THE LATE EMPEROR MEIJI TENNO

Title: A Handbook of Modern Japan

Author: Ernest W. Clement

Release date: May 4, 2021 [eBook #65253]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: MFR, Heather McNamara and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

A HANDBOOK

OF MODERN JAPAN

Uniform with this Work

JAPAN AS IT WAS AND IS: A Handbook of Old Japan. By Richard Hildreth. In two volumes. A reprint edited and revised, with notes and additions, by Ernest W. Clement and an Introduction by William Elliot Griffis. With maps and 100 illustrations. 12mo, in slip Case. $3.00 net.

A. C. McClurg & Co.

Chicago

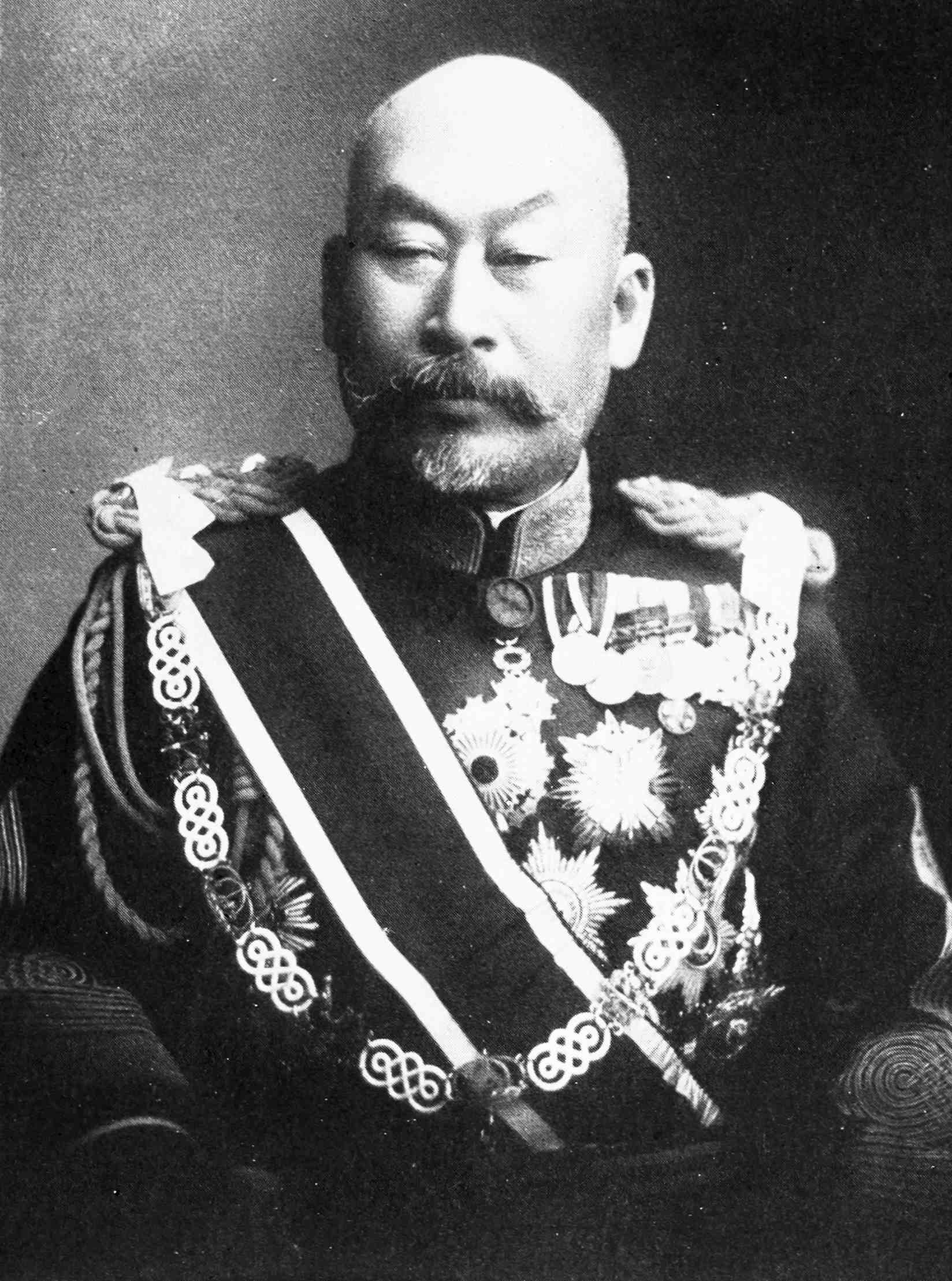

THE LATE EMPEROR MEIJI TENNO

New Revised Edition

WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

NINTH EDITION

THOROUGHLY REVISED AND BROUGHT DOWN TO DATE

WITH ADDITIONAL CHAPTERS ON

THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

AND

GREATER JAPAN

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1913

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1903; 1905; 1913

Copyrighted in Great Britain

UNIVERSITY PRESS · JOHN WILSON

AND SON · CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

To the Memory of my Father

and my Mother

THIS book, as its title indicates, is intended to portray Japan as it is rather than as it was. It is not by any means the purpose, however, to ignore the past, upon which the present is built, because such a course would be both foolish and futile. Moreover, while there are probably no portions of Japan, and very few of her people, entirely unaffected by the new civilization, yet there are still some sections which are comparatively unchanged by the new ideas and ideals. And, although those who have been least affected by the changes are much more numerous than those who have been most influenced, yet the latter are much more active and powerful than the former.

In Japan reforms generally work from the top downward, or rather from the government to the people. As another1 has expressed it, “the government is the moulder of public opinion”; and, to a large extent, at least, this is true. We must, therefore, estimate Japan’s condition and public opinion, not according to the great mass of her people, but according to the “ruling class,” if we may transfer to Modern Japan a term of Feudal Japan. For, as suffrage in Japan is limited by the amount of taxes paid, “theviii masses” do not yet possess the franchise, and may be said to be practically unconcerned about the government. They will even endure heavy taxation and some injustice before they will bother themselves about politics. These real conservatives are, therefore, a comparatively insignificant factor in the equation of New Japan. The people are conservative, but the government is progressive.

This book endeavors to portray Japan in all its features as a modern world power. It cannot be expected to cover in great detail all the ground outlined, because it is not intended to be an exhaustive encyclopædia of “things Japanese.” It is expected to satisfy the specialist, not by furnishing all materials, but by referring for particulars to works where abundant materials may be found. It is expected to satisfy the average general reader, by giving a kind of bird’s-eye view of Modern Japan. It is planned to be a compendium of condensed information, with careful references to the best sources of more complete knowledge.

Therefore, a special and very important feature of the volume is its bibliography of reference books at the end of each chapter. These lists have been prepared with great care, and include practically all the best works on Japan in the English language. In general, however, no attempt has been made to cover magazine articles, which are included in only very particular instances.

There are two very important works not included in any of the lists, because they belong to almost all; they are omitted merely to avoid monotonous repetition. These two books of general reference areix indispensable to the thorough student of Japan and the Japanese. Chamberlain’s “Things Japanese”2 is the most convenient for general reference, and is a small encyclopædia. “The Mikado’s Empire,”3 by Dr. Griffis, is a thesaurus of information about Japan and the Japanese.

After these, one may add to his Japanese library according to his special taste, although we think that Murray’s “Story of Japan,” also, should be in every one’s hands. Then, if one can afford to get Rein’s two exhaustive and thorough treatises, he is well equipped. And the “Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan” will make him quite a savant on Japanese subjects. It should be added, that those who have access to Captain Brinkley’s monumental work of eight volumes on Japan will be richly rewarded with a mine of most valuable information by one of the best authorities. “Fifty Years of New Japan” is valuable and unique, because it is written by Japanese, each an authority in his department.4 For the latest statistics, “The Japan Year Book” is invaluable.

We had intended, but finally abandoned the attempt, to follow strictly one system of transliteration. Such a course would require the correction of quotations, and seemed scarcely necessary. Indeed, the doctors still disagree, and have not yet positively settled upon a uniform method of transliteration.x After all, there is no great difference between Tōkiō and Tōkyō; kaisha and kwaisha; Iyeyasu and Ieyasu; Kyūshiu, Kiūshiu, Kyūshū, and Kiūshū. There is more divergency between Ryūkyū, Riūkiū, Liukiu, Luchu, and Loo Choo; but all are in such general use that it would be unwise, in a book like this, to try to settle a question belonging to specialists. The fittest will, in time, survive. We have, however, drawn the line on “Yeddo,” “Jeddo,” and similar archaisms and barbarisms, for which there is neither jot nor tittle of reason. But it is hoped that the varieties of transliteration in this book are too few to confuse.

The author is under special obligations to Professor J. H. Wigmore, formerly a teacher in Tōkyō, and now Dean of the Northwestern Law School, Chicago, for kind criticisms and suggestions; to Mr. Frederick W. Gookin, the art critic, of Chicago, for similar assistance, and for the chapter on “Æsthetic Japan,” which is entirely his composition; and also under general obligations for the varied assistance of many friends, too numerous to mention, in Japan and America. He has endeavored to be accurate, but doubts not that he has made mistakes. He only asks that the book be judged merely for what it claims to be,—a Handbook of Modern Japan.

Ernest Wilson Clement.

xi

THE eight years which have elapsed since this book was revised have been so crowded with great events that another revision seems advisable in order to make the book yet more timely and as valuable as possible. Whenever it was practicable, the statements and statistics in both the body and the appendix of the book have been brought up to date. In some cases, but only a very few, it was impossible to alter the text without breaking up the paging; therefore the original text was allowed to stand, and the corrections have been indicated in notes or some other way. A new chapter, moreover, has been added, with new illustrations, and presents as concisely and yet as comprehensively as possible the facts which warrant its caption, “Greater Japan.”

Tōkyō, January, 1913.

