Title: The Land of Desolation: Being a Personal Narrative of Observation and Adventure in Greenland

Author: I. I. Hayes

Release date: April 6, 2019 [eBook #59217]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Robert Tonsing, Bryan Ness and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The following pages are a record of a visit to Greenland, made in the summer of 1869, with a small party of friends, in the steam-yacht of Mr. William Bradford, whose widely celebrated pictures of Arctic scenery have received such deserved commendation; for, whether we consider the difficulties of the subject which that artist has undertaken, or the unusual exposures and hazards he has encountered, his success has been commensurate with his zeal, talent, and unflagging energy.

Since Mr. Bradford was desirous only of obtaining materials for his easel, the voyage was a leisurely one, being mostly near the coast, where halts were from time to time made at such places as presented special attractions to the painter. The summer was therefore devoted to the study of the picturesque rather than to the scientific; yet numerous opportunities were afforded in the latter direction, especially with respect to observing the formation of Greenland glaciers and icebergs—subjects which have not hitherto received much attention. Facilities never before enjoyed by Americans were also 8 obtained for visiting the site of the colonies of the ancient Northmen, who occupied that country from the tenth to the fifteenth centuries, and whose restless love of adventure led them even so far from their native homes as our own shores, at least five hundred years before the renowned voyage of Columbus.

Our range of the Greenland coast was more than a thousand miles, terminating a good way beyond the last outpost of civilization on the globe, in the midst of the much dreaded “ice-pack” of Melville Bay.

PART THE FIRST. | |

RUINS. | |

PAGE |

|

Ice and Breakers |

17 |

Free from Danger |

20 |

A hopeful Town in a hopeless Place |

26 |

Eric the Red |

39 |

“The Arctic Six” |

45 |

Up the Fiord in an Oomiak |

51 |

The Ruins of Ericsfiord |

62 |

The Northmen in Greenland |

71 |

The Northmen in America |

77 |

| 10 | |

The Last Man |

82 |

A Disconsolate Lover |

92 |

The Church at Julianashaab |

98 |

A Greenland Parliament |

101 |

A Greenland Ball |

112 |

PART THE SECOND. | |

PALACES OF NATURE. | |

Ice and Snow |

125 |

Glaciers and Icebergs |

129 |

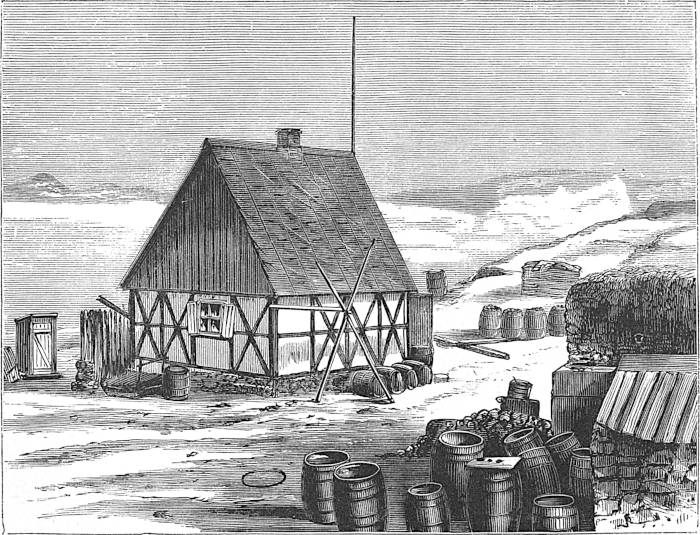

The Solitary Hut of Peter Motzfeldt |

137 |

The Glacier |

146 |

Crossing the Glacier |

153 |

Speculations |

166 |

| 11 | |

Measurements of Glaciers |

172 |

The Birth of an Iceberg |

175 |

A Narrow Escape |

179 |

Icebergs Critically Examined |

186 |

Man versus Mosquitoes |

197 |

A Picnic on the Glacier |

201 |

Bound for the Arctic Circle |

206 |

PART THE THIRD. | |

UNDER THE MIDNIGHT SUN. | |

Across the Arctic Circle |

215 |

Beyond Civilization |

240 |

Ice-Navigation |

253 |

Hunting by Steam |

263 |

12

CHAPTER V.

| |

Among the Ice-fields of Melville Bay |

284 |

The Last White Man |

294 |

The Fiord of Aukpadlartok |

309 |

Upernavik |

318 |

Disco Island |

328 |

Jacobshavn |

339 |

A Week at Godhavn |

348 |

PAGE |

|

Frontispiece. |

|

27 |

|

46 |

|

63 |

|

67 |

|

93 |

|

104 |

|

119 |

|

147 |

|

160 |

|

162 |

|

167 |

|

170 |

|

207 |

|

221 |

|

224 |

|

226 |

|

228 |

|

231 |

|

233 |

|

238 |

|

241 |

|

247 |

|

254 |

|

256 |

|

261 |

|

268 |

|

278 |

|

287 |

|

291 |

|

| 14 | 295 |

299 |

|

303 |

|

307 |

|

310 |

|

312 |

|

317 |

|

322 |

|

337 |

|

347 |

15

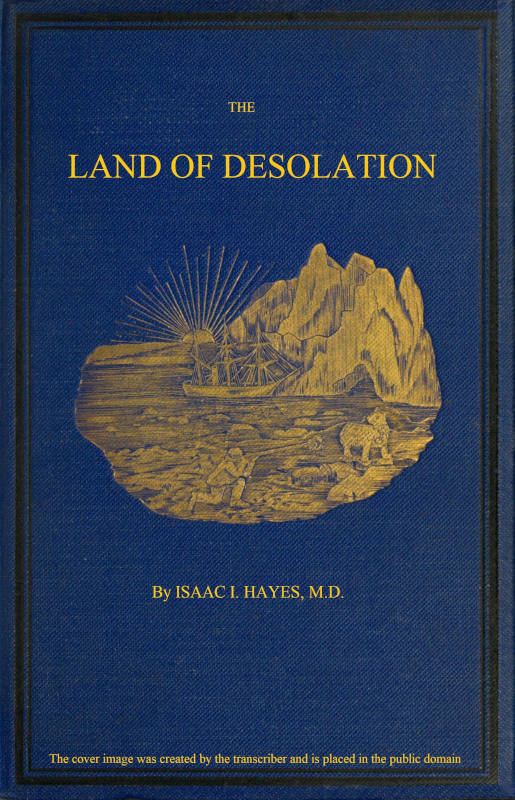

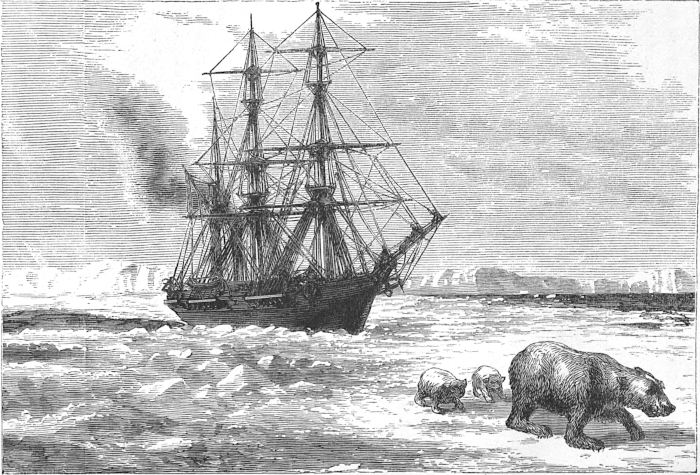

On a gloomy night in the month of July, 1585, the ship Sunshine, of fifty tons, “fitted out,” as the old chronicles inform us, “by divers opulent merchants of London, for the discovery of a north-west passage, came, in a thick and heavy mist, to a place where there was a mighty roaring as of waves dashing on a rocky shore.” The captain of this ship was brave old John Davis, who, when he had discovered his perilous situation, put off in a boat, and thereby discovered that his ship was “embayed in fields and hills of ice, the crashing together of which made the fearful sounds that he had heard.” The ship drifted helplessly through the night, and when the morning dawned, “the people saw the tops of mountains white with snow, and of a sugar-loaf shape, standing above the clouds; while at their base the land was deformed and rocky, and the shore was everywhere beset with ice, which made such irksome noise that the land was called ‘The Land of Desolation.’”

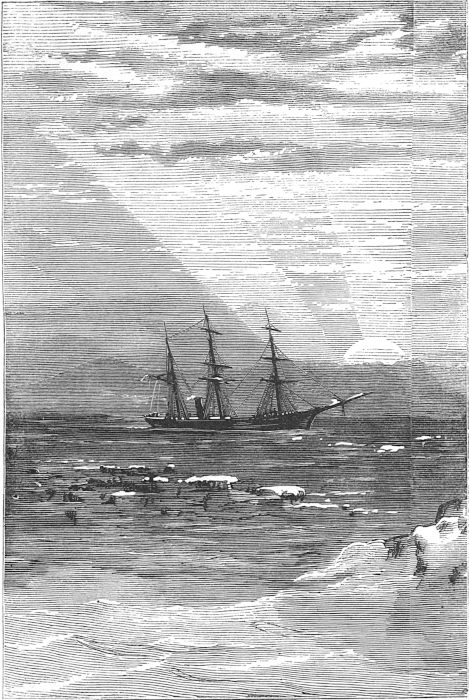

On a gloomy night in the month of July, 1869, the ship Panther, of three hundred and fifty tons, fitted out for a 18 summer voyage by a party in pursuit of pleasure, came in like manner, through a thick and heavy mist, to a place where there was a mighty roaring as of waves dashing on a rocky shore. The captain of this ship was John Bartlett, who, when he had discovered his perilous situation, put off in a boat, and returned with the knowledge that the Panther, like the Sunshine of old, was embayed in “fields and hills of ice,” the crashing together of which made the fearful sounds that he had heard; and then, when the morning dawned, “the people saw the tops of mountains white with snow, and of a sugar-loaf shape, standing above the clouds; while at their base the land was deformed and rocky,” and the shore was everywhere beset with ice, which made such “irksome noise,” that the people knew their ship had drifted to the self-same spot where the Sunshine had drifted nearly three hundred years before, and that the land before them was Davis’s “Land of Desolation.”

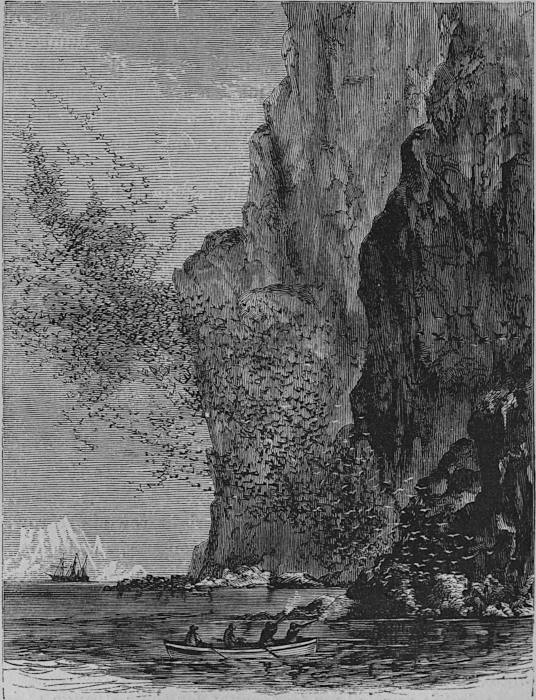

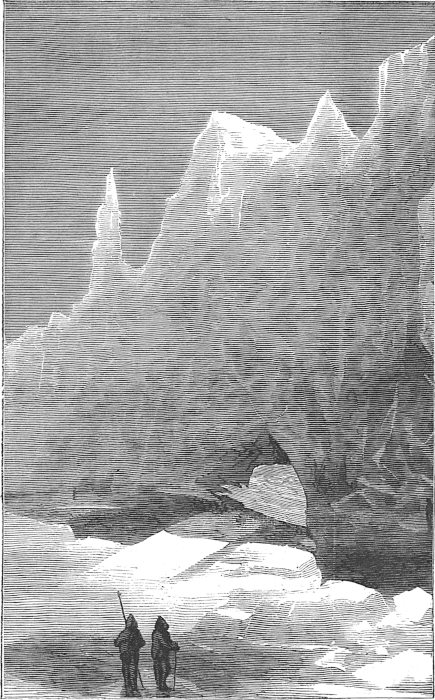

A mysterious land to them, and one around which clung many marvellous associations. Its legends had been the wonder of their boyhood; its grandeur was now their admiration. They had heard of it as a land of fable; tradition had peopled it with dwarfs and giants; history recorded that a race of men once occupied it whose fleets of ships traversed the waters in which their own vessel was now so grievously beset, bearing merchandise to hamlets of peace and plenty. Their eyes naturally sought a spot whereon to locate the home of this ancient people; but nothing could they discover save sterile rocks and desert wastes of ice. They saw dark cliffs which rose threateningly above them abruptly from the sea, and beyond these their eye wandered away into the interior, which the snows of centuries had converted into a vast plain of desolate whiteness. Returning from this limitless perspective, the eye fell upon the troubled waters. There were no signs of 19 life anywhere: desolation frowned on every side. Yet the spectacle was sublime; and, as if to render that sublimity the more complete, there was added soon an aspect of the terrible. This came in the form of a gale of wind, which speedily rose to a tempest. Rain, hail, and snow swept down upon the ship, and every distant object was hidden except when the storm-curtain was occasionally rent asunder, and a mountain peak was exposed, with the clouds breaking against its sides. The creaking and groaning ice was around them everywhere, and an occasional iceberg of enormous magnitude broke through the gloom, and, while moving on through the angry and troubled waters, received with cold indifference the fierce lashings of the sea.

