Title: The gabled farm

or, young workers for the King.

Author: Catharine Shaw

Release date: June 20, 2024 [eBook #73876]

Language: English

Original publication: London: John F. Shaw and Co

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

[The Arundel Family series]

OR

YOUNG WORKERS FOR THE KING.

BY

CATHARINE SHAW

AUTHOR OF

"ONLY A COUSIN," "HILDA," "IN THE SUNLIGHT," "DICKIE'S ATTIC,"

"SOMETHING FOR SUNDAY," ETC.

"I ask Thee for the daily strength,

To none that ask denied,

And a mind to blend with outward life

While walking by Thy side;

Content to fill a little space,

If Thou be glorified."

New Edition.

LONDON:

JOHN F. SHAW AND CO.

48, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

STORIES BY CATHARINE SHAW

Author of "CAUGHT BY THE TIDE."

Price Three Shillings and Sixpence each, with Illustrations.

THE STRANGE HOUSE; OR, A MOMENT'S MISTAKE.

LILIAN'S HOPE.

DICKIE'S SECRET.

DICKIE'S ATTIC.

ON THE CLIFF; OR, ALICK'S NEIGHBOURS.

FATHOMS DEEP; OR, COURTENAY'S CHOICE.

HILDA; OR, SEEKETH NOT HER OWN.

Price Half-a-Crown each, Large Crown 8vo, with Illustrations.

IN THE SUNLIGHT AND OUT OF IT.

NELLIE ARUNDEL: A TALE OF HOME LIFE.

ONLY A COUSIN.

ALICK'S HERO.

LONDON:

JOHN F. SHAW & CO., 48, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

DEDICATED

TO

My Mother

AND

Her Grandchildren.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

XXIII. "MOTHER'S EYES ARE VERY TIRED"

BE brave, my brother!

He whom thou servest slights

Not even His weakest one;

No deed, tho' poor, shall be forgot,

However feebly done.

The prayer, the wish, the thought,

The faintly-spoken word,

The plan that seemed to come to nought,

Each has its own reward.

Be brave, my brother!

Enlarge thy heart and soul,

Spread out thy free, glad love;

Encompass earth, embrace the sea,

As does that sky above.

Let no man see thee stand

In slothful idleness,

As if there were no work for thee

In such a wilderness.

Be brave, my brother!

Stint not the liberal hand,

Give in the joy of love;

So shall thy crown be bright, and great

Thy recompense above;

Reward, not like the deed—

That poor weak deed of thine;

But like the God Himself who gives,

Eternal and divine.

H. BONAR.

THE GABLED FARM;

OR,

Young Workers for the King.

A HOT DAY AT NO. 8.

A JULY sun was blazing down on a square in Bloomsbury, and seemed particularly to blaze on No. 8, with its wide windows and warm west aspect. At any rate the children thought so, who were listlessly playing in the drawing room. Since early morning the blinds had been down; since middle-day the sun-blinds had been unrolled; but nothing would keep out the burning rays, and the house seemed baked through and through.

"It is perfectly intolerable!" said a boy of fourteen, laying himself flat on the hearthrug, and stretching out both arms as far as they would go, with a long, low whistle, indicating extreme heat.

"If we only had something to look forward to!" said Ada, a girl of thirteen, who was pretending to read, but felt too hot to do anything in earnest.

"Yes," assented Arthur; "but the bother is we don't know that papa can get away; and it makes it ten times hotter to think we shall have to bear this for another six weeks."

"Perhaps the weather will change," suggested a quiet, pretty girl, who sat working in the darkest corner of the room.

"It won't, Nellie; you see if it does!" said Arthur scornfully. "Not if we're to stay in town!"

Nellie looked down for a moment at the face of her half-brother, as if she were going to speak; but she did not, and went on with her work.

"I cannot think how you can work, Nellie, when we are all dying of heat," said Ada, grumbling.

While Arthur raised his eyes to the gentle face, and said lazily, "Yes; why do you work, Nell?"

"I have tried both ways," said Nellie, "and I find I am less weary and miserable when I have something to do. And besides—"

"Well?" said Arthur lazily.

"I was thinking just now of what papa told us this morning, and that helped me to—"

"Bear the heat patiently? It didn't me, I can tell you, Nell. To be shut up in a top attic, with the sun next door to you, and not a breath of air; and to be ill of fever, and no fruit, and no cool water; and no chance of country when you were better; and no friends to care whether you lived or died; and no work and no comfort; and no end to it all? No; I don't see that thinking of that, helps one to feel less hot and cross!"

Arthur turned his flushed face, which was more sympathizing than he knew, towards his sister, and kicked his foot impatiently on the rug.

"But there is an end to it, after all, Arthur, in this case; because papa says that this poor creature has a home preparing which will be—"

Arthur looked enquiringly.

"Joy for evermore," said Nellie reverently.

Arthur moved uneasily. "I don't see the good of it," he said. "Do you suppose this woman is willing to wait to have all her good things there?"

"Papa said she was. She told him that if she had had everything comfortable, as she used in the old days, she should never have been driven by despair, as she has been, to find that the love of Christ is worth more than everything else in the world!"

Arthur turned his head restlessly again, and after a moment's pause said, hesitating, "Walter thinks like that, doesn't he?"

"Indeed he does," answered Nellie; "and oh, it is such a comfort when one does."

Softly as the conversation had been carried on, it had disturbed Ada's reading. She pushed her book away, almost peevishly.

"Ada, lie down on the sofa, and I will read you both to sleep," said Nellie, looking at her kindly.

"Oh, no!" said Ada. "I'm not sleepy, and I can't do anything to-day; I feel I don't know how. I shall go and see how they are getting on upstairs."

"Worse still," groaned Arthur. But he did not do more to dissuade her; and they heard her ascend the many stairs till she reached the nursery, where her footsteps paused, and then there was a shout of, "Oh, Ada, Ada! Have you come to play with us?"

Five little ones, of various ages, were scattered about the large nursery. There were three wide, low windows, looking out on an expanse of sky, circumscribed by endless roofs and chimneys, giving the children also a good view of the pretty garden in the square.

Near one of these windows sat the nurse, a pleasant-looking young woman, and on her lap, untroubled by the intense heat, sat a chubby baby of about a year old. Close by, and just under the low windowsill, a little couch was arranged, and on it a boy of eight years lay, lying so that his weary little face could just peep through the bottom pane of glass.

Hearing Ada's step, he turned abruptly round and looked eagerly at her. "Is mamma come home yet?" he asked.

"No," said Ada. "Oh, Mary, isn't it awfully hot? I could not settle to anything down in the drawing room, and so I came to see how nearly roasted you all are."

"Oh, we are not roasted at all, Ada," said a grave little girl looking towards the empty grate, "'cause there's no fire!"

The others laughed, and Ada declared it made her hotter to think of it.

"Ada, do tell us a story, or read to us," said a little girl of about five years, who was playing in a corner with her constant companion, Netta, and their two dolls.

"Yes, do," added Netta, running to a little shelf, and taking down a book and eagerly turning over the leaves.

"Well—if I am not too hot," said Ada, looking persuadable, and taking the rocking-chair which the children invitingly pushed forward.

"Near to me, please," said poor little Tom.

And they accordingly moved nearer his window; while the nurse put the baby on the ground and began to prepare for tea.

"Once upon a time," began Ada, closing the book and looking straight before her.

"Oh, yes, that's it!" said Isabel, settling herself to listen with perfect contentment, her arm round Netta's shoulder, and their respective dolls on their laps.

"Once upon a time there was a cat, a very respectable, fat, well-fed cat. Not one of the cats that walk up and down our back garden wall; not one of the cats that live on the roofs of the houses near us; oh, no! A real comfortable country cat, who had a real barn to mouse in, and a real hay-loft to sleep in, and real grass to eat if she felt sick."

"Do cats eat grass?" said Dolly, the grave child.

"Hush!" said the others.

"One day when the gardener went into a nice warm shed, he thought he heard a rustle, and searching about for the cause, he found pussy in an old box with three of the sweetest kittens you ever saw beside her.

"'Now that's a fine thing,' said the gardener roughly; 'however did you get in here! But one thing is, it ain't much trouble to turn you out again.'

"He was just going to do it when a bright thought struck him, 'If I let you stay,' he said crossly, 'you must catch all the mice that eat my seeds!'

