[Transcriber's Note: Several variant spellings of, for example,

"medecine" and "Mormon", have been retained from the original.]

INDEX OF CHAPTERS

INDEX OF ILLUSTRATIONS

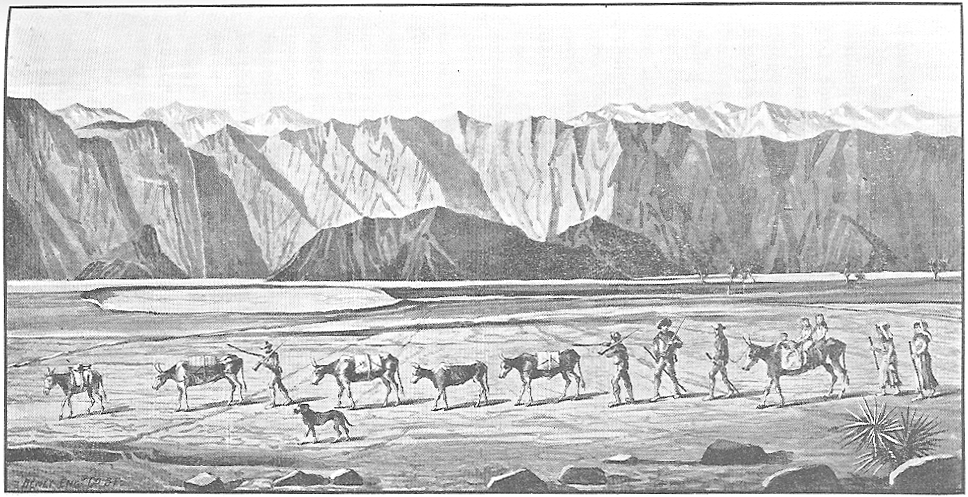

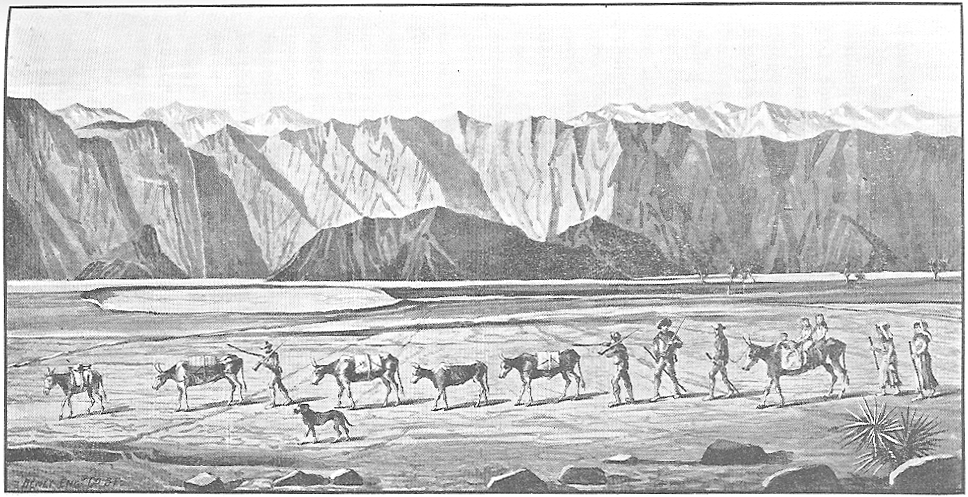

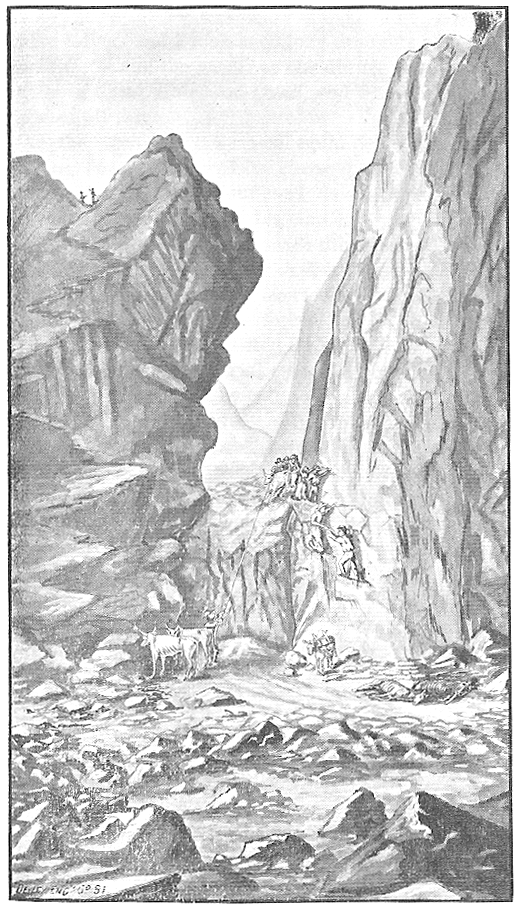

Leaving Death Valley—The Manly Party on the March After Leaving Their Wagons.

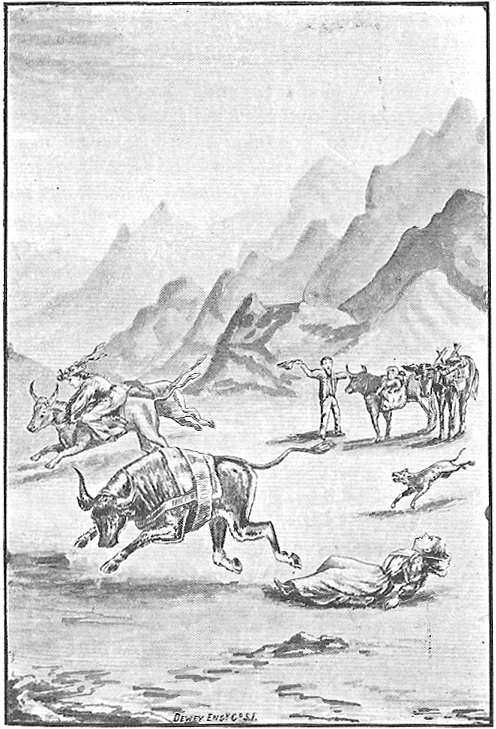

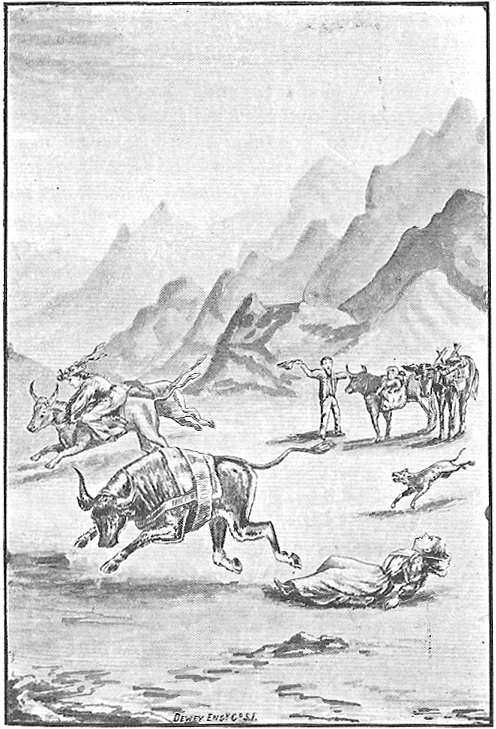

The Oxen Get Frisky.

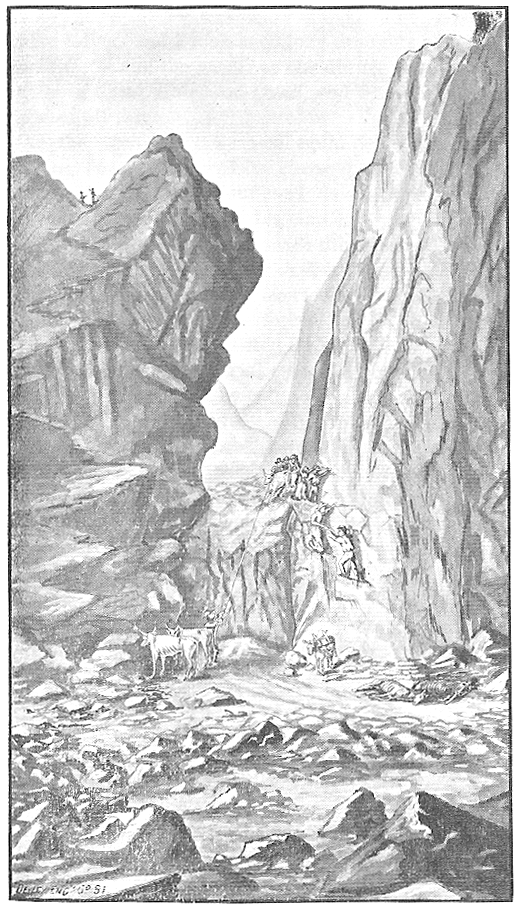

Pulling the Oxen Down the Precipice.

