Title: Baldy of Nome

Author: Esther Birdsall Darling

Release date: March 1, 2004 [eBook #11758]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Charles Aldarondo, Graeme Mackreth, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Baldy of Nome, by Esther Birdsall Darling

To

My Mother

whose unfailing kindness to all

animals is one of my earliest

and happiest memories

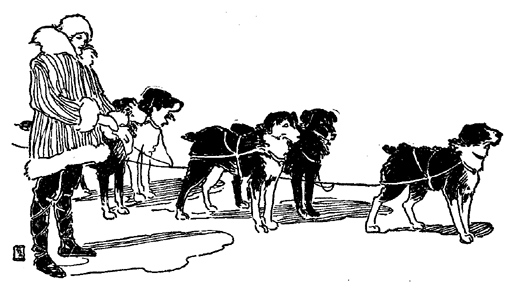

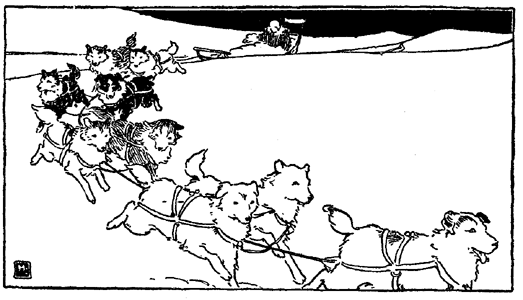

THE RACING TEAM

II. WHERE EVERY DOG HAS HIS DAY

V. THE WOMAN, THE RACERS, AND OTHERS

VI. TO VISIT THOSE IN AFFLICTION

VIII. A TRAGEDY WITHOUT A MORAL AND A COMEDY WITH ONE

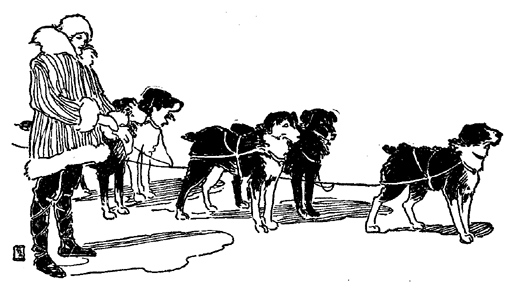

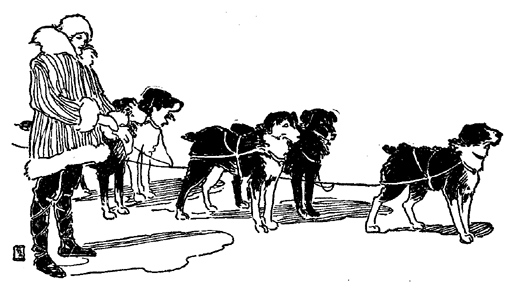

THE START OF AN ALASKAN DOG TEAM RACE

THE TRAIL HAD GROWN EXCEEDINGLY ROUGH

AN OVATION FOR THE PLUCKY LITTLE SCOTCHMAN

THE CAR COASTED DOWN ALL THE HILLS

AN ALASKAN SWEEPSTAKES

TEAM

Fay Dalzene, driver

Baldy knew that something was wrong. His most diverting efforts had failed to gain the usual reward of a caress, or at least a word of understanding; and so, dog-like to express his sympathy, he came close beside his friend and licked his hand. Always, before, this had called attention to the fact that Baldy was ready to share any trouble with the boy—but to-day the rough and grimy little hand, stiff and blue from the cold, did not respond, and instead only brushed away the tears that rolled slowly down the pinched cheeks. Sometimes the slight body shook with sobs that the boy tried manfully to suppress; but when one is chilled, and tired and hungry, and in the shadow of a Great Tragedy, the emotions are not easy to control.

With unseeing eyes and dragging steps, the boy trudged along the snowy trail, dreading the arrival at Golconda Camp. For there was the House of Judgment, where all of the unfortunate events of that most unhappy day would be reviewed sternly, though with a certain harsh justice, that could result in nothing less than a sentence of final separation from Baldy. And so when the dog in his most subtle and delicate manner showed his deep love for the boy, it only made the thought of the inevitable parting harder to bear.

So completely was Ben lost in his own gloomy reflections that he did not hear the sound of bells behind him; and it was not until a cheery voice called out demanding the right of way that he stepped aside to let a rapidly approaching dog team pass. As it came closer he saw that it was the Allan and Darling team of Racers, and for the moment his eyes brightened with interest and admiration as he noticed with a true dog-lover's appreciation the perfect condition of the fleet-footed dogs, and the fine detail of sled and equipment.

Then his glance fell upon Baldy—thin, rough coated, and showing evidences of neglect; upon Baldy to whom he could not now even offer food and shelter, and a wave of bitterness swept over him.

"Come along, sonny, if you're going our way," and in the kindly little man at the handle-bars the boy recognized "Scotty" Allan, the most famous dog driver in Alaska. To the boy "Scotty" represented all that was most admirable in the whole North, and he stood speechless at the invitation to ride with him behind a team that had always seemed as wonderful as Cinderella's Fairy Coach. He hesitated, and then the Woman in the sled beckoned encouragingly. "Get in with me; and your dog may come too," she said as she rearranged the heavy fur robes to make room. The boy advanced with painful shyness, and awkwardly climbed into the place assigned him. The Woman laid her hand on Baldy's collar to draw him in also, but the boy exclaimed quickly, "No, ma'am, don't do that, please; he ain't really cross, but he won't ride in anythin' as long's he's got a leg to stand on; an' sometimes he growls if people he don't know touches him."

"Dogs and boys never growl at me, because I love them; and he does not look as if he really had a leg to stand on," she replied smilingly. But the boy nervously persisted. "Please let him go—his legs is all right. He looks kind o' run down jest now 'cause he"—the boy felt a tightening at his throat, and winked hard to keep the tears from starting again—"'cause he ain't got much appetite. But when he's eatin' good his legs is jest great. Why, there ain't no other dog in Golconda that's got as strong legs as Baldy when he's—when he's eatin' good," he repeated hastily. "An' Golconda's plumb full o' fine dogs."

"If that's so," said "Scotty," "I think I shall have to take a look at those Golconda wonders before the winter fairly sets in; and maybe you can give me a few pointers."

For a mile or so the boy sat spellbound, drinking in the casual comments of "Scotty" upon the dogs in the team, as if they were pearls of wisdom dropping from the lips of an Oracle. He was not so much interested in the Woman's replies, for they displayed a lack of technical information that contrasted unfavorably in the boy's mind with the keen and accurate insight that Allan showed in every word on that most vital subject.

Vaguely the boy remembered having once heard that she had become a partner in the racing team for mere amusement of the sport, instead of from a serious, high-minded interest, and that of course did not entitle her to the same respect you could feel for one to whom the care and culture of the dog assumed the dignity of a vocation. Then, too, she had spoken slightingly of Baldy's legs. As a human being he could not but respond to her friendly overtures, but as a dog fancier she held no place in his esteem.

As they approached the divide where the trail for Golconda branched from the main road, an idea suddenly came to the boy. He had watched the harmony between Allan and his dogs; had noted their willingness, their affection for "Scotty," and his consideration for them. And as the pace became slower, and he realized that they were nearly at the end of this fate-given interview, he tremblingly gasped out the question that had been seething through his mind with such persistence. "Mr. Allan, would you like to buy Baldy?"

"Buy Baldy!" exclaimed the man in surprise. "Why, I thought you and Baldy were chums—I had no idea he was for sale."

"He wasn't till jest now, not till I saw how yer dogs love you; but I got t' git rid of him. It's been comin' fer a long time, an' I guess to-day's finished it."

The man leaned over and looked into the tear-stained face. "Are you in some trouble about him? Perhaps it's not so bad as you think, and maybe we can help you without taking Baldy."

But the boy went on determinedly. "No, sir, I want you to take him; it'd be the best thing fer him, an' I kin stan' it someway. A feller has ter stan' a lot o' things he don't like in this world, but I hope," feelingly, "all of 'em ain't as hard as givin' up his best friend."

As if to avoid the sympathy he felt was forthcoming, he plunged hastily into the details that had led to the unexpected offer. "I'm Ben Edwards. Maybe you knew my father; he was killed in the cave-in on the June Fraction. Baldy was only a little pup then, but Dad was awful fond of him."

"I remember," said the Woman thoughtfully; "and you have been in difficulties since, and need the money you could get for Baldy. Is that it?"

"It ain't only the money, but none o' the men at the Camp care much fer Baldy, an' they ain't kind to him. Only Moose Jones. When he was here he wouldn't let the men tease Baldy ner me, an' he made the cook give me scraps an' bones ter feed him. An' once he licked Black Mart fer throwin' hot water on Baldy when he went ter the door o' Mart's cabin lookin' fer me. I think Moose Jones is the best man in the world, an' about the strongest," volunteered the boy loyally.

