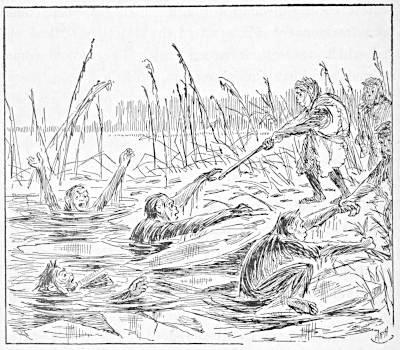

THE BATTLE IN THE SWAMP.

Title: From Monkey to Man, or, Society in the Tertiary Age

Author: Austin Bierbower

Illustrator: H. R. Heaton

Release date: October 5, 2020 [eBook #63379]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

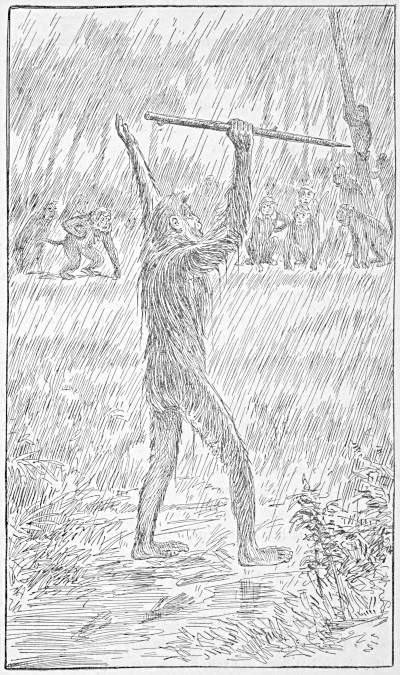

THE BATTLE IN THE SWAMP.

A Story of the Missing Link

SHOWING THE FIRST STEPS IN INDUSTRY, COMMERCE, GOVERNMENT,

RELIGION AND THE ARTS

WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE GREAT EXPEDITION FROM COCOANUT

HILL AND THE WARS IN ALLIGATOR SWAMP

BY

AUSTIN BIERBOWER

Author of “The Virtues and Their Reasons,” “The Socialism of Christ,”

“The Morals of Christ,” Etc.

Illustrated by H. R. HEATON

CHICAGO

INGERSOLL BEACON CO

1906

COPYRIGHT 1906

BY

WM. H. MAPLE

CHICAGO

M. A. DONOHUE & COMPANY

PRINTERS AND BINDERS

407-429 DEARBORN STREET

CHICAGO

The extraordinary interest which this book has excited has induced the publisher to issue a new and revised edition at a reduced price, believing that, as it is the first attempt at a prehistoric novel, it will have a wide reading. The subject, the characters and the period are here for the first time introduced into fiction.

The scenes are laid in the Tertiary Age when, according to the Darwinian Theory, men were emerging from the Ape, and they portray the supposed exploits of our ancestors at that stage of development. The author has aimed to exhibit the features of the time—climate, foliage, animals, etc.—as understood by Geologists and Biologists, and to be scientifically accurate, with no more variations in proportion than are usual in historic fiction.

If Evolution is the true theory of man’s origin there is a long period of forgotten history, covering thousands of centuries, during which men lived and fought and learned, and this book seeks to revivify it and make it realizable. In this period nearly all the arts and industries were started, and the author suggests their crude origin in a variety of episodes. The origin of arms, building, religion and government, the first use of fire and clothing and the primitive form of many social and business problems are indicated in the course of a simple story.

In addition to its valuable scientific hints, the work is rich in practical wisdom. It is also spiced throughout with a vein of quiet humor which provokes mirth and makes it highly entertaining as well as instructive.

The illustrations by H. R. Heaton, an artist of national reputation, are believed to be the best work of his genius.

| Page | |

| Frontispiece | |

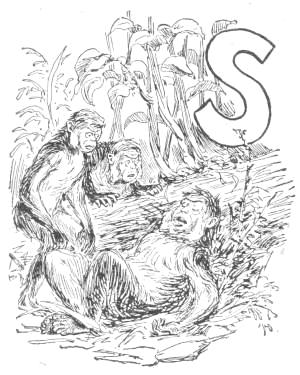

| Sosee’s Mother Encounters the Snake | 10 |

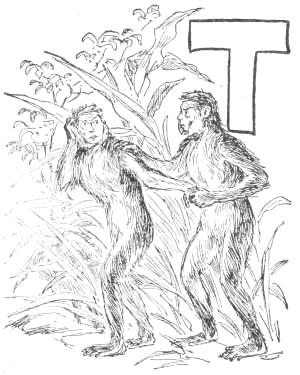

| Shamboo’s Ride | 20 |

| The Robbers of the Ammi | 31 |

| “See Beloved How the Mighty Fall at the Word of Simlee and the Stroke of Shoozoo” | 36 |

| “I Have Brought One of the Ammi Instead” | 51 |

| Koree and Sosee Encounter a Monster | 58 |

| The Rescue of Orlee | 69 |

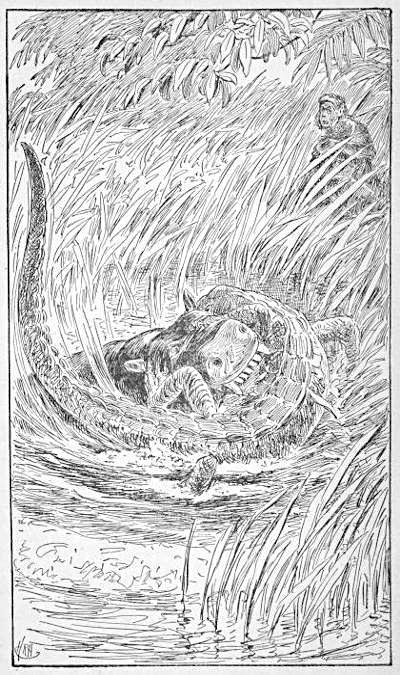

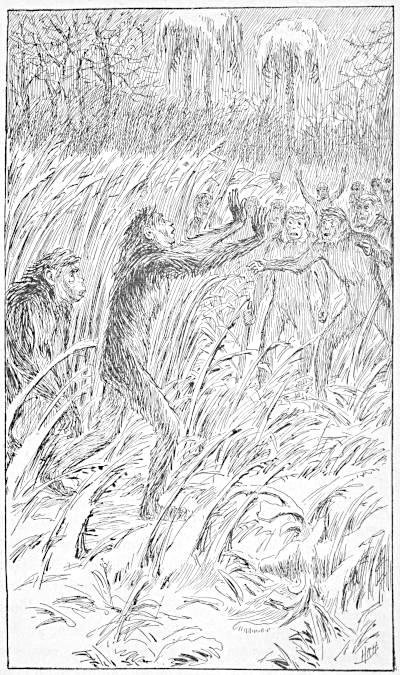

| The Battle in the Swamp | 80 |

| The Catastrophe | 97 |

| The Fight with the Fire-monster | 102 |

| The Greedy Oko | 120 |

| Pounder’s Mishap | 129 |

| The Battle Begins | 139 |

| Koree’s Challenge | 149 |

| The Retreat of the Lali | 161 |

| Sosee Warns the Ammi | 172 |

| The Wood-Eating Animal in the Camp of the Ammi | 191 |

| The Ammi Breaking Through the Ice | 198 |

| Sosee’s Strategy | 212 |

| Return of the Ammi to Cocoanut Hill | 225 |

About ninety years after the fight between the Monkeys and Snakes on Cocoanut Hill, which was five hundred thousand years before our era, and near the end of the Tertiary Age, Sosee was sitting on a limb sucking a mango, when Koree came up in great consternation.

“The fat baboon, from across the swamp,” he said, “has carried off Orlee while her mother was hunting berries in the bushes.”

“If you love me, Koree,” replied Sosee, uttering a wild scream, “you will fetch her back, and bring me the tail of the baboon before night.”

Sosee, who spoke these words, was a comely girl of twelve years, one of the new race which had recently separated from the Apes, and would no longer recognize them as equals. There was a hostility between the Apes and these upstarts, and frequent incursions were made from the territory of one on that of the other.

The Apes had mostly retreated to the swamps and forests beyond, while the new race were occupying the[8] region about Cocoanut Hill, which their ancestors of two generations before had taken, after many conflicts, from the Apes, and from which they had driven the savage beasts. Here the parents of Sosee were living, and here Sosee had grown to womanhood.

