Title: Heart's Desire

Author: Emerson Hough

Release date: February 24, 2005 [eBook #15159]

Most recently updated: December 14, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

E-text prepared by Al Haines

This being in Part the Story of Curly, the Can of Oysters, and the Girl from Kansas

This continuing the Relation of Curly, the Can of Oysters, and the Girl from Kansas; and introducing Others

Beginning the Cause Celebre which arose from Curly's killing the Pig of the Man from Kansas

Continuing the Story of the Pig from Kansas, and the Deep Damnation of his Taking Off

This being the Story of a Paradise; also showing the Exceeding Loneliness of Adam

How the Said Eve arrived on the Same Stage with Eastern Capital, to the Interest of All, and the Embarrassment of Some

Showing how Paradise was lost through the Strange Performance of a Craven Adam

This being the Story of a Parrot, Certain Twins, and a Pair of Candy Legs

How the Men of Heart's Desire surrendered to the Softening Seductions of Croquet and Other Pastimes

How Tom Osby, Common Carrier, caused Trouble with a Portable Annie Laurie

Telling how Two Innocent Travellers by Mere Chance collided with a Side-tracked Star

Concerning Goods, their Value, and the Delivery of the Same

This describing Porter Barkley's Method with a Man, and Tom Osby's Way with a Maid

Proposing Certain Wonders of Modern Progress, as wrought by Eastern Capital and Able Corporation Counsel

This being the Story of a Cow Puncher, an Osteopath, and a Cross-eyed Horse

Concerning Real Estate, Love, Friendship, and Other Good and Valuable Considerations

Showing the Dilemma of Dan Anderson, the Doubt of Leading Citizens, and the Artless Performance of a Pastoral Prevaricator

How Benevolent Assimilation was checked by Unexpected Events

Showing Wonders of the Thirst of McGinnis, and the Faith of Whiteman the Jew

How the Girl from the States kept the Set of Twins from being broken

The Story of a Sheriff and Some Bad Men; showing also a Day's Work, and a Man's Medicine

The Strange Story of the King of Gee-Whiz, and his Unusual Experience in Foreign Parts

Showing further the Uncertainty of Human Events, and the Exceeding Resourcefulness of Mr. Thomas Osby

This being the Story of a Sheepherder, Two Warm Personal Friends, and their Love-letter to a Beautiful Queen

The Pleasing Recountal of an Absent Knight, a Gentle Lady, and an Ananias with Spurs

The Story of a Surprise, a Success, and Something Else Very Much Better

"It looks a long ways acrost from here to the States," said Curly, as we pulled up our horses at the top of the Capitan divide. We gazed out over a vast, rolling sea of red-brown earth which stretched far beyond and below the nearer foothills, black with their growth of stunted pines. This was a favorite pausing place of all travellers between the county-seat and Heart's Desire; partly because it was a summit reached only after a long climb from either side of the divide; partly, perhaps, because it was a notable view-point in a land full of noble views. Again, it may have been a customary tarrying point because of some vague feeling shared by most travellers who crossed this trail,—the same feeling which made Curly, hardened citizen as he was of the land west of the Pecos, turn a speculative eye eastward across the plains. We could not see even so far as the Pecos, though it seemed from our lofty situation that we looked quite to the ultimate, searching the utter ends of all the earth.

"Yours is up that-a-way;" Curly pointed to the northeast. "Mine was that-a-way." He shifted his leg in the saddle as he turned to the right and swept a comprehensive hand toward the east, meaning perhaps Texas, perhaps a series of wild frontiers west of the Lone Star state. I noticed the nice distinction in Curly's tenses. He knew the man more recently arrived west of the Pecos, possibly later to prove a backslider. As for himself, Curly knew that he would never return to his wild East; yet it may have been that he had just a touch of the home feeling which is so hard to lose, even in a homeless country, a man's country pure and simple, as was surely this which now stretched wide about us. Somewhere off to the east, miles and miles beyond the red sea of sand and grama grass, lay Home.

"And yet," said Curly, taking up in speech my unspoken thought, "you can't see even halfway to Vegas up there." No. It was a long two hundred miles to Las Vegas, long indeed in a freighting wagon, and long enough even in the saddle and upon as good a horse as each of us now bestrode. I nodded. "And it's some more'n two whoops and a holler to my ole place," said he. Curly remained indefinite; for, though presently he hummed something about the sun and its brightness in his old Kentucky home, he followed it soon thereafter with musical allusion to the Suwanee River. One might have guessed either Kentucky or Georgia in regard to Curly, even had one not suspected Texas from the look of his saddle cinches.

It was the day before Christmas. Yet there was little winter in this sweet, thin air up on the Capitan divide. Off to the left the Patos Mountains showed patches of snow, and the top of Carrizo was yet whiter, and even a portion of the highest peak of the Capitans carried a blanket of white; but all the lower levels were red-brown, calm, complete, unchanging, like the whole aspect of this far-away and finished country, whereto had come, long ago, many Spaniards in search of wealth and dreams; and more recently certain Anglo-Saxons, also dreaming, who sought in a stolen hiatus of the continental conquest nothing of more value than a deep and sweet oblivion.

It was a Christmas-tide different enough from that of the States toward which Curly pointed. We looked eastward, looked again, turned back for one last look before we tightened the cinches and started down the winding trail which led through the foothills along the flank of the Patos Mountains, and so at last into the town of Heart's Desire.

"Lord!" said Curly, reminiscently, and quite without connection with any thought which had been uttered. "Say, it was fine, wasn't it, Christmas? We allus had firecrackers then. And eat! Why, man!" This allusion to the firecrackers would have determined that Curly had come from the South, which alone has a midwinter Fourth of July, possibly because the populace is not content with only one annual smell of gunpowder. "We had trees where I came from," said I. "And eat! Yes, man!"

"Some different here now, ain't it?" said Curly, grinning; and I grinned in reply with what fortitude I could muster. Down in Heart's Desire there was a little, a very little cabin, with a bunk, a few blankets, a small table, and a box nailed against the wall for a cupboard. I knew what was in the box, and what was not in it, and I so advised my friend as we slipped down off the bald summit of the Capitans and came into the shelter of the short, black pinons. Curly rode on for a little while before he made answer.

"Why," said he, at length, "ain't you heard? You're in with our rodeo on Christmas dinner. McKinney, and Tom Osby, and Dan Anderson, the other lawyer, and me,—we're going to have Christmas dinner at Andersen's 'dobe in town to-morrer. You're in. You mayn't like it. Don't you mind. The directions says to take it, and you take it. It's goin' to be one of the largest events ever knowed in this here settlement. Of course, there's goin' to be some canned things, and some sardines, and some everidge liquids. You guess what besides that."

I told him I couldn't guess.

"Shore you couldn't," said Curly, dangling his bridle from the little finger of his left hand as he searched in his pocket for a match. He had rolled a cigarette with one hand, and now he called it a cigarrillo. These facts alone would have convicted him of coming from somewhere near the Rio Grande.

"Shore you couldn't," repeated Curly, after he had his bit of brown paper going. "I reckon not in a hundred years. Champagne! Whole quart! Yes, sir. Cost eighteen dollars. Mac, he got it. Billy Hudgens had just this one bottle in the shop, left over from the time the surveyors come over here and we thought there was goin' to be a railroad, which there wasn't. But Lord! that ain't all. It ain't the beginnin'. You guess again. No, I reckon you couldn't," said he, scornfully. "You couldn't in your whole life guess what next. We got a cake!"

"Go on, Curly," said I, scoffingly; for I knew that the possibilities of Heart's Desire did not in the least include anything resembling cake. Any of the boys could fry bacon or build a section of bread in a Dutch oven—they had to know how to do that or starve. But as to cake, there was none could compass it. And I knew there was not a woman in all Heart's Desire.

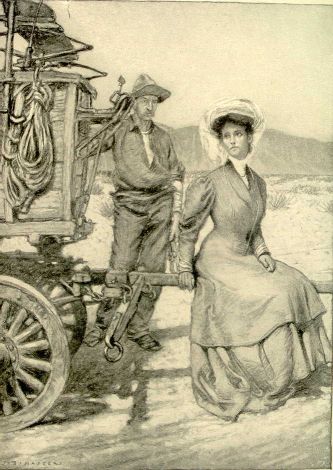

Curly enjoyed his advantage for a few moments as we wound on down the trail among the pinons. "Heap o' things happened since you went down to tend co'te," said he. "You likely didn't hear of the new family moved in last week. Come from Kansas."

