PEEPS AT HERALDRY

AGENTS

AMERICA . . . . THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK

AUSTRALASIA . . OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

205 Flinders Lane, MELBOURNE

CANADA . . . . THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD.

St. Martin's House, 70 Bond Street, TORONTO

INDIA . . . . . MACMILLAN & COMPANY, LTD.

Macmillan Building, BOMBAY

309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA

PLATE I.

frontispiece

frontispiece

HERALD, SHOWING TABARD ORIGINALLY WORN OVER MAIL ARMOUR.

PEEPS AT

HERALDRY

BY

PHŒBE ALLEN

CONTAINING 8 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR AND NUMEROUS LINE

DRAWINGS IN THE TEXT

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1912

TO MY COUSIN

ELIZABETH MAUD ALEXANDER

[pg vi]

CONTENTS

[pg vii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PLATE |

|

|

| 1. |

Herald showing Tabard, originally Worn over Mail Armour |

frontispiece |

| |

|

FACING PAGE |

| 2. |

The Duke of Leinster |

9 |

| |

Arms: Arg. saltire gu.

Crest: Monkey statant ppr., environed round the loins and chained or.

Supporters: Two monkeys environed and chained or.

Motto: Crom a boo. |

|

| 3. |

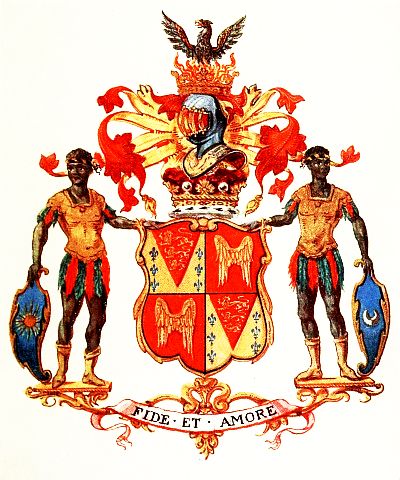

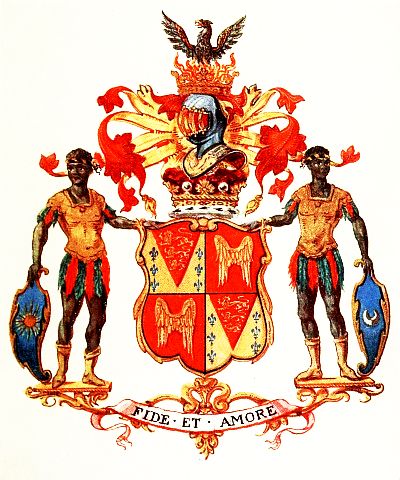

Marquis of Hertford |

17 |

| |

Arms: Quarterly, 1st and 4th, or on a pile gu., between 6 fleurs-de-lys az.,

3 lions passant guardant in pale or; 2nd and 3rd gu.,

2 wings conjoined in lure or. Seymour.

Crest: Out of a ducal coronet or a phœnix ppr.

Supporters: Two blackamoors.

Motto: Fide et amore. |

|

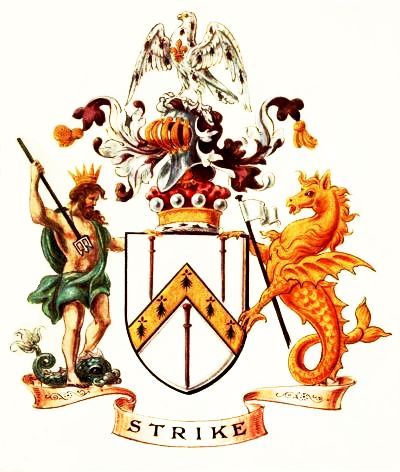

| 4. |

The Earl of Scarborough |

40 |

| |

Arms: Arg. a fesse gu. between 3 parrots vert, collared of the second.

Crest: A pelican in her piety.

Supporters: Two parrots, wings inverted vert.

Motto: Murus aëneus conscientia sana. |

|

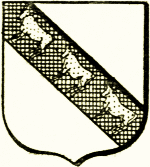

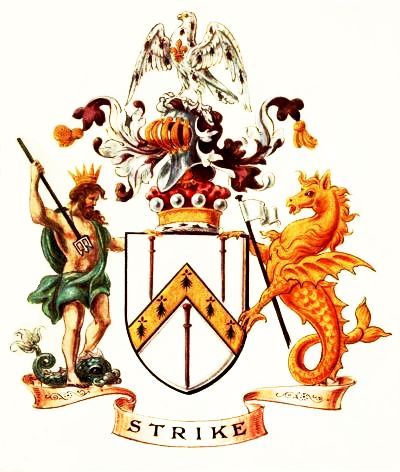

| 5. |

Baron Hawke |

48 |

| |

Arms: Arg. a chevron erminois between three pilgrim's staves purpure.

Crest: A hawk, wings displayed and inverted ppr., belled and charged

on the breast with a fleur-de-lys or.

Supporters: Dexter, Neptune; sinister, a sea-horse.

Motto: Strike. |

|

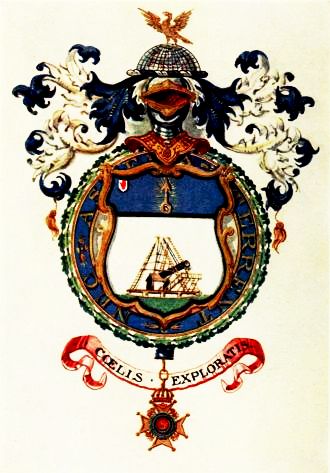

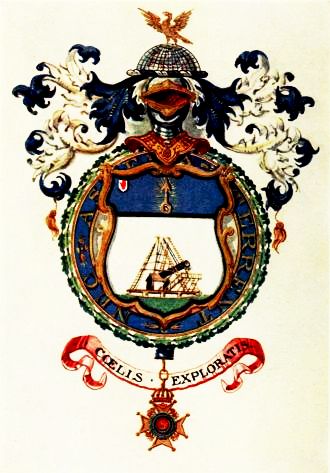

| 6. |

Sir William Herschel |

72 |

| |

Arms: Arg. on mount vert, representation of the 40 feet reflecting telescope

with its apparatus ppr.,

on a chief az., the astronomical symbol of Uranus irradiated or.

Crest: A demi-terrestrial sphere ppr., thereon an eagle, wings elevated or.

Motto: Cœlis exploratis. |

|

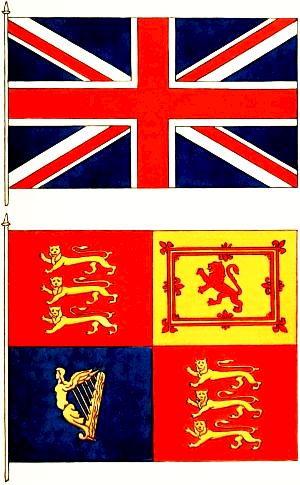

| 7. |

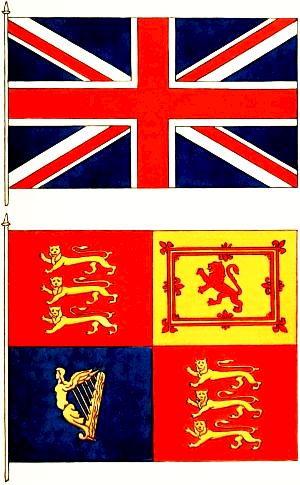

The Flags of Great Britain |

80 |

| |

(1) The Union Jack, (2) The Royal Standard. |

|

| 8. |

A Crusader in Mail Armour |

on the cover |

| Also fifty-five small black and white illustrations throughout the text. |

[pg viii]

"... The noble science once

The study and delight of every gentleman."

"And thus the story

Of great deeds was told."

[pg 1]

PEEPS AT HERALDRY

CHAPTER I

AN INTRODUCTORY TALK ABOUT HERALDRY

What is heraldry?

The art of heraldry, or armoury, as the old writers

called it, consists in blazoning the arms and telling the

descent and history of families by certain pictorial signs.

Thus from age to age an authenticated register of

genealogies has been kept and handed on from generation

to generation. The making and keeping of these

records have always been the special duty of a duly

appointed herald.

Perhaps you think that explanation of heraldry

sounds rather dull, but you will soon find out that

very much that is interesting and amusing, too, is

associated with the study of armorial bearings.

For heraldry, which, you know, was reckoned as

one of the prime glories of chivalry, is the language

that keeps alive the golden deeds done in the world,

and that is why those who have once learnt its

[pg 2]

secrets are always anxious to persuade others to learn

them too.

"Although," says the old writer, Montague; "our

ancestors were little given to study, they held a knowledge

of heraldry to be indispensable, because they considered

that it was the outward sign of the spirit of

chivalry and the index also to a lengthy chronicle of

doughty deeds."

Now, it is in a language that is all its own that

heraldry tells its stories, and it is unlike any other in

which history has been written.

This language, as expressed in armorial bearings,

contains no words, no letters, even, for signs and devices

do the work of words, and very well they do it. And

as almost every object, animate and inanimate, under

the sun was used to compose this alphabet, we shall find

as we go on that not only are the sun, moon and stars,

the clouds and the rainbow, fountains and sea, rocks

and stones, trees and plants of all kinds, fruits and

grain, pressed into the service of this heraldic language,

but that all manner of living creatures figure as well in

this strange alphabet, from tiny insects, such as bees and

flies and butterflies, to the full-length representations of

angels, kings, bishops, and warriors. Mythical creatures—dragons

and cockatrices, and even mermaidens—have

also found their way into heraldry, just as we find traditions

and legends still lingering in the history of nations,

like the pale ghosts of old-world beliefs.

And as though heavenly bodies and plants and

[pg 3]

animals were not sufficient for their purpose, heralds

added yet other "letters" to their alphabet in the

shape of crowns, maces, rings, musical instruments,

ploughs, scythes, spades, wheels, spindles, lamps, etc.

Each of these signs, as you can easily understand,

told a story of its own, as did also the towers, castles,

arches, bridges, bells, cups, ships, anchors, hunting-horns,

spears, bows, arrows, and many other objects,

which, with their own special meaning, we shall gradually

find introduced into the language of heraldry.

