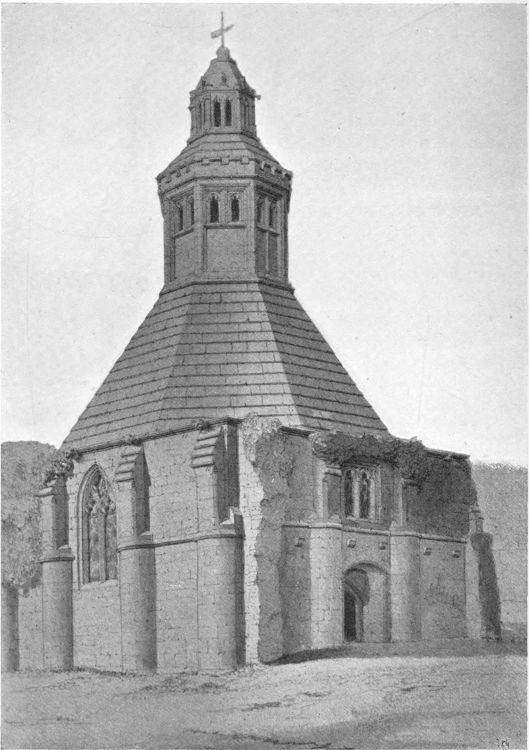

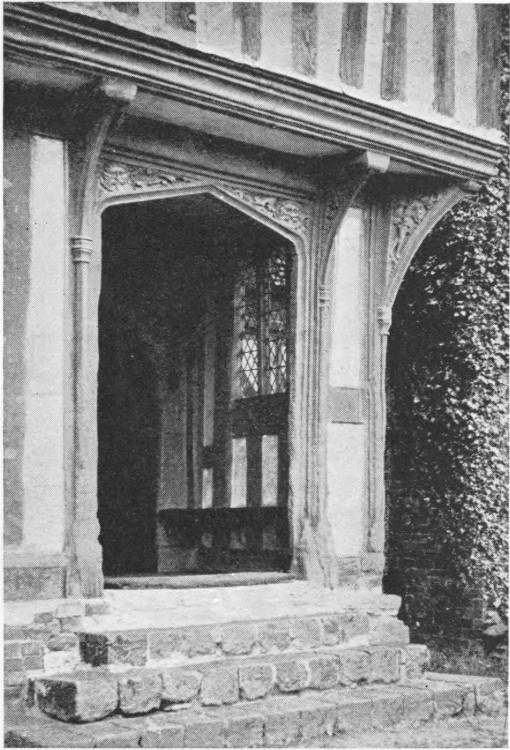

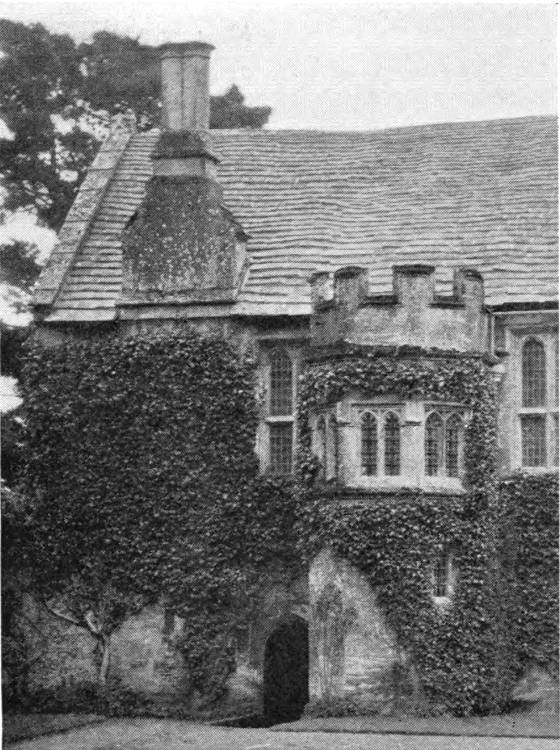

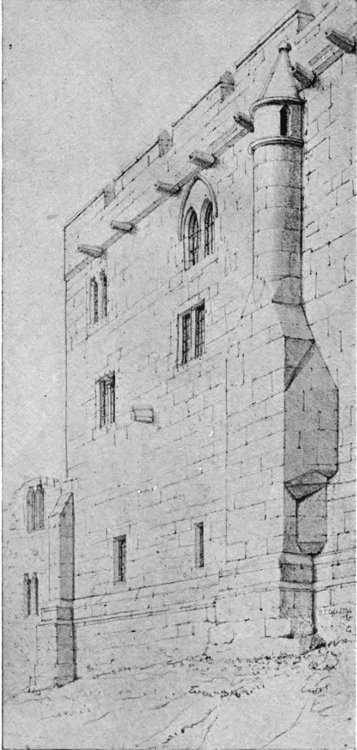

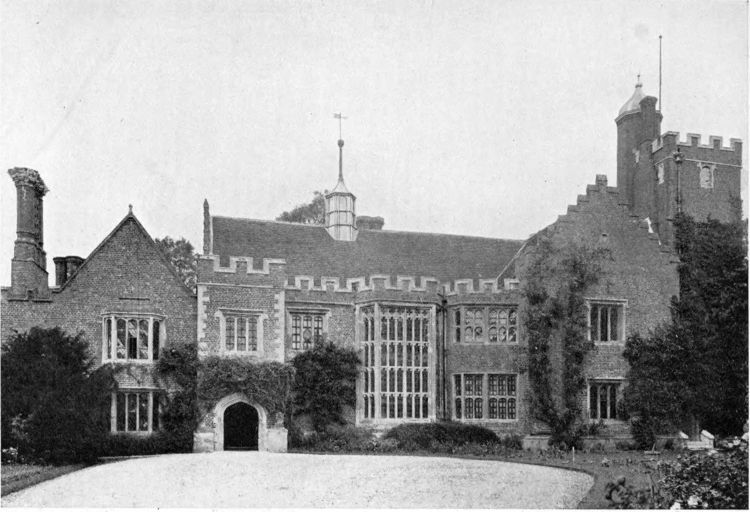

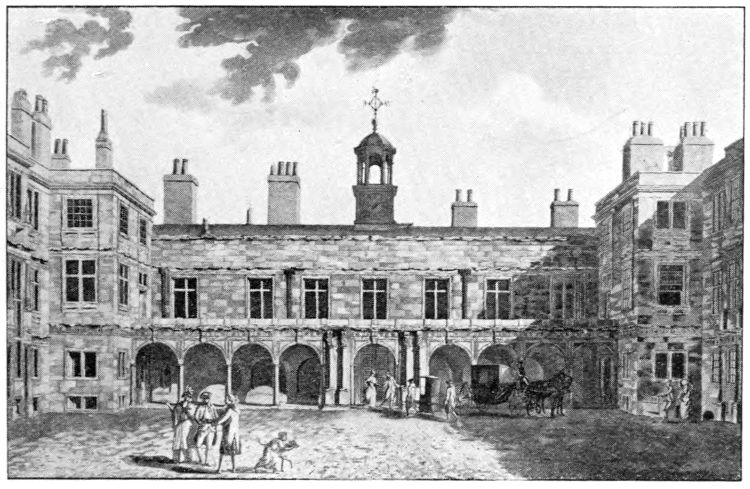

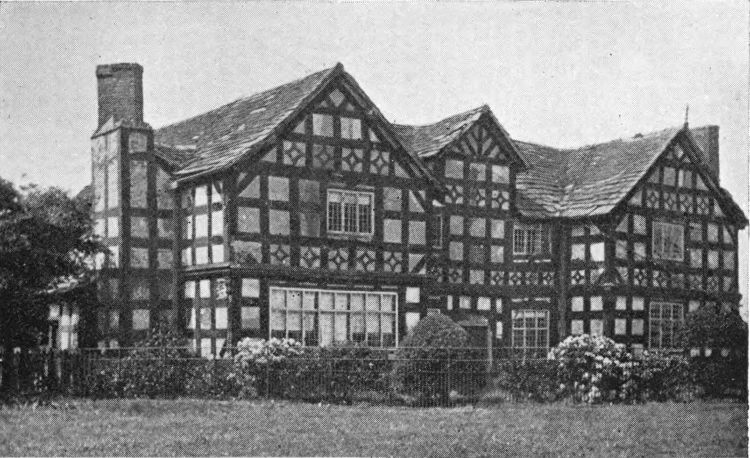

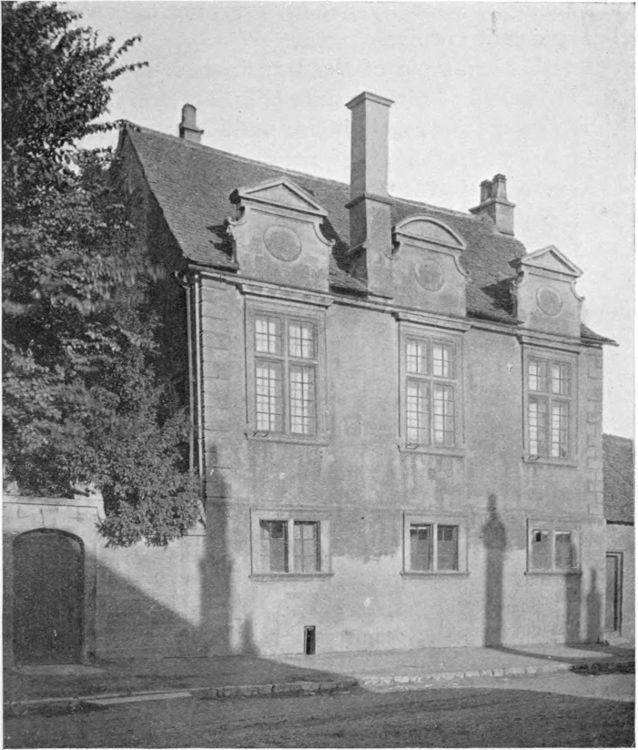

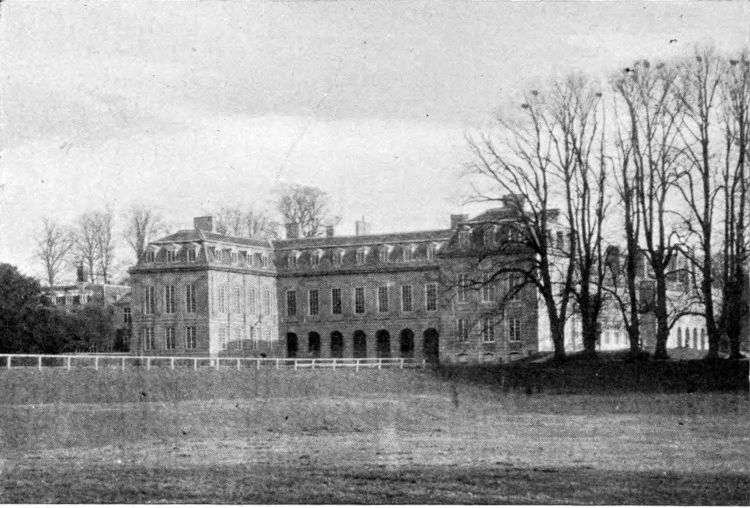

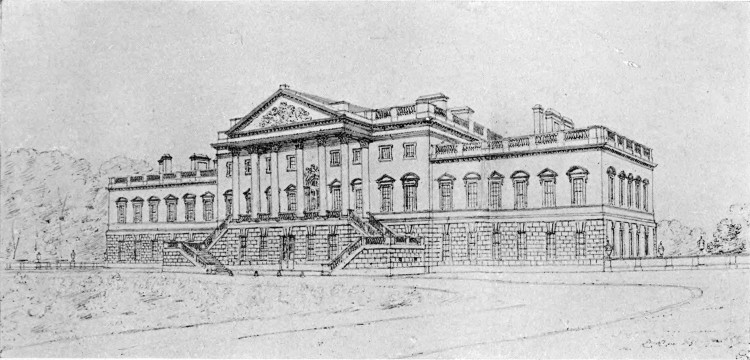

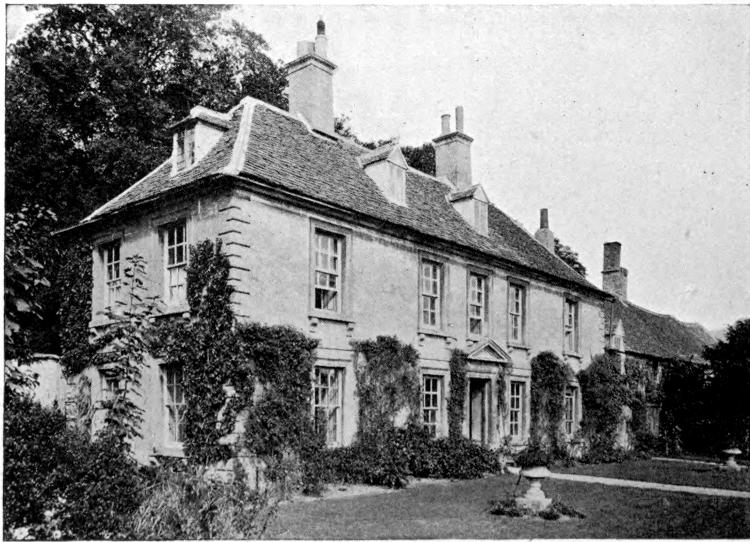

SHELDONS, WILTSHIRE.

Title: The Growth of the English House

Author: J. Alfred Gotch

Release date: March 6, 2022 [eBook #67574]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: B. T. Batsford, 1909

Credits: MWS, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The Growth of the

ENGLISH HOUSE

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

ARCHITECTURE OF THE RENAISSANCE IN ENGLAND. Illustrated by a Series of Views and Details from Buildings erected between the years 1560 and 1635, with Historical and Critical Text. Containing 145 folio Plates reproduced from Photographs, together with measured drawings, plans, details, &c., dispersed throughout the text. 2 vols., large folio, in cloth portfolios, gilt, $50.00 net; or 2 vols., handsomely bound in half morocco, gilt, $60.00 net.

“A work of national importance. Though these halls are with us now, it would be rash to say that we shall have them for ever, but while these volumes remain we shall always have a splendid memorial of the most splendid remains of the England of the past.”—The Daily News.

EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ENGLAND. An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Development of the Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean Periods, 1500–1625. With 87 Collotype and other Plates and 230 Illustrations in the Text from Drawings by various accomplished Draughtsmen, and from Photographs specially taken. Medium 8vo. $9.00 net.

This work is quite independent and distinct, both in plan and illustration, from the author’s larger work, and is in no sense a reduced or cheaper edition of it. Of the 317 Illustrations only about twelve are taken from the larger book.

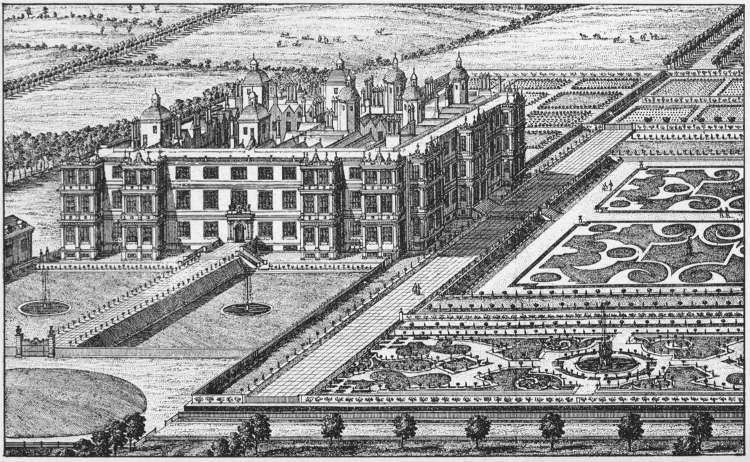

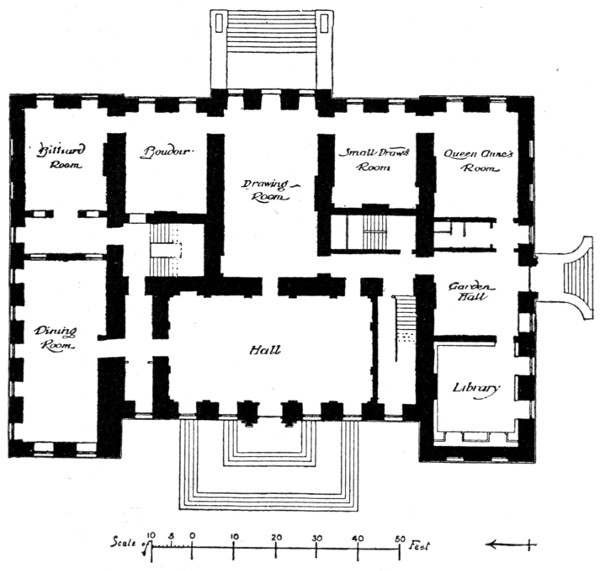

SHELDONS, WILTSHIRE.

A Short History of

its Architectural Development from

1100 to 1800

By

J. ALFRED GOTCH,

F.S.A., F.R.I.B.A.

Author of “Architecture of the Renaissance in England,”

“Early Renaissance Architecture in England,” &c.

London, B.T.Batsford

New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons

M CM IX

[v]

Printed at The Darien Press, Edinburgh.

The object aimed at in the following pages is to tell the story of the growth of the English house from its first appearance in a permanent form down to the time of our grandfathers, when it lost much of its interest. Although it is a history of domestic architecture, no deep architectural knowledge is required to understand it; technical terms are avoided as far as may be, and of such as are used a glossary will be found at the end of the volume. The reader unacquainted with architecture will be able to follow the story without difficulty; but he who already knows something of our English buildings will of course be better able to link it up with the general development of English architecture. It is the main stream of progress which is followed, but there are many pleasant backwaters and interesting tributaries which it is impossible to explore in the space at command. Those who are desirous of pursuing the subject more minutely will have no difficulty in finding books dealing with particular periods—Mediæval, Tudor, Early Renaissance, or Late Renaissance. Hitherto, however, the panorama has not been unrolled from end to end in one volume.

To render the subject intelligible numerous illustrations are essential, and thanks are due to all who have kindly contributed in this respect, especially to the publishers, Messrs Batsford, whose assistance in this[vi] and other respects has been invaluable. In view of the many admirable books which appear from year to year, it becomes increasingly difficult to avoid familiar ground; indeed the mediæval period presents very few fine examples which have not at one time or another been figured. The reader is therefore requested not to be impatient if he meets with a number of old friends in the early part of the book, and to be equally considerate if, in the periods where examples are more abundant, he misses some of the best-known houses, inasmuch as the aim has been, so far as was compatible with the proper treatment of the subject, to illustrate the text with unfamiliar buildings.

In order not to distract attention, footnotes and references have been avoided, and with a view to help those who are not conversant with the subject, there will be found, in addition to the short glossary, a chronological list of the principal buildings tabulated under the reigns of the English monarchs.

J. A. G.

Weekley Rise, near Kettering,

September 1909.

[vii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | INTRODUCTION—THE NORMAN KEEP | 1 |

| II. | THE KEEP DESCRIBED | 7 |

| III. | THE FORTIFIED MANOR HOUSE OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY—THE DOMINANCE OF THE HALL | 24 |

| IV. | THE COURSE OF MEDIÆVAL BUILDING IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY | 44 |

| V. | THE LATER MANOR HOUSE OF THE MIDDLE AGES | 67 |

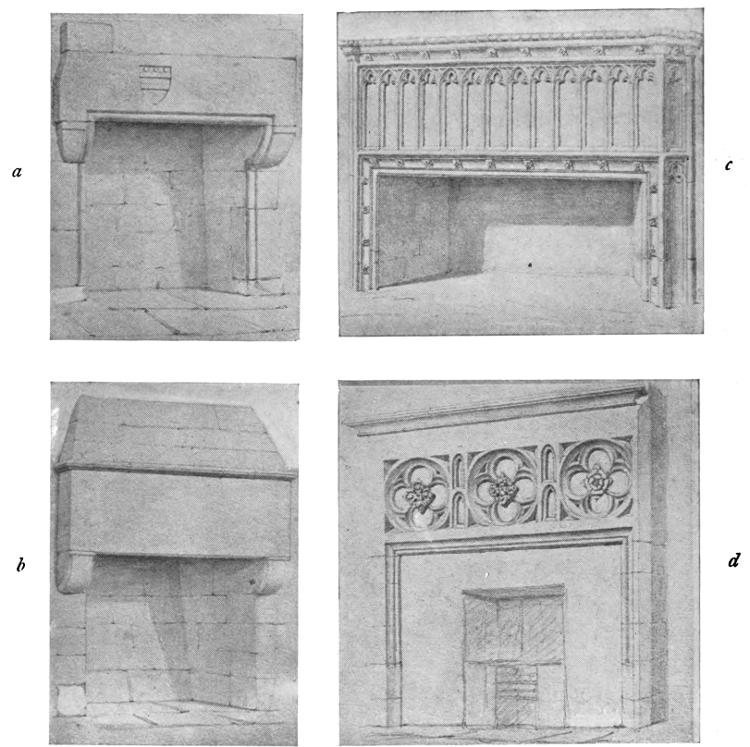

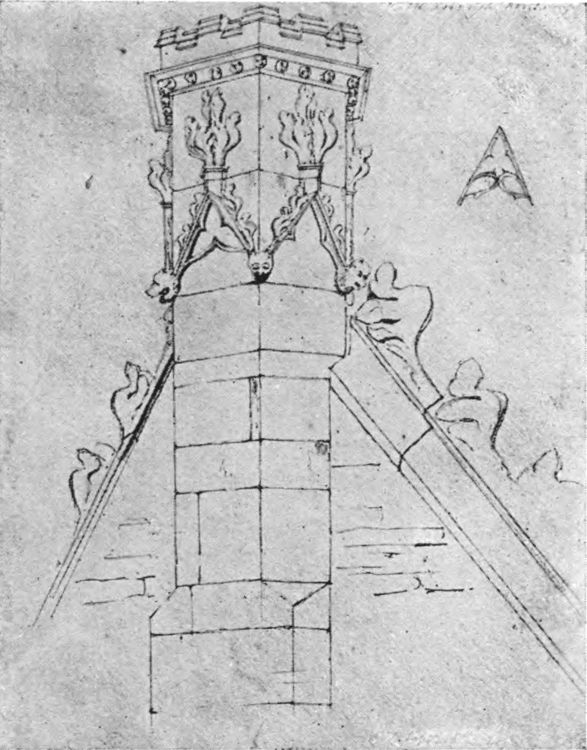

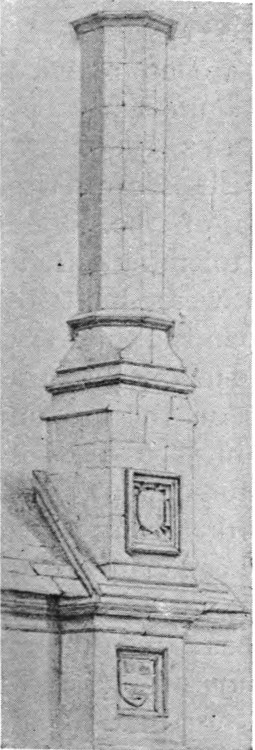

| VI. | MEDIÆVAL DOMESTIC FEATURES—DOORWAYS, WINDOWS, FIREPLACES, CHIMNEYS, ROOFS AND CEILINGS, STAIRCASES | 87 |

| VII. | EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY—COMING OF THE ITALIAN INFLUENCE | 126 |