"Whether puss would have promised I do not know; but the gardener probably knew she would be willing to try, and so, with another sour look, he gave the box a push, and went out and slammed the door.

"Pussy felt very relieved, though a little shaken in her spirits. 'My dear kitties,' she said, 'you have had a narrow escape. Who would have thought he would have come in! He has not been in here, to my knowledge, for at least a month; but then certainly I am not always at his heels. However, here we are, and now to make the best of it. He has shut the door, too, so we must catch mice or starve.' Pussy raised her eyes to the roof, and to her relief perceived that there were apertures under the rafters where she could creep out if her prison got too strait for her.

"Some little time passed on. Pussy found plenty of mice, but she had not been accustomed to such close confinement. And one evening as it was getting dusk, she whispered to her kitties, 'Now, my dears, if you'll be very still and not quarrel, I'll take a turn up the garden, I think.'

"'Oh, mother,' said No. 1, who was affectionate, 'shall you be sure to come back!'

"'Oh, mother,' said No. 2, who was greedy, 'shall you be able to bring us something nice!'

"'Oh, mother,' said No. 3, who was daring, 'how I wish I could go with you!'

"'Yes, yes, my dears,' said pussy hurriedly; 'but if you ask so many questions, I shall never get away.'

"With these words she proceeded to jump on a sack of potatoes that stood near, and from thence to a shelf under the ceiling, where she came to a pause. Her kittens watched her anxiously with beating hearts. Where would she get next? She went peeping about at the different holes under the rafters, but did not seem to make up her mind to go through any of them.

"Now you must know—what I am not sure that the kittens yet knew—that cats have long whiskers, which in a wonderful way are made to grow out just as far as the widest part of their bodies, and pussy could feel if these were touched, and if they were, she did not venture to push her body into the hole.

"She found one to suit her at last, and before her kittens could wink, she had safely jumped to the ground outside, and was scampering along the wide garden path.

"Left to themselves for the first time, the kittens felt quite proud for a minute or two, and then they began to think of mischief.

"'Do you think we could get out of this box?' said No.3, the bold one.

"'We might get something nice to eat,' said No. 2, the greedy one.

"'I am afraid mother would not like it,' said No. 1, the affectionate one.

"'Nonsense,' said No. 3; 'I mean to try.' After several efforts, and tumbling back into the box, No. 3 did balance himself on the edge, and did jump to the ground.

"'Now, No. 2, where are you?' he mewed in rather a doleful tone; for though a brave kitten, he felt he would like a companion if this led him into a scrape.

"'I am getting up as fast as I can,' said No. 2; 'but did it hurt you to jump?'

"'Always take care of yourself,' sneered No. 3; 'but come along, or mother will be back.'

"No. 2 managed to scramble up, and jump down, and they both set off in search of pleasure, leaving No. 1 alone; for they knew from her character that it was useless to try to persuade her.

"'I shall clamber up this sack of potatoes as mother did,' said No. 3.

"'I do not care about that at all,' said No. 2. 'I fancy there is something good on that table.'

"With these words, he cautiously climbed up an old hamper, and then up a slanting board, and so with great care on to the table, over which he went with increasing disappointment; for there was nothing there fit for a kitten to eat, though a mouse might have had a feast. At last, either from vexation or because he was getting nervous, he missed his footing, and being but young yet, he stumbled, and fell to the ground with a blow which nearly stupified him. He lay quite still, and as it was so dark, No. 3 did not perceive the disaster, and went on with his explorations till a sudden fear came over him, and he hastened back to the box.

"Do what he would, however, the sides were too steep for him to climb; and in despair, after many fruitless efforts, he lay down at last, cold, and tired, and sleepy, and began to cry.

"He would have given anything to be inside instead of outside the box, when he heard his mother climbing up the ivy which covered the shed. But wishing was of no use; and with melancholy interest, he heard her lightly spring to the table, and then to the ground very near him, and then softly make her way, as so many times before, into their comfortable home.

"When there, she made a great stir. Now pussy had come home in no mood 'to put up with nonsense,' as she said, and she proceeded to give the spoils of her expedition to No. 1, without a moment's hesitation. And while the little kitten tasted her first mouthful of a delicious piece of mutton-chop, her mother made many remarks as to the effects of obedience and disobedience, little dreaming that one at least of her darlings lay so near her in the sorest need of comfort. When the chop was finished between them—"

The children had been so absorbed in Ada's story that they had not heard the slight bustle of an arrival, and were extremely surprised at this moment to hear their mamma's step at the very door.

Amid exclamations and welcomes she came forward, and after a comprehensive glance at them all, from the baby upwards, she went straight to the little couch, and bent lovingly over her little invalid.

His arms clasped tightly round her neck, and he said ruefully, "You've been so long away, mamma!"

"So very long, darling? Only a few hours. And how is my little Tom, Mary? And baby?"

"Baby's all right ma'am," said Mary, holding him up for inspection with great pride; "but Master Tom has felt the heat a good deal, and your being away too."

The mother gave a little sigh, and then turned to the others, still, however, holding Tom's little frail fingers. "So you are all, I suppose, as hot as you can be, and much too hot for a piece of good news?"

"Oh, no, mamma! Is it—is it that we are really to go to South Bay?"

Their mother nodded, smiling; whereupon there were shouts and a great hubbub, and then the little ones found that Nellie and Arthur had come up to share in the rejoicings, and were looking as radiant as could be.

"Oh, it is too delightful!" said Ada, rapturously kissing her mamma over and over, till Nellie came behind and said gently,—

"Do you not think we had better all go down and leave the little ones to their tea?"

"Yes," said their mother. "They will all be glad to get to bed."

And so, with one kiss for her fat baby, she left the room, followed by Arthur, and Nellie, and Ada.

"Our tea is just ready, mamma," said Nellie, "and I will go and make it. I am sure you must be tired."

"I am, dear," answered Mrs. Arundel, "and I will soon be down."

Tea was spread this evening in the schoolroom at the back, which was as fresh and cool as the dining room was close and hot.

"What a good thought," said Mrs. Arundel with a sigh of relief as she took her seat at the tea-tray.

"Yes; that was Arthur," said Nellie. "He was saying, when we came down just now to put something away, how cool it would be, and so I told Simmons to bring it here. I thought you would not mind, mamma, even if you did not think it necessary."

"No, indeed, dear; and it is very pleasant."

The young people were too considerate to ask their tired mother any questions, though they were burning with curiosity as to the proposed trip, and as to how the change in their parents' plans had been brought about.

They had not, however, very long to wait; for after the first cup of tea had been swallowed, Mrs. Arundel began of her own accord.

"I have not told you, dears, a piece of the news which is quite a trial to me. We are to go; but your papa is afraid he will not be able to come at all this summer, or only for a few days at most."

"Oh, mamma!" they all exclaimed dolefully; and Mrs. Arundel did not speak for a minute. "Well," she said, trying to brighten up, "it is quite a trial, but we must all do the best we can. Perhaps, after all, papa may find he can get away, and it will be a great pleasure for you all to have such a nice change; and for dear little Tom."

"I am sorry," said Arthur; "for papa has been looking forward to it; and we were to have had some jolly boating too."

"It will be a disappointment to us all, my dear; but it does not seem as if it were possible just now; and papa will not have us wait, because of the heat."

"But he will have that to bear all alone," said Ada; "it's a wretched nuisance."

Mrs. Arundel looked up quickly. "Dear Ada, I do not quite like you to say 'nuisance;' when our Father points out a path for us, we must not call it that."

"Oh, mamma, I did not mean anything wrong, only it does seem so hard!"

"'We know that all things work together for good to them that love God,'" said her mother softly, as if speaking more to herself than them. And then she went up the long flights of stairs till she came into her own room over the drawing room, where were two little cots. One of these was empty, for baby was not in bed yet; but at the other one she knelt down, and laid her head op the pillow beside little Tom.

GETTING READY.

IT was a happy party that met at breakfast the next morning. "Going out of town" to London children means a very delightful change from bricks and mortar, glaring sunshine and hot pavements, to fresh meadows, hedges and trees, or the exquisite delights of the sea-side. Then there is the packing up; the bustle; the drive through London in a cab; the anticipation; the journey; the intense expectation as to what the new place will be like—these and a hundred more thoughts will be recognised by London children as belonging to "going out of town."

Dr. Arundel sat at the bottom of the table, with Netta and Isabel on either side of him, and he looked as pleased and smiling as all the rest.

