Title: The Irish Penny Journal, Vol. 1 No. 49, June 5, 1841

Author: Various

Release date: August 30, 2017 [eBook #55460]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by JSTOR www.jstor.org)

| Number 49. | SATURDAY, JUNE 5, 1841. | Volume I. |

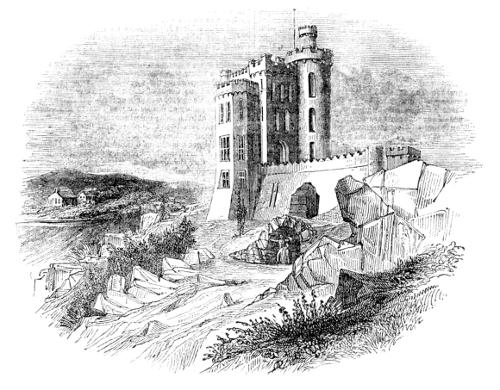

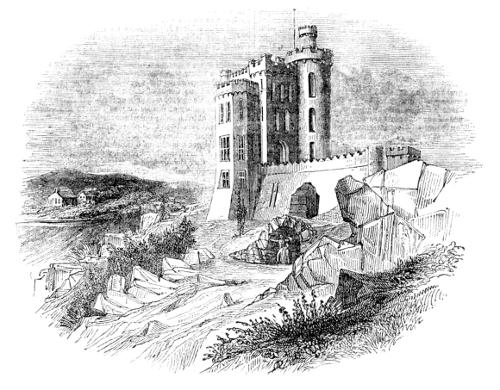

Our metropolitan readers, at least, and many others besides, are aware of the magnificent but not easily to be realised project, recently propounded, of erecting a town on the east side of Malpas’s or Killiney Hill—a situation certainly of unrivalled beauty and grandeur. Plans, most satisfactory, and views prospective as well as perspective of this as yet non-existent Brighton or Clifton, have been laid before the public, with a view to obtain the necessary ways and means to give it a more substantial reality; but alas! for the uncertainty of human wishes! Queenstown, despite the popularity of our sovereign, is not likely, for some time at least, to present a rivalry, in any thing but its romantic and commanding site, to the busy, bustling, and not very symmetrically built town which has been erected in honour of Her august eldest uncle. The good people of Kingstown may therefore rejoice; their glory will not for some time at least be eclipsed; and the lovers of natural romantic scenery who have not money—they seldom have—to employ in promising speculations, may also rejoice, for the wild and precipitous cliffs of Killiney are likely to retain for some years longer a portion of their romantic beauty; the rocks will not be shaped into well-dressed forms of prim gentility; the purple heather and blossomy furze, “unprofitable gay,” may give nature’s brilliant colouring to the scenery, and the wild sea-birds may sport around: the time has not arrived when they will be destroyed or banished from their ancient haunt by the encroachment of man.

But however this may be, the first stone of the new town has been laid; nay, the first building—no less a building than “Victoria Castle”—has been actually erected; and, as a memorial of one of the gigantic projects of this speculating nineteenth century of ours, we have felt it incumbent on us to give its fair proportions a place in our immortal and universally read miscellany, in order to hand down its pristine form to posterity in ages when it shall have been shaped by time into a genuine antique ruin.

Of the architectural style and general appearance of Victoria Castle, our engraving gives a good idea. Like most modern would-be castles, it has towers and crenellated battlements and large windows in abundance, and is upon the whole as unlike a real old castle as such structures usually are. It is, however, a picturesque and imposing structure of its kind, and, what is of more consequence to its future occupants, a cheerful and commodious habitation, which is more than can be said of most genuine castles, or of many more classical imitations of them; and its situation, on a terrace on the south side of Killiney Hill, is one as commanding and beautiful as could possibly be imagined.

Nothing in nature can indeed surpass the beauty, variety, and extent of the prospects which may be enjoyed from this spot or its immediate vicinity, and we might fill a whole number of our Journal in describing their principal features. To most of our readers, however, they must be already familiar, and to those who have not had the pleasure of enjoying a sight of them, it will convey a sufficient general idea of what[Pg 386] they must be, to acquaint them that Killiney Hill from the same point commands, towards the west, views of the far-famed Bay of Dublin, the city, and the richly-cultivated and villa-studded plains by which it is surrounded, towards the north, the bold, rugged promontory of Howth, with the islands of Dalkey, Ireland’s eye, Lambay, and the peaked mountain-ranges of Down and Lowth in the extreme distance; and lastly, towards the east and south, the sea, and the lovely Bay of Killiney, with its shining yellow strand, curved into the form of a spacious and magnificent amphitheatre, from which, as in seats above each other, ascend the richly-wooded hills, backed by the mountains of Dublin and Wicklow, with all their exquisite variety of forms and fitful changes of colour. In short, it may truly be said of this delightful situation, that though other localities may possess some individual character of scenery of greater beauty or grandeur, there are few if any in the British empire that could fairly be compared with it for its variety and general interest.

Of the great interest of Killiney to the naturalist, and the geologist more particularly, we have already endeavoured to give our readers some notion in a paper, in a recent number, from the pen of our able and accomplished friend Dr Schouler; and Killiney is scarcely less interesting to the antiquary than to the man of science. Though till a recent period its now cultivated and thickly inhabited hills and shores presented the virgin appearance of a country nearly in the state which nature left it, the numerous monuments of antiquity scattered about them clearly evinced that man had been a wanderer if not an inhabitant here in the most remote times. Numerous kistvaens containing human skeletons have been found between the road and the sea, undoubtedly of pagan times; and we have ourselves seen in our young days six very large urns of baked clay, containing burned bones, which were discovered in sinking the foundations for a cottage, near the road between the Killiney and Rochestown hills. We have also seen several sepulchral stone circles, now no longer remaining; and there is yet to be seen of the same period, a fine cromleac, situated near Shanganagh, and that most remarkable and interesting pagan temple, near the Martello tower, with its judgment chair, and the figures of the sun and moon sculptured on one of the stones within its enclosure. Nor is Killiney without its monument of Christian piety of as early date as any to be found in Ireland. In the beautiful ivied ruin of its parish church, the antiquary may enjoy a sight of one of the most characteristic examples of the temples erected by the Irish immediately after their conversion to Christianity, and make himself intimate with a style of architecture not now to be found in other portions of the British empire.

P.

BY WILLIAM CARLETON.

When Tom had expressed an intention of relating an old story, the hum of general conversation gradually subsided into silence, and every face assumed an expression of curiosity and interest, with the exception of Jemsy Baccagh, who was rather deaf, and blind George M’Givor, so called because he wanted an eye; both of whom, in high and piercing tones, carried on an angry discussion touching a small law-suit that had gone against Jemsy in the Court Leet, of which George was a kind of rustic attorney. An outburst of impatient rebuke was immediately poured upon them from fifty voices. “Whisht with yez, ye pair of devils’ limbs, an’ Tom goin’ to tell us a story. Jemsy, your sowl’s as crooked as your lame leg, you sinner; an’ as for blind George, if roguery would save a man, he’d escape the devil yet. Tarenation to yez, an’ be quiet till we hear the story!”

