Title: The Gourmet's Guide to London

Author: Lieut.-Col. Newnham-Davis

Release date: October 17, 2016 [eBook #53304]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Clare Graham and Marc D'Hooghe at Free

Literature (online soon in an extended version, also linking

to free sources for education worldwide ... MOOC's,

educational materials,...) Images generously made available

by the Internet Archive.

The pleasures of the table

are common to all ages and

ranks, to all countries and

times; they not only harmonise

with all the other

pleasures, but remain to

console us for their loss.—

Brillat Savarin.

In describing in this book some of the restaurants and taverns in and near London, I have selected those that seem to me to be typical of the various classes, giving preference to those of each kind which have some picturesque incident in their history, or are situated amidst beautiful surroundings, or possess amongst their personnel a celebrated chef or maître d'hôtel.

The English language has not enough nicely graduated terms of praise to enable me to give to a fraction its value to each restaurant, from the unpretentious little establishments in Soho to such palaces as the Ritz and Savoy, but I have included no dining-place in this volume that does not give good value for the money it charges.

Twelve years ago I wrote a somewhat similar book, "Dinners and Diners," which ran through two editions, but when I looked it through last year I found that there had been so many changes in the world of restaurants, so many old houses had vanished and so many new ones had arisen, that it was easier to write a new book than to bring the old one up to date. Mr Astor very kindly gave me permission to use in this volume any of the series of "Dinners and Diners" articles that appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette, but it will be found that I have availed myself very sparingly[Pg x] of his kind permission. The chapters of this book appeared, with very few exceptions, in Town Topics, and I am indebted to the editor of that paper for his leave to gather them into book form.

Mr Grant Richards, the publisher of this book, quite agrees with me that no advertisements of restaurants shall find a place within its covers.

Should "The Gourmet's Guide to London" find a welcome from an appreciative public, and should, in due time, other editions of it be called for, I shall hope to broaden its scope to include in it some of the hostelries of Brighton and other seaside towns, also those of the great cities and great ports, and to describe some of those fine old country inns scattered about the kingdom where good old English cookery is still to be found in good old English surroundings.

For the French of the menus I do not hold myself responsible. The kitchen writes the French that it talks and who am I, a mere Briton, that I should attempt to alter it?

N. NEWNHAM-DAVIS.

| page | ||

| I | OLD ENGLISH FARE | 1 |

| II | SIMPSON'S IN THE STRAND | 6 |

| III | A WALK DOWN FLEET STREET | 12 |

| IV | THE CARLTON | 19 |

| V | TWO LITTLE SOHO RESTAURANTS | 26 |

| VI | A RAG-TIME DINNER | 32 |

| VII | THE CAFÉ ROYAL | 38 |

| VIII | OYSTER-HOUSES | 46 |

| IX | WHITEBAIT AT GREENWICH | 53 |

| X | THE CECIL | 59 |

| XI | CLARIDGE'S | 67 |

| XII | THE EUSTACE MILES RESTAURANT | 73 |

| XIII | THE PRINCES' RESTAURANT | 81 |

| XIV | THE CRITERION | 86 |

| XV | SOME CHOP-HOUSES | 92 |

| XVI | SOME GRILL-ROOMS | 99 |

| XVIII | IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS | 115 |

| XIX | A REGIMENTAL DINNER | 122 |

| XX | "JOLLY GOOD" | 128 |

| XXI | IN THE SHADOW OF THE PALACE THEATRE | 134 |

| XXII | THE WELCOME CLUB | 141 |

| XXIII | GOLDSTEIN'S | 147 |

| XXIV | THE MITRE | 152 |

| XXV | IN THE HANDS OF PI(E)RATES | 158 |

| XXVI | APPENRODT'S | 166 |

| XXVII | THE BURFORD BRIDGE HOTEL | 174 |

| XXVIII | THE RITZ | 180 |

| XXIX | SOME OUTLYING RESTAURANTS | 190 |

| XXX | THE KING'S GUARD | 195 |

| XXXI | THE OLD BULL AND BUSH | 201 |

| XXXII | THE BERKELEY | 206 |

| XXXIII | THE JOYS OF FOREIGN TRAVEL | 214 |

| XXXIV | A SUPPER TRAIN | 220 |

| XXXV | THE ADELAIDE GALLERY | 226 |

| XXXVI | THE COMPLEAT ANGLER | 235 |

| XXXVII | ARTISTS' ROOMS | 241 |

| XXXVIII | THE PICCADILLY RESTAURANT | 249 |

| XXXIX | THE RENDEZVOUS | 255 |

| XL | THE PALL MALL RESTAURANT | 261 |

| XLI | IN JERMYN STREET | 267 |

| XLII | THE MEN WHO MADE THE SAVOY | 272 |

| XLIII | THE DUTIES OF A MAÎTRE D'HÔTEL | 279 |

| XLIV | THE SAVOY TO-DAY | 283 |

| XLV | THE RESTAURANT DES GOURMETS | 290 |

| XLVI | THE MAXIM RESTAURANT | 294 |

| XLVII | BIRCH'S | 300 |

| XLVIII | A CITY BANQUET | 308 |

| XLIX | THE CAVENDISH HOTEL | 313 |

| L | THE RÉUNION DES GASTRONOMES | 320 |

| LI | THE LIGUE DES GOURMANDS | 325 |

| LII | THE CAVOUR RESTAURANT | 333 |

| LIII | VERREY'S | 338 |

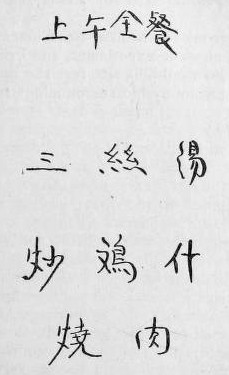

| LIV | THE CATHAY RESTAURANT | 345 |

| LV | THE WHITE HORSE CELLARS | 353 |

| LVI | THE MONICO | 360 |

| LVII | THE ITALIAN INVASION | 365 |

| LVIII | THE HYDE PARK HOTEL | 371 |

| LIX | YE OLDE GAMBRINUS | 378 |

| LX | MY SINS OF OMISSION | 384 |

| THE CHESHIRE CHEESE | Frontispiece |

| to face page | |

| M. ESCOFFIER | 24 |

| M. RITZ | 184 |

| JOSEPH CARVING A DUCK | 276 |

| MRS LEWIS | 314 |

When a foreigner or one of our American cousins, or a man from one of the Colonies, comes to England, the first question he generally asks is: "Where can I get a typical good old English dinner?" Good old English fare is by no means too abundant in London—and old English fare I would define as being the very best native material, cooked in the plainest possible manner. We talk of English cookery, though it should really be termed British cookery, for Irish stew and Welsh lamb, Scotch beef and cock-a-leekie soup, and even a haggis, can fairly be included in the comprehensive term.

When men on short commons on an exploring expedition, or on a sporting trip, or on active service, talk of the good things they will eat when they get home to England, the first idea that occurs to most of them is how delightful it will be to eat a good fried sole once again; and with fried sole may be coupled English bacon, for no bacon anywhere else in the world is as good as that which the kitchenmaids fry in thousands of British kitchens. Perhaps the Channel sole and the bacon of the Southern Counties, Oxford marmalade and Cambridge sausages belong to the home breakfast-table more than to meals in the haunts of the gourmet, though the sole plays a most important part in many dinners, and the Christmas dinner turkey would be unhappy without its accompanying sausages. It is, however, at lunch-time,[Pg 2] the time of pasties, puddings and pies, that old English cookery is seen at its best.

