THEOLOGY & PHILOSOPHY

HISTORY ❦ CLASSICAL

FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

ESSAYS ❦ ORATORY

POETRY & DRAMA

BIOGRAPHY

ROMANCE

New York: E. P. DUTTON & CO.

Title: An Anatomical Disquisition on the Motion of the Heart & Blood in Animals

Author: William Harvey

Author of introduction, etc.: Ernest Albert Parkyn

Editor: Ernest Rhys

Translator: Robert Willis

Release date: January 1, 2022 [eBook #67065]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: J. M. Dent & Co

Credits: Thiers Halliwell, Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The text of this e-book has been preserved as in the original, including inconsistent capitalisation and hyphenation. Archaic and inconsistent spellings have also been preserved except where obviously misspelled in the original.

To assist readers, an additional item (‘Editor’s Introduction’) has been added to the table of contents, and an alphabetic jump-table has been inserted at the beginning of the index. Hyperlinks have been added to index entries and the table of contents, and to cross-references within the text. Page numbers are shown in the right margin and footnotes are located at the end. Footnotes are listed at the end.

Spelling inconsistencies include (but are not limited to) the following:

Fifty/Fiftie

enjoy/enioye

natural/naturall

physitians/physicians

book/booke

aëreal/aereal/aërial

Corrected misspellings include the following:

preceive → perceive

under-their → understand their

retrogade → retrograde

aditional → additional

aud → and

so → to

Valkveld → Vlackveld

slugglishly → sluggishly

The cover image of the book was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

PRINTED BY HAZELL, WATSON AND

VINEY, LD., LONDON AND AYLESBURY

vii

However much the renewal of classical learning in the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries may have furthered the development of letters and of art, it had anything but a favourable influence on the progress of science. The interest awakened in the literature of Greece and Rome was shown in admiration not only for the works of poets, historians, and orators, but also for those of physicians, anatomists, and astronomers. In consequence scientific investigation was almost wholly restricted to the study of the writings of authors like Aristotle, Hippocrates, Ptolemy, and Galen, and it became the highest ambition to explain and comment upon their teachings, almost an impiety to question them. Independent inquiry, the direct appeal to nature, were thus discouraged, and indeed looked upon with the utmost distrust if their results ran counter to what was found in the works of Aristotle or Galen. This spell of ancient authority was broken by the anatomists of the sixteenth century, who determined at all costs to examine the human body for themselves, and to be guided by what their own observations revealed to them; and it was finally overcome by the independent genius of two men working in very different scientific spheres, Galileo and Harvey. These illustrious observers were contemporaries during the greater part of their lives, and were some years together at the famous University of Padua. Galileo and Harvey refused to be bound by the teachings of Aristotle and Galen, and appealed from these authorities to the actual facts of nature which any man could observe forviii himself. Their scientific work is therefore of interest, not only for the innate value of the discoveries they made, but also because it shows them as pioneers in that independent spirit of scientific inquiry to which the great advance in natural knowledge since their time is so largely due.

Harvey’s work, by which his name has been made immortal, strikingly illustrates this. He was the first to show the nature of the movements of the heart, and how the blood moved in the body. He did so by putting on one side authority, and directly appealing to observation and experiment. The completeness of the success with which this independent line was taken, as exemplified in his treatise “On the Movement of the Heart and Blood,” is such as to excite the admiration of every modern physiologist. “C’est un chef-d’œuvre,” says a distinguished French physiologist, Flourens, “ce petit livre de cent pages est le plus beau livre de la physiologie.”1

The discovery made by Harvey was this: That the blood passed from the heart into the arteries, thence to the veins, by which it was brought back to the heart again; that the blood moved more or less in a circle, coming back eventually to the point from which it started. In a phrase, there was a Circulation of the Blood. Moreover, this circulation was of a double nature—one circle being from the right side of the heart to the left through the lungs, hence called the Pulmonary or Lesser Circulation; the other from the left side of the heart to the right, through the rest of the body, known as the Systemic or Greater Circulation. Further, that it was the peculiar office of the heart to maintain this circulation by its continuous rhythmic beating as long as life lasts.

This appears very plain and simple to us now—so easy that he who runs may read: as important asix simple, for without this knowledge it is no exaggeration to say that a real understanding of any important function of the human body was impossible. And hence it has been contended with much force that not only the science of physiology, but the scientific practice of medicine date from this discovery. “To medical practice,” says Sir John Simon, “it stands much in the same relation as the discovery of the mariner’s compass to navigation; without it, the medical practitioner would be all adrift, and his efforts to benefit mankind would be made in ignorance and at random. . . . The discovery is incomparably the most important ever made in physiological science, bearing and destined to bear fruit for the benefit of all succeeding ages.”2

When Harvey first approached the subject, there were all kinds of crude and fantastic ideas regarding the functions and uses of the heart, bloodvessels, and blood—that the heart was the workshop in which were elaborated the spirits, a due supply of which was necessary for many parts of the body; that from the heart the arteries carried spirits, the veins nutriment to the different parts of the body; that the arteries contained blood and air mixed together, or only air; that fuliginous vapours, whatever they may be, passed from the heart along the bloodvessels; that the septum of the heart, by which its two sides are completely separated, was riddled with minute holes, like a fine sieve, through which the blood percolated from the right to the left side; again, that the heart was the organ in which the heat of the body was produced. Another favourite theory was that the blood moved from the heart along certain bloodvessels and back again by exactly the same channels, after the manner of the rise and fall of the tides, to which in fact the movement was likened. More curious still, even the best informed appeared to believe that the arteries terminated in nerves.

x

Notwithstanding these curious and erroneous speculations there was not wanting exact and wide knowledge of the anatomy of the human body. Indeed, before Harvey was born there had lived and died a most remarkable man known to fame as the “Father of Anatomy.” This was Vesalius. Vesalius’s knowledge of the human body was so profound that the only wonder is that he did not forestall Harvey in the discovery of the circulation. As the result of dissections of the body at the time when they could be carried out only with great difficulty, and often at the risk of severe penalties, Vesalius published, when only twenty-eight years of age, a treatise on Anatomy3 which cannot fail to excite the astonishment and admiration of any modern acquainted with the subject. This work is illustrated with fine engravings made from drawings by John Calcar, a Flemish artist, and pupil of Titian.4

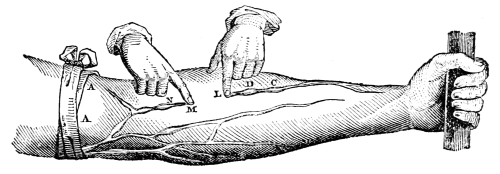

The distribution of the bloodvessels in the lungs and many other parts of the body, the general structure of the heart, the valves in the veins, were all known before Harvey arrived on the scene. More than this, the circulation through the lungs, or the Pulmonary Circulation, appears to have been known to one person at least. Michael Servetus, famous for his martyrdom on account of his religious opinions, in one of his theological works5 does actually describe the blood as passing from the right side of the heart to the left through the lungs, and gives good reasons for his belief. Servetus, in his early days, had been with Vesalius prosector to John Guinterius of Andernach when Professor of Anatomy at Paris. Guinterius6 speaks with admiration of the knowledge and abilities of his two young assistants. Like Vesalius, Servetus was therefore well acquainted with the anatomy of the body; but more, he was a physiologist; and no doubtxi when the cruelty of theological dispute sent him to the stake at the age of forty-four, it deprived physiology of a most promising investigator. The book in which the account of the Pulmonary Circulation is found has a most curious history. All copies of it, except one, were burnt with Servetus. This copy became the property of D. Colladon, one of his judges. After passing through the library of the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel it came into the hands of a Dr. Mead, who undertook in 1723 to issue a quarto edition of it, but before completion the sheets were seized at the instance of Dr. Gibson, Bishop of London, and destroyed. The Duc de Valise is said to have given 400 guineas for the original copy, and at his sale it brought 3,810 livres. It is now in the National Library at Paris. It may well be questioned therefore whether the discovery of Servetus was ever known to the anatomists, including Harvey, who wrote after his death. One of these was Realdus Columbus, who published a work on Anatomy7 six years after Servetus died, in which he shows that he clearly understood the valves of the heart, and describes the passage of the blood through the lungs. Columbus has been claimed as the real discoverer of the circulation and as having forestalled Harvey. But neither Servetus nor Columbus had any notion of the Greater or Systemic Circulation. And the latter actually says the heart is not muscular, and speaks of a to-and-fro movement of the blood in the veins.