"Then there's a girl," said I; for I was far Westerner enough to know that all the girls ever seen west of the Pecos came from Kansas, the same as all the baled hay and all the fresh butter. Potatoes came from Iowa; but butter, hay, and girls came from Kansas. I asked Curly if the head of the new family came from Leavenworth.

"'Course he did," said Curly. "And I'll bet a steer he'll be postmaster or somethin' in a few brief moments." This in reference to another well-known fact in natural history as observed west of the Pecos; for it was matter of common knowledge among all Western men that the town of Leavenworth furnished early office-holders for every new community from the Missouri to the Pacific.

Curly continued; "This feller'll do well here, I reckon, though just now he's broke a-plenty. But what was he goin' to do? His team breaks down and he can't get no further. Looks like he'd just have to stop and be postmaster or somethin' for us here for a while. Can't be Justice of the Peace; another Kansas man's got that. As to them two girls—man! The camp's got on its best clothes right this instant, don't you neglect to think. Both good lookers. Youngest's a peach. I'm goin' to marry her." Curly turned aggressively in his saddle and looked me squarely in the eye, his hat pushed back from his tightly curling red hair.

"That's all right, Curly," said I, mildly. "You have my consent. Have you asked the girl about it yet?"

"Ain't had time yet," said he. "But you watch me."

"What's the name of the family?" I asked as we rode along together.

"Blamed if I remember exactly," replied Curly, scratching his head, "but they're shore good folks. Old man's sort o' pious, I reckon. Anyhow, that's what Tom Osby says. He driv along from Hocradle cañon with 'em on the road from Vegas. Said the old man helt services every mornin' before breakfast. More services'n breakfast sometimes. Tom, he says old Whiskers—that's our next postmaster—he sings a-plenty, lifts up his voice exceeding. Say," said Curly, turning on me again fiercely, "that's one reason I'd marry the girl if for nothing else. It takes more'n a bass voice and a copy of the Holy Scriptures to make a Merry Christmas. Why, man, say, when I think of what a time we all are going to have,—you, and me, and Mac, and Tom Osby, and Dan Anderson, with all them things of our'n, and all these here things on the side—champagne and all that,—it looks like this world ain't run on the square, don't it?"

I assured Curly that this had long been one of my own conclusions. Assuredly I had not the bad manners to thank him for his invitation to join him in this banquet at Heart's Desire, knowing as I did Curly's acquaintance with the fact that young attorneys had not always abundance during their first year in a quasi-mining camp that was two-thirds cow town; such being among the possibilities of that land. I returned to the cake.

"Where'd we git it?" said Curly. "Why, where'd you s'pose we got it? Do you think Dan Anderson has took to pastry along with the statoots made and pervided? As for Dan, he ain't been here so very long, but he's come to stay. We're goin' to send him to Congress if we ever get time to organize our town, or find out what county we're in. How'd our Delergate look spreadin' jelly cake? Nope, he didn't make it. And does it look any like Mac has studied bakery doin's out on the Carrizoso ranch? You know Tom Osby couldn't. As for me, if hard luck has ever driv me to cookin' in the past, I ain't referrin' to it now. I'm a straight-up cow puncher and nothin' else. That cake? Why, it come from the Kansas outfit.

"Don't know which one of 'em done it, but it's a honey," he went on. "Say, she's a foot high, with white stuff a inch high all over. She's soft around the aidge some, for I stuck my finger intoe it just a little. We just got it recent and we're night-herdin' it where it's cool. Cost a even ten dollars. The old lady said she'd make the price all right, but Mac and me, we sort of sized up things and allowed we'd drop about a ten in their recepticle when we come to pay for that cake. This family, you see, moved intoe the cabin Hank Fogarty and Jim Bond left when they went away,—it's right acrost the 'royo from Dan Anderson's office, where we're goin' to eat to-morrer.

"Now, how that woman could make a cake like this here in one of them narrer, upside-down Mexican ovens—no stove at all—no nothing—say, that's some like adoptin' yourself to circumstances, ain't it? Why, man, I'd marry intoe that fam'ly if I didn't do nothing else long as I lived. They ain't no Mexican money wrong side of the river. No counterfeit there regardin' a happy home—cuttin' out the bass voice and givin' 'em a leetle better line of grass and water, eh? Well, I reckon not. Watch me fly to it."

The idiom of Curly's speech was at times a trifle obscure to the uneducated ear. I gathered that he believed these newcomers to be of proper social rank, and that he was also of the opinion that a certain mending in their material matters might add to the happiness of the family.

"But say," he began again shortly, "I ain't told you half about our dinner."

"That is to say—" said I.

"We're goin' to have oysters!" he replied.

"Oh, Curly!" objected I, petulantly, "what's the use lying? I'll agree that you may perhaps marry the girl—I don't care anything about that. But as to oysters, you know there never was an oyster in Heart's Desire, and never will be, world without end."

"Huh!" said Curly. "Huh!" And presently, "Is that so?"

"You know it's so," said I.

"Is that so?" reiterated he once more. "Nice way to act, ain't it, when you're ast out to dinner in the best society of the place? Tell a feller he's shy on facts, when all he's handin' out is just the plain, unfreckled truth, for onct at least. We got oysters, four cans of 'em, and done had 'em for a month. They're up there." He jerked a thumb toward the top of old Carrizo Mountain. I looked at the snow, and in a flash comprehended. There, indeed, was cold storage, the only cold storage possible in Heart's Desire!

"Tom Osby brought 'em down from Vegas the last time he come down," said Curly. "They're there, sir, four cans of 'em. You know where the Carrizo spring is? Well, there's a snowbank in that cañon, about two hundred yards off to the left of the spring. The oysters is in there. Keep? They got to keep!

"Them's the only oysters ever was knowed between the Pecos and the Rio Grande," he continued pridefully. "Now I want to ask you, friend, if this ain't just a leetle the dashed blamedest, hottest Christmas dinner ever was pulled off?"

"Curly," said I, "you are a continuous surprise to me."

"The trouble with you is," said Curly, lighting another cigarette, "you look the wrong way from the top of the divide. Never mind about home and mother. Them is States institooshuns. The only feller any good here is the feller that comes to stay, and likes it. You like it?"

"Yes, Curly," I replied seriously, "I do like it, and I'm going to stay if I can."

"Well, you be mighty blamed careful if that's the way you feel about it," said Curly. "I got my own eye on that girl from Kansas, and I serve notice right here. No use for you or Mac or any of you to be a-tryin' to cut out any stock for me. I seen it first."

We dropped down and ever down as we rode on along the winding mountain trail. The dark sides of the Patos Mountains edged around to the back of us, and the scarred flanks of big Carrizo came farther and farther forward along our left cheeks as we rode on. Then the trail made a sharp bend to the left, zigzagged a bit to get through a series of broken ravines, and at last topped the low false divide which rose at the upper end of the valley of Heart's Desire.

It was a spot lovely, lovable. Nothing in all the West is more fit to linger in a man's memory than the imperious sun rising above the valley of Heart's Desire; nothing unless it were the royal purple of the sunset, trailed like a robe across the shoulders of the grave unsmiling hills, which guarded it round about. In Heart's Desire it was so calm, so complete, so past and beyond all fret and worry and caring. Perhaps the man who named it did so in grim jest, as was the manner of the early bitter ones who swept across the Western lands. Perhaps again he named it at sunset, and did so reverently. God knows he named it right.

There was no rush nor hurry, no bickering nor envying, no crowding nor thieving there. Heart's Desire! It was well named, indeed; fit capital for the malcontents who sought oblivion, dreaming, long as they might, that Life can be left aside when one grows weary of it; dreaming—ah! deep, foolish, golden dream—that somewhere there is on earth an Eden with no Eve and without a flaming sword!

The town all lay along one deliberate, crooked street, because the arroyo along which it straggled was crooked. Its buildings were mostly of adobe, with earthen roofs, so low that when one saw a rainstorm coming in the rainy season (when it rained invariably once a day), he went forth with a shovel and shingled his roof anew, standing on the ground as he did so. There were a few cabins built of logs, but very few. Only one or two stores had the high board front common in Western villages. Lumber was very scarce and carpenters still scarcer. How the family from Kansas had happened to drift into Heart's Desire—how a man of McKinney's intelligence had come to settle there—how Dan Anderson, a very good lawyer, happened to have tarried there—how indeed any of us happened to be there, are questions which may best be solved by those who have studied the West-bound, the dream-bound, the malcontents. At any rate, here we were, and it was Christmas-time. The very next morning would be that of Christmas Day.