I was a passenger on board the Panther, and shared with my companions the emotions which the Land of Desolation first inspired.

Under ordinary circumstances, there can be no more comfortable situation on board a ship than that of passenger. You are not expected to know any thing, and, if wise, you will not want to know any thing. You are content to trust to the captain, who is presumed to be quite competent to look to the safety of his ship, and therefore to your own. So far as human ingenuity can possibly be exercised to escape danger, his, you are sure, will be, and you trust to him as to a superior being—at least you know he has all the interest at stake that you have, and something more; for the handling of a ship in a storm is like the manœuvring of troops on the field of battle; success brings glory to the commander, and the acquisition of it is perhaps all the more precious that it is not shared with any body.

In our case there was a still further motive to confidence. Our captain owned one-half the ship, which was a Newfoundland screw-steamer, and was built unusually strong. Besides this, we had confidence in his judgment, which was the next best thing to confidence in his caution; and then, to crown all, he was a thoroughly good fellow. To quote the gentleman who devoted himself to the duties of sagaman for the cruise, “A roaring, tearing, jolly tar was he, as ever boxed the compass on the 21 sea.” During the eight days occupied in coming over from St. John’s, we had all conceived a high opinion of his qualities. He might be sometimes a little rash and venturesome, but rashness, as every body knows, is a safer quality than timidity; and we bore in recollection the old saying, “Nothing venture, nothing have.” We might, perhaps, have found a little fault with him at first for having run us in so close to the Land of Desolation without halting for daylight and better weather; but then we all knew that to “heave to” was something which the captain had a great horror of and he spoke of heaving to with such constant disrespect that the people generally had conceived the idea that it was a peculiarly terrible thing to indulge in. It seemed, therefore, that we were all right, and must necessarily escape shipwreck, even when the peril appeared greatest—when, for instance, we found ourselves threatened with an island rock on the one side and an island of ice on the other, in a sea white with foam, and breaking everywhere so wildly that the captain’s trumpet-voice could scarce be heard above the tumult.

The worst of it was, we did not know within fifty miles of where we were. “There,” said the captain, triumphantly, with his outspread hand upon the chart of Baffin’s Bay, covering at least ten thousand square miles of land and sea, “There’s where we are!” It was certain, at all events, that we had drifted within a line of skerries, for the waves broke on all sides, and where the rocks did not keep us from going, the ice did.

We had made the land with the intention of seeking a modern fishing-station of Danes and Esquimaux, which we knew to lie somewhere on that part of the coast; but where we could not even guess. As well seek charity in a bigot as hunt for a harbor in such weather, on a coast where there are neither light-houses nor pilots.

22

Yet we knew that human beings might be started somewhere if we only could free ourselves from our uncomfortable predicament, and the storm only would hold up. But it would not and did not until after we had, without exactly knowing how it came about, at length found ourselves in the open sea, and had given the Land of Desolation a wide berth.

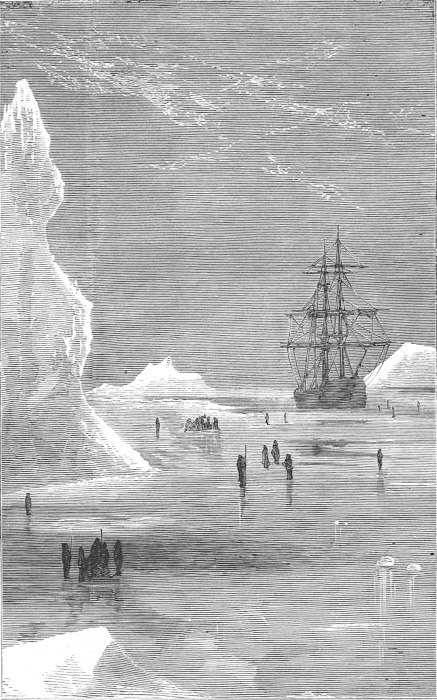

The weather clearing finally, the Panther was pointed for a promising opening in the belt of ice which beset the shore; and now, without much risk or difficulty, we got behind a cluster of islands not far from the main-land and a good way to the south of where we had been so much troubled.

Here there was no ice at all, and we began to look up the fishing-town. First of all the signal-gun was fired, and the Panther whistled her loudest. This woke the echoes, and startled some sea-gulls, but nothing more. Then we crept cautiously along, passing island after island, the Panther whistling constantly and the guns firing occasionally.

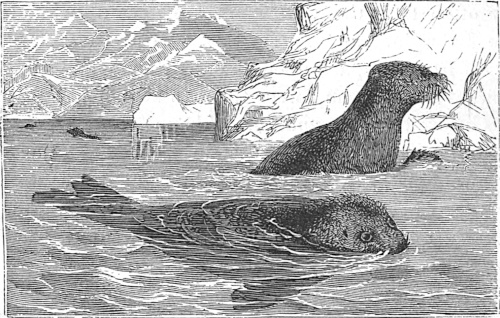

Presently we saw something dark moving upon the water, which appeared to have the body of a beast, and the head and shoulders of a man. It might be a marine centaur! who could tell? In fact, we rather expected to see some such monsters long before; and if the sea had been alive with them, we would not have been, I think, much surprised.

“Hi! hi!” was the first greeting of this strange-looking creature, with a voice that sounded very human “Hi! hi!” and afterwards he shouted, “Me Julianashaab pilot!” an announcement which greatly delighted us, even if the pilot did come in such very questionable shape.

He was not long in arriving alongside, and then, after getting the bight of a rope under each end of him, we 23 hauled him in on deck, whereupon the head and shoulders speedily shook themselves out from the body, and our marine centaur stood forth with the proper complement of legs to show his affinity to man.

To see a pilot shed himself thus is not to increase one’s confidence in him. And then his looks were by no means prepossessing. A broad face that was all cheeks, except what was mouth, with the least speck of a nose, and nothing to mention in the way of eyes, might be a curious study for a naturalist, but was hardly the sort of thing one seems to stand in need of when he seeks a harbor along a very ugly coast. And then his body was all covered with hair, and was all wet, as if he had just risen from the bottom of the sea. Besides, he smelt fishy. Yet this was clearly the best we could do if we ever meant to get into port, and, disregarding his unprepossessing appearance, the captain called him aft and ordered him to point out Julianashaab.

“Eh, tyma!” he answered; and off he started for the bridge, and off soon started the Panther under his direction.

Julianashaab we found to be no easy port to make, even with a marine centaur for a pilot. The Panther was twisted and turned about so much among the islands, and our pilot spoke so strangely, and made so many strange gestures, that he fairly turned the captain’s head. The captain would indeed hardly believe that we were going anywhere at all, but were, on the contrary, whirling about for the temporary amusement of this creature whom we had fished up out of salt water.

The fact is, Julianashaab is some twenty miles from the sea, on the bank of a very long and tortuous frith or fiord, which is studded with islands. Difficult of access at all times, it is peculiarly so in July, for then the ice from the 24 Spitzbergen side of Greenland comes drifting down with the great polar current, a branch of which sweeps around Cape Farewell into Davis’s Strait and Baffin’s Bay, and proceeds north for a while before it is deflected to the westward to join the ice-incumbered stream that chills the region of Labrador, and bathes the coast of America even to the Floridas. Cape Farewell is in latitude 59° 49´, and Julianashaab lies some eighty miles to the north and west of it; that is to say, in latitude 60° 44´, or 5° 48´ south of the Arctic circle. It is not, therefore, much nearer the North Pole than St. Petersburg, Russia, though in a very different climate.

It was fortunate that we secured even this strange pilot when we did, else we should have lain outside all the night; for there was a night, even although it was scarce deserving the name. When one can plainly see to read by the light of the sun as late as ten o’clock P.M., there is not much of a night to boast of. There was a faint twilight even at midnight, and to this was added the light of the moon, which threw its brightness on the summits of the snow-clad mountains, and trailed its silvery splendors away over the rippled waters of the fiord.

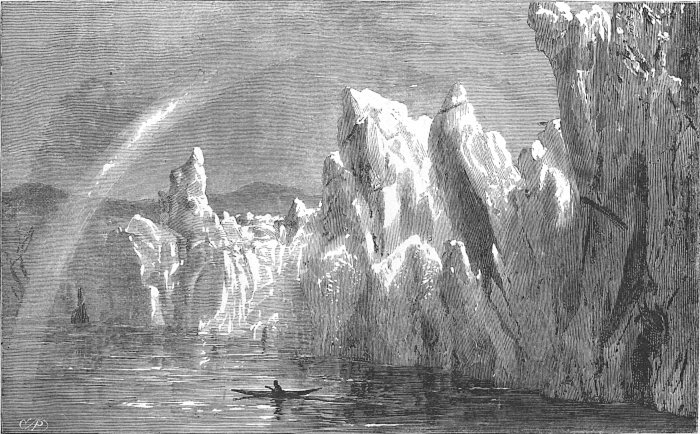

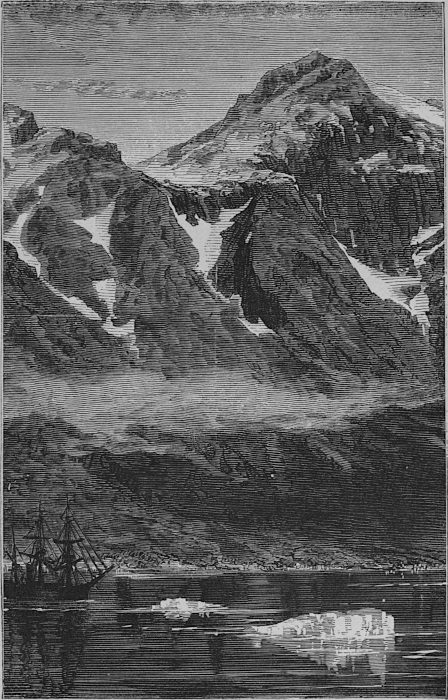

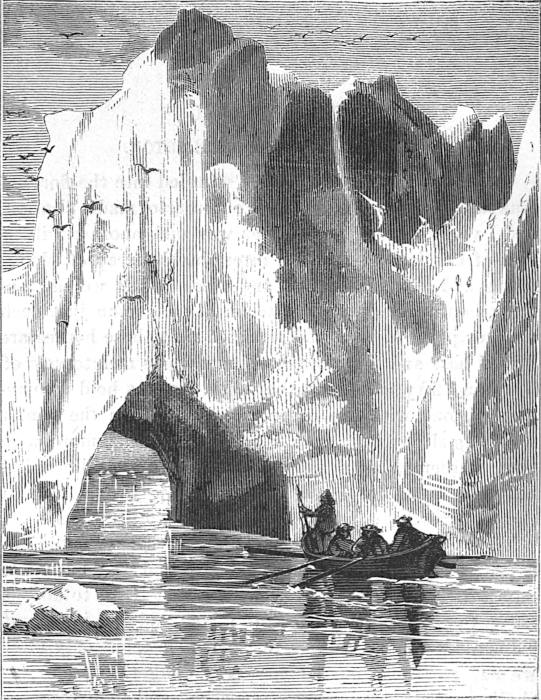

The scene as we passed on was most impressive. There is indeed in a still arctic night, whether in the winter or summer, a sublimity which one does not feel in a night elsewhere. We passed through many groups of icebergs, and in the moonlight their shapes, at all times full of strange suggestions, were converted into objects of the most fantastic description. The faces and forms of men and beasts were fashioned there in the light and shadow of the night, occasionally with wonderful distinctness. As we passed on, we were sometimes in the cold shelter of a cliff, while the icebergs before us glittered in a full blaze of light, as if they were mammoth gems; again we would 25 pass so near a berg that it seemed but awaiting an opportunity to topple over upon and overwhelm us; and all the while no sounds disturbed the air but the monotonous pulsations of the steamer and the hollow gurgle of the waves of her making as they broke within the icy caves.

