Title: Edith and Her Ayah, and Other Stories

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release date: August 19, 2019 [eBook #60138]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Edith and her Ayah, and Other Stories, by A. L. O. E.

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/edithherayahothe00aloe |

A · L · O · E

Edith and

her Ayah

AND OTHER STORIES

T. NELSON AND SONS. LONDON, EDINBURGH AND NEW YORK.

WHATSOEVER A MAN SOWETH THAT SHALL HE ALSO REAP

EDITH AND HER AYAH,

AND OTHER STORIES.

BY

A. L. O. E.

AUTHOR OF “EXILES IN BABYLON,” “TRIUMPH OVER MIDIAN,”

“THE YOUNG PILGRIM,” ETC.

LONDON:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

1872.

| I. | EDITH AND HER AYAH, | 7 |

| II. | THE BUTTERFLY, | 20 |

| III. | THE PENITENT, | 29 |

| IV. | THE REPROOF, | 37 |

| V. | THE VASE AND THE DART, | 40 |

| VI. | THE JEWEL, | 49 |

| VII. | THE STORM, | 57 |

| VIII. | THE SABBATH-TREE, | 65 |

| IX. | THE WHITE ROBE, | 76 |

| X. | CROSSES, | 84 |

| XI. | THE TWO COUNTRIES, | 93 |

| XII. | DO YOU LOVE GOD? | 102 |

| XIII. | THE IMPERFECT COPY, | 106 |

| XIV. | A STORY OF THE CRIMEA, | 112 |

| XV. | “I HAVE A HOME, A HAPPY HOME,” | 119 |

BLESSINGS ARE UPON THE HEAD OF THE JUST. PROV. 10:6

“Mamma,” said little Edith, looking up from the toys with which she was playing at the feet of her mother—“mamma, why does Motee Ayah never come in to prayers?”

Mrs. Tuller was seated at her desk in the large room of her bungalow (house) in India. The day was hot; the blazing sun shone with fiery glare; but the light came into the room so much softened by green blinds and half-closed shutters, that the place was so dark that the lady could scarcely see to write. The punkah, a kind of huge fan, moving gently to and fro above her, made a[8] refreshing air which would have sent her papers fluttering in every direction had not weights been placed to keep them down.

Mrs. Tuller paused in her writing, but did not reply to the question asked by her child regarding her ayah, or native nurse.

“Mamma,” said little Edith again, “does not Motee Ayah love the Lord Jesus?”

“Alas, my child, she does not know him!”

“But will you not teach her, mamma?” and the fair-haired girl looked up in her mother’s face with such a pleading look in her soft gray eyes, that, touched by her interest in the poor heathen, Mrs. Tuller bent down, kissed fondly the brow of her child, and whispered, “My love, I will try.”

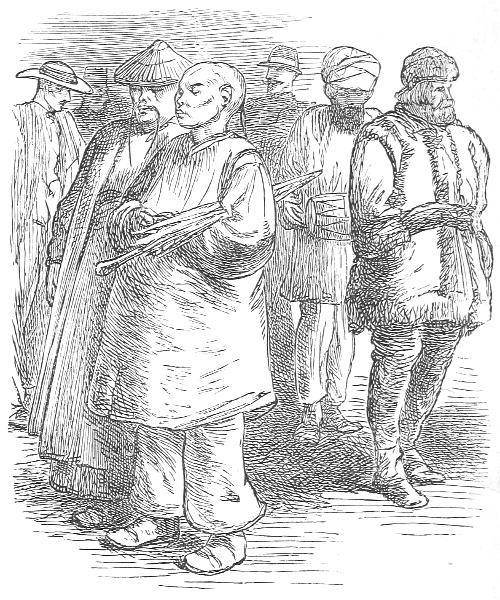

Nor did Mrs. Tuller forget her promise. Again and again she spoke to Motee of the Christian’s faith and the Christian’s God. It saddened the heart of the lady to feel that to seek to teach Motee religion was like trying to write upon water. The ayah joined her dark hands together, listened, or seemed to listen, said, “Very good, very good,” to everything that the beebee (lady)[9] told her, but always returned to her idol, a hideous little wooden image, and performed her poojah (worship) to Vishnu, as if she had never heard of a purer religion. Mrs. Tuller grew quite disheartened about her. Sometimes the lady blamed her own imperfect knowledge of the language, and sometimes she felt almost angry with the ayah for her blindness and hardness of heart.

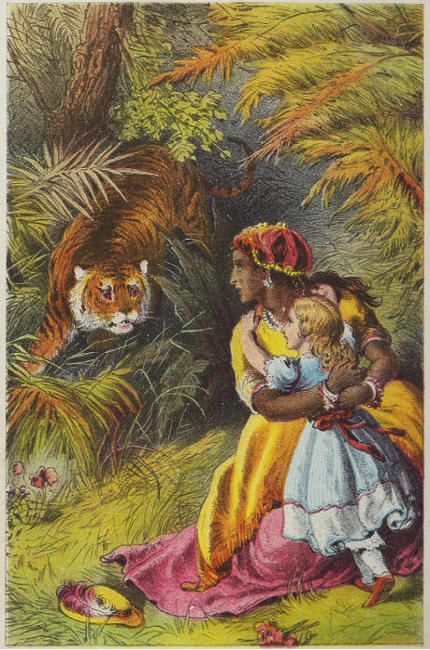

TEACHING THE AYAH.

Poor Motee had been brought up from infancy amongst idolaters; she had never[10] been taught truth when a child, and now error bound her like a chain. Motee had actually been led to think it honourable to her family that, many years before, there had been a suttee in it; that is to say, a poor young widow had burnt herself with the dead body of her husband. Happily, our Government has forbidden suttees—no widow can thus be burnt now; but still the cruel heathen religion hurts the bodies as well as the souls of the Queen’s dark subjects in India. Motee’s own father had died on a pilgrimage to what he believed to be a holy shrine. Travelling on foot for hundreds of miles under a burning sun, the poor idolater’s strength had given way, and he had laid himself down by the roadside, sick, faint, and alone, to die far away from his home. Poor Motee had never reflected that the religion which had thus cost the lives of two of her family could not be a religion of heavenly love. She worshipped Vishnu, for she knew no better; and when her lady spoke to her of the Lord, the ayah only said to herself, that the God of the English was not the God of the Hindu, and[11] that she herself must do what all her fathers had done.

Mrs. Tuller’s words had little power, but her example and that of her husband were not without some effect upon the ignorant ayah. Motee knew that the sahib (master) who prayed with his family, never used bad words, nor was unkind to his wife, nor beat his servants, nor took bribes. Motee knew that the beebee who read her Bible was gentle, generous, and kind. The ayah could not but respect the religion whose fruits she saw in the lives of her master and mistress.

But it was not only the lady’s words and the lady’s example that were used as means to draw the poor Hindu to God. Little Edith had never heard the beautiful saying, that “the nearest road to any heart is through heaven,” and she would not have known its meaning if she had heard it, but the English child had been taught that the Saviour listens to prayer. Every night and morning Edith, at her mother’s knee, repeated the few simple words, “Lord Jesus, teach me to love thee!” and now, of her[12] own accord, she added another short prayer. Mrs. Tuller caught the soft whispered words from the lips of her darling, “Lord Jesus, teach poor Motee Ayah to love thee!” The mother took no outward notice, but from her heart she added “Amen” to the prayer of her child.

The hot season passed away; the time had come when Mr. Tuller and his family could enjoy what is called “camp life,” and move from place to place, living not in a house but a tent. The change was pleasant to the party, most of all to little Edith. She delighted in running about and playing with the goats, pulling the ropes, watching the black servants taking down the tents, or in riding on her little white pony. Edith’s cheeks, which during the hot weather had grown quite thin and pale, became plump and rosy once more; and merry was the sound of her childish voice as she gambolled in and out of the tent.

One day, as Edith was playing outside, near the edge of a jungle or thicket, her attention was attracted by a beautiful little fawn, that seemed almost too young to run[13] about, and which stood timidly gazing at the child with its soft dark eyes.

“Pretty creature, come here,” cried Edith, beckoning with her small white hand; “have you lost your mother, little fawn? Come and share my milk and bread,—come, and I will make you my pet, and love you so much, pretty fawn!”

As all her coaxing could not lure the timid creature to her side, Edith advanced towards it. The fawn started back with a frightened look, and fled into the jungle as fast as its weak, slender limbs could bear it.

The merry child gave chase, following the fawn, and calling to it as she ran, pushing her way as well as she could between the tall reeds and grass, which were higher than her own curly head.

Motee soon missed her charge, and quickly hurried after Edith. So eager, however, was the child in pursuit of the fawn, that she was some distance from the tents before the ayah overtook her.