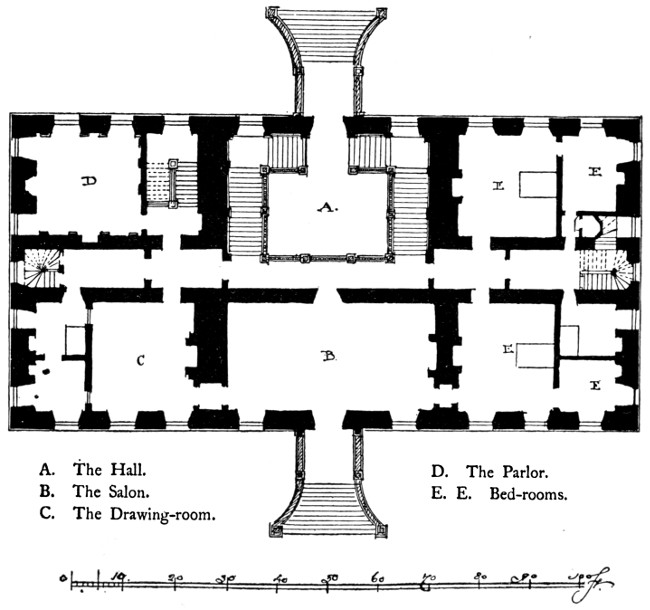

| VIII. | LATE SIXTEENTH CENTURY—SYMMETRY IN PLANNING | 141 |

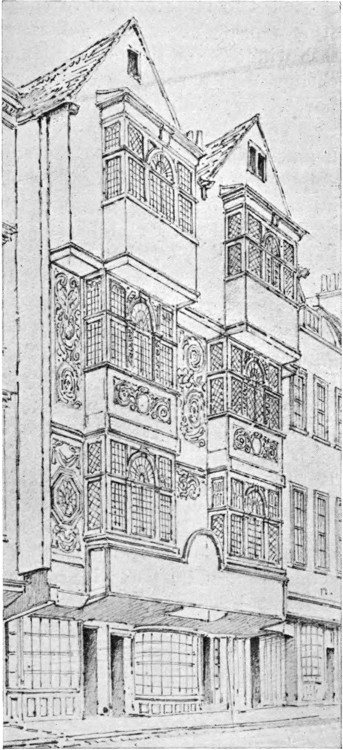

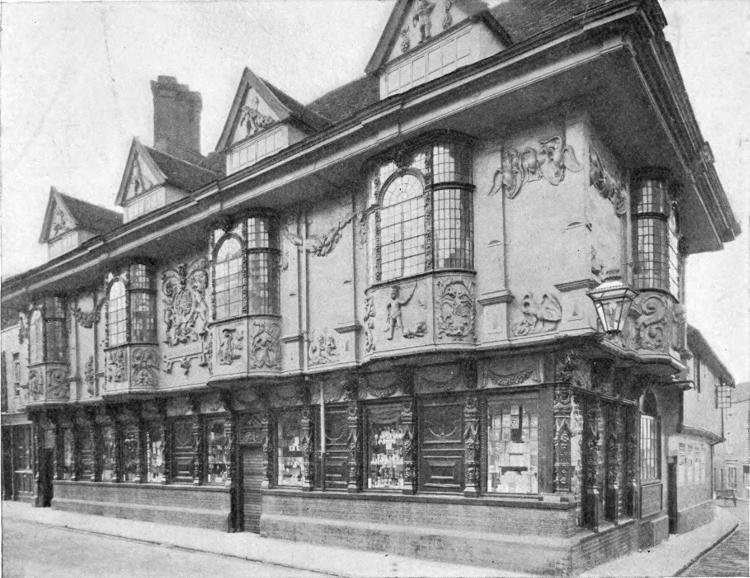

| IX. | ELIZABETHAN AND JACOBEAN HOUSES—EXTERIORS | 157 |

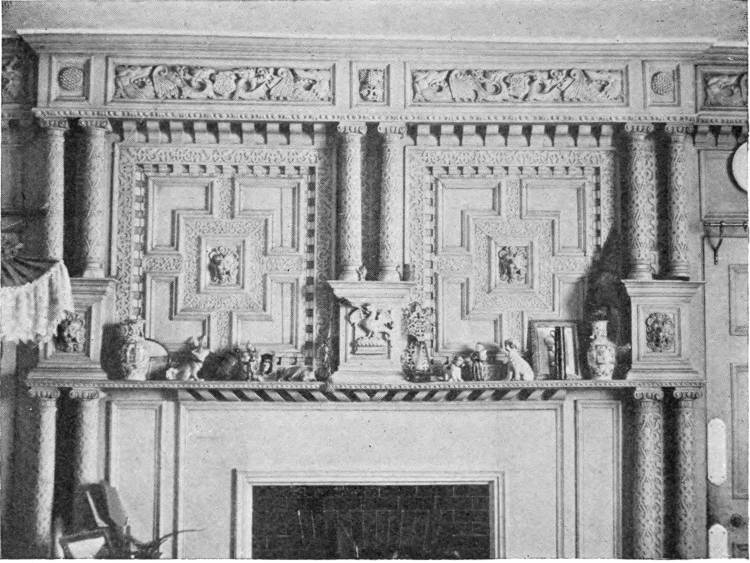

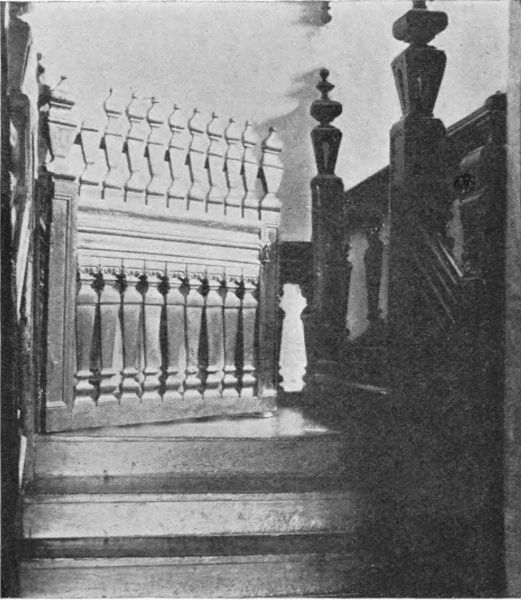

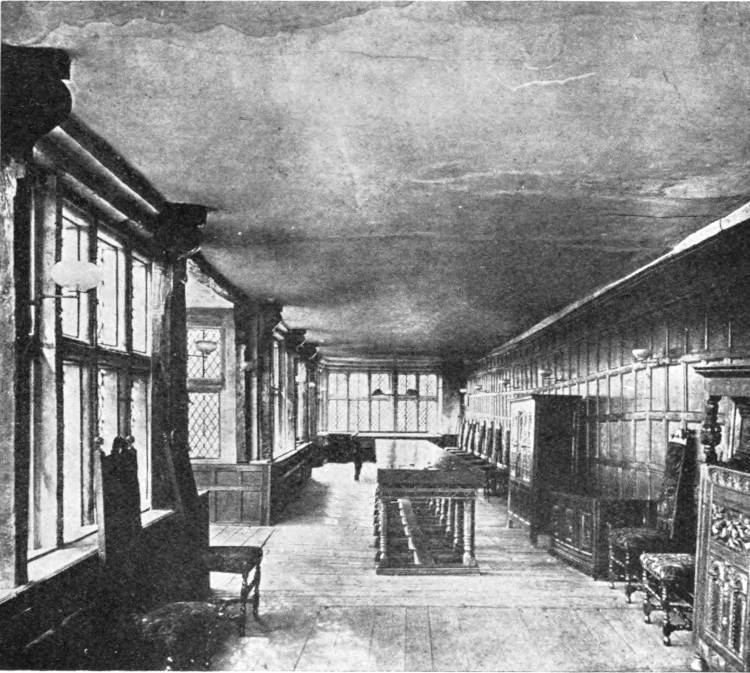

| X. | ELIZABETHAN AND JACOBEAN HOUSES—INTERIORS | 186 |

| XI. | SEVENTEENTH CENTURY—PERSONAL DESIGN—TRANSITIONAL TREATMENT | 205 |

| XII. | CLASSIC DETAIL ESTABLISHED—INFLUENCE OF THE AMATEURS[viii] | 221 |

| XIII. | EIGHTEENTH CENTURY EXTERIORS—THE PALLADIAN STYLE | 233 |

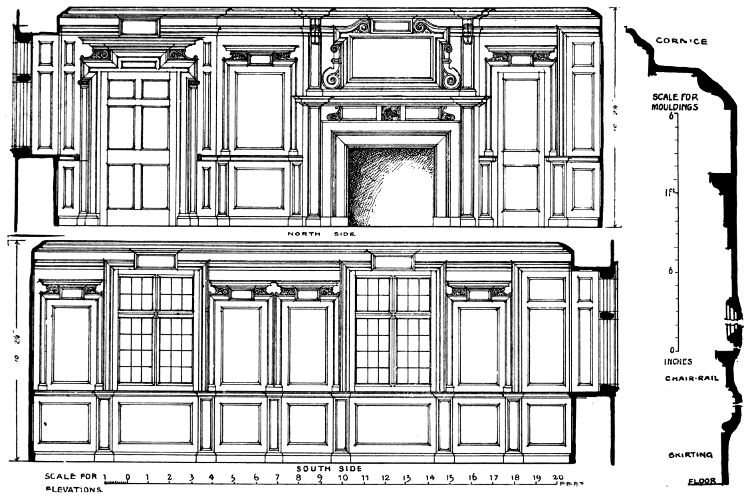

| XIV. | LATE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES—INTERIORS—DETAILS AND FEATURES | 259 |

| CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF BUILDINGS | 303 | |

| GLOSSARY | 309 | |

| BRIEF LIST OF BOOKS | 313 | |

| INDEX TO ILLUSTRATIONS | 315 | |

| INDEX | 325 |

[1]

Norham Castle, Northumberland.

Those who, in the course of their wanderings through the remote districts of England, whether on business or on pleasure bent, have seen the lonely tower on the hillside, or the grey ruins of some ancient dwelling gleaming through the spaces of encircling trees, have no doubt often speculated as to the precise significance of these remnants of antiquity. They may have dismissed them from consideration as being relics of a past order of things having no connection with the concerns of the present day. Yet to the dweller in a modern house these maimed survivals have as much interest as have his own ancestors; and the home to which he returns after his travels can trace its descent step by step from those rugged masses of stone which roused his interest as he passed them by.

It is not difficult for any one to trace a likeness between the house of to-day and that of, let us say, the time of Elizabeth; but the resemblance between an Elizabethan manor house and a Norman castle or a Northumbrian peel-tower is not by any means so obvious, yet the descent of one from the other can be clearly[2] established. It is the object of the following pages not only to show how this can be done, but to trace briefly the continuous changes which have transformed, in the course of some seven or eight centuries, the gaunt and desolate keep into the comfortable mansion or villa of our own experience.

Everybody knows that an Englishman’s house is his castle, but it should also be remembered that in early times an Englishman’s castle was his house. Castles were not necessarily military strongholds; many of them were so, but many of them, again, were nothing more than fortified houses, and it is in these fortified houses that we must seek the first germs of our own homes, the earliest evidences of domestic architecture.

In this inquiry we need not trouble ourselves about Roman villas; they were exotic, and there is no reason to believe that they had any influence on English houses. Nor need we spend much time on the centuries which elapsed between the extinction of the Roman civilisation and the Norman Conquest. The country was widely populated during those years, but any one who has climbed the bleak downs whereon its inhabitants clustered, or scrambled up the vast earthworks which were the strongholds of its chieftains, may well wonder how the race survived. Some kind of shelter from the weather there must have been, probably in the shape of wooden buildings. But such primitive structures cannot be considered as architecture, and we will now concern ourselves only with buildings of a permanent nature on which a certain amount of trained skill has been bestowed, buildings, in fact, which convey definite information as to their arrangement, and may be classed, more or less, as works of art. Such buildings—at any rate so far as they are dwellings—are not to be found of a date prior to the Conquest, nor, with few exceptions, for more than half a century later.

[3]

The “castles” of the Conqueror were probably merely the huge earthworks which he found scattered throughout the land. Any new works which he caused to be made were probably of wood. It was not until the middle of the twelfth century that stone buildings superseded to any great extent these wooden structures; at least few existing remains can be dated earlier than then; and it is in the midst of the great ditches of these earthen “castles” that many of the stone keeps of that time were built, the encircling outer mounds being further strengthened by stone walls.

The few remains of the stone castles built during the reigns of the Conqueror and his sons do not provide us with any definite link between themselves and their predecessors of wood, although it is probable that they embodied in a permanent form the kind of accommodation previously provided in more perishable materials; the most important part of this accommodation being the hall. They certainly do not seem to have had any long ancestry on the other side of the Channel, for it is doubtful whether any building of this nature in Normandy can be dated prior to the Conquest. But although the exact causes which determined their shape are still to seek, it is clear that the fashion became established of erecting stone castles, wherein the keep was the principal building.

The keep was the domestic part of the castle; it contained the rooms used by the owner and his family. Surrounding it at some distance was the outer wall strengthened according to circumstances by projecting towers and entered through a fortified gatehouse. The extent and intricacy of the defences varied according to the importance of the castle; but these matters belong rather to military architecture than to domestic, and all that need be said is that those retainers who overflowed from the towers and other permanent buildings were[4] housed in temporary wooden buildings within the courtyard.

Wooden buildings were indeed the ordinary dwellings of the time. There must have been many more people outside than inside the castles, even if we regard the castles which have survived as only a small part of those which actually existed. The ordinary manor houses, as well as the homes of the peasantry, were built of wood and have in consequence entirely disappeared. It is true that there are many wooden houses (or houses of wood and plaster) still to be found in all parts of England, but they are all of a much later date. It is doubtful if a single specimen of the twelfth century survives. It must also be remembered that not infrequently the inferior rooms of a stone house, such as the kitchen, were built of wood.

The keep, then, is the earliest form of English house built in permanent fashion. It was not, as some suppose, a prison or dungeon, or even the last refuge of a beleaguered garrison; it was the ordinary home of the family. In examining the ruins of a castle where the keep is the principal remnant, it is not necessary to postulate a vast array of other buildings, and to wonder what they were, and whither they have disappeared. It was probably the only considerable building, the remainder of the establishment consisting of a wall of enclosure and various minor buildings, mostly of wood.

What, then, was the accommodation in these keeps, these homes of our ancestors of the twelfth century, of the men who slew Thomas à Becket, of the barons who revolted against Henry II.?

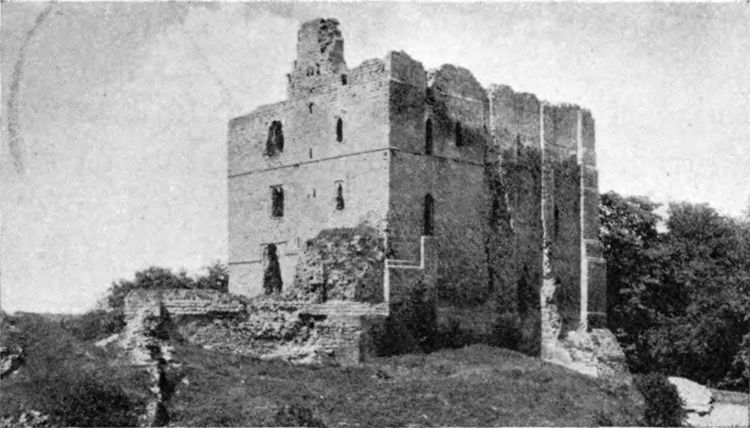

1. Castle Rising, Norfolk. The Keep.

The keeps were massive rectangular structures several storeys in height, with walls of great thickness. Their size varied according to the requirements of the owner. Some were about 90 ft. square, others but 30 or 40 ft. They were not necessarily exactly square,[5] but, as a rule, their sides were of nearly equal length. The White Tower of the Tower of London, begun by order of the Conqueror in the later years of the eleventh century, measures 118 by 107 ft. The keep of Rochester Castle, built about 1130, is 70 ft. square. Castle Hedingham in Essex, built about the same time, is 60 by 55 ft.; the keep of Dover Castle (about 1154) is 90 ft. square; Castle Rising (Fig. 1), probably a few years later in date, is 75 by 60 ft.; Kenilworth, dating from the third quarter of the century, is 87 by 54 ft.; while the Peak Castle in Derbyshire, erected about 1176, measures some 40 by 36 ft. These are all outside measurements, and as the walls were very thick, seldom less than 8 ft., and sometimes as much as 16 or 20 ft., the available space within them was much less than their total area. Nevertheless, after deducting the thickness of the walls, there remained in the largest such huge rooms as that in the[6] Tower of London, 90 ft. long by 37 ft. wide; in the medium-sized, such as Hedingham, rooms 38 by 31 ft.; while in the smallest, such as the Peak Castle, the space was 22 by 19 ft., equal to the drawing-room of an ordinary house of the present day. But although the rooms were spacious, they were few in number, and badly lighted. As a rule there was but one room on each floor; some of the more important, however, such as Rochester and Castle Rising, had two large rooms on each floor and one or two smaller, but this was the exception rather than the rule. Occasionally a chapel was added; sometimes it occupied part of the floor space inside the walls; sometimes, as at Coningsburgh, it was contrived within the thickness of the wall itself, augmented by hollowing out one of the huge buttresses. But the chapel was always small—space was too valuable for it to be otherwise; and it was used not only for sacred purposes, but also not infrequently as a private room for the lord.

There are many examples of Norman keeps remaining in various parts of the country, but it will be sufficient to describe two of them as being typical of their fellows. One, although not of the largest size, was yet a fine building; it is Hedingham Castle in Essex: the other is small, the Peak Castle in Derbyshire. The former is among the very few of existing keeps that can be dated earlier than the reign of Henry II. who came to the throne in 1154. The chaotic times of his predecessor, Stephen, saw the erection of many castles which became the scenes of frightful oppression and outrage; but after his death they were razed to the ground, and apparently with great thoroughness, since no examples, it may be said, are to be found which can be safely dated between the years 1135 and 1154, during which period he nominally reigned over England.

[7]

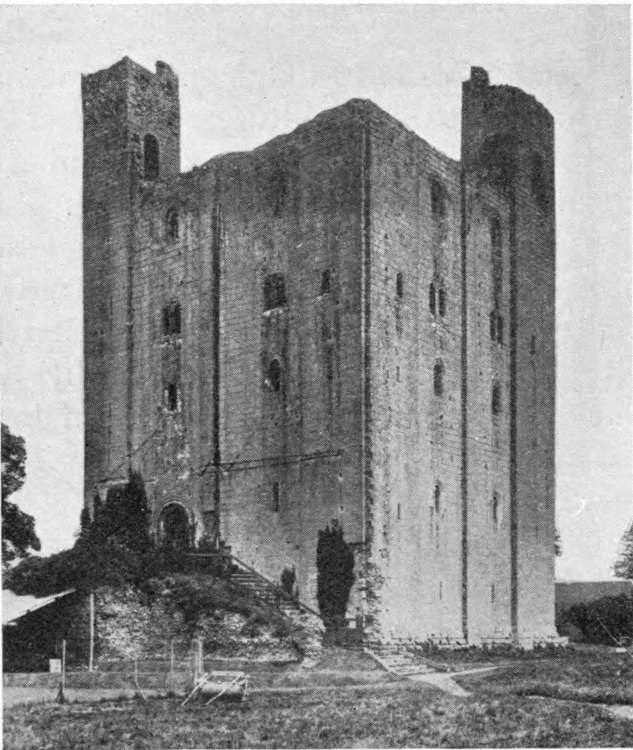

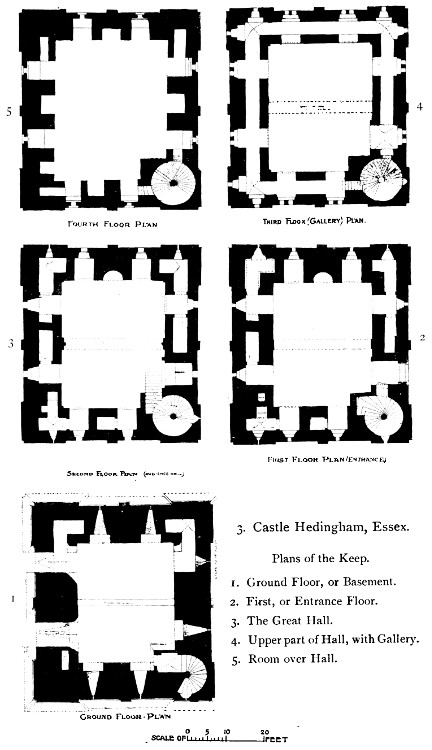

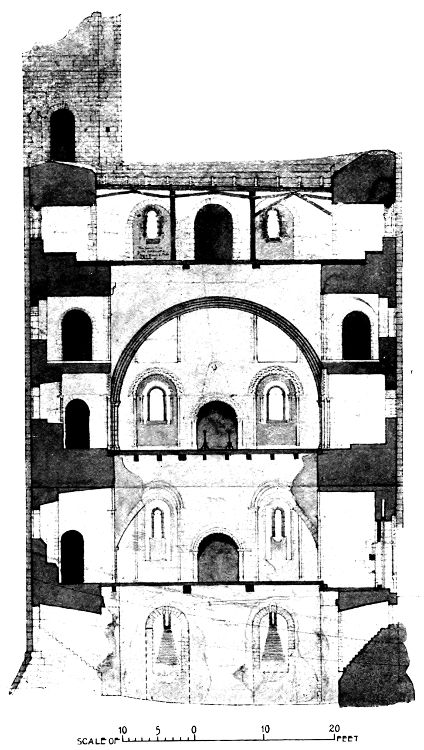

The great keep at Castle Hedingham is a fine specimen of the work of the twelfth century. Its exact date has not been ascertained, but its arrangement and its architectural detail point to the same date as Rochester Castle (about 1130), and good authorities go so far as to suggest that the same designer was employed on both. It has all the characteristics of an early keep; a vast, plain mass of masonry, slightly broken by the long vertical lines of shallow buttresses and angle turrets, and pierced at each floor with small windows—smallest near the ground where most accessible (Fig. 2). The entrance, as at Peak Castle, and all early keeps, is some feet above the ground, and in this case is approached by a flight of steps; it leads into the first floor, below which at the ground level, or thereabouts, is the cellar or store-room, approached only from the room above it. The plan is quite simple (Fig. 3), consisting of a large room (38 by 31 ft.) on each floor, enclosed by thick walls which are honeycombed with mural chambers and recesses. Some of these chambers are garde-robes, others were no doubt used as sleeping places by the family and principal guests. Over the entrance floor were two others; first the hall, a room with two tiers of windows, the upper of which gave on to a gallery or triforium which made the circuit of the building in the thickness of the wall: above the hall another room very similar to that on the entrance floor.