“Ay,” said Tom, “Scripthur says that when the blind leads the blind, both will fall into the ditch; but God help the lame that have blind George to lead them; we might aisily guess where he’d guide them to, especially such a poor innocent as Jemsy there.” This banter, as it was not intended to give offence, so was it received by the parties to whom it was addressed with laughter and good humour.

“Silence, boys,” said Tom; “I’ll jist take a draw of the pipe till I put my mind in a proper state of transmigration for what I’m goin’ to narrate.”

He then smoked on for a few minutes, his eyes complacently but meditatively closed, and his whole face composed into the philosophic spirit of a man who knew and felt his own superiority, as well as what was expected from him. When he had sufficiently arranged the materials in his mind, he took the pipe out of his mouth, rubbed the shank-end of it against the cuff of his coat, then handed it to his next neighbour, and having given a short preparatory cough, thus commenced his legend:—

“You must know that afther Charles the First happened to miss his head one day, havin’ lost it while playin’ a game of ‘Heads an’ Points’ with the Scotch, that a man called Nolly Rednose, or Oliver Crummle, was sent over to Ireland with a parcel of breekless Highlanders an’ English Bodaghs to subduvate the Irish, an’ as many of the Prodestans as had been friends to the late king, who were called Royalists. Now, it appears by many larned transfigurations that Nolly Rednose had in his army a man named Balgruntie, or the Hog of Cupar; a fellow who was as coorse as sackin’, as cunnin’ as a fox, an’ as gross as the swine he was named afther. Rednose, there is no doubt of it, was as nate a hand at takin’ a town or castle as ever went about it; but then, any town that didn’t surrendher at discretion was sure to experience little mitigation at his hands; an’ whenever he was bent on wickedness, he was sure to say his prayers at the commencement of every siege or battle; that is, he intended to show no marcy in, for he’d get a book, an’ openin’ it at the head of his army, he’d cry, ‘Ahem, my brethren, let us praise God by endeavourin’ till sing sich or sich a psalm;’ an’ God help the man, woman, or child, that came before him after that. Well an’ good: it so happened that a squadron of his psalm-singers were dispatched by him from Enniskillen, where he stopped to rendher assistance to a part of his army that O’Neill was leatherin’ down near Dungannon, an’ on their way they happened to take up their quarthers for the night at the Mill of Aughentain. Now, above all men in the creation, who should be appointed to lead this same squadron but the Hog of Cupar. ‘Balgruntie, go off wid you,’ said Crummle, when administering his instructions to him; ‘but be sure that wherever you meet a fat royalist on the way, to pay your respects to him as a Christian ought,’ says he; ‘an’, above all things, my dear brother Balgruntie, don’t neglect your devotions, otherwise our arms can’t prosper; and be sure,’ says he, with a pious smile, ‘that if they promulgate opposition, you will make them bleed anyhow, either in purse or person; or if they provoke the grace o’ God, take a little from them in both; an’ so the Lord’s name be praised, yeamen!’

Balgruntie sang a psalm of thanksgivin’ for bein’ elected by his commander to sich a holy office, set out on his march, an’ the next night he an’ his choir slep in the mill of Aughentain, as I said. Now, Balgruntie had in this same congregation of his a long-legged Scotchman named Sandy Saveall, which name he got by way of etymology, for his charity; for it appears by the historical elucidations that Sandy was perpetually rantinizin’ about sistherly affection an’ brotherly love: an’ what showed more taciturnity than any thing else was, that while this same Sandy had the persuasion to make every one believe that he thought of nothing else, he shot more people than any ten men in the squadron. He was indeed what they call a dead shot, for no one ever knew him to miss any thing he fired at. He had a musket that could throw point blank an English mile, an’ if he only saw a man’s nose at that distance, he used to say that with aid from above he could blow it for him with a leaden handkerchy, meaning that he could blow it off his face with a musket bullet; and so by all associations he could, for indeed the faits he performed were very insinivating an’ problematical.

Now, it so happened that at this period there lived in the castle a fine wealthy ould royalist, named Graham or Grimes, as they are often denominated, who had but one child, a daughter, whose beauty an’ perfections were mellifluous far an’ near over the country, an’ who had her health drunk, as the toast of Ireland, by the Lord Lieutenant in the Castle of Dublin, undher the sympathetic appellation of ‘the Rose of Aughentain.’ It was her son that afterwards ran through the estate, and was forced to part wid the castle; an’ it’s to him the proverb colludes, which mentions ‘ould John Grame, that swallowed the castle of Aughentain.’

Howsomever, that bears no prodigality to the story I’m narratin’. So what would you have of it, but Balgruntie, who had heard of the father’s wealth and the daughter’s beauty, took a holy hankerin’ afther both; an’ havin’ as usual said his prayers an’ sung a psalm, he determined for to clap his thumb upon the father’s money, thinkin’ that the daughter[Pg 387] would be the more aisily superinduced to folly it. In other words, he made up his mind to sack the castle, carry off the daughter and marry her righteously, rather, he said, through a sincere wish to bring her into a state of grace, by a union with a God-fearin’ man, whose walk he trusted was Zionward, than from any cardinal detachment for her wealth or beauty. He accordingly sent up a file of the most pious men he had, picked fellows, with good psalm-singin’ voices and strong noses, to request that John Graham would give them possession of the castle for a time, an’ afterwards join them at prayers, as a proof that he was no royalist, but a friend to Crummle an’ the Commonwealth. Now, you see, the best of it was, that the very man they demanded this from was commonly denominated by the people as ‘Gunpowdher Jack,’ in consequence of the great signification of his courage; an’, besides, he was known to be a member of the Hell-fire Club, that no person could join that hadn’t fought three duels, and killed at least one man; and in ordher to show that they regarded neither God nor hell, they were obligated to dip one hand in blood an’ the other in fire, before they could be made members of the club. It’s aisy to see, then, that Graham was not likely to quail before a handful of the very men he hated wid all the vociferation in his power, an’ he accordingly put his head out of the windy, an’ axed them their tergiversation for bein’ there.

‘Begone about your business,’ he said; ‘I owe you no regard. What brings you before the castle of a man who despises you? Don’t think to determinate me, you cauting rascals, for you can’t. My castle’s well provided wid men, an’ ammunition, an’ food; an’ if you don’t be off, I’ll make you sing a different tune from a psalm one.’ Begad he did, plump to them, out of the windy.

