TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—Illustration can be relocated if necessary for project’s graphic needings.

FURNITURE

OF THE OLDEN TIME

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

FURNITURE

OF

THE OLDEN TIME

BY

FRANCES CLARY MORSE

NEW EDITION

With a New Chapter and Many New Illustrations

“How much more agreeable it is to sit in the midst of old furniture like Minott’s clock, and secretary and looking-glass, which have come down from other generations, than amid that which was just brought from the cabinet-maker’s, smelling of varnish, like a coffin! To sit under the face of an old clock that has been ticking one hundred and fifty years—there is something mortal, not to say immortal, about it; a clock that begun to tick when Massachusetts was a province.”

H. D. Thoreau, “Autumn.”

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1926

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1902 and 1917,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped November, 1902. Reprinted April, 1903;

July, 1905; February, 1908; September, 1910; September, 1913.

New edition, with a new chapter and new illustrations, December, 1917.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

To my Sister

ALICE MORSE EARLE

Contents

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Chests, Chests of Drawers, and Dressing-Tables | 10 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Bureaus and Washstands | 41 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Bedsteads | 64 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Cupboards and Sideboards | 84 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Desks | 117 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Chairs | 154 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Settles, Settees, and Sofas | 213 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Tables | 242 |

| CHAPTER IX[viii] | |

| Musical Instruments | 280 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Fires and Lights | 315 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Clocks | 348 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Looking-glasses | 374 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Doorways, Mantels, and Stairs | 411 |

| ———— | |

| Glossary | 451 |

| Index of the Owners of Furniture | 459 |

| General Index | 465 |

List of Illustrations

| Lacquered Desk with Cabinet Top | Frontispiece | |

| ILLUS. | PAGE | |

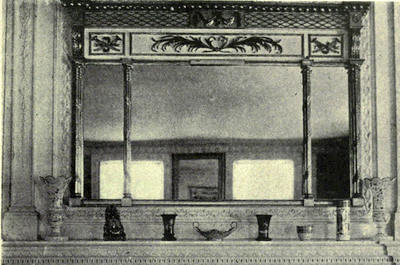

| Looking-glass, 1810-1825 | 10 | |

| 1. | Oak Chest, about 1650 | 11 |

| 2. | Olive-wood Chest, 1630-1650 | 13 |

| 3. | Panelled Chest with One Drawer, about 1660 | 14 |

| 4. | Oak Chest with Two Drawers, about 1675 | 15 |

| 5. | Panelled Chest with Two Drawers, about 1675 | 16 |

| 6. | Carved Chest with One Drawer, about 1700 | 17 |

| 7. | Panelled Chest upon Frame, 1670-1700 | 18 |

| 8. | Panelled Chest upon Frame, 1670-1700 | 18 |

| 9. | Panelled Chest of Drawers, about 1680 | 19 |

| 10. | Panelled Chest of Drawers, about 1680 | 20 |

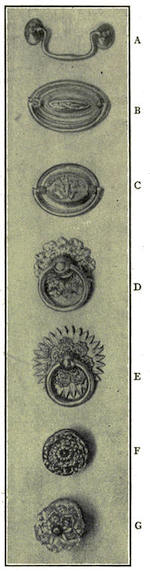

| 11. | Handles | 21 |

| 12. | Six-legged High Chest of Drawers, 1705-1715 | 22 |

| 13. | Walnut Dressing-table, about 1700 | 23 |

| 14. | Lacquered Dressing-table, about 1720 | 24 |

| 15. | Cabriole-legged High Chest of Drawers with China Steps, about 1720 | 26 |