The Cocoanut Hill region was a large tract, in what is now Southern France, stretching from Alligator Swamp toward the mountains in the distance. This section was plentifully covered with fruit trees—mangos, palms, figs and limes; the under brush furnished berries and succulent herbs; the waters of the swamp, which bordered this land, abounded in fish, frogs, turtles, snakes and alligators; while great flocks of ducks, geese and other water fowl frequented it at seasons. The forests abounded in Uri, Woolly Oxen, Musk-Deer and other game. This abundance of vegetable and animal life supplied food for the Ammi, as the new race was called, and they would have lived in comfort but for the attacks of the Apes beyond the water, who, keeping an envious eye on these fruits, often came over the Swamp for food.

Shortly before the event of which we speak, some apes in one of these predatory incursions, were met by a larger number of the Ammi, when several of the former were killed, and one, a small boy, taken prisoner. The Ammi, expecting the Apes to attempt reprisals for this, kept a watch at night, while during the day they guarded their children.

Several times on the day mentioned signs of approaching Apes had been seen. Gimbo, the grandfather of Sosee, who still persisted in walking on four feet,[9] (although the Ammi generally had begun to walk upright), said he could scent the trail of the Apes, and had noticed the marks of one walking on four feet. But Gimbo was deemed a garrulous old man, somewhat unreliable, who claimed exceptional wisdom about the animals lower than men, so that little attention was given to his warning.

The mother of Orlee, however, had observed a sudden starting up of geese from the swamp; but this also raised little suspicion, as they might have been startled by a fox. Later, however, her keen sense of hearing detected successive splashings in the water, as if made by plunging alligators or turtles on the approach of an enemy. She was, accordingly, slow to leave the spot where her child was playing—a girl of three years, the sister of Sosee.

Gaining confidence, however, with the restored silence of the swamp, she took a club with which she usually warded off reptiles when hunting berries, or killed them when requiring them for food; and, armed in this way, she waded into the swamp, still keeping, however, in sight of her child.

As the berries were plentiful, she had soon eaten all she wanted, making thereof her morning meal, when she was attracted by some luscious ones farther in the swamp, which she hurried to get for the child. Having filled her hands she was next startled by a huge snake of the Boa species, which swung suddenly down from a tree, like a great vine and sought to fasten its coils around her.

SOSEE’S MOTHER ENCOUNTERS THE SNAKE.

Dropping the berries and uttering a wild scream, she seized the serpent, and, sinking her nails and teeth in its flesh, began a fatal struggle with it. The snake, which had fastened one coil about her leg, swung round violently with the intention of encircling her waist. Her screams startled the child, which began crying, and the two noises attracted the attention of Koree, the lover of Sosee, who was sporting in a puddle near by.

Koree started to the rescue of the woman, but, in the tangled underbrush could not find her; but, instead, he ran against a gigantic ape, which had also been startled by the cries, and, in his fright, was running about in confusion. This ape gave Koree a powerful blow with his fist, and then ran out of the swamp to where the child was playing. Seizing the child he next ran with it into the bushes and was out of sight.

Too weak, or too frightened, to follow, Koree now hurried back to give the alarm, when he encountered Sosee on the tree, as we have related. Sosee’s screams and calls to Koree to rescue the child roused some men near by, who now all rushed for the swamp.

As they approached they saw the mother of the child emerging from the bushes carrying the huge snake in triumph about her neck, part of which was hanging down in long folds, pending from her arms. Never was a woman prouder over a necklace of diamonds or pearls. Her bloody face and arms added to the terror inspired by her Amazonian air, as, with a proud step, she advanced to the men and threw down her trophy.

Disburdened of her load, and sinking from the stimulant of battle, she now became faint, through loss of blood, and was about to drop to the ground; for, in the struggle with the serpent, she had been severely bitten and wrenched, so that her own blood was mingled with that of the reptile on her body.

As she was about to faint away, however, she observed that her child was gone, when all the excitement returned which had attended her in battle, and, on hearing of its capture, she sent up a wail which echoed through the forest, and flew into a rage that terrified the bystanders.

The events related in the preceding chapter occurred, as we have said, about ninety years after the fight between the Monkeys and Snakes on Cocoanut Hill. As the time of the Ammi is reckoned from this fight, we shall go back, for awhile, to the affairs which immediately preceded it.

The Apes of all kinds had, till then, been roving promiscuously over the country along with wild beasts of every description. The forests being free to all, and likewise the swamps, there was a scene like that of the jungles of Central Africa to-day. Land and water teemed with life, and were animated with struggles for the food of the region. Gigantic lions, tigers, woolly rhinoceroses, mastodons, cave-bears and other savage beasts sported in their favorite element. Serpents were particularly abundant, especially in the great Alligator Swamp, from which they emerged to the high country to catch rabbits and other game. The Apes, which were mostly vegetarians, did not at first interfere[14] with the more savage beasts hunting in these forests; so that there was an endless variety of animals in the region of which we speak.

The Apes at this time lived mostly on trees, especially at night. This was necessary on account of the more savage beasts which roamed over the ground. When game became scarce the tigers and some other animals attacked the Apes, and often killed them. The weaker animals which could not climb the trees were generally in danger of becoming the prey of the stronger ones.

This arboreal life became in time irksome to the Apes, many of whom had made some progress in methods of living and hunting. These were, accordingly, anxious to acquire a right to the ground, and security in its possession. They had become so large that a fall from a tree was a serious matter. Nor was a tree always convenient to climb when they were in danger.

They could not, however, come to the ground while so many savage beasts occupied it. A sleeping ape was liable to suffer death if met by a tiger, especially in recent years when many fights occurred between the two. The Apes, accordingly, conceived the project of ridding the country of the more dangerous animals.

There were two principal species of Apes at this time, the Ammi, who afterwards became known as men, and the Lali, who were the enemies of the Ammi on the other side of the swamp; and, though there had come to be marked differences between the two, (of which we shall presently speak,) they were, at this time, both living together as Apes (the Man-Apes of Biology), and were[15] alike interested in ridding the country of the stronger beasts.

A council was, accordingly, called to take measures for their common welfare. In this council they gave their respective views without those formalities which now attend such gatherings. They spoke mainly in gestures and growls, which constituted all there was of language then, (articulate speech not having been developed beyond a few broken sounds). One, Shamboo, believed to be the great-grandfather of Sosee, was the acknowledged leader of the Apes, and he directed the deliberations of this assembly. Speaking in the manner indicated, this Ape harangued the multitude to the following effect:

“Tailed Apes, upright Apes, Baboons and Monkeys of low degree: I am tired living on trees. I am getting too old and fat to climb, and cannot go up in the air every time I want to sleep. My eyes are bad, and can’t tell a rotten limb from a sound one. Only two days ago, while eating a cocoanut, the limb broke on which I was sitting, and I fell to the ground, striking a porcupine; and there has been a sick monkey ever since. Just before the big rain I was chased up a tree by a hyena, when, before I got out of reach, he seized my tail, already reduced to a stump, and I had to let go of either the tree or my tail. I stuck to the tree, but to-day I am a tailless Ape! Why should the ground be conceded to tigers and snakes? The earth was made for monkeys. Our food is mostly on the ground, and it is easier to walk on a level than up and down. We can run faster than[16] we can climb. We cannot fly, like the birds, and there is no easy way for such big folks to get up a tree. But we dare not come to the ground. If we do we must fight some brute. The tigers want the earth; and we can’t afford to maintain perpetual war. I am, therefore, for peace, and so favor killing off our enemies. If the forces of the trees will but combine, dropping their disputes about the milk that is in the cocoanut, they can conquer the forces of the earth. Resolve, then, monkeys all, to make a fight for the land, and not be so often found up a stump. True to your ape-hood, join me in an oath to drive out the ground-beasts. Everything in this valley will then be ours. We shall have the plants and berries, and frogs, and little fishes. We can then lie down to sleep without falling off, and run about without getting tired. Whoever loves monkeykind will, therefore, follow my advice. Now, all of you who are resolved to drive out the beasts which claim this land, swear with me by scratching your top rib while I crack this butternut and eat the kernel.”

The eloquence of Shamboo gained the assembly to his proposition. Every rib got a scratch, and the solemnity of the hour was felt in every breast. An aged priest of the Mountain Apes bowed low his head, breathing a blessing on the undertaking; and from that hour the savage beasts of Cocoanut Hill were doomed.

The plan of attack on the beasts was two-fold. One method was to associate together and make a combined assault by two’s or more, according to the strength of their antagonists. The other was to get on trees and spring upon the enemy when asleep or at other disadvantage. In this way they hoped to so worry the larger beasts that they would quit the region of their own accord.