"Papa is always so unselfish," thought Nellie, as she glanced at his peaceful face.

"When are we to go?" asked Ada, as soon as she could squeeze in the question.

"On Saturday, if we can arrange it all," said her father.

"And to-day is Wednesday! Oh, Nellie, how delightful!" said Ada. "It will be all bustle and packing from morning till night!"

"Delightful!" said her father, imitating her smilingly. "And poor mamma thinks so too, I suppose? 'All bustle and packing!'"

"Don't you, mother?" asked Arthur wistfully.

"Not the bustle, dear; but the fact of going I do like very much."

"And where are we to go?" said Ada.

"Oh, to South Bay!" said their father. "And mamma and I are going down to-day to look for lodgings."

"Are you? Why that is jolly; it is something like going!" exclaimed Arthur.

"So all my dear children must try to carry out their own duties faithfully," said Dr. Arundel. "For the heat will be very great, and you will all be a little excited; and perhaps, dear children," he said gravely, "just a little cross and inclined to quarrel in consequence; so you must be watchful. We shall not be home to-night, Nellie; but I hope by tea-time to-morrow to see you all again in peace."

When their father and mother were fairly gone after breakfast, and the children had waved the last good-bye to them from the window, they turned round to the unusually empty room, and Ada exclaimed, "Come along, Nellie, now we'll begin to pack!"

"Oh, yes!" said Netta rapturously, "let us."

Nellie put her hand gently on Netta's shoulder, and was going to speak, but the hubbub drowned her voice.

"Yes; I shall get all my doll's things together, and we can pack them into the play-box, all ready," said Isabel turning to the door.

"I shall do nothing of the sort," said Arthur. "What's the good of packing up so long before? I shall get my painting, and have a long morning at it, that is if I am not too lazy."

At last Nellie's soft tones could be heard, and she spoke a little entreatingly. "Netta dear, and Isabel, I am so sorry to disappoint you; but mamma told me particularly she wished everything to go on as usual. She wished you little ones to go for your early walk, and then to have lessons."

"Lessons!" said Netta dolefully.

"Lessons! When we are going to the sea-side," added Isabel rather crossly.

"Mamma said so," said Nellie; "and the time will pass all the more quickly if we are industrious," she added cheerfully.

Ada stood frowning at the table. This was not at all her idea of preparing for the sea-side, and she did not like it at all.

"But, Nellie, there is lots to do, and I'm sure the children would not hurt for once."

"No; we would be so good," entreated the little girls, "and help you so much, Nellie!"

"Yes; give them a holiday, Nellie, and let us get on with all sorts of things," said Ada decidedly.

"I must not, Ada," answered Nellie, looking distressed; "mamma said what it was to be, and it must be so."

"Well, I declare," said Ada, "it is too bad; you might if you liked, Nellie, you know."

Nellie did not make any answer, but took her now pouting little sisters by the hand, and went upstairs with them. They met the nurse on the landing with the baby in her arms.

"We are all ready for a walk, Miss Nellie," she said.

"They will soon be ready, too," answered Nellie; "you go down, Mary, with the others, and I will put on their things to-day."

Meanwhile Ada and Arthur had been left to themselves in the dining room. Ada was twisting the tassel of her apron round and round spitefully; and Arthur was leaning against the window with his hands in his pockets.

"I hate you to vex Nellie," he said, suddenly turning to her.

"I don't vex her," answered Ada defiantly; "she vexes me."

"It can't be so pleasant grinding with those young ones that you need set them all cross to begin with."

"I can't help it; she should have let them have a holiday."

"But mamma said—"

"Nonsense! Nellie has plenty of authority to alter if she pleased, and you know she has."

"Oh, well," said Arthur, "it's of no use quarrelling; so I'll leave you to your own reflections."

He swung himself out of the room, and met the two little girls in the hall coming down to join their nurse, who was already walking up and down the pavement waiting for them.

They were still looking vexed and disappointed, so being a kind boy, he wished he could do something, but hardly knew what.

"Look here, Isabel; will Mary let you get a pennyworth of sweets somewhere?"

"Oh, yes, Arthur!" said Netta, brightening. "What sort? And shall we bring them back to you?"

"Any sort you like for yourselves," said he, fumbling for the penny. "And look here—" glancing under their hats—"be good girls to Nellie when you come home, won't you? 'Cause it's so hot, and mamma did say so."

"All right," said Netta, "we will." And away they bounded.

While Arthur felt one of those sudden bits of intense happiness which will come some day in fulness when the Lord says, "Well done, good and faithful servant."

But with the thought of having done the least thing to please Him came a sudden pang that, a minute ago, perhaps he had displeased Him in speaking hastily to Ada, and he turned again into the dining room.

Ada's "reflections" which Arthur had alluded to were not pleasant ones. A heavy cloud brooded over her, and she got up directly she saw him, and walked past him without speaking.

"I'm sorry if I vexed you," said Arthur, bolting into the subject for fear of not getting it said.

"It does not matter, thank you," she answered proudly, and shut the door on him without looking up.

Arthur felt angry in his turn; but he soon remembered that, however much Ada was in fault, he had said something which had annoyed her, and he determined to be as kind as possible when next they met, if he could. He soon sought for Nellie, and found her in the nursery sitting by little Tom, with her work in her hand.

Tom raised his eyes pleased. "Are you come, Arthur; I should like to build some bricks."

"All right," said Arthur; "but why are you not out to-day, Tom?"

"It is too hot, and it makes my head ache."

"You'll like the sea and all the fun there?" said Arthur.

"I don't know," said Tom listlessly.

"But you will see all the ships, and the donkeys, and the great waves tumbling in!"

"Yes," said Tom doubtfully; "but I shall not care about it, my back will ache so."

"Poor little Tom!" said Nellie softly, stroking his thin hand.

Arthur paused in getting out the bricks, and looked at him silently. What could he say? What pleasures were there in store for this helpless child? He could not run, or dig, or ride on donkeys, or sail ships. What could he say to enliven him? He did not think of anything just then, so he turned again to the bricks, and placing a small invalid table over the couch, he began to build a wonderful edifice, while Tom grew interested in spite of himself.

"That is like the church you go to," said Tom. "Mary and Simmons wheeled me as far as that one day, and I saw it; and I know it is like that."

"Well, I think it is, now you say so, though I did not mean it for it. But look here, I'll make it as much like as I can remember, and if you think of anything, you must tell me."

They built on happily for nearly an hour, Arthur cleverly weaving into his building a true history of a man named Black Tom, who was a bricklayer at the works. And he brought in for his little brother's benefit all the information he had himself picked up about building. Also how Black Tom's boy was employed on the scaffolding, and how he fell and was taken up very much hurt, and had to be conveyed to the hospital. So an hour quickly slipped away, and the children would soon be home.

"Will he ever be able to walk again, do you think?" asked Tom, when Arthur paused.

"I don't know about that; but one thing I can tell you, he has no mother or nurse like you, and lies now on his back in a little close room, with nothing to see and nothing to do."

"Does he? Where is he? Does he never go out?"

"Never; because papa goes to see him, and he told me so. And they have no easy perambulator like you, Tom, to lay him in. And he never gets sight of the park as you do, or of trees, or even shops, and looks all day long just upon the same old ceiling and ugly paper of his little dull room!"

Tom glanced round his pleasant nursery, and at the bricks which Arthur was replacing in their box.

"I never thought of that," he said, and sighed deeply.

"We have brought you some of our sweets, Tom," said Dolly, running in and holding out a little paper.

"Oh, thank you!" said Tom. "And I have been having such a nice play with Arthur."

Nellie's little girls had quite recovered their spirits when they came to the schoolroom, and their lessons were got through without any further difficulty.

Ada looked in once with a very black face; but no one spoke to her, and she did not vouchsafe any remark, but, after looking at what they were about, took herself off to her own room, where she turned out her things on the floor, and sat down amongst the confusion to pick out what she wanted to take with her to South Bay.

Out of humour with everyone, and with herself above all, she soon grew tired and hot. The ribbons seemed endless; the gloves would not pair; unexpected holes and rents appeared in garments she had thought were quite ready for packing; and at length, thoroughly disheartened, she laid her head on the side of the bed near which she was seated and began to cry.

She was startled by a cheerful "Hulloa! Here's a mess!" And Arthur came striding across the forlorn room, and perched himself on the footboard of her bedstead.

