Title: Snap: A legend of the Lone Mountain

Author: Clive Phillipps-Wolley

Illustrator: H. G. Willink

Release date: August 10, 2022 [eBook #68725]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1892

Credits: Al Haines

A LEGEND OF THE LONE MOUNTAIN

BY

C. PHILLIPPS-WOLLEY

AUTHOR OF 'SPORT IN THE CRIMEA AND CAUCASUS' ETC.

WITH THIRTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS BY H. G. WILLINK

NEW EDITION

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

AND NEW YORK: 15 EAST 16th STREET

1892

All rights reserved

TO SMALL CLIVE.

I suppose that you'll cost me the deuce of a lot,

I suppose I must pay and look pleasant,

Though you're only a small insignificant dot—

My three-year-old warrior—at present.

But if ever you need the paternal 'tip,'

If ever you sin and must suffer,

Be brave and go straight, or I'll 'give you gyp'—

If I don't you may call me 'a duffer.'

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. FERNHALL v. LOAMSHIRE

II. 'MOP FAUCIBUS HÆSIT'

III. SNAP'S REDEMPTION

IV. THE FERNHALL GHOST

V. THE ADMIRAL'S 'SOCK-DOLLAGER'

VI. THE BLOW FALLS

VII. LEAVE LIVERPOOL

VIII. THE MANIAC

IX. 'THAT BAKING POWDER'

X. AFTER SCRUB CATTLE

XI. BRINGING HOME THE BEAR

XII. BRANDING THE 'SCRUBBER'

XIII. WINTER COMES WITH THE 'WAVIES'

XIV. A NIGHT OF ADVENTURE

XV. FOUNDING 'BULL PINE' FIRM

XVI. BEARS

XVII. IN THE BRÛLÊ

XVIII. THE LOSS OF 'THE CRADLE'

XIX. THE GAMBLERS 'PUT UP'

XX. LONE MOUNTAIN

XXI. AT THE TOP

XXII. AT THE END OF THE ROPE

XXIII. READING THE WILL

XXIV. SNAP'S SACRIFICE

XXV. THE FLIGHT OF THE CROWS

XXVI. SNAP'S STORY

XXVII. CONCLUSION

ILLUSTRATIONS.

IN THE CHIMNEY ... Frontispiece [missing from source book]

'GOOD-BYE' [missing from source book]

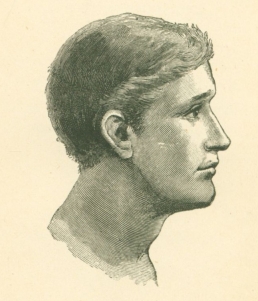

SNAP

'What on earth shall we do, Winthrop?' asked one of the Fernhall Eleven of a big fair-faced lad, who seemed to be its captain.

'Do! I'll be shot if I know, Wyndham,' he replied. 'It is bad enough to be a bat short, but really I don't know that we can spare a bowler.'

'Ah, well,' suggested another of the group, 'though Hales did very well for the Twenty-two, it isn't quite the same thing bowling against such a team as Loamshire brings down; he might not "come off" after all, don't you know.'

A quiet grin spread over the captain's face. No one knew better than he did the spirit which prompted Poynter's last remark.

Good bowler though he was, Poynter had often been a sad thorn in Winthrop's side. If you put him on first with the wind in his favour, Poynter would be beautifully good-tempered, and bowl sometimes like a very Spofforth. Only then sometimes he wouldn't! Sometimes an irreverent batsman from Loamshire who had never heard of Poynter's break from the leg would hit him incontinently for six, and perhaps do it twice in one over. Then Poynter got angry. His arms began to work like a windmill. He tried to bowl rather faster than Spofforth ever did; about three times as fast as Nature ever meant John Poynter to. The result of this was always the same. First he pitched them short, and the delighted batsman cut them for three; then he pitched them up, and that malicious person felt a thrill of pleasure go through his whole body as he either drove them or got them away to square leg. Then Winthrop had to take him off. This was when the trouble began. Sullenly Poynter would take his place in the field—and it was not every place in the field which suited him. If you put him in the deep field, he growled at the folly which risked straining a bowler's arm by shying. If you put him close in, he grumbled at the risk he ran of having those dexterous fingers of his damaged by a sharp cut or a 'sweet' drive. For of course he always expected to be put on again, and from the time that he reached his place until the time that he was again put into possession of the ball he did nothing but watch his rival with malicious envy, making a mental bowling analysis for him, in which he took far more note of the hits (or wides if there were any) than he did of the maiden overs which were bowled.

But Frank Winthrop was a diplomatist, as a cricket captain should be, so, though he grinned, he only replied, 'That's true enough, Poynter, but I must have some ordinary straight stuff, such as Hales's, to rest you and Rolles, and put these fellows off their guard against your curly ones.'

'Yes, I suppose it is a mistake to bowl a fellow good balls all the time. It makes him play too carefully,' replied the self-satisfied Poynter.

'Well, but, Winthrop,' insisted the first speaker, 'if you don't do without a change bowler, what will you do? That other fellow in the Twenty-two doesn't bowl well enough, but there are lots of them useful bats.'

'I know all that, but I've made up my mind,' replied the young autocrat. 'I shall play a man short, if I can't persuade Trout' (an irreverent sobriquet for their head-master) 'to let Snap Hales off in time.'

When a captain of a school eleven says that he has made up his mind, the intervention of anyone less than a head-master is useless, so that no one protested.

As the group broke up Wyndham put his arm through Winthrop's, and together they strolled towards the door of the school-house.

'Are you going up to see "the head," Major?' he asked.

'Yes,' replied Winthrop.

'What! about Snap Hales?' demanded Wyndham.

'Yes,' again replied Winthrop, 'about that young fool Snap.'

'What has he been up to now?' demanded his chum.

'Oh, he has been cheeking Cube-root again. It seems old Cube-root couldn't knock mathematics into him anyhow, so he piled on the impositions. Snap did as many lines as he could, but even with three nibs in your pen at once there is a limit to the number which a fellow can do in a day, and Master Snap has so many of these little literary engagements for other masters as well as old Cube that at last he reached a point beyond which no possible diligence would carry him.'

'Poor old Snap!' laughed Wyndham.

'Then, as he had just got into the eleven,' continued Winthrop, 'he didn't like to give up his half-hour with the professional; the result of all which was that yesterday old Cube asked him for his lines and was told—

'"I haven't done them, sir."

'"Haven't done them, sir: what do you mean?" thundered Cube.

'"I hadn't time, sir," pleaded Snap.

'"Not time! Why, I myself saw you playing cricket to-day for a good half-hour. What do you mean by telling me you had not time?" asked Cube.

'"I had not time, sir, because——" Snap tried to say, but Cube stopped him with that abominable trick of his, you know it.

'"Yēēs, Hales, yēēs! Yēēs, Hales, yēēs! So you had no time, Hales! Yēēs, Hales, yēēs!"

'"No, sir, I was obliged to——"

'"To tell me a lie, sir! Yēēs, Hales, yēēs."

'Here Snap's beastly temper gave out, and instead of waiting till he got a chance of telling his story properly to old Cube, who, although he loves mathematics and hates a lie, is a good chap after all, he deliberately mimicked the old chap with—

'"Nōō, sir, nōō! Nōō, sir, nōō!"

'Of course the other fellows went into fits of laughter, and old Cube had fits too, only of another kind, and I expect I shall get "fits" from the Head for trying to get the young idiot off for this match. But I really don't see how we can get on without him,' Winthrop added, as he left his friend at the door, and plodded with a heavy heart up to the head-master's sanctum.

What happened there the narrator of this truthful story does not pretend to know. The inside of a headmaster's library was to him a place too sacred for intrusion, and it was only through the foolish persistence of certain unwise under-masters that he was ever induced to enter it. Whenever he did, he left it with a note of recommendation from that excellent man to the school-sergeant. It was not quite a testimonial to character, but still something like it, and always contained an allusion to one of the most graceful of forest trees, the mournful, beautiful birch. I am told that this is the favourite tree of the Russian peasant. I dare say. I am told he is still uneducated. It was education which, I think, taught me to dislike the birch.

But I am wandering. The only words which reached me as I stood below, wondering if my leave out of bounds would be granted or not—and I had very good reasons for betting on the 'not'—were these:

'Very well, if he is no good as a bat it won't much matter. I'll do what I can for you, only win the toss and go in first.'