But perhaps by now you are beginning to wonder

how you can possibly learn one-half of what all these

signs are meant to convey, but you will not wonder

about that long, for heraldry has its own well-arranged

grammar, and grammar, as you know, means fixed

rules which are simple guides for writing or speaking

a language correctly.

Moreover, happily both for teacher and learner, the

fish and birds and beasts (as well as all the other objects

we have just mentioned) do not come swarming on to

our pages in shoals and flocks and herds, but we have

to do with them either singly or in twos and threes.

Now, even those people who know nothing about

heraldry are quite familiar with the term, "a coat of

arms." They know, too, that it means the figure of a

shield, marked and coloured in a variety of ways, so as

to be distinctive of individuals, families, etc.

But why do we speak of it as a coat of arms when

there is nothing to suggest such a term?

[pg 4]

I will tell you.

In the far-away days of quite another age, heraldry

was so closely connected with warlike exploits, and its

signs and tokens were so much used on the battle-field

to distinguish friends from foes, that each warrior wore

his own special badge, embroidered on the garment or

surcoat which covered his armour, as well as, later on,

upon the shield which he carried into battle.

And this reminds us of the poor Earl of Gloucester's

fate at the Battle of Bannockburn. For, having forgotten

to put on his surcoat, he was slain by the enemy,

though we are told that "the Scottes would gladly have

kept him for a ransom had they only recognized him

for the Earl, but he had forgot to put on his coat of

armour!"

On the other hand, we have good reason to remember

that the "flower of knighthood," Sir John Chandos,

lost his life because he did wear his white sarcenet robe

emblazoned with his arms. For it was because his feet

became entangled in its folds (as Froissart tells us) in

his encounter with the French on the Bridge of Lussac,

that he stumbled on the slippery ground on that early

winter's morning, and thus was quickly despatched by

the enemy's blows.

"Now, the principal end for which these signs were

first taken up and put in use," says Guillim, "was

that they might serve as notes and marks to distinguish

tribes, families and particular persons from the other.

Nor was this their only use. They also served to

[pg 5]

describe the nature, quality, and disposition of their

bearer."

Sir G. Mackenzie goes farther, and declares that

heraldry was invented, or, at any rate, kept up, for

two chief purposes:

First, in order to perpetuate the memory of great

actions and noble deeds. Secondly, that governors

might have the means of encouraging others to perform

high exploits by rewarding their deserving subjects by

a cheap kind of immortality. (To our ears that last

sentence sounds rather disrespectful to the honour of

heraldry.)

Thus, for example, King Robert the Bruce gave

armorial bearings to the House of Wintoun, which

represented a falling crown supported by a sword, to

show that its members had supported the crown in its

distress, while to one Veitch he gave a bullock's head,

"to remember posterity" that the bearer had succoured

the King with food in bringing some bullocks to the

camp, when he was in want of provisions.

Some derive their names as well as their armorial

bearings from some great feat that they may have

performed. Thus:

"The son of Struan Robertson for killing of a wolf

in Stocket Forest by a durk—dirk—in the King's

presence, got the name of Skein, which signifies a dirk

in Irish, and three durk points in pale for his arms."

We shall meet with numbers of other instances in

heraldry where armorial bearings were bestowed upon

[pg 6]

the ancestors of their present bearers for some special

reason, which is thereby commemorated.

Indeed, it is most interesting and amusing to collect

the legends as well as the historical facts which explain

the origin and meaning of different coats of arms.

Here are a few instances of some rather odd charges.

(A charge is the heraldic term given to any object

which is charged, or represented, on the shield of a coat

of arms.)

To begin with the Redman family:

They bear three pillows, the origin of which Guillim

explains—viz.: "This coat of arms is given to the

Redman family for this reason: Having been challenged

to single combat by a stranger, and the day and the

place for that combat having been duly fixed, Redman

being more forward than his challenger, came so early

to the place that he fell asleep in his tent, whilst waiting

for the arrival of his foe.

"The people being meanwhile assembled and the

hour having struck, the trumpets sounded to the combat,

whereupon Redman, suddenly awakening out of

his sleep, ran furiously upon his adversary and slew

him. And so the pillows were granted to him as

armorial bearings, to remind all men of the doughty

deed which he awakened from sleep to achieve."

In many cases the charges on a coat of arms reflect

the name or the calling of the bearer.

When this happens they are called "allusive" arms,

sometimes also "canting," which latter word is a literal

[pg 7]

translation of the French term, armes chantantes,

although, as a matter of fact, armes parlantes is a more

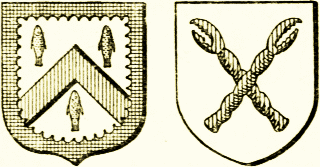

usual term. Here are some examples of allusive arms.

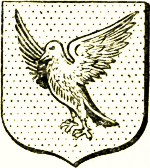

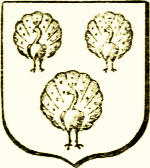

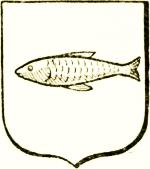

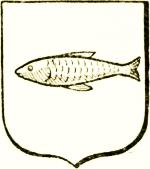

The Pyne family bear three pineapples, the Herrings

bear three herrings, one, Camel of Devon, bears a

camel passant; the Oxendens bear three oxen; Sir

Thomas Elmes bears five elm-leaves; three soles figure

on the coat of arms of the Sole family, and to the

description of the last armorial charge, old Guillim

quaintly adds:

"By the delicateness of his taste, the sole hath

gained the name of the partridge of the sea."

The arms of the Abbot of Ramsey furnish, perhaps,

one of the most glaring examples of canting heraldry, for

on his shield a ram is represented struggling in the sea!

On the shield of the Swallow family we find the mast

of a ship with all its rigging disappearing between the

capacious jaws of a whale, whilst the Bacons bear a boar.

But whoever designed the coat of arms of a certain

Squire Malherbe must have surely been in rather a

spiteful mood, and certainly had a turn for punning.

For on that gentleman's shield we find three leaves of

the stinging-nettle boldly charged!

In the armorial bearings of the Butler family we see

allusion made to their calling in the charge of three

covered cups, which commemorates the historical fact

that the ancestor of the present Marquis of Ormonde,

Theobald Walter by name, was made Chief Butler of

Ireland by Henry II. in 1171, an office which was held

[pg 8]

by seven successive generations of the Ormonde family.

The family of Call charge their shield very appropriately

with three silver trumpets.

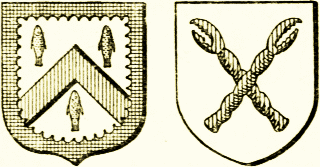

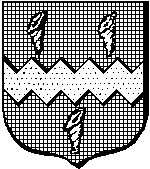

The Foresters bear bugle horns; the Trumpingtons,

three trumpets.

Three eel-spears were borne by the family of Strathele,

this being the old name given to a curious fork, set in

a long wooden handle, and used by fishermen to spear

the eels in mud.

The Graham Briggs charge a bridge upon their coat

of arms.

A tilting spear was granted as his armorial bearings

to William Shakespeare, which he bore as a single

charge; a single spear was also borne appropriately by

one Knight of Hybern.

As a last example of allusive arms, we may quote a

comparatively modern example—viz., the coat of arms

of the Cunard family.

Here we find three anchors charged upon the field,

in obvious allusion to Sir Samuel Cunard, the eminent

merchant of Philadelphia and the founder of the House

of Cunard.

CHAPTER II

THE SHIELD—ITS FORM, POINTS, AND TINCTURES

Nothing is more fascinating in the study of heraldry

than the cunning fashion in which it tells the history

either of a single individual or of a family, of an institution,

[pg 9]

or of a city—sometimes even of an empire—all

within the space of one small shield, by using the signs

which compose its language. It is astounding how much

information can be conveyed by the skilful arrangement

of these signs to those who can interpret them.

For armorial bearings were not originally adopted for

ornament, but to give real information, about those who

bore them.

PLATE 2.

THE DUKE OF LEINSTER.

Arms.—Arg: saltire gu:

Crest.—Monkey statant ppr. environed round the loins and chained or.

Supporters.—Two monkeys environed and chained or.

Motto.—Crom a boo.

Thus every detail of a coat of arms has its own

message to deliver, and must not be overlooked. Let

us begin with the shield, which is as necessary a part of

any heraldic achievement1

as the canvas of a painting is to the picture portrayed upon it.

It actually serves as the vehicle for depicting the

coat of arms.

The word "shield" comes from the Saxon verb scyldan,

to protect, but the heraldic term "escutcheon," derived

from the Greek skûtos, a skin, reminds us that in olden

days warriors covered their shields with the skins of

wild beasts.

Early Britons used round, light shields woven of

osier twigs, with hides thrown over them, whilst the

Scythians and Medes dyed their shields red, so that

their comrades in battle might not be discouraged by

seeing the blood of the wounded. The Roman Legionary

bore a wooden shield covered with leather and

strengthened with bars and bosses of metal, whilst the

[pg 10]

Greek shield was more elaborate, and reached from a

man's face to his knee. Homer describes Æneas'

shield in the "Iliad" thus:

"Five plates of various metal, various mould,

Composed the shield, of brass each outward fold,

Of tin each inward, and the middle gold."

But whether the shield were of basket-work or metal,

whether it were borne by a savage hordesman or by a

nobly equipped and mounted knight, it has always

ranked as its bearer's most precious accoutrement, the

loss of which was deemed an irreparable calamity and

a deep disgrace to the loser.

How pathetically King David laments over "the

shield of the mighty which was vilely cast away," when

Saul was slain! And everyone knows that when their sons

went forth to battle the Spartan mothers admonished

them to return either "with their shield or upon it"!

That they should return without a shield was unthinkable!

Thus, naturally enough, the shield was

chosen to bear those armorial devices which commemorated

the golden deeds of its owner.

It was probably in the reign of Henry II. that shields

were first used in this way; until then, warriors wore

their badges embroidered upon their mantles or robes.