"Well, Ada, so this is packing is it? I told you it was too soon to begin, and now you've proved it. The way to pack is, wait till the last moment, then seize a carpet bag, rush to your drawers, take out one of each sort of thing, stuff them in as quick as lightning, squeeze them in somehow, lock it up, rush down stairs, jump into a cab, and hope you've left nothing behind."

Ada laughed, in spite of her bad spirits, and would have cheered up had she not looked once more on the hopeless confusion.

"I am so dreadfully tired and hot," she said dolefully.

"I should think so; quite enough to give you the blues for a week. Shall I help you put 'em back?"

"Oh, do!" said Ada.

"Here goes then." And faster than they came out, Arthur stuffed them in—ribbons, neckties, gloves, handkerchiefs, collars, and clothes.

"Oh, that's my best dress!" said Ada, catching at him as he took a last armful.

"More shame to you," said Arthur, stopping short. "Whatever would mamma say? And if I might suggest, is not that your best hat?"

"Yes," said Ada; "I meant to put those in carefully."

"Then I'd have left them where they were till the last moment. Now, Ada, the room's clear again, and the children have done school, and I'm going down there to have a splendid painting go, till dinner; come along too."

"Very well," said Ada, sighing; "but I meant to have done so much this morning, and the time has all been wasted."

When they reached the schoolroom, Nellie was putting away the last few things belonging to lessons; and as Ada entered she turned round pleasantly, saying, "Now, Ada, I can see to things if you like."

"I was going to paint now," said Ada a little ungraciously; "and besides, I am dreadfully tired of packing."

Arthur laughed, and glanced quizzically at her.

"I was so sorry I could not help you, dear," said Nellie; "but you see how it was."

"Yes, I see," answered Ada, beginning to feel very much ashamed, but not willing to own it.

"But I can go now; what shall we begin upon? How much have you done?" asked Nellie.

Arthur wanted to speak very much, but he managed to run off for a glass of water for painting, and Ada contrived to say, "Why I got disheartened, and Arthur helped me make the room tidy again; but I am so tired now that I would rather not do any more before dinner, if you don't mind."

"I only thought perhaps we ought to get a few of our own clothes together, Ada, or there will be so much to see to at last."

"Very well," said Ada reluctantly; "but mine are in such a mess."

She followed her sister, however, to their room, and watched her in silence while she took out their clothes one by one and laid them in little heaps on the bed. No remark was made as to the disordered state of her drawers, though she knew how much forbearance it must need to avoid condemning.

"Now, Ada," said Nellie at last, "you can come and fold all this heap off this chair one by one, and lay them on the bed so, and when we have done all the large things we will look at the ribbon drawer."

Ada groaned at the thought, but she did manage to do her share pretty well; and then Nellie proceeded to sort out the "ribbon drawer."

"There is never so long a task but it gets finished, if we go at it patiently," she said, smiling. "Which ties do you want to take with you?"

"Oh, all of them! Never mind sorting them out; put them in wholesale."

"I daresay; to irritate your temper when you get there. No; tell me which. Come, I am helping you, so it is not so very hard just to decide."

So Nellie went through the things one by one till the drawer was empty; and Ada ran off with a little heap of odds and ends to decorate the dolls with.

After dinner the sisters sat down to work, and Nellie coaxed Ada to get a few stitches done to her clothes, so that before night they might be placed in the box. And with the promise of locking the box and having something to show for their pains, quite a nice heap of things were finished off. And when Ada went to bed, she felt very well satisfied with herself.

That night, as Nellie sat turning over the leaves of her Bible after she had read her usual chapter, her eyes fell upon these words: "'I can do all things through Christ which strengtheneth me;'" and she thought how true they had been to her that day.

"What are you reading?" asked Ada sleepily from her comfortable bed.

"'I can do all things through Christ which strengtheneth me,'" answered Nellie thoughtfully.

"Through Christ's strength?" thought Ada dreamily. "Not my strength—I don't think I know anything about Christ's strength."

SOUTH BAY.

"I SUPPOSE you all want to hear everything," said Dr. Arundel cheerfully, as he looked round on the expectant faces of the party who sat at tea the following evening.

"Yes, everything," answered Ada; and the others certainly did not say no.

"Well, we went to South Bay, and, as you know, it takes nearly three hours in the train. When we arrived there, we were hurried into a little shaky omnibus, and were driven into the town, and set down, according to our wish, in the very middle of all the lodgings."

"I suppose you do not care to know how many houses we went over? Nor how many disappointments we had before we found the right place?"

"Did you find the right place?" asked Arthur.

"I think we did. After wandering about till we were nearly footsore, we caught sight of a little settlement on the cliff about ten minutes' walk from the sea.

"'What is that, I wonder?' said mamma, quite brightening up.

"And we turned our steps that way, though I will confess to you, children, that I had not much hope it would turn out anything after all. But it was something, and just the very something we had been longing for. It was a small farm, with high, pointed gables; and, to our great joy, up in one of the windows close to the lane was the welcome word 'lodgings.'

"A pleasant middle-aged woman came to the door, and asked us to enter. I assure you we were not loath to do so. The glaring sun and the unusual fatigue made us glad to sit down, and the woman seemed to understand this; for she did not offer any remark for a moment, but turned to a little toddling child who hung to her skirts, and said coaxingly,—

"'Now, Alfy, granny wants you to go in the garden; run away, there's a good little boy.'

"Master Alfy, however, preferred to stare at us, and his grandmother again tried to coax him, 'See, Alfy, here's a bit of cake; now, darling, run into the garden, do deary.'

"Alfy took the cake and ate it, but remained where he was; and as mamma had by this time got a little rested, we proceeded to look at the lodgings."

The children made sundry exclamations, but their papa soon went on with his story.

"Downstairs, looking into the lane and across to the orchard, was the sitting room, which we shall take our meals in, and the kitchen belonging to the farm; then on the other side of the house, and looking over a sweet-smelling old-fashioned garden, are two rooms, which we shall use for our drawing room and nursery. From these, you can see the sea very well, and the garden and meadow slope away down to South Bay, and the fringe of houses close by the sea. These, however, are nearly hidden from the farm by some few trees at the bottom of their first field."

"How delightful!" burst from many lips.

"Then," resumed Dr. Arundel, "upstairs there are endless rooms, enough for all of you to be as comfortable as possible. The only difficulty will be for you to find your way about; for you go up three stairs, and down three stairs, and up three stairs again in the most fascinating manner."

The children all understood this, and it raised their hopes beyond everything.

Suddenly Netta laid her head on her father's arm, "But you won't be there, papa. What shall we do without you? And how dull you will be! I am so very, very sorry."

All the faces were turned full of feeling towards him. "We all are," said Ada, "only it is of no use keeping on saying so."

"Yes, my dears, so we are," he answered, looking at them all, "but it has seemed to me that I have been called to stay in London this summer. You know the physician who had undertaken my work has been suddenly taken ill; and at this time of year, everyone has made arrangements, and it was too late to find anyone else. There are a good many sick ones round us, and I cannot leave them. No; we must be patient. Perhaps further on in the autumn, I may get away; and I hope even now to come down and look in on you once or twice during your stay."

The children sighed; it was a great disappointment to them; and they felt almost guilty to be so delighted when their dear father could not share it.

The final packing up was more like Arthur's advice to Ada than the elders would have chosen. Certainly the servants, as well as Nellie and Ada, had not been idle during the two days of Mrs. Arundel's absence. But it was, nevertheless, a great bustle to pack up for so large a family. And when at last on Saturday afternoon they really did drive away from No. 8 in two cabs, and the carriage for mamma and Tom, they all were perfectly certain they had left the very thing behind that they wanted most.

Dr. Arundel was obliged to wish them good-bye at the station. They were in two adjoining carriages, in one of which Nellie, Arthur, and the little girls were established, with Simmons, the housemaid; and in the other Tom's little couch had been laid, and by him sat his mother, while at the further window Ada and the nurse and baby were making themselves as comfortable as possible.

Dr. Arundel looked at all the happy faces, and as he clasped his wife's hand, he whispered, "We have much to be thankful for, my love; may God bless you all, and strengthen little Tom."

Mrs. Arundel's eyes were full of tears as she glanced at the pale face beside her, and then back at her husband, and she only managed to say good-bye rather brokenly. But just as the train began to move, she whispered hurriedly, "Indeed I know it, so many mercies; I am not unthankful."

