Title: In Kentucky with Daniel Boone

Author: John T. McIntyre

Illustrator: Ralph L. Boyer

A. Edwin Kromer

Release date: November 13, 2021 [eBook #66720]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Penn Publishing Company

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was made using scans of public domain works put online by Harvard University Library's Open Collections Program.)

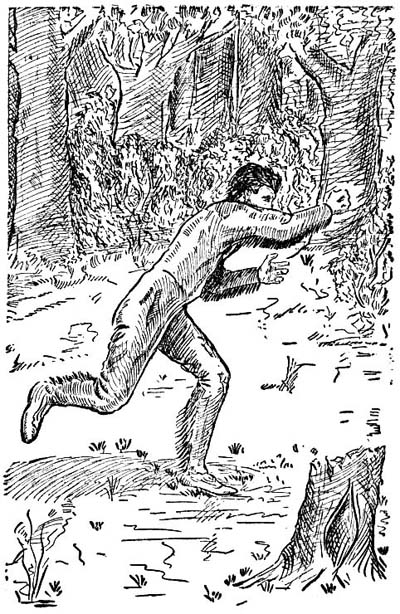

HIS SWIFT EYES SEARCHED IT FOR THE SIGN

By

JOHN T. McINTYRE

Illustrations by

Ralph L. Boyer and A. Edwin Kromer

THE PENN PUBLISHING

COMPANY PHILADELPHIA

1913

COPYRIGHT

1913 BY

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

| I. | The Gray Lizard Speaks | 7 |

| II. | A Coming Struggle | 18 |

| III. | Daniel Boone, Marksman | 33 |

| IV. | In the Wilderness | 61 |

| V. | Captured by the Shawnees | 70 |

| VI. | Boone in the Wilderness | 93 |

| VII. | Attacked! | 105 |

| VIII. | The Three Boys Ride On a Mission | 114 |

| IX. | Defending a Log Cabin | 125 |

| X. | A Night Experience | 139 |

| XI. | The Battle of Point Pleasant | 147 |

| XII. | The Fort at Boonesborough | 164 |

| XIII. | Conclusion | 174 |

| XIV. | Sketch of Boone’s Life | 185 |

[4]

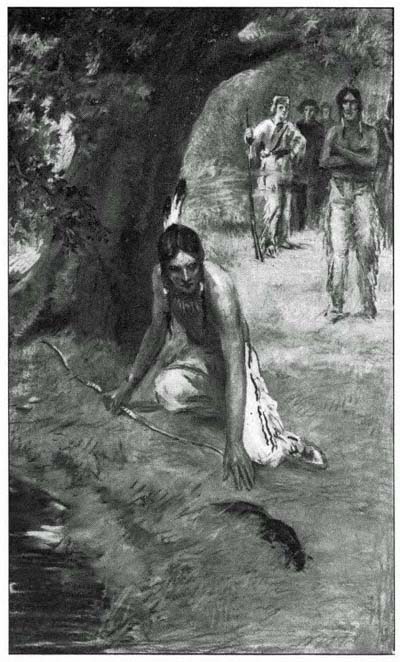

| His Swift Eyes Searched It For the Sign | Frontispiece |

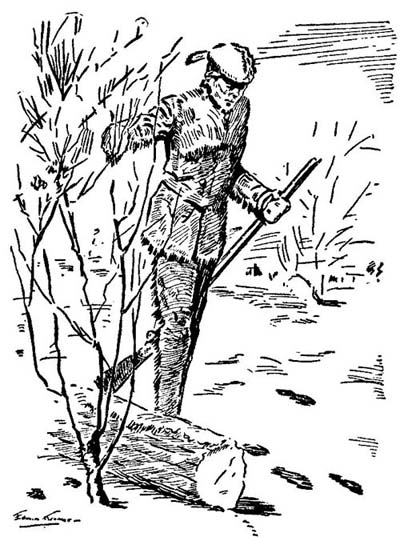

| Closely Boone Studied the Trail | 75 |

| The Rifles Spoke Through the Port-Holes | 136 |

| He Increased His Speed | 159 |

[6]

In Kentucky With Daniel Boone

Along the trail which wound along the banks of the Yadkin, in North Carolina, rode a tall, sinewy man; he had a bronzed, resolute face, wore the hunting shirt, leggins and moccasins of the backwoods, and had hanging from one shoulder a long flint-locked rifle. A small buck, which this unerring weapon of the hunter had lately brought down, lay across his saddle bow.

Away along the trail, at a place where the river bent sharply, a cloud of dust arose[8] in the trail; and as the hunter rode forward he kept his keen eyes upon this.

“Horsemen,” he told himself. “Two of them, I reckon, judging from the dust.”

Nearer and nearer rolled the cloud; at length the riders within it could be seen. One was a middle-aged man who rode a powerful black horse; the other was a boy of perhaps thirteen whose mount was a long-legged young horse, with a wild eye and ears that were never still.

Catching sight of the hunter, the man on the big black drew rein.

“What, Daniel!” cried he. “Well met!”

“How are you, Colonel Henderson?” replied the backwoodsman. “I didn’t calculate on seeing you to-day.”

“I rode over for the express purpose of having a talk with you,” said Colonel Henderson. “I was at your house, but they told me you’d gone away early this morning to try for some game.”

The hunter glanced down at the buck[9] across his saddle. There was a discontented frown upon his brow.

“Yes, gone since early morning,” he said. “And this is all I got. The hunting ain’t so good in the Yadkin country as it was once. As a boy I’ve stood in the door of my father’s cabin and brought down deer big enough to be this one’s granddaddy.”

The boy on the long-legged horse bounced up and down in his saddle at this; the nag felt his excitement and began to rear and plunge.

“Steady, boy, steady,” said Colonel Henderson. “Hold him in.”

“It’s all right, uncle,” replied the lad. “He don’t mean anything by it.” Then to the hunter, as his mount became quiet: “That was good shooting, Mr. Boone, wasn’t it? And,” pointing to the carcass of the buck, “so was that. Right behind the left shoulder; and it left hardly a mark on him.”

Daniel Boone smiled.

[10]“I always treat my old rifle well,” said he, humorously. “And she never goes back on me.”

“Some time ago I had a talk with John Finley,” said Colonel Henderson. “He told me wonderful tales of the hunting country beyond the Laurel Ridge.”[1]

Daniel Boone’s eyes went toward the northwest where the great mountain chain reared its peaks toward the sky until they were enveloped in a blue mist.

“Beyond the Laurel Ridge,” said he, “there is a country such as no man has ever seen before. Such hills and valleys, such forests and streams and plains can only be in one place in the world. And there are deer and bear and fur animals; and buffalo cover the plains. Also,” and a grim look came into his face, “there are redskins!”

There was a short silence; Colonel Henderson looked at the backwoodsman very thoughtfully.

[11]“For some time,” said he, “it has seemed to me that these settlements are not what they should be. The laws enforced by the British governor Tryon, have sown discontent among the people. New emigrants go to other places where there are better laws and less taxes.”

Daniel Boone nodded.

“Tax gatherers, magistrates, lawyers and such like live like aristocrats,” said he, “and the farmers and other settlers are asked to support them. We are here in the settlements, it seems, for no other purpose than to give these fellows a soft living. And they take our money and treat us like servants. A peddler who hucksters among the Indians is thought a better man than the one who has cut a form out of the wilderness with his axe.”

There was a bitterness in the man’s tone which seemed to please the other.

“There are a great many who feel just as you do about it,” said he. “And it was[12] this very thing that I rode over to speak about.”

Daniel Boone shook his head.

“Signing writings and sending them to Tryon will do no good,” said he. “He’s a tyrant and understands nothing but oppression.” Then in a longing tone, his eyes on the distant hills, “I wish I were away from the Yadkin for good and all. No man can be free here as long as we have public officers who think of nothing but plunder.”

“As I said before,” said Colonel Henderson, in a satisfied tone, “there are a great many others who are of the same way of thinking as you. But they have nowhere to go; if a new country was opened for them, they would sell their farms, pack their goods upon their horses’ backs and be gone.”

There was something in the speaker’s tone that took the attention of the backwoodsman. His keen eyes studied[13] Colonel Henderson’s face; but he said nothing.

“Ever since I heard Finley talk of the country beyond the ridge,” said the colonel, resuming after a moment, “I’ve felt that such a rare region should be opened up for settlement.”

“Right!” cried Daniel Boone and his eyes began to glow.

“But,” said the colonel, “I’ve also felt that it should not be done until the country was explored further—until it had been penetrated to its interior, until its streams were worked out on a chart, a trail made for the passage of emigrants and the most promising places fixed upon for settlements.”

