Title: Early Carriages and Roads

Author: Sir Walter Gilbey

Release date: October 22, 2021 [eBook #66597]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Fay Dunn, Fiona Holmes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.

Hyphenation has been standardised.

Footnotes were moved to the ends of the text they pertain to and numbered in one continuous sequence.

BY

SIR WALTER GILBEY, Bart.

ILLUSTRATED

London

VINTON & CO., Ltd., 9, New Bridge Street, E.C.

1903

The use of carriages, coaches and wheeled conveyances have had an intimate relationship with the social life of English people from an early period in history.

Many instructive books have appeared on the subject of carriages generally, but these have been for the most part written by experts in the art of coach and carriage building.

In this publication, attention has been given to the early history of wheeled conveyances in England and their development up to recent times.

Elsenham Hall, Essex.

April, 1903.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| First Use of Wheeled Vehicles | 2 |

| Badness of Early Roads | 3 |

| Saxon Vehicles and Horse Litters | 4 |

| Continental Carriages in the 13th and 14th Centuries | 8 |

| Conveyances in Henry VI.’s Time | 11 |

| “Chariots” First Used on Great Occasions | 12 |

| First Use of Carriages: called Coaches | 13 |

| Coaches in France | 15 |

| Coaches First Used by Queen Elizabeth | 16 |

| Duke of Brunswick, 1588, Forbids Use of Coaches | 20 |

| The Stage Waggon | 21 |

| The Introduction of Springs | 23 |

| Steel Springs Introduced | 24 |

| The First Hackney Coaches | 26 |

| Excessive Number of Coaches in London | 28 |

| Hackney Carriages and the Thames Watermen | 30 |

| Hackney Carriages a Nuisance in London | 32 |

| Licensed Hackney Carriages | 33 |

| Coaches with “Boots” | 35 |

| Carriages in Hyde Park | 38 |

| Coach and Cart Racing | 40 |

| Regulations for Hackney Carriages | 41 |

| Pepys on Carriages | 43 |

| Glass Windows in Carriages | 45 |

| Improvements in Carriages | 47 |

| Pepys’ Private Carriage | 50 |

| Carriage Painting in Pepys’ Day | 52 |

| The First Stage Coaches | 54 |

| Objections Raised to Stage Coaches | 56 |

| Seventeenth Century High Roads | 62 |

| Hackney Cabs as a Source of Revenue | 66 |

| Manners of the Cabman | 69 |

| Cab-driving a Lucrative Occupation | 70 |

| Coaches and Roads in Queen Anne’s Time | 73 |

| [vi] | |

| Coaching in George I.’s and II.’s Reigns | 74 |

| Dean Swift on Coaches and Drivers | 76 |

| Roads in the 18th Century | 78 |

| Speed of the 18th Century Stage Coach | 80 |

| The Application of Springs | 84 |

| Outside Passengers | 87 |

| Roads in George III.’s Time | 88 |

| Improvements in Stage Coaches | 90 |

| The Mail Coach | 91 |

| Regulations for Mail and Stage Coaches | 94 |

| Mail Coach Parade on the King’s Birthday | 95 |

| The Mail Coachman and Guard | 97 |

| “The Road” in Winter | 100 |

| Passenger Fares | 102 |

| Difference Between Stage and Mail Coach | 102 |

| The “Golden Age” of Coaching | 104 |

| Fast Coaches | 106 |

| Heavy Taxation of Coaches | 111 |

| Early Cabs | 112 |

| Private and Stage Coaches, 1750-1830 | 116 |

| Varieties of Carriage | 120 |

| PAGE | ||

| “Going to Bury Fair” | Frontispiece | |

| Hammock Waggon | 5 | |

| Horse Litter | 7 | |

| Flight of Princess Ermengarde | 9 | |

| Queen Elizabeth’s Travelling Coach | 17 | |

| Hackney Coaches in London, 1637 | 29 | |

| Coach of Queen Elizabeth’s Ladies | 35 | |

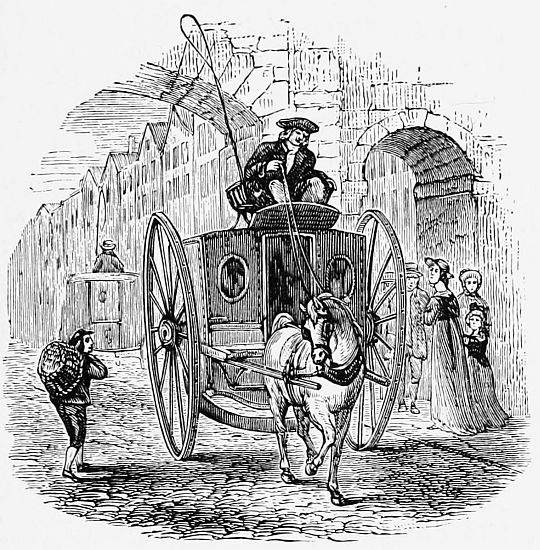

| The Machine, 1640-1700 | Face 56 | |

| Mr. Daniel Bourn’s Roller Wheel Waggon, 1763 | 79 | |

| Travelling Posting Carriage (1), 1750 | 83 | |

| Travelling Posting Carriage (2), 1750 | 85 | |

| Portrait of Mr. John Palmer | Face 92 | |

| Portrait of Mr. Macadam | 104 | |

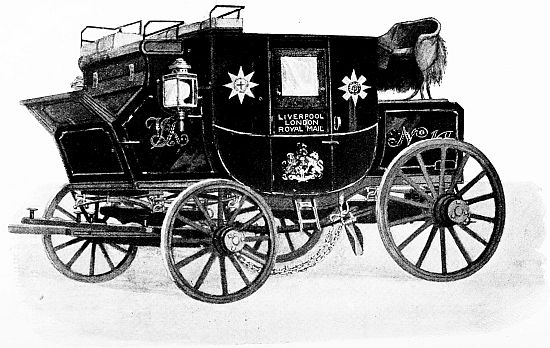

| Royal Mail Coach | 108 | |

| London Hackney Cab (Boulnois’ Patent) | 115 | |

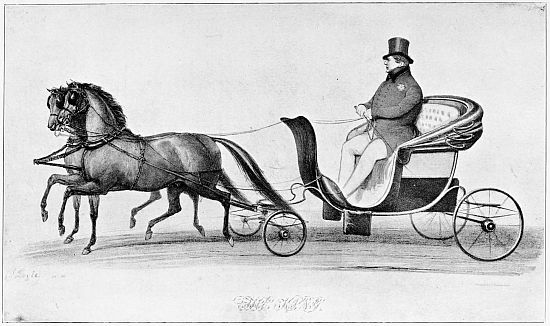

| Travelling Post, 1825-35 | Face 118 | |

| King George IV. in His Pony Phaeton | 120 | |

John Bale Sons and Danielsson Ltd.

GT Titchfield Street

LONDON.

Only some three hundred and fifty years have elapsed since wheeled conveyances for passengers came into use in England; but, once introduced, they rapidly found favour with all classes of society, more especially in cities. The progress of road-making and that of light horse-breeding are so intimately connected with the development of carriages and coaches that it is difficult to dissociate the three. In the early days of wheeled traffic the roads of our country were utterly unworthy of the name, being, more particularly in wet weather, such quagmires that they were often impassable.

Over such roads the heavy carriages of our ancestors could only be drawn by teams of heavy and powerful horses, strength being far more necessary than speed; and for many[2] generations the carriage or coach horse was none other than the Great or Shire Horse. Improved roads made rapid travel possible, and the increase of stage coaches created a demand for the lighter and more active harness horses, for production of which England became celebrated.

If comparatively little has been said concerning horses, it is because the writer has already dealt with that phase of the subject in previous works.[1]

[1] The Great Horse, or War Horse; Horses, Past and Present. By Sir Walter Gilbey, Bart. (Vinton and Co., Ltd.)

FIRST USE OF WHEELED VEHICLES.

Wheeled vehicles for the conveyance of passengers were first introduced into England in the year 1555. The ancient British war chariot was neither more nor less than a fighting engine, which was probably never used for peaceful travelling from place to place. Carts for the conveyance of agricultural produce were in use long before any wheeled vehicle was adapted for passengers. The ancient laws and institutes of Wales, codified by Howel Dda, who reigned from A.D. 942 to 948, [3]describe the “qualities” of a three-year-old mare as “to draw a car uphill and downhill, and carry a burden, and to breed colts.” The earliest mention of carts in England that some considerable research has revealed is in the Cartulary of Ramsay Abbey (Rolls Series), which tells us that on certain manors in the time of Henry I. (1100-1135) there were, among other matters, “three carts, each for four oxen or three horses.”

BADNESS OF EARLY ROADS.

That carriages did not come into use at an earlier period than the sixteenth century is no doubt due to the nature of the cattle tracks and water-courses which did duty for roads in England. These were of such a nature that wheeled traffic was practically impossible for passengers, and was exceedingly difficult for carts and waggons carrying goods.

In old documents we find frequent mention of the impossibility of conveying heavy wares by road during the winter. For example, when Henry VIII. began to suppress the monasteries, in 1537, Richard Bellasis, entrusted with the task of dismantling Jervaulx Abbey, in Yorkshire, refers to the quantity of lead used for[4] roofing purposes, which “cannot be conveyed away till next summer, for the ways in that countrie are so foule and deepe that no carriage (cart) can pass in winter.”

