Title: Wings and Stings: A Tale for the Young

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release date: August 6, 2019 [eBook #60065]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tim Lindell, David E. Brown, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

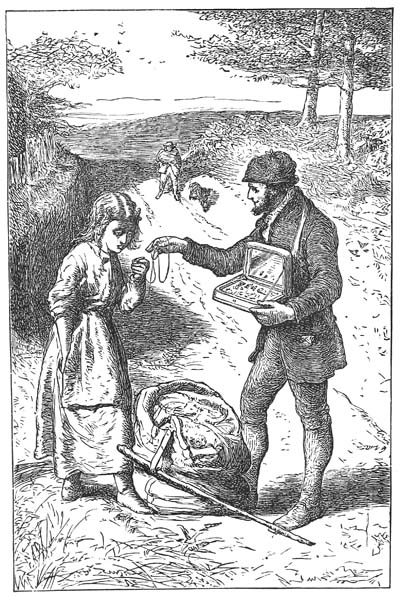

COMING TO THE RESCUE

page 48

WINGS AND STINGS.

A Tale for the Young.

BY

A. L. O. E.,

AUTHOR OF “THE SILVER CASKET,” “THE ROBBERS’ CAVE,”

ETC. ETC.

How doth the little busy bee

Improve each shining hour,

And gather honey all the day

From every opening flower!

Watts.

LONDON:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

1879.

WHAT is the use of a preface? Most of my young readers will regard it as they would a stile in front of a field in which they were going to enjoy haymaking; as something which they hastily scramble over, eager to get to what is beyond. Such being the case, I think it best to make my preface as short, my stile as small as possible, not being offended if some of my friends should skip over it at one bound. To the more sober readers I would say, If you look for some fun in the little field which you are going to enter, remember that in haymaking[vi] there is profit as well as amusement; in turning over thoughts in our minds, as in turning over newly-mown grass, we may “make hay while the sun shines,” which will serve us when cloudier days arise.

A. L. O. E.

| I. | THE BIG HIVE AND THE LITTLE ONE, | 9 |

| II. | SOME ACCOUNT OF A WATERFALL, | 26 |

| III. | A FLATTERING INVITATION, | 36 |

| IV. | HOME LESSONS AND HOME TRIALS, | 46 |

| V. | CONVERSATION IN THE HIVE, | 59 |

| VI. | A STINGING REPROOF, | 69 |

| VII. | A WONDERFUL BORE, | 80 |

| VIII. | A CHASE, AND ITS CONSEQUENCES, | 88 |

| IX. | PRISONS AND PRISONERS, | 109 |

| X. | A CONFESSION, | 117 |

| XI. | A SUDDEN FALL, | 131 |

| XII. | AN UNPLEASANT JOURNEY, | 140 |

| XIII. | WINGS AND STINGS, | 151 |

“HAD you not better go on a little faster with your work, Polly?” said Minnie Wingfield, glancing up for a minute from her own, over which her little fingers had been busily moving, and from which she now for the first time raised her eyes.

“I wish that there were no such thing as work!” exclaimed Polly, from her favourite seat by the school-room window, through which she had been watching the bees[10] thronging in and out of their hive, some flying away to seek honied treasure, some returning laden with it to their home.

“I think that work makes one enjoy play more,” replied Minnie, her soft voice scarcely heard amidst the confusion of sounds which filled the school-room; for there was a spelling-class answering questions at the moment, and the hum of voices from the boys’ school-room, which adjoined that of the girls, added not a little to the noise.

The house might itself be regarded as a hive, its rosy-cheeked scholars as a little swarm of bees, and knowledge as the honey of which they were in search, drawn, not from flowers, but from the leaves of certain dog’s-eared books, which had few charms for the eyes of Polly Bright.

“I never have any play,” said the little girl peevishly. “As soon as school is over, and I should like a little fun, there is Johnny to be looked after, and the baby to be carried. I hate the care of children—mother[11] knows that I do—and I think that baby is always crying on purpose to tease me.”

THE BIG HIVE.

“Yet it must be pleasant to think that you are helping your mother and doing your duty.”

Polly uttered a little grunting sound,[12] which did not seem like consent, and ran her needle two or three times into her seam, always drawing it back instead of pushing it through, which every one knows is not the way to get on with work.

“Why, even these little bees,” Minnie continued, “have a sort of duty of their own; and how steadily they set about it!”

“Pretty easy duty,—playing amongst flowers and feasting upon honey!”

“Oh but—”

“Minnie Wingfield, no talking allowed in school!” cried the teacher from the top of the room, turning towards the corner near the window. “Polly Bright, you are always the last in your class.”

This time the lazy fingers did draw the needle through, but a cross, ill-tempered look was on the face of the little girl; while her companion, Minnie, colouring at the reproof, only worked faster than before.

We will leave them seated on their bench, with their sewing in their hands, and passing[13] through the little window, as only authors and their readers can do, cross the narrow garden, with its small rows of cabbages and onions, bordered by a line of stunted gooseberry bushes, and mixing with the busy inhabitants of the hive, glide through the tiny opening around which they cluster, and enter the palace of the bees. Now I have a suspicion that though my young readers may be well acquainted with honey-comb and honey, and have even had hives on a bench in their own gardens, they never in their lives have been inside one, and are totally ignorant of the language of bees. For your benefit, therefore, I intend to translate a little of the buzzing chit-chat of the winged nation; and, begging you to consider yourself as little as possible, conduct you at once to the palace of Queen Farina.

A very curious and beautiful palace it is; the Crystal Palace itself is not more perfect in its way. Look at the long lines of cells, framed with the nicest care, row above row,[14] built of pure white wax, varnished with gum, and filled with provisions for the winter. Yonder are the nurseries for the infant bees; these larger apartments are for the royal race; that, largest of all, is the state-chamber of the queen. How strait are the passages—just wide enough to let two travellers pass without jostling! And as for the inhabitants of this singular palace, or rather, I should say, this populous city, though for a moment you may think them all hurrying and bustling about in utter confusion, I assure you that they are governed by the strictest order—each knows her own business, her own proper place. I am afraid that before you are well acquainted with your small companions, you may find some difficulty in knowing one from another, as each bee looks as much like her neighbour as a pin does to a pin. I am not speaking, of course, of her majesty the queen, distinguished, as she is, from all her subjects by the dignified length of her figure and the[15] shortness of her wings; but you certainly would not discover, unless I told you, that the little creature hanging from the upper comb is considered a beauty in Bee-land. You must at once fancy your eyes powerful microscopes, till a daisy is enlarged to the size of a table, and the thread of a spider to a piece of stout whip-cord; for not till then can you find out the smallest reason why Sipsyrup should be vain of her beauty. Yet why should she not pride herself on her slender shape or her fine down? Vanity may seem absurd in a bee, but surely it is yet more so in any reasonable creature, to whom sense has been given to know the trifling worth of mere outside looks; and I fear that I may have amongst my young readers some no wiser than little Sipsyrup.

She is not buzzing eagerly about like her companions, who are now working in various parties; some raising the white walls of the cells; some carrying away small cuttings of wax, not to be thrown away, but used in[16] some other place, for bees are very careful and thrifty; some putting a fine brown polish on the combs, made of a gum gathered from the buds of the wild poplar; some bringing in provisions for the little workmen, who are too busy to go in search of it themselves. No; Sipsyrup seems in her hive as little satisfied as Polly in her school-room, as she hangs quivering her wings with an impatient movement, very unworthy of a sensible bee.

“A fine morning this!” buzzed an industrious young insect, making bee-bread with all her might. I may here remark that the subject of the weather is much studied in hives, and that their inhabitants show a knowledge of it that might put to shame some of the learned amongst us. I am not aware that they ever make use of barometers, but it is said that they manage seldom to be caught in a shower, and take care to keep at home when there is thunder.

“A fine morning, indeed,” replied Sipsyrup.[17] “Yes; the sunshine looks tempting enough, to be sure; no doubt the flowers are all full of honey, and the hills covered with thyme; but of what use is this to a poor nurse-bee like me, scarcely allowed to snatch a hasty sip for myself, but obliged to look after these wretched little larvæ” (that is the name given to young baby-bees), “and carry home tasteless pollen to make bread for them, when I might be enjoying myself in the sunshine?”

“We once were larvæ ourselves,” meekly observed Silverwing.

“Yes, and not very long ago,” replied Sipsyrup rather pertly, glancing at the whitish down that showed her own youth; for it was but three days since she had quitted her own nursery, which may account for her being so silly a young bee.

“And but for the kindness of those who supplied our wants when we were poor helpless little creatures, we should never have lived to have wings,” continued her companion.

[18]“Don’t remind me of that time,” buzzed Sipsyrup, who could not bear to think of herself as a tiny, feeble worm. “Anything more weary and tiresome than the life that I led, shut up all alone in that horrid cell, spinning my own coverlet from morning till night, I am sure that I cannot imagine. Ah, speaking of that spinning, if you had only seen what I did yesterday.”

