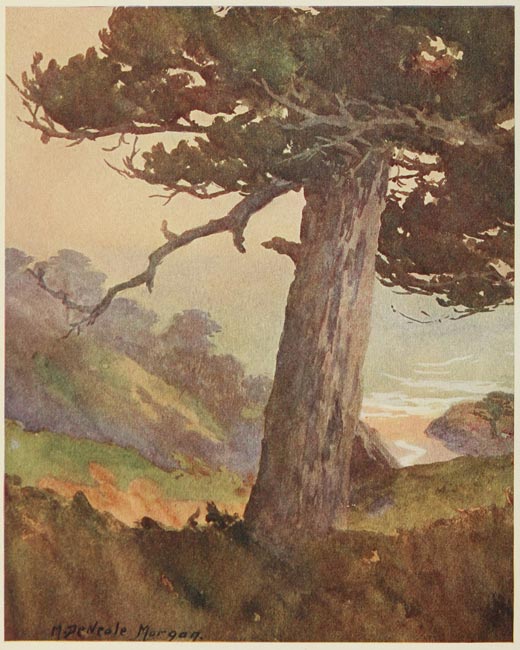

THE GATE OF VAL PAISO CANYON, MONTEREY

From Original Painting by M. De Neale Morgan

Title: On Sunset Highways: A Book of Motor Rambles in California

Author: Thos. D. Murphy

Release date: July 25, 2018 [eBook #57580]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive. The map and cover are courtesy of the

California History Room, California State Library,

Sacramento, California.)

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

"SEE AMERICA FIRST" SERIES

Each in one volume, decorative cover, profusely illustrated

| CALIFORNIA, ROMANTIC AND BEAUTIFUL | |

| By George Wharton James | $6.00 |

| NEW MEXICO: The Land of the Delight Makers | |

| By George Wharton James | $6.00 |

| SEVEN WONDERLANDS OF THE AMERICAN WEST | |

| By Thomas D. Murphy | $6.00 |

| A WONDERLAND OF THE EAST: The Mountain and Lake Region of New England and Eastern New York | |

| By William Copeman Kitchin, Ph.D. | $6.00 |

| ON SUNSET HIGHWAYS (California) | |

| By Thomas D. Murphy | $6.00 |

| TEXAS, THE MARVELLOUS | |

| By Nevin O. Winter | $6.00 |

| ARIZONA, THE WONDERLAND | |

| By George Wharton James | $6.00 |

| COLORADO: THE QUEEN JEWEL OF THE ROCKIES | |

| By Mae Lacy Baggs | $6.00 |

| OREGON, THE PICTURESQUE | |

| By Thomas D. Murphy | $6.00 |

| FLORIDA, THE LAND OF ENCHANTMENT | |

| By Nevin O. Winter | $6.00 |

| SUNSET CANADA (British Columbia and Beyond) | |

| By Archie Bell | $6.00 |

| ALASKA, OUR BEAUTIFUL NORTHLAND OF OPPORTUNITY | |

| By Agnes Rush Burr | $6.00 |

| UTAH: THE LAND OF BLOSSOMING VALLEYS | |

| By George Wharton James | $6.00 |

| NEW ENGLAND HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS FROM A MOTOR CAR | |

| By Thomas D. Murphy | $6.00 |

| VIRGINIA: THE OLD DOMINION. As seen from its Colonial waterway, the Historic River James | |

| By Frank and Cortelle Hutchins | $5.00 |

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

On Sunset

Highways

A Book of Motor Rambles

in California

New and Revised Edition

BY THOS. D. MURPHY

AUTHOR OF

"IN UNFAMILIAR ENGLAND WITH A MOTOR CAR,"

"SEVEN WONDERLANDS OF THE AMERICAN WEST,"

"NEW ENGLAND HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS," ETC.

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOR FROM ORIGINAL PAINTINGS,

MAINLY BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS, AND THIRTY-TWO

DUOGRAVURES FROM PHOTOGRAPHS.

ALSO ROAD MAP COVERING ENTIRE STATE.

BOSTON

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1915, by

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

Copyright, 1921, by

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

All Rights Reserved

Made in U. S. A.

The publishers tell me that the first large edition of "On Sunset Highways" has been exhausted and that the steady demand for the book warrants a reprint. I have, therefore, improved the occasion to revise the text in many places and to add descriptive sketches of several worth-while tours we subsequently made. As it stands now I think the book covers most of the ground of especial interest to the average motorist in California.

One can not get the best idea of this wonderful country from the railway train or even from the splendid electric system that covers most of the country surrounding Los Angeles. The motor that takes one into the deep recesses of hill and valley to infrequented nooks along the seashore and, above all, to the slopes and summits of the mountains, is surely the nearest approach to the ideal.

The California of to-day is even more of a motor paradise than when we made our first ventures on her highroads. There has been a substantial increase in her improved highways and every subsequent year will no doubt see still further extensions. The beauty and variety of her scenery will always remain and good roads will give easy access to many hereto almost inaccessible sections. And the charm of her romantic history will not decrease as the years go by. There is a growing interest in the still existing relics of the mission days and the Spanish occupation which we may hope will lead to their restoration and preservation. All of which will make motoring in California more delightful than ever.

I do not pretend in this modest volume to have covered everything worth while in this vast state; neither have I chosen routes so difficult as to be inaccessible to the ordinary motor tourist. I have not attempted a guide-book in the usual sense; my first aim has been to reflect by description and picture something of the charm of this favored country; but I hope that the book may not be unacceptable as a traveling companion to the motor tourist who follows us. Conditions of roads and towns change so rapidly in California that due allowance must be made by anyone who uses the book in this capacity. Up-to-the-minute information as to road conditions and touring conveniences may be had at the Automobile Club in Los Angeles or at any of its dozen branches in other towns in Southern California.

In choosing the paintings to be reproduced as color illustrations, I was impressed with the wealth of material I discovered; in fact, California artists have developed a distinctive school of American landscape art. With the wealth and variety of subject matter at the command of these enthusiastic western painters, it is safe to predict that their work is destined to rank with the best produced in America—and I believe that the examples which I show will amply warrant this prediction.

THE AUTHOR.

| I | A MOTOR PARADISE | 1 |

| II | ROUND ABOUT LOS ANGELES | 19 |

| III | ROUND ABOUT LOS ANGELES | 43 |

| IV | ROUND ABOUT LOS ANGELES | 62 |

| V | THE INLAND ROUTE TO SAN DIEGO | 82 |

| VI | ROUND ABOUT SAN DIEGO | 110 |

| VII | THE IMPERIAL VALLEY AND THE SAN DIEGO BACK COUNTRY | 126 |

| VIII | THE SAN DIEGO COAST ROUTE | 150 |

| IX | SANTA BARBARA | 178 |

| X | SANTA BARBARA TO MONTEREY | 198 |

| XI | THE CHARM OF OLD MONTEREY | 225 |

| XII | MEANDERINGS FROM MONTEREY TO SAN FRANCISCO | 252 |

| XIII | TO BEAUTIFUL CLEAR LAKE VALLEY | 277 |

| XIV | THE NETHERLANDS OF CALIFORNIA | 296 |

| XV | A CHAPTER OF ODDS AND ENDS | 311 |

| XVI | OUR RUN TO YOSEMITE | 343 |

| XVII | LAKE TAHOE | 358 |

In making acknowledgment to the photographers through whose courtesy I am able to present the beautiful monotones of California's scenery and historic missions, I can only say that I think that the artistic beauty and sentiment evinced in every one of these pictures entitles its author to be styled artist as well as photographer. These enthusiastic Californians—Dassonville, Pillsbury, Putnam, and Taylor—are thoroughly in love with their work and every photograph they take has the merits of an original composition. I had the privilege of selecting, from many thousands, the examples shown in this book and while I doubt if thirty-two pictures of higher average could be found, it must not be forgotten that these artists have hundreds of other delightful views that would grace any collection. I heartily recommend any reader of the book to visit these studios if he desires appropriate and enduring mementos of California's scenic beauty.

