OUR EGYPTIAN OBELISK:

CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLE.

ENGRAVED FROM A PHOTOGRAPH.

Title: Cleopatra's needle

with brief notes on Egypt and Egyptian obelisks

Author: Sir Erasmus Wilson

Release date: July 22, 2023 [eBook #71253]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Brain & Co

Credits: deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

OUR EGYPTIAN OBELISK:

CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLE.

ENGRAVED FROM A PHOTOGRAPH.

BY ERASMUS WILSON, F.R.S.

CLEOPATRA’S NEEDLE AT ALEXANDRIA.

LONDON: BRAIN & CO., 26, PATERNOSTER ROW.

ENTERED AT STATIONERS’ HALL.

TO HIS ESTEEMED FRIENDS,

CHARLES ALFRED SWINBURNE

AND

HENRY PALFREY STEPHENSON,

WHOSE JUDICIOUS COUNSELS

HAVE AIDED HIM IN CARRYING OUT

THE PROJECT OF SECURING

THE BRITISH OBELISK

TO GREAT BRITAIN,

THIS LITTLE WORK IS AFFECTIONATELY

DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR.

[Pg v]

The accompanying pages are intended as an introduction to the magnificent Egyptian Obelisk which is about to take its place among the monuments of London. This Obelisk was hewn in the renowned quarries of Syené, at the extreme southern boundary of Egypt, and was thence floated down the stream of the Nile to Heliopolis, the City of the Sun. It was erected, as one of a pair, in front of the seat of learning wherein Moses received his education, and stood in that position for about 1,600 years. Shortly before the Christian era it was conveyed to Alexandria, where it has remained until the present time, and is now on its voyage to the banks of the Thames. Its age, therefore, may be computed at upwards of 3,000 years.

At that early period, when other nations had not yet awakened into the dawn of civilisation, Egypt had made substantial progress in architecture and sculpture; and the British Obelisk may be taken as an [Pg vi] admirable example of their excellence. The hieroglyphs which adorn its surface, inform us that it was erected by a powerful Pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty, Thothmes III.; and that, 200 years later, it was carved with the name of another illustrious Egyptian potentate, Rameses the Great. The sculptures of Thothmes occupy the central line of each face of the shaft from top to bottom, and those of Rameses the side lines; so that, at a glance, we are enabled to compare the art of sculpture at periods of two centuries apart.

Heliopolis was the On of the Bible, and one of the cities of the Land of Goshen, where Abraham sought refuge when driven by famine out of Canaan. It was at Heliopolis that Joseph endured his slavery and imprisonment, and was rewarded by the Pharaoh of his day with the hand of Asenath, the daughter of Potipherah, a priest and ruler of On. Here he received in his arms his aged father Jacob, and Jacob fell on his neck and wept with joy at the recovery of his long-lost and well-beloved son: whilst in the neighbourhood of Heliopolis is still shown the venerable sycamore tree, under which, according to traditional report, the Holy Family took shelter in their flight into Egypt.

These are some of the interesting associations which will crowd into the mind when we look upward at this colossal monolith, and of which it was once the silent spectator. Ancient Egypt, Egyptian enlightenment and refinement, scenes and acts of Bible history—are, as it were, [Pg vii] realised by the presence of this stately object of art in the midst of our ancient, although, compared with itself, very modern, city. This, however, is not all; for our Obelisk was a witness to the fall of the Greek and the rise of Roman dominion in Egypt, and revives in our memory the brilliant exploits of Nelson at Aboukir, and the grievous loss sustained by Britain in the death of Abercromby, at Alexandria.

After the battle of Alexandria, in 1801, it had been the eager wish of the British army and navy to convey this Obelisk to England as a memorial of their victory. Weightier considerations frustrated their efforts.

In 1820, the matter was revived, and the Obelisk was formally presented by Mehemet Ali to the British nation, through His Majesty George IV.[1]

In 1822, a distinguished naval officer, Admiral W. H. Smyth, F.R.S., drew up a statement of plans by which the transport of the Obelisk might be accomplished; and Mehemet Ali offered to assist the undertaking by building a pier expressly for the purpose.[2]

In 1832, the propriety of making an endeavour to procure the Obelisk was discussed in Parliament, and supported by Joseph Hume, a sum of money being proposed for the purpose.

In 1867, Lieutenant-General Sir James Alexander directed his attention to the same subject, and read a Paper on the existing state of the [Pg viii] Obelisk, before the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[3] In 1875, he visited Alexandria for the purpose of ascertaining the actual condition of the Obelisk, and the possibility of getting it into British possession. A letter from Mr. Arthur Arnold to Lord Henry Lennox, First Commissioner of Works, dated April, 1876, and published in his book, entitled, “Through Persia by Caravan,” exhibits one of the results of Sir James Alexander’s exertions, and may be regarded as the most recent official report on the Obelisk question.[4]

While in Egypt, Sir James Alexander became acquainted with Mr. John Dixon, C.E., who had given considerable attention to the subject of the Obelisk and to the mode of its transport to England. Mr. Dixon had already made some successful explorations of the Great Pyramid, and had then brought his skill and experience, as a civil engineer, to bear on the practical question of the means and contrivance by which the transport of our Obelisk might be effected.

Such was the state of affairs in November, 1876, when Sir James Alexander first broached the subject to the author of these pages. Shortly afterwards the writer had an interview with Mr. John Dixon; succeeded by a conference, in which he was assisted by the judgment and advice of two valued friends—Mr. Charles Alfred Swinburne, of Bedford Row, and Mr. Henry Palfrey Stephenson, civil engineer. The conclusion [Pg ix] arrived at in this conference was, that the undertaking was practicable; and an agreement was shortly afterwards (January 30th, 1877) signed, by which Mr. John Dixon engaged to set up the Obelisk on the banks of the Thames safe and sound.

The incidents of voyage, the shipwreck, the abandonment and recovery of the cylinder-ship “Cleopatra,” together with her subsequent adventures, form an episode of surpassing interest, which has already been partly analysed in the journals of the day; but must now be left, for the completion of its history, until the Obelisk shall have been safely erected in London, on a site worthy of its antiquity and symbolical significance, and of the dignity of the metropolis of Great Britain. A happy chance already points to the precincts of Westminster Abbey, with its harmonious architectural and classical surroundings:—Westminster Hall, the Houses of Parliament, the Government Offices, the Horse-Guards, the Admiralty, Trafalgar Square, the Thames, and the most beautiful of its bridges, as a possible site; and in very truth, no better place can be found for it in our great city, even should Queen Anne graciously condescend to step from her pedestal at St. Paul’s, to make way for her more ancient monumental companion.

In the compilation of these pages, the writer has availed himself of all the sources of information which his leisure has permitted him to consult; and he now takes the opportunity of expressing his especial [Pg x] obligations to the works of—Birch, Bonomi, Mariette, Sir Gardner Wilkinson, Sir Henry Rawlinson, George Rawlinson, Burton, Chabas, Pierret, Sharpe, Lane, Admiral Smyth, Rev. George Tomlinson, Parker, W. R. Cooper, Bayle St. John, Lady Duff Gordon, and Miss Edwards; although these authors represent only a portion of the writers in whose pages he has sought for instruction.

London.

December, 1877.

[Pg xi]

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| Alexander the Great and Alexandria | 1 |