"And where's Moose Jones now?" asked "Scotty." "I used to see him prospecting out near the Dexter Divide last winter."

"He was at Dexter first, an' then he was at Golconda fer a while; but in spring he went ter St. Michael, an' from there up ter the new strike at Marshall."

"And you miss him very much?" questioned the Woman.

"Yes, ma'am, I miss him a lot, an' so does Baldy. He was awful good ter animals an' kids. He had a pet ermine that 'ud come in ter see him every night in his cabin, an' he wouldn't let Mart an' some o' the fellers set a trap fer the red mother fox that was prowlin' round the place t' git somethin' fer her babies. Said he'd make trap-bait fer bears o' the first feller that tried t' git 'er."

"Excellent idea."

"Oh, he didn't really mean it serious. Why, Moose is so kind he hates ter kill anythin'—even fer food. Sometimes when he's been livin' on bacon an' beans fer months, he lets a flock o' young ptarmigan fly by him 'cause he says they look so soft an' pretty an' fluttery he don't like ter shoot 'em; an' Moose is a dead shot. He's mighty handy with his fists too, an' next ter Mr. Allan I guess Moose knows more about dogs than any man in Alaska; an' he said he'd bet some day there'd be a reg'lar stampede ter buy Baldy."

"A prophet," exclaimed the Woman. "You see we are the forerunners. But who is Black Mart?"

"Oh, he's a miner that's workin' the claim next ter Golconda. He's a friend o' the cook there, an' comes over ter eat pretty often. Him and Moose had some trouble once over some minin' ground, an' Mart kinda takes it out on all Moose's friends, even if they's only boys an' dogs, don't he, Baldy?" And Baldy wagged that he certainly did. "Now the cook says they've got work dogs enough belongin' ter the claim ter feed, without supportin' my mangy cur in idleness. Mr. Allan," earnestly, "he ain't mangy, an' he's the most willin' dog I ever seen fer any one that loves him. But he ain't sociable with every one, an' he don't like bein' handled rough."

"Scotty" looked at Baldy with a practiced and critical eye. "Those are all points in his favor," he remarked. "You can't do much with a dog that gives his affection and obedience indiscriminately."

"Besides, he ain't no cur—he's one o' them Bowen-Dalzene pups, an' you know there ain't a poor dog in the lot. They give him to me 'cause he wasn't like any o' the others in the litter, an' would 'a' spoiled the looks o' the team when they was old enough ter be hitched up," continued Ben breathlessly. "He was sort o' wild, too, an' he wouldn't pay attention t' any of 'em when I was round, an' they said I might as well take him fer keeps as t' have him runnin' away t' git t' me all the time."

"And your mother does not like him, and thinks it would be best not to keep him now?"

"She really does like him; but she does the washin' fer the Camp, an' helps with the dishes, an' sews when she kin git a job at it. But there ain't none of 'em reg'lar, an' sometimes there ain't more'n enough fer us two t' live on. Then she gits pretty tired an' discouraged like, an' says Baldy's a useless expense, an' keeps me from doin' my chores, 'cause I like t' play with him, an'—"

"Yes, yes, I see," broke in the Woman hastily, anxious to spare him any further revelations of a painful nature. "I know exactly how it is; but maybe we could make some arrangement with your mother about the dog. We will take a sort of an option on him; you can keep him with you, and we will pay a certain sum for the privilege of being permitted to buy him outright before the stampede actually begins."

The boy looked at her suspiciously, but there was no smile on her lips, and she rose a notch in his estimation. She evidently did realize, in a slight degree, what an unusual bargain was being offered in his heart-breaking sacrifice.

"An' it ain't 'cause his appetite's gone that makes him thin. I wasn't tellin' the truth about that," he stammered desperately; "he's jest hungry." The child's mouth quivered and he hesitated, yet he was determined to tell the whole of the sordid little tragedy now that he had begun. "But spendin' too much time with him when I should be workin' ain't the worst. To-day I done somethin' that mebbe she'll think ain't exac'ly square; an' my mother believes if you ain't square in this world you ain't much worth while."

"You're not, son," agreed "Scotty" heartily. "Your mother's right."

"My father was allers called Honest Ben Edwards out here on the Third Beach Line, an' Mother says she'd ruther have that mem'ry o' him than all the fortunes that's been made in Alaska by lyin' an' steal-in' an' jumpin' other people's claims."

"Right again, Ben. Nothing can take that from her, and a name like that is the best thing a man can leave his son."

"This mornin' she gave me some money fer a new pair o' mittens fer her, an' shoes fer me; an' the cook asked me t' buy a kitchen knife an' a few pans fer him. I walked inter town t' git 'em, an' Baldy come with me, though she said I was foolish t' be bothered with him. But I told her it was awful lonesome on the trail, an' she said I could take him this time." He paused for breath, visibly embarrassed.

"And you forgot all about your errands," hazarded the Woman.

"No, ma'am, I didn't exac'ly forgit, but when I was passin' the Court House an' I seen a big crowd inside, I went in, too, ter listen a minute.

"That lawyer Fink, that got up the Kennel Club, an' has the bully dog team, an' Daly, the feller with the smile that makes you feel like there's sunshine in the room, was a-talkin' agin each other; an' their fightin' was so excitin' an' so smooth an' perlite too, that everybody was a-settin' on the edges o' their chairs a-waitin' fer what was a-comin' next."

"So you were interested in what the lawyers had to say?"

"Yes, sir. Ever since my mother told me the story about President Lincoln a while ago, I been wantin' t' be a lawyer when I grow up. He didn't have no more book-learnin' than me at first, but he wouldn't let nothin' stop him, an' jest see what he done."

"Lincoln is to be your model, then? Well, you're right to aim high, Ben. You can practice his simple virtues of being honest and kind and industrious every day, and anywhere. And the education must be managed someway," added the Woman thoughtfully.

"After Mother read me that speech o' Mr. Lincoln's at Gettysburg, when all the people was jest dumb from their feelin's bein' so solemn an' deep; an' some o' his other speeches that was fine, I begun t' go t' town whenever there was t' be any good speakin', even when I had t' walk both ways."

"Shows your determination, as a starter," replied "Scotty" encouragingly. "And were you always repaid for your tramp?"

"Most allers, Mr. Allan. Last Fourth o' July I heerd Judge Tucker tell in his pleasant voice 'at sounds like he likes talkin' t' you all that Virginia's done fer our country, an' I wished I was from Virginia too. But mebbe some day I'll make some boy wish he was from Alaska by bein' fine an' smart an' gentle like Judge Tucker."

"Virginia or Alaska, Ben—it's all the same, so long as you're proud of your state, and give your state a chance to be proud of you."

"Yes, ma'am; that's what Mother says. Then I heerd Tom Gaffney recitin' Robert Emmett's last speech, on St. Patrick's day, at Eagle Hall, an' I near cried at the end; an' I don't cry easy. It takes somethin' pretty bad t' make me cry," and he looked furtively toward Baldy.

"I'm sure it does, sonny; any one can see that you're game, all right; but that speech always makes me cry too."

The boy regarded "Scotty" appreciatively. Here was a typical Alaskan, a sturdy trailsman, touched by the tender, pitiful things of life, just like a little boy that hasn't had time to become hardened. Ben felt that they would be friends.

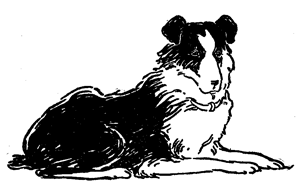

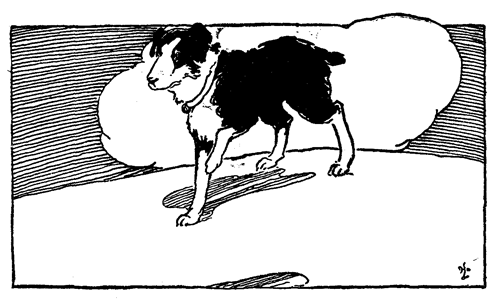

SCOTTY AND BALDY

"I like all kinds o' speakin', too; not jest the fiery sort that makes you want t' fight fer your country, an' mebbe die fer it like Robert Emmett; but the kind that jest makes you want t' be good ter folks an' dogs, an' do the best you kin when things is agin you, an' you don't see much ahead—"

The Woman nodded gravely. "Yes, I know. It's the most difficult sort of bravery—the sort without flags, and music, and cheers to keep you up to the firing line."

"That's the kind, ma'am. Mebbe you know Bishop Rowe. That's what he preaches—jest doin' your best all the time, like you was in some big race. When he's in Nome I allers go t' St. Mary's. He talks plain an' simple, an' cheers you up—I guess kinda the way Lincoln talked—jest like he knew all about people's troubles an' didn't blame 'em fer mistakes, but wanted t' help 'em t' do better. Sometimes his talks don't sound smooth, an' made up beforehand, but you never forgit 'em."

