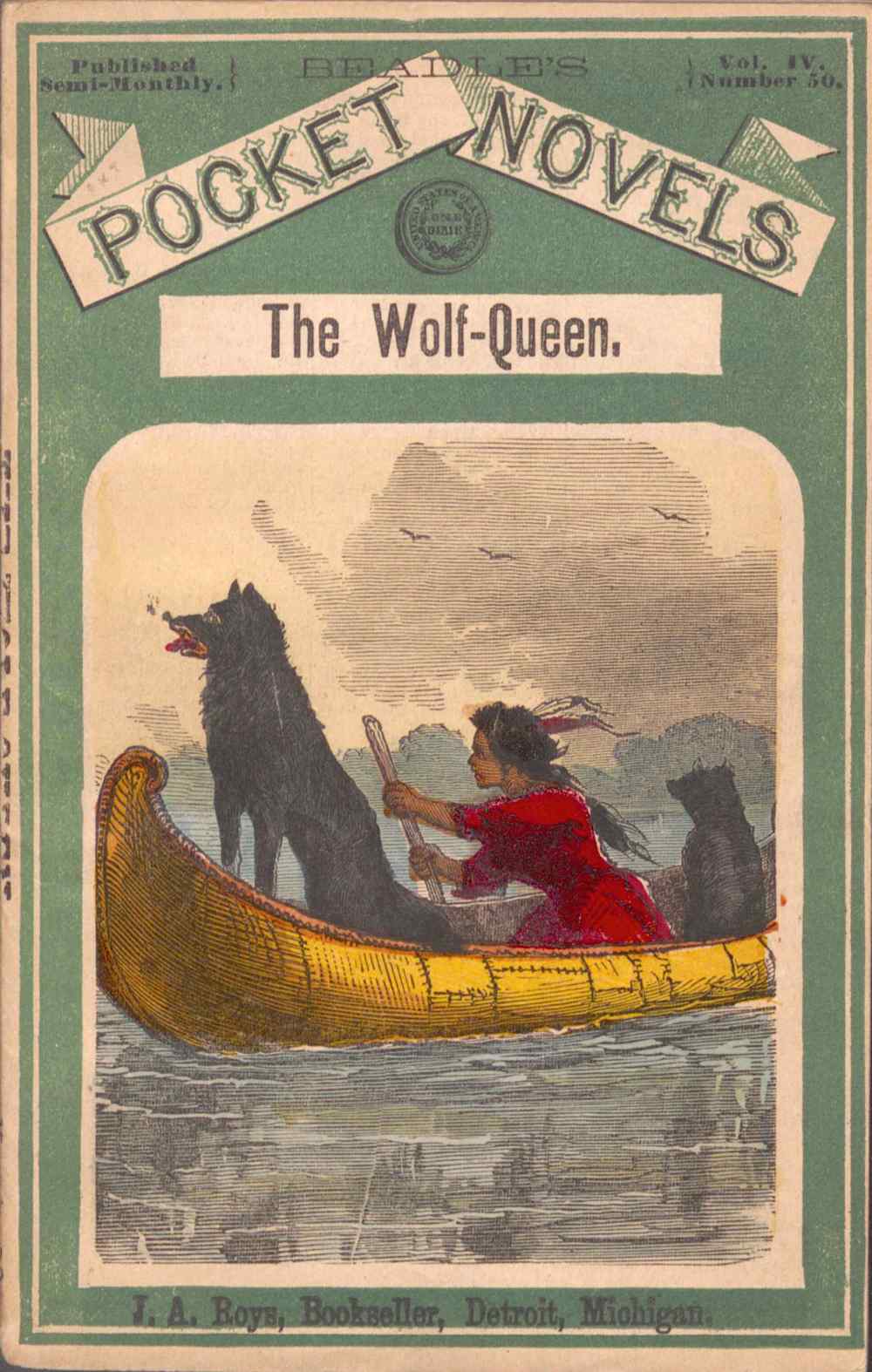

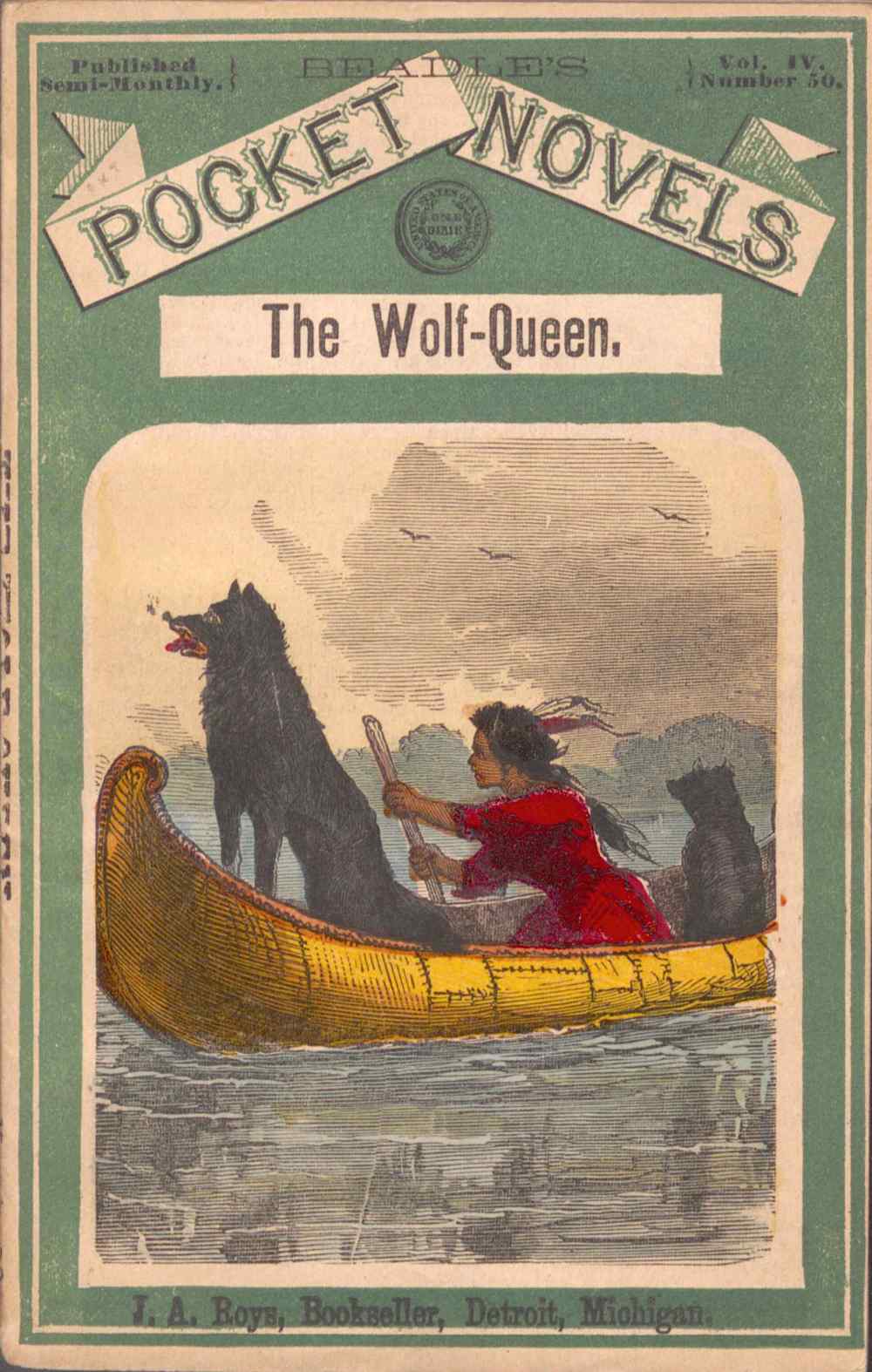

Title: The Wolf Queen; or, The Giant Hermit of the Scioto

Author: T. C. Harbaugh

Release date: June 22, 2021 [eBook #65667]

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Susan Carr and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois University Digital Library at http://digital.lib.niu.edu/)

BY CAPT. CHARLES HOWARD,

Author of “The Elk King,” (Pocket Novel No. 45.)

NEW YORK:

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by

FRANK STARR & CO.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | THE RIVER COMBAT. | 9 |

| II. | THE HERMIT AND HIS CAVE. | 12 |

| III. | JIM GIRTY AND HIS PRISONER. | 18 |

| IV. | THE EVENTS OF THAT NIGHT. | 22 |

| V. | THE MYSTERIOUS DEATH-SHOTS. | 27 |

| VI. | OUT OF THE CAVE TO DOOM. | 31 |

| VII. | ALASKA IN HER FRENZY. | 36 |

| VIII. | JIM GIRTY TRIUMPHS. | 40 |

| IX. | ONE OF ALASKA’S WHIMS. | 45 |

| X. | THE FATE OF WELL-LAID PLANS. | 50 |

| XI. | THE MOLES ON THE SHOULDER. | 56 |

| XII. | NOT YET! NOT YET! | 60 |

| XIII. | THE BAFFLED RENEGADE. | 66 |

| XIV. | SQUAW VENGEANCE, AND SQUAW RAGE. | 71 |

| XV. | A LEAF FROM THE HERMIT’S LIFE. | 75 |

| XVI. | THE KING OF THE WOLVES. | 78 |

| XVII. | THE CONFERENCE ON THE KNOLL. | 80 |

| XVIII. | SIMON GIRTY IN HIS WAR-PAINT. | 82 |

| XIX. | A CHANGE IN AFFAIRS. | 85 |

| XX. | THE BLOODY MEETING. | 89 |

| XXI. | THE LIGHT OF OTHER DAYS. | 94 |

[Pg 9]

THE WOLF-QUEEN;

OR,

THE GIANT HERMIT OF THE SCIOTO.

