Title: Two Colored women with the American Expeditionary Forces

Author: Addie W. Hunton

Kathryn M. Johnson

Release date: March 6, 2023 [eBook #70223]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Brooklyn Eagle Press

Credits: hekula03, Quentin Campbell, Thiers Halliwell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note

The cover image was restored by Thiers Halliwell and is placed in the public domain.

See end of this document for details of corrections and other changes.

Left-click any illustration to see a larger version.

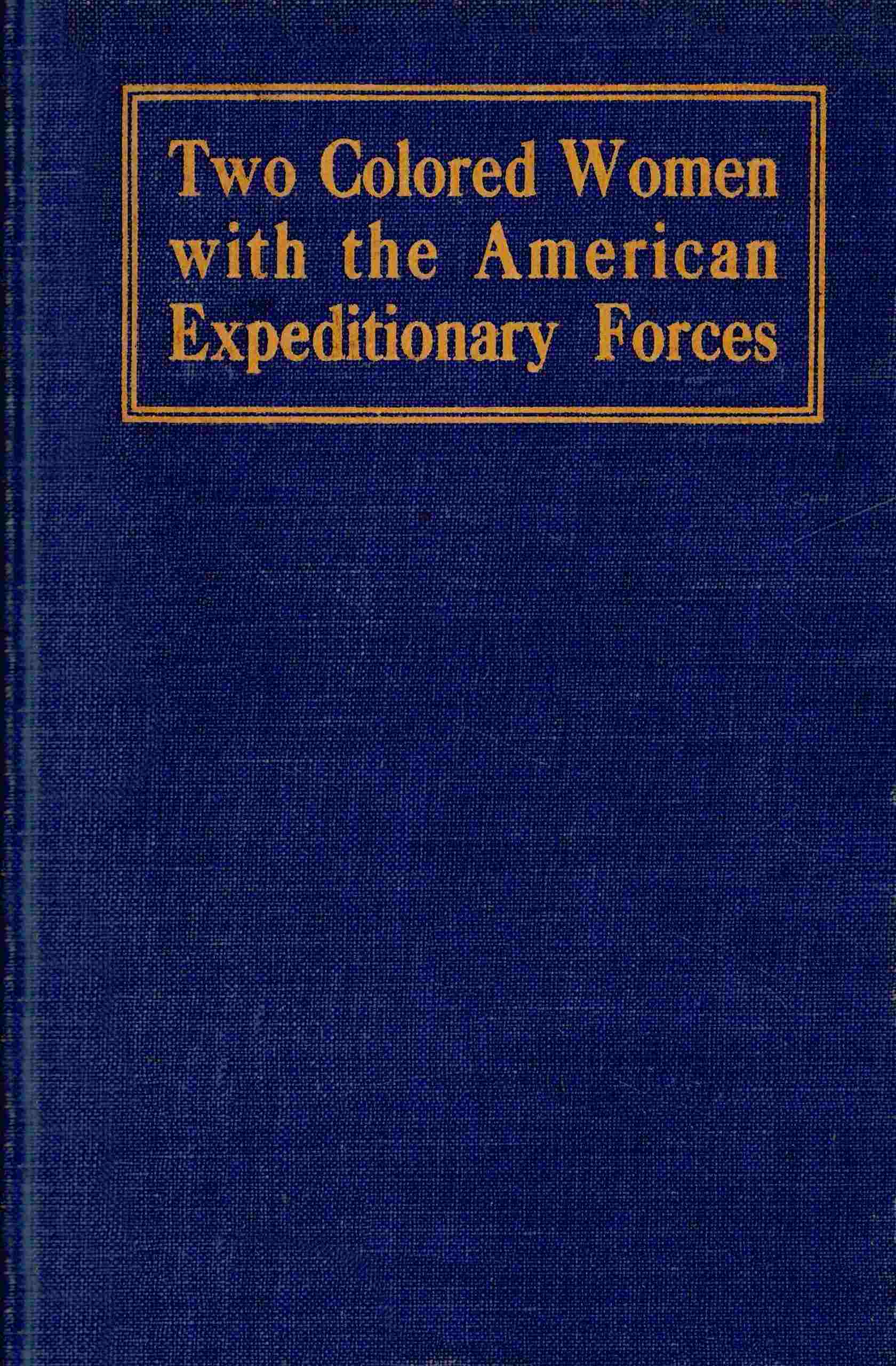

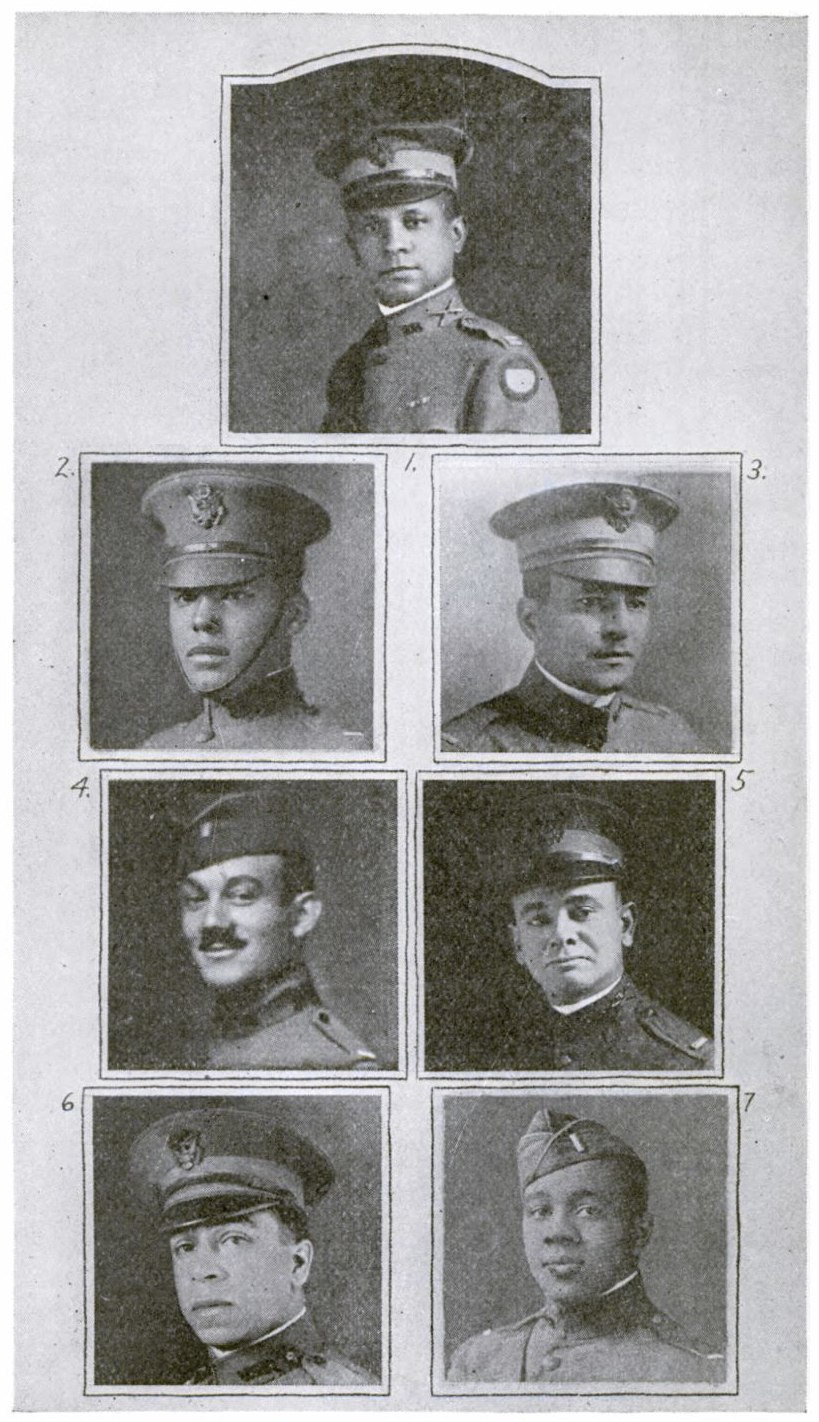

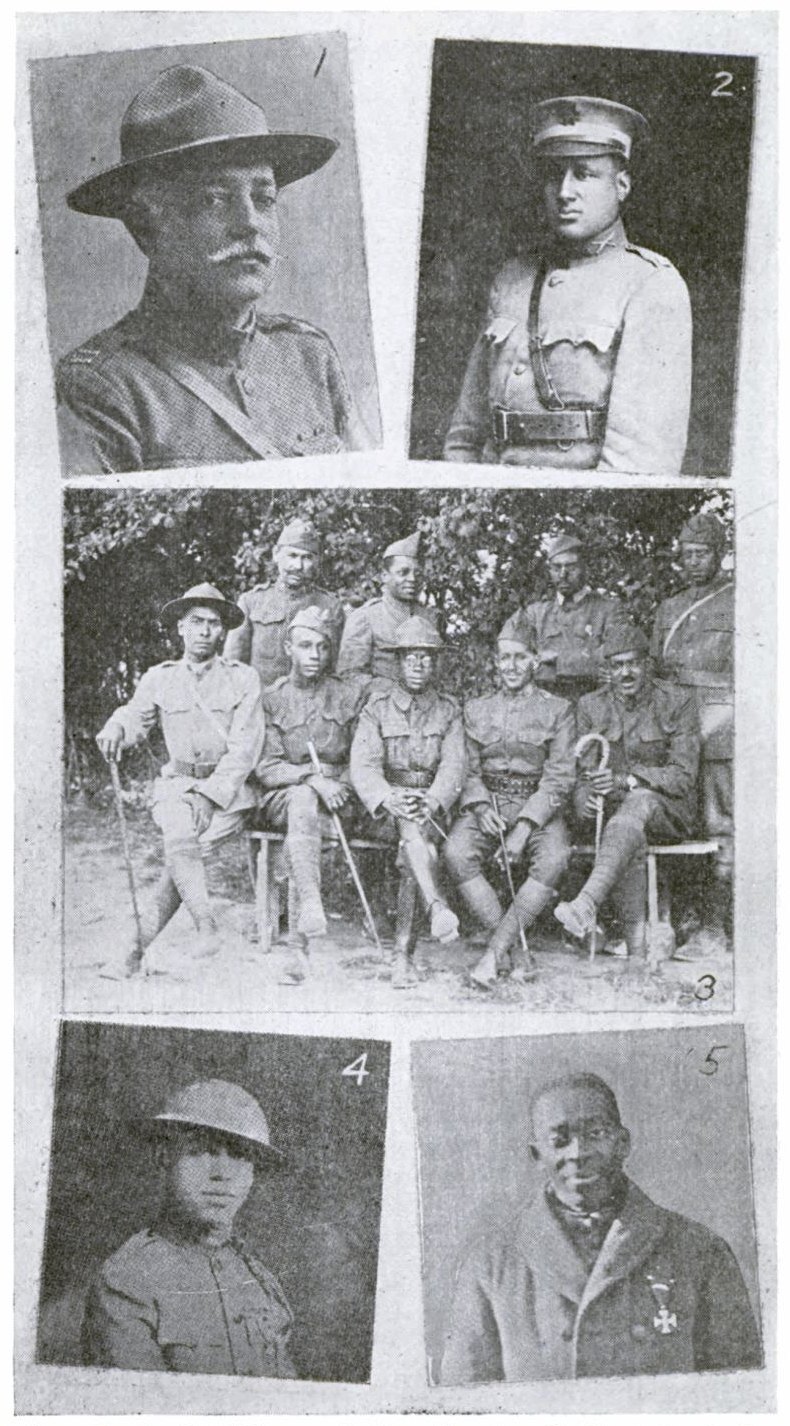

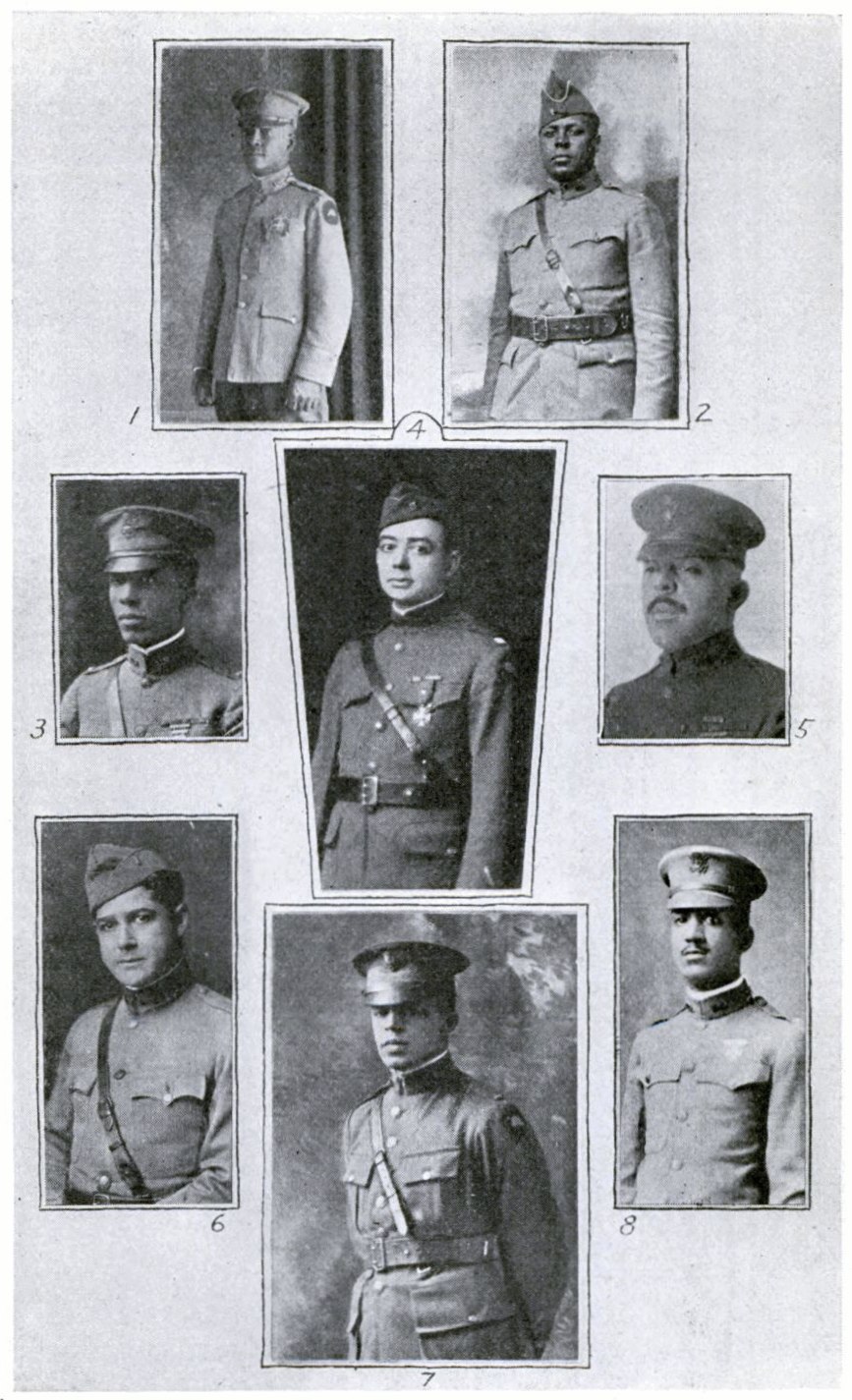

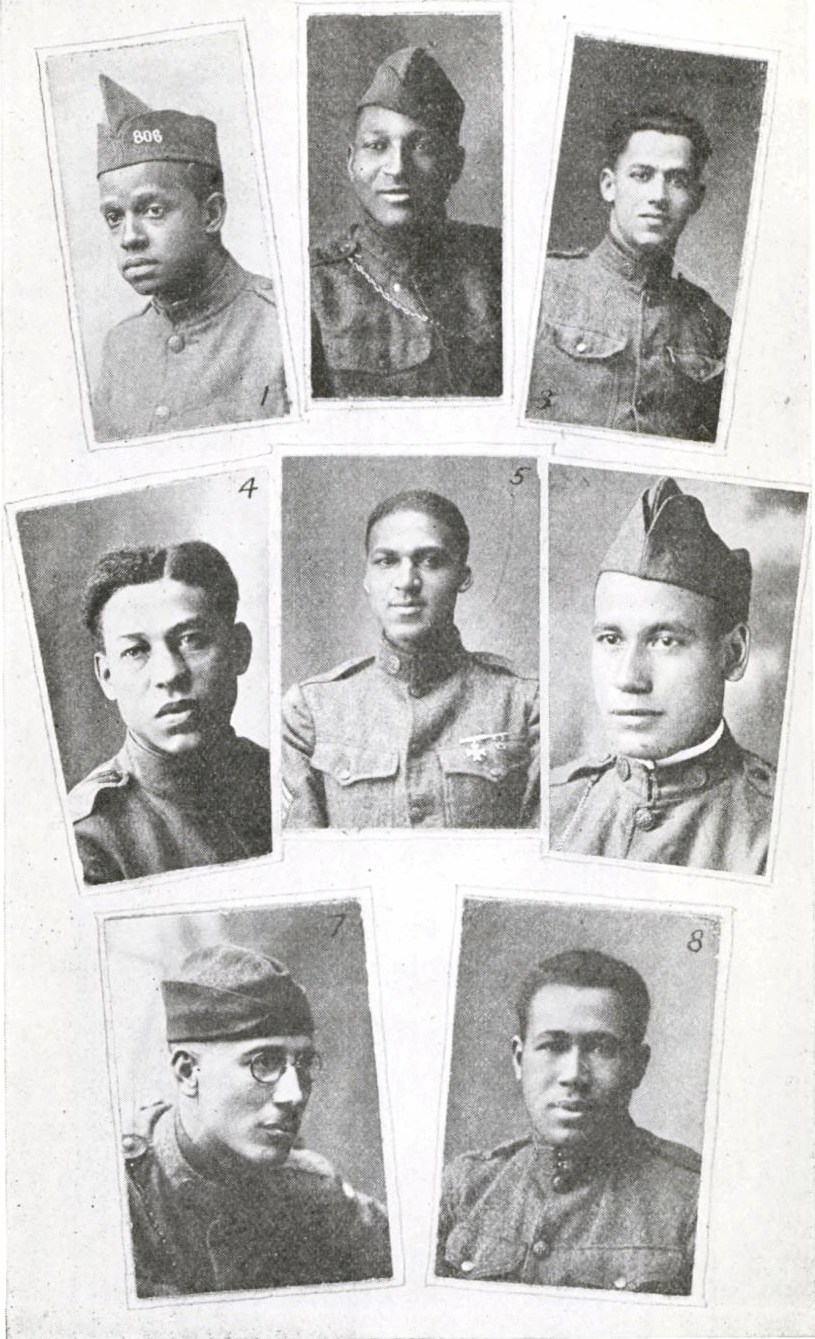

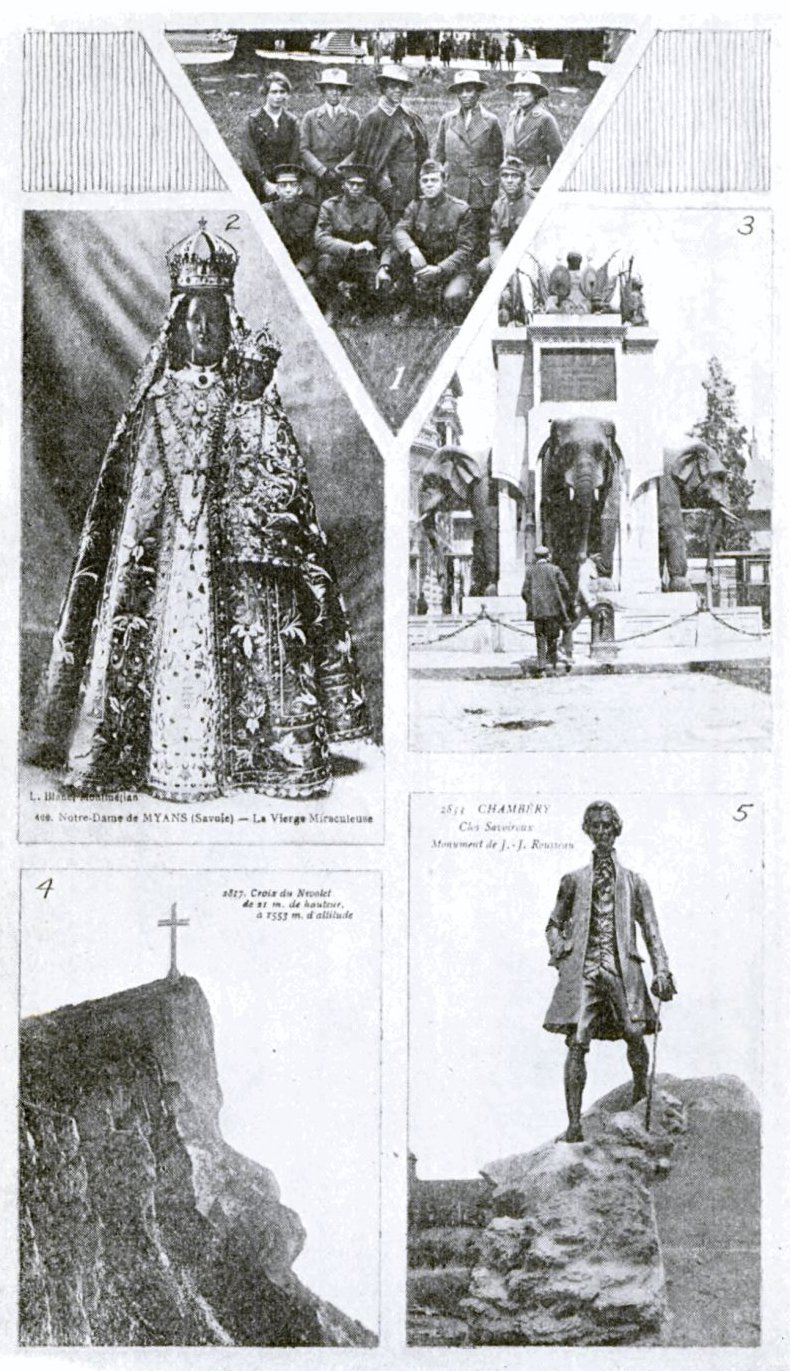

I. and II. Col. Franklin A. Denison and Lt. Col. Otis B. Duncan, the highest ranking colored officers in France. III. Col. Charles Young, the highest ranking colored officer in the United States Army. IV. Major Rufus M. Stokes. V. Major Joseph H. Ward.

By

ADDIE W. HUNTON

and

KATHRYN M. JOHNSON

Illustrated

BROOKLYN EAGLE PRESS

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

Copyright, 1920, by Kathryn M. Johnson

and

Addie W. Hunton

All Rights Reserved

Dedicated to the women of our race, who gave so trustingly and courageously the strength of their young manhood to suffer and to die for the cause of freedom.

With recognition and thanks to the authors quoted in this volume and to the men of the A. E. F. who have contributed so willingly and largely to the story herein related.

| †Foreword | 5 |

| †The Call and the Answer | 9 |

| †First Days in France | 15 |

| *The Y. M. C. A. and Other Welfare Organizations | 22 |

| *The Combatant Troops | 41 |

| †Non-Combatant Troops | 96 |

| †Pioneer Infantries | 112 |

| †Over the Canteen in France | 135 |

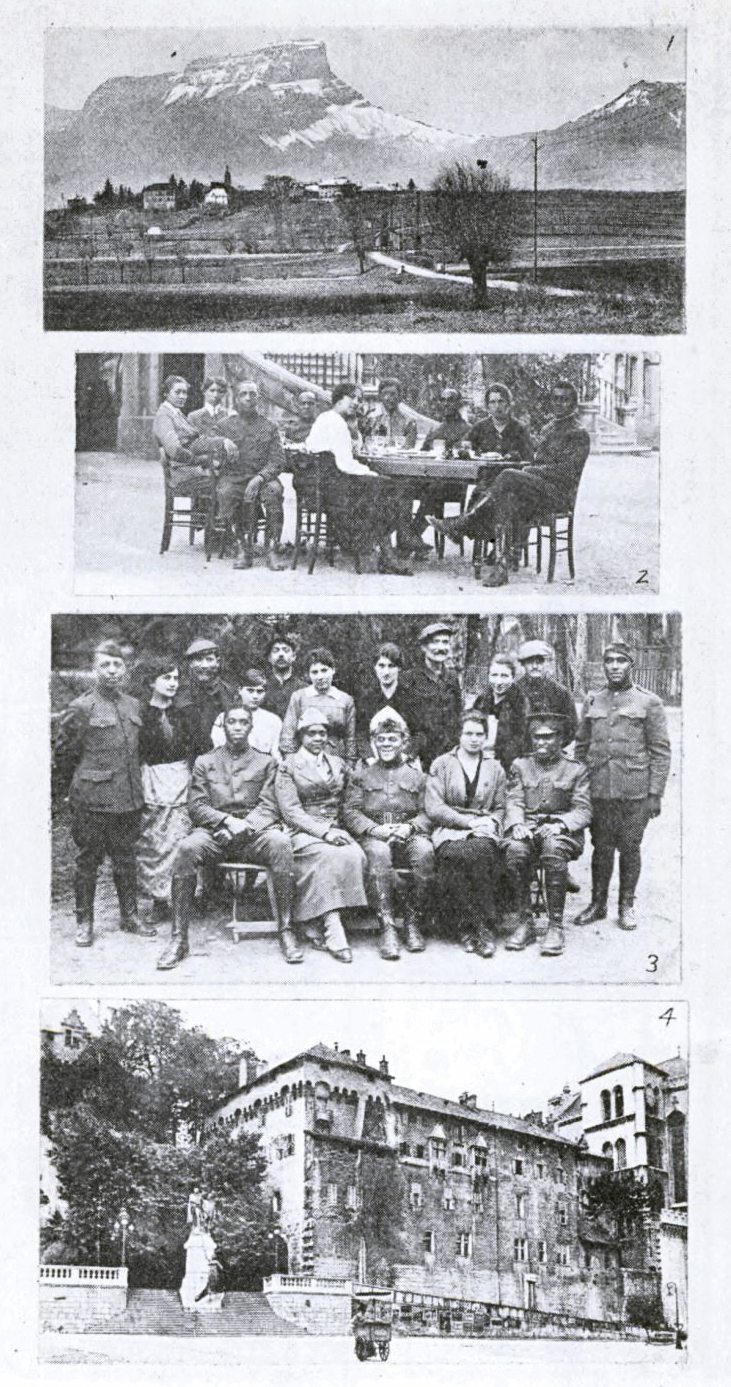

| †The Leave Area | 159 |

| *Relationships with the French | 182 |

| *Education | 199 |

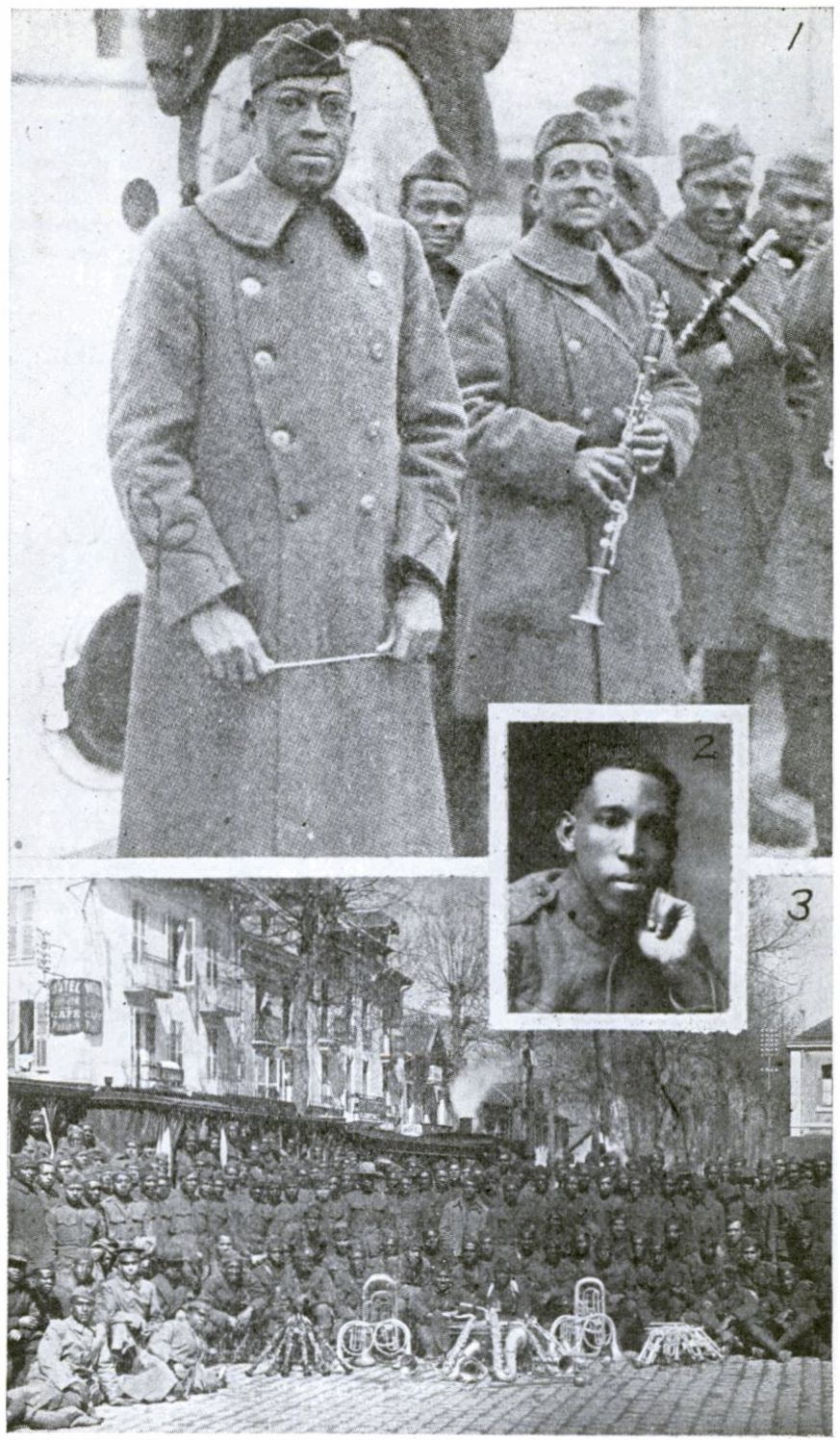

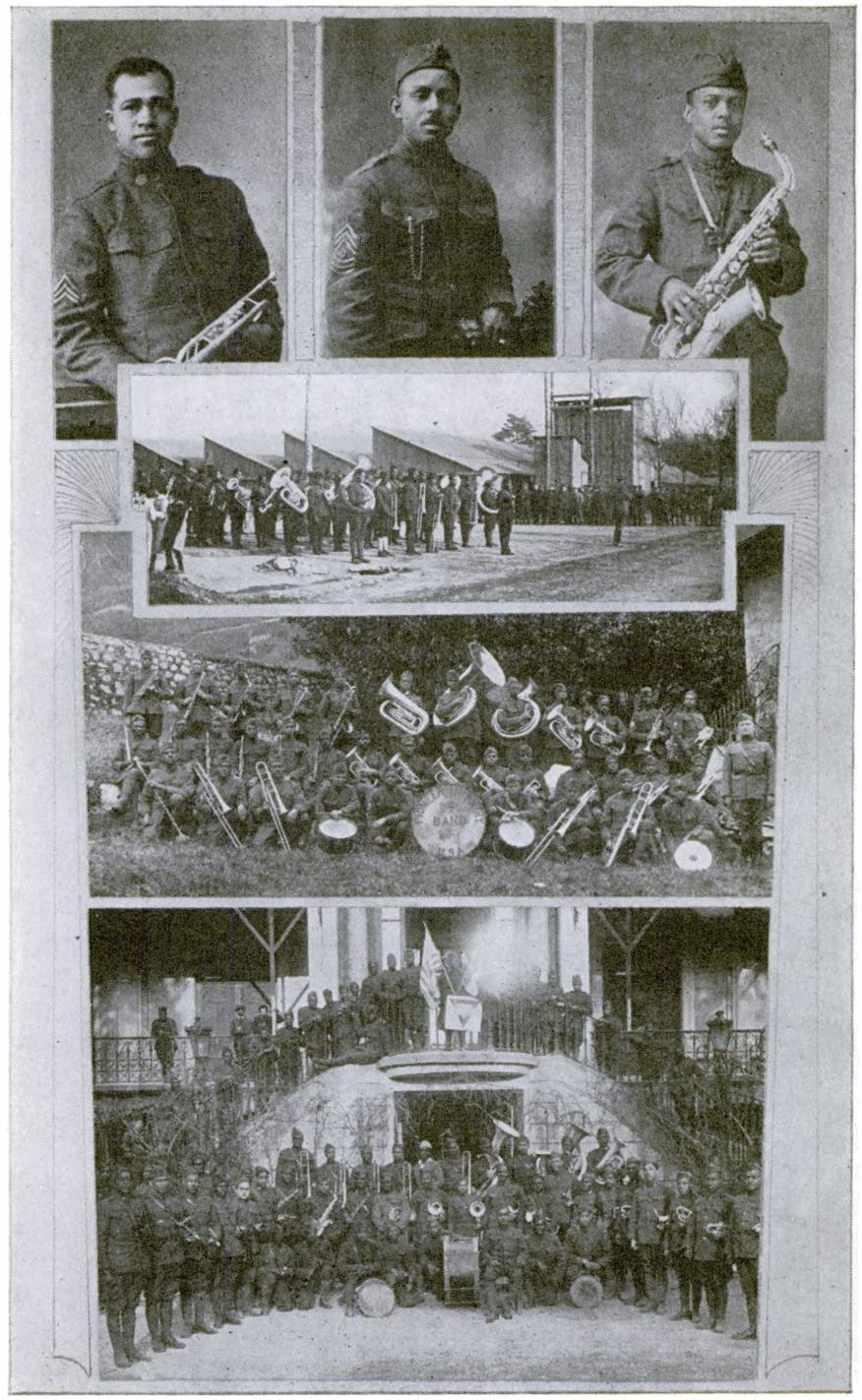

| †The Salvation of Music Overseas | 217 |

| *Religious Life Among the Troops | 227 |

| †Reburying the Dead | 233 |

| †Stray Days | 241 |

| *Afterthought | 253 |

| ———— | |

| † By Addie W. Hunton. | |

| * By Kathryn M. Johnson. | |

