Title: Saddle, Sled and Snowshoe: Pioneering on the Saskatchewan in the Sixties

Author: John McDougall

Illustrator: J. E. Laughlin

Release date: March 23, 2020 [eBook #61659]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

"I made a fire, and by melting snow boiled my kettle." (Page 33.)

PIONEERING ON THE SASKATCHEWAN

IN THE SIXTIES.

BY

JOHN McDOUGALL,

Author of "Forest, Lake and Prairie: Twenty Years of Frontier

Life in Western Canada," etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY J. E. LAUGHLIN.

TORONTO:

WILLIAM BRIGGS,

WESLEY BUILDINGS.

MONTREAL: C. W. COATES. HALIFAX: S. F. HUESTIS.

1896.

Entered according to Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand eight hundred and ninety-six, by WILLIAM BRIGGS, at the Department of Agriculture.

CONTENTS.

Old Fort Edmonton—Early missionaries—Down the Saskatchewan by dog-train—Camp-fire experiences—Arrival at home—Daily occupations

A foraging expedition—Our hungry camp—A welcome feast—Dogs, sleds and buffalo bull in a tangle—In a Wood Cree encampment—Chief Child, Maskepetoon and Ka-kake—Indian hospitality—Incidents of the return trip

Scarcity of food—The winter packet—Start for Edmonton for the eastern mails—A lonely journey—Arrive at Fort Edmonton—Start for home—Camping in a storm—Improvising a "Berlin"—Old Draffan—Sleeping on a dog-sled en route—A hearty welcome home

Trip to Whitefish Lake—Mr. Woolsey as a dog-driver—Rolling down a side hill—Another trip to Edmonton—Mr. O. B. as a passenger—Perils of travel by ice—Narrow escape of Mr. O. B.—A fraud exposed—Profanity punished—Arrival at Edmonton—Milton and Cheadle—Return to Victoria

Mr. Woolsey's ministrations—An exciting foot-race—Building operations—Gardening—Stolen (?) buffalo tongues—Addled duck eggs as a relish—A lesson in cooking—A lucky shot—Precautions against hostile Indians

The summer brigade—With the brigade down the Saskatchewan—A glorious panorama—Meet with father and mother on the way to Victoria—Privations of travel—A buffalo crossing—Arrival at Victoria—A church building begun—Peter Erasmus as interpreter

In search of the Stoneys—An Indian avenger—A Sunday at Fort Edmonton—Drunken Lake carousals—Indian trails—Canyon of the Red Deer—I shoot my father—Amateur surgeons—Prospecting for gold—Peter gets "rattled"—A mysterious shot—Friends or foes?—Noble specimens of the Indian race—A "kodak" needed—Among the Stoneys—Prospecting for a mission site—A massacre of neophytes—An Indian patriarch—Back at Victoria again

Provisions diminishing—A buffalo hunt organized—Oxen and Red River carts—Our "buffalo runners"—Meet with Maskepetoon—Maskepetoon shakes hands with his son's murderer—An Indian's strange vow—Instance of Indian watchfulness—"Who-Talks-Past-All-Things"—Come upon the buffalo—An exciting charge—Ki-you-ken-os races the buffalo—Peter's exciting adventure—Buffalo dainties—Return home—War parties—Indian curiosity—Starving Young Bull's "dedication feast"—Missionary labors

The fall fishing—A relentless tooth-ache—Prairie and forest fire—Attacked by my dogs—A run home—A sleepless night—Father turns dentist—Another visit to Edmonton—Welcome relief—Final revenge on my enemy

Casual visitors—The missionary a "medicine man"—"Hardy dogs and hardier men"—A buffalo hunt organized—"Make a fire! I am freezing!"—I thaw out my companion—Chief Child—Father caught napping—Go with Mr. Woolsey to Edmonton—Encounter between Blackfeet and Stoneys—A "nightmare" scare—My passenger scorched—Rolling down hill—Translating hymns

Visited by the Wood Stoneys—"Muddy Bull"—A noble Indian couple—Remarkable shooting—Tom and I have our first and only disagreement—A race with loaded dog-sleds—Chased by a wounded buffalo bull—My swiftest foot-race—Building a palisade around our mission home—Bringing in seed potatoes

Mr. Woolsey's farewell visit to Edmonton—Preparing for a trip to Fort Garry—Indians gathering into our valley—Fight between Crees and Blackfeet—The "strain of possible tragedy"—I start for Fort Garry—Joined by Ka-kake—Sabbath observance—A camp of Saulteaux—An excited Indian—I dilate on the numbers and resources of the white man—We pass Duck Lake—A bear hunt—"Loaded for b'ar"—A contest in athletics—Whip-poor-wills—Pancakes and maple syrup—Pass the site of Birtle—My first and only difference with Ka-kake

Fall in with a party of "plain hunters"—Marvellous resources of this great country—A "hunting breed"—Astounding ignorance—Visit a Church of England mission—Have my first square meal of bread and butter in two years—Archdeacon Cochrane—Unexpected sympathy with rebellion and slavery—Through the White Horse Plains—Baptiste's recklessness and its punishment—Reach our destination—Present my letter of introduction to Governor McTavish—Purchasing supplies—"Hudson's Bay blankets"—Old Fort Garry, St. Boniface, Winnipeg, St. John's, Kildonan—A "degenerate" Scot—An eloquent Indian preacher—Baptiste succumbs to his old enemy—Prepare for our return journey

We start for home—A stubborn cow—Difficulties of transport—Indignant travellers—Novel method of breaking a horse—Secure provisions at Fort Ellice—Lose one of our cows—I turn detective—Dried meat and fresh cream as a delicacy

Personnel of our party—My little rat terrier has a novel experience—An Indian horse-thief's visit by night—I shoot and wound him—An exciting chase—Saved by the vigilance of my rat terrier—We reach the South Branch of the Saskatchewan—A rushing torrent—A small skin canoe our only means of transport—Mr. Connor's fears of drowning—Get our goods over

A raft of carts—The raft swept away—Succeed in recovering it—Getting our stock over—The emotionless Scot unbends—Our horses wander away—Track them up—Arrive at Carlton—Crossing the North Saskatchewan—Homes for the millions—Fall in with father and Peter—Am sent home for fresh horses—An exhilarating gallop—Home again

Improvements about home—Mr. Woolsey's departure—A zealous and self-sacrificing missionary—A travelling college—I feel a twinge of melancholy—A lesson in the luxury of happiness—Forest and prairie fire—Father's visit to the Mountain Stoneys—Indians gathering about our mission—Complications feared

Maskepetoon—Council gatherings—Maskepetoon'a childhood—"Royal born by right Divine"—A father's advice—An Indian philosopher—Maskepetoon as "Peace Chief"—Forgives his father's murderer—Arrival of Rev. R. T. Rundle—Stephen and Joseph—Stephen's eloquent harangue—Joseph's hunting exploits—Types of the shouting Methodist and the High Church ritualist

Muh-ka-chees, or "the Fox"—An Indian "dude"—A strange story—How the Fox was transformed—Mr. The-Camp-is-Moving as a magician

Victoria becomes a Hudson's Bay trading post—An adventure on a raft—The annual fresh meat hunt organized—Among the buffalo—Oliver misses his shot and is puzzled—My experience with a runaway horse—A successful hunt—My "bump of locality" surprises Peter—Home again

Father and I visit Fort Edmonton—Peter takes to himself a wife—Mr. Connor becomes school teacher—First school in that part of the country—Culinary operations—Father decides to open a mission at Pigeon Lake—I go prospecting—Engage a Roman Catholic guide—Our guide's sudden "illness"—Through new scenes—Reach Pigeon Lake—Getting out timber for building—Incidents of return trip

Another buffalo hunt—Visit Maskepetoon's camp—The old chief's plucky deed—Arrival of a peace party from the Blackfeet—A "peace dance"—Buffalo in plenty—Our mysterious visitor—A party of Blackfeet come upon us—Watching and praying—Arrive home with well-loaded sleds—Christmas festivities

We set out with Maskepetoon for the Blackfoot camp—A wife for a target—Indian scouts—Nearing the Blackfeet—Our Indians don paint and feathers—A picture of the time and place—We enter the Blackfoot camp—Three Bulls—Buffalo Indians—Father describes eastern civilization—The Canadian Government's treatment of the Indians a revelation—I am taken by a war chief as a hostage—Mine host and his seven wives—Bloods and Piegans—I witness a great dance—We leave for home—A sprained ankle—Arrival at the mission

We visit the Cree camp—I lose Maple and the pups—Find our Indian friends "pound-keeping"—The Indian buffalo pound—Consecrating the pound—Mr. Who-Brings-Them-In—Running the buffalo in—The herd safely coralled—Wholesale slaughter—Apportioning the hunt—Finis

ILLUSTRATIONS.