DEATH VALLEY

IN '49.

_____________________

IMPORTANT CHAPTER OF

California Pioneer History.

_____________________

—THE—

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A PIONEER, DETAILING HIS LIFE FROM A

HUMBLE HOME IN THE GREEN MOUNTAINS TO THE

GOLD MINES OF CALIFORNIA; AND PARTICULARLY

RECITING THE SUFFERINGS OF THE BAND

OF MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN WHO

GAVE "DEATH VALLEY" ITS NAME.

_____________________

BY WILLIAM LEWIS MANLY.

_____________________

SAN JOSE. CAL.:

THE PACIFIC TREE AND VINE CO.

1894.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1894, by

WM. L. MANLEY,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D.C.

TO

THE PIONEERS OF CALIFORNIA,

THEIR CHILDREN AND GRANDCHILDREN,

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED,

WITH THAT HIGH RESPECT AND REGARD

SO OFTEN EXPRESSED IN ITS PAGES,

BY THE AUTHOR.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

Birth, Parentage.—Early Life in Vermont.—Sucking Cider through a Straw.

CHAPTER II.

The Western Fever.—On the Road to Ohio.—The Outfit.—The Erie Canal.—In the Maumee Swamp.

CHAPTER III.

At Detroit and Westward.—Government Land.—Killing Deer.—"Fever 'N Agur."

CHAPTER IV.

The Lost Filley Boy.—Never Was Found.

CHAPTER V.

Sickness.—Rather Catch Chipmonks in the Rocky

Mountains than Live in Michigan.—Building the

Michigan Central R.R.—Building a

Boat.—Floating down Grand River.—Black

Bear.—Indians Catching Mullet.—Across the Lake

to Southport.—Lead Mining at Mineral

Point.—Decides to go Farther West.—Return to

Michigan.

CHAPTER VI.

Wisconsin.—Indian Physic.—Dressed for a Winter

Hunting Campaign.—Hunting and Trapping in the

Woods.—Catching Otter and Marten.

CHAPTER VII.

Lead Mining.—Hears about Gold in

California.—Gets the Gold Fever.—Nothing will

cure it but California.—Mr. Bennett and the Author

Prepare to Start.—The Winnebago Pony.—Agrees

to Meet Bennett at Missouri River.—Delayed and Fails

to Find Him.—Left with only a Gun and

Pony.—Goes as a Driver for Charles

Dallas.—Stopped by a Herd of

Buffaloes.—Buffalo Meat.—Indians.—U.S.

Troops.—The Captain and the Lieutenant.—Arrive

at South Pass.—The Waters Run toward the

Pacific.—They Find a Boat and Seven of them Decide

to Float down the Green River.

CHAPTER VIII.

Floating down the River.—It begins to

roar.—Thirty Miles a Day.—Brown's

Hole.—Lose the Boat and make two

Canoes.—Elk.—The Cañons get

Deeper.—Floundering in the Water.—The Indian

Camp.—Chief Walker proves a Friend.—Describes

the Terrible Cañon below Them.—Advises Them

to go no farther down.—Decide to go

Overland.—Dangerous Route to Salt Lake.—Meets

Bennett near there.—Organize the Sand Walking

Company.

CHAPTER IX.

The Southern Route.—Off in Fine Style.—A

Cut-off Proposed.—Most of Them Try it and

Fail.—The Jayhawkers.—A New

Organization.—Men with Families not

Admitted.—Capture an Indian Who Gives Them the

Slip.—An Indian Woman and Her Children.—Grass

Begins to Fail.—A High Peak to the West.—No

Water.—An Indian Hut.—Reach the Warm

Spring.—Desert Everywhere.—Some One Steals

Food.—The Water Acts Like a Dose of

Salts.—Christmas Day.—Rev. J.W. Brier Delivers

a Lecture to His Sons.—Nearly Starving and

Choking.—An Indian in a Mound.—Indians Shoot

the Oxen.—Camp at Furnace Creek.

CHAPTER X.

A Long, Narrow Valley.—Beds and Blocks of

Salt.—An Ox Killed.—Blood, Hide and Intestines

Eaten.—Crossing Death Valley.—The Wagons can

go no farther.—Manley and Rogers Volunteer to go for

Assistance.—They Set out on Foot.—Find the

Dead Body of Mr. Fish.—Mr. Isham Dies.—Bones

along the Road.—Cabbage Trees.—Eating Crow and

Hawk.—After Sore Trials They Reach a Fertile

Land.—Kindly Treated.—Returning with Food and

Animals.—The Little Mule Climbs a Precipice, the

Horses are Left Behind.—Finding the Body of Captain

Culverwell.—They Reach Their Friends just as all

Hope has Left Them.—Leaving the Wagons.—Packs

on the Oxen.—Sacks for the Children.—Old

Crump.—Old Brigham and Mrs. Arcane.—A Stampede

[Illustrated.]—Once more

Moving Westward.—"Good-bye, Death

Valley."

CHAPTER XI.

Struggling Along.—Pulling the Oxen Down the

Precipice [Illustrated.]—Making

Raw-hide Moccasins.—Old Brigham Lost and

Found.—Dry Camps.—Nearly

Starving.—Melancholy and Blue.—The Feet of the

Women Bare and Blistered.—"One Cannot form an

Idea How Poor an Ox Will Get."—Young Charlie

Arcane very Sick.—Skulls of Cattle.—Crossing

the Snow Belt.—Old Dog Cuff.—Water Dancing

over the Rocks.—Drink, Ye Thirsty

Ones.—Killing a Yearling.—See the

Fat.—Eating Makes Them Sick.—Going down

Soledad Cañon—A Beautiful

Meadow.—Hospitable Spanish People.—They

Furnish Shelter and Food.—The San Fernando

Mission.—Reaching Los Angeles.—They Meet Moody

and Skinner.—Soap and Water for the First Time in

Months.—Clean Dresses for the Women.—Real

Bread to Eat.—A Picture of Los

Angeles.—Black-eyed Women.—The Author Works in

a Boarding-house.—Bennett and Others go up the

Coast.—Life in Los Angeles.—The Author

Prepares to go North.

CHAPTER XII.

Dr. McMahon's Story.—McMahon and Field, Left behind

with Chief Walker, Determine to go down the

River.—Change Their Minds and go with the

Indians.—Change again and go by

themselves.—Eating Wolf Meat.—After much

Suffering they reach Salt Lake.—John Taylor's Pretty

Wife.—Field falls in Love with her.—They

Separate.—Incidents of Wonderful Escapes from

Death.

CHAPTER XIII.

Story of the Jayhawkers.—Ceremonies of

Initiation—Rev. J.W. Brier.—His Wife the best

Man of the Two.—Story of the Road across Death

Valley.—Burning the Wagons.—Narrow Escape of

Tom Shannon.—Capt. Ed Doty was Brave and

True.—They reach the Sea by way of Santa Clara

River.—Capt. Haynes before the Alcalde.—List

of Jayhawkers.

CHAPTER XIV.

Alexander Erkson's Statement.—Works for Brigham

Young at Salt Lake.—Mormon Gold Coin.—Mt.

Misery.—The Virgin River and Yucca Trees.—A

Child Born to Mr, and Mrs. Rynierson.—Arrive at

Cucamonga.—Find some good Wine which is good for

Scurvy.—San Francisco and the Mines.—Settles

in San Jose.—Experience of Edward Coker.—Death

of Culverwell, Fish and Isham.—Goes through Walker's

Pass and down Kern River.—Living in Fresno in

1892.

CHAPTER XV.

The Author again takes up the History.—Working in a

Boarding House, but makes Arrangements to go

North.—Mission San Bueno Ventura.—First Sight

of the Pacific Ocean.—Santa Barbara in

1850.—Paradise and Desolation.—San Miguel,

Santa Ynez and San Luis Obispo.—California Carriages

and how they were used.—Arrives in San Jose and

Camps in the edge of Town.—Description of the

place.—Meets John Rogers, Bennett, Moody and

Skinner.—On the road to the Mines.—They find

some of the Yellow Stuff and go Prospecting for

more—Experience with Piojos—Life and

Times in the Mines—Sights and Scenes along the Road,

at Sea, on the Isthmus, Cuba, New Orleans, and up the

Mississippi—A few Months Amid Old Scenes, then away

to the Golden State again.

CHAPTER XVI.

St. Louis to New Orleans, New Orleans to San

Francisco—Off to the Mines Again—Life in the

Mines and Incidents of Mining Times and

Men—Vigilance Committee—Death of Mrs.

