Title: Old Days at Beverly Farms

Author: Mary Larcom Dow

Contributor: Katharine P. Loring

Release date: May 31, 2019 [eBook #59642]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Door of the Larcom House where Mrs. Dow lived

BY

MARY LARCOM DOW

PUBLISHED AND SOLD BY

NORTH SHORE PRINTING CO.

FIVE WASHINGTON STREET

BEVERLY, MASSACHUSETTS

1921

COPYRIGHT 1921

BY

KATHARINE P. LORING

During the last month of his life, Mr. Dow asked his friend and pastor, Rev. Clarence Strong Pond, to see that "Old Days at Beverly Farms," written by Mrs. Dow, was printed. He also asked me to write a sketch of her life to publish with it. The answer is this little book, a loving tribute from many friends.

Beside those whose names appear on its pages, Mrs. Alice Bolam Preston has drawn the front door and knocker of the "Homestead." Mrs. Bridgeford and Mrs. Edwin L. Pride supplied the originals of the portraits. Mrs. Howard A. Doane, "Elsie," has collected information, in which task she has been helped by many of the neighbors. The money, without which we could have done nothing, has been given by Mrs. F. Gordon Dexter, Mrs. Charles M. Cabot, Miss Elizabeth W. Perkins and Miss Louisa P. Loring.

Mrs. William Caleb Loring bought Mrs. Dow's house after her death and gave it to[Pg 6] St. John's Parish for a parish house. She directed that a tablet should be placed in it to preserve the memory of our friend.

In examining the titles Mr. Samuel Vaughan found that Mrs. Dow's great grandfather, Jonathan Larcom, did not sell his slaves. He was administrator of his father, David Larcom's estate in 1775. In the appraisal, six slaves are mentioned by name, valued at £106 13s. 4d. but none are mentioned in the division. It appears that they became free when their master died. All slaves were considered free in Massachusetts when the State Constitution was adopted in 1780.

Katharine P. Loring

| Page | |

| Sketch of Mary Larcom Dow | 9 |

| Old Days at Beverly Farms | 25 |

| Lucy Larcom—A Memory | 63 |

| Letters written by Mrs. Dow | 68 |

| Appreciation by Sarah E. Miller | 79 |

| Extracts from letters about Mrs. Dow | 81 |

"It seems as if the spirit had dropped out of Beverly Farms since Molly Ober died."

One of her friends said this and the others feel it. For sixty years or more she was the leader in the real life of the place. And speaking of friends, there is no limit of them, for her genial kindly nature allowed us all to claim that prized relationship.

Mary Larcom Ober was the daughter of Mary Larcom and Benjamin Ober. Mrs. Ober's parents were Andrew and Molly, (Standley) Larcom. Andrew's father and mother were Jonathan and Abigail (Ober) Larcom; they had eight children, the three youngest of whom are connected with this story. The oldest of these three was David who married Elizabeth Haskell known as "Aunt Betsey"; they had a son David. The next brother was Benjamin whose first[Pg 10] wife was Charlotte Ives, and his second, Lois Barrett. Of this second marriage, one of the daughters was Lucy Larcom, the poetess and the editor also of the "Lowell Offering." Andrew Larcom was the youngest of these brothers. Thus it is that his granddaughter, our Mary, was a cousin in the next generation of Lucy Larcom; although she was older than Mary they were always great friends and what Lucy tells us in "A New England Girlhood" of her experience is as true of one as of the other little girl.

"Our parents considered it a duty that they owed to the youngest of us to teach us doctrines. And we believed in our instructors, if we could not always digest their instructions."

"We learned to reverence truth as they received it and lived it, and to feel that the search for truth was the one chief end of our being. It was a pity that we were expected to begin thinking upon hard subjects so soon, and it is also a pity that we were set to hard work while so young. Yet[Pg 11] these were both the inevitable results of circumstances then existing, and perhaps the two belonged together. Perhaps habits of conscientious work induce thought and habits of right thinking. Certainly right thinking naturally impels people to work."

Mr. Andrew Larcom lived on the farm where Mr. Gordon Dexter now lives; here our Mary's mother was born and passed her childhood. It was a delightful farm with much less woodland than now and its boundaries were much larger; salt hay was cut on the marsh land that stretched toward the sea, and where it ended above the beach there were thickets of wild plum, whose purple fruit made delicious preserves. This marsh was not drained as it is now, little rivers of water ran through it at high tide reflecting the sunlight.

When Benjamin Ober, who was first mate of an East Indiaman, married Mary Larcom they went to live in the house on the north side of Mingo Beach Hill. It was a smaller house then, and close to the road, with a[Pg 12] lovely outlook over the sea. A page of Lucy Larcom's gives so charming an account of "the Farms" it must be quoted here, as Mary Ober was fond of it. The old homestead was where Andrew and Mary Larcom lived, while "Uncle David" and "Aunt Betsey" lived in the house which we know as Mary Ober's house in the middle of the village.

"Sometimes this same brother would get permission to take me on a longer excursion, to visit the old homestead at the "Farms." Three or four miles was not thought too long a walk for a healthy child of five years, and that road in the old time, led through a rural Paradise beautiful at every season,—whether it was the time of song sparrows and violets, or wild roses, or coral-hung barberry bushes, or of fallen leaves and snow drifts. We stopped at the Cove Brook to hear the cat birds sing, and at Mingo Beach to revel in the sudden surprise of the open sea and to listen to the chant of the waves always[Pg 13] stronger and grander there than any where along the shore. We passed under dark wooded cliffs out into sunny openings, the last of which held under its skirting pines the secret of the prettiest wood path to us, in all the world, the path to the ancestral farm-house."

"Farther down the road where the cousins were all grown up men and women, Aunt Betsey's cordial old-fashioned hospitality sometimes detained us a day or two. We watched the milking, fed the chickens and fared gloriously. Aunt Betsey could not have done more to entertain us had we been the President's children."

"We took in a home-feeling with the words 'Aunt Betsey' then and always. She had just the husband that belonged to her in my Uncle David, an upright man, frank-faced, large of heart and spiritually-minded. He was my father's favorite brother, and to our branch of the family,[Pg 14] 'the Farms' meant Uncle David and Aunt Betsey."

The Farms was of greater relative importance in those days. The farms were fairly fertile and were carefully tilled. Their owners, former sea captains, were well-to-do, there were two good schools and the Third Social Library was founded in 1806. The first catalogue, written in 1811, is still preserved, there are some books marked "Read at Sea," among them "The Saint's Everlasting Rest," "Edwards on Affliction" and the first volume of Josephus, cheerful reading for the young captains.

Toward the middle of the century summer fishing took the place of merchant voyages, so the sea-men turned to shoe making in the winter. Almost every house had its little 10 x 10 shoe shop, in which was room for one man on a low stool, a chair for a visitor, an iron stove, a bench with tools, the oval lap-stone to peg shoes on, with rolls and scraps of leather, withal a pungent smell.

In the house on Mingo Beach Hill our Mary Larcom Ober was born in 1835 and[Pg 15] here her father died in the same year. There was an older sister Abigail, who died when she was a young woman.

After a while, the widow returned to her father's home; in 1840 she was married to her cousin David Larcom the younger, and they lived in the Larcom House at the Farms. As his father, the first "Uncle David" died, in the same year, his widow, "Aunt Betsey", moved upstairs. David and his wife with her children Abby and Mary lived below; four children were born to them David, Lydia, Joseph and Theodore.

From Mingo Beach Hill and the homestead the West Farms school was nearer, so Mary must first have gone to school in the little square building which was later for one year the High School, now since many years a dwelling house near Pride's Crossing. After the family moved to the Farms she probably went to the East Farms school, which was nearly opposite the church. She spent some time at the Francestown Academy, Hillsboro County, New Hampshire, and finished her education at the State Normal School in[Pg 16] Salem where she was graduated with the second class after its foundation. She with her sister Abby worked their way through this school by binding shoes. This was the women's share of the hand-made shoe described in Lucy Larcom's "Hannah binding shoes."

