Title: A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments, Now Entituled the Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, Volume 10 (of 17)

Translator: Sir Richard Francis Burton

Release date: November 26, 2018 [eBook #58360]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Richard Hulse and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

“The pleasure we derive from perusing the Thousand-and-One Stories makes us regret that we possess only a comparatively small part of these truly enchanting fictions.”

A PLAIN AND LITERAL TRANSLATION OF THE ARABIAN NIGHTS ENTERTAINMENTS. NOW ENTITULED

Limited to one thousand numbered sets, of which this is

During the last dozen years, since we first met at Cairo, you have done much for Egyptian folk-lore and you can do much more. This volume is inscribed to you with a double purpose; first it is intended as a public expression of gratitude for your friendly assistance; and, secondly, as a memento that the samples which you have given us imply a promise of further gift. With this lively sense of favours to come I subscribe myself

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MA’ARUF THE COBBLER AND HIS WIFE FATIMAH | 1 | ||

| (Lane, The Story of Ma’aruf, III. 671–732.) | |||

| CONCLUSION | 54 | ||

| TERMINAL ESSAY | 63 | ||

| INDEX OF THE TENTH VOLUME | 303 | ||

| APPENDIX I.— | |||

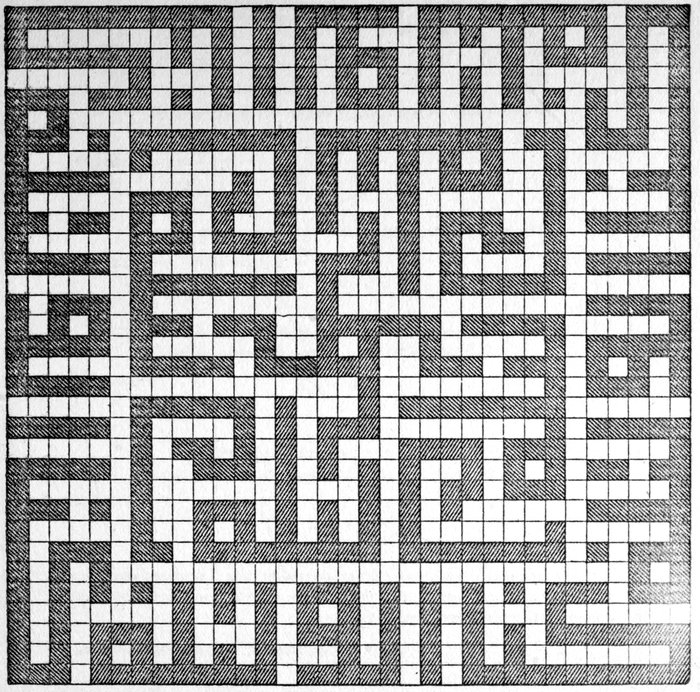

| I. Index to the Tales and Proper Names | 309 | ||

| II. Alphabetical Table of the Notes (Anthropological, &c.) | 322 | ||

| III. Alphabetical Table of First Lines— | |||

| A. English | 393 | ||

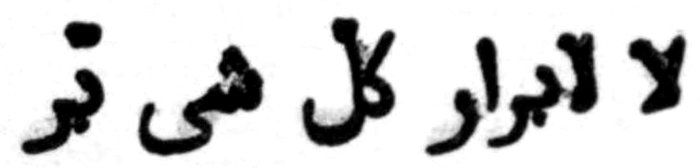

| B. Arabic | 421 | ||

| IV. Table of Contents of the various Arabic Texts— | |||

| A. The Unfinished Calcutta Edition (1814–1818) | 448 | ||

| B. The Breslau Text | 450 | ||

| C. The Macnaghten Text and the Bulak Edition | 457 | ||

| D. The same with Mr. Lane’s and my Version | 464 | ||

| APPENDIX II.— | |||

| Contributions to the Bibliography of the Thousand and One Nights and their Imitations, by W. F. Kirby | 465 | ||

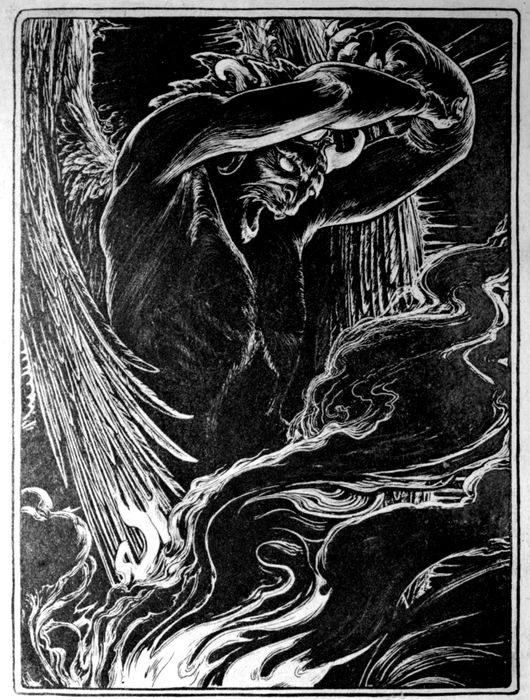

There dwelt once upon a time in the God-guarded city of Cairo a cobbler who lived by patching old shoes.[1] His name was Ma’aruf[2] and he had a wife called Fatimah, whom the folk had nicknamed “The Dung;”[3] for that she was a whorish, worthless wretch, scanty of shame and mickle of mischief. She ruled her spouse and used to abuse him and curse him a thousand times a day; and he feared her malice and dreaded her misdoings; for that he was a sensible man and careful of his repute, but poor-conditioned. When he earned much, he spent it on her, and when he gained little, she revenged herself on his body that night, leaving him no peace and making his night black as her book;[4] for she was even as of one like her saith the poet:—

Amongst other afflictions which befel him from her one day she said to him, “O Ma’aruf, I wish thee to bring me this night a vermicelli-cake dressed with bees’ honey.”[5] He replied, “So Allah 2Almighty aid me to its price, I will bring it thee. By Allah, I have no dirhams to-day, but our Lord will make things easy.”[6] Rejoined she,——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased to say her permitted say.