Bennett

CHAPTER XVII.

Mines and Mining—Adventures and Incidents of the

Early Days—The Pioneers, their Character and

Influence—Conclusion

DEATH VALLEY IN '49.

THE

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A

PIONEER

CHAPTER I.

St. Albans, Vermont is near the eastern shore of Lake

Champlain, and only a short distance south of

"Five-and-forty north degrees" which separates the

United States from Canada, and some sixty or seventy miles

from the great St. Lawrence River and the city of Montreal.

Near here it was, on April 6th, 1820, I was born, so the

record says, and from this point with wondering eyes of

childhood I looked across the waters of the narrow lake to the

slopes of the Adirondack mountains in New York, green as the

hills of my own Green Mountain State.

The parents of my father were English people and lived near

Hartford, Connecticut, where he was born. While still a little

boy he came with his parents to Vermont. My mother's maiden

name was Phoebe Calkins, born near St. Albans of Welch

parents, and, being left an orphan while yet in very tender

years, she was given away to be reared by people who provided

food and clothes, but permitted her to grow up to womanhood

without knowing how to read or write. After her marriage she

learned to do both, and acquired the rudiments of an

education.

Grandfather and his boys, four in all, fairly carved a farm

out of the big forest that covered the cold rocky hills. Giant

work it was for them in such heavy timber—pine, hemlock,

maple, beech and birch—the clearing of a single acre

being a man's work for a year. The place where the maples were

thickest was reserved for a sugar grove, and from it was made

all of the sweet material they needed, and some besides.

Economy of the very strictest kind had to be used in every

direction. Main strength and muscle were the only things

dispensed in plenty. The crops raised consisted of a small

flint corn, rye oats, potatoes and turnips. Three cows, ten or

twelve sheep, a few pigs and a yoke of strong oxen comprised

the live stock—horses, they had none for many years. A

great ox-cart was the only wheeled vehicle on the place, and

this, in winter, gave place to a heavy sled, the runners cut

from a tree having a natural crook and roughly, but strongly,

made.

In summer there were plenty of strawberries, raspberries,

whortleberries and blackberries growing wild, but all the

cultivated fruit was apples. As these ripened many were peeled

by hand, cut in quarters, strung on long strings of twine and

dried before the kitchen fire for winter use. They had a way

of burying up some of the best keepers in the ground, and

opening the apple hole was quite an event of early spring.

The children were taught to work as soon as large enough. I

remember they furnished me with a little wooden fork to spread

the heavy swath of grass my father cut with easy swings of the

scythe, and when it was dry and being loaded on the great

ox-cart I followed closely with a rake gathering every

scattering spear. The barn was built so that every animal was

housed comfortably in winter, and the house was such as all

settlers built, not considered handsome, but capable of being

made very warm in winter and the great piles of hard wood in

the yard enough to last as fuel for a year, not only helped to

clear the land, but kept us comfortable. Mother and the girls

washed, carded, spun, and wove the wool from our own sheep

into good strong cloth. Flax was also raised, and I remember

how they pulled it, rotted it by spreading on the green

meadow, then broke and dressed it, and then the women made

linen cloth of various degrees of fineness, quality, and

beauty. Thus, by the labor of both men and women, we were

clothed. If an extra fine Sunday dress was desired, part of

the yarn was colored and from this they managed to get up a

very nice plaid goods for the purpose.

In clearing the land the hemlock bark was peeled and traded

off at the tannery for leather, or used to pay for tanning and

dressing the hide of an ox or cow which they managed to fat

and kill about every year. Stores for the family were either

made by a neighboring shoe-maker, or by a traveling one who

went from house to house, making up a supply for the

family—whipping the cat, they called it then. They paid

him in something or other produced upon the farm, and no money

was asked or expected.

Wood was one thing plenty, and the fireplace was made large

enough to take in sticks four feet long or more, for the more

they could burn the better, to get it out of the way. In an

outhouse, also provided with a fireplace and chimney, they

made shingles during the long winter evenings, the shavings

making plenty of fire and light by which to work. The shingles

sold for about a dollar a thousand. Just beside the fireplace

in the house was a large brick oven where mother baked great

loaves of bread, big pots of pork and beans, mince pies and

loaf cake, a big turkey or a young pig on grand occasions.

Many of the dishes used were of tin or pewter; the milk pans

were of earthenware, but most things about the house in the

line of furniture were of domestic manufacture.

The store bills were very light. A little tea for father

and mother, a few spices and odd luxuries were about all, and

they were paid for with surplus eggs. My father and my uncle

had a sawmill, and in winter they hauled logs to it, and could

sell timber for $8 per thousand feet.

The school was taught in winter by a man named Bowen, who

managed forty scholars and considered sixteen dollars a month,

boarding himself, was pretty fair pay. In summer some smart

girl would teach the small scholars and board round among the

families.

When the proper time came the property holder would send

off to the collector an itemized list of all his property, and

at another the taxes fell due. A farmer who would value his

property at two thousand or three thousand dollars would find

he had to pay about six or seven dollars. All the money in use

then seemed to be silver, and not very much of that. The whole

plan seemed to be to have every family and farm

self-supporting as far as possible. I have heard of a note

being given payable in a good cow to be delivered at a certain

time, say October 1, and on that day it would pass from house

to house in payment of a debt, and at night only the last man

in the list would have a cow more than his neighbor. Yet those

were the days of real independence, after all. Every man

worked hard from early youth to a good old age. There were no

millionaires, no tramps, and the poorhouse had only a few

inmates.

I have very pleasant recollections of the neighborhood

cider mill. There were two rollers formed of logs carefully

rounded and four or five feet long, set closely together in an

upright position in a rough frame, a long crooked sweep coming

from one of them to which a horse was hitched and pulled it

round and round. One roller had mortices in it, and projecting

wooden teeth on the other fitted into these, so that, as they

both slowly turned together, the apples were crushed. A huge

box of coarse slats, notched and locked together at the

corners, held a vast pile of the crushed apples while clean

rye straw was added to strain the flowing juice and keep the

cheese from spreading too much; then the ponderous screw and

streams of delicious cider. Sucking cider through a long rye

straw inserted in the bung-hole of a barrel was just the best

of fun, and cider taken that way "awful" good while

it was new and sweet.

The winter ashes, made from burning so much fuel and

gathered from the brush-heaps and log-heaps, were carefully

saved and traded with the potash men for potash or sold for a

small price. Nearly every one went barefoot in summer, and in

winter wore heavy leather moccasins made by the Canadian

French who lived near by.

About 1828 people began to talk about the far West. Ohio

was the place we heard most about, and the most we knew was,

that it was a long way off and no way to get there except over

a long and tedious road, with oxen or horses and a cart or

wagon. More than one got the Western fever, as they called it,

my uncle James Webster and my father among the rest, when they

heard some traveler tell about the fine country he had seen;

so they sold their farms and decided to go to Ohio, Uncle

James was to go ahead, in the fall of 1829 and get a farm to

rent, if he could, and father and his family were to come on

the next spring.

Uncle fitted out with two good horses and a wagon; goods

were packed in a large box made to fit, and under the wagon

seat was the commissary chest for food and bedding for daily

use, all snugly arranged. Father had, shortly before, bought a

fine Morgan mare and a light wagon which served as a family

carriage, having wooden axles and a seat arranged on wooden

springs, and they finally decided they would let me take the

horse and wagon and go on with uncle, and father and mother

would come by water, either by way of the St. Lawrence river

and the lakes or by way of the new canal recently built, which

would take them as far as Buffalo.

So they loaded up the little wagon with some of the

mentioned things and articles in the house, among which I

remember a fine brass kettle, considered almost indispensable

in housekeeping. There was a good lot of bedding and blankets,

and a quilt nicely folded was placed on the spring seat as a

cushion.

As may be imagined I was the object of a great deal of

attention about this time, for a boy not yet ten years old

just setting out into a region almost unknown was a little

unusual. When I was ready they all gathered round to say good

bye and my good mother seemed most concerned. She

said—"Now you must be a good boy till we come in

the spring. Mind uncle and aunt and take good care of the

horse, and remember us. May God protect you." She

embraced me and kissed me and held me till she was exhausted.

Then they lifted me up into the spring seat, put the lines in

my hand and handed me my little whip with a leather strip for

a lash. Just at the last moment father handed me a purse

containing about a dollar, all in copper cents—pennies

we called them then. Uncle had started on they had kept me so

long, but I started up and they all followed me along the road

for a mile or so before we finally separated and they turned

back. They waved hats and handkerchiefs till out of sight as

they returned, and I wondered if we should ever meet

again.