Soon after graduation, Mary was appointed teacher in a grammar school at Brewster on Cape Cod. The next year she was engaged for a school in Castine, Maine. Here she found the pupils were big boys, almost men grown, and she feared she would not be able to manage them. However, when they found that she was a good teacher who could give them what they wanted to learn, there was no trouble.

Then in 1858 and 1859 our Miss Ober began to teach the Farms School (the two schools being united) on Indian Hill just above Pride's Crossing station; the building was remodelled later and is now the house of Mrs. James F. Curtis. Grades were unknown, she had some twenty to thirty pupils of all ages, but she managed to keep them in order and to teach them so well that they always remembered what they learned. She stimulated the bright[Pg 17] children to greater effort and she encouraged the dull ones so that they were surprised into understanding. One of her old girls told me how they loved her but feared her in school, and enjoyed her when out. She especially liked boiled lobster and dandelion greens served together; whenever these viands were for dinner the child was told by her mother to bring the teacher home to share them, and "then what a good time we had." She smiled as she said it, but there was a tear in her eye.

At about this time Miss Ober was engaged to an attractive young man, a teacher in the Beverly Farms school. There was every promise of a happy life, but unfortunately he died. Miss Ober went on with her school until 1870, except during 1862 and 1865, but she was not strong and her health was impaired.

In a much loved and worn volume of Whittier's poems, given to Mary Ober in 1858-1859 is written in her own hand, "the happiest winter of my life." Pinned to a leaf is a cutting, with the following epitaph from an old English burial ground:

The poems she marked are: "The Kansas Emigrants," "Question of Life," and "Gone," in this last poem she underscored the verse:

These are keys to her thoughts, she believed in abolition, in the saving of the Union, she was absorbed in the Civil War, in the going away of relatives and friends, and she took great interest in the work of the Sanitary Commission. My grandmother, Mrs. Charles G. Loring, worked in the commission rooms in Boston by day, in the evening she would bring materials and drive about in her buggy to distribute them among the neighbors, collecting the finished garments to be carried back to Boston by an early train. Mary Ober often went with her, helping in all ways, and they became great friends; it was partly[Pg 19] through her influence that Mary went to Florida for the benefit of her health in the winter of 1871. The next winter she took a school in Georgia under the "Freedman's Bureau" where she taught the little darkies, who adored her. In 1872 and 1873 she taught the children of the poor whites in the school at Wilmington, North Carolina, and it was here that she met Sarah E. Miller who was to be her devoted, life-long friend. This was the Tileston School founded by Mrs. Mary Hemenway, its principal was Miss Amy Bradley; it was perhaps the best known school carried on by the northerners in the South.

For two years longer she taught half terms in Beverly Farms and then as she regained health and strength, from 1875 to 1899 Miss Ober was head of the Farms School, then in Haskell Street, beginning with a salary of $180. She never had a large salary. It was considered the best school in the town. The building was the wooden one, now a house, on the next lot to the brick school. She kept up with[Pg 20] the times, introduced grades and had several assistants as the years went on. She continued her career as a most successful teacher, she was strict but just and kind, always interested in her children whether in school or afterward, keeping in touch with them and following their careers with sympathy. When Mr. Charles H. Trowt was elected Mayor of the City she wrote: "And you were my curly-headed, fair-haired little boy in school."

She had a happy home with her mother and stepfather; "Uncle David" she always called him, though she maintained the relation of a loving daughter. Her mother died in the spring of 1876 and Mr. Larcom died in 1883.

Miss Ober was always a great reader, she chose the best books and kept in touch with the topics of the day. We all remember her long walks in the woods and fields, her delight in the first spring flowers and the song of the birds; she shared Bryant's regret in the autumn, but her winters were made cheerful by her hospitality at home. Friends[Pg 21] were always dropping in to read, to sew or to have a good game of whist in the afternoon or evening.

Another quotation from "A New England Girlhood" seems appropriate here.

"The period of my growing up had peculiarities which our future history can never repeat, although something far better is undoubtedly already resulting thence. Those peculiarities were the natural development of the seed sown by our sturdy Puritan ancestry. The religion of our fathers overhung us children like the shadow of a mighty tree against the trunk of which we rested, while we looked up in wonder through the great boughs that half hid and half revealed the sky. Some of the boughs were already decaying, so that perhaps we began to see a little more of the sky than our elders; but the tree was sound at its heart. There was life in it that can never be lost to the world."

In reading this charming biography one is impressed with the strict doctrine under which Lucy Larcom was brought up. Miss Ober's theology was more liberal. The church at the Farms was established in 1829 under the auspices of the First Parish in Beverly, (Unitarian) it was called simply the "Christian Church" and it was some years before it became Baptist. Miss Ober was an active and devoted member of the church and a good helper in parish work.

It seems as if their common interest in the church and love for flowers must have first attracted her to Mr. James Beatty Dow, to whom she was married in 1889. Mr. Dow was a Scotchman with the virtues of that race. Of course he had a good education, he was a gardener by profession and a successful one. Beside his work for the church and the Sunday school he was interested in civic affairs; at one time he was representative at The Great and General Court and he was a member of the School Committee of Beverly.

Mrs. Dow did not give up her school until ten years after her marriage but she paid more[Pg 23] attention in equally successful manner to housekeeping and social duties. Miss Miller, her friend from the days of the Wilmington School, was a constant and welcome guest. They loved books, they read and played together, they formed reading clubs to discuss works of importance and enjoyed poetry and good fiction. There were flashes of wit and a lightness of touch in Mrs. Dow's approach which were quite un-English, they may be attributed to her Larcom ancestry. The Larcoms were the La Combes of Languedoc, Huguenots who escaped to Wales, later moved to the Isle of Wight, and thence came to New England in the ship Hercules in 1640. The Obers came from Abbotsbury in England in early days, there is every reason to believe that they were also of Huguenot descent, by name "Auber," but this is not proved.

The years passed rapidly, the quiet life at the Farms broken by little excursions to the theatre, concerts and visits to friends in Boston, with occasional trips to the White Mountains, New York and other places. There were endless interests and accomplishments and[Pg 24] enjoyments. The World War brought grief and tragedy and abounding opportunity for sympathy and action; by no one was a saner interest taken in all its phases than by Mary Dow.

As time passed and strength failed, Mrs. Dow never grew old; she joked about her "infirmities" but we did not see them. She mastered them and kept on in her lively active interests and duties to the end.

During the winter of 1919-20 Mr. Dow was very ill. His wife nursed him with too great devotion and her strength gave out. Mercifully, she was spared a long illness, she died on the eleventh of June, 1920. Mr. Dow lingered until the sixteenth of September.

This is the end of the story, or is it the beginning?

In writing these hap-hazard memories of the old days at Beverly Farms, I did not mean that they should be egotistical, but in spite of my good intentions I am afraid they are. You see it is almost impossible to separate yourself from your own memories! I throw myself upon the mercy of the Court!

Summer of 1916.

We have a little Reading Club here at Beverly Farms. We read whatever happens to come up, from Chesterton's Dickens to "The Woman who was Tired to Death," interspersed with real poems from "North of Boston." I belong to the Club. I am the oldest member of it, in fact, I am the oldest person in New England—on stormy days! When the weather is fine and the wind south-west, I am young enough to have infantile paralysis!

One day, in my enforced absence from the Club, my colleagues conspired against me,[Pg 26] and with no regard to my feelings, selected me to write up some remembrances of old Beverly Farms. Hence these tears! Elsie Doane belongs to this Club. Elsie is behind me about half a century, if you allow the Family Bible to know anything about so indifferent a thing as age. She was one of the few infants under my care when she was pupil and I was teacher, who had a real love for literature for literature's sake, and we had good chummy times when it was stormy and we carried dinner to school, and ate it peacefully in an atmosphere that smelt of a leaky furnace and fried doughnuts, in spite of open windows.