When Crummle’s men returned to Balgruntie in the mill, they related what had tuck place, an’ he said that afther prayers he’d send a second message in writin’, an’ if it wasn’t attended to, they’d put their trust in God an’ storm the castle. The squadron he commanded was not a numerous one; an’ as they had no artillery, an’ were surrounded by enemies, the takin’ of the castle, which was a strong one, might cost them some snufflication. At all events, Balgruntie was bent on makin’ the attempt, especially afther he heard that the castle was well vittled, an’ indeed he was meritoriously joined by his men, who piously licked their lips on hearin’ of such glad tidings. Graham was a hot-headed man, without much ambidexterity or deliberation, otherwise he might have known that the bare mintion of the beef an’ mutton in his castle was only fit to make such a hungry pack desperate. But be that as it may, in a short time Balgruntie wrote him a letter, demandin’ of him, in the name of Nolly Rednose an’ the Commonwealth, to surrendher the castle, or if not, that, ould as he was, he would make him as soople as a two-year-ould. Graham, afther readin’ it, threw the letther back to the messengers wid a certain recommendation to Balgruntie regardin’ it; but whether the same recommendation was followed up an’ acted on so soon as he wished, historical retaliations do not inform.

On their return the military narrated to their commander the reception they resaved a second time from Graham, an’ he then resolved to lay regular siege to the castle; but as he knew he could not readily take it by violence, he determined, as they say, to starve the garrison leisurely an’ by degrees. But, first an’ foremost, a thought struck him, an’ he immediently called Sandy Saveall behind the mill-hopper, which he had now turned into a pulpit for the purpose of expoundin’ the word, an’ givin’ exhortations to his men.

‘Sandy,’ said he, ‘are you in a state of justification to-day?’

‘Towards noon,’ replied Sandy, ‘I had some strong wristlings with the enemy; but I am able, undher praise, to say that I defated him in three attacks, and I consequently feel my righteousness much recruited. I had some wholesome communings with the miller’s daughter, a comely lass, who may yet be recovered from the world, an’ led out of the darkness of Aigyp, by a word in saison.’

‘Well, Sandy,’ replied the other, ‘I lave her to your own instructions; there is another poor benighted maiden, who is also comely, up in the castle of that godless sinner, who belongeth to the Perdition Club; an’, indeed, Sandy, until he is somehow removed, I think there is little hope of plucking her like a brand out of the burning.’

He serenaded Sandy in the face as he spoke, an’ then cast an extemporary glance at the musket, which was as much as to say ‘can you translate an insinivation?’ Sandy concocted a smilin’ reply; an’ takin’ up the gun, rubbed the barrel, an’ pattin’ it as a sportsman would pat the neck of his horse or dog, wid reverence for comparin’ the villain to either one or the other.

‘If it was known, Sandy,’ said Balgruntie, ‘it would harden her heart against me; an’ as he is hopeless at all events, bein’ a member of that Perdition Club’——

‘True,’ said Sandy, ‘but you lave the miller’s daughter to me?’

‘I said so.’

‘Well, if his removal will give you any consolidation in the matther, you may say no more.’

‘I could not, Sandy, justify it to myself to take him away by open violence, for you know that I bear a conscience if any thing too tendher and dissolute. Also I wish, Sandy, to presarve an ondeniable reputation for humanity; an’, besides, the daughter might become as reprobate as the father if she suspected me to be personally concarned in it. I have heard a good deal about him, an’ am sensibly informed that he has been shot at twice before, by the sons, it is thought, of an enemy that he himself killed rather significantly in a duel.’

‘Very well,’ replied Sandy; ‘I would myself feel scruples; but as both our consciences is touched in the business, I think I am justified. Indeed, captain, it is very likely afther all that we are but the mere instruments in it, an’ that it is through us that this ould unrighteous sinner is to be removed by a more transplendant judgment.’

Begad, neighbours, when a rascal is bent on wickedness, it is aisy to find cogitations enough to back him in his villany. And so was it with Sandy Saveall and Balgruntie.

That evenin’ ould Graham was shot through the head standin’ in the windy of his own castle, an’ to extenuate the suspicion of sich an act from Crummle’s men, Balgruntie himself went up the next day, beggin’ very politely to have a friendly explanation with Squire Graham, sayin’ that he had harsh ordhers, but that if the castle was peaceably delivered to him, he would, for the sake of the young lady, see that no injury should be offered either to her or her father.

The young lady, however, had the high drop in her, and becoorse the only answer he got was a flag of defiance. This nettled the villain, an’ he found there was nothin’ else for it but to plant a strong guard about the castle to keep all that was in, in—and all that was out, out.

In the mean time, the very appearance of the Crumwellians in the neighbourhood struck such terror into the people, that the country, which was then only very thinly inhabited, became quite desarted, an’ for miles about the face of a human bein’ could not be seen, barrin’ their own, sich as they were. Crummle’s track was always a bloody one, an’ the people knew that they were wise in puttin’ the hills an’ mountain passes between him an’ them. The miller an’ his daughter bein’ encouraged by Sandy, staid principally for the sake of Miss Graham; but except them, there was not a man or woman in the barony to bid good-morrow to or say Salvey Dominey. On the beginnin’ of the third day, Balgruntie, who knew his officialities extremely well, an’ had sent down a messenger to Dungannon to see whether matters were so bad as they had been reported, was delighted to hear that O’Neill had disappeared from the neighbourhood. He immediately informed Crummle of this, and tould him that he had laid siege to one of the leadin’ passes of the north, an’ that, by gettin’ possession of the two castles of Aughentain and Augher, he could keep O’Neill in check, and command that part of the country. Nolly approved of this, an’ ordhered him to proceed, but was sorry that he could send him no assistance at present; ‘however,’ said he, ‘with a good cause, sharp swords, an’ aid from above, there is no fear of us.’

They now set themselves to take the castle in airnest. Balgruntie an’ Sandy undherstood one another, an’ not a day passed that some one wasn’t dropped in it. As soon as ever a face appeared, pop went the deadly musket, an’ down fell the corpse of whoever it was aimed at. Miss Graham herself was spared for good reasons, but in the coorse of ten or twelve days she was nearly alone. Ould Graham, though a man that feared nothing, was only guilty of a profound swagger when he reported the strength of the castle and the state of the provisions to Balgruntie an’ his crew. But above all things, that which eclipsed their distresses was the want of wather. There was none in the castle, an’ although there is a beautiful well beside it, yet, farcer gair, it was of small responsibility to them. Here, then, was the poor young lady placed at the marcy of her father’s murdherer; for however[Pg 388] she might have doubted in the beginnin’ that he was shot by the Crumwellians, yet the death of nearly all the servants of the house in the same way was a sufficient proof that it was like masther like man in this case. What, however, was to be done? The whole garrison now consisted only of Miss Graham herself, a fat man cook advanced in years, who danced in his distress in ordher that he might suck his own perspiration, and a little orphan boy that she tuck undher her purtection. It was a hard case, an’ yet, God bless her, she held out like a man.

