Title: Under Honour's Flag

Author: Eric Lisle

Illustrator: G. Henry Evison

Release date: October 31, 2019 [eBook #60604]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tim Lindell, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

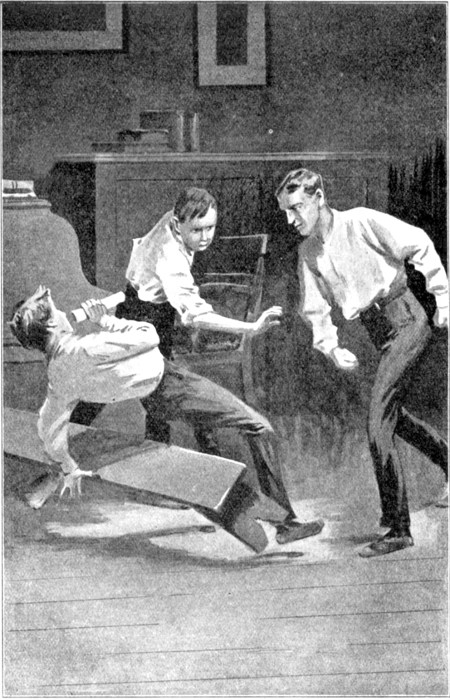

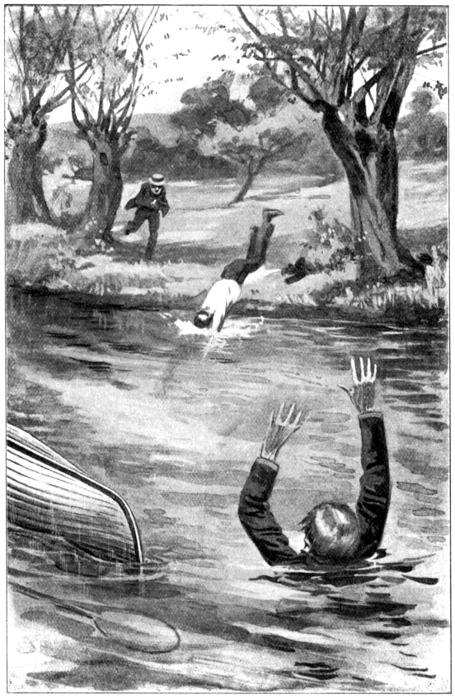

"Forgetful of all precaution Elgert struck a savage blow at him."

Frontispiece. [see p. 257.

Under Honour's

Flag

By the

REV. ERIC LISLE

WITH ORIGINAL ILLUSTRATIONS BY

G. H. EVISON.

LONDON

FREDERICK WARNE & CO

AND NEW YORK

(All rights reserved)

Butler & Tanner

The Selwood Printing Works

Frome and London

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | A Strange Affair | 1 |

| II | A Cruel Implication | 15 |

| III | Mr. St. Clive proves himself a True Friend | 25 |

| IV | Ralph's First Day at School | 35 |

| V | Making Things Straight | 45 |

| VI | An Early Morning Spin | 55 |

| VII | Horace Elgert Goes a little Too Far | 65 |

| VIII | A Mysterious Midnight Visitor | 75 |

| IX | Altogether Beyond Explanation | 84 |

| X | Counsels and Promises | 94 |

| XI | Going in for Grinding | 103 |

| XII | The Stolen Banknote | 113 |

| XIII | Divided Opinions | 122 |

| XIV | By the River Side | 131 |

| XV | The Lost Pocket-Book | 140 |

| XVI | Things look Black for Ralph | 150 |

| [Pg vi]XVII | The Plot that Failed | 159 |

| XVIII | Where the Banknote Went | 168 |

| XIX | The Lame Horse once more | 177 |

| XX | To Mr. St. Clive's | 186 |

| XXI | A House of Refuge | 195 |

| XXII | An Afternoon Ramble | 204 |

| XXIII | The Ruin and the Lonely House | 213 |

| XXIV | For the Sake of Revenge | 222 |

| XXV | Just in Time | 231 |

| XXVI | Tom Warren Speaks His Mind | 240 |

| XXVII | In the Dead of the Night | 249 |

| XXVIII | The Next Day | 259 |

| XXIX | What Tinkle and Green Caught | 268 |

| XXX | What Detained Ralph Rexworth | 277 |

| XXXI | The Tables are Turned | 286 |

| XXXII | Flogged and Expelled | 294 |

| XXXIII | Conclusion | 303 |

UNDER HONOUR'S FLAG

The late autumn afternoon was rapidly drawing in, closing ominously and sullenly, as if rebelling against the approach of the winter, and the nearer coming of the night.

Great banks of purple vapour rose in the west; and sinking towards the earth, spread abroad in hazy wreaths, which seemed to possess, in a fainter degree, the hues of their parent clouds above.

The air was heavy with moisture, which condensed and dripped from the red leaves of the sycamore, the brown of the beech, and the yellow of lime and poplar. It glistened on the rich green of the crimson-berried hollies; it begemmed the festooning webs of the weaving spiders; and brought with it a chilling breath which seemed to strike through one.

In that gloaming hour a man and youth toiled wearily up the steep hill over which the main road runs before it descends into the quaint old town of Stow Ormond; yet as they reached the summit they hastened[Pg 2] their steps, with the air of those who were drawing near to a welcome resting-place.

The man was tall and refined-looking; and though a crisp, curling beard and full moustache hid the greater part of his face, the features visible revealed determination and strong will, and their bronzed hue showed plainly that their owner had lived beneath warmer skies than those of England. And yet, despite health and good looks and strength of will, an expression of anxiety was there; and as he walked along he appeared to be more occupied with his own thoughts than in attending to the remarks of the lad by his side, whose questions he frequently left unanswered.

The boy was so like the man that there could be little room for doubting that they were father and son; a well-built, handsome youth, with the same bronzed cheek, but with an expression on his face which indicated the utmost disgust with his surroundings. This was his first experience of a damp, chill autumn mist, and he did not like it in the least.

Both the travellers were comfortably clad, though their clothes seemed cut more for comfort than with a regard to fashion; indicating that they certainly were not from the workshop of any fashionable tailor.

Reaching the top of the hill, the two wayfarers paused; and the man, pointing down into the town which lay before them, said, with a sigh of relief:

"There you are, Ralph! That is our destination for to-night; it may be our haven for many days."

"Funny looking place," laughed the boy. "But all these English towns are funny, after the plains and the mountains. And it is funny," he added, "that I am an English boy, and yet am talking like that."

"Not funny, lad, seeing that you have never set foot in your native land before. Ah me, it is not funny to me! It comes back like the faces of old familiar friends. The scenes of childhood's happiness, and youth's hopes and follies. All changed, and yet nothing changed; and I myself unchanged, and yet most changed of all! Come," he went on, "you are tired, for we have walked a long way, and have had a long railway journey into the bargain. Unless things are altered down there, we shall find a comfortable old inn where we can put up, Ralph—a real old English inn. Quite different from the hotels where we have stopped. Come on, lad!"

Changing his handbag from one cramped hand to the other, the lad obeyed the call, and trudged forward briskly with the strong, elastic step of buoyant youth. At first he poured out a string of questions relative to life in English towns; but one or two being unanswered, he glanced towards his father, and perceiving him buried in thought again, he walked on in silence, yet keen-eyed, noting everything around.

A few scattered cottages and outlying buildings[Pg 4] passed, the pair were in the precincts of the town itself; and almost one of the first houses they came to was the one the father sought—a quaint, thatched, many-gabled old place, with commodious stabling and a great creaking sign-post near the horse trough, giving the information to all who cared to possess it that this was the Horse and Wheel Inn, wherein might be found accommodation for both man and beast.

"Just the same! Nothing changed!" murmured the man as the two arrived at the spot. "Twenty years have brought no revolution here. Come, lad!" And he entered the old hostelry.

A bonnie waiting-maid met them; and in response to the man's query if they could have a room she called the landlord, a portly old fellow, with bald head fringed with grey hair, a pair of twinkling merry eyes beneath overhanging brows, and a face wherein all the principal features seemed to be entered into a competition as to which could look the ruddiest.

"Have a room, sir?" said this individual, in a voice which seemed to proceed from his boots. "Ay, that you can, sir, and all else that you require. Here, Mary girl, show the gentleman to Number Ten! Have the bags carried up, and serve their dinner in the private room."

"Number Ten!" said the guest, as he heard the number given. "Come on, Ralph, I know the way!"[Pg 5] And he led his son upstairs with the air of one who did indeed know, much to the worthy landlord's astonishment, who murmured to himself as he waddled off to attend to some waggoners—

"He must ha' been here before; but I don't remember his face in the least."

