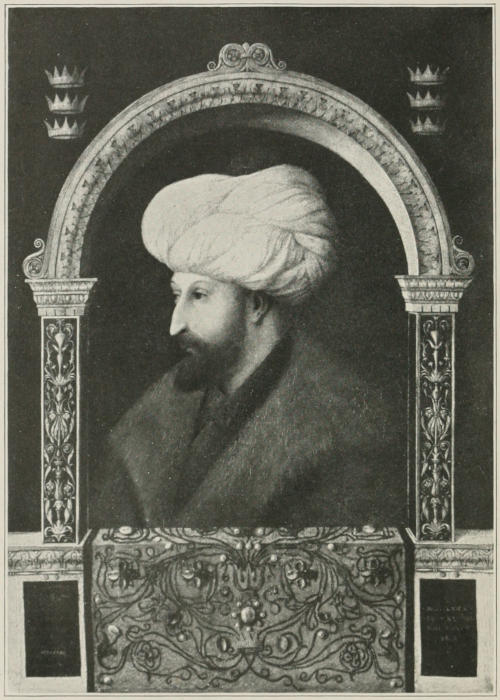

Sultan Mehmed II, the Conqueror

From the portrait by Gentile Bellini in the Layard Collection

Photograph by Alinari Brothers, Florence

Title: Constantinople old and new

Author: H. G. Dwight

Release date: June 8, 2023 [eBook #70946]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: C. Scribners sons

Credits: Tim Lindell, Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

CONSTANTINOPLE OLD AND NEW

Sultan Mehmed II, the Conqueror

From the portrait by Gentile Bellini in the Layard Collection

Photograph by Alinari Brothers, Florence

CONSTANTINOPLE

OLD AND NEW

BY

H. G. DWIGHT

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1915

Copyright, 1915, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published September, 1915

A number of years ago it happened to the writer of this book to live in Venice. He accordingly read, as every good English-speaking Venetian does, Mr. Howells’s “Venetian Life.” And after the first heat of his admiration he ingenuously said to himself: “I know Constantinople quite as well as Mr. Howells knew Venice. Why shouldn’t I write a ‘Constantinople Life’?” He neglected to consider the fact that dozens of other people knew Venice even better than Mr. Howells, perhaps, but could never have written “Venetian Life.” Nevertheless, he took himself and his project seriously. He went back, in the course of time, to Constantinople, with no other intent than to produce his imitation of Mr. Howells. And the reader will doubtless smile at the remoteness of resemblance between that perfect little book and this big one.

Aside, however, from the primary difference between two pens, circumstances further intervened to deflect this book from its original aspiration. As the writer made acquaintance with his predecessors in the field, he was struck by the fact that Constantinople, in comparison with Venice and I know not how many other cities, and particularly that Turkish Constantinople, has been wonderfully little “exploited”—at least in our generation and by users of our language. He therefore turned much of his attention to its commoner aspects—which Mr. Howells in Venice felt, very happily, under no obligation to do. Then the present writer found[viii] himself more and more irritated by the patronising or contemptuous tone of the West toward the East, and he made it rather a point—since in art one may choose a point of view—to dwell on the picturesque and admirable side of Constantinople. And soon after his return there took place the revolution of 1908, whose various consequences have attracted so much of international notice during the last five years. It was but natural that events so moving should find some reflection in the pages of an avowed impressionist. Incidentally, however, it has come about that the Constantinople of this book is a Constantinople in transition. The first chapter to be written was the one called “A Turkish Village.” Since it was originally put on paper, a few weeks before the revolution, the village it describes has been so ravaged by a well-meaning but unilluminated desire of “progress” that I now find it impossible to bring the chapter up to date without rewriting it in a very different key. I therefore leave it practically untouched, as a record of the old Constantinople of which I happened to see the last. And as years go by much of the rest of the book can only have a similar documentary reference.

At the same time I have tried to catch an atmosphere of Constantinople that change does not affect and to point out certain things of permanent interest—as in the chapters on mosque yards, gardens, and fountains, as well as in numerous references to the old Turkish house. Being neither a Byzantinist nor an Orientalist, and, withal, no expert in questions of art, I realise that the true expert will find much to take exception to. While in matters of fact I have tried to be as accurate as possible, I have mainly followed the not infallible Von Hammer, and most of my Turkish translations are borrowed[ix] from him or otherwise acquired at second hand. Moreover, I have unexpectedly been obliged to correct my proofs in another country, far from books and from the friends who might have helped to save my face before the critic. I shall welcome his attacks, however, if a little more interest be thereby awakened in a place and a people of which the outside world entertains the vaguest ideas. In this book, as in the list of books at its end, I have attempted to do no more than to suggest. Of the list in question I am the first to acknowledge that it is in no proper sense a bibliography. I hardly need say that it does not begin to be complete. If it did it would fill more pages than the volume it belongs to. It contains almost no original sources and it gives none of the detailed and classified information which a bibliography should. It is merely what I call it, a list of books, of more popular interest, in the languages more commonly read by Anglo-Saxons, relating to the two great periods of Constantinople and various phases of the history and art of each, together with a few better-known works of general literature.

I must add a word with regard to the spelling of the Turkish names and words which occur in these pages. The great difficulty of rendering in English the sound of foreign words is that English, like Turkish, does not spell itself. For that reason, and because whatever interest this book may have will be of a general rather than of a specialised kind, I have ventured to deviate a little from the logical system of the Royal Geographical Society. I have not done so with regard to consonants, which have the same value as in English, with the exception that g is always hard and s is never pronounced like z. The gutturals gh and kh have been so softened by the Constantinople dialect that I generally avoid[x] them, merely suggesting them by an h. Y, as I use it, is half a consonant, as in yes. As for the other vowels, they are to be pronounced in general as in the Continental languages. But many newspaper readers might be surprised to learn that the town where the Bulgarians gained their initial success during the Balkan war was not Kîrk Kiliss, and that the second syllable of the first name of the late Mahmud Shefket Pasha did not rhyme with bud. I therefore weakly pander to the Anglo-Saxon eye by tagging a final e with an admonitory h, and I illogically fall back on the French ou—or that of our own word through. There is another vowel sound in Turkish which the general reader will probably give up in despair. This is uttered with the teeth close together and the tongue near the roof of the mouth, and is very much like the pronunciation we give to the last syllable of words ending in tion or to the n’t in needn’t. It is generally rendered in foreign languages by i and sometimes in English by the u of sun. Neither really expresses it, however, nor does any other letter in the Roman alphabet. I have therefore chosen to indicate it by î, chiefly because the circumflex suggests a difference. For the reader’s further guidance in pronunciation I will give him the rough-and-ready rule that all Turkish words are accented on the last syllable. But this does not invariably hold, particularly with double vowels—as in the name Hüsséïn, or the word seráï, palace. Our common a and i, as in lake and like, are really similar double vowel sounds, similarly accented on the first. The same rules of pronunciation, though not of accent, apply to the few Greek words I have had occasion to use. I have made no attempt to transliterate them. Neither have I attempted to subject well-known words or names of either language to my somewhat[xi] arbitrary rules. Stamboul I continue so to call, though to the Turks it is something more like Îstambol; and words like bey, caïque, and sultan have long since been naturalised in the West. I have made an exception, however, with regard to Turkish personal names, and in mentioning the reigning Sultan or his great ancestor, the Conqueror, I have followed not the European but the Turkish usage, which reserves the form Mohammed for the Prophet alone.

This is not a book of learning, but I have required a great deal of help in putting it together, and I cannot close this prefatory note without acknowledging my indebtedness to more kind friends than I have space to name. Most of all I owe to Mr. E. L. Burlingame, of Scribner’s Magazine, and to my father, Dr. H. O. Dwight, without whose encouragement, moral and material, during many months, I could never have afforded the luxury of writing a book. I am also under obligation to their Excellencies, J. G. A. Leishman, O. S. Straus, and W. W. Rockhill, American ambassadors to the Porte, and especially to the last, for cards of admission, letters of introduction, and other facilities for collecting material. Among many others who have taken the trouble to give me assistance of one kind or another I particularly wish to express my acknowledgments to Arthur Baker, Esq.; to Mgr. Christophoros, Bishop of Pera; to F. Mortimer Clapp, Esq.; to Feridoun Bey, Professor of Turkish in Robert College; to H. E. Halil Edhem Bey, Director of the Imperial Museum; to Hüsseïn Danish Bey, of the Ottoman Public Debt; to H. E. Ismaïl Jenani Bey, Grand Master of Ceremonies of the Imperial Court; to H. E. Ismet Bey, Préfet adjoint of Constantinople; to Kemaleddin Bey, Architect in Chief of the Ministry of Pious Foundations; to Mahmoud[xii] Bey, Sheikh of the Bektash Dervishes of Roumeli Hissar; to Professor Alexander van Millingen; to Frederick Moore, Esq.; to Mr. Panayotti D. Nicolopoulos, Secretary of the Mixed Council of the Œcumenical Patriarchate; to Haji Orhan Selaheddin Dedeh, of the Mevlevi Dervishes of Pera; to A. L. Otterson, Esq.; to Sir Edwin Pears; to Refik Bey, Curator of the Palace and Treasury of Top Kapou; to E. D. Roth, Esq.; to Mr. Arshag Schmavonian, Legal Adviser of the American Embassy; to William Thompson, Esq.; to Ernest Weakley, Esq.; and to Zia Bey, of the Ministry of Pious Foundations. My thanks are also due to the editors of the Atlantic Monthly, of Scribner’s Magazine, and of the Spectator, for allowing me to republish those chapters which originally came out in their periodicals. And I am not least grateful to the publishers for permitting me to change the scheme of my book while in preparation, and to substitute new illustrations for a large number that had already been made.

Hamadan, 6th Sefer, 1332.

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I | |

| Stamboul | 1 |

| Chapter II | |

| Mosque Yards | 33 |

| Chapter III | |

| Old Constantinople | 74 |

| Chapter IV | |

| The Golden Horn | 113 |

| Chapter V | |

| The Magnificent Community | 148 |

| Chapter VI | |

| The City of Gold | 189 |

| Chapter VII | |

| The Gardens of the Bosphorus | 227 |

| Chapter VIII | |

| The Moon of Ramazan | 265[xiv] |

| Chapter IX | |

| Mohammedan Holidays | 284 |

| Chapter X | |

| Two Processions | 301 |

| Chapter XI | |

| Greek Feasts | 318 |

| Chapter XII | |

| Fountains | 352 |

| Chapter XIII | |

| A Turkish Village | 382 |

| Chapter XIV | |

| Revolution, 1908 | 402 |

| Chapter XV | |

| The Capture of Constantinople, 1909 | 425 |

| Chapter XVI | |

| War Time, 1912-1913 | 459 |

| Masters of Constantinople | 545 |

| A Constantinople Book-Shelf | 549 |

| Index | 555 |

| Sultan Mehmed II, the Conqueror | Frontispiece |

| From the portrait by Gentile Bellini in the Layard Collection | |

| PAGE | |

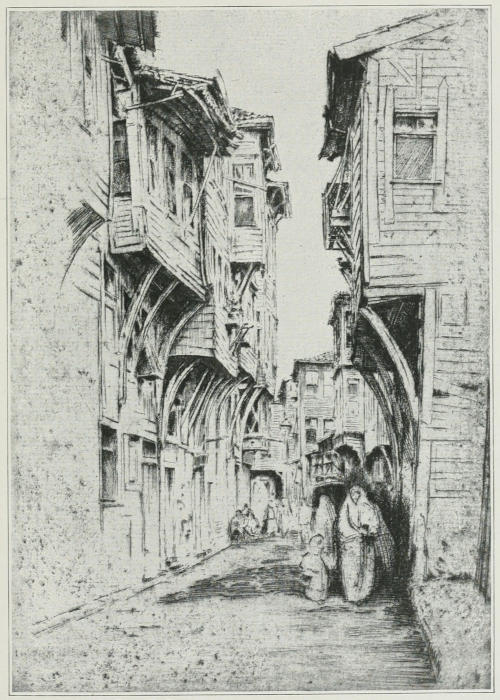

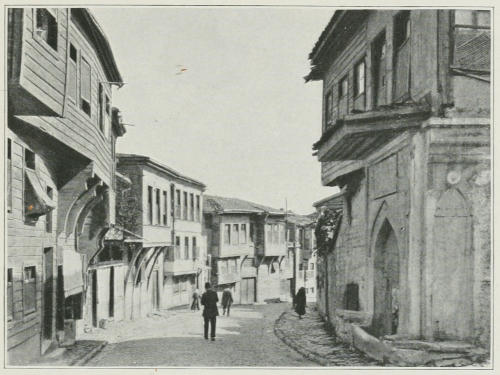

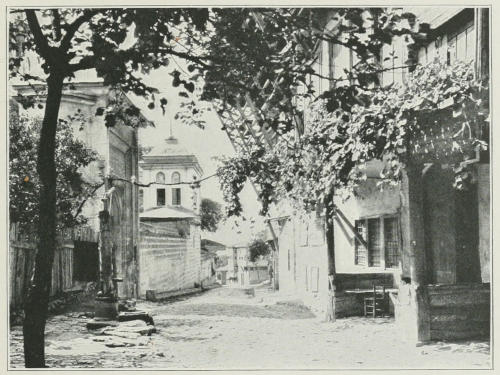

| A Stamboul street | 5 |

| From an etching by Ernest D. Roth | |

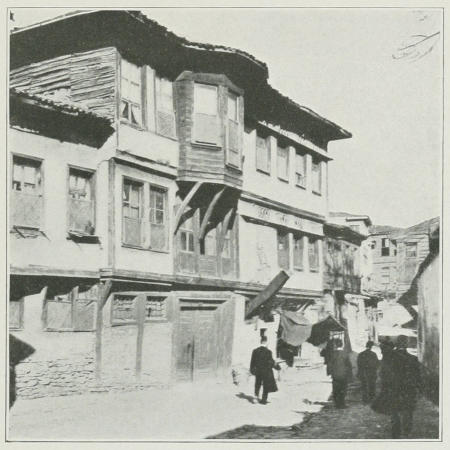

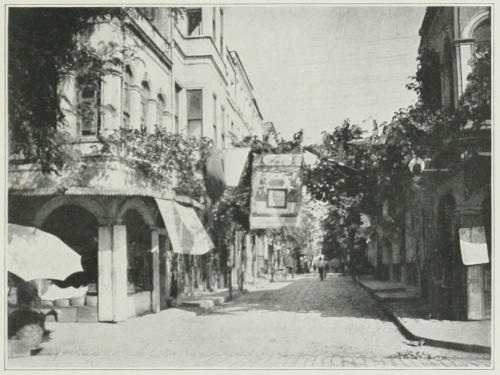

| Divan Yolou | 9 |

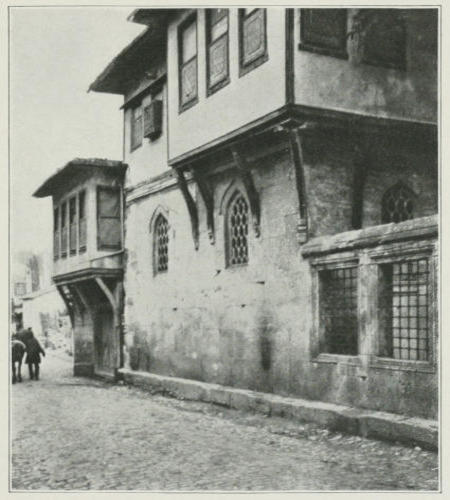

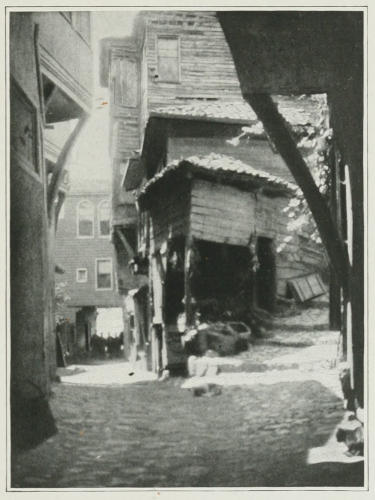

| A house in Eyoub | 11 |

| A house at Aya Kapou | 12 |

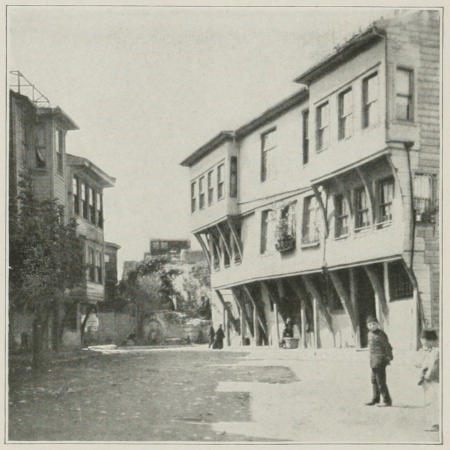

| The house of the pipe | 13 |

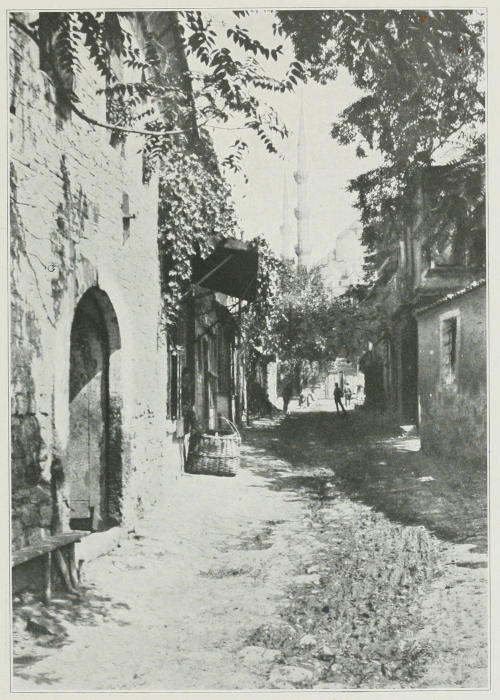

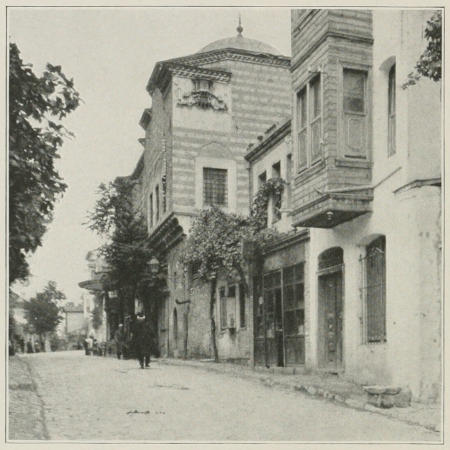

| That grape-vine is one of the most decorative elements of Stamboul streets | 21 |