“Right again,” said Daniel Boone. “I’ve been in the country and so have Finley and some others; but none of us has studied it. To do that would take a year or more; and to live a year so far from the settlements a man would have to make up his mind to troubles from the Indians.”

[14]“The Shawnees claim it,” said the colonel. “If it is what I want, I will buy it from them.”

“It’s a hunting-ground for Cherokees, Shawnees and Chickasaws,” said Boone, and he shook his head as he spoke. “So far as I could see, it belonged to all of them. And it’s a fighting place; when two hunting parties meet, the hatchet, knife and arrow begin their work.”

Once more the colonel regarded the backwoodsman attentively.

“I never knew the prospect of danger or hard work to hold you back in anything you wanted to do,” he said.

Boone laughed.

“I’ve always tried not to let them, I reckon,” said he.

“This fall,” and the colonel spoke slowly, “I am going to send an exploring party into the northwest country; and later, if it’s what I think it is, I’ll want a party of trail makers and a man to treat with the[15] Shawnees. How would you like to take charge of this matter for me?”

For a moment Boone sat his horse, staring at the speaker.

“You mean it?” he said, at last.

“I do.”

The backwoodsman held out a strong brown hand; Colonel Henderson gripped it.

“I’m with you,” said Boone, in a tone of deep satisfaction. “It’s a thing I’ve been sort of dreaming of for years. That great region, now given over to the Indian hunters and wild beasts, is calling the white man. I heard its voice as I stood among the lonely hills, in the forests, and upon the banks of its rivers. Once there with their families, their plows and their horses, their cabins built, the settler will meet——”

“Death!” said a strange voice; and, startled, both Boone and Colonel Henderson turned their eyes in the direction from which it came.

An Indian stood there—an ancient savage,[16] clad in skins upon which were painted queer symbols. Strings of amulets, bears’ claws and the teeth of foxes and wolves hung about him; his face was lined with the deep wrinkles of great age, his eyes were small, black, and glittered coldly like those of a snake.

“What, Gray Lizard!” said Boone, in surprise. “Are you here?”

The old Indian advanced a step or two, supporting himself by a long staff. Keenly the serpent eyes gazed at the three whites.

“Death will meet the paleface,” said he. “He will never build his lodge in the country beyond the mountains. Let him once pass the great gap, and he is no more.”

Boone laughed.

“I’ve been through the gap, Gray Lizard,” he said, good-naturedly; “and so have other white men. And we still live.”

The cold eyes fixed themselves upon the resolute face; one skinny finger was lifted until it pointed at Boone’s breast.

[17]“You have,” said Gray Lizard. “You have, and you are marked. Let your rifle once more break the silence of the hills or ring over the waters of the red man’s rivers, and your death song is sung.”

Then he turned to Colonel Henderson, and continued:

“And you, white chief, take care! The Gray Lizard has known these many moons of what you mean to do, and now he warns you. If you love your friends, do not send them beyond the Laurel Ridge. For in the wilderness their fate awaits them at the hands of the Shawnees.”

He turned and was about to go; then he paused, and added:

“The Gray Lizard is old. He has seen many things. He knew the Yadkin when the white man was a stranger on its banks. Take warning by his words: do not venture beyond the blue hills.”

Then, his long staff ringing on the stones, he went limping down the trail.

As the strange figure of the old Cherokee went halting along the river trail, the eyes of Boone and his companions followed curiously.

“A queer sort of customer,” commented Colonel Henderson. “I don’t recall ever having seen him before.”

“He’s a wonder worker and medicine man,” said Boone. “And he spends a good bit of his time on the fringe of the settlements. Sometimes,” and here a frown came upon his brow, “I’ve thought him more of a spy than anything else.”

“At any rate he knows how to creep up on one secretly,” said the colonel, with a laugh. And then, more soberly: “And he seemed rather earnest in his sayings.”

[19]Daniel Boone nodded his head.

“All these old redskins are crafty,” said he. “They spend their days and nights finding out ways of imposing on their fellow savages. And managing to do this without trouble they think they can impose in the same way upon the white man.”

“I see,” said Colonel Henderson.

“If they can put fear in the hearts of the whites,” continued Boone, “the whites will not venture into the wilderness. A settler killed now and then is the common way; but there are others, and I’ve heard a warning spoken by a prophet hung with totems before to-day.”

The boy who had been staring after the figure of Gray Lizard now spoke.

“I’ve been wondering where I saw him before, and now I’ve remembered, Uncle Dick,” said he. “Yesterday I rode up the river to visit the camp of the young braves who are to take part in the games. It was there I saw him; among the lodges.”

[20]“Ah!” said Boone; “and so the braves have come in for the games, eh?”

“More than a score of them,” replied the lad. “And a fine looking lot they are, sir,” with admiration.

The backwoodsman nodded.

“They are sure to be,” said he, grimly. “The redskins seldom send any but the pick of their villages.”

“It’s been three days since they pitched their camp,” said the lad. “And they’ve been hard at work ever since, practicing with their bows and rifles, and throwing their hatchets at marks. There’s a good runner or two among them,” added the boy; “and they have some fine horses.”

“I’ve always been against these games,” said Daniel Boone, as he shook his head.

Colonel Henderson looked at him in surprise.

“Why,” said he, “how is that? Athletic games always seemed to me to be good for the youngsters.”

[21]“So they are,” agreed Boone. “Mighty good. But these of ours are a mistake, because the lads don’t put enough heart in ’em. They don’t take ’em serious enough.”

The colonel smiled.

“It’s all in the spirit of fun,” said he.

But Boone shook his head.

“That’s where you’re wrong, colonel,” said he, “and that’s where the boys are also wrong. There ain’t many of us whites on this border; but over beyond the Laurel Ridge the Indians lie in clouds. And that they haven’t blotted us out long since is because away down in their hearts they’ve thought we’re better’n they are, for we’ve always showed we could give them odds and beat them at anything they cared to do.”

“And now, you think——”

“Our young men are letting them pull out ahead too often; and that’s not a good thing to have happen. Once let the red man get the notion that he’s better than the white, and this border’ll be turned into a[22] wilderness—there won’t be a settlement but won’t feel the tomahawk and the torch. The white man will be turned back from the west for twenty years to come.”

“I see.” Colonel Henderson looked thoughtful. “I never thought of that, Daniel; and now that you put it before me I can see that you are right.”

The boy had listened to what the backwoodsman had to say with much attention. Now he spoke.

“Eph Taylor was along when I rode up to the Shawnee camp yesterday,” said he. “And as we went he told me how the young braves crowed over them last fall, and how they promised to beat them even worse this year. And when we got to the camp all the young warriors grinned at us and talked a lot among themselves. Eph knows some of their language and said it was all about us, and about the games and how they were going to run away from us in everything we tried.”

[23]Boone looked at Henderson and nodded, grimly.

“Do you see?” said he. “That’s how it will begin. Five years from now these same young redskins will have a voice in the councils of their tribe. Let them carry this feeling of being better than us into those councils, and nothing will hold them back from a bloody war.”

“Well, Noll,” said Colonel Henderson to his nephew, “you see what you’ve got before you.”

The tone was half laughing; but when Oliver Barclay made reply it was with all the seriousness in the world.

“Eph and I talked about it as we rode back home,” said he. “And we made up our minds to give them a hard fight for each match as it came along. Eph and I are to arrange everything to-day; that’s why I am riding over to see him.”

“Well,” said Colonel Henderson, “I suppose you may as well go on if that’s[24] what you are about. I have some business to talk over with Mr. Boone, and will ride back to his farm with him. Will you be home to-night?”

Noll shook his head.

“I don’t think so,” he replied. Then with a laugh: “When I get down to plotting with Eph Taylor there’s no telling when I’ll get through.”

He shook the rein, and the long-legged young horse brandished its heels in most exuberant fashion. The boy waved his hand to the two men.

“Good-bye,” said he. Then to Boone, “Going to be at the games to-morrow, Mr. Boone?”

“Maybe,” said the backwoodsman.

“Come along,” suggested Noll. “Maybe something’ll happen that’ll please you.”

Boone looked at the strong young figure sitting the fiery horse so easily, the clear eyes, the confident smile. And his bronzed face wrinkled in a laugh of pleasure.

[25]“Well, Noll,” said he, “I’ll go. But mind you this: I’ll expect something more than I saw a year ago.”

“I can promise you that, anyhow,” said the boy. “And maybe there’ll be more. Good-bye.”

