Title: Trotwood's Monthly, Vol. I, No. 6. March, 1906

Author: Various

Editor: John Trotwood Moore

Release date: January 21, 2020 [eBook #61215]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, hekula03, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| VOL 1. | NASHVILLE, TENN., MARCH, 1906. | NO. 6 |

| MAJOR J. W. THOMAS | Frontispiece |

| HOW THE BISHOP FROZE | John Trotwood Moore |

| EARLY APPLES—A SOUTHERN OPPORTUNITY | R. A. Wilkes |

| THE ARMY HORSE | O. M. Norton |

| THE HISTORY OF THE HALS | John Trotwood Moore |

| MAMMY AND MEMORY | Poem |

| NITRIFICATION OF THE SOIL | Wm. Dennison |

| THE GREAT NEW SOUTH | |

| BRE’R WASHINGTON’S CONSOLATION | Old Wash |

| CONCERNING LITTLENESS | John Trotwood Moore |

| OLE COTTON TAIL | Old Wash |

| STORIES OF THE SOIL | |

| HISTORIC HIGHWAYS OF THE SOUTH | John Trotwood Moore |

| A FAMOUS HORSE RACE | B. M. Hord |

| WITH OUR WRITERS | |

| WITH TROTWOOD—Personal Department | |

| BUSINESS DEPARTMENT |

Just as the forms are closing for the March edition of TROTWOOD’S MONTHLY comes news of the death of Major John Wilson Thomas, who was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on August 24, 1830, and died in Nashville, February 12, 1906.

At the age of 28 he entered railroad work, and was in harness continually up to the time of his death, being at that time President of the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railroad.

We regret that limited time and space will not permit us to give a detailed account of the many incidents that made up the life of this great and good man, but we are safe in saying that a more popular man never lived in the South—or elsewhere. The “Old Man,” as he was affectionately called by his employes, was ever ready to listen with a sympathetic ear to the story of the unfortunate, and encouragement was always freely given. Every employe under him was supposed to do his very best. He demanded everything there was in a man, and got it; not from fear, but through the love they had for him. His word was law and his decision final, for right and justice always prevailed. No man was ever loved and respected more by his employes than Major Thomas, and his record as a railroad man was seldom if ever equaled. He did not grow up with the road, but it grew up with him, and he made it what it is to-day.

Somebody will take his place as president of the N., C. & St. L. road, but there is no one to take his place in the hearts of his friends. He was a great and good man.

[Through the kindness of John C. Winston & Co., publishers, of Philadelphia, Pa., we are permitted to give to our readers this treat, being one of the chapters from the forthcoming novel of John Trotwood Moore, entitled “The Bishop of Cottontown,” now in the Winston press, and which will be issued by them early in March. This novel has been pronounced truly great by many publishers’ readers. It deals with child labor in the Southern cotton mills and the Bishop is the kindly old preacher and ex-trainer of ante-bellum thoroughbreds, who is the hero of the book.—E. E. Sweetland, Business Manager.]

It was ten o’clock and the Bishop was on his way to church. He was driving the old roan of the night before. A parody on a horse, to one who did not look closely, but to one who knows and looks beyond the mere external form for that hidden something in both man and horse which bespeaks strength and reserve force, there was seen through the blindness and the ugliness and the sleepy, ambling, shuffling gait a clean-cut form, with deep chest and closely ribbed; with well drawn flanks, a fine, flat steel-turned bone, and a powerful muscle, above hock and forearms, that clung to the leg as the Bishop said, “like bees aswarmin’.”

At his little cottage gate stood Bud Billings, the best slubber in the cotton mill. Bud never talked to any one except the Bishop, and his wife, who was the worst Xantippe in Cottontown, declared she had lived with him six months straight and never heard him come nearer speaking than a grunt. It was also a saying of Richard Travis that Bud had been known to break all records for silence by drawing a year’s wages at the mill, never missing a minute and never speaking a word.

Nor had he ever looked any one full in the eye in his life.

As the Bishop drove shamblingly along down the road, deeply preoccupied in his forthcoming sermon, there came from out of a hole, situated somewhere between the grizzled fringe of hair that marked Bud’s whiskers and the grizzled fringe above that marked his eye-brows, a piping, apologetic voice that sounded like the first few rasps of an old rusty saw; but to the occupant of the buggy it meant, with a drawl:

“Howdy do, Bishop?”

A blind horse is quick to observe and take fright at anything uncanny. He is the natural ghost-finder of the highways, and that voice was too much for the old roan. To him it sounded like something that had been resurrected. It was a ghost-voice, arising after many years. He shied, sprang forward, half wheeled and nearly upset the buggy, until brought up with a jerk by the powerful arms of his driver. The shaft-band had broken and the buggy had run upon the horse’s rump, and the shafts stuck up almost at right angles over his back. The roan stood trembling with the half turned, inquisitive muzzle of the sightless horse—a paralysis of fear all over his face. But when Bud came forward and touched his face and stroked it, the fear vanished, and the old roan bobbed his tail up and down and wiggled his head reassuringly and apologetically.

“Wal, I declar, Bishop,” grinned Bud, “kin yo’ critter fetch a caper?”

The Bishop got leisurely out of his buggy, pulled down the shafts and tied up the girth before he spoke. Then he gave a puckering hitch to his underlip and deposited in the sand, with a puddling plunk, the half cup of tobacco juice that had closed his mouth.

He stepped back and said very sternly:

“Whoa, Ben Butler!”

“Why, he’un’s sleep a’ready,” grinned Bud.

The Bishop glanced at the bowed head, cocked hind foot and listless tail: “Sof’nin’ of the brain, Bud,” smiled the Bishop; “they say when old folks begin to take it they jus’ go to sleep while settin’ up talkin’. Now, a horse, Bud,” he said, striking an attitude for a discussion on his favorite topic, “a horse is like a man—he must have some meanness or he c’u’dn’t live, an’ some goodness or nobody else c’u’d live. But git in, Bud, and let’s go along to meetin’—’pears like it’s gettin’ late.”

This was what Bud had been listening for. This was the treat of the week for him—to ride to meetin’ with the Bishop. Bud, a slubber-slave—henpecked at home, browbeaten and cowed at the mill, timid, scared, “an’ powerful slow-mouthed,” as his spouse termed it, worshipped the old Bishop and had no greater pleasure in life, after his hard week’s work, than “to ride to meetin’ with the old man an’ jes’ hear him narrate.”

The Bishop’s great, sympathetic soul went out to the poor fellow, and though he had rather spend the next two miles of Ben Butler’s slow journey to church in thinking over his sermon, he never failed, as he termed it, “to pick up charity even on the road-side,” and it was pretty to see how the old man would turn loose his crude histrionic talent to amuse the slubber. He knew, too, that Bud was foolish about horses, and that Ben Butler was his model!

They got into the old buggy, and Ben Butler began to draw it slowly along the sandy road to the little church, two miles away up the mountain side.

Bud was now in the seventh heaven. He was riding behind Ben Butler, the greatest horse in the world, and talking to the Bishop, the only person who ever heard the sound of his voice, save in deprecatory and scary grunts.

It was touching to see how the old man humored the simple and imposed-upon creature at his side. It was beautiful to see how, forgetting himself and his sermon, he prepared to entertain, in his quaint way, this slave to the slubbing machine.

Bud looked fondly at the Bishop—then admiringly at Ben Butler. He drew a long breath of pure air, and sitting on the edge of the seat, prepared to jump if necessary, for Bud was mortally afraid of being in a runaway, and his scared eyes seemed to be looking for the soft places in the road.

“Bishop,” he drawled after a while, “huc-cum you name sech a hoss”—pointing to the old roan—“sech a grand hoss, for sech a man—sech a man as he was,” he added humbly.

“Did you ever notice Ben Butler’s eyes, Bud?” asked the old man knowingly.

“Blind,” said Bud sadly, shaking his head—“too bad—too bad—great—great hoss!”

“Yes, but the leds, Bud—that hoss, Ben Butler there, holds a world’s record—he’s the only cock-eyed hoss in the world.”

“You don’t say so—that critter!—cock-eyed?” Bud laughed and slapped his leg gleefully. “Didn’t I always tell you so? World’s record—great—great!”

Then it broke gradually through on Bud’s dull mind.

He slapped his leg again. “An’ him—his namesake—he was cock-eyed, too—I seed him onct at New ’Leens.”

“Don’t you never trust a cock-eyed man, Bud. He’ll flicker on you in the home-stretch. I’ve tried it an’ it never fails. Love him, but don’t trust him. The world is full of folks we oughter love, but not trust.”

“No—I never will,” said Bud as thoughtfully as he knew how to be—“nor a cock-eyed ’oman neither. My wife’s cock-eyed,” he added.