“What was that?” inquired Silverwing.

“As I flew past a sunny bank, facing the south, I noticed a small hole, at the entrance of which I saw one of our cousins, the poppy-bees. Her dress, you must know, is different from ours” (Sipsyrup always thought something of dress). “It is black, studded on the head and back with reddish-gray hairs, and her wings are edged with gray. Wishing to notice a little more closely her curious attire, I stopped and wished her good-day. Very politely she invited me into her parlour, and I entered the hole in the bank.”

[19]“A dull, gloomy place to live in, I should fear.”

“Dull! gloomy!” exclaimed Sipsyrup, quivering her feelers at the recollection; “why, the cell of our queen is a dungeon compared to it. The hole grew wider as we went further in, till it appeared quite roomy and large, and all round it was hung with the most splendid covering, formed of the leaves of the poppy, of a dazzling scarlet, delightful to behold. Since I saw it, I have been scarcely able to bear the look of this old hive, with its thousands of cells, one just like another, and all of the same white hue.”

“Had the poppy-bee a queen?” inquired Silverwing.

“No; she is queen, and worker, and everything herself; she has no one to command her, no one to obey; no waspish companion like Stickasting there.”

“What’s that? who buzzes about me?” cried a large thick bee, hurrying towards[20] them with an angry hum. Stickasting had been the plague of the hive ever since she had had wings. She was especially the torment of the unfortunate drones, who, not having been gifted with stings like the workers, had no means of defence to protect them from their bullying foe. When a larva, her impatient disposition was not known. She had spun her silken web like any peaceable insect, then lain quiet and asleep as a pupa or nymph. But no sooner did the young bee awake to life, than, using her new powers with hearty good-will, she ate her way through the web at such a quick rate, that the old bees who looked in pronounced at once that she was likely to be a most active worker. Nor were they disappointed, as far as work was concerned; no one was ready to fly faster or further, no one worked harder at building the cells; but it was soon discovered that her activity and quickness were not the only qualities for which she was remarkable. If ever bee[21] had a bad temper, that bee was Stickasting. Quarrelling, bullying, attacking, fighting, she was as bad as a wasp in the hive. No one would ever have trusted larvæ to her care. Sipsyrup might neglect or complain of her charge, but Stickasting would have been positively cruel. Her companionship was shunned, as must be expected by all of her character, whether they be boys or bees; and she seldom exchanged a hum, except of defiance, with any creature in the hive.

Sipsyrup, the moment that she perceived Stickasting coming towards her, flew off in alarm, leaving poor Silverwing to bear the brunt of the attack.

“Who buzzes about me?” repeated Stickasting fiercely, flying very close up to the little nurse-bee.

“Indeed, I never named you,” replied Silverwing timidly, shrinking back as close as she could to the comb.

“If you were not talking against me yourself,[22] you were listening to and encouraging one who did. Who dare say that I am waspish?” continued Stickasting, quivering her wings with anger till they were almost invisible. “It is this gossip and slander that make the hive too hot to hold us. I once thought better of you, Silverwing, as a quiet good-natured sort of a bee, but I now see that you are just like the rest, and as silly as you are ugly.”

This was a very provoking speech—it was intended to be so; but Silverwing was not a creature ready to take offence; whatever she felt, she returned no answer—an example which I would strongly recommend to all in her position, whether standing on six feet or on two.

But Stickasting was resolved to pick a quarrel if possible, especially with one whom she considered less strong than herself; for she was not one of those generous beings who scorn to take advantage of the weakness of another. Stickasting much resembled[23] the class of rude, coarse-minded boys, who find a pleasure in teasing children and annoying little girls, and like to show their power over those who dare not oppose it.

“I owe you a grudge, Silverwing, for your conduct to me yesterday. When I was toiling and working at the cells like a slave, not having time to go out for refreshment, I saw you fly past me two or three times, and not a drop of honey did you offer me.”

“I was carrying pollen for my little larvæ,” gently replied Silverwing. “It is not my office to supply the builders, though I am sure that I should do so with pleasure; but the baby-bees are placed under my charge, and you know what care they need till they begin to spin.”

“Yes, idle, hungry, troublesome creatures that they are! Have they not set about their spinning yet? I’ll make them stir themselves,”—and Stickasting made a movement towards the nursery-cells.

[24]“The larvæ do not like to be disturbed!” cried Silverwing, anxious for her charges, and placing herself between them and the intruder.

“Like! I daresay not,—but who cares what they like! Get out of the way; I’ll prick them up a little!”

“You shall not come near them!” hummed the little nurse, resolutely keeping her place.

“I say that I shall,—who shall hinder me? Get out of my way, or I’ll let you feel my sting.”

Silverwing trembled, but she did not stir, for she was a faithful little bee. As the hen is ready to defend her chickens from the hawk, and even the timid wren will fight for her brood, so this feeble insect would have given up her life rather than have forsaken the little ones confided to her care.

But she was not left alone to struggle with her assailant. Two of her winged companions came to the rescue; and Stickasting,[25] who had no wish to encounter such odds, and was fonder, perhaps, of bullying than of fighting, no sooner saw Waxywill and Honeyball on the wing, than with an angry hum she hurried out of the hive.

I WISH that all little nurses were as trustworthy as Silverwing, or as kind and patient with their charges! While Polly Bright has sat in her mother’s cottage trimming her bonnet, till it looks as absurd as pink ribbons can make it, the poor baby has been crying unheeded in his cradle, except that now and then, when vexed more than usual by the noise, with an almost angry look she pauses for a moment to rock the cradle with her foot. She does not notice that little Johnny has been clambering up by the pail, which her mother has set aside for her washing, till the[27] sudden sound of a fall, and a splash, and a child’s frightened cry, startle her, and she sees little streams running all over the stone floor, and Johnny flat on his face in the middle of a loud roar,—and a pool of water.

A MISHAP.

Up she jumps, not in the best of tempers. Poor Johnny is dragged up by one arm, and receives one or two slaps on the back, which only makes him cry louder than before; he stands a picture of childish misery, with dripping dress and open mouth, the tears rolling down his rosy cheeks, helpless and frightened, as his careless sister shakes and scolds him, and shakes him again, for what was the effect of her own negligence.

[28]Happily for the little boy, Minnie Wingfield is a near neighbour, and comes running at the sound of his distress.

“Why, what is the matter, my dear little man?” are her first words as she enters the cottage.

“Look here! did you ever see anything like it? His dress clean on to-day! I cannot turn my back for a moment but he must be at the pail,—naughty, tiresome, mischievous boy!” and poor Johnny received another shake. “A pretty state the cottage is in,—and there—oh, my bonnet! my bonnet!” exclaimed Polly, as she saw that in her hurry and anger she had thrown it down, and that, pink ribbons and all, it lay on the floor, right across one of the little streams of water.

“Never mind the bonnet; the poor child may be hurt, and—oh, take care, the baby will be wetted!” and without waiting for Polly’s tardy aid, Minnie pushed the cradle beyond reach of danger.

[29]While Polly was yet bemoaning her bonnet, and trying to straighten out its damaged ribbons, Minnie had found out something dry for the shivering little boy, had rubbed him, and comforted him, and taken him upon her knee; then asking him to help her to quiet poor baby, had hushed the sickly infant in her arms. Was there no pleasure to her kind heart when its wailing gradually ceased, and the babe fell into a sweet sleep,—or when Johnny put his plump arms tight round her neck, and pressed his little lips to her cheek?

There are some called to do great deeds for mankind, some who bestow thousands in charity, some who visit hospitals and prisons, and live and die the benefactors of their race. But let not those who have not power to perform anything great, imagine that because they can do little, they need therefore do nothing to increase the sum of happiness upon earth. There is a terrible amount of suffering caused by neglect of, or[30] unkindness to, little children. Their lives—often how short!—are embittered by harshness, their tempers spoiled, sometimes their health injured; and can those to whose care the helpless little ones were confided, imagine that there is no sin in the petulant word, the angry blow, or that many will not have one day to answer for all the sorrow which they have caused to their Lord’s feeble lambs, to those whose spring-time of life should be happy?

Would my readers like to know a little more of Minnie Wingfield, whose look was so kind, whose words were so gentle, that her presence was like sunshine wherever she went? She lived in a little white cottage with a porch, round which twined roses and honeysuckle. There was a little narrow seat just under this porch, where Minnie loved to sit in the summer evenings with her work, or her book when her work was done, listening to the blackbird that sang in the apple-tree, and the humming of the[31] bees amidst the blossoms. Little Minnie led a retired life, but by no means a useless one. If her mother’s cottage was the picture of neatness, it was Minnie who kept it so clean. Her brother’s mended stockings, his nicely-washed shirts, all did credit to her neat fingers. Yet she could find time to bestow on the garden, to trim the borders, to water the plants, to tie up the flowers in which her sick mother delighted. Nor did Minnie neglect the daily school. She was not clever, but patient and ever anxious to please; her teacher regarded her as one of her best scholars, and pointed her out as an example to the rest. But Minnie’s great enjoyment was in the Sunday-school; there she learned the lessons which made duty sweet to her, and helped her on the right way through the week. The small Bible which had been given to her by her father, with all his favourite verses marked, was a precious companion to Minnie: not studied as a task-book, or carelessly read as a matter[32] of custom; but valued as a treasure, and consulted as a friend, and made the rule and guide of daily life.