He was a good fellow, our Head, and from Winthrop's face as he came downstairs I expect that he thought so.

I was quite right about that leave out of bounds. The head-master felt, no doubt quite properly, that on such a day as the day of the Loamshire match, when there were sure to be lots of visitors about, it would not do for one of the school's chief ornaments to be absent. It was very hard upon me because, you see, I could only buy twelve tarts for my shilling at the tuckshop, whereas if I had got leave out of bounds I could have got thirteen for the same money, only four miles from school! That sense of duty to the public which no doubt will lead me some day to take a seat in the House of Commons enabled me to bear up under my trouble, and about two o'clock I was watching the match with my fellows on the Fernhall playing fields.

Ah, me! those Fernhall playing fields! with their long level stretches of green velvet, their June sunshine and wonderful blue skies! What has life like them nowadays? On this day they were looking their very best, and, though I have wandered many a thousand miles since then, I have never seen a fairer sight. Forty acres there were, all in a ring fence, of level greensward, every yard of it good enough for a match wicket, and the ring-fence itself nothing but a tall rampart of green turf, twelve or fourteen feet high, and broad enough at the top for two boys to walk upon it abreast.

Out in the middle of this great meadow the wickets were pitched, and I really believe that I have since played billiards on a surface less level than the two-and-twenty yards which they enclosed. The lines of the crease gleamed brightly against the surrounding green, and the strong sun blazed down upon the long white coats of the umpires, the Fernhall eleven (or rather ten, for Snap was still absent), and two of the strongest bats in Loamshire.

But, though fourteen figures had the centre of the ground to themselves, there was plenty of vigorous, young life round its edges. There, where the sun was the warmest, with their backs up against the bank which enclosed the master's garden, sat or lay some four hundred happy youngsters, anxiously watching every turn of the match, keen critics, although thoroughgoing partisans. Like young lizards, warmed through with the sun, lying soft against the mossy bank, the scent of the flowers came to them over the garden hedge, and the soft salt breeze came up from the neighbouring sea. You could hear the lip and roll of its waves quite plainly where you lay, if you listened for it, for after all it was only just beyond that green bulwark of turf behind the pavilion. Many and many a time have we boys seen the white foam flying in winter across those very playing-fields, and gathered sea-wrack from the hedges three miles inland. By-and-by, when the match was over, most of the two-and-twenty players in it would race down to the golden sands and roll like young dolphins in the blue waves, for Fernhall boys swam like fishes in those good old days, and such a sea in such sunshine would have tempted the veriest coward to a plunge.

But the match was not over yet, although yellow-headed Frank Winthrop began to think that it might almost as well be. He was beginning to despair. It was a one-day match: the school had only made 156, while the county had only two wickets down for 93; of course there was no chance of a second innings; the two best bats in Loamshire seemed set for a century apiece; Poynter had lost his temper and seemed trying rather to hurt his men than to bowl them, and everyone else had been tried and had failed. What on earth was an unfortunate captain to do? Just then a figure in a long cassock and college cap, a fine portly figure with a kindly face, turned round, and, using the back of a trembling small boy for a desk, wrote a note and despatched the aforesaid small boy with it to the rooms of the Rev. Erasmus Cube-Root. A minute or two before, Winthrop had found time to exchange half-a-dozen words with 'the Head' whilst in the long field, and now he turned and raised his cap to him, while an expression of thankfulness overspread his features. The two Loamshire men at the wickets were Grey and Hawker, both names well known on all the cricket-fields of England, and one of them known and a little feared by our cousins at the Antipodes. This man, Hawker, had been heard to say that he was coming to Fernhall to get up his average and have an afternoon's exercise. It looked very much as if he would justify his boast. He was an aggravating bat to bowl to, for more reasons than one. One of his tricks, indeed, seemed to have been invented for the express purpose of chaffing the bowler.

As he stood at the wicket his bat was almost concealed from sight behind his pads, his wicket appeared to be undefended, and all three stumps plainly visible to his opponent. Alas! as the ball came skimming down the pitch the square-built little athlete straightened himself, the bat came out from its ambush, and you had the pleasure of knowing that another six spoiled the look of your analysis. If he was in very high spirits, and you in very poor form, he would indulge in the most bewildering liberties, spinning round on his heels in a way known to few but himself, so as to hit a leg ball into the 'drives.' Altogether he was, as the boys knew, a perfect Tartar to deal with if he once got 'set.'

Grey, the other bat, was quite as exasperating in his way as Hawker, only it was quite another way. He it was who had broken poor Poynter's heart. You did not catch him playing tricks. You did not catch him hitting sixes, or even threes; but neither did you catch him giving the field a chance, launching out at a yorker, or interfering with a 'bumpy' one. Oh, no! It didn't matter what you bowled him, it was always the same story. 'Up went his shutter,' as Poynter feelingly remarked, 'and you had to pick up that blessed leather and begin again.' Sometimes he placed a ball so as to get one run for it, sometimes he turned round and sped a parting ball to leg, and sometimes he snicked one for two. He was a slow scorer, but he seemed to possess the freehold of the ground he stood upon. No one could give him notice to quit. Such were the men at the wicket, and such the state of the game, when a tall, slight figure came racing on to the ground in very new colours, and with fingers which, on close inspection, would have betrayed a more intimate acquaintance with the ink-pot than with the cricket-ball. Although it would have been nearer to have passed right under the head-master's nose, the new-comer went a long way round, eyeing that dignitary with nervous suspicion, and raising his cap with great deference when the eye of authority rested upon him. As soon as he came on to the ground he dropped naturally into his place, and anyone could have seen at a glance that, whatever his other merits might or might not be, Snap Hales was a real keen cricketer. When a ball came his way there was no waiting for it to reach him on his part. He had watched it, as a hawk does a young partridge, from the moment it left the bowler's hands, and was halfway to meet it already. Like a flash he had it with either hand—both were alike to him—and in the same second it was sent back straight and true, a nice long hop, arriving in the wicket-keeper's hands at just about the level of the bails.

But Winthrop had other work for Snap to do, and at the end of the over sent him to replace Rolles at short-slip.

'By George, Towzer, they are going to put on Snap Hales,' said one youngster to another on the rugs under the garden hedge.

'About time, too,' replied his companion; 'if he can't bowl better than those two fellows he ought to be kicked.'

'Well, I dare say both you and he will be, if he doesn't come off to-day. I expect it was your brother who got him off his lines to-day, and he won't be a pleasant companion for either of you if the school gets beaten with half-a-dozen wickets to spare.'

Towzer, the boy addressed, was brother to the captain of the eleven, and his fag. Snap Hales, when at home, lived near the Winthrops, so that in the school, generally, they were looked upon as being of one clan, of which, of course, Frank Winthrop was the chief. Willy Winthrop was Towzer's proper name, or at least the name he was christened by; but anyone looking at the fair-haired jolly-looking little fellow would have doubted whether his godfathers were wiser than his schoolfellows. No one would ever have dreamed of him as a future scholar of Balliol, nor, on the other hand, as a sour-visaged failure. He was a bright, impertinent Scotch terrier of a boy, and his discerning contemporaries called him Towzer.

But we must leave Towzer for the present and stick to Snap. Everyone was watching him now, and none more closely or more kindly than the man whom Snap considered chief of his born enemies, 'the Head.' 'Yes, he is a fine lad,' muttered that great man, 'I wish I knew how to manage him. He has stuff in him for anything.' And indeed he might have, though he was hardly good-looking. Tall and spare, with a lean, game look about the head, the first impression he made upon you was that he was a perfect athlete, one of Nature's chosen children. Every movement was so easy and so quick that you knew instinctively that he was strong, though he hardly looked it; but his face puzzled you. It was a dark, sad-looking face, certainly not handsome, with firm jaw and somewhat rugged outlines, and yet there was a light sometimes in the big dark eyes which gave all the rest the lie, and made you feel that his masters might be right, after all, when they said, 'There is no misdoing at Fernhall of which "that Hales" is not the leader.'

At any rate he appeared to be out of mischief just now.

'Round the wicket, sir?' asked the umpire as Snap took the ball in hand.

'No, Charteris, over,' was the short reply, as Hales turned to measure his run behind the sticks.

'What! a new bowler?' asked Hawker of the wicket-keeper as he took a fresh guard; 'who is he?'