In the Eastern counties, and no doubt elsewhere in England, our ancestors used the water-courses and shallow stream beds as their roads. This is clear to anyone who is at pains to notice the lie and course of old bye-ways; and it is equally clear that a stream when low offered a much easier route to carts, laden or empty, than could be found elsewhere. The beds of the water courses as a general rule are fairly smooth, hard and gravelled, and invited the carter to follow them rather than to seek a way across the wastes. In process of use the banks and sides were cut down by the wheels or by the spade; and eventually the water was diverted into another channel and its old bed was converted into a road.

SAXON VEHICLES AND HORSE LITTERS.

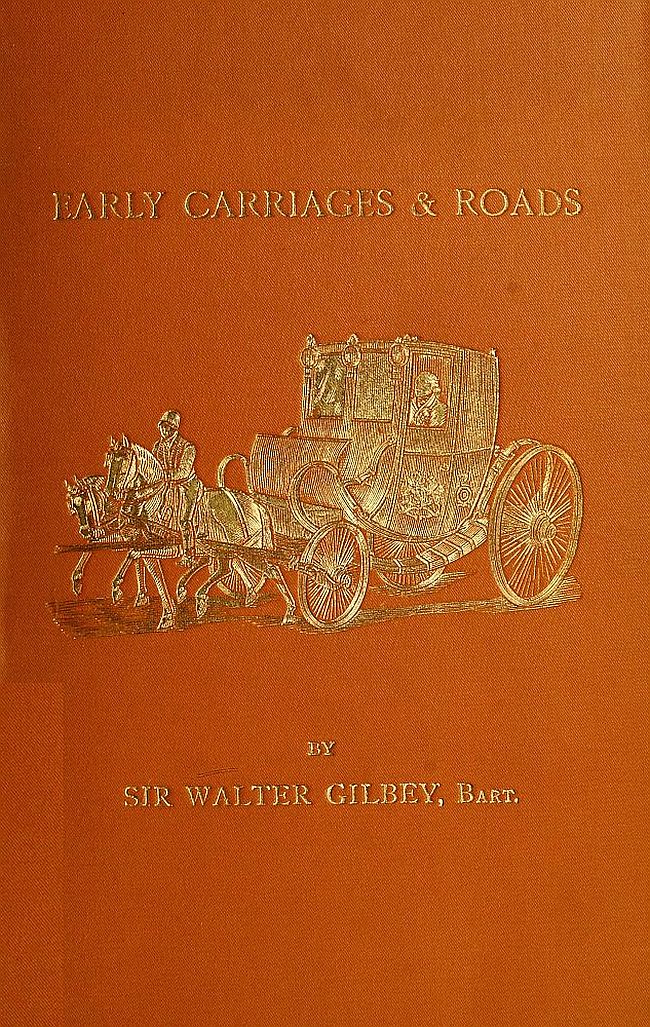

Strutt states that the chariot of the Anglo-Saxons was used by distinguished persons for travel. If the illustrations from which he describes them give a fair idea of their proportions and general construction, they must have been singularly uncomfortable[5] conveyances. The drawing is taken from an illuminated manuscript of the Book of Genesis in the Cotton Library (Claud. B. iv.), which Strutt refers to the ninth century, but which a later authority considers a production of the earlier part of the eleventh. The original drawing shows a figure in the hammock waggon, which figure represents Joseph on his way to meet Jacob on the latter’s arrival in Egypt; this figure has been erased in order to give a clear view of the conveyance, which no doubt correctly represents a travelling[6] carriage of the artist’s own time, viz., A.D. 1100-1200.

HAMMOCK WAGGON.

Supposed to have been in use in England about

A.D. 1100-1200.

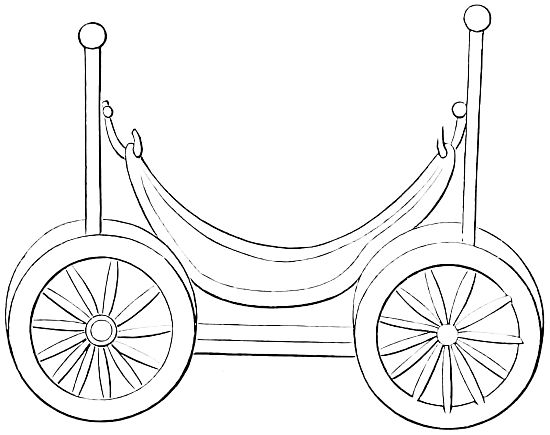

Horse litters, carried between two horses, one in front and one behind, were used in early times by ladies of rank, by sick persons, and also on occasion to carry the dead. Similar vehicles of a lighter description, carried by men, were also in use.

William of Malmesbury states that the body of William Rufus was brought from the spot where he was killed in the New Forest in a horse-litter (A.D. 1100). When King John fell ill at Swineshead Abbey, in 1216, he was carried in a horse-litter to Newark, where he died. For a man who was in good health to travel in such a conveyance was considered unbecoming and effeminate. In recording the death, in 1254, of Earl Ferrers, from injuries received in an accident to his conveyance, Matthew Paris deems it necessary to explain that the Earl suffered from gout, which compelled him to use a litter when moving from place to place. The accident was caused by the carelessness of the driver of the horses, who upset the conveyance while crossing a bridge.

The illustration is copied from a drawing which occurs in a manuscript in the British Museum (Harl. 5256).

Froissart speaks of the English returning “in their charettes” from Scotland after Edward III.’s invasion of that country, about 1360; but there is little doubt that the vehicles referred to were merely the baggage carts which accompanied the army used by the footsore and fatigued soldiers.

HORSE LITTER USED A.D. 1400-1500.

The same chronicler refers to use of the “chare” or horse-litter in connection with Wat Tyler’s insurrection in the year 1380:—

“The same day that these unhappy people of Kent were coming to London, there returned from Canterbury the King’s mother, Princess of Wales, coming from her pilgrimage. She was in great jeopardy to have been lost, for these people came to her chare and dealt rudely with her.”

As the chronicler states that the “good lady” came in one day from Canterbury to London, “for she never durst tarry by the way,” it is evident that the chare was a “horse-litter,” the distance exceeding sixty miles.

The introduction of side-saddles by Anne of Bohemia, Richard II.’s Queen, is said by Stow to have thrown such conveyances into disuse: “So was the riding in those whirlicotes and chariots forsaken except at coronations and such like spectacles:” but when the whirlicote or horse-litter was employed for ceremonial occasions it was a thing of great magnificence.

CONTINENTAL CARRIAGES IN THE 13TH AND 14TH CENTURIES.

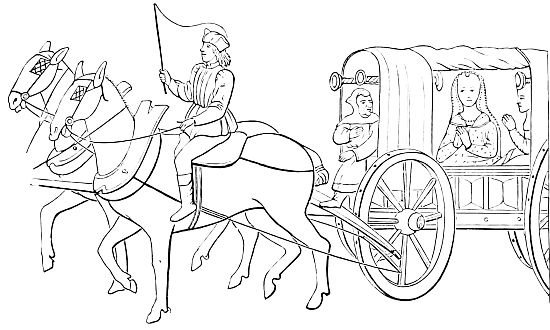

Carriages were in use on the continent long before they were employed in England. In 1294, Philip the Fair of France issued an edict whose aim was the suppression of luxury; under this ordinance the wives of citizens were forbidden to use carriages, and the prohibition appears to have been rigorously enforced. They were used in Flanders during the first half of the fourteenth century; an ancient Flemish chronicle in the British Museum (Royal MSS. 16,[9] F. III.) contains a picture of the flight of Ermengarde, wife of Salvard, Lord of Rouissillon.

THE FLIGHT OF PRINCESS ERMENGARDE.

Carriage used about 1300-1350 in Flanders.

The lady is seated on the floor boards of a springless four-wheeled cart or waggon, covered in with a tile that could be raised or drawn aside; the body of the vehicle is of carved wood and the outer edges of the wheels are painted grey to represent iron tires. The conveyance is drawn by two horses driven by a postillion who bestrides that on the near-side. The traces are apparently of rope, and the outer trace[10] of the postillion’s horse is represented as passing under the saddle girth, a length of leather (?) being let in for the purpose; the traces are attached to swingle-bars carried on the end of a cross piece secured to the base of the pole where it meets the body.

Carriages of some kind appear also to have been used by men of rank when travelling on the continent. The Expeditions to Prussia and the Holy Land of Henry, Earl of Derby, in 1390 and 1392-3 (Camden Society’s Publications, 1894), indicate that the Earl, afterwards King Henry IV. of England, travelled on wheels at least part of the way through Austria.

The accounts kept by his Treasurer during the journey contain several entries relative to carriages; thus on November 14, 1392, payment is made for the expenses of two equerries named Hethcote and Mansel, who were left for one night at St. Michael, between Leoban and Kniltelfeld, with thirteen carriage horses. On the following day the route lay over such rugged and mountainous country that the carriage wheels were broken despite the liberal use of grease; and at last the narrowness of the way obliged the Earl to exchange his own carriage for two smaller ones better suited to the paths of the district.