And was not Minnie happy? In one sense she certainly was so, but still she had her share of this world’s trials. The kind father whom she had fondly loved had died the year before; and besides the loss of so dear a friend, his death had brought poverty upon his family. It was a hard struggle to make up the rent of the little cottage, which Mrs. Wingfield could not bear to quit, for did not everything there remind her of her dear husband,—had he not himself made the porch and planted the flowers that adorned it! Often on a cold winter’s day the little fire would die out for want of fuel, and Minnie rise, still hungry, from the simple meal which she had spared that there might be enough for her parent and her brother.

Mrs. Wingfield’s state of health was another source of sorrow. She was constantly ailing, and never felt well, and[33] though saved every trouble by her attentive child, and watched as tenderly as a lady could have been, the sufferings of the poor woman made her peevish and fretful, and sometimes even harsh to her gentle daughter.

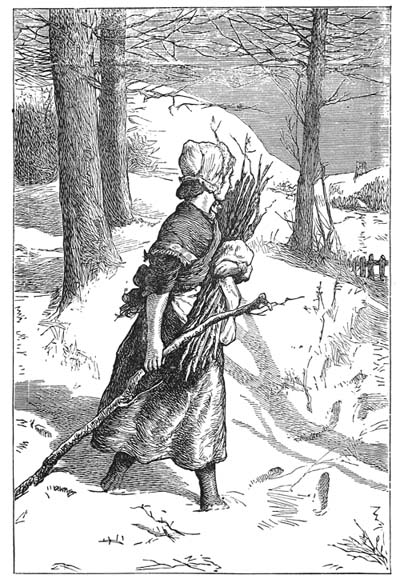

MINNIE WITH THE FIREWOOD.

[35]Tom, her brother, was also no small trial to Minnie. Unlike her, he had little thought for anything beyond self; he neither considered the comfort nor the feelings of others. If Minnie was like sunshine in the cottage of her mother, Tom too often resembled a bleak east wind; and though Mrs. Wingfield and her daughter never admitted such a thought, their home was happiest when Tom was not in it.

But it is time to return to our hive.

WAXYWILL and Honeyball had both come to the assistance of Silverwing, and she buzzed her thanks in a grateful way to both, though different motives had brought them to her aid, for they were very different bees in their dispositions.

Honeyball was a good-humoured, easy kind of creature. Very ready to do a kindness if it cost her little trouble, but lazy as any drone in the hive. Honeyball would have liked to live all day in the bell of a foxglove, with nothing to disturb her in her idle feast. It was said in the hive that[37] more than, once she had been known to sip so much, that at last she had been unable to rise, and for hours had lain helpless on the ground. Sipsyrup, who, like other vain, silly creatures, was very fond of talking about other people’s concerns, had even whispered that Honeyball had been seen busy at one of the provision-cells stored for the winter’s use, which it is treason in a bee to touch; but as those who talk much generally talk a little nonsense, we may hope that there was no real ground for the story.

Waxywill was one of whom such a report would never have been believed; there was not a more honourable or temperate worker in the hive. Yet Stickasting herself was scarcely less liked, so peevish and perverse was the temper of this bee. If desired to do anything, it was sure to be the very thing which she did not fancy. Were cells to be built—she could not bear moping indoors; if asked to bring honey—she always found out that her wings were tired. She could[38] not bear submission to the laws of the hive, and once actually shook her wings at the queen! When she flew to help Silverwing, it was less out of kindness to her than the love of opposing Stickasting. And yet Waxywill was not an ungenerous bee; she had more sense too than insects generally possess; she would have been respected and even loved in the hive, had not her stubborn, wilful temper spoilt all.

We will now follow Sipsyrup in her hasty flight, as, leaving both her friend and her charges behind, she made her retreat from Stickasting. How delightful she found the fine fresh air, after the heated hive! Now up, now down, she pursued her varying course, sometimes humming for a moment around some fragrant flower, then, even before she had tasted its contents, deserting it for one yet more tempting. Deeply she plunged her long tongue into its cup; her curious pliable tongue, so carefully guarded by Nature in a nicely fitting sheath.[39] “Sheathe your tongue!” was an expression which the gossipping little bee had heard more often than she liked, especially from the mouth of Waxywill. It might be an expressive proverb in other places than Bee-land, for there are tongues whose words are more cutting than swords, that much need the sheath of discretion.

The movements of the lively insect were watched with much interest by Spinaway the spider, from her quiet home in a rosebush. Sipsyrup, disdaining the narrow garden of the school, had winged her way over the wall, and turning into a narrow green lane that was near, was now sporting with the blossoms by Mrs. Wingfield’s porch. Spinaway was a clever, artful spider, somewhat ambitious too in her way. She had made her web remarkably firm and strong, and expected to be rewarded by nobler game than the little aphis, or bony gnat. She had once succeeded in capturing a blue-bottle fly, and this perhaps it was that raised[40] her hopes so high, that she did not despair of having a bee in her larder.

“Good-morning,” said Spinaway in a soft, coaxing tone, as Sipsyrup came fluttering near her. “You seem to have travelled some distance, my friend, and if you should like to rest yourself here, I am sure that you would be heartily welcome.”

Sipsyrup was a young, inexperienced bee, but she did not much fancy the looks of the spider, with her hunchback and long hairy legs. She politely, therefore, declined the invitation, and continued her feast in a flower.

“I am really glad to see a friend in a nice quiet way,” continued the persevering spider. “I find it very dull to sit here all day; I would give anything to have wings like a bee.”

Sipsyrup, who loved gossip, advanced a little nearer, taking care to keep clear of the web.

“I do long to hear a little news of the[41] world, to know what passes in your wonderful hive. I am curious to learn about your queen; your manner and style of dress is such, that I am sure that you must have been much about the court.”

Settling upon a leaf, still at a safe distance, Sipsyrup indulged her taste for chit-chat, glad to have so attentive a listener. Spinaway soon heard all the gossip of the hive,—how the present queen had killed in single combat the queen of another swarm, whilst the bees of both nations watched the fight; and how the hostile band, when they saw their queen dead, had submitted to the conqueror at once. How a slug had last morning crept into the hive and frightened her out of her wits, but had been put to death by fierce Stickasting before it had crawled more than an inch. Sipsyrup then related—and really for once her conversation was very amusing—all the difficulties and perplexity of the people of the hive as to how to get rid of the body of the intruder.[42] She herself had been afraid to venture near the monster, but Silverwing and the rest had striven with all their might to remove the dead slug from their hive.

“And did they succeed?” said Spinaway, much interested.

“Oh, it was quite impossible to drag out the slug! We were in such distress—such a thing in the hive—our hive always kept so neat and clean that not a scrap of wax is left lying about!”

“What did you do?” said the spider; “it really was a distressing affair.”

“Waxywill thought of a plan for preventing annoyance. She proposed that we should cover the slug all over with wax, so that it should rather appear like a piece of the comb than a dead creature left in the hive.”

“A capital plan!” cried Spinaway. “And was the thing done?”

“Yes, it was, and before the day was over.”

“So there Mrs. Slug remains in a white[43] wrapping,” laughed the spider; “a warning to those who go where they are not wanted. You were, I daresay, one of the foremost in the work.”

“Not I; I would not have touched the ugly creature with one of my feelers!”

“I beg your pardon!” said the spider; “indeed, I might have judged by your appearance that nothing but the most refined and elegant business would ever be given to you. You look as though you had never touched anything rougher than a rose.”

This speech put Sipsyrup in high good-humour; she began to think that she had judged the spider harshly, and that she really was an agreeable creature in spite of her ugly hunch.

“If you speak of delicate work,” observed the bee very politely, “I never saw anything so fine as your web.”

“It is tolerably well finished,” said the spider with a bow; “would you honour me by a closer inspection?”

[44]“Oh, thank you, I’m not curious in these matters,” replied Sipsyrup, still feeling a little doubtful of her new friend.

“You have doubtless remarked,” said Spinaway, “that each thread is composed of about five thousand others, all joined together.”

“No, really, I had no idea of that—how wonderfully fine they must be!”

“I am surprised that you did not see it; at least if the powers of your eyes equal their beauty. I never beheld anything like them before—their violet colour, their beautiful shape, cut, as it were, into hundreds of divisions, like fine honey-comb cells, and studded all over with most delicate hair. I would give my eight eyes for your two!”

“Two!” cried Sipsyrup, mightily pleased; “I have three more on the back of my head.”