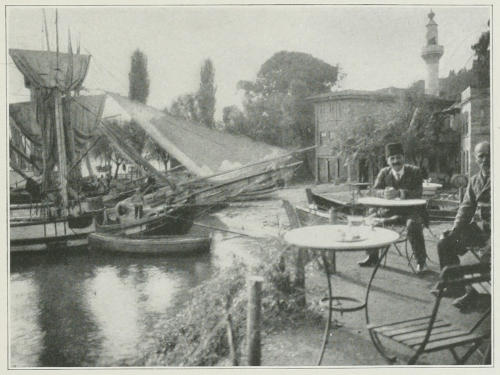

| A waterside coffee-house | 23 |

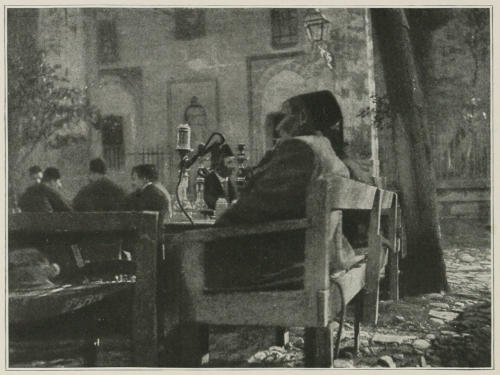

| “Drinking” a nargileh | 26 |

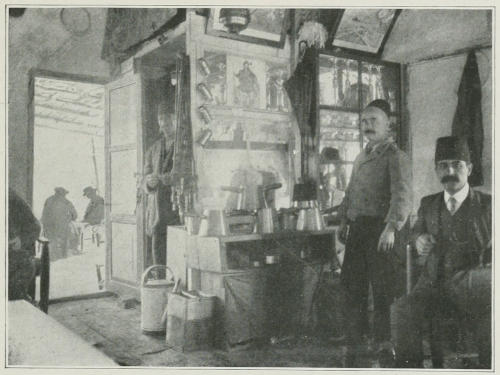

| Fez-presser in a coffee-house | 27 |

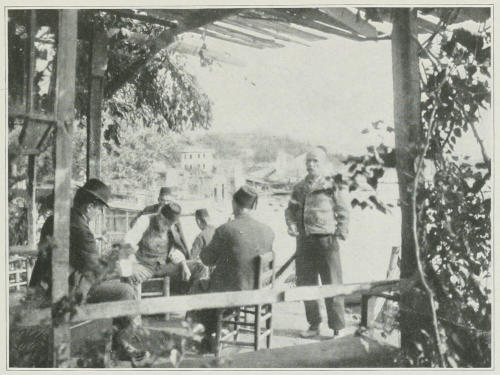

| Playing tavli | 29 |

| The plane-tree of Chengel-kyöi | 31 |

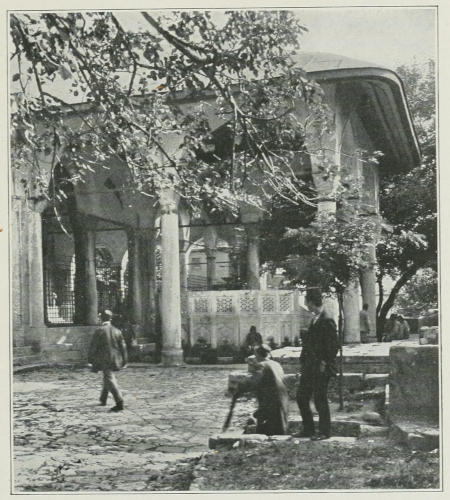

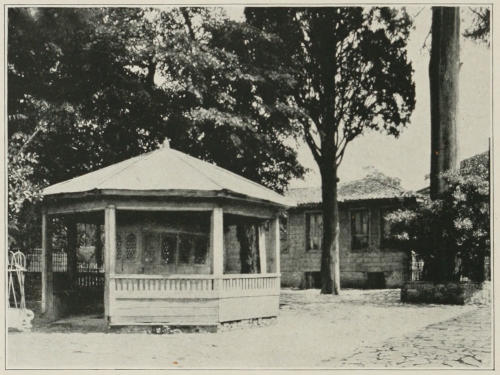

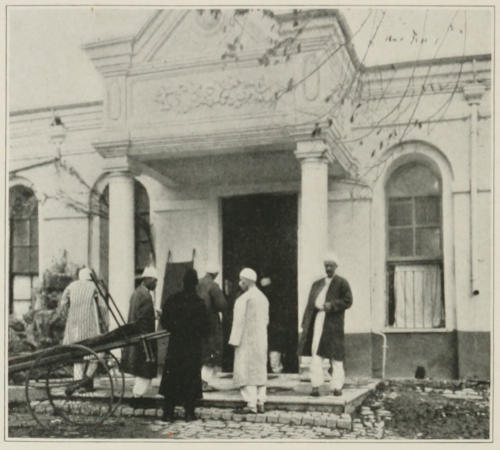

| The yard of Hekim-zadeh Ali Pasha | 35 |

| “The Little Mosque” | 37 |

| From an etching by Ernest D. Roth | |

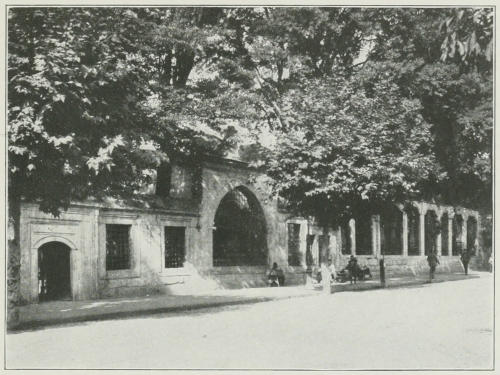

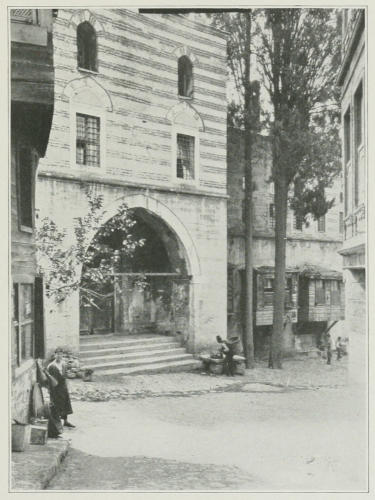

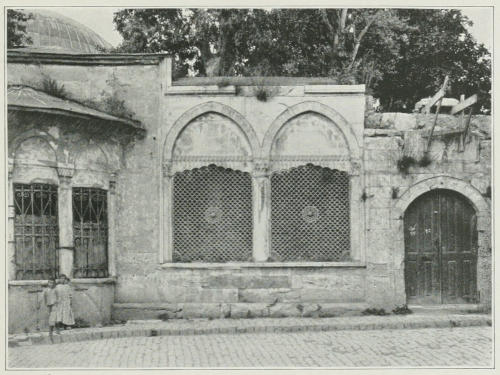

| Entrance to the forecourt of Sultan Baïezid II | 40 |

| Detail of the Süleïmanieh | 41 |

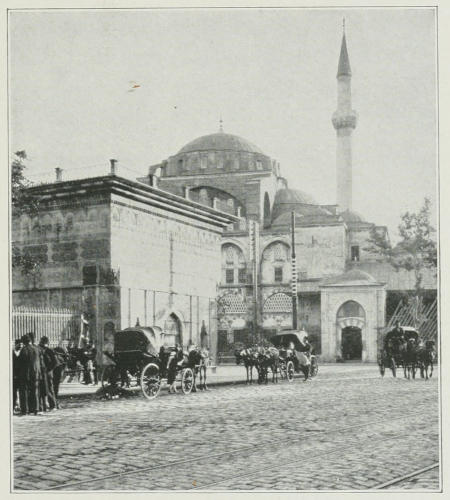

| Yeni Jami | 43 |

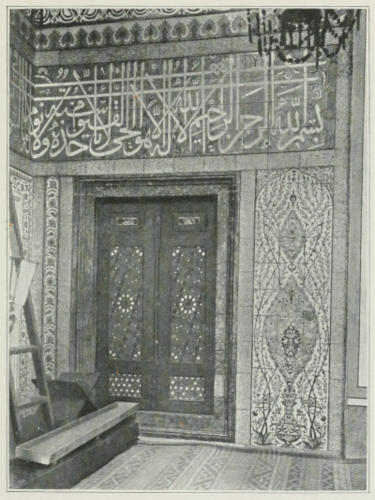

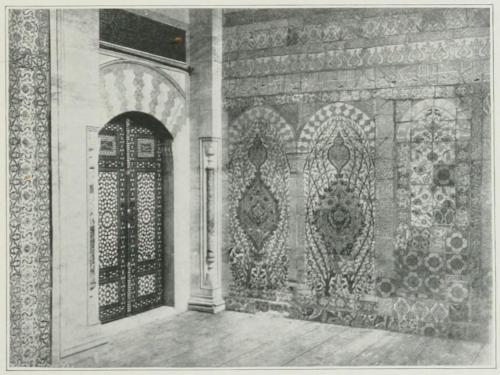

| Tile panel in Rüstem Pasha | 50 |

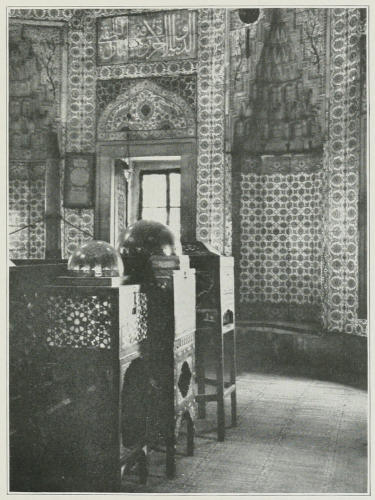

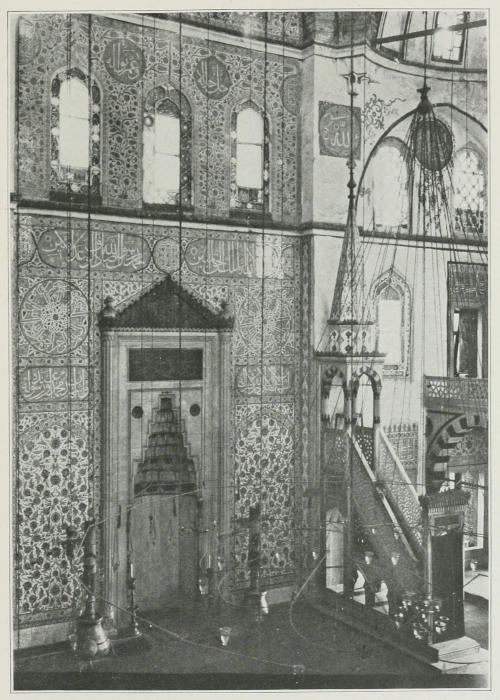

| The mihrab of Rüstem Pasha | 51[xvi] |

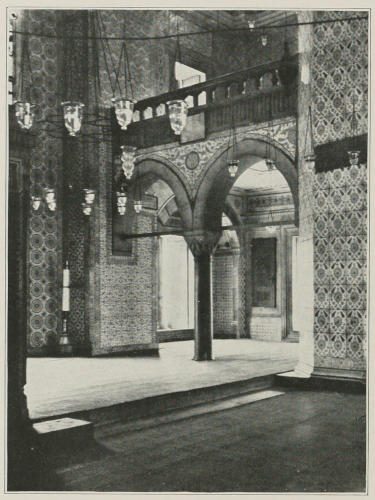

| In Rüstem Pasha | 52 |

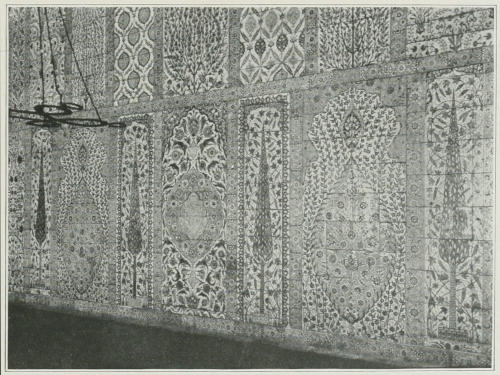

| Tiles in the gallery of Sultan Ahmed | 53 |

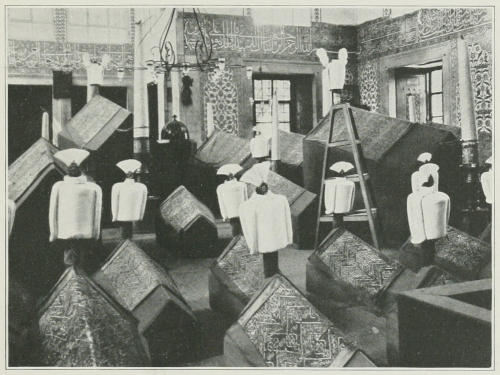

| The tomb of Sultan Ahmed I | 57 |

| In Roxelana’s tomb | 59 |

| The türbeh of Ibrahim Pasha | 63 |

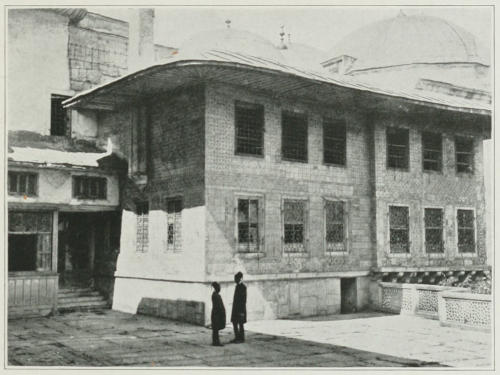

| The court of the Conqueror | 64 |

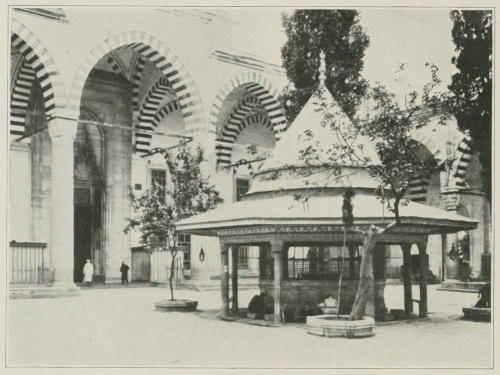

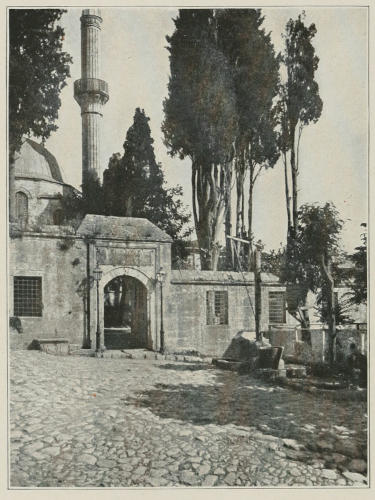

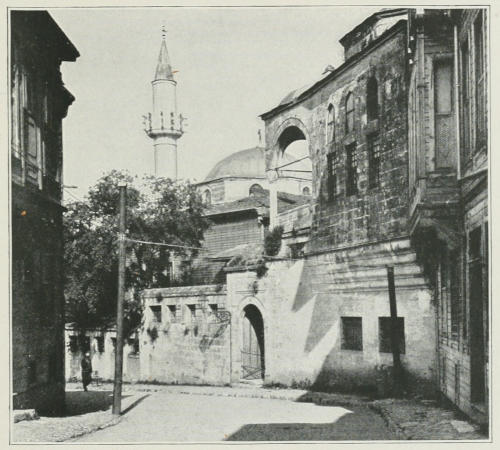

| The main entrance to the court of Sokollî Mehmed Pasha | 65 |

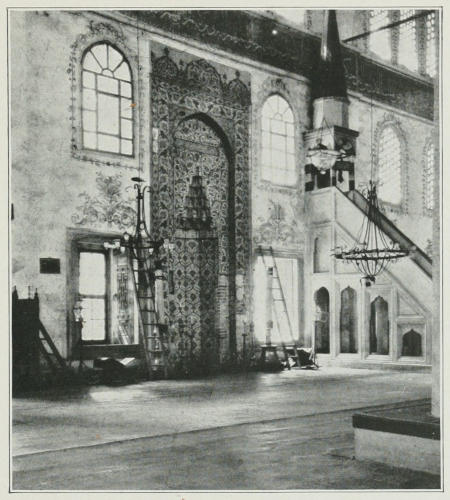

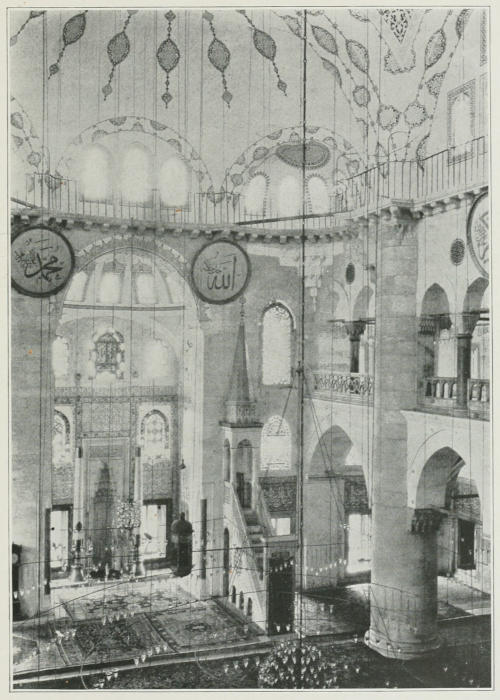

