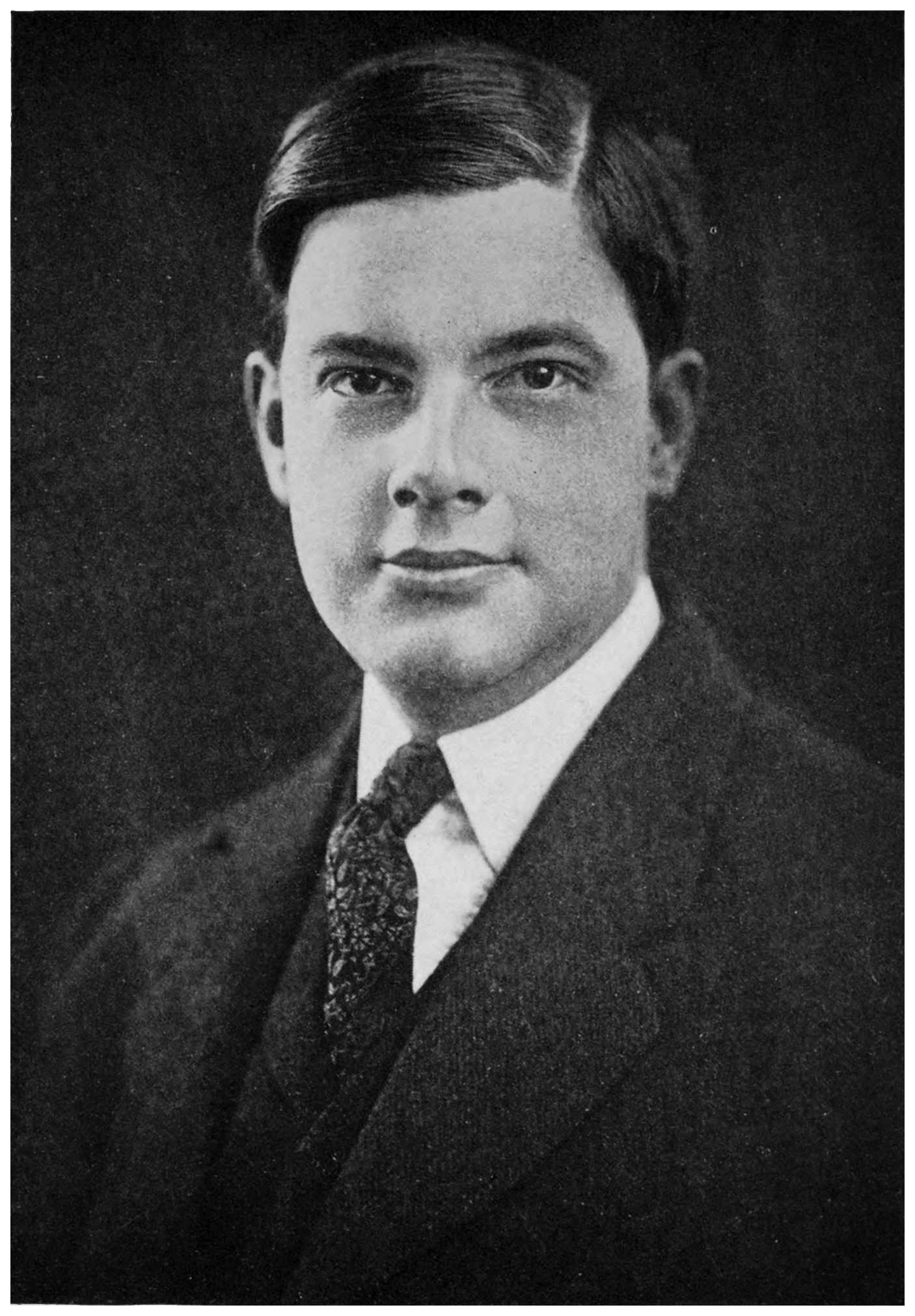

© Underwood and Underwood

JOYCE KILMER, AGE 30

LAST CIVILIAN PORTRAIT

Title: Joyce Kilmer

poems, essays and letters in two volumes. Volume 1, memoirs and poems

Author: Joyce Kilmer

Editor: Robert Cortes Holliday

Release date: June 20, 2021 [eBook #65652]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Tim Lindell, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of the illustrations usually may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Cover created by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain.

© Underwood and Underwood

JOYCE KILMER, AGE 30

LAST CIVILIAN PORTRAIT

JOYCE KILMER

EDITED WITH A MEMOIR

BY ROBERT CORTES HOLLIDAY

VOLUME ONE

MEMOIR AND POEMS

NEW YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

Copyright, 1914, 1917, 1918

By George H. Doran Company

Printed in the United States of America

TO THE MEMORY OF

JOYCE KILMER

vii

Many persons have contributed exceedingly valuable service to the preparation of these volumes. Credit has been gratefully acknowledged, wherever feasible, in the course of the text. To make anything like a full record, however, of the names of that remarkable society, the ardent and devoted friends of Joyce Kilmer, would require a chapter. Though particular reference should be made in this place to the invaluable assistance of: Kilmer’s life-long friend and lawyer, Louis Bevier, Jr.; his especial friend, Thomas Walsh; and his office associate, John Bunker.

Permission has been most cordially granted by the editors of the following magazines for the reprinting of the poems from France: Scribner’s Magazine, Good Housekeeping, The Saturday Evening Post, America, and The Bookman. Essays and miscellaneous pieces have been gathered, with the warm approval of the editors of these publications, from these sources: The Bookman, The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Bellman, The Catholic World, Poetry: A Magazine of Verse,viii he Smart Set, Munsey’s Magazine and Puck—a curiously assorted company, highly expressive of the catholicity of the mind these pages reflect.

The article on Hilaire Belloc, originally one of Kilmer’s lectures, was first printed in the American edition of Belloc’s “Verses.” The early poems have been chosen from Kilmer’s first book, “A Summer of Love,” now out of print, rights to which are held by Mrs. Aline Kilmer. Poems not otherwise credited have been reprinted from the volumes already published by George H. Doran Company.

R. C. H.

New York, 1918.