He was silent a moment. Then he showed the old man a scar on his forehead: “She done that last month—busted a plate on my head.”

“That’s bad,” said the Bishop consolingly—“but you ortenter aggravate her, Bud.”

“That’s so—I ortenter—least-wise, not whilst there’s any crockery in the house,” said Bud sadly.

“There’s another thing about this hoss,” went on the Bishop—“he’s always spoony on mules. He ain’t happy if he can’t hang over the front gate spoonin’ with every stray mule that comes along. There’s old long-eared Lize that he’s dead stuck on—if he c’u’d write he’d be composin’ a sonnet to her ears, like poets do to their lady love’s—callin’ them Star Pointers of a Greater Hope, I reck’n, an’ all that. Why, he’d ruther hold hands by moonlight with some old Maria mule than to set up by lamplight with a thoroughbred filly.”

“Great—great!” said Bud slapping his leg—“didn’t I tell you so?”

“So I named him Ben Butler when he was born. That was right after the war, an’ I hated old Ben so an’ loved hosses so, I thought ef I’d name my colt for old Ben maybe I’d learn to love him, in time.”

Bud shook his head. “That’s ag’in nature, Bishop.”

“But I have, Bud—sho’ as you are born I love old Ben Butler.” He lowered his voice to an earnest whisper: “I ain’t never told you what he done for po’ Cap’n Tom.”

“Never heurd o’ Cap’n Tom.”

The Bishop looked hurt. “Never mind, Bud, you wouldn’t understand. But maybe you will ketch this. Listen now.”

Bud listened intently with his head on one side.

“I ain’t never hated a man in my life but what God has let me live long enough to find out I was in the wrong—dead wrong. There are Jews and Yankees. I useter hate ’em worse’n sin—but now what do you reckon?”

“One on ’em busted a plate on yo’ head?” asked Bud.

“Jesus Christ was a Jew, an’ Cap’n Tom jined the Yankees.”

“Bud,” he said cheerily after a pause, “did I ever tell you the story of this here Ben Butler here?”

Bud’s eyes grew bright and he slapped his leg again.

“Well,” said the old man, brightening up into one of his funny moods, “you know my first wife was named Kathleen—Kathleen Galloway when she was a gal, an’ she was the pretties’ gal in the settlement an’ could go all the gaits both saddle an’ harness. She was han’som’ as a three-year-old an’ cu’d out-dance, out-ride, out-sing an’ out-flirt any other gal that ever come down the pike. When she got her Sunday harness on an’ began to move, she made all the other gals look like they were nailed to the road-side. It’s true, she needed a little weight in front to balance her, an’ she had a lot of ginger in her make-up, but she was straight and sound, didn’t wear anything but the harness an’ never teched herself anywhere nor cross-fired nor hit her knees.”

“Good—great!” said Bud, slapping his leg.

“Oh, she was beautiful, Bud, with that silky hair that ’ud make a thoroughbred filly’s look coarse as sheep’s wool, an’ two mischief-lovin’ eyes an’ a heart that was all gold. Bud—Bud”—and there was a huskiness in the old man’s voice—“I know I can tell you because it will never come back to me ag’in, but I love that Kathleen now as I did then. A man may marry many times, but he can never love but once. Sometimes it’s his fust wife, sometimes his secon’, an’ often it’s the sweetheart he never got—but he loved only one of ’em the right way, an’ up yander, in some other star, where spirits that are alike meet in one eternal wedlock, they’ll be one there forever.

“Her daddy, ole man Galloway, had a thoroughbred filly that he named Kathleena for his daughter, an’ she c’u’d do anything that the gal left out. An’ one day when she took the bit in her teeth an’ run a quarter in twenty-five seconds, she sot ’em all wild an’ lots of fellers tried to buy the filly an’ get the old man to throw in the gal for her keep an’ board.

“I was one of ’em. I was clerkin’ for the old man an’ boardin’ in the house, an’ whenever a young feller begins to board in a house where there is a thoroughbred gal, the nex’ thing he knows he’ll be—”

“Buckled in the traces,” cried Bud slapping his leg gleefully, at this, his first product of brilliancy.

The old man smiled: “’Pon my word, Bud, you’re gittin’ so smart. I don’t know what I’ll be doin’ with you—so ’riginal an’ smart. Why, you’ll quit keepin’ an old man’s company—like me. I won’t be able to entertain you at all. But, as I was sayin’ the next thing he knows, he’ll be one of the family.

“So me an’ Kathleen, we soon got spoony an’ wanted to marry. Lots of ’em wanted to marry her, but I drawed the pole an’ was the only one she’d take as a runnin’ mate. So I went after the old man this a way: I told him I’d buy the filly if he’d give me Kathleen. I never will forgit what he said: ‘They ain’t narry one of ’em for sale, swap or hire, an’ I wish you young fellers ’ud tend to yo’ own business an’ let my fillies alone. I’m gwinter bus’ the wurl’s record wid ’em both—Kathleena the runnin’ record an Kathleen the gal record, so be damn to you an’ don’t pester me no mo’.’”

“Did he say damn?” asked Bud aghast—that such a word should ever come from the Bishop.

“He sho’ did, Bud. I wouldn’t lie about the old man, now that he’s dead. It ain’t right to lie about dead people—even to make ’em say nice an’ proper things they never thought of whilst alive. If we’d stop lyin’ about the ungodly dead an’ tell the truth about ’em, maybe the livin’ ’u’d stop tryin’ to foller after ’em in that respect. As it is, every one of ’em knows that no matter how wicked he lives there’ll be a lot o’ nice lies told over him after he’s gone, an’ a monument erected, maybe, to tell how good he was. An’ there’s another lot of half pious folks in the wurl it ’u’d help—kind o’ sissy pious folks—that jus’ do manage to miss all the fun in this world an’ jus’ are mean enough to ketch hell in the nex’. Get religion, but don’t get the sissy kind. So I am for tellin’ it about old man Galloway jus’ as he was.

“You orter heard him swear. Bud—it was part of his religion. An’ wherever he is to-day in that other world, he is at it yet, for in that other life, Bud, we’re just ourselves on a bigger scale than we are in this. He used to cuss the clerks around the store jus’ from habit, an’ when I went to work for him he said:

“‘Young man, maybe I’ll cuss you out some mornin’, but don’t pay no ’tention to it—it’s just a habit I’ve got into, an’ the boys all understand it.’

“‘Glad you told me,’ I said, lookin’ him square in the eye—‘one confidence deserves another. I’ve got a nasty habit of my own, but I hope you won’t pay no ’tention to it, for it’s a habit, an’ I can’t help it. I don’t mean nothin’ by it, an’ the boys all understand it, but when a man cusses me I allers knock him down—do it befo’ I think’—I said—‘jes’ a habit I’ve got.’

“Well, he never cussed me all the time I was there. My stock went up with the old man an’ my chances was good to get the gal, if I hadn’t made a fool hoss-trade; for with old man Galloway a good hoss-trade covered all the multitude of sins in a man that charity now does in religion. In them days a man might have all the learnin’ and virtues an’ graces, but if he c’u’dn’t trade hosses he was tinklin’ brass an’ soundin’ cymbal in that community.

“The man that throwed the silk into me was Jud Carpenter—the same fellow that’s now the whipper-in for these mills. Now, don’t be scared,” said the old man soothingly as Bud’s scary eyes looked about him and he clutched the buggy as if he would jump out—“he’ll not pester you now—he’s kept away from me ever since. He swapped me a black hoss with a star an’ snip that looked like the genuine thing, but was about the neatest turned gold-brick that was ever put on an unsuspectin’ millionaire.

“Well, in the trade he simply robbed me of a fine mare I had, that cost me one-an’-a-quarter. Kathleen an’ me was already engaged, but when old man Galloway heard of it, he told me the jig was up an’ no such double-barrel idiot as I was sh’u’d ever leave any of my colts in the Galloway paddock—that when he looked over his gran’-chillun’s pedigree he didn’t wanter see all of ’em crossin’ back to the same damned fool! Oh, he was nasty. He said that my colts was dead sho’ to be luffers with wheels in their heads, an’ when pinched they’d quit, an’ when collared they’d lay down. That there was a yaller streak in me that was already pilin’ up coupons on the future for tears and heartaches an’ maybe a gallows or two, an’ a lot of uncomplimentary talk of that kind.

“Well, Kathleen cried, an’ I wept, an’ I’ll never forgit the night she gave me a little good-bye kiss out under the big oak tree an’ told me we’d hafter part.

