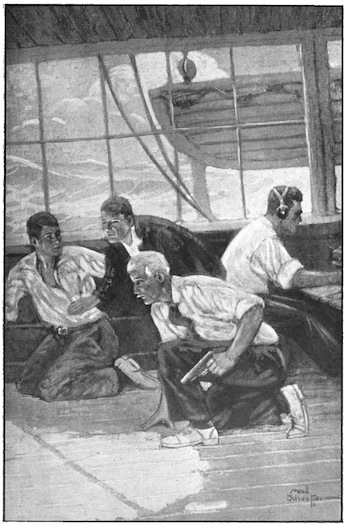

They were all crouched low to avoid being seen from the deck.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Radio Boys on Secret Service Duty, by Gerald Breckenridge This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Radio Boys on Secret Service Duty Author: Gerald Breckenridge Release Date: May 1, 2012 [EBook #39574] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RADIO BOYS *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

CONTENTS

They were all crouched low to avoid being seen from the deck.

THE RADIO BOYS ON SECRET SERVICE DUTY

By GERALD BRECKENRIDGE

Author of

“The Radio Boys on the Mexican Border,” “The Radio Boys with the Revenue Guards,” “The Radio Boys’ Search for the Inca’s Treasure,” “The Radio Boys Rescue the Lost Alaska Expedition.”

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers, New York

Copyright, 1922

By A. L. BURT COMPANY

THE RADIO BOYS ON SECRET SERVICE DUTY

Made in “U. S. A.”

“Excuse me for butting in, stranger,” said a pleasant voice at the door of the Pullman stateroom, “but I heard you talkin’ to these boys about the old mining camps in these California mountains. It’s kind of tiresome with nobody to talk to, ridin’ all day. Mind if I come in? Mebbe I can tell you some things interesting to easterners. I’m an old-timer here.”

“Come right in,” said Mr. Temple, rising and extending his hand. “My name’s Temple, George Temple. And this is my son, Bob, and his chums, Jack Hampton and Frank Merrick.”

“My name’s Harlan, Ed Harlan,” said the other, advancing. “I was born and raised in the mountains. My dad was a forty-niner from Tennessee.”

He was a slim middle-aged man in black, with a black sombrero worn at a rakish angle.

Those who have read The Radio Boys on the Mexican Border are familiar with Mr. Temple and the three chums. Living in country homes on the far end of Long Island, they had been drawn by a web of circumstances into international intrigue on the Mexican Border. Jack’s father, representative of a syndicate of independent oil operators, had been kidnapped by Mexican rebels seeking to embroil the government with that of the United States. The boys had gone into Mexico and rescued him. Now Mr. Temple, a New York importer, was making a business trip to San Francisco and taking them with him.

Radio had played no unimportant part in their adventures. In fact, it had been instrumental in bringing them to a successful conclusion. It was Mr. Hampton, a scientific man enthusiastic over the development of radio telephony long before the craze swept the country, who had introduced the boys to it. He was licensed by the government to build a transmission station on his Long Island estate and use an 1,800-metre wave length for trans-oceanic experiment. When he went to the Southwestern oil fields, he also erected a station there, using the same wave length previously assigned him.

These two stations not only provided exceptional opportunities for the boys to learn the intricacies of radio telephony but also provided a method of helping defeat the ends sought by the Mexican rebels. In their invasion of Mexico, moreover, the boys found several radio stations which were links in a chain that had been built by German spies operating in Mexico against the United States during the World War.

Frank and Bob also owned an all-metal airplane outfitted with radio, which had played a leading role in their Mexican border adventure. Frank was an orphan living with the Temples. Bob’s mother was dead. The two estates of Mr. Hampton and Mr. Temple adjoined. Jack, the oldest of the trio, was 19, while Frank and Bob were a year younger, Frank being the youngest of the three. All attended Harrington Hall Military Academy, and were on their summer vacation when the Mexican border adventures immediately preceding these about to be recorded occurred.

On their way to San Francisco the party had gone by a circuitous route through Denver in order to visit the Mile High City of the Rockies. They were now on the last day of their journey and passing through the Sierras down the famous Feather River Canyon.

Accompanied by Mr. Harlan the group made its way to the observation platform on the rear of the Flyer. Hour after hour they sat there while the scenery about them gradually changed its character with the passing of the afternoon, the mountains giving way to foothills and seeming to recede farther and farther to the rear. In reality, of course, the train was drawing away from them and descending into the lower ranges.

Harlan was a pleasant companion, and from him the boys learned more intimate history of California than they ever had been able to obtain from textbooks. He told them of the days of ’49 and the treasure seekers; how the latter had come overland by wagon trails in some cases, fighting Indians and starvation, leaving many in nameless graves by the wayside during the long trek across the desert and through the mountains; how, in other cases, the adventurers had sailed in windjammers, or ships propelled by sails alone and without engine power, spending as much as a year in the long trip from the eastern seaboard clear around South America and Cape Horn, although the majority had sailed merely to the Isthmus of Panama and crossing by horseback or in wagons, had taken ship on the other side for San Francisco.

“Those were the days,” said Harlan. “Of course, I didn’t experience them personally, for I’m just a young man now. But my father was a forty-niner, came out from Tennessee. And the stories he used to tell of San Francisco in the early days made me mad because I hadn’t lived there then.

“She was just a crazy little town of crazy little wooden shacks, built any whichway over the hills, but the people that built her were the hardy spirits of all the world and the breath of romance must have been in the very air.”

At a question from Frank, who, like his chums, was intensely interested in these stories of early California, Mr. Harlan launched into a description of the Spanish Dons inhabiting the land before the invasion of the gold seekers.

Mexico, he recalled to the boys, used to own California. The best Spanish families lived there on grants of land from the King of Spain which had been passed down from generation to generation.

The estates were huge, and the Dons lived on them pretty much absolute masters of their Indians and peons. It was an easy, gracious sort of existence, without hurry, without the bustle and haste introduced later by the Americans with their multifarious machinery. If the Don stirred abroad, he rode a mount jingling with fanciful and costly trappings, and he himself dressed like a cavalier of old. At night his hacienda would resound to music while the gentry from miles around danced and their carriages and horses filled his ample stables and stood under the drooping pepper trees.

Then came the gold seekers scarring the hills of the northern part of the state with their mines. And in their wake came the farmers and ranchers with their new-fangled farm machinery. They took the rich valleys where the countless herds of the Dons had roamed in the past, and began making that marvelous soil produce crops of wheat. The old order with its lazy ways could not survive before the new day with its energy and modern business methods. The Dons went to the wall.

“To-day,” said Harlan, in his drawling southern voice, “there are some of their descendants left. But they cut little figure in the present-day California.”

Jack spoke up with unexpected heat.

“Well, I think it’s a shame,” he said. “I know that we are supposed to believe our own ways of living are the best, but I, for one, wish California had stayed the way it was.”

Bob leaned toward Frank and assumed a confidential tone.

“He’s thinking of Senorita Rafaela,” he said.

She was the daughter of Don Fernandez y Calomares, a wealthy Mexican of pure Castilian descent living in a palace in northern Mexico. The Don was leader of the Mexican rebels who, as related in The Radio Boys on the Mexican Border, had captured Mr. Hampton. Jack and Bob in the latter’s airplane had gone to the rescue, and the young Spanish girl had given them valuable aid.

At Bob’s words, which although low spoken were intended to reach Jack’s ear, the latter flushed. Then he reached over and pulling Bob’s cap down over his eyes started to shake him good-naturedly. In a moment all three boys were entangled. Mr. Temple laughed and explained the situation to Mr. Harlan. The two men watched the chums amusedly, until a sudden lurch as the train whirled around a sharp curve threatened to send Jack flying overboard.

With a quick movement Mr. Harlan seized Jack by the coat and pulled him back to safety.

“That was a close call,” said Mr. Temple gravely. “You boys ought to be more careful.”

At Oroville, which he explained was in the heart of the apple country, Mr. Harlan left the party. All were sorry to bid him farewell, for he had been a jolly and informative companion. Dinner was served, and the party returned to the club car where Mr. Temple settled down with his cigar and a newspaper. Presently the chums grew tired of reading, and once more sauntered out to the observation platform.

