Title: The magic speech flower; or, Little Luke and his animal friends

Author: Melvin Hix

Release date: March 15, 2005 [eBook #15367]

Most recently updated: December 14, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Garcia and the PG Online

Distributed Proofreading Team.

By MELVIN HIX, B. Ped., Principal of Public School 9, Long Island City, New York City.

The aim of the author is to retell these familiar stories of childhood in such way as to give added interest to first and second grade pupils.

Fourth Avenue and 30th Street, New York

LONDON, BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

CHAPTER

I. THE FINDING OF THE MAGIC FLOWER

II. LITTLE LUKE AND THE BOB LINCOLNS

III. THE STORY OF THE SUMMER LAND

IV. BOB LINCOLN'S STORY OF HIS OWN LIFE

V. LITTLE LUKE MAKES FRIENDS AMONG THE WILD FOLK

VI. LITTLE LUKE AND KIT-CHEE THE GREAT CRESTED FLYCATCHER

VII. WHY THE KIT-CHEE PEOPLE ALWAYS USE SNAKE-SKINS IN NEST-BUILDING

VIII. LITTLE LUKE AND NICK-UTS THE YELLOWTHROAT

IX. WHY MOTHER MO-LO THE COWBIRD LAYS HER EGGS IN OTHER BIRDS' NESTS

X. THE STORY OF O-PEE-CHEE THE FIRST ROBIN

XI. HOW THE ROBIN'S BREAST BECAME RED

XII. HOW THE BEES GOT THEIR STINGS

XIII. THE STORY OF THE FIRST SWALLOWS

XIV. LITTLE LUKE AND A-BAL-KA THE CHIPMUNK

XV. HOW A-BAL-KA GOT HIS BLACK STRIPES

XVI. HOW A-BAL-KA THE CHIPMUNK HELPED MEN

XVII. LITTLE LUKE AND MEE-KO THE RED SQUIRREL

XVIII. THE STORY OF THE FIRST RED SQUIRRELS

XIX. HOW THE RED SQUIRREL BECAME SMALL

XX. LITTLE LUKE AND MOTHER MIT-CHEE THE RUFFLED PARTRIDGE

XXI. WHY THE FEATHERED FOLK RAISE THEIR HEADS WHEN THEY DRINK

XXII. LITTLE LUKE AND FATHER MIT-CHEE

XXIII. THE STORY OF THE FIRST PARTRIDGE

XXV. MOTHER WA-POOSE AND OLD BOZE THE HOUND

XXVI. MOTHER WA-POOSE AND OLD KLAWS THE HOUSE CAT

XXVIII. WHY THE WILD FOLK NO LONGER TALK THE MAN-TALK

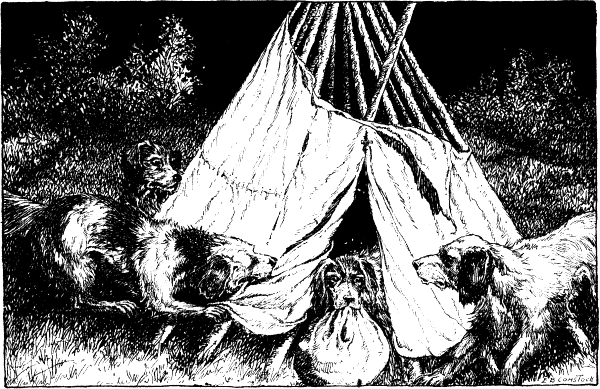

XXIX. THE TALE OF SUN-KA THE WISE DOG

XXX. HOW THE DOG'S TONGUE BECAME LONG

XXXI. THE STORY OF THE FAITHFUL DOG

It was June and it was morning. The sky was clear and the sun shone bright and warm. The still air was filled with the sweet odor of blossoming flowers. To little Luke, sitting on the doorstep of the farmhouse and looking out over the fresh fields and green meadows, the whole earth seemed brimful of happiness and joy.

From the bough of an apple tree on the lawn O-pee-chee the Robin chanted his morning song. "Te rill, te roo, the sky is blue," sang he.

From the lilac bush Kil-loo the Song Sparrow trilled, "Sweet, sweet, sweet, sweet, the air is sweet."

Over in the meadows Zeet the Lark fluttered down upon a low bush and sang, "Come with me, come and see," over and over. Then he dropped down into the grass and ran off to the nest where his mate was sitting on five speckled eggs.

Bob-o'-Lincoln went quite out of his wits with the joy of life. He flew high up into the air, and then came fluttering and falling, falling and quivering down among the buttercups and daisies. He was very proud of himself and wanted everybody to know just who he was. So he sang his own name over and over. With his name-song he mixed up a lot of runs and trills and thrills that did not mean anything to anybody but himself and his little mate nestling below him in the grass. To her they meant, "Life is love, and love is joy."

Old Ka-ka-go the Crow, sitting on the top of the tall maple, felt that on such a morning as this he, too, must sing. So he opened his beak and croaked, "Caw, caw, caw, caw." What he meant to say was, "Corn, corn, corn, corn." Sam, the hired man, heard him and came out of the barn door with his gun. Old Ka-ka-go spread his black wings and flapped off to the woods on the side of the mountain.

Far up in the blue sky Kee-you the Red-shouldered Hawk wheeled slowly about in great circles. When he saw Sam with his gun, he screamed, "Kee-you, kee-you, kee-you," over and over.

That was a poor song, but a good war cry; It sent every singer plunging to cover. O-pee-chee the Robin hid himself among the thick branches of the apple tree. Kil-loo the Song Sparrow hopped into the thickest part of the lilac bush. Zeet the Lark and Bob Lincoln squatted in the thick grass. Not a bird note was to be heard.

But Ka-be-yun the West Wind was not afraid of the warrior hawk. He breathed softly among the branches of the trees and set every little leaf quivering and whispering. Then he ran across the meadows and the wheat fields. As he sped along, great waves like those of the sea rolled in wide sweeps across the meadow and through the tall wheat.

To little Luke it seemed as if the leaves and grass and wheat all whispered, "Come away. Come and play." Just then a great bumblebee flew by and now the call was clear. "Come away, come away! Follow, follow, follow me!"

The boy jumped up and ran down the path into the garden. There he met Old Klaws the House Cat, with a little brown baby rabbit in his mouth. "You wicked old cat," said little Luke, "drop it, drop it, I say." But Old Klaws only growled and gripped the little rabbit tighter. Little Luke seized the old cat by the back of the neck and choked him till he let go. The little brown rabbit looked up at him with his big round eyes, as much as to say, "Thank you, little boy, thank you." Then he hopped off into the thicket of berry bushes, where Old Klaws could not catch him again.

Little Luke went on down the path, through the garden gate, and into the meadow beyond. All at once Bob Lincoln sprang up out of the grass right before his feet.

Little Luke thought he would find Bob Lincoln's nest. So he got down upon his knees and began to look about in the grass very carefully. He did not find the nest, but he did find a fine cluster of ripe, wild strawberries. He forgot all about the nest and began to pick and eat the sweet berries. So he ate and ate till his lips and fingers were red as red wine and smelled strongly of ripe strawberries.

Suddenly, as he put out his hand for another cluster, up sprang a black and brown and yellow bird. That was Mrs. Bob Lincoln. Little Luke put aside the grass and there was the nest. It was so cunningly hidden that he could never have found it by looking for it.

Mr. and Mrs. Bob Lincoln were greatly frightened. They fluttered and quivered about, and talked to each other, and scolded at the boy. Little Luke could not understand what they said, but part of it sounded like, "Let it be! Don't touch, don't touch! Go away, please, p-l-e-a-s-e, go away." So he got up and said, "All right, don't be afraid. I'll not take your eggs, I'll go right away." And so he did.

When he had gone two or three rods, Mrs. Bob Lincoln fluttered down to her nest and settled herself quietly over her eggs. But Mr. Bob flew to a tall weed in front of little Luke. There he sat and swung and teetered and sang his merriest song. To the little boy it seemed as if he was trying to say, "Thank you, thank you, little boy."

There was an old apple tree standing near the meadow fence. On one of its branches was the nest of O-pee-chee the Robin. Both Mr. and Mrs. O-pee-chee had gone away to pick worms from the soft, fresh earth in the garden.

As little Luke drew near to the tree, he saw Mee-ko the Red Squirrel crouching by the side of the nest with a blue egg in his front paws. He had not yet broken the shell when he saw little Luke. At first he thought he would run away. But he wanted that egg; so he squatted very quietly where he was and hoped the little boy would not see him.

But little Luke's eyes were very keen. He saw Mee-ko and guessed what he was about. So lie picked up a small round stone and threw it at the robber squirrel. His aim was so true that the stone flicked Mee-ko's tail where it curled over his shoulders.

Mee-ko was so scared that he dropped the egg back into the nest and ran along the branch and across to another. From the end of that he dropped down to the fence and scampered along the rails up toward the woods on the side of the mountain.