"Eloquence of the heart instead of the tongue," murmured the Woman.

"An' last August I went every night fer near a week, when Mr. Wickersham was talkin' men inter sendin' him t' Washington, no matter what they felt an' said agin his goin' when he wasn't before 'em."

"You have certainly had a variety of orators, and a wide range of subjects."

"You kin see I ain't missed a single chanct t' hear any of 'em since I made up my mind t' be a great man"—and then appalled by his lengthy burst of eloquence the child colored violently and concluded in confusion—"an' this mornin' I got so interested in them speeches o' Daly's an' Fink's, I must 'a' lost all track o' time, fer when I come out it was noon, an' Baldy was gone."

"You must indeed have been absorbed to forget Baldy. Where did you find him?"

"One o' the school kids told me the pound-man had got him, so I went over t' the pound on the Sand Spit as fast as I could run. I explained t' the man that Baldy wasn't a Nome dog; that we live five miles out at Golconda—but he said he was gittin' pretty sick o' that excuse. That no boy's dog ever really lived in Nome, so fur's he could find out; that all of 'em was residin' in the suburbs, an' only come in t' spend a day now an' then."

"It's a strange thing," mused the Woman, "that all pound-men are sarcastic and sceptical. It seems an inevitable part of their occupation. They never believed me when I was a little girl, either. Then what?"

"He said the only thing that concerned him was that Baldy was in town when he found him, and hadn't no license. Besides, he thought the dog was vicious 'cause he growled when the wire was around his neck. Pretty near any dog 'ud do that ef he had any spirit in him; an' Baldy's jest full o' spirit."

Both the Woman and "Scotty" looked involuntarily at Baldy who stood, dejected and uneasy; and then exchanged a glance in which amusement and pity struggled for expression.

"The pound-man said ef I didn't pay the $2.50 t' git him out, an' another $2.50 t' git him a license, he'd sell the dog along with a lot o' others he'd ketched durin' the week. I tuk Mother's money, an' what the cook give me, an' got Baldy out, an' bought him a license so's he'd be safe nex' time. Now," sadly, "there ain't goin' t' be any nex' time."

"There really did not seem to be any other way out of it for the moment," observed the Woman sympathetically.

"No, ma'am, but it wasn't very honest t' use the cook's money, ner Mother's; it'll take a long time t' pay 'em back, an' I guess Mother won't have much patience with Baldy after this. I wouldn't mind gittin' punished myself, but I don't want him blamed. He'd be a lot better off with you, Mr. Allan; an' mebbe ef you'd feed him up, an' give him a chanct, he'd be a racer some day. He'd never lay down on you, an'," almost defiantly, "he's got good legs."

"Scotty" felt the dog's legs, and noted the breadth of his chest. "What do you want for him, Ben?"

"Would ten dollars be too much?" asked the boy, eagerly.

"Ten dollars would be too little," quickly exclaimed the Woman. "You see we are getting ahead of all the others who do not know his fine points yet, and we should be willing to pay something extra for this opportunity. Do you think that twenty-five dollars would be fair, considering that we are in on the ground floor?"

"Yes, ma'am, that's lots more'n I expected. But it ain't so much the money I'm gittin' as the home he's gittin' an' the trainin' an' all."

"Well, that's a bargain, then; come to my husband's office—Darling and Dean, on Front Street, you know—the first time you are in town, and we will give you a check; and you can bring Baldy with you then."

"I guess," slowly, "you'd better take him now. It 'ud be easier fer me t' let him go while I'm kinda worked up to it. Mebbe ef I thought about it fer a few days I wouldn't be able t' do it, an' he mightn't have another chanct like this in his whole life."

He drew a frayed bit of rope from a torn pocket, and tied it to the old strap that served as Baldy's collar—handing the end to "Scotty."

In the deepening shadows of the chill November dusk the boy's face was ashen. He stooped over as if to see that the knot in the rope was secure at the dog's neck—but the Woman knew in that brief instant the trembling blue lips had been pressed in an agony of renunciation against Baldy's rough coat.

"Thank you both very much," he said in a tone that he tried to keep steady. "Thank you fer the ride and fer—fer everything."

He did not trust himself to look at the dog again, but stepped quickly into the Golconda Trail.

"You must come to see Baldy often," the Woman called to him.

"Yes, ma'am, I'll be glad to—after a while," he replied gratefully.

And then as "Scotty" gave the word to the impatient Racers, and the team swung round to return to Nome, there came to them out of the grayness a voice, faint and quavering like an echo—"Some day you'll be glad you've got Baldy."

Baldy's entrance into the Allan and Darling Kennel had failed to attract the interest that the arrival of a new inmate usually created. He was an accident, not an acquisition, and the little comment upon his presence was generally unfavorable.

Even Matt, who took care of the dogs, and was a sort of godfather to them all, shook his head dubiously over Baldy. "He don't seem to belong here, someway," had been his mild criticism; while the Woman complained to "Scotty" that he was one of the most unresponsive dogs she had ever known.

"He's not exactly unresponsive," maintained "Scotty" justly; "but he's self-contained, and it's hard for him to adjust himself to these recent changes. It's all strange to him, and he misses the boy. You can't watch him with Ben and say that he's not affectionate; but he gives his affection slowly, and to but few people. One must earn it."

The Woman regarded Baldy with amused contempt. "So one must work hard for his affection, eh? Well, with all of the attractive dogs here willing to lavish their devotion upon us, I think it would hardly be worth while trying to coax Baldy's reluctant tolerance into something warmer."

"Scotty" admitted that Baldy could hardly be considered genial. "He's like some people whose natures are immobile—inexpressive. It's going to take a little while to find out if it's because there is nothing to express, or because he is undemonstrative, and has to show by his conduct rather than by his manners what there is to him."

It was true that Baldy was unmistakably ill at ease in his new quarters, and did not feel at home; for he was accustomed neither to the luxuries nor to the restrictions that surrounded him. His early experiences had been distinctly plebeian and uninteresting, but they had been quite free of control.

Born at one of the mining claims in the hills, of worthy hard-working parents, he had, with the various other members of the family, been raised to haul freight from town to the mine. But his attachment for Ben Edwards had intervened, and before he was really old enough to be thoroughly broken to harness, he had taken up his residence at Golconda.

Here his desultory training continued, but a lesson in sled pulling was almost invariably turned into a romp, so that he had only acquired the rudiments of an education when he came under "Scotty's" supervision.

His complete ignorance in matters of deportment, and possibly, too, his retiring disposition, made him feel an intruder in the exclusive coterie about him; and certainly there was a pronounced lack of cordiality on the part of most of the dogs toward him. This was especially true of Tom, Dick, and Harry, the famous Tolman brothers, who were the Veterans of Alaska Dog Racing, and so had a standing in the Kennel that none dared question. That is, none save Dubby, who recognized no standard other than his own; and that standard took no cognizance of Racers as Racers. They were all just dogs—good or bad—to Dubby.

The fact that Tom, Dick, and Harry had been in every one of those unique dashes across the snow-swept wastes of Seward Peninsula, from Bering Sea to the Arctic Ocean and return, and had never been "out of the money," did not count greatly in his rigid code. The same distance covered slowly by freighters in pursuance of their task of earning their daily living would seem to him far more worthy of respect and emulation. And so, when the Tolman brothers, who were apt to be quarrelsome with those "not in their class," showed a coldness toward Baldy that threatened to break into open hostility at the slightest excuse, Dubby promptly ranged himself on the side of the newcomer with a firmness that impressed even Tom, Dick, and Harry with a determination to be at least discreet if not courteous.

They had learned, with all of the others in the Kennel, to treat with a studied politeness—even deference—the wonderful old Huskie whose supremacy as a leader had become a Tradition of the North; and who was still in fighting trim should cause for trouble arise. He did not rely alone on his past achievements, which were many and brilliant, but he maintained a reputation for ever-ready power which is apt to give immunity from attack.

Dubby's attitude toward the Racers generally was galling in the extreme. Usually he ignored them completely, turning his back upon them when they were being harnessed, and apparently oblivious of their very existence; except as such times when he felt that they needed suggestions as to their behavior.

There was, in a way, a certain injustice in Dubby's contempt for what might be called the sporting element of the stable; for, like college athletes, they were only sports incidentally, and for the greater part of the year they were as ready and willing to do a hard day's work in carrying goods to the creeks as were the more commonplace dogs who had never won distinction on the Trail.

