Title: The Sin of Monsieur Antoine, Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: George Sand

Illustrator: Pierre Vidal

Translator: George Burnham Ives

Release date: February 21, 2022 [eBook #67460]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: G. Barrie & son, 1900

Credits: Dagny and Laura Natal Rodrigues (Images generously made available by Hathi Trust Digital Library.)

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER

I. EGUZON

II. THE MANOR OF CHÂTEAUBRUN

III. MONSIEUR CARDONNET

IV. THE VISION

V. THE DRIBE

VI. JEAN THE CARPENTER

VII. THE ARREST

VIII. GILBERTE

IX. MONSIEUR ANTOINE

X. A GOOD ACTION

XI. A GHOST

XII. INDUSTRIAL DIPLOMACY

XIII. THE STRUGGLE

XIV. FIRST LOVE

XV. THE STAIRCASE

XVI. THE TALISMAN

XVII. THAW

XVIII. STORM

XIX. THE PORTRAIT

XX. THE FORTRESS OF CROZANT

XXI. MONSIEUR ANTOINE'S NAP

XXII. INTRIGUE

XXIII. THE DEVIL'S ROCK

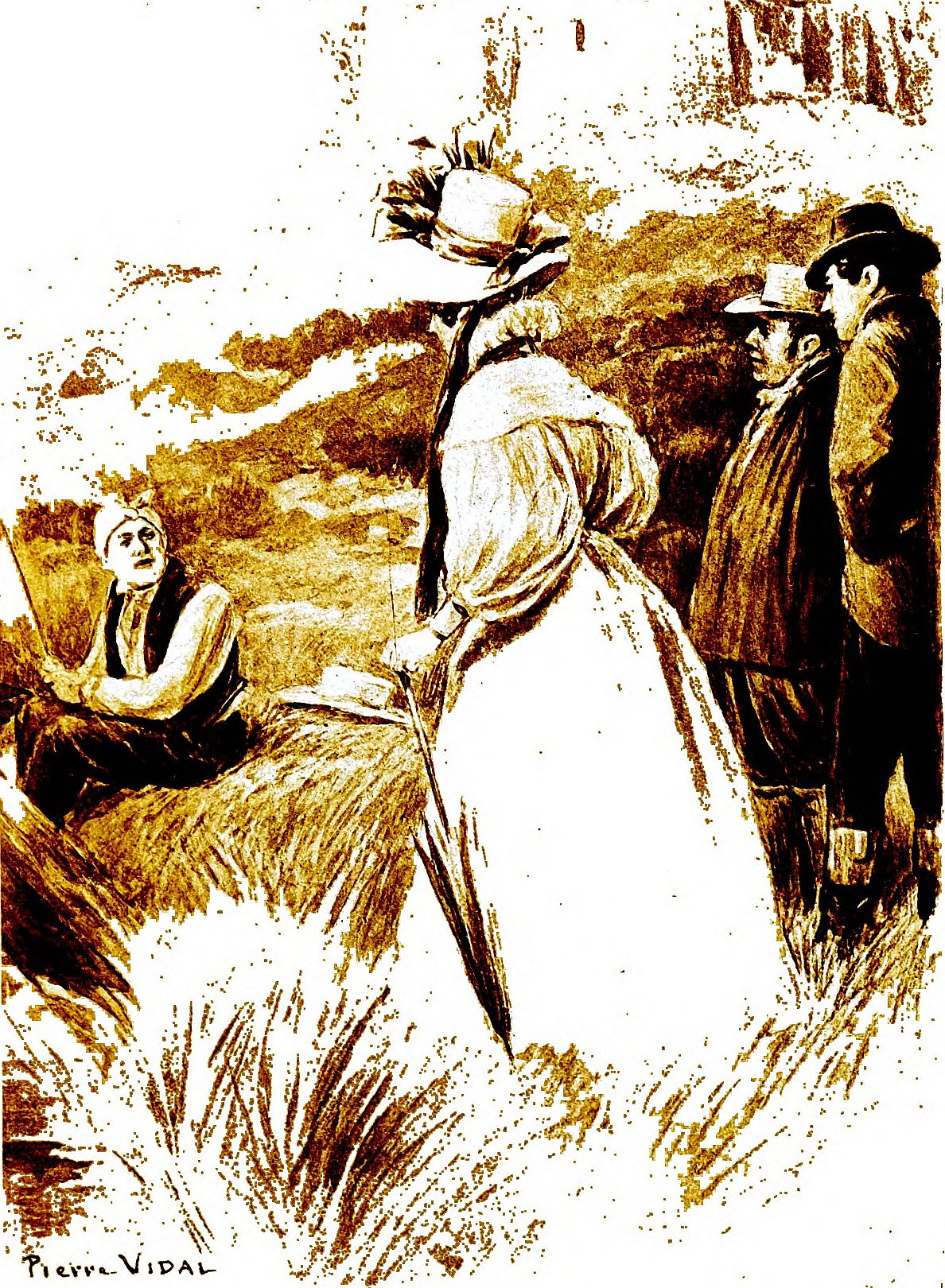

EMILE'S FIRST MEETING WITH GILBERTE.

EMILE ENTERTAINED BY MONSIEUR ANTOINE.

MONSIEUR DE BOISGUILBAULT TRIES EMILE'S HORSE.

EMILE IN CONFERENCE WITH HIS FATHER.

EMILE EXAMINES THE PORTRAIT OF THE MARQUISE DE

BOISGUILBAULT.

GALUCHET SURPRISED.

EMILE'S FIRST MEETING WITH GILBERTE.

A fresh young voice was singing, or rather humming, at a little distance, one of those sweet melodies, which are peculiar to the country. And the châtelain's daughter, the bachelor's child, whose mother's name was a mystery to the whole neighborhood, appeared at the corner of a clump of eglantine, as lovely as the loveliest wild flower of that charming solitude.

I wrote the Sin of Monsieur Antoine in the country, during a season of tranquillity, outward and inward, such as seldom occurs in one's life. It was in 1845, a period when criticism of society, as it was, and dreams of an ideal society attained in the press a degree of freedom of development comparable to that of the eighteenth century. Some day, perhaps, people will find it difficult to believe the trivial but exceedingly characteristic fact I am about to mention.

At that period, if one wished to be independent, to maintain directly or indirectly the boldest ideas opposed to the vices of the existing social organization and to give expression to the liveliest hopes of the philosophical sentiment, it was hardly possible to apply to the opposition newspapers. The most advanced of them unfortunately had not readers enough to give satisfactory publicity to the ideas one desired to put forth. The more moderate nourished a profound aversion for socialism, and, in the course of the last ten years of Louis-Philippe's reign, one of these organs of the reformist opposition, the most important by reason of its age and the number of its subscribers, did me the honor several times to ask me for a serial novel, always on the condition that it should contain nothing of a socialistic tendency.

That condition was very difficult, perhaps impossible of fulfilment, to a mind absorbed by the sufferings and the needs of its generation. There are very few serious-minded artists who do not allow themselves to be influenced in their work by the threats of the present or the promises of the future, with more or less adroit circumlocution, with more or less effusion and enthusiasm. Moreover it was the time to say all that one thought, all that one believed. It was one's duty to do it, because it was possible. As the social war did not seem imminent, the monarchy, making no concessions to the needs of the people, seemed powerful enough to defy longer than it did the current of ideas.

These ideas, at which only a small number of conservative minds had as yet taken fright, had really taken firm root only in a small number of observant and laborious minds. So long as they seemed to have no application to political actualities, the ruling power worried very little about theories and allowed every man to make one for himself, to publish his dream, to construct the future city innocently in his chimney corner, in the garden of his imagination.

The conservative journals became therefore the refuge of the socialist novel. Eugène Sue published his in the Débats and the Constitutionnel. I published mine in the Constitutionnel and the Epoque. At about the same time the National was attacking the socialistic writers in its feuilletons, and overwhelming them with very bitter insults or very clever satire.

The Epoque, a journal which had a very brief life, but which began by surpassing in ardor all the conservative and absolutist organs of the moment, was the frame wherein I was given absolute liberty to publish a socialistic novel. On all the blank walls of Paris was placarded in huge letters: Read the Epoque! Read the Sin of Monsieur Antoine!