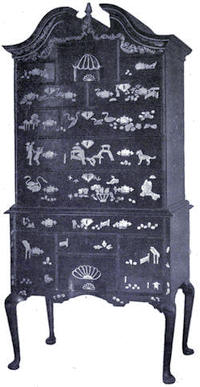

| 16. | Lacquered High-boy, 1730 | 27 |

| 17. | Inlaid Walnut High Chest of Drawers, 1733 | 28 |

| 18. | Inlaid Walnut High Chest of Drawers, about 1760 | 29 |

| 19. | “Low-boy” and “High-boy” of Walnut, about 1740 | 30 |

| 20. | Walnut Double Chest, about 1760 | 32 |

| 21. | Double Chest, 1760-1770 | 33 |

| 22. | Block-front Dressing-table, about 1750 | 34 |

| 23. | Dressing-table, about 1760 | 35 |

| 24. | Chest of Drawers, 1740 | 36 |

| 25. | High Chest of Drawers, about 1765 | 37 |

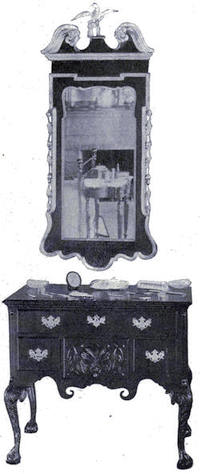

| 26. | Dressing-table and Looking-glass, about 1770 | 39 |

| 27. | Walnut Dressing-table, about 1770 | 40 |

| [x] | Looking-glass, 1810-1825 | 41 |

| 28. | Block-front Bureau, about 1770 | 42 |

| 29. | Block-front Bureau, about 1770 | 43 |

| 30. | Block-front Bureau, about 1770 | 45 |

| 31. | Kettle-shaped Bureau, about 1770 | 44 |

| 32. | Serpentine-front Bureau, about 1770 | 46 |

| 33. | Serpentine-front Bureau, about 1785 | 47 |

| 34. | Swell-front Inlaid Bureau, about 1795 | 48 |

| 35. | Handles | 49 |

| 36. | Dressing-glass, about 1760 | 50 |

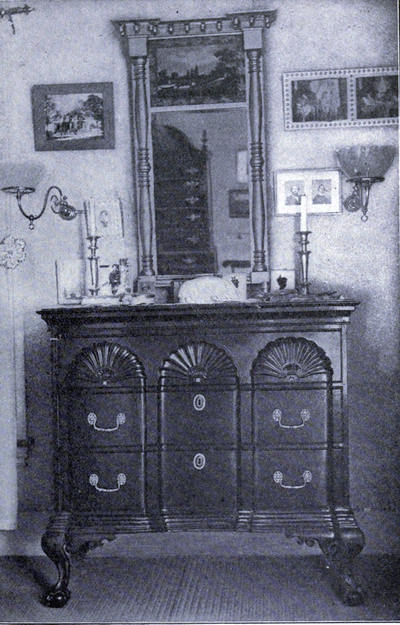

| 37. | Bureau and Dressing-glass, 1795 | 51 |

| 38. | Bureau and Dressing-glass, about 1810 | 52 |

| 39. | Bureau and Miniature Bureau, about 1810 | 53 |

| 40. | Dressing-table and Glass, about 1810 | 54 |

| 41. | Case of Drawers with Closet, 1810 | 55 |

| 42. | Bureau, about 1815 | 56 |

| 43. | Bureau, 1815-1820 | 57 |

| 44. | Empire Bureau and Glass, 1810-1820 | 58 |

| 45. | Basin Stand, 1770 | 59 |

| 46. | Corner Washstand, 1790 | 60 |

| 47. | Towel-rack and Washstand, 1790-1800 | 61 |

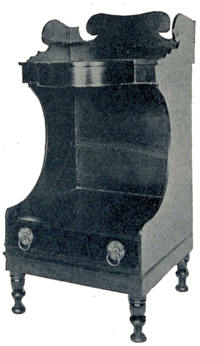

| 48. | Washstand, 1815-1830 | 62 |

| 49. | Night Table, 1785 | 62 |

| 50. | Washstand, 1800-1810 | 63 |

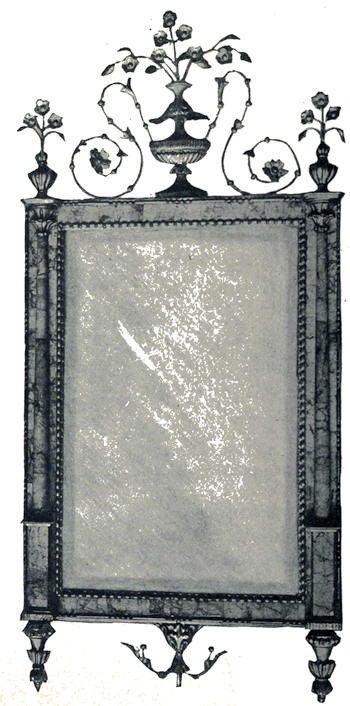

| Looking-glass, about 1770 | 64 | |

| 51. | Wicker Cradle, 1620 | 65 |

| 52. | Oak Cradle, 1680 | 65 |

| 53. | Bedstead and Commode, 1750 | 66 |

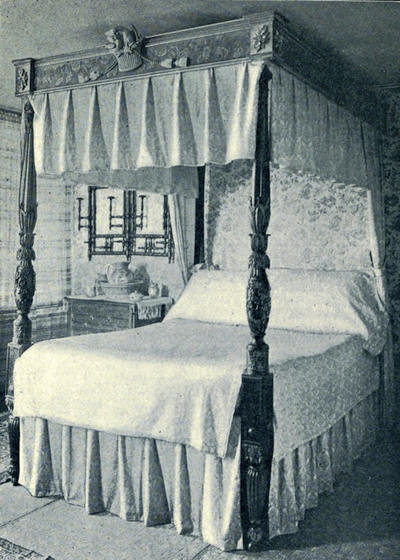

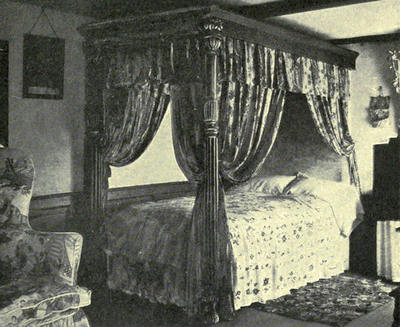

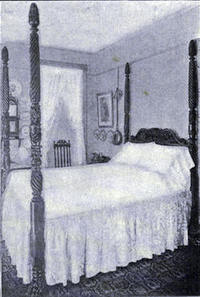

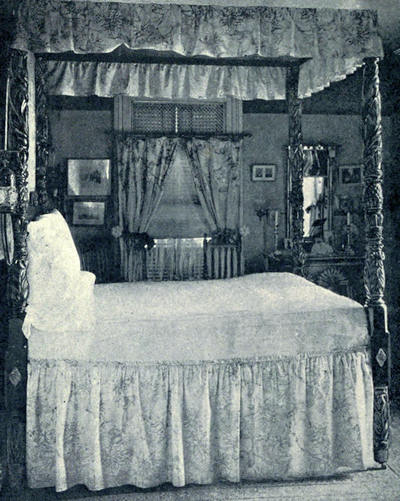

| 54. | Field Bedstead, 1760-1770 | 67 |

| 55. | Claw-and-ball-foot Bedstead, 1774 | 69 |

| 56. | Bedstead, 1780 | 70 |

| 57. | Bedstead, 1775-1780 | 71 |

| 58. | Bedstead, 1789 | 72 |

| 59. | Bedstead, 1795-1800 | 74 |

| 60. | Bedstead, 1800-1810 | 75 |

| 61. | Bedstead, 1800-1810 | 76 |

| 62. | Bedstead, 1800-1810 | 77 |

| 63. | Bedstead, 1800-1810 | 78 |

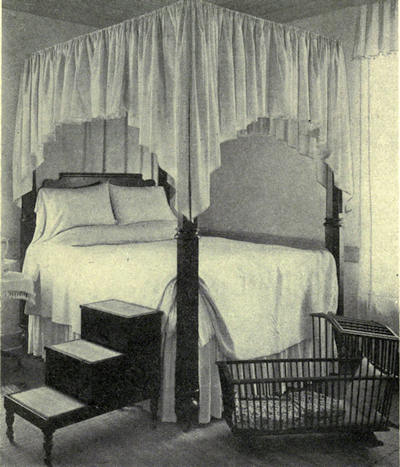

| 64.[xi] | Bedstead and Steps, 1790 | 79 |

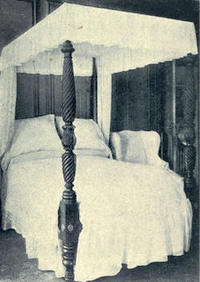

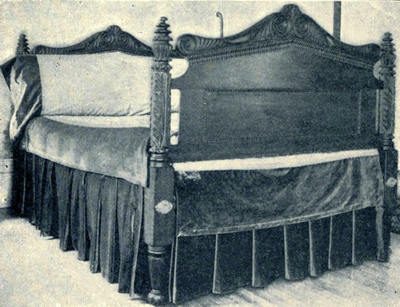

| 65. | Low-post Bedstead, about 1825 | 80 |

| 66. | Low-post Bedstead, 1820-1830 | 81 |

| 67. | Low Bedstead, about 1830 | 82 |

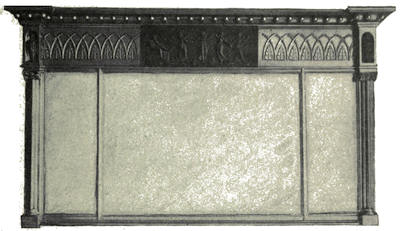

| Looking-glass, 1770-1780 | 84 | |

| 68. | Oak Press Cupboard, 1640 | 85 |

| 69. | Press Cupboard, about 1650 | 87 |

| 70. | Carved Press Cupboard, 1680-1690 | 88 |

| 71. | Corner “Beaufatt,” 1740-1750 | 90 |

| 72. | Kas, 1700 | 92 |

| 73. | Chippendale Side-table, about 1755 | 93 |

| 74. | Chippendale Side-table, 1765 | 94 |

| 75. | Shearer Sideboard and Knife-box, 1792 | 97 |

| 76. | Urn-shaped Knife-box, 1790 | 99 |

| 77. | Urn-shaped Knife-box, 1790 | 99 |

| 78. | Knife-box, 1790 | 100 |

| 79. | Hepplewhite Sideboard with Knife-boxes, 1790 | 102 |

| 80. | Hepplewhite Serpentine-front Sideboard, 1790 | 104 |

| 81. | Hepplewhite Sideboard, about 1795 | 105 |

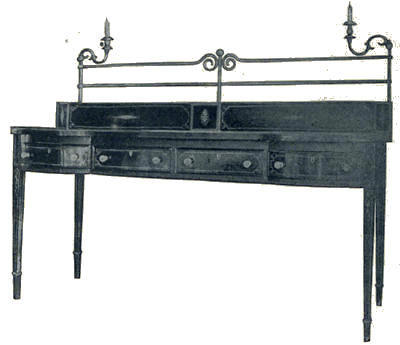

| 82. | Sheraton Side-table, 1795 | 106 |

| 83. | Sheraton Side-table, 1795 | 107 |

| 84. | Sheraton Sideboard with Knife-box, 1795 | 108 |

| 85. | Sheraton Sideboard, about 1800 | 109 |

| 86. | Sheraton Sideboard, about 1805 | 110 |

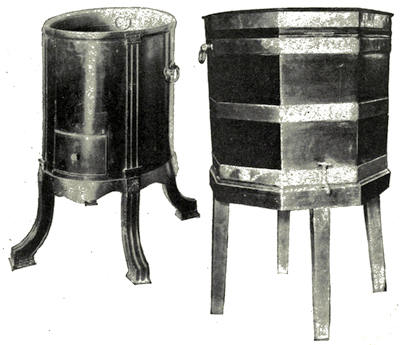

| 87. | Cellarets, 1790 | 111 |

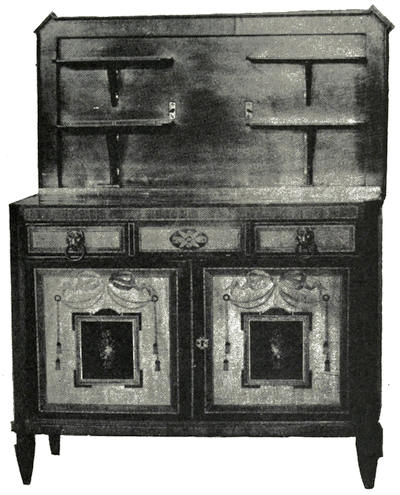

| 88. | Sideboard, 1810-1820 | 113 |

| 89. | Empire Sideboard, 1810-1820 | 114 |

| 90. | Mixing-table, 1790 | 115 |

| 91. | Mixing-table, 1810-1820 | 116 |

| Looking-glass, about 1760 | 117 | |

| 92. | Desk-boxes, 1654 | 118 |

| 93. | Desk-box, 1650 | 118 |

| 94. | Desk, about 1680 | 119 |

| 95. | Desk, about 1680 | 120 |

| 96. | Desk, 1710-1720 | 121 |

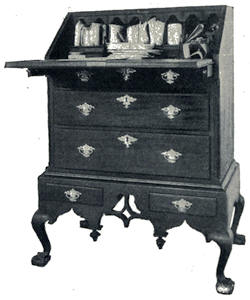

| 97. | Cabriole-legged Desk, 1720-1730 | 124 |

| 98. | Cabriole-legged Desk, 1760 | 125 |

| 99. | Desk, 1760 | 126 |

| 100.[xii] | Desk, about 1770 | 127 |

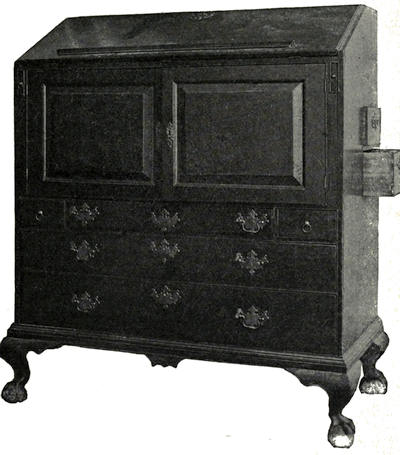

| 101. | Block-front Desk, Cabinet Top, about 1770 | 128 |

| 102. | Block-front Desk, about 1770 | 129 |

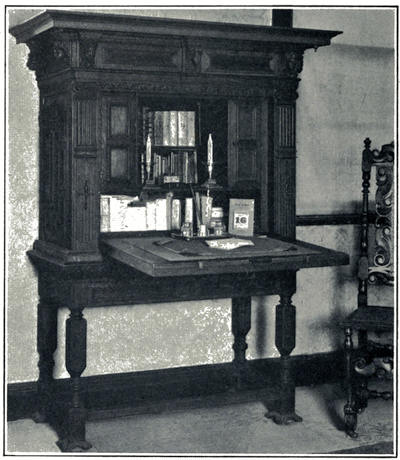

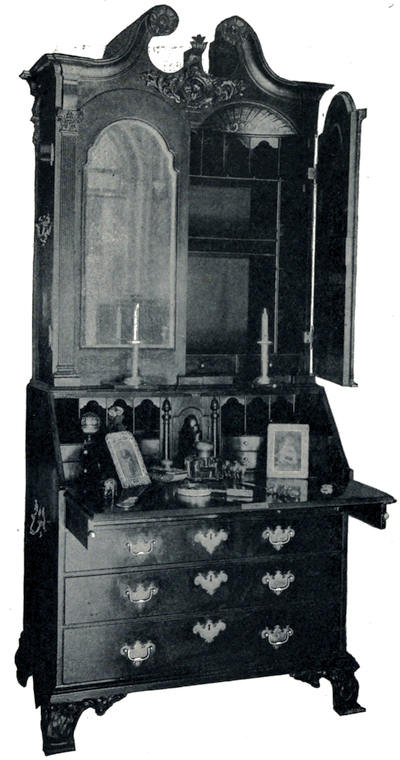

| 103. | Desk with Cabinet Top, about 1770 | 130 |

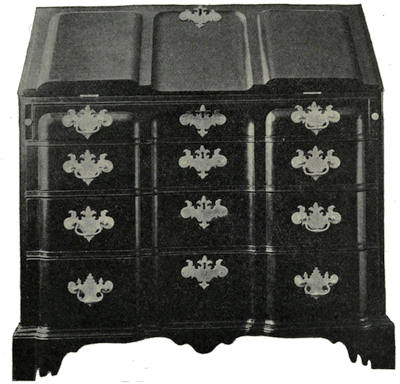

| 104. | Block-front Desk, about 1770 | 133 |

| 105. | Kettle-front Secretary, about 1765 | 135 |

| 106. | Block-front Writing-table, 1760-1770 | 136 |

| 107. | Serpentine-front Desk, Cabinet Top, 1770 | 137 |