ix

| PAGE | |

| Memoir | 17 |

| POEMS FROM FRANCE | |

| Rouge Bouquet | 105 |

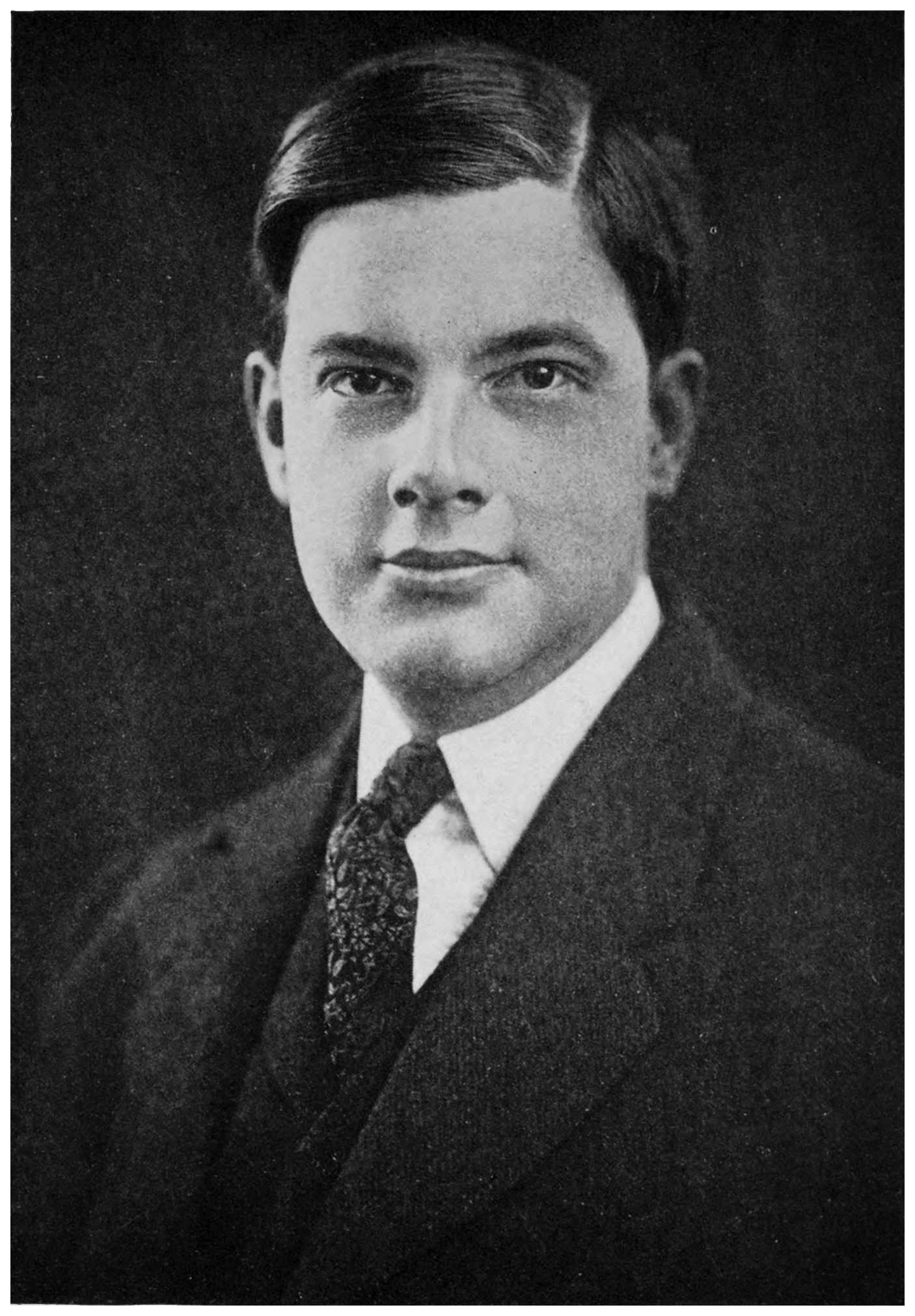

| The Peacemaker | 108 |

| Prayer of a Soldier in France | 109 |

| When the Sixty-ninth Comes Back | 110 |

| Mirage du Cantonment | 113 |

| POEMS AT HOME | |

| Wartime Christmas | 117 |

| Main Street | 118 |

| Roofs | 120 |

| The Snowman in the Yard | 122 |

| A Blue Valentine | 124 |

| Houses | 127 |

| In Memory | 128 |

| Apology | 131 |

| The Proud Poet | 133 |

| Lionel Johnson | 137 |

| Father Gerard Hopkins, S.J. | 138 |

| Gates and Doors | 139 |

| The Robe of Christ | 142 |

| The Singing Girl | 145 |

| The Annunciation | 146 |

| Roses | 147 |

| The Visitation | 149 |

| Multiplication | 150 |

| Thanksgiving | 152 |

| The Thorn | 153x |

| The Big Top | 154 |

| Mid-ocean in War-time | 157 |

| Queen Elizabeth Speaks | 158 |

| In Memory of Rupert Brooke | 159 |

| The New School | 160 |

| Easter Week | 163 |

| The Cathedral of Rheims | 165 |

| Kings | 169 |

| The White Ships and the Red | 170 |

| The Twelve-Forty-Five | 174 |

| Pennies | 178 |

| Trees | 180 |

| Stars | 181 |

| Old Poets | 183 |

| Delicatessen | 185 |

| Servant Girl and Grocer’s Boy | 190 |

| Wealth | 192 |

| Martin | 193 |

| The Apartment House | 194 |

| As Winds That Blow Against a Star | 196 |

| St. Laurence | 197 |

| To a Young Poet Who Killed Himself | 198 |

| Memorial Day | 200 |

| The Rosary | 201 |

| Vision | 202 |

| To Certain Poets | 203 |

| Love’s Lantern | 205 |

| St. Alexis | 206 |

| Folly | 208 |

| Madness | 210 |

| Poets | 211 |

| Citizen of the World | 212xi |

| To a Blackbird and His Mate Who Died in the Spring | 213 |

| The Fourth Shepherd | 215 |

| Easter | 218 |

| Mount Houvenkopf | 219 |

| The House with Nobody in It | 220 |

| Dave Lilly | 223 |

| Alarm Clocks | 226 |

| Waverley | 227 |

| EARLY POEMS | |

| In a Book-shop | 231 |

| Slender Your Hands | 232 |

| Sleep Song | 233 |

| White Bird of Love | 234 |

| Transfiguration | 236 |

| Ballade of My Lady’s Beauty | 237 |

| For a Birthday | 239 |

| Wayfarers | 242 |

| Princess Ballade | 244 |

| Lullaby for a Baby Fairy | 246 |

| A Dead Poet | 248 |

| The Mad Fiddler | 249 |

| The Grass in Madison Square | 251 |

| Said the Rose | 252 |

| Metamorphosis | 254 |

| For a Child | 255 |

| The Clouded Sun (To A. S.) | 256 |

| The Poet’s Epitaph | 259 |

| Beauty’s Hair | 260 |

| The Way of Love | 262 |

| Chevely Crossing | 267 |

| The Other Lover | 270 |

xiii

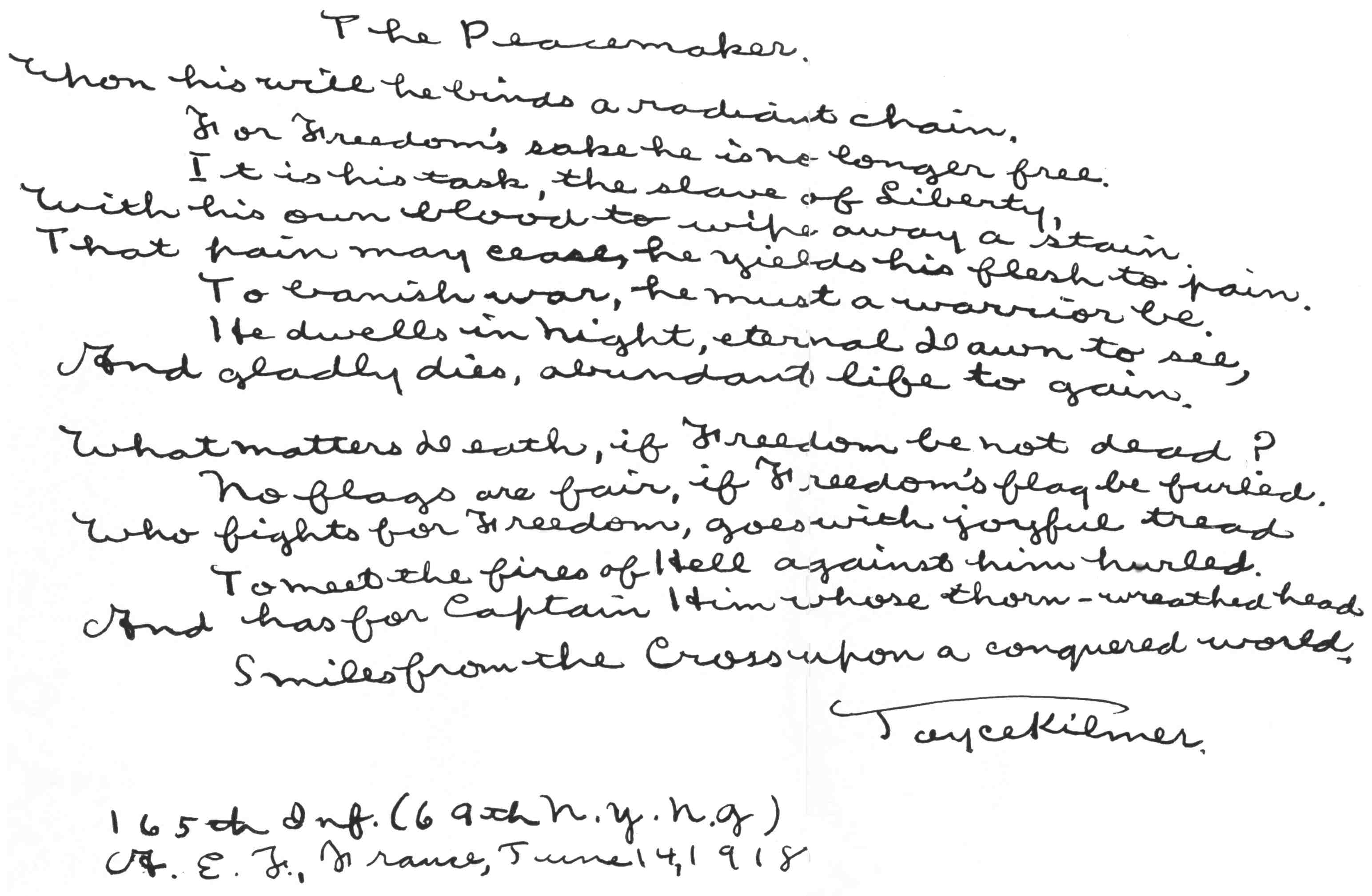

| Joyce Kilmer, Age 30 | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Fac-simile of autograph manuscript of “The Peacemaker” | 108 |

| Joyce Kilmer, Age 21 | 240 |

17

It is the felicity of these pages that they cannot be dull. It is their merit, peculiar in such a memoir, that they cannot be sad. It is their novelty that they can be restricted in appeal only by the varieties of the human species. It is their good fortune that they can be extraordinarily frank. It is their virtue that they cannot fail to do unmeasurable good. And it is their luck to abide many days.

With their subject how could it be otherwise? They make not a wreath, but a chronicle, and in their assembled facts tell a bright chapter in the history of our time. If there is one word which more than any other should be linked with the name of this gallant figure now claimed (and rightly) by so many elements of the nation, that word certainly is “American.” A character and a career so racy, typical of all that everybody likes to believe that at our best we are, can hardly be matched, I think, outside of stories.

Joyce Kilmer was reported in the papers as having said, just before he sailed for France, that he was “half Irish,” and that was why he belonged with18 the boys of the Sixty-ninth. His birth was not exactly eloquent of this fact. Though, indeed, he was, as will appear, a much more ardent Irishman than many an Irishman born—that is, in the sense of keenly savouring those things which are fine in the Irish character, and with characteristic gusto feeling within himself an affinity with them. Later, in a letter from France to his wife, he was more explicit on this point:

As to the matter of my own blood (you mentioned this in a previous letter) I did indeed tell a good friend of mine who edits the book-review page of a Chicago paper that I was “half Irish.” But I have never been a mathematician. The point I wished to make was that a large percentage—which I have a perfect right to call half—of my ancestry was Irish. For proof of this, you have only to refer to the volumes containing the histories of my mother’s and my father’s families. Of course I am American, but one cannot be pure American in blood unless one is an Indian. And I have the good fortune to be able to claim, largely because of the wise matrimonial selections of my progenitors on both sides, Irish blood. And don’t let anyone publish a statement contrary to this.