REMARKABLE achievements are worthy of remarkable acclaim. This justifies our desire to add still another expression to those already written relative to the career of the colored American soldiers in the late World War. The heroic devotion and sacrifice of that career have won appreciative expressions from those who, from a personal point of view, know but little of the details. How much more then should they who walked side by side with those brave men in France realize the merit of their service and chant their praises. Surely they should be best able to interpret sincerely and sympathetically, lovingly and gratefully for our soldiers, as they may not for themselves, something of the vicissitudes through which they passed as members of the American Expeditionary Forces.

We feel, too, that almost fifteen months of continuous service that carried us practically over all parts of France, and afforded a heart to heart touch with thousands of men, is a guarantee of the knowledge and devotion that has inspired this volume.

Memories will ever crowd the mind and cause the eye to kindle with the light of loving sympathy as we recall our months of service at the base of supplies on the coast of France. For there we were privileged to learn something of the life and spirit of the stevedores, labor battalions and engineers whom we served—more than 25,000 of them—who, through all the desolate days of war, never ceased in their efforts to connect America with Chateau Thierry, Verdun, Sedan, St. Mihiel and other great battle centers of France. There we beheld combat troops, filled with the spirit of adventure arriving fresh from America to follow the trail to the already war-worn front. And there came also those regiments that we called Pioneer Infantries, the imprints of whose deeds of duty and daring are stamped all over France.

We followed our depot companies and engineers through those isolated stretches and wastes where they performed tasks so essential in the plans for victory.

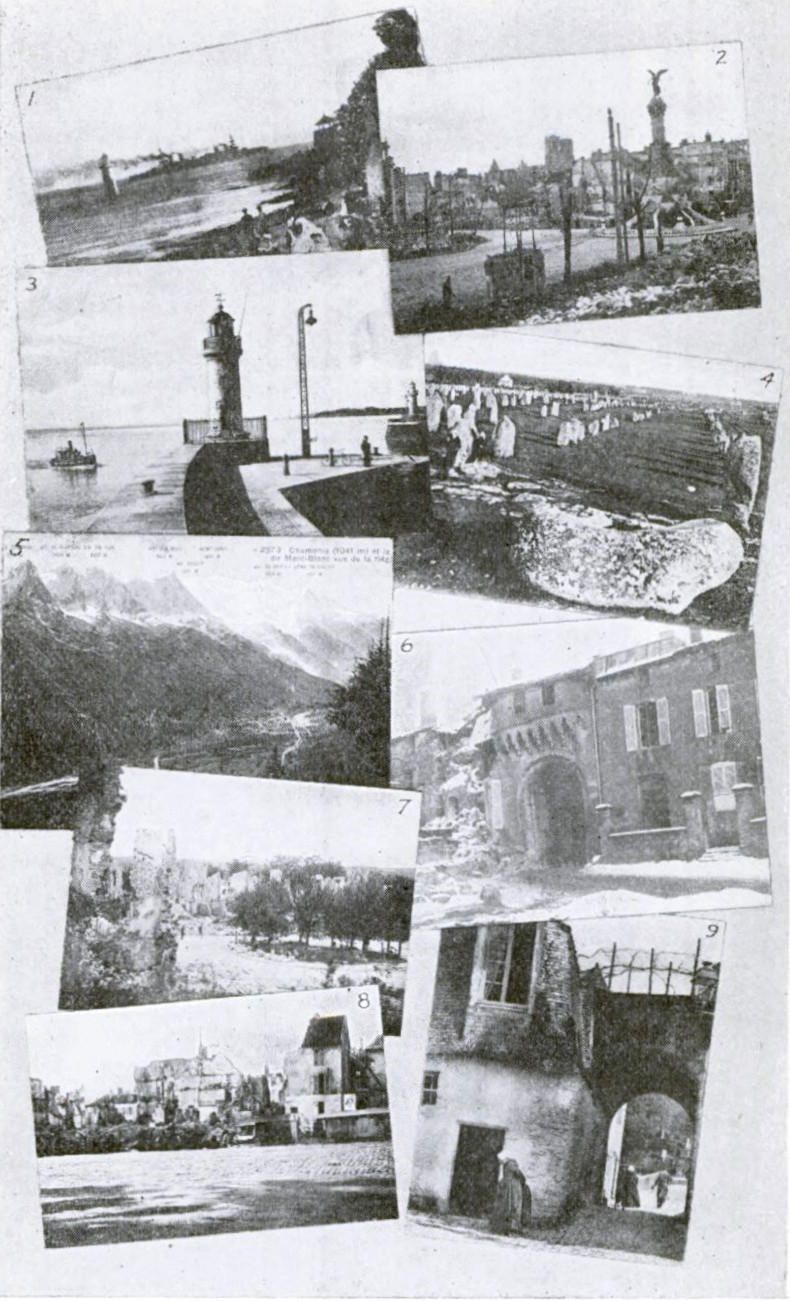

After many months we went away from the confusion of war to beautiful southern France. There we worked to make happy the days of the men who came for rest and recreation to that wonderful Alpine region of Savoie. There in the Leave Area, by the side of shimmering Lake Bourget, we learned something more of the life of our soldiers as they fought or worked on French soil. Every week, for five months or more, a thousand or so men poured into Chambery and Challes-les-Eaux, and we saw in them the gladness or depression of their service.