They would not sleep aboard the train again as they would reach their destination near midnight. For a time they gossiped in low voices, so as not to disturb two men whispering together on the other side of the platform. All three sat in silence, slumped down in their chairs and at first staring out at the landscape bathed in magical moonlight. Gradually Jack and Bob yielded to the soporific influences of their surroundings, with the car wheels beating a monotonous and sleep-inducing lullaby.

Presently the two men who had been whispering raised their voices slightly in argument. Then one ceased abruptly, cast a keen glance toward the boys, said a word or two in a low voice to his companion, and they arose and entered the car. Frank, who like his companions had been sitting with his cap pulled down over his eyes, had not been asleep, however, and as the others left the platform he shook Jack and Bob into wakefulness.

“Did you hear that?” he demanded excitedly.

His two chums rubbed their eyes, and looked puzzled.

“Hear what?” asked Jack.

“What those fellows said.”

“What fellows?” asked Bob.

“Why, those two men who were out here,” Frank said impatiently. “I believe you were actually asleep.”

“Guess I was,” said Bob, yawning. “But what was it they said? And were they talking to you?”

“They were whispering to each other,” said Frank. “I didn’t mean to listen. But they raised their voices, and I overheard. Then one of them looked our way—to see if we heard, I suppose—and they got up and left.”

“Well, what was it?” demanded Jack.

“Shh,” said Frank, nervously. “The door’s open and that man—the one that got suspicious of us—is staring out at us. Listen,” he whispered, “I’m going in to talk to Uncle George. You fellows stretch and yawn presently and get up and go to our stateroom. Then pretty soon I’ll bring Uncle George in, and we can shut the door and I’ll tell you.”

“Now, what is it, Frank?” asked Mr. Temple, when he and the three chums were all gathered in their staterooms with the door locked behind them. “What’s all this mystery?”

“Yes, what is it you overheard out there on the observation platform?” demanded Jack. “You certainly seem excited enough. What’s it all about?”

“Spoiled my nap,” grumbled big Bob. “It better be good or they won’t be able to find you.”

And picking up a pillow he started to belabor his chum with it. Frank laughed and warded him off.

“Take him away,” he said. “He’s a wild man. How can I talk if he smothers me?”

“Sit down, Bob,” Mr. Temple commanded his son. Bob sank back on the couch grumbling.

“Uncle George,” said Frank, assuming a serious manner and lowering his voice, “I know you are puzzled by my request for you to come back here. But I didn’t dare explain out there in the club car. Those men were sitting too close, and I believe they were watching me. One was, at least. You see, while Jack and Bob were snoozing out on the observation platform, I was awake. And I overheard just enough of the conversation between those two men to understand there was a big plot afoot.”

“Plot?” queried Mr. Temple. “What plot? What are you talking about? Plot against whom?”

“Against the United States,” said Frank. “I tell you I couldn’t hear much. Only a few words here and there reached me. But I gathered there was a plot afoot to smuggle a large number of Chinese coolies into the country, and that these men had a hand in it.”

Mr. Temple leaned forward.

“What’s that?” he said.

“Yes, sir,” answered Frank, stoutly. “That’s what they said. I can’t repeat the exact words. There were only snatches here and there that reached me. But my mind kept following the thought between the words. Oh, you know how it is.”

Mr. Temple nodded. He had a great respect for Frank’s intelligence. Often before he had been witness to the lad’s almost uncanny ability to guess another’s thoughts.

“But just what was said, Frank?” he asked. “Anything that you could hear definitely?”

“Yes,” said Frank, “there was. There was something about Ensenada. Isn’t that in Mexico, on the seacoast somewhere?”

“Peninsula of Lower California, Mexican territory,” said Jack. “Go on.”

“And there was something, too, about Chinese coolies and motor boats and night running and——” Frank paused for dramatic effect. He obtained it.

“And what?” demanded big Bob.

“And radio,” added Frank, triumphantly. “That was when I heard best. One of the two men was explaining something to the other, and he became excited and raised his voice. He said: ‘With Handby in the revenue force keeping us in touch, we’ll be fixed right. We’ve got the radio station at the cove completed, and can guide the coolie boats past every danger.’”

“Radio?” cried Jack. “Whew. These fellows must be well organized.”

“And a spy in the revenue forces, too,” commented Bob. “You certainly did have your ears open, Frank.”

Frank turned to the older man.

“So there you are, Uncle George,” said he. “That’s what I heard. Then, after one of them said that about the radio station and this man Handby, in the revenue forces—I’m sure the name was Handby—he suddenly realized they had raised their voices and might have been overheard. So they left the platform. But I’m sure he was suspicious of me, although we all did seem to be snoozing. Now what had we better do?”

“This is a serious matter, boys,” said Mr. Temple. “Do you know anything about the smuggling traffic in Chinese coolies?”

“I know we have some kind of law barring them from entrance into the country,” said Jack. “But I’m hazy about it.”

Frank and Bob nodded agreement.

“Well,” said Mr. Temple, “in the days when this country of California was being settled by pioneers and immigrants, not only from the eastern part of our country but from foreign lands, too, the white people grew alarmed at the arrival of large numbers of Chinese laborers or coolies, as they are called.

“These people had utterly different standards of life. Due to the crowded conditions in their country, for China you will recall has about one-quarter of the entire population of the world, the Chinese coolie learns to exist on less food than the white man and to dress more cheaply, too.

“Accordingly the Chinaman works for less than the white laborer or the Negro, even. Consequently, the early-day Californians began to worry at the influx of coolies, fearing they would cheapen living conditions and wages. Their legislators made such a fuss that the government at Washington made a treaty with China barring Chinese coolies from the country.”

“But we have a good many Chinamen here, Father,” big Bob protested.

“Oh, yes,” said his father, “the treaty created exempt classes. That is, Chinamen who are merchants, professional men, students or travelers are admitted.”

“How long ago was that, Uncle George?” asked Frank.

“During President Arthur’s administration,” was the reply. “The treaty was signed at Washington in 1881 and ratified at Pekin a short time later.”

“And have there been no Chinese coolies admitted since then?” asked Jack.

“Not officially,” replied Mr. Temple. “During the World War some labor battalions of Chinese coolies, under contract to do work behind the lines in France, passed through the country, but they were guarded to prevent escape.

“However, as I understand it, there has been a steady traffic along our borders in the smuggling of Chinese coolies into the country. This is especially true along the Pacific Coast, although smuggling rings have been discovered in operation along the Mexican and Canadian borders in the past, and only a few months ago a cargo of Chinese coolies was smuggled into New York harbor.

“The reason for wanting them, of course, is that they provide cheap labor, the cheapest, in fact. There are men and syndicates in California, operating ranches, fruit and truck farms, who will pay well to have a batch of coolie laborers delivered to them, and no questions asked. Consequently, smuggling rings come into being for the purpose of supplying this illicit demand.”

“Well, what shall we do about this information, Uncle George?” said Frank. “Don’t you think we ought to tell the authorities?”

“I certainly do,” said Mr. Temple. “When we reach San Francisco, I shall lay this matter before the Secret Service the first thing tomorrow, and you will have to go along to tell them what you overheard.”

“Meanwhile,” commented Jack, “these two fellows would escape.”

“Well, we can’t help that,” decided Mr. Temple. “We are not officers of the law, and can’t arrest them. As for shadowing them, to see where they go on reaching San Francisco, for I suppose that’s their destination, that is out of the question, too. In the first place, they already have a suspicion that Frank overheard them, and accordingly they would be on watch. In the second place, we all will be ready for a good night’s rest when we arrive. Anyhow, I imagine that from what Frank overheard the revenue officers will get a good enough clue to enable them to run down this gang.”

“You mean,” questioned Frank, “that knowing this man Handby is a spy, they can watch him and learn who are his confederates?”

“Something like that,” said Mr. Temple.

After that the conversation became desultory. Mr. Temple lay outstretched on the couch with cigar and newspaper. The boys wandered out again into the club car, and beyond to the observation platform. It was growing late, and they were nearing Oakland. The transcontinental railroad lines end at that city on San Francisco Bay, and the trip to the metropolis is completed by ferry—a short run of twenty minutes.

“I can sniff the salt water,” said Jack. “Smell it. We must be getting close to the Bay.”

All three chums grew exhilarated at the prospect of soon reaching the world-famous city, which is the Gateway to the Pacific and is unlike any other city in America, with the Latin-like gayety of its populace, its 30,000 Chinamen forming a city of their own within the larger city, and its waterfront crowded with traffic of the Orient—spicy and mysterious.