Dr. Arundel smiled brightly in answer, and they were quickly out of sight.

THE GABLED FARM.

OH the delicious smell of the sea as they emerged from the little station at South Bay!

The elder ones volunteered to walk, and as the omnibus was considered too shaky for Tom, a fly had been previously ordered, and stood waiting for them.

The light frame of his couch, with his slender form, was easily lifted and placed across the two seats, and they were soon driving along by the edge of the sea before turning up the road which led to the Downs. Tom stretched his neck to see as much as he could, and his mother tried to raise him a little, but he looked so anxious and haggard that she begged him to be satisfied to leave it all till to-morrow. The child lay back exhausted, and the mother's eyes sought the nurse's anxiously.

"He will be better after his tea, ma'am," said Mary, in answer to this look; "and to-morrow I hope he will be quite himself; won't you, dear?"

They were soon mounting the little hill that led to the farm, and Mrs. Arundel said to Mary, "I hope you will not find this very heavy to push him up and down."

"Oh, no, I do not think we shall; we must all help!" answered Mary pleasantly. "You know, ma'am, we can't expect London pavements at South Bay."

"Here we are!" said Mrs. Arundel as they drew up before a gabled whitewashed house, with a gay little garden in front, and wide-open white curtained windows, with old-fashioned tiny diamond lattices.

By the time Tom had been safely lifted out, and the nurse, baby, and Dolly had been introduced to their nursery, there was a sound of voices, and Mrs. Arundel turned to greet her merry party from the station.

"How delicious!" said Ada.

"Delightful!" said Arthur, bounding up.

"This is lovely, mamma!" said Nellie.

And Isabel and Netta joined in the chorus of gratification; while Simmons gave smiling approval.

"What a jolly sitting room! And that dear old bay window! I say, Ada, we'll have nice times here," said Arthur.

"What a little drawing room!" exclaimed Ada, rushing across the landing into the room looking towards the sea.

"Yes; that is my sanctum," said their mother, smiling.

"Quite right, too," said Arthur; "for I believe we do make an awful row sometimes."

"Where's the nursery?" asked Ada.

"Here," said Dolly's little voice from the crack of the door close by. "I've been watching you all this time. This is my nursery, and I like it very much; but Tom doesn't."

"Let's see," said Arthur. "Oh, here you are, all of you, quite settled in, I declare! Tea spread on the table, and baby looking as if he would eat the loaf if he could!"

"Yes, he is so hungry," said Mary.

"I am not," said Tom wearily. "I wish I could come in with you, mamma; I don't like being here."

"So you shall, dear, when we have taken our bonnets off. It is all strange at present, but we shall soon get happy. Arthur dear, help Simmons and Mrs. Ross up with some of our things."

They soon came down again, and Simmons and Arthur lifted the moveable part of Tom's couch from the nursery to the sitting room sofa. And there, slightly propped up with pillows, he was able to look round, and began to feel himself more at home.

"I don't want any tea," he still assured them.

"Just one mouthful," said his mother with gentle decision as she held his drinking-cup to his lips.

He obeyed without further demur, and then, placing the cup on his little table, which had been brought with them in the train, and putting one tiny piece of bread and butter between his lips, Mrs. Arundel left him while she attended to the others. And amid all the little bustle of preparation, Tom forgot to be cross, and unnoticed by all but his watchful mother, gradually took up piece after piece of his bread and butter till it had all disappeared. He looked all the better for it.

And happily no one said, "There, you did want your tea after all;" though it was on the tip of Ada's tongue several times.

By the time tea was over, it was getting dusk, and Mrs. Arundel advised them not to explore till the next day.

"Oh, mamma," said Nellie, "would you mind our just running down for a peep at the sea!"

Mrs. Arundel could not say no, and telling them "to wrap up, for it was very different from London," she went to see after her little flock, and in no time heard the three hurry out of the house and scamper down the quiet lane.

The little ones were soon tucked into the white fragrant beds; and Tom had been lifted upstairs on his light frame, and was now lying in the twilight waiting for his mother's good-night kiss.

He stretched out his hand and stroked her face, then said suddenly, "I wish I could run off down the lane with them."

"I wish you could, my precious," she answered tenderly; "but, Tom, God has willed it differently, and we must try and be willing. Do try, my dearest!"

"I can't," said Tom in a stifled voice. "It makes it worse to come here and half see it all. I would rather have stayed in London."

"I hope it will do you good, my dear; and you will find to-morrow that there are some pleasures you can share."

"I don't think there will be. Even baby could grab at the flowers at our nursery window the minute he came in; but I—, I could only be lifted as usual on to the sofa, and stick there."

A hot tear fell on little Tom's face.

"There now, I have made you cry," he said penitently. "Oh, mamma, I wish I could bear it better!"

He clasped his arms about her neck, and after a minute or two, she whispered his prayer, and then tenderly kissing him, she got up to go away.

Tom would like to have seen her face—the face he loved so much—but it was too dark; and he could only guess by her step that she was dejected and sorrowful. This made him very sorrowful too, and burning tears rolled down his cheeks when her footfall sounded on the last stair. Being left alone reminded him of that other boy who had no mother; that boy who had no white soft bed at the sea-side to rest in, but was probably at this moment in a dark, unhealthy room, looking at the shadow of the flickering gas-lamp on the dirty blind, in hot, dirty London.

"I wish I had not grieved her," he thought, as he had thought a hundred times before; "but I can't help it; I'm a miserable little boy, and always shall be, till the end!"

"Till the end!" Was there an end? The thought roused him again, for he was almost asleep. What made him think of that? Was it that beautiful evening star shining so calmly down upon him? Or was it words which his mother and father often spoke to him, and which, by the Holy Spirit's power, were coming back to him? He could not tell; and while he thought about it, his tired eyes closed, and he slept.

When Mrs. Arundel lifted her blind the next morning, and looked out over the orchard laden with fruit, with its grass sparkling in the morning dew and sunshine, she espied two figures, arm-in-arm, pacing up and down the lane. They were Ada and Arthur. No time must be lost on this first morning; and they were drinking in the fresh sea breezes, and enjoying, as perhaps only town folks can, the first morning at the sea-side. Very dear to their mother were these eldest children of hers; but how she longed to see in them, besides their bright earthly promise, the germ of heavenly growth.

"May Thy kingdom come in their hearts!" she said as she turned away.

A handful of gravel crashing against her window roused Nellie from her slumbers. She started up frightened, and then smiled as she guessed what it was.

"Nellie, Nellie!" called Arthur. "It's eight o'clock, and we want breakfast!"

"What a lovely Sunday," said Mrs. Arundel, when she came down stairs and found Nellie cutting the bread and butter.

"Yes; it is indeed, mamma. How I wish papa were here with us."

"Come, Arthur; come, Ada," called Mrs. Arundel from the door, "I am sure you must be hungry."

"That we are, and I never did see such a jolly place, mamma! That orchard, when the dew is off, will be as cool and as shady as possible; and when we are tired of the beach—"

"Which we shall not be," interrupted Ada.

"Oh, yes, we shall; one cannot be everlastingly on the beach! It is the very thing to complete our enjoyment."

"It is very nice," said Mrs. Arundel, "and is an especial pleasure to me, because I shall be able to take my work there when I do not care to go far."

After breakfast they all gathered together, and their mother read a short passage from the Bible, and prayed a very simple prayer that all could understand, asking God their Father to take care of them, thanking Him for all His gifts, and praying that they might be enabled to live to His glory.

After this, all who were old enough prepared themselves, and at half-past ten set off to walk inland to a little church about a mile away.

After dinner, Mrs. Arundel told them to bring their books to the orchard, and little Tom was wheeled under the shade of one of the largest trees, and they established themselves in various comfortable attitudes round him. The baby rolled on the grass at their feet, Dolly was absorbed in a Sunday picture book at Nellie's knee, and the rest were sitting, with Sunday faces calm and bright, waiting to hear a story which their mother was going to read aloud. The two servants, with the maid from the farm, soon passed, going to afternoon service in South Bay. And as long as the bells were chiming, Mrs. Arundel sat silent, listening to the peaceful sound, and thinking of all whom she loved who were far away.

The children were awed by the stillness and the music floating up on the soft wind; and when the last note died away, they sat perfectly quiet, till Mrs. Arundel turned to them and opened the book.

