The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Very Black, by Dean Evans This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Very Black Author: Dean Evans Release Date: March 10, 2010 [EBook #31586] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE VERY BLACK *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

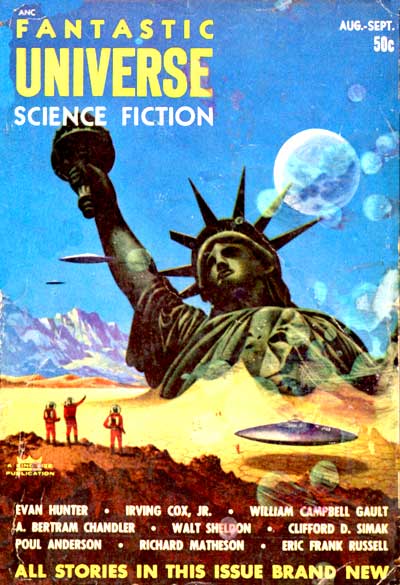

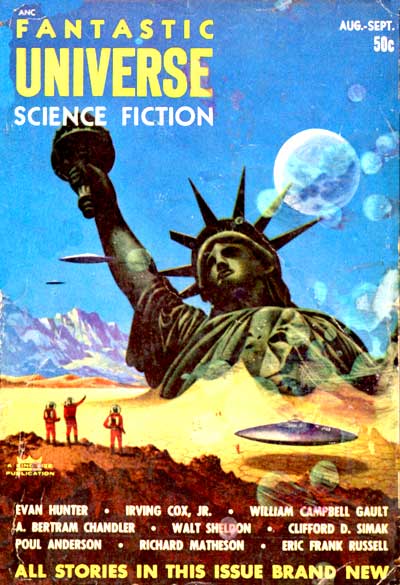

This etext was produced from Fantastic Universe Aug-Sept 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Jet test-pilots and love do not mix too happily as a rule—especially with a ninth-dimensional alter ego messing the whole act.

There was nothing peculiar about that certain night I suppose—except to me personally. A little earlier in the evening I'd walked out on the Doll, Margie Hayman—and a man doesn't do that and cheer over it. Not if he's in love with the Doll he doesn't—not this doll. If you've ever seen her you'll give the nod on that.

The trouble had been Air Force's new triangular ship—the new saucer. Not radio controlled, this one—this one was to carry a real live pilot. At least that's what the doll's father, who was Chief Engineer at Airtech, Inc., had in mind when he designed it.

The doll had said to me sort of casually, "Got something, Baby." She called me baby. Me, one eighty-five in goose pimples.

"Toss it over, Doll," I said.

"No strings on you, Baby." She'd grinned that little one-sided grin of hers. "No strings on you. Not even one. You're a flyboy, you are, and you can take off or land any time any place you feel like it."

"Stake your mom's Charleston cup on that," I said.

She nodded. Her one-sided grin seemed to fade slightly but she hooked it up again fast. A doll—like I said. This was the original model, they've never gone into production on girls like her full-time.

She said, "Therefore, I've got no right to go stalking with a salt shaker in one hand and a pair of shears for your tailfeathers in the other."

"You're cute, Doll," I said, still going along with her one hundred percent.

"Nice—we get along nice."

"Somebody oughta set 'em up on that."

"So far."

"Huh?" I blinked. I hate sour notes. That's why I'm not a musician. You never get a sour note in a jet job—or if you do you don't get annoyed. That's the sour note to end all sour notes.

"Brace yourself, Baby," she said.

I took a hitch on the highball glass I was holding and let one eye get a serious look in it. "Shoot," I told her.

"This new job—this new saucer the TV newscasts are blatting about. You boys in the Air Force heard about it yet?"

"There's been a rumor," I said. I frowned. Top secret—in a pig's eyelash!

"Uh-huh. Is it true this particular ship is supposed to carry a pilot this time?"

"Where do they dig up all this old stuff?" I growled. "Hell, I knew all about that way way back this afternoon already."

"Uh-huh, Is it also true they've asked a flyboy named Eddie Anders to take it up the first time? This flyboy named Eddie Anders being my Baby?"

I got bored with the highball. I tossed it down the hole in my head and put the glass on a table. "You're psychic," I said.

She shrugged. "Good looking, maybe. Nice shape, maybe. Peachy disposition, maybe. Psychic, unh-unhh. But who else would they ask to do it?"