It doesn't smell that way now, for Mr. Little has made the school-house of that day a pretty summer home for whomsoever will live in it. Elsie promises to set me right whenever I go astray as to what happened at old Beverly Farms, how it looked, what legends it had—how its people lived and behaved, and so forth, and so forth. She is a foxy little thing, and I suspect that when she is floored on my reminiscences, she will appeal to her mother, who, she says is older than she is! We do not[Pg 27] promise any coherence in our stories. It will be somewhat of a hash that we shall give our listeners wherein it will be difficult to decide whether it is "fish, flesh, fowl, or good red herring." But we have no reporter at our Club, so we give our memories free rein.

I often wish I could catch and fix, by the kodak of memory, some of the celebrities of my childhood, in this little village.

What a character, for instance, was Uncle David Larcom! Among the old Puritans who were his ancestors, and among whom he was raised, what a constant surprise he must have been! Certainly no hero of a dime novel could have done more startling and audacious things. He ran off to sea in his youth and stayed away from the village for three years. During that time, he had seen and experienced enough to satisfy Tom Sawyer; he had messed with Indian Lascars and acquired a taste for curry and red pepper which he never lost. And with the love for stimulating diet he gained a love for stimulating stories, and could draw the very longest kind of an innocent bow, that carried far and never hurt anybody.

Who could forget his yarns of the sea serpent and his life on the old English Brig? "Has he got to the old English brig?" his waggish son would inquire, as he listened from an adjoining room.

He gave away a wonderful old mirror, beautifully carved, with a lion's head at the bottom, and a boy astride a goose at the top, with leaves and bunches of grapes at the sides, and glass, as it seems to me, almost an inch thick. It hangs now in the drawing room of its possessor restored to pristine beauty and bearing an inscription setting forth that it came from the wreck of the "Schooner Hesperus."

Uncle David told this yarn when he gave away the beautiful mirror. Nobody had ever before heard of this connection with the Schooner Hesperus. My own impression is that the mirror was brought to the old house, which I now own, by Aunt Betsey Larcom, the great grandmother of Elsie Doane. Dear old Uncle David! Sometimes his language was not choice, but how big his heart was!

After he uncoiled his sea legs and settled[Pg 29] down to teaming, mildly flavored with farming was there ever a more generous or a more kindly neighbor?

People often cheated him, in fact, he almost seemed to like being cheated.

His patient wife once remarked that he always wanted to give his own things away, and buy things for more than people asked for them. He would match Uncle Toby's army in Flanders for profanity, but he would go miles to help a sick friend, or, (and this is to my mind, the last test of friendship in a horse owner) turn out his old "Bun" on the stormiest night that ever raged, to help a brother teamster up a hill. And when were ever his own rakes and plows and forks at home? Weren't they always lent out somewhere? What a reverence for all things sacred, way down in the bottom of his large heart he always had! How deferential to ministers he was! How angry he would be at any unnecessary breaking of the "Sah-bath" as he called it. How steadily he read, (though he wouldn't go to church) all day and all the evening of the Lord's Day—taking up[Pg 30] his book at night, where he left it to feed his "critturs," and holding his sperm oil lamp in his hand as he finished his day of rest. Some of his expressions remain in my mind as, for instance "From July to Eternity," to indicate his weariness at something too much prolonged. He liked to exaggerate as well as Mark Twain did, as when he used to wish on a furiously stormy night, that he were way over on Half Way Rock, always being careful to have a tremendous fire going, and a pitcher of cider at hand, before he expressed the desire. The memory of his good, religious father was always with him, and when he was in a particularly genial frame of mind, he would sing snatches of the old tunes he had heard his father sing:—

was one of his special favorites.

His kindly handsome face, his enormous size, his laugh, which was ten laughs in one, are among the clear remembrances of my childhood.

And I can hardly close this sketch better than by quoting his old family doctor's words: "Swear, yes, but his swearing was better than some folks' praying."

I should like to "summon from the vasty deep" some of the other old people, both white and black, who lived here in the old days. Just back of where Mr. Flick's stable now stands at Pride's Crossing lived Jacob Brower, a little old man of Dutch descent, with his wife and family. She was a sister of Mrs. Peter Pride, who lived in the first house west of the Pride's Crossing station. I remember Aunt Pride as an extremely handsome, tall, dark, dignified woman. She belonged to the Thissell family. Lucy and Frank Eldredge came of this family, and Willis Pride, and I suppose "Thissell's Market" claims relation too!

The next house east of the station, on the other side of the road was a tumble down old house innocent of paint, and black with age, inhabited by three old African women—named Chloe Turner, Phillis Cave and Nancy Milan, all widows.

The house, after the railroad cut it off from the main road, was so near the track that one could almost step from the rock doorstep to the rails, and the old crazy structure shook every time an infrequent train passed, we had four trains to Boston daily then. I remember how the old house smelt and how the rickety stairs creaked under one's feet.

When my great great-grandfather, David Larcom, married the widow of John West and brought her to his home (now the Gordon Dexter place) she brought with her as part of her dower, a negro woman, a remarkable character, named Juno Freeman. This woman was the mother of a large family. Mary Herrick West's father was a Captain Herrick and he brought Juno, a slave from North Carolina in his ship.

Juno's children took the Larcom name and remained as slave property in the Larcom family, till, in my great-grandfather's time they were sold. My uncle Rufus told me that this ancestor, Jonathan Larcom, was sharp, and, hearing that all slaves in Massachusetts were to be freed, sold his.

The old house I have mentioned was given to Juno Larcom, it being on the land known as the "gate pasture" and in after years, when Mr. Franklin Haven wanted to open an avenue there, he took a land rent from my stepfather, David Larcom, had the old house torn down, and put a little house for Nancy Milan (who was then the only survivor of the three old widows) right by my piazza, on the east side, and there Aunt Milan died peacefully in the spring of 1869.

Aunt Milan's mother, Phillis Cave, was brought to Danvers in the boot of Judge Cave's chaise, and afterwards somehow drifted to Beverly. Judge Cave's daughter, Maria Cummins, wrote the "Lamplighter," a book of great popularity in this region, in her day. Phillis worked in the best Beverly families, the Rantouls, Endicotts, and others, and used to walk to Beverly, work all day, and walk home at night. I remember wondering if all the washing she did had made the palms of her hands so much whiter than the rest of her.

Aunt Chloe and Aunt Milan were pretty lazy old things, but everybody liked them[Pg 34] and contributed good naturedly to their support. After Aunt Milan came down to live by us, Mr. Asa Larcom and my step-father furnished a good deal of her living, and the town gave her fifty cents a week. She never could hear of the poor house. Wherever Aunt Chloe got the candy and nuts she always had on hand for children, I cannot imagine. She wore a pumpkin hood (a headgear made of wadded woolen or silk, with a little back frill,) and the Brazil nuts used to be taken out of the back of the hood. My brother David said he used to eat candy from the same receptacle, but then he was a Larcom and had imagination!

The old brick meeting house had a wooden bench built upstairs near the choir, and there these three black persons sat, every Sunday, thro' their peaceful lives. I think that was a pretty low down trick of those old Baptists, particularly as the ladies in question always sat at our tables.

We old dwellers at Beverly Farms,—Obers and Haskells and Woodberrys and Williamses and Larcoms, are pretty well snarled up as to[Pg 35] relationship, and I am always coming upon some new relative in an odd way.

For instance, Miss Haven gave me the other day the appraisal of my great grandfather's estate, that same David Larcom of slave times. He died in 1779 possessed of £899 sterling, all in real estate. I found in the appraisal and settlement among his children, that my old friend Mrs. Lee and I have probably a common ancestor, Jonathan Larcom. It amuses us, because we have never before found any trace of commingling blood. I fancy it would be pretty difficult to find any two old Beverly Farmites, who are not related. My principal pride in the old paper is that it sets forth, over the signature of the Judge of Probate in Ipswich, that a Larcom once was worth about $5,000! (His brother's estate was appraised at £219 15s. 6d. Ed.)