"He does not recognize me," mused his guest, in his turn. "How should he, after all those years? Poor old Simon, he has not changed much! A little stouter, a little huskier, and more shaky; that is all. Time has dealt gently with him!"

The meal, which was ordered and duly served, proved that the Horse and Wheel, whatever it might do for beasts, claimed no more than its due when it came to accommodating the beast's master, man; and the appetites of the travellers enabled them to do ample justice to the food, served in a room rendered all the more cheerful by the roaring fire—a good, old-fashioned English fire—which blazed away in the capacious fireplace.

But the meal over, the gentleman rose and donned hat and coat, turning to his son when he had done so.

"Ralph," he said, "I am going out by myself. I have not brought you across the ocean and to this place for nothing. I have business to do here which may affect all your future life. What that business is, lad, I cannot tell you just now; but you shall know of it presently. I shall not be away long—not [Pg 6]more than an hour or two—and you can spend the time as you like. I do not suppose that you will find much in the shape of literature here, beyond a copy or two of some local paper or an agricultural magazine. They won't interest you much, so you must occupy the time as best you can. Prospect around a bit, but don't miss your way, or you will find it harder to pick up trails again here than you would out yonder where we have come from."

"I shall be all right, father," the boy answered, rather pleased than otherwise to be left alone for a little. Every lad of fourteen with any spirit in him rather likes that kind of thing.

"Of course you will be. You cannot very well get into harm, and you are not the boy to get into mischief. Well, good-bye, my lad, and to-morrow if all is well, I will show you what English rural scenery is like, and you will find it is more beautiful than it has seemed to you yet." And with that the gentleman went out, leaving the boy alone.

At first Ralph wandered round the rooms and examined all the funny, old-fashioned pictures, and frowned at some old-time Dresden ornaments of shepherds and shepherdesses in Court attire, as though he was not quite sure whether they were intended for pagan idols or not; and then, getting tired of this, he put on his hat and strolled down into the inn yard, where he found more to interest him in[Pg 7] an ostler who was busily grooming a couple of powerful waggon horses. Ralph had never seen a real cart-horse before, for the horses he had been accustomed to were little, thin, wiry creatures, all sinew and bone, and spirit—horses that could go, and would go, until they dropped, but pigmies compared to these mighty creatures—the largest of all the species.

Then he picked up a long coil of rope lying near and examined it with critical eye, which yet seemed to disapprove of its texture and quality; and then, idly fashioning a running noose at one end, he coiled that rope up, and sent it with a flying jerk over a post thirty feet away.

The man stared and paused in his work.

"Ay, but ye couldn't do that again, sir," he ventured; and Ralph, with a little flush of something like conceit, immediately repeated his performance.

"That be main clever," said the man, and he shambled off to get "Tom" and "Garge" and "Luke" to come and see the young gentleman's wonderful deed.

Ralph was delighted, and he varied his work by sending the noose over one of the men as he ran at full speed across the yard. It was nothing to him; he had handled a rope as soon as he had handled anything, and he wondered at the surprise the thing caused to these men.

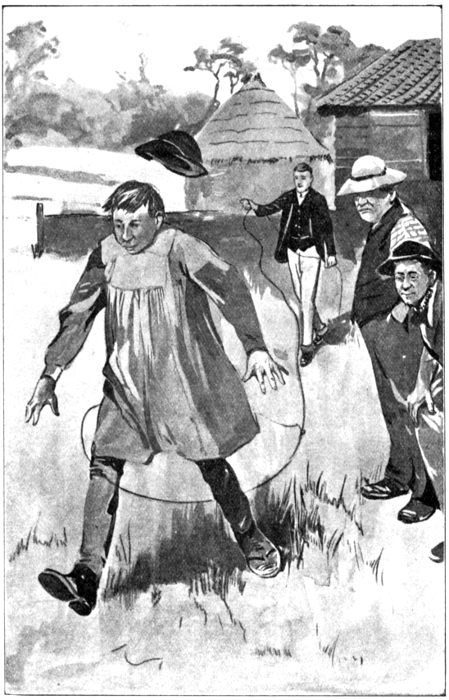

"Sending the noose over one of the men as he ran at

full speed across the yard." p. 7

A drove of cattle passed, and Ralph paused and regarded them with interest. They were good beasts, but nothing like the troublesome wild cattle which he had known. They seemed perfectly contented with everything in this life.

"They are very quiet," he observed, and the man nodded.

"They be quiet enough, sir, but there be a bull in yonder paddock; ye will see him in a minute, for they will be coming to drive him back to his shed; and he be very savage. He ha' killed two poor chaps now, and it be a risky job dealing with him. He be quiet enough as a rule; but when his temper is bad, then he is bad, too—and very bad."

"I would like to see him," was the boy's answer; and almost before the words were out of his mouth he had his wish granted; for a fierce bellow of deep-voiced rage was heard, and rushing along, a broken halter streaming behind, there came a magnificent black bull, while in his rear, shouting and waving their arms in distress, ran two men, who had evidently been engaged in bringing the monster home when he had turned upon them, and sent them spinning this way and that ere he darted off.

Every one in the way rushed to the nearest cover without ceremony; and then a wild scream of terror broke on the air, and Ralph saw, directly in the fierce creature's path, a pretty girl, seemingly but a year younger than himself; a girl transfixed with fright,[Pg 9] standing there, directly in the pathway of horrible injury, if not death!

And what could he do? He who had been used to cattle was the only one who kept his courage. Had he been in the saddle and armed with a good stock whip the thing would have been touch and go; but he had nothing, and he could not tackle the bull empty-handed.

Stay, there was one thing—the rope! A chance, but a slender one. Quick as a flash he put a couple of turns round the post he had been aiming at and gathered the noose for a cast. The bull came thundering along the road, head down, tail out, snorting with rage and defiance. If it kept on like that it would pass quite close to him. He put another turn round the post. The shorter the rope the better the chance; and then, hand and eye acting in unison, he sent the noose round his head and made his cast. If he succeeded the bull would be over, if he failed the girl must go down.

And succeed he did. It was to him quite an easy throw. The noose settled fairly over those curving horns. There was a jerk, a roar of rage and fear, and the great struggling creature was hurled forward so violently, through the force of its flight, that it fell in a cloud of scattered mud and stones, and lay half stunned and wholly bewildered.

Ralph, with a cry of thankfulness, ran forward,[Pg 10] and pulled the girl from her dangerous proximity to its mighty legs, just as a gentleman, pale with terror, rushed from a shop near by, where he had been giving some orders.

"Irene!" he cried. "My little Irene! Thank Heaven that you are safe!" Then, as he saw the bull still noosed, and now in the hands of several men, he went on—

"But who did that? Who stopped the bull in that way?" and a dozen hands pointed to Ralph, who stood there feeling rather confused and awkward, and wishing that he could run away. Young ladies were more terrible things in his eyes than were angry bulls; and this young lady was thanking him so prettily, while her father, for so the gentleman was, kept shaking his hand, hardly able to voice his gratitude. He seemed overcome with a sense of the good hand of Providence in the matter.

"You are staying at the inn," he said. "I must return and express my thanks to your father. I will take my little daughter home first and then come back. Perhaps he will be in by then. What is your name, my dear young gentleman?"

"Ralph Rexworth," the lad answered. And the gentleman answered—

"And mine is Hubert St. Clive, and if ever I can be of service to you I shall think nothing too much to enable me to show some return for what you have done for me and mine this evening."

It was really a relief to Ralph when Mr. St. Clive had gone, and he was glad to get back to his room and escape the curious and admiring crowd, though even then he could not shut the landlord out, nor prevent the admiration of the maid, who would come in on all sorts of pretexts just to have a peep at him; and so the evening wore on, and the time for his father's return drew near.

But no father came, and at last Ralph began to grow anxious. He could not tell why, but he felt nervous. Had he been alone on the great Texan plains, where his boyhood had been passed, he would not have cared in the slightest; but here he was so lonely, everything was so different. His father had been gone nearly five hours, and Ralph did not know what to make of it.

And ten came and went, and eleven; and the landlord looked in restlessly, for the old fellow was beginning to have uneasy suspicions that his guest had gone off and did not mean to return again, and there was the dinner unpaid for.

Still, he could not turn this lonely boy out, so he suggested at last that Ralph should go to bed.

"Most like your father has been detained, sir, and he won't be back till the morning," he suggested. "Even if he does he can ring us up. We likes to get to bed as soon as we can after closing time, for the days are long enough, and we do not get too much rest."

So the landlord said, and Ralph took the hint and[Pg 12] went to his room. Throwing himself beside his bed, he prayed as he had never prayed before, asking his Heavenly Father to quickly send back to him his own dear parent.

To bed, but not to sleep. What could have happened to his father? Had he met with any accident? A thousand fears and questions presented themselves to the boy's mind, until at last he fell into a restless sleep, to dream that his father was calling to him for aid; and when he awoke it was to the alarming knowledge that he was still alone—his father had not come back.