"A point," I conceded.

"Fork in the road coming up," the Doll said.

"Huh?"

"Fork—look. It'll be voluntary, won't it? You don't have to do it? They won't think the worse of you if you refuse?"

"Huh?" I gawked at her.

"I'm scared, Baby."

Her eyes weren't blue anymore. They'd been blue before but not now. Now they were violet balls that were laying me like somebody taking a last long look at the thing down inside the nice white satin before they close the cover on it for the final time.

"Have a drink, Doll," I said. I got up, went to the liquor wagon. "Seltzer? There isn't any mixer left."

"Asked you something, Baby."

I took her glass over. I handed it to her. My own drink I poured down that same hole in my head. I said finally, "Nice smooth bourbon but I like scotch better."

"They've already crashed four of this new type on tests, haven't they?"

I nearly choked. That was supposed to be the very pinnacle of the top secret stuff. But she was right of course. Four of the earlier models had cracked up. No pilots in them at the time—radio controlled. But jobs designed to carry pilots nevertheless.

"Some pitchers have great big ugly-looking ears," I said.

She didn't seem to mind. She said, "Or maybe I'm really psychic as you said. Or maybe my Dad's being Chief at Airtech has something to do with it."

"Somebody oughta stitch a zipper across his big fat yap," I said. "And weld the damn thing shut."

"He told only me," she said softly. "And then only because of you. You see, Baby, he isn't like us. He's got old fashioned notions you and I've got strings tied around each other already just because you gave me a ring."

I stared at her.

"Crazy, isn't it? He isn't sensible like us."

"Can the gag lines, Doll," I said sourly. "The old bird's okay."

And that fetched a few moments of silence in the room—thick pervading silence. A silence to be broken at any fractional second and heavy—supercharged—because of it.

I said finally, "Somebody has to take it up. It might as well be me. And they've already asked me."

"You could refuse, Baby."

"Sure I could. It's voluntary. They don't horsewhip a guy into it."

"Uh-huh—voluntary. And you can refuse." She stopped, waited, then, "Making me get right down there on the hard bare floor on both knees, Baby? All right. None of us should be proud. None of us has a right to be proud, have we?

"All right, Baby. I'm down there—way, way down there. I'm asking you not to take that ship up. I'm begging you—begging, Baby. Look, on me you've never seen anything like this before. Begging!"

I looked at my empty glass. The taste in my mouth was suddenly bitter. "No strings, we said," I said harshly. "A flyboy, we said. Guy who can take off and land anywhere, anytime he likes. Stuff like that we just got through saying."

She didn't answer that. I waited. She didn't answer. I got up finally, got my lousy new officer's cap off the TV set and went over to the door. I opened the door. I went on through.

But before I closed it I heard her whisper. That's the trouble with whispers, they go incredible distances to get places. The whisper said, "That's right, Baby. Right as rain. No strings—ever!"

When you don't have any scotch in the house you'd be surprised how well rum will do—even Jamaica rum. I was on my own davenport in my own apartment and there were two shot glasses in front of me. I was taking turns on them so they wouldn't wear out. And what was keeping these glasses busy was me and a fifth of the Jamaica rum in my right hand. And that's when it all began.

Across the room a rather stout woman was needling a classic through the television screen and at the same time needing a shave rather badly. I wasn't paying any attention to her. I was thinking about the Doll. Wondering, worrying a little. And that's when it began.

That's when the voice said, "Mr. Anders, would you do me the goodness to forget that bottle for a moment?"

The voice seemed to be coming from the TV screen although the stout lady hadn't finished her song. The voice was like the disappointed sigh of a poor old bloke down to his last beer dime and having to look up into the bartender's grinning puss as the bartender downs a nice bubbly glass of champagne somebody bought for him. Poor guy, I thought. I downed glass number one. And then glass number two. And then I looked over at the TV screen.

That sent a little shiver up my spine. I dropped my eyes to the glasses, filled them once more. Strong stuff, Jamaica rum. At the first the taste is medicine. A little later the taste is pleasant syrup. And a little later still the taste is delightful. But strong—the whole way strong. I downed glass number one.

I figured I wouldn't touch glass number two yet. I brought up my eyes, let them go over to the TV screen again.