The following year, as we were wandering through the moors of Crozant and among the ruins of Châteaubrun, a rustic field in which my pen had always taken delight, a Parisian friend of mine called out facetiously to the half-civilized shepherds of those solitudes: "Have you read the Epoque? Have you read the Sin of Monsieur Antoine?" And as they fled, terrified by those incomprehensible words, he said to me with a laugh: "How evident it is that these socialistic novels go to the heads of the country people!"

An old woman, an excellent talker, came to Châteaubrun to reprove me because I had written a book full of lies about her and her master. She thought that I had intended to introduce the proprietor of the château and herself on my stage. She had heard of the book. People had told her that there was not a word of truth in it. It was impossible to make her understand what a novel is, and yet she invented one herself, for she told us of the assassination of Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette, who were stabbed in their carriage by the populace of Paris. They who accuse socialistic writers of inflaming people's minds should remember that they have forgotten to teach the peasants to read.

Shall I deny, now that the masses are stirring, the communism of Monsieur de Boisguilbault, a very eccentric and yet not altogether imaginary character in my novel? God forbid, especially after the socialists have been accused, in every key, of preaching the division of property.

The diametrically opposite idea, that of common ownership by association, should be the least dangerous of all in the eyes of the conservatives, since it is unfortunately the least understood and the least popular among the masses. It is especially antipathetic in the country districts and can be realized only by the initiative of a strong government or by a philosophic, religious and Christian renovation, the work of centuries it may be!

Attempts to form workingmen's associations have been made, however, among the best informed, the most moral, the most patient portion of the industrial population of the large cities. Enlightened governments, whatever their motto, will always protect these associations, because they offer a refuge to the genuinely social and religious thought of the future. Probably imperfect at their birth, they will perfect themselves in time, and when it is clearly proved that they do not destroy, but, on the contrary, preserve respect for family and property, they will insensibly lead to reciprocity among all classes, and to a union of interests and attachments,—the only path of safety open to the society of the future.

GEORGE SAND.

There are few localities in France as unattractive as the town of Eguzon on the confines of La Marche and Berry, in the southwest part of the latter province. Eighty to a hundred houses, all of more or less wretched appearance, with the exception of two or three whose opulent proprietors we will not name for fear of offending their modesty, line the two or three streets and surround the public square of that municipality, famous for leagues around by reason of the litigious nature of its population and the difficulty of reaching it. Despite this last drawback, which will soon disappear, thanks to the laying out of a new road, Eguzon sees many travellers boldly traverse the solitudes by which it is surrounded and risk the springs of their carrioles on its terrible pavement. The only inn is situated on the only square, which seems the more vast because it has one side open to the fields as if awaiting the new buildings of future citizens; and this inn is sometimes compelled, in the summer, to invite its too numerous guests to accept accommodation in the neighboring houses, which are thrown open to them, we are bound to say, with much hospitality. Eguzon, you see, is the central point of a picturesque neighborhood dotted with imposing ruins, and whether one desires to visit Châteaubrun, Crozant, Prugne-au-Pot, or the still habitable and inhabited château of Saint-Germain, he must necessarily sleep at Eguzon, in order to start betimes on these different excursions on the following morning.

Several years ago, one lowering, stormy evening in June, the good people of Eguzon opened their eyes to their fullest extent to see a young man of attractive exterior crossing the square to leave the town just after sunset. The weather was threatening; it was growing dark more quickly than usual, and yet the young traveller, after taking a light repast at the inn, where he halted just long enough to rest his horse, rode boldly away toward the north, heedless of the representations of the innkeeper, and apparently caring naught for the dangers of the road. None knew him; he had answered all questions with an impatient gesture only, and all remonstrances with a smile. When the sound of his horse's hoofs had died away in the distance, the loafers about the inn said to one another:

"That fellow knows the road well or doesn't know it at all. Either he has been over it a hundred times and knows every stone by name, or he doesn't suspect what sort of a place it is, and will find himself in a deal of trouble."

"He's a stranger and not of these parts," said a knowing individual with a judicial air. "He wouldn't listen to anything but his own head; but half an hour hence, when the storm breaks, you'll see him coming back again."

"If he doesn't break his neck first, going down the Pont des Piles," observed a third.

"Faith!" said the bystanders in chorus, "that's his business! Let's go and close our shutters, so that the hail won't break our window-panes."

And throughout the village there was a great noise of doors and windows being hastily barred, while the wind, which was beginning to moan over the moors, outstripped the breathless maid-servants, and sent back into their faces the folding leaves of the heavy shutters wherein the mechanics of the province, in conformity with the traditions of their ancestors, spared neither oak nor iron bolts. From time to time a voice could be heard from one end of the street to the other, and such remarks as these were shouted from doorway to doorway: "Is all yours in?" "Ah oua! I've got two loads still on the ground." "And I've got six standing!" "Well, I don't care, mine are all in the barn." They were talking about hay.

The traveller, riding an excellent Brenne hackney, left the clouds behind him and, quickening his pace, flattered himself that he could outstrip the storm; but, at a sudden turn in the road, he realized that he must inevitably be taken in flank. He unfolded his cloak, which was strapped to his valise, tied his cap under his chin, and, digging his spurs into his horse, galloped on once more, hoping at least to reach and cross, by daylight, the dangerous spot that had been described to him. But his hope was disappointed; the road became so difficult that he had to go at a footpace and watch his horse to keep him from falling over the rocks with which the ground was strewn. When he reached the top of the ravine of La Creuse, the storm-cloud had enveloped the whole sky; it was quite dark, and he could judge the depth of the abyss he was skirting only by the dull, muffled roar of the torrent.

With the rashness of his twenty years the young man disregarded his horse's prudent hesitation and forced him to take the chances of a descent which the docile beast found more uneven and steeper at every step. But suddenly he stopped and threw himself back on his haunches, and his rider, who was slightly startled by the shock, saw, by the light of a brilliant flash, that he was on the extreme edge of a perpendicular precipice, and that another step would infallibly have hurled him to the bottom of La Creuse.

The rain was beginning to fall, and a furious squall twisted the tops of the old chestnut trees on the level of the road. The west wind forced man and horse alike toward the stream, and the danger became so real that the traveller was obliged to dismount, in order to present less surface to the wind and to guide his horse more surely in the darkness. What the lightning flash had enabled him to see of the landscape had seemed wonderfully beautiful to him; moreover, his situation whetted the task for adventure which is characteristic of youth.

A second flash enabled him to distinguish his surroundings, and he profited by a third to familiarize himself with the objects nearest at hand. The road was not narrow, but its very width made it hard to follow. There were some half a dozen vaguely defined tracks, marked only by hoof-prints and wheel-ruts, forming divers paths, interlaced as if by chance, on the slope of a hill; and as there was neither hedge, nor ditch, nor any sign of cultivation, those who passed that way had climbed the hill wherever they happened to choose; thus with each season a new road was opened, or some old one reopened which time and nonuse had closed. Between each two of these capricious tracks were little mounds of rock or tufts of furze, which looked just alike in the darkness, and as no two of them were on the same level it was difficult to pass from one to the other without risking a fall which might well end in the abyss; for they all sloped sidewise as well as forward, so that one must lean backward and to the left. Thus no one of these winding paths was safe; for since the spring all had been trodden equally hard, the natives taking any one of them at random in broad daylight; but, on a dark night, it was of the greatest importance not to lose one's footing, and the young man, who was more careful of the knees of the horse he loved than of his own life, concluded to halt behind a rock that was high enough to shelter them both from the violence of the wind, and to wait there until the sky should brighten up a bit. He leaned against Corbeau, and, raising a corner of his waterproof cloak in such wise as to protect his companion's quarters and the saddle, he fell into a romantic reverie, as well pleased to hear the howling of the tempest as the good people of Eguzon, assuming them to be thinking of him at all at that moment, supposed him to be anxious and disappointed.