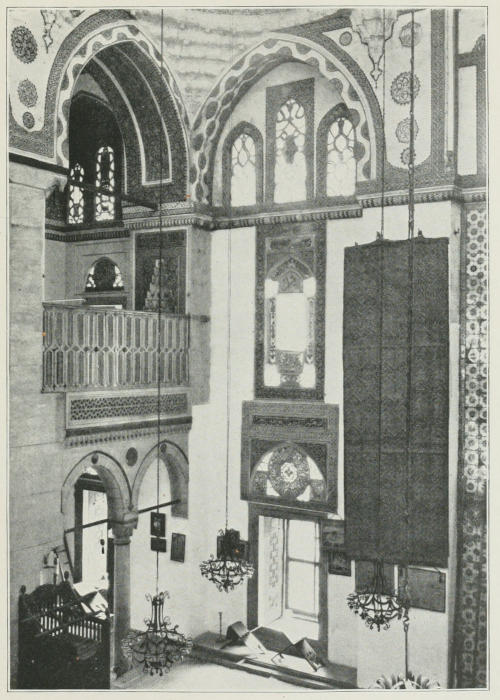

| The interior of Sokollî Mehmed Pasha | 67 |

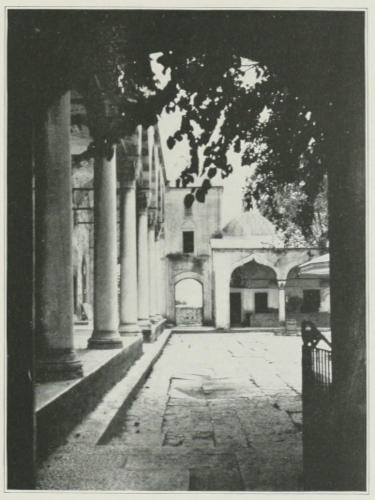

| The court of Sokollî Mehmed Pasha | 69 |

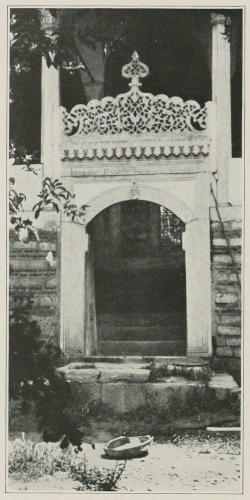

| Doorway in the medresseh of Feïzoullah Effendi | 70 |

| Entrance to the medresseh of Kyöprülü Hüsseïn Pasha | 71 |

| The medresseh of Hassan Pasha | 72 |

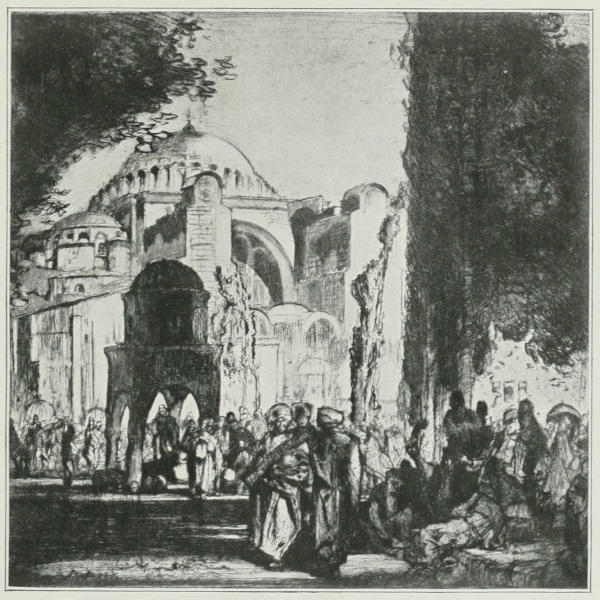

| St. Sophia | 77 |

| From an etching by Frank Brangwyn | |

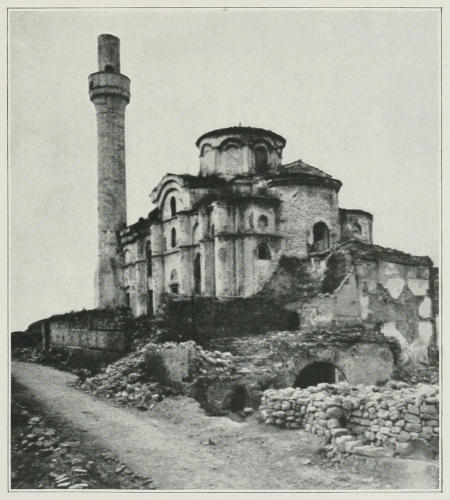

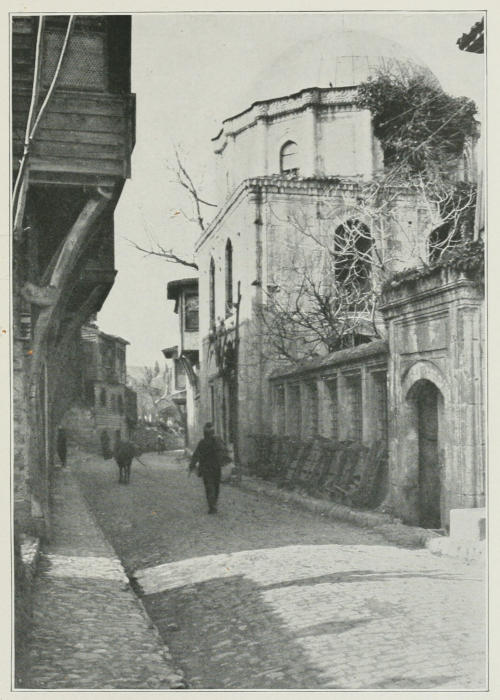

| The Myrelaion | 83 |

| The House of Justinian | 86 |

| The Palace of the Porphyrogenitus | 90 |

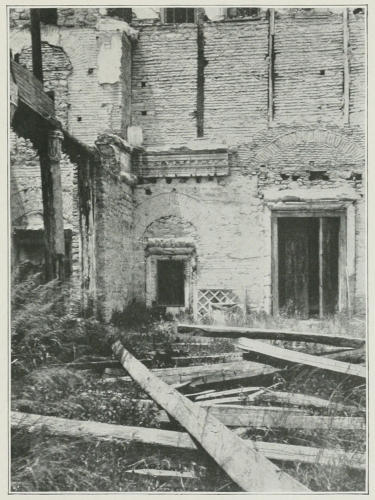

| Interior of the Studion | 93 |

| Kahrieh Jami | 97 |

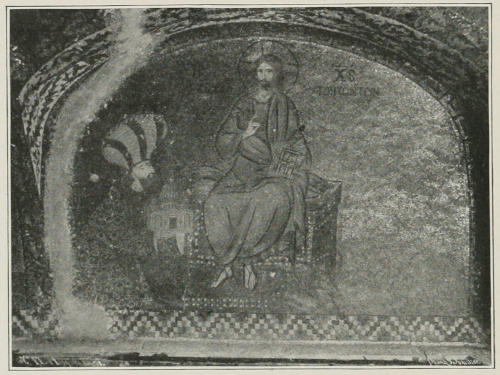

| Mosaic from Kahrieh Jami: Theodore Metochites offering his church to Christ | 98 |

| Mosaic from Kahrieh Jami: the Massacre of the Innocents | 101 |

| Giotto’s fresco of the Massacre of the Innocents, in the Arena chapel, Padua | 101 |

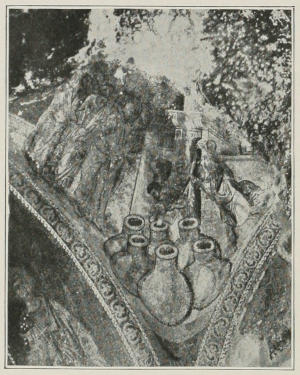

| Mosaic from Kahrieh Jami: the Marriage at Cana | 104 |

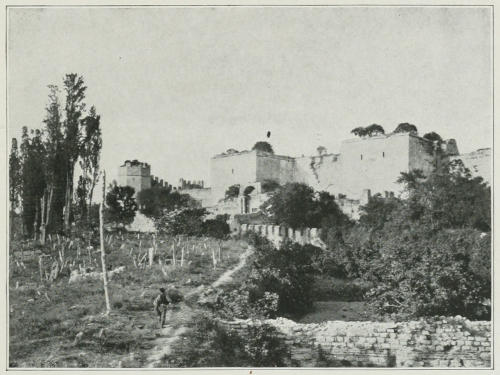

| The Golden Gate | 109[xvii] |

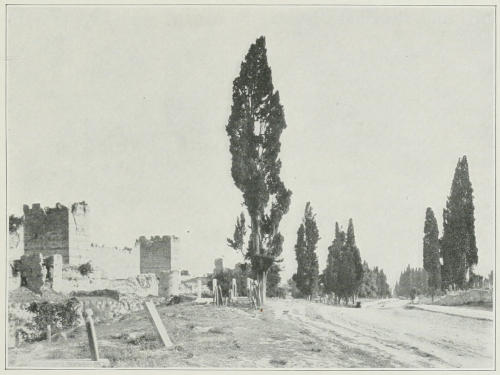

| Outside the land walls | 111 |

| A last marble tower stands superbly out of the blue | 112 |

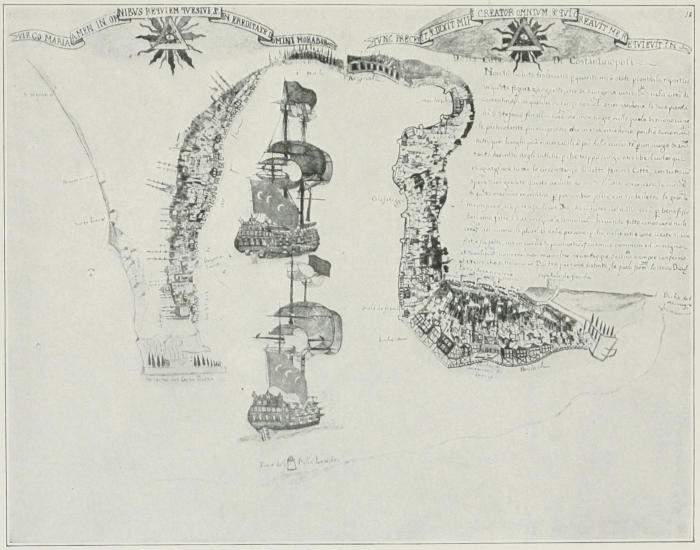

| The Golden Horn | 115 |

| From the Specchio Marittimo of Bartolommeo Prato | |

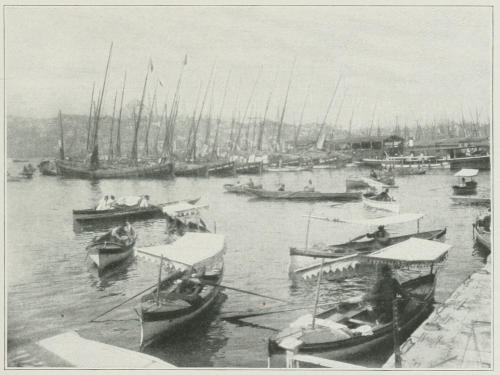

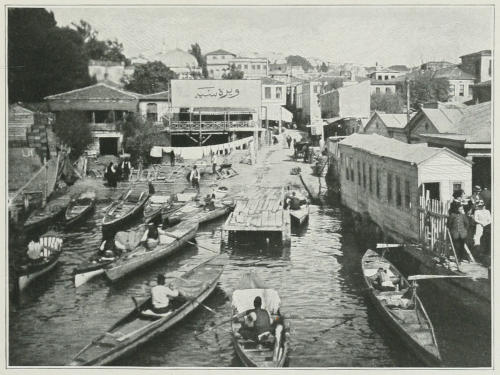

| Lighters | 118 |

| Sandals | 119 |

| Caïques | 121 |

| Sailing caïques | 122 |

| Galleons that might have sailed out of the Middle Ages anchor there now | 123 |