Far to the North we took our way, over devastated areas, and dwelt midst the loneliness of poppy-covered fields in “No Man’s Land.” In those Cities of the Dead, we beheld our soldiers summoned to the supreme test of their loyalty and patience in the re-burying of the fallen American heroes.

Back again to the coast we went to join in the great “Battle of Brest”—the battle for the morale of the tired, anxious soldier waiting for transportation back to home and native friendships. For six weeks, from early morning to midnight, our huts at Pontanezen echoed to the tread of thousands of feet. During that period it is estimated that fifty thousand colored soldiers passed through the camp. Battle scenes and war adventures were ended, but the memory was yet deeply poignant, and often silences revealed the depths of experiences beyond the power of all words. Because of all this, we strive to humbly recount the heart throbs of our heroes.

Again the authors have written because to them it was given to represent in France the womanhood of our race in America—those fine mothers, wives, sisters and friends who so courageously gave the very flower of their young manhood to face the ravages of war. That we then should make an effort to interpret with womanly comprehension the loyalty and bravery of their men seems not only a slight recompense for all they have given, but an imperative duty.

We believe that undervaluation is a more subtle and unkind foe than overvaluation, so that we have not refrained in our story from a large measure of praise for a large measure of loyal and patriotic service, performed ofttimes under the most trying conditions.

We have had no desire to attain to an authentic history, but have rather aimed to record our impressions and facts in a simple way. But wherever historical facts have been used, it has been largely to justify the measure of praise accorded and to offset the criticisms of prejudiced minds.

This volume is written at a time when, after the shock of terrific warfare, the world has not yet found its balance—when, in the midst of confusion, justice and truth call loudly for the democracy for which we have paid.

If for all time the world is to be free from the murderous scourge called war, it must make universal and eternal the practical application of the time-worn theory of the brotherhood of man. May this volume written in all love and truth, though perhaps imperfectly, serve to lift some souls nearer to this ideal.

[9]

THE great thrilling, throbbing spirit of war did not reach the United States until that memorable spring of 1918. Then it came in a mighty tidal wave of vitalized force and energy. Our country, woefully late, was at last awakened to terrific speed. Great human cargoes and innumerable tons of supplies held transports and ships to their guards. Cities, towns and villages were suddenly transformed into great inspirational centers of war activity. Meanwhile we were watching the map of France, noting with deep anxiety the stubborn resistance of the war-weary French to the slow but certain advance of the enemy. Once again it moved with pitiless and determined face toward Paris—the heart stream of all France. Although General Joffre had once checked the German raiders and sent them to confusion and death, their lesson was not yet learned and they were again throwing human force against the principles of right. But now that so many of the heroes of France had fallen, how would the foe be met? Surely there was urgent need of a strong army to stand at the Marne once again.

The American Forces already in France were calling not only for help, but haste. Suddenly, we found ourselves included in this call with passport in hand. Not all at once did its full significance come to us, but in those waiting days, as we sat at our desk and tried to concentrate on[10] war-work at home, quite unconsciously, we would find the passport in our hands and our eyes searching the war map on the wall. Slowly we began to realize that we were to make an effort to reach “over there” where thousands of our own men had gone and other thousands must go.

Then one dark afternoon, as the rain came down in torrents, the buzz of the telephone at our elbow told us our time had come. We asked no questions, for those were days of deep secrecy, but looked for the last time at the war map in the office—studied it as never before, wondering where in that war-wrecked country across the Atlantic we would find our place of service. We breathed a little prayer, said good-bye to our fellow workers, knowing that tomorrow we would be on the ocean eastward bound and went out to meet her who was to try the unknown with us and who would prove the faithful companion of all our “overseas” life. There was no sleep that night for us; friends came and went, and two ever faithful ones lingered lovingly for the last possible service.

Of necessity, in those days, there were strict laws and many sentries at the docks, so that when we entered there was little hope of rejoining our loved ones for a second adieu. We took the precaution, however, to beg them to wait for a final sign of parting and while going through the ordeal of having baggage examined and passed, learned that our sailing time had been delayed four hours. We determined upon an effort to rejoin those waiting so patiently outside the dock. Making[11] a wide detour, we passed quietly by the sentry who was striding to and fro with gun on his shoulder. Now whether he could not quite grasp the fact that colored women were really going to join the American Expeditionary Forces, or had seen the close clinging hug given one of the women by the little lad and lassie near him—or whether the twinkle in our eye did it, we do not know—but we passed, and in that very act much of the sadness of our parting was removed. We rode across 14th Street, a jolly party, had our lunch and returned to the dock, where from an upper pier with smiles and tears all mingled, we waved a final adieu.

How wonderful is love at such a time! There they stood lovingly and lingeringly—the cousin of one of us who had come all the way from the Middle West for this leave-taking; two brave children with the dear little woman whose true and tried devotion made us know that she would mother them as her own till we came back to take her place; and that other friend with whom we had crossed in peaceful days, joyously roaming over England and the Continent. That last picture remained with us, to cheer us for all the months of our absence.

And now there was no turning back. Months ago the war zone was just six hundred miles from the coast of France—but now the United States was at war, and as we stepped on the gang plank, war-zone passes were surrendered. We were crusaders[12] on a quest for Democracy! How and where would that precious thing be found?

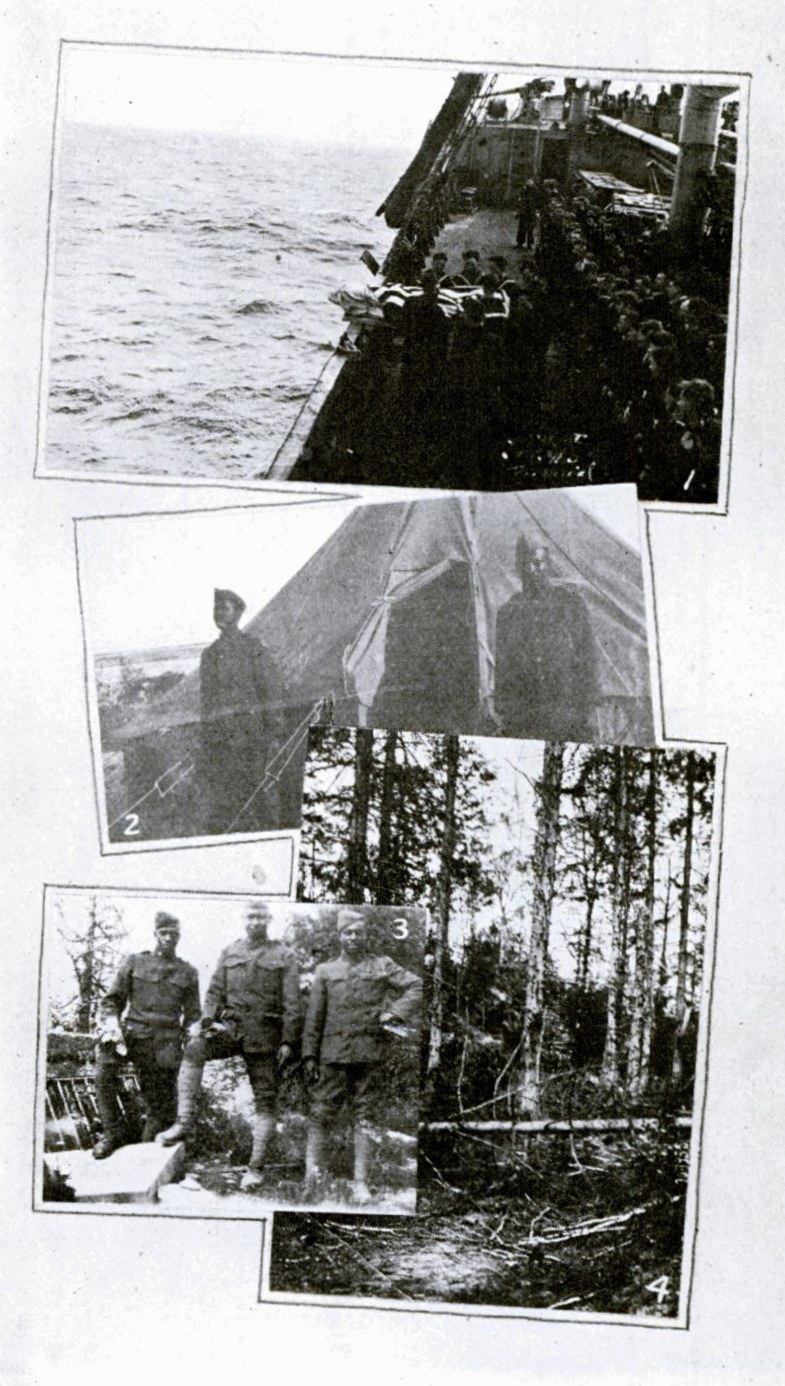

What a spectacle was that sun-lit bit of New York harbor that June afternoon! All about us were transports filled with khaki-clad men, crowding port holes, every bit of deck and perched on every beam. These thousands of youths of fearless and deathless spirit, would quickly follow us over there, and many of them, in war’s thunderous tumult, quickly pay the supreme sacrifice. How they whistled, sang and cheered as our little French liner, Espagne, steamed slowly away from them to brave alone the sea peril of that time!

First to the south and then to the east we sailed over seas of glass, with never a storm or gale, but tremendous speed. They were cheerful days, although they were ever-watchful ones, with life-belts close at hand. No lights showed on deck at night nor on the whole horizon. Yes, just once! By the big blazing cross at the foremast, we saw the form of a hospital ship, bringing its toll of human wreckage to the waiting hands and hearts of its native heath.

For all the trip there was no anxious face or word that revealed the danger that so constantly lurked near us. Even the frequent summons for life-boat drills were answered with mirthful banter. An unfailing, kindly courtesy, and, in many cases, real comradeship marked the fellow-workers with whom we crossed. Perhaps it was due to the quiet but wonderful personality of the leader of this group, Mr. William J. Sloane, Chairman of the[13] War Council of the Young Men’s Christian Association. The four hundred Polish recruits entertained us with song, verse and dance; while usually we had music and movies in the salon. Our Sunday afternoon at sea, we sat in the dining salon with the sun’s rays stealing through the closed portholes and falling upon us in long, flickering, gold lines. Dr. Henry Coffin talked to us in his forceful way of heroes of old. Some one sang “Speed Away,” and then there was a triumphal outburst of “Eternal Father Strong to Save!” The morning of the ninth day we entered the Gironde River and steamed slowly between vine-clad heights, overtopped by stately chateaux; between flowering meadows, with picturesque villas, up to Bordeaux. It was thus we “Answered the Call.”

[14]

[15]

THERE are many American boys now who are quite familiar with the Louvre, Boulevards, Notre Dame and Napoleon’s Tomb at Paris but who know absolutely nothing of the Metropolitan Museum, Fifth Avenue and its Cathedral, or Grant’s Tomb. The many ports of France were particularly the home of the colored soldiers, so that landing at Bordeaux it did not seem strange to be greeted first of all by our own men. But it did seem passing strange that we should see them guarding German prisoners! Somehow we felt that colored soldiers found it rather refreshing—even enjoyable for a change—having come from a country where it seemed everybody’s business to guard them.

Bordeaux was singularly the home of colored soldiers. They were in the camps there by the thousands. In fact, as we landed at Bordeaux, it seemed every man’s home. So crowded and varied was its population, one could almost believe that during the nine days of silence on the ocean, Paris had been passed by the enemy. There were many Colonial troops, Chinese laborers and, more or less maimed French soldiers. The French government had been removed to that city in which the blending of the finest in old and new architecture made it a charming substitute for Paris. Sitting in the park that evening, looking out upon the teeming life about us, with crowds of black-robed women[16] and helpless soldiers filling in the picture, there came to us our first definite realization of the cost of war.

Our first dinner in France, with butter and real ice cream, was an unfortunate delusion, for it in no way prepared us for all the lean days to follow. Especially not for the war-breakfast the next morning—a thick piece of dark bread, a hard-boiled egg and a cup of black coffee—all thrown at us in unsweetened confusion; for while we waited for sugar, we were informed that for the future we must use a liquid substitute supplied us in bottles.

But Paris was our destination, and we rode all day over that part of France so full of historical memories—past Tours with its Cathedral of Royal Staircase and Towers; past Blois with its chateau of historical pre-eminence; past Orleans, over which the spirit of Jeanne d’Arc eternally hovers—on to Paris.

Rue d’Aguesseau! Who does not know it now! That short, narrow street made famous by the Young Men’s Christian Association. For there were the Headquarters of that organization for all its vast service to the American Expeditionary Forces. It was to 12 Rue d’Aguesseau that the precious letters from home were sent. There, in the crowded foyer, they were read and often answered. There friends were met and conferences held. How can any Y secretary who went through it all ever forget the intricate processes of “Movement Orders” and “Transportation” that somehow carried one all over the building and[17] included several excursions from the first to the fifth floor, with the perverse little elevator generally out of order! Really it was far better named ascenseur, for when on rare occasions it did respond to the push of the button and take one up, there was always the warning sign not to descend in it.

It was always necessary to report to the Paris Headquarters in changing one’s base of service. Hence, we have several distinct pictures of the city as we saw it at different intervals during our fifteen months in France. We remember Paris at Christmas time, 1918, when President Wilson had but recently arrived there; when the forces that had for so long fought against cold and darkness were triumphant at last. Warmth and light flooded the very soul of the city. The American was the dominating figure, but the French were riotously happy, for peace had come—a Victorious Peace! We remember, too, the Paris of the late summer of 1919, when after her great victory parade—in which all the victors participated except our own colored soldiers—she began to realize her real condition. The foreigners had mostly gone, the lights were less brilliant than in winter. It was a quiet but wise Paris, bravely facing her tremendous work of reconstruction. But the saddest picture was our first. It was the summer of 1918, Paris was again in the war zone. We entered a city of darkness and our taxicab literally felt its way to the hotel. Here and there dim green lights, heavily hooded, peeped out at us, and we learned that[18] they were simply guides to caves for those unhappy wayfarers caught beneath the enemy’s shell. On that June night, the great Gare d’Orsay was a seething mass of aristocracy, peasantry and soldiers. The same was true of all other railroad stations, for soldiers were forcing their way to the front and refugees their way to the rear. But all life seemed concentrated in those terminals; over the city itself there was deep silence. Even the days were heavy with dark forebodings. The French went quietly to their business by day and to their cellars by night, as the Germans menaced and shattered with shell and bomb. The day of the British and Belgian soldiers in Paris had almost passed—that of the American scarce begun. The many French soldiers one saw there were, for the most part, heartbreaking in their poor torn bodies. We had just seen the children at Bordeaux who used to play among the flowers and marble statues of the parks and look from the windows now close-shuttered. We looked in vain in the Louvre, Notre Dame and other repositories for their priceless treasures, but they were hidden, and ugly sandbags hugged the architecture against the ruthless attacks of the foe. True, the shop-keeper tried to extol and press her wares upon us as of old, but, with the above picture before us, bread tickets in our hands and meatless days, we felt most keenly that it was not the Paris in which, just ten years before, we had lived so joyously for many weeks. It was a bleeding, war-harassed city with its deadly foe pressing upon it. But faith at Paris was not wholly dead;[19] the spirit of Jeanne d’Arc still lived and Saint Genevieve still kept faithful vigil through the long dark hours of waiting. To such a Paris we went, and somehow seemed a part of it. The warning of the siren, air-battles by night and “Big Bertha” bombs by day were accepted as a part of grim war. Meanwhile we prepared for work in the camp.

Those last days in America and first days in France brought us into close touch with the fine spirits who guided the women’s work for the War Council of the Young Men’s Christian Association. In the United States, we had gathered inspiration and vision for our service from the highly efficient and spiritual chairman—Mrs. F. Louis Slade. Closely associated with Mrs. Slade was Mrs. Elsie Meade, whose warm sympathy and steady hand was such a comfort, first, to the out-going women in America, and later in France with its ever-changing camp life. There was Miss Crawford, whose alert service and cheerful word in the office at home and in France meant so much to the Y woman who sought information. Our first assignment in France was made by Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., and the second by Miss Ella Sachs, both of whom gave to the Young Men’s Christian Association a wealth of devoted service—purely for the love of their country. There was Miss Martha McCook, who for so long stood so faithfully at the head of the women’s personnel abroad. Who of the secretaries will ever forget Dr. Cockett? Giving herself first to pioneer work in the camp, she[20] afterwards stood as a tower of strength and knowledge to the newly-arrived secretary.

The colored women who served overseas had a tremendous strain placed upon their Christian ideals—but the officials whom we have mentioned, one and all, as did now and then a regional secretary like Miss Susanne Ridgeway at St. Nazaire, Miss Harris at Aix-les-Bains or the Misses Watson and Shaw at Brest, helped them to keep their faith in the democracy of real Christian service.

A whole volume of interest centers about those two weeks in Paris. The conferences from which we gathered facts and details that would find practical expression on the field; the meeting of old friends and the making of new; the full realization of the restrictions of the army and its penalties for disobedience; the fortitude and fineness of the French—all this and more crowded upon us in those days and wonderfully strengthened us for our task. And then, one day, one of us faced toward Brest and the other toward St. Nazaire to love and serve our men at those ports.

[21]

All honor is due the faithful men and women of both races at home, who by a great expenditure of time, money and energy, made possible the operation of the great plan of bringing comfort and relief to the soldiers through the Welfare Organizations overseas. And while there was disappointment in the hopes of many an honest heart, in that there were prejudices and discriminations often shown to the colored race, and sometimes injustices to the soldiers of both races, still, the army would have been a barren place had these institutions not existed. The great good that was done gives much hope for the possibilities of organized welfare effort in the future.