There were no stockings hung up in Heart's Desire that Christmas Eve, for all the population was adult, male, and stern of habit. The great moon flooded the street with splendor. Afar there came voices of rioting. There were some adherents to the traditions of the South in regard to firecrackers at Yuletide, albeit the six-shooter furnished the only firecracker obtainable. Yet upon that night the very shots seemed cheerful, not ominous, as was usually the case upon that long and crooked street, which had seen duels, affairs, affrays,—even riots of mounted men in the days when the desperadoes of the range came riding into town now and again for love of danger, or for lack of aguardiente. It was so very white and solemn and content,—this street of Heart's Desire on Christmas Eve. Far across the arroyo, as Curly had said, there gleamed red the double windows of the cabin which had been preempted by the man from Leavenworth. To-night the man from Leavenworth sat with bowed head and beard upon his bosom.

Christmas Day dawned, brilliant, glorious. There was not a Christmas tree in all Heart's Desire. There was not a child within two hundred miles who had ever seen a Christmas tree. There was not a woman in all Heart's Desire saving those three newcomers in the cabin across the arroyo. Yet these new-comers were acquainted with the etiquette of the land. There was occasion for public announcement in such matters.

At eleven o'clock in the morning the man from Leavenworth and the Littlest Girl from Kansas came out upon the street. They were ostensibly bound to get the mail, although there had been no mail stage for three days, and could be none for four days more, even had the man from Leavenworth entertained the slightest thought of getting any mail at this purely accidental residence into which the fate of a tired team had thrown him. Yet there must be the proper notification that he and his family had concluded to abide in Heart's Desire; that he was now a citizen; that he was now entitled by the length of his beard to be called "'Squire," and to be accepted into all the councils of the town. This walk along the street was notice to the pure democracy of that land that all might now leave cards at the cabin across the arroyo. One need hardly doubt that the populace of Heart's Desire was lined up along the street to say good morning and to receive befittingly this tacit pledge of its newest citizen. Moreover, as to the Littlest Girl, all Heart's Desire puffed out its chest. Once more, indeed, the camp was entitled to hold up its head. There were Women in the town! Ergo Home; ergo Civilization; ergo Society; and ergo all the rest. Heretofore Heart's Desire had wilfully been but an unorganized section of savagery; but your Anglo Saxon, craving ever savagery, has no sooner found it than he seeks to civilize it; there being for him in his aeon of the world no real content or peace.

"I reckon the old man is goin' to take a look at the post-office to see how he likes the place," said Curly, reflectively, as he gazed after the gentleman whom he had frankly elected as his father-in-law. "He'll get it, all right. Never saw a man from Leavenworth who wasn't a good shot at a postoffice. But say, about that Littlest Girl—well, I wonder!"

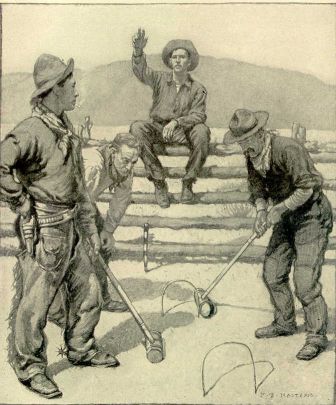

Curly was very restless until dinner-time, which, for one reason or another, was postponed until about four of the afternoon. We met at Dan Anderson's law office, which was also his residence, a room about a dozen feet by twenty in size. The bunks were cleaned up, the blankets put out of the way, and the centre of the room given over to a table, small and home-made, but very full of good cheer for that time and place. At the fireplace, McKinney, flushed and red, was broiling some really good loin steaks. McKinney also allowed his imagination to soar to the height of biscuits. Coffee was there assuredly, as one might tell by the welcome odor now ascending. Upon the table there was something masked under an ancient copy of a newspaper. Outside the door of the adobe, in the deepest shade obtainable, sat two soap boxes full of snow, or at least partly full, for Tom Osby had done his best. In one of these boxes appeared the proof of Curly's truthfulness—three cans of oysters, delicacies hitherto unheard of in that land! In the other box was an object almost as unfamiliar as an oyster can,—an oblong, smooth, and now partially frost-covered object with tinfoil about its upper end. A certain tense excitement obtained.

"I wonder if she'll get frappe enough," said Dan Anderson. He was a Princeton man once upon a time.

"It don't make no difference about the frappy part," said Curly, "just so she gets cold enough. I reckon I savvy wine some. I never was up the trail, not none! No, I reckon not! Huh?"

We agreed on Curly's worldliness cheerfully; indeed, agreed cheerfully that all the world was a good place and all its inhabitants were everything that could be asked. Life was young and fresh and strong. The spell of Heart's Desire was upon us all that Christmas Day.

"Now," said Curly, dropping easily into the somewhat vague position of host, when McKinney had finally placed his platter of screeching hot steaks upon the table. "Now, then, grub pi-i-i-i-le!" He sang the summons loud and clear, as it has sounded on many a frosty morning or sultry noon in many a corner of the range. "Set up, fellers," said Curly. "It's bridles off now, and cinches down, and the trusties next to the mirror." (By this speech Curly probably meant that the time was one of ease and safety, wherein one might place his six-shooter back of the bar, in sign that he was in search of no man, and that none was in search of him. It was not good form to eat in a private family in Heart's Desire with one's gun at one's belt.)

We sat down and McKinney uncovered the cake which had been made by the wife of the man from Leavenworth. It appeared somewhat imposing. Curly wanted to cut into it at the first course, but Dan Anderson rebelled and coaxed him off upon the subject of oysters. There was abundance for all. The cake itself would have weighed perhaps five or six pounds. There was a part of a can of oysters for each man, any quantity of wholesome steaks and coffee, with condensed milk if one cared for it, and at least enough champagne for any one who cared for precisely that sort of champagne.

It was nightfall before we were willing to leave the little pine table. Meantime we had talked of many things; of the new strike on the Homestake, of the vein of coal lately found in the Patos, of Apache rumors below Tularosa, and other matters interesting to citizens of that land. We mentioned an impending visit of Eastern Capital bent upon investigating our mineral wealth. We spoke of the vague rumor that a railroad was heading north from El Paso, and might come close to Heart's Desire if all went well; and, generous in the enthusiasm of the hour, we builded upon that fancy, ending by a toast to Dan Anderson as our first delegate to Congress. Dan bowed gravely, not knowing the future any more than ourselves. Nor should it be denied that there was talk of the new inhabitants across the arroyo. The morning promenade of the man from Leavenworth had been productive of results; add to these the results of so noble a feast as this Christmas dinner of ours, and it was foregone that our hearts must expand to include in welcome all humanity west of the Pecos.

After all, no man is better than the prettiest woman in his environment. As to these girls from Kansas, it is to be said that there had never before been a real woman in Heart's Desire. You, who have always lived where there is law, and society, and women, and home,—you cannot know what it is to see all these things gradually or swiftly dawning upon your personal horizon. Yet this was the way of Heart's Desire, where women and law and property were not.

It was perhaps the moon, or perhaps youth, or perhaps this state of life to which I have referred. Assuredly the street was again flooded with a grand, white moonlight, bright almost as a Northern day, when we looked out of the little window.

Dan Anderson was the first to speak, after a silence which had fallen amidst the dense tobacco smoke. "It cost us less than fifteen dollars a plate," said he. "I've paid more for worse—yes, a lot worse. But by the way, Mac, where's that other can of oysters? I thought you said there were four."

"That's what I said," broke in Tom Osby. "I done told Mac I ought to bring 'em all down, but he said only three."

"Well," said McKinney, always a conservative and level-headed man, "I allowed that if they would keep a month, they would keep a little longer. Now you all know there's goin' to be a stage in next week, and likely it'll bring the president of the New Jersey Gold Mills, who's been due here a couple of weeks. Now here we are, hollerin' all the time for Eastern Capital. What's the right thing for us to do when we get any Eastern Capital into our town? This here man comes from Philadelphy, which I reckon is right near the place where oysters grows. What are you goin' to do? He's used to oysters; like enough he eats 'em every day in the year, because he's shore rich. First thing he hollers for when he gets here is oysters. Looks like you all didn't have no public spirit. Are we goin' to give this here Eastern man the things he's used to, kinder gentle him along like, you know, and so get all the closeter and easier to him, or are we goin' to throw him down cold, and leave him dissatisfied the first day he strikes our camp? It shore looks to me like there ain't but one way to answer that."