My good neighbor, Mrs. Goddard, came in last evening and brought me a fragrant bouquet of thyme and rosemary and marjoram and sage, which makes me remember that I have not yet tried to describe Aunt Betsey Larcom's garden in those ancient days.

The striped grass is still growing in one corner of my garden—the very same roots that were there in my childhood, and up to a year or so ago, the old lilac bush that Uncle Ed. Larcom picked blossoms from when he was a small boy, was there too. Aunt Betsey's garden was a beautiful combination of use and loveliness. All along the stone wall grew red-blossomed barm and in the long beds were hyssop (she called it isop) and rue and marigolds and catnip and camomile and sage and sweet marjoram and martinoes. Martinoes were funny things with a beautiful, ill-smelling bloom which looked like an orchid, and when the blossoms dropped there succeeded an odd shaped fruit, with spines and a long tail, which was used for pickles. Then there were king cups, a glorified buttercup, and a lovely little blue flower called "Star of Bethlehem" and four o'clocks. Right here I want to say that Frank Gaudreau has more varieties of four o'clocks than I ever supposed were known to lovers of flowers and I think he deserves the thanks of the village for his pretty garden.

All the different herbs were carefully gathered by Aunt Betsey, and tied in bundles, and hung up to the rafters of the old attic. Sometimes I fancy I can smell them now on a damp day, and I like to recall the dear old lady in her tyer and cap, busy with her simples. I like to think of her as my tutelar divinity for I came to love her dearly, though I am sure that when I was first landed in her house, I was a big trial. Elsie Doane remembered another garden of that time, where, she says, they never picked a flower. I remember it too, but I had forgotten that they didn't pick the flowers. It flourished right where the engine house and those other buildings stand, and Elsie thinks the garden reached way out to the sign post. Uncle Asa Ober owned that garden—the ancestor of Mrs. Lee and Mrs. Perkins and Mrs. Hooper and Helen Campbell, and many others of our fast fading away villagers. His two stepdaughters were cousins to my mother, and they had a little shop in an ell that ran from the house to the street, where they did dressmaking and millinery.

Right in front of the shop was the garden[Pg 38] all fenced in, but I had the right of way for I could sing! And whenever I learned a new music from Joe Low's Singing School, I used to be called in to act as prima donna to the two ladies.

There were cucumbers in the garden extension and artichokes by the old walls.

But my regrets are not for the gardens. We have gardens now, but nobody can bring back the beautiful fields, stretching from the woods to the sea, where cows and oxen grazed. Nobody can bring back the brooks, now polluted and turned into ditches. Nobody can bring back the roadsides bordered with wild roses, now tunneled and bean-poled out of all beauty. I do love some of our summer people, particularly those who have kept their hands off and have not removed the old landmarks, but I find it hard to forgive the bean-poling and the cementing. Look at the lovely old Sandy Hill Road (West Street). Over these happy summer fields of the olden days walked James Russell Lowell and his beautiful betrothed, Maria White. Later he came again,—but without her. Among those[Pg 39] old first visitors to our Shore were John Glen King and Ellis Gray Loring. These two gentlemen married sisters, southern women I think; they took kindly to our New England cookery. Mrs. King, one day, asked my aunt, Mrs. Prince, if she could give them a salt fish dinner, with an Essex sauce. Mrs. Prince knew all about a salt fish dinner, but the Essex sauce floored her, and she humbly acknowledged her ignorance. "Oh," said Mrs. King, "it is very simple. You take thin slices of fat pork and fry them out." Mrs. Prince laughed and proceeded to her kitchen to make "pork dip." Mrs. King also liked a steamed huckleberry pudding and she said "And please, Mrs. Prince, make it all huckleberries, with just enough flour to hold them together." We got four or five cents a quart when we picked these same huckleberries. I did not have a very big bank account in that direction, owing to my short sight, and to my preference for making corn stalk fiddles with a jack-knife. I remember making one on a Sunday morning, uninterrupted by the "Sabbathday dog" which was supposed to lie in wait for Sabbath breakers.

Diagonally opposite my house lived Mr. Nathaniel Haskell, a little old gentleman, who wore a cut away blue coat, with buttons on the tail, over which, in cool weather, he put a green baize jacket. How funny he looked. He was interested in what he called the tar-iff, and he was awfully afraid of lightning. I remember the whole family filing into our dining room whenever a specially dark cloud appeared. I do not think a single descendant of "Uncle Nat" is left here, tho' there was a large family.

There was a cheese press in our back yard and "changing milk" was a great scheme. One week all the milk from four or five farms would be sent to us and my mother would make delicious sage cheese.

Then, the next week all the milk would go to "Uncle Nat's," and so on, till all the cow owners were supplied with cheeses, which were duly greased with butter and put on shelves to dry, a sight to make the prophet smile.

I wish I could get a picture of Beverly Farms as it looked to my child's eyes. I came over to "the Road," as it was called by my[Pg 41] maternal relatives, when I was five years old. They lived in that Paradise now occupied by millionaires, the region that holds the Gordon Dexter place, the Moore place, the Swift place, and part of the Paine place. At that time, the whole section was long green fields bordered by woods, the "log brook" running through it. There were then three roads in Beverly Farms, the road now called Hale Street, the beautiful old Sandy Hill Road (West Street) and the Wenham road (Hart Street). My two homes after my mother's widowhood were at the Gordon Dexter place, and at my father's old homestead, at Mingo's Beach (where Bishop McVickar lived). There were about twenty houses at that time, between Beach Hill and Saw Mill Brook. This was West Farms and the Schoolhouse stood just back of Pride's Crossing station—afterwards removed to where it now stands as a dwelling house, occupied by the heirs of Thomas Pierce.

There was then no railroad and the main road ran by Mr. Bradley's greenhouses, and along where the railroad now is, coming out[Pg 42] near the schoolhouse. That part of Hale Street where the Catholic church is, was then Miller's Hill, a pasture, where I have often tried to pick berries. The railroad came in 1845. The little shanties where the laborers who were building the road lived temporarily with their families, were a great curiosity. I used to run away and peep into them and I can remember how they smelled. My mother, who did the work of twenty women every day almost as long as she lived, made knotted "comforters" for these shanties. Our way of getting to Beverly and Salem was by stage coaches between Gloucester and Salem. In my few journeys in these delightful conveyances I used to clamber to the top seat and sit with Mr. Page the kindly driver, who was one of our first conductors on the railroad.

To the house where I now live my happy life, I was brought at five years. I could then read about as well as I can now. I found in this old house a garret, a beautiful garret, where bundles of herbs hung from the rafters, and where books, books galore had collected in old sea chests. Fancy my delight, at finding,[Pg 43] one red letter day, Christopher North's, "Lights and Shadows of Scottish Life."

There were other books not so well fitted for the education of a child, but it was all fish that came to my net, and I calmly read up to my tenth year, "The Criminal Calendar," "Tales of Shipwrecks," Barber's "Historical Massachusetts," Paley's "Moral Philosophy," Pollock's "Course of Time," Alleine's "Alarm to the Unconverted," Richardson's "Pamela" and the "Spectator!" Some years afterwards, when I had read the covers off this miscellaneous collection of books, some of the earlier summer people, the elder Lorings and Kings, I think, put a small library into Uncle Pride's house and gave us Jacob Abbott's Rollo Stories and a few other delights. Please picture to yourself the "light of other days" by which the reading and sewing and knitting of old Beverly Farms used to go on at night.