And with that he rode forward along the river trail, while Daniel Boone and Colonel Henderson turned their horses’ heads in the opposite direction. A mile further on Noll overtook Gray Lizard plodding on with the help of his long staff. The magician gave the boy a sidelong glance as he passed; but Noll did not check the lope of his horse, pushing on until he reached a place where a second trail branched away from the river, winding among the huge forest trees and losing itself in the billowing ocean of foliage.

He struck into this, and after an hour’s riding came in sight of a well-built log house, surrounded by broad fields, from which the crops had lately been harvested.

[26]Before the cabin door sat a tall, lank boy in a hunting shirt, busily engaged in cleaning a long flint-locked rifle. At the sound of the rapid hoof-beats he looked up. Recognizing Oliver, who was still some distance off, he waved his hand in greeting; then he turned his head and spoke to some one within the cabin.

Drawing rein before the door, young Barclay threw himself from the saddle.

“Well, Eph,” said he, as he tied his mount to a post, “I suppose you all but gave up hope of me.”

Eph Taylor had a long, droll looking face, and as he shook his head he twisted his countenance into an expression of comic denial.

“No,” said he. “I reckoned you’d be along some time soon. This thing of ours was too important to let go by.”

He rammed a greased cloth down the barrel of the rifle, and twisting it about, withdrew it once more.

[27]“I saw Sandy,” added he.

At this Noll Barclay was all eagerness.

“Did you!” exclaimed he. “And what did he say?”

“Suppose I let him speak for himself,” said Eph, with the same comical twist to his long face. “He came over this afternoon to talk things over with us. Ho! Sandy! Can you come here for a little?”

A short, tow-haired youth appeared at the door of the cabin; he carried a halter in one hand and a brad-awl in the other. He nodded to Oliver good-humoredly.

“Glad to see you again,” said he. “How are you?”

His accent was broadly Scotch, and there was a round-bodied heartiness to him which at once inspired good will.

“I’m in right good health,” said Oliver. “And I’m glad enough to see you, Sandy.”

Sandy Campbell laughed. He placed a strap of the halter against the door frame and punctured it with the awl.

[28]“I was mighty taken with your notion,” stated he. “And when I got done with my work, I rode over to hear more about it.”

Oliver Barclay sat down upon a rough settle which stood beneath a cottonwood; he looked at the other two boys with earnest eyes.

“What we talked over yesterday, Eph,” said he, “seemed good reason enough for us to make an attempt to get the best of the Cherokees. But what I heard this afternoon puts a different face on it altogether.”

Eph Taylor looked up from his rifle in surprise.

“You don’t mean to say that you have changed your mind!” said he.

Oliver shook his head.

“Not a bit of it,” answered he. “Indeed, I’m firmer about it than ever. But to just make an attempt to best the Indians won’t do now; we must beat them!”

Both Eph and Sandy looked at him inquiringly.

[29]“You say you heard something,” said Sandy Campbell. “What was it?”

“As I rode down the trail with my uncle,” said Noll, “we met Mr. Boone.”

The face of Eph Taylor took on an expression of interest.

“Oh, it was something he said, was it? Well, then, I allow it was worth listening to, for Dan’l Boone always talks as the crow flies—in a straight line.”

And then, while his two friends listened with great attention, Oliver repeated the words of the backwoodsman. When he had finished, Sandy nodded his head.

“It sounds much like the truth of the matter,” said he.

“It is the truth!” declared Eph, emphatically. “If we give these redskins a chance to crow over us in little things, they’ll think they can do it in big things. To-morrow we must take ’em in hand and give them a good thrashing—a regular good one that they’ll not forget in a hurry.”

[30]“I’m all ready for my part of it,” grinned Sandy. “Or, at least I will be as soon as this halter’s finished. That old Soldier horse couldn’t have been better for the work if he’d been picked out of a hundred. He’s got a back as wide as a floor; and I’ve been practicing with him all summer, never thinking I’d have any use for it.”

“It’s lucky you did,” spoke Eph. “And I reckon the things you do’ll make the redskins open their eyes. As for me,” and he fondled the long rifle lovingly, “I got old Jerusha here; and when she begins to talk I allow there won’t be many Shawnees that’ll use better language.”

Oliver smiled and nodded. To strangers there would have been a boastful note in the words of young Taylor; but not to those who knew him. The boy was a wonderful shot at all distances, but it never occurred to him to take any personal credit for this. Oddly enough he gave it all to his rifle.

“Nobody with half an eye could miss[31] with her,” he’d frequently declare. “She’s the greatest old shooting iron ever made.”

Oliver sat smiling and nodding at Eph’s faith in his piece, and while he did so his eyes went to the spot where the long-legged young horse was tied. Sandy noticed the look and his glance also went in the same direction.

“The Hawk will do his share,” said he with an air of expert judgment. “He has speed and bottom and in a long race he’ll break the hearts of those Indian nags.”

“Just like his master’ll break the hearts of the Shawnees that’ll run against him,” spoke Eph Taylor, with confidence.

“I’m not so sure of that,” said Oliver; and as he spoke a sound from across the fields toward the line of forest took their attention. The sinking sun glanced from the lithe bronze body of a young Indian who was running swiftly and low, like a hound. “There’s the fellow I’m to fight it out against,” added the white boy. “And[32] any one who comes in ahead of him will have speed, indeed.”

Eph Taylor nodded.

“He’s good,” admitted he. “But I count on him, Injun like, only to use his legs in the race. To beat him, all you’ve got to do is to use your head as well.”

Mounted upon his powerful bay horse, Daniel Boone the following day rode toward Holman’s Ford. This point was some eight miles from Hillsboro, and it was here that the young men of the settlement met each fall for their hardy frontier games.

Keen-sighted youths, bearing long barrelled flint-locks, eagerly awaited this, the test of their skill; sturdy wrestlers burned to match their thews against each other; and the runners, both horse and man, were equally anxious to show their quality.

The sun had reached high noon when the backwoodsman reached the ford, dismounted and tied his nag to a tree. A long line of wagons, the horses tied to the wheels, stood on the river bank; the settlers[34] and their families were gathered beneath the trees. Apart from these were the athletes of farm and forest, well-grown boys and brawny young men; they stood about in knots and discussed the probabilities of each event. A smaller knot than any of the others stood at the foot of a huge cottonwood; a hail went up from this as Boone went by; and he paused as he recognized Oliver Barclay, Eph Taylor and Sandy Campbell.

“Well, youngsters,” said the pioneer, “how is it going?”

Eph Taylor grinned.

“There ain’t been much done yet, Mr. Boone,” said he. “And even with the little we’ve gone through, we’ve had trouble with the redskins.”

The eyes of Boone went to a cleared space among the trees where a number of lodges had been erected; upon some skins, thrown upon the ground, lay a half score of keen-looking Shawnees. To the trees near by[35] were fastened a number of rangy-looking horses.

“What’s wrong?” asked the backwoodsman.

“We’ve had the jumps,” said Eph, “and none of the Indians entered for them. So Eben Clarke won ’em all. Then there was the throwing of the stone and big Sam Dutton put it further than any one else, by a good bit. The first thing the Shawnees took any interest in was the swim. It was across the river and back, to start at the word and all together. A slippery little redskin entered for that; he got into the water like a streak; and he was a real good swimmer. George Collins was off in the front and the little Shawnee went by him like a fish. Then George began to stretch out and grab the water in armfuls and pull himself after him. But he never caught him till they got to the middle of the stream on the way back. Sandy here was in the race,” and Eph grinned. “He[36] thinks he’s a swimmer, but he was still on the way over when George and the redskin were coming back. Just as George caught the Indian they both ran afoul of Sandy. And because George went ahead from that on and won the race the Shawnees say the whole consarned thing was a put up job to beat them out of the race.”

“And it’s not so,” said Sandy, with indignation. “If I interfered with anybody it was with George Collins. I dived to get out of the Indian’s way when I saw him coming and I went straight into George.”

“There’s only one of them who understands any English, beside old Gray Lizard,” said Oliver, “and that’s the tall fellow covered with the bearskin. We took the trouble to explain the matter to them; but they just shake their heads and candidly think the worst of us.”

“Injuns,” stated Boone, “can never be got to quite believe the white man. Maybe it’s because they’ve been beaten so often[37] and in so many ways that they’ve come to think that he can’t have played fair with him.”

The wrestling was now going forward, and big Sam Dutton, he of the “stone throw,” was disposing of opponent after opponent with ease. There being little interest manifested in this because of its one-sidedness, the master of ceremonies, a stout, humorous-looking man, called out:

“I reckon we’ll now have the fancy riders out getting ready.” Then in a lower tone to those near him, “This is a thing the Injuns always win, and our boys ought to be ashamed of themselves for letting ’em. Trick riding ought to be as easy for a white as a redskin.”