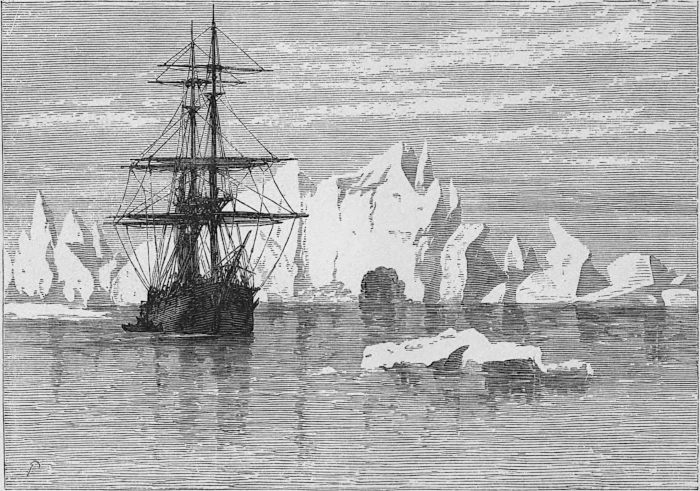

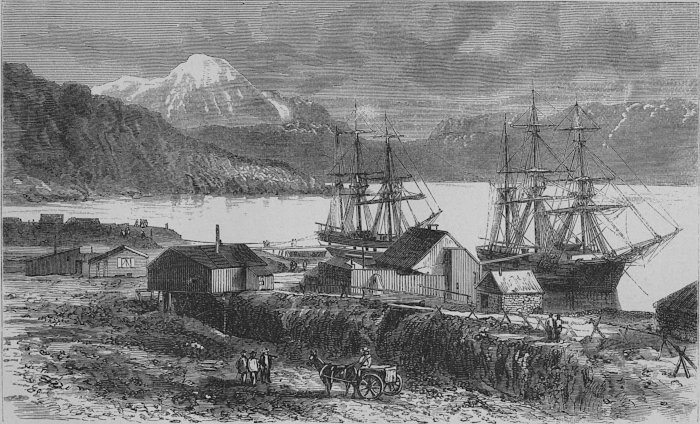

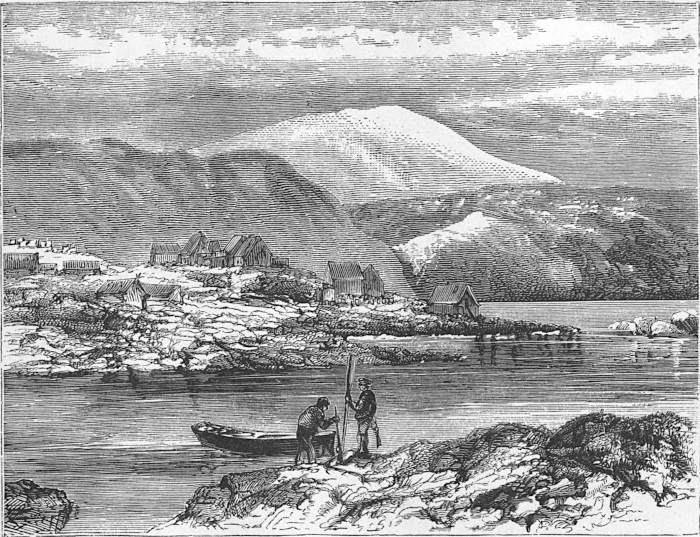

At length our pilot told us we were approaching our destination, and as the light of day began to replace the brightness of the moon, he whirled the Panther into a little bight, and a few rude habitations, a flag-staff, and the belfry of a little mission church, appeared before us on a dark rocky hill-side.

“Julianashaab!” said our pilot, pointing to it with as much pride and satisfaction as if he were overlooking the finest city of the world. Poor man, he knew no better! He little dreamed how miserable was his lot to be only a Julianashaaber, and dwell in peace! For this was indeed his home. He had gone down the fiord hunting seals and to gather the eggs of wild fowl upon the islands, and when he saw the Panther he had just begun his work.

Down went the anchor with its usual rush and rattle, and immediately the rocks were alive with people, who, aroused from their peaceful slumbers by the strange noise, sallied forth as suddenly as the witches from Kirk Alloway. Looking forward to a closer scrutiny of them when the day had fully come, we sought our bunks, and, exhausted with the excitement of the night and the constant exposure of the past few days, we turned in to sleep the sleep of weariness.

This “Land of Desolation,” to which we had come, is the Greenland of history and of the present time. All the southern part of it, as far up as the sixty-first degree of latitude, is called the “District of Julianashaab,” and the town of Julianashaab is its capital. This town is one of the most flourishing in the whole country. It is, perhaps, the most pleasantly situated of all of them, and, standing in a region full of historic and legendary interest, it presents a good type of Greenland life, past and present, and it is well worth looking at. Being the residence of the Governor of the “District,” something of additional importance is attached to it on that account. Country squires who come up to London; backwoodsmen casting their curious eyes about them in Washington; children on a holiday excursion to a neighboring village, are not seized with greater wonder at what they behold, than is the hunter from some remote station of the Julianashaab District, when, after having braved the dangers of flood and field, he finds himself observing the latest fashions, and learning how the world moves generally in the town of Julianashaab. So much, therefore, for its social and political importance.

29

They call it a colony, and its governor, or director, is the colonibestyrere, which is to say, the steerer of it. There are eleven other colonibestyreres in the country, one for each of the other eleven “Districts,” which extend northward one above the other from Julianashaab to the very confines of the habitable globe. The northernmost is Upernavik, beyond which there are no Christian people, or people of any kind living on the earth, except a few skin-clad savages. And, strange enough, this most northern place of Christian occupation bears a name which signifies “the summer place,” derived from Upernak, or, as it might be better spelt, Oopernak, the native Esquimaux word for summer.

Julianashaab, on the other hand, expresses a compliment to royalty. It was founded nearly a hundred years ago, at which time a king sat on the Danish throne who had a queen named Juliana. So, in honor of her majesty, they called this hopeful place the haab of Juliana, which is to say, in English, Julia’s Hope. I could but wonder if all the expectations that the name bespeaks were ever realized; for if so, the founders of it must have been extremely modest. I was especially impressed with this feeling when I landed next morning, on a visit to the governor’s house, and was greeted there by the principal part of the population.

Not a soul of them had, I believe, ever gone to bed after our arrival; but, on the contrary, had remained as they began—gazing at the Panther all the morning. When they first saw signs of activity on board, they expressed their delight in a very hilarious fashion; calling to each other, laughing, and running about from place to place, singly and in flocks, in a manner to indicate a very lively state of feeling. The little huts from which they emerged were scarcely distinguishable from the rocks themselves, and the people appeared to be coming out of the earth, and dropping into it again like prairie-dogs. Great was the rush when I got in my boat and started for the landing-place. Here they formed themselves in two lines, a hundred or more of them—men, women, and children—all talking or laughing, and all much delighted. Some 30 pointed with their fingers; others remarked the singular performances of my tailor; others said, properly enough, what an odd-looking thing a round-topped hat was; and they all stood their ground while I marched between the two files, not one of them willing to forego for a moment the gratification of the passion of curiosity, which it is pleasant to know that arctic frosts can no more destroy than civilization unseat from its prying stool.

To see yourself gazed at by so many persons, even although they may be half-savage, is an embarrassing circumstance; and I should no doubt have felt bashful about running the gauntlet of their eyes had not another sense than that of sight claimed its legitimate right of precedence, and with such remarkable energy, too, that all minor emotions were impossible. Accordingly, I made my way through the crowd without any delay whatever, and, in fact, with a speed not at all calculated to give that opportunity for close examination which is always desirable to a traveller. The fact is, like the pilot we had picked up, they smelt fishy, and, had I not been most positively informed otherwise, I should have written the inhabitants of Julianashaab down as amphibious creatures of a fishy nature. And it would have been no very unnatural mistake either—not so bad, at least, as Sir John Mandeville’s imagining boles of cotton to be woolly hens.

To explain all this, it is needful only to observe that, this Hope of Juliana being nothing but a fishing-town, the people are all fishermen, and therefore every thing smells of fish exceedingly. The odor extended everywhere; the wharf and rocks were strewn with fish, and the air seemed charged with fish that had evaporated. I became in a little while saturated thoroughly; so much so, indeed, that I felt myself hardened sufficiently to approach and examine the people more carefully than I had done at first.

31

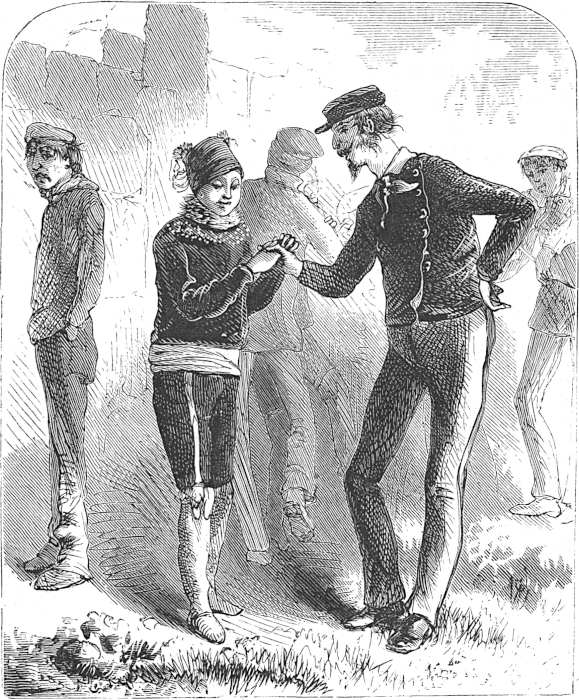

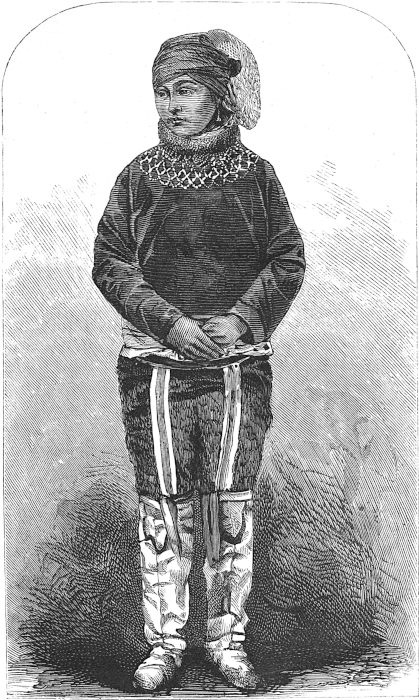

They proved to be of many shades of color, from the tawny hue of the native Esquimaux (Greenlanders they call them here), to the almost pure Caucasian complexion, with transparent skin and rosy cheeks. Of this latter class was one girl especially, who stood apart from the rest as if she were superior to them, and yet could not wholly restrain her curiosity. Her hair, which was auburn, was very abundant, and had been arranged with much care. A red silk handkerchief was tied about the forehead, and ribbons without stint fluttered from the knob of hair which stood up on the crown of her head. The labors of her toilet had evidently been performed with the greatest nicety. Her boots were as red as her handkerchief and quite as spotless; her trowsers were of the choicest and most shining seal-skin, neatly ornamented with needle-work and beads. Then her jacket, which was of some bright color to match, looked very jaunty. It met the trowsers at the hips, where it was trimmed with a broad band of eider-down. About the neck there was a collar of the same material, and the beads upon the breast and around the wrists, where there was more eider-down, were quite dazzling.