“O Missee Baba,” cried the panting nurse, “why you run away from your Motee?”

“I want to catch the pretty fawn; I want to take it to mamma; it is too little to be by itself,—I’m afraid the jackals will get it!”

“I am afraid that the jackals will get Missee Baba,” cried the ayah, catching the little girl up in her arms. “Missee must come back to the beebee directly.”

Edith was a good little child, and made no resistance, though she looked wistfully into the bushes after the fawn, and called out to it again and again in hopes of luring it back. Motee attempted to return to the tents, but did not feel sure of the way,—the vegetation around grew so high that she could scarcely see two yards before her. She walked some steps with Edith in her arms, then stopped and looked round with a frightened air.

“Motee, why don’t you go on?” asked Edith.

“O Missee Baba, we’re lost!” cried the poor Hindu; “lost here in the dreadful jungle, full of wild beasts and snakes!”

Edith stared at her ayah in alarm, yet at that moment the little child remembered her mother’s lessons. “Don’t be so frightened,[15] Motee,” said the fair-haired English girl; “the Lord Jesus can save us, and show us the way to mamma.”

There was comfort in that thought, which the poor heathen could not have drawn from calling on Vishnu and the thousand false gods which the ignorant Hindus adore. The little child could feel, as the woman could not, that even in that lonely jungle a great and a loving Friend was beside her!

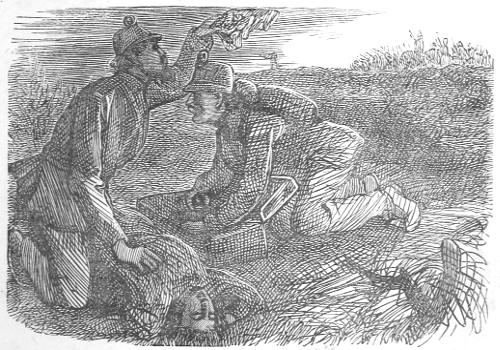

Again Motee tried to find her way, again she paused in alarm. What was that dreadful sound, like a growl, that startled the ayah, and made her sink on her knees in terror, clasping all the closer the little girl in her arms! Motee and Edith both turned to gaze in the direction from which that dreadful sound had proceeded. What was their horror on beholding the striped head of a Bengal tiger above the waving grass! Motee uttered a terrified scream,—Edith a cry to the Lord to save her. It seemed like the instant answer to that cry when the sharp report of a rifle rang through the thicket, quickly succeeded by a second; and the wild beast, mortally wounded, lay rolling[16] and struggling on the earth! Edith saw nothing of what followed; the shock had been too great for the child; senseless with terror she lay in the arms of her trembling ayah!

Edith’s father, for it was he whom Providence had sent to the rescue, bore his little darling back to the tent, leaving his servants, who had followed his steps, to bring in the spoils of the tiger. It was some time before Edith recovered her senses, and then an attack of fever ensued. Mrs. Tuller nursed her daughter with fondest care, and with scarcely less tenderness and love the faithful Motee tended the child. The poor ayah would have given her life to save that of her little charge.

On the third night after that terrible adventure in the woods came the crisis of the fever. Mrs. Tuller, worn out by two sleepless nights, had been persuaded to go to rest, and let Motee take her turn of watching beside the child. The tent was nearly dark,—but one light burned within it,—Edith lay in shadow,—the ayah could not see her face,—a terror came over the[17] Hindu,—all was so still, she could not hear any breathing,—could Missee Baba be dead! Motee during two anxious days had prayed to all the false gods that she could think of to make Missee Edith well; but the fever had not decreased. Now, in the silence of the night, poor Motee Ayah bethought her of the English girl’s words in the jungle. Little Edith had said that the Lord could save them,—and had he not saved from the jaws of the savage tiger? Could he not help them now? The Hindu knelt beside the charpoy (pallet) on which lay the[18] fair-haired child, put her brown palms together, bowed her head, and for the first time in her life breathed a prayer to the Christian’s God: “Lord Jesus, save Missee Baba!”

THE AYAH PRAYING.

“O Motee! Motee!” cried little Edith, starting up from the pillow with a cry of delight, and flinging her white arms round the neck of the astonished Hindu, “the Lord has made you love him,—I knew he would,—for I prayed so hard. And oh, how I love you, Motee—more than ever I did before!” The curly head nestled on the bosom of the ayah, and her dark skin was wet with the little child’s tears of joy.

Edith, a few minutes before, had awoke refreshed from a long sleep, during which her fever had passed away. And from that hour her recovery was speedy; before many days were over the child was again sporting about in innocent glee. And from that night the ayah never prayed to an idol again. Willing she now was to listen to all that the beebee could tell of a great and merciful Lord. Of the skin of the tiger that the sahib had slain a rug was made,[19] which Edith called her praying-carpet. Upon this, morning and night, the white English girl and her ayah knelt side by side, and offered up simple prayers to Him who had saved them from death. Mrs. Tuller’s words had done less than her example in drawing a poor wandering soul to God; but the prayer lisped by her little lamb had had greater effect than either.

Oh, if, in our dear land, all the little ones who have no money to give to the missionary cause, who have never even seen an idolater, would lift up their hands and hearts to the Lord, saying, “Teach the poor heathen to love thee!” how rich a harvest of blessings would be drawn down by such a prayer on those who know not the truth, and still sit in darkness and the shadow of death!

BUY THE TRUTH AND SELL IT NOT. Prov. 23:23.

A party of boys had been playing in the fields on a sunny afternoon in the bright month of June. They had been chasing a gay butterfly, which, in its uncertain flight, had led them over hedge and ditch, till at last the beautiful prize was won, and the brilliant insect remained a helpless prisoner in the hands of its pursuers. Alas, for the butterfly! A few moments before so gay and so free, sometimes resting on a blossom, then fluttering up towards the sky, its lovely wings were rudely torn away, and it lay quivering in the agonies of death. At this moment Ella Claremont, a young lady of the village, approached the[21] party; she had seen the chase and its close, and looked with regret on the poor mangled butterfly. “Why did you not let it live?” said she; “it had never harmed you, and it was so happy. You easily took away its little life,” she added; “but could any of you, could any power on earth, give that life back again?”

A HELPLESS PRISONER.

The boys looked one upon another, and were silent, till the eldest of them, Giles, replied, “I am sorry that I killed it, but I did not know that there was any harm.”

“Surely,” said Ella, in a very gentle voice, “in a world where there is so much pain, one would be sorry to add, even in the least degree, to the amount of it. There is another feeling,” continued she, “that should make us merciful to every creature; we should look upon it as one of the wonderful works of God.”

“Why,” said Anthony, “a butterfly is only a caterpillar after it has wings.”

“True; but what human skill could form a caterpillar! It has been calculated that in a single caterpillar there are sixty thousand muscles!”

An exclamation of astonishment burst from the boys.

“They must be finer than spiders’ threads,” cried Giles.

“I daresay,” replied the lady, “that you are not aware that each separate spider’s thread is said to be formed of about three thousand joined together.”

“The world seems full of wonders,” exclaimed little Robert.

“It is indeed; the more we search into God’s works, the more wisdom and skill do we behold.”

“I’ll not kill a butterfly again,” said Giles.

“I never see one fluttering in the sun,” continued Ella, “without thinking of those lines:—

“That sounds very pretty,” said Giles; “but I don’t understand it.”

“It is not very difficult to explain,” replied Ella. “The butterfly teaches us a joyful lesson; it is what is called a type of immortality! You see the lowly caterpillar crawling over a leaf,—it cannot raise itself towards the sky,—it cannot leave the earth; in this it is like what we are now. Then, as you know, it seems to die; it is wrapped up in its little covering, and there it lies without motion or feeling—that is like what we must be.”

“Ah! I see; when we are in our coffins,[24] dead and buried,” cried Robert. “But the bright butterfly soon bursts from the dark case, and we do not rise from our graves.”

“We shall,” replied Ella earnestly; “we all shall rise again. No longer prisoners bound to earth, no longer creeping on amidst trials and sorrows, but free, happy, glorious, shining in the beams of the Sun of Righteousness. ‘For the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised’ (1 Cor. xv. 52). Why should we fear death—why should we dread being laid in the cold tomb? When we think of the hope set before us, well may we cry, ‘O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?’” (1 Cor. xv. 55).

There was a deep silence for a few moments; nothing was heard but the song of a lark high overhead, as it soared towards the sky.

Then Giles spoke in a tone of awe, “Will all rise again?”

“Yes, all.”

“Will all rise to be free, and happy, and glorious?”

“Alas, no!” replied Ella.

“How can we tell,” continued the boy,[25] after a little hesitation, “whether we shall be among the happy ones?”