"I made a fire, and by melting snow boiled my kettle" ... Frontispiece

"The dogs and sleds went sliding in around him"

"There he sat, his eyes bulging out with fear"

"The discharge of shot, bounding from this, struck both father and his horse"

"To save my life I had to climb to the top of the staging"

"I got Tom up, and held him close over the fire"

"I bounded from before him for my life"

"I headed her out again into the lake"

"I took deliberate aim, and fired at him"

"We went at a furious rate on that swirling, seething, boiling torrent"

"Tying our clothes in bundles above our heads, we started into the ice-cold current"

"Slapping his head, I turned his course to smooth ground"

"Maskepetoon calmly ...took out his Cree Testament ... and began to read"

"This strange Indian, without looking at us, sang on"

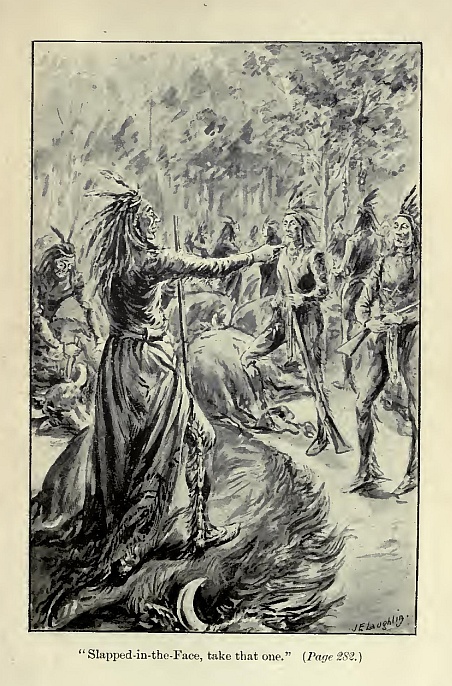

"Slapped-in-the-Face, take that one"

SADDLE, SLED AND SNOWSHOE

Old Fort Edmonton—Early missionaries—Down the Saskatchewan by dog-train—Camp-fire experiences—Arrival at home—Daily occupations.

In my previous volume, "FOREST, LAKE AND PRAIRIE," which closed with the last days of 1862, I left my readers at Fort Edmonton. At that time this Hudson's Bay post was the chief place of interest in the great country known as the Saskatchewan Valley. To this point was tributary a vast region fully six hundred miles square, distinguished by grand ranges of mountains, tremendous foot hills, immense stretches of plain, and great forests. Intersecting it were many mighty rivers, and a great number of smaller streams. Lakes, both fresh and alkaline, dotted its broad surface.

Over the entire length and breadth of this big domain coal seemed inexhaustible. Rich soil and magnificent pasturage were almost universal. But as yet there was no settlement. The peoples who inhabited the country were nomadic. Hunting, trapping, and fishing were their means of livelihood, and in all this they were encouraged by the great Company to whom belonged the various trading-posts scattered over the wide area, and of which Fort Edmonton was chief.

For the collecting and shipping of furs Edmonton existed. For this one definite purpose that post lived and stood and had its being. A large annual output of the skins and furs of many animals was its highest ambition. Towards this goal men and dogs and horses and oxen pulled and strained and starved. For this purpose isolation and hardship almost inconceivable were undergone. For the securing and bringing in to Edmonton of the pelts of buffalo and bear, beaver and badger, martin and musk-rat, fisher and fox, otter and lynx, the interest of everyone living in the country was enlisted. Thirteen different peoples, speaking eight distinct languages, made this post their periodic centre; and while at Edmonton was shown the wonderful tact and skill of the Hudson's Bay Company in managing contending tribes, yet nevertheless many a frightful massacre took place under the shadow of its walls.

This was the half-way house in crossing the continent. Hundreds of miles of wildness and isolation were on either hand. About midway between and two thousand feet above two great oceans—unique, significant, and alone, without telegraphic or postal communication—thus we found Fort Edmonton in the last days of the last month of the year 1862.

Edmonton had been the home of the Rev. R. T. Rundle, the first missionary to that section, who from this point made journeys in every direction to the Hudson's Bay Company's posts and Indian camps.

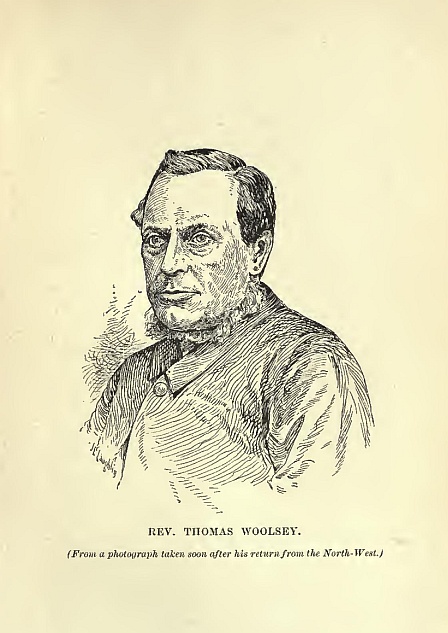

Following him, later on, the Roman Catholic Church sent in her missionaries. These, at the time of which I write, had a church in the Fort, and the beginning of a mission out north, about nine miles from the Fort; also one at Lake St. Ann's, some forty miles distant. When the Rev. Thomas Woolsey came into the North-West, he too made Edmonton his headquarters for some years, and, like his predecessor, travelled from camp to camp and from post to post.

Even in those early days, one could not help predicting a bright future for this important point, for in every direction from Edmonton, as a centre, Nature has been lavish with her gifts. The physical foundations of empire are here to be found in rich profusion, and in 1862, having gone into and come out of Edmonton by several different directions, I felt that I would run but little risk in venturing to prophesy that it would by-and-by become a great metropolis.

The second day of January, 1863, saw a considerable party of travellers wind out of the gate of the Fort and, descending the hill, take the ice and begin the race down the Big Saskatchewan; Mr. Chatelaine, of Fort Pitt, and Mr. Pambrun, of Lac-la-biche, with their men, making, with our party, a total of eight trains. There being no snow, we had to follow the windings of the river. For the first eighty or ninety miles our course was to be the same, and it was pleasant, in this land of isolation, to fall in with so many travelling companions.

It was late in the day when we got away, but both men and dogs were fresh, so we made good time and camped for the night some twenty-five miles from the Fort. Climbing the first bank, we pulled into a clump of spruce, and soon the waning light of day gave place to the bright glare of our large camp-fire. Frozen ground and a few spruce boughs were beneath us and the twinkling stars overhead.

There being at this time no snow, our home for the night is soon ready, the kettles boiled, the tea made and pemmican chopped loose, and though we are entirely without bread or fruit or vegetables, yet we drink our tea, gnaw our pemmican and enjoy ourselves. The twenty-five-mile run and the intense cold have made us very hungry. Most of our company are old pioneers, full of incident and story of life in the far north, or out on the "Big Plains" to the south. We feed our dogs, we tell our stories, we pile the long logs of wood on our big fire, and alternately change our position, back then front to the fire. We who have been running hard, and whose clothes are wet with perspiration, now become ourselves the clothes-horses whereon to dry these things before we attempt to sleep. Then we sing a hymn, have a word of prayer, and turn in.

The great fire burns down, the stars glitter through the crisp, frosty air, the aurora dances over our heads and flashes in brilliant colors about our camp, the trees and the ice crack with the intense cold, but we sleep on until between one and two, when we are again astir. Our huge fire once more flings its glare away out through the surrounding trees and into the cold night. A hot cup of tea, a small chunk of pemmican, a short prayer, and hitching up our dogs, tying up our sled loads and wrapping up our passengers, we are away once more on the ice of this great inland river. The yelp of a dog as the sharp whip touches him is answered from either forest-clad bank by numbers of coyotes and wolves; but regardless of these, "Marse!" is the word, and on we run, making fast time.