Altogether she was very pretty. Her complexion was a dark brunette, but very delicate. When I approached to speak to her, she blushed and ran away, which was the only fault I had to find with her. The little, savage, coy coquette would not let me have a word with her, but got behind a house, taking good care, however, to show herself from time to time around the corner, peeping there, after the very simple and artless fashion of coquettes the world over. She was not, however, allowed to remain there undisturbed; for following after me came a young gentleman from the Panther, who immediately proceeded to invest the house, stealing around in the rear of it. 32 When he had fairly cornered her she did not seem at all afraid, but spoke to him civilly enough; and then from that time forward, whatever might be my disposition towards a better acquaintance with this lively maiden of Julianashaab, my chances were clearly gone forever; for afterwards she smiled only on this young gentleman. It is said (such was the influence of his engaging manners and the delicacy of his flattery) that she gave him her red boots at the very first interview.

This young gentleman bore among his shipmates the name of Prince; but whether that name was natural to him, or whether it was, as some asserted, on account of a fancied resemblance to the Prince of Wales, or whether on account of his being the prince of good-fellows (which is more likely than all), is not important. But Prince he was, and like a prince he behaved. Concordia was the name, as afterwards appeared, of the coy damsel. I shall hereafter have occasion to relate how the Prince actually (as was said) proposed to abandon the Panther that he might make Concordia as happy a little princess as ever was Cinderella.

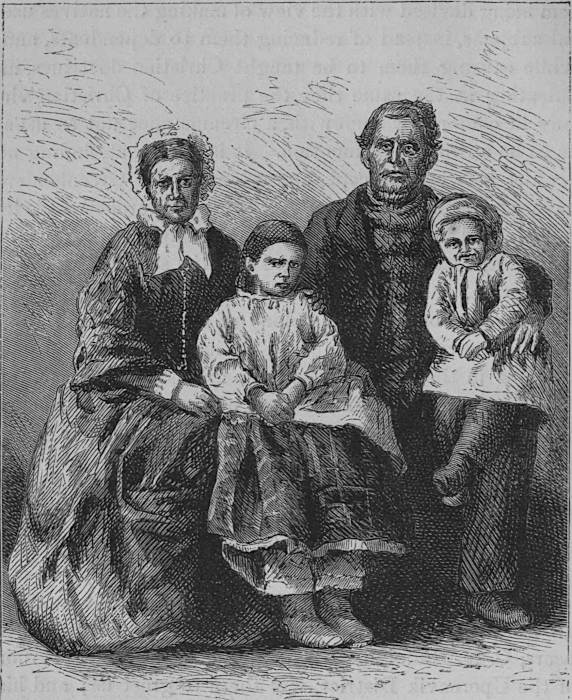

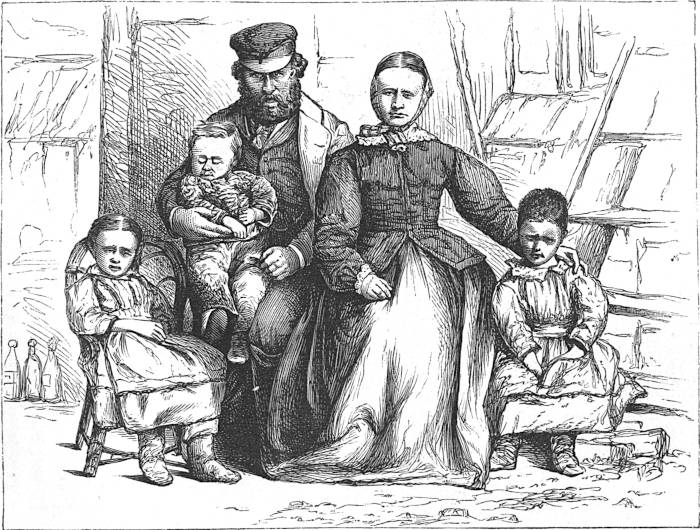

Proceeding up the path after leaving the native population, I encountered a man who was a full-blooded Dane in appearance, and I should not have known otherwise had he not told me afterwards that his mother had some native blood in her veins. He had been born here in the infant days of the colony, and when we fell into conversation he expatiated upon its growth, and manifested much pride in its prosperity. For a long while he had been the assistant bestyrere; but now he steers an island of his own, some thirty miles away, and he is at present up on a visit, with his family, to see the metropolitan sights. They had seen the church, the parson, the governor and his wonderful store-rooms, and now, to cap the climax, here had unexpectedly 33 come an Oomeasoak (big boat) that could breathe, and had feet to kick through the water with! What a journey up to town this had been, to be sure! How envious this would make their fellow-villagers, when they got home and told of all the wonders they had seen!

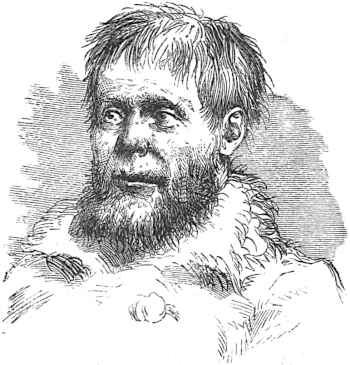

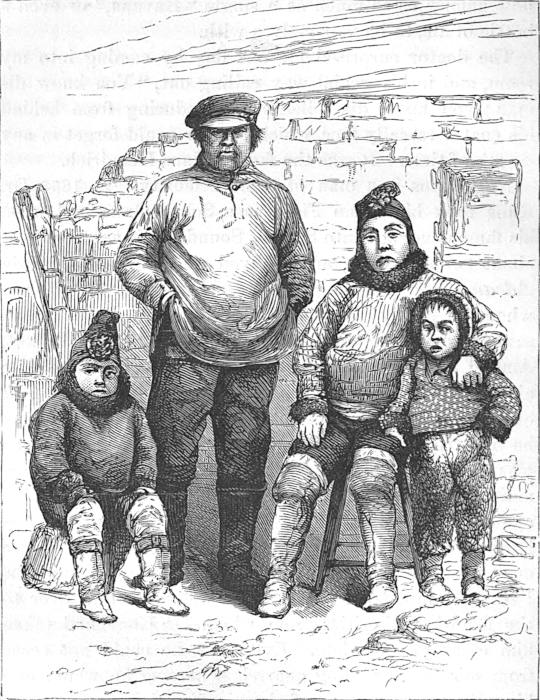

The name of this man was Peter Motzfeldt, and a very field of moss he was, if a ripe and fresh old age can be called so. Seventy bleak arctic winters had passed above his head, but not a single one had apparently gone into his heart, or even scattered frost upon his coal-black hair. He was as lively and elastic as if he were but twenty, which was the time when he first took service with the Royal Greenland Fishing Company, in whose employ he has been ever since. He had never been to Denmark, and he did not wish to go. It was all that he could do (naturally enough) to look after his two-and-twenty children, two boat-loads of which he had brought up with him to town.

This was the fiftieth anniversary of his employment by the Company, and the Company, in recognition of his faithfulness, had sent him a present, which was unfortunately, he said, down at Kraksimeut, where he lived. I thought he might have started with some of it on board the boat, and was the further confirmed in that suspicion when I ascertained that the present was an importation from Santa Cruz, and that there was no such token of civilization anywhere in Julianashaab as a public bar-room.

He promised to call upon me in the Panther, and devote himself to my service if I needed him. That I should need him was most evident, for he was perfectly charged with local knowledge, and besides that, had been with Captain Graah in the exploration which the Danish Government had ordered of this region in 1828–30. His name was therefore familiar to me already, from Graah’s narrative. He went with me to the government-house, and there left 34 me to present myself before Colonibestyrere Kursch, who I was glad to find (as I have usually found elsewhere with educated Danes) spoke English fluently, and, gratified with the welcome, I felt quite at home immediately, and began already to entertain a high opinion of Julianashaab. If my first introduction to the Land of Desolation had been somewhat rough, my first intercourse with its people (barring the fishy odor which they carried about with them) was decidedly pleasant.

Mr. Kursch was kind enough to furnish me with some charts of the coast, all drawn with that care and nicety for which the Danish hydrographers are famous. Afterwards we went together over to the house of the missionary, who lived at the opposite end of the town. In going there, we passed two store-houses, the Parliament-house (even here they can not do without a Parliament), the doctor’s house, numerous turf-covered huts of the natives, a few of better construction, where some half-breed families reside (including the catechist, the assistant bestyrere, the blacksmith, and the carpenter); then we crossed a narrow, dashing stream upon a bridge, and were at the church and parsonage.

The church is quite a picturesque little building, constructed of wood (of course brought from Denmark), as are indeed all the buildings put up by the Government. The walls are double, and, the space between being made quite air-tight by calking, the interior is easily warmed. Indeed there is little suffering from cold at any time of year in any of the buildings at Julianashaab. They need no fire during three months of the summer, and for the winter the home government sends them out a liberal supply of coal. As a further protection, the houses (which are but one story high) are all plastered over on the outside with pitch, which closes tightly every crack and cranny, and protects them from the weather.

35

If the church had not been black, it would have been in all respects neat and tidy. Black though it was, it was a pleasant sight to see this house of God here in the desert, and by its very appearance giving proof unmistakable of good, earnest, Christian work. “Cleanliness before godliness,” was meant for men, but it will do for a church as well.

The same neatness was observable at the pastor’s house. The little building was surrounded with a yard and garden, which was inclosed with a white fence; and in every window of the house plants were growing in brightly-painted pots, filling the rooms with their delicious perfume.

In the pastor I met with a great surprise. I had seen him before in 1860–61 at Upernavik, away up among the polar frosts, almost a thousand miles beyond his present residence. It seemed as if he could not quit Greenland; as if his heart and soul were in his missionary work, and he would not give it up. He had been compelled to ask for change of residence, for the Upernavik winters had been too much for him. I had scarcely crossed the threshold, when I distinguished a pleasant smile and gentle voice that had welcomed me before. “Can this be Mr. Anthon?” I asked.

“Yes;” and the good pastor opened wide his eyes, greatly astonished to see me there; but, recovering himself presently, he addressed me by name, and then called his wife and sister, and I could almost think myself back again in the same neat parsonage where I had first met this interesting family years before. A lovely girl and a bright-eyed boy had been added to the group since then; but now, as then, there was soon a bottle of wine upon the table, fragrant coffee in the urn, some Danish fare soon followed; and there was plenty of Danish heartiness all 36 round. In the afternoon we strolled up the bank of a little stream that runs beside the church and parsonage, and came upon a broad valley, in the centre of which there is a lake. Around the lake there were extensive pasture-grounds, upon which were browsing a herd of cows and a flock of goats. At this I was not a little surprised, for although I knew that in former times cattle had been reared here in great numbers, I had received the impression that at the present time they would not thrive. Mr. Anthon informed me that there was no difficulty in raising them, except the very important one of forage for the winter, for at Julianashaab the grass never grows high enough for hay. Farther up the fiord, however, it is abundant; but since the hay must all be brought in boats, it was both a tedious and expensive operation to gather it. Yet he managed to keep three cows; the governor had an equal number; the doctor had two; others had each one; and, indeed, all the well-to-do people in the village—Danes, half-breeds, and the better class of Greenlanders—had a daily supply of milk the year round.