This complaint was greeted by a laugh from those at whom it was aimed; and the laugh was still echoing when a young Shawnee ran out and across the green. To a tree some distance away he affixed a mark of painted bark, then he paced off a score of[38] yards, turned, drew a tomahawk and waved it as though in challenge. Then the sinewy, bronzed arm went back and the hatchet whizzed through the air; true and fair it struck the mark, burying itself an inch or more in the tree.

A yell went up from the young braves at this; there were challenging glances thrown right and left; but as none of the whites appeared disposed to accept, a fresh mark was put up. Another Shawnee stepped forward and drew out a heavy-bladed knife. For an instant he balanced it in his hand, then launched it forward like a lightning flash, straight to the heart of the mark.

Another whoop arose, and again the triumphant challenging glances went around from the young savages.

“They reckon there ain’t none of you got it in you to do a thing like that,” stated the master of ceremonies.

“Just you wait till the shooting,” answered a voice, and a murmur went up[39] from among the whites. “We’ll show ’em then.”

“Well, you ought to,” answered the stout man. “You’ve lived all your lives with rifles in your hands, and it’s not much to your credit that you can shoot. But,” and he waved one pudgy finger at them, “don’t be too sure of the shooting, even at that. Maybe you ain’t heard that Long Panther is here to-day! And anybody that’s acquainted with that young redskin knows a Shawnee with a good eye and a steady hand.”

Here those horsemen entered for the fancy riding galloped out into the open space. To a man they were Indians, in all the bravery of paint and plumes.

“Not a single one of you!” exclaimed the fat master of ceremonies, reproachfully, his gaze going from the array of confident savages to the circle of lolling young whites. “Not a single one; not a thing do you know about riding but to get into the[40] saddle and sit there like an old dame in a rocking-chair. Not a single——”

But there he paused, for just then there rode into the open space a round-bodied youth with a cheerful, good-natured face, and mounted upon an ambling white horse, as fat and unlike the fiery brutes bestridden by the Shawnees as could well be imagined. A roar went up at sight of this unexpected entry; even the stoical savages grinned in ironic enjoyment of the situation.

Gravely the master of ceremonies shook the newcomer’s hand.

“Young man,” said he, gratefully, “you may not have much chance, but you have got pluck. What’s your name and the name of that young animal you’re a-riding?”

“I’m Sandy Campbell,” replied that good-natured youth, “and this,” patting the fat white horse on the neck, “is Soldier, a plow horse, fifteen years old, belonging to the man I work for.”

[41]Another shout went up from the by-standers; but the master of ceremonies held up his hand.

“It’s not your turn to laugh,” stated he. “He’s making a try; and that’s something more than any of you have the enterprise to do.”

The word was given; one after another the young braves set their horses into a gallop; when at full speed they leaped from the backs of their mounts and, clinging to the streaming manes, ran a dozen or more yards by their sides; then with agile swings they were astride them once more. Then with a rush they approached the starting point, bringing up sharply and in picturesque fashion, the front hoofs of the horses pawing the air.

All eyes now turned upon Sandy Campbell and the sleek sided Soldier. Quietly Sandy gave the white horse the word and calmly the placid beast obeyed. At a stoical gallop he began circling the clearing; his[42] movements were as regular as those of a rocking-horse; and Sandy sat him in total unconcern while shouts and laughter greeted them on every hand. Then Sandy threw his right leg across the horse’s broad back, sitting him sideways; it looked like an uncouth beginning of the feat performed by the Shawnees and a titter of expectancy began. This changed to a roar of derision as the fat boy slid from his perch to the ground.

But if they had watched keenly, they would have perceived that he alighted with a soft, practiced accuracy; also that the long comic bounds which followed at the side of the calmly galloping Soldier were really as light as those of a rubber ball. Then with one higher than the others, and never putting a hand upon his horse, he was upon its back once more; and Soldier drew up, switching his tail and regarding the green distance with sleepy eyes.

Without waiting for the surprised applause[43] of the settlers to grow to the height it naturally would have reached, one of the young Shawnees shook his rein; his nimble steed darted away like the wind, an arrow flew ahead, performed a graceful arch and stack in the ground. Racing at full speed the horse swooped down upon it; clinging with one foot and one hand the brave stooped, caught the feathered shaft, and recovering, waved it above him triumphantly.

Soldier was at once put into motion; when he had attained his best speed, Sandy’s hat flew ahead to one side, and a long hunting knife followed, falling to the other side, but a dozen or more yards further along. Heading his galloping horse between these, Sandy stooped and caught the hat; then recovering like a flash, he threw himself to the opposite side, gripping the shaft of the knife as he sped by.

The shout which greeted this made the echo from across the Yadkin ring lustily;[44] the settlers now awoke to the fact that the round-faced youth and his fat plow horse knew what they were about. And so they eagerly acclaimed and urged them to do their best.

Trick after trick of horsemanship was performed by the Indians, and all with the ease of experts and the dash of perfect confidence. But their feats showed little imagination, and in this those of the white boy were vastly superior. Each time they displayed something new he duplicated it with an added touch, leaving them open-mouthed and aghast.

At last one of them, and their finest rider by far, broke from the line and called something to Sandy, a something which was evidently a defiance. Putting his horse to gallop, he, with much effort, swaying and uncertainty, got upon his feet and there remained until he had completed the circle, when he leaped to the ground. While the yells of the Indians were still greeting this[45] bit of daring, Sandy started Soldier once more. With perfect ease, and greatly helped by the beast’s broad back and its rocking-horse motion, the boy got upon his feet; after making a complete round, he leaped up, turned a somersault, alighted expertly upon the platform-like back, and once more stood erect; then standing upon one foot and with the other twiddling in the air, he galloped around once more.

This was the last straw. The Shawnees could not hope to outdo this, and so retired. While the whites gathered about Sandy and his steed, Boone turned to Oliver and Eph.

“I reckon your friend didn’t learn them things in Carolina,” said he.

Oliver laughed, delighted.

“No,” he replied. “At home, in Scotland, he was a rider in a circus; and he’s been practicing and training the white horse for some time.”

“Friends!” called the master of ceremonies,[46] “the time is drawing on, and as there are three contests still to be decided, we’d best get at them. The race for horses is next; riders will line across the trail.”

At this summons, Oliver Barclay sprang from Hawk, his long-legged young horse, untied and mounted him; and as it happened as he rode to the end of the forming line, he found himself next the tall young Shawnee whom they had pointed out to Boone as being able to talk English.

“Umph!” said this personage, his swift eyes running over the points of the horse. “You ride?”

Oliver nodded. The young brave bestrode a bony, long barreled horse with small ears and a wicked head. Its bared teeth gleamed as it snapped viciously at the horses within reach.

“Maybe you run,” ventured the Shawnee. Again Oliver nodded; and a glint of satisfaction came into the keen black eyes of the brave.

[47]“Heap good!” said he. “Long Panther will beat you in both.”

Oliver smiled.

“The Long Panther is a good rider,” said he. “We have seen him many times break the wild horse, and manage the swift one. And he can run. Only yesterday I saw him flying along the trail like a wolf in the track of an antelope. But,” and the boy shook his head, “to win to-day, even Long Panther must do his best.”

“White boy shoot?” asked Long Panther; but Oliver shook his head.

“Not enough to match myself against experts,” said he. “But there are a few who will handle the rifle to-day, Long Panther, whom it will not be easy to draw away from.”

The Shawnee lifted his head proudly.

“The red man will win,” said he. “His eye is like the eagle’s, his hand as steady as the head of a rattlesnake before it strikes.”

[48]The glance of the master of ceremonies ran along the line of horsemen. Then he pointed to a lone tree far down the river trail from which a flag was flying.

“You ride to that, around it, and back,” said he. “And now, when I drop my hat, you start.”

Once more the glance went along the line to assure him that all was still as it should be. Then the hat fell.

With a rush the horses shot forward along the trail; a cloud of dust overhung them and it was hard to tell who led or who trailed in the rear. Then little by little the compactness of the mass was lost; the runners began to stretch out, the swift going to the front, and the others falling back. At the flag the dust ascended in a great column; then the riders were seen plunging through it on the way to the finish.

“Long Panther in the lead!” cried Eph Taylor, straining his eyes to make out the[49] contestants. “And he’s riding like as if he was part of the horse.”

“I don’t see anything of young Noll,” said Boone.