The sun was sinking, a great fiery ball, in the leaden west, at the close of an autumn day, in the year 1804, when a solitary canoe descended the Scioto, then vastly swollen by recent rains.

The single occupant of the tiny bark was a youth of two and twenty summers, clad in buck-skin. His beardless face gave him an extremely womanish expression. Its smooth surface was yet untanned by the rays of the sun, which fairness of skin proclaimed him a novice in backwoods life.

He plied the oars deftly and noiselessly, and kept in the middle of the stream. Ever and anon he glanced upward at the ragged cliffs that hung over the murky and turbulent waters like the hand of doom. But, at last, he passed beyond the precipitous banks, and gained the mouth of the Scioto’s nosiest tributary.

Here he rested upon his oars a moment, as if to decide a mental debate, then ran his canoe up the new stream, toward the left bank of which he presently steered.

“So far without accident,” he murmured in an audible tone, not before glancing furtively around. “Simon Kenton may be a great hunter; but he is a sorry prophet. What! did he think I would wait until he returned from the hazardous expedition he is about to undertake, and leave Eudora the while in Jim Girty’s hands? And when, in the ebullition of anger, as I will admit—I called him a lunatic, and told him that I would rescue the girl without the aid of his potent[10] arm, he said, with a sneer I shall never forget: ‘Go, rash boy, and meet the reward for spurning the counsels of your elders. Go to the death prepared for you by the Wolf-Queen.’”

“The Wolf-Queen!” the young man continued, after a sneer for the prophecy of the king of backwoodsmen. “If such a creature exists, I want to meet her; and I have no reason for doubting her existence, for Simon Kenton says he once trembled in her presence. And Simon Kenton never lies. I will pit my strength against the Amazon, and her wolfish guard. Though rash and young in the ways of the woods, Mayne Fairfax is not a coward, else why came he from cultivated Virginia to the dark death-paths of Ohio? No; I—My God!”

The exclamation was called into being by the terrible sight that suddenly burst upon the young hunter’s vision.

Scarce the distance of a hundred yards up-stream, a canoe shot from the bush-fringed bank, and bore down upon the young Virginian.

In the center of the bark stood the very person he had lately expressed a desire to meet—the dreaded Wolf-Queen—dreaded alike by Indians and whites.

She towered six feet above her moccasins, and her frame seemed built of iron. She wore a frock of tanned doe-skin, the fringes of which touched her knees. The leggins which fitted her nether limbs to a fault, were composed of panther skins, secured to the moccasins by painted strips of deer-hide. Over all these garments she wore a long, dark robe whose ample folds disappeared in the canoe, and lent a royal aspect to its strange wearer. Her head was surrounded by a dress, composed of white heron-feathers, and among her raven locks, which streamed over her shoulders, and covered her beaded bosom, were curiously, but not distastily, woven the gaudy feathers of the North American oriole.

The features, more than the dress of the singular being so suddenly encountered on the swollen stream, commanded the hunter’s attention.

They belonged to a woman in the noon, or summer of life. Here and there a wrinkle was to be seen, and a sadly strange beauty pervaded her countenance. But the eyes—those faithful[11] indexes of the human heart—proclaimed their possessor—a white woman—mad!

Yes, the unmistakable fire of insanity blazed fiercely in those baleful orbs, and told the single beholder that she was a perfect demon, when the paroxysm of lunacy swayed her.

But she was not alone.

On either side of her stood a huge black wolf, while at her feet sat a monster gray one. A collar of deer-skin, elaborately beaded, encircled the necks of the fierce brutes, and from their shaggy backs the muddy water dripped.

The sight was enough to blanch the boldest cheek, and Mayne Fairfax could not repress a shriek of terror. It bubbled to his lips unsummoned.

He now had ocular proof that the dreadful Wolf-Queen was not a myth.

The canoe and its terrible freight approached with an impetus received from the swift waters. No oars were needed to keep it in the center of the stream—a swift current did this service for the Wolf-Queen, who stood erect in the bark, clutching a drawn bow.

Mayne Fairfax’s presence of mind soon returned. He griped his rifle, but ere it struck his shoulder the twang of a bow-string smote his ears, and a barbed shaft buried itself in his right breast. Instantaneously a faintness stole over him, but the courageous hunter repressed it, as the canoe of the Amazon grated against his.

He would not die without a struggle, and therefore seized his rifle for the second time, for the purpose of braining his antagonist.

At that moment the gray wolf left his post.

The clubbed rifle dropped into the canoe, as the wolf buried his fangs in the hunter’s throat, and the brave fellow staggered back, trying to tear the mad animal from his breast.

In that terrible moment Simon Kenton’s last words burst doomfully and prophetically upon his mind!

But his end was not yet.

For in the fateful moment that followed the lupine attack, the sharp report of a rifle rent the air; the wolf relinquished his hold with a groan, and fell at Mayne Fairfax’s feet—dead!

[12]

The Wolf-Queen turned toward the shore, and saw a great coonskin cap surmounting a clump of prickly pears. Instantly a cry, but half earthly, escaped her lips, and a minute later she was flying down the stream, vainly trying to stanch the crimson tide that flowed from the gray wolf’s heart; while at her feet crouched the black monsters, drinking the warm blood of their lifeless companion.

The young hunter’s canoe began to drift toward the Scioto, and upon its gory bottom, as motionless as a corpse, lay Mayne Fairfax.

Suddenly the pear bushes parted, and a backwoods giant, bearing a long but deadly-looking rifle sprung into the stream, and intercepted the drifting canoe.

He looked over the side, and shook his head doubtingly.

“Poor lad! poor lad!” he murmured, with rough but genuine indications of sorrow. “I’m afraid he’s going to cross the river.”

Then, standing in the water in the middle of the tributary, he stanched the blood that poured from the lacerated throat, which he bound with the soft linings of his grotesque cap.

“There!” he cried, surveying his work. “That doctoring will do until I reach home. This young chap must not die. He’s too brave to perish in the springtime of his life. I wonder what brought him alone to these parts!”

Then with the interrogative still quivering his lips, he towed the boat ashore, moored it to a clump of alder bushes, and raising the unconscious youth in his arms, darted away into the great forest, where strange fortunes and adventures awaited him and the human burden he bore.

Now and then a groan parted the lips of the unconscious Virginian, as the giant rapidly bore him through the wood, throughout the recesses of which the somber shades of night were gathering.

[13]

At length the surface of the ground grew hilly, and the giant approached so near the Scioto that the swash of the waters against its new banks could be distinctly heard. He followed the course of the stream for some distance, when he turned aside, and darted into a small ravine once the bed of a tributary of the Scioto. In the banks of the ravine were just discernible several gloomy apertures, into one of which the backwoodsman disappeared.

Five steps from the orifice brought him to a strong oaken door, seemingly imbedded in the limestone rock, and a short fumbling in the gloom above his head threw wide the portal.

Dark as the night without was the gloom beyond the stone threshold; but a joyful bark greeted the giant’s ears, and a dog sprung forward to greet him.

“Home again, Wolf,” said the man, securing the door. “And I’ve brought you a friend—a friend as near dead, I should judge, as you get them, for, with an arrow sticking near through one, and the awfulest torn throat you ever saw, things must look dangerous.”

The speaker moved forward, and, without the aid of a light, tenderly placed Mayne Fairfax upon a couch, deep with soft dressed skins. Then he ignited a tiny pile of bark films, which soon communicated a warmth to a heap of sticks, which blazed and crackled with some fury.

“Here, Wolf, quit smelling around the patient,” cried the giant, turning to his charge. “I’m the doctor in this case, and I’m about to see what can be done. May be he isn’t so badly hurt as I opine. That arrow,” he continued, after a long silence, during which he had critically examined the hunter’s wounds, “that arrow must be pulled through. I’m not much of a surgeon, but I reckon as how I have managed some pretty dangerous cases. Here goes! If that arrow ain’t taken out, a certain young man will never shoulder a rifle again.”

A protuberance on the young hunter’s back told the giant that the arrow had nearly gone through the body, and delicately, yet firmly, the rude surgeon set to work. His keen hunting-knife first severed the shaft; then made the incision, and the remainder of the shaft was withdrawn. Then some[14] astringent liniment was rubbed on and into the wounds, which were covered with strong adhesive plasters.

As this operation was completed, Mayne Fairfax groaned and opened his eyes.

His first inquiry regarded his situation.

“You’re in the home of Bill Hewitt,” answered the giant, “and he has just pulled the arrow of that madwoman from your body. Luckily, as I have discovered, it struck no vital part. The deviation of an inch, either to the right or the left, would have rendered my surgical operations unnecessary. So you may begin to believe in special providences.”

Fairfax tried to answer, but the condition of his throat, torn by the jaws of the gray wolf, baffled him.

“I’ll dress your breathing apparatus right now,” said Hewitt, “and then I opine you can chatter away like a parrot.”

The young hunter never winced under the pain occasioned by the dressing of his throat.

“It’s best for you to stay down for a few days,” said Hewitt, after completing the operation. “Exertion of body may irritate your breast wound, and end in something disagreeable. I’ll stay with you all the time, for I don’t go visiting much in these parts, nor these times. Now just lay still, but talk to me while I get supper for two; tell me all about yourself, and what brought you alone away down here. Boy, you look like a Virginian.”

“I am a Virginian,” answered Fairfax, watching the giant’s backwoods culinary operations. “My name is Fairfax.”

“Fairfax!” cried the backwoodsman, quickly turning upon the speaker. “What Fairfax?”

“The son of Ronald Fairfax, of Roanoke.”

“I knew him,” said the giant.

“That is singular. When did you leave Virginia?”