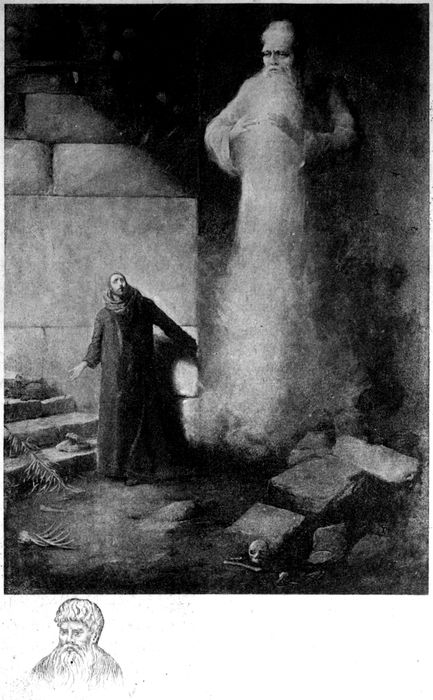

She resumed, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that Ma’aruf the Cobbler said to his spouse, “If Allah aid me to its price, I will bring it to thee this night. By Allah, I have no dirhams to-day, but our Lord will make things easy to me!” She rejoined, “I wot naught of these words; whether He aid thee or aid thee not, look thou come not to me save with the vermicelli and bees’ honey; and if thou come without it I will make thy night black as thy fortune whenas thou marriedst me and fellest into my hand.” Quoth he, “Allah is bountiful!” and going out with grief scattering itself from his body, prayed the dawn-prayer and opened his shop, saying, “I beseech thee, O Lord, to vouchsafe me the price of the Kunafah and ward off from me the mischief of yonder wicked woman this night!” After which he sat in the shop till noon, but no work came to him and his fear of his wife redoubled. Then he arose and locking his shop, went out perplexed as to how he should do in the matter of the vermicelli-cake, seeing he had not even the wherewithal to buy bread. Presently he came up to the shop of the Kunafah-seller and stood before it distraught, whilst his eyes brimmed with tears. The pastry-cook glanced at him and said, “O Master Ma’aruf, why dost thou weep? Tell me what hath befallen thee.” So he acquainted him with his case, saying, “My wife is a shrew, a virago who would have me bring her a Kunafah; but I have sat in my shop till past mid-day and have not gained even the price of bread; wherefore I am in fear of her.” The cook laughed and said, “No harm shall come to thee. How many pounds wilt thou have?” “Five pounds,” answered Ma’aruf. So the man weighed him out five pounds of vermicelli-cake and said to him, “I have clarified butter, but no bees’ honey. Here is drip-honey,[7] however, which is better 3than bees’ honey; and what harm will there be, if it be with drip-honey?” Ma’aruf was ashamed to object, because the pastry-cook was to have patience with him for the price, and said, “Give it me with drip-honey.” So he fried a vermicelli-cake for him with butter and drenched it with drip-honey, till it was fit to present to Kings. Then he asked him, “Dost thou want bread[8] and cheese?”; and Ma’aruf answered, “Yes.” So he gave him four half dirhams worth of bread and one of cheese, and the vermicelli was ten nusfs. Then said he, “Know, O Ma’aruf, that thou owest me fifteen nusfs; so go to thy wife and make merry and take this nusf for the Hammam;[9] and thou shalt have credit for a day or two or three till Allah provide thee with thy daily bread. And straiten not thy wife, for I will have patience with thee till such time as thou shalt have dirhams to spare.” So Ma’aruf took the vermicelli-cake and bread and cheese and went away, with a heart at ease, blessing the pastry-cook and saying, “Extolled be Thy perfection, O my Lord! How bountiful art Thou!” When he came home, his wife enquired of him, “Hast thou brought the vermicelli-cake?”; and, replying “Yes,” he set it before her. She looked at it and seeing that it was dressed with cane-honey,[10] said to him, “Did I not bid thee bring it with bees’ honey? Wilt thou contrary my wish and have it dressed with cane-honey?” He excused himself to her, saying, “I bought it not save on credit;” but said she, “This talk is idle; I will not eat Kunafah save with bees’ honey.” And she was wroth with it and threw it in his face, saying, “Begone, thou pimp, and bring me other than this!” Then she dealt him a buffet on the cheek and knocked out one of his teeth. The blood ran down upon his breast and for stress of anger he smote her on the head a single blow and a slight; whereupon she clutched his beard and fell to shouting out and saying, “Help, O Moslems!” So the neighbours came in and freed his beard from her grip; then they reproved and reproached her, saying, “We are all content to eat Kunafah with cane-honey. Why, then, wilt thou oppress this poor man thus? Verily, this is 4disgraceful in thee!” And they went on to soothe her till they made peace between her and him. But, when the folk were gone, she sware that she would not eat of the vermicelli, and Ma’aruf, burning with hunger, said in himself, “She sweareth that she will not eat; so I will e’en eat.” Then he ate, and when she saw him eating, she said, “Inshallah, may the eating of it be poison to destroy the far one’s body.”[11] Quoth he, “It shall not be at thy bidding,” and went on eating, laughing and saying, “Thou swarest that thou wouldst not eat of this; but Allah is bountiful, and to-morrow night, an the Lord decree, I will bring thee Kunafah dressed with bees’ honey, and thou shalt eat it alone.” And he applied himself to appeasing her, whilst she called down curses upon him; and she ceased not to rail at him and revile him with gross abuse till the morning, when she bared her forearm to beat him. Quoth he, “Give me time and I will bring thee other vermicelli-cake.” Then he went out to the mosque and prayed, after which he betook himself to his shop and opening it, sat down; but hardly had he done this when up came two runners from the Kazi’s court and said to him, “Up with thee, speak with the Kazi, for thy wife hath complained of thee to him and her favour is thus and thus.” He recognised her by their description; and saying, “May Allah Almighty torment her!” walked with them till he came to the Kazi’s presence, where he found Fatimah standing with her arm bound up and her face-veil besmeared with blood; and she was weeping and wiping away her tears. Quoth the Kazi, “Ho man, hast thou no fear of Allah the Most High? Why hast thou beaten this good woman and broken her forearm and knocked out her tooth and entreated her thus?” And quoth Ma’aruf, “If I beat her or put out her tooth, sentence me to what thou wilt; but in truth the case was thus and thus and the neighbours made peace between me and her.” And he told him the story from first to last. Now this Kazi was a benevolent man; so he brought out to him a quarter dinar, saying, “O man, take this and get her Kunafah with bees’ honey and do ye make peace, thou and she.” Quoth Ma’aruf, “Give it to her.” So she took it and the Kazi made peace between them, saying, “O wife, obey thy husband; and thou, O man, deal kindly with her.[12]” 5Then they left the court, reconciled at the Kazi’s hands, and the woman went one way, whilst her husband returned by another way to his shop and sat there, when, behold, the runners came up to him and said, “Give us our fee.” Quoth he, “The Kazi took not of me aught; on the contrary, he gave me a quarter dinar.” But quoth they, “’Tis no concern of ours whether the Kazi took of thee or gave to thee, and if thou give us not our fee, we will exact it in despite of thee.” And they fell to dragging him about the market; so he sold his tools and gave them half a dinar, whereupon they let him go and went away, whilst he put his hand to his cheek and sat sorrowful, for that he had no tools wherewith to work. Presently, up came two ill-favoured fellows and said to him, “Come, O man, and speak with the Kazi; for thy wife hath complained of thee to him.” Said he, “He made peace between us just now.” But said they, “We come from another Kazi, and thy wife hath complained of thee to our Kazi.” So he arose and went with them to their Kazi, calling on Allah for aid against her; and when he saw her, he said to her, “Did we not make peace, good woman?” Whereupon she cried, “There abideth no peace between me and thee.” Accordingly he came forward and told the Kazi his story, adding, “And indeed the Kazi Such-an-one made peace between us this very hour.” Whereupon the Kazi said to her, “O strumpet, since ye two have made peace with each other, why comest thou to me complaining?” Quoth she, “He beat me after that;” but quoth the Kazi, “Make peace each with other, and beat her not again, and she will cross thee no more.” So they made peace and the Kazi said to Ma’aruf, “Give the runners their fee.” So he gave them their fee and going back to his shop, opened it and sat down, as he were a drunken man for excess of the chagrin which befel him. Presently, while he was still sitting, behold, a man came up to him and said, “O Ma’aruf, rise and hide thyself, for thy wife hath complained of thee to the High Court[13] and Abú Tabak[14] is after thee.” So he shut his shop and 6fled towards the Gate of Victory.[15] He had five Nusfs of silver left of the price of the lasts and gear; and therewith he bought four worth of bread and one of cheese, as he fled from her. Now it was the winter season and the hour of mid-afternoon prayer; so, when he came out among the rubbish-mounds the rain descended upon him, like water from the mouths of water-skins, and his clothes were drenched. He therefore entered the ‘Ádiliyah,[16] where he saw a ruined place and therein a deserted cell without a door; and in it he took refuge and found shelter from the rain. The tears streamed from his eyelids, and he fell to complaining of what had betided him and saying, “Whither shall I flee from this whore? I beseech Thee, O Lord, to vouchsafe me one who shall conduct me to a far country, where she shall not know the way to me!” Now while he sat weeping, behold, the wall clave and there came forth to him therefrom one of tall stature, whose aspect caused his body-pile to bristle and his flesh to creep, and said to him, “O man, what aileth thee that thou disturbest me this night? These two hundred years have I dwelt here and have never seen any enter this place and do as thou dost. Tell me what thou wishest and I will accomplish thy need, as ruth for thee hath got hold upon my heart”. Quoth Ma’aruf, “Who and what art thou?”; and quoth he, “I am the Haunter[17] of this place.” So Ma’aruf told him all that had befallen him with his wife and he said, “Wilt thou have me convey thee to a country, where thy wife shall know no way to thee?” “Yes,” said Ma’aruf; and the other, “Then mount my back.” So he mounted on his back and he flew with him from after supper-tide till daybreak, when he set him down on the top of a high mountain——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased saying her permitted say.