Just at this moment Alfy ran out from the wide-open front door, and crossed the road, to have a good look at the new visitors. His exit was unnoticed evidently, for no one followed him, and he made his way, not at all abashed, into the midst of the little party. The children were all rather surprised, and there was a pause to see what he would do. "Me, too," he said, and seated himself amongst them very complacently.

"Here, Alfy," said Nellie, "I have some pictures here, come and see them!"

Alfy turned round, and after examining her gentle face for a minute, he scrambled to his feet and trotted towards her; and as they were far enough away not to interrupt the others, Mrs. Arundel began her reading, and Nellie kept her two little ones happy and good for half an hour.

Just as Mrs. Arundel was shutting her book, Mrs. Ross appeared at the door, and shading her eyes with her hand, looked anxiously in every direction, at last calling in not a very pleased voice, "Alfy! Alfy! Wherever are you?"

"Here he is," said Mrs. Arundel, raising her voice a little just to reach the anxious grandmother.

"Oh, dear, ma'am, I'm sure I beg pardon for him—a naughty boy! However did he come troubling you ladies?" said Mrs. Ross, coming near.

"Oh, never mind, he has been very good."

"I suppose it was this way. Molly, the girl, was off to church, and his grandfather was having a nap, and I must needs fall asleep too. I beg your pardon, ma'am. You see we're old folks to have him on us like; but it's all we can do for him that's gone," glancing at her black Sunday gown.

"Your son's child?" asked Mrs. Arundel kindly, sympathising with the trouble in the old woman's face.

"Yes, ma'am, our only one. His wife died when Alfy was a year old; and just a year after that, our boy went out one ugly night fishing, and a storm came on, and the boats came back without his!"

All eyes were turned on Mrs. Ross; and even Alfy looked sober. Seeing them silently ask for more, she went on.

"A few days afterwards we did find him, thank God; but our brave, handsome boy, you would not have known him, ma'am; and we laid him by his young wife up there under the trees where you went this morning; and then we took Alfy home to us altogether."

"I daresay it is a comfort in some ways," said Mrs. Arundel, looking at his pretty little face, and thinking of the sailor-father.

"Yes, ma'am," said Mrs. Ross hesitating, "it is in some ways; when I think of him that's gone it is. But we're getting old, father and me, and sometimes I'm afraid whether we look after him enough; and we haven't time or strength to be always at his heels. I am afraid for him if anything happened to us, or if he were to run wild. That's what our own Alfred never did, ma'am."

Mrs. Arundel looked thoughtful. And as the children were getting tired of sitting, Mrs. Ross took Alfy's hand and led the way to show them a little brook where she could pick them some water-cresses for tea. They all ran off after her; and Nellie came up to Tom, and placing the good-natured baby by his side on the perambulator, within the circle of his arm, she pushed them slowly up and down the shady lane, while Mrs. Arundel walked by her side, and they enjoyed one of those peaceful seasons that come but seldom to mothers and elder daughters of large families, and are prized accordingly.

Nellie and her stepmother loved each other dearly, and each truly sought to be a comfort to the other. It was wonderful how many ways Nellie found of doing little things for her mamma. While in her turn, Mrs. Arundel tried to fill a mother's place to the girl whom she had taken to her heart a desolate, motherless child, of four years old, just fifteen years ago.

This Sunday was long remembered; for that week a new era opened in the lives of some of that happy little party.

THREE-AND-SIXPENCE.

"MAMMA! What time may we bathe?" was Ada's first question the next morning when they were fairly seated at breakfast.

"I have been thinking it over," answered Mrs. Arundel, "and I know you and Arthur would generally like to bathe before breakfast."

"That we should!" said Arthur. "Bathing in the middle of the day is 'girls' time.'"

"So should I," said Ada; "but oh, mamma, what a pity we did not go this morning!"

Mrs. Arundel smiled. "I thought for the first day that you would have excitement enough, so by-and-by we will see about it."

"And may we bathe?" asked Netta; including, as she always did, her beloved companion Isabel.

"Yes, with Nellie; and I shall sit on the beach and watch you, and see what brave little girls I have."

The moment breakfast and prayers were done, there was a general rush for hats and jackets. Long before Mrs. Arundel could be ready, Arthur, Ada, Isabel, and Netta were off down the lane; and Nellie was almost as anxious as they to get off. But she waited first to help to get Tom ready, and place him in his little carriage; and then, while the nurse put on her hat, she amused the little ones and held the baby.

At last they were all ready to start. Mrs. Arundel had spoken to Mrs. Ross about the dinner, and now came out, followed by Simmons, who would push little Tom, and take it in turns with the nurse to carry the baby, while for a change, Tom often asked them to set him by his side and give him a ride too.

The nursery party went down the hill more quickly than Nellie and Mrs. Arundel cared to go, and were established on the sands when they arrived. Arthur soon spied them, for he had been on the watch, and now rushed up with a face full of eagerness.

"Here you are!" he exclaimed, opening out his mother's beach chair, and longing to see her established.

But his mother was not ready yet. She went first to little Tom's side and fixed up a sort of parasol shade over him, and then put him so that he could see as much as possible without raising his head more than was permitted.

He smiled gratefully as the shade came over his face.

"You can see pretty well now, darling?" she said, putting her face down to the level of his.

"Yes, mamma, pretty well," he said, sighing a little.

The others waited round. They knew from experience that everyone in the family had to give place to the comfort of the poor little invalid; so it was not till their mother seemed satisfied that the most had been done that could be, that they claimed her attention.

"Now, mamma, you promised us some pails and spades!"

"To be sure," said Mrs. Arundel, producing a half-crown which seemed ready; "and Arthur is the eldest, so he must lay it out to good advantage."

"Could we get anything for Tom?" whispered Ada.

"Not with that, I think; but if you see anything that would amuse him, you can let me know; or stay—suppose I give you another shilling, and you use your very best discretion to get something suitable. Suitable, mind!"

The words were hardly out of Mrs. Arundel's mouth, before the children were off, Ada dragging Dolly along as fast as her little legs could carry her towards the shops.

Mrs. Arundel looked after them, smiling, when she was startled by a slight cry from Tom. A large mastiff had come up, and was putting his cool nose right up to little Tom's face.

A young lady in deep mourning sprang forward, and said quickly: "He will not hurt you, dear, in the least!" And then, coming up to them, she apologised for her dog, and tried to make friends with Tom.

"I was only startled for a moment," said Tom, looking up, rather ashamed of his fright.

"Yes," said a clear ringing voice; "and he is so big, and came so very near! But he is as gentle as can be. Come here, Lion, and show this little boy how good you can be."

Then turning to Mrs. Arundel, and finding that her face did not rebuke her for interesting the little invalid, she showed him how her dog would fetch a stick, carry her basket, and do various little tricks.

Presently she raised her veil, and then they could see her striking face and great beauty. She was probably a few years older than Nellie, but her face was full of interest and sorrow. Nellie made up her mind that it was a sorrow carried patiently, and not fought against; though she could not have told why she thought so.

Then the stranger called her dog to lie down beside her, and Mrs. Arundel and Nellie seated themselves close to little Tom, and began to think of taking out their work.

But the work did not come to much, for before long they heard a considerable crunching of the shingle behind them, and in another moment the troop came up, breathless and excited.

"Where are your pails?" said Mrs. Arundel in amazement, seeing them all empty-handed, and making up her mind that they had lost the half-crown.

"Oh, mamma!" Ada whispered eagerly. "We haven't brought them with us; but they are all right, and we are going back for them. But, mamma, there was nothing suitable for Tom under three-and-sixpence—but oh, do let us spend that! We will give the extra out of our own money."

"But, my dear, three-and-sixpence is a great deal. Whatever toy could cost that, that he could play with?"

"Oh, mamma, he'll hear!" said Ada. "But do trust us; it isn't a toy, and it isn't waste, and do trust us to buy it!"

Mrs. Arundel would have hesitated still; but the eager faces, and the necessity for secrecy, overcame her prudent objections, so she took another half-crown from her purse, and they were off again instantly.

The young lady, who had been near enough to Mrs. Arundel to gather the meaning of it all, smiled pleasantly when they were again out of sight, and said in a low tone, "They seem very fond of your little boy."

"Oh, yes! He is our first care." Then with a glance, which the young lady understood, towards the little couch, Mrs. Arundel turned the conversation to other subjects.