Detailed maps covering any proposed tour can be had by application to the Automobile Club of Southern California.

The Author.

| COLOR PLATES | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| THE GATE OF VAL PAISO CANYON, MONTEREY | Frontispiece |

| HILLSIDE NEAR MONTEREY | 1 |

| CLOISTERS, SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO | 72 |

| PALM CANYON | 132 |

| WILD MUSTARD, MIRAMAR | 194 |

| POPPIES AND LUPINES | 198 |

| OAKS NEAR PASO ROBLES | 214 |

| CYPRESS POINT, MONTEREY | 225 |

| ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON HOUSE | 234 |

| EVENING NEAR MONTEREY | 242 |

| A FOREST GLADE | 246 |

| THE PACIFIC NEAR GOLDEN GATE | 277 |

| A DISTANT VIEW OF MT. TAMALPAIS | 311 |

| VERNAL FALLS, YOSEMITE | 350 |

| NEVADA FALL, YOSEMITE | 352 |

| ON THE SHORE OF LAKE TAHOE | 372 |

| DUOGRAVURES | |

| SAN GABRIEL MISSION | 64 |

| CORRIDOR, SAN FERNANDO MISSION | 74 |

| CAMPANILE, PALA MISSION | 106 |

| SAN DIEGO MISSION | 110 |

| A BACK COUNTRY OAK | 134 |

| ROAD TO WARNER'S HOT SPRINGS | 146 |

| A BACK COUNTRY VALLEY | 148 |

| TORREY PINES, NEAR LA JOLLA | 158 |

| RUINS OF CHAPEL, SAN LUIS REY | 164 |

| ENTRANCE TO SAN LUIS REY CEMETERY | 166 |

| FATHER O'KEEFE AT SAN LUIS REY | 168 |

| A CORNER OF CAPISTRANO | 170 |

| ARCHES, CAPISTRANO | 172 |

| RUINED CLOISTERS, CAPISTRANO | 174 |

| RUINS OF CAPISTRANO CHURCH BY MOONLIGHT | 176 |

| GIANT GRAPEVINE NEAR CARPINTERIA | 184 |

| ARCADE, SANTA BARBARA | 186 |

| THE OLD CEMETERY, SANTA BARBARA | 188 |

| THE FORBIDDEN GARDEN, SANTA BARBARA | 190 |

| BELL TOWER, SANTA YNEZ | 204 |

| INTERIOR CHURCH, SAN MIGUEL | 216 |

| ARCADE, SAN MIGUEL | 218 |

| DRIVE THROUGH GROUNDS, DEL MONTE HOTEL | 228 |

| CARMEL MISSION | 236 |

| CYPRESSES, POINT LOBOS | 240 |

| OLD CYPRESSES ON THE SEVENTEEN-MILE DRIVE, MONTEREY | 244 |

| CHURCH AND CEMETERY, SAN JUAN BAUTISTA | 252 |

| A LAKE COUNTY BYWAY | 284 |

| ON THE SLOPES OF MT. ST. HELENA | 290 |

| SAN ANTONIO DE PADUA | 328 |

| RUINS OF LA PURISIMA | 332 |

| A ROAD THROUGH THE REDWOODS | 338 |

| MAPS | |

| ROAD MAP OF CALIFORNIA | 374 |

On Sunset Highways

California! The very name had a strange fascination for me ere I set foot on the soil of the Golden State. Its romantic story and the enthusiasm of those who had made the (to me) wonderful journey to the favored country by the great ocean of the West had interested and delighted me as a child, though I thought of it then as some dim, far-away El Dorado that lay on the borders of fairyland. My first visit was not under circumstances tending to dissolve the spell, for it was on my wedding trip that I first saw the land of palms and flowers, orange groves, snowy mountains, sunny beaches, and blue seas, and I found little to dispel the rosy dreams I had preconceived. This was long enough ago to bring a great proportion of the growth and progress of the state within the scope of my own experience. We saw Los Angeles, then an aspiring town of forty thousand, giving promise of the truly metropolitan city it has since become; Pasadena was a straggling village; and around the two towns were wide areas of open country now teeming with ambitious suburbs. We visited never-to-be-forgotten Del Monte and saw the old San Francisco ere fire and quake had swept away its most distinctive and romantic features—the Nob Hill palaces and old-time Chinatown. 2

Some years intervened between this and our second visit, when we found the City of the Angels a thriving metropolis with hundreds of palatial structures and the most perfect system of interurban transportation to be found anywhere, while its northern rival had risen from debris and ashes in serried ranks of concrete and steel. A tour of the Yosemite gave us new ideas of California's scenic grandeur; there began to dawn on us vistas of the endless possibilities that the Golden State offers to the tourist and we resolved on a longer sojourn at the first favorable opportunity.

A week's stay in Los Angeles and a free use of the Pacific Electric gave us a fair idea of the city and its lesser neighbors, but we found ourselves longing for the country roads and retired nooks of mountain and beach inaccessible by railway train and tram car. We felt we should never be satisfied until we had explored this wonderland by motor—which the experience of three long tours in Europe had proved to us the only way to really see much of a country in the limits of a summer vacation.

And so it chanced that a year or two later we found ourselves on the streets of Los Angeles with our trusty friend of the winged wheels, intent on exploring the nooks and corners of Sunset Land. We wondered why we had been so long in coming—why we had taken our car three times to Europe before we brought it to California; and the marvel grew on us as we passed out of the streets of the city on to the perfect boulevard that led through green fields to the western Venice by the sea. It is of the experience of the several succeeding weeks 3 and of a like tour during the two following years that this unpretentious chronicle has to deal. And my excuse for inditing it must be that it is first of all a chronicle of a motor car; for while books galore have been written on California by railroad and horseback travelers as well as by those who pursued the leisurely and good old method of the Franciscan fathers, no one, so far as I know, has written of an extended experience at the steering wheel of our modern annihilator of distance.

It seems a little strange, too, for Southern California is easily the motorist's paradise over all other places on this mundane sphere. It has more cars to the population—twice over—and they are in use a greater portion of the year than in any other section of similar size in the world and probably more outside cars are to be seen on its streets and highways than in any other locality in the United States. The matchless climate and the ever-increasing mileage of fine roads, with the endless array of places worth visiting, insure the maximum of service and pleasure to the fortunate owner of a car, regardless of its name-plate or pedigree. The climate needs no encomiums from me, for is it not heralded and descanted upon by all true Californians and by every wayfarer, be his sojourn ever so brief?—but a few words on the wonders already achieved in road-building and the vast plans for the immediate future will surely be of interest. I am conscious that any data concerning the progress of California are liable to become obsolete overnight, as it were, but if I were to confine myself to the unchanging in this 4 vast commonwealth, there would be little but the sea and the mountains to write about.

Los Angeles County was the leader in good roads construction and at the time of which I write had completed about three hundred and fifty miles of modern highway at a cost of nearly five million dollars. I know of nothing in Europe superior—and very little equal—to the splendid system of macadam boulevards that radiate from the Queen City of the Southwest. The asphalted surface is smooth and dustless and the skill of the engineer is everywhere evident. There are no heavy grades; straight lines or long sweeping curves prevail throughout. Added to this is a considerable mileage of privately constructed road built by land improvement companies to promote various tracts about the city, one concern alone having spent more than half a million dollars in this work. Further additions are projected by the county and an excellent maintenance plan has been devised, for the authorities have wisely recognized that the upkeep of these splendid roads is a problem equal in importance with building them. This, however, is not so serious a matter as in the East, owing to the absence of frost, the great enemy of roads of this type.

Since the foregoing paragraph was first published (1915) the good work has gone steadily on and despite the sharp check that the World War administered to public enterprises, Los Angeles County has materially added to and improved her already extensive mileage of modern roads. A new boulevard connects the beach towns between Redondo and Venice; a marvelous scenic road replaces 5 the old-time trail in Topango Canyon and the new Hollywood Mountain Road is one of the most notable achievements of highway engineering in all California. Many new laterals have been completed in the level section about Downey and Artesia and numerous boulevards opened in the foothill region. Besides all this the main highways have been improved and in some cases—as of Long Beach Boulevard—entirely rebuilt. In the city itself there has been vast improvement and extension of the streets and boulevards so that more than ever this favored section deserves to be termed the paradise of the motorist.