| The Cradle of Christian Theology | 2 |

| Succession of Persians, Greeks, and Romans in Egypt | 3 |

| The Ptolemies and the Cæsars | 4 |

| Queen Cleopatra | 5 |

| Cleopatra and Anthony | 6 |

| Shakspeare’s Cleopatra | 7 |

| Queen Berenice: Coma Berenicis | 9 |

| Cleopatra’s Needles | 10 |

| Inscription on the Bronze Supports of Cleopatra’s Needles | 11 |

| Date of Erection of Cleopatra’s Needles at Alexandria | 12 |

| Cæsarium; or Palace of the Cæsars | 12 |

| The British, or London Obelisk | 13 |

| The Pharaohs, Thothmes III. and Rameses II. | 14 |

| Signification of “Cartouche” | 16 |

| Age of the British Obelisk | 17 |

| Battle of Alexandria in 1801 | 17 |

| Cleopatra’s Needle in 1801 | 17 |

| Burial of the British Obelisk with Obsequies | 18 |

| Obelisks and Needles | 19 |

| Monoliths of Syenite | 20 |

| Dimensions and Proportions of the Obelisk | 21 |

| The Paris Obelisk | 22 |

| Beauty and Durability of Syenite | 23 |

| Injury done by Sand-storms | 24 |

| Probable effect of British Climate | 25 |

| Time required to complete an Obelisk | 25 |

| Colossal Obelisks | 26 |

| Obelisks Carved when Erect | 27[Pg xii] |

| Pliny, the Younger, on Obelisks | 28 |

| Transport of Obelisks | 29 |

| Journey of the British Obelisk | 29 |

| Adoption of Obelisks by the Greeks | 30 |

| Export of Obelisks to Rome | 31 |

| Galleys of the Greeks and Romans | 32 |

| Maritime Prejudices of the Egyptians | 33 |

| Circumnavigation of Africa | 34 |

| The Emperor Constantine’s Love of Obelisks | 34 |

| The Obelisk of Constantinople | 35 |

| Ruins of Alexandria | 36 |

| Pompey’s Pillar at Alexandria | 37 |

| Diocletian’s Title to Pompey’s Pillar | 38 |

| Cairo and the Delta | 40 |

| Ismailia, a Health Resort | 41 |

| The Marvellous Nile | 42 |

| The Seven Cataracts of the Nile | 42 |

| Lady Duff Gordon and her “Letters from Egypt” | 43 |

| Christianity and Theology | 44 |

| West Bank of the Nile | 45 |

| Memphis and England’s Colossus | 46 |

| The Great Pyramids of Geezeh | 51 |

| The Patriarch of Pyramids | 52 |

| The Colossal Sphynx | 53 |

| East Bank of the Nile | 56 |

| The Land of Goshen and Field of Zoan | 56 |

| Heliopolis and its Obelisk | 58 |

| Cartouches of the Pharaoh Usertesen | 60 |

| Temple of the Sun, dedicated to Ra and Tum | 61 |

| The Obelisk, Symbol of the Rising Sun and Life | 63 |

| Pharaoh’s Needles | 63 |

| Napoleon’s Address to the Army of the Pyramids | 64 |

| What have the Obelisks looked down upon | 64 |

| Abraham, Jacob, and Joseph in the Land of Goshen | 65 |

| Village of Matareeah; the Virgin’s Tree | 65 |

| Hot Sulphur Springs of Helwân | 66 |

| Chronology of Ancient Egypt | 68 |

| Manetho, the Egyptian Chronologist and Priest | 70 |

| Analogies between Obelisk and Pyramid | 72 |

| Ornamentation of Obelisks | 74 |

| Scientific Knowledge evinced in their Construction | 74[Pg xiii] |

| Carving of the Obelisk | 75 |

| Legend of the British Obelisk, by M. Chabas | 76 |

| The Flaminian Obelisk, of the Porta del Popolo | 79 |

| Legend of the Flaminian Obelisk | 81 |

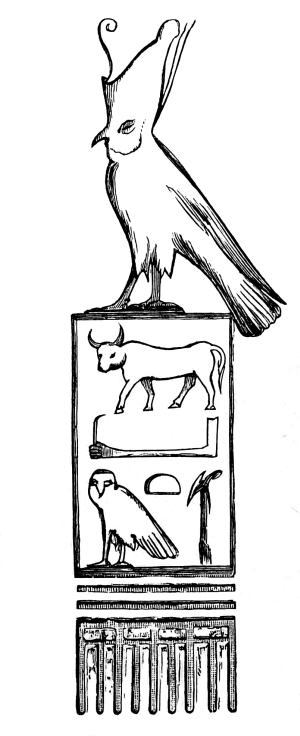

| Standard of the King | 82 |

| The Grand Assemblies called Panegyries | 86 |

| Legend of the Paris Obelisk | 87 |

| Legend of the Alexandrian Obelisk | 88 |

| Moses and the British Obelisk | 89 |

| The Pharaoh of the Exodus | 90 |

| Era of Joseph in Egypt | 90 |

| Nile Voyage from Cairo to Thebes | 90 |

| Habits of the Crocodile | 91 |

| Geology of Egypt | 92 |

| The Mighty Ruins of Thebes | 93 |

| Memnonian Colossi; the Vocal Memnon | 94 |

| Earthquake before the Christian Era | 96 |

| Granite Colossus of Rameses the Great | 98 |

| Queen Hatasou’s Western Obelisks | 99 |

| Village of Luxor | 100 |

| Tomb Architecture | 100 |

| Reign of the Mummies | 101 |

| The Pylon and Propylon | 103 |

| The Architect of Karnak | 106 |

| Colossal Statues and Sphynxes | 107 |

| Obelisk of Thothmes I. at Karnak | 108 |

| Obelisk of Hatasou, appropriated by Thothmes III. | 108 |

| Usertesen’s Sanctuary | 109 |

| Lost Obelisks of Amenophis III. | 110 |

| The Luxor Obelisks | 111 |

| Obelisks of Rameses II. | 113 |

| Confusion of Thothmes and Hatasou, Seti and | |

| Rameses, and Rameses and Thothmes | 114 |

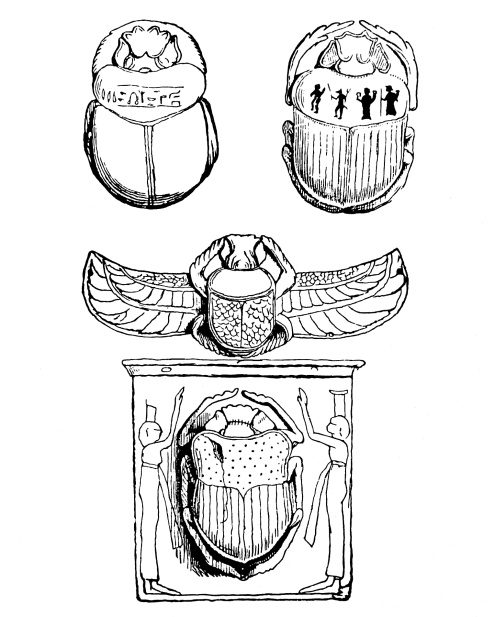

| Sacred Scarabæi and Manufacture of Antiques | 117 |

| Humanity of the Egyptians | 119 |

| Symbolism of the Scarabæus | 120 |

| Voyage from Luxor to As-souan | 121 |

| Unfinished Obelisk at As-souan | 122 |

| Mode of cleaving Obelisks from the Rock | 123 |

| “Beautiful Philæ” and “Pharaoh’s Bed” | 125 |

| Obelisks of Philæ | 126 |

| The Bankes Obelisk | 128[Pg xiv] |

| Resistance of Religious Faith to Theodosian Violence | 131 |

| Hieroglyphic Writing; how deciphered | 133 |

| The Rosetta Stone | 134 |

| Cartouches of Ptolemy and Cleopatra | 135 |

| Apotheosis of Egyptologists | 137 |

| Usertesen and his Obelisks, Heliopolis and Biggig | 138 |

| Monolithic Monuments of the Hebrews | 144 |

| Abyssinian Obelisks | 145 |

| Inscription on the Biggig Obelisk | 147 |

| Obelisks of Thothmes I. | 148 |

| Obelisks of Queen Hatasou | 148 |

| Obelisks of Thothmes III. | 149 |

| Obelisk of Amenophis II. | 152 |

| Inscription on the Syon House Obelisk | 153 |

| Obelisks of Amenophis III. | 154 |

| Obelisks of Seti I., or Osirei | 154 |

| Obelisks of Rameses II. | 156 |

| Obelisks of Menephtah I. | 158 |

| Obelisks of Psammeticus I. and II. | 159 |

| Obelisks of Nectanebo I., or Amyrtæus | 160 |

| Obelisks of Nectanebo II. | 162 |

| Prioli Obelisk at Constantinople | 164 |

| Obelisk of Nahasb | 166 |

| Assyrian Obelisks | 166 |

| Ptolemaic Obelisks of Philæ | 167 |

| The Bankes Obelisk at Kingston-Lacy Hall | 167 |

| Albani Obelisk | 168 |

| Roman Obelisks | 168 |

| Obelisks at Alnwick | 170 |

| Obelisks in the Florence Museum | 170 |

| The Arles Obelisk | 170 |

| Egyptian Founders of Obelisks | 172 |

| Aggregate number of Obelisks | 174 |

| Bonomi’s List of Altitudes of Obelisks | 176 |

| Classification and Distribution of Obelisks | 178 |

| Site of the British Obelisk | 182 |

[Pg xv]

APPENDIX.

| PAGE | |

| Extract from “Bombay Courier,” 1802 | 185 |

| Consul Briggs to the Right Hon. Sir Benjamin Blomfield, 1820 | |

| presentation of the Obelisk to George the Fourth, | |

| by Mehemet Ali | 186 |

| General Sir James Alexander; | |

| Paper read at the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1868 | 190 |

| Plan of Transport of the Obelisk, by Captain Boswell, R.N. | 193 |

| Report by Mr. Arthur Arnold, to Lord Henry Lennox, | |

| respecting state of Obelisk and Plans of Transport, 1876 | 195 |

| Captain Methven’s Plan of Transport, and Estimate | 197 |

| Admiral Smyth’s Plans of Transport | 199 |

| Transport of the Luxor Obelisk to Paris, 1831-36 | 200 |

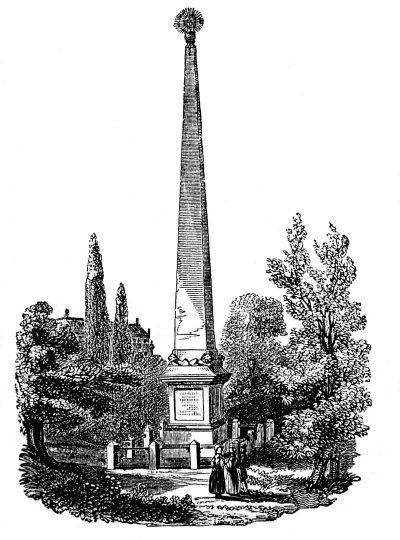

| Carrick-a-Daggon Monument, | |

| in memory of General Browne Clayton, | |

| one of the Heroes of Alexandria | 205 |

| The British Ensign; half-mast, March 28th, | |

| in memory of our gallant and victorious Abercromby | 207 |

| Translation of the Legend of the British Obelisk, | |

| by Demetrius Mosconas | 207 |

| Ancient Heroic Poem in honour of Thothmes III., | |

| translated from the Tablet of Phtamosis | 210 |

| M. Mosconas’ recent Work | 213 |

[Pg xvi]

ILLUSTRATIONS.