Luckily, there was as much daylight then, as now. The lamp that illuminated my childish evenings was a glass lamp, that held about a cup full of whale oil, "sperm oil," it was called. There were two metal tubes at the[Pg 44] top of this lamp, thro' which protruded two cotton wicks. These wicks could be pulled up for more light or pulled down for economy, by means of a pin. No protection whatever was afforded from the flame, and my hair was singed in front most of the time, as I crept close with book or stocking, to this illumination. One use of the old oil lamp was medicinal. If there were a croupy child in the house, he might be treated immediately, in the absence of a doctor, to a dose from the lamp on the mantel. I remember my blessed brother David being ministered unto in that way. After this, came the fluid lamp, with an alcoholic mixture that was dangerous, but clean.

In hunting about among ancestors, I am sometimes reminded of the story of Dr. Samuel Johnson's marriage. The lady to whom he proposed, demurred a little. She said she had an uncle who was hanged. Dr. Johnson assured her that that need make no difficulty, for he had no doubt that he had several who ought to have been hanged. I remember my disgust at finding that I was related thro' my maternal grandmother, Molly Standley, to[Pg 45] "Aunt Massy." Aunt Massy, (her real name was Mercy) was a mildly insane, gray-haired, stoutish woman, who lived just before you reach the fountain at the top of the hill, on Hale St. There was a well with a windlass and bucket at one side of her old house and Aunt Massy used to lean on the well curb and abuse the passers by. She remembered all the mean things one's relatives ever did, and how she could scold! I was often sent to Mr. Perry's grocery store where Pump Cottage now stands and I used to try to get by without hearing her uplifted voice. But if I had a new gown there was no escape.

The two districts I have mentioned, (East and West Farms) were divided by "Saw Mill Brook," the little half choked stream that now filters under the road between Mr. Hardy's and Mr. Simpkins' places. It was a beautiful brook in those old days, clear water running through fields, with trout in it. The saw mill must have stood about where that collection of tenement houses now is.

The "child in the mill pond" belongs to the legendary history of Beverly Farms.

Coming down the hill towards Beverly, the most terrible shrieks would often be heard, but if one crossed the brook to West Farms, all was silent. I never heard these shrieks, I took good care never to be caught over there after dark. I should have liked to see the little screech owl, who, no doubt, had his quiet home up back of the mill, and sang his evening song, after the miller had closed his gates. We villagers have a question to propose to all our friends of uncertain age,—"Do you remember the saw-mill?" If, inadvertently, they confess to its acquaintance, it settles the question of age. It is as good as a Family Bible.

Miss Culbert showed me the other day, a great find, the remnant of the "Third Social Library of Beverly." I had never heard of such a library and was greatly interested. It is now in our beautiful branch library, in a neat book case made by one of the Obers, in whose house the Library was placed. I mean the old Joseph Ober house which stood where Mrs. Charles M. Cabot's house is.

Elsie did not live opposite that house then, but she was going to live there. I dare say[Pg 47] she wouldn't read any one of those books, any more than I would. The books date back to 1810, and many of the honored names I have been mentioning are there, all written down in beautiful handwriting, and with a tax of ten cents opposite their names, for the carrying on of this little library. There are two sermons of the beloved Joseph Emerson, who preached at Beverly before there was any church here, a funeral sermon preached on the occasion of Dr. Perry's grandfather's death, loads of sermons by Jonathan Edwards, great bundles of religious magazines, and other interesting antiquities. Not one story, no fiction of any sort. Those forefathers of ours fed on strong meat. Among the curiosities are several letters from anxious fathers in Boston, making the most vigorous and pathetic protest against a proposed second theatre in Boston on Common Street.

A second theatre in Boston! The souls of young people in peril! One sighs to think what these good fathers would have said if they could have pulled aside the curtain of the future and seen little Beverly with crowds of[Pg 48] children accompanied by their fathers and mothers and uncles and aunts and cousins, all pouring into the "movies!" (One of these movies named for Lucy Larcom!) One must go on, and now we are trying to hope that some good may come out of the "movies!" If our little religious library was the "Third Social" there must have been two more in old Beverly.

I want you to go back in your mind to a Sunday of that time when even a walk to the woods or to the beach was wicked, when the only books that were proper to read were religious books, when there were three religious services every Sunday and pretty awfully long services. My cousin and my sister and I crawled up a long ladder to the third floor of our barn, among the pigeons' nests, and, nestling down in the hay, produced a novel, a real novel, a wishy washy thing, that no money could hire me to read today, and with quiet whisperings read that wicked book. We were in mortal terror lest "Aunt Phebe" should suspect our deep degradation, and "Aunt Phebe" was not a foe either. She was a beautiful, big, kindly woman, as Mrs.[Pg 49] Crowell, her step-daughter, would gladly attest.

One whose memory goes back like Elsie Doane's and mine must remember the old brick meeting house. My memories of it are pretty hazy and I fancy Elsie will have to go farther back than her mother, for information about that fine specimen of architecture. It had neither cupola nor spire and must have been pretty ugly. It must have been the second meeting house, in which I recall the beautiful alto Mrs. Otis Davis's mother used to sing. I shall never forget how affected my childish ears were when she sang "Oh, when thou city of my God shall I thy Courts ascend" as the choir rendered the anthem "Jerusalem."

Speaking of meeting houses, our third and present, one of the most beautiful and "resting" buildings one could worship God in, is a lasting memorial of the taste and genius of our beloved Mrs. Whitman. To her and to Mr. Eben Day, we owe its beauty; and to the generous old church members we owe its existence at all, for they gave freely to its construction.

The first minister I have much recollection of was Mr. Hale, who lived with his family in the house now owned by Miss Lizzie Hull. My step-father bought a horse from him, and named him "Sumner." That was Mr. Hale's Christian name. I have often wondered how Mr. Hale felt to have a horse named for him, but I am sure Uncle David meant it as a compliment.

In those far away days we had a hermit of our own. It would be more damaging to a claim of youthfulness, on the part of my readers to remember "Johnny Widgin," than to remember the saw-mill.

One late afternoon, coming out with my playmates from Mr. Gordon Dexter's avenue, then my grandfather's lane, we saw a most grotesque figure, standing by "Rattlesnake Rock," just across the railroad—a tall man, of perhaps fifty years, to us, of course, "an old man." His trousers, which, thro' all the years I perfectly remember, were of some kind of once white material, with little bows of red ribbon and silk sewed all over them. He spoke to us gently but we were all terrified and[Pg 51] ran home as fast as our legs could carry us. This singular being afterwards came and went in the village for several years, cooking his own little vile smelling messes on kindly disposed women's stoves, sleeping in barns, repeating chapter after chapter of the Old Testament for the edification of his hearers, and always gentle and kindly. I recall his recitation of the last chapter of Malachi beginning "And they shall all burn like an oven." He was, no doubt, mildly insane and of Scandinavian descent, but nobody ever knew anything definite about him. He lived a part of his time, in warm weather, in a hole or cave of rocks, on the beach formerly owned by Mr. Samuel T. Morse, below Colonel Lee's. He had a similar retreat at York Beach. He finally faded out of our lives, no one knew how. He may have been taken up in a chariot of fire like his beloved prophet Elijah, for all that any of us ever knew of his departure from these earthly scenes. He was supposed to be Norwegian, hence his name "Johnny Widgin." My grandfather said that if he could not pronounce "the thick of my thumb" in[Pg 52] any way but the "tick of my tumb" he was Norwegian. That settled it in my mind, for my grandfather was my oracle. (Andrew Larcom, Grandfather Ober had died, Ed.)

My grandfather did not go much to church but he loved his Bible and Psalm book and from several things that I remember about him, I think he was Unitarian in belief, though in those days I did not know a Unitarian from a black cat, and whenever I heard of one, I supposed he must be a terrible kind of being. I was a grown woman, when one day, speaking of Starr King and his love for the White Hills and his loyalty in keeping California in the Union during the Civil War, the woman to whom I was speaking said "Well, he wasn't a good man." "Not a good man," I said. "Why" said she, "You know he was a Universalist." We have got on a little since that time in toleration, but we need to get on a little more.