She said, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that the Marid having taken up Ma’aruf the Cobbler, flew off with him and set him down upon a high mountain and said to him, “O mortal, descend this mountain and thou wilt see the gate of a city. Enter it, for therein thy wife cannot come at thee.” He then left him and went his way, whilst Ma’aruf abode in amazement and perplexity till the sun rose, when he said to himself, “I will up with me and go down into the city: indeed there is no profit in my abiding upon this highland.” So he descended to the mountain-foot and saw a city girt by towering walls, full of lofty palaces and gold-adorned buildings which was a delight to beholders. He entered in at the gate and found it a place such as lightened the grieving heart; but, as he walked through the streets the townsfolk stared at him as a curiosity and gathered about him, marvelling at his dress, for it was unlike theirs. Presently, one of them said to him, “O man, art thou a stranger?” “Yes.” “What countryman art thou?” “I am from the city of Cairo the Auspicious.” “And when didst thou leave Cairo?” “I left it yesterday, at the hour of afternoon-prayer.” Whereupon the man laughed at him and cried out, saying, “Come look, O folk, at this man and hear what he saith!” Quoth they, “What doeth he say?” and quoth the townsman, “He pretendeth that he cometh from Cairo and left it yesterday at the hour of afternoon-prayer!” At this they all laughed and gathering round Ma’aruf, said to him, “O man, art thou mad to talk thus? How canst thou pretend that thou leftest Cairo at mid-afternoon yesterday and foundedst thyself this morning here, when the truth is that between our city and Cairo lieth a full year’s journey?” Quoth he, “None is mad but you. As for me, I speak sooth, for here is bread which I brought with me from Cairo, and see, ’tis yet new.” Then he showed them the bread and they stared at it, for it was unlike their country bread. So the crowd increased about him and they said to one another, “This is Cairo bread: look at it;” and he became a gazing-stock in the city and some believed him; whilst others gave him the lie and made mock of him. Whilst this was going on, behold, up came a merchant riding on a she-mule and followed by two black slaves, and brake a way through the people, saying, “O folk, are ye not ashamed to mob this stranger and make mock of 8him and scoff at him?” And he went on to rate them, till he drave them away from Ma’aruf, and none could make him any answer. Then he said to the stranger, “Come, O my brother, no harm shall betide thee from these folk. Verily they have no shame.”[18] So he took him and carrying him to a spacious and richly-adorned house, seated him in a speak-room fit for a King, whilst he gave an order to his slaves, who opened a chest and brought out to him a dress such as might be worn by a merchant worth a thousand.[19] He clad him therewith and Ma’aruf, being a seemly man, became as he were consul of the merchants. Then his host called for food and they set before them a tray of all manner exquisite viands. The twain ate and drank and the merchant said to Ma’aruf, “O my brother, what is thy name?” “My name is Ma’aruf and I am a cobbler by trade and patch old shoes.” “What countryman art thou?” “I am from Cairo.” “What quarter?” “Dost thou know Cairo?” “I am of its children.[20]” “I come from the Red Street.[21]” “And whom dost thou know in the Red Street?” “I know such an one and such an one,” answered Ma’aruf and named several people to him. Quoth the other, “Knowest thou Shaykh Ahmad the druggist?[22]” “He was my next neighbour, wall to wall.” “Is he well?” “Yes.” “How many sons hath he?” “Three, Mustafà, Mohammed and Ali.” “And what hath Allah done with them?” “As for Mustafà, he is well and he is a learned man, a professor[23]: Mohammed is a druggist and opened him a shop beside that of his father, after he had married, and his wife hath borne him a son named Hasan.” “Allah gladden thee with good news!” said the merchant; and Ma’aruf continued, “As for Ali, he was my friend, when we were boys, and we always played together, I and he. We used to go in the guise of the children of the Nazarenes and enter the church and steal the books of the Christians and sell them and buy food with the 9price. It chanced once that the Nazarenes caught us with a book; whereupon they complained of us to our folk and said to Ali’s father:—An thou hinder not thy son from troubling us, we will complain of thee to the King. So he appeased them and gave Ali a thrashing; wherefore he ran away none knew whither and he hath now been absent twenty years and no man hath brought news of him.” Quoth the host, “I am that very Ali, son of Shaykh Ahmad the druggist, and thou art my playmate Ma’aruf.”[24] So they saluted each other and after the salam Ali said, “Tell me why, O Ma’aruf, thou camest from Cairo to this city.” Then he told him all that had befallen him of ill-doing with his wife Fatimah the Dung and said, “So, when her annoy waxed on me, I fled from her towards the Gate of Victory and went forth the city. Presently, the rain fell heavy on me; so I entered a ruined cell in the Adiliyah and sat there, weeping; whereupon there came forth to me the Haunter of the place, which was an Ifrit of the Jinn, and questioned me. I acquainted him with my case and he took me on his back and flew with me all night between heaven and earth, till he set me down on yonder mountain and gave me to know of this city. So I came down from the mountain and entered the city, when the people crowded about me and questioned me. I told them that I had left Cairo yesterday, but they believed me not, and presently thou camest up and driving the folk away from me, carriedst me to this house. Such, then, is the cause of my quitting Cairo; and thou, what object brought thee hither?” Quoth Ali, “The giddiness[25] of folly turned my head when I was seven years old, from which time I wandered from land to land and city to city, till I came to this city, the name whereof is Ikhtiyán al-Khatan.[26] I found its people an hospitable folk and a kindly, compassionate for the poor man and selling to him on credit and believing all he said. So quoth I to them:—I am a merchant and have preceded my packs and I need a place wherein to bestow my baggage. And they believed me and assigned me a lodging. Then quoth I to them:—Is there any of you will lend me a thousand dinars, till my loads arrive, 10when I will repay it to him; for I am in want of certain things before my goods come? They gave me what I asked and I went to the merchants’ bazar, where, seeing goods, I bought them and sold them next day at a profit of fifty gold pieces and bought others.[27] And I consorted with the folk and entreated them liberally, so that they loved me, and I continued to sell and buy, till I grew rich. Know, O my brother, that the proverb saith, The world is show and trickery: and the land where none wotteth thee, there do whatso liketh thee. Thou too, an thou say to all who ask thee, I’m a cobbler by trade and poor withal, and I fled from my wife and left Cairo yesterday, they will not believe thee and thou wilt be a laughing-stock among them as long as thou abidest in the city; whilst, an thou tell them, An Ifrit brought me hither, they will take fright at thee and none will come near thee; for they will say, This man is possessed of an Ifrit and harm will betide whoso approacheth him. And such public report will be dishonouring both to thee and to me, because they ken I come from Cairo.” Ma’aruf asked:—“How then shall I do?”; and Ali answered, “I will tell thee how thou shalt do, Inshallah! To-morrow I will give thee a thousand dinars and a she-mule to ride and a black slave, who shall walk before thee and guide thee to the gate of the merchants’ bazar; and do thou go into them. I will be there sitting amongst them, and when I see thee, I will rise to thee and salute thee with the salam and kiss thy hand and make a great man of thee. Whenever I ask thee of any kind of stuff, saying, Hast thou brought with thee aught of such a kind? do thou answer, “Plenty.[28]” And if they question me of thee, I will praise thee and magnify thee in their eyes and say to them, Get him a store-house and a shop. I also will give thee out for a man of great wealth and generosity; and if a beggar come to thee, bestow upon him what thou mayst; so will they put faith in what I say and believe in thy greatness and generosity and love thee. Then will I invite thee to my house and invite all the merchants 11on thy account and bring together thee and them, so that all may know thee and thou know them,”——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased to say her permitted say.