“So you’ve got to questioning before you’re half through with your story, eh?” cried Hewitt, with a strange smile. “Well, I’ll tell you; but you must go on with your tale; and perhaps I’ll tell you mine, some day. Perhaps, I say, and some day. I left Rockbridge county a matter of twenty-one years ago.”

“Three months since I stood in my father’s house,” resumed young Fairfax, whose countenance told that he would have[15] questioned his preserver further; “and were it not for the existence of that accursed renegade, Jim Girty, I would be there this night.”

“Yes, curse Jim Girty, boy,” muttered Hewitt. “Oh that curses could kill.”

“Yes, yes,” hissed Mayne Fairfax, and his nervous hands closed in silent anger. “Near Rockbridge county the family of Nicholas Morriston rather rashly dwelt alone in the wilderness. The father was a hotheaded man, who lived in fancied security, while Indian raids were being made all around him. One night, poor fellow, he paid dearly for his rashness, for often had I entreated him to remove his family to a place of safety. One night, I say, when too late to fly, he paid the penalty attached to stubbornness. But not only did he suffer, but every member of his family, save one, fell beneath the swoop of the white hawk.”

“The red hawks, you mean,” interrupted Hewitt.

“No, no. The destroying band was led by Jim Girty, whose evil passions had been inflamed by the beauty, the innocence and grace of Eudora Morriston.”

“I anticipate the remainder of your narrative, boy,” suddenly interrupted the giant hermit. “Eudora Morriston is now Jim Girty’s prisoner, and it is she whom you seek in the land of the dread Wolf-Queen and her tribe.”

“Yes. By tarrying, perhaps months, in Chillicothe, I might have secured the assistance of the renowned Simon Kenton; but the thought of Eudora’s situation—growing more precarious every day—caused me to spurn the great hunter’s offer, and, alone, I swore to rescue her or perish in the attempt.”

“You’re a brave boy, a brave boy!” cried the giant, admiringly. “I had a little boy once—a tiny fellow with golden hair, and the prettiest eyes you ever saw. But where he is now, God knows. You love Eudora Morriston?”

A flush suffused Mayne Fairfax’s temples.

“Yes, but she knows it not. I never breathed aught to her of my passion.”

For a long time the hunter was silent, and the outward workings of his countenance, told of mental struggles in the mysterious unseen.

[16]

“I loved once—a long while ago,” he said, at length, fixing his gaze upon the reclining hunter. “But I don’t think I love anybody now, save my boy—wherever he is—and Wolf, here,” and he stroked the mastiff’s shaggy hide. “These hands,” he quickly continued, stretching forth his broad palms, “are red with the gore of a fellow-creature, whose skin was as fair as yours, my boy. With the brand of Cain upon my brow, I fled Virginia—fled between two days, and here I am, a cave-hermit, on the verge of fifty years, with a giant’s frame, unracked by disease; but with hair and beard almost as white as driven snow.

“Yes, yes,” he continued, as though the young hunter had put a question, “it is a terrible thing to kill a fellow-creature in the first heat of passion; but I will not tell you aught further of that dark night, now. Boy, from that day to this I have not taken a human life—nor ever will I, not even the life of an Indian. I will assist you to recover the sweet creature you seek—together we will snatch her, unharmed, from the fangs of the white wolf—Jim Girty; but into whatever precarious situations we may fall, remember, boy, that these hands shed no human blood. These fists are enough for a score of red-skins. They have proved themselves thus in times gone by. But here, our supper is ready. I’ll prop you up with these skins, and you can make out to eat, I hope.”

The repast proved quite nutritious to Mayne Fairfax, and not a word passed between the twain until it had ended, and the still smoking remains thrown to Wolf.

“Boy, did you ever hear your father speak of William Hewitt?” suddenly questioned the giant.

“Never to my knowledge,” answered the young man.

“Strange, when we knew each other so well,” soliloquized the hermit, in a semi-audible tone. “But, perhaps, he would have his heirs remain ignorant of that dark night, as well he might. But, my boy, I’d give my right arm, nay, my very life, to know what became of him—my boy.”

“I will make every inquiry when I return,” said Fairfax.

“But how shall I know the result of your inquiries?”

“I will return and make them known to you.”

[17]

“How can I reward you?” cried Hewitt, grasping the young man’s hands.

“Say nothing about that. I am already rewarded. But—what was that?”

“My door-bell,” said the giant, with a smile, as he rose to his feet and hastened to the mouth of the cave.

A minute later Fairfax heard the massive oaken door open and close, and a confused murmur of voices approaching him.

“Boy,” suddenly said the giant, leading a tall and athletic young Indian into the mellow light of the fire, “here is the only visitor I have. The Bible says that it is not good for man to be alone always, so I picked up a companion. This is Oonalooska, the bravest young warrior of his tribe.”

Mayne Fairfax stretched forth his hand, and the young brave pressed it with no small degree of feeling.

“So the madwoman struck the white hunter?” said Oonalooska, half interrogatively, still retaining Fairfax’s hand.

“Yes; her shaft pierced my breast, and her wolf tore my throat.”

“She will be like a great storm now,” returned the Shawnee, “because one of her wolves is dead. Oonalooska fears for the Pale Flower in the Shawnee village.”

“Then she is there!” cried the young hunter, with eagerness.

“Yes,” answered Oonalooska, “she is under the fiery eyes of the White Wolf, and unless he guards her well, Alaska will tear her from him, and put her to the torture.”

“No, no!” cried Mayne Fairfax. “Hewitt, I feel strong enough to go and rescue her.”

“You’re as weak as a kitten,” said the giant, with a smile for the young hunter’s futile effort to rise. “We will send Oonalooska back to the village, and he shall report affairs for us. It will be a terrible conflict if affairs reach such a climax between Girty and Alaska, the Wolf-Queen; but Girty may still possess the strange influence he has held over her in days gone by. I am certain that a crisis will not be reached in the Shawnee village for some time.”

“But send Oonalooska thither at once,” cried Fairfax, “and tell him to tell Eudora that a friend seeks her rescue.[18] And, Shawnee,” here he addressed Oonalooska, “if you can save the Pale Flower at once, do so, and convey her hither.”

“Oonalooska will not sleep,” was the reply; “but to overcome the White Wolf and Alaska he must have the cunning of his white friends.”

“I cannot leave this young man until his sores are healed,” said Hewitt. “But that will not be long. Then we will baffle Jim Girty, and you, who hate him, can send him to Watchemenetoc.”

The Indian’s eyes flashed at the hermit’s last sentence, and a minute later Oonalooska was gone.

James Girty was one of a quartette of brothers to which the notorious Simon belonged. He became the prisoner of the Indians early in Braddock’s ill-fated campaign, when he was in his fourteenth year, and was adopted by the Shawnees. Growing to manhood, he loved the life and customs of the red rovers of the trackless forests, and hated all whom they hated. His passions were as fiery as Simon’s, but for some unaccountable reasons, he has not figured as conspicuously on the page of history.

Simon Girty, notwithstanding his multitudinous crimes, possessed a few good qualities; but James possessed not one. Simon often pleaded for the life of a prisoner, James never; and his countenance was the incarnation of all that is repulsive.

At the opening of our romance he had attained his sixty-ninth year, notwithstanding which he still possessed a giant’s frame and a giant’s strength.

So well did he bear the burden of his years, that he looked beneath fifty, and scarce a gray hair was visible upon his head. His eyes still flashed the fire of manhood’s prime, from beneath long, midnight lashes, and not a crow’s foot furrowed[19] his forehead. His face was covered by splotches of red hair, through which cutaneous eruptions, caused by his dissolute habits, were constantly making their appearance. When not influenced by wine, he was not quarrelsome; but for many years he had drawn scarce a single sober breath. He was an unerring marksman, and his influence over the Indians was unbounded.

While hunting in Virginia he encountered Eudora Morriston, whose beauty fanned the fires of his evil nature; and, as Mayne Fairfax has already related, he swooped down upon the happy home, at the head of a band of Shawnees, massacred every one of its inmates, save the beautiful girl, whom he bore to the Indian village, and placed under the guardianship of two of the most pliant of his red tools.

Bright and translucently beautiful upon the Shawnee village broke the morn that followed the transaction of the events related in the foregoing chapters.

James, or as he was commonly called, Jim Girty, would have slumbered late, had he not been startled from his sleep by the grip of a human hand upon his arm. He opened his baleful eyes, and beheld a middle-aged savage bending over him. The first streaks of morning but illy dispersed the gloom of his lodge, and the renegade sprung to his feet, with the oath, never absent from his lips.

“Alaska is a storm!” cried the Indian, springing from Girty’s side, and throwing aside the curtain of skins that served for a door. “See! she goes to the lodge of the Pale Flower. Her wolves will kill the guards, and tear to pieces the White Wolf’s prisoner. Last night the Lone Man shot Alaska’s gray wolf, and she will now have the blood of the white captive for it.”

Astounded at the sight to which the savage directed his gaze—the Wolf-Queen, guarded by a dozen terrible wolves, and followed by near a hundred Indians, advancing toward the lodge where dwelt his prisoner, guarded by but ten braves—Jim Girty jerked his rifle from its pins over his couch, and bounded to the scene.

He seemed to fly over the ground, and threw himself between Eudora’s guards, as the foremost wolves were preparing for the combat.

[20]

“Back!” he yelled, fixing his gaze upon Alaska. “Why does Alaska seek the life of my prisoner?”

“Ha! ha! ha!” laughed the madwoman, long and loud. “’Tis for the White Wolf to question, but for Alaska to answer. Last night Alaska met a young pale-faced hunter on the little stream. She pierced him with her shaft, but he was brave. He would use his rifle as a club. Alaska’s gray wolf—the only snow wolf of Alaska’s band—sought the hunter’s throat, when the Lone Man, concealed by many bushes, shot Lupino. Now lies he cold and dead in Alaska’s wigwam. She must have blood for his, and that blood must flow from the Pale Flower’s heart.”