My uncles on my mother's side were great hunters. Foxes and minks and woodchucks were plentiful in those days and a good many of them fell into my uncles' traps. I remember[Pg 53] remonstrating with my uncle "Ed Larcom," about traps, telling him it was cruel, and that I didn't see how a good kind man like him could earn his living that way. "Oh," he said, "They were made for me!" Doesn't the Bible say "And he shall have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over all the cattle, and over every living thing that creepeth upon the earth?" My uncles all said there was no better eating than a good fat woodchuck; that the chucks fed on grain and roots and clean things. The manner of cooking was to parboil them, stuff with herbs and bake.

Some years ago, I was invited to join the Daughters of the Revolution, and to this end to look up my ancestry. To my surprise I could not find a single forbear of mine who was connected in any way with wars or rumors of wars, and I reported that I hadn't been able to find any of my kin who ever wanted to kill anything but a woodchuck. Since this writing, my cousin, Dr. Abbott, still living, at the age of ninety-five in Illinois, has informed me that my remote ancestor,[Pg 54] Benjamin Ober, did valiant work on the sea in the Revolution.

Elsie Doane seems to think that these scraps of antiquity would not be quite satisfactory without mention of "Jim" Perry's grocery store, though she never bought a pound of coffee in it, and, if she says she did, she thinks she is her mother. It was our only store and so was quite a feature. It was presided over by Mr. James Perry, a tall dignified man, whom his wife in her various offices as helpmate, always called "Mr. Perry." Mr. Perry was color blind and whenever my mother sent me for blue silk or blue yarn, he always selected green or purple.

You may wonder how blue silk comes to be a grocery product, but this was really a department store. When we had a half cent coming to us, Mrs. Perry always produced a needle, for the exact change. You see how honest we were! This honest department store stood, in fact it was Pump Cottage, for I think Pump Cottage is the same old jackknife with different blades and handles. Farther up, on the Wenham Road, lived Deacon Joseph[Pg 55] Williams, a beautiful old gentleman, with a disposition as sunny as a ripe peach. His house was small and his family large. All the Williamses in this region would look back to that little house as their old family homestead, and I was sorry when Mr. Doane decided that it could not be remodelled, but had to be taken down.

Deacon Williams had a dog, a little black fellow named Carlo, who always followed the good man about except on Sundays. On Sundays, Carlo took a look at his master and then went and lay down dejectedly. But, as I have intimated before, when you remember the Sundays of those days, a sensible dog really had the best of it. In a former page of these odds and ends of memory I have mentioned Uncle Ed Larcom and his fondness for hunting. A good many of us aborigines of old Beverly Farms will remember his talks of his dog Tyler, a mongrel dog, half bull dog and half Newfoundland, as Uncle Ed pronounced it. Tyler, according to his master (and his master was the most accurate teller of stories that ever lived, always telling his yarns in [Pg 56]exactly the same words,) was a most remarkable dog, understanding what one said to him as well as a man, going a mile if he were merely told to fetch a missing jacket, and as full of fun and tricks as a monkey. Uncle Ed used to delight his young audiences with anecdotes of Tyler, and in his old age, when mind and memory began to fail, it was rather hard to hear him say, "Did I ever tell you about my dog Tyler?"

He must have been named for John Tyler. It was hard on a good dog to be named for John Tyler, one of the poorest presidents we ever had.

There seems to be a great deal of interest among our summer people in the old houses still left at Beverly Farms. I have mentioned the James Woodbury house now owned by Mr. J. S. Curtis; another very old house is the William Haskell house, owned by Mr. Gordon Dexter. I have a little doubt as to whether the date on the house is right. I have a very strong impression that Aunt Betsey Larcom, born Haskell, told me in my childhood that her father built the house in which Aunt Betsey[Pg 57] was born, in 1775. She also said that when they dug the well back of the house, they struck a spring and were never able to finish stoning it, a fact which accounted for its never running dry, when all the other wells in the village gave out. I think Mr. Dexter bought it of the James Haskell heirs, but I am not able to state what relation James Haskell (Skipper Jim) was to Mr. William Haskell, or how he came into possession of it.

I wonder how many people are now left in Beverly Farms who ever tasted food cooked in a brick oven. I am sure there are not many. But those of us who ate of an Indian pudding or a pot of baked beans from that ancient source of supply will never forget the deliciousness of that kind of cookery.

The pudding would stand straight up in its earthen pan, a quivering red, honey-combed mass, surrounded with a sea of juice to be eaten with rich real cream in clots of loveliness. The beans would be brown and whole, with the crisp home cured pork on top. That old New England cookery, it seems to me, filled a big bill for health and physical nourishment.[Pg 58] We did not know much about proteins and calories and fibrins, in fact, we had never heard of them. But we somehow hit upon the best combinations as to taste and efficiency. We almost never had candy, and we rarely had all flour bread. A good deal of Indian meal went into my mother's bread.

Our amusements in those days were primitive enough. On Old Election Day, which came the last Wednesday in May, there was just one thing to do. We youngsters had an election cake all shining with molasses on top, and raisins in the middle, and we went down to the beach and dug wells in the sand. Now and then we hunted Mayflowers (saxifrage) and played about the old fort left from the Revolution and now owned by Mr. F. L. Higginson. Evenings we had parties and played Copenhagen and hunt the slipper or knit the family stockings by our dim oil lamps. Winters, there were singing schools. Those were great larks if we came at the money to buy a copy of the "Carmina Sacra," or the "Shawm." I still think they were[Pg 59] fine collections of tunes, comprising all the old standbys. Mrs. Lee's father, Mr. John Knowlton, was a wonderful singing master, and a great disciplinarian, with a beautiful bass voice. He would stand a good deal of fun at the recess, but when Mr. Knowlton struck his bell and took up his violin, we all knew it meant singing and no nonsense. I think my grandfather, Benjamin Ober, and Elsie's great-grandfather, Deacon David Larcom, were also singing masters in the old days, but neither Elsie nor I remember them,—old as we are.

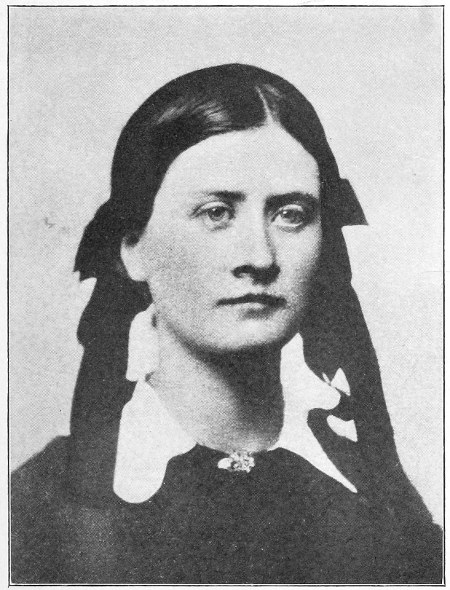

From a Daguerreotype taken about 1859

Over "t'other side," as we called it, in the house now owned by Mr. J. S. Curtis, lived Uncle "Jimmy" Woodbury. He must have been a "character." He was once very much troubled by rats in his barn. So he conceived a plan for getting rid of them at his neighbor's expense. Uncle David Preston's estate, where Miss Susan Amory's house now stands, was diagonally opposite.

Uncle "Jimmy" wrote a letter to the rats, in which he told them that in Uncle David's barn was more corn and better corn than they[Pg 60] were getting in his barn, and he strongly recommended that they move. Then Uncle Jimmy kept watch and on a beautiful moonlight night he had the satisfaction of beholding a long line of rodents with an old gray fellow as leader, crossing the road on their way to Uncle David's. (I tell the story as it was told to me). Uncle Jimmy's daughter, Mary, married Dr. Wyatt C. Boyden, for many years the skilful family physician of half the town. The fine public spirited Boydens of Beverly are her descendants.