He didn't have any eyes. That was the first thing that struck me. There were other things of course, such as the fact he didn't have any arms or legs. He didn't have any head either, in case he had eyes in the first place. He was a black swirling bioplastic mass of something or other and he was doing a graceful tango directly in front of the TV screen, thereby blocking off from view the stout woman who needed a shave.

He said, "Do you have any idea what I am, Mr. Anders?"

"Sure," I said. "Somebody's blennorrheal nightmare."

"Incorrect, Mr. Anders. This substance is not mucous. Mucous is very seldom black."

"Mucous is very seldom black," I mimicked.

"Correct, Mr. Anders."

So all right. So they were making Jamaica rum a little stronger these days. So all right! Next time I wouldn't get rum, I'd get scotch. Hell with rum. I dismissed the thought from my mind. I picked up glass number two, downed it. I wondered if the Doll was feeling sorry for herself.

"Incorrect, Mr. Anders," he said. "The rum is no stronger than usual."

I jerked. I stared at the black sticky-looking thing he was. I shut my eyes tightly, snapped them open again. Then I worked the glasses again with the bottle.

"Don't be shocked, Mr. Anders. I'm not a mind reader. It's just that you discarded the thought of a moment ago. I picked it up, see?"

"Sure," I said. "You picked it out of the junk pile of my mind, where all my little gems go."

"Correct, Mr. Anders."

It was about time to empty the glasses again. I varied the routine this time by picking up number-two glass first.

"Light a cigarette, Mr. Anders."

I'm a guy to go along with a gag. I fished a cigarette out, lit it "Lit," I said. And just at that instant the stout dame without the shave hit a sour one way up around A above high C. My ears cringed. I forgot the cigarette and glared across the room, trying to see through the black swirling mass that stood in front of the TV screen.

"Puff, Mr. Anders."

I puffed. The puff sounded like somebody getting his lips on a very full glass of beer and quickly sucking so that foaming clouds don't go down the sides of the glass and all over the bar. I didn't have any cigarette.

"Ah!"

I blinked. The black swirling mass was going gently to and fro. At about head height on a man my cigarette was sticking out from it and a little curl of smoke was coming from the end. Even as I looked the curl ceased and then a big blue cloud of smoke barreled across the room toward my face.

"Your cigarette, Mr. Anders."

"Nice trick," I said. "Took it out from between my lips and I never felt it. Nice trick."

"Incorrect, Mr. Anders. When the singer flatted that particular note your attention was diverted momentarily. Your senses are exceptional, you see. Your ears register pain at false sounds. Therefore, you discarded the thoughts of your cigarette during the moment you suffered with the singer. Following this reasoning, your cigarette went into abandonment. And I salvaged it. No trick at all, really."

I thought, to hell with the shot glasses. I put the rum bottle to my lips and tilted it up and held it there until it wasn't good for anything anymore. Then I took it down by the neck and heaved it straight at the black mass.

The television screen didn't shatter, which proved something or other. The bottle didn't even reach the screen. It hit the black swirling mass about navel high. It went in, sank in like slamming your fist into a fat man's stomach. And then it rebounded and clattered on the floor.

"Scream!" I said thickly. "You dirty black delusion—scream!"

"I am screaming, Mr. Anders. That hurt terribly."

He sort of unfolded then, like unfolding a limp wool sweater in the air. And from this unfolding, something came forth that could have been somebody's old fashioned idea of what a rifle looked like. He held it up in firing position, pointed at my head.

"Don't be alarmed, Mr. Anders. This is to convince you. A gun, yes, a very old gun—a Brown Bess, they used to call it. I just took it from the City Museum, where it was on display."

He had a nice point-blank sight on my forehead. Now he moved the gun, aimed it off me, pointed, it across the room toward the open windows.

"Note the workmanship, Mr. Anders. Note the stock. Someone put a little effort on the carving. Note the sentiment carved here."

The rum was working hard now. I could feel it climbing hand over hand up from my knees.

"Let me read what it says, Mr. Anders—'Deathe to ye Colonies'. Note the odd wording, the spelling. And now watch, Mr. Anders."

The gun came up a trifle, stiffened. There was a loud snapping sound, a click of metal on metal—Flintlock. As all the ancient guns were.

And then came the roar. Wood across the room—the window casing—splintered and flew wildly. Smoke and smell filled my senses.