[22]

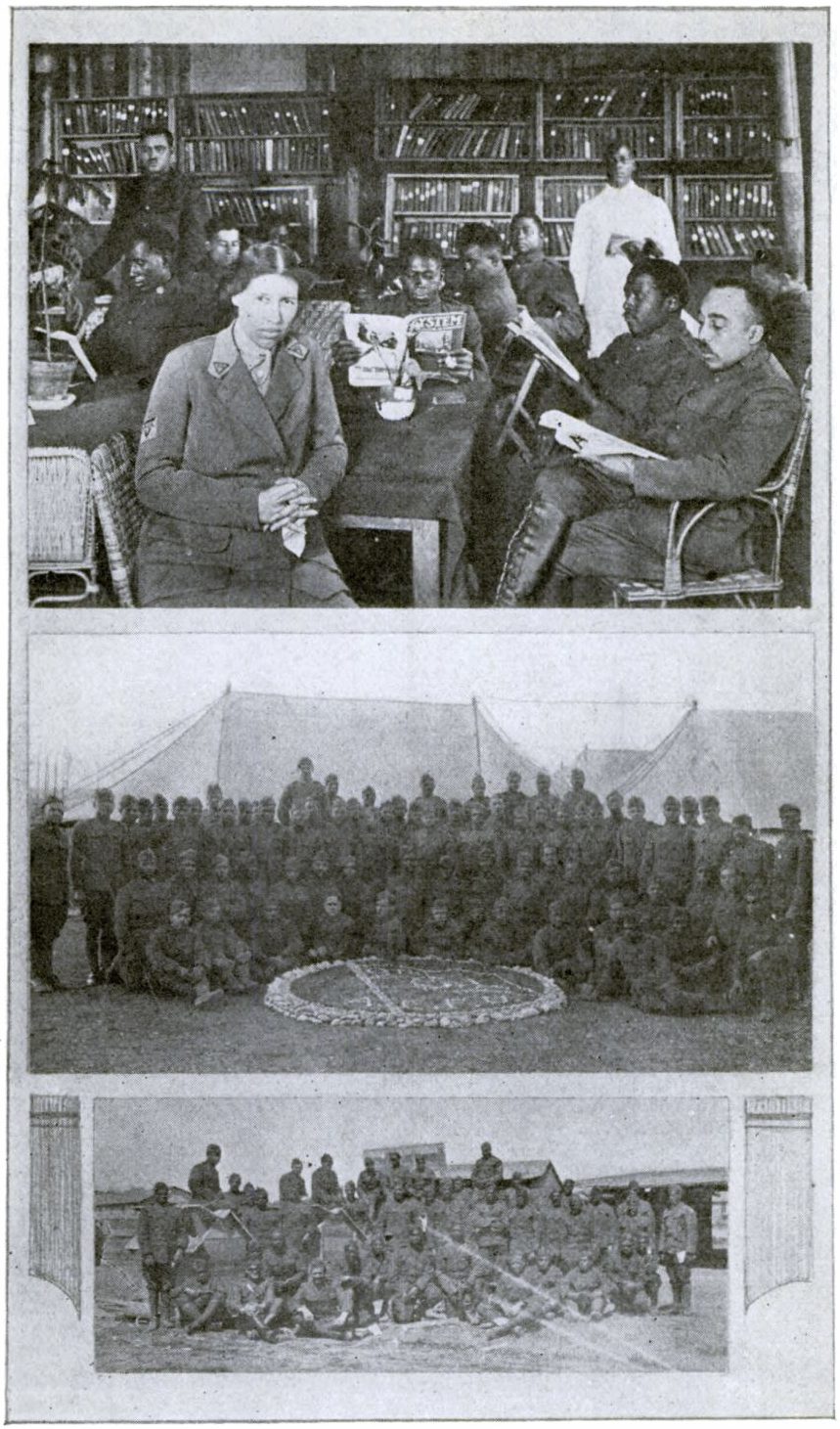

IT was our privilege to go overseas as welfare worker under the auspices of the Y. M. C. A., and from the time we entered active duty until we finished our work at Camp Pontanezen, we can conscientiously say that we had the greatest opportunity for service that we have ever known; service that was constructive, and prolific with wonderful and satisfying results.

The contact with a hundred thousand men, many of whom it was our privilege to help in a hundred different ways; men who were groping and discouraged; others who were crying loudly for help, that they might acquire just the rudiments of an education, and so establish connection with the anxious hearts whom they had left behind; and still others who had a depth of understanding and a breadth of vision that was at once a help and an inspiration.

It was a wonderful spirit that prompted the Y. M. C. A. to offer its vast facilities to this service; to cheer and encourage; to administer to the spiritual and physical needs; and to establish a connecting link between the soldier and the home; that home which ever kept for him a beckoning candle in the window, and a fire that was ever aglow.

And no less wonderful was the spirit of the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the Knights of Columbus,[23] the Jewish Welfare Board, and the Y. W. C. A.

For the privilege of serving in this capacity we shall ever be grateful, and not only for the privilege of service, but for the privilege of contact with a wonderful and soulful people; for the privilege of seeing their beautiful gardens, their fertile fields, their snowcapped mountains and winding rivers; for the privilege of gathering inspiration from their wealth of architectural beauty, their wonderful art galleries and cultural centers; and for the privilege of serving in even the smallest way to help in the preservation of the treasures of this wonderful civilization, for the generations of the future.

But to help to mar the beauty and joy of this service was ever-present war, with its awful toll of death and suffering; and then the service of the colored welfare workers was more or less clouded at all times with that biting and stinging thing which is ever shadowing us in our own country, and which marked our pathway through all our joyous privilege of giving the best that was within us of labor and devotion.

Upon our arrival in Paris we met Mr. Matthew Bullock and his staff of four secretaries, including the first colored woman, who had been ordered home as persona non grata to the army; this was done on recommendation of army officials in Bordeaux, who had brought from our southland their full measure of sectional prejudice.

This incident resulted in the detention of many secretaries, both men and women, from sailing for[24] quite a period of time, and no more women came for nearly ten months, thus leaving three colored women to spread their influence as best they could among 150,000 men.

An incident, in some respects similar, occurred in connection with the work in the city of Brest. During the days when it became the greatest embarkation port in France, at times there were as many as forty thousand men of color, at Camp Pontanezen, waiting for transportation home, and up until about the 18th of June, 1919, there was only one colored Y man there and no women. This, too, at a time when Paris had as many as forty colored men and women, who had returned from their posts of duty, and were willing and anxious for reassignment. This spectacle would no doubt have continued until the close of the work, had not the writers remained in Paris for a period of ten days, requesting continuously that they be permitted to go to Brest. They were finally admitted through the intercession of Mr. W. S. Wallace, who had become the head of the personnel department. When they arrived they were told by the secretary at the head of the woman’s work for that region, that she had tried repeatedly to get colored women, but for some reason the Paris office had refused to send them. But the Paris office had said each time, upon being questioned with regard to the matter, that the office at Brest did not desire colored women secretaries. This misunderstanding came about, no doubt, when, one year previous, the first colored woman sent there had been[25] returned to Paris. With the necessary tact and investigation on the part of the proper authorities, the matter could no doubt have been very easily adjusted, when the original men in authority at Brest had been replaced by others who were more reasonable, and who had more sympathy for the colored men; in that case we would not have been confronted with the spectacle of numbers of colored workers idle in Paris for a period of from four to six weeks, just one night’s ride from thousands of colored soldiers, who were necessarily centered at the great home-going port. Had they been there they could have been of wonderful service, at a time when waiting was a task that tried men’s souls.

Commendable things were accomplished, however, through the limited number of colored secretaries, the sum total of whom finally became seventy-eight men and nineteen women, the rank and file of whom were splendid, giving excellent service in whatever portion of the A. E. F. to which they happened to be assigned.

Among those who gave especially valiant service were Mr. Matthew Bullock, of Boston, Mass., who served with the 369th Infantry; Mr. H. O. Cook, of Kansas City, Mo., who served with the 371st; and Mr. E. T. Banks, of Dayton, Ohio, who served with the 368th. All of these men were cited for bravery as a result of their services with the combatant troops. Mr. Banks went over the top with his men in the Vienne, La Chateau sector, of the Argonne Forest. Mr. Cook gave gallant service[26] in the Champagne offensive, working tirelessly until he was gassed; while Mr. Bullock could be seen at all times making his way under tremendous shell fire that he might reach his men with necessary supplies; all of these men won high praise for their services in giving first aid to the wounded.

While there is very little exception to the rule that the colored soldiers were generally and wonderfully helped by the colored secretaries, and while the official heads of the Y. M. C. A. at Paris were in every way considerate and courteous to its colored constituency, still there is no doubt that the attitude of many of the white secretaries in the field was to be deplored. They came from all parts of the United States, North, South, East and West, and brought their native prejudices with them. Our soldiers often told us of signs on Y. M. C. A. huts which read, “No Negroes Allowed”; and sometimes other signs would designate the hours when colored men could be served; we remember seeing such instructions written in crayon on a bulletin board at one of the huts at Camp I, St. Nazaire; signs prohibiting the entrance of colored men were frequently seen during the beginning of the work in that section; but always, when the matter was brought to the attention of Mr. W. S. Wallace, the regional secretary, he would immediately see that they were removed.