On our way up I had found a buck deer frozen into the ice, and had chopped the antlers from his head and "cached" them in a tree to take home with me; but when I told my new companions of my find, they were eager for the meat, which they said would be good. I had not yet eaten drowned meat, but when I came to think of it I saw there was reason in what they said, and so promised to do my best to find the spot where the buck was frozen in. As it was night—perhaps three o'clock—when we came to the place, I was a little dubious as to finding the deer. However, I was born with a large "bump of locality" and a good average memory, and presently we were chopping the drowned deer out of the ready-to-hand refrigerator. This done we drove on, and stopped for our second breakfast near the Vermilion. We were through and away from this before daylight, and hurrying on reached our turning-off point early in the afternoon, where we bade our friends good-bye, and, clambering up the north bank of the Saskatchewan, disappeared into the forest.

Taking our course straight for Smoking Lake, the whole length of which we travelled on the ice, we climbed the gently-sloping hill for two miles and were home again, having made the 120 miles in less than two days.

When I jumped out of bed next morning my feet felt as if I were foundered, because of the steady run on the frozen ground and harder ice; but this soon passed away. Mr. O. B., whom we had left at home, was greatly rejoiced at our return. He had been very lonely. I described to him our visit, and told him of the nice fat, tender beef on which the Chief Factor had regaled us on Christmas and New Year's day; and surely it was not my fault that, when the portion of the meat of the drowned deer which had been brought home was cooked, he thought it was Edmonton beef, and pronounced it "delicious," and partook largely of it, and later on was terribly put out to learn it was a bit of a drowned animal we had found in the river.

Holidays past, we faced our work, which was varied and large: fish to be hauled home; provisions to be sought for, and, when found, traded from the Indians; timber to be got out and hauled some distance; lumber to be "whipped,"—that is, cut by the whip-saw; freight to be hauled for Mr. Woolsey, who had some in store or as a loan at Whitefish Lake—all this gave us no time for loitering. Men, horses, dogs, all had to move. Moreover, we had to make our own dog and horse sleds, and sew the harness for both dogs and horses. That for the dogs we made out of tanned moose skins; that for the horses and oxen, out of partly tanned buffalo hide, known as "power flesh," the significance of which I could never comprehend, unless the sewing of them, which was powerfully tedious, was what was meant. Turn which way you would there was plenty to do, and, from the present day standpoint, very little to do it with.

Mr. Woolsey and Mr. O. B. kept down the shack, and the rest of us—that is, Williston, William, Neils and myself—went at the rest of the work. First we hauled the balance of our fish home, then we made a trip to Whitefish Lake and brought the freight which had been left there. Mr. Steinhauer and two of his daughters accompanied us back to Smoking Lake, the former to confer with his brother missionary, and the girls to become the pupils of Mr. Woolsey. The opportunity of being taught even the rudiments was exceedingly rare in those days in the North-West, and Mr. Steinhauer was only too glad to take the offer of his brother missionary to help in this way. The snow was now from a foot to twenty inches deep. The cold was keen. To make trails through dense forests and across trackless plains, to camp where night caught us, without tent or any other dwelling, and with only the blue sky above us and the crisp snow and frozen ground beneath, were now our every-day experience.

A foraging expedition—Our hungry camp—A welcome feast—Dogs, sleds and buffalo bull in a tangle—In a Wood Cree encampment—Chief Child, Maskepetoon and Ka-kake—Indian hospitality—Incidents of the return trip.

About the middle of January we started for the plains to find the Indians, and, if possible, secure provisions and fresh meat from them. William and Neils, with horses and sleds, preceded us some days. Williston and I in the meantime went for the last load of fish, then we followed our men out to the great plains. In those days travelling with horses was tedious. You had to give the animals time to forage in the snow, or they would not stand the trip. From forty to sixty miles per day would be ordinary progress for dogs and drivers, but from ten to twenty would be enough for horses in the deep snow and cold of winter; thus it came to pass that, although William and Neils had preceded us some days, nevertheless we camped with them our second night out, close beside an old buffalo pound which had been built by the Indians.

It was said by the old Indians that if you took the wood of a pound for your camp-fire, a storm would be the result; and as we did take of the wood that night, a storm came sure enough, and William's horses were far away next morning. As we had but little provisions, Williston and I did not wait, but leaving the most of our little stock of dried meat with the horse party, we went on in the storm, and keeping at it all day, made a considerable distance in a south-easterly direction, where we hoped to fall in with Indians or buffaloes, or possibly a party bent on the same errand as ourselves from the sister mission at Whitefish Lake.

That night both men and dogs ate sparingly, for the simple reason that we did not have any more to eat. In these northern latitudes a night in January in the snow with plenty of food is, under the best of circumstances, a hardship; but when both tired men and faithful dogs are on "short commons" the gloom seems darker, the cold keener, the loneliness greater than usual. At any rate, that is how Williston and I felt the night I refer to. The problem was clear on the blackboard before us as we sat and vainly tried to think it out, for there was very little talking round our camp-fire that night. The known quantities were: an immense stretch of unfamiliar country before us; deep, loose snow everywhere around us; our food all gone; both of us in a large measure "tenderfeet." The unknown: Where were the friendly Indians and the buffaloes, and where was food to be found? But being tired and young we went to sleep, and with the morning star were waiting for the daylight in a more hopeful condition of mind.

Driving on in the drifting snow, about 10 a.m. we came upon a fresh track of dog-sleds going in our direction. This, then, must be the party from Whitefish Lake. The thought put new life both into us and our dogs. Closely watching the trail, which was being drifted over very fast by the loose snow, we hurried on, and soon came to where these people had camped the night before. Pushing on, we came up to them about the middle of the afternoon. They turned out to be Peter Erasmus and some Indians from Whitefish Lake Mission; but, alas for our hopes of food, like ourselves they were without provisions. However, we drove on as fast as we could, and had the supreme satisfaction of killing a buffalo cow just before sundown that same evening. Very soon the animal was butchered and on our sleds, and finding a suitable clump of timber, we camped for the night. Making a good large camp-fire, very soon we were roasting and boiling and eating buffalo meat, to the great content of our inner man. What a contrast our camp this night to that of the previous one! Then, hunger and loneliness and considerable anxiety; now, feasting and anecdote and joke and fun. Our dogs, also, were in better spirits.

There was one drawback—we had no salt. My companion Williston had left what little we had in one of our camps. He pretended he did not care for salt, and he and the others laughed at me because I longed for it so much. The fresh meat was good, but "Oh, if I only had some salt!" was an oft-repeated expression from my lips. Later we fell in with old Ben Sinclair, who sympathized with me very much, and rummaging in the dirty, grimy sack in which he carried his tobacco and moccasins and mending material, he at last brought up a tiny bit of salt tied up in the corner of a small rag, saying: "My wife Magened, he very good woman, he put that there; you may have it;" and thankful I was for the few grains of salt. As Williston had lost ours, and had laughed at me for mourning over the loss, and especially as the few grains old Ben gave me would not admit of it, I did not offer him a share, but made my little portion last for the rest of that journey.

Six hungry, hard-travelled men and twenty-four hungrier and also harder-travelled dogs left very little of that buffalo cow (though a big and fat animal) to carry out of the camp. Supper, or several suppers, for six men and twenty-four dogs, and then breakfast for six men, and the cow was about gone; but now we had pretty good hope of finding more. This we did as we journeyed on, and at the end of two days' travel we sighted the smoke of a large camp of Indians.

"The dogs and sleds went sliding in around him."

Nothing special had happened during those two days, except that once our dogs and an old buffalo bull got badly tangled up, and we had to kill the bull to unravel the tangle. It happened in this wise: We started the bull, and he galloped off, almost on our course, so we let our dogs run after him, and the huge, clumsy fellow took straight across a frozen lake, and coming upon some glare ice just as the dogs came up to him, he slipped and fell, and the dogs and sleds went sliding in all around him. Thus the six trains got tangled up all around the old fellow, who snorted and shook his head, and kicked, but could not get up. We had to kill him to release our dogs and sleds.

The camp we came to had about two hundred lodges, mostly Wood Crees. They were glad to see us, and welcomed us right hospitably. We went into Chief Child's tent, and made our home there for the short time we were in the camp; but we may be said to have boarded all over this temporary village, for I think I must have had a dozen suppers in as many different tents the first evening of our arrival; and I could not by any means accept all the invitations I had showered upon me. While eating a titbit of buffalo in one tent, and giving all the items of news from the north I knew, and asking and answering questions, behold! another messenger would come in, and tell me he had been sent to take me to another big man's lodge—and thus, until midnight, I went from tent to tent, sampling the culinary art of my Indian friends, and imparting and receiving information. I had a long chat with the grand old chief, Maskepetoon; renewed my acquaintance with the sharp-eyed and wiry hunter and warrior, Ka-kake, and made friends with a bright, fine-looking young man who had recently come from a war expedition. He had been shot right through his body, just missing the spine, and was now convalescing. My new friend, some four or five years after our first meeting, gave up tribal war and paganism, and heartily embraced Christianity. He became as the right hand of the missionary, and to-day is head man at Saddle Lake.