He went all the faster because Father O-pee-chee flew down into the branches of the apple tree just as little Luke threw the stone. He saw Mee-ko and understood exactly what had happened. He flew a little way after the thieving squirrel. Then he came back and lit on the highest branch of the apple tree and began to sing. "Te rill, te roo, I thank you; te rill, te roo, I thank you," the little boy thought he said.

Little Luke went over to the fence. In a bush beside the fence there was a big spider's web. Old Mrs. Ik-to the Black Spider had built the web as a trap to catch flies in. But this time there was something besides a fly in the trap. Ah-mo the Honey Bee had blundered, into the web and was trying hard to get away.

Old Mrs. Ik-to was greatly excited. She was not sure whether she wanted bee meat for dinner or not. She knew very well that bees are stronger than flies and that they carry a dreadful spear with a poisoned point.

Mrs. Ik-to ran down her web a little way, then she stopped and shook it. Ah-mo the Honey Bee was not so much entangled by the web that he could not sting and the old spider knew that. So she ran back again to one corner of the web.

Little Luke stood and watched poor Ah-mo for a moment. Then he took a twig from the bush and set him free. Ah-mo rubbed himself all over with his legs and tried his wings carefully to see if they were sound. Then he flew up from the ground and buzzed three times round little Luke's head.

The little boy was not afraid. He knew that bees never sting anyone who does not hurt or frighten them, and besides, he thought the buzzing had a friendly sound to it. It seemed to him as if Ah-mo was trying to say, "Thank you, little boy, thank you," as well as he could.

When Ah-mo had flown away, little Luke looked around to see what old Mrs. Ik-to was doing, but he could not find her.

Leaving the old spider to mend her web as well as she could, little Luke got over the fence into the pasture. As he was going along he heard Mrs. Chee-wink making a great outcry. She was flying about a little bushy fir tree not bigger than a currant bush. "Chee-wink, to-whee; chee-wink, to-whee!" she called. Little Luke thought she was saying, "Help! Help! Come here, come here!" And so she was.

He went up toward the fir bush. As he walked along, he picked up a stout stick that was lying on the ground. When he came to the bush, Mrs. Chee-wink flew off to a tall sapling near by and watched him without saying a word.

At first he could not see anything to disturb anybody. But he knew that Mrs. Chee-wink would never have made all that fuss for nothing. So he took hold of the fir bush and pulled the branches apart. Then he understood. He had almost put his hand on A-tos-sa the Big Blacksnake.

A-tos-sa had a half-grown bird by the wing and was trying to swallow it. The young bird was strong enough to flutter a good deal and Mother Chee-wink had flapped her wings in the snake's eyes and pecked his head, so that he had not been able to get a good hold.

Little Luke struck at once. The stick hit the snake and he let go of the bird and slid down to the ground. Little Luke hit him again, this time squarely on the head. Then with a stone he made sure that A-tos-sa would never try to eat young birds again.

After he had finished with the snake, he picked up the young bird which had fallen to the ground. It seemed more scared than hurt, so he put it carefully into the nest, where there were two other young birds. Then he went on up toward the woods.

Mrs. Chee-wink flew back to the fir bush. She looked first at the dead snake and then at her nest. Then she said, "Chee-wink, chee-wink, to-whee, chee-wink, to-whee," two or three times very softly and settled down quietly on her nest. Of course that meant, "Thank you, little boy, thank you!"

Up above the fir bush in the pasture stood an old apple tree, all alone by itself. On a dead branch was Ya-rup the Flicker. He was using the hard shell of the dead branch for a drum. "Rat, a tat, tat," he went faster and faster, till the beats ran into one long resounding roll. Then he stopped and screamed, "Kee-yer, kee-yer!" Perhaps he meant, "Well done! good boy! good boy!"

You see he had seen little Luke's battle with the blacksnake and was drumming and screaming for joy. Little Luke stopped under the old apple tree and listened to Ya-rup's drumming and screaming for a while. Then he went on up to the edge of the big woods.

There he found an old trail which he followed a long way till it forked. Right in the fork of the trail, he saw a young bird. Its feathers were not half grown and of course it could not fly. Little Luke knew that it must have fallen out of the nest by accident. So he ran after the frightened little bird and picked it up very carefully. Just then O-loo-la the Wood Thrush flew down into a bush by the side of the trail and began to plead, "Pit'y! pit'y! don't hurt him! Let him go, little boy; please let him go!" he seemed to say.

Little Luke looked around for the nest. Soon he saw it in a tangle of vines that ran over a dogwood bush.

Very carefully he picked his way through the bushes toward the nest. O-loo-la seemed to guess what he meant to do and hopped from bush to bush without saying a word.

When the little boy went to put the young bird back into the nest, he saw why he had fallen out. There were three young birds in it, and they filled it so full that there was scarcely room for another. Little Luke saw that the bird he held was smaller than the others. So he took one of them out and put his bird down into the middle of the nest. Then he put the bigger one back. When this one snuggled down into the nest, it was quite full.

When little Luke went back into the trail, O-loo-la flew to a branch over his head and began to sing very happily. The little boy thought that he, too, was trying to say, "Thank you, little boy, thank you."

Little Luke took the left-hand trail and followed it till he came to a beautiful spring which gushed from under a tall rock. He lay down upon his stomach and took a long drink of the cool, sweet water.

Just beside the spring stood a big beech tree. Near the ground two large roots spread out at a broad angle. Little Luke sat down between the roots and leaned his head against the tree. It was a very comfortable seat. So he sat there and dreamed with his eyes wide open. Just what he was dreaming about he did not know. He only knew that he felt very happy and very quiet.

Mee-ko the Red Squirrel ran out upon a branch just over his head and peeked and peered at him with his bright, inquisitive eyes. As little Luke sat very still, Mee-ko cocked his long tail up over his shoulders and sat and watched him.

Little Luke felt so very comfortable and quiet that he closed his eyes for a moment. At least it seemed only a moment to him. All at once he heard a loud hum. He opened his eyes and there was Ah-mo the Honey Bee just before his face. When Ah-mo saw that little Luke was watching him, he flew down toward the spring and lit upon a beautiful flower.

Little Luke was surprised; he had not seen that flower before. It was a very beautiful flower. He leaned over and looked at it. Its petals were blue as the sky, except near the heart, where they were pink as a baby's fingers; and its heart was as yellow as gold.

Little Luke reached out his hand to pick the strange flower. As soon as Mee-ko saw what he was doing, he fairly screamed. To little Luke it seemed as if he said, "Stop, stop, let it be. Leave it alone. Go away."

Little Luke was used to Mee-ko's scolding. He had heard it many times before, but never before had he thought there was any sense in it. It seemed very queer to him that he could understand the speech of a squirrel.

In his surprise he forgot about the strange flower and sat looking up at Mee-ko. At once Mee-ko became quiet. He ran along the branch and down the tree behind little Luke. Then he leaped to the ground and ran across to another tree. When he thought he was safe, he began to talk and scold again. To the little boy it seemed as if Mee-ko was saying, "Come here, come away, follow me, follow me!"

But little Luke did not care to chase Mee-ko. He knew he could not catch him, and besides, he wanted the strange flower. As soon as he reached out his hand for it again, Mee-ko began to scold more angrily than before. "Stop, let it alone, go away," he screamed.

"That is queer," thought little Luke; "I wonder what is the matter with him. What can he care about the strange flower?"

Just then Ah-mo the Honey Bee flew up toward little Luke and then back again to the flower. Little Luke reached over and seized the flower. The stem was strong and he pulled it up, root and all. He put it to his nose. Its odor was strangely sweet. From the broken stem some clear juice oozed out upon his hand. Ah-mo the Honey Bee flew down and sipped it. Then he rose and began to buzz around little Luke's head. Without thinking, the little boy put his hand to his lips and his mouth was filled with a strange, sweet taste. At the same time a mist rose before his eyes, a strange feeling ran through his body, and his head swam.

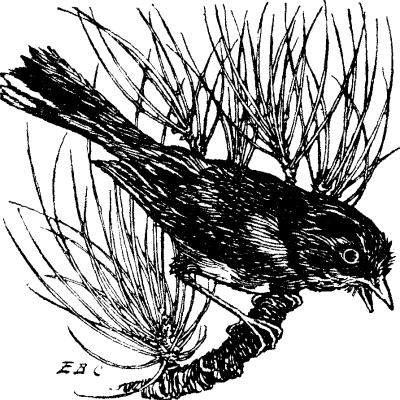

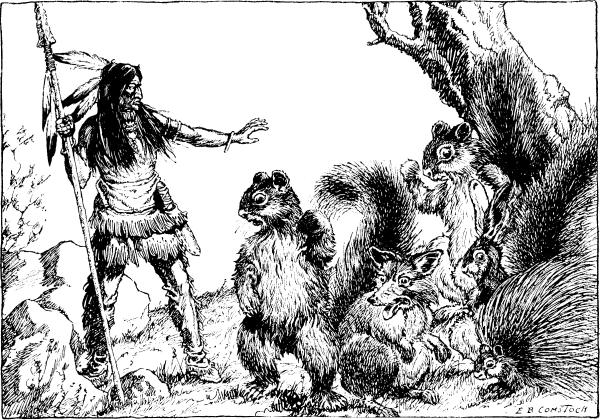

In a moment the strange feeling passed away and the mist cleared from before his face. He looked up and could scarcely believe his eyes. There in a half circle around him sat a strange company—the strangest he had ever seen.