I was up with uncle very soon and we rolled down through

St. Albans and took our road southerly along in sight of Lake

Champlain. Uncle and aunt often looked back to talk to me,

"See what a nice cornfield!" or, "What nice

apples on those trees," seeming to think they must do all

they could to cheer me up, that I might not think too much of

the playmates and home I was leaving behind.

I had never driven very far before, but I found the horse

knew more than I did how to get around the big stones and

stumps that were found in the road, so that as long as I held

the lines and the whip in hand I was an excellent driver.

We had made plans and preparations to board ourselves on

the journey. We always stopped at the farm houses over night,

and they were so hospitable that they gave us all we wanted

free. Our supper was generally of bread and milk, the latter

always furnished gratuitously, and I do not recollect that we

were ever turned away from any house where we asked shelter.

There were no hotels, or taverns as they called them, outside

of the towns.

In due time we reached Whitehall, at the head of Lake

Champlain, and the big box in Uncle's wagon proved so heavy

over the muddy roads that he put it in a canal boat to be sent

on to Cleveland, and we found it much easier after this for

there were too many mud-holes, stumps and stones and log

bridges for so heavy a load as he had. Our road many times

after this led along near the canal, the Champlain or the

Erie, and I had a chance to see something of the canal boys'

life. The boy who drove the horses that drew the packet boat

was a well dressed fellow and always rode at a full trot or a

gallop, but the freight driver was generally ragged and

barefoot, and walked when it was too cold to ride, threw

stones or clubs at his team, and cursed and abused the

packet-boy who passed as long as he was in hearing. Reared as

I had been I thought it was a pretty wicked part of the world

we were coming to.

We passed one village of low cheap houses near the canal.

The men about were very vulgar and talked rough and loud,

nearly every one with a pipe, and poorly dressed, loafing

around the saloon, apparently the worse for whisky. The

children were barefoot, bare headed and scantly dressed, and

it seemed awfully dirty about the doors of the shanties. Pigs,

ducks and geese were at the very door, and the women I saw

wore dresses that did not come down very near the mud and big

brogan shoes, and their talk was saucy and different from what

I had ever heard women use before. They told me they were

Irish people—the first I had ever seen. It was along

here somewhere that I lost my little whip and to get another

one made sad inroads into the little purse of pennies my

father gave me. We traveled slowly on day after day. There was

no use to hurry for we could not do it. The roads were muddy,

the log ways very rough and the only way was to take a

moderate gait and keep it. We never traveled on Sunday. One

Saturday evening my uncle secured the privilege of staying at

a well-to do farmer's house until Monday. We had our own food

and bedding, but were glad to get some privileges in the

kitchen, and some fresh milk or vegetables. After all had

taken supper that night they all sat down and made themselves

quiet with their books, and the children were as still as mice

till an early bed time when all retired. When Sunday evening

came the women got out their work—their sewing and their

knitting, and the children romped and played and made as much

noise as they could, seeming as anxious to break the Sabbath

as they had been to have a pious Saturday night. I had never

seen that way before and asked my uncle who said he guessed

they were Seventh Day Baptists.

After many days of travel which became to me quite

monotonous we came to Cleveland, on Lake Erie, and here my

uncle found his box of goods, loaded it into the wagon again,

and traveled on through rain and mud, making very slow

headway, for two or three days after, when we stopped at a

four-corners in Medina county they told us we were only 21

miles from Cleveland. Here was a small town consisting of a

hotel, store, church, schoolhouse and blacksmith shop, and as

it was getting cold and bad, uncle decided to go no farther

now, and rented a room for himself and aunt, and found a place

for me to lodge with Daniel Stevens' boy close by. We got good

stables for our horses.

I went to the district school here, and studied reading,

spelling and Colburn's mental arithmetic, which I mastered. It

began very easy—"How many thumbs on your right

hand?" "How many on your left?" "How many

altogether?" but it grew harder further on.

Uncle took employment at anything he could find to do.

Chopping was his principal occupation. When the snow began to

go off he looked around for a farm to rent for us and father

to live on when he came, but he found none such as he needed.

He now got a letter from father telling him that he had good

news from a friend named Cornish who said that good land

nearly clear of timber could be bought of the Government in

Michigan Territory, some sixty or seventy miles beyond

Detroit, and this being an opportunity to get land they needed

with their small capital, they would start for that place as

soon as the water-ways were thawed out, probably in April.

We then gave up the idea of staying here and prepared

to go to Michigan as soon as the frost was out of the

ground. Starting, we reached Huron River to find it

swollen and out of its bank, giving us much trouble to get

across, the road along the bottom lands being partly

covered with logs and rails, but once across we were in

the town and when we enquired about the road around to

Detroit, they said the country was all a swamp and 30

miles wide and in Spring impassible. They called it the

Maumee or Black Swamp. We were advised to go by water,

when a steamboat came up the river bound for Detroit we

put our wagons and horses on board, and camped on the

lower deck ourselves. We had our own food and were very

comfortable, and glad to have escaped the great

mudhole.

We arrived in Detroit safely, and a few minutes answered to

land our wagons and goods, when we rolled outward in a

westerly direction. We found a very muddy roads, stumps and

log bridges plenty, making our rate of travel very slow. When

out upon our road about 30 miles, near Ypsilanti, the thick

forest we had been passing through grew thinner, and the trees

soon dwindled down into what they called oak openings, and the

road became more sandy. When we reached McCracken's Tavern we

began to enquire for Ebenezer Manley and family, and were soon

directed to a large house near by where he was stopping for a

time.

We drove up to the door and they all came out to see who

the new comers were. Mother saw me first and ran to the wagon

and pulled me off and hugged and kissed me over and over

again, while the tears ran down her cheeks. Then she would

hold me off at arm's length, and look me in the eye and

say—"I am so glad to have you again"; and then

she embraced me again and again. "You are our little

man," said she, "You have come over this long road,

and brought us our good horse and our little wagon." My

sister Polly two years older than I, stood patiently by, and

when mother turned to speak to uncle and aunt, she locked arms

with me and took me away with her. We had never been separated

before in all our lives and we had loved each other as good

children should, who have been brought up in good and moral

principles. We loved each other and our home and respected our

good father and mother who had made it so happy for us.

We all sat down by the side of the house and talked pretty

fast telling our experience on our long journey by land and

water, and when the sun went down we were called to supper,

and went hand in hand to surround the bountiful table as a

family again. During the conversation at supper father said to

me—"Lewis, I have bought you a smooth bore rifle,

suitable for either ball or shot." This, I thought was

good enough for any one, and I thanked him heartily. We spent

the greater part of the night in talking over our adventures

since we left Vermont, and sleep was forgotten by young and

old.

Next morning father and uncle took the horse and little

wagon and went out in search of Government land. They found an

old acquaintance in Jackson county and Government land all

around him, and, searching till they found the section corner,

they found the number of the lots they wanted to locate

on—200 acres in all. They then went to the Detroit land

office and secured the pieces they had chosen.

Father now bought a yoke of oxen, a wagon and a cow, and as

soon as we could get loaded up our little emigrant train

started west to our future home, where we arrived safely in a

few days and secured a house to live in about a mile away from

our land. We now worked with a will and built two log houses

and also hired 10 acres broken, which was done with three or

four yoke of oxen and a strong plow. The trees were scattered

over the ground and some small brush and old limbs, and logs

which we cleared away as we plowed. Our houses went up very

fast—all rough oak logs, with oak puncheons, or hewed

planks for a floor, and oak shakes for a roof, all of our own

make. The shakes were held down upon the roof by heavy poles,

for we had no nails, the door of split stuff hung with wooden

hinges, and the fire place of stone laid up with the logs, and

from the loft floor upward the chimney was built of split

stuff plastered heavily with mud. We have a small four-paned

window in the house. We then built a log barn for our oxen,

cow and horse and got pigs, sheep and chickens as fast as a

chance offered.

As fast as possible we fenced in the cultivated land,

father and uncle splitting out the rails, while a younger

brother and myself, by each getting hold of an end of one of

them managed to lay up a fence four rails high, all we small

men could do. Thus working on, we had a pretty well cultivated

farm in the course of two or three years, on which we produced

wheat, corn and potatoes, and had an excellent garden. We

found plenty of wild cranberries and whortleberries, which we

dried for winter use. The lakes were full of good fish, black

bass and pickerel, and the woods had deer, turkeys, pheasants,

pigeons, and other things, and I became quite an expert in the

capture of small game for the table with my new gun. Father

and uncle would occasionally kill a deer, and the Indians came

along and sold venison at times.