His distress was now intensified, and old Simon, the landlord, was very perplexed; but he was a good-hearted old fellow, and he saw that the boy was provided with a good breakfast, reminding him that Mr. St. Clive would be certain to be round in the morning, as he had not come the evening before, and that then they could consult with him as to what was best to be done.

"You have your breakfast, anyhow," he said. "No one is worth much without their food. Mr. St. Clive is a very good gentleman, and he owes you a lot for having saved his little daughter. I am quite sure that he will be ready to advise you."

"But where can my father have got to?" asked Ralph, and the old man shook his head.

"It is more than I can say, sir. Perhaps he will be back soon."

But no father came; and when Mr. St. Clive arrived, which he did soon after breakfast was over, he was informed of Ralph's trouble, and he looked very grave indeed.

"Run away! Nonsense, Simon?" he said to the landlord, after he had been told. "That is absurd! If this gentleman had desired to do anything so base as desert his son, he would never have brought him all the way to England in order to do so. I will see the young gentleman."

"My dear lad," he greeted Ralph, when he was shown into the room where the boy was. "I was unable to return last evening, but I understand that it would have been no use had I done so. Your father has not come back, I hear."

"No, sir," replied Ralph; "and I feel very troubled, for I cannot imagine what has kept him away. He said he would only be a short time."

"You do not know where he was going, or whether he knew any one in the locality?"

But Ralph shook his head.

"I do not know, sir. Father did not tell me anything. We have lived all my life on the ranch in Texas, and when mother died last year father sold the ranch and brought me to England; but he did not tell me why."

"It is strange; but still, it is foolish to make trouble. He may have found his business take longer than he anticipated, and—well, Simon?"

"Beg pardon, Mr. St. Clive, but one of the men from Little Stow has just come in, and he has brought me this. He says that he found it in Stow Wood, just by the Black Mere."

And what was it that he had found? What was it that should wring a cry of grief from Ralph Rexworth? Only a hat—broken, as from a blow, and with an ominous red smear upon it. Only a hat; but that hat was never bought in England. It was the hat which his father was wearing when he left the inn the previous evening; and there it lay now upon the table, a grim, silent explanation of why that father had not returned.

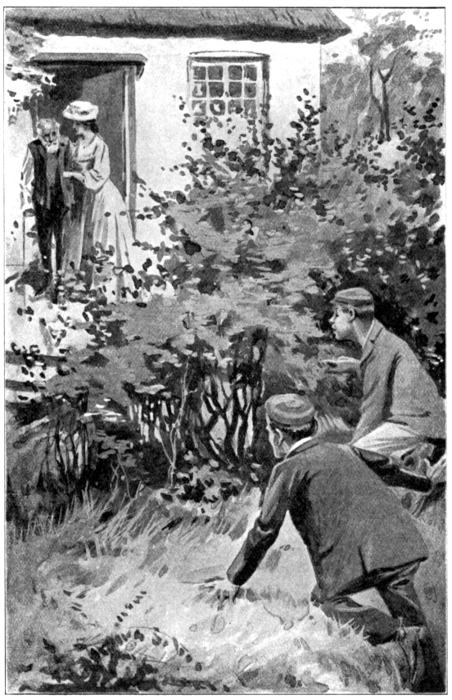

"My dear lad, it is foolish to give way to grief before you are sure that there is cause for it"—so said Mr. St. Clive to Ralph Rexworth, trying to comfort the boy and restore his confidence. "I admit that this, coupled with your father's absence, looks serious; but still, we do not know what explanation there may be to it. Come, try and be brave; trust in God, even though the very worst may have befallen; idle grief is useless. Let us go to Stow Wood and examine the place; perhaps we may discover something which this man may have overlooked. Pluck up your courage, and hope for the best; and Ralph, remember, that whatever happens you have a friend in myself, who counts it a privilege to be able to do anything to show how grateful he is to you for what you did yesterday."

Ralph, with an effort, subdued his feelings, and replied gratefully—

"You are very kind to me, sir. Let us do as you suggest. Will you take me to the place? I do not know anything of the country here, of course."

"I will go with you, and we will have this man accompany us, and show us exactly where he found this hat. Come, we will start at once."

Stow Wood was about a mile and a half from the inn, a rather dismal-looking place, where the grass grew long and dank, and where stoats and rats found a safe retreat from which to sally forth at night upon their marauding expeditions; and the grimmest, most lonely spot was around the deep pool, known locally as the Black Mere.

A dark, motionless pool it was; in some parts covered with green weed, surrounded by coarse grass.

Local superstition said that it was haunted, and though sensible people laughed at that, still the appearance of the spot was enough to give rise to such a legend.

"I found the hat just here, sir," said the man, bending down and pointing to a clump of blind-nettle. "You can see where it was lying, sir."

Mr. St. Clive and Ralph stopped and examined the place. It was clear that something resembling a struggle had taken place here, for the tall grass was trampled and beaten flat, and, in some places, the earth itself had been cut up, as though by the heels of boots. Mr. St. Clive felt very grave—if ever anything seemed to tell of a tragedy, this did—and he said to Ralph—

"My poor boy, I must own that there seems every appearance of foul play here. We shall have to see[Pg 17] the police. You are quite sure that your father told you nothing, however unimportant it may seem, which might give us an inkling of where he was going?"

"He said nothing, sir," answered Ralph sadly. "It is all a mystery to me. But now we are here we may as well learn all that we can."

"What more can we learn, Ralph?" asked Mr. St. Clive. "This silent spot will not speak and tell us what happened."

"Not to you perhaps, but it will speak to me, sir. I have been brought up on the plains, remember, and grass and trees may tell me more than they can tell to you. First, sir, is this a direct road to anywhere? I mean, is it a general thoroughfare?"

Mr. St. Clive shook his head.

"No, Ralph. It is a rarely frequented spot. The village people are half afraid of it. It is a short cut from Stow Ormond to Great Stow, and it would argue that your father must have been familiar with the place for him to have taken it."

"Where else besides Great Stow does it lead to, sir?"

"Why, my lad, to nowhere in particular. It takes you out the other side of Stow Common, and, of course, from there you can go where you will."

Ralph nodded.

"So that we may suppose that any one crossing here would be going to Great Stow?"

"Yes. It would save him going all round through Little Stow."

"Very well, sir. Now we will go to the side of the wood nearest to the inn."

"Why?" asked Mr. St. Clive in surprise.

"Because I want to know whether my father crossed this place in going from the inn; and if so, I want to try and see where he went to. There is a lot to learn here, sir; but I must start at the beginning."

Mr. St. Clive was impressed, though he could not understand what Ralph meant; and so together they went back to that part of the wood which bordered upon Stow Ormond, and here Ralph began to walk to and fro, carefully surveying the grass, until presently he stopped and said—

"My father did cross here. He got over that stile."

"How do you know, Ralph?" asked Mr. St. Clive. "I confess that I see nothing to indicate it."

"Why, it is quite clear, sir," answered the boy. "See, the ground here is soft and muddy, and this is the imprint of my father's foot here in this soft red clay. That has taken the mark like wax. That is his square-toed boot."

Mr. St. Clive had to admit that so far the boy was correct. Some one wearing a square-toed boot had stepped into a little heap of clay, and the footmark was quite clearly defined.

"Now," Ralph went on, pointing to the stile, "here is a mark of clay on the stile, so he must have crossed[Pg 19] here, and here the grass has been trodden down as he went on."

This latter sign was nothing like so clear, but the boy, used to reading tracks in the far-off West, showed the man how the blades of grass were turned from the weight that had trodden on them; and as they walked forward the traces became even plainer, leading past the pool, and on towards the common; and Ralph gave a cry as he studied the ground.

"Here are two people walking now," he said; "and one wears pointed boots!"

"The man who brought the hat to us," suggested Mr. St. Clive.

"No, sir. He wore big boots, with nails in them. You can see the marks of those quite plainly, and he came here last of all."

"How do you know that?" demanded Mr. St. Clive, very interested.

"Because the marks that he has made are over all the others," was the explanation. "Let us go on."

They followed the traces, faint though they seemed, until they reached the common; and here, though Ralph studied the ground for nearly an hour, he could discover nothing. Several roads crossed the common, and the men must have traversed one of these, but which one there was nothing to show.

Back to the pool they went, and here Ralph paused; and Mr. St. Clive, looking at him inquiringly, said—

"Well, what now, my boy? Have you learnt anything?"

"Yes—a lot, sir; but I do not understand it. Let me tell you what these signs tell me. My father crossed here alone, and went somewhere across the common, and I do not think that it could have been very far away. Then he came back alone——"

"But the second man?" queried Mr. St. Clive.