The lake abounds in trout, a few of which were caught, and, when we returned for dinner, Mrs. Anthon had them for us on the table. She had, besides, some Greenland beef, and Greenland milk and butter; some smoked Greenland salmon too, and some Greenland venison; also some radishes and lettuce from her garden: and now, when these were, after a while, comfortably settled in their proper places with a glass of good old Santa Cruz punch, and an old Dutch pipe was brought to keep it company, and the governor and his assistant, and the doctor and Motzfeldt had come in to join us, we fell into a lively talk of Greenland and its legends; and it was not until a new day was breaking above the solemn hills around that I found my way back to the Panther. For fear, however, 37 the reader should think we “made a night of it” at the parsonage, I will remind him that the “break of day” there, in the early part of July, is about two o’clock.

I have rarely passed a more pleasant evening or one more profitable. Our conversation ran mostly upon events of the past rather than of the present; for Julianashaab, although not without interest in itself, is doubly interesting from its locality. It stands on historic ground. Here was the spot that we were seeking when the Panther drove in among the “hills and fields of ice” upon the Land of Desolation; a spot which history had made famous, and legend and tradition had been busy with; where brave old Eric the Red had come nearly nine centuries ago, and, with his followers, founded a sort of independent state.

The fiord on the banks of which stands this modern town of Julianashaab extends some forty miles beyond; but, while the modern town stands alone, in ancient days hamlets were dotted beside it everywhere; thousands of cattle once browsed where there are now but a few cows; and peace and plenty reigned here once among a Christian people, who, after maintaining themselves through nearly five hundred years, undisturbed by the elements of discord that afflicted the world elsewhere, became at length extinct, and, while they passed away, left only a few meagre records of their growth and progress, and ruins of their decay. These ruins, I had learned, were still to be seen at many points of the fiord, the walls of some of the buildings being, even at this late period, in a tolerable state of preservation.

To visit these ruins was, in fact, our principal object in putting into Julianashaab. Around them, indeed, centred the principal interest of the voyage—at least, so far as concerned myself; and I did not quit, therefore, the house 38 of the good pastor until we had planned an expedition to the place where the founder of this ancient people dwelt, and the church wherein he worshipped, in those latter days of his life when he had abandoned his war-god, Odin, for the Prince of Peace.

I had hoped Peter Motzfeldt would offer to accompany us, as he had visited some of the ruins forty years before with Captain Graah; but other engagements preventing him, Mr. Anthon was good enough to undertake to be our guide.

The fiord on the border of which stands the colony of Julianashaab is now known as the fiord of Igalliko, meaning, “the fiord of the deserted homes:” the deserted homes being the desolate and long-abandoned ruins of the Norse buildings which are scattered along its picturesque banks.

Its ancient name was Ericsfiord, so named by Red Eric, in commemoration of his discovery, and for the perpetuation of his fame—a sad commentary, truly, upon the instability of human designs, that a name meant to recall the memory of a great achievement should be replaced by one expressive of decay and ruin.

This fiord is a grand inlet from the sea, and is from two to five miles wide. To all appearances, it is a great river, flowing along majestically between its banks. It does not, however, stand alone, for there are many others in Greenland that much resemble it. It is one of a multitude of similar inlets that give such peculiar character to the Greenland coast. In fact, there is no other coast like it, if we except that of Norway. But, unlike the fiords of Norway, glaciers descend into nearly all of them. These glaciers, by their steady growth, have changed the aspect of the country greatly since the Northmen first went there and gave it the name which it at present bears. That it is a misnomer, need hardly be mentioned, though the application of it came about in a very simple way. Davis’s “Land of Desolation” suits the country much better than Eric’s “Greenland.”

40

The name Ericsfiord, like that of Magellan’s Strait, Hispaniola, etc., commemorates a discovery. Perhaps I should rather say, like that of America, it commemorates a re-discovery; for as America was known long before Columbus’s time, so also was Greenland before Eric’s, if we are to credit (and we have no reason to doubt them) the ancient sagas of Iceland. According to these, one Gunnibiorn landed in Greenland in the year 872.

Eric was a high-spirited son of a jarl of Jadar, in Norway, who, opposing the encroachments of the king upon his feudal rights, in common with his class, was forced to flee the country. Escaping with his son, he established himself in Iceland, which was then being peopled by such refugees from tyranny and wrong, and a society was being formed which, for love of liberty and the actual possession of republican freedom, has never been excelled. These Icelanders were then, and they continued to be for centuries afterwards, the most intellectual and refined people of the north of Europe; and this is not surprising when it is remembered that the best blood of Norway and Denmark went to swell its population. In fact, Iceland gave literature and laws to the whole of Scandinavia. The child was wiser than the parent. Her writers first put in shape the Norse mythology; and many of the most distinguished families of Norway and Denmark are now proud to trace their origin back to the old freedom-loving jarls and sea-kings who founded a nation upon a rock which had been forced up by terrestrial fires into an atmosphere so cold and forbidding that the snows gathered upon its lofty summits, while volcanic heat wrestled in the bowels of its mountains.

Eric received his surname of Red, or Rothe, from the color of his hair; and his corresponding disposition doubled the significance of 41 the name when it was made to signify “he of the red hand,” as well as of the red head. The truth is, he was, according to all accounts, much addicted to the then popular pastime of cutting people’s throats; and for his last offense of this description he was banished from Iceland for a space of three years. The immediate offense was for killing a churlish knave who would not return a borrowed door-post, which was always a sacred object, and was preserved with pious care by the Scandinavians. Perhaps if the borrowed article had been a book instead of a door-post, as in the case of fighting St. Colomba, the decree might have been different.

Being banished, where should Eric go? He could not return to Norway, and there was no place where he could set his foot with any safety. So he bethought him of the legendary land of Gunnibiorn, for, according to the Iceland Landnama, or Doomsday-book of Aré the Wise, that was the name of the man who had visited the land to the west of Iceland. This land Eric would go in search of, and risk his life and every thing upon the hazard.

He set sail from Bredifiord, in Iceland, some time during the summer of the year 983, in a small half-decked ship, and in three days he sighted land. Not altogether liking the looks of it, he coasted southward until he came to a turning-place, or Hvarf, now called Cape Farewell. Thence he made his way northward to the present site of Julianashaab, where he passed the three years of his forced exile. He liked the country well, as much as he had disliked it before when he saw it from the other side. Upon the meadow-lands beside the fiord immense herds of reindeer were browsing on the luxurious grass; sparrows chirruped among the branches of the little trees. He thought the place would do to settle in, and named it Greenland.

But to be precise, as it is always well to be, I quote from an old 42 Norse saga of the before-mentioned Aré the Wise—a saga written in Iceland about the year 1100, the original of which was in existence up to 1651, and a copy of which is still preserved in Copenhagen. Thus runs the tale:

“The land which is called Greenland was discovered and settled from Iceland. Eric the Red was the man from Bredifiord who passed thither from hence [Iceland] and took possession of that portion of the country now called Ericsfiord. But the name he gave the whole country was Greenland. ‘For,’ quoth he, ‘if the land have a good name, it will cause many to come hither.’ He first colonized the land fourteen or fifteen winters before Christianity was introduced into Iceland, as was told by Thorkil Gelluson in Greenland, by one who had himself accompanied Eric thither.” This Thorkil Gelluson was uncle to Aré the Wise, and the historian was pretty likely, therefore, to be accurate in his information.

Upon returning to Iceland, Eric was graciously received; and what with the fine name he had given to his new country, and the fine promises he held out, he had no trouble in obtaining all he asked for—that is, twenty-five ships loaded with adventurous people, and all the appliances for building up a colony. Thus provided, he set sail in the year 985; but only fourteen of these ships ever reached their destination. Some of the remaining eleven were lost at sea; others were wrecked upon the eastern coast of Greenland; others put back to Iceland in distress.

Eric was resolved to found a nation for himself, and these fourteen cargoes of people gave him a sufficient nucleus. He went far up his fiord and began a settlement. A house was also built nearer to the sea—probably a look-out-house; for Eric expected other ships, and 43 he, like a prudent man that he was, would set a watch for them. The ruins of this house may still be seen, and are not five minutes’ walk from the pastor’s house at Julianashaab.

According to his expectations, other ships arrived, bringing cattle, sheep, and horses; likewise his wife, and sons and daughters. The settlement grew and prospered. Norwegians, Danes, Icelanders, people from the Hebrides, from the British Isles, from Ireland, and even from the south of Europe, came there in ships to trade. Emigrants poured in, new towns were built, new farms were cleared, and ambitious and adventurous men searched up and down the coast for other fields whereon to display their enterprise. How far north the most adventurous went we can not certainly know; but Rafn places one of their expeditions in latitude 75°, a point to which the stoutest ships of modern times can not now go without encountering serious risk. And all this was ventured, eight hundred years ago, in half-decked ships and open boats. It is positively known that one of their expeditions reached as far as Upernavik, latitude 72° 50´, a stone having been discovered near there, in 1824, by Sir Edward Parry, bearing the following inscription in Runic characters:

“Erling Sighvatson and Biorn Thordarson and Eindrid Oddson on Saturday before Ascension week raised these marks and cleared ground. 1135.”

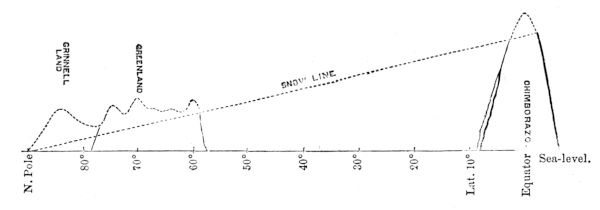

Think of “clearing ground” in Greenland up in latitude 72° 50´! What kind of ground would now be found to clear? Naked wastes alone; and the desert sands are not more unproductive. But, as intimated already, the climate has certainly changed during the seven hundred years since this event happened; in evidence of which, it is not unimportant to observe that, in the old chronicles of the voyages of 44 those ancient Northmen, there is very little mention made of ice as a disturbing element in navigation. And this brings us back to where we started—to the growth of glaciers in the Greenland fiords. From these glaciers come the icebergs, and a fiord which receives a glacier is not habitable.

There was no glacier in Ericsfiord when Eric went there, and there are none now, but it is surrounded by them. The mountains are of such peculiar formation that they keep back the frozen flood from Ericsfiord itself; and thus it was that this spot of earth was and still is fit for human life—an oasis in a desert, a patch of green in a wilderness of ice. But to this subject we shall have occasion to refer hereafter more at length.

Eric named his first settlement Brattahlid. The next he called Gardar; another, the Norse name of which has been lost, now bears the Esquimaux name of Krakortok, which means, “the place of the white rocks.” The rocks are of the same metamorphic character as elsewhere in that neighborhood, and only differ from them in having, by one of Nature’s freaks, been made of lighter hue than those of the region round about.

The fiord forks a short distance above Julianashaab, the southern branch leading to Brattahlid and Gardar, the northern, to Krakortok, which place it was our design to visit first.

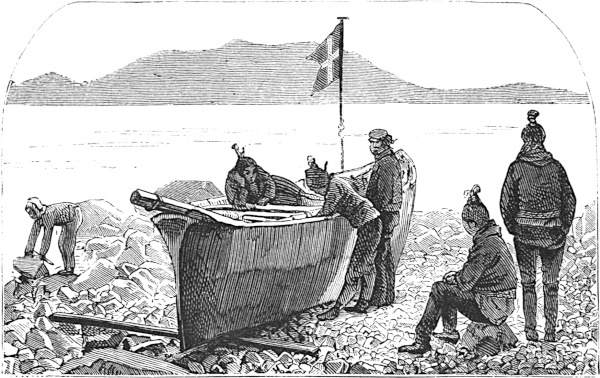

Mr. Anthon not only offered to be our pilot, as before stated, but he likewise offered us his Greenland boat. We had boats of our own, and good ones too; but then what so appropriate for a Greenland fiord as a Greenland boat? So, at least, said our pastor-pilot, and so we were all willing to confess. But what was a Greenland boat?