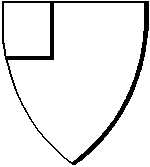

In studying the heraldic shield, its shape must

be considered first, because that marks the period in

history to which it belongs.2

[pg 11]

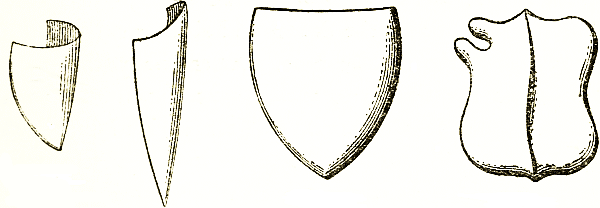

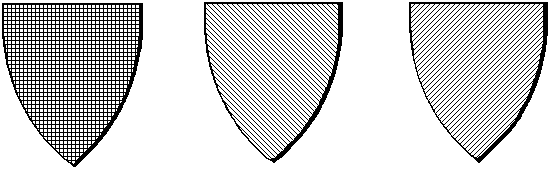

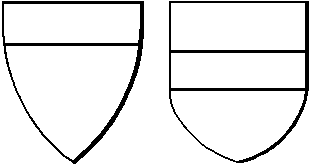

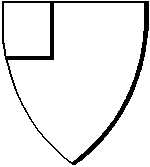

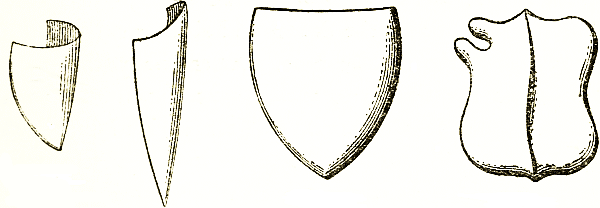

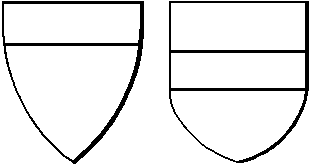

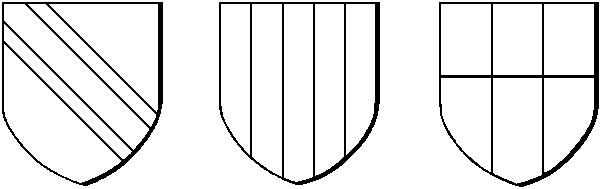

Thus a bowed shield (Fig. 1) denotes those early

times when a warrior's shield fitted closely to his person,

whilst a larger, longer form, the kite-shaped shield, was

in use in the time of Richard I. (Fig. 2). This disappeared,

however, in Henry III.'s reign, giving way to

a much shorter shield known as the "heater-shaped"

(see Fig. 3).

Another form of shield had a curved notch in the

right side, through which the lance was passed when

the shield was displayed on the breast (Fig. 4).

The shield of a coat of arms usually presents a plain

surface, but it is sometimes enriched with a bordure—literally

border. This surface is termed the "field,"

"because, as I believe," says Guillim, "it bore those

ensigns which the owner's valour had gained for him on

the field."

Fig. 1. Fig. 2. Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

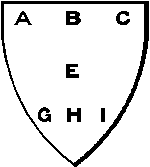

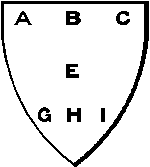

The several points of a shield have each their respective

names, and serve as landmarks for locating the

exact position of the different figures charged on the

field. (In describing a shield, you must always think

of it as being worn by yourself, so that in looking at a

[pg 12]

shield, right and left become reversed, and what appears

to you as the right side is really the left, and vice

versa.)

Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5, A, B, C, mark the chief—i.e., the

highest and most honourable point of the shield—A marking

the dexter chief or upper right-hand side of the shield,

B the middle chief, and C the sinister or left-hand side

of the chief. E denotes the fess point, or centre;

G, H, and I, mark the base of the shield—G and

I denoting respectively the dexter and sinister sides of the

shield, and H the middle base. After the points of a

field, come the tinctures, which give the colour to a

coat of arms, and are divided into two classes. The first includes the two

metals, gold and silver, and the five colours proper—viz., blue, red, black,

green, purple. In heraldic language these tinctures are described as "or,"

"argent" (always written arg:), "azure" (az:), "gules" (gu:),3

"sable" (sa:), "vert," and "purpure." According to Guillim, each

tincture was supposed to teach its own lesson—e.g.,

"as gold excelleth all other metals in value and purity,

so ought its bearer to surpass all others in prowess and

virtue," and so on.

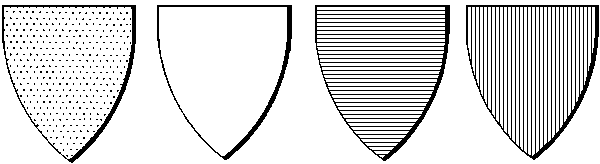

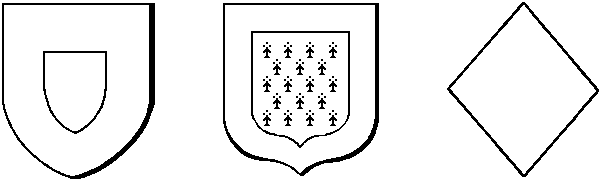

In the seventeenth century one Petrosancta introduced

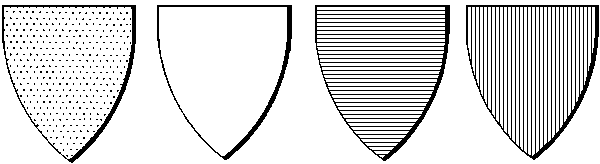

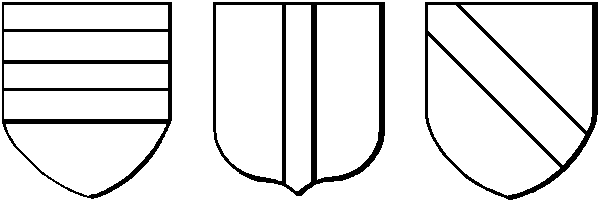

the system of delineating the tinctures of the

[pg 13]

shield by certain dots and lines, in the use of which we

have a good example of how heraldry can dispense

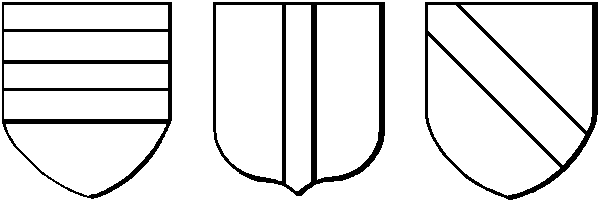

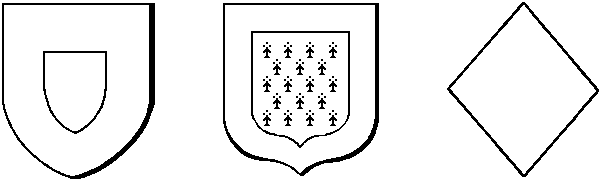

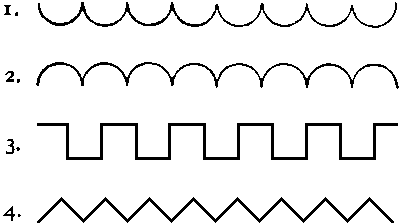

with words. Thus pin-prick dots represent or (Fig. 6);

a blank surface, argent (Fig. 7); horizontal lines, azure

(Fig. 8); perpendicular, gules (Fig. 9); horizontal and

perpendicular lines crossing each other, sable (Fig. 10);

diagonal lines running from the dexter chief to the

sinister base, vert (Fig. 11); diagonal lines running in

an opposite direction, purpure (Fig. 12).

Fig. 6.—Or.Fig. 7.—Arg.Fig. 8.—Az.

Fig. 9.—Gu.

Fig. 10.—Sa.Fig. 11.—V.Fig. 12.—Purpure.

Two other colours, orange and blood-colour, were

formerly in use, but they are practically obsolete now.

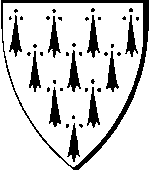

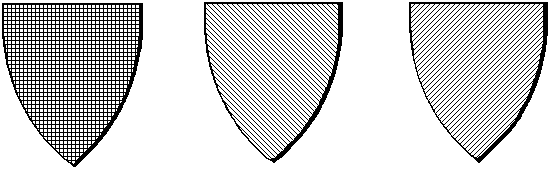

Furs constitute the second class of tinctures. Eight

kinds occur in English heraldry, but we can only

mention the two most important—viz., ermine and

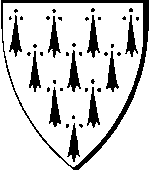

[pg 14]

vair. The former is represented by black spots on a

white ground (Fig. 13).4 As shields were anciently

covered with the skins of animals, it is quite natural

that furs should appear in armorial bearings. "Ermine,"

says Guillim, "is a little beast that hath his being in the

woods of Armenia, whereof he taketh his name."

Many legends account for the heraldic use of ermine,

notably that relating how, when Conan Meriadic landed

in Brittany, an ermine sought shelter from his pursuers

under Conan's shield. Thereupon the

Prince protected the small fugitive, and

adopted an ermine as his arms.

Fig. 13.—Ermine.

From early days the wearing of

ermine was a most honourable distinction,

enjoyed only by certain privileged

persons, and disallowed to them in

cases of misdemeanour. Thus, when,

in the thirteenth century, Pope Innocent III. absolved

Henry of Falkenburg for his share in the murder of

the Bishop of Wurtzburg, he imposed on him as a

penance never to appear in ermine, vair, or any other

colour used in tournaments. And, according to Joinville,

when St. Louis returned to France from Egypt,

"he renounced the wearing of furs as a mark of

humility, contenting himself with linings for his garments

made of doeskins or legs of hares."

[pg 15]

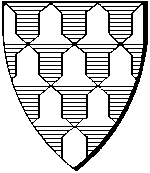

As to vair, Mackenzie tells us that it was the skin of

a beast whose back was blue-grey (it was actually

meant for the boar, for which verres was the Latin

name), and that the figure used in heraldry to indicate

vair represents the shape of the skin when the head

and feet have been taken away (Fig. 14). "These

skins," he says, "were used by ancient governors to

line their pompous robes, sewing one skin to the

other."

Fig. 14.—Vair.