| 108. | Serpentine or Bow-front Desk, about 1770 | 138 |

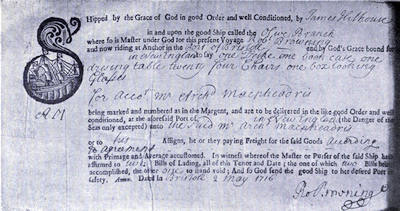

| 109. | Bill of Lading, 1716 | 139 |

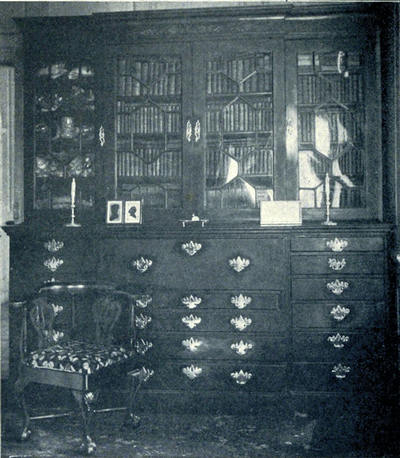

| 110. | Bookcase and Desk, about 1765 | 142 |

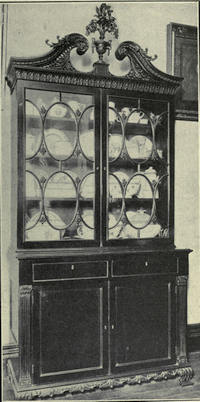

| 111. | Chippendale Bookcase, 1770 | 143 |

| 112. | Hepplewhite Bookcase, 1789 | 144 |

| 113. | Maple Desk, about 1795 | 146 |

| 114. | Desk with Cabinet Top, 1790 | 147 |

| 115. | Sheraton Desk, 1795 | 149 |

| 116. | Tambour Secretary, about 1800 | 150 |

| 117. | Sheraton Desk, 1800 | 151 |

| 118. | Sheraton Desk, about 1810 | 152 |

| 119. | Desk, about 1820 | 153 |

| Looking-glass, 1720-1740 | 154 | |

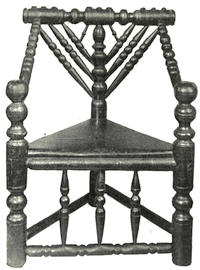

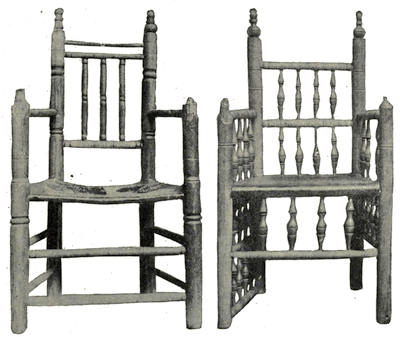

| 120. | Turned Chair, Sixteenth Century | 155 |

| 121. | Turned High-chair, Sixteenth Century | 156 |

| 122. | Turned Chair, about 1600 | 157 |

| 123. | Turned Chair, about 1600 | 157 |

| 124. | Wainscot Chair, about 1600 | 158 |

| 125. | Wainscot Chair, about 1600 | 159 |

| 126. | Leather Chair, about 1660 | 160 |

| 127. | Chair originally covered with Turkey Work, about 1680 | 160 |

| 128. | Flemish Chair, about 1690 | 161 |

| 129. | Flemish Chair, about 1690 | 161 |

| 130. | Cane Chair, 1680-1690 | 162 |

| 131. | Cane High-chair and Arm-chair, 1680-1690 | 163 |

| 132. | Cane Chair, 1680-1690 | 164 |

| 133. | Cane Chair, 1680-1690 | 166 |

| 134. | Cane Chair, 1680-1690 | 166 |

| 135. | Turned Stool, 1660 | 167 |

| 136. | Flemish Stool, 1680-1690 | 167 |

| 137.[xiii] | Cane Chair, 1690-1700 | 168 |

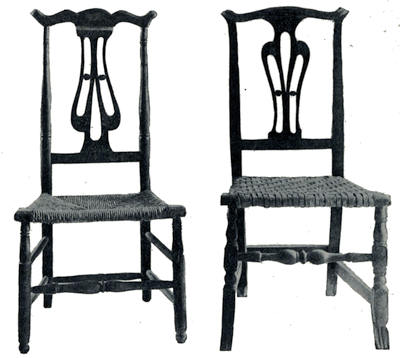

| 138. | Queen Anne Chair, 1710-1720 | 168 |

| 139. | Banister-back Chair, 1710-1720 | 169 |

| 140. | Banister-back Chair, 1710-1720 | 169 |

| 141. | Banister-back Chair, 1710-1740 | 170 |

| 142. | Roundabout Chair, about 1740 | 170 |

| 143. | Slat-back Chairs, 1700-1750 | 171 |

| 144. | Five-slat Chair, about 1750 | 172 |

| 145. | Pennsylvania Slat-back Chair, 1740-1750 | 173 |

| 146. | Windsor Chairs, 1750-1775 | 174 |

| 147. | Comb-back Windsor Rocking-chair, 1750-1775 | 175 |

| 148. | High-back Windsor Arm-chair and Child’s Chair, 1750-1775 | 176 |

| 149. | Windsor Writing-chair, 1750-1775 | 177 |

| 150. | Windsor Rocking-chairs, 1820-1830 | 178 |

| 151. | Dutch Chair, 1710-1720 | 179 |

| 152. | Dutch Chair, about 1740 | 180 |

| 153. | Dutch Chair, about 1740 | 180 |

| 154. | Dutch Chair, 1740-1750 | 181 |

| 155. | Dutch Chair, 1740-1750 | 181 |

| 156. | Dutch Chairs, 1750-1760 | 182 |

| 157. | Dutch Roundabout Chair, 1740 | 183 |

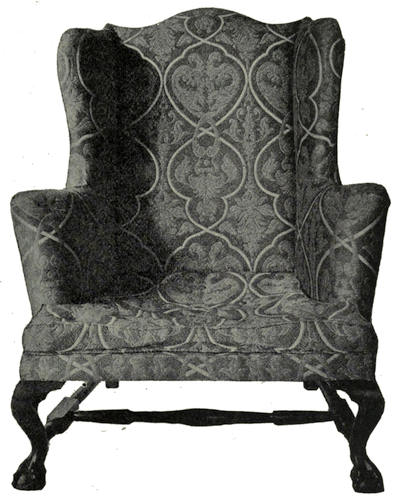

| 158. | Easy-chair with Dutch Legs, 1750 | 184 |

| 159. | Claw-and-ball-foot Easy-chair, 1750 | 185 |

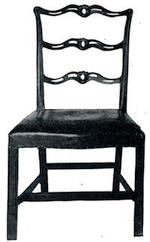

| 160. | Chippendale Chair | 186 |

| 161. | Chippendale Chair | 186 |

| 162. | Chippendale Chair | 187 |

| 163. | Chippendale Chair | 187 |

| 164. | Chippendale Chair | 189 |

| 165. | Chippendale Chairs | 188 |

| 166. | Chippendale Chair | 190 |

| 167. | Roundabout Chair | 190 |

| 168. | Extension-top Roundabout Chair, Dutch | 191 |

| 169. | Roundabout Chair | 192 |

| 170. | Chippendale Chair | 192 |

| 171. | Chippendale Chair | 193 |

| 172. | Chippendale Chair | 193 |

| 173. | Chippendale Chair | 194 |

| 174.[xiv] | Chippendale Chair | 194 |

| 175. | Chippendale Chair in “Chinese Taste” | 195 |

| 176. | Chippendale Chair | 196 |

| 177. | Chippendale Chair | 196 |

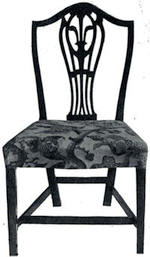

| 178. | Hepplewhite Chairs | 198 |

| 179. | Hepplewhite Chair | 197 |

| 180. | Hepplewhite Chair, 1785 | 199 |

| 181. | Hepplewhite Chair, 1789 | 199 |

| 182. | Hepplewhite Chair, 1789 | 200 |

| 183. | French Chair, 1790 | 201 |

| 184. | Hepplewhite Chair, 1790 | 201 |

| 185. | Arm-chair, 1790 | 202 |

| 186. | Transition Chair, 1785 | 202 |

| 187. | Hepplewhite Chair | 203 |

| 188. | Hepplewhite Chair | 203 |

| 189. | Hepplewhite Chair | 204 |

| 190. | Hepplewhite Chair | 204 |

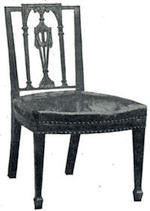

| 191. | Sheraton Chair | 205 |

| 192. | Sheraton Chairs | 206 |

| 193. | Sheraton Chair | 207 |

| 194. | Sheraton Chair | 207 |

| 195. | Sheraton Chair | 208 |

| 196. | Sheraton Chair | 208 |

| 197. | Sheraton Chair | 209 |

| 198. | Painted Sheraton Chair, 1810-1815 | 209 |

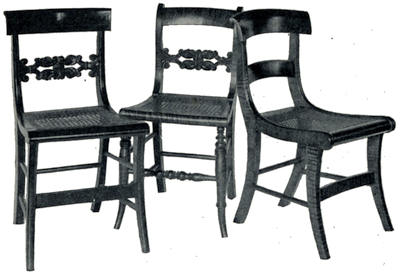

| 199. | Late Mahogany Chairs, 1830-1845 | 210 |

| 200. | Maple Chairs, 1820-1830 | 212 |

| Looking-glass, 1770-1780 | 213 | |

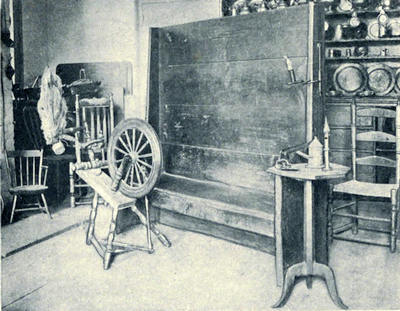

| 201. | Pine Settle, Eighteenth Century | 214 |

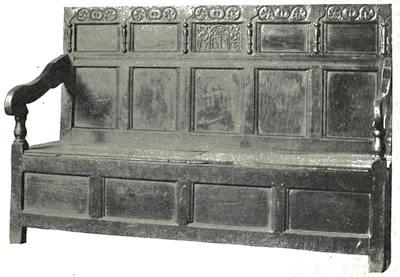

| 202. | Oak Settle, 1708 | 215 |

| 203. | Settee covered with Turkey work, 1670-1680 | 216 |

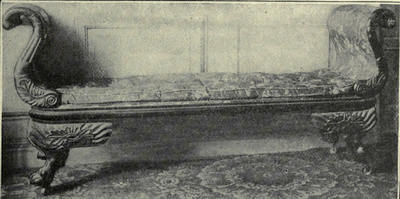

| 204. | Flemish Couch, 1680-1690 | 217 |

| 205. | Dutch Couch, 1720-1730 | 218 |

| 206. | Chippendale Couch, 1760-1770 | 218 |

| 207. | Chippendale Settee, 1760 | 219 |

| 208. | Sofa, 1740 | 220 |

| 209. | Chippendale Settee | 221 |

| 210. | Double Chair, 1760 | 222 |

| 211.[xv] | Chippendale Double Chair and Chair in “Chinese Taste,” 1760-1765 | 224 |