There was Mo-neen the Woodchuck, Unk-wunk the Hedgehog, A-pe-ka the Polecat, Wa-poose the Rabbit, A-bal-ka the Chipmunk, Tav-wots the Cottontail, Mic-ka the Coon, and Shin-ga the Gray Squirrel. At one end of the line stood Mit-chee the Partridge, Ko-leen-o the Quail, and O-he-la the Woodcock. On the branches above them were Ya-rup the Flicker, O-pee-chee the Robin, O-loo-la the Wood Thrush, Har-por the Brown Thrasher, Chee-wink the Ground Robin, Tur-wee the Bluebird, Zeet the Lark, and Bob Lincoln. Little Luke was surprised to see the last two, for he had never seen them in the woods before.

"What can have happened to me?" said little Luke aloud. All the creatures in that strange assembly stirred slightly and looked at Wa-poose the big Rabbit. Wa-poose hopped forward a step or two and stood up on his hind legs. His ears were stretched straight up over his head, his paws were crossed in front of him, and he looked very queer.

Then to little Luke's surprise, he spoke. "Man Cub," said Wa-poose, "a wonderful thing has happened to you. You have found the Magic Speech Flower and tasted its blood. By its power you are able to understand the speech of all the wild folk of field and forest. This great gift has come to you because your heart has been full of loving kindness toward all the creatures that the Master of Life has made.

"Only he can find the Magic Flower who, between the rising and the setting of the sun, has done five deeds of mercy and kindness toward the wild folk of forest and field. These five deeds you have done."

Wa-poose paused. For a moment there was silence. All the wild folk looked steadfastly at the little boy, who in turn gazed at them with wonder-filled eyes. Then he spoke. "Five deeds! What five deeds have I done?" he asked, forgetting all about his morning's work.

"This morning you saved my child from the fierce jaws of Klaws the House Cat. You drove off Mee-ko the thieving Red Squirrel when he was trying to steal the eggs from the nest of O-pee-chee. You helped Ah-mo escape from the trap of wicked old Ik-to. You saved Chee-wink's fledglings from the cruel fangs of A-tos-sa, and you put the young one back into O-loo-la's nest safely.

"Two things you must remember if you wish to keep this magic power. You must never needlessly or in sport hurt or kill any of the wild creatures that the Master of Life has made and you must tell no one what has happened to you. If you give heed to these two things, we will all be your friends. When you walk abroad, you shall see us when no one else can, and we will talk with you and teach you all the wisdom and the ways of the wild kindreds."

Just then the sound of footsteps was heard coming down the trail. The gray mist rose again before little Luke's eyes and he heard someone say, "Wake up, little boy, it is almost noon. Your Aunt Martha will have dinner on the table before you can get back to the farmhouse."

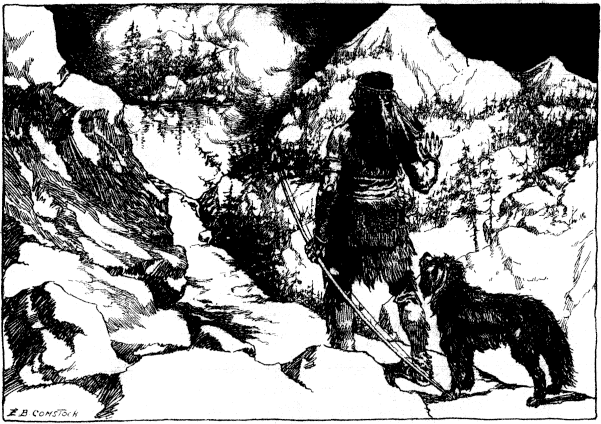

Little Luke looked up and there was Old John the Indian, who lived in a lonely cabin on the other side of the mountain, and sometimes came to the farmhouse to sell game he had killed or baskets that he had woven.

Little Luke sprang up and rubbed his eyes. Not one of the wild folk was to be seen. But he held in his hand a broken and crumpled flower. He put the flower into his pocket and went along down the trail toward the farmhouse with Old John.

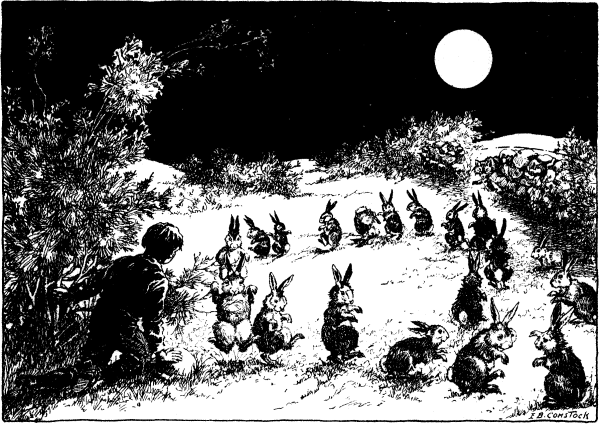

That night little Luke dreamed of the Magic Flower. The next morning, as soon as he had finished his breakfast, he ran down through the garden and into the meadow. He was eager to see his wild friends again and to try his new gifts, "Perhaps," he thought, "it was only a dream after all."

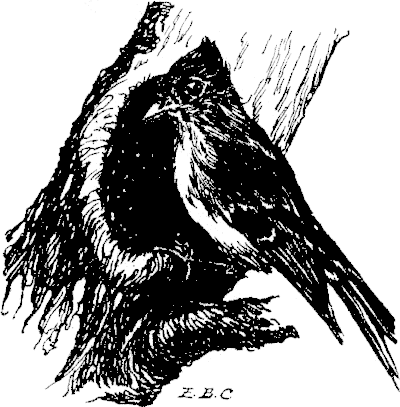

As soon as Bob Lincoln saw him, he came flying across the meadow to meet him, his black and white uniform gleaming in the bright sunlight. "Good morning, little boy, good morning," he trilled, and his voice sounded like the tinkling of a silver bell.

"Good morning, Bob Lincoln," said the little boy, delighted that he really could understand Bob Lincoln's language. "How is Mrs. Bob Lincoln this morning?"

"Come and see, come and see," trilled Bob Lincoln, in his sweetest and friendliest voice.

Little Luke walked over to the nest. When she heard him coming, Mrs. Bob Lincoln was scared and flew up from the nest.

But as soon as she saw who it was, she fluttered down upon the top of a tall weed and said, "Oh, it's you, is it, little boy? I heard someone coming and I was frightened, but I am not afraid of you." And so she sat swinging and teetering on the tall weed.

The little boy looked at the nest and admired the pretty eggs. "Oh, they're coming on finely," said Mrs. Bob Lincoln. "In a day or two I will show you five of the handsomest baby Bob Lincolns you will ever see. I heard them peeping inside of the shells this morning."

The little boy looked at the father and mother birds. "Bob Lincoln," said he, "I wish you would tell me why you and Mrs. Bob Lincoln are so unlike. Your coat is white and black; her dress is black and brown and yellow. You do not look as if you belonged to the same family."

"Well," said Bob Lincoln, "that is a long story."

"Oh, please tell it," said little Luke; "I want so much to hear it."

"Well," said Bob Lincoln, "we have both had our breakfast and I have sung my morning song. So if Mrs. Bob will excuse me [Mrs. Bob gracefully bowed her permission] I will take the time. You go over there and sit down under the old apple tree and I will come and find a comfortable twig and tell you all about it."

When little Luke had seated himself cozily with his back against the trunk of the old apple tree, Bob Lincoln began his story.

"Long, long ago when the world was new," said he, "the first Bob Lincoln family lived in a beautiful country in the distant north. In that country it was always summer. None of those who dwelt in that land knew what winter was.

"Ke-honk-a the Gray Goose, who spent half the year in northern Greenland, had mentioned it, but the people of the Summer Land did not understand him. They had never felt winds or seen ice or snow.

"But there came a time when Ke-honk-a said, as he flew over, 'Winter is coming, winter is coming.' But nobody understood and nobody cared. Why should they care about winter when they did not know what it was?

"Soon after this the people of the Summer Land noticed a change in the weather. One half of the year was cooler than the other half. The first time this happened they did not mind it at all. Indeed, they rather liked it. It was pleasant to have a change.