Without recognizing the fact, I was now fairly in the field as a pioneer, and taking my first lessons in the university of God as a student in a great new land. Running after a dog-train all day, partaking of many suppers, talking more or less all the time until midnight, then to bed—thus the first night was spent in camp.

Next morning we traded our loads of provisions—calfskin bags of pounded meat, cakes of hard tallow, bladders of marrow-fat, bales of dried meat, and buffalo tongues. In a short time Williston and I had all we could pack on our sleds, or at any rate all our dogs could haul home. And now it required some skill and planning to load our sleds. To pack and wrap and lash securely as a permanent load for home, some four hundred pounds of tongues and cakes and bladders of grease and bags of pounded meat, on a small toboggan, some eight feet by one foot in size; then on the top of this to tie our own and our dogs' provisions for the return journey, also axe, and kettle, and change of duffels and moccasins; and in the meantime answer a thousand questions that men and women and children who, as they looked on or helped, kept plying us with, took some time and patient work; but by evening we were ready to make an early start next day.

In the meantime the hunters had been away killing and bringing in meat and robes. With the opening light, and all day long, the women had been busy scraping hides and dressing robes and leather, pounding meat, rendering tallow, chopping bones wherewith to make what was termed "marrow-fat," bringing in wood, besides sewing garments and making and mending moccasins. Only the men who had just come home from a war party, or those who came in the day before with a lot of meat and a number of hides, were now the loungers, resting from the heavy fatigues of the chase or war. The whole scene was a study of life under new phases, and as I worked and talked I was taking it all in and adapting language and idiom and thought to my new surroundings.

Another long evening of many invitations and many suppers, also of continuous catechism and questionings, then a few hours' sleep, during which the temperature has become fearfully cold, and with early morn we are catching our dogs, who are now rested, and with what food we gave them and that which they have stolen have perceptibly fattened.

Our Whitefish Lake friends are ready also, and we make a start. Our loads are high and heavy. Many an upset takes place. To right the load, to hold it back going down hill, to push up the steep hills, to run and walk all the time, to take our turn in breaking the trail (for we are going as straight as possible for home, and will not strike our out-bound trail for many miles, then only to find it drifted over)—all this soon takes the romance out of winter tripping with dogs; but we plod on and camp some thirty-five or forty miles from the Indian camp. The already tired drivers must work hard at making camp and cutting and packing wood before this day's work is done; then supper and rest, and prayer and bed, and long before daylight next morning we are away, and by pushing on make from forty to fifty miles our second day.

That night we sent a message back to the Indian camp. The message was about buffaloes, of which we had seen quite a number of herds that afternoon. The messenger was a dog. Peter Erasmus had bought a very, fine-looking dog from an old woman, and I incidentally heard her, as she was catching the dog, say to him: "This is now the sixth time I have sold you, and you came home five times. I expect you will do so again." And sure enough the big fine-looking fellow turned out a fraud. Peter was tired of him, and was about to let him go, when I suggested using him to tell the Indians about the buffaloes we had seen; so a message in syllables was written and fastened to the dog's neck, and he was let loose. He very soon left our camp, and, as I found out later, was in the Indian camp when the people began to stir next morning. We let him go about eight o'clock at night, and before daylight next morning he had made the two days' journey traversed by us. As an Indian would say, "The old woman's medicine is strong!"

There were six very weary men in our camp that night, thirty-three years ago. Floundering through the snow for two long days, pushing and righting and holding back those heavy sleds, whipping up lazy dogs, etc., chopping and carrying wood, shovelling snow—well, we wanted our supper. But after supper, what a change! Joke and repartee, incident and story followed, and while the wolves howled and the wind whistled and the cold intensified, with our big blazing fire we were, in measure, happy. Three of the six have been dead many years; the other three, though aging fast, are now and then camping as of old, still vigorous and hale.

During the next morning's tramp we separated, each party taking the direct course for home. That afternoon we met William and Neils, who had been all this time finding their horses, which strayed away the night of the storm, when we camped together by the old pound. Surely the spirit of the old structure had been avenged because of our burning some of it, for the storm had come, the horses had been lost, and our men had been in a condition of semi-starvation for some days. We told them where they could find buffaloes and the Indian camp, gave them some provisions and drove on. Having the track, we made the old pound the same evening, and, nothing daunted, proceeded to make firewood of its walls. To our camp there came that night the tall young Indian Pakan, who is now the chief of the Whitefish and Saddle Lake Reserves. He seemed to resent the desecration of the pound, but our supper and company and the news of buffaloes made him forget this for the time. He and two or three others were camped not far off, on their way out to the plains.

Two long days more, with the road very heavy, and sometimes almost no road at all, brought us late the second night to our shack, where Mr. Woolsey and Mr. O. B. were delighted to greet us once more. They had been lonely and were anxious about us.

Scarcity of food—The winter packet—Start for Edmonton for the eastern mails—A lonely journey—Arrive at Fort Edmonton—Start for home—Camping in a storm—Improvising a "Berlin"—Old Draffan—Sleeping on a dog-sled en route—A hearty welcome home.

That trip with dog-train was enough for Williston. He did not want any more of such work, so I took an Indian boy who had joined our party and started out again. Later on I traded Williston to William for Neils, the Norwegian, who made several trips with me. During that winter the Indian camps at which we could obtain provisions were never nearer than about 150 miles, and were sometimes much farther away; and as we intended building the next spring on the site of the new mission, at the river, we had to make every effort to secure a sufficiency of provisions. When we had neither flour nor vegetables, animal food alone went fast. Then, besides the hauling of food long distances, we had to transport lumber and timber and other material from where we were living to the new and permanent site on the river bank, which was some thirty-five miles distant. Sometimes with the dog-teams 'we took down a load' of lumber to the river and returned the same day, thus making the seventy-mile round trip in the day. The horses would take from three to four days for the same trip.

It was some time in February that, having started from our first encampment on the way out, long before daylight one dark morning we saw the glimmer of a camp-fire, and wondered who it could be; but as the light was right on our road, we found when we came up that it was the one winter packet from the east on its way to Edmonton. Mr. Hardisty was in charge of the party, and the reason they had stopped and made a fire on our road—which they should have crossed at right angles—was that through the darkness of the winter morning they had missed their way, and were waiting for daylight to show them their course.

Mr. Hardisty gave me some items of news from the outside world, and also told me, what was tantalizing in the extreme, that there were letters for Mr. Woolsey and myself in the packet, but that this was sealed and could not be opened until they reached Edmonton. How I did long for those letters from home and the loved ones there. But longing would not open the sealed packet box.

With the first glimmering of day we parted, the winter packet to continue its way through the deep snow and uncertain trail on to Edmonton; we to make our way out to the Indian camps. These were continually moving with the buffalo, so that the place that knew them to-day might possibly never know them again forever, so big is this vast country, and so migratory in their habits are its peoples.

In due time we found one of the camps, and trading our loads made for home; but as this was the stormy and windy season of the year, we made slow progress. Finally we reached Mr. Woolsey, and I importuned him to let me go for our mail, which he finally consented to do, but said he could not spare anyone to go with me. However, I was so eager that I resolved to go alone. My plan was to send Neils and the boy Ephraim out for more provisions, and I would accompany them as far as the spot where we had seen the packet men some two weeks before. Then I should take their trail, and try and keep it to Edmonton. Mr. Woolsey very reluctantly assented to all this.

About three o'clock one dark, cloudy morning found us at the "parting of the ways," and bidding Neils and Ephraim good-bye, I put on my snowshoes and took the now more or less covered trail of the packet men. I had about 250 pounds of a load, consisting of ammunition and tobacco that Mr. Woolsey had borrowed from the Hudson's Bay Company, and was now returning by me. I had great faith in my lead dog "Draffan," a fine big black fellow, whose sleek coat had given him his name, "Fine-cloth." In fact, all four of my dogs were noble fellows, and away we went, Draffan smelling and feeling out the very indistinct trail, and I running behind on snowshoes. It was my first trip alone, and I could not repress a feeling of isolation: but then the object, "letters from home," was constantly in my thoughts and spurring me on. By daylight I came to the snow-drifted dinner camp of the packet men; by half-past ten I was at their night encampment. I am doing well, thought I, and here I unharnessed my dogs and made a fire, and by melting snow boiled my kettle, but did not feel very much like eating or drinking. The whole thing was inexpressibly lonely. The experience was a new one and not too pleasant.