The Treasurer also records the sale of an old carriage at Friola for three florins. The exchange of the Earl’s “own carriage” is the significant entry: it seems very unlikely that a noble of his rank would have travelled so lightly that a single cart would contain his own luggage and that of his personal retinue; and it is also unlikely that he used one baggage cart of his own. The record points directly to the conclusion that the carriages were passenger vehicles used by the Earl himself.

CONVEYANCES IN HENRY VI.’s TIME.

It was probably possession of roads unworthy of the name that deterred the English from following the example of their continental neighbours, for forty years later the horse-litter was still the only conveyance used by ladies. On July 13, 1432, King Henry VI. writes to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishops of Winchester and Durham, and the High Treasurer, in connection with the journeyings of Joan of Navarre, widow of Henry IV.:—

“And because we suppose that she will soon remove from the place where she is now, that ye order for her also horses for two chares and let her remove thence into whatever place within our kingdom that she pleases.”

“CHARIOTS” FIRST USED ON GREAT OCCASIONS.

There is still some little doubt concerning the date when the carriage or coach was first seen in England; but it seems certain that wheeled vehicles of some kind were used on great ceremonial occasions before the coach suitable for ordinary travel came into vogue.

When Catherine of Aragon was crowned with Henry VIII., on June 24, 1509, she was, says Holinshed, conveyed in a litter followed by “chariots covered, with ladies therein.” Similarly when Anne Boleyn passed in state through London she was borne in a litter followed by ladies in a chariot. From these records it is clear that the horse-litter was considered the more dignified conveyance.

The litter used by princesses and ladies of high degree on state occasions was very richly furnished. The poles on which it was supported were covered with crimson velvet, the pillows and cushions with white satin, and the awning overhead was of cloth of gold. The trappings of the horses and dress of the grooms who led them were equally splendid. Ancient records contain minute particulars of the materials purchased for litters on special occasions, and[13] these show with what luxury the horse-litter of a royal lady was equipped.

In this connection we must note that Markland, in his Remarks on the Early Use of Carriages in England, discriminates between the “chare” and the horse-litter: the chare gave accommodation to two persons or more and was used for ordinary purposes of travel, and he believes that it ran on wheels; whereas the horse-litter accommodated only one person, and that usually a lady of high rank, on ceremonial occasions.

The chariot was clearly rising in esteem at this period, for when Queen Mary went in state to be crowned in the year 1553, she herself occupied a chariot. It is described as “a chariot with cloth of tissue, drawn with six horses”; and it was followed by another “with cloth of silver and six horses,” in which were seated Elizabeth and Anne of Cleves.

FIRST USE OF CARRIAGES; CALLED COACHES.

We are now come to the period when the coach proper was introduced into England. Stow, in his Summary of the English Chronicles, says that carriages were not used in England till 1555, when Walter Rippon built one for the Earl of Rutland, “this[14] being the first ever made.” Taylor, the “Water Poet,” in his life of Thomas Parr, states that Parr was 81 years old “before there was any coach in England.” Parr was born in 1483, so the year in which he reached 81 would be 1564; in that year William Boonen, a Dutchman, brought from the Netherlands a coach which was presented to Queen Elizabeth; and Taylor, on Parr’s authority, mentions this as the “first one ever seen here.”

The obvious inference is that Parr had not heard of or (what is more probable considering his advanced age) had forgotten the coach built eleven years earlier for a much less conspicuous person than the sovereign. There is also mention in the Burghley Papers (III., No. 53) quoted by Markland, of Sir T. Hoby offering the use of his coach to Lady Cecil in 1556. It is quite likely that the coach brought by Boonen from the Netherlands served as a model for builders in search for improvements, as we read in Stow’s Summary: “In 1564, Walter Rippon made the first hollow, turning coach, with pillars and arches, for her Majesty Queen Elizabeth.” What a “hollow, turning” coach may have been it is difficult to conjecture. Drawings of a hundred years[15] later than this period show no mechanism resembling a “turning head” or fifth wheel. Captain Malet[2] says that the Queen suffered so much in this vehicle, when she went in it to open Parliament, that she never used it again. The difference between the coach for ordinary travel and the chariot for ceremony is suggested by the next passage in the Summary: “In 1584 he (Rippon) made a chariot throne with four pillars behind to bear a crown imperial on the top, and before, two lower pillars whereon stood a lion and a dragon, the supporters of the arms of England.”

[2] Annals of the Road, London, 1876.

Queen Elizabeth, according to Holinshed, used a “chariot” when she went to be crowned at Westminster in 1558.

COACHES IN FRANCE.

By way of showing how the old authorities differ, mention may be made of the coach which Henry Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel, brought from France and presented to the Queen, it is said, in 1580. This vehicle is cited as the first coach ever seen in public but inasmuch as we have ample evidence to[16] prove the last statement incorrect, apart from the fact that the Earl died in 1579, nothing more need be said about it.

France does not seem to have been very far ahead of Britain in the adoption of coaches. In 1550 there were only three in Paris; one belonged to the Queen of Francis I., another to Diana of Poitiers, and the third to René de Laval, who was so corpulent that he could not ride. Mr. George Thrupp, in his History of the Art of Coach Building (1876), observes that “there must have been many other vehicles in France, but it seems only three covered and suspended coaches.”

COACHES FIRST USED BY QUEEN ELIZABETH.

Queen Elizabeth travelled in a coach, either the one built by Walter Rippon or that brought by Boonen (who, by the way, was appointed her coachman), on some of her royal progresses through the kingdom. When she visited Warwick in 1572, at the request of the High Bailiff she “caused every part and side of the coach to be opened that all her subjects present might behold her, which most gladly they desired.”

The vehicle which could thus be opened[17] on “every part and side” is depicted incidentally in a work executed by Hoefnagel in 1582, which Markland believed to be probably the first engraved representation of an English coach. As will be seen from the reproduction here given, the body carried a roof or canopy on pillars, and the intervening spaces could be closed by means of curtains.

QUEEN ELIZABETH’S TRAVELLING COACH.

About the year 1582.

Queen Elizabeth seems to have preferred riding on a pillion when she could; she rode thus on one occasion from London to Exeter, and again we read of her going in state to St. Paul’s on a pillion behind her Master of the Horse. Sir Thomas Browne, writing to his son on October 15, 1680, says: “When Queen Elizabeth came to Norwich, 1578, she came on horseback[18] from Ipswich by the high road to Norwich, but she had a coach or two in her train.”

Country gentlemen continued to travel on horseback, though ladies sometimes made their journeys by coach. The Household Book of the Kytson family of Hengrave in Suffolk contains the following entry under date December 1, 1574: “For the hire of certain horses to draw my mistress’ coach from Whitsworth to London 26 shillings and 8 pence.”

Other entries show that “my mistress” occupied the coach: whence it would appear that not all our country roads in Queen Elizabeth’s time were impassable during the winter, as we might reasonably infer from many contemporary records. The horse-litter, as we may well suppose, was an easier conveyance than the early springless coach: for example, in Hunter’s Hallamshire we find mention of Sir Francis Willoughby’s request in 1589 to the Countess of Shrewsbury to lend her horse-litter and furniture for his wife, who was ill and unable to travel either on horseback or in a coach.

It may be observed here that the latest reference we have found to the use of the horse-litter occurs in the Last Speech of Thomas Pride (Harleian Miscellany): in[19] 1680 an accident happened to General Shippon, who “came in a horse-litter wounded to London; when he paused by the brewhouse in St. John Street a mastiff attacked the horse, and he was tossed like a dog in a blanket.”

Owing no doubt to their patronage by royalty, coaches grew rapidly popular. William Lilly, in a play called “Alexander and Campaspes,” which was first printed in 1584, makes one of his characters complain of those who had been accustomed to “go to a battlefield on hard-trotting horses now riding in easy coaches up and down to court ladies.” Stow, referring to the coach brought to England by Boonen, says:—

“After a while divers great ladies, with as great jealousy of the Queen’s displeasure, made them coaches and rid in them up and down the countries, to the great admiration of all the beholders, but then by little and little they grew usual among the nobilitie and others of sort, and within twenty years became a great trade of coach making.”

This confirms the statement of Lilly above quoted: it is quite clear therefore that, about 1580, coaches had come into general use among the wealthy classes. Their popularity became a source of anxiety to those who saw in the use of a coach the coming degeneracy of men and neglect of horsemanship.

DUKE OF BRUNSWICK, 1588, FORBIDS USE OF COACHES.

In 1588, Julius Duke of Brunswick issued a proclamation forbidding the vassals and servants of his electorate to journey in coaches, but on horseback, “when we order them to assemble, either altogether or in part, in times of turbulence, or to receive their fiefs, or when on other occasions they visit our court.” The Duke expressed himself strongly in this proclamation, being evidently resolved that the vassals, servants and kinsmen who “without distinction young and old have dared to give themselves up to indolence and to riding in coaches,” should resume more active habits.