She finished, and stepped forward, while her grip tightened on the long-bladed knife that glittered in the first beams of the sun.

Girty’s rifle shot to his shoulder.

He did not dare shoot the Wolf-Queen, for she knew not the value of life, and her death at his hands would soon be followed by his, by the claws and fangs of her wolves.

He directed his weapon at the head of her favorite wolf—a monster black fellow, around whose neck was a wide beaded collar, and over the shaggy back dropped a rich mantle.

“If Alaska does not stay her hand,” he cried, “the White Wolf will have Leperto’s blood!”

The Wolf-Queen suddenly paused, and glanced from Girty to the threatened wolf. Indecision ruled her form, and Girty was on the eve of triumph, when an old Indian, bent with more than three-score years and ten, stepped to Alaska’s side.

His eyes flashed with a fire seldom seen in the orbs of age, when his gaze fell upon the renegade.

“Let the White Wolf shoot Leperto,” he cried, addressing the madwoman. “Old Miantomah will give her another. Let the Pale Flower die for the act of the Lone Man, and if the White Wolf resists, let Alaska’s wolves, his brothers, tear him to pieces.”

Miantomah exercised a weird influence over the Wolf-Queen, and, inspired by his words, she spoke to her wolves.

The mad animals fixed their eyes upon Girty, and crawled forward.

[21]

It was a critical moment.

“Shall an old, empty-headed man rule a mad-woman with his forked tongue?” cried Girty, appealing to the crowd of warriors. “Let the White Wolf’s brothers gather around him. He has led them to victory, and will they now desert him for a crack-headed squaw?”

“No!” cried Oonalooska, drawing his tomahawk, and springing to Girty’s side. “Oonalooska is not a squaw. Warriors, follow him!”

His action electrified the warriors, and, a moment later, all, save a dozen, surrounded Girty, and displayed a hollow square glistening with knives, to the Wolf-Queen.

“Back to your wigwam now, and bury your dead!” cried Girty, in triumph.

Alaska regarded him in silence.

He repeated the command.

“Alaska moves not hence without the Pale Flower’s blood,” she at length replied. “Her braves are on the war-path, and at their head, marches the great Tecumseh, against whom the White Wolf dare not stand. They will return ere yon ball of fire again rises over the hills. Then, let the White Wolf fear, then will Alaska have the Pale Flower’s heart. Here she will remain until Tecumseh comes,” and she seated herself upon the ground, in the midst of her wolves.

At the mention of Tecumseh’s name, Girty’s guard exchanged looks of fear. The great chief was on ill terms with the renegade, and, fearing to incur the anger of Tecumseh, several braves deserted Girty, and went over to the mad-woman.

“Be firm!” cried Girty, lowering upon the disaffection. “They who stand by me shall be rewarded, and Tecumseh will act justly when he comes.”

This retained a goodly portion of his guard.

The long hours wore away, both parties longing, yet fearing, for the night.

Oonalooska knew that Tecumseh would favor the Wolf-Queen, and, with a determined resolve in his heart, he stepped into the lodge, where knelt a trembling girl, praying to her God for deliverance.

[22]

He touched her arm.

She looked up, her eyes bathed in pearly tears.

“Let the Pale Flower tremble not,” whispered the young brave. “Tecumseh will not return till midnight, and ere he comes Oonalooska will save the White Wolf’s captive. The young hunter lives in the lodge of the great Lone Man.”

Then he turned away, without noticing the look of gratitude Eudora bestowed upon him.

Oh, for the night!

What had it in store for Eudora Morriston—life or death?

Slowly the hours of that beautiful autumn day wore away, and the shades of evening seemed a century in making their appearance.

The squaws of the “town” brought a repast to Girty and his band; but Alaska dispatched several warriors to her own wigwam, the capacious larder of which was soon empty for the benefit of herself and wolves.

The terrible animals never took their eyes from Girty, whose distasteful form blocked the doorway of Eudora’s lodge.

“Never fear, girl,” he said, one time, turning upon his prisoner, who sat listlessly upon her couch of skins. “The wolves shan’t eat you. I have great influence over Tecumseh, and the chief will quickly drive the crazy woman to her wigwam.”

A better dissembler than “Jim” Girty never trod the woods of Ohio. He knew that the great Shawnee chieftain lived in superstitious awe of the Wolf-Queen, and that, upon his return, his prisoner would be given over to the fangs of the wolves. And while he spoke to Eudora he was plotting to get her beyond the village before Tecumseh returned.

[23]

The young girl deigned no reply to his words, but in silence set to work to arrange the disheveled locks which hung over her shoulders.

She was very beautiful—the possessor of a symmetrical form faultless in the minutest particular, large, black eyes, lustrous beneath raven lashes, and a wealth of raven hair, which enhanced her transcendent loveliness. She wore the coronet of her seventeenth year, though weeping for the fate of her parents and golden-haired sisters, mercilessly butchered in her sight, caused her to look beyond her years.

The words of Oonalooska shot a cheering ray of hope into her heart, and caused that guiltless organ to beat for joy. “The young hunter lives,” he had said; but what “young hunter” did he mean? Quite a number of “young hunters” had been enraptured by her beauty, though none had she ever bade hope for the dimpled hand that could send an arrow unerringly to the target, and direct the bullet with an accuracy unequaled by many well-known frontiersmen of those “dark and bloody days.”

Among her admirers, Mayne Fairfax had called oftenest at her home, now a heap of ashes, and she had evinced a partiality for his companionship, which had driven the others from the field.

Was he the “young hunter” who sought her in the Indian village?

Her rapid heart-beats proclaimed that she hoped so.

The afternoon was nearing its close when Girty summoned Oonalooska to his side.

The young brave obeyed with alacrity, and was surprised to hear the renegade make the following proposition:

“Tecumseh must not meet the Pale Flower in the lodge,” said Girty, in a low tone, that it might not reach the ears of Alaska, who was within common earshot. “The chief hates me, but he also fears me. Without a second thought he would deliver the white-faced girl to Alaska. To-morrow he will decide otherwise. Not far from this lodge dwell the exiled Mingoes, on whose grounds no hostile warrior dares to tread. To-night, then, will not Oonalooska guide the Pale Flower thither, and guard her until the White Wolf commands their return?”

[24]

Eagerly Oonalooska promised to grant Girty’s request, and the plans for the escape were quickly formed.

While the plot was discussed by the warrior and the renegade, dark clouds were creeping from the west, and soon the whole sky was overcast—which harbingered a storm. Through a rift in the opaque masses, the dying rays of the sun fell upon the Shawnee village, and when night prevailed Girty threw a cordon of braves around Eudora’s lodge. Alaska witnessed the precautionary movement, but instead of encircling the cordon with her braves, she moved nearer the aperture of the wigwam, which she made discernible by torches, thrust into the yielding earth.

Girty thought it best to keep Eudora ignorant of the destination he intended for her; but told Oonalooska to say that he would conduct her to a place of safety, beyond the reach of all her enemies.

The night was the incarnation of gloom, and every waning moment brought Tecumseh and his braves nearer the village. The chief had promised to return upon that particular night, and he had never broken his word. In the rear of the wigwam Girty had placed several braves upon whom he could rely, and, as the first peal of thunder reverberated through the forest, and far down the Scioto, Oonalooska’s keen knife gashed the thin bark in the rear of Eudora’s couch.

A peal of thunder in autumn always startled the Shawnees, and, believing it the harbinger of Tecumseh’s approach, the most timid glided over to the Wolf-Queen.

Girty did not murmur at their late disaffection, for he knew that Alaska would not move till the arrival of the giant chief.

“Oonalooska is ready,” whispered the brave, turning from the perforated bark to the maiden, whose eyes had witnessed the operation.

“Then let us hasten,” she said in tremulous accents, “lest Tecumseh’s arrival doom me to the teeth of the mad-woman’s wolves.”

Tenderly, noiselessly, Oonalooska lifted Eudora in his arms, and glided through the slit, and past the posted guards in the rear of the wigwam. Once beyond the confines of the village, he walked rapidly, experiencing no difficulty in picking his way rightly in the cimmerian gloom.

[25]

Presently he entered the forest, and when he had placed a hill between himself and the village, he paused, and drew a torch from beneath his wolf-skin robe.

“Oonalooska does not possess the eyes of the owl,” he said, with a smile, as he ignited a wisp of bark films with the flints. “The wood is dark, and unless fire guides Oonalooska, he may wander to the Mingoes, whither the White Wolf has sent him.”

“But may not Oonalooska’s torch encounter Tecumseh?” asked Eudora, who feared the worst.

“No; the great chief and his braves will cross the creek into the lodges. Oonalooska must have fire. It will keep the wolves away.”

The mere mention of the wolves sent an icy shudder to Eudora’s heart. From the jaws of the ravenous animals she had first been snatched by the chivalrous red-man, who was once more bearing her through the labyrinthine recesses of the Scioto forest.

The hermit home of William, or, as he called himself, “Bill,” Hewitt, was about fourteen miles from the Shawnee village, and Oonalooska rapidly traversed the dreary miles. The crisp leaves gave forth a weird sound, as the Indian’s moccasined feet touched them, and the great drops of rain that pattered down through the giant, leafless trees, added to the ghostliness of the moment. Sure enough, the wolves struck the trail, and, at last, Oonalooska saw many a pair of fiery eyes far in his rear.

He felt Eudora shudder as a chorus of yells smote her ear; but he assured her that they would reach the hermit’s cave in safety, when he knew that the issue was doubtful.

At length the warrior uttered a light cry, as he gained the summit of a knoll, from which he indistinctly heard the roar of a little cataract that poured its waters into the Scioto.