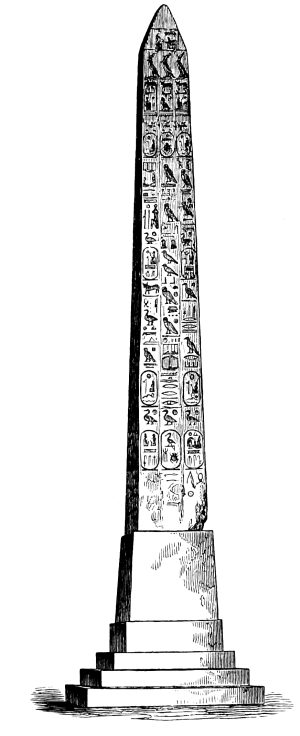

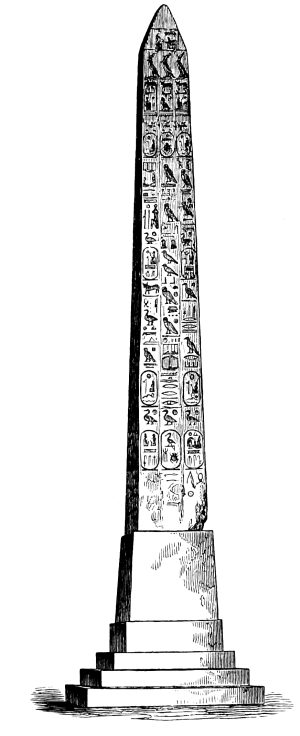

| British Obelisk (Frontispiece). | |

| Alexandrian Obelisk (Vignette on Title-page). | |

| PAGE | |

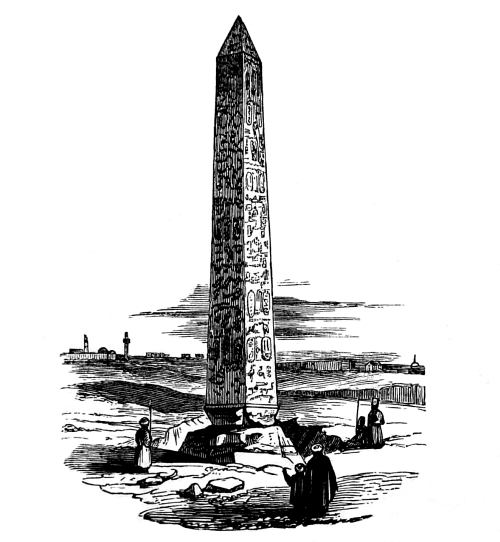

| Paris Obelisk | 22 |

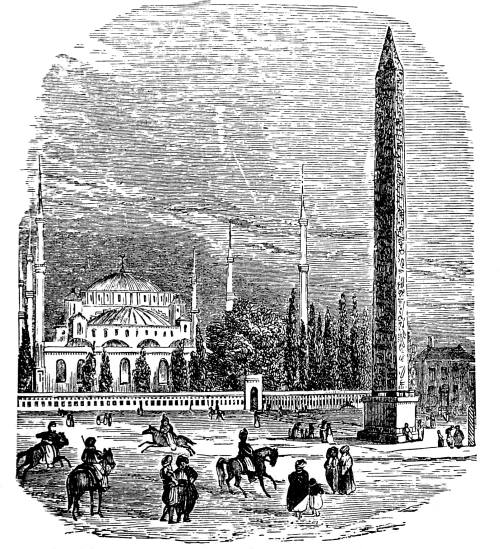

| Obelisk at Constantinople | 35 |

| Pompey’s Pillar at Alexandria | 37 |

| The Colossal Sphynx | 54 |

| Obelisk of Usertesen at Heliopolis | 59 |

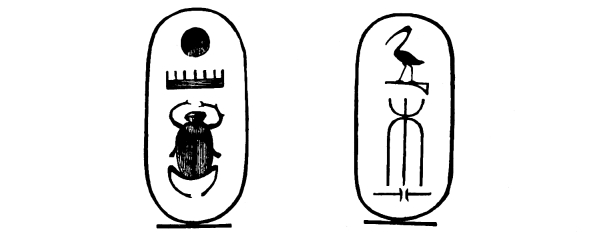

| Cartouches of Usertesen | 60 |

| Standard of the King | 82 |

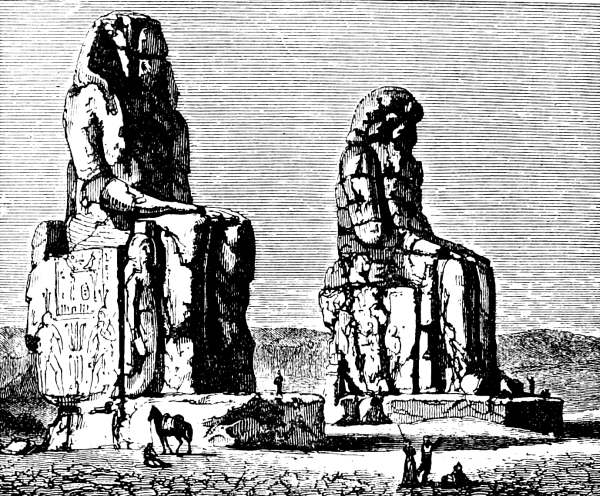

| Memnonian Colossi, the Vocal Memnon | 94 |

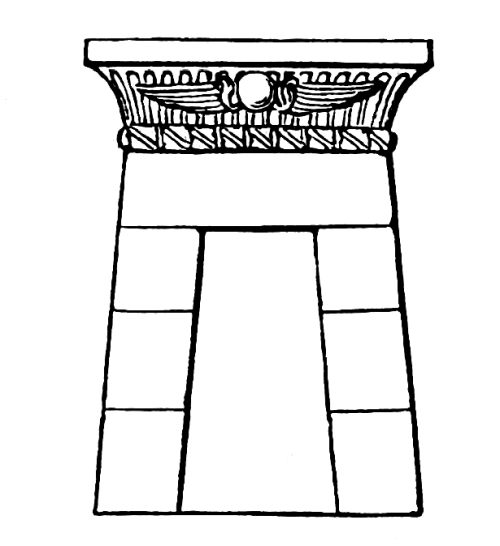

| Pylon of a House or Temple | 103 |

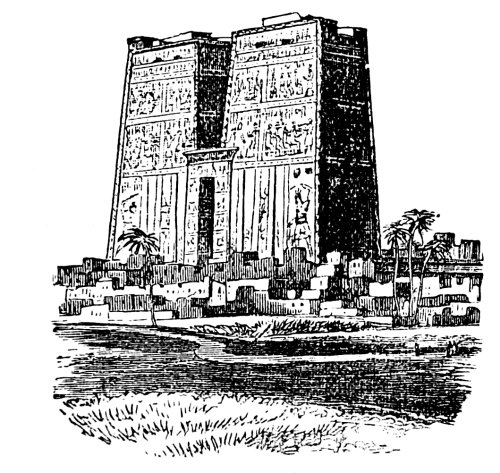

| Propylon of the Temple at Edfoo | 105 |

| Plan of Ornamentation of the Entrance of | |

| an Egyptian Temple | 111 |

| Sacred Scarabæi | 116 |

| Engraved Under-surface of Scarabæi | 118 |

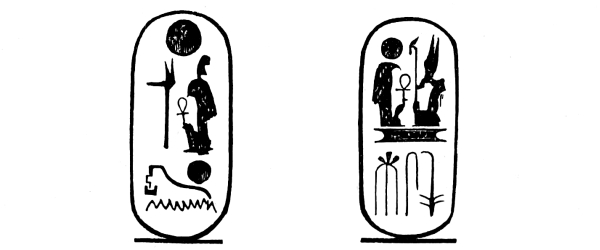

| Cartouches of Ptolemy and Cleopatra | 135 |

| Obelisk at Axum in Abyssinia | 145 |

| Cartouches of Thothmes III. | 150 |

| Cartouches of Rameses II. | 156 |

| British Museum Obelisks | 161 |

| Obelisk at Arles | 171 |

[Pg 1]

More than twenty-two centuries ago—that is to say, about three hundred and thirty-two years before the birth of Christ—a Greek general, after a victorious campaign against the Persian rulers of Egypt, and a triumphant progress along the eastern boundary of the Delta (at that time the heart of the Egyptian kingdom), embarked in his galley on the Rosetta branch of the Nile, and swept down its stream to the Mediterranean Sea. Veering to the west, he steered along the African coast, and very soon came in sight of a small narrow island, called Pharos, lying at a short distance from the shore, and separated from it by a deep-sea channel capable of floating ships of heavy burden. This island served as a ready-made breakwater to the channel inside, and seemed intended to convert it into a natural harbour. It was on this [Pg 2] very spot that the city of Alexandria sprung into existence, in obedience to the command of the victorious general already mentioned, who, indeed, was no less a personage than Alexander the Great, King of Macedonia, the first of a line of Greek kings who reigned over Egypt for three hundred years.

On the island of Pharos was laid the foundation of a magnificent lighthouse. The centre of the island was connected with the mainland by means of a mole, or causeway, three-quarters of a mile long; and this causeway contributed additional security to the harbour. Warehouses, docks, and streets, interspersed with temples, palaces, and monuments, sprung into existence with inconceivable rapidity; and that which originally was nothing more than a poor little fishing village, called Rhacotis, was speedily converted into the greatest and most flourishing city of the world, the chief seaport of Egypt, distinguished alike for its commercial prosperity and for its influence as a seat of learning. Here was established the celebrated library of Alexandria, the resort of philosophers from all the surrounding countries—from Greece, from [Pg 3] Rome, from Babylon, from Jerusalem, from Persia, and from Palestine: here creeds were argued and debated; here Athanasius and Arian disputed; here the Holy Bible was translated into Greek (the common language of the people), for the benefit of the Alexandrian Jews; here the Evangelist Mark preached the gospel of Christ; and here the groundwork was laid of a future religion of brotherly love, moderation, and peace.

It was the habit of the human kind in those early ages—as, alas! is too often the case in the present day—to be puffed up by success and enfeebled by indulgence. So it fell out with the princes of Persia; for, in the latter years of their reign of two centuries in Egypt, the rulers became indolent and incompetent; they relied on others for the performance of duties which were inseparably their own; they enlisted an army of mercenaries in Greece; the mercenaries grew bold and powerful, and, in due time, seized on the possessions of their masters. The Greeks, in their turn, rushed forward to a similar fate; they conquered the world, and then, growing indifferent and luxurious, [Pg 4] it was the easy task of the Romans to conquer them. Too enervated and too listless to maintain the greatness they had achieved, they purchased for their defence the help of the Roman soldiery; and the Roman legions, nothing loth, were not long before they occupied the throne of their employers. Three centuries saw the beginning and the ending of Greek rule in Egypt. Pompey and Julius Cæsar, fighting for the supremacy of the world, precipitated themselves on the oft-disputed battle-ground of Egypt; Pompey for refuge, Cæsar in pursuit; Pompey welcomed by false friends with the poniard, while, shortly afterwards, Cæsar fell by the hand of his colleagues and of his friend Brutus. And so it happened that Augustus, the renowned Roman emperor, became supreme sovereign of Egypt just thirty years before the Christian era; and Egypt was governed by the Romans for seven hundred years.

