DAN TOTHEROH

The Last Dragon

By

DAN TOTHEROH

Author of “DAVID HOTFOOT”

Illustrated by

ELEANOR OSBORN EADIE

NEW YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1927,

By GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

THE LAST DRAGON

— A —

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO KAY

WHO FIRST SAW

THE LAST DRAGON

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Meadow and the Woodlot | 13 |

| II | Peter Enters the Woodlot | 23 |

| III | Mr. Dragon Meets the Children | 30 |

| IV | Grandma Meets the Dragon | 44 |

| V | Goodbye, Dragon | 57 |

| VI | The Dragon Taps on the Window | 64 |

| VII | Going Backwards | 74 |

| VIII | Crubby | 85 |

| IX | The Enchanted Silver Toes | 97 |

| X | Allan the Armorer | 110 |

| XI | On the King’s Great Highway | 116 |

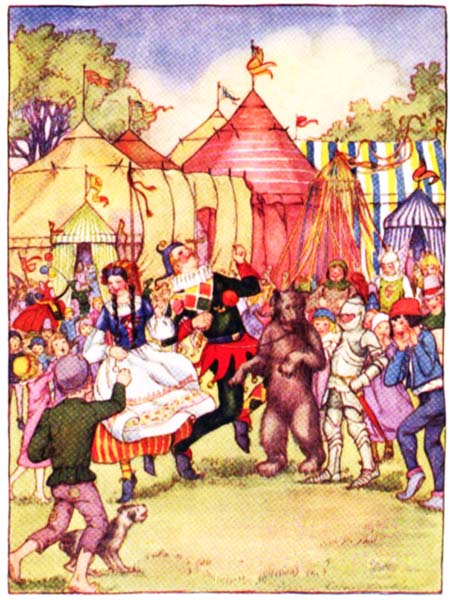

| XII | Peter Goes to the Fair and What He Finds There | 126 |

| XIII | The Princess with Toes of Silver | 137 |

| XIV | Peter and Mig, the Magician | 151 |

| XV | On Toward Giggletown | 159 |

| XVI | Dallahan | 164 |

| XVII | Once More on the King’s Great Highway | 168 |

| XVIII | Back Again | 179 |

| PAGE | |

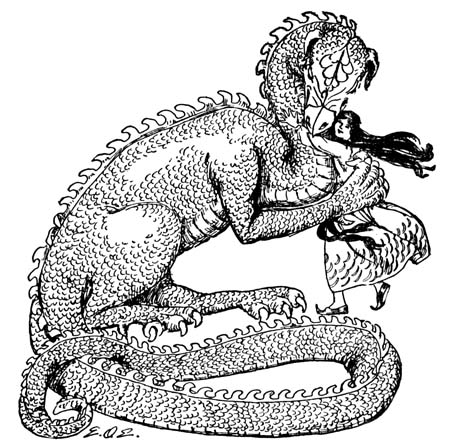

| “On with ye Fight!” | 25 |

| “Look at Them Running from Me” | 33 |

| Grandma | 45 |

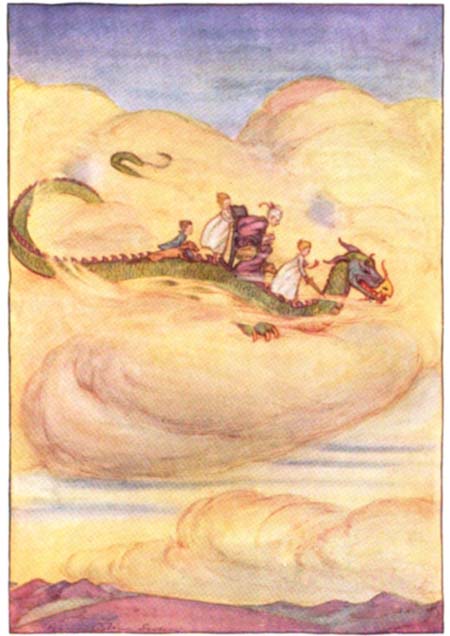

| Peter Was Standing on the Dragon’s Neck | 78 |

| Silver Toes Escapes from the Old Witch | 106 |

| Grandma and the Children Come to Be Measured for Suits of Mail | 111 |

| Beppo Balances Peter’s Sword on His Chin | 130 |

| “Yes, You Have Me Always, Dear Dragon!” | 183 |

THE LAST DRAGON

THE LAST DRAGON

THE meadow and the adjoining woodlot were just right for valiant knights and fair ladies that springy Saturday afternoon. The meadow, soft and green and open, was right for the pavilion where the jousting match could take place,—the big beech tree at the far, sun-rising end made such a delightful canopy over the king’s judgment throne—and then after the bout, and the victorious knight was sent forth to do battle with the dragon, there was no more mysterious lurking place for a coily, fire-breathing beast than the shadowy woodlot with its thick thimble berry thicket; its black cave under the drippy spring-shelf, and its close-grown oaks and maples.

Indeed, there was always something terrifying[14] to the children about the woodlot, even when the sun pierced through its wall of branches and leaves. The thimble berry thicket had never been completely explored, and as for the oozy cave—well, Johnathan had ventured in as far as the first bend once, holding a bit of lighted candle, but the candle had been blown out, and he had rushed back to wide-eyed Peter and Janet Jane who had stayed outside, peering in at the cave’s black mouth.

Johnathan, when he could get his breath, vowed he saw something strange around the bend, just before the candle flickered out, but Johnathan had a vivid imagination (it was he who made-up all the plays and all the games that took place in the meadow and spilled over into the woodlot on Saturdays) and whether he really did see something strange around the bend or had just imagined it, Peter and Janet Jane could not be sure. Their mother said he had just imagined it, of course! “What nonsense, Johnathan! You’re too old to imagine such things! No wonder you were so poor in arithmetic this month!” Johnathan really didn’t see the connection.

[15]But that wasn’t all about the woodlot! Peter, just six, said he had heard a lion roaring in the thimble berry thicket one stilly evening when he had gone back to find his lost cap in the meadow, but then Peter had a generous share of imagination too. “Lions are only in Africa or in a circus,” Janet Jane had said with feminine authority, but Peter replied in his well-known lisp and with his head cocked, that there was no good reason why a lion couldn’t be found in a thimble berry thicket just as well as a badger or a chipmunk, and no amount of argument could convince him otherwise. Suppose lions didn’t eat thimble berries? Couldn’t one have been in the thicket for some other reason, or couldn’t one have been there for no reason at all? Why should there always be a reason for things? Peter liked to go places for no reason. Maybe lions did too!

Janet Jane pretended to be skeptical about the possibility of unknown and terrifying things lurking in the woodlot, until one morning early, having gone alone to the meadow to find mushroom buttons, she had seen a pixie stick his head out and grin broadly at her, wriggling his pointed[16] ears like a rabbit at the same time. As Janet Jane stared at him, another pixie, wearing a pink sunbonnet, although he looked very much like a boy-pixie, otherwise, bobbed up over the first pixie’s shoulder and wriggled his long nose at her, just like a rabbit too.

Then Janet Jane, who stood rooted to the spot with astonishment, declared that the two pixies began to sing, one in tenor and one in bass. Strangely enough, she remembered the words of the song. It went:

Now, this sounded suspicious to Johnathan because Janet Jane was just learning to cook, and she was always singing receipts, and some of her proposed dishes were queer indeed. Therefore, it was strange that the two pixies she saw that early morning should sing receipts too, but Janet Jane said, “Not at all!” They were doing it just to poke fun at her. Pixies always poked[17] fun, anyhow. They were like brownies in that respect, and not at all like fairies who are too well brought up to poke fun.

They sang the song through twice with a different tune each time, and after that Janet Jane managed to say, “Shooo!” at the pixies, and they had vanished into the woodlot. Stooping to pick up her spilled mushroom basket, Janet Jane heard the rude fellows laughing at her—Oh, high, shrill laughter like a tree-squirrel’s bark.

So you see, since Janet Jane was sure she had seen the pixies, and since Peter was sure he had heard the lion, and Johnathan was sure of something mysterious in the cave, around the first bend, there was no doubt that the woodlot was terrifying, and that the victorious knight who ventured into it with drawn wooden sword was almost sure to meet with adventure.

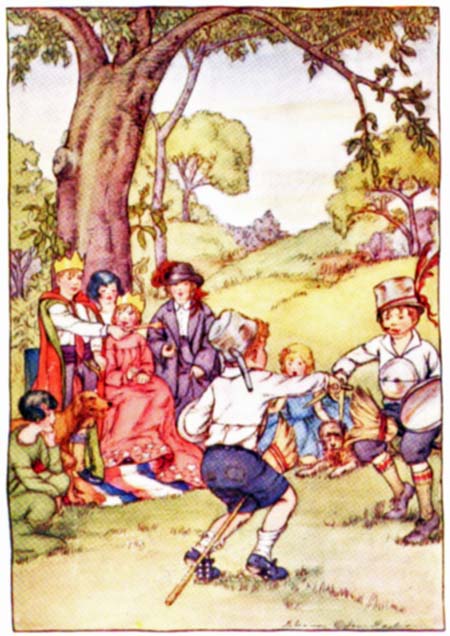

It was just after breakfast that memorable Saturday morning when the children congregated in the soft, green and open meadow sprinkled with cowslips and Johnny-jump-ups. The little troop broke through the willow clump at the sunsetting end of the meadow, and advanced[18] solemnly in the direction of the big beech tree where the king’s throne was already waiting. Johnathan and Billy Rose had fixed it after school on Friday.