The same tendency on the one side and the same feeling on the other in this country led to the introduction of a Bill in Parliament in November, 1601, “to restrain the excessive use of coaches,” but it was rejected. Whereupon:—

“Motion was made by the Lord Keeper, that forasmuch as the said Bill did in some sort concern the maintenance of horses within this realm, consideration might be had of the statutes heretofore made and ordained touching the breed and maintenance of horses. And that Mr. Attorney-general should peruse and consider of the said statutes, and of some fit Bill to be drawn and prefered to the house touching[21] the same, and concerning the use of coaches: which motion was approved of the House.”

It does not appear, however, that any steps were taken by the Parliament of the time to check the liberty of those who could afford it to indulge in coaches.

They were probably little used except in London and large towns where the streets afforded better going than country roads: though, as we have seen, Queen Elizabeth took coaches with her when making a progress. The coach seems to have been unknown in Scotland till near the end of the century, for we read that when, in 1598, the English Ambassador to Scotland brought one with him “it was counted a great marvel.”

THE STAGE WAGGON.

About 1564 the early parent of the stage coach made its appearance. Stow says: “And about that time began long waggons to come in use, such as now come to London from Canterbury, Norwich, Ipswich, Gloucester, &c., with passengers and commodities.” These were called “stages”: they were roomy vehicles with very broad wheels which prevented them sinking too deeply into the mud: they travelled very slowly, but[22] writers of the period make frequent allusions to the convenience they provided. Until the “long waggon” came into use the saddle and pack horse were the only means of travelling and carrying goods: this conveyance was largely used by people of small means until late in the eighteenth century, when stage coaches began to offer seats at fares within the reach of the comparatively poor.

Some confusion is likely to arise when searching old records from the fact that words now in current use have lost their original meaning. Thus in an Act passed in the year 1555 for “The amending of High Ways,” the preamble states that certain highways are “now both very noisome and tedious to travel in and dangerous to all passengers and ‘cariages.’” We might read this to mean vehicles for the conveyance of passengers; but the text (which empowers local authorities to make parishioners give four days’ work annually on the roads where needed) shows us that the “cariage” or “caryage” is identical with the “wayne” or “cart” used in husbandry. “Carriage” is used in the same sense in a similar Act of Elizabeth dated 1571, which requires the local authority to repair certain[23] streets near Aldgate which “become so miry and foul in the winter time” that it is hard for foot-passengers and “caryages” to pass along them.

THE INTRODUCTION OF SPRINGS.

It is impossible to discover when builders of passenger vehicles first endeavoured to counteract the jolting inseparable from the passage of a primitive conveyance over rough roads by means of springs. Homer tells us that Juno’s car was slung upon cords to lessen the jolting: and the ancient Roman carriages were so built that the body rested on the centre of a pole which connected the front and rear axles, thus reducing the jolt by whatever degree of spring or elasticity the pole possessed.

To come down to later times, Mr. Bridges Adams in English Pleasure Carriages (1837) refers to a coach presented by the King of Hungary to King Charles VII. of France (1422-1461), the body of which “trembled.” Mr. George Thrupp considers that this probably indicates a coach-body hung on leather straps or braces, and was a specimen of the vehicle then in use in Hungary. At Coburg several ancient carriages are preserved: one of those built in 1584 for the[24] marriage ceremony of Duke John Casimir, the Elector of Saxony, is hung on leather braces from carved standard posts which, says Mr. Thrupp, “are evidently developed from the standards of the common waggon. The body of this coach is six feet four inches long and three feet wide: the wheels have wooden rims, but over the joints of the felloes are small plates of iron about ten inches long.”

In regard to these iron plates it will be remembered that the wheels of the coach represented in the “Flemish Chronicle” of the first half of the fourteenth century referred to on pp. 8-9, is furnished with complete iron tires. Neither this vehicle, nor that of Queen Elizabeth, a sketch of which is given on p. 17 are furnished with braces of any kind. It would not be judicious to accept these drawings as exactly representing the construction of the carriages, but if the artist has given a generally accurate picture it is difficult to see how or where leather braces could have been applied to take the dead weight of the coach body off the under-carriage.

STEEL SPRINGS INTRODUCED.

Mr. Thrupp states that steel springs were first applied to wheel carriages about[25] 1670,[3] when a vehicle resembling a Sedan chair on wheels, drawn and pushed by two men, was introduced into Paris. This conveyance was improved by one Dupin, who applied two “elbow springs” by long shackles to the front axle-tree which worked up and down in a groove under the seat. The application of steel springs to coaches drawn by horses was not generally practised until long afterwards: in 1770 Mons. Roubo, a Frenchman, wrote a treatise on carriage building, from which we learn that springs were by no means universally employed.

[3] See page 84.

When used, says Mr. Thrupp,

“They were applied to the four corners of a perch carriage and placed upright, and at first only clipped in the middle to the posts of the earlier carriages, while the leather braces went from the tops of the springs to the bottoms of the bodies without any long iron loops such as we now use; and as the braces were very long we find that complaints were made of the excessive swinging and tilting and jerking of the body. The Queen’s coach is thus suspended. Four elbow springs, as we should call them, were fastened to the bottom of the body, but again the ends did not project beyond the bottom, and the braces were still far too long; and Mons. Roubo doubts whether springs were much use.”

The doubt concerning the value of springs[26] was shared in this country; for Mr. Richard Lovell Edgeworth, in his Essay on the Construction of Roads and Carriages (1817), tells us that in 1768 he discovered that springs were as advantageous to horses as to passengers, and constructed a carriage for which the Society of English Arts and Manufactures presented him with a gold medal. In this carriage the axletrees were divided and the motion of each wheel was relieved by a spring.

Travel in a springless coach over uneven streets and the roughest of roads could not have been a sufficiently luxurious mode of progress to lay the traveller open to charge of effeminacy. Taylor, the Water Poet, was no doubt biased in favour of the watermen, but he probably exaggerated little when he wrote, in 1605, of men and women “so tost, tumbled, jumbled and rumbled” in the coach of the time.

THE FIRST HACKNEY COACHES.

It was in the year 1605 that hackney coaches came into use; for several years these vehicles did not stand or “crawl” about the streets to be hired, but remained in the owners’ yards until sent for. In 1634 the first “stand” was established in[27] London, as appears from a letter written by Lord Stafford to Mr. Garrard in that year:—

“I cannot omit to mention any new thing that comes up amongst us though ever so trivial. Here is one Captain Bailey, he hath been a sea captain, but now lives on land about this city where he tries experiments. He hath created, according to his ability, some four hackney coaches, put his men into livery and appointed them to stand at the Maypole in the Strand, giving them instructions at what rate to carry men into several parts of the town where all day they may be had. Other hackney men veering this way, they flocked to the same place and performed their journeys at the same rate so that sometimes there is twenty of them together which dispose up and down, that they and others are to be had everywhere, as watermen are to be had at the waterside.”

Lord Stafford adds that everybody is much pleased with the innovation. It may here be said, on the authority of Fynes Morryson, who wrote in 1617, that coaches were not to be hired anywhere but in London at that time. All travel (save in the slow long waggons) was performed on horseback, the “hackney men”[4] providing horses at from 2½d. to 3d. per mile for those who did not keep their own.

[4] See Horses Past and Present, by Sir Walter Gilbey, Bart. Vinton & Co., 1900.

The number of coaches increased rapidly[28] during the earlier part of the seventeenth century.

EXCESSIVE NUMBER OF COACHES IN LONDON.

The preamble of a patent granted Sir Saunders Duncombe in 1634 to let Sedan chairs refers to the fact that the streets of London and Westminster “are of late time so much encumbered and pestered with the unnecessary multitude of coaches therein used”; and in 1635 Charles I. issued a proclamation on the subject. This document states that the “general and promiscuous use” of hackney coaches in great numbers causes “disturbance” to the King and Queen personally, to the nobility and others of place and degree; “pesters” the streets, breaks up the pavements and cause increase in the prices of forage. For which reasons the use of hackney coaches in London and Westminster and the suburbs is forbidden altogether, unless the passenger is making a journey of at least three miles. Within the city limits only private coaches were allowed to ply, and the owner of a coach was required to keep four good horses or geldings for the king’s service.

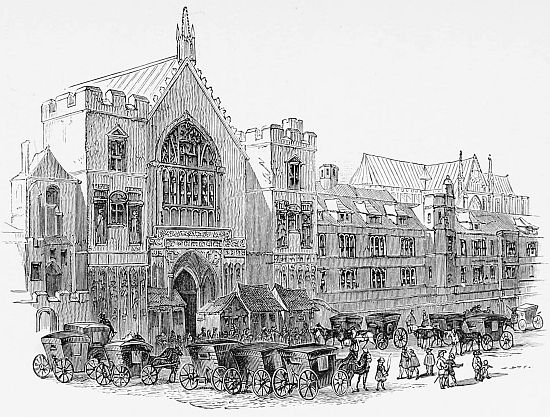

HACKNEY COACHES IN LONDON, 1637.

This proclamation evidently produced the

desired effect, for in 1637 there were only[29]

[30]

sixty hackney carriages in London: the

majority of these were probably owned by

James Duke of Hamilton, Charles’ Master

of the Horse, to whom was granted in July

of that year power to license fifty hackney

coachmen in London, Westminster and the

suburbs, and “in other convenient places”;

and this notwithstanding the fact that in

1636 the vehicles “in London, the suburbs

and within four-mile compass without are

reckoned to the number of six thousand and

odd.”[5]

[5] Coach and Sedan Pleasantly Disputing for Place and Precedence, the Brewer’s Cart being Moderator. Published at London by Robert Raworth for John Crooch in 1636.