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Physiography |

1 |

| II. | Industrial Japan |

16 |

| III. | Travel, Transportation, Commerce |

29 |

| IV. | People, Houses, Food, Dress |

44 |

| V. | Manners and Customs |

60 |

| VI. | Japanese Traits |

76 |

| VII. | History (Old Japan) |

90 |

| VIII. | History (New Japan) |

102 |

| IX. | Constitutional Imperialism |

118 |

| X. | Local Self-Government |

133 |

| XI. | Japan as a World Power |

146 |

| XII. | Legal Japan |

159 |

| XIII. | The New Woman in Japan |

175 |

| XIV. | Language and Literature |

191 |

| XV. | Education |

209 |

| XVI. | Æsthetic Japan |

222 |

| XVII. | Disestablishment of Shintō |

237 |

| XVIII. | Confucianism, Bushidō, Buddhism |

250 |

| XIX. | Japanese Christendom |

262 |

| XX. | Twentieth Century Japan |

277 |

| XXI. | The Mission of Japan |

289 |

THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR |

305 | |

GREATER JAPAN |

329 | |

APPENDIX |

343 | |

INDEX |

415 | |

xv

| Page | |

|---|---|

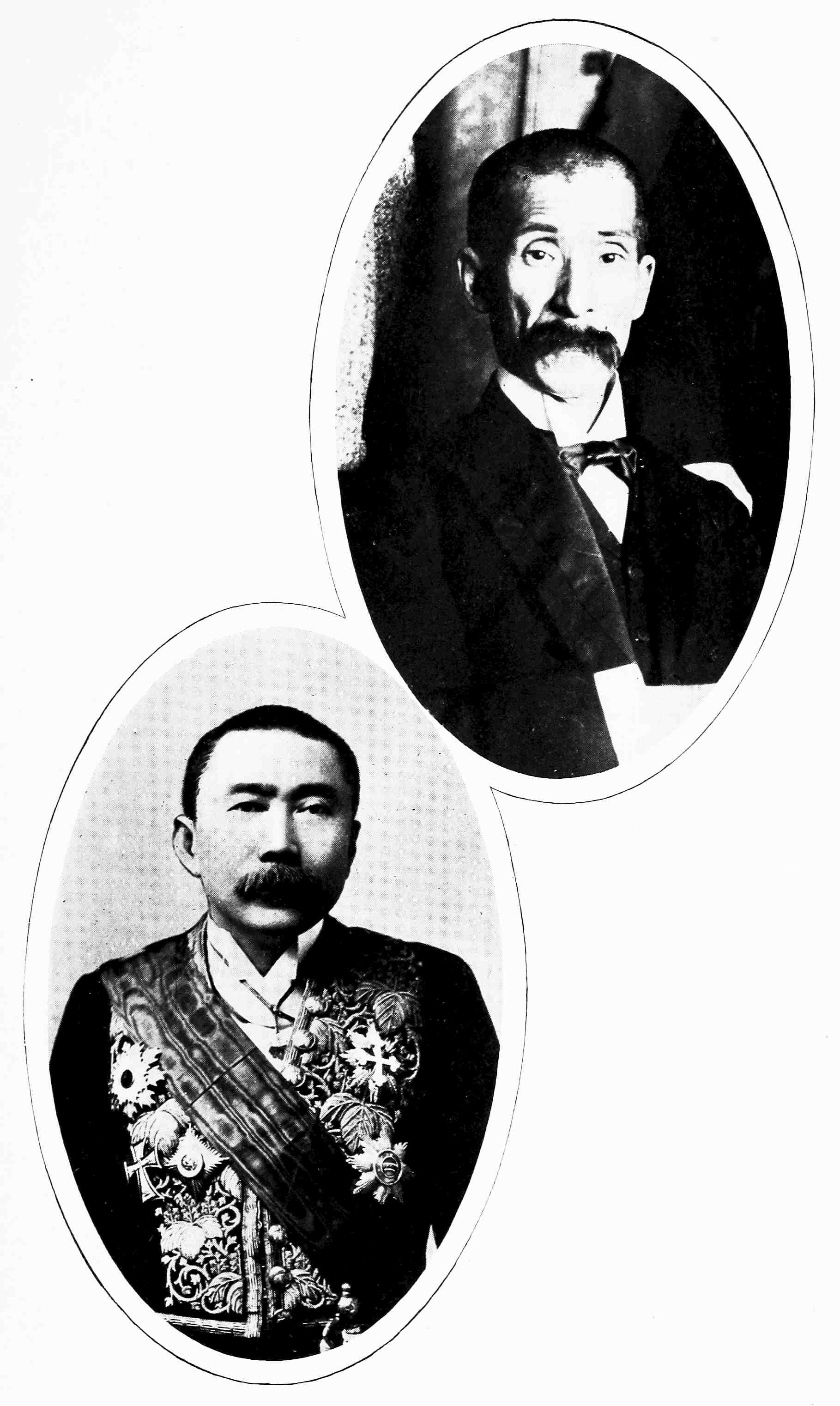

The Late Emperor Meiji Tenno |

Frontispiece |

Nagasaki Harbor |

10 |

Lighthouse Inland Sea |

10 |

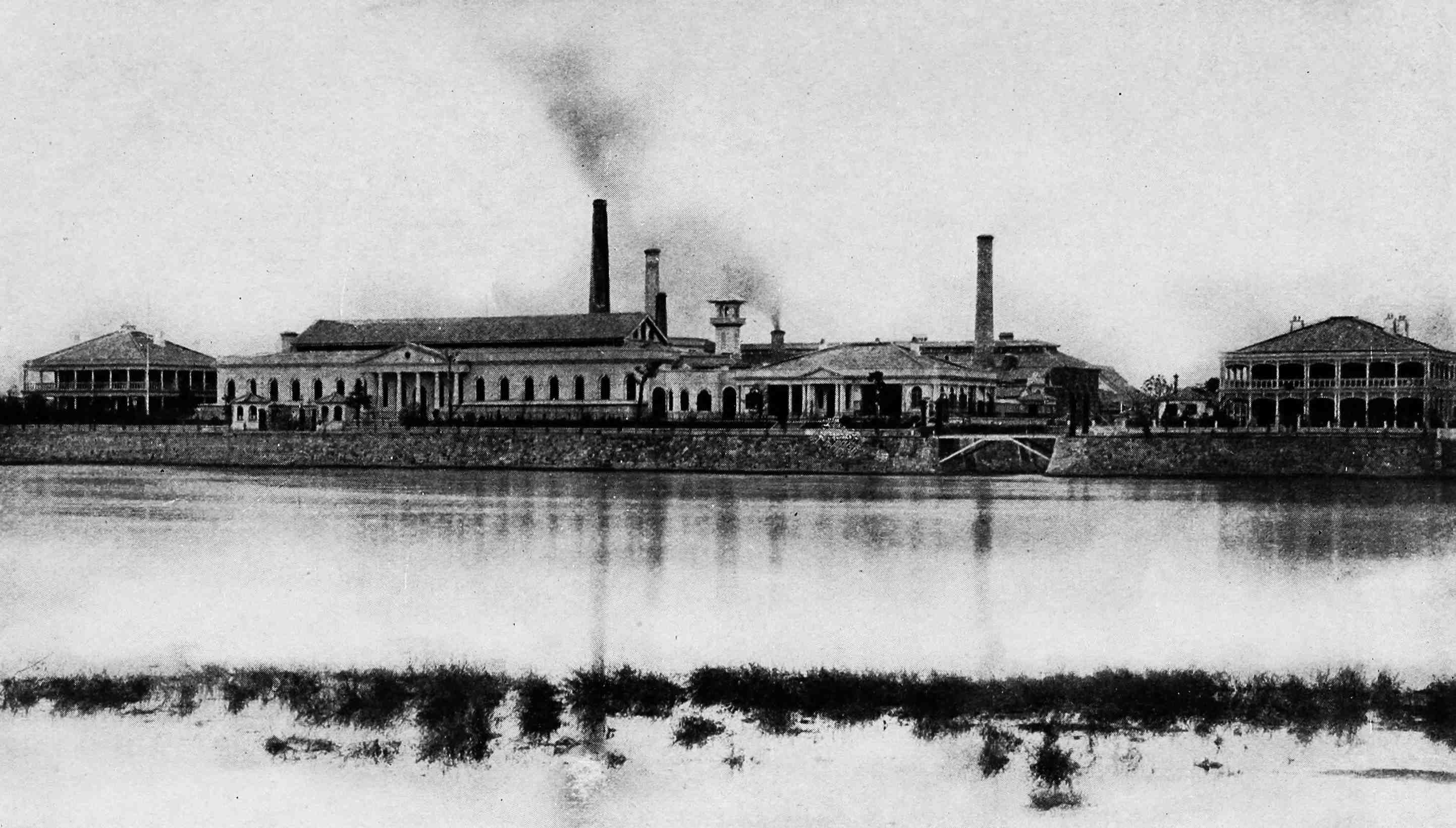

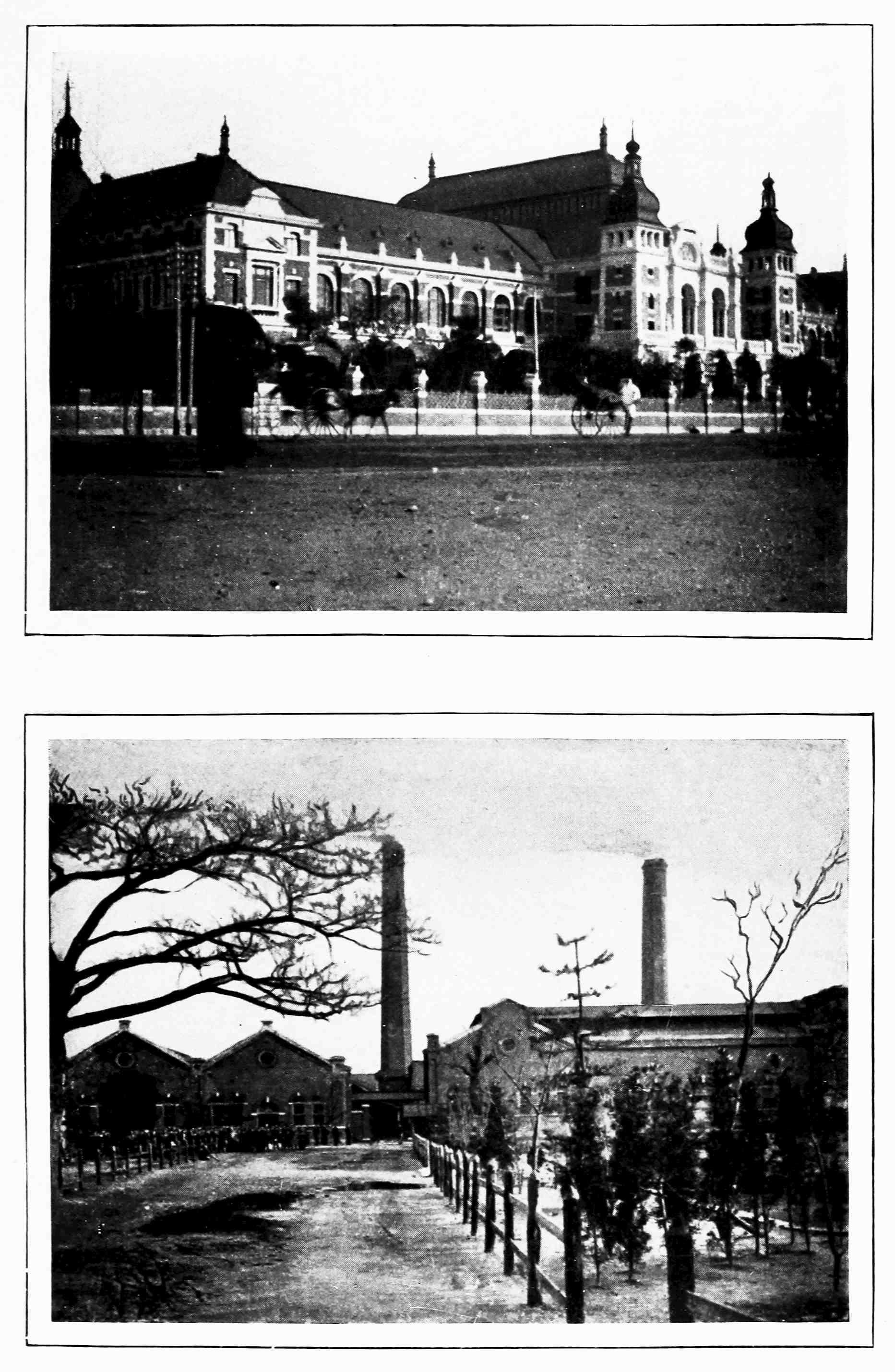

Cotton Mills, Ōsaka |

20 |

First Bank, Tōkyō |

38 |

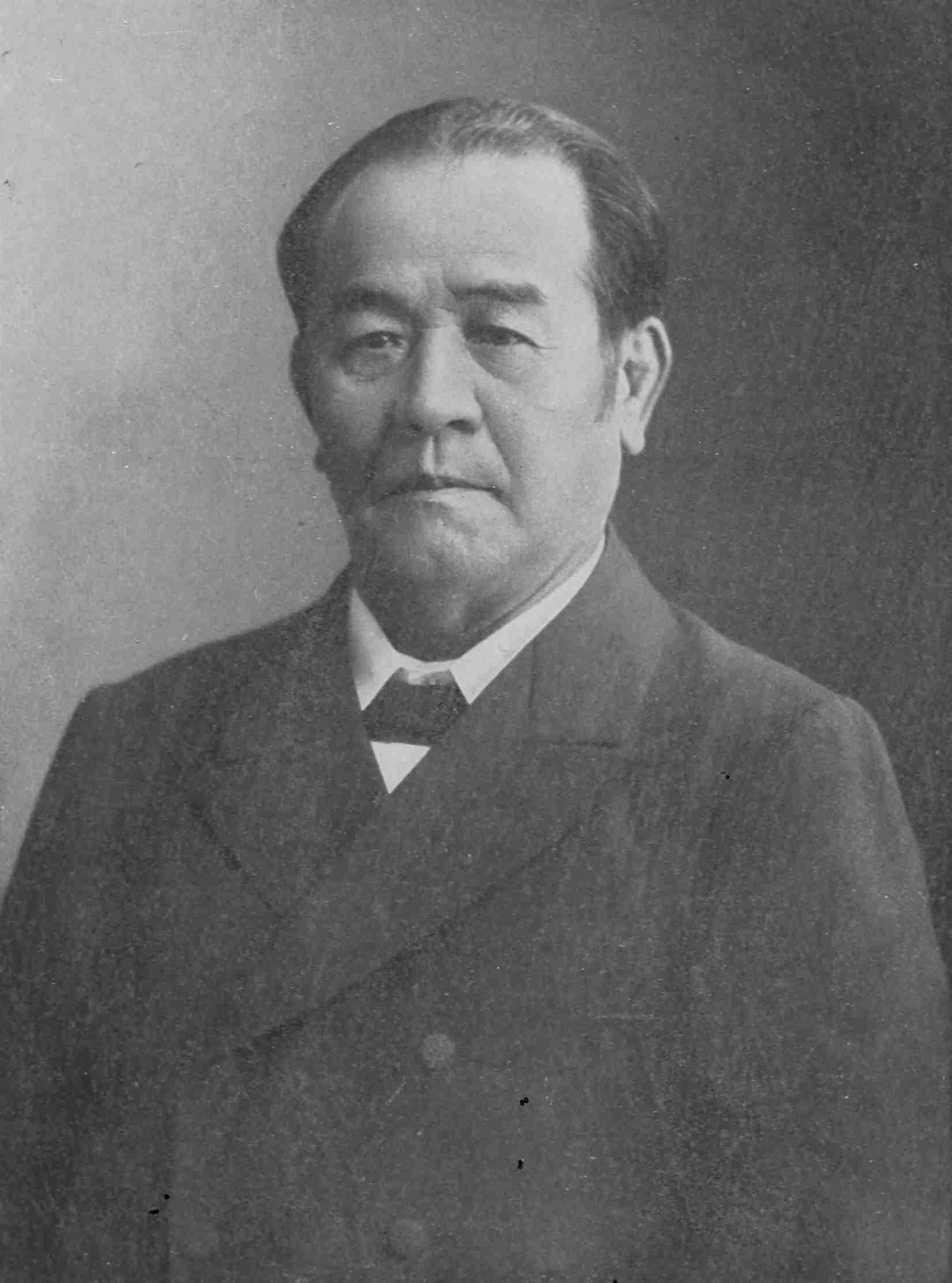

Baron Shibusawa |

42 |

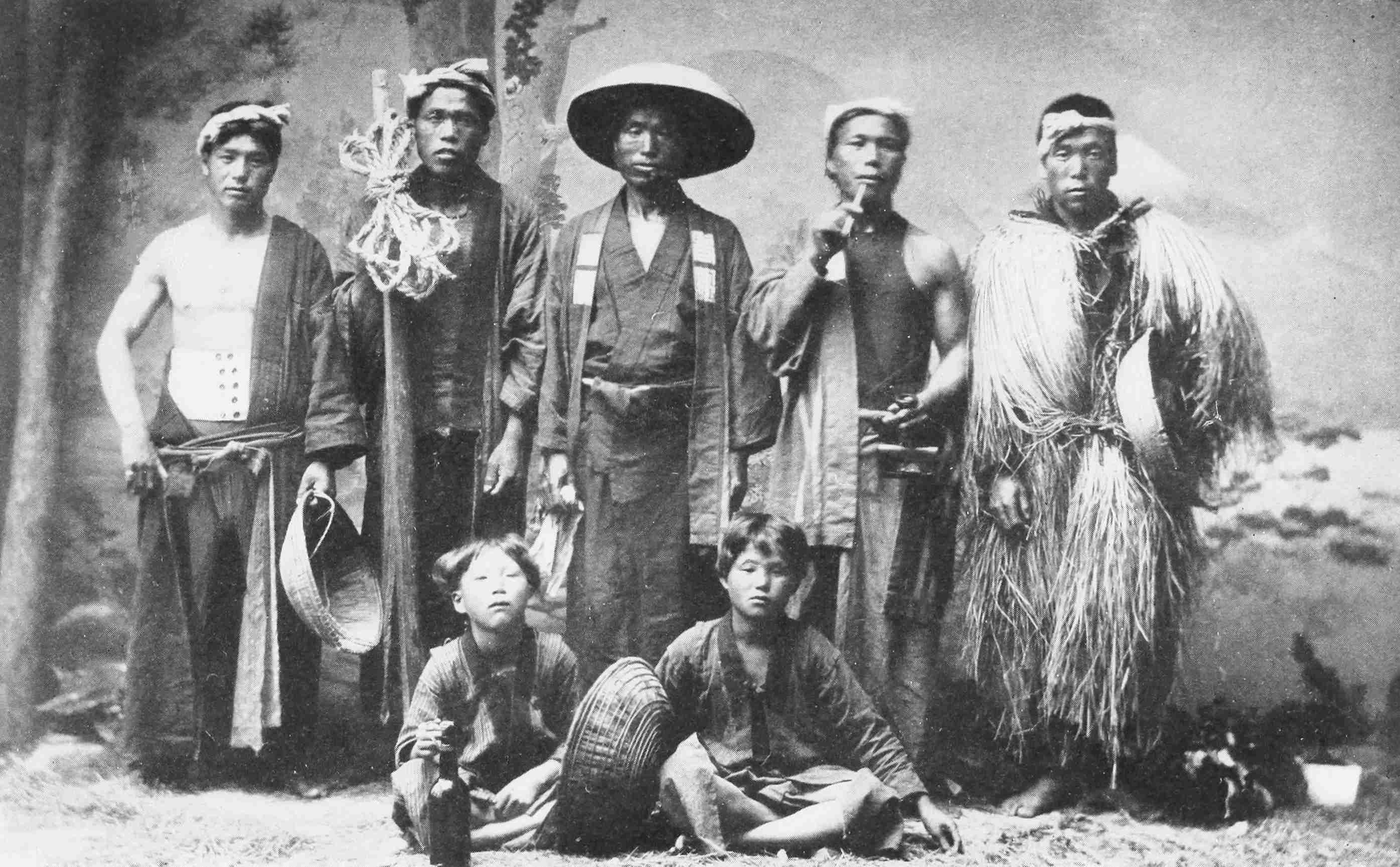

Group of Country People |

46 |

New Year’s Greeting |

64 |

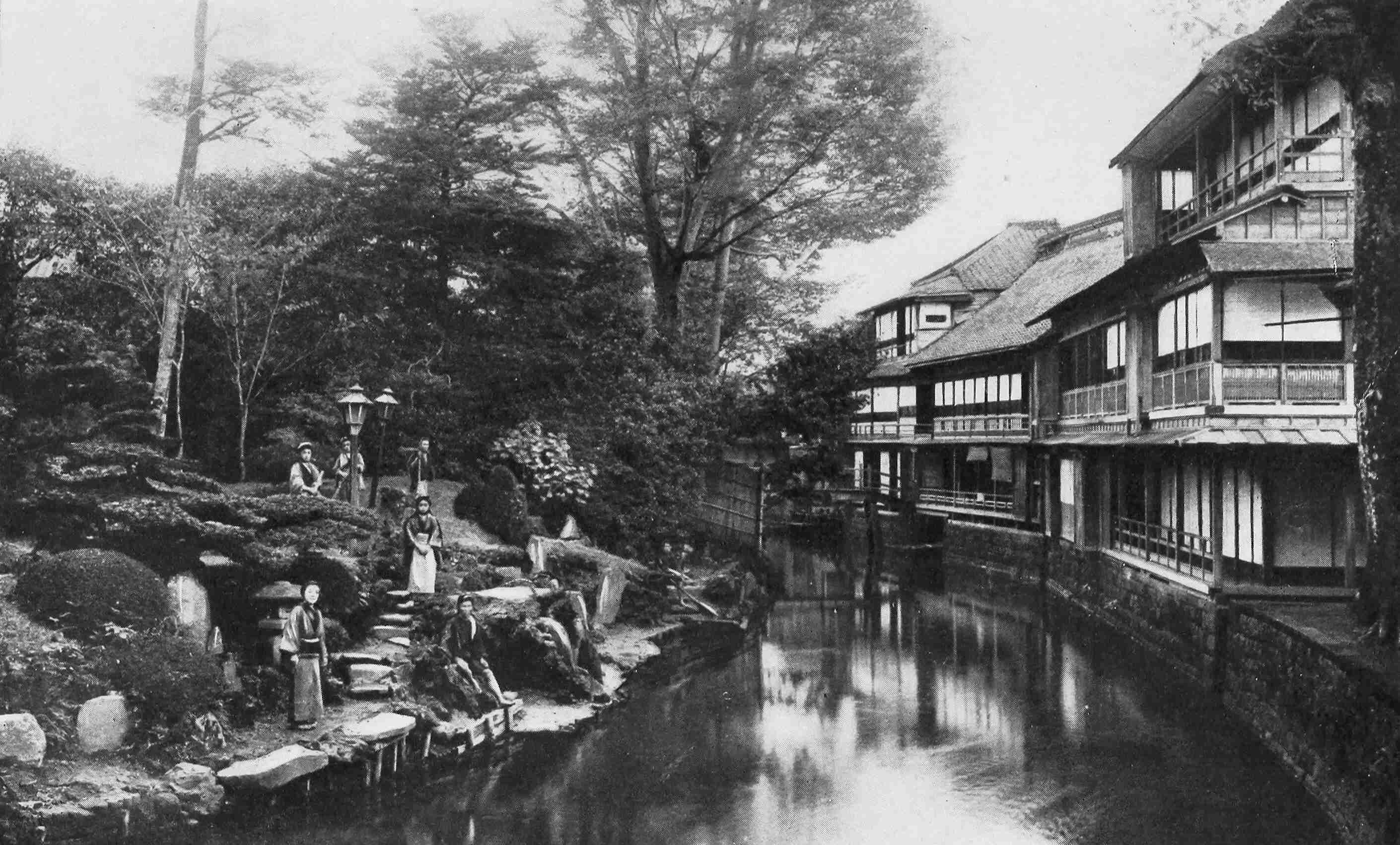

Garden at Ōji |

78 |

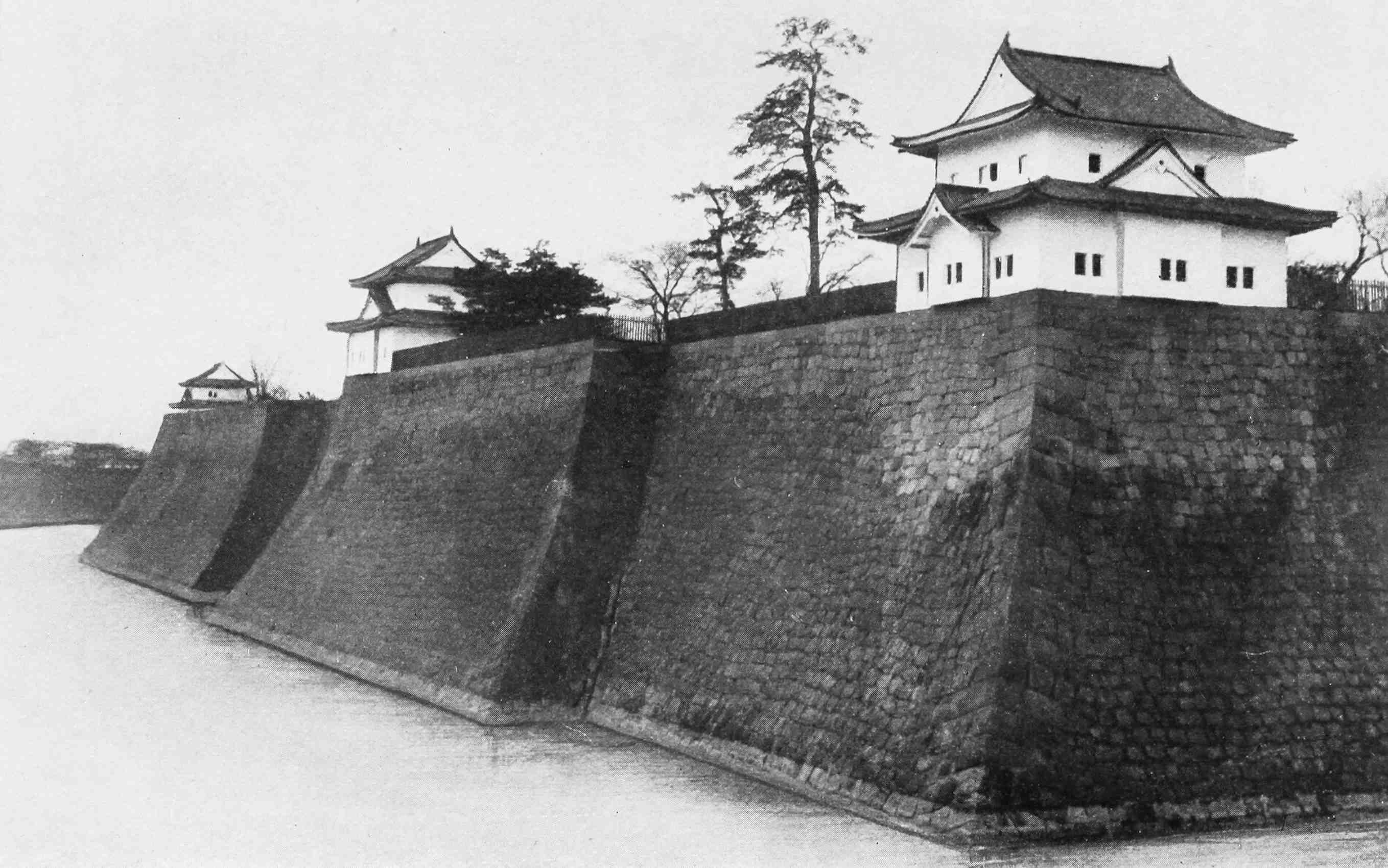

Ōsaka Castle |

92 |

Perry Monument, near Uraga |

106 |

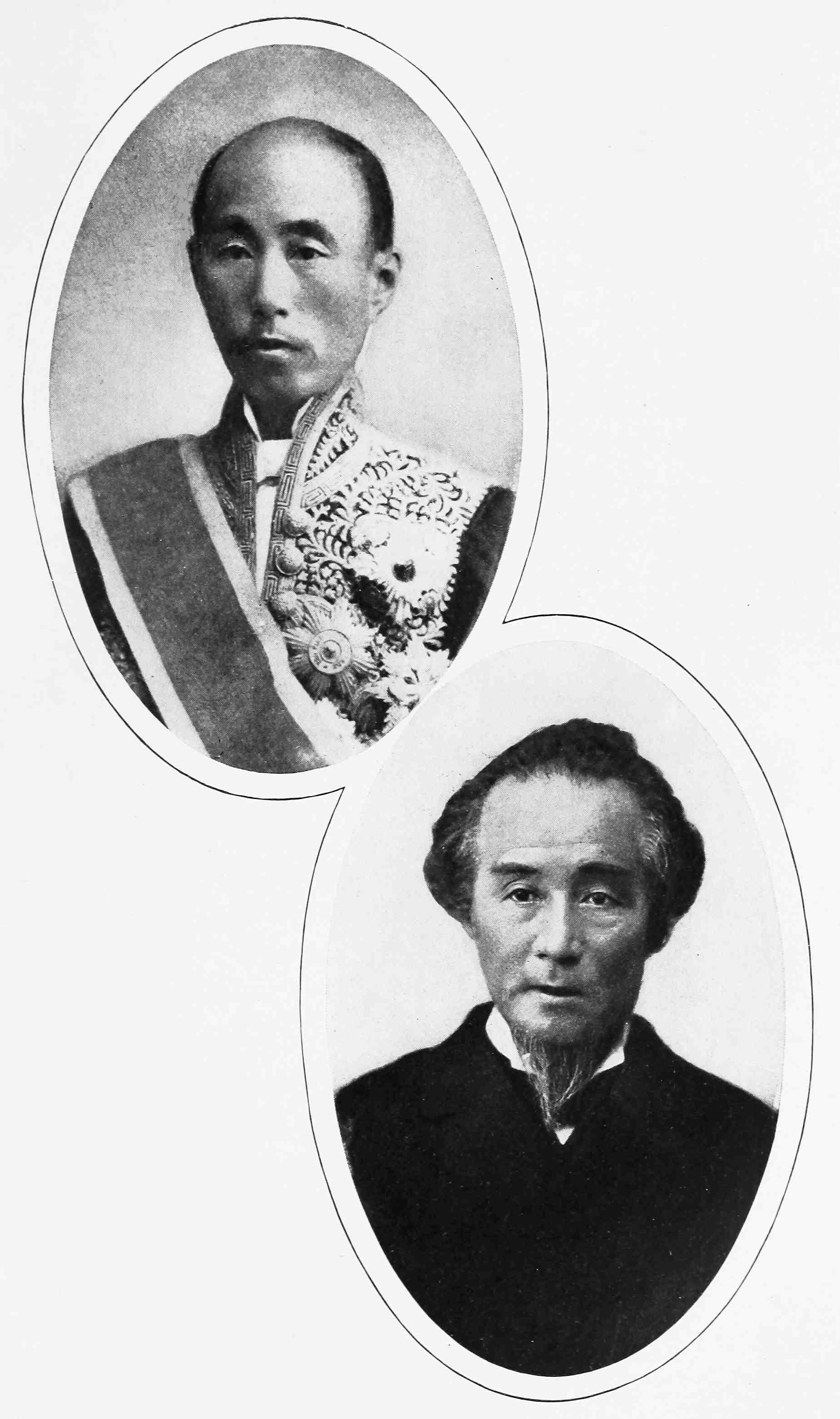

Statesmen of New Japan: Prince Sanjō and Count Katsu |

116 |

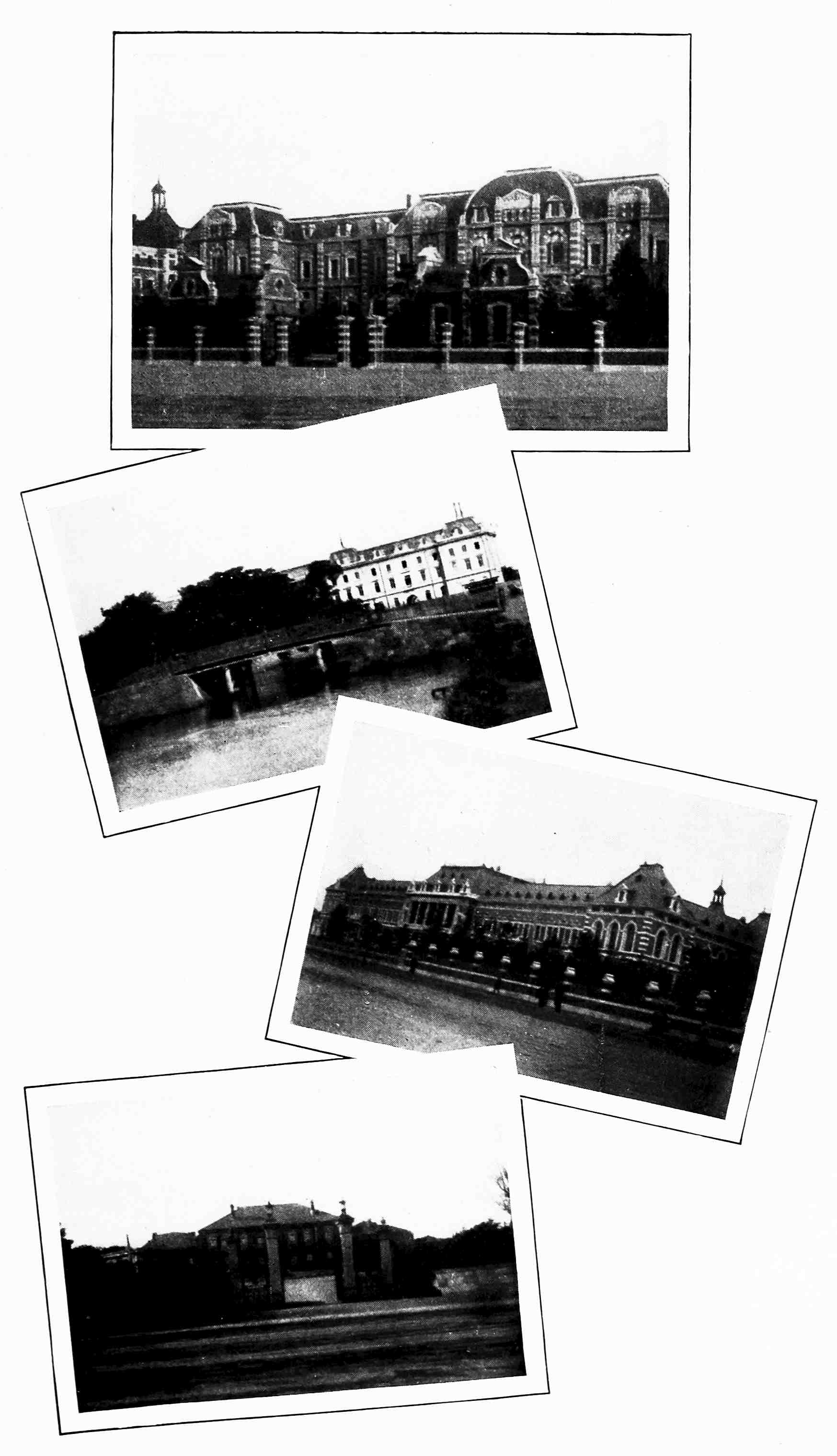

Departments of State: Navy, Agriculture and Commerce, Justice, Foreign Affairs |

126 |

Naval Leaders of Japan: Admiral Enomoto, Admiral Kabayama |

136 |

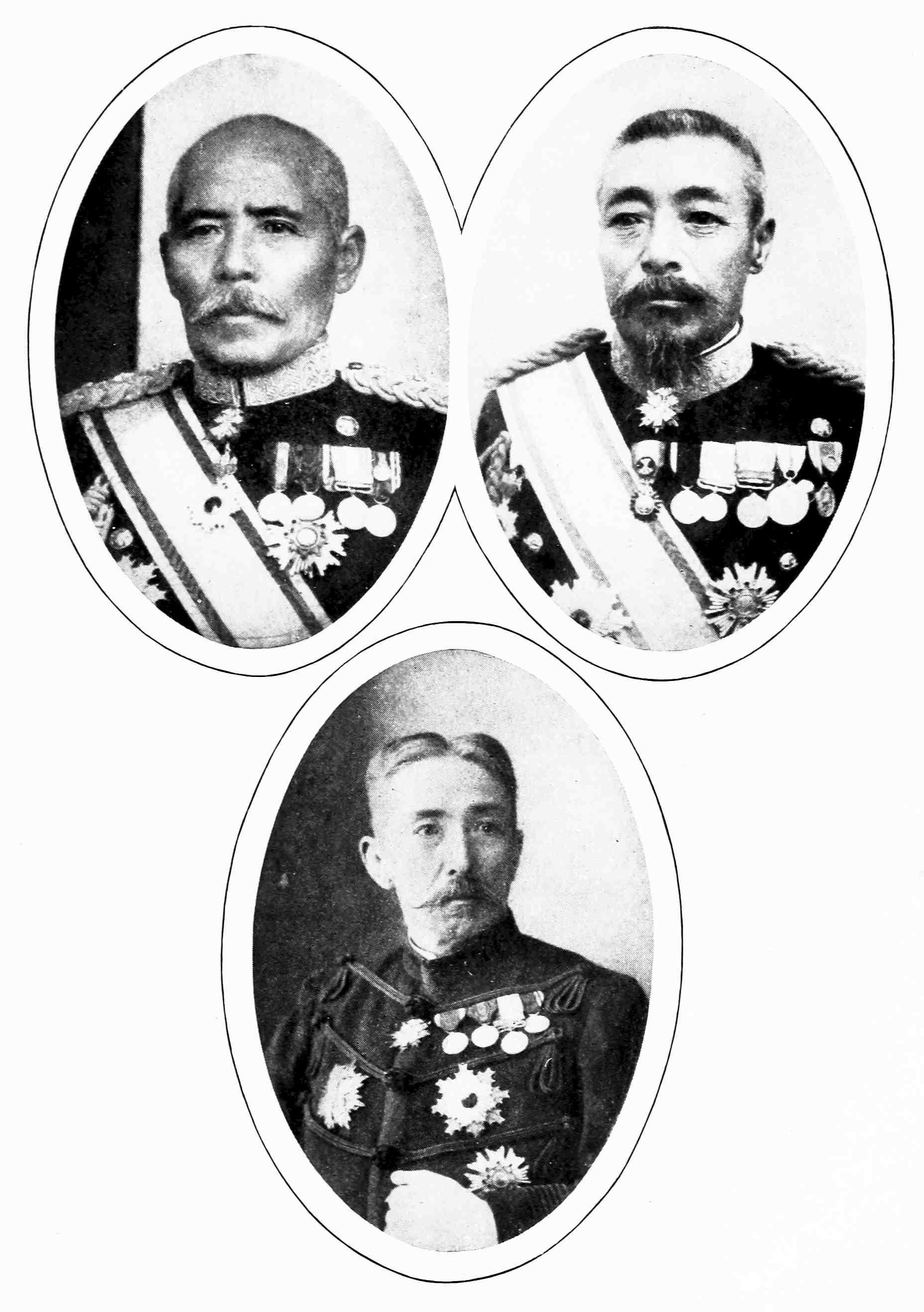

Distinguished Land Commanders: General Baron Kuroki, General Baron Oku, General Baron Nodzu |