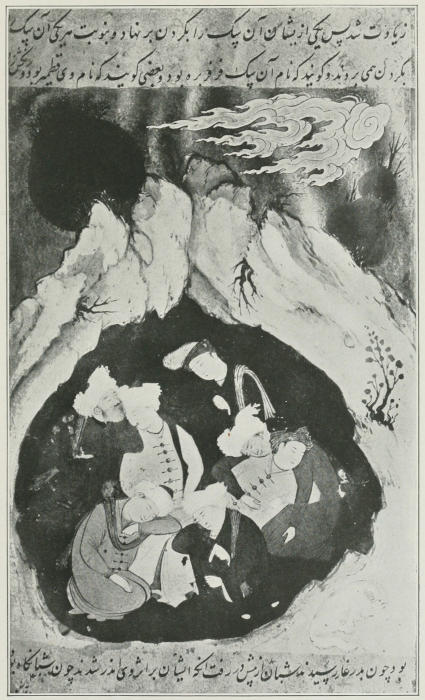

| The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus | 125 |

| From a Persian miniature in the Bibliothèque Nationale | |

| The mihrab of Pialeh Pasha | 131 |

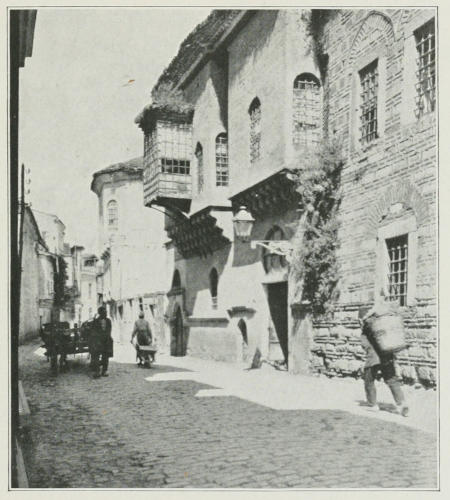

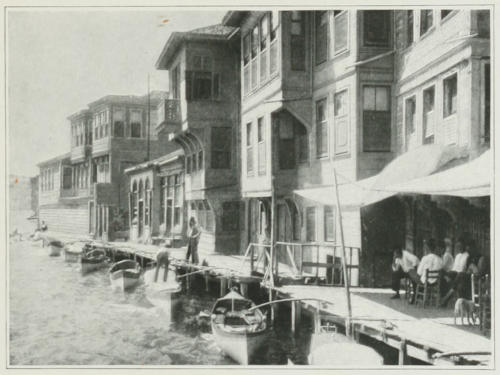

| Old houses of Phanar | 133 |

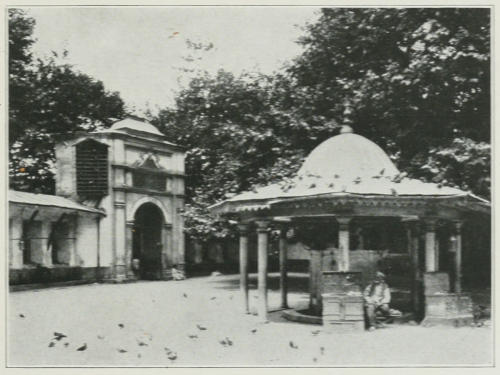

| The outer court of Eyoub | 135 |

| Eyoub | 137 |

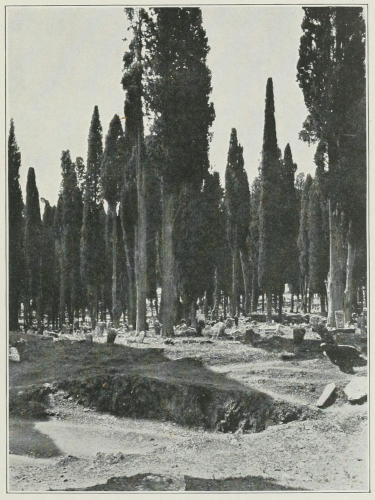

| The cemetery of Eyoub | 141 |

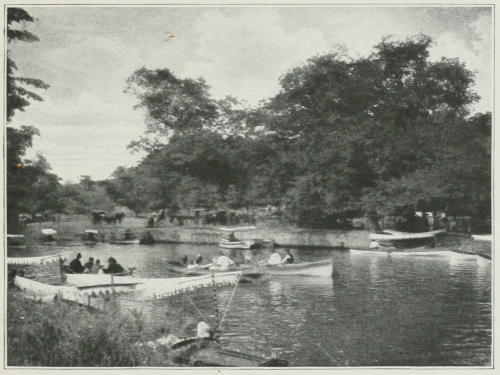

| Kiat Haneh | 145 |

| Lion fountain in the old Venetian quarter | 153 |

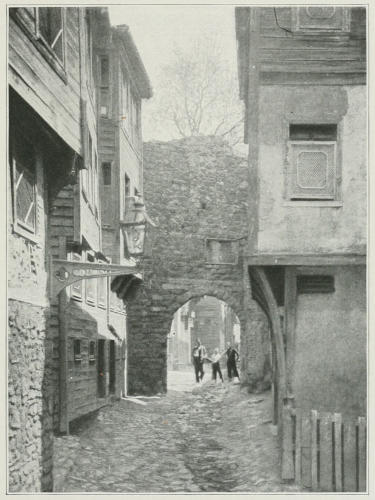

| Genoese archway at Azap Kapou | 155 |

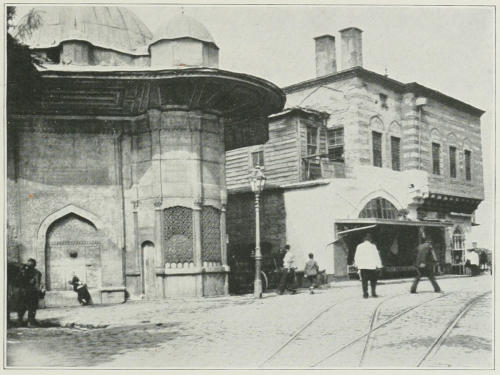

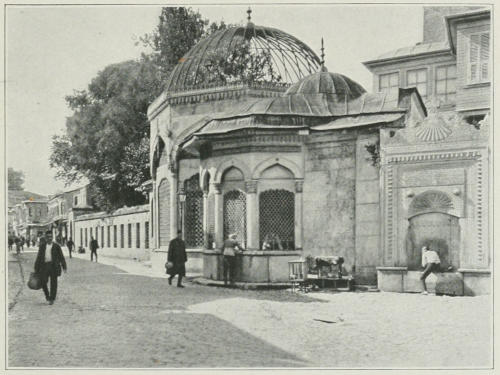

| The mosque of Don Quixote and the fountain of Sultan Mahmoud I | 165 |

| Interior of the mosque of Don Quixote | 167 |

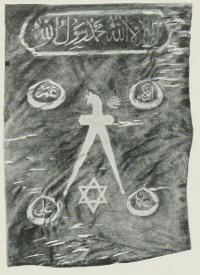

| The admiral’s flag of Haïreddin Barbarossa | 169 |

| Drawn by Kenan Bey | |

| Grande Rue de Pera | 180 |

| The Little Field of the Dead | 181 |

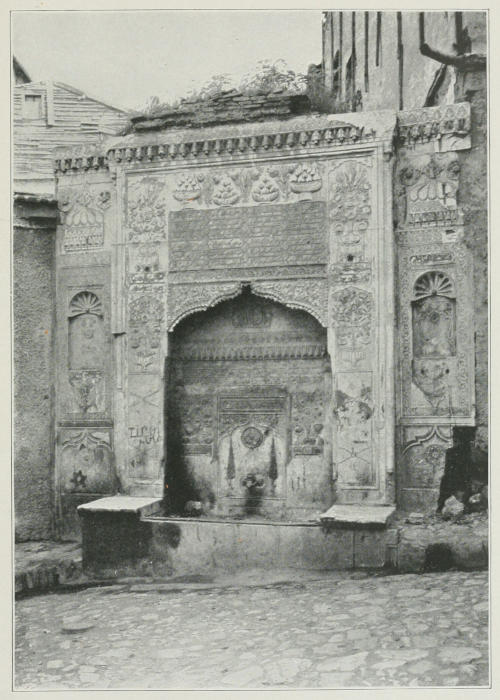

| The fountain of Azap Kapou | 183[xviii] |

| Fountain near Galata Tower | 185 |

| The Kabatash breakwater | 187 |

| Fresco in an old house in Scutari | 191 |

| The Street of the Falconers | 199 |

| Fountain in the mosque yard of Mihrîmah | 201 |

| Tiles in the mosque of the Valideh Atik | 203 |

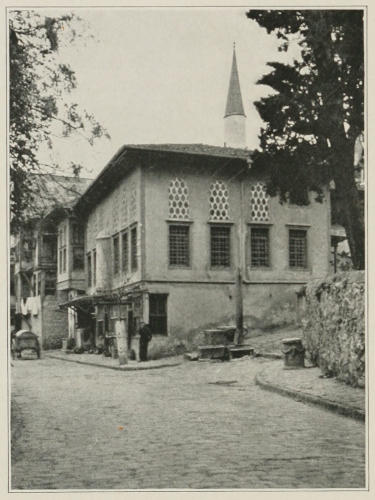

| Chinili Jami | 204 |

| The fountains of the Valideh Jedid | 205 |

| Interior of the Valideh Jedid | 207 |

| The Ahmedieh | 209 |

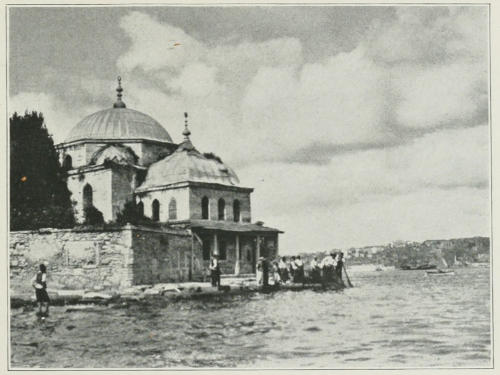

| Shemsi Pasha | 211 |

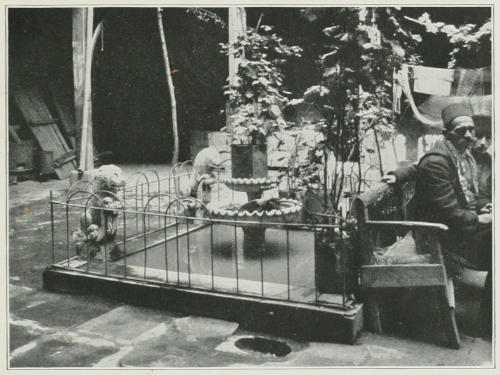

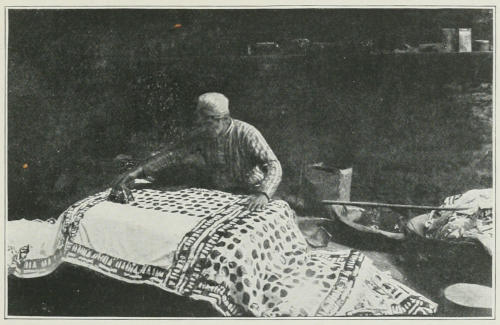

| The bassma haneh | 213 |

| Hand wood-block printing | 215 |

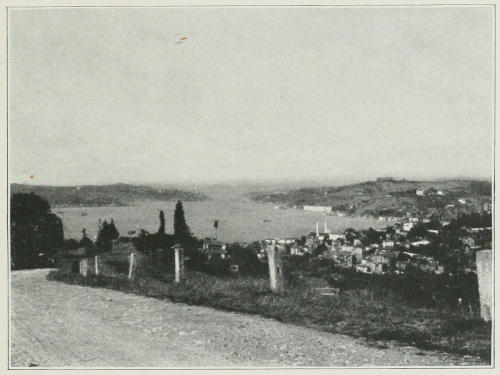

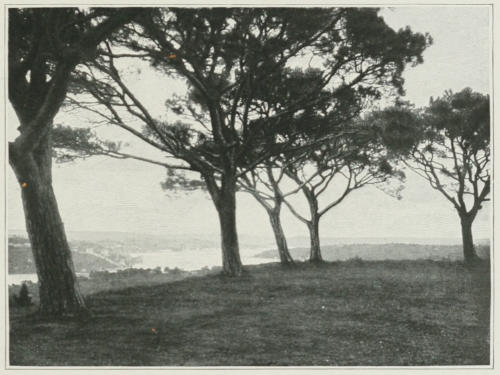

| The Bosphorus from the heights of Scutari | 217 |

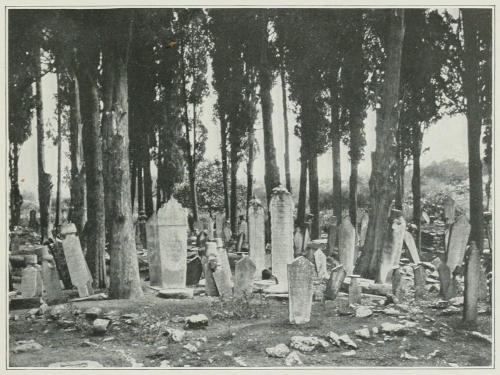

| Gravestones | 221 |

| Scutari Cemetery | 223 |

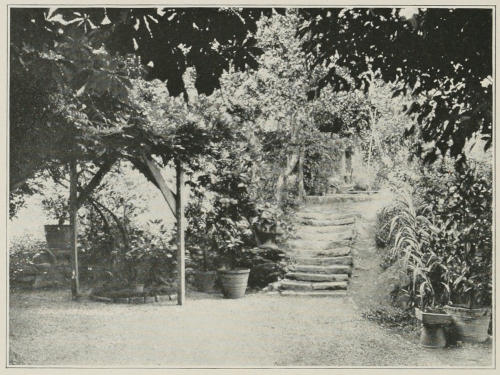

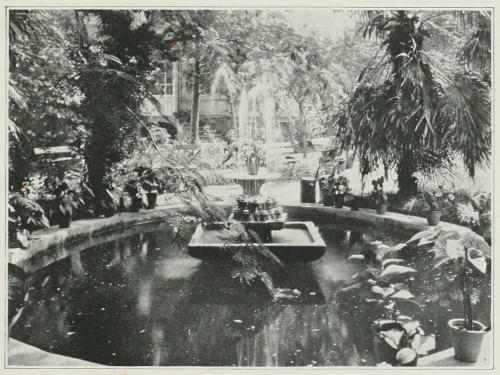

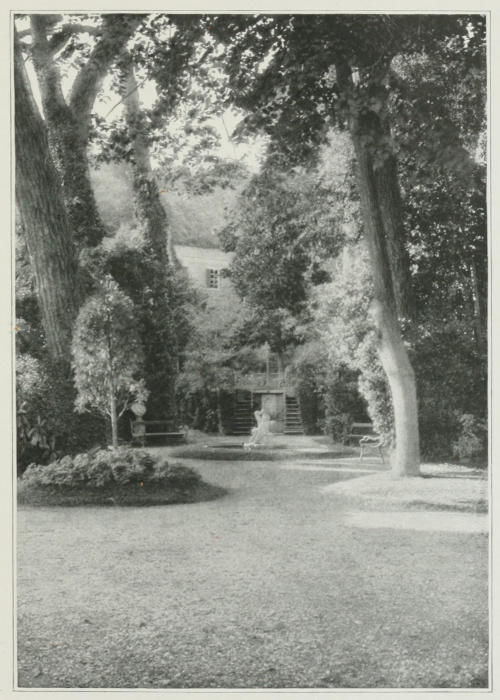

| In a Turkish garden | 230 |

| A Byzantine well-head | 232 |

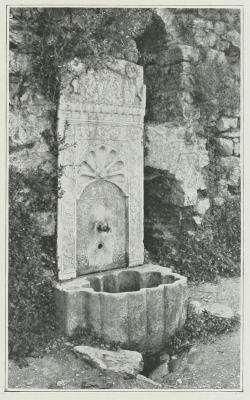

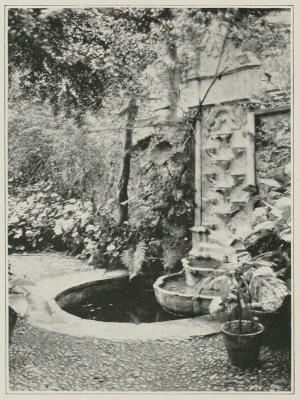

| A garden wall fountain | 233 |

| A jetting fountain in the garden of Halil Edhem Bey | 235 |

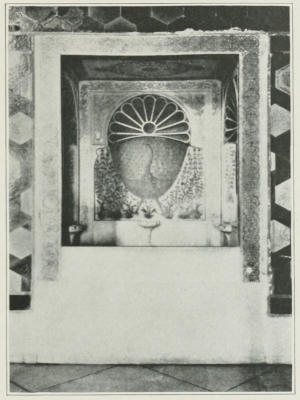

| A selsebil at Kandilli | 236 |

| A selsebil of Halil Edhem Bey | 237 |

| In the garden of Ressam Halil Pasha | 239 |

| The garden of the Russian embassy at Büyük Dereh | 241 |

| The upper terrace of the French embassy garden at Therapia | 243[xix] |

| The Villa of the Sun, Kandilli | 249 |

| An eighteenth-century villa at Arnaout-kyöi | 252 |

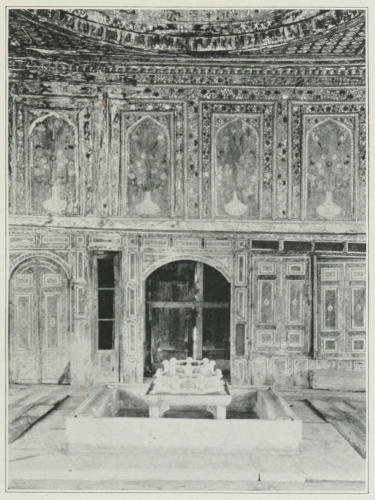

| The golden room of Kyöprülü Hüsseïn Pasha | 253 |

| In the harem of the Seraglio | 261 |

| The “Cage” of the Seraglio | 263 |

| A Kara-gyöz poster | 271 |

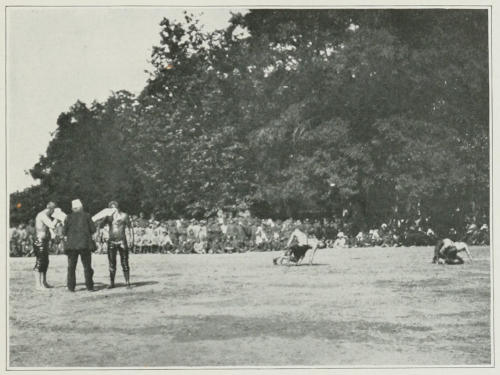

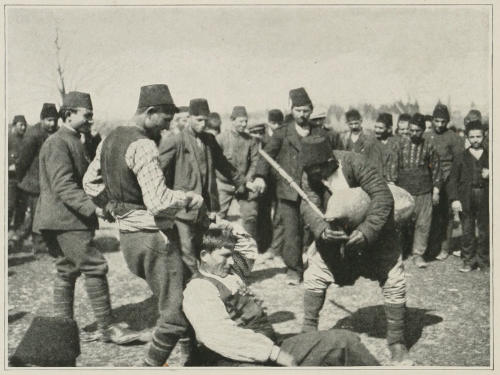

| Wrestlers | 275 |

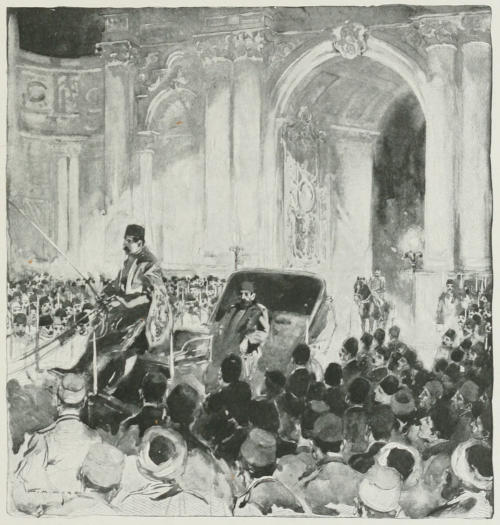

| The imperial cortège poured from the palace gate | 281 |

| From a drawing by E. M. Ashe | |

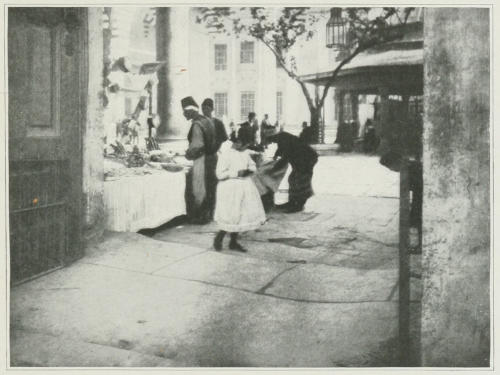

| Baïram sweets | 289 |

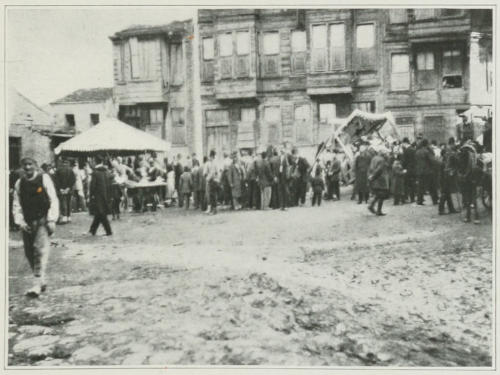

| The open spaces of the Mohammedan quarters are utilised for fairs | 295 |

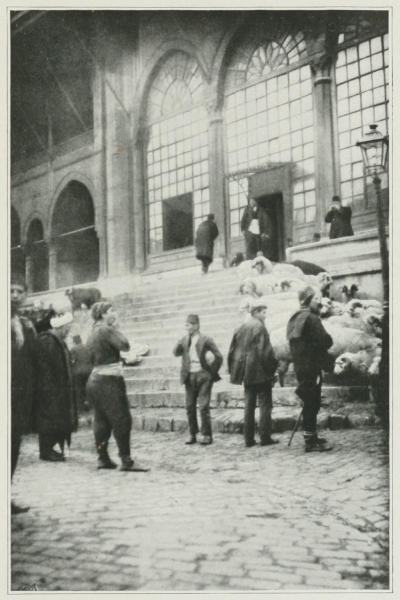

| Sheep-market at Yeni Jami | 299 |

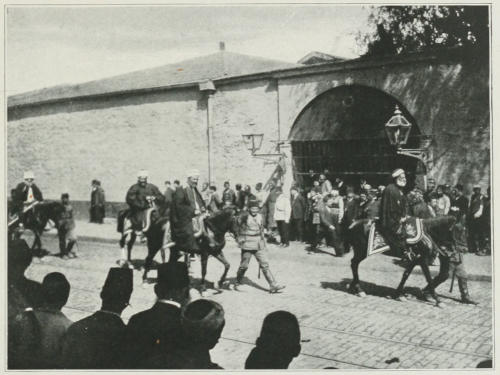

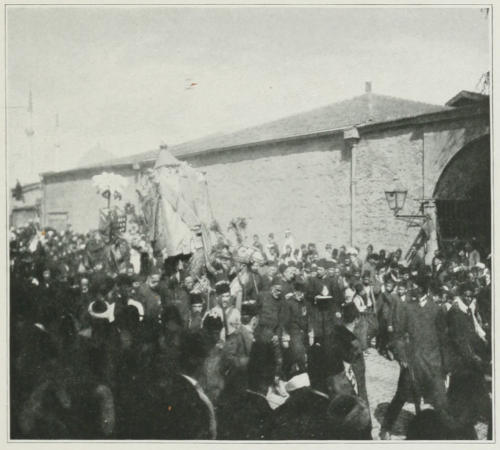

| Church fathers in the Sacred Caravan | 305 |

| Housings in the Sacred Caravan | 306 |

| The sacred camel | 307 |

| The palanquin | 308 |

| Tied with very new rope to the backs of some thirty mules ... were the quaint little hair trunks | 309 |