She continued, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that the merchant Ali said to Ma’aruf, “I will invite thee to my house and invite all the merchants on thy account and bring together thee and them, so that all may know thee and thou know them, whereby thou shalt sell and buy and take and give with them; nor will it be long ere thou become a man of money.” Accordingly, on the morrow he gave him a thousand dinars and a suit of clothes and a black slave and mounting him on a she-mule, said to him, “Allah give thee quittance of responsibility for all this,[29] inasmuch as thou art my friend and it behoveth me to deal generously with thee. Have no care; but put away from thee the thought of thy wife’s misways and name her not to any.” “Allah requite thee with good!” replied Ma’aruf and rode on, preceded by his blackamoor till the slave brought him to the gate of the merchants’ bazar, where they were all seated, and amongst them Ali, who when he saw him, rose and threw himself upon him, crying, “A blessed day, O Merchant Ma’aruf, O man of good works and kindness[30]!” And he kissed his hand before the merchants and said to them, “Our brothers, ye are honoured by knowing[31] the merchant Ma’aruf.” So they saluted him, and Ali signed to them to make much of him, wherefore he was magnified in their eyes. Then Ali helped him to dismount from his she-mule and saluted him with the salam; after which he took the merchants apart, one after other, and vaunted Ma’aruf to them. They asked, “Is this man a merchant?;” and he answered, “Yes; and indeed he is the chiefest of merchants, there liveth not a wealthier than he; for his wealth and the riches of his father and forefathers are famous among the merchants of Cairo. He hath partners in Hind and Sind and Al-Yaman 12and is high in repute for generosity. So know ye his rank and exalt ye his degree and do him service, and wot also that his coming to your city is not for the sake of traffic, and none other save to divert himself with the sight of folk’s countries: indeed, he hath no need of strangerhood for the sake of gain and profit, having wealth that fires cannot consume, and I am one of his servants.” And he ceased not to extol him, till they set him above their heads and began to tell one another of his qualities. Then they gathered round him and offered him junkets[32] and sherbets, and even the Consul of the Merchants came to him and saluted him; whilst Ali proceeded to ask him, in the presence of the traders, “O my lord, haply thou hast brought with thee somewhat of such and such a stuff?”; and Ma’aruf answered, “Plenty.” Now Ali had that day shown him various kinds of costly clothes and had taught him the names of the different stuffs, dear and cheap. Then said one of the merchants, “O my lord, hast thou brought with thee yellow broad cloth?”: and Ma’aruf said, “Plenty”! Quoth another, “And gazelles’ blood red[33]?”; and quoth the Cobbler, “Plenty”; and as often as he asked him of aught, he made him the same answer. So the other said, “O Merchant Ali had thy countryman a mind to transport a thousand loads of costly stuffs, he could do so”; and Ali said, “He would take them from a single one of his store-houses, and miss naught thereof.” Now whilst they were sitting, behold, up came a beggar and went the round of the merchants. One gave him a half dirham and another a copper,[34] but most of them gave him nothing, till he came to Ma’aruf who pulled out a handful of gold and gave it to him, whereupon he blessed him and went his ways. The merchants marvelled at this and said, “Verily, this is a King’s bestowal for he gave the beggar gold without count, and were he not a man of vast wealth and money without end, he had not given a beggar a handful of gold.” After a while, there came to him a poor woman and he gave her a handful of gold; whereupon she went away, blessing him, and told the other beggars, who came to him, one after other, and he gave them each a handful of gold, till he disbursed the thousand dinars. Then he struck hand upon hand 13and said, “Allah is our sufficient aid and excellent is the Agent!” Quoth the Consul, “What aileth thee, O Merchant Ma’aruf?”; and quoth he, “It seemeth that the most part of the people of this city are poor and needy; had I known their misery I would have brought with me a large sum of money in my saddle-bags and given largesse thereof to the poor. I fear me I may be long abroad[35] and ’tis not in my nature to baulk a beggar; and I have no gold left: so, if a pauper come to me, what shall I say to him?” Quoth the Consul, “Say, Allah will send thee thy daily bread[36]!”; but Ma’aruf replied, “That is not my practice and I am care-ridden because of this. Would I had other thousand dinars, wherewith to give alms till my baggage come!” “Have no care for that,” quoth the Consul and sending one of his dependents for a thousand dinars, handed them to Ma’aruf, who went on giving them to every beggar who passed till the call to noon-prayer. Then they entered the Cathedral-mosque and prayed the noon-prayers, and what was left him of the thousand gold pieces he scattered on the heads of the worshippers. This drew the people’s attention to him and they blessed him, whilst the merchants marvelled at the abundance of his generosity and openhandedness. Then he turned to another trader and borrowing of him other thousand ducats, gave these also away, whilst Merchant Ali looked on at what he did, but could not speak. He ceased not to do thus till the call to mid-afternoon prayer, when he entered the mosque and prayed and distributed the rest of the money. On this wise, by the time they locked the doors of the bazar,[37] he had borrowed five thousand sequins and given them away, saying to every one of whom he took aught, “Wait till my baggage come when, if thou desire gold I will give thee gold, and if thou desire stuffs, thou shalt have stuffs; for I have no end of them.” At eventide Merchant Ali invited Ma’aruf and the rest of the traders to an entertainment and seated him in the upper end, the place of honour, where he talked of nothing but cloths and jewels, and whenever they made mention to him of aught, he said, “I have plenty of it.” Next day, he again repaired to the market-street where he showed a 14friendly bias towards the merchants and borrowed of them more money, which he distributed to the poor: nor did he leave doing thus twenty days, till he had borrowed threescore thousand dinars, and still there came no baggage, no, nor a burning plague.[38] At last folk began to clamour for their money and say, “The merchant Ma’aruf’s baggage cometh not. How long will he take people’s monies and give them to the poor?” And quoth one of them, “My rede is that we speak to Merchant Ali.” So they went to him and said, “O Merchant Ali, Merchant Ma’aruf’s baggage cometh not.” Said he, “Have patience, it cannot fail to come soon.” Then he took Ma’aruf aside and said to him, “O Ma’aruf, what fashion is this? Did I bid thee brown[39] the bread or burn it? The merchants clamour for their coin and tell me that thou owest them sixty thousand dinars, which thou hast borrowed and given away to the poor. How wilt thou satisfy the folk, seeing that thou neither sellest nor buyest?” Said Ma’aruf, “What matters it[40]; and what are threescore thousand dinars? When my baggage shall come, I will pay them in stuffs or in gold and silver, as they will.” Quoth Merchant Ali, “Allah is Most Great! Hast thou then any baggage?” and he said, “Plenty.” Cried the other, “Allah and the Hallows[41] requite thee thine impudence! Did I teach thee this saying, that thou shouldst repeat it to me? But I will acquaint the folk with thee.” Ma’aruf rejoined, “Begone and prate no more! Am I a poor man? I have endless wealth in my baggage and as soon as it cometh, they shall have their money’s worth, two for one. I have no need of them.” At this Merchant Ali waxed wroth and said, “Unmannerly wight that thou art, I will teach thee to lie to me and be not ashamed!” Said Ma’aruf, “E’en work the worst thy hand can do! They must wait till my baggage come, when they shall have their due and more.” So Ali left him and went away, saying in himself, “I praised him whilome and if I blame him now, I make myself out a liar and become of those of whom it is 15said:—Whoso praiseth and then blameth lieth twice.”[42] And he knew not what to do. Presently, the traders came to him and said, “O Merchant Ali, hast thou spoken to him?” Said he, “O folk, I am ashamed and, though he owe me a thousand dinars, I cannot speak to him. When ye lent him your money ye consulted me not; so ye have no claim on me. Dun him yourselves, and if he pay you not, complain of him to the King of the city, saying:—He is an impostor who hath imposed upon us. And he will deliver you from the plague of him.” Accordingly, they repaired to the King and told him what had passed, saying, “O King of the age, we are perplexed anent this merchant, whose generosity is excessive; for he doeth thus and thus, and all he borroweth, he giveth away to the poor by handsful. Were he a man of naught, his sense would not suffer him to lavish gold on this wise; and were he a man of wealth, his good faith had been made manifest to us by the coming of his baggage; but we see none of his luggage, although he avoucheth that he hath a baggage-train and hath preceded it. Now some time hath past, but there appeareth no sign of his baggage-train, and he oweth us sixty thousand gold pieces, all of which he hath given away in alms.” And they went on to praise him and extol his generosity. Now this King was a very covetous man, a more covetous than Ash’ab[43]; and when he heard tell of Ma’aruf’s generosity and openhandedness, greed of gain got the better of him and he said to his Wazir, “Were not this merchant a man of immense wealth, he had not shown all this munificence. His baggage-train will assuredly come, whereupon these merchants will flock to him and he will scatter amongst them riches galore. Now I have more right to this money than they; wherefore I have a mind to make friends with him and 16profess affection for him, so that, when his baggage cometh whatso the merchants would have had I shall get of him; and I will give him my daughter to wife and join his wealth to my wealth.” Replied the Wazir, “O King of the age, methinks he is naught but an impostor, and ’tis the impostor who ruineth the house of the covetous;”——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased saying her permitted say.