But Dubby was ultra-conservative; and while "Scotty" must have had some strange human reason for all of these silly dashes with an absolutely empty sled, in his opinion hauling a boiler up to Hobson Creek would be a far more efficacious means of exercise, and would be a practical accomplishment besides. Dubby was of a generation that knew not racing. Of noted McKenzie River parentage, he came from Dawson, where he was born, down the Yukon to Nome with "Scotty" Allan. He had led a team of his brothers and sisters, six in all, the entire distance of twelve hundred miles, early manifesting that definite acknowledged mastery over the others that is indispensable in a good leader. He had realized what it meant to be a Pioneer, had penetrated with daring men the waste places in search of fame, fortune and adventure; and had carried the heavy burdens of gold wrested from rock-ribbed mountain, and bouldered river bed. He had helped to take the United States Mail to remote and inaccessible districts, and had sped with the Doctor and Priest to the bedside of the sick or dying in distant, lonely cabins.

He and his kind have ever shared the toil of the development of that desolate country that stretches from the ice-bound Arctic to where the gray and sullen waters of Bering Sea break on a bleak and wind-swept shore. They figure but little in the forest-crowned Alaska of the South, with its enchanted isles, emerald green, in the sunlit, silver waves; but they are an indispensable factor in the very struggle for mere existence up beyond the chain of rugged Aleutians whose towering volcanoes are ever enveloped in a sinister shroud of smoke. Up in the eternal snows of the Alaska of the North, the unknown Alaska—the Alaska of Men and Dogs.

THE ALASKA OF MEN AND DOGS

June 1—the Steamer Corwin at the Edge of The Ice, Five Miles

from Shore

And so it is not strange that in such a land where the dog has ever played well his rôle of support to those who have faced its dangers and conquered its terrors, that his importance should be at last freely acknowledged, and the fact admitted that only the best possible dogs should be used for all arduous tasks.

Toward this end the Nome Kennel Club was organized. The object was not alone the improvement of the breeds used so extensively, but also, since the first President was a Kentuckian, of equal importance was the furnishing of a wholesome and characteristic sport for the community.

And Nome, once famed for her eager, reckless treasure-seekers in that great rush of 1900; famed once for being the "widest open" camp in all Alaska, now in her days of peace and quiet still claims recognition. Not only because of the millions taken out annually by her huge dredgers and hydraulics; not only because she is an important trading station that supplies whalers and explorers with all necessary equipment for their voyages in the Arctic; not only because of her picturesque history; but because she possesses the best sled dogs to be found, and originated and maintains the most thrilling and most difficult sport the world has ever known—Long Distance Dog Racing.

Previous to the advent of these races any dog that could stand on four legs, and had strength enough to pull, was apt to be pressed into service; but since they have become a recognized feature of the life there, a certain pride has manifested itself in the dog-drivers, and dog-owners, who aim now to use only the dogs really fitted for the work. Even the Eskimos, who were notorious for their indifferent handling of their ill-fed, overburdened beasts, have joined in the "better dog" movement, which is a popular and growing one.

According to Dubby's stern law, however, most of the Racers—the long-legged, supple-bodied Tolmans, the delicately built Irish Setters, Irish and Rover, and numberless others of the same type, would have been condemned to the ignominy of being mere pets; useless canine adjuncts to human beings—creatures that were allowed in the house, and were given strangely repulsive bits of food in return for degrading antics, such as sitting on one's hind legs or playing dead.

Occasionally there was, for some valid reason, an exception to his disapproval; as in the case, for instance, of Jack McMillan. For while he could not but deplore Jack's headstrong ways, and his intolerance of authority in the past, he nevertheless felt a certain admiration for the big tawny dog who moved with the lithe ease of the panther, and held himself with the imposing dignity of the lion. An admiration for the dog whose reputation for wickedness extended even to the point of being called a "man-eater," and was the source, far and near, of a respect largely tempered with fear.

There was always an air of repressed pride about Jack when he listened to the thrilling accounts of his crimes told with dramatic inspiration to horrified audiences; a pride which is not seemly save for great worth and good deeds. Yet in spite of these grave faults of character Dubby accorded McMillan the recognition due his wonderful strength and keen intelligence; for Dubby, while intolerant of mere speed, was ever alert to find the sterner and more rugged qualities in his associates.

Perhaps it was partly because Baldy possessed no trivial graces and manifested no disdain for the homely virtues of the work dogs whose faithfulness has won for them an honorable place in the community, that Dubby had soon given unmistakable signs of friendliness that helped to make Baldy's new home endurable.

While Dubby's championship was a great comfort, there were many things of every-day occurrence that surprised and annoyed Baldy. Out of the bewilderment that had at first overwhelmed him he had finally evolved two Great Rules of Conduct, which he observed implicitly—to Pull as Hard as he Could, and to Obey his Driver. This code of ethics is perfect for a trail dog of Alaska, but it was in the minor things that he was constantly perplexed—things in which it was difficult to distinguish between right and wrong, or at least between folly and wisdom. To tell where frankness of action became tactlessness, and the renunciation of passing pleasures a pose. It was particularly disconcerting to see that virtue often remained unnoticed, and that vice just as often escaped retribution; and what he saw might have undermined Baldy's whole moral nature, but for the simple sincerity that was the key-note to his character. As an artless dog of nature he was accustomed, when the world did not seem just and right to him, to show it plainly—an attitude not conducive to popularity; and it often made him seem surly when as a matter of fact he was only puzzled or depressed. He could not feign an amiability to hide hatred and vindictiveness as did the Tolmans, and it was a constant shock to him to note how the hypocrisy of Tom and his brothers deluded their friends into a deep-seated belief in their integrity. Even after such depravity as chasing the Allan girl's pet cat, stealing a neighbor's dog-salmon, or attacking an inoffensive Cocker Spaniel, he had seen Tom so meek and pensive that no one could suspect him of wrong-doing who had not actually witnessed it; and he had seen the Woman, when she had actually witnessed it, become a sort of accessory after the fact, and shield Tom from "Scotty's" just wrath, which was extraordinary and confusing.

The confinement of a Kennel, too, no matter how commodious, was most trying. Even the vigorous daily exercise was "personally conducted" by Matt; and Baldy longed for the freedom that had been his when alone, or preferably with the boy, he had roamed through the far stretches of rank grass, tender willows, and sweet-smelling herbs in summer, or over the wide, snowy plains in winter.

Then, later, the boy came to Baldy; and there were blissful periods when he would lie with his head on Ben's lap; when the repressed enmity of the haughty Tolmans, the cold indifference of the magnificent McMillan, and even Matt's eternal vigilance were forgotten. Periods when his companion's toil-hardened hands stroked the sleek sides and sinewy flanks that no longer hinted of insufficient nourishment; and caressing fingers lingered over the smooth and shining coat that had once been so rough and ragged.

To see Baldy receiving the same care and consideration as his stable-mates, who had won the plaudits of the world, justified the boy's sacrifice; and in spite of his loneliness he always left Baldy with a happy heart.

"We'll show 'em some day we was worth while, won't we, Baldy?" he would whisper confidently; and Baldy's reply was sure to be a satisfactory wag of his bobbed tail, signifying that he certainly intended to do his best.

With the boy's more frequent visits Baldy's horizon began to widen almost imperceptibly. He even looked forward to those moments when, with George Allan and his friend Danny Kelly, Ben stood beside him discussing his points and possibilities.

Up to the present his world had included but two friends—the boy and Moose Jones. Annoyed and sometimes abused at the Camp, he had felt that there was no real understanding between himself and most of those with whom he came into association, and it had made him gloomy and suspicious. Now he knew, with the intuition so often found in children and animals, that George and Danny, as well as Ben, comprehended, at least in part, the emotions he could not adequately express—gratitude for kindness and a desire to please; and in return he endeavored to show his appreciation of this understanding by shy overtures of friendliness. He even licked George's hand one day—a caress heretofore reserved exclusively for Ben Edwards—and he escorted Danny Kelly the full length of the town to his home in the East End, much as he dreaded the confines of the narrow city streets where he was brought into close contact with strange people and strange dogs.

At Golconda, in his absorbing affection for the boy, he had more or less ignored the others of his kind—they meant nothing to him. But now the advantages of plenty of food and excellent care were almost offset by his occasional contact with the quarrelsome dogs of the street, and his constant companionship with the distinguished company into which he had come reluctantly and in which he seemed so unwelcome.

In "Scotty" Baldy discerned a compelling personality to whom he rendered willing allegiance and respect, as well as a dawning affection. And it was with much gratification that he had heard occasionally after inspection comments in a tone that contained no trace of regret at his presence, even if it had as yet inspired no particular enthusiasm. To be sure Allan found some merit in the least promising dogs as a rule, and perhaps the faint praise he was beginning to bestow on Baldy had in it more or less of the impersonal approval he gave to all dogs who did not prove themselves hopelessly bad. But it seemed at least a step in the right direction when "Scotty" had said, replying to criticism of the Woman, "No, he is certainly not fierce, and by no means so morose as he looks. So far I must confess he's proving himself a pretty good sort."