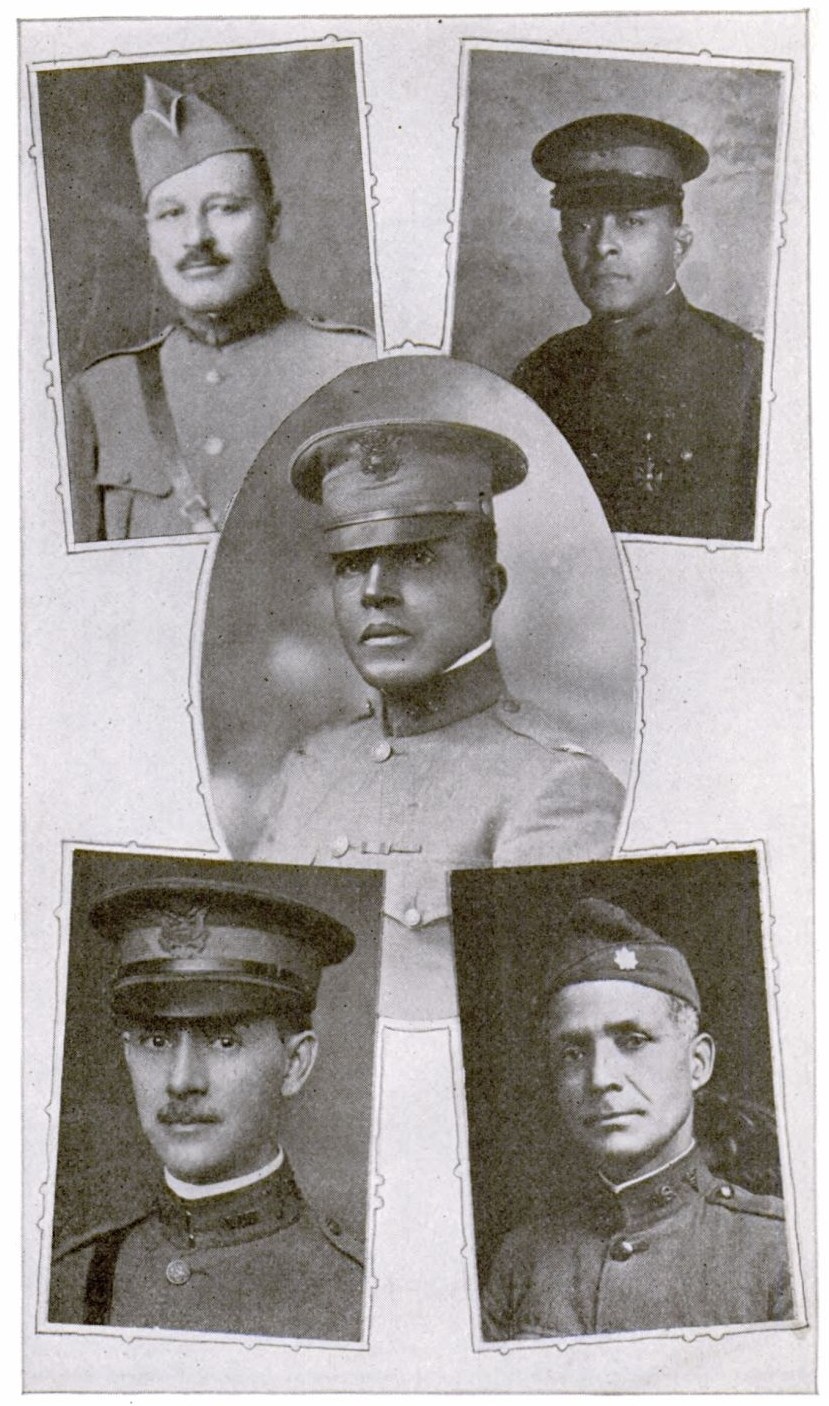

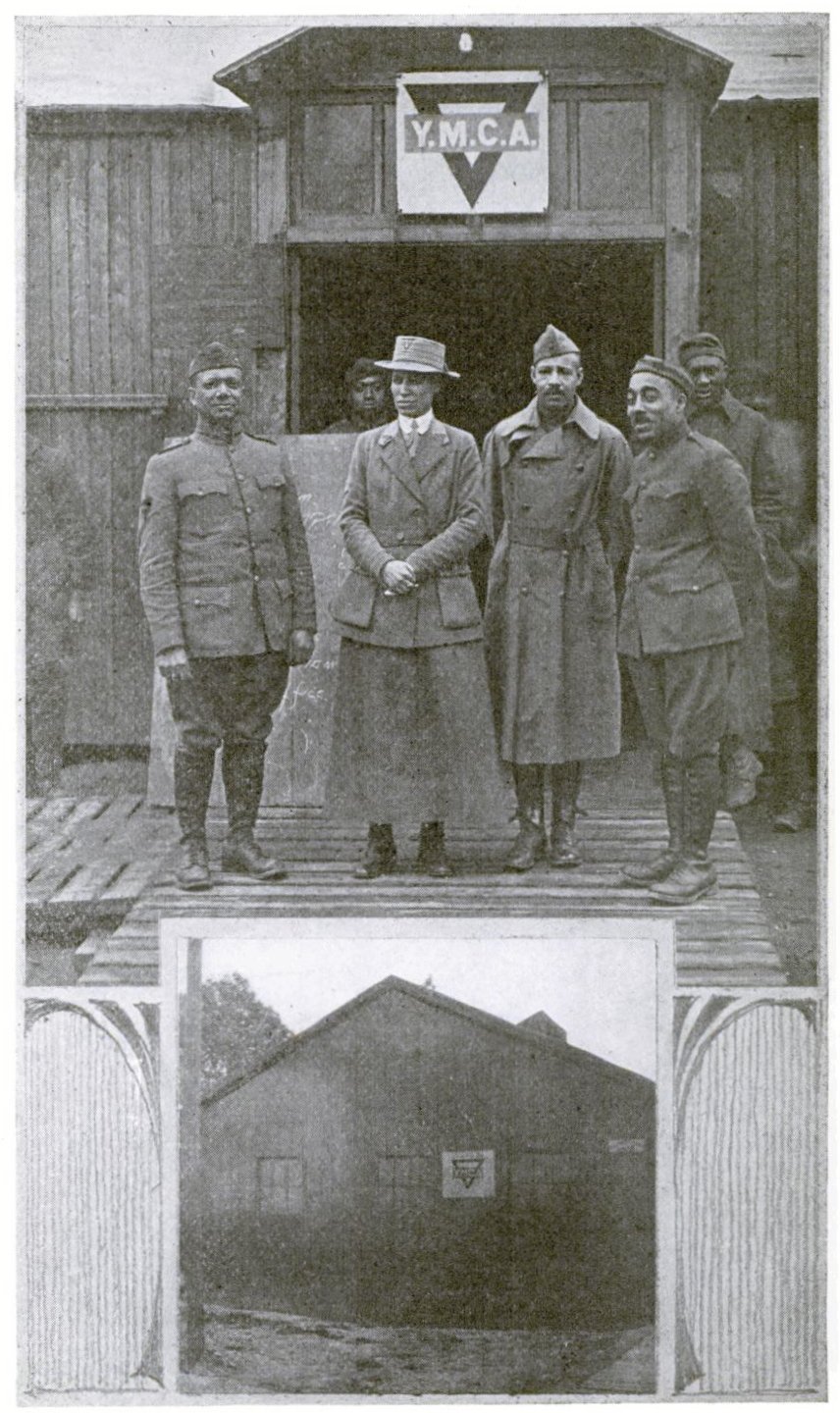

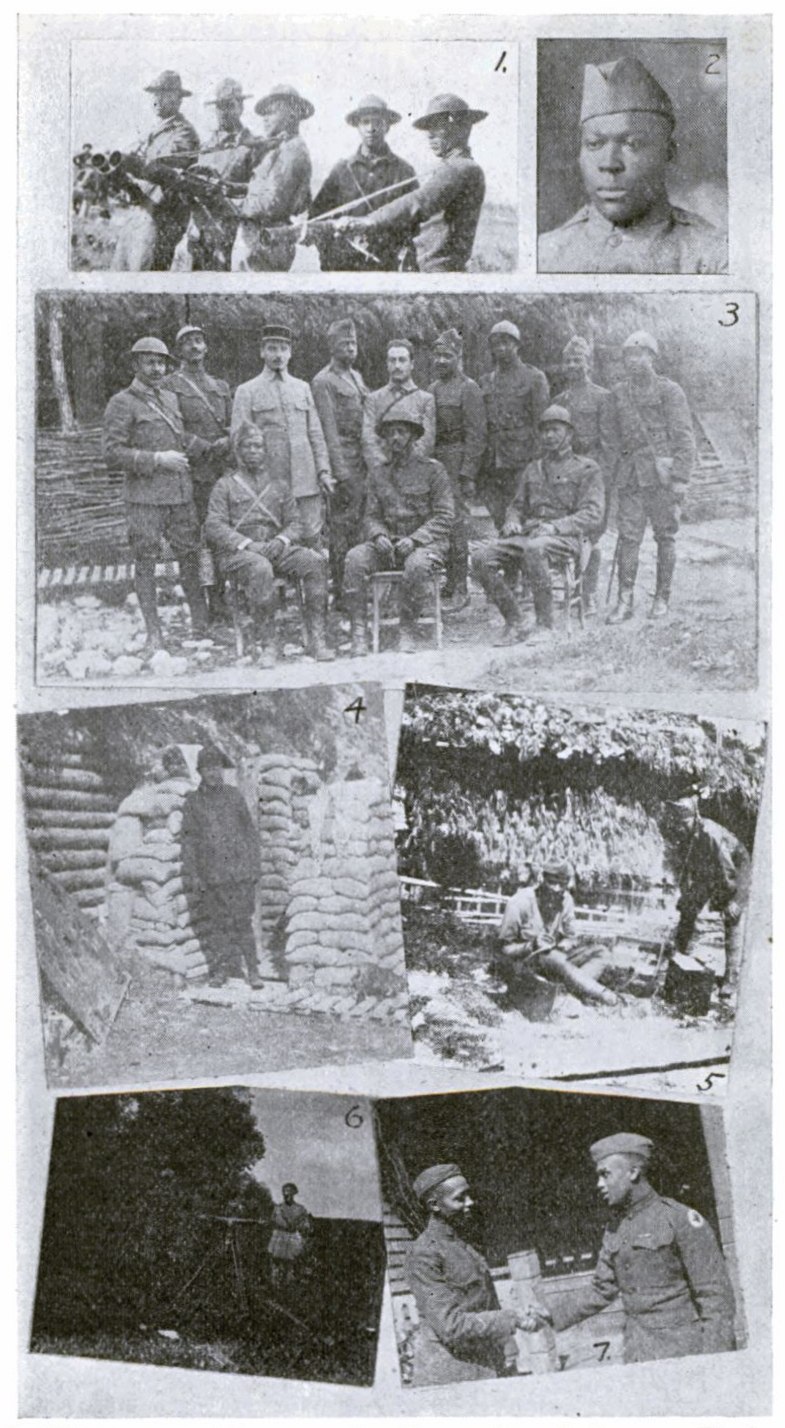

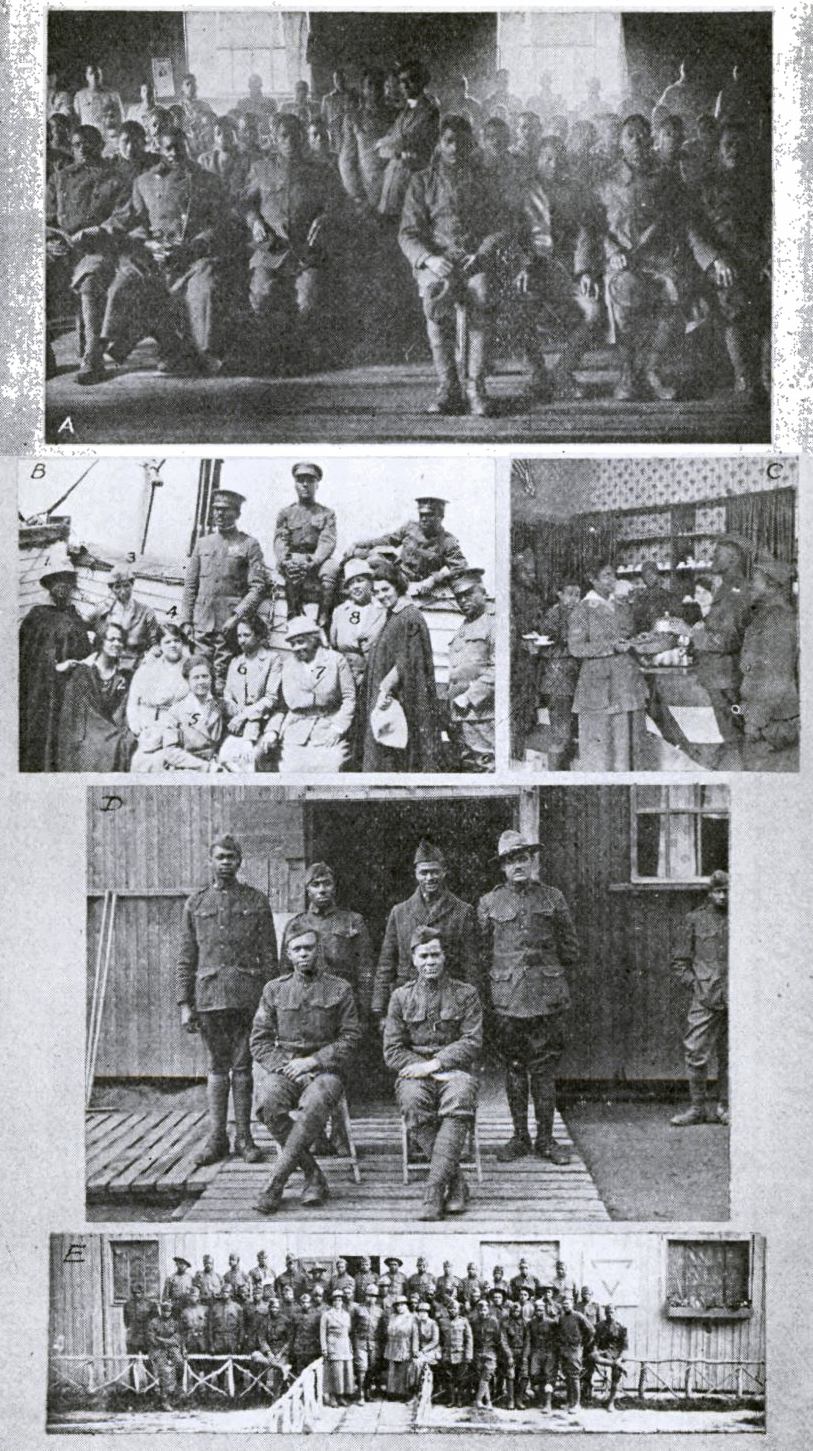

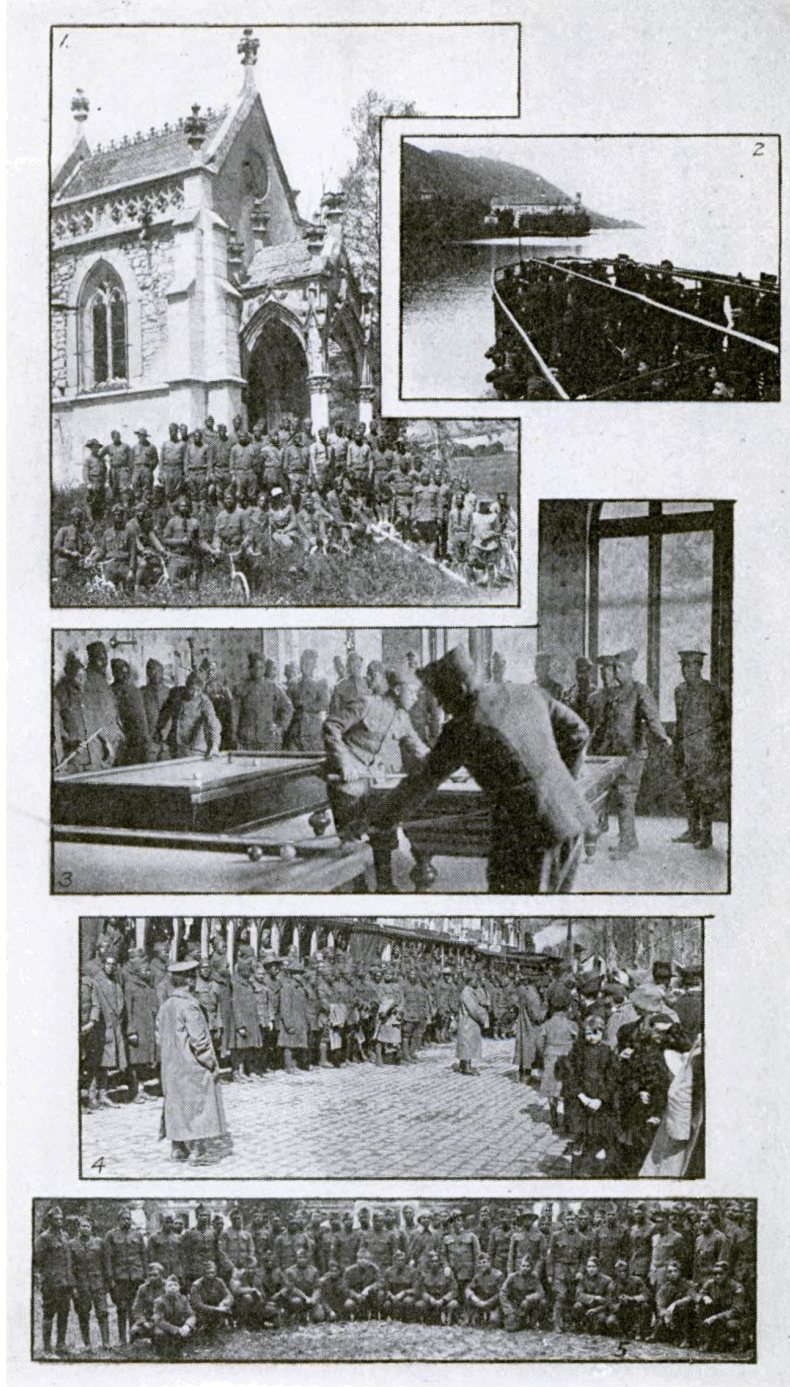

Group of Y.M.C.A, Workers, Including the Three Secretaries Who Were Cited for Bravery

1. Miss Turner. 2. Mr. Matthew Bullock. 3. Mrs. Craigwell. 4. Misses Edwards and Rochon, and Mr. Owens. 5. Misses Phelps and Suarez. 6. Mr. H. O. Cook. 7. Miss Hagan. 8. Mr. E. T. Banks.

Sometimes, even, when there were no such signs,[27] services to colored soldiers would be refused. One such soldier came to the Leave Area, and one day, while on a hike to Hannibal’s Pass, he confided to the writer that he was beginning to see the Y. M. C. A. from a different view-point, since he had been where there were colored secretaries. That at one time, up at the front, he had been marching for two days, was muddy to the waist, cold and starving, because he had had nothing to eat during the entire journey. He came across a Y. M. C. A. hut, went in, and asked them to sell him a package of cakes. They refused to sell it to him under the plea that they did not serve Negroes.

The writer remembers an appeal that came to her one Sunday morning while at St. Nazaire. A Sergeant in the Medical Corps desired her to use her influence to help to get him out of the guard house. On investigation she learned that he had been placed there for doing violence to a Y. M. C. A. secretary. This secretary served in a hut just two blocks from the one in which the writer served. It happened to be immediately across the street from the dispensary, where the sergeant was on duty. Instead of coming to the colored hut, he went across the street to the one nearer. The secretary, with much indignation, told him that he did not serve Negroes. The sergeant went back to the dispensary, feeling outraged. The next day this same Y. M. C. A. secretary went into the dispensary and asked for some medicine. The sergeant told him he must wait until those ahead of him were served; but the secretary persisted that he was in a hurry, and must be served at once;[28] whereupon the sergeant, still smarting under the insult of the day before, unceremoniously ejected him from the building.

One secretary had a colored band come to his hut to entertain his men. Several colored soldiers followed the band into the hut. The secretary got up and announced that no colored men would be admitted. The leader of the band, a white man, by the way, immediately informed his men that they need not play; whereupon all departed and there was no entertainment. Some huts would permit colored men to come in and purchase supplies at the canteen, but would not let them sit down and write, while others received them without any discrimination whatever.

Quite a deal of unpleasantness was experienced on the boats coming home. One secretary in charge of a party sailing from Bordeaux, attempted to put all the colored men in the steerage. They rebelled and left the ship; whereupon arrangements were made to give them the same accommodations as the others.

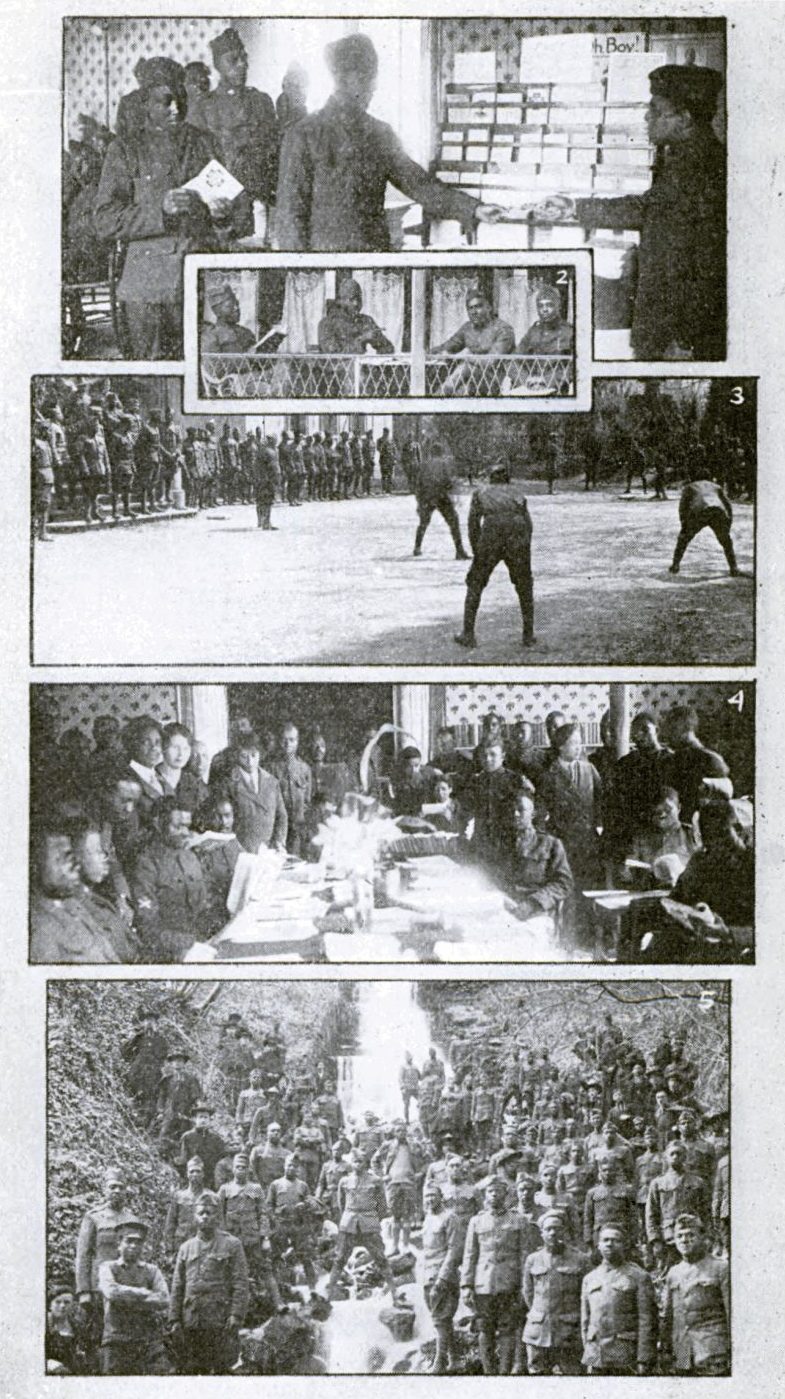

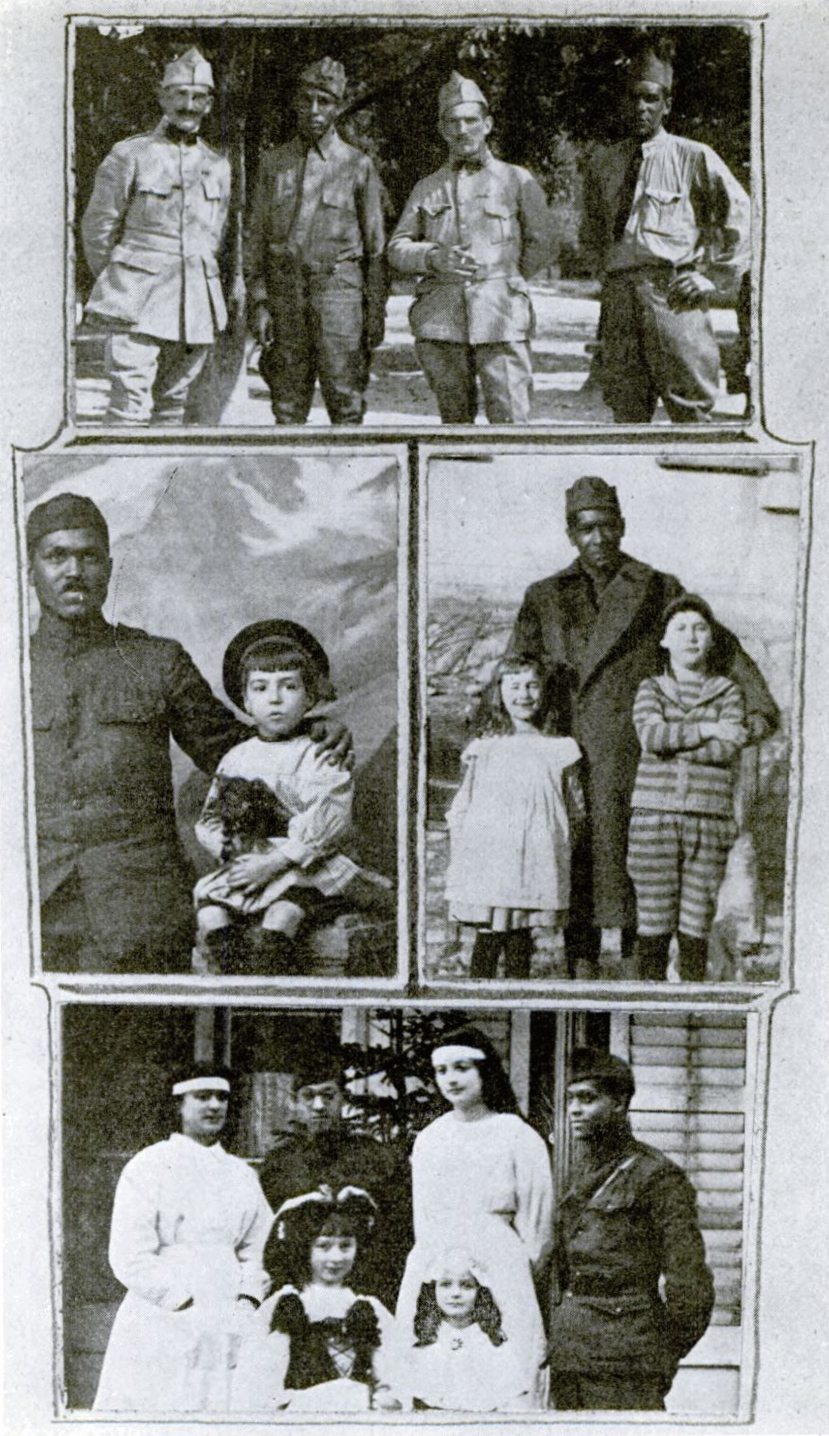

Huts Showing Scarcity of Colored Secretaries and Some Discriminations Practiced

1. Hut 5, Camp Lusitania, St. Nazaire. The largest Y. M. C. A. hut in France, with full staff of three secretaries. From left to right—J. C. Croom, Kathryn M. Johnson, F. O. Nichols, traveling Lecturer on Civics, and Walter Price.

2. Last Y. M. C. A. hut built in France, showing sign in upper right corner, reading, “Colored Soldiers Only.”

On another boat there were nineteen colored[29] welfare workers; all the women were placed on a floor below the white women, and the entire colored party was placed in an obscure, poorly ventilated section of the dining-room, entirely separated from the other workers by a long table of Dutch civilians. The writer immediately protested; the reply was made that southern white workers on board the ship would be insulted if the colored workers ate in the same section of the dining-room with them, and, at any rate, the colored people need not expect any such treatment as had been given them by the French.

But Y. M. C. A. secretaries were not always responsible for discriminations that occurred in the Y. M. C. A. huts. In some places, commanding officers would order signs put up. On another page is a picture of a hut located at Camp Guthrie, near St. Nazaire. The small sign just on the right of the picture says, “Colored Soldiers Only.” The hut secretary here was a colored man, the Rev. T. A. Griffith, formerly of Des Moines, Iowa, and Topeka, Kan. To this hut came many white soldiers to listen to his sermons, and to get into the ice cream line at the canteen. At the same time many of the colored soldiers went to the other hut, where there was a white secretary, to be served in the ice cream line. In time these boys were told that they must get out of the line and be served at their own hut. Simultaneously Rev. Griffith was told to keep the white men out of his line, and let them be served where there were white secretaries. Rev. Griffith did not do this, but left the order to be enforced by the colonel who had made it. When the colonel saw that his order was not being recognized at the colored hut, he had the sign put up as shown in the picture. Rev. Griffith made a number of efforts to get the sign removed, but to no avail.

The following is a copy of an order issued in another section:

[30]

HEADQUARTERS CONCENTRATION CAMP

S. O. S. Troops—Remacourt

Memorandum

Y. M. C. A.

There are two Y. M. C. A.’s, one near the camp, for white troops, and one in town, for the colored troops. All men will be instructed to patronize their own Y.

By order of Col. Doane.

John A. Schweitzer, 1st Lt. Inf.,

Adjutant.

May, 1919.

But there were splendid men among both secretaries and army officials, who honestly and actively opposed discrimination. Mention already has been made of our personal knowledge of Mr. W. S. Wallace at St. Nazaire, who was always on the alert to see that the colored soldiers had a square deal; while at Brest we found an equally fine spirit in the person of Major Roberts, the army welfare officer.