[8]

Then came the roof, round which was a rampart walk protected by the battlements, and leading to the four angle turrets which rose above the general mass of the building. Access to these various floors was given by a commodious circular staircase more than 11 ft. in diameter. There were thus four main rooms; the basement, the entrance floor, the hall of two storeys, and the room over it. All these, except the basement, were warmed by a large fireplace, and lighted—if lighted it can be called—by eight small windows. The hall had in addition eight two-light windows in the triforium.[10] There is no room which can be identified as the kitchen; there is no indication that the windows were glazed.

2. Castle Hedingham, Essex. The Keep (cir. 1130).

The head of the entrance door is visible on the left: the opening on the right is modern.

3. Castle Hedingham, Essex.

Plans of the Keep.

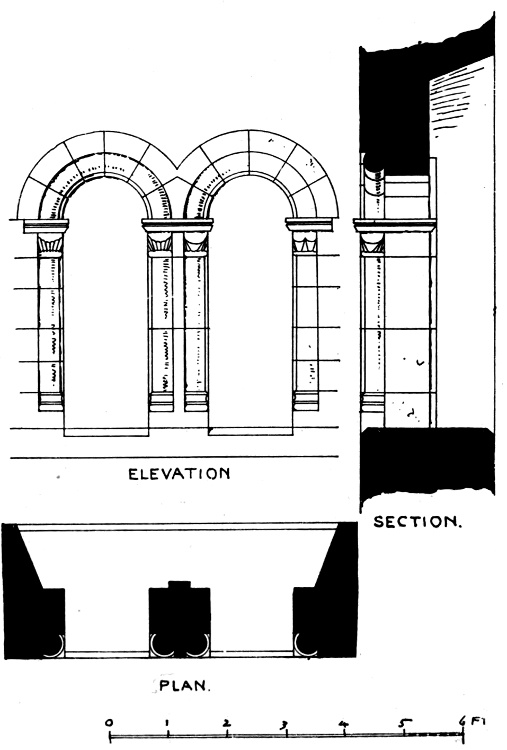

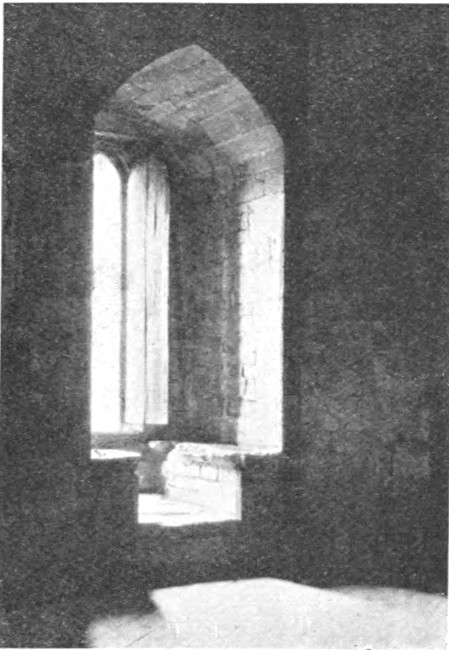

4. Castle Hedingham, Essex.

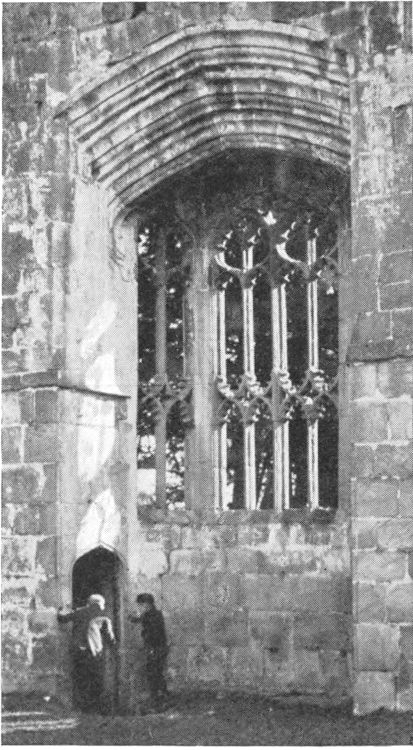

A window of the gallery in the hall.

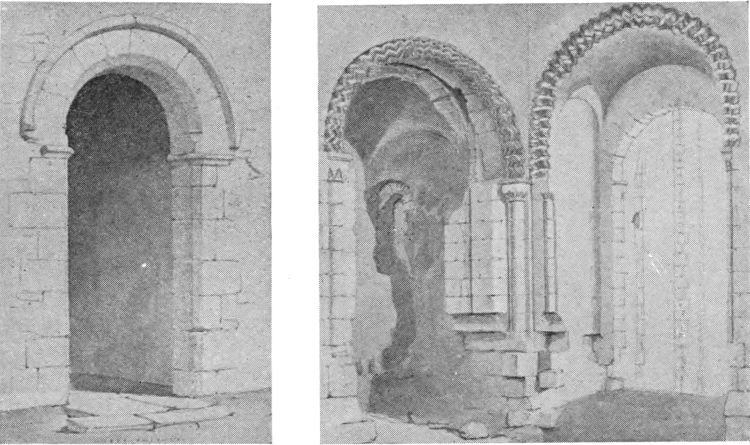

Against the means of attack which were then available this place was impregnable, but the safety thus assured must have been both gloomy and draughty. In its way, however, it was a lordly residence; the main rooms were spacious, the smaller rooms were considerable in number, the staircase was of ample width. The gallery must have afforded a certain amount of quasi-privacy to those who were not privileged to occupy the mural chambers. The architectural detail of the doorways, windows, arches, and fireplaces is good (Figs. 4, 5, 6). Across the middle of the entrance floor and of the hall is thrown a fine bold semicircular arch, of nearly 30 ft. span, to carry the floor of the room over (see section, Fig. 5); the whole treatment is simple, sturdy, and splendid, as befitted the chief stronghold of[12] the race for whom it was built, the De Veres, Earls of Oxford.

5. Castle Hedingham, Essex.

Section of the Keep.

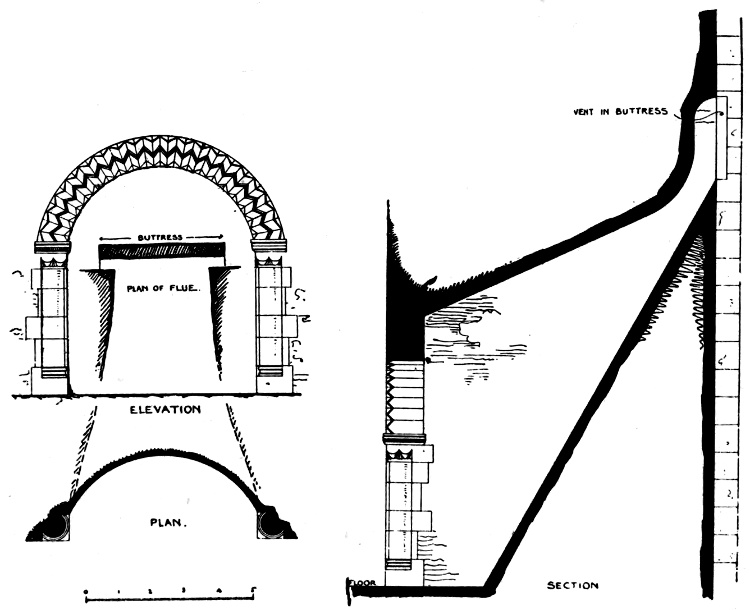

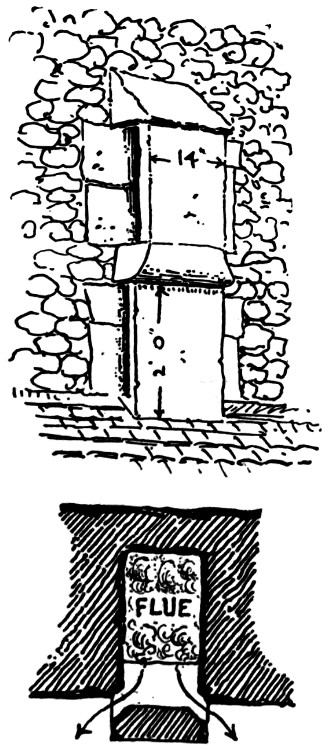

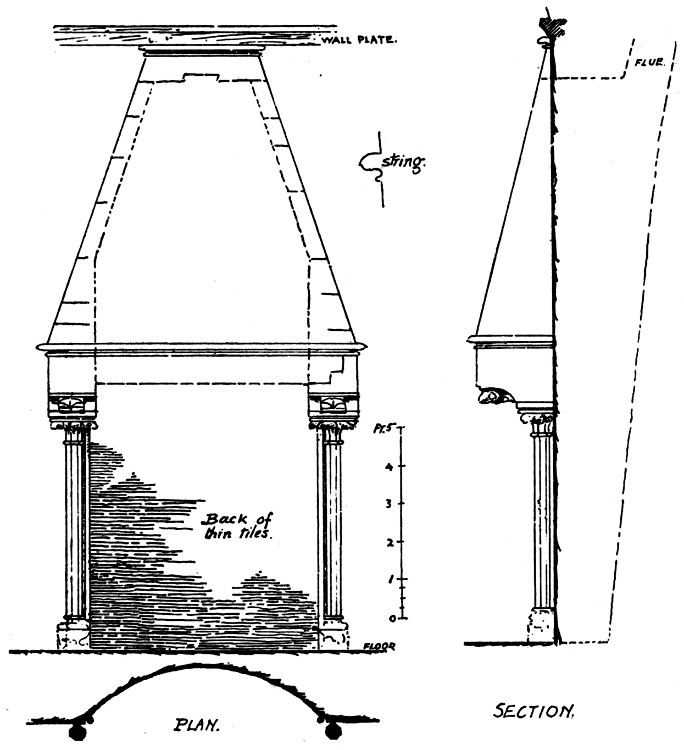

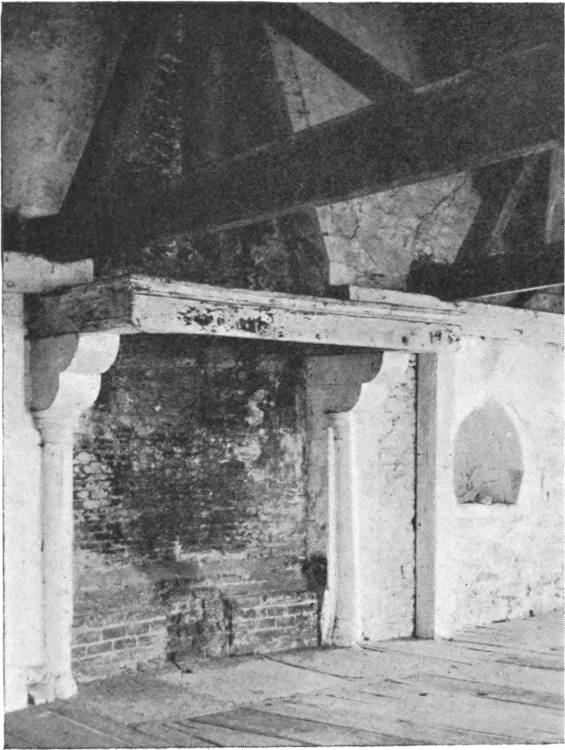

6. Castle Hedingham, Essex.

A Fireplace. Showing the short flue leading to a vertical vent in the face of the wall.

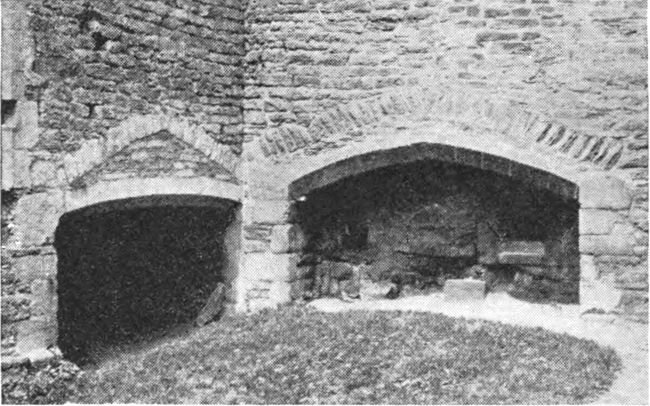

The fireplaces had not a flue such as we understand it, that is a long shaft running up the whole height of the building and crowned by a chimney; instead of this they had a short funnel contrived in the wall, and leading almost directly to small vertical openings in the face of the wall, cleverly concealed in the angle of a buttress (Fig. 6). The fireplaces, moreover, were mere recesses in the wall surmounted by round arches; there was no attempt at a projecting hood or any such ornamental feature as we are accustomed to think of as a chimney-piece. These things were to come later. They were, however, of generous size, as indeed they[13] might well be, for it must be remembered that the windows were not glazed, and although they were too small to make the place cheerful, they were quite large enough to make it cold, and as each side of the room had an outside wall, the wind, from whatever quarter it blew, would find its way in. It is true that there were wooden shutters to the windows, which could be shut at night, but in spite of this there was every inducement to maintain a large fire; the volume of the flame may have overcome the disadvantage of the short flue, but the smoke must have had difficulty in escaping through the small vents, and doubtless much of it eventually found its way out through the open windows.

The sleeping accommodation was very meagre. The lord, and perhaps some of his family, had separate retiring places; they could not be called rooms, for they were only such chambers as could be contrived in the thickness of the walls; and in point of size, although not at all in point of luxury, were comparable to a sleeping compartment on a modern train de luxe. The household, men and women, old and young, slept in the great hall, a custom which conduced neither to comfort nor the observance of the proprieties. In the same room the whole establishment had its meals. During the greater part of the day the men, at any rate, were occupied with outdoor pursuits.

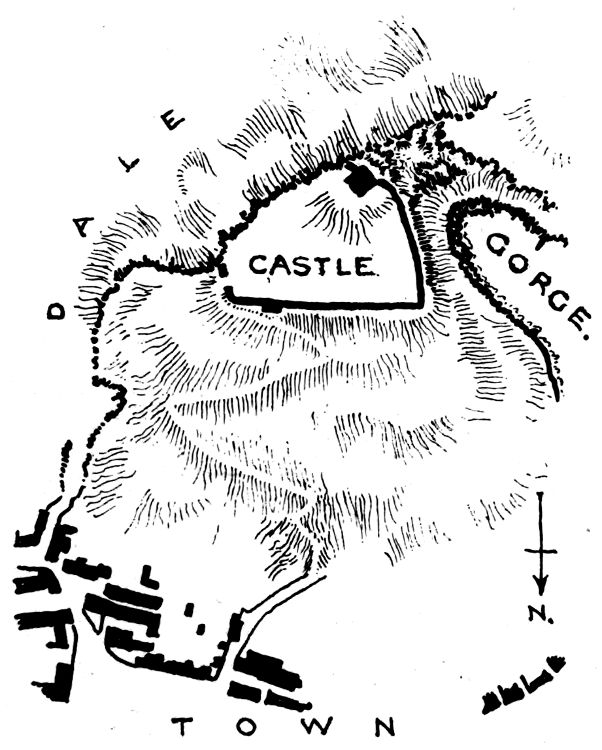

The Peak Castle, at Castleton in Derbyshire (Fig. 10, p. 19), is an extremely interesting example of an early dwelling. Its situation may be described as highly romantic, although that adjective of course expresses a sentiment which is of comparatively modern origin. Up to about the middle of the eighteenth century, travellers regarded such desolate places as Old Sarum, or ruins so difficult of access as the Peak Castle, with feelings approaching to horror. It was only towards the end of[14] that century, or in the early years of the nineteenth, that the romantic aspect was appreciated. It is tolerably certain that romance had no part in the selection of this site for a dwelling, but rather the assurance of security which it offered. An extremely steep spur of the rocky hill which forms one side of a precipitous dale—one of the dales for which Derbyshire is famous—is deeply bitten into by a gorge which almost severs it from its parent ridge (Fig. 7). An irregular triangle of rocky ground is thus formed rising steeply from its longest side up to the opposite angle, and bounded on one side by the precipitous slope of the dale, and on the other by the sheer descent of the gorge. No site could be better protected by nature. The side next the gorge is absolutely inaccessible. The side next the dale offers interesting hazards to good climbers. The remaining side is a grass slope steeper than most modern roofs, and traversed by a zigzag path up which the breathless visitor toils painfully. The town lies at the foot of the slope; the castle, of no great extent, is placed at its[15] summit. The keep is built in the extreme angle, where the gorge desists from finally biting its way through the side of the dale and leaves a narrow rugged strip of rock to connect the almost detached triangle from its parent hillside. A stone flung from one side of the keep would fall sheer down the gorge; flung from the opposite side would drop some 40 or 50 ft. on to the steep slope of the dale, and thence descend with huge and rapid bounds to the bottom.

7. Peak Castle, Derbyshire.

Plan of the Site.

The summit of the triangle was enclosed by a wall running from the gorge to the dale, thus forming a good-sized courtyard. It was of course on the slope, and to make it rather more level, the lower part was raised, partly it would seem on vaulted chambers, partly by filling up earth against the wall. These chambers have never been explored, but workmen who have repaired the wall bear testimony to their existence, and if the description they give of some of the articles found in them has been rightly interpreted, it would seem that the Romans had made use of them. This is still a matter for conjecture, and so is the exact arrangement of such buildings as were adjacent to the wall.

There were apparently two entrances to the courtyard. The chief of these was adjacent to the dale, and from the remains of the arch stones would appear to have been some 5 or 6 ft. wide. Here is said to have been the porter’s rooms, and if this were the main entrance, custom would place the porter there. At the other end of the wall, against the gorge, are the remains of what has been called the sally-port; but the work has been so much defaced as to render its purpose obscure. Between these two features there is a rectangular buttressed projection which may have contained rooms, while overlooking the gorge is a recess in the wall which seems to have been a window. It is said—but[17] the statement has not been properly verified—that there are remains of the foundations of a structure which carried a drawbridge across the narrow upper end of the gorge; and it is almost certain that an ancient track leads along the hill on the further side of the gorge in the direction of the castle. All these points are of interest, and are worthy of further investigation; but that part of the ruins which most readily repays a visit is the keep. This has been described as merely a prison or a watch-tower; but from the carefully selected position of the castle, from what is known of its history, from the fact that the little town of Castleton clusters at its foot, and from a comparison with other castles, it would seem that the tower is the small keep of a small castle, and was its most secure dwelling-place. References in the great Roll of the Pipe show that a considerable number of soldiers were accommodated here; it is also recorded that in 1157 Malcolm of Scotland made his personal submission to Henry II. here, and that that king was again here in 1163, when the castle must have had even more restricted accommodation.

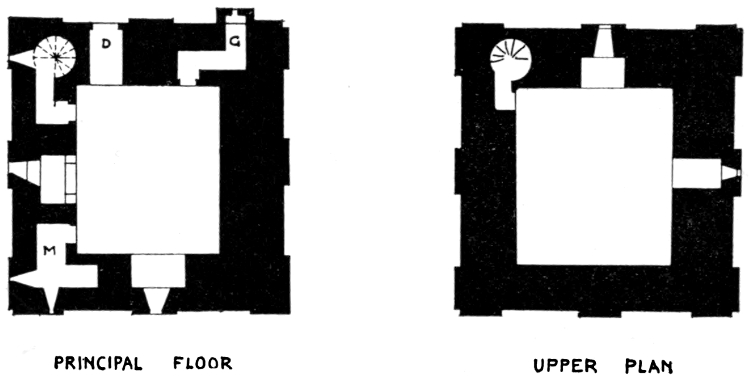

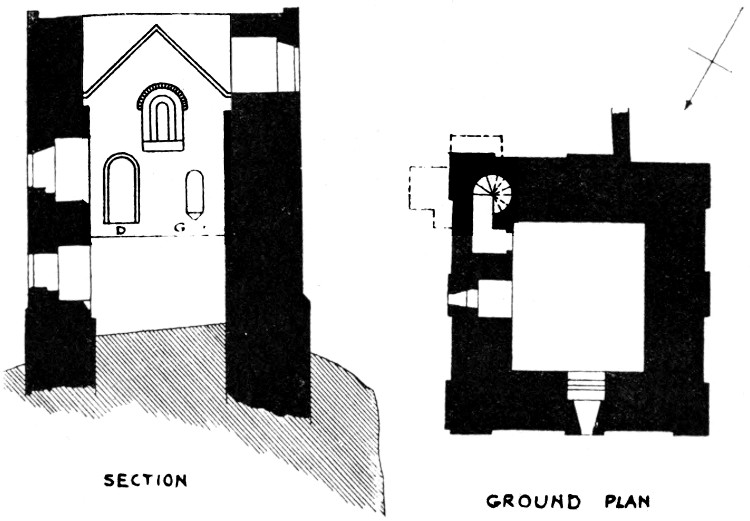

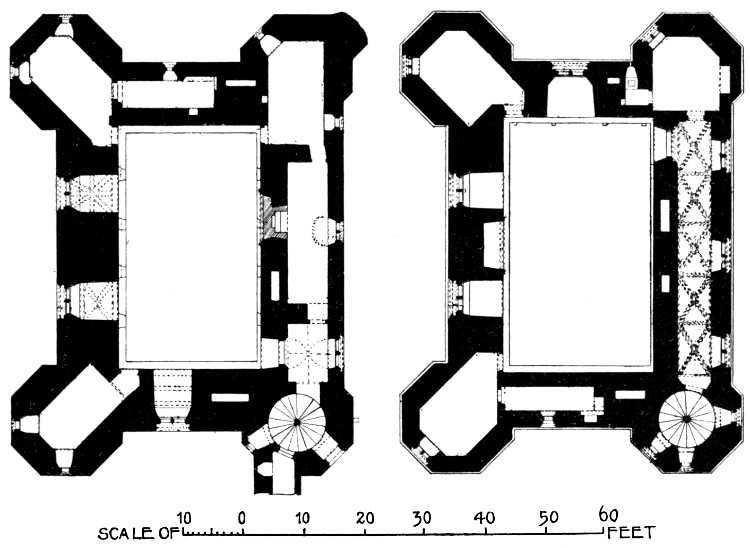

8. The Peak Castle, Derbyshire (1176.)

Plans of the Keep.