Of course even the Woman, who admitted frankly that first impressions counted much with her, knew that it was not always wise to judge by appearances, for she had seen the successful development of the most unlikely material. There was the case of Tom, Dick, and Harry. No one would ever have supposed in seeing them, so alert and with the quickness and grace of a cat in their movements, that in their feeble mangy infancy they had only been saved from drowning by their excellent family connections, and their appealing charm of responsiveness. A responsiveness that in maturity made them favorites with every one who knew them, and prompted the tactful ways that convinced each admirer that his approval was the last seal to their satisfaction in the fame they had won. When Tom leaned against people confidingly, and put up his paw in cordial greeting; and Dick and Harry, so much alike that it was nearly impossible to tell them apart, stood waiting eagerly for the inevitable words of praise, it was hard indeed to realize that their perfect manners were a cloak for morals that rough, uncultured Baldy would condemn utterly.

With the departure of the last boats of the summer there is no connecting link with the great, unfrozen outside, except the wireless telegraph and the United States Government Dog Team Mail that is brought fifteen hundred miles, in relays, over the long white trail from Valdez. Then, with the early twilight of the long Arctic winter, which lasts until the dawn of the brilliant sunshine and pleasant warmth of May, there come the Dog Days of Nome. Days that are heralded by an increased activity in dog circles, a mysterious fascination that weaves itself about all prospective entries to the races, and the introduction of a strange dialect called "Deep Dog Dope," which is the popular means of communication between all people regardless of age, sex or nationality—from the Federal Judge on the Bench to the tiniest tots in Kindergarten.

The town gives itself up completely to the gripping intensities and ardors of this period when all dog men assemble in appropriate places to talk over the prospects of the coming Racing Season. Accordingly George and Danny were in the habit of meeting in the Kennel, each afternoon, to consider the burning questions of the hour, with all of the certain knowledge and wide experience that belonged to their mature years—for George and Danny were seven and eight respectively.

Often Ben, whose mother had obtained work in town so that he might go to school regularly, joined in these important discussions; and while somewhat older than his companions, he greatly enjoyed being with them, for they were manly little fellows and had picked up much valuable dog lore from "Scotty" and Matt.

The Woman, too, for no apparent reason, was frequently at these serious conclaves, and was apt to voice rather trifling views on the weighty matters in debate. George felt that she was entitled only to the courteous toleration one accords the weaker sex in matters too deep for their inconsequent minds to grasp fully; for even if she was his father's racing partner, she had openly acknowledged that she considered dogs a pastime, and not a life study, which naturally proved her mental limitations.

THE WOMAN

One of the events already assured was a race for boys under nine years of age. "It's too bad you're too old for it, Ben," George had exclaimed sympathetically. "Father's told Danny and me we can use some of his dogs; and he'd 'a' been glad t' do the same for you. When I want t' drive fast dogs, and go t' the Moving Pictures at night, and drink coffee, I wish I was old too; but now I can see that gettin' old's pretty tough on a feller sometimes."

"Mebbe there'll be a race fer the older boys later," replied Ben hopefully. "I dunno as I could do much myself, but I sure would like t' try Baldy out. He minds so quick I think he'd be a fine leader; an' it looks like he'd be fast from the way he chases rabbits and squirrels out on the tundra."

"You can't allers tell about that," observed Dan pessimistically. "I got a dog that's a corker when he's just chasin' things; but when I put a harness on him he ain't fit for a High School Girl's Racin' Team, an' you know what girls is for gettin' speed out of a dog. 'You poor tired little doggie, you can stop right here an' rest if you want to; I don't care if they do get ahead of us,'" and Danny finished his remarks in the high falsetto and mincing inflection he attributed to the youthful members of a sex that in his opinion, as well as in George's, has no right to engage in the masculine occupation of Dog Mushing.

"Of course," said George, looking thoughtfully at Baldy, who was lying contentedly at Ben's feet, and giving voice to the wisdom of "Scotty" or Matt in such discussions, "of course, in a dog that's goin' in for the Big Race, you got t' have more'n speed. You can't depend on just that for four hundred and eight miles. There's got t' be lots of endurance an' the dogs had ought t' really enjoy racin' t' do their best. But for this race we're goin' in, Danny, I guess speed's the whole thing. Speed, an' the dog's mindin' you." George glanced involuntarily toward Jack McMillan, who sat with his head resting against the Woman's knee. "You can't do anythin' at all, no matter how fast dogs is, if they don't mind."

"I'm afraid, Mr. McMillan," commented the Woman seriously, "that these personalities are meant for you. Just because your first owner spoiled you, and the second paid the highest price ever given for a dog in the North, all accuse you of thinking yourself far too important to be classed with the common herd whose chief virtue is obedience. They say you lost a great race by being ungovernable. Guilty, or not guilty?" The brown eyes that had been wont to blaze so fiercely now looked pleadingly into the Woman's face, and the sable muzzle was pressed more closely against her. "They started you off all wrong, Jack. They let you become headstrong, and then tried to force you arbitrarily into their ways, instead of persuading you. If you had been a human being, all this would have been considered Temperament, but being only a dog it was Temper, and was dealt with as such." McMillan gravely extended his paw in appreciation of her championship.

"Oh, I didn't only just mean Jack when I was talkin' about dogs not mindin'," explained George with embarrassed haste; for he knew of the Woman's fondness for the dog and did not wish to hurt her feelings, much as he condemned her judgment in selecting such a favorite.

Her preference had dated from the night when she had entered the Kennel after a long absence, and had seen the stranger in the half light of the June midnight. He had changed somewhat since the imperious days when he had threatened the life of his trainer, and she had not recognized the Incorrigible in the handsome dog who had greeted her with such flattering cordiality.

He soon manifested an abject devotion to her, and would barely listen even to "Scotty" when she was near—the moment he heard her footsteps howling insistently till she ignored all of the others and came directly to him. It became a matter of pride with her to take him into the streets where people would still look askance at the erstwhile "man-eater," and comment on her courage in handling the "brute." While she and the "brute" had the little joke between them, which she later confided to Ben, that Jack McMillan's misdemeanors were merely the result of an undisciplined nature handled unsympathetically, and that at heart he was the gentlest dog in Nome.

"Jack minds all right now," ventured Ben. "I seen him the other day with Mr. Allan, an' he minded as good as any of 'em—even Kid."

"Well, none of them could do better than that. 'Scotty' says that Kid has every admirable quality that a dog could possibly possess, and that without a doubt he is the most promising racing leader in Alaska. But of course Jack would have to mind or he would not be here. The first thing a new dog must realize is that 'Scotty' is the sole authority, and that obedience is the first law of the Kennel. Even with his first racing driver I believe it was more a case of misunderstanding on both sides than wilful disobedience. But it grew to a point where it became almost a matter of life or death for one or the other."

"Moose Jones said they had t' break his tusks t' use him at all, an' that it took three men t' hold him away from his driver sometimes; an' that 'Scotty' was the only man in the whole North that could git the best of him without breakin' his spirit. An' he seems terrible fond o' 'Scotty'—I mean Mr. Allan—now."

"You may call him 'Scotty,' Ben; he doesn't mind in the least. He's 'Scotty' to every Alaskan from Juneau to Barrow, Eskimos included—age no restraint. Yes, Jack is fond of 'Scotty,' but it took a battle royal to bring about this permanent peace."

"It's a wonder he wasn't killed before you an' 'Scotty' got him, if they was all so scared t' handle him."

"He would have been killed except that his enormous strength and unusual alertness made him too valuable. So in spite of their fears they kept him, but he was watched incessantly; and after his tusks were broken he became even more rebellious, and grew to distrust every one about him. Poor old fellow." She turned the handsome head toward the boy. "Look at him, Ben. Would you believe that they used to frighten naughty children by telling them that Jack was out looking for them?"

It was a fact that his name had once carried a suggestion of grim terror and impending disaster in Nome. And the dark hint that McMillan of the Broken Tusks was in the neighborhood struck consternation to the hearts of infant malefactors, and had been the source of much unwilling virtue, and many a politic repentance on the part of those offenders hitherto only impressed by the threatened arrival of the Policeman.

Ben regarded Jack with admiration and pity. He was sorry for even a dog that has been misunderstood.

"No, ma'am, he don't look vicious, but he sure does look powerful. If a man had a whole team like Jack there'd hardly be a chanct t' beat him, I s'pose."

"I'm not so sure of that, Ben. Of course the team counts for a great deal; so, too, does the skill of the driver. But there are many other things that enter into this contest that do not have to be considered usually. Given a mile of smooth track and horses in perfect condition, well mounted, the fastest one is apt to win. In a race that lasts for over three days and nights, however, through the roughest sort of country, in weather that may range from a thaw to a blizzard, and with fifteen or twenty dogs to manage, the Luck of the Trail is an enormous factor. One team may run into a storm, and be delayed for hours, that another may escape entirely; and a trivial accident may put the best team and driver entirely out of commission."