It’s an ould sayin’ that there’s no tyin’ up the tongue of Fame, an’ it’s also a true one. The account of the siege had gone far an’ near in the counthry, an’ none of the Irish, no matter what they were who ever heard it, but wor sorry. Sandy Saveall was now the devil an’ all. As there was no more in the castle to shoot, he should find something to regenerate his hand upon: for instance, he practised upon three or four of Graham’s friends, who undher one pretence or other were seen skulkin’ about the castle, an’ none of their relations durst come to take away their bodies in ordher to bury them. At length things came to that pass, that poor Miss Graham was at the last gasp for something to drink; she had ferreted out as well as she could a drop of moisture here an’ there in the damp corners of the castle, but now all that was gone; the fat cook had sucked himself to death, and the little orphan boy died calmly away a few hours afther him, lavin’ the helpless lady with a tongue swelled an’ furred, and a mouth parched and burned, for want of drink. Still the blood of the Grahams was in her, and yield she would not to the villain that left her as she was. Sich then was the transparency of her situation, when happening to be on the battlements to catch, if possible, a little of the dew of heaven, she was surprised to see something flung up, which rolled down towards her feet; she lifted it, an’ on examinin’ the contents, found it to be a stone covered with a piece of brown paper, inside which was a slip of white, containing the words, ‘Endure—relief is near you!’ But, poor young lady, of what retrospection could these tidings be to one in her situation?—she could scarcely see to read them; her brain was dizzy, her mouth like a cindher, her tongue swelled an’ black, an’ her breath felt as hot as a furnace. She could barely breathe, an’ was in the very act of lyin’ down undher the triumphant air of heaven to die, when she heard the shrill voice of a young kid in the castle yard, and immediently remembered that a brown goat which her lover, a gentleman named Simpson, had, when it was a kid, made her a present of, remained in the castle about the stable during the whole siege. She instantly made her way slowly down stairs, got a bowl, and havin’ milked the goat, she took a little of the milk, which I need not asseverate at once relieved her. By this means she recovered, an’ findin’ no further anticipation from druth, she resolved like a hairo to keep the Crumwellians out, an’ to wait till either God or man might lend her a helpin’ hand.

Now, you must know that the miller’s purty daughter had also a sweetheart called Suil Gair Maguire, or sharp-eye’d Maguire, an humble branch of the great Maguires of Enniskillen; an’ this same Suil Gair was servant an’ foster-brother to Simpson, who was the intended husband of Miss Graham. Simpson, who lived some miles off, on hearin’ the condition of the castle, gathered together all the royalists far an’ near; an’ as Crummle was honestly hated by both Romans an’ Prodestans, faith, you see, Maguire himself promised to send a few of his followers to the rescue. In the mean time, Suil Gair dressed himself up like a fool or idiot, an’ undher the protection of the miller’s daughter, who blarnied Saveall in great style, was allowed to wandher about an’ joke wid the sogers; but especially he took a fancy to Sandy, and challenged him to put one stone out of five in one of the port-holes of the castle, at a match of finger-stone. Sandy, who was nearly as famous at that as the musket, was rather relaxed when he saw that Suil Gair could at least put in every second stone, an’ that he himself could hardly put one in out of twenty. Well, at all events it was durin’ their sport that fool Paddy, as they called him, contrived to fling the scrap of writin’ I spoke of across the battlements at all chances; for when he undhertook to go to the castle, he gave up his life as lost; but he didn’t care about that, set in case he was able to save either his foster-brother or Miss Graham. But this is not at all indispensable, for it is well known that many a foster-brother sacrificed his life the same way, and in cases of great danger, when the real brother would beg to decline the compliment.

Things were now in a very connubial state entirely. Balgruntie heard that relief was comin’ to the castle, an’ what to do he did not know; there was little time to be lost, however, an’ something must be done. He praiched flowery discourses twice a-day from the mill-hopper, an’ sang psalms for grace to be directed in his righteous intentions; but as yet he derived no particular predilection from either. Sandy appeared to have got a more bountiful modelum of grace than his captain, for he succeeded at last in bringin’ the miller’s daughter to sit undher the word at her father’s hopper. Fool Paddy, as they called Maguire, had now become a great favourite wid the sogers, an’ as he proved to be quite harmless and inoffensive, they let him run about the place widout opposition. The castle, to be sure, was still guarded, but Miss Graham kept her heart up in consequence of the note, for she hoped every day to get relief from her friends. Balgruntie, now seein’ that the miller’s daughter was becomin’ more serious undher the taichin’ of Saveall, formed a plan that he thought might enable him to penethrate the castle, an’ bear off the lady an’ the money. This was to strive wid very delicate meditation to prevail on the miller’s daughter, through the renown that he thought Sandy had over her, to open a correspondency wid Miss Graham; for he knew that if one of the gates was unlocked, and the unsuspectin’ girl let in, the whole squadron would soon be in afther her. Now, this plan was the more dangerous to Miss Graham, because the miller’s daughter had intended to bring about the very same denouncement for a different purpose. Between her friend an’ her enemies it was clear the poor lady had little chance; an’ it was Balgruntie’s intention, the moment he had sequestrated her and the money, to make his escape, an’ lave the castle to whosomever might choose to take it. Things, however, were ordhered to take a different bereavement: the Hog of Cupar was to be trapped in the hydrostatics of his own hypocrisy, an’ Saveall to be overmatched in his own premises. Well, the plot was mentioned to Sandy, who was promised a good sketch of the prog; an’ as it was jist the very thing he dreamt about night an’ day, he snapped at it as a hungry dog would at a sheep’s trotter. That night the miller’s daughter—whose name I may as well say was Nannie Duffy, the purtiest girl an’ the sweetest singer that ever was in the counthry—was to go to the castle an’ tell Miss Graham that the sogers wor all gone, Crummle killed, an’ his whole army massacrayed to atoms. This was a different plan from poor Nannie’s, who now saw clearly what they were at. But never heed a woman for bein’ witty when hard pushed.

‘I don’t like to do it,’ said she, ‘for it looks like thrachery, espishilly as my father has left the neighbourhood, and I don’t know where he is gone to; an’ you know thrachery’s ondacent in either man or woman. Still, Sandy, it goes hard for me to refuse one that I—I——well, I wish I knew where my father is—I would like to know what he’d think of it.’

‘Hut,’ said Sandy, ‘where’s the use of such scruples in a good cause?—when we get the money, we’ll fly. It is principally for the sake of waining you an’ her from the darkness of idolatry that we do it. Indeed, my conscience would not rest well if I let a soul an’ body like yours remain a prey to Sathan, my darlin’.’

‘Well,’ said she, ‘doesn’t the captain exhort this evenin’?’

‘He does, my beloved, an’ with a blessin’ will expound a few verses from the Song of Solomon.’

‘It’s betther then,’ said she, ‘to sit under the word, an’ perhaps some light may be given to us.’