Charles I. can hardly have shared the dislike exhibited by some of his subjects to wheel passenger traffic, for in 1641 we find him granting licenses for the importation of horses and enjoining licensees to import coach horses, mares, and geldings not under 14 hands high and between the ages of three and seven years.

HACKNEY CARRIAGES AND THE THAMES WATERMEN.

The number of cabs, then called hackney coaches, soon produced an effect upon the earnings of the Thames watermen, who,[31] until these vehicles were introduced, enjoyed the monopoly of passenger traffic. Thomas Dekker[6] refers to the resentment felt by the watermen in 1607, two years after the hackney couch made its appearance:—

“The sculler told him he was now out of cash, it was a hard time; he doubts there is some secret bridge made over to hell, and that they steal thither in coaches, for every justice’s wife and the wife of every citizen must be jolted now.”

[6] A Knight’s Conjuring Done in Earnest. By Thomas Dekker. London: 1607.

There seems to have been good reason for the preference given the hackney coach over the waterman’s wherry. The preamble of an Act passed in 1603 “Concerning Wherrymen and Watermen” shows that the risks attending a trip on the Thames were not inconsiderable, and that love of novelty was not the only motive which caused the citizens of London to take the hackney coach instead of the wherry. This Act forbade the employment of apprentices under 18 years of age, premising that:—

“It hath often happened that divers and sundry people passing by water upon the River of Thames between Windsor and Gravesend have been put to great hazard and danger of the loss of their lives and goods, and many times have perished and been drowned in the said River through the unskilfulness[32] and want of knowledge or experience in the wherrymen and watermen.”

In 1636, when, as we have seen, there were over 6,000 coaches, private and hackney, in London, Sedan chairs also were to be hired in the streets; and the jealousy with which the hackney coachman regarded the chairman was only equalled by the jealousy with which the waterman regarded them both. We quote from “Coach and Sedan,” the curious little publication before referred to:—

“Coaches and Sedans (quoth the waterman) they deserve both to be thrown into the Thames, and but for stopping the Channel I would they were, for I am sure where I was wont to have eight or ten fares in a morning, I now scarce get two in a whole day. Our wives and children at home are ready to pine, and some of us are fain for means to take other professions upon us.”

HACKNEY CARRIAGES A NUISANCE IN LONDON.

By the year 1660, the number of hackney coaches in London had again grown so large that they were described in a Royal Proclamation as “a common nuisance,” while their “rude and disorderly handling” constituted a public danger. For these reasons the vehicles were forbidden to stand in the streets for hire, and the drivers were directed to stay in the yards until they[33] might be wanted. We can well understand that the narrowness of the streets made large numbers of coaches standing, or “crawling,” to use the modern term, obstacles to traffic; and it is interesting to notice that the earliest patent granted in connection with passenger vehicles (No. 31 in 1625) was to Edward Knapp for a device (among others) to make the wheels of coaches and other carriages approach to or recede from each other “where the narrowness of the way may require.”

LICENSED HACKNEY CARRIAGES.

In 1662, there were about 2,490 hackney coaches in London, if we may accept the figures given by John Cressel in a pamphlet, which we shall consider on a future page. It was in this year that Charles II. passed a law appointing Commissioners with power to make certain improvements in the London streets. One of the duties entrusted to them was that of reducing the number of hackney coaches by granting licenses; and only 400 licenses were to be granted.

These Commissioners grossly abused the authority placed in their hands, wringing bribes from the unfortunate persons who applied for licenses, and carrying out their[34] task with so little propriety that in 1663 they were indicted and compelled to restore moneys they had wrongfully obtained. In regard to this it is to be observed that one of the 400 hackney coach licenses sanctioned by the Act was a very valuable possession. We learn from a petition submitted by the hackney coachmen to Parliament that holders of these licenses, which cost £5 each, sold them for £100. The petition referred to is undated, but appears to have been sent in when William III.’s Act to license 700 hackney coaches (passed in 1694) was before Parliament.

The bitterness of the watermen against Sedan chairs seems to have died out by Pepys’ time, but it was still hot against the hackney coaches, as a passage in the Diary sufficiently proves. Proceeding by boat to Whitehall on February 2, 1659, Samuel Pepys talked with his waterman and learned how certain cunning fellows who wished to be appointed State Watermen had cozened others of their craft to support an address to the authorities in their favour. According to Pepys’ informant, nine or ten thousand hands were set to this address (the men were obviously unable to read or write) [35]“when it was only told them that it was a petition against hackney coaches.”

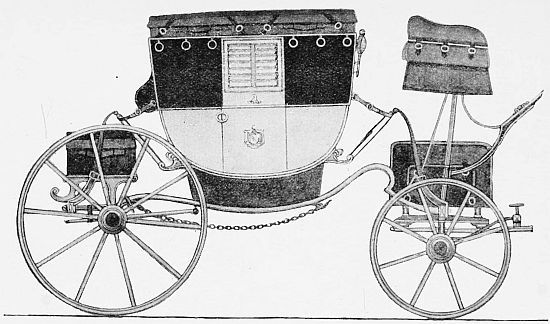

COACHES WITH “BOOTS.”

From Coach and Sedan (see page 30), we obtain a quaint but fairly graphic description of the coach of this period:—

“The coach was a thick, burly, square-set fellow in a doublet of black leather, brasse button’d down the breast, back, sleeves and wings, with monstrous wide boots, fringed at the top with a net fringe, and a round breech (after the old fashion) gilded, and on his back an atchievement of sundry coats [of arms], in their proper colours.”

COACH OF QUEEN ELIZABETH’S LADIES.

Showing near-side “Boot.”

The “boots” were projections at the sides of the body between the front and back wheels, as shown in the drawing of the coach occupied by Queen Elizabeth’s ladies; and there is much evidence to support the opinion that these boots were not covered.[36] Taylor in The World Runnes on Wheeles describes the boot with picturesque vigour:—

“The coach is a close hypocrite, for it hath a cover for any knavery and curtains to veil or shadow any wickedness; besides, like a perpetual cheater, it wears two boots and no spurs, sometimes having two pairs of legs in one boot, and often-times (against nature) most preposterously it makes fair ladies wear the boot; and if you note, they are carried back to back like people surprised by pirates, to be tied in that miserable manner and thrown overboard into the sea.”

These two fanciful descriptions explain very clearly what the “boot” was and how occupied. The “monstrous width” referred to in Coach and Sedan confirms the statement by Taylor that sometimes “two pairs of legs” occupied it, the proprietors of the legs sitting back to back. “No trace of glass windows or perfect doors seems to have existed up to 1650” (Thrupp), so we can well understand that the passengers who were obliged to occupy the boot of a stage coach (for these as well as hackney coaches were so built) on a prolonged journey would have an exceedingly uncomfortable seat in cold or wet weather.

It was no doubt an open boot which was occupied by the writer of the curious letter quoted by Markland. Mr. Edward Parker[37] is addressing his father, who resided at Browsholme, near Preston, in Lancashire; the letter is dated November 3, 1663:—

“I got to London on Saturday last; my journey was noe ways pleasant, being forced to ride in the boote all the waye. Ye company yt came up with mee were persons of greate quality as knights and ladyes. My journey’s expense was 30s. This traval hath soe indisposed mee yt I am resolved never to ride up againe in ye coatch. I am extreamely hott and feverish; what this may tend to I know not, I have not as yet advised with any doctor.”

Sir W. Petty’s assertion that the splendour of coaches increased greatly during the Stuart period recalls a passage in Kennett’s History of England. George Villiers, the great favourite of James I. who created him Duke of Buckingham, had six horses to draw his coach (“which was wondered at then as a novelty and imputed to him as a mast’ring pride”). The “stout old Earl of Northumberland,” not to be outdone by the upstart favourite, “thought if Buckingham had six, he might very well have eight in his coach, with which he rode through the city of London to the Bath, to the vulgar talk and admiration.” The first coaches were drawn by two horses only; love of display led to the use of more for town use, but the deplorable condition of the country roads[38] justified the use of as many as quagmires might compel.

How much a coach weighed in these early days we do not know: Mr. R. L. Edgeworth, writing in 1817, says, “now travelling carriages frequently weigh above a ton;” and as carriages had undergone vast improvements by that date, we are justified in concluding that those of a hundred or a hundred and fifty years earlier weighed a great deal more.

CARRIAGES IN HYDE PARK.

During the Commonwealth (1649-1659), it was the fashion to drive in “the Ring” in Hyde Park. The Ring is described by a French writer,[7] as two or three hundred paces in diameter with a sorry kind of balustrade consisting of poles placed on stakes three feet from the ground; round this the people used to drive, in Cromwell’s time, at great speed, as appears from a letter dated May 2, 1654, from a gentleman in London to a country friend, quoted by Mr. Jacob Larwood in his Story of the London Parks, (1872):—

[7] M. Misson. Memoirs and Observations of a Journey in England, 1697.