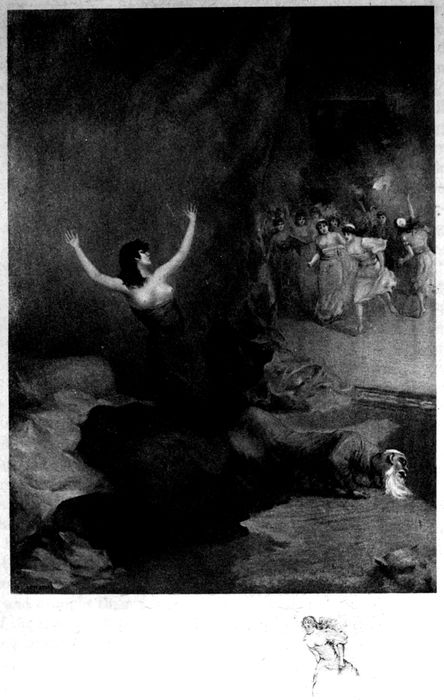

She pursued, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that when the Wazir said to the King, “Methinks he is naught but an impostor, and ’tis the impostor who ruineth the house of the covetous;” the King said, “O Wazir, I will prove him and soon know if he be an impostor or a true man and whether he be a rearling of Fortune or not.” The Wazir asked, “And how wilt thou prove him?”; and the King answered, “I will send for him to the presence and entreat him with honour and give him a jewel which I have. An he know it and wot its price, he is a man of worth and wealth; but an he know it not, he is an impostor and an upstart and I will do him die by the foulest fashion of deaths.” So he sent for Ma’aruf, who came and saluted him. The King returned his salam and seating him beside himself, said to him, “Art thou the merchant Ma’aruf?” and said he, “Yes.” Quoth the King, “The merchants declare that thou owest them sixty thousand ducats. Is this true?” “Yes,” quoth he. Asked the King, “Then why dost thou not give them their money?”; and he answered, “Let them wait till my baggage come and I will repay them twofold. An they wish for gold, they shall have gold; and should they wish for silver, they shall have silver; or an they prefer for merchandise, I will give them merchandise; and to whom I owe a thousand I will give two thousand in requital of that wherewith he hath veiled my face before the poor; for I have plenty.” Then said the King, “O merchant, take this and look what is its kind and value.” And he gave him a jewel the bigness of a hazel-nut, which he had bought for a thousand sequins and not having its fellow, prized it highly. Ma’aruf took it and pressing it between his thumb and forefinger brake it, for it was brittle and would not brook the squeeze. Quoth the King, “Why hast thou broken the jewel?”; and Ma’aruf laughed and said, “O King 17of the age, this is no jewel. This is but a bittock of mineral worth a thousand dinars; why dost thou style it a jewel? A jewel I call such as is worth threescore and ten thousand gold pieces and this is called but a piece of stone. A jewel that is not of the bigness of a walnut hath no worth in my eyes and I take no account thereof. How cometh it, then, that thou, who art King, stylest this thing a jewel, when ’tis but a bit of mineral worth a thousand dinars? But ye are excusable, for that ye are poor folk and have not in your possession things of price.” The King asked, “O merchant, hast thou jewels such as those whereof thou speakest?”; and he answered, “Plenty.” Whereupon avarice overcame the King and he said, “Wilt thou give me real jewels?” Said Ma’aruf, “When my baggage-train shall come, I will give thee no end of jewels; and all that thou canst desire I have in plenty and will give thee, without price.” At this the King rejoiced and said to the traders, “Wend your ways and have patience with him, till his baggage arrive, when do ye come to me and receive your monies from me.” So they fared forth and the King turned to his Wazir and said to him, “Pay court to Merchant Ma’aruf and take and give with him in talk and bespeak him of my daughter, Princess Dunyá, that he may wed her and so we gain these riches he hath.” Said the Wazir, “O King of the age, this man’s fashion misliketh me and methinks he is an impostor and a liar: so leave this whereof thou speakest lest thou lose thy daughter for naught.” Now this Minister had sued the King aforetime to give him his daughter to wife and he was willing to do so, but when she heard of it she consented not to marry him. Accordingly, the King said to him, “O traitor, thou desirest no good for me, because in past time thou soughtest my daughter in wedlock, but she would none of thee; so now thou wouldst cut off the way of her marriage and wouldst have the Princess lie fallow, that thou mayst take her; but hear from me one word. Thou hast no concern in this matter. How can he be an impostor and a liar, seeing that he knew the price of the jewel, even that for which I bought it, and brake it because it pleased him not? He hath jewels in plenty, and when he goeth in to my daughter and seeth her to be beautiful, she will captivate his reason and he will love her and give her jewels and things of price: but, as for thee, thou wouldst forbid my daughter and myself these good things.” So the Minister was silent, for fear of the King’s anger, and said to himself, “Set the curs on the 18cattle[44]!” Then with show of friendly bias he betook himself to Ma’aruf and said to him, “His highness the King loveth thee and hath a daughter, a winsome lady and a lovesome, to whom he is minded to marry thee. What sayst thou?” Said he, “No harm in that; but let him wait till my baggage come, for marriage-settlements on Kings’ daughters are large and their rank demandeth that they be not endowed save with a dowry befitting their degree. At this present I have no money with me till the coming of my baggage, for I have wealth in plenty and needs must I make her marriage-portion five thousand purses. Then I shall need a thousand purses to distribute amongst the poor and needy on my wedding-night, and other thousand to give to those who walk in the bridal procession and yet other thousand wherewith to provide provaunt for the troops and others[45]; and I shall want an hundred jewels to give to the Princess on the wedding-morning[46] and other hundred gems to distribute among the slave-girls and eunuchs, for I must give each of them a jewel in honour of the bride; and I need wherewithal to clothe a thousand naked paupers, and alms too needs must be given. All this cannot be done till my baggage come; but I have plenty and, once it is here, I shall make no account of all this outlay.” The Wazir returned to the King and told him what Ma’aruf said, whereupon quoth he, “Since this is his wish, how canst thou style him impostor and liar?” Replied the Minister, “And I cease not to say this.” But the King chid him angrily and threatened him, saying, “By the life of my head, an thou cease not this talk, I will slay thee! Go back to him and fetch him to me and I will manage matters with him myself.” So the Wazir returned to Ma’aruf and said to him, “Come and speak with the King.” “I hear and I obey,” said Ma’aruf and went in to the King, who said to him, “Thou shalt not put me off with these excuses, for my treasury is full; so take the keys and spend all thou needest and give what thou wilt and clothe the poor and do thy desire and have no care for the girl and the handmaids. When the baggage shall come, do what thou wilt with thy wife, by way of generosity, and we will have patience with thee anent the marriage-portion till then, for there is no manner of difference betwixt me and thee; none at 19all.” Then he sent for the Shaykh Al-Islam[47] and bade him write out the marriage-contract between his daughter and Merchant Ma’aruf, and he did so; after which the King gave the signal for beginning the wedding festivities and bade decorate the city. The kettle drums beat and the tables were spread with meats of all kinds and there came performers who paraded their tricks. Merchant Ma’aruf sat upon a throne in a parlour and the players and gymnasts and effeminates[48] and dancing-men of wondrous movements and posture-makers of marvellous cunning came before him, whilst he called out to the treasurer and said to him, “Bring gold and silver.” So he brought gold and silver and Ma’aruf went round among the spectators and largessed each performer by the handful; and he gave alms to the poor and needy and clothes to the naked and it was a clamorous festival and a right merry. The treasurer could not bring money fast enough from the treasury, and the Wazir’s heart was like to burst for rage; but he dared not say a word, whilst Merchant Ali marvelled at this waste of wealth and said to Merchant Ma’aruf, “Allah and the Hallows visit this upon thy head-sides[49]! Doth it not suffice thee to squander the traders’ money, but thou must squander that of the King to boot?” Replied Ma’aruf, “’Tis none of thy concern: whenas my baggage shall come, I will requite the King manifold.” And he went on lavishing money and saying in himself, “A burning plague! What will happen will happen and there is no flying from that which is fore-ordained.” The festivities ceased not for the space of forty days, and on the one-and-fortieth day, they made the bride’s cortège and all the Emirs and troops walked before her. When they brought her in before Ma’aruf, he began scattering gold on the people’s heads, and they made her a mighty fine procession, whilst Ma’aruf expended in her honour vast sums of money. Then they brought him in to Princess Dunya and he sat down on the high divan; after which 20they let fall the curtains and shut the doors and withdrew, leaving him alone with his bride; whereupon he smote hand upon hand and sat awhile sorrowful and saying, “There is no Majesty and there is no Might save in Allah, the Glorious, the Great!” Quoth the Princess, “O my lord, Allah preserve thee! What aileth thee that thou art troubled?” Quoth he, “And how should I be other than troubled, seeing that thy father hath embarrassed me and done with me a deed which is like the burning of green corn?” She asked, “And what hath my father done with thee? Tell me!”; and he answered, “He hath brought me in to thee before the coming of my baggage, and I want at very least an hundred jewels to distribute among thy handmaids, to each a jewel, so she might rejoice therein and say, My lord gave me a jewel on the night of his going in to my lady. This good deed would I have done in honour of thy station and for the increase of thy dignity; and I have no need to stint myself in lavishing jewels, for I have of them great plenty.” Rejoined she, “Be not concerned for that. As for me, trouble not thyself about me, for I will have patience with thee till thy baggage shall come, and as for my women have no care for them. Rise, doff thy clothes and take thy pleasure; and when the baggage cometh we shall get the jewels and the rest.” So he arose and putting off his clothes sat down on the bed and sought love-liesse and they fell to toying with each other. He laid his hand on her knee and she sat down in his lap and thrust her lip like a tit-bit of meat into his mouth, and that hour was such as maketh a man to forget his father and his mother. So he clasped her in his arms and strained her fast to his breast and sucked her lip, till the honey-dew ran out into his mouth; and he laid his hand under her left-armpit, whereupon his vitals and her vitals yearned for coition. Then he clapped her between the breasts and his hand slipped down between her thighs and she girded him with her legs, whereupon he made of the two parts proof amain and crying out, “O sire of the chin-veils twain[50]!” applied the priming and kindled the match and set it to the touch-hole and gave fire and breached the citadel in its four corners; so 21there befel the mystery[51] concerning which there is no enquiry; and she cried the cry that needs must be cried.[52]——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased to say her permitted say.

She resumed, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that while the Princess Dunya cried the cry which must be cried, Merchant Ma’aruf abated her maidenhead and that night was one not to be counted among lives for that which it comprised of the enjoyment of the fair, clipping and dallying langue fourrée and futtering till the dawn of day, when he arose and entered the Hammam whence, after donning a suit for sovrans suitable he betook himself to the King’s Divan. All who were there rose to him and received him with honour and worship, giving him joy and invoking blessings upon him; and he sat down by the King’s side and asked, “Where is the treasurer?” They answered, “Here he is, before thee,” and he said to him, “Bring robes of honour for all the Wazirs and Emirs and dignitaries and clothe them therewith.” The treasurer brought him all he sought and he sat giving to all who came to him and lavishing largesse upon every man according to his station. On this wise he abode twenty days, whilst no baggage appeared for him nor aught else, till the treasurer was straitened by him to the uttermost and going in to the King, as he sat alone with the Wazir in Ma’aruf’s absence, kissed ground between his hands and said, “O King of the age, I must tell thee somewhat, lest haply thou blame me for not acquainting thee therewith. Know that the treasury is being exhausted; there is none but a little money left in it and in ten days more we shall shut it upon emptiness.” Quoth the King, “O Wazir, verily my son-in-law’s baggage-train tarrieth long and there appeareth no news thereof.” The Minister laughed and said, “Allah be gracious to thee, O King of the age! Thou art none other but heedless with respect 22to this impostor, this liar. As thy head liveth, there is no baggage for him, no, nor a burning plague to rid us of him! Nay, he hath but imposed on thee without surcease, so that he hath wasted thy treasures and married thy daughter for naught. How long therefore wilt thou be heedless of this liar?” Then quoth the King, “O Wazir, how shall we do to learn the truth of his case?”; and quoth the Wazir, “O King of the age, none may come at a man’s secret but his wife; so send for thy daughter and let her come behind the curtain, that I may question her of the truth of his estate, to the intent that she may make question of him and acquaint us with his case.” Cried the King, “There is no harm in that; and as my head liveth, if it be proved that he is a liar and an impostor, I will verily do him die by the foulest of deaths!” Then he carried the Wazir into the sitting-chamber and sent for his daughter, who came behind the curtain, her husband being absent, and said, “What wouldst thou, O my father?” Said he “Speak with the Wazir.” So she asked, “Ho thou, the Wazir, what is thy will?”; and he answered, “O my lady, thou must know that thy husband hath squandered thy father’s substance and married thee without a dower; and he ceaseth not to promise us and break his promises, nor cometh there any tidings of his baggage; in short we would have thee inform us concerning him.” Quoth she, “Indeed his words be many, and he still cometh and promiseth me jewels and treasures and costly stuffs; but I see nothing.” Quoth the Wazir, “O my lady, canst thou this night take and give with him in talk and whisper to him:—Say me sooth and fear from me naught, for thou art become my husband and I will not transgress against thee. So tell me the truth of the matter and I will devise thee a device whereby thou shalt be set at rest. And do thou play near and far[53] with him in words and profess love to him and win him to confess and after tell us the facts of his case.” And she answered, “O my papa, I know how I will make proof of him.” Then she went away and after supper her husband came in to her, according to his wont, whereupon Princess Dunya rose to him and took him under the armpit and wheedled him with winsomest wheedling (and all-sufficient[54] are woman’s wiles whenas she would aught of men); and she ceased not 23to caress him and beguile him with speech sweeter than the honey till she stole his reason; and when she saw that he altogether inclined to her, she said to him, “O my beloved, O coolth of my eyes and fruit of my vitals, Allah never desolate me by less of thee nor Time sunder us twain me and thee! Indeed, the love of thee hath homed in my heart and the fire of passion hath consumed my liver, nor will I ever forsake thee or transgress against thee. But I would have thee tell me the truth, for that the sleights of falsehood profit not, nor do they secure credit at all seasons. How long wilt thou impose upon my father and lie to him? I fear lest thine affair be discovered to him, ere we can devise some device and he lay violent hands upon thee? So acquaint me with the facts of the case for naught shall befal thee save that which shall begladden thee; and, when thou shalt have spoken sooth, fear not harm shall betide thee. How often wilt thou declare that thou art a merchant and a man of money and hast a luggage-train? This long while past thou sayest, My baggage! my baggage! but there appeareth no sign of thy baggage, and visible in thy face is anxiety on this account. So an there be no worth in thy words, tell me and I will contrive thee a contrivance whereby thou shalt come off safe, Inshallah!” He replied, “I will tell thee the truth, and then do thou whatso thou wilt.” Rejoined she, “Speak and look thou speak soothly; for sooth is the ark of safety, and beware of lying, for it dishonoureth the liar and God-gifted is he who said:—