I do not know of any eating-house that makes a speciality of the mutton-chop pudding with oysters, that Abraham Hayward praises so unrestrictedly, but now and again I meet in restaurants such good English dishes as Lancashire hot-pot and gipsy pie, which is an admirable stew of chicken and cabbage; shepherd's pie, in which the minced meat is covered with a well-browned layer of mashed potato, I am given sometimes at shooting luncheons. Toad-in-the-hole and bubble-and-squeak are pleasant memories of my schoolboy days, but if some Frenchman, who has studied Dickens, asked me where he could eat the stew described in "The Old Curiosity Shop," which consisted of tripe, and cow-heel, and bacon, and steak, and peas and cauliflower, new potatoes and asparagus "all worked up together in one delicious gravy," I should have to admit my inability to direct him. A fish pie is excellent at any meal, but a woodcock pie or a snipe pudding, I think, should be reserved for the dinner-table. The pork-pie now seems sacred to railway refreshment-rooms, picnics and race-courses. Oysters are real British fare, though other countries have learned from us to appreciate them; but I fancy that the old Romans first taught the gentlemen who clothed themselves in woad tattooings what delicacies they had waiting for them in their shallow waters. Oysters are admirable creatures when eaten out of their deep shell, and they play their part well in oyster soup and scalloped oysters and oyster fries. And there are many puddings and "made dishes" that would be incomplete without the presence of oysters in them. Jugged duck and oysters is a good old British dish, and there are oysters in the majestic pudding of the Cheshire Cheese. I may perhaps be allowed to[Pg 3] suggest to some cooks who put the oysters into puddings and pies with the other raw materials that a better way is to cook the dish, then remove the crust or paste, slip in the oysters, fix the crust again and cook till the oysters are warmed through.

The typical British dinner most often quoted is that which the Lord Dudley of the thirties, a noted epicure, declared was a dinner "fit for an emperor," and it runs thus: "A good soup, a small turbot, a neck of venison, duckling with green peas, or chicken with asparagus, and an apricot tart." Of British soups turtle always takes precedence in the list of honour, but as the turtle comes from Ascension or the West Indies, it can hardly claim to be a denizen of these islands. Hare soup and mock turtle, mulligatawny, mutton broth and pea soup are distinctively British, though the curry powder in the mulligatawny—a soup which takes its name from two Tamil words: Mŭllĭgă = pepper, and Tunni = water—comes, of course, from India. Oxtail soup has a good British sound, but I fancy that French housewives first discovered the virtue that there is in the tail of an ox.

Lord Dudley loved a turbot, but other judges of good British dinners sometimes give the preference to cod. Walker, of "Original" fame, gave a Christmas Day dinner to two friends, and the fare he provided for them was: crimped cod, a woodcock a man, and plum pudding. One of the most typical British dinners I have eaten was that which a gallant colonel, who very worthily filled the mayoral chair at Westminster, used to give annually at the Cavour Restaurant. It consisted of a large turbot, a sucking-pig nicely roasted, and apple pudding. Roast sucking-pig is a dinner dish better understood in England than anywhere else in the world, except, perhaps, in China. When the Duke of Cambridge,[Pg 4] brother of George the Fourth, was entertained in princely fashion at Belvoir, and was shown the menu of a dinner on which a great French chef had exhausted all his inventiveness, and was asked if there were any dishes not included in the feast for which he had a fancy, answered that he would like some roast pig and an apple dumpling, both good British dishes. His son, the Commander-in-Chief of our days, also had a liking for pork, and, at one time, word went round the British army that at inspection lunches it was wise to give his Royal Highness pork chops. Of course, the British army overdid it, and the old Duke had so many pork chops put before him in the course of a year that at last their presence on the menu was far more likely to assist in the securing of an unfavourable report on a regiment than was their absence. Gravy soup, a grilled sole, a boiled hen pheasant stuffed with oysters, and an open tart formed the favourite dinner of a renowned gourmet of my acquaintance.

Of the made dishes that belong to British cookery, jugged hare, I think, has the leading place. Yorkshire pudding is as British as Stonehenge is, and mince pies can claim to be to-day exactly what they were when the Puritans used to preach against them. Marrow bones and Welsh rarebits, buck rarebits, and stewed tripe and onions are old British supper dishes, but the early closing laws have killed the old-fashioned British supper in eating-houses.

Good British cookery in London has not fared well in its battle against the invasion of good French cookery, and the number of houses which made a speciality of British fare has decreased woefully in the last twenty years. The old Blanchard's and its half-a-crown British dinner is a memory of the past (for the new Blanchard's turned towards the goddess A la), and the "Blue Posts" in Cork Street has been[Pg 5] converted into a club. It was curious that the prosperity of this typical old English house depended to a great extent on a German head waiter; for Frank, who had all the best traditions of British cookery at heart, had served under the old Emperor Wilhelm in the great war, and had been wounded by a French bayonet thrust. There were certain rules of the house that were excellent. One was that, no matter what orders you might give beforehand, no fish was ever put near the fire until the man who had ordered it was inside the building, which ensured it going to table cooked to the second; and another was that the steaks, which were a great stand-by of the house, were cut from the mass of beef just in time to be transferred at once to the grill, thus making sure that none of the juices should drain away.

But there are still some temples of British cookery left in Cockaigne, and to some of them presently I will direct your steps.

A wide entrance glowing with light, with Simpson's plain to see, on a wrought-iron sign above it, is in the great block of the Savoy Hotel building in the Strand, for the new Simpson's, though it retains all its old associations and its old manager and its old head cook—Mr Davey, the polite, white-haired little ruler of the roast, who wears a velvet cap, and who for forty-six years has seen the joints turn before the vast open fire in the kitchen—is now under the rule of the great organisation that controls the Savoy.

Come into the entrance hall, where you can give up your hat and coat to an attendant; though if you have been accustomed all your life to take them into Simpson's you will still find in the dining-room stands on which to hang them. The hall, with its marble pillars, white panels and groined roof, is light and airy; a staircase runs down from it to the smoking-room, and another one runs up to the dining-rooms upon the first floor. There is a tobacconist's stall in it, and if the door of the expense bar to one side be open you see through it shelves of bottles and flasks. Through the wide door leading into the big dining-room you see white-jacketed waiters moving hither and thither, and white-coated and white-capped carvers pushing the dinner waggons, crowned with big plated covers, before them, and as a background the fine fireplace, with its carved wooden overmantel[Pg 7] and its little marble pilasters, and a picture of a knight and lady of Plantagenet days feasting let into the central space.

Mr N. Wheeler, the rosy-faced manager, white-haired, and wearing the frock-coat of ceremony, will probably greet you as you go into the dining-room. He has seen all the various transformations of Simpson's Chess Divan, which was originally Ries's Divan, and he probably knows more about good old English fare than any man living. When we have eaten our turbot and saddle of mutton we will ask him how it is that these two best of British dishes are sent to table at Simpson's in such absolutely perfect condition. But before we choose our seats at one of the tables let us look round the room. The old Simpson's is still fresh in my memory. The painted garlands of flowers and studies of fish, flesh and fowl on the walls, glazed to a deep rich colour by the London atmosphere, the ground-glass windows, the big bar opening into the room, with Rembrandtesque shadows in its depths; the great dumb-waiter, which looked like a catafalque, in the centre of the room; the folded napkins in the glasses on the mantelpiece; the horsehair-stuffed, black-cushioned chairs and benches; the divisions with brass rails and dingy little curtains on the rails.

The pens with their brass rails are still in the old place, but they are modernised pens; the wood is oak, and there is a comfortable padded back of brown leather to lean against. The eating-room has been transformed into a banqueting hall. The walls are panelled with light oak, with pilasters to give variety, and an inlay of lighter wood at the corners of the panels. There is a white frieze with good modelling on it, and round the white-clothed tables which fill but do not crowd the floor space are chairs copied from a fine Chippendale example. A good old English[Pg 8] clock is on a bracket, and fine cut-glass lustre chandeliers hang from the ceiling. In old days the waiters at Simpson's were mostly British veterans, and in the upstairs room Charles Flowerdew, the head waiter, a genial old soul who always offered his favourites amongst the customers a pinch from his snuff-box, had a wealth of anecdotes about the great men of the Victorian era who were habitués of Simpson's. The waiters of to-day are Britons, but they are young men, and if anyone has doubts whether Englishmen properly trained can be as quick and silent in the service of a dining house as foreigners are, I would advise the doubter to eat a meal at Simpson's and to watch how the waiters do their work. The boys who take round the vegetables become in time full-blown serving-men. The waiters no longer wear the dress-coats, heroes of many clashes with sauce-boats and plates of soup, which used to be the official garb of the British waiter. They wear white washing jackets, with at the breast a little black shield, and on it the crest of the house—the knight of a set of chessmen. All the tips are pooled, with the result that all the serving-men work for the general good.