Their appearance scattered two chubby meadow mice into a desperate rush for their holes, and a flock of Jenny wrens fled chittering, indignant at being disturbed, like little gray ladies at a tea party. There was quite an impressive procession advancing toward the king’s throne. It had formed at the back door of the Baxter house, under the alert eyes of Grandma, watching from her upstairs window, and led by Johnathan who of course was king, King Arthur, no less, it wound through the rose garden, up the lane past the fish pond, over the creek bridge, through the truck garden, skirted the barn and wriggling through the orchard it bobbed its ten small heads to escape hitting the low branches of the willow clump, filing through a tunnel of green leaves to the open spaces of the dewy meadow.

Yes, there were ten in that procession, including the Irish setter named Nap, and the airedale[19] named Jerry. First, as we said before, there was Johnathan Baxter, King Arthur, dressed in the green and red portiere with tassels, that had graced so many courtly ceremonies. The paper crown was on the kingly head, and in the royal hand was the oak-wood scepter. Close on his majesty’s heels walked her majesty, Queen Guinevere, Janet Jane Baxter, resplendent in a long pink mother hubbard, one of Mrs. Baxter’s cast-off garments, made theatrical and queenly by the silver paper stars that were pinned around the hem. Following her was Susan Oliver, five years old, bearing up the queen’s train, a child with eyes like mulberries and a blue-black cloud of hair. She was pouting because she felt it was her turn to be the queen, and before the procession started it was very doubtful if she would play at all. The promise of queenship next Saturday finally quieted her, although she carried the train with a disdainful air that ruined the dignity of the queen, since it dragged the ground on one side and looped up too far on the other, showing the queen’s long, spindly legs.

After Susan Oliver came the two knights carrying[20] their wooden swords, the chubby and blond-curled Peter Baxter as Sir Launcelot, and the taller and older Billy Rose as Sir Galahad. They walked heads high, little noses up, wearing tin-can armor with pride. Their broomstick horses were waiting for them, tied to saplings under the beech tree.

Directly behind the knights was the public, three small girls, Mary, Kath and Polly, who were allowed to furnish their own costumes. Mary wore fluffy skirts like a bare-back rider; Kath dragged a green train that rivalled the queen’s in length and caused a serious argument before the procession started, and Polly’s seven years were lost in a riding suit of her mother’s, with boots that might have belonged to the famous Puss.

The procession went twice around the meadow, stopping after the second circuit before the throne. King Arthur took his seat on a bench covered with a piece of red, white and blue bunting, and his queen sat down beside him. The pouting Susan Oliver stood behind the queen and stared down at the top of her sandy head.[21] Sandy hair wasn’t nearly as nice for a queen as black hair—no, not nearly! Susan was supposed to fan the queen, but she had purposely forgotten the fan, which is as much as we’ll say right here regarding Susan’s disposition. The public of three scattered itself right and left of the throne and took postures of deep interest.

After a silence, the king rose and pushing back his crown that had worked down over his eyes, he spoke in tones that seemed to arise from his shoes, his chin pressed down against his throat to produce the effect. “On with ye fight, and the victor will enter yonder forest to slew ye dragon who has been spreading terror and destruction through out ye countryside.”

He sat down, and the queen smiled at him and said, “Ye spoke well, O King,” but the king did not answer her. A queen should never speak in public unless the king asked her a question, and then she should only reply in as few words as possible.

At the king’s command, the knights drew their swords and pointed them down to the ground and bowed very low to the king. Then they went to[22] the saplings and untied their horses and mounted them. The fiery steeds leaped up and down and nearly threw the knights off, and the grass of the meadow was torn up by whirling feet.

“Quiet with ye horses and on with ye fight!” finally commanded the king and at once, just as if they understood, the horses calmed down, and the knights drew apart, lifting their swords to wait for the final signal from King Arthur.

King Arthur stood up; raised his hand; held it steady for a breathless moment; then let it drop quickly to his side. The public showed renewed interest. The blond and chubby knight, Sir Launcelot, made the first dash for his opponent. The wooden swords clashed and the furious battle was on.

ALTHOUGH the opponents were so unevenly matched, the fight was an exciting one and not a bit one-sided. Small Peter fought with tiger ferocity and a definite show of assurance, for it had been arranged before hand that Sir Launcelot should win. Galahad had won the Saturday before.

With a sturdy lunge of his wooden sword, Peter unhorsed Billy Rose who executed a trick fall and lay on his back, legs and arms in the air like some huge beetle turned over on its shell. Peter was on him in a moment; drove home the sword; pulled it out and wiped away the gore on his sky-blue cape.

Billy Rose did a spectacular death scene consisting of many kicks and contortions, adding much to the pleasure of the court and the public. It was a very long death scene, many minutes[24] elapsing before Sir Galahad was quiet enough for the victorious Sir Launcelot to put his foot on the corpse and raise his sword to the king in salute.

“Go ye now into the forest and find ye dragon that eats every week a maiden from our smiling village!” commanded the great king Arthur, and Sir Launcelot bowed and stalked away toward the thick foliage of the woodlot.

It was strange and terrifying that at the moment the chubby Peter reached the first maple, the one that breaks from the group and runs out into the meadow, a cloud, very black and heavy, passed over the sun, swimming up out of nowhere in an otherwise clear blue sky. A wind sighed through the maple leaves and whispered about something all through the thimble berry thicket. The meadow darkened. Peter’s hand tightened on his sword. He looked straight before him; then looked back. The court and the public and his rival, Sir Galahad, and the two dogs seemed to be miles and miles away—shadowy, blurred figures. Peter felt all alone in the big world and very small. What chance would he have against [25]that lion he had heard roaring in the thicket that fearful evening? Oh, but he had his sword. Didn’t he always want to do noble deeds? Didn’t he envy Johnathan because Johnathan was a Boy Scout and did a good deed every day? To kill a lion would be a good deed, wouldn’t it, that is if the lion were aching to eat somebody, right at that moment. Of course, if the lion were minding his own business, that would be different. Again Peter looked forward; again looked back.

“ON WITH YE FIGHT!”

King Arthur pointed with his scepter and like a voice in a dream came his command: “Pause not, Sir Launcelot! Go kill ye dragon!”

“All right, King,” replied Peter in a tiny, trembly voice, and advanced a few more steps.

He passed the maple; passed the second maple; passed the third. He was in the woodlot now, almost hidden from his companions. How very still it was. The wind had finished whispering to the thimble berry thicket and had frisked away. Not a leaf stirred any place. Far off, Peter could hear the dripping of the spring. He thought of the black cave and of what Johnathan had told[26] him about the strange something around the first bend. He paused, hearing his heart beating.

To give himself courage, he spoke aloud, addressing himself in that well-known lisp: “Go on, Peter Baxter. Don’t be scared. Don’t you know that there’s no more dwagons? In the whole, whole world there’s not a dwagon any place. They’re all dead.”

But even as he spoke he doubted the truth of his words. If there were pixies there could be dragons. Why should all the dragons be dead? People went on living and dragons were dead. To small Peter, dragons seemed much more important than people. Yes, somehow, somewhere dragons lived, and there was no reason to doubt that a dragon might live in the shadowy woodlot along with the lion and the pixies.

Peter’s feet ventured down the twisting path that would eventually arrive at the spring, and found himself safely past the thimble berry thicket. That was a relief. Nothing had broken the silence save the barking of Jerry, the airedale, and that was a comforting sound. Still, he wondered why Jerry and Nap had not[27] followed him. They usually did. That was strange!

Now, here was the spring and the drippy, over-hanging shelf of stones and black earth, all sewn together with tiny root-threads, and right beyond the shelf was the entrance of the cave! Small Peter planted his stocky legs before the black hole; gulped once or twice; mustered up all his courage and spoke in a squeaking lisp that was meant to be a rumbling growl. “Come forth, Dwagon!” His wooden sword was clutched tightly in his little hand. Nothing happened so Peter repeated his command: “Come forth, Dwagon!”

Still nothing happened and becoming more bold, Peter stepped closer to the cave’s mouth; thrust his sword into the hole and rumbling it at last, cried for the third time, “Come forth, Dwagon!”

A long-drawn hissing sound answered him. He fell back. The hissing sound died. What was the matter with him? His imagination was doing strange things. He hadn’t really heard a hissing sound. He hadn’t really heard anything.

[28]Well, he had done his duty. He had called three times and nothing had happened. He would return to the court and tell his story to the king. He was turning to go, when there issued from the hole a deep, deep sigh; then a yawn and then another deep, deep sigh. Before Peter even had time to think, the deep, deep sigh ended in the most entrancing little chuckle, and two fiery eyes blazed in the hole. A long green nose was thrust slowly forth, followed by a broad and lazy smile. The eyes came into the daylight. The fire faded out of them. They were a soft, light blue, like the sky, and looked as if they had just opened from a deep and dreamless sleep.