"And that there one answer," said Tom Osby, "is now a-reclinin' in the snowbank up on Carrizy."

"I reckon that's so, all right, Mac," assented Curly, reflectively. "I could have et one more oyster or so, but I can quit if it's for the good of the country."

"Well, I'm feeling just a little bit guilty as it is," said Dan Anderson, who was in fairly good post-prandial condition. "Here we are, eating like lords. Now who knows what that poor family from Kansas is having for Christmas dinner? Mac, I appoint you a committee of one to see how they are getting along. Pass the hat. Make it about ten for the cake. Come on, now, let's find out about these folks."

Curly was distinctly unhappy all the time McKinney was away. It was half an hour before the latter came back, but the look on his face betrayed him. Dan Anderson made him confess that he still had the ten dollars in his pocket, that he had been afraid to knock at the door, and that he had learned nothing whatever of the household from Kansas. McKinney admitted that his nerve had failed, and that he dared not knock, but he said that he had summoned courage enough to look in at the window. The family had either finished its dinner long ago, had not eaten, or did not intend to eat at all. "The table looked some shy," declared McKinney. Beyond this he was incoherent, distressed, and plainly nervous. Silence fell upon the entire group, and for some time each man in Dan Andersen's salon was wrapped in thought. Perhaps each one cast a furtive look from the tail of his eye at his neighbors. Of all present, Curly seemed the happiest. "Didn't see the Littlest Girl?" he asked. McKinney shook his head.

"Well, I guess I'll be gettin' up to see about my wagon before long," said Tom Osby, rising and knocking his pipe upon his boot-heel. "I've got a few cans of stuff up here in my load that I don't really need. In the mornin', you know—well, so long, boys."

"I heard that Jim Peterson killed a deer the other day," suggested Dan Anderson. "I believe I'll just step over and see if I can't get a quarter of venison for those folks."

"Shore," said McKinney, "I'll go along. No, I won't; I'll take a pasear acrost the street and have a look at a little stuff I brung up from the ranch yesterday."

"No Christmas," said Curly, staring ahead of himself into the tobacco smoke, and indulging in a rare soliloquy. "No Christmas dinner—and this here is in Ameriky!"

It is difficult to tell just how it occurred; but presently, had any one of us turned to look about him, he must have found himself alone. The moonlight streamed brilliantly over the long street of Heart's Desire. . . . The scarred sides of old Carrizo looked so close that one might almost have touched them with one's hand. . . .

It was about three miles from the street, up over the foot-hills, along the fiat cañon which debouched below the spring where lay the snowbank. There were different routes which one could take. . . .

I knew the place very well from Curly's description, and found it easy to follow up the trickle of water which came down the cañon from the spring. Having found the spring, it was easy to locate the spot in the snowbank where the oysters had been cached. I was not conscious of tarrying upon the way, yet, even so, there had been feet more swift than mine. As I came up to the spring, I heard voices and saw two forms sitting at the edge of the snowbank.

"Here's another one!" called out Dan Anderson as I appeared; and forthwith they broke into peals of unrighteous laughter. "You're a little slow; you're number three; Mac was first."

"I thought I heard an elk as I came up," said I, as I sat down beside the others and tried to look unconcerned, although plainly out of breath.

"Elk!" snorted McKinney, as he arose and walked to the other edge of the snowbank. "Here's your elk tracks." McKinney, foreman on Carrizoso, was an old range-rider, and he was right. Here was the track, plunging through the snow, and here was a deep hole where an elk, or something, had digged hurriedly, deeply, and, as it proved, effectively.

"Elk!" said McKinney again, savagely. "Damn that cow puncher! He took to his horse, 'course he did, and not one of us thought of ridin'. Who'd ever think a man would ride up here at all, let alone at night? Come on, fellers, we might as well go home."

"Well, I'm pleased to have met you, gentlemen," said Anderson, lighting a philosophic pipe, "and I don't mind walking back with you. It's a trifle lonesome in the hills after dark. Why didn't you tell me you were coming up?" He grinned with what seemed to us bad taste.

When we got down across the foot-hills and into the broad white street of Heart's Desire, we espied a dark figure slowly approaching. It proved to be Tom Osby, who later declared that he had found himself unable to sleep. He had things in his pockets. By common consent we now turned our footsteps across the arroyo, toward the cabin where dwelt the family from Kansas.

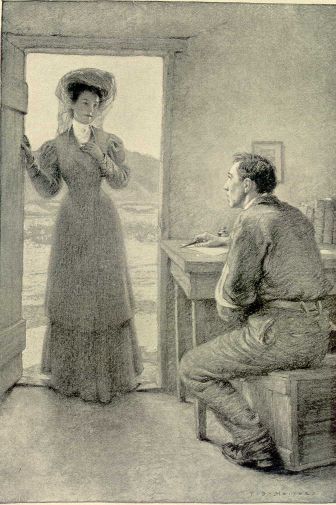

The house of the man from Leavenworth was lighted as though for some function. There were no curtains at the windows, and even had there been, the shock of this spectacle which went on before our eyes would have been sufficient to set aside all laws and conventions. With hands in pockets we stood and gazed blankly in at the open window. There was a sound of revelry by night. The narrow Mexican fireplace again held abundance of snapping, sparkling, crooked pinon wood. The table was spread. At its head sat the next postmaster; near him a lately sorrowful but now smiling lady, his wife, the woman from Kansas. The elder daughter was busy at the fire. At the right of the man from Leavenworth sat none less than Curly, the same whose cow pony, with bridle thrown down over its head, now stood nodding in the bright flood of the moonlight of Heart's Desire. At the side of Curly was the Littlest Girl from Kansas, and she was looking into his eyes.

It was thus that the social compact was first set on in the valley of Heart's Desire.

A vast steaming fragrance arose from the bowl which stood at the head of the table. In the home of the girl from Kansas there was light, warmth, comfort, joy. It was Christmas, after all.

"By the great jumpin' Jehossophat!" said Tom Osby, "them's our oysters!"

"And to think," mused Dan Anderson, softly, as we turned away,—"we fried ours!"

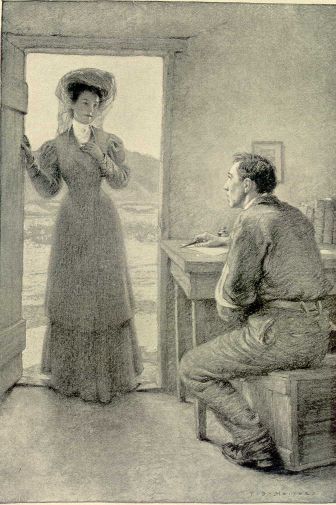

A great many abdomens have been injured in the pastime known as the "double roll." Especially has this been the case with persons not native to the land of Heart's Desire or the equivalent thereof. Even those born to the manner, and possessed of the freedom of a vast landscape whose every particular was devoted to the behoof of any man seized with a purpose of attaining speed and efficiency with firearms, did not always reach that smoothness and precision in the execution of this personal manoeuvre which alone could render it safe to themselves or impressive to the beholder. The owner of this accomplishment was never apt to find himself much crowded with company, in the way either of participants or spectators. Yet the art was a simple and harmless one, pertaining more especially to youth, enthusiasm, and the fresh air of high altitudes, which did ever evoke saltpetreish manifestations.

The evolution of the "double roll" is executed by taking a six-shooter—let us hope not one of those pitiful toys of the East—upon each forefinger, each weapon so hanging balanced on the trigger-guard and the trigger itself that it shall be ready to turn about the finger as upon a pivot, and shall be ready for instant discharge, the thumb cocking the weapon as it turns; yet so that it shall none the less be discharged only when the muzzle of the weapon is pointed away from the operator's person and not toward it.

It is best for the ambitious to begin this little sport with an empty weapon. Thus one will readily observe that the click of the hammer is all too often heard before the whirl of the gun is fairly under way, and while the muzzle is pointed midway of the operator's person; the weight of the heavy gun being commonly sufficient to pull back the trigger and so discharge the piece. When the ambitious soul has learned to do this "roll" with one empty gun, he may try it with two empty guns. If he finds it possible thus to content himself, it will perhaps be all the better for him. To stand upright, with a gun in each hand, even an empty gun, and so revolve the same while its own cylinder is revolving, is not wholly easy, though when one has finally gotten both hemispheres of his brain into accord with his forefingers, he will ever thereafter be able to understand fully the double revolution of the earth upon its axis and around the sun; provided always that he is able to perform the "double roll" without hitch or break, pulling right and left forefinger alternately and rapidly until he has heard what in his tentative case must be a series of six double clicks.