And now to look at the bill of fare. There are no such foreign innovations as hors d'œuvre allowed at Simpson's, where the only concessions to France are in the wine cellar and that little French rolls as well as household bread are in the bread baskets. You can obtain a fish dinner of three kinds of fish for three and ninepence; but we will order just what we feel our appetite demands, and take no account of set dinners. If your taste is for turtle soup, a plate of that luxury will cost you three shillings, but, if one of the simpler British soups will content you, hare, pea, mock turtle, Scotch hotch-potch, oxtail, giblet or mulligatawny are priced[Pg 9] at one shilling or one and sixpence. Then comes the important question of fish, and the choice really lies between a Sole Souchet, which Simpson's ought to write Zouchet, boiled codfish and oyster sauce, and boiled turbot and lobster sauce—the last one of the dishes on which Simpson's prides itself. Until I chatted with Mr Wheeler on the subject I always understood that a turbot to come to table in perfection should be hung for several days, but Mr Wheeler denounces this as rank heresy. A turbot should be nicked to draw off the blood of the fish, it should be soaked for twenty-four hours, and then it is ready to be boiled. It is instructive to watch a real habitué of Simpson's who prefers cod to turbot when a portly white-clad carver wheels his waggon up to the table. There must be the right proportion of liver with the fish and the due quantity of oyster in the sauce, or there will be dire threats of report to higher quarters. A boiled potato to anyone who knows what is good English fare is not to be accepted without criticism, and he would be a bold carver who dared to give the knowledgeable man a helping of saddle of mutton without a slice of the brown. But before we go on to the supreme matter of the saddle let me point out to you that whether you eat sole, or cod, or turbot, it means an item of two shillings on your bill.

The joints ring the changes on roast sirloin, boiled beef, boiled leg of mutton, roast loin of veal and bath chap, and saddle of mutton, and it is the saddle that is the favourite dish. Forty saddles a day is the quantity consumed at Simpson's, and now that the new room is opened sixty are required. Simpson's employs a buyer whose duty in life is to travel about England buying saddles wherever the finest mutton is to be procured. For fourteen days the saddles hang in the stock-room at Simpson's in[Pg 10] a temperature of 38°, then they are moved for two or three days to another store, through which there is a current of air, and then they are ready for the fire. And whether you eat of the mutton, the beef, or the veal, your portion and the accompanying vegetables will cost you half-a-crown.

We will not trifle with such kickshaws as salmi of game, or Irish stew, or jugged hare, and to finish our dinner we will take a helping of one of the pies or puddings on the bill of fare, or, better still, a good scoop of Stilton cheese or a wedge of Cheshire.

If you wish to be as British in your drinking as in your eating, there is cool British ale from the cask, which comes to table in a tankard, and cider, and the whisky of Scotland and that of Ireland. The house is also celebrated for its moderate-priced Bordeaux and Burgundy wines, bottled in the cellars.

If we go upstairs before leaving we can see the dining-room to which ladies are admitted—a handsome room of white with marble pillars—and you will notice the great bunches of wild flowers which adorn all the tables. On this floor there is a smaller private banqueting-room, and the new white Adams' Room, the double windows of which look into the Strand on one side and the entrance courtyard on the other. It is a handsome room, with settees by the window tables, and at night hanging baskets and lamps on the cornice throw light up to the ceiling to be reflected down into the room.

Down in the smoking-room on the basement level you will find a little band of chess-players, faithful to the old Divan, hard at the game, using the old chess-boards and the huge pieces of the Divan days, and it may further gratify your love for antiquarian lore to know that Simpson's stands on the site occupied by the old Fountain tavern, of which Strype[Pg 11] wrote: "A very fine tavern, with excellent vaults, good rooms for entertainments, and a curious kitchen for the dressing of meat." It was at the Fountain that the opponents of Walpole held their meetings and that the Earl of Derwentwater and the other Jacobite lords on trial for rebellion, being taken daily backwards and forwards between the Tower and Westminster, made favour with their jailer to let them halt for an hour to eat what they expected to be their last good dinner on earth.

Doctor Samuel Johnson stands in bronze before St Clement Danes and faces his beloved Fleet Street. If the great dictionary maker took his eyes off the book he holds in his hands, got down from his pedestal without knocking over the inkpot which is perilously near his clumsy old feet, and started for a walk down the street he loved so well, his remarks on the changes that have been made by time and the architects would be instructive. What would he say to Street's Law Courts? And with what sesquipedalian words would he lament the disappearance of Temple Bar and the appearance in its stead of the pantomime Griffin? And how the old man would snort and fume to find the taverns he was used to frequent altered out of recognition, or moved from their old places. The Rainbow's lamp would bring him to a halt, for the Rainbow stands to-day where Farr the barber set up his coffee-house, "by inner Temple Gate." Farr was "presented," in 1657, as an abuse by his neighbours, who protested against the smell of the coffee, but were in reality afraid that the new drink was going to oust canary and other wines. Johnson knew the old tavern in the brave days when Alexander Moncrieff was the host, when it still, though its "stewed cheeses" and its stout were celebrated, called itself a coffee-house, and the largest room[Pg 13] was the coffee-room, with a lofty bay-window at the south end looking into the Temple. In this bay the table was set for the worthies who frequented the house, and they could, through a glazed screen, see all that went on in the kitchen. The old Doctor, reading on the door-jamb that the Rainbow is occupied by the Bodega Company, would discourse learnedly on the meaning and uses of a Bodega. He would note with approval Groom's little coffee-house, a few steps farther on, which, though it did not exist in his days, for it dates back only to 1818, is one of the few establishments still existing which lives by the sale of coffee as a beverage, and prospers on its best Mocha at threepence a cup.

The Cock in its present condition would puzzle the old man most consumedly, and he would look across the street to see what has become of that tavern's old site; but if he went inside the house he would find that Grinling Gibbons' wood-carving of the cock had flown across the street, and that in the upper room is the panelling from the old alehouse in which the festive Pepys drank and sang and ate a lobster and afterwards "mightily merry" took Knip for a moonlight row on the Thames. It would be useless to talk to the Doctor of Tennyson and the plump head-waiter of the Cock, but pilgrims following the footsteps of those poets who have lunched in Fleet Street will find that the Cock is still a house where the "perfect pint of stout" and the "proper chop" are reached out with deft hands to customers, and that no head waiter unless he be plump is ever engaged for the upper room.

The Devil Tavern, which Ben Jonson made so famous by his Apollo Club, and which stood between Temple Bar and the Middle Temple Gate, was bought by Messrs Child, the bankers, in 1787, some years after the death of Samuel Johnson, when it had[Pg 14] fallen into disuse, and was pulled down and dwelling-houses erected on its site. Ben's "Welcome" and the Apollo bust were transferred to the bank. The most famous of all the Johnsonian taverns, the Mitre, was another of the old houses to fall a victim to bankers, for four years after the Doctor's death it ceased to be a tavern, became in turn Macklin's Poets' Gallery and Saunders's auction-rooms, and was finally pulled down that on its site "Hoare's New Banking-house" should be erected. Joe's Coffee-house in Mitre Court borrowed the derelict name when the Mitre closed its shutters, and set up a copy of Nollekins' bust of the Doctor as homage to his memory.

Opposite to Wine Office Court, the Sage of Fleet Street would stop in his shamble and would wait for an opportunity to cross the road. If Doctor Johnson hated the transit of the roadway when the traffic was but of hackney carriages and the coaches of aldermen and stage coaches and horsemen, how would he face the hurtling streams of taxi-cabs and motor omnibuses which nowadays jostle in the road? And what, when he had crossed the road, would he think of Fuller's little sweet-stuff shop which, gay with colour, has fastened itself, where there used to be a dingy wine merchant's office with cobwebbed bottles of old port in its dim, solemn windows, on the Fleet Street front of the Old Cheshire Cheese? The new-comer looks like a bright stamp stuck on some musty old parchment deed. Doctor Johnson would, I am sure, growl as he rolled through the narrow entrance into the court and on to the door of the old tavern.