But a third and much more serious precursor of Harvey as the discoverer has been brought forward in the person of Andreas Cæsalpinus8 of Arezzo, justly renowned as the earliest of botanists. He actually used the word “circulation” in regard to the passage of the blood through the lungs. The claims of Cæsalpinus have been taken up with enthusiasm, not to sayxii bitterness, in Italy; and in 1876 his statue was erected with much pomp and speechmaking in Rome, and an inscription placed upon it recording that he was the first discoverer of the circulation of the blood. It is much to be regretted that this display was not altogether free from a desire to depreciate Harvey. Wonder may well be expressed at this procedure, even after allowing for well-meant patriotic ardour, when it is learnt that in his works Cæsalpinus speaks of the arteries ending in nerves, of the septum of the heart being permeable, and its valves acting imperfectly, and of the veins carrying blood to the body for its nourishment. The statements made by Cæsalpinus, which at first sight point to his knowledge of the circulation, are altogether discounted on perusal of his works, and it becomes impossible to believe that he had any clear idea of the circulation as we understand it to-day. The misconception has no doubt arisen from the interpretation of isolated passages in the light of what we now know regarding the circulation. Moreover, it is impossible to believe, seeing how well the works of Cæsalpinus were known, that, had he ever been regarded as putting forward in them the doctrine of the circulation as we now understand it, such a new and startling view would not have attracted the attention of the distinguished anatomists who were his contemporaries or immediate successors. But that none of them ever for a moment saw any such doctrine in the works of Cæsalpinus is shown by their writings, and by the surprise with which Harvey’s discovery was received.

Even Shakespeare has been cited as being acquainted with the circulation of the blood, because he refers to its movement. This only illustrates the confusion which has often been made of movement with circulation. From the earliest times it had been believed there was movement of the blood, but there was no clear or correct idea as to the nature of the movement.xiii The view may be ventured that another confusion is responsible for a good deal that has been said about Harvey having been forestalled in the discovery. It is confusing the passage through the lungs of some blood with the whole mass of it. It is difficult to believe, on taking a broad view of all their statements on the subject, that any of Harvey’s predecessors realised that the whole mass of the blood was continually passing through the lungs. Had they done so it is further difficult to see how the systemic circulation should have escaped them. But of this they certainly had no idea.

We may admit all this previous knowledge without its detracting from the greatness and merit of Harvey’s work. Although the same anatomical facts, and even a glimmering of the Pulmonary Circulation may have been present to the minds of his predecessors or contemporaries, yet the genius, the spark of originality by which was discovered the proper relation to one another of the former, the true significance and meaning of the latter, belongs to Harvey and to him alone.

As was said by one of the best informed minds9 of the eighteenth century: “It is not to Cæsalpinus, because of some words of doubtful meaning, but to Harvey, the able writer, the laborious contriver of so many experiments, the staid propounder of all the arguments available in his day, that the immortal glory of having discovered the Circulation of the Blood is to be assigned.”

William Harvey was born on April 1, in the year 1578, at Folkestone, the eldest of seven sons of a well-to-do Kentish yeoman. When ten years old he was sent to the Grammar School at Canterbury, and remained there until he was fifteen. He then proceeded to Caius College, Cambridge, where after three years’ residence he took the usual degree. Desiring to enter the medical profession, he adopted a course, notxiv unusual at that time, of going abroad to study at a Continental University, a course due to the absence of scientific teaching in the English Universities on the one hand, and to its excellence in those of the Continent on the other. Consequently, in the year 1597, when nineteen years of age, Harvey directed his steps towards Padua, then famous throughout Europe for its medical school, and especially for its school of anatomy. Earlier in the century the chair of Anatomy had been filled by Vesalius; it was now occupied by another celebrated anatomist, known as Fabricius of Aquapendente. Harvey enjoyed the advantage of studying anatomy under this great teacher, and the visitor to Padua to-day can see the little anatomical theatre with its carved desks, over one of which, no doubt, our illustrious discoverer leant with eager attention whilst Fabricius demonstrated on the body below. We can see the professor with pride explaining to his pupils the valves in the veins which he had discovered, yet not appreciating their meaning and importance; that was to be done a few years hence by the young student listening above. It is very interesting to learn that at this time Galileo was also a professor at Padua, and was lecturing with such success that students flocked to hear him from all parts of Europe. Surely it is difficult to imagine any seat of learning more distinguished and attractive than the University of Padua must have been during the five years Harvey spent there. At the end of this time he received his degree of doctor, the diploma for which is couched in the most eulogistic language, showing how by his studies and abilities he had attracted the attention and earned the commendation of the distinguished professors who then held the chairs of Anatomy, Medicine, and Surgery in the University. He now returned to England, and was granted the degree of Doctor of Medicine by the University of Cambridge.

xv

Soon after, Harvey settled in London and began to practise. In 1607 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, and in 1615 was appointed Lecturer in Anatomy to that ancient and important foundation. In 1609 he had been elected physician to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

In 1616, the year Shakespeare died, Harvey probably began in his classes to teach that doctrine which has immortalised his name. He began to show his pupils, and whoever else desired to be present, from dissections of the human body and of animals, and by experiment when necessary, the true office of the heart, the true course of the movement of the blood in the body. This he continued to do for more than ten years, listening patiently to objections, indeed inviting criticisms so that the complete truth might be discovered free from any falsities or misconceptions. At last, upon the earnest entreaties of his most distinguished medical friends, he was persuaded to publish his discovery to the world. These facts are of interest in throwing some light on Harvey’s character. A discoverer who waits years before publishing what he is firmly convinced in his own mind is a new idea, not to say a great discovery, must be possessed of that calmness of mind and abnegation of self which we associate with the true philosopher. A discoverer who employs so long an interval to give opportunity for criticism, and to deal with objections, must indeed be wedded to truth.

This devotion to truth, however, had its reward, for it resulted in one of the most remarkable scientific treatises ever written. When, in 1628, Harvey published at Frankfort-on-Main, his book on “The Movement of the Heart and Blood,” he gave his reasons for believing the blood to circulate, and explained the use of the heart in language so simple, so clear, so exact, that now, nearly three hundred years afterwards, the most accomplished physiologist can hardly improvexvi on it. This assuredly is a fact almost unique in the history of science.

And yet with all this the fact remains that Harvey never really knew, from the nature of the case could not know, how the blood passed from the arteries to the veins—how, in other words, an essential part of the circulation was actually accomplished. The blood passes from the arteries to the veins through minute microscopic tubes termed capillaries. In Harvey’s day the microscope was not sufficiently powerful to reveal such fine structures to human vision, and he was therefore necessarily ignorant of their existence. Looked at from this point of view, the discovery affords a very good example of what has been aptly termed the scientific use of the imagination. Although, with his imperfect microscope, it was impossible for him to know how the blood actually passed from the arteries to the veins, yet as the result of his observations and experiments he was able to infer and to state the grounds for his inference in clear, forcible, and most convincing language, that the blood must circulate, and circulate in one direction only, viz. from the heart into the arteries, thence to the veins, by which it was brought back to the heart again. His imagination was thus enabled to bridge over the gulf between the arteries and veins which his eyes, with the imperfect instrument then alone at his disposal, were quite unable to cross. It was not until four years after Harvey’s death that the microscope had been sufficiently improved to enable an Italian anatomist named Malpighi,10 in the year 1661, to actually observe the capillaries uniting by their networks arteries and veins.