“The old man maybe sized me up all right as bein’ a fool, but he missed it on my bein’ a quitter. I had no notion of being fired an’ blistered an’ turned out to grass that early in the game. I wrote her a poem every other day, an’ lied between heats, till the po’ gal was nearly crazy, an’ when I finally got it into her head that if it was a busted blood vessel with the old man, it was a busted heart with me, she cried a little mo’ an’ consented to run off with me an’ take the chances of the village doctor cuppin’ the old man at the right time.

“The old lady was on my side and helped things along. I had everything fixed even to the moon, which was shinin’ jes’ bright enough to carry us to the Justice’s without a lantern, some three miles away, an’ into the nex’ county.

“I’ll never fergit how the night looked as I rode over after her, how the wildflowers smelt, an’ the fresh dew on the leaves. I remember that I even heard a mockin’-bird wake up about midnight as I tied my hoss to a lim’ in the orchard nearby, an’ slipped aroun’ to meet Kathleen at the bars behin’ the house. It was a half mile to the house an’ I was slippin’ through the sugar-maple trees along the path we’d both walked so often befo’, when I saw what I thought was Kathleen comin’ towards me. I ran to meet her. It wa’n’t Kathleen, but her mother—an’ she told me to git in a hurry, that the old man knew all, had locked Kathleen up in the kitchen, turned the brindle dog loose in the yard, an’ was hidin’ in the woods nigh the barn, with his gun loaded with bird-shot, an’ that if I went any further the chances were I’d not sit down agin for a year. She had slipped around through the woods just to warn me.

“Of course I wanted to fight an’ take her anyway—kill the dog an’ the old man, storm the kitchen an’ run off with Kathleen in my arms as they do in novels. But the old lady said she didn’t want the dog hurt—it being a valuable coon-dog—and that I was to go away out of the county an’ wait for a better time.

“It mighty nigh broke me up, but I decided the old lady was right an’ I’d go away. But ’long towards the shank of the night, after I had put up my hoss, the moon was still shinin’, an’ I c’u’dn’t sleep for thinkin’ of Kathleen. I stole afoot over to her house just to look at her window. The house was all quiet an’ even the brindle dog was asleep. I threw kisses at her bed-room window, but even then I c’u’dn’t go away, so I slipped around to the barn and laid down in the hay to think over my hard luck. My heart ached an’ burned an’ I was nigh dead with love.

“I wondered if I’d ever get her, if they’d wean her from me, an’ give her to the rich little feller whose fine farm j’ined the old man’s an’ who the old man was wuckin’ fur—whether the two wouldn’t over-persuade her whilst I was gone. For I’d made up my mind I’d go befo’ daylight—that there wasn’t anything else for me to do.

“I was layin’ in the hay, an’ boylike, the tears was rollin’ down. If I c’u’d only kiss her han’ befo’ I left—if I c’u’d only see her face at the winder!

“I must have sobbed out loud, for jus’ then I heard a gentle, sympathetic whinny an’ a cold, inquisitive little muzzle was thrust into my face, as I lay on my back with my heart nearly busted. It was Kathleena, an’ I rubbed my hot face against her cool cheek—for it seemed so human of her to come an’ try to console me, an’ I put my arms around her neck an’ kissed her silky mane an’ imagined it was Kathleen’s hair.

“Oh, I was heart-broke an’ silly.

“Then all at onct a thought came to me, an’ I slipped the bridle an’ saddle on her an’ led her out at the back door, an’ I scratched this on a slip of paper an’ stuck it on the barn do’:

“‘You wouldn’t let me ’lope with yo’ dorter, so I’ve ’loped with yo’ filly, an’ you’ll never see hair nor hide of her till you send me word to come back to this house an’ fetch a preacher.’

(Signed) “‘HILLIARD WATTS.’”

The old man smiled, and Bud slapped his leg gleefully.

“Great—great! Oh, my, but who’d a thought of it?” he grunted.

“They say it ’u’d done you good to have been there the nex’ mornin’ an’ heurd the cussin’ recurd busted—but me an’ the filly was forty miles away. He got out a warrant for me for hoss-stealin’, but the sheriff was fur me, an’ though he hunted high an’ low he never could find me.”

“Well, it went on for a month, an’ I got the old man’s note, sent by the sheriff:

“‘Come on home an’ fetch yo’ preacher. Can’t afford to lose the filly, an’ the gal has been off her feed ever since you left.

“Oh, Bud, I’ll never forgit that homecomin’ when she met me at the gate an’ kissed me an’ laughed a little an’ cried a heap, an’ we walked in the little parlor an’ the preacher made us one.

“Nor of that happy, happy year, when all life seemed a sweet dream now as I look back, an’ even the memory of it keeps me happy. Memory is a land that never changes in a world of changes, an’ that should show us our soul is immortal, for memory is only the reflection of our soul.”

His voice grew more tender, and low: “Toward the last of the year I seed her makin’ little things slyly an’ hidin’ ’em away in the bureau drawer, an’ one night she put away a tiny half-finished little dress with the needle stickin’ in the hem—just as she left it—just as her beautiful hands made the last stitch they ever made on earth....

“Oh, Bud, Bud, out of this blow come the sweetest thought I ever had, an’ I know from that day that this life ain’t all, that we’ll live agin as sho’ as God lives an’ is just—an’ no man can doubt that. No—no—Bud, this life ain’t all, because it’s God’s unvarying law to finish things. That tree there is finished, an’ them birds, they are finished, an’ that flower by the road-side an’ the mountain yonder an’ the world an’ the stars an’ the sun. An’ we’re mo’ than they be, Bud—even the tiniest soul, like Kathleen’s little one that jes’ opened its eyes an’ smiled an’ died, when its mammy died. It had something that the trees an’ birds an’ mountains didn’t have—a soul—an’ don’t you kno’ He’ll finish all such lives up yonder? He’ll pay it back a thousandfold for what He cuts off here.”

Bud wept because the tears were running down the old man’s cheeks. He wanted to say something, but he could not speak. That queer feeling that came over him at times and made him silent had come again.

The Bishop laughed outright as his mind went back again.

“Well,” he went on reminiscently, “I’ll have to finish my tale an’ tell you how I throwed the cold steel into Jud Carpenter when I got back. I saw I had it to do, to work back into my daddy-in-law’s graces an’ save my reputation.

“Now, Jud had lied to me an’ swindled me terribly, when he put off that old no-count hoss on me. Of course, I might have sued him, for a lie is a microbe which naturally develops into a lawyer’s fee. But while it’s a terrible braggart, it’s really cowardly an’ delicate, an’ will die of lock-jaw if you only pick its thumb.

“So I breshed up that old black to split-silk fineness, an’ turned him over to Dr. Sykes, a friend of mine living in the next village. An’ I said to the Doctor, ‘Now remember he is yo’ hoss until Jud Carpenter comes an’ offers you two hundred dollars for him.’

“‘Will he be fool enough to do it?’ he asked, as he looked the old counterfeit over.

“‘Wait and see,’ I said.

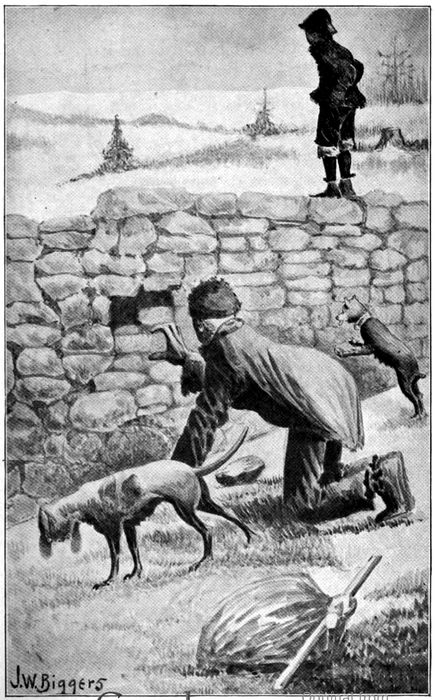

“I said nothin’, laid low an’ froze an’ it wa’n’t long befo’ Jud come ’round as I ’lowed he’d do. He expected me to kick an’ howl; but as I took it all so nice he didn’t understand it. Nine times out of ten the best thing to do when the other feller has robbed you is to freeze. The hunter on the plain knows the value of that, an’ that he can freeze an’ make a deer walk right up to him, to find out what he is. Why, a rabbit will do it, if you jump him quick, an’ he gets confused an’ don’t know jes’ what’s up; an’ so Jud come as I thort he’d do. He couldn’t stan’ it no longer, an’ he wanted to rub it in. He brought his crowd to enjoy the fun.

“‘Oh, Mr. Watts,’ he said grinnin’, ‘how do you like a coal black stump-sucker?’

“‘Well,’ I said, indifferent enough—‘I’ve knowed good judges of hosses to make a hones’ mistake now an’ then, an’ sell a hoss to a customer with the heaves thinkin’ he’s a stump-sucker. But it ’u’d turn out to be only the heaves an’ easily cured.’