“When my Lord Protector’s coach came into the Park with Colonel Ingleby and my Lord’s three daughters, the coaches and horses flocked about them like some miracle. But they galloped (after the mode court-pace now, and which they all use wherever they go) round and round the Park, and all that great multitude hunted them and caught them still at the turn like a hare, and then made a lane with all reverent haste for them and so after them again,[8] and I never saw the like in my life.”

[8] The following sentence from Misson explains this reference. He says of the way people drive in the Ring: “When they have turned for some time round one way they face about and turn the other.”

There is an interesting letter from the Dutch Ambassadors to the States General, dated October 16, 1654, which is worth quoting here. The Ambassadors give particulars of the accident to explain why no business has been done lately:—

“His Highness [Oliver Cromwell], only accompanied with Secretary Thurloe and some few of his gentlemen and servants, went to take the air in Hyde Park, where he caused some dishes of meat to be brought, where he had his dinner; and afterwards had a mind to drive the coach himself. Having put only the Secretary into it, being those six grey horses which the Count of Oldenburgh[9] had presented unto His Highness who drove pretty handsomely for some time. But at last, provoking these horses too much with the whip, they grew unruly and ran so fast that the postilion could not hold them in, whereby [40]His Highness was flung out of the coach box upon the pole.... The Secretary’s ankle was hurt leaping out and he keeps his chamber.”

[9] This suggests that the North German province of Oldenbourg was famed then, as now, for its breed of coach horses.

From this it is evident that when six horses were used a postillion rode one of the leaders and controlled them; while the driver managed the wheelers and middle pair. When four horses were driven it was the custom to have two outriders, one to ride at the leaders’ heads and one at the wheelers’; in town this would be merely display, but on a journey the outrider’s horses might replace those of the team in case of accident, or more frequently, be added to the team to help drag the coach over a stretch of bad road.

COACH AND CART RACING.

John Evelyn in his Diary refers to a coach race which took place in the Park on May 20, 1658, but gives no particulars. Mr. Jacob Larwood observes that at this period and for a century later coach-racing was a national sport; some considerable research through the literature of these times, however, has thrown no light upon this sport, and while we need not doubt that coaches when they chanced to meet on suitable ground did make trials of speed, it is open[41] to question whether the practice was ever developed into a sport. It may be that Mr. Larwood had in mind the curious cart-team races described by Marshall in his Rural Economy of Norfolk, published in 1795.

This writer tells us that before Queen Anne’s reign the farmers of Norfolk used an active breed of horses which could not only trot but gallop. He describes as an eyewitness the races which survived to his day; the teams consisted of five horses, which were harnessed to an empty waggon:—

“A team following another broke into a gallop, and unmindful of the ruts, hollow cavities and rugged ways, contended strenuously for the lead, while the foremost team strove as eagerly to keep it. Both were going at full gallop, as fast indeed as horses in harness could go for a considerable distance, the drivers standing upright in their respective waggons.”

REGULATIONS FOR HACKNEY CARRIAGES.

The Act of 1662 has already been referred to in connection with the number of hackney coaches in London; we may glance at it again, as it gives a few interesting particulars. No license was to be granted to any person following another trade or occupation, and nobody might take out more than two licenses. Preference was to be given to[42] “ancient coachmen” (by which expression we shall doubtless be right in understanding, not aged men but men who had followed the calling in previous years), and to such men as had suffered for their service to Charles I. or Charles II.

Horses used in hackney coaches were to be not less than fourteen hands high. The fares were duly prescribed by time and distance; for a day of twelve hours the coachman was to be paid not over 10s.; or 1s. 6d. for the first and 1s. for every subsequent hour. “No gentleman or other person” was to pay over 1s. for hire of a hackney coach “from any of the Inns of Court or thereabouts to any part of St. James’ or the city of Westminster (except beyond Tuttle Street)”; and going eastwards the shilling fare would carry the hirer from the Inns of Court to the Royal Exchange; eighteenpence was the fare to the Tower, to Bishopsgate Street or Aldgate. This Act forbade any hackney coach to ply for hire on Sunday; thus the hackney carriage was placed in the same category as the Thames wherries and barges. The restrictions concerning the persons to whom licenses might be granted obviously afforded the Commissioners opportunity for the malpractices we have already mentioned.

PEPYS ON CARRIAGES.

For further information concerning this period we naturally turn to Mr. Pepys, who patronised the hackney coach so frequently that when he was considering the propriety of setting up his own private carriage, he justified his decision to do so by the fact that “expense in hackney coaches is now so great.” Economy was not the only motive; on the contrary, this entry in his Diary appears to have been merely the salve to a conscience that reproached his vanity. In 1667 he confides more than once to the Diary that he is “almost ashamed to be seen in a hackney,” so much had his importance increased: and on July 10, 1668, he went “with my people in a glass hackney coach to the park, but was ashamed to be seen.” The private carriage he set up in December of that year will be referred to presently.

The public conveyance available for hire in Pepys’ time was evidently a cumbrous but roomy conveyance; as when a great barrel of oysters “as big as sixteen others” was given him on March 16, 1664, he took it in the coach with him to Mr. Turner’s: a circumstance that suggests the vehicle was built with boots.

No doubt many of these hackney carriages had formerly been the private property of gentlemen, which when old and shabby were sold cheaply to ply for hire in the streets.

Coaches with boots were being replaced by the improved “glass coach” a few years later, and of course the relative merits of the old and new styles of vehicle were weighed by all who were in the habit of using hackney coaches. It was one of the old kind to which Pepys refers in the following passage:—

August 23, 1667. “Then abroad to Whitehall in a hackney coach with Sir W. Pen, and in our way in the narrow street near Paul’s going the back way by Tower Street, and the coach being forced to put back, he was turning himself into a cellar [parts of London were still in ruins after the Great Fire], which made people cry out to us, and so we were forced to leap out—he out of one and I out of the other boote. Query, whether a glass coach would have permitted us to have made the escape?”

Other objections to glass coaches appear in the following entry:—

September 23, 1667. “Another pretty thing was my Lady Ashley speaking of the bad qualities of glass coaches, among others the flying open of the doors upon any great shake; but another was that my Lady Peterborough being in her glass coach with the glass up, and seeing a lady pass by in a coach whom she would salute, the glass was so clear that she thought it had been open, and so ran her head through the glass and cut all her forehead.”

The usage of the time appears to have been for the driver of a hackney carriage to fill up his vehicle as he drove along the streets somewhat after the manner of a modern ‘bus conductor, if we correctly understand the following entry in the Diary:—

February 6, 1663. “So home: and being called by a coachman who had a fare in him he carried me beyond the Old Exchange, and there set down his fare, who would not pay him what was his due because he carried a stranger [Pepys] with him, and so after wrangling he was fain to be content with sixpence, and being vexed the coachman would not carry me home a great while, but set me down there for the other sixpence, but with fair words he was willing to it.”

Whence it also appears that some members of the public objected to this practice. The cabman of that time was evidently an insolent character, for Pepys refers contemptuously to a “precept” which was drawn up in March, 1663, by the Lord Mayor, Sir John Robinson, against coachmen who “affronted the gentry.”

GLASS WINDOWS IN CARRIAGES.

Glass was used in carriages at this time, as the entries quoted from Pepys’ Diary on pages 43 and 44 tell us. Mr. Thrupp states that “no trace of glass windows or perfect doors seem to have existed up to[46] 1650.” Glass was in common use for house windows before that date, and Mr. Thrupp refers to the statement that the wife of the Emperor Ferdinand III. rode in a glass carriage so small that it contained only two persons as early as 1631. The manufacture of glass was established in England in 1557[10] (Stow), but plate glass, and none other could have withstood the rough usage which coaches suffered from the wretched roads, was not made in England until 1670; previous to that date it was imported from France. A patent (No. 244) was granted in 1685 to John Bellingham “for making square window glasses for chaises and coaches.”

[10] James I., by Proclamation, in 1615, forbade the manufacture of glass if wood were used as fuel, on the ground that the country was thereby denuded of timber. In 1635 Sir Robert Maunsell perfected a method of manufacturing “all sorts of glass with sea coale or pitt coale,” and Charles I. forbade the importation of foreign glass in order to encourage and assist this new industry.

Pepys writes in his Diary, December 30, 1668: “A little vexed to be forced to pay 40s. for a glass of my coach, which was broke the other day, nobody knows how, within the door while it was down: but I do doubt that I did break it myself with my[47] knees.” Forty shillings for a single pane seems to indicate that it was plate glass. This passage also shows us that the lower part of the coach door must have received the glass between the outer woodwork and a covering of upholstery of some kind. Had there been wooden casing inside Pepys would not have broken it with his knees, and had it been uncovered the accident could not have escaped discovery at the moment.

IMPROVEMENTS IN CARRIAGES.

With reference to the introduction of springs: the patent granted to Edward Knapp in 1625 protected an invention for “hanging the bodies of carriages on springs of steel”: the method is not described. Unfortunately, the Letters Patent of those days scrupulously refrain from giving any information that would show us how the inventor proposed to achieve his object. Knapp’s springs could not have been efficacious, for forty years later ingenious men were working at this problem. On May 1, 1665, Pepys went to dine with Colonel Blunt at Micklesmarsh, near Greenwich, and after dinner was present at the

“... trial of some experiments about making of coaches easy. And several we tried: but one did [48]prove mighty easy (not here for me to describe, but the whole body of the coach lies upon one long spring), and we all, one after another, rid in it; and it is very fine and likely to take.”