9. The Peak Castle, Derbyshire

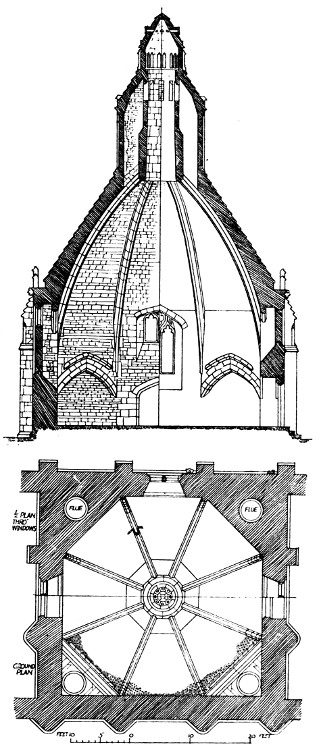

The keep itself, which was built in 1176, is very similar in arrangement to the peel-towers of the Scottish border and to the towers which elsewhere formed the nucleus of many fortified houses. It probably represents the first step in domestic planning, and may be regarded as one of the earliest ancestors of the great houses of later centuries.

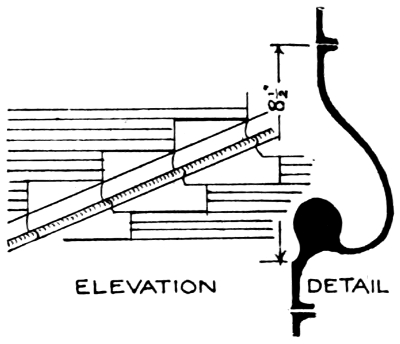

It consisted of two main floors (Figs. 8, 9); beneath the lower was perhaps a store-room, although this is not certain. The debris with which the lower part of the building is filled has not been investigated; excavation might determine whether there ever was a cellar, and also whether there was any internal communication[18] with a natural cave or passage which undoubtedly passes through the rock beneath it, and from which a tortuous and difficult descent can be made to the great Peak Cavern which is approached along the gorge so frequently mentioned. Above the upper chamber was the roof, originally of steep pitch (see section, Fig. 9), but which may have been raised and flattened so as at once to form a third chamber and to give more convenience for the purposes of watching and defence.

At its best, at any rate, the keep can only have contained four rooms, and it is quite possible that it only had two. The upper and better of these was that into which the entrance door opened (at D, Fig. 8), a door some 6 or 8 ft. from the ground, and doubtless approached by a wood ladder. Near this door a circular staircase of about 5 ft. in diameter led up to the roof and down to the lower room (Fig. 9), which was dimly lighted by two small windows, but otherwise was devoid of any feature whatever. The floors were of wood. The upper room, about 22 by 19 ft. in size, was also lighted by two small windows; in one wall was a garde-robe (G) with a shoot corbelled out from the wall; in another was a small mural chamber (M) occupying one corner of the building and lighted by a very small window on two of its sides. So far, this keep is just like many others, although on a small scale; but here there is no sign of a fireplace or flue. Some means of warming the place, and, on occasion, of cooking, there must have been; and the probability is that a fire was contrived on the floor, and that the smoke was carried away by a flue of wood and plaster. It would not have been beyond the ingenuity of the time to provide a hearth to carry the fire.

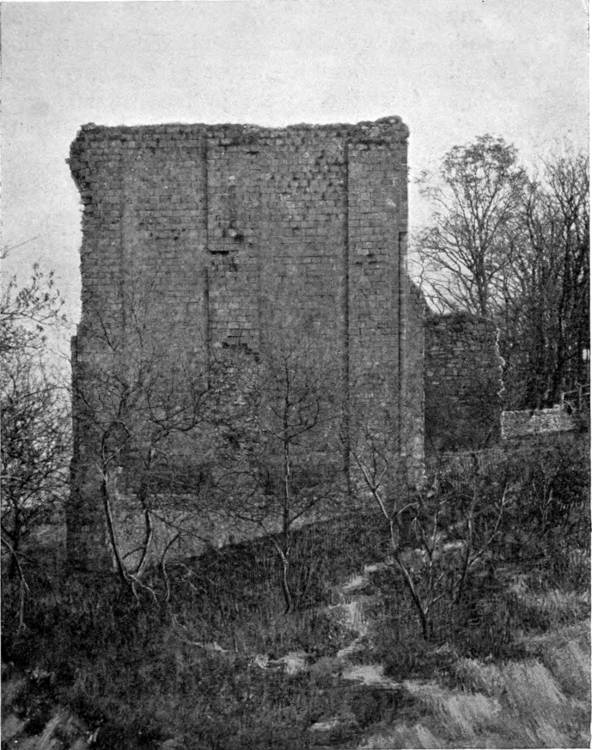

10. The Peak Castle, Derbyshire (1176).

South-west Face.

The exterior of the keep has suffered so much that hardly any detail is left, nearly all the facing stone[19] having disappeared. The most perfect side is that towards the gorge, difficult of access (Fig. 10). From it, however, we learn that the building consisted of a plain mass of ashlar work broken at the angles and[20] the middle of each side by a shallow projecting pier. Each corner of the building has a small circular shaft with cap and base of the ordinary Norman type. The window openings must have been narrow, as was usually the case, and probably of very simple detail, matching that of the doorway and the shoot of the garde-robe. At the parapet level there were probably four turrets rising from the angle buttresses, but all traces of them have gone. Indeed all that can be gathered of the external appearance is that it was of the usual severe type and that the detail was of the simplest.

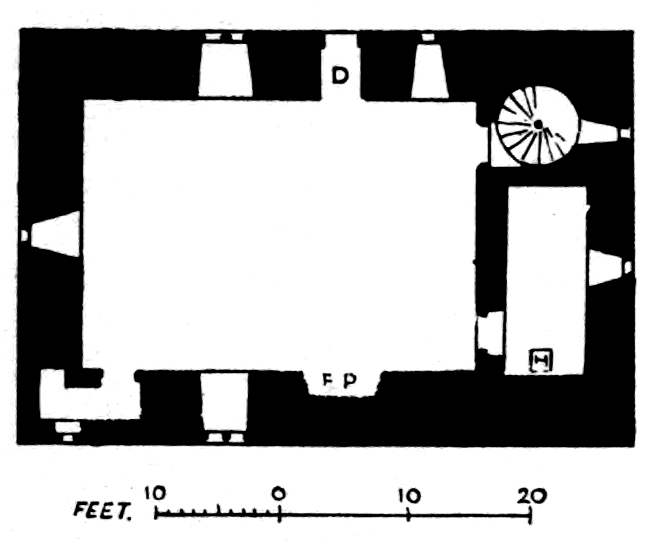

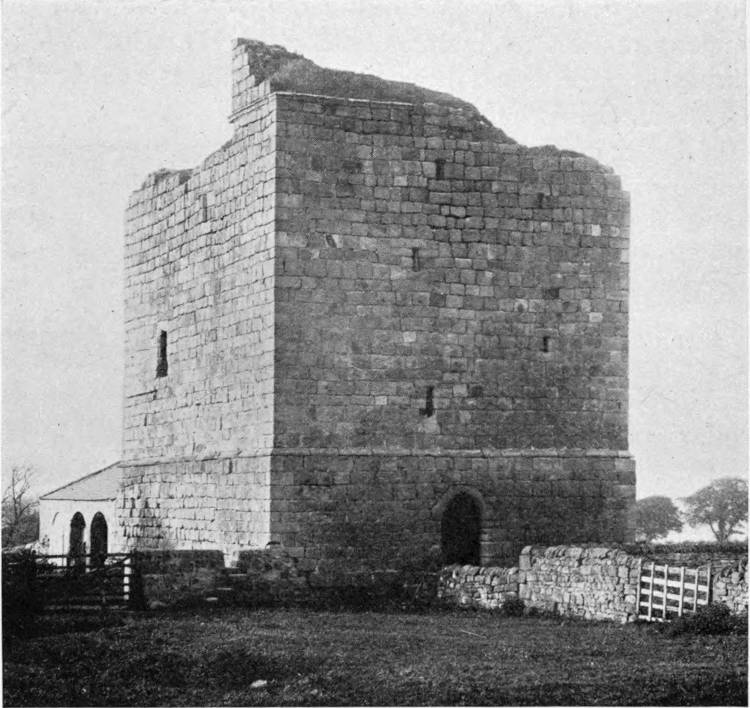

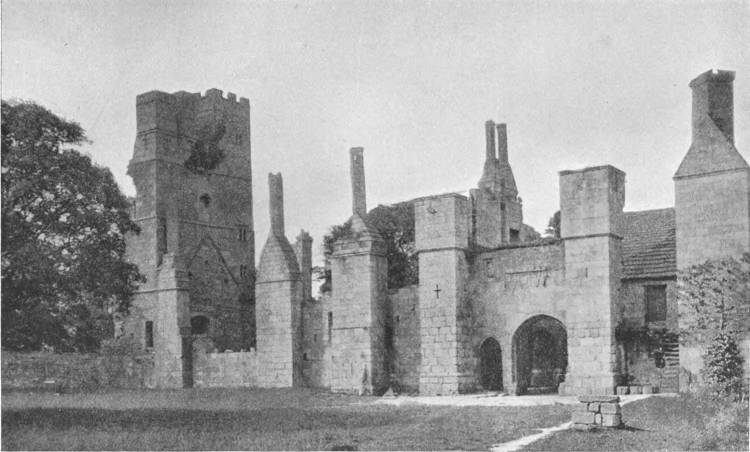

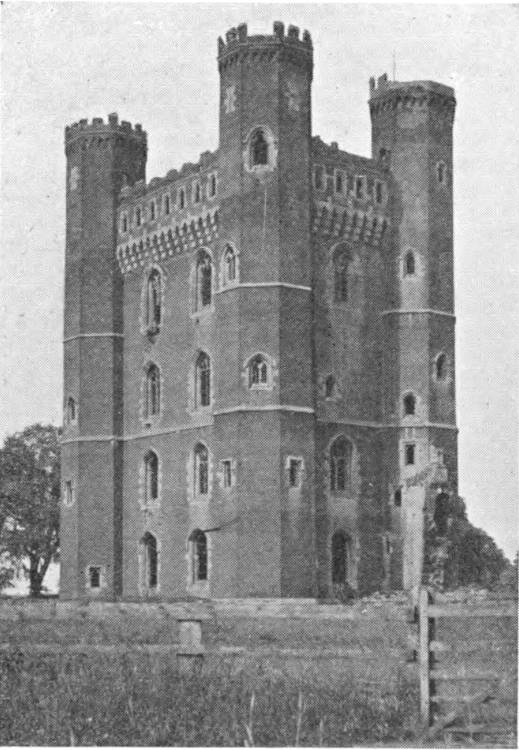

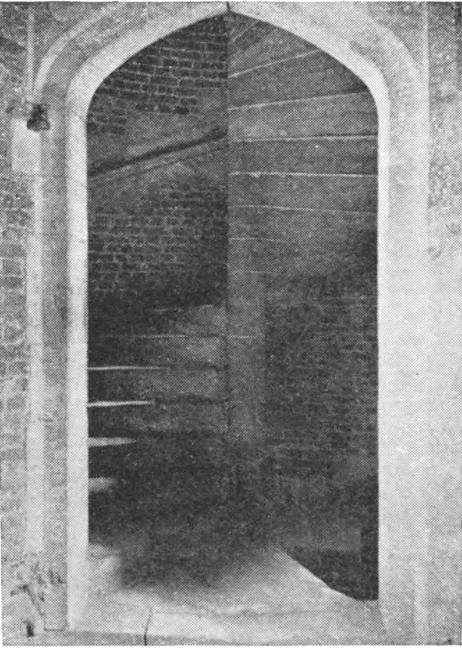

While castles and their keeps were still in full occupation, but towards the later years of their existence, there were built a number of fortified manor houses of stone. It is quite probable that these buildings embodied in permanent materials a type of plan that had long prevailed in a less durable form. The keep was contrived so as to be as economical of space as possible; the rooms were piled one on the top of the other. But where defensive precautions were not so imperative, and space was not so valuable, the rooms were placed alongside of each other on the ground. The manor house, therefore, followed a type of plan somewhat different from that of the keep, but in both cases the hall was the principal apartment; it was the sleeping, eating, and living room of the household. As years went by the keep type of plan fell into disuse; its singular lack of comfort may easily account for this. The manor house type, on the contrary, survived, and it is this type which has been developed, through century after century, into the house of modern times. It is, however, curious to find a few late survivals of the keep, some of them built long after the necessity for castles had disappeared; others, owing to their geographical position, being the natural expression of the wants of the district. Among[21] the former is Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire, built by Lord Treasurer Cromwell in the fifteenth century, the same who built the great manor house of South Wingfield in Derbyshire. Both of these houses will be more fully mentioned in their chronological order. Among the latter are many of the peel-towers of Northumberland, which continued to be built with the ancient restricted arrangements until the accession of James I. Cocklaw Tower, near Hexham, is a fairly late example (Figs. 11, 12); it was built in the sixteenth century and contained hardly more accommodation than the Peak Castle. At the ground level was a cellar entered from the outside by a doorway protected by machicolations. Above the cellar was the hall, entered by an external door several feet above the ground, and above this was another room of the same size. Each of these rooms had a fireplace, and a few small windows, unglazed. A small chamber also led from each of them; that on the principal floor retains traces of painted decoration. In its floor is a square hole which afforded the only access to a blind chamber or vault beneath, which may have been a dungeon or may have been merely a garde-robe pit. A circular staircase led from the cellar to the upper floors and thence to the battlements. The fact that so small and uncomfortable a house was built at a time when further south there were already large and commodious mansions, is an eloquent[22] commentary on the disturbed state of the Border. This is further illustrated by the fact that almost immediately after the two kingdoms were united under one sovereign, many of the old peels were enlarged by the addition of a Jacobean wing of considerably greater capacity than the original house. Chipchase Castle is one of the most striking instances, as the new work took the form of a fair-sized manor house to which the peel became a mere antiquated adjunct. Other instances, some of rather later date, are to be seen at Belsay Castle, Halton Castle, and Bitchfield Tower.

11. Cocklaw Tower, Northumberland (16th cent.).

Plan of Principal Floor.

D, Door, several feet above the level of the ground; H, Hole in floor; F P, Fireplace.

12. Cocklaw Tower, Northumberland (16th cent.).

[23]

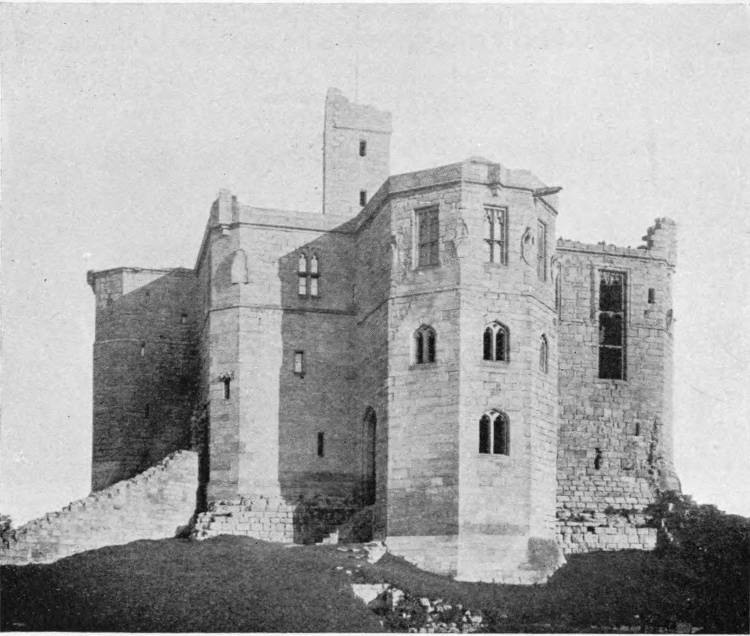

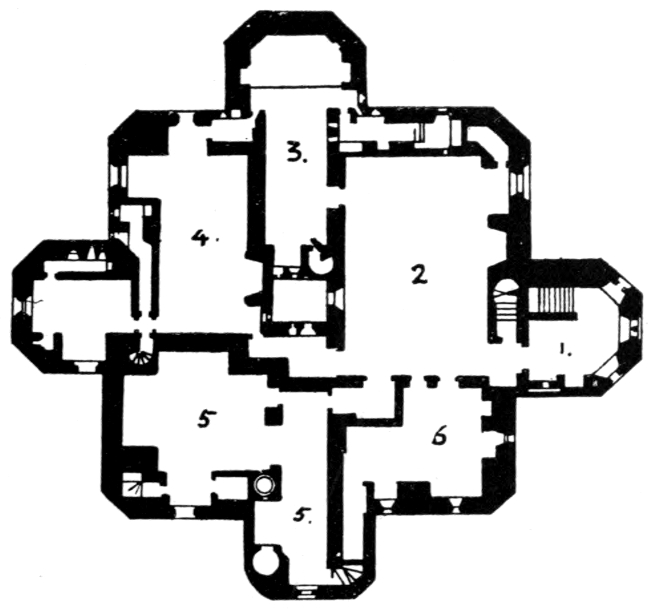

Another notable example of the survival of the keep is that at Warkworth Castle in the same county (Fig. 45, p. 82). This is of peculiar interest inasmuch as it was built about the year 1440, and exhibits a great amount of skill in packing into a small compass the various rooms which, by that period, had become necessary to the comfort of the more wealthy. But in spite of the ingenious planning, this keep was deserted within thirty years of its erection in favour of a new hall built on the ground floor with contiguous kitchens in the usual fashion. These places are mentioned here before taking leave of the keep, to show how its influence survived long after it had been generally abandoned.

[24]

Although the first germ of the house of to-day is to be found in the Norman keep, its more direct ancestor was the fortified manor house. The chief room here, as in the keep, was the hall; indeed it was of greater relative importance in the manor house than in the castle. In the latter it had rooms of equal size above and below it, rooms which must have helped to lessen the pressure on its space. In the former it was not so much the heart of the house as the house itself. It was often the only considerable room in the building, supplemented by a kitchen and a “chamber” or two. So overmastering was its importance that the house was called “the hall,” a designation which, to this day, is applied to the principal house in a parish. There were, however, supplementary rooms, some for the master, and some for the servants; in the earlier examples, indeed, the plural is hardly admissible; there was one for the master, called the “solar,” and there was a kitchen, or a kitchen department, which was the headquarters of the servants. The hall lay between the two; at one end was the kitchen with whatever it had of pantry and buttery; at the other was the solar, a small room for the private occupation of the lord—a room generally upstairs, and over a cellar or store place. Other rooms there were none. The hall was the house; everybody lived[25] there when indoors, everybody ate there, everybody slept there.

The household stores, if put away anywhere, went to the cellar; the food was cooked in the kitchen, there was a pantry where it was kept when not in the kitchen, there was a buttery where the drink was served: the lord, when he desired privacy, sought his solar. The rest of the household presumably never had privacy even if they desired it. It was an elementary state of things, and the story of domestic architecture is made up of the efforts to obtain greater privacy and more comfort. It was a long and gradual development. The hall remained for centuries the centre and kernel of the house; but at one end of it the solar gradually swelled into suites of apartments for the family; at the other, the kitchen grew into the servants’ wing, with scullery, larders, pantry, and many other subdivisions. When we remember this primitive type of plan and then look at the plan of an Elizabethan manor house (usually quite simple in its arrangements), it becomes less difficult to imagine the stages through which it must have passed since the time of the hall, solar, and kitchen; and it is easy, on the other hand, to see how the simple Elizabethan plan grew into the complicated arrangements necessary for our comfort to-day.

The hall, then, being pre-eminently the principal room, requires our first attention. It was necessarily of large size, and it was lofty. In the majority of instances it was of one storey with an open timber roof, and consequently it completely separated from each other the subsidiary rooms built at either end of it. This is observable down to Elizabethan days, when[26] the family apartments and the servants’ quarters had each grown into a considerable wing of at least two storeys in height. Each wing had to have its own staircases, and on the upper floor the hall interposed an impassable barrier between the two ends of the house.

The hall was planned so that the entrance was at the servants’ end, where most of the traffic was. The bulk of the floor space was thus left clear for the tables, and for the purposes of daily life. The lord and his family sat at the “high table” at the upper end, farthest away from the draughty entrance. There was at this end a raised platform some 6 inches high, called the daïs, and it was on the daïs that the high table was placed. Judging from the floor levels of the earliest houses, there would not seem to have been a daïs, unless it were a movable platform. Through the wall at the upper end a doorway led to the family room or rooms. The two long sides of the hall were usually free from any buildings, and were occupied by the windows. At Minster Lovel in Oxfordshire, however—a splendid house of the Lovels, now in hopeless ruin—the lofty hall was flanked on one side with a building of two storeys. The windows on the opposite side were large and long, set fairly high up in the thick wall, of fine Perpendicular design, and finished at the top with the usual simple tracery. Those on the side flanked by the two-storey building were so much curtailed by it as to retain nothing below the tracery.

The entrance was generally cut off from the rest of the hall by a screen (at any rate in later years). The screen did not extend the full height of the hall, but stopped short some 10 or 12 ft. high, and was connected to the end wall by a floor, which thus at once served as a ceiling to the entrance passage, and formed a gallery, usually called the minstrels’ gallery, though indeed it may well be doubted[27] whether in many of the smaller houses it was put to regular use, inasmuch as there was no convenient means of access. The fire was frequently, though not by any means always, placed on a hearth in the middle of the floor, yet not exactly the middle, but rather towards the end where the family sat. There are plenty of instances where the hall was warmed by a fireplace even in fairly early times. There are also instances as late as the sixteenth century of hearths being constructed on the floor. At Deene Hall in Northamptonshire, built in the time of Edward VI., there was no fireplace in the hall until the father of the late Lord Cardigan (of Balaclava fame) caused one to be made. The roof shows by the absence of cross-braces in one of its bays where the louvre for the escape of smoke used to stand.

These general dispositions were, of course, subject to variations in particular instances, but the main idea of entering the hall at its lower end, of the kitchens being at this end and the solar or family rooms at the other, is so universal as to furnish a clue to the unravelling of the mysteries of many a complicated ruin.