One fall after work was done and preparations were made for

the winter, father said to me:—"Now Lewis, I want

you to hunt every day—come home nights—but keep on

till you kill a deer." So with his permission I started

with my gun on my shoulder, and with feelings of considerable

pride. Before night I started two deer in a brushy place, and

they leaped high over the oak bushes in the most affrighted

way. I brought my gun to my shoulder and fired at the bounding

animal when in most plain sight. Loading then quickly, I

hurried up the trail as fast as I could and soon came to my

deer, dead, with a bullet hole in its head. I was really

surprised myself, for I had fired so hastily at the almost

flying animal that it was little more than a random shot. As

the deer was not very heavy I dressed it and packed it home

myself, about as proud a boy as the State of Michigan

contained. I really began to think I was a capital hunter,

though I afterward knew it was a bit of good luck and not a

bit of skill about it.

It was some time after this before I made another lucky

shot. Father would once in a while ask me:—"Well

can't you kill us another deer?" I told him that when I

had crawled a long time toward a sleeping deer, that I got so

trembly that I could not hit an ox in short range.

"O," said he, "You get the buck

fever—don't be so timid—they won't attack

you." But after awhile this fever wore off, and I got so

steady that I could hit anything I could get in reach of.

We were now quite contented and happy. Father could plainly

show us the difference between this country and Vermont and

the advantages we had here. There the land was poor and stony

and the winters terribly severe. Here there were no stones to

plow over, and the land was otherwise easy to till. We could

raise almost anything, and have nice wheat bread to eat, far

superior to the "Rye-and-Indian" we used to have.

The nice white bread was good enough to eat without butter,

and in comparison this country seemed a real paradise.

The supply of clothing we brought with us had lasted until

now—more than two years—and we had sowed some flax

and raised sheep so that we began to get material of our own

raising, from which to manufacture some more. Mother and

sister spun some nice yarn, both woolen and linen, and father

had a loom made on which mother wove it up into cloth, and we

were soon dressed up in bran new clothes again. Domestic

economy of this kind was as necessary here as it was in

Vermont, and we knew well how to practice it. About this time

the emigrants began to come in very fast, and every piece of

Government land any where about was taken. So much land was

ploughed, and so much vegetable matter turned under and

decaying that there came a regular epidemic of fever and ague

and bilious fever, and a large majority of the people were

sick. At our house father was the first one attacked, and when

the fever was at its height he was quite out of his head and

talked and acted like a crazy man. We had never seen any one

so sick before, and we thought he must surely die, but when

the doctor came he said:—"Don't be alarmed. It is

only 'fever 'n' agur,' and no one was ever known to die of

that." Others of us were sick too, and most of the

neighbors, and it made us all feel rather sorrowful. The

doctor's medicines consisted of calomel, jalap and quinine,

all used pretty freely, by some with benefit, and by others to

no visible purpose, for they had to suffer until the cold

weather came and froze the disease out. At one time I was the

only one that remained well, and I had to nurse and cook,

besides all the out-door work that fell to me. My sister

married a man near by with a good farm and moved there with

him, a mile or two away. When she went away I lost my real

bosom companion and felt very lonesome, but I went to see her

once in a while, and that was pretty often, I think. There was

not much going on as a general thing. Some little neighborhood

society and news was about all. There was, however, one

incident which occurred in 1837, I never shall forget, and

which I will relate in the next chapter.

About two miles west father's farm in Jackson county Mich.,

lived Ami Filley, who moved here from Connecticut and settled

about two and a half miles from the town of Jackson, then a

small village with plenty of stumps and mudholes in its

streets. Many of the roads leading thereto had been paved with

tamarac poles, making what is now known as corduroy roads. The

country was still new and the farm houses far between.

Mr. Filley secured Government land in the oak openings, and

settled there with his wife and two or three children, the

oldest of which was a boy named Willie. The children were

getting old enough to go to school, but there being none, Mr.

Filley hired one of the neighbor's daughters to come to his

house and teach the children there, so they might be prepared

for usefulness in life or ready to proceed further with their

education—to college, perhaps in some future day.

The young woman he engaged lived about a mile a half

away—Miss Mary Mount—and she came over and began

her duties as private school ma'am, not a very difficult task

in those days. One day after she had been teaching some time

Miss Mount desired to go to her father's on a visit, and as

she would pass a huckleberry swamp on the way she took a small

pail to fill with berries as she went, and by consent of

Willie's mother, the little boy went with her for company.

Reaching the berries she began to pick, and the little boy

found this dull business, got tired and homesick and wanted to

go home. They were about a mile from Mr. Filley's and as there

was a pretty good foot trail over which they had come, the

young woman took the boy to it, and turning him toward home

told him to follow it carefully and he would soon see his

mother. She then filled her pail with berries, went on to her

own home, and remained there till nearly sundown, when she set

out to return to Mr. Filley's, reaching there yet in the early

twilight. Not seeing Willie, she inquired for him and was told

that he had not returned, and that they supposed he was safe

with her. She then hastily related how it happened that he had

started back toward home, and that she supposed he had safely

arrived.

Mr. Filley then started back on the trail, keeping close

watch on each side of the way, for he expected he would soon

come across Master Willie fast asleep. He called his name

every few rods, but got no answer nor could he discover him,

and so returned home again, still calling and searching, but

no boy was discovered. Then he built a large fire and put

lighted candles in all the windows, then took his lantern and

wont out in the woods calling and looking for the boy.

Sometimes he thought he heard him, but on going where the

sound came from nothing could be found. So he looked and

called all night, along the trail and all about the woods,

with no success. Mr. Mount's home was situated not far from

the shore of Fitch's Lake, and the trail went along the

margin, and in some places the ground was quite a boggy marsh,

and the trail had been fixed up to make it passably good

walking.

Next day the neighbors were notified, and asked to assist,

and although they were in the midst of wheat harvest, a great

many laid down the cradle and rake and went out to help

search. On the third day the whole county became excited and

quite an army of searchers turned out, coming from the whole

country miles around.

Mr. Filley was much excited and quite worn out an beside

himself with fatigue and loss of sleep. He could not eat.

Yielding to entreaty he would sit at the table, and suddenly

rise up, saying he heard Willie calling, and go out to search

for the supposed voice, but it was all fruitless, and the

whole people were sorry indeed for the poor father and

mother.

The people then formed a plan for a thorough search. They

were to form in a line so near each other that they could

touch hands and were to march thus turning out for nothing

except in passable lakes, and thus we marched, fairly sweeping

the county in search of a sign. I was with this party and we

marched south and kept close watch for a bit of clothing, a

foot print or even bones, or anything which would indicate

that he had been destroyed by some wild animal. Thus we

marched all day with no success, and the next went north in

the same careful manner, but with no better result. Most of

the people now abandoned the search, but some of the neighbors

kept it up for a long time.

Some expressed themselves quite strongly that Miss Mount

knew where the boy was, saying that she might have had some

trouble with him and in seeking to correct him had

accidentally killed him and then hidden the body

away—perhaps in the deep mire of the swamp or in the

muddy waters on the margin of the lake. Search was made with

this idea foremost, but nothing was discovered. Rain now set

in, and the grain, from neglect grew in the head as it stood,

and many a settler ate poor bread all winter in consequence of

his neighborly kindness in the midst of harvest. The bread

would not rise, and to make it into pancakes was the best way

it could be used.

Still no tidings ever came of the lost boy. Many things

were whispered, about Mr. Mount's dishonesty of character and

there were many suspicions about him, but no real facts could

be shown to account for the boy. The neighbors said he never

worked like the rest of them, and that his patch of cultivated

land was altogether too small to support his family, a wife

and two daughters, grown. He was a very smooth and affable

talker, and had lots of acquaintances. A few years afterwards

Mr. Mount was convicted of a crime which sent him to the

Jackson State Prison, where he died before his term expired. I

visited the Filley family in 1870, and from them heard the

facts anew and that no trace of the lost boy had ever been

discovered.

The second year of sickness and I was affected with the

rest, though it was not generally so bad as the first year. I

suffered a great deal and felt so miserable that I began to

think I had rather live on the top of the Rocky Mountains and

catch chipmuncks for a living than to live here and be sick,

and I began to have very serious thoughts of trying some other

country. In the winter of 1839 and 1840 I went to a

neighboring school for three months, where I studied reading,

writing and spelling, getting as far as Rule of Three in

Daboll's arithmetic. When school was out I chopped and split

rails for Wm. Hanna till I had paid my winter's board. After

this, myself and a young man named Orrin Henry, with whom I

had become acquainted, worked awhile scoring timber to be used

in building the Michigan Central Railroad which had just then

begun to be built. They laid down the ties first (sometimes a

mudsill under them) and then put down four by eight wooden

rails with a strips of band iron half an inch thick spiked on

top. I scored the timber and Henry used the broad axe after

me. It was pretty hard work and the hours as long as we could

see, our wages being $13 per month, half cash.

In thinking over our prospect it seemed more and more as if

I had better look out for my own fortune in some other place.