“‘Is that so?’ said Jud, changing his tone.

“‘Yes,’ I said, ‘an’ I’ve knowed better judges of hosses to sell a nervous hoss for a balker that had been balked only onct by a rattle head. But in keerful hands I’ve seed him git over it,’ I said, indifferent like.

“‘Indeed?’ said Jud.

“‘Yes, Jud,’ said I, ‘I’ve knowed real hones’ hoss traders to make bad breaks of that kind, now and then—honest intentions an’ all that, but bad judgment,’—sez I—‘an’ I’ll cut it short by sayin’ that I’ll just give you two an’ a half if you’ll match that no-count wind-broken black as you thort that you swapped me.’

“‘Do you mean it?’ said Jud, solemn-like.

“‘I’ll make a bond to that effect,’ I said solemnly.

“Jud went off thoughtful. In a week or so he come back. He hung aroun’ a while an’ said:

“‘I was up in the country the other day, an’ do you kno’ I saw a dead match for yo’ black? Only a little slicker an’ better lookin’—same star an’ white hind foot. As nigh like him as one black-eyed pea looks like another.’

“‘Jud,’ I said, ‘I never did see two hosses look exactly alike. You’re honestly mistaken.’

“‘They ain’t a hair’s difference,’ he said. ‘He’s a little slicker than yours—that’s all—better groomed than the one in yo’ barn.’

“‘I reckon he is,’ said I, for I knew very well there wa’n’t none in my barn. ‘That’s strange,’ I went on, ‘but you kno’ what I said.’

“‘Do you still hold to that offer?’ he axed.

“‘I’ll make bond with my daddy-in-law on it,’ I said.

“‘Nuff said,’ an’ Jud was gone. The next day he came back leading the black, slicker an’ hence no-counter than ever, if possible.

“‘Look at him,’ he said, proudly—‘a dead match for yourn. Jes’ han’ me that two an’ a half an’ take him. You now have a team worth a thousan’.’

“I looked the hoss over plum’ surprised like.

“‘Why, Jud,’ I said as softly as I cu’d, for I was nigh to bustin’, an’ I had a lot of friends come to see the sho’, an’ they standin’ ’round stickin’ their old hats in their mouths to keep from explodin’—‘Why, Jud, my dear friend,’ I said, ‘ain’t you kind o’ mistaken about this? I said a match for the black, an’ it peers to me like you’ve gone an’ bought the black hisse’f an’ is tryin’ to put him off on me. No—no—my kind frien’, you’ll not fin’ anything no-count enuff to be his match on this terrestrial ball.’

“By this time you c’u’d have raked Jud’s eyes off his face with a soap-gourd.

“‘What? W-h-a-t? He—why—I bought him of Dr. Sykes.’

“‘Why, that’s funny,’ I said, ‘but it comes in handy all round. If you’d told me that the other day I might have told you,’ I said—‘yes, I might have, but I doubt it—that I’d loaned him to Dr. Sykes an’ told him whenever you offered him two hundred cash for him to let him go. Jes’ keep him,’ sez I, ‘till you find his mate, an’ I’ll take an oath to buy ’em.’”

Bud slapped his leg an’ yelled with delight.

“Whew,” said the Bishop—“not so loud. We’re at the church.

“But remember, Bud, it’s good policy allers to freeze. When you’re in doubt—freeze!”

[Note: Mr. Wilkes has made a life study of this subject and speaks from a practical standpoint, at the request of the editor of Trotwood’s. He has, of course, confined his paper to the hill lands of the Middle South; but in the publicity which will be given by this publication, it is to be hoped other sections of the South will take advantage of this wonderful opportunity where their conditions are favorable.—Ed.]

Nature never gave to any people a fairer heritage than to the farmers of Middle Tennessee. With a rich soil, a mild climate and an abundant rainfall, it is in truth a garden spot. Adapted to the growth of nearly every product necessary for man’s sustenance, covered with forests, underlaid with minerals and phosphates, midway between the cold blasts of the North and the excessive heat of the South, with cold, pure water pouring from under every hill, and not a taint of malaria in the atmosphere, it is the ideal farmer’s home. With all its advantages and opportunities there should be the highest degree of success and prosperity, and the owner of a Middle Tennessee farm should be the happiest and most contented man that lives. That such is not the case in recent years, however, is a lamentable fact.

Distinctly an agricultural people, prosperity depends upon the success of the farmers, and that they are not prospering as they should is an undeniable fact. The reason for this can be found in the fact that Tennessee farmers have failed to realize the results of the marvelous expansion and upheaval of the industrial conditions that have come as the result of building railways and the invention of labor-saving machinery. There was a time when the owners of these rich hills and valleys could successfully meet all competitors in the markets then accessible, and growing all their own supplies, the sale of their surplus products kept the balance always in their favor. But with the building of railways that opened up vast acres of rich territory, and the invention of machinery that multiplied many fold the products of labor, new centers of production were made accessible, and where Tennesseans once had the markets all to themselves, new competitors came in, and with this new competition came the beginning of the end of their supremacy in growing many standard products. Failing to realize the new state of affairs, and unwilling to acknowledge defeat in lines they had so long excelled in, they continued their efforts to compete with these new forces in the same lines of production, and in the unequal contest sacrificed much of their rich soil rather than be driven from their beaten paths into lines to which they were strangers. They failed to look facts squarely in the face and to recognize their true condition, and continued to struggle against an ever-increasing balance that in the end could only bring disaster. Take a plain business view of the situation and consider the chances an average Middle Tennessee farmer has in growing grain crops upon his rolling land and steep hillsides, rich though they be, when he must meet in competitive markets grain grown in that great area known as the West, with its broad, level fields and virgin soil, where the labor of one man controlling perfect working machinery so far surpasses the same labor upon his restricted, rough area. Labor is always the greatest cost of production, and the physical character of a large part of Middle Tennessee will always prevent that economical use of machinery that is available to the Western farmer in growing grain and other farm products in the handling of which machinery is effective. No people can permanently prosper who must meet in competitive markets the cheaper grown products of more favored sections, for while they may have a degree of prosperity in periods of high prices like the present, yet, when the low price periods come, as come they will, they bring loss and often ruin to the weak competitor, for it is Nature’s law that only the fittest shall survive. What then is to be the future of Middle Tennessee farming? This question is hard to answer, not for a lack of answer to the question, nor for a lack of products that can be grown with success, but rather because there are so many ways to meet it, and so many products to select from, and such a variety of soils to select for, that it is more a question of adaptability and location, and the fitness and taste of the individual than a want of ways to meet the issue. There are many owners of large, level farms that may still compete in growing all ordinary farm products, and there are many who grow certain lines of live stock and have special markets for their surplus, and others whose soil and location make profitable different lines; and to these classes changes in their mode of farming may not be desirable.

But the majority of Middle Tennessee farmers have only small farms, all more or less rolling, and many of them too rough and steep for the economical use of machinery, and for these some change in their system is an absolute necessity.

There should be grown upon every farm two distinct lines of products—the one for home consumption, for these can always be utilized for much more than their market value, and Tennessee farmers as a rule pursue the right course in regard to their own supplies; but it is in the products that are grown for market that the mistake has been made, and they must change this line, and grow those that give greater returns per acre, and a greater value for the labor, and quit growing those lines that bring them in direct competition with labor that is supplemented by the use of machinery.

While much of the virgin soil has been washed from the rich hills of this Middle Tennessee country in the endeavor to meet competition and to regain lost supremacy, yet its natural advantages are so great and the soil is so richly stored with the elements of plant food that it recuperates rapidly, and when under a new system, with intensive farming, and a proper rotation and selection of crops that suit its varied soil, and in the sale of which her farmers can stand upon the top round of the ladder, and look down upon, instead of up to, their competitors, as they do now, then will this grand commonwealth flourish as it never did, and its farmers will reap a harvest of prosperity unsurpassed by that of any farmers upon earth.