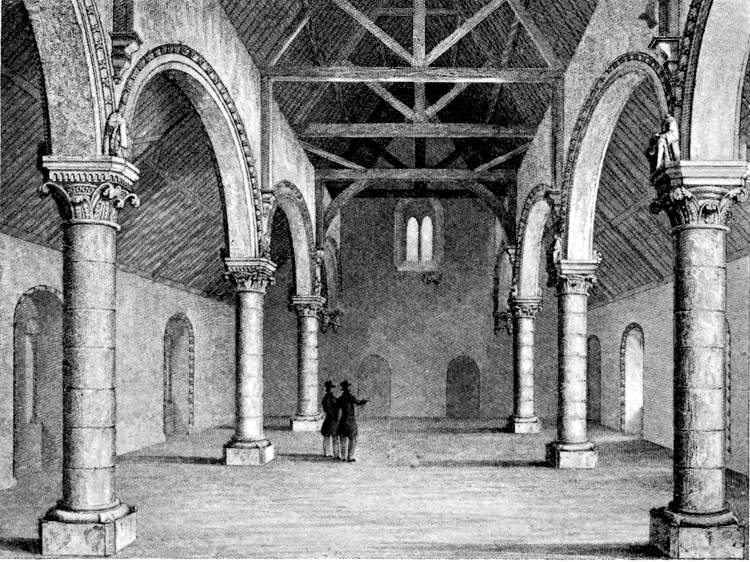

The finest example in England of an early hall is to be found at Oakham Castle in Rutland. It is of such a large size, 65 ft. long by 43 ft. wide, that it serves for the Law Courts of the county, the Assizes, Quarter Sessions, and County Court being all held within its four walls. The fittings necessary for these purposes rather obscure its original appearance, which was as spacious as a good-sized parish church, and very much of the same character. It is divided into what may be termed nave and aisles separated by fine bold arcades (Fig. 13).

13. Oakham Castle.

Interior of the Hall.

This disposition is extremely interesting, as it at once raises the question of the resemblance between[28] ecclesiastical and domestic architecture, and takes us immediately to the root of the matter, namely, that architecture is essentially a noble form of construction, embellished suitably to its purpose. It follows, therefore, that church and house architecture are only likely to differ in so far as their purposes differ. Here at Oakham was a space to be covered of much the same area as a church, and it was covered in the same way. The means at the disposal of the builders forbade very wide spans, therefore they divided the width of the building by two walls carried on a series of arches. The middle space (or nave) was of no greater width than could be covered by a timber roof resting on the arcaded walls. The two outer spaces (or aisles) were covered by narrower roofs leaning against the walls of the nave.[29] This simple solution of a constructional problem was applied equally to churches or houses, but it so happens that there were many churches of a width demanding such a treatment and but few houses. The churches have survived, while the houses have mostly disappeared; and consequently the disposition which is in reality constructional, has become associated with church architecture. So too with various features, such as doors and windows. These were treated, broadly speaking, in the same way whether in churches or houses, but in the former they were, as a rule, more elaborately embellished. Their general forms were the same; that is to say, when arches were round in churches they were round in houses; when pointed in the one they were pointed in the other. When mullions, tracery, and cusping became the fashion in churches, they became also, though in less degree, the fashion in houses. This, however, is to be observed that, as a rule, more elaboration and more fancy were bestowed upon ecclesiastical work than upon domestic. So far as windows are concerned the practical necessity of having some means of opening and closing those in houses led to the dividing of them into manageable sizes by means of horizontal cross-bars or transomes, which are much more frequent in houses than in churches.

This similarity of treatment between the two classes of buildings, although only what might be expected on reflection, has led to much confusion in the popular mind, and has resulted in many an old hall being looked upon as a chapel.

But to return to Oakham Castle. Strictly speaking it was not a castle, but merely a strongly defended manor house. It lies in a large enclosure surrounded by the ruins of a wall. The wall shows no signs of having been guarded by the towers customary in a[30] castle, but is built on the summit of an embankment, which may be the remains of an extremely ancient stronghold. The height and steepness of the bank, increased by the height of the wall, although the latter was ill-constructed, must have rendered attack difficult. The enclosure was entered through a gatehouse, which has entirely disappeared and only lives in a record of the fourteenth century. This record is an Inquisition of the year 1340, and is interesting as enumerating the accommodation of the place at the time. It says that the castle was well walled, and contained one hall, four chambers, and one kitchen; there were also two stables, one grange for hay, one house for prisoners, one chamber for the porter, and one drawbridge with iron chains (this indicates the gatehouse). There was also a free chapel within the castle. Such was the accommodation of an important house in the fourteenth century.

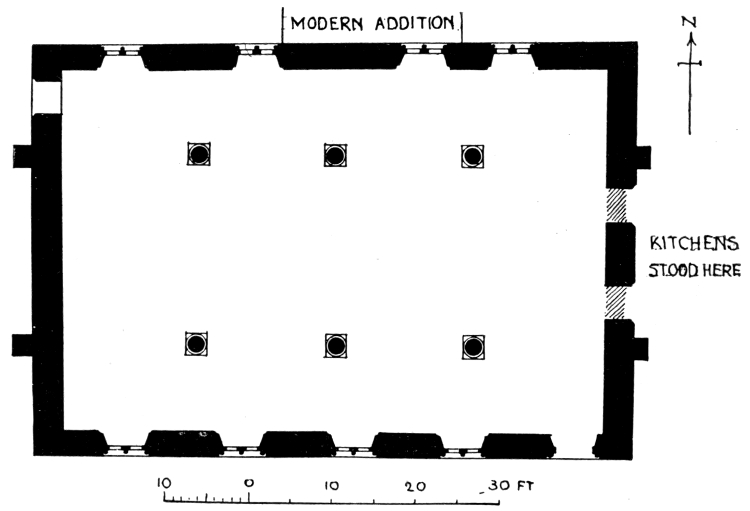

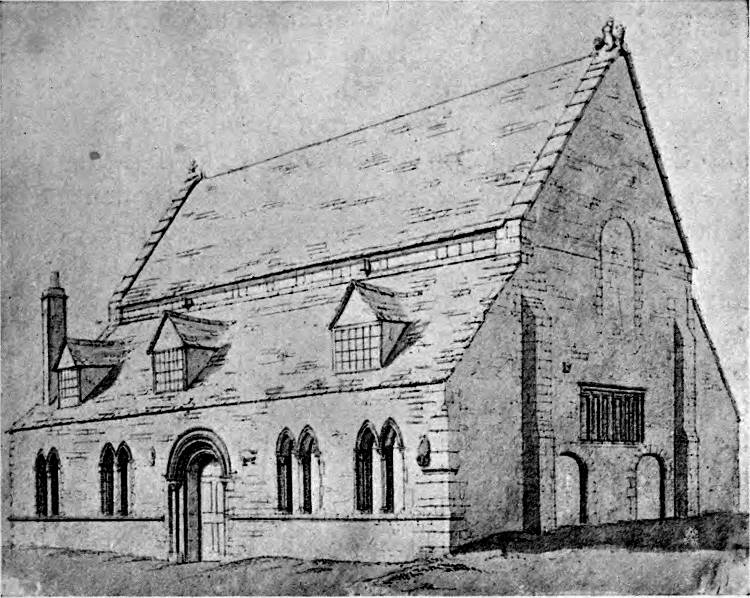

14. Oakham Castle, Rutland (cir. 1180).

The Hall.

[31]

The hall is the only building left, and it is clear from its architectural features that the four chambers and the kitchen could only have been of one storey in height, at any rate so far as they were contiguous to the building. The overpowering importance of the hall is thus further established. Its plan is of the usual type (Fig. 14). The entrance door was at the end of one of its sides, although many years ago it was removed, for greater convenience in relation to modern uses, to its present position in the middle.

15. Oakham Castle, Rutland (cir. 1180).

The Hall.

The door was originally at the right-hand end of the front. The original window in the gable is shown as blocked up; that immediately above the doors is of late date.

In the end adjacent to the entrance were two doors[32] (there are also indications of a third at the end of the north aisle) which led to the kitchen, the pantry, and buttery. At the upper end was a door which led to the solar and subsequently, no doubt, to the four chambers, mentioned in the Inquisition, which replaced it. At the time when the hall was built, about 1180, the probability is that there were not so many as four chambers, but merely the solar. There is no fireplace, so the fire must have been on a central hearth, with a louvre over it in the roof; but the present roof having been rebuilt affords no evidence on this point. The lighting was from small windows in the side walls, supplemented by a larger one in the gable over the doors to the kitchen (Fig. 15). The side walls are necessarily not very lofty, and the light from the small windows had a long way to travel, consequently the place must have been but ill-lighted although far more cheerful than contemporary keeps. The lighting was wholly inadequate for modern purposes, and has therefore been increased by means of dormers.

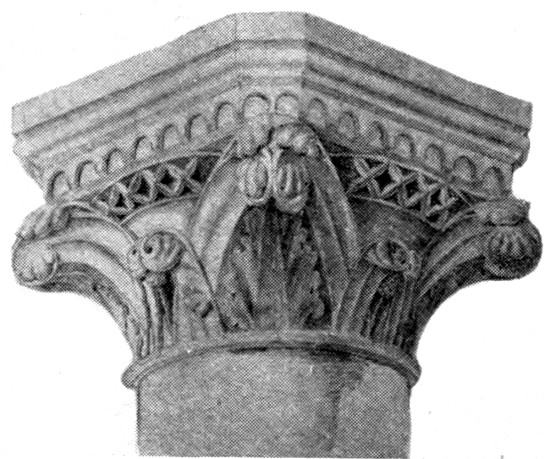

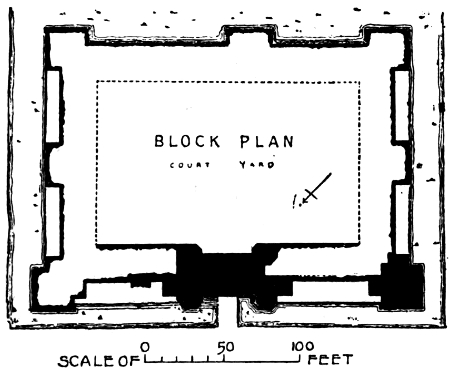

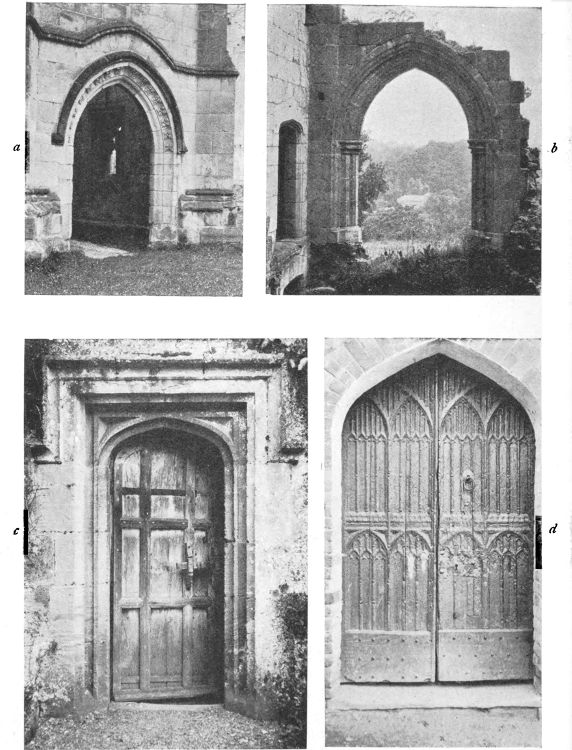

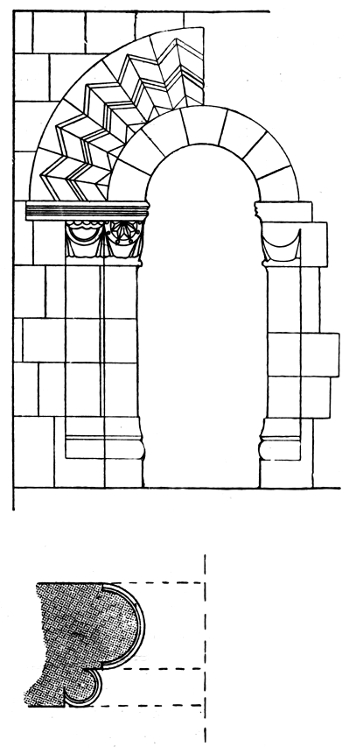

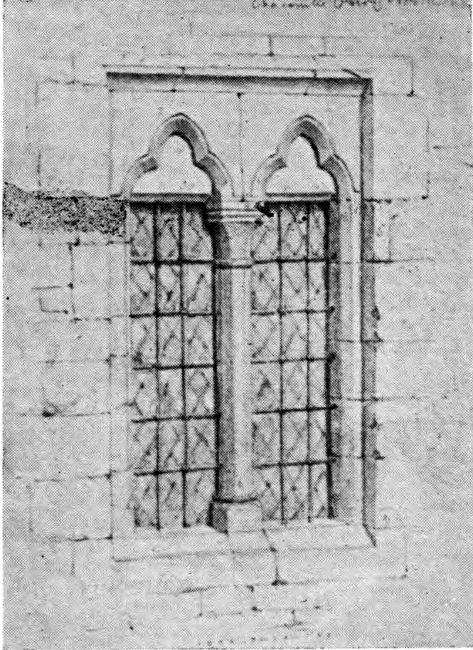

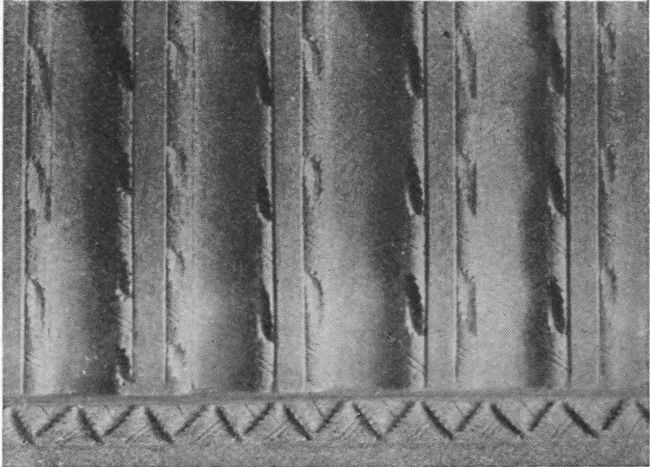

The style of the work is such as marks the buildings of the later years of the twelfth century. The four arches of the arcades are semicircular and of about 15 ft. span; they rest on massive round pillars (Fig. 13), and where they spring from the end walls they rest on corbels of unusual and quaint design. The entrance door is round-headed and of two orders, the outer being carried on a shaft and cap. The windows are of two lights, with pointed heads, the mouldings carried on shafts externally; the tympanum is filled in solid, thus making the actual light square-headed. Internally each window is set in a deep recess under a round-headed arch carried down to the floor, thus differing from church windows which usually have a sill the full thickness of the wall. The angles of the windows inside and[33] out, as well as the outer angles of the doorway, are ornamented with the dog-tooth. The illustrations make this short description plainer than many words, and they show how in general treatment the door and windows closely resemble contemporary work in churches.

There are no indications of a screen at the entrance end, nor of a daïs at the upper, inasmuch as the ornament of the window-recesses goes down to the floor in all cases, whereas had there been a permanent daïs, it would have stopped short to accommodate it.

16. Oakham Castle.

Pier cap.

The pillars of the arcade have vigorously carved caps admirably designed (Fig. 16), and they support, between the springing of the arches, quaint figures of musicians. Two of the heads which support a corbel on the wall near the entrance are supposed to represent Henry II. and his queen. The whole of the work is excellent in design and execution, and the hall, both in its arrangement and its building, is the most valuable example left of its period.

The hall at Oakham is typical, as to its main features, of all others down to the end of the sixteenth century. That is to say, the hall was the principal room; it was entered through the screens; at the lower end were the kitchens, at the upper the family rooms. It was nearly always a lofty apartment of one storey with an open timber roof. The principal changes that took[34] place in the room itself were the elimination of the pillars and the contriving of a roof to cover it in one span from wall to wall; the provision of larger windows, and especially of a bay window at the daïs end; the addition of a porch to protect the front entrance from the weather. The other changes which affected it were those which took place in the rooms at either end; the growth of the solar into a suite of rooms, and the provision of separate sleeping accommodation for the servants. By the end of the sixteenth century these changes had very materially affected the size and plan of the house, and they ultimately led to the extinction of the hall as a living room; but this development will be further considered in a later chapter.

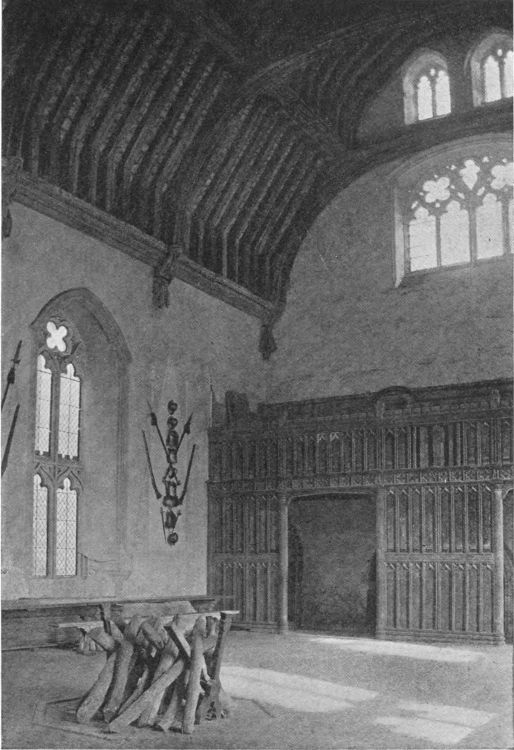

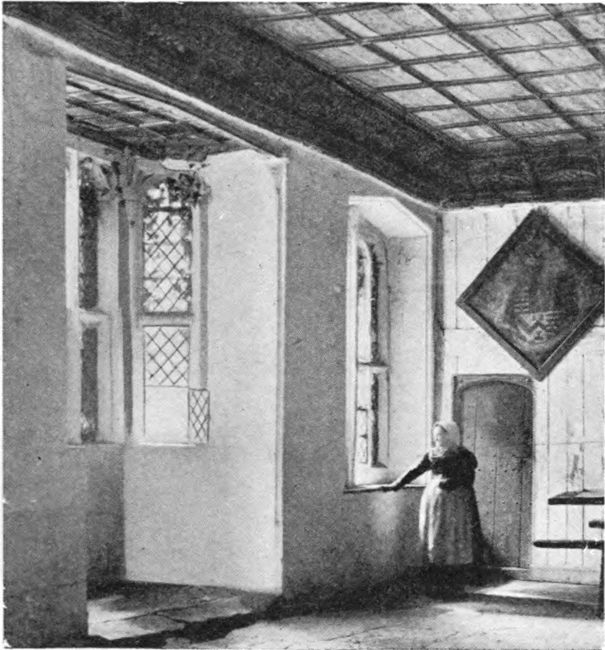

17. Cothele House, Cornwall (time of Henry VII.).

The Great Hall.

[35]

An illustration of a late hall (of the time of Henry VII.) is given in Fig. 17, from Cothele House in Cornwall. It shows the large window, the fireplace, and the start of the open roof. The daïs has disappeared, as it has in most old houses, but the door leading to the family rooms is visible in the corner. It gives a good idea of the appearance of a mediæval hall.

All the changes which took place in the treatment of dwellings tended towards the increase of comfort. The growth, it is true, was slow, and if a modern critic were compelled to dwell in them, the difference to him between a house of the twelfth century and one of the thirteenth would hardly be perceptible; both would be intolerable. But gradually the number of rooms increased both at the upper and lower ends of the hall. The keep still survived in a modified form, and often formed the nucleus round which the rest of the house grew. At Stokesay in Shropshire, which dates from about 1240, or sixty years later than Oakham, there is still a keep, but it is almost detached from the actual house, and may have served as the final stronghold to which the inhabitants could retreat in times of stress. At Longthorpe in Northamptonshire, some two miles to the west of Peterborough, there is a very interesting though small example of a keep or peel-tower attached to the house, and forming an integral part of it. The house was built in the latter part of the thirteenth century, and has undergone many alterations; but the tower remains in good preservation, as also does a contemporary gable adjacent to it, the only remnant of the original house.

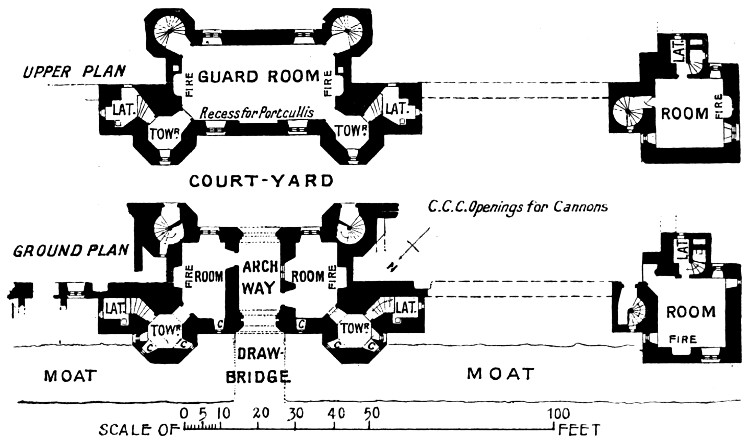

The most usual method of protecting these manor houses was to surround them with a moat, across which a drawbridge led to a strongly defended gateway. Bodiam Castle in Sussex, on the borders of Kent[36] (Fig. 18), is an excellent example of a moated structure. It was built in 1386 as a place of defence, rather than as a dwelling-house. In hilly districts moats were impossible, and in such cases advantage was taken of a precipitous piece of ground which might furnish natural protection on as many sides as possible. Aydon Castle in Northumberland is a striking instance of the latter kind of defence, being situated on the edge of a ravine. Although inhabited, it still retains much of its original appearance, and many of its original features.

18. Bodiam Castle, Sussex (1386).

Showing the Moat.

19. Stokesay Castle, Shropshire (cir. 1240–90).

Ground Plan.