“I would give anything to see them, if they are but equal to the faceted ones. No creature in the world could boast of such a[45] set! Might I beg—would you favour me?”—

Silly Sipsyrup! foolish bee! not the first, however, nor, I fear, the last, to be caught by sugary words. Blinded by vanity, forward she flew—touched the sticky, clammy web—entangled her feet—struggled to get free—in vain, in vain!—quivered her wings in terrified efforts—shook the web with all her might—but could not escape. Her artful foe looked eagerly on, afraid to approach until the poor bee should have exhausted herself by her struggles. Ah, better for Sipsyrup had she kept in her hive, had she spent all the day in making bee-bread, to feed the little larvæ in their cells!

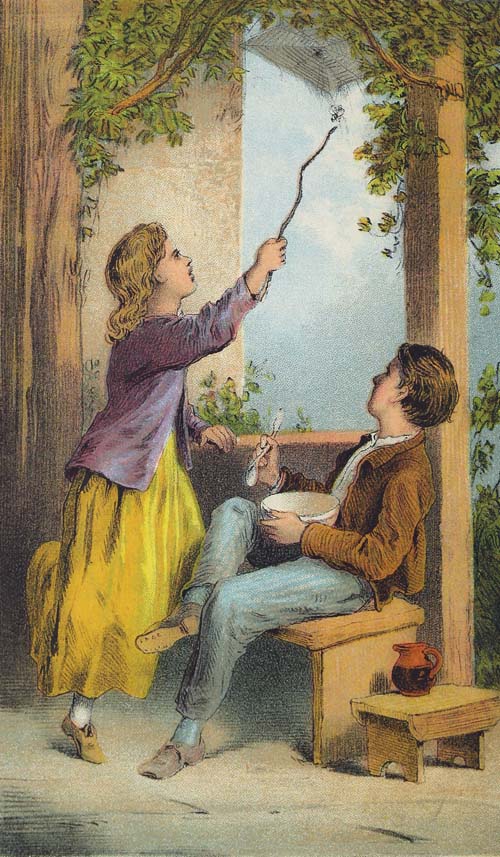

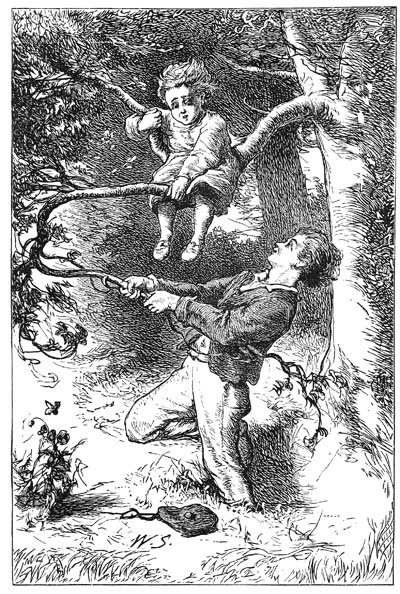

BUZZ, buzz, buzz!—“There’s a bee in a web!” cried Tom, looking up from the bowl of porridge which he was eating in the rose-covered porch.

“Poor thing!” said Minnie, rising from her seat.

“A precious fright it must be in! what a noise it makes!” cried her brother.

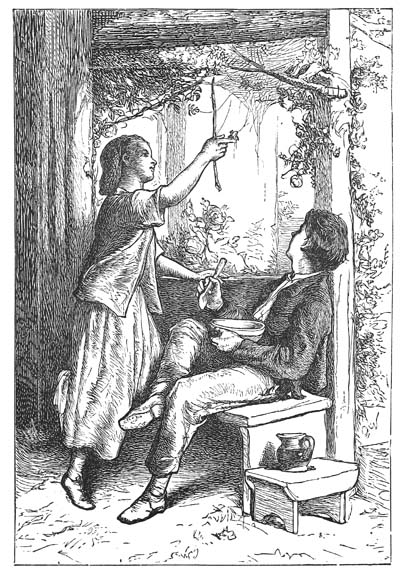

“It is not much entangled—I think that I could set it free!”—and Minnie ran up to the web.

“And be stung for your pains. Nonsense—leave it alone. It is good fun to watch it in its struggles.”

POOR SIPSYRUP IN A SNARE.

“It never can be good fun to see any creature in misery,” replied Minnie; and with the help of a little twig, in a very short time poor Sipsyrup was released from the web.

“Poor little bee!” said Minnie, “it has hurt its wing, and some of the web is still clinging to its legs. I am afraid that it cannot fly.”

“I hope that it will sting you!” laughed Tom. “Are you going to nurse and pet it here, and get up an hospital for sick bees?”

“I think that it must belong to our school-mistress’s hive. I will carry it there,[48] and put it by the opening, and let its companions take care of it.” And notwithstanding Tom’s scornful laugh, Minnie bore off the bee on her finger.

“You are the most absurd girl that I ever knew,” said he on her return. “What does it matter to you what becomes of one bee? I should not mind smothering a whole hive!”

“Ah, Tom,” said his sister, “when there is so much pain in the world, I do not think that one would willingly add ever so little to it. And I have a particular feeling about animals. You know that they were placed under man, and given to man, and they were all so happy until—until man sinned; now, innocent as they are, they share his punishment of pain and of death; and it seems hard that we should make that punishment more bitter!”

“Then my tender-hearted sister would never taste mutton, I suppose.”

“No; the sheep are given to us for food;[49] but I would make them as happy as I could while they lived. O Tom, we are commanded in the Bible to be ‘tender-hearted,’ and ‘merciful,’ and surely to be cruel is a grievous sin!”

MINNIE AND THE BEE.

[51]“I wonder that you did not crush the spider that would have eaten up your bee.”

“Why should I? She did nothing wrong. It is Nature that has taught her to live on such food; I would be merciful to spiders as well as to bees.”

“You carried off her dinner—she would not thank you for that.”

“Perhaps I did foolishly,” said Minnie with a smile; “but I cannot see a creature suffering and not try to help it.”

“I wish that you saw the green-grocer’s horse with his bones all starting through his skin, and the marks of the blows on his head. What would you say to the master of that horse?”

“Oh, I wish that he would remember that one verse from the Bible, ‘Blessed are[52] the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.’ Without mercy, what would become of the best—without mercy, we all should be ruined for ever. And if only the merciful can obtain mercy, oh! what will become of the cruel?”

“Pshaw!” cried Tom, not able to dispute the truth of Minnie’s words, but not choosing to listen to them, for he had too many recollections of bird-nesting, cockchafer-spinning, and worrying of cats, to make the subject agreeable. Some find it easier to silence an opponent with a “pshaw!” than by reason or strength of argument; and this was Tom’s usual way. He did not wish to continue the conversation, and, perhaps with a view to change its subject, said in a sudden, abrupt tone, as he stirred his porridge with his pewter spoon—

“You’ve not put a morsel of sugar in my bowl.”

“Yes, indeed, I put some,” replied Minnie.

[53]“But you know that I like plenty; I have told you so a thousand times.”

“But, dear Tom, I have not plenty to give you—we have nearly come to the end of our little store. And you know,” continued she, lowering her voice, “that we cannot buy more until we are paid for these shirts.”

The little girl did not add that for the last three days she had not tasted any sugar herself.

“Nonsense!” cried Tom, starting up from his seat, and hastily entering the cottage. He took down from the shelf a large broken cup, which was used to contain the store of sugar. Mrs. Wingfield was lying asleep in the back-room, being laid up with a worse headache than usual.

Fearing lest her mother should be roused from her sleep, Minnie followed her brother, her finger on her lip, a look of anxious warning on her face. But both look and gesture were lost upon Tom, who was thinking of nothing but himself.

[54]“Here’s plenty for to-day,” he said in a careless tone, emptying half the supply into his bowl.

“But, Tom—our poor mother—she is ill, you know—”

“Well, I’ve not taken it all.”

“But we cannot afford—”

“Don’t torment me!” cried Tom angrily, helping himself to more.

“Oh, dear Tom,” said the little girl, laying her hand upon his arm.

“I’ll not stand this nonsense!” exclaimed the boy fiercely; and turning suddenly round, he flung the rest of the sugar into the dusty road. “There—that serves you right; that will teach you another time to mind your own business and leave me alone;” and noisily setting down the empty cup, the boy sauntered out of the cottage.

Something seemed to rise in Minnie’s throat; her heart was swelling, her cheek was flushed with mingled sorrow and indignation. Oh, how much patience and meekness[55] we require to meet the daily little trials of life!

Minnie was roused by her mother’s feeble, fretful voice. “I wish that you and Tom had a little more feeling for me. You have awoke me with your noise.”

“I am sorry that you have been disturbed, dear mother; I’ll try and not let it happen again. Do you feel better now?”

“No one feels better for awaking with a start,” returned Mrs. Wingfield peevishly. “I should not have expected such thoughtlessness from you.”