“Did you call me, little boy?” asked the dragon, as yards and yards of him, bright green like the meadow grass, oozed from the cave.

“Y-yes-yes, sir, I did,” gasped Peter, “but—but I didn’t think—”

The dragon continued to smile, oh, so sweetly, and tears gathered in his light blue eyes. “You didn’t think dragons lived any more,” he sighed, stretching out his great gold claws like a sleepy[29] cat, “and you’re almost right, because I am the last dragon in all the world”—and two big tears the size of cups of clear water, dropped to the ground.

“I WONDER what’s keeping Peter so long in the woodlot?” wondered Janet Jane, remembering the pixie in the pink sunbonnet.

“I don’t know,” said Johnathan, remembering the strange something he had sensed behind the bend in the black cave.

“I bet he’s eating thimble berries,” guessed Billy Rose who was always practical. “That’s no fair, you know.”

“I’m not going to play any more!” announced small Susan Oliver, tossing her dark head and dropping the queen’s train. She was one of those children who always cry and spoil the game just at the wrong moment.

“Let’s play something more exciting,” suggested Mary in the bare-back rider’s costume. “How about circus?”

“No!” thundered Johnathan. “Wait till Sir[31] Launcelot comes back. He’ll tell us how he slew the dragon and that will be exciting enough.”

“I’m going right straight home,” wailed Susan Oliver, her face all puckered up, just as though she had bitten into a crab apple.

“All right, if you go home, Susan Oliver, you won’t be Queen Guinevere next Saturday!” began Janet Jane, when somebody shouted, “Here comes Peter now!” And they all looked toward the woodlot.

There was Peter advancing with a very important stride, his sword clasped firmly, a smile of triumph on his round, shining face. Nap, the setter, and Jerry, the airedale, began to bark, their hair on end.

“Look! What’s that behind him?” cried Billy Rose.

“Where?”

“There!”

A gasp went up from all the children. “Why, it’s a—it’s a—”

“It’s a real dragon!” squealed Janet Jane, and the rest of them took it up—“A real dragon! A real dragon!”

[32]Susan Oliver opened her mouth like a red O and began to scream. Nap and Jerry fled, yelping. The group broke and began to run in all directions.

Peter stopped advancing and raised his sword over his curly head. “Hey, Johnathan! Wait a minute! Wait a minute, Johnathan!”

Behind him, the last dragon chuckled. “Look at them running from me, just like old times,” he said, with the slightest touch of pride in his voice; and then in a tone tinged with melancholy, “If they only knew.”

On the edge of the meadow, the frightened children paused and looked back, just to make sure they had really seen the dragon. They saw small Peter sympathetically shake his blonde head and then reach over and pat the dragon on his broad, green back.

Johnathan and Billy Rose were together near the willow clump, and Johnathan said: “He looks like a very nice dragon, don’t you think?”

“Yes, and very tame,” agreed Billy. “He’s smiling, I believe.”

“Peter’s patting him!”

[33]

“LOOK AT THEM RUNNING FROM ME”

[34]“He can’t be very vicious.”

“He doesn’t seem to breathe fire,” observed the well-informed Johnathan.

Peter called again. “Hey, Johnathan! Don’t run away!”

“I’m going back,” said Johnathan, sticking out his chest. “Come on, Billy.”

“Sure! Who’s afraid?”

The two boys started back across the meadow. The sun was bright again. All the cowslips and Johnny-jump-ups were standing erect, and the Jenny wrens were chirping in the maples. A cheerful little wind romped through the green grass. There was no terror and no mystery. It was all very clear and simple. There was just a dragon in the woodlot.

Peter and the last dragon met the children in the middle of the meadow. As soon as Janet Jane saw Johnathan and Billy Rose start back, she came too and that gave the others courage. Susan Oliver tiptoed up last, ready to fly at a moment’s notice, her little dancing feet as restless on the meadow grass as tufts of thistledown. They formed in a new-moon crescent and stared[35] at the curious dragon. Jerry sat down very politely beside Nap, they didn’t even sniff, and stared with their tongues sticking out.

“Mr. Dwagon,” introduced Peter, “this is Johnathan Baxter, my brother. Johnathan, I want you to meet Mr. Dwagon, the last dwagon in the whole, whole world.”

Again the dragon smiled. “Delighted to meet you, Johnathan,” he said. “You’ve got Peter’s small nose, haven’t you, and there’s something about your eyes that are alike, but why do you wear a crown?”

Johnathan blushed. “Oh, I was just playing King Arthur,” he apologized.

“Ah, King Arthur,” sighed the dragon, “there was a king!”

“Oh, did you know him?” exclaimed Johnathan.

“Very well indeed. Of course, he was a great enemy of my family, and I was taught to hate him from my cradle, but”—And here he winked very slowly, “deep down in my heart I really admired him.”

[36]Janet Jane spoke breathlessly: “And, and did you know Queen Guinevere?”

“Oh, yes, and a very beautiful queen she was. I saw her once, dressed in a bright red velvet gown with gold slippers on her little feet. Is that who you’re supposed to be?”

“Y-yes, sir,” blushed Janet Jane, hanging her sandy head and pulling at the pink mother hubbard.

“Mr. Dwagon, that’s my sister, Janet Jane Baxter,” Peter continued with his introductions.

The dragon cocked his head. “Yes, I can see a resemblance—Yes, the nose again—and the eyes. Pleased indeed to meet you, Janet Jane.”

“And the boy with the freckles is Billy Rose.”

“Delighted to meet you too, Billy, but I’m sorry to see that your armor’s rusted. You should take better care of it. In my day, the knights were very careful of their armor. Those who were careless soon lost their heads.”

“Y-yes, sir,” stammered Billy Rose.

Finally they were all introduced, even Nap and Jerry, and right away questions began to fly.

[37]“Were you in the woodlot all the time?” this from Janet Jane.

“No, not all the time,” replied the dragon.

“I know,” cried Johnathan, “you were behind the first bend in the cave and you blew out my candle.”

“I can’t answer that correctly,” returned the dragon, “because I’m not sure where I was. You see, I got lost and then I went to sleep for ages and ages and ages.”

“Oh, I see. And are you really the last dragon in the whole, whole world?”

“Don’t talk about that, Janet Jane!” reprimanded Peter. “He’ll cry if you ask him that. See?”

The dragon’s big blue eyes were again filling with tears, but he managed to blink them back, and then he said in a trembly voice: “I’m the last dragon because we’ve lost our purpose in life, and when a thing loses its purpose it dies out. Once upon a time, brave knights used to go out to fight dragons, and we served our purpose in that way—making heroes, you know,—but that’s long past.” In spite of his efforts a[38] tear ran down his cheek. “So you see, I’ve become gentle and sweet, and I don’t think I like myself a bit this way.”

“Oh, but we like you!” cried the children in a shrill chorus, and Nap and Jerry barked, quivering all over.

The dragon broke into happy smiles. “Do you honestly?”

“Oh, yes, we do!”

“Well, that makes it so pleasant,” purred the dragon, again stretching out his great gold claws like a sleepy cat.

Billy Rose jumped in with: “What do you eat, dragon? I thought—”

The dragon interrupted. “Well, I used to eat fire out of volcanoes, but since most of the volcanoes are extinct now, I’ve taken to eating grass.” Again he looked disgusted, just as you might look if you had to eat milk-toast all the time.

“Is—is that what makes you so green?” ventured Janet Jane.

“No, I don’t think so. My dear mother was green. I take after her.”

[39]“And did she have blue eyes too?”

“Yes,” said the dragon. “She was a very beautiful lady. People said all sorts of cruel things about her, but she really had a fine soul. She was killed by a knight who had a flaming sword. It wasn’t a fair fight at all because the sword was a magic one.”

“Oh, how unfortunate,” sympathized Janet Jane, and her voice trembled.

“Oh, please don’t cry,” requested the dragon, “because then I’ll cry and I’m trying very hard to break myself of that habit.”

Indeed, he was blinking so fast with his long lashes that the children could feel a little breeze against their cheeks.

“But—but what are you going to do now?” Johnathan asked quickly, feeling he must change the subject.

The dragon thought for a moment; seemed to find the question difficult; turned his head this way and that way; looked up at the blue sky; looked down again; blinked his eyes; smiled; sighed; reached out and plucked a Johnny-jump-up; held it to his long green nose; smelled it;[40] threw it aside, and finally said, rather coquettishly, “I’d—I’d like to stay with you children for awhile.”

“Oh, that would be fine!” Johnathan said.

“But—but mother says we can’t have any more pets,” said Janet Jane, sadly, “Jerry was the last.”

“A dragon isn’t a pet,” spoke up the practical Billy Rose, “but if you don’t want him, I’ll take him!”

There had leaped up in Billy’s mind a vivid picture of a side-show with a great canvas sign over the front reading, “The Last Dragon.” He himself would be the barker in long checked trousers and high silk hat—“Here you are, folks! Here you are! The only dragon in the whole world! Step right up, folks! Step right up!”

The Baxter family cried in a chorus: “But we do want him!”

“But you just said you couldn’t have any more pets,” argued Billy.

“And you just said a dragon isn’t a pet!” returned Janet Jane, tossing her head.