My dogs hardly had time to roll and shake themselves from the long run of the morning when I was sticking their heads into the collars again, and away jumped the faithful brutes, Draffan scenting and feeling the much-blinded road. On we went, the dogs with their load, and I on my light snowshoes, keeping up a smart run across plains, through bluffs of willow and poplar, over hills and along valleys. About the middle of the afternoon, or later, I noticed the snow was lessening, and presently I took off my snowshoes, and also my coat, and tying these on the sled, started up the dogs with a sudden sharp command, and away they jumped. We increased our speed, and went flying westward toward the setting sun; for though I had never been over this country before, I had an idea that Edmonton was about on our course. On towards sundown I noticed a well-timbered range of dark hills in the distance, and said to myself, "There is where we must camp," and I could not help already feeling a premonition of great loneliness coming over me.

On we sped, the dogs at a sharp trot, with an occasional run, and I on what you might call two-thirds or three-fourths speed, when all of a sudden we came into a well-beaten road, which converged into our trail, and now, with the solid, smooth track under their feet, my noble team fairly raced away, making my sledge swing in good shape.

Thinking to myself that I might catch up to or meet some party travelling in this evidently well-frequented road, I put on my coat, seated myself on the sled, and my hardy team went flying on the best tracked road they had struck that winter. Presently we came to the edge of a great hill, which I found to be but the beginning of a large, deep valley. Hardly had I time to get astride the sled, and with my feet brake or help to steer its course, when down, down, down, at a dead hard run, went my dogs. Then over a sloping bottom, and to my great astonishment out we came on the banks of a big river.

"What is this?" thought I; "surely I have missed my way." I had never heard of a large stream emptying into the Saskatchewan from the south side. While thus perplexed and anxious, my dogs took a short jump over a cut bank, and I was landed, sled and dogs and all, on the ice of this big river. Then I looked up westward, and to my surprise saw in the waning light the wings or fans of the old wind-mill which stood on the hill back of Fort Edmonton. I could hardly believe my eyes, but on sped my eager dogs. Soon we were climbing the opposite bank, and presently, just as the guard was about to shut the eastern gate of the Fort, we dashed in and were at our journey's end.

"Where did you come from to-day, John?" asked my friend, Mr. Hardisty. My reply was, "About fifteen miles north of where we saw you the other morning." "No," said he; but nevertheless it was true. They had travelled all that day after we had seen them, as they left us at the first approach of daylight; then they had started long before daylight the next morning, and it was evening when they reached Edmonton; while I had done the same distance and fifteen miles more—that is, I had made a good round hundred miles that day, my first trip alone.

Right glad I was at being thus relieved from camping alone that night, and with my letters all cheering, and the kind friends of the place, I thoroughly enjoyed the hospitality of Old Fort Edmonton. It was Friday night when I reached the Fort. Spending Saturday and Sunday with the Hudson's Bay officers and men, I started on my return trip Monday, about 10.30 a.m., and by night had made the camp where I had lunched on the way out. To some extent I had got over the shrinking from being alone, so I chopped and carried wood for my camp, made myself as comfortable as I could, fed my dogs, and listened to the chorus of wolves and coyotes as they howled dismally around me. Then the wind got up, and with gusts of wild fury came whistling through the trees which composed the little bluff in which I was camped. Soon it began to drift, so I turned up my sled on its edge to the windward, and stretching my feet to the fire, wrapped myself in buffalo and blanket, and went to sleep.

When I awoke I jumped up and made a fire, and looking at my watch, saw it was two o'clock. The wind had become a storm. I went out of the woods to where I thought the trail should be, and felt for it with my feet (for I had grown to have great faith in Draffan and his wonderful instinct, and thought that if I could start him right he would be likely to keep right), and there under the newly drifted snow was the frozen track. I then went back to the camp and harnessed my dogs, and as I had little or no load, I made an improvised cariole, or what was termed a "Berlin," out of my wrapper and sled lashings, and when ready drove out to where I had discovered the track.

The storm was now raging, the night was wild, and the cold intense; but, wrapped in my warm robe, I stretched myself in the "Berlin," and getting as flat as possible in order to lessen the chances of upsetting, when ready I gave the word to Draffan, saw that he took the right direction, and then covering up went to sleep. With sublime faith in that dog I slept on. If I woke up for a moment, I merely listened for the jingle of my dog-bells, and by the sound satisfied myself that my team were travelling steadily, and then went to sleep again.

When coming up I had noticed a long side hill, and I said to myself: "If we are on the right track I will most assuredly upset at that point"—and sure enough I did wake up to find myself rolling, robe and all, down the slope of the hill. I was compensated for the discomfort by being thus assured that my faithful dogs had kept the right track. Jumping up, I shook myself and the robe, righted the sled, stretched the robe into it, and then giving my leader a caress and a word of encouragement, I put on my snowshoes and away we went at a good run, old Draffan picking the way with unerring instinct. Thus we kept it up until daylight, when we stopped and I unharnessed the dogs, and, making a fire, boiled my kettle and had breakfast. Then, starting once more, I determined to cut across some of the points of the square we had made coming up; and for about four hours we went straight across country, and striking our provision trail opposite Egg Lake, I took off my snowshoes and got into the "Berlin." My dogs bounded away on the home-stretch, we still having about forty or forty-five miles to go, and it was already past noon.

All day it had stormed, but now we were on familiar ground, and right merrily my noble dogs rang the bells, as across bits of prairie and through thickening woods we took our way northward. I was so elated at having successfully made the trip up to this point, that I could not sit still very long, but, running and riding, kept on, never stopping for lunch. Thus the early dusk of the stormy day found us at the southerly end of Smoking Lake, and some twelve or fifteen miles from home. Here I again wrapped myself in my robe, and lying flat in the sled, felt I could very safely leave the rest to old Draffan and a kind Providence, and go to sleep, which I did, to wake up as the dogs were climbing the steep little bank at the north end of the lake. Then a run of two miles and I was home again.

Mr. Woolsey was so overjoyed he took me in his arms, and almost wept over me. He brought dogs, sled and my whole outfit into the house. The kind-hearted old man had passed a period of great anxiety; had been sorry a thousand times that he had consented to my going to Edmonton; had dreamed of my being lost, of my bleeding to death, of my freezing stiff; but now with the first tinkle of my dog-bells he was out peering into the darkness, and shouting, "Is that you, John?" and my answer, he assured me, filled him with joy. He did not ask for his mail, did not think of it for a long time, he was so thankful that the boy left in his care had come back to him safe and sound. For my part I was glad to be home again. The uncertain road, the long distance, the deep snow, the continuous drifting, storm, the awful loneliness, were all past. I had found Edmonton, had brought the mail, was home again beside our own cheery fire, and was a proud and happy boy.

In a day or two Neils and Ephraim came in from the camp, and we once more, a reunited party, made another start for more provisions, and, later on, yet another for the same purpose, never finding the Indians in the same place, but always following them up. We were successful in reaching their camps and in securing our loads; so that my first winter on the Saskatchewan gave me the opportunity of covering a large portion of the country, and becoming acquainted with a goodly number of the Indian people. I also had constant practice in the language, and was now quite familiar with it.

Trip to Whitefish Lake—Mr. Woolsey as a dog-driver—Rolling down a side hill—Another trip to Edmonton—Mr. O. B. as a passenger—Perils of travel by ice—Narrow escape of Mr. O. B.—A fraud exposed—Profanity punished—Arrival at Edmonton—Milton and Cheadle—Return to Victoria.

Some time in March, Mr. Woolsey, wishing to confer with his brother missionary, Mr. Steinhauer, concluded to go to Whitefish Lake, and to take the Steinhauer girls home at the same time. He, moreover, determined to take the train of dogs Neils had been driving, and drive himself; but as there had been no direct traffic from where we were to Whitefish Lake, and as the snow was yet quite deep, we planned to take our provision trail out south until we would come near to the point where our road converged with one which came from Whitefish Lake to the plains. This meant travelling more than twice the distance for the sake of a good road, but even this paid us when compared with making a new road through a forest country in the month of March, when the snow was deep. We were about two and a half days making the trip, travelling about 130 miles, but, burdened as Ephraim and I were with three passengers, "the longest way round proved the shortest way home."