Minnie’s eyes were so brimful of tears that she dared not shut them, lest the drops should run over on her cheek. She knew that her mother would not like to see her cry, so, turning quietly away, she went to the small fire to make a little tea for the invalid.

There was nothing that Mrs. Wingfield enjoyed like a cup of warm tea; and when Minnie brought one to the side of her bed,[56] with a nice little piece of dry toast beside it, even the sick woman’s worn face looked almost cheerful. As soon, however, as she had tasted the tea, she set down the cup with a displeased air.

“You’ve forgotten the sugar, child.”

“Not forgotten, mother, but—but I have none.”

“More shame to you,” cried Mrs. Wingfield, her pale face flushing with anger; “I am sure that a good deal was left this morning. You might have thought of your poor sick mother; she has few enough comforts, I am sure.”

Poor Minnie! she left the room with a very heavy heart; she felt for some minutes as if nothing could cheer her. Angry with her brother, grieved at her mother’s undeserved reproach, as she again sat down to work in the little porch, her tears fell fast over her seam. Presently Conscience, that inward monitor to whose advice the little girl was accustomed to listen, began to make[57] itself heard. “This is foolish, this is wrong,—dry up your tears, they can but give pain to your sick mother. You must patiently bear with the fretfulness of illness, and not add to its burden by showing that you feel it. You know that you have not acted selfishly, you need not regret your own conduct in the affair,—is not that the greatest of comforts? But I know very well,” still Conscience whispered in her heart, “that you never will feel quite peaceful and happy till no anger remains towards your brother. A little sin disturbs peace more than a great deal of sorrow; ask for aid to put away this sin.”

Minnie listened to the quiet voice of Conscience, and gradually her tears stopped and her flushed cheek became cool. She made a hundred excuses in her mind for poor Tom. He had been always much indulged,—he would be sorry for what he had done,—how much better he was than other boys that she knew, who drank, or swore, or stole.[58] And for herself, what a sin it was to have felt so miserable! How many blessings were given her to enjoy! She had health, and sight, and fingers able to do work; and neither she nor her mother had difficulty in procuring it, the ladies around were so kind. Then there was the church, and the school, and the Best of Books;—and the world was so beautiful, with its bright sun and sweet flowers,—there was so much to enjoy, so much to be thankful for! And Minnie raised her eyes to the blue sky above, all dotted over with rosy clouds; for it was the hour of sunset, and she thought of the bright happy place to which her dear father had gone, and how she might hope to join him there, and never know sorrow again. What wonder, with such sweet thoughts for her companions, if Minnie’s face again grew bright, and she worked away in her little porch with a feeling of peace and grateful love in her breast which a monarch might have envied.

POOR Sipsyrup! how sadly she stood at the entrance of the hive, where her gentle preserver had left her. The fine down, of which she had been so vain, was all rubbed and injured by her struggles in the web; one of her elegant wings was torn; she felt that all her beauty was gone! She had hardly courage to enter the hive, and was ashamed to be seen by the busy bees flocking in and out of the door. I am not sure that insects can sigh, or I am certain that she must have sighed very deeply. The first thing that gave her the least feeling of comfort was the[60] sound of Silverwing’s friendly hum;—the poor wounded insect exerted her feeble strength, and crept timidly into the hive.

“Sipsyrup!—can it be!” cried Honeyball, rousing herself from a nap as the bee brushed past her.

“Sipsyrup, looking as though she had been in the wars!” exclaimed Waxywill, who, in the pride of her heart, had always looked with contempt on her vain, silly companion.

“My poor Sipsyrup!” cried Silverwing, hastening towards her. Their feelers met (that is the way of embracing in Bee-land), the kind bee said little, but by every friendly act in her power showed her pity and anxiety to give comfort.

What pleased Sipsyrup most was the absence of Stickasting, who had not returned to the hive which she had left an hour before in a passion.

After resting for a little on a half-finished cell, while Silverwing with her slender tongue gently smoothed her ruffled down,[61] and brought a drop of honey to refresh her, Sipsyrup felt well enough to relate her sad story, to which a little group of surrounding bees listened with no small interest. Sipsyrup left altogether out of her account the fine compliments paid her by Spinaway, she could not bear that her vanity should be known; but she gained little by hiding the truth, as this only made her folly appear more unaccountable.

MINNIE AT THE HIVE.

[63]“I cannot understand,” said Waxywill, “how any bee in her senses could fly into a web with her eyes open.”

“When there was not even a drop of honey to be gained by it,” hummed Honeyball.

Sipsyrup hastened to the end of her story, and related how she had been saved from the spider by the timely help of a kind little girl.

“May she live upon eglantine all her life,” exclaimed Silverwing with enthusiasm, “and have her home quite overflowing with honey and pollen!”

[64]“This is the strangest part of your adventure,” said Honey ball; “this is the very first time in my life that I ever heard of kindness shown to an insect by a human being.”

“I thought that bees were sometimes fed by them in winter,” suggested Silverwing.

“Fed with sugar and water!—fit food for a bee!” cried Honeyball, roused to indignation upon the only subject that stirred her up to anything like excitement. “And have you never heard how whole swarms have been barbarously murdered, smothered in the hive which they had filled with so much labour, that greedy man might feast upon their spoils!”

“If you talk of greediness, Honeyball,” drily observed Waxywill, “I should say, Keep your tongue in a sheath.”

“I am glad that it is not the custom for men to eat bees as well as their honey,” laughed Silverwing.

“Oh, they are barbarous to everything,[65] whether they eat it or not,” exclaimed Waxywill, with an angry buzz. “Have I not seen a poor butterfly, basking in the sun, glittering in her vest of purple and gold—ah, Sipsyrup, in your very best day, you were no better than a blackbeetle compared to her!”

An hour before, Sipsyrup would have felt ready to sting Waxywill for such an insolent speech, but the pride of the poor bee was humbled; and when Waxywill observed her silence and noticed her drooping looks, she felt secretly ashamed of her provoking words. She continued: “Have I not seen the butterfly, I say, dancing through the air, as though life was all sunshine and joy!—I have seen a boy look on her—not to admire, not to feel pleasure in beholding her beauty, but eager to lay that beauty in the dust, and seize on his little victim. I have watched him creeping softly, his hat in his hand, as anxious about his prize, as if to destroy a poor insect’s happiness was the way to secure[66] his own. Now the unconscious butterfly rose, high above the reach of her pursuer, then sank again to earth, to rest upon a flower, whose tints were less bright than its wings. Down came the hat—there was a shout from the boy—the butterfly was prisoner at last. If he had caught it to eat it, as the spider caught Sipsyrup, I could have forgiven him—for men as well as bees must have food, and I suspect that they do not live entirely upon honey; but it made me wish for a hundred stings when I saw the wretched insect lying on the ground, fluttering in the agonies of death. The boy had barbarously torn off its bright beautiful wings, and had not even the mercy to put it out of pain by setting his foot upon it.”

“It had never injured him,” murmured Silverwing.

“It had never injured any one—it desired nothing but to be allowed to spend its short life in peace.”

“How would the boy have liked to have[67] had his wings torn off,” said Honeyball, “for the amusement of some creature stronger than himself?”

“Men and boys are worse than hornets,” muttered Waxywill.

“But we have found one of human-kind,” hummed Silverwing cheerfully, “who could be merciful even to a bee. Perhaps in the world there may be others like her, too noble, too generous to use their strength to torture and destroy what cannot resist them.”

Waxywill and Honeyball now took their departure—I fear rather for their own pleasure than for the benefit of the hive; as Waxywill was not in a humour to work, and Honeyball was always in a humour to idle. As soon as they had flown out of reach of hearing, poor Sipsyrup said, in a very dull tone,—

“I wonder what is to become of me now, poor unhappy insect that I am. I fear that I shall never be able to fly; and to live on[68] here in this wretched way is almost worse than to be eaten by a spider.”

“Oh, you should not say so,” replied gentle Silverwing; “you can still crawl about, and you are safe in your own home.”

“Safe!—I am miserable! With what pleasure I had thought of joining the first swarm that should fly off. I am tired of the hive—this noisy, bustling hive—I have lost everything that I cared for, everything that made life pleasant—my beauty, my strength, my power of flying; I have nothing left—”

“But your duties,” added Silverwing; “make them your pleasures. My dear friend, if you no more can be pretty, you may still be useful; if you no more can be admired, you can still be loved. You may not be able to go far, or to see much; but there are better joys to be found in your own home.”

Before the night closed, both the little nurse-bees were busy feeding the larvæ.

THE sunset was still casting a red glow over the earth, throwing the long shadows of the trees on the ground, and lighting up the cottage windows, as Polly Bright stood at the door of her cottage, watching for her mother’s return.