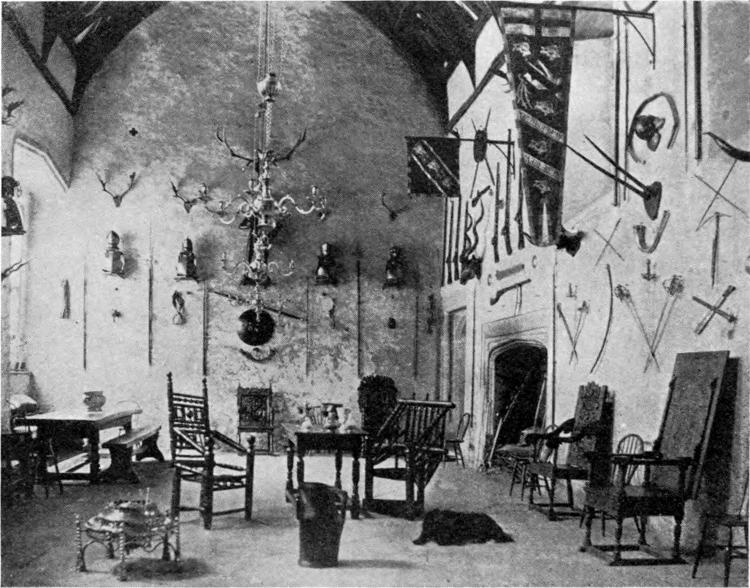

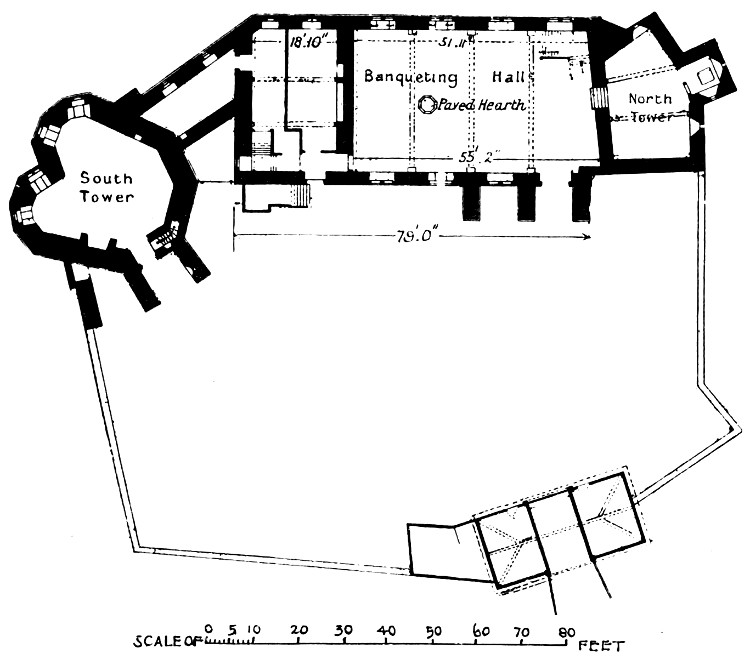

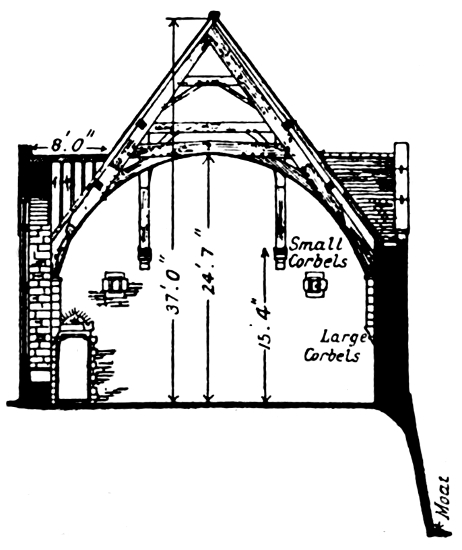

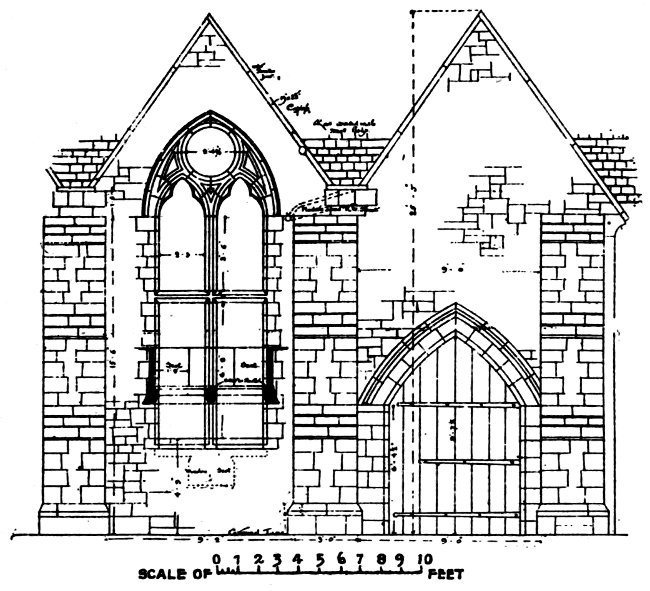

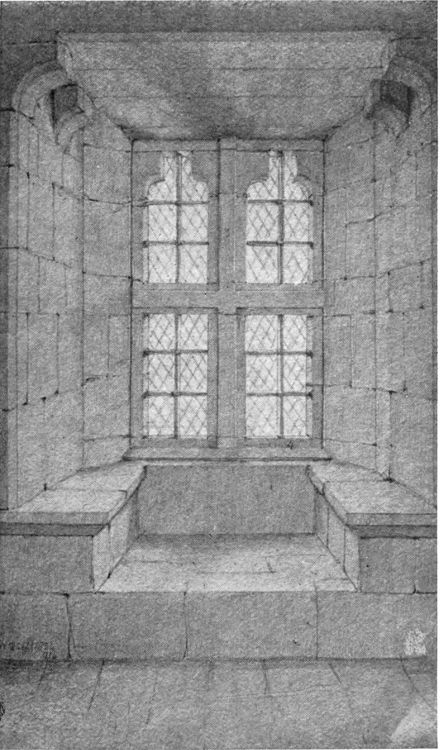

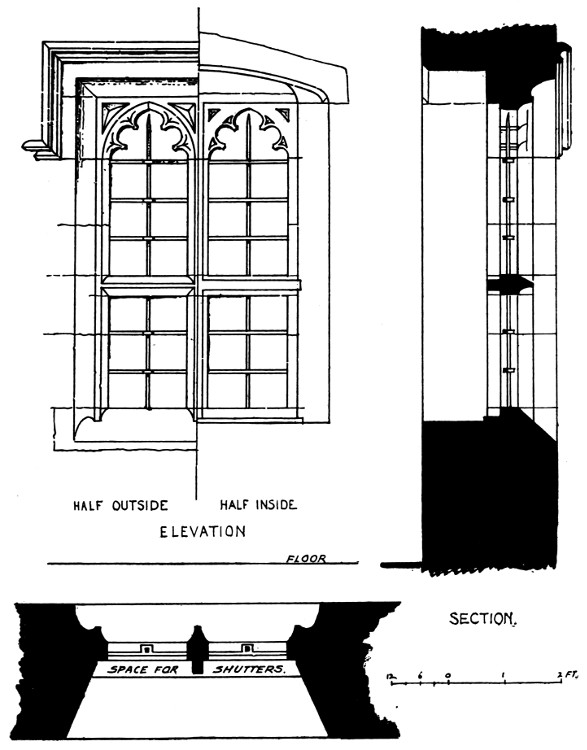

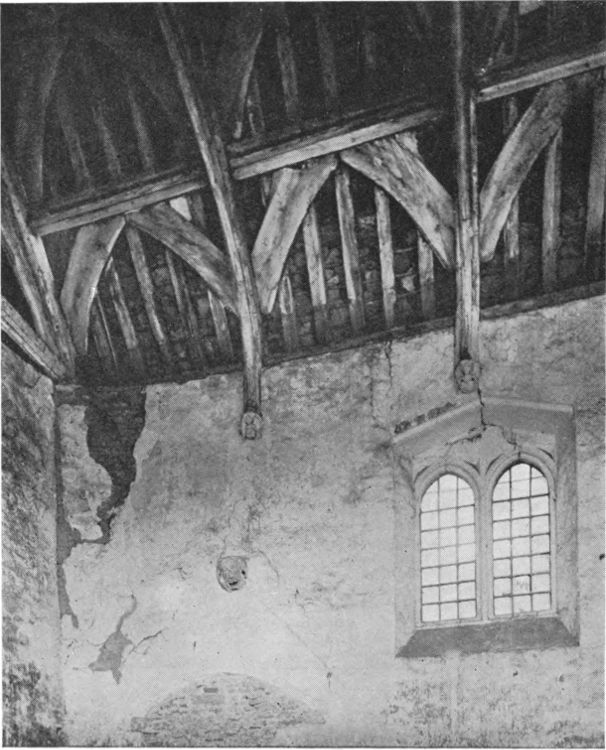

Stokesay (about 1240–1290) was defended by a moat, crossed no doubt by a drawbridge, and entered through a gatehouse. The original fortified gatehouse, however, has been replaced by a picturesque half-timber structure of Elizabeth’s time, and the drawbridge by a solid[37] approach. The gateway led into a large courtyard, on the opposite side of which stood, and still stands, the house (see plan, Fig. 19). The chief apartment, as usual, is the hall, not so large as that at Oakham, but still of fair size, 52 by 31 ft., that is to say large enough to contain, with plenty of space to spare, two complete houses such as now form the streets of a growing town. It is covered with a simply designed open timber roof (see section, Fig. 20), the principal rafters of which rest on plain built-out corbels. There were no buttresses to counteract its thrust, until it was found necessary to build some on the courtyard side. Unlike Oakham, the[38] hall at Stokesay has rooms attached to it at each end. At the lower end they are of three storeys, at the upper of two. Applying the usual rule the three-storeyed part (marked on the plan “North Tower”) ought to have been for the servants’ or retainers’ use; and it is possible that in early days it was. The lowest storey was doubtless a cellar, the upper ones, however, are furnished with large fireplaces, which point to their occupation by a superior class of persons. In later years the topmost room was enlarged and made more cheerful by adding some overhanging half-timber work in which plenty of windows were introduced (Fig. 21). The kitchen must have stood at this end, but there are no remains of it left. There was at one time a return wing running east from the north tower; it was built of wood, and contained kitchens, probably of a date subsequent to the hall. These rooms at the lower end were approached by a wooden stair within the hall, a rather unusual arrangement. From the upper end of the hall access was obtained by an external flight of stone steps to the solar, or lord’s chamber, which had a large fireplace, and on either side of it a small window looking into the hall, so that the lord—or more probably, considering the immutability of human nature, the lady—could overlook that apartment after retiring from it. The solar was embellished in later times with panelling[40] and a fine wood chimney-piece, and thus rendered a very pleasant room. Beneath the solar was, as usual, a cellar or store place on the ground floor, and beneath that another cellar underground. Outside and beyond the solar stands the massive south tower or keep of three storeys, with one room on each floor. They have fireplaces, but the windows are small, and were never glazed, but merely closed with shutters.

20. Stokesay Castle.

Section of Great Hall.

In the end wall are two small windows opening from the solar.

21. Stokesay Castle (General View).

The hall and adjoining rooms are to the right; the south tower is in the centre; the Elizabethan gatehouse to the left.

22. Stokesay Castle.

Window and Doorway of the Hall.

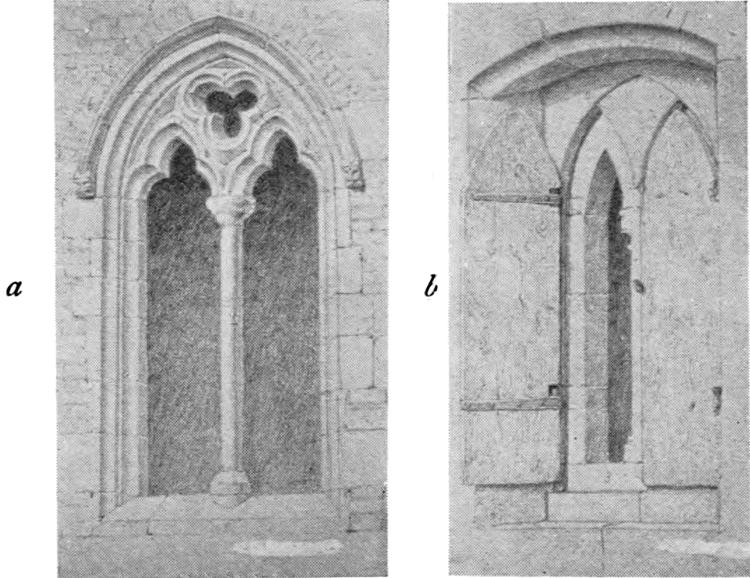

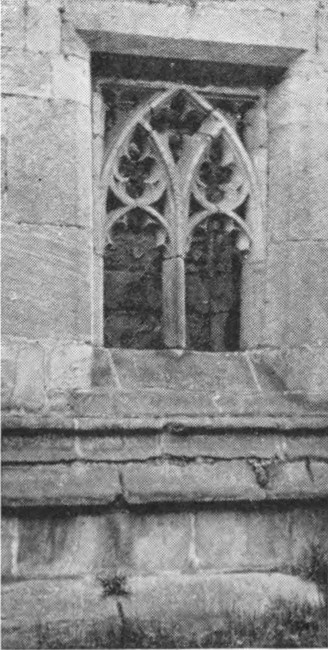

It must be borne in mind that hitherto windows had not been glazed. They were usually of small size for purposes of security, and no doubt their smallness was an advantage so far as the inlet of cold air was concerned. But they rendered the rooms gloomy to the last degree, and the unlucky people of the time must often have had the choice of two evils, icy draughts, or the darkness which followed the closing of the shutters. No wonder the fireplaces were made large, yet even[41] with a blazing fire in the middle of the hall, none of its heat being lost up the chimney, the plight of the household must have resembled that of travellers round a camp fire who complain of being roasted on one side and frozen on the other.

In the hall at Stokesay, however, the windows are large, and the lights are of such ample width as to offer but little protection against attack. They are two lights wide and two lights high, the upper ones being pointed and cusped, and surmounted by a circular eye (Fig. 22). This eye and the upper lights were glazed, but the lower ones were merely closed with shutters. This amount of glazing is a decided advance in comfort, and so is the size of the windows, which must have rendered the hall quite a cheerful place, in striking contrast to the gloom of the tower, where the small windows provide a patch of light which only renders the general darkness more pronounced (Fig. 23).

23. Stokesay Castle.

Window in South Tower—Showing shutter and stone seats.

The glazing of windows was carried out in a fitful way. Some windows in buildings as early as Stokesay were already glazed, others even so late as the end of the fifteenth century were not so treated. In the scanty remains of Abingdon Abbey the so-called Prior’s Room has never had glass in its windows. This room is of the early Decorated period (c. 1300) and whether[42] devoted to the prior or not, it was of sufficient importance to have a fine fireplace and plastered walls ornamented with coloured lines. The windows of the adjoining guest-house (if such were its purpose) have likewise never been glazed. These are of much later date—towards the end of the fifteenth century. They, too, lighted rooms of some importance, 30 ft. long, warmed by a large fire, handsomely roofed, and decorated in places with elaborate ornament.[1] Horn was occasionally used as a material for glazing prior to the general use of glass.

The improvement in domestic arrangements which is observable in the actual buildings at Stokesay is also noticeable in such contemporary accounts of building works as have been preserved. The Liberate Rolls of Henry III.’s time (1232–1269) contain many orders issued in respect of the king’s houses which were scattered up and down the country in almost every southern county from Kent to Hereford, and northwards to Northamptonshire and Nottingham. They nearly all point towards making the houses more comfortable. Windows were to be glazed to prevent draughts; porches were to be built to external doors; passages of communication were to be made from one building to another; roofs and walls were to be wainscoted; windows were to be enlarged; fireplaces were to be built; garde-robes were to be made less offensive; in some cases drainage was to be executed as a protection to health. Everything goes to show that Henry’s aim was to make his houses more convenient and more comfortable. In addition to structural alterations there are many orders for decoration. Buildings were to be[43] whitewashed inside and out; windows were to be filled with painted glass, either heraldic or setting forth some scriptural subject, notably the story of Dives and Lazarus; shutters were to be painted with the king’s arms; and most frequently of all, rooms were to be painted green spangled with gold stars. It is quite clear that houses were gradually becoming not merely places of safety and of shelter from winter and rough weather, but places of pleasure and delight; not merely lairs but homes.

[44]

The king, of course, may be supposed to have had unlimited means at his disposal for the improvement of his houses, and to have been better able than less exalted personages to gratify his wishes; but his subjects were also actuated by the same desires, and an examination of the large houses of the fourteenth century shows a considerable advance in the provision of rooms for special purposes, and indicates that the old restricted accommodation was no longer sufficient for the changing habits of the time. This expansion of the house was general, and was not confined to any particular district. To mention a few instances, there are in the North Alnwick Castle, built by the Percys about 1340, of which all but the external walls has been modernised; and Raby Castle, the home of the Nevills, Earls of Westmorland, built about 1378, also largely modernised. In the Midlands are Kenilworth Castle, almost rebuilt by John of Gaunt in the closing years of the fourteenth century; Warwick Castle, also almost entirely rebuilt by Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, a few years earlier; Broughton Castle in Oxfordshire, built by the De Broughtons about the beginning of the fourteenth century; Drayton House in Northamptonshire, by Simon de Drayton in 1328; and Haddon Hall in Derbyshire, where the greater part of the work is of this period. In the South is Penshurst Place for which a licence to crenellate was granted to John de Pulteney in 1341.

[45]

The smaller houses of this period do not, of course, show such extensive improvements as the large places just mentioned, nevertheless in them may be seen the same tendency towards greater civilisation. Even in the far North, where the disturbed state of the Border retarded the development of household comfort, we have the commodious house of Naworth in Cumberland, and the smaller house of Yanwath in Westmorland. In Yorkshire is Markenfield Hall; in Cheshire, Baguley, of which little besides its timber hall is left; in Northamptonshire the small but fine house at Northborough; in Berkshire is Sutton Courtney, so much altered, however, as to have lost its original character; while in Somerset is the very curious “Castle” of Nunney, where the rooms are placed over each other more after the fashion of the earlier keeps than of the long and low manor houses which were by this time the prevailing type.

In all these houses the hall was still the chief apartment, but it is supplemented by more subsidiary rooms than are to be found in earlier examples. The references in contemporary literature and documents are not numerous, but we have already seen that at Oakham in the Inquisition of 1340 the house consisted of a hall, four chambers, and a kitchen. If we turn to Chaucer, who lived during a large part of the fourteenth century, dying in 1400, we find in the few incidental references to domestic arrangements which occur that the hall was by far the most important room, although it had “chambers” and a “bower” to supplement it.

It is perhaps from the “Cook’s Tale of Gamelyn” that the best idea of a house may be gained, with its gatehouse, courtyard, and turreted hall. He tells us how his muscular hero Gamelyn, the prototype of Shakespeare’s Orlando, came with his friends to his ancestral[46] home, held by his false brother, and how the gate was shut and locked against them by the porter, who resolutely refused them admission to the courtyard. Gamelyn, however, smote the wicket with his foot, broke the pin and effected an entrance. The porter he chased across the yard, broke his neck and threw him into a well. He and his friends then made merry with the brother’s meat and wine, while the latter hid himself in a “little turret,” for which we owe him our thanks, as showing that such features had a use. Meanwhile the gate had been flung open to admit all who cared to go in “or ride,” a touch which brings home to us the fact that hardly any of these gatehouses were wide enough to admit wheeled vehicles, which of course were somewhat rare in those days; the entrances were contrived only for foot passengers and horsemen. Presently the fortunes of the day changed, Gamelyn was overpowered and bound to a post in the hall, and the false brother emerged from the “selleer” (solar) to taunt him. For two days and nights Gamelyn stood bound without meat or drink, but then, thinking he had fasted too long, he besought Adam the “spencer” to free him. Adam hesitated to let him go out of “this bour,” but ultimately consented, and took him into the “spence” and gave him supper. The spence was the pantry, and the spencer the presiding genius of that place. It would be beside the mark to enter into the details of Gamelyn’s further adventures, suffice it to say that by Adam’s advice he let himself appear to be still bound to the post; the hall presently filled with his brother’s guests who cast their eyes on the captive as they came in “at hall door.” At a preconcerted signal, Gamelyn and Adam possessed themselves of some stout cudgels which the good spencer had provided, and between them they cudgelled the whole company,[47] taking especial delight in dealing with the “men of holy Church.”

This glimpse into a fourteenth-century mansion is the longest which Chaucer vouchsafes; we read elsewhere of “halls, chambers, kitchens, and bowers,” and the “chamber” is occasionally mentioned as the alternative room to the hall so far as the owner and his wife are concerned. The difference between a “bower” and a “chamber” does not emerge very clearly. Adam, as we have seen, speaks of the hall as “this bour,” but as a rule the term is applied to a room in order to distinguish it from that apartment. It seems quite clear that to Chaucer the hall was the chief room, almost synonymous with the house, the other rooms he mentions being the merest accessories.