And as he and you and I stand in the narrow doorway and look to the right at the little bar, a harmony in dark colours with the old china punch-bowls in their accustomed corner, and glass and[Pg 15] pewter and silver catching reflections of light amidst the black of old oak; and to the left at the old dining-room kept exactly as it was in Doctor Johnson's time; and to the front at the old oak staircase leading to the rooms above, let me explain to you that each white-haired generation of frequenters of the Cheshire Cheese finds fault with the arrangements made for the newer generation. When Johnson and Goldsmith ceased to use the house I am sure that the comfortable gentlemen who had sat at the long table and had listened to their conversation found that of an evening the talk had grown dull; and when Colonel Lawrence, who had carried one of the colours of the 20th Regiment at the battle of Minden, had been a crony of Goldsmith, and had hobnobbed with him and with Johnson over the port at the Cheese, died, the company at the long table must have lamented that all the "good old sort" and the good old customs were passing away. A sturdy supporter of the Cheese, who is some fifteen years older than I am, sighs for the days when he was first allowed to sit at the table where the Deputy-Governor of Newgate and a head clerk of Somerset House led the conversation. And when I go into the Cheese nowadays and find that two score belles from Baltimore, or half-a-hundred pretty Puritans from Philadelphia, have taken possession of the lower room, are drinking tea with their lunches, are talking like an aviary in commotion, and are more intent on buying souvenirs of Johnson than on appreciating the delights of the pudding, I sigh for the days thirty years ago when the Cheese was a grumpy man's paradise. I am quite sure that when Mr Dollamore, a host of the Cheese who has grown to heroic size as seen through the mists of time, died, people of that day thought that the great pudding would never again be mixed and carved by a master hand. I look[Pg 16] back now to the serious expression, the sort of expression we all assume as we enter a church door, that used to come upon the face of smiling Mr Moore as the vast pudding was carried in and he prepared to pierce its snowy covering. When Henry Todd, a waiter who entered Mr Dollamore's service two years before the battle of Waterloo, left the house and his portrait was painted by subscription and given as an heirloom to be hung in the dining-room, no one believed that young William Simpson, then just entering the service of the Cheese, would live to be even a more famous head waiter, to have his portrait painted to be hung in honour in the coffee-room, and to give his name to one of the rooms upstairs.

And now, having explained that if an old frequenter of the Cheshire Cheese sometimes grumbles at changes it is only through affection for the old house, let us go into the dining-room and sit down and look around us. We will leave Doctor Johnson's seat at the long table, with its brass tablet and his portrait above it, for the Shade of the great man. You shall sit in Oliver Goldsmith's seat with your back to the windows looking out into Cheshire Cheese Court, roofed in now to make a second dining-room; I will sit opposite to you, and we will take note of our surroundings. The approval of the old Doctor can be safely guaranteed. The sawdust on the floor; the wide grate with a shining copper kettle on the hob; the old mirror; the churchwarden pipes on the window-sill; the green-curtained cosy corner by the door, just like the squire's pew in many old churches; the black-handled knives and forks arranged in a row of black oak hutches; the willow-patterned plates and dishes; the queer old receptacle for umbrellas in the middle of the floor; the wire blinds, and the old tables and oak high-backed settles are to-day[Pg 17] exactly as they were when Johnson in the flesh frequented the tavern. The "greybeard" and the leathern jack, gifts from Mr Seymour Lucas, R.A., are quite in keeping with the room, and such of the pictures as are not old deal with incidents in Johnson's life or are sketches of the room and of the worthies who have frequented it. The manager of to-day keeps the house just as it used to be a century and a half ago, and being so, it is one of the most interesting old buildings in London.

Upstairs are the kitchen, where the woman cook responds to the verbal shorthand shouts of the waiters by putting chops and steaks on to the grill and clanging the oven door as good things to bake go into its recesses, and other old rooms, in which are some interesting relics of the old lexicographer, the chair in which he always sat at the Mitre, and other things curious and quaint, but they must await inspection till after lunch, for to-day is a pudding day, and the fat waiter with a moustache is waiting for our orders.

The pudding in its great earthenware bowl stands on a little table in the middle of the room. It is a triumph of old British cookery. In it are larks, kidneys, oysters, mushrooms, steak, and there are ingredients in the gravy which are a secret of the house. There are many imitations of the Cheshire Cheese pudding, but no such pudding unless it comes from the Cheshire Cheese kitchen has quite the right taste and quite the right richness of gravy. There is no stint in the helpings at the Cheshire Cheese. Any man with an appetite has only to ask for a "follow" to obtain it, and there are traditions that some men of mighty capacity have even had three helpings. Monday, Wednesday and Friday are pudding days. There is generally Irish stew on non-pudding days, and the Cheese Irish stew is admirable. Marrow[Pg 18] bones are another speciality of the house, and a Cheshire Cheese bone holds much marrow. The typical Cheshire Cheese meal, however—and I am sure Doctor Johnson would agree with me—is The Pudding, and the strong Scotch ale of the house therewith; stewed cheese, which comes to table in a shallow little pan accompanied by hot toast, and to finish up a bowl of the Cheshire Cheese punch served from an old china bowl with a good old-fashioned silver ladle. But beware of drinking too much of this punch, being deceived by its apparent innocence. I know one man who, saying it was as mild as mother's milk, drank the greater portion of a bowl of punch, remarked that he was a boy again, and behaved as a boy, and not until noon next day came to the conclusion that he was a very elderly man with a headache.

If all the great French chefs all the world over were canvassed for an opinion as to which amongst them is the greatest cook of the day, I am sure that the majority of votes would be in favour of M. Auguste Escoffier, the Maître-Chef of the Carlton Restaurant in London. When any restaurant is exceeding successful, whether it appeals to popular taste, or to the taste of the most cultured classes, there is sure to be amongst those men who have brought it fame or brought it popularity, some strongly marked personality, a great organiser, a great cook, or, perhaps, a great maître d'hôtel, such as poor dead Joseph was. And the commanding personality at the Carlton is M. Escoffier, who, had he been a man of the pen and not a man of the spoon, would have been a poet, and who, wearing the white cap and the white jacket, makes the sense of taste respond to the beautiful things he invents, just as the sense of hearing thrills to the cadence of a poet's words, or the melody of a great composer's music. And M. Escoffier holds that things which are beautiful to the taste should be fair to the eye, and should have pleasant-sounding titles. He, for instance, rechristened frogs, making them "nymphes," and nymphes à l'Aurore has a place in his great book on modern cookery.

The following is a typical Escoffier menu. It is for a little supper after the Opera, and was published[Pg 20] in Le Carnet d'Epicure, a magazine, to the pages of which M. Escoffier is a prolific contributor.

Gelée de Poulet aux Nids d'Hirondelles.

Soufflé d'Ecrevisses Florentine.

Côtelettes d'Agneau de Lait Favorite.

Petits Pois Frais.

Ortolans au Champagne.

Salade d'Oranges.

Asperges de Serre.

Pêches à la Fraisette des Bois.

Baisers de Vierge.

Mignardises.

The menu reads as delicately as the dishes would taste. The baisers de Vierge are twin meringues, the cream perfumed with vanilla and holding crystallised white rose leaves and white violets. Over each pair of meringues is a veil of spun sugar. This is worthy of the man who conceived the bombe Nero, a flaming ice, who gave all London a new entremet in fraises à la Sarah Bernhardt, and who added a new glory to a great singer by creating the pêche Melba.

M. Escoffier is a little below the middle height, grey haired, and grey of moustache. His face is the face of an artist, or a statesman, and the quick eyes tell of his capacity for command. The quiet little man who, amidst all the clangour of the great white-tiled kitchen below the restaurant of the Carlton, seems to have nothing to do except to occasionally glance at the dishes before they leave his realm or to give a word of counsel when some very delicate entremet is in the making, to taste a sauce or give a final touch to the arrangement of some elaborate cold entrée, has organised his brigade of vociferous cooks of all nations as thoroughly as Crawford organised the Light Division of Peninsular fame. There is never any difficulty, for every difficulty has[Pg 21] been foreseen. Only a man who has climbed the ladder from its lowest rung possesses such knowledge and such authority. M. Escoffier began his career as a boy in the kitchen of his uncle's restaurant in Nice. He went to Russia to the kitchen of one of the Grand Dukes, he served in the Franco-Prussian War as the Chef de Cuisine to the General Staff of the Army of the Rhine, and he knows the bitterness of captivity in the hands of an enemy. He was with Maréchal MacMahon at the Elysée and left the Grand Hotel at Rome when Ritz and he and Echenard came to London to make history at the Savoy. He writes with a very pretty wit on subjects connected with his profession, and he is married to a lady who, under her maiden name of Delphine Daffis, is well known in France as a poetess, and who has recently been decorated with the violet ribbon as Officier d'Académie.