“Well, in a way it isn’t and in a way it is,” replied Billy.

[41]“I found him, didn’t I?” Peter demanded, glaring at Billy Rose.

The dragon chuckled, quivering all the way down his sides. “Don’t fight over me, children. I belong to all of you, but of course—” He turned to Peter and smiled broadly— “Of course Peter really woke me up. He believed I was asleep in the cave, and because he called me I came out. He doesn’t think that he really thought I was there, but—” And he put out one of his arms and took Peter to him and hugged him. The hug was so gentle that the rest of the children became very encouraged, and before long they were perched all over the dragon, and the dragon purred with contentment.

“I tell you what we’ll do!” announced Johnathan, putting his cheek against the dragon’s cheek. “Mother’s out shopping, right now. We can hide Mr. Dragon in the nursery without her knowing a thing about it.”

“But there’s Grandma,” said Janet Jane.

“Oh, Grandma’s all right,” piped up Peter, pressing his cheek against the dragon’s other[42] cheek. “She knows a lot of stories about dwagons.”

“Oh, she does, does she?” asked the dragon. “I’d like to meet your grandmother, if that’s the case.”

“You certainly may!” thrilled Janet Jane. “She’s awfully sweet. She has peppermints in her pocket and under her pillow at night. She’ll probably give you one.”

“Peppermints?” enquired the dragon.

“Yes, little round candies. They’re good for indigestion and things like that.”

“Then I’ll ask her for one,” the dragon said. “I never used to have indigestion when I ate fire, but since I’ve taken to grass—oh, me, oh, my!” And an expression of remembered pain passed over the dragon’s brow.

“Do you want to come and hide in our nursery, Mr. Dragon?” timidly pursued Johnathan.

“Yes, if I won’t get you into trouble,” the dragon returned, thoughtfully. “I’m afraid your mother won’t understand it if she should discover me in the nursery.”

“Well, we could explain it,” spoke up small [43]Peter. “We explained a squirrel once, and a long pink worm, and—and—”

“And a potato bug!” cried Janet Jane.

“Yes, an’ a potato bug. Now, it’s awful hard to explain a potato bug!”

“But it’s harder to explain a dragon,” the dragon said, and sighed again. “I know because I’ve had experience.”

Johnathan looked up at the sun. “Well, if you’re going to take a chance we’ll have to do it right away, because it’s almost twelve o’clock, and Mother will be back home to fix lunch. Please come on, won’t you, Mr. Dragon?”

“Well, all right—if you insist!” said the dragon, and he started for the house, led by small Peter striding ahead in all his glory, the wooden sword clutched tightly in his hand.

THEY filed through the willow clump tunnel, wriggled through the orchard, skirted the barn, passed over the truck garden, the dragon stepping daintily to avoid trampling the new carrots and beets, passed over the creek bridge, went up the lane past the fish pond, and winding through the rose garden they saw Grandma Baxter, in her lavender cap, at the window of her upstairs bedroom.

Now, Grandma Baxter had been dreaming all by herself in the little room, seated in her famous rocking chair. Why was the rocking chair famous? Well, because in the first place, it came clear across the Atlantic ocean in the May Flower, and had rocked through many a storm; and in the second place, George Washington once sat in it, and in the third place, it could talk—a creaky sort of talk that only Grandma could understand, and it told her fascinating stories of the English forest in which it was born, and of all its adventures; and it was heard to chuckle in the middle of the night and rock back and forth when no one was in it, and Grandma would chuckle with it.

[45]

GRANDMA

[46]Did I say Grandma was dreaming? Yes. She had been dreaming of things that had happened ever so long ago, before there were automobiles, before there were electric lights, before there were phonographs, before there was Jello and corn-flakes; Oh, before there were many, many things ready and waiting, but not thought of yet. And as Grandma sat there dreaming, she wore a funny little smile. It wasn’t only a funny little smile—it was also a wise little smile, and a kind little smile, and somewhere, mixed up in it, was a sad little smile. Grandma was that way, anyhow. She was all sorts of things at once. You never knew exactly what was going to pop out next from Grandma.

From her dreams she awoke to see the children and the dragon, and you won’t be surprised when I say that Grandma, for the moment, believed she[47] was still dreaming. She rubbed her eyes; she looked again; she said, “Dear me!” She rubbed her eyes a second time. But the next minute she had hopped up like a purple finch in her lavender gown, the rustle of a bag of peppermints in the silk pocket, and out of the window popped her little head with the lavender cap all awry. “Heigho!” cried Grandma, “what’s all this?” And the dragon heard her at once, and stopped. He looked up at the window and his blue eyes twinkled, and he said to Peter who stood by his ear. “Is that Grandma?”

“Yes, that’s Grandma,” said Peter, and he waved his sword at the old lady, calling: “Hello, Grams, I want you to meet Mr. Dwagon, the last dwagon in the whole, whole world.”

“Oh, how-do-you-do, Mr. Dragon?” replied Grandma, leaning far out of the window. “So delighted you called. Bring him around the front way, Peter. Never take a dragon through the kitchen.” And before Peter, or Johnathan, or any one else could reply, Grandma had popped out of sight.

[48]“Quite delightful, isn’t she?” chuckled the dragon.

“We told you she was,” thrilled Janet Jane.

“Keep to the right of the tulips, if you don’t mind, Mr. Dragon,” directed Johnathan.

On the front steps of the Baxter house Grandma was impatiently waiting, her sharp eyes, behind their spectacles, just twinkling, and her pretty white hands fluttering with excitement, just like butterflies all on a summer day. You would have thought the dragon and she were old, old friends to have seen the way they greeted each other, and indeed it occurred to Johnathan that perhaps Grams had seen the dragon before, some strange place or another. Grams was tricky that way.

“Well, I’ll just have to kiss you, that’s all there is to it!” Grandma exclaimed, and down the steps she flew, all in a rustle of silk, and pressed her lips against the dragon’s green cheek.

“The nicest thing that’s ever happened to me,” purred the dragon, “since my lady mother kissed me.” And his gold claws stretched out like velvet.

[49]“I found him, Grams!” Peter crowed, sticking out his chest.

“Of course you did!” Grandma chortled, hugging Peter. “Who else is more likely to find a beautiful dragon?”

“And now we’ve got to hide him some place,” said Janet Jane, “but I’m afraid he’s a little large.”

On the road that winds up the hill from the town, was heard the hum of a motor car. Johnathan was the first to hear the warning sound. “There comes Mother,” he shouted. “Get Mr. Dragon upstairs, quick!”

Never was there such a frantic scramble. If you’ve never tried to put a perfectly healthy, perfectly normal, full-sized dragon into a modern house that was built for perfectly normal people, you’ll have no idea of the difficulty. Let me tell you it took strategy! It was push and pull and grunt and squeal with all the children bracing their legs and straining their backs, and the dragon puffing and holding in his waist-line and letting it out, and crying: “Oh, dear me, dear, dear me, this will never, never do! No, never, never do!” every two or three seconds. If Grandma[50] hadn’t been there to superintend it is very doubtful whether the children would have manœuvered him into the house, but she was full of helpful suggestions, and the dragon’s glittering tail was half way up the hall stairs by the time Mrs. Baxter had driven her bright blue automobile around to the garage.

However, and unfortunately, half way up the stairs was not in the nursery and under Peter’s bed as Johnathan had planned. It was indeed far from that. The dragon’s head was in the nursery and his shoulders and part of his back, but that distressingly long tail of his was certainly a problem. “Couldn’t you curl it around you like a cat?” Grandma suggested.

“Under the present cramped circumstances that’s impossible,” the dragon told her, a helpless tear in each eye.

“Seems to me,” said Johnathan, pondering, “that I read some place where dragons could turn themselves into any size they wished.”

Janet Jane clapped her hands, gleefully. “Yes, I read that too. It’s in my red fairy book. Can’t[51] you turn yourself into a little green worm, Mr. Dragon, just for the time being?”

“I’m sorry but I can’t do that either. I’ve lost the formula.”

“Gracious! Can’t you possibly remember it?” Grandma urged, frantically.

“No. I always had a remarkably poor memory. It was a very complicated formula and there was a magic verse tacked onto it that was extremely difficult. When I was little I got many a spanking from my stern father for not remembering it.”

“There’s a magic verse in my red fairy book,” said Janet Jane. “Maybe that will help? It begins:

The dragon shook his head and said mournfully: “That doesn’t help me a bit, I’m sorry to say. It has to be your own particular magic verse, like your own particular porridge bowl or your own particular napkin ring, before it does any[52] good. Well, I suppose I’d better withdraw and go back to the cave. It’s no good staying here and getting all you children into trouble.” And the dragon sighed so deeply that all the curtains in the nursery were blown out of the windows and one of the fat feather pillows flew off Peter’s little bed.

The children sent up a cry of disapproval that was interrupted by the voice of Mrs. Baxter who had just entered the house through the French doors on the side porch. “What are you children doing in doors?” called up Mrs. Baxter. “I thought I told you to play in the meadow until luncheon?”