While welfare organizations other than the Y. M. C. A. did not employ colored workers, still, we had the opportunity of observing the attitude they assumed toward the colored troops. It was a part of the multiplicity of the duties of colored Y women to visit the hospitals; here they found colored soldiers placed indiscriminately in wards with white soldiers, while officers were accorded the same treatment as were their white comrades. However, we learned that in some places, colored officers would be placed in wards with private soldiers, instead of being given private rooms, as was[31] their military right; and one soldier tells how, after being twice wounded in the Argonne drive, he was taken to Base Hospital No. 56; here he, and others, waited three days before they could secure the attention of either a doctor or a nurse; but when these attendants finally came, the colored soldiers were taken from the hospital beds and placed on cots which were shoved into one end of the room where there was no heat; they then received medical attention, always after the others had been well attended, and were given the food that remained after the others had been served.

There was one notable incident of discrimination on the part of the Knights of Columbus. It occurred at Camp Romagne, where there were about 9,000 colored soldiers engaged in the heartbreaking task of re-burying the dead. The white soldiers here were acting as clerks, and doing the less arduous tasks. The Knights of Columbus erected a tent here and placed thereon a sign to keep colored soldiers away. The colored soldiers, heartsore because they, of all the soldiers, German prisoners, etc., that there were in France, should alone be forced to do this terrible task of moving the dead from where they had been temporarily buried to a permanent resting place, immediately resented the outrage and razed the tent to the ground. The officers became frightened lest there should be mutiny, mounted a machine gun to keep order, and commanded the four colored women who were doing service there to proceed at once to Paris.

[32]

As a rule, only words of praise were heard for the Salvation Army, whose field of service was very small but very excellent.

The Y. W. C. A. was another welfare organization with overseas workers; their field of service was among the women welfare workers of other organizations, and the French war brides who were waiting to come to America with their American soldier husbands. No colored representative of this organization was sent over, as the number of colored women was so small that she would have had no field in which to operate. Few, if any, of the white Y. W. C. A. workers gave any attention to this little colored group, notwithstanding the fact that they were women, and Americans, just like the others. One, however, remembers a greeting of much insulting superiority and snobbishness, by one of its representatives whom she met on the street. After that she always felt it necessary to keep in places where they were not to be seen. Of course, all of them were not of this type, but there was no way of being sure of those who were not. As an organization there is no doubt that much good was accomplished by them, especially in furnishing reasonable and comfortable hotel accommodations for women welfare workers in Paris, and also in caring for the wives of soldiers who were waiting to come home, in the crowded seaport cities.

The largest Y. M. C. A. hut in France was one built at Camp Lusitania, St. Nazaire, for the use of colored soldiers. It was the first hut built for[33] our boys, and for its longest period of service was under the supervision of Rev. D. Leroy Ferguson, of Louisville, Ky. It reached its highest state of efficiency and cleanliness under Mr. J. C. Croom, of Goldsboro, N. C. It did service for 9,000 men, and had, in addition to the dry canteen, a library of 1,500 volumes, a money-order department which sometimes sent out as much as $2,000 a day to the home folks; a school room where 1,100 illiterates were taught to read and write; a large lobby for writing letters and playing games; and towards the close of the work, a wet canteen, which served hot chocolate, lemonade and cakes to the soldiers.

To this hut one of us was assigned, and served there for nearly nine months. The work was pleasant and profitable to all concerned, and no woman could have received better treatment anywhere than was received at the hands of these 9,000 who helped to fight the battle of St. Nazaire by unloading the great ships that came into the harbor. Among the duties found there were to assist in religious work; to equip a library with books, chairs, tables, decorations, etc., and establish a system of lending books; to write letters for the soldiers; to report allotments that had not been paid; to establish a money order system; to search for lost relatives at home; to do shopping for the boys whose time was too limited to do it themselves; to teach illiterates to read and write; to spend a social hour with those who wanted to tell her their stories of joy or sorrow.

All of this kept one woman so busy that she[34] found no time to think of anything else, not even to take the ten days’ vacation which was allowed her every four months. In a hut of similar size among white soldiers, there would have been at least six women, and perhaps eight men. Here the only woman had from two to five male associates. Colored workers everywhere were so limited that one person found it necessary to do the work of three or four.

Just on the suburbs of St. Nazaire, about two miles from Camp Lusitania, was another hut, the second oldest for colored men in France. Here the other one of the writers spent six months of thrilling, all-absorbing service; while about six miles out, in the little town of Montoir, where thousands of labor troops and engineers had permanent headquarters, the third of the colored women to come to this section ran a large canteen, supplying chocolate, doughnuts, pie and sometimes ice cream to the grateful soldiers. This hut was far too small for the number of soldiers it had to entertain, but it was made large in its hospitality by the genial, good-natured, energetic Mr. William Stevenson, its first hut secretary, now Y. M. C. A. secretary, Washington, D. C. He started the work in a tent, and built it up to a veritable thriving beehive of activity.

There were several other localities in the neighborhood of St. Nazaire, where one colored secretary would be utilized to reach an isolated set. They usually worked in tents. Other places where Y. M. C. A. buildings, huts or tents for colored[35] soldiers were located, were Bordeaux, Brest, Le Mans, Challes-les-Eaux, Chambery, Marseilles, Joinville, Belleau Wood, Fere-en-Tardenois, Orly, Is-sur-Tille, Remacourt, Chaumont, and Camp Romagne near Verdun.

Rolling canteens ran out from some places, reaching points where the soldiers had no Y. M. C. A. conveniences. This was a small automobile truck, equipped with material for serving chocolate and doughnuts, and operated by a chauffeur, and a Y woman who dispensed smiles and sunshine to the ofttimes homesick boys, along with whatever she had to tempt their appetites.

The last, and perhaps the most difficult piece of constructive work done by the colored workers, was at Camp Pontanezen, Brest. It has been told in another chapter how one of the writers received Brest as her first appointment, and how she was immediately informed upon her arrival that because of the roughness of the colored men, she would not be allowed to serve them. That woman went away with the determination to return to Brest, and serve the colored men there, if there was any way to make an opening; so after finishing her work in the Leave Area, she and her co-worker, who had been relieved from duty at Camp Romagne, were finally permitted to go there, as has been previously explained.

Upon their arrival, they were told that they would be assigned to Camp President Lincoln, where there were about 12,000 S. O. S. troops. Here there were several secretaries and chaplains, and the[36] need was greater at Camp Pontanezen, where there were 40,000 men, and only one colored secretary. The writers requested that they be located there. The appointment was held up for one day, and finally they became located at Soldiers’ Rest Hut, in the desired camp.

They were told that they must retain a room in the city, as the woman’s dormitory at Camp Pontanezen was filled to its capacity. But they contended that to do so would take them away from the soldiers at a time in the evening when they could be of the greatest service. Finally, it was arranged for them to stay in the hut, much to the dissatisfaction of the white secretary in charge.

The next morning before they left their room, a message was received, telling them that transportation would be at the door at any moment they desired, to take them back to Brest; that Major Roberts, the Camp Welfare Officer, had said that they must not stay in the hut. Upon investigation by Mr. B. F. Lee, Jr., the lone colored secretary at this tremendous camp, it was learned that Major Roberts had been told that the women were uncomfortable, and did not wish to stay.

Mr. Lee explained that such was not true. The Welfare Officer then visited the hut, talked with the women, recognized the situation, gave his consent to their staying, and assured them that he was willing and ready to do anything in his power to make them comfortable, and assist in equipping the hut. The white secretary, seeing that the women were going to stay, acquiesced in the situation,[37] instead of moving out, and did everything he could to assist.

After this there was no difficulty experienced at Camp Pontanezen. The camp secretary and his staff put every means at our disposal to assist us in the work, while the head of the women’s work was at all times helpful and sympathetic. From the time she received us at Brest, until our departure, she showed us every consideration and courtesy due Y. M. C. A. secretaries.

During the nearly seven weeks there, the chief of the women’s work for France paid the city a visit, in order that she might, among other things, visit the colored work.

The two women remained in the same hut about two weeks, when Major Roberts gave one of the most beautiful huts in the camp to the colored soldiers. It had been occupied by the 106th Engineers, and had been built for their own private use. It contained a beautiful stage; a large auditorium, seating 1,100 people, with a balcony and boxes for officers. It also had a beautiful library and reading room, as well as a wet canteen. To this hut came Mr. B. F. Lee, Jr., and one of the women, while the other remained at Soldiers’ Rest Hut, and became its hut secretary. To join them came two other women from Paris, one of whom was placed in each hut, making the total number of women secretaries, four.

The new hut was quickly gotten in order, sleeping quarters being arranged, a new library built, and[38] a game room made by removing partitions from under the balcony.

There were several other large huts at Camp Pontanezen, that were used for long periods exclusively by colored soldiers; but in the absence of colored women, white women, sometimes as many as five in a hut, gave a service that was necessarily perfunctory, because their prejudices would not permit them to spend a social hour with a homesick colored boy, or even to sew on a service stripe, were they asked to do so. But the very fact that they were there showed a change in the policy from a year previous, when a colored woman even was not permitted to serve them.

In nearly all the Y. M. C. A. huts, in every section of France, moving pictures would be operated every afternoon and evening. Many times before the movies, some kind of an entertainment would be furnished by the entertainment department of the Y. M. C. A. There were shows furnished by French or American dramatists; concert parties by singers and musicians of all nationalities, and frequently a lecture on health and morals. The movies and shows were the most popular forms of entertainment, and on these occasions the huts would always be crowded, as all entertainments given by the Y. M. C. A. were free.

The organization also did much to promote clean morals among the men, by the free distribution of booklets, tracts, and wholesome pictures. This literature would be placed in literature cases, and the men would select their own material, while the[39] pictures would be placed in parts of the hut where they would be easily visible. Some of the booklets which were unusually popular among the men were “Nurse and Knight,” “Out of the Fog,” “When a Man’s Alone,” “The Spirit of a Soldier,” and “A Square Deal”; while quantities of other stories with sharply drawn morals were distributed by the thousands and thousands of copies.

All told, the Y. M. C. A., with a tremendous army of workers, many of whom were untrained, did a colossal piece of welfare work overseas. The last hut for the colored Americans in France was closed at Camp Pontanezen, Brest, on August 3, 1919, by one of the writers; the two of them having given the longest period of active service of any of the colored women who went overseas.

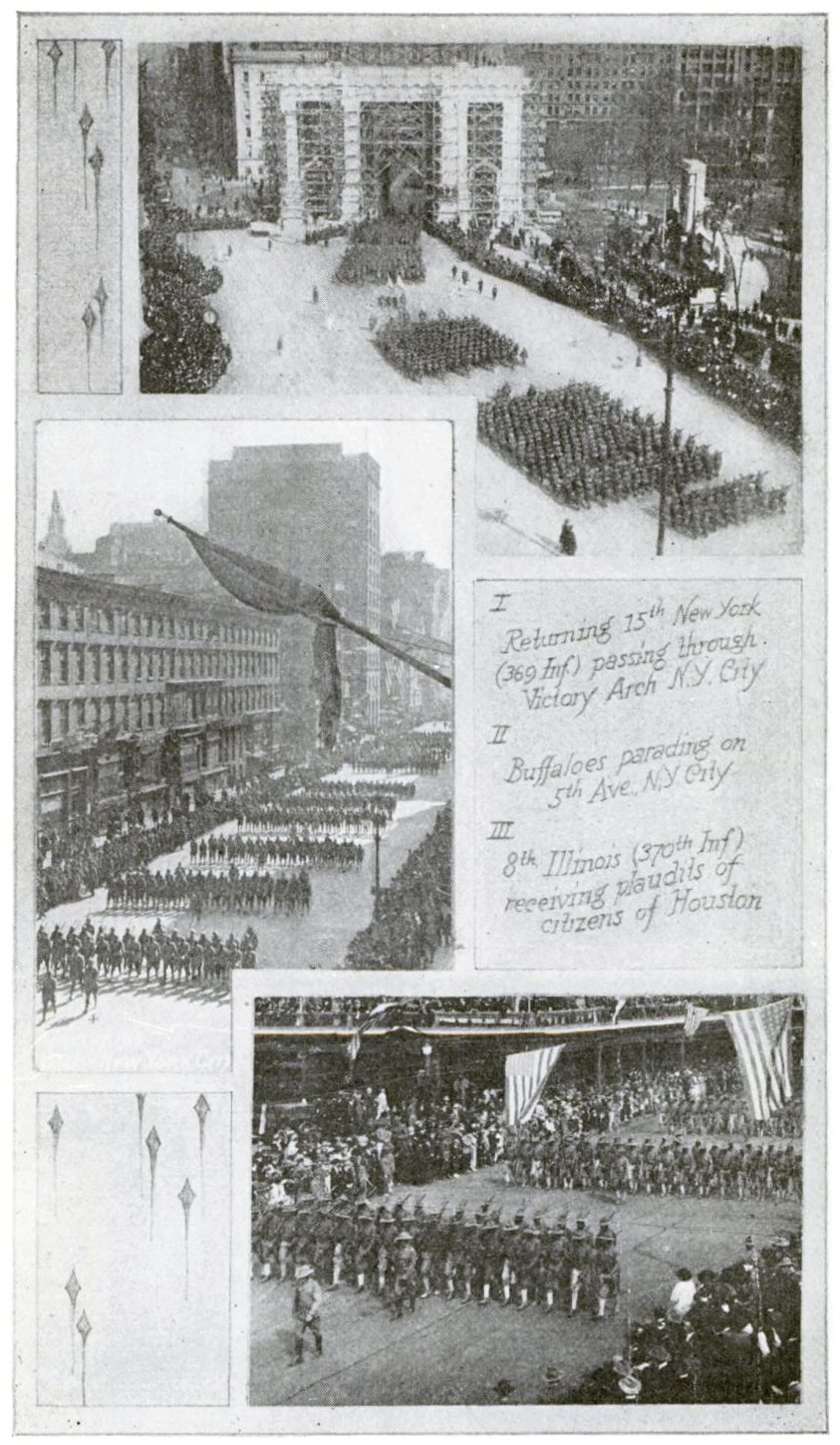

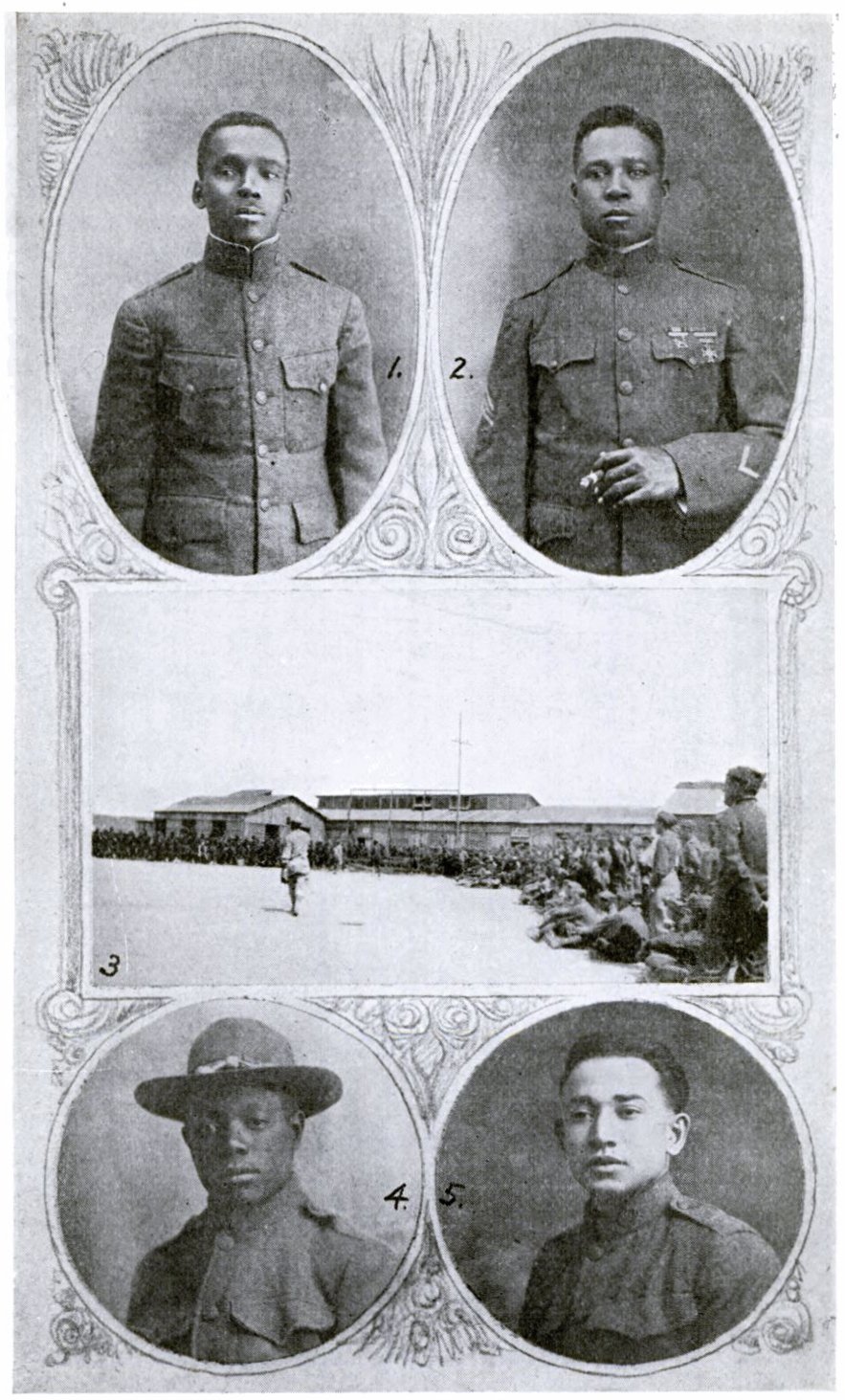

I Returning 15th New York (369 Inf.) passing through Victory Arch N.Y. City

II Buffaloes parading on 5th Ave. N.Y. City

III 8th Illinois (370th Inf.) receiving plaudits of citizens of Houston

[40]

“These men are high of soul, as they face their fate on the shell-shattered earth, or in the skies above, or in the waters beneath; and no less high of soul are the women with torn hearts and shining eyes; the girls whose boy lovers have been struck down in their golden morning, and the mothers and wives to whom word has been brought that henceforth they must walk in the shadow.”

Theodore Roosevelt, in “The Great Adventure.”*

——

* By permission of Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[41]

IT was our greatest hope, when we left that great city of the Middle West, in May, 1918, that we might have the privilege of serving those soldiers whom we had seen march proudly away about six months before, and entrain for the city of the South, there to prepare to take their part on the great western front, in the world’s greatest war. It was at once a joyous and heart-aching privilege to follow them from the spacious 8th Regiment Armory, through the penetrating breeze from Lake Michigan, in order that we might see them bid a last adieu to those who loved them most; the mothers, wives, and sweethearts who clung to the car windows and steps for a last tearful embrace, as the train prepared to move slowly away, bearing its burden of human freight, some of whom were not to return, but were to remain resting in those fields whose blood-red poppies seemed death’s perfect emblem of crimson beauty.

But failing to have the privilege of serving them, we desired in all earnestness of heart to serve whatever other colored regiments were marshaled in battle array against the foe; those who were facing the shot and shell; the poison gas and liquid flame; the bombs from above and the mines from beneath; who were struggling through barbed wire entanglements, and sleeping in trenches and dugouts; who were suffering in all possible ways from the wicked ingenuity of the Germans; who[42] went for days without food and drink; and who offered themselves as a supreme sacrifice to help to make the world safe for democracy.