He said, “Know, then, O my lady, that I am no merchant and have no baggage, no, nor a burning plague; nay, I was but a cobbler in my own country and had a wife called Fatimah the Dung, with whom there befel me this and that.” And he told her his story from beginning to end; whereat she laughed and said, “Verily, thou art clever in the practice of lying and imposture!” Whereto he answered, “O my lady, may Allah Almighty preserve thee to veil sins and countervail chagrins!” Rejoined she, “Know, that thou imposedst upon my sire and deceivedst him by dint of thy deluding vaunts, so that of his greed for gain he married me to thee. Then thou squanderedst 24his wealth and the Wazir beareth thee a grudge for this. How many a time hath he spoken against thee to my father, saying, Indeed, he is an impostor, a liar! But my sire hearkened not to his say, for that he had sought me in wedlock and I consented not that he be baron and I femme. However, the time grew longsome upon my sire and he became straitened and said to me, Make him confess. So I have made thee confess and that which was covered is discovered. Now my father purposeth thee a mischief because of this; but thou art become my husband and I will never transgress against thee. An I told my father what I have learnt from thee, he would be certified of thy falsehood and imposture and that thou imposest upon Kings’ daughters and squanderest royal wealth: so would thine offence find with him no pardon and he would slay thee sans a doubt: wherefore it would be bruited among the folk that I married a man who was a liar, an impostor, and this would smirch mine honour. Furthermore an he kill thee, most like he will require me to wed another, and to such thing I will never consent; no, not though I die![55] So rise now and don a Mameluke’s dress and take these fifty thousand dinars of my monies, and mount a swift steed and get thee to a land whither the rule of my father doth not reach. Then make thee a merchant and send me a letter by a courier who shall bring it privily to me, that I may know in what land thou art, so I may send thee all my hand can attain. Thus shall thy wealth wax great and if my father die, I will send for thee, and thou shalt return in respect and honour; and if we die, thou or I and go to the mercy of God the Most Great, the Resurrection shall unite us. This, then, is the rede that is right: and while we both abide alive and well, I will not cease to send thee letters and monies. Arise ere the day wax bright and thou be in perplexed plight and perdition upon thy head alight!” Quoth he, “O my lady, I beseech thee of thy favour to bid me farewell with thine embracement;” and quoth she, “No harm in that.”[56] So he embraced her and knew her carnally; after which he made the Ghusl-ablution; then, donning the dress of a white slave, he bade the syces saddle him a thoroughbred steed. Accordingly, they 25saddled him a courser and he mounted and farewelling his wife, rode forth the city at the last of the night, whilst all who saw him deemed him one of the Mamelukes of the Sultan going abroad on some business. Next morning, the King and his Wazir repaired to the sitting-chamber and sent for Princess Dunya who came behind the curtain; and her father said to her, “O my daughter, what sayst thou?” Said she, “I say, Allah blacken thy Wazir’s face, because he would have blackened my face in my husband’s eyes!” Asked the King, “How so?”; and she answered, “He came in to me yesterday; but, before I could name the matter to him, behold, in walked Faraj the Chief Eunuch, letter in hand, and said:—Ten white slaves stand under the palace window and have given me this letter, saying:—Kiss for us the hands of our lord, Merchant Ma’aruf, and give him this letter, for we are of his Mamelukes with the baggage, and it hath reached us that he hath wedded the King’s daughter, so we are come to acquaint him with that which befel us by the way. Accordingly I took the letter and read as follows:—From the five hundred Mamelukes to his highness our lord Merchant Ma’aruf. But further. We give thee to know that, after thou quittedst us, the Arabs[57] came out upon us and attacked us. They were two thousand horse and we five hundred mounted slaves and there befel a mighty sore fight between us and them. They hindered us from the road thirty days doing battle with them and this is the cause of our tarrying from thee.——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased saying her permitted say.

She said, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that Princess Dunya said to her sire, “My husband received a letter from his dependents ending with:—The Arabs hindered us from the road thirty days which is the cause of our being behind time. They also took from us of the luggage two hundred loads of cloth and slew of us fifty Mamelukes. When the news reached my husband, he cried, Allah disappoint them! What ailed them to wage war with the Arabs for the sake of two hundred loads of merchandise? 26What are two hundred loads? It behoved them not to tarry on that account, for verily the value of the two hundred loads is only some seven thousand dinars. But needs must I go to them and hasten them. As for that which the Arabs have taken, ’twill not be missed from the baggage, nor doth it weigh with me a whit, for I reckon it as if I had given it to them by way of an alms. Then he went down from me, laughing and taking no concern for the wastage of his wealth nor the slaughter of his slaves. As soon as he was gone, I looked out from the lattice and saw the ten Mamelukes who had brought him the letter, as they were moons, each clad in a suit of clothes worth two thousand dinars, there is not with my father a chattel to match one of them. He went forth with them to bring up his baggage and hallowed be Allah who hindered me from saying to him aught of that thou badest me, for he would have made mock of me and thee, and haply he would have eyed me with the eye of disparagement and hated me. But the fault is all with thy Wazir,[58] who speaketh against my husband words that besit him not.” Replied the King, “O my daughter, thy husband’s wealth is indeed endless and he recketh not of it; for, from the day he entered our city, he hath done naught but give alms to the poor. Inshallah, he will speedily return with the baggage, and good in plenty shall betide us from him.” And he went on to appease her and menace the Wazir, being duped by her device. So fared it with the King; but as regards Merchant Ma’aruf he rode on into waste lands, perplexed and knowing not to what quarter he should betake him; and for the anguish of parting he lamented and in the pangs of passion and love-longing he recited these couplets:—