“We—we—” began Johnathan, but Grandma silenced him. “Let me attend to this, Johnathan,” she said, and started down stairs, stepping daintily so as not to tread on the dragon’s tail. She had hoped to meet Mrs. Baxter in the living room and prevent her from coming into the hall, but she was too late. At the bottom of the stairs, Mrs. Baxter was standing gazing in horror at the long green tail.

“What is that ugly thing?” she demanded.

[53]“Be calm, Kate, be calm,” said Grandma, “it’s only a dragon.”

“A dragon? For heaven’s sake, where did it come from?”

“Peter found it.”

“Found it? How could he find a dragon?”

“Very easily—easier than finding a pocket-book,” said Grandma.

“Oh, isn’t it terrible? Where are the children? Has it eaten any of them yet? I’ll run and phone for the police and the fire department.”

Grandma stopped her before she could get to the telephone. “Don’t be nonsensical, Kate!” she snapped, standing on her tiptoes. “The children are perfectly safe. It’s an adorable dragon.”

“Adorable? Who ever heard of an adorable dragon?” cried Mrs. Baxter. “Why, that long green tail was perfectly hideous. What is it doing upstairs?”

“The children were trying to hide it in the nursery, and I was helping them,” replied Grandma, her head wagging proudly.

“Are you insane, Grandma Baxter? Helping the children to hide a dragon in the nursery! It[54] was bad enough when you bought them that vicious nanny goat.”

“That nanny goat wasn’t vicious,” returned Grandma with dignity. “It butted no one but the butcher’s boy and he deserved it because he hit the perfectly innocent beast with a sling-shot.”

Grandma had no sooner spoken than a sharp shriek came from upstairs, followed by frightened sobs. It was Susan Oliver doing just the wrong thing at the wrong time, as usual. It seemed that in trying to wriggle further upstairs, the dragon had accidentally flipped Susan with one of his fin-like scales, not hurting her a bit, but frightening her into tears. Quite naturally, Mrs. Baxter believed that the dragon was doing harm to the children, and she ran to the foot of the stairs and called, “Children! Come down here at once! All of you!”

Susan Oliver stopped crying, and there was silence and a pause. Mrs. Baxter called again: “Children! Do you hear me? Come down at once!”

What was her surprise to see them all come sliding down on the dragon’s back and off his[55] tail, just as if he were a nice, shiny bannister, the exciting kind, long and smooth with a curve in it. First came Peter in his armor, and then Johnathan in his kingly robes, and then Janet Jane in the pink wrapper, and then Billy Rose in his rusty armor, and then Kath in her green train, and then Mary in the circus rider’s costume, and then Polly in her mother’s riding habit. Susan Oliver was the only one who did not take the slide. She was too busy crying and missed an experience that the other children talked about for ages afterwards. To slide down a real dragon’s back is something that doesn’t happen to every one, let me tell you.

The children landed together in a heap on the floor at Mrs. Baxter’s feet, and instantly they untangled themselves and the three little Baxter’s encircled their mother and began to plead: “Oh, please don’t be cross with him, Mother!” “Please let us keep him, Mother!” “Please don’t send him away, Mother!” “He’s beautiful, Mother!” “We love him, Mother!”

Billy Rose drew apart with Kath and Polly and Mary, ready any moment to say: “Let me[56] take him, Mrs. Baxter. My mother won’t mind.” And this was quite true. Billy’s mother allowed him to do quite as he pleased and consequently he was always getting into trouble. Even practical people find themselves in trouble if they are permitted to do exactly as they please. Now isn’t that so?

“Children, be quiet!” Mrs. Baxter commanded. “It’s nonsense to think that you could keep a big monster like that in our house. Why, we couldn’t even go upstairs without stepping on him. Besides, he may be gentle now but no dragon could live around children for any length of time without desiring to eat one of them for his breakfast.”

“No, Mother, he only eats grass,” piped Peter.

“Hush, Peter. And another thing, you know how your father feels about pets in the house. If he objects to dogs and cats, what would he say about a great big dragon? No, my dears, your dragon has to go!”

NOW you really can’t blame Mrs. Baxter, if you look at her side of it. To her dragons were vicious, ugly beasts and she just didn’t have imagination enough to see one of them smile. She was a very, very fond mother and wanted to protect her children from all harm, which is not at all unusual for very, very fond mothers from tiny humming-bird mothers clear up to mothers like yours and mine. Maybe Mrs. Baxter gave all her own share of imagination to the children when they were born and had none left for herself, and maybe it was because when she was a little girl she had been taught to fear dragons.

At any rate, there was no help for it now, and so out the dragon had to go. He backed out sheepishly, because there wasn’t room for him to turn around and depart with dignity. When[58] his drooping head passed Mrs. Baxter’s skirts, he raised his big blue eyes and looked at her so sweetly, but Mrs. Baxter, poor Mrs. Baxter, could only see his ugly, ugly nose and his big white teeth. That was really too bad because she might have relented had she seen that sad, sad smile all quivery with threatening tears.

“Goodbye, children!” the dragon called, lingering on the gravel walk.

“Goodbye, dear, dear dragon,” they replied in a gulpy chorus.

And now he was going away from them, dragging his green tail slowly, looking back longingly over his shoulder.

“It’s an outrage to send that poor beast away like this,” stormed Grandma, wagging a finger in Mrs. Baxter’s face. “Don’t you know that he’s all alone in the world?”

“He hasn’t a single friend!” half-sobbed Johnathan.

“Thank heavens he hasn’t,” said Mother Baxter. “Suppose there were lots of them, all trying to hide in children’s nurseries?”

“Maybe there are,” said Grandma, the strangest[59] expression in her eyes. “Maybe there are, who knows?”

The dragon’s tail was just disappearing around the corner of the front porch when Mr. Baxter, the tall, nice-looking father of Johnathan, Janet Jane and Peter, drove up in his own automobile, having just come from the city. When he saw the group standing in the doorway, strangely agitated, he rushed up to Mrs. Baxter and demanded to know what had happened. He thought it couldn’t be anything less than robbers or a fire, from the expressions on all their faces.

“Don’t get excited, James!” Grandma said sternly, before Mrs. Baxter could speak. “Kate has just sent a dragon away.”

“A what away?”

“A dragon.”

Mr. Baxter threw back his head and burst into loud laughter. “A dragon? What are you talking about?”

“Oh, I knew you wouldn’t understand,” snapped Grandma, irritated.

“He’s going around the house, this very minute, back to the woodlot, poor thing!” Janet cried.[60] “Go and look for him, Daddy. He’s the sweetest, the dearest, the—”

Peter and Johnathan had swooped down upon their father. “Yes, yes, Dad!” they both shouted—“Come and see how nice he looks!” And they pulled him over to the end of the veranda and pointed out the dragon, who was slowly dragging himself toward the rose garden.

“See, there he is!” Johnathan said. “I wish he’d turn around.”

“Oh, dwagon! Dwagon! Turn around!” called Peter, and the dragon turned, but his face was still very, very sad, and his checks were drenched with tears.

“Smile nice, Dragon,” instructed Johnathan—“smile nice for Daddy.”

The dragon hesitated a moment; blinked fiercely; sniffed so loudly that Peter and Johnathan could hear him plainly, and then forced a smile. It was a weak, watery smile and quickly vanished.

“You children are talking the greatest lot of nonsense I’ve ever listened to,” said their father. “Where did you get such imaginations?”

“It’s not imagination, Daddy,” protested Johnathan.[61] “The dragon’s standing right there by the red rose bush. Can’t you see him, honest?” His big eyes were searching his father’s face.

“No, and you can’t either. What is this, April fool? Come on, let’s stop this joking and go into luncheon. This is Daddy’s Saturday afternoon off and we’re going to take a long auto ride up to Sulphur Springs and the Indian Rocks.”

Now, you really must feel sorry because Daddy Baxter could not see the dragon. Once he could see dragons and pixies and everything else that’s delicious and exciting, but the crystal key that opens the door to that magic world had been lost somewhere along the twisting road that runs in and out from childhood days to middle age. Big cities had done it, and high, high office buildings, and crowds on street cars, and business deals, and the rattle, rattle, rattle of the subway trains. Heigho, where was there room for a dragon in all that, may I ask you? He would have had his tail cut off as quick as a wink, and even a tiny pixie would have to be pretty spry, I tell you!

And so the dragon went on his lonesome way and the children took off their garments of[62] Arthur’s court, and washed up for luncheon which they tried to swallow, but couldn’t very well because of annoying little sob-lumps in their throats. Even the thought of Sulphur Springs and Indian Rocks could not cheer them up.

This is rather a belittling thing to tell on Billy Rose, but since nothing really came of it, I suppose there’s no harm in telling. That practical boy can stand a little chuckle at his expense, anyhow. The door of the Baxter house had no sooner closed before Billy had slipped away from Kath, Polly, Mary and Susan Oliver, and rushing around the veranda, he began calling, “Oh, Mr. Dragon! Wait a minute, Mr. Dragon! Oh, Mr. Dragon!”

He ran through the rose garden, up the lane skirting the fish pond, over the creek bridge, through the truck garden, past the barn, calling and calling, “Oh, Mr. Dragon! Mr. Dragon! I want to talk business with you, Mr. Dragon!” Not a sound answered him, and there wasn’t a glimpse of the dragon anywhere—just the marks of his golden claws on the gravel paths of the garden, and the sweep of his bright green tail.