“The Pale Flower is near the Lone Man’s lodge,” said the Shawnee, and he dashed down the knoll, the foot of which he reached as the foremost wolf poked his head over the summit.

Once or twice he was forced to turn and beat the band off with his torch, and, at last, almost exhausted, he dashed into the limestone corridor of Hewitt’s home.

[26]

He had not time to give the signal—the jerking of a deer-thong in the darkness overhead—for the wolves were snapping at his lovely burden, and while his lips uttered a peculiar whoop, he turned and sent one giant fellow to the ground with his torch. The weapon struck the animal in the mouth, and, the great tusk closing on it, it was jerked from his hand.

He shrieked again as his right hand throttled the leader of the lupine band, and hurled him senseless among his companions. The dying torch lent a terribly tragic view to the scene. Pale as death, Eudora reclined upon the left arm of the Indian, as single-handed he fought the bloodthirsty gang, and her lips parted with a joyful cry, as the strong door was burst open, and she found herself borne into a warm apartment.

With clubbed rifle, the giant hermit sprung among the wolves, and before him they divided and scattered like sheep. They had encountered the invincible before.

“Fly, cowards!” cried Hewitt, as he reëntered the cave, to find Eudora kneeling before the couch of her wounded lover.

He had thrown one arm around her neck, and his lips were whispering something in her ears—probably the story of tender passion.

“We will have the whole Shawnee nation to fight now,” said Hewitt, when Eudora had related her trials while in the hands of Girty. “And ere morn Tecumseh will be at our door. The wolves of Alaska will track Eudora hither, and then for the conflict. It must be near dawn now.”

As he finished he drew aside a skin, that hung against the wall, and disappeared in a dark passage.

Oonalooska awaited his return in silence, while Fairfax and Eudora conversed in low whispers.

Suddenly the skin flew aside, and Hewitt sprung into the cave.

His long beard was filled with tiny particles of decayed wood, and sparks of fire seemed to dart from his dark orbs. But his voice was as calm as a midsummer day.

“Fifty-three braves are nearing us,” he said. “They are headed by Tecumseh and Alaska, who is surrounded by her accursed wolves. Jim Girty is not with them.”

[27]

Oonalooska’s expression remained immobile, and Eudora threw a look at her wounded lover, but her lips uttered nothing. Her dark eyes shot a mingled look of determination and defiance toward the door.

All at once a tomahawk struck the oaken planks, and a terrible yell followed.

It was the war-whoop of Tecumseh!

Leperto, the petted wolf, answered it with a dismal howl.

Let us witness the return of Tecumseh, and follow the great chief and the Wolf-Queen to the hermit’s cave.

Jim Girty did not desert his post, when he found the wigwam tenantless. On the contrary, he told his band to increase their vigilance, and remained immobile in the doorway of the lodge. He knew when Oonalooska disappeared with his prisoner, and he breathed freer than he had done for long hours. A run of three hours would bring the young brave to the homes of the exiled Mingoes, across the threshold of which, even Tecumseh, with all his greatness, dared not step, upon other than a friendly mission.

He felt that he could conciliate Tecumseh, and that, when the spasm of frenzy, that now ruled Alaska’s heart, passed away, he could command Oonalooska to return with the captive.

The storm, which proved of brief duration, did no damage to the village, and midnight brought Tecumseh.

Several braves deserted Alaska to greet the returning band, and presently the mighty Shawnee, with angry countenance, faced the white-faced renegade.

Jim Girty had learned to read his chieftain’s face, and in the ghostly glare of the torches, he read thereon an unsuccessful expedition. Tecumseh was in a fit mood to wreak vengeance on any man who owned a white skin.

[28]

With drawn tomahawk he paused before the renegade, and shouted, as his eyes drank in the whole scene:

“White Wolf, deliver the Pale Flower to Alaska!”

“The White Wolf will obey his chief,” answered Girty, shooting the mad-woman a singular look. “Let Tecumseh enter the lodge, and lead the captive to the Wolf-Queen.”

As he finished, he stepped aside, and Tecumseh sprung into the lodge.

One loud yell parted the chief’s lips as his eyes fell upon the untenanted couch, and a moment later his brawny hand closed on Girty’s throat.

“White Wolf’s tongue is forked!” he cried. “Let him tell Tecumseh where the Pale Flower is, or die!”

“The White Wolf knows not,” gasped the white liar. “She has been stolen while we watched.”

The chief’s grip relaxed, and, at his command, Girty was bound, and a guard placed over him.

Alaska could scarcely be restrained from throwing her wolves upon the prostrate renegade.

A brief examination revealed the gash in the bark, and instantly the braves were called. One was missing—Oonalooska, the son of Okalona, the aged Medicine of the Shawnees. He was the traitor, and, if captured, his doom would be a terrible one, and speedy.

Tecumseh’s blood boiled in his dark veins, and his angry passions were stirred to their depths. All fatigue incurred by the recent war-expedition, instantly left him, and he called around him a band of picked warriors. Alaska panted to pursue the traitor, and his companion, and throwing herself at the head of the party, she placed her wolves upon Oonalooska’s trail, and away they went, through the forest, toward the hermit’s cave.

The renegade was not permitted to accompany the pursuing party; instead, he found himself under the vigilant eyes of five braves, who bore him to his lodge, and threw themselves around it.

He knew that his captivity would not last beyond the return of Tecumseh, over whom, when calm, he held some influence.

The war-whoop of Tecumseh and the dismal howl of Leperto,[29] that ushered in the clear, frosty autumn morning, was answered by a savage growl from the hermit’s canine companion, who yearned to encounter the mad-woman’s wolves.

No human answer following the blow delivered by Tecumseh’s tomahawk, the chief bestowed a second upon the door, and shouted:

“Tecumseh, the war-chief of the Shawnees, demands the person of Oonalooska, the red traitor, and the Pale Flower. Let the Lone Man speak!”

The hermit’s answer was not long delayed.

“Is Tecumseh an empty fool, that he should seek the blood of the Pale Flower, snatched from her home by the lying White Wolf? If he is not, let him return to his lodge, the greatest chief of the Shawnee nation.”

“The Wolf-Queen seeks the Pale Flower. Tecumseh wants the traitor Oonalooska,” was the reply.

“Then let Tecumseh take them!” was the defiant reply, at which a second war-cry smote the air, and the Shawnee drew back from the portals.

“Tecumseh will take them!” he cried, “and beside Oonalooska shall burn the Lone Man of the woods.”

“No, no!” shrieked mad Alaska. “The Lone Man shot Lupino. He shall die by the teeth of Alaska’s wolves.”

“So be it,” answered Tecumseh, and in a loud tone he commanded his warriors to heap fagots against the door of the cave.

The command was obeyed with alacrity, and Tecumseh and several of his favorite chiefs drew back to witness the work of burning out the besieged whites. Near him stood the Wolf-Queen, amid her wolfish guard, and the terrible light of anticipated vengeance danced in her eyes.

The work went on without interruption for many minutes, during which period the golden god of day lazily scaled the oriental horizon, and threw his warm beams upon the swarthy band.

Suddenly the sharp report of a rifle rent the gentle breeze that flitted through the woods, and the stalwart chief, whose shoulder touched Tecumseh, staggered back with a bloody, crushed temple.

Instantly the braves left their work, and gathered around[30] the stricken chief. Whence came the deadly missile? An examination showed that the ball had been fired from an elevated position, and the leafless top of every tree was scanned with vengeful eyes. But the mysterious slayer remained undiscovered.

“Back!” shouted Tecumseh, after a prolonged search, and the warriors returned to the cave. “Haste with the work! Tecumseh yearns to see the traitor, and the Lone Man die.”

At length the last gathered bough was thrust into the mouth of the cave, and Tecumseh turned to Nethoto, a chief not below his august self in prowess, when a second rifle report smote his ears; and Nethoto staggered back—dead!

Horror-stricken, Tecumseh shrunk aghast from the work of death, and for the first time in all his life displayed a frightened face to his braves.

He felt that his turn would come next, and instantly, as if in confirmation of that mental conclusion, a voice rung throughout the forest.

“Let Tecumseh hasten to his lodge, else he never steps upon another war-trail!”

The savages gazed wildly around as the tones fell upon their ears, and then looked at their chief, who seemed to have grown into a statue—so motionless and pale he stood.

Alaska was the first to break the silence.

“Ha! ha! ha!” she laughed, as she caught one of her wolves, and threw him upon the dead body of Nethoto. “The Great Spirit slays Nethoto, who once struck Alaska with a whip. Let Tecumseh return to the village; but Alaska and her wolves will stay. They will enter the Lone Man’s cave and devour him. The Great Spirit loves Alaska and her wolves. Ha! ha! ha!” and she clapped her hands with glee to see the wolves tear Nethoto to pieces.

Tecumseh knew not how to act. He feared the Wolf-Queen, in awe of whom his warriors stood, and at his bidding they would remain. If he stayed, death would soon enter his heart.

The Wolf-Queen did not notice his indecision. With fiendish delight she was throwing wolf after wolf upon the dead chief.

[31]

All at once her brutal actions came to an abrupt termination.

A third shot echoed throughout the wood, and Leperto, the king of the wolves, sprung back from the corpse—a corpse himself.

A heart-chilling shriek welled from Alaska’s throat, as she sprung forward and pressed the dead wolf to her bosom. A moment she gazed wildly around, as if searching for the mysterious slayer, and then, with an indescribable horror of countenance, she darted from the tragic spot, followed by her wolves, Tecumseh and his braves.

It was the first time that Tecumseh ever turned his back upon the foe.

Convulsively to her heart the crazy queen pressed Leperto. She tried to stanch his crimson tide with her long tresses, but it seemed to flow the faster, and her trail was one of gore.