This delighted Saveall’s heart, who now looked upon pretty Nannie as his own; indeed, he was obliged to go gradually and cautiously to work, for cruel though Nolly Rednose was, Sandy knew that if any violent act of that kind should raich him, the guilty party would sup sorrow. Well, accordin’ to this pious arrangement, Balgruntie assembled all his men who were not on duty about the hopper, in which he stood as usual, an’ had commenced a powerful exhortation, the substratum of which was devoted to Nannie; he dwelt upon the happiness of religious love; said that scruples were often suggested by Satan, an’ that a heavenly duty was but terrestrial when put in comparishment wid an earthly one. He also made collusion to the old Squire that was popped by Sandy; said it was often a judgment for the wicked man to die in his sins; an’ was gettin’ on wid great eloquence an’ emulation, when a low rumblin’ noise was heard, an’ Balgruntie, throwin’ up his clenched hands an’ grindin’ his teeth, shouted out, ‘Hell and d——n, I’ll be ground to death! The mill’s goin’ on! Murdher! murdher! I’m gone!’ Faith, it was true enough—she[Pg 389] had been wickedly set a-goin’ by some one; an’ before they had time to stop her, the Hog of Cupar had the feet and legs twisted off him before their eyes—a fair illustration of his own doctrine, that it is often a judgment for the wicked man to die in his sins. When the mill was stopped, he was pulled out, but didn’t live twenty minutes, in consequence of the loss of blood. Time was pressin’, so they ran up a shell of a coffin, and tumbled it into a pit that was hastily dug for it on the mill-common.

This, however, by no manner of manes relieved poor Nannie from her difficulty, for Saveall, finding himself now first in command, determined not to lose a moment in tolerating his plan upon the castle.

‘You see,’ said he, ‘that a way is opened for us that we didn’t expect; an’ let us not close our eyes to the light that has been given, lest it might be suddenly taken from us again. In this instance I suspect that fool Paddy has been made the chosen instrument; for it appears upon inquiry that he too has disappeared. However, heaven’s will be done! we will have the more to ourselves, my beloved—ehem! It is now dark,’ he proceeded, ‘so I shall go an’ take my usual smoke at the mill window, an’ in about a quarther of an hour I’ll be ready.’

‘But I’m all in a tremor after sich a frightful accident,’ replied Nannie: ‘an’ I want to get a few minutes’ quiet before we engage upon our undhertakin.’

This was very natural, and Saveall accordingly took his usual seat at a little windy in the gable of the mill, that faced the miller’s house; an’ from the way the bench was fixed, he was obliged to sit with his face exactly towards the same direction. There we leave him meditatin’ upon his own righteous approximations, till we folly Suil Gair Maguire, or fool Paddy, as they called him, who practicated all that was done.

Maguire and Nannie, findin’ that no time was to be lost, gave all over as ruined, unless somethin’ could be acted on quickly. Suil Gair at once thought of settin’ the mill a-goin’, but kept the plan to himself, any further than tellin’ her not to be surprised at any thing she might see. He then told her to steal him a gun, but if possible to let it be Saveall’s, as he knew it could be depended on. ‘But I hope you won’t shed any blood if you can avoid it,’ said she; ‘that I don’t like.’ ‘Tut,’ replied Suil Gair, makin’ evasion to the question, ‘it’s good to have it about me for my own defence.’

He could often have shot either Balgruntie or Saveall in daylight, but not without certain death to himself, as he knew that escape was impossible. Besides, time was not before so pressin’ upon them, an’ every day relief was expected. Now, however, that relief was so near—for Simpson with a party of royalists an’ Maguire’s men must be within a couple of hours’ journey—it would be too intrinsic entirely to see the castle plundhered, and the lady carried off by such a long-legged skyhill as Saveall. Nannie consequentially, at great risk, took an opportunity of slipping his gun to Suil Gair, who was the best shot of the day in that or any other part of the country; and it was in consequence of this that he was called Suil Gair, or Sharp Eye. But, indeed, all the Maguires were famous shots; an’ I’m tould there’s one of them now in Dublin that could hit a pigeon’s egg or a silver sixpence at the distance of a hundred yards.[1] Suil Gair did not merely raise the sluice when he set the mill a-goin’, but he whipped it out altogether an’ threw it into the dam, so that the possibility of saving the Hog of Cupar was irretrievable. He made off, however, an’ threw himself among the tall ragweeds that grew upon the common, till it got dark, when Saveall, as was his custom, should take his evenin’ smoke at the windy. Here he sat for some period, thinkin’ over many ruminations, before he lit his cutty pipe, as he called it.

‘Now,’ said he to himself, ‘what is there to hindher me from takin’ away, or rather from makin’ sure of the grand lassie, instead of the miller’s daughter? If I get intil the castle, it can be soon effected; for if she has any regard for her reputation, she will be quiet. I’m a braw handsome lad enough, a wee thought high in the cheek bones, scaly in the skin, an’ knock-knee’d a trifle, but stout an’ lathy, an’ tough as a withy. But, again, what is to be done wi Nannie? Hut, she’s but a miller’s daughter, an’ may be disposed of if she gets troublesome. I know she’s fond of me, but I dinna blame her for that. However, it wadna become me now to entertain scruples, seein’ that the way is made so plain for me. But, save us! eh, sirs, that was an awful death, an’ very like a judgment on the Hog of Cupar! It is often a judgment for the wicked to die in their sins! Balgruntie wasna that’—— Whatever he intended to say further, cannot be analogized by man, for, just as he had uttered the last word, which he did while holding the candle to his pipe, the bullet of his own gun entered between his eyes, and the next moment he was a corpse.

Suil Gair desarved the name he got, for truer did never bullet go to the mark from Saveall’s own aim than it did from his. There is now little more to be superadded to my story. Before daybreak the next mornin’, Simpson came to the relief of his intended wife; Crummle’s party war surprised, taken, an’ cut to pieces; an’ it so happened that from that day to this the face of a soger belongin’ to him was never seen near the mill or castle of Aughentain, with one exception only, and that was this:—You all know that the mill is often heard to go at night when nobody sets her a-goin’, an’ that the most sevendable scrames of torture come out of the hopper, an’ that when any one has the courage to look in, they’re sure to see a man dressed like a soger, with a white mealy face, in the act, so to say, of havin’ his legs ground off him. Many a guess was made about who the spirit could be, but all to no purpose. There, however, is the truth for yez; the spirit that shrieks in the hopper is Balgruntie’s ghost, an’ he’s to be ground that way till the day of judgment.

Be coorse, Simpson and Miss Graham were married, as war Nannie Duffy an’ Suil Gair; an’ if they all lived long an’ happy, I wish we may all live ten times longer an’ happier; an’ so we will, but in a betther world than this, plaise God.”

“Well, but, Tom,” said Gordon, “how does that account for my name, which you said you’d tell me?”