He also, in a letter from France, quoted with much relish the remark of Father Francis P. Duffy19 that he was “half German and half human.” English and Scotch strains made up another half or three quarters. The English goes straight back to one Thomas Kilburne, church warden at Wooddilton, near Newmarket, in Cambridgeshire, who came to Connecticut in 1638. The “e” was lost apparently in Massachusetts, and the word became, as in his mother’s maiden name, Kilburn.

Soldier blood, too, flowed in his veins—though it is likely that this fact for the first time occurred to him, if at all, when his nature rose white-hot to arms. He was, so to say, a Colonial Dame on both sides, as members of both his father’s and his mother’s family fought in the American Revolution; and members of his father’s family in the French and Indian wars.

Alfred Joyce Kilmer (as he was christened) was born at New Brunswick, New Jersey, December 6, 1886, son of Annie Kilburn and Frederick Kilmer. Though he seems always to have been, in familiar address and allusion, called Joyce, the Alfred did not disappear from his address and signature until he began, as more or less of a professional writer, to publish his work, when it went the way of the Newton in Mr. Tarkington’s name, and the Enoch in Mr. Bennett’s. Then “Joyce Kilmer” acquired a20 fine humorous disdain for what he regarded as the florid note in literary signatures of three words (or, worse still to his mind, the A. Joyce kind of thing); and he enjoyed handing down, with much relish of the final and judicial character of his utterance, the opinion that the proper sort of a trademark, so to say, for success in letters was something short, pointed, easy to say and to remember, such as Rudyard Kipling, Mark Twain, O. Henry, Joseph Conrad, and so on through illustrations carried, at length, to intentionally infuriating numbers.

As a small boy, Kilmer is described by those who knew him then as the “funniest” small boy they ever saw, by which is meant, apparently, that he was an odd spectacle. And this, of course, is so altogether in line with literary tradition that it would have been odd if he had not been an oddity in the way of a spectacle. He wore queer clothes, it seems, ordinary stockings with bicycle breeches, and that sort of thing. He didn’t altogether fit in somehow, couldn’t find himself, was somewhat of an outsider among the juvenile clans; he was required to fight other boys a good deal; he evidenced a pronounced inability to comprehend anything at all of arithmetic; and somewhere between eight and twelve (so the report goes) he contracted a violent passion for21 a lady, of about thirty-five, who was his teacher at school; a passion which endured for a considerable time, and became a hilarious legend among the youth about him of jocose humour.

It is told that at “Prep” school, when this goal seemed rather unlikely of his attainment, he made up his mind to stand at the head of his class; and with something like the later Kilmerian exercise of will he accomplished his purpose.

Kilmer was graduated from Rutgers College in 1904, and received his A. B. from Columbia in 1906. His University life seems to have been, in outward effect, fairly normal. There is no ready evidence that he “shone” particularly, and none that he failed to “shine.” He was not deported by the authorities, and he was not unanimously hailed the idol of his classmates. He became a member of Delta Upsilon fraternity: and he was, of course, active in college journalism. Then as always he appears to have been zestful in living well, to have counted sufficient to the day the excellence thereof, and to have been too warm with life to be calculating in expenditures. He retained in the years that followed—and it seems to have been the college memory he retained most distinctly—a humorous recollection of his consuming his allowance on an abundance of rich22 viands during the first few days of each month, and being reduced to the necessity of living precariously on a meagre ration of crackers and sandwiches thereafter—until next income day.

Characteristic of the vehement manner in which he went after life, as a Sophomore Kilmer became engaged to Miss Aline Murray, of New Jersey, a step-daughter of Henry Mills Alden, editor of Harper’s Magazine. Upon leaving Columbia he took up the business of making a living in the way of an elder American intellectual tradition, by teaching school in a (more or less) rural community. He returned to New Jersey and began his career as instructor of Latin at Morristown High School. So slight a lad he was, even several years after this time, that it is difficult to picture him in the disciplinary adventures of the classic figure of this calling. His problems at Morristown doubtless were dissimilar to those of his early, Hoosier, prototype. He married and became a householder. His son, Kenton, was born. In religion he had been bred an Episcopalian, and during this period in New Jersey (it is told) he acted as a lay reader in this church.

He soon concluded, apparently, that pedagogy was, so to say, no life for a boy. At the conclusion of a year’s teaching he tore up the roots he had23 planted, and, together with the young lady he had married, and the son born to them, and with a few youthful poems in his pocket, he advanced upon the metropolis, even in the classic way, on the ancient quest of conscious talent.

The rapidity and brilliance of Joyce Kilmer’s success has altogether obscured his very democratic beginnings. As his initial occupation in New York, he obtained, by a lucky chance, employment as editor of a journal for horsemen, though of horses he had no particular knowledge—to be exact, no such knowledge whatever. Here finding little to do, and discovering one day in a desk drawer a bulky manuscript, he decided—as he was editor—to edit it. This, apparently, he did with youthful energy. The little job he mentioned with some satisfaction to his employer, a fine portly sportsman with a crimson face and an irascible temper. The young editor explained that the manuscript evidently had been written by a man familiar with horses, but one apparently innocent of the art of literary composition. “Young man,” bellowed his employer, “I would have you understand I have been through the best veterinary college in the world, and I have been a veterinary myself for over forty years.” His wife, he added, was his amanuensis,24 and he guessed she knew something about writing. The editorship came to an abrupt termination.

Then followed a brief sojourn, at a salary of (I think) eight dollars a week, as retail salesman in the book store of Charles Scribner’s Sons, a dignity which the young littérateur wore with humorous dignity for exactly two weeks. A distinct mental impression of him of this time presents him as decidedly like an Eton boy in general effect, and it seems that a large white collar and a small-size high hat should have gone with him to make the picture quite right. One who met him then felt at once a gracious, slightly courtly, young presence. He gave forth an aroma of excellent, gentlemanly manners. He frequently pronounced, as an indication that he had not heard you clearly, the word “Pardon?”—with a slight forward inclination of his head, which, altogether, was adorable. His smile, never far away, when it came was winning, charming. It broke like spring sunshine, it was so fresh and warm and clear. And there was noticeable then in his eyes a light, a quiet glow which marked him as a spirit not to be forgotten. So tenderly boyish was he in effect that his confreres among the book clerks accepted with difficulty the story that he was married.25 When it was told that he had a son they gasped their incredulity. And when one day this extraordinary elfin sprite remarked that at the time of his honeymoon he had had a beard they felt (I remember) that the world was without power to astonish them further.

As a retail salesman, however, this exceedingly interesting young man did not make a high mark. One’s general impression of him “on the floor” is a picture of a happy student, standing, entranced, frequently with his back to the door (which theoretically he should have been watching for incoming customers), day after day engrossed in perusing a rare edition of “Madame Bovary.” One sensational feat of business he did as a clerk perform. Misreading, in his newness to these hieroglyphics, the cypher in which in stores the prices of books are marked on the fly leaves of the volumes, he sold to a lady a hundred-and-fifty-dollar book for a dollar and a half. This transaction being what is termed a “charge sale,” not a “cash sale,” and amid some excitement the matter being immediately rectified, disaster for the amateur salesman was averted.

At Scribner’s a close friendship was, almost at once, formed between the youthful poet and another then unpublished writer acting at that time in the26 same capacity of clerk—a friendship which was never diminished by the numerous shiftings of Kilmer’s fields of activity, the multitudinous, diverse and ardent interests which he acquired in an ever-mounting measure, and the steady addition of numberless friends of all classes who eagerly yielded him their devotion. It was rather a friendship which was continually cemented by increasing and closer bonds. It was a part of Kilmer’s spirit to make his first friend in his literary life a sharer as far as was possible in each new success of his own. One among many, innumerable, instances of this was his contriving, by his influence with the editor (at that time another intimate, Louis H. Wetmore), to work his friend into a position somewhat rivaling his own at the period (1912–1913) when he was the bright and shining star reviewer for the New York Times Review of Books. The regular Tuesday lunching together of these two friends when their offices were widely separated became, at least in their own fancy, an American literary institution. The two were united in all the symbols of affection between men. And at seasons of rejoicing and adversity the Kilmer house was to his friend as his own. It is to this one who among all of Joyce Kilmer’s friends owes him the greatest debt of friendship has come27 the supreme trust of writing, within the power of his many and conscious limitations, this Memoir, and editing these volumes.

Dropping the very small bird which he held in his hand in the way of a secure salary, the spectacular bookseller, somewhat to twist the figure, plunged again into uncharted seas, and became a lexicographer, as an editorial assistant in the work of preparing a new edition of the Standard Dictionary. He blithely began his Johnsonian labours by defining ordinary words assigned to him, at a pay of five cents for each word defined. This is a very different thing indeed from receiving a rate of five cents a word for writing. It is a task at which you can obtain an average of perhaps ten or twelve dollars a week, though some weeks “stickers” will hold you back. It soon became apparent, evidently, that it was advisable to put this very capable pieceworker on a salary; and he was rapidly promoted, with corresponding increases in remuneration (reaching an amount of something like four times his initial earnings), to more advanced phases of the work: research into dates of birth (involving correspondence with living celebrities); research into the inception of inventions (as, for example, the introduction of the barrier into horse racing); together with the28 defining of words of contemporary origin, in, for instance, the nomenclature of aviation. In this last mentioned department, it was his office to call upon authorities, such as the Wright brothers, and upon presentation of his credentials to receive precise information. He interviewed famous tobacco importers, and coffee merchants; compiled in the New York Public Library material about fans; unearthed for use as an illustration a picture of a strange bird; or was assigned to collect for this purpose designs of ancient mouldings.