Ptolemy was the family surname of the Greek kings, and Cæsar that of the Roman emperors; so that it is not an uncommon thing to speak of the reign of the Ptolemies and the reign of the Cæsars; but as there were [Pg 5] queens as well as kings among the Greeks, the prevailing name of the sovereign ladies was Cleopatra. The last of the Ptolemies left behind him, at his death, two sons and two daughters; both the sons were named Ptolemy, and the eldest daughter, Cleopatra.[5]

Cleopatra, says a popular author on the Greek dynasty (Samuel Sharpe), “had been a favourite name in Greece and with the royal families of Macedonia and Alexandria for at least four hundred years. What prettier name could be given to a little girl in her cradle, than to call her the pride of her father.” Nevertheless Cleopatra was harshly dealt with by her brother: their father had directed that his eldest son and daughter should rule conjointly; but Ptolemy endeavoured to secure the throne for himself, and Cleopatra was obliged to fly the country. In this emergency Cleopatra sought and secured the assistance of Julius Cæsar; her brother was beaten in battle and drowned in his endeavours to escape the pursuit of the victorious army, and she was restored to the throne by Cæsar to rule conjointly with her younger brother. [Pg 6]

After the death of Cæsar, Cleopatra fell into disfavour with Mark Anthony. Mark Anthony was then at Tarsus, sovereign of the East, and tripartite ruler of the then known world. Tarsus is familiar to ourselves as the birthplace of the Apostle Paul, and the city which, in the infancy of Christianity, was enlightened by his teachings. It was situated on the river Cydnus; and here Cleopatra was commanded to appear before her powerful master Anthony, to meet the charges of misgovernment that had been made against her. “The beauty, sweetness, and gaiety of this young Queen,” says Sharpe, “joined to her great powers of mind, which were all turned to the art of pleasing, had quite overcome Anthony; he had sent for her as her master, but he was now her slave. Her playful wit was delightful; her voice was an instrument of many strings; she spake readily to every ambassador in his own language; and was said to be the only sovereign of Egypt who could understand the language of all her subjects:—Greek, Egyptian, Ethiopic, Troglodytic, Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac. With these charms, at the age of five-and-twenty, Anthony could deny her nothing.” [Pg 7]

Our compassion is beginning to be enlisted for the sovereign and the judge; for behold, the culprit approaches:—“She entered the river Cydnus with the Egyptian fleet, in a magnificent galley. The stern was covered with gold; the sails were of scarlet cloth; and the silver oars beat time to the music of flutes and harps. The Queen, dressed like Venus, lay under an awning embroidered with gold, while pretty dimpled boys, like Cupids, stood on each side of the sofa fanning her. Her maidens, dressed like sea-nymphs and graces, handled the silken tackle, and steered the vessel; as they approached the town of Tarsus, the winds wafted the perfumes and the scent of the burning incense to the shores, which were lined with crowds who had come out to see her land.”

Shakspeare pursues the tempting theme in the same rapturous tone, having doubtless derived his history of Cleopatra, like Sharpe, from Plutarch.

The Roman soldier marvelled at the loveliness of his hostess and the splendour of her entertainment, and was not unwilling to repeat his visit. Each sumptuous feast surpassed in gorgeous profusion that which had gone before it, until a bet was laid that Cleopatra would give a banquet which should cost £60,000. She came to the entertainment adorned with two magnificent earrings of pearl, the largest in the world, and part of her suite of crown-jewels. In the midst of the feast an attendant set before her a cup of vinegar; she took a pearl from her ear and dropped it into the vinegar, and, when it was dissolved, she drank off the contents of the cup as a pledge to her distinguished [Pg 9] guest. One of Anthony’s friends, Plancus, adjudged that Anthony had lost the bet, and taking the other pearl from her ear, sent it to Italy, where it was cut in two and made into a pair of earrings for the statue of Venus, in the Pantheon of Rome.

A pleasant compliment had been paid, some two hundred years before that time, to another great Queen of Egypt, Berenice, the wife of Ptolemy Euergetes. Euergetes had been called to the wars, and Berenice, who was remarkable for a splendid head of hair, vowed, in her grief, that she would cut it all off and offer it as a sacrifice to the gods if her husband returned in safety. Ptolemy was victorious, the hair was dutifully cut off, and hung up in the Temple of Venus; after a time the hair disappeared, and Conon, the astronomer, being appealed to, declared that it had been carried off by Jupiter, who spreading it forth in the azure vault of heaven, had made of it a constellation of seven stars, which, to this day, is known as the “Coma Berenicis;” literally, Berenice’s head of hair. There must have been grand prizes to be drawn in those lucky days by the fortunate: to be installed in [Pg 10] the starry firmament could not otherwise be regarded than as a distinguished and lasting honour; and an astronomer who was desirous of standing well with the Court, had it in his power to pay an agreeable compliment. We can fancy Astronomer Conon, after a courteous reception at the palace, saying, as he took his leave, “Your name, Madam, shall be enrolled among the constellations, to shine brightly for ever and ever more.” It was a pretty piece of scientific patronage, and convincing; for, of course, no further search was made for Berenice’s curls.

These pleasant stories convey to us, as well as anything can, the admiration of the Egyptians for their lovely ones, and the ideal inspiration which associates itself with a name. We can no longer wonder that two superb obelisks, chiselled in the best period of Egyptian art, sculptured in the rose-coloured granite of the renowned quarries of Syené at the extremest limit of the kingdom, and set up in the midst of the regal city, made doubly lustrous by the presence of its beautiful Queen, and probably within the precincts of her favourite palace, should have received the name of Cleopatra’s Needles; nor, that [Pg 11] that name should be borne by them to all futurity.[6]

We assume, therefore, that the name of Cleopatra, associated with the two beautiful obelisks brought from Heliopolis, represents the popularity of the Queen, and the affectionate regard of her subjects, rather than any participation of herself in their transport or erection; and we are borne out in that presumption by Mr. Waynman Dixon’s recent discovery of an inscription, engraved in Greek and Latin on the bronze supports of the standing obelisk. The inscription to which we refer reads as follows:—

Anno VIII. Cæsaris;—Barbarus, præfectus Ægypti, posuit;—Architectore Pontio.

“In the eighth year of Cæsar (Augustus), Barbarus, prefect of Egypt, erected this, Pontius being the architect.” [Pg 12]

Now, the eighth year of the reign of Cæsar Augustus, which he himself dated from the battle of Actium, was twenty-three years before the birth of Christ; and, consequently, seven years after the death of Cleopatra. It is not, however, at all improbable that Queen Cleopatra may have designed as well as contributed to the decoration of the palace during her lifetime, and that the setting-up of the obelisks may have been part of her plan. History likewise informs us that this grand palace of the Cæsars, the Cæsarium, was not finally completed until fifty years later—namely, in the reign of Tiberius. Mr. Sharpe says of it, that “it stood by the side of the harbour, and was surrounded with a sacred grove. It was ornamented with porticoes, and fitted up with libraries, paintings, and statues, and was the most lofty building in the city. In front of this temple they set up two ancient obelisks which had been made by Thothmes III., and carved by Rameses II.; and which, like the other monuments of the Theban kings, have outlived all the temples and palaces of their Greek and Roman successors. One of the [Pg 13] obelisks has fallen to the ground, but the other is still standing, and bears the name of Cleopatra’s Needle.” Both obelisks, and consequently both Needles, are reported as having been standing at the end of the twelfth century.

And this brings us to the question:—What are these obelisks? and more particularly:—What is the British obelisk, of which its fellow at Alexandria is termed Cleopatra’s Needle? The answer is:—that the sculptures on the four sides of the monument, its hieroglyphs or sacred writing, or more popularly, its picture-writing, declare it to be an invocation addressed to the deities of Egypt; a proclamation of the grandeur and deserts of the Pharaoh, by whom it is dedicated; his victories; his construction of temples and monuments; his love of justice, and his other exalted qualities, not forgetting the erection of this obelisk; the proclamation concluding with a prayer for health and a strong life. In the present instance the petitioner-in-chief is Thothmes III., and in the second place, Rameses II. Thothmes III., also called Thothmes the Great, was a distinguished Pharaoh, of a [Pg 14] distinguished dynasty, the eighteenth, renowned for its grandeur and magnificence; and of his reign it has been said that Egypt could then plant the boundary of her territory wherever she chose. Rameses II. was likewise styled “Rameses the Great;” and by the Greek historian Herodotus, Sesostris: he was a Pharaoh of the nineteenth dynasty; in his early days a victorious soldier; and during the remainder of his long reign, a devoted cultivator of the arts of civilisation and peace. So that those who are discontent with the euphonious title of “Cleopatra’s Needle,” and prefer to be rigorously precise in their language, must contrive to familiarise their voice and their ear with the less euphonious title of “Thothmes-Rameses obelisk.”

This obelisk bears evidence of having been constructed at the command of Thothmes, inasmuch as the legend of that monarch occupies the place of honour on its shaft—namely, the central portion of the face of the monument, extending from the top to the bottom; while the two sides of each face are devoted to that of Rameses. It is furthermore worthy of note, that about two hundred years must have intervened between the [Pg 15] action of Thothmes and that of Rameses in relation to this obelisk. And consequently that the central and side columns of hieroglyphs represent periods of art of, at least, two centuries apart. It is also not a little singular that a king of vast renown, like Rameses the Great, should have preferred to publish the record of his own brilliant titles by the side of those of his distinguished predecessor, rather than raise a separate obelisk as an independent memorial of himself. Was it a submissive deference to the grandeur of his ancestor? Was it the ambition of linking his own name with that of the magnificent Thothmes? Or was it a part of that eccentricity of character which led him to stamp his escutcheon on several other works of his predecessors, and in some instances to obliterate their names in order to give his own a prominent place? In the present instance, we should be unwilling to treat of the combination as a blot, but would rather condone the offence—if such it be—and congratulate ourselves that the obelisk bears the insignia of two such grand Pharaonic personages. Thothmes III. and Rameses II. were undoubtedly the two greatest monarchs among [Pg 16] the Pharaohs of Egypt; and the latter, besides being remarkable for the construction of temples and for his magnificent sculptures, was equally so for his eagerness to render his name universal. His cartouche[7] is to be met with extensively distributed all over Egypt, and also in those neighbouring countries which had been conquered by the Egyptian arms. He is the author of a considerable number of Egyptian obelisks; and his desire to occupy with his titles every vacant space of stone, is exhibited, not only by the writing on the British obelisk, but also [Pg 17] by his appropriation of two sides of two obelisks erected in the great temple of Karnak by Thothmes the First. With respect to the age of our own monument, it seems not improbable that the order for the British obelisk was given about sixteen hundred years before the Christian era; and consequently that its age, at the present time, may be taken to be about 3,500 years.