A Greenland boat is a curiosity in marine architecture. Mr. Anthon took us down to look at the one he had offered us. It was turned bottom up on a scaffolding, so that we could stand under it and almost see through it, for it was semi-transparent like a bladder. When I thumped it with a stick, it rattled like a drum.

“There it is,” said the pastor; “how do you like the looks of it?”

“What! that thing?” exclaimed the captain, with ill-concealed contempt; “go to sea in a thing like that?”

“Certainly,” said the pastor; “why not?”

Then he called three or four people, who had it off the scaffolding in a twinkling and down into the water, where it floated like a balloon that had been set adrift by mistake upon the sea.

“It’s a woman’s boat,” explained the pastor.

“Oh yes, I see,” answered the professor; “made by women. Quite an interesting object.”

It was certainly made with great cunning. It was about thirty-six feet long, by six feet wide, and two and a half deep. There was not a peg, or nail, or screw in it, so far as we could see; and, judging by the same method of inspection, it was all leather.

The pastor asked again how we liked the looks of it, now that it was in the water.

To confess the truth, it looked a little too balloonish to suit 47 any body’s fancy. The captain broke into a laugh. The professor speculated upon the quantity of stones that would be required to ballast it, measured by the ton; our sagaman began to institute comparisons between it and the ancient Phœnician craft, contending that the latter possessed decided advantages in a sea-way, which nobody doubted for a moment. The photographers came running along after it with their camera; the artists ran after it with their pencils—particularly a young gentleman much given to caricature (who, for short, bore the euphonious name of Blob), and who in a twinkling above a golden sea, sailing away like a kite, with our trader for a bob. The trader was not there at first, but he came up in time to make a liberal offer of pork and beans, or a note of hand, in exchange for it—any thing of that description would be so handy to have on board the Panther—a boat thirty-six feet long—handy as the door-plate in the Toodles house.

Some one asked Mr. Anthon if he would not be good enough “to have the thing shoved off, that we might get a touch of its quality.”

“Of course—by all means,” replied the pastor. Then he called the crew together.

“Now, shades of Harvard and Oxford defend us, what a crew! and what a rig!” exclaimed the Prince, breaking into a laugh as the crew appeared.

And he was quite right. It was a strange rig for a boat’s crew, without any sort of doubt. Very long boots that reached above the knees, of divers colors and pretty shape, gave a trim and natty look to the pedal extremities. Then they wore seal-skin pantaloons, very short, beginning where the boots left off and ending midway on the hips, where they met a jacket bright of hue, and lined with 48 fawn-skin. This jacket was trimmed around the neck with black fur, beneath which peeped up a white covering to the throat. The hair was drawn out of the way, and tied with red ribbon on the top of the head; and altogether the costume was calculated to show off the respective figures of the crew to the greatest possible advantage.

Then the Prince laughed again when the pastor called their names. “They’re a jolly lot,” said he.

“Go along,” said Mr. Anthon; “go along, Maria, and take the others with you.”

Maria proved to be stroke-oar, and she called, “Catherina, Christina, Dorothea, Nicholina, Concordia, here, come along.”

And off they all ran, chattering and giggling at an amazing rate; and they tumbled into the boat in a manner that made the captain fairly frown to see such lack of discipline. We were all much amused to see the gay and lively manner in which they skipped over the thwarts to their respective places, brimful of fun and mischief, and altogether making quite a shocking exhibition for a boat’s crew, whose duties we are usually in the habit of seeing performed in a very sober manner. But they quieted down a little when a more sedate individual (who proved to be the coxswain)—dressed in short boots and long seal-skin pantaloons, and a cap instead of ribbons on the head—came along, and, taking the steering-oar, gave the order to “shove off.”

The order was executed in handsome style, and the boat shot out over the little harbor very swiftly, each of the crew rising with the stroke of the oar; and bending to their work with a will, this singular-looking crew made their boat fairly hum again.

“Fine oarsmen!” exclaimed somebody who had just come up, and had not 49 heard the roster called.

“Oarsmen!” replied the pastor, laughing at somebody’s exceeding innocence. “Oarsmen! why, dear me, they are oarswomen!”

“Oars what?”

“Oarswomen, to be sure.”

“Oarswomen! Man alive! and do they always pull the boat?”

“Always,” replied the pastor; “always. A man will never pull an oar in a woman’s boat. He would think it a humiliation and disgrace. The most he will do is to take the steering-oar, which is, indeed, quite legitimate business for him. He has his own small boat, the handling of which requires skill, while the woman’s boat requires none. A man steers the boat now; the other six, who pull the oars, are all of the other sex, and I could not wish for a better crew.”

Upon being asked what duties as a crew they usually performed, he answered:

“They row me about from place to place, as my pastoral duties call me; they gather hay for the cows, and bring home the fish (principally capelin and cod) that the fishermen catch and dry at distant places. Besides this, they do any thing they are told to do, and do not hesitate to expose themselves in any weather, unless it should blow too hard for the safety of the boat.”

“Has such a boat any particular name?” the captain asked.

“We call it an oomiak, which signifies, simply, a woman’s boat; while the man’s boat is called a kayak.”

Here the Prince, who was growing somewhat impatient over this long catechizing, broke in with a query as to whether they pulled the oomiak to-morrow, in case we should conclude to go in her?

50 “Certainly,” replied the pastor.

“Just that same precious crew?”

“The same crew exactly.”

“Including the bow-oar you call Concordia?”

“Including her, of course. She is the life of the crew, and I could never get along without Concordia.”

“Nor I,” replied the Prince. “The boat will do for me. Sink or swim, survive or perish, I ship in that craft for one. Pipe the dear creatures back.”

So the pastor called to them to return, which they did in splendid style; and, every body agreeing with the Prince, it was forthwith arranged that we should go in the oomiak upon the morrow.

As the boat came in, the Prince proffered assistance, in a very gallant manner, to the bow-oar, but the girl hurried from the gunwale and ran, laughing, away. Nothing daunted, however, he gave chase; but, fleet as a young deer, she outstripped him and disappeared in the village, where the Prince was observed afterwards to be wandering around looking for her disconsolately.

The morning came fresh and sparkling as the eyes of our fair oarswomen, who, singing to the music of their splashing oars, came stealing over the still waters, bearing the good pastor in his arctic gondola, while we were yet at breakfast.

Their arrival alongside made a sensation. Such a boat, propelled in such a fashion, was a sight new to sailors’ eyes; and it did not seem easy for our people to reconcile such uses and occupations for womankind with a sailor’s ideas of gallantry; for a sailor is always quite willing for a woman to be a princess, and as such he would always like to look upon her, but he would never want her for a cook. He could never be happy unless he could abuse the cook, and he never would abuse a woman. But as for pulling at an oar, why, what in the world should he ever do, if he were not allowed to express his preferences as to what might happen to the eyes of any one who disturbed the stroke? and he never would condemn a woman’s eyes. Clearly, a woman would not do to pull an oar. But they were good to have a little pleasantry with, even if they did not understand a word that was said to them.

The people all crowded their heads over the bulwarks when the strange boat came up, and Welch addressed himself thus to the stroke-oar, when he had made out her peculiar style of costume: “Ah! my beauty, from the cut of your rig, it’s a blood-relation of Brian O’Lin’s that 52 you are;” which created a good laugh at the girl’s expense, without her, however, being at all aware of the cause of it. Not getting any response from that quarter, he turned his attention to the bow-oar. “And my bow-oar, honey, with the red top-knot: ah! sure and she’s a beauty. Say, my darlin, you’re the one I’d like to be shipmates with till the boat sinks.”

The bow-oar, more compliant than the stroke, nodded, smiled graciously, and said, “Ab!” and a great deal more which Welch did not understand.

“Ab?” he repeated, inquiringly; “and a pity it is that a foreigner you are, for I’d like to have a bit of a chat with you.”

Somebody told Welch that ab meant yes.

“And you’ll be shipmates with me?” inquired the sailor, with eagerness.

The bow-oar said “Ab!” again.

“Ah, then, and it’s too willin’ ye are, honey, entirely; and I’ll not ship with you at all, at all. But you’re a well-rigged craft alow and aloft, for all that, and I’d like to have the overhaulin’ of you.”

“You’ll get overhauled yourself, and your hull scuttled, and your top-gallant rigging scattered over the sea, if you tackle that craft again,” was the sharp reply which the fireman received to this very lively address. But it did not come from the bow-oar. It was from the Prince, who had just got out of bed, and, without pausing to comb his hair, had rushed to the gangway, to behold in the bow-oar the fair Concordia, and to discover that a sailor was making advances to her. The Prince was quite indignant. He soon, however, had Concordia on deck, when the others followed, and then, conducting them all to the galley, the Prince fed them bountifully. Meanwhile, preparation was being made for the journey. Some of us, however, embraced the 53 opportunity to examine with more care than we had been able to before the strange-looking boat in which it was proposed to perform the journey.

We go down into it before the cargo is stowed, and Mr. Anthon explains to us the method of its construction. It is not at all likely that the reader of this book will ever desire or have occasion to make such a boat for his own use; but it may perhaps not be uninteresting to him to know how he might proceed, if he should so desire. According to the pastor, it would be something after this fashion:

You will first obtain five round sticks of wood thirty-six feet long, more or less, according to the length you desire to make the boat. These must be as light as possible, and not over two inches in diameter. Since the country produces no wood, you will of course have to go to the governor for the materials, which he keeps in his store-house, replenishing the stock each year by shipments from Denmark. But since you will not find a stick thirty-six feet long, you will have to procure several, which you lash together until you have obtained the requisite length. Having done this, you place three of them on the ground parallel with each other, the outer ones being six feet apart. Then across them, at the middle, you lash, with firm thongs of raw seal-hide, a piece of inch plank three inches wide and six feet long. Then you bring the ends of the three long sticks together, lashing them firmly. Next you lash other pieces of board across at intervals of two feet. Of course these are of different lengths. Thus you have obtained the bottom of your oomiak. This done, you proceed to erect the skeleton, fastening the stem and stern posts firmly with lashings; also the ribs. The ribs in their place, you secure along the inside of them, at about sixteen inches above the floor, a strip of plank. On this you place the thwarts, the middle 54 one being six feet long, the others shorter, as you approach either end. Ten thwarts is the proper number. This completes the skeleton, all but the placing of the rails or gunwales, which are the two remaining thirty-six feet sticks. These being fastened with thongs to the ribs, and to the stem and stern posts, your skeleton is finished, and it is exceedingly light, strong, and elastic. But now, instead of covering this novel sort of boat-skeleton with planking, you stretch over it a coat of seal-hide (it can scarcely be called leather). It has been, however, tanned and dried, and afterwards thoroughly saturated with oil, until it is as impervious to water as a plate of iron. A number of skins are necessarily required, and these the women will sew together for you so firmly with sinew thread that not a drop of water can find its way through the seams. This skin coat, being cut and fashioned to fit the skeleton as neatly as a slipper to the foot, is drawn on and firmly tied. It is very soft when you draw it on, but when it dries it is as tight and hard as a drum-head; and when the skin becomes a little old, the light will come through it as through parchment. When afloat in the oomiak, you can always discover how much water you are drawing by looking through the side of it. This is not a pleasant operation, however, for a novice or a nervous person, since one can hardly resist the impression that he is in a very treacherous sort of craft.

This light and elastic boat is propelled with short oars having broad blades, which are tied to the gunwale, instead of being thrust out through rowlocks. These oars are shod with bone, to protect them from the ice. A single mast is erected in the bow, upon which is run up a square sail when the wind is fair. If the owner of the boat is rich enough, he gets the material for his sail from the governor; but if 55 not, he makes it out of seal-skins.

I have observed that he gets the wood from the governor’s stores: not all of it, however, for the obliging sea brings him an occasional tree that has floated with the ocean current from the forests of Siberia; or a plank, perhaps, that has fallen overboard from a passing vessel; or a spar or other portion of a wreck. Thus, before the Danes came here, did the Esquimaux obtain all the wood they used. From this source they also procured their iron, in the shape of spikes, nails, bands, and bars, attached to these waifs of the sea. Thus do the ocean currents, which carry heat and cold to the uttermost parts of the earth, scatter also blessings to mankind.