"One moment, sir. He came alone, and he stopped to light another cigar just here. Look, here is the match half-burnt, and the stump of the one he threw away."

"Yes; go on," said Mr. St. Clive, nodding his head. "You have reason for what you say."

"Now, some one followed my father back, and he wore rather small boots with pointed toes——"

"Plenty of gentlemen do that. I wear such boots myself, you see."

"I know, sir. This man was dodging my father, and when he stopped to light his cigar the man stopped too, just over there behind that hedge."

"My dear lad, what makes you say that?"

"The mark of his feet are there, and I think he fired at my father more than once. He fired once and missed, I know, because this tree has got a bullet in the bark, and I am going to have it out! Then he ran forward, and there must have been a fight, and father fell just here. Look, you can surely see where he lay? See the length where the grass is crushed;[Pg 21] and see these two marks—a heel and a toe; that means, that some one knelt beside him, and——. Look, look, sir!"

A glimmer of something bright in the long grass caught Ralph's eye, and, stooping, he picked up a watch and chain, and a purse, which had evidently been thrown hastily aside.

"Whoever killed my father searched him, and wanted something in particular. It was no robber, for then he would have taken these and not thrown them down."

Mr. St. Clive could only look on in silence. There was something very strange in the boy thus unfolding the incidents of a strange mystery, reading them from almost invisible signs upon the grass. And Ralph continued—

"Then the man ran away and came back with a cart—you can see the marks of the wheels. See, they come close up here! And here he drove off again. I suppose that father was in the cart—that is what he brought it for. The horse went a bit lame, too, in the off forefoot. That is all the place can tell me, sir."

All! Mr. St. Clive was amazed that the boy was able to see so much, and he followed his reasoning, noting how one footmark partly obliterated another, proving that it had been made after it. That a strange meeting had taken place in that lonely wood seemed indeed all too likely, but beyond that all was[Pg 22] mystery. Why had Mr. Rexworth entered this place, whither was he going, and who was the man who had come after him?

Ralph had his knife out, and was busily cutting away the bark of one of the trees which stood close by. His action proved that he had not been wrong in his conjecture—a flattened piece of lead was embedded there, and Frank put it into his pocket.

"Perhaps one day that may tell me some more," he said.

But there was nothing more to do there, though Mr. St. Clive said that he would see that the wood was searched through, and that the mere was dragged; and then, trying to speak comforting words to Ralph, he returned with him to Stow Ormond. And as they entered the inn, a tall, handsome gentleman, with one hand in a sling, came out, and seeing Mr. St. Clive, greeted him with: "Hallo, St. Clive, I hear that your little girl had a narrow escape last night!"

Mr. St. Clive frowned.

"Yes, from your bull, Lord Elgert. You ought to have the brute properly guarded. If it had not been for this young gentleman, Irene might have been killed."

Lord Elgert stared at Ralph, and his look was not pleasant.

"Oh, is this the young man who noosed him? Well, he has broken the bull's knees; but, however, it is fortunate that he was at hand. By the way, what is[Pg 23] this that Simon tells me. Something has happened in Stow Wood?"

"I fear so," replied Mr. St. Clive; and he narrated briefly what they had discovered.

Was it fancy, or did Ralph notice that handsome face turn a shade paler when mention was made of the bullet cut from the tree? Somehow the boy did not like this wealthy gentleman, though he knew not why he should regard him with enmity. When Mr. St. Clive had concluded, Lord Elgert said—

"Dear, dear! How strange! But still, you do not know that anything has happened. You will tell the police, of course. Can you give a description of your father, my boy?"

"I can show his likeness, sir," replied Ralph, taking out his pocket-book. "Here it is!"

Lord Elgert took the photograph, but as he looked at it he gave a whistle of surprise.

"So this is the missing man?" he said. "St. Clive, perhaps, I can tell you something of interest. Last night my place was broken into, and I woke up to hear a man in my study. I went down and switched on the electric light, so that I could see the rascal quite plainly. He turned and tried to bolt, but I closed with him, and in the rough-and-tumble he managed to cut my hand open and clear off. St. Clive, I am positive that the man was none other than the original of this likeness, and——"

He was interrupted by a passionate cry of pain and[Pg 24] anger, and Ralph, snatching the photograph from his hand, stood confronting him with blazing eyes.

"It is false!" he cried. "You know it is false! I believe that you are responsible for my father's disappearance!"

"I believe that you are responsible for my father's disappearance."

So did Ralph Rexworth cry in his anger; and Lord Elgert started, and his face grew dark with rage.

"You impudent young dog!" he shouted, raising his stick; and the blow would have fallen, had not Mr. St. Clive stopped it with his arm.

"Lord Elgert," he said sternly; for he was shocked at the callous way in which the charge had been made, "I cannot stand by and allow that. You have made a very serious charge——"

"Nothing so serious as that young rascal has made. I am surprised that you stand by and listen to it, St. Clive; but you always were antagonistic to me! I assert what is fact. My place was broken into——"

"Did any one but yourself see this man?"

"An absurd question! Who was there to see him? By the time the alarm was given he was gone. I shall have to tell the police of that photograph; it will be wanted to help in tracing him. I expect this story is all nonsense; and upon inquiry it will[Pg 26] be found that the farthest these two have travelled is from London. Most probably this boy, who makes such unfounded charges, knew well the business which brought his father here. The story of what happened in the woods is really too romantic. If two people were there, the second was most likely an accomplice; and they have gone off, leaving the boy here to see what he can learn, or pick up. You are easily deceived, St. Clive." And Lord Elgert turned upon his heel with a mocking laugh.

But ere he could go, Ralph stood in his path, regarding him with a fixed stare.

"I do not know you," he said. "I never saw you before; but I can tell friend from enemy, and you are an enemy. I am only a boy; but one day I will bring your words back to you, and make you prove them."

"Out of my way, you young rascal!" came the answer, "or I will have you in prison before long. St. Clive, I wish you joy of your young friend. Take my advice, and keep a sharp eye on the silver, if you suffer him to enter your house."

Ralph would have surely been provoked into some foolish action had not Mr. St. Clive laid a gentle hand upon his shoulder, and led him back into the inn; and then the boy quite broke down.

"Oh, sir! Oh, sir!" he cried. "To say such things about my dear father—my dear, kind father! But he shall prove them," he added fiercely. "I[Pg 27] will make him prove them. I believe that he knows something."

"Ralph," answered Mr. St. Clive quietly, "because Lord Elgert has been both unkind and foolish, that is no reason why you should talk wildly. To say that Lord Elgert has had anything to do with your father's disappearance, seems to me to be the very height of folly. He is a rich man, and one of our justices——"

"Where does he live, sir?" queried Ralph suddenly.

"At Castle Court, near Great Stow. Ah," he added, as he saw Ralph's look, "I know what you are thinking—that it is in the direction whither your father was going! But remember, that will be equally applicable to Lord Elgert's story that your father was going there. It is most likely that some one in a measure resembling your father, did break into Castle Court—we have not the slightest reason for discrediting Lord Elgert's statement—and in the confusion of the struggle, he did not clearly distinguish his opponent, and so says that he resembles this photograph. Mistaken identity is a common occurrence, and——"

"You do not believe his story, sir? I could not bear to think that."

"I do not, Ralph. If I did so, I should still feel my debt of gratitude to you; but I do not believe it. I am not so foolish as to mistake between a gentleman and a thief; and though I have not seen your father, I think that I can see him in you and your[Pg 28] manner. Now be brave, and do not trouble about what his lordship said. He was angry because you spoke as you did; and though it was natural, your language was not very polite." And Mr. St. Clive smiled slightly. "Now let us talk sensibly. First, you cannot stay here by yourself; therefore, disregarding the warning I have received, I invite you to be my guest for the time, until we can see what is best to be done. What money have you of your own?"

"Only a few shillings, but there is the purse, sir." And Ralph opened the purse which they had picked up in Stow Wood. "Here are five sovereigns, and two five-pound notes, sir."

"Then we had better pay the innkeeper and make a start. Simon"—as the old fellow came in answer to the bell—"I am going to take this young gentleman home with me. If his father should return, or if letters arrive, you will let us know. Make out your bill. And, Simon, I suppose that you did not recognize Mr. Rexworth at all?"

"Why, no, sir; I cannot say that I did! But he knew the place, sir; and when I told the girl to show him up to No. 10, sir, he just went straight up to it. He knew the Horse and Wheel, sir."

"Well, get your bill ready."

The old man went out. It was something of a relief to know that he was going to be paid; for he had begun to have some doubts about the matter.

So it came about that Ralph Rexworth was taken home by Mr. St. Clive; and there he was received with kindness and warmth by that gentleman's wife, while little Irene smiled shyly, and put out one dainty little hand for him to take in his brown palm.