We have now lying before us an engraving, for which we are indebted to Captain Cotton, of Quex Park, in Thanet; an engraving published by Colnaghi, in May, 1803,[8] which bears the following legend:—“The obelisk at Alexandria, generally called Cleopatra’s Needle, as cleared to its base by the British troops in Egypt, and similar to the one lying by it, intended to be brought to England. From the original drawing by Lieut.-Colonel Montresor, 80th Regiment, in the possession of the Right Honourable the Earl of Cavan, then Commanding-in-chief His Majesty’s forces in Egypt.” In this engraving, Cleopatra’s Needle stands close to the sea, on a square [Pg 18] pedestal mounted on three step-like plinths; and is surrounded with broken arches, which may possibly have belonged to a magnificent temple or palace; while behind it are the towers and ruins of a part of the ancient city wall, and in the distance, stretching away into the sea, the promontory, on which stands the smaller lighthouse, or Pharillon. In recent photographs little is seen of these massive and extensive ruins; the Needle is sunk in a hole, the pedestal being lost to the sight, in a stonemason’s yard; and the fallen obelisk is buried in the sand. “In 1849,” says Mr. Macgregor, the celebrated canoe traveller, “this neglected gift was only half buried; but, in 1869, it was so completely hidden, that not even the owner of the workshop, where it lies, could point out to me the exact spot of its sandy grave.” The Rev. Alfred Charles Smith corroborates the forlorn condition of the fallen obelisk at about the same date. “It is not only prostrate,” he says, “but buried beneath a mass of rubbish; and, I doubt not, is now hopelessly covered in by the foundations of a house, for which preparations were being made at the time of our visit. We were so far [Pg 19] benefited by the labours of the workmen, that we had a better view of the prostrate obelisk than has fallen to the lot of recent travellers, inasmuch as, in excavating the ground at this spot, the labourers had uncovered nearly the entire length of the recumbent granite, and as they were just about to fill-in the earth around, I suppose we were the last tourists who have looked in upon the open grave of this renowned relic, * * * * though I am bound to add it is the most dilapidated, weather-worn, and ill-conditioned of all its brethren on the banks of the Nile.” Nous verrons.

The term “Needle” is familiar to our ear as designating a pointed shaft soaring upwards into the sky. In this sense we adopt it as the name of certain pointed rocks rising perpendicularly out of the sea, such as the “Needles” of the Isle of Wight; and it has been similarly applied to two of the obelisks of Heliopolis, Pharaoh’s Needles, which were removed by Constantine. It is a term peculiarly suitable to the obelisk, which, according to Johnson, is “a magnificent high piece of solid marble or other fine stone, having usually four faces, and lessening upwards by degrees till it ends in a point like a pyramid.” [Pg 20] The term obelisk is of Greek origin, derived from the word “obelos,” a spit; conveying the idea of a pointed implement; but its Arab synonym is still more explicit—namely, “meselleh,” which literally means “a packing needle or skewer;” the ancient Egyptian name of obelisk being tekn.

The Egyptian obelisks have two other important features:—first, they are monoliths, and secondly, they are hewn out of the quarries of rose-coloured granite of Syené. By monolith is meant “a single stone,” from the Greek words “monos,” one or single, and “lithos,” a stone, and is intended to signify that the object is formed of a single piece; therefore we have good reason for our wonder when we see before us a stately shaft of granite consisting of a single piece, very little short of a hundred feet in height, and weighing nearly two hundred tons.[9]

The Egyptian obelisk has another peculiarity; it is rarely uniform in breadth on all its four sides; the opposites agree, but the neighbouring [Pg 21] sides differ. This difference is clearly not intentional, but a possible consequence of the method of splitting so gigantic a shaft from its mother-rock. The British obelisk, for example, measures 7 feet 5 inches in breadth at its base on one side, and close upon 8 feet (7 ft. 10½ in.) on the adjoining side—a difference of five inches and a-half; while similar measurements of the Alexandrian obelisk give 7 feet 9¾ inches, and 8 feet 2¼ inches—a difference of only two inches and a-half. The proper proportions of the shaft of an obelisk, exclusive of its pyramidion, are said to be ten times the breadth of the base. Now if we apply this rule to the British obelisk, its height should be nearly eighty feet, whereas its extremest height, from the base to the point, is sixty-eight feet five inches and a-half. From its base of 7 feet 5, or 7 feet 10½ inches, it tapers gradually upwards to a breadth of 4 feet 10 inches, or 5 feet 1 inch; and then contracts into a pointed pyramid of 7 feet 6 inches high. The Alexandrian obelisk is hardly so tall as the British obelisk, and measures 67 feet 2 inches. But when the British obelisk shall have been raised on its pedestal of ten feet square, and mounted on plinths, the monument will then have an altitude of over eighty feet. Comparing it with the Paris obelisk, the latter is seventy-six feet and a-half in height, consequently nearly eight feet higher than the British obelisk: whereas one of Pharaoh’s Needles, set up before the Lateran Church in Rome, was originally more than 108 feet high; but having lost part of its base, at present measures 105 feet 7 inches. [Pg 22]

The Paris obelisk, brought from Luxor,

and now standing in the Place de la Concorde.

A work of Rameses II.

[Pg 23] The rose-coloured granite of Syené, the so-called “Syenite,” has acquired a world-wide reputation for its beauty of colour, the lustre of its polish, and its hardness of texture. In the dry climate of Upper Egypt, where a rainy day occurs only four or five times in the year, this granite may be said to be absolutely indestructible; and therefore it is that the Egyptian sculptures and obelisks, more than four thousand years old, come down to us almost as fresh as if they had just issued from the workman’s hand. The engraving of the hieroglyphs is often several inches in depth, its hollows carefully polished, and the work comparable to the delicate carving of a gem. [Pg 24]

But although the Egyptian climate deals tenderly with these beautiful objects, the sand-storms are not so merciful: showers of sand are often precipitated with the violence of small shot against the polished stone; and the sharp particles of sand, by successive battery, leave their impression on the surface: at first the polish alone is blurred; but by degrees the picture-writing itself is worn away. This is apparent on the Alexandrian obelisk, of which the two sides exposed to the fury of the land-storms are seriously corroded, while the sea-face is but little injured. The British obelisk shows similar marks of wear from causes of the same kind, but has further to complain of the rapacity of travellers, who have damaged it considerably in their endeavours to carry away fragments of so brilliant a memorial of ancient times. The angles of the shaft have been chipped in many places; and as a refinement of mischief, even the perpendicular sides of some of the hieroglyphs have likewise been chiselled away. When we come to the patriarch of obelisks at Heliopolis, that of King Usertesen I., we shall find that the Nile has been busy with its sheen, and has [Pg 25] left his mark of annual overflow on the lower part of its shaft; whilst elsewhere we have the account of a fragment of an ancient obelisk set up in the midst of a garden, in the perfumed atmosphere of luxuriant flowers, in which the wild bees have puttied up the channels of the hieroglyphics with their tenacious combs. But another and a graver trial is in waiting for our obelisk:—How will it accommodate itself to the climate of the British metropolis? It will endure: of that we can have no doubt; neither will it fail in our respect and admiration even when it has lost some of its pristine loveliness, and has submitted to harmonise its tone with the dulness of its surroundings.

The hewing, the carving, and the burnishing of one of these huge monoliths, under any circumstances, must have been a laborious undertaking, and have required a considerable period for its completion. Thus we are in formed that one of the obelisks of Heliopolis, one of Pharaoh’s Needles, a work of Thothmes III., occupied thirty-six years in its elaboration. It is the tallest of its race, and now stands as a memorial of the Emperors Constantine and Constantius, [Pg 26] in front of the Lateran Church at Rome; whereas another obelisk, now standing at Karnak (also of the Thothmes period, but executed under the direction of Queen Hatasou, daughter of Thothmes I., and sister of the second and third Thothmes), is stated, in an inscription on its base, to have been, with its fellow, hewn from the quarry and erected in the short period of seven months. Queen Hatasou’s obelisk is the second in altitude of the obelisk family, measuring 97 feet 6 inches;[10] while that of St. John Lateran, when entire, measured about 108 feet.