Vair was first used as a distinctive badge by the

Lord de Courcies when fighting in

Hungary. Seeing that his soldiers were

flying from the field, he tore the lining

from his mantle and raised it aloft as

an ensign. Thereupon, the soldiers

rallied to the charge and overcame the

enemy.

Cinderella's glass slipper in the fairy-tale,

which came originally from France, should really

have been translated "fur," it being easy to understand

how the old French word vaire was supposed to

be a form of verre, and was rendered accordingly.

Much might still be said about "varied fields"—i.e.,

those which have either more than one colour or a

metal and a colour alternatively, or, again, which have

patterns or devices represented upon them. We can,

however, only mention that when the field shows small

squares alternately of a metal and colour, it is described

as checky, when it is strewn with small objects—such

[pg 16]

as fleurs-de-lys or billets—it is described as

"powdered" or "sown." A diapered field is also to

be met with, but this, being merely an artistic detail,

has no heraldic significance. Therefore, whereas in

blazoning armorial bearings one must always state if

the field is checky or powdered, the diaper is never

mentioned.

In concluding this chapter we must add that one of

the first rules to be learnt in heraldry is that in arranging

the tinctures of a coat of arms, metal can never be

placed upon metal, nor colour upon colour. The field

must therefore be gold or silver if it is to receive a

coloured charge, or vice versa. This rule was probably

made because, as we said above, the knights originally

bore their arms embroidered upon their mantles, these

garments being always either of cloth of gold or of

silver, embroidered with silk, or they were of silken

material, embroidered with gold or silver.

CHAPTER III

DIVISIONS OF THE SHIELD

Although in many shields the field presents an unbroken

surface, yet we often find it cut up into divisions

of several kinds. These divisions come under the head

of simple charges, and the old heralds explain their

origin—viz.: "After battles were ended, the shields of

soldiers were considered, and he was accounted most

[pg 17]

deserving whose shield was most or deepest cut. And

to recompense the dangers wherein they were shown to

have been by those cuts for the service of their King

and country, the heralds did represent them upon their

shields. The common cuts gave name to the common

partitions, of which the others are made by various conjunctions."

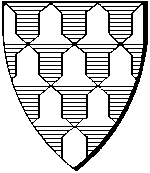

PLATE 3.

MARQUIS OF HERTFORD.

Arms.—Quarterly 1st and 4th Or on a pile gu: between 6 fleurs de lys az:

3 lions passant guardant in pale or.

2nd and 3rd gu: 2 wings conjoined in lure or. Seymour.

Crest.—Out of a ducal coronet or, a phœnix ppr.

Supporters.—Two blackamoors.

Motto.—Fide et amore.

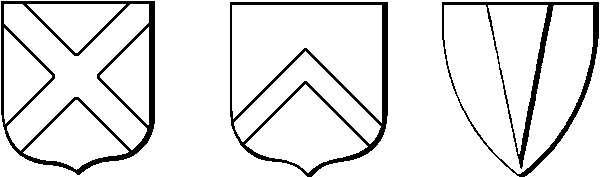

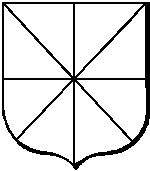

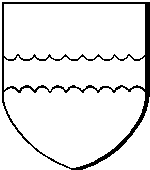

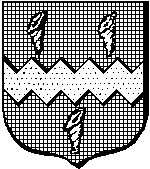

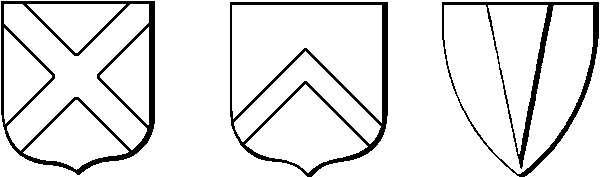

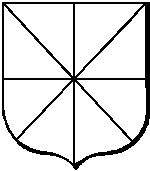

The heraldic term given to these partition-lines of the

field is ordinaries. There are nine of these, termed

respectively, chief, fesse, bar, pale, cross, bend, saltire,

chevron, and pile.

Fig. 15.Fig. 16.

The chief, occupying about the upper third of the

field, is marked off by a horizontal line (Fig.

15); the fesse, derived from the Latin fascia,

a band, is a broad band crossing the centre of

the field horizontally, and extends over a

third of its surface (Fig. 16). The bar is very like

the fesse, but differs from it, (a) in being much

narrower and only occupying a fifth portion of the

field, (b) in being liable to be placed in any part of

the field, whereas the fesse is an immovable charge,

(c) in being used mostly in pairs and not singly. Two

or three bars may be charged on the same field, and

when an even number either of metal or fur alternating

with a colour occur together, the field is then described

[pg 18]

as barry, the number of the bars being always stated,

so that if there are six bars, it is said to be "barry of

six," if eight, "barry of eight" (Fig. 17). The pale,

probably derived from palus, a stake, is also a broad

band like the fesse, but runs perpendicularly down the

shield, instead of horizontally across it (Fig. 18).

Fig. 17.Fig. 18.Fig. 19.

The cross, which is the ordinary St. George's Cross,

is pre-eminently the heraldic cross, out of nearly four

hundred varieties of the sacred sign. It is really a

simple combination of the fesse and pale. Bend is

again a broad band, but it runs diagonally across the

field from the dexter chief to the sinister base. It is

supposed to occupy a third portion of the field, but

rarely does so (Fig. 19). The saltire is the familiar

St. Andrew's Cross, owing its name probably to the

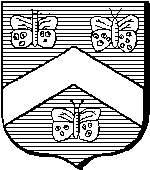

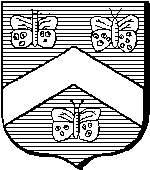

French salcier (see Fig. 20). The chevron, resembling

the letter V turned topsy-turvy, is a combination of a

bend dexter and a bend sinister, and is rather more than

the lower half of the saltire. The French word chevron,

still in use, means rafters (Fig. 21). The pile, derived

from the Latin for pillar, is a triangular wedge, and when

[pg 19]

charged singly on a field may issue from any point of

the latter, except from the base (Fig. 22). If more than

one pile occurs, we generally find the number is three,

although the Earl of Clare bears "two piles issuing

from the chief." Many old writers, notably amongst

the French, attribute a symbolical meaning to each

of these ordinaries. Thus, some believe the chief to

represent the helmet of the warrior, the fesse his belt

or band, the bar "one of the great peeces of tymber

which be used to debarre the enemy from entering any

city." The pale was thought by some to represent the

warrior's lance, by others the palings by which cities

and camps were guarded; the cross was borne by those

who fought for the faith; the bend was interpreted by

some to refer to the shoulder-scarf of the knight,

whilst others describe it as "a scaling-ladder set aslope."

Another variety of the scaling-ladder was represented

by the saltire. The chevron, or rafters, were held to

symbolize protection, such as a roof affords, whilst the

pile suggests a strong support of some sort.

Fig. 20.Fig. 21.Fig. 22.

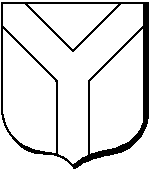

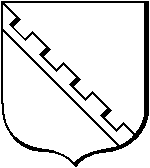

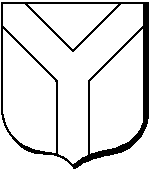

There is a tenth ordinary, which is known as the

[pg 20]

"shakefork" (Fig. 23). Practically unknown in

English heraldry, it is frequently met with in Scotch

arms. It is shaped like the letter Y

and pointed at its extremities, but

does not extend to the edge of the

field. Guillim attributes its origin to

"an instrument in use in the royal

stables, whereby hay was thrown up

to the horses" (surely this instrument

must have been next-of-kin to our

homely pitchfork?), and he believes the shakefork to

have been granted to a certain Earl of Glencairne, who

at one time was Master of the King's Horse.

Fig. 23.

Many historical stories are connected with the different

charges we have just been describing, but we have

only space to mention two, referring respectively to the

fesse and the saltire.

The former reminds us of the origin of the arms of

Austria, which date from the Siege of Acre, where our

Cœur-de-Lion won such glory. It was here that

Leopold, Duke of Austria, went into battle, clad in a

spotlessly white linen robe, bound at the waist with his

knight's belt. On returning from the field, the Duke's

tunic was "total gules"—blood-red—save where the

belt had protected the white of the garment. Thereupon,

his liege-lord, Duke Frederic of Swabia, father of

the famous Frederic Barbarossa, granted permission to

Leopold to bear as his arms a silver fesse upon a blood-red

field.

[pg 21]

The saltire, recalling the French form of scaling-ladder

of the Middle Ages, reminds us of how the

brave Joan of Arc placed the salcier with her own

hands against the fort of Tournelles. And we remember

how, when her shoulder was presently pierced

by an English arrow, she herself drew it out from the

ghastly wound, rebuking the women who wept round

her with the triumphant cry: "This is not blood, but

glory!"

Fig. 24.

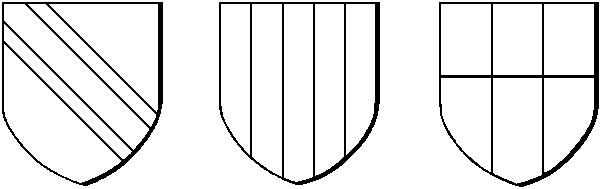

In addition to the ordinaries, there are fifteen sub-ordinaries.

These less important divisions of the shield

are known in heraldry as the canton, inescutcheon,

bordure, orle, tressure, flanches, lozenge,

mascle, rustre,

fusil, billet, gyron, frette, and roundle.

Owing to

limited space, we cannot go into detail with regard

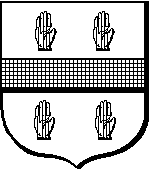

to these charges, but we may mention that the canton,

from the French word for a corner, is placed, with rare

exceptions, in the dexter side of the field, being supposed

to occupy one-third of the chief. It is often

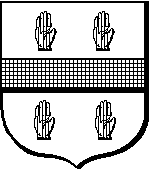

added as an "augmentation of honour"

to a coat of arms. The badge of a

baronet, the red hand, is generally

charged on a canton, sometimes also

on an inescutcheon, and it is then

placed on the field, so as not to interfere

with the family arms (Fig. 24).