"I thank you very much," the little lass said. "I think that horrid bull would have killed me if it had not been for you." And Mrs. St. Clive shuddered as she listened; for her husband had told her how great was the peril from which Irene had been rescued.

Leaving the two young people to make friends, Mr. St. Clive took his wife aside and told her of the strange position in which their young guest was placed.

"The boy does not seem to have a friend in the world," he said. "And he is undoubtedly a gentleman, Kate. What is to be done? His father may return; but I confess that it looks as if a tragedy had taken place. It was wonderful how the lad pieced together traces which were invisible to me. I fear that something bad has occurred. As to Lord Elgert's idea, I do not put much faith in it. Elgert is too fond of thinking evil of people—he is one of the most merciless men on the bench. What shall we do, Kate?"

"Do?" replied his wife, with a fond smile. "Why, Hubert, you have already determined what to do!"

Her husband laughed pleasantly.

"I confess that I have. Still, I like to have your desire run with my own. You want this lad to stay here?"

"Yes, Hubert. If he is lonely and friendless, let us be his friends; for had he not rescued her, our dear little daughter would have been killed."

So husband and wife agreed; but when they went to Ralph they found that he was not quite willing to accept the invitation.

"I know how kind it is of you," the boy said. "And it is true that I have no friends, and nowhere to go; but I—I cannot live on your charity. I want to earn my living somehow."

"That is good, Ralph," was the hearty reply of Mr. St. Clive; "but you must be reasonable. There is such a thing as unreasonable pride. You cannot earn your living in any calling as a gentleman, without you are fitted for it. Your life on the plains, and life here, or in London, would be very vastly different. If you had friends in Texas we might send you back again——"

"No, no, sir!" cried Ralph, interrupting him. "I could not go back. Here I must stay for two reasons. I must live to find out what has become of my father, and I must clear his name from the accusation that man made."

"Your first reason is good; your second I do not think that you need worry over. Then you will stay? Well, then, you must certainly let the wish of my[Pg 31] wife and of Irene conquer your pride. I want to help you all I can; and if presently it is better for you to go, I promise you that I will not seek to detain you."

"Do stop, Ralph," added Irene, who, pet as she was, had stolen into her father's study, and heard what was said. "I want you to stay; and I want you to teach me how to throw a rope like that, though I should never dare to throw it at a bull. Please stay."

And somehow Ralph looked down into that upturned little face, and he could not say "no."

"It is very good of you, sir," he murmured, to Mr. St. Clive, "especially after what Lord Elgert said——"

"My lad, do not be so sensitive concerning that."

"But I cannot help it, sir. He first called my father a thief; and he—he—you know what he said about your silver?"

And Ralph turned very red.

Mr. St. Clive understood, and sympathized. He liked Ralph all the better for being keenly sensitive about it.

"There, let it go, my dear boy. Now, once more, business. Have you any luggage, save these two handbags?"

"In London, sir. Two great trunks. Father left them at the station. Here are the papers for them." And the boy took a railway luggage receipt from his pocket-book.

"This is important. We may find something to[Pg 32] help us in those trunks," cried Mr. St. Clive. "Of course, I am not legally justified in touching them, Ralph; but, under the circumstances, I think that I might do so. We must have them here, and examine their contents. We may then discover what brought your father to Stow Ormond; and that, in its turn, might give us some clue as to what may have happened."

"I do not think there is much doubt as to what has happened," sighed the boy. But Mr. St. Clive would not listen to that.

"Never look at the darkest side, lad. There is a kind Providence over all, and we must never despair. Now, our very first task must be to obtain your travelling trunks without delay."

Mr. St. Clive lost no time in putting this resolution into practice. The trunks were got down from London, and opened; but, to their disappointment, their contents revealed nothing which tended in any way to throw a light upon the mystery—clothing, a few mementoes of their Texan home, and—and in view of Ralph's future welfare this was most important—banknotes and gold to the amount of £3,000!

"No need to feel yourself dependent upon any one now, Ralph," was the remark of Mr. St. Clive, as they counted this money; "and no need to give another thought to Lord Elgert's suspicions. People possessed of so much money do not go breaking into houses,[Pg 33] risking their liberty for the sake of what they may be able to steal."

Now, though Irene St. Clive was delighted, and would have been quite content for Ralph to have stayed as her companion, her father did not look at matters in that way; and he had a serious talk with Ralph, having first quietly questioned him in order to ascertain his acquirements.

"You see, Ralph," he said, "what a man needs in England is quite different from what he may need abroad. You can ride, shoot, and round up cattle; but that is no good here. Your father has given you a general education, so that you are not a dunce; but it is nothing like what you will need as a gentleman here. Knowledge is power and your desire to clear up the matter of your father's disappearance demands that you should acquire all the power obtainable. My advice—I have no right to insist, remember—but my advice is that you should spend a couple of years at a first-class school—we have a splendid one here—and if you work honestly during that time, with your intellect you ought to have made a good headway. What do you say?"

The boy knit his brows. To one who had passed his days in a wild, free life, such a prospect did not hold out many charms; but then Ralph was fond of learning, and had sometimes sighed that he could not learn more. Besides, his one object in life was to solve the matter of his father's disappearance,[Pg 34] and clear his name from any foul charge. In his heart, Ralph had resolved ever to live under honour's flag. He looked up, and answered frankly—

"I will be guided entirely by you, sir, unless my father comes back; then, of course, I should do whatever he directed."

"My feeling is, that had your father elected to remain in England he would certainly have sent you to school. Now, Ralph, I am going to be frank with you. We have, as I have said, a splendid school near here; but amongst its pupils is Horace Elgert. I fear that he takes after his father somewhat; and if Lord Elgert has said anything, or does say anything to him when he knows you are there, young Horace may try to make it unpleasant for you. Do you understand?"

"Perfectly, sir," replied Ralph.

"And will you go there?"

Ralph looked Mr. St. Clive in the face, and he answered firmly:

"Yes, sir. The boy's being there is nothing to me. I will go."

"Good!" replied Mr. St. Clive, with a nod of appreciation. "We will go over and see the Headmaster to-morrow."

"He is a fine young fellow, but his past life has been spent amidst very different scenes, and he is far from having a fitting education. But he is very intellectual and will acquire knowledge quickly. His father must have been a gentleman, and he has taught his son to be one also."

It was Mr. St. Clive who spoke, and his words were addressed to Dr. Beverly, the principal of Marlthorpe College—the best school in all the county.

A fine-looking man was the doctor, tall, erect, dignified, with firm face and piercing eyes—eyes which could look terribly severe when their owner was angry, but which otherwise were gentle, and even mirthful.

Dr. Beverly was proud of his school, but prouder still of his work. He did not labour to make scholars only, but also to build up men—good, noble men—who should be a credit to the old school, and a blessing to their country. Work or play, the doctor believed in everything being done as well as it could be, for his watchword was "Whatever you do, do it to the[Pg 36] glory of God," and nothing can be done to God's glory that is not done as well as it possibly can be.

Mr. St. Clive had explained how Ralph came to be under his care, and had told the doctor how much he owed to him; and he finished by mentioning the cruel statement which Lord Elgert had made, and the angry way in which Ralph had answered it.

"I tell you this," he said, "that you may know everything. I attach no weight to Elgert's statement myself—it is too absurd, but you must exercise your own discretion," and the doctor smiled slightly.

"Lord Elgert is rather prone to make rash statements," he said. "I shall be quite willing to receive your young friend, and I will do my best to turn him into a good man."

"That I am sure of," was the hearty reply, "and I am also sure that you will have good material to work upon. Then I will bring Ralph over."

"And do you propose that he shall board here entirely, or return to you every Saturday, as most of the lads do?"

"Oh, come home. That is how I did in my day—you know I want to watch the boy. Good-day, doctor," and Mr. St. Clive came away.

Marlthorpe College was a splendid old building, with large playing fields at the back, and a great quadrangle in front, to which entrance was gained through a pair of great iron gates, against which the porter's lodge was built.

The school itself was at the other side of the quadrangle, directly facing the gates—a two storey building, with the hall, in which the whole school assembled upon special occasions, below, and with the classrooms above. It had two wings; the one to the right being the doctor's own residence, and that on the left the undermaster's quarters.

At the back there were again buildings on the right and left—on the left junior dormitories, the dining-hall, and matron's rooms; and on the right senior dormitories and studies.

Mr. St. Clive drove home and told Ralph the result of his visit.

"I am sure that you will like the doctor," he said, "and you will find your companions a nice lot of fellows. Of course there will be some unpleasant ones; and Ralph, if things are as they used to be, you will find that there are two sets of fellows—those who mean to work honestly, and those who never intend to take pains. I need not ask which set you will belong to," and Mr. St. Clive smiled. "But now," he added, "I want you to try and be brave. You have a very terrible sorrow, I know; and it is hard to put it from my mind——"

"It is never from my mind, sir," interrupted Ralph sadly. "I am always thinking of it."