| 212. | Chippendale Double Chair, 1750-1750 | 225 |

| 213. | Chippendale Settee, 1770 | 226 |

| 214. | French Settee, 1790 | 227 |

| 215. | Hepplewhite Settee, 1790 | 228 |

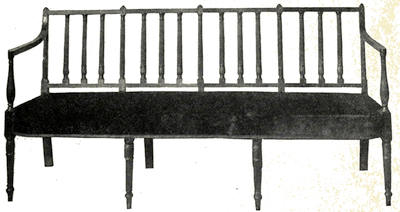

| 216. | Sheraton Settee, 1790-1795 | 229 |

| 217. | Sheraton Sofa, 1790-1800 | 230 |

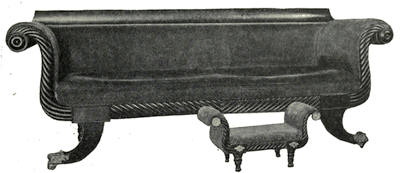

| 218. | Sheraton Sofa, about 1800 | 230 |

| 219. | Sheraton Settee, about 1805 | 231 |

| 220. | Sheraton Settee, 1805-1810 | 232 |

| 221. | Empire Settee, 1800-1810 | 232 |

| 222. | Empire Settee, 1816 | 233 |

| 223. | Sheraton Settee, 1800-1805 | 234 |

| 224. | Sofa in Adam Style, 1800-1810 | 235 |

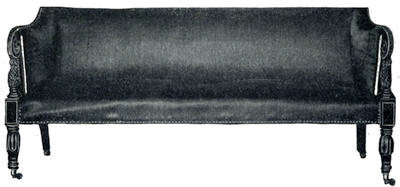

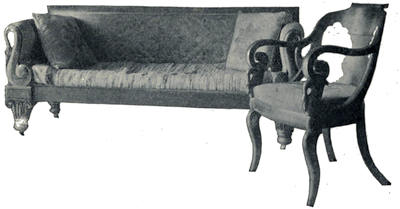

| 225. | Sofa, 1815-1820 | 236 |

| 226. | Sofa, about 1820 | 237 |

| 227. | Cornucopia Sofa, about 1820 | 238 |

| 228. | Sofa and Miniature Sofa, about 1820 | 239 |

| 229. | Sofa about 1820 | 239 |

| 230. | Sofa and Chair, about 1840 | 240 |

| 231. | Rosewood Sofa, 1844-1848 | 241 |

| Looking-glass, 1750-1780 | 242 | |

| 232. | Chair Table, Eighteenth Century | 243 |

| 233. | Oak Table, 1650-1675 | 244 |

| 234. | Slate-top Table, 1670-1680 | 245 |

| 235. | “Butterfly Table,” about 1700 | 245 |

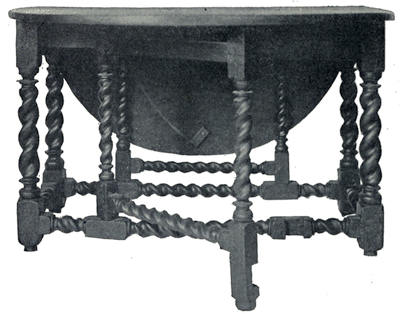

| 236. | “Hundred-legged” Table, 1675-1700 | 246 |

| 237. | “Hundred-legged” Table, 1680-1700 | 247 |

| 238. | Gate-legged Table, 1680-1700 | 248 |

| 239. | Spindle-legged Table, 1740-1750 | 249 |

| 240. | “Hundred-legged” Table, 1680-1700 | 250 |

| 241. | Dutch Table, 1720-1740 | 251 |

| 242. | Dutch Card-table, 1730-1740 | 251 |

| 243. | Claw-and-ball-foot Table, about 1750 | 252 |

| 244. | Dutch Stand, about 1740 | 253 |

| 245. | “Pie-crust” Table, 1750 | 253 |

| 246. | “Dish-top” Table, 1750 | 254 |

| 247.[xvi] | Tea-tables, 1750-1760 | 254 |

| 248. | Table and Easy-chair, 1760-1770 | 255 |

| 249. | Tripod Table, 1760-1770 | 256 |

| 250. | Chinese Fretwork Table, 1760-1770 | 256 |

| 251. | Stands, 1760-1770 | 258 |

| 252. | Tea-table, about 1770 | 258 |

| 253. | Chippendale Card-table, about 1765 | 259 |

| 254. | Chippendale Card-table, 1760 | 260 |

| 255. | Chippendale Card-table, about 1765 | 261 |

| 256. | Pembroke Table, 1760-1770 | 262 |

| 257. | Pembroke Table, 1780-1790 | 262 |

| 258. | Lacquer Tea-tables, 1700-1800 | 263 |

| 259. | Hepplewhite Card-table with Tea-tray, 1785-1790 | 264 |

| 260. | Hepplewhite Card-tables, 1785-1795 | 265 |

| 261. | Sheraton Card-table, 1800 | 266 |

| 262. | Sheraton Card-table, 1800-1810 | 266 |

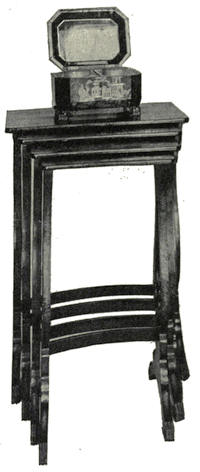

| 263. | Sheraton “What-not,” 1800-1810 | 267 |

| 264. | Sheraton Dining-table and Chair, about 1810 | 267 |

| 265. | Sheraton Work-table, about 1800 | 268 |

| 266. | Sheraton Work-table, 1810-1815 | 268 |

| 267. | Maple and Mahogany Work-tables, 1810-1820 | 269 |

| 268. | Work-table, 1810 | 270 |

| 269. | Work-table, 1810 | 270 |

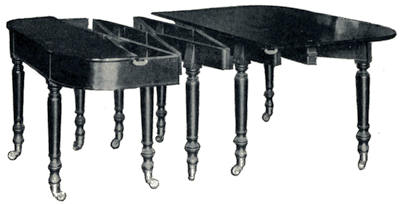

| 270. | Hepplewhite Dining-table, 1790 | 271 |

| 271. | Pillar-and-claw extension Dining-table, 1800 | 272 |

| 272. | Pillar-and-claw Centre-table, 1800 | 273 |

| 273. | Extension Dining-table, 1810 | 274 |

| 274. | Accordion Extension Dining-table, 1820 | 274 |

| 275. | Card-table, 1805-1810 | 275 |

| 276. | Phyfe Card-table, 1810-1820 | 275 |

| 277. | Phyfe Card-table, 1810-1820 | 276 |

| 278. | Phyfe Sofa-table, 1810-1820 | 277 |

| 279. | Pier-table, 1820-1830 | 278 |

| 280. | Work-table, 1810-1820 | 279 |

| Looking-glass, 1760-1770 | 280 | |

| 281. | Stephen Keene Spinet, about 1690 | 282 |

| 282. | Thomas Hitchcock Spinet, about 1690 | 284 |

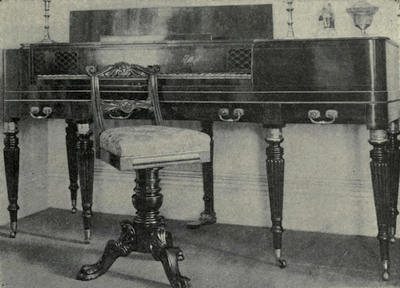

| 283. | Broadwood Harpsichord, 1789 | 285 |

| 284.[xvii] | Clavichord, 1745 | 288 |

| 285. | Clementi Piano, 1805 | 290 |

| 286. | Astor Piano, 1790-1800 | 292 |

| 287. | Clementi Piano, about 1820 | 293 |

| 288. | Combination Piano, Desk, and Toilet-table, about 1800 | 294 |

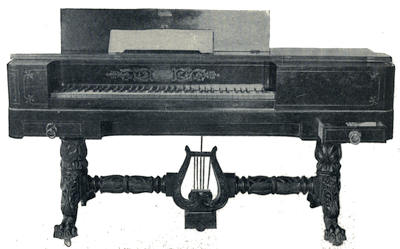

| 289. | Piano, about 1830 | 295 |

| 290. | Peter Erben Piano, 1826-1827 | 296 |

| 291. | Piano-stool, 1820-1830 | 298 |

| 292. | Piano, 1826 | 299 |

| 293. | Piano-stools, 1825-1830 | 300 |

| 294. | Table Piano, about 1835 | 301 |

| 295. | Piano, 1830 | 302 |

| 296. | Music-stand, about 1835 | 303 |

| 297. | Music-stand, about 1835 | 303 |

| 298. | Dulcimer, 1820-1830 | 304 |

| 299. | Harmonica or Musical Glasses, about 1820 | 305 |

| 300. | Music-stand, 1800-1810 | 306 |

| 301. | Music-case, 1810-1820 | 307 |

| 302. | Harp-shaped Piano, about 1800 | 308 |

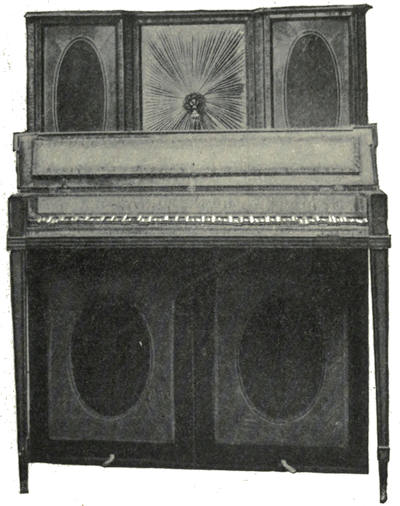

| 303. | Cottage Piano, or Upright, 1800-1810 | 309 |

| 304. | Chickering Upright Piano, 1830 | 310 |

| 305. | Piano, about 1840 | 311 |

| 306. | Hawkey Square Piano, about 1845 | 312 |

| 307. | Harp, 1780-1790 | 313 |

| Looking-glass, 1785-1795 | 315 | |

| 308. | Kitchen Fireplace, 1760 | 316 |

| 309. | Andirons, Eighteenth Century | 317 |

| 310. | Andirons, Eighteenth Century | 317 |

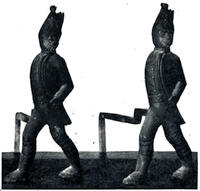

| 311. | “Hessian” Andirons, 1776 | 318 |

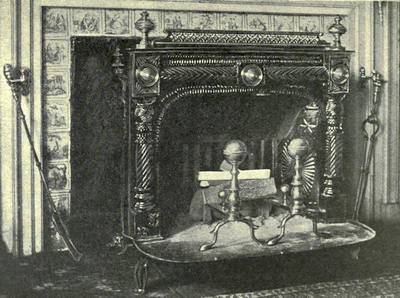

| 312. | Fireplace, 1770-1775 | 319 |

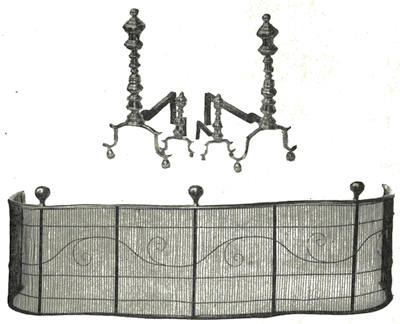

| 313. | Steeple-topped Andirons and Fender, 1775-1790 | 320 |

| 314. | Andirons, Creepers and Fender, 1700-1800 | 321 |

| 315. | Brass Andirons, 1700-1800 | 322 |

| 316. | Brass-headed Iron Dogs, 1700-1800 | 322 |

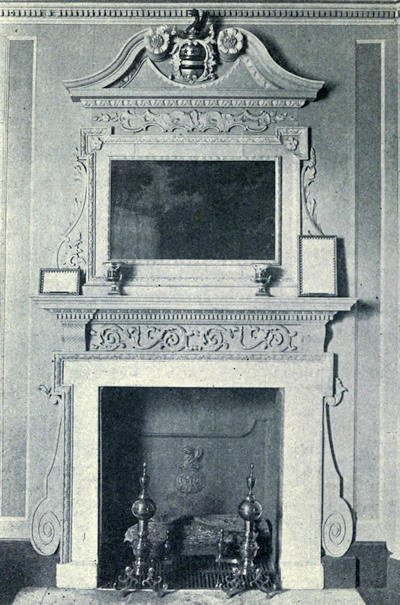

| 317. | Mantel at Mount Vernon, 1760-1770 | 324 |

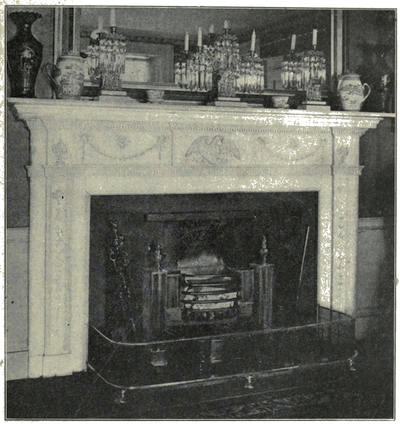

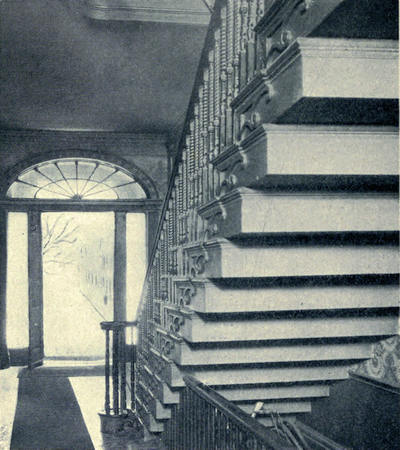

| 318. | Mantel with Hob-grate, 1776 | 325 |

| 319. | Franklin Stove, 1745-1760 | 327 |

| 320. | Iron Fire-frame, 1775-1800 | 328 |

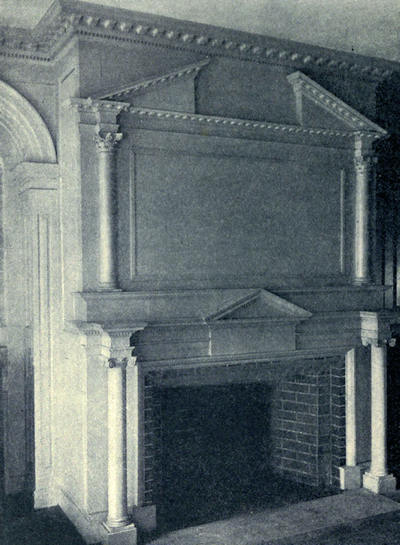

| 321.[xviii] | Betty Lamps, Seventeenth Century | 329 |

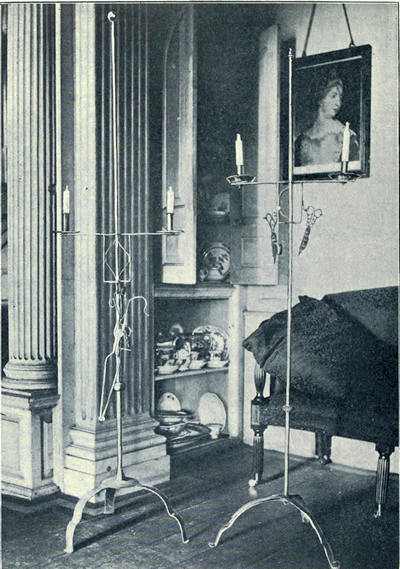

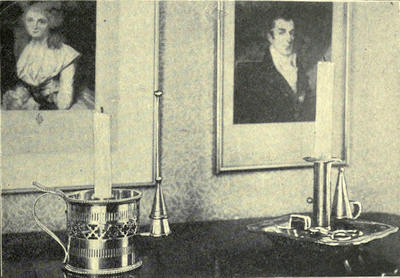

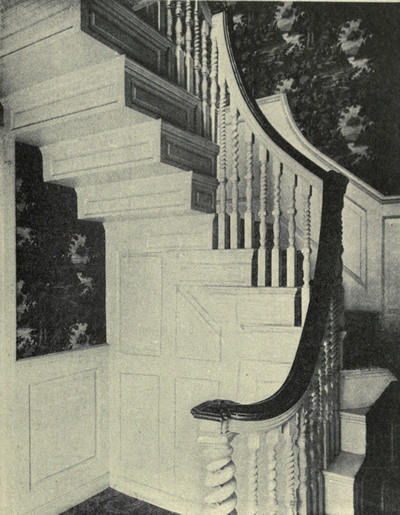

| 322. | Candle-stands, First Half of Eighteenth Century | 330 |

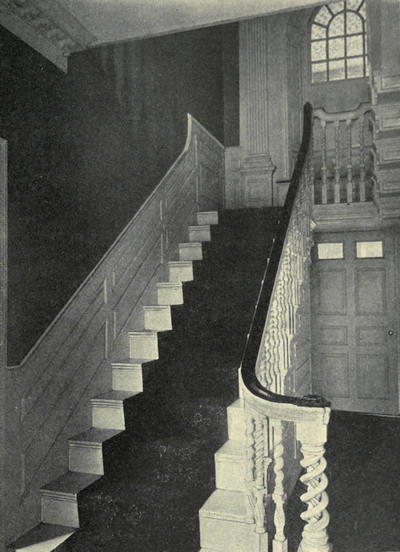

| 323. | Mantel with Candle Shade, 1775-1800 | 332 |

| 324. | Candlesticks, 1775-1800 | 333 |

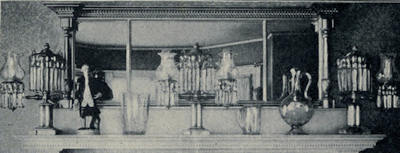

| 325. | Crystal Chandelier, about 1760 | 334 |

| 326. | Silver Lamp from Mount Vernon, 1770-1800 | 335 |

| 327. | Glass Chandelier for Candles, 1760 | 336 |

| 328. | Embroidered Screen, 1780 | 338 |

| 329. | Sconce of “Quill-work,” 1720 | 340 |

| 330. | Tripod Screen, 1770 | 341 |

| 331. | Tripod Screen, 1765 | 341 |

| 332. | Candle-stand and Screen, 1750-1775 | 342 |

| 333. | Chippendale Candle-stand, 1760-1770 | 343 |

| 334. | Bronze Mantel Lamps, 1815-1840 | 344 |

| 335. | Brass Gilt Candelabra, 1820-1840 | 345 |

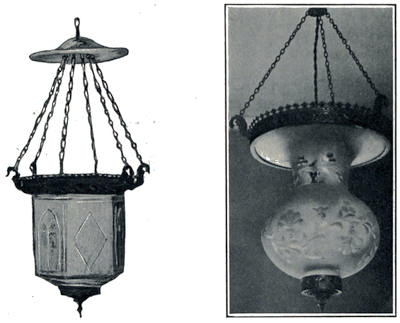

| 336. | Hall Lantern, 1775-1800 | 346 |

| 337. | Hall Lantern, 1775-1800 | 346 |

| 338. | Hall Lantern, 1760 | 347 |

| Looking-glass, First Quarter of Eighteenth Century | 348 | |

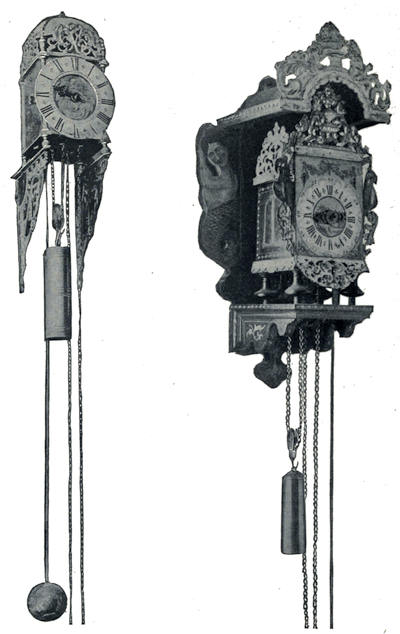

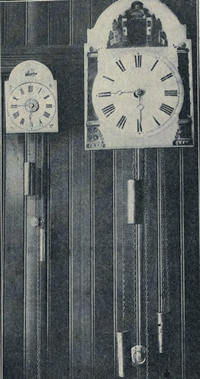

| 339. | Lantern or Bird-cage Clock, First Half of Seventeenth Century | 349 |

| 340. | Lantern Clock, about 1680 | 350 |

| 341. | Friesland Clock, Seventeenth Century | 350 |

| 342. | Bracket Clocks, 1780-1800 | 352 |

| 343. | Walnut Case and Lacquered Case Clocks, about 1738 | 354 |

| 344. | Gawen Brown Clock, 1765 | 356 |

| 345. | Gawen Brown Clock, 1780 | 356 |

| 346. | Maple Clock, 1770 | 357 |

| 347. | Rittenhouse Clock, 1770 | 357 |

| 348. | Tall Clock, about 1770 | 359 |

| 349. | Miniature Clock and Tall Clock, about 1800 | 360 |

| 350. | Tall Clock, 1800-1810 | 361 |

| 351. | Wall Clocks, 1800-1825 | 362 |

| 352. | Willard Clock, 1784 | 363 |

| 353. | Willard Clocks, 1800-1815 | 364 |

| 354. | Hassam Clock, 1800 | 366 |

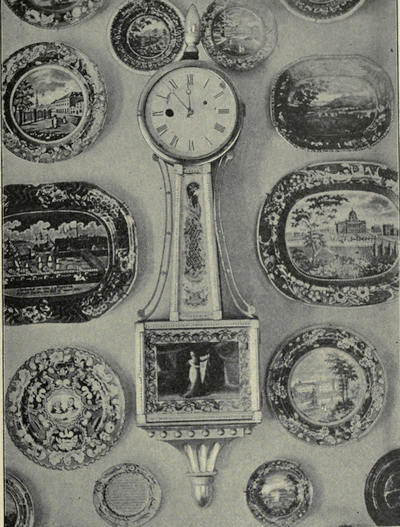

| 355. | “Banjo” Clock, 1802-1820 | 367 |

| 356. | Presentation Clock, 1805 | 368 |

| 357.[xix] | Banjo Clock or Timepiece, 1802-1810 | 368 |

| 358. | Willard Timepiece, 1802-1810 | 369 |

| 359. | Lyre Clock, 1810-1820 | 369 |

| 360. | Lyre-shaped Clock, 1810-1820 | 370 |

| 361. | Eli Terry Shelf Clocks, 1824 | 371 |

| 362. | French Clock, about 1800 | 372 |

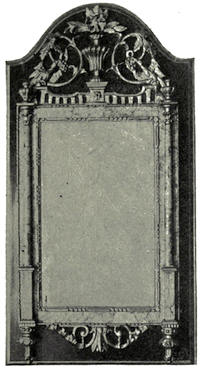

| Looking-glass, First Quarter of the Eighteenth Century | 374 | |

| 363. | Looking-glass, 1690 | 375 |

| 364. | Looking-glass, 1690 | 376 |

| 365. | Looking-glass, about 1730 | 378 |

| 366. | Pier Glass in “Chinese Taste,” 1760 | 380 |

| 367. | Looking-glass, about 1760 | 382 |

| 368. | Looking-glass, 1770-1780 | 383 |

| 369. | Looking-glass, 1725-1750 | 384 |