He said, chuckling, "Let's call it the Abandonment Theory for lack of a better name. This old Brown Bess hasn't been thought of acquisitively for some years. It's been in the museum—abandoned. Therefore subject to the discarded junk pile as you yourself so cleverly put it before. Do I make myself clear, Mr. Anders?"

Perfectly—oh, perfectly, Mr. Bioplast. The rum was going around my eyes now. Going up and around and headed like an arrow for the hunk of my brain that can't seem to hide fast enough.

I guess I made it to the bedroom but I wouldn't put any hard cash on it. And I guess I passed out.

The morning was a bad one as all bad ones usually are. But no matter how bad they get there's always the consoling thought that in a few hours things will ease up. I hugged this thought through a needle shower, through three cups of coffee in the kitchen. What I was neglecting in this reasoning was the splintered wood in the living room.

I saw it on my way out. It hit me starkly, like the blasted section of a eucalyptus trunk writhing up from the ground. I stopped dead in the doorway and stared at it. Then I got out my knife and got at it.

I probed but it was going to take more than a pocket knife. The ball—and it was just that—was buried a half inch in the soft pine of the casing.

I closed the knife and went to the phone and got Information to ring the museum.

"You people aren't missing a Brown Bess musket," I said. It was a question, of course, but not now—not the way I had said it. "Nobody stole anything out of the museum last night, did they?"

Sweat was oozing over my upper lip. I could feel it. I could feel sweat wetting the phone in my hand. The woman on the other end told me to wait. I said, "Yeah"—not realizing. I waited, not realizing, until a man's voice came on.

"You were saying something about a Brown Bess musket, mister?" A cold sharp voice—a gutter voice but with the masking tag of official behind it. Like the voice of someone behind a desk writing something on a blotter—a real police voice.

I put the phone down. I pulled all the shades in the living room, went out the door, locked it behind me and drove as fast as you can make a Buick go, out to the field. But fast!

The XXE-1 was ready. She'd been ready for weeks. There wasn't a mechanical or electronic flaw in her. We hoped, I hoped, the man who designed her hoped. The Doll's father—he hoped most of all. Even lying quiescent in her hangar, she looked as sleek as a Napoleon hat done in poured monel. When your eyes went over her you knew instinctively they'd thrown the mach numbers out the window when she was done.

I went through a door that had the simple word Plotting on it.

The Doll's father was there already behind his desk, studying something as I came in. He looked up, smiled, said, "Hi, guy."

I flipped a finger at him. I wondered if the Doll had told him about last night.

"Wife and I were going to suggest a snack when we got home last night but you had already gone, and Marge was in bed."

I didn't look at him. "Left early, Pop. Growing boy."

"Yeah. You look lousy, guy."

I put my teeth together. I still didn't look at him. "These nights," I said vaguely.

"Sure."

I could feel something in his voice. I took a breath and put my eyes on his. He said, "I'm a hell of an old duck."

"Not so old, Pop."

"Sure I am. But not too old to remember back to the days when I wasn't too old." There was a grave look in his eyes.

I didn't have to answer that. The door banged open and Melrose, the LC, came in. He jerked a look at both of us, butted a cigarette he'd just lit—lighted another, butted that. He ran a hand through thick graying hair and frowned.

"Anybody got a cigarette?" he said sourly. "Couldn't sleep last night. This damned responsibility. Worried all night about something we hadn't thought of."

Pop looked up. Melrose went on. "Light—travels in a straight line, no?" He blinked small nervous eyes at us. Then, "Can't go around corners unless it's helped, you see. I mean just this. The XXE-One is expected to hit a significant fraction of the speed of light once it gets beyond the atmosphere. Now here's the point—how in hell do we control it then?"

He waited. I didn't say anything. Pop didn't say anything. Melrose ran a hand through his hair once more, muttered goddamit to himself, turned around and went barging out the door.

Pop said wryly, "Another quick memo to the Pentagon. He never heard of the Earth's gravity."

"He's heard," I said. "It's just that it slipped his mind these last few years."

Pop grinned. He handed me a sheaf of typewritten notes. "These'll just about make it. You'll notice the initial flight is charted pretty damn closely."

"Thanks, Pop. I better take these, somewhere else to look 'em over. Melrose might be back."

"Pretty damn closely," he repeated. "Almost as closely as if she was going up under radio control...." He stopped. He looked at me from under his eyebrows.

I studied him. "Already told the brass I'd take her up, Pop." I kept my voice down.

"Sure, guy. Sure. Uh—you mention it to Marge?"