The successive flashes soon afforded him a sufficient acquaintance with the surrounding country. Directly in front of him the road climbed the opposite slope of the ravine, equally steep and presenting difficulties of the same nature. The Creuse, a clear, swift stream, flowed not very noisily at the foot of the precipice and drew its banks together to pass with a dull, never-ending roar under the arches of an old bridge that seemed in a very dilapidated condition. The view opposite was limited by the steep incline; but at the left he could catch glimpses of sloping, well-cultivated meadows, through the middle of which the stream wound; and opposite our traveller, on the crest of a hill bristling with huge boulders interspersed with rich vegetation, rose the dilapidated towers of a vast ruined manor. But, even if it had occurred to the young man to seek shelter there from the storm, it would have been difficult to find a way of reaching it; for there was no apparent communication between the road and the ruin, and another ravine, traversed by a stream that emptied into the Creuse, separated the two hills. The site was most picturesque and the pallid gleam of the lightning imparted a touch of the terrible which one would have sought in vain by daylight. Gigantic chimneys, exposed by the falling of the roofs, towered up toward the heavy clouds that hovered over the château and seemed to rend it asunder. When the sky was lighted by the swift flashes, the ruins were outlined in white against the dark background of the atmosphere, and, on the contrary, when the eyes had accustomed themselves to the succeeding darkness, they formed a dark mass against a lighter horizon. A large star, which the clouds seemed not to dare to cover, shone a long while over the haughty donjon, like a carbuncle on a giant's head. At last it disappeared, and the torrents of rain, falling with redoubled force, made it impossible for the traveller to distinguish anything except through a thick veil. The water, falling on the rocks near by and on the ground hardened by the recent extreme heat, rebounded like white foam and at times resembled clouds of dust raised by the wind.

As he moved forward to shelter his horse more effectually behind the rock, the young man discovered that he was not alone. Another man had come to that spot in search of shelter, or perhaps had taken possession of it first. It was impossible to tell, in those alternations of dazzling light and intense darkness. The horseman had not time to obtain a good view of the pedestrian; he seemed to be wretchedly dressed and not of very attractive appearance. Indeed he seemed inclined to keep out of sight by crouching as far under the rock as possible; but as soon as he concluded, from an exclamation of the traveller, that he was discovered, he unhesitatingly addressed him in a loud, clear voice:

"This is bad weather for riding, monsieur, and if you're wise you will go back to Eguzon to sleep."

"Much obliged, my friend," replied the young man, making his stout, lead-handled hunting-crop whistle through the air, in order to give his problematical companion to understand that he was armed.

The latter understood the warning and answered it by tapping the rock, as if absent-mindedly, with an enormous holly staff, which broke off several splinters of stone. The weapon was stout and so was the wrist that wielded it.

"You won't go far to-night in such weather," continued the pedestrian.

"I shall go as far as I choose," replied the horseman, "and I should not advise anybody to take it into his head to delay me on the way."

"Are you afraid of robbers that you meet friendly overtures with threats? I don't know what province you come from, my young man, but you hardly seem to know what province you are in. Thank God, there are neither highwaymen, nor assassins among us."

The stranger's proud but frank tone inspired confidence. The young man rejoined more mildly:

"You're of this province, are you, comrade?"

"Yes, monsieur, I am, and always shall be."

"You are right to propose to remain here; it's a beautiful country."

"Not always though! At this moment, for instance, it's none too pleasant; the weather is venting its spite, and it will be bad all night."

"Do you think so?"

"I am sure of it. If you follow the valley of the Creuse you'll have the storm for company till to-morrow noon, but I fancy that you didn't start out so late without expecting to find shelter near at hand?"

"To tell you the truth, I am inclined to think that the place I am going to is farther away than I supposed at first. I fancied that they tried to keep me at Eguzon by exaggerating the distance and the bad condition of the roads; but I see, from the little progress I have made in an hour, that they hardly overstated it."

"Not to be inquisitive, where might you be going?"

"To Gargilesse. How far do you call it?"

"Not far, monsieur, if you could see where you are going; but, if you don't know the country, it will take you all night; for what you see from here is nothing in comparison with the break-neck places you have to descend to go from the ravine of La Creuse to that of Gargilesse, and you risk your life to boot."

"Well, my friend, will you undertake to guide me, for a good round sum?"

"No, monsieur, thank you."

"Is the road very dangerous that you are so disobliging?"

"The road is not dangerous to me, for I know it as well as you probably know the streets of Paris; but what reason have I for passing the night in getting drenched just to please you?"

"I am not particular about it, and I can do without your help; but I didn't ask you to favor me for nothing; I offered you——"

"Enough! enough! you are rich and I am poor, but I am not a beggar yet, and I have reasons for not making myself the servant of the first comer. However, if I knew who you were——"

"Are you suspicious of me?" said the young man, whose curiosity was aroused by his companion's proud and fearless character. "To prove that distrust is an unworthy feeling, I will pay you in advance. How much do you want?"

"I beg your pardon, excuse me, monsieur, I want nothing; I have neither wife nor children, I need nothing for the moment; besides I have a friend, a good fellow, whose house is not far away, and I shall take advantage of the first flash to go there and have supper and sleep on a good bed. Why should I deprive myself of that for you? Let us see! is it because you have a good horse and new clothes?"

"I like your pride, so far as that goes! But it seems to me not well done of you to refuse an exchange of favors."

"I have done you all the service in my power by telling you not to take any risks at night in such vile weather, on roads that will be impassable in half an hour. What more do you want?"

"Nothing. When I asked for your assistance I wanted to ascertain the character of the people of this neighborhood, that's all. I see now that their good will toward strangers is limited to words."

"Toward strangers!" cried the native, in a melancholy and reproachful tone which impressed the traveller. "In Heaven's name isn't that too much for those who have never done us aught but harm? I tell you, monsieur, men are unjust; but God's sight is clear, and he knows well that the poor peasant allows himself to be shorn, without revenging himself, by the shrewd people who come from the great cities."

"Have the people from the cities done so much harm in your country districts, pray? That is a fact that I know nothing of and am not responsible for, as this is my first visit."

"You are going to Gargilesse. I suppose of course you are going to see Monsieur Cardonnet? You are either a relation or friend of his, I am sure?"

"Who is this Monsieur Cardonnet, whom you seem to hold in ill-will?" asked the young man, after a moment's hesitation.

"Enough, monsieur," the peasant replied; "if you don't know him anything that I could say would hardly interest you, and if you are rich you have nothing to fear from him. The poor people are the only ones he has a grudge against."

"But after all," rejoined the traveller, with a sort of restrained emotion, "it may be that I have reasons for wanting to know what people in this country think of this Monsieur Cardonnet. If you refuse to give any reason for your bad opinion of him, it must be because you have some personal spite against him, not at all creditable to yourself."

"I am accountable to nobody," retorted the peasant, "and my opinion is my own. Good-night, monsieur. See, the rain is a little less violent. I am sorry to be unable to offer you a shelter; but I have only the château you see yonder, which is not mine. However," he added, after taking a few steps, and as if regretting that he had not shown more respect for the duties of hospitality, "if your heart should prompt you to come and ask a bed for the night, I can answer for it you would be welcome."

"Is yonder ruin occupied?" asked the traveller, who had to descend the ravine to cross the Creuse, and had walked along beside the peasant, supporting his horse by the rein.

"It is a ruin, in truth," his companion replied, repressing a sigh; "but although I am not so very old, I have seen that château in perfect repair, and so magnificent, outside as well as inside, that a king would have been well lodged there. The owner didn't spend a great deal, but it didn't require much repairing, it was so solid and well built; and the walls were so well laid, the stone mantels and window frames so beautifully carved that it would have been impossible to make it any finer than the architects and masons did when they built it. But everything goes, riches like all the rest, and the last lord of Châteaubrun has just repurchased the château of his ancestors for four thousand francs."

"Is it possible that such a mass of stone, even in its present condition, is worth so little?"

"What is left would still be worth a good deal if one could take it down and carry it away; but where in this vicinity can he find workmen and machines capable of pulling down those old walls? I don't know what they built with in old times, but that cement is so hard that you would say the towers and high walls are made of a single stone. And then, you see how it was planted on the very top of a mountain, with precipices on all sides! What carts and what horses could carry down such materials? Unless the hill crumbles they will stay there as long as the rock that holds them, and there are still ceilings enough left to cover one poor gentleman and one poor girl."

"So this last of the Châteaubruns has a daughter, has he?" asked the young man, pausing to look at the manor with more interest than he had yet shown. "And she lives there?"

"Yes, yes, she lives there among the gerfalcons and screech-owls, and yet she is young and pretty, all the same. There's no lack of air and water here, and in spite of the new laws against free hunting, we still see hares and partridges now and then on the lord of Châteaubrun's table. Look you, if you have no business that compels you to risk your life to arrive before daybreak, come with me; I will undertake to procure you a warm welcome at the château. Even if you should arrive there alone, without recommendation, it's enough that the weather is bad and that you have the face of a Christian, to ensure your being well received and well treated at Monsieur Antoine de Châteaubrun's."