Sandy Campbell was trying to keep the sun out of his eyes by holding his outspread hands over them; he searched the dusty cloud as it rolled toward them.

“I see him!” he shouted, in high excitement. “I see him!”

“Where?” demanded Eph, eagerly.

“He’s about the sixth rider—far back in the dust.”

“Sixth!” cried Eph, and his voice was husky with disappointment.

“But he’s coming along swiftly,” said Sandy. “The Hawk is stretching over the ground like a rabbit.”

“I see him now!” shouted Eph. “I see him! But he’s not sixth—he’s fourth!”

“He’s passed two of them since I spoke,” said Sandy, and then with a whoop, “There goes another to the rear!”

[50]“And still another!” cried Eph, dropping his beloved Jerusha and waving his long arms. “He’s second!”

“Do you see Long Panther look over his shoulder?” called Sandy. “See how his teeth show—even at that distance! He looks as vicious as that ugly brute of a horse of his.”

Whirling out of the dust came the bony steed ridden by the Shawnee; its sweeping stride covered the ground with astonishing speed, its rider was bent low over its neck, his eagle plumes mingling with the steed’s flying mane. But if the stride of the Indian’s steed ate up the distance, the long legs of Hawk devoured it. The eyes of the young animal fairly flowed with excitement; his wide nostrils showed red; his flying hoofs made dazzling play as they flashed and reflashed, in and out, up and down; his sleek hide was flecked with foam.

“One hundred yards to go!” cried Sandy.

[51]“And the Hawk’s nose is at the Injun’s knee!” shouted Eph Taylor, arms still waving madly.

Lower and still lower bent Long Panther, whiter and whiter gleamed his teeth; faster and still faster flew the thundering hoofs of the wicked looking steed. But nothing on four feet could have outstepped the rush of the flame-eyed Hawk; no one who ever sat in a saddle could have outdone in determination the boy who bestrode him. In a half dozen mighty bounds the Hawk was nose and nose with the horse of the Indian; and then he was ahead, daylight showing between them true and fair; when he flashed by the finish he was a winner by a good half dozen yards.

White boy and red slipped from their horses almost side by side as the roar of applause went up from the crowd. Leaning against the heaving side of his mount, the Long Panther stood for a moment staring into the face of Oliver Barclay. Then,[52] without a word, he turned, leaving his horse standing in the trail and strode toward the lodges among the trees.

Amid the tumult of shouting the stout master of ceremonies was not idle. The next event was the shooting at all distances—and with all weapons; and the targets and marks were set up with all possible speed.

“Yes, friends,” cried the stout man at the top of his voice, addressing a throng gathered about Oliver and the Hawk, “I know how you feel, for I feel just that way myself. It’s a good boy and a good colt. But let’s get ahead with things. Now we have the shooting on our hands—shooting with rifles or with bows and arrows, the white man and his red brother to have the use of his favorite weapon. If a white wants to use a bow, let him do so and the fates prosper him; if a red prefers a rifle, let him take it by all means and use it to the best of his courage and eyesight.”

[53]As the riflemen came forward, each with his long weapon in his grip, the throng followed and formed a sort of half circle behind them. Several of the Indians also advanced, their long bows tautly strung, their quivers full of arrows.

One by one the rifles cracked, and the bowstrings sang; mark after mark was shot away, and marksman after marksman fell back defeated. Eph Taylor advanced time after time, Jerusha in his hand; fondly he’d cuddle the smooth stock against his cheek, and when the old weapon’s sharp voice rang out, it was to announce the planting of a bullet in the heart of the target.

After three-quarters of an hour the last Shawnee was eliminated; and the struggle seemed between Eph Taylor and a gray-haired, keen-eyed hunter from the region toward the ridge. It was nip and tuck between this pair; neither seemed able to perform a feat which the other could not[54] duplicate. The ringing of the shots, the spatting of the ball, the fall of wand or coin, or the snuffing out of candles went on with monotonous regularity; but at length this was broken by the appearance of the magician, Gray Lizard. With his amulets of skulls and claws, and pouches filled with potent charms hanging from him, his staff in his hand and his ratty old eyes filled with contempt, he advanced to the place where the riflemen were standing.

“What child’s work!” cried he. “What pastime for the papooses of the village! Again and again do you repeat what you have done before. And nothing comes of it. The Shawnee is about to go! but before he goes he would like to show his white brother what he thinks is a real test of skill.” Then to the master of ceremonies, “Is it the white man’s will?”

The stout official scratched his head.

“It’s against all the rules that I ever heard tell of,” he announced. “But I’m[55] for letting them do it. What do you say, lads?”

A shout of assent went up from the settlers; for all were eager to see what the redskin marksman would do.

The Gray Lizard turned and held up one hand toward the little knot of savages who stood in a gloomy array at one side.

“Long Panther, by jickety!” said Eph, who had been looking toward the Indians, curiously.

“I thought he was so tarnal mad at being licked in the hoss race that he didn’t mean to shoot at all,” said the old hunter who had been pressing Eph close. “But here he comes, as proud as a she wolf with seven pups, and a-meaning to outshoot all creation if it can be done any way at all.”

Long Panther advanced with erect head and a face like bronze, so utterly devoid of expression was it; but his keen swift eyes were full of fire and insolent challenge.[56] His manner was that of one who felt himself master of the situation.

“The Gray Lizard spoke well,” said he. “To shoot at sticks and lights is work for the papoose, and not for the warrior. I ask but one shot; and then let any of you do as well, and I am content to say the white man is better than the Shawnee.”

As he spoke his swift eyes went about among the trees; upon a huge dead limb of an oak, near to the trunk, sat a gray squirrel, his bushy tail held erect, his deft forepaws stroking his moustache.

“A live mark!” said Long Panther, as he fitted an arrow to his string. “I will take it through the skin at the back of its neck and pin it to the tree.”

Almost before he ceased to speak, the arrow flew upon its mission; and the next instant the squirrel, pinned exactly as the Shawnee marksman had said, was struggling for release.

A hush fell upon the crowd; and as a[57] boy nimbly ascended the oak and liberated the squirrel, the master of ceremonies spoke.

“Men, it was a good shot. And, now, speak up. Can any of you do the like?”

Eph and the old hunter were shaking their heads when Daniel Boone stepped forward.

“The brave,” said Boone, slowly, “has made a good shot. No one will gainsay that. But it was a trick.”

All eyes were upon him; Long Panther gave him a look of fierce disdain.

“The shot,” said the young warrior, “was fair, and was seen by all.”

Boone nodded.

“But for all that it was a trick,” said he. “It was a shot that can be made only with an arrow. A marksman can’t pin a squirrel to a tree trunk with a rifle bullet, Long Panther, as you know very well.”

A murmur went up from the whites; there was an eager assent to this way of looking at the matter.

[58]“But,” continued Boone, coolly, “you said that if any of us could do as well, you’d admit yourself beaten.” He balanced his heavy rifle in his strong hands, a smile upon his bronzed face. “Very well. To equal your trick shot which cannot be done with a rifle, I will do one which can’t be done with an arrow.”

A huge gum tree reared its mighty head upon the river bank; upon a limb part way up lay a red squirrel, blinking at the assemblage with his shrewd little eyes. The heavy rifle began to lift toward this mark.

“Long Panther,” said Boone, quietly, his eyes never leaving the tiny ball of red fur so high in the air, “if I bring down the little beast, dead, and with never a mark of the bullet on him, will you admit it as good a shot as your own?”

“I will!” cried the Shawnee, promptly.

The long rifle cracked, a shower of particles of bark flew up from the limb directly[59] under the squirrel; the concussion threw the little animal whirling into the air; it fell to the ground at the foot of the gum tree—dead.[2]

In an instant it was in the hands of Long Panther; his swift eyes searched it for the sign that would give him victory.

“Well?” asked Boone, after a moment.

The young warrior lifted his face.

“It is without a mark,” said he. Then as he turned away, he added in a voice of wonder, “The white man is indeed a mighty hunter.”

And when the foot-racers took their places a few moments later to decide the question of speed and endurance, Oliver Barclay was one of them. But there were no Indians among them. Curiously, the boy cast his eyes about, the words of the Gray Lizard occurring to him. Sure[60] enough, there were the redskins mounted, their camp equipment upon the backs of the packhorses. With no thought of triumphing over a beaten foe, but filled with disappointment at not having the chance to try himself against the famed runner, Oliver stepped aside to Long Panther’s horse.

“What! are you going before the race is run?” asked he, astonished.

The young warrior looked down into the face of the white boy long and intently; then he spoke.