This performance with an empty six-shooter is but a pale and spiritless form of the sport of high altitudes. Instead there should be twelve reports, so closely sequent as to sound as one string of explosion. Thus executed the game is a fine one, the finer for being risky. So to stand erect, with an eight-inch Colt in either hand, each arm at full length, one gun shooting joyously down the centre of the street of your chosen town, the other shooting as cheerfully up the same street—to do this actually, with bark of powder and attending puffs of dust cut—this is indeed delightsome when the heart is full of red blood, and the chest swells with charged wine o' life, and the eyes gleam and the muscles harden for very search of some endeavor immediate and difficult! It is the more delightsome when this moment of man-frenzy finds one in such a town as was this of Heart's Desire; where, indeed, a man could do precisely as he pleased; where it was not accounted wrong or ill-balanced to claim the whole street for a half moment or so of a cloudless morning, and so to ease one's self of the pressure of the joy of living. To own this little world, to live free of touch or taint of control or guidance, to be brother to the mountains, cousin of the free sky—to live in Heart's Desire and be a man—ah! would that were possible for all of us to-day! Were it so, then assuredly we should exult and take unto ourselves all the privileges of the domain, perhaps even to the extent of attempting the "double roll."

Curly's wooing of the Littlest Girl, sped apace by his unrighteous appropriation of our can of oysters, in which he had held no fee simple, but only an individual and indeterminate interest, had prospered beyond all just deserts of a red-headed cow puncher with a salary of forty-five dollars a month. He had already, less than two months after the installation of the new postmaster, announced to his friends his forthcoming nuptials, and ever since the setting of the happy date had comported himself with an air of ownership of the town and a mere tolerance of its inhabitants.

Perhaps, if we were each and every one of us a prospective bridegroom, as was Curly upon this morning in question, we should be all the more persuaded to execute the "double roll" in mid-street, as proof to the public that all was well. Perhaps, also, if there should thus appear to any of us, adown street upon either hand, an object moving slowly, pausing, resuming again across the line of gun-vision its slow advance—ah! tell me, if that slow-moving object crossing the bridegroom's joyous aim were a pig,—a grunting, fat, conceited pig,—arrogating to itself much of that street wherefrom one's fellow-citizens had for a moment of grave courtesy withdrawn—tell me, if you were a bridegroom, soon to be happy, and if you could do the "double roll" with loaded guns and no danger to your bowels, and if while so engaged you should see within easy range this black, sleek pig, with its tail curled tightly, egotistically, contemptuously, over its back, what, as a man, would you do? What, as a man, could you do in a case like that, in a land where there was no law, where never a court had sat, where never such a thing as a case at law had been known? Consider, what would be the abstract right and justice of this matter, repeating that you were a bridegroom and twenty-three, and that the air was molten wine and honey mingled, and that this pig—but then, the matter is absurd! There is but one answer. It was right—indeed, it was inevitable—that Curly should shoot the pig; because in the first place it had intruded upon his pastime, and because in the second place he felt like it.

And yet over this act, this simple, inevitable act of justice, arose the first law case ever known in Heart's Desire, a cause which shook that community to the centre of its being, and for a time threatened its very continuance. Ah, well! perhaps the time had come. Perhaps the sun was now to set over all the valleys of Heart's Desire. Perhaps this was the beginning of the end. The law, they say, must have its course. It had its course in Heart's Desire.

But not without protest, not without struggle. There were two factions from the start. Strange to say, that most bitterly opposed to Curly was headed by no less a person than his own intended father-in-law, the man from Leavenworth. It was his pig. The rest of us had lived at Heart's Desire for a considerable time, but there had hitherto seemed no need for law. Order we already had in so far as order is really needed; though the importance of order, or indeed the importance of law, is a matter very much overrated. No man at Heart's Desire ever dreamed of locking his door. His horse might doze saddled in the street if he liked. No man spoke in rudeness or coarseness to his neighbor, as do men in the cities where they have law. No man did injustice to his neighbor, for fair play and an even chance were gods in the eyes of all, eikons above each pinon-burning hearth in all that valley of content. The speech of man was grave and gentle, the movements of man were easy and unhurried; neither did any man work by rule, or by clock, or by order. There was no such thing as want or hunger; for did temporary poverty encompass one, was there not always the house of Uncle Jim Brothers, and could not one there hang up his gun behind the door and so obtain credit for an indefinite length of time, entitling him to eat at table with his peers? Had there been such a thing as families in Heart's Desire, be sure such a thing as a woman or child engaged in any work had been utterly unknown. It was a land of men, big, grave, sufficient men, each with a gun upon his hip, and sometimes two, guaranty of peace and calm and content. And any man who has ever lived in a Land Before the Law knows that this is the only fit way of life. Alas! that this scheme, this great, happy simple, perfect scheme of society should be subverted. And, be it remembered, this was by reason of nothing more than a pig, an artless, lissom pig, it is true; an infrequent, somewhat prized, a little petted and perhaps spoiled pig, it is true; yet, after all, no fit cause of elemental strife.

But now came this man from Leavenworth, fresh from litigious soil, bearing with him in his faded blue army overcoat germs of civilization, seeds of discontent. He wailed aloud that the pride of the community, meaning this pig, which he had brought solitary in a box at the tail of the wagon when he moved in, was now departed; that there was naught left to distinguish this community from any other camp in the mountains; that the pig had been the light of his home, the apple of his eye, the pride of the community; that he had entertained large designs in connection with this pig the following fall; that its taking off was a shame, an outrage, a disgrace, an act utterly illegal, and one for which any man in Kansas would promptly have had the law of his neighbor.

Hitherto the "double roll," even in connection with a curly-tailed black pig, had not been considered actionable in Heart's Desire; but the outcry made by this man from Leavenworth, now the postmaster of the town and in some measure a leader in the meetings of the population, began to attract attention. It began to play upon the nicely attuned instrument of Public Spirit. What, indeed, asked the community gravely, was to separate Heart's Desire in the eye of Eastern Capital, from any other camp in the far Southwest? Once the town could claim a pig, which no other camp of that district could do. Now it could do so no more forever. This began to put a different look upon the face of things.

"It seems like the ole man took it some hard," said Curly, lighting a cigarrillo. "He don't seem to remember that I was due to be a member of the family right soon, same as the pig. I don't like to think I'm shy when it comes to comparison with a shoat. Gimme time, and I reckon I could take the place of the pig in my new dad's affections. But I say deliberate that pigs has got no call to be in a cow country, not none, unless salted. Say, can't we salt this one? Then, who's the worse off for it? What's all this furse about, anyway?"

"That's right, Curly," said Dan Anderson, who stood with hands in pockets and pipe in mouth, leaning against the door-jamb in front of his "law office." "You have enunciated a great principle of law in that statement. They have got to prove damages. Moreover, you have got a counter-claim. It's laceratin' to be compared to a shoat."

"And me just goin' to be married," said Curly.

"Sure, it ain't right."

"Andersen," said I, moving up to the group, "did you ever hear of such things as champerty and maintenance? The first thing you know, you'll get disbarred for stirring up litigation."

"Keep away from my client," said Dan Anderson, grinning. "You're jealous of my professional success, that's all. Neither of us has had a case yet, and now that it looks like I was going to get one, you're jealous. Do you want to pass up the first lawsuit ever held in the county? Come now, I'm bored to death. Let's have some fun."

Curly began to shift uneasily on his feet. His hat went still farther back on his red, kinky curls.

"Law!" said he. "Law! You don't mean—" For the first time in his life Curly grew pale. "Why, I'll clean out the hull bunch!" he said, the red surging back in his face and his hand instinctively going to his gun.

"No, you won't," said Dan Anderson. "Do you want to bust up your marriage with the girl from Kansas?"

"Sho'!" said Curly, and fell thoughtful. "This looks bad," said he; "mighty bad." He sat down and began to think. I do not doubt that Dan Anderson at that moment was a disgrace to his profession, though later he honored it. He winked at me.

"Don't you tamper with my client," said he; and then resumed to Curly; "What you need is a lawyer. You've got to have legal advice. It happens that the full bar of Heart's Desire is now present talking to you. Take your pick. I've got a mighty good idea which is the best lawyer of this bar, but I wouldn't tell you for the world that I'm the one. Take your pick. Here's the whole legal works of the town, us two. Try the Learned Counsel on my right."