This coöperation was important as being the beginning of association among Apes. By uniting in two’s and three’s for attack or defense they learned to confederate, and so laid the foundations of society. Till that time they had roamed the forests and jungles solitary, each one hunting alone his food, like the tigers, and forming no lasting or frequent attachments. They met the opposite sex casually at a spring or in the fruit regions. They did not recognize their own children, or care for them except for a few years after birth, until they could roam[18] for themselves. Only occasionally did they meet for a common purpose, and then only for a little while. They were not gregarious, though they sometimes met in large numbers where food was abundant, and became slightly acquainted. They chattered or fought while together, and then parted to see one another perhaps no more.

Having now, however, formed a League of the Apes, offensive and defensive, these animals, who disputed with the tigers the right to be called the lords of the land, soon became acquainted with one another, and therefore learned to like each other better. They found that they had many common interests, and there sprang up warm attachments between them. Their mutual disagreements disappeared before their disagreements with the tigers. They learned to help one another that they might destroy a common enemy, founding their unity on their common hatred. Many sentiments were, accordingly, developed, to which ape-hood had before been a stranger. Hearts were touched where before there were thought to be only stomachs, and a new sentiment—love—was awakened in the race; and when they parted after a night’s watch, or fight, they often presented one another with a cocoanut or bull-frog. Unselfishness gradually took the place of unrestrained competition, and a monkey etiquette grew up and became recognized. Some of the apes became noticeably polite, especially to the opposite sex, and there was soon quite a little social intercourse between them. They would go out by two’s and three’s for food or water, as well as for a fight, and thus they learned to labor together, as well as fight together.

Nor was this all. Having got together in a league, it was not easy to separate them. They came together to stay, and they stayed to co-operate in many measures besides their own defense. After their wars certain industries sprang up, among which was the damming of part of the Swamp (where it was entered by a stream), so as to form a lake, in which they could with more convenience drink and wash. Having tasted the sweets of association, they wished, in short, to remain in society; and when subsequently the younger ones became restive, and tried to regain the liberty of independent or single life, the older heads compelled them to adhere to the social compact.

Scarcely had they formed their alliance for war, when they set out for the enemy. Their chief foe was the tigers and snakes, because these were most numerous, although there were some lions, pachyderms, bears, and other savage beasts, of which also they meant to rid the country. One proposed that they all start out together, saying that while they would thus be fighting as a whole, the enemy, which would be fighting singly, could be easily overcome. Shamboo opposed this plan, however, as likely to attract too much attention, and, perhaps, to cause the tigers also to confederate. “Let us,” he said, “indeed, fight each enemy singly; but it does not require more than three apes to kill one tiger.”

They accordingly broke up into small bands, and started on a tiger hunt. On the first day of the War of the Beasts, a body of three, led by Shamboo, climbed a Yew tree near the Swamp, where a great tiger was[20] known to come to slake his thirst. It was agreed, or rather laid down by Shamboo as the method of attack, that when the tiger should pass under the tree, one of them, the youngest and strongest, should drop upon the tiger’s back, and fasten his jaws in his neck, when the rest would follow and dispatch their victim.

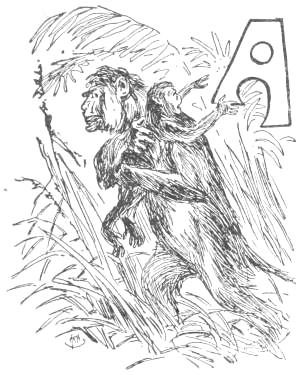

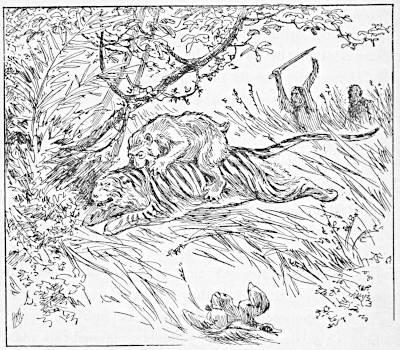

SHAMBOO’S RIDE.

Scarcely had this been resolved upon, when the tiger appeared, marching slowly toward their tree. He was carrying a sheep in his mouth, and his great show of muscular strength and fierce expression seemed to despise danger. The ape who had been chosen to drop on the tiger drew back in fear, and told Shamboo to do that part himself.

No time was to be lost, and, before the words of the timid ape were fully uttered, Shamboo dropped upon the tiger. His great weight crushed the beast to the ground, and compelled it to let go of the sheep. The tiger immediately got up, however, and, not knowing what to do, in his embarrassment, started on a full run. Shamboo clung to his back, and away they both went, like John Gilpin, dashing over hill and dale and through jungle and forest. The deer fled at their approach, squirrels ran up the trees, a flock of ducks started from a pool near by, and the flight of birds and beasts from their path was like the stampede which precedes a prairie fire. Shamboo’s teeth were fixed in the tiger’s neck, and his feet like spurs were sunk in his sides.

So they ran, and the earth rapidly receded behind them. The other two apes followed, but at a distance, so that the tiger and Shamboo were practically alone, and must soon, it seemed, try their strength in single combat. The tiger, however, was too scared to take an inventory of what he was carrying, while Shamboo’s thoughts were divided equally between how to hold on and how to let go. The tiger himself soon solved this problem for Shamboo by running through a hole in a thicket which was too small to admit both, so that Shamboo was knocked off. He fell into a cluster of bushes, and the fall was so violent as to cause him to turn several summersets, so that he did not know in which direction he had been going. The tiger, lightened of his load, but not of his scare, kept on, and was soon out of sight and out of this story.

Shamboo picked himself up and, looking round, spied the other two apes coming slowly toward him. He limped back to them with an air of disappointment, rather than of suffering, and, without uttering a word, fell upon the younger ape, who had shown cowardice, and killed him for his breach of military discipline in disobeying orders.

The fame of that ride and that fight remains to the time of this story, though there are different versions of it among the Ammi and the Apes beyond the Swamp.

And long subsequent to this time, when the descendants of these Apes got to riding on the backs of horses and cattle, there was a legend ascribing the origin of the uses of beasts of burden to this unwilling ride of Shamboo; and in the mythology of the later Apes Shamboo became the god of Domestication.

In the course of the contest with the tigers, which lasted several years, many improvements were made in the art of warfare, which afterwards served the Apes in time of peace. After the experience of Shamboo and others, who attacked unarmed the savage beasts, they found it advisable to fight at a distance. Taking their position on trees, which was done for safety, the problem was how to reach the enemy. They commonly showered cocoanuts and other large fruits upon them, which, while annoying to small animals, had little effect on tigers. They next carried stones up the trees for missiles, which they dropped with some effect. In time they became expert at throwing, and could strike a tiger’s head ten paces off. Shoozoo claimed to have killed a hyena at a distance of many alligators’ lengths with a rock larger than his head; but Shoozoo had a reputation for lying, which was greatly developed during the war.

The Apes also broke off branches of trees, with which they pounded the savage beasts, not only by throwing them from the trees as missiles, but by using them as clubs, until they became skilled in the art of pounding, as well as of making clubs. When catamounts, bears and other climbing beasts attacked them on the trees, and fought paw to paw with them, they used the stones as knives, and often cut their assailants fatally, having learned to select sharp stones for this purpose, and, in time, to sharpen them specially. Before the war they had used stones only to crack nuts. But now they learned both to use them for many other purposes, and to make them into the size and shape which best suited them.

The first manufactures of the Apes were thus of military implements, their necessity being the mother of invention. In time of peace, however, they found new uses for these implements, like their descendents who afterwards beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning-hooks. The missiles with which they had attacked the tigers they soon used for hunting, and in time for building. When they came down from the trees, and lived more on the earth, they knocked cocoanuts down, instead of climbing after them; they killed birds and rabbits by throwing stones at them, instead of lying in wait for them, and they speared fish with their clubs which they had learned to sharpen. They could thus act at a greater distance, and so had more power, both to defend themselves from wild beasts, and to obtain food.

Shoozoo, the liar just mentioned, told some wonderful stories of a stone which he sharpened and the exploits he performed with it. He saw a lion, he said, sleeping at the foot of a tree, when, throwing the stone, he cut the tree from its stump, which, falling on the lion, killed him; and he would have brought the dead lion to verify the story, but it was so big that all the monkeys of Cocoanut Hill could not have carried it away; but he showed the sharpened stone as evidence.

He related also that when hunting owls at night, after killing all that were in the forest, and having nothing more to throw at, he threw his stone at the moon, and hit it with such force that he cut off a piece; and, as evidence of this, he pointed to the moon, which was, indeed, seen to have a large piece gone, so that many Apes believed him for once, though they knew he was habitually a liar. For the evidence of their senses was generally deemed enough for the Apes. Shamboo, however, doubted the story and asked Shoozoo why he did not bring home the other piece of the moon. “When I cut it off,” he replied, “it fell into the Swamp and was swallowed by an alligator. I expect to catch that alligator, and then I will show you the rest of the moon.”