"Last night."

"I see." His eyes got suddenly far away. I left him like that. Hell with him—hell with the whole family!

It was in the evening paper, tucked in the second section. They treated it lightly. It seemed the night watchman had opened the rear door of the museum for a breath of air or maybe a smoke. Or maybe to kitchie-koo some babe under the chin in the alley.

That's the only way it could have happened. And he'd discovered the empty exhibit case at 2:10 in the morning. The case still had a little white card on it that told about the Brown Bess musket and the powder horn and the ball shot inside.

But the little white card lied in its teeth. There weren't any such things in the case at all. And he'd notified the curator at once.

There was also mention of a mysterious phone call which couldn't be traced.

Things like this don't happen in 1953. So I didn't get loaded that night. I went home, went to the davenport, sat down and told myself they don't happen. Things like this have never happened, will never happen. What occurred last night was something in the bottom of a bottle of Jamaica rum.

"Thinking, Mr. Anders?"

I took a slow breath. He was swaying gently in the air a foot from my elbow and he was still a black mucous scum, as he had been the night before. I got up.

I said, "I'm not loaded tonight. I haven't had a thing all day." I took two steps toward him.

He wasn't there.

I took another breath—a very very slow breath. I turned around and went back to the davenport.

He was back again.

"They'll find that musket," he said. "I have no use for it now. You see I wanted it only to convince you, Mr. Anders."

I put my hands on my knees and didn't look at him. I was suddenly trying to remember where I'd put that Luger I'd brought home from Germany a couple years back.

"You're not quite convinced yet, Mr. Anders?"

Where in the hell did I put it?

"Very well, Mr. Anders. Now hear this, please. Now watch me." He stirred at about hip height. A shelf-like section of the black mass protruded a little distance from the main part of him. On this shelf suddenly lay a rusted penknife.

"A very little boy, Mr. Anders. And a very long while ago. A talented boy, one of those who has what might be called an exceptional imagination. This boy cherished a penknife when he was quite small. Pick up the knife, Mr. Anders."

The knife was suddenly in my lap. I picked it up. It was rusty. It had a flat bone handle. "Museums again," I whispered to myself.

"So highly did this boy prize his knife that he went to great pains to carve his name very very carefully on one side of the bone handle. Turn the knife over, Mr. Anders."

The name was Edward Anders.

"You lost it when you were eleven. You wouldn't remember though. I found it in an attic where it lay unnoticed. As the years went by you gradually forgot about the knife, you see, and when your mind had completely abandoned the thoughts of it, it was mine—had I wanted it. As a matter of fact I didn't. I retrieved it just today."

I put the knife down. Sweat was coming on my forehead now, I could feel it. I was remembering. I was remembering the knife and what was scaring me even more was I was remembering the very day I had lost it. In the attic.

I said very carefully, "All right. You've made your point. You can take it from there."

"Quite so, Mr. Anders. You now admit I exist, that I have extraordinary powers. I am your own creation, Mr. Anders. As I said before you have exceptional senses, including imagination. And yes, imagination is the greatest of all the senses.

"Some humans with this gift often imagine ludicrous things, exciting things, horrifying things—depending don't you see, on mood, emotion. And the things these mortals imagine become real, are actually, created—only they don't know it, of course."

He stopped. He was probably giving me time to soak that up. Then he went on. "You've forgotten to keep trying to remember where you put that Luger, Mr. Anders. I just picked up the abandoned thought as it left your consciousness just now."

I gulped down something that tried to rise in my throat. I didn't like this guy.

"You created me when you were fourteen, Mr. Anders. You imagined me as a swashbuckling pirate. The only difference between me and the others who have been created in times past is that I have attained the ninth dimension. I am the first to do that. Also the first to capture the secrets of your own third dimension. Naturally then, it would be a pity for me to die."

"Get out," I said.

"Forgive me, Mr. Anders. My time is short. I die tomorrow."

"That's swell. Now get out."

"We're not immortal, you see. When our creators die their imaginations die with them. We too die. It follows. But for some time I've had an idea."

"Out," I said again. "Get the hell out of here!"

"You're going to die tomorrow, Mr. Anders, in that new flying saucer. And I must die with you. Except that I've had this idea."