'An importation from the Twenty-two; got his colours last week,' answered Wyndham, and a smile spread over Hawker's face, as he saw in fancy a timid beginner pitching him half-volleys to be lifted over the garden hedge, or leg-balls with which to break the slates on the pavilion.

But Hawker had to reserve his energy for a while, being much too good a cricketer to hit wildly at anything. With a quiet, easy action the new bowler sent down an ordinary good-length ball, too straight to take liberties with, and that was all. Hawker played it back to him confidently, but still carefully, and another, and another, of almost identical pitch and pace, followed the first. 'Not so much to be made off this fellow after all,' thought Hawker, 'but he will get loose like the rest by-and-by, no doubt.' Still it was not as good fun as he had expected. The fourth ball of Snap's first over was delivered with exactly the same action as its predecessors, but the pace was about double that of the others and Hawker was only just in time to stop it. It was so very nearly too much for the great man that for a moment it shook his confidence in his own infallibility. That momentary want of confidence ruined him. The last ball of the over was not nearly up to the standard of the other four; it was short-pitched and off the wicket, but it had a lot of 'kick' in it, and Hawker had not come far enough out for it. There was an ominous click as the ball just touched the shoulder of his bat, and next moment, as long-slip remarked, he found it revolving in his hands 'like a stray planet.'

Don't talk to me of the lungs of the British tar, of the Irish stump orator, or even of the 'Grand Old Man' himself! They are nothing, nothing at all, to the lungs we had in those days. It was Snap's first wicket for the school, and Snap was the school's favourite, as the scapegrace of a family usually is, and caps flew up and fellows shouted until even Hawker didn't much regret his discomfiture if it gave the boys such pleasure. He was very fond of Fernhall boys, that sinewy man from the North, and, next to their own heroes, Fernhall liked him better than most men. Even now they show the window through which he jumped on all fours, and many a neck is nearly dislocated in trying to follow his example.

In the next over from his end Hales had to deal with Grey, and he found his match. He tried him with slow ones, he tried him with fast ones, he tried to seduce him from the paths of virtue with the luscious lob, to storm him with the Eboracian pilule or ball from York. It was not a bit of good, up went the shutter, and a maiden over left Snap convinced that the less he had to do with Grey the better for him, and left Grey convinced that Fernhall had got a bowler at last who bowled with his head. Was it wilfully, I wonder, that Snap gave Grey on their next meeting a ball which that steady player hit for one? It may not have been, and yet there was a grin all over the boy's dark face as he saw Grey trot up to his end. That run cost Loamshire two batsmen in four balls—one bowled leg before wicket, and the other clean-bowled with an ordinary good-length ball rather faster than its fellows.

Those old fields rang with Hales's name that afternoon, and at 6.30, thanks chiefly to his superb bowling, the county had still two to score to win, and two wickets to fall. One of the men still in was Grey. At the end of the over the stumps would be drawn, and the game drawn against the school, even if (as he might do) Snap should bowl a maiden. That, however, could hardly be; even Grey would hit out at such a crisis. At the very first ball the whole school trembled with excitement. The Loamshire man played well back and stopped a very ugly one, fast and well pitched, but it would not be altogether denied, and curled in until it lay quiet and inoffensive, absolutely touching the stumps.

Ah, gentlemen of Loamshire! if you want to win this match why can't you keep quiet? Don't you think the sight of that fatal little ball, nestling close up to his wicket, is enough to disconcert any batsman in the last over of a good match? And yet you cry, 'Steady, Thompson, steady!' Poor chap, you can see that he is all abroad, and the boy's eyes at the other end are glittering with repressed excitement. He is fighting his first great battle in public, and knows it is a winning one. There is a sting and 'devil' in the fourth ball which would have made even Grace pull himself together. It sent Thompson's bails over the long-stop's head, and mowed down his wicket like ripe corn before a thunder-shower.

And now the chivalry of good cricket was apparent; Loamshire had no desire to 'play out the time.' Even as Thompson was bowled, another Loamshire man left the pavilion, ready for the fray. If it had been 'cricket,' Hawker, the Loamshire captain, would have gladly played out the match. As it was, his man was ready to finish the over. As the two men passed each other the new-comer gave his defeated friend a playful dig in the ribs, and remarked, 'Here goes for the score of the match, Edward Anson, duck, not out!'

As there was only one more ball to be bowled, and only two runs to be made to secure a win for Loamshire, I'm afraid Anson hardly meant what he said. Unless it shot underground or was absolutely out of reach, that young giant, who 'could hit like anything, though not much of a bat,' meant at any rate to hit that one ball for four. By George, how he opened his shoulders! how splendidly he lunged out! you could see the great muscles swell as he made the bat sing through the air, you could almost see the ball going seaward; and yet—and yet——

The school had risen like one man; they had heard that rattle among the timber; they knew that Snap's last 'yorker' had done the trick; cool head and quick hand had pulled the match out of the fire, and even his rival Poynter was one of the crowd who caught young Hales, tossed him on to their shoulders, and bore him in triumph to the pavilion, whilst the chapel clock struck the half-hour.

Boys in the fifth form at Fernhall shared a study with one companion. Monitors of course lived in solitary splendour, with a bed which would stand on its head, and allowed itself to be shut up in a cupboard in the corner. Small boys who had not attained even to the fringe of the school aristocracy lived in herds in bare and exceedingly untidy rooms round the inner quads. Even in those days there were monitors who were worshippers of art. Some of them had curtains in their rooms of rich and varied colouring; one of them had a plate hung up which he declared was a piece of undoubted old Worcester. Tomlinson was a great authority on objects of virtù, and a rare connoisseur, but we changed his plate for one which we bought for sixpence at Newby's, and he never knew the difference. Then there was one fellow who had several original oil paintings. These represented farmyard scenes and were attributed indifferently to Landseer, Herring, and a number of other celebrated artists. Whoever painted them, these pictures were the objects of more desperate forays than any other property within the school limits. I remember them well as adorning the room of a certain man of muscle, to whom, of course, they belonged merely as the spoils of war. The rightful owner lived three doors off, but I don't think that he ever had the pluck to attempt to regain his own.

However, in the small boys' rooms there were none of these luxuries of an effete civilisation. There was a book-shelf full of ragged books, none of which by any chance ever bore the name of anyone in that study; there was a table, a gas-burner, a frying-pan, and a kettle. These last-named articles might have been seen in every study at Fernhall, from the study of the monitor to that of the pauper, as we called that unfortunate being who had not yet emerged from the lower school. In the long nights of winter, when the wild sea roared just beyond the limits of their quad, and the spray came flying over the sea-wall to be dashed against their study windows, all Fernhall boys had a common consolation. They called it brewing: not the brewing of beer or of any intoxicating liquor, but of that cheering cup of tea which consoles so many thousands, from the London charwoman to the pig-tailed Chinaman, from the enervated Indian to the half-frozen Russian exile in Siberia. At first the headmasters of Fernhall tried hard to put down this practice. Sergeants lurked about our passages, confiscated our kettles, carried away the frying-pans full of curly rashers from under our longing eyes, and 'lines' and flagellations were all we got in exchange. At last a new era began. A great reformer arrived, a 'Head' of liberal leanings and wide sympathy. This man frowned on coercion, and, instead of taking away our kettles, gave us a huge range of stoves on which to boil them. From a cook's point of view, no doubt, the range of stoves was a great improvement on the old gas-burner, but, in spite of the liberality of the 'Head,' small clusters of boys still stood night after night on those old study tables and patiently fried their bacon over the gas.