The farm was pretty small for all of us. There were three

brothers younger than I, and only 200 acres in the whole, and

as they were growing up to be men it seemed as if it would be

best for me, the oldest, to start out first and see what could

be done to make my own living. I talked to father and mother

about my plans, and they did not seriously object, but gave me

some good advice, which I remember to this

day—"Weigh well every thing you do; shun bad

company; be honest and deal fair; be truthful and never fear

when you know you are right." But, said he, "Our

little peach trees will bear this year, and if you go away you

must come back and help us eat them; they will be the first we

ever raised or ever saw." I could not promise.

Henry and I drew our pay for our work. I had five dollars

in cash and the rest in pay from the company's store. We

purchased three nice whitewood boards, eighteen inches wide,

from which we made us a boat and a good sized chest which we

filled with provisions and some clothing and quilts. This,

with our guns and ammunition, composed the cargo of our boat.

When all was ready, we put the boat on a wagon and were to

haul it to the river some eight miles away for embarkation.

After getting the wagon loaded, father said to

me;—"Now my son, you are starting out in life

alone, no one to watch or look after you. You will have to

depend upon yourself in all things. You have a wide, wide

world to operate in—you will meet all kinds of people

and you must not expect to find them all honest or true

friends. You are limited in money, and all I can do for you in

that way is to let you have what ready money I have." He

handed me three dollars as he spoke, which added to my own

gave me seven dollars as my money capital with which to start

out into the world among perfect strangers, and no

acquaintances in prospect on our Western course.

When ready to start, mother and sister Poll came out to see

us off and to give us their best wishes, hoping we would have

good health, and find pleasant paths to follow. Mother said to

me:—"You must be a good boy, honest and

law-abiding. Remember our advice, and honor us for we have

striven to make you a good and honest man, and you must follow

our teachings, and your conscience will be clear. Do nothing

to be ashamed of; be industrious, and you have no fear of

punishment." We were given a great many "Good

byes" and "God bless you's" as with hands, hats

and handkerchiefs they waved us off as far as we could see

them. In the course of an hour or so we were at the water's

edge, and on a beautiful morning in early spring of 1840 we

found ourselves floating down the Grand River below

Jackson.

The stream ran west, that we knew, and it was west we

thought we wanted to go, so all things suited us. The stream

was small with tall timber on both sides, and so many trees

had fallen into the river that our navigation was at times

seriously obstructed. When night came we hauled our boat on

shore, turned it partly over, so as to shelter us, built a

fire in front, and made a bed on a loose board which we

carried in the bottom of the boat. We talked till pretty late

and then lay down to sleep, but for my part my eyes would not

stay shut, and I lay till break of day and the little birds

began to sing faintly.

I thought of many things that night which seemed so long. I

had left a good dear home, where I had good warm meals and a

soft and comfortable bed. Here I had reposed on a board with a

very hard pillow and none too many blankets, and I turned from

side to side on my hard bed, to which I had gone with all my

clothes on. It seemed the beginning of another chapter in my

pioneer life and a rather tough experience. I arose, kindled a

big fire and sat looking at the glowing coals in still further

meditation.

Neither of us felt very gleeful as we got our breakfast and

made an early start down the river again. Neither of us talked

very much, and no doubt my companion had similar thoughts to

mine, and wondered what was before us. But I think that as a

pair we were at that moment pretty lonesome. Henry had rested

better than I but probably felt no less keenly the separation

from our homes and friends. We saw plenty of squirrels and

pigeons on the trees which overhung the river, and we shot and

picked up as many as we thought we could use for food. When we

fired our guns the echoes rolled up and down the river for

miles making the feeling of loneliness still more keen, as the

sound died faintly away. We floated along generally very

quietly. We could see the fish dart under our boat from their

feeding places along the bank, and now and then some tall

crane would spread his broad wings to get out of our way.

We saw no houses for several days, and seldom went on

shore. The forest was all hard wood, such as oak, ash, walnut,

maple, elm and beech. Farther down we occasionally passed the

house of some pioneer hunter or trapper, with a small patch

cleared. At one of these a big green boy came down to the bank

to see who we were. We said "How d'you do," to him,

and, getting no response, Henry asked him how far is was to

Michigan, at which a look of supreme disgust came over his

features as he replied—"'Taint no far at

all."

The stream grew wider as we advanced along its downward

course, for smaller streams came pouring in to swell its tide.

The banks were still covered with heavy timber, and in some

places with quite thick undergrowth. One day we saw a black

bear in the river washing himself, but he went ashore before

we were near enough to get a sure shot at him. Many deer

tracks were seen along the shore, but as we saw very few of

the animals themselves, they were probably night visitors.

One day we overtook some canoes containing Indians, men,

women and children. They were poling their craft around in all

directions spearing fish. They caught many large mullet and

then went on shore and made camp, and the red ladies began

scaling the fish. As soon as their lords and masters had

unloaded the canoes, a party started out with four of the

boats, two men in a boat, to try their luck again. They ranged

all abreast, and moved slowly down the stream in the still

deep water, continually beating the surface with their spear

handles, till they came to a place so shallow that they could

see the bottom easily, when they suddenly turned the canoes

head up stream, and while one held the craft steady by

sticking his spear handle down on the bottom, the other stood

erect, with a foot on either gunwale so he could see whatever

came down on either side. Soon the big fish would try to pass,

but Mr. Indian had too sharp an eye to let him escape

unobserved, and when he came within his reach he would turn

his spear and throw it like a dart, seldom missing his aim.

The poor fish would struggle desperately, but soon came to the

surface, when he would be drawn in and knocked in the head

with a tomahawk to quiet him, when the spear was cut out and

the process repeated. We watched them about an hour, and

during that time some one of the boats was continually hauling

in a fish. They were sturgeon and very large. This was the

first time we had ever seen the Indian's way of catching fish

and it was a new way of getting grub for us. When the canoes

had full loads they paddled up toward their camp, and we

drifted on again.

When we came to Grand Rapids we had to go on shore and tow

our boat carefully along over the many rocks to prevent

accident. Here was a small cheap looking town. On the west

bank of the river a water wheel was driving a drill boring for

salt water, it seemed through solid rock. Up to this time the

current was slow, and its course through a dense forest. We

occasionally saw an Indian gliding around in his canoe, but no

houses or clearings. Occasionally we saw some pine logs which

had been floated down some of the streams of the north. One of

these small rivers they called the "Looking-glass,"

and seemed to be the largest of them.

Passing on we began to see some pine timber, and realized

that we were near the mouth of the river where it emptied into

Lake Michigan. There were some steam saw mills here, not then

in operation, and some houses for the mill hands to live in

when they were at work. This prospective city was called Grand

Haven. There was one schooner in the river loaded with lumber,

ready to sail for the west side of the lake as soon as the

wind should change and become favorable, and we engaged

passage for a dollar and a half each. While waiting for the

wind we visited the woods in search of game, but found none.

All the surface of the soil was clear lake sand, and some

quite large pine and hemlock trees were half buried in it. We

were not pleased with this place for it looked as if folks

must get their grub from somewhere else or live on fish.

Next morning we were off early, as the wind had changed,

but the lake was very rough and a heavy choppy sea was

running. Before we were half way across the lake nearly all

were sea-sick, passengers and sailors. The poor fellow at the

helm stuck to his post casting up his accounts at the same

time, putting on an air of terrible misery.

This, I thought was pretty hard usage for a land-lubber

like myself who had never been on such rough water before. The

effect of this sea-sickness was to cure me of a slight fever

and ague, and in fact the cure was so thorough that I have

never had it since. As we neared the western shore a few

houses could be seen, and the captain said it was Southport.

As there was no wharf our schooner put out into the lake again

for an hour or so and then ran back again, lying off and on in

this manner all night. In the morning it was quite calm and we

went on shore in the schooner's yawl, landing on a sandy

beach. We left our chest of clothes and other things in a

warehouse and shouldered our packs and guns for a march across

what seemed an endless prairie stretching to the west. We had

spent all our lives thus far in a country where all the

clearing had to be made with an axe, and such a broad field

was to us an entirely new feature. We laid our course westward

and tramped on. The houses were very far apart, and we tried

at every one of them for a chance to work, but could get none,

not even if we would work for our board. The people all seemed

to be new settlers, and very poor, compelled to do their own

work until a better day could be reached. The coarse meals we

got were very reasonable, generally only ten cents, but

sometimes a little more.

As we travelled westward the prairies seemed smaller with

now and then some oak openings between. Some of the farms

seemed to be three or four years old, and what had been laid

out as towns consisted of from three to six houses, small and

cheap, with plenty of vacant lots. The soil looked rich, as

though it might be very productive. We passed several small

lakes that had nice fish in them, and plenty of ducks on the

surface.