"But this gentleman is poor, it seems, and I am reluctant to impose on his goodness of heart."

"On the contrary, you will gratify him. Come, the storm, you see, is going to begin again with more violence than before, and my conscience would trouble me if I should leave you thus all alone on the mountain. You mustn't bear me ill-will because I refused my services. I have my reasons, which you could not judge fairly, and which there is no need of my telling you; but I shall sleep better if you follow my advice. Besides, I know Monsieur Antoine; he would be angry with me for not holding fast to you and taking you to his house; he would be quite capable of running after you, which would be a bad thing for him after supper."

"And you don't think that his daughter would be displeased to have a stranger arrive thus unexpectedly?"

"His daughter is his daughter; that is to say, she is as good as he is, if not better, although that seems hardly possible."

The young man hesitated some time longer, but, drawn on by a romantic attraction, and already drawing in his imagination the portrait of the pearl of beauty he was about to find behind those frowning walls, he said to himself that he was not expected at Gargilesse until the following day; that by arriving at midnight he should disturb his parents in their sleep; and, lastly, that it would be downright imprudence to persist in his plan, and that his mother would certainly dissuade him from it, if she could see him at that moment. Moved by all the excellent reasons which a man gives himself when the demon of youth and curiosity takes a hand, he followed his guide in the direction of the old château.

After climbing with difficulty a very steep road, or rather a stairway cut in the rock, our travellers reached the entrance of Châteaubrun in about twenty minutes. The wind and the rain redoubled in violence, and the young man hardly had leisure to observe the huge portal, which offered to his sight, at that moment, nothing more than an ill-defined mass of formidable proportions. He noticed simply that the seignorial portcullis was replaced by a wooden fence like those which enclose all the fields in the province.

"Wait a moment, monsieur," said his guide. "I will climb over and get the key; for latterly old Janille has minded to have a padlock here, as if there were anything to steal in her master's house! However, her intentions are good, and I don't blame her."

The peasant scaled the fence very cleverly, and, while awaiting for him to return and admit him, the young man tried in vain to make out the arrangement of the ruined masses of architecture which he could see confusedly inside the courtyard; it was like a glimpse of chaos.

After a few moments he saw several persons approaching. The gate was speedily opened; one took his horse, another his hand, and a third went ahead carrying a lantern, which was very essential for their guidance among the rubbish and brushwood that obstructed their passage. At last, after passing across part of the courtyard and through several enormous dark rooms, open to all the winds of heaven, they reached a small oblong room with an arched ceiling, which might formerly have been used as a pantry or as a store-room between the kitchen and the stables. This room had been cleaned and whitewashed, and was used by the lord of Châteaubrun as salon and dining-room. A small fireplace had recently been built there, with mantel and uprights of polished, glistening wood; the huge cast-iron plate, which had been taken from one of the great fireplaces and which filled the whole back, together with the great fire-dogs of polished iron, sent out the heat and light beautifully into the bare white room, which, with the aid of a small tin lamp, was perfectly lighted. A chestnut table, which could be made to hold as many as six covers on great occasions, a few straw-seated chairs, and a German cuckoo clock, purchased from a peddler for six francs, composed the whole furniture of this modest salon. But everything was scrupulously clean; the table and chairs, roughly carved by some local cabinet-maker, shone in a way that bore witness to the assiduous use of the brush and duster. The hearth was carefully swept, the floor sanded in the English fashion, contrary to the customs of the province; and in an earthenware pot on the mantel was a huge bunch of roses mingled with wild-flowers plucked on the hillside roundabout.

At first glance there was nothing cherché, in the poetic or picturesque sense, in that modest interior; and yet, on examining it more closely, one would see that, in that abode, as in all those of all mankind, the natural taste and temperament of its presiding genius had governed in the choice as in the arrangement of the furniture. The young man, who then entered the room for the first time, and who was left alone there for a moment while his hosts busied themselves in preparations to make him as comfortable as possible, soon formed an idea of the mental condition of the inhabitants of that retreat. It was evident that they had refined habits and that they still felt a craving for the comforts of life; that, being in a very precarious financial condition, they had had the good sense to proscribe every species of mere external vanity, and had chosen, for their place of assemblage, among the few still intact apartments in that great building, the one that could most easily be kept clean, heated, furnished and lighted; and that, nevertheless, they had instinctively given the preference to a well-proportioned, attractive room. This little nook was in fact the first floor of a square pavilion added, toward the close of the Renaissance, to the venerable buildings which looked upon the principal courtyard. The artist who had planned this sharp-angled turret had done his best to soften the transition from one to the other of two such different styles. For the shape of the windows he had gone back to the defensive system of loop-holes and small apertures through which to watch the enemy; but it was easy to see that the small round windows had never been intended to fire cannon through, and that they were simply for purposes of ornament. Being tastefully framed with red brick and white stone, in alternation, they formed an attractive setting for the interior of the room, and divers recesses between the windows decorated in the same way, avoided the necessity for papers, hangings, or even articles of furniture, with which the wall might have been covered, without adding to their simple and pleasant aspect.

In one of these recesses, the base of which, about three feet from the floor, was formed by a flagstone white as snow and glistening like marble, stood a pretty little rustic spinning-wheel, with its distaff filled with brown flax; and as he contemplated that slight and primitive instrument of toil the traveller lost himself in reflections from which he was roused by the rustling of a woman's dress behind him. He turned hastily; but the sudden rapid beating of his youthful heart was checked by a severe disappointment. It was an old servant, who had entered the room noiselessly, thanks to the fine sand with which the floor was covered, and was leaning over to throw an armful of wild grapevine roots on the fire.

"Come near the fire, monsieur," she said, lisping with a sort of affectation, "and give me your cap and cloak, so that I can have them dried in the kitchen. That's a fine cloak for the rain; I don't know what they call this material, but I've seen it in Paris. It would be a good thing to see such a cloak on Monsieur le Comte's shoulders! But it must cost a lot, and besides, he hasn't said that he would wear it. He thinks he's still twenty-five years old, and he declares that the water from the sky never yet gave an honest man a cold; however, he began to have a touch of sciatica last winter. But a man isn't afraid of those things at your age. Never mind, warm your bones all the same; here, turn your chair like this and you'll be more comfortable. You're from Paris, I am sure; I can tell by your complexion, which is too fresh for our country; a fine country, monsieur, but very hot in summer and very cold in winter. You will say that it's as cold to-night as a night in November; that's true enough, but what can you expect? it's on account of the storm. But this little room is very comfortable, very easy to heat; in a moment you'll see if I'm not right. We are lucky to have plenty of dead wood. There are so many old trees about here, and we can keep the oven going all winter just with the brambles that grow in the courtyard. To be sure, we don't do much cooking. Monsieur le Comte is a small eater and his daughter's like him; the little servant is the heartiest eater in the house; why, he has to have three pounds of bread a day; but I bake for him separate, and I don't spare the rye. That's good enough for him, and with a little bran it goes farther and isn't bad for the health. Ha! ha! that makes you laugh, does it? and me too. You see, I have always liked to laugh and talk; the work goes off just as fast, for I like to be quick in everything. Monsieur Antoine is like me; when he has once spoken, off you must go like the wind. So we have always agreed on that point. You'll excuse us, monsieur, if we keep you waiting a little while. Monsieur has gone down the cellar with the man who brought you here, and the stairs are so broken down that they can't go very fast; but it's a fine cellar, monsieur; the walls are more than ten feet thick, and it's so far underground that when you're down there you feel as if you were buried alive. Really! it's a funny feeling. They say that there was a time when they used to put prisoners of war there; now, we don't put anybody there and our wine keeps very well. What delays us is that our child has already gone to bed; she had a sick headache to-day because she went out in the sun without a hat. She says that she means to get used to it, and that she can get along without hat or umbrella just as well as I can; but she's mistaken; she's been brought up like a young lady, as she should have been, poor child! for when I say our child, I don't mean that I am Mademoiselle Gilberte's mother; she's no more like me than a goldfinch is like a sparrow; but as I brought her up, I have always kept the habit of calling her my girl: she would never let me stop calling her thou. She's such a sweet child! I am sorry she's in bed, but you will see her to-morrow; for you won't go away without breakfast, you won't be let go, and she'll help me to serve you a little better than I can do alone. It's not courage that I lack, however, monsieur, for I have a good pair of legs; I have always been thin, as you see me, with my short body, and you would never think me as old as I am. Come! how old would you call me?"