If I have given so much space to a sketch of the great Maître-Chef, it is not that he is the only man of talent amongst the personnel of the Carlton. M. Kreamer, the manager, is eminent amongst his fellows. In the restaurant M. Besserer, light of hair, and with a light curling moustache, is an admirable Maître d'Hôtel, and the Carlton grill-room (to which I shall give attention when I write of the grill-rooms of London) owes much of its popularity to its manager, Signor Ventura.

And now for a little ancient history. Her Majesty's Opera House, with a colonnade surrounding it in which were shops and a little restaurant, Epitaux's, where the Iron Duke and other famous men gave dinner-parties in the early Victorian days, stood at the corner of the Haymarket and Pall Mall. If I wrote of the glories and the disasters of the big house of song I should have to write a book. When a company bought the site, and the Carlton and His[Pg 22] Majesty's Theatre rose on it, the colonnade disappeared from three sides, and all the shops on those sides also vanished except the offices of Justerini and Brooks. These wine merchants held to their old position, and their window front was encased in the building of the new hotel without the business of the firm suffering a day's interruption. A cigar store has since then found an abiding place on the Pall Mall frontage. The name of Epitaux's was taken by the restaurant next door to the Haymarket Theatre, but was eventually dropped in favour of a more attractive title, the Pall Mall.

The tall porter outside the entrance of the Carlton in Pall Mall sets the swing door in motion to let us through; coats and hats, cloaks and furs are garnered from us as we pass through the ante-room, and then we are in the palm lounge, that happy inspiration of the architect which has been copied in other hotels through the length and breadth of the habitable world. The double glass roof, letting in light but keeping out draughts, was a novelty when the hotel was built. But, though this palm court has been copied far and wide, it has never been bettered. The terrace breaks up pleasantly the great width of floor space. The tall palms, and the flowers and smaller palms before the terrace, and the green cane easy-chairs give a sylvan touch to this great hall in the heart of London; and, as an instance of perfect taste, notice the little medallions of Wedgwood ware dependent from the capitals of the creamy marble pilasters.

Up the broad flight of steps we go into the restaurant, a restaurant the colouring in which is such that it never clashes with the hues of any lady's dress. The garlands of golden leaves on the ceiling, the artful use of mirrors and evergreens to give the illusion that outside the windows north and west there are gardens, the cut-glass chandeliers converted into[Pg 23] electroliers, and giving a soft rosy light, the brown and deep rose of the carpet, the lighter rose of the chairs, the gilt cornice, the œil de bœuf windows towards the palm lounge, all form a perfect setting for charming people eating delicate foods. The keynote of the restaurant in decoration, as in the dinners which come from Escoffier's kitchen, is refinement. It is a pity, perhaps, that there is not daylight to brighten the restaurant from end to end, and that the electric lamps are always alight; but at dinner-time this is no drawback. An excellent string band plays on the terrace, but it is as well at dinner-time to choose a table far enough away from the musicians to ensure comfortable converse.

And now to describe to you a typical Carlton dinner. It is not easy, for I have so many memories of so many typical dinners there. Once the annual banquet of my old regiment was held at the Carlton in a great space of the restaurant screened off from the other diners. That was a noble feast! Again a memory comes to me of a silver wedding dinner, for which the table was decorated with creamy white and light pink roses, with silvered leaves. Escoffier composed for the occasion a dinner all white and pink, in which the Bortch was the deepest note of colour, the filets de poulets à la Paprika halved the two hues, and the flesh of an agneau de lait formed the highest light in the picture. That was the second occasion on which M. Escoffier sent to a dining-table the pêches Aiglon, the first occasion being a supper which Madame Sarah Bernhardt gave to Sir Henry Irving and other stars of our stage.

But most distinctive of all the dinners of ceremony at which I have been a guest at the Carlton was the dinner which Mr William Heinemann, the well-known publisher, gave to celebrate the publication by his firm of Escoffier's great work, "A Guide[Pg 24] to Modern Cookery." The dinner was the idea of the Maître-Chef, who suggested that the best way to criticise the book would be to invite some of the men in whose judgment the publisher had faith to eat a dinner cooked by the man who had written the book. We were fourteen in all, mostly "ink-stained wretches," and amongst the signatures on the menu, which I religiously pasted opposite the title-page of my autographed copy of the work, are those of Sir Douglas Straight and of T. P. O'Connor, of a member of the great house of Harmsworth, and of other men whose palates are as keen as their pens.

This was the menu of the dinner and the list of the wines we drank that 30th May 1907:

Melon Cantaloup.

Caviar de Sterlet.

Tortue Claire.

Velouté Froid de Volaille.

Mousseline d'Ecrevisses Orientale.

Jeune Agneau Piqué de Sauge.

Morilles à la Crème.

Petits Pois à l'Anglaise.

Poularde Ena.

Trou Normand.

Cailles aux Raisins.

Asperges d'Argenteuil.

Pêches Sainte Alliance.

Mignardises.

Vins.

Vodka.

Amontillado, Dry.

Berncastler Doctor, 1893.

Heidsieck and Co., Dry, 1892.

Pommery and Greno, Nature, 1900.

Château Lafitte, 1878.

Dow's Port, 1887.

Café Double—Grandes Liqueurs.

The velouté froid is a test dish, for only a master hand can give it the right consistency without allowing it to become pasty. The mousselines were beautifully light, each in the form of a cygnet, surrounding a central figure of a swan. The poularde Ena was the one dish in the banquet to which, because of its richness, I kissed my hand and passed it by. The combination of quails and grapes is one of M. Escoffier's happiest inspirations, and the pêches Ste Alliance is one of those delicate entremets in which Escoffier excels any other great chef of to-day, or of the past. The trou Normand is rather a violent stimulus to appetite, and consists of a liqueur-glass of old brandy. When M. Escoffier came with the coffee, to ask us what our verdict was on his dinner, our only difficulty was to find a sufficiency of complimentary adjectives.

There is a little restaurant in Old Compton Street, the Au Petit Riche, with the outside of which I was acquainted for some years before I put foot inside it. It so evidently kept itself to itself that I felt that my presence might be resented. It has little casemented windows in white frames, and inside the windows are muslin curtains, on a rail, hung sufficiently high to prevent anyone from looking over them. Below the windows are green tiles, and above it a stretch of little panes of bottle-glass in white frames to give additional light to the rooms inside. A little ground-glass lantern hung outside the door, and the name of the restaurant was painted over the window, but there was no bill of fare put up outside, no attempt to draw in a diner unless he had made up his mind to dine at the Au Petit Riche and nowhere else. I had been told all about the restaurant by those gallant souls who experiment at every new eating-place that springs up between Shaftesbury Avenue and Oxford Street, and though all I heard about the little place was pleasant and interested me, I felt that the Petit Riche was not anxious to make my acquaintance. But when the Petit Riche put up outside its windows an illuminated sign and its number, 44, in big figures, I felt that it had abandoned its haughty reserve and[Pg 27] was beckoning to me, and the rest of London, to come in. And in I went, and have been going in at intervals ever since, for the little restaurant is artistic and French and amusing.

When you open the glazed door and go in you are faced by the question: "On the level or down below?" A door to the right leads into the little series of rooms on the ground floor, and a flight of stairs plunges down into the basement. Come, first of all, through the door to the right. We are in the first of three little rooms, with light-coloured walls. A row of small tables is on either side of each room, and in the first room a white desk, with palms on it, faces towards the door. A score of pretty little French waitresses, Bretonnes all, in white and black, are bustling about, and Mademoiselle, if she is not sitting at the white desk, will probably receive you at the door and smile and pilot you to a table. And I should, before going any further, explain to you who Mademoiselle is, and tell you the story of the Au Petit Riche. A good Breton and his wife came to London and established a little restaurant in Old Compton Street, and with them came their two very pretty daughters. And they made the Au Petit Riche a corner of Brittany in London. The chef, who had graduated at the Escargot d'Or, a big bourgeois house near the Halles in Paris, is a Breton by birth, and all the merry little waitresses are from Brittany. The elder of the two daughters married a young journalist and for a while left the restaurant, but when her father and mother thought that the time had come for them to retire, she and her husband took up the management of the restaurant, with her sister to help them. And Mademoiselle, fresh and smiling, with a bunch of roses pinned to her blouse, is in command in the upper rooms, while Madame, as gracious as she is handsome, sits at her desk in one of the lower[Pg 28] rooms with a great bowl of flowers before her, and laughs with the young artists, who form a large portion of the clientele of the Au Petit Riche, and controls the waitresses, and sends the waiters, of whom there are two, out to fetch the wine, which comes from a wineshop a few paces away.