“Right,” said Tom; “begad I was near forgettin’ it. Why, you see, sich was their veneration for the goat that was the manes, undher God, of savin’ Miss Graham’s life, that they changed the name of Simpson to Gordon, which signifies in Irish gor dhun, or a brown goat, that all their posterity might know the great obligations they lay undher to that reverend animal.”

“An’ do you mane to tell me,” said Gordon, “that my name was never heard of until Oliver Crummle’s time?”

“I do. Never in the wide an’ subterraneous earth was sich a name known till afther the prognostication I tould you; an’ it never would either, only for the goat, sure. I can prove it by the pathepathetics. Denny Mullin, will you give us another draw o’ the pipe?”

Tom’s authority in these matters was unquestionable, and, besides, there was no one present learned enough to contradict him, with any chance of success, before such an audience. The argument was consequently, without further discussion, decided in his favour, and Gordon was silenced touching the origin and etymology of his own name.

This legend we have related as nearly as we can remember in Tom’s words. We may as well, however, state at once that many of his legends were wofully deficient in authenticity, as indeed those of most countries are. Nearly half the Irish legends are ex post facto or postliminious. There is no record, for instance, that Oliver Cromwell ever saw the castle of Aughentain, or that any such event as that narrated by Tom ever happened in or about it. It is much more likely that the story, if ever there was any truth in it, is of Scotch origin, as indeed the names would seem to import. There is no doubt, however, that the castle of Aughentain, which is now in the possession of a gentleman named Browne we think, was once the property of a family called Graham. In our boyhood there was a respectable family of that name living in its immediate vicinity, but we know not whether they are the descendants of those who owned the castle or not.

[1] The celebrated Brian Maguire, the first shot of his day, was at this time living in Dublin.

Having given in a former number some account of the natural history of this valuable little creature, we now proceed, in accordance with our promise, to give a description of the various modes of taking and curing it; and as the Dutch were the first to see the importance, and devote themselves to the improvement, of the herring fishery, we shall commence with them.

So early as the year 1307, the Dutch had turned their attention to this subject; and lest any of our more thoughtless or less informed readers should deem the matter one of secondary consideration, or probably of even less, we shall lay before them some statistical accounts of the Dutch fisheries,[Pg 390] extracted from returns of the census of the States-General, taken in the year 1669. In that year the total amount of population was 2,400,000.

| Of whom were employed as fishermen, and in equipping fishermen with their boats, tackle, conveying of salt, &c. | 450,000 |

| Employed in the navigation of ships in foreign trade, | 250,000 |

| Shipwrights, handicraftsmen, and manufacturers, | 650,000 |

| Inland fishermen, agriculturists, and labourers, | 200,000 |

| Gentry, statesmen, soldiers, and inhabitants in general, | 850,000 |

| Total, | 2,400,000 |

Thus nearly a fifth of the population of Holland was entirely engaged in and supported by the herring and deep-sea fishery, and thus arose the saying that “the foundations of Amsterdam were laid on herring bones;” and hence did De Witt assert that “Holland derived her main support from the herring fishery, and that it ought to be considered as the right arm of the republic.”

Before Holland was humbled upon the seas, and whilst she was at the pinnacle of her prosperity, she had ten thousand sail of shipping, with 168,000 mariners, afloat. Of these no less than 6400 vessels, with 112,000 mariners, were employed in and connected with the herring fishery alone, “although the country itself affords them neither materials, nor victual, nor merchandise, to be accounted of, towards their setting forth.” When we come to the subject of curing, we shall take occasion to point out the modes by which the Dutch attained their excellence, and established this surprising trade; but at present we have but to describe their manner of fishing.

The Great Fishery commences on the 24th of June, and terminates on the 31st of December, and is carried on in the latitudes of Shetland and Edinburgh, and on the coast of Great Britain, with strong-decked vessels called busses, manned by fourteen or fifteen men, and well supplied with casks, salt, nets, and every material requisite for catching and curing at sea. Each buss has generally fifty, and must not have less than forty nets of 32 fathoms in length each, 8 fathoms in depth, and a buoy-rope of 8 fathoms; an empty barrel less than a herring barrel is attached to each buoy-rope. This fleet of nets, as it is called, is divided by buoys into four parts, by which their position is marked and their taking in facilitated; the buoys at the extreme ends are painted white, with the owners’ and vessels’ names upon them. By the Dutch fishery laws it is provided that the yarn of the nets must be of good unmixed Dutch or Baltic hemp, which must be inspected before use by sworn surveyors; the yarn must be well spun; and each full net, or fourth part of a fleet, must be 740 meshes in length and 68 in depth, and the nets must be inspected and marked before they can be used.

The Dutch always shoot their nets, that is, cast them into the sea, at sunset, and take them in before sunrise. In shooting them they cast them to windward, so that the wind may prevent the vessel from coming upon them. The whole of the nets are attached to four strong ropes joined to each other, and are taken in by means of the capstan, to which four or five men attend, whilst four more shake out the fish.

The Small Fishery, or fresh-herring fishery, is carried on to the east of Yarmouth in deep water, with flat-bottomed vessels without keels, so formed for the purpose of being run ashore in any convenient place.

It is forbidden by the 15th and 16th articles of the Dutch fishery laws to gut the herrings taken by the small fishery either at sea or ashore, under pain of one month’s imprisonment, and a fine of five guilders for every hundred herrings, as well as the confiscation of the herrings, unless special permission has been obtained from the king, at the request of the States.

The Pan Fishery is carried on in the rivers, inland seas, and on the coast of Holland, within three miles of the shore.

The same prohibition, under similar penalties, that exists against curing fish taken in the small fishery, extends to this.

We have given the first place to the Dutch in this account, in consequence of their having been the first to see the importance of the fishery, but they take the lead no longer; the English and Scotch have successfully rivalled them in curing, and for the quantity taken during the season the Norwegians surpass all others. The Norwegian is a wholesale fishery, every description of ship and boat being in demand. They have curing stations on shore, to which the boats bring the fish as fast as they are caught; and there are large vessels with barrels and salt lying out amongst the fishers, buying from those who do not wish to lose time by going ashore. Every description of net, as well as every sort of vessel, is in requisition; some fishing at anchor, some sailing, and others hauling their seines on shore, but the grand method is as follows:—

An immense range of nets with very small meshes so small as to prevent the herrings from fastening in them, is extended round a shoal of fish, and gradually moved towards some creek or narrow inlet of the sea. The nets are drawn close and made fast across the entrance, and the enormous body of herrings thus crowded up into a narrow space is taken out and cured at leisure. This mode of fishing is called a “lock.”

The following passage from a letter written by a gentleman who witnessed the fishery near Hitteroe, to Mr Mitchell of Leith, will give our readers some idea of its extent:—

“On the other side of the Sound we saw what is termed a lock, that is, several nets joined together, forming a bar before a small bay, into which the herrings were crowded. In this place there were several thousand barrels of herrings, so compactly confined together that an oar could stand up in the mass. There were in the neighbourhood of Hitteroe altogether about four or five thousand nets, and about two thousand boats and vessels; and there were caught, according to the opinion of several intelligent persons, this day (24th January 1833), not less than ten thousand barrels.”