“There will be but two classes then,” said Ella, “as there are but two classes amongst those called Christians now. We may divide all who have heard of a Saviour into those who love God, and those who love sin. Those who love sin will awake to misery; those who love God will awake to glory.”

“But,” said the boy anxiously, “there may be some who love God and really try to obey him, and yet sin sometimes.”

“All sin sometimes,” replied Ella. “There is not one human being free from sin.”

“Then,” said Giles, “I should be afraid that, when the trumpet sounded, my sins would be like chains, and keep me down, so that I could not rise.”

Every eye was turned towards Ella; every ear anxiously listened for her reply; for every young heart was conscious of some sin, and felt the difficulty which Giles had started.

“It would have been so,” replied Ella, “had not the Saviour died for sinners like us. His blood washes us quite clean from[26] all guilt—that is, if we really believe on him and love him. Let us look upon our sins as chains now, and struggle hard to burst them, and pray for grace to help us: then, if we are Christ’s people, we shall rise joyfully in that great day when ‘the Lord himself shall descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God’” (1 Thess. iv. 16).

“I think,” said Giles, after a pause, “that sins are like chains, and very hard to break too. There is temper, now! I know that I’ve a bad temper; I determine over and over again that I will get rid of it; but the harder I struggle, the tighter the chain seems to grow.”

“And mother is trying to cure me of saying bad words,” cried little Robert; “but it’s no use—they will come; I say them when I’m not thinking about it.”

“Have you tried prayer?” inquired Ella. “Do you not know the precious promises, ‘If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him’ (James i. 5). ‘Ask, and it shall be given[27] you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you’ (Luke xi. 9). These words have often been such a comfort to me, when I felt how heavy my chain was, and how weak my efforts to get rid of it. And now, my young friends, I must leave you; will you think over what I have said?”

“Yes, miss, and thank you for it,” said Giles, touching his cap.

Ella paused as she was turning to depart, and gazed upon the sky, all bright with the evening sun, setting amidst clouds of crimson and gold.

“How glorious!” she cried, “how beautiful that work of God! He, too, speaks of the resurrection; he sinks to rise again!

“Farewell, my children. Whether we shall see each other again on this earth,[28] who shall dare to say? But we shall meet again when the last trumpet sounds, and the dead hear the Saviour’s voice, and the saints awake in his likeness. Let us live now as those who are waiting for the Lord, and who long for the hour of his appearing.”

THE HAND OF THE DILIGENT MAKETH RICH

“What is the matter with you, Charley?” said George Mayne, as he returned home from the factory, and found his little brother crying violently on the door-step. “What has vexed you, Charley, my boy?”

“Oh, my father will never forgive me,” sobbed the child.

“I cannot think that, he is so good and so kind. Come, dry up your tears, and tell me what has happened; perhaps I may be able to help you out of your trouble.”

CHARLEY’S GRIEF.

It was some time before, soothed by the kindness of his brother, the boy became calm enough to explain the cause of his grief. With a voice half choked with tears he began: “Father had sent me to pay the baker—he had given me a half-crown to do[31] it—he had trusted me; and now it is all—all gone! Oh, father will never forgive me!” and he burst into a fresh agony of sorrow.

“You lost the money, did you? Well, father can ill afford it, but he will forgive you for an accident, I am sure.”

“But it was not an accident, that is the worst of it! You see, I met Jack and Ben; they were playing at pitch-farthing, and they called to me to join them.”

“But father has forbidden us to keep company with those idle boys.”

“I know it—but I disobeyed him—I was very wrong—and I am very miserable.”

“I hope that you did not join the game?”

“Not at first—I told them that I had given father my solemn promise never to gamble; but they jeered me, and laughed at me—and I played with them—and they got all my money from me—the half-crown that was not mine, with which I had been trusted. Oh, father will never forgive me!”

“Now, Charley, do you know what I advise you to do?” said George. “Go to father at once, confess your fault to him, let not one sin lead you to another.”

“Confess to him!—I dare not.”

“I will go with you, Charley; I will plead for you.”

“But father is so poor; he will be in debt, and he cannot bear that! He will be so angry. Oh, cannot I say that some one snatched the half-crown out of my hand?”

“Charley, Charley!” cried his brother, almost sternly, “the Evil One is tempting you. He has gained one victory over you; would you be his slave entirely? Pray to God for strength to struggle against this temptation: remember that liars have no place in heaven. I will plead for you, I say; and as for the money, I have been saving up pence for the last six months to buy a particular book which I have much wished to have—I have just enough of money, and I will pay the debt.”

“O George, how good you are! But if the debt is paid, need I confess?”

“Yes; you have not only lost the money, but broken father’s command, and broken your own promise. Hide nothing. Take my hand, Charley, and come with me at once; every moment that we delay doing[33] what is right, we add to the difficulty of doing it.”

So hand in hand the two brothers appeared before their father, who was resting himself after a hard day’s work. George encouraged poor Charley to confess his fault; he entreated forgiveness for the offender; he placed in the hand of his father his own hard-earned savings. The parent opened his arms, and pressed both his sons to his heart! Then making Charley sit down beside him, the good man thus addressed his repentant child:—

“I forgive you, my boy, for the sake of your brother; but there is another Friend whom you have offended, whose commandment you have broken, whose forgiveness you must seek.”

“I know that I have sinned against God,” said Charley sadly.

“And for whose sake do you hope to be forgiven?”

Charley looked up in the face of his father, and replied, “I hope for forgiveness for the sake of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

“And if you are grateful to an earthly[34] brother for pitying you, and pleading for you, and paying your debt, how can you be thankful enough to that heavenly Saviour who shed his own blood to win for you a free pardon, and who now is pleading for you at the right hand of God?”

Charley was silent, but his eyes filled with tears.

“And now, George, my boy, bring me the Bible,” said his father; “it is time for our evening reading.”

“What part shall I read?” inquired George, reverently opening the sacred book.

“Oh, let him read of some one who had sinned and was forgiven!” said poor Charley.

At his father’s look of assent, George turned to the touching story of the woman who, weeping and penitent, sought for mercy from the Saviour, and found it.

“Behold, a woman in the city, which was a sinner, when she knew that Jesus sat at meat in the Pharisee’s house, brought an alabaster-box of ointment, and stood at his feet behind him weeping, and began to wash his feet with tears, and did wipe them with the hairs of her head, and kissed his feet,[35] and anointed them with the ointment. Now when the Pharisee which had bidden him saw it, he spake within himself, saying, This man, if he were a prophet, would have known who and what manner of woman this is that toucheth him: for she is a sinner. And Jesus answering, said unto him, Simon, I have somewhat to say unto thee. And he saith, Master, say on. There was a certain creditor which had two debtors; the one owed five hundred pence, and the other fifty. And when they had nothing to pay, he frankly forgave them both. Tell me, therefore, which of them will love him most? Simon answered and said, I suppose that he to whom he forgave most. And he said unto him, Thou hast rightly judged. And he turned to the woman, and said unto Simon, Seest thou this woman? I entered into thine house, thou gavest me no water for my feet: but she hath washed my feet with tears, and wiped them with the hairs of her head. Thou gavest me no kiss: but this woman, since the time I came in, hath not ceased to kiss my feet. My head with oil thou didst not anoint: but this woman[36] hath anointed my feet with ointment. Wherefore I say unto thee, Her sins, which are many, are forgiven; for she loved much: but to whom little is forgiven, the same loveth little. And he said unto her, Thy sins are forgiven” (Luke vii. 37-48).

ENTER NOT INTO THE PATH OF THE WICKED. Prov.

A lady and her young daughter were travelling by train. Two gentlemen occupied seats in the same carriage, and presently entered into conversation with each other. Their language was such as pained their fellow-traveller to hear. The sacred name of the Deity lightly uttered, the profane oath on their lips, showed how little they regarded that solemn warning, “For every idle word men shall speak, they shall give an account the day of judgment.” Fearful of uttering her thoughts to the strangers, the lady turned to her daughter, who, after having shown[38] the fidgety restlessness common to children upon a journey, now sat still with open eyes and ears, a wondering listener to the conversation.

IN THE TRAIN.

Anxious to divert the attention of Adine, the lady pointed out to her various objects on the road, and then proceeded to repeat anecdote after anecdote from the funds of a well-stocked memory. Adine was soon all attention; and at last even the gentlemen, having worn out their own subject of conversation,[39] paused to listen to the mother entertaining her child.

“Did I ever tell you the story of a great king,” said the lady, “who once overheard two of his courtiers speaking in a way greatly to displease him? He gently drew back the curtains of his tent, and uttered this quiet reproof: ‘Remove a little further, gentlemen, for your king hears you!’