Walking began to get pretty tiresome. Great blisters would

come on our feet, and, tender as they were, it was a great

relief to take off our boots and go barefoot for a while when

the ground was favorable. We crossed a wide prairie and came

down to the Rock river where there were a few houses on the

east side but no signs of habitation on the west bank. We

crossed the river in a canoe and then walked seven miles

before we came to a house where we staid all night and

inquired for work. None was to be had and so we tramped on

again. The next day we met a real live Yankee with a one-horse

wagon, peddling tin ware in regular Eastern style. We inquired

of him about the road and prospects, and he gave us an

encouraging idea—said all was good. He told us where to

stop the next night at a small town called Sugar Creek. It had

but a few houses and was being built up as a mining town, for

some lead ore had been found there. There were as many Irish

as English miners here, a rough class of people. We put up at

the house where we had been directed, a low log cabin, rough

and dirty, kept by Bridget & Co. Supper was had after dark

and the light on the table was just the right one for the

place, a saucer of grease, with a rag in it lighted and

burning at the edge of the saucer. It at least served to made

the darkness apparent and to prevent the dirt being visible.

We had potatoes, beans and tea, and probably dirt too, if we

could have seen it. When the meal was nearly done Bridget

brought in and deposited on each plate a good thick pancake as

a dessert. It smelled pretty good, but when I drew my knife

across it to cut it in two, all the center was uncooked

batter, which ran out upon my plate, and spoiled my

supper.

We went to bed and soon found it had other occupants beside

ourselves, which, if they were small were lively and spoiled

our sleeping. We left before breakfast, and a few miles out on

the prairie we came to a house occupied by a woman and one

child, and we were told we could have breakfast if we could

wait to have it cooked. Everything looked cheap but cheery,

and after waiting a little while outside we were called in to

eat. The meal consisted of corn bread, bacon, potatoes and

coffee. It was well cooked and looked better than things did

at Bridget's. I enjoyed all but the coffee, which had a rich

brown color, but when I sipped it there was such a bitter

taste I surely thought there must be quinine in it, and it

made me shiver. I tried two or three times to drink but it was

too much for me and I left it. We shouldered our loads and

went on again. I asked Henry what kind of a drink it was.

"Coffee," said he, but I had never seen any that

tasted like that and never knew my father to buy any such

coffee as that.

We labored along and in time came to another small place

called Hamilton's Diggings where some lead mines were being

worked. We stopped at a long, low log house with a porch the

entire length, and called for bread and milk, which was soon

set before us. The lady was washing and the man was playing

with a child on the porch. The little thing was trying to

walk, the man would swear terribly at it—not in an angry

way, but in a sort of careless, blasphemous style that was

terribly shocking. I thought of the child being reared in the

midst of such bad language and reflected on the kind of people

we were meeting in this far away place. They seemed more

wicked and profane the farther west we walked. I had always

lived in a more moral and temperate atmosphere, and I was

learning more of some things in the world than I had ever

known before. I had little to say and much to see and listen

to and my early precepts were not forgotten. No work was to be

had here and we set out across the prairie toward Mineral

Point, twenty miles away. When within four miles of that place

we stopped at the house of Daniel Parkinson, a fine looking

two-story building, and after the meal was over Mr. Henry

hired out to him for $16 per month, and went to work that day.

I heard of a job of cutting cordwood six miles away and went

after it, for our money was getting very scarce, but when I

reached the place I found a man had been there half an hour

before and secured the job. The proprietor, Mr. Crow, gave me

my dinner which I accepted with many thanks, for it saved my

coin to pay for the next meal. I now went to Mineral Point,

and searched the town over for work. My purse contained

thirty-five cents only and I slept in an unoccupied out house

without supper. I bought crackers and dried beef for ten cents

in the morning and made my first meal since the day before,

felt pretty low-spirited. I then went to Vivian's smelting

furnace where they bought lead ore, smelted it, and run it

into pigs of about 70 pounds each. He said he had a job for me

if I could do it. The furnace was propelled by water and they

had a small buzz saw for cutting four-foot wood into blocks

about a foot long. These blocks they wanted split up in pieces

about an inch square to mix in with charcoal in smelting ore.

He said he would board me with the other men, and give me a

dollar and a quarter a cord for splitting the wood. I felt

awfully poor, and a stranger, and this was a beginning for me

at any rate, so I went to work with a will and never lost a

minute of daylight till I had split up all the wood and filled

his woodhouse completely up. The board was very

coarse—bacon, potatoes, and bread—a man cook, and

bread mixed up with salt and water. The old log house where we

lodged was well infested with troublesome insects which worked

nights at any rate, whether they rested days or not, and the

beds had a mild odor of pole cat. The house was long, low and

without windows. In one end was a fireplace, and there were

two tiers of bunks on each side, supplied with straw only. In

the space between the bunks was a stationary table, with

stools for seats. I was the only American who boarded there

and I could not well become very familiar with the

boarders.

The country was rolling, and there were many beautiful

brooks and clear springs of water, with fertile soil. The

Cornish miners were in the majority and governed the locality

politically. My health was excellent, and so long as I had my

gun and ammunition I could kill game enough to live on, for

prairie chickens and deer could be easily killed, and meat

alone would sustain life, so I had no special fears of

starvation. I was now paid off, and went back to see my

companion, Mr. Henry. I did not hear of any more work, so I

concluded I would start back toward my old home in Michigan,

and shouldered my bundle and gun, turning my face eastward for

a long tramp across the prairie. I knew I had a long tramp

before me, but I thought best to head that way, for my capital

was only ten dollars, and I might be compelled to walk the

whole distance. I walked till about noon and then sat down in

the shade of a tree to rest for this was June and pretty warm.

I was now alone in a big territory, thinly settled, and

thought of my father's home, the well set table, all happy and

well fed at any rate, and here was my venture, a sort of

forlorn hope. Prospects were surely very gloomy for me here

away out west in Wisconsin Territory, without a relative,

friend or acquaintance to call upon, and very small means to

travel two hundred and fifty miles of lonely

road—perhaps all the way on foot. There were no laborers

required, hardly any money in sight, and no chance for

business. I knew it would be a safe course to proceed toward

home, for I had no fear of starving, the weather was warm and

I could easily walk home long before winter should come again.

Still the outlook was not very pleasing to one in my

circumstances.

I chose a route which led me some distance north of the one

we travelled when we came west, but it was about the same.

Every house was a new settler, and hardly one who had yet

produced anything to live upon. In due time I came to the Rock

River, and the only house in sight was upon the east bank. I

could see a boat over there and so I called for it, and a

young girl came over with a canoe for me. I took a paddle and

helped her hold the boat against the current, and we made the

landing safely. I paid her ten cents for ferriage and went on

again. The country was now level, with burr-oak openings. Near

sundown I came to a small prairie of about 500 acres

surrounded by scattering burr-oak timber, with not a hill in

sight, and it seemed to me to be the most beautiful spot on

earth. This I found to belong to a man named Meachem, who had

an octagon concrete house built on one side of the opening.

The house had a hollow column in the center, and the roof was

so constructed that all the rain water went down this central

column into a cistern below for house use. The stairs wound

around this central column, and the whole affair was quite

different from the most of settlers' houses. I staid here all

night, had supper and breakfast, and paid my bill of

thirty-five cents. He had no work for me so I went on again. I

crossed Heart Prairie, passed through a strip of woods, and

out at Round Prairie. It was level as a floor with a slight

rise in one corner, and on it were five or six settlers. Here

fortune favored me, for here I found a man whom I knew, who

once lived in Michigan, and was one of our neighbors there for

some time. His name was Nelson Cornish. I rested here a few

days, and made a bargain to work for him two or three days

every week for my board as long as I wished to stay. As I got

acquainted I found some work to do and many of my leisure

hours I spent in the woods with my gun, killing some deer,

some of the meat of which I sold. In haying and harvest I got

some work at fifty cents to one dollar per day, and as I had

no clothes to buy, I spent no money, saving up about fifty

dollars by fall. I then got a letter from Henry saying that I

could get work with him for the winter and I thought I would

go back there again.

Before thinking of going west again I had to go to

Southport on the lake and get our clothes we had left in our

box when we passed in the spring. So I started one morning at

break of day, with a long cane in each hand to help me along,

for I had nothing to carry, not even wearing a coat. This was

a new road, thinly settled, and a few log houses building. I

got a bowl of bread and milk at noon and then hurried on

again. The last twenty miles was clear prairie, and houses

were very far apart, but little more thickly settled as I

neared Lake Michigan. I arrived at the town just after dark,

and went to a tavern and inquired about the things. I was told

that the warehouse had been broken into and robbed, and the

proprietor had fled for parts unknown. This robbed me of all

my good clothes, and I could now go back as lightly loaded as

when I came. I found I had walked sixty miles in that one day,

and also found myself very stiff and sore so that I did not

start back next day, and I took three days for the return

trip—a very unprofitable journey.