The young man thought that, thanks to this question, he would be able to put in a word at last, to thank her and to guide her, for he was very desirous of fuller details concerning Mademoiselle Gilberte; but the good woman did not await his reply, but continued volubly:

"I am sixty-four years old, monsieur, that is to say, I shall be on Saint-Jean's day, and I do more work alone than three young hussies could ever do. My blood runs quick, you see, monsieur. I am not from Berry, I was born in Marche, more than half a league from here; so you can understand it. Ah! you are looking at our child's work? Do you know that is spun as even and fine as the best spinner in the province can do it? She wanted me to teach her to spin. 'Look you, mother,' she said, for she always calls me that; she never knew her own mother and always loved me as if I was, although we were about as much alike as a rose and a nettle; 'look you, mother,' she said, 'all that embroidery and drawing and nonsense they taught me at the convent will never do me any good here. Teach me to spin and knit and sew, so that I can help you make father's clothes.'"

Just as the good woman's indefatigable monologue was beginning to be interesting to her weary auditor, she left the room, as she had already done several times; for she did not remain quiet a moment, and, while talking, had covered the table with a coarse white cloth, laid plates, glasses and knives; had swept the hearth, wiped the chairs and rekindled the fire ten times, always resuming her soliloquy at the point where she had let it drop. But this time her voice, which began to lisp in the passageway outside the door, was drowned by other stronger voices, and the Comte de Châteaubrun and the peasant who had guided our traveller at last appeared before him, each carrying two large earthenware jugs which they placed on the table. Not until then had the young man had an opportunity to see their faces distinctly.

Monsieur de Châteaubrun was a man of some fifty years, of medium height, with a noble and commanding figure, broad-shouldered, with a neck like a bull, the limbs of an athlete, a skin quite as tanned as his companion's, and large hands, calloused and roughened by hunting and by the sunlight and the cold air; a genuine poacher's hands, if such things can be, for the worthy nobleman had too little land not to hunt on that of other people.

He had a frank, ruddy, smiling face, a firm walk and the voice of a stentor. His hunting costume, neat and clean although patched at the elbow, his coarse shirt, his leather gaiters, his grizzly beard which was patiently waiting for Sunday,—everything about him indicated that his life was rough and wild, whereas his pleasant face, his hearty, affectionate manners and an ease of bearing, not unmixed with dignity, recalled the courteous gentleman and the man who was accustomed to protect and assist, rather than to be protected and assisted.

His companion the peasant was not nearly as presentable. The storm and the muddy roads had wrought havoc with his jacket and his shoes. While the nobleman's beard may have been six or seven days old, the villager's was fully fourteen or fifteen. He was thin, bony and wiry, several inches taller than the other, and although his face also expressed good-nature and cordiality, it had, if we may so describe it, flashes of malevolence, of melancholy and haughty aloofness. It was evident that he had more intelligence or was more unfortunate than the lord of Châteaubrun.

"Well, monsieur," said the nobleman, "are you a little dryer than you were? You are welcome here and my supper is at your service."

"I am grateful for your generous welcome," replied the traveller, "but I am afraid you will deem me lacking in courtesy if I do not tell you first of all who I am."

"No matter, no matter," rejoined the count, whom hereafter we shall call Monsieur Antoine, as he was generally called in the neighborhood; "you can tell me that later, if you choose; so far as I am concerned, I have no questions to ask you, and I consider that I can satisfy the demands of hospitality without making you give your names and titles. You are travelling, you are a stranger in the province, caught by an infernal night at the very gate of my house; those are your titles and your claims. In addition you have an attractive face and a manner that pleases me; I believe therefore that I shall be rewarded for my confidences by the pleasure of having accommodated a good fellow. Come, sit you down, and eat and drink."

"You are too kind and I am touched by your frank and amiable manner of welcoming strangers. But I do not need any refreshment, monsieur, and it is quite enough that you should allow me to wait here until the end of the storm. I had supper at Eguzon hardly an hour ago. So do not serve anything for me, I beg you."

"You have supped already? why, that's no reason! Is your stomach one of those that can digest only one meal at a time? At your age I would have supped every hour in the night if I had had the chance. A ride in the saddle and the mountain air are quite enough to renew the appetite. To be sure, one's stomach is less obliging at fifty; so that I consider myself well-treated if I have half a glass of good wine with a crust of stale bread. But do not stand on ceremony here. You have come in the nick of time, for I was just about to sit down, and as my poor little one has a sick-headache to-day, Janille and I were very depressed at the idea of eating alone: so your arrival is a comfort to us, and this good fellow's too, my old playmate, whom I am always glad to see. Come, sit you down here beside me," he said to the peasant, "and you, Mère Janille, opposite me. Do the honors; for you know I have a heavy hand, and when I undertake to carve, I cut the joint and platter and cloth, and sometimes the table, and you don't like that."

The supper which Dame Janille had spread on the table with an air of condescension consisted of a goat's-milk cheese, a sheep's-milk cheese, a plate of nuts, a plateful of prunes, a large round loaf of rye bread, and four jugs of wine brought by the master in person. The table-companions set about discussing this frugal meal with evident satisfaction, with the exception of the traveller, who had no appetite, and who was well content to observe the good grace with which the worthy host invited him, without embarrassment or false shame, to partake of his splendid banquet. There was in that cordial and ingenuous ease something at once fatherly and childlike which won the young man's heart.

True to the law of generosity which he had imposed upon himself, Monsieur Antoine asked his guest no questions and even avoided remarks which might suggest curiosity in disguise. The peasant seemed a little more uneasy and was more reserved. But soon, being insensibly drawn into the general conversation which Monsieur Antoine and Dame Janille had begun, he laid aside his reserve and allowed his glass to be filled so often that the traveller began to stare in amazement at a man capable of drinking so much, not only without losing his wits but without departing from his usual self-possession and gravity.

But with the master of the house it was very different. He had not drunk half of the contents of the jug beside him when his eye began to kindle, his nose to turn red and his hand to tremble. However he did not lose his wits, even after all the jugs had been emptied by himself and his friend the peasant—for Janille, whether from economy or from natural sobriety, merely poured a few drops of wine into her water, and the traveller, having made a heroic effort to swallow the first bumper, abstained from further indulgence in that sour, cloudy and execrable beverage.

EMILE ENTERTAINED BY MONSIEUR ANTOINE.

But this time, her voice, which began to lisp in the passage-way outside the door, was drowned by other stronger voices, and the Comte de Châteaubrun and the peasant who had guided our traveller at last appeared before him, each carrying two large earthenware jugs which they placed on the table.

The two countrymen, however, seemed to enjoy it hugely. After a quarter of an hour, Janille, who could not live without moving about, left the table, took up her knitting and began to work in the chimney corner, constantly scratching her head with her needle, but never disturbing the thin bands of hair, still black as a crow's wing, which protruded from under her cap. That spruce little old woman might once have been pretty; her delicate profile did not lack distinction, and if she had been less affected, less intent upon appearing fashionable and knowing, our traveller would have been attracted to her as well.

The other persons, who, in the absence of the young lady, formed Monsieur Antoine's household, were a young peasant, of some fifteen years, wide-awake and light-footed, who performed the functions of factotum, and an old hunting-dog, with a lifeless eye, thin flanks and a melancholy, dreamy air; he lay beside his master and dropped asleep philosophically between every two mouthfuls that he gave him, calling him monsieur with a gravely jocose air.

They had been at table more than an hour, and Monsieur Antoine seemed in nowise weary of sitting there. He and his friend the peasant lingered over their little cheeses and their great tankards with the majestic indifference which is almost an art in the native Berrichon. Putting their knives alternately to that appetizing morsel, the odor of which was devoid of any agreeable quality, they cut it into small pieces, which they placed carefully on their earthenware plates and ate crumb by crumb on their rye bread. Between every two mouthfuls they took a swallow of the native wine, after touching their glasses and exchanging such compliments as: "Here's to you, comrade!" "Here's to you, Monsieur Antoine!" or: "Here's your good health, old fellow!" "The same to you, master!"