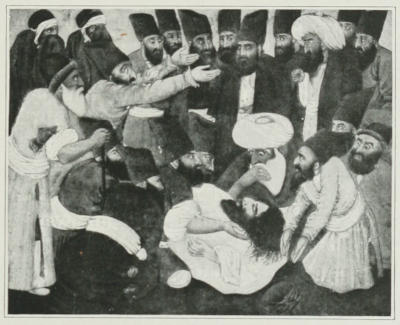

| A Persian miniature representing the death of Ali | 311 |

| Valideh Han | 313 |

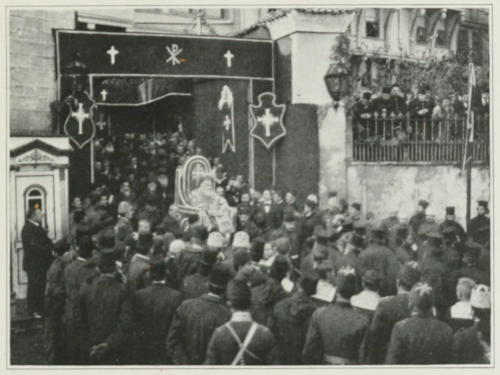

| Blessing the Bosphorus | 321 |

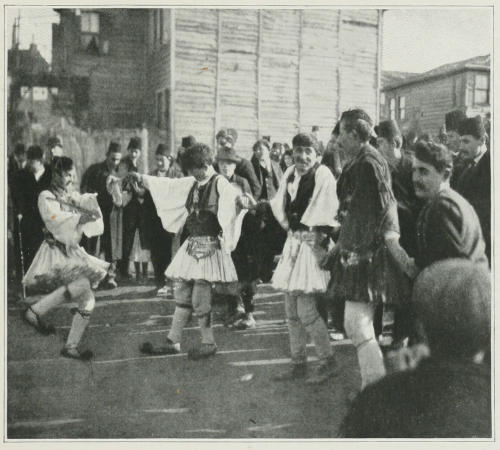

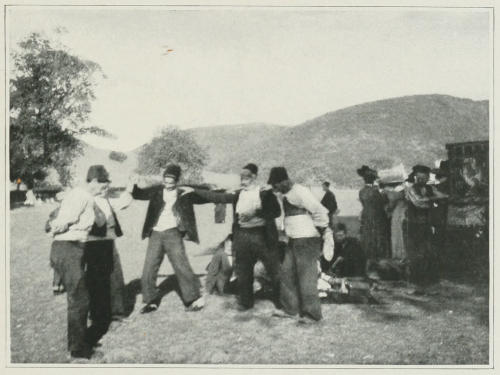

| The dancing Epirotes | 325 |

| Bulgarians dancing | 336 |

| Greeks dancing to the strains of a lanterna | 337 |

| The mosque and the Greek altar of Kourou Cheshmeh | 348[xx] |

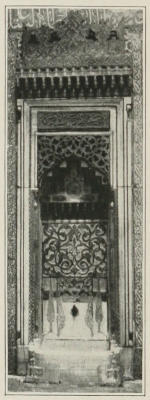

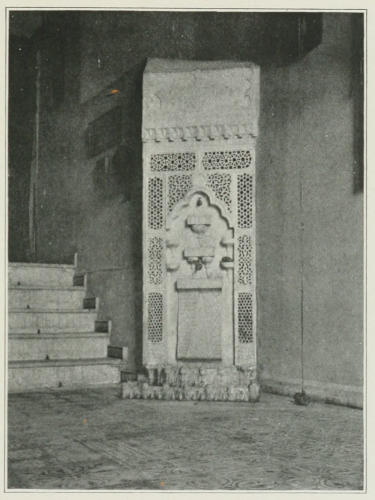

| Wall fountain in the Seraglio | 354 |

| Selsebil in Bebek | 355 |

| The goose fountain at Kazlî | 356 |

| The wall fountain of Chinili-Kyöshk | 357 |

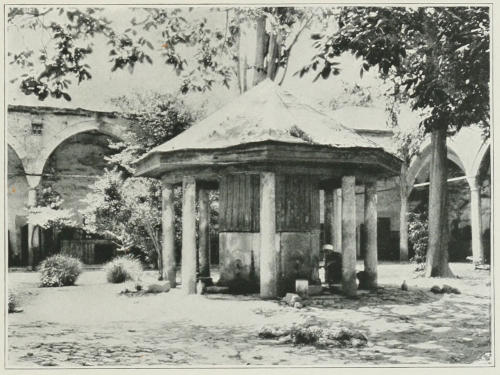

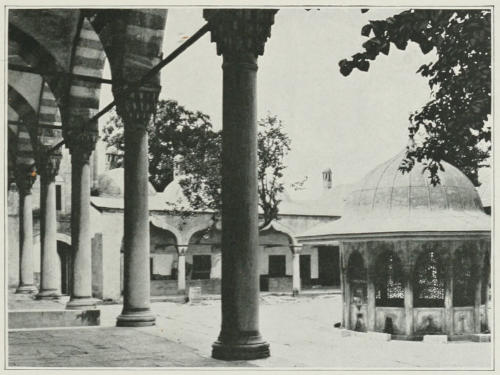

| Shadrîvan of Kyöprülü Hüsseïn Pasha | 359 |

| Shadrîvan of Ramazan Effendi | 360 |

| Shadrîvan of Sokollî Mehmed Pasha | 361 |

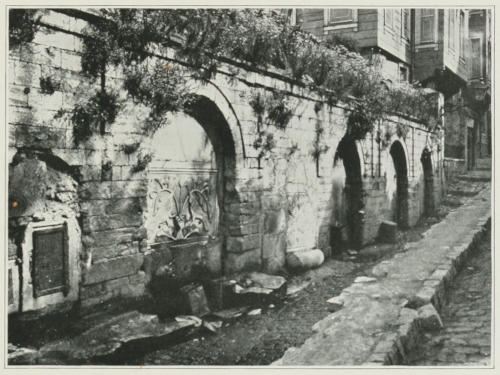

| The Byzantine fountain of Kîrk Cheshmeh | 365 |

| The two fountains of Ak Bîyîk | 368 |

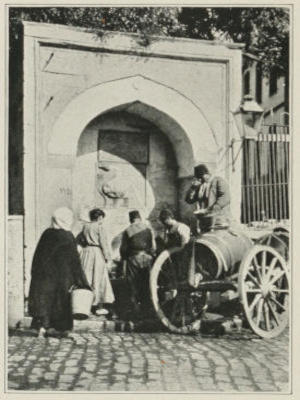

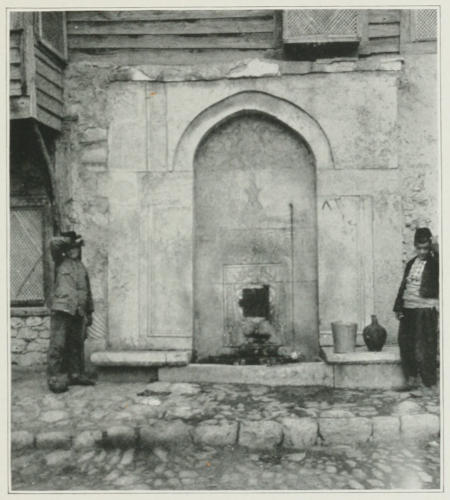

| Street fountain at Et Yemez | 371 |

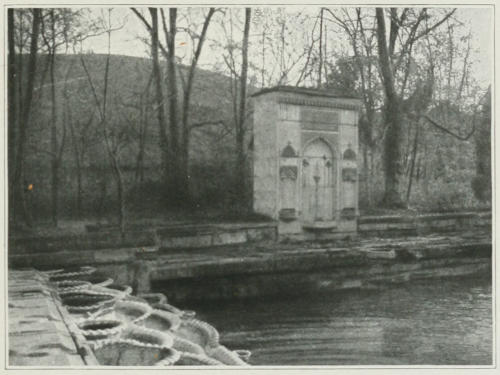

| Fountain of Ahmed III in the park at Kiat Haneh | 373 |

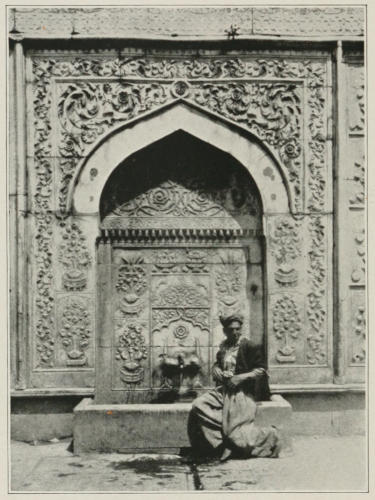

| Detail of the fountain of Mahmoud I at Top Haneh | 374 |

| Fountain of Abd ül Hamid II | 375 |

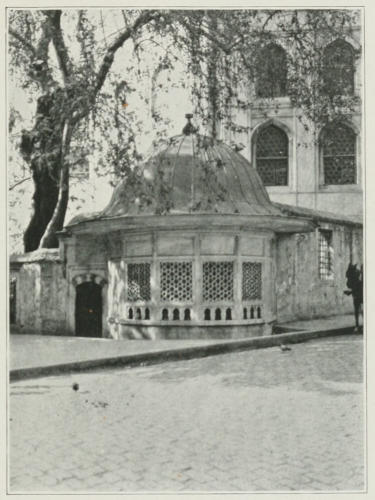

| Sebil behind the tomb of Sultan Mehmed III | 377 |

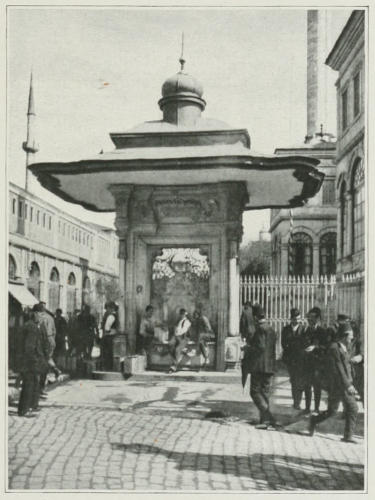

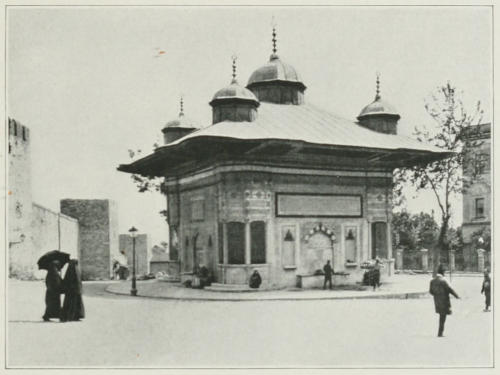

| Sebil of Sultan Ahmed III | 379 |

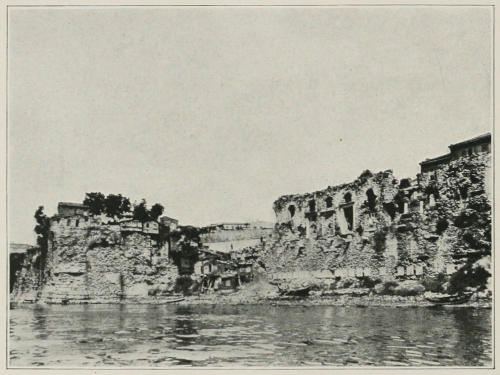

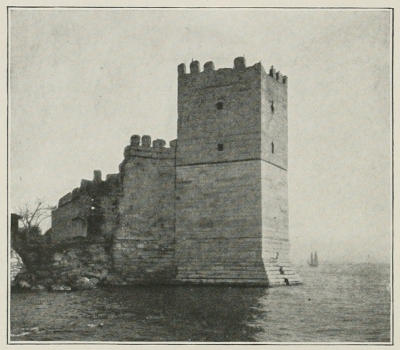

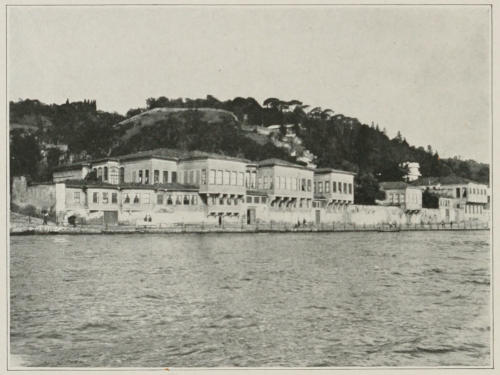

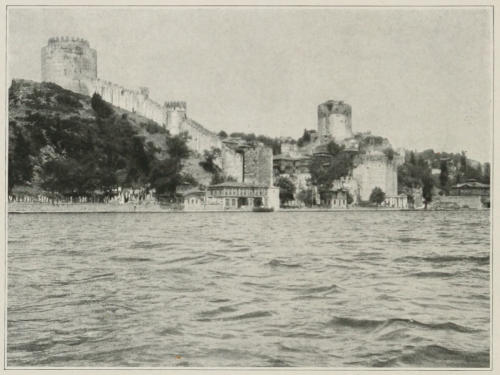

| Cut-Throat Castle from the water | 384 |

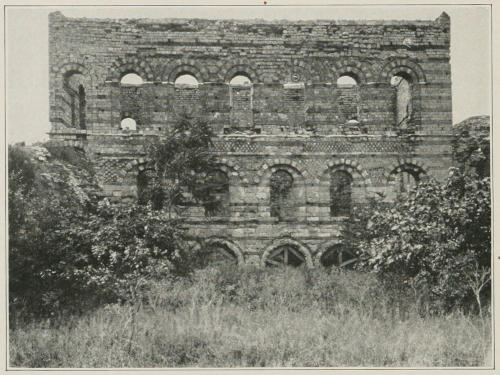

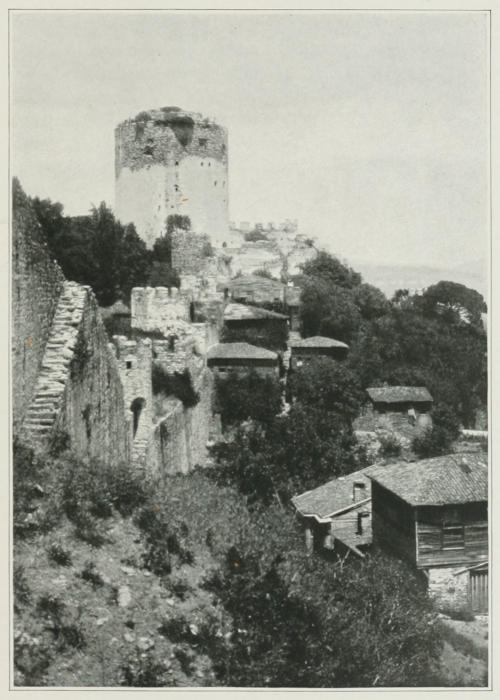

| The castle of Baïezid the Thunderbolt | 385 |

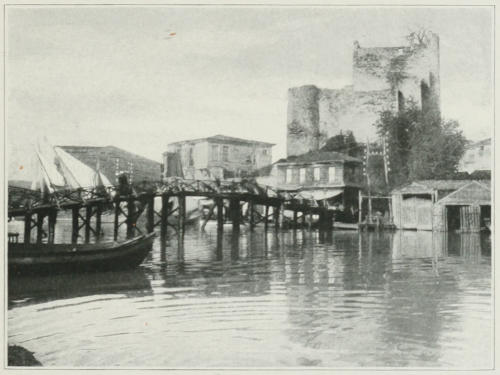

| The north tower of the castle | 387 |

| The village boatmen and their skiffs | 397 |

| In the market-place | 399 |

| Badge of the revolution: “Liberty, Justice, Fraternity, Equality” | 405 |

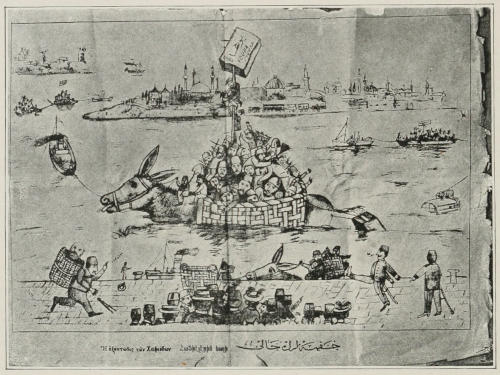

| Cartoon representing the exodus of the Palace camarilla | 412 |

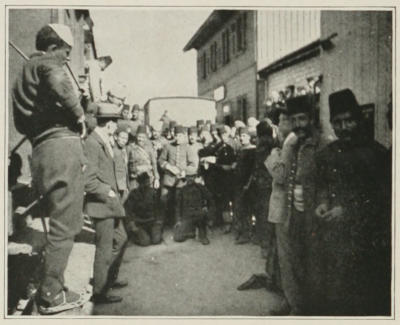

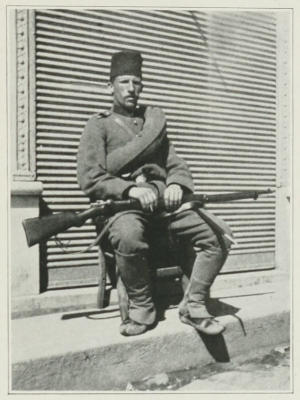

| Soldiers at Chatalja, April 20 | 428 |

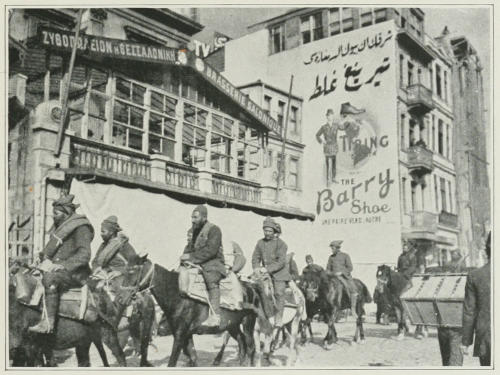

| Macedonian volunteers | 437 |

| A Macedonian Blue | 439[xxi] |

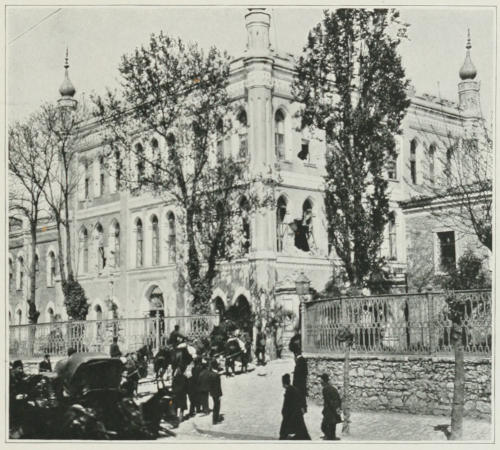

| Taxim artillery barracks, shelled April 24 | 441 |

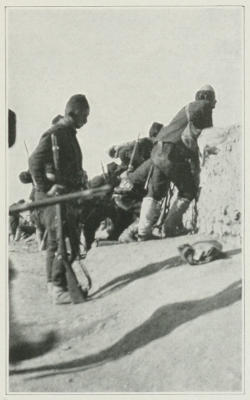

| They were, in fact, reserves posted for the afternoon attack on Tash Kîshla | 443 |