"That's so," agreed Danny. "That's what happened the year 'Scotty' lost the race to Seppala, an' came in second. Don't you know, George, your father told us it was near the end o' the run, an' the dogs was gettin' pretty tired, so he put a loose leader at the head t' give 'em new life—sort t' ginger 'em up. I guess that dog was as tired as the rest, an' nervous, 'cause he missed the trail in a terrible blow an' got separated from 'Scotty' an' went back t' the Road House they'd left last, like he'd been learned t' do. O' course 'Scotty' looked for him a while an' then went back for him. But it lost the race, all right, an' the cinch he had on breakin' the record. With them four hours lost, an' what he done later, he'd 'a' made the best time ever known in a dog race in Alaska. Gee, it was awful."

The Woman sighed. "Well, at least they can't blame the loss of that race on you, can they, Jack? It certainly was hard luck, but we will have to be good sports and try it again. Perhaps you'll develop a dog star of the first magnitude for us in your race, boys."

George and Danny looked serious. It was a difficult problem—this assembling of a racing team, and the responsibility weighed heavily upon them. Why, it meant the possibility of making a juvenile Record, and winning a Cup, and naturally required a critical consideration of even the smallest details.

"If I could only take some o' the Sweepstakes Dogs," mused George regretfully, "it 'ud be dead easy; but Father says it wouldn't be fair t' the fellers that hasn't a racin' stable t' pick from. We got t' use some o' the untried ones. I been thinkin' o' Spot for a leader. He seems sort o' awkward, 'cause he's raw-boned, an' ain't filled out yet; but all the other dogs like him, an' he'd ruther run than eat."

"Isn't he pretty young for that position?" hazarded the Woman. "Let me see, he can't be much more than a year old now."

She remembered when he had been a common little fellow, but a short time ago, sprawling in every mud-puddle, or wobbling uncertainly after the many strange alluring things in the streets. Matt, who seemed to have second sight in regard to the invisible, latent good points in all horses and dogs, had picked him up in the pound for a mere nothing; and to him there was granted the vision of a brilliant future for the vagrant puppy. "Mark my words," he had said decisively when Spot's fate hung in the balance, "you can't go wrong on him; he'll be a credit to us all some day." And so Spot was rescued from death, or at least from a life of poverty and obscurity, and given to George Allan to become his constant companion.

"You know," she persisted, "if a leader is too young he's apt to become over-zealous and important the way Irish did the day we loaned him to Charlie Thompson in the first Moose Handicap. Don't you remember he was disgusted at the way they were being managed by a rank novice, so he took his place in front of a rival team that was being well driven, and led them to victory, with the whole town cheering and yelling? You don't want that to happen to you, because your leader is inexperienced."

"It ain't the same thing at all," explained George patiently; for it is ever the man's part to try to be patient with the feminine ignorance of dogs and baseball and other essential things about which women seem to have no intuition. "You see, I ain't goin' to drive him loose. A dog shouldn't ever be a loose leader unless he's a wonder at managin' all the rest, an' young dogs ain't generally had the trainin' for it. After a dog has showed he can find the trail, an' keep it, an' set the pace, an' make the others mind him, bein' a loose leader's kind of an honor he's promoted to; like bein' a General in the army. He don't have t' be hitched up to the tow-line any more, an' pull; he just has t' think, an' keep the team out o' trouble."

"It's too bad that dogs aren't driven with lines instead of spoken orders—then there wouldn't be all of the bother about a leader every time." Both George and Danny looked at her for a moment with a contempt they barely succeeded in concealing. Even Ben Edwards was unpleasantly surprised, and he was not given to regarding her vagaries with unfriendly criticism.

Drive with lines! Bother about a leader! Why, if dogs were driven with lines there would be no more interest in driving a dog team than there is in driving a delivery wagon, or running an automobile. All of the fascination of having your dogs answer to your will, voluntarily and intelligently, would be lost in the mechanical response to the jerk and the pull of the reins.

She was utterly hopeless. There was no use of a further waste of words with her on such matters.

George turned to Danny and Ben. They were discerning, and capable of grasping a dog man's point of view. "Then there's Queen, for one wheeler. You know we're only allowed three dogs, an' we got t' be mighty careful."

"I expect it's pretty near 's important t' git the right wheel dogs as 'tis a leader, ain't it, George? Bein' next t' the sled an' so close t' the driver an' load, they allers seem t' kinda manage the business end o' things."

"That's right, Ben. That's why we got t' be sure o' gettin' good wheelers. In racin' there's no load, but it takes some managin' just the same t' keep the sled right on side hills an' goin' down steep slopes. O' course in a short race I wouldn't get into the sled at all, an' on the runners at the back I can get my feet on the brake easy. But Father an' Matt say that you want your wheelers t' know just what their duties is if the brake gets out o' order, or any thin' goes wrong."

"Wheelers have to be clever, and strong and tractable then—rather a big order," murmured the Woman somewhat meekly, as one seeking information.

"Yes, ma'am," replied Danny politely, "all o' that, an' I was just wonderin' if Queen 'ud do for the place."

Queen, another present of Matt's to George, was a Gordon Setter with a strong admixture of native blood, and was hopeless as a regular team dog because of her high-strung and irritable disposition. Naturally nervous, she had become, with the advent of her first family, so fierce that it was dangerous for any one to approach her except George, and for him she cheerfully left her puppies to be of service in sled pulling.

"Oh, I think she'll do; when you know Queen an' like her she ain't so bad; an' besides not bein' able t' take any o' the real racers don't leave us much choice."

"Do you—don't you think you could use Baldy?" suggested Ben eagerly. "He's no locomotive like McMillan, ner a flyin' machine like them Tolman dogs an' Irish an' Rover; but you've no idea how powerful an' willin' he is till you've tried him. Just give him a show, George. I'm 'most sure he'd make good. Moose Jones allers said he would."

There was a moment of serious consideration on the part of George, while Danny eyed Baldy critically, and remarked with discrimination, "Better take him; some o' these common lookin' dogs has the right stuff in 'em. If looks was everythin' I guess you an' me 'ud be scrappin' over Oolik Lomen or Margaret Winston, that new fox-hound Russ Downing just got from Kentucky. But you an' me know too much t' get took in by just good looks, George."

"All right, Ben. I'll take Baldy for the other wheel dog," said George as he ran his hand over Baldy's sturdy, muscular body. "He'll be able to show somethin' o' what's in him in this dash. Now we'd better see about Danny's team."

The Woman's observation that she thought Jemima, being black, would make a more artistic wheel-mate for Queen from the standpoint of color harmony, than would white-faced sable Baldy, was silently ignored, as was merited.

And so, in defiance of Art, and in spite of her evident prejudice against him, Baldy made one of George Allan's Racing Team.

Danny, after much discussion and deep thought, selected Judge for his leader, and Jimmie and Pete as wheelers. They were all steady and reliable, and made up a more dependable team than George's uncertain combination of youthful Spot, fiery Queen, and untried Baldy.

Ben was elated that the latter had been accepted by such experts as being worthy a place in the coming event. And as he left the Kennel to rush home to tell his mother the great news, he pictured Baldy in his coming rôle of wheeler in so distinguished a company. "I'm mighty glad I give him up when I did," he thought cheerfully. "Baldy is sure gettin' his chanct now."

The last two weeks before the Alaska Juvenile Race, as the Nome Kennel Club had announced it, were busy ones, not only for the boys who were to actually take part in it, but for all of their friends as well. For those who had not teams for the event had more than likely loaned a dog, a sled or a harness to one of the contestants, and consequently felt a deep personal interest in all incidents connected with the various entries.

To Ben Edwards the time was full of diversions, for every afternoon on his way home from school he stopped at the Kennel to curry and brush Baldy or help George and Danny in the care of the other dogs whose condition was of such moment now.

When George felt that he should give Spot special training to fit him for his new position as leader, or took Queen out under the strict discipline he knew would be necessary to prepare her for the ordeal, he would ask Ben to hitch Baldy to one of the small sleds and give him a run.

Baldy's nature had always expressed itself best in action, and Ben was delighted with the ease with which he adjusted himself to serious sled work. There were no more romps, no more games, but his pace became even and steady, and he required no threats and no inducements to make him do his best.

"There's one thing about Baldy," admitted George freely, "you don't have t' jolly him along all the time. Why, even with Spot I have to say 'Snowbirds' an' 'Rabbits' every little while when I want him to go faster, an' then you should see him mush. You know that's what Father says t' Tom, Dick 'an' Harry, an' Rover an' Irish. It's fine with any of 'em that's got bird-dog blood, an' you know Spot's part pointer. O' course they don't have t' really see snowbirds an' rabbits, but they just love t' hear about 'em, an' begin t' look ahead right away. An' if they do happen t' see 'em, they pretty nearly jump out o' their harness, they're so crazy for 'em."