"The next year it was cooler and the next still cooler. And so it went on for some years, each winter getting colder than that which had gone before.

"One day a dull, gray cloud came up out of the north and hid the face of the sun. Out of its gray bosom there came floating to earth a whole flock of big, white snowflakes. The people of the Summer Land were amazed.

"As the great flakes came wavering lazily down through the air, they looked at them and thought that they must be some new kind of winged creatures. 'What a lot of them,' thought they, 'there must be to make that great cloud which hides the sun!'

"In a short time the sun shone out from behind the gray cloud. In the twinkling of an eye all the snowflakes were gone. 'Strange, strange!' thought the people of the Summer Land. 'What has become of all those white-winged creatures?'

"The next winter so many snowflakes fell that they hid the brown earth for many weeks. This happened again and again, and the people of the Summer Land began to understand what winter was. The snow became so deep for months at a time that they found it hard to get food.

"After a while life became so hard for them that they felt that something must be done. So they summoned a Great Council to consider the matter. After much talk they decided to send a messenger to the Master of Life, who lived far away among the western mountains, to beg him to come and help them. For their messenger they chose the swallow, the swiftest of all the birds.

"The swallow flew for many days, until at last he reached the lodge of the Master of Life, and told his story.

"'Go back,' said the Master when he had heard it, 'and after four moons I will come to visit you. Summon all the people of the Summer Land to a Great Council and I will tell them what they must do.'

"At the time appointed, the Master of Life came. When all the people of the Summer Land had assembled, he spoke to them and said, 'I have heard of your troubles and have thought of a plan to help you.

"'Henceforth, so long as the world shall last, there shall be summer and winter in this land. Half the year shall be summer and half the year shall be winter.

"'While summer reigns, this is a pleasant land, and you may live here and find plenty of food. Before winter comes, you must leave this land and journey far away to the south, to another country where summer always reigns. But when the snow melts and winter returns to his home in the distant north, summer shall come again to this land, and so it shall be every year.

"'When summer comes back, you may return with it and dwell in your own home until it is time for the return of winter.'

"When the people of the Summer Land heard this, some were glad, some were sorry, and some were angry.

"'What!' said the angry ones, 'shall we leave our pleasant homes on account of winter? No, indeed; we will stay.' And so they did.

"When summer was over and the cold winds began to blow, the Bob Lincoln family, obeying the command of the Master of Life, set out for the Southland. On and on they traveled for many days.

"At last they came to the end of the land, and before them was the great, salt sea. But far on to the southward, they could dimly see islands rising out of the salt water.

"So they flew bravely on across the great, salt sea, till they reached the islands; and beyond these islands they saw others. On and on they flew from island to island until they reached another great land like the home they had left behind them. In it there were vast meadows and forests, mountains and rivers. In that land it is always summer and food is plenty all the year round. There in the pleasant meadows, the Bob Lincolns stopped and there they lived happily for half a year.

"When it was time for summer to revisit the Summer Land, the Bob Lincolns returned also and this they did every year.

"In those days all the Bob Lincolns wore black and white clothes like mine. But, as you see, this black and white dress is very con-spic'-u-ous.

"Now it happened that in their journeyings to and fro, the Bob Lincolns met many enemies, and these enemies wrought sad havoc in their ranks. When they were flying in the air, the hawks and the eagles would swoop upon them and kill them. If they sat upon the ground, the weazels and the minks, the wildcats and other four-footed prowlers, would pounce upon them and devour them. Even the Red Men, with their feathered arrows, would shoot them. So many of them were killed that they began to fear that soon none of their family would be left alive.

"So they called a family council, to consider their sad state and decide what it was best to do. When they were all assembled together, they talked the matter over and decided to go and ask aid from the Master of Life.

"'I have heard your complaint,' said the Master of Life when they had finished, 'and I am willing to assist you. But first you must understand that the cause of all your trouble is your love of fine clothes. Your black and white uniforms are very beautiful, but they are too con-spic'-u-ous for your safety. By day your enemies can spy you afar because you are black; by night they can see you because you are white.

"'Hereafter you shall wear different clothing. No longer shall your feathers be black and white; they shall be black and brown and yellow. When you sit upon the ground you shall look like the dry, brown grass, and when you fly through the air your enemies shall not be able to mark your flight from a distance. Thus it shall come to pass that, if you act wisely, you shall live in peace and safety.'

"When they heard this the Bob Lincolns were grieved at heart. They loved their gay black and white uniforms and sorrowed at the thought of parting with them. So they humbly begged the Master of Life to let them keep their gay clothing and tell them some other way of escaping their enemies.

"'There is no other way,' said he. 'But tell me, when do you suffer least from your enemies? Is it when you are dwelling in your old northern home, or when you are dwelling in the sunny Southland?' 'When we are dwelling in our old homes,' answered the Bob Lincolns.

"'Very well, then,' said the Master of Life, 'while you are dwelling in your old home, all the male Bob Lincolns may wear their black and white garments. Nevertheless they shall suffer for their vanity, for their enemies shall find and slay many of them.

"'But your wives and sisters must be content with a quieter dress. It is they who have the most to do with tending your nests and rearing your young ones. If they should wear your gay black and white garments, your enemies would find and kill you all, and the Bob Lincoln family would perish from the earth,'

"That is the story," said Bob Lincoln, "that my grandfather told me long ago in our distant winter home in the Southland. If you keep watch, little boy, for a month or so, you will see me put off my black and white suit for one just like Mrs. Bob Lincoln's. Then you will know that we are getting ready for our journey to our distant winter home in the sunny Southland, far away across the great, salt sea."

"Now," said Bob Lincoln, when he had finished his story, "it's time for me to be off to see how Mrs. Bob Lincoln is getting along."

And off he flew before little Luke had time to thank him for his pleasant story. The little boy sat quietly for a while under the old apple tree. Then he got up and went slowly back to the house.

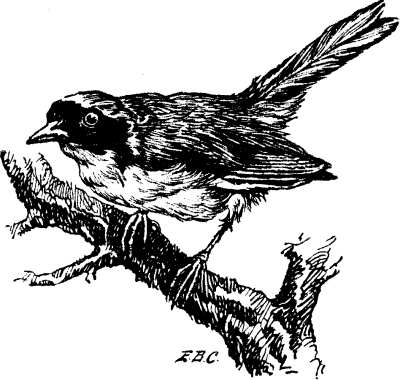

During the long summer days little Luke went often to visit the Bob Lincolns. The more he watched them, the more he grew to love them. Bob Lincoln himself was the merriest, jolliest fellow of all the little boy's feathered friends.

Little Luke saw the baby birds as soon as they had broken their shells. He watched the anxious parents feed them. And how those young Bob Lincolns could eat! How their busy parents had to work to support the little family! Back and forth over the meadow the old birds flew hour after hour, searching for food for their hungry babies. And they were always hungry! Whenever they heard anyone coming, they would close their eyes, stretch their long necks, and open wide their yellow mouths.

The young birds grew larger and hungrier every day. And every day Bob Lincoln became busier and quieter. Little Luke noticed that the jolly little fellow did not sing so much and that his gay coat was becoming rusty. One by one his bright feathers fell out and dull brown or yellow ones took their place, until at last he looked just like his little wife.

"Well, little boy," said Bob Lincoln one morning, "we must be getting ready to move. These youngsters can fly pretty well, and it is time for us to go. I am sorry, for I love our meadow home, and a long and dangerous journey is before us."

"Tell me about it," said little Luke.

"Well," said Bob Lincoln, "you must know that I was hatched in this very meadow. There were five of us and I am the only one that is left.

"When we young ones had learned to fly pretty well, we started south. After a few days we reached a land where there were broad marshes covered with reeds. There we stopped for a while. But the men of that country hunted us with their fire-sticks. They called us reed birds arid liked us to eat. They shot many of our friends, but for a few days our family all escaped. But one morning we heard a sound like thunder and our mother fell to the ground and we saw her no more.

"This frightened us and we flew on to the southward for many days. Of course wherever we found a good place, we stopped to rest and eat. But we did not stop for long until we came to a land where there were great fields of rice. There we found great flocks of our kindred, who had grown fat by feeding upon the rice.

"But here again were men with their fire-sticks and they killed two of my brothers. All the time we stayed there, we lived in fear. So after some days we left the rice land and went on toward the south. We crossed the great, salt sea and at last found the winter home of our kindred.

"In the spring we came back again to this meadow. And here I found Mrs. Bob Lincoln. I courted her with my sweetest songs, and after a short time we were married and set up house-keeping.

"That autumn I led a family of my own on the long journey to our southern home. Three times have I made the journey to and from this meadow, and each time some of my family have fallen a prey to our many enemies. But the men with their fire-sticks are the worst of all. Why are they so cruel to us?"

"Alas," said Bob Lincoln, after a pause, "I dread this journey. Not many of my friends have escaped so long. I fear I shall never return. But it cannot be helped, we must go. I think, little boy, we shall start this morning. So I will say good-bye now."