“Not long will Tecumseh remain in his beaded lodge,” hissed the great chief to a plumed Indian, at whose side he ran. “He will return, and hunger shall drive the pale ones, with the red traitor, from the hole in the ground, and the blood of Sagasto and Nethoto shall be poured upon their heads.”

The mad-woman thought of nothing but her dead wolf; but very soon other and more terrible thoughts would rule her shattered brain.

During the brief siege described in the foregoing chapter, but two persons occupied the cave. These were Mayne Fairfax and the beautiful Eudora Morriston.

The young hunter reclined on the couch, and Eudora sat beside him, holding one of his hands in hers.

“I wonder how this will end, Mayne,” she said, gazing into his deep eyes, that never grew weary of gazing into her face.

“I do not know, Eudora,” replied the hunter; “but I feel[32] that the end is not far distant. The capitulation of the hermit’s fort, in my mind, is but a question of time. If Tecumseh can not burn the door, he can starve us out. But hark, girl! That sounded like a rifle shot.”

“And that shriek, Mayne!” cried the girl. “An Indian has fallen beneath the Lone Man’s rifle. Perhaps it was Tecumseh?”

“No, no, Eudora. Hewitt did not fire that shot. He sheds the blood of no fellow-man. If an Indian fell, it was beneath Oonalooska’s aim. Listen! That was the voice of Tecumseh.”

The conversation ceased, and in the silence that followed the lovers heard the second shot, that sent Nethoto to the earth.

“Another!” cried Eudora. “Where do the shots come from, Mayne?”

“From the top of a giant oak,” answered the young hunter. “Yon subterranean passage ends beneath the trunk of a great, hollow tree. Inside, steps lead to the top of the giant, from whence Oonalooska is smiting the red men.”

“What a singular man the hermit is!” cried Eudora, as the faint tones of the Wolf-Queen—faint to the cave listeners—came from the wood. “He is a mystery to the savages. Girty hates, but fears him, and, to Tecumseh, he is an enigma. I—”

“The third shot!” interrupted Mayne, and a minute later the giant hermit stepped into the cave.

“Our enemies are routed,” he said, bestowing a smile upon the lovers. “Beneath Oonalooska’s rifle fell two chiefs and Leperto.”

“Alaska’s wolf,” said Eudora, turning to Fairfax. “The poor woman will be inconsolable now.”

“Oonalooska wanted to shoot the queen, but I covered the flint with my hand in time to save her life. I could not witness the killing of that poor mad-woman, though if we ever fall into her hands we will receive no mercy.”

“Her wolves tore Oonalooska’s venison once,” hissed the chief, who stood beside the hermit, and he added, in an undertone. “Some day when Lone Man is abroad, Oonalooska’s flint will not be covered by a pale hand.”

[33]

“Do you think our enemies will return?” asked the young Virginian, looking into the hermit’s face.

“Yes. Already I believe that Tecumseh’s spies lurk in the vicinity, and, ere long, the chief will return with a large force, which can not be successfully resisted. I know Tecumseh as few men know him. I have watched him grow to manhood, unforgiving and vindictive.”

“In view of our situation, then, what do you propose?” questioned Fairfax, with eagerness.

“Flight—to Chillicothe,” was the reply.

“Not by day?”

“No; to the contrary. We are not far from the river, which I believe will not be guarded to-night. From this cave leads a passage which terminates not a great ways from the river. That passage I have never had occasion to use, having never, until this day, been besieged. Above the termination of that passage, the crust has not been broken. We will use that to-night, and near dawn, no accidents intervening, we will be beyond danger. My boy, can you crawl to the opening of the passage? Thence we will assist you to the boat.”

“Yes,” cried Fairfax, rising with a mighty effort, that sent a thousand painful arrows throughout his frame, “I feel strong again—the events of the last twenty-four hours have made me a giant.”

Hewitt shook his head doubtingly, and faintly smiled, as a sense of giddiness forced the young hunter upon the couch again.

“Tecumseh will not return before nightfall,” continued the hermit, after a brief silence, “and while they besiege the cave, we will be flying up the river to Chillicothe—which, for us, means safety.”

Then the strange man drew a repast from his store, and the victuals were discussed with a relish, and conversation in which they tried to forget their perilous situation.

Slowly the day waned, and, at length, a growl from the mastiff, who lay at the brush-burdened door, told the hunted that an Indian was near.

Then Oonalooska disappeared in the subterranean passage, already used during the progress of our romance; but presently[34] returned with the information that several spies were in the wood, at the mouth of the cave.

The hour for escape had arrived.

“I’ve lived in this hole in the ground for eighteen years,” said the hermit, taking a mournful survey of the cave, whose walls were lined with the skins of all animals, “and you may think that it goes hard with me to leave it. But if I stay here now, Alaska’s wolves will drink Hewitt blood. I want to live till I can see my boy again, and—” here he turned away, and muttered in an undertone: “Yes, I’d like to see her, too. I could forgive her now; but, oh, God! will I ever meet my wife on earth more?”

A great tear dewed his tawny cheek, and a tremor crossed his giant frame, as he turned to the trio.

“Well, we’re ready now,” he said, calm again. “Here, girl, take the extra rifle. I’ve heard tell as how you can use it.”

“I can and will, if I must,” said Eudora, proudly, as she took the proffered firearm.

The hermit stepped to the further end of the cave, and revealed a gloomy passage, by throwing aside a wolf-skin that concealed it.

“Lead off, Oona,” he said, addressing the Indian. “Wolf and I’ll bring up the rear.”

The Indian dropped upon all fours, and entered the passage; and the dog bounded in, in advance of his master.

“Good-by, old home,” said the hermit, taking a last look at the apartment. “Mebbe I’ll come back again, and mebbe I won’t, that’s all.”

The curtain fell and the cave was tenantless.

The underground corridor seemed interminable; but, at last, Oonalooska paused. The end was reached.

It was the noiseless work of a few moments to admit an invigorating current of night-air into the gloomy way, and the Shawnee emerged upon terra firma.

“Now for the river,” whispered Hewitt, throwing himself in advance of the party.

The night was dark around, though many stars twinkled in the blue overhead.

[35]

Eudora trod in the hermit’s tracks, and her lover leaned upon the arm of Oonalooska.

At length they stood upon the right bank of the Scioto. It was lined with thick clumps of weeping willows, the leaves of which touched the dark water, causing many faint ripples, that fell ominously upon the ears of the hunted quartette.

The hermit glided from his companions, and, after a long absence, returned with the startling information that his boat was gone!

Mayne Fairfax’s groan of despair was stifled by Hewitt’s hand, and in his ear were breathed these words:

“We are within thirty feet of a gang of red-skins.”

The hermit turned to Oonalooska, when a grunt from his dog startled every one.

Instantaneously the tramp of many feet smote the ears of the imperiled ones, and a circle of Indians seemed to rise from the earth.

“Spare all!” was heard the voice of Jim Girty, as he rushed forward, at the head of the main band.

He met the man he feared—the strong hermit—in whose arms he was but a child.

Hewitt raised the renegade above his head, and tossed him far out into the Scioto. Oonalooska fought nobly, and would have escaped had he not stumbled over a prostrate Indian, and been seized before he could rise. Mayne Fairfax, weak from his wounds, did not resist, and he and Eudora, who fought valiantly with clubbed rifle, were made prisoners.

It cost the Shawnees a Herculean struggle to secure the hermit and it was not until the entire band rushed upon him en masse , that he became a captive.

At the conclusion of the victory, a chief sent a shrill whoop through the forest.

“Why shout the Shawnees?” asked the hermit, with a nonchalance which, under the circumstances was truly wonderful.

“Manitowoc calls Tecumseh,” was the reply. “The great chief and Alaska are at the Lone Man’s hole in the ground.”

[36]

The reply sent an indescribable feeling to the prisoners’ hearts, and no wonder.

All—with, perhaps, a single exception—felt that they had marched from the cave to doom.

The shrill whoop was answered by the glare of a multitude of torches, and the rushing sound of many feet.

All the prisoners, save Oonalooska, were unbound, but closely guarded. The swarthy Shawnee stood proudly erect, with his hands tied upon his back, and his nether limbs bound by tried deer-thongs. He looked defiance at his captors, in whose faces he read the terrible doom. Tecumseh would speak for him when he arrived.

Suddenly the great chief halted before the circle, and a shout of triumph parted his red lips as his eyes fell upon Oonalooska. The captive calmly returned that vengeful look, and something like a sarcastic smile, played with his lips.

A step behind Tecumseh towered Alaska, the Wolf-Queen, and a wild cry rose from her throat, as she discovered Eudora, standing beside the hermit, who seemed her mighty protector.

The next moment she flung her torch to the earth, and caught up one of her mad black wolves. Her eyes flashed their fire upon the maiden, as she executed a forward step, with the snarling animal poised above her head. Her mad intention could not be mistaken. She had long been in the habit of hurling her animals upon the objects of her vengeance, and the white, glistening teeth were instantly buried in that with which they came in contact.

Now for Eudora’s delicate flesh were these dread fangs intended, and before the maid could shrink, the wolf went hissing through the air. A shriek parted the girl’s pale lips, as[37] the giant hermit threw himself before her, and his great hand shot forward, to close on the animal’s throat.

The Indians shrunk back, amazed at the dexterity and fearlessness displayed by the hermit, whose teeth were gritted, and whose eyes glared at the Wolf-Queen, as he throttled her pet at arm’s length.

Not a sound disturbed the scene, save the frantic gasps for fleeting breath made by the dying wolf. Even Alaska stared aghast, unable to move, and the remainder of her wolfish guard crouched at her feet, and quietly watched the death of their companion.

At length a shudder passed over the animal’s frame, and the hermit tossed him at Alaska’s feet.