To these troops we owe much for our splendid record in the World War. They summoned with superhuman strength the courage to overcome the galling and heart-breaking discriminations which they had known before they crossed the seas; the open and public discussion as to whether colored men should be allowed to fight; the tragedy of Houston, and the resulting discouragement at Des Moines;1 the impudence of the commanding officer at Camp Funston, and the pre-arranged and infamous plan to discredit colored officers on the battlefields; all this was sufficient to sap their very life blood before it had a chance to crimson the soil of Flanders Fields; and it was to these troops that we felt we owed all that could be given of service and devotion.

But we were not permitted to do this service for which we longed so much, and consequently our chapter on Combatant Troops must be a record of facts which we have gathered from officers and men of the different organizations who have so kindly and willingly come to our assistance. True, it is a brief record; the full record must be left to those who write the histories; but we hope it is quite sufficient to establish for all time the fact that these troops lived up to the full measure of their opportunity; that whether under white or colored leadership, they fought bravely and with undaunted courage; that their spirit of[43] patience and long suffering enabled them to overcome even the battle of prejudice, which had followed them even into that war-torn country, and which at times was more ominous and terrible than any war-weary conflict; and finally that they won for themselves a crown whose glory and beauty will increase with the passing of the years.

COLORED OFFICERS AND THE 92nd DIVISION

The American colored men had very small opportunity to get training that would fit them for officers before going overseas; there was only one graduate of West Point available, Col. Charles Young, of Wilberforce, Ohio; unfortunately the army found him physically unfit, and retired him from active service just one day before a long list of brigadier generals was made, among whom he was sixth in line for promotion. He was finally called back into active service, and since the war has ended has been sent to Africa. A white colonel remarked in his introduction of Colonel Young to a large meeting held at St. Mark’s M. E. Church, 53rd Street, New York City, in December, 1919, and in the hearing of the writer, that it was very plain that the only reason why this dark-skinned military officer had been retired, was that the army did not want a black general.

For a number of years preceding our entrance into the war, no colored students had been admitted to West Point, and no colored man had ever entered[44] the Naval Academy at Annapolis. One colored school, however—Wilberforce University—had maintained for a number of years a department of military tactics supported by the government. Here Colonel Young, and other regular army officers had been kept from time to time as instructors. During the war 65 men, graduates and undergraduates of the school, received commissions as officers.

The small number who had received limited training here, however, was quite inadequate to be of much service among any considerable number of troops; and the problem of how to train colored officers became quite a vexation; the camps that gave six weeks’ training to white men did not wish to admit them, and there were many who argued that colored men should not be allowed to become soldiers, and that therefore there would be no need for colored officers. Southern congressmen were particularly alarmed over any prospects of colored men learning to use guns.

After some weeks of agitation, however, the war department decided to establish a training camp at Des Moines, Iowa, where about 1,100 men entered for the three months’ course. Over six hundred received commissions as 2nd Lieutenants, 1st Lieutenants, or Captains. There seemed to be a rule that no colored man in training should receive a commission higher than that of captain. Most of these men were college graduates, and on the whole were of a very high type.

[45]

They were assigned to the 92nd Division, and to any other units where colored officers were allowed to serve, and were needed; but the record of the 92nd Division shows more than that of any other organization the ability of the officers of the Des Moines Training School.

The 92nd Division was composed of the 365th and 366th Infantries, and the 350th Machine Gun Battalion, which made up the 183rd Infantry Brigade, commanded by General Barnum; and the 367th and 368th Infantries, together with the 351st Machine Gun Battalion, which made up the 184th Infantry Brigade, commanded by General Hay. These two Brigades, commanded by colored officers as high as the rank of captain, together with the 167th Artillery Brigade, commanded with few exceptions, by white officers, made up the 92nd Division, which was under the command of Major General Ballou.

Major General Ballou had had charge of the Training School at Des Moines, at which time his rank was that of colonel. Through the influence of friends, some colored men included, he was promoted, and given charge of this large body of colored troops; but before he left for France, even, he caused an order to be issued, known as Bulletin No. 35, which must have operated in no small degree to destroy his influence with his men, and cause a humiliation of spirit among them which would take away whatever desire they might have had to lay down their lives that Democracy might live. The following is the text of the Bulletin:

[46]

HEADQUARTERS 92nd DIVISION,

Camp Funston, Kan.

March 28, 1918.

Bulletin No. 35.

1. It should be well known to all colored officers and men that no useful purpose is served by such acts as will cause the “Color Question” to be raised. It is not a question of legal rights, but a question of policy, and any policy that tends to bring about a conflict of races, with its resulting animosities, is prejudicial to the military interests of the 92nd Division, and therefore prejudicial to an important interest of the colored race.

2. To avoid conflicts the Division Commander has repeatedly urged that all colored members of his command, and especially the officers and non-commissioned officers should refrain from going where their presence will be resented. In spite of this injunction, one of the sergeants of the Medical Department has recently precipitated the precise trouble that should be avoided, and then called on the Division Commander to take sides in a row that should never have occurred, and would not have occurred had the sergeant placed the general good above his personal pleasure and convenience. This sergeant entered a theatre, as he undoubtedly had a legal right to do, and precipitated trouble by making it possible to allege race discrimination in the seat he was given. He is entirely within his legal rights in the matter, and the theatre manager is legally wrong. Nevertheless the sergeant is guilty of the greater wrong in doing anything, no matter how legally correct, that will provoke race animosity.

3. The Division Commander repeats that the success of the Division with all that that success implies, is [47] dependent upon the good will of the public. That public is nine-tenths white. White men made the Division, and can break it just as easily as it becomes a trouble maker.

4. All concerned are again enjoined to place the general interest of the Division above personal pride and gratification. Avoid every situation that can give rise to racial ill-will. Attend quietly and faithfully to your duties, and don’t go where your presence is not desired.

5. This will be read to all organizations of the 92nd Division.

By Command of Major General Ballou.

Allen J. Greer,

Lieutenant Colonel General Staff,

Chief of Staff.

Official:

Edw. J. Turgeon,

Captain, Assistant Adjutant, Acting Adjutant.

Nothing that General Ballou could do in the way of prosecuting the theatre manager, which he is said to have done, could alleviate the moral effect of this order upon men who were being sent to another country to fight for the preservation of the very privileges of which they at that very moment were being denied.

The 92nd Division as a complete unit received no training as such in the United States, but arrived in France by regiments, the entire number having[48] landed at Brest by June 20, 1918. The four infantry regiments went into training at Bourbon les Bains, where they remained seven weeks, when they were sent to the Vosges Sector; they remained there from August 23 to September 20, and were then sent into the region of the Argonne Forest, where they were partially engaged in the great Meuse-Argonne Drive. It was here that the 368th Regiment was sent over the top, without being equipped with rifle grenades, instruments that were absolutely necessary for use in the destruction of German machine-gun nests. Very few of the officers and none of the enlisted men had ever seen such a grenade, and the absence of this weapon in warfare where guns alone were practically useless, caused a retreat which resulted in several of the colored officers being arrested and sent to prison for cowardice. Capt. Leroy Godman, a colored attorney from Columbus, Ohio, secured a record of the facts, and after his return to America, was instrumental in having them presented to the War Department; this action resulted in the release and exoneration of the officers, and the stigma of cowardice was removed from the entire regiment, and public notice of it was given in the newspapers throughout the entire country.

The 92nd Division was never permitted until two days before the signing of the Armistice to function in battles as an entire unit. The following bulletin by Brigadier General Erwin shows how certain parts were at all times kept in reserve:

[49]

HEADQUARTERS 92nd DIVISION

A. P. O. 766

A. E. F.

January 27, 1919.

Bulletin No. 13.

1. Participation of the 92nd Division in Major and Battle operations during the war.

St. Die Sector, Vosges, Aug. 23, 1918–Sept. 20, 1918.

Entire 92nd Division, less Division Artillery.

Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Sept. 26, 1918–Sept. 20, 1918.

Entire 92nd Division (less Division Artillery and Train,

368th Infantry, 3d Battalion 365th Infantry, 1st Battalion

366th Infantry, 3d Battalion 367th Infantry, 1st Battalion

317th Military Police) in reserve. 1st Army Corps.

92nd Division (less 183d Brigade, 317th Engineers and Train, Division Artillery, Det. Co. A 317th M.P.) in reserve. 38th Army Corps.

Sept. 20–Oct. 4, 1918.

368th Inf. and Companies A. & B. 351st M. G. Bn., as liaison troops between 1st Army (American) and 4th French Army operating in the Provision Brigade with 11th Cuirassiers, under command Colonel Durand.

Sept. 26–30, 1918.

MARBACHE SECTOR

Oct. 9–Nov. 11, 1918.

Entire 92nd Division to be centered as date of actual arrival in sector.

Offensive Operation

2nd Army, Nov. 10–11, 1918.

Entire 92d Division in Marbache Sector, attacking direction Corny.

Patrols, raids, and defense of raids are not mentioned here. They are local in character, and concern only the[50] units involved. These entries are to be made by company commanders, in strict compliance with the following extracts from G. O.

Discretion must be used by company commanders.

Dates and locations of some minor operations as described above are the following,—(to be entered only by elements actually engaged).

Repulse of enemy raid, C. R. Mere Henry,

23 hours. 25–26 Aug., 1918.

St. Die Sector.

Repulse of enemy raid, Trapelle,

Sept. 1–2, 1918.

Repulse of enemy raid, C. R. Palon,

6 to 8 hours. Sept. 9, 1918.

St. Die Sector, Vosges.

Repulse of enemy raid, Trapelle,

Sept. 19, 1918.

St. Die, Vosges Sector.

In case where units have operated under independent command, as in the case of the 317th Engineers, in the Meuse Argonne Offensive, appropriate notation should be made under supervision of organization commanders concerned.

By command of Brigadier General Erwin.

C. K. Wilson,

Col. General Staff, Chief of Staff.

Official:

Edward J. Turgeon,

Maj. Infantry, Adj.

[51]

This bulletin shows that from September 26 to 30, 1918, the entire 368th Infantry, and one battalion each of the 365th, 366th, and 367th were engaged in action in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, and that, from September 30 to October 4, the 183rd Brigade, composed of the 365th and 366th Infantries, was actively engaged in the same offensive. But at no time is the entire 92nd Division shown to be in active service except on November 10 and 11, when it is reported to be attacking in the direction of Corny.

During its activities the Division lost 248 men and 7 officers killed and died of wounds. There were a number of individual citations for bravery, and one entire battalion belonging to the 367th Infantry was awarded the Croix de Guerre. On the morning of the signing of the Armistice the 365th Infantry had taken several hundred yards of the battle front, the 366th had captured and was still in possession of several kilometers of territory, and the 367th was nearest to the coveted stronghold of Metz of any of the units of the Allied Armies. Had the war lasted another day, the entire Division, along with six other divisions, had been selected to absorb the first shock of the battle.

Because of some unusually interesting things that happened in connection with the 367th Infantry, and because it has the distinction of having the only entire unit of the 92nd Division that was awarded the Croix de Guerre, its full history follows in some detail:

[52]

The 367th Infantry

The 367th Infantry came into existence at Camp Upton, N. Y., during the latter part of October, 1917. Sixty per cent of the soldiers who composed this regiment were from the State of New York, the South furnished 20 per cent, while the remainder came from New England and the West. It was commanded by Colonel Moss, a regular army man, originally from Louisiana, and an authority on military tactics, having published several books on the subject. He took charge of the regiment on November 2, 1917, and spent the winter in giving it what is said to have been the most thorough training of all the drafted regiments. He also christened the organization with the name of Buffaloes; this name had been given to colored soldiers by the Indians, in the early western pioneer days, when colored troops made it so interesting for the Red Men in frontier warfare, as to remind them of the buffaloes of their own great western plains. The name was finally adopted by the entire 92nd Division.

On June 10, 1918, the regiment embarked for[53] France, landing at Brest on June 19. They rested for a few days in dog tents, pitched on the cold wet ground at Camp Pontanezen, and then entrained for Haute Saone, where they were given seven weeks’ intensive training in trench warfare and gas instruction, along with the other regiments of the 92nd Division. Several officers, both white and colored, were given additional training in the American Training School at Gondrecourt.

On August 22, the regiment took over its first trenches at the front in the Vosges Sector, where they remained until September 18, during which time numerous raids, patrols, etc., were planned and executed.

One of the interesting things that happened to them while in this sector, was the dropping of propaganda literature from German aircraft. The following circular was picked up by them on September 3, 1918:

TO THE COLORED SOLDIERS OF THE UNITED

STATES ARMY

“Hello, boys, what are you doing over here? Fighting the Germans? Why? Have they ever done you any harm? Of course some white folks and the lying English-American papers told you that the Germans ought to be wiped out for the sake of humanity and Democracy. What is Democracy? Personal freedom; all citizens enjoying the same rights socially and before the law. Do you enjoy the same rights as the white people do in America, the land of freedom and Democracy, or are you not rather treated over there as second class citizens?

“Can you get into a restaurant where white people dine? Can you get a seat in a theatre where white people sit? Can you get a seat or a berth in a railroad car, or can you even ride in the South in the same street car with the white people?

“And how about the law? Is lynching and the most horrible crimes connected therewith, a lawful proceeding in a Democratic country? Now all this is entirely different in Germany, where they do like colored people;[54] where they treat them as gentlemen and as white men, and quite a number of colored people have fine positions in business in Berlin and other German cities. Why, then, fight the Germans only for the benefit of the Wall Street robbers, and to protect the millions that they have loaned to the English, French, and Italians?

“You have been made the tool of the egotistic and rapacious rich in America, and there is nothing in the whole game for you but broken bones, horrible wounds, spoiled health, or death. No satisfaction whatever will you get out of this unjust war. You have never seen Germany, so you are fools if you allow people to make you hate us. Come over and see for yourself. Let those do the fighting who make the profit out of this war. Don’t allow them to use you as cannon fodder.

“To carry a gun in this service is not an honor but a shame. Throw it away and come over to the German lines. You will find friends who will help you.”

After leaving the Vosges Sector, the organization was sent to the Marbache Sector, where it joined the other regiments of the 92nd Division just outside of Toul. It was here that the First Battalion distinguished itself by coming to the rescue of the 56th Infantry on the left. Captain Morris, and Lieutenants Hunton, Dabney, and Davidson were instrumental in having the terrific fire which was being directed at the regiment, turned onto their own organization, thus enabling the suffering troops to retire to safety; they were at the same time able to hold their own ground and take over the territory of the retiring soldiers. For this action the Battalion was cited in glowing terms by a French General, and awarded the Croix de Guerre. It was[55] also given special mention by Major General Ballou.

Staff officers of this regiment tried very hard to prevent entrance of men into French homes. One medical sergeant tells of order issued in French and English, fixing penalty for such at living on bread and water in pup tents for 24 hours, and being forced to hike 18 miles with pack.

After the signing of the Armistice, the regiment was sent to the forwarding camp at Le Mans. Here some interesting things happened by way of race discrimination. On January 21, 1919, General Pershing made a visit to the camp for the purpose of reviewing the troops. Following is a memorandum posted for the benefit of the colored troops:

HEADQUARTERS FORWARDING CAMP

American Embarkation Center.

A. P. O. 762.

Memorandum: No. 299—E. O.

To All Organizations.

January 21, 1919.

1. For your information and guidance.

Program Reference Visit of General Pershing

9:30 A.M. Arrive Forwarding Camp. All troops possible, except colored to be under arms.

Formation to be designed by General Longan.

Only necessary supply work and police work to be performed up to the time troops are dismissed in order that they may prepare for reception of General Pershing. As soon as dismissed, men to get into working clothes and go to their respective tasks in order that Commander-in-Chief [56]may see construction going on. (Work of dry delousing plant not to be interrupted.) Colored troops will be passed through wet delousing process as planned.

Colored troops will furnish usual police details, and their work not interrupted.

Colored troops who are not at work, to be in their quarters, or in their tents, kitchens, delousing plants, etc., to be inspected.

Route followed to be designated by General Longan.

Plan of Forwarding Camp as planned to be in possession of General Longan to show Commander-in-Chief.

11:00 A.M. Leave Forwarding Camp going to Classification Camp by way of Spur.

Officers not on duty will assemble at these Headquarters at 9:15 A.M.

By Command of Brigadier General Longan.

Richard M. Levy,

Major C. A. C., U. S. A., Camp Adjutant.

HEADQUARTERS, 367th INFANTRY,

A. P. O. 766, A. E. F.

January 21, 1919.

To Organization Commanders for their information, guidance and compliance.

Men will be kept busy at all times. Area formerly used for tents will be levelled, ditches filled in, ditches along road will be carefully policed.

By Order of Colonel Bassett.

Elmer A. Bruett.

When General Pershing came, he noted the absence of the colored troops, and asked for them. He was told that they were at work. Whereupon[57] he set another day for a return trip, in order that he might review them also.

Another order prescribing the eating place for colored officers at the Le Mans Evacuation Camp was as follows:

HEADQUARTERS AREA D.

January 25, 1919.

Memorandum C. O. 367th Infantry:

White officers desiring meals in their quarters will have their orderlies report to Lieutenant Williams at the tent adjoining Area Headquarters for cards to present at Officers’ Mess.

All Colored Officers will mess at Officers’ Mess in D.-17.

F. M. Crawford,

1st Lt. Infantry, Area “D.”

The Efficiency Board

Several references have been made to efficiency boards and their efforts to remove colored officers from the 92nd Division and other colored organizations. In order that a clear idea may be conveyed as to the type of men who suffered from these injustices, as well as how these boards operated, the life, training, and experience of the first officer of the 92nd Division to undergo such an ordeal, follows in detail:

Captain Matthew Virgil Boutte was born in New Iberia, Louisiana, of Creole parentage; his father was a sugar planter, of the type that used to strap[58] his gun on his saddle girth for protection, and go to the poles and vote, in the days when guns were used to maintain white supremacy in that State.

He sent his son to Straight University, New Orleans, from 1898 to 1903, where he received the rudiments of an education. Afterwards young Boutte went to Fisk, where he finished a high school course, and a four years’ college course; thence to the University of Illinois, where he graduated as a chemist and pharmacist; he then taught quantitative chemistry at Meharry Medical College, and opened a drugstore in Nashville, Tenn. This he disposed of after receiving his commission at the Des Moines Training School. While in Nashville, he joined the Tennessee National Guard, the only Colored National Guard Company in the South. With six months’ training there as a private, he entered the Des Moines School, and was one of the few who received the commission of captain.

On November 1, 1917, he went to Rockford, Ill., where he attended Machine Gun School at Camp Grant, and organized Company 350, Machine Gun Battalion. His company was well trained not only in military tactics, but also to such a high degree of athletic efficiency, that it received a loving cup for winning a cross country run; also won cup for individual running in whole brigade. The winner, Sergeant Bluitt, was afterward commissioned lieutenant.

On June 6, 1918, Captain Boutte sailed for France, with the advance officers’ party of the 92nd Division. They landed at Brest where the colored[59] officers received a taste of the American segregation that afterwards became so annoying in France. Rooms for the entire party, white and colored, had been reserved at the Hotel Continental, but the colored officers were told to go to Camp Pontanezen, where they would find barracks; there they were to sleep on boards with no mattresses, and only one blanket apiece. Captain Boutte protested, and the party returned to Brest, where they discovered that the white officers had not made the French people understand that the rooms held in reserve were for them, and consequently had gone elsewhere. Captain Boutte, being able to speak French quite fluently, was able to get the reserved rooms for the six colored officers. He was sent from Brest to Bourbon les Bains to serve as billeting officer. Here he was told not to take the French people’s kindness for friendship, but to treat them just as he had been taught to treat white people at home. When they found that his ability to speak French gave him ready entrée into French homes, they relieved him of all work as billeting officer, so that he would have no occasion for going among the French people.