“I don’t see those fellows,” whispered Frank to his chums, surveying the figures in the club car behind them. “Maybe they left the train.”

But at that very moment, the coolie smuggler who had suspected Frank of overhearing him was tipping the porter to learn to what hotel the boys and Mr. Temple had ordered their baggage sent.

“Well, boys,” said Mr. Temple at breakfast next morning. “I’m going to be busy today talking business with my Pacific Coast representatives. First of all, however, Frank and I shall have to go and lay before the government people this information as to what he overheard. I suppose, Bob, that you and Jack want to go along.”

“Righto, Father,” said Bob.

They sat at table in the Palace Hotel on Market Street in San Francisco. This is one of the most famous hostelries in the world. Lotta’s Fountain is on Market Street outside. Nearby is the intersection of Market, Geary and Kearney Streets—the busiest spot in all the great city. The offices of the big newspapers are adjacent. The hotel itself has housed famous men and women from all parts of the world, has been the scene of great municipal balls and other festivities, and in addition is the Mecca for which head all the prospectors of the gold country and the Yukon when they strike it rich, as they say.

Mr. Temple’s business in the city was to consult with the western representative of the big exporting and importing firm of which he was the head. Frank’s father had been his partner, and on his death had made Mr. Temple his son’s guardian and administrator of his estate.

“We’ll stay a week, if all goes well,” said Mr. Temple. “Of course, if my business engagements take up too much of my time we might stay a day or two longer, as there are some points of interest I intend to visit while here. I’ve been in San Francisco before, but, for one thing, I’ve never gone to the top of Mt. Tamalpais, across the Bay in the Marin County peninsula. I want to make that trip. I suppose,” he added, with a smile, “you won’t object if I am forced to stay more than a week.”

“Oh, yes,” said Jack laughing, “we’ll be awfully put out. We don’t want to see a thing.”

Suddenly Frank pushed back his chair and with an incoherent cry started to dart away. Bob seized him by the coat. Frank writhed in his grasp and attempted to twist free. He was highly excited.

“Hold on,” said Bob. “What’s the matter?”

Then Frank managed to obtain sufficent control of his voice to explain.

“Let me go,” he demanded. “I saw that man who was on the train—the fellow who was explaining the smuggling plot.”

“Where, where?” demanded Bob, also gaining his feet.

“He was breakfasting over there,” said Frank, pointing to a table near the exit. “I caught just a glimpse of him. I think he was watching us. Come on.”

Turning, he darted off with Bob at his heels.

“Don’t leave the hotel,” called Mr. Temple, sharply. “People are watching us.”

“Excuse me,” said Jack, who had stood undecided whether to follow his chums. “I’ll be right back.”

And he, too, walked rapidly away.

With a sigh, Mr. Temple picked up his morning paper. But he was unable to concentrate on his reading. His eyes wandered anxiously toward the door despite himself. In a few minutes, however, his anxiety was relieved. He saw the forms of the three boys appear. From their expressions, he gathered that they had been unsuccessful.

“No use,” said Frank. “He had disappeared.”

“There are three doorways to as many streets,” explained Jack, sinking into his chair. “Each of us went a different way, but we couldn’t see him.”

“Maybe he’s a guest here,” said Bob, “and went to his room.”

“Good idea,” said Frank. “Why didn’t I think of that before? I’ll just go and describe him to the room clerk and see if he’s here, and maybe I can learn his name.”

He would have gone at once, but Mr. Temple restrained him.

“Finish your breakfast first, Frank,” said he. “You have barely touched your eggs and bacon. If the man is a guest here, you can get the information just as well a half hour from now.”

The boys finished breakfast in record time. Mr. Temple sighed.

“You fellows are in such a hurry,” said he. “If you are going to lead me the wild chase here that you did in New Mexico I’ll wish I had never brought you. Here I go and plan a little sightseeing trip, and the first thing you do before ever arriving at San Francisco is to become involved in a plot. It won’t do, you know.”

Nevertheless, he got to his feet, signed the breakfast check and followed the boys toward the clerk’s desk.

“No,” said the latter, after Frank had described minutely the mysterious stranger. “I am quite sure I was not on duty last night when the Flyer came in, but I was talking to the night clerk when the arrivals registered. I remember your faces well, for instance. I am quite sure I would have noted such a man as you describe if he had been among the number.”

Disappointed, Frank turned away.

“So much for that,” he said to his friends. “But, do you know? I wonder if that fellow happened to be in the breakfast room by accident, or whether he was watching us?”

“Watching us?” said Bob. “Oh, you’ve got this plot stuff on the brain, old thing. Why would he be watching us?”

“To see whether we went to the authorities,” said Frank. “If he saw us go to the authorities, he would be pretty certain we had overheard enough of his conversation out on the observation platform last night to make us suspicious, at least.”

Mr. Temple was struck with the force of Frank’s reasoning.

“Look here,” he said, to the three chums. “Frank is right. If there is a big plot afoot, and this fellow suspects us of having gained some knowledge of it, he probably would do just as Frank says.”

“Suppose you called up the Secret Service men, Mr. Temple,” suggested Jack, “and asked one of them to call on you here at the hotel? Wouldn’t that be better than to go to them?”

“Very good, Jack,” approved the older man. “A government agent could make his way direct to our suite without arousing suspicion if he takes precautions, while, if Frank is correct and we are being shadowed, we could not stir out of the hotel without being followed. Do you boys stay here and keep your eyes open, while I go to our rooms and telephone. If you see any more of this fellow, call me. If not, come up in half an hour. By then probably a government man will have arrived.”

The half-hour passed quickly for the boys who sat in the lobby, intensely interested in the life of the big hotel going on around them, and especially in the Oriental men-servants in their gorgeous native costumes flitting in and out on noiseless soft-soled slippers. They saw no sign of the man Frank believed was shadowing them and, at the end of the allotted period of time, took the elevator to their third-floor suite overlooking Market Street.

Barely had they entered the sitting room than there came a low knock on the door, repeated three times, and Mr. Temple sprang to open it.

“There’s the government agent,” he said. “That’s the signal he said he would give.”

As he opened the door, an alert, slim man of 30 stepped inside and closed the door quickly behind him.

“Pardon my abruptness,” he said, in a low voice. “Are you Mr. Temple?”

“I am.”

“And I am Inspector Burton,” said the other, flipping back the right lapel of his coat and displaying a small gold shield. “You wanted to see me?”

“I did,” said Mr. Temple. “Won’t you sit down?”

Inspector Burton took off his hat and accepted the proffered chair. He looked inquiringly at the boys. Mr. Temple introduced them.

“Now,” said Mr. Temple, “you probably were somewhat mystified by my message. I did not want to say anything over the telephone about the nature of the business on which we wanted to see you. Yet I did want you to come here without being seen. That was why I asked you to take precautions.”

The other nodded.

“In our business,” he said, “we receive many strange calls. So I was not much surprised. I may as well tell you, however, that the clerk, who can be trusted, knows that I am here.”

He shot a searching glance at his hosts.

Mr. Temple nodded.

“I see,” he said. “We might have been enemies trying to lure you into a trap. That was a wise precaution on your part. But,” he added, leaning forward, “we are not enemies; merely good citizens who have come into possession of certain information which we believe you ought to have.”

“Wait a minute,” said Inspector Burton, in a low voice, and leaping to his feet, he gained the door in two strides, threw it open, peered out, then disappeared.

While the others still sat where he had left them, regarding each other in speechless surprise, Inspector Burton returned, closed and locked the door, and resumed his chair as if nothing out of the ordinary had occurred.

“Thought I heard someone listening outside the door,” he explained. “When I opened it there was nobody in sight. Your room is only two doors from an angle in the hall. So I ran to the turning and looked along the corridor, but it was empty.”

“Now, what is it?” he asked.

Mr. Temple explained, and when he had concluded, Frank once more rehearsed the scraps of conversation which he had overheard the two low-voiced men drop on the observation platform of their train the previous night.

Inspector Burton’s eyes blazed with satisfaction. He pounded one clenched hand into the palm of the other, repeating the gesture several times.

“Good,” said he. “Good.”

Turning to Frank he commanded:

“Describe these men for me.”