"But you must not brood over it. To do that, will unfit you for all else. Leave it with God, Ralph, and do not let even so great a grief interfere with life's[Pg 38] duties. Will you promise me to try and remember this?"

"I will indeed, sir," answered Ralph. "If I have lost father, I mean to try and think that he knows, and just do that which would please him."

"That is good; but still better is it to remember that we have to try and do that which shall please our Heavenly Father. Now, Ralph, I suppose that out where you made your home, blows often were the only way of settling troubles. I do not say that blows are never justifiable, for sometimes we are placed in such circumstances as warrant fighting, but do not be too ready to quarrel, or to avenge every fancied insult with your fist. But there, I am sure that I can leave that to you. Now come to lunch, and then we must see about starting."

"I am so glad that you are coming home every week, Ralph," so said Irene St. Clive, when she heard of the arrangements which her father had made. "My own lessons are finished on Friday, and we can have all Saturday to ourselves. I shall count all the days until each Saturday comes."

So with kindly words to cheer him on his way, Ralph started off with Mr. St. Clive, and was introduced to Dr. Beverly; and Ralph felt that he liked the doctor from the very first moment that he saw him; and he determined that he would do all that he could to get on and prove to Mr. St. Clive that he meant to keep his word.

Then when his friend had gone, the doctor questioned Ralph to see just what he knew; and at the conclusion of the examination he laid his hand on his shoulder.

"My boy," he said, "it is my desire always to have the fullest confidence in my scholars, and also to enjoy their confidence. I want you to remember that I desire to be your friend as well as your master, and that out of school hours I am always glad to see any of my boys who want to talk with me. I do not mean who want to come tale-bearing," he added, and Ralph smiled as he answered—

"Thank you, sir. I think I understand."

"You will have to be in the Fourth Form at first, that is the lowest Form in the Senior House," the doctor continued. "But if you work well, you will soon be in the Fifth. Now, if you will come with me I will introduce you to your master, Mr. Delermain, and I think you will find him ever ready to help you in any way he can."

Ralph thanked the Head again, and followed him, with more of curiosity than of nervousness, to make the acquaintance of the boys with whom he was to study; and twenty pairs of eyes glanced up as the Head opened the door, and then dropped as quickly when they saw who had entered.

But the master rose from his seat and came forward to meet the doctor, who said, patting Ralph on the shoulder—

"I have brought you a new scholar, Mr. Delermain. This is Ralph Rexworth, and he is the young gentleman of whom you have heard—the one who saved Mr. St. Clive's daughter." Hereat the eyes were stealthily raised, and glances of something like respectful awe followed. Of course every one there had heard of the incident about the bull, and of the disappearance of Mr. Rexworth.

"Rexworth is rather backward," the Head continued. "His life has been spent abroad, and he has not had the opportunities for study; but I believe that he will soon pick up." And with this Dr. Beverly went, and Mr. Delermain, having spoken a few words of welcome, beckoned to a boy to come forward.

"Warren, let Rexworth sit beside you this afternoon, and give him a set of the sums we are doing. If you find them too difficult," he added to Ralph, "do not hesitate to come to me."

But Ralph did not need to ask for aid, he could do the sums and the exercises that followed. Indeed, he did better than some who had been there longer, notably one big lad with a sickly flabby face, who was seated at the bottom of the class, and who received a reprimand from his master for his indolence.

"It is shameful, Dobson! Here, a new boy has done better than you have. Your idleness is disgraceful."

A writing exercise followed; and Ralph was bending over his book, when flop!—a wad of wet blotting-paper[Pg 41] hit him in the cheek. He looked up, but every one seemed busy with their work, so wiping his cheek he put the wet mass on one side, and went on with his task. Flop! A second wad came. Ralph noted the direction, and saw that at the end of the form Dobson was seated, and Ralph had his suspicions. Pretending to be absorbed in his work, he kept a covert watch; and presently he was rewarded by seeing Dobson extract a third wad from his mouth, where he had been chewing it into a convenient pellet, and under cover of the boy in front of him prepare to fire it by a flick of his thumb. Ralph raised his eyes and looked him full in the face, and, somehow, Dobson seemed confused. He turned red, and bent over his work hastily; and no more pellets were fired at Ralph that afternoon.

It seemed rather a wearisome afternoon to the boy, used as he was to his open-air life, but he worked away with all his might; and presently the bell rang and work was over; and then Warren, the boy beside whom he had sat, came to him and held out his hand.

"I am first monitor of our form," he said, "and I hope that we shall be friends. If you come with me I will take you round the school."

"Rexworth."

Ralph turned as his name was called; his master stood there.

"I want you a few minutes. Warren, you can take[Pg 42] him round afterwards. I want to arrange about his study."

"We have only got one vacant, sir," the monitor said. "Charlton has that."

"I know," was the quiet answer; and then, when Warren ran off, the master turned to Ralph.

"Rexworth," he said, "I must explain that in our form every two boys have one study between them, and as you heard Warren say, we have only one study that is not fully occupied. A lad named Charlton has it, and you must chum with him. It is about him I want to speak to you."

"Yes, sir," said Ralph, wondering why his master spoke so gravely.

"Rexworth, I am sorry to say that Charlton is not quite in favour with his schoolmates. His father got into some trouble and has disappeared—it is supposed that he is dead—and the boy managed to gain a scholarship at another and poorer school, and has come here. He is a real nice lad, but very weakly and timid, and the others put upon him, partly on that account, partly because of his father's disappearance, and partly because he is poor—a sad crime in the eyes of many. It would have been wiser, I think, if he had not come here, but Dr. Beverly wished him to do so. I wish, Rexworth, that you would try to be his friend, for he needs one; some of the lads are nice enough to him, but he seems so very much alone."

"I would like to help him, sir," was the ready answer. And the master smiled.

"I thought that I was not mistaken in you," he said. "Look, there the lad is. Charlton, come here."

The lad came up. He was a pale boy, very delicate in appearance, and with a sad, wistful face.

"Yes, sir," he said.

"Charlton, there is only one vacancy in our studies, and that is with you. Rexworth will have to chum with you." The boy cast a startled glance at Ralph. "Take him and show him where it is, and try to make him feel at home."

"Yes, sir." The boy beckoned to Ralph. "Please come with me," he said, in troubled tones, as if he doubted whether Ralph would care about sharing the study with him.

"Have we got to be chums?" asked Ralph; and the other boy nodded.

"Yes. That is what we call it. It means sharing studies; but you need not speak to me if you don't want to, and I will not be in the study much. I am not as it is, for they are always disturbing me and spoiling my things."

"They! Who?" demanded Ralph; and the lad answered—

"The other chaps and the Fifths. Dobson, in ours, and Elgert of the Fifth, are the worst. They go in and spoil my things."

"They have no business to, of course?"

"Go in? No, of course not—only the two who chum have any right in it. Here we are, and—there, they are in now!"—as a scuffling and burst of laughter came from the inside of the study before which the boy had halted. "Oh, what are they doing! Will you stop until they have gone?"

"Not I," answered Ralph grimly. "That study is mine as well as yours, and I mean to see that we have it to ourselves, Charlton. Come on, and we will see what is up." And saying this, Ralph threw open the door and walked into the little room, followed by his companion.

A burst of laughter greeted Ralph's ears as he opened the study door, and some one said:

"Look sharp. Here he comes! Hurry up there, Elgert!"

But the laughter died away somewhat awkwardly when the boys saw that Charlton was not alone, and one or two of the boys came up to Ralph.

"Hallo, you new fellow! They surely haven't put you to chum with Charlton, have they? What a shame! I should kick against it. Some one else must make room for you."

Such were the remarks of those who had taken a fancy to Ralph, but he paid no heed to it all. He just calmly gazed round, as if counting the number of boys there and taking their measure; and then he quite as calmly shut the door, locked it, and put the key in his pocket. Those present looked in surprise for a moment—some laughed, and one, a tall, handsome boy, came haughtily up to him.

"What do you mean by that?" he demanded. "How dare you lock that door?"

Ralph regarded him with the utmost coolness. No one had told him who the boy was, and yet he seemed to know—he felt sure that this was none other than Horace Elgert himself.

"Wait a bit," he said calmly. "So far as I understand, this study belongs to Charlton and myself. We have a perfect right to lock the door."

"But not to lock us in," retorted Elgert. "Open it at once, and think yourself lucky that you don't get a licking for your impudence!"

"Steady!" was Ralph's answer. "It seems to me that if you had not been where you have no right to be, you would not have got locked in; and now that you are here, you must wait my pleasure as to going out."