These experiments were made before a committee appointed by the Royal Society, from whose records it appears that on a previous date Colonel Blunt had “produced another model of a chariot with four springs, esteemed by him very easy both to the rider and horse, and at the same time cheap.”

This arrangement of springs evidently did not give such satisfactory results as the one mentioned above by Pepys. On May 3, 1665, we learn from Birch’s History of the Royal Society:—

“Mr. Hook produced the model of a chariot with two wheels and short double springs, to be drawn with one horse; the chair [seat] of it being so fixed upon two springs that the person sitting just over or rather a little behind the axle-tree was, when the experiment was made at Colonel Blount’s house, carried with as much ease as one could be in the French chariot without at all burthening the horse.”

Mr. Hook showed:—

“Two drafts of this model having this circumstantial difference, one of these was contrived so that the boy sitting on a seat made for him behind the chair and guiding the reins over the top of it, drives the horse. The other by placing the chair clear behind the wheels, the place of entry being also behind and the saddle on the horse’s back being to be borne up [49]by the shafts, that the boy riding on it and driving the horse should be little or no burden to the horse.”

It seems to have been this latter variety of Colonel Blount’s invention, or a modification of it, which Pepys saw on January 22, 1666, and describes as “a pretty odd thing.”

On September 5, 1665, Pepys writes:—

“After dinner comes Colonel Blunt in his new chariot made with springs. And he hath rode, he says now, this journey many miles in it with one horse and outdrives any coach and outgoes any horses, and so easy, he says. So for curiosity I went into it to try it and up the hill to the heath and over the cart ruts, and found it pretty well, but not so easy as he pretends.”

Colonel Blunt, or Blount, seems to have devoted much time and ingenuity to the improvement of the coach, for on January 22, 1666, the committee again assembled at his house

“—to consider again of the business of chariots and try their new invention which I saw my Lord Brouncker ride in; where the coachman sits astride upon a pole over the horse but do not touch the horse, which is a pretty odd thing: but it seems it is most easy for the horse, and as they say for the man also.”

On February 16, 1667, a chariot invented by Dr. Croune was produced for inspection[50] by the members of the Royal Society and “generally approved.” No particulars of the vehicle are given: we are only told that “some fence was proposed to be made for the coachman against the kicking of the horse.”

PEPYS’ PRIVATE CARRIAGE.

On October, 20, 1668, Pepys went to look for the carriage he had so long promised himself “and saw many; and did light on one [in Cow Lane] for which I bid £50, which do please me mightily, and I believe I shall have it.” Four days later the coach-maker calls upon him and they agree on £53 as the price. But on the 30th of the same month Mr. Povy comes “to even accounts with me:” and after some gossip about the court,

“—— he and I do talk of my coach and I got him to go and see it, where he finds most infinite fault with it, both as to being out of fashion and heavy, with so good reason that I am mightily glad of his having corrected me in it: and so I do resolve to have one of his build, and with his advice, both in coach and horses, he being the fittest man in the world for it.”

Mr. Povy had been Treasurer and Receiver-General of Rents and Revenues to James, Duke of York: Evelyn describes him as [51]“a nice contriver of all elegancies.” The opinion of such a personage on a point of fashion would have been final with a man of Pepys’ temperament, and we hear no more about the coach with which Mr. Povy “found” most infinite fault.

On 2 November, 1668, Pepys goes “by Mr. Povy’s direction to a coach-maker near him for a coach just like his, but it was sold this very morning.” Mr. Povy lived in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and Lord Braybrooke remarks, “Pepys no doubt went to Long Acre, then, as now, celebrated for its coach-makers.” On November 5,

“With Mr. Povy spent all the afternoon going up and down among the coach-makers in Cow Lane and did see several, and at last did pitch upon a little chariot whose body was framed but not covered at the widow’s that made Mr. Lowther’s fine coach; and we are mightily pleased with it, it being light, and will be very genteel and sober: to be covered with leather and yet will hold four.”

The carriage gave great satisfaction when it came home, but the horses were not good enough for it: and on December 12 Pepys records that [52]“this day was brought home my pair of black coach-horses, the first I ever was master of. They cost me £50 and are a fine pair.”

CARRIAGE PAINTING IN PEPYS’ DAY.

Pepys’ position as an official at the Navy Office was not considered by his detractors to give him the social status that entitled him to keep his own coach, and soon after he became the owner of it a scurrilous pamphlet appeared which, incidentally, gives us a description of the arms or device with which it was decorated. After denouncing Pepys for his presumption in owning a carriage at all the writer proceeds:—

“First you had upon the fore part of your chariot tempestuous waves and wrecks of ships; on your left hand forts and great guns and ships a-fighting; on your right hand was a fair harbour and galleys riding with their flags and pennants spread, kindly saluting each other. Behind it were high curled waves and ships a-sinking, and here and there an appearance of some bits of land.”

If this is a true description, it would seem as though Pepys’ idea of the “very genteel and sober” cannot be measured by modern standards of sober gentility: however that may be, the Diarist takes no notice of the pamphlet and continues to enjoy possession “with mighty pride” in a vehicle which he remarks (March 18, 1669), after a drive in Hyde Park, he [53]“thought as pretty as any there, and observed so to be by others.”

In the following April, however, we find him resolving to have “the standards of my coach gilt with this new sort of varnish, which will come to but forty shillings; and contrary to my expectation, the doing of the biggest coach all over comes not to above £6, which is not very much.” One morning, a few days later: “I to my coach, which is silvered over, but no varnish yet laid on, so I put it in a way of doing.” Again, in the afternoon:—

“I to my coach-maker’s and there vexed to see nothing yet done to my coach at three in the afternoon, but I set it in doing and stood by it till eight at night and saw the painter varnish it, which is pretty to see how every doing it over do make it more and more yellow, and it dries as fast in the sun as it can be laid on almost, and most coaches are nowadays done so, and it is very pretty when laid on well and not too pale as some are, even to show the silver. Here I did make the workmen drink, and saw my coach cleaned and oiled.”

There is a passage in the Diary (April 30, 1669), which suggests that it was not unusual for people of station and leisure to superintend the painting of their carriages; as Pepys found at the coach-maker’s [54]“a great many ladies sitting in the body of a coach that must be ended [finished] by to-morrow; they were my Lady Marquess of Winchester, Lady Bellassis and other great ladies, eating of bread and butter and drinking ale.”

On the day after that he spent at the coach-maker’s, Pepys, on his return from office, takes his wife for a drive: “We went alone through the town with our new liveries of serge, and the horses’ manes and tails tied with red ribbons and the standards there gilt with varnish, and all clean, and green reins, that people did mightily look upon us; and the truth is, I did not see any coach more pretty, though more gay, than ours, all the day.”

Samuel Pepys’ child-like pride in his carriage was no doubt a source of amusement to his contemporaries, but it has had the result of giving us more minute details concerning the carriages of Charles II.’s time than we can obtain from the pages of any other writer.

THE FIRST STAGE COACHES.

We must now turn to the stage coach which had come into vogue about the year 1640.[11] Chamberlayne,[12] writing in 1649, says:—

[11] History of the Art of Coach Building. By George A. Thrupp, 1876.

[12] The Present State of Great Britain. By Chamberlayne, 1649.

“There is of late such an admirable commodiousness, both for men and women, to travel from London to the principal towns of the country that the like hath not been known in the world, and that is by stage coaches, wherein any one may be transported to any place sheltered from foul weather and foul ways, free from endamaging one’s health and one’s body by hard jogging or over violent motion on horseback, and this not only at the low price of about a shilling for every five miles, but with such velocity and speed in one hour as the foreign post can make but in one day.”

There were two classes of coach in the seventeenth century. Mons. Misson[13] says, “There are coaches that go to all the great towns by moderate journeys; and others which they call flying coaches that will travel twenty leagues a day and more. But these do not go to all places.” He also refers to the waggons which “lumber along but heavily,” and which he says are used only by a few poor old women. Four or four miles and a half in the hour was the speed of the ordinary coach.

[13] Memoirs and Observations of a Journey in England, 1697.

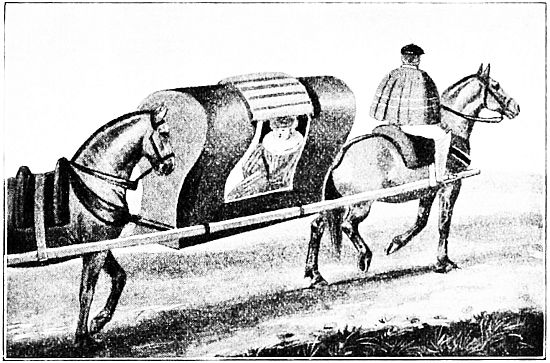

The coaches that travelled between London and distant towns were similar in construction to the hackney coach, which plied for hire in the streets, but were built on a larger scale. They carried eight [56]passengers inside, and behind, over the axle, was a great basket for baggage and outside passengers, who made themselves as comfortable as they might in the straw supplied. The “insides” were protected from rain and cold by leather curtains; neither passengers nor baggage were carried on the roof; and the coachman sat on a bar fixed between the two standard posts from which the body was hung in front, his feet being supported by a footboard on the perch.