"Good-bye, Bob Lincoln," said little Luke, "I hope it will not be as you fear. I shall look for you again next May."

The Bob Lincoln family started on their long southern journey and little Luke went sadly back to the house. Now that the Bob Lincolns were gone, the meadow no longer seemed so pleasant to him.

While little Luke spent a good deal of his time with the Bob Lincoln family, he did not neglect his other friends among the wild folk. Almost every day he had long talks with one or more of them. Thus it came to pass that he soon became exceeding wise with the wisdom of the wild kindreds; for his eyes were sharper and his ears keener than those of any other of the house people.

There was Sam, the hired man, who thought he knew a good deal about the wild folk. And there was Old Bill, the hunter, who had done little besides hunting and trapping all his long life; even these did not begin to know the beasts and birds as little Luke knew them. Before the Finding of the Magic Flower, he had thought them marvels of woodcraft and fieldcraft. Now they seemed to him almost blind and deaf.

As he went about with them, he found that for all their boasting (and they often boasted) they really knew little about the wild folk. Many times they would pass Wa-poose the Rabbit sitting unseen on his form within a few feet of them. Mother Mit-chee the Ruffled Partridge made her nest in plain sight on the ground beside the old trail and they passed by a hundred times and never saw her. And so it was with many others of the wild folk. Often they went quietly about their business before the very eyes of the house people who did not see them.

During that summer little Luke spent much time with Old John the lone Indian, who lived at the foot of Black Mountain. For Old John, seeing the little boy's love of woodcraft and his wonderful keenness of ear and eye, and understanding, came to love him more than he had loved anyone or anything for many years.

He would make some excuse to come to the farmhouse. Then, when his pretended business was finished, he would sit with the little boy on an old bench on the lawn and tell him stories of the Red Men or of the wild folk.

Sometimes, too, the little boy would go up the trail and sit by the spring where he had found the Magic Speech Flower and wait for the old Indian. Or, when Old John started for home, he would go along with him up into the woods and there they would sit on a fallen log and talk of the old days when the Red Men dwelt in that land, or of the wood folk they saw and heard about them. These were most enchanting tales, and little Luke enjoyed them exceedingly.

And he learned that in some matters Old John was very wise. But these were mostly concerned with hunting and trapping. Little Luke did not like the idea of killing any of his wild friends, even though he knew that their flesh and fur were very useful. He knew, too, that the Law of the Wild Kindred allowed everyone to kill to supply his need and so he did not much mind the killing in Old John's stories, for he knew that the old man never killed any creature needlessly.

And he learned, too, that the old Indian had some strange notions about the wild folk. He believed that long ago they had all been very much like men. "In those days," he said, "the animals could talk and build wigwams just as the Red Men did." He believed, too, that the forefathers of some tribes of the Red Men had been animals, and that the forefathers of some of the animal kindreds had been men. All this seemed queer to the boy, but not half so queer as it would have seemed before the Finding of the Magic Speech Flower and his talks with the wild folk.

Now the tale of the Finding of the Magic Flower was told abroad among all the tribes of the wild folk round about. For this reason, as time went on, many of them came to see the wonderful Man Cub (as they often called little Luke) who could speak and understand the language of the wild kindreds.

In that way little Luke came to know many of the wild folk that he had never seen before. Some of them were furry folk, who lived in the woods and fields and along the brooks, and some were beautiful feathered folk, who came down from the tops of the tall pines and spruces and hemlocks.

These were mostly bird folk who had once lived in the Summer Land and had learned to travel southward before the return of Pe-boan the cruel Winter King. They loved the upper spaces of the great forests, and there they lived as some of the water folk live in the lower depths of the great sea.

These bird folk hated the open fields and even the lower air, in the thick forests, seemed heavy and unpleasant to them. So they seldom came down from their airy homes in the upper branches of the great trees. For this reason little Luke did not see much of them, but when he did see one of them, it was as if he had seen an angel.

Down in the far corner of the orchard stood an old apple tree. Some of its limbs were dead and the rest of it was so covered with orchard moss that it seemed gray with age. As little Luke was passing one day, he noticed a round hole in one of its branches. "Now," thought he to himself, "I'll climb up and take a peep into that hole." And so he did.

As he looked into the dark cavity, there was a sudden explosion, which sounded like the noise made by an angry cat. The little boy jumped back so quickly that he almost fell to the ground. Just then he heard someone in the branches of the tree above him. "Whee-ree, whee-ree," sounded a mocking; voice, that made little Luke think that somebody was making fun of him. He looked up and saw Kit-chee the Great Crested Flycatcher.

"Ah-ha!" said Kit-chee; "so she scared you, did she?"

The little boy moved his hand toward the hole.

"Better not; better not," said Kit-chee; "that's Mother Kit-chee in there. She doesn't like to be disturbed, and she has a temper of her own, and a sharp bill to go with it."

"Excuse me, Father Kit-chee," said the little boy; "I didn't know. I only wanted to see what was in that hole."

"All right," said Kit-chee. "We don't mind you. Perhaps, if you ask her politely, she'll come out and let you take a peep."

"Pray, Mother Kit-chee," said the little boy, "aren't you hungry? There are some nice flies and bugs out here, and besides, if you will be kind enough to allow me, I should like a peep at your nest and eggs."

"Oh, very well," answered Mother Kit-chee, "I'll do anything to oblige you, when you speak in that way." And out she came.

Both Father Kit-chee and Mother Kit-chee were rather handsome, dignified birds. They each wore a coat of butternut brown, mixed with olive green, and a vest pearl gray toward the throat and yellow lower down.

"Thank you," said the little boy to Mother Kit-chee as she came out, "I'll not disturb anything. I'll be very careful." And so he was. He looked down into the hole, where he saw five creamy-white eggs, streaked lengthwise with brown. But the queerest thing he saw was a snake-skin which formed part of the nest.

"There's the skin of a snake," exclaimed the little boy. "How did that come there? Did the snake try to steal your eggs, and did you kill him?"

"Oh, no," replied Father Kit-chee, "I found that skin over yonder in the pasture. You know that A-tos-sa the Snake sheds his skin when it grows old and stiff, and grows a new one that fits him better. We just pick up the cast-off skins and build them into our nests."

"What on earth do you do it for?" asked the little boy. "I wouldn't want such a thing around my bed. I don't like snakes, or even their skins."

"I don't like snakes either," said Kit-chee, "but it's a custom in our family to use their skins in nest-building. Wherever you find a home of one of our tribe, there you will find a snake-skin. I've heard my grandfather say that our kinfolk, who dwell far to the south beyond the big seawater, have the same custom. There's a tradition about it, too."

"Oh, please tell me about it," said the little boy. "I'm sure it will be an interesting story."

"Very well; anything to please you," said Kit-chee.

"Long, long ago," began he, "when the world was new, all the beasts and birds were at peace with each other. In those days it was summer all the year round. After a while a change came."

"Oh, yes, I've heard about that," said the little boy. "Pe-boan the cruel Winter King came down from the frozen North and drove off Ni-pon the Queen of Summer. Then the animals and birds got hungry and began to kill each other. I've heard about that several times."

"Yes," said Kit-chee, "that was the way it was. The animals and birds began to kill and rob each other. No nest was safe. Mee-ko the Red Squirrel, A-tos-sa the Snake, Ka-ka-go the Crow, and many others learned to rob our nests and eat our young ones.

"Every one of the birds tried to hide her nest, but in spite of the best that they could do, the robbers would often find them. The worst of all our enemies was Kag-ax the Weasel. The Kit-chee families suffered terribly. They built their nests as we do now in holes in trees. Kag-ax is a good climber and has sharp eyes. It was almost impossible to hide a nest from him.

"After a while things got so bad that the Kit-chee family came together in a council. They talked over their troubles and made up their minds to go to the Master of Life and ask him to help them. And so they did.

"'I am sorry for you,' said he, when he had heard their story, 'and will tell you what to do. As you say, your worst enemy is Kag-ax the Weasel. Now Kag-ax is more afraid of A-tos-sa the Snake than of any other creature in the whole world. He cannot bear even the sight of a snake-skin. You must weave a snake-skin into each one of your nests. Then he will not dare to trouble you.'

"'But how shall we get the snake-skins?' asked Grandfather Kit-chee, the head of the family.

"'That is easy,' answered the Master of Life. 'A-tos-sa, as you know, sheds his skin. If you look sharp, you can find the cast-off skins almost anywhere. Do as I have said, and you will be safe. Even Mee-ko the Squirrel and others of your enemies will be afraid of the snake-skin and let your nests alone.'

"The Kit-chee family did as the Master of Life told them to do. From that time to this they always have woven a snake-skin into their nests, and their nests have seldom been robbed."