"Law!" said Curly. "Why—law—lawyers! Then who—say, now, I'll pay for the pig. I didn't mean nothing, no way." Then Dan Anderson rose to certain heights. "You can't settle it that way," said he. "That's too easy. Oh, you can pay for the pig easy enough; but how about the majesty of the law? Where is the peace and dignity of the commonwealth to come in? This is criminal. Nope, you choose. You need a lawyer."

"You—you-all got me locoed," said Curly, nervously. "Law! Why, I don't want no law. There ain't never been no co'te set here. Down to the county-seat, over to Lincoln, that's all right; but here—why, they don't want no law here. Besides, I can't choose between you two fellers. I like you both. You're both white men. Ef you could rope and shoot better, I could git either one of you a job cowpunchin' any day, and that's a heap better'n practisin' law. I couldn't make no choice between you fellers. Say, I'll have you both." This with a sudden illumination of countenance.

"That would be unconstitutional," said Dan Anderson, solemnly, "and against public policy as well. That would be cornering the whole legal supply of the community, Curly, and it wouldn't leave anybody for the prosecution."

"Sho'!" said Curly. Then suddenly he added: "There's the old man. Don't you never doubt he'd prosecute joyful. And there never was a man from Kansas didn't know some law. Why, onct, down on the Brazos—"

"He can't act as attorney-at-law," said Anderson. "He's never been admitted to the bar. Say, you flip a dollar."

The thought of chance-taking appealed to Curly. He flipped the dollar.

"Heads, me," said Dan Anderson; and so it fell. That young man smiled blithely. "We'll skin 'em, Curly," said he. "You'll be as free as air in less'n a week."

"Now," said Dan Anderson to me, "it's all right thus far. Next we have got to get a Justice of the Peace, and then we've got to get the prisoner arrested."

"'Rested!" said Curly. "Who? Me?"

"Of course," drawled his newly constituted attorney. "Didn't you kill the pig? You just hang around for a little, for when we need you, we don't want to have to hunt all over the country."

"All right," said Curly, dubiously.

"Where's Blackman?" said Dan Anderson, again addressing me. "We have got to have a judge, or we can't have any trial. Come on and let's hunt him up. Curly, don't you run away, mind. You trust to me, and I'll get you clear, and get you married, both."

"All right," said Curly again, "I'll just sornter down to the Lone Star, and when you-all want me I'll be in there, either takin' a drink or playin' a few kyards."

"Let's get Blackman now," said Curly's lawyer. Blackman was the duly constituted Justice of the Peace in and for Heart's Desire. Nobody knew precisely when or how he had been elected, and perhaps indeed he never was elected at all. There must be a beginning for all things. The one thing certain as to Blackman was that he had once been a Justice of the Peace back in Kansas, which fact he had not been slow to announce upon his arrival in Heart's Desire. Perhaps from this arose the local custom of calling him Judge, and perhaps from his wearing the latter title arose the supposition that he really was a judge. The records are quite silent as to the origin of his tenure of office. The office itself, as has been intimated, had hitherto been one purely without care. At every little shooting scrape or other playfulness of the male population Blackman, Justice of the Peace, became inflated with importance and looked monstrous grave. But nothing ever came of these little alarms, so that gradually the inflations grew less and less extensive. They might perhaps have ceased altogether had it not been for this malignant zeal of Dan Anderson, formerly of Princeton, and now come, hit or miss, to grow up with the country.

Blackman was ever ready enough for a lawsuit, forsooth pined for one. Yet what could he do? He could not go forth and with his own hands arrest chance persons and hale them before his own court for trial. The sheriff, when he was in town, simply laughed at him, and told his deputies not to mix up with anything except circuit-court matters, murders, and more especially horse stealings. Constable there was none; and policeman—it is to wonder just a trifle what would have happened to any such thing as a policeman or town marshal in the valley of Heart's Desire! In short, there was neither judicial nor executive arm of the law in action. One may, therefore, realize the hindrances which Dan Anderson met in getting up his lawsuit. Yet he went forward in the attempt patiently, driven simply by ennui. He did not dream that he was doing something epochal.

Blackman, Justice of the Peace, was sitting in the office of the Golden Age when we found him, reading the exchanges and offering gratuitous advice to the editor. He was a shortish man, thick in body, with sparse hair and hay-colored, ragged mustache. His face was florid, his pale eyes protruded. He was a wise-looking man, excellently well suited in appearance for the office which he filled. We explained to him our errand. Gradually, as the sense of his own new importance dawned upon him, he began to swell, apparently until he assumed a bulk thrice that which he formerly possessed. His spine straightened rigidly; a solemn light came into his eye; a cough that fairly choked with wisdom echoed from his throat. It was a great day for Blackman, J. P.

"Do I know this man, this cow puncher?" said he. "Of course I know him, damn him, and I know what he done, too. Such a high-handed act never ought to be tolerated, sir! Destroyin' property—why, a-destroyin' of life and property, for he killed the pig—and this new family of citizens dependin' in part on the pig fer their sustenances this comin' season; to say nothin' of his nigh shootin' me up as I was crossin' the street from the post-office! Try him! Why, of course we ought to try him. What show have we got if we go on this lawless way? What injucement can we offer Eastern Capital to settle in our midst if, instead of bein' quiet and law-abidin', we go on a-rarin' and a-pitchin' and a-runnin' wide open, every man for hisself? What are we here for, you, and you, and me, if it ain't to set in trile over such britches of the peace?"

"You're in," said Dan Anderson, succinctly. "Get over to your 'dobe. We'll hold this trial right away. I reckon all the boys'll know about it by this time. I'll go over and get the prisoner. But, hold on! He ain't arrested yet. Who'll serve the warrant? Ben Stillson (the sheriff) is down on the Hondo, and his deputy, Poe, is out of town. There ain't a soul here to serve a paper. Looks like the court was some rusty, don't it?"

"Warrant!" said the Justice, "warrant! You don't need no warrant. Wasn't he seen a-doin' the act?"

"Oh, but it wasn't a real first-class felony," demurred Dan, with some shade of conscience left.

"Well, I'll arrest him myself," said the Justice. "He's got to be brought to trile."

"Well, now," I ventured to suggest, "that doesn't look exactly right, either, since you are to try the case, Judge. It's legal, but it isn't etiquette."

Blackman scratched his head. "Maybe that's so," said he. Then turning to me, "S'pose you arrest him."

"He can't," said Dan Anderson. "He's the prosecuting attorney—only other lawyer in town. It wouldn't look right for either the judge or prosecutor to make the arrest. Curly might not like it." This all seemed true enough, and we fell into a quandary.

"I'll tell you," said Dan Anderson at length. "I'd better arrest him myself. I'm going to defend him, so it would look more regular for me to bring him in. Looks like he wasn't afraid of the verdict. We ain't, either. I want you to remember, Judge, if you don't clear him—"

Here counsel for the Territory interrupted, feeling that the majesty of the law was not fully observed by threatening the trial judge in advance.

"Well, come along, then," said Anderson. "Let that part of it go. Come over and let's get out the warrant."

I was not with them when the warrant was issued, though that part of the proceeding might naturally have seemed rather the duty of the prosecution than of the defence. Dan Anderson afterward told me that Blackman could not find his law book (he had only one, a copy of the statutes of Kansas) for a long time, and then couldn't find the proper place in it. Legal blanks did not exist in Heart's Desire, and all legal forms had departed from Blackman's mind in this time of excitement. Dan Anderson himself drew the warrant. As it was read later by himself to Curly at the Lone Star, it did not lack a certain charm. It began with "Greeting," and ended with, "Now, therefore, in the name of God and the Continental Congress." Anderson did not crack a smile in reading it, and so far as that is concerned, the warrant worked as well as any and better than some. Curly, because he felt that he was in the hands of his friends, made no special demurrer to the terms of the "writ," and in a few moments the Lone Star was empty and Blackman's adobe was packed.

"Order! order! gentlemen!" called Blackman, Justice of the Peace, clearing his throat. "This honorable justice court is now in session. Gentlemen, what is your pleasure?"