Among the many products that can be grown with the greatest assurance of success, I know of none with results more certain and sure to give rich returns for the labor bestowed, nor more exempt from hurtful competition, than that of growing the early varieties of apples upon the hills and uplands of this great basin. Ninety-five per cent of all the apples grown are winter varieties, and with the utmost care in handling, and the best facilities that cold storage can give for keeping them, there is a period of several months in the early summer when the markets are bare of apples, except a remnant of stale cold storage stock; and it is at this scarce period when prices are highest, competition least and demand greatest, that our early apples are at their best, and supply an urgent demand for the fruit acids so necessary at this season to the people of cold climates, to eliminate the effects of living many months upon rich, heating foods. Fruit acids are Nature’s remedy for many ills, and they are indispensable where the winters are long and cold; and in no fruit are these acids so rich and so well adapted to the needs of man as in the apple; and no apple is ready for use at so opportune a time as these Tennessee grown early kinds. They are ready for use at a season when all fruits are scarce, and the market is an open one, from which Tennesseans can reap a rich harvest if they will take advantage of the opportunity presented. Only a few years since fruits were a luxury of the rich, and were not considered articles of food; but as their value became known under the modern rational ideas of living, they have quickly become necessities; and where obtainable, are staple foods upon the tables of every class and condition of man. Among fruits the apple stands pre-eminent for its many uses and great healthfulness; and he is a poor provider indeed who does not supply his family with this, the most healthful and palatable dish that can go upon his table in some of its many prepared forms. The supply of apples has not increased in the same ratio that consumption has, for it takes time to grow orchards, and older orchards die; but the demand is an ever increasing one. These early apples sell much higher than the winter varieties, and the territory that can grow them is so limited that low prices need not be feared. They cost much less to grow, for they mature before the drouths and storms of summer come, and are less subject to damage by insects and fungus disease. Middle Tennessee is the heart of the territory that can grow choice apples that mature in that bare season, the months of June and July, and should, and I believe will, be the center of this industry in the years to come. Farther South the apple does not grow with any success, and north of us they do not mature in time to compete, and there is only a small zone east and west of us that can grow them, and we have at least two months with practically no competition, and an unlimited demand. With the rapid and constantly improving facilities for moving this class of freight these apples can be put into any of the cities in perfect condition, shipped in ordinary cars without the heavy ice changes that most fruits must bear. With the limited area available for their production, and the small amount now grown, it will take years to furnish an adequate supply; and the greatest danger will be the scarcity and not an overproduction, for with greater supplies the buyers will come and the markets will be at our doors.

With more growers and greater supplies will come organization. Associations will be formed, and instead of haphazard individual shipments, the crop will be handled in a systematic way, and be distributed to meet the needs of the different markets. The railroads will be ready helpers along these lines, for they realize the importance to their own interests of fostering enterprises of this kind. The L. & N. R. R. is now doing a great work in encouraging the increased growth of this class of products and give assurance of their ready co-operation at all times. This industry has passed the experimental stage, and it is an assured fact that these early apples will become a standard production of Middle Tennessee. It has been demonstrated by practical tests that the hills of Tennessee are especially adapted to this class of fruits, and the great success that has followed the efforts of the few who had the foresight to anticipate the coming results, and the nerve to back their views is a sure indication of what the future will develop along this line.

The pioneer in this line of business was Mr. W. L. Wilkes, of Spring Hill, Tennessee, and the success that he achieved has been followed by the planting of many large orchards around him that will soon be yielding a harvest to their owners. He is too modest to say much of the profits, but the facts are so patent that his neighbors are following his example and a revolution is taking place in the farming of that section. He claims that there is better profit in growing these apples now than when he began, for the business was then a venture, and the fruit was unknown upon the market, but now growing them is an assured fact, and there is a demand for all that can be supplied. The question of varieties, too, has been settled by experience, while then it was a matter of test.

Fruit well grown and handled has ever been the most profitable of all crops; and certainly a better opportunity was never offered to any people than this one offers to the farmers of Tennessee and other Southern States. Knowing what has already been done and the success already achieved, it offers an opportunity to the man who has a taste for fruit growing and has the energy and capacity to properly care for an orchard, and the patience to wait for its fruiting, an assurance of success greater than that of almost any other business. And when his orchard has passed its fruitful age, and ceased to be profitable, it leaves the soil as rich as that of a virgin forest, as an inheritance for his children.

It must not be inferred that good results will be had in growing apples, or any kinds of fruit without up-to-date methods of culture; for fruits do not take kindly to careless and slovenly ways. There are many details necessary to success, and explicit directions cannot be given in an article of this kind that will be a sufficient guide to those who have no practical knowledge of fruit growing. There are some general rules, however, that apply in all cases, and that cannot be too strongly emphasized. No one should go into commercial fruit growing without first considering well their surroundings as to soil, location, shipping facilities and other matters of that kind, and more especially to their own fitness for the business. A man must have an adaptability to, and a taste for, any business to make a success of it, for each individual has, more or less, an adaptation for some calling; and many of the failures in life are the result of the individual’s failing to get into the right channel.

The right person with the proper surroundings, having settled the question of planting in the affirmative, there will come many matters of detail that will require the exercise of common sense and judgment, and for the practice of which no specific rules can be given. I do not know any better way to help beginners than to tell them some of the things they should not do, and thereby prevent their making some costly mistakes.

The most important question to be decided by a commercial planter is that of varieties, for they must be of the kinds to suit the market demands, must be regular bearers and barrel-fillers, and must ripen in succession. Don’t plant many varieties, for they must be shipped in carloads, and each variety should be ample for that purpose. Don’t plant novelties, the kinds that have all the good points and that never fail to bear, regardless of frosts and freezes, and are so often palmed off at fancy prices by smooth-talking salesmen who always have the perfect kinds; for when your “perfect kinds” begin to show up their crops of crabs and seedlings your smooth agent will be far away practicing his games upon other suckers. The perfect apple is yet a vision of the future, and need not be expected until the perfect man comes.

Confine your commercial planting to well tested kinds that have succeeded in locations similar to yours. Don’t buy inferior trees because they are cheap. You are planting for a lifetime, and your time and money will be worse than wasted trying to grow profitable orchards from inferior stock. Life is too short to waste it waiting for diseased trees to drag along for years and then die just as their fruitings should begin. Buy the best trees that you can get; for if you are not willing to pay a fair price for good stock, don’t go into the business; for that very fact is conclusive proof that you have missed your calling. Having made your selection of varieties, and bought good trees, don’t let them lie around exposed to sun and air until half dead and then blame the nurseryman if they fail to grow. A tree is a thing of life and loses vitality every hour it is exposed, and it will need all of its vitality in adapting itself to its new home, and to recover from its rude removal from where it grew. Don’t buy old trees, thinking you will gain a year’s time in growth and fruiting, for such will not be the case. All experienced planters agree that one-year apple trees will live better, grow better and bear fruit as early as older ones. They can be bought for less money, are easier to plant and can be pruned to grow the style of tree you want. Only the thrifty, healthy trees are large enough for planting at one year old, and in buying them you run no risk of getting inferior stock.

Don’t plant without a thorough preparation of the soil, for no after care will compensate for the bad effect of careless preparation. The first year is the crucial period in the life of a tree; it has lost in removal many of its roots, and practically all of those fine, fibrous feeders through which it drank life from the soil; and while nature has stored in its cells a reserve supply of vitality, yet it needs every aid that can be given to enable it to overcome the loss of roots and the shock of removal and to succeed in its efforts to become established in its new home. Do not forget that the success or failure of your orchard will be largely owing to the manner of planting and to the treatment that it gets during the first year.

Having planted first-class, one-year trees in well prepared soil, cut them down to stubs eighteen to twenty-four inches high and let them branch close to the ground, for if there is a single reason for growing a long-bodied tree I have never heard it. On the contrary, there are many reasons against it. Let every twig that starts grow the first year, for they will be needed to furnish leaves to assimilate the food taken up by the roots, and to return the solid part to increase the growth of trees and root. You have now only the question of cultivation, and that should be the best that you can give. Plant the orchard in some suitable crop, preferably a low growing one, that requires hoe work, but leave ample space next to the trees for continuous cultivation, and keep that space clear of grass and weeds, for the trees cannot compete in their new surroundings with these gross drinkers of the water that is in the soil, that will be so badly needed to start their growth. Should the summer be dry, keep a dust mulch by frequent cultivation with light harrows or sweeps until the fall rains come, and if your soil is reasonably fertile, the growth the trees will make will be a surprise and pleasure, and the hardest period in growing your orchard will be a thing of the past. Get all the information you can from practical fruit growers; study the bulletins of the National Agricultural Department and of the State Experimental Station; read the papers and magazines that treat of these subjects; seek every available source of information; and having digested the opinions and practices of others, formulate your own opinions, map out the course you believe most suitable to your surroundings and follow the dictates of your own judgment. Continue this line of action through the coming years, adapting your methods to suit the condition of your orchard from year to year, and if you have exercised good common sense success is as certain to reward your efforts as anything in this life can be certain that is dependent upon human effort and the vicissitudes of drouths, storms and frosts.

Knowing that the method of purchase and the kind of horse required in the military service of the United States is a matter of interest to both horse breeders and dealers, the scarcity of horses meeting these requirements has caused me to write this article, for Trotwood’s.