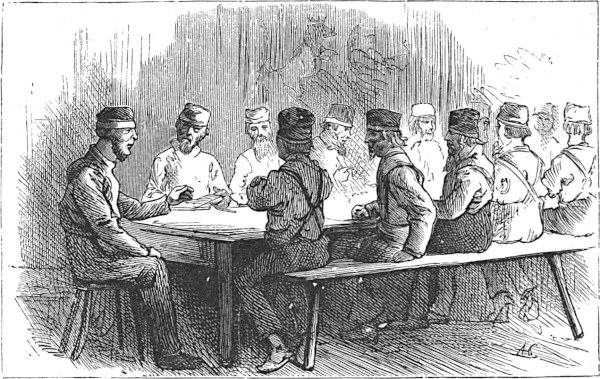

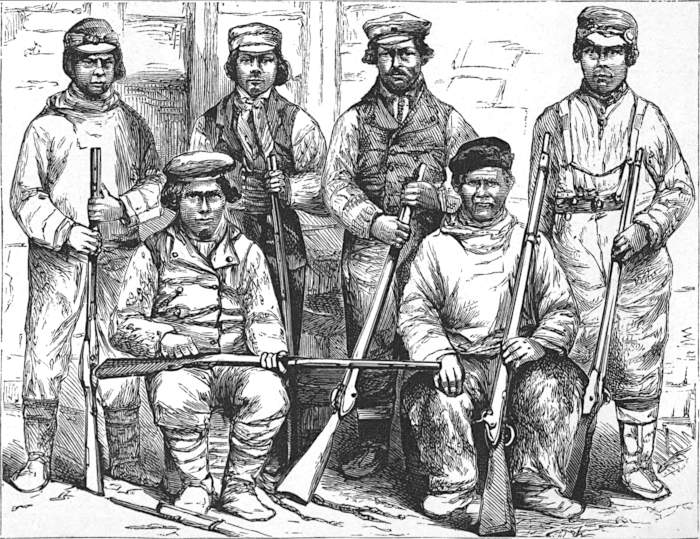

After some unavoidable delays (always occurring when any body sets out anywhere and some other body is to go with him), we finally got all our traps in the oomiak. The photographers were aboard with their cameras, baths, and plates; the artists with their sketch-books, stools, and pencils; the surveyors with their sextants, barometers, compasses, and tape-lines; the hunters with their weapons, game-bags, and ammunition; the steward with his cooking fixtures, and substantial eatables and drinkables; “the Arctic Six” were at their stations; and “All aboard!” was the signal to shove off. The fair oarswomen dipped their paddles, rising with the act, and coming down with a good solid thud upon the thwart when the paddles took the water. The light boat shot away from the ship over the unruffled waters of the silvery-surfaced fiord; and at last we were off.

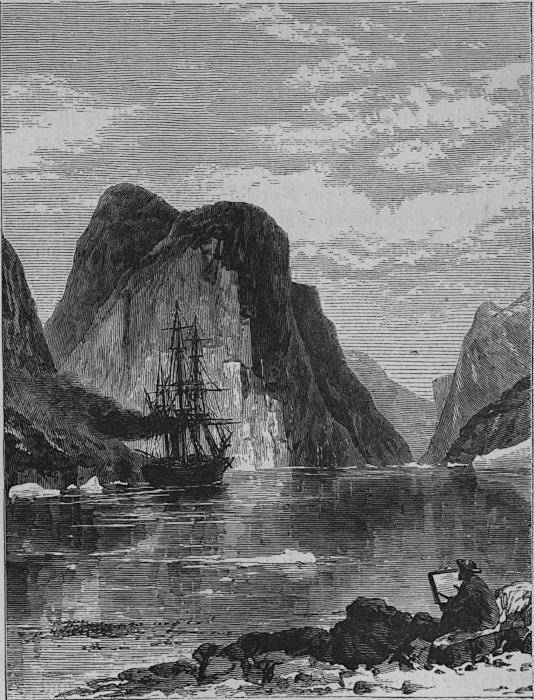

The day could not have been better chosen. The sky was cloudless; and the great mountains, by which we were on every side surrounded, climbed up into a pearly atmosphere, and their crests of ice and snow blended softly with the pure and lovely air. Every body was in the 56 best possible spirits; every thing was novel, from the boat and its strange crew to the strange shore past which we were gliding, and which presented sometimes cliffs of immense height, and sometimes slopes of green, above which the atmosphere quivered in the sun’s warm rays.

I could but contrast my situation with that of a few days before, when I was sweltering in the summer heat of New York. The atmosphere was soft like that of budding spring, though close to the Arctic Circle, and within the region lighted by the midnight sun.

The scenery was everywhere grand and inspiring. The shores, though destitute of human life, were yet rich in historical association. As we passed along, it was hard to realize that voices were not calling to us from the shore; and where miles of rich meadow-land stretched before us, girdling the cliffs with green, the fancy, now catching the lowing of cattle and the bleating of sheep, would sometimes detect the shouts of herdsmen; while again we seemed to hear,

the “song and oar” of some gay inhabitant of the fiord, descendant of that brave band of men who, under the leadership of sturdy Eric, had on these sloping plains, beneath the ice-crowned hills and within the rampart of the ice-girt isles, sought an asylum from their enemies.

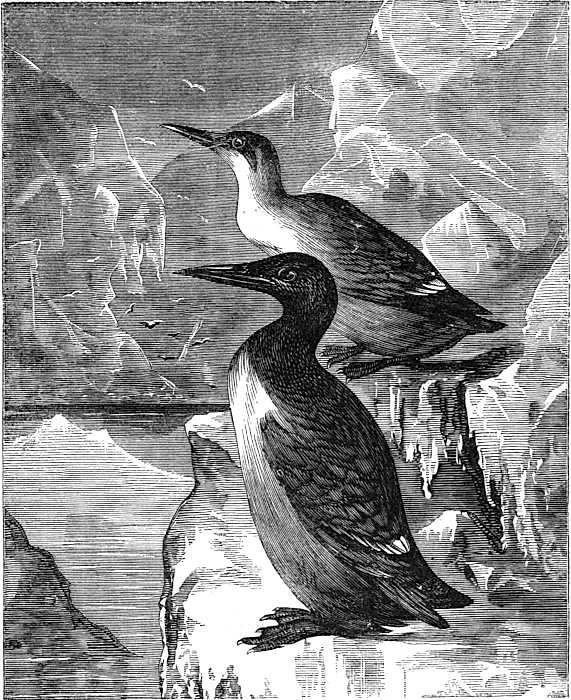

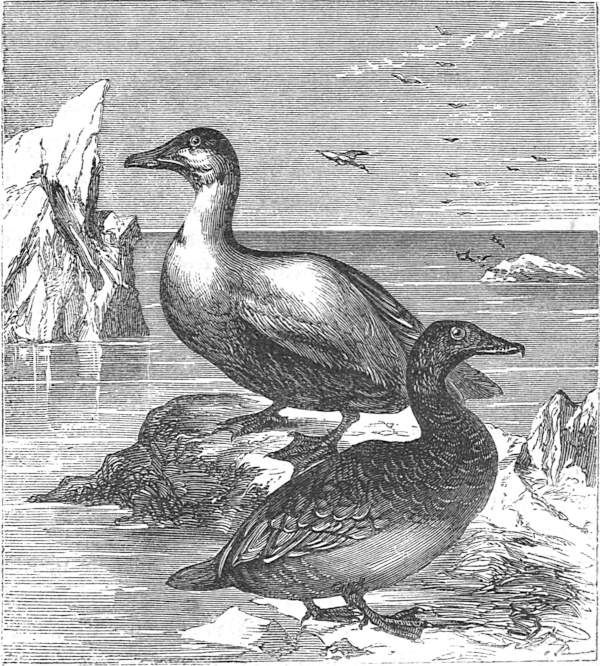

But if the fancy discovered those evidences of life, as it recalled the people who once were happy here in this peaceful, pastoral scene, the eye failed to detect any such tokens whatever. An occasional seal, that put up its half-human head to peer at us, or a sparrow or butterfly, that hovered about us when we neared the shore, or now and then a flock of water-fowl, were the only living things we saw.

57

The spirit of the scene was contagious. Even our native crew were not wanting in the emotional feelings of the hour. Encouraged by their pastor, they broke forth in concert, and with rich melodious voices, timed to the paddles’ stroke, they sang an old Norse hymn:

and as the refrain was echoed back to us over the waters from hill and dale, it struck the fancy more and more that human voices came to us from the depths of those solitudes.

Five hours of this pleasant experience brought us near the end of the fiord, where the water is narrowed to about two miles; but long before this the solemnity of the day had been at times broken by incidents very different from those above described. In fact, there was a great deal of liveliness mingled with the seriousness which every body felt at times, perhaps in spite of himself. The Prince was, as usual, at the bottom of the most of it. That young gentleman had come out to enjoy himself, and have a good time of it generally, and his disposition was not to be restrained by any of the ghosts of ancient Northmen who might haunt the fiord. He attached himself to Concordia as a matter of course. Speaking metaphorically, there can be no doubt that he had had his eye upon that pantalooned lady (now bow-oar) ever since he first discovered her peeping around the corner of the house in Julianashaab. It was not to be supposed, therefore, that he would on the present occasion relax his visual energies, and his first procedure was to place himself beside her on the thwart, where he carried his admiration so far as to insist upon 58 relieving the fair oarswoman of her oar, which resulted in a great deal of sport between the parties immediately interested, and filled the minds of the other damsels with immense disgust—whether because no one offered them the same gallant attentions, or whether because the bow-oar was constantly interfering with the stroke, was not discovered; but I greatly suspect it was the latter rather than the former.

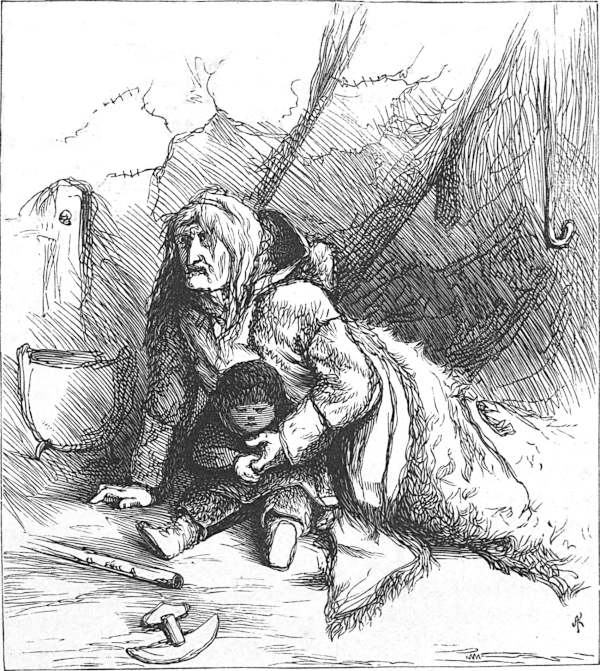

Thus, with alternate gayety and solemnity, did we speed on through the pleasant sunshine. In a general way we might say that there was universal enjoyment in that oomiak; but outside of it there was not altogether so happy a condition of affairs. The lively proceedings of Concordia and the Prince struck terror into one heart which beat its troubled discord in the confinement of a native kayak. The unhappy possessor of this discordant heart was a half-breed, whose name was Marcus, and who, although a half-savage, was yet wholly a Christian in the matter of name and baptism.

This Marcus was a fine-looking fellow, with brown hair and eyes, a frank open face, the complexion, though not the features, leaning rather to the Esquimaux than the Danish hue. The only trouble with him was—and this appeared to distress him greatly—that he loved Concordia. Judging from that distress, he must have loved her desperately.