If lexicography was Kilmer’s venerable occupation, by political faith he was at the time, this very young, young man, a socialist. He subscribed for and frequently contributed to the Call newspaper. And the height of his effervescence was in addressing meetings of the proletariat. He was, it must be said, a burning “young radical.” He frequented, to some extent, a club of that name. And with a joyous consciousness of being in the character of his surroundings he ate meals at the Rand School of Social Science. He rapidly acquired a wonderful string of queer acquaintances, in whose idiosyncrasies he took immense delight. Some, not of the persuasion, fancied that as an adherent of the socialist party he was merely enamoured29 of an intellectual idea. At any rate, whenever in conversation he spoke of socialism, as he frequently did, his graceful, amiable young features assumed a very firm and earnest aspect. Exactly the point of transition, if there was any decided point, I cannot recall, but from the proletariat he passed to the literati. A “man of letters” became a great word with him. And he looked rather proudly about as he said it, as a Scot might speak of the doughty deeds of the Scotch. He was wont to refer, too, to the “intellectual aristocracy.” His luncheon engagements were now mostly with this order of humanity, and his anecdotes featured such figures as Richard Le Gallienne and Bliss Carman—men whose personalities delighted his heart beyond measure.

How absurdly juvenile he looked. But you would have noted, as you observed him, that he had a very fine head, something like that of Arthur Symons (without the moustache), I thought; or, according to Mr. Le Gallienne’s sympathetic picture in The Bookman: “Though the resemblance was perhaps only a spiritual expression, his then thin, austere young face, with those strangely strong and gentle eyes (eyes that seemed to have an independent, dominating existence), reminded me of Lionel30 Johnson, for whom he had already a great admiration, and whose religion he was afterwards to embrace.” Or, again, he seemed as if he might be a comely youth out of ancient Greece. I think that what I mean is that he was so unlike all other young men anyone had ever seen walking about, so much brighter and purer, or some indescribable thing, that he did not seem altogether real. A feeling which I think was shared by many, and which I have never quite been able to make articulate, Mr. Le Gallienne has most happily expressed with his own easy charm; that is the “hint of destiny” in this “very concentrated, intense young presence—masculine intense, not feminine:”

We have all met young people who give us that—beautiful, brilliant, lovely natured, so superabundant in all their qualities (and particularly perhaps in some quality of emanating light)—as to make them suggest the supernatural, and touched, too, with the finger of a moonlight that has written “fated” upon their brows. Probably our feeling is nothing more mysterious than our realisation that temperaments so vital and intense must inevitably tempt richer and swifter fates than those less wild winged.

Above all, this young gentleman was the portrait of a poet, even (in those days) of the type of literary31 sophistication which is (or was) called decadent! There was about him a perceptible aroma of literary self-consciousness. He had begun to contribute to magazines and newspapers the verses which he soon gathered into a first volume, “A Summer of Love” (an “author’s book,” as the trade term has it), verses patently derivative in character (as whose early verses are not?), showing the influences of various masters.

He had already become a bit of a celebrity, arriving at twenty-five in Who’s Who. In conversation he spoke with striking fluency and precision, and a rather amusing effect of authority; all of which, together with a ready command, rather incongruous for his years, of very apt words little employed in speech, gave a general impression, I fancy, of something of an infant prodigy. He wrote in a letter of this time of the poems of Coventry Patmore:

I have come to regard them with intense admiration. Have you read them? Patmore seems to me to be a greater poet than Francis Thompson. (Kilmer, had by the way, just given a lecture at Columbia University on Francis Thompson.) He has not the rich vocabulary, the decorative erudition, the Shelleyan enthusiasm, which distinguish the “Sister Songs” and the “Hound of Heaven,” but32 he has a classical simplicity, a restraint and sincerity which make his poems satisfying. Some of his shorter poems, such as “Alexander and Lycon” and “The Toys,” approach Landor in their Greek economy. Of course, the “Angel in the House,” and many other of his poems, are marred by Tennysonian influences. But the “Unknown Eros” is a work of stupendous beauty. It is certainly supreme among modern religious poems. That part of it devoted to Eros and Psyche is remarkably daring and remarkably fine. Psyche symbolizes the soul, and Eros the love of God. Their amour is described with realistic minuteness, even with humorous flippancy, and yet the whole poem is alive with religious feeling.

The finding of Patmore, by the way, was what might be called a finger-post in Kilmer’s life. The fortunate introduction was performed by, it is my impression, Kilmer’s friend Thomas Walsh.

If in cold print to-day there is a slightly preposterous didactic quality in these remarks of this youthful character, it should be instantly noted as a tribute to the charm that was his that in the presence of so much handsomeness and grace, combined with so much flexibility of mind and agile humour, even this was an engaging thing.

There was to Kilmer nothing whatever dry-as-dust33 about the erudite business of lexicography; instead his impressionable nature found among his co-workers a rich, a colourful, an exciting school of humanity. He glowed continually with affectionate amusement at the motley band of literary adventurers, intellectual soldiers of fortune, who apparently were his colleagues. One, the most motley perhaps of all (the long cherished dream of whose ancient bachelor life it was one day to write a popular song), touched, for the first time, I think, the deepest spring of his song—his profound and wide-ranging humanity.

And then, lo! the aesthete became a churchman. After a couple of years or so of lexicographic employment, work on the dictionary was completed, and Kilmer entered what, with immense gusto, he described as “religious journalism.” He became literary editor of The Churchman.

He had completed a very thorough course in uptown New York apartment house life (living, I34 think, in rapid succession in some half dozen specimens of “the great stone box cruelly displayed severe against the pleasant arc of sky”); and now removing to the suburban village of Mahwah, New Jersey, in the Ramapo foothills, he entered upon his career as one of the world’s most accomplished commuters. He used to say, with a spacious gesture of the arm and a haughty inflation of the chest, that it was no life at all, no life at all, for a man not to swing around an orbit of at least sixty miles a day between his office and his home. His home, even so!

What more exhilarating experience than the owning of a home! And one paid one’s installments on the building loan with the fine pride of a man exercising a noble prerogative. Yes, he often walked to Suffern along the Erie track, and meditated on “what a house should do, a house that has sheltered life,”

35

As became a churchman, he began to hold forth to his companion on the train to and from the city on the fascinations of the Anglican poets. Either his enthusiasm for the subject resulted in a series of articles on the theme, or an assignment for such a series of articles resulted in his enthusiasm, I don’t know which. The significant point is that it was just as like to have been either way about. “Passon Hawker”—Robert Stephen Hawker—Vicar of Morwenstow, a coast life-guard in a cassock—who can recite off hand the deeds of his piety and his valour? Well, on the Erie smoker he became one of the most romantic figures of story. Robert Herrick, in a manner of speaking, went home many a night on the Twelve-Forty-Five (Robert Herrick, that is, with his “Unbaptized Rhimes” left out), and Bishop Coxe returned on the Seven-Fifty-Six in the morning.

Kilmer had already done a few book reviews for The Nation and for the New York Times; but at The Churchman he acquired such a proficiency at this exercise that he was able, jocularly, to regard Arnold Bennett, as a literary journalist, as a “mere amateur.” The real reward of “religious journalism,” however, it soon developed, was the opportunity of writing a feature which the secular might36 call an editorial, but the proper name of which this editor pronounced, in the tone and with the manner of one who was consciously engaged in something grand, gloomy and peculiar, as a “meditation.”

The real meditations of Joyce Kilmer, however, were not “meditations” so called, and partook in no wise of the nature of editorials. He had been, in the main, a graceful troubadour who thrummed pleasant things to his lady-love, and had a bright eye to his singing robes. He had thought it rather fine, too, that refrain in imitation of Richepin:

He had even been much taken, artistically, with the thought of absinthe:

It was when his business took him near to God, when his exploring spirit, upon a peak in Darien, beheld that:

that he began to be a poet. “Trees,” which more than all the rest he had written put together made37 his reputation, appeared in Poetry. A Magazine of Verse in August, 1913.

At about this period it was that he was altogether born again. Then, doubtless in castigatory reaction against his own aesthetic and “decadent” wild oats, entered into his fibre that sovereign disdain for the intellectual flub-dub which later gave such a delightful note of “horse-sense” to all his humorous thought—the Johnsonian sting (“and don’t you think you were an ass?”) which found its earliest biting expression in the verses “To a Young Poet Who Killed Himself.”

“I’ve been leading a rather active life, for several days,” was with a gay salute of the hand, a frequent Kilmerian remark. In 1912 the direction of the New York Times Review of Books fell into the hands of a high-spirited young man, a Max-Beerbohmian character, with a decided taste for gaiety in reviews, Mr. Wetmore, who conducted that organ through what is known in New York journalistic tradition as its “meteoric period.” Mr. Wetmore’s wit perceived in Kilmer his happiest rocket. Not only given his head but egged on by his editor to strive for sublime heights of fantasy, this fairly unknown contributor shot in a series of reviews which for readability was, the applause now indicated, an38 altogether new thing in the book pages of an American newspaper. “This is a bad book, a very bad book, indeed,” so ran the style. “It is bad because it makes this reviewer feel old and fat and bald.” If, together with their humorous assumption of a jovial cocksureness of manner, the literary judgments expressed were, of necessity, snap-shot judgments, there was nothing snap-shot nor assumed about a certain quality in them which in general effect was the most striking of all, namely, the reflection in a very positive way of a radiantly clean and wholesome young nature, abounding in mental and spiritual health.