San Diego County has set a like example in this good work, having expended a million and a half on her highways and authorized a bond issue of two and one-half millions more, none of which has been as yet expended. While the highways of this county do not equal the model excellence of those of Los Angeles County, the foundation of a splendid system has been laid. Here the engineering problem was a more serious one, for there is little but rugged hills within the boundaries of the county. Other counties are in various stages of highway building; still others have bond issues under consideration—and it is safe to say that when this book comes from the press there will not be a county in Southern California that has not begun permanent road improvement on its own account.

I say "on its own account" because whatever it may do of its own motion, nearly every county in the state is assured of considerable mileage of the new state highway system, now partially completed, 6 while the remainder is under construction or located and surveyed. The first bond issue of eighteen million dollars was authorized by the state several years ago, a second issue of fifteen millions was voted in 1916, and another of forty millions a year later, making in all seventy-three millions, of which, at this writing, thirty-nine millions is unexpended. Counties have issued about forty-two millions more. It is estimated that to complete the full highway program the state must raise one hundred millions additional by bond issues.

The completed system contemplates two great trunk lines from San Diego to the Oregon border, one route roughly following the coast and the other well inland, while lateral branches are to connect all county seats not directly reached. Branches will also extend to the Imperial Valley and along the Eastern Sierras as far as Independence and in time across the Cajon Pass through the Mohave Desert to Needles on the Colorado River. California's wealth of materials (granite, sand, limestone, and asphaltum) and their accessibility should give the maximum mileage for money expended. This was estimated by a veteran Pittsburgh highway contractor whom I chanced to meet in the Yosemite, at fully twice as great as could be built in his locality for the same expenditure.

California was a pioneer in improved roads and it is not strange that mistakes were made in some of the earlier work, chiefly in building roadways too narrow and too light to stand the constantly increasing heavy traffic. The Automobile Club of Southern California, in conjunction with 7 the State Automobile Association, recently made an exhaustive investigation and report of existing highway conditions which should do much to prevent repetition of mistakes in roads still to be built. The State Highway Commission, while admitting that some of the earlier highways might better have been built heavier and wider, points out that this would have cut the mileage at least half; and also that at the time these roads were contracted for, the extent that heavy trucking would assume was not fully realized. Work on new roads was generally suspended during the war and is still delayed by high costs and the difficulty of selling bonds.

At this writing (1921) the two trunk lines from San Diego to San Francisco are practically completed and the motorist between these points, whether on coast or inland route, may pursue the even tenor of his way over the smooth, dustless, asphalted surface at whatever speed he may consider prudent, though the limit of thirty-five miles now allowed in the open country under certain restrictions leaves little excuse for excessive speeding. It is not uncommon to make the trip over the inland route, about six hundred and fifty miles, in three days, while a day longer should be allowed for the coast run.

In parts where the following narrative covers our tours made before much of the new road was finished, I shall not alter my descriptions and they will afford the reader an opportunity of comparing the present improved highways with conditions that existed only yesterday, as it were.

Road improvement has been active in the 8 northern counties for several years, especially around San Francisco. I have gone into the details concerning this section in my book on Oregon and Northern California, and will not repeat the matter here, since the scope of this work must be largely confined to the south. It is no exaggeration, however, to say that to-day California is unsurpassed by any other state in mileage and excellence of improved roads and when the projects under way are carried out she will easily take first rank in these important particulars unless more competition develops than is now apparent. Thus she supplies the first requisite for the motor enthusiast, though some may declare her matchless climate of equal advantage to the tourist.

If the motor enthusiast of the Golden State can take no credit to himself for the climate, he is surely entitled to no end of credit for the advanced state of affairs in public highway improvement. In proportion to the population he is more numerous in Southern California than anywhere else in the world, and we might therefore expect to find a strong and effective organization of motorists in Los Angeles. In this we are not disappointed, for the Automobile Club of Southern California has a membership of more than fifty thousand; it was but seven thousand when the first edition of this book was printed in 1915—a growth which speaks volumes for its strides in public appreciation. Its territory comprises only half a single state, yet its membership surpasses that of its nearest rival by more than two to one. It makes no pretense at being a "social" club, all its energies being devoted 9 to promoting the welfare and interests of the motorist in its field of action, and so important and far-reaching are its activities that the benefits it confers on the car owners of Southern California are by no means limited to the membership. Practically every owner and driver of a car is indebted to the club in more ways than I can enumerate and as this fact has gained recognition the membership has increased by leaps and bounds. I remember when the sense of obligation to become a member was forced upon me by the road signs which served me almost hourly when touring and this is perhaps the feature of the club's work which first impresses the newcomer. Everywhere in the southern half of California and even on a transcontinental highway the familiar white diamond-shaped signboard greets one's sight—often a friend in need, saving time and annoyance. The maps prepared and supplied by the club were even a greater necessity and this service has been amplified and extended until it not only covers every detail of the highways and byways of California, but also includes the main roads of adjacent states and one transcontinental route as well. These maps are frequently revised and up-to-the-minute road information may always be had by application to the Touring Department of the club.

When we planned our first tour, at a time when road conditions were vastly different from what they are now, our first move was to seek the assistance of this club, which was readily given as a courtesy to a visiting motorist. The desired information was freely and cheerfully supplied, but I 10 could not help feeling, after experiencing so many benefits from the work of the club, that I was under obligations to become a member. And I am sure that even the transient motorist, though he plans a tour of but a few weeks, will be well repaid—and have a clearer conscience—should his first move be to take membership in this live organization.

We found the club an unerring source of information as to the most practicable route to take on a proposed tour, the best way out of the city, and the general condition of the roads to be covered. The club is also an authority on hotels, garages and "objects of interest" generally in the territory covered by its activities. Besides the main organization, which occupies its own building at Adams and Figueroa Streets, Los Angeles, there are numerous branch offices in the principal towns of the counties of Southern California, which in their localities can fulfill most of the functions of the club.

The club maintains a department of free legal advice and its membership card is generally sufficient bail for members charged with violating the speed or traffic regulations. It is always willing to back its members to the limit when the presumption of being right is in their favor, but it has no sympathy with the reckless joy rider and lawbreaker and does all it can to discourage such practices. It has been a powerful influence in obtaining sane and practical motor car legislation, such as raising the speed limit in the open country to thirty-five miles per hour, and providing severer penalties against theft of motor cars. One of the most valuable services of the club has been its relentless pursuit 11 and prosecution of motor car thieves and the recovery of a large percentage of stolen cars. In fact, Los Angeles stands at the head of the large cities of the country in a minimum of net losses of cars by theft and the club can justly claim credit for this. The club has also done much to abate the former scandalous practices of many towns in fixing a very low speed limit with a view of helping out local finances by collecting heavy fines. This is now regulated by state laws and the motorist who is willing to play fair with the public will not suffer much annoyance. The efforts of the club to eliminate what it considers double taxation of its members who must pay both a horse power fee and a heavy property tax were not successful, but the California motorist has the consolation of knowing that all taxes, fines and fees affecting the motor car go to the good cause of road maintenance.

Another important service rendered by the club is the insurance of its members against all the hazards connected with operation of an automobile. Fire, theft, liability, collision, etc., are written practically at cost. The club also maintains patrol and trouble cars which respond free of cost to members in difficulty.

Besides all this, the club deserves much credit for the advanced position of California in highway improvement. It has done much to create the public sentiment which made the bond issues possible and it has rendered valuable assistance in surveying and building the new roads. It has kept in constant touch with the State Highway Commission and its superior knowledge of the best and shortest routes 12 has been of great service in locating the new state roads.