Established at a table in the first of the upstairs rooms, a glance at the walls will tell anyone that the place is a haunt of artists, for the pictures are just the omnium gatherum of artistic trifles that an artist generally puts on the walls of his den. Pencil drawings, rough things in charcoal, etchings, mezzotints, caricatures, sketches in colour, Japanese coloured prints—a gallery of scraps at which a Philistine would turn up his nose, but which look comfortable and homelike to the eye artistic. And at the head of the carte du jour, which a little waitress holds out to you, there is a good black and white of the exterior of the little restaurant—there is the atmosphere of art about the place.

Let us look down the list of dishes and order our dinner. The little waitress, on chance, has addressed us in French, but if she is answered in English can carry on a conversation in that language. There are two soups on the list, consommé Colbert, which costs sixpence, no doubt because of the egg, and crème Cressonière, which costs only threepence, and we will choose the cheaper of the two. Amongst the fish dishes, the salmon and the sole cost a shilling, but we will choose the vol au vent de Turbot Joinville, which costs ninepence. Amongst the entrées is an item, two quails en Cocotte, for a shilling. Curiosity prompts me to suggest that we should order this, having in mind what the price of a single quail is on a club bill of fare, but we shall be on safer ground in ordering one of the dishes of the house, the filet mignon Petit Riche, which costs a shilling, and with[Pg 29] it some peas, fourpence, and some new potatoes, also fourpence. Amongst the entremets is a Pêche Petit Riche, which the little waitress strongly recommends, but beignets de pommes at threepence seems to me a more fitting ending for our repast.

There is no long waiting for one's food at the Au Petit Riche; the soup arrives almost immediately and is wonderful value for threepence. The vol au vent is an admirable little fish pie, and the filet mignon a most toothsome morsel of meat, while the beignets are all that they should be. The little waitress, when we have arrived at the filet mignon stage of the dinner, asks with the utmost solicitude: "Do you like eet?" and I have replied for both of us "Very much indeed." At the table to one side of us are a young couple whose dinner has consisted of curried chicken and plum pudding au Rhum, and at the table to our other side, two ladies are eating a typical woman's dinner of hors d'œuvre, poached eggs and spinach, and a vanilla ice. The Au Petit Riche finds room on its small carte du jour for dishes to suit all tastes.

The little waitress brings the total of the bill on a bit of green paper; and having finished our dinner, and having paid for it, we will go down into the lower rooms before leaving the restaurant. In the lower rooms every table is always occupied, and I fancy that the habitués of the restaurant prefer them to the upper ones. One of them is decorated with golden fleurs-de-lis on a blue ground, and another is an admirable representation of the kitchen of a Breton farmhouse, crockery and all complete. There is a great buzz of talk in these lower rooms, and Madame la Patronne, sitting at her desk amidst the tables, takes her share in the conversation and attends to the making out of the bills at one and the same time.

If you go to the Au Petit Riche in the right frame mind you will be abundantly amused and interested, and you will get wonderful value for the very small sum your dinner will cost you.

And now for my other little restaurant in Soho. It is the Moulin d'Or at 27 Church Street. When Karl Thiele, who was in the employ of Peter Gallina at the Rendez-Vous Restaurant, married the pretty book-keeper at the Richelieu Restaurant, they determined to set up in business on their own account, and took a ground-floor room in Church Street, gave it a good-looking window, put a row of little trees outside, hung baskets of ferns within, and christened it Le Moulin d'Or, hoping that their mill would grind golden grist. It was a doll's house restaurant when I first discovered it two years ago, and the great ambition then of its proprietor and proprietress was that they might in time become sufficiently prosperous to add the first-floor room to their establishment. They have prospered, and when I lately went to dine there I found that the lower room with a restful green paper had been increased in size by taking in the passage, and that upstairs is a new restaurant room also with green walls and a large window, the dream realised of the young couple. And not only have these improvements and additions been made, but quite close to the Moulin d'Or there has been put up a wonderful windmill with electrically lighted sails which revolve, and below it a hand pointing in the direction of the restaurant and a transparency whereon see inscribed the prices of the table d'hôte meals, luncheon, and dinner, and supper, for the Moulin d'Or has both its carte du jour and its table d'hôte meals. For half-a-crown, on the occasion of my last visit, I could have eaten hors d'œuvre, made my choice between a consommé and a crème soup and partaken of salmon, filet de bœuf, roast chicken and caramel[Pg 31] cream, but I preferred to turn my attention to the carte du jour, and ordered crème Suzette, 6d.; truite au bleu, 1s. 3d.; escalope de veau Viennoise, 10d.; haricots verts, 6d.; and an omelette au Rhum, 10d., all very well cooked and served piping hot. The restaurant has not yet a wine licence, but for all that a special wine is reserved for it at a neighbouring wineshop, an excellent light burgundy, Château Villy, at 4s. 6d. a quart, and 2s. 6d. a pint, and, besides, there is a quite comprehensive wine list. Karl Thiele and his wife, looking for new kingdoms to conquer, have moved to Brighton, where they are established in St James's Street, and the new host at the Moulin d'Or is M. Combes, a very young man, assisted by a very young wife. They are, in spite of their youth, maintaining the reputation of the house for good cookery.

My little French cousin who has married the Comte de St Solidor (if that is not his exact title it is, literally, next door to it) has brought her Breton husband across the Channel to make the acquaintance of his English relatives, and is desperately anxious that he shall not be depressed by London. He is a jolly, round-faced Frenchman, with a rather straggly light beard and a great head of intractable light hair, and, were it not that he cannot speak a word of our language, might pass for a young Yorkshire squire. My little French cousin was particularly afraid that Robert, that is his first name, would suffer all the tortures of ennui on Sunday, for her mother, who was English-born, had told her that the English in England spend their Sunday afternoons, when they are grown-up, in singing hymns, and when they are children in repeating aloud the catechism. I told my little cousin to have no fear, that London Sundays are no longer what they were when her mother was a child, and I offered to take charge of Robert and herself on their first Sunday in London, from after lunch-time till bed-time, and to try and keep them amused.

I asked my little French cousin whether rag-time had penetrated to Brittany, and she, pitying my ignorance, told me that at Dinard, last summer, they had talked to rag-time music, and bathed to it, and had[Pg 33] even played syncopated chemin de fer to it, as well as danced to it. But, when I asked her if at Dinard she had ever eaten to it, she said, "But no," and gave a mimetic sketch of eating food to the air of "Everybody's doing it now," which was very funny. That settled where we should dine on Sunday, and I wrote off at once to the Imperial Restaurant to secure a dinner-table for four, and asked another cousin, a British one, to complete the partie carrée.

The afternoon of Sunday caused me no anxiety. Robert is devoted to music, so I took him and the Comtesse to the Queen's Hall to one of Sir Henry Wood's concerts, and on to the Royal Automobile Club to tea, and neither of them showed any sign of being oppressed by Sabbath gloom.

At ten minutes past eight I was waiting in the vestibule between the street entrance and the restaurant, where a marble bust of the late King Edward smiles at each customer who enters. I had ordered my dinner, a very simple one—potage Germiny, truites au bleu, noisettes de mouton, new peas and potatoes, ham and spinach, asparagus, and a bombe, and a magnum of Goulet, 1900, to drink therewith. For ten minutes I sat in the window-seat watching pretty ladies and men of all ages and types pass through the vestibule, give up their coats and cloaks, shake hands, and go in little coveys into the restaurant. The orchestra in the distance was sawing away at an operatic overture, the ante-room was comfortably warmed, and as dinner was the only event of the evening I did not fidget because my little cousin delayed in her coming. I was not the only solitary man waiting. In front of the fireplace stood a beautiful young man, with sleeve-links and studs and buttons to his white waistcoat that must have cost a fortune. Now and again he glanced at the clock, a work of art, in which a gilded cupid points with a[Pg 34] finger to the revolving girdle of hours on a vase, and when he had ascertained how late she was already he surveyed the other human creatures about him with tolerant pride and slight hauteur. I have no gift of telepathy, but I was quite sure that he was waiting for some very beautiful lady of the stage, and pitied those of us who had no such divinity to be our guest.