There are times when you look yourself in the eye and don't like what you see. Or maybe what you see scares the living hell out of you. When those times come along some little something inside tells you you'd better watch out. Then the doubts creep in. After that the melancholy. And from that instant on you aren't very sane anymore.

"Out!" I yelled. "Out, out, OUT! Get the hell out!"

"One moment, Mr. Anders. Now as to this idea of mine. There's this woman—this Margie Hayman. This woman you call the Doll."

That one jerked me around.

"Exactly. Now listen very carefully. You aren't entirely you anymore, Mr. Anders. I mean, you aren't the complete whole individual you as you once were. You love this woman. Something inside you has gone out and is now a part of her."

"Therefore, if you will just discard the thought of her sometime between now and when you take that ship up I can attach myself to her sentient being, don't you see, and thereby exist—at least partly—even though you yourself are dead."

I pushed myself unsteadily to my feet. I stared at the entire black repulsive undulating mass before me. I took a step toward it.

"It isn't much to ask, Mr. Anders. You've quarrelled with her. You want no more of her. You've practically told her that. All I ask is that you finish the job—forget her. Discard her—throw her into the mental junk pile of Abandonment."

I didn't take any more steps. Something inside me was screaming, was ripping at my guts, was roaring with all the cacaphony of all the giant discords of all eternity. Something inside my brain was sucking all my strength in one tremendous, surging power-dive of wish fulfillment. I was willing the black mucous mass of him out of my consciousness.

He was no longer there. The only thing to prove he'd ever been there at all was a very-old, very-rusty penknife over on the table in front of the davenport—the knife with my name carved on the bone handle.

After that I went unsteadily to the dresser in the living room. I got the Doll's picture down off the dresser. I undressed. I took the picture to bed with me. The lights burned in my bedroom the entire night.

Lieutenant Colonel Melrose looked weatherbeaten. His graying hair was pulled here and there like a rag mop that's dried dirty—stiff. He had a freshly lit cigarette between his lips. He grinned nervously when he saw me, butted the cigarette, said in a thin voice, "This is it, Anders. Ship goes up in twenty minutes."

"I know," I said.

He poked another cigarette at his lips. He said, "What?" in a startled tone.

"Nothing," I said. "All right, I'll get ready."

He lit the cigarette, took a puff that made the smoke do a frenetic dance around his nostrils. He jabbed it at an ashtray, bobbed his head in a convulsive movement, said, "Righto!"

They strapped me in. Pop came to the open hatch. He stuck his head in, grinned, said, "Hi, guy," softly. There was something in his eyes. The Doll had told him how I hate sour notes.

"How's the Doll, Pop?" I forced myself to say it.

"Swell, Ed. Just got a call from her. On her way out here to see you take off. Looks like she won't make it now though."

I didn't say anything. His eyes went down to the wallet I had propped up on my knees. The wallet was open, celluloid window showing. Inside the window was the Doll's picture.

"Tell her that, Pop," I said.

"Yeah, guy. Luck."

They shut the hatch.

There was no doubt about the takeoff. If one thing was perfected in the XXE-1 it was that. The ship rose like the mercury in a thermometer on a hot day in July. I took it slow to fifty thousand feet.

"Fifty thousand," I said into the throat mike.

"Hear you, Anders." Melrose's voice.

"Smooth," I said. "Radar on me?"

"On you, Anders."

I let the ship have a little head. This job used the clutch of a tax collector's claws for fuel. It just hooked itself on the nothing around us and yanked—and there we were.

One hundred thousand.

"Double that," I said into the mike.

"Yeah, Anders. How is it?"

"Haven't yet begun. Radar still on me?"

I heard a nervous laugh. He was nervous. "The General—General Hotchkiss just said something, Anders. He—ha, ha—he said you're on plot like stitches in a fat lady's hip. Ha, ha! He's got us all in stitches. Ha, ha!"

Ha, ha!

This was it. I released my grip on the accelerator control, yet it slide up. They say you can't feel speed in the air unless there's something relative within vision to tip you off. They're going to have to revise that. You can not only feel speed you can reach out and break hunks off it—in the XXE-1, that is. I shook my head, took my eyes off the instruments and looked down at the Doll on my lap.

"Melrose?"

"Hear you, Anders."

"This is it. Reaching me on radar still?"

"Naturally."

"All right."

This was it. This was where the other four ships like the XXE-1—the radio controlled models—had disintegrated. This was where it happened, and they didn't come back anymore.