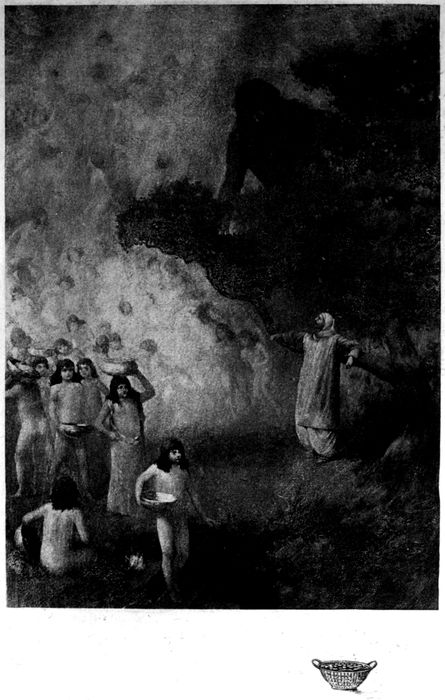

And when he ended his verses, he wept with sore weeping, for indeed the ways were walled up before his face and death seemed to him better than dreeing life, and he walked on like a drunken man for stress of distraction, and stayed not till noontide, when he came to a little town and saw a plougher hard by, ploughing with a yoke of bulls. Now hunger was sore upon him; and he went up to the ploughman and said to him, “Peace be with thee!”; and he returned his salam and said to him, “Welcome, O my lord! Art thou one of the Sultan’s Mamelukes?” Quoth Ma’aruf, “Yes;” and the other said, “Alight with me for a guest-meal.” Whereupon Ma’aruf knew him to be of the liberal and said to him, “O my brother, I see with thee naught with which thou mayst feed me: how is it, then, that thou invitest me?” Answered the husbandman, “O my lord, weal is well nigh.[62] Dismount thee here: the town is near hand and I will go and fetch thee dinner and fodder for thy stallion.” Rejoined Ma’aruf, “Since the town is near at hand, I can go thither as quickly as thou canst and buy me what I have a mind to in the bazar and eat.” The peasant replied, “O my lord, the place is but a little village[63] and there is no bazar there, neither selling nor buying. So I conjure thee by Allah, alight here with me and hearten my heart, and I will run thither and return to thee in haste.” Accordingly he dismounted 28and the Fellah left him and went off to the village, to fetch dinner for him whilst Ma’aruf sat awaiting him. Presently he said in himself, “I have taken this poor man away from his work; but I will arise and plough in his stead, till he come back, to make up for having hindered him from his work.[64]” Then he took the plough and starting the bulls, ploughed a little, till the share struck against something and the beasts stopped. He goaded them on, but they could not move the plough; so he looked at the share and finding it caught in a ring of gold, cleared away the soil and saw that it was set centre-most a slab of alabaster, the size of the nether millstone. He strave at the stone till he pulled it from its place, when there appeared beneath it a souterrain with a stair. Presently he descended the flight of steps and came to a place like a Hammam, with four daïses, the first full of gold, from floor to roof, the second full of emeralds and pearls and coral also from ground to ceiling; the third of jacinths and rubies and turquoises and the fourth of diamonds and all manner other preciousest stones. At the upper end of the place stood a coffer of clearest crystal, full of union-gems each the size of a walnut, and upon the coffer lay a casket of gold, the bigness of a lemon. When he saw this, he marvelled and rejoiced with joy exceeding and said to himself, “I wonder what is in this casket?” So he opened it and found therein a seal-ring of gold, whereon were graven names and talismans, as they were the tracks of creeping ants. He rubbed the ring and behold, a voice said, “Adsum! Here am I, at thy service, O my lord! Ask and it shall be given unto thee. Wilt thou raise a city or ruin a capital or kill a king or dig a river-channel or aught of the kind? Whatso thou seekest, it shall come to pass, by leave of the King of All-might, Creator of day and night.” Ma’aruf asked, “O creature of my lord, who and what art thou?”; and the other answered, “I am the slave of this seal-ring standing in the service of him who possesseth it. Whatsoever he seeketh, that I accomplish for him, and I have no excuse in neglecting that he biddeth me do; because I am Sultan over two-and-seventy tribes of the Jinn, each two-and-seventy thousand in number every one of which thousand ruleth over a thousand Marids, each Marid over a thousand Ifrits, each Ifrit over a thousand Satans and each Satan over a thousand Jinn: and they are all under command of me and may not gainsay me. As 29for me, I am spelled to this seal-ring and may not thwart whoso holdeth it. Lo! thou hast gotten hold of it and I am become thy slave; so ask what thou wilt, for I hearken to thy word and obey thy bidding; and if thou have need of me at any time, by land or by sea rub the signet-ring and thou wilt find me with thee. But beware of rubbing it twice in succession, or thou wilt consume me with the fire of the names graven thereon; and thus wouldst thou lose me and after regret me. Now I have acquainted thee with my case and—the Peace!”——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased to say her permitted say.

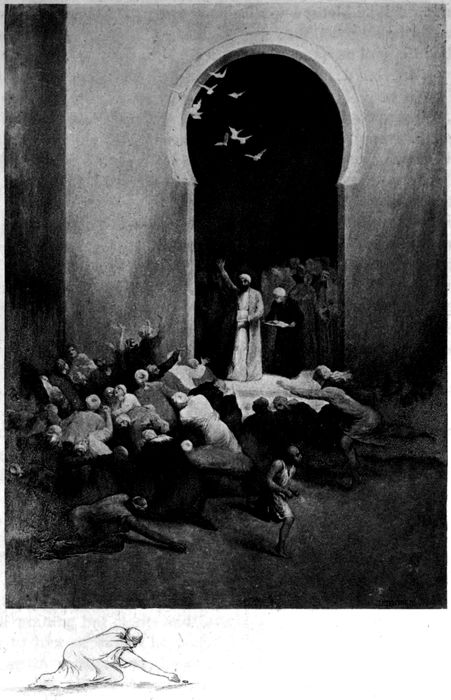

She continued, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that when the Slave of the Signet-ring acquainted Ma’aruf with his case, the Merchant asked him, “What is thy name?” and the Jinni answered, “My name is Abú al-Sa’ádát.[65]” Quoth Ma’aruf, “O Abu al-Sa’adat what is this place and who enchanted thee in this casket?”; and quoth he, “O my lord, this is a treasure called the Hoard of Shaddád son of Ad, him who the base of ‘Many-columned Iram laid, the like of which in the lands was never made.[66]’ I was his slave in his lifetime and this is his Seal-ring, which he laid up in his treasure; but it hath fallen to thy lot.” Ma’aruf enquired, “Canst thou transport that which is in this hoard to the surface of the earth?”; and the Jinni replied, “Yes! Nothing were easier.” Said Ma’aruf, “Bring it forth and leave naught.” So the Jinni signed with his hand to the ground, which clave asunder, and he sank and was absent a little while. Presently, there came forth young boys full of grace, and fair of face bearing golden baskets filled with gold which they emptied out and going away, returned with more; nor did they cease to transport the gold and jewels, till ere an hour had sped they said, “Naught is left in the hoard.” Thereupon out came Abu al-Sa’adat and said to Ma’aruf, “O my lord, thou seest that we have brought forth all that was in the hoard.” Ma’aruf asked, “Who be these beautiful 30boys?” and the Jinni answered, “They are my sons. This matter merited not that I should muster for it the Marids, wherefore my sons have done thy desire and are honoured by such service. So ask what thou wilt beside this.” Quoth Ma’aruf, “Canst thou bring me he-mules and chests and fill the chests with the treasure and load them on the mules?” Quoth Abu al-Sa’adat, “Nothing easier,” and cried a great cry; whereupon his sons presented themselves before him, to the number of eight hundred, and he said to them, “Let some of you take the semblance of he-mules and others of muleteers and handsome Mamelukes, the like of the least of whom is not found with any of the Kings; and others of you be transmewed to muleteers, and the rest to menials.” So seven hundred of them changed themselves into bât-mules and other hundred took the shape of slaves. Then Abu al-Sa’adat called upon his Marids, who presented themselves between his hands and he commanded some of them to assume the aspect of horses saddled with saddles of gold crusted with jewels. And when Ma’aruf saw them do as he bade he cried, “Where be the chests?” They brought them before him and he said, “Pack the gold and the stones, each sort by itself.” So they packed them and loaded three hundred he-mules with them. Then asked Ma’aruf, “O Abu al-Sa’adat, canst thou bring me some loads of costly stuffs?”; and the Jinni answered, “Wilt thou have Egyptian stuffs or Syrian or Persian or Indian or Greek?” Ma’aruf said, “Bring me an hundred loads of each kind, on five hundred mules;” and Abu al-Sa’adat, “O my lord accord me delay that I may dispose my Marids for this and send a company of them to each country to fetch an hundred loads of its stuffs and then take the form of he-mules and return, carrying the stuffs.” Ma’aruf enquired, “What time dost thou want?”; and Abu al-Sa’adat replied, “The time of the blackness of the night, and day shall not dawn ere thou have all thou desirest.” Said Ma’aruf, “I grant thee this time,” and bade them pitch him a pavilion. So they pitched it and he sat down therein and they brought him a table of food. Then said Abu al-Sa’adat to him, “O my lord, tarry thou in this tent and these my sons shall guard thee: so fear thou nothing; for I go to muster my Marids and despatch them to do thy desire.” So saying, he departed, leaving Ma’aruf seated in the pavilion, with the table before him and the Jinni’s sons attending upon him, in the guise of slaves and servants and suite. And while he sat in this state behold, up came the husbandman, 31with a great porringer of lentils[67] and a nose-bag full of barley and seeing the pavilion pitched and the Mamelukes standing, hands upon breasts, thought that the Sultan was come and had halted on that stead. So he stood open-mouthed and said in himself, “Would I had killed a couple of chickens and fried them red with clarified cow-butter for the Sultan!” And he would have turned back to kill the chickens as a regale for the Sultan; but Ma’aruf saw him and cried out to him and said to the Mamelukes, “Bring him hither.” So they brought him and his porringer of lentils before Ma’aruf, who said to him, “What is this?” Said the peasant, “This is thy dinner and thy horse’s fodder! Excuse me, for I thought not that the Sultan would come hither; and, had I known that, I would have killed a couple of chickens and entertained him in goodly guise.” Quoth Ma’aruf, “The Sultan is not come. I am his son-in-law and I was vexed with him. However he hath sent his officers to make his peace with me, and now I am minded to return to city. But thou hast made me this guest-meal without knowing me, and I accept it from thee, lentils though it be, and will not eat save of thy cheer.” Accordingly he bade him set the porringer amiddlemost the table and ate of it his sufficiency, whilst the Fellah filled his belly with those rich meats. Then Ma’aruf washed his hands and gave the Mamelukes leave to eat; so they fell upon the remains of the meal and ate; and, when the porringer was empty, he filled it with gold and gave it to the peasant, saying, “Carry this to thy dwelling and come to me in the city, and I will entreat thee with honour.” Thereupon the peasant took the porringer full of gold and returned to the village, driving the bulls before him and deeming himself akin to the King. Meanwhile, they brought Ma’aruf girls of the Brides of the Treasure,[68] who smote on instruments of music and danced before him, and he passed that night in joyance and delight, a night not to be reckoned among lives. Hardly had dawned the day when there arose a great cloud of dust which presently lifting, discovered seven hundred mules laden with stuffs and attended by muleteers and baggage-tenders and cresset-bearers. With them came Abu al-Sa’adat, riding on a she-mule, in the guise of a caravan-leader, 32and before him was a travelling-litter, with four corner-terminals[69] of glittering red gold, set with gems. When Abu al-Sa’adat came up to the tent, he dismounted and kissing the earth, said to Ma’aruf, “O my lord, thy desire hath been done to the uttermost and in the litter is a treasure-suit which hath not its match among Kings’ raiment: so don it and mount the litter and bid us do what thou wilt.” Quoth Ma’aruf, “O Abu al-Sa’adat, I wish thee to go to the city of Ikhtiyan al-Khutan and present thyself to my father-in-law the King; and go thou not in to him but in the guise of a mortal courier;” and quoth he, “To hear is to obey.” So Ma’aruf wrote a letter to the Sultan and sealed it and Abu al-Sa’adat took it and set out with it; and when he arrived, he found the King saying, “O Wazir, indeed my heart is concerned for my son-in-law and I fear lest the Arabs slay him. Would Heaven I wot whither he was bound, that I might have followed him with the troops! Would he had told me his destination!” Said the Wazir, “Allah be merciful to thee for this thy heedlessness! As thy head liveth, the wight saw that we were awake to him and feared dishonour and fled, for he is nothing but an impostor, a liar.” And behold, at this moment in came the courier and kissing ground before the King, wished him permanent glory and prosperity and length of life. Asked the King, “Who art thou and what is thy business?” “I am a courier,” answered the Jinni, “and thy son-in-law who is come with the baggage sendeth me to thee with a letter, and here it is!” So he took the letter and read therein these words, “After salutations galore to our uncle[70] the glorious King! Know that I am at hand with the baggage-train: so come thou forth to meet me with the troops.” Cried the King, “Allah blacken thy brow, O Wazir! How often wilt thou defame my son-in-law’s name and call him liar and impostor? Behold, he is come with the baggage-train and thou art naught but a traitor.” The Minister hung his head groundwards in shame and confusion and replied, “O King of the age, I said not this save because of the long delay of the baggage and because I feared the loss of the wealth he hath wasted.” The King exclaimed, “O 33traitor, what are my riches! Now that his baggage is come he will give me great plenty in their stead.” Then he bade decorate the city and going in to his daughter, said to her, “Good news for thee! Thy husband will be here anon with his baggage; for he hath sent me a letter to that effect and here am I now going forth to meet him.” The Princess Dunya marvelled at this and said in herself, “This is a wondrous thing! Was he laughing at me and making mock of me, or had he a mind to try me, when he told me that he was a pauper? But Alhamdolillah, Glory to God, for that I failed not of my duty to him!” On this wise fared it in the Palace; but as regards Merchant Ali, the Cairene, when he saw the decoration of the city and asked the cause thereof, they said to him, “The baggage-train of Merchant Ma’aruf, the King’s son-in-law, is come.” Said he, “Allah is Almighty! What a calamity is this man![71] He came to me, fleeing from his wife, and he was a poor man. Whence then should he get a baggage-train? But haply this is a device which the King’s daughter hath contrived for him, fearing his disgrace, and Kings are not unable to do anything. May Allah the Most High veil his fame and not bring him to public shame!”——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased saying her permitted say.