The work was published at Frankfort doubtless that it might be more easily disseminated over the Continent. It made a sensation among the learned of all countries. Its conclusions were opposed by the olderxvii physicians; but by the younger scientific men it was by no means received with disfavour. Amongst the latter was the philosopher Descartes, whose name was then a power in Europe. The philosophical, yet keenly practical mind of Descartes grasped the discovery with avidity and supported it with ardour. In his celebrated “Discours de la Méthode,”11 he refers to the discovery of “an English physician,” and describes with enthusiasm the anatomy and use of the heart. Although we have no certain information on the point it is quite possible that Descartes may have known Harvey, for in the year 1631 he is said to have paid a visit to England; and in his second reply to Riolan Harvey refers to “the ingenious and acute Descartes,” and says the honourable mention of his name demands his acknowledgments. Thus the discovery became widely known and largely adopted.

One result of the publication of his discovery was only in keeping with the experience of many great and original minds before and after his time. In the things of this world his discovery was of little service to him. His practice fell off. Patients feared to put themselves under the care of one who was accused by his envious detractors of being crack-brained, and of putting forward new-fangled and dangerous doctrines. One who knew Harvey writes as follows: “I have heard him say that after his booke of the Circulation of the Blood came out he fell mightily in his practice, and ’twas believed by the vulgar that he was crack-brained, and all the physitians were against him, with much adoe at last in about 20 or 30 years time it was received in all the universities in the world, and as Mr. Hobbs says in his book ‘De Corpore,’ he is the only man perhaps that ever lived to see his own doctrine established in his lifetime.”12

There was one striking exception to this treatment.xviii The King, Charles I., not only appointed Harvey his physician, but showed the liveliest interest in his discovery. Harvey explained his new doctrine on the body before the King. Whatever opinions may be held regarding the moral and political character of that unfortunate monarch, it must be admitted that in aiding and befriending Vandyke and Harvey he showed himself an enlightened patron of both art and science. Harvey continued the King’s physician, and held this position when, in 1641, Charles declared war against the Parliament. It is here curious to learn that although openly declared enemies the Parliament was still mindful of the King’s person, for not only with their consent, but by their desire, Harvey remained his physician.13 Notwithstanding his intimate connection with the Court, Harvey appears to have taken no active part in the great political struggle now taking place. The little solicitude he had for it is shown by an anecdote told of him at the first battle of the Civil War. “When King Charles,” says a contemporary author,14 “by reason of the tumults left London, Harvey attended him, and was at the fight of Edgehill with him: and during the fight the Prince and the Duke of York were committed to his care. He told me that he withdrew with them under a hedge, and tooke out of his pocket a booke and read. But he had not read very long before a bullet of a great gun grazed on the ground near him, which made him remove his station.” This anecdote well illustrates Harvey’s calm and peaceful character. This was also shown by the restrained and dignified manner in which he treated the many writers who attacked him, sometimes in anything but choice language, after the publication of his great discovery. Anything like controversy for controversy’s sake was wholly foreign to his nature. “To return evil speaking with evil speaking,” he remarks in a reply to one of his critics,xix “I hold to be unworthy of a philosopher and a searcher after truth. I believe I shall do better and more advisedly if I meet so many indications of ill breeding with the light of faithful and conclusive observation.”15 To many of the attacks made on his discovery or on himself, he therefore did not condescend to reply. And when from the eminence of his opponents he felt called upon to do so, he replied with the utmost courtesy and kindliness. But whilst admitting the high claims to distinction on other grounds of his antagonist, he proceeded on this particular question to utterly demolish him with clear facts and stern irrefutable arguments and experiments. He called upon his opponents to observe the facts and make the experiments for themselves, instead of citing the opinions of authors centuries old, or making long discourses on spirits, fuliginous vapours, and the tides of Euripus. This is well illustrated in his replies to Riolan. The arguments of Riolan would hardly seem to have entitled him to the honour of the special notice of the great discoverer. But probably his position as Anatomist in the University of Paris, and of physician to the Queen-Mother, Marie de Medicis, made Harvey pick out his criticisms as a suitable excuse for replying to his opponents. Harvey’s mode of argument is well shown by the following admirable remarks on the Manner and Order of Acquiring Knowledge, in his introduction to the work on “The Generation of Animals”: “Sensible things are of themselves and antecedent; things of intellect however are consequential and arise from the former, and indeed we can in no way attain to them without the help of the others. And hence it is that without the due admonition of the senses, without frequent observation and reiterated experiment, our mind goes astray after phantoms and appearances. Diligent observation is therefore requisite in every science, and the senses are to be frequently appealed to. We are, I say, to strivexx after personal experience, not to rely on the experience of others: without which indeed no one can properly become a student of any branch of natural science.” Referring to his own particular work he says: “I would not have you therefore, gentle reader, to take anything on trust from me concerning the Generation of Animals: I appeal to your own eyes as my witness and judge. For as all true science rests upon those principles which have their origin in the operation of the senses, particular care is to be taken that by repeated dissection the grounds of our present subject be fully established. . . . The method of investigating truth commonly pursued at this time therefore is to be held erroneous and almost foolish, in which so many inquire what others have said, and omit to ask whether the things themselves be actually so or not.”

When the King made Oxford his headquarters, Harvey was with him, and was appointed head of Merton College. But in 1646, on Oxford surrendering to the Parliamentary forces, he gave up his wardenship and quitted the city. Having no call to take an active part in the political contest, and now verging on threescore-and-ten, he retired from his position of physician to the King and went to London, where he was hospitably entertained in the houses of his brothers, who were wealthy merchants in the City. Here he no doubt once again devoted himself to scientific observation, the nature of which became evident, when in 1651 he was persuaded, somewhat against his own inclination, by his friend, Dr. George Ent, to allow the publication of his book on “The Generation of Animals.” In this work he appears as a pioneer in the difficult science of Embryology, working under most adverse conditions, for he had no microscope worthy of the name. Whilst, therefore, of no great value in the light of our present knowledge, it is a monument of the author’s industry and of his enthusiastic devotion to physiological research.xxi It contains a great number of acute and interesting observations; and he had evidently made many more, for he says that his papers on the Generation of Insects were lost as a result of the tumults which arose at the outbreak of the Civil War. He told Aubrey that no grief was so crucifying to him as the loss of these papers. The King took a direct personal interest in these investigations,16 and supplied him with deer from the Royal Parks in order to further them.

In two respects the work on Generation is worthy of more than a mere passing notice, and entitles its author to the possession of almost prophetic genius. The first is the enunciation of the great generalisation omne vivum ex ovo. Although this particular phrase is nowhere to be found, as is often erroneously stated, in the treatise on Generation, yet a perusal of Exercises I., LI., and LXII. will convince any one that Harvey had grasped this great idea, which has since been so abundantly verified. The other is his doctrine of Epigenesis, or the formation of the new organism from the homogeneous substance of the germ by the successive differentiation of parts, that all parts are not formed at once and together, but in succession one after the other. He put forward this doctrine of Epigenesis in contradistinction to that of Metamorphosis, according to which the germ was suddenly transformed into a miniature of the whole organism which subsequently grew. This is certainly very remarkable, and entitles him to be regarded as a forerunner of Caspar Wolff, Von Baer, and the modern Evolutionary School, which sees in the development of the organism from the ovum a passage from the homogeneous to the heterogeneous by a gradual process of differentiation, from a germ in which there is no sign of any of the parts of the adult to an organism with all its many and varied organs. Commenting on certain passages of Exercise XLV., in which Harvey specially refersxxii to this subject, the late Professor Huxley remarked: “In these words, by the divination of genius, Harvey in the seventeenth century summarised the outcome of the work of all those who, with appliances he could not dream of, are continuing his labours in the nineteenth century.”17

In addition to his long sojourn in Italy as a student, Harvey made several other visits to the Continent. In 1630 he consented to accompany the young Duke of Lennox in his travels abroad. He had returned by 1632, for in that year he was formally appointed physician to Charles I. Again, in 1636 he accompanied the Earl of Arundel on his embassy to the Emperor, and was absent some nine months. According to Aubrey, in 1649 Harvey, with his friend Dr. George Ent, again visited Italy. Some doubt has been thrown on this journey, but it receives support from a letter of Harvey’s to John Nardi, of Florence, written on November 30, 1653, in which he concludes by asking his correspondent to mention his name to his Serene Highness the Duke of Tuscany, “with thankfulness for the distinguished honour he did me when I was formerly in Florence.”