Mr. Woolsey was not a good dog-driver. He could not run, or even walk at any quick pace, so he had to sit wedged into his cariole, from start to finish, between camps, while I kept his train on the road ahead of mine; for if he upset—which he often did—he could not right himself, and I had to run ahead and fix him up. His dogs very soon got to know that their driver was a fixture on the sled, and also that I was away behind the next train and could not very well get at them because of the narrow road, and the great depth of snow on either side of it. However, things reached a climax when we were passing through a hilly, rolling country on the third morning of our trip. Those dogs would not even run down hill fast enough to keep the sleigh on its bottom, and I had to run forward and right Mr. Woolsey and his cariole a number of times. Presently, coming to a side hill, Mr. Woolsey, in his sled, rolled over and over, like a log, to the foot of the slope.

There, fast in the cariole, and wedged in the snow, lay the missionary. The lazy dogs had gently accommodated themselves to the rolling of the sled, and also lay at the foot of the hill, seemingly quite content to rest for awhile.

Now, thought I, is my chance, and without touching Mr. Woolsey or his sled, I went at those dogs, and in a very short time put the fear of death into them, so that when I spoke to them afterwards they jumped. Then I unravelled them and straightened them out, and rescuing Mr. Woolsey from his uncomfortable position, I spoke the word, and the very much quickened dogs sprang into their collars as if they meant it, and after this we made better time.

Mr. and Mrs. Steinhauer were delighted to have their daughters home, and also glad to have a visit from our party. We spent two very pleasant days with these worthy people, who were missionaries of the true type. Going back I hitched my own dogs to Mr. Woolsey's cariole, and thus kept him right side up with much less trouble, and also made better time back to Smoking Lake.

With the approach of spring we prepared to move down to the river. We put up a couple of stagings, also a couple of buffalo-skin lodges, in one of which Mr. Woolsey and Mr. O. B. took up their abode, while the rest of our party kept on the road, bringing down from the old place our goods and chattels, lumber and timber, etc. As the days grew warmer, we who were handling dogs had to travel most of the time in the night, as then the snow and track were frozen. While the snow lasted we slept and rested during the warm hours of the day, and in the cool of the morning and evening, and all night long, we kept at work transporting our materials to the site of the new mission. The last of the season is a hard time for the dog-driver. The night-work, the glare or reflection of the snow, both by sun and moonlight; the subsidence of the snow on either side of the road, causing constant upsetting of sleds; the melting of the snow, making your feet wet and sloppy almost all the time; then the pulling, and pushing, and lifting, and walking, and running,—these were the inevitable experiences. Indeed, one had to be tough and hardy and willing, or he would never succeed as a traveller and tripper in the "great lone land" in those days.

The snow had almost disappeared, and the first geese and ducks were beginning to arrive, when suddenly one evening Mr. Steinhauer and Peter Erasmus turned up, en route to Edmonton; and Mr. Woolsey took me to one side and said, "John, I am about tired of Mr. O. B. Could you not take him to Edmonton and leave him there. You might join this party now going there."

In a very few hours I was ready, and the same night we started on the ice, intending to keep the river to Edmonton. The night was clear and cold, and for some time the travelling was good; but near daylight, when about thirty miles on our way, we met an overflow flood coming down on top of the ice. There must have been from sixteen to eighteen inches of water, creating quite a current, and as we were on the wrong side of the river it behoved us to cross as soon as possible, and go into camp. There was a thick scum of sharp float ice on the top of the flood, about half an inch thick. When I drove my dogs into the overflow they had almost to swim, and the cariole, notwithstanding I was steadying it, would float and wobble in the current. Unfortunately, as the cold water began to soak into the sled, and reached my passenger, Mr. O. B., he blamed me for it, and presently began to curse me roundly, declaring I was doing it on purpose. All this time I was wading in the water and keeping the sled from upsetting; but when he continued his profanity I couldn't stand it any longer, so just dumped him right out into the overflow and went on. However, when I looked back and saw the old fellow staggering through the water, and fending his legs with his cane from the sharp ice, I returned and helped him ashore, but told him I would not stand any more swearing.

We then climbed the bank on the north side, and had to remain there for two days till the waters subsided. About eight o'clock the second night the ice was nearly dry, and frozen sufficiently for us to make a fresh start. We proceeded up the river, picking our way with great care, for there were now many holes in the ice, caused by the swift currents which had been above as well as beneath for the last two days. My passenger never slept, but sat there watching those holes, and dreading to pass near them, constantly afraid of drowning—in fact, I never travelled with anyone so much in dread of death as he was.

Morning found us away above Sturgeon River, and as the indications pointed to a speedy "break up," we determined to push on. Presently we came to a place where the banks were steep and the river open on either side. The ice, though still intact in the middle, was submerged by a volume of water running nearly crossways in the river. Some of our party began to talk of turning back, but as we were now within twenty-five miles of Edmonton, I was loath to return with my old passenger, so concluded to risk the submerged ice-bridge before us. I told Mr. O. B. to get out of the cariole; then I fastened two lines to the sled, took hold of one myself, and gave him the other, telling him to hang on for dear life if he should break through. I then drove my dogs in. Away they went across, we following at the end of the lines, stepping as lightly as we could, and as the dogs got out on the strong ice they pulled us after them.

Having crossed, I set to work to wring out the blankets and robes in the cariole, Mr. O. B. looking on. At the bottom there was a parchment robe—that is, an undressed hide. This, I said, I would not take any further, as it was comparatively useless anyway, but now, soaked and heavy, it was an actual encumbrance.

"You will take it along," said Mr. O. B.

"No, I will not," said I; but as there was good ice as far as I could see ahead, I told him to go on, and that I would overtake him as soon as I was through fixing the things in the sled. Reluctantly he started, and by-and-by when I came to the hide I found it so heavy that I did as I said I would, and pitched it into the stream. When I came up with Mr. O. B., instead of stepping into the cariole, he turned up everything to look for the hide, and, not finding it, began to rave at me, using the foulest and most blasphemous language.

I merely looked at him and said, "Get in, or I will leave you here." He saw I was in earnest, and got into the sled in no good humor, and on we drove; but as I ran behind I was planning some punishment for the old sinner, who had posed as such a saint while with Mr. Woolsey.

Very soon everything came as if ready to hand for my purpose. As we were skirting the bank we came to a place where the ice sloped to the current, and just there the water was both deep and rapid. Here I took a firm grip of the lines from the back of the cariole, and watching for the best place, shouted to the dogs to increase their speed. Then I gave a stern, quick "Chuh!" which made the leader jump close to the edge of the current, and as the sled went swinging down the sloping ice, I again shouted "Whoa!" and down in their tracks dropped my dogs. Out into the current, over the edge of the ice, slid the rear end of the cariole. Mr. O. B. saw he dare not jump out, for the ice would have broken, and he would have gone under into the strong current. There he sat, his eyes bulging out with fear as he cried, "For God's sake, John, what are you going to do?" while I stood holding the line, which, if I slackened, would let him into the rapid water, from which there seemed to be no earthly means of rescue.

"There he sat, his eyes bulging out with fear."

After a while I said, "Well, Mr. O. B., are you ready now to apologize for, and take back the foul language you, without reason, heaped on me a little while since?" And Mr. O. B., in most abject tones and terms, did make ample apology. Then slackening the line a little, I let the sled flop up and down in the current, and finally accepted his apology on condition that he would behave himself in the future. My dogs quickly pulled him out of his peril, and on we went. Presently we were joined by Mr. Steinhauer and Peter, who had gone across a point, they having light sleds, which enabled them to make their way for a short distance on the bare ground.

We reached Edmonton that evening, and I was glad to transfer my charge to some one else's care. I was not particular who took him, for, like Mr. Woolsey, I was tired of the old fraud.

The Chief Factor said to me that evening, "So you brought Mr. O. B. to Edmonton. You will have to pay ten shillings for every day he remains in the Fort."

"Excuse me, sir," I answered, "I brought him to the foot of the hill, down at the landing, and left him there. If he comes into the Fort I am not responsible."

Shortly after this Lord Milton and Dr. Cheadle came along en route across the mountains, and Mr. O. B. joined their party. If any one should desire more of his history, these gentlemen wrote a book descriptive of their journey, and in this our hero appears. I am done with him, for the present at any rate.