My story is to deal with several sojourns in the Sunset State during the months of April and May of consecutive years. We shipped our car by rail in care of a Los Angeles garage and so many follow this practice that the local agents are prepared to receive and properly care for the particular machines which they represent and several freight-forwarding companies also make a specialty of this service. On our arrival our car was ready for the road and it proved extremely serviceable in getting us located. Los Angeles is the logical center from which to explore the southern half of the state and we were fortunate in securing a furnished house in a good part of the city without much delay. We found a fair percentage of the Los Angeles population ready to move out on short notice and to turn over to us their homes and everything in them—for a consideration, of course.

On our second sojourn in the city we varied things by renting furnished apartments, of which there are an endless number and variety to choose from, and if this plan did not prove quite so satisfactory and comfortable as the house, it was less expensive. We also had experience on several later occasions with numerous hotels—Los Angeles, as might be expected, is well supplied with hotels of all degrees of merit—but our experience in pre-war days would hardly be representative of the present time, especially when rates are considered. The Alexandria and Angelus were—and doubtless are—up 13 to the usual metropolitan standards of service and comfort, with charges to correspond. The Gates, where we stopped much longer, was a cleanly and comfortable hotel with lower rates and represents a large class of similar establishments such as the Clark, the Stillwell, the Trinity, the Hayward, the Roslyn, the Savoy, and many others. One year we tried the Leighton, which is beautifully located on Westlake Park and typical of several outlying hotels that afford more quiet and greater convenience for parking and handling one's car than can be found in the business district. Others in this class are the Darby, the Hershey Arms, the Hollywood, and the Alvarado. Los Angeles, for all its preeminence as a tourist city, was long without a resort hotel of the first magnitude, leaving the famous Pasadena hostelries such as the Green, Raymond, Maryland and Huntington, to cater to the class of patrons who do not figure costs in their quest for the luxurious in hotel service. This shortage was supplied in 1920 by the erection of the Ambassador Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard—one of the largest resort hotels in the world. The building is surrounded by spacious grounds and the property is said to represent an investment of $5,000,000. It is one of the "objects of interest" in Los Angeles and will be visited by many tourists who may not care to pay the price to become regular guests. After our experience with hotels, apartments and rented houses, we finally acquired a home of our own in the "Queen City of the Southwest," which, of course, is the most satisfactory 14 plan of all, though not necessarily the cheapest.

Prior to the Great War Los Angeles had the reputation of being a place where one could live well at very moderate cost and hotels and restaurants gave the very best for little money. This was all sadly changed in the wave of profiteering during and following the war. The city acquired a rather unenviable reputation for charging the tourist all the traffic would bear—and sometimes a little more—until finally Government statistics ranked Los Angeles number one in the cost of living among cities of its class. The city council undertook to combat the tendency to "grab" by passing an ordinance limiting the percentage of rental an owner might charge on his property—a move naturally contested in the courts. At this writing, however, (1921), the tendency of prices is distinctly downward and this may reasonably be expected to continue until a fair basis is reached. It is not likely, however, that pre-war prices will ever return on many items, but it is certain that Los Angeles will again take rank as a city where one may live permanently or for a time at comparatively moderate cost.

Public utilities of the city never advanced their prices to compare with private interests. You can still ride miles on a street car for a nickel and telephone, gas and electric concerns get only slightly higher rates than before the war. Taxes have advanced by leaps and bounds, but are frequently excused by pointing out that nowhere do you get so much for your tax money as in California. 15

Naturally, the automobile and allied industries loom large in Los Angeles. Garages from the most palatial and perfectly equipped to the veriest hole-in-the-wall abound in all parts of the town. Prices for service and repairs vary greatly but the level is high—probably one hundred per cent above pre-war figures. Competition, however, is strong and the tendency is downward; but only a general wage lowering can bring back the old-time prices. Gasoline is generally cheaper than in the East, while other supplies cost about the same. The second-hand car business has reached vast proportions, many dealers occupying vacant lots where old cars of all models and degrees brave the sun—and sometimes the rain—while waiting for a purchaser. Cars are sold with agreement to buy back at the end of a tour and are rented without driver to responsible parties. You do not have to bring your own car to enjoy a motor tour in California; in fact this practice is not so common as it used to be except in case of the highest-grade cars.

Another plan is to drive your own car from your Eastern home to California and sell it when ready to go back. This was done very satisfactorily during the period of the car shortage and high prices for used cars following the war, but under normal conditions would likely involve considerable sacrifice. The ideal method for the motorist who has the time and patience is to make the round trip to California in his own car, coming, say, over the Lincoln Highway and returning over the Santa Fe Trail or vice versa, according to the time of the year. The latter averages by far the best of the 16 transcontinental roads and is passable for a greater period of the year than any other. In fact, it is an all-year-round route except for the Raton Pass in New Mexico, and this may be avoided by a detour into Texas. This route has been surveyed and signed by the Automobile Club of Southern California and is being steadily improved, especially in the Western states.

Although California has perhaps the best all-the-year-round climate for motoring, it was our impression that the months of April and May are the most delightful for extensive touring. The winter rains will have ceased—though we found our first April and a recent May notable exceptions—and there is more freedom from the dust that becomes troublesome in some localities later in the summer. The country will be at its best—snow-caps will still linger on the higher mountains; the foothills will be green and often varied with great dashes of color—white, pale yellow, blue, or golden yellow, as some particular wild flower gains the mastery. The orange groves will be laden with golden globes and sweet with blossoms, and the roses and other cultivated flowers will still be in their prime. The air will be balmy and pleasant during the day, with a sharp drop towards evening that makes it advisable to keep a good supply of wraps in the car. An occasional shower will hardly interfere with one's going, even on the unimproved country road.

For there is still unimproved country road, despite all I have said in praise of the new highways. A great deal of our touring was over roads seldom good at their best and often quite impassable during 17 the heavy winter rains. There were stretches of "adobe" to remind us of "gumbo" at home; there were miles of heavy sand and there were rough, stone-strewn trails hardly deserving to be called roads at all! These defects are being mended with almost magical rapidity, but California is a vast state and with all her progress it will be years before all her counties attain the Los Angeles standard. We found many primitive bridges and oftener no bridges at all, since in the dry season there is no difficulty in fording the hard-bottom streams, and not infrequently the streams themselves had vanished. But in winter these same streams are often raging torrents that defy crossing for days at a time. During the summer and early autumn months the dust will be deep on unimproved roads and some of the mountain passes will be difficult on this account. So it is easy to see that even California climate does not afford ideal touring conditions the year round. Altogether, the months of April, May, and June afford the best average of roads and weather, despite the occasional showers that one may expect during the earlier part of this period. It is true that during these months a few of the mountain roads will be closed by snow, but one can not have everything his own way, and I believe the beauty of the country and climate at this time will more than offset any enforced omissions. The trip to Yosemite is not practical during this period over existing routes, though it is to be hoped the proposed all-the-year road will be a reality before long. The Lake Tahoe road is seldom open before the middle of June, and this delightful trip can not be taken during 18 the early spring unless the tourist is content with the railway trains.

Our several tours in California aggregated more than thirty thousand miles and extended from Tia Juana to the Oregon border. The scope of this volume, however, is confined to the southern half of the state and the greater part of it deals with the section popularly known as Southern California—the eight counties lying south of Tehachapi Pass. Of course we traversed some roads several times, but we visited most of the interesting points of the section—with some pretty strenuous trips, as will appear in due course of my narrative. We climbed many mountains, visited the endless beaches, stopped at the famous hotels, and did not miss a single one of the twenty or more old Spanish missions. We saw the orange groves and palms of Riverside and Redlands, the great oaks of Paso Robles, the queer old cypresses of Monterey, the Torrey Pines of La Jolla, the lemon groves of San Diego, the vast wheatfields of the San Joaquin and Salinas Valleys, the cherry orchards of San Mateo, the great vineyards of the Napa and Santa Rosa Valleys, the lonely beauty of Clear Lake Valley, the giant trees of Santa Cruz, the Yosemite Valley, Tahoe, the gem of mountain lakes, the blossoming desert of Imperial, and a thousand other things that make California an enchanted land. And the upshot of it all was that we fell in love with the Golden State—so much in love with it that what I set down may be tinged with prejudice; but what story of California is free from this amiable defect? 19

When we first left the confines of the city we steered straight for the sunset; the wayfarer from the far inland states always longs for a glimpse of the ocean and it is usually his first objective. The road, smooth and hard as polished slate, runs for a dozen miles between green fields, with here and there a fringe of palms or eucalyptus trees and showing in many places the encroachments of rapidly growing suburbs. So seductively perfect is the road that the twenty miles slip away almost before we are aware; we find ourselves crossing the canal in Venice and are soon surrounded by the wilderness of "attractions" of this famous resort.