As one of the general prime movers in, and for a number of years Corresponding Secretary of The Poetry Society of America, Kilmer engaged on the side in activities which for many another would have been in themselves almost a whole job. A fervent Dickensonian, he was for a long period president and (one felt) the animating principle of the American Dickens Fellowship. He accumulated offices to such an extent that I am doubtful if anyone but himself knew exactly how many employments he had altogether, or at any one moment. He conducted the Poetry department of The Literary Digest for something like nine years, an obligation39 which he continued to fulfill even from Camp Mills, Long Island, to the time when he sailed for France. For a time he conducted a similar department in Current Literature, and also did a quarterly article on poetry for, I think, the Review of Reviews. Among his earlier essays in the lecture field was a paper on “The Drama as an Instrument of Sex Education,” read before a regular meeting of the Society of Sanitary and Moral Prophylaxis held at the New York Academy of Medicine, in December, 1913. The society with the playful name, I recollect, got seriously interested in the matter of sex education as then expounded. Their views on the drama in this connection were enlarged by acquisition of the idea that though “‘The Great Love’ is, in my opinion, one of the most skilfully constructed plays presented on the New York stage for many a year, I am quite serious in saying that as a factor in sex education, it is a thousand times inferior to ‘Bertha the Beautiful Cloak Model.’”

As Kilmer was always decidedly what is termed a ready writer, what I should attempt to describe as a natural writer (a startling exception to the rule that easy writing makes hard reading), so he appeared to have the gift of speaking readily in public. On frequent occasions, at any rate in his early talks,40 he neglected altogether to prepare any outline beforehand, and even sometimes to choose a subject. Every now and then, I have known him repeatedly to say to his companion at dinner, without, however, any trace at all of nervousness: “Now, look here: Put your mind on this. Stop all that gossip. Tell me what I’m to talk about. I have to begin” (looking at his watch) “in twenty-five minutes.”

He was particularly active in the affairs of the Authors’ Club, and was a member of the Vagabonds, the Columbia University Club and the Alianza Puertorriguena. In 1913 he ceased, officially, to be a churchman. For a brief period he contemplated the prospect of a professorship, lecturing on English Literature at the University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee. Then, to his great delight, he became a newspaper man—as he continually put it, with much relish in the part, “a hard newspaper man.” He became a special writer for the New York Times Sunday Magazine. I am sure he saw himself in fancy as one of those weather-beaten characters bred in the old-time newspaper school of booze, profanity and hard knocks, his only text-book the police-court blotter and the moulder of his youth a particularly brutal night city-editor. He maintained, with humorous arrogance against41 opposing argument, the thesis that every great writer had got his “training” as a newspaper man. He delighted to point, as illustrations of this, to Dickens, to Thackeray, and to a lot more, who, in any strict sense of the word, were not “newspaper men” at all. Hard pressed, he even stood ready to make some such hilariously sweeping assertion as that George Eliot, Shakespeare, Tennyson and Robert Browning were, properly perceived, “newspaper men.”

At any rate, this hard newspaper man had to begin with a comical equipment for his task: he would never learn to typewrite and he knew nothing of shorthand. Or rather, he was remarkably well equipped, as one of the outstanding traits of his character was the fearless zest with which, so to say, he took the hurdles of life, and a peculiar faculty in triumphing over such obstacles as his own limitations. He rapidly invented a curious system of abbreviations and marks to remind him of points, which served him as an interviewer as effectively as any knowledge of stenography could have done. He energetically entered upon his occupation as a feature writer with the customary themes of the “Sunday story.” He interviewed, figuratively speaking, the man who had discovered the missing42 link, and he got from the latest inventor of perpetual motion all the arresting details of his machine. And a lively part of the early Sunday morning ritual at his home was the advance calculating with a tape measure of the week’s income from space writing.

It was later that he created his own highly successful type of literary interview. An intelligent perception of the business, a perception which is not general, perhaps is required fully to appreciate the fact that in this department of newspaper work he was an exceedingly skillful journalist. The secret of his really brilliant success in this field lay in large part in his instinct for luring the distinguished subject of his interview into provocative statements, enabling him to employ such heads as: “Is O. Henry a Pernicious Literary Influence?” “Godlessness Mars Most Contemporary Poetry,” “Americans Lack Loyalty To Their Writers,” “Shackled Magazine Editors Harm Literature,” “Declares Our Rich Authors Make Cheap Literature” and “Says American Literature Is Going To the Dogs.”

At the time of the death of James Whitcomb Riley, Kilmer hurried to the Catskills for his interview with Bliss Carman. On his way back to the43 city, by way of his home at Mahwah, he dashed with his usual impetuosity in front of the moving train he was seeking to board, was knocked down and hurled or dragged a considerable distance, and taken to the Good Samaritan Hospital at Suffern, New York, with three ribs fractured and other injuries; where, wiring immediately to New York for his secretary, he dictated an interview as engaging and as full of journalistic craft as any he ever wrote. He seemed much more intent on his Sunday story, it is reported by H. Christopher Watts, who was acting as his secretary at that time, than on his predicament.

I did not see Kilmer at this time myself, but I have an idea that, when he had relieved his mind of the anxiety concerning his article, he entered into the spirit of his experience with much relish. It isn’t every day that one gets hit by a train, nor everybody that has three ribs broken. Exhilarating kind of thing, when you see it that way! I remember one time when I was practically in hospital myself he went to a good deal of trouble to come to see me. He seemed to admire my predicament very much, and, beaming upon me, remarked in high good humour that it must be an entertaining thing to be so completely at the mercy of circumstances44 over which you had no control. When shall we look upon his like again!

I really doubt very much whether anybody ever enjoyed food more than Kilmer. The slender youth had become a decidedly stocky young man, who ate mammoth meals with prodigious satisfaction. He delighted upon sitting down to breakfast to maintain, with almost savage earnestness (such was the amusing effect), that the most fitting dish for that meal was steak. As a matter of fact, however, his habit was to miss his breakfast altogether through haste to catch his train, except for a cup of coffee and a piece of buttered toast which, when he missed the ’bus, he ate, a mouthful every dozen or so leaps, on his way down the hill (almost a mountain) to the station. Sundays, however, with the whole day at home, he apparently regarded among other things as a sort of barbecue. Looking over the morning table it was his custom to inquire with the air of a man making a fairly satisfactory beginning, what was scheduled for dinner.

Kilmer never ate any lunch, as the ordinary world understands the word—about the first hour of the afternoon he went (when his means had become45 such that he could afford it) to a sort of Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner every day. How proceeding directly to his office he did any work afterward, was always considerable of a mystery to me. And lunching alone he doubtless regarded as a misanthropic perversion. His luncheons and his frequent dinners in town alone represented what many would regard as a rather arduous social life, which however arduous, however, never failed to include the weekly luncheon with his mother, Mrs. Kilburn-Kilmer. As an epilogue, so to say, to his meal it was his wont to have, speaking his order slowly so as to suck the full flavour of the idea, “a large black cigar.”

One time being in the city with his family for a period after the birth of one of his children, he gave a series of Sunday morning breakfasts at a fashionable restaurant (it was a pleasant crotchet with him that he was “a fashionable young man”), entertainments which were distinguished by, first, the fact the guests so abundantly represented the world of journalism that they filled a good portion of the room, and, secondly, by the circumstance of their lingering at the board until mid-day diners began to arrive.

How a poet could not be a glorious eater, it was one of Kilmer’s whims to say, he could not see; for46 the poet was happier than other men by reason of his acuter senses, and as his eyes delighted in the beauty of the world, so should his palate thrill with pleasure in the taste of the earth’s bounteous yield for the sustenance of men. The romance, too, of the things we eat he felt lustily.

He had another, and a decidedly quaint, notion of food. He firmly believed that hearty eating was an adequate physical compensation for loss of sleep. He was fond of declaring his faith in this fantastic idea by means of a story of some “ancient receptive child” (friend of his) who managed to bring up a family of seven (or so) children by ill-paid hack-work occupying most of the day and night—a noble success due entirely to noble meals.

And “this man’s” days were long, long days: Kilmer’s home, a place of boundless week-end hospitality and almost equally boundless domesticity47 (guests being obliged to exercise much agility in clambering about toys with which the stairs were laden), was also year after year a place of almost unbelievable literary industry. The trying idiosyncrasies of the artistic temperament were about as discernible in Kilmer as kleptomania. He was, as you may say, social and domestic in his habits of writing to an amazing degree. Night after night he would radiantly walk up and down the floor singing a lullaby to one of his children whom he carried screaming in his arms while he dictated between vociferous sounds to his secretary or wife—his wife frequently driven by the drowsiness of two in the morning to take short naps with her head upon the typewriter while the literally tireless journalist filled and lighted his pipe.

This, however, was an atmosphere of cloistral seclusion compared with Kilmer’s office at the New York Times. Here, where he regularly got through each week enough hard work to hold down three or four fairly capable young men, he maintained a sort of salon for a ludicrous variety of picturesque characters with nothing in particular to do and no place else to go, ranging from types of patrician leisure to stray dogs of the literary world visibly out of a job.

48

The latter class, indeed, apparently regarded him as a kind of a clearing house for employment. A singularly convincing commentary on the radiating humanity of this brilliant young man was one rather grotesque feature of his mail. In addition to a constant and copious stream of requests from persons but slightly known, or quite unknown to him, for advice as to how to succeed in letters, and for his personal imprimatur on their enclosed manuscripts, he was apparently constantly in receipt of innumerable epistolary stories of extraordinary distress, suffered (generally) by elderly characters defeated in the lists of literature. Though there was in Kilmer’s robust nature a decided distaste, somewhat analogous to the innate aversion of the clean in spirit to moral obliquity, for what he termed “ineffectual people,” there was too an amusing strain of paternal feeling toward most of those of all ages with whom he was in contact. And this feeling he did not neglect, whenever the occasion arose, to translate into practical effect.