Spring was now open, the snow nearly gone, and we had to make our way back from Edmonton as best we could. I cached the cariole, hired a horse, packed him with my dog harness, blankets, and food, and thus reached Victoria, which father had designated as the name of the new mission. My dogs, having worked faithfully for many months, and having travelled some thousands of miles, sometimes under most trying circumstances, were now entering upon their summer vacation. How they gambolled and ran and hunted as they journeyed homeward!

Mr. Woolsey's ministrations—An exciting foot-race—Building operations—Gardening—Stolen (?) buffalo tongues—Addled duck eggs as a relish—A lesson in cooking—A lucky shot—Precautions against hostile Indians.

With the opening spring Indians began to come in from the plains, and for several weeks we had hundreds of lodges beside us. Mr. Woolsey was kept busy holding meetings, attending councils, visiting the sick, acting as doctor and surgeon, magistrate and judge; for who else had these people to come to but the missionary? A number of them had accepted Christianity, but the majority were still pagan, and these were full of curiosity as to the missionary and his work, and keenly watching every move of the "praying man" and his party. The preacher may preach ever so good, but he himself is to these people the exponent of what he preaches, and they judge the Gospel he presents by himself. If he fails to measure up in manliness and liberality and general manhood, then they think there is no more use in listening to his teaching. Very early in my experience it was borne in upon me that the missionary, to obtain influence on the people, must be fitted to lead in all matters. If short of this, their estimate of him would be low, and their respect proportionately small, and thus his work would be sadly handicapped all through.

While Mr. Woolsey was constantly at work among the people, the rest of us were fencing and planting a field, whipsawing lumber, taking out timber up the river, and rafting it down to the mission, also building a house, and in many ways giving object lessons of industry and settled life to this nomadic and restless people.

It was at this time that I got a name for myself by winning a race. The Indians had challenged two white men to run against two of their people. The race was to be run from Mr. Woolsey's tent to and around another tent that stood out on the plain, and back home again—a distance in all of rather more than two-thirds of a mile. I was asked to be one of the champions of the white men, and a man by the name of McLean was selected as the other. Men, women, and children in crowds came to see the race, and Mr. Woolsey seemed as interested as any. The two Indians came forth gorgeous in breech-cloth and paint. My partner lightened his costume, but I ran as I worked.

At a signal we were away, and with ease I was soon ahead. When I turned the tent, I saw that the race was ours, for my partner was the first man to meet me, and he was a long distance ahead of the Indians. When within three hundred yards of the goal, a crack runner sprang out from before me. He had been lying in the grass, with his dressed buffalo-skin over him, and springing up he let the skin fall from his naked body, then sped away, with the intention of measuring his speed with mine. I had my race already won, and needed not to run this fellow, but his saucy action nettled me to chase him, and I soon came up and passed him easily, coming in about fifty yards ahead.

Thus I had gained two races, testing both wind and speed. That race opened my way to many a lodge, and to the heart of many a friend in subsequent years. It was the best introduction I could have had to those hundreds of aborigines, among whom I was to live and work for years.

A few weeks sufficed to consume all the provisions the Indians had brought with them, and a very large part of ours also; so the tents were furled, and the people recrossed the Saskatchewan, and, ascending the steep hill, disappeared from our view for another period, during which they would seek the buffalo away out on the plains.

We went on with our work of planting this centre of Christian civilization. Though we had visits from small bands, coming and going all summer, the larger camps did not return until the autumn. All this time we were living in skin lodges. Mr. Woolsey aimed at putting up a large house, in the old-fashioned Hudson's Bay style—a frame of timber, with grooved posts in which tenoned logs were fitted into ten-foot spans—and as all the work of sawing and planing had to be done by hand, the progress was slow. My idea was to face long timber, and put up a solid blockhouse, which could be done so much more easily and quickly, and would be stronger in the end; but I was overruled, so we went on more slowly with the big house, and were smoked and sweltered in the tents all summer. However, taking out timber and rafting it down the river took up a lot of my time.

Then there was our garden to weed and hoe. One day when I was at this, we dined on buffalo tongue. Quite a number of these had been boiled to be eaten cold, and as our sleigh dogs were always foraging, it was necessary to put all food up on the stagings, or else the dogs would take it. As soon as I was through dinner I went back to my hoeing and weeding, but looking over at the tent, I saw Mr. Woolsey leaving it, and thought he must have forgotten to put those tongues away. As our variety was not great, I did not want the dogs to have these, so I ran over to the tent just in time to save them. I thought it would be well to make Mr. Woolsey more careful in the future; so, putting away the tongues, I scattered the dishes around the tent, and left things generally upset, as if a dozen dogs had been there, and then went back to my work, keeping a sharp watch on the tent.

When Mr. Woolsey came back he went into the tent, and very soon came out again shaking his fist at the dogs. Presently he shouted to me, "John, the miserable dogs have stolen all our tongues!"

"That is too bad," said I; "did you not put them away?"

"No, I neglected to," he answered. "I shall thrash every one of these thieving clogs."

Of course I did not expect him to do this, but at any rate I did not want to see him touch Draffan, my old leader, so I ran over to the tent, and could not help but laugh when I saw Mr. Woolsey catch one of the dogs, and, turning to me, say, "This old Pembina was actually licking his lips when I came back to the tent. I all but caught him in the act of stealing the tongues."

I can see old Pembina as he stood there looking very sheepish and guilty. Mr. Woolsey stood with one hand grasping the string, and with the other uplifted, holding in it a small riding whip; but just as he was about to bring it down, the expected relenting came, and he said, as he untied the dog, "Poor fellow, it was my fault, anyway." I let him worry over the thought that the tongues were gone until evening, when I brought them out, and Mr. Woolsey, being an Englishman, was glad they were saved for future use.

Our principal food that summer was pemmican, or dried meat. We had neither flour nor vegetables, but sometimes, for a change, lived on ducks, and again varied our diet with duck eggs. We would boil the large stock ducks whole, and each person would take one, so that the individual occupying the head of the table was put to no trouble in carving. Each man in his own style did his own carving, and picked the bones clean at that. Then, another time, we would sit down to boiled duck eggs, many a dozen of these before us, and in all stages of incubation. While the older hands seemed to relish these, it took some time for me to learn that an egg slightly addled is very much improved in taste.

Our horses often gave us a lot of trouble, because of the extent of their range, and many a long ride I had looking them up. On one of these expeditions I was accompanied by an Indian boy, and, having struck the track, we kept on through the thickets and around lakes and swamps, till, after a while, we became very hungry. As we had no gun with us, the question arose, how were we to procure anything for food? My boy suggested hunting for eggs. I replied, "We cannot eat them raw." "We will cook them," he answered. So we unsaddled and haltered our horses, and, stripping off our clothes, waded out into the rushes and grasses of the little lake we were then beside. We soon found some eggs, and while I made the fire, my companion proceeded with what, to me, was a new mode of cooking eggs. He took the bark off a young poplar, and of this made a long tube, tying or hooping it with willow-bark; then he stopped up one end with mud from the lake shore, and, as the hollow of the tube was about the diameter of the largest egg we had, he very soon had it full of eggs. Stopping up the other end also with mud, he moved the embers from the centre of the fire, laid the tube in the hot earth, covered it over with ashes and coals, and in a few minutes we had a deliciously-cooked lunch of wild duck eggs. I had learned another lesson in culinary science.

On another horse-hunt we found the track late in the day, and, following it up, saw that we must either go back to the mission for the night, or camp without provisions or blankets. The latter we could stand, as it was summer, but the former was harder to bear. While we were discussing what to do, we heard the calling of sand-hill cranes, and presently saw five flying at a distance from us. Watching them, we saw them light on the point of a hill about half a mile off. Laughingly, I said to my boy in Indian phraseology, "I will make sacrifice of a ball." So I got my gun-worm, drew the shot from my old flintlock gun, and dropped a ball in its place; and as there was no chance of a nearer approach to the cranes, I sighted one from where I stood, then elevated my gun, and fired. As we watched, we saw the bird fall over, and my boy jumped on his horse and went for our game. We then continued on the track as long as we could see it, and, as night drew on, pitched our camp beside some water, and made the crane serve us for both supper and breakfast. I might try a shot under the same conditions a hundred times more, and miss every time, but that one lucky hit secured to us a timely repast, and enabled us to continue on the trail of our horses, which we found about noon the next day.