There is little to remind us of its Italian namesake save the wide stretch of sea that breaks into view and an occasional gondola on the tiny canal; in the main it is far more suggestive of Coney Island than of the Queen of the Adriatic. To one who has lost his boyish zeal for "shooting the shoots" and a thousand and one similar startling experiences, or whose curiosity no longer impels him toward freaks of nature and chambers of horror, there will be little diversion save the multifarious phases of humanity always manifest in such surroundings. On gala days it is interesting to differentiate the types that pass before one, from the countryman from the inland states, "doing" California and getting his first 20 glimpse of a metropolitan resort, to the fast young sport from the city, to whom all things have grown common and blase and who has motored down to Venice because he happened to have nowhere else to go.

With the advent of prohibition the atmosphere of the place has noticeably changed—the tipsy joy-rider is not so much in evidence nor is the main highway to the town strewn with wrecked cars as of yore. But for all this, Venice seems as lively as ever and there is no falling off in its popularity as a beach resort. This is evidenced by the prompt reconstruction of the huge amusement pier which was totally destroyed by fire in 1920. It has been replaced by a much larger structure in steel and concrete—a practical guarantee against future conflagrations—and the amusement features are more numerous and varied than of yore. It is still bound to be the Mecca of the tourist and vacationist who needs something a little livelier than he will find in Long Beach and Redondo.

But to return from this little digression—and my reader will have to excuse many such, perhaps, when I get on "motorological" subjects—I was saying that we found little to interest us in the California Venice save odd specimens of humanity—and no doubt we ourselves reciprocated by affording like entertainment to these same odd specimens. After our first trip or two—and the fine boulevards tempted us to a good many—we usually slipped into the narrow "Speedway" connecting the town with Ocean Park and Santa Monica. Why they call it the Speedway I am at a loss to know, for it is 21 barely a dozen feet wide in places and intersected with alleys and streets every few feet, so that the limit of fifteen miles is really dangerously high. The perfect pavement, however, made it the most comfortable route—though there may be better now—and it also takes one through the liveliest part of Ocean Park, another resort very much like Venice and almost continuous with it. These places are full of hotels and lodging-houses, mostly of the less pretentious and inexpensive class, and they are filled during the winter season mainly by Eastern tourists. In the summer the immense bathing beaches attract crowds from the city. The Pacific Electric brings its daily contingent of tourists and the streets are constantly crowded with motors—sometimes hundreds of them. All of which contribute to the animation of the scene in these popular resorts.

In Santa Monica we found quite a different atmosphere; it is a residence town with no "amusement" features and few hotels, depending on its neighbors for these useful adjuncts. It is situated on an eminence overlooking the Pacific and to the north lie the blue ranges of the Santa Monica Mountains, visible from every part of town. Ocean Drive, a broad boulevard, skirts the edge of the promontory, screened in places by rows of palms, through which flashes the blue expanse of the sea. At its northern extremity the drive drops down a sharp grade to the floor of the canyon, which opens on a wide, sandy beach—one of the cleanest and quietest to be found so near Los Angeles.

This canyon, with its huge sycamores and 22 clear creek brawling over the smooth stones, had long been an ideal resort for picnic parties, but in the course of a single year we found it much changed. The hillside had been terraced and laid out with drives and here and there a summer house had sprung up, fresh with paint or stucco. The floor of the valley was also platted and much of the wild-wood effect already gone. All this was the result of a great "boom" in Santa Monica property, largely the work of real estate promoters. Other additions were being planned to the eastward and all signs pointed to rapid growth of the town. It already has many fine residences and cozy bungalows embowered in flowers and shrubbery, among which roses, geraniums and palms of different varieties predominate.

Leaving the town, we usually followed the highway leading through the grounds of the National Soldiers' Home, three or four miles toward the city. This great institution, in a beautiful park with a wealth of semi-tropical flowers and trees, seemed indeed an ideal home for the pathetic, blue-coated veterans who wandered slowly about the winding paths. The highway passes directly through the grounds and one is allowed to run slowly over the network of macadam driveways which wind about the huge buildings. At the time of which I write, there were some thirty-five hundred old soldiers in the Home, few of whom had not reached the age of three score and ten. Their infirmities were evidenced by the slow and even painful manner in which many moved about, by the crowded hospitals, and the deaths—which averaged 23 three daily. True, there were some erect, vigorous old fellows who marched along with something of the spirit that must have animated them a half century ago, but they were the rare exceptions. Visitors are welcomed and shown through all the domestic arrangements of the Home; the old fellows are glad to act in the capacity of guides, affording them, as it does, some relief from the monotony of their daily routine. So perfect are the climatic conditions and so ideally pleasant the surroundings that it seems a pity that the veterans in all such homes over the country might not be gathered here. We were told that this plan is already in contemplation, and it is expected, as the ranks of the veterans are decimated, to finally gather the remnant here, closing all other soldiers' homes. It is to be hoped that the consummation of the plan may not be too long delayed, for surely the benign skies and the open-air life would lengthen the years of many of the nation's honored wards.

We passed through the grounds of the Home many times and stopped more than once to see the aviary—a huge, open-air, wire cage filled with birds of all degrees, from tiny African finches half the size of sparrows to gorgeous red, blue, green, and mottled parrots. Many of these were accomplished conversationalists and it speaks well for the old boys of the Home that there was no profanity in the vocabulary of these queer denizens of the tropics. This and other aviaries which we saw impressed upon us the possibilities of this pleasant fad in California, where the birds can live the year 24 round in the open air in the practical freedom of a large cage.

Returning from the Home one may follow Wilshire Boulevard, which passes through one of the most pretentious sections of the city, ending at beautiful Westlake Park; or he may turn into Sunset Boulevard and pass through Hollywood. A short distance from the Home is Beverly Hills, with its immense hotel—a suburban town where many Los Angeles citizens have summer residences. A vast deal of work has been done by the promoters of the town; the well-paved streets are bordered with roses, geraniums, and rows of palm trees, all skillfully arranged by the landscape-gardener. It is a pretty place, though it seemed to us that the sea winds swept it rather fiercely during several of the visits we made. Another unpleasant feature was the groups of oil derricks which dot the surrounding country, though these will doubtless some time disappear with the exhaustion of the fields. The hotel is of a modified mission type, with solid concrete walls and red tile roof, and its surroundings and appointments are up to the famous California standard at such resorts.

Hollywood is now continuous with the city, but it has lost none of that tropical beauty that has long made it famous. Embowered in flowers and palms, with an occasional lemon grove, its cozy and in some cases palatial homes never fail to charm the newcomer. Once it was known as the home of Paul de Longpre, the flower painter, whose Moorish-looking villa was the goal of the tourist and whose gorgeous creations were a never-failing 25 wonder to the rural art critic. Alas, the once popular artist is dead and his art has been discredited by the wiseacres; he was "photographic"—indeed, they accuse him of producing colored photographs as original compositions. But peace be to the painter's ashes—whether the charge of his detractors be true or not, he delighted thousands with his highly colored representations of the blooms of the Golden State. His home and gardens have undergone extensive changes and improvements and it is still one of the show places of the town.

The Hollywood school buildings are typical of the substantial and handsome structures one sees everywhere in California; in equipment and advanced methods her schools are not surpassed by any state in the Union.