By the way, the old vernacular of the village ought not to perish from the earth. It was unique. Our ancestors just hated to pronounce any word correctly, even when they were fairly good scholars and spellers. They called a marsh a "mash." Capt. Timothy Marshall, the rich man of the place, was called Capt. "Mashall"; Mr. Osborne was Mr. "Osman"; the Obers were "Overs", a lilac was a "laylock" a blue jay was a blue "gee," etc.

In closing these rambling papers of the old days at Beverly Farms, my conscience accuses me a little of not sufficiently emphasizing[Pg 61] the virtues of the villagers. Truly, they were a good, interesting, law-abiding, religious people. Everybody went to church; a tramp was unknown; a drunken person was nearly as much an astonishment as a circus would have been. It would be unfair to class them as rude fishermen and shoemakers for they came of the old Puritan ancestry, who built their churches and schoolhouses on a convenient spot, before they attended to anything else, and they paid their debts so promptly that Mr. William Endicott, the good merchant of Beverly, said that he never had any hesitation in selling on credit to "Farms" people. As one got on to middle life, almost every householder had his horse, his cows and often a yoke of oxen. Our favorite conveyance to school, in deep snows, was an ox team with poles on the sides of the sled, where we held on with shouts and screams of laughter.

Nobody thought of hiring a nurse in cases of serious illness. The neighbors came with willing hands and helped out. It was a peaceful little hamlet, with kind, straightforward, honest inhabitants, and the small[Pg 62] remnant of us who are left have reason to be proud of our ancestry.

Elsie repeated to us, the other day, the epitaph on her great-grandfather's grave stone, the Deacon David Larcom, who built my old house, who asked the town for a cemetery for this village and was laid to rest there in 1840, the first one to be buried in its peaceful shadows: "His life exhibited in rare combination and in an uncommon degree all the excellencies of the husband, the father, the citizen and the Christian."

The epitaph was written by Lucy Larcom, whose home here was on West Street. After she left Beverly for Lowell, and was a factory girl, she wrote for the "Lowell Offering," a little magazine published by the nice New England working girls. Copies of this little magazine were in the wonderful attic of my house when I came here. They were probably scented with Aunt Betsey's simples that hung from the roof.

How I wish I could have foreseen how very precious they would be to me now.

Head enlarged from a group taken about 1899

By Mary Larcom Dow

Extracts from the Beacon, published in Beverly for a charity November 1, 1913.

I am proud to be asked to record some of my pleasant days with my mother's cousin, Lucy Larcom. It will, of course, be natural to me to speak principally of the six or seven years during which she lived at Beverly Farms, the only time in which she had a real home of her own. It has always seemed strange to me that Doctor Addison in his biography of her, should have dismissed that part of her life with so few words. I know that it meant a great deal to her.

My very first recollection of her was as a child, when she, as a young lady, came to my house (then owned by "Aunt Betsey") spoken of so affectionately in "A New England Girlhood." Afterward, when I bought the old house, she expressed her great pleasure and when I told her I had spent all my money[Pg 64] for it, she said that was quite right; it was like the turtle with his shell, a retreat.

When she came here in 1866, she was in her early forties, a beautiful, gracious figure, with flowing abundant brown hair, and a most benignant face. She was then editor of "Our Young Folks." She took several sunny rooms near the railroad station, almost opposite "The witty Autocrat." He dated his letters from "Beverly Farms by the Depot," not to be outdone by his Manchester neighbors. The house was then owned by Captain Joseph Woodberry, a refined gentleman of the old school.

She brought with her at first, to these pleasant rooms, a favorite niece who resembled her in looks and in temperament, and she at once proceeded, with her exquisite taste, to make a real home for them. The bright fire on the hearth where we sat and talked and watched the logs fall apart and the sparks go out, was a great delight to her, and I have always thought that that beautiful poem "By the Fireside" must have been written "in those days."

The woods and fields of Beverly Farms were then accessible to all of us, and she knew just where to find the first hepaticas and the rare spots where the linnea grew, and the rhodora and the arethusa, and that last pathetic blossom of the year, the witch hazel, and she could paint them too.

To this home by the sea, came noted people; Mary Livermore, Celia Thaxter, whose sea-swept poems were our great delight, and many others. I recall one great event when Mr. Whittier came and took tea. He was so gentle and simple. The conversation turned on the softening of religious creeds, and he gave us some of his own experiences. He told us that when Charles Kingsley came to America, he went to see him at the Parker House, and as they walked down School Street, Mr. Whittier expressed his appreciation to Mr. Kingsley for his work in that direction. Mr. Kingsley laughed and said,—"Why, when I first went to preach at Eversley, I had great difficulty in making my parishioners believe that God is as good as the average church member."

There was a comfortable lounge in the living room at Beverly Farms, by an east window, and by that window was written "A Strip of Blue."

I do not think that Lucy Larcom had a very keen sense of humor, but she enjoyed fun in others, and was always amused at my absurd exaggerations and at my brother David's comical sea yarns. This brother of mine strongly resembled her in face and build, and also in his determination not to be poor. They would be rich, and they were rich to the end of the chapter. Her income must have been always slender, but I do not think I ever heard her say she could not afford anything. If she wanted her good neighbor, Mr. Josiah Obear, to harness up his red horse and rock-away and take her about the countryside, she said so, and we would go joyfully off, coming home, perhaps from the Essex fields, with a box of strawberries for her simple supper. Always the simple life with nature was her wish.

She was decidedly old-fashioned, and though I do not suppose she thought plays and cards[Pg 67] and dancing wicked, she had still a little shrinking from them. I remember that now and then we played a game called rounce, a game as innocent and inane as "Dumb Muggins" but she always had a little fear that Captain Woodberry would discover it, which pleased me immensely.

Those pleasant days at Beverly Farms came too soon to an end, and for the last part of her life I did not see so much of her. She remains to me a loving and helpful memory of a serene and child-like nature, and "a glad heart without reproach or blot," and I am glad to lay this witch hazel flower of memory upon the grave of that daughter of the Puritans, Lucy Larcom.

Beverly Farms,

April 25, 1893.

My dear Miss Baker:

I get such pleasant letters from you that I quite love you, though I dare say I should not know you if I met you in my porridge dish being such a short sighted old party. And liking you, when you joined those other despots and lie awake o' nights, thinking how you can pile up more work and make life a burden to school ma'ams, means a good deal!!

Here is Miss Fanny Morse, now, whom I have always considered a Christian and a philanthropist, commissioning me to count and destroy belts of caterpillars' eggs for which the children are to have prizes!

The children indeed! The prizes are at the wrong end! Miss Wilkins and I come home nights—"meeching" along—our arms full of the twigs—from which the nasty worms are beginning to crawl!

And now come you, asking for a tree! Yes, yes, dear body, we will do our possible, only if you hear of my raiding somebody's barn yard for the necessary nourishment of said[Pg 69] tree, or stealing a wheelbarrow or a pick and shovel, please think of me at my best.

Now as to Mr. Dow, I must write his part seriously, I suppose, as he is a grave old Scotchman.

He says he will use a part of the money—after proper consultation with the selectmen, etc. And he suggests that a part of the money be used to take care of the triangle and the trees already planted. He will write you when he has decided where to put additional trees. And if I live through the week I will write you whether we got a '92 tree in anywhere.

Yours very much,

Mary L Dow.

Miss Baker was Secretary of the Beverly Improvement Society; these letters refer to her work.—(Editor.)

Beverly Farms, March 21, 1899

My Dear Miss Baker:

I want very much to go to Mrs. Gidding's high tea but I do not get out of school till 3.30 and the train leaves at 3.34.

But after I am graduated from a school, for good and all, I mean to go to some of the rest of these "feasts of reason and flow of soul." We are making fine progress with the wurrums and Miss Wilkins is prospering with her enterprise in Wenham.

Yours truly

Mary L. Dow.