The British cousin arrived to time, and not very long afterwards my French cousins appeared. She looked at the clock and declared that they were late because Robert could not find his evening studs, and Robert laughed, as men do when called upon to substantiate a white fib told by their wives. She had asked me whether she ought to dine in her hair, or in a hat, and I had answered that either way would be quite correct. She had decided not to wear a hat in order to be quite English, and she looked entirely charming. I could not help glancing at the beautiful young man who monopolised the fire to see what he thought of my star guest. He was slightly interested, but he answered my glance by one which meant "Wait and see."

I had secured a corner table at a reasonable distance from the band, which occupies a platform about half-way down the room, and we enthroned the little cousin on the chair in the angle, so that she could see everybody and everything in the room. Every table but one was occupied, and that I knew was reserved for the beautiful young man whom we had left looking with a frown at cupid's finger. My little French cousin was in high spirits, and Robert acted as an amiable chorus. She recognised that the room was French—it is a copy of one of the salons at Fontainebleau, and perceived that the pictures of cupids, which are between the round windows and the tall casemented glasses, were inspired by Boucher. She liked the carved marble mantelpiece and the crystal[Pg 35] and gold electroliers. I was called upon to tell her who everybody was at the other tables, and I launched out recklessly into fiction. I knew by sight a dozen of our fellow-diners, and the rest I described as M.P.'s and ladies of title, officers of the Household Brigade, and divettes of the Gaiety, Daly's, the Lyric, and the Shaftesbury, which they probably are, celebrated painters and prima donnas, according to their appearance. My British cousin choked over a bone of the trout, so he said, but my little French cousin and her spouse were much impressed by my exhaustive acquaintance with all the celebrities of my native city, which was just the effect I wished to produce.

Little Oddenino, going the round of the tables, saying a word or two to all his clientele, came to our corner, asked if all was as it should be, took up the menu, and lifted his eyebrows. Of course I know that to follow the noisettes by ham was inartistic, but being in the vein of romance I said that my little French cousin was passionately fond of ham, and demanded it at all her meals, and not that I prefer ham to mutton, which would have been the truth. The little man bowed and smiled and passed on; My cousin asked who he was, and when I replied, "Oddy," she inquired if it was he who would presently make the rag-time. Pleased to be on bed-rock truth at last I gave her a shorthand sketch of Oddenino's career; how Turin is his native town; how he opened one of the great hotels at Cimiez, and earned the thanks of the late Queen Victoria and a fine tie-pin when she stayed there; how he was manager of the East Room at the Criterion, and of the Café Royal, and from the latter restaurant stepped two doors farther down Regent Street and built the Imperial Restaurant. I described story upon story of banqueting-rooms that are to be found on the Glasshouse Street side, and how Freemasons—good, charitable British Freemasons,[Pg 36] not troublesome political French Freemasons—feast in them in great numbers every night in the year. I sketched out the little man's other ventures, and I ended by telling her that Oddenino is a man of much consideration in the Italian colony in London, and has been decorated by his king. Surely she did not expect a Cavaliere to make rag-time music? And my little French cousin said "assuredly not."

When we had come to the noisettes' stage of our dinner the beautiful young man whom we had left waiting in the vestibule came in—alone. He looked as gloomy as Hamlet, and held in his hand a letter, which he tore into small pieces and thrust into the ice pail beside his table. "The poor animal!" said my little cousin pityingly. "He is dining with an excuse." He drank two glasses of champagne in quick succession, and then felt strong enough to sup his soup.

About this period a change came over the music of the band, which had conscientiously worked off the barcarole from "Hoffman," a Viennese waltz and a minuet. A clean-shaven young man, Mr Gideon, the clever composer of the rag-time successes who had been eating his dinner like the rest of us, took his place at the piano, and the orchestra subordinated itself to his leadership. Mr Gideon can make the piano speak as few men can, and my little French cousin and Robert both pricked up their ears and even let the asparagus get cold in their new-found interest. When Mr Gideon, dispensing with orchestral aid, sang "Honolulu," and here and there a girl's voice joined in the refrain, my little cousin turned sharply to me. "Ought one to sing?" she asked, and I told her that it was as she pleased. She listened with all her ears to catch the words, and at last trilled out with the rest: "Ma onaleuleu oné leu," and then laughed at her own boldness.

A quarter of an hour later my little French cousin, with both elbows on the table, a cigarette between her fingers, and sipping at intervals some crème de menthe, was singing "Hitchy Koo" with the best of them, and Robert was booming away harmonising a bass bouche-fermeé accompaniment. It was curious how this general singing brought together those who dined. We had been separate little parties before, but the humanity of song made us into one big friendly audience. Even the beautiful young man recovered his spirits sufficiently to try to start an eye flirtation with my little cousin.

The heat in the room grew and the atmosphere thickened with tobacco smoke, but we all sat on till close on eleven o'clock, when the vestibule doors were opened to let out the smoke and let in the cold air, and the ladies put their stoles round their necks, and the men called for their bills. Mine, including cigars and liqueurs, came to exactly a guinea a head.

Before bidding me good-night my little cousin, speaking for herself and Robert, said that they had well dined and had amused themselves, and that the Britannic Sunday was not frightening. But I told her that all our Sunday entertainment was not yet at end, that Robert, when he had taken her home to their hotel, was going to drink a whisky-and-soda with me at the club, and that then I would take him on to an hospitable house, where chemin de fer is played, and that if there was no police raid she would see him back about five a.m.

My little French cousin looked at me to see whether I was serious, laughed in my face, and taking Robert by the arm led him to the taxi that was waiting for them.

One of the questions people are fond of asking and, like "jesting Pilate," do not stay to have answered, is, "Which is the best place in London at which to dine?" This is generally only a prologue to their opinion on the subject, but when it is an inquiry, and not an overture, I always reply by another question, "Whom are you going to take out to dine?" for there are so many "best places" that the selection of the right one depends entirely on what are the tastes of the person, or persons, you wish to please.—If a man were to answer my question by saying that he wished to entertain some bachelors of his own ripe age and ripe tastes, and that he would like to go somewhere where the food is very good, the rooms comfortable, and where there is no band to interfere with conversation, I should diagnose his case at once as a Café Royal one.

The Café Royal is pleasantly conservative, and it is more like a good French restaurant of the Second Empire than is any other dining-place I know in London. Its fame has reached to all other countries in the world, and a French waiter who hopes to become in due time a manager looks on an engagement at "The Café" as a step in his career. Therefore, if ever you feel inclined to be tight-fisted in the matter of tips to the waiters at the Café Royal, reflect that you may meet them again where their good word can help to make a meal comfortable for you. Once in Paris, when I went to dine at Maire's, far[Pg 39] up the boulevards, a restaurant into which I had not been for years, I was surprised to be received as though I was the prodigal son of the establishment, a maître d'hôtel taking especial care to find a pleasant table for me, and suggesting various dishes from the carte du jour, which shaped into a dinner after my own heart. I asked him if I had ever seen him before, and he replied: "I waited on monsieur at the Café Royal in the days when he used to drink the Cliquot vin rosée." I pause here to sigh regretfully over the memory of that cuvée of Cliquot, at which many men shied because of its colour, but which was the most delightful wine that ever came from the great house of the widow of Rheims. On the first occasion that I entered the restaurant of the Esplanade Hotel in Berlin, feeling rather like a boy going to a new school, I was received by a maître d'hôtel who knew that I liked a table at the side of the room, suggested to me three of the lightest dishes on the carte as my dinner, and told me that he remembered that at the Café Royal I always asked for the table in the far corner of the first room and that I liked short and light dinners.

It may be that in a few years, when the Quadrant of Regent Street must be rebuilt, and all the other houses in it will be obliged to conform in some respects to the Piccadilly Hotel, the sample building of the new style, the Café Royal as we know it to-day may be altered in appearance and in the arrangement of its rooms, but I hope that this will not happen in my time. It was the first restaurant at which I learned the joys of dining out in pleasant company—a sole Colbert, a Chateaubriand and pommes sautés, an omelette au rhum and a bottle of good Burgundy was my idea of a suitable dinner in those my strenuous days, and I have for the house all the affection I have for old friends.[Pg 40] The influence of Madame Nicols is against any unnecessary change. An old lady with white hair and dressed in black walks every day through the rooms of the Café Royal, and the habitués know that this is Madame Nicols on her tour of inspection. She still gives personal supervision to the work in the linen-room, as she did in the early days of the café, and her wish is that everything should remain as much as is possible as it was when M. Nicols was alive.