Mrs. Bright was a hard-working woman, who, during the absence of her husband, a soldier in the Crimea, earned many an honest shilling as charwoman in the house of the Squire on the hill. She generally managed to let Polly have the advantage of attending the school in the morning. Though herself unable to read, she liked the idea of her[70] daughter being a scholar; and as plain-work was also taught in the school, she thought that what Polly acquired there might make her not only more learned, but more useful. But it was only for attendance in the morning that the charwoman’s child could be spared from her home. During her mother’s frequent absence, all the charge of the cottage, and care of the children, belonged of course to Polly Bright.

I cannot say that the little parlour could compare in neatness with that of Mrs. Wingfield. There was a chest of drawers in one of the corners, and on it was heaped a strange medley of things. Tea-pot and broken jug, old shawl and a baby’s rattle, nutmeg-scraper, bellows, saucepan and books, were piled in sad confusion. Nor would I have advised you to have attempted to open one of the drawers. They were sometimes too full to be opened at all, and stuck tight against every effort, as if aware that they were not fit to be seen. Polly was too fond of adorning[71] herself to care for adorning her cottage. She was not aware how far better it looks to be simple, neat, and clean, and dressed according to our station, than to be decked out with gaudy finery, and try to ape the appearance of those whom Providence has placed above us.

You will remember that we visited this cottage in the third chapter, and there is little change in the appearance of things there now. The damp on the floor occasioned by Johnny’s accident has dried up, and so have the tears of the little boy, who, seated upon a stool near his sister’s feet, is cramming his mouth with bread and butter, with an air of great content. But the thin sickly baby is still in his cradle, still uttering his feeble, unheeded wail, for the poor little creature is teething hard, and has no other way of expressing his pain. Polly never notices his heated lips and swelled gums; she is more occupied with herself this evening than usual, for Mrs. Larkins,[72] the farmer’s wife, has invited her to tea, and as soon as her mother returns to take her place, she will be off to amuse herself at Greenhill. Oh yes; you might be certain that some gay meeting was expected! Look at the necklace of false coral round her neck, the half-soiled lace which she has sewn round her frock, and her hair all in papers at this hour of the day; you would laugh were you to see her, but to me the sight of her folly is really too sad for laughing. Of what is she thinking as she quickly untwists the papers, and curls her long hair round her fingers? Her thoughts are divided between impatience at her mother’s delay, fears of herself being late for the party, and wishes that the pedlar would only happen to call at her cottage.

She had heard that day, from one of her school-fellows, that a man had been going about the neighbourhood with a pack so full of beautiful things, that such a collection had never before been seen in the village.[73] Polly had been particularly tempted by the description of some brooches made of false diamonds, and exactly like real ones, as the girl, who had never seen a jewel in her life, very positively affirmed. One of these fine brooches was to be had for sixpence—how eager was Polly to be its possessor! She counted over her little treasure of pence, and found that she had sufficient for the purchase.

But how was she to find the pedlar? Had Polly not been tied to the cottage by what she called “these tiresome children,” she would long ago have gone in search of him. She could hardly expect him to pass down her little lane, but she was near enough to the high-road to see if any one passed along it in going through the village. At one time she had set little Johnny to watch, and more than once her hopes had been raised as the little fellow shouted aloud, “There’s the man!” But Polly came running first to see a drover[74] with pigs, then the baker with his little cart going his rounds;—she had a disappointment, poor Johnny a slap, and he was sent crying into the cottage. This was rather hard upon him, poor little fellow. How could a child, not three years old, be expected to know the difference between a pedlar and a baker?

But all was quiet again in the cottage, Johnny occupied with his supper, and Polly with her curl-papers, when in through the open door who should make her entrance but Stickasting. She came in, as usual, in no amiable mood, quite ready to take offence on the very shortest notice. She first settled on the little baby’s arm; but the infant lay perfectly still, half-comforted in his troubles by sucking his thumb: the most passionate bee in the world could find no excuse for being angry with him. Stickasting rested for a few moments on the thin, tiny arm, then rose and approached Polly Bright.

Every sensible person knows that when a[75] bee or a wasp hovers near, the safest way is to keep quiet and take no notice; but Polly was not a very sensible person, and being not very courageous either, was quite frightened when the insect touched her face. If Stickasting had mistaken it for a flower, she would very soon have found out her blunder, and left the little girl in peace; but, starting back with a cry, Polly struck the bee, and Stickasting, roused to fury, quickly returned the blow. Mad with passion, the insect struck her sting so deep, that it was impossible to withdraw it again, and she left it behind, which occasions certain death to a bee.

Stickasting felt at once that she had thrown away her life in a wild desire for revenge; that her destruction was caused by her own violent act—she crawled feebly a few inches from the spot where she fell, and expired—a victim to her temper.

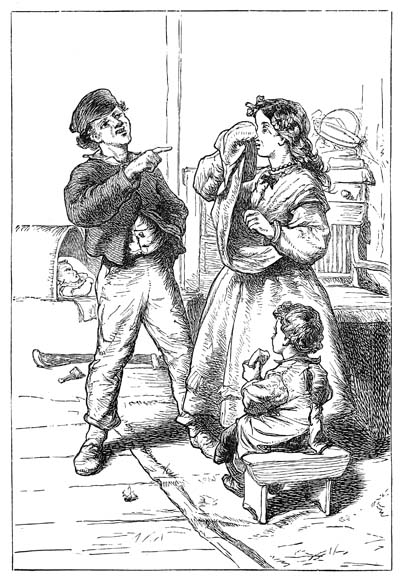

Loud was the scream which Polly Bright uttered on being stung; so loud that it[76] brought, from the opposite cottage, both Minnie Wingfield and her brother. On finding out the cause of Polly’s distress, Minnie hastily ran back for the blue-bag, or a little honey, to relieve the pain of her school-fellow. But Tom, who had very little pity in his nature, stood shaking with laughter at the adventure.

POOR STICKASTING.

“Stung by a bee!—stung on the very tip of the nose!—what a beauty you will look at Greenhill to-night!—ha! ha! ha!—if you could only see how funny you look, your hair half in curl-papers, and half hanging down, and your eyes as red with crying as[77] the coral round your neck! You are for all the world like silly Sally!”

TOM LAUGHING AT POLLY.

[79]“It does not show much, does it?” said poor Polly anxiously, as Minnie returned with the blue-bag.

“It is swelling!” cried Tom—“swelling higher and higher!—’twill be just like the turkey-cock’s comb!”

“Then I can’t go to-night!—I will not go!” exclaimed Polly, sitting down and bursting into tears.

Tom laughed louder, Minnie in vain tried to comfort,—all Polly’s happiness was for the time overthrown by a bee! It rested but on trifles, and a trifle was enough to make her wretched for the rest of that day.

THE sun set, the rooks in the squire’s park had gone to roost, the bats flew round the ivy-covered tower of the village church. The hive was becoming quiet and still, the bees hanging in clusters prepared to go to sleep; but Stickasting had never returned. Silverwing listened in vain for the well-known sound of her angry hum, and wondered what could have delayed her companion. But never again was the poor bee to fly back to the hive, never again to labour at the waxen cells; and, alas! how little was her presence missed—still less was it regretted.

[81]The next morning was warm, bright, and sunny, the bees were early on the wing. The larvæ were beginning to spin their webs, and therefore no longer required food; so Silverwing was free to range over the fields, and gather honey for the hive. So tempting was the day, that even Honeyball shook her lazy wings and crept to the door; there stood for a few moments, jostled by her more active fellow-servants, and finally flew off in quest of food.

How delightful was the air!—how fragrant the breeze! The buttercups spread their carpet of gold, and the daisies their mantle of silver over the meadows, all glittering with the drops of bright dew. Honeyball soon found a flower to her taste, and never thought of quitting it till she had exhausted all its honied store. She had a dim idea that it was her duty to help to fill the cells, but poor Honeyball was too apt to prefer pleasure to duty.

“I should like to have nothing to do,”[82] she murmured, little thinking that a listener was near.

“Like to have nothing to do! Is it from a hive-bee that I hear such words?—from one whose labour is itself all play?”

Honeyball turned to view the speaker, and beheld on a sign-post near her the most beautiful bee that she had ever seen. Her body was larger than that of a hive-bee, and her wings were of a lovely violet colour, like the softest tint of the rainbow.[A]

Honeyball felt a little confused by the address, and a little ashamed of her own speech; but as all bees consider each other as cousins, felt it best to put on a frank, easy air.

“Why, certainly, flying about upon a morning like this, and making elegant extracts from flowers, is pleasant enough for a time. But may I ask, lady-bee,” continued[83] Honeyball, “if you think as lightly of working in wax?”

“Working in wax!” half contemptuously replied Violetta; “a soft thing which you can bend and twist any way, and knead into any shape that you choose. Come and look at my home here, and then ask yourself if you have any reason to complain of your work.”

Honeyball looked forward with her two honey-combed eyes, and upwards and backwards with her three others, but not the shadow of a hive could she perceive anywhere. “May I venture to ask where you live?” said she at last.

“This way,” cried Violetta, waving her feeler, and pointing to a little round hole in the post, which Honeyball had not noticed before. It looked gloomy, and dark, and strange to the bee; but Violetta, who took some pride in her mansion, requested Honeyball to step in.