146 |

Military Leaders of New Japan: Field-Marshal Ōyama and Field-Marshal Yamagata |

150 |

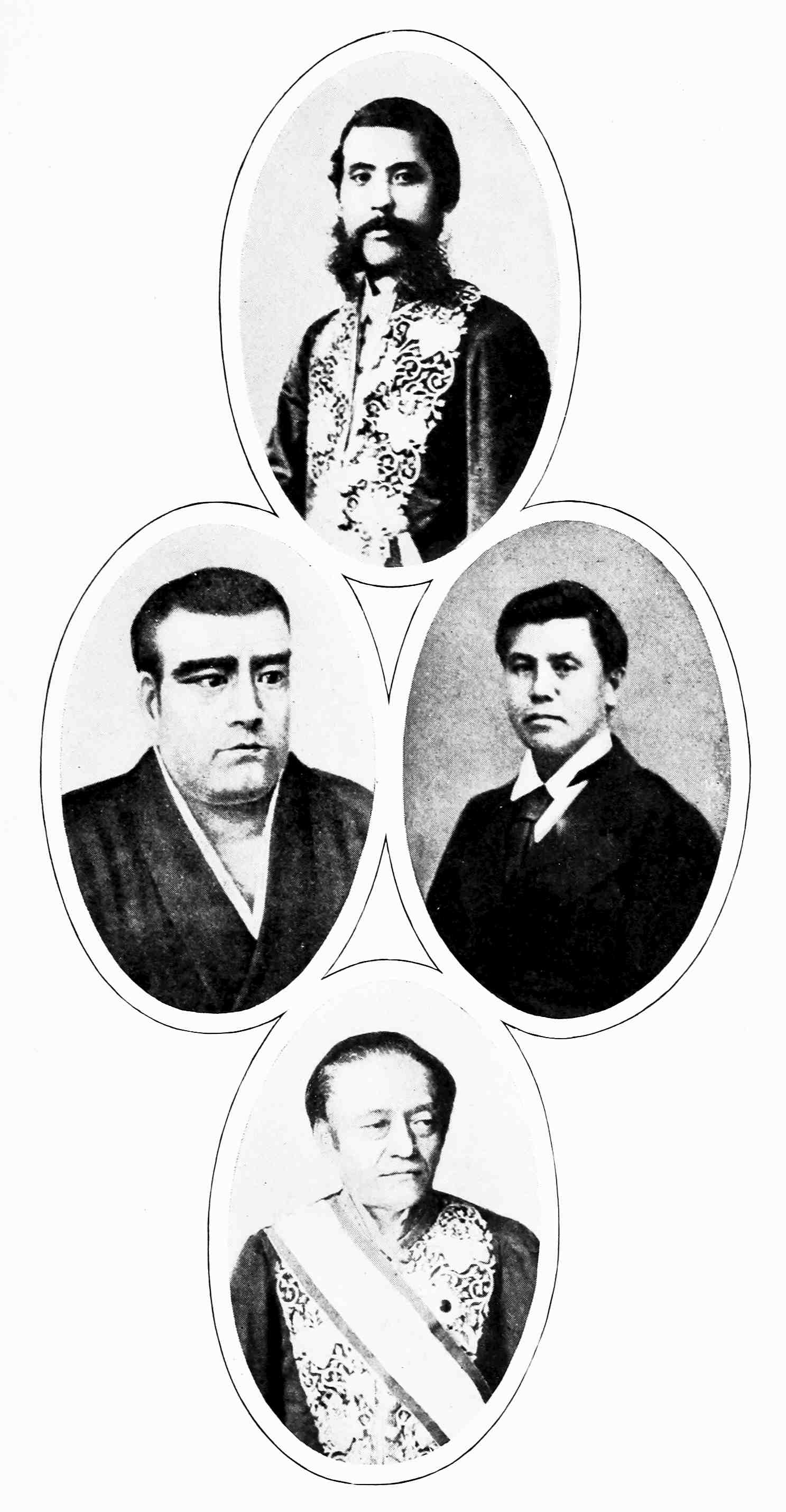

Statesmen of New Japan: Count Ōkuma, Marquis Inouye, Count Itagaki, Marquis Matsukata |

156 |

Court Buildings, Tōkyō |

164 |

The Mint, Ōsaka |

164xvi |

Statesmen of New Japan: Ōkubo, Saigō, Kido, and Prince Iwakura |

172 |

H. I. M. the Empress |

188 |

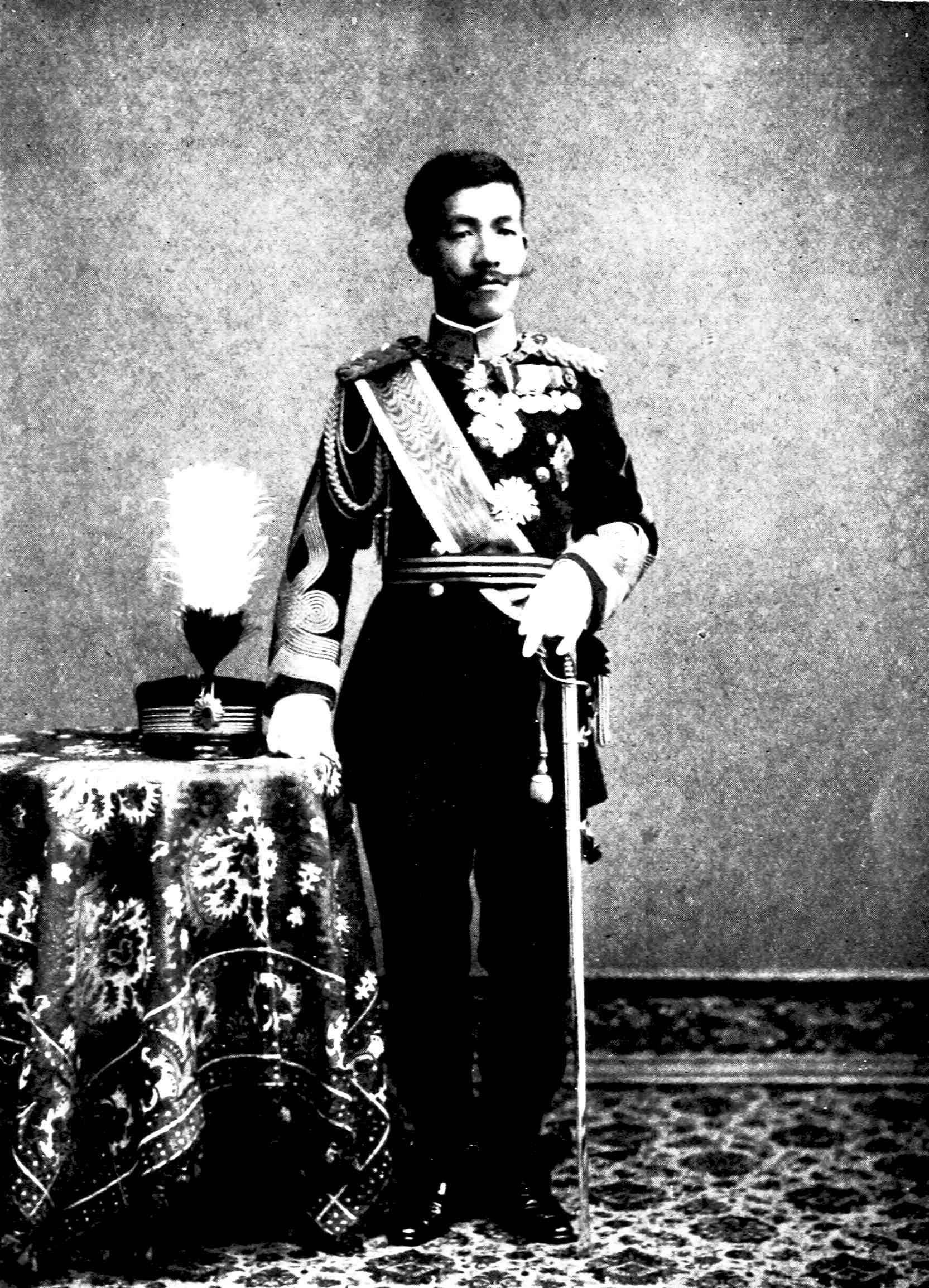

H. I. M. the Crown Prince |

196 |

Imperial University Buildings, Tōkyō |

210 |

Educators and Scientists of Japan: Baron Ishiguro, Viscount Mori, Mr. Fukuzawa, Dr. Kitasato |