We had to have lumber to make anything like a home for semi-civilized men and women to dwell in. In my humble judgment, the hardest labor of a physical kind one could engage in is dog-driving, and the next to that "whip-sawing" lumber. I have had to engage in all manner of work necessary to the establishing of a settlement in new countries, but found nothing harder than these. I had plenty of the former last winter, and now occasionally try the latter, and, in the hot days of summer, find it desperately hard work.

In the midst of our building and manufacture of timber and lumber, rafting and hauling, fencing and planting, weeding and hoeing, every little while there would come in from the plains rumors of horse-stealing and scalp-taking. The southern Indians were coming north, and the northern Indians going south; and although we did not expect an attack, owing to our being so far north, and also because the Indian camps were between us and our enemies, nevertheless we felt it prudent to keep a sharp lookout, and conceal our horses as much as possible by keeping them some distance from where we lived. All this caused considerable riding and work and worry, and thus we were kept busy late and early.

The summer brigade—With the brigade down the Saskatchewan—A glorious panorama—Meet with father and mother on the way to Victoria—Privations of travel—A buffalo crossing—Arrival at Victoria—A church building begun—Peter Erasmus as interpreter.

Along about the latter part of July, the "Summer Brigade," made up of several inland boats left at Edmonton, and manned by men who had been on the plains for the first or summer trip for provisions and freight, now returned, passing us on its way to Fort Carlton to meet the regular brigades from Norway House and York Factory, as also the overland transport from Fort Garry, which came by ox carts. Mr. Hardisty was with the boats, and he invited me to join him until he should meet the brigade in which my father and mother had taken passage from Norway House. Mr. Woolsey kindly consented, so I gladly took this opportunity of going down to meet my parents and friends.

I had come up the Saskatchewan as far as Fort Carlton, and had gone three times on the ice up and down from Victoria to Edmonton; but this run down the river was entirely new to me and full of interest. The boats were fully manned, and the river was almost at flood-tide, so we made very quick time. Seven or eight big oars in the hands of those hardy voyageurs, keeping at it from early morning until late evening, with very little cessation, backed as they were by the rapid swirl of this mighty glacier-fed current, sent us sweeping around point after point in rapid succession, and along the lengths of majestic bends. A glorious panorama met our view: Precipitous banks, which the rolling current seemed to hug as it surged past them; then tumbling and flattening hills, which, pressing out, made steppes and terraces and bottoms, forming great points which, shoving the boisterous stream over to the other side, seemed to say to it, "We are not jealous; go and hug the farther bank, as you did us just now;" varied forest foliage, rank, rich prairie grass and luxuriant flora continuously on either bank, fresh from Nature's hand, delightfully arranged, and most pleasing to the eye and to the artistic taste. No wonder I felt glad, for amid these new and glorious scenes, with kind, genial companionship, I was on my way to meet my loved ones, from some of whom I had now been parted more than a year. At night our boats were tied together, and one or two men kept the whole in the current while the others slept. At meal times we put ashore for a few minutes while the kettles were boiled, and then letting the boats float, we ate our meal en route.

Early in the middle of the second afternoon we sighted two boats tracking up the southerly bank of the river. Pulling over to intercept them, I was delighted to find my people with them. The Hudson's Bay Company had kindly loaded two boats and sent them on from Carlton, in advance of the brigade, so that father and family should have no delay in reaching their future home. Thanking my friend Hardisty for the very pleasant run of two hundred miles he had given me with him, I transferred to the boat father and mother and my brother and sisters were in. We were very glad to meet again. What sunburnt, but sturdy, happy girls my sisters were! How my baby brother had grown, and now was toddling around like a little man!

Mother was looking forward eagerly to the end of the journey. Already it had occupied a month and more on the way up—half that time in the low country, where water and swamp and muskeg predominate; where flies and mosquitoes flourish and prosper, and reproduce in countless millions; where the sun in the long days of June and July sends an almost unsufferable heat down on the river as it winds its way between low forest-covered banks. The carpenter, Larsen, whom my father was bringing from Norway House, met with an accident, through the careless handling of his gun, and for days and nights mother had to help in nursing and caring for the poor fellow. No wonder she was anxious to reach Victoria, and have change and rest. Forty days and more from Norway House, by lake and river, in open boat—long hot days, long dark, rainy days—with forty very short nights, and yet many of these far too long, because of the never-ceasing mosquito, which, troublesome enough by day, seemed at night to bring forth endless resources of torture, and turn them loose with tireless energy upon suffering humanity. But no one could write up such experiences to the point of realization. You must go through them to know. Mother has had all this, and much more, to endure in her pioneering and missionary life.

Only a day or two before I met them, our folks had the unique sight of witnessing the crossing through the river of thousands of buffalo. The boatmen killed several, and for the time being we were well supplied with fresh meat. Our progress now was very much different to mine coming down. The men kept up a steady tramp, tramp on the bank, at the end of seventy-five or one hundred yards of rope from the boat. Four sturdy fellows in turn kept it up all day, rain or shine, and though our headway was regular, yet because of the interminable windings of the shore, we did not seem to go very far in a day. Several times father and I took across country with our guns, and brought in some ducks and chickens, but the unceasing tramp of the boats' crews did not allow of our going very far from the river.

I think it was the tenth day from my leaving Victoria that I was back again, and Mr. Woolsey welcomed his chairman and colleague with great joy. Mother was not loath to change the York boat for the large buffalo-skin lodge on the banks of the Saskatchewan.

The first thing we went at was hay-making on the old plan, with snath and scythe and wooden forks, and as the weather was propitious we soon had a nice lot of hay put up in good shape; then as father saw at once that the house we were building would take a long time to finish, and as we had some timber in the round on hand, he proposed to at once put up a temporary dwelling-house and a store-house. At this work we went, and Mr. Woolsey looked on in surprise to see these buildings go up as by magic. It was a revelation to him, and to others, the way a man trained in the thick woods of Ontario handled his axe; for, without question, father was one of the best general-purpose axemen I ever came across.

It was my privilege to take a corner on each of these buildings, which is something very different from a corner on wheat or any such thing, but, nevertheless, requires a sharp axe and a steady hand and keen eye; for you must keep your corner square and plumb—conditions which, I am afraid, other cornermen sometimes fail to observe.

Then father sent me up the river with some men to take out timber and to manufacture some lumber for a small church. While we were away on this business, father and Larsen, the carpenter, were engaged in putting the roof on, laying the floors, putting in windows and doors to the log-house, and otherwise getting it ready for occupancy. Despatch was needed, for while a skin lodge may be passable enough for summer, it is a wretchedly cold place in winter, and father was anxious to have mother and the children fairly housed before the cold weather set in.

In the meantime Peter Erasmus had joined our party as father's interpreter and general assistant, and was well to the front in all matters pertaining to the organization of the new mission.

In search of the Stoneys—An Indian avenger—A Sunday at Fort Edmonton—Drunken Lake carousals—Indian trails—Canyon of the Red Deer—I shoot my father—Amateur surgeons—Prospecting for gold—Peter gets "rattled"—A mysterious shot—Friends or foes?—Noble specimens of the Indian race—A "kodak" needed—Among the Stoneys—Prospecting for a mission site—A massacre of neophytes—An Indian patriarch—Back at Victoria again.

Father had been much disappointed at not seeing the Mountain Stoneys on his previous trip west, as time did not permit of his going any farther than Edmonton; but now with temporary house finished, hay made, and other work well on, and as it was still too early to strike for the fresh meat hunt, he determined, with Peter as guide, to make a trip into the Stoney Indian country. Mr. Woolsey's descriptions of his visits to these children of the mountains and forests, of their manly pluck, and the many traits that distinguished them from the other Indians, had made father very anxious to visit them and see what could be done for their present and future good.

Accordingly, one Friday morning early in September, father, Peter and I left the new mission, and taking the bridle trail on the north side, began our journey in search of the Stoneys. We had hardly started when an autumn rainstorm set in, and as our path often led through thick woods, we were soon well soaked and were glad to stop at noon and make a fire to warm and dry ourselves. Continuing our journey, about the middle of the afternoon we came upon a solitary Indian in a dense forest warming himself over a fire, for the rain was cold and had the chill of winter in it.

This Indian proved to be a Plain Cree from Fort Pitt, on the trail of another man who had stolen his wife. He had tracked the guilty pair up the south side to Edmonton, and found that they had gone eastward from there. I told him that a couple had come to Victoria the day before, and he very significantly pointed to his gun and said: "I have that for the man you saw." We left him still warming himself over his fire, and, pushing on, reached Edmonton Saturday evening. Father held two services on Sunday in the officers' mess-room, both well attended.