In about half an hour the shopping party came back, and advanced with their hands behind them, looking eagerly happy. Arthur came first, and going up to little Tom, placed in his hand a small parcel, saying, "That's your share of the spades and pails!"

They all gathered round to see, even Simmons and Mary getting up to peep over the little shoulders; and very much surprised were they to see Tom's thin fingers take out of the paper a nice little telescope!

"How kind!" he said, flushing up. "Do you think I shall be able to see through it lying so?"

"Oh, yes," said his mother, looking delighted. "It will be the very thing, Tom. How nice it was of them all to think of it."

"And here are our spades," said the little ones, bursting out with their news, now the grand presentation was over. "See, mamma, such beauties, and the pails only fourpence each!"

"Splendid!" said Nellie. "And such nice spades. Well, you will be happy!"

"Don't you want a spade?" said Dolly, looking up in Nellie's face.

"No, dear; though I am a sea-side baby, I will confess," she said laughingly, turning to the stranger, who seemed quite interested by the family party.

The young lady smiled. "Ah, I am too old for that!" she said, shaking her head. "But I expect you could dig for a whole morning with pleasure."

"Yes," said Nellie; "I believe I could. Come along, Dolly, and let us begin."

The tide had been going down for some hours, and a nice flat strip of sand was left dry. Simmons volunteered to push Tom a little way along this, and Mary joined her with the baby.

Left thus together, as it were, Mrs. Arundel turned to the young lady, as if to finish the sentence which had been interrupted. "We never talk of him before him," she said, following the perambulator with her eyes. "He is very quick, and thinks too much about himself already; I mean his thoughts are too much centred on his affliction."

"It must be a great trial," said the young lady sympathisingly.

"Yes," said his mother, still looking after him, "yes; but we do know from whom it comes."

"Ah! That is the only comfort."

"You know that comfort too, then?"

"Yes," she answered in her turn. But it was a very reserved word, and Mrs. Arundel could not ask any more just then.

"Was it an accident?" asked the young lady presently.

"Yes; when he was nearly two years old; such a darling! The nurse—not this one—put him on the table against my often-repeated injunctions, and as she turned round to reach his hat, the child leant after her and fell. He has never sat up since."

"How sad!"

"Very, very sad! But one day my boy will, I trust, know what it is to be all right again, and have no aches and weariness. Here they come back, and I think he looks as if he were tired. Simmons, we will return home, and leave the others to their digging. How happy they all look!"

She turned to the stranger to say good morning. "Do you stay long?" she asked.

"I live here at present."

"Then we shall meet again, I doubt not."

"My name is Christina Arbuthnot."

"And mine is Mrs. Arundel."

"Thank you so much; it will be very pleasant to meet."

With a word to Nellie and the nurse, who both seemed inclined to finish the morning on the beach, Mrs. Arundel turned homewards, her little son's anxious face giving her such a heart-sinking that she felt as if she could hardly walk along. But by-and-by, she lifted her eyes to the blue sky and took courage. She remembered in whose hand she was, and that nothing could happen to her boy but by His permission.

"He knows, He cares," she said to herself; and if the eyes that still looked up were dimmed with tears, they were tears of submissive faith, that trusted when she could not see.

AN UNEXPECTED ARRIVAL.

IT was not very late when Mrs. Arundel reached the farm.

Hearing the noise of wheels before she expected it, Mrs. Ross came to the door to see, and Mrs. Arundel told her that this first day the excitement had been rather too much for Tom, and that they had come home to rest.

Simmons and she soon tucked him up comfortably on the little sofa in the tiny sitting room, and with his tired eyes watching his mother sit down to her desk, he soon forgot himself, and fell peacefully asleep.

About half-past one the beach party began to return. Nurse and the little ones first, and very soon Nellie and all the rest.

When they were at tea that evening, Netta spied the postman coming up the hill. And there was a general rush to the door, in which, however, poor Netta, being small, lost her chance. Ada was the successful one, and laid the letter down in triumph before her mother.

"From papa!" she said.

Mrs. Arundel opened it in silence; while the children looked on expectantly.

"Oh, Nellie!" said Mrs. Arundel, "Who do you think has come? Oh, Nellie!"

Nellie turned pale; and Mrs. Arundel read—

"Prepare yourselves for a great surprise. When I was seated at my

solitary tea on Saturday evening, the door opened, and Walter walked

in! Yes, my dear son from India! But he must tell you all about it

himself. When he has finished his business, he will come down to South

Bay, about Wednesday, I suppose; so tell Nellie to keep back her

impatience till then. I am too busy to say more to-day."

Nellie's colour came again; but she burst into tears.

Mrs. Arundel rose quickly, and putting her arm round her shoulder, kissed her affectionately. "Dear Nellie, how nice it will be," she said; "don't cry; I am afraid I did not prepare you enough."

Nellie's tears caused general consternation; and when she looked up and saw the woe-begone faces of her little sisters, she could not help laughing, which astonished them much. So she soon recovered, and once more they settled to their tea, and to the joyful anticipations of Walter's visit.

Arthur and Ada were very full of it, and, to judge by what they said, intended to monopolise him entirely. Nellie looked radiant after her first agitation was over, and Mrs. Arundel sympathised so thoroughly with her, that she looked radiant too. The children were so excited with this news that they soon finished tea, and almost without asking permission set off for a walk inland, leaving everything scattered about.

Their mother began to put the room to rights. "They will have to be tidy," she said emphatically, half aloud; "for if everyone throws everything down, we shall not be able to move."

On the eventful Wednesday, dinner was soon swallowed, and four or five of them hurried off to meet the three o'clock train.

Tom was lifted across on his couch to the grass in the orchard, where he lay looking up into the trees, and thinking. His little telescope was held tightly in one thin hand; and the other stretched out listlessly, catching at the grass and clover.

Mrs. Arundel came over the road to glance at him, and he looked up in her face as if wishing to say something. She knew the look, and waited.

"I suppose they are all very glad about Walter?" he said gravely.

"Very glad; it is so nice for us."

"It will not be nice for me; I shall not wish to see him; I don't remember him."

"But, dear Tom, he is your brother, and so kind, and when you know him, you will love him."

"No, mamma, I shall not," he answered quietly; "nothing makes any difference to me. They will all be off for walks away from me. No; I wish he were not coming."

Mrs. Arundel could not keep back a sigh, and Tom was quick to perceive it. He hated himself for his petulance, and yet he felt unable to overcome it.

"You must watch for them coming up the lane, dear," she said, trying to speak cheerfully; "and when you first hear them or see them, give a sound on your little whistle and I will come out."

"All right!" said Tom, with a trifle more energy. And then finding he could look up into the trees with his telescope, he began to adjust it, and Mrs. Arundel went indoors.

Tom was the first to hear the sound of the approaching party, and in his excitement gave a very shrill whistle, which brought his mother running out long before anything was to be seen.

But in a few minutes, they came within sight over the brow of the little hill. Nellie, looking the picture of happiness, leaning on the arm of a sunburnt, pleasant young man of about twenty-two, who was laughing and talking, and holding Isabel by his disengaged hand.

The others were conveying his bag, umbrella, &c.; for Walter certainly should not have anything to carry this first day.

He came forward quickly when he saw his stepmother, and kissed her affectionately; and before Tom had time to object, he had stooped and kissed him also, saying with a sweet smile, "Ah, Tom! Here's somebody come that will be able to push you along finely!"

Tom looked astonished, and then a little ashamed as his eyes rested on his mother's face. And her touched and grateful smile set him thinking even in that moment of arrival how it was that his mother could love him so much. He thought he would ask her some day.

After tea nobody seemed inclined to walk down into the town again, so they gathered round their mother and Walter in the orchard. And with the sweet air blowing up gently from the sea, and the scent of the flowers coming over from the garden, he explained to them how it was that he came so suddenly, and what were his plans.

"I should not have taken you by surprise if I could have helped it; but one of the partners of our firm was coming over on business, and was thrown from his horse and seriously hurt at the last moment. They were obliged to send someone trustworthy, and luckily fixed on me; so with only twenty-four hours' notice I was off, instead of him, in the steamer in which his passage was taken."

"Jolly!" said Arthur.

"Very," answered Walter, smiling; "for I should not have come in such style on my own account."