216 |

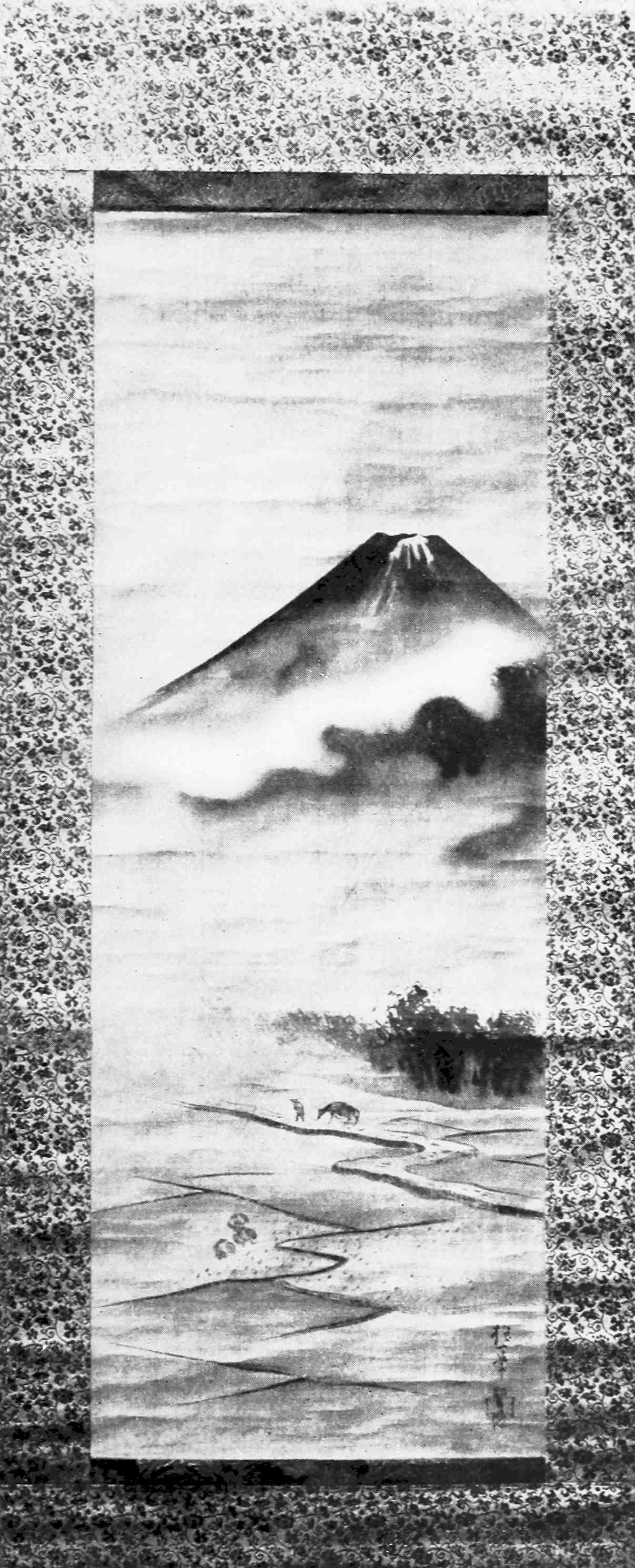

Painting by Ho-Itsu: View of Fuji-San |

224 |

Painting by Yasunobu: Heron and Lotus |

230 |

Group of Pilgrims |

252 |

Buddhist Priests |

252 |

Gospel Ship, “Fukuin Maru” |

268 |

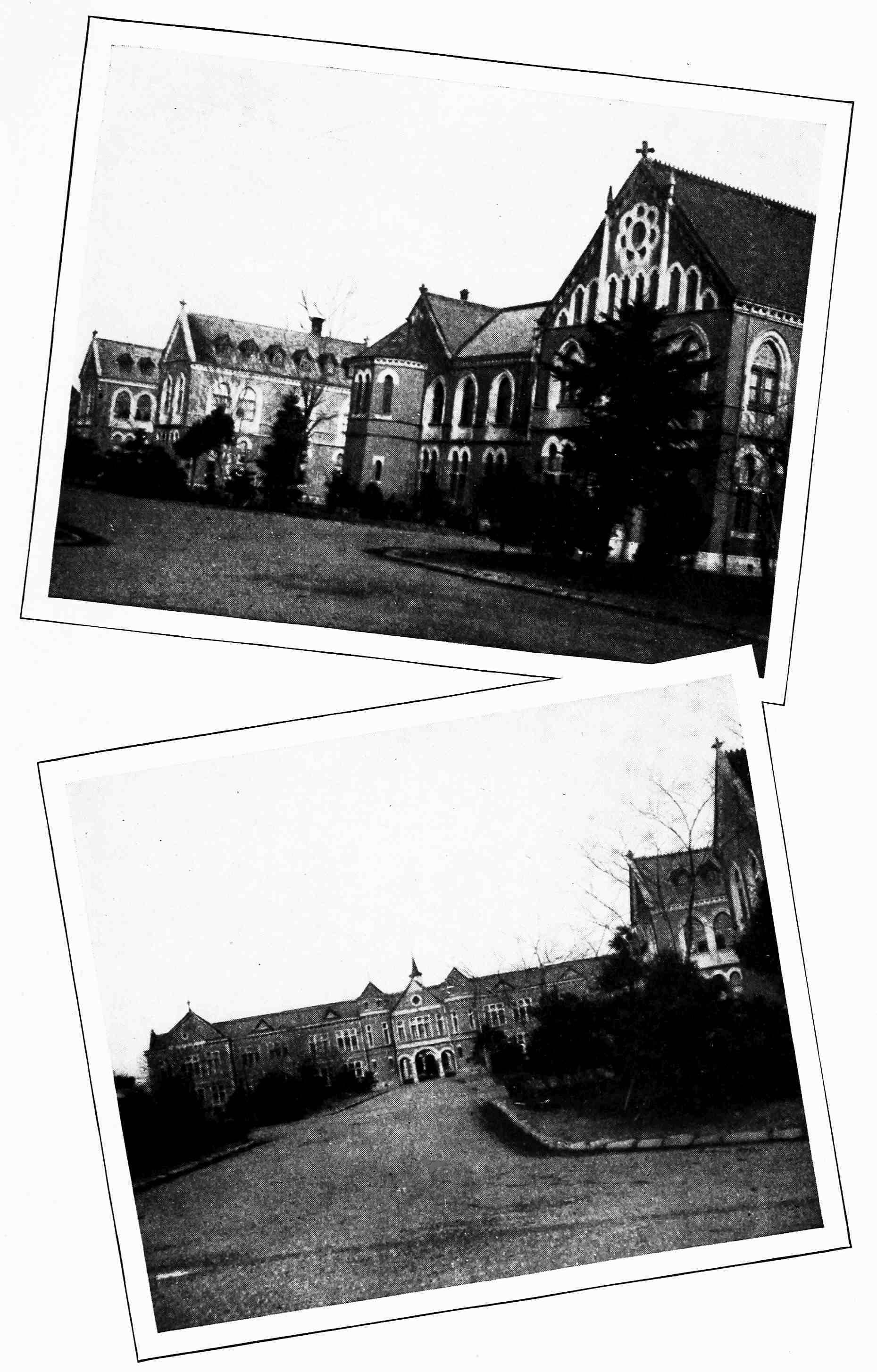

Y. M. C. A. Summer School, Dōshisha, Kyōto |

268 |

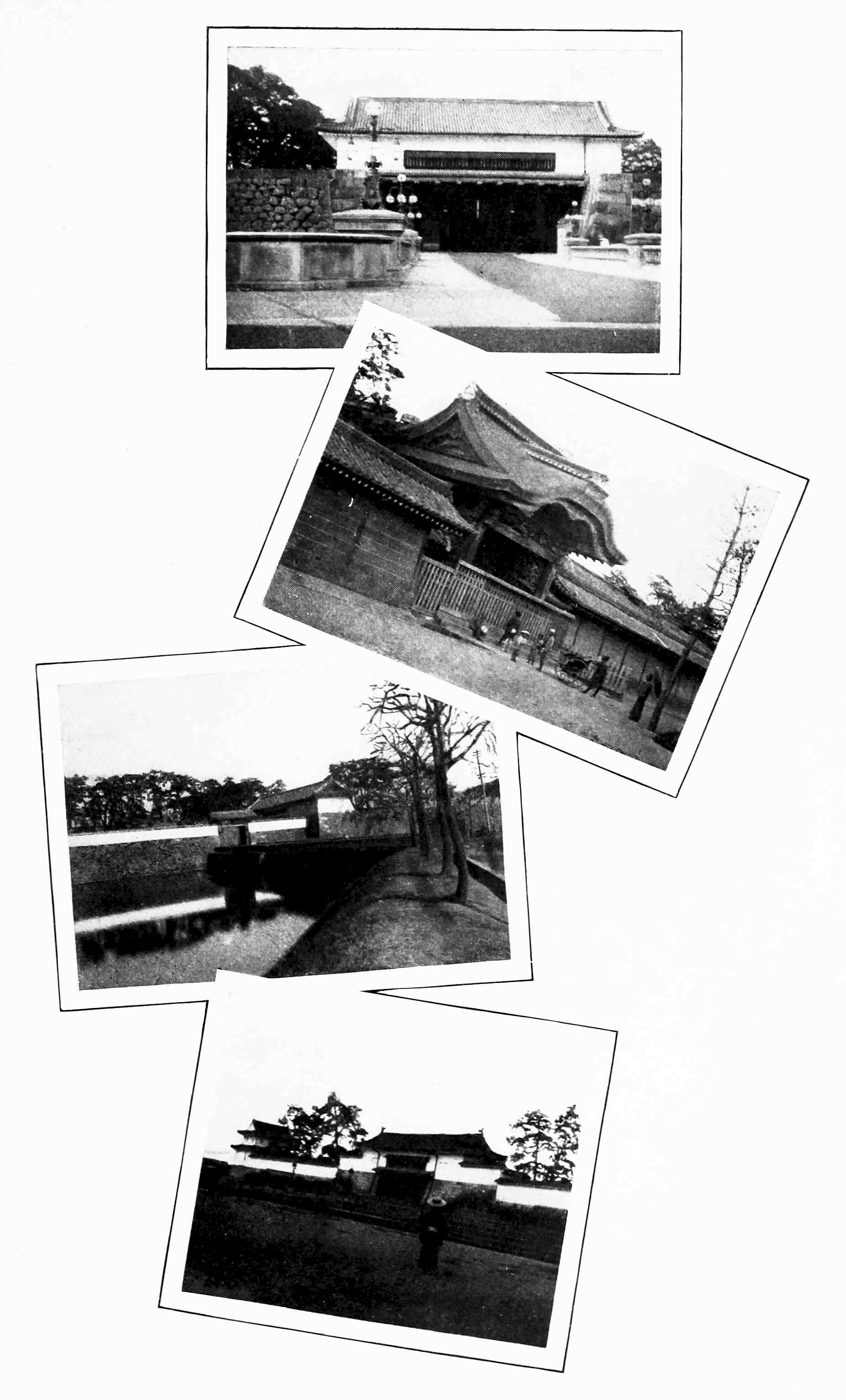

Four Gates: Palace, Tōkyō; Palace, Kyōto; Sakurada, Tōkyō; Nijō Castle, Kyōto |

282 |

The Naval Hero of the War, Admiral Togo |

306 |

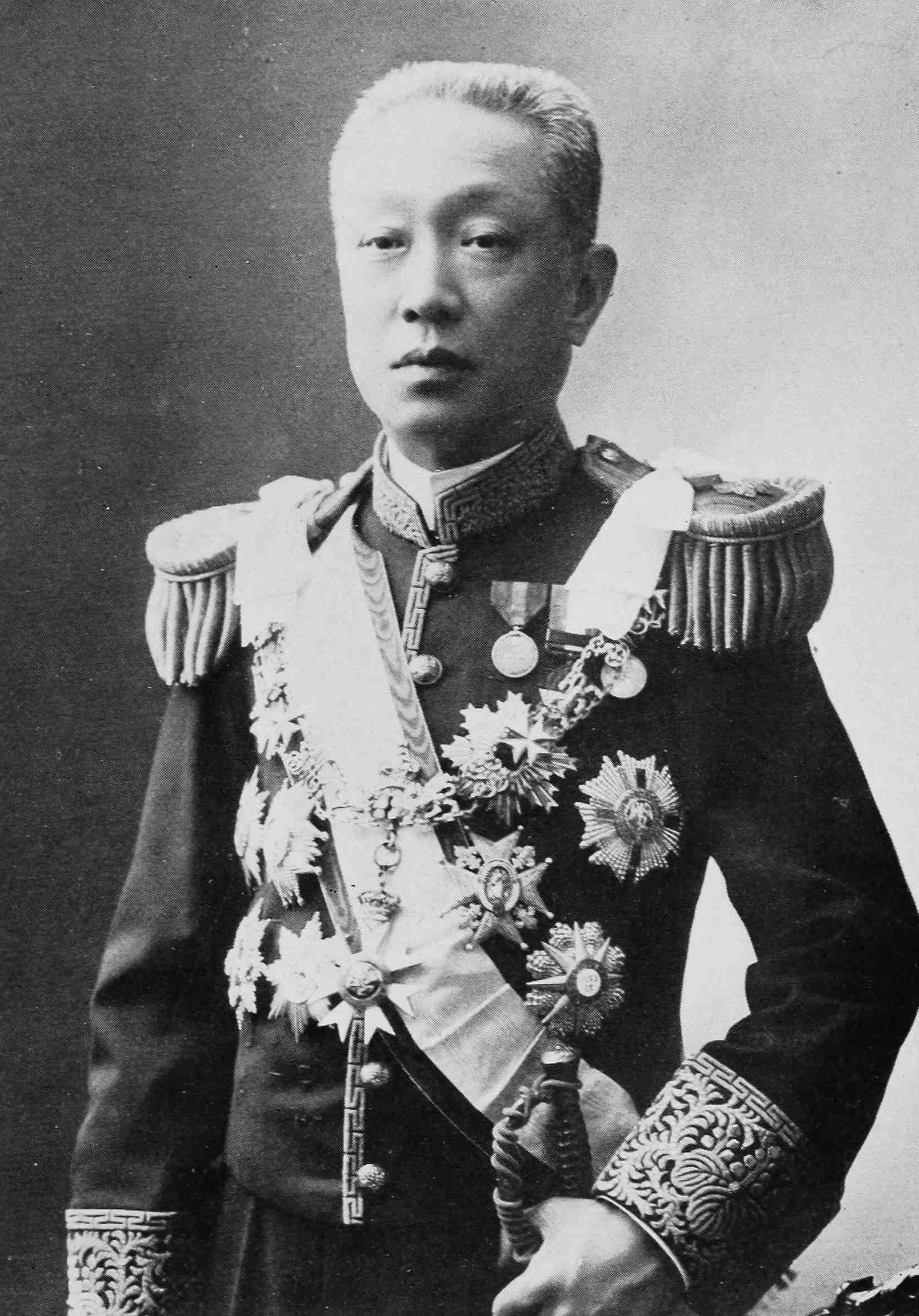

Distinguished Naval Commanders: Admiral Uriu, Admiral Kamimura, Commander Hirose |

310 |

Distinguished Land Commanders: General Baron Kodama, General Count Nogi, Admiral Prince Itō |

316 |

The Japanese Peace Envoys: Count Komura, Minister Takahira |

318 |

H. I. M. the Emperor |

330 |

Marquis Saionji |

332 |

Statesmen of New Japan: Marquis Katsura and Prince Itō |

336 |

Viscount Sone |

338 |

General Viscount Terauchi |

344 |

Military Review, Himeji |

360 |

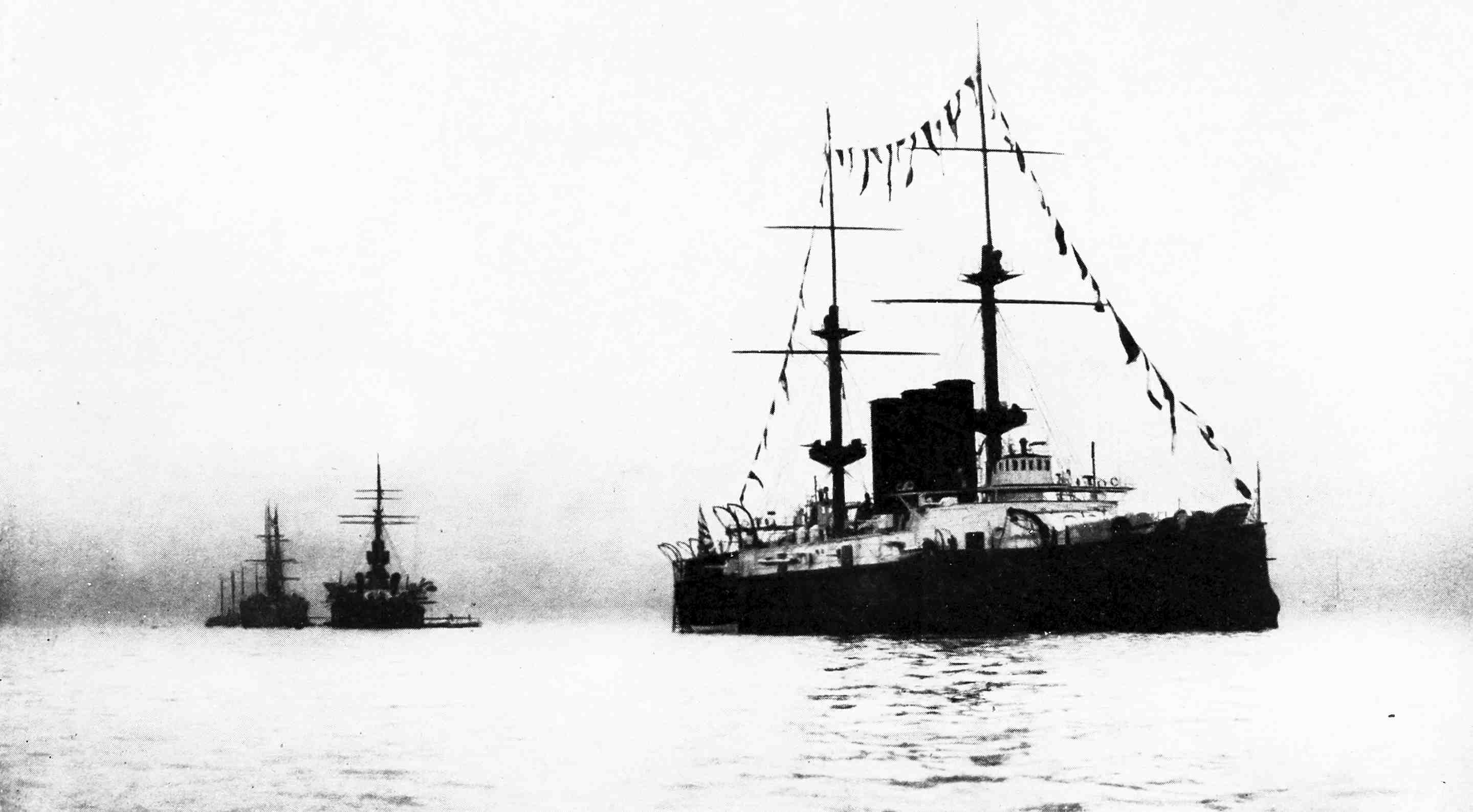

“Shikishima” in Naval Review, Kōbe |

384 |

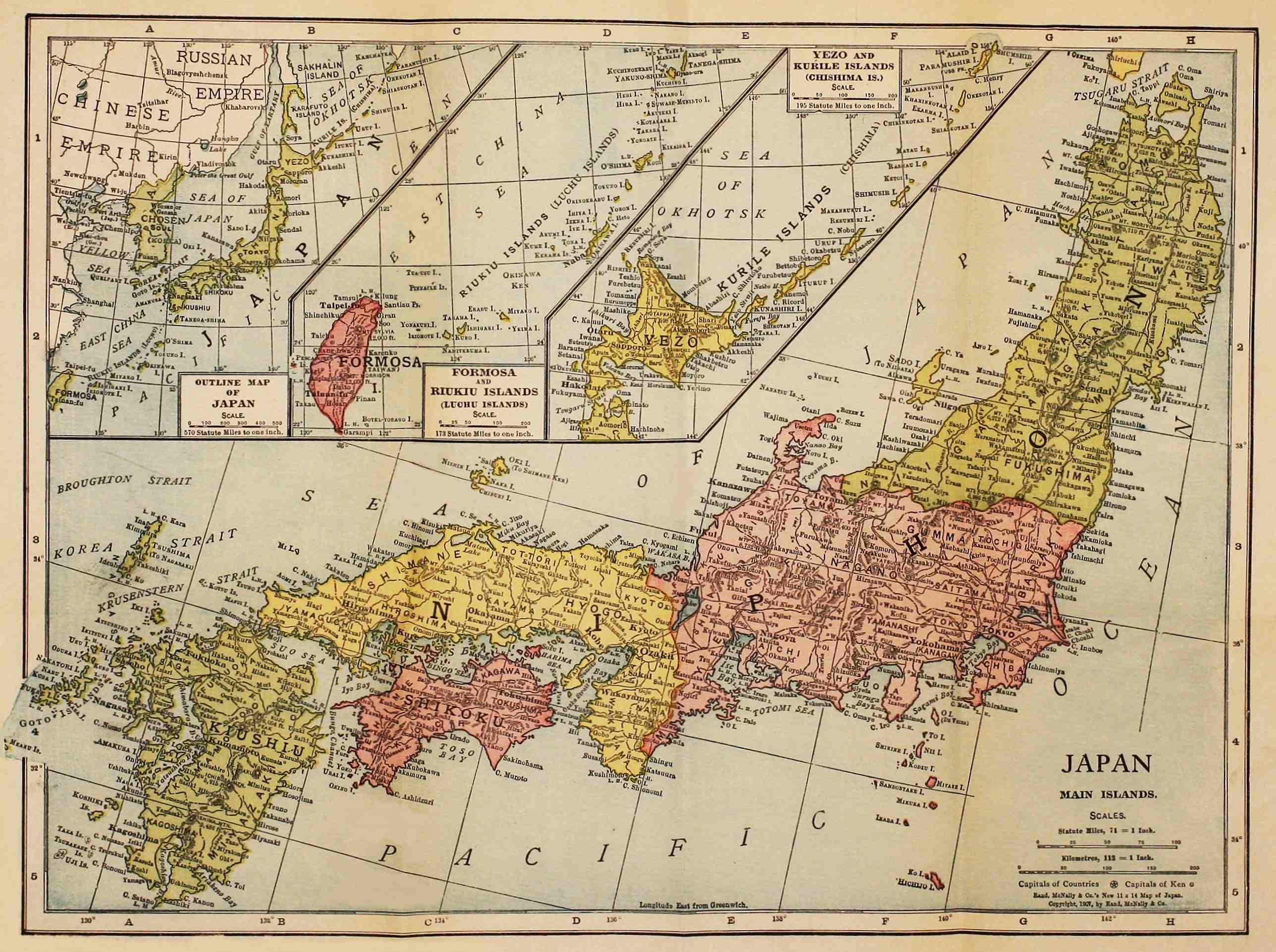

Map of Japan |

342 |

a like a in father

e „ e „ men

i „ i „ pin

o „ o „ pony

u „ oo „ book

ai as in aisle

ei „ weigh

au as o in bone

ō „ „ „ „

ū as oo in moon

i in the middle of a word and u in the middle or at the end of a word are sometimes almost inaudible.

The consonants are all sounded, as in English: g, however, has only the hard sound, as in give, although the nasal ng is often heard; ch and s are always soft, as in check and sin; and z before u has the sound of dz. In the case of double consonants, each one must be given its full sound.

There are as many syllables as vowels. There is practically no accent; but care must be taken to distinguish between o and ō, u and ū, of which the second is more prolonged than the first.

Be sure to avoid the flat sound of a, which is always pronounced ah.

1

A HANDBOOK

OF

MODERN JAPAN

Outline of Topics: Situation of country; relation to the United States; lines of communication; “Key of Asia.”—Area of empire.—Divisions: highways, provinces, prefectures, principal cities and ports.—Dense population; natives and foreigners; Japanese abroad.—Mountains, volcanoes, hot springs, earthquakes.—Lakes, rivers, bays, harbors, floods, tidal waves.—Epidemics, pests.—Climate: temperature, winds (typhoons), moisture, ocean currents.—Flora and fauna.—Peculiar position: Japan and the United States.—Bibliography.

THE Japanese may appropriately be called “our antipodal neighbors.” They do not live, it is true, at a point exactly opposite to us on this globe; but they belong to the obverse, or Eastern, hemisphere, and are an Oriental people of another race. They are separated from us by from 4,000 to 5,000 miles of the so-called, but misnamed, Pacific Ocean; but they are connected with us by many lines of freight and passenger vessels. In fact, in their case, as in many other instances, the “disuniting ocean” (Oceanus dissociabilis) of the Romans has2 really disappeared, and even a broad expanse of waters has become a connecting link between the countries on the opposite shores. It may be, in a certain measure, correct to say, as pupils in geography are taught to express it, that the Pacific Ocean separates the United States from Japan; but it is, in a broader and higher sense, just as accurate to state that this ocean binds us with our Asiatic neighbors and friends in the closest ties. Japan was “opened” by the United States; has been assisted materially, politically, socially, educationally, and morally by American influences in her wonderful career of progress; and she appreciates the kindliness and friendship of our people. We, in turn, ought to know more about our rapidly developing protégé, and no doubt desire to learn all we can concerning Japan and the Japanese.

The development of trade and commerce has been assisted by the power of steam to bring Japan and the United States into close and intimate relations. There are steamship lines from San Francisco, Vancouver, Tacoma, Seattle, Portland, and San Diego to Yokohama or Koōbe; and there are also a great many sailing vessels plying between Japan and America. The routes from San Francisco and San Diego direct to Japan are several hundred miles farther than the routes from the more northerly ports mentioned above. The time occupied by the voyage across the Pacific Ocean varies according to the vessel, the winds and currents, etc.; but it may be put3 down in a general way at about 14 days. The fast royal mail steamers of the Canadian Pacific line often make the trip in much less time, and thus bring Chicago, for instance, within only a little more than two weeks’ communication with Yokohama. It must, therefore, be evident that Japan is no longer a remote country, but is as near to the Pacific coast of America, in time of passage, as the Atlantic coast of America was twenty years ago to Europe.

It is true that the steamers of the San Francisco and San Diego lines, especially those carrying mails and passengers, go and come via Honolulu, so that the voyage to Japan thus requires a few more days than the direct trip would take. But, as Hawaii is now part of the United States, our country has thus become only about 10 days distant from Japan. Moreover, as the Philippine Islands are also a portion of our country, and Formosa has been for several years a part, of Japan, the territories of the two nations are brought almost within a stone’s throw, and the people almost within speaking distance, of each other. This proximity of the two nations to each other should be an incentive to draw even more closely together the ties, not only historical, commercial, and material, but also political, social, educational, intellectual, moral, and religious, that bind them to each other, and, so far as possible, to make “Japan and America all the same heart.”