Unfortunately this was not the worst of their misdoings. Besides the appetising smell of the bacon and the delicious aroma of chicory or tea, there was too often a strong flavour of 'bird's-eye' or 'latakia' about the passages. Almost to a man, the school smoked. How it had crept in I don't pretend to know, but the habit had been growing in the school for years until it was almost universal. This was the one thing which our new head-master would not tolerate at any price, and it was pretty well understood throughout the school that his dealings with the first offender detected in the act would be short and severe. About the time of the Loamshire match he had taken to beating up our quarters in person, not, I think, from any desire to detect the smokers in the act, but from a hope that the fear of his coming might act as a deterrent. About a week after Snap Hales's great bowling feat, Fernhall was brewing as usual. The dusk had fairly set in; a crowd of boys were jostling one another with the cans and frying-pans at the great public stoves, and Snap and many others were breaking school-rules as usual in their own studies. Mind, I am pledged to serve up my boys au naturel and not smothered in white sauce, so that if you don't like my menu you had better take warning in time. The bacon had been finished, the hot rolls from the tuckshop had been submitted to digestions which were capable of dealing even with hot rolls and butter, and now Snap Hales, Billy Winthrop, and one Simpson were desperately endeavouring to enjoy, or appear to enjoy, the forbidden pleasures of tobacco. Billy had an elaborately carved meerschaum between his teeth, while Snap lay full length on an extemporised divan, making strange noises and strange faces in his endeavours to get on terms with a 'hubble-bubble.' Billy's jaws ached with the weight of the meerschaum, and Snap was as blown with trying to make his instrument of torture draw as if he had been running the school mile. Simpson was in a corner cutting up some 'sun-dried honeydew,' which he had procured in a cake—'such,' he said, 'as the trappers of the North-West always use.' To tell the truth, he liked 'whittling' at that cake of tobacco with his knife a great deal better than smoking it, for the first two or three whiffs invariably sent a cold chill through his frame and a conviction that, like Mark Twain, he had inadvertently swallowed an earthquake.

Suddenly the boys stopped talking; there was a heavy rap at the door, preceded by a vain attempt to open it, and followed by the command, in deep tones, to 'open this door.'

'Nix! by Jove!' whispered Simpson, whiter now than ever with fright.

'Rot!' replied Snap unceremoniously. 'It's only that fool Lane, up to some of his jokes. Go to Bath, Legs,' he added at the top of his voice.

'Open this door at once,' thundered someone on the other side, while lock and hinge rattled beneath the besieger's hands.

'Don't you wish you may get it, old chap,' 'Shove away, and be hanged to you,' 'Try your skull against the panel, blockhead,' and several similar remarks, were now hurled at the enemy by those in the study. Meanwhile, preparations for repelling an assault were rapidly being made.

'Boys, open this door, don't you know who is speaking to you?' said the voice once more.

'Oh yes, we know,' laughed Snap, 'and we are getting ready to receive you, sir.'

'Deuced well old Legs imitates the Head, doesn't he?' whispered Billy Winthrop.

'Not badly,' answered Snap in the same tone. 'Have you got everything ready?' he added.

'Yes,' said Billy; 'but let me try my fire-arm first,' and, dipping the nose of a large squirt into the inkpot, he filled it, and then discharged it at a venture through the key-hole. The result was satisfactory. From the sounds of anger and hasty retreat in the passages the boys guessed that the shot had told, and indulged in a burst of triumphant laughter in consequence. But the enemy was back again in a minute wrenching furiously at the door, which now began to give.

'Let us die in the breach,' cried Snap, catching up a large mop, which he had used earlier in the day to clean his study floor, and emptying over it the remains of the cold coffee. 'Billy, stand by with your blunderbuss. Simpson, at the next shove let the door go!' he whispered, and the boys took up their places—Snap with his mop in rest opposite the entrance, Simpson with his hand on the key, and Billy's deadly weapon peeping over his leader's shoulder. At the next assault Simpson let the door go, and Hales rushed headlong out to meet the foe, getting the whole of Billy's charge down the back of his neck as he went. Someone knocked up the mop, so that it cannoned from him to another of the attacking party, whom it took fairly in the face, plastering him up against the opposite wall, a full-length portrait of 'the Head!'

For once Snap's spirits deserted him. The mop fell from his nerveless hand. He even forgot to say that he did not do it. It was too gross a sin even for a schoolboy to find excuses for. Nor had 'the Head' much to say—partly, perhaps, because 'mops and coffee' was not a favourite dish with him, and he had had rather more of it at his first essay than he cared to swallow, and partly, no doubt, because (diplomat though he was) for the life of him he could not remember what was the dignified thing to do under such unusual circumstances. The Sergeant recovered himself first.

'They've all been smoking, Sir!' he asserted maliciously. 'I suppose I'd better take their pipes.'

'Yes, Sergeant, and their names,' replied the Head.

'No need of that,' muttered our implacable foe. 'I know this here study better nor ever a one in Fernhall.'

'Hales, and you, Winthrop minor, report yourselves to me in my library after morning school to-morrow,' said the Head, and, slowly turning, the great man went, his mortar-board somewhat on one side, while down the long cassock which he wore the streams of coffee ran.

Two minutes after his departure, No. 19, the scene of the fray, was full of friends and of sympathisers.

'You'll get sacked, of course,' remarked one of these, 'but,' he added, 'I don't see that there is anything worse than that which Old Petticoats can do.'

'You don't think he could hang us, for instance, eh, Legs?' asked Snap sarcastically. 'Well, you are a nice, cheerful chap, you are!' he added.

'Never mind, old fellow,' urged another, 'they will give you a good enough character for Sandhurst, and what do you want more?'

'You want a good deal for Sandhurst now, Viper!' replied Snap; 'they'd rather have a blind mathematician than a giant who didn't know what nine times nine is.'

In spite of their comforters our friends felt for at least five minutes that there was something in their world amiss. Then suddenly Snap began to laugh, quite softly and to himself at first, but the laugh was infectious, so that in half a minute every boy in the passage was holding his sides, and laughing until the tears ran down his cheeks. By-and-by inquiries were made for Simpson, who had not been seen since the opening of the door. In answer to the shouts addressed to him, a sepulchral voice replied, and after some search the unfortunate wretch was produced from behind the door, white with fear and tobacco-smoke, flat as a cake of his own beloved honeydew, his knees trembling, and his hair on end with terror. Luckily for him, he had drawn the door back upon himself, and had remained unnoticed behind it ever since.

In spite of the tragedy with which it had begun, the remainder of the evening was spent in adding one more to the works of art which adorn Boot Hall Row, to wit, one life-size portrait of the Very Reverend the Head-master of Fernhall, drawn upon the wall against which he had so recently been flattened, in charcoal, by one Snap Hales; while underneath was written, to instruct future generations:

IN MEMORIAM, JUNE 22, 1874.

'MOP FAUCIBUS HÆSIT'

It was all very well to keep a stiff upper lip when the other boys were looking on, but when Snap and Towzer got up to their dormitories they began to give way to very gloomy thoughts indeed. Snap Hales especially had a bad time of it with his own thoughts. It did not matter so much for young Winthrop. His mother was a rich woman and an indulgent one. His expulsion would grieve her, but he would coax her to forgive him in less than no time, he knew. It was very different for Snap. He had no mother, nor any relative but a guardian, who was as strict as a Pharisee, and too poor himself to help Snap, even if he had had the will to, which he had not. Over and over again Snap had been told that his whole future depended on his school career, and it appeared to him that that career was about to come to a speedy and by no means honourable end.

But that was not all. Snap's greatest friend on earth was his school-chum's mother. Mrs. Winthrop had always been almost a mother to Snap, and had won the boy's heart by the confidence she showed in him. Snap didn't like being expelled; he didn't like Towzer being expelled; but still less did he like the prospect of being told that he, Snap Hales, had led the young one into mischief. And yet that was what was before him. Snap was sitting on the edge of his bed, half undressed, and meditating somewhat in this miserable fashion, when a bolster caught him full in the face. Looking up quickly, he caught sight of a face he knew grinning at him over his partition. It was one of B. dormitory. B. had had the impertinence to attack F. That bolster was the gage of battle. Silently Snap slipped out, bolster in hand. Someone had relit the gas and turned it up as high as he dared. Round and under it were ten or a dozen white-robed figures, armed with what had once been pillows, but now resembled nothing so much as thick ropes with a huge knot at the end.

A week ago Snap had crept into B. dormitory and driven a block of yellow soap well home into the open mouth of the captain of B. That hero's snores had ceased, but he had sworn vengeance as soon as he was able to swear anything. This then was B.'s vengeance, and the blows of the contending parties fell like hail. At first, respect for their master's beauty-sleep kept them quiet, and they fought grimly and quietly like rats in a corner. Gradually, though, their spirits rose, and the noise of battle increased. 'Go it, Snap, bash his head in,' cried one. 'Let him have it in the wind,' retorted another, and all the while even the speakers were fighting for dear life.

Suddenly a diversion occurred which B. to this day declares saved F. from annihilation. Unobserved by any of the combatants, a short man with an enormous 'corporation' had stealthily approached them, the first intimation which they had of his presence being the stinging cuts from his cane on their almost naked bodies. No one stopped for a second dose, so that the little man was pouring out the vials of his wrathful eloquence over a quiet and orderly room, when his gaze suddenly lit upon an ungainly figure trying to sneak unobserved into B. room. It was the miserable Postlethwaite, butt and laughing-stock of both rooms, who, having no taste for hard knocks, had been quietly learning his repetition for the next day by the light of a half-extinguished gas-jet in the corridor. Like a hawk upon its prey, the man with the figure pounced upon poor Postlethwaite.