I sucked in oxygen and let the accelerator control go over all the way.

Pulling a ship out of a steep dive, yes. Blackout then, yes. If the wings stay with you everything's fine and you live to mention the incident at the bar a little while later. Blackout accelerating—climbing—is not in the books. But blackout, nevertheless. Not just plain blackout but a thick mucous, slimy undulating blackout—the very black.

The very very black.

General Hotchkiss, "What's he saying, Melrose?"

Melrose, "Doesn't answer."

General Eaton, "Try again."

Melrose, "Yes sir."

General Hotchkiss, "What's he saying, Melrose?"

General Eaton, "Still nothing?"

Melrose, "Nothing."

General Hotchkiss, "Dammit, you've still got him on radar, haven't you?"

Melrose, "Yes sir."

General Hotchkiss, "Well, dammit, what's he doing?"

Melrose, "Still going up, sir."

General Eaton, "How far up?"

Melrose, "Signal takes sixty seconds to get back, sir."

General Hotchkiss, "God in heaven! One hundred and twenty thousand miles out! Halfway to the moon. How much more fuel has he?"

Melrose, "Five seconds, sir. Then the auto-switch cuts in. Power will go off until he nears atmosphere again. After that, if he isn't conscious—well, I'm awfully afraid we've lost another ship."

General Eaton, "Cold blooded—"

The purple drapes before my eyes were wavering. Hung like rippled steel pieces of a caisson suspended by a perilously thin whisper of thread, they swayed, hesitated, shuddered their entire length, then began to bend in the middle from the combined weights of thirteen galaxies. The bend became a cracking bulge that in another second would explode destruction directly into my face. I screamed.

"Is—is that you, Anders?"

I screamed good this time.

"An—Anders! You all right? What happened? I couldn't get through to you?"

I took my hand from the accelerator control and stared numbly at it. The mark of it was deep in the skin. I sucked in oxygen.

"Anders! Your power is off. When you hear the signal you've got just three more seconds. You know what to do then. You've been out of the envelope, Anders! You broke through the atmosphere!"

And then I heard him speak to somebody else—he must have been speaking to somebody else, he couldn't have meant me—"Crissake, give me a cigarette. The guy's still alive."

I suppose I was grinning when they unstrapped me and slid me out of the hatch. They were grinning back at any rate. The ground held me up surprisingly—like it always had all my life before. They'd stopped grinning now, their eyes were eating the inside of the ship. They weren't interested in me anymore—all they wanted was the instruments' readings.

My feet could still move me. Knew where to go. Knew where to find the door that had the simple word Plotting on it.

The Doll was there with her father. The two of them didn't say anything, just looked at me—just stared at me. I said, "He tried damned hard. He put everything he had in it. He got me. He had me down and there wasn't any up again for the rest of the world. For me there wasn't."

They stared. Pop stared. The Doll stared.

"Just one thing he forgot," I muttered. "He gave me the tip-off himself and then he forgot it. He told me I wasn't all me anymore, that a part of me had gone out to you since I was supposed to be in love with you. And that's where the tip-off lies. I wasn't all me anymore but I hadn't lost anything. You know why, Doll?"

They stared.

"Simple—any damn fool would tumble. If I wasn't all me, then you weren't all you. Part of you was me—get it? And you weren't scheduled to bust out today. Not you—me! And that's what he couldn't work over. That's what brought me down again. He couldn't touch that." I stopped for a moment.

I said suddenly, "What the hell you guys staring at?" I growled.

"That's my Baby," said the Doll.

"No strings," I said.

"Like we said." Her words were soft petals. "Like we said, Baby. Just like we said."

"Sure. Only damn it, I don't like it that way. I want strings, see? I want meshes of 'em, balls of 'em, like what comes in yarn—get it?"

The Doll grinned. "Sure, Baby—you're sure you want it that way?"

"Sure I'm sure. I just said it, didn't I? Didn't I?"

"You just said it, Baby." She left her father's side, came over to me, put her arm in mine, pulled close. We turned, started to go out the door.

"Where you guys going?" asked Pop. We turned again. He looked like something was skipped somewhere on a sound track he'd been listening to. I grinned.

"Gotta look for a Brown Bess," I said. "Museum just lost one."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Very Black, by Dean Evans

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE VERY BLACK ***

***** This file should be named 31586-h.htm or 31586-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/1/5/8/31586/

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.