“It may be,” he said, “that the time will come when you and I will run a race. And if it should, see to it that you are as swift as the antelope of the plains; for it may be that you will have much at stake.”

And with that Long Panther rode off along the trail after his fellow braves.

That Boone had in mind an adventure beyond the Laurel Ridge was soon noised abroad.

“Going on a big hunt,” said one of the settlers to another. “Taking John Finley, who some years ago led a party to the Louisa River[3] region, and some others.”

“Means to stay for some time, too, I hear,” said the other.

The first speaker nodded.

“Dan’l’s boys are big enough to look after things now,” said he. “And I guess[62] they have money enough to last a while. And besides the fun of the hunt, Boone’ll bring back rich furs, for they say the country he’s going into just swarms with game.”

But that Boone had any thought other than hunting was not known to the settlements; that Colonel Henderson contemplated having the backwoodsman inspect the wilderness as a preliminary to planting colonies therein was kept a close secret.

It was one fine day in May in the year 1769 that the little party assembled for the start. Besides Boone and Finley, there were James Moncey, John Stuart, William Cool and Joseph Holden, hardy woodsmen, dead shots and men who could be depended upon in any emergency.

Besides the sinewy, deep-winded horses which they rode, they had a number of pack animals laden with blankets, ammunition and camp equipment and provisions.

“We need not take much food,” said Boone, and Finley had agreed with him. “A little meal and salt and such like, that’s all. For the country into which we’re going, boys, is a paradise for riflemen. The streams have never been fished[63] except by the wandering Injuns; the herds of deer and buffalo are endless; the small game, both furred and feathered, are not to be counted.”

Each of the adventurers had slung across his back the very long, flint-lock rifle made famous by their breed and generation; they also carried keen, heavy knives and hatchets; only a few pistols were to be seen among them. They wore deerskin hunting shirts and tanned leggins of the same material; their powder-horns and bullet-pouches swung from their shoulders.

Boone and the others had said good-bye to their families and now sat their horses in the trail along the Yadkin, having a last word with Colonel Henderson, who had ridden from Hillsboro to see them off. Noll Barclay had borne him company, and Eph Taylor, eager and curious, had journeyed from the forest-encircled farm to hear the latest word.

“I suppose,” Oliver said to his uncle,[64] “that you have reasons, but I can’t see why Eph and I could not ride with Mr. Boone on this adventure as well as not.”

“You are too young,” spoke the colonel, after the fashion of a man who had heard the suggestion in many forms before.

Boone looked at the straight, slight form of the lad, and then at the lanky Eph. He nodded his agreement with the other.

“Too young,” said he. “There are times, lads, when years count, and this is one of them. It’s not only your being short of endurance but of judgment that makes it impossible to take you along this time. You look at this thing as a bit of fun, and that is just what it is not. In a year or two, though,” he added, “you’ll both have picked up years and experience.”

“But in a year or two,” objected Noll, “there may be no trips into the wilderness.”

Both Boone and Colonel Henderson laughed.

[65]“The wilderness will be there for many years to come,” spoke the colonel.

“And this, I think, is not the last trip into it by many,” said Daniel Boone.

Young Barclay had talked over the adventure of the wilderness with both Eph and Sandy, and while none of them hoped to be taken along on the expedition, they, like every lad for miles around, longed to have fate play an unexpected prank in their behalf.

“I don’t expect anything to happen,” Oliver had said, fervently. “But you can never tell.”

However, it did not happen, and the two boys watched the hardy band ride along the trail for the river, leading their pack animals, and plunge into the budding green sea of the forest.

Now began the long hardship of the journey across the mountains. For some days the going was not so difficult, because ways had been hewn in the forests by settlers[66] tilling the land round about; but in a little while they penetrated beyond the settled district and were voyaging in the trackless wilderness where the foot of the white man had seldom fallen. They now followed the winding paths made by buffalo and other large animals as being attended with less labor than pushing their way through the dense undergrowth and interlacing vines. Through deep ravines, down roaring mountain streams, descending into wonderful valleys, fording deep rivers, they held their way across the mountain ridge which streaked so blue across the sky-line; and at length they found themselves on the verge of that far country of which they had been in search.

Here and there in the journey they had come across the tracks of redskins; once across the tree tops they had seen tall, pale columns of smoke lifting, which told of a camp of some size. And having no desire to become better acquainted with the wandering[67] tribesmen, they had always changed their course and brought into play all those wiles known to the students of woodcraft to throw off their trail any one who might stumble upon it.

“It’s always best to be careful,” said Boone, during one of these sudden shifts in their course. “As far as I know there’s no big party in this region, because it belongs to no one tribe and is visited only by the hunters. But never take a chance that can be avoided—that’s the safe course to follow.”

However, as Daniel Boone had said to Colonel Henderson, the beautiful land of Kentucky was used, from time to time, as something more than a hunting-ground. Bands of Chickasaws, Shawnees and Cherokees frequently met in the heart of the wild, and when they did, savage fighting followed. So desperate were these conflicts that the region became known by an Indian name signifying “dark and bloody ground.”

Before the band of white men, as they[68] stood upon an eminence of the ridge on the day they first sighted Kentucky, was a vast rolling country, roamed by herds of horned beasts, splendid streams and valleys which promised a rich yield to the hand which drove the plow through it.

But after a space given to wonder and admiration, Boone noted that the sun was slipping little by little behind the green rim of the forest.

“I think, boys,” suggested he, “we’d better look for a likely place to camp for the night. To-morrow we’ll plunge into the new country and have a close-at-hand look at everything.”

In the mountain-side was a small gorge across which a cottonwood had fallen and hidden by a dense growth of thicket. Limbs were cut by hatchet and knife and placed against the fallen tree in such a manner as to form a sort of roof. Bark was pulled from those trees which gave it readily, and fitted over the limbs; soft balsam boughs[69] were placed in the bottom of the gorge for beds; and here the adventurers made a home in the wilds which they kept until the winter came with its snow and rigors.

A turkey was roasted above the coals, impaled upon a ramrod; flap-jacks were baked upon heated stones, and full of the spirit of the thing and gifted with wonderful appetites the adventurers fell to and made a hearty meal.

Then, afterward, they stretched out upon the soft boughs and watched the moon drift across the sky while they talked of what was to come. All was peace; save for the cry of some night bird, or the stirring of the breeze among the trees, there was no sound.

Then, without a word of warning, there was a sudden crash from the black looming forest, and the ring of a rifle-shot went echoing and reëchoing from level to level until it died away in the stillness.

As the ring of the rifle died away, the little band in the hut reached for their fire-arms; with pieces cocked and ready, they stole out and crouched close to the ground, silently waiting. But nothing followed; whoever fired the shot was a long distance away and the firing of the shot had nothing to do with them.

“It may have been a signal,” said Boone, as he arose on one knee, his keen eyes searching the great shafts of gray moonlight which lay trailing on the mountain-side. “But it’s not likely. If we’ve enemies hereabouts they’d not take that way of getting news of us to each other. For one thing, we’d hear it; for another, powder is a hard thing for a redskin to get, at best,[71] and I reckon they’re not in a hurry to waste any of it.”

“Must have been a shot by some red hunter to stop a catamount that had come to his camp,” said Finley. “This looks to be a likely country for critters of that kind.”

The shot, so surprising and unexpected, formed a subject for conversation during the remainder of the evening; then, posting a guard outside the hut, the explorers rolled themselves in their blankets and went quietly to sleep.

After a breakfast of broiled squirrel next morning, Boone, Finley and Stuart started out, their muskets across their shoulders, to examine the aspect of the surrounding country. If what they had come through in crossing the ridge had seemed trackless, this was infinitely more so; there were myriads of small animals and birds; the deer seemed merely wondering and possessed no fear of them. Near by was one of the[72] northern branches of the Louisa, and this they followed for miles; each day was given to a venture, during the entire summer and the ensuing fall. Always some of the party remained at the hut in the gorge, while the others took the buffalo paths in search of new discoveries.

November came with its chilly nights; then fell December with its sudden frosts, its flurries of snow and its long nights; and it was in that same month of December that the first mishap befell them.

It was but a few days before Christmas that Boone and Stuart started off in a direction seldom taken on former occasions. There was a light snow upon the ground—not enough to impede their progress—but sufficient to plainly show the tracks of anything that had passed that way. The timber wolves had grown especially numerous since the winter had set in, and their prints were scattered all about in the cane-brakes and through the woods. Once they[73] came upon the clear trace of a catamount, and nothing would have pleased them better than to have followed the beast and tried their rifles upon it; however, they were in the wilderness for more important things than mere hunting, so they passed the tempting trail and pushed on, intent upon the lay of the ground, the quality of the soil, the timber and the natural drainage.