'What brings you out here, sir?' he cried. 'What do you mean by it, sir? Why aren't you in bed, sir?'

'Please, sir,' began Postlethwaite.

'Don't answer me, sir,' thundered the master. 'You don't please me, sir! you're the most impertinent boy in the school, sir! Do me a thousand lines to-morrow, sir!'

'Please, sir——'

'Please, sir, please, sir, didn't I tell you not to say, please, sir?' cried the now furious pedagogue, fairly dancing with rage, butting at the trembling lout with his portly stomach, and driving his flaming little nose and bright eyes almost into his victim's face.

Poor 'Postle' was now a trembling white shadow nearly six feet high, penned in a corner, with the solid round figure of his foe dancing angrily in front of him.

'Please, sir, please, sir,' continued the master savagely. 'I'll please you, sir. I'll thrash you within an inch of your life. I'll cane you on the spot, sir!'

'Please, sir,' whined the miserable Postle, and this time he would be heard. 'Please, sir, I haven't got a spot, sir!'

An uncontrollable titter burst from all those hitherto silent beds, and the fiercest-mannered and kindest-hearted little man in Fernhall retired to his room, to indulge in an Homeric laugh, having set a score of impositions, not one of which he would remember next day. As for Postle, he crept away, quite ignorant that he had made a joke, but terribly nervous lest his enemy should again find him out.

Next morning, after lecture, Snap Hales was preparing with Billy Winthrop to meet his doom. They had hardly had time to exchange a dozen words with Frank Winthrop since the event of the night before, and now as they approached the Head's house they saw him coming towards them. His honest brown face wore a graver look than usual, and even Snap felt his friend's unspoken rebuke.

'You fellows need not go up to the Head,' he said quietly, 'the monitors have leave to deal with your case.'

That was all, and our school-hero passed on; but his words raised a world of speculation in our minds, for the whole school, of course, knew at once of this message to Snap and Towzer. Of course we understood that the monitors could, in exceptional cases, interfere, and from time to time used their privilege, but this was mostly in such disgraceful cases as were best punished privately. A thief might be tried and punished by the upper twelve, but not a mere breaker of school-rules. Even expulsion need not carry more than school disgrace with it, but the sentence of the monitors' court meant the cut direct from Fernhall boys, now and always, at Fernhall, and afterwards in the world. And what had even Hales or Towzer done to merit this?

The half-hour before dinner was passed in speculation. Then someone put up a notice on the notice-board, and we were told by one who was near enough to read it that it was to the effect that the monitors would hold a roll call directly after dinner in place of the usual first hour of school, and at this every Fernhall boy was specially warned to be present. There was no need to enforce this. Every name was answered to at that roll-call, and, for once, in every case by the boy who bore it.

The roll-call was held in the big schoolroom, a huge and somewhat bare building, full of rough ink-stained desks and benches, with a raised platform at the further end. On this, when the roll-call was over, stood the whole Sixth, with their prisoners, Snap and Towzer. Frank was there (the captain of the Eleven), and beside him even a greater than he, the School captain, Wyndham—first in the schools, first in the football-field, and first in everything, except perhaps cricket, at which his old chum Frank Winthrop was possibly a little better than he. I think that, much as we admired Winthrop, Wyndham was first of our school heroes. He could do so many things, and did them all well.

After everyone had answered his name a great hush of expectation fell upon us all. Then Wyndham came to the front and spoke. We had none of us heard many speeches in those days; would that at least in that respect life in the world were more like old school times! Perhaps it was because it was the first speech that we had ever heard that it roused us so. Perhaps it was a very poor affair really. But I know that we thought none of those old Athenians would have 'been in it' with Wyndham, and I personally can remember all he said even now. There were no masters present, of course, so that he spoke sometimes even in school slang, a boy talking to boys, and plunged right into the middle of what he had to say at once.

'You know,' he said, 'the scrape into which Hales and Winthrop minor have got themselves, and you probably know what the punishment is for an offence like theirs. What the punishment ought to be, I mean. Your Head-master is going to leave it to you to say what their punishment shall be; it is for you to say whether they shall go or stay.

'Oh yes, I know,' Wyndham continued as he was half of us with our hands raised, or our mouths open, 'you are ready to pronounce sentence now. But it won't do. You must hear me out first. I am here by Mr. Foulkes's permission to plead for Hales and Winthrop, and I had to beg hard for that permission, for the breach of school rules was as bad as it could be. Not, mind you, that our Head cared twopence about the mop; he laughed, when he told me of that, as much as you fellows could have done; but he won't have smoking at any price, and he is justly annoyed, because, in spite of the serious scrape they were in, two of the boys reported to him for the disturbance in F. dormitory last night were Hales and Winthrop. You know the Head remembers quite as well as we do how splendidly Hales pulled the Loamshire match out of the fire' (cheers), 'and he wants to keep him at Fernhall; but you know discipline is more essential in a school than a good bowler in an eleven.

'Now, then, as to this smoking. I am not going to talk any soft rubbish to you fellows. We have all smoked. I have certainly, and I told the Head that if Hales went I ought to go. It was a great deal worse in us than in you fellows. We ought to have set an example and did not. As to the sin of smoking I haven't a word to say. My father smokes, and he is the best man I know. There is no mention of tobacco in the Bible, so the use of it can't have been forbidden there. It isn't bad form, whatever some folks say, for the first gentleman in Europe sets us the example; but (and here is the point) it is a vice in a Fernhall boy because it is a breach of discipline. Now, that ought to be enough for boys half of whom want commissions in the army, the very breath of whose life is discipline; but, as we are discussing this thing amongst ourselves quietly, I'll tell you why I think the Head considers smoking a bad thing for us. We are all youngsters and have our work to do. To do it well, we want clear heads and sound minds. Tobacco is a sedative, and sends the brain to sleep—soothes it, say the smokers. Quite so, by rendering it torpid. Men don't paint or write with their pipes in their mouths. They may dream with them there before beginning the day's work, or doze with them there when the work is done, but down they go when the chapter has to be written or the portrait painted. As to the effect of tobacco on your bodies, you know as well as I do whether the men who win the big races are heavy smokers. Why! I would as soon eat a couple of apples before running the mile as smoke a pipe. Besides all this, we can't afford to smoke good tobacco, and bad tobacco is poison. We don't want loafers, and smoking means loafing. You don't play football or cricket with a pipe in your mouth, do you? No! and I want more players and fewer smokers. Old Fernhall has never yet taken a back seat in school athletics' (here the cheering silenced the speaker). 'Very well, then don't let her now; but, mind you, "jumpy" nerves won't win the Ashburton shield, or short winds break the mile record.

'I want the school to give up smoking. I've been here now longer than any of you, and I love the old school more than any of you can love her. She has made me, God bless her, and I want to do her one good turn before I leave' (here Wyndham's voice got quite husky, but I suppose it was only a touch of hay-fever). 'I believe most of you fellows would like to do me a good turn' (shouts of applause). 'I'm sure that there is no Fernhall boy to whom I would not do one' (here the very oak benches seemed in danger of being broken. The enthusiasm was getting dangerous). 'If that is so,' he continued, 'give up smoking until you leave Fernhall. The Head is sick of trying to stop smoking by punishment. He says that the whip is not the thing to manage a good horse with, and he believes heart and soul in his boys. He does not want to see the school fail in its sports. He doesn't want to sack Towzer and Snap' (dear old chap, he even knew our nicknames), 'but as head of this school, as colonel of our regiment, he must and will have discipline. So he puts it to you in this way, and he puts you on your honour as gentlemen to keep to his terms if you accept them.

'If you choose voluntarily to pledge yourselves to give up smoking as a body, he on his part will ignore the events of last night altogether' (wild excitement in the pit). 'Now, Fernhall, will you show you're worthy of such a brick as our Head? Will you do me one good turn before I leave? Will you keep Towzer and Snap, or your pipes?'

'Towzer and Snap! Towzer and Snap!' came the answer from four hundred boys' voices, in a regular storm of eager reply.

'Very well, hands up for the boys,' said the Captain, and a forest of hard young fists went up into the air.