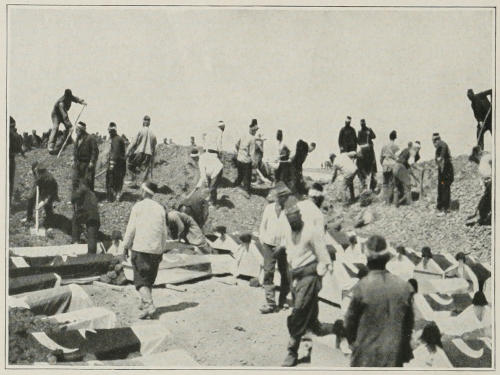

| Burial of volunteers, April 26 | 446 |

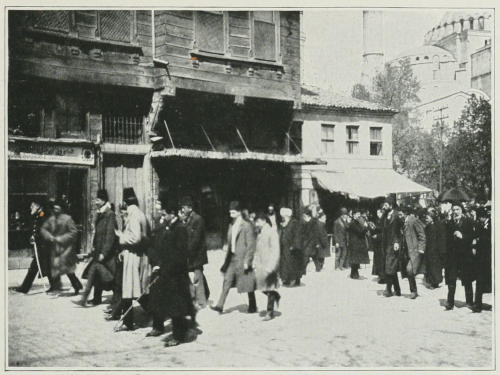

| Deputies leaving Parliament after deposing Abd ül Hamid, April 27 | 447 |

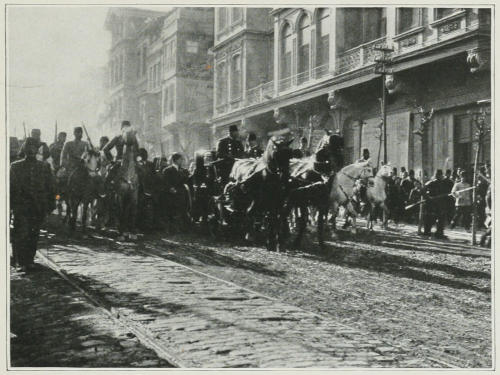

| Mehmed V driving through Stamboul on his accession day, April 27 | 451 |

| Mehmed V on the day of sword-girding, May 10 | 453 |

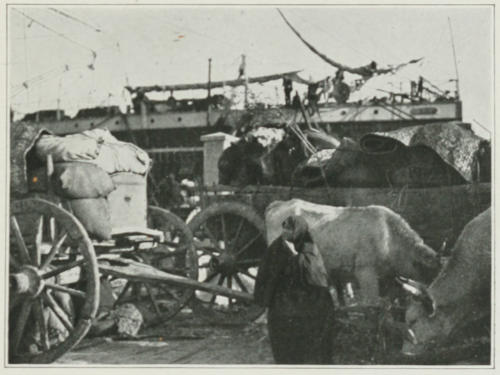

| Arriving from Asia | 460 |

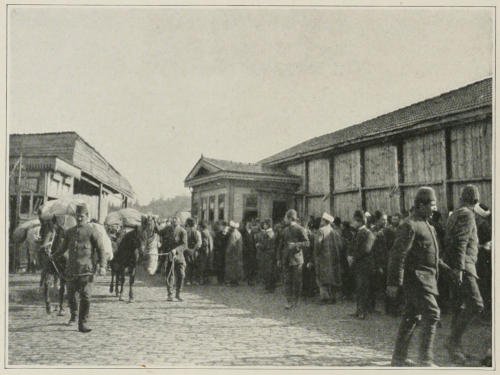

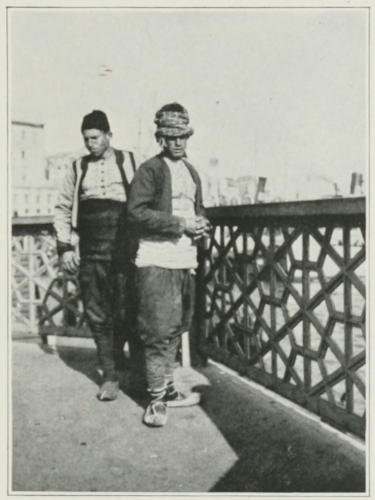

| Reserves | 461 |

| Recruits | 462 |

| Hand in hand | 463 |

| Demonstration in the Hippodrome | 465 |

| Convalescents | 480 |

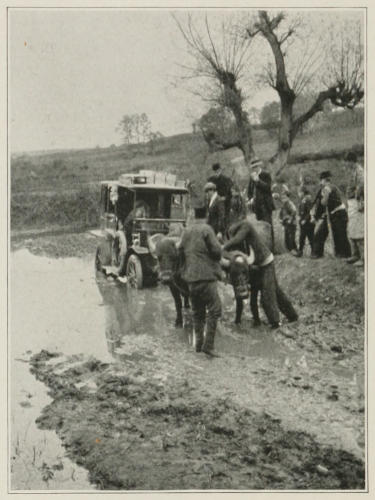

| Stuck in the mud | 482 |

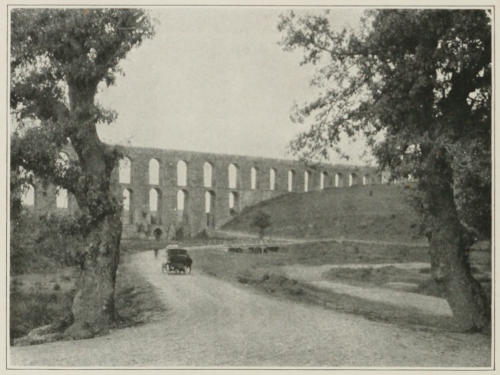

| The aqueduct of Andronicus I | 484 |

| Fleeing from the enemy | 485 |

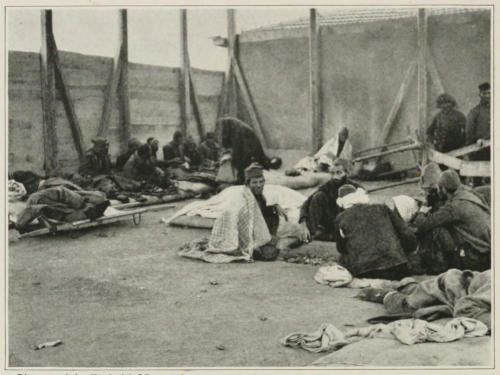

| Cholera | 498 |

| Joachim III, Patriarch of Constantinople | 501 |

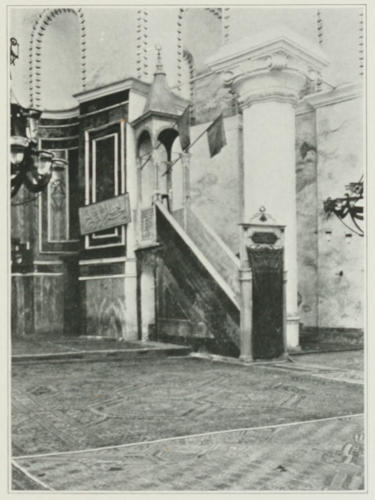

| The south pulpit of the Pantocrator | 503 |

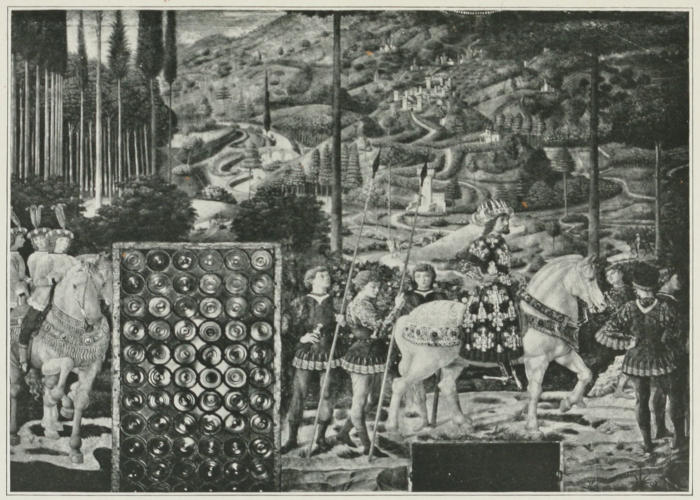

| Portrait of John VII Palæologus as one of the Three Wise Men, by Benozzo Gozzoli. Riccardi Chapel, Florence | 505 |

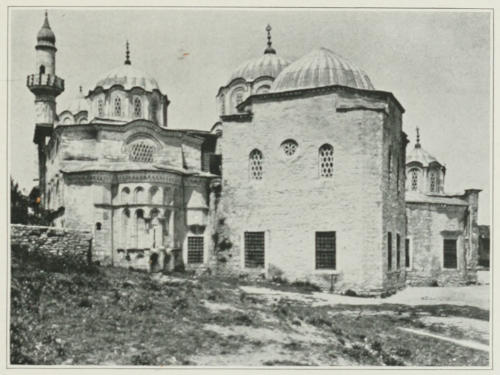

| Church of the All-Blessed Virgin (Fetieh Jami) | 515 |

| The lantern-bearers | 517 |

| The dead Patriarch | 519 |

| Exiles | 523 |

| Lady Lowther’s refugees | 526 |

| Peasant embroidery | 532 |

| Young Thrace | 533 |

I, a Persian and an Ispahani, had ever been accustomed to hold my native city as the first in the world: never had it crossed my mind that any other could, in the smallest degree, enter into competition with it, and when the capital of Roum was described to me as finer, I always laughed the describer to scorn. But what was my astonishment, and I may add mortification, on beholding, for the first time, this magnificent city! I had always looked upon the royal mosque, in the great square at Ispahan, as the most superb building in the world; but here were a hundred finer, each surpassing the other in beauty and in splendour. Nothing did I ever conceive could equal the extent of my native place; but here my eyes became tired with wandering over the numerous hills and creeks thickly covered with buildings, which seemed to bid defiance to calculation. If Ispahan was half the world, this indeed was the whole. And then this gem of cities possesses this great advantage over Ispahan, that it is situated on the borders of a beautiful succession of waters, instead of being surrounded by arid and craggy mountains; and, in addition to its own extent and beauty, enjoys the advantage of being reflected in one never-failing mirror, ever at hand to multiply them.... “Oh! this is a paradise,” said I to those around me; “and may I never leave it!”

—J. J. Morier, “The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan.”

If literature could be governed by law—which, very happily, to the despair of grammarians, it can not—there should be an act prohibiting any one, on pain of death, ever to quote again or adapt to private use Charles Lamb and his two races of men. No one is better aware of the necessity of such a law than the present scribe, as he struggles with the temptation to declare anew that there are two races of men. Where, for instance, do they betray themselves more perfectly than in Stamboul? You like Stamboul or you dislike Stamboul, and there seems to be no half-way ground between the two opinions. I notice, however, that conversion from the latter rank to the former is not impossible. I cannot say that I ever really belonged, myself, to the enemies of Stamboul. Stamboul entered too early into my consciousness and I was too early separated from her to ask myself questions; and it later happened to me to fall under a potent spell. But there came a day when I returned to Stamboul from Italy. I felt a scarcely definable change in the atmosphere as soon as we crossed the Danube. Strange letters decorated the sides of cars, a fez or two—shall I be pedantic enough to say that the[2] word is really fess?—appeared at car windows, peasants on station platforms had something about them that recalled youthful associations. The change grew more and more marked as we neared the Turkish frontier. And I realised to what it had been trending when at last we entered a breach of the old Byzantine wall and whistled through a long seaside quarter of wooden houses more tumble-down and unpainted than I remembered wooden houses could be, and dusty little gardens, and glimpses of a wide blue water through ruinous masonry, and people as out-at-elbow and down-at-the-heel as their houses, who even at that shining hour of a summer morning found time to smoke hubble-bubbles in tipsy little coffee-houses above the Marmora or to squat motionless on their heels beside the track and watch the fire-carriage of the unbeliever roll in from the West.

I have never forgotten—nor do successive experiences seem to dull the sharpness of the impression—that abysmal drop from the general European level of spruceness and solidity. Yet Stamboul, if you belong to the same race of men as I, has a way of rehabilitating herself in your eyes, perhaps even of making you adopt her point of view. Not that I shall try to gloss over her case. Stamboul is not for the race of men that must have trimness, smoothness, regularity, and modern conveniences, and the latest amusements. She has ambitions in that direction. I may live to see her attain them. I have already lived to see half of the Stamboul I once knew burn to the ground and the other half experiment in Haussmannising. But there is still enough of the old Stamboul left to leaven the new. It is very bumpy to drive over. It is ill-painted and out of repair. It is somewhat intermittently served by the scavenger. Its geography is almost past finding out,[3] for no true map of it, in this year of grace 1914, as yet exists, and no man knows his street or number. What he knows is the fountain or the coffee-house near which he lives, and the quarter in which both are situated, named perhaps Coral, or Thick Beard, or Eats No Meat, or Sees Not Day; and it remains for you to find that quarter and that fountain. Nevertheless, if you belong to the race of men that is amused by such things, that is curious about the ways and thoughts of other men and feels under no responsibility to change them, that can see happy arrangements of light and shade, of form and colour, without having them pointed out and in very common materials, that is not repelled by things which look old and out of order, that is even attracted by things which do look so and therefore have a mellowness of tone and a richness of association—if you belong to this race of men you will like Stamboul, and the chances are that you will like it very much.

You must not make the other mistake, however, of expecting too much in the way of colour. Constantinople lies, it is true, in the same latitude as Naples; but the steppes of Russia are separated from it only by the not too boundless steppes of the Black Sea. The colour of Constantinople is a compromise, therefore, and not always a successful one, between north and south. While the sun shines for half the year, and summer rain is an exception, there is something hard and unsuffused about the light. Only on certain days of south wind are you reminded of the Mediterranean, and more rarely still of the autumn Adriatic. As for the town itself, it is no white southern city, being in tone one of the soberest. I could never bring myself, as some writers do, to speak of silvery domes. They are always covered with lead, which goes excellently with the stone[4] of the mosques they crown. It is only the lesser minarets that are white; and here and there on some lifted pinnacle a small half-moon makes a flash of gold. While the high lights of Stamboul, then, are grey, this stone Stamboul is small in proportion to the darker Stamboul that fills the wide interstices between the mosques—a Stamboul of weathered wood that is just the colour of an etching. It has always seemed to me, indeed, that Stamboul, above all other cities I know, waits to be etched. Those fine lines of dome and minaret are for copper rather than canvas, while those crowded houses need the acid to bring out the richness of their shadows.

Stamboul has waited a long time. Besides Frank Brangwyn and E. D. Roth, I know of no etcher who has tried his needle there. And neither of those two has done what I could imagine Whistler doing—a Long Stamboul as seen from the opposite shore of the Golden Horn. When the archæologists tell you that Constantinople, like Rome, is built on seven hills, don’t believe them. They are merely riding a hobby-horse so ancient that I, for one, am ashamed to mount it. Constantinople, or that part of it which is now Stamboul, lies on two hills, of which the more important is a long ridge dominating the Golden Horn. Its crest is not always at the same level, to be sure, and its slopes are naturally broken by ravines. If Rome, however, had been built on fourteen hills it would have been just as easy to find the same number in Constantinople. That steep promontory advancing between sea and sea toward a steeper Asia must always have been something to look at. But I find it hard to believe that the city of Constantine and Justinian can have marked so noble an outline against the sky as the city of the sultans. For the mosques of the sultans, placed exactly where[7] their pyramids of domes and lance-like minarets tell most against the light, are what make the silhouette of Stamboul one of the most notable things in the world.

A Stamboul street

From an etching by Ernest D. Roth

Of the many voyagers who have celebrated the panorama of Constantinople, not a few have recorded their disappointment on coming to closer acquaintance. De gustibus ... I have small respect, however, for the taste of those who find that the mosques will not bear inspection. I shall presently have something more particular to say in that matter. But since I am now speaking of the general aspects of Stamboul I can hardly pass over the part played by the mosques and their dependencies. A grey dome, a white minaret, a black cypress—that is the group which, recurring in every possible composition, makes up so much of the colour of the streets. On the monumental scale of the imperial mosques it ranks among the supreme architectural effects. On a smaller scale it never lacks charm. One element of this charm is so simple that I wonder it has not been more widely imitated. Almost every mosque is enclosed by a wall, sometimes of smooth ashler with a pointed coping, sometimes of plastered cobblestones tiled at the top, often tufted with snapdragon and camomile daisies. And this wall is pierced by a succession of windows which are filled with metal grille work as simple or as elaborate as the builder pleased. For he knew, the crafty man, that a grille or a lattice is always pleasant to look through, and that it somehow lends interest to the barest prospect.

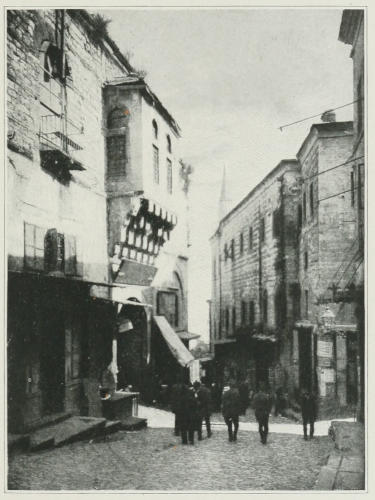

There is hardly a street of Stamboul in which some such window does not give a glimpse into the peace and gravity of the East. The windows do not all look into mosque yards. Many of them open into the cloister of a medresseh, a theological school, or some other pious[8] foundation. Many more look into a patch of ground where tall turbaned and lichened stones lean among cypresses or where a more or less stately mausoleum, a türbeh, lifts its dome. Life and death seem never very far apart in Constantinople. In other cities the fact that life has an end is put out of sight as much as possible. Here it is not only acknowledged but taken advantage of for decorative purposes. Even Divan Yolou, the Street of the Council, which is the principal avenue of Stamboul, owes much of its character to the tombs and patches of cemetery that border it. Several sultans and grand viziers and any number of more obscure persons lie there neighbourly to the street, from which he who strolls, if not he who runs, may read—if Arabic letters be familiar to him—half the history of the empire.

Of the houses of the living I have already hinted that they are less permanent in appearance. Until very recently they were all built of wood, and they all burned down ever so often. Consequently Stamboul has begun to rebuild herself in brick and concrete. I shall not complain of it, for I admit that it is not well for Stamboul to continue burning down. I also admit that Stamboul must modernise some of her habits. It is a matter of the greatest urgency if Stamboul wishes to continue to exist. Yet I am sorry to have the old wooden house of Stamboul disappear. It is not merely that I am a fanatic in things of other times. That house is, at its best, so expressive a piece of architecture, it is so simple and so dignified in its lines, it contains so much wisdom for the modern decorator, that I am sorry for it to disappear and leave no report of itself. If I could do what I like, there is nothing I should like to do more than to build, and to set a fashion of building, from less perishable[9] materials, and fitted out with a little more convenience, a konak of Stamboul. They are descended, I suppose, from the old Byzantine houses. There is almost nothing Arabic about them, at all events, and their interior arrangement resembles that of any palazzo of the Renaissance.

Divan Yolou

The old wooden house of Stamboul is never very tall. It sits roomily on the ground, seldom rising above two storeys. Its effect resides in its symmetry and proportion, for there is almost no ornament about it. The doorway is the most decorative part of the façade. Its two leaves open very broad and square, with knockers in the form of lyres, or big rings attached to round plates of intricately perforated copper. Above it there will often be an oval light filled with a fan or star of swallow-tailed[10] wooden radii. The windows in general make up a great part of the character of the house, so big and so numerous are they. They are all latticed, unless Christians happen to live in the house; but above the lattices is sometimes a second tier of windows, for light, whose small round or oval panes are decoratively set in broad white mullions of plaster. For the most original part of its effect, however, the house counts on its upper storey, which juts out over the street on stout timbers curved like the bow of a ship. Sometimes these corbels balance each other right and left of the centre of the house, which may be rounded on the principle of a New York “swell front,” only more gracefully, and occasionally a third storey leans out beyond the second. This arrangement gives more space to the upper floors than the ground itself affords and also assures a better view. If it incidentally narrows and darkens the street, I think the passer-by can only be grateful for the fine line of the curving brackets and for the summer shade. He is further protected from the sun by the broad eaves of the house, supported, perhaps, by little brackets of their own. Under them was stencilled of old an Arabic invocation, which more rarely decorated a blue-and-white tile and which nowadays is generally printed on paper and framed like a picture—“O Protector,” “O Conqueror,” “O Proprietor of all Property.” And over all is a low-pitched roof, hardly ever gabled, of the red tiles you see in Italy.

A house in Eyoub

A house at Aya Kapou

The inside of the house is almost as simple as the outside—or it used to be before Europe infected it. A great entrance hall, paved with marble, runs through the house from street to garden, for almost no house in Stamboul lacks its patch of green; and branching or double stairways lead to the upper regions. Other big halls are[11] there, with niches and fountains set in the wall. The rooms opening out on either hand contain almost no furniture. The so-called Turkish corner which I fear is still the pride of some Western interiors never originated anywhere but in the diseased imagination of an upholsterer. The beauty of an old Turkish room does not depend on what may have been brought into it by chance, but on its own proportion and colour. On one side, covering the entire wall, should be a series of cupboards and niches, which may be charmingly decorated with painted flowers and gilt or coloured moulding. The[12] ceiling is treated in the same way, the strips of moulding being applied in some simple design. Of real wood-carving there is practically none, though the doors are panelled in great variety and the principle of the lattice is much used. There may also be a fireplace, not set off by a mantel, but by a tall pointed hood. And if there is a second tier of windows they may contain stained glass or some interesting scheme of mullioning. But do not look for chairs, tables, draperies, pictures, or any of the thousand gimcracks of the West that only fill a room without beautifying it. A long low divan runs under the windows, the whole length of the wall, or perhaps of two, furnished with rugs and embroidered cushions.[13] Other rugs, as fine as you please, cover the floor. Of wall space there is mercifully very little, for the windows crowd so closely together that there is no room to put anything between them, and the view is consciously made the chief ornament of the room. Still, on the inner walls may hang a text or two, written by or copied from some great calligraphist. The art of forming beautiful letters has been carried to great perfection by the Turks, who do not admit—or who until recently did not admit—any representation of living forms. Inscriptions, therefore, take with them the place of pictures, and they collect the work of famous calligraphs as Westerners collect other works of art. While a real appreciation of this art[14] requires a knowledge which few foreigners possess, any foreigner should be able to take in the decorative value of the Arabic letters. There are various systems of forming them, and there is no limit to the number of ways in which they may be grouped. By adding to an inscription its reverse, it is possible to make a symmetrical figure which sometimes resembles a mosque, or the letters may be fancifully made to suggest a bird or a ship. Texts from the Koran, invocations of the Almighty, the names of the caliphs and of the companions of the Prophet, and verses of Persian poetry are all favourite subjects for the calligrapher. I have also seen what might very literally be called a word-picture of the Prophet. To paint a portrait of him would contravene all the traditions of the cult; but there exists a famous description of him which is sometimes written in a circle, as it were the outline of a head, on an illuminated panel.