The Apes of Cocoanut Hill, however, who placed little confidence in Shoozoo’s stories, placed less in his promises; although the next generation, which accepted him as the founder of their religion, believed him to be a better man, and accepted his stories as history and his promises as prophecy; so that what was incredible to contemporaries became indisputable to posterity; and the[26] traditions that gathered about his name were sufficient to silence the doubts in a generation later which they had raised in a generation before. In course of time the bigger stories only gained credence, the rest being forgotten; so that what was received with most distrust was handed down with most confidence; and the farther they got from the time of their performance the easier it was thought to be to get at the truth about them.

For many generations every alligator that was killed was opened in order to find the moon; and, though it was often claimed to be found, there was never as much confidence in the story of its recovery as of its loss; for the Apes early learned to distinguish between religious stories, and only accepted those for which there was adequate evidence. The uninterrupted testimony of the fathers, which had come down in regular succession, and had never been doubted, was deemed the best evidence. Apes have accordingly differed about the incidentals of the story; for many accounts have come down about the details, which are not to be reconciled; but as to the great essentials—that the holy Shoozoo actually did knock off a piece of the moon, and that an alligator swallowed it—there is a substantial agreement; and as often as the moon, in generations later, appeared in crescent form, the festival of the Holy Crescent was celebrated by throwing sharpened stones in the air in honor of the great exploit of their Founder, Shoozoo.

But, though Shoozoo, who passed in one generation for a liar, and in the next for a God, left a questionable heritage to the Apes, they still retained out of his age[27] something of substantial value. The use of implements was invented, and the arts of making and using them were handed down to Monkeys and Men.

After the savage beasts had been driven from the region of Cocoanut Hill, and the Apes had come down from the trees, and were habitually on the ground, they found themselves encountering new dangers. The snakes were troublesome. The snakes had, indeed, been troublesome before, but it was mainly when they climbed the trees for birds’ nests or fruits. The Apes did not then encounter them so often, and amid the greater dangers from the four-footed beasts, did not find it necessary to make war against them. But now, when the Apes walked more on the ground, they met the snakes oftener, and under more disagreeable circumstances. The snakes, moreover, had greatly multiplied since the destruction of the savage beasts, many of which devoured, or fought with, snakes, or else lived on the same food. With the departure, accordingly, of the enemies of the serpents, and their increase of sustenance, the serpents became powerful, and at last threatened to drive the Apes from the region. It became dangerous to walk abroad, especially[29] near the Swamp. At night they disturbed the slumbers of the Apes. Shoozoo declared that he once found two in his ear when he awoke, and that he had swallowed some big ones during the night, although Shamboo declared contemptuously that he only had worms.

Many precautions were, from time to time, taken against the snakes. Some of the Apes persisted in still sleeping in the trees. Most of them, however, sought holes in the ground and caves in the rocks, which they fortified by piling brush and earth at the entrance; while others, not finding holes conveniently at hand, dug them and covered them with brush, so as to form a mound. The race had thus begun to build, and one of the first arts—architecture—was founded. The home originated in a fight against the serpent.

The snakes, however, soon attacked these homes, and all the more eagerly because of the food stored in them. For the Apes found that they could put their structures to many uses not before known. They would hold their provisions, as well as themselves, and would protect such provisions from the weather, as well as from the snakes, and so preserve them for a longer time. Their homes accordingly became store-houses, and this facility for keeping provisions by storage stimulated the collection of them. Instead of gathering only what they wanted to eat at the time, the Apes now picked up all they could find, and placed it in their dug-outs. They soon learned to allow nothing to go to waste, and became economical. They even collected when they did not want anything, from the mere fact that they could store it, and thus[30] became provident. They believed they might want in the future, and so often stored large quantities; for some Apes early became avaricious. They got in time to be as proud of their possessions as of their homes, and often gathered from a feeling of ambition. Shoozoo claimed that he had enough fruits in his mound to feed all the Apes of Cocoanut Hill for a lifetime; which nobody of that generation believed, and nobody of the next doubted.

These great quantities of fruits, we say, attracted the snakes, who were soon found more plentiful about the homes than about the swamps. Wealth always has its enemies, and a snake no more than a man, will work for what he can get more easily. It was thought easier to get cocoanuts in Shoozoo’s dug-out than by climbing a tree.

One day an ape, who had made a large collection, found, on returning home, that all his store was gone. The snakes had broken in and eaten what they could, and destroyed the rest by half eating it. The only sign of the thieves was an old snake which had eaten so much that he could not get away, and lay, like a drunken man, helpless on the ground. The ape soon dispatched him; but that did not satisfy the ape. He was indignant, and in his sense of suffering wrong we have the first appearance of the ethical sentiment. The sense of wrong in others appears before we recognize it in ourselves. The snakes did not feel the wrong; nor did the same monkey when afterwards he went to steal some of Shoozoo’s fruit (and found none), although he felt an indignation at Shoozoo that might be called an incipient sense of the wrong of falsehood. He wanted to charge Shoozoo with lying; but as that would have disclosed his own theft, or attempt at it, he suppressed his indignation in his prudence.

THE ROBBERS OF THE AMMI.

Other depredations were committed by the snakes, so that almost every ape soon had a property grievance. Added to this was a growing personal animosity between the Apes and the Snakes. As they had frequent contests over the fruits, they had learned to fight, and so to hate, each other, and finally to look upon each other as public enemies.

Nor was all the fault with the snakes. For as soon as the Apes got to accumulating, they scoured the swamps as well as the hills for provisions, and so met the Snakes in their own element, who had to fight for the ungathered fruits as well as the gathered. In fact, through their strongly developed acquisitiveness, the Apes had drained the country so generally of its productions, that there was not enough left to support the Snakes, so that the latter had to become criminals and attack the gathered stores. Whenever the rich gather up everything so close as to leave nothing for the poor, the latter will turn criminals, whether they be snakes or men, and will steal from the rich, whether these be men or monkeys.

There, accordingly, sprang up an antagonism between the Snakes and the Monkeys, which had all the bitterness of class feeling, as well as of race prejudice, and soon an irrepressible conflict was impending. The Monkeys demanded the extirpation of the Snakes as violently as[33] they had, in the preceding campaign, demanded that of the tigers; and from one end of the highlands to the other was heard the cry, “The snakes must go.”

“Steppers and crawlers,” said Shamboo, “cannot live in the same country. If there is anything a monkey hates it is to tramp on a snake. Only to-day one bit me in the heel, and to-morrow I shall crush his head. Enmity is declared between our race and theirs. A snake in the grass can never be loved by our seed; and so, until there shall be no more Snakes, or else no more Monkeys, the conflict must go on. We came down from the trees to the ground only to find others who had got still closer to the ground, and were climbing the land as we had climbed the trees; and it is a question whether belly or feet shall walk the earth. When the Apes got down off the trees they got up on their feet; and we do not mean to again walk through life on four feet to look for snakes.”

The fight with the snakes, which now began, was not remarkable except for the stories to which it gave rise. The reptiles were nearly all driven from the country before it was over, although many of them took refuge in the Swamp. But many tales of prowess were related of that war, which made it famous in after times, and caused it to be the event from which subsequent time was reckoned. Shoozoo claimed to have killed more snakes and bigger snakes than any of the rest, and, as none could boast much of their actual exploits, which were small compared with those claimed by Shoozoo, they all took to lying, and thus started the habit of making snake stories, which has come down to their descendants. These accounts were so great that the next generation, which was the first to believe them, ascribed marvelous powers to the heroes of this war, and so made it the commencement of an epoch, as well as preserved the stories, with additions, for their future theology.

“Why do you not,” asked Simlee, a young gorilla for whom Shoozoo had formed an attachment, “bring home one of those big snakes of which you kill so many, and proudly lay it at my feet?”

“Is it not enough,” retorted Shoozoo, “that I bring home the story of it? The honor that comes from snakes is not in having them, but in killing them.”

“But I want the proof of both your exploits and your love,” replied she; “the other baboons bring something to their loved ones, and the girls are all taunting me with your failures and your neglect. I am pining for snakes.”

Shoozoo felt embarrassed, but, being always ready with a promise when he lacked an achievement, said:

“I will bring you the great dragon of the swamp, the winged alligator that rules these waters and darkens the sun when he flies.”