'Hands up for the pipes,' cried Wyndham with a grin. Not a hand stirred.

'Bravo, gentlemen. I accept your promise. The monitors have handed over all their own pipes, cigars, and other smoking paraphernalia to the Head. We did that before coming to you. Now we want you to hand over all your pipes to us, to be labelled, stored, and returned when you leave. It is agreed, I suppose,' and not waiting for an answer he turned and shook hands with Snap and Towzer, and then, pushing them off the platform, he said, 'There, take them back, you fellows; they are a bad lot, I'm afraid, but I think you have bought them a bargain.'

Snap and Towzer hardly realised what had happened to them for the first few minutes. When they did they bolted up to the Head to thank him. No one ever saw Hales so subdued as he was that afternoon. He had pulled steadily against the powers that be ever since he had come to school, yet when he came down from the library all he could say was, 'By George, he's a trump. Why! he chaffed me about the mop, and wanted to know if we all used mops to clean out our brew-cans.'

The array of pipes, ranging from the black but homely 'cutty' to a chef d'œuvre in amber and meerschaum, which filled one of Mr. Foulkes's big cupboards, was a sight worth seeing, and if the time of our mile was not better next year it certainly was not worse: there were more players in the football field, and the fact that they had bought back their two favourites by a piece of self-denial did much to elevate the character, not only of the redeemed ones, but of the School itself.

For one whole term (until Wyndham left) not a pipe was smoked within the school limits, and if smoking ever did go on again it certainly never again became the fashion, but was looked on rather as a loafer's habit than as the badge of manhood.

For a week after the reprieve recorded in the last chapter Snap and Towzer went about like cats who had been whipped for stealing cream. They honestly desired not to be led into temptation, and hoped that no one would leave the jug on the floor. For a week, perhaps, even if this had happened, these two penitent kittens would have made believe that they did not see it.

The holidays were now rapidly approaching, and the glorious July weather seemed expressly sent for the gorgeous frocks and sweetly pretty faces which would soon adorn playground and chapel during 'prize week.'

Snap and Towzer were in Frank Winthrop's study, Towzer getting his big brother's tea ready, and Snap looking on. After a while the conversation turned upon a subject of immense interest, just then, to all Fernhall boys.

'Major,' said Snap to Winthrop the elder, 'what do you fellows think of the ghost?'

'Think!' replied the monitor with wonderful dignity, 'why, that you lower school fellows have been getting out of your dormitories and playing tunes upon combs, jew's-harps, and other instruments of music, when you ought to have been asleep, with a lump of yellow soap between your jaws to keep you quiet.'

'Oh, stow that,' replied Snap, 'fellows don't play such tunes as the Head has heard for the last week on jew's-harps and combs. Either those fellows who belong to the "concert lot" had a hand in it, or there is something fishy about it. I say, Frank, be a good chap and tell us, are the Sixth in it?'

'The Sixth in it, I should think not,' replied Winthrop; 'but I can't answer for all the monitors, even if I wanted to.'

Snap winked at Towzer at this rather cautious denial, remarking:

'Well, it is a good thing the ghost has not forgotten his music. He has been here every year since Fernhall was a school.'

'Yes,' broke in Billy, lifting his snub nose from the depths of an empty coffee-cup, 'and to-night is the night of the Ninth; the night, you know, on which it walks round the Nix's garden and across the lawn.'

'Does it?' quoth Frank. 'Well, if it is wise, it won't walk across that lawn to-night. If it does, it will get snuff, I can tell you.'

'Why, Major, why should it get "bottled" to-night more than any other night, and who is to "bottle" a ghost?' inquired Snap indignantly.

'Never you mind, young 'un, but you may bet your bottom dollar that if the ghost walks to-night it will be walking in the quad at punishment drill for the rest of this term.'

As this was all the boys could get from their senior, they had to be content with it, and before long took their departure. At the bottom of the stairs Snap took Billy's arm, and conferred earnestly with him as to what the great man's prophecy might mean.

'Well, you see,' said Towzer, looking abnormally wise, 'old Frank is precious thick with the Beauty' (a daughter of 'the Head'), 'and after the match the other day I saw them having a long talk together, and, unless I am mistaken, he was showing her just the way the ghost ought to come.'

'By Jove, Towzer,' cried Snap, 'Scotland Yard won't have a chance with you when you grow up. One of the "Shilling Shocker" detectives would be a fool to you. You've got it, my lad; there is a deep-laid and terrible plot on foot, as the papers say, and one aimed at a time-honoured and respected institution, our friend the ghost. Let's go and see Elizabeth.'

Now Elizabeth was a lady, if a kind heart and gentle ways with small boys could make her one, although the humble office which she held was that of needlewoman at Fernhall. In these degenerate days a maid-servant and a wife together are supposed to mend me, tend me, and attach the fickle button to the too often deserted shirt. But they are only supposed to. They don't as a matter of fact, and indeed the manner of life of my buttons is decidedly loose. But in those old days the ancient needle-woman of Fernhall wielded no idle weapon. Her needle and thimble were the sword and shield with which she attacked and overcame the untidiness of four hundred boys, and in spite of the wild tugging at buttons and collars as the Irishman of the dormitory sang out 'Bell fast,' 'Double in,' while the last of the chapel chimes were in the air, no clean shirt at any rate came buttonless to the scratch.

To Elizabeth, then, the boys betook themselves, and, being special favourites, she took them into her own little snuggery, and they had tea again. Oh no, don't feel alarmed, gentle reader: two teas, ten teas if you like, matter nothing to Fernhall boys—their hides are elastic, and even the pancakes of Shrove Tuesday merely cause a slight depression of spirits for the next twenty-four hours.

'Now, 'Lizabeth, you dear old brick, we want you to tell us something. What's up to-night at "the house"?'

'Nothing that I know of, Master Winthrop, except that some of them officers is a coming up from their barracks to dinner with Miss Beauty and the other young ladies as is staying here.'

'Oh! o—o—oh, as the man said when the brickbat hit him where he'd meant to put his dinner; and what, Lizzie darling, may they be going to do after dinner?'

'Piano-punching, I suppose, dear, and a little chess with the governor; and then what——?'

'Bed? It will be slow for them, won't it?'

'No, Master Hales, piano-punching indeed, when Miss Beauty plays sweet enough to wake the blessed dead.'

'Did wake them, "Grannie," the other night, didn't she, and they seem to have taken an active share in the musical part of the entertainment?'

'There's no talking with such a random boy as you, but there, if you want to know, that's just what they have all come about. They say that when Miss Beauty was going to bed the other night she heard that soft, wailing music, like what we hear here every year just about this time, and she was so sure that there was something really unnatural about it that the Professor has given her leave to sit up with the other guests, and Captain Lowndes, and the rest in the monitors' common room, to see if they can catch the ghost, and for goodness sake don't you say as I told you, but if you knows the ghost tell him not to walk to-night, as the Professor says such nonsense must be stamped out for good. There now!'

Poor old Elizabeth looked as if she had committed a crime, and puffed and blew and pulled at her two little chin tufts (for, alas, she was bearded like the pard) in a way that nearly sent the boys into convulsions at her own tea-table. But they contained themselves (and about three plates full of muffins), and by-and-by departed.

There was a long and earnest conversation in a certain study that night. There was a surplice missing from amongst the properties of the choir, and then the four hundred wended sleepily from chapel to their dormitories.

In half an hour the lights were out in all windows save those of the head-master's house; stillness fell upon Fernhall; a big bright moon came out upon the scene and made those long grass meadows gleam like the silver sea just beyond them; a bat or two whirled about above the master's orchard, and but for them, and the merry party up at the house, Fernhall, once the smuggler's home, now the busy public school, slept to the lullaby of the summer waves.

* * * * * *

Fernhall slept, its busy brain as quiet as if no memories of an evil past hung thickly round that grey old house by the sea. Could it be that such evil deeds were done there in the storied days of old? At least there was some ground for the country folks' legends and superstitions. Not a rood of ground under or around the 'House' was solid; it was all a great warren, only that the tunnelling and burrowing had been done by men and not by conies.