He had a comical manner of terming his elders “young” So-and-So. I was six years his senior, which at the period of life at which we met represented a considerable difference in experience. And yet, throughout our association, in spiritual49 force he was the oak, I the clinging vine. And I know of cases where this was quite as much so when the other man was something like fifteen years the elder. One such instance, ludicrous in its contrast between the two men, was confessed to me with deep feeling just the other day.

“So-long” or “good-bye” was seldom Kilmer’s parting word. It was rather a word he continually used which will be thought of as peculiarly his as long as his memory endures, the closing word of “Rouge Bouquet.” The last time I saw him at his home, then at Larchmont Manor, New York, my companion (in marriage) and I upon leaving almost missed our car, which started a block or so from the Kilmer house. As the three of us dashed after it, Kilmer stopped this car by what seemed to me something like sheer force of his willing it to stop. Then, as he dropped away from the race, there came from him high and clear out of the night (and always shall I hear it ring) his benediction: “Farewell! Children.” Yes, it is even so; as the spirit is measured and the frailties of the soul are numbered, how many who knew this wondrous boy were his “children”!

The wisdom of the maxim “A busy man is never too busy to do one thing more” was indisputable in50 the spectacle of Kilmer. Though this was not, so far as I recollect, a maxim he employed, he had one of his own something like it, which admirably summed up his practical philosophy. When confronted by some financial dilemma, he was fond of declaring: “The demand creates the supply. A sound economic principle.” He seemed to crave serious responsibilities and insistent obligations as some men crave liquor; and he grew more rosy as these increased.

There was nothing incongruous to Kilmer about the incongruity expressed in a communication written in 1916 to the Reverend Edward F. Garesché, S. J.; a letter which began by saying, “I am sorry that your letter of October 11 has been so long unanswered, but this has been the busiest month of my life”; which then told of his looping the loop of the country in lecture engagements; proceeded to discuss a matter which had made a strong appeal to his heart, the founding of an Academy of Catholic Letters to be called the Marian Institute; and concluded51 with the remark, “I will gladly take on the work of acting secretary until the members make their own selection.”

In 1913, Kilmer’s daughter Rose, nine months of age, was stricken with infantile paralysis. It was then, upon his bringing his family to town to give his daughter the treatment of a specialist, when he came to my house to tell me of this, that I first distinctly realised that this young man was remarkable—in a manner far beyond mere talent. The idea which he kept firmly before his mind was that it had been declared there was no occasion to fear her death as a result of her affliction. During the course of his stay with me that day he said several times, “Well, there are lots of people worse off than I am.” This idea, too, it was apparent, he felt he must hold before him. And then, with his amazing and unconquerable flair for life, he launched upon the theme that this was a “very interesting disease,” and he elaborated the thought that an infirmity of the body frequently resulted in an increased vitality of the mind.

“I like to feel that I have always been a Catholic,”52 was a sentiment frequently expressed by Kilmer. It has repeatedly been declared by friends very close to him that his minute knowledge of pious customs and practices of which a life-long Catholic might easily be ignorant was a constant surprise to them, but that with respect to religion as particularised in himself he kept silent, would never discuss the steps that led to his conversion, and it was only by chance they discovered he was a daily communicant. It was late in 1918 that Kilmer astonished the little world that then comprised his family, his friends and acquaintances by entering, with his wife, the Roman Catholic Church. One afternoon not long after this occurrence he not so much invited as directed me over the telephone to meet him that night for dinner at the Columbia Club. His purpose soon became clear. This was the only solemn hour I ever spent with Kilmer. I think it well to record here what he deeply impressed upon me: that it was this searing test of his spirit which had come upon him in the affliction of his daughter that fixed his religion.

Kilmer did not become a great patriot when his country entered the world war. He was, of course, the same in fibre then as before. Only then was known to him and visible to others what was latent53 in his heart. And in this sense it was, I think, that it was clear to him that he did not become, but had always been a Catholic, though he had not earlier realised it. He tried all things and held fast to that which he found good. He was inwardly driven to seek until his spirit found its home. That only the time of his conversion was, in a sense, accidental, and that the conversion itself was inevitable, must be evident in the fact that he was never really himself before he became, as we say, a convert. Then his fluid spirituality, his yearning sense of religion, was stabilized. What is the “secret,” as we say, of all that has been told of his ability? His courage, his mental and physical energy, were, manifestly, unusual. But his character, in the faith that he embraced, found its tempered spring. His talent was a wingéd seed which in the rich soil which had mothered so much art found fructification.

It is not an unsupported assertion to say that he was in his time and place the laureate of the Catholic Church. His sentiments as to the function of a Catholic poet he has expressed very positively in his essays and lectures. He joyed in the new proof given by Helen Parry Eden “that piety and mirth may comfortably dwell together.” “A convert to Catholicism,” he wrote of Mr. Yeats on Lionel54 Johnson, “is not a person who wanders about weeping over autumn winds and dead leaves, mumbling Latin and sniffing incense.” Nor is it necessary to lay æsthetic hands on the church’s treasures, “and decorate rhymes with rich ecclesiastical imagery and the fragrant names of the saints.” But in Faith one may find “that purity and strength which are the guarantees of immortality.”

And, once a Catholic, there never was any possibility of mistaking Kilmer’s point of view: in all matters of religion, art, economics and politics, as well as in all matters of faith and morals, his point of view was obviously and unhesitatingly Catholic. Considerable as were his gifts and skill as a politician in the business of his career, the veriest zealot could not say that he did not do the most unpolitic things in the service of his faith. A very positive figure, he laboured tirelessly, alternating from one field to another, for the Catholic Church.

As a brilliant interpretative critic of Catholic writers, such as Crashaw, Patmore, Francis Thompson, Lionel Johnson and Belloc, he brought, I think I may venture to say, an altogether new touch into Catholic journalism in America, a striking and distinguished blend of “piety and mirth,” which had the rare and highly effective quality of55 being both engaging and highly illuminating even to, as Kilmer would amiably have said, the Pagan. Impetus, of course, was given to his style in this by his admiration for the brilliant school of English Catholic journalists, an impetus doubtless accelerated by the personal acquaintance with Belloc, the Chestertons and the Meynells he gained in a flying visit to England in 1914 to rescue his mother from war difficulties in London; when, during a few odd moments before his return, he established a lively connection with the Northcliffe papers and T. P.’s Weekly. Even so, Kilmer almost, or quite, alone transplanted this particular spark; and his note of witty common sense and spiritual sensibility was particularly Kilmerian, too.

One day about four years ago the village Post Office at Mahwah did a totally unprecedented and most extraordinary business in outgoing mail, and Kilmer was again multiplied manifold. The neat circulars which he had printed and with which he stuffed the mail box announced that the author of “Trees,” a member of the staff of the New York Times, etc., etc., “offered the following lectures for the coming season.” The result may best be epitomised in the parable of the gentleman who cast his bread upon the waters to have it come back to56 him in the form of sardine sandwiches. The rapid development of Kilmer’s lecture business, which soon assumed the proportions of no mean career in itself, immensely extended his force as a quickening influence in the Catholic world. Before societies and educational institutions in many places, frequently travelling as far as Notre Dame, Indiana, and Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, he flung his bright portraits of “seekers after that real but elusive thing called beauty, a thing which they found in their submission to her who is the mother of all learning, all culture, and all the arts, the Catholic Church.”

As a literary lecturer and a reader of his own poems before secular audiences his success was no less abundant. In “the only combination of its kind since Bill Nye and James Whitcomb Riley,” as the circular of the J. B. Pond Lyceum Bureau stated it, “the young American Poet” and the author of “Pigs is Pigs” contributed considerably to the lightening of the rigours of existence by an extended repetition of “a joint evening of readings from their works.” Ellis Parker Butler, in a letter before me, writes of his partner on the programme:

57

He was a most charming travelling companion and an ideal team-mate for the purpose we had in mind. I would not have thought of going “on tour” if I had not met Kilmer. My idea was never to “go on tour” but, after I had met Kilmer, to “go on tour with Kilmer.” He was altogether lovable and loved.

It would be a decidedly false estimate of Kilmer which failed to note, even with some emphasis, that he was an excellent man of business. He “played the game,” in the exceedingly difficult job of earning a thoroughly competent living at the literary profession, with a dexterity which, it was frequently apparent, was at once an inspiration and a despair to those who sought to rival him. The Kilmer cult which grew apace was considerably accelerated by a rich Kilmerian strategy. And he delivered to the little world of intensely intense literary societies and blue-nosed salons which hung upon his lips the pure milk of the word with a strongly humorous consciousness of the feat as a part of the immense sport of living.

Kilmer’s “act” as it was observed from behind the scenes is excellently presented by an associate in the office of the New York Times. This writer says in the Philadelphia Press:

58

Our editor analysed him into three distinct manners: Kilmer, the literary man; Kilmer, the lecturer; and Kilmer, himself. His first appearance in the office would give you the cue to him for the day. If he came in grinning with his pipe drawing well, we would know that nothing was to be feared; he was himself. When he got his “literary” manner on, the symptom was a tapping of his eyeglass, with his right hand on the fingers of his left. When he appeared in his cutaway coat and a particularly pastoral necktie, we knew that on that day the elderly ladies of This Literary Club or the young ladies of That Academy were to be treated to a discourse on certain aspects of Victorian verse.