“I would rather have plain snakes,” she said; “I would entwine them in my hair, and, like the girls of Jo and Kibboo, drape them as trophies about my neck.”

“Never doubt my love,” he replied, “You shall be ensnaked; and my conquests and your adornments will be the pride of all monkeydom.”

Simlee, thus reassured, ran laughing up a tree, while Shoozoo departed to achieve, or invent, fame.

Arming himself with a club and a vivid imagination he went out, like Don Quixote, for snakes and glory.

“SEE, BELOVED, HOW THE MIGHTY FALL AT THE WORD OF SIMLEE AND THE STROKE OF SHOOZOO.”

He had not gone far when he encountered an enormous snake, the first real one he had found since the war, notwithstanding his stories, and one which would, indeed, have delighted Simlee and given Shoozoo fame as its slayer, had he brought it home. But, instead of Shoozoo making for the snake, the snake made for Shoozoo. Back he turned excitedly, and there was a long race between the snake and the monkey, the monkey keeping ahead and gaining; and long after the snake ceased to follow Shoozoo continued to run. At last, however, Shoozoo panting and almost out of breath, climbed a tree, and looked about to take in the situation. And, though he did not see the snake, he nevertheless would not come down, but remained in the tree till night, when[37] he sneaked home by a route different from that by which he came.

On nearing the place where he had left Simlee in the morning, and wondering what account he should give of his day’s adventure, he found another huge snake lying in his path. He started back in fright; but, assuring himself that it was dead, he approached with courage. “This,” he said, “is my opportunity; it will both satisfy Simlee and astonish the rest.” And so, shouldering the snake he bore it proudly back to Simlee, and laid it at her feet with these words:

“See, beloved, how the mighty fall at the word of Simlee and the stroke of Shoozoo!”

Simlee leaped from the tree with glee, and taking up the snake, called to the other girls who were sitting among the branches or lying about the mounds, to witness her good fortune.

“That’s the same snake,” replied one, “that was brought here two days ago by Kibboo, and thrown away this morning because it had begun to smell.”

At this Simlee grew angry, and flew at the girl with open jaws, tearing her hair and beating her face; and there would have been as hot a fight between the women as between the men and the snakes, but for the return of the warriors with their trophies, when the curiosity of the female apes, which was greater than their anger, put an end to the quarrel, and they all ran to possess themselves of the snakes for ornaments.

We have said that the stories of the exploits of this war have been handed down in the religion of the Apes. This is due not so much to the achievements of the heroes as to the accounts of them by Shoozoo, who was much more active in relating battles than in fighting them; so that, as the heroes of the Trojan War owe more to Homer than to their own prowess, (for many great men lived before Agamemnon, whose exploits are forgotten for want of an imaginative historian); so the heroes of the fight about Cocoanut Hill are chiefly indebted to the Homer of the Apes for his reports of them. As gods, demi-gods, heroes and fair women rose from a ten days’ skirmish on the banks of the Scamander, so divinities, good and bad, had their origin in the Cocoanut Hill battles by reason of a good telling. Shoozoo was, fortunately, unlike Homer, both warrior and historian, and so, like Xenophon and Cæsar, made himself the chief character in his accounts. The other apes nearly all drop out of history, and their deeds are[39] ascribed to him, who at the time of this story, was deemed the chief character in that conflict; showing that for future fame a good liar is better than a good fighter.

Thus the driving out of the snakes from Cocoanut Hill came in time to be wholly attributed to Shoozoo, so that, like St. Patrick, he was honored for the entire service of their expulsion. The great dragon, or flying alligator, of which he only spoke to Simlee as an excuse, was, in time, believed to have been actually killed by him, as a primitive St. George. The snake that had entered the mound of one of the apes, and gorged himself with its treasured fruits, and which was killed by the ape, was alleged to have been slain by Shoozoo while guarding great treasures in a cave, as Siegfried slew the Nibelungen dragon. The expulsion of the snakes from Cocoanut Hill found its way into various stories about a primitive pair of apes—Shoozoo and Simlee—whose fruit was stolen by snakes, for which the snakes were driven from the country; reversing the story of Adam and Eve, who took the fruit from the snake and were themselves expelled, instead of the snake. Had Adam been his own biographer, like Shoozoo, the story of Eden might have been reversed.

The long contest and great enmity engendered between the Monkeys and the Snakes, also caused in time the serpent to be taken to represent everything bad, and this conflict came in the Apian Mythology to be represented as the conflict between good and evil, in which a great serpent fought with Shoozoo and was overcome by him, but not altogether slain; so that, as in the[40] Persian Theology, the contest between good and evil still went on, although Shoozoo was expected to come again in the great future, and put the serpent entirely under his feet.

Also, as the serpent came to represent evil, it was believed that the great winged alligator, with which Shoozoo fought, was the King of Evil, or Devil, and, that, being the chief of serpents, he led all assaults against the interests of the Apes. He was pictured with wings, tail, and great claws, and was supposed to be the power that ruled over Alligator Swamp, or the Land of the Bad. Apes frightened their children by saying that the great flying Alligator would come up out of the Swamp and devour them. Simian demonology thus had its birth. Like Juno springing from the head of Jove, it issued full grown out of the imagination of Shoozoo, with an alligator for its only foundation in fact.

It will thus be seen that the fight between the Monkeys and Snakes on Cocoanut Hill, which was important in the history, became more important in the mythology of the Apes, and, from its prominence in their profane and sacred traditions, it is natural that the Apes should make it the commencement of an epoch.

After the Snakes had been driven from the region of Cocoanut Hill, and the land thus rid of both wild beasts and reptiles, the Apes, who had now undisputed possession, got to fighting among themselves for the land. Those, therefore, who had united for defense now divided for conquest.

There were two principal varieties of Apes, as we have said,—the Ammi from whom the Men are descended, and the Lali, who, while resembling the former, were inferior in manners, and more closely resembled the present Orang-outang. They had both sprung from the same original stock, and, until several generations before, lived together in a more southerly country. At length they separated, (while still in the south), the Ammi going eastward, and the Lali westward, like the separation between Abraham and Lot.

Being thus separated, and so removed from mutual influence, they soon diverged in customs. The Ammi, under more favorable circumstances, began to walk erect,[42] to live more on the ground, to find many uses for their hands, and to make some progress in speech. The Lali, who had wandered into a less hospitable country, made no progress whatever, but rather degenerated; so that when, generations later, the two varieties met again on Cocoanut Hill, there were marked differences between them.

They had both come to the Cocoanut Hill country in a great migration of monkeys from the South, the Ammi coming from the southeast and the Lali from the southwest. This migration was caused by the failure of fruits in the south on account of some cataclysm in Nature of which we have no reliable accounts; and monkeys of every kind came north, so that there were soon all the varieties of which we have spoken in the Cocoanut Hill region. And this failure of fruits, we may add, was a principal cause of the providence of the Monkeys in laying up stores; for they were anxious that a second famine should not occur like that in the land from which they had come.

These apes, having therefore met again, met with differences such as did not separate them in the south country; and, though they imitated one another to some extent (the Lali picking up some of the sounds of the Ammi, and so acquiring by degrees the habit of speaking, and also walking at times upright and using their hands), there were, nevertheless, irremovable differences between the two; and, though they made common cause as long as they had to fight tigers and snakes, they again asserted their differences with the return of peace, and so found it impossible to assimilate.

In view of this incongeniality the Ammi in time were found associating wholly among themselves, and the Lali likewise among themselves. Jealousies and suspicions arose between the two, and frequently fights. Class distinctions gave rise to class controversies, and finally to class wars. The Lali were soon hated as much as the snakes by the Ammi, who conceived the project of driving them from the country; and the Lali, in turn, resolved also to get the country for themselves.

After several conflicts, in which now one party and then the other was successful, and after several temporary compromises, in which they tried to live together, the Lali, partly vanquished and partly persuaded, consented to withdraw to the lands beyond the Swamp, leaving the Ammi in possession of the Cocoanut Hill region.

The separation, however, was no settlement. The Lali claimed the land which they did not take, and hoped to get in the future what they were willing to surrender for the present. The two parties stood, like Germany and France over Alsace and Lorraine, growling much, but doing little. Occasionally they made incursions into each other’s territory, and carried away some fruit or provisions; but, though they talked chiefly of war, they lived mainly in peace. Separated by snakes and swamps, they were kept at peace by the difficulty of coming together. The danger of crossing, and the delay in going around the Swamp, were too great for war.

This was the condition and situation of the two forces which occupied the world as known to our ancestors at the time of this story.