The buying of horses is done by the Quartermaster’s Department of the army, the number of horses bought at any one time depending on the needs of the service at that time. This number may vary from one to two to hundreds and even thousands. Bids are advertised for, giving the number of horses required, and the date on which they are to be delivered to the government. Then contractors or dealers in horses put in their bids at the prices at which they will furnish the required number of horses. The bids are opened on a certain date, and the lowest bidder is given the contract. Soon after the contract is awarded, a Board of Officers is appointed to inspect and buy the horses that the contractor brings before the Board, providing, of course, that the horses fulfill the specifications of the contract.

A horse purchasing Board usually consists of from three to five members. One of these officers is from the Quartermaster’s Department, U. S. Army, the others being usually members of the Cavalry or Artillery; there is also a Veterinarian to inspect the horses in regard to soundness. He may be either a Quartermaster’s Veterinarian (civilian) or a Veterinarian of the Cavalry or Artillery.

The horses bought consist principally of two types, viz.: the Cavalry horse, weighing from 950 to 1,150 pounds; and the Artillery horse, weighing from 1050 to 1300 pounds.

Cavalry Horse: The requirements of most contracts say that the horses must be sound and well-bred; gentle under the saddle; free from vicious habits, with free and prompt action at the walk, trot and canter; without blemish or defect; with easy mouth and gait, and otherwise to conform to the following description: a gelding of uniform or hardy color; in good condition; from 15 ¼ to 16 hands high; weight from 950 to 1150 pounds; age from four to eight years; head and ears small; forehead broad; eyes large and prominent; vision perfect in every respect; shoulders long and sloping well back; chest full, broad and deep; forelegs straight and standing well under; barrel large and increasing from girth toward flank; back short and straight; loins and haunches broad and muscular; hocks well bent and under the horse; pasterns slanting and feet small and sound.

Artillery Horse: The Artillery horse has in general about the same requirements described for the Cavalry horse, with the following exceptions: weight being from 1050 to 1300 pounds; should be more of a draught horse type, as he is required to work in harness, as well as under saddle; shoulders should be well-muscled, so as to give good support to the collar; hindquarter should be heavy and strong; the horse should not be what is known as “beefy” or lymphatic type, but should be active on his feet and thus able to turn quickly.

Price: The price at present ranges from a hundred and fifty to a hundred and seventy-five dollars, probably about a hundred and sixty for Cavalry horses; Artillery horses being somewhat higher, one hundred and sixty-five to one hundred and eighty dollars.

When a horse is shown to the Board for purchase he is inspected by the Board first in regard to general conformation, height, weight, muscular development, bones, etc.; whether he is high in withers, thus liable to sore back and bruises by saddle; length of back, thus whether able to carry weight; should have short back with good muscular development; should not be ewe-necked or bull-necked, thus hard to control and never making a good saddle animal.

Color: Bays, browns, blacks and sorrels are the colors best suited for the service. Grays are sometimes taken, there often being a gray horse troop in the regiment, but are not as preferable as the hardier colors.

Sex: Only geldings are accepted, mares and stallions not being taken, excepting in times of great necessity, as during war.

Gaits: Walk, trot and canter being the three gaits prescribed by Army Regulations, pacing or single-foot horses are not desired in the service. And here is where the writer expects to receive Trotwood’s condemnation. However, if they do pace they are used in the army, and the writer has often noticed how quickly both officers and men will pick a pacing horse, or one that single-foots for their mount if allowed to do so, thus proving, that although we may condemn the pacer openly, deep down in our hearts we have a soft spot for him who carries us many miles with so little effort to himself or us.

After the horse is inspected for general conformation he is trotted to see his action, also to see whether he goes sound, is a paddler, string-halt, interferes, etc. He is then examined by the Veterinarian as to defects, age, eyesight, etc. If affected with any enlargement or weakness of tendons, hocks as to spavins, thorough-pins, curbs; examining pasterns for sidebones, ringbones, quittor, wire scars, etc., he is rejected. Sometimes horses are taken with small splints, also with small wire scars, especially in this Western country, where wire fences are so common. If shod, shoes are removed to examine feet thoroughly for quarter-crack, false-quarter, founder, corns, etc. The eyes are thoroughly examined for any signs of defects, and in this country, Middle West, where periodic ophthalmia is so often seen, it is often hard to tell where a horse has had a few light attacks of it in the past, and it is well for the Veterinarian to reject a horse that is the least suspicious, thus being on the safe side.

If the horse examined is not sound in every respect he should be rejected, and any one desiring to furnish horses for an army contract had better read carefully the specifications stated above and then start out to compare the horses of his neighborhood with the specifications as set forth, and he will find that there are very few that are truly sound and able to pass muster. Where the horse is accepted by the purchasing Board he is branded on the left shoulder with the letters “U. S.,” and often there is also branded on his hoof a number, and he is then ready for shipment to the place where he is needed for service.

Besides the two classes of horses mentioned, there are also a few very heavy draught horses bought for two batteries of siege Artillery, these horses weighing from 1300 to 1500 pounds. There are also bought by the government a few horses for special purposes, as horses used in the Fire Department and horses used in the Quartermaster’s Department as drivers, etc.

The specifications of most contracts say that the horses shall be well bred, but owing to the scarcity at present of horses, and the high prices paid for highly bred horses, we often find in the service horses that show none or very little indication of any breeding.

Horses that fail to give good service, or are not able to do the work required, or are unsuited for the purpose for which they were bought, are inspected and condemned and sold at public auction to the highest bidder; when condemned are branded with the letters “I. C.” (inspected and condemned). This brand is placed on the side of the neck under the mane.

“Uncle Berry,” continued Mr. Peyton, “I find, arrived in Tennessee in the month of February, 1806. In the spring of that year he made a match of mile heats, $500 a side, over the Hartsville course, with Henrietta against Cotton’s Cygnet, which he won.

“The old men of the neighborhood manifested great sympathy for the young stranger, and predicted that Lazarus Cotton would ruin him.

“This was his first race in Tennessee, and I witnessed his last, which was run over the Albion course at Gallatin, in 1862.

“Shortly after the race at Hartsville, Uncle Berry trained a famous quarter race mare called Sallie Friar, by Jolly Friar, and made a match for $500 a side, which was run on Goose Creek, near the Poison Knob. Sallie was the winner, and she was afterwards purchased by Patton Anderson, who ran her with great success.

“In the fall of 1806 Uncle Berry won with Post Boy the Jockey Club purse, three mile heats, at Gallatin, beating General Jackson’s Escape and others. Escape was the favorite, and the General and Mrs. Jackson, who were present, backed him freely. Before this race he sold Post Boy to Messrs. Richard and William L. Alexander for $1,000 in the event of his winning the race, after which he was withdrawn from the turf. Here he first met General Jackson and made a match with him on Henrietta against Bibb’s mare for $1,000 a side, two mile heats, equal weights, though the General’s mare was two years older than Henrietta, to come off in the spring of 1807 at Clover Bottom. The result proved that Uncle Berry underrated the horses and trainers of the Tennessee turf, as the General’s mare, a thoroughbred daughter of imported Diomed, won the race.

“The General, though deprived of the pleasure of being present on that interesting occasion (having been summoned as a witness in the trial of Aaron Burr at Richmond) showed that his heart was in the race, as appears from a letter to his friend, Patton Anderson, dated June 16, and published in Parton’s ‘Life of Jackson,’ from which I quote:

“‘At the race I hope you will see Mrs. Jackson; tell her not to be uneasy. I will be home as soon as my obedience to the precept of my country will permit. I have only to add as to the race, that the mare of Williams’ is thought here to be a first-rate animal of her size; but if she can be put up to it, she will fail in one heat. It will be then proper to put her up to all she knows at once.’

“This is Jacksonian. Not many men would take the responsibility of giving orders of how to run a race at the distance of five hundred miles. This error of underrating an adversary, especially such an adversary, was a heavy blow to Uncle Berry, from which he did not fully recover until he started Haynie’s Maria, mounted by Monkey Simon, against him.

“Not long after this defeat he set out to search for a horse with which to beat General Jackson, and purchased from General Wade Hampton, of South Carolina, a gelding called Omar, bringing him to Tennessee. After recruiting his horse at Captain Alexander’s, near Hartsville, he went to Nashville and offered General Jackson a match for $1,000 a side, three mile heats, according to rule. This the General declined, offering instead the same terms as to weight, as in the former race, in which he was allowed two years’ advantage, a proposition which, of course, was not accepted.

“Unable to get a race in Tennessee, Uncle Berry took his horse to Natchez, Miss., traveling through the swamps of the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations, and entered him in a stake, three mile heats, $200 entrance; but his bad luck pursued him, and just before the race his horse snagged his foot, and he paid forfeit. He remained near Natchez twelve months and nursed his horse as no other man could have done, until he was perfectly restored to health and in condition for the approaching fall races of 1808. Writing to Col. George Elliott, he urged him to come to Natchez and bring fifteen or twenty horses to bet on Omar, and also to bring Monkey Simon to ride him, which Colonel Elliott did.