Under the basement of the head-master's house were huge cellars, such cellars as would have appeared a world too wide even for the most bibulous of scholars. A cupboard of very tiny dimensions would have held all the strong liquors which our Head drank in a year. These cellars had two entrances, one from the house, and the other half a mile away, below what was now low-water mark. For year by year the waves encroach upon Fernhall, and in time those old smugglers who made and used these vaults will get their own again. They, no doubt, many of them, have gone to Davy Jones's locker, but their chief sleeps sound on shore, in a stately vault, which blazons his name and his virtues to the world. In his day smuggling was a remunerative and genteel profession, and he and all his race were past masters in the craft. Living far from the great centres of life, upon a bleak and dangerous coast, little notice was taken of the quiet old squire who yearly added acre to acre and whiled away the cheerless days with such innocent pursuits as sea-fishing and yachting.

Fernhall yokels say that the last squire and his wife did not agree. She was not a native of the Fernhall moorland, but a soft south-country thing with a laugh in her eye and bright clothes on her back when she first came amongst them; a parson's daughter, some said, but no one knew and few cared. Very soon she grew, like the rest of the people round her, silent, serious, or sad—a quiet grey shadow, with the laugh and bright clothes stored away perhaps somewhere with her memories of that sunny south. All at once her face was missed from church and market, but no one cared to ask whither she had gone. Someone, with grim Fernhall humour, suggested that the Squire had added to the 'spirits' in his subterranean vaults.

That was all, then, and to-night was the anniversary of her strange disappearance. There are nights when the world is still and you can feel that she is resting. There are other nights when the stillness is as deep, nay, deeper; but it is not the stillness of rest. The silence is throbbing and alive with some sad secret, and the listening earth is straining to catch it. This was such a night. The whitely gleaming grass stretched away until it reached a vague land of moonlit shadows. The waves were almost articulate in their meanings. The leaves of the poplars kept showing their white underside in the moonlight, until the whole trees swung in the night breeze, a grove of sheeted spectres. Anyone watching the scene was at once seized with the idea that something was going to happen, and, like the watchful stars and bending trees, strained every nerve to listen.

At last it came, faint and far off, sad but unutterably sweet, a low wail of plaintive music—so low that at first it seemed the mere coinage of an overwrought fancy. Nearer it came, and nearer, now growing into a full wave of sound, now ebbing away—the mere echo of a sigh, but always coming nearer and nearer, until it seemed to pause irresolutely by the gate which divides the master's garden from the monitors' lawn. Was it another fancy, or were there for a moment a crowd of white, eager faces pressed against the window which looks upon that lawn? Fancy assuredly, for the moon now gleamed back blankly from the glass. For a moment a little cloud no bigger than a man's hand passed over the moon, and as it cleared away a deep-drawn sigh attracted the watcher's eyes to the garden gate. The moon was full upon it; you could see it shake if it shook ever so little. In that listening midnight you could almost hear the flowers whispering to each other, but the gate neither creaked nor shook, and yet someone had passed through it, someone with bent head, and slow, tired feet, who sighed and told the beads of her rosary as she passed. The moonlight played strange tricks that night; it seemed to cling to and follow that silent figure, leaving a white track on the dew-laden grass. And now it paused for one moment before that window, through which those tear-dimmed eyes had so often and so longingly turned towards her own loved south, and as she paused the silence broke, the window was dashed open, and three athletic figures, figures of men who feared neither man nor devil, sprang out with shouts of laughter, surrounded that white figure, still so strangely quiet, and demanded—its name! At the open window from which the three had issued were now gathered half a dozen ladies, looking half amused, half frightened. Among them was Beauty, the Head's daughter.

With boisterous laughter, that jarred harshly upon the stillness of that midsummer night, the three had dashed upon their prey. Why, then, do they pause? It seemed to those who watched that some whisper had reached their ears and chilled their courage. For one moment the figure's arms were raised aloft, and then the men recoiled, and it passed on as if unconscious of these things of clay, steady and stately, with head bent, slow feet, and hands which still told the rosary beads. For a moment it stood large and luminous on the skyline of that hill which overhangs the sea, the favourite 'look-out' of the old lords of Fernhall; for a moment it raised its sheeted arms as if calling down a curse upon the fated mansion, and then floated seaward and was gone.

The chapel-bell tolled one, and again the Fernhall ghost had baffled the inquisitive investigations of disbelieving men, and had asserted itself in spite of the nineteenth century, the —th Regiment, and the new Head-master. In vain Beauty sought an explanation from her discomfited cavaliers; all she could elicit was that there was something uncanny about it, something not fit for ladies to hear, and she had better go to bed and think no more about it. It would not come again for a year, anyway. So, at last, mightily dissatisfied, the ladies went, and when the men were driving home to barracks long and heartily pealed their laughter and gallant Captain Lowndes vowed again and again that 'That boy would make a right good soldier, sir, hang me if he wouldn't! What was it he said again, the young scoundrel? "I've not a rag on except this surplice, Captain, and, by Jove, if you don't take your hands off I'll drop that. If the ladies don't like me in the spirit, I must appear in the flesh."'

'Well, Snap, how are you this morning? You look very down in the mouth.'

'Yes, sir, I don't feel very lively,' replied Snap.

The speakers were Admiral Christopher Winthrop and our old friend Harold, or Snap Hales. The mid-summer term had come to an end, and the boys were all at home at Fairbury for the holidays. Frank and Billy Winthrop were somewhere about the home-farm, and the old Admiral was down at the bottom of the lawn, by the famous brook, intent on the capture of a certain 'sock-dollager' who had been fighting a duel with the sailor for the last three weeks. So far the cunning and shyness of the trout had been more than a match for the skill and perseverance of the red-faced, grey-haired old gentleman on the bank, but the Admiral had served a long apprenticeship in all field-sports, and it would go hard with him if that four-pounder did not, sooner or later, lie gasping at his feet.

'Try an alder, sir,' suggested Snap, who, though no fisherman himself, had long since learnt the name of every fly in the Admiral's book.

'No,' replied that worthy disciple of Walton, 'I'll give him just one more turn with the dun,' and, so saying, he proceeded with the greatest care to strain the gut of another of Ogden's beautiful little flies.

'But what is the matter with you, Snap, that you are not, as you say, very lively?' urged the Admiral, speaking with some difficulty, his mouth being at the moment full of dry gut.

'Characters came to-day, Admiral,' replied Snap; 'didn't you get Frank's and Billy's?'

'Yes, and a precious bad one Master Billy's was; the only good part of it was the writing. Mr. Smith writes:—"Hand-writing shows great improvement; is diligent and anxious to improve." Unfortunately Billy's writing speaks for itself, even if, like me, you can't read a word of it.' And the old man chuckled to himself at his own shrewdness.

'Frank's was good enough, I suppose, sir?' asked Snap.

'Yes, Hales, as good as it could be. Frank is one of the right sort. He can work like a—like a Winthrop (and the old boy swelled with pride), and play like a——'

'Vernon,' said a soft, sweet voice behind the Admiral, who, turning, found himself face to face with his sister-in-law, a slight, graceful woman, who was beautiful still, in spite of the grey in her hair and the lines which showed that trouble had not spared even sweet Dolly Vernon, as her friends had called her before she married the dead squire of Fairbury.

'Ah, Chris! Chris!' she cried, shaking her finger at him, 'what a vain old sea-dog you are! So, all my boy's virtues are Winthrop, and all his vices Vernon, are they? For shame, sir!'

The Admiral had been supreme on his own quarterdeck; he was still supposed to be supreme about the home farm and in the coverts. As a matter of fact, he was nothing of the kind, but simply his fair sister's most loyal henchman and most obedient slave. When his brother had died, leaving Mrs. Winthrop with two great boys to bring up and the estate to manage, the Admiral had at first acted as his sister-in-law's agent from a distance. As the years went on, and the boys grew up, the Admiral found that the management of the estate from a distance was more than he could undertake, so that at last he had settled in a little cottage in the park, and practically lived with his sister-in-law at the Hall.

'Yes, sister, yes,' replied the old gentleman apologetically, '"plays like a Vernon," of course that's what I meant; and you know,' he added slyly, 'that Dr. Foulkes said that his cricket was, if anything, better than his classics.'

'And how about his vices?' persisted Mrs. Winthrop.

'Pooh! Frank hasn't got any,' asserted her brother-in-law.

'Hasn't he?' she asked with a little doubtful smile; 'and what do you say to that, Harold? You are his bosom friend.'

Snap reddened up to the eyes.

'No, Mrs. Winthrop, I don't think he has. Dr. Foulkes seems to think they all belong to me. My uncle says that according to my character I have a monopoly of all the qualities undesirable in a boy who has his way to make in the world.'