| 370. | Looking-glass, 1770-1780 | 386 |

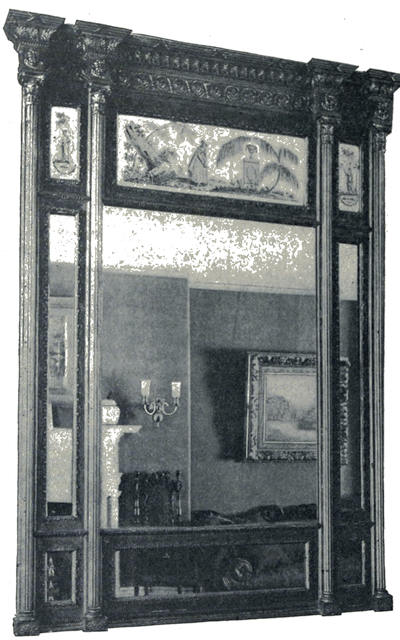

| 371. | Mantel Glass, 1725-1750 | 387 |

| 372. | Looking-glass, 1770 | 388 |

| 373. | Looking-glass, 1770 | 388 |

| 374. | Looking-glass, 1776 | 389 |

| 375. | Looking-glass, 1780 | 390 |

| 376. | Looking-glasses, 1750-1790 | 392 |

| 377. | Looking-glass, 1790 | 393 |

| 378. | Looking-glass, 1780 | 393 |

| 379. | Enamelled Mirror Knobs, 1770-1790 | 394 |

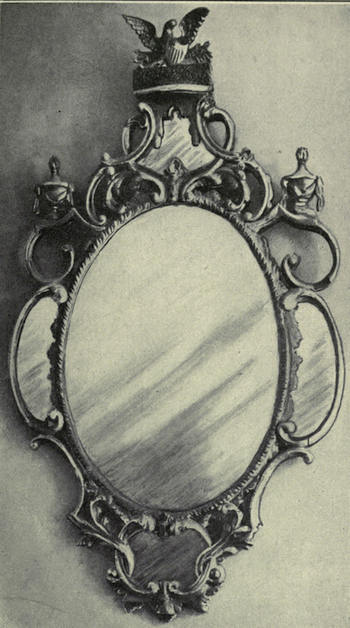

| 380. | Girandole, 1770-1780 | 395 |

| 381. | Looking-glass, Adam Style, 1780 | 396 |

| 382. | Looking-glass, 1790 | 397 |

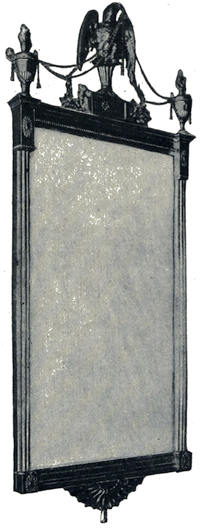

| 383. | Hepplewhite Looking-glass, 1790 | 398 |

| 384. | Mantel Glass, 1783 | 399 |

| 385. | Looking-glass, 1790-1800 | 400 |

| 386. | “Bilboa Glass,” 1770-1780 | 402 |

| 387. | Mantel Glass, 1790 | 403 |

| 388. | Mantel Glass, 1800-1810 | 404 |

| 389. | Cheval Glass, 1830-1840 | 405 |

| 390. | Looking-glass, 1810-1825 | 406 |

| 391. | Looking-glass, 1810-1815 | 407 |

| 392. | Looking-glass, 1810-1825 | 408 |

| 393. | Pier Glass, 1810-1825 | 409 |

| 394.[xx] | Looking-glass, 1810-1825 | 410 |

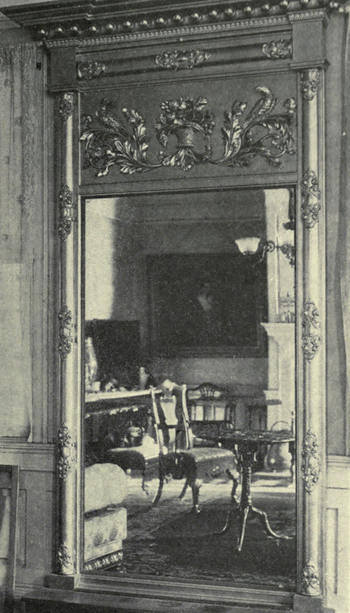

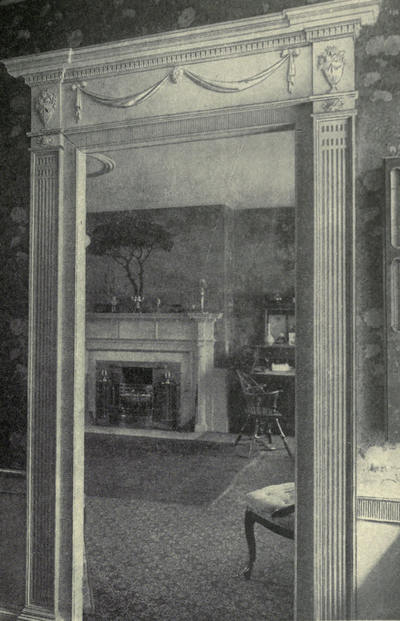

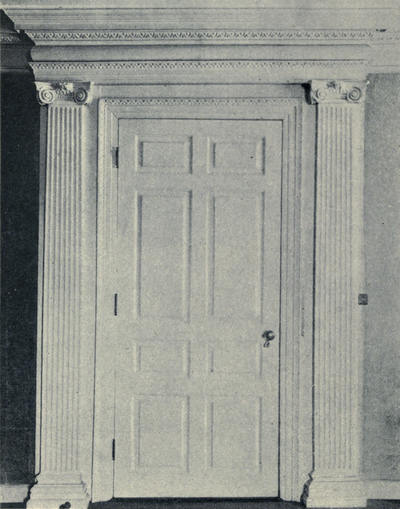

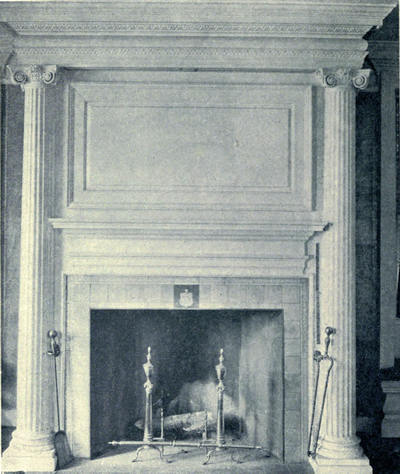

| Looking-glass | 411 | |

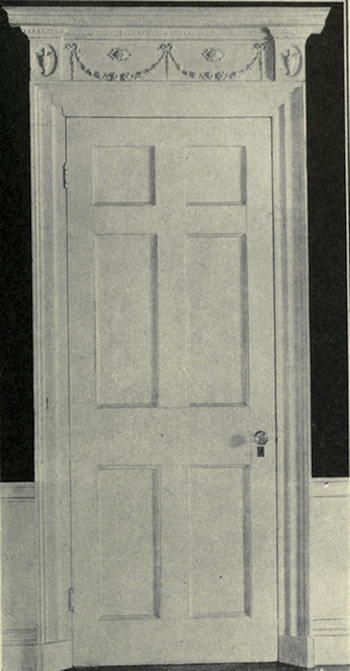

| 395. | Doorway and Mantel, Cook-Oliver House | 413 |

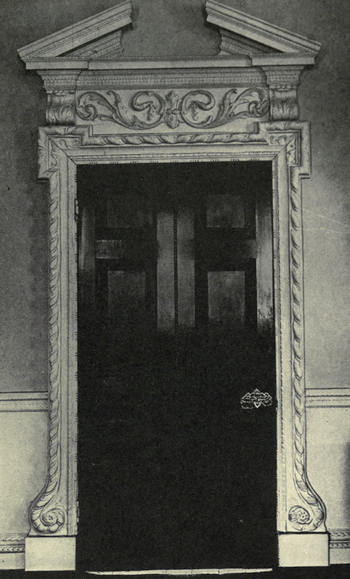

| 396. | Doorway, Dalton House | 414 |

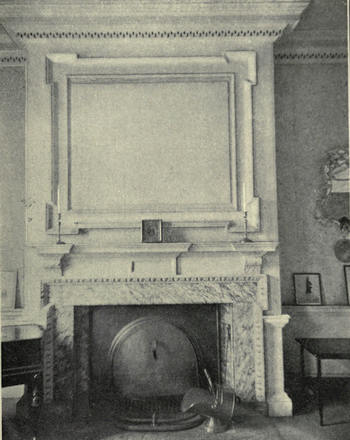

| 397. | Mantel, Dalton House | 416 |

| 398. | Mantel, Dalton House | 417 |

| 399. | Hall and Stairs, Dalton House | 418 |

| 400. | Mantel, Penny-Hallett House | 419 |

| 401. | Doorway, Parker-Inches-Emery House | 420 |

| 402. | Mantel, Lee Mansion | 421 |

| 403. | Landing and Stairs, Lee Mansion | 422 |

| 404. | Stairs, Harrison Gray Otis House | 424 |

| 405. | Mantel, Harrison Gray Otis House | 425 |

| 406. | Stairs, Robinson House | 426 |

| 407. | Stairs, Allen House | 427 |

| 408. | Balusters and Newel, Oak Hill | 428 |

| 409. | Stairs, Sargent-Murray-Gilman House | 429 |

| 410. | Mantel, Sargent-Murray-Gilman House | 430 |

| 411. | Mantel, Kimball House | 431 |

| 412. | Mantel, Lindall-Barnard-Andrews House | 432 |

| 413. | Doorway, Larkin-Richter House | 433 |

| 414. | Doorway, “Octagon” | 434 |

| 415. | Mantel, “Octagon” | 435 |

| 416. | Mantel, Schuyler House | 436 |

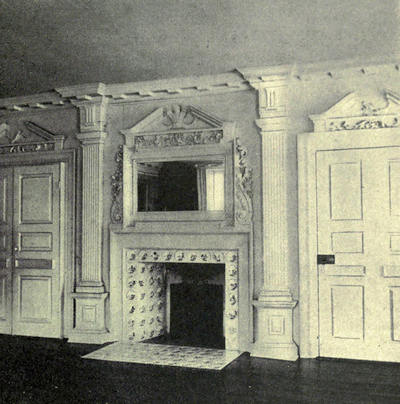

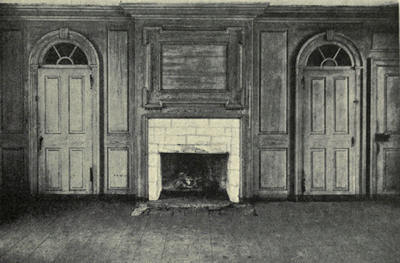

| 417. | Mantel and Doorways, Manor Hall | 438 |

| 418. | Mantel and Doorways, Manor Hall | 439 |

| 419. | Mantel, Manor Hall | 440 |

| 420. | Doorway, Independence Hall | 441 |

| 421. | Stairs, Graeme Park | 442 |

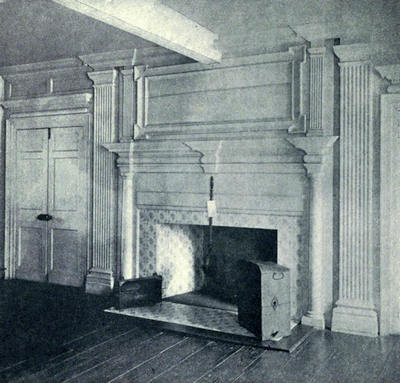

| 422. | Mantel and Doorways, Graeme Park | 443 |

| 423. | Doorway, Chase House | 445 |

| 424. | Entrance and Stairs, Cliveden | 446 |

| 425. | Mantel, Cliveden | 447 |

| 426. | Fretwork Balustrade, Garrett House | 448 |

| 427. | Stairs, Valentine Museum | 449 |

| 428. | Mantel, Myers House | 450 |

FURNITURE

OF THE OLDEN TIME

Furniture of the Olden Time

INTRODUCTION

THE furniture of the American colonies was at first of English manufacture, but before long cabinet-makers and joiners plied their trade in New England, and much of the furniture now found there was made by the colonists. In New Amsterdam, naturally, a different style prevailed, and the furniture was Dutch. As time went on and the first hardships were surmounted, money became more plentiful, until by the last half of the seventeenth century much fine furniture was imported from England and Holland, and from that time fashions in America were but a few months behind those in England.

In the earliest colonial times the houses were but sparsely furnished, although Dr. Holmes writes of leaving—

“The Dutchman’s shore,

With those that in the Mayflower came, a hundred souls or more,

Along with all the furniture to fill their new abodes,

To judge by what is still on hand, at least a hundred loads.”

If one were to accept as authentic all the legends told of various pieces,—chairs, tables, desks, spinets, and even pianos,—Dr. Holmes’s estimate would be too moderate.

The first seats in general use were forms or benches, not more than one or two chairs belonging to each household. The first tables were long boards placed upon trestles. Chests were found in almost every house, and bedsteads, of course, were a necessity. After the first chairs, heavy and plain or turned, with strong braces or stretchers between the legs, came the leather-covered chairs of Dutch origin, sometimes called Cromwell chairs, followed by the Flemish cane chairs and couches. This takes us to the end of the seventeenth century. During that period tables with turned legs fastened to the top had replaced the earliest “table borde” upon trestles, and the well-known “hundred legged” or “forty legged” table had come into use.

Cupboards during the seventeenth century were made of oak ornamented in designs similar to those upon oak chests. Sideboards with drawers were not used in this country until much later, although there is one of an early period in the South Kensington Museum, made of oak, with turned legs, and with drawers beneath the top.

Desks were in use from the middle of the seventeenth century, made first of oak and later of cherry and walnut. Looking-glasses were owned by the wealthy, and clocks appear in inventories of the latter part of the century. Virginals were mentioned during the seventeenth century, and spinets were not uncommon in the century following.

With the beginning of the eighteenth century came the strong influence of Dutch fashions, and chairs and tables were made with the Dutch cabriole[3] or bandy leg, sometimes with the shell upon the knee, and later with the claw-and-ball foot. Dutch high chests with turned legs had been in use before this, and the high chest with bandy legs like the chairs and tables soon became a common piece of furniture. With other Dutch fashions came that of lacquering furniture with Chinese designs, and tables, scrutoirs or desks, looking-glass frames, stands, and high chests were ornamented in this manner.

The wood chiefly used in furniture was oak, until about 1675, when American black walnut came into use, and chests of drawers, tables, and chairs were made of it; it was the wood oftenest employed in veneer at that time.

Sheraton wrote in 1803: “There are three species of walnut tree, the English walnut, and the white and black Virginia. Hickory is reckoned to class with the white Virginia walnut. The black Virginia was much in use for cabinet work about forty or fifty years since in England, but is now quite laid by since the introduction of mahogany.”

Mahogany was discovered by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1595. The first mention of its use in this country is in 1708. Mr. G. T. Robinson, in the London Art Journal of 1881, says that its first use in England was in 1720, when some planks of it were brought to Dr. Gibbon by a West India captain. The wood was pronounced too hard, and it was not until Mrs. Gibbon wanted a candle-box that any use was made of the planks, and then only because the obstinate doctor insisted upon it. When the candle-box was finished, a bureau (i.e. desk) was[4] made of the wood, which was greatly admired, and as Mr. Robinson says, “Dr. Gibbon’s obstinacy and Mrs. Gibbon’s candle-box revolutionized English household furniture; for the system of construction and character of design were both altered by its introduction.” It is probable that furniture had been made in England of mahogany previous to 1720, but that may be the date when it became fashionable.

The best mahogany came from Santiago, Mexican mahogany being soft, and Honduras mahogany coarse-grained.

The earliest English illustrated book which included designs for furniture was published by William Jones in 1739. Chippendale’s first book of designs was issued in 1754. He was followed by Ince and Mayhew, whose book was undated; Thomas Johnson—1758; Sir William Chambers—1760; Society of Upholsterers—about 1760; Matthias Lock—1765; Robert Manwaring—1766; Matthias Darly—1773; Robert and J. Adam—1773; Thomas Shearer (in “The Cabinet-makers’ London Book of Prices”)—1788; A. Hepplewhite & Co.—1789; Thomas Sheraton—1791-1793 and 1803.

Sir William Chambers in his early youth made a voyage to China, and it is to his influence that we can attribute much of the rage for Chinese furniture and decoration which was in force about 1760 to 1770.