Having made this digression on the antiquities of the Apes and a bit of their history, in which we have seen the origin of their religion, government and industries, and of many of their customs, we shall now return to the scenes beginning this story, which are nearly a century later.

Sosee had come down from the tree in which she received the news of the rape of Orlee, described in Chapter I, and, though she had given orders to Koree to bring back the child, she did not herself remain inactive. She rushed into the crowd, and, calling upon all, with wild screams, to rescue the child, went herself into the Swamp, and without any notion of where she was going, wandered about aimlessly till night, being completely lost. She found her way back only by the light of the moon, whose position in the heavens was some guide in her wanderings. Nor would she have returned at all, had she not hoped that some one else had, in the mean while, brought back the child.

On returning to the place from which she had started, she was distressed to learn that Orlee was not found, and she could scarcely be restrained from immediately starting again in pursuit of her. As Koree, however, had not yet returned, having searched farther and later than any, except Sosee, she hoped that he, inspired by her[46] love, would come back with success. She had most confidence in him because she had most love for him, believing that what most pleased her fancy would best serve her purpose.

Her first disappointment in love was when she saw Koree return without the child; for in this crisis she felt more for her sister than for her lover, the newly lost being ever dearer than the long loved. Koree had failed to meet her expectation, or rather her desire; and in times of disappointment the little that is lacking outweighs all that is not.

“You have failed to bring back Orlee and the tail of the fat baboon,” she said, “Despair of my love till you fetch me both.”

This was spoken in the half-articulate manner already explained, as was the balance of the conversation (which we translate, however, into modern expression).

“What all the race of the Ammi could not do,” he replied, “you ought not to blame your lover for not accomplishing.”

“The love of one,” she retorted, “can do more than the indifference of many. If Orlee is ever found it will be by love, and not by numbers.”

“I will yet fetch her back,” he said; “love’s work is not exhausted in one effort, but requires time for its fruit. She will come in response to your love acting through mine. Neither man nor monkey shall defeat me, or excel me, in this task.”

“Go, then,” she said, “and I will go with you. Love co-operates, and never commands only.”

“I will go,” he replied: “and not care whether I return. With Sosee at my side, I could roam forever, indifferent whither we come, so we be still together. Had we not gone alone before we would not have returned without Orlee; but we came back to see each other. Love left behind defeats its own purpose sent before. If we separate we will be hunting each other, instead of keeping our thoughts on Orlee.”

“Let us then go,” she said, “and keep ourselves and our purposes united, and resolve not to return till we come with her.”

“I will go; for then will I have everything with me, and nothing to come back for.”

“If you go for my company only,” she said, “and not for the child, you will soon have neither. To be my lover you must want what I want, and not merely want me; and if you do not get it you will soon be without me, for love must achieve success to be rewarded with love.”

“I want more your wish than my own, and will give up everything for it.”

“Except me.”

“Yes, and you even.”

“You mean thing! I won’t go with you.”

“Well,” he replied, “I won’t go alone.”

“You don’t care for me a bit,” she said.

“You only care for me to serve your purpose,” he retorted.

“I will get Kibboo to go with me,” she next said.

“He may go,” replied Koree, “and I will stay with Alee till you return. She is a better climber, and can run faster than you.”

“Boo! hoo! she has no hair on her back, and is meaner than you. She ran from a little snake which I could bite in two.”

“But she loves me, and never quarrels with me.”

“She don’t love you; she only hates me, and wants to make you do so. She loves Ki, and picked the fleas off him when he came from the Swamp this evening.”

“Do you love me, Sosee?” he next asked with more tenderness.

“I won’t tell you,” she replied, sobbing.

“Will you go with me, and stay with me?”

“I never said I wouldn’t.”

Here followed a long pause, during which Sosee sobbed and sighed, and Koree looked about in his mind for some excuse for making peace without seeming to want to. Sosee came to his relief, however, with a question.

“Koree?”

“Well?”

“Will you go with me to find Orlee?”

Sosee, too proud to ask for his love, had asked for his service.

“Yes,” he replied, glad to give both, “and will not come back till we find her.”

“Won’t that be delightful! to hunt and find her together!”

“Yes,” he replied, “and let us start to-night, and before morning we may find her.”

But night and weariness had settled down upon them, and as the older men and women had determined to wait till morning before recommencing the search, the two lovers concluded to do likewise, saying that they could then search with greater vigor.

They then walked awhile, though weary, in the moonlight, and discoursed of love and Orlee, he speaking of his devotion and she of her confidence that he would bring back her sister.

“How approvingly,” he said “the monkey in the moon looks down upon our love.”

“And upon our resolution,” she replied.

They then parted to sleep for the night; and soon their love, their weariness and their purpose were all forgotten, except in disturbed dreams, in which he thought of wandering through unknown swamps with Sosee, and she pictured the rescue of her sister by a heroic lover.

In the silence and longing of that night, however, Koree audibly breathed the following sentiment, which is the first poetry made by the human race:

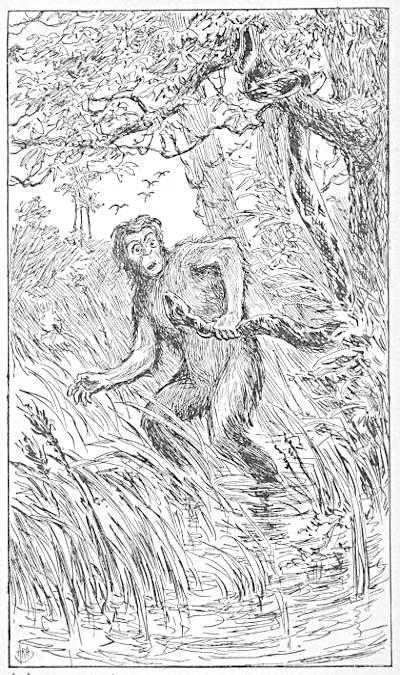

As rosy-colored Morn advanced to greet the opening eyes of monkeys and men, and spread her beams over Cocoanut Hill, lifting at last the veil of mists which hung over Alligator Swamp, a fat baboon was seen wending his way with a child in his arms to the settlement of the Lali. All night long he had traversed wood and swamp, picking his way through bush and fen, eluding the serpent and fleeing from the cry of the catamount, his only companion the moon, and his only hope the morning.

“I have avenged the rape of Soolee,” he said, as he approached the assembled Apes who were expecting the several warriors back which had gone to the country of the Ammi to recover the child that had been recently captured by them.

Great chatterings and shouts of gratification went up from the Lali as they saw one of their number thus return victorious. Only the mother of Soolee appeared distressed.

“Where is my child?” she asked.

“I have brought one of the Ammi instead,” was the response of the warrior.

“A man,” replied she, “is no compensation for a monkey; and the finding of another is no comfort to a mother for the loss of her own.”

I HAVE BROUGHT ONE OF THE AMMI INSTEAD.

“You can have her for a slave,” was the reply. “You lost one, and you get one: it makes no difference whether you have the same or not.”

The mother, however, was not satisfied, although the rest thought her grievance a small matter. The honor of the Apes was asserted by the reprisal; and when the[52] public interest is conserved the multitude cares little for the individual loss.

Orlee was placed in charge of this woman, who, notwithstanding her dissatisfaction, was delighted, not only at having a child, but at the fact that it represented the vengeance of her people. This double relation to the infant made her both love the child and mistreat it, the first because it was a child, and the latter because it stood in place of her own.

It was customary for the Apes, and also for the Men, when they had taken prisoners from each other, to reduce them to slavery, a custom which had arisen, however, only since their separation; for prior to that, they had neither property nor interest in each other’s work; and so neither man nor ape was believed to be worth anything. But, in acquiring property they put value on men as well as on cocoanuts, and kept each other as a treasure where before they had killed each other as a nuisance. Some even went to war for the prisoners, and the more valuable they found men to be the more they fought them, until they soon came to want enemies more than friends, and to like them better than allies. They fought for something instead of against something, and numbered their prisoners rather than their victories. Both sides became kidnappers, instead of warriors, and the principle and practice of slavery was established, as a result of learning the worth of men.

The warrior Oboo, who had brought Orlee to the Lali, was seen all day to hang around the woman in whose charge the child had been placed. Some thought it was[53] on account of his interest in the child; but shrewder apes said it was on account of his interest in the woman. As the newly-arrived child had obtained a mother he thought it ought also to have a father. The female ape did not repel the advances of the warrior, but said that if he would also restore her own child he might be father to both. The mother was, however, much comforted for the loss of her child by this gain of a father for it. The two wanted both to attend to the new child, the result of which was that the child received no attention, which proved serious, as we shall see. For they paid so much attention to each other that they often wholly forgot the child.