[63]“That’s funny,” said Billy Rose, standing still and scratching his puzzled head. “Where could he have disappeared so soon?”

Finally he had to give up his quest and go home, thoroughly disgusted, wondering if this dragon business weren’t just a lot of nonsense, but of course, you must remember that Billy Rose was practical. He did not hear as he went through the rose garden what the silver snail said to the green grasshopper, and he did not hear what the green grasshopper replied to the silver snail. Nor did he hear a tiny chuckle that came from a polka-dot lady bug as she sat swinging her feet on the edge of a rose petal. If he had heard those little, velvet sounds and had put two and two together, just like an arithmetic of voices,—snail’s voice, grasshopper’s voice, lady bug’s voice, he might have known where the dragon went, after looking back from the place where the red rose bush grows.

THAT night there was a full moon that rose above the woodlot and poured silver into the meadow, and all the little owls were out, talking it over with each other. The yellow-striped spiders were very, very busy with their spinnerets, spinning great silver webs to catch the dew diamonds, and I think the mushrooms were up to some pearly mischief in the silvery grass.

The night was as bright as a polished coin, a coin that’s kept by a miser man and is polished every day with a green, green rag. Up in the nursery the children slept, if you could really call it sleeping—Peter, Johnathan and Janet Jane. Across the hall, Grandma sat, sat all night in her famous rocking chair—rocking, rocking, rocking—the gentle creak, creak, creak like the tick of a clock in the stillness of the house. Oh,[65] Grams, how your little eyes are snapping; how your fingers are weaving in and out; how your silken gown is rustling, and the peppermints are clicking. What are you up to, Grams, in your famous rocking chair? Rock, rock, rock,—creak, creak, creak.

All night, sitting there, watching the moon through your little window, seeing it slowly climb up over the tree-tops. Now, you look like a pixie, Grams—Now, you look like an elf—And now you look young and fragile and all spun-glass like a fairy—and yet sometimes, Grams—Oh, sometimes you look like a dragon!

And what is disturbing the children? What dreams make them toss and breathe funny little noises into the nursery, so that Peter’s rocking horse opens its glassy eyes so round, and rocks a little on its rockers, and Janet Jane’s Raggedy Ann turns and speaks to Johnathan’s china pig who is so haughty and superior because he holds so many pennies in his round, china stomach.

One o’clock, two o’clock, three o’clock—the hours are noiselessly running away, tiptoeing off to the place where all the hours meet—the place[66] where all the yesterdays live and the yesteryears, and the once upon a times, and the spirits of all the clocks that have run down for good.

The moon begins to sink in the west. There is the promise of something bright in the east. The little owls know it and put their dark glasses on, to prepare for the unwelcome glare of the sun. Four o’clock! Grandma is still rocking. Now her ears are pricked up sharp like the ears of a dog, and under her lavender cap that’s all awry there are two little bumps like a pair of horns, soft and tender like mushroom buttons.

Five o’clock! A faint red ribbon in the east. There is such a quiet over everything—such a breathlessness. If you listened real hard, you could hear the tiny beating of the lady bug’s heart as she slept on the silk of the rose petal.

What’s that? What’s that sound? Tap, tap, tap,—The branches of the white oak against the windows? No, it couldn’t be that. There’s not a breath of wind, and besides it’s too regular for that. Tap, tap, tap. Somebody throwing colored creek-pebbles at the windows of the nursery? No. Too regular for that, also. Must be the[67] tapping of fingers, but what hand could reach way up to the second story?

Tap, tap, tap. Now, three pair of eyes are opened at once in the nursery, and three pair of ears listen, and three hearts go pump, pump, pump. Johnathan, Peter and Janet Jane sit up straight in their white night clothes and look at each other with the roundest, roundest eyes. There is a little prickling all along the roots of their bright, bright hair.

Tap, tap, tap again, and there in the wide nursery window, the one on the east side over the veranda, was the smiling face of the dragon, and one gently-tapping golden claw.

“Dragon!” cried the three little Baxters all together, and from their beds they leaped and ran to the window. Johnathan unlatched it and flung it wide open, and three small mouths were kissing the dragon’s cheeks. He was standing on his hind legs, and he was so tall that he could easily have rested his forelegs on the roof of the Baxter house if he had so desired.

“Dwagon—Dwagon, where did you go?” cried Peter.

[68]“Oh, just around the corner,” returned the dragon, mysteriously.

“Around what corner, Dwagon?”

“Oh, the same old corner—the one just out of sight. You know—there’s one every place”—And he winked broadly.

“Oh, that corner,” said Johnathan, smiling wisely. “Yes, I know. I go around that corner all the time. It’s nice around there, isn’t it?”

“Yes, full of pleasant surprises, always different, you know. But as soon as you get around that corner, you come to another corner, and so you keep on going, around and around.”

“Yes, until you almost forget to come back,” pursued Johnathan, “and you’re almost lost, and then your mother calls you.”

The dragon smiled. “Yes, and then your mother calls you, and you have to go in and wash your neck and ears—but, by the sword of St. George, this is no time to moralize. The sun’s already warm on my back—(his voice sank down to a gentle whisper) so it’s time we’re going, children.”

“Going?” echoed Janet Jane.

[69]“Going where?” asked Peter, all breathless.

“Going with me, on my back, for a long, long ride.”

For a moment the children appeared utterly astonished, their red mouths open like baby birds in a nest at feeding time, and then it all became very simple and not a bit unusual, just as it had felt when the dragon first entered the meadow.

“Will you come with me?” the dragon asked, and the children answered in a chorus, “Yes, Dragon, because we love you.”

“Shh, not so loud,” warned the dragon, a gold finger to his lips, “we don’t want to wake up your father and mother. They won’t understand in the least, and it would be so hard and take so long to explain. Now, put your arms around my neck, and I’ll hoist you on my back.”

“But can we go this way?” asked Janet Jane, indicating her white night gown.

“Certainly. It will be so nice, riding through the springy world, just with your night gowns on,” said the dragon.

“Oh, yes,” cried Peter, “I like that!”

“And so do I,” added Johnathan.

[70]“Won’t we catch cold, though?” asked Janet Jane, always the little mother.

“Not in the least. It’s as warm as a stove on my back from the fire I used to eat, you know, and in the night”—

“Ooh, will we stay all night, Dwagon?”

“Maybe,” smiled the dragon. “Who can tell what you’ll do when you go riding on a dragon’s back. Come along.”

There were giggles, and breathless Oooohs! and shrill Weeeeees!—and the next moment, the nursery was emptied of its children, and the dragon’s face had vanished from the window. Only the sun was there, peeping through on the three empty beds with their three dented pillows and their tumbled sheets and comforters.

Quickly the dragon walked around the house, proudly carrying his precious burden, and the dogs, Nap and Jerry, came running as fast as they could from their round beds in the barn. They looked quite amazed when they saw the little Baxters perched on the dragon’s back, but they did not bark. Instead, they began to smile, their tongues sticking out, and as the dragon[71] stopped to look up at Grandma’s window, they leaped aboard and sat, still smiling, at the bare feet of the children.

“Is it all right for Nap and Jerry to come, too?” Janet Jane enquired of the dragon.

“Why, certainly! Do you think we’d leave them behind when we’re going adventuring?” The dragon seemed indignant.

I said he was looking up at Grandma’s window, didn’t I? Well, he continued to look up steadily, and the children followed his eyes. Slowly the little window under the eaves opened out, slowly, slowly, as if hands were gently pushing it, but there were no hands to be seen.

Do you remember how apples bob on the water after you’ve ducked for them on Halloween, and they’ve fooled you, and seem to laugh at you as they bob and bob, higher and higher? Well, that was the way Grandma’s head bobbed up over the window sill after the windows had opened very wide. First bobbed the lavender cap; then the soft white hair; then the bright eyes behind the steel-rimmed spectacles, the crinkly mouth, the proud, defiant chin, all[72] creased with little furrows like crumpled silk, and now the lavender silk shoulders encased in the lavender shawl with tiny white butterflies.

What was Grams doing? Why, she was rising, higher and higher. Now, her tiny hands are seen—now her tiny feet. She was sitting in her famous rocking chair and rising like a bird, or like a giant mushroom that springs up over night. In her lap was her knitting bag that was filled with the strangest, most fascinating things under the bright balls of colored yarn.

“Grams!” the children called in frightened wonder. “Grams! Look out!”

But Grandma only smiled serenely and sailed through the window, seated calmly in her rocker, coming straight down to the dragon’s back, where the rocking chair lighted, oh, so nice and gently, and rocked a little, creaking contentedly. “Well!” breathed Grandma, “here I am!”

“Oh, Grams, are you going with us?” asked Peter.

“Why, of course. I’m just like Nap and Jerry when it comes to adventuring. It was I who told Mr. Dragon where to hide until morning. I[73] knew if he returned to the cave, maybe none of us would have the courage to get him back again.”

“So you sent him around the corner,” smiled Johnathan.

“Yes, my dear, around the corner.” Then Grandma tapped with her little slippered foot on the dragon’s back—a magic little tapping, three times with the heel and then once with the toe. “Are we ready, Mr. Dragon?” she called.