“Adine,” continued the mother, with a flushed cheek and beating heart, for she wished, yet feared, to make her lesson plain to the older listeners, “may not some people yet need such a reproof?”

“It would be of no use, mamma,” replied the child simply; “for, let us remove as far as we can, our heavenly King always hears us!”

There was not another oath uttered during the remainder of that journey; the lesson had not been given in vain.

“Not at school again, Harry?” said the teacher, Willy Thorn, as he seated himself in the little parlour of Widow Brown, and regarded with a kind but almost sad countenance the flushed face of her grandson. “You have not been with us for a month, Harry, and I fear that you never go to church. I had hoped better things of you, my boy.”

“It’s all from the bad company that he gets into,” said the widow, taking off her spectacles and wiping the glasses. “He is a good lad at heart, sir; but you see as how he has no firmness—he can’t say No. Harry intends to do well one hour, and forgets all[41] about it the next; but I’ll be bound you’ll see him at school and at church too, some day or other.”

“He knows not how long he may have the opportunity of doing either. Remember, Harry, the fate of your young companion, Sam Porter, hurried in one instant into eternity—not one moment given him to repent, to call on his Saviour!—all his opportunities past for ever!”

Harry sighed and looked down.

“Well, my boy,” said Thorn, more cheerfully, “if you have made good resolutions and broken them a hundred times, try again; try with faith and prayer, and God may give you the victory yet! I heard a little allegory to-day. I thought that it might interest, and perhaps benefit you; so, as it is too dark at present for reading, I will repeat it to you, if Mrs. Brown would like to hear it.”

“I am quite agreeable,” said the old woman, leaning back in her arm-chair.

“What is an allegory?” inquired Harry.

“Real truths shown in fiction. You will understand better what an allegory is when[42] you have listened to this. It is called the story of

“THE VASE AND THE DART.

“A young boy entered a beautiful garden, which extended as far as the eye could reach. Through the whole length of it stretched a narrow avenue, bordered with overhanging trees. Slowly the boy pursued his way along it, listening to the songs of the birds, and admiring the green foliage above him, through which, here and there, streamed the rays of the glorious sun. He quickly perceived that he was not alone; on either side, all down the long avenue, stood a line of maidens, beautiful to behold. They were all robed in white, with wreaths of fresh flowers on their heads, and greeted the boy with a bright smile of welcome. Each held in her right hand a vase of gold, in her left a sharp iron dart.”

“I do not understand this allegory at all,” said Harry. “Did any one ever see such maidens as these?”

“These maidens,” replied Thorn, “are well known to all—they are called Opportunities.[43] Who has not met with opportunities of doing good, opportunities of receiving good?”

THE ROWS OF MAIDENS.

“I see, sir. Pray go on.”

“As the boy approached the first maiden, she held out her vase to him, and invited him to take the contents. On the golden vase appeared the word Prayer, and the sweetest, fairest fruits were heaped up within[44] it; but the boy scarcely glanced at the proffered gift. ‘It is wearisome!’ he cried; so pushed it aside and passed on.”

“Opportunity for prayer!” cried old Mrs. Brown. “Ah, sir, who can count how many times we have pushed that away from us! God forgive us!”

“The boy sauntered on,” resumed Willy Thorn, “and soon another fair maiden stood before him: she also held forth a vase of bright gold, full of pieces of glittering silver. On it was inscribed the word Knowledge.”

“Here is the opportunity of gaining learning at school,” said Mrs. Brown, who was an intelligent old woman, and had read a good deal in her youth.

“But the boy scarcely glanced at the proffered gift. ‘It is troublesome!’ he cried; so pushed it aside and passed on.

“A short space further on another maiden stopped him, with a bright and joyous countenance. Her gold vase contained the loveliest flowers, and on it appeared written, Acts of Kindness to others. The boy looked at it wistfully for a moment, tempted by the sweet perfume of the beautiful blossoms.[45] Opportunity smiled, but selfishness stayed the hand of the boy, half stretched out to empty the vase: he pushed it aside and passed on.

“The next maiden who greeted him was calm and fair, with a grave and earnest look. Her vase was full of refined gold, and this was the motto which it bore: Attendance at the House of God. A sound of church-bells came on the breeze, and the sweet music of a distant hymn; but in vain they fell on the boy’s listening ear. ‘It is dull!’ he cried; pushed the rich vase aside, and passed on.”

“But you said, sir,” observed Harry, “that the maidens held darts in their left hands, as well as vases in their right. What do you mean by them?”

“You shall hear before I end my story. So the boy reached another maiden, who looked like an angel from heaven. Her eyes shone like stars in the calm blue sky, and the tones of her voice thrilled deep into the heart. Her vase was overflowing with sparkling jewels, brighter than those which monarchs wear. On it shone in glittering letters, The Word of God.”

“Oh, I hope that he put out his hand and took that!” cried the aged woman, resting hers on her Bible.

“Opportunity cried, ‘Oh, pass me not by! Search the Scriptures, that can make you wise unto salvation.’ She held forth her vase with imploring look, but the boy was intent on pursuing his way. ‘I care not for it!’ he cried; so pushed it aside and passed on.”

“Well, he might have the same opportunity of reading the Bible again and again,” said Harry.

“Not the same,” replied Willy Thorn; “the boy could not retrace one step of his way. No moment of time can ever be recalled. Every opportunity of doing good once past, whatever others may arise, that opportunity is past for ever!

“‘I shall meet with more maidens,’ said the boy. ‘I see an endless number before me; doubtless they carry vases as precious as those which I have rejected.’ But even as he spoke the words, he came suddenly on a black iron gate, and he could pass on no further. Shuddering, he read on the gate the solemn word, Death!

“Then would he gladly have turned round: then would he have earnestly asked for one more opportunity for prayer—one more opportunity of doing what is right; but the last had been passed—he had slighted the treasure of the last! Nor can we despise opportunities, and not suffer for doing so; if they offer the vase, they also carry the punishment meet for those who neglect its contents. As the boy stood trembling at the gate of Death, a dart came hissing through the air, and inflicted on him a burning wound: then came another and another; every opportunity despised sent its messenger of vengeance, and the wretched boy, writhing with the arrows of conscience in his soul, sank down at the gate, and perished!”

“Alas!” cried Harry, “where can I then find safety, for I have neglected more opportunities than I can number of doing good and receiving good?”

“Ask the Lord for pardon through the blood of the Saviour!” exclaimed Thorn. “‘Now is the accepted time, now is the day of salvation;’ neglect not this[48] opportunity—it may be your last! O my young friend! no day leaves you as it found you; every day brings its opportunities of prayer, praise, reading the Bible, and obeying God’s laws; every day you have chosen either the vase or the dart.”

Dear reader, to you would I address a few words. If this little story has raised the thought in your heart, “How have I improved my opportunities?” oh, push it not aside and pass on! Let not the day close without prayer; seize the golden prize while yet it is offered to you, or hope not to escape the dart!

As a lady was walking across Hyde Park, rather early in the day, she happened to take her handkerchief out of her pocket, and drew out with it, by accident, a little red case. It fell on the path, and rolled almost to the feet of a poor girl who was standing near. The child was clad in rags, her hair was rough, her face and hands dirty; she was one who had no one to care for her, no one to teach her what was right. Half eager, half afraid, she stretched out her hand to seize the prize, but first turned round to see that she was not observed, and met the eye of the lady.

“Stop!” said Mrs. Claremont, who had heard the case drop on the ground; “stop, little girl, you are in danger of losing something!” and while the astonished Ann knew not what could possibly be meant by such strange words, the lady quietly stooped down and picked up the case herself.

She then again addressed the child; her manner was not angry, but calm and kind, and Ann, notwithstanding her fear and shame, felt a pleasure in listening to so gentle a voice.

“Come beside me while I rest on this bench,” said Mrs. Claremont, “and tell me what I meant, when I said that you were in danger of losing something.”

Ann only stared at her, and made no answer.

“Do you know that you have a soul?”

“I know nothing about it,” muttered the girl.

“Then,” said Mrs. Claremont, “I will show you what you were going to take, and explain to you what you were in danger of losing.”

“I’ve got nothing to lose,” thought Ann,[51] but she watched the lady with some curiosity.

THE LADY AND THE LITTLE GIRL.

“You see,” continued Mrs. Claremont, “this little red case. It has nothing fine about it,—it looks old and worn. Did you think it worth stealing?”

“I thought there was something in it.”

“You thought right; the most precious part is within. So it is with you, and all people, my child. Your body, which can be[52] seen and felt, is like the case of the jewel; your soul is the jewel itself.”

“What is a soul?” said Ann.