No stretch of road in California—and that is almost saying in all the world—is more tempting to the motorist than the twenty miles between Los Angeles and Long Beach. Broad, nearly level, and almost straight away, with perfect surface and not a depression to jolt or jar a swiftly speeding car, Long Beach Boulevard would put even a five-year-old model on its mettle. It is only the knowledge of frequent arrests and heavy fines that keeps one in reasonable bounds on such an ideal speedway and gives leisure to contemplate the prosperous farming lands on either side. Sugar beets, beans, and small grains are all green and thriving, for most of the fields are irrigated. There is an occasional walnut grove along the way and in places the road is bordered with ranks of tall eucalyptus trees, stately and fragrant. Several fine suburban homes 26 adjoin the boulevard and it is doubtless destined to be solidly bordered with such.

Long Beach is the largest of the suburban seaside towns—the new census gives it a population of over 55,000—and is more a place of homes than its neighbor, Venice. Its beach and amusement concomitants are not its chief end of existence; it is a thriving city of pretty—though in the main unpretentious—homes bordering upon broad, well-paved streets, and it has a substantial and handsome business center. You will especially note its churches, some of them imposing stone structures that would do credit to the metropolis. Religious and moral sentiment is strong in Long Beach; it was a "dry" town, having abolished saloons by an overwhelming vote, long before prohibition became the law of the land. The town is pre-eminently the haven of a large number of eastern people who come to California for a considerable stay—as cheaply as it can possibly be done—and there are many lodging-houses and cottages to supply this demand. And it is surprising how economically and comfortably many of these people pass the winter months in the town and how regularly they return year after year. Many others have become permanent residents and among them you will find the most enthusiastic and uncompromising "boosters" for the town—and California. And, indeed, Long Beach is an ideal place for one to retire and take life easy; the climate is even more equable than that of Los Angeles; frost is almost unknown and the summer heat is tempered by the sea. The church and social activities appeal to many and the seaside amusement features 27 are a good antidote for ennui. There are not a few old fellows who fall into a mild dissipation of some sort at one or the other of the catch-penny affairs along the promenade. I was amused at one of these—a grizzled old veteran, who confessed to being upwards of seventy—who could not resist the fascination of the shooting galleries; and I knew another well over eighty who was a regular bather in the surf all through the winter months.

A little to the east of Long Beach is Naples, another of the seaside towns, which has recently been connected with Long Beach by a fine boulevard. It gives promise of becoming a very pretty place, though at present it does not seem much frequented by tourists. About equally distant to the westward is San Pedro, the port of Los Angeles, and really a part of the city, a narrow strip some two miles wide connecting the village and metropolis. This was done to make Los Angeles an actual seaport and to encourage the improvement of San Pedro Harbor. The harbor is largely artificial, being enclosed by a stone breakwater built jointly by Government appropriations and by bond issues of the citizens of Los Angeles. The ocean is cut off by Catalina Island, which shelters San Pedro to some extent from the effects of heavy storms and makes the breakwater practicable. It is built of solid granite blocks of immense size, some of them weighing as much as forty tons each. It is a little more than two miles long and the water is forty-five feet deep at the outer end where the U. S. Lighthouse stands. There is no bar, and ocean-going vessels can go to anchor under their own 28 steam. There are at present about eight miles of concrete wharfage and space permits increasing this to thirty miles as traffic may require. Improvements completed and under way represent an investment of more than twenty million dollars. The World War put San Pedro on the map as a great ship-building point; there are two large yards for construction of steel ships and one for wooden vessels. These will be of great interest to the tourist from inland states. A dry dock of sufficient capacity for the largest ocean-going steamers is under construction and will afford every facility for repairing and overhauling warships and merchant vessels. All of which indicates that Los Angeles' claim as an ocean port of first magnitude has a substantial foundation and that its early fulfillment is well assured. A broad boulevard now joins the widely separated parts of the city and a large proportion of the freight traffic goes over this in motor trucks, which, I am told, give cheaper and quicker service than the steam railroad.

Aside from the shipyards, San Pedro has not much to interest the tourist; there is a pretty park at Point Fermin from which one may view some magnificent coast scenery. A steep descent near at hand takes one down to an ancient Spanish ranch house curiously situated on the water's edge and hidden in a jungle of neglected palms and shrubbery. On an eminence overlooking the town and harbor is located Fort McArthur with several disappearing guns of immense caliber. There are also extensive naval barracks and storehouses on the 29 wharf and usually several United States warships are riding at anchor in the harbor.

The new boulevard from San Pedro to Redondo, however, has quite enough of beauty to atone for any lack of it on the way to the harbor town from the city, especially if one is fortunate in the day. In springtime the low rounded hills on either side are covered with verdure—meadows and grain fields—and these are spangled with great dashes of blue flowers, which in some places have almost gained the mastery. The perfect road sweeps along the hillsides in wide curves and easy grades and there is little to hinder one from giving rein to the motor if he so elects. But we prefer an easy jog, pausing to gather a handful of the violet-blue flowers and to contemplate the glorious panorama which spreads out before us. Beyond a wide plain lie the mountain ranges, softened by a thin blue haze through which snow-capped summits gleam in the low afternoon sun. As we come over the hill just before reaching Redondo, the Pacific breaks into view—deep violet near the shore and shimmering blue out toward the horizon.

We enter the town by the main street, which follows the shore high above the sea and is bordered by many pleasant cottages almost hidden in flowers. It is one of the most beautifully situated of the coast towns, occupying a sharply rising hill which slopes down to a fine beach. On the bluff we pass a handsome park—its banks ablaze with amethyst sea moss—and the grounds of Hotel Redondo, (since closed and falling into decay) elaborately laid out and filled with semi-tropical plants and flowers, 30 favored by the frostless climate. The air is redolent with fragrance, borne to us on the fresh sea-breeze and, altogether, our first impressions of Redondo are favorable indeed—nor has further acquaintance reversed our judgment.

There are the customary resort features, though these are not so numerous or extensive as at Venice. Still, Redondo is not free from the passion for the superlative everywhere prevalent in California, and proudly boasts of the "largest warm salt-water plunge on earth and the biggest dancing pavilion in the state." There is a good deal of fishing off shore, red deep-sea bass being the principal catch. Moonstones and variegated pebbles are common on the beach and there are shops for polishing and setting these in inexpensive styles. If you are not so fortunate as to pick up a stone yourself, you will be eagerly supplied with any quantity by numerous small urchins, for a slight consideration.

Redondo is not without commercial interest, for it is an important lumber port and a supply station for the oil trade. There are car shops and mills of various kinds. Another industry which partakes quite as much of the aesthetic as the practical is evidenced by the acres of sweet peas and carnations which bloom profusely about the town.

In returning from Redondo to the city we went oftenest over the new boulevard by the way of Inglewood, though we sometimes followed the coast road to Venice, entering by Washington Street. These roads were not as yet improved, though they were good in summer time. Along 31 the coast between Redondo and Venice one passes Hermosa and Manhattan Beaches and Playa del Rey, three of the less frequented resorts. They are evidently building on expectations rather than any great present popularity; a few seaside cottages perched on the shifting sands are about all there is to be seen and the streets are mere sandy trails whose existence in some cases you would never suspect were it not for the signboards. We stuck closely to the main streets of the towns which, in Manhattan, at least, was pretty hard going. It is a trip that under present conditions we would not care to repeat, but when a good boulevard skirts the ocean for the dozen miles between these points, it will no doubt be one of the popular runs. (The boulevard has since been built, enabling one to follow the sea from El Segundo to Redondo with perfect ease and comfort.)

I have written chiefly of the better-known coast towns, but there are many retired resorts which are practically deserted except for the summer season. One may often find a pleasant diversion in one of these places on a fine spring day before the rush comes—and if he goes by motor, he can leave at his good pleasure, should he grow weary, in sublime indifference to railroad or stage time-tables. A Los Angeles friend who has a decided penchant for these retired spots proposed that we go to Newport Beach one Saturday afternoon and we gladly accepted this guidance, having no very clear idea ourselves of the whereabouts of Newport Beach.