Frank complied. At the description of the man who had scrutinized Frank on the train and whom Frank believed he had seen again at breakfast, Inspector Burton uttered an exclamation.

“Do you know him?” asked Frank, eagerly.

“Indeed I do,” said Inspector Burton. “I believe I saw him in the lobby downstairs, although he did not see me as far as I could tell. He was lurking behind a pillar.”

“Who is he?”

“He’s a man of many aliases. Folwell will do as well as any other. ‘Black George’ is his name in the underworld, because of his swarthy complexion and raven black hair. He’s the leader of a powerful gang of underworld characters, a gang with ramifications in many cities not only here but on the China Coast, too. He’s been responsible for many deviltries on the Pacific Coast for years, but we have never been able to lay anything definite at his door. It’ll be a feather in the cap of any man who can get the goods on ‘Black George’.”

Frank was excited, and showed it. His chums were, too. Mr. Temple could not restrain an exclamation.

“Then what this young man overheard will be of some value to you?” he demanded.

“Value?” repeated Inspector Burton. “It will, indeed. Lately the smuggling of Chinese coolies into the country has enormously increased. We know they are coming in but we cannot stop them. We suspected, of course, that there was a leak somewhere in our forces. We have managed to stop the smuggling across the border on land pretty well. But all our efforts to put a stop to bringing in of Chinese by water have been unavailing. We have a fleet of fast revenue cutters and sub chasers operating off the coast of Southern California, but somehow the coolie smugglers coming up from Mexico manage to elude us in the night and land their human cargo in some unlocated cove whence, undoubtedly, they are whisked inland by waiting motor cars and hidden.”

“I should think you could patrol the whole coast, if necessary, and locate the rendezvous,” said Jack.

Inspector Burton shook his head with a wry smile.

“My young friend,” said he, “if you knew more about the ways of government, you would think differently. We have to do a tremendous amount of work on small appropriations and with a limited force. Ours is not a spectacular branch of the service, and the gentlemen in Congress see no occasion to spend money on us. They prefer to spend it where it will show. Moreover, now that the World War has increased the national debt, they are shouting for economy. Instead of giving us more men and money, the men who hold the purse strings are cutting us down.”

Mr. Temple nodded understandingly.

“But this tip about Handby,” said Frank, returning to the first subject, “won’t that help you?”

“It will, indeed,” said Inspector Burton. “Handby is employed in Southern California, operating out of Los Angeles and San Diego. Just to show you how valuable I consider your information, I’ll say that since sitting here I have made up my mind to make a trip immediately to the south myself. Handby shall be put under surveillance at once.”

“Won’t you arrest him and try to make him confess?” queried Jack.

“No. That would scare off the others. I’ll watch Handby in hope that he will lead us to his associates, and thus we will be enabled to scoop in a number of the crooks and break up the smuggling ring.”

“About this radio station in the cove?” said Frank. “You remember? I told you I overheard ‘Black George’ telling his companion the radio at the cove would keep in touch with the coolie boats?”

Inspector Burton nodded.

“That’s important, of course,” he said. “But as I told you we haven’t sufficient men to make a systematic search of the coast. We’ll have to depend on Handby to betray the station to us.”

“Not necessarily,” interrupted Jack.

Inspector Burton glanced at him inquiringly.

“The government certainly has a powerful radio station or two out here on the Pacific Coast,” said Jack. “Hasn’t it?”

“Why, yes,” answered Inspector Burton. “There’s a big one right here in San Francisco. But, to tell you the truth, I’ve never paid much attention to radio.”

“Well, Jack has,” said Mr. Temple, smiling. “He and his father are radio fans. They have several big stations of their own under special government license, on Long Island and in New Mexico. Jack probably knows more about radio than about anything else.”

“I don’t know whether to take that as a compliment or a slap,” laughed Jack.

“A compliment, my boy, a compliment,” said Mr. Temple, patting him on the shoulder.

“Well,” said Jack, “I’ll confess I was caging a bit when I asked whether the government had stations out here. I know it has. You know, you fellows”—turning to his chums—“how dad and I have studied the history of radio development. I remember that as far back as 1910 or 1912 the Federal Telegraph Company carried on radio experiments out here between stations at San Francisco, Stockton, Sacramento and Los Angeles.”

“Is that so?” said Inspector Burton, regarding Jack with increased respect. “Well, what did you mean awhile ago when you intimated it wasn’t necessary to trail Handby in order to locate the smuggling ring’s radio plant.”

“Can you obtain the use of the government radio stations?” countered Jack.

“Certainly.”

“Well, then, to begin with, we can obtain the approximate location of the smugglers’ radio. Of course, they will speak in code, and probably they will use a high wave length in order to avoid the confusion of any amateur sending stations cutting in. Let the government stations here and at Los Angeles tune until they pick up code. If it is weak here and strong at Los Angeles, then the station sending code is nearer the latter city.”

“Well, that won’t help us much,” said Inspector Burton, disappointedly. “We know, of course, that it is bound to be in the southern part of the state, probably even below Los Angeles, in order that the coolie boats can make their run from Mexico in one night.”

“I see,” said Jack, composedly. “But that wasn’t the only thing I had in mind.”

“What else?”

“Let an expert at solving codes listen in when once the code conversations are picked up. He can take down what he hears. The probability is he can work out a solution. To a genuine expert, as I understand it, there is no code that cannot be solved.”

“But,” objected Mr. Temple, “the code picked up and deciphered might be from some station like yours, Jack.”

“In which case you mean it would be about legitimate business?” said Jack. “But the government will have licensed stations listed, and their codes on file. No, I believe it would be a good move to put a code expert at work at the Los Angeles station.”

“So do I,” said Inspector Burton, warmly. “I want to thank you. And I want to thank you, too,” he added, turning to Frank. “Your information will undoubtedly prove to be of the very greatest value.”

He rose.

“I shall have to go now,” he said. “I suppose you all will be viewing the city and taking in the sights. I wish I could stay to show it to you. But that cannot be. What you have told me makes it necessary for me to leave at once for the south. I shall arrange my affairs here and take the night train to Los Angeles. I may not see you again. But I know you will be interested in the outcome and”—turning to Mr. Temple—“if you give me your address I promise to let you know.”

Mr. Temple took out a business card and handed it to the other. Then he accompanied him to the door.

“Good-bye,” called the chums, in chorus. “Good luck.”

“Well,” said Bob, when his father returned, “that’s that. Now, Dad, you will want to attend to your business affairs today. What do you suggest we do?”

“Hire a car,” said his father, promptly, “and drive around the city. Be back here at five. Then we’ll dress and have dinner in one of the city’s famous restaurants. San Francisco is noted for its wonderful dining places. Afterward, we can all go to a theatre or just walk around and view the city at night.”

“Where to, first?” queried Frank. “I vote for the Cliff House and Seal Rocks. Here in the guide book it says ‘the seals play sportively in the restless tide.’ And Sutro Baths are nearby, too, I gather—the largest indoor salt water pool in the world.”

All three chums stood on the Market Street sidewalk before the Palace Hotel. The hour was near eleven. The usual early morning fog which had hung over the city, as it does practically every day of the year, had been dissipated for an hour or more. The sky was cloudless and blue, the sunshine brilliant. A brisk breeze blew along the tremendously wide thoroughfare, which is the widest of all the great city streets of the land, so wide, in fact, that it accommodates four street car lines with the width of an ordinary street left over on each side between the outer tracks and the curbs.

“How delightfully cool and exhilarating!” commented big Bob, drawing in and expelling great lungfuls of the crisp air. “I haven’t felt so peppy in days.”

“The guide book says that’s the San Francisco climate,” said Frank. “Cool, snappy days all the year round.”

“Your car, sir,” said a uniformed doorman to Jack.

They looked up to find a handsome limousine drawn to the curb. This was the car they had ordered for the day. The boys moved toward it.

“We ought to decide right now where we want to go,” declared Frank.

Jack had an inspiration.

“I’ll tell you what, fellows,” he said. “Father gave me the name and address of a man who invented some new radio equipment, and advised me to look him up. Suppose we do that, first. Then we can go sightseeing. It just occurred to me. Wonder where that address is.”

He began leafing over the pages of a small memorandum book.

“Here it is. Bender, Silas Bender. 1453 Mission Street. Let’s ask the chauffeur how far away that is.”