"Thank you," said the little boy, "that was a good story. Now I must be going home. There's Aunt Martha calling for dinner." And he slid down out of the old apple tree and went across the orchard to the house.

Among little Luke's bird friends was little Nick-uts the Yellowthroat. He was a dainty little fellow, with an olive green back, a bright yellow breast, and a black mask across his face that made him look like a highwayman. Though he was lively and nervous, he had a gentle disposition and a sweet voice. His home was in some low bushes in the pasture.

Whenever little Luke went up to see him, he would hop up on a branch and call out, "Which way, sir? Which way, sir?" And when the little boy started to go away, he would say, "Wait a minute. Wait a minute."

Every time the little boy went for the cows he would stop and chat a moment with Mr. and Mrs. Nick-uts. To be sure, Mrs. Nick-uts never had much to say. She was a quiet little body, not so fidgety as Nick-uts, and besides, she had to stay close at home and see to the eggs and babies.

One morning, as little Luke was going for the cows, he saw Nick-uts bobbing around very excitedly.

"Come here. Come here," called Nick-uts, when he saw the little boy; "I want some help." And he hopped over by the nest.

Little Luke went over to the nest and looked in. "Look there," said Nick-uts, "see that big, ugly egg. Take it out, please."

"Take it out?" said little Luke. "Why should I do that? Isn't it yours?"

"No, indeed," said Nick-uts, "it's old Mother Mo-lo's. The nasty old wretch laid it in there while we were away from home. She's always sneaking around, the lazy old thing, to lay her eggs in some other bird's nest. She's cowardly too. She always picks out the nest of one smaller than herself. I wish I were big enough to give her a sound thrashing.

"Please take the egg out," he went on. "I can't do it myself, and if you don't take it out, we shall have to leave the nest and our own eggs and build a new one."

Little Luke took the egg out of the nest and threw it on the ground. "Why don't Mother Mo-lo build a nest of her own?" he asked.

"Oh, she can't. She doesn't know enough," answered Nick-uts. "In the old days she had a chance to learn the same as the rest of us. She wouldn't learn then, and now she can't. I don't believe she ever tries.

"She sneaks around and steals her eggs into the nests of other birds, and some of them are so silly they don't know the difference. They hatch the egg and bring up the young one as if it were their own. The young Mo-los are greedy things and they eat up everything away from the other little birds. Besides, they grow so fast that they crowd out the other young ones, so that they fall to the ground and die. I've known old Mother Mo-lo to fool O-loo-la the Wood Thrush that way. It's a shame for a decent bird to be imposed upon like that.

"She tried the trick twice on me last year. Once we managed to roll the egg out, and once we built a second floor to the nest, but we lost two of our own eggs by doing it."

"You said that Mother Mo-lo had a chance to learn to build a nest," said little Luke. "Tell me about it."

"Well," said Nick-uts, "since you have been so kind as to help me, I'll try. I haven't heard the story for a long while, perhaps I can't remember it very well. But I'll do the best I can."

"In the beginning," said he, "the Master of Life made the world. When he had finished the land and the sea, the mountains and the meadows, he made the fishes, and then the four-footed kindreds. Last of all, he created the birds. But he didn't make them all at the same time. The last ones were Father and Mother Mo-lo.

"When Mother Mo-lo began to fly about, the other birds went to her and offered to teach her how to build a nest.

"'Come with me,' said the oven bird; 'I'll show you how to build a nest on the ground where no one will find it. You must just push up some of the dry leaves in the forest, and then put some grass and twigs under them. It's very easy.'

"'For my part,' said the woodpecker, 'I wouldn't build on the ground anyway. I should be afraid that a deer or a bear or some other creature would step on me. If you want a safe nest, I'll show you how to build one. You just find a dead limb, not too dead, and bore a deep hole into it. Put a little soft, rotten wood in the bottom, and there you are!

"'That must be a close, stuffy kind of a nest; enough to smother one,' said the oriole scornfully. Come with me and I will teach you to hang your nest on the end of an elm branch. You just weave together some hair and grass and moss and hang it on a slender, swinging branch, where nothing can get to it. Then you'll be safe. The wind will rock your babies to sleep for you and you'll have plenty of fresh air.'

"'I wouldn't like that at all,' said the sand martin. 'I'd be seasick the first half hour. A good hole in a sandbank suits me much better. To be sure, the sand sometimes caves in. But that doesn't matter much. A little hard work will clear your doorway.'

"'What do you do when the high waters come?' asked the phoebe bird. 'For my part,' continued she, 'I like a rock ledge for a foundation with another one above for a roof. The rock never caves in on you. A little hair and grass, nicely laid down, with a little moss on the outside, and you are comfortable and safe. You'll never be drowned out there.'

"'I don't like rocks,' said the robin. 'A fork in a tree suits me much better. Just lay down a few sticks for a foundation, then weave together some twigs and grass and plaster the inside with some good thick mud, and you have a serviceable nest, good enough for anyone. A few feathers in the bottom will make it soft and comfortable. It may not be so elegant as some others, but it suits me.'

"And so it went on. Each one of the birds praised its own nest and offered to show Mother Mo-lo how to build one like it.

"But Mother Mo-lo cared little for what they said. She wasn't even polite enough to pretend to pay attention. She was too conceited. thought that she was handsome and knew about all there was to be known."

"Handsome?" said little Luke; "the ugly old thing! It can't be that she had ever looked at herself."

"Oh, I don't know," said Nick-uts, "the sillier people are, the wiser they think themselves. And it's always the ugly ones who think themselves the most beautiful."

"Well," said little Luke, "I've seen a good deal of her, but I never thought her handsome in the least. You know she follows the cows about so much that we house people call her the cowbird."

"Well, at any rate," said Nick-uts, "she thought she knew a great deal more than she really did.

"So she said to the other birds, very haughtily, 'You are all very kind, and I am very much obliged to you. But I think I can get along without your help. I know how to build a nest that will suit me better than any of yours.'

"'Indeed, is that so?' cried the other birds. 'You must have learned very quickly. Who was your teacher anyway?'

"'Oh,' said Mother Mo-lo, 'nobody taught me, but I know how just the same.'

"'Very well,' said the other birds, 'we only wanted to be kind and help you. But we won't bother you any more. Good-bye.' And they all flew away to attend to their own affairs.

"After a while Mother Mo-lo tried to build a nest. First she tried to bore a hole in a dead branch, but she couldn't do it. Then she tried the sandbank, but the sand caved in and got in her eyes and almost smothered her. Then she tried the other kinds of nests. But every one was a failure. At last she gave it up, and ever since then she has laid her eggs in other birds' nests and let them rear her young ones for her."

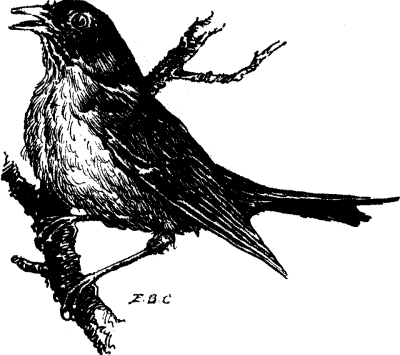

One day little Luke heard Old John the Indian speak of redbreast as Little Brother O-pee-chee. He wanted to ask the old man about the name, but did not get a chance. So the next morning he went down to the apple tree in the meadow and asked Father Redbreast about it.

"That," answered redbreast, "is an old tale which both the Red Men and our people know. According to the story, the first redbreast was an Indian boy, and that is why he calls us Little Brothers."

"Tell me about it," said the little boy.

"Long, long ago," began Father Redbreast, "there was a tribe of Indians which dwelt in the distant Northland. Their chief, who was a wise man and a brave warrior, had an only child, a little son. The boy was a bright little fellow, but not very strong. Somehow he was not so big and hardy as the other Indian boys. But his father loved him more than anything else in the world and wanted him to become the wisest man and the greatest warrior of his tribe.

"'My son,' said the old chief one day, 'you are about to become a warrior. You know the custom of our tribe. You must go apart and fast for a long time. The longer you fast, the greater and wiser you will become. I want you to fast longer than any other Indian has ever fasted. If you do this, the Good Man-i-to, the Master of Life, will come to you in a dream and tell you what you must do to become wise in council and brave, strong, and skillful in war.'

"'Father,' said the boy, 'I will do whatever you bid me. But I fear that I am not able to do what you wish.'

"'Make your heart strong,' answered the father, 'and all will be well. Most of the young men fast only four or five days. I want you to fast for twelve days, then you will have strong dreams. Now I will go into the forest and build your fasting lodge for you. Make yourself ready, for to-morrow you must begin your fast.'

"The little boy said no more and on the morrow his father took him to the fasting lodge and left him there. The boy stretched himself upon a mat, which his mother had made for him, and lay still.

"Each day the old chief went and looked at his son and asked him about his dreams. Each time the boy answered that the Man-i-to had not come.