The entire quantity taken on the coast of Norway during the fall of 1832 and the spring of 1833 was estimated at 680,000 barrels, which was considered to be a fair average take.

We come now to the home fishery, in which Yarmouth takes the lead in the size of vessels and magnitude of tackle employed. The fishing is carried on by the Yarmouth men in decked vessels called “luggers,” from 20 to 50 tons burthen, having three masts, and rigged with three lugsails, topsails, mizou, foresail, and jib: the crew of the largest consisting of twelve men and a boy, who are paid according to the quantity of fish caught. Each ordinary vessel carries two hundred nets of 48 feet in length and 30 in depth, each having meshes of 1 inch or 1⅛ inch, as usual in herring nets. Of these nets they shoot one hundred at a time, reserving the other hundred for cases of accident or mishap. When launched, each net is attached by two seizings of 1½ inch rope, having a depth of 18 feet, to a four-stranded (generally 4 inch) warp of 3600 feet in length; this warp is made fast to a rope from the bow of the vessel, which in stormy weather can be let out to ease the strain, to the extent of 100 fathoms, or 600 feet. For each net there are two buoys (4-gallon barrels) made fast to the warp, and there are four buoys besides, to mark the distances, two for the quarter and three-quarter stations, painted red and white quarterly, one for the half distance or middle of the fleet, painted half red and half white, and one for the extremity, painted all white; each of them has painted on it the names of the ship, master, owner, and port, in order that they may be restored in case of breaking away during bad weather; and so good an understanding exists upon this subject amongst the fishermen, that the nets are always restored by the finder to the owner upon payment of only 1s. for each net; and no one must suffer a stray net to drift away; if seen, it must be taken in. This fishery commences in the beginning of October, and lasts little more than two months. The nets are shot after the Dutch fashion, at sunset; but if the appearances are favourable, they are taken in once or twice during the night, and again at sunrise. 100 barrels of herrings are frequently taken by these nets at a single haul, and 600 barrels may be considered as a fair average fishing for one vessel during the season. The number of decked vessels employed at Yarmouth alone in the fishery is about 500.

Next, and likely from its steady increase soon to become the first, is the Scotch fishery.

Like the Norwegian, every description of boat and net is to be found employed amongst the Scottish islands, but the most regularly employed vessels are open undecked boats, of 28 to 32 feet in length, or thereabouts, and 9 to 11 feet in breadth, usually rigged with two masts and two sails. They have on board from twelve to thirty nets of from 150 to 186 feet in length each, and from 20 to 31 feet in depth.

From the Report by the Commissioners of the British Herring Fishery, of the fishery of 1838, year ending 5th April 1839, it appears that there were then engaged in the fishery 11,357 boats, decked and undecked, throughout England and[Pg 391] Scotland, manned by 50,238 men and boys, and employing 85,573 persons in all, including coopers, packers, curers, and labourers.

Of the entire number of vessels, about 9000 belonged to Scottish ports.

The entire quantity of herrings exported amounted to 239,730½ barrels, of which 195,301 barrels were Scotch; and of those exported, 149,926 barrels were sent to and disposed of in Ireland.

The entire quantity of herrings taken by Scottish boats, and cured both for home use and exportation, was 495,589 barrels; the total by English and Scotch 555,559¾ barrels; but this return does not include the Yarmouth fishery, the herrings there being always smoked, or made into what are called red herrings.

We need not describe the Prussian and other methods, as they resemble some one or other of those already mentioned. Come we now to our own, which we have purposely reserved to the last.

Amongst the fishermen of Ireland, the men of Kinsale have long been the admitted leaders; and the Kinsale hookers are celebrated throughout the nautical world as among the best sea-boats that ever weathered a gale. They are half-decked vessels, with one mast, carrying a fore and aft mainsail, foresail, and jib, and are usually manned by four men and a boy. They are seldom used in the herring fishery, being for the most part confined to the deep-sea line fishery upon the Nymph bank, where cod, ling, hake, haddock, turbot, plaice, &c., abound in such quantity that many persons affirm it to be second only to the banks of Newfoundland. But the usual mode of fishing for herrings, and which is adopted all along the south, south-west, and west coast of Ireland, especially at Valencia and Kenmare, is with the deep-sea seine. This is formed sometimes for the express purpose, but frequently by a subscription of nets. Fifteen men bring a drift-net each, 20 fathoms or 120 feet in length, and 5 fathoms or 30 feet in depth; these are all joined together, five nets in length, and three in depth, so that the whole seine is 600 feet in length and 90 feet in depth, with a cork-rope (that is, a rope having large pieces of cork attached to it at intervals) at the top, and leaden sinkers attached to the foot-rope, which unites all the nets at the bottom. Two warps of 60 fathoms each are requisite, and there are brails (small half-inch ropes) attached to the foot-rope, which are of use to haul upon, in order to purse up the net and prevent the fish from escaping.

The seine is shot from a boat whilst it is being pulled round the shoal of fish. All having been thrown over, the warp is hauled upon until the net is brought into ten fathoms’ depth of water, when the brails and foot-rope are hauled in, and the fish is tucked into the largest boat. In this manner 80,000 to 100,000 herrings (about 100 barrels) may be taken at a haul. But where the people are too poor to supply themselves with nets or boats, many contrivances are made use of. For boats, the curragh, made of wicker and covered with a horse’s skin, or canvass pitched, is used, and often even this cannot be had; sometimes the people load a horse with the nets, mount him and swim him out, shooting the nets from his back; and for nets, in many places, the people use their sheets, blankets, and quilts, which they subscribe and sew together, often to the number of sixty, and the fish thus taken are divided in due proportion amongst the subscribers.