In his old age Harvey was honoured in a striking manner by those best fitted to judge of the merit and value of his life’s work. His statue was erected in the hall of the College of Physicians. As an acknowledgment, as it were, of this remarkable compliment, he built at his own expense a Convocation Hall and a Library as additions to the College, and contributed books, curiosities, and surgical instruments for the Library and Museum. Not content with this, he made over to the College, the year before he died, his paternal estate, stipulating that a certain sum out of it should be employed every year for the delivery of an Oration in commemoration of benefactors of the College, and of those who had added anythingxxiii to medical knowledge during the year. This Oration is annually delivered by some distinguished member of the medical profession, and is inseparably associated with the name of Harvey. This graceful act shows how in his declining years Harvey’s thoughts were turned to the future. It had for its object to further the progress of scientific knowledge, to stimulate studies in the pursuit of which he had shown himself such a master. He wished when old and infirm, bereft of the power of again entering the arena of active work and investigation, to still do something to increase and extend that knowledge which is of so great service to mankind—a knowledge of the human body in health and in disease.

Harvey died on June 3, in the year 1657, in the eightieth year of his age, and was buried at the village of Hempstead, in Essex, in a vault which had been built by his brother Eliab.

E. A. Parkyn.

London, November, 1906.

xxiv

The following is a list of Harvey’s works, and of the more important references to his life and discovery:—

“MS. Memorandum Book,” dated 1616, entitled “Prælectiones Anatomicæ Universalis.” It is in Harvey’s handwriting, and contains the origin of the Circulation. (In the British Museum.) A Facsimile was published in 1886 by the College of Physicians.

“MS. De Musculis,” 1627, in Harvey’s handwriting. (Brit. Mus.) A Notice on this manuscript was published in 1850 by G. E. Paget, M.D.

“MS. of Prescriptions,” 1647. (Brit. Mus.)

“MS. Diploma of Doctor of Medicine” to Harvey by University of Padua, April 25, 1602. (In the College of Physicians.)

“MS. Illuminated Grant of M.D.,” by University of Padua to an Englishman, Thomas Heron, which is witnessed by “Guigliomo Harveo Consiliaris Magnificæ Nationis Anglæ.” It is dated March 19, 1602. (Brit. Mus.)

“MS. Oratio Harveiana,” 1661, ab. E. Greaves. (Brit. Mus.)

“De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis,” Frankfort-on-Main, 1628. First English edition published by R. Lowndes, with preface by Zachariah Wood, Physician of Rotterdam, 1653.

“Anatomical Examination of the Body of Thomas Parr, aged 152 years,” made in 1635, but not published until 1669 in Betts’ “De Ortu et Natura Sanguinis.”

“Two Disquisitions in Reply to John Riolan, jun.,” 1649.

“De Generatione Animalium,” London, 1651; in English, 1653.

“Biographica Britannica,” 1750. The Life of Harvey, containing much curious information and discussion, isxxv evidently that on which all subsequent biographies are based.

“Harveii Opera Omnia,” edited by Dr. Akenside, with Life by Thomas Lawrence, M.D., 1766.

“Lives and Letters of Eminent Persons,” by John Aubrey, 1813.

“Records of William Harvey, with Notes,” by James Paget, of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, 1846.

“The Works of William Harvey,” translated by Robert Willis, M.D. (Sydenham Society, 1848). This excellent translation has been followed in the present volume.

“Histoire de la Découverte de la Circulation du Sang,” par M. J. P. Flourens, 1854.

“Circulation of the Blood: its History, Cause, and Course,” by G. H. Lewes in “Physiology of Common Life,” 1859.

“Memorials of Harvey,” collected by J. H. Aveling, 1875.

“William Harvey: a history, etc.,” by Robert Willis, M.D., 1878.

“Roll of the Royal College of Physicians,” by William Munk, M.D., 2nd ed., 1878.

Huxley on “Evolution,” in “Encyclopædia Britannica,” 9th ed., 1878.

“Experimental Physiology,” by Sir R. Owen, 1882.

“A Defence of Harvey,” by George Johnson, M.D., 1884.

“Masters of Medicine: William Harvey,” by D’Arcy Power 1897.

xxvi

In the present edition of Harvey’s Treatise on the Circulation of the Blood, which is reprinted from the Sydenham Society’s edition of 1847, the footnotes by Willis, the editor and translator of that edition, are distinguished by brackets from Harvey’s original notes.

xxvii

| AN ANATOMICAL DISQUISITION ON THE MOTION OF THE HEART AND BLOOD IN ANIMALS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION | ||

| DEDICATION | ||

| INTRODUCTION | ||

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | THE AUTHOR’S MOTIVES FOR WRITING | |

| II. | OF THE MOTIONS OF THE HEART, AS SEEN IN THE DISSECTION OF LIVING ANIMALS | |

| III. | OF THE MOTIONS OF ARTERIES, AS SEEN IN THE DISSECTION OF LIVING ANIMALS | |

| IV. | OF THE MOTION OF THE HEART AND ITS AURICLES, AS SEEN IN THE BODIES OF LIVING ANIMALS | |

| V. | OF THE MOTION, ACTION, AND OFFICE OF THE HEART | |

| VI. | OF THE COURSE BY WHICH THE BLOOD IS CARRIED FROM THE VENA CAVA INTO THE ARTERIES, OR FROM THE RIGHT INTO THE LEFT VENTRICLE OF THE HEART | xxviii |

| VII. | THE BLOOD PERCOLATES THE SUBSTANCE OF THE LUNGS FROM THE RIGHT VENTRICLE OF THE HEART INTO THE PULMONARY VEINS AND LEFT VENTRICLE | |

| VIII. | OF THE QUANTITY OF BLOOD PASSING THROUGH THE HEART FROM THE VEINS TO THE ARTERIES; AND OF THE CIRCULAR MOTION OF THE BLOOD | |

| IX. | THAT THERE IS A CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD IS CONFIRMED FROM THE FIRST PROPOSITION | |

| X. | THE FIRST POSITION: OF THE QUANTITY OF BLOOD PASSING FROM THE VEINS TO THE ARTERIES. AND THAT THERE IS A CIRCUIT OF THE BLOOD, FREED FROM OBJECTIONS, AND FARTHER CONFIRMED BY EXPERIMENT | |

| XI. | THE SECOND POSITION IS DEMONSTRATED | |

| XII. | THAT THERE IS A CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD IS SHOWN FROM THE SECOND POSITION DEMONSTRATED | |

| XIII. | THE THIRD POSITION IS CONFIRMED: AND THE CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD IS DEMONSTRATED FROM IT | |

| XIV. | CONCLUSION OF THE DEMONSTRATION OF THE CIRCULATION | |

| XV. | THE CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD IS FURTHER CONFIRMED BY PROBABLE REASONS | |

| XVI. | THE CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD IS FURTHER PROVED FROM CERTAIN CONSEQUENCES | xxix |

| XVII. | THE MOTION AND CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD ARE CONFIRMED FROM THE PARTICULARS APPARENT IN THE STRUCTURE OF THE HEART, AND FROM THOSE THINGS WHICH DISSECTION UNFOLDS | |

| THE FIRST ANATOMICAL DISQUISITION ON THE CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD, ADDRESSED TO JOHN RIOLAN | ||