But Japan is also an Asiatic country, and thus holds a peculiar relation to the countries on the4 eastern coast of the mainland of Asia. The islands of Japan stretch along that shore in close proximity to Siberia, Korea, and China, and are not far distant from Siam. With all of those countries she enters, therefore, into most intimate relationship of many kinds. With Russia the relation is one of rivalry, of more or less hostility, at present passive, but likely to be aroused into activity by some unusually exasperating event. In any case, Japan is the only Far-Eastern power that can be relied upon to check the aggressions of Russia; and this fact the wise statesmen of Great Britain have clearly recognized by entering into the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. Toward Korea, China, and Siam, Japan sustains a natural position of leadership, because she is far in advance of all those nations in civilization. Ties geographical, racial, social, political, intellectual, and religious, bind them more or less closely together, so that Japan can more sympathetically and thus more easily lead them out into the path of progress. The natural and common routes of trade and travel from the United States to those countries run via Japan, which thus becomes, in more senses than one, “the key of Asia”; and for that very reason she is also the logical mediator between the East and the West.

The Japanese call their country Dai Nihon, or Dai Nippon (Great Japan), and have always had a patriotic faith in the reality of its greatness. But this delightful delusion is rudely dispelled when the5 fact is expressed statistically, in cold figures, that the area of the Empire of Japan is about 175,000 square miles,5 or only a little more than that of California. It has, however, a comparatively long coast line of more than 18,000 miles. The name Nihon, or Nippon (a corruption of the Chinese Jih-pên, from which was derived “Japan”), means “sun-source,” and was given because the country lay to the east from China. It is for this reason that Japan is often called “The Sunrise Kingdom,” and that the Imperial flag contains the simple design of a bright sun on a plain white background.6

Japan proper comprises only the four large islands, called Hondo, Shikoku, Kyūshiu, and Yezo (Hokkaidō); but the Empire includes also Korea, Formosa, the Pescadores, and about 4,000 small islands, of which the Ryūkyū (Loo Choo) and the Kurile groups are the most important. Japan proper lies mainly between the same parallels of latitude7 as the States of the Mississippi valley, and presents even more various and extreme climates than may be found from Minnesota to Louisiana.

The extreme northern point of the Empire of Japan is 50° 56´ N., and the extreme southern point is 21° 45´ N. The extreme eastern point is 156° 32´ E., and the extreme western point 119° 18´ E. These extremes furnish even greater varieties of climate6 than those just mentioned. The Kurile Islands at the extreme north are frigid, and have practically no animal or vegetable life; while the beautiful island of Formosa at the extreme south is half in the tropics, with a corresponding climate, and abounds in most valuable products. Marcus Island, farther out in the Pacific, has guano deposits worth working.

Japan proper is divided geographically into nine “circuits,” called Gokinai, Tōkaidō, Tōsandō, Hokurikudō, Sanindō, Sanyōdō, Nankaidō, Saikaidō, Hokkaidō. The word dō, which appears in all the names except the first, means “road” or “highway.” Some of these appellations are not much used at present; but others are retained in various connections, especially in the names of railways, banks, companies, or schools. A common official division of the largest island (Hondo) is into Central, Northern, and Western. Japan proper was also subdivided into 85 Kuni (Province), the names of which are still retained in general use to some extent. But, for purposes of administration, the empire is divided into 3 Fu (Municipality) and 43 Ken (Prefecture), besides Yezo (or Hokkaidō) and Formosa, each of which is administered as a “territory” or “colony.” The distinction between Fu and Ken is practically one in name only. These large divisions are again divided: the former into Ku (Urban District) and Gun (Rural District); and the latter into Gun. There are also more than 50 incorporated Cities (Shi) within the Fu7 and Ken.8 Moreover, the Gun is subdivided into Chō (Town) and Son (Village).

But, while the prefix “great” does not apply to Japan with reference to its extent, it is certainly appropriate to the contents of that country. Within the Empire of Japan are great mountains with grand scenery, great and magnificent temples, great cities, and a great many people. For, while the area of Japan is only one-twentieth of that of the United States, the population is about one-half as numerous. Even in the country districts the villages are almost continuous, so that it is an infrequent experience to ride a mile without seeing a habitation; and in the large cities the people are huddled very closely together. The latest official statistics, those of 1909, give the total population of Japan as 53,500,000, of whom the males exceed the females by about 600,000; and as of late years the annual increase has amounted to about 700,000, the present population (1912) may fairly be estimated at more than 55,000,000.9

The number of foreigners resident in Japan in 1909 exceeded 17,000, of whom more than half were Chinese, and less than a quarter were British and American. The number of Japanese in 1909 living abroad was 301,000, of whom 100,000 were in the United States (chiefly in Hawaii), 97,000 in China, and only a few in British territory.

Japan is a mountainous country. The level ground,8 including artificial terraces, is barely 12 per cent of the area of the whole empire. A long range of high mountains runs like a backbone through the main island. The highest peak is the famous Fuji, which rises 12,365 feet above the sea-level, and is a “dormant volcano,” whose last eruption occurred in 1708. Its summit is covered with snow about ten months in the year.10 There are several other peaks of more than 8,000 feet elevation, such as Mitake, Akashi, Shirane, Komagatake, Aso, Asama, Bandai, some of which are active volcanoes. Eruptions happen not infrequently; and earthquakes, more or less severe, registered by the seismometer, are of daily occurrence, although most of the shocks are not ordinarily perceptible. There are also several excellent hot springs, of sulphuric or other mineral quality, as at Ikao, Kusatsu, Atami, Hakone, Arima, Onsen. The mountainous character of Japan has also its pleasant features, because it furnishes means of escape from the depressing heat of summer. Karuizawa, Nikkō, Miyanoshita, Hakone, Arima, Chūzenji are the most popular summer resorts.

There are not many, or large, lakes in Japan. Lake Biwa, 50 miles long and 20 miles wide at its widest point, is the largest and most famous. Hakone Lake, the “Asiatic Loch Lomond,” is beautiful, and especially noted for the reflection of Mount Fuji in its water by moonlight. Lake Chūzenji, in the Nikkō mountains, is regarded by many as “unrivalled9 for beauty” and “hardly surpassed in any land.”

There are many beautiful waterfalls, such as Kegon, Urami, and others in the Nikkō district, Nunobiki at Kōbe, Nachi in Kii, etc.

There are numerous rivers, short and swift; and it is these streams, which, after a rainy season, swelling and rushing impetuously down from the mountains, overflow their sandy banks and cause annually a terrible destruction of life and property. The most important rivers are the Tone, the Shinano, the Kiso, the Kitakami, the Tenryū, in the main island, and the Ishikari in Yezo. The last is the longest (about 400 miles); the next is the Shinano (almost 250 miles); but no other river comes up even to 200 miles in length. The Tenryū-gawa11 is famous for its rapids. Some of these rivers are navigable by small steamers.

Japan, with its long and irregular coast line, is particularly rich in bays and harbors, both natural and artificial, which furnish shelter for the shipping of all kinds. The “open ports,” which formerly numbered only 6 (Nagasaki, Yokohama, Hakodate, Ōsaka, Kōbe, Niigata), have reached the figure 36; and the growing foreign commerce annually demands further enlargement. Of the old ports, Niigata is of no special importance in foreign commerce; but, of the new ports, Kuchinotsu in Kyūshiu, Muroran in Yezo (Hokkaidō), and especially Bakan and Moji,10 on opposite sides of the Straits of Shimonoseki, are rapidly growing. In this connection it is, perhaps, not inappropriate to make mention of the far-famed “Inland Sea,” known to the Japanese as Seto-no-uchi (Between the Straits), or Seto-uchi, which lies between the main island, Shikoku and Kyūshiu.

The long coast line of Japan is a source of danger; for tidal waves occasionally spread devastation along the shore. These, with floods, earthquakes, eruptions, typhoons, and conflagrations, make a combination of calamities which annually prove very disastrous in Japan.

The country is subject to epidemics, like dysentery, smallpox, cholera, plague, and “La Grippe,” which generally prove quite fatal. In 1890, for instance, some 50,000 Japanese were attacked by cholera, and about 30,000 died; and during two seasons of the “Russian epidemic” large numbers of Japanese were carried away. In both cases the foreigners living in Japan enjoyed comparative immunity. And now, on account of the advance in medical science, more stringent quarantine, and better sanitary measures, the mortality among Japanese has been considerably diminished: This fortunate result is largely due to the efforts of such men as Dr. Kitasato, whose fame as a bacteriologist is world-wide. The zoölogical pests of Japan are fleas, mosquitoes, and rats, all of which are very troublesome; but modern improvements minimize the extent of their power.

NAGASAKI HARBOR, AND LIGHTHOUSE INLAND SEA

11

But, in spite of the drawbacks just enumerated, Japan is a beautiful spot for residence. “The aspect of nature in Japan ... comprises a variety of savage hideousness, appalling destructiveness, and almost heavenly beauty.” The climate, though somewhat debilitating, is fairly salubrious, and on the whole is very delightful. The extremes of heat and cold are not so great as in Chicago, for instance, but are rendered more intolerable and depressing by the humidity of the atmosphere. No month is exempt from rain, which is most plentiful from June on through September; and those two months are the schedule dates for the two “rainy seasons.” September is also liable to bring a terrible typhoon. Except in the northern, or in the mountainous, districts, snow is infrequent and light, and fogs are rare. The spring is the most trying, and the autumn the most charming season of the year.12

On account of the extent of Japan from north to south, the wide differences of elevation and depression, and the influence of monsoons and ocean currents, there is no uniformity in the climate. For instance, the eastern coast, along which runs the Kuro Shio (Black Stream), with a moderating influence like that of the Gulf Stream, is much warmer than the western coast, which is swept by Siberian breezes and Arctic currents. The excessive humidity is due to the insular position and heavy rainfall. Almost all portions of the country12 are subject more or less to sudden changes of weather. It is also said that there is in the air a great lack of ozone (only about one-third as much as in most Western lands); and for this reason Occidentals at least are unable to carry on as vigorous physical and mental labor as in the home lands. Foreign children, however, seem to thrive well in Japan.

“Roughly speaking, the Japanese summer is hot and occasionally wet; September and the first half of October much wetter; the late autumn and early winter cool, comparatively dry, and delightful; February and March disagreeable, with occasional snow and dirty weather, which is all the more keenly felt in Japanese inns devoid of fireplaces; the late spring rainy and windy, with beautiful days interspersed. But different years vary greatly from each other.”13

In Japan “a rich soil, a genial climate, and a sufficient rainfall produce luxuriant vegetation” of the many varieties of the three zones over which the country stretches. In Formosa, Kyūshiu, Shikoku, and the Ryūkyū Islands, “the general aspect is tropical”; on the main island the general appearance is temperate; while Yezo and the Kurile Islands begin to be quite frigid. The commonest trees are the pine, cedar, maple, oak, lacquer, camphor, camellia,13 plum, peach, and cherry; but the last three are grown for their flowers rather than for their fruit or wood. The bamboo, which grows abundantly, is one of the most useful plants, and is extensively employed also in ornamentation.

In the fauna of Japan we do not find such great variety. Fish and other marine life are very abundant; fresh-water fish are also numerous; and all these furnish both livelihood and living to millions of people. Birds are also quite numerous; and some of them, like the so-called “nightingale” (uguisu), are sweet singers. The badger, bear, boar, deer, fox, hare, and monkey are found; cats, chickens, dogs, horses, oxen, rats, and weasels are numerous; but sheep and goats are rare. Snakes and lizards are many; but really dangerous animals are comparatively few, except the foxes and badgers, which are said to have the power to bewitch people!

In conclusion, attention should be called once more to the physiographical advantages of Japan, and it may be of interest to set them forth from the point of view of a Japanese who has indulged in some prognostications of the future of his nation. From the insular position of Japan, he assumes an adaptability to commerce and navigation; from the situation of Japan, “on the periphery of the land hemisphere,” and thus at a safe distance from “the centre of national animosities,” he deems her comparatively secure from “the depredations of the world’s most conquering nations”; from the direction of her chief14 mountain system (her backbone), and “the variegated configurations of her surface,” he thinks that “national unity with local independence” may easily be developed. Likewise, because more indentations are found on the eastern than on the western sides of the Japanese islands, except in the southwestern island of Kyushiu, where the opposite is true; because the ports of California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia are open toward Japan; because the Hoang-Ho, the Yangtze Kiang, and the Canton rivers all flow and empty toward Japan; because the latter thus “turns her back on Siberia, but extends one arm toward America and the other toward China and India”; because “winds and currents seem to imply the same thing [by] making a call at Yokohama almost a necessity to a vessel that plies between the two continents,”—he conceives of his native country as a nakōdo (middleman, or arbiter) “between the democratic West and the Imperial East, between the Christian America and the Buddhist Asia.”

But since these comparisons were made, the geography of Eastern Asia and the Pacific Ocean has been altered. Japan has acquired Formosa and Korea; the United States has assumed the responsibility of the Philippines; and China is threatened with partition through “spheres of influence.” Japan, therefore, seems now to be lying off the eastern coast of Asia, with her back turned on Russia with Siberian breezes and Arctic currents, her face turned toward America, with one hand15 stretched out toward the Aleutian Islands and Alaska and the other toward the Philippines, for the hearty grasp of friendship.

For more detailed information concerning the topics treated in this chapter, the reader is referred to “The Story of Japan” (Murray), in the “Story of the Nations” series; “The Gist of Japan” (Peery); and “Advance Japan” (Morris).

For pleasant descriptions of various portions of Japan, “Jinrikisha Days in Japan” (Miss Scidmore); “Lotos-Time in Japan” (Finck); “Japan and her People” (Miss Hartshorne); “Unbeaten Tracks in Japan” (Miss Bird, now Mrs. Bishop); “Every Day Japan” (Lloyd); and “Japan To-Day” (Scherer) are recommended.

The most complete popular work on the country is the “Hand-Book for Japan” (Chamberlain and Mason), 8th edition; and the most thorough scientific treatment is to be found in Rein’s “Japan.”

Students of seismology should consult Prof. John Milne’s works.

16

Outline of Topics: Agriculture; petty farming; small capital and income; character of farmer; decrease of farmers; principal products; rice; tea; tobacco; silk; cotton; camphor; bamboo; marine products and industries.—Mining.—Engineering.—Shipbuilding.—Miscellaneous industries.—Mechanical industries.—Shopping in Japan.—Wages and incomes.—Guilds, labor unions, strikes, etc.—Mr. Katayama.—Socialism.—Bibliography.

THE chief occupation of the Japanese is agriculture, in which the great mass of the people are employed. On account of the volcanic nature and the mountainous condition of the country, there are large portions not tillable;14 and for the same reason, perhaps, the soil in general is not naturally very fertile. It must be, and can be, made so by artificial means; but as yet not half of what is fairly fertile soil is under cultivation. Large portions of arable land, particularly in Yezo and Formosa, can be made to return rich harvests, and are gradually being brought under man’s dominion. But it can be readily understood that if for any reason the crops fail, severe suffering will ensue, and perhaps become widespread. The prosperity of the country depends largely upon the prosperity of its farmers.

17

Farming, like almost everything in that land of miniatures, is on a limited scale, as each man has only a very small holding. “There is no farm in Japan; there are only gardens” (Uchimura). Even a “petty farmer” of our Northwest would ridicule the extremely insignificant farms of the Japanese, who, in turn, would be astounded at the prodigious domains of a Dalrymple. A careful investigator, Dr. Karl Rathgen, has summed up the situation as follows: “In Japan are to be found only small holdings. A farm of five chō15 (twelve acres) is considered very large. As a rule the Japanese farmer is without hired labor and without cattle. The family alone cultivates the farm, which, however, is so small that a large share of the available labor can be devoted to other purposes besides farming, such as the production of silk, indigo, tobacco. The average holding for the whole of Japan (excluding the Hokkaidō) for each agricultural family is 8.3 tan15 (about two acres), varying from a maximum of 17.6 tan in the prefecture of Aomori to a minimum of 5.3 tan in the prefecture of Wakayama.” “There are no large landed proprietors in Japan.”