She pursued, It hath reached me, O auspicious King, that when Merchant Ali asked the cause of the decorations, they told him the truth of the case; so he blessed Merchant Ma’aruf and cried, “May Allah Almighty veil his fame and not bring him to public shame!” And all the merchants rejoiced and were glad for that they would get their monies. Then the King assembled his troops and rode forth, whilst Abu al-Sa’adat returned to Ma’aruf and acquainted him with the delivering of the letter. Quoth Ma’aruf, “Bind on the loads;” and when they had done so, he donned the treasure-suit and mounting the litter became a thousand times greater and more majestic than the King. Then he set forward; but, when he had gone half-way, behold, the King met him with the troops, and seeing him riding in the 34Takhtrawan and clad in the dress aforesaid, threw himself upon him and saluted him, and giving him joy of his safety, greeted him with the greeting of peace. Then all the Lords of the land saluted him and it was made manifest that he had spoken the truth and that in him there was no lie. Presently he entered the city in such state procession as would have caused the gall-bladder of the lion to burst[72] for envy and the traders pressed up to him and kissed his hands, whilst Merchant Ali said to him, “Thou hast played off this trick and it hath prospered to thy hand, O Shaykh of Impostors! But thou deservest it and may Allah the Most High increase thee of His bounty!”; whereupon Ma’aruf laughed. Then he entered the palace and sitting down on the throne said, “Carry the loads of gold into the treasury of my uncle the King and bring me the bales of cloth.” So they brought them to him and opened them before him, bale after bale, till they had unpacked the seven hundred loads, whereof he chose out the best and said, “Bear these to Princess Dunya that she may distribute them among her slave-girls; and carry her also this coffer of jewels, that she may divide them among her handmaids and eunuchs.” Then he proceeded to make over to the merchants in whose debt he was stuffs by way of payment for their arrears, giving him whose due was a thousand, stuffs worth two thousand or more; after which he fell to distributing to the poor and needy, whilst the King looked on with greedy eyes and could not hinder him; nor did he cease largesse till he had made an end of the seven hundred loads, when he turned to the troops and proceeded to apportion amongst them emeralds and rubies and pearls and coral and other jewels by handsful, without count, till the King said to him, “Enough of this giving, O my son! There is but little left of the baggage.” But he said, “I have plenty.” Then indeed, his good faith was become manifest and none could give him the lie; and he had come to reck not of giving, for that the Slave of the Seal-ring brought him whatsoever he sought. Presently, the treasurer came in to the King and said, “O King of the age, the treasury is full indeed and will not hold the rest of the loads. Where shall we lay that which is left of the gold and jewels?” And he assigned to him another place. As for the Princess 35Dunya when she saw this, her joy redoubled and she marvelled and said in herself, “Would I wot how came he by all this wealth!” In like manner the traders rejoiced in that which he had given them and blessed him; whilst Merchant Ali marvelled and said to himself, “I wonder how he hath lied and swindled, that he hath gotten him all these treasures[73]? Had they come from the King’s daughter, he had not wasted them on this wise! But how excellent is his saying who said:—

So far concerning him; but as regards the King, he also marvelled with passing marvel at that which he saw of Ma’aruf’s generosity and openhandedness in the largesse of wealth. Then the Merchant went in to his wife, who met him, smiling and laughing-lipped and kissed his hand, saying, “Didst thou mock me or hadst thou a mind to prove me with thy saying:—I am a poor man and a fugitive from my wife? Praised be Allah for that I failed not of my duty to thee! For thou art my beloved and there is none dearer to me than thou, whether thou be rich or poor. But I would have thee tell me what didst thou design by these words.” Said Ma’aruf, “I wished to prove thee and see whether thy love were sincere or for the sake of wealth and the greed of worldly good. But now ’tis become manifest to me that thine affection is sincere and as thou art a true woman, so welcome to thee! I know thy worth.” Then he went apart into a place by himself and rubbed the seal-ring, whereupon Abu al-Sa’adat presented himself and said to him, “Adsum, at thy service! Ask what thou wilt.” Quoth Ma’aruf, “I want a treasure-suit and treasure-trinkets for my wife, including a necklace of forty unique jewels.” Quoth the Jinni, “To hear is to obey,” and brought him what he sought, whereupon Ma’aruf dismissed him and carrying the dress and ornaments in to his wife, laid them before her and said, “Take these and put them on and welcome!” When she saw this, her wits fled for joy, and she found among the ornaments a pair of anklets of gold set with jewels of the handiwork of the magicians, 36and bracelets and earrings and a belt[74] such as no money could buy. So she donned the dress and ornaments and said to Ma’aruf, “O my lord, I will treasure these up for holidays and festivals.” But he answered, “Wear them always, for I have others in plenty.” And when she put them on and her women beheld her, they rejoiced and bussed his hands. Then he left them and going apart by himself, rubbed the seal-ring whereupon its slave appeared and he said to him, “Bring me an hundred suits of apparel, with their ornaments of gold.” “Hearing and obeying,” answered Abu al Sa’adat and brought him the hundred suits, each with its ornaments wrapped up within it. Ma’aruf took them and called aloud to the slave-girls, who came to him and he gave them each a suit: so they donned them and became like the black-eyed girls of Paradise, whilst the Princess Dunya shone amongst them as the moon among the stars. One of the handmaids told the King of this and he came in to his daughter and saw her and her women dazzling all who beheld them; whereat he wondered with passing wonderment. Then he went out and calling his Wazir, said to him, “O Wazir, such and such things have happened; what sayst thou now of this affair?” Said he, “O King of the age, this be no merchant’s fashion; for a merchant keepeth a piece of linen by him for years and selleth it not but at a profit. How should a merchant have generosity such as this generosity, and whence should he get the like of these monies and jewels, of which but a slight matter is found with the Kings? So how should loads thereof be found with merchants? Needs must there be a cause for this; but, an thou wilt hearken to me, I will make the truth of the case manifest to thee.” Answered the King, “O Wazir, I will do thy bidding.” Rejoined the Minister, “Do thou foregather with thy son-in-law and make a show of affect to him and talk with him and say:—O my son-in-law, I have a mind to go, I and thou and the Wazir but no more, to a flower-garden that we may take our pleasure there. When we come to the garden, we will set on the table wine, and I will ply him therewith and compel him to drink; for, when he shall have drunken, he will lose his 37reason and his judgment will forsake him. Then we will question him of the truth of his case and he will discover to us his secrets, for wine is a traitor and Allah-gifted is he who said:—

When he hath told us the truth we shall ken his case and may deal with him as we will; because I fear for thee the consequences of this his present fashion: haply he will covet the kingship and win over the troops by generosity and lavishing money and so depose thee and take the kingdom from thee.” “True,” answered the King.——And Shahrazad perceived the dawn of day and ceased to say her permitted say.