“You cannot doubt my honour,” said she,[84] observing that the hive-worker hesitated, “or be suspicious of a cousin?”

Honeyball assured her that she had never dreamed of such a thing, and entered the hole in the post.

For about an inch the way sloped gently downwards, then suddenly became straight as a well, so dark and so deep, that Honeyball would have never attempted to reach the bottom, had she not feared to offend her new acquaintance. She had some hopes that this perpendicular passage might only be a long entrance leading to some cheerful hive; but after having explored to the very end, and having found nothing but wood to reward her search, she crept again up the steep narrow way, and with joy found herself once more in the sunshine.

“What do you think of it?” said Violetta, rather proudly.

“I—I do not think that your hive would hold many bees. Is it perfectly finished, may I inquire?”

[85]“No; I have yet to divide it into chambers for my children, each chamber filled with a mixture of pollen and honey, and divided from the next by a ceiling of sawdust. But the boring was finished to-day.”

“You do not mean to say,” exclaimed Honeyball in surprise, “that that long gallery was ever bored by bees!”

“Not by bees,” replied Violetta, with a dignified bow, “but by one bee. I bored it all myself.”

The indolent Honeyball could not conceal her amazement. “Is it possible that you sawed it all out with your teeth?”

“Every inch of the depth,” Violetta replied.

“And that you can gather honey and pollen enough to fill it?”

“I must provide for my children, or they would starve.”

“And you can make ceilings of such a thing as sawdust to divide your home into cells?”

[86]“This is perhaps the hardest part of my task, but nevertheless this must be done.”

“Where will you find sawdust for this carpenter’s work?”

“See yonder little heap; I have gathered it together. Those are my cuttings from my tunnel in the wood.”

“You are without doubt a most wonderful bee. And you really labour all alone?”

“All alone,” replied Violetta.

Honeyball thought of her own cheerful hive, with its thousands of workers and divisions of labour, and waxen cells dropping with golden honey. She scarcely could believe her own five eyes when she saw what one persevering insect could do. Her surprise and her praise pleased the violet-bee, who took pride in showing every part of her work, describing her difficulties, and explaining her manner of working.

“One thing strikes me,” said Honeyball, glancing down the tunnel; “I should not much like to have the place of your eldest[87] larva, imprisoned down there in the lowest cell, unable to stir till all her sisters have eaten their way into daylight.”

Violetta gave what in Bee-land is considered a smile. “I have thought of that difficulty, and of a remedy too. I am about to bore a little hole at the end of my tunnel, to give the young bee a way of escape from its prison. And now,” added Violetta, “I will detain you no longer, so much remains to be done, and time is so precious. You probably have something to collect for your hive. I am too much your friend to wish you to be idle.”

Honeyball thanked her new acquaintance and flew away, somewhat the wiser for her visit, but feeling that not for ten pairs of purple wings would she change places with the carpenter-bee.

“THERE’S the pedlar! Oh dear! and just as mother has gone out!” cried Polly, who on beginning her afternoon business of nurse to the little children, saw, or thought that she saw, at the end of her lane, a man with a pack travelling along the high-road. “There he is. Oh, if I could only stop him, or if any one would look after the baby whilst I am gone! Minnie Wingfield! Ah, how stupid I am to forget that she is now at the afternoon school! I think that baby would keep very quiet for five minutes; he cannot roll out of his cradle. But Johnny, he’d be[89] tumbling down, or setting the cottage on fire; I cannot leave him for a minute by himself.—Johnny,” said she suddenly, “I want to catch the pedlar and see his pretty things; will you come with me, like a good little boy?”

Johnny scrambled to his feet in a moment, to the full as eager as herself. Polly held his fat little hand tight within her own, and began running as fast as she could drag him along. But the poor child’s round heavy figure and short steps were altogether unsuited for anything like a race. Polly felt him as a dead weight hanging to her arm. In vain she pulled, dragged, and jerked, now began to encourage, and now to scold; poor Johnny became tired, frightened, and out of breath, and at last fairly tumbled upon his face.

“Get up—I’m in such a hurry!”—no answer but a roar. “Stupid child! he’ll be gone!”—Johnny bellowed louder than before. “There, I’ll leave you on the road, you[90] great tiresome boy; you have half pulled out my arm with dragging you on. I’ll leave you there, and silly Sally may get you.”

Then, without heeding the poor little child’s cries and entreaties that she would stop, as he lay on the ground, half suffocated with sobs, Polly Bright, thinking only of the prize which her vanity made her so much desire, hastened after the pedlar.

POOR SALLY.

Silly Sally, who has been twice mentioned in my tale, was a poor idiot-woman who lived with some kind neighbours on a common about two miles from the village. She was perfectly harmless, and therefore allowed to go about with freedom wherever she chose; but the terrible misfortune, alas! exposed her to the scorn and sometimes even persecution of wicked children, who made the worst use of the senses left them, by tormenting one already so much afflicted. Poor Sally used to wander about the lanes, uttering her unmeaning sound. Perhaps[91] even she had some pleasure in life, when the sun shone brightly and the flowers were out, for she would gather the wild roses from the bank, or the scarlet poppies from the field, and weave them into garlands for her head. Nothing pleased her more than when she found a long feather to add to her gaudy wreath. If the poor witless creature[92] had delight in making herself gay, Polly at least had no right to laugh at her.

Timid and easily frightened, the idiot felt a nervous terror for schoolboys, for which they had given her but too much cause. She had been hooted at, even pelted with mud, pursued with laughter like a hunted beast. Twice had Minnie to interfere with her brother, pleading even with tears for one so helpless and unhappy. If there be anything more brutal and hateful than cruelty to a harmless animal, it is heartless barbarity to a defenceless idiot—to one who bears our image, is descended from our race, and whose only crime is the being most unfortunate. Deal gently, dear children, with the poor senseless idiot; we trust that there is a place in heaven even for him. The powers denied him in this world may be granted in the next; and in a brighter realm, although never here below, he may be found at his Lord’s feet, clothed and in his right mind.

On hastened the little girl, breathless and[93] panting. At the place where the roads joined she looked anxiously up the highway, to see if she had not been mistaken in her distant view of the traveller. No; there was the pedlar, pack and all, and no mistake, but walking more briskly than might have been expected from his burden and the warmth of the afternoon. His pack must have been much lightened since he first set out with it.

Polly called out; but he either did not hear, or did not attend. The wind was blowing the dust in her face, she was tired with her vain attempts to drag poor Johnny, her shoes were down at heel and hindered her running; for it by no means follows that those who wish to be fine care to be tidy also. But the brooch of false diamonds—the coveted brooch—the thought of that urged her on to still greater efforts; even the remembrance of her swelled nose was lost in the hope of possessing such a beautiful ornament. Polly, as she shuffled hastily[94] along, saw more than one person meet the pedlar. If they would but stop him—if only for one minute—to give her time to get up with him at last. No one stopped him—how fast he seemed to walk! Polly’s face was flushed and heated, her hair hung about her ears—would that we were as eager and persevering in the pursuit of what really is precious, as the girl was in that of a worthless toy!

At last her gasped-out “Stop!” reached the ear of the pedlar. He paused and turned round, and in a few minutes more his pack was opened to the admiring eyes of Polly. Ah, how she coveted this thing and that! how she wished that her six pennies were shillings instead! A cherry-coloured neckerchief, a pink silk lace, a large steel pin, and a jewelled ring,—how they took her fancy, and made her feel how difficult it is to decide when surrounded by many things alike tempting!

But at last the wonderful brooch of false[95] diamonds was produced. There was only one left in the pedlar’s stock. How fortunate did Polly think it that it also had not been sold! Neckerchief, lace, pin, or ring was nothing compared to this. She tried it on, had some doubts of the strength of the pin, tried in vain to obtain a lessening of the price. It ended in the girl’s placing all her pence in the hand of the pedlar, and carrying home her prize with delight. She had had her wish. Her vanity was gratified—the brooch was her own; but to possess is not always to enjoy.

POLLY AND THE PEDLAR.

[97]Polly returned to her cottage with much slower steps; she was heated, and tired, and perhaps a little conscious that she had not been faithful to her trust. As she came near her home she quickened her pace, for to her surprise she heard voices within, and voices whose tones told of anxiety and fear. These were the words which struck her ear, and made her pause ere she ventured to enter,—

[98]“What a mercy it is that I returned for the basket that I had forgotten! If I had not, what would have become of my poor babe!” exclaimed Mrs. Bright in much agitation.

“I can’t understand how it happened,” replied another voice, which Polly knew to be that of Mrs. Wingfield.

“You may well say that,” said the mother. Polly could hear that she was rocking her chair backwards and forwards, as she sometimes did when hushing the sick child to sleep. “I left Polly in charge of the children: I came back to find her gone, and my poor, poor baby in a fit.”

Polly turned cold, and trembled so that she could hardly stand.