It has been suggested as probable that the obelisk was brought, in the rough state, to the spot where it was to stand, and that it was smoothed and polished there previously to its erection. And a farther question arises:—Was it erected plain, and afterwards carved in the erect position, or was it carved before it was set up? If the former of these suppositions be admitted, then the hewing and erecting of the pair [Pg 27] of monoliths in seven months is not so marvellous, especially when we call to mind the vast number of artificers always at the command of the Egyptian Government. There is clear evidence that carving after erection was practicable, and not unusual; for it must have been in the erect position that the side columns of engraving were added to the British obelisk by Rameses, and no doubt that also on the Thothmes obelisk at Karnak. The inscription on the base of Queen Hatasou’s obelisk affords an additional argument in proof of the ornamentation of the column being subsequent to erection, inasmuch as it informs us that the whole shaft was gilt from top to bottom; and although, at the present time, all trace of gold has vanished, the surface of the stone bears evidence of having been left rough, as if prepared to receive a thin coating of plaster such as was in common use among the builders of the temples, when painting was resorted to; the hollows of the carvings being left smooth and polished. The same inscription likewise states that the obelisk was capped with gold, the spoils of war, wrested from the enemies of the country. [Pg 28]

Pliny the younger, after mentioning the Syenite granite as sown with fiery spots, remarks, that a certain king of Egypt was admonished in a dream to set up obelisks. “The kings of Egypt,” he says, “in times past, as it were upon a strife and contention one to exceed another, made of this stone certain long beames, which they called obelisks, and the very Egyptian name implieth so much.” Rameses, he observes, “pitched on end another obeliske which carried in length a hundred foot, wanting one, and on every side four cubits square.”[11] “It is said that Ramises above named kept 2,000 men at work about this obeliske;” and to secure its safe erection, “caused his own son to be bound to the top thereof. * * * Certes, this obeliske was a piece of work so admirable, that when Cambyses had won the city where it stood, by assault, and put all within to fire and sword, and burnt all before him as far as to the very foundation and underpinning of the obeliske, [Pg 29] commanded expressly to quench the fire; and so, in a kind of reverence, yet unto a mass and pile of stone, spared it, who had no regard at all of the city besides.”[12]

When the obelisk was completed at Syené, the next step was that of its removal to the spot where it was destined to stand. This was usually effected by excavating beneath it a dry dock, and fixing therein two large barges. When all was properly adjusted, the water was let into the dock, and as the barges rose they lifted up their burden, and formed a raft, which was then floated down the stream of the Nile. In the case of the British obelisk, the destination of the raft was Heliopolis, a distance, as the crow flies, of nearly 600 miles: subsequently, as we know, the obelisk was conveyed to Alexandria, adding nearly 150 miles more, and making a real total of 730 miles. And if to these figures we allow 3,000 for the journey home, we have reason to hail our obelisk as a not inconsiderable traveller. [Pg 30]

We can hardly be surprised that the Greeks and the Romans should have been fascinated with the delicate beauty of the obelisks, and should have desired to possess them. Two hundred and eighty-four years before the birth of Christ, Ptolemy Philadelphus built a tomb for his wife Arsinoë at Alexandria, which he enriched with an obelisk fifty-six feet high. The obelisk had been cut, as usual, in the quarry of Syené during the reign of the last of the Egyptian Pharaohs, Nectanebo II.; it had not been engraved, but its date may be stated as about six hundred years before the Christian era. The architect, Satyrus, transported it in a somewhat similar manner to that already described. “He dug a canal to it as it lay upon the ground, and moved two heavily-laden barges underneath it. The burdens were then taken out of the barges, and as they floated higher they raised the obelisk off the ground. He then found it a task as great, or greater, to set it up in its place; and this Greek engineer would surely have looked back with wonder on the labour and knowledge of mechanics which must have been used in setting [Pg 31] up the obelisks, colossal statues, and pyramids which he saw scattered over the country.” It was erected, according to Pliny, “in the haven of Arsinoë * * * but for that it did hurt to the ship docks there, one Maximus, a governor of Egypt under the Romans, removed it from thence into the market-place of the said city (Rome), cutting off the top of it, intending to put a finial thereupon gilded, which afterwards was forelet and forgotten.” This description corresponds with that of the obelisk now standing behind the church of St. Maria Maggiore, in Rome, which is wanting both in inscription and pyramidion; but its present height is stated to be only 48 feet 5 inches, in lieu of 56 feet. This latter circumstance may be accounted for on the supposition of its having been broken before it was finally erected at Rome—an accident by no means unusual with the Roman obelisks—and by the probable squaring of its base for the purpose of securing a steadier foundation.

The Emperor Augustus, the conqueror of the last of the Ptolemies, and pioneer of the Roman dynasty, who took possession of the throne of Egypt thirty years before the Christian era, signalised his artistic [Pg 32] taste by sending four beautiful obelisks to Rome: one of the period of Seti I. and his son Rameses II.; one of that of Psammeticus II.; and two without inscription or pyramidion, of which one is ascribed to Nectanebo. These obelisks now occupy places of honour in Rome—one in the Piazza del Popolo, the elegant Flaminian obelisk; one on the Piazza de Monte Citorio; one behind the church of St. Maria Maggiore; and the remaining one in the Piazza Quirinale. That on the Monte Citorio was originally planted in front of the church of St. Lorenzo in Lucina, where it acted as the gnomon or pointer of a sun-dial erected by Augustus; and the two plain obelisks were set up in front of his mausoleum.

The means employed by Augustus for the transport of these obelisks was a galley propelled by 300 oars-men. The war-ships of the Greek and Roman dynasties were sometimes of imposing magnitude and strength, and were furnished with a number of rams. One of these ships “was 420 feet long, and fifty-seven feet wide, with forty banks of oars. The longest oars were fifty-seven feet long, and weighted with lead at the handles, [Pg 33] that they might be the more easily moved. This huge ship was to be rowed by 4,000 rowers; its sails were to be shifted by 400 sailors, and 3,000 soldiers were to stand in ranks upon deck. There were seven beaks in front, by which it was to strike and sink the ships of the enemy. The royal barge in which the king and Court moved on the quiet waters of the Nile, was nearly as large as this ship of war. It was 330 feet long, and forty-five feet wide.”

This maritime power of Egypt calls to mind two leading prejudices of the ancient Egyptians, which very much influenced their destiny: they were averse to change, preferring, in all things, to remain as they were, rather than risk the uncertainty of reform; and, secondly, they had a religious horror of the ocean, believing it to be a breach of the divine law to endeavour to subdue it, and attempt to navigate it. Therefore, when we hear of ships from Alexandria finding their way through the Pillars of Hercules (otherwise the Straits of Gibraltar) to England, we recognise at once the adventure of neighbouring nations, [Pg 34] particularly that of the Phœnicians, who traded with Cornwall, exchanging wheat for metal more than five hundred years before the Christian era. The last of the Egyptian kings, Nectanebo II., made a struggle against this ancient prejudice, and fitted up a fleet in the Red Sea, manned by Phœnicians. His ships, steering steadily to the south, and afterwards following the line of the coast, succeeded in rounding the Cape of Good Hope, and reaching the Straits of Gibraltar, and so accomplished the circumnavigation of Africa. The voyage lasted between two and three years, and the captain returned in safety to Egypt, but without his ships; he consequently failed to obtain credit for, or belief in, his success. [Pg 35]

The obelisk at Constantinople, standing in the open space of the Atmeidan, near the church of St. Sophia. It is square at the base, and supported at the corners upon four small metallic blocks, which rest on a narrow pedestal. Its present height is only fifty feet; but seeing that it was originally the companion at Heliopolis of the great obelisk of St. John Lateran, it must therefore have been shortened, possibly as a consequence of accident. It was conveyed to Byzantium by Constantine, and erected on its present site, probably by Theodosius. The figure is not to be commended for its exactness; the monument is evidently much too tall. The mosque in the background is that of the Sultan Achmet.

[Pg 36] Constantine, the first Christian among the emperors of Rome, conveyed to Byzantium, as a decoration for his new city of Constantinople, an obelisk of the period of Thothmes III., which now graces the Atmeidan, or Hippodrome: it stood originally at Heliopolis, and was one of the Needles of Pharaoh. He likewise, in all probability, sent to Arles the obelisk which is now standing in that city. It was found, in later times, grown over with bushes, and partly buried in a garden at the port of La Roquette. Charles the Second and Catherine de Medicis ordered its disinterment, and it was erected at Arles, as a memorial of Louis the Great, in the year 1676. Constantine directed the removal of another obelisk from Heliopolis, and this he also intended for Constantinople; but dying previously to its arrival at Alexandria, it was conveyed to Rome by his son Constantius. This latter is the beautiful obelisk set up in the Piazza of St. John Lateran at Rome: it is the tallest obelisk known; and although it has lost three feet of its base, measures at present 105 feet 7 inches. It bears the signets of Thothmes III. and Thothmes IV., and is the obelisk previously mentioned as having occupied thirty-six years in the preparation. The temple of Serapis at Alexandria formerly possessed two fine obelisks, but both have now disappeared; they, probably, may also have found their way to Rome. The ruins of this temple were called the citadel; and all that remains of both is Pompey’s Pillar, which was erected in one of the principal courts of the temple. [Pg 37]

Pompey’s Pillar at Alexandria.

Pompey’s Pillar is a magnificent column, placed on a hillock just outside the walls of the old town. It is cut out of red syenic granite; is beautifully polished, and is said to be the largest monolithic pillar in the world; its total height, according to Captain Smyth, being 99 feet 4¾ inches; or, in round numbers, 100 feet, including the pedestal; its girth, near the base, being nearly 28 feet. It is [Pg 38] surmounted with a Corinthian capital, of a differently coloured granite from that of the shaft, and of inferior workmanship, and stands on a short stump of a broken obelisk about four feet high, inverted, and built into the pedestal; the surface of the obelisk being covered with hieroglyphs. The column was ascended by the French in 1798, and by Captain Smyth in the spring of 1822. Captain Smyth wished to ascertain its qualification for astronomical purposes; but found it too unsteady for delicate observations; and, moreover, that it had an inclination to the south-west, in the direction opposite to that of the prevailing north-east wind. It has an inscription on the pedestal, which cost much time and perseverance to make out,[13] and was at length deciphered as follows:—

“Consecrated to the adorable Emperor Augustus Diocletian, the tutelar divinity of Alexandria, by Pontius, prefect of Egypt.”

[Pg 39] This inscription clearly settles the personality of the column, and is an answer to those by whom it has been called “The Pillar of Severus,” and “The Pillar of Hadrian.” One author believes that it might have been erected by Ptolemy Euergetes, as a record of the recovery of some thousands of pictures and statues which had been carried off by Cambyses. But the true story appears to be this:—In the year 297 of the existing era, Egypt had risen in rebellion against her rulers, and Alexandria, always contumacious, was subdued by Diocletian after a siege of eight months. Diocletian, riding among the obstructions which encumbered the fallen city, was nearly thrown from his horse. His escape from accident doubtless prompted a grateful feeling in his heart towards the Father of Mercies, and he erected this pillar as a witness of his faith, surmounting it with a statue of his horse, which has long since disappeared. Nevertheless, the ancient prejudices of our affections are ever ready to spring forth, like buried seeds in a garden; and a deep-felt regard for the old consul, Pompey, who had been [Pg 40] so treacherously assassinated on the shores of Egypt, now competes with the better claims of Diocletian for the honour of this magnificent memorial; just as the obelisks of Alexandria will, to the end of time, ever be remembered in association with the memory of Cleopatra.