They had gone on for some hours in this way when Stuart heard Boone, who was some yards in advance, give an exclamation of surprise. The backwoodsman had paused and was bending over, studying something intently.

“What is it?” asked Stuart, as he hastened forward.

Silently Boone pointed at the snow; there, distinctly printed, was the trail of many moccasined feet.

“Injuns!” said Stuart, astonished.

Strange as it might seem, the little band[74] of adventurers had not caught sight of a red man since they had started out in the previous spring; and this had, somehow, caused the idea to grow among them that this particular region was being avoided by the Indian hunting parties, at any rate for the time being.

Closely Boone studied the trail; some peculiarity of the moccasin imprints struck him.

“They are Shawnees,” said he; “and as far as I can make out, there must be a score of them.”

“That many, at least,” spoke Stuart, his eyes also examining the trail. “A hunting party pushing toward the river; maybe in search of fur.”

Boone nodded, but somewhat dubiously. The sudden appearance of a large band of savages at that precise time disquieted him; he felt in it the promise of future danger.

[75]

CLOSELY BOONE STUDIED THE TRAIL

“They’ve found meat scarce, I suppose,” suggested Stuart, as they went on through[76] the forest, “and so they had to go farther away from home.”

“It would have pleased me just as well if they’d taken another direction, then,” said Boone. “We’re getting on too well with our work to be disturbed just now.”

Ahead was a dense clump of dark, gloomy pine woods, on the edge of which was a fringe of dwarf oaks. A heavy growth of bush and climbing thorns had sprung up among these last; and as the two whites came to this, their long rifles in the hollow of their arms, there came a sudden rush, a fierce yell of exultation, and they found themselves borne to the ground, disarmed and bound with leather thongs.

With their rifles, hatchets and hunting knives in the possession of their captors, and their hands firmly secured behind their backs, they were permitted to rise, and found themselves looking into a circle of grim, copper-colored faces, and being examined by narrow, threatening eyes.

[77]It was a party of Shawnees, and evidently the same whose tracks they had come across a short time before. The braves were in their full panoply of war; they carried bows and scalping knives, quivers of arrows were on their backs, tomahawks were in their belts; a few ancient looking rifles were the only fire-arms to be seen among them, however, and the powder-horns and bullet-pouches were fewer still.

A powerful looking savage, evidently a chief, and the leader of the band, now spoke.

“The white faces hunt in the hunting-grounds of the Shawnee,” said he, in very bad English.

But Boone looked at him with cool, humorous eye.

“The great chief is mistaken,” said he. “The white man would not so wrong his red brother.”

The Shawnee chief said something to his[78] followers, no doubt interpreting the saying of the backwoodsman; there came a series of grunts and ejaculations from them; their copper-colored faces grew grimmer still, their eyes even more threatening than before.

“Yesterday we heard the rifle of the white face,” spoke the Shawnee leader, turning again to Boone; “to-day we have heard it. We have seen the remains of deer and buffalo which he has killed; we have seen his beaver traps in the streams.” There was a moment’s pause, then the savage added: “What has the white face to say?”

“You might have heard our rifles speak for many days, if you had been here,” replied Boone. “And that you have seen the carcasses of deer and other animals which we have killed is quite likely. But what of that? The country is open to hunters, is it not? Do not the Chickasaws and the Cherokees hunt their meat and fur[79] in these woods and mountains? Why, then, do the Shawnees claim it as their own?”

“The Chickasaws and the Cherokees are thieves!” pronounced the Shawnee chief. “We have taken the war-path against them; we will make a wailing in their lodges, an emptiness in their villages.”

“You treat your white brother with injustice when you ambush him and take away his arms. You have suffered no wrong at his hands,” maintained Boone.

Again the chief translated to his braves, and again came the grunts and ejaculations. But in spite of the threatening looks and the tightening of the savage circle, the backwoodsman proceeded fearlessly.

“If any one hunts in this region without right, it is the red man,” declared he. “The whole of the country below the great river belongs to the white face. Many moons ago, at the great council at Fort Stanwix, the league of the Iroquois turned over this land to the colonists. Does the[80] red brother deny this? Does he not mean to keep faith?”

What Boone said was true, and the Shawnee knew it, but in the southern tribes the right of the league to cede the territory had always been denied. So the chief regarded Boone with fierce-eyed anger.

“The white face is as cunning as the snake,” said he, “and his tongue is as crooked.”

Then turning away from them he gave a signal; the band at once started off, the two captives in their midst, guarded by a half dozen lean, hawk-like braves. Some miles away among the hills was the Shawnee camp, a dozen or more deerskin lodges erected in a sheltered place. Fires were burning outside the tepees; several young men were cooking strips of meat upon pointed sticks.

The whites were bound to heavy stakes driven firmly into the ground; then the[81] band gathered about the fires, and when the meat was cooked began to eat it in silence.

“Well,” said Stuart, who had said very little since their capture, “it has a bad look.”

“It might be worse,” replied Boone, coolly, his calm eyes studying the Shawnees at the camp-fires. “There is a good chance for us yet.”

“To escape?”

Boone nodded.

“But how?”

The calm eyes twinkled as they turned upon the speaker.

“Don’t offer me any puzzles to answer,” said Boone. “I have no more notion ‘how’ than you have. But the chance will come in some way; and it will be for us to be ready to take hold of it.”

Though Boone had never been taken captive by the Indians before, he knew, from talks with those who had, and from his knowledge of savage ceremony, that in cases[82] like their own, a certain form was always gone through before torture and death were resorted to.

“They’ll keep us,” he told Stuart, “and try to get us to come into the tribe. It’s a strange kink in their natures that though they hate the white, they seldom fail to try to make him one of them by adoption if they have the chance.”

“You think they’ll try and make Shawnees of us?”

“It’s like as not,” answered Boone.

“Before I’ll be a renegade, I’ll die,” said Stuart, stoutly.

Boone nodded.

“I don’t know as I blame you in that,” spoke he. “A renegade is as mean a critter as walks the earth. But it’d be just as well if we kept our feelings on that point from the Shawnees.”

“You mean——”

“That if we’re asked to join the tribe, we’d better not refuse. It’s life if we can[83] deceive them, and death by horrible torture if we refuse.”

“I don’t like the notion of even seeming to be an Injun,” spoke Stuart, who was a brave man and stubborn in his courage. “But whatever you think best, that I will do.”

That night they were given a couple of bearskins to lie upon, and their bonds were looked to with much care. They slept fairly well but were awake at dawn when the savages began to stir about the camp. Some meat and a sort of porridge made of Indian corn, crushed between two smooth stones, was given to them; and after they had eaten, the Shawnee chief approached, followed by the eldest of his warriors. Silently they sat before their prisoners, seeming to study them with the utmost attention. After a space the chief spoke.

“The white faces are prisoners; they were taken in war by Black Wolf and his braves; they are without arms, they are helpless.”

[84]Neither Stuart nor Boone made any reply to this; but the warriors, upon the words of Black Wolf being interpreted to them, expressed their approval by nods and throaty murmurs.

“Far away, toward the rising sun, are the friends of the white face, far away where the morning first touches the forest are his lodges. Neither friends nor lodges will he ever see again.”

There was another pause; Black Wolf studied the expressions of their faces intently. But still they made no reply. The chief then resumed:

“You have killed in the hunting-grounds of the Shawnees, and for this your lives belong to Black Wolf and his braves. But the chief would spare you; he does not wish to see you die. Rather would he see you, his brothers, living in the wigwams of the Shawnees and taking to the war-path against his people’s foes.”

This being repeated in the Shawnee[85] tongue to the elder warriors, was greeted with a chorus of approving grunts. And then Black Wolf asked:

“What does the white face say?”

“The Shawnee chief is a noble hunter and a warrior whose fame runs beyond the blue ridge,” said Daniel Boone. “And his words are as straight as the young birch by the waterside. It is true that the pale-face’s friends are far away, and that his lodge is many days across the hills; and for both of these his heart is sore. But he would not lose his life. Other friends he can make; other lodges he can build; but he has one life only, and when that is gone he cannot call it back.”

Black Wolf repeated this to his counselors and again came the chorus of grunted approval.

“It is well spoken,” praised the Shawnee chief. “Do you, then, give up your people and will you go to the villages of the Shawnee and make them your home?”

[86]“To save my life—yes.”

“And you?” asked Black Wolf, his eyes going to Stuart.

“I say the same,” replied that worthy.

“It is well,” said the chief.