At that rate, the feast might well last all night, and the traveller, who had exhausted himself in efforts to appear to eat and drink, although he avoided doing it as far as possible, was beginning to find it difficult to contend against his drowsiness, when the conversation, which had thus far been concerned with the weather, the hay crop, the price of cattle and the new growth of the vines, gradually took a turn which interested him deeply.

"If this weather continues," said the peasant, listening to the rain which was falling in torrents, "the streams will fill up this month as they did in March. The Gargilesse is not in good humor and Monsieur Cardonnet may suffer some damage."

"So much the worse," rejoined Monsieur Antoine; "it would be a pity, for he has made some extensive and valuable improvements on that little stream."

"True, but the little stream snaps its fingers at them," replied the peasant, "and for my part I don't think it would be such a great pity."

"Yes it would, yes it would! that man has already spent more than two hundred thousand francs at Gargilesse, and it needs only a fit of temper on the part of the river, as we say, to ruin it all."

"Well, would that be such a great misfortune, Monsieur Antoine?"

"I don't say that it would be an irreparable misfortune for a man who is said to be worth a million," rejoined the châtelain, who in his sincerity persisted in misunderstanding his guest's hostile feeling toward Monsieur Cardonnet; "but it would be a pity none the less."

"And that is just why I should laugh in my sleeve if a little hard luck should make that hole in his purse."

"That's a wicked feeling to have, old fellow! Why should you have a grudge against this stranger? He has never benefited or injured you or me."

"He has injured you, Monsieur Antoine, and me and the whole province. Yes, I tell you that he has done it on purpose and that he will keep on doing it to everybody. Let the buzzard's beak grow and you'll see how he'll come down on your poultry-yard."

"Still your wrong-headed ideas, old fellow! for you have wrong-headed ideas, as I've told you a hundred times. You are down on the man because he's rich. Is that his fault?"

"Yes, monsieur, it is his fault. A man who started perhaps as low as I did, and who has gone ahead so fast, isn't an honest man."

"Nonsense! What are you talking about? Do you imagine that a man can't make a fortune without stealing?"

"I don't know anything about it, but I believe it. I know that you were born rich and that you are not rich now. I know that I was born poor and always shall be poor; and it's my opinion that if you'd gone off to some other country without paying your father's debts, and if I had made it my business to cheat and shave and scrape, we might both be riding in our carriages to-day. I beg your pardon, if I offend you!" added the peasant in a proud, uncompromising tone, addressing the young man, who gave very decided indications of painful excitement.

"Monsieur," said the châtelain, "it may be that you know Monsieur Cardonnet, that you are in his employ or are under some obligation to him. I beg you to pay no heed to what this worthy villager may say. He has exaggerated ideas on many subjects which he doesn't fully understand. You may be sure that he is neither malignant nor jealous at bottom, nor capable of inflicting the slightest injury on Monsieur Cardonnet."

"I attach little importance to his words," replied the young stranger. "I am simply astonished, monsieur le comte, that a man whom you honor with your esteem should take pleasure in blackening another man's reputation without having the slightest fact to allege against him and without knowing anything of his antecedents. I have already asked your guest for some information concerning this Monsieur Cardonnet, whom he seems to hate personally, and he refused to give me any explanation of his sentiments. I leave it to you: is it possible for one to base a just opinion on gratuitous imputations, and if you or I should form an opinion unfavorable to Monsieur Cardonnet, would not your guest have been guilty of an unworthy act?"

"You speak according to my heart and my mind, young man," replied Monsieur Antoine. "You," he added, turning to his rustic guest and striking the table angrily with his fist, while he looked at him with an expression in which affection and kindliness triumphed over displeasure, "you are wrong, and you will be good enough to tell us at once what grievance you have against the said Cardonnet, so that we can judge whether it has any force. If not, we shall consider that you have a soured mind and an evil tongue."

"I have nothing to say more than everybody knows," replied the peasant calmly, and with no sign of being intimidated by the sermon. "We see things and judge them as we see them; but as this young man doesn't know Monsieur Cardonnet," he added, with a penetrating glance at the traveller, "and since he is so anxious to know what sort of man he is, do you tell him yourself, Monsieur Antoine; and when you have given the main facts I will fill in the details. I will tell monsieur the cause and the effect, and he can judge for himself unless he has some better reason than mine for not saying what he thinks."

"All right, I agree," said Monsieur Antoine, who paid less attention than his companion to the young man's increasing agitation. "I will tell things as they are, and, if I go astray, I authorize Mère Janille, who has the memory and accuracy of an almanac, to interrupt and contradict me. As for you, you little rascal," he said, turning to the page in short jacket and wooden shoes, "try not to stare into the whites of my eyes so when I speak to you. Your fixed stare gives me the vertigo, and your wide-open mouth looks like a well that I may fall into. Well, what is it? what are you laughing at? Understand that a ne'er-do-well of your age should never presume to laugh in his master's presence. Stand behind me and behave as respectfully as Monsieur."

As he spoke, he pointed to his dog, and his manner was so serious and his voice so loud as he made the jest, that the traveller wondered if he were not subject to spasms of seignorial domination altogether out of keeping with his usual good-nature. But a glance at the boy's face was enough to convince him that it was simply a game to which he was well-used, for he cheerfully took his place beside the dog and began to play with him, without a trace of sulkiness or shame.

However, as Monsieur Antoine's manners were marked by an originality which could hardly be understood at the first meeting, the young man believed that he was beginning to grow light-headed by dint of much drinking, and he determined not to attach the least importance to what he was about to say. But it very rarely happened that the count lost his head, even after he had lost his legs, and he had resorted to his favorite pastime of bantering his neighbors only to divert the painful impression to which this discussion had given rise as between his guests.

"Monsieur," he began.

But he was at once interrupted by his dog, who, being also accustomed to his habit of jesting, concluded that he was the person addressed and walked up to his master and touched his arm, capering as friskily as his age would permit.

"Well, Monsieur," he continued, looking down at him with a playful stare, "what does this mean? Since when have you been as ill-bred as a human being? Go to sleep at once, and don't you ever make me spill wine on the tablecloth again, or you'll have Dame Janille about your ears. It was on a fine spring day last year, young man——" continued Monsieur Antoine.

"Excuse me, monsieur," interposed Janille, "it was only the 19th of March, so it was still winter."

"Is it worth while haggling over a difference of two days? What is certain is that it was magnificent weather, as warm as it is in June, and quite dry too."

"That's true enough," exclaimed the little groom, "for I couldn't water monsieur's horse at the little fountain."

"That has nothing to do with it," said Monsieur Antoine, tapping the floor with his foot; "hold your tongue, boy. You may speak when you're spoken to; just open your ears in order to improve your mind and your heart, if there's room for improvement. I was saying, then, that I was returning from a country fair one beautiful day, and walking quietly along on foot, when I met a tall man, very handsome although he was little if any younger than I, and his black eyes and pale, almost yellow complexion gave him a somewhat harsh and forbidding look. He was in a cabriolet, driving down a steep hill, strewn with loose stones as our fathers used to build roads, and was urging his horse forward, apparently unconscious of the danger. I could not help warning him. 'Monsieur,' said I, 'no four-wheeled, three-wheeled or two-wheeled carriage has ever gone down this hill, in the memory of man. In my opinion it is likely to result in breaking your neck, even if it is not impossible, and if you prefer a road that is a little longer but much safer, I'll show you the way.'

"'Much obliged,' he replied with just a suspicion of surliness, 'this road seems to me practicable enough and I promise you that my horse will come out all right.'

"'That's your business,' said I, 'and what I said was said from purely human motives.'

"'I thank you, monsieur, and as you are so courteous, I shall be glad to reciprocate. You are on foot, going in the same direction that I am; if you will get in with me, you will reach the valley sooner and I shall have the pleasure of your company.'"

"All that is true," said Janille; "you told it just like that the same evening except that you said that the gentleman had on a long blue overcoat."

"Excuse me, Ma'mselle Janille," said the child, "monsieur said black."

"Blue, I tell you, master upstart!"

"No, Mère Janille, black."

"Blue, I am sure of it!"

"I could swear it was black."

"Come, come, stop your quarrelling, it was green!" cried Monsieur Antoine. "Don't interrupt again, Mère Janille; and you, you naughty varlet, go to the kitchen and see if I am there, or put your tongue in your pocket; take your choice."

"I would rather listen, monsieur; I won't speak again."