"Baldy's part bird-dog, too," said Ben, "but I been watchin' him close, an' it ain't anythin' outside that makes him want t' go; it's more like he feels a sort o' duty about doin' the very best he kin fer any one that's usin' him. He's allers willin' t' do more'n his share; an' he's lots happier when he's workin' hard than when he's just lyin' idle in the stable, or bein' trotted out by Matt fer a walk."

"I wisht I was like that," muttered Danny gloomily. "That bein' happiest when you're workin' hard must be great; but I guess it's only dogs an' mebbe some men that's like that. I don't know o' any boys that's got such feelin's."

NOME, ALASKA—FROM BERING SEA

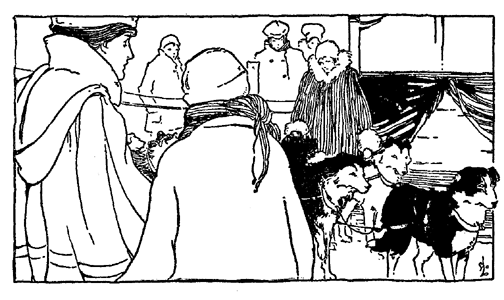

When the day of the Boys' Race arrived, a day clear, and beautiful, and only a degree or two below zero, it seemed as if all of Nome had decided to celebrate the momentous occasion; going in crowds to the starting place, which was a broad, open thoroughfare on the outskirts of town. Those especially interested in the individual teams gathered at the various kennels to see the dogs harnessed and the young drivers prepared for their test as trailsmen in the coming struggle.

It was Saturday, and a general holiday, and Ben's mother had given him permission to go to the Kennel early; so that when George and Dan arrived they found their dogs smooth and shining from the energetic grooming that Ben had given them.

"It's awful good of you, Ben," said George appreciatively. "Danny an' me came in plenty o' time t' do it ourselves, an' Matt said he'd help us too; an' now you've got 'em lookin' finer'n silk. I'll bet even Father'll say they're as fine as a Sweepstakes Team, an' he's mighty partic'lar, I can tell you. But I don't see how you got Queen t' stand for it."

"I talked to 'er jest the way you do, an' then walked straight up to 'er so's she'd see I wasn't afeared. Moose Jones says it's no use tryin' t' do anything with a dog that knows you're scared. He told me the reason your father made a good dog out o' Jack McMillan was because he wasn't afeared of him, an' give the dog an even break in the terrible fight they had."

"Father always does that," responded George proudly. "He believes you got t' show a dog once for all that you're master of him at his very best. If you tie a dog o' McMillan's spirit, an' beat him t' make him obey, he always thinks he hadn't a fair chance. But if you can show him that he can't down you, no matter how good a scrap he puts up, he'll respect you an' like you the way Jack does Dad."

"I don't believe me an' Queen'd ever have any trouble now," observed Ben thoughtfully. "Some way I guess we kinda understand each other better'n we did before."

"Well, it sure shows you got courage," exclaimed Dan admiringly. "I wouldn't touch that snarlin' brute o' George's, not if I could win this race by it, an' you know what I'd do fer that." He examined Judge, Jimmie, and Pete, with profound satisfaction. They were compactly built, of an even tan color, short haired, bob-tailed, and all about the same size, being brothers in one litter. Their sturdy legs suggested strength and their intelligent faces spoke of amiability as well as alertness. They were indeed worthy sons of the fleet hound mother—Mego—whose puppies rank so high in the racing world beyond the frozen sea. "They just glisten, Ben. You must 'a' worked hard t' get 'em lookin' as smooth an' shinin' as the fur neck-pieces the girls wear."

"O' course I wanted t' git Baldy ready fer his first race; an' doin' little things fer the other dogs is about the only way I kin pay everybody round here fer all they're doin' fer him."

Baldy was fast learning not to despise the detail that had made the new life so irksome before he realized how necessary it is in a large Kennel; and he now stood patiently waiting for his harness, while long discussions took place as to the adjustment of every strap, and the position of every buckle.

"Scotty" and Matt had come in to be ready with counsel and service, if necessary; then the Allan girls and many of the children from the neighborhood arrived, and later the Woman appeared with the Big Man whom Baldy some way associated invariably with her, and a yellow malamute whom Baldy invariably associated with him.

The Big Man always spoke pleasantly to the dogs, and had won Baldy's approval by not interfering—as did the Woman—in Kennel affairs; and the malamute—the Yellow Peril, as the Woman had named him—was plainly antagonistic to the Racers, at whom he growled with much enthusiasm. And so Baldy was glad to see the Big Man and the Peril amongst the acquaintances and strangers who were thronging into the place.

George brought out a miniature racing sled—his most prized possession—and a perfect reproduction of the one "Scotty" used in the Big Races, being built strongly, but on delicate lines. Danny pulled another, only a trifle less rakish, beside it. They were conversing in low tones. "We got pretty nearly half an hour t' wait, Dan, an' it's fierce t' have all these people that don't know a blame thing about racin' standin' round here givin' us fool advice. Why, if we was t' do what they're tellin', we'd be down an' out before we reached Powell's dredge on Bourbon Creek. Most of 'em don't know any more 'bout dogs 'n I do 'bout—'bout—"

"'Rithmetic," suggested Danny promptly.

"Well, anyway, we got t' run our own race. Dad says there ain't any cut an' dried rules for dog racin' beyond knowin' your dogs, an' usin' common sense. Each time it's different, 'cordin' t' the dogs, the distance, the trail an' the weather. An' you have t' know just what it's best t' do whatever happens, even if it never happened before."

"Gee," sighed Danny heavily, "winnin' automobile races an' horse races is takin' candy from babies besides this here dog racin'. I hadn't any idea how much there was to it till we begun t' train the dogs, an' talk it over with your father. I was awful nervous last night, I don't believe I slept hardly any, worryin' about the things that can go wrong, no matter how careful you are."

"I didn't sleep any, either. I got t' thinkin' about Queen hatin' Eskimos, an' chasin' 'em every time she gets a chance. It 'ud be a terrible thing if she saw one out on the tundra, an' left the trail t' try and ketch him; or if she smelled some of 'em in the crowd an' made a break for 'em just when she ought t' be ready t' start. An' you know there's bound t' be loads of Eskimos, 'cause they'd rather see a dog race than eat a seal-blubber banquet."

"That's so; but Spot is good friends with all the natives 'round town, an' he's stronger'n Queen, an' wouldn't leave the trail for anything but snowbirds or rabbits, so he'd hold 'er down. An' I guess Baldy'd be kinda neutral, 'cause he don't pay attention t' Eskimos or anything when he's workin'. I never saw a dog mind his own business like Baldy. That's worth somethin' in a race." The inactivity was becoming unbearable. "George, if you and Ben'll get the dogs into harness, I'll go an' see what's doin' with some of the others. It'll sort o' fill in time."

Ben and George hitched the dogs to the respective sleds after Spot, in the exuberant joy of a prospective run, had dashed madly about, barking boisterously, a thing absolutely prohibited in that well-ordered household. "Scotty" and Matt refrained from all criticism of George's leader, knowing that both the boy and dog were unduly excited by the noisy, laughing groups surrounding them. Queen, while she waited with very scant patience for the strange situation, diverted herself by nipping viciously at any one who went past, and Baldy stood quiet and different save when Ben Edwards was near, or "Scotty" spoke kindly to him.

Mego's sons, as was natural with such a parent, and with Allan's training since they were born, behaved with perfect propriety; and there were many compliments for Dan's team, which manifested a polite interest in the development of affairs.

Shortly Dan returned with somewhat encouraging information about the rival teams.

"Bob's got three dogs better matched 'n yours as t' size," he remarked judicially, "but his leader, old Nero, 's most twelve, you remember, 'nd wants t' stop an' wag his tail, an' give his paw t' every kid that speaks to him. Bill's got some bully pups, but his sled's no good; it's his mother's kitchen chair nailed onto his skiis. Jimmie's team's a peach, an' so's his sled; but Jim drives like a—like a girl," finished Mr. Kelly scornfully, with the tone of one who disposes of that contestant effectively and finally. "For looks an' style, I can tell you, George, there ain't any of 'em that's a patch on my team. Some Pupmobile!"

He glanced proudly at the wide-awake dogs who showed their breeding and education at every turn, and then toward George's ill-assorted collection: Spot, rangy, raw-boned, and awkward, Queen fretful and mutinous, and Baldy so stolid that it was evident he was receiving no inspiration from the enthusiasm about him.