One day he came in, obviously decked out for a lecture. Without his having said a word about it, the assistant Sunday editor spoke up: “Let’s cut out work this afternoon and hear Kilmer lecture.” A look of horror overspread his face. “For heaven’s sake, don’t,” he said. “I couldn’t go through with it.” I don’t believe any of us ever did hear him.

A thing which I found very singular was that, in manner Kilmer was apt, in the two or three later years of his life, to give strangers on their first meeting the impression of being somewhat too dignified for so young a man, of being, as his office associate John Bunker in an admirable, even a remarkable,59 portrait of him at this period published in America, says, “in fact just a trifle pompous.” Mr. Bunker continues: “This was due partly to his physical appearance, and also, insofar as it had any basis in reality, to that protective instinct which quickly teaches a sensitive and imaginative spirit to cast a veil between itself and the outer world.”

I myself think this effect had its origin in the same perverse instinct which causes you, immediately after talking with a deaf person, to speak very loud to your next auditor whom you very well know can hear perfectly; that is, it was the result of being keyed up to appearing on an elevated platform before a curious throng. He one time astonished me by the declaration that it was only by, quite early in his life, drastically schooling himself to the task, one then exceedingly trying and hateful to him, that he became able to rise and “speak” at all. The most entertaining recollection, by the way, that I have of the Kilmerian pontifical manner is of a time when he generously invited me to have my shoes polished with him, thrust his hand deep into his pocket to pay the boy, paused, and with a very large gesture directed him to call in again later in the day.

There is first-rate perspicacity in the remark of one of Kilmer’s friends, Laurence J. Gomme, that60 at one score and ten he was, in the amount that he had lived, about seventy years old. Something of the force and sharpness of Mr. Bunker’s evocation of the man as he was at last resides, I think, in the circumstance that here is no blending in the mind of the flower and the bud. He says: “When I first met Kilmer he had just passed his thirtieth year, but he gave me the impression of being somewhat older. I afterwards spoke of this to him, and it was his theory that newspaper work had served to age him. The truth was that it was due not merely to his newspaper work, but generally to the incessant and intense mental activity, the extraordinary and flaming energy, whereby he crowded into ten years the experiences of several ordinary lifetimes.” And this touch of the slight Bunker portrait is, I feel, essential to any fuller picture:

As to his physical aspect, he was stockily built and about medium height, and his habit of body was what I should call plump, though later, under the stress of military drill, he changed somewhat in this last respect. I noted at once that he had a remarkable head—well rounded, with broad and high forehead and a very pronounced bulge at the back, covered thickly with dark, reddish-brown hair. But his eyes were his most remarkable feature. They were of the unusual colour of red, and they had a most61 peculiar quality which I can only inadequately suggest by saying that they literally glowed. It actually seemed as if there were a fire behind them, not a leaping and blazing fire, but a steady and unquenchable flame which appeared to suffuse the whole eyeball with a brooding light. This characteristic was so striking that I cannot help dilating on it. And I observed later on that this glow, this brooding and somewhat sombre light, never left his eyes even in his most weary or most care-free moments, so that they gave the impression of what I believe was the fact—the impression of a brain behind them which was working intensely and perhaps even feverishly every hour of the waking day.

The better poet Kilmer became, as his friend Richardson Wright says in his admirable “Appreciation” in The Bellman, the less like a poet he acted. And after he grew up, he would about as soon have æstheticised, off the platform, as he would have forged a check. Whenever he did refer to poetry as related to himself he, as the slang term has it, took it smiling. One of Kilmer’s most pronounced pet aversions was the phrase, utterly mawkish to him, about “prostituting” one’s talent. He one time explained to me, with considerable apparent pride, that he used every idea three times: in a poem, in an article, and in a lecture.

62

Charles Willis Thompson, an editorial writer of the New York Times, and to whom belongs the credit of first taking, as editor of the Sunday Magazine and Book Review, Kilmer’s “stuff” in any amount, inspired, so to say, the poem “Delicatessen,” in this way. Mr. Thompson happened to remark to Kilmer that of course there were a lot of things which couldn’t be treated in poetry. Kilmer declared he would like to know what they were. Mr. Thompson cast about in his mind for the most ridiculous theme for a poem he could think of, and finally proclaimed that no one could possibly write a poem about such a thing as a delicatessen shop. “I’ll write a poem about a delicatessen shop,” Kilmer promptly replied. “It will be a long poem. I’ll sell it to a high-brow magazine. It will be much admired. And it will be a good poem.” He insisted on betting on this the sum of several dollars.

The origin of “The Twelve-Forty-Five” I do not exactly know. But I remember shortly before that poem was written, sitting disgusted and miserable with Kilmer in that horrible “Jersey City shed” waiting for the midnight train. Taking out of his mouth that villainously large, fifty-cent pipe (mentioned in all genuine appreciations) Kilmer, with a fervour almost violent, suddenly exclaimed: “I63 certainly do like railroad stations! They are fine places!” The very famous poem “The White Ships and The Red” (a poem so wonderfully effective that it was at once reprinted all over the country and in Europe) was a newspaper assignment. He rather liked the poem when he saw it in the paper; though, with his feet cocked up on his desk, he spoke apologetically of what he felt to be the failure of the latter stanzas to link up perfectly with the first, explaining that a luncheon appointment, at which he chatted for an hour or two, had split the writing of it into two sittings. That the author of this “Lusitania” poem thoroughly felt and meant what he said, is, I fancy, sufficiently proven by the event to permit of this being told.

The point is, that Kilmer was a poet, an artist of a high order, a perfectly conscious master of what he was doing. The febrile gush of emotion he loathed. He knew finely that:

There was nothing accidental about the effect of his own verse, any more than there was “luck” in his64 worldly success. He achieved the one as he did the other by a masculine heart and mind. And while all things were necessary and joyous, it was impossible not to feel that, after all, throughout his day “the rhymer’s honest trade” was his primary concern.

He was sufficiently grounded in literature to feel, as Mr. Le Gallienne says, no “weariness with those literary methods which had sufficed for Chaucer and Shakespeare and Milton, or Catullus or Bion, or François Villon—content, with reverent ambition, to tread that immortal path.”

In his religious mysticism a trace, and more than a trace, has been found of Crashaw, of Vaughan, of Herbert, and of Belloc and Chesterton. And there is no difficulty at all about finding in Kilmer hints of Patmore, and there may be easily recognised something of the accents of A. E. Housman and of Edwin Arlington Robinson. He did, indeed, to put it in a racy phrase, have the drop on those who do not know that all art that endures must have its roots in a constant interrogation of the “unimpeachable testimony” of the ages. His song was as old as the hills, and as fresh as the morning. Precisely in this, in fact, is his remarkableness, his originality, as a contemporary poet; and in this will be, I think,65 his abiding quality. “Simple and direct, yet not without subtle magic,” wrote Father James J. Daly, S.J., in a review of “Trees and Other Poems,” printed in America, his verse “seems artlessly naïve, yet it possesses deep undercurrents of masculine and forceful thought; it is ethical in its seriousness, and yet as playful and light-hearted as sunlight and shadows under summer oaks.” And this admirable summing up of Kilmer’s talent leaves little more in the way of direct criticism to be said.

Mr. Le Gallienne with felicitous tact of phrase has touched upon this, that “no young poet of our time has so reverently, on so many pages, in so many different ways, so playfully at times, as in that masterpiece of playful reverence, ‘A Blue Valentine,’ woven through the texture of his song the love of his lady—that lady ‘Aline,’ whose name will be gently twined about his as long as the printed word endures.” A misquotation in the Ladies’ Home Journal led to an interesting tribute to the author of “Trees.” Many readers of the Journal were somewhat startled to find the editor attributing to John Masefield the lines:

66

The following issue of the magazine contained this correction and acknowledgment by Mr. Bok:

I am free to confess that I did not know the correct author. I had been reading John Masefield that morning and unconsciously wrote his name as the author of these lines. A number of friends have pointed to the error and supplied the knowledge. The author is Joyce Kilmer, and to him I owe, and here express, my sense of deep apology. The exquisite lines were worthy of John Masefield, but that does not make them less worthy of their rightful author, as all will agree who read his beautiful work in his book “Trees and Other Poems.”

As one, somewhat effusive commentator has remarked, “Trees” just could not be confined within the covers of a book. At once reprinted in newspapers throughout the United States (and still being so reprinted) it was crowned in that warmest of all ways in which a work of literature can be honoured, by being cut out by the world and pasted in its hat. In one version it reads, in part, in this way:

Cuando contemplo un arbol pienso: nunca vere un poema tan bello y tan intenso.

Un arbol silencioso que con ansia se aferra a la dulce y jugosa entrans de la tierra.

67

Un arbol que mirando los cielos se extansia y en oracion levanta los brazos noche y dia.

Many of Kilmer’s poems have been translated into Spanish by Salomon de la Selva, Enriquez Urenia and others, and have appeared in a number of prominent South American papers.