| A SECOND DISQUISITION TO JOHN RIOLAN; IN WHICH MANY OBJECTIONS TO THE CIRCULATION OF THE BLOOD ARE REFUTED | ||

| LETTERS | ||

| TO CASPAR HOFMANN, M.D. | ||

| TO PAUL MARQUARD SLEGEL, OF HAMBURG | ||

| TO THE VERY EXCELLENT JOHN NARDI, OF FLORENCE | ||

| IN REPLY TO R. MORISON, M.D., OF PARIS | ||

| TO THE MOST EXCELLENT AND LEARNED JOHN NARDI, OF FLORENCE | ||

| TO JOHN DANIEL HORST, PRINCIPAL PHYSICIAN OF HESSE-DARMSTADT | ||

| TO THE DISTINGUISHED AND LEARNED JOHN DAN. HORST, PRINCIPAL PHYSICIAN AT THE COURT OF HESSE-DARMSTADT | xxx | |

| TO THE VERY LEARNED JOHN NARDI, OF FLORENCE, A MAN DISTINGUISHED ALIKE FOR HIS VIRTUES, LIFE, AND ERUDITION | ||

| TO THE DISTINGUISHED AND ACCOMPLISHED JOHN VLACKVELD, PHYSICIAN AT HARLEM | ||

| APPENDIX | ||

| THE ANATOMICAL EXAMINATION OF THE BODY OF THOMAS PARR, WHO DIED AT THE AGE OF ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY-TWO YEARS; MADE BY WILLIAM HARVEY | ||

| THE LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT OF WILLIAM HARVEY, M.D. | ||

| INDEX | ||

AN ANATOMICAL DISQUISITION

ON THE

MOTION OF THE HEART AND

BLOOD IN ANIMALS

3

Most Illustrious Prince!

The heart of animals is the foundation of their life, the sovereign of everything within them, the sun of their microcosm, that upon which all growth depends, from which all power proceeds. The King, in like manner, is the foundation of his kingdom, the sun of the world around him, the heart of the republic, the fountain whence all power, all grace doth flow. What I have here written of the motions of the heart I am the more emboldened to present to your Majesty, according to the custom of the present age, because almost all things human are done after human examples, and many things in a King are after the pattern of the heart. The knowledge of his heart, therefore, will not be useless to a Prince, as embracing a kind of Divine example of his functions,—and it has still been usual with men4 to compare small things with great. Here, at all events, best of Princes, placed as you are on the pinnacle of human affairs, you may at once contemplate the prime mover in the body of man, and the emblem of your own sovereign power. Accept therefore, with your wonted clemency, I most humbly beseech you, illustrious Prince, this, my new Treatise on the Heart; you, who are yourself the new light of this age, and indeed its very heart; a Prince abounding in virtue and in grace, and to whom we gladly refer all the blessings which England enjoys, all the pleasure we have in our lives.

Your Majesty’s most devoted servant,

William Harvey.

London, 1628.

5

To his very dear Friend, Doctor Argent, the excellent and accomplished President of the Royal College of Physicians, and to other learned Physicians, his most esteemed Colleagues.

I have already and repeatedly presented you, my learned friends, with my new views of the motion and function of the heart, in my anatomical lectures; but having now for nine years and more confirmed these views by multiplied demonstrations in your presence, illustrated them by arguments, and freed them from the objections of the most learned and skilful anatomists, I at length yield to the requests, I might say entreaties, of many, and here present them for general consideration in this treatise.

Were not the work indeed presented through you, my learned friends, I should scarce hope that it could come out scatheless and complete; for you have in general been the faithful witnesses of almost all the instances from which I have either collected the truth or confuted error; you have seen my dissections, and at my demonstrations of all that I maintain to be objects of sense, you have been accustomed to6 stand by and bear me out with your testimony. And as this book alone declares the blood to course and revolve by a new route, very different from the ancient and beaten pathway trodden for so many ages, and illustrated by such a host of learned and distinguished men, I was greatly afraid lest I might be charged with presumption did I lay my work before the public at home, or send it beyond seas for impression, unless I had first proposed its subject to you, had confirmed its conclusions by ocular demonstrations in your presence, had replied to your doubts and objections, and secured the assent and support of our distinguished President. For I was most intimately persuaded, that if I could make good my proposition before you and our College, illustrious by its numerous body of learned individuals, I had less to fear from others; I even ventured to hope that I should have the comfort of finding all that you had granted me in your sheer love of truth, conceded by others who were philosophers like yourselves. For true philosophers, who are only eager for truth and knowledge, never regard themselves as already so thoroughly informed, but that they welcome further information from whomsoever and from whencesoever it may come; nor are they so narrow-minded as to imagine any of the arts or sciences transmitted to us by the ancients, in such a state of forwardness or completeness, that nothing is left for the ingenuity and industry of others; very many, on the contrary,7 maintain that all we know is still infinitely less than all that still remains unknown; nor do philosophers pin their faith to others’ precepts in such wise that they lose their liberty, and cease to give credence to the conclusions of their proper senses. Neither do they swear such fealty to their mistress Antiquity, that they openly, and in sight of all, deny and desert their friend Truth. But even as they see that the credulous and vain are disposed at the first blush to accept and to believe everything that is proposed to them, so do they observe that the dull and unintellectual are indisposed to see what lies before their eyes, and even to deny the light of the noonday sun. They teach us in our course of philosophy as sedulously to avoid the fables of the poets and the fancies of the vulgar, as the false conclusions of the sceptics. And then the studious, and good, and true, never suffer their minds to be warped by the passions of hatred and envy, which unfit men duly to weigh the arguments that are advanced in behalf of truth, or to appreciate the proposition that is even fairly demonstrated; neither do they think it unworthy of them to change their opinion if truth and undoubted demonstration require them so to do; nor do they esteem it discreditable to desert error, though sanctioned by the highest antiquity; for they know full well that to err, to be deceived, is human; that many things are discovered by accident, and that many may be learned indifferently from any quarter, by an8 old man from a youth, by a person of understanding from one of inferior capacity.

My dear colleagues, I had no purpose to swell this treatise into a large volume by quoting the names and writings of anatomists, or to make a parade of the strength of my memory, the extent of my reading, and the amount of my pains; because I profess both to learn and to teach anatomy, not from books but from dissections; not from the positions of philosophers but from the fabric of nature; and then because I do not think it right or proper to strive to take from the ancients any honour that is their due, nor yet to dispute with the moderns, and enter into controversy with those who have excelled in anatomy and been my teachers, I would not charge with wilful falsehood any one who was sincerely anxious for truth, nor lay it to any one’s door as a crime that he had fallen into error. I avow myself the partisan of truth alone; and I can indeed say that I have used all my endeavours, bestowed all my pains on an attempt to produce something that should be agreeable to the good, profitable to the learned, and useful to letters.

Farewell, most worthy Doctors,

And think kindly of your Anatomist,

William Harvey.

9

AN ANATOMICAL DISQUISITION

ON THE

MOTION OF THE HEART AND

BLOOD IN ANIMALS

As we are about to discuss the motion, action, and use of the heart and arteries, it is imperative on us first to state what has been thought of these things by others in their writings, and what has been held by the vulgar and by tradition, in order that what is true may be confirmed, and what is false set right by dissection, multiplied experience, and accurate observation.

Almost all anatomists, physicians, and philosophers, up to the present time, have supposed, with Galen, that the object of the pulse was the same as that of respiration, and only differed in one particular, this being conceived to depend on the animal, the respiration on the vital faculty; the two, in all other respects, whether with reference to purpose or to motion, comporting themselves alike. Whence it is affirmed, as by Hieronymus Fabricius of Aquapendente, in his book on “Respiration,” which has lately appeared, that as the pulsation of the heart and arteries does not suffice for the ventilation and refrigeration of the blood, therefore were the lungs fashioned to surround the heart. From this it appears, that whatever has hitherto been said upon the systole and diastole, on the motion of10 the heart and arteries, has been said with especial reference to the lungs.