“Yes, indeed, Grandame,” returned the dragon. “We’re off, down the highway.”

And before the children even knew they had started, the landscape was gliding by on each side of them, faster and faster, like streaks of hills and streaks of trees. Looking back, their house was gone in the twinkling of an eye. Looking ahead, they seemed to be running straight into the rising sun. And it was Sunday morning and all the bells were ringing.

AT first the landscape was familiar to the children—there was the white church, and there was Red Hill where they coasted every winter, and there was the road to Indian Rocks, and there was the puppy farm where Nap was born, and now they were way, way out in the country where the duck farm was.

However, it wasn’t long before things changed a great deal, like being in a different part of the United States, the children thought, or maybe in a different country altogether, yet Grandma seemed to recognize things, and her eyes appeared sharper, and her lips caught sparkly expressions like a little pool catching bits of sunshine.

Once in awhile, they would pass through little towns and then through big cities, and then there[75] was something strangely familiar about these places,—places not really known and yet maybe they were pictures in books. Look, surely that place was on page one hundred and two of the American history. All the houses were so old-fashioned, and the people wore such funny clothes. There was that young man Johnathan had put a mustache on with pen and ink in the Fourth reader.

“Merciful heavens!” cried Grandma, suddenly. “Look, children, there’s your father when he was a little boy!”

“Where, Grams?”

“Right there, in front of that gray house with the dormer windows, and the iron stag on the lawn. It was just after he had his curls cut off.”

“Oh, how funny he looks, chasing that big hoop!” giggled Janet Jane.

“He looks just like that tin-type in the brown-plush album,” said Johnathan.

“That picture was taken the very next day after this—Oh, James!” called Grandma, starting up from her rocker, but no sooner had she called than the street and the house with the dormer[76] windows had vanished, and they were out on a long, long stretch of white road.

What fun it was! It was just like riding along on the nicest, smoothest railroad in the world, even nicer than that, because the dragon made no stops and therefore caused no bumps. It was like riding on a great train with Indian rubber wheels that ran on tracks of velvet, and the dragon’s back was so broad and so comfortable, because the further back the dragon went, the broader and broader he became, and longer and longer stretched his tail. You could lie down flat and stare up at the sky, if you wanted to, only the children were too excited to do that. They didn’t want to miss a thing, you know. As long as they lived, they might never do this again.

The long, straight, stretch of road ended in another town, a puzzling town with a funny wooden church made of logs enclosed in a high stockade. All the houses were of logs too. The streets were unpaved, and all chopped up and muddy, and there were no automobiles. The citizens of this town used oxen and shaggy horses to cart in wood and food stuffs from the surrounding[77] forest that was very thick and very black. Men wore coon skin caps and suits of deer skin, and women wore dresses of deer skin also, but now and then a young girl wore a bright print gown and a poke bonnet with flowers. All the men carried rifles.

“Lands alive!” Grandma exclaimed. “There’s your great grandfather, when he was a little boy!”

“Oh, where, Grams?”

“Riding on that cart with his father and his mother, and his little sister Barbara who grew up to be a famous nurse in the Civil war.”

“The little boy with the scar over his eye?” asked Peter.

“Yes. He got that from an Indian arrow.”

Grandma was very excited. “Of course, he won’t know me like this, because he died when I was only a little girl.”

“How could he be dead when he’s right here?” asked Janet Jane.

“Because we’re back when he was alive, I suppose. But that makes me feel very queer,” said Grandma. She tapped sharply on the dragon’s back, and the dragon turned his head to listen as[78] he rounded a sharp corner. “Where on earth are we going, Dragon?” demanded the old lady, leaning far out of her rocking chair to catch the dragon’s reply.

“We’re going backwards,” the dragon said, a twinkle in his eye—“backwards down the road of time.”

“Why, certainly,” said Grandma, taking it as a matter of course. “How stupid of me not to know.”

“Going backwards? Isn’t that rather strange?” asked Janet Jane.

“Well, it isn’t exactly what’s being done every day, but it becomes perfectly natural when you get on a dragon’s back. It’s the natural direction for a dragon to go.”

“How long a trip do you think it’ll be?” asked Peter who was standing up on the dragon’s neck like a sailor at the prow of a ship, letting the wind whistle around his ears and blow his night gown back like a white sail, and ruffle all his sunny hair. In his hand he carried his wooden sword. That was peculiar. How did he happen to have that? He didn’t have it in the nursery, he was sure.

PETER WAS STANDING ON THE DRAGON’S NECK LIKE A SAILOR AT THE PROW OF A SHIP

[79]“We’ll probably go as far back as the days of the dragon,” Grandma answered.

A cheer went up from the children, and Nap and Jerry barked, just on general principle, I suppose.

The dragon heard them and turned his head around again, smiling merrily; then dashed on, down more miles of straight road, lined with poplar trees.

Back—back—back—past years—past centuries. “There’s Abraham Lincoln!” Grandma would cry—“There’s Jefferson and Adams—There’s George Washington!”

“Not so fast, Mr. Dragon!” called Johnathan, “I want to get a good look at George Washington!” But I guess the dragon didn’t hear him. At any rate, George Washington was gone in a moment too.

“And here’s the Mayflower! My gracious, we’re going over the ocean!”

At that, the famous rocking chair began to creak and creak and became younger and[80] younger. Its shiny wood looked as if it would sprout green leaves any moment.

It kept the children busy, I tell you, riding past such sights, and their eyes became tired, and their brains reeled with the wonder of it all.

“It’s like reading a big, fat history book,” said Johnathan, just after they had seen Louis the twelfth, “only, of course, it’s much more exciting this way. I wish arithmetic was like this.”

“I’m getting awful hungry,” piped Peter.

“It must be awful late,” said Janet Jane. “Look how dark the sky is.”

“No, it’s not late,” said Grandma, fumbling in her mysterious knitting bag. “It’s just getting dark because we’re coming into the Dark Ages.”

“Wheeeee!” cried Johnathan, “that’s when they had children’s crusades, isn’t it?”

“Yes, and many dragons,” said Grandma. She stopped fumbling in her knitting bag and drew forth some little sandwiches done up in oiled paper, and then some oranges and red, red apples. “Did you say you were hungry, Peter?”

“Oh, yes, Grams—awful!” Peter said.

“I’m hungry too, Grams!” said Johnathan.

[81]“And so am I,” said Janet Jane. “You must remember we didn’t have any breakfast.”

“Then come and eat your luncheon.”

There was a rush and a scramble that the dragon must have felt clear down his spine, because he turned and once more smiled.

“Wouldn’t the dragon like a sandwich too?” asked Peter thoughtfully, before he took his share from Grandma.

“I hardly think so,” Grandma replied. “One of these little sandwiches wouldn’t make much of an impression on him I’m afraid. Besides, I believe he’s headed straight for that great volcano over there. Now that we’re back in the Dark Ages he can eat fire again.”

The children looked, and sure enough, far off against the dark sky was a great, cone-shaped mountain with smoke rising from it.

“It looks like a knight’s helmet with a black plume, from here,” said Johnathan who could always see things like that. He could see trees as turtles, and rocks as old men with whiskers, and he could see the other way around too—old men as rocks, you know.

[82]“Maybe we’ll go right up to the crater,” squealed Janet Jane. “I always wanted to look down a crater.”

“But you can’t if it’s erupting,” said Johnathan.

“Maybe we can on a dragon’s back,” said Grandma. “Just wait and see. Have another sandwich, Peter?”

“Yes, please, Grams. And Nap would like another sandwich too.”

As they rode along, eating and talking at a great rate, they passed strange companies of horsemen on the road, and regiments of armored soldiers.

“Must be having a war,” observed Johnathan, after they had passed their fifteenth company of warriors.

“I think they’re attacking that castle on the hill,” Grandma said, pointing up to the right.

Surely it looked like it, because all the troops were headed in that direction, and many had grouped at the base of the craggy mountain on which the castle perched like a gray bird on top of a church steeple.

[83]“I wish the dragon wouldn’t get too close to them,” said Janet Jane. “We’re not protected very well in these night gowns.”

“Why didn’t Mr. Dragon tell us to bring our armor along?” said Johnathan.

“I’ve got my sword,” Peter piped up, proudly.

But they needn’t have worried because the dragon was only intent on getting his own luncheon, and kept straight as a crow flies toward the volcano.

Now, they were so close to the fiery mountain that they could hear it mumbling and grumbling to itself like an angry old man. Likewise, they could hear it hissing like a whole nest of snakes, and they could smell the fumes of the black smoke and the boiling lava.

Quickly they began to climb the steep mountain, and before they got to the top and to the crater, the dragon was wading in molten fire. But he didn’t seem to mind it a bit, and his back remained just as pleasant to ride on, keeping perfectly cool.

“Home at last,” sighed the dragon as they[84] stopped short on the very edge of the seething crater—“Home at last. No more indigestion.” And at that he stuck his head down into the boiling crater and drank and drank and drank.

AFTER the dragon had finished his luncheon, he became very warm—so warm that those on his back felt like pieces of browning toast, so it was suggested that they should all go to a cave that the dragon knew about, and step off on something more comfortable.