We have advanced at present no further than the portal of the country which stands supreme in the production of these interesting relics of former grandeur, the obelisks; and yet we have made acquaintance with nearly twenty which have emigrated from their native land. Rome is the fortunate possessor of ten; France, of two; Constantinople, of two; and England, of Cleopatra’s Needle and four or five smaller ones. Let us now take a step further onwards, and visit them in their parental home. Four hours and a-half in the railway-train (express) suffice to transport us from Alexandria to Cairo, a distance of 130 miles. Cairo, the queen of Eastern cities, is the present metropolis of Egypt, the seat of its government, and the residence of its ruler, Ismail Pasha, the Khedive, Viceroy of the Sultan of Turkey. It is situated at the [Pg 41] apex or head of the Delta, and forms the nob of the fan, of which the ribs, radiating northwards towards the sea, are the seven branches of the Nile; or, we may prefer to regard it as one of the three points of the triangle termed Delta; Alexandria and Port Said, 140 miles apart, occupying the other two points. Port Said, indeed, is bidding fair to become the rival of Alexandria, and will grow in importance with the Suez Canal, of which it is the entrance. Already we hear of the defences of the sea-board between Alexandria and Port Said, and the protection of a work which is identified with the intrinsic prosperity of England. An Egyptian Bournemouth or Torquay, in the meantime, has established itself on the line of the canal, and invalids are already migrating for health to Ismailia, to luxuriate in the balmy and exhilarating climate of Egypt.

Cairo is comparatively a modern city, being 1,200 years the junior of Alexandria, and possesses few traces of antiquity. A fragment of an obelisk helps to pave one of its entrance-gates—alas! to what base uses fallen!—probably a work of Usertesen, of Thothmes, or of Rameses. But if we turn our back upon the Delta, the land of prolific produce, [Pg 42] the battle-field of many centuries, and the grave of innumerable ancient cities, and gaze towards the south, we see before us that wonderful river, which, rising in the bosom of Africa, and bursting through the granite rocks of Syené—the As-souan, or gate of Egypt—precipitates itself, a foaming cataract,[14] into the valley of Egypt, and pursues its meandering course, without tributary and without bridge, for more than 600 miles in a straight line from Syené to Cairo. [Pg 43] It is a river of poetry and of fertility; for nine months of the year the northern breeze (the Etesian wind) blows against its stream from early morning until night, to waft the travellers, in the sylph-like Nile-boat, called Dahabeeyah, through their journey of health and recreation. At night the boat is moored for its rest; the wind is lost in sleep, but wakens to its duties in the early morn; while rain is a thing almost unknown. In the month of June the Nile rises at Syené; and during August, September, and October, the low flat land of the Delta is converted into a sheet of water, which diffuses richness and fruitfulness throughout the grimy soil.

Lady Duff Gordon, in her agreeable “Letters from Egypt,” under date 1863-5 (the time of the mutiny), tells us how she passed a winter at El-Uksur, residing in the French house—a ruinous building, which had been occupied by the French officers who had charge of the expedition for conveying the Luxor Obelisk to Paris. She takes especial note of “a whole wet day,” as an event unknown in Thebes for ten years. During her [Pg 44] residence in Upper Egypt, she watched the annual rising of the Nile, and remarks that the water was at first green, and soon after blood-red; the apparent colour being, in both cases, probably due to refraction of light. Some authors speak of the waters of the Nile as being greenish-brown, and brown; and others as yellow. Mr. A. C. Smith calls the Nile “yellow, muddy, and sluggish:” when filtered it throws down a considerable deposit of mud, containing an abundance of organic matter, but is then sweet, soft, and peculiarly palatable. As an example of Egyptian veneration for the grand old river, Lady Duff Gordon observes, that whenever a marriage is celebrated, and the bridegroom has “taken the face” of his bride—that is, has looked upon that which is habitually concealed from view, namely, the face—she is conducted to the river bank to gaze upon the Nile.

Lady Duff Gordon, who had a warm heart for every living thing, tells us a story which is worthy of reflected thought even in the sunny atmosphere of the mysterious obelisk. She had a Nubian child offered her as a slave: when she went to look after the gift, she found it [Pg 45] among the pots and kettles, cuffed and ill-treated by every one, saving perhaps only the dog. She brought it to her room, warmed it in her bosom, dressed it, and made it comfortable; nay, indulged it, and won its confidence—in the world’s language, its love. The child wept sorely when its good and kind mistress returned home to England; but the mistress provided tenderly for her adopted, and secured its comforts during her absence. When Lady Duff Gordon returned to Egypt, the little negress held a prominent place in her thoughts: she took it again into her guardianship; but the child was no longer the same; she was self-willed, she was disobedient; the slave had learnt—alas! too readily—to despise her mistress! holding her to be an accursed Christian, a giaour. Verily the father of all evil is ignorance, which for ever stands sentry over the tree of knowledge. Need we not all—charity?

On our right hand, as we look forward into the south, is the site of ancient Memphis, founded by Menes, first of the kings of Egypt. Here stood once a magnificent temple, dedicated to the god Ptah, the [Pg 46] representative of “Creation;” but at present, a collection of ruinous tombs, together with some broken colossal statues, partly engulphed in sand, are all that remains of its original greatness. One of these relics, a colossal statue of Rameses the Great, is believed to belong to England, and only awaits removal to a fitting resting-place. It has the reputation of being beautifully carved in fine sandstone, but is corroded and blackened by the action of water, in which it lies immersed at every rising of the Nile. Dean Stanley, in allusion to this same locality, observes:—

“One other trace remains of the old Memphis. It had its own great temple, as magnificent as that of Ammon at Karnak, dedicated to the Egyptian Vulcan, Ptah. Of this not a vestige remains. But Herodotus describes that Sesostris—that is, Rameses—built a colossal statue of himself in front of the great gateway. And there, accordingly, as it is usually seen by travellers, is the last memorial of that wonderful king, to be borne away in their recollections of Egypt. Deep in the forest of palms before described, in a little pool of water left by the [Pg 47] inundations, which year by year always cover the spot, lies a gigantic trunk, its back upwards. The name of Rameses is on the belt. The face lies downwards, but is visible in profile and quite perfect, and the very same as at Ipsambul, with the only exception that the features are more feminine and more beautiful, and the peculiar hang of the lip is not there.” Of the immediate neighbourhood he says:—“For miles you walk through layers of bones and skulls, and mummy swathings, extruding from the sand, or deep down in shaft-like mummy-pits; and amongst these mummy-pits are vast galleries filled with mummies of ibises in red jars, once filled, but now gradually despoiled.”

Mr. Bayle St. John, who, for his heresies in Egyptology and floutings of obelisks, almost puts himself out of the pale of quotation, has a word to say about the colossal statue at Memphis, which is worth noting as expressing the views of the tranquil lounger rather than those of the hurried traveller. In his “Village Life in Egypt” (1852), he says:—“After a long ride, a reedy pond covered with wild ducks, a [Pg 48] stone bridge, and some sluice-gates, warned us that we were approaching the buried skeleton of Memphis. Vast mounds rose on all hands among the palm-trees, evidently the remains of a continuous wall of unburnt bricks, and we were soon moving along the sward-covered sloping banks of the lake, in which the palm-groves that cover the site of the ancient city, admire their graceful forms. Behind, in a hollow in the ground, was the colossal statue which we had come to see. It lay on its face, its pensive brow buried in mud, and part of the features concealed by some still-lingering water. The Arabs call it Abu-l-Hôn, and say it is a giant king, turned by God, ‘in ancient times and seasons past,’ into stone for some great crime. They are not at all astonished at the interest felt by infidels in this petrified sinner, because we come of the same accursed stock, and feel deserving of the same punishment. A few hovels rising amidst the palm-trees near the statue, bear the name of Mitraheny, formerly a place of some importance, but now not even wearing the appearance of having seen better days. Here dwelt old Fatmeh, the guardian of the fallen monarch, [Pg 49] who could have told strange things of his history, had any been curious enough to question her.” On another occasion he says: “The following morning I went to visit my old friend Abu-l-Hôn, the father of terror, who still lies nose down in the hollow at Mitraheny, as he has lain for thousands of years. It is a pretty long walk, first through the grove to Bedreshein, and then along the winding gisr to the great grove of Mitraheny. The place is a beautiful one. A small lake in the cooler time of the year, before the thirsty sun comes and drinks up every scrap of moisture except the river, spreads in the centre of the grove, dotted with little islands, that multiply as the season advances. A close greensward, from which thousands of palms spring at regular intervals, creeps down on all sides after the receding water * * * immense numbers of aquatic birds make it their resort. About sunrise it is perfectly covered with wild ducks, which come back regularly at evening after dark. Herons dot its shores all day, admiring, it seems, their ungainly forms, which it reflects; and a variety of little birds, [Pg 50] peculiar to the country, flutter with dancing flight about its archipelago of sedgy islands. * * * The statue was near the southern extremity of the lake. During many years it was under the protection of an old dame, who entirely devoted herself to its custody. Formerly, various consuls gave her a little pension; but this gratuity was at length withdrawn, and she subsisted on the voluntary gifts of travellers, always believing, however, that the English nation would at length hear of the care she took of their property, and reward her by a pension of £5 a year. Such was the extent of her ambition. In this hope she lived and died. I found her son occupying the same post, and indulging in the same expectations. He had inherited her little house and some sheep, and professed to do nothing but watch over the comfort of the petrified king in the hole. * * * It would be good, instead of spending a great deal of money in carrying an ugly obelisk[15] to England, to devote a little to raising this extraordinary statue on its old base, otherwise, some fine day we shall hear of its being broken up to be burnt for lime.”