“Simon’s appearance on the field alarmed the trainer of the other horse, who had known him in South Carolina, and, suspecting that Omar was a bite, he paid forfeit.

“As Simon was a distinguished character, and made a conspicuous figure on the turf of Tennessee for many years, it may be well to give some account of him. His sobriquet of ‘Monkey Simon’ conveys a forcible idea of his appearance. He was a native African, and was brought with his parents when quite young to South Carolina, before the prohibition of the slave trade took effect. In height he was four feet six inches, and weighed one hundred pounds. He was a hunchback with very short body and remarkably long arms and legs. His color and hair were African, but his features were not. He had a long head and face, a high and delicate nose, a narrow but prominent forehead, and a mouth indicative of humor and firmness. It was rumored that Simon was a prince in his native country. I asked Uncle Berry the other day if he thought it was true. He replied, ‘I don’t know; they said so, and if the princes there had more sense than the rest he must have been one of ’em, for he was the smartest negro I ever saw.’ Colonel Elliott, speaking of Simon after his death, said he was the coolest, bravest, wisest rider he ever saw mount a horse, in which opinion Uncle Berry fully concurs.

“Simon was an inimitable banjo player and improvised his songs, making humorous hits at everybody; even General Jackson did not escape him. Indeed, no man was his superior in repartee.

“On one occasion Colonel Elliott and James Jackson, with a view to a match race for $1,000 a side, a dash on two miles, on Paddy Carey against Colonel Step’s mare, consented to lend Simon to ride this mare.

“Colonel Step not only gave Simon $100 in the race, but stimulated his pride by saying they thought they could win races without him, whereas he knew their success was owing to Simon’s riding. Somewhat offended at the idea of being lent out, and by no means indifferent to the money, Simon resolved to win the race, if possible; and nodding his head, said: ‘I’ll show ’em.’ The mare had the speed of Paddy and took the track, and Simon, by his consummate skill and by intimidating the other rider, managed to run him far out on the turns, while he rested his mare for a brush on the stretches.

“On reaching the last turn Simon found the mare pretty tired, and Paddy, a game four miler, locked with her, and he boldly swung out so far as to leave Paddy in the fence corner. The boy came up and attempted to pass on the inside, but Simon headed him off, and growled at him all the way down the quarter stretch, beating him out by a neck. Simon could come within a hair’s breadth of foul riding and yet escape the penalty. Colonel Elliott lost his temper, which he rarely did, and abused Simon, saying, ‘not satisfied with making Paddy run forty feet further than the mare on every turn, he must ride foul all the way down the quarter stretch.’

“The Colonel repeated these charges until at length Simon answered him with, ‘Well, Colonel Elliott (as he always called him), I’ve won many a race that way for you, and it is the first time I ever heard you object to it.’”

Much has been said and written of the tenderness and care bestowed by the Arabs on their favorite horses, but I doubt whether any Arabian since the time of the Prophet ever showed such devotion to his favorite steed as Uncle Berry to the thoroughbreds under his care. In fact, his kindly nature embraced all domestic animals. For many years he resided on a rich, productive farm near Gallatin, where he trained Betsy Malone, Sarah Bladen and many other distinguished race horses; raised fine stock and fine crops and proved himself to be one of the best farmers in the neighborhood. He had pets of all kinds—huge hogs that would come and sprawl themselves to be rubbed, and game chickens that would feed from his hand, and followed him if he left home on foot, often obliging him to return and shut them up.

He raised many celebrated racers for himself and others, and so judicious was his system that, at the age of two, they had almost the maturity of three-year-olds. His last thoroughbred was a chestnut filly, foaled in 1859, by Lexington, dam Sally Roper (the dam of Berry), which was entered in a stake for three-year-olds, $500 entrance, two mile heats, to come off over the Albion course, near Gallatin, in the fall of 1862. This filly was, of course, a great favorite with Uncle Berry. She never associated with any quadruped after she was weaned, her master being her only companion. At two years old she was large and muscular and very promising, and in the summer of 1861 I urged Uncle Berry to send her to the race course (where I had Fannie McAlister, dam of Muggins, and several other animals in training), that she might be gentled and broken to ride. His reply was: “I have been thinking of your kind offer—I know she ought to be broke, but, poor thing! she don’t know anything; she has never been anywhere, and has never even been mounted. I am afraid she will tear herself all to pieces.” But he finally consented for my colored trainer, Jack Richlieu, to take her to the track. On meeting Mrs. Williams a few days afterwards, I inquired for Uncle Berry. Her reply was: “He is well enough as to health, but he is mighty lonesome since the filly went away.”

But of all the horses he ever owned, Walk-in-the-Water was his especial favorite. In the language of Burns, he “lo’ed him like a vera brither.” He was a large chestnut gelding, foaled in 1813, by Sir Archie, dam by Gondola, a thoroughbred son of Mark Anthony, and these two were the only pure crosses in his pedigree, yet he was distinguished on the turf until fifteen years old, more especially in races of three and four mile heats.

I was present when Walk, at nineteen years of age, ran his last race, of four mile heats, over the Nashville course, against Polly Powell.

Uncle Berry, several years before, had presented him to Thomas Foxall, with a positive agreement that he would neither train nor run him again; having a two-year-old in training, Mr. Foxall took up the old horse merely to gallop in company with him, a few weeks before the Nashville meeting.

It became well known that the mare would start for the four mile purse, and she was so great a favorite that no one would enter against her.

The proprietor, to prevent a “walkover,” induced Foxall to allow him to announce Walk-in-the-Water, whose name would be sure to draw a crowd. There was a large attendance, and the game old horse made a wonderful race, considering his age, running a heat and evidently losing in consequence of his want of condition. When the horses were brought out I missed Uncle Berry, and went in search of him. I found him in the grove alone, sitting on a log and looking very sad. “Are you not going up to see old Walk run?” I inquired. “No, I would as soon see a fight between my grandfather and a boy of twenty,” he replied.

In the year 1827, when Walk was fourteen years old, Uncle Berry took him and several colts that were entered in stakes to Natchez, Miss., traveling by land through the terrible swamps of the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations. The colts had made very satisfactory trial runs in Tennessee, but suffered so severely from the journey that they either paid forfeits or lost their stakes, so that Walk-in-the-Water was the only hope for winning expenses. He was entered in the four mile race of the Jockey Club, and his only competitor was the b. gelding Archie Blucher, fifteen years old, a horse of great fame as a “four miler” in Mississippi.

On the evening before the race the Jockey Club met and changed the rule, reducing the weight on all horses of fifteen years or upward to one hundred pounds, leaving all others their full weight, or one hundred and twenty-four pounds, three pounds less for mares and geldings.

This extraordinary proceeding would not have been tolerated by the gentlemen who, at a later day, composed that Club, but Uncle Berry protested in vain against the injustice done him. He, however, concluded to run Walk, giving his half brother twenty-one pounds advantage in weight. Walk had the speed of Blucher, and when the drum tapped, took the track, with Blucher at his side, and these two game Archies ran locked through the heat, Walk winning by half a length. The second heat was a repetition of the first, and never was a more tremendous struggle witnessed on a race course—a blanket would have covered the horses from the tap of the drum to the close of the race.

Any man who has watched a favorite horse winning a race, out of the fire and blue blazes at that, can appreciate Uncle Berry’s feelings during that terrible struggle. The horses swung into the quarter stretch, the eighth and last mile, and Uncle Berry, seeing the sorrel face of his old favorite ahead, cried out at the top of his voice, “Come home, Walk, come home! Your master wants money, and that badly.” After the race he expressed his opinion of the Club in no measured terms. Though habitually polite and respectful, particularly toward the authorities of a Jockey Club, he was a man of undaunted courage and ready to resist oppression, irrespective of consequences, but his friends interposed and persuaded him to let the matter pass.

When he reached the stables the horses were being prepared for their night’s rest, and he made them each an address. “Jo,” he said to a Pacolet colt, named Jo Doan, that had lost his stake in slow time, “you won’t do to tie to; I’ve always done a good part by you. I salted you out of my hand while you sucked your mammy; you know what you promised me before you left home (alluding to a trial run), and now you have thrown me off among strangers,” and he passed on, complaining of the other colts. The groom was washing old Walk-in-the-Water’s legs while he stood calm and majestic, with his game, intelligent head, large, brilliant eyes, inclined shoulders and immense windpipe, looking every inch a hero. When Uncle Berry came to him he threw his arms around his neck and said, bursting into tears, “Here’s a poor old man’s friend in a distant land.”