The inescutcheon is a smaller shield

placed upon the field, and, when borne singly, it

occupies the centre (Fig. 25). Three, or even five,

[pg 22]

escutcheons may be borne together. The bordure

(Fig. 26) is a band surrounding the field, which may be

either void—that is, bearing no kind of device—or it

may have charges upon it, as in the arms of England,

where the bordure is charged with eight lions. The

orle and the tressure are only varieties of the bordure,

just as the mascle, rustre, and fusil, are variations of

the diamond-shaped figure known as the "lozenge"

(Fig. 27). The latter is always set erect on the field.

The arms of an unmarried woman and a widow are

always displayed on a lozenge. The mascle—a link of

chain armour—is a lozenge square

set diagonally, pierced in the centre

with a diamond-shaped opening, whilst

the rustre is a lozenge pierced with a

round hole. The fusil is a longer and

narrower form of diamond.

Fig. 25.Fig. 26.Fig. 27.

Fig. 28.

The billet is a small elongated rectangular

figure, representing a block

of wood, and is seldom used. The gyron (Fig. 28),

which is a triangular figure, does not occur in English

[pg 23]

heraldry as a single charge, but what is termed a

coat gyronny is not unusual in armorial bearings,

when the field may be divided into ten, twelve, or

even sixteen pieces. All arms borne by the Campbell

clan have a field gyronny. The origin of the word

is doubtful; some trace it to the Greek for curve,

others to a Spanish word for gore or gusset. The

introduction of a gyron into heraldry dates from

the reign of Alfonso VI. of Spain, who, being sore

beset by the Moors, was rescued by his faithful knight,

Don Roderico de Cissnères. The latter, as a memento of

the occasion, tore three triangular pieces from Alfonso's

mantle, being henceforward allowed to represent the

same on his shield in the shape of a gyron. The frette,

formerly known as a "trellis," from its resemblance to

lattice-work, is very frequent in British heraldry; it also

occurs as a net in connection with fish charges. In the

Grand Tournament held at Dunstable to celebrate

Edward III.'s return from Scotland,

one Sir John de Harrington bore "a

fretty arg., charged upon a sable field."

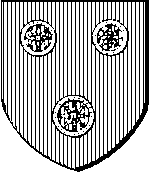

The roundlet is simply a ring of

metal or colour, and is much used in

coats of arms at all periods of heraldry.

The family of Wells bears a roundlet to

represent a fountain, whilst the Sykes

charge their shield with three roundlets, in allusion to

their name, "sykes" being an old term for a well.

Fig. 29.

In Fig. 29 we see an example of a shield charged with

an inescutcheon within a bordure.

[pg 24]

CHAPTER IV

THE BLAZONING OF ARMORIAL BEARINGS

In this chapter we shall deal with blazoning, in

which "the skill of heraldry" is said to lie.

The word "blazon" in its heraldic sense means the

art of describing armorial bearings in their proper terms

and sequence.

"To blazon," says Guillim, "signifies properly the

winding of a horn, but to blazon a coat of arms is to

describe or proclaim the things borne upon it in their

proper gestures and tinctures" (i.e., their colours and

attitudes) "which the herald was bound to do."1

The herald, as we know, performed many different

offices. It was his duty to carry messages between

hostile armies, to marshal processions, to challenge to

combat, to arrange the ceremonial at grand public

functions, to settle questions of precedence, to identify

the slain on the battle-field—this duty demanded an

extensive knowledge of heraldry2—to announce his

sovereign's commands, and, finally, to proclaim the

[pg 25]

armorial bearings and feats of arms of each knight as he

entered the lists at a tournament.

Probably because this last duty was preceded by a

flourish or blast of trumpets, people learnt to associate

the idea of blazoning with the proclamation of armorial

bearings, and thus the term crept into heraldic language

and signified the describing or depicting of all that

belonged to a coat of arms.

The few and comparatively simple rules with regard to

blazoning armorial bearings must be rigidly observed.

They are the following:

1. In depicting a coat of arms we must always begin

with the field.

2. Its tincture must be stated first, whether of metal

or colour. This is such an invariable rule that the

first word in the description of arms is always the

tincture, the word "field" being so well understood

that it is never mentioned. Thus, when the field of a

shield is azure, the blazon begins "Az.," the charges

being mentioned next, each one of these being named

before its colour. Thus, we should blazon Fig. 44

"Or, raven proper." When the field is semé with

small charges such as fleur-de-lys, it must be blazoned

accordingly "semé of fleur-de-lys," in the case of cross-crosslets,

the term "crusily" is used.

3. The ordinaries must be mentioned next, being

blazoned before their colour. Thus, if a field is divided

say, by bendlets (Fig. 30), the diminution of bend, it is

blazoned "per bendlets," if by a pale (Fig. 18), "per

[pg 26]

pale," or "per pallets," if the diminutive occurs, as in

Fig. 31, whilst the division in Fig. 32 should be

blazoned "pale per fesse." The field of Fig. 17 is

blazoned "arg., two bars gu." All the ordinaries and

subordinaries are blazoned in this way except the chief,

(Fig. 15), the quarter (blazoned "per cross or

quarterly") the canton, the flanch, and the bordure.

These, being considered less important than the other

divisions, are never mentioned until all the rest of the

shield has been described. Consequently, we should

blazon Fig. 48 thus, "Arg., chevron gu., three soles

hauriant—drinking, proper, with a bordure invected sa."

Fig. 30.Fig. 31.Fig. 32.

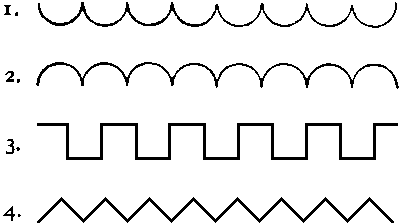

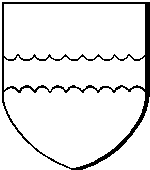

The term invected reminds us that so far we have

only spoken of ordinaries which have straight unbroken

outlines. But there are at least thirteen different ways

in which the edge of an ordinary may vary from the

straight line. Here, however, we can only mention the

four best-known varieties, termed, respectively, engrailed,

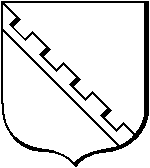

(Fig. 33, 1), invected (2), embattled (3), and indented

(4).

Other varieties are known as wavy, raguly, dancetté,

dovetailed,

nebuly, etc. Whenever any of these varieties occur,

[pg 27]

they must be blazoned before the tincture. Thus in

describing the Shelley arms, Fig. 50, we should say:

"Sa, fesse indented, whelks or." Fig. 34 shows a

bend embattled, Fig. 35 a fesse engrailed.

Fig. 33.

Fig. 34.

Fig. 35.

4. The next thing to be blazoned

is the principal charge on the field.

If this does not happen to be one

of the chief ordinaries, or if no

ordinary occurs in the coat of arms,

as in Fig. 38, then that charge should

be named which occupies the fesse

point, and in this case the position

of the charge is never mentioned, because it is understood

that it occupies the middle of the field. When

there are two or more charges on the same field, but

none actually placed on the fesse point, then that

charge is blazoned first which is nearest the centre and

then those which are more remote. All repetition of

words must be avoided in depicting a coat of arms,

the same word never being used twice over, either in

describing the tincture or in stating a number.

[pg 28]

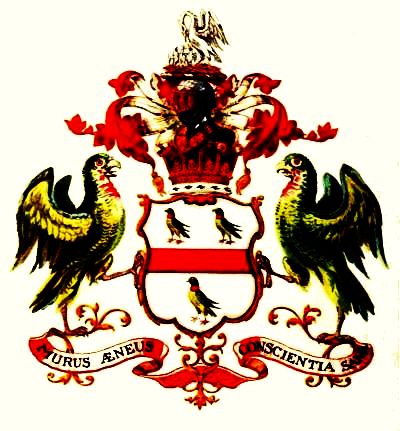

Thus, in blazoning Lord Scarborough's arms (see

coloured plate), we must say: "Arg., fesse gu., between

three parrots vert, collared of the second," the second

signifying the second colour mentioned in the blazon—viz.,

gules. Again, if three charges of one kind occur

in the same field with three charges of another kind,

as in the arms of Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury,

who had three roundles and three mitres, to avoid

repeating the word three, they are blazoned, "Three

roundles with as many mitres."

When any charge is placed on an ordinary, as in

Fig. 41, where three calves are charged upon the bend,

if these charges are of the same colour as the field

instead of repeating the name of the colour, it must be

blazoned as being "of the field."

We now come to those charges known as "marks of

cadency." They are also called "differences" or

"distinctions."

Fig. 36.

Cadency—literally, "falling down"—means in

heraldic language, "descending a scale," and is therefore

a very suitable term for describing the descending

degrees of a family. Thus "marks of cadency" are

certain figures or devices which are employed in

armorial bearings in order to mark the distinctions

between the different members and branches of one and

the same family. These marks are always smaller than

other charges, and the herald is careful to place them

where they do not interfere with the rest of the coat of

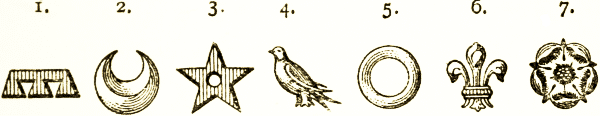

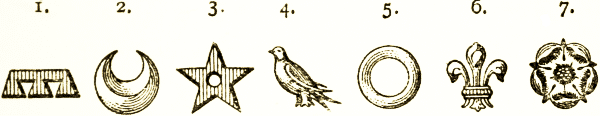

arms. There are nine marks of cadency—generally

[pg 29]

only seven are quoted—so that in a family of nine sons,

each son has his own special difference. The eldest son

bears a label (Fig. 36, 1); the second, a crescent, (2);

third, a mullet (3)—the heraldic term for the rowel

of a spur3; the fourth, a martlet (4)—the heraldic

swallow; the fifth, a roundle or ring (5); the sixth,

a fleur-de-lys (6); the seventh, a rose (7); the

eighth, a cross moline; and the ninth, a double quatrefoil.

The single quatrefoil represents the heraldic primrose.