"Now then," continued the châtelain, "I hesitated a moment between the fear of breaking my bones if I accepted and of being considered a coward if I refused. 'After all,' I said to myself, 'this fellow doesn't look like a lunatic, and seems to have no reason for risking his life. I have no doubt he has a wonderful horse and an excellent wagon.' I took my place beside him, and we began to descend the precipice at a fast trot, without a single false step on the part of the horse, or a moment's loss of resolution and self-possession on the part of the master. He talked to me about this thing and that and asked me many questions about the province; and I confess that I answered a little crookedly, for I was not altogether easy in my mind. 'So far so good,' I said to him when we reached the bank of the Gargilesse without accident; 'we have come safely down the break-neck, but we can't cross the water here; it's as low as possible, but even so, it is not fordable at this point; we must go up a little way to the left.'

"'Do you call this water?' said he, shrugging his shoulders; 'for my part I see nothing but stones and rushes. Nonsense! the idea of turning aside for a dry stream!'

"'As you choose,' I rejoined, a little mortified. His scornful audacity stung me; I knew that he was going straight into a veritable gulf, and yet, as I am not naturally a coward, and as I did not like the idea of being called one, I declined his offer to allow me to get down. I would have liked him to be punished by having reason to be well frightened, even at the expense of having a dip in the river myself, although I don't like water.

"But I had neither the satisfaction nor the mortification: the cabriolet did not founder. In the centre of the stream, which has dug out a channel with beveled edges, so to speak, in that spot, the horse was in up to his nostrils; the carriage was lifted up by the current. The gentleman in the green overcoat—for it was green, Janille—lashed the horse; she lost her footing, floundered, swam, and by a miracle landed us on the bank, with no other injury than a rather cool foot-bath. I did not lose my wits, I can swim as well as any man, but my companion admitted that he knew no more about it than a stick of wood; and yet he had neither faltered, nor swore, nor changed color. He's a plucky fellow, I thought, and his self-possession did not displease me, although there was something scornful in his perfect tranquillity as there is in the devil's laugh.

"'If you are going to Gargilesse, we can go on together, for I am going there too,' I said.

"'Very good,' he replied. 'Where is Gargilesse?'

"'Oh! then you are not going there?'

"'I am not going anywhere to-day,' said he, 'and I am ready to go anywhere.'

"I am not superstitious, monsieur, and yet my old nurse's stories came into my mind, I don't know why, and I had a moment of idiotic distrust, as if I were sitting beside Satan in a cabriolet. I glanced furtively at this individual who travelled thus across mountains and rivers, with no end in view, apparently just for the pleasure of exposing himself or me with him to danger; and I, like a booby, had let him persuade me to get into his infernal gig!

"Seeing that I did not speak, he thought it advisable to reassure me.

"'My way of travelling about the country surprises you, I see,' he said; 'the fact is that I propose to set up a manufacturing establishment in whatever place seems to me the most suitable. I have some money to invest—whether for myself or for other people is of little consequence to you, I suppose; but you can help me, with a few hints, to attain my object.'

"'Very good,' I said, my confidence being fully restored when I found that he talked sensibly; 'but, before advising you, I must know what sort of an establishment you propose to set up.'

"'If you will answer all the questions I ask you, that will be enough,' he said, evading my question. 'For example, what is the maximum force of this little stream we have just crossed, between this spot and the point where it empties into the Creuse?'

"'It is very irregular; you have just seen it at its minimum; but freshets are frequent and tremendous; and if you choose to inspect the principal mill, formerly the property of the religious community of Gargilesse, you will be convinced of the havoc wrought by the torrent, of the constant damage suffered by that poor old building, and of the utter folly of laying out much money on it.'

"'But by laying out money, monsieur, the unruly forces of nature can be confined! Where the poor, rustic mill goes under, the powerful, solidly built factory will triumph!'

"'True,' I replied, 'in every river the big fish eat the little ones.'

"He did not take up that suggestion but continued to question me as we drove along. I, being obliging as a matter of duty, and something of an idler by nature, took him everywhere. We went into several mills, he talked with the millers, examined everything with great care, and returned to Gargilesse, where he talked with the mayor and the principal men of the town, requesting me to introduce him to them at once. He accepted the curé's invitation to dinner, allowed himself to be made much of without ceremony, and hinted that he was in a position to render greater services than he received. He talked little, but listened eagerly and asked questions about all manner of things, including some that seemed to have little connection with business: for instance, whether the people in this neighborhood were sincerely pious or only superstitious; whether the bourgeois were fond of luxuries or sacrificed them to economy; whether the prevailing opinion was liberal or democratic; of what sort of men the general council of the department was made up—and Heaven knows what else! At night he hired a guide and went to Le Pin to sleep, and I did not see him again for three days. Then he drove by Châteaubrun and stopped at my door, to thank me, he said, for the courtesy I had shown him; but in reality I think to ask me some more questions. 'I shall return in a month,' he said, as he took leave of me, 'and I think that I shall decide on Gargilesse. It is central, and I like the place, and I have an idea that your little stream, to which you give such a bad name, will not be very difficult to subdue. It will cost me less to control it than the Creuse; and, moreover, the little risk that we ran in crossing it and that we overcame, makes me think that it is my destiny to conquer in this spot.'

"And with that he left me. That man was Monsieur Cardonnet.

"Less than three weeks after, he returned with an English mill engineer and several mechanics of the same nation; and since then he has kept earth and stone and iron constantly in commotion at Gargilesse. Being entirely absorbed by his work, he rises before daybreak and is the last to go to bed. No matter what the weather may be, he is in the mud up to his knees; not a movement on the part of his workmen escapes him; he knows the why and how of everything, and is pushing forward the construction of an enormous mill, a dwelling-house, with garden and buildings, sheds, dams, roads and bridges—in a word, a magnificent establishment. During his absence, his agents had managed the purchase of the property without allowing his name to appear. He paid a high price, but people thought at first that he didn't understand business and that he had come here to take it easy. They laughed at him still more when he increased the wages of his workmen, and when, to induce the municipal council to allow him to divert the course of the stream as he chose, he agreed to build a road, which cost him an enormous sum. They said: 'He's a fool; the extravagance of his plans will ruin him.' But after all is said, I believe he's as shrewd as most men, and I will wager that he will prove to be successful in his choice of a location and in the investment of his money. The stream troubled him a good deal last autumn, but luckily it has been very quiet this spring, and he will have time to finish his buildings before the rains come again, if we have no unusual storms during the summer. He does things on a large scale, and puts in more money than is necessary, that's the truth; but if he has a passion for finishing quickly what he has begun, and has the means and the inclination to pay a high price for the sweat of the poor laboring man's brow, where is the harm? It seems to me that it's an extremely good thing, on the contrary, and that, instead of calling the man a hare-brained fool, as some do, or a crafty speculator, as others do, we ought to thank him for bestowing on our province the advantage of industrial activity, I have said! Now let the other side take its turn."

Before the peasant, who had continued to nibble at his bread with a thoughtful expression, was prepared to begin, the young man thanked Monsieur Antoine warmly for his narrative and for his generous interpretation of Monsieur Cardonnet's course. Without admitting that he was in any way connected with that gentleman, he seemed to be deeply touched by the judgment of his character which the Comte de Châteaubrun expressed, and he added:

"Yes, monsieur, I believe that by seeking the best side of things one goes astray less often than by doing the opposite. A determined speculator would be parsimonious in the details of his undertaking, and then one would be justified in suspecting his rectitude. But when we see an intelligent and active man pay handsomely for labor——"

"One moment, if you please," interposed the peasant. "You are upright men and noble hearts; I am glad to believe it of this young gentleman, as I am sure of it in your case, Monsieur Antoine. But, meaning no offence, I will venture to tell you that you see no farther than the end of your nose. Look you. I will suppose that I have a large sum of money to invest, and that my purpose is not to obtain simply a fair and legitimate return from it, as it is right for everybody to do, but to double or treble my capital in a few years. I am not foolish enough to announce my purpose to the people I am forced to ruin. I begin by wheedling them, by making a show of generosity, and, to remove all distrust, by making myself appear, if need be, a brainless prodigal. That done, I have my dupes where I want them. I have sacrificed a hundred thousand francs, I will say, on those little wiles. A hundred thousand francs is a deal of money for the province! but, so far as I am concerned, if I have several millions, it's simply the bonus that I pay. Everybody likes me; although some laugh at my simplicity, the greater number pity me and esteem me. No one takes any precautions. Time flies fast and my brain still faster; I have cast the net and all the fish are nibbling. First the little ones—the small fry that you swallow without anyone noticing it; then the big ones, until they have all disappeared."