In a letter from France to Edward W. Cook, who in quest of material for a book on contemporary poets had written Kilmer asking several questions, Kilmer commented, among other things, on his “earlier efforts in poetry” (as the questionnaire apparently had put it), in a manner which is evidence again of how perfectly well he knew what he was about. “If what I nowadays write is considered poetry,” he announced, “then I became a poet in November, 1913.” Admirable for hard-headedness, directness and precision, it is a statement which leaves the critic no point upon which to take issue. His early poems “were only the exercises of an amateur, imitations, useful only as technical training.” The peculiar thing about these highly skilful experiments in various forms of craftsmanship is that they were so very much better as poems than the derivative efforts usually written at this period of apprenticeship, “so free,” as Mr. Le Gallienne68 notes, “from those artistic immaturities which have made many old great poets angrily denounce unlicensed reprinters of their ‘first editions.’” And in this fact they have a decided, and a perfectly legitimate, interest for the observer of the development of his talent—though Kilmer declared “they were worthless, that is, all of them which preceded a poem called ‘Pennies,’ which you will find in my book ‘Trees and Other Poems.’” He added, “I want all of my poems written before that to be forgotten.”

He was writing, one remembers, to a gentleman with whom he was so slightly acquainted that he addressed him as “Dear Mr. Cook,” with the measure of whose sympathy and critical acumen, it is to be inferred, he was not conversant, and who presumably was about to estimate (with what perspective he could not perceive) his earliest productions. It were better to head off any uncertainty in the matter. Also, we all know, one’s hot impatience with one’s strivings of yesterday is mellowed by time into an amiable and appreciative tolerance of one’s earnest efforts of twenty years ago. It is difficult to think that Kilmer at fifty would have had an unjust scorn of those charming exercises on the poetic scales he wrote at twenty-one.

69

Anyhow, no man can, by decree or otherwise, obliterate his past; both the good and the bad that he has done continue to pursue him. Ten times thrice happy is he, rarest of men, who, like Kilmer, never penned a line or said a word or did a deed that can arise to bring confusion to those that love him. The world does not willingly let die those verses on which glistens the dew of his tender youth. They are brought forth for praise by no mean critics in tribute to his memory. And in conformity with the wishes of those most jealous of his good name as a poet a representative selection of his early poems is reprinted in these volumes.

He that lives by the pen shall perish by the pen, saith the wisdom of James Huneker. For a sapling poet, within a few short years and by the hard business of words, to attain to a secretary and a butler and a family of, at length, four children, is a modern Arabian Nights Tale. Equally impossible is it, seemingly, to accomplish another thing, which is a remarkable part of Kilmer’s distinction. From first to last, from the verses contributed to Moods in 1909 to the last poem he wrote, “The Peacemaker,” printed in the Saturday Evening Post in October, 1918, Kilmer was a poet’s poet. “A pretty good poet,” said such a poet (shaking his head at his conviction70 of the truth of this) as Bliss Carman. His poems were repeatedly adjudged high places among the best poems read before the Poetry Society. Among competitive honours, under the name of “John Langdon” he won easily enough with his poem, “The Annunciation,” first prize in the Marian Poetry contest conducted by The Queen’s Work, in July, 1917, an award competed for by a great number of poets, including many in other countries. He was a poet’s poet who declared (with considerable vehemence, I remember) that he certainly wished he had written “Casey At The Bat.” He one time said in praise of a book of essays that it was “that kind of glorified reporting which is poetry.” As a singer of the simpler annals of humanity his place will draw closer and closer, I think, to that of the most widely loved poet of our own era. Only the name of James Whitcomb Riley expresses in greater measure the rich gift of speaking with authentic song to the simplest hearts. A man who believes that churches are devices of the devil and literature a syrup for crack-brained females can enjoy, with profit to his soul, “The House With Nobody In it,” “Dave Lilly” and “The Servant Girl and the Grocer’s Boy” equally with “The Old Swimmin’-Hole” and “Little Orphant Annie.”

71

If Colonel Roosevelt had never done anything other than what he has done in writing, he would undoubtedly be highly esteemed as an American man of letters. And people have made very creditable reputations as humourists who never wrote anything like as humorous essays as those of Joyce Kilmer. They fairly reek with the joy of life. They explode with intellectual robustness. They are fragrant in fancy, richly erudite in substance, touch-and-go in manner, poetic in feeling, rocking with mirth, and display an extraordinary flair for style. If it should seem that I am not here measuring my words I suggest a reference to a piece of documentary evidence called “The Gentle Art of Christmas Giving,” a “Sunday story” in the New York Times, here reprinted. Writing at top-notch speed, never looking again at what he had written, intentionally producing a readily marketable commodity, from which profit must be realised quickly, Kilmer was an exceedingly rare bird in America; that is, a belletristic journalist. There is always the touch to his work of a man of letters. Decidedly Bellocian, Chestertonian, certainly his humorous essays are. But that it was a good deal more an affinity of mind with, than an imitation of, those splendidly humorous English philosophers is borne72 out by this: Joyce Kilmer did not talk poetry, but he did talk exactly like his essays, which admirably present the brave humorous wisdom of the man as his intimate friends knew him.

Official critical authority did not dampen his verve. As a contributing editor of “Warner’s Library of the World’s Best Literature,” he supplied the articles on Madison Cawein, John Masefield, William Vaughn Moody and Francis Thompson. He contributed prefaces to various volumes of standard authors. Excellent examples of this department of his activity are his Introduction to Thomas Hardy’s “The Mayor of Casterbridge” in the Modern Library, his introduction to the American edition of the “Verses” of Hilaire Belloc, and the introduction to the volume “Dreams and Images,” his anthology of Catholic poets. The Introduction to this Anthology is dated 165th Regiment, Camp Mills, Mineola, N. Y., August, 1917, just a year before Sergeant Kilmer’s death in battle. Doubtless few know that at one time Kilmer had drawn a contract to write a “Life” of Father Tabb. Because of peculiar complications in the situation this enterprise, most unfortunately, fell through. In 1916 Kilmer was called to the faculty of the School of Journalism of New York University, in73 succession to Arthur Guiterman, to lecture on “Magazine and Newspaper Verse.” The object of the course, which was open to outsiders as well as to those enrolled in the School of Journalism, was to familiarise the students with the practical side of writing verse for publication.

It seems rather a misnomer, and something of an absurdity, to say that Kilmer was ever neutral in anything. But in the political sense he was a neutral, and, if it may be put that way, neutral to a pronounced degree, preceding the entrance of the United States into the war. His keen feeling for the sturdy virtues and robust customs of Old England, Merrie England, was of course, patent. His delight in London, and the English countryside, which he knew from a child, was manifest. The pillars of his fairly large literature were, of course, English. His profound sense of integrity was violently jolted by the violation of Belgium. As the war went on, however, he developed an attitude which was quite capable of being interpreted as Pro-German, by anyone interested in so interpreting it. The explanation of this attitude is simple enough. Instinctively a combative character intellectually,74 his humorous essays, which expressed him so intimately, almost without exception found their spring in his running counter to some current idea. As he one time remarked, he was “bored by feminism, futurism, free love;” and, too, he was invariably for the under dog. It may seem rather grotesque to present Germany by implication as an under dog in the early years of the war; the point is, the force of the argument was so overwhelmingly against Germany that Kilmer reacted to this in a characteristic fashion, stood boldly against the current, and was, in fact, a neutral—until the sinking of the Lusitania. All reports agree, including even reports from sources of strong anti-English feeling where Kilmer’s inclination to see what could be said for Germany was coveted, that from this point on his manner was altogether hostile to Germany. Outside of his Lusitania poem he did not, so far as I know, denounce the deed; but the unanimity and the precision with which the change in him is fixed by all who observed him is striking.

Kilmer’s successive literary passions were a curious medley. He seemed to have been born with a great love for Scott, and he held stoutly to Sir Walter throughout the years. In his burly days he found a humorous sport in defending, with jovial75 emphasis, the old-fashioned chivalrous romance against the scientific modern novel. In his æsthetic period he had a touch, hardly more, of Oscar Wilde, though early in his literary career he experienced a rather severe case of Swinburneitus. Some time shortly after this he was very much intrigued by the Celtic revival. Shaemas O’Sheel, a friend dating back to Columbia days, bears testimony that an early boast of Kilmer’s was that an ancestor of his had been hanged for taking a rebel’s part in ’ninety-eight. And though as we know, Kilmer’s immediate ancestry was not Irish, a Gaelic enthusiast who has made a specialty of the Irish language, suggests in his ardour, that the name Kilmer is a derivation of Mac Gilla Mor. At any rate, an affection for Ireland—her literature, her lore, her traditions, and her people—was indeed natural with him.

In his Yeats period Kilmer had about chosen “Nine Bean Rows” as the name of his house then in the course of construction, though it was not altogether “of clay and wattles made.” The thing which deterred him from this decision was that persons unacquainted with the poem “Innisfree,” to whom he spoke of the matter, conceived his address as Number Nine Beanrose Avenue. What a funny street, they said, that is. Literary merely, of76 course, that; and though a part of the whole, remote from later, deeper and graver things. Something inherently Irish in Kilmer undoubtedly was felt by many, Irish themselves and very much so, who, in some cases, are “quite certain” that the fact of their being Irish was the reason why he regarded them and their work as writers with friendship. He did, indeed, like all manner of Irish. He liked the Irish fairies, he liked Lady Gregory, he liked most decidedly the poor Irish people who went to the Catholic church, and (as he later showed), of all soldiers, Irish soldiers he liked best.

Everything chivalrous and sacrificial appealing to his deepest instincts, he felt noble “delight in hopes that were vain.” It is not at all improbable that had he been an Irishman born and resident in Ireland he would have been among the martyrs of Easter Week. In certain qualities of his soul a kinship with these spirits may readily be traced. Some of them, I have been told, he knew personally; and his reverence for Plunkett he has written.

77