After a little discussion, it developed the address given—on the first street paralleling Market to the south—lay on the route to Golden Gate Park, the Cliff House and Seal Rocks, whither the boys wanted to go. Accordingly, all piled into the car and sped away.

Mr. Bender maintained a little equipment store supplying radio apparatus. The shop was empty of customers when the boys arrived, and, at the ringing of the bell on their entrance, a medium-sized man, brisk and alert, came from the rear room outfitted as workshop. His thinning hair was rumpled. He was in his shirt sleeves.

“What can I do for you, gentlemen?” he asked inquiringly.

Jack stepped forward.

“Are you Mr. Bender?”

“I am.”

“Well, I’m Jack Hampton,” said Jack, extending his hand. “Here’s a note from my father. I believe you have met him.”

“Mr. Hampton the engineer?”

Jack nodded.

“Say, I am glad to meet you,” said Mr. Bender enthusiastically. “Yes. I know your father. When he was on the Coast some years ago on his way to Alaska I met him. He’s enthusiastic about radio telephony. We had a number of very pleasant talks. I remember him very well. But here, I’m keeping you standing. Won’t you come back into my workshop and sit down. Bring your friends.”

Jack accomplished the necessary introductions, and they followed Mr. Bender into the room in the rear.

For a time the boys were kept busy examining various radio appliances, which the energetic Mr. Bender kept thrusting at them. All the time he kept up a running fire of comment.

“Now this,” he said, taking up a small device of unusual shape, “is a sound detector. The only similar device in the field so far is the radio compass, but it is clumsy and unreliable. With this device, however, I am quite certain I have solved the problem of locating the point of origin of any strange or unusual sounds in the air.”

Jack gave an exclamation.

“What say?” asked Mr. Bender, turning toward him.

Jack could hardly conceal his impatience.

“How does it work?” he asked eagerly.

“Well, suppose we wanted to locate the point of origin of some strange message heard at the radio station out at Golden Gate Park. First, we would use a sound detector there, and find out along what line the strange sound came to the station. It might be up the coast or down, or east, southeast or northeast. Suppose it came from down the coast, or south. Then, at a point southeast of this city, we would again apply the sound detector and again at a third point south of the second. When at all three stations, the strange sound was loudest, we would have three bearings upon the point of its origin. Where they intersected, the——”

“The smuggler’s cove would be located,” said Frank quick-tongued.

The next moment he was covered with confusion as Mr. Bender regarded him blankly. So intent had the inventor been upon the description of his device and the method of its operation that he was aware only of an interruption but did not realize the nature of it.

Jack and Bob glared at Frank.

“Eh?” said Mr. Bender. “What say?”

“I just said something about the point of origin being where the lines intersected,” declared Frank, considering it wise to withhold the whole truth, inasmuch as the matter of the smugglers was not his to divulge.

“Yes, certainly,” said Mr. Bender, abstractedly. “Yes, project imaginary lines from each station and where they intersect will be the station you are hunting.”

Abruptly he put aside the sound detector as if, now that he had explained its operation, it were of no more value.

“Here,” he said, taking up a suitcase, and swinging it around, “is a radio receiving device that can be carried easily in this small suitcase. And here”—putting down the suitcase before the boys could examine it and taking up a finger ring from a workbench—“is the smallest receiving set I have yet devised. It is, as you see, in the shape of a ring and can be worn without the presence of the device being suspected.”

“Mr. Bender,” said Frank, “will you excuse my friends and me for a few moments while we step aside and have a little confab. I believe we will have a proposal to make that will interest you.”

“I know what you mean,” said Frank, as Mr. Bender withdrew, leaving them alone. “That sound detector, hey? If the Secret Service man had that he would be able to locate the smuggler’s cove.”

“That’s it, exactly,” said Jack. “Inspector Burton said he would not be leaving for Los Angeles until tonight. I believe we ought to get hold of him at once and tell him about this possibility.”

“I’m with you,” said Bob. “But we don’t know how to reach him. Suppose I call Father at the office of his business representative, and ask him to get Inspector Burton.”

“Good idea,” said Jack. “I didn’t know just how to work it. But if your father gets Inspector Burton to come up here, we will not be revealing anything to Mr. Bender, and the inspector can tell as much or little as he wants.”

“Then I’ll telephone father,” said Bob. “I saw a telephone in the store when we came in. I suppose Mr. Bender will let me use it.”

“And I’ll explain as much as necessary to Mr. Bender,” said Jack.

Accordingly, he called the inventor back to the workroom while Bob telephoned Mr. Temple, and explained they were inviting a man to come up and talk to him about the sound detector.

“I can’t tell you any more than that now, Mr. Bender,” said Jack. “But I promise you, of course, that your invention is not in any danger of being stolen. On the contrary, the man we have asked to come here may put you in the way of making your fortune.”

“Look here,” said Mr. Temple, “you boys have done a fine stroke of business for the government today. Suppose you play a little tonight?”

They were finishing dinner at a famous restaurant. All about them were tables with gay little parties. The concealed orchestra was playing a popular air. Mr. Temple leaned back, sighed comfortably and lighted a cigar. The boys went on with their dessert.

“It was a good stroke of business, Dad, wasn’t it?” said Bob. “Getting that old inventor with his sound detector at just the right moment, and catching Inspector Burton before he left for the south. With that invention, he ought to be able to locate the smugglers’ radio station.”

“Sh, Bob, not so loud,” warned Frank. “Somebody might hear us.”

All looked around furtively. They occupied a separate table, however, and there was none other near enough for its occupants to overhear their conversation.

“For my part,” said Jack, “I’m sorry we aren’t going to be in on the outcome of this business.”

“Same here,” said Frank. “Here we go and start the ball to rolling, and then have to drop out, without a chance to see where it rolls to.”

“Hard luck,” agreed Bob. “That’s what it is.”

Mr. Temple shook his head.

“I should think you would have had enough adventures on the Mexican border,” he said, “to last you the rest of your lives. Yet here you are lamenting because you can’t have more. Besides, this matter can be of no particular concern to you.”

“Just the same,” said Frank, “it is. We have a personal interest in the matter. We started it by overhearing the plotters. Then we found this inventor with his sound detector that probably will enable the Secret Service to locate the smugglers’ radio plant and secret cove. Now we are calmly shouldered out of the way. It’s hard luck, as Bob says.”

Mr. Temple smiled tolerantly.

“You can’t expect me to sympathize with you very much,” he said. “Well, now, which shall it be? The theatre or a prowl around Chinatown?”

Chinatown? In a moment the pessimism of the boys vanished. They were all smiles.

“Chinatown by all means,” said Jack, emphatically.

“Righto,” agreed Bob.

“With its opium dens and hatchet men and gambling clubs and all,” declared Frank.

“Oh, it isn’t what it used to be,” deprecated Mr. Temple. “I understand Chinatown is quite civilized now. Nevertheless, I expect we shall find much to interest us. I’ll speak to the head waiter. Probably he can direct us to a guide.”

On being consulted, the head waiter agreed to obtain them a guide. Presently, the boys and Mr. Temple were on their way by auto to the unique city within a city which constitutes San Francisco’s Chinatown, a quarter housing more than 30,000 Chinese. Oriental in every characteristic, with narrow alleys and courts, cellars, sub-cellars and sub-sub-cellars, the dragon roofs of Chinatown lie just below Nob Hill, the old aristocratic quarter of San Francisco with its veritable palaces of stone. From the terraces of the latter, one can look down into the alleys of Chinatown. So close neighbors are these two opposite districts of the city by the Golden Gate.

At the corner of Grant (once called Dupont) and California Streets, the guide halted their car and the party alighted. The boys looked around them with delight. In every direction were houses and stores speaking of the Orient. Close at hand on one corner was a Catholic church, one of the landmarks of the district. On another corner was a restaurant from which came strange Chinese music.

Up the California Street hill droned a strange little cable car, its sides open and passengers facing outward. Below, clear in the moonlight, lay the Bay with a lighted ferryboat making the crossing.

While the boys were drinking it all in, and staring owl-eyed at the slippered Chinamen in baggy pants and blouses shuffling past, their guide was in converse with a stranger. Now he approached Mr. Temple and touched his cap.

“Sorry, sir,” he said, “but this is where I leave you. I’ll turn you over to this man.”