He arose, and the elder braves did likewise; turning to them he spoke briefly and to what he said they apparently agreed with readiness. One of the warriors took out his knife, approached the captives and severed the thongs which bound them.

Black Wolf signed for them to get up.

“My young men are about to start upon a hunt,” said he. “It were well if the white brothers went with them.”

The hunting party was already making ready; and in half an hour or so it filed out of the camp and along a buffalo track which led toward the west. The two white men trudged along the track, Boone whistling a snatch of an old English air, Stuart morose and heavy of brow.

[87]Finally the latter spoke.

“Why are we taken out with a hunting party and provided with no weapons? It hasn’t a reasonable look!”

Boone stopped his whistling.

“The whole idea of this party is just a little game of the redskins. It’s not their purpose to hunt,” said he.

“Not their purpose to hunt?” echoed the other.

Boone nodded.

“Just keep your eye peeled,” spoke he. “Do you see how the varmints go along—careless and never noticing us? Never a look do they give us, so far as I can see. But,” and he covertly clutched his companion’s arm in his strong grip, “they’re noticing us, never fear. They see everything we do, every look we give away from the track we’re following. This is not a hunt, comrade; it’s a test of our intentions. They are trying us. And the trial will go on in different ways for days. Some one[88] will always be watching us; to try and escape will mean death for us.”

“A pleasant outlook,” said Stuart, gloomily.

“But don’t forget,” said Boone, “that this watch upon us will not last always. Let us make it seem as if we were contented enough. If they lay little traps for us to fall into, let us step over them. No matter how good the chance seems for a while, we must not try to get away; for it will only win us a dozen or so arrows in our backs. After a little while they’ll grow slack in their watching. If they see us living quietly as they live, doing the things they do, they’ll come to trust us more and more. And then our chance will come—and we’ll make the best of it.”

Keeping up an intent observation of the savages, Stuart gradually came to the conclusion that what Boone said was true. Not a moment passed but they found themselves closely watched by the Shawnees.[89] And so he came to see that his friend’s plan was the solution of their situation. The gloomy look vanished and the frowns followed; his manner grew as care-free as could well be imagined; he also whistled a catch now and then; and more than once he laughed light-heartedly over some small incident of the march, a thing which was not thrown away upon their red brothers.

That night they spent in a lodge which Black Wolf gave up to them; as before, they were not bound and apparently were unguarded. But both knew that the sharp eyes of the bronze warriors were peering at the lodge, that lurking forms hung silently in the shadows, and swift-winged arrows were ready to sing their death song should they make an attempt to escape.

And so it went one day after another until a full week had passed. Adventure after adventure did the Shawnees take them upon; at times they were left apparently alone for hours in the forest; the[90] temptation was great, but they conquered it; and always were they glad they had done so, for it was shown afterward that in each case the savages had been at no great distance, and that the thing had been one of the traps which Boone had foretold.

Little by little, in the face of this plainly shown content of the white brothers for their lot, the Shawnees became lax in their vigilance, and finally upon the seventh night of their captivity, the active-minded Boone saw their first real chance of escape. All was still in the redskin camp; the fires smouldered under coverings of ash; a pale, wintry moon looked down upon the wilderness. It had been an active day for the savages; it had been thought that a party of Cherokees had entered the region, and all the warriors of Black Wolf’s band had been ranging the woods searching for their trail. And so these braves, whose duty it was to keep a careful eye upon the adopted whites, grew heavy eyed as the night wore on;[91] their deep breathing told the wide-awake Boone that all were asleep.

Stuart, also, was asleep; carefully Boone awoke him.

“The time’s come,” he whispered in the ear of the surprised backwoodsman. “Make no noise; all the critters are as sound as rocks.”

Softly they crept through the opening in the lodge; like cats they moved among the other wigwams until they gained the shadows. Then Boone halted.

“What now?” asked Stuart, in a whisper.

“We’ve left our rifles behind. Wait here.”

“You don’t mean to go back!” Stuart was amazed.

“I must. Do you realize what it would mean to be away here in the wilderness without the means of getting game for food? Man, we’d die.”

Seeing the force of this, Stuart released[92] the hold he had taken upon Boone’s shoulder. Back into the Indian encampment stole Daniel Boone; straight to the tepee of Black Wolf he went, and, from his place in the shadows, Stuart saw the brave pioneer stoop and enter. Then followed a long pause. The waiting man could hear the heavy throbs of his own heart. Each moment he expected to hear the war-whoop of the Shawnee, and to see the camp spring into activity.

But fortune smiled upon the daring Boone, for after a time he appeared, the two rifles in his hands, and their powder-horns and bullet-pouches slung upon his shoulders. Silently he recrossed into the shadows; quietly he gave Stuart his own piece, his own horn and pouch; then creeping like wild things of the wilderness, they stole away into the depths where the night would hide them from all hostile eyes.

All that night the two adventurers pressed steadily away from the Indian encampment; they made, as far as they could reckon it, in the general direction of their camp in the gorge. The pale moon filtered through the bare branches of the trees, the stars twinkled helpfully; and when morning came dimly above the higher hills they found that they had judged their direction with singular accuracy. They were not more than a mile or two from their own camp.

“Pretty good, for going it blind,” said Boone, well pleased. “And now I suppose we’ll give the boys a surprise. Having been missing for all this time they’ll reckon we’re gone for good.”

But it was themselves who received the[94] surprise; arriving in sight of the gorge they saw no friendly morning smoke; hurrying forward they entered the hut; no one was there; everything of any value was gone.

“Injuns!” cried Boone.

“Or they somehow heard about us being taken by the redskins, and have gone back to the settlements,” said Stuart.

Just what happened at the camp during the seven days’ captivity of Boone and Stuart among the Shawnees has never been written. There is no record in the annals of the time that they returned to civilization; the confusion of the camp as found by Boone might have meant that it had been deserted hastily, or that the party therein had been murdered and robbed. But which was the truth he probably never knew.

For some time the two hardy adventurers remained staring at the remains of the shelter which had been their home for more than a half year.

[95]“Well,” said Boone, “I reckon they’re gone.”

“Gone they are,” agreed Stuart. “And as we don’t know how or why, it’s my opinion that this is no safe place for us.”

Rapidly, but thoroughly, they ransacked the camp for ammunition; but none was to be found; then they made their way into the cane-brakes, carefully covering their tracks as they went, and took up their camp in a secluded place where an enemy could not come upon them without their having due warning of his approach.

From that time on the pair shifted their camp with each day; they lived much like the wild things of the wilderness about them, seldom making a move in any direction without studying the prospects and calculating their chances. But in spite of all this, Boone, with his usual hardihood, continued to make his inspection of the country; they extended their explorations in many directions; and though they lived[96] in constant peril of their lives, and their food was reduced to the meat they could kill, they were not of the sort to cuddle fear to their breasts and increase their hardships by complaint. Accustomed to hard living they took their situation calmly enough; never once did it occur to them that it would be best to leave their work incompleted and return home.

“But,” said Boone, one night by their carefully-masked camp-fire, “I’d like to have powder and ball. There are only a half dozen charges between us; and every time I let off my rifle I feel that we’re slipping that much nearer the finish of the whole matter.”

Some weeks went by in this way; and one morning as they followed a buffalo path they heard a steady, long “clump-clump-clump” advancing toward them from the direction in which they had come.

“Buffalo?” asked Stuart, puzzled.

Boone listened, then shook his head.

[97]“Horses,” said he. “And horses that are being ridden.”

With one accord they left the track; they took up posts behind the trees, their rifles held ready for anything which might occur.

In a very little while the hoof-beats became quite close at hand; then from out of the undergrowth which lined the path rode a couple of bronzed white men, well armed, and leading a pair of packhorses. Amazed, Daniel Boone called out:

“Hello, stranger! Who are you?”

The riders checked their steeds and turned their heads in the direction of the hail.

“Hello!” cried one. “Is that you, Dan’l?”

“White men and friends,” answered they in the customary manner of the wilderness.

“As I live,” cried Boone, starting forward, “I think it’s my brother, Squire.”

At this one of the men slid from his horse’s back.

“Dan’l!” he exclaimed.

[98]The two clasped hands, their eyes full of pleasure.

“We came upon your tracks yesterday,” said Squire Boone, who was Daniel’s junior by some years. “But we had more trouble in following it than if you’d been a couple of black foxes anxious to save your pelts.”

Daniel and John Stuart looked at each other.

“We took a lot of trouble to cover those tracks up from time to time,” said Stuart, grimly. “And we did it to save our scalps.”

“Ah!” said Squire. “Injuns?”

“Shawnees!” answered his brother.