A Japanese farm is so insignificant, partly because a Japanese farmer has only a very small capital, and needs only a slight income to support life. It has been estimated that a man so fortunate as to own a farm of five chō15 obtains therefrom an annual income of 100 or 120 yen.15 And yet the Japanese18 farmers are very careful and thoroughly understand their business. “In spade-husbandry,” says Dr. Griffis, “they have little to learn”; but “in stock-raising, fruit-growing, and the raising of hardier grains than rice, they need much instruction.”16

A Japanese farmer is hard-working, industrious, stolid, conservative, and yet, by reason of his fatalistic and stoical notions, in a way happy and contented. “Left to the soil to till it, to live and die upon it, the Japanese farmer has remained the same, ... with his horizon bounded by his rice-fields, his water-courses, or the timbered hills, his intellect laid away for safe-keeping in the priest’s hands, ... caring little who rules him, unless he is taxed beyond the power of flesh and blood to bear.” He is, however, more than ordinarily interested in taxation, for the land-tax of three and one-third per cent of the assessed value of the land amounts to about half the national revenue, and is no inconsiderable part of the state, county, town, and village taxes. It would have reverted to the original rate of two and one-half per cent; but it has been still further increased on account of the Russo-Japanese War.17

19

The principal products of the Japanese farms are rice, barley, wheat, millet, maize, beans, peas, potatoes (Irish and sweet), turnips, carrots, melons, eggplants, buckwheat, onions, beets, and a large white bitter radish (daikon). A very good average yield is fifty bushels to an acre. The entire annual production of rice varies each year, but averages about 46,000,000 koku;18 and the annual exportation of rice runs from about 8,000,000 yen to over 10,000,000 yen. The list of fruits19 and nuts grown in Japan includes pears, peaches, oranges, figs, persimmons, grapes, plums, loquats, apricots, strawberries, bananas, apples, peanuts, chestnuts, etc.

Among other important Japanese productions must be mentioned, of course, tea, tobacco, and mulberry trees. Of these the last is, perhaps, indigenous; but the other two are importations in their origin. The culture of tea is most extensively carried on in the middle and southern districts. The annual production is now about 7,000,000 kwan;20 the annual export trade is valued at over 10,000,000 yen. The price of tea runs from five cents to six dollars per pound, of which the last is raised at Uji, near Kyōto. The Japanese are a tea-drinking people; they use that beverage at meals and between meals, at all20 times and in all places. It is true that they drink it from a very small cup, which holds about two tablespoonfuls, but they drink, as we are told to pray, “without ceasing.” Hot water is kept ever ready for making tea, which is sipped every few minutes, and is always served, with cake or confectionery, to visitors.21

Tobacco was introduced into Japan by the Portuguese, but its use was at first strictly prohibited. The practice of smoking, however, rapidly spread until it became well-nigh a universal custom, not even restricted to the male sex. The Lilliputian pipe would seem to indicate that only a limited amount of the weed is used; but smoking, like tea-drinking, is practised “early and often.” The Japanese tobacco is said to be “remarkable for its mildness and dryness.”

The silk industry is the most important in relation to Japan’s foreign trade, and is on the increase. Silk is sent away to American and European markets chiefly in its raw state, but is also manufactured into handkerchiefs, etc. The exports of silk for the year 1910 amounted to about $90,000,000, or about two-fifths of the entire export trade. It would, of course, be beyond the limits of this chapter to enter into the description of the details of sericulture; it may be sufficient here to state that only the stolid patience of Orientals can well endure the slow, tedious, and painstaking process of feeding the silkworms.22

COTTON MILLS, ŌSAKA

21

Cotton-spinning is a comparatively new industry in Japan, but is growing rapidly. Cotton is, of course, the principal material for the clothing of the common people, who cannot afford silk robes. But Japan, though raising a great deal of cotton, cannot supply the demand, and imports large quantities from India and America. It is only within a short time that cotton-spinning by machinery has become a Japanese industry; formerly all the yarn was spun by hand; but in 1907 there were 136 cotton-mills in Japan. Some are very small concerns; but in Osaka, Nagoya, and Tōkyō there are comparatively large and flourishing mills. Ordinary workmen receive from 12 to 20 sen a day; skilled laborers make from 30 to 40 sen; girls earn from 10 to 20 sen, and children only a few sen per day; but the stockholders receive dividends of from 10 to 20 per cent per annum.

Since Japan acquired Formosa from China, she has had added to her resources another very important and valuable product, in which she possesses practically a monopoly of the world’s market and a supply supposed to be sufficient for the demands of the whole world for this entire century. It has been estimated, for instance, that the area of interior districts in which the camphor tree is found will reach over 1,500 miles. The camphor business of Japan in Formosa is in the hands of a British firm, to whom, as highest bidder, the government let out its monopoly for a fixed term of years.23

22

Perhaps the most generally useful product of Japan is the bamboo,24 which “finds a use in every size, at all ages, and for manifold purposes,” or, as Huish expresses it, “is used for everything.” Rein and Chamberlain each takes up a page or more for an incomplete list of articles made from bamboo; so that Piggott is surely right when he states that it is “an easier task to say what is not made of bamboo.”

Inasmuch as Japan is an insular country, with a long line of sea-coast, it is natural that fishing should be one of the principal occupations of the people, and that fish, seaweed, and other marine products should be common diet. From ancient times down to the opening of Japan, the fishing industry was a simple occupation, somewhat limited in its scope; but since the Japanese have learned from other nations to what extent marine industries are capable of development, fishing has become the source of many and varied lines of business. The canning industry, for instance, is of quite recent origin, but is growing rapidly. Whaling and sealing are very profitable occupations. Smelt-fishing by torchlight by means of tame cormorants was largely employed in olden times, and is kept up somewhat even to the present day. The occupation of a fisherman, though arduous and dangerous, is not entirely prosaic, and, in Japan, contributes to art. The return home of the fishing-smacks23 in the afternoon is an interesting sight; and the aspect of the sea, dotted with white sails, appeals so strongly to the æsthetic sense of the Japanese that it is included among the “eight views” of any locality.

Mining is also a flourishing industry in Japan, as the country is quite rich in mineral resources. Coal is so extensively found that it constitutes an item of export. Copper, antimony, sulphur, and silver are found in large quantities; gold, tin, iron, lead, salt, etc., in smaller quantities. Oil, too, has sprung up into an important product.25

Engineering, perhaps, deserves a paragraph by itself. This department in the Imperial University is flourishing, and sends forth annually a large number of good engineers. In civil engineering the Japanese have become so skilful that they have little need now of foreign experts except in the matter of general supervision.

It is worthy of special notice that the Japanese have become quite skilful in ship-building, so that they now construct vessels of various kinds, not only for themselves but for other nations. The Mitsu Bishi Company, Nagasaki, has constructed for the Oriental Steamship Company three fine passenger steamers of 13,000 tons each. At the Uraga Dockyard large American men-of-war have been satisfactorily repaired; and on October 15, 1902, a small United States gunboat was launched,—“the first24 instance in which Japan has got an order of shipbuilding from a Western country.”26

Among the minor miscellaneous industries which can only be mentioned are sugar-raising, paper-making (there are a number of mills which are paying well), dyeing, glass-blowing, lumber, horse-breeding, poultry, pisciculture, ice, brick, fan, match, button, handkerchief, pottery, lacquer, weaving, embroidery, sake and beer brewing, soy, etc. The extent and variety of the industries of Modern Japan are also clearly evidenced in a short article about “The Ōsaka Exhibition” of 1903 in the Appendix.

In what we style “the mechanical arts” the Japanese excel, and have a world-wide reputation. With their innate æsthetic instincts they make the most commonplace beautiful. It is a trite saying that a globe-trotter, picking up in a native shop a very pretty little article, and admiring it for its simplicity and exquisite taste, is likely to find it an ordinary household utensil. Japanese lacquer work is distinctive and remarkable for its beauty and strength; lacquered utensils, such as bowls, trays, etc., are not damaged by boiling soups, hot water, or even cigar ashes. In porcelain and pottery, the Japanese are celebrated for the artistic skill displayed in manufacture and ornamentation. “The bronze and inlaid metal work of Japan is highly esteemed.” Japanese swords, too, are remarkable weapons with “astonishing cleaving power.” To summarize this25 paragraph, it may be said that the Japanese have turned what we call mechanical industries into fine arts, which display a magnificent triumph of æstheticism even in little things.27

This chapter would be incomplete without a paragraph concerning Japanese shops, or retail stores, which are among the first curiosities to attract and rivet a foreigner’s attention. The building is, perhaps, a small, low, frame structure, crowded among its fellows on a narrow lane. The floor is raised a foot or so above the ground, and is covered, as usual, with thick matting. Spread out on the floor or on wooden tiers or on shelves are the goods for sale. The shopkeeper sits on his feet on the floor, and calmly smokes his pipelet, or fans himself, or in winter warms his hands over the hibachi (fire-bowl). He greets you with a profound bow and most respectful words of welcome, but makes no attempt to effect a sale, or even to show an article unless you ask to see it. He is imperturbably indifferent whether or not you make a purchase; either way, it is all right. He will politely display anything you want to see; and, even if, after making him much trouble, you buy nothing or only an insignificant and cheap article, he sends you away with as profound a bow and as polite expressions as if you had bought out the shop. Whether you buy little or much or even nothing, you are always dismissed with “Arigatō gozaimasu” and “Mata irasshai,” which are very respectful26 phrases for “Thank you” and “Come again.” Having dropped into “a veritable shoppers’ paradise,” you will quickly “find yourself the prey of an acute case of shopping fever before you know it!” It is, indeed, true, to quote further from this same writer, that “to stroll down the Broadway [known as the Ginza] of Tokio of an evening is a liberal education in every-day art.”28

From what has already been written, it is easily noticeable that wages and incomes, like so many things in petite Japan, are insignificant. It may be added that ordinary mechanics earn on an average over 50 sen a day, and the most skilful seldom get more than double that amount; that carpenters earn from 70 to 100 sen a day; that street-car drivers and conductors receive 12 or 15 yen per month, and other workmen of the common people about the same. Even an official who receives 1,000 yen per year is considered to have a snug income. It will be inferred from this that the cost of living is proportionately cheaper, whether for provisions or for shelter or for clothes, and that the wants, the absolute necessities, of the people are few and simple. Literally true it is, that a Japanese man “wants but little here below, nor wants that little long.” With rice, barley, sweet potatoes, other vegetables, fish, eggs, tea, and even sweetmeats in abundance and very cheap, a Japanese can subsist on little and be contented and happy with enough, or even less than that. But,27 unfortunately, the new civilization of the West has carried into Japan the itch for gold and the desire for more numerous and more expensive luxuries, and has increased the cost of living without increasing proportionately the amount of income or wages.29

Industrial Japan has already become more or less modified by features of Occidental industrialism, such as guilds, trade unions, strikes, co-operative stores. It is true that feudal Japan also had guilds, which are, however, now run rather on modern lines. One of the oldest, strongest, and most compact is that of the dock coolies, who without many written rules are yet so well organized that they have almost an absolute monopoly, with frequent strikes, which are always successful. Others of the guilds are those of the sawyers, the plasterers, the stonemasons, the bricklayers, the carpenters, the barbers, the coolies (who can travel all over the empire without a penny and live on their fellows), the wrestlers, the actors, the gamblers, the pickpockets, etc. The beggars’ guild is now defunct. The labor unions of modern days include the iron-workers, the ship-carpenters, the railway engineers, the railway workmen, the printers, and the European-style cooks. The last-mentioned is one in which foreigners resident in Japan necessarily take a practical interest! The only unions which have become absolute masters of the situation are those of the dock coolies, the railway laborers, and the railway engineers. As for28 co-operative stores, there are a dozen or more in Tōkyō, Yokohama, and Northern Japan.

The perfect organization of these modern unions is due largely to the efforts of a young man named Sen Katayama, who is the champion of the rights of the laboring man in Japan. He spent ten years in America and made a special study of social problems. He is the head of Kingsley Hall, a social settlement of varied activity in the heart of Tōkyō, and editor of the “Labor World,” the organ of the working classes. That the changes rapidly taking place in the industrial life of Japan will raise up serious problems, there is no doubt; what phases they will assume cannot be foreseen. But “socialistic” ideas are carefully repressed in modern Japan.

“Japan and its Trade” and “Advance Japan” (Morris); “The Yankees of the East” (Curtis); “Japan in Transition” (Ransome), chap. x.; “The Awakening of the East” (Leroy-Beaulieu), chaps. iv. and v.; “Dai Nippon” (Dyer), chaps. viii. and xi.; and especially Rein’s “Industries of Japan,” in which the subject is treated in great detail with German thoroughness. But to keep pace with the rapid progress along industrial and commercial lines, one really needs current English newspapers and magazines, such as are mentioned in the chapter on “Language and Literature.” The reports of the British and United States consular officials are also very useful in this respect.

“The Japan Year Book,” issued annually, is a veritable cyclopedia of important facts and figures.

29

Outline of Topics: Travelling in Old Japan; vehicles of Old and New Japan; jinrikisha; railway travel; telegraph and telephone; street-car, bicycle, and automobile; steamships.—Postal system.—Oil, gas, and electric light.—Foreign commerce; variety of imports.—Mixed corporations.—Stock and other exchanges.—Banking system; coinage; monetary standard.—Baron Shibusawa on business ability of Japanese, prospects of industrial and commercial Japan, and financial situation.—Bibliography.

ONE of the most common and most important indications of a great change in the life and civilization of Japan is to be seen in the improved modes of travel and transportation. The ancient method, though in some sections pack-horses and oxen were used, was essentially pedestrian. The common people travelled on foot, and carried or dragged over the road their own baggage or freight. Couriers, carrying the most important despatches, relied upon fleetness of foot. The higher classes and wealthy people, even though not themselves making any exertions in their own behalf, were carried about in vehicles by coolies, who, with their human burdens, tramped from place to place. On water, too, travel and transportation depended mostly upon human muscular exertion, as all boats, small or large, had to be propelled by oars or poles, except when favored with a30 breeze to swell the sails and allow the boatmen a respite from their toil. But all this hard labor developed, of course, a strength of limb and a power of endurance that even in recent years have enabled the Japanese soldiers to march and fight in either the piercing cold and deep snow of Manchuria or the blistering heat of Formosa. A life of constant outdoor exposure to wind, rain, cold, or heat has toughened and browned the skin, and made an altogether hardy race out of the common people; while the lack of this regular exercise and calisthenic training has left its mark in the comparatively weak constitutions of those who travelled, not on their own feet, but on the shoulders of others.

The common vehicles of the olden days were ordinary carts for freight and norimono and kago for passengers. The norimono is a good-sized sedan-chair or palanquin, in which the rider can sit in a fairly comfortable position. The kago is a sort of basket in which the traveller takes a half-sitting, half-reclining posture, not altogether comfortable—at least for tall foreigners. At present the norimono is seldom if ever employed except for corpses or invalids, but the kago is still used in mountainous regions, where nothing else is available. It must be understood, of course, that the nobles and their retainers often rode on horseback; but the great mass of the people walked and the few rode in kago or norimono.

Now, however, modes of travel have changed greatly, and are changing year by year. There are still many pedestrians; the kago is yet to be seen;31 boats are propelled by stern-end oar or laboriously pushed along with poles; and pack-horses and oxen—even in the streets of Tōkyō—are in frequent use. But there are many other means of communication and transportation. There have come into use the horse-car, the stage, the jinrikisha, the railroad, with the telegraph and the telephone; the modern row-boat, the steamboat; the bicycle, the automobile, and the electric railway, with the electric light to show the road by night. An excellent postal system and various other modern contrivances for facilitating the means of communication have been adopted.

The most common mode of conveyance at present, in all possible localities, is the jin-riki-sha (man-power-carriage), or “Pull-man car,” as it has been wittily called. This is a two-wheeled “small gig,” or large baby-carriage, pulled by one or more men. A ride in a jinrikisha, after one has become accustomed to human labor in that capacity, is really comfortable and delightful. The coolies who pull these vehicles develop swiftness and endurance, but are comparatively short-lived. There is also a two-wheeled freight cart manipulated in the same fashion. It has been estimated that in the Empire there are almost 1,350,000 hand-carts, about 185,000 jinrikishas, about 28,000 ox-carts, more than 66,000 other freight carts, and almost 100,000 carriages and wagons. The business of transportation thus furnishes occupation to thousands of people, but gives to each engaged therein only a scanty remuneration,32 which is often insufficient for the support of life, after the tax has been paid. The fee for a jinrikisha ride averages about 12 or 15 sen per ri (2½ miles), or varies from 20 to 30 sen per hour. If a coolie makes 50 sen in one day, he is fortunate, and is lucky to average 25 or 30 sen per day; for some days he may be wearily waiting and watching from dawn to the dead of night without receiving scarcely a copper. Hard, indeed, is their lot; and their death rate is rather high.30

But even the jinrikisha will eventually be supplanted for long journeys wherever a railroad goes. There are now in Japan over 6,000 miles of railway, and in Korea and South Manchuria there are 641 and 706 miles more. There is one continuous line of railroad from Aomori in the extreme north to Shimonoseki in the extreme south of the main island, and then, after crossing the Straits of Shimonoseki, there is another unbroken line from Moji to Nagasaki and Kagoshima or Kumamoto. In the island of Yezo (Hokkaidō) is a short line built by American engineers after American models; but all other railroads in33 Japan were built and are operated according to the British methods. The rate of fare is 1 sen per mile for third class, 2 sen for second class, and 3 sen for first class, and the rate of speed rarely exceeds 20 or 25 miles per hour; but fortunately the people are not in such a hurry as Americans. Recently, however, express trains, running at the rate of 30 or more miles per hour, have been started on several of the roads, especially between large and important places. Dining-cars and sleeping-cars, too, may be found on some of the lines; and the American check system is used for baggage. The government owns most of the railways; in 1906, the Twenty-second Diet adopted a bill for buying up the seventeen largest private lines. This may have been desirable from a strategic point of view; but from the business standpoint it was not advisable, for the government lines are not so well managed. The best line in the country was a private one, the Sanyō Railway Company, operating west from Kōbe.31

Railroads have been naturally accompanied, and often preceded, by telegraph lines, which now keep the various parts of the empire in close communication with Tōkyō and with each other. During 1910 the telegrams numbered over 28,000,000, and are increasing rapidly in number every year. The Japanese syllabary has lent itself easily to a code like the Morse Code.32 Telephones, too, have been34 introduced and are growing in favor so rapidly that the government cannot keep up with the petitions for installation. According to the latest reports, there were over 100,000 telephones in all Japan. There are many public slot telephones, which can be used for a few minutes for 5 sen.