There is much doubt as to why the label was

chosen for the eldest son's badge, but though many

writers interpret the symbolism of the other marks of

cadency in various ways, most are agreed as to the

meaning of the crescent, mullet, and martlet—viz., the

crescent represents the double blessing which gives

hope of future increase; the mullet implies that the

third son must earn a position for himself by his own

knightly deeds; whilst the martlet suggests that the

younger son of a family must be content with a very small

portion of land to rest upon. As regards the representation

[pg 30]

of the other charges, the writer once saw the

following explanation in an old manuscript manual of

French heraldry—namely: "The fifth son bears a ring,

as he can only hope to enrich himself through marriage;

the sixth, a fleur-de-lys, to represent the quiet, retired

life of the student; the seventh, a rose, because he

must learn to thrive and blossom amidst the thorns of

hardships; the eighth, a cross, as a hint that he should

take holy orders; whilst to the ninth son is assigned the

double primrose, because he must needs dwell in the

humble paths of life."

Fig. 37.

The eldest son of a second son would charge his

difference as eldest son, a label, upon his father's

crescent (Fig. 37), to show that he was descended

from the second son, all his brothers

charging their own respective differences on

their father's crescent also. Thus, each eldest

son of all these sons in turn becomes head of his own

particular branch.

When a coat of arms is charged with a mark of

cadency, it is always mentioned last in blazoning, and is

followed by the words, "for a difference." Thus

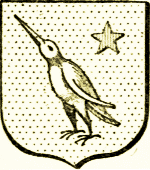

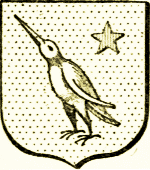

Fig. 43 should be blazoned, "Or, kingfisher with his

beak erected bendways4 proper with a mullet for a

difference gu.," thus showing that the arms are borne

by a third son.

[pg 31]

CHAPTER V

COMMON OR MISCELLANEOUS CHARGES

After the "proper charges" which we have just been

considering, we come to those termed "common or

miscellaneous."

(How truly miscellaneous these are we have already

shown in our first chapter.) Guillim arranges these

charges in the following order:

Celestial Bodies.—Angels, sun, moon, stars, etc.

Metals and Minerals.—Under this latter title rank

precious stones and useful stones—such as jewels and

millstones, grindstones, etc., also rocks.

Plants and other Vegetatives.

Living Creatures.—These latter he divides into two

classes—viz., "Those which are unreasonable, as all

manner of beasts" and "Man, which is reasonable."

To begin with the heavenly bodies.

Angels, as also human beings, are very rare charges,

though Guillim quotes the arms of one Maellock Kwrm,

of Wales, where three robed kneeling angels are

charged upon a chevron, and also the coat of arms of

Sir John Adye in the seventeenth century, where three

cherubim heads occur on the field. Both angels and

men, however, are often used in heraldry as supporters.

Charles VI. added two angels as supporters to the

arms of France, and two winged angels occur as such

in the arms of the Earl of Oxford.

[pg 32]

Supporters, you must understand, are those figures

which are represented standing on either side of a

shield of arms, as if they were supporting it. No one

may bear these figures except by special grant, the

grant being restricted to Peers, Knights of the Garter,

Thistle, and St. Patrick, Knights Grand Cross, and

Knights Grand Commanders of other orders.

Charges of the sun, moon, and other heavenly bodies

are comparatively rare. One St. Cleere rather aptly

bears the "sun in splendour," which is represented as a

human face, surrounded by rays. Sir W. Thompson's

shield is charged with the sun and three stars. The

sun eclipsed occurs occasionally in armorial bearings; it

is then represented thus: Or, the sun sable.

The moon occurs very often in early coats of arms,

either full, when she is blazoned "the moon in her

complement," or in crescent. The Defous bear a very

comical crescent, representing a human profile. Of

these arms, the old herald says severely: "A weak eye

and a weaker judgment have found the face of a man in

the moon, wherein we have gotten that fashion of representing

the moon with a face."

The moon is certainly not in favour with Guillim,

for, after declaring that she was the symbol of inconstancy,

he quotes the following fable from Pliny to her

discredit:

"Once on a time the moon sent for a tailor to make

her a gown, but he could never fit her; it was always

either too big or too little, not through any fault of his

[pg 33]

own, but because her inconstancy made it impossible to

fit the humours of one so fickle and unstable."

The sixth Bishop of Ely had very curious arms, for

he bore both sun and moon on his shield, the sun "in

his splendour" and the moon "in her complement."

Stars occur repeatedly as heraldic charges. John

Huitson of Cleasby bore a sixteen-pointed star; Sir

Francis Drake charged his shield with the two polar

stars; whilst Richard I. bore a star issuing from the horns

of a crescent. The Cartwrights bear a comet; whilst

the rainbow is charged on the Ponts' shield, and is also

borne as a crest by the Pontifex, Wigan, and Thurston

families. The Carnegies use a thunderbolt as their crest.

We now come to the elements—fire, water, earth,

and air, which all occur as charges, but not often, in

armorial bearings.

Fire, in the form of flames, is perhaps the most

frequent charge. The Baikie family bear flames, whilst

we have seen the picture of a church window in

Gloucestershire, where a coat of arms is represented

with a chevron between three flames of fire. The

original bearer of these arms distinguished himself, we

were told, by restoring the church after it had been

burnt down. Fire often occurs in combination with

other charges, such as a phœnix, which always rises out

of flames, the salamander,1 and the fiery sword.

[pg 34]

Queen Elizabeth chose a phœnix amidst flames as

one of her heraldic charges. Macleod, Lord of the

Isles of Skye and Lewis, bears "a mountain inflamed"—literally,

a volcano—on his shield, thus combining the

two elements, earth and fire.

"Etna is like this," says Guillim; "or else this is

like Etna."

Water, as we know, is usually represented by roundlets,

but the earth may figure in a variety of ways when

introduced into heraldry.

In the arms of one King of Spain it took the shape

of fifteen islets, whilst one Sir Edward Tydesley charged

his field with three mole-hills.

Jewels pure and simple occur very rarely as charges.

A single "escarbuncle" was borne by the Empress

Maud, daughter of Henry I., as also by the Blounts of

Gloucester. Oddly enough, however, mill-stones were

held to be very honourable charges, because, as they

must always be used in pairs, they symbolized the

mutual dependence of one fellow-creature on the

other. They were therefore considered the most

precious of all other stones.

The family of Milverton bear three mill-stones.

Plants, having been created before animals, are considered

next.

Trees, either whole or represented by stocks or

branches, are very favourite charges, and often reflect

the bearer's name.

Thus, one Wood bears a single oak, the Pines, a pineapple

[pg 35]

tree, the Pyrtons, a pear-tree. Parts of a tree are

often introduced into arms. For example, the Blackstocks

bear three stocks, or trunks, of trees, whilst

another family of the same name charge their shield

with "three starved branches, sa." The Archer-Houblons

most appropriately bear three hop-poles erect

with hop-vines. (Houblon is the French for hop.)

Three broom slips are assigned to the Broom family;

the Berrys bear one barberry branch; Sir W. Waller,

three walnut leaves. Amongst fruit charges, we may

mention the three golden pears borne by the Stukeleys,

the three red cherries which occur in the arms of the

Southbys of Abingdon, and the three clusters of grapes

which were bestowed on Sir Edward de Marolez by

Edward I. One John Palmer bears three acorns, and

three ashen-keys occur in the arms of Robert Ashford

of Co. Down.

A full-grown oak-tree, covered with acorns and

growing out of the ground, was given for armorial

bearings by Charles II. to his faithful attendant, Colonel

Carlos, as a reminder of the perils that they shared together

at the lonely farmhouse at Boscobel, where the

king took refuge after the Battle of Worcester. Here, as

you probably all know, Charles hid himself for twenty-four

hours in a leafy oak-tree, whilst Cromwell's soldiers

searched the premises to find him, even passing under

the very branches of the oak. Carlos, meanwhile,

in the garb of a wood-cutter, kept breathless watch

close by. On the Carlos coat of arms a fesse gu.,

[pg 36]

charged with three imperial golden crowns, traverses

the oak.

In blazoning trees and all that pertains to them, the

following terms are used: Growing trees are blazoned

as "issuant from a mount vert"; a full-grown tree, as

"accrued"; when in leaf, as "in foliage"; when bearing

fruit, as "fructed," or seeds, as "seeded." If

leafless, trees are blazoned "blasted"; when the roots

are represented, as "eradicated"; stocks or stumps of trees

are "couped." If branches or leaves are represented

singly, they are "slipped." Holly branches, for some

odd reason, are invariably blazoned either as "sheaves"

or as "holly branches of three leaves."

Some of our homely vegetables are found in heraldry.

One Squire Hardbean bears most properly three bean-cods

or pods; a "turnip leaved" is borne by the

Damant family, and is supposed to symbolize "a good

wholesome, and solid disposition," whilst the Lingens

use seven leeks, root upwards, issuing from a ducal

coronet, for a crest. Herbs also occur as charges. The

family of Balme bears a sprig of balm, whilst rue still

figures in the Ducal arms of Saxony. This commemorates

the bestowal of the Dukedom on Bernard of

Ascania by the Emperor Barbarossa, who, on that

occasion, took the chaplet of rue from his own head

and flung it across Bernard's shield.

Amongst flower charges, our national badge, the rose,

is prime favourite, and occurs very often in heraldry.

The Beverleys bear a single rose, so does Lord Falmouth.

[pg 37]

The Nightingale family also use the rose as a

single charge, in poetical allusion to the Oriental legend

of the nightingale's overpowering love for the "darling

rose." The Roses of Lynne bear three roses, as also

the families of Flower, Cary, and Maurice. Sometimes

the rose of England is drawn from nature, but it

far oftener takes the form of the heraldic or Tudor

rose. Funnily enough, however, when a stem and

leaves are added to the conventional flower, these are

drawn naturally.

There are special terms for blazoning roses. Thus,

when, as in No. 7 of Fig. 36, it is represented with

five small projecting sepals of the calyx, and seeded, it

must be blazoned "a rose barbed and seeded"; when

it has a stalk and one leaf it is "slipped," but with a

leaf on either side of the stalk, it is "stalked and

leaved." A rose surrounded with rays is blazoned "a

rose in sun" (rose en soleil). Heraldic roses are by no

means always red, for the Rocheforts bear azure roses,

the Smallshaws a single rose vert, whilst the Berendons

have three roses sable.