This warrior, Oboo, had not a good reputation among the Lali. Several scandals had already disgraced him, and his attention to this new woman was looked upon with suspicion.

“No good will come of it,” said an observant ape, who remembered his gallantries to others, and who was aware that he seized every pretext to ingratiate himself with a susceptible female ape. His bravery, however, had made him a favorite among the women, although his gallantry had much to do with it. He was a Simian “Masher,” and twice got his head pounded by male apes who did not like his attentions to their female friends.

This ape was charged with starting out for the child, not because he wanted it, but because he wanted the mother, and because he hoped that his bravery would be rewarded with her love. Thus are the motives of apes, like those of men, impugned from jealousy, and our greatest[54] warriors are traduced by their rivals. No pains were spared to suggest these suspicions to the woman herself, especially by another ape who had loved her, and had likewise started for her child and come back unsuccessful. These two male apes finally came together, and when one charged the other with cowardice, and was charged in turn with “spooniness,” they came to blows, or rather scratches, and would have killed each other had not the woman interposed.

“There is not much difference between you in virtue,” she said, “and whoever brings back my child shall be thought the braver.”

“Will you give up that ape if I bring back your child?” asked the new-comer.

“Yes, but I will stay with him till then for having brought this one,” was her reply.

The ape departed at this rebuff, divided in his thoughts between the purpose of recovering the child and that of punishing his rival for his insolence and his success.

The morning after the quarrel and make-up between Koree and Sosee, these two lovers started out to rescue Orlee from the captivity just mentioned. They tried in vain to induce the Ammi to go out as a body to recapture her, but nearly all except these two had exhausted their strength and their interest the day before. An excitement did not last as long with the Ammi as with their present descendants, and when they were not all interested they were quickly reconciled to an outrage. Koree and Sosee, however, in their first ardor of love, knew no rest, and had not yet learned to despair.

Arming themselves, therefore, with clubs and sharp stones, they started around the Swamp, intending to travel by day and at night to steal upon the camp of the Lali and take the child by some artifice. They kept along the border of the Swamp, and where it was not too deep to wade, cut across its waters. The danger of neither wild beasts nor serpents terrified them. They were together, and were fixed on one purpose. Koree[56] was willing to die with his Sosee, and Sosee believed she was in no danger with her Koree. So with resignation or confidence they marched on, heedless of a plunging alligator or swinging python which occasionally disturbed the stillness of the Swamp. Occasionally they stopped to gather mussels or climb after nuts; for they did not think it necessary to take provisions with them. The supplies of scouts and armies in those days were light—they foraged on the country. They marched without chart or compass, and yet rarely missed their way; for they had learned to guide themselves by the sun and the lay of the land. If occasionally, in the thick of the forest, they could not get their bearings, they emerged from the swamp to look at the mountains with whose ranges they were familiar.

It was not easy for primitive man to get lost, and it did not much matter if he was lost. Wherever he placed his foot he was at home, carrying his citizenship with him. Everywhere around were his possessions—the ungathered fruits and fish and game. Everywhere were his friends—the chance baboon or man that he might meet. Only recently, with the association which we mentioned, had there sprung up attachments for individuals. Before that their love was for the race, and anyone represented that race about equally well, as in the case of dogs. Even since they had come to associate, their attachments were not permanent; and they relied much on chance-comers for their society. Should they, therefore, be lost, they would not feel that they were among strangers, any more than that they were away from home.

“If we do not find Orlee will we go back?” asked Koree.

“We will not go back till we find her,” replied Sosee.

“We could live nicely in this forest,” said he; “there is plenty of food, and we need no company.”

“When we find Orlee,” she replied, “we will have company.”

“Two is company,” said he, “and when we find her and take her to her mother, shall we not come here to live?”

“Let us first find her,” she persisted; “we can then decide what to do next.”

“There is nothing that we can lack here,” mused Koree; “a forest and a swamp include all human desires;” and then, after a pause, he added, “and Sosee.”

“And Orlee,” interposed Sosee.

“Love in a cottage” was long antedated by “love in a forest.” A sycamore tree was cottage enough for our first parents.

“O! O! O! O!” ejaculated Sosee, too frightened to say more, as she suddenly ran up a tree.

“Oo! Oo! Oo! Oo!” shrieked Koree, as he ran up another tree.

The cause of this sudden fright was a huge mammoth which slowly lifted itself from a clump of bushes and walked toward the lovers. A great hairy elephant, twice as large as those now existing, with long front legs, carrying his bushy body high up in the air, and a back gradually sloping to the ground, like a giraffe—such was the monster that confronted them.

KOREE AND SOSEE ENCOUNTER A MONSTER.

Sosee had run up a slim sapling which this beast could easily have torn up with his trunk, or from which he could have shaken her down like a cocoanut; while Koree had run up a tree stout enough, indeed, to resist uprooting or shaking, but so low that the monster could easily have reached him with his long trunk. Their safety lay, therefore, in their silence, and they were accordingly quiet,—quiet even for lovers.

The mammoth was in no hurry to leave the place. He browsed about slowly, picking up bunches of grass, or reaching after leaves. Once he picked a trunk full of leaves from the tree in which Koree was sitting; but he took no notice of Koree, whether because he did not see him, or because he did not care for him. Koree and Sosee alone were concerned,—not the pachyderm. They remained simply quiet, and left the great beast in undisputed possession of the field. Never were two lovers more cruelly interrupted, and never did an unwelcome intruder stay so long.

“Two is company,” said Koree to himself, “and three is a great big crowd.”

The lovers could neither touch nor speak.

“Would that our trees were nearer,” whispered Koree.

“Or stouter,” replied Sosee.

“Or taller,” returned Koree.

“Never did I think,” muttered Sosee, “that anything so great could come between our love.”

“Ugh!” shuddered they both.

The huge beast kept on eating, unconscious that he was a bore.

“I wonder when that brute will get enough,” muttered Sosee in impatience.

“If he is going to fill all that big carcass,” replied Koree, “we are up here for all day.”

“Our only hope is that the leaves of these trees will give out,” replied she, “so that he must go elsewhere to finish his dinner.”

“Or that he will want to take something to drink with his meal,” replied Koree, “and so go to the Swamp to wet his snout.”

These breathings of the lovers were unnoticed by the monster, who took them for whisperings of the wind, and went on leisurely eating.

“Never did I see such an appetite,” said Sosee.

“Or one so contented with its dinner,” added Koree.

“I don’t like this seat,” grumbled Sosee, “I wish we were on the same tree.”

“I neither want to sit up here,” returned Koree, “nor get down.”

“I’m hungry,” said Sosee, after a long pause. “Never did I sit so long at a meal, and not eat anything.”

“If this meal of the brute goes on much longer,” said Koree, “we will both starve, or else be eaten.”

Just then, to the inexpressible relief of the tired, hungry and bored lovers, the animal showed signs of satiety. He quit eating, looked around with an air of satisfaction, stretched himself, and made a start, as if about to leave the place. Their gratification, however, was short. He walked around a few steps, and then, to[61] their dismay, lay down under the tree on which Koree was perched, and disposed himself for an afternoon nap.

Koree looked at Sosee, and was silent.

Sosee returned the look, but was too disgusted and empty for utterance.

“If that beast sleeps as long as he eats,” she said, “we will get neither supper nor slumber to night.”

“We will, however,” returned Koree, “be safe; for neither ape nor snake will attack us with such a watch at our door. So one danger wards off another.”

They were now reconciling themselves to spend the balance of the day, and perhaps the night, in this situation, and also to add to their weariness, hunger and disgust, the additional discomforts of sleeplessness and danger. For as Sosee had never slept on a tree (the Ammi having come to the ground before her birth), it was feared that, although her feet were still prehensile, and served her well in climbing, they might fail her from lack of practice when it came to holding to a limb when asleep. Koree determined not to sleep under these circumstances, both because he could not trust himself on a tree when asleep, and because he wanted to watch Sosee in order to rescue her from the mammoth in case she should fall. Love up a tree was thus faithful to the last.

While they were making their preparations for a continued disappointment, however, an accident, which at first seemed disastrous, came happily to their relief. Koree, in restlessly changing his position, fell off the tree, and came down with a thump on the back of the mammoth.

Whether Koree or the monster was more frightened we know not. Koree, however, was uninjured, the great beast breaking his fall, for the huge back of the animal reached, when lying down, well up toward the branches on which Koree was sitting. Sosee was, perhaps, the most frightened of all, as one is often most scared at the danger of another; and she gave a scream which the animal hearing, believed, in connection with the thump on his back, to be caused by some other animal that was attacking him.