There is a romance in the history of most restaurants that have existed for any length of time, and the rise of the Café Royal from small beginnings is interwoven with the Franco-Prussian War and with the rise and destruction of the Commune. On 11th February 1865 M. Daniel Nicols, who had been in the wine trade at Bercy, that part of Paris where the great wine depots are, opened a modest little café-restaurant in the lower part of Regent Street. It occupied the space where the entrance and hall now are. A photograph of the front of the house at that time is extant, showing the plate-glass window with a broad brass band below it, and on the glass in white letters announcements of the good things to be found within. In front of the modest doorway stands M. Nicols, looking very proud of his establishment, while two of his friends lean gracefully against the pilasters of the entrance, and the head waiter stands respectfully a step or two farther back. On the little balcony before the windows of the entresol stand the ladies of M. Nicols' family. The interior of the window was in those days decked with salads and with any foods that looked tempting, to catch the attention of the passer-by. In fact, it was just such an unpretentious little restaurant as any young foreigner coming to London and determined to make a competence might start nowadays hoping that Fortune would turn her[Pg 41] wheel in his direction. But most young foreigners do not have the chance, or the judgment, to establish themselves in Regent Street. I have a dim memory when I was a schoolboy of being impressed by some stuffed pheasants in the Café Royal window, and at the time of the great war I was first taken inside it to meet there a distant connection of my family, a Buonapartist, who had been one of the Empress's ministers during the short period when the Government of France fell into her hands and had gone into exile when the Republic was proclaimed. Those are my first two recollections of the Café Royal.

It was the flood of non-combatants and political exiles, business men, authors and actors; Red Republicans, Monarchists, and Buonapartists, whom the war and the political upheavals in France sent over to this country, that made the fortune of the little restaurant. However they might differ as to the colour of their politics, they were all Frenchmen, they all sighed for the blue skies of France; they found in the Café Royal a little corner of their beloved native land, and they naturally all gravitated to it. The house was much too small for the number of its frequenters, when, fortunately, the old Union Tavern in Glasshouse Street came into the market, was bought, and converted into the café as we know it, with its painted ceiling and its wealth of gilding, and the restaurant and the private dining-rooms were established on the other floors. This was the first of many extensions and alterations. A building on the Air Street side was absorbed, and a billiard-room established on the ground floor, but very soon the billiard-tables were given marching orders, and the space they occupied was turned into a grill-room. An enlargement of the kitchen, the installation of a lift on the Air Street side, the making of a little ante-room and cloakrooms outside the restaurant—before[Pg 42] this improvement any man waiting for a lady who was going to dine with him did so in the passage leading to the café or on the stairs—and the construction somewhere very near the roof of a masonic temple and a ballroom were all additions.

M. Nicols and Madame Nicols gave personal attention to all details, and the experience M. Nicols had gained at Bercy was of great use to him in laying down the fine cellar of wines, particularly of red wines, which is the great pride of the house. To draw a very fine distinction, I would say of the Café Royal that it is a restaurant to which gourmets go to drink fine wines and to eat good food therewith, while at other first-class restaurants gourmets go to eat good food and to drink fine wines therewith. The only cellar of red wines that I know which can compare with that of the Café Royal is the cellar of Voisin's in Paris. The wine-list of the Café Royal is splendidly comprehensive, and in its pages are to be found all the fine wines grown in Europe, even Switzerland being recognised, and the wines of the Rhone Valley above the Lake of Geneva being given a place in the book. M. Delacoste, the first manager I remember at the Café Royal, under M. Nicols, was a great authority on wines, and he bought so largely that there came a time when M. Nicols recognised that his clients with the utmost good will could never drink all the wine laid down for them, and sold a portion of it by auction. Other managers of the Café Royal have been Wolschleger; Oddenino, who was appointed when M. Nicols died in 1897, and during whose tenancy of the post many of the improvements in the house were made; Gerard, mighty of girth, who had been in the kitchen of the Café Anglais under Dugleré, and who moved on to the Ocean Hotel, Sandown; and now Judah, who had been manager of the Cecil, and who keeps a very steady hand on the tiller. M. Judah,[Pg 43] on the occasion of the visit of the President of the French Republic to London in 1913, was created an officer of the Order of Mérite Agricole.

Sportsmen have always had a special affection for the Café Royal. The men who were prominent in the revival of road-coaching were all patrons of the restaurant, and any night you may see half-a-dozen well-known owners of race-horses dining there. The Stage, the Stock Exchange, and Literature also have a liking for the old house, and hunting men love it.

When I mentioned it as the ideal place for a dinner of bachelor gourmets, I did not mean that men do not bring their wives and sisters and sweethearts there. They do. But the Café Royal does not lay itself out to capture the ladies. I never heard of anyone having afternoon tea there, and when a lady tells me that she likes dining at the Café Royal I always mentally give her a good mark, for it shows that she places in her affections good things to drink and good things to eat before those "springes to catch woodcock," gipsy bands in crimson coats, and palm lounges.

In the great gilded cage of the restaurant and the big room the windows of which open on to Glasshouse Street, the custom is to eat the lunch of the day, or to select dishes from it, while dinner is an à la carte meal. If one entertains a lady at dinner one probably orders a dinner which canters through the accepted courses, and I have by me the menu of such a one:

Hors d'œuvre Russe.

Pot-au-feu.

Sole Waleska.

Noisette d'agneau Lavallière.

Haricots verts à l'Anglaise.

Parfait de foie gras.

Caille en cocotte.

Salade.

Pôle Nord.

And with this dinner we drank a good bottle of St Marceaux.

But men when they dine together think little of the rightful sequence of courses, and order what their taste prompts them to eat. I have dined at the Café Royal, and dined well on moules Marinières—and one can eat moules at the Café without fear, half a cold grouse, a salad and a petit Suisse cheese. When the ham is a dish of the day it always tempts me, for the Café Royal hams are princes of their kind, and the cold mousses that the chef de cuisine, M. François Maître, makes are beautifully light. The specialities of the cuisine of the Café Royal are œufs Magenta, œufs Wallace, homard Thérmidor, sole Beaumanoir, filet de sole Simone, darne de saumon à l'Ecossaise, truite Dartois, turbotin Paysanne, poularde bisque, faisan Carême, perdreau à la Royal, caille Châtelaine, poulet sauté Sigurd, suprême de volaille à la Patti, tournedos Figaro, noisette de pré salé moderne, côte d'agneau Sultane, filet de bœuf Cambacères, selle d'agneau favorite.

Down in the café a table d'hôte meal is served, wonderful value for very few shillings, but I am not smoke-proof, and I like eating my meals without the taste and smell of tobacco added to them. The grill-room is always full, and perhaps more solid eating, of juicy fillets and grilled chops and cutlets, is done there than anywhere else in the house, except in the banqueting-rooms. I have banqueted with the Bons Frères, a club of cheery connoisseurs who like their dinner to be light and the songs that follow it also to be airy, in the great gilded banqueting-room with, as part of its decoration, many crowned N's, which might stand for Napoleon, but really indicate Nicols; I have dined in smaller rooms with the Foxhunters' Lodge, and with many other groups of good Freemasons and good diners; I have assisted at "Au Revoir" banquets without number, and I know when I am bidden to[Pg 45] feast in a private room at the Café Royal that I shall be given a good dinner on sound if perhaps conservative lines. This menu of a banquet given not long since, which is typical, will convey more what I mean than many words of description:

Natives.

Petite Marmite.

Saumon Sauce Genévoise.

Blanchailles.

Caille à la Cavour.

Jambon d'York aux Petits Pois.

Caneton de Rouen à la Presse.

Salade d'Orange.

Asperges Sauce Divine.

Bombe Alexandra.

Friandises.

Os à la Moëlle.

Café.

Dessert.

Vins.

Graves Monopole, Dry.

Heidsieck and Co., 1898.

Louis Roederer, 1899.

Ch. Le Tertre, 1888.

Martinez Port, 1884.

Denis Mouniés, 1860.

Liqueurs.

As a final word of praise for the Café Royal, let me record that just as many of its waiters grow grey-headed in its service, so the steps of any man who is a lover of good cheer and who has been an habitué of the restaurant seem unconsciously to lead him to its doors. It was my first love amongst the restaurants, and—well, you know how the proverb runs.