Although he spoke jestingly, Mrs. Winthrop knew enough of Snap to see that there was a good deal of earnest in his jest. His guardian, Mr. Howell Hales, a solicitor in large practice, had never had time or inclination to do more than his bare duty by his fatherless nephew, so that Fairbury Court had become the boy's real home, and Mrs. Winthrop almost unconsciously had filled the place of mother to him.

'What is it, Snap,' she said now, laying her hand on his strong young arm, and looking up into his face inquiringly, 'have you got a worse character than usual?'

'Yes! worse than usual,' laughed Snap grimly; and then, seeing that his hard tone had hurt his gentle friend, his voice softened, and he added, 'Yes, Mrs. Winthrop, it is very bad this time, so bad that the Head doesn't want me to go back next term.'

'Not to go back next term? why, that's expulsion,' blurted out the Admiral.

'No, sir, not quite as bad as that; it's dismissal,' suggested Snap.

'I don't see any difference. Chopping straws I call that,' said old Winthrop.

'Splitting hairs don't you mean, Chris?' asked Mrs. Winthrop with a half-smile; 'but I see the difference, Snap. There is no disgrace about this, is there?'

'No, I didn't think so,' replied Snap, 'but my uncle says I am a disgrace to my family and always shall be.'

'He always did say that,' muttered the Admiral. 'Never mind what your uncle says; I mean,' added the old gentleman, correcting himself, 'don't take it too much to heart. You see he has very strict ideas of what young lads should be.'

'What is it that you have been doing, Snap? Is it too bad to tell me?' asked Mrs. Winthrop after a while.

For a moment the boy hung his head, thinking, and then raised it with a proud look in his eyes.

'No, dear,' he said, dropping unconsciously into an old habit, 'it isn't, and so it can't be very bad!' And with that he told the whole foolish story of his share in the smoking orgy, of his reprieve, of the mop incident and the bolster fight, and, last of all, of that Fernhall ghost.

At this part of the recital of his wrongdoings the Admiral's face, which had been growing redder and redder all the time, got fairly beyond control, and the old gentleman nearly went into convulsions of laughter. 'Shameful, sir; gross breach of discipline, sir; ha! ha! ha! "Don't like me in the spirit, had better take me in the flesh." Capital—cap—infamous, I mean, infamous. Your uncle never did anything like that, sir, not he,' spluttered the veteran; 'couldn't have done if he had tried,' he added sotto voce.

'But,' said Mrs. Winthrop, after a pause, 'what are you going to do, Snap?'

'My uncle wants me to go into the Church or Mr. Mathieson's office,' replied the boy.

'The Church or Mr. Mathieson's office—that is a strange choice, isn't it?' asked his friend. 'Which do you mean to do?'

'Neither,' answered Snap stoutly; 'I'm not fit for one, and I should do no good in the other. I shall do what some other fellows I know have done. I'll emigrate and turn cow-boy. I like hard work and could do it,' and half consciously he held out one of his sinewy brown hands, and looked at it as if it was a witness for him in this matter.

'What does your uncle say to that, Snap?' asked the Admiral.

'Not much, sir, bad or good. He says I am an ungrateful young wretch for refusing to go into Mr. Mathieson's office, and that I shall never come to any good. But, then, I've heard that from him often enough before,' said Snap grimly, 'and I think he will let me go, and that is the main point.'

'And when do you mean to start?' asked the Admiral.

'Oh, as soon as he will let me, sir. You see, my father left me a few hundred pounds, so that I dare say when Mr. Hales sees that my mind is made up he will let me go. You don't think much worse of me, I hope, sir, do you?'

'Worse of you?' said the old sailor stoutly, 'no! You are a young fool, I dare say, but so was I at your time of life. Come up to lunch!' And, planting his rod by the side of the stream, he turned towards the house, Mrs. Winthrop and Snap following him.

At lunch Snap had to tell the whole story again to Billy and Frank, but when he came to the point at which he had decided to 'go west,' instead of eliciting the sympathy of his audience, he only seemed to rouse their envy.

'By Jove,' said Frank, 'if it wasn't for this jolly old place I should wish that I had got your character and your punishment, Snap!'

For a week or more both the Admiral and his sister had been very unlike their old selves, so quiet were they and distrait, except when by an effort one or the other seemed to rouse to a mood whose merriness had something false and strained in it, even to the unobservant young eyes of the boys. Why was it that at this speech of Frank's Mrs. Winthrop's sweet eyes filled with sudden tears, and that piece of pickle went the wrong way and almost choked the Admiral? Perhaps, if you follow the story further, you may be able to guess.

After lunch they all wandered down again to the trout-stream, where 'Uncle's Ogden,' as they called the Admiral's rod, stood planted in the ground, like the spear of some knight-err ant of old days. It was a lovely spot, this home of the Winthrops—such a home as exists only in England; beautiful by nature, beautiful by art, mellowed by age, and endeared to the owners by centuries of happy memories. The sunlight loved it and lingered about it in one moss-grown corner or another from the first glimpse of dawn to the last red ray of sunset. The house had been built in a hollow, after the unsanitary fashion of our forefathers; round it closed a rampart of low wooded hills, which sheltered its grey gables from the winter winds; and in front of it a close-cropped lawn ran from the open French windows of the morning-room to the sunlit ripples of the little river Tane as it raced away to the mill on the home-farm.

For five centuries the Winthrops had lived at Fairbury, not brilliantly, perhaps, but happily and honestly, as squires who knew that their tenants' interests and their own were identical; sometimes as soldiers who went away to fight for the land they loved, only to come back to enjoy in it the honours they had won. It was a fair home and a fair name, and so far, in five centuries, none of the race had done anything to bring either into disrepute. No wonder the Winthrops loved Fairbury.

But I am digressing, and must hark back to the Admiral, who has stolen on in front of his followers and is now crouching, like an old tiger, a couple of yards from the bank of the brook. Above him, waving to and fro almost like that tiger's tail, is the graceful, gleaming fly-rod, with its long light line, which looks in the summer air no thicker than gossamer threads. In front of the old gentleman's position, and on the other side of the stream, is a crumbling stone wall, and for a foot or two from it, between it and the Admiral, the water glides by in shadow. Had you watched it very carefully, you might, if you were a fisherman, have detected a still, small rise, so small that it hardly looked like a rise at all. Surely none but the most experienced would have guessed that it was the rise of the largest fish in that stream. But the Admiral was 'very experienced,' and knew almost how many spots there were on the deep, broad sides of the four-pounder whose luncheon of tiny half-drowned duns was disturbing the waters opposite. At last the fly was dry enough to please him, and Admiral Chris let it go. A score of times before, in the last few days, he had had just as good a chance of beguiling his victim, and each time his cast had been light and true, so that the harshest of critics or most jealous of rivals (the same thing, you know) could have found no fault in it. Each time the fly, dry as a bone and light as thistle-down, had lit upon the stream just the right distance above the feeding fish, and had sailed over him with jaunty wings well cocked, so close an imitation of nature that the man who made it could hardly have picked it out from among the dozen live flies which sailed by with it. But a man's eyes are no match for a fish's, and the old 'sock-dollager' had noticed something wrong—a shade of colour, a minute mistake in form, or something too delicate even for Ogden's fingers to set right—and had forthwith declined to be tempted. But this time fate was against the gallant fish. The Admiral had miscalculated his cast, and the little dun hit hard against the crumbling wall and tumbled back from it into the water 'anyhow.'

Though a mistake, it was the most deadly cast the Admiral could have made. A score of flies had fallen in the same helpless fashion from that wall in the last half-hour, and as each fell the great fish had risen and sucked them down. This fell right into his mouth. He saw no gleam of gut in the treacherous shadow, he had seen no upright figure on the bank for an hour and a half; he had no time to scrutinise the fly as it sailed down to him, so he turned like a thought in a quick brain, caught the fly, and knew that he too was caught, almost before the Admiral had had time to realise that he had for once made a bad cast. And then the struggle began; and such is the injustice of man's nature that even gentle Mrs. Winthrop did not feel a touch of compassion for that gallant little trout, battling for his life against a man who weighed fifteen stone to his four pounds, and had had as many years to learn wisdom in, almost, as the fish had lived weeks. No doubt she would have felt sorry for the fish if she had thought of these things, but then you see she didn't think of them.

'By George! I'm into him,' shouted the Admiral.