“When I speak to you, you think of what I say—the part of you that thinks is the soul; if any were kind to you, you would love them—the part that loves is the soul. You can see that tree; it lives, but it has no soul in it, it cannot love or think. Do you understand me now?”

“Yes,” answered the girl.

“You cannot see this jewel, because the case is shut; I am going to open the case, and show it to you.”

Mrs. Claremont unclosed the little case, and Ann beheld a very beautiful jewel, which sparkled like a star in the rays of the sun.

“This jewel was given to my great-grandmother on her marriage,” said Mrs. Claremont.

“Oh, how bright and fine it is!” cried Ann; “it does not look at all old!”

“It will never look old. When I and my children’s children are in their graves, it will look beautiful and fresh as ever! And so it is with the soul. Our bodies must be laid[53] in the tomb, but our souls—those jewels within—will never, never die!”

“Where will they be when our bodies are dead?” asked Ann.

“Either in happiness or in misery, according as we have been God’s faithful people here or not,” replied Mrs. Claremont. “Now tell me, my poor child, for which should we care most,—the case or the jewel, the body or the soul?”

“The soul,” answered Ann.

“And it was your soul which you were putting in danger even now; for sin is the ruin of the soul. It is written in God’s Word, ‘What shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his own soul, or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?’ To procure a few more comforts for your weak perishing body, would you throw away the precious jewel within?”

Ann looked at the lady very sadly, and then replied, “No one ever spoke to me in this way before; no one cares for my soul!”

“O my child, there is One who cares for it, One to whom it is very precious! The Lord Jesus Christ left the glory of[54] heaven to come and save poor souls. He bought yours with his life’s blood. He died on the cross, that it might shine for ever in glory!”

“Does the Lord really care for me?” inquired Ann anxiously. “Why, then, am I so wretched and so poor?”

“He does care for you; he does love you; you are precious to him. And as for being poor and wretched—look again at this beautiful jewel, and tell me where you think that it came from first.”

“I cannot tell.”

“It came from the dust,—it was dug from the dark earth. It had no great beauty then; those who did not know its real value would have despised and thrown it away; but there were those who knew that it was precious. So we too belong to the dust, fallen sinful creatures; and we would have lain there for ever, had not the Lord had pity upon us and raised us, and brought us into the sunlight of his gospel.”

“If the jewel was not bright at first, what makes it so bright now?” inquired Ann.

“It has been cut and polished, and so it is[55] with our souls. God sends them poverty or trials here, to prepare them to shine in his palace above! If the jewel had been a living thing it would not have liked to have been cut, but it would never have been bright without it.”

“I should like to know more about the Lord who cares for my soul, and bought it with his blood,” sighed Ann.

“Have you a Bible or Testament, my child?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Can you read?”

“No,” said Ann sadly.

“There is a Ragged School near, to which you might go and be taught, and hear about the Lord Jesus, and what he has done for your soul.”

“I know where the school is,” said Ann.

“Go, then, and you will be made welcome, my poor little friend. I do not remain in London myself, but I will leave with the teacher some clothes, and a beautiful Bible, which shall be yours as soon as you can read it.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” said the girl.

“And one little word before we part, perhaps never to meet again in this world,” continued Mrs. Claremont. “If you cannot read you can pray—have you ever prayed to God?”

“Never,” replied Ann.

“Your soul can never be safe until you do. Kneel down, morning and evening, and at least repeat these few words: ‘O Lord, forgive my sins, and make my heart clean by thy Spirit, for Jesus Christ’s sake.’ So short a prayer you can remember, can you not, if I repeat it over to you two or three times?”

“I think so,” said Ann.

“Pray with your whole heart, my child, and God, for the sake of the Saviour, will hear and bless you. Love him who first loved you, believe in his mercy, and obey his holy commandments. Then what matter if for a few years, or months, or days, you be called upon to wait or suffer here? Death will soon unclose the worn-out case, and remove the precious jewel to that glorious place where tears shall be wiped from every eye, and sorrow and sighing shall flee for ever away!”

THE FEAR OF THE LORD IS THE BEGINNING OF WISDOM. Prov. ix. 10

A little vessel was floating over the Sea of Tiberias; the Lord Jesus and his disciples were within it. “And there arose a great storm of wind, and the waves beat into the ship, so that it was now full. And Jesus was in the hinder part of the ship, asleep on a pillow; and they awake him, and say unto him, Master, carest thou not that we perish? And he arose, and rebuked the wind, and said unto the sea, Peace, be still! And the wind ceased, and there was a great calm” (Mark iv. 37-39). The tossing waves sank down at his word, and the obedient waters lay like a sheet of glass,[58] reflecting the blue sky above! “And he said unto his disciples, Why are ye so fearful? how is it that ye have no faith? And they feared exceedingly, and said one to another, What manner of Man is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?” (Mark iv.)

Dear little reader, are you in trouble or temptation? Then are you like the disciples on the stormy Sea of Tiberias. Perhaps your relations are harsh and unkind, or perhaps you are a poor orphan without a friend in the world, and are ready to say, “No man careth for my soul!” But you have one Friend, a powerful Friend, a loving Friend, who has led you on your voyage through life until now, and will lead you to the end! The Lord Jesus is beside you, though you see him not. Hear what he says to those who love him: Can a woman forget her sucking child! yea, they may forget, yet will I not forget thee (Isa. xlix. 15).

Or are you in great poverty, hungry and weary? You can scarcely earn your daily bread, you have no comfort, no rest, no home! In the bitterness of your heart, you cry, “Lord, carest thou not that we perish?” O[59] my child, the Saviour is not asleep! He knows your trials, he has felt them all—the Lord of heaven and earth once “had not where to lay his head!” Behold, the eye of the Lord is upon them that fear him, upon them that hope in his mercy; to deliver their soul from death, and to keep them alive in famine (Ps. xxxiii. 18, 19). Many are the afflictions of the righteous; but the Lord delivereth him out of them all (Ps. xxxiv. 19). Ask the Lord to help you, to feed you, to comfort you, above all, to give you his Holy Spirit; for if we love and trust in him, then our light affliction, which is but for a moment, worketh for us a far more exceeding and eternal weight of glory. Then the rough wind of trouble will but bring you on more quickly towards heaven, and even here below Jesus may bid the waves of affliction be still, and there shall be a great calm!

Or are you in the storm of temptation? You wish to please God, you wish to go to heaven, but you feel as though the way were too hard for you. You think, “I cannot resist that temptation; I can give up all but that one sin. If I do not join my companions[60] in what is wrong, I shall be despised; if I do not tell such a falsehood, I shall be beaten; if I do not work or sell on Sundays, I shall be starved!” In such a storm of temptation turn to the Saviour still; for in that he himself hath suffered being tempted, he is able to succour them that are tempted (Heb. ii. 18). Cry, “Lord, save me or I perish! Give me thy Holy Spirit, that I may be ready to follow thee through trouble and temptation. Whatever I may suffer here, oh, keep me faithful to thee!”

Think on this one great truth, dear reader. The comfort of the voyage matters little in comparison to the place where we are going. The voyage of life cannot last very long; the fiercest storm must soon pass away! Look at these two different passengers, and think which of them you would pity.

See one vessel bounding gaily over the bright water, the wind in her favour, the sun shining upon her; and look at that man on her deck! He is a slave; he is going to suffering and misery, he dreads to arrive at the port. Do you not pity him? Yet his case is happy compared with that of those[61] who forget God—who, caring but for pleasure, living only for this world, are yet hurrying on to death—and after death the judgment! Poor slaves of sin! do they not know that—

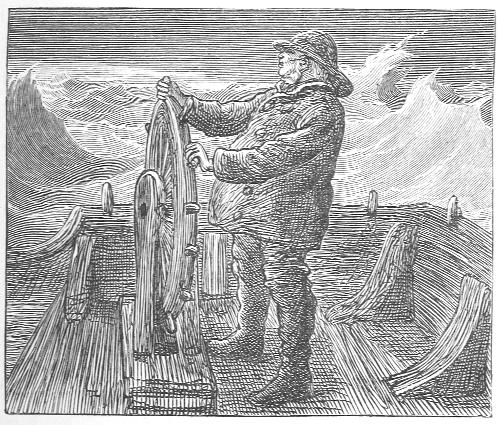

THE MAN AT THE WHEEL.

Now look at this other man in a storm-tossed vessel! He is going home. He is going to riches, and honour, and happiness, and home! Though the waves rise high,[62] they will not overwhelm him; though the clouds are so dark, there is a sunshine in his heart! On the shore he knows that all will be peace, and he can smile in the midst of the storm! Do you pity him? But far happier is the Christian, however afflicted here; for his heart, and his hopes, and his home, are in heaven, and he is on his way to God! His sins forgiven through the blood of his Saviour, his courage supported by the power of God’s grace! Blessed is the man that endureth temptation: for when he is tried, he shall receive the crown of life, which the Lord hath promised to them that love him! (James i. 12).