The cave was over the volcano and then away to the west on the side of a black, black lake. It was a very large cave filled with stalagmites and stalactites that formed many gaily colored columns, and many fantastic rooms. Through this cave a black river ran, slowly and sadly.

When the dragon entered the cave, everything was pitch black, but all the dragon had to do was open his mouth and out leaped a flaming torch that lit up the cave a great distance all around. Way, way back in the earth, around[86] the first bend, or the second bend, or the third—(really, Johnathan couldn’t count all the bends, they were so confusing) the dragon had a very cozy apartment of three rooms—a parlor, a bedroom and a kitchen. Of course, everything was cozy on a very large scale. The three rooms were big enough to accommodate all the Baxter house and leave room to spare for a garage and a back yard; and yet the dragon said it was considered a modest dwelling. All his relatives lived in much larger and much more handsome quarters. He was just a modest dragon with a modest income, and without much of a reputation, not a bit like St. George’s dragon, for instance.

“Now, make yourselves perfectly at home,” said the dragon, lying down flat on the parlor floor and stretching until he groaned. “I’m pretty tired from that long run backwards.”

“I can well believe so!” exclaimed Grandma, fumbling in her mysterious knitting bag and drawing forth a little bottle which she proceeded to shake, vigorously. “What you need is a good alcohol rub and I’m going to give it to you.”

“Oh, no!” protested the dragon. “There’s too[87] much of me to rub. You’d be exhausted in no time.”

“Exhausted? Stuff and nonsense!” snapped Grandma. “Besides, the children can help.”

“Oh, yes, yes!” they cried, and rushed all around the reclining dragon.

Grandma poured a little clear liquid in each outstretched palm, and then they all began to rub up and down, back and across—rubbed and rubbed and rubbed. They rubbed his back. They rubbed his chest. They rubbed his ribs and the length of his tail and the tired soles of his feet. And how the dragon adored those kind hands rubbing him! He lay back and purred like a kitten when it is having its fur rubbed the right way. Indeed, you had to rub the dragon’s scales the right way too, or else you tickled him and he rolled about in spasms of laughter.

And as they rubbed him, so intently occupied, they did not notice a little round door open in the side of the room, and a little head as brown as a hazel nut and shaped rather like a hazel nut too, came poking out cautiously, like a mouse pokes from a hole before it darts for the cupboard[88] where the cheese is kept. Then followed the round, fat stomach of a tiny old man dressed all in brown, the color of the earth. He was only about twelve inches high but carried himself with a great deal of dignity, as most little things do, if you’ve ever noticed. His face and hands were all lumpy as if they had pebbles in them, and his tiny eyes looked like bright creek-pebbles stuck in the face of a mud-pie man.

Still unnoticed, he walked pompously over to the dragon, and stood by the great beast’s pointed ear (he could have crawled into it easily) and bending down he whispered something in a voice that sounded like the buzz of a gnat.

At once, the dragon grinned from ear to ear and sat up, exclaiming: “Crubby! My old friend Crubby!” And he took the tiny man up in one of his golden claws and held him close to one of his enormous eyes, and studied him carefully. The little man looked very serious and severe and demanded, “Where have you been, sir? Give an account of yourself.”

And the dragon explained, meekly: “I’ve been looking ahead, Crubby.”

[89]“Oh, yes,” said Crubby, sarcastically, the most knowing expression on his old, old face, “you always were ahead of your time.”

“Yes,” agreed the dragon, tears threatening to roll down his cheeks, “but I got too far ahead, this trip.”

Crubby seemed to be grimly delighted. “Umm, I thought so! I thought so! Well, smarty, what did you learn by looking ahead?”

“Very little that was pleasant,” the dragon admitted, sadly. “I found myself all out-of-date and very, very lonesome. That is, lonesome until I found Grandame and the children.”

“Oh,” muttered the tiny man, not at all pleased.

The dragon hastened on to explain. “You see, they believed in me, Crubby. They gave me a place in their world, do you understand? So I might have stayed up there in the future all the time, if their mother and their father hadn’t sent me back to the Dark Ages again.”

“It’s just as well that they did!” said Crubby. “You don’t belong there for one moment.”

The dragon sighed. “Maybe not—maybe not—but, Crubby, let me introduce you to my new[90] friends, fresh from the future. Turn around, Crubby.”

Crubby didn’t seem at all excited about meeting Grandma and the children. He took his time about turning around on the dragon’s palm, and then he stood just like a Fourth of July orator on a platform, and bowed very distantly, with his right hand pressed to his chest, the fingers spread out.

“This is Crubby,” announced the dragon with a great deal of pride. “He’s my most intimate friend.” And Johnathan instantly thought of a mouse and an elephant, although mice and elephants are really not supposed to be friendly the least little bit.

“Oh, isn’t he the cutest little fellow!” cried Janet Jane, really meaning it, but Crubby did not seem to like this a bit. His pride was hurt, and he deliberately snubbed Janet Jane and all the rest, for that matter, by turning his back. He faced the dragon once more, and the dragon looked lovingly at him and said, “Dear old Crubby, I’m so happy to see you again, and I’m so[91] grateful I didn’t take you with me when I was looking ahead.”

“I wouldn’t have gone if you’d asked me,” said the impudent little mite, turning his pimple-of-a-nose up in the air.

“You would have had a most miserable time,” the dragon went on.

“I don’t doubt it,” snapped Crubby, “judging by what it’s done to you!”

“Now, just how do you mean that, Crubby?” asked the dragon. “Do I look so terrible?”

“You certainly do!”

“How? Have I lost my good looks?” The dragon was really distressed, and Grandma couldn’t help whispering to Peter that she thought Crubby had a very mean disposition.

“In the first place,” Crubby continued, relentlessly, “you’re all out of condition. Imagine you, a perfectly healthy, athletic dragon being exhausted after a little run like that! You ought to be ashamed of yourself!”

The dragon looked sheepish and tried to defend himself: “It wasn’t a little run, Crubby. It[92] was a very long run, clear from 1927 back to 1227.”

But Crubby waived that excuse aside and said, testily, “Don’t talk nonsense. I’m going to run you up the volcano and back, every morning before breakfast, to harden up your muscles again. What would become of you now if a knight should take it into his head to do battle with you?”

“Am I really as soft as that?” queried the dragon, pathetically. “My, you make me afraid!”

“You ought to be! You’re soft and you’re fat!”

“Fat?” exclaimed the dragon. “How could that be, when I was almost starved, living on grass?”

“No more excuses!” commanded the little man, wagging a finger in the dragon’s face. “For let me tell you, this is no time for you to be making excuses!”

“Just what do you mean by that, Crubby? Tell me, what has happened since I’ve been away?”

“Oh, a terrible thing,” said Crubby, “and it’s all your fault for delving into the future.”

[93]Surely, here was excitement and adventure beginning already, and the children, led by Grams, tiptoed up closer to catch every tiny chirp of the little brown gnome.

“What do you mean?—tell me, Crubby!” begged the dragon, but Crubby took his time, cleared his throat, adjusted his brown belt, took a few turns up and down, and then said planting himself very firmly with his legs wide apart, “Your Princess Silver Toes is gone.”

“What?” cried the dragon—“Silver Toes gone? And I was saving her as a beautiful surprise for the children. But how could she be gone? She was enchanted!”

“Yes, she was enchanted, but an enchanted princess can be stolen, can’t she, you idiotic fellow!” fairly screamed the irritable little man—“Oh, I warned you never to go looking ahead.”

“But who has stolen her, Crubby? Who has stolen my Silver Toes?” The dragon was really distressed.

“Now, who do you suppose? Have you forgotten your enemies so soon?”

“Yes, I have,” admitted the dragon, ready to[94] weep. “I’ve forgotten my enemies and I’ve forgotten the magic formula that changes my shape and makes me invisible.”

“Oh, my beard and my nose!” cried Crubby, although he didn’t have a beard. “Such a thing I’ve never, never heard. Now suppose I’d forgotten it? You’d be in a nice muddle, wouldn’t you?”

“But you haven’t, Crubby! Oh, please say you haven’t!”

“Well,” drawled the tiny man, keeping the dragon in terrible suspense—“Well,—I just wonder now—I just wonder. Maybe I have.”

“But your memory was always much better than mine, Crubby. You know you haven’t forgotten it,” stammered the poor dragon.

Finally Crubby gave in. “No, I really haven’t,” he admitted, “which is certainly fortunate for you. However, that isn’t important, right at this moment.”

The dragon agreed. “The important thing is Silver Toes. Who stole her, Crubby? Please tell me.”

For another agonizing minute, Crubby kept[95] them all in suspense; then he said to the dragon, “Come to the door with me,” and the dragon obeyed. Grandma and the children followed, puzzled and excited.

In the thick mud by the river bank, just where the black water flowed from the cave, Crubby pointed down to a large footprint that was shaped for all the world, Johnathan thought, like a four-leaf clover or a shamrock.

“Now, what does that look like?” demanded Crubby, and the dragon said immediately, his brow all puckered—“Why, that’s the footprint of Dallahan, the Irish dragon.”

“Yes!” hissed Crubby, “Dallahan! Now what do you think of that?”