The thistle, being also our national badge, has a

special importance in our eyes, but next to the "chiefest

among flowers, the rose, the heralds ranked the fleur-de-lys,"

because it was the charge of a regal escutcheon,

originally borne by the French kings. Numerous

legends explain the introduction of the lily into armorial

bearings, but we can only add here that although the

fleur-de-lys is generally used in heraldry, the natural

[pg 38]

flower is occasionally represented—as in the well-known

arms of Eton College; three natural lilies, silver, are

charged upon a sable field, one conventional fleur-de-lys

being also represented. Amongst other flower charges,

three very pretty coats of arms are borne respectively

by the families of Jorney, Hall, and Chorley. The first

have three gilliflowers, the second, three columbines,

and the last, three bluebottles (cornflowers).

Three pansies were given by Louis XV. to his

physician, Dr. Quesnay, as a charge in a coat of arms,

which he drew with his own royal hand; and to come

to modern times, Mexico has adopted the cactus as the

arms of the Republic, in allusion to the legend connected

with the founding of the city in 1325, when it is said

that the sight of a royal eagle perched upon a huge cactus

on a rocky crevice, with a serpent in its talons, guided

the Mexicans to the choice of a site for the foundations

of their city.

One last word as to cereals.

The Bigland family bear two huge wheat-ears, which,

having both stalk and leaves, are blazoned "couped and

bladed." As in the case of trees, when represented

growing, wheat-ears are described as "issuant out of a

mount, bladed and eared." Three ears of Guinea

wheat, "bearded like barley," are borne by Dr. Grandorge

(Dr. Big-barley); three "rie stalks slipped and

bladed" occur in the arms of the Rye family; whilst

"five garbes" (sheaves) were granted to Ralph Merrifield

by James I.

[pg 39]

Wheat-sheaves (garbes) are very favourite charges.

Lord Cloncurry bears three garbes in chief; Sir Montague

Cholmeley bears a garbe in the base of his shield,

as does also the Marquis of Cholmondeley.

Garbes and wheat-ears were also much used as crests.

The Shakerleys have a sheaf of corn for their crest,

on the left of which is a little rabbit, erect, and resting

her forefeet on the garbe; Sir Edward Denny's crest is

a hand holding five wheat-ears; whilst Sir George

Crofton has seven ears of corn as his crest.

Though quite out of order amongst cereals, we may

mention what is, I believe, a rather rare example of the

representation of the fern in heraldry, Sir Edward

Buckley's crest—a bull's head out of a fern brake.

CHAPTER VI

ANIMAL CHARGES

In dealing with charges of living creatures, we shall

observe the following order: (a) "Animals of all sort

living on the earth"; (b) "such as live above the earth";

(c) "watery creatures"; (d) "man."

First, amongst the animals, come those with undivided

feet—elephant, horse, ass. Second, those with

cloven feet—bull, goat, stag, etc. Third, those beasts

that have many claws—lions, tigers, bears, etc.

To blazon animal charges, many special terms are

required, describing their person, limbs, actions, attitudes,

etc.

[pg 40]

"And as," says Guillim, "these beasts are to explain

a history, they must be represented in that position

which will best show it."

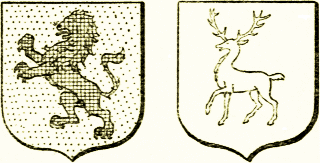

Fig. 38.Fig. 39.

Moreover, each beast was to be portrayed in its

most characteristic attitude. Thus, a lion should be

drawn erect with wide-open jaws and claws extended, as

if "about to rend or tear." In this posture he is

blazoned rampant (Fig. 38). A leopard must be represented

going "step by step" fitting his

natural disposition; he is then passant. A

deer or lamb "being both gentle creatures,"

are said to be trippant (Fig. 39), and so on;

the heraldic term varying, you understand, to suit

the particular animal charge that is being blazoned.

Living charges when represented on a shield must

always, with rare exceptions, appear to be either looking

or moving towards the dexter side of the shield

(see Fig. 39). The right foot or claw is usually

placed foremost as being the most honourable limb

(see Fig. 38).

The elephant, having solid feet, is mentioned first,

although the lion is really the only animal—if we

except the boar's head—which occurs in the earliest

armorial bearings. The Elphinstones charge their

shield with an elephant passant, whilst the Prattes bear

three elephants' heads erased. This term implies that

they have been torn off and have ragged edges.

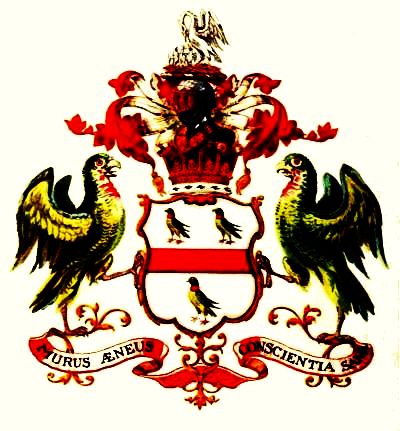

PLATE 4.

THE EARL OF SCARBOROUGH.

Arms.—Arg: a fesse gu: between 3 parrots vert collared of the second.

Crest.—A pelican in her piety.

Supporters.—Two parrots, wings inverted vert.

Motto.—Murus aēnēus conscientia sana.

[pg 41]

After describing this charge, Guillim rather comically

gives us this story:

"An elephant of huge greatness was once carried in

a show at Rome, and as it passed by a little boy pried

into its proboscis. Thereupon, very much enraged, the

beast cast the child up to a great height, but received

him again on his snout and laid him gently down, as

though he did consider that for a childish fault a

childish fright was revenge enough."

Fig. 40.

Horses, of course, figure largely in armorial bearings.

One, William Colt, bears three horses "at full speed"

(Fig. 40). So also does Sir Francis

Rush—probably in allusion to his

name—whilst horses' heads couped—that

is, cut off smoothly—occur very

frequently. A demi-horse was granted

as a crest to the Lane family in recognition

of Mistress Jane Lane's heroism

in riding from Staffordshire to the

South Coast on a roan horse, with King Charles II.

behind her, after the disastrous Battle of Worcester.

Donkeys were evidently at a discount with heralds.

The families of Askewe and Ayscough bear three asses

passant charged on their shield, and there is an ass's

head in the arms of the Hokenhalls of Cheshire.

Oxen occur fairly often in heraldry. The Oxendens

bear three oxen; three bulls occur in the arms of Anne

[pg 42]

Boleyn's father, the Lord of Hoo, whilst the same arms

were given by Queen Elizabeth to her clockmaker,

Randal Bull of London. The Veitchs bear three cows'

heads erased, a rather uncommon charge, as female

beasts were generally deemed unworthy of the herald's

notice. The Veales bear three calves passant (Fig. 41),

anent which Guillim adds: "Should

these calves live to have horns, which

differ either in metal or colour from

the rest of their body, there must be

special mention made of such difference

in blazoning them." Hereby,

he reminds us of the important rule

for blazoning animals with horns and

hoofs. Goats and goats' heads are often used in

heraldry. A single goat passant is borne by one,

Baker; three goats salient—leaping—occur in the

Thorold arms, whilst the Gotley family—originally

Goatley—charge a magnificent goat's head on their

shield.

Fig. 41.

Bulls, goats, and rams, when their horns differ in

tincture from the rest of their body, are blazoned

"armed of their horns," these latter in their case being

regarded as weapons. When, however, special mention

is made of a stag's antlers, he is said to be "attired of

his antlers," his horns being regarded as ornaments.

(The branches of his antlers are termed tynes.)

Stags, as you would expect, are highly esteemed by

the old heralds, who employed various terms in blazoning

[pg 43]

them. Thus, a stag in repose was "lodged," looking

out of the field, "at gaze"; in rapid motion, he was

"at speed" or "courant"; whilst, when his head was

represented full face and showing only the face, it was

blazoned as "cabossed" from the Spanish word for

head. (Many of these terms we shall find in blazoning

other animal charges.) Early heralds make careful distinction

between a hind or calf, brockets, stags and

harts. (A hind, you know, is the female, calf is the

infant deer, brocket the two-year-old deer, stag the five-year-old,

and hart the six-year-old deer.)

The Harthills very properly bear a "hart lodged on a

hill;" a single stag, his back pierced by an arrow, occurs

in the Bowen arms, and the Hynds bear three hinds.

Three bucks "in full course" are borne by the Swifts.

Deer's heads are very common charges, generally occurring

in threes. In the coat of arms of the Duke of

Wurtemberg and Teck, we find three antlers charged

horizontally across the shield.

A reindeer is drawn in heraldry with double antlers,

one pair erect and one drooping.

The boar was deemed a specially suitable badge for a

soldier, who should rather die valorously upon the

field than secure himself by ignominious flight. Both

the Tregarthens and Kellets bear a single boar, whilst a

boar's head, either singly or in threes, occurs very constantly

in coats of arms. A boar is blazoned "armed

of his tusk" or "armed and langued," when his tongue

is shown of a different tincture. Moreover, as Mr. Fox-Davies

[pg 44]

reminds us in his interesting "Guide to

Heraldry," an English boar's head is described as

"couped" or erased "at the neck," but the Scotch

herald would blazon the same charge as "couped and

erased" "close."

The Earl of Vere takes a boar for his crest, in allusion

to his name, verre being the Latin for boar.

The Grice family bear a wild boar, formerly called a

"grice."

The Winram family bear a single ram, the Ramsays

of Hitcham bear three rams on their shield.

A very pretty coat of arms belongs to the Rowes of

Lamerton in Devon, "gu: three holy lambs with staff,

cross and banner arg:."

Foremost amongst the beasts that have "many

claws" is the lion; next to him come the tiger,

leopard, bear, wolf, ranking more or less as the aristocrats

amongst their kind, whilst the cat, fox, hare, etc.,

are placed far beneath them. Of all the animal charges,

none is more popular amongst the heralds of all times

and lands than the lion. Extraordinary care was taken

to blazon the king of beasts befittingly. Fig. 38 has

already shown you a "lion rampant," and so indispensable

was this attitude considered by the early heralds to

the proper representation of a lion, that if they were

obliged to depict a "lion passant"—that is, "one that

looked about him as he walked"—he was then blazoned

as a leopard.