That action aroused the queen.

Quick as thought she stooped and seized a second wolf, when Tecumseh threw himself between her and the hermit.

“The Lone Man will kill all Alaska’s children,” he said, gazing straight into her eyes. “If she would save the rest, let her give him over to Tecumseh, and he shall die in the great lodge.”

A change suddenly became visible in the mad-woman’s eyes, and she dropped the wolf she had raised.

“Ha! ha! ha!” she laughed, “the Lone Man shall be torn to pieces by Alaska’s children in the great lodge, and the Pale Flower and her lover shall die there, too. But, ho! ho! who have we here? The White Wolf, ha! ha! ha!” and her eyes fell upon the renegade, who had just emerged, dripping, from the river.

Tecumseh turned upon him.

“The White Wolf is faithful,” he said. “He has captured the white ones, and the red traitor,” and he added in a tone unheard by Alaska, “Tecumseh will keep his promise.”

A moment later the whites were bound, and Tecumseh ordered the return to the village. As the band started forward the hermit called the chief to his side.

“The young white hunter is weak,” he said, nodding to Mayne Fairfax, who tottered along like a drunken man. “He fell beneath Alaska’s wolf and arrow. The Lone Man would support the young hunter.”

[38]

Tecumseh owned a heart susceptible of pity, and he commanded the hands of the hermit to be made free.

“Now let the Lone Man support the young hunter,” he said, returning to the head of his band, and Mayne Fairfax acknowledged the Indian’s kindness in audible tones, as he stepped to Hewitt’s side, and leaned upon his strong arm.

During that midnight march the Shawnees taunted Oonalooska with the fate in store for him. He maintained a taciturnity for a long time, when a remark from Tecumseh drew forth the words that bubbled to his lips.

The chief called his red prisoner the son of a sorcerer, for against the father of Oonalooska, Tecumseh had long borne a silent hatred.

The words stung Oonalooska to the quick.

“If Oonalooska’s father does talk with Watchemenetocs, he never gave a poor Pale Flower a head as empty as the hollow of his hand—he never made a prisoner a devil!”

A flash of rage overspread Tecumseh’s face, and he wheeled with uplifted tomahawk.

“Strike!” hissed Oonalooska, shooting him a glance of resignation. “Oonalooska is ready to enter the great lodge among the stars. Yes, yes, Tecumseh’s father struck a squaw, and made her a—”

He suddenly paused, for the eyes of Alaska fell upon him.

“Tecumseh will not strike the traitor!” said the great Indian, suddenly lowering the hatchet, and becoming wonderfully calm. “He will see him die in the village—not by fire, no, not by fire, for Tecumseh never burns an enemy.”

Again the march was resumed, with Tecumseh thoughtful, at the head of the band.

By degrees Oonalooska approached the hermit, and at length walked at his side.

“Oona,” said Hewitt, in the lowest of whispers, “when struck Tecumseh’s father a white-face?”

“Many, oh, so many moons ago, when the ground was white with feathers that fell from great birds in the clouds,” was the figurative answer, as softly uttered as the question had been.

“Where is the pale-face now?”

“She walks with her wolves,” was the reply, and the[39] speaker bestowed a look upon Alaska, whose tranquil, almost thoughtful countenance breathed not of insanity.

Hewitt raised his eyes to a contemplation of her face, vividly revealed by the glare of the torch borne by the brave in advance of her.

The workings of his countenance told that memory was busy, and, as he turned his eyes from the lunatic, his lips parted.

“So like, yet so unlike,” he murmured. “Oh, my God, can it be?—no, no, I will not think thus, and yet those lips—those lips—God, why did I fly my home that fearful night?” he suddenly interrupted himself, and a moment later he groaned. “But my boy—my Edgar. Oh Heaven, does he live? Oonalooska!”

The Indian touched the hermit’s arm significantly.

“Oona, whence came poor mad Alaska?”

Oonalooska started at the hermit’s tone.

“From the great land beyond the northern Kiskepila Sepe,[1]” he answered.

“From Virginia,” murmured Hewitt, “the land where I was happy once. Oona?”

“Hush!” whispered the captive brave as a shout burst from the vanguard. “The Shawnees are near their lodges.”

A moment later, the prisoners gained the summit of a high knoll, and, in the center of the valley that turned away from its foot, nestled the Indian village, upon which the day was breaking.

Suddenly Alaska turned upon the hermit.

“Ha! ha! ha!” she laughed, pointing toward the village. “Yonder the Lone Man and his friends will feel the fangs of Alaska’s children.”

Never before, in the broad light of noon, had Hewitt been so near the mad-woman, and as her eyes fell upon him he started back, exclaiming:

“My God! dispel my dreadful doubts. More like one, once beloved by me, she grows!”

And the queen laughed more discordantly at his words, whose import she did not comprehend.

[40]

Jim Girty, the renegade, lowered fierce looks upon the hermit, as the band marched toward the village, and once or twice his fingers clutched his tomahawk, whose keen edge he would fain have buried in the giant’s brain. But he dared not strike, for Hewitt was Tecumseh’s prisoner, and he bided his time for vengeance.

When Tecumseh returned to his lodge, after the destructive, mysterious shots, Girty effected a reconciliation with him, and was released. The renegade at once entered into the plans of the chief for the recapture of the whites, and led a band of braves to the banks of the Scioto to cut off their escape in that direction. For he knew that the hermit would never inhabit a cave without more than one avenue of escape, and his belief was verified, as the reader has witnessed.

Before departing on his mission, he had exacted from Tecumseh an oath to the effect that Eudora, if recaptured, should not be delivered over to the Wolf-Queen; but, on the contrary, should remain his prisoner, as before.

On the confines of the Indian “town” great numbers of women and children greeted the triumphant band, but Tecumseh would not permit a single birch to be applied to the persons of his prisoners.

Straight to the council-house marched the august chief and an imperative wave of the hand summoned the warriors to their accustomed positions.

Alaska followed, but paused without the line of braves, and fixed her eyes upon Tecumseh.

“The white-faces and the red traitor shall be tried at once,” said the chief, striding to the center of the structure. “The Pale Flower is White Chief’s prisoner. Now let Tecumseh’s chiefs speak.”

[41]

For a moment silence reigned, and then the renegade strode from his position.

His baleful eyes flashed hatred upon the prisoners, who stood bound, near the center post of the council-house, and his words sounded like icy drops falling upon red-hot iron.

“The White Chief speaks for death,” he cried, “for death at the stake! The pale-faces and the red-skinned traitor have slain two of Tecumseh’s bravest chiefs. Shall they long escape the doom they merit? I will claim my prisoner,” and he strode toward Eudora. “Ha! girl!” he hissed, in her ear, as his great hand closed on her delicate arm, “you never dreamed that I am in league with powers not of earth. All the powers of heaven and hell can not baffle Jim Girty. You are mine—mine—mine! That word is sweeter to me than wildwood honey.”

“One word with her before we part,” said Mayne Fairfax, smothering his rage, and stepping towards Eudora. “If God permits devils to triumph, then we never meet again. Eudora—”

The captive turned, but ere Fairfax could execute another step nearer her, Girty’s arm shot from his shoulder, and the young hunter went to the earth like a stricken statue.

“There! weakling!” cried the brute, darting a fierce look upon his fallen foe. “I’ll teach you how to interfere in other people’s business. Lay still there, or I’ll kick you to pieces.”

And again grasping Eudora’s arm, he hurried her toward the further end of the council-house.

The blow worked the hermit into a terrible passion, and had his hands then been free, the renegade would have paid dearly for the insult. Even mad Alaska did not witness the scene without emotion, for she suddenly stooped and raised one of her wolves above her head. But a look from Tecumseh, to whom she looked as though for authority, subdued her passion, and the animal was returned to his companions.

After a while, Mayne Fairfax regained his senses, and drew himself to his feet, by the aid of Hewitt’s garments.

“Oh, if I were free, boy!” whispered the giant, “I would walk across this council-house and choke that devil to death[42] But his time is coming. Hark! a new arrival!” and the hermit listened to the shouts nearing them from beyond the collection of lodges.

The shouts rapidly increased in distinctness, and presently the new-comers burst upon the sight of all.

The party consisted of three half-naked braves, and Tecumseh’s famous brother, the Prophet.

Through his devilish incantations, Laulewasikaw swayed the Indian mind to no common degree, and, sooner than disobey his commands, the Shawnees would have plucked their eyes from their sockets, or severed their most useful members.

His arrival was quite unexpected, and Tecumseh’s countenance told that he would rather that Laulewasikaw were at that time in his lodge at Greenville.

The Prophet advanced to the center of the house, and greeted the warriors assembled, then strode to Tecumseh, with whom he conversed for a short time in low tones. It was plainly manifest that the conversation was not agreeable to Tecumseh, for Laulewasikaw suddenly turned from him and sought Jim Girty.

“The council must proceed!” cried Tecumseh, intending, if possible, to prevent a conversation between his brother and the renegade. “The pale-faces must die, and the braves know that Tecumseh burns no prisoners at the tree. What, then, shall be their doom?”

After a moment of deathly silence, several chiefs arose and declared for crawling the gantlet, which punishment found favor in the eyes of Tecumseh.

“We will hear from Laulewasikaw, our Prophet,” said the renegade. “He will talk with the Manitou.”

Tecumseh frowned at this, but he dared not cross the path of his brother, the red sorcerer.

The Prophet left Girty’s side and walked to the middle ground. His single eye threw fierce glances at the three prisoners, calmly awaiting their doom, and he knew that they were in his power. His sorcery could doom them to any death desirable.