Walk-in-the-Water won more long races than any horse of his day. If I can procure the early volumes of the American Turf Register, I will in a future number give some account of his performances.

Haney’s Maria was a most extraordinary race nag at all distances, probably not inferior to any which has appeared in America since her day. She was bred by Bennet Goodrum, of Virginia, who moved to North Carolina, where she was foaled in the spring of 1808; from there he removed to Tennessee, and, in the fall of 1809, sold Maria to Capt. Jesse Haney, of Sumner County. She was by imported Diomed, one of the last of his get when thirty years of age. Her first dam was by Taylor’s Bel-Air (the best son of imported Medley), second dam by Symmes’ Wild Air, third dam by imported Othello, out of an imported mare.

She was a dark chestnut, exactly fifteen hands high, possessing great strength, muscular power, and symmetry, the perfect model of a race horse. Maria commenced her turf career at three, and ran all distances from a quarter of a mile to four mile heats, without losing a race or heat until she was nine years old. In the fall of 1811 she ran a sweepstake over the Nashville course, entrance $100, two mile heats, beating General Jackson’s colt, Decatur, by Truxton; Col. Robert Bell’s filly, by imported Diomed, and four others; all distanced the first heat, except Bell’s filly. This defeat aroused the fire and combative spirit of General Jackson almost as much as did his defeat by Mr. Adams for the Presidency, and he swore “by the Eternal” he would beat her if a horse could be found in the United States able to do so. But, although the General conquered the Indians, defeated Packenham, beat Adams and Clay, crushed the monster bank under the heel of his military boot, he could not beat Maria, in the hands of Uncle Berry.

In the fall of 1812, over the same course, she won a sweepstake, $500 entrance, four mile heats, beating Colonel Bell’s Diomed mare, a horse called Clifden, and Col. Ed Bradley’s “Dungannon.” (General Jackson was interested in Dungannon.) This was a most exciting and interesting race, especially to the ladies, who attended in great numbers; those of Davidson County, with Aunt Rachel Jackson and her niece, Miss Rachel Hays, at their head, backing Dungannon, while the Sumner County ladies, led by Miss Clarissa Bledsoe, daughter of the pioneer hero, Col. Anthony Bledsoe, bet their last glove on little Maria. After this second defeat, General Jackson became terribly in earnest, and before he gave up the effort to beat Maria, he ransacked Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia and Kentucky. He was almost as clamorous for a horse as was Richard in the battle of Bosworth Field. He first wrote Col. William R. Johnson to send him the best four mile horse in Virginia, without regard to price, expressing a preference for the famous Bel-Air mare, Old Favorite. Colonel Johnson sent him, at a high price, the celebrated horse, Pacolet, by imported Citizen, who had greatly distinguished himself as a four miler in Virginia. In the fall of 1813, at Nashville, Maria won a sweepstake, $1,000 entrance, $500 forfeit, four mile heats, beating Pacolet with great ease, two paying forfeit. It was said that Pacolet had received an injury in one of his fore ankles. The General, being anything but satisfied with the result, made a match on Pacolet against Maria for $1,000 a side, $500 forfeit, four mile heats, to come off over the same course, the fall of 1814; but, Pacolet being still lame, he paid forfeit. These repeated failures only made the General more inflexible in his purpose, and, in conjunction with Mr. James Jackson, who then resided in the vicinity of Nashville, he sent to South Carolina and bought Tam O’Shanter, a horse distinguished in that state.

The fall of 1814 Maria won, over the same course, club purse of $275, two mile heats, beating Tam O’Shanter, William Lytle’s Royalist, and two or three others.

A few days after, over the same course, she won a proprietor’s purse, $350, only one starting against her. About this time General Jackson sent to Georgia and purchased of Colonel Alston Stump-the-Dealer, but, for some cause, did not match him against Maria. The General then sent to Kentucky and induced Mr. DeWett to come to the Hermitage with his mare (reputed to be the swiftest mile nag in the United States), with a view of matching her against Maria. Mr. DeWett trained his mare at the Hermitage. In the fall of 1814, at Clover Bottom, Maria beat this mare for $1,000 a side, dash of a mile. In the fall of 1815 General Jackson and Mr. DeWett ran the same mare against Maria, dash of half a mile, for $1,500 a side, $500 on the first quarter, $500 on six hundred yards, and $500 on the half mile, all of which bets were won by Maria, the last by one hundred feet. This was run at Nashville. The next week, over same course, she won a match $1,000 a side, mile heats, made with General Jackson and Col. Ed Ward, beating the Colonel’s horse, Western Light. Soon after this race she was again matched against her old competitor, DeWett’s mare, for $1,000 a side, over the same course (which was in McNairy’s Bottom, above the sulphur spring), Maria giving her a distance (which was then 120 yards) in a dash of two miles. Colonel Lynch, of Virginia, had been induced to come and bring his famous colored rider, Dick, to ride DeWett’s mare. Before the last start Uncle Berry directed his rider (also colored) to put the spurs to Maria from the tap of the drum. But, to his amazement, they went off at a moderate gait, DeWett’s mare in the lead, making the first mile in exactly two minutes. As they passed the stand Uncle Berry ordered his boy to go on, but the mares continued at the same rate until after they entered the back stretch, Maria still a little in the rear, when the rider gave her the spurs and she beat her competitor one hundred and eighty yards, making the last mile in one minute and forty-eight seconds. All who saw the race declared that she made the most extraordinary display of speed they ever witnessed.

When Uncle Berry demanded an explanation of his rider he learned that Dick, who professed to be a conjurer, or spiritualist, had frightened the boy by threatening that if he attempted to pass ahead of him until they ran a mile and a quarter, he would lift him out of his saddle, or throw down his mare by a mere motion of his whip, which the boy fully believed. Most negroes at that time, and some white people in this enlightened age, believe in these absurdities. The speed of Maria was wonderful. She and the famous quarter race horse, Saltram, were trained by Uncle Berry at the same time, and he often “brushed” them through the quarter stretch, “and they always came out locked.” Whichever one got the start kept the lead.

After the last race above mentioned, some Virginians present said that there were horses in Virginia that could beat Maria. Captain Haney offered to match her against any horse in the world, from one to four mile heats, for $5,000.

Shortly after this conversation, meeting General Jackson, Captain Haney informed him what had passed, and the General, in his impressive manner, replied: “Make the race for $50,000, and consider me in with you. She can beat any animal in God’s whole creation.”

In March, 1816, at Lexington, Ky., she beat Robin Gray (sire of Lexington’s third dam) a match, mile heats, for $1,000 a side. The next month she beat at Cage’s race paths in Sumner County, near Bender’s Ferry, Mr. John Childress’ Woodlawn filly, by Truxton, a straight half mile for $1,000 a side, giving her sixty feet. Maria won this race by two feet only. This was the first race I ever saw, and I was greatly impressed with the beautiful riding of Monkey Simon.

After the race Maria was taken by Uncle Berry to Waynesboro, Ga., where she bantered the world, but could not get a race. There were very few jockey clubs in the country at that time.

In January, 1817, Maria was returned to Captain Haney in Sumner County, and soon afterwards sold by him to Pollard Brown, who got her beaten at Charleston in a four mile heat race with Transport and Little John, when she was nine years old. Maria carried over weight, ran under many disadvantages, and lost the race by only a few feet.

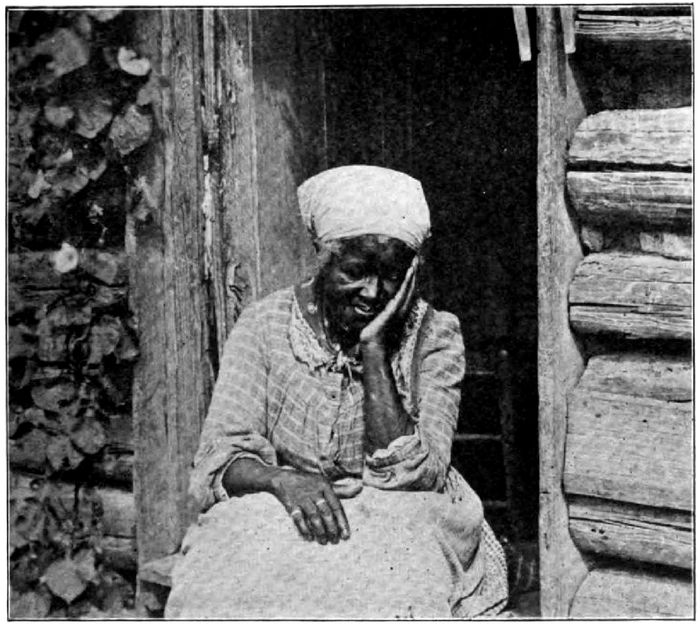

Photo by Julie A. Royster, Raleigh, N. C.