Thomas Chippendale lived and had his shop in St. Martin’s Lane, London. Beyond that we know but little of his life. His book, “The Gentleman’s[5] and Cabinet-Maker’s Director,” was published in 1754, at a cost of £3.13.6 per copy. The second edition followed in 1759, and the third in 1762. It contains one hundred and sixty copper plates, the first twenty pages of which are taken up with designs for chairs, and it is largely as a chair-maker that Chippendale’s name has become famous. His furniture combines French, Gothic, Dutch, and Chinese styles, but so great was his genius that the effect is thoroughly harmonious, while he exercised the greatest care in the construction of his furniture—especially chairs. He was beyond everything a carver, and his designs show a wealth of delicate carving. He used no inlay or painting, as others had done before him, and as others did after him, and only occasionally did he employ gilding, lacquer, or brass ornamentation.

Robert and James Adam were architects, trained in the classics. Their furniture was distinctly classical, and was designed for rooms in the Greek or Roman style. Noted painters assisted them in decorating the rooms and the furniture, and Pergolesi, Angelica Kaufmann, and Cipriani did not scorn to paint designs upon satinwood furniture.

Matthias Lock and Thomas Johnson were notable as designers of frames for pier glasses, ovals, girandoles, etc.

Thomas Shearer’s name was signed to the best designs of those published in 1788 in “The Cabinet-Makers’ Book of Prices.” His drawings comprise tables of various sorts, dressing-chests, writing-desks, and sideboards, but there is not one chair among[6] them. He was the first to design the form of sideboard with which we are familiar.

As Chippendale’s name is used to designate the furniture of 1750-1780, so the furniture of the succeeding period may be called Hepplewhite; for although he was one of several cabinet-makers who worked together, his is the best-known name, and his was probably the most original genius. His chairs bear no resemblance to those of Chippendale, and are lighter and more graceful; but because of the attention he paid to those qualifications, strength of construction and durability were neglected. His chair-backs have no support beside the posts which extend up from the back legs, and upon these the shield or heart-shaped back rests in such a manner that it could endure but little strain.

Hepplewhite’s sideboards were admirable in form and decoration, and it is from them and his chairs that his name is familiar in this country. His swell or serpentine front bureaus were copied in great numbers here.

His specialty was the inlaying or painting with which his furniture was enriched. Satinwood had been introduced from India shortly before this, and tables, chairs, sideboards, and bureaus were inlaid with this wood upon mahogany, while small pieces were veneered entirely with it. The same artists who assisted the Adam brothers painted medallions, wreaths of flowers or arabesque work upon Hepplewhite’s satinwood furniture. Not much of this painted furniture came to this country, but the fashion was followed by our ancestresses, who were[7] taught, among other accomplishments, to paint flowers and figures upon light wood furniture, tables and screens being the pieces usually chosen for decoration.

Thomas Sheraton published in 1791 and 1793, “The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book”; in 1803, his “Cabinet Dictionary”; in 1804, “Designs for Household Furniture,” and “The Cabinet-Maker, Upholsterer, and General Artist’s Encyclopedia,” which was left unfinished in 1807.

“The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book” is largely taken up with drawings and remarks upon perspective, which are hopelessly unintelligible. His instructions for making the pieces designed are most minute, and it is probably due to this circumstantial care that Sheraton’s furniture, light as it looks, has lasted in good condition for a hundred years or more.

Sheraton’s chairs differ from Hepplewhite’s, which they resemble in many respects, in the construction of the backs, which are usually square, with the back legs extending to the top rail, and the lower rail joining the posts a few inches above the seat. The backs were ornamented with carving, inlaying, painting, gilding, and brass. The lyre was a favorite design, and it appears in his chair-backs and in the supports for tables, often with the strings made of brass wire.

Sheraton’s sideboards are similar to those of Shearer and Hepplewhite, but are constructed with more attention to the utilitarian side, with sundry[8] conveniences, and with the fluted legs which Sheraton generally uses. His designs show sideboards also with ornamental brass rails at the back, holding candelabra.

His desks and writing-tables are carefully and minutely described, so that the manifold combinations and contrivances can be accurately made.

Sheraton’s later furniture was heavy and generally ugly, following the Empire fashions, and his fame rests upon the designs in his first book. He was the last of the great English cabinet-makers, although he had many followers in England and in America.

After the early years of the nineteenth century, the fashionable furniture was in the heavy, clumsy styles which were introduced with the Empire, until the period of ugly black walnut furniture which is familiar to us all.

While there have always been a few who collected antique furniture, the general taste for collecting began with the interest kindled by the Centennial Exposition in 1876. Not many years ago the collector of old furniture and china was jeered at, and one who would, even twenty years since, buy an old “high-boy” rather than a new black walnut chiffonier, was looked upon as “queer.” All that is now changed. The chiffonier is banished for the high-boy, when the belated collector can secure one, and the influence of antique furniture may be seen in the immense quantity of new furniture modelled after the antique designs, but not made, alas, with the care and thought for durability which were bestowed upon furniture by the old cabinet-makers.

Heaton says: “It appears to require about a century for the wheel of fashion to make one complete revolution. What our great-grandfather bought and valued (1750-1790); what our grandfathers despised and neglected (1790-1820); what our fathers utterly forgot (1820-1850), we value, restore, and copy!”

Since the publication of this book in 1902, many old houses in this country have been restored by different societies interested in the preservation of antiquities. These historic houses have been carefully and suitably furnished, thus carrying out what should be our patriotic duty, the gathering and preserving of everything connected with our history and life. Thus much furniture has been rescued, not only from unmerited oblivion, but from probable destruction.

CHAPTER I

CHESTS, CHESTS OF DRAWERS, AND DRESSING-TABLES

THE chest was a most important piece of furniture in households of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It served as table, seat, or trunk, besides its accepted purpose to hold valuables of various kinds.

Chests are mentioned in the earliest colonial inventories. Ship chests, board chests, joined chests, wainscot chests with drawers, and carved chests are some of the entries; but the larger portion are inventoried simply as chests.

All woodwork—chests, stools, or tables—which was framed together, chiefly with mortise and tenon, was called joined, and joined chests and wainscot chests were probably terms applied to panelled[11] chests to distinguish them from those of plain boards, which were common in every household, and which were brought to this country on the ships with the colonists, holding their scanty possessions.

The oldest carved chests were made without drawers beneath, and were carved in low relief in designs which appear upon other pieces of oak furniture of the same period.

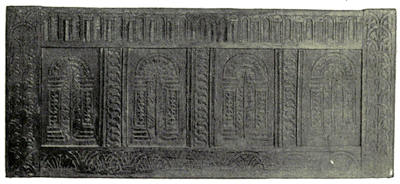

Illus. 1.—Oak Chest, about 1650.

Illustration 1 shows a chest now in Memorial Hall, at Deerfield, which was taken from the house where the Indians made their famous attack in 1704. The top of the chest is missing, and the feet, which were continuations of the stiles, are worn away or sawed off. The design and execution of the carving are unusually fine, combining several different patterns, all of an early date. Chests were carved in the arch design with three or four panels, but seldom as elaborately as this, which was probably made before 1650.

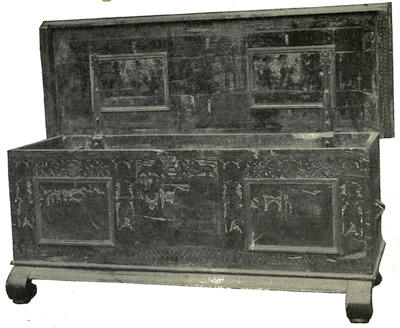

Illustration 2 shows a remarkable chest now owned by Mrs. Caroline Foote Marsh of Claremont-on-the-James,[12] Virginia. Until recently it has remained in the family of D’Olney Stuart, whose ancestor, of the same name, was said to be of the royal Stuart blood, and who brought it with him when he fled to Virginia after the beheading of Charles I.

The feet have been recently added, and should be large balls; otherwise the chest is original in every respect. It is made entirely of olive-wood, the body being constructed of eight-inch planks. The decoration is produced with carving and burnt work. Upon the inside of the lid are three panels, the centre one containing a portrait in burnt work of James I. with his little dog by his side. The two side panels portray the Judgment of Solomon, the figures being clad in English costumes; in the left panel the two kneeling women claim the child; in the right the child is held up for the executioner to carry out Solomon’s command to cut it in two. The outside of the lid has the Stuart coat of arms burnt upon it. Upon the front of the chest are four knights, and between them are three panels, surrounded by a moulding, which is now missing around the middle panel. These three panels are carved and burnt with views of castles; and around the lock, above the middle panel, are carved the British lions supporting the royal coat of arms. The chest measures six feet in length and is twenty-four inches high.

Chests with drawers are mentioned as early as 1650, and the greater number of chests found in New England have one or two drawers.

Illus. 2.—Olive-wood Chest, 1630-1650.

Illustration 3 shows a chest with one drawer owned by the Connecticut Historical Society, made about 1660. There is no carving upon this chest, which is panelled and ornamented with turned spindles and drops. The stiles are continued below the chest to form the feet.

Illus. 3.—Panelled Chest with One Drawer, about 1660.

A chest with two drawers is shown in Illustration 4, made probably in Connecticut, as about fifty of this style have been found there, chiefly in Hartford County. The top, back, and bottom are of pine, the other portions of the chest being of American oak. The design of the carving is similar upon all these chests, and the turned drop ornament upon the stiles, and the little egg-shaped pieces upon the drawers, appear upon all. They have been found with one or two drawers or none, but usually with two. This chest is in Memorial Hall, at Deerfield.

A chest with two drawers owned by Charles R. Waters, Esq., of Salem, is shown in Illustration 5. The mouldings upon the front of the frame are carved in a simple design. The wood in the centre of the panels is stained a dark color, the spindles and mouldings being of oak like the rest of the chest.

Illus. 4.—Oak Chest with Two Drawers, about 1675.

A number of chests carved in a manner not seen elsewhere have been found in and about Hadley, Massachusetts, and this has given them the name of Hadley chests. The carving in all is similar, upon the front only, the ends being panelled, and all have three panels above the drawers, with initials carved[16] in the middle panel. The other two panels have a conventionalized tulip design, which is carved upon the rest of the front, in low relief. The carving is usually stained while the background is left the natural color of the wood.

Illustration 6 shows a Hadley chest with one drawer owned by Dwight M. Prouty, Esq., of Boston.

Illus. 5.—Panelled Chest with Two Drawers, about 1675.

Carved chests with three drawers are rarely found in any design, although the plain board chests were made with that number.

Illustration 7 and Illustration 8 show chests mounted upon frames. Illustration 8 stands thirty-two inches high and is thirty inches wide, and is made of oak, with one drawer. It is in the collection of Charles R. Waters, Esq., of Salem. Illustration 7[17] is slightly taller, with one drawer. This chest is in the collection of the late Major Ben: Perley Poore, at Indian Hill. Such chests upon frames are rarely found, and by some they are supposed to have been made for use as desks; but it seems more probable that they were simple chests for linen, taking the place of the high chest of drawers which was gradually coming into fashion during the latter half of the seventeenth century, and possibly being its forerunner. Chests continued in manufacture and in use until after 1700, but they were probably not made later than 1720 in any numbers, as several years previous to that date they were inventoried as “old,” a word which was as condemnatory in those years as now, as far as the fashions were concerned.

Illus. 6.—Carved Chest with One Drawer, about 1700.

Chests of drawers appear in inventories about[18] 1645. They were usually made of oak and were similar in design to the chests of that period.

The oak chest of drawers in Illustration 9 is owned by E. R. Lemon, Esq., of the Wayside Inn, Sudbury. It has four drawers, and the decoration is simply panelling. The feet are the large balls which were used upon chests finished with a deep moulding at the lower edge. The drop handles are of an unusual design, the drop being of bell-flower shape. This chest of drawers was found in Malden.

Illus. 7 and Illus. 8—Panelled Chests upon Frames, 1670-1700.

Illustration 10 shows a very fine oak chest of four drawers, owned by Dwight M. Prouty, Esq., of Boston. The spindles upon this chest are unusually good, especially the large spindles upon the stiles. There is a band of simple carving between the drawers. The ends are panelled and the handles are wooden knobs.

Illus. 9.—Panelled Chest of Drawers, about 1680.

From the time that high chests of drawers were introduced, during the last part of the seventeenth century, the use of oak in furniture gradually ceased, and its place was taken by walnut or cherry, and later by mahogany. With the disuse of oak came a change in the style of chests, which were no longer made in the massive panelled designs of earlier years.

The moulding around the drawers is somewhat of a guide to the age of a piece of furniture. The earliest moulding was large and single, upon the frame around the drawers. The next moulding consisted[20] of two strips, forming a double moulding. These strips were in some cases separated by a plain band about half an inch in width.

Illus. 10.—Panelled Chest of Drawers, about 1680.

Later still, upon block front pieces a small single moulding bordered the frame around the drawers, while upon Hepplewhite and Sheraton furniture the moulding was upon the drawer itself. Early in the eighteenth century,[21] about 1720, high chests were made with no moulding about the drawers, the edges of which lapped over the frame.

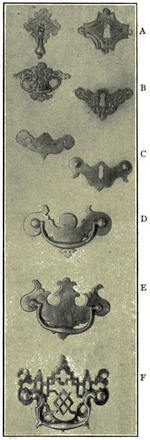

Illustration 11.

Another guide to the age of a piece of furniture made with drawers is found in the brass handles, which are shown in Illustration 11 in the different styles in use from 1675. The handle and escutcheon lettered A, called a “drop handle,” was used upon six-legged high chests, and sometimes upon chests. The drop may be solid or hollowed out in the back. The shape of the plate and escutcheon varies, being round, diamond, or shield shaped, cut in curves or points upon the edges, and generally stamped. It is fastened to the drawer front by a looped wire, the ends of which pass through a hole in the wood and are bent in the inside of the drawer.

A handle and escutcheon of the next style are lettered B. They are found upon six-legged and early bandy-legged high chests. The plate of the[22] handle is of a type somewhat earlier than the escutcheon. Both are stamped, and the bail of the handle is fastened with looped wires.

Illus. 12.—Six-legged

High Chest of Drawers,

1705-1715.

Letter C shows the earliest styles of handles with the bail fastened into bolts which screw into the drawer. Letters D, E, and F give the succeeding styles of brass handles, the design growing more elaborate and increasing in size. These are found upon desks, chests of drawers, commodes, and other pieces of furniture of the Chippendale period.

The earliest form of high chest of drawers had six turned legs, four in front and two in the back, with stretchers between the legs, and was of Dutch origin, as well as the high chest with bandy or cabriole legs, which was some[23] years later in date. Six-legged chests were made during the last quarter of the seventeenth century, and were usually of walnut, either solid or veneered upon pine or whitewood; other woods were rarely employed.