"Day by day the boy became weaker and weaker. On the eleventh day he spoke to his father.

"'Oh, my father,' said he, 'I am not strong enough to fast longer. I am very weak. The Man-i-to has not come to me. Let me break my fast.'

"'You are the son of a great warrior,' said the father sternly; 'make your heart strong. Yet a little while and the Man-i-to will surely come to you. Perhaps he will come to-night.'

"The boy shook his head sadly and his father went back to his wigwam.

"The next day when he drew near to the fasting lodge, he heard someone talking within it.

"'My father has asked too much,' said a voice which sounded like, and yet unlike, the voice of his son. 'I am not strong enough. He should have waited until I became older and stronger. Now I shall die.'

"'It was not the will of the Man-i-to,' said another voice, 'that you should become a great warrior. But you shall not die. From this time you shall be a bird. You shall fly about in the free air. No longer shall you suffer the pain and sorrow which fall to the lot of men.'

"The old chief could wait no longer. He opened the door of the lodge and looked within. No one was there, only a brown bird with a gray breast flew out of the door and perched upon a branch above his head.

"The old chief was very sad, but the bird spoke to him and said, 'Do not mourn for me, my father, for I am free from pain and sorrow. It was not the will of the Man-i-to that I should become the greatest warrior of the tribe. But because I was obedient to you and did the best I could, he has changed me into a bird.

"'From this time, as long as the world shall last, I shall be the friend of man. When the cold winds blow and ice covers the streams, I shall go away to the warm land of the South. But in the spring, when the snows begin to melt, I shall return. And when the children hear my voice, they shall be happy, knowing that the long, cold winter is over. Do not mourn for me, my father. Farewell!'

"Ever since then, when the Indian children hear a robin singing, they say, 'There is O-pee-chee, the bird that was once an Indian boy.' And no Indian boy ever hurts a robin."

When the robin had finished his story, little Luke thought for a moment. Then he said, "That's a very interesting story. But there is one thing about it I don't understand."

"What is that?" asked Father Redbreast.

"Why," said the little boy, "you said that O-pee-chee's breast was gray. How does it come that yours is red?"

"That is another story," answered Father Redbreast.

"I should like very much to hear it. Please tell me about it," said little Luke.

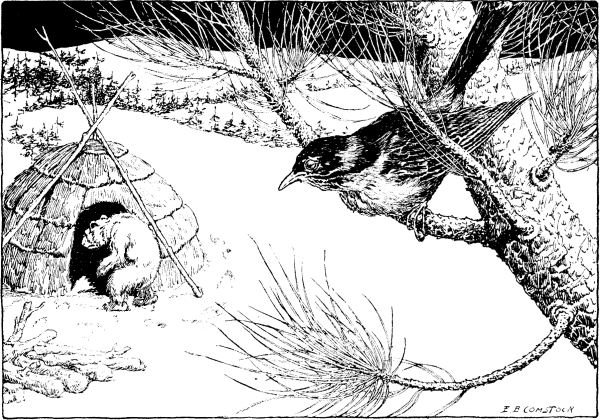

"Once upon a time," said Father Redbreast, "long after the days of the first robin, old Mah-to the great White Bear dwelt alone in the far Northland. He was the king of all the bears and was very cunning and cruel. He was so selfish that he did not like anybody else even to come into his country.

"If a hunter wandered into the region where he lived, he would lie in wait for him and kill him. One stroke of his mighty paw and the man would fall, to rise no more. He killed so many of them that the hunters began to be afraid to go into that land. As for the beasts and birds, they all feared him and kept as far away from him as they could.

"After a time a brave hunter with his son wandered into the kingdom of the great bear to hunt. Day after day old Mah-to followed the man and boy. But the hunter was cautious as well as, brave, and the old bear was afraid of his sharp arrows and did not dare to attack him openly.

"When the snow began to fall, the hunter built a lodge and kindled a fire. He cut down a great many trees and brought the wood close to the door of the lodge.

"'Now,' said he, to his son, 'we must keep the fire going day and night. Then we shall not freeze.'

"Old Mah-to, who was sneaking about the lodge, heard this and thought, 'I will watch and wait until they have gone away or are asleep, and then I will put out the fire. Then they will have to go away or else freeze.'

"But the hunter was very careful. When he went out to hunt, he left the boy in the lodge to keep the fire burning. The old bear was afraid of the fire, which he thought was some kind of magic, and so he did not dare to touch the boy. At night the hunter and the boy watched the fire by turns, and so kept it burning brightly.

"The old bear watched for many days before his chance came. At last one day when the hunter had gone away, the little boy fell asleep and allowed the fire to burn low.

"'Now,' thought the old bear, 'now is my chance.' So he walked into the lodge and trampled the fire with his great, wet feet, until he thought he had put it all out. He meant to kill the boy, but the fire scorched his feet and scared him. So he went away again to the edge of the forest and sat there licking his burnt paws, waiting to see what would happen.

"Now O-pee-chee had followed the man and the boy into the Northland. He watched the old bear and saw what he did. When he went away, the robin flew down and scratched about among the ashes until he found a small, live coal. Then he brought some splinters and dry moss and laid them upon the coal and fanned it with his wings until the fire caught the wood and burned up strong and bright.

"The heat of the blazing splinters scorched his breast and made it red, but the robin did not stop until the fire was blazing brightly.

"Just then the hunter walked into the lodge and saw what the robin was doing. He saw, too, the big footprints of the great bear and he knew that the robin had saved his life and the life of his boy.

"All that winter the good hunter fed the kind robin and sheltered it in his lodge. When he went back again to his people, he told them the story, and they grew to love the robin more than before. To this day they are never tired of telling their children the story of O-pee-chee the Robin and how his breast became red."

Little Luke was fond of watching the bees. He was not afraid of them, for he knew that if he did not disturb or annoy them, they would not sting him.

One morning the bees in one of Uncle Mark's hives seemed greatly excited. They buzzed and buzzed about the hive, till there was a great swarm of them in the air. All at once they started in a body and flew down toward the orchard.

The little boy followed them. They settled in a great bunch on the branch of an apple tree. The little boy ran back and told Uncle Mark that the bees had swarmed. Then Uncle Mark and Sam the hired man took a beehive, a ladder, and a saw and went down to the orchard. Sam climbed the ladder, sawed off the limb, and lowered the bees to the ground. Uncle Mark set the hive over the swarm and left it awhile. He knew that the bees would settle down in the hive and soon feel at home and begin to gather honey. And so they did. But Sam the hired man was stung several times. One of his eyes swelled shut and one of his cheeks looked as if he had the toothache.

"Why did your friends sting Sam?" asked little Luke the next day of his friend Ah-mo the Honey Bee.

"Oh," answered Ah-mo, "he was too rough. The bee people have sharp tempers and ever since they got stings they are apt to use them when they get angry."

"Got stings!" exclaimed the little boy. "Didn't the bee people always have stings?"

"Oh, no," answered Ah-mo; "not always."

"How did they get them?" asked little Luke. "Tell me about it."

"Long, long ago, when the world was new," said Ah-mo, "the bee folk had no stings. They were just as busy workers as they are to-day. All day long and all summer long they flew from flower to flower and gathered wax and honey, which they stored against the winter, when there would be no flowers and no honey.

"But many of the other creatures liked honey as well as the bees. They would watch the bees till they found out where their storehouses were. Then they would break them open and steal all the honey. This was bad for the bee people. For without their honey they would starve to death during the long, cold winters.

"At last matters got so bad with the bee people that they sent a messenger to the Master of Life to ask him to come to their aid. When he had heard about their trouble, he said to their messenger, 'Go back to your people. In two moons I will come to visit you. By that time I shall have thought out a way to help you.'

"The bee people were very glad. They told their cousins, the hornets and the wasps, that the Master of Life had promised to assist them against their enemies. At the end of the two moons, the Master of Life came and all the bees assembled to meet him. The wasps and the hornets came also.

"'I have thought of a way to help you,' said the Master of Life to them. 'From this day you shall have stings. Hereafter, if anyone comes to steal your honey, you will be able to defend yourselves.'

"The bees were greatly pleased. They were no longer afraid of their enemies and did not try to hide their storehouses as they had done before.

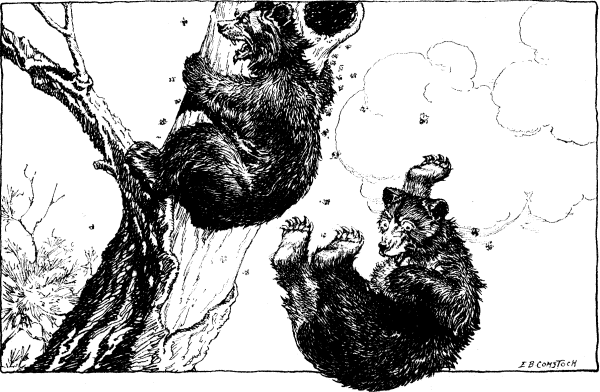

"Now the worst of all the enemies of the bee people was Moo-ween the Black Bear. One day Mr. and Mrs. Moo-ween were walking by a hollow tree where the bees had made their home. They looked up and saw many of the bee folk going in and out of a hole in the tree.