Horse-cars are largely used in cities, but are being gradually supplanted by electric cars. The bus in the city and the stage in the country are in common use, but cannot be recommended for comfort. Bicycles are very popular, and are cheaply manufactured in Japan; even Japanese women have begun to ride, while young men are very skilful as trick riders and rapid as “scorchers.” Automobiles also are coming into a limited use.

In a country where formerly no ships large enough to make long voyages were allowed to be made, steamship companies are now flourishing. The Ōsaka Shōsen Kwaisha (Osaka Merchant Marine Company) is a very large and prosperous corporation, whose business is chiefly coasting trade, but which also runs to Formosa, the Ryūkyū Islands, the Bonin Islands, Korea, China, and America. The largest steamship company in Japan, and one of the largest in the world, is the Nippon Yūsen Kwaisha (Japan Mail Steamship Company). It has a fleet of 88 vessels with 300,000 tons; and maintains not only a frequent coasting service, but also several foreign lines, to Siberia, Korea, China, India, Australia, Europe, and America. This is the line which runs35 fortnightly from Seattle to Hongkong with excellent passenger accommodations. The Tōyō Kisen Kwaisha (Oriental Steamship Company) is a Japanese organization with three fine vessels running about once a month from San Francisco to Hawaii, Japan, China, and Manila. The word Maru33 in such combinations as “America Maru” or “Kaga Maru” is a special suffix always attached to the name of a ship.

In Old Japan there was no official postal system, and letters were despatched by private messengers and relays of couriers. When Japan was opened to the world, some of the foreign nations represented there maintained special post-offices of their own, but these were gradually abandoned. It was in 1872 that the modern postal system of Japan was organized on American models; and it was only five years later when Japan was admitted to the International Postal Union. The twenty-fifth anniversary of this event was celebrated with great éclat in Tōkyō in 1902. The Japanese postal system has been gradually improved during its quarter-century of existence, so that in some respects it excels its model, the United States postal system, and is really one of the most efficient in the world. It includes registration, money orders, parcel post, reply postal cards, postal savings,34 and universal free delivery. Letter postage is 3 sen within the empire and 10 sen to all countries of the International Postal Union; postal cards are 1½ and 4 sen respectively.36 We also beg leave to remind Americans that letter postage to Japan is not 2 cents, but 5 cents, per ounce.

Oil is most extensively used for lighting purposes; but gas and electricity are also employed, and bring good dividends to companies furnishing such illumination. A very large amount of oil has been annually imported from the United States and Russia; but as rich fields have been found in Northern Japan,35 the Standard Oil Company is also interested in a Japanese corporation, the International Oil Company, organized to work Japanese fields. Foreign capital has also been invested in the Ōsaka Gas Company, and is sought by the Tōkyō Gas Company, as well as by several electric and steam railway companies. The first buildings erected for the Imperial Diet were supplied with electric lights, but caught fire in some way, and were totally destroyed. This calamity was laid at the door of a flaw in the electric lighting apparatus, and so frightened the Emperor that he decided not to use the electric lights in the palace; but if my memory serves me rightly, after one or two nights of imperfect and unsatisfactory lighting, he resorted once more to electricity.

The foreign trade of Japan had increased from $13,123,272 in 1868 to $265,017,161 in 1902,—twenty-fold in a third of a century.36 Of recent years the imports have been larger than the exports; in37 1898 they were more than $55,000,000 in excess; in 1900, almost $41,500,000 in excess; but in 1901 the difference was only about $1,750,000. The chief articles of export are silk (either raw, or partly or wholly manufactured), cotton yarn and goods, matches, coal, high-grade rice, copper, camphor, tea, matting, straw braid, and porcelain. The principal imports are raw cotton, shirting and printed cotton, mousseline, wool, cotton velvet, satin, cheap rice, flour, sugar, petroleum, oil cake, peas and beans, machinery, iron and steel (including nails and rails), steamers, locomotives, and railway carriages. The exports are sent chiefly to the United States, Great Britain and colonies (especially Hongkong), China, and France; while the imports come mostly from Great Britain and colonies (especially England, India, and Hongkong), the United States, Germany, France and colonies, and China.

The variety in the geographical distribution of the imports of Japan may be faintly illustrated by the following partial list of supplies taken by an American family from Tōkyō to the summer resort of Hakone: soap from England and America, cocoa from England, butter from California, cornstarch from Buffalo, N. Y., Swiss milk, Holland candles, pickles from England, Scotch oatmeal, American rolled oats and cracked wheat, flour from Spokane Falls, Washington, canned goods from San Francisco, Kansas City, Chicago, and Omaha, and evaporated cream from Illinois.

The first mixed corporation, composed of Japanese38 and foreigners, to be licensed under the new Commercial Codes after the new treaties went into effect in 1899, was the Nippon Electric Company, in which a large electric company of Chicago is specially interested.

Japan has several stock exchanges and chambers of commerce in various localities, and these are all under the strictest supervision and close restrictions.

It was in 1872 that National Bank Regulations were first issued, and a few banks were established; but in 1876 it was found necessary to make radical amendments in those regulations in the way of affording greater facilities for the organization of banks. The result was that by 1879 there were 153 national banks in the country; and in 1886 the further organization of national banks was stopped. In the mean time the Yokohama Specie Bank had been organized (in 1880) for the support of the foreign trade; and (in 1882) the Bank of Japan (Nippon Ginkō) had been organized to “secure proper regulations of the currency.” In 1897 the Industrial Bank, and later provincial agricultural-industrial banks were organized to give special banking facilities to local agricultural and industrial circles. The Bank of Formosa, the Colonial Bank of Hokkaidō, and a Credit Mobilier complete the list of official institutions. By 1899 all the national banks had either been changed into private banks or had gone out of existence. Private banks number almost 1,700, of which the Mitsui, the Mitsubishi, the Hundredth, the Sumitomo, the Fifteenth (Nobles’), the First, and the Yasuda are the strongest. Savings-banks39 are also quite numerous (652), and are helping to develop habits of thrift and economy among the common people.37

FIRST BANK, TŌKYŌ

The first Japanese mint was established at Ōsaka in 1871, and has been actively at work ever since; and there is an institution in Tōkyō for the manufacture of paper money. The coins now chiefly used the copper, nickel, silver, and gold; but in the country districts it is still possible to find brass coins of less than mill values. The copper pieces are ½ sen (5 rin), 1 sen, and 2 sen; the 5 sen piece is the only nickel coin; the silver pieces are 5 sen, 10 sen, 20 sen, and 50 sen; and the gold coins are 5 yen, 10 yen, and 20 yen. There are also paper notes of 1 yen and upward: these are issued only by the Bank of Japan, and amounted in 1910 to over 400,000,000 yen.

In 1897 Japan adopted the gold standard, so that exchange fluctuations with the Occident are slight, and the Japanese currency has a fixed value, at the rate of about 50 cents for the yen.38

Concerning the prospects of industrial and commercial Japan, it may be well to note the views39 of Baron Shibusawa, one of the foremost of Japanese merchants and financiers. In referring to the capacity of the Japanese for business, the Baron says:—

“There are, however, four peculiarities in the Japanese character which make it hard for the people to achieve40 business success. These are: Firstly, impulsiveness, which causes them to be enthusiastic during successful business and progressive even to rashness when filled with enthusiasm; secondly, lack of patience, which causes easy discouragement when business is not so successful; thirdly, disinclination for union; and fourthly, they do not honor credit as they should, which is so important a factor in financial success. These four peculiarities are to be met with in Japanese business men in a more or less marked degree.

“Although Japan, as a country, is old, yet her commercial and industrial career being new, there are necessarily many points of incompleteness. For example, although we have many railways, yet there is no close connection made between the railway station and the harbor. Again, although we have railways, yet we have no appropriate cars, etc. To complete such work and to open up the resources of the country, and to allow Japan to benefit from them, we need more capital. The capital we have in the country is not enough. So what is now wanted in Japan is foreign capital. A great proportion of the Japanese people, however, are opposed to the idea of sharing any profits equally with any other nation. Their exclusiveness in this respect is a distinct relic of the old era. They ignore altogether the fact that, with the assistance of foreign capital, the profits would be quadrupled. The very idea of sharing with an outside power is distasteful to them. For instance, I have been endeavoring for many years by word and deed to obtain a revision of the laws relative to the ownership of land in Japan by foreigners. I may say that Marquis Itō and other public men are of my opinion in the matter. Because, however, of this exclusive element in Japan, it has still been found impossible to allow foreigners to own Japanese land. Until this change is41 made, foreign investors will naturally feel that there is little safety for their investments.

“I am also anxious to introduce the idea of a system of trusteeship in order to encourage foreign nations to invest their money in Japanese enterprises. There are very many uncompleted works in Japan, which need outside money to finish them and which would return good profits. I feel assured that it would be possible for prominent Japanese bankers and capitalists to make themselves personally responsible for the money of the foreign investor. By such a system the security of the investment would be much increased, and the foreign investor would have the assurance that his money was safe, even if the business in which it had been invested may have ceased to exist. The entire loss caused by the failure of Japanese business enterprises would thus be borne by the Japanese.

“The day will come when Japan will compete with the powers already in the field on all lines of manufactured goods, but this time must necessarily be far distant. The trouble at present is that, while the Japanese can imitate everything, they cannot, at the same time, invent superior things. But the trade of the Oriental countries will come to be regarded as Japan’s natural share, and she is already well capable of supplying it.

“The resources of Japan are very varied and very fair in quantity at present. Raw silk and tea are abundant, while coal is plentiful, as also copper and silver; gold is not so much so. I hope to see our plentiful water supply turned into good account and harnessed to produce electric energy. This would be a great saving of expense and would cheapen the cost of production very much. Oil has been found in several districts and will take the place of coal to a large extent, and it is possible that if fully developed its export trade may be made to42 the neighboring countries. In Hokkaidō we have rich coal and silver mines and oil wells, while in Formosa we have rich gold mines. The iron we use in our iron works in Kiūshiu comes partly from several mines of Japan and partly from China.

“My hope for the future is that foreign capital may be brought into the country and that the economic position of the country may be made so secure as to leave no doubt possible in the mind of the world as to the stability of the Japanese Empire.”

We also take pleasure in quoting the same high authority upon the subject of the present financial situation in Japan, as follows:40—

“The present financial difficulty in Japan is only the natural sequence of the over-expansion of business of some years ago. In every country there are waves of prosperity followed by periods of depression. I have known, in the economic history of Japan since the Restoration, five or six such waves. They do not necessarily injure the real financial standing of the country. The peculiarities of the Japanese business character have much to answer for in the way of increasing the appearance of financial insecurity during the times of depression. After the prosperous times of 1893 came the war with China and the subsequent indemnity. Much of the money paid by China was spent in Japan, and the Japanese people came to the conclusion that this increased circulation of money would be permanent. They acted impulsively in many enterprises, and rushed into all kinds of business because the government had over-expanded its enterprises after the war. The depression reached its height in 1900 and 1901, and businesses were abandoned or reduced because it was not such easy work as formerly. By proper management our national income can be made still greater than our expenditure.”

BARON SHIBUSAWA

43

The national debt of Japan January, 1913, was more than 2,500,000,000 yen ($1,250,000,000), of which almost 1,500,000,000 yen ($750,000,000) was in foreign loans.

For interesting accounts of travel when and where modern conveniences were not available, read “Unbeaten Tracks in Japan” (Bird); “The Mikado’s Empire” (Griffis); “Noto, an Unexplored Corner of Japan” (Lowell); “Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan” (Hearn); and papers in the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. For similarly interesting accounts of travel with modern conveniences read “Jinrikisha Days in Japan” (Scidmore); “Japan and her People” (Hartshorne); “The Yankees of the East” (Curtis); “Japan To-day” (Scherer); “Every Day Japan” (Lloyd).

On the industrial and commercial phases of these topics, consult books, papers, magazines, and pamphlets mentioned in the bibliography of the preceding chapter; especially, for the latest statistics, “The Japan Year Book.”

44

Outline of Topics: Ainu; ethnology; two types; comparative stature and weight; intellectual and moral qualities.—Classes in society of old and new régimes; social principle.—Family and empire.—Houses; public buildings; rooms; foreign architecture.—Gardens.—Food; meals; table manners; foreign cooking.—Undress and dress; European costume.—Bathing.—Bibliography.

WHO were the aborigines of Japan is yet a disputed question. Remains have been found of a race of dwarfs who dwelt in caves and pits, but who these people were is not positively known. They may have been contemporary with the Ainu, whom many call “the aborigines of Japan.” It is certain, however, that the Ainu were once a very numerous nation, “the members of which formerly extended all over Japan, and were in Japan long before the present race of Japanese.” But the latter gradually forced the former northward, until a final refuge was found in Yezo and the Kurile Islands. There the Ainu are now living, but are slowly dying out as a race; there are at present only about 17,000 remaining. They are said to be “the hairiest race in the whole world,” “of sturdy build,” filthy in their habits (bathing is unknown), addicted45 to drunkenness, and yet “of a mild and amiable disposition.” Their religion is nature-worship.41

It is well known that the Japanese are classed under the Mongolian (or Yellow) Race. They themselves boastfully assert that they belong to the “golden race,” and are superior to Caucasians, who belong to the “silver race”! As Mongolians, they are marked, not only by a yellowish hue, of many shades from the darkest to the lightest, but also by straight black hair (rather coarse), scanty beard, rather broad and prominent cheek-bones, and eyes more or less oblique. Some think that the Japanese people show strong evidences of Malay origin,42 and claim that the present Emperor, for instance, 46 is of a striking Malay type. It is not impossible, nor even improbable, that Malays were borne on the “Japan Current” northward from their tropical abodes to the Japanese islands; but there is no historical record of such a movement. Therefore the best authorities, like Rein and Baelz, do not acknowledge more than slight traces of Malay influence. A more recent theory concerning the origin of the real Japanese—or Yamato men, as they called themselves—is that they are descendants of the Hittites, whose capital was Hamath, or Yamath, or Yamato!

There are two distinct types of Japanese: the oval-faced, narrow-eyed, small aristocratic class; and the pudding-faced, full-eyed, flat-nosed, stout common people. Of these, the latter is the one claimed to be Malay. The plebeians, having always been accustomed to hard labor by the sweat of the brow, are comparatively strong; the others, having been developed by centuries of an inactive life, have inherited weak constitutions. Indeed, the people, as a whole, are subject to early maturity and early decay. There is a Japanese proverb to this effect: “At ten, a god-like child; at twenty, a clever man; from twenty-five on, an ordinary man.” And, in spite of the fact that there have been remarkable exceptions to this rule, careful investigation by Japanese supports the truth of the proverb. And yet there seems to be no 47 doubt that modern education and conditions of life show a gradual improvement in this respect.

GROUP OF COUNTRY PEOPLE

The average Japanese, compared with the average European or American, has a lower stature43 with a long body and short legs. A good authority states that “the average stature of Japanese men is about the same as the average stature of European women”; and that “the [Japanese] women are proportionately smaller.” Some one has wittily called the Japanese “the diamond edition of humanity.”

The Japanese also weigh much less than Europeans. The average weight of young men of twenty years of age in Europe is about 144 pounds, while the average weight of the strongest young men of the suburban districts of Tōkyō was only about 121 pounds; which gives the European an advantage of 23 pounds.

The Japanese are very quick to learn. Their minds are strong in observation, perception, and memory, and weak in logic and abstraction. As born lovers of nature, they have well-trained powers of observation and perception, so that their minds turn readily to scientific pursuits. And as the ancient Japanese system of education followed Chinese models, the power of memorizing by rote has been strongly developed, so that the Japanese mind has little difficulty in becoming a storehouse of historical and other facts. But, as the powers of reasoning and abstraction have not been well trained, the48 Japanese do not take so readily to mathematical problems and metaphysical theorems.

The typical Japanese is loyal, filial, respectful, obedient, faithful, kind, gentle, courteous, unselfish, generous.44 His besetting sins are deception, intemperance, debauchery,—and these are common sins of humanity. In respect to these evils, he is unmoral rather than immoral; and in his case these sins should not be considered so heinous as in the case of one who has been taught and knows better.45 And it is with reference to these very evils that Shintō, Buddhism, and Confucianism have been a complete failure in Japan, and that Christianity is making its impress upon the nation.