I was now ready to go west, and coming across a pet deer

which I had tamed, I knew if I left it it would wander away

with the first wild ones that came along, and so I killed it

and made my friends a present of some venison. I chose still a

new route this time, that I could see all that was possible of

this big territory when I could do it so easily. I was always

a great admirer of Nature and things which remained as they

were created, and to the extent of my observation, I thought

this the most beautiful and perfect country I had seen between

Vermont and the Mississippi River. The country was nearly

level, the land rich, the prairies small with oak openings

surrounding them, very little marsh land and streams of clear

water. Rock River was the largest of these, running south.

Next west was Sugar River, then the Picatonica. Through the

mining region the country was rolling and abundantly watered

with babbling brooks and health-giving springs.

In point of health it seemed to me to be far better than

Michigan. In Mr. Henry's letter to me he had said that he had

taken a timber claim in "Kentuck Grove," and had all

the four-foot wood engaged to cut at thirty-seven cents a

cord. He said we could board ourselves and save a little money

and that in the spring he would go back to Michigan with me.

This had decided me to go back to Mineral Point. I stopped a

week or two with a man named Webb, hunting with him, and sold

game enough to bring me in some six or seven dollars, and then

resumed my journey.

On my way I found a log house ten miles from a neighbor

just before I got to the Picatonica River. It belonged to a

Mr. Shook who, with his wife and three children, lived on the

edge of a small prairie, and had a good crop of corn. He

invited me to stay with him a few days, and as I was tired I

accepted his offer and we went out together and brought in a

deer. We had plenty of corn bread, venison and coffee, and

lived well. After a few days he wanted to kill a steer and he

led it to a proper place while I shot it in the head. We had

no way to hang it up so he rolled the intestines out, and I

sat down with my side against the steer and helped him to pull

the tallow off.

It was now getting nearly dark and while he was splitting

the back bone with an axe, it slipped in his greasy hands and

glancing, cut a gash in my leg six inches above the knee. I

was now laid up for two or three weeks, but was well cared for

at his house. Before I could resume my journey snow had fallen

to the depth of about six inches, which made it rather

unpleasant walking, but in a few days I reached Mr. Henry's

camp in "Kentuck Grove," when after comparing notes,

we both began swinging our axes and piling up cordwood,

cooking potatoes, bread, bacon, coffee and flapjacks

ourselves, which we enjoyed with a relish.

I now went to work for Peter Parkinson, who paid me

thirteen dollars per month, and I remained with him till

spring. While with him a very sad affliction came to him in

the loss of his wife. He was presented by her with his first

heir, and during her illness she was cared for by her mother,

Mrs. Cullany, who had come to live with them during the

winter. When the little babe was two or three weeks old the

mother was feeling in such good spirits that she was left

alone a little while, as Mrs. Cullany was attending to some

duties which called her elsewhere. When she returned she was

surprised to see that both Mrs. Parkinson and the babe were

gone. Everyone turned out to search for her. I ran to the

smokehouse, the barn, the stable in quick order, and not

finding her a search was made for tracks, and we soon

discovered that she had passed over a few steps leading over a

fence and down an incline toward the spring house, and there

fallen, face downward, on the floor of the house which was

covered only a few inches deep with water lay the unfortunate

woman and her child, both dead. This was doubly distressing to

Mr. Parkinson and saddened the whole community. Both were

buried in one grave, not far from the house, and a more

impressive funeral I never beheld.

I now worked awhile again with Mr. Henry and we sold our

wood to Bill Park, a collier, who made and sold charcoal to

the smelters of lead ore. When the ice was gone in the

streams, Henry and I shouldered our guns and bundles, and made

our way to Milwaukee, where we arrived in the course of a few

days. The town was small and cheaply built, and had no wharf,

so that when the steamboat came we had to go out to it in a

small boat. The stream which came in here was too shallow for

the steamer to enter. When near the lower end of the lake we

stopped at an island to take on food and several cords of

white birch wood. The next stopping place was at

Michilamackanac, afterward called Mackinaw. Here was a short

wharf, and a little way back a hill, which seemed to me to be

a thousand feet high, on which a fort had been built. On the

wharf was a mixed lot of people—Americans, Canadians,

Irish, Indians, squaws and papooses. I saw there some of the

most beautiful fish I had ever seen. They would weigh twenty

pounds or more, and had bright red and yellow spots all over

them. They called them trout, and they were beauties, really.

At the shore near by the Indians were loading a large white

birch bark canoe, putting their luggage along the middle

lengthways, and the papooses on top. One man took a stern seat

to steer, and four or five more had seats along the gunwale as

paddlers and, as they moved away, their strokes were as even

and regular as the motions of an engine, and their crafts

danced as lightly on the water as an egg shell. They were

starting for the Michigan shore some eight or ten miles away.

This was the first birch bark canoe I had ever seen and was a

great curiosity in my eyes.

We crossed Lake Huron during the night, and through its

outlet, so shallow that the wheels stirred up the mud from the

bottom; then through Lake St. Clair and landed safety at

Detroit next day. Here we took the cars on the Michigan

Central Railroad, and on our way westward stopped at the very

place where we had worked, helping to build the road, a year

or more before. After getting off the train a walk of two and

one half miles brought me to my father's house, where I had a

right royal welcome, and the questions they asked me about the

wild country I had traveled over, how it looked, and how I got

along—were numbered by the thousand.

I remained at home until fall, getting some work to do by

which I saved some money, but in August was attacked with

bilious fever, which held me down for several weeks, but

nursed by a tender and loving mother with untiring care, I

recovered, quite slowly, but surely. I felt that I had been

close to death, and that this country was not to be compared

to Wisconsin with its clear and bubbling springs of

health-giving water. Feeling thus, I determined to go back

there again.

With the idea of returning to Wisconsin I made plans for my

movements. I purchased a good outfit of steel traps of several

kinds and sizes, thirty or forty in all, made me a pine chest,

with a false bottom to separate the traps from my clothing

when it was packed in traveling order, the clothes at the top.

My former experience had taught me not to expect to get work

there during winter, but I was pretty sure something could be

earned by trapping and hunting at this season, and in summer I

was pretty sure of something to do. I had about forty dollars

to travel on this time, and quite a stock of experience. The

second parting from home was not so hard as the first one. I

went to Huron, took the steamer to Chicago, then a small,

cheaply built town, with rough sidewalks and terribly muddy

streets, and the people seemed pretty rough, for sailors and

lake captains were numerous, and knock downs quite frequent.

The country for a long way west of town seemed a low, wet

marsh or prairie.

Finding a man going west with a wagon and two horses

without a load, I hired him to take me and my baggage to my

friend Nelson Cornish, at Round Prairie. They were glad to see

me, and as I had not yet got strong from my fever, they

persuaded me to stay a while with them and take some medicine,

for he was a sort of a doctor. I think he must have given me a

dose of calomel, for I had a terribly sore mouth and could not

eat any for two or three weeks. As soon as I was able to

travel I had myself and chest taken to the stage station on

the line for the lake to Mineral Point. I think this place was

called Geneva. On the stage I got along pretty fast, and part

of the time on a new road. The first place of note was Madison

the capital of the territory, situated on a block of land

nearly surrounded by four lakes, all plainly seen from the big

house. Further on at the Blue Mounds I left the stage, putting

my chest in the landlord's keeping till I should come or send

for it.

I walked about ten miles to the house of a friend named A.

Bennett, who was a hunter and lived on the bank of the

Picatonica River with his wife and two children. I had to take

many a rest on the way, for I was very weak.

Resting the first few days, Mrs. Bennett's father, Mr. J.P.

Dilly, took us out about six miles and left us to hunt and

camp for a few days. We were quite successful, and killed five

nice, fat deer, which we dressed and took to Mineral Point,

selling them rapidly to the Cornish miners for twenty-five

cents a quarter for the meat. We followed this business till

about January first, when the game began to get poor, when we

hung up our guns for a while. I had a little money left yet.

The only money in circulation was American silver and British

sovereigns. They would not sell lead ore for paper money nor

on credit. During the spring I used my traps successfully, so

that I saved something over board and expenses.

In summer I worked in the mines with Edwin Buck of

Bucksport, Maine, but only found lead ore enough to pay our

expenses in getting it. Next winter I chopped wood for

thirty-five cents per cord and boarded myself. This was poor

business; poorer than hunting. In summer I found work at

various things, but in the fall Mr. Buck and myself concluded

that as we were both hunters and trappers, we would go

northward toward Lake Superior on a hunting expedition, and,

perhaps remain all winter. We replenished our outfit, and

engaged Mr. Bennett to take us well up into the north country.