Mr. Thrupp states that in 1662 there were only six stage coaches in existence; which assertion does not agree with that of Chamberlayne, quoted on a previous page; the seventeenth century writer tells us that in his time—1649—stage coaches ran “from London to the principle towns in the country.” It seems, however, certain that the year 1662 saw a great increase in the number of “short stages”—that is to say, coaches running between London and towns twenty, thirty, forty miles distant.

OBJECTIONS RAISED TO STAGE COACHES.

This is proved by the somewhat violent

pamphlet written by John Cressel, to which

reference was made on page 33. This

publication, which was entitled The Grand

[57]

Concern of England Explained, appeared

in 1673. It informs us that the stage

coaches, to which John Cressel strongly

objects:—

“Are kept by innkeepers ... or else ... by such persons as before the late Act for reducing the number of hackney coaches in London [see page 33] to 400, were owners of coaches and drove hackney. But when the number of 400 was full and they not licensed, then to avoid the penalties of the Act they removed out of the city dispersing themselves into every little town within twenty miles of London where they set up for stagers and drive every day to London and in the night-time drive about the city.”

“THE MACHINE.” A.D. 1640-1750.

These intruders,[14] whose number John Cressel says is “at least 2,000,” paid no £5, and took bread from the mouths of the four hundred licensed hackney coachmen.

[14] Owing to the profitable nature of the business these unlicensed hackney coaches increased until on November 30, 1687, a Royal Proclamation was issued appointing new Commissioners with authority to make an end of them.

John Cressel’s purpose in writing his pamphlet was to call the attention of Parliament to the necessity which, in his opinion, existed for the suppressing all or most of the stage coaches and caravans which were then plying on the roads; and incidentally he gives some interesting particulars concerning the stage coach service of his time. Taking[58] the York, Chester and Exeter coaches as examples, he says that each of these with forty horses apiece carry eighteen passengers per week from London.[15] In the summer the fare to either of these places was forty shillings and in winter forty-five shillings; the coachman was changed four times on the way, and the usual practice was for each passenger to give each coachman one shilling.

[15] The stage coach carried six passengers, and a coach left London for each of the towns named three times a week.

The journey—200 miles—occupied four days. These early “flying coaches” travelled faster than their successors of a later date. The seventeenth century London-Exeter coach did the journey, one hundred and seventy-five miles, in ten days, whereas in 1755, according to “Nimrod,” proprietors promised “a safe and expeditious journey in a fortnight.”

The “short stages,” i.e., those which ran between London and places only twenty or thirty miles distant, were the hackney coaches which had not been fortunate enough to obtain licenses under Charles II.’s Act. These were drawn by four horses and[59] carried six passengers, making the journey to or from London in one day. There were, John Cressel states, stage coaches running to almost every town situated within twenty or twenty-five miles of the capital; and it is worth observing that at this date letters were sent by coach. Coaches ran on both sides of the Thames from Windsor and Maidenhead, and “carry all the letters, little bundles and passengers which were carried by watermen.”

This writer’s arguments against coaches are worthless as such, but they throw side lights on the discomforts of travel at the time. He considered it detrimental to health to rise in the small hours of the morning to take coach and to retire late to bed. With more reason he enquired,

“Is it for a man’s health to be laid fast in foul ways and forced to wade up to the knees in mire; and afterwards sit in the cold till fresh teams of horses can be procured to drag the coach out of the foul ways? Is it for his health to travel in rotten coaches and have their tackle, or perch, or axle-tree broken, and then to wait half the day before making good their stage?”

John Cressel was prone to exaggeration, but there is plenty of reliable contemporary evidence to show that his picture of the coach roads was not overdrawn. Yet when[60] this advocate for the suppression of coaches seeks to rouse public sentiment, he reproaches those men who use them for effeminacy and indulgence in luxury! One of his quaintest arguments in favour of the saddle horse is that the rider’s clothes “are wont to be spoyled in two or three journies”; which is, he urges, an excellent thing for trade as represented by the tailors.

John Cressel, it will be gathered from this, viewed the innovation from a lofty stand-point. He describes the introduction of stage coaches as one of the greatest mischiefs that have happened of late years to the King. They wrought harm, he said:

(1) By destroying the breed of good horses, the strength of the nation, and making men careless of attaining to good horsemanship, a thing so useful and commendable in a gentleman.

(2) By hindering the breed of watermen who are the nursery for seamen, and they the bulwarks of the kingdom.

(3) By lessening His Majesty’s revenues; for there is not the fourth part of saddle horses either bred or kept now in England that there was before these coaches set up, and would be again if suppressed.

Travelling on horseback was cheaper than by coach. The “chapman” or trader could hire a horse from the hackneyman at from 6s. to 12s. per week. John Cressel estimates that a man could come from “York,[61] Exeter or Chester to London, and stay twelve days for business (which is the most that country chapmen usually do stay), for £1 16s., horse hire and horse meat 1s. 2d. per day.” From Northampton it cost 16s. to come to London on horseback, from Bristol 25s., Bath 20s., Salisbury 20s. or 25s., and from Reading 7s.

If men would not ride, John Cressel urged them to travel in the long waggons which moved “easily without jolting men’s bodies or hurrying them along as the running coaches do.” The long waggon was drawn by four or five horses and carried from twenty to twenty-five passengers. He proposed that there should be one stage per week from London to each shire town in England; that these should use the same team of horses for the whole journey, that their speed should not exceed thirty miles a day in summer and 25 in winter, and that they should halt at different inns on each journey to support the innkeeping business. If these proposals were carried out, the writer thought stage coaches would “do little or no harm.”

John Cressel’s pamphlet was answered by another from the pen of a barrister, who showed up the futility of his arguments and[62] deductions, but did not find great fault with his facts and figures.

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY HIGH ROADS.

It is commonly believed that the introduction of stage coaches produced the first legislative endeavour to improve the country roads; this is not the case: nor had the sufferings of travellers by “long waggon” any influence upon legislators if comparison of dates be a reliable test; for it was not until 1622 that any attempt was made to save the roads. In that year James I. issued a Proclamation in which it was stated that inasmuch as the highways were ploughed up by “unreasonable carriages,” and the bridges shaken, the use of four-wheeled carts for carrying goods and agricultural produce was forbidden, carts with two wheels only being allowed.

In 1629 Charles I. issued a Proclamation confirming that of his father, and furthermore forbidding common carriers and others to convey more than twenty hundredweight in the two-wheeled vehicles which were lawful, and also forbidding the use of more than five horses at once; the avowed object being to prevent destruction of the road.

We may fairly reason from the terms of[63] this Proclamation that it was recognised that on occasion five horses might be required to draw one ton along the roads; and from this we can form our own idea of the condition to which traffic and rains might reduce the highways.

In 1661 the restrictions on cart traffic were modified by Charles II.’s Proclamation, which permitted carts and waggons with four wheels, and drawn by ten or more horses, to carry sixty or seventy hundredweight, and forbade more than five horses to be harnessed to any four-wheeled cart unless the team went in pairs. The orders issued thus by Proclamation were made law by two Acts of Charles II. in 1670; the second of which forbade the use of more than eight horses or oxen unless harnessed two abreast.

In 1663 the first turnpike gate was erected; this novelty was put on the Great North Road to collect tolls for repair of the highway in Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdon, where in places it had become “ruinous and almost impassable.” The turnpike was so unpopular that for nearly a century no gate was erected between Glasgow and Grantham.

Nothing more clearly proves the badness[64] of the roads in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, than the number of patents granted to inventors for devices calculated to prevent carriages from over-turning. The first invention towards this end was patented in 1684, and between that date and 1792 nine more patents were granted for devices to prevent upsetting, or to cause the body of the vehicle to remain erect though the wheels turned over.

Few thought it worth trying to discover a method of improving the roads which caused accidents. In 1619, one John Shotbolt took out a patent for “strong engines for making and repairing of roads”; another was issued in 1699 to Nathaniel Bard, who also protected “an engine for levelling and preserving roads and highways”; and in the same year Edward Heming was granted a patent for a method of repairing highways “so as to throw all the rising ridges into the ruts.” History omits to tell us what measure of success rewarded these inventions: if the Patent Specification files form any guide to an opinion, inventors gave up in despair trying to devise means of keeping the roads in order, for not until 1763 does another ingenious person appear with a remedy thought worthy of letters patent.

Repairs to the highways were effected by forced labour when their condition made improvement absolutely necessary. Thus, in 1695, surveyors were appointed by Act of Parliament to require persons to work on the road between London and Harwich, which in places had become almost impassable. Labourers were to be paid at local rates of hire, were not to be called upon to travel more than four miles from home, nor to work more than two days in the week: nor were they liable to be summoned for road-mending during seed, hay and harvest-time. This Act also revised the system of tolls on vehicles: any stage, hackney, or other coach and any calash or chariot was to pay 6d. toll; a cart 8d. and a waggon 1s.