But as the structure and movements of the heart differ from those of the lungs, and the motions of the arteries from those of the chest, so seems it likely that other ends and offices will thence arise, and that the pulsations and uses of the heart, likewise of the arteries, will differ in many respects from the heavings and uses of the chest and lungs. For did the arterial pulse and the respiration serve the same ends; did the arteries in their diastole take air into their cavities, as commonly stated, and in their systole emit fuliginous vapours by the same pores of the flesh and skin; and further, did they, in the time intermediate between the diastole and the systole, contain air, and at all times either air, or spirits, or fuliginous vapours, what should then be said to Galen, who wrote a book on purpose to show that by nature the arteries contained blood, and nothing but blood; neither spirits nor air, consequently, as may be readily gathered from the experiments and reasonings contained in the same book? Now if the arteries are filled in the diastole with air then taken into them (a larger quantity of air penetrating when the pulse is large and full), it must come to pass, that if you plunge into a bath of water or of oil when the pulse is strong and full, it ought forthwith to become either smaller or much slower, since the circumambient bath will render it either difficult or impossible for the air to penetrate. In like manner, as all the arteries, those that are deep-seated as well as those that are superficial, are dilated at the same instant, and with the same rapidity, how were it possible that air should penetrate to the deeper parts as freely and quickly through the skin, flesh, and other structures, as through the mere cuticle? And how should the arteries of the fœtus draw air into their cavities through the abdomen of the mother and the body of the womb? And how should seals, whales, dolphins, and other cetaceans, and fishes of every11 description, living in the depths of the sea, take in and emit air by the diastole and systole of their arteries through the infinite mass of waters? For to say that they absorb the air that is infixed in the water, and emit their fumes into this medium, were to utter something very like a mere figment. And if the arteries in their systole expel fuliginous vapours from their cavities through the pores of the flesh and skin, why not the spirits, which are said to be contained in these vessels, at the same time, since spirits are much more subtile than fuliginous vapours or smoke? And further, if the arteries take in and cast out air in the systole and diastole, like the lungs in the process of respiration, wherefore do they not do the same thing when a wound is made in one of them, as is done in the operation of arteriotomy? When the windpipe is divided, it is sufficiently obvious that the air enters and returns through the wound by two opposite movements; but when an artery is divided, it is equally manifest that blood escapes in one continuous stream, and that no air either enters or issues. If the pulsations of the arteries fan and refrigerate the several parts of the body as the lungs do the heart, how comes it, as is commonly said, that the arteries carry the vital blood into the different parts, abundantly charged with vital spirits, which cherish the heat of these parts, sustain them when asleep, and recruit them when exhausted? and how should it happen that, if you tie the arteries, immediately the parts not only become torpid, and frigid, and look pale, but at length cease even to be nourished? This, according to Galen, is because they are deprived of the heat which flowed through all parts from the heart, as its source; whence it would appear that the arteries rather carry warmth to the parts than serve for any fanning or refrigeration. Besides, how can the diastole [of the arteries] draw spirits from the heart to warm the body and its parts, and, from without, means of cooling or tempering them? Still further,12 although some affirm that the lungs, arteries, and heart have all the same offices, they yet maintain that the heart is the workshop of the spirits, and that the arteries contain and transmit them; denying, however, in opposition to the opinion of Columbus, that the lungs can either make or contain spirits; and then they assert, with Galen, against Erasistratus, that it is blood, not spirits, which is contained in the arteries.

These various opinions are seen to be so incongruous and mutually subversive, that every one of them is not unjustly brought under suspicion. That it is blood and blood alone which is contained in the arteries is made manifest by the experiment of Galen, by arteriotomy, and by wounds; for from a single artery divided, as Galen himself affirms in more than one place, the whole of the blood may be withdrawn in the course of half an hour, or less. The experiment of Galen alluded to is this: “If you include a portion of an artery between two ligatures, and slit it open lengthways, you will find nothing but blood;” and thus he proves that the arteries contain blood only. And we too may be permitted to proceed by a like train of reasoning: if we find the same blood in the arteries that we find in the veins, which we have tied in the same way, as I have myself repeatedly ascertained, both in the dead body and in living animals, we may fairly conclude that the arteries contain the same blood as the veins, and nothing but the same blood. Some, whilst they attempt to lessen the difficulty here, affirming that the blood is spirituous and arterious, virtually concede that the office of the arteries is to carry blood from the heart into the whole of the body, and that they are therefore filled with blood; for spirituous blood is not the less blood on that account. And then no one denies that the blood as such, even the portion of it which flows in the veins, is imbued with spirits. But if that portion which is contained in the arteries be richer in spirits, it is still to be believed that these spirits are inseparable from the blood, like those13 in the veins: that the blood and spirits constitute one body (like whey and butter in milk, or heat [and water] in hot water), with which the arteries are charged, and for the distribution of which from the heart they are provided, and that this body is nothing else than blood. But if this blood be said to be drawn from the heart into the arteries by the diastole of these vessels, it is then assumed that the arteries by their distension are filled with blood, and not with the ambient air, as heretofore; for if they be said also to become filled with air from the ambient atmosphere, how and when, I ask, can they receive blood from the heart? If it be answered: during the systole; I say, that seems impossible; the arteries would then have to fill whilst they contracted; in other words, to fill, and yet not become distended. But if it be said: during the diastole, they would then, and for two opposite purposes, be receiving both blood and air, and heat and cold; which is improbable. Further, when it is affirmed that the diastole of the heart and arteries is simultaneous, and the systole of the two is also concurrent, there is another incongruity. For how can two bodies mutually connected, which are simultaneously distended, attract or draw anything from one another; or, being simultaneously contracted, receive anything from each other? And then, it seems impossible that one body can thus attract another body into itself, so as to become distended, seeing that to be distended is to be passive, unless, in the manner of a sponge, previously compressed by an external force, whilst it is returning to its natural state. But it is difficult to conceive that there can be anything of this kind in the arteries. The arteries dilate, because they are filled like bladders or leathern bottles; they are not filled because they expand like bellows. This I think easy of demonstration; and indeed conceive that I have already proved it. Nevertheless, in that book of Galen headed “Quod Sanguis continetur in Arteriis,” he quotes14 an experiment to prove the contrary: An artery having been exposed, is opened longitudinally, and a reed or other pervious tube, by which the blood is prevented from being lost, and the wound is closed, is inserted into the vessel through the opening. “So long,” he says, “as things are thus arranged, the whole artery will pulsate; but if you now throw a ligature about the vessel and tightly compress its tunics over the tube, you will no longer see the artery beating beyond the ligature.” I have never performed this experiment of Galen’s, nor do I think that it could very well be performed in the living body, on account of the profuse flow of blood that would take place from the vessel which was operated on; neither would the tube effectually close the wound in the vessel without a ligature; and I cannot doubt but that the blood would be found to flow out between the tube and the vessel. Still Galen appears by this experiment to prove both that the pulsative faculty extends from the heart by the walls of the arteries, and that the arteries, whilst they dilate, are filled by that pulsific force, because they expand like bellows, and do not dilate because they are filled like skins. But the contrary is obvious in arteriotomy and in wounds; for the blood spurting from the arteries escapes with force, now farther, now not so far, alternately, or in jets; and the jet always takes place with the diastole of the artery, never with the systole. By which it clearly appears that the artery is dilated by the impulse of the blood; for of itself it would not throw the blood to such a distance, and whilst it was dilating; it ought rather to draw air into its cavity through the wound, were those things true that are commonly stated concerning the uses of the arteries. Nor let the thickness of the arterial tunics impose upon us, and lead us to conclude that the pulsative property proceeds along them from the heart. For in several animals the arteries do not apparently differ from the veins; and in extreme parts of the body, where the arteries are minutely subdivided,15 as in the brain, the hand, &c., no one could distinguish the arteries from the veins by the dissimilar characters of their coats; the tunics of both are identical. And then, in an aneurism proceeding from a wounded or eroded artery, the pulsation is precisely the same as in the other arteries, and yet it has no proper arterial tunic. This the learned Riolanus testifies to, along with me, in his Seventh Book.