“Is there no one who could go for a doctor?” continued the agitated mother; “another fit may come on—I would give the world to see him!”

“I am so feeble,” replied Mrs. Wingfield, “that I am afraid—”

[99]“Take the baby, then, and I’ll go myself; not a moment is to be lost.”

“No, no; there’s my boy Tom,” cried Mrs. Wingfield, as she saw her son run hastily into her little cottage, which was just opposite to Mrs. Bright’s.

“Oh, send him, in mercy send him!” cried the mother; and her neighbour instantly crossed over to fulfil her wishes, passing Polly as she did so, and looking at her with mingled surprise and scorn, though in too much haste to address her.

“My boy, my own darling!” murmured the anxious mother, pressing her sick child to her bosom, “what will your father say when he hears of this?” Except her low, sad voice, the cottage was so still that the very silence was terrible to Polly; it would have been a relief to have heard the feeble, fretful wail which had made her feel impatient so often.

With pale, anxious face and noiseless step, dreading to meet her mother’s eye, the[100] unhappy girl stole into the cottage. There sat Mrs. Bright, her bonnet thrown back from her head, her hair hanging loose, her gaze fixed upon the child in her arms; whilst the poor little babe, with livid waxen features and half-closed eyes, lay so quiet, and looked so terribly ill, that but for his hard breathing his sister would have feared that his life had indeed passed away.

Mrs. Bright raised her head as Polly entered, and regarded her with a look whose expression of deep grief was even more terrible than anger. She asked no question; perhaps the misery in which she saw the poor girl made her unwilling to add to her suffering by reproach; or perhaps, and this was Polly’s own bitter thought, she considered her unworthy of a word. Whatever was the cause, no conversation passed between them, except a few short directions from the mother about things connected with the comfort of the baby, as poor Polly,[101] with an almost bursting heart, tried to do anything and everything for him.

POLLY IN DISGRACE.

In the meantime Tom had gone for the doctor, though with an unwillingness and desire to delay which had made his mother both surprised and indignant.

“He should go by the fields,” he said,[102] though he well knew that to be the longest way; and he would have done so, had not Mrs. Wingfield roused herself to such anger, that even her rude and undutiful son did not dare to disobey her.

The doctor came in about an hour, Tom having happily found him at home, and, with an anxiety which those who have attended beloved ones in the hour of sickness only can tell, Mrs. Bright and Polly listened for his opinion of the case. The doctor examined the child, and asked questions concerning his illness: “How long had the fit lasted?” There was a most painful pause. Mrs. Bright looked at her daughter. Polly could not utter a word; it was not till the question was repeated that the distressing reply, “No one knows,” was given.

“Was the child long ailing?”

“How was he when you left him?” said Mrs. Bright to the miserable Polly.

“Very well—that’s to say—I don’t exactly—he was—I think—”

[103]“There has been gross negligence here,” said the doctor sternly; “gross negligence,” he repeated, “and it may cost the child his life.”

Polly could only clasp her hands in anguish; but the mother exclaimed, “Oh, sir, is there no hope for my boy?”

“While there is life there is hope,” replied the doctor in a more kindly tone; “he must be bled at once. Have you a basin here?” he added, taking a small instrument-case from his pocket.

Polly was at all times timid and nervous, and quite unaccustomed to self-command, and now, when she would have given worlds to have been useful, her hand shook so violently, her feelings so overcame her, that there was no chance of her doing anything but harm.

“Give the basin to me, dear,” said a gentle voice behind her; Minnie Wingfield had just entered the cottage. “You look so ill, you must not be present. Go up-stairs, Polly; I will help your mother.”

[104]“Oh, what shall I do?” cried the miserable girl, wringing her hands.

“Go and pray,” whispered Minnie as she glided from her side; and Polly, trembling and weeping, slowly went up the narrow wooden staircase, and entering her little chamber, sank down upon her knees.

“Oh, spare him, only spare him, my darling little brother!” she could at first utter no other words. She had never loved the baby as she did now, when she feared that she might be about to lose him, and bitterly she lamented her own impatient temper that had made her weary of the duty of tending him. Oh, that we would so act towards our relations, that if death should remove any one from our home, our grief should not be embittered by the thought, “I was no comfort or blessing to him while he was here, and now the opportunity of being so is gone for ever!”

But the most terrible thought to Polly was, that the baby’s danger might be partly[105] owing to her neglect. Should he die—should the little darling be taken away—could her mother ever forgive her? As Polly sobbed in an agony of grief, something fell from her bosom upon the floor; she started at the sight of her forgotten brooch, that which she had coveted so much, that which had cost her so dear. Snatching it up, and springing to her feet, with a sudden impulse she ran to the window, and flung it far out into the lane. Then once more falling on her knees, again she prayed, but more calmly, and she implored not only that the baby might live, but that her own weak, vain heart might be cleansed, that she might henceforth live not only for herself, but do her duty as a faithful servant of God. She rose somewhat comforted, and creeping down-stairs, listened ere she ventured to enter the little parlour.

“I hope that he may do well now. I shall send something for him to-night. Keep him quiet. I shall call here to-morrow.” These[106] were the doctor’s parting words, and they were a great relief to Polly. She came in softly, and bent down by the baby, now laid again in his little cradle, and looking white as the sheet that was over him; she would have kissed his thin, pale face, but she feared to disturb the poor child. Her heart was full of mingled sorrow and love; she felt as though she could never bear to leave him again.

“Thank you, Minnie, my girl,” said Mrs. Bright earnestly; “you have been a real comfort to me in my time of need. Your mother is a happy woman to have such a child.”

“Can I do anything else for you now?” said Minnie; “if you would allow me to sit up instead of you to-night?”

“No, no; I could not close an eye. But I should be glad if you would bring Johnny home, my dear; it is near his bed-time, and I do not think that he will disturb the baby.”

[107]“I will bring him with pleasure; where is he?” said Minnie.

“Where is he?” repeated Mrs. Bright; “is he not at your home?”

“No; he has not been there all day.” Polly started as if she had been stabbed.

“Then where is he?” cried Mrs. Bright, looking anxiously round. “Is he up-stairs, Polly?” The miserable girl shook her head. Her fears for the baby had made her quite forget her little brother, and it now flashed across her mind that she had not passed him in the lane, when she had retraced her steps to the cottage. Where could he have gone, where could he be now?

Mrs. Bright had endured much, but her cup seemed now to overflow. She walked close up to Polly, laid a heavy grasp upon her shoulder, and said, in a tone which the girl remembered to her dying day, “When was your brother last with you?”

“About two hours ago, just before you returned home,” faltered Polly.

[108]“And where did you leave him?”

“In the lane, near the high-road.”

“Go and find him,” said the mother, between her clenched teeth, “or never let me set eyes on you again!”

Polly rushed out of the cottage, and began her anxious search up and down the lane, by the hedge, in the ditch, along the road, asking every person that she met, and from every one receiving the same disheartening answer. No one had seen the boy, no one could think what had become of him. He was too young to have wandered far; had he run towards the road, he must have been met by Polly—if the other way, he must have been seen by his mother; he could not have got over the hedge; there was no possibility of his having lost his way. Many neighbours joined in the search; many pitied the unhappy mother, but she was less to be pitied than Polly.

WE will now return to our little friend, Honeyball, whom we left flying from the curious dwelling of the carpenter-bee. We will follow her as she lazily proceeded along the lane in which were situated the cottages of Mrs. Wingfield and Mrs. Bright, the sweet flowers in the garden of the former rendering it a favourite resort for bees. This was not long after noon, and therefore a few hours before all the troubles related in the last chapter had occurred, while Polly and her two little charges were yet safe in their own comfortable cottage.

[110]Honeyball looked at Spinaway busily mending her net, torn by the adventure of Sipsyrup, and laughed as she thought of the folly of her companion. Honeyball was not vain enough to be enticed by sugared words; her dangers arose from quite another source—her greediness and great self-indulgence. Her eye was now attracted by a little bottle hung up by the porch, not far from the rosebush; it had been placed there by Tom to catch wasps. Perhaps he had hoped to entrap some others of the winged tribes, for he had just taken a fancy to make a collection of insects, and woe unto any small creature that might fall into his merciless hands!

Honeyball alighted on the bottle, then fluttered to the top, allured by the sugary scent. The brim was sticky; she unsheathed her long bright tongue, tasted, approved, and then sipped again. At this moment she heard a buzz near her, and looking up with her back eyes, perceived her friend Silverwing.

[111]“Do come from that huge, bright, hard cell,” cried the bee; “I am sure that it never was formed by any of our tribe, and I do not believe that it holds honey.”

“It holds something very good, and in such abundance too,” replied Honeyball; “a thousand honeysuckles would not contain so much!”

“There is danger, I am certain that there is danger,” cried Silverwing. “What if it should have been placed there on purpose to catch us?”

“You think me as foolish as Sipsyrup!”

“No, not foolish, but—”