Think of those who have already landed on the happy shore, but not till they had passed through the storm. There are saints who have suffered, and martyrs who have died for the Lord! They do not wish now that their trials had been less;—sweet is to them the remembrance of the storm! When holy St. John, banished to Patmos for the sake of the gospel, saw heaven opened, and its glory appearing, what did he behold there? These are his words:—

“After this I beheld, and, lo, a great multitude, which no man could number, of all nations, and kindreds, and people, and tongues, stood before the throne, and before the Lamb, clothed with white robes, and palms in their hands. And one of the elders answered, saying unto me, What are these which are arrayed in white robes? and whence came they? And I said unto him, Sir, thou knowest. And he said to me, These are they which came out of great tribulation, and have washed their robes, and made them white in the blood of the Lamb. Therefore are they before the throne of God, and serve him day and night in his temple: and he that sitteth on the throne shall dwell among them. They shall hunger no more, neither thirst any more; neither shall the sun light on them, nor any heat. For the Lamb which is in the midst of the throne shall feed them, and shall lead them unto living fountains of waters: and God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes” (Rev. vii. 9, 13-17).

HE THAT LOVETH PLEASURE SHALL BE A POOR MAN. Prov. 21

It was on a bright Sunday afternoon that the teacher, Willy Thorn, on returning from church, met three of his scholars sauntering towards one of the London parks. They perceived his approach at some little distance, and instantly began to conceal in their pockets something that they had been carrying in their hands. Their nearness to a very tempting stall, upon which fruit and sweetmeats were sold, made Willy guess too truly the cause of the hasty movement. He thought it better, however, at first to take no apparent notice of the fact that the boys had been breaking the Fourth Commandment[66] by buying upon God’s holy day.

“Well, my lads,” said Thorn, when he came up to them, “you are going, I see towards the park. I will go with you; we will enjoy the fresh air and bright sunshine together, and perhaps have a little discourse, which may be profitable as well as pleasant.”

The boys were usually very fond of the society of Willy Thorn; but just now, with their pockets full of cakes and nuts, they would have preferred being without it. However, no objection was made; they reached the park, and seated themselves under the shade of a large tree, for the sun was hot, and the shelter of the foliage was pleasant on that sultry afternoon.

Willy Thorn looked upwards at the leafy boughs which hung above him, through whose screen a long bright ray, here and there, pierced like a diamond lance. “This tree has put an allegory into my mind,” said he. “Boys, are you in the mood for a story?”

A story was always welcome, and in the[67] expectation of being amused, the scholars half forgot that their teacher’s presence was delaying their intended feast.

“Methought,” began Thorn, “that I had a dream; and in my dream I beheld a large and venerable tree. It was several thousand years old—so you may imagine its size; but it showed no signs of age; its leaves were as fresh, its fruit as abundant, as when the Israelites of old encamped under its refreshing shade. This tree was called the Sabbath-tree. It was given by its Lord as one of the richest blessings which was ever bestowed upon man. Freely might all partake of its fruit; but all were forbidden by a voice Divine to break even the smallest bough from the sacred tree.

“I saw in my dream that many thronged to the spot where the Sabbath-tree rose, like a beautiful green temple, in the midst of the plain; and I stood aside to mark the effect of its fruit on those who came to gather it. It strewed the ground in some places so thickly, that it shone like a carpet of gold.”

“I suppose,” said Bat Nayland, one of the boys, “that the fruits of the Sabbath-tree[68] are,—going to church, praying, praising, and reading the Bible?”

Thorn smiled in assent, and continued: “I saw one haggard man come, faint with hunger, to the spot. He threw himself down on the soft grass, and fed eagerly on the nourishment freely provided. And I marked joy on his pale face as he ate of the fruit of the Sabbath-tree, and I remembered the holy words, Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they shall be filled.

“I saw an aged woman reach the tree. She was so feeble that she had hardly power to stoop to gather the fruit; but as she tasted it, her strength returned, her bent form became more erect, she walked with a firmer step, and I remembered that it is written, They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength.

“Next, a miserable sufferer approached; on his countenance was an expression of pain. He was sick—grievously sick of the malady of sin, fatal to all who cannot find a cure. But he knew the healing powers of the tree. He fed, and even as he fed health[69] returned to his faded cheek, the anguish of his soul passed away, and the sufferer found himself whole.”

“I thought,” said the eldest of the boys, “that there was but one cure for sin!”

“True, most true,” replied Thorn, with an approving look; “but in due observance of Sabbath duties, we learn how to seek and where to find that cure.

“I had watched in my dream, with a rejoicing heart, thousands gathering the precious fruit, and receiving nourishment, strength, and healing; but now, alas! my attention was attracted by yet greater multitudes, who thronged to the spot only, as I became painfully aware, to break and injure the beautiful tree. Some enemy had hung up a hatchet on its trunk, with Disobedience marked on the handle, and of this numbers made very free use to cut down large boughs from the tree.

“‘I am going on a jovial merry-making in the country,’ cried one; ‘I and my family shall have a treat. I want some wood to mend up my broken car.’

“‘Hold!’ exclaimed the youth who had[70] been healed, attempting to stay the hand of the Sabbath-breaker; ‘are there not six groves nigh at hand?—had you not better cut what you want from them?’

“‘No!’ cried the man impatiently, swinging the hatchet aloft; ‘there is no tree so convenient as this!’ and for the sake of a little pleasure in the country with merry companions, he cut a branch from the Sabbath-tree!

“Then came a woman with a face full of care. She had not faith to trust in him who clotheth the lilies, and provideth for the ravens. ‘I want wood for a stall,’ said she, ‘whereon to sell my sweetmeats. I must earn some more pence for my living; necessity owns no law;’ and taking the hatchet of Disobedience, she also brought down a leafy bough, treading under foot as she did so a quantity of the ripe, precious fruit. Not content with thus breaking the Sabbath herself, she demanded that those who bought at her stall should each bring, in addition to their money, a fagot stolen from the holy tree!”

When Thorn came to this part of his[71] story, his scholars glanced consciously at each other. They all now felt convinced that their teacher was aware that they had been buying from a stall on Sunday.

“It was grievous,” continued Thorn, “to see what multitudes trampled on the Sabbath fruit, broke away twigs, snapped branches, to help on their business or aid their amusements. Some wanted wickets for cricket, one man required a handle for his spade; and though a very little delay would have enabled them to procure wood from a lawful quarter, they were too thoughtless, too covetous, or too impatient to reverence the Sabbath-tree.

“But soon I beheld in my dream, that while none could faithfully partake of the fruit without benefit, none without injury could break off a single branch. As I watched, much did I marvel to see how disobedience brought down punishment! The man who had repaired his car by Sabbath-breaking, had little pleasure from his intended treat. As he was driving from a public-house, suddenly a wheel of the vehicle came off, he and his party were flung out on[72] the road, and sorely bruised by the fall. In some cases, the wood so unlawfully taken appeared to turn at once into dust! The man digging with his Sabbath spade, found it suddenly snap asunder, and the splinter ran into his hand, inflicting a terrible wound.”

“Oh, but how could that be?” exclaimed one of the boys. “Many a fellow goes larking on Sunday, and the wheel of his car never comes off! I don’t know what this part of your story can mean.”

“It means,” replied Willy gravely, “that disobedience to God, the wilful breaking of his holy commandment, unless the sin be repented of and renounced, is certain to bring punishment in another world, and very frequently also in this. There are multitudes of lost, miserable sinners, who may trace their first steps on the path of ruin to breaking the Sabbath of God. No one ever yet, on his death-bed, could say that he really profited by money so gained, or that he had no reason to regret a pleasure gained by disobeying his Maker’s command.

“The poor woman who sold sweetmeats, I found in my dream, was not long in suffering[73] the penalty of disobedience. In one of the fagots so sinfully laid upon her stall, the serpent Remorse had lain coiled, unnoticed, unseen! As she was counting her unholy gains, made by not only sinning herself, but causing others to sin, the fierce reptile darted at her breast!—with difficulty was the serpent torn from its hold, and the poor sufferer sank on the ground, bleeding, fainting, trembling at her danger, and weeping for her sin! It was some time before she was able feebly to creep to the spot where comfort and healing might yet be procured by a proper use of the fruits of the Sabbath-tree.