"Of course you can beat me drivin' without half tryin', George, an' if Spot's feet wasn't so big, an' Queen didn't have such a rotten disposition, an' Baldy knew he was alive, it 'ud be a regular cinch for you. But the way things is, believe me, I'm goin' t' give you a run for your money, with good old Mego's 'houn' dogs.'"

Both George and Dan had, of course, like all small boys in Nome, at one time or another, made swift and hazardous dashes of a few hundred yards, in huge chopping bowls purloined from their mothers' pantries; and drawn by any one dog that was available for the instant, and would tamely submit to the degradation. An infantile amusement, they felt now, in the face of this real Sporting Event that was engaging the attention of the entire town. And to complete the feeling that this was indeed no mere child's play, the Woman came to them with two cups of hot tea to warm them up, and steady their nerves on the trail. This they graciously accepted and drank, in spite of its very unpleasant taste; for "Scotty" always drank tea while giving Matt the last few necessary directions before a race.

"All ready, boys, time to leave," called the Big Man cheerily. "Peril and I will go ahead, and charge the multitudes so that you can get through."

The Allan girls pressed forward hurriedly to give George two treasured emblems of Good Luck—a four-leaf clover in a crumpled bit of silver paper, and a tiny Billiken in ivory, the cherished work of Happy Jack, the Eskimo Carver.

Equally potent charms in the form of a rabbit's foot, and a rusty horseshoe were tendered Danny by his staunch supporters.

At the big door of the Kennel the boys stopped for a final word. "We won't make a sound if we should have to pass on the trail," said George. "We'll be as silent as the dead," an expression recently acquired, and one which seemed in keeping with these solemn moments. "All the dogs know our voices, an' if we should speak they might stop just like they have when we've been exercisin' 'em, an' wanted t' talk things over. We'll pull the hoods of our parkas over our heads, an' turn our faces away so's not to attract 'em. Dan, I do want t' win this race awful bad, 'cause o' my father mostly, but you bet I hope you'll come in a close second."

"Same to you, George," and they made their way to the middle of the street, where they fell in behind the Big Man and the Peril, and were flanked by the Woman and "Scotty," Matt and Ben, with most of the others who had waited for this imposing departure.

The other entries had already arrived at the starting point, where there was much confusion and zeal in keeping the bewildered dogs in order. It was a new game, and they did not quite comprehend what was expected of them.

At last, however, the Timekeeper, and Starter, assisted by various members of the Kennel Club, had cleared a space into which the first entry was led with great ceremony. It was Bob, with the cordial, if ancient, Nero in the lead.

They were to leave three minutes apart; the time of each team being computed from the moment of its departure till its return, as is always done in the Great Races.

The Timekeeper stood with his watch in his hand, and the Starter beside him. Bob, eager for the word, spoke soothingly to the dogs to keep them quiet. He was devoutly hoping that Nero would not discover any intimate friend in the crowd and insist upon a formal greeting; for Nero's affability was a distinct disadvantage on such an occasion.

At last the moment came, and the Starter's "Go" was almost simultaneous with Bob's orders to his leader, whose usual dignified and leisurely movements were considerably hastened by the thunderous applause of the spectators.

It was a "bully get-away," George and Dan agreed, and only hoped that theirs would be as satisfactory.

Bill followed with equal ease, and equal approbation.

Jim, justifying Dan's earlier unfavorable report, lost over a minute by letting his dogs become tangled up in their harness, and then coaxing them to leave instead of commanding.

"Wouldn't that jar you?" whispered Dan disgustedly. "Why, your sister Helen does better'n that in those girly-girly races, even if she does say she'd rather get a beatin' herself than give one to a dog."

But the general public looked with more lenient eyes upon such mistakes, and Jim left amidst the same enthusiasm that had sped the others on their way.

When Dan and his dogs lined up there was much admiration openly expressed.

"Looks like a Sweepstakes team through the wrong end of the opry glasses, don't it?" exclaimed Matt with justifiable pride to Black Mart Barclay, who happened to be next him.

Mart scrutinized the entry closely. "Not so bad. Them Mego pups is allers fair lookers an' fair go-ers, so fur's I ever heered t' the contrary," he admitted grudgingly.

There was an air of repressed but pleasurable expectation about the little "houn' dogs," as they patiently waited for their signal to go. Their racing manners were absolutely above reproach. Unlike Nero, they quite properly ignored the merely social side of the event, and were evidently intent upon the serious struggle before them; and equally unlike Queen and Baldy, they showed neither the peevishness of the one, nor the apathy of the other.

By most people the race was practically conceded to Dan before the start.

It seemed an endless time to George before it was his turn; but when he finally stepped into place, the nervousness that had made the wait almost unbearable disappeared completely. The hood of his fur parka had dropped back, and his yellow hair, closely cropped that it should not curl and "make a sissy" of him, gleamed golden in the sunlight above a face that, usually rosy and smiling, was now pale and determined.

In that far world "outside," George Allan would have been at an age when ringlets and a nurse-maid are just beginning to chafe a proud man's spirit; but here in the North he was already "Some Musher,"1 and was eager to win the honors that would prove him a worthy son of the Greatest Dog Man in Alaska.

True to their several characteristics, Spot manifested an amiable and wide-awake interest in all about him, Queen repelled all advances with snaps and snarls, and Baldy quivered with a dread of the unknown, and was only reassured when he felt Ben Edwards' hand on his collar, and listened to the low, encouraging tones of the boy's voice.

THE START OF AN ALASKAN DOG TEAM RACE

"Too bad, Matt," drawled Black Mart, "that the little Allan kid's usin' Baldy. He was allers an ornery beast, an' combin' his hair an' puttin' tassels an' fancy harness on him ain't goin' t' make a racer outen a cur."

Ben's face flushed hotly. "It ain't just beauty that counts, Baldy; it's what you got clear down in your heart that folks can't see," he thought, and clung the more lovingly to the trembling dog.

Matt carefully shook the ashes from his pipe. "It's a mighty good thing, Mart, that people an' dogs ain't judged entirely by looks. If they was, there's some dogs that's racin' that would be in the pound, an' some men that's criticizin' that would be in jail."

"Ready."

George, poised lightly on the runners at the back of the trim sled, firmly grasped the curved top, and repeated the word to Spot, who held himself motionless but in perfect readiness for the final signal.

"Go."

With unexpected buoyancy and ease, Spot darted ahead, and for once Queen forgot her grievances, and Baldy his fears; as in absolute harmony of action, the incongruous team sped quickly down the length of the street, and over the edge of the Dry Creek hill; to reappear shortly on the trail that led straight out to the Bessie Bench.

The Road House there was the turning point, where the teams would pass round a pole at which was stationed a guard; and the collection of buildings which marked the end of half of the course looked distant indeed to the five young mushers who with their teams had now become, to the watchers in Nome, merely small moving black specks against the whiteness of the snow.

George and Dan had discussed the matter fully in the preceding days, and had decided that, like "Scotty," they would do all of the real driving on the way home. So it was not at all disconcerting, some time before they reached the turn, to meet two of the teams coming back. The third, Jim's, had been diverted at the Road House by a large family of small pigs in an enclosure surrounded by wire netting; and Jim's most alluring promises and his direst threats were both unavailing against the charms of the squealing, grunting creatures, the like of which his spellbound chargers had never seen before.

Dan was several hundred feet ahead of George, and the latter could but look with some misgivings at the even pace of Judge, Jimmie and Pete; a pace that as yet showed no sign of weakening. Of course should Mego's pups prove faster than his own team, he would loyally give all credit due the driver and dogs; but it would be a bitter disappointment indeed if Spot did not manifest the wonderful speed that Matt had always predicted for him, and if there was no evidence in superior ability, of the long hours of careful attention that George had devoted to his education as a leader.

When Dan's team finally rounded the pole, and was headed toward him, George realized that the work of Mego's sons evinced not only mechanical precision, but the intelligence of their breeding, and the advantages of their early training by "Scotty." Dan would indeed, as he had boasted, "give them a run for their money."

"Mush, Spot, Queen, Baldy," and there was a slight increase in briskness, which was checked again as they swung by the guard.

"Now then, Spot," and George gave a peculiar shrill whistle that to the dog meant "Full Speed Ahead."

He watched the distance between himself and Dan decrease slowly at first; then more rapidly until they were abreast of one another. True to their compact they did not speak, and the inclination of Spot to stop for the usual visit beside his stable mates received no encouragement. Instead he got a stern command to "Hike, and hike quick!"

Beyond were the other teams, almost together, and to George it seemed as if he barely crept toward Bob and Bill; though there was a steady gain to the point where he could call out for the right of way to pass—a privilege the driver of the faster team can demand.

But just behind him came Dan, whose dogs now felt the inspiration of the stiff gait set them by their friends; and both boys knew that from now on the race was between them alone.