He was a little confused, but he meant well. It seemed incumbent upon the prosecutor to make some sort of a statement, but the attorney for the defence interposed. He moved for the discharge of the prisoner on the ground that there was no Territorial law and no city ordinance violated; he pointed out that Heart's Desire was not a city, neither a town, but had never been organized, established, or begun, even to the extent of the filing of a town site plat; he therefore denied the existence of any municipal law, since there had never been any municipality; he intimated that the pig had perhaps been killed accidentally, or perhaps in self-defence; it was plain that the prisoner was wrongfully restrained of his liberty, etc.

The ire of Blackman, J. P., at all this was something to behold. He to be deprived of his opportunity thus lightly? Hardly! He overruled the objections at once, and rapped loudly for order.

"The trile will go on," said he.

"Then, your Honor," cried Dan Andersen, springing to his feet, "then I shall resort to the ancient bulwark of our personal liberties. I shall sue out a writ of habeas corpus, and take this prisoner out of custody. I'll sue this court on its bond! I'll take a change of venue! We'll leave no stone unturned to set this innocent man free and restore him to the bosom of his family!"

This speech produced a great effect on the audience, as murmurs of approbation testified, but the doughty Justice of the Peace was not so easily to be reckoned with. He pointed out that there was no officer to serve a writ of habeas corpus; that the court had given no bond to anybody and did not propose to do so; that there was no other court to which to apply for a change of "vendew," as he termed it; and reiterated once more that the "trile must go on." The prosecution was, therefore, once more called upon to state the case. Again the attorney for the defence protested, a foreshadowing of his fighting blood reddening his face.

"I call for a jury," said he. "Does this court suppose we are going to leave the liberty of this prisoner in the hands of a judge openly and notoriously prejudiced as to the facts of this case? I demand a trial by a jury of the defendant's peers."

Blackman reddened, but was game. "Jury goes," said he. "Count out twelve fellers there, beginnin' next the door."

"Twelve!" said Dan Andersen, for the moment almost losing his gravity. "I thought this court might be content with six for a justice's jury; but realizing the importance of this court, we are willing to agree on twelve."

It was so agreed. The jury took in every man in the little room but three. "They'll do for a veniry," said Blackman, J. P., learnedly. Under the circumstances, one can perhaps forgive him for becoming at times a trifle mixed as to the legal proceedings.

At least, it was easy to agree as to the jury; for obviously the population of the place was fully acquainted with all the facts in the case, and each one had freely expressed his opinion upon the one side or the other. There seemed to be no reason for excusing any juror for cause; and upon the other hand, there are often very good reasons in a Land Before the Law for not bringing up personal matters of this kind. Indeed, the trial judge settled all that. He looked over the twelve good men and true thus segregated, and remarked briefly: "They're his peers, all right. The trile will now proceed."

Whereupon he swore them solemnly and made a record in his fee book, to the later consternation of his jurors. "Ain't this court a notary, too?" said Blackman later. "And ain't a notary entitled to so much fee for administerin' a oath? And didn't I administer twelve oaths?" There was small answer to this, after all. The laborer is worthy of his hire; and Blackman really labored in this case as in all likelihood few justices have before or since.

The prosecuting attorney, who, it may be seen, held his office much as did the justice of the peace, by the doctrine of nemine contradicente, now arose and made the opening statement. There, was some doubt as to whether this was a civil or criminal trial, but there was no doubt whatever of the existence of a trial of some kind; neither did there exist any doubt as to the importance of this, the first case the prosecuting attorney had ever tried, outside of moot courts. It was the first speech he had ever made in public, barring college "orations," carefully memorized, and an occasional Fourth of July speech, which might have been better for more memorizing. The attorney for the prosecution, however, arose to the occasion—at least to a certain extent. He spoke in low and feeling tones of the struggling little community of hardy souls thus set down apart in the far-off mountain country of the West; of its trials, its hopes, its ambitions, of its expectations of becoming a mountain emporium which should be the pride of the entire Territory; he went on to mention the necessity for law and order, pointing out the danger to the public interests of the community which must lie in a general reputation for ruffianism and lawlessness, showing how Eastern Capital must ever be timid in visiting a town of such reputation, apart from investing any money therein; then, changing to the personal phases of the case, he spoke of the absolute disregard of law shown in the act charged, mentioned the red-handed deed of this lawless and dangerous person who had thus slain a pig, no less the pride of the community than the idol of the family now bereft.

At this point the jury began to look much perturbed and solemn, and the prisoner very red and uneasy. Prosecution closed by offering to prove all charges by competent testimony. This latter was a dangerous proposition to advance. We could not well ask the jurymen to testify, and of the "veniry," more than half had now slipped out for a hurried and excited visit to the Lone Star, there to advise any possible new arrivals of what was going on at Blackman's adobe.

Counsel for the defence arose calmly to make his opening statement. The man was a natural trial lawyer. It was simply destiny which had driven him into this comedy, as destiny had driven him to Heart's Desire. It was not comedy now, when Dan Anderson faced judge and jury here in Blackman's adobe. There came a swift, sudden chill, a gripping as of iron, a darkening, a shrinking of the heart of each man in that little room. It was the coming of the Law! Ah! Dan Anderson, you ruined our little paradise; and now its walls are down forever, even the walls of our city of content.

Dan Anderson stood, young, tall and grave, one hand in the bosom of his shirt, for hardly one present wore a coat. He had his audience with him before he spoke. When he began he caught them tighter to his cause, using not merely flowing rhetoric of speech, but the close-knit, advancing, upbuilding argument of a man able to "think on his feet,"—that higher sort of oratory which is most convincing with an American audience or an American jury.

The statement of the prosecution, said Dan Anderson, was on the whole a fair one, and no discredit to the learned brother making it. None would more readily than himself yield acquiescence to the statement that law and order must prevail. Without law there could be nothing but anarchy. Under anarchy progress was at an end. The individual must give up something of his rights to the state and the community. He gave up a certain amount of liberty, but received therefor an equivalent in protection. The law was, therefore, no oppressor, no monster, no usurer, no austere being, reaping where it had not sown. The law was nothing to be dreaded, nothing to be feared; and, upon the other hand, it was nothing to be scorned.

There must be a beginning, continued Dan Anderson. There must be something established. The pound measure was one pound, the same all over the country; a yard measure was a yard, and there was no guesswork about it. It was the same. It was a unit. So with the law. It must be the same, a unit, soulless, unfeeling, just, unchangeable. There was nothing indeterminate in it. The attitude of the law was thus or so, and not otherwise. It was not for the individual to pass upon any of these questions. It was for the courts to do so, the approved machinery set aside, under the social compact, for reducing the friction of the wheels of society, for securing the permanency of things beneficial to that society, and for removing things injurious thereto. The Law itself was immutable. The courts must administer that Law without malice, without feeling, impersonally, justly.

In so far as there had hitherto been no Law in Heart's Desire, went on the speaker, thus far had our citizens dwelt in barbarism, had indeed been unfit, under the very definition of things, to bear the proud title of citizens of America, the justest, the most order-loving, as well as the bravest and the most aggressive nation of the world. The time had now come for the establishment in this community of the Law, that beneficent agency of progress, that indispensable factor, that inseparable attendant upon civilization. Upon the sky should blaze no more the red riot of anarchy and barbarism. Upon the summit of the noble mountain overtopping this happy valley there should sit no more the grinning figure of malevolent and unrestrained vice, but the pure form of the blind Goddess of Justice, holding ever aloft over this happy land the unfaltering sword and the unwavering scales, so that all might look thereon, the rightdoers in smiling security, the wrong-doing in terror of their deeds. This was the Law!

"And now, gentlemen of this jury," said Dan Anderson, "I stand here before you to make no excuses for this Law, to palliate nothing in the way of its workings, to set no tentative or temporizing date for the time of the arrival at this place of the image of the Law. I say to you here to-day, at this hour, that image now sits there enthroned above us. The Law is not to come—it has come, it is here!"

The old days were, therefore, done, he went on. Henceforth we must observe the Law. We were here now with the intention of observing that Law. Should we therefore fear it? Should we dread the decision of this distinguished servant of the Law? By no means. To show that the Law was no dragon, no demon, he would now, in the very face of that Law, proceed to clear this innocent man of that cloud of doubt and suspicion which for a brief moment the social body had cast upon him. He would show to the gentlemen of this jury and to this honorable court that there had been no violation of the Law through any act of this honest, open-faced, intelligent young gentleman, long known among them as an upright and fair-dealing man. The Law, just and exact, would now protect this prisoner. The Law was no matter of haphazard. The prosecution must show that some specific article of the Law had been violated.