This was beginning school life with a vengeance, but Ralph believed in settling things once and for all, and his indignation was hot as he saw what these half dozen lads had been doing.

But Horace Elgert was not a boy to be spoken to like that, and he came striding up to Ralph to take the key by force.

"I will soon settle you," he began, and he aimed a blow at this impertinent new boy's head, only somehow the blow did not get there. Ralph adroitly stepped aside, and the Honourable Horace Elgert stumbled to the ground violently.

"A fight! A fight!" cried the rest; but Ralph smiled and shook his head.

"Oh, no, my friends. I have something better to do, and this is not the place for fighting."

They were staggered. They could not understand this coolness and, moreover, they had all heard about Ralph having tackled the bull, and the story had grown somewhat. They stood considerably in awe of this boy from the Western plains, and they began to wish that they were anywhere else than in his study.

Horace Elgert got up, his face white with passion but he made no more attempts to take the key from Ralph.

"You are right," he said, in suppressed tones; "this is not the place to fight. Open the door, and we will soon settle things."

"Presently," was all the answer he got. "Now, then, let us see what you have been up to."

He glanced round at the books tumbled on the floor, at a desk upset, at an ink-bottle on its side, and then turned to his chum.

But Charlton was standing, looking very white, and staring at a picture on the wall—the picture of a lady, and beneath it some one had written—

"This is Charlton's mammy. But where is his daddy? Puzzle—Find daddy, and tell the police."

Ralph felt his nerves tingle. He felt sure that Elgert had done that, and he remembered the words of Lord Elgert respecting his own father.

"Who did that?" he said, and no one answered. He went up to Elgert. "Did you do it?"

"Well, if I did, what is it to do with you? Mind your own business!"

"Take that scrawl down. Quick, or I shall lose my temper, and then I fancy some one will get hurt! Down with it! That is right"—as the other, considerably startled, pulled the writing down. "Give it to me."

It was remarkable how the daring of the one lad held the half dozen in check. Elgert handed him the paper, and Ralph tore it up and threw the fragments into his face.

"Now then, you have upset this room. Just put it straight again, and look sharp about it!" he said. "And please to understand that Charlton and I are chums, and mean to stick together. Oh, and I want a word with you"—and he walked up to Dobson, who turned a trifle more pasty-looking than before. "Do you know what these are?"

Ralph produced two wads of chewed blotting-paper from his pocket as he spoke, and Dobson blustered—

"You keep to your chum, since you are so thick with him. I don't want anything to do with you. I say, you chaps, are you going to let him crow over you like this? Rush him!"

"Good advice; only, why don't you do the rushing first?" said Ralph. "I asked you if you recognized these. If you don't, I will tell you what they are—they are pieces of blotting-paper, which you chewed and then threw at me. They came out of your mouth,[Pg 49] and they are going back there again—when I have mopped up this ink which you have spilt." Ralph suited the action to the word, and presented the two unpalatable-looking objects to Dobson, who was at once a coward and a bully. "Now, then, open your mouth!"

"I won't! Who do you think that you are? I—— Oh!"

For Ralph did not argue. He grabbed hold of Dobson, and with a quick jerk sent him backwards across the little study table.

"Oh, oh! You are breaking my back!" howled the bully.

"Open your mouth!"

"I won't! Oh, help me, you fellows—he will break my back! Oh! Ugh! Ow! I am choking!" For, just as he opened his mouth to yell, Ralph had pushed both those pieces of blotting-paper in.

"Now, then, take them," he said. "Quick, or it will be the worse for you!"

Dobson, with many queer grimaces, had to comply—it was the most unsavoury morsel which he had tasted for many a day.

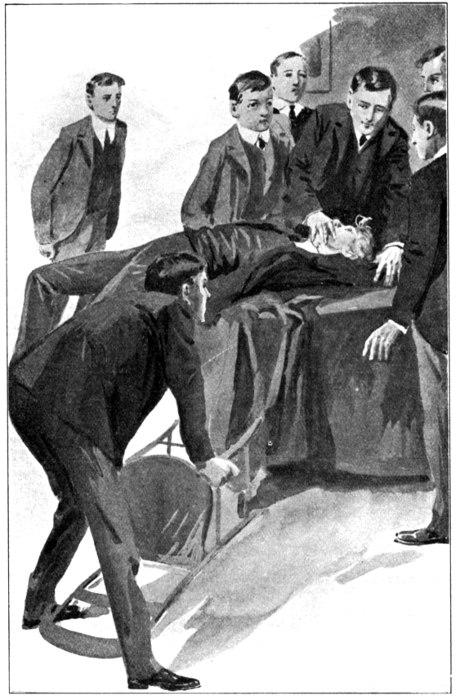

"Dobson, with many queer grimaces, had to comply." p. 49

"Now! Ah, I see that you have straightened things!" Ralph went on. "Now you chaps can go, and the next time you want to come into our study take my advice and ask leave, or there will be more trouble. Clear out!"

And he unlocked the door and flung it open.

And out those half dozen boys went, looking considerably crestfallen and stupid, and knowing also that they were cowards—they were all frightened by Ralph, so greatly does one of dauntless bearing affect a number.

But one boy turned, and that one was Horace Elgert, and he came back and gave Ralph look for look.

"Look here, you new fellow!" he said, "you have been very clever, but you have done a bad day's work for yourself. You have made one enemy at least. As for that insult which you offered me, you will have to fight me for it; and as for you, you miserable cub"—and he turned towards Charlton, who cowered back before his raised fist—"as for you, I will——"

"Hold hard—you will do nothing!" answered Ralph, with the utmost good humour. "You are talking tall, that is all about it. Now, take my advice, and go; and when you are calmer, you will see things differently. And then, as to fighting—well, I shall not run away in the meantime. Clear!"

And with that he shut the door and locked it behind his discomfited foes. Then, seating himself, he looked at the bewildered Charlton, and laughed again as he saw the look of admiration in his face.

"There, I think that has taught them a lesson! We shall not have them upset our study again," he said. "One must maintain one's rights, and we may[Pg 51] as well begin as we mean to go on. So this is our study, is it?"

"Yes, if you will share it with me," the other boy said. And Ralph answered—

"Share it? Of course I shall share it with you! Did not you hear Mr. Delermain say that we were to share it?"

"But most fellows don't like me, because—because——"

"Never mind why," interrupted Ralph, anxious to spare the boy's feelings. "I heard something about your father being gone; well, my father is gone, you know"—and Ralph's voice shook a little—"and so we two ought to be chums, and help each other. Then, I suppose that you know more than I do; for, except at roping a steer or rounding up a herd of cattle, I am afraid that I am not of much use. You will be able to help me on no end."

"What! I help you?" gasped Charlton. "How can I do that?"

"You know Greek and Latin, and goodness knows how much more, that I am only just at the beginning of, and you will be able to give me a hand with it. I want to get on and pick up things as quickly as I can."

"I might help you that way, if you would let me," the boy said doubtfully. And Ralph laughed.

"What a chap you are! Have I not told you that I shall be downright thankful: and there you keep[Pg 52] on about if I will let you. Come, shake hands upon it! Charlton, we two are chums, and we are going to stick together and help each other. Is that so?"

"Yes, if you will. I shall be so glad to have a chum, because it has been rather lonely sometimes; and then, you see, I am not very strong, and I am not brave like you, and the fellows know it, and they try to play all sorts of tricks upon me. Do you really mean to be my chum, Rexworth?"

"Really and truly! Now, let us go down, and then you can show me what the place is like," was Ralph's answer. And the two, descending to the playground were met by Warren, who stopped and looked from Ralph to Charlton, and then asked—

"I say, Rexworth, what have you been up to so soon? There is Dobson declaring that he will do all manner of things to you. You seem to have been having some fun already."

So Ralph explained what had happened, and the monitor laughed until the tears ran down his cheeks.

"Well, all I can say is that you are a cool hand," was his comment, "and I am not sorry that you have taught Dobson a lesson. You have not much to fear from him, but you will find that Elgert, for all he is an Honourable, has precious little honour about him. He will pay you back if he gets the chance, be sure of that. However," he went on, "I am glad that you[Pg 53] two are chums, for I think you will like each other; but there is the bell for tea. Come on, or we shall be late."

The rest of that day passed without further incident and at last the boys—evening preparation and supper over—went trooping to their dormitories, there to laugh and chat as they undressed; and many glances were bestowed upon Ralph. His exploit of that afternoon had been spoken of, and there was no attempt to play any jokes upon one who was prepared to take his own part so vigorously.

But presently the laughing suddenly stopped, and something like a hush of surprise succeeded the noise. Warren seated on the edge of his bed, looked round to see what had happened—he thought that one of the masters had come in unexpectedly; but he saw his companions standing glancing across towards the spot where Ralph's bed was, and he, following their gaze, saw that the boy who was ready to face half a dozen of his companions, was down on his knees, his head bent upon his hands in prayer.