He drew a small bundle of sticks, tied with deer-thongs, beneath his long robe, and spread them upon the ground,[43] each the distance of several inches from its neighbors. Then after mumbling some gibberish with upturned face, and hands crossed upon his breast, he applied fire to the first stick. It burned freely, and was soon consumed. Another and another followed it to an ashy state, until every stick, save one, was consumed, and the last stubbornly refused to burn!

All eyes were centered upon the Prophet, during this heathenish specimen of his sorcery, and around the lips of Tecumseh played a smile of contempt.

In the great Shawnee’s mind there always existed a disbelief in sorcery, and at times he was outspoken against the black arts his brother practiced. But, in a convocation of his chiefs and warriors, he never dared to declaim against Laulewasikaw.

After several efforts—persistent ones they seemed to all save the prisoners—to fire the last and stubborn stick, the Prophet rose to his feet.

“The great Prophet of the Manitou will speak the doom of the pale lips, and their brother, the red traitor. The Manitou speaks through Laulewasikaw: ‘The skin must be torn from their bodies, when the Manitou’s lights appear, and then they must burn!’”

This terrible doom sent a thrill to every heart beneath the roof of the council-house, and drew a shriek from Eudora’s bloodless lips.

“My God!” cried Fairfax with pallid cheeks—for well might that sentence, which even Tecumseh could not affect, drive the color from the bravest face. “Flayed alive, and then burned!”

All knew that such a doom had resulted from Laulewasikaw’s brief conversation with the renegade.

Tecumseh made an effort to throw it aside. He argued eloquently against its brutality, but all to no effect. He reminded his braves that since he became a chief no prisoner had died at the stake, and to sustain his honour, he hoped that their votes would sustain him.

Briefly, sneeringly, and bitterly Laulewasikaw replied:

“Dared the Shawnees disobey the commands of the Great Spirit? If so, let them abide the consequences, which would prove swift and terrible.”

[44]

Seeing himself defeated, Tecumseh turned his back upon his brother, and commanded the voting to proceed.

The sole ballot, a great club, upon which were carved many devices intelligible only to the savage mind, was handed to the nearest warrior. Around the circle it swiftly passed. Those who decided for death by crawling the gantlet, struck the earth once with the club; those who decided for the dreadful doom pronounced by the sorcerer, bestowed two blows upon terra-firma.

Our friends held their breath as the club went round the living, doomful circle, and ere it returned to him who first handed it, they read the decision.

Nearly twenty braves had the manhood to sustain Tecumseh’s honor; but the others, slaves to the prophet’s cunning, decided the vote.

Flayed alive and then burned!

The result was hailed with gleeful shouts by the concourse of squaws assembled beyond the circle of warriors.

“To the strong lodge with the prisoners!” commanded Tecumseh, vainly trying to bridle his rage. “Great Spirit, know that Tecumseh does not sanction the work of Watchemenetoc.”

Among the braves who sprung forward to obey his command was the renegade, who did not attempt to conceal his triumph.

“I hold the best hand, now,” he hissed, as he paused before the giant hermit. “I’ll blunt the keen edge of my knife, and it will tear the covering from your heart.”

The hermit gritted his teeth, and something like a tremor passed over his frame. It was the tremor attesting the gathering of his Samsonian strength. The next moment, his bonds burst with a sharp noise, and his fingers griped Jim Girty’s throat!

Tighter and tighter grew the terrible grip; Girty’s eyes stared wildly at his foe, his tongue protruded from his throat, and his color changed to a sickly hue.

Tecumseh smiled at Hewitt’s action, and looked for Alaska; but she and her wolves stood not among the throng of women.

For some moments the savages gazed upon the scene spellbound,[45] when, with sudden impulse, they sprung at the giant. A score of hands grasped his arm, and, unresisting, he let Girty slide from his grip to the earth, where he lay blackened and motionless.

The next moment they were being hurried toward the prison-lodge, there to await their dreadful doom.

“I guess I’ve choked that devil to death,” whispered Hewitt to the weak young hunter, whom he supported at his side. “But I guess, too, that we’re in for it to-night, unless something mighty uncommon turns up. I thought that mad-woman would do something for us; but I reckon that she sees revenge in the fate proclaimed for us by the man she hates. Oh! I’d like to know who she is; but I guess that I will never know now.”

A few minutes later, the door of the strong hut closed behind them.

While the Shawnee council was deciding the doom of the three hunters, Alaska silently left the spot, and sought her wigwam. Her countenance bore but few traces of insanity. The wild fire of lunacy had grown dim in her eyes, and a casual observer would have believed her possessed of sanity.

From a cache beneath several strips of bark, comprising a portion of the floor of her lodge, she drew some large pieces of illy-cooked venison which she fed to her wolves that crowded around, eager for their daily repast.

“Ah! my children!” she cried, as piece after piece of venison dropped into the red mouths; “the White Chief would cheat you out of the meat of the pale-faces, and Oonalooska, the red traitor. Shall he do it? The giant slew Lupino, your brother, and now he is among our lodges. Hist!” and springing to her feet, she bounded to the door of the wigwam.

“The council is ended, and the red-men conduct the three[46] pale men to the strong lodge. But, ha! ha! ha! why leans the White Chief on the shoulder of Laulewasikaw? He walks as though he were drunk with the fire-water of the pale-faces in Chillicothe. And the White Lily walks beside Kalaska, to the White Chief’s lodge. Why is all this? Alaska’s ears must hear it!” and from the lodge she bounded toward the party who were just leaving the council-house.

“Whose fingers closed on White Chief’s throat?” she demanded of the Prophet, when her eye—once more fired with insanity—fell upon the renegade’s throat.

“The giant pale-face,” answered the sorcerer. “He dies to-night.”

“Yes, curse him!” hissed Jim Girty, placing his hand on his throat, which still bore the marks of Hewitt’s fingers, “I’ll file teeth in my knife, and by Heaven! I’ll saw his skin off by inches! Then I’ll throw him to Alaska’s wolves.”

The renegade’s words did not please the mad queen.

“When the White Chief throws the Lone Man to Alaska’s children, his flesh would be cold,” she said. “They shall not touch him after the White Chief’s knife has robbed him of his skin. They shall tear his throat, and the throats, too, of the young hunter and Oonalooska.”

“Curse her mad whims!” grated Girty, motioning the Prophet to resume his march.

Alaska did not follow, but turned on her heel and resought her lodge.

“The White Chief must keep his eyes on Alaska,” said Laulewasikaw, “or she will have her wolves upon the Shawnees’ prisoners, and his knife will not touch their flesh.”

“I will watch the mad she-devil,” hissed the renegade. “When night comes, I will throw a guard around her wigwam, and she shall be my prisoner until the bones of the hated three become ashes beneath the stake.”

“But who will be so brave as to guard Alaska and her wolves?” asked the Prophet.

The question nonplussed the renegade.

“Ah! the White Chief is puzzled!” said Laulewasikaw; “but the Great Prophet of the Shawnees can cut the sinews. In his paint-bag he carries the juice of a leaf that kills.”

The eyes of the renegade lighted up with a new, fierce[47] fire, and he bade the Prophet keep silent until some future time.

The remainder of the distance to the renegade’s lodge was traversed in silence, and again Eudora found herself beneath Jim Girty’s roof.

“My throat feels better, now,” he said. “Oh, curse that giant villain; his hand seemed a mighty vice moved by some infernal machinery, and I saw every star that ever glittered in the sky since the creation. Now let Laulewasikaw speak of the leaf that kills.”

Thus spoke the renegade when the twain found themselves in a lodge, belonging, by the right of erection, to the Prophet. Several guards had been stationed by Eudora’s prison, rendering her escape impossible.

Before the Prophet answered Girty, he drew a bunch of leaves from his medicine-pouch, and bruised them between two small, flat stones. A greenish liquid exuded from the leaves, and into this the Indian dipped his finger.

“Long ago Laulewasikaw discovered the juice that kills,” said the Prophet, looking up at Girty, who had watched his movements with feverish impatience. “Now let the White Chief and a trusty brave go to Alaska’s lodge, and let him throw to her wolves venison drunk with the juice of Watchemenetoc’s plant. Without her wolves, Alaska can do nothing.”

“I fear not the mad queen,” said Girty; “but her wolves.”

“Has the White Chief a brave in his band who is not afraid to enter Alaska’s lodge?”

“Yes,” said Girty, quickly. “Newaska is welcome to Alaska’s lodge. Her wolves wag their tails when he approaches.”

“Ah! he shall go!” cried the Prophet. “When the sun goes down he must go to the queen’s lodge, and awhile after he has sat down in the midst of her children, we will take the prisoners to the forest.”

“I will seek Newaska at once,” cried the renegade, springing to his feet. “My hour of triumph over all I hate is at hand, and once more Jim Girty will be enemyless!”

The Prophet remained in the lodge, and a short time[48] after the renegade’s departure, a young brave entered the structure.

It was Newaska, the young warrior deputed to poison Alaska’s wolves.

For a number of years the young Shawnee had been a favorite of the Wolf-Queen’s; often he had slept in her double lodge, and caressed the lupine gang whose fangs were harmless playthings to him. But, by and by Jim Girty drew him into his band of merciless braves, and Newaska became the renegade’s most pliant tool.

To the Prophet, by the poisoner, the White Chief sent several pieces of venison, into which the sorcerer infused a quantity of the juice of the deadly nightshade.

“Now,” said he, “Newaska will throw the venison to Alaska’s children, and step from her lodge.”

“When does it send them on the trail of death?” asked the young brave, thrusting the meat into a pouch beneath his robe.

“Before Newaska can repeat the names of the chiefs of his nation,” was the reply. “He must get Alaska beyond his sight before he feeds her children.”

“Newaska will work like the serpent,” said the brave, and glided from the Prophet’s lodge.

Meanwhile the day passed quickly to the doomed prisoners in the strong lodge. They saw no hope with cheering lay ahead.