He started from his sleep and his position at once, and, without looking for the cause of danger, rushed through the forest, while Koree ran up another tree and waited till the brute was at a safe distance. Then both he and Sosee came down, and returned thanks to the great Shoozoo for their deliverance.

The two lovers had no other adventure until they came the next afternoon to the farther side of the swamp, where the Lali were settled. There they were astonished at the multitude of the Lali, who greatly outnumbered the Ammi, fairly swarming in the trees and in the open country beyond.

It was not deemed safe to venture out of the Swamp in the presence of so many apes, some of whom would doubtless recognize them as belonging to the Ammi; so they determined to hide in the bushes till night, and then reconnoitre.

In the meantime they had abundant opportunity to watch the movements of the Apes, who kept in groups, as if fearing an attack, although an occasional one was seen alone, and some few came even into the Swamp. The two lovers did not fear the approach of single apes, or even of a small group; for, as there were many varieties among the Lali, and not a single kind only, as among the Ammi, the appearance of a new kind raised[64] no suspicion. The Ammi, or Men, moreover, were hardly distinguishable from certain of the Lali, at least by the Apes.

“The chance of finding Orlee among so many,” said Sosee, “is not good; and if we find her we cannot take her from them.”

“Wait till it is dark,” replied Koree, “and the groups will disperse, when we can both approach them without suspicion, and carry her off without resistance. Trust your lover.”

“I trust you, or I should have not come with you, or have asked you to come,” she answered; “but I see no way to accomplish our object.”

“Do you see that big baboon beyond the crowd walking alone with an ape?” he next asked. “He looks like the fellow that struck me when Orlee was carried off.”

“It must be the same,” replied Sosee; “for there is a child near him which looks like Orlee.”

“I think that is only a young monkey,” replied Koree, “which has been taken out by its parents.”

“The three pay no attention to the other Apes,” replied Sosee, “and are wandering still farther from them. Let us approach them; in their absorption it will cause no alarm.”

“If it is the baboon which I think it is, he will know me,” replied Koree. “At least I cannot mistake him.”

“If we could get a little nearer,” said she, “I could tell whether it is Orlee or not.”

“But we cannot get near the child without getting near the parents,” replied Koree.

“She has wandered off from her keepers,” retorted Sosee. “Let us approach slowly.”

“Wait till it is darker,” said he. “We can then get near enough to recognize her without being recognized by them.”

“They pay no attention to the child,” continued she, “which is moving away from them; and if she goes much farther we can get near enough to see her distinctly without their noticing us.”

“They seem, however,” said he, “to be much interested in something. Such earnestness among monkeys has a meaning.”

“It cannot concern the child,” replied she, “and between their absorption and her distance, we can get her away while they are thinking about themselves.”

“I hate the looks of that baboon,” mused Koree.

“I like the looks of that child,” replied Sosee.

“I will get her if it is Orlee,” he said, “but I want to avoid a blow from that brute. We had better be sure it is Orlee before we take the risk of a broken head in finding out.”

“The child keeps upright far more than the others, which makes me think it is not theirs,” said Sosee.

“I should like to have the child just to avenge the blow I received,” said Koree; “but I don’t want to have a second blow to avenge.”

“I will take the blow if you will get the child,” replied Sosee.

“As long as the two old apes are so near it, we could not carry it off if we got it,” he said. “They would pursue us and overtake us with our load.”

“Two ought to be able to resist two; and Orlee would help us,” replied she.

“Before our fight could end the other apes would come to their succor,” said he.

“Perhaps,” suggested Sosee, “they would give up Orlee if I would stay with them instead.”

“I do not like that suggestion,” replied Koree, “I will get Orlee and keep you. Would you rather have Orlee than me?”

“I was not thinking of that, but only of Orlee.”

They had now approached near enough to see the girl distinctly, whom they recognized to be Orlee. She had wandered so far from her keepers that they did not observe the approaching lovers. Koree and Sosee concluded to steal up to Orlee, and, without raising any suspicion, lead her in the direction of the Swamp and then hurry with her into the bushes where they could not be followed. As it was getting dark the time seemed propitious for their scheme.

The couple in charge of Orlee, were, as will be surmised, Oboo, the ape who had carried her off, and the woman Oola, in whose charge she had been placed. This ape continued his attendance on this woman without interruption, having, while the other Lali were amusing themselves in groups, wandered off with her and the child to be alone. This accounts for their distance from the rest of the Apes. They were so much absorbed, moreover, with each other, that they did not notice that the child, Orlee, had wandered away from them, and was now almost out of their sight, and entirely out of their[67] thoughts. Oboo and the woman simply kept up their love-making, while Koree and Sosee were approaching their prize. What made one pair of lovers forgetful made the other pair alert. Love shuts and opens the eyes of mortals in turn, and lays off the harness from one which it puts on another.

As soon as Orlee recognized her sister she gave a scream of joy which disconcerted the plans of Sosee and Koree. It also startled Oboo and the woman out of their bliss, who now experienced all the horrors of interruption which the other two lovers had suffered the day before on the appearance of the mammoth. Oboo felt most disappointed, and the woman most frightened. They sprang up, and, for a minute, were bewildered, thinking that some curious apes, perhaps rivals, had come suddenly upon them, through jealousy or stupidity, to interrupt their tète-a-tète. The woman instinctively sprang in the direction of the child, while Oboo looked around to see who was the cause of the interruption. Soon they both took in the situation and started in pursuit of the child.

Koree, perceiving that no time was to be lost, had picked up the child and started for the Swamp, Sosee following at full speed. The child, frightened by the bustle, set up a combined screaming and chattering, which attracted the attention of the other Apes and called a large number of them into the pursuit. The scene for a few minutes was like that of a couple of foxes pursued by a pack of hounds, in which the foxes were fast making for the woods.

All now depended on whether Koree and Sosee with the child could reach the Swamp in time to conceal themselves before the Lali should arrive. For so dense was the under-growth in the Swamp that it was next to impossible to discover man or beast that should attempt to hide there.

Sosee could easily have gained the Swamp in time for safety, but Koree, who was encumbered with the child, and so could not run as fast as she, was in danger of capture by Oboo, who was fast gaining upon him. Sosee, indeed, had already reached the Swamp, and was about to plunge into its thickets and out of danger, when she turned to see if Koree and the child were making their escape.

She was horrified to perceive that the pursuers were close upon them; and so, instead of saving herself, she turned on them, and made a desperate effort to rescue her companions. Before she could reach them, however, Koree was overtaken by Oboo, when, releasing the child,[69] he dealt Oboo a powerful blow, which stunned him, and, at the same time, avenged the blow received by Koree from the same ape some days before. Sosee now came up, and, flying at the ape with screams and scratches, dealt him another blow scarcely less severe than that administered by Koree. These two blows compelled the ape to loose his hold for the moment.

THE RESCUE OF ORLEE.

Released in this way from his pursuers, Koree picked up the child and again started for the woods, while the ape, recovering from his blows, again started in pursuit. He was gaining on Koree a second time, and would have overtaken him again, had not the course of Koree and[70] Sosee now begun to diverge; for in their anxiety to escape neither had noticed the direction taken by the other in their new start, and so they became separated.

Oboo, observing the beauty and agility of Sosee, felt a desire to possess her which outweighed his anxiety for the child. “She is prettier than the old woman,” he said to himself, “and I will go for her.” Oboo always had time, even in a fight or a race, to observe an attractive female, and his head was invariably turned by the sight, no matter at what business he was engaged. He accordingly turned from the pursuit of Koree and Orlee, and started after the girl. The scratches and pounding which he had received from her were no warning to him, but rather increased his infatuation by testifying to her spirit. Love at first sight is greater among Apes than among Men, and overcomes more obstacles. Accustomed to fight for their females, and often to take them by overcoming them in fight, the love of our primitive ancestors was often “love at first fight.” Oboo, therefore, forgot his heroism in his passion, and, abandoning all that he had set out to accomplish, started in pursuit of his pleasure before he was yet out of his pain, and thought of enjoying the caresses of a lover, while still smarting under her blows. The battle of Mars thus turned into the battle of Cupid, and the warrior, turned lover, continued the pursuit without much changing his method.

While Oboo was thus pursuing Sosee, Koree with the child in his arms had reached the thicket, and was safe. Other apes came up, indeed, to the edge of the swamp, and penetrated its depths; but, as it was getting dark,[71] they soon turned back, discontinuing the pursuit. While there were many things to be found in the Swamp, their experience had taught them that nothing was ever found there which was sought for. They might get other apes or other game, but any particular thing that had escaped in that tangled waste was deemed irretrievably lost.