“While the poor woman was in sorrowful penitence, doing all that lay in her power to show her regret for the past, the boys who had purchased at her stall—who had wilfully broken the Sabbath, not to supply real wants, but to indulge their own greedy inclinations—”

“I’ll tell you what one of them did, sir!” exclaimed Bat Nayland, springing up from the ground: “he just emptied his pockets of what he had bought, said that he was heartily ashamed, and seeing an old lame[74] beggar near, he gave every crumb of his purchases to him!”

THE LAME BEGGAR.

And suiting his action to his words, off[75] darted the boy, and astonished a ragged old man on crutches, by bestowing upon him at once all his cakes and his nuts!

Dear young readers! if any of you have been tempted to disobey your Master’s commandment, by buying on the day which the Lord hath set apart for himself, oh, consider it not as a trifling transgression.

Resolve with prayer henceforth never to break the smallest twig from the Sabbath-tree, but to feed on its sacred fruits with faith, and hope, and love. Be assured, then, dear children, that they will become sweeter and sweeter to your taste, and prepare you for the enjoyment of that Tree of Life which is in the midst of the paradise of God.

HE THAT WALKETH UPRIGHTLY WALKETH SURELY. Prov. 10:9

“What was that noise in the street?” exclaimed Mrs. Claremont, laying down the pen suddenly. Ella sprang to the window.

“O mother, something must have happened! some accident! there is a crowd collecting round a poor little girl!”

“We may be of some use!” cried Mrs. Claremont, and she and her daughter were at the street door in a few seconds.

“What is the matter? is any one hurt?” inquired the lady of a milk-woman who was standing looking on.

“A child knocked down by a horse, I[77] believe, ma’am. They should take the poor thing to the hospital.”

Mrs. Claremont waited to hear no more; the crowd made way for her, and she was soon at the side of a young girl who was crying violently, and the state of whose crushed bonnet and soiled dress showed that she had been down on the road.

“I don’t think there’s any bones broken, only she’s frightened,” observed a baker among the spectators; “I saw the horse knock her down as she was crossing the road.”

“Come this way, my poor child, out of the crowd,” said Mrs. Claremont, leading the little girl towards the house; “we will soon see if the injury is severe.”

The weeping child soon stood in the hall; hartshorn and water was brought to her by Ella, but on tasting it, the girl pushed it away in disgust, in a peevish and irritable manner. In vain Mrs. Claremont sought for any trace of injury; the road had been soft after much rain, and not a scratch nor a bruise appeared; yet still the girl cried as if in agony of pain or of passion.

“Where are you hurt?” inquired Ella soothingly; the child only answered by a fresh burst of tears.

“I am thankful that no harm seems done,” said Mrs. Claremont.

“There is harm!” sobbed the girl; “all spoiled, quite, quite spoiled!”

“What is spoiled?”

THE SPOILED DRESS.

“My dress, my beautiful new dress!” and the ladies now observed, for the first time, the absurd and unsuitable manner in which[79] the child had been clothed. Now, indeed, her finery was half covered with mud; but the pink bonnet, though crushed, the white dress, though stained and torn, the gay blue necklace, and hair in curl-papers, showed too plainly the folly of the wearer.

“What is your name?” inquired Ella.

“Sophy Trimmer.”

“Where does your father live?”

“He lives just round the corner.”

“You should be very thankful that your life has been spared,” said Mrs. Claremont.

Sophy did not look at all thankful, she only glanced sadly down on her torn dress, and whimpered, “Just new on to-day.”

“You remind me,” said the lady, “of a story which I read in the papers some years ago. A lady was going in a vessel to Scotland, and carried with her a quantity of jewels to the value of a thousand pounds. She thought so much of these jewels, that she was heard to say, that she would almost as soon part with life itself as lose them. An accident happened to the vessel on the way to Scotland; the water rushed into[80] the cabins, and the poor lady was taken out drowned.”

“That is a shocking story,” said Sophy.

“She could not carry her jewels with her to another world. But there is one ornament which even death itself has no power to take away.”

“What can that ornament be?”

“An ornament more precious than the crown of the Queen, ‘the ornament of a meek and quiet spirit, which is, in the sight of God, of great price’ (1 Pet. iii. 4). The poorest may wear this—the rich are poor without it. O my child, care not to appear fair in the eyes of your fellow-mortals, but in the sight of God; your ‘adorning, let it not be that outward adorning of plaiting the hair, and of wearing of gold, or of putting on of apparel; but let it be the hidden man of the heart, in that which is not corruptible’” (1 Pet. iii. 3, 4).

“What do you mean by ‘corruptible?’” said Sophy.

“That which time can destroy. Nothing in this world lasts for ever: flowers bloom and decay; the fruit which was delicious[81] one week, the next is only fit to be thrown away; the loveliest face grows wrinkled; the finest form must soon turn to dust in the tomb.”

“I don’t like to think of such things,” said Sophy; “they make me sad.”

“They would make us sad, indeed, were this world our all. But we look forward, in faith, to a place where there is no corruption, no change, no death, because no sin; we hope to wear white robes in heaven which will never be defiled with a stain. Do you know, Sophy, what makes them so white?”

Sophy shook her head.

“We are all weak and sinful, less fit to appear before a holy God in our own righteousness, than you are to enter the Queen’s palace in those soiled garments. It is ‘the blood of Jesus Christ which cleanseth from all sin;’ through his merits, and his mercy, you may appear spotless before the judgment-seat of God, if you believe in him now, and ‘keep yourself from idols.’”

“I have nothing to do with idols,” said the girl peevishly.

“More perhaps than you think. Anything[82] that you love better than the Lord is an idol. The miser loves money best; that is his idol.”

“Like old Levi, who half starves himself to scrape up pence,” interrupted Sophy.

“The ambitious man makes power his idol—some make their children their idols.”

“Like Mrs. Porter, who—”

“Hush,” said Mrs. Claremont, “you have nothing to do with the idols of your neighbours; try and find out what is your own.”

“I do not think that I have any.”

“Do you then love God with all your heart? Is it your chief business to serve him; your greatest delight to do his will?”

“No; of course, I like to amuse myself like other people.”

“Have you ever given up any one thing to show your love to him who made you?”

Sophy looked vexed, but made no reply.

“Whom do you like best to please? Whom do you like best to serve? Have you no idol which you decked out this very morning in all the finery which you could collect?”

“I suppose that you mean myself.”

“Yes; self is the idol of the vain, their[83] hopes and joys are bound up in self, therefore their hopes and joys are amongst the corruptible things which must pass away. O my young friend, the foolish pleasures which you felt this morning in these fanciful clothes, in one moment was changed to pain; and but for the mercy of God, your own poor body might now have been lying crushed and lifeless. Why rest your happiness upon that which cannot last, and which may, any hour, be taken away from you for ever?”

“Gay, gaudy clothing always gives me a feeling of pain when I look upon it,” observed Ella; “I believe that with so many it has been the first step to misery here and hereafter.”

“It is like the gay bait on the hook,” said her mother, “not in itself deadly, but covering a fatal snare. Oh, ‘love not the world, neither the things that are in the world. If any man love the world, the love of the Father is not in him. And the world passeth away, and the lust thereof: but he that doeth the will of God abideth for ever’” (1 John ii. 15, 17).

WHATSOEVER A MAN SOWETH THAT SHALL HE ALSO REAP

There was unusual silence in the little Sunday school when Ella Claremont, its gentle teacher, entered it for the first time in deep mourning. All had known of her sorrow; all had heard that her brave young brother had died of wounds received in battle in a far distant land. They thought of him whom they had seen some few months before so bright and happy, with a smile and a kind word for all, now lying cold in his bloody grave; and there was not a heart in the school-room which did not feel sorrow and sympathy.

Ella could not at first address her school;[85] her words seemed choked; the tears gathered slowly in her eyes; but she found strength in silent prayer, and spoke at length to her pupils, but in a trembling voice.

“Dear children, I have had much sorrow since we last met and talked of the joys of heaven—a beloved brother has, I trust, through Christ’s merits, joined the bright hosts rejoicing there. But should not I meekly bear the cross which my heavenly Father sees good to send me? To every one passing through this life is given a cross—a trial to bear. To some it is so light that they scarcely feel it; with others so heavy that it bows them to the dust. Each of you knows, or will know, its weight. But let none be afraid nor cast down. The cross prepares for the crown. There is something from God’s Word inscribed on every cross; and if we have but faith to read it, it makes the heavy, light; and the bitter, sweet! ‘Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord’ (Rev. xiv. 13), is the inscription on mine.”

Every one passing through life has some cross to bear! Yes; amongst those young[86] girls assembled in the school-room there were some whose trials were deep, who had much need to read the inscription to make them endure the burden.