P.S. My regards to your father. I am sorry he has been ill. I told my sub-committee that I thought, if Mr. Baker had been present when my resignation was accepted, they would have sent me some little pleasant message to remember. It seemed to me that after teaching about a century in the town they might have at least told me to go to the d——, or something of that sort.

M.L.D.

"Beverly Farms-by-the-Depot" 1918.

Dearly Beloved G.P.:

"Pink" has just brought me this little squigley piece of paper, so that my letter to you may be of the same size as hers—some people are so fussy. You sent me nine or ten bushels of love, and I have used them all up, and am hungry for more, for that kind of diet my appetite is always unappeased.

How I do wish we had you within touching distance as well as within loving distance; I have always had a great desire to see more of you since first my eyes fell upon you. I do just hate to get so old that perhaps I shall never see you again in the flesh. But I'll be sure to look for you, and now and then, when you get a particularly good piece of good luck,—I shall have had something to do with it. That does not mean that the undertaker has been called and to hear James and Sarah Elizabeth talk, you would suppose that nothing could kill me—I only mean that 84 years is serious; but, for the life of me, I never do get very serious for long at a time.

Jimmy and I have been out to Northfield[Pg 72] for five days, went to meeting and sang psalms for seven hours a day. Jimmy takes to meetings, being as Huxley said of somebody "incurably religious"—and really I did not talk much.

The country was so sweet and beautiful, the spirit of the place was like the New Jerusalem come down again. We slept in the dormitory in the little iron beds side by side, "Each in his narrow bed forever laid", only we did not stay forever.

We meant to come home by way of the Monadnock region, and we had a few drives along the Contacook River, but we ran into a Northeaster, and came ingloriously home.

Have not you been in lovely places, and in great good fortune in your vacation? I am glad of it.

I love you—so does Jimmy—and Sambo, and so would Billy, the neighbors' dog, who hangs about me for rice and kidneys, if he knew you. As to Pink, she flourishes like a green bay horse, teaches French and is in good spirits. Molly goes away on a vacation tomorrow. Poor Jim! With us for cooks!

Remember him in your prayers.

Thine, thine, Molly Polly.

Beverly Farms.

Jan. 25, 1919.

My Dear Mrs. Goddard:

I didn't know till the other day, when I accidentally met Mr. Hakanson, that you had had an anxious and worried time this winter, with Mr. Goddard in the hospital. I am glad to know that he is able to be at home now. Tell him with my love, that our old neighbor, Mrs. Goodwin, once broke her leg, and she told me that though she expected to be always lame, that in a year she could not remember which leg was broken.

I hope you and the boys have been well, in this winter of worries. As to ice, I am scared to death of it, nothing else ever keeps me in the house.

My old assistant at school, declares that one winter she dragged me up and down Everett St., every school day! Nothing like the quietness of this winter at Beverly Farms was ever seen. I think I must suggest to the Beacon St. people to come down. We have[Pg 74] had a good many dark days, but now and then, I lie in my bed and watch the sun come up and glorify the oaks on your hill.

And then I quote to "Jim" Emerson's lines:

And he likes that about as well as he likes the stars in the middle of the night!

By the way, we are thinking of going to Colorado and Florida next month for a few weeks. We have got the bits in our teeth, though we may have to go to the City Home when we get back. We mean to try the month of March in warmer climes. We haven't anything to wear—but that does not matter.

Miss Miller comes down now and then, always serene, though what she finds in the inlook or the outlook is difficult to see. Serenity in her case, does not depend on outward circumstances.

God bless you all, and we shall be glad to see our kind sensible neighbors back.

Affectionately,

Mary L. Dow.

My Dear Mrs. Goddard:

I told the nice young person at your door, that I hoped I should some day soon see your dear face, and so I do hope. But I understand all your busy moments, and you understand my limitations, my having been born so many years ago; and we both know what fine women we both be, and that's all about it!

Then there never was such a salad as we had for our fourth of July dinner. And I did have a little real oil, too good for any hawked about stuff. I put it right on to those dear little onions, and that happy looking lettuce! And that isn't all about that, for there are still carrots—gentle and sweet—for our tomorrow's lunch. I told "Jim" they were good for the disposition and he said he didn't need carrots for his! Men are awfully conceited. And I am so pleased to see Mr. Goddard a'walking right off, without a limp to his name. James and Miss Miller send love, and so do I, while the beautiful hill holds you and always.

Mary Larcom Dow.

Monday, July 7, 1919.

Mrs. Dow wrote to a California friend, Mrs. Gertrude Payne Bridgeford, a short time before her death:

"I'd give my chance of a satin gown to see you, and I hope I shall live to do that, but if I don't, remember that I love you always, here or there, and I quote here my favorite verse from Weir Mitchell,

Her prayer was answered for the twilight was brief.

Dear Elsie:

As soon as Mary said "E. Sill"—I found the Fool's Prayer directly.

It was in my mind and would not stay out. How well it expresses that our sins are often not so bad as our blunders! A splendid prayer for an untactful person. Perhaps I should not go so far as to say that want of tact is as bad as want of virtue—but it is pretty bad! From that defect, you will go scot free! But I often blunder.

Your TAT is here, I am keeping it as a hostage.

Thine,

Your Old Schoolma'am.

Friday, April 9, 1920.

"Wouldn't it be lovely if one could fall—like a leaf from a tree?"

"Longevity is the hardest disease in the world to cure, you are beat from the start, and get worse daily!"

"Ah, dear, sometimes I wish—almost wish—I did not love life so well! But I try to think that if it is not a long dreamless sleep bye and bye, that I shall take right hold of that other existence and love it too!"

And speaking of Mr. Dow's serious illness she wrote:

"I try to believe that God will not take him first—and leave me with no sun in the sky—nor bird in the bush—no flower in the grass."

BY

SARAH E. MILLER

It was in the autumn of 1872 that I first met my friend, Mary Larcom Ober, at Wilmington, North Carolina, where we were teaching in the same school.

In the spring of 1873, she invited me to her home in Beverly Farms.

How well I remember that first happy visit to beautiful Beverly Farms, and the first walk in its woods. We went through the grounds of the Haven estate and then to Dalton's hill which has such a fine outlook.

From that time my friend's home held a welcome for me whenever I chose to come, and the welcome lasted till the close of her life.

What a hospitality, rest and peace there was in the dear "house by the side of the road," and a never-failing kindness and love. What cheer at Thanksgiving and Christmas festivals when friends and neighbors came in to bring greetings, and stayed for friendly chat or a game of cards.

In the first years of our friendship, I made close acquaintance with the woods of Beverly Farms, for we lived our summer afternoons mostly out of doors in those days. We had two favorite places under the trees, one, on a little hill deep in the pines, the other, with glimpses of the sea, and we took our choice of these from day to day.

Here in the company of books, birds and squirrels we used to sit, read and sew till the last beams of sunlight crept up to the tops of the pines, then gathered up books and work and went home.

I learned much of book-lore in those days from my friend, much also of wood-lore. She knew the places where the spring flowers were hidden, hepeticas, violets, blood-root, the nodding columbines, and all the others, and we searched them out together.

The memory of those first years at Beverly Farms, and of all the following years are among the most precious possessions that I hold.

S. E. M.

From Mrs. Cora Haynes Crosby:

"I have known and loved her, our dear wonderful friend who has left us, ever since I can remember, and what a friend she has been.

Not only was she dear to father and mother, but just as precious with her great, noble, beautiful spirit to all of us younger ones, for she was no older than we.

That happy outlook on life, her love of everything beautiful and fine in nature, books and people, made her an inspiration to all who knew her."

From a letter by Mrs. Margaret Haynes Pratt:

"Ever since I was a little girl, Molly has been almost a member of our household. As a child, her visits were as much a joy to me as to mother and father.

I never thought of her as old, even then—and a child generally marks off the years in relentless fashion, for Molly was always young to me, as she must have been to everyone who knew her.

It is wonderful to have had a nature that so helps all who knew her to believe that life is immortal."