Marcus was a great favorite with the pastor, and he always accompanied him everywhere he went. His duty was a simple one enough, but a very necessary one, as boating is performed in the Greenland fiords. It was to paddle along beside the oomiak in the capacity of courier, if occasion made it necessary to use one; or, in case of need, to act as outrider—two functions which at once suggest the dangers of oomiak navigation. Suppose, for instance, Mr. Anthon is 59 caught in a heavy blow, and is broadside to the wind. His boat is liable to be blown over, owing to its lightness. Marcus is near at hand; he pulls up quickly alongside, seizes the gunwale of the boat, bears his weight upon it, and prevents a catastrophe. Again, the oomiak runs against a sharp piece of ice, which the steersman has not seen in time to avoid; a hole is cut in the skin, and in rushes the water. The boat is headed for the land, and the pastor and his ladies get ashore with their lives. But where shall they go, or what shall they do? They are, perhaps, on an island, or, if not, they have to scale a mountain and descend again before they can reach a settlement. Marcus saves them this labor, and very likely their lives, by flying away in his kayak and bringing succor.

Twice during the day it seemed to me that we had met with a fatal accident of this nature. The skin of the boat was cut and the water entered, but the circumstance caused no alarm. The cuts proved to be small, and one woman only left her oar to repair them. This she did, and very speedily, by thrusting into the cut a small piece of blubber, which answered every purpose until we reached a convenient landing-place, when the boat was drawn up on the beach far enough for the woman to get at the hole with the sinew-threaded needle, when a patch was quickly fastened over it, and the skin was as good as ever.

That Marcus was jealous of the Prince, any body could see with half an eye. But a kayak is a most inconvenient place for a jealous lover. It is only a little over a foot wide, and does not weigh half as much as the man himself. If he meditates mischief to his rival, his own situation becomes a very dangerous one, since the least indiscretion in his movements, or the imprudent withdrawal of his eyes from his frail boat, would very likely cause him to find himself suddenly 60 floating head down, with his bladder-like kayak inextricably fastened to his heels—a position that would very speedily cure the most ardent lover in the world of the highly ridiculous passion of jealousy.

Compromising, therefore, between the impulse of jealousy and the restraints of prudence, Marcus paddled close to the forward part of our oomiak, where the Prince and Concordia were seated, as if he would overhear their conversation, and so possess himself of some remark of the fickle lady to treasure up against her, thus the more effectually to insure the destruction of his peace of mind—a pastime, by-the-way, in which lovers are very apt to indulge themselves.

If this was, however, his design, he unfortunately failed in it, since there was no conversation audible. Like Hai-dee, our heroine had long since discovered that her Don did not understand a word she said. Yet, judging from his liveliness of manner, the Prince must have learned something agreeable to his feelings; and it was clear enough that he was being instructed after a fashion quite equal, if not superior, to the ordinary forms of speech, for this fair lady of the oar

which seemed to be quite enough to satisfy her capricious fancy.

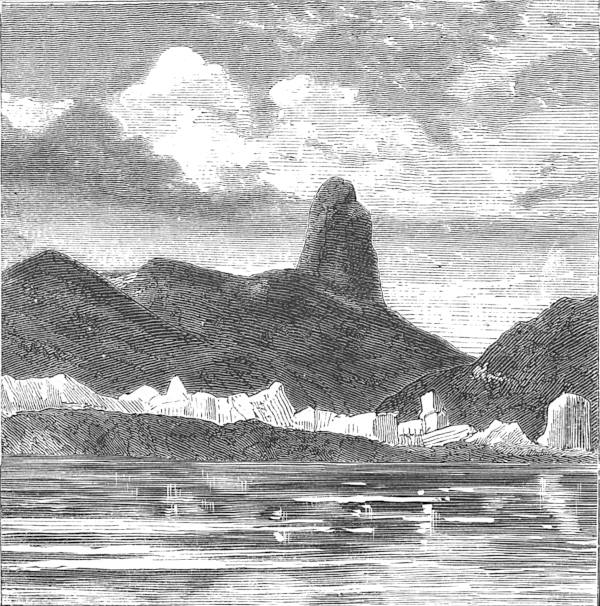

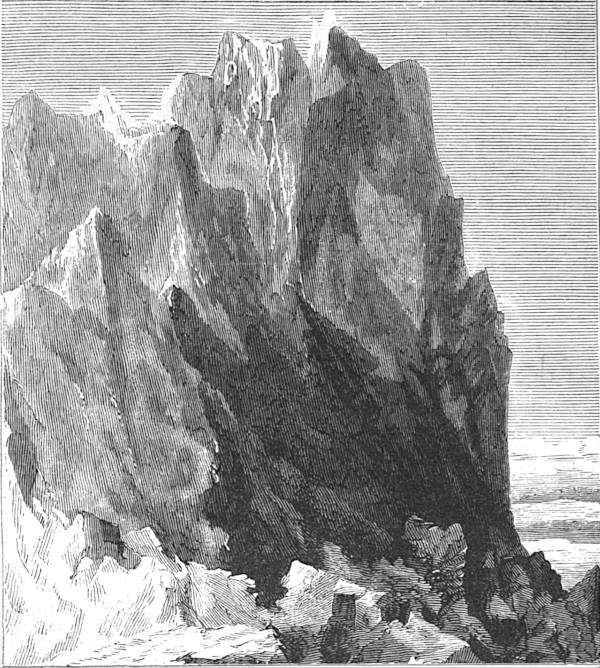

The time passed scarcely less pleasantly to the rest of the party than to the Prince, although in a very different manner. At least there was no lack of lively episodes, and we all found ourselves much surprised when we discovered that we were approaching the end 61 of the fiord, which had now assumed less the appearance of a river and more that of a lake. Before us the water was lost to view by a great curve, from the middle of which there appeared a fine valley stretching away to the base of the Redkammen, one of the noblest mountains to the artist’s eye, and one of the boldest landmarks to the mariner in all the country, conspicuous as Greenland is for its lofty and commanding scenery.

And there Redkammen stood in its solitary grandeur, away up in a streak of fleecy summer clouds, its white top now melting with them into space, now standing out against a sky of tenderest blue. Then came a cloak of darker vapor, which, resting on the mountain’s summit, trailed away into the heavens, bridging the space which divides the known from the vast unknown.

We were not long now in reaching our destination, which was the foot of the extensive green slope on the north side of the fiord. Above this slope, and from a quarter to half a mile from the bank, the cliffs rise perpendicularly to an altitude of fifteen hundred feet. To our right, as we approached, rose a lofty range of hills, which separates the two branches of the fiord. Beyond these once flourished the colonies of Brattahlid and Gardar. Behind and to the left of us lies the island of Aukpeitsavik, which extends almost to Julianashaab.

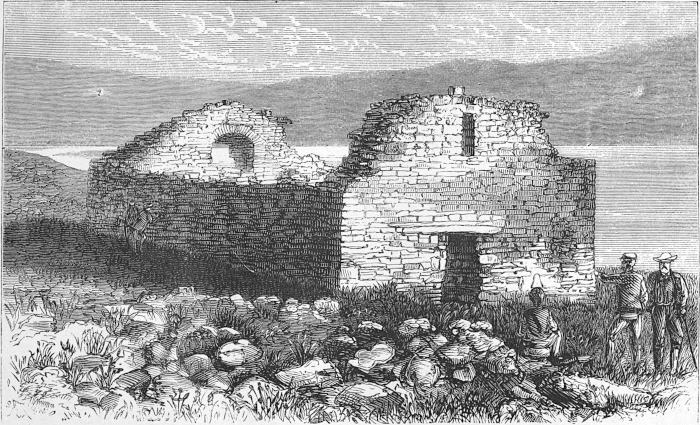

Our first concern was to discover if the church which we knew to have existed there was still standing. To our great satisfaction, its walls were seen upon the green slope long before we reached the land, although a cliff some thirty feet high, which formed its background, prevented us from observing it clearly until we had come almost to the shore.

Upon landing, there was a great scramble for the honor of first entrance into the ruin. The scramble was over a tangled growth of trailing junipers, crake-berry, whortle-berry, and willow bushes, which grew in a rich grassy sod that exhibited many plants in bloom, among which were conspicuous the dandelion, butter-cup, bluebell, crow’s-foot, and cochlearia.

Leaving the party to their various occupations—the artists to their several chosen tasks, the crew to get the boat ashore and cook the dinner, the lovers to their jealousies, and the maids to their coquetry, I set out with two friendly assistants to make a complete survey of the ground.

65

The hill-side upon which stood the ancient town of Krakortok is much broken, but there are many level patches, rich with vegetation, which seem to have been once cultivated, and even now appear like arable lands. Small streams course through them, giving a fine supply of clear fresh water. Beside these streams the angelica grows to the height of three feet. The stem of this plant furnishes the only native production of the soil that the Esquimaux use for food, if we except the cochlearia or scurvy grass, which is but little valued, and is not nutritious. It is said that the old Northmen cultivated barley here, and no one would doubt that such a thing were possible. Even at the present time, if one might judge by the day of our visit as typical of the season, barley might grow and ripen readily. Yet Mr. Anthon informed me that such days were liable to be followed by severe frosts, and that in any case the season is too short for complete fruition. There is, therefore, no attempt made in any part of Greenland, not even here in Ericsfiord, to raise any thing more than the ordinary garden vegetables—namely, such of the crucifera as lettuce, radishes, and cabbage—all of which flourish admirably as far up as the Arctic Circle. The agricultural products of Greenland are not, therefore, to be regarded as important in a commercial point of view, though, with care, each inhabitant of Ericsfiord might be well provided with every needful garden luxury. Potatoes would grow, I believe, if they would only take the trouble to cultivate them properly. To perfect any of the cereals would, however, be at present a hopeless undertaking.

66

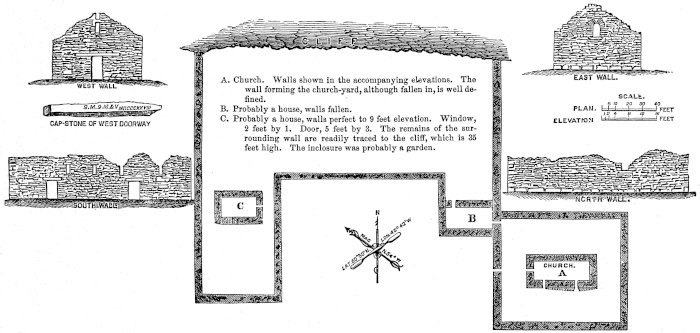

Yet the whole region about Krakortok bears evidence of former cultivation. Garden patches were in the neighborhood of all the buildings. The church and two other buildings were inclosed by a wall, the outlines of which I had no difficulty in determining, and which, judging from the mass of stones, must have been about five feet high.

The church interested me most. Its walls are still quite perfect to from ten to eighteen feet altitude, and even the form of the gable is yet preserved. The door-ways, three in number, are not in the least disturbed by time; the windows are mostly entire, except on the north side, and the arched window in the eastern end is nearly perfect. Beneath this window was the chancel, and the church was constructed with singular exactness as to orientation. This could scarcely be by accident, for the same accuracy is to be observed in all the other sacred buildings that have been discovered in the neighborhood—the walls standing within less than one degree of the meridian line, and even this may have been an error of my instrument which I had not the means of correcting, rather than an error of the Northmen. They were evidently close observers of the movements of the heavenly bodies, and must have known the north with great exactness, and they built their church walls accordingly. These walls were four and a half feet thick. The stones were flat, and no cement appears to have been used other than blue clay.

In one angle of the church-yard there had been a building which I supposed to have been the almonry; and in another part was the house of the priest or bishop, the walls of which are still perfect to the top of the door-way, and one of the windows.

69

Outside the church wall, but not far removed from it, there was a building evidently of much pretension. It was divided into three compartments, and was sixty-four by thirty-two feet. There was another still farther to the westward, others to the east, and one on the natural terrace above the church. Altogether the cluster of buildings which composed the church estate—where dwelt the officers who governed the country round about, and administered in this distant place, at what was then thought to be “the farthest limit of the habitable globe,” the ordinances of the pope at Rome—were nine in number: a church, a tomb, an almonry, five dwellings, and one round structure; the walls of which latter building had, like those of the church-yard, completely fallen, but the outline of the foundation was preserved. The walls had been four feet thick, and the diameter of the building in the clear was forty-eight feet. It had but one door-way, which opened towards the church.