yet no atrocities were known to have been committed in the capital, the Kaiser’s unrestrained savages being there under the eyes of the representatives of the Powers.

A Dutch gentleman named Couzy, of Amsterdam, was staying at Mont, a village in the hills above Comblain au Pont, when war broke out. Having missed the last train which the Belgians ran to Dinant, he was obliged to return to Mont, where he witnessed the arrival of thousands of Uhlans and many batteries of German artillery. Mr. Couzy declared that the treatment of the Belgians by the enemy was merciless. He was witness of many horrible scenes. He was present when, after the discovery of the bodies of two German officers in a horse-dealer’s yard at Comblain au Pont, seventy villagers were brought before the commanding officer. Without question,{60} the officer selected thirty, who were shot without any form of trial whatever. Several of these men were known to Mr. Couzy as honest and trustworthy citizens.

On another occasion a number of villagers were searched for weapons. A young Dutchman, also known to Mr. Couzy, had upon him a razor which he used daily. Immediately he was placed against a wall and shot.

A refugee arriving at Maastricht from Bassenge stated that ten thousand Germans came from the direction of Louvain, and began to burn everything that had been left standing and shoot everyone opposed to them. Two hundred of the villagers were driven out by the Germans and ordered to hold their hands above their heads. Anyone who dropped his hands for an instant was shot, and anyone who looked at or showed sympathy with the victims shared the same fate. They were marched for two hours, and during that time many shots whistled over their heads. The Germans then stopped and threatened that the first who looked back would be shot.

A Senator’s Story.

“M. Leon Hiard, senator of Hainaut, one of the largest manufacturers in Belgium, lived at Haine Saint Pierre, where before the battle of Mons the Germans requisitioned everything. He states that, revolver in hand, threatening death for unpunctuality or disobedience, the German officers spread terror into the hearts of the inhabitants. At Peronne the mayor, M. Gravis, had very imprudently caused all the arms of the inhabitants to be{61} deposited at his house instead of the town-hall. He also carried a revolver, and some of his carts had been used to bar a road.” The Daily Express correspondent continues—

“He was taken before the German general at the town-hall with his secretary. The séance was short. ‘Vous fusillé,’ said the general, and the unfortunate man was led out blindfolded and shot. As the secretary was following him a more kindly officer said in his ear, ‘Mais filez-donc, imbécile,’ and pushed him on one side.

“The body of M. Gravis was propped up against a wall for forty-eight hours as an example to the town. Men were billeted in all the houses, and although in the better houses the officers behaved with some restraint, in the peasants’ cottages unbridled licence was the rule.

“Women were treated infamously, indescribable scenes of debauchery taking place, while all the possessions of the unfortunates were wilfully wasted and destroyed. The fiery-tempered people were being driven to reprisals, so that an excuse for further cruelty might be found.”

What General von Boehn said.

I take the following extract from a long dispatch in the Daily Chronicle, from Mr. E. Alexander Powell, the Special Correspondent of the New York World:—

“Three weeks ago the Government of Belgium requested me to place before the American people, through the medium of the New York World, a list of specific{62} and authenticated atrocities committed by German armies upon Belgian non-combatants.

“To-day General von Boehn, commanding the Ninth Imperial Field Army, and acting as mouthpiece of the German General Staff, has asked me to place before the American people the German version of the incidents in question....

“General von Boehn began by asserting that the accounts of the atrocities perpetrated on Belgian non-combatants were a tissue of lies.

“ ‘Look at these officers about you,’ he said; ‘they are gentlemen like yourselves. Look at the soldiers marching past in the road out there. They are most of them the fathers of families. Surely you do not believe that they would do the things they have been accused of.’

“ ‘Three days ago, General,’ I said, ‘I was in Aerschot. The whole town is now but a ghastly, blackened, bloodstained ruin!’

“ ‘When we entered Aerschot,’ he replied, ‘the son of the Burgomaster came into the room, drew a revolver, and assassinated my Chief of Staff. What followed was only retribution. The townspeople only got what they deserved!’

“ ‘But why wreak your vengeance on women and children?’

“ ‘None have been killed,’ the General asserted positively.{63}

“ ‘I’m sorry to contradict you, General,’ I asserted, with equal positiveness, ‘but I have myself seen their mutilated bodies. So has Mr. Gibson, Secretary of the American Legation at Brussels, who was present during the destruction of Louvain.’

“It is War!”

“ ‘Of course, there is always danger of women and children being killed during street fighting,’ said the General, ‘if they insist on coming into the street. It is unfortunate, but it is war.’

“ ‘But how about the woman whose body I saw with the hands and feet cut off? How about the white-haired man and his son whom I helped to bury outside of Sempst, and who had been killed merely because the retreating Belgians had shot a German soldier outside their house? There were 22 bayonet wounds in the old man’s face. I counted them. How about the little girl, two years old, shot while in her mother’s arms by a Uhlan, and whose funeral I attended at Heyst-op-den-Berg? How about the old man that was hung from the rafters of his house by the hands and roasted to death by a bonfire being built under him?’

“The General seemed somewhat taken aback by the amount and exactness of my data. ‘Such things are horrible if they are true,’ he said. ‘Of course, our soldiers, like soldiers in all armies, sometimes get out of hand, and do things which we would never tolerate if we knew it. At Louvain, for example, I sentenced two{64} soldiers to 12 years’ penal servitude apiece for assaulting a woman.’

“ ‘Apropos of Louvain,’ I remarked, ‘why did you destroy the library? It was one of the literary store-houses of the world.’

“ ‘We regretted that as much as anyone else,’ answered the General. ‘It caught fire from the burning houses, and we could not save it.’

“ ‘But why did you burn Louvain at all?’ I asked.

“ ‘Because the townspeople fired on our troops. We actually found machine-guns in some of the houses; and,’ smashing his fist down upon the table, ‘whenever civilians fire upon our troops we will teach them a lasting lesson. If the women and children insist on getting in the way of bullets, so much the worse for women and children.’

“ ‘How do you explain the bombardment of Antwerp by Zeppelins?’ I queried.

“ ‘The Zeppelins have orders to drop their bombs only on fortifications and soldiers,’ he answered.