Warren felt a thrill of shame. He was a real good lad at heart, but somehow he did not do that—none of them did—they thought that public prayers were enough; and yet he had promised his mother that each night he would kneel alone in prayer.

Some of the boys were tittering, some looked grave. Warren suddenly found himself resolved. "If a thing should be done, do it at once," was his motto. He gave[Pg 54] one hasty glance round, half ashamed, half defiant, and then, in the sight of all his companions, the Fourth Form monitor also knelt down by his bed, following the brave example set by Ralph Rexworth.

It was quite a common thing for new boys at Marlthorpe College to be made the victims of practical jokes during their first night in the school; but such was the impression which Ralph Rexworth had made, that no tricks were attempted with him. A boy who could take his own part so vigorously was not the sort that it was safe to take liberties with.

Nor was that the only reason. With Dobson and his friends it was quite sufficient, but with the better boys, that quiet kneeling down to pray had not been without effect. Some of them recognized that to do that might require more courage than to deal as he had done with those who had invaded his study—a moral courage, far greater and better than a physical; and they realized that a boy who possessed that courage was not a fit subject for stupid jokes.

So Ralph slept peacefully until the morning, when, used to early rising all his life, he opened his eyes before any of the other boys were awake.

At first he felt puzzled with his surroundings, but he soon remembered; and propping himself upon his[Pg 56] elbow he lay watching the faces of the others, wondering what sort of lads they would prove to be, and how he should get on with them, and whether he would be able to master the lessons which they were engaged upon.

Then he looked at Charlton, and thought how sad he looked, even in his sleep; and he noted how often he sighed. Perhaps he was dreaming of his father.

That sent him thinking of his own father, and the mystery of his fate; and he pondered whether it would ever be possible for him—a lonely boy in this strange land—to find out the truth concerning his parent's disappearance. But he was not altogether alone; it was wrong to think of himself in that light. God had given him a friend in Mr. St. Clive, and another in Mrs. St. Clive, and yet a third—a very nice, lovable third—in Irene! Ralph, who had never had anything to do with girls, thought Irene the sweetest, dearest little friend that it would be possible to find.

A bell rang, and his companions stretched and yawned and opened their eyes; and though some grunted and turned over again, determined to have every minute they could, several jumped up at once, and hastily pulling on their clothes began sluicing and splashing in good, honest, cold water.

"Hallo! Awake? Slept well?" queried Warren seeing that Ralph was preparing to follow the example of these last boys. "Any one try any games with you in the night?" And he came and sat down on Ralph's[Pg 57] bed, and grinned when the new boy answered that he had not been disturbed.

"I suppose they thought better of it. That is your basin!" he added, pointing to one washstand. "Mind that they don't take all the water, or you will either have to sneak another fellow's, or go and get some more for yourself. Look sharp, and then we will go and have a turn with the bells, and a spin afterwards, I like to get all I can before breakfast; it seems to set a fellow up for the day."

Ralph nodded, and began vigorously sluicing and polishing; and the boys, too busy about their own business, paid no attention to him. He was quite capable of looking after himself, in their opinion. At last, all ready to accompany the monitor, he quietly repeated his action of the previous night—he knelt down in prayer.

That staggered even Warren. As a whole, the boys were good lads, but even those who had been accustomed to evening prayers in their homes did not seem to think that morning prayers were quite as important. They wanted to scramble off to play as quickly as possible. The Head always read prayers in school, and that was enough; and here was this new fellow wasting precious time in this way!

A few sneered and giggled; some shrugged their shoulders, and ran off; some looked grave; and Warren sat nursing his foot, and pondering; while Charlton turned red.

But they made no remarks; and when Ralph rose from his knees, the three went out together. Warren was turning over a decidedly new leaf. If he had not annoyed Charlton before, he had left him pretty much alone, and now he was admitting him to his company. Well, Charlton was Rexworth's chum, and if he wanted Rexworth he must have the chum as well.

Charlton hardly expected the monitor to be friendly to him, but he waited for his chum, and Warren waited, too.

"Let us get down and have a try at the bells," suggested the monitor, leading the way. And Ralph inquired innocently—

"Ringing bells, do you mean?"

Whereat Warren stared, and felt just a little less respect for the new boy. What sort of a fellow could he be if he didn't know what dumb-bells were?

"Ringing bells?" he repeated. "No; dumb-bells—exercises, you know! Come on, I will show you."

"I never saw bells like those," was Ralph's comment, when a pair was produced. "How do you use them?"

Warren went through a set of exercises, and then handed them to Ralph, who laughed, and said—

"Why, they don't weigh anything! I don't see much exercise in this!"

"They are six-pounders," was the answer; "quite as heavy as you will want. Now try this exercise—do it a dozen times."

Warren showed Ralph the right way, and off he went;[Pg 59] Charlton, who had also got a pair of bells, doing the same. And, to Ralph Rexworth's surprise, he found that those weights at which he had laughed soon made him feel tired, and that Charlton could keep on longer than he could. He could not understand that.

"I don't see why it should be," he said.

And a voice replied—

"Because you are exercising muscles which you have not tried much before, my lad." And he turned, to see Mr. Delermain watching him.

"Try again," said the master. "Only once; this sort of thing must be done gradually. Go slow, and take time."

Ralph obeyed: but dumb-bells certainly made his arms ache. And then Warren suggested Indian clubs.

"Indian clubs," repeated Ralph, "and what are they? I never saw the Indians use clubs. They have knives and hatchets, and spears and bows, and some of them use guns, too, and shoot wonderfully well; but I never saw them use clubs."

Now that speech caused a smile, but it was a very respectful smile; for here was a boy who had actually seen real Indians. That was something, even if he did not know what Indian clubs were!

However, the clubs were produced, and Ralph was shown how to swing them. And, as a natural result of his first attempt, he hit his head a smart crack, evoking a burst of laughter thereby.

"Slow and steady," he answered; "I shall get it in time. I don't understand these things; but if you get me a coil of rope, I will show you one or two little things that I do not think any of you can do."

"A coil of rope—that is easily supplied," said Mr. Delermain; and when it was brought, he said: "Now, Rexworth, let us see what you can do." And all the boys stood round while Ralph took the rope and made a running noose at one end.

"Give me plenty of room," he said, and he commenced to whirl the noose round and round his head, letting the rope run out as he did so; until at last he held the very end in his hand, and the rest was twirling round and round him in a perfect circle.

"One of you try to do that," he said.

And try they did, in vain. They could not even get it to go in a circle, and it made their arms ache dreadfully.

Then he made the circle spin round him on its edge just as if that rope was a hoop; and afterwards he actually jumped through it as it was going, explaining that the cowboys on the ranches frequently indulged in such tricks as these, and were experts at it—far more so than the Indians themselves.

Then nothing would do but that he must show them how a lasso was thrown. And though several, including the master, essayed to try, not one of them was able to send the noose over Ralph's shoulders, though[Pg 61] he caught them, one after the other, without the slightest trouble.

"It is what one is used to," he said laughing. "I have not had much to do with bells and clubs—nothing to do with them, indeed—but I have played with a rope all my life."

Dobson had come in with his friends, and he stood and glared. Elgert came in, and looked angry. This new boy was evidently on the way to become a favourite in the school, and, unless something was done, he might rival them. Though just then they did not speak to each other about it, both Dobson and Elgert arrived at the same conclusion—namely, that something should be done, and that Ralph Rexworth should be humbled and disgraced.

Then Warren suggested a spin, and of course Charlton went, and two or three other boys—who found Ralph very good company—had to come too; and since they did come, they could not ignore the boy they had all neglected in the past. Poor Charlton, he could hardly understand it, it almost frightened him!

It was delightful out in the fields, in the fresh morning, with the dew still sparkling on the leaves, and with the air full of the songs of the wild birds. There is a charm and sweetness and delight about the early morning which they who are late risers have no idea of. It sets the nerves tingling and the blood dancing, and makes one feel as if he were walking on air, and not on solid earth.

Away they went across the playing field, and out on the common, on towards Great Stow; arms well back, shoulders square, bodies gently sloped, going with good, long, swinging strides.

Ralph was in his element now, for running, equally with rope work, was an accomplishment practised by all those amongst whom he had lived. A very necessary accomplishment, seeing that the ability to run swiftly, and to keep up without fagging, might mean all the difference between life and death in a land where the natives were quarrelsome and quite ready to go upon the warpath upon the least provocation.

Some of the boys outstripped him at the first go off, but he kept on running low, swinging well from the hips, and those who had gone with a spurt at first soon found that he could, to use Warren's expression, "run circles round them, and then beat them hollow."