Mr. Temple regarded him sharply, then looked at the other.

“Isn’t that a bit unusual?” he asked.

“No, sir,” said the original guide, “this man has certain territory here which we let him cover by agreement. When he has shown you around, you’ll find me here, sir, and I’ll continue with you. Shall I dismiss the car, sir? You’ll spend some time here, and might as well dismiss it now and get another later, rather than have it eat up fares.”

“Very well,” said Mr. Temple. “Here.” And he handed the man a bill.

Under the conduct of the new guide, the party started down Grant Street. The original guide watched their disappearing figures several minutes, then walked over to the chauffeur at the wheel of the hired car.

“Gave me a tenner, George,” said he. “Here’s your split. I wonder what ‘Black George’ wants with ’em. Look like fruity pickin’s all right.”

“Easy, pal. Easy,” said the chauffeur, low-voiced. “What the Big Chief wants with ’em is his own business. We had our orders to pick ’em up an’ we carried ’em out. Climb in and we’ll blow.”

The other complied, and the car departed.

Meantime, midway of the next block the party had come to a halt. The new guide, a capable man of middle age with a twinkling eye turned to Mr. Temple.

“Now, sir,” he said, “just what would you like to see?”

“Nothing rough,” said Mr. Temple hastily, looking at the boys. “Just show us the usual tourist places.”

“Oh, Father,” protested Bob, aggrievedly. “We want to see the sights.”

“The young man wants some excitement,” said the guide, slyly. “Well, maybe we can show him a thing or two.”

Mr. Temple did not like the man’s tone. Nevertheless, he made no comment.

“Lead on,” he said shortly.

Flanked by Bob and his father, and followed by Jack and Frank, the guide brought them presently to the mouth of a dark alley. There he paused.

“Up here’s the Joss House,” he said. “Chinamen’s temple, you know. Follow me single file. It’s dark in this here alley, but we’ll soon be all right.”

Obediently, they fell into line behind him and stumbled along through Stygian darkness, only the dim light from the street over their shoulders. Presently, the close walls on either hand turned sharply to the right, and they emerged into a narrow courtyard. It was so dark their surroundings could only be guessed at.

“Look here, my man,” said Mr. Temple, “I went to a Joss House in Chinatown once years ago, and I don’t seem to remember this route.”

“It’s all right,” said the guide. “The place is just ahead here through a door. Follow right along.”

Mr. Temple took several more steps, the boys after him, then halted again. Once more he started to protest, but at that moment the guide turned and grappled with him while a number of other shadowy forms materialized out of the darkness and closed with the boys.

The boys and Mr. Temple fought valiantly, but numbers were against them. Moreover, the attackers threw over the head of each a sack that muffled their outcries and prevented the boys and Mr. Temple from directing their blows. Taken altogether by surprise, they were quickly overcome. Then their hands were tied and they were raised to their feet, and the sacks, which were almost suffocating them, were removed.

A revolver was shoved threateningly into each face.

“Won’t do you much good to scream,” said a voice in the darkness, “but if you do, you know what you’ll get.”

There was a grim earnestness about the tone which commanded belief.

“If it’s money you want——” gasped Mr. Temple, who was breathing heavily.

“Shut up,” said his guard. “Now march.”

With two guards to each, the four prisoners were shoved along the broken cobbles of the dim courtyard until a door in a wall was reached. Through this they entered a corridor even blacker than the courtyard behind. There were no lights. One of the guards, however, threw the rays of a flashlight ahead.

An iron door barred the way. A little wicket was opened as the flashlight played over it, and a slanting almond eye stared out unwinkingly. The man with the flashlight advanced, uttered a word in a low voice that the boys could not overhear, and then the door was opened.

Down another pitch black corridor, several turns, and the party halted before a second door. The procedure was similar to that gone through with at the first door. Again they were admitted.

All this time, shuffling along in a silence broken only by an occasional stumble or muttered curse, on the part of one of the guards, they had been descending. It seemed to the boys as if they had stumbled down so many various flights of steps that they must be in the very bowels of the earth. At last a third door was opened, and Mr. Temple and the boys were shoved ahead accompanied only by the man who had been their guide and betrayer.

They stood in a dimly lighted room of Oriental magnificence.

Two men sat at a table. One was inscrutable. He was an old Chinaman. The other wore a sinister smile. He was the man of the train—“Black George.”

The heavy iron door closed behind them with a slight grating sound. Jack turned his head. The door could not be distinguished from the wall. Hangings of thick silken stuffs covered it.

“Black George” continued to smile unpleasantly, the Chinaman to regard them inscrutably. Neither spoke. The atmosphere was close and heavy, and pungent with strange Oriental odors and scents. The boys waited for Mr. Temple to take the initiative, and he was sizing up the situation.

Obviously they were trapped. And not for money. The presence of “Black George,” whom they had overheard on the train and who had spied on them since at the Palace Hotel, meant only one thing to Mr. Temple. That was, that the underworld leader suspected them of having learned something of his plans.

Why had he brought them here? Again, there could be only one answer. He wanted to prevent them from informing on him to the authorities. Either he would hold them prisoner, or intimidate them with threats so that, when released, they would fear to betray him.

How much did he know? Was he aware that they already had conferred with Inspector Burton? Had he shadowed the boys to the inventor’s store? Did he know or suspect the plan to utilize Inventor Bender’s device for locating the radio station at the smugglers’ cove?

Mr. Temple told himself it was not possible that “Black George” knew to what lengths they had gone already. Otherwise, of what use to him to capture them? The damage already was done. And, if he did not know that they already had laid their information before the authorities and that even now the move to locate the smugglers’ radio was launched, then it behooved him and the boys not to tell. For, if they told, “Black George” would be forewarned, and Inspector Burton’s plans to round up the smuggling band would be thwarted.

Mr. Temple glanced quickly at the boys. Would they tell? Each in turn caught his eye and gave him a scarcely perceptible nod of reassurance. It gave him something of a shock, for he realized that their active minds also had been sizing up the situation and, probably, had arrived at the same conclusions as he. They were letting him know that they could be counted upon.

Good boys! For a moment, a little mist obscured his eyes. He had been accustomed to thinking of them only as youngsters. But this summer was opening his eyes. They had played men’s parts on the Mexican border. They could be counted on in this unfortunate business, too.

All these thoughts, which require some time to record, had passed through Mr. Temple’s mind with lightning-like rapidity. Not a word had been spoken since their entrance.

“Black George” continued to smile at them evilly, the Chinaman to regard them with the impassive and inscrutable countenance of his race, their false guide to stand motionless to one side.

“What is the meaning of this outrage?” demanded Mr. Temple angrily.

He determined to adopt the attitude that the ordinary citizen not in possession of the key to the situation would be likely to adopt under similar circumstances. It would not do to let “Black George” see they suspected his reason for entrapping them. That would indicate to him that they already had taken action against him.

“If it is money you want,” he said, “say so and be done with it.”

“Black George” spoke at last.

“My dear Mr. Temple,” he said, “perhaps we may get some of your money, too, before we finish with you. But that isn’t our first object.”

Turning to their attendant he commanded:

“Bring some chairs and then leave us.”

Silently but swiftly, the man brought lacquered stools without back supports, placed one behind each of the four, then lifted the hangings and disappeared.

“Sit down,” said “Black George” in a suave voice, “and let us talk things over.”

They complied.

“I hope,” said “Black George,” “that my men did not handle you roughly. They had instructions not to, and if they disobeyed they shall be punished.”

“Come, come,” said Mr. Temple, “drop this note of hospitality and come to the point. We are prisoners, we have been foully entrapped. What is your object?”

Dropping something of his suavity and letting more of his true character show, “Black George” leaned forward.

“I think you know, Mr. Temple,” He said, “my reason for bringing you here.”

“What do you mean?”

Mr. Temple was determined to maintain an attitude of outraged innocence.

“I mean,” said the other, his voice growing more harsh, “that you have been meddling in matters that did not concern you.”

“Explain.”

“Your young men”—with a sweep of the hand that indicated the three chums—“overheard words not intended for their ears on the Flyer from the East. They sat on the observation platform while I was in conversation with a companion.”

“Well?”

“No, it’s far from well,” said the other menacingly. “You called Inspector Burton to your apartment at the Palace.”

He paused and looked fixedly at Mr. Temple.