On July 7 he was returned to his company. He instructed his men to such a point of efficiency that the inspector of machine-gun tactics commended his work. On July 24 he was placed under close arrest. While under arrest he was forced to ride from one town to another in an open wagon, and between two armed guards, in order that his spirit might be thoroughly crushed, and[60] his humiliation made complete. Twenty-three specifications under the 96th Article of War were placed against him. These dealt with duties imposed upon the Commanding Officer of the Company by the Commanding Officer of the Battalion. After he had been under close arrest for eight days, the charges were submitted to him; following are samples of specifications:

“Why did you command your first sergeant to remain at home instead of having him on the field of drill, as commanded from headquarters?”

“Why did your mess sergeant not have his bill of fare posted on a certain day?”

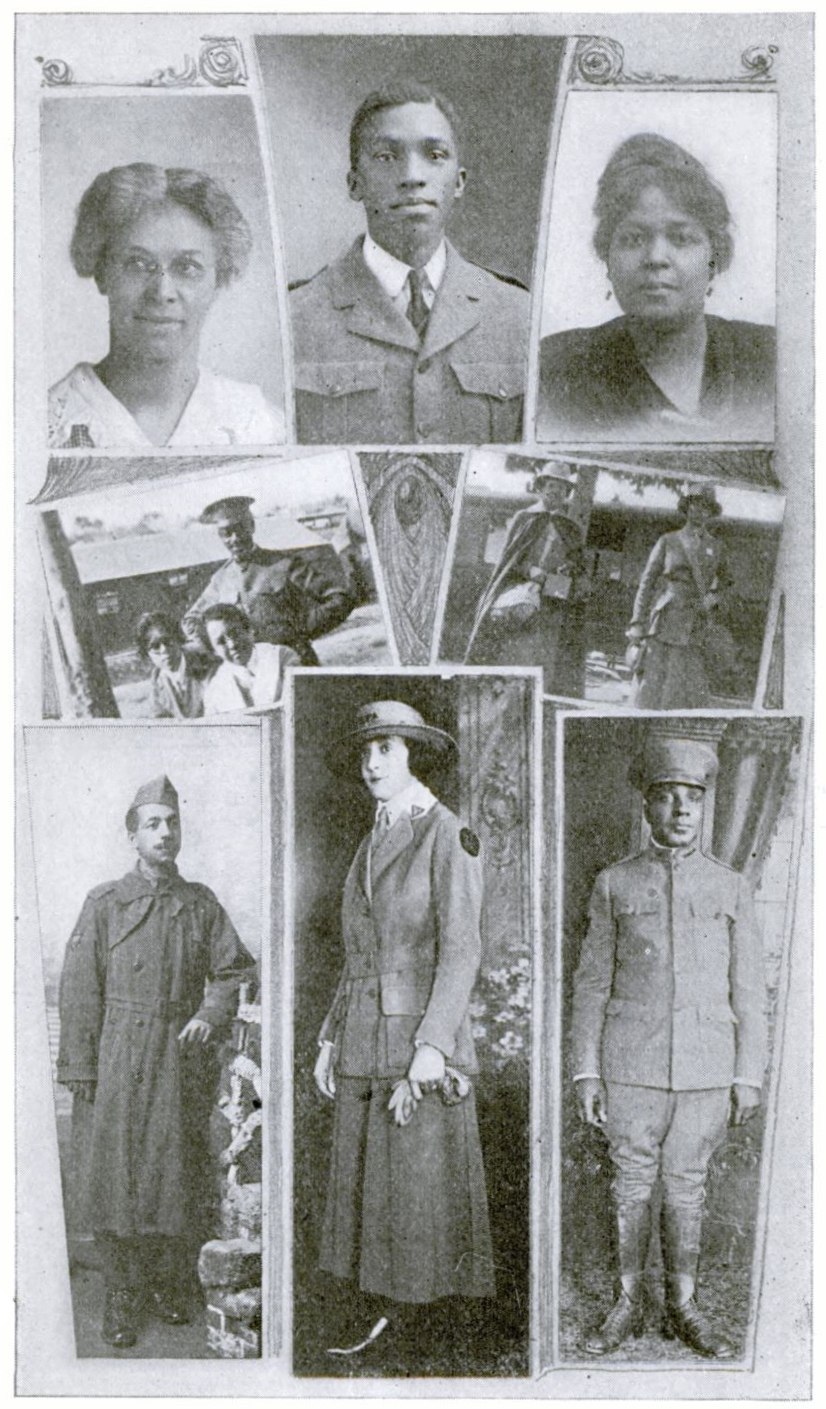

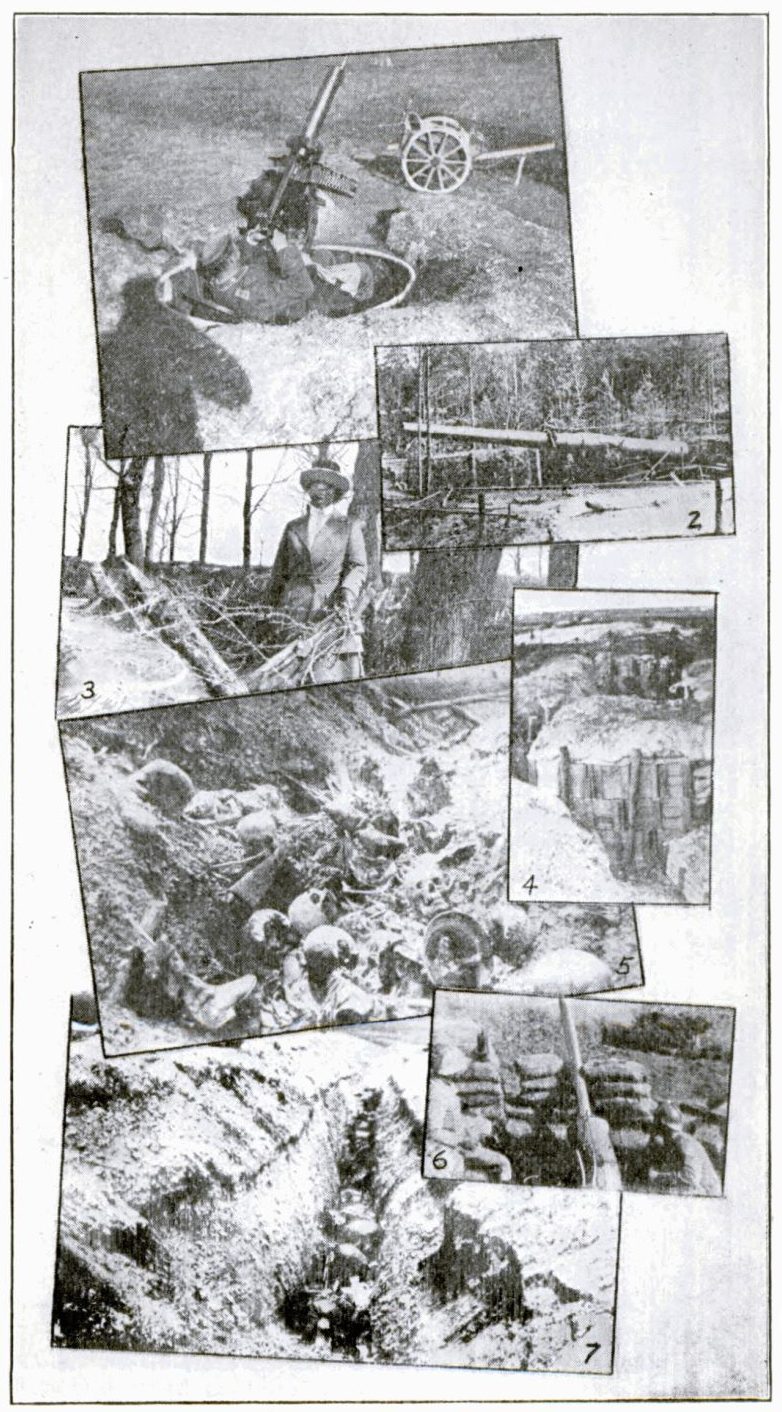

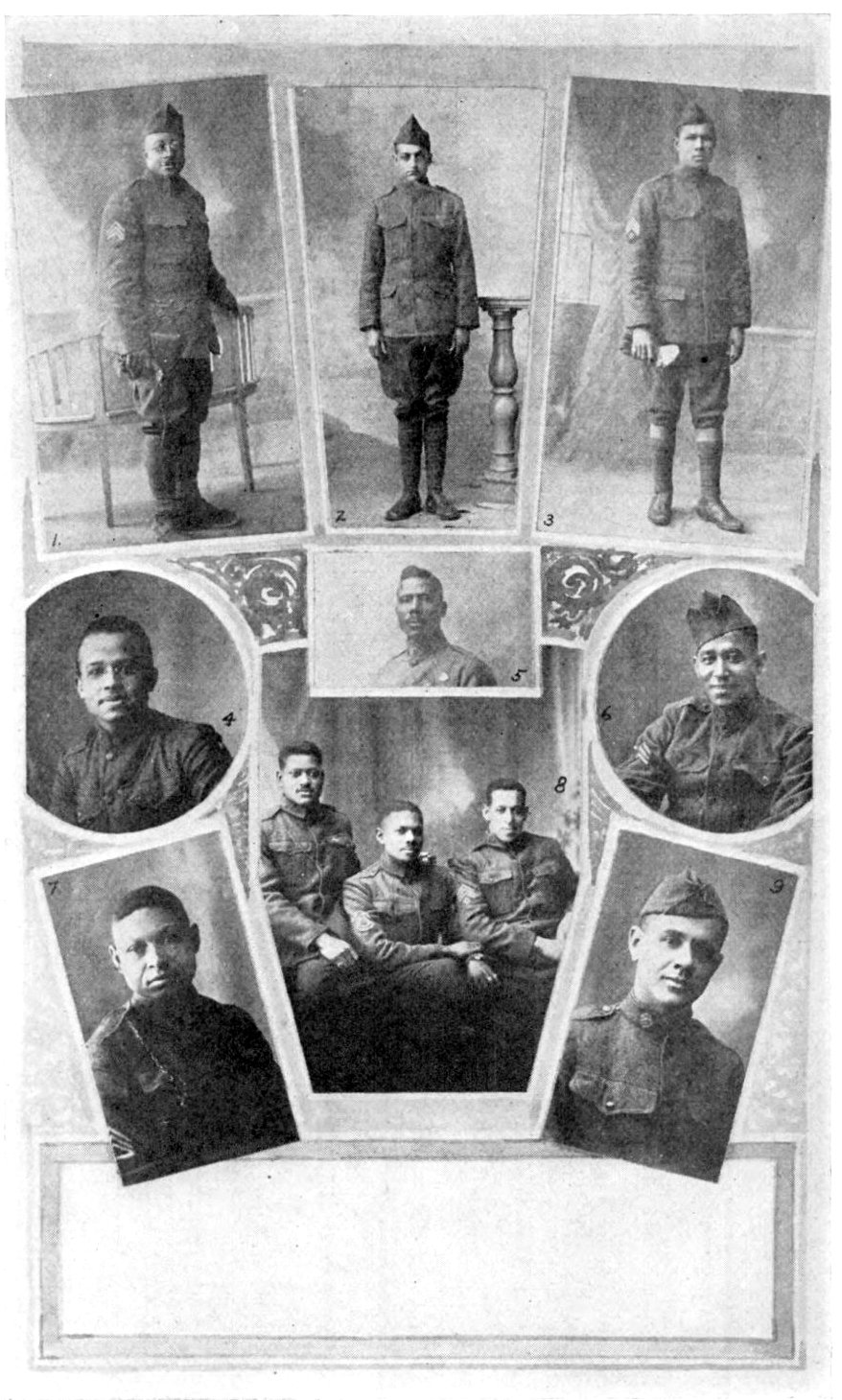

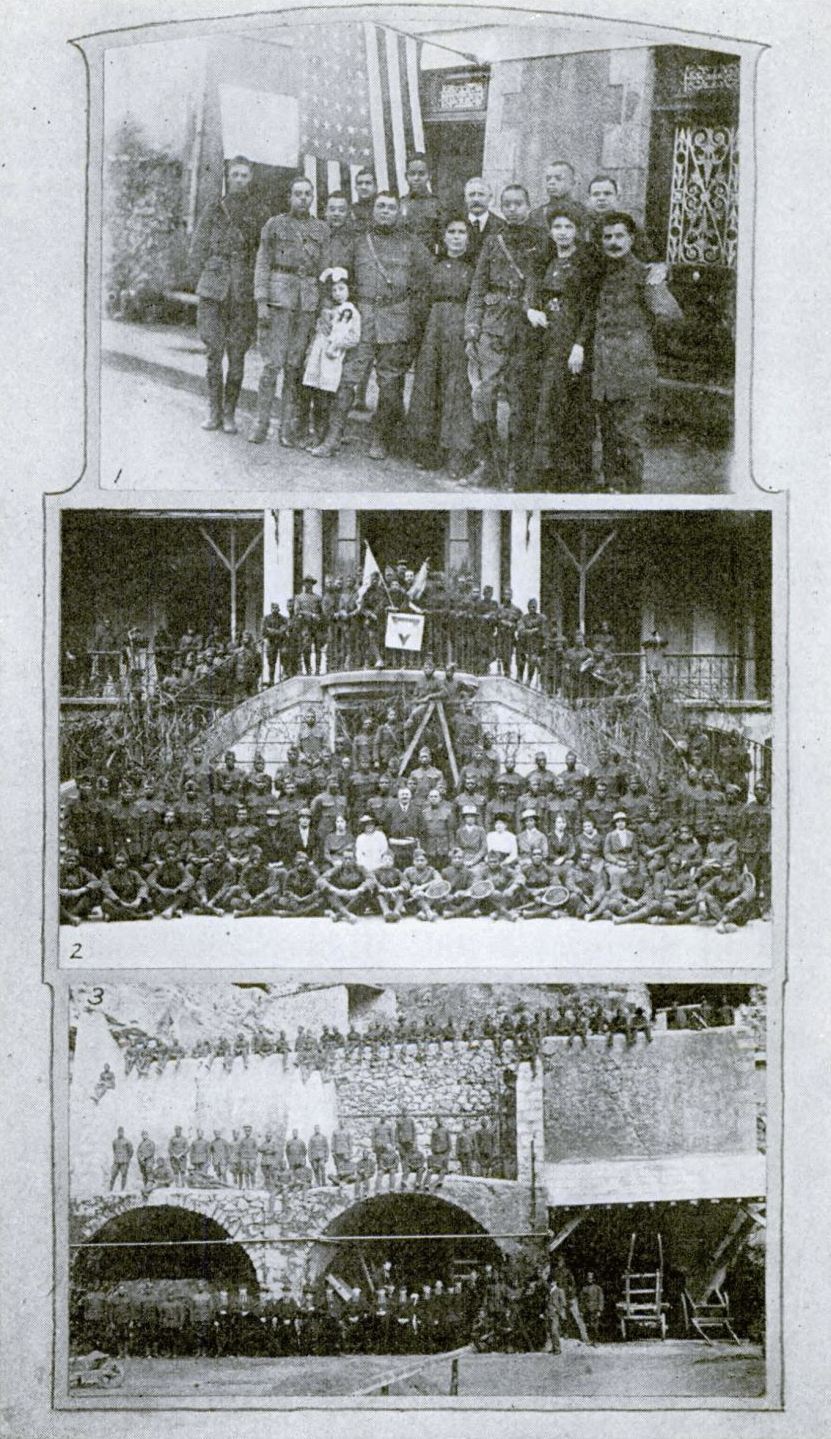

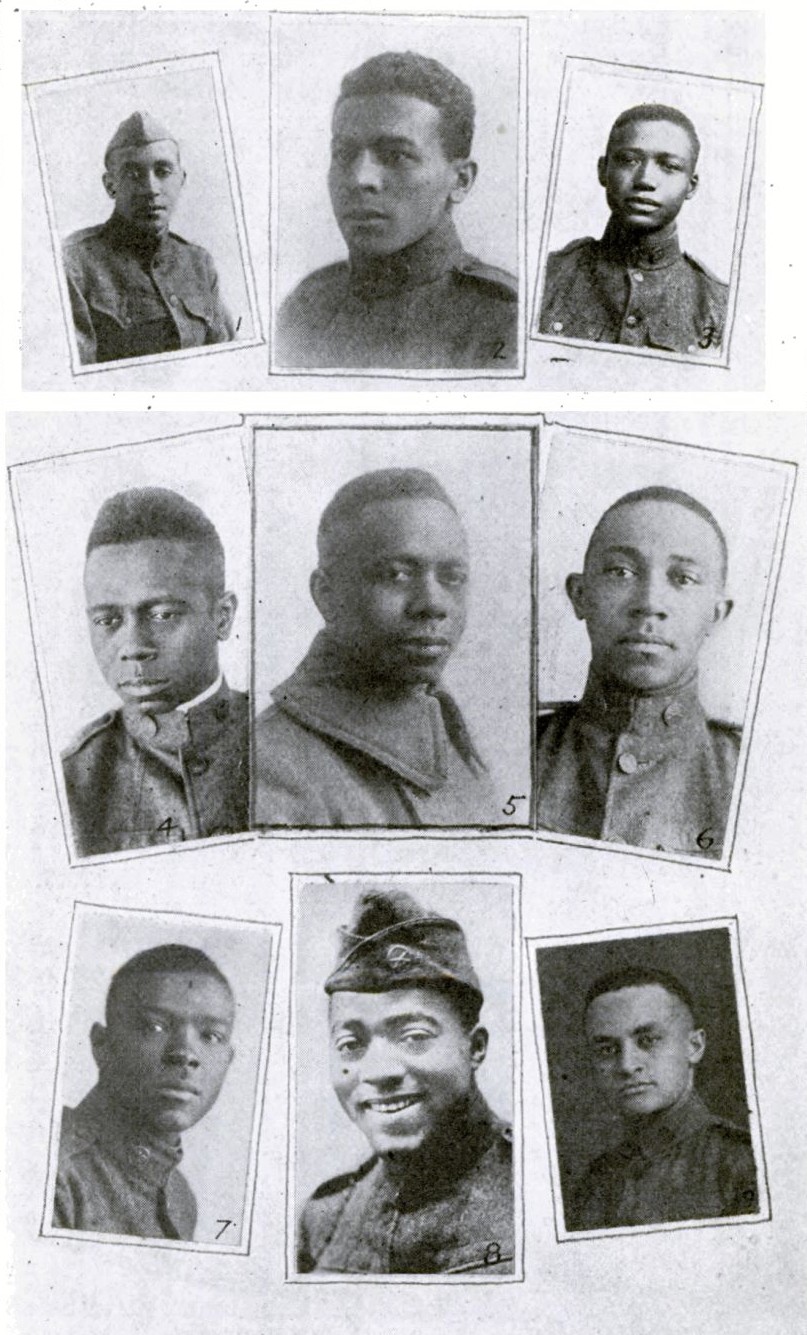

Group of Officers of 92nd Division

1. Capt. Matthew Virgil Boutte. 2. Lieut. J. Williams Clifford. 3. Lieut. Benjamin H. Hunton. 4. Lieut. Frank L. Drye. 5. Lieut. Frank L. Chisholm. 6. Lieut. Ernest M. Gould. 7. Lieut. Victor R. Daly.