That is why the beasts in our national arms, although

[pg 45]

they are really lions and meant for such, are not called

so, because their undignified attitude reduces them to

the rank of heraldic leopards! A lion rampant—and

other beasts of prey as well—is generally represented

with tongue and claws of a different tincture from the

rest of his person; he is then blazoned "langued and

unguled," the latter term being derived from the Latin

for a claw. A lion in repose is blazoned "couchant"

when lying down with head erect and forepaws extended;

he is "sejant"—sitting; seated with forepaws erect,

he is "sejant rampant"; standing on all fours, he is

"statant"—standing; standing in act to spring, he is

"salient"—leaping; when his tail is forked and raised

above his back, he is said to have a "queue fourchée"—literally

a forked tail. (This last attitude is not

often seen.) But when he is represented running across

the field and looking back, then the heralds label the king

of beasts "coward!"

A single lion is a very frequent charge, but two lions

are rarer. The Hanmers of Flintshire, descended from

Sir John Hanmer in the reign of Edward I., have two

lions, and we find two lions "rampant combatant"—that

is, clawing each other—"langued armed" in the

Wycombe coat of arms; whilst one, Garrad of London,

bears two lions "counter-rampant"—i.e., back to back,

and very droll they look. Demi-lions rampant also

occur in armorial bearings.

The different parts of a lion are much used; the

head, either erased or couped, the face cabossed, the

[pg 46]

paws, borne either singly or in twos and threes, and

lastly, we find the tail represented in various postures.

The Corkes bear three lions' tails.

The tiger follows the lion and has terms of blazon

peculiar to himself. Thus, the single tiger borne by Sir

Robert Love is depicted as "tusked, maned and

flasked." In the arms of the De Bardis family, a

tigress is represented gazing into a mirror, which lies

beside her on the ground. This odd charge alludes to

the fable that a tigress, robbed of her whelps, may be

appeased by seeing her own reflection in a glass. A

tiger's head is used but seldom as a separate charge.

Apparently the bear stood higher in favour with the

old heralds. The family of Fitzurse charge their shield

with a single bear passant, the Barnards have a bear

"rampant and muzzled," whilst the Beresfords' bear is

both "muzzled and collared." The Berwycks bear a

bear's head, "erased and muzzled," and three bears'

heads appear in the arms of the Langham, Brock, and

Pennarth families.

A wolf is borne by Sir Edward Lowe of Wilts, Sir

Daniel Dun, and by the Woods of Islington. A wolf's

head appears very early in armorial bearings; Hugh,

surnamed Lupus, Earl of Chester and nephew of

William I., used a wolf's head as his badge.

[pg 47]

CHAPTER VII

ANIMAL CHARGES (continued)

After "ravenous fierce beastes," we come to dogs,

foxes, cats, squirrels, etc. Sporting dogs are very

favourite charges, and are frequently termed talbots

in heraldry.1

(A mastiff with short ears was termed an alant.)

The Carricks and Burgoynes bear one talbot on their

shield, whilst the Talbot family have three talbots

passant.

The Earl of Perth has a "sleuthhound, collared and

leashed" for his crest; that of the Biscoe family is a

greyhound seizing a hare. A dog chasing another

animal must be blazoned either "in full course" or

"in full chase." A foxhound nosing the ground is

described as "a hound on scent."

The fox rarely figures in heraldry. One Kadrod-Hard

of Wales bore two "reynards counter salient,"

and "the Wylies do bear that wylie beast, the fox";

whilst three foxes' heads erased are borne respectively by

the Foxes of Middlesex and one Stephen Fox, of Wilts.

A fox's face is blazoned a "mask."

Cats occur fairly often in heraldry. "Roger Adams

and John Hills, both of the City of London," we are

[pg 48]

told, "bear cats"; Sir Jonathan Keats charges three

"cats-a-mountain"—wild cats—upon his shield, as also

do the Schives of Scotland; the Dawson-Damer's crest

is a tabby cat with a rat in her mouth. She would be

blazoned as preying.

The dog, fox, and cat have each their typical meaning

in heraldry. The dog symbolizes courage, fidelity,

affection, and sagacity; the fox, great wit and cunning;

the cat, boldness, daring, and extraordinary foresight,

so that whatever happens she always falls on her feet.

She was formerly the emblem of liberty, and was borne

on the banners of the ancient Alans and Burgundians

to show that they brooked no servitude.

The squirrel is rather a favourite charge, notably in

the arms of landed gentry—such as the Holts, Woods,

Warrens—because the little nut-cracker is typical of

parks and woodland property. It occurs either singly

or in pairs or trios. It is always represented sejant, and

usually cracking nuts, as seen in the arms of the

Nuthall family.

A hedgehog usually figures in the arms of the Harris,

Harrison, Herries, and Herrison families, and is undoubtedly

borne in allusion to their surname, hérisson

being the French for hedgehog. Lord Malmesbury—family

name Harris—bears a hedgehog in his coat of

arms. It is generally blazoned as an "urcheon" in

heraldry. The hare occurs but rarely in English arms;

the Clelands bear one as a single charge, and the

Trussleys charge their shield with three little hares

playing bagpipes, probably in allusion to the hare's

traditional love of music. The rabbit—known to heralds

as a coney—is oftener met with in armorial bearings;

the Strodes of Devon bear three conies couchant; the

Conesbies, three conies sejant; the Cunliffes, three

conies courant.

PLATE 5.

BARON HAWKE.

Arms.—A chevron erminois between three pilgrim's staves purpure.

Crest.—A hawk, wings displayed and inverted ppr.

belled and charged on the breast with a fleur de lys or.

Supporters.—Dexter, Neptune, Sinister, a Sea-horse.

Motto.—Strike.

[pg 49]

Three moles are borne by Sir John Twistledon, of

Dartford, Kent—a mole was sometimes blazoned "moldiwarp"—whilst

the Rattons very aptly bear a rat.

We cannot say much of the toads,2 tortoises, serpents,

grasshoppers, spiders, and snails which occur in heraldry.

The Gandys of Suffolk bear a single tortoise passant,

and a tortoise erected occurs on the Coopers' coat of arms.

Serpents are blazoned in terms peculiar to themselves.

Thus, a serpent coiled, is said to be nowed—knotted—from

the French nœud, a knot; when upright

on its tail, it is erect; gliding, it is glissant also

from the French; when biting its tail, it is blazoned

embowed. The Falconers bear a "serpent embowed";

one Natterley has an "adder nowed"—natter is

the German for adder—and Sir Thomas Couch of

London charges an adder "curling and erect" upon

his shield.

To the Greek, the grasshopper signified nobility;

hence amongst the Athenians a golden grasshopper

worn in the hair was the badge of high lineage. In later

[pg 50]

days the heralds considered the grasshopper a type of

patriotism, "because in whatever soil a grasshopper is

bred, in that will he live and die."

Spiders were not only held symbolical of industry,

but they were highly esteemed for their supposed

properties of healing.3

One family of Shelleys bears three "house-snails"

so termed in heraldry to imply that they carry their

shells. A type of deliberation in business matters

and perseverance is supposed to be furnished by the

common snail.

The "creatures that live above the earth"—i.e.,

having wings—come next.

Fig. 42.

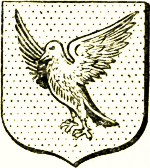

Various heraldic terms are in use for blazoning bird

charges—viz.:

A bird flying is "volant" (Fig. 42); preparing to fly,

is "rising" (Fig. 44); when its wings are spread open,

they are "displayed"; when folded,

they are "close (see Fig. 43)." Birds of

prey and barn-door cocks are "armed."

Thus, the eagle is blazoned as "armed

of his beak and talons"; the cock as

"armed of his beak and spurs"; he

is also blazoned as "combed and

jellopped"—that is, with his crest and

wattles. An eagle or any other bird of prey devouring

[pg 51]

its prey is described as "preying." In blazoning a very

old eagle, the French heralds use a special term, pamé;4

our English equivalent would be "exhausted," thereby

alluding to the popular notion that with advancing age

an eagle's beak becomes so hooked that it is unable to

take any nourishment, and so dies of inanition. Birds

that have web feet and no talons are usually blazoned

"membred." A swan with her wings raised is said to

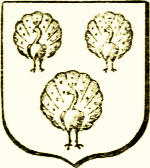

be "expansed"; a peacock with his tail displayed is

said to be "in his pride" (Fig. 45); with folded tail he

is a peacock "close." A pelican feeding her young is

a "pelican in her piety" (see Plate III.); when

wounding her breast, she is said to be "vulning."

The crane is another bird which enjoys a blazoning

term which is all its own—namely, "a crane in its

vigilance." It is so described when, as in the Cranstoun

arms, it is represented holding a stone in its foot.

This charge refers to the old myth, that a crane on duty

as a sentinel always holds a stone in its foot, so that in

the event of its dropping asleep the sound of the falling

stone may act as an alarum.

Falcons are blazoned "armed, jessed and belled."

A falcon is usually called "goshawk" in heraldry.

Swans, geese, ducks, and other web-footed birds

occur rarely in heraldry. The Moore family bear one

swan, the Mellishes two, and three swans' necks are

charged upon the Lacys' shield. One, John Langford,

bears a single wild goose. Three wild duck volant

[pg 52]

appear in the arms of the Woolrich family. Three

drakes—a very favourite charge—are borne by the

Yeos. The Starkeys bear one stork, the Gibsons

three.

Fig. 43.

Three herons occur in the arms of Heron, one kingfisher

in those of one, Christopher Fisher (Fig. 43).

Viscount Cullen, whose family name

is Cockayne, bears three cocks; three

capons are borne by the Caponhursts;

whilst, drolly enough, three cocks

are borne by the Crow family. The

Alcocks bear three cocks' heads.

Eagles are of such wide and

constant occurrence in heraldry that

we cannot attempt to do justice to them here. A

single eagle is borne by the Earls of Dalhousie and

Southesk, and by seven families of Bedingfield. A