We followed him out Stevenson Boulevard 32 into Whittier Road, a newly built highway running through a fertile truck-gardening country to the pleasant village founded by a community of Quakers who named it in honor of their beloved poet. One can not help thinking how Whittier himself would have shrunk from such notoriety, but he would have no reason to be ashamed of his namesake could he see it to-day—a thriving, well-paved town of some eight thousand people. It stands in the edge of a famous orange-growing section, which extends along the highway for twenty miles or more and which produces some of the finest citrus fruit in California. Lemon and walnut groves are also common and occasional fig and olive trees may be seen. The bronze-green trees, with their golden globes and sweet blossoms, crowd up to the very edge of the highway for miles—with here and there a comfortable ranch-house.

We asked permission to eat our picnic dinner on the lawn in front of one of these, and the mistress not only gladly accorded the privilege, but brought out rugs for us to sit upon. A huge pepper tree screened the rays of the sun; an irrigating hydrant supplied us with cool crystal water; and the contents of our lunch-baskets, with hot coffee from our thermos bottles, afforded a banquet that no hotel or restaurant could equal.

Further conversation with the mistress of the ranch developed the fact that she had come from our home state, and we even unearthed mutual acquaintances. We must, of course, inspect the fine grove of seven acres of Valencias loaded with fruit about ready for the market. It was a beautiful 33 grove of large trees in prime condition and no doubt worth five or six thousand dollars per acre. The crop, with the high prices that prevailed at that time, must have equaled from one-third to half the value of the land itself. Such a ranch, on the broad, well-improved highway, certainly attains very nearly the ideal of fruit-farming and makes one forget the other side of the story—and we must confess that there is another side to the story of citrus fruit-farming in California.

The fine road ended abruptly when we entered Orange County, a few miles beyond Whittier, for Orange County had done little as yet to improve her highways, and we ran for some miles on an old oiled road which for genuine discomfort has few equals. One time it was thought that the problem of a cheap and easily built road was solved in California—simply sprinkle the sandy surface with crude oil and let it pack down under traffic. This worked very well for a short time until the surface began to break into holes, which daily grew larger and more numerous until no one could drive a motor car over them without an unmerciful jolting. And such was the road from Fullerton to Santa Ana when we traversed it, but such it will not long remain, for Orange County has voted a million and a quarter to improve her roads and she will get her share of the new state highway system as well. (All of which, I may interject here, has since come to pass and the fortunate tourist may now traverse every part of the county over roads that will comfortably admit of all the speed the law allows).

Santa Ana is a quiet town of fifteen thousand, 34 depending on the fruit-raising and farming country that surrounds it. It is a cozy place, its wide avenues shaded by long rows of peppers and sycamores and its homes embowered by palms and flowers. Almost adjoining it to the northeast is the beautiful village of Orange—rightly named, for it is nearly surrounded by a solid mass of orange and lemon groves. In the center of its business section is a park, gorgeous with palms and flowers. The country about must be somewhat sheltered, for it escaped the freeze of 1913 and was reveling in prosperity with a great orange and lemon crop that year.

Just beyond the mountain range to the east is Orange County Park, which we visited on another occasion. It is a fine example of the civic progress of these California communities in providing pleasure grounds where all classes of people may have inexpensive and delightful country outings. It is a virgin valley, shaded by great oaks and sycamores and watered by a clear little river, the only departure from nature being the winding roads and picnic conveniences. There are many beautiful camping sites, which are always occupied during the summer. Beyond the park the road runs up Silverado Canyon, following the course of the stream, which we forded many times. It proved rough and stony but this was atoned for many times over by the sylvan beauty of the scenes through which we passed. The road winds through the trees, which overarch it at times, and often comes out into open glades which afford views of the rugged hills on either hand. We had little difficulty in finding our 35 way, for at frequent intervals we noted signs, "To Modjeska's Ranch," for the great Polish actress once had a country home deep in the hills and owned a thousand-acre ranch at the head of Silverado Canyon. Here about thirty years ago she used to come for rest and recreation, but shortly before her death sold the ranch to the present owners, the "Modjeska Country Club." It is being exploited as a summer resort and is open to the public generally. A private drive leads some three or four miles from the public road to the house, which is sheltered under a clifflike hill and surrounded by a park ornamented with a great variety of trees and shrubs. This was one of Modjeska's fads and her friends sent her trees and plants from every part of the world, one of the most interesting being a Jerusalem thorn, which appears to thrive in its new habitat. The house was designed by Stanford White—an East-Indian bungalow, we were told, but it impresses one as a crotchety and not very comfortable domicile. The actress entertained many distinguished people at the Forest of Arden, as she styled her home, among them the author of "Quo Vadis," who, it is said, wrote most of that famous story here. The place is worth visiting for the beauty of its surroundings as well as its associations. A great many summer cottages are being built in the vicinity and in time it will no doubt become a popular resort, and, with a little improvement in the canyon road, a favorite run for motorists.

Leaving "Arden," we crossed the hills to the east, coming into the coast highway at El Toro, a rather strenuous climb that was well rewarded by 36 the magnificent scenes that greeted us from the summit. The wooded canyon lay far beneath us, diversified by a few widely separated ranch-houses and cultivated fields, with the soft silver-gray blur of a great olive grove in the center. It was shut in on either side by the rugged hill ranges, which gradually faded into the purple haze of distance. The descent was an easy glide over a moderate grade, the road having been recently improved. At the foot of the grade we noticed a road winding away among the hills, and a sign, "To the silver mines," where we were told silver is still mined on a considerable scale.

I have departed quite a little from the story of our run to Newport Beach, but I hope the digression was worth while. From Santa Ana a poor road—it is splendid concrete now—running nearly south took us to our destination. It was deserted save for a few shopkeepers and boarding-house people who stick to their posts the year round. There was a cheap-looking hotel with a number of single-room cottages near by. We preferred the latter and found them clean and comfortable, though very simply furnished. The meals served at the hotel, however, were hardly such as to create an intense desire to stay indefinitely and after our second experience we were happy to think that we had a well-filled lunch-basket with us. The beach at Newport is one of the finest to be found anywhere—a stretch of smooth, hard sand miles long and quite free from the debris which disfigures the more frequented places. We were greeted by a wide sweep of quiet ocean, with the dim blue outlines 37 of Santa Catalina just visible in the distance. To the rear of the beach lies the lagoon-like bay, extending some miles inland and surrounding one or two small islands covered with summer cottages. Eastward is Balboa Beach and above this rise the rugged heights of Corona Del Mar. A motor boat runs between this point and Newport, some five or six miles over the green, shallow waters of the bay. We proved the sole passengers for the day and after a stiff climb to the heights found ourselves on a rugged and picturesque bit of coast. Here and there were great detached masses of rock, surrounded by smooth sand when the tide was out, and pierced in places by caves. We scrambled down to the sand and found a quiet, sheltered nook for our picnic dinner—which was doubly enjoyable after the climb over the rocks and our partial fast at the hotel. Late in the afternoon we found our boat waiting at the wharf at Corona and returned to Newport in time to drive to Los Angeles before nightfall.

Newport is only typical of several retired seaside resorts—Huntington Beach, Bay City, Court Royal, Clifton, Hermosa, Playa del Rey, and others, nearly all of which may be easily reached by motor and which will afford many pleasant week-end trips similar to the little jaunt to Newport which I have sketched.

And one must not forget Avalon—in some respects the most unique and charming of all, though its position on Santa Catalina, beyond twenty miles of blue billows, might logically exclude it from a motor-travel book. There are only 38 twenty-five miles of road in the island—hardly enough to warrant the transport of a motor, though I believe it has been done. But no book professing to deal with Southern California could omit Avalon and Catalina—and the motor played some part, after all, for we drove from Los Angeles to San Pedro and left the car in a garage while we boarded the Cabrillo for the enchanted isle. We were well in advance of the "season," which invariably fills Avalon to overflowing, and were established in comfortable quarters soon after our arrival. The town is made up largely of cottages and lodging-houses, with a mammoth hotel on the sea front. It is situated on the crescent-shaped shore of a beautiful little bay and climbs the sharply rising hill to the rear in flower-covered terraces.