Dear reader, are you in trial? Have you known what it was to weep when you had none to comfort you—to wish that the weary day were over, or the more weary night at an end—to wonder why God sent you such sorrows? For you I now write down what were the crosses of some of the children in Ella’s school; for you I write down what were the inscriptions upon them. Perhaps you may find amongst them the same trial as your own, and feel strengthened to bear your cross.

Mary Edwards was very poor—hers was a heavy cross. One of seven children, and her father blind; often and often had she come to school faint with hunger and sick at heart. But for the kindness of friends, the family would have been half-starved. Mary had never known what it was to have a blanket to cover her; very seldom had she been able to eat till she was satisfied; her clothes had been mended over and over[87] again, to keep them from falling to pieces; ill did they protect her when the cold wind blew through the broken pane, or found its way through the crevices in her miserable hut. Yet Mary had comfort in the midst of her poverty; she remembered him “who, though he was rich, yet for our sakes he became poor.” She had read the inscription on her cross: “Hath not God chosen the poor of this world rich in faith, and heirs of the kingdom which he hath promised to them that love him?” (James ii. 5). And Mary would meekly repeat the hymn of good Bishop Heber:—

Amy Blackstone never spoke of her cross; she bore it in silence without complaining. Her father was a drunkard—her mother never entered the house of God. If she heard the name of the Holy One uttered in her home, it was but in an oath or a profane[88] jest. She never complained, as I have said; for, while others would have been complaining, she was praying. Fervently did she pray for her unhappy parents—fervently for herself, that evil example might not draw her from God. Many a silent tear she shed over her cross; and this was the inscription upon it: “I reckon that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be revealed in us” (Rom. viii. 18).

All pitied Ellen Payne, for her cross was sharp. A lingering, painful disease had taken the strength from her limbs, the colour from her cheek. She never rejoiced in one waking hour free from pain, and often the night passed without sleep. The doctors gave no hope, medicine no relief. She had nothing to look forward to but pain, increasing pain, till she should sink into an early grave. This was her cross; and this was the inscription upon it: “Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life” (Rev. ii. 10).

Jane White had been a deserted child; she had never known a parent’s care. She[89] seemed one of the neglected, despised ones of earth, with none to love her, and none to love. She felt lonely and desolate. This was her cross; and this was the inscription upon it: “When my father and my mother forsake me, then the Lord will take me up” (Ps. xxvii. 10).

ANN BROWN.

Ann Brown lived with her aunt. Few of the girls were better dressed, or seemed more comfortably provided for, than she. Had she, then, no cross to bear? Yes; for[90] she dwelt with a worldly family, who laughed at her for being “righteous overmuch.” When she would not join in profaning the Sabbath—when she showed that she cared not for gay dressing or ill-natured gossip—she became the object of ridicule and scoffs, more painful to bear than blows. This was her cross; but sweet was the inscription upon it: “If ye suffer for righteousness’ sake, happy are ye: and be not afraid of their terror, neither be troubled” (1 Pet. iii. 14).

Mary Wade’s cross was in the depth of her own heart—the struggle to conquer a passionate, violent temper. She desired to obey God, she wished to live to his glory; but sin seemed too strong for her; she yielded to temptation again and again, until she was almost in despair. Her health had been bad when she was an infant; much of her peevishness and impatience were owing to the effects of this. But no one seemed to make allowance for natural infirmity; her companions did not like her; and, worst of all, she felt that she was sinning, and bringing discredit on the Christian name. Poor[91] child! hers was an unpitied cross; but there was hope in the inscription upon it: “There hath no temptation taken you but such as is common to man: but God is faithful, who will not suffer you to be tempted above that ye are able; but will with the temptation also make a way to escape, that ye may be able to bear it” (1 Cor. x. 13).

Elizabeth Brown was a sad little girl, but none knew the cause of her sadness. She had once been the most thoughtless child in the school, full of mischief, full of gaiety, never thinking of God. Her heart had been on earth—her only wish had been to enjoy herself. Much trouble and sorrow had she given to her gentle teacher, much grief to her pious parents; for she had laughed at good advice, and cared little for punishment. But now the gay child had grown thoughtful: a text heard at church had struck her, and sunk deep into her heart: “Be not deceived; God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap. For he that soweth to his flesh, shall of the flesh reap corruption; but he that[92] soweth to the Spirit, shall of the Spirit reap life everlasting” (Gal. vi. 7, 8). What had she been sowing for eternity? She thought of her neglected Bible, her broken Sabbaths, words of untruth and of unkindness, her mother disobeyed, her teacher disregarded! Could God forgive her after all that she had done? Would he ever admit her to heaven? She feared that her sins were too many to be pardoned. This fear was her cross. Oh! praised be God for the precious inscription upon it: “The blood of Jesus Christ his Son cleanseth us from all sin” (1 John i. 7). Jesus said, “Him that cometh to me I will in no wise cast out” (John vi. 37).

Blessed are they who thus mourn for sin, for they shall be comforted. Blessed is the sorrow that worketh repentance! Blessed are they who so bear the cross that they shall inherit the crown!

BUY THE TRUTH AND SELL IT NOT. Prov. 23:23.

When walking through the streets of London, have you not sometimes met a party of strangers, and felt sure that they belonged to another land, because they spoke not the English tongue? Had you listened to them, you would not have understood them; they conversed in the language of their own country.

My young friend, what language do you speak? If I knew but that, I should soon guess to what country you belong.

Perhaps you answer, “I am English. I know no language but my own.” True, in one sense you are English, and you may[94] thank God for it! You were born in England, and here may spend all the years or days of your mortal life. But your real country is in another world, where you will live for ever! Thousands and millions of years may pass, but you will be still remaining in the country which you have chosen. So, again I ask, What language do you speak? To what country do you belong?

FOREIGNERS.

The one is a bright and glorious place, where sorrow and pain are unknown. Its citizens are angels and redeemed saints, who, with shining crowns and harps of gold, rejoice before the throne of God. The language which they speak is truth.

The other country is too terrible to describe. Happiness never enters there, but pain, grief, and remorse abide for ever! Its inhabitants are the tempter and his evil ones—hardened sinners who would not repent, who chose the broad way that leadeth to destruction. And what is the language which its citizens have learned? The language of Satan is falsehood.

O my dear young reader, with anxious love would I once more repeat my question—let your heart answer it—What language do you speak—to what country do you belong?

Yet, mistake me not. There are some whose lips were never stained with falsehood, who yet cannot be counted among the citizens of heaven. The proud, the self-righteous, who trust to their own merits, who love not the Saviour who suffered for[96] all,—these may have learned the language of truth, even as foreigners may learn the tongue of our land; but they belong not to the country of holiness and joy.

And others there are who have fallen into sin, whom the “father of lies” has tempted and deceived; yet God’s mercy may prepare a heavenly home even for them, if, believing and repenting, they turn to the truth. Thus, St. Peter thrice uttered a terrible falsehood, but repented with bitter tears, and, through the atoning blood of his Lord, was received into heaven a glorious martyr.

But oh, dread a falsehood as you would dread a serpent; it leaves a stain and a sting behind. If you have ever been led into this deadly sin, implore for pardon, like St. Peter. Like St. Peter, when next placed in temptation, speak the truth firmly, faithfully, fearlessly; for truth is the language of heaven.

There are four chief causes which lead to the guilt of lying—folly, covetousness, malice, and fear. Examine your own life, and see if any one of these has ever tempted you to utter a falsehood.

It was folly which made Richard tell a traveller the wrong road when asked the way to the next village. He thought little of the sin of his lie—it seemed to him but an excellent jest; but the jest cost a neighbour his life! The stranger was a doctor, travelling in haste to attend a patient who had been taken with a fit. Richard’s falsehood made the medical man lose half an hour, when every minute was precious. Oh, what anxious hearts awaited his arrival! But he came too late; he found the sufferer at the point of death, with his desolate family weeping around him!

It was covetousness which made Sally declare that her fruit had only been gathered that morning, when she knew it to be the refuse of yesterday’s market. Did she forget that God’s eye was upon her—that her words could not pass unnoticed by him—that she would have to answer for them at the day of judgment?

It is covetousness that makes Nelly stand begging in the streets, telling to passers-by her pitiful tale of a father in hospital and a family starving. Will the money which[98] she gains by falsehood and hypocrisy bring with it a blessing or a curse? Oh, “What is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?” (Matt. xvi. 26).

It is malice that makes Eliza invent strange stories of her neighbours. She delights to spread a slander, or to give an ill name. She mixes a little truth with a great deal of falsehood, and cares not what misery she inflicts. Whom does she resemble? Not the citizens of Zion. What language does she speak? Not the language of Heaven.

It was cowardice which drew Peter into falsehood when asked who had broken the china vase: he dreaded a blow; he dared not speak the truth. Do you not blush for him, little reader, who feared man rather than God?