The house of the pipe

However, I did not start out to describe the interior of Stamboul, of which I know as little as any man. That, indeed, is one element of the charm of Stamboul—the sense of reserve, of impenetrability, that pervades its Turkish quarters. The lattices of the windows, the veils of the women, the high garden walls, the gravity and perfect quiet of the streets at night, all contribute to that sense. From the noisy European quarter on the opposite bank of the Golden Horn, where life is a thing of shreds and patches, without coherent associations and without roots, one looks over to Stamboul and gets the sense of another, an unknown life, reaching out secret filaments to the uttermost parts of the earth. Strange faces, strange costumes, strange dialects come and go, on errands not necessarily too mysterious, yet mysterious enough for one who knows nothing of the literature of the East, its habits, its real thought and hope and belief. We[15] speak glibly of knowing Turkey and the Turks—we who have lived five or ten or fifty years among them; but very few of us, I notice, have ever known them well enough to learn their language or read their books. And so into Stamboul we all go as outsiders. Yet there are aspects of Stamboul which are not so inaccessible. Stamboul at work, Stamboul as a market-place, is a Stamboul which welcomes the intruder—albeit with her customary gravity: if a man buttonholes you in the street and insists that you look at his wares you may be sure that he is no Turk. This is also a Stamboul which has never been, which never can be, sufficiently celebrated. The Bazaars, to be sure, figure in all the books of travel, and are visited by every one; but they are rather sighed over nowadays, as having lost a former glory. I do not sigh over them, myself. I consider that by its very arrangement the Grand Bazaar possesses an interest which can never disappear. It is a sort of vast department store, on one floor though not on one level, whose cobbled aisles wander up hill and down dale, and are vaulted solidly over with stone. And in old times, before the shops or costumes of Pera were, and when the beau monde came here to buy, a wonderful department store it must have been. In our economic days there may be less splendour, but there can hardly be less life; and if Manchester prints now largely take the place of Broussa silk and Scutari velvet, they have just as much colour for the modern impressionist. They also contribute to the essential colour of Constantinople, which is neither Asiatic nor European, but a mingling of both.

A last fragment of old Stamboul is walled in the heart of this maze, a square enclosure of deeper twilight which is called the Bezesten. Tradition has it that the shopkeepers of the Bezesten originally served God as well[16] as mammon, and were required to give a certain amount of time to their mosques. Be that as it may, they still dress in robe and turban, and they keep shorter hours than their brethren of the outer bazaar. They sit at the receipt of custom, not in shops but on continuous platforms, grave old men to whom it is apparently one whether you come or go, each before his own shelf and cupboard inlaid with mother-of-pearl; and they deal only in old things. I do not call them antiques, though such things may still be picked up—for their price—in the Bezesten and out of it, and though the word is often on the lips of the old men. I will say for them, however, that on their lips it merely means something exceptional of its kind. They could recommend you an egg or a spring lamb no more highly than by calling it antika. At any rate, the Bezesten is almost a little too good to be true. It might have been arranged by some Gérôme who studied the exact effect of dusty shafts of light striking down from high windows on the most picturesque confusion of old things—stuffs, arms, rugs, brasses, porcelain, jewelry, silver, odds and ends of bric-à-brac. In that romantic twilight an antique made in Germany becomes precious, and the most abominable modern rug takes on the tone of time.

The real rug market of Constantinople is not in the Bazaars nor yet in the hans of Mahmoud Pasha, but in the Stamboul custom-house. There the bales that come down from Persia and the Caucasus, as well as from Asia Minor and even from India and China, are opened and stored in great piles of colour, and there the wholesale dealers of Europe and America do most of their buying. The rugs are sold by the square metre in the bale, so that you may buy a hundred pieces in order to get one or two you particularly want. Burly[17] Turkish porters or black-capped Persians are there to turn over the rugs for you, shaking out the dust of Asia into the European air. Bargaining is no less long and fierce than in the smaller affairs of the Bazaars, though both sides know better what they are up to. Perhaps it is for this reason that the sale is often made by a third party. The referee, having first obtained the consent of the principals to abide by his decision—“Have you content?” is what he asks them—makes each sign his name in a note-book, in which he then writes the compromise price, saying, “Sh-sh!” if they protest. Or else he takes a hand of each between both of his own and names the price as he shakes the hands up and down, the others crying out: “Aman! Do not scorch me!” Then coffees are served all around and everybody departs happy. As communications become easier the buyers go more and more to the headquarters of rug-making, so that Constantinople will not remain indefinitely what it is now, the greatest rug market in the world. But it will long be the chief assembling and distributing point for this ancient trade.

There are two other covered markets, both in the vicinity of the Bridge, which I recommend to all hunters after local colour. The more important, from an architectural point of view, is called Mîssîr Charshî, Corn or Egyptian Market, though Europeans know it as the Spice Bazaar. It consists of two vaulted stone streets that cross each other at right angles. It was so badly damaged in the earthquake of 1894 that many of its original tenants moved away, giving place to stuffy quilt and upholstery men. Enough of the former are left, however, to make a museum of strange powders and electuaries, and to fill the air with the aroma of the East. And the quaint woodwork of the shops, the dusty[18] little ships and mosques that hang as signs above them, the decorative black frescoing of the walls, are quite as good in their way as the Bezesten. The Dried Fruit Bazaar, I am afraid, is a less permanent piece of old Stamboul. It is sure to burn up or to be torn down one of these days, because it is a section of the long street—almost the only level one in the city—that skirts the Golden Horn. I hope it will not disappear, however, before some etcher has caught the duskiness of its branching curve, with squares of sky irregularly spaced among the wooden rafters, and corresponding squares of light on the cobblestones below, and a dark side corridor or two running down to a bright perspective of water and ships. All sorts of nuts and dried fruits are sold there, in odd company with candles and the white ribbons and artificial flowers without which no Greek or Armenian can be properly married.

This whole quarter is one of markets, and some of them were old in Byzantine times. The fish market, one of the richest in the world, is here. The vegetable market is here, too, at the head of the outer bridge, where it can be fed by the boats of the Marmora. And all night long horse bells jingle through the city, bringing produce which is sold in the public square in the small hours of the morning. Provisions of other kinds, some of them strange to behold and stranger to smell, are to be had in the same region. In the purlieus of Yeni Jami, too, may be admired at its season a kind of market which is a specialty of Constantinople. The better part of it is installed in the mosque yard, where cloth and girdles and shoes and other commodities meet for the raiment of man and woman are sold under awnings or big canvas umbrellas. But other sections of it, as the copper market and the flower market, overflow[19] beyond the Spice Bazaar. The particularity of this Monday market is that it is gone on Tuesday, being held in a different place on every day of the week. Then this is a district of hans, which harbour a commerce of their own. Some of these are hotels, where comers from afar camp out in tiers of stone galleries about an open court. Others are places of business or of storage and, as the latter, are more properly known by the name kapan. The old Fontego or Fondaco dei Turchi in Venice, and the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, are built on the same plan and originally served the same purpose. The Italian word fondaco comes from the Arabic fîndîk, which in turn was derived from the πανδοχεῖον of Constantinople. But whether any of these old stone buildings might trace a Byzantine or Venetian ancestry I cannot say. The habit of Stamboul to burn up once in so often made them very necessary, and in spite of the changes that have taken place in business methods they are still largely used. And all about them are the headquarters of crafts—wood-turning, basket-making, amber-cutting, brass-beating—in alleys which are highly profitable to explore.

One of the things that make those alleys not least profitable is the grape-vine that somehow manages to grow in them. It is no rarity, I am happy to report. That grape-vine is one of the most decorative elements of Stamboul streets; and to me, at least, it has a whole philosophy to tell. It was never planted for the profit of its fruit. Vines allowed to grow as those vines grow cannot bear very heavily, and they are too accessible for their grapes to be guarded. They were planted, like the traghetto vines in Venice, because they give shade and because they are good to look upon. Some of them are trained on wires across the street, making of the[20] public way an arbour that seduces the passer-by to stop and taste the taste of life.

Fortunately there are special conveniences for this, in places where there are vines and places where there are not. Such are the places that the arriving traveller sees from his train, where meditative citizens sit cross-legged of a morning over coffee and tobacco. The traveller continues to see them wherever he goes, and never without a meditative citizen or two. The coffee-houses indeed are an essential part of Stamboul, and in them the outsider comes nearest, perhaps, to intimacy with that reticent city. The number of these institutions in Constantinople is quite fabulous. They have the happiest tact for locality, seeking movement, strategic corners, open prospects, the company of water and trees. No quarter is so miserable or so remote as to be without one. Certain thoroughfares carry on almost no other form of business. A sketch of a coffee-shop may often be seen in the street, in a scrap of sun or shade, according to the season, where a stool or two invite the passer-by to a moment of contemplation. And no han or public building is without its facilities for dispensing the indispensable.

That grape-vine is one of the most decorative elements of Stamboul streets

I know not whether the fact may contribute anything to the psychology of prohibition, but it is surprising to learn how recent an invention coffee-houses are, as time goes in this part of the world, and what opposition they first encountered. The first coffee-shop was opened in Stamboul in 1554, by one Shemsi, a native of Aleppo. A man of his race it was, an Arab dervish of the thirteenth century, who is supposed to have discovered the properties of the coffee berry. Shemsi returned to Syria in three years, taking with him some five thousand ducats and little imagination of what uproar his successful enterprise[23] was to cause. The beverage so quickly appreciated was as quickly looked upon by the orthodox as insidious to the public morals—partly because it seemed to merit the prohibition of the Koran against intoxicants, partly because it brought the faithful together in places other than mosques. “The black enemy of sleep and of love,” as a poet styled the Arabian berry, was variously denounced as one of the Four Elements of the World of Pleasure, one of the Four Pillars of the Tent of Lubricity, one of the Four Cushions of the Couch of Voluptuousness, and one of the Four Ministers of the Devil—the other three being tobacco, opium, and wine. The name of the drug may have had something to do with the hostility it encountered. Kahveh, whence café and coffee, is a[24] slight modification of an Arabic word—literally meaning that which takes away the appetite—which is one of the names of wine.

A waterside coffee-house

Süleïman the Magnificent, during whose reign the kahveji Shemsi made his little fortune, took no notice of the agitation against the new drink. But some of his successors pursued those who indulged in it with unheard-of severity. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries coffee-drinkers were persecuted more rigorously in Constantinople than wine-bibbers have ever been in England or America. Their most unrelenting enemy was the bloody Mourad IV—himself a drunkard—who forbade the use of coffee or tobacco under pain of death. He and his nephew Mehmed IV after him used to patrol the city in disguise, à la Haroun al Rashid, in order to detect and punish for themselves any violation of the law. But the Greek taverns only became the more popular. And the latter sultan was the means of extending the habit to Europe—which, for the rest, he no doubt considered its proper habitat. To be sure, it was merely during his reign that the English made their first acquaintance of our after-dinner friend. It was brought back from Smyrna in 1652 by a Mr. Edwards, member of the Levant Company, whose house was so besieged by those curious to taste the strange concoction that he set up his Greek servant in the first coffee-house in London. There, too, coffee was soon looked upon askance in high places. A personage no more strait-laced than Charles II caused a court to hand down the following decision: “The Retayling of Coffee may be an innocente Trayde; but as it is used to nourysshe Sedition, spredde Lyes, and scandalyse Greate Menne, it may also be a common Nuisaunce.” In the meantime an envoy of Mehmed IV introduced coffee in 1669 to the court of[25] Louis XIV. And Vienna acquired the habit fourteen years later, when that capital was besieged by the same sultan. After the rout of the Turks by John Sobiesky, a vast quantity of the fragrant brown drug was found among the besiegers’ stores. Its use was made known to the Viennese by a Pole who had been interpreter to a company of Austrian merchants in Constantinople. For his bravery in carrying messages through the Turkish lines he was given the right to establish the first coffee-house in Vienna.

The history of tobacco in Turkey was very much the same. It first appeared from the West in 1605, during the reign of Ahmed I. Under Mourad IV a famous pamphlet was written against it by an unconscious forerunner of modernity, who also advocated a mediæval Postum made of bean pods. Snuff became known in 1642 as an attempt to elude the repressive laws of Sultan Ibrahim. But the habit of smoking, like the taste for coffee, gained such headway that no one could stop it. Mahmoud I was the last sultan who attempted to do so, when he closed the coffee-houses for political reasons in 1730.

There is, it is true, a coffee habit, whose abuse is no less demoralising than that of any other drug. But it is so rare, and Stamboul coffee-houses are so different from American or even most European cafés, that it is hard to imagine their causing so much commotion. Nothing stronger than coffee is dispensed in them—unless I except the nargileh, the water-pipe, whose effect is wonderfully soothing and innocent at first, though wonderfully deadly in the end to the novice. The tobacco used is not the ordinary weed but a much coarser and stronger one, called toumbeki. Smoking is the more germane to coffee-shops, because in the Turkish idiom you drink tobacco.[26] You may also drink tea, in little glasses, as the Persians do. And to desecrate it, or coffee either, with the admixture of milk is an unheard-of sacrilege. But you may content yourself with so mild a refreshment as a bit of rahat locoum, more familiar to you, perhaps, as Turkish Delight, and a glass of water.

“Drinking” a nargileh

Fez-presser in a coffee-house

The etiquette of the coffee-house, of those coffee-houses which have not been too much infected by Europe, is one of their most characteristic features. I have seen a newcomer salute one after another each person in a crowded coffee-room, once on entering the door, and again on taking his seat, and be so saluted in return—either by putting the right hand on the heart and uttering the greeting merhaba, or by making the temenna, that[27] triple sweep of the hand which is the most graceful of salutes. I have also seen the entire company rise on the entrance of an old man, and yield him the corner of honour. As for the essential function of the coffee-house, it has its own traditions. A glass of water comes with the coffee, and a foreigner can usually be detected by the order in which he takes them. A Turk sips his water first. He lifts his coffee-cup, whether it possess a handle or no, by the saucer, managing the two in a dexterous way of his own. And custom favours a rather noisy enjoyment of the cup that cheers, as expressing appreciation and general well-being. The current price for a coffee, in the heart of Stamboul, is ten para—something like a penny—for which the waiter will say: “May God give you blessing.” Mark, too, that you do not tip[28] him. I have often been surprised to be charged no more than the tariff, although I gave a larger piece to be changed, and it was perfectly evident that I was a foreigner. That is an experience which rarely befalls a traveller even in his own land. It has further happened to me to be charged nothing at all, nay, to be steadfastly refused when I persisted in attempting to pay, simply because I was a traveller, and therefore a “guest.”

Altogether the habit of the coffee-house is one that requires a certain leisure. Being a passion less violent and less shameful than others, I suppose, it is indulged in with more of the humanities. You do not bolt coffee as you bolt the fire-waters of the West, without ceremony, in retreats withdrawn from the public eye. Neither, having taken coffee, do you leave the coffee-house. On the contrary, there are reasons why you should stay—and not only to take another coffee. There are benches to curl up on, if you would do as the Romans do, having first neatly put off your shoes from off your feet. There are texts and patriotic pictures to look at, to say nothing of the wonderful brass arrangements wherein the kahveji concocts his mysteries. There is, of course, the view. To enjoy it you sit on a low rush-bottomed stool in front of the coffee-shop, under a grape-vine, perhaps, or a scented wistaria, or a bough of a neighbourly plane-tree; and if you like you may have an aromatic pot of basil beside you to keep away the flies. Then there are more active distractions. For coffee-houses are also barber shops, where men cause to be shaved not only their chins but different parts of their crowns, according to their countries; and a festoon of teeth on a string or a suggestive jar of leeches reminds you how catholic was once the art of the barber in other parts of the world. There is also the resource of games—such as backgammon,[29] which is called tavli and played in Persian, and draughts, and cards. They say, indeed, that bridge came from Constantinople. There is a club in Pera which claims the honour of having communicated that passion to the Western world. But I must confess that I have yet to see an open hand of the long narrow cards you find in a coffee-house.

Playing tavli

The great resource of coffee-houses, however, is the company you meet there. The company is better at certain hours than at others. Early in the day the majority of the habitués may be at work, while late in the evening they will have disappeared altogether. For Stamboul has not quite forgotten the habits of the tent. At night it is a deserted city. But just before[30] and just after dark the coffee-houses are full of a colour which an outsider is often content to watch through lighted windows. They are the clubs of the poorer classes. Men of a street, a trade, or a province meet regularly at coffee-houses kept often by one of their own people. So much are the humbler coffee-houses frequented by a fixed clientèle that the most vagrant impressionist can realise how truly the old Turkish writers called them Schools of Knowledge. Schools of knowledge they must be, indeed, for those capable of taking part in their councils. Even for one who is not, they are full of information about the people who live in Stamboul, the variety of clothes they wear, the number of dialects they speak, the infinity of places they come from. I am at the end of my chapter and I cannot stop to descant on these things—much less on the historic guilds which still subsist in the coffee-house world. The guilds are nearly at the end of their chapter, too. Constitutions and changes more radical are turning them into something more like modern trade-unions. Their tradition is still vivid enough, though, for it to be written, as in the laws of Medes and Persians, that no man but one of Iran shall drive a house-builder’s donkey; that only a Mohammedan Albanian of the south shall lay a pavement or a southern Albanian who is a Christian and wears an orange girdle shall lay railroad ties; that none save a landlubber from the hinterland of the Black Sea may row a caïque or, they of Konia peddle yo’ourt, or——

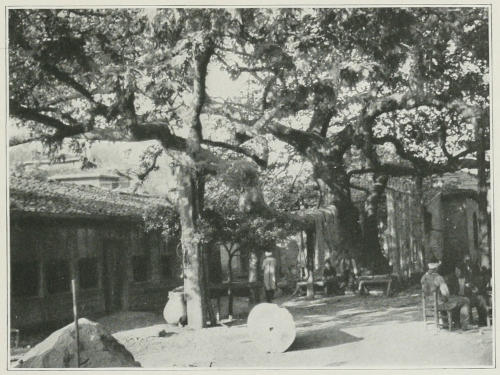

The plane-tree of Chengel-kyöi

It is no use for me to go on. I would fill pages and I probably would not make it any clearer how clannish these men are. Other things about them are just as interesting—to the race of men that likes Stamboul. That first question, for instance, that comes to one on[31] the arriving train, at the sight of so many leisurely and meditative persons, returns again and again to the mind. How is it that these who burst once out of the East with so much noise and terror, who battered their way through the walls of this city and carried the green standard of the Prophet to the gates of Vienna, sit here now rolling cigarettes and sipping little cups of coffee? Some conclude that their course is run, while others upbraid them for wasting so their time. For my part, I like to think that such extremes may argue a complexity of character for whose unfolding it would be wise to wait. I also like to think that there may be some people in the world for whom time is more than money. At any rate, it pleases me that all the people in the world are not the same. It pleases me that some are content to sit in[32] coffee-houses, to enjoy simple pleasures, to watch common spectacles, to find that in life which every one may possess—light, growing things, the movement of water, and an outlook on the ways of men.