“Now,” he resumed, “I want to know just how much of my conversation these boys overheard, and just what they told Inspector Burton.”

Further pretence of innocence was useless.

“And if we refuse to tell?” queried Mr. Temple.

“Black George” grinned evilly. He looked long at Mr. Temple and the boys in turn. Then he addressed the silent old Chinaman.

“Would your men like to play with them?” he asked.

“Um.”

“Would they like to torture those young boys?”

“Um.”

“Would they like to apply the water cure and the red-hot needles?”

“Um.”

“And pull out fingernails?”

“Um.”

The old Chinaman never changed expression.

In spite of their courageous spirits, the boys shivered. Mr. Temple thought only of the boys, not of himself. Would these scoundrels really torture them? It was unbelievable. Yet if they should——

“Look here,” he said gruffly, “quit this nonsense. This is the twentieth century, and such things are not done. We are not children to be frightened by such talk.”

“Ah,” said “Black George” smoothly, “but this is San Francisco’s Chinatown. Don’t forget that. You probably thought it was not possible to trap you, either. But you notice it was done. Your presence here ought to be sufficient indication to you that torture is not impossible.”

“You, scoundrel,” blazed Mr. Temple, “you’ll pay for this. Others know where I have gone. My original guide from the restaurant is waiting for me, and——”

“One of my men,” said “Black George” succinctly. “And your chauffeur, too.”

“Well and good, but the head waiter at the restaurant has my name and——”

“My man, too,” said “Black George.” He rose suddenly, walked close to Mr. Temple, and leaned over and glared into his face.

“Furthermore,” he added, “supposing you get out of this scrape, don’t try to make trouble for them. My agents don’t know all I do, but I protect the men useful to me. Understand?”

As Mr. Temple kept silence, controlling his features, but in reality sore at heart, “Black George” started to move backward slowly.

Suddenly big Bob, who all the time had been quietly working his hands free from the hastily tied bonds, leaped upon him. Bob’s hands went around the other’s throat, throttling him and preventing him from crying out.

At the same moment, Frank and Jack, who also had been working at their bonds and with equal success, leaped for the old Chinaman. The latter moved with surprising swiftness for one of his age. Springing from the chair, he waved a long dagger which mysteriously appeared in his talon-like hand and began to shout a shrill jabber of Chinese words.

Jack leaped in low, arms extended, making a flying tackle as he so often had done on the football field at Harrington Hall Military Academy. The old Chinaman started to move backward, waving his dagger.

Frank swung the lacquered stool upon which he had been seated aloft and sent it hurtling through the air. His aim was deadly. The heavy stool caught the Chinaman square on the side of the head, just as Jack pinned him around the knees.

He went down like a log, his dagger clattering to the floor.

The old Chinaman, whose name they came later to know as Wong Ho and who was a very evil man with many ruffians at his command, was unconscious but breathing heavily. When Frank ascertained that, their fears that they had killed him passed away. While Jack attended to tying him up, Frank turned his attention to Bob and “Black George.”

Mr. Temple was out of the fight. He had recovered from his amazement and dashed in to help his son with more valor than discretion. “Black George,” threshing about wildly in the endeavor to break Bob’s grip on his throat, had lashed out with his feet. A tremendous kick had caught Mr. Temple in the stomach and sent him reeling and gasping to the floor, where he was very sick, indeed.

Like a bulldog, Bob held on. Yet in “Black George” he had an opponent worthy of his mettle. That underworld leader had not gained his supremacy by his wits alone. He was a tremendous rough-and-tumble fighter.

Back and forth they threshed on the floor as Frank paused above them, uncertain where to strike to aid his comrade. Bob still gripped “Black George” about the throat, but the gangster had so powerful a grasp on his hands that he was unable to bring a fatal pressure to bear.

Suddenly, and by an almost superhuman effort, “Black George” heaved himself up to his feet with Bob clinging to him. He must not be allowed to win. Frank swung aloft another lacquered stool, remembering the execution wrought previously on Wong Ho by the same method, and brought it down on “Black George’s” head.

The stool splintered in his grasp. “Black George” relaxed, went limp, then collapsed.

“Whew,” said Bob, panting. “I guess I’d have gotten him, Frank, but I don’t know. He’s a tough fighter.”

Jack’s voice behind them rose in a scream.

“Look out. Here they come.”

They whirled to face the new danger. And in through the doorway behind the hangings poured a dozen ruffians. Jack bounded to the side of his companions. The newcomers were Chinese, and evil looking they were in the dim light of that subterranean room, with their glaring almond eyes and yellow faces. They gripped revolvers and long knives, and as their eyes took in the two figures of their leaders on the floor a hoarse murmur arose and they started to surge forward.

It was a tense moment. The boys resolved to sell their lives dearly.

Then two things occurred. The leader of the newcomers and only white man of the group—the same man who had acted as their guide and betrayed them—halted the onrush with a gesture of authority. And Mr. Temple, pallid from the effects of the kick in the stomach, pulled himself to his feet and stood swaying in front of the boys.

“We surrender,” said Mr. Temple, “but I warn you not to ill-treat us.”

The leader nodded, turned to the group behind him, bade two of their number step aside, and the others to leave. Grumbling and unwilling but evidently cowed by his authority, they obeyed.

As the hangings fell behind the last to leave, the guide, whom later they came to know as Matt Murphy, turned to them, his face grim enough.

“Ye showed sense,” he said. “They’d ha’ killed ye.”

Stooping over “Black George” he examined him hastily. Then he did the same by Wong Ho.

“Here,” he said to the two Chinese attendants, “one of you get Doctor Marley at once. The other help me.”

With the man who sprang to his aid, Murphy started to lift the unconscious form of “Black George.” Then he bethought him of his prisoners, and addressed Mr. Temple.

“Stay in this room,” he said, “and I can protect ye. The only way out is the way you come, an’ nothin’ could save ye from these yellow devils if ye get started. I’ll be back.”

Without more ado, he and his silent assistant disappeared with their burden, returning almost at once for the still unconscious Wong Ho.

After his second departure the three boys and Mr. Temple were left undisturbed for a long period. Their first act was to take account of injuries. Frank and Jack had come off unscathed. Bob was sore about the shins from kicks delivered by “Black George,” but otherwise unhurt. Mr. Temple’s kick in the stomach had been the most serious injury received, but he was rapidly recovering.

“I’m not blaming you boys for your gallant attempt to win freedom,” said Mr. Temple, “but our position now could hardly be worse.”

“I’m sorry, Dad, if you think I made matters worse by jumping on that rascal,” said Bob. “When I saw him threatening you I saw red.”

“Anyhow,” declared Frank, “if we had captured them, Uncle George, without being surprised by these others, we might have used them as hostages to obtain our freedom.”

Mr. Temple shook his head.

“Perhaps,” said he, “but it was a very long chance. However, we shall have to make the best of it.”

“At least we have won a respite,” said Jack. “We have pretty well laid out their two leaders. They won’t recover for some time to come, if I’m any judge of broken heads. And meantime it isn’t likely, is it, that this other fellow, who seems to be one of their lieutenants, will do anything to us?”

“Probably you are right, Jack,” said Mr. Temple, “and we will be kept prisoners but not harmed, pending the recovery of this ‘Black George’ if not the Chinaman. But afterward——”

He left the sentence unfinished, but Bob took up his thought.

“We can face that when we have to, Dad,” he said. “We’re safe enough.”

“Yes, I presume we are safe for the present,” said his father. “Nevertheless, do you realize there is no friend at large who has any idea of our whereabouts, or knew that we came sightseeing to Chinatown tonight? We did not tell the clerk at the hotel. The only persons who know are the people that villain declared are his creatures—the head waiter at the restaurant, and the chauffeur and our original guide.”

“But surely,” expostulated Frank, “when we fail to return to the hotel, there’ll be a big uproar. You are a man of importance, and your business representative here as well as the hotel people will get the police on the case.”

“Very true,” said Mr. Temple, thoughtfully. “Yet this is evidently a well-organized gang that has captured us, and we might be hidden away forever in such a place as this without being found.”

“But you forget Inspector Burton,” said Frank. “When he hears of our disappearance, he will put two and two together and will realize that we have fallen into the hands of the man whose plans we thwarted—namely, this ‘Black George’.”