Nor let any one imagine that the uses of the pulse and the respiration are the same, because under the influence of the same causes, such as running, anger, the warm bath, or any other heating thing, as Galen says, they become more frequent and forcible together. For, not only is experience in opposition to this idea, though Galen endeavours to explain it away, when we see that with excessive repletion the pulse beats more forcibly, whilst the respiration is diminished in amount; but in young persons the pulse is quick, whilst respiration is slow. So is it also in alarm, and amidst care, and under anxiety of mind; sometimes, too, in fevers, the pulse is rapid, but the respiration is slower than usual.

These and other objections of the same kind may be urged against the opinions mentioned. Nor are the views that are entertained of the offices and pulse of the heart, perhaps, less bound up with great and most inextricable difficulties. The heart, it is vulgarly said, is the fountain and workshop of the vital spirits, the centre from whence life is dispensed to the several parts of the body; and yet it is denied that the right ventricle makes spirits; it is rather held to supply nourishment to the lungs; whence it is maintained that fishes are without any right ventricle (and indeed every animal wants a right ventricle which is unfurnished with lungs), and that the right ventricle is present solely for the sake of the lungs.

1. Why, I ask, when we see that the structure of both ventricles is almost identical, there being the same16 apparatus of fibres, and braces, and valves, and vessels, and auricles, and in both the same infarction of blood, in the subjects of our dissections, of the like black colour, and coagulated—why, I say, should their uses be imagined to be different, when the action, motion, and pulse of both are the same? If the three tricuspid valves placed at the entrance into the right ventricle prove obstacles to the reflux of the blood into the vena cava, and if the three semilunar valves which are situated at the commencement of the pulmonary artery be there, that they may prevent the return of the blood into the ventricle; wherefore, when we find similar structures in connexion with the left ventricle, should we deny that they are there for the same end, of preventing here the egress, there the regurgitation of the blood?

2. And again, when we see that these structures, in point of size, form, and situation, are almost in every respect the same in the left as in the right ventricle, wherefore should it be maintained that things are here arranged in connexion with the egress and regress of spirits, there, i.e. in the right, of blood? The same arrangement cannot be held fitted to favour or impede the motion of blood and of spirits indifferently.

3. And when we observe that the passages and vessels are severally in relation to one another in point of size, viz., the pulmonary artery to the pulmonary veins; wherefore should the one be imagined destined to a private or particular purpose, that, to wit, of nourishing the lungs, the other to a public and general function?

4. And, as Realdus Columbus says, how can it be conceived that such a quantity of blood should be required for the nutrition of the lungs; the vessel that leads to them, the vena arteriosa or pulmonary artery being of greater capacity than both the iliac veins?

5. And I ask further: as the lungs are so close at hand, and in continual motion, and the vessel that supplies them is of such dimensions, what is the use17 or meaning of the pulse of the right ventricle? and why was nature reduced to the necessity of adding another ventricle for the sole purpose of nourishing the lungs?

When it is said that the left ventricle obtains materials for the formation of spirits, air to wit, and blood, from the lungs and right sinuses of the heart, and in like manner sends spirituous blood into the aorta, drawing fuliginous vapours from thence, and sending them by the arteria venosa into the lungs, whence spirits are at the same time obtained for transmission into the aorta, I ask how, and by what means, is the separation effected? and how comes it that spirits and fuliginous vapours can pass hither and thither without admixture or confusion. If the mitral cuspidate valves do not prevent the egress of fuliginous vapours to the lungs, how should they oppose the escape of air? and how should the semilunars hinder the regress of spirits from the aorta upon each supervening diastole of the heart? and, above all, how can they say that the spirituous blood is sent from the arteria venalis (pulmonary veins) by the left ventricle into the lungs without any obstacle to its passage from the mitral valves, when they have previously asserted that the air entered by the same vessel from the lungs into the left ventricle, and have brought forward these same mitral valves as obstacles to its retrogression? Good God! how should the mitral valves prevent regurgitation of air and not of blood?

Further, when they dedicate the vena arteriosa (or pulmonary artery), a vessel of great size, and having the tunics of an artery, to none but a kind of private and single purpose, that, namely, of nourishing the lungs, why should the arteria venalis (or pulmonary vein), which is scarcely of similar size, which has the coats of a vein, and is soft and lax, be presumed to be made for many—three or four, different uses? For they will have it that air passes through this vessel from the18 lungs into the left ventricle; that fuliginous vapours escape by it from the heart into the lungs; and that a portion of the spirituous or spiritualized blood is distributed by it to the lungs for their refreshment.

If they will have it that fumes and air—fumes flowing from, air proceeding towards the heart—are transmitted by the same conduit, I reply, that nature is not wont to institute but one vessel, to contrive but one way for such contrary motions and purposes, nor is anything of the kind seen elsewhere.

If fumes or fuliginous vapours and air permeate this vessel, as they do the pulmonary bronchia, wherefore do we find neither air nor fuliginous vapours when we divide the arteria venosa? why do we always find this vessel full of sluggish blood, never of air? whilst in the lungs we find abundance of air remaining.

If any one will perform Galen’s experiment of dividing the trachea of a living dog, forcibly distending the lungs with a pair of bellows, and then tying the trachea securely, he will find, when he has laid open the thorax, abundance of air in the lungs, even to their extreme investing tunic, but none in either the pulmonary veins, or left ventricle of the heart. But did the heart either attract air from the lungs, or did the lungs transmit any air to the heart, in the living dog, by so much the more ought this to be the case in the experiment just referred to. Who, indeed, doubts that, did he inflate the lungs of a subject in the dissecting-room, he would instantly see the air making its way by this route, were there actually any such passage for it? But this office of the pulmonary veins, namely, the transference of air from the lungs to the heart, is held of such importance, that Hieronymus Fabricius, of Aquapendente, maintains the lungs were made for the sake of this vessel, and that it constitutes the principal element in their structure.

But I should like to be informed wherefore, if the pulmonary vein were destined for the conveyance of19 air, it has the structure of a blood-vessel here. Nature had rather need of annular tubes, such as those of the bronchia, in order that they might always remain open, not have been liable to collapse; and that they might continue entirely free from blood, lest the liquid should interfere with the passage of the air, as it so obviously does when the lungs labour from being either greatly oppressed or loaded in a less degree with phlegm, as they are when the breathing is performed with a sibilous or rattling noise.

Still less is that opinion to be tolerated which (as a twofold matter, one aëreal, one sanguineous, is required for the composition of vital spirits,) supposes the blood to ooze through the septum of the heart from the right to the left ventricle by certain secret pores, and the air to be attracted from the lungs through the great vessel, the pulmonary vein; and which will have it, consequently, that there are numerous pores in the septum cordis adapted for the transmission of the blood. But, in faith, no such pores can be demonstrated, neither in fact do any such exist. For the septum of the heart is of a denser and more compact structure than any portion of the body, except the bones and sinews. But even supposing that there were foramina or pores in this situation, how could one of the ventricles extract anything from the other—the left, e.g., obtain blood from the right, when we see that both ventricles contract and dilate simultaneously? Wherefore should we not rather believe that the right took spirits from the left, than that the left obtained blood from the right ventricle, through these foramina? But it is certainly mysterious and incongruous that blood should be supposed to be most commodiously drawn through a set of obscure or invisible pores, and air through perfectly open passages, at one and the same moment. And why, I ask, is recourse had to secret and invisible porosities, to uncertain and obscure channels, to explain the passage of the blood into the left ventricle, when there is so20 open a way through the pulmonary veins? I own it has always appeared extraordinary to me that they should have chosen to make, or rather to imagine, a way through the thick, hard, and extremely compact substance of the septum cordis, rather than to take that by the open vas venosum or pulmonary vein, or even through the lax, soft, and spongy substance of the lungs at large. Besides, if the blood could permeate the substance of the septum, or could be imbibed from the ventricles, what use were there for the coronary artery and vein, branches of which proceed to the septum itself, to supply it with nourishment? And what is especially worthy of notice is this: if in the fœtus, where everything is more lax and soft, nature saw herself reduced to the necessity of bringing the blood from the right into the left side of the heart by the foramen ovale, from the vena cava through the arteria venosa, how should it be likely that in the adult she should pass it so commodiously, and without an effort, through the septum ventriculorum, which has now become denser by age?