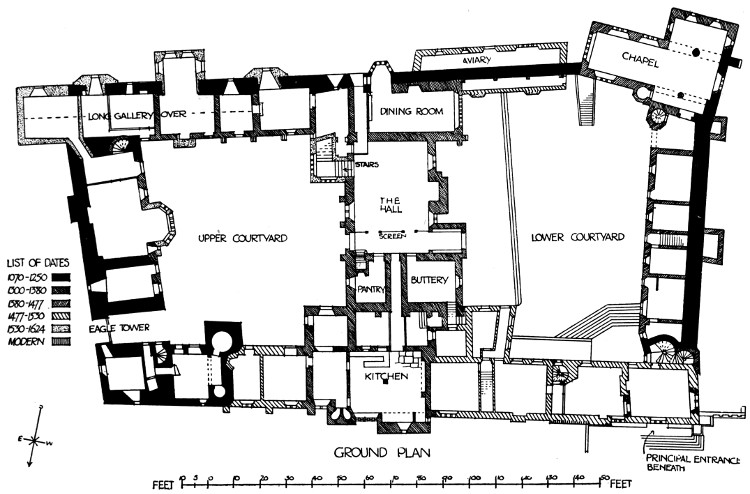

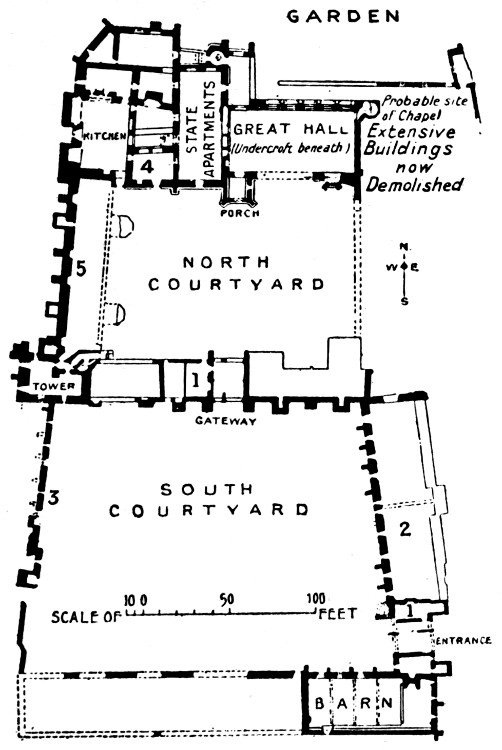

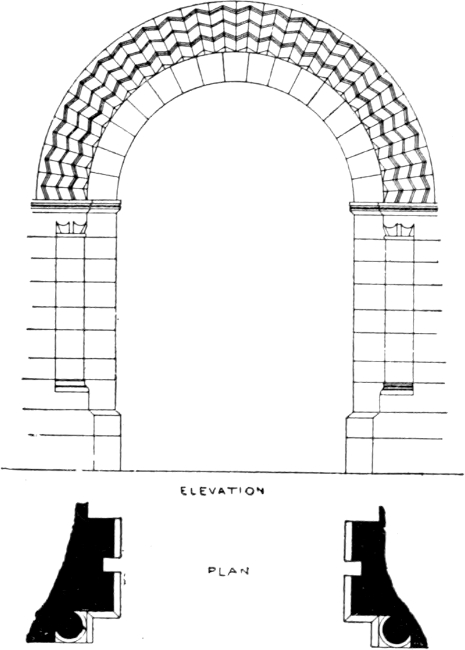

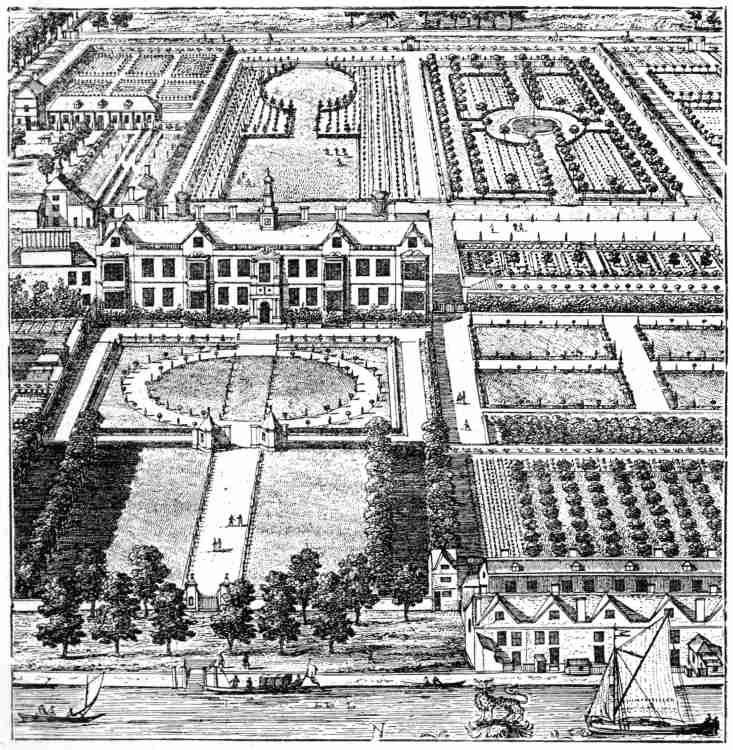

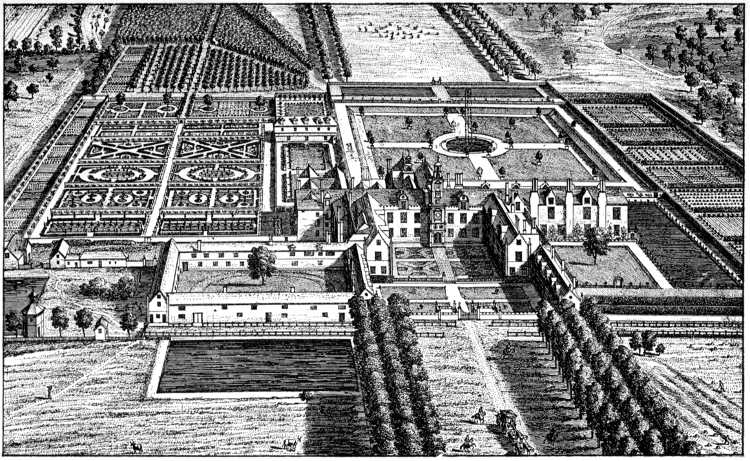

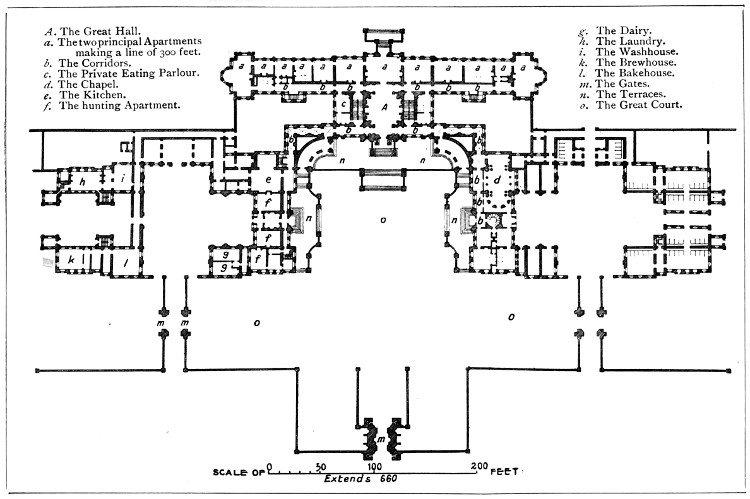

The most complete and most interesting house of this period is the well-known Haddon Hall in Derbyshire. It consists of two courts (Fig. 24), the hall being placed in the wing which divides them. It is thus protected on both of its long sides and is thereby enabled to have larger windows than if it had been on an outside wall. The exterior walls of the earlier parts of Haddon have comparatively few windows in them, and these of small size; and as the kitchen is one of the rooms so lighted it is dark, in spite of a larger window inserted in the sixteenth century, to a degree which horrifies housewives of the present day. Haddon being built on the slope of a hill could not be protected by a moat, hence it was more than ever necessary to be careful about external apertures. Some parts of Haddon are of the twelfth century, including much of the west wall, portions of the chapel (at the south-west corner), and the lower parts of the south and east walls and of the Peverel or Eagle tower; the licence granted to Richard de Vernon to fortify his house of Haddon with a wall 12 ft. high[49] without crenellations is still preserved. This licence was granted by John, Earl of Morteigne, who, in 1199, became King John. The extent of this early work shows that already in the twelfth century there was a large house here, its area being little less than at the present day. But during the fourteenth century it was practically rebuilt on the lines which now remain, inasmuch as work of this period is to be found over the whole building. The extent of the house, and particularly the multiplicity of rooms, go to show how vastly the desire for comfort had increased by this time. Much other work was done in later years; the chapel was either enlarged or altered, and a range of rooms was added or rebuilt in the fifteenth century. In the early part of the sixteenth many of the rooms were embellished and modernised by Sir George Vernon, “the King of the Peak”; and yet later his daughter Dorothy and her husband Sir John Manners built the beautiful long gallery on the top of earlier rooms and laid out the garden with its picturesque terraces and noble flight of steps.

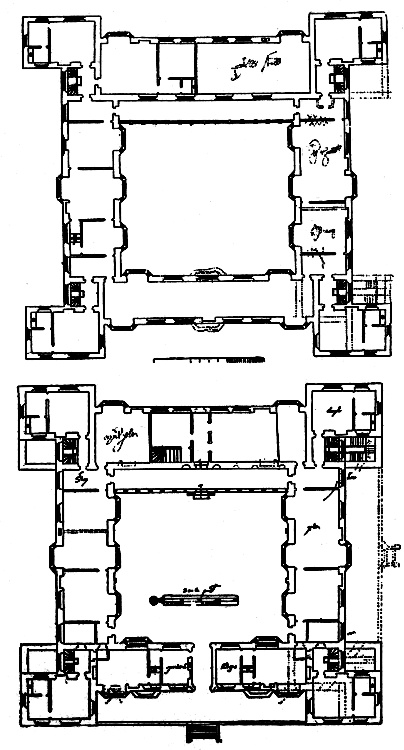

24. Plan of Haddon Hall, Derbyshire.

It is of great interest to see here the work of various hands, and to realise how, generation after generation, the owners did what they could to bring their ancient home up to the prevailing standard of comfort and beauty. But the particular point which is of interest now is that although much of the existing work is of later date, yet it is clear that in the fourteenth century Haddon was of almost the same extent as we see it to-day. Civilisation had taken many strides since its little neighbour, the Peak Castle, had been built.

It is curious to observe on a plan of the house how much thicker the external walls are than the internal, and how few windows look outwards; they nearly all look into the courts, and of those that look out over the country most are of later date. The plan also shows[50] very clearly how the disposition of the hall follows the orthodox lines. It is entered through a porch at the end of one of its sides; the porch leads into the “screens”; on the right is the hall entered through a panelled wood screen with two openings. On the left are three doorways—one to the buttery, one to the kitchen passage, and the third to the pantry. At the end of the screens is a door leading into the upper court. The kitchen department is large, rambling, and ill-lighted, but when the house was in full occupation an enormous amount of work had to be done here, and doubtless the fire itself sufficiently supplemented the scanty daylight.

At the upper end of the hall is a range of rooms of two storeys, devoted to the use of the family; and doubtless in the fourteenth century it was already of two storeys, although apparently it only extended at that period from the front or west side of the hall as far eastwards as to overlap the east side of the upper court. It is difficult to disentangle these rooms from the additions and alterations of later years, for in the early part of the sixteenth century the rooms immediately contiguous to the south end of the hall were improved, and a new range was built on the top of the curtain wall, which ran from the hall wing westwards to the chapel. Again, towards the close of the same century, the long gallery was built over the ground floor rooms forming the south side of the upper court, and apparently this wing was prolonged in order to give that extreme length to the gallery which was so characteristic of Elizabeth’s time. This prolongation carried the south front beyond the line of the east front, an arrangement very unlikely to have been adopted while the house was still fortified.

Another curious and instructive feature is the gallery or gangway which is carried along the east side of the hall. This is not an original gallery, but was erected in[51] order to connect the south rooms with those on the north, which previously had been completely severed from each other by the lofty hall.

Haddon Hall, therefore, taken as a fourteenth-century dwelling, shows that protection from casual attack was still essential, but that there was a great amount of separate accommodation for the members of the household. The rooms, however, were arranged without much regard to convenience. They were placed in long and somewhat straggling ranges of single apartments leading one into the other. Privacy was much more studied than it had been in the preceding centuries, but it was provided to a degree that falls far short of modern requirements.

The fact that the only entrance through which a wheeled vehicle could enter the place was a secondary archway up the hill beneath the Eagle Tower, brings home to us again the fact that the usual means of locomotion was at that time either on foot or on horseback.

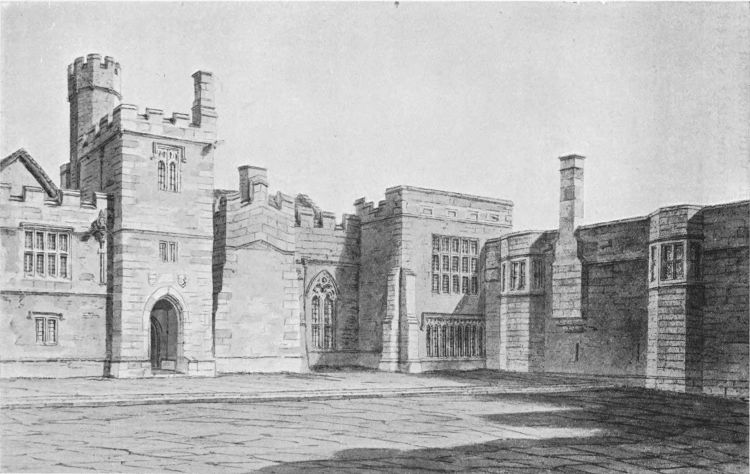

The view (Fig. 25) is taken in the lower courtyard, looking towards the great hall. The entrance door is placed in a projecting porch, over which a low tower is carried up. The staircase to the upper part of the tower is in an octagonal turret, which rises in picturesque fashion sufficiently high above the roof to give access to the leads. To the right of the porch is the great chimney-stack of the hall, now deprived of its original tall shaft. Beyond the chimney is one of the fourteenth-century windows of the hall with simple but characteristic tracery. Then comes the projecting end of the dining-room with its early sixteenth-century window of many lights in width, but only one in height; above this is a later window, not so wide, but divided into three lights as to its height. The return wing on the right contains the rooms built early in the sixteenth century over the[53] original wall of the twelfth century. The interest of the composition is increased by the absence of large windows on the ground floor of this wing, where, as the plan indicates, there was no need to have them.

25. Haddon Hall, Derbyshire (View in the Lower Courtyard).

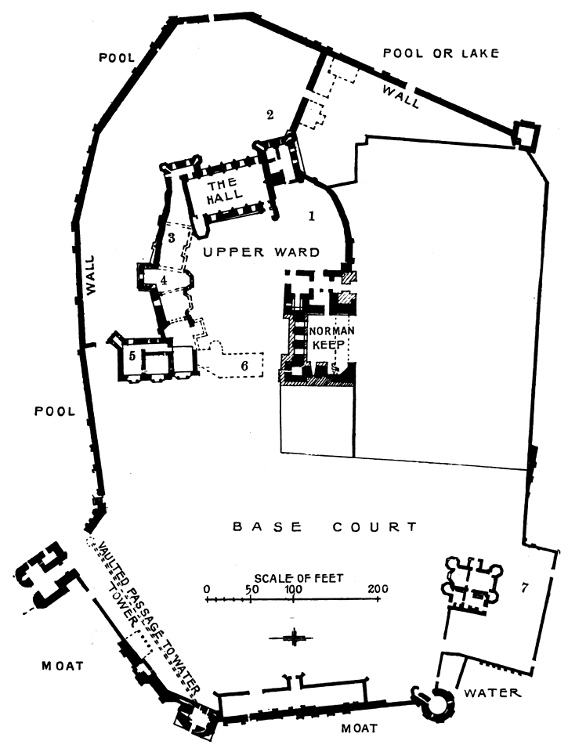

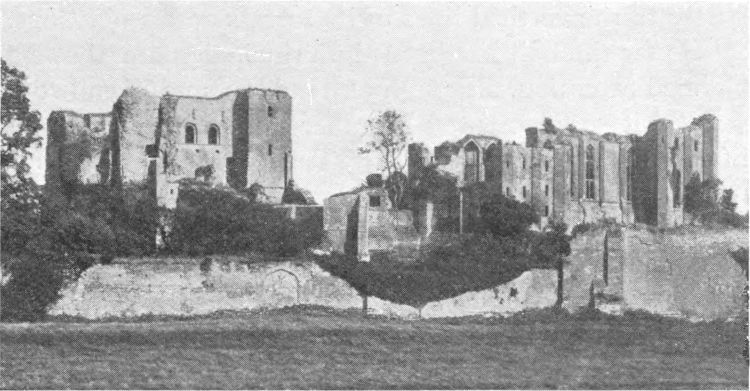

Another great house, dating largely from late in the fourteenth century, is Kenilworth Castle, which, though primarily a place of strength, has much that is interesting purely as domestic architecture. It has been held by kings and great nobles; some of the most celebrated names in English history are linked with its story; it has withstood sieges, when its walls enclosed despairing and disease-stricken men; it has witnessed the most gorgeous pageants of a gorgeous age. Reality and romance have vied to make it famous. It is worthy of far more careful study than can be bestowed upon it here, where it can only be briefly used to throw its light on the progress of domestic architecture through some four centuries. As a fortified place of dwelling it goes back to Saxon times; as a stone house it was occupied between four and five hundred years; it has been a ruin for nearly three hundred. In extent the site is very considerable, embracing some eight or nine acres of fortified enclosure (Fig. 26), but the walls, the towers, and the gateways which made its defences; the ditches, the moat, and the pool or lake which further secured it, do not fall within the range of the present inquiry; it is only the inner or upper ward which need detain us. The earliest of the buildings which form this ward is the great keep, situated at the north-east corner, the home of the family in Norman times. In its main characteristics it resembled the other large keeps which have been already described (Chapter II.), and its date may be placed at the end of the third quarter of the twelfth century. There must have been other contemporary buildings somewhere in the vast enclosure, mostly of wood, but some also of[55] stone: they have, however, all disappeared, and it is only from scattered fragments of early work that their character can be surmised. Doubtless during the next two centuries the descendants of the builders, the Clintons, or those who displaced them—the king, Simon de Montfort, Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, son of Henry III., Roger Mortimer, and the rest—added to the meagre and comfortless accommodation of their predecessors. Indeed it is on record that large sums were expended on buildings and repairs during the reigns of John and Henry III. But anything they may have built must have been swept away in the great rebuilding undertaken by John of Gaunt towards the end of the fourteenth century, about 1392; and it is not improbable from the irregular shape of the plan that his new buildings followed the main lines of those they superseded. By far the greater part of the upper ward is of this date. Starting from the west end of the keep, the kitchens on the north (now almost entirely gone), the great hall on the west, the white hall and other chambers on the south, are all John of Gaunt’s work. Where he left off, Dudley, Earl of Leicester, began, nearly two hundred years later; and although Leicester’s buildings are fairly large in themselves, they are small in comparison with those of “time-honoured Lancaster.”

[56]

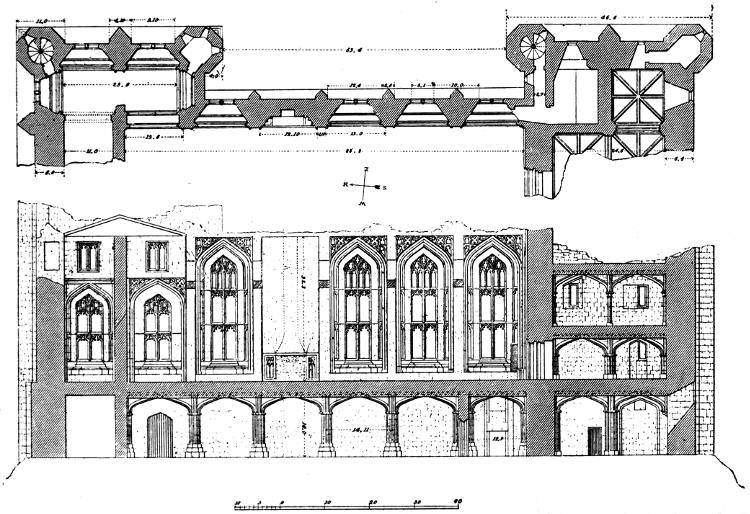

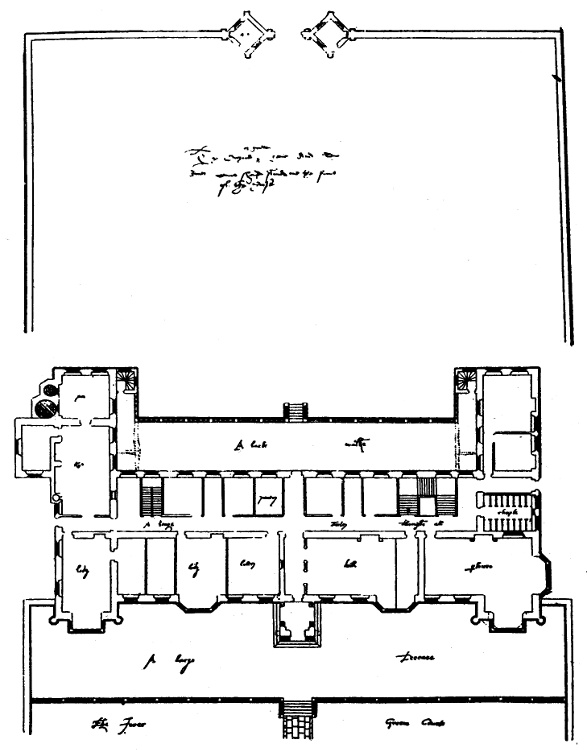

26. Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire.

Ground Plan.