After the foreign statistics which we have laid before our readers, they will doubtless expect us to inform them how many vessels and what number of hands are now employed in the Irish fishery. This, however, we are unable to do. The Commissioners of the Herring Fishery have their jurisdiction confined to Scotland and England, almost exclusively to Scotland, the fishery of which is thriving under their fostering care in a most surprising manner. By their judicious attention to the encouragement of careful curing, and the distribution of small aids in money to poor fishermen, the number of boats employed in 1839 exceeded that of the former year by 78; and the progressive increase in the fishery is fully exemplified by the following table, showing the quantity of herrings cured during the five years preceding the return now before us:—

| Year | 1835 | 277,317 | barrels. |

| ” | 1836 | 497,614¾ | ” |

| ” | 1837 | 397,829¼ | ” |

| ” | 1838 | 507,774¾ | ” |

| ” | 1839 | 555,559¾ | ” |

By this table it appears that the Scotch fishery has doubled its amount in five years, without any description of bounty being given. It may, however, be as well to state, before concluding this paper, that it appears, by the Reports of the Irish Commissioners, whose sittings terminated in the year 1830, that during the time that Ireland possessed a Fishery Board, the number of persons employed in the fishery had more than doubled. At the time of the first appointment of Commissioners of Irish Fisheries in 1819, the number of men employed was estimated at 30,000. By the first return which they could venture to pronounce accurate, being for the year ending 5th April 1822, the number was 36,192 men; 5th April 1823, the number was 44,892 men, being an increase of 8700; at 5th April 1824, the number was 49,448, being an increase on the preceding year of 4556; 5th April 1825, the number was 52,482, being an increase on the preceding year of 3034; and the numbers went on regularly progressing every year during the existence of the Board, until its termination, as the following extract from the last Report will best exhibit. It is for the year 1830, at which time the bounty had been reduced to one shilling per barrel:—

“The Commissioners have still the gratification to find, from the returns made by the local inspectors, that the number of fishermen still continues to experience a yearly increase. The gross amount, as taken from the returns of the preceding year, was 63,421 men. The gross amount, as taken from the returns of the present year, is 64,771 men, being an increase on the past year of 1350 men.”

By the same report it appeared that the number of decked vessels was 345; tonnage 9810; men 2147—half-decked vessels 769; tonnage 9457; men 3852—row-boats 9522; men 46,212.

The quantity of herrings cured for bounty in the year ending 5th April 1830, was 16,855 barrels, the bounty on which was £842 15s.

The tonnage bounty paid to vessels engaged in the cod and ling fishery was £829 10s; and the bounty on cured cod, &c. was £960.

There is not in the reports that we have seen any attempt at estimating the quantity of herrings caught, which is somewhat extraordinary, considering the accuracy with which the number of fishermen, curers, coopers, &c., was ascertained; but the quantity cured is given above.

Whilst, however, the number of fishermen employed in the fisheries generally, increased so very considerably during the period that the Irish Fishery Board was in operation, it is an extraordinary, and to us inexplicable fact, that the quantity of herrings cured for bounty in any one season never exceeded 16,855 barrels, so that even the high bounty of 4s per barrel was not sufficient to induce the Irish fishermen to cure their herrings in a proper manner. In short, the fishery board, in so far as the primary object of its formation was concerned, was totally inoperative, and the people of this country were as dependent then as now upon the Scotch curers for the requisite supply of the staple luxury of the poorer classes.

It is impossible to say to what extent the fisheries may have fallen off, if at all, in Ireland, since the abolition of the fishery board; but as the quantity of salted herrings imported into Ireland from Scotland has not materially increased since, it may be presumed that as many herrings are caught and cured now as at any former period.

The alleged decline of the Irish fisheries has by many been attributed entirely to the withdrawal of the bounties and the fishery board. But when we consider the exceedingly trifling amount of bounty paid on herrings in any one year, the discontinuance of so small a sum as £842 15s 7d (the amount in 1829-30) could not possibly have any perceptible influence upon a branch of industry which gave employment to 75,366 persons.

Nor could the discontinuance of the grants made for harbours and small loans to poor fishermen have produced any material influence upon the fisheries, as the total amount advanced in ten years for these two objects was only £39,508 18s 2d, or less than £4000 a-year.

There is then but one other point of view in which the withdrawal of the fishery board could have operated injuriously, namely, the absence of that supervision and authority in regulating the fisheries which the officers of the board exercised to a certain extent, and which in our opinion ought to have been continued.

The various modes of curing herrings will form the subject of a future article.

[The following specimens of the Icelandic Sagas have been closely translated for the Irish Penny Journal, from the publications of the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries, Copenhagen.]

And now the enemy of the whole human race, the devil himself, saw how his kingdom began to be laid waste, he who always persecutes human nature, and he saw how much on the other hand God’s kingdom prospered and increased; thereat he now felt great envy, and he puts on the human form, because he could so much the more easily deceive men, if he looked like a man himself. It so happened that King Olave was on a visit at Œgvald’s Ness,[2] about the anniversary of our Lord Jesus Christ’s nativity; and as all were regularly seated in the evening, and preparations were making for the drinking bout, and they were waiting until the royal table should be covered, there came an old one-eyed man into the hall with a silk hat on his head; he was very talkative, and could relate divers kinds of things; he was led forward before the king, who asked him the news, to which he replied, that he could relate various matters about the ancient kings and their battles. The king asked whether he knew who Œgvald was, he whom the Ness was called after. He answered, “He dwelt here on the Ness, and dearly loved a cow, so that she would follow him wherever he led her, and he would drink her milk; and therefore people that love cattle say that man and cow shall go together. This king fought many a battle, and once he strove with the king of Skorestrand; in that battle fell many a man, and there fell also King Œgvald, and he was afterwards buried aloft here on the Ness, and his barrow will be found here a little way from the house; in the other barrow lies the cow.” The drinking bout was now held according to usage, and all the diversions that had been appointed. Afterwards many went away to sleep. Then the king had that old man called to him, and he sat on the footstool by the king’s bed, and the king asked him about many matters, which he explained well, and like an experienced man. And when he had related much and explained many things well, the king became constantly the more desirous to hear him; he therefore staid awake a great part of the night, and continued to ask him about many things. At last the bishop reminded him in a few words that the king should stop speaking with the man; but the king thought he had related a part, but that another was still wanting. Far in the night, however, the king at last fell asleep, but awoke soon after, and asked whether the stranger was awake; he did not answer. The king said to the watchers that they should lead him up, but he was not found. The king then stood up, had his cupbearer and cook called to him, and asked whether any unknown man had gone to them when they were preparing the guest-chamber. The head cook said, “There came a little while ago, sire, a man to us, and said to me, as I was preparing the meat for a savoury dish for you, ‘Why do you prepare such meat for the king’s table as choice food for him, which is so lean?’ I told him then to get me some fatter and better meat, if he had any such. He said, ‘Come with me, and I will show you some fat and good meat, which is fit for a king’s table.’ And he led me to a house, and showed me two sides of very fat flesh; and this have I prepared for you, sire!” The king now saw it was a wile of the devil, and said to the cook, “Take that meat now, and cast it into the sea, that none may eat thereof; and if any one tastes of it, he will quickly die. But whom do you suppose that devil to have been, the stranger guest?” “We know not,” said they, “who it is.” The king said, “I believe that devil took upon himself Odin’s form.” According to the king’s command the meat was carried out, and cast into the sea; but the stranger was nowhere found, and search was made for him round about the Ness, according to the king’s commandment.—From Olave Tryggvason’s Saga.

[2] The Norse word which becomes ness as the termination of several British localities and The Noze in our maps of Norway, means “promontory” (literally “nose”) and must not be confounded with The Ness in the county of Londonderry, which is in Irish “the waterfall.”

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; John Menzies, Prince’s Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.