Illus. 13.—Walnut Dressing-table,

about 1700.

The earliest six-legged chests were made with the single moulding upon the frame about the drawers, and with two drawers at the top, which was always flat, as the broken arch did not appear in furniture until about 1730. The lower part had but one long drawer, and the curves of the lower edge were in a single arch.

The six-legged high chest of drawers in Illustration 12 belongs to F. A. Robart, Esq., of Boston. It is veneered with the walnut burl and is not of the earliest type of the six-legged chest, but was made about 1705-1715. The handles are the drop handles shown in letter A, and the moulding upon the frame around the drawers is double. There is a shallow drawer in the heavy cornice at the top, and the lower part contains three drawers.

Dressing-tables were made to go with these chests of drawers, but with four instead of six legs. Their tops were usually veneered, and they were, like the high chests, finished with a small beading around the curves of the lower edge.

The dressing-table in Illustration 13 also belongs to Mr. Robart, and shows the style in which that piece of furniture was made.

The names “high-boy” and “low-boy” or “high-daddy” and “low-daddy” are not mentioned in old records and were probably suggested by the appearance of the chests mounted upon their high legs.

Illus. 14.—Dressing-table, 1720.

High chests, both six-legged and bandy-legged, with their dressing-tables were sometimes decorated with the lacquering which was so fashionable during the first part of the eighteenth century.

Illustration 14 shows a dressing-table or low-boy[25] from the Bolles collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is covered with japanning, in Chinese designs. This dressing-table is the companion to a lacquered high-boy, with a flat top, in the Bolles collection. The handle is like letter C, in Illustration 11. That and the moulding around the drawers place its date about 1720.

Coming originally from the Orient, japanned furniture became fashionable, and consequently the process of lacquering or japanning was practised by cabinet-makers in France and England about 1700, and soon after in this country.

The earliest high chests with cabriole or bandy legs are flat-topped, and have two short drawers, like the six-legged chests, at the top. They are made of walnut, or of pine veneered with walnut. The curves at the lower edge are similar to those upon six-legged chests and are occasionally finished with a small bead-moulding.

Illus. 15.—Cabriole-legged High Chest

of Drawers with China Steps,

about

1720.

The bandy-legged high-boy in Illustration 15 is owned by Dwight Blaney, Esq. It is veneered with walnut and has a line of whitewood inlaid around each drawer. The moulding upon the frame surrounding the drawers is the separated double moulding, and the handles are of the early stamped type shown in Illustration 11, letter B. The arrangement of drawers in both lower and upper parts is the same as in six-legged chests. A reminder of the fifth and sixth legs is left in the turned drops between the curves of the lower edge.

Steps to display china or earthenware were in use during the second quarter of the eighteenth century.

They were generally movable pieces, made like the steps in Illustration 15, in two or three tiers, the lower tier smaller than the top of the high chest, forming with the chest-top a set of graduated shelves upon the front and sides.

The broken arch, which had been used in chimney pieces during the seventeenth century, made its appearance upon furniture in the early years of the eighteenth century, and the handsomest chests were made with the broken arch top.

A lacquered or japanned high-boy in the Bolles collection, owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is shown in Illustration 16. It is of later date than the lacquered dressing-table in Illustration 14, having the broken arch. The lacquering is inferior in[27] design to that upon the dressing-table, and at the top is a scroll design following the outline of the top drawers and the moulding of the broken arch.

Illus. 16.—Lacquered

High-boy, 1730.

A large and a small fan are lacquered upon the lower middle drawer, and on the upper one is a funny little pagoda top, with a small fan, both in lacquer. The handles are of an early type, and the moulding around the drawers is a double separated one. Such japanned pieces are rare and of great value.

A fine high chest is shown in Illustration 17, from the Warner house in Portsmouth. It is of walnut and is inlaid around each drawer. The upper middle drawer is inlaid in a design of pillars with the rising sun[28] between them, and below the sun are inlaid the initials J. S. and the date 1733.

Illus. 17.—Inlaid Walnut High

Chest of

Drawers, 1733.

The lower drawer has a star inlaid between the pillars, and a star is inlaid upon each end of the case. The knobs at the top are inlaid with the star, and the middle knob ends in a carved flame.

J. S. was John Sherburne, whose son married the daughter of Colonel Warner. The legs of this chest were ruthlessly sawed off many years ago, in order that it might stand in a low-ceilinged room, and it is only in comparatively recent years that it has belonged to the branch of the family now owning the Warner house. A double moulding runs upon the frame around the drawers, and the original handles were probably small, of the type in Illustration 11, letter C.

Illus. 18.—Inlaid Walnut High

Chest

of Drawers, about 1760.

A walnut high chest of a somewhat later type is shown in Illustration 18, belonging to Mrs. Rufus Woodward of Worcester. It is of walnut veneered upon pine, and the shells upon the upper and lower middle drawers are gilded, for they are, of course, carved from the pine beneath the veneer. The frame has the separated double moulding around the drawers. A row of light inlaying extends around each drawer, and in the three long drawers of the upper part the inlaying simulates the division into two drawers, which is carried out in the top drawers of both the upper and lower parts. The large handles and the fluted columns at the sides would indicate that this chest was made about 1760-1770.

Illustration 19 shows a “high-boy” and “low-boy” of walnut, owned by the writer. The drawers,[30] it will be seen, lap over the frame. The “high-boy” is original in every respect except the ring handles, which are new, upon the drawers carved with the rising sun or fan design.

It was found in the attic of an old house, with the top separate from the lower part and every drawer out upon the floor, filled with seeds, rags, and—kittens, who, terrified by the invasion of the antique hunter, scurried from their resting-places, to the number of nine or ten, reminding one of Lowell’s lines in the “Biglow Papers”:—

“But the old chest won’t sarve her gran’son’s wife,

(For ’thout new furnitoor what good in life?)

An’ so old claw foot, from the precinks dread

O’ the spare chamber, slinks into the shed,

Where, dim with dust, it fust and last subsides

To holdin’ seeds an’ fifty other things besides.”

Illus. 19.—“Low-boy” and “High-boy” of Walnut, about 1740.

But carefully wrapped up and tucked away in one of the small drawers were the torches for the upper and the acorn-shaped drops for the lower part. These drops were used as long as the curves followed those of the lower part of six-legged chests, but were omitted when more graceful curves and lines were used, as the design of high chests gradually differed from the early types.

Illus. 20.—Walnut Double Chest,

about

1760.

The “low-boy,” or dressing-table, was made to accompany every style of high chest. The low-boy in Illustration 19 shows the dressing-table which was probably used in the room with the bandy-legged high-boy, flat-topped or with the broken arch cornice. It is lower than the under part of the high-boy, which is, however, frequently supplied with a board top and sold as a low-boy, but which can be easily detected from its height and general appearance. The measurements of this high-boy and low-boy are

| HIGH-BOY, lower part | LOW-BOY |

| 3 feet high | 2 feet 4 inches high |

| 3 feet 1½ inches long | 2 feet 6 inches long |

| 21 inches deep | 18 inches deep |

The high-boy measures seven feet from the floor to the top of the cornice.

High chests and dressing-tables were made of maple, often very beautifully marked, in the same style as the chests of walnut and cherry. The high chest was sometimes made with the drawers extending nearly to the floor, and mounted upon bracket, ogee, or claw-and-ball feet. This was called a double chest, or chest-upon-chest.

The double chest in Illustration 20 is in the Warner house at Portsmouth. It is of English walnut, and the lower part is constructed with a recessed cupboard like the writing-table in Illustration 106. The handles upon this chest are very massive, and upon the ends of both the upper and lower parts are still larger handles with which to lift the heavy chest.

Illus. 21.—Mahogany Double Chest, 1765.

A double chest which was probably made in Newport, Rhode Island, about 1760-1770, is shown in Illustration 21. The lower part is blocked and is carved in the same beautiful shells as Illustration 31 and Illustration 106. This double chest was made for John Brown of Providence, the leader of the party who captured the Gaspee in 1772, and one of the four famous Brown brothers, whose name is perpetuated in Brown University. This chest is now owned by a descendant of John Brown, John Brown Francis Herreshoff, Esq., of New York.

Illus. 22.—Block-front Dressing-table, about 1750.

A low-boy of unusual design, in the Warner house, is shown in Illustration 22. The front is blocked, with a double moulding upon the frame around the drawers. The bill of lading in Illustration[35] 109 specified a dressing-table, brought from England to this house in 1716, but so early a date cannot be assigned to this piece, although it is undoubtedly English, like the double chair in Illustration 212, which has similar feet, for such lions’ feet are almost never found upon furniture made in this country.

Illus. 23.—Dressing-table, about 1760.

The shape of the cabriole leg is poor, the curves being too abrupt, but the general effect of the low-boy is very rich. The handles are the original ones, and they with the fluted columns and blocked front determine the date of the dressing-table to be about 175O.

The low-boy in Illustration 23 is probably of slightly later date. It has the separated double moulding upon the frame around the drawers, and the curves of the lower part are like the early high chests, but the carving upon the cabriole legs, and the fluted columns at the corners, like those in Chippendale’s designs, indicate that it was made after 1750. Upon the top are two pewter[36] lamps, one with glass lenses to intensify the light; a smoker’s tongs, and a pipe-case of mahogany, with a little drawer in it to hold the tobacco. This dressing-table is owned by Walter Hosmer, Esq.

Illus. 24.—Chest of Drawers, 1740.

The little chest of drawers in Illustration 24 belongs to Daniel Gilman, Esq., of Exeter, New Hampshire, and was inherited by him. It is evidently adapted from the high-boy, in order to make a smaller and lower piece, and it is about the size of a small bureau. The upper part is separate from the lower part, and is set into a moulding, just as the upper part of a high-boy sets into the lower. The handles and the moulding around the drawers are of the same period as the ones upon the chest in Illustration 20.

Illus. 25.—High Chest of Drawers, about 1765.

The furniture made in and around Philadelphia was much more elaborately carved and richly ornamented than that of cabinet-makers further north, and the finest tables, high-boys, and low-boys that are found were probably made there. They have large handles, like letter F, in Illustration 11, and finely carved applied scrolls.

The richest and most elaborate style attained in such pieces of furniture is shown in the high chest in Illustration 25, which is one of the finest high chests known. The proportions are perfect, and the carving is all well executed. This chest was at one time in the Pendleton collection, and is now owned by Harry Harkness Flagler, Esq., of Millbrook, New York.

Illus. 26.—Dressing-table and

Looking-glass, about 1770.

Such a chest as this was in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s mind when he wrote: “After all, the moderns have invented nothing better in chamber furniture than those chests which stand on four slender legs, and send an absolute tower of mahogany to the ceiling, the whole terminating in a fantastically carved summit.”

The dressing-table and looking-glass in Illustration 26 are also owned by Mr. Flagler. The looking-glass is described upon page 385. The dressing-table is a beautiful and dainty piece of furniture of the same high standard as the chest last described. The carving upon the cabriole legs is unusually elaborate and well done. It will be noticed that the lower edge of these pieces is no longer finished in the simple manner of the earlier high-boys and low-boys, but is cut in curves, which vary with each piece of furniture.

In Illustration 365 upon page 378 is a low-boy of walnut, owned by the writer, of unusually graceful proportions, the carved legs being extremely slender. The shell upon this low-boy is carved in the frame below the middle drawer instead of upon it, as is usual.

The dressing-table in Illustration 27 also belongs to the writer. It is of walnut, like the majority of similar pieces, and is finely carved but is not so graceful as Illustration 365. The handles are the original ones and are very large and handsome.

High chests and the accompanying dressing-tables continued in use until the later years of the eighteenth century.

Illus. 27.—Walnut Dressing-table, about 1770.

Hepplewhite’s book, published in 1789, contains designs for chests of drawers, extending nearly to the floor, with bracket feet, one having fluted columns at the corners, and an urn with garlands above the flat top. It is probable, however, that high chests of drawers were not made in any number after 1790.

CHAPTER II

BUREAUS AND WASHSTANDS

THE word “bureau” is now used to designate low chests of drawers. Chippendale called such pieces “commode tables” or “commode bureau tables.” As desks with slanting lids for a long period during the eighteenth century were called “bureaus” or “bureau desks,” the probability is that chests of drawers which resembled desks in the construction of the lower part went by the name of “bureau tables” because of the flat table-top. Hepplewhite called such pieces “commodes” or “chests of drawers.” As the general name by which they are now known is “bureau,” it has seemed simpler to call them so in this chapter.

Bureaus were made of mahogany, birch, or cherry, and occasionally of maple, while a few have been found of rosewood. Walnut was not used in serpentine[42] or swell front bureaus, although walnut chests of drawers are not uncommon, which look like the top part of a high chest, with bracket feet, and handles of an early design; and so far as the writer’s observation goes, few bureaus with three or four drawers were made of walnut.

Illus. 28.—Block-front Bureau, about 1770.

The wood usually employed in the finest bureaus is mahogany, and the earliest ones are small, with the serpentine, block, or straight front, and with the top considerably larger than the body, projecting nearly an inch and a half over the front and sides, the edge shaped like the drawer fronts. The early handles are large and like letter E in Illustration 11.

The block front is, like the serpentine or yoke front, carved from one thick board. It is found more frequently in this country than in England. The block-front bureau in Illustration 28 is owned by Dwight M. Prouty, Esq., of Boston, and is a very good example, with the original handles.

Illus. 29.—Block-front Bureau, about 1770.

The small bureau in Illustration 29 is in the Warner house in Portsmouth. It is of mahogany, with an unusual form of block front, the blocking being rounded. The shape of the board top corresponds to the curves upon the front of the drawers. The handles are large, and upon each end is a massive handle to lift the bureau by.

Illustration 30 shows a block-front bureau owned by the writer. Chippendale gives a design of a bureau similar to this, with three drawers upon rather high legs, under the name of “commode table.”

Illus. 31.—Kettle-shaped Bureau, about 1770.

The height of the legs brings the level of the bureau top about the same as one with four drawers. One handle and one escutcheon were remaining upon this bureau, and the others were cast from them. The block front with its unusually fine shells would indicate that this piece, which came from Colchester, Connecticut, was made by the same Newport cabinet-maker as the writing-table in Illustration 106, and the double chest in Illustration 21, which were made about 1765. The looking-glass in the illustration is described upon page 410.

Illus. 30.—Block-front Bureau, about 1770.