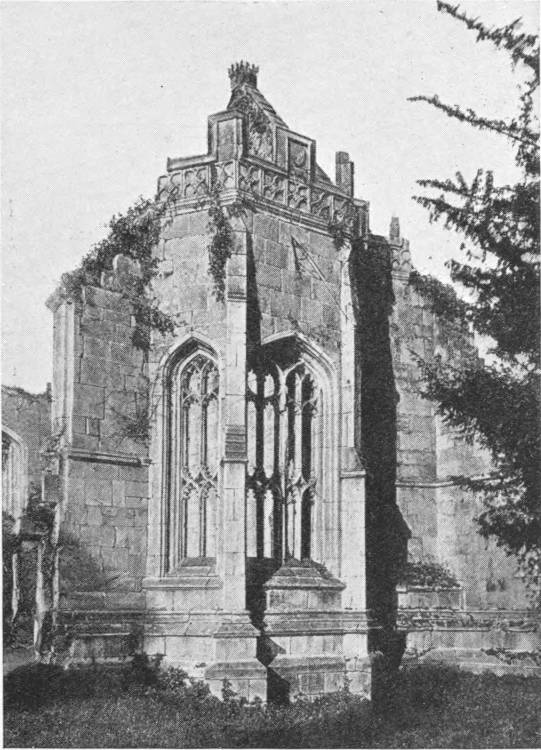

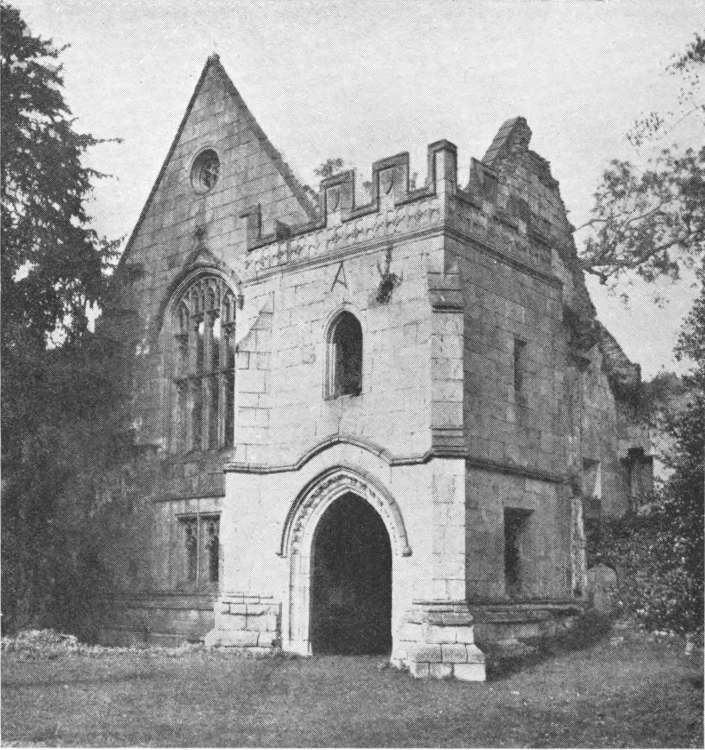

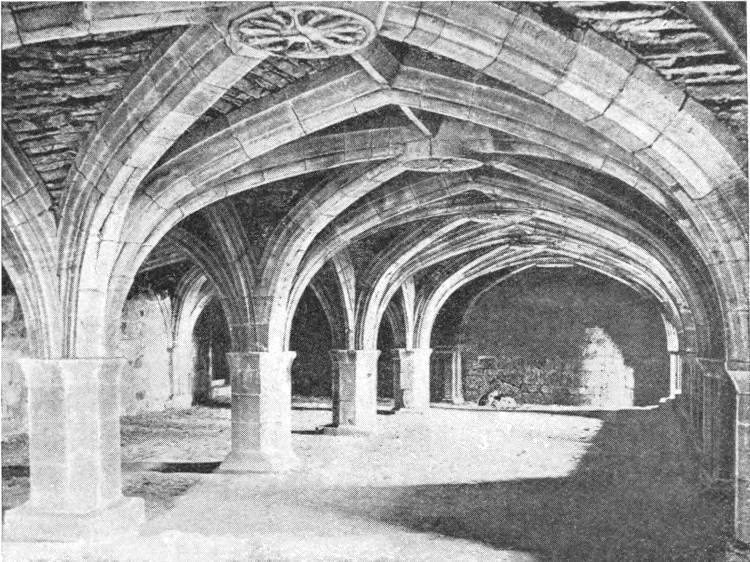

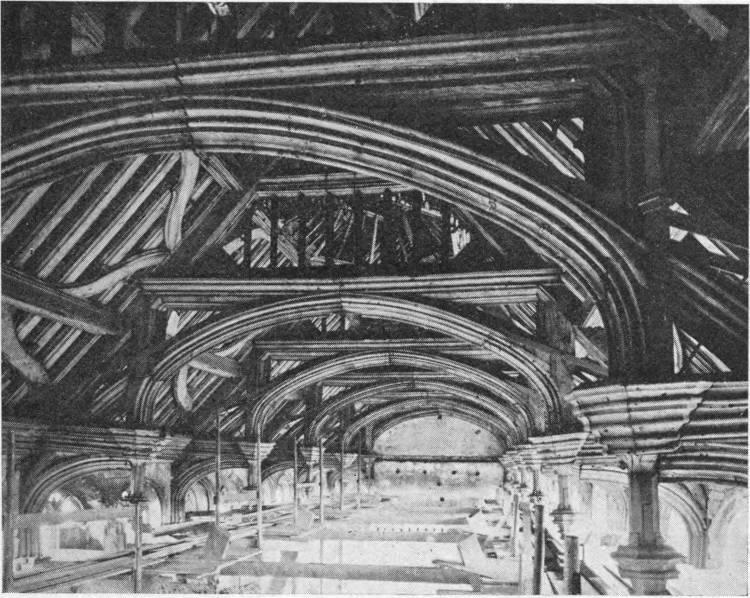

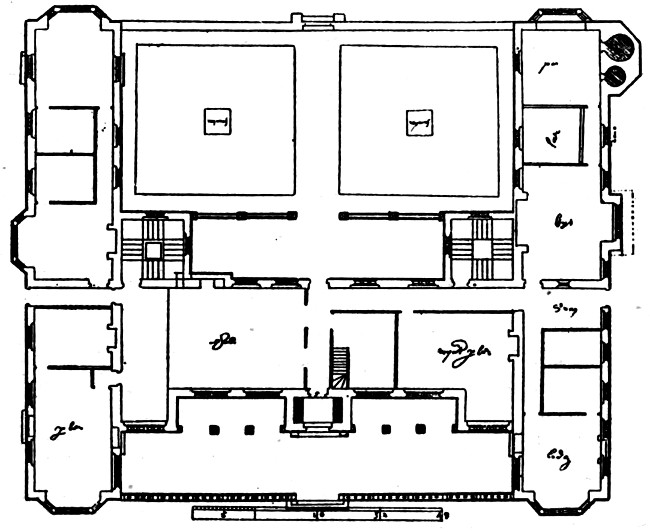

The range of chambers built by John of Gaunt shows how enormously domestic requirements had increased since the days when the restricted accommodation of a keep had sufficed for the housing of the lord and his family; or those when the subsidiary rooms attached to so fine a hall as that at Oakham were merely four “chambers” and a kitchen. The great hall, 90 ft. long by 45 ft. wide, occupied nearly the whole of the west front. It stood on a vaulted undercroft (see section, Fig. 27), and was entered at the north end of its east[57] side up a flight of steps, which eventually led into the “screens.” To the right or north of the entrance were the buttery, the kitchen, and other servants’ quarters. Beyond them, and projecting on the west front, was a tower called the Strong Tower, used as a place of detention for persons of consequence, some of whom have[58] here, as others in the Tower of London, left melancholy mementoes of weary hours in the shape of their coats-of-arms scratched upon the walls.

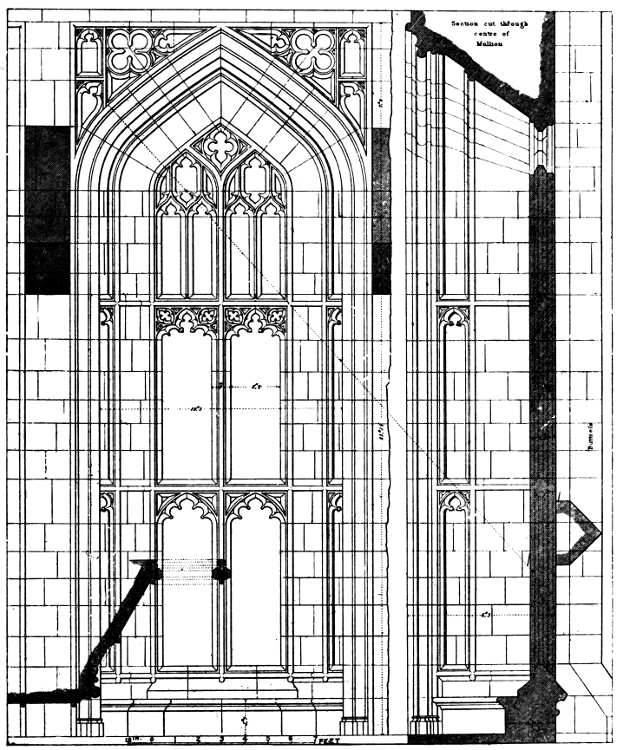

27. Kenilworth Castle. The Great Hall (cir. 1392).

The upper figure shows the plan of one side: the lower is the longitudinal section through the hall and undercroft.

28. Kenilworth Castle.

A Window of the Great Hall.

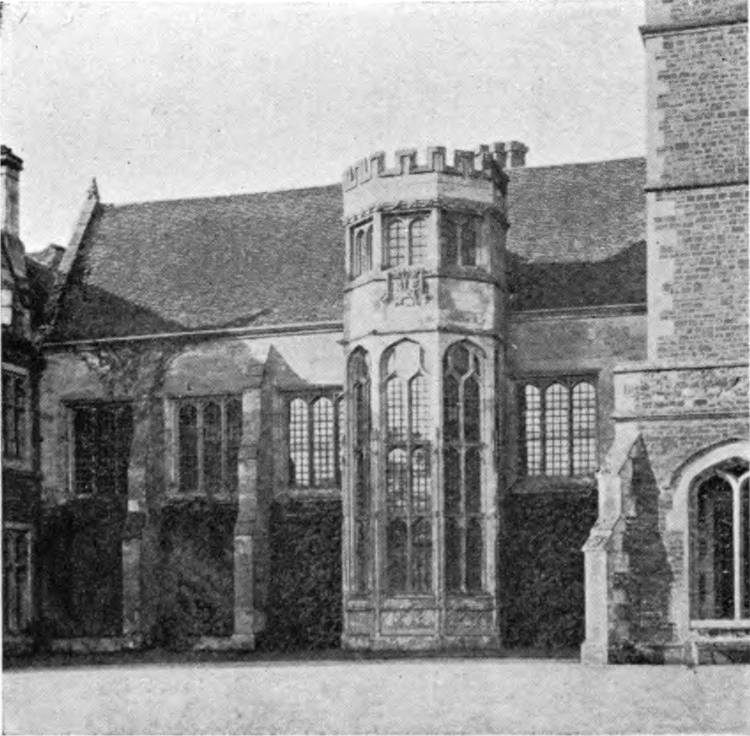

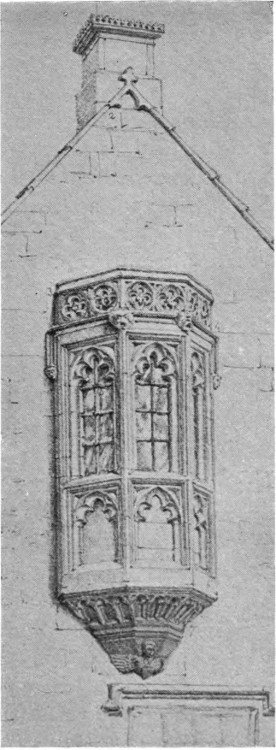

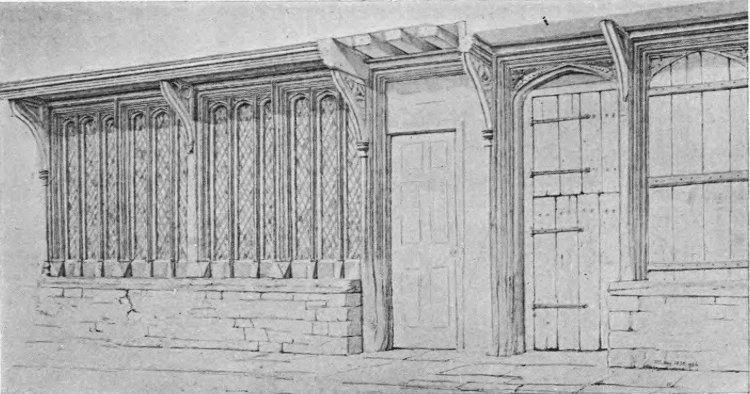

The hall itself was a noble apartment, admirably built in the best period of the Perpendicular style, lighted by large and lofty windows (Figs. 27, 28), and covered with an open timbered roof, which has long since disappeared. It must have been one of the finest halls of its time. At the upper or daïs end there is, on the east side, an octagonal bay window, with a fireplace in the south-west corner; while on the west is a tower, used on this floor as a buffet, and giving access by a passage to the range of rooms on the south front which were rooms of state and family apartments. About midway along their south front stood a large garde-robe tower. The two towers which project from the west front and balance each other at either end of the hall are a foretaste of the symmetry which was, in later years, to play so important a part in the disposition of great houses. The general arrangement of the hall, with the kitchens at one end and the family rooms at the other, conforms to the usual type so frequently mentioned, which may also be seen very clearly at Haddon. The bay window at the daïs end is an early example of an arrangement which afterwards became universal. The hall fire was not placed on the floor in the middle of that apartment, but in two fireplaces, one in either side wall about half way between the screen and the daïs.

The planning is, as usual, wasteful; the same accommodation might have been obtained with far less outlay and much more convenience, and a study of Elizabethan plans shows how far more surely and much more cheaply the designer of that day obtained his effects than did his predecessor of the fourteenth century.

29. Kenilworth Castle—View from the North-west.

(The keep is on the left; the great hall on the right.)

There can be no doubt that the Elizabethan designer[59] aimed at effect as well as at convenience of arrangement. But it is doubtful how far the designer of the fourteenth century had both these objects in view. No doubt he sought for effect in each building; that is to say, he strove to produce a noble hall, an impressive tower, a pleasant range of minor buildings. But his general arrangements were mostly haphazard; he built as circumstances dictated, either following the lines of previous buildings, or hurriedly placing his new rooms where at first sight they seemed to be wanted, without much caring whether they came awkwardly or not. He probably had an eye for the picturesque, for it is doubtful whether all the towers and turrets which broke his sky-line were built for necessity. Here at Kenilworth he displayed, as already remarked, some feeling for symmetry on the west front. When Leicester came to build his addition on the east, towards the end of the sixteenth century, there can be little doubt that considerations of symmetry dictated the form of the buildings, for instead of adopting the long and low[60] fashion then so much in vogue, he piled his rooms up in order to balance the lofty mass of the ancient keep. This is very apparent on a view made in 1620,[2] where these two large blocks are joined by a low range of buildings called “Henry VIII.’s Lodgings,” which have since then been entirely destroyed.

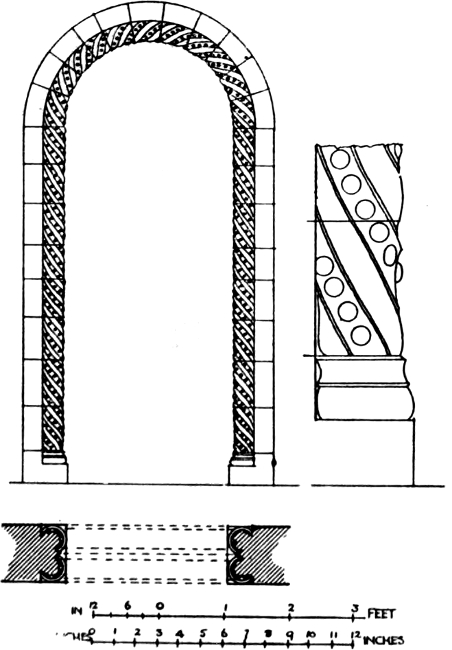

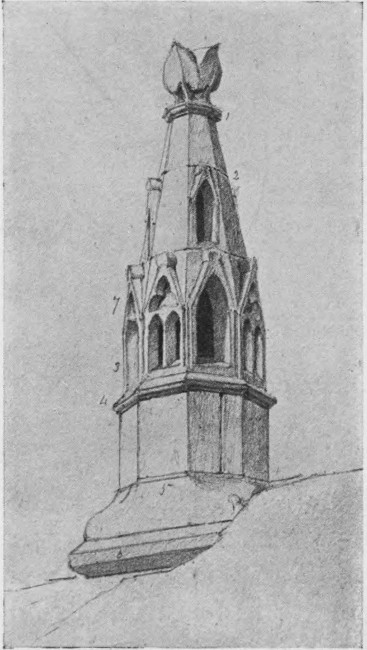

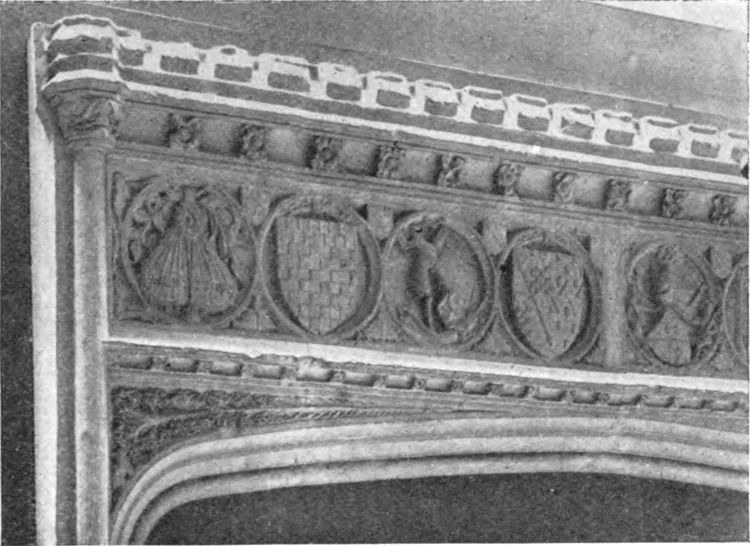

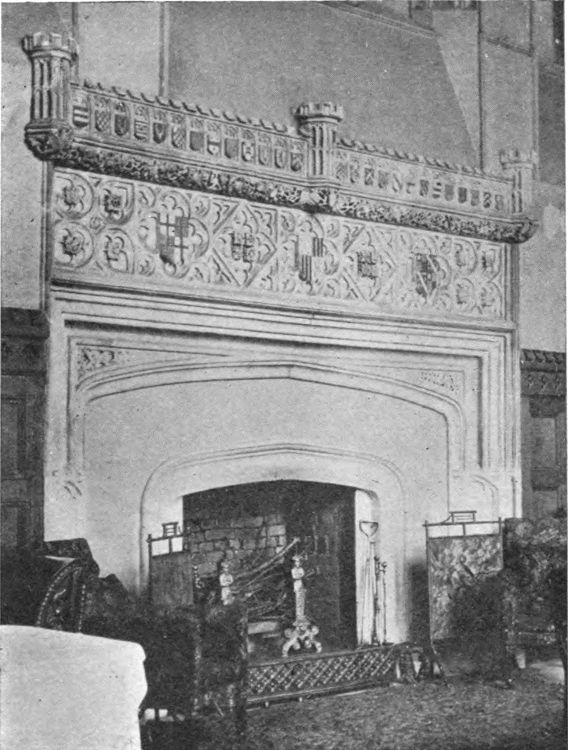

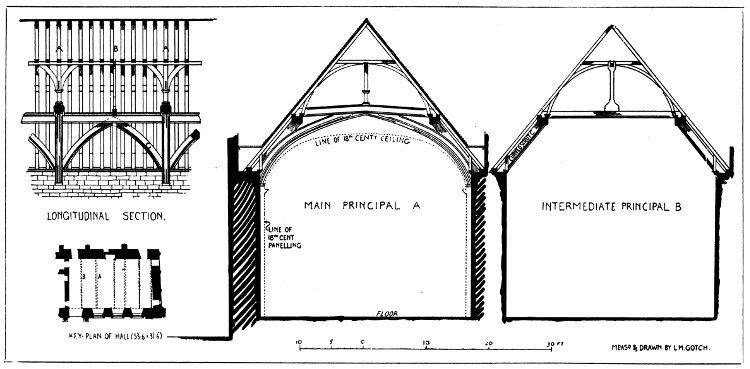

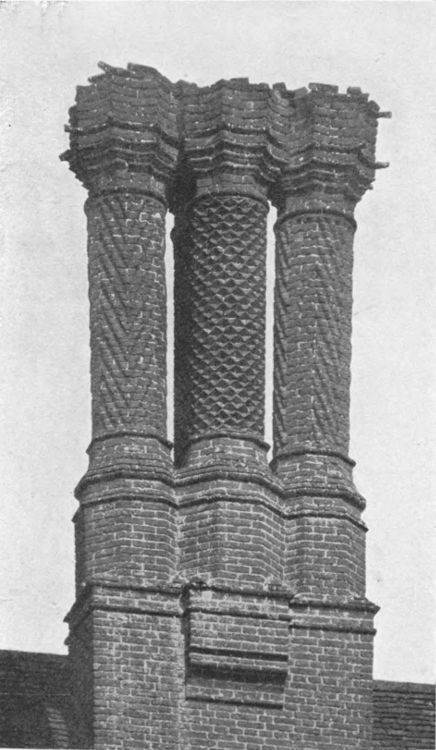

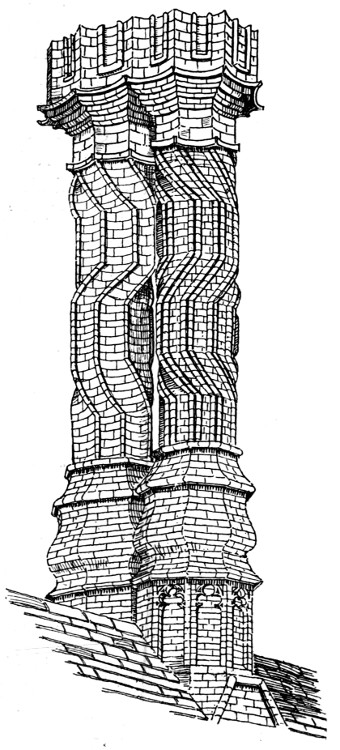

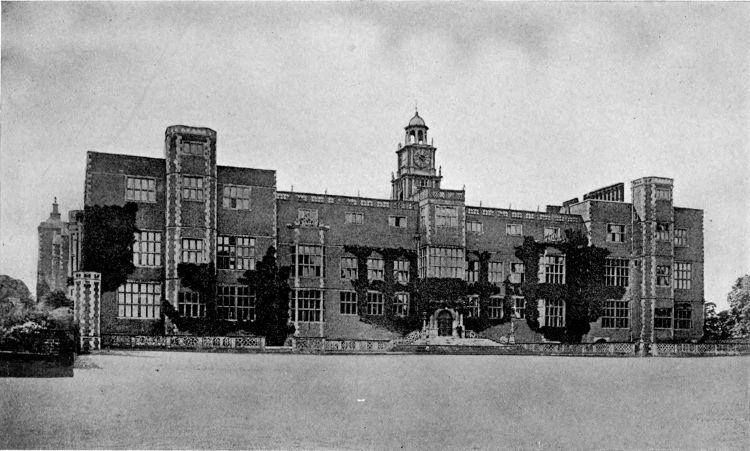

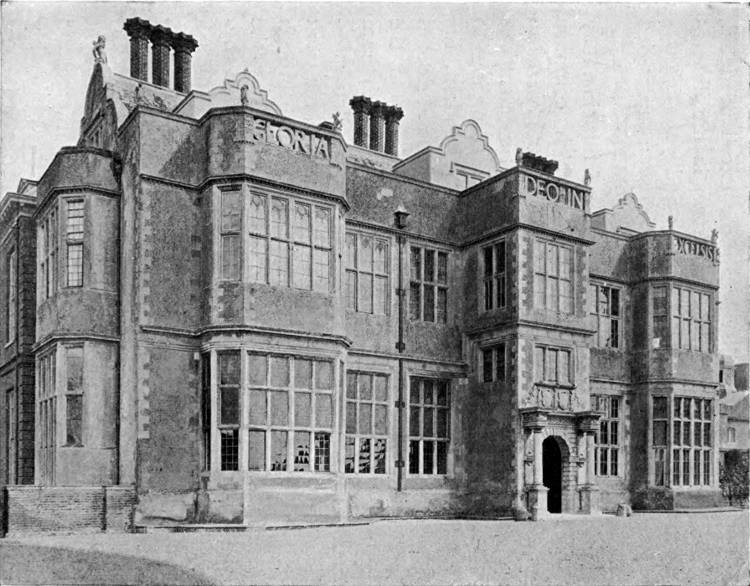

The view (Fig. 29) shows the Norman keep on the left, and the range containing the fourteenth-century hall on the right. The difference of treatment between the two periods is plainly visible. The keep is massive and stern with but few windows; the hall is lighter and more graceful, partly owing to its lofty windows, and partly to the vertical lines of its turrets and projections.