I often wonder what a Turk, a Turk of the people, would make of a Western church. In an old cathedral close, perhaps, he might feel to a degree at home. The architecture of the building would set it apart from those about it, the canons’ houses and other subsidiary structures would not seem unnatural to him, and, though the arrangement of the interior would be foreign, he would probably understand in what manner of place he was—and his religion would permit him to worship there in his own way. But a modern city church, and particularly an American city church, would offer almost nothing familiar to him. It would, very likely, be less monumental in appearance than neighbouring buildings. There would be little or no open space about it. And strangest of all would be the entire absence of life about the place for six days out of seven. The most active institutional church can never give the sense a mosque does of being a living organism, an acknowledged focus of life. The larger mosques are open every day and all day, from sunrise to sunset, while even the smallest is accessible for the five daily hours of prayer. And, what is more, people go to them. Nor do they go to them as New Yorkers sometimes step into a down-town church at noontime, feeling either exceptionally pious or a little uneasy lest some one catch them in the act. It is as much a matter of course as any other habit of life,[34] and as little one to be self-conscious about. By which I do not mean to imply that there are neither dissenters nor sceptics in Islam. I merely mean that Islam seems to be a far more vital and central force with the mass of those who profess it than Protestant Christianity.

However, I did not set out to compare religions. All I wish is to point out the importance of mosques and their precincts in the picture of Constantinople. The yards of the imperial mosques take the place, in Stamboul, of squares and parks. Even many a smaller mosque enjoys an amplitude of perspective that might be envied by cathedrals like Chartres, or Cologne, or Milan. These roomy enclosures are surrounded by the windowed walls which I have already celebrated. Within them cypresses are wont to cluster, and plane-trees willingly cast their giant shadow. Gravestones also congregate there. And there a centre of life is which can never lack interest for the race of men that likes Stamboul. Scribes sit under the trees ready to write letters for soldiers, women, and others of the less literate sort. Seal cutters ply their cognate trade, and cut your name on a bit of brass almost as quickly as you can write it. Barbers, distinguishable by a brass plate with a nick in it for your chin, are ready to exercise another art upon your person. Pedlers come and go, selling beads, perfumes, fezzes, and sweets which they carry on their heads in big wooden trays, and drinks which may tempt you less than their brass receptacles. A more stable commerce is visible in some mosque yards, or on the day of the week when a peripatetic market elects to pitch its tents there; and coffee-houses, of course, abound. Not that there are coffee-houses in every mosque yard. I know one small mosque yard, that of Mahmoud Pasha—off the busy street of that name[35] leading to the Bazaars—which is entirely given up to coffee-houses. And a perfect mosque yard it is, grove-like with trees and looked upon by a great portico of the time of the Conqueror. There is something both grave and human about mosque yards and coffee-houses both that excellently suits them to each other. The combination is one that I, at any rate, am incapable of resisting. I dare not guess how many days of my life I have I cannot say wasted in the coffee-houses of Mahmoud Pasha, and Yeni Jami, and Baïezid, and Shah-zadeh, and Fatih. The company has an ecclesiastical tinge. Turbans bob much together and the neighbouring fountains of ablution play a part in the scene. And if the company does not disperse altogether it thins very much when the voice of the müezin, the chanter, sounds[36] from his high white tower. “God is most great!” he chants to the four quarters of the earth. “I bear witness that there is not a god save God! I bear witness that Mohammed is the Prophet of God! Hasten to the worship of God! Hasten to permanent blessedness! God is most great!”

The yard of Hekim-zadeh Ali Pasha

In the mosque the atmosphere is very much that of the mosque yard. There may be more reverence, perhaps, but people evidently feel very much at home. Men meet there out of prayer time, and women too, for what looks like, though it may not always be, a sacra conversazione of the painters. Students con over their Koran, rocking to and fro on a cushion in front of a little inlaid table. Solitary devotees prostrate themselves in a corner, untroubled by children playing among the pillars or a turbaned professor lecturing, cross-legged, to a cross-legged class in theology. The galleries of some mosques are safety-deposit vaults for their parishioners, and when the parish burns down the parishioners deposit themselves there too. After the greater conflagration of the Balkan War thousands of homeless refugees from Thrace and Macedonia camped out for months in the mosques of Stamboul. Even the pigeons that haunt so many mosque yards know that the doors are always open, and are scarcely to be persuaded from taking up their permanent abode on tiled cornices or among the marble stalactites of capitals.

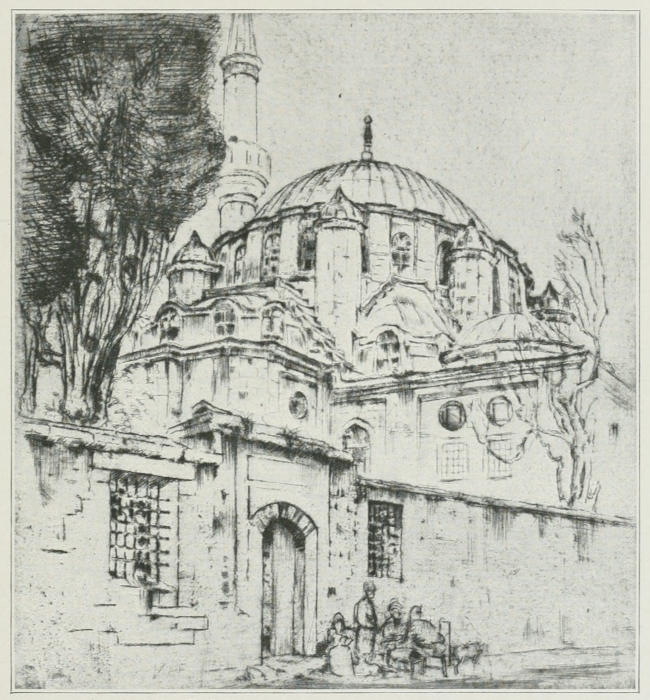

“The Little Mosque”

From an etching by Ernest D. Roth

One thing that makes a mosque look more hospitable than a church is its arrangement. There are no seats or aisles to cut up the floor. Matting is spread there, over which are laid in winter the carpets of the country; and before you step on to this clean covering you put off your shoes from off your feet—unless you shuffle about in the big slippers that are kept in some mosques for foreign[39] visitors. The general impression is that of a private interior magnified and dignified. The central object of this open space is the mihrab, a niche pointing toward Mecca. It is usually set in an apse which is raised a step above the level of the nave. In it is a prayer-rug for the imam, and on each side, in a brass or silver standard, an immense candle, which is lighted only on the seven holy nights of the year and during Ramazan. At the right of the mihrab, as you face it, stands the mimber, a sort of pulpit, at the top of a stairway and covered by a pointed canopy, which is used only for the noon prayer of Friday or on other special occasions. To the left, and nearer the door, is a smaller pulpit called the kürsi. This is a big cushioned armchair or throne, reached by a short ladder, where the imam sits to speak on ordinary occasions. There will also be one or more galleries for singers, and in larger mosques, usually at the mihrab end of the left-hand gallery, an imperial tribune enclosed by grille work and containing its own sacred niche. The chandeliers are a noticeable feature of every mosque, hanging very low and containing not candles but glass cups of oil with a floating wick. I am afraid, however, that this soft light will be presently turned into electricity. From the chandeliers often hang ostrich eggs—emblems of eternity—and other homely ornaments.

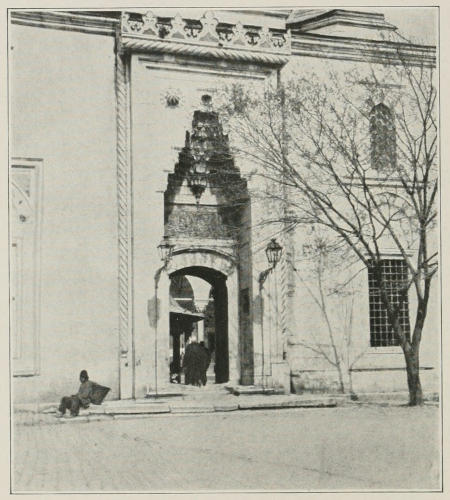

Entrance to the forecourt of Sultan Baïezid II

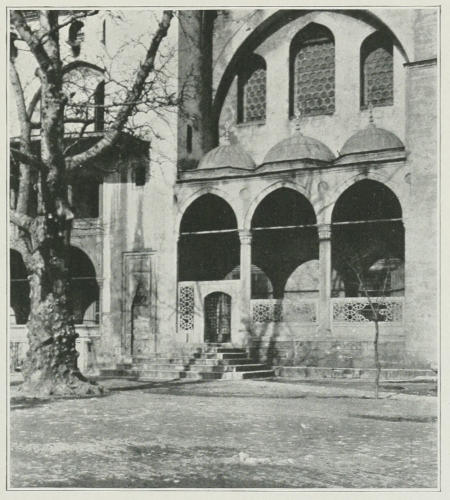

Detail of the Süleïmanieh

The place of the mosque in the Turkish community is symbolised, like that of the mediæval cathedral, by its architectural pre-eminence. Mark, however, that Stamboul has half a dozen cathedrals instead of one. It would be hard to overestimate how much of the character of Stamboul depends on the domes and minarets that so inimitably accident the heights between the Golden Horn and the Marmora. And on closer acquaintance the[40] mosques are found to contain almost all that Stamboul has of architectural pretension. They form an achievement, to my mind, much greater than the world at large seems to realise. The easy current dictum that they are merely more or less successful imitations of St. Sophia takes no account of the evolution—particularly of the central dome—which may be traced through the mosques of Konia, Broussa, and Adrianople, and which reaches its legitimate climax in Stamboul. The likelier fact is that the mosque of Stamboul, inspired by the same remote Asiatic impulse as the Byzantine church, absorbed[41] what was proper to it in Byzantine art, refining away the heaviness or overfloridness of the East, until in the hands of a master like Sinan it attained a supreme elegance without losing any of its dignity. Yet it would be a mistake to look for all Turkish architecture in Sinan. The mosques of Atik Ali Pasha and of Sultan Baïezid II are there to prove of what mingled simplicity and nobility was capable an obscure architect of an earlier century. His name is supposed to have been Haïreddin, and he, first among the Turks, used the monolithic shaft and the stalactite capital. How perfect they are, though, in the[42] arcades of Baïezid! Nothing could be better in its way than the forecourt of that mosque, and its inlaid minarets are unique of their kind. Nor did architecture die with Sinan. Yeni Jami, looking at Galata along the outer bridge, is witness thereof. The pile of the Süleïmanieh, whose four minarets catch your eye from so many points of the compass, is perhaps more masculine. But the silhouette of Yeni Jami, that mosque of princesses, has an inimitable grace. The way in which each structural necessity adds to the general effect, the climactic building up of buttress and cupola, the curve of the dome, the proportion of the minarets, could hardly be more perfect. Although brought up in the vociferous tradition of Ruskin, I am so far unfaithful to the creed of my youth as to find pleasure, too, in rococo mosques like Zeïneb Sultan, Nouri Osmanieh, and Laleli Jami. And the present generation, under men like Vedad Bey and the architects of the Evkaf, are reviving their art in a new and interesting direction.

To give any comprehensive account of the mosques of Stamboul would be to write a history of Ottoman architecture, and for that I lack both space and competence. I may, however, as an irresponsible lounger in mosque yards, touch on one or two characteristic aspects of mosques and their decoration which strike a foreigner’s eye. The frescoing or stencilling of domes and other curved interior surfaces, for instance, is an art that has very little been noticed—even by the Turks, judging from the sad estate to which the art has fallen. Some people might object to calling it an art at all. Let such a one be given a series of domes and vaults to ornament by this simple means, however, and he will find how difficult it is to produce an effect both decorative and dignified. The restorers of the nineteenth century spoiled[45] many a fine interior by their atrocious baroque draperies or colour-blind colour schemes. If I were a true believer I could never pray in mosques like Ahmed I or Yeni Jami, because the decorator evidently noticed that the prevailing tone of the tiles was blue and dipped his brush accordingly—into a blue of a different key. Yet there are domes which prove how fine an art the Turks once made of this half-mechanical decoration. One of the best in Stamboul is in the tomb of the princes, behind the Shah-zadeh mosque. The stencilling is a charming arabesque design in black, dark red, pale blue, and orange, perhaps happily toned by time, which a recent restoration was wise enough to spare. The tomb of Roxelana and the great tomb beside Yeni Jami also contain a little interesting stencilling. But the most complete example of good work of this kind is outside Stamboul, in the Yeni Valideh mosque of Scutari. The means used are of the simplest, the colours being merely black and dull red, with a little dull yellow; but the lines are so fine and so sapiently spaced on their broad background of white that the effect is very much that of a Persian shawl. A study of that ceiling should be made compulsory for every decorator of a mosque—and might yield suggestions not a few to his Western cousin.

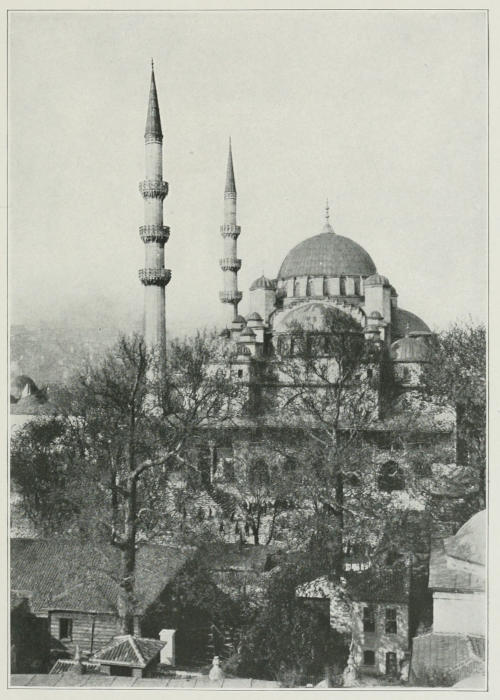

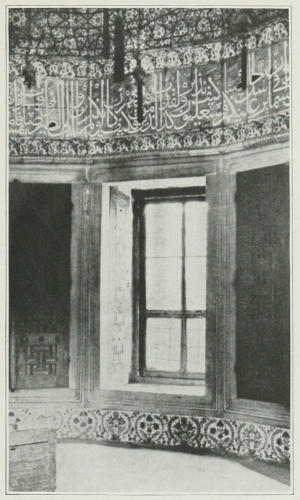

Yeni Jami

The windows of mosques are another detail that always interests me. They are rarely very large, but there are a great many of them and they give no dim religious light, making up a great part as they do of the human sunniness of the interior. A first tier of square windows stand almost at the level of the floor, and are provided with folding shutters which are carved with many little panels or with a Moorish pattern of interlaced stars. Higher up the windows are arched and are made more interesting by the broad plaster mullions of[46] which I have already spoken. These make against the light a grille of round, oval, or drop-shaped openings which are wonderfully decorative in themselves. The same principle is refined and complicated into a result more decorative still when the plaster setting forms a complete design of arabesques, flowers, or writing, sometimes framing symmetrically spaced circles or quadrangles, sometimes composing an all-over pattern, and filled in with minute panes of coloured glass. Huysmans compared the windows of Chartres to Persian rugs, because the smallness of the figures and their height above the floor make them merely conventional arrangements of colour. Here, however, we have the real principle of the Oriental rug. Turkish windows contain no figures at all, nor any of that unhappy attempt at realism that mars so much modern glass. The secret of the effect lies in the smallness of the panes used and the visibility of the plaster design in which they are set. And what an effect of jewelry may be produced in this way is to be seen in the Süleïmanieh, and Yeni Jami—where two slim cypresses make delicious panels of green light above the mihrab—besides other mosques and tombs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Mosques are even more notable than private houses for the inscriptions on their walls. Every visitor to St. Sophia remembers the great green medallions bearing the names of the chief personages of Islam in letters of gold. In purely Turkish mosques similar medallions may be seen, or large inscriptions stencilled like panels on the white walls, or small texts hanging near the floor. But there is a more architectural use of writing, above doors and windows or in the form of a frieze. When designed by a master like Hassan Chelibi of Kara Hissar, the great calligrapher of Süleïman’s time, and executed[47] in simple dark blue and white in one of the imperial tile factories, this art became a means of decoration which we can only envy the Turks. Such inscriptions are always from the Koran, of course, and they are often happily chosen for the place they occupy. Around the great dome of the Süleïmanieh, and lighted by its circle of windows, runs this verse: “God is the light of the heavens and of the earth. His light is like a window in the wall, wherein a lamp burns, covered with glass. The glass shines like a star. The lamp is kindled from the oil of a blessed tree: not of the east, not of the west, it lights whom he wills.”

It is not only for inscriptions, however, that tiles are used in mosques. Stamboul, indeed, is a museum of tiles that has never been adequately explored. Nor, in general, is very much known about Turkish ceramics. I suppose nothing definite will be known till the Turks themselves, or some one who can read their language, takes the trouble to look up the records of mosques and other public buildings. The splendid tiles of Süleïman’s period have sometimes been attributed a Persian and sometimes a Rhodian origin—for they have many similarities with the famous Rhodian plates. The Turks themselves generally suppose that their tiles came from Kütahya, where a factory still produces work of an inferior kind. The truth lies between these various theories. That any number of the tiles of Constantinople came from Persia is impossible. So many of them could not have been safely brought so far overland, and it is inconceivable that they would have fitted into their places as they do, or that any number of buildings would have been erected to fit their tiles. The Rhodian theory is equally improbable, partly for similar reasons though chiefly because the legend of Rhodes is all but exploded.[48] The Musée de Cluny is almost the last believer in the idea that its unrivalled collection of Rhodian plates ever came from Rhodes. Many of them probably came from different parts of Asia Minor. That tiles were produced in Asia Minor long before the capture of Constantinople we know from the monuments of Broussa, Konia, and other places. They were quite a different kind of tile, to be sure, of only one colour or containing a simple arabesque design, which was varied by a sort of tile mosaic. Many of them, too, were six-sided. The only examples of these older tiles in Constantinople are to be seen at the Chinili Kyöshk of the imperial museum—the Tile Pavilion—and the tomb of Mahmoud Pasha. It is a notorious fact, however, that the sultans who fought against the Persians brought back craftsmen of all kinds from that country and settled them in different parts of the empire. Selim I, for instance, when he captured Tabriz, imported the best tile makers of that city, as well as from Ardebil and Kashan—whence one of the words for tiles, kyashi—and settled them in Isnik. This is the city which under an older name had already produced the historian Dion Cassius and the Nicene Creed. Other factories are known to have existed in Kastambol, Konia, Nicomedia, and Constantinople itself. One is supposed to have been in Eyoub, though no trace of it remains to-day unless in the potteries of Chömlekjiler. Another, I have been told, flourished at Balat. I know not whether it may have been the same which Sultan Ahmed III transferred in 1724 from Nicæa to the ruined Byzantine palace of Tekfour Seraï. A colony of glass-blowers there are the last remnant to-day of the tile makers of two hundred years ago.

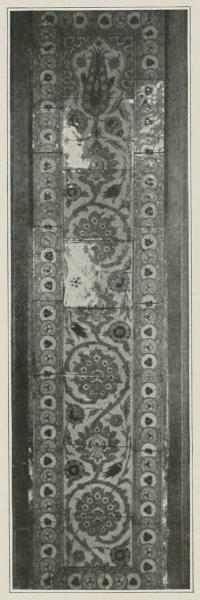

Tile panel in Rüstem Pasha