Illustration 31 shows a mahogany bureau of the style known as “kettle” shape, owned by Charles R. Waters, Esq., of Salem. Desks and secretaries were occasionally made with the lower part in this style, and many modern pieces of Dutch marqueterie with kettle fronts are sold as antiques. But little marqueterie furniture was brought to this country in old times, and even among the descendants of Dutch families in New York State it is almost impossible to find any genuine old pieces of Dutch marqueterie.

Illus. 32.—Serpentine-front Bureau,

about 1770.

A bureau with serpentine front is shown in Illustration 32. It is made in two sections, the upper part with four drawers being set into the moulding around the base in the same manner as the top part of a high-boy sets into the lower part. The bureau is owned by Charles Sibley, Esq., of Worcester.

The bureaus described so far all have the small single moulding upon the frame around the drawer. From the time when the designs of Shearer and[47] Hepplewhite became fashionable, bureaus were made with a fine bead moulding upon the edge of the drawer itself or without any moulding.

The serpentine-front bureau in Illustration 33 belongs to Mrs. Johnson-Hudson of Stratford, Connecticut. The corners are cut off so as to form the effect of a narrow pillar, which is, like the drawers and the bracket feet, inlaid with fine lines of holly. The bracket feet and the handles would indicate that this bureau was made before 1789.

Illus. 33.—Serpentine-front Bureau, about 1785.

A bureau of the finest Hepplewhite type is shown in Illustration 34, owned by Mrs. Charles H. Carroll of Worcester. The base has the French foot which[48] was so much used by Hepplewhite, which is entirely different from Chippendale’s French foot. The curves of the lower edge, which are outlined with a line of holly, are unusually graceful; the knobs are brass.

Illus. 34.—Swell-front Inlaid Bureau, about 1795.

Illustration 35 shows the styles of handles chiefly found upon pieces of furniture with drawers, after 1770. A is a handle which was used during the last years of the Chippendale period, and the first years of the Hepplewhite. B and C are the oval pressed brass handles found upon Hepplewhite furniture. They were made round as well as oval, and[49] were in various designs; the eagle with thirteen stars, a serpent, a beehive, a spray of flowers, or heads of historic personages—Washington and Jefferson being the favorites.

Illustration 35.

D is the rosette and ring handle, of which E shows an elaborate form. These handles were used upon Sheraton pieces and also upon the heavy veneered mahogany furniture made during the first quarter of the nineteenth century. F is the brass knob handle used from 1800 to 1820. G is the glass knob which, in clear and opalescent glass, came into use about 1815 and which is found upon furniture made for twenty years after that date, after which time wooden knobs were used, often displacing the old brass handles.

Looking-glasses made to swing in a frame are mentioned in inventories of 1750, and about that date may be given to the dressing-glass with drawers, shown in Illustration 36. It was owned by Lucy Flucker, who took it with her when, in opposition to her parents’ wishes, she[50] married in 1774 the patriot General Knox. It is now in the possession of the Hon. James Phinney Baxter, Esq., of Portland, Maine. Such dressing-glasses were intended to stand upon a dressing-table or bureau.

Illus. 36.—Dressing-glass,

about 1760.

A bureau and dressing-glass owned by the writer are shown in Illustration 37. The bureau is of cherry, with the drawer fronts veneered in mahogany edged with satinwood. A row of fine inlaying runs around the edge of the top and beneath the drawers. This lower line of inlaying appears upon inexpensive bureaus of this period, and seems to have been considered indispensable to the finish of a bureau. The dressing-glass is of mahogany and satinwood with fine inlaying around the frame of the glass and the edge of the stand. The base of the bureau is of a plain type, while that of the dressing-glass has the same graceful curves that appear in Illustration 34.

Illus. 37.—Bureau and Dressing-glass, 1795.

The bureaus in Illustration 34 and Illustration 37 are in the Hepplewhite style. The bureau and dressing-glass in Illustration 38 are distinctly Sheraton, of the best style. They are owned by Dwight Blaney, Esq., of Boston, and were probably made about 1810. The carving upon the bureau legs and upon the corners and side supports to the dressing-glass is finely executed. The handles to the drawers are brass knobs.

A bureau of the same date is shown in Illustration 39. It was owned originally by William F. Lane, Esq., of Boston. Mr. Lane had several children, for whom he had miniature pieces of furniture made, the little sofa in Illustration 228 being one. The small bureau upon the top of the large one was part of a bedroom set, which included a tiny four-post bedstead.

Illus. 38.—Bureau and Dressing-glass, about 1810.

This miniature furniture was of mahogany like the large pieces. The handles upon the large bureau are not original. They should be rosette and ring, or knobs similar to those upon the small bureau. The bureaus are now owned by a daughter of Mr. Lane, Mrs. Thomas H. Gage of Worcester.

Illus. 39.—Bureau and Miniature

Bureau, about 1810.

Bureaus of this style were frequently made of cherry with the drawer fronts of curly or bird’s-eye maple, the fluted pillars at the corner and the frame around the drawers being of cherry or mahogany.

There was added to the bureau about this time—perhaps evolved from the dressing-glass with drawers—an upper tier of shallow drawers, usually three. The dressing-table shown in Illustration 40 is owned by Charles H. Morse, Esq., of Charlestown, New Hampshire. It stands upon high legs turned and reeded, and a dressing-glass is attached above the three little drawers. The handles should be rings or knobs.

The case of drawers with closet above, in Illustration 41, is owned by Mrs. Thomas H. Gage, of Worcester. It is of mahogany, the doors of the closet being of especially handsome wood. The carving at the top of the fluted legs is fine, and the piece of furniture is massive and commodious.

Illus. 40—Dressing-table and Glass, 1810.

Illus. 41.—Case of Drawers with

Closet, 1810.

The bureau in Illustration 42 is also owned by[55] Mrs. Gage, and is a very good specimen of the furniture in the heavy style fashionable during the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

It was probably made to match a four-post bedstead with twisted posts surmounted by pineapples. The drawer fronts are veneered, like those of all the bureaus illustrated in this chapter except the first four, and there is no moulding upon the edge of the drawers.

Illustration 43 shows the heaviest form of bureau, made about the same time as the last one shown, with heavily carved pillars and bears’ feet. The drawer fronts are veneered and have no moulding upon the edge. This bureau is owned by Mrs. S. B. Woodward of Worcester, and it is a fine example of the furniture after the style of Empire pieces.

The bureau in Illustration 44 is owned by Charles H. Morse, Esq., of Charlestown, and shows the latest type of Empire bureau, with ball feet, and large round veneered pillars. The three Empire bureaus shown have the last touch that could be added, a back piece above the tier of small drawers.

Illus. 42.—Bureau, about 1815.

The bureaus have the top drawer of the body projecting beyond the three lower drawers, and supported by the pillars at the sides. This and the[57] shallow tier of small drawers, and the back piece are typical features of the Empire bureau, which may have the rosette and ring handle or the knob of brass or glass.

Illus. 43.—Bureau, 1815-1820.

The toilet conveniences of our ancestors seem to our eyes most inadequate, and it is impossible that a very free use of water was customary, with the tiny bowls and pitchers which were used and the small and inconvenient washstands. A “bason frame[58]” appears in an inventory of 1654. Chippendale designed “bason stands” which were simply a tripod stand, into the top of which the basin fitted.

Illus. 44.—Empire Bureau and Glass, 1810-1820.

They were also called wig stands because they were kept in the dressing-room where the fine gentleman halted to remove his hat, and powder his wig. The basin rested in the opening in the top, and in the little drawers were kept the powder and other accessories of the toilet. The depression in the[59] shelf was for the ewer, probably bottle shaped, to rest in, after the gentleman had poured the water into the basin, to dip his fingers in after powdering his wig.

Illus. 45.—Basin Stand, 1770.

The charming little basin or wig stand in Illustration 45 is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The wood is mahogany and the feet are a flattened type of claw and ball, giving the little stand, with its basin and ewer, some stability, unless an unwary pointed toe should be caught by the spreading legs. The acanthus leaf is carved on the knees, and the chamfered corners above have an applied fret.

The drawings of Shearer, Hepplewhite and Sheraton show both square and corner washstands of mahogany with slender legs.

The washstand in Illustration 46 is of mahogany, and differs from the usual corner stand in having the enclosed cupboard. It was made from a Hepplewhite design and is owned by Francis H. Bigelow, Esq., of Cambridge.

The corner washstand in Illustration 47 is owned by the writer. It is of mahogany, and the drawers[60] are finely inlaid, probably after a Sheraton design.

Illus. 46.—Corner Washstand,

1790.

The little towel-rack is of somewhat later date and is made of maple, stained. The washbowl and pitcher are dark-blue Staffordshire ware, with the well-known design of the “Tomb of Franklin” upon them.

While the corner washstand possessed the virtues of taking up but little room, and being out of the way, the latter consideration must have been keenly felt by those who, with head thrust into the corner, were obliged to use it.

A square washstand of more convenient shape, but still constructed for the small bowl and pitcher, is shown in Illustration 48. It is of mahogany and is in the style that was used from 1815 to 1830. This washstand is owned by Mrs. E. A. Morse of Worcester.

Both corner and square washstands have an opening in the top, into which was set the washbowl, and two—sometimes three—small openings for the little cups which were used to hold the soap.

Hepplewhite’s book, published in 1789, shows[61] designs of “night tables” like the one in Illustration 49, but they are not often found in this country.

Illus. 47.—Towel-rack and Washstand, 1790-1800.

This table is of mahogany, with tambour doors, and a carved rim around the top, pierced at each side to form a handle. The wood of the interior of the drawer is oak, showing that the table was probably made in England. It is owned by the writer.

Illus. 48.—Washstand, 1815-1830.

There are several drawings in the books of Hepplewhite and Sheraton of washstands and toilet-tables with complicated arrangements for looking-glasses and toilet appurtenances, but such pieces of furniture could not have been common even in England, and certainly were not in this country.

Illus. 49.—Night Table, 1785.

In Illustration 288 upon page 294 is shown a piano which can be used as a toilet-table, with a looking-glass and trays for various articles, but it must have been, even when new, regarded less from the utilitarian side, and rather as a novel and ornamental piece of furniture.

Illus. 50.—Washstand, 1800-1810.

A washstand of different design is shown in Illustration 50. The front is of bird’s-eye maple and mahogany, and the top is of curly maple with mahogany inlay around the edge. The sides are mahogany. The two drawers are shams, and the top lifts on a hinge disclosing a compartment for a pitcher and bowl. The tapering legs end in a spade foot, and a large brass handle is upon each side. The other handles are brass knobs. This stand was made after instructions given by Sheraton thus, “The advantage of this kind of basin stand is, that they may stand in a genteel room, without giving offense to the eye, their appearance being somewhat like a cabinet.” The washstand is owned by the writer.

CHAPTER III

BEDSTEADS

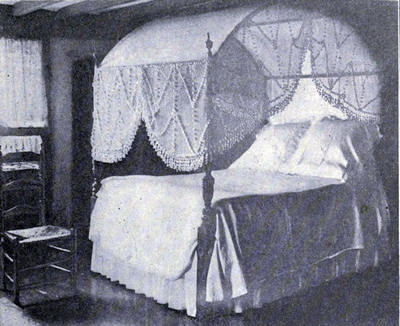

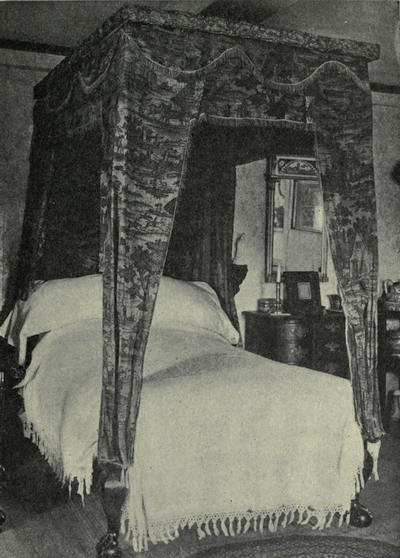

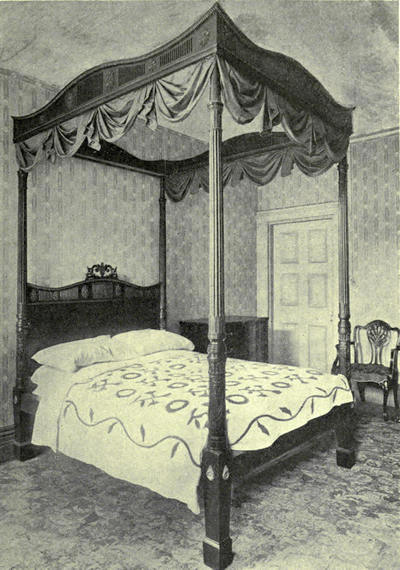

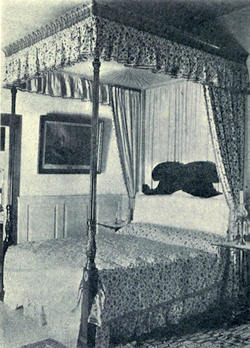

ONE of the most valuable pieces of furniture in the household of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was the bedstead with its belongings. Bedsteads and beds occupy a large space in inventories, and their valuation was often far more than that of any other article in the inventory, sometimes more than all the others. In spite of the great value placed upon them, none have survived to show us exactly what was meant by the “oak Marlbrough bedstead” or the “half-headed bedstead” in early inventories. About the bedstead up to 1750 we know only what these inventories tell us, but the inference is that bedsteads similar to those in England at that time were also in use in the colonies. The greater portion of the value of the bedstead lay in its furnishings,—the hangings, feather bed, bolster, quilts, blankets, and coverlid,—the[65] bedstead proper, when inventoried separately, being placed at so low a sum that one concludes it must have been extremely plain.

Illus. 51.—Wicker Cradle, 1620.

Several cradles made in the seventeenth century are still in existence. Illustration 51 shows one which is in Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth, and which is said to have sheltered Peregrine White, the first child born in this country to the Pilgrims. It is of wicker and of Oriental manufacture, having been brought from Holland upon the Mayflower, with the Pilgrims.

Illus. 52.—Oak Cradle,

1680.

The cradle in Illustration 52 is of more substantial build. It is of oak, and was made for John Coffin, who was born in Newbury, January 8, 1680. Sergeant Stephen[66] Jaques, “who built the meeting house with great needles and little needles pointing downward,” fashioned this cradle, whose worn rockers bear witness to the many generations of babies who have slept within its sturdy frame. It is now in the rooms of the Newburyport Historical Society.