"Now," continued Dan Anderson, casting an eye about him as calmly as could have done any old trial lawyer examining the condition of his jury, "what are the charges made by the Territory? The prosecution specifies no section or paragraph of the statutes of this Territory holding it unlawful to shoot any dangerous wild beast at large in this community. But we do not admit that this prisoner shot anything, or shot at anything whatever. We shall prove that at the time mentioned he was engaged in a simple, harmless, and useful pastime, a pastime laudable of itself, since it tends to make the participant therein a better and more useful citizen. There is no Territorial law forbidding any act which he is here charged with committing. Neither has the body social in this thriving community placed upon its records any local law, any indication that a man may not, without let or hindrance, do any act such as those charged vaguely against this good young man, who has only availed himself of his right under the Constitution to bear arms, to assemble in public, and to engage in the pursuit of happiness."

The prosecution, he said, had introduced reference to a certain pig, alleging that it was slain by the act of the prisoner. He would not admit that there had been any pig, since no corpus delicti was shown; but in any event this was no civil suit now in progress. We were not here to assess value upon a supposititious pig, injured in a supposititious manner, and not represented here of counsel. No law had been violated. Why, then, his client had been thus ruthlessly dragged into court, to his great personal chagrin, his loss of time, his mental suffering, the attorney for defence could not say. It was injustice of a monstrous sort! Prosecution might well feel relieved if no retaliatory action were later taken against them for false imprisonment. This innocent young man must at once be discharged from custody.

When Dan Anderson sat down there was not a man in the jury who was not bathed in perspiration. Abstruse thought was hard at work. Blackman, J. P., perspiring no less than any member of the jury, drew himself up, but he was troubled.

"Evidence f'r the State," the Judge finally managed to stammer, turning to the attorney for the prosecution.

But it never came so far along as that. There was a sound of many footsteps; voices came murmuring, growing louder. The door was pushed open from without, and in came much of the remaining population of Heart's Desire, so far as it could gain room. The man from Leavenworth was there, his whiskers wagging unintelligibly. McKinney was there, and Doc Tomlinson and Tom Osby, and everybody else; and, pushing through the crowd, there came the Littlest Girl from Kansas, her apron awry, her hair blown, her face flushed, her eyes moist with tears.

"Curly!" cried she as at last her eyes caught sight of him. "Come right on out of here, this minute! Come along!"

What would you have? The Law is the Law; but there are such things as supreme courts. It was useless for Blackman, J. P., to rap and call for order. It had probably been useless for any man to undertake to stop the prisoner at the bar, thus adjured. At any rate he arose and said politely to the jurors, "Fellers, I got to go"—and so went, no man raising hand to restrain him.

As to Dan Anderson, he himself admitted his wish that the case had gone on. "I wanted to cross-examine," said he.

That night, over by the arroyo, we met Curly and the Littlest Girl walking in the moonlight. Curly was quiet. The Littlest Girl was tremulous, content. Curly, pausing as we approached, mumbled some shamefaced thanks.

"Curly," said Dan Anderson, his voice queer, "I didn't do it for pay. I did it—I don't know why—"

A new mood was upon him. A lassitude as of remorse appeared to relax him, body and mind. An hour later he and I sat in the glorious flood of the light of the moon of Heart's Desire, and we fell silent, as was the way of men in that place. At length Dan Anderson turned his face to the top of old Carrizo, the restful, the impassive. He gazed long without speaking, as though he plainly saw something there at the mountain top.

"Listen," he whispered to me, a moment later, and his eyes did not quite keep back the tears. "She's there—the Goddess. The Law has come to Heart's Desire. May God forgive me! Why could we not have stayed content?"

But little did Dan Anderson foresee that day how swiftly was to come further ruin for the kingdom of oblivion which we thought that we had found.

"There'll be women next!" I said to him bitterly; though this was a vague threat of a thing impossible.

His reply was a look more than half frightened.

"Don't!" he said.

Two months had passed since the wedding of Curly and the Littlest Girl, and nothing further had happened in the way of change. The man from Philadelphia had not come, and, to the majority of the population of Heart's Desire at least, the railroad to the camp remained a thing as far distant as ever in the future. Life went on, spent in the open for the most part, and in silent thoughtfulness by choice. Blackman, J. P., now languished in desuetude among the fallen remnants of an erstwhile promising structure of the law; and there being no further occupation for the members of the bar, the latter customarily spent much of the day sitting in the sun.

"You might look several times at me," said Dan Andersen one day, without preface or provocation, "and yet not read all my past in these fair lineaments."

This seemed unworthy of notice. A man's past was a subject tabooed in Heart's Desire. Besides, the morning was already so warm that we were glad to seek the shade of an adobe wall. Conversation languished. Dan Anderson absent-mindedly rolled a cigarrillo with one hand, his gaze the while fixed on the horizon, on which we could see the faint loom of the Bonitos, toothed upon the blue sky, fifty miles away. His mind might also have been fifty miles away, as he gazed vaguely. There was nothing to do. There was only the sun, and as against it the shade. That made up life at Heart's Desire. It was a million miles away to any other sort of world; and that world, in so far as it had reference to a past, was a subject not mentioned among the men of Heart's Desire. Yet this morning there seemed to be something upon Dan Andersen's mind, as he edged a little farther along into the shade, and felt in his pocket for a match.

"No, you wouldn't think; just to look at me, my friend," said he, "you wouldn't think, without runnin' side lines, and takin' elevations for dips, spurs, and angles, that I had ever been anything but a barrister; now, would you? Attorney and Counsellor-at-law, all hours of the day and night: that bill of specifications is engraved on my brow, ain't it? You like enough couldn't believe that I was ever anything else—several things else, could you?"

His speech still failed of interest, except as it afforded additional proof of the manner in which Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and the like disappeared from the speech of all men at Heart's Desire. Dan Anderson sat down in the shade, his long legs stretched out in front of him. "My boy," said he, "you can gaze at me if you ain't too tired. As a matter of fact, in this pernicious age of specialization I stand out as the one glitterin' example of success in more than one line. Why, once I was a success as a journalist—for a few moments."

There was now a certain softness and innocence in his voice, which had portent, although I did not at that time suspect that he really had anything of consequence upon his soul. Without more encouragement he went on.

"My brother," said he, "when I first came out of Princeton I was burnin' up with zeal. There was the world, the whole wide world, plunged into an abyss of error and wrongdoin'. I was the sole and remainin' hope. Like all great men, I naturally wanted to begin the savin' as early as possible; and like everybody else who comes out of Princeton, I thought the best medium for immediate salvation was journalism. I wasn't a newspaper man. I never said that at all. I was a journalist.

"Well, dad got me a place on a paper in New York, and I worked on the dog-fight department for a time, it havin' been discovered that I was noted along certain lines of research in Princeton. I knew the pedigree and fightin' weight of every white, black, or brindle pup in four States. Now, a whole lot of fellows come out of college who don't know that much; or if they do, they don't know how to apply their knowledge. Now dogs, that's plumb useful.

"I was still doin' dogs when the presidential campaign came along, or rather, that feature of our national customs which precedes the selection of the People's Choice. First thing, of course, the People's Choice had to take a run over the country—which was a good thing, too, because he didn't know much about it—and let the people in general know that he was their choice. I went along to tell the other people how he broke it to them."

I confess I sat up at this, for there was now so supreme an innocence in Dan Anderson's eye that one might have been morally certain that something was coming. "From dogs to politics—wasn't that a little singular?" I asked.

"Yes," said he; "but you have to be versatile in journalism. The regular man who was to have gone on that special presidential car got slugged at an art gatherin'. I didn't ask for the place. I just went and told the managin' editor I was ready if he would give me an order for expense money. It wouldn't have been good form for him to look up and pay any attention to me, so I got the job. I needed to see the country just as much as the People's Choice did.

"Three other fellows went along,—newspaper men. I was the only real journalist. We did the presidential tour for ten towns a day. I watched what the other fellows did, and in about two hours it was easy. Everything's easy if you think so. Folks made a lot of fuss about gettin' along in the world. That's all a mistake.

"People's Choice tore it off in fine shape. Comin' into Basswood Junction he turns to his Honorable Secretary, and says he, 'Jimmy, what's this?' Jimmy turns to his card cabinet, and says he: 'Prexie, this is Basswood Junction. Three railroads come in here—and get away as soon as they can. Four overall factories and a reaper plant. Population six thousand, and increasin' satisfactory. Hon. Charles D. Bastrop, M.C., from this district, on the straight Republican ticket for the last three hundred years; world without end.'