"What do you mean by all your metaphors?" said Monsieur Antoine, shrugging his shoulders. "If you go on talking figuratively, I am going to sleep. Come, hurry, it's getting late."

"What I mean is plain enough," continued the peasant. "When I have once ruined all the small concerns that competed with me I become a more powerful lord than your ancestors were before the Revolution, Monsieur Antoine! I govern over the head of the laws, and while I have a poor devil locked up for the slightest peccadillo, I take the liberty to do whatever pleases me or suits my convenience. I take everybody's property—with their daughters and wives thrown in, if they take my fancy—I control the business and supplies of a whole department. By my skill I have forced down the price of crops; but, when everything is in my hands, I raise prices to suit myself, and, as soon as I can safely do it, I obtain a monopoly and starve the people. And then it's a small matter to kill off competition; I soon get control of the money, which is the key to everything. I do a banking business on the sly, wholesale and retail. I oblige so many people, that I am everybody's creditor and everybody belongs to me. People find out that they no longer like me; but they see that I am to be feared, and the most powerful handle me carefully, while the small fry tremble and sigh all about me. However, as I have some intelligence and cunning, I play the great man from time to time. I rescue a few families, I contribute to some charitable organization. It is a method of greasing the wheel of my fortune, which rolls on the more rapidly for it; for people begin again to have a little esteem for me. I am no longer considered kind-hearted and foolish, but just and great. From the prefect of the department to the village curé and from the curé to the beggar, everyone is in the hollow of my hand; but the whole province suffers and no one detects the cause. No other fortune than mine will increase, and every modest competence will shrink, because I shall have dried up all the springs of wealth, raised the price of the necessaries of life and lowered that of the superfluities—just the reverse of what should be. The dealer will find himself in trouble and the consumer too. But I shall prosper because I shall be, by virtue of my wealth, the only resource of dealer and consumer alike. And at last people will say, 'What in heaven's name is happening? the small tradesmen are stripped and the small buyers are stripped. We have more pretty houses and more fine clothes staring us in the face than we used to have, and all those things cost less, so they say; but we haven't a sou in our pockets. We have all been frantic to make a show and now we are consumed by debts. But Monsieur Cardonnet isn't responsible for it all, for he does good and, if it weren't for him, we should all be ruined. Let us make haste and do something for Monsieur Cardonnet; let him be mayor, prefect, deputy, minister, king, if possible, and the province is saved!'

"That, messieurs, is the way I would make other people carry me on their backs if I were Monsieur Cardonnet, and it is what I am very sure Monsieur Cardonnet intends to do. Now, tell me that I am wrong to look askance at him; that I am a prophet of evil, and that nothing of what I predict will happen. God grant that you may be right! but for my part I can feel the hail coming in the distance, and there is only one hope that sustains me; it is that the stream will be less foolish than men; that it will not allow itself to be bridled by the fine machines they put between its teeth, and that some fine morning it will give Monsieur Cardonnet's mills a body blow that will sicken him of playing with it, and will induce him to take his capital and its consequences and carry it somewhere else. Now, I have said my say. If I have formed a hasty judgment, may God who has heard me forgive me!"

The peasant had spoken with great animation. The fire of keen insight darted from his blue eyes, and a smile of sorrowful indignation played about his mobile lips. The traveller examined that strongly-marked face, shaded by a heavy grizzly beard, wrinkled by fatigue, by exposure to the air, perhaps by disappointment as well; and, despite the pain that his language caused, he could not help thinking him handsome, and admiring, in the facility with which he bluntly expressed his thoughts, a sort of natural eloquence instinct with sincerity and love of justice; for, although his words, of which we have failed to express all the rustic homeliness, were simple and sometimes vulgar, his gestures were emphatic and the tone of his voice commanded attention. A feeling of profound depression had taken possession of his hearers, while he drew without any artifice, and unsparingly, the portrait of the pitiless and persevering rich man. The wine had had no effect upon him, and every time that he raised his eyes to the young man's face, he seemed to look into his very soul and sternly question him. Monsieur Antoine, although slightly affected by the weight of the wine he was carrying, had lost nothing of his harangue, and submitting as usual to the ascendancy of that mind, of stouter temper than his own, he heaved a deep sigh from time to time.

When the peasant had finished, "May God forgive you, indeed, my friend, if your judgment is at fault," he said, raising his glass as an offering to the Deity: "and if you are right, may Providence avert such a scourge from the heads of the poor and weak!"

"Listen to me, Monsieur de Châteaubrun, and you too, my friend," cried the young man, taking a hand of each of his companions in his own, "God, who hears all the words of man, and who reads their real sentiments in the depths of their hearts, knows that these evils are not to be dreaded, and that your apprehensions are only chimeras. I know the man of whom you speak; I know him well; and, although his face is cold, his character obstinate, his intellect active and strong, I will answer to you for the loyalty of his purposes and the noble use he will make of his fortune. There is something alarming, I agree, in the firmness of his will, and I am not surprised that his inflexible manner has caused a sort of vertigo here, as if a supernatural being had appeared in the midst of your peaceful fields. But that strength of purpose is based upon moral and religious principles, which make him, if not the mildest and most affable of men, the most rigidly just and the most royally generous."

"So much the better, deuce take it!" rejoined the châtelain, clinking his glass against the peasant's. "I drink to your health, and I am happy to have reason to esteem a man when I am on the point of cursing him. Come, don't be obstinate, old fellow, but believe this young man, who talks like a book and knows more about the subject than you and I do. Why, he says that he knows Cardonnet! that he knows him well! what more do you want? He will answer for him. So we need not worry any more. And now, friends, let us go to bed," continued the châtelain, delighted to accept the guaranty of a man of whom he knew nothing at all, not even his name, for a man of whom he knew little; "the clock is striking eleven, and that's an undue hour."

"I am going to take my leave of you," said the traveller, "and continue my journey, asking your permission to come soon to thank you for your kindness."

"You shall not go away to-night," cried Monsieur Antoine; "it is impossible, it rains bucketfuls, the roads are drowned, and you couldn't see your own feet. If you persist in going, I never want to see you again."

He was so urgent and the storm was in fact so fierce that the young man was fain to accept the proffered hospitality.

Sylvain Charasson—that was the name of the page—brought a lantern, and Monsieur Antoine, taking the traveller's arm, guided him among the ruins of the manor-house in search of a bedroom.

All the floors of the square pavilion were occupied by the Châteaubrun family; but, in addition to that small wing which was intact and recently restored, there was an enormous tower on the other side of the courtyard, the oldest part, the highest, the thickest, the most impervious of the whole pile, the rooms which it contained, one above another, being arched with stone and even more solidly constructed than the square pavilion. The band of speculators who had purchased the château several years before for purposes of demolition, and had carried away all the wood and iron to the last door-hinge, had found nothing to demolish on the lower floors, and Monsieur Antoine had had one floor cleaned and closed, for use on the rare occasions when he had an opportunity to entertain a guest. It had been a great display of magnificence on the poor fellow's part to replace the doors and windows and put a bed and a few chairs in that apartment, which was not necessary for the accommodation of his family. He had made the effort cheerfully, saying to Janille: "It isn't everything to be comfortable yourself; you must think about being able to give your neighbor shelter." And yet, when the young man entered that dismal feudal donjon, and found himself, as it were, confined in a jail, his heart sank, and he would gladly have followed the peasant, who went, as his custom was, to lie on the fresh straw with Sylvain Charasson. But Monsieur Antoine was so pleased and so proud to be able to do the honors of a guest chamber, despite his poverty, that his young guest felt bound to accept for his lodgings one of the frowning prisons of the Middle Ages.

However, there was a good fire in the huge fireplace, and the bed, which consisted of a mattress of oat-chaff with a thick quilt spread upon it, was not to be despised. Everything was cheap and clean. The young man soon drove away the melancholy thoughts that assail every traveller quartered in such a place, and, despite the rumbling of the thunder, the cries of the night-birds and the roar of the wind and rain, which shook his windows, while the rats made furious assaults upon his door, he was soon sound asleep.