[Pg 51] This colossal statue is recognised as an authentic portrait of Rameses II., “the celebrated conqueror, of the nineteenth dynasty.” It was discovered, says Mariette, by Captain Caviglia, about the year 1820, and was presented to the British nation by Mehemet Ali. For three parts of the year it lies under water. There is reason to believe that it stood originally against the pylon of the Temple of Vulcan (Ptah), its face turned to the north; but of the temple itself not a vestige remains. According to custom, as evinced at Luxor and Karnak, there ought to have been another similar statue for the opposite side of the doorway, but we have searched for it in vain. Beyond the fact of correct portraiture it possesses no scientific value. According to Sharpe, the statue is forty-five feet in height.

Further on is Geezeh, with its magnificent group of pyramids, which are regarded, with much reason, as among the seven wonders of the world; and skirting the western bank of the river for, may be, fifty miles are [Pg 52] other pyramids of inferior dimensions, amounting in the whole to close upon a hundred; one while in groups, as at Abooseer, Sakkarah, and Dashoor, another while in single file. The largest of the three great pyramids of Egypt was built by King Suphis, better known by the name of Cheops, as a resting-place for his embalmed body; the next in size was erected by his brother Susuphis or Chephren; and the third, which was cased in the red granite of Syené, is that of the son of Cheops—Menkara, also called Mycerinus. Besides these three, which are the great[16] pyramids, there are six smaller ones in this group: and, fifteen miles further on, at the village of Sakkarah, is a pyramid built in steps, or platforms, which is said to be the oldest in the world;[17] older, by 500 or 700 years, than those of Cheops and Chephren; although these latter were erected 2,120 years before the birth of Christ, and, therefore, date back to a period of nearly 5,000 years. [Pg 53]

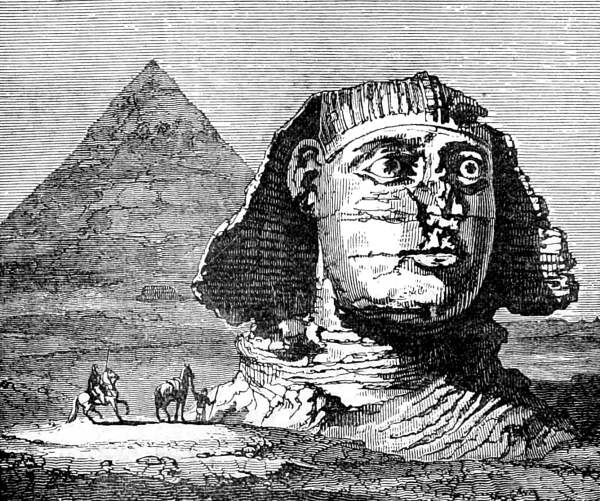

The Sphynx, with the great pyramid of Chafra,

Susuphis or Chephren in the background.

A quarter of a mile to the south and east of the great pyramid is the colossal statue of the Sphynx, carved out of the summit of a rock, which crops up like an island in the midst of the sandy desert. The statue represents the couching body of a lion, with the head of a man, the union of power with intelligence, and is typical of royalty. The face, thirty feet in length by fourteen in breadth, has been much mutilated; its entire height is 100 feet, and its paws, which are fifty [Pg 54] feet long, embrace a considerable area, having in its centre a sacrificial altar, and a space for religious worship. This huge memento of the past dates back to a period antecedent to the pyramids themselves, and marks the spot where two ancient temples formerly stood, one dedicated to Isis, the other to Osiris; both of which Cheops declares, on a tablet preserved in the museum at Boulak, were purified and restored by himself; whilst a neighbouring site was selected for the [Pg 55] foundation of his own pyramid. The paws of the Sphynx are covered with inscriptions, among which is the following very interesting one, transcribed and translated by the distinguished Egyptologist, Dr. Thomas Young:—

“Even now,” writes Dean Stanley, “after all that we have seen of colossal statues, there was something stupendous in the sight of that enormous head, * * * its vast projecting wig, its great ears, its open eyes, the red colour still visible on its cheek, the immense projection of the lower part of its face. Yet what must it have been when on its head there was the royal helmet of Egypt; on its chin the royal beard; when the stone pavement, by which men approached the pyramids, ran up [Pg 56] between its paws; when, immediately under its breast an altar stood, from which the smoke went up into the gigantic nostrils of that nose now vanished from the face, never to be conceived again.”[18]

On our left hand, as we still stand gazing forward into the south, in the direction of the coming wavelets of the tawny Nile, is a desert plain, afore-time called the “Land of Goshen,” lying between Cairo and the Suez Canal. It was here that Abraham found an abiding-place 1,920 years before the birth of Christ, when, driven out of Syria by the floods, he sought in Egypt herbage for his flocks and herds, and sustenance for his retainers. Here, in various stages of decay, are the ancient cities of the Hebrews, where Hebrew, until very recently, was the prevailing language of the people. Here we find On, or Onion, still bearing its Hebrew appellation, and Rameses and Pithom, and Succoth and Hieropolis. Nearer the Mediterranean Sea is “the field of Zoan” (Psalms, chap. lxxviii. ver. 12, 43), with the ruins of the ancient [Pg 57] city of San, or Tanis, remarkable for the vast extent of the foundation of a once magnificent temple, teeming with monuments and obelisks. Here, says Mr. Macgregor, “you see about a dozen obelisks, all fallen, all broken; twenty or thirty great statues, all monoliths of porphyry and granite, red and grey.” Isaiah had afore-time levelled his reproaches against San:—“The princes of Zoan are become fools, the princes of Nopth (Memphis) are deceived; they have also seduced Egypt, even they that are the stay of the tribes thereof.” (Chap. xix. ver. 13.) And here was the gap through which the nations of Arabia, Syria, and Persia maintained intercourse with Egypt, one while as peaceful traders, another while as fugitives and outlaws, and again as enemies in arms. Here the shepherds or pastors made their predatory incursions, and conquered and subjected Lower Egypt; here the children of Israel began their exodus; and here, also, the Persians, the Greeks, and the Romans found an easy portal for their hostile invasion.

Eight miles away from Cairo, in the midst of a plot of sugar-cane, verdant with the luxuriance of its foliage, there stands forth against [Pg 58] the sky a magnificent obelisk, the first that we have yet seen implanted on the spot where it was erected by its artificers. This obelisk bears the cartouche of Usertesen I.[19] (a Pharaoh of the twelfth dynasty, who ascended the throne 1,740 years before the Christian era), engraven on its face. It is not only the earliest and most ancient of all known obelisks, but it may be said to be the first page of the monumental history of Egypt: antecedent to it there is no record of monuments, save the pyramids and some ruined temples and tombs; but coeval with it, and illustrating the reign and acts of Usertesen, are the tombs of Beni Hassan, and the sanctuary, with its beautiful polygonal columns at Karnak, built by Usertesen himself. [Pg 59]

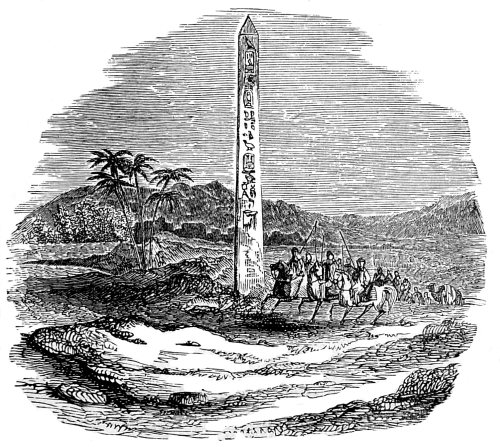

The obelisk of Usertesen at Heliopolis, the most ancient obelisk in existence. In the background may be seen the Mokattan range of mountains, the barrier between the valley of Egypt and the Red Sea.

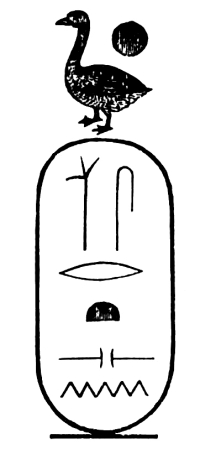

The cartouches of Usertesen, as seen on the obelisk, represent his first and second names: the former, which implies divinity, consists of the sun’s disk, a scarabæus, and a pair of human arms; and the oval is [Pg 60] surmounted with two figures—a shoot of a plant and a bee, each supported on a hemisphere. These latter are royal titles, and imply the dominion of the king, or sun, over the south and the north, in addition to that part of the globe which is embraced by his own proper path, from east to west. The second oval contains the letters which constitute the word “Usertesen,” and is surmounted by a disk representing the sun and a goose, the latter being the hieroglyph for “son,” therefore, “son of the sun.” So that the entire emblem may be supposed to read thus:—“The king; born and being of the sun; son of the sun; Usertesen.”

The Cartouches of Usertesen.

[Pg 61] On the spot occupied by this obelisk there formerly stood a temple dedicated to the sun—to Ra, the rising sun; and to Toum or Tum, the setting sun. It is uncertain whether Usertesen founded the temple himself, or whether, as was the custom among the Pharaohs of Egypt, he simply contributed to its decoration and completion. But his name being sculptured on the face of the obelisk, serves to identify it with him. The temple of the sun was surrounded with habitations and temples of inferior mark, and became a city which, in their language, the Greeks named Heliopolis. Originally, there were two of these obelisks, as was lately corroborated by the discovery of the foundation of its fellow; but the shaft itself has long since disappeared, and nothing, save this one solitary obelisk, remains of the important city, in which Egyptians and Hebrews were united for many centuries in holy brotherhood. This monument, like the rest of the great obelisks of Egypt, was hewn in the quarries of rose-red granite of Syené. It is 67 feet 4 inches in height, and its pyramidion, now bare and without carving, was originally capped with gilt-bronze or some other metallic covering. Its [Pg 62] hieroglyphs form a single central column, boldly and clearly carved, surmounted with the tutelar emblem and the standard of the king, and followed by the proper name and family name of Usertesen. The obelisk is stained for some distance up its shaft by the waters of the Nile, and, with its pedestal, is buried six or seven feet deep in the alluvium deposited by the stream.