Andreas Laurentius,18 resting on the authority of Galen19 and the experience of Hollerius, asserts and proves that the serum and pus in empyema, absorbed from the cavities of the chest into the pulmonary vein, may be expelled and got rid of with the urine and fæces through the left ventricle of the heart and arteries. He quotes the case of a certain person affected with melancholia, and who suffered from repeated fainting fits, who was relieved from the paroxysms on passing a quantity of turbid, fetid, and acrid urine; but he died at last, worn out by the disease; and when the body came to be opened after death, no fluid like that he had micturated was discovered either in the bladder or in the kidneys; but in the left ventricle of the heart and cavity of the thorax plenty of it was met with; and then21 Laurentius boasts that he had predicted the cause of the symptoms. For my own part, however, I cannot but wonder, since he had divined and predicted that heterogeneous matter could be discharged by the course he indicates, why he could not or would not perceive, and inform us that, in the natural state of things, the blood might be commodiously transferred from the lungs to the left ventricle of the heart by the very same route.

Since, therefore, from the foregoing considerations and many others to the same effect, it is plain that what has heretofore been said concerning the motion and function of the heart and arteries must appear obscure, or inconsistent or even impossible to him who carefully considers the entire subject; it will be proper to look more narrowly into the matter; to contemplate the motion of the heart and arteries, not only in man, but in all animals that have hearts; and further, by frequent appeals to vivisection, and constant ocular inspection, to investigate and endeavour to find the truth.

22

When I first gave my mind to vivisections, as a means of discovering the motions and uses of the heart, and sought to discover these from actual inspection, and not from the writings of others, I found the task so truly arduous, so full of difficulties, that I was almost tempted to think, with Fracastorius, that the motion of the heart was only to be comprehended by God. For I could neither rightly perceive at first when the systole and when the diastole took place, nor when and where dilatation and contraction occurred, by reason of the rapidity of the motion, which in many animals is accomplished in the twinkling of an eye, coming and going like a flash of lightning; so that the systole presented itself to me now from this point, now from that; the diastole the same; and then everything was reversed, the motions occurring, as it seemed, variously and confusedly together. My mind was therefore greatly unsettled, nor did I know what I should myself conclude, nor what believe from others; I was not surprised that Andreas Laurentius should have said that the motion of the heart was as perplexing as the flux and reflux of Euripus had appeared to Aristotle.

At length, and by using greater and daily diligence, having frequent recourse to vivisections, employing a variety of animals for the purpose, and collating numerous observations, I thought that I had attained to the truth, that I should extricate myself and escape from this labyrinth, and that I had discovered what I so much desired, both the motion and the use of the heart and arteries; since which time I have not hesitated to23 expose my views upon these subjects, not only in private to my friends, but also in public, in my anatomical lectures, after the manner of the Academy of old.

These views, as usual, pleased some more, others less; some chid and calumniated me, and laid it to me as a crime that I had dared to depart from the precepts and opinion of all anatomists; others desired further explanations of the novelties, which they said were both worthy of consideration, and might perchance be found of signal use. At length, yielding to the requests of my friends, that all might be made participators in my labours, and partly moved by the envy of others, who receiving my views with uncandid minds and understanding them indifferently, have essayed to traduce me publicly, I have been moved to commit these things to the press, in order that all may be enabled to form an opinion both of me and my labours. This step I take all the more willingly, seeing that Hieronymus Fabricius of Aquapendente, although he has accurately and learnedly delineated almost every one of the several parts of animals in a special work, has left the heart alone untouched. Finally, if any use or benefit to this department of the republic of letters should accrue from my labours, it will, perhaps, be allowed that I have not lived idly, and, as the old man in the comedy says:

For never yet has any one attained

To such perfection, but that time, and place,

And use, have brought addition to his knowledge;

Or made correction, or admonished him,

That he was ignorant of much which he

Had thought he knew; or led him to reject

What he had once esteemed of highest price.

So will it, perchance, be found with reference to the heart at this time; or others, at least, starting from hence, the way pointed out to them, advancing under the guidance of a happier genius, may make occasion to proceed more fortunately, and to inquire more accurately.

24

In the first place, then, when the chest of a living animal is laid open and the capsule that immediately surrounds the heart is slit up or removed, the organ is seen now to move, now to be at rest;—there is a time when it moves, and a time when it is motionless.

These things are more obvious in the colder animals, such as toads, frogs, serpents, small fishes, crabs, shrimps, snails, and shell-fish. They also become more distinct in warm-blooded animals, such as the dog and hog, if they be attentively noted when the heart begins to flag, to move more slowly, and, as it were, to die: the movements then become slower and rarer, the pauses longer, by which it is made much more easy to perceive and unravel what the motions really are, and how they are performed. In the pause, as in death, the heart is soft, flaccid, exhausted, lying, as it were, at rest.

In the motion, and interval in which this is accomplished, three principal circumstances are to be noted:

1. That the heart is erected, and rises upwards to a point, so that at this time it strikes against the breast and the pulse is felt externally.

2. That it is everywhere contracted, but more especially towards the sides, so that it looks narrower, relatively longer, more drawn together. The heart of an eel taken out of the body of the animal and placed upon the table or the hand, shows these particulars;25 but the same things are manifest in the heart of small fishes and of those colder animals where the organ is more conical or elongated.

3. The heart being grasped in the hand, is felt to become harder during its action. Now this hardness proceeds from tension, precisely as when the forearm is grasped, its tendons are perceived to become tense and resilient when the fingers are moved.

4. It may further be observed in fishes, and the colder blooded animals, such as frogs, serpents, &c., that the heart, when it moves, becomes of a paler colour, when quiescent of a deeper blood-red colour.

From these particulars it appeared evident to me that the motion of the heart consists in a certain universal tension—both contraction in the line of its fibres, and constriction in every sense. It becomes erect, hard, and of diminished size during its action; the motion is plainly of the same nature as that of the muscles when they contract in the line of their sinews and fibres; for the muscles, when in action, acquire vigour and tenseness, and from soft become hard, prominent, and thickened: in the same manner the heart.

We are therefore authorized to conclude that the heart, at the moment of its action, is at once constricted on all sides, rendered thicker in its parietes and smaller in its ventricles, and so made apt to project or expel its charge of blood. This, indeed, is made sufficiently manifest by the fourth observation preceding, in which we have seen that the heart, by squeezing out the blood it contains becomes paler, and then when it sinks into repose and the ventricle is filled anew with blood, that the deeper crimson colour returns. But no one need remain in doubt of the fact, for if the ventricle be pierced the blood will be seen to be forcibly projected outwards upon each motion or pulsation when the heart is tense.

These things, therefore, happen together or at the same instant: the tension of the heart, the pulse of its26 apex, which is felt externally by its striking against the chest, the thickening of its parietes, and the forcible expulsion of the blood it contains by the constriction of its ventricles.

Hence the very opposite of the opinions commonly received, appears to be true; inasmuch as it is generally believed that when the heart strikes the breast and the pulse is felt without, the heart is dilated in its ventricles and is filled with blood; but the contrary of this is the fact, and the heart, when it contracts [and the shock is given], is emptied. Whence the motion which is generally regarded as the diastole of the heart, is in truth its systole. And in like manner the intrinsic motion of the heart is not the diastole but the systole; neither is it in the diastole that the heart grows firm and tense, but in the systole, for then only, when tense, is it moved and made vigorous.