"How long are you likely to be able to stay?" asked Mrs. Arundel. "Or perhaps you do not know?"

"I think three clear months. So, as my father tells me you are here for a month, if you will have me, I have come to stay."

"Indeed we will," said Mrs. Arundel; "and shall only be too delighted."

"I have brought something for all of you to do!"

"Have you?" said Arthur. "What sort of thing?"

"Ah! I am going to leave you in uncertainty till the day after to-morrow."

"What an age!" exclaimed Ada. "But, after all, I do not expect it will be anything nice to do."

Nellie looked pained. "I dare say it will, Ada; Walter would not propose anything disagreeable."

"We shall see," said Ada.

"I am sure it will be nice," said Isabel; "for Walter looks so kind!"

"Dear little girl!" he said. "I am glad you trust me."

WALTER'S TREAT.

"WHO likes donkey rides?" asked Walter the next morning.

Plenty of voices answered, "Oh, I do!"

"Who has heard of Melton Castle, three miles from here?"

"I think we all have," said mamma.

"Who likes rolled tongue and pickled salmon?"

"What nonsense!" exclaimed Ada. "You are only trying to take us in. Though there are donkeys and Melton Castle, there are certainly no rolled tongue and pickled salmon."

"Are there not? So much you know, Miss Ada."

"But, Walter, you should not tell them your bill of fare so early in the day," said Nellie, laughing.

"Well, anyone who likes all these dainties combined, must be at this door at half-past eleven precisely."

"What for?" asked Netta with wide-open eyes.

"You will see. By the bye, Netta, do you like a saddle or a chair?"

"A saddle, of course," answered Netta with dignity; "should not you, Isabel? That is, if you mean for a donkey ride."

"But what are you going to do, Walter?" asked Arthur; "but I guess."

"A picnic!" growled Walter in a sepulchral tone.

They all laughed joyfully.

"But mamma, how can she go? And Tom?"

"All arranged for. You shall behold at half-past eleven," said Walter.

"I believe Nellie is in the secret," said Ada a little jealously.

"Nellie is always in all my secrets," said Walter, smiling at her.

Nellie blushed with pleasure; but she only said, "But mamma is in the secret too."

"Of course," said Isabel; "nothing could be done without mamma."

Before half-past eleven the children were all assembled; and five minutes before that time, six donkeys came up and took their stand near the door.

The children counted and counted, but could not make out how six would be enough to "go round." Walter was lying under a tree in the orchard, and all he did was to laugh at all their questions and leave them unanswered.

Still, he kept his eye on them all, and when an open carriage drove up, he leapt from the ground and hurried across the road.

"Nellie is going to condescend to a donkey," he said, laughing, "and so I shall choose the best for her."

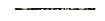

Next came Arthur and Ada,

and the riding party were all ready.

She came out at the moment, and he mounted her first of all. And then Dolly was placed in a little arm-chair; Netta and Isabel, with their curls dancing in the sunshine, had saddles; but Walter had discovered there were some to be obtained with a sort of hoop round them, and with these they seemed delighted.

Next came Arthur and Ada, and the riding party were all ready.

Mrs. Arundel, Tom, and the baby, with the two servants and two hampers, were packed into the carriage.

"Where are you going to ride?" asked Isabel anxiously.

"Oh, I walk! No donkeys for me, thank you," answered Walter; "my legs are too long."

"So they are," said Dolly; "they would touch."

Mrs. Ross and Alfy came to the door to see them off. The carriage started at the pace of the donkeys, Walter generally walking by Nellie, and holding Dolly's bridle.

Shouts, screams, and laughter filled the air as the donkeys jogged their riders up and down. Tom leaned as far as he dared to see the merry party, and could not help enjoying their pleasure, though he kept on telling himself "it was very hard."

Arthur managed to urge his donkey alongside of the carriage. "Where are the 'goodies'?" he asked mysteriously of his mother.

She pointed to the coachman's seat.

"Pickled salmon?"

His mother laughed. "No questions, sir," she said.

By-and-by the ruins of the old castle appeared against the sky, and very soon the carriage pulled up at a low boundary-wall, after which they would have to walk.

Tom's perambulator had been fastened to the back of the carriage, and he was now placed on it. The coachman and the donkey-boy were engaged to carry the hampers up the hill for them, and Walter took Tom in charge; while shawls, rugs, and baskets occupied most of the others.

They found the hill in the burning sun rather fatiguing, but were rewarded when they reached the top by finding that part of the inside of the castle was in deep shade, and that overhanging the moat there were two fine old trees, which looked very inviting. Baskets, wraps, and hampers were quickly deposited, and the young people soon spread over the ruins in every direction.

Mrs. Arundel, with Nellie's help, aided by the two servants, now began to unpack the hampers. Tom, very interested, lay looking at them, suggesting where the viands were to be put.

"Who lent you the cloth?" he asked.

"It is one of ours, from home," said his mother.

"I am so thirsty!" he said, as he saw sundry bottles of water and lemonade lifted out.

"Wait till they come, dear," said his mother.

The servants had a little "nursery table," as Mrs. Arundel called it, spread at a short distance for baby and Dolly; but on this at present was laid nothing but some very tempting-looking rolls, with some tarts and cakes. As to Tom, he felt so dreadfully hungry that he held his whistle in his hand, only waiting a word from his mother to give the promised signal.

"Now, dear," said Mrs. Arundel, "we are all ready."

And before she had time to finish the sentence, Tom gave a whistle, which woke the echoes and brought the hungry party trooping back.

"You can do something, you see," said Nellie, smiling.

"Well, I declare," said Arthur, walking round the table-cloth, and surveying the viands. "Here's a spread! Well done, mother!"

"It is 'well done, Walter,'" said Mrs. Arundel; "more than half this came from London!"

"Pickled salmon, tongue, chickens, tarts, salad, rolls, blanc-mange, cakes, lemonade, and a lot more! Well done, Walter!"

"I'm glad you are satisfied; now then to enjoy it. But first we will ask a blessing." He raised his hat reverently, and calling to Dolly to be still a moment, he thanked God for giving them all this pleasure.

Mrs. Arundel said she should begin by helping the "nursery table," and sent a goodly supply by Arthur, who was head waiter. After that they all fell to, and did ample justice to all that Walter and Mrs. Arundel had prepared.

"There is no water left, Nellie," said Netta. "What shall we do? I am so thirsty."

"I know where we can get some more," said Ada. "I saw a little cottage down the other side, and there was a board up, 'Water or tea to be obtained here.'"

"Capital!" said Walter. "Where are the empty bottles?"

"We will fetch it, won't we, Arthur?" said Ada, jumping up.

"All right," said Arthur, taking a last bite of a nice tart. "And look here, mother, I don't think I have quite finished. Don't you clear it all away!" And with a laugh, he and Ada scampered off.

"Supposing we sing to pass away the time," suggested Walter.

"Mamma can sing," said Isabel, "and so can Nellie."

"Well, perhaps they will sing a duet first."

They willingly complied; and the sweet sound filled the old ruin, and seemed to float away on the wind. Walter lay with closed eyes; and when they had finished, no one spoke for a moment.

"Now you sing," said Dolly, getting up from her little table, and trotting round to her eldest brother.

He started up. "I? Well I will sing a funny one; and then when the others come we will see if we can sing something all together."

"Mamma," said Ada, when they came back breathless, and Nellie was pouring out the cool fresh water, "it is such a nice little cottage, and such a nice woman; she has a table under a great mulberry tree; and she said, 'Should we want tea? Because of putting on the water.'"

"Yes; we will go down there presently and tell her. I thought I had heard there was a cottage."

"So nice!" said Ada.

Arthur sat down by his mother and pretended he had not finished dinner; but after one more tart, he protested the run had taken away his appetite, and turned from the table.

"We were going to have some more singing," said Mrs. Arundel.

"Oh, that was what we heard!" answered Ada. "We could not think what it was."

"What shall we sing, Walter?" asked Mrs. Arundel. "See, I have a few hymn sheets here. The first is, 'O God, our help in ages past.'"

"That is dear papa's favourite," said Mrs. Arundel; "how I wish he were here!"

"Yes," said Ada, sighing; "I often think of him all alone, only it spoils one's pleasure so to think about it."

"We will sing it, then, in remembrance of him," said Walter.

Mary, the nurse, sang a nice second, and they all drew together into one circle, and the familiar words sounded wonderfully sweet with all the voices.