There is not much to detain the casual visitor in the village itself, especially in the dull season; no doubt there is more going on in the summer, when vacationists from Los Angeles throng the place. The deserted "tent city"—minus the tents—the empty pavilion, the silent dance hall and skating-rink, all mutely testify of livelier things than we are witnessing as we saunter about the place.

But there is one diversion for which Catalina is famous and which is not limited to the tourist season—here is the greatest game fishing-"ground" in the world, where even the novice, under favorable conditions, is sure of a catch of which he can boast all the rest of his life. Our friend who accompanied us was experienced in the gentle art of Ike Walton as practiced about the Isle of Summer, and 39 before long had engaged a launch from one of the numerous "skippers" who were lounging about the pier. We were away early in the morning for Ship Island, near the isthmus, where the great kelp beds form a habitat for yellowtail and bass, which our skipper assured us were being caught daily in considerable numbers. Tuna, he said, were not running—and he really made few promises for a fisherman. Our boat was a trim, well-kept little craft, freshly painted and scoured and quite free from the numerous smells that so often cling about such craft and assist in bringing on the dreaded mal de mer. Fortunately, we escaped this distressing malady; by hugging the shore we had comparatively still water and when we reached our destination we found the sea quiet and glassy—a glorious day—and our skipper declared the conditions ideal for a big catch. Our hooks were baited with silvery sardines—not the tiny creatures such as we get in tins, but some six or eight inches in length—and we began to circle slowly above the kelp beds near Ship Rock. Before long one of the party excitedly cried, "A strike!" and the boat headed for the open water, since a fish would speedily become entangled in the kelp and lost.

There are few more exciting sports than bringing a big yellowtail to gaff, for he is one of the gamest of sea fighters, considering his size. At first he is seized with a wild desire to run away and it means barked knuckles and scorched fingers to the unwary fisherman who lets his reel get out of control. Then begin a long struggle—a sort of see-saw play—in which you gain a few yards on your 40 catch only to lose it again and again. Suddenly your quarry seems "all in," and he lets you haul him up until you get a glimpse of his shining sides like a great opal in the pale green water. The skipper seizes his gaff and you consider the victory won at last—you are even formulating the tale you are going to tell your eastern friends, when—presto, he is away like a flash. Your reel fairly buzzes while three hundred yards of line is paid out and you have it all to do over again. But patience and perseverance at last win—if your tackle does not break—and the fish, too exhausted to struggle longer, is gaffed and brought aboard by the skipper, who takes great delight in every catch, since a goodly showing at the pier is an excellent advertisement for himself and his boat.

By noon we had three fine yellowtails and a number of rock bass to our credit and were quite ready for the contents of our lunch-baskets. We landed on the isthmus—the narrow neck of land a few hundred feet in width about the center of the island—and found a pleasant spot for our luncheon. In the afternoon we had three more successful battles with the gamey yellowtails—and, of course, the usual number "got away." Homeward bound, we had a panorama of fifteen miles of the rugged island coast—bold, barren cliffs overhanging deep blue waters and brown and green hills stretching along dark little canyons running up from the sea. In rare cases we saw a cottage or two in these canyons and in places the hillsides were dotted with wild flowers, which bloom in great variety on the island. At sunset we came into the clear waters 41 of Avalon Harbor and our skipper soon proudly displayed our catch on the pier.

After dinner we saw a curious spectacle down at the beach—thousands of flying fish attracted and dazzled by the electric lights were darting wildly over the waters and in some instances falling high and dry on the sands. On the pier were dozens of men and boys with fish spears attached to ropes and they were surprisingly successful in taking the fish with these implements. They threw the barbed spear at the fish as they darted about and drew it back with the rope, often bringing the quarry with it. The fish average about a foot in length and, we were told, are excellent eating. They presented a beautiful sight as thousands of them darted over the dark waters of the bay, their filmy, winglike fins gleaming in the electric lights.

Besides fishing, the sportsman can enjoy a hunt if he chooses, for wild goats are found in the interior, though one unacquainted with the topography of the island will need a guide and a horse. The country is exceedingly rugged and wild, there are few trails, and cases are recorded of people becoming hopelessly lost. We had no time for exploring the wilds of the interior and perhaps little inclination. On the morning before our homeward voyage we went out to the golf links lying on the hillsides above the town, not so much for the game—on my part, at least, for I had become quite rusty in this royal sport and Avalon links would be the last place in the world for a novice—as for the delightful view of the town and ocean which the site affords. Below us lay the village, bending around 42 the crescent-shaped bay which gleamed through the gap in the hills, so deeply, intensely blue that I could think of nothing so like it as lapis lazuli—a solid, still blue that hardly seemed like water. After a few strokes, which sent the balls into inaccessible ravines and cactus thickets, I gave it up and contented myself with watching my friend struggle with the hazards—and such hazards! Only one who has actually tried the Avalon links can understand what it means to play a round or two of the nine holes; but, after all, the glorious weather, the entrancing view, and the lovely, smooth-shaven greens will atone for a good many lost balls and no devotee of golf who visits the island should omit a game on the Avalon links.

Many changes have been wrought in the state of things in Catalina since the foregoing paragraphs were first written. Formerly the island belonged to the Bannings—an old Los Angeles family—who declined to sell any part or parcel of the soil until 1918, when they disposed of their entire interests to a Chicago capitalist. The new owner began a campaign of development and freely sold homesites in the island to all comers. A fine new hotel, the St. Catherine, was built to replace the old Metropolitan, which burned down, and many other notable improvements have been made. Great efforts have been made to attract tourists to the island and to sell sites to any who might wish a resort home in Avalon. A new million-dollar steamer, the "Avalon," makes a quicker and more comfortable trip than formerly and we may predict that the popularity of Catalina will wax rather than wane. 43

Our rambles described in the preceding chapter were confined mainly to the coast side of the city, but there is quite as much to attract and delight the motorist over toward the mountains. Nor are the mountains themselves closed to his explorations, for there are a number of trips which he may essay in these giant hills, ranging from an easy upward jog to really nerve-racking and thrilling ascents. Remember I am dealing with the motor car, which will account for no reference to famous mountain trips by trolley or mule-back trail, familiar to nearly every tourist in California. Of our mountain jaunts in the immediate vicinity of Los Angeles we may refer to two as being the most memorable and as representing the two extremes referred to.

Lookout Mountain, one of the high hills of the Santa Monica Range near Hollywood, has a smooth, beautifully engineered road winding in graceful loops to the summit. It passes many wooded canyons and affords frequent glimpses of charming scenery as one ascends. Nowhere is the grade heavy—a high-gear proposition for a well-powered car—and there are no narrow, shelf-like places to disturb one's nerves. The ascent begins through lovely Laurel Canyon out of flower-bedecked Hollywood, and along the wayside are many attractive spots for picnic dinners. At one of these, 44 fitted with tables and chairs, and sheltered by a huge sycamore, we paused for luncheon, with thanks to the enterprising real estate dealer who maintained the place for public use.

From Lookout Point one has a far-reaching view over the wide plain surrounding the city and can get a good idea of the relative location of the suburban towns. The day we chose for the ascent was not the most favorable, the atmosphere being anything but clear. The orange groves of Pasadena and San Gabriel were half hidden in a soft blue haze and the seaside view was cut off by a low-hanging fog. To the north the Sierras gleamed dim and ghostly through the smoky air, and the green foothills lent a touch of subdued color to the foreground. At our feet lay the wide plain between the city and the sea, studded with hundreds of unsightly oil derricks, the one eye-sore of an otherwise enchanting landscape. Descending, we followed a separate road down the mountain the greater part of the distance, thus avoiding the necessity of passing other cars on the steeper grades near the summit.