“Yes,” admitted Mr. Temple, “there is a little hope for us there. Yet Inspector Burton planned to leave for southern California tonight to watch Handby as well as try to locate the smugglers’ radio with Inventor Bender’s sound detector. He may not hear of our disappearance for some time.”

“But, Dad,” said Bob, “it’ll be in all the papers in a day or two. The news will be telegraphed to the papers in southern California, and probably he will read it.”

“There is some hope of that, of course,” admitted his father.

For some time longer the discussion continued along this vein. Then Murphy again made his appearance, and put an end to it.

“You’re to write a note to the Palace,” he said, “telling the hotel people to cancel your rooms an’ give your baggage to bearer. Send a check, too, for your bill. An’ don’t write nothin’ phony. Tell ’em you’re goin’ for a sea voyage with a friend. That’ll fix it if there are any questions asked about you by friends you may have in the city. Here’s paper an’ pen,” he added, laying the articles on the table. “Git busy an’ write.”

“And if I refuse?” demanded Mr. Temple.

“If you’re a man of sense,” said Murphy roughly, “ye’ll do as you’re told.”

All thought of that devious passage which was the only entrance to the room, of the barred doors across it, and of the villainous, armed Chinamen along the route. Murphy was right. Mr. Temple would have to obey.

“But, look here,” he said, taking up the pen and preparing to write. “What are you going to do with us?”

“The Big Boss is gonna take ye to sea with him while he recuperates,” said Murphy. “Ye give him a fractured skull that’ll take him a while to get over. But the minute he opens his eyes he plans what to do with ye an’ tells me. He says he’ll save ye up to deal with when he recovers. He’s savin’ ye up for himself. See?”

They saw. Only too plainly. “Black George” was a vengeful man who meant to exact full measure for his injuries. With a sinking heart, Mr. Temple wrote the note demanded. Note in hand, Murphy paused at the door for a last word ere departing.

“I wouldn’t like to be in your shoes,” he said.

This was a blow. Decidedly, a blow.

As the door closed behind Murphy, Mr. Temple and the boys looked at each other with dismay written plainly on every countenance. They were to be taken to sea at once, and to an unnamed destination. Furthermore, Mr. Temple had been compelled to write to the Palace Hotel management a note which would prevent suspicion being aroused by their failure to return to their rooms. Mr. Temple’s business associates would inquire for him at the hotel next day, when he failed to keep appointments, and would be told of the explanation contained in the note. They might consider his departure abrupt and unusual, but certainly they would not be likely to consider it so strange as to demand investigation by the police.

What hope was there that their disappearance would cause a police investigation that might, possibly, lead to their relief? Or that at least would be heralded in the papers, and so come, perhaps, to the attention of Inspector Burton, who could guess the solution?

None.

Without a word spoken, these thoughts passed through the minds of all. They realized they were in the hands of a very shrewd scoundrel, who had foreseen the possibilities of the situation and had taken care to guard against the arousing of public suspicion over their disappearance.

There was this other phase, too, to be considered—namely, that “Black George” might vent his anger against them for their attack upon him in fiendish tortures. As Mr. Temple thought of this, he groaned aloud.

“Boys,” he said, without raising his head from his hands, “I’ve certainly gotten you into a terrible situation.”

Big Bob laid a hand on his father’s shoulder.

“Don’t take it so hard, Dad,” he said. “We aren’t dead yet.”

“No,” said Frank, his spirits rebounding, “and we are not likely to be dead, either, for some time to come. Why, Uncle George, we have bested this rascal at every turn so far. It’s true, we are his prisoners. But, without his knowing it, we already have set the machinery of the government in motion to put an end to his smuggling of Chinese coolies. And in the fight, we most certainly got the best of him and his Chinese friend.”

Mr. Temple raised his head, and looked a bit more hopeful.

“Besides,” declared Jack, “we were in some pretty tight places on the Mexican border, and yet came through with flying colors. And I’m confident we will do so again.”

Mr. Temple even essayed a trace of a smile, as he regarded the tall, handsome, curly-haired lad. Jack was a year older than Bob and, though not so stout of frame, was fully as tall. Both were an inch under six feet. And Jack, like his companions, was hard as nails.

“Why, Jack,” said Mr. Temple, “I believe you like to be in a bad hole. Actually, I believe you are enjoying yourself.”

“Bob and Jack had most of the fun on the Mexican border, flying to the Calomares ranch and rescuing Mr. Hampton, while I was left behind at the cave with nothing to do but——”

Big Bob thwacked his chum on the back resoundingly.

“Yes, with nothing to do but save the day and half kill a husky Mexican officer,” he said. “You certainly were out of luck!”

“Oh, that’s all right,” said Frank. “Just the same, you fellows had more fun out of that adventure than I did. Now it looks as if I was declared in. And I can’t say that I’m entirely grief-stricken.”

Mr. Temple shook his head.

“You boys will be the death of me,” he said.

Nevertheless, their sturdy courage and optimism cheered him greatly.

For some time the talk went back and forth, the boys doing their best to cheer Mr. Temple. They realized dimly how great was his anxiety, far more on their account than on his own. And by belittling the dangers and persisting in regarding the whole matter as a lark, they hoped to dispel his gloom to some extent.

The various objects of the room came in for attention. The room itself proved to be steel-walled, and circular, the walls covered with heavy Oriental hangings. No lights were suspended from the ceilings. The only light came from several tinted bowls on a massive walnut table, very low and stained with age. Investigation disclosed electric light bulbs within the bowls.

“Let’s find the switch and throw the room into darkness when they come for us,” cried Frank eagerly. “Then we can jump them and gain the upper hand.”

The big door close to where he stood grated slightly and swung open and Matt Murphy stood in the aperture.

Had he heard, wondered Frank. He gave no sign.

“Come,” he said.

Mr. Temple and the boys regarded each other gravely. Without a word spoken and without premeditation, they clasped hands. Then Bob sprang to take the lead from his father. If danger threatened in the corridor, he would receive the brunt, rather than let his father accept that exposed position. Jack forced Frank to fall in behind Mr. Temple, and then himself brought up the rear.

But nothing unexpected occurred in the corridor, and they reached the dark courtyard, after passing through the guarding doors, without mishap. If any of them thought to cry out for help now that the outer air was gained, that thought speedily was dispelled. Matt Murphy leaned close, revolver in hand.

“One word and you are all dead men,” He said. Then he waved toward a clump of shadowy figures ahead, which the boys and Mr. Temple could discern as their eyes became more accustomed to the darkness.

“Chinese,” he said, “an’ awful quick with their knives. I’m warnin’ ye. That’s all.”

Thereupon Murphy fell silent, standing beside Mr. Temple. And the group ahead, between the prisoners and the dark mouth of the alley exit to the streets of Chinatown, also was motionless. A slight sound, sibilant, as of whispering, came from it. Murphy, however, vouchsafed no conversation.

“What are we waiting for?” whispered Frank, the irrepressible.

“Ye’ll see in a minute,” answered Murphy, shortly.

Out of the doorway behind them, a moment later, debouched a little cavalcade. In the center of a group of six or eight bobbing heads rose a dark object that swayed perilously as it lurched through the door. Murphy sprang toward it with a low-voiced curse.

“Careful there, ye haythens,” he commanded.

The object steadied and came closer. Then the boys could see it was a closed palanquin, borne by eight Chinese.

“Whew,” whispered Frank, impressed in spite of himself. “I didn’t know there were any of those things left in existence.”

“Must be that old Chinaman we laid out,” ventured Bob.

The burden bearers passed the little group. Silken curtains were drawn tightly about the palanquin, and the boys could not see within. It disappeared with its bearers, looking in the darkness like some gigantic spider, into the mouth of the alley across the court. Murphy joined them.

“Come,” he said. “An’ remember. One cry out o’ ye an’ ye are all dead.”

“Was that the old Chinaman?” whispered Frank.

Murphy, a talkative man himself, already had noted that irrepressible quality in Frank. He chuckled grimly.

“Ye’d talk in hell, youngster, wouldn’t ye?” he said. “No old Wong Ho stays here. That was the Big Boss.”

They were moving across the courtyard, obedient to Murphy’s command. The guard of Chinamen had closed around them.

“But, say,” asked Frank, “will they carry that thing through the streets?”

“Shut up,” growled Murphy, “an’ do what you’re told. Here we are. Now in with you.”