"'What lots of honey there must be in that tree,' said Moo-ween. 'How good it would taste. Let us climb up and take it away from the bees.' So the two bears began to climb the tree.

"But the bees were not afraid of them. They did not fly away and leave the bears to eat their honey, as they had always done before. Instead, they flew down and began to sting the bears. The two bears could not understand it. They had never been stung before and they groaned and growled with pain. The bees settled upon their eyes, their ears, and their noses, and stung them again and again, until they had to let go of the tree, and fell to the ground. There they rolled over and over, growling and groaning and snapping their teeth. The bees kept on stinging them. The bears could not stand it. They got up and ran away as fast as they could, Since that time the bee folk have had stings and the courage to use them whenever any creature, little or big, attempts to annoy or injure them."

In May little Luke had watched Mr. and Mrs. Lun-i-fro the Eave Swallows while they had built their queer, pocket-shaped, mud hut beneath the eaves of the big barn. He saw them on the muddy shores of the river, rolling little pellets of mud, which they carried to the barn and built into their nest, and wondered at their odd ways.

"I wish," he often said to himself, "that they could talk. I would ask them how they learned to do it." At that time he had no idea he would ever be able to talk to them.

After he had found the Magic Speech Flower he often talked to Father and Mother Lun-i-fro. But their talks were always short, for the two swallows were always too busy chasing gnats and flies through the air to spend much time on anything else.

Early in September the swallows began to gather in large flocks. The young ones, who were now finishing their lessons in flying, were introduced to the rest of the tribe and the little boy often saw them training in squads. They would sit in a long row upon the peak of the barn roof. Suddenly they would start off all together and fly about for a while. Then they would come back and settle down upon the roof again.

One day as little Luke was watching them, Father Lun-i-fro happened to light upon a fence stake near him. "Father Lun-i-fro," said the little boy, "what are you swallow folk doing these days?"

"We are holding our councils and getting ready to go to the sunny Southland for the winter," answered the old swallow.

"Before you go," said the boy, "I wish you would tell me how you learned to build your nests in such an odd way."

"Well," said Father Lun-i-fro, "since you have been so nice to us this summer, I'll tell you."

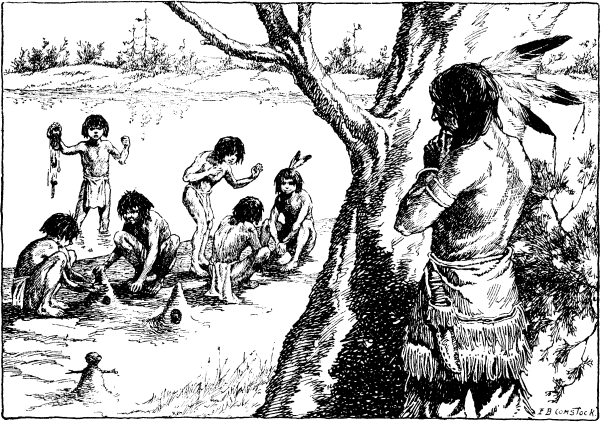

"Long, long ago," went on the old swallow, "there was an Indian village upon the top of a high hill.

"The grown-up people of the village were very good. But alas! the children were naughty. They were so disobedient that they could never be trusted to mind anything that their parents said to them. The old people often talked to them and did their best to make them behave better, but it did no good. As soon as their backs were turned, those naughty children would begin to quarrel and fight and steal and run away.

"The old people were much troubled. The woods were full of bears and panthers and wolves, and they felt sure that some time the wicked children would be eaten up by them.

"They did everything they could think of to make it so pleasant for the children that they would stay at home. They made bows and arrows for the boys, and Indian dolls for the girls, and all sorts of playthings for all of them, but it did no good. They would run away just the same.

"At last the elders of the village held a council to see if they could not think of some plan to make their children behave better. After much talk it was thought best to call in all the children and have the village chief talk to them. This was done, but it did no good. The next day they ran away just the same. Their parents had to search far into the night before they found them. This time the old folks were very angry.

"Another council was held. They talked the matter over a long time and made up their minds to send for Gloos-cap the good and wise Magician, who was yet upon the earth. And so they did.

"When he came he found that, as usual, the children had run away from home and could not be found. They had already been gone two or three days.

"Gloos-cap frowned and looked very stern. 'I will find them,' said he, 'and when I find them I will punish them as they deserve.'

"By his magic power he was able to follow their trail, which their parents had not been able to find.

"At length he saw them. They were playing about on the muddy shore of a small lake. Out of the mud they were making many different kinds of objects, especially little wigwams.

"He walked down to where they were. 'You naughty children,' said he, 'are you not ashamed of yourselves, to disobey your parents and make them so much sorrow and trouble?'

"'No, we are not,' spoke up one bold, saucy little fellow. 'We don't care for what they say. We've been having a good time all by ourselves.'

"'Very well,' said Gloos-cap, 'since you are not willing to obey your parents, you shall never trouble them any more. You shall become birds. Since you love to play in the mud, you shall always build your nests of mud; and since you love to gad about so much, you shall wander about the earth forever.'

"And so it has been with the swallow folk since that time.

"But," went on the old swallow, "our foreparents learned their lesson, and since that time we always bring up our children to be very obedient. No doubt you have noticed how very well they mind."

One of little Luke's best friends among the wild folk was A-bal-ka the Chipmunk. He was a dainty little fellow about five inches long, with a tail of the same length. His coat was of a yellowish-brown color, with black stripes running down his back. This fine, striped coat made him look much prettier than his cousin Mee-ko the Red Squirrel.

He was a clean, jolly, little chap, and very fond of singing, though he knew but two songs. One was a sharp chip, chip, chip, which he would sometimes keep up for a long time. At a distance it sounded like the call note of some bird. The other was a cuck, cuck, cuck, which sounded much like the song of the Cuckoo. A curious thing about this song was that one could scarcely tell where it came from. Little Luke was often deceived by it. Sometimes when it sounded as if A-bal-ka was near by, he was really a good way off, and when it sounded as if he were a good way off, he was really close by.

Beside these songs, A-bal-ka had an odd way of saying chip, chur-r-r-r-r, when he was scared. This meant, "I am not afraid of you," and he never said it till he was safe in some hole where no one could get at him.

A-bal-ka never harmed any one, nor did he scold and steal like Mee-ko the Red Squirrel. Yet he had many foes. Ko-ko-ka the Owl, Ak-sip the Hawk, Kee-wuk the Fox, Kag-ax the Weasel, Ko-sa the Mink, and A-tos-sa the Snake were always ready to pounce upon him at sight and make a meal of him. Even Mee-ko was not to be trusted. Sometimes he would chase A-bal-ka and rob him of the nuts which he was carrying to his storehouse. He would have robbed the storehouse, too, if he could have got into it. But A-bal-ka's door was too small, and his hallways too narrow for Mee-ko.

Little Luke knew all about A-bal-ka's underground dwelling. The way he found out was this: Uncle Mark and Sam the hired man were digging stones on the hillside in the edge of the woods for the foundations of a new barn. While at this work, they uncovered the home of one of A-bal-ka's brothers. It was made up of a long, winding passageway, ending in a sleeping chamber, near which was a storehouse, and in this storehouse there was a large quantity of nuts. These nuts were all good ones. The greater part of them were little, three-cornered beech nuts, which the squirrels like better than anything else. In all there was as much as half a bushel of nuts, enough to last a chipmunk all winter. The bedroom was a neat, little, round chamber, nicely filled with leaves, grass, and moss. In such a house as this, with its store of nuts, a chipmunk could live snug and warm all winter long and come out sleek and fat in the spring.

Because of A-bal-ka's many enemies, he was very watchful. He seldom went far from home, and when he did venture to go abroad, he nearly always followed the same path. At first it ran along under the side of a fallen log. From the end of this, a few quick leaps carried him to a brush pile. A jump or two more brought him to a rock and yet a few more to a stone fence. Once there, he felt safe. At the least alarm, he could run into a hole too small for any of his foes except, perhaps, A-tos-sa, whom he dreaded more than any of the others.

All along the stone fence stood nut trees,—oaks, hazels, walnuts, beeches, and others. And at one end was a cornfield.

This made it very handy for A-bal-ka. He could gather the nuts which fell upon the stone fence, and when he went for corn, he could keep to the fence and thus avoid his enemies. Early in the fall he began to fill his storehouse. To and fro he went along the fence with his cheek-pouches full of corn and nuts.

Little Luke often amused himself by watching him. He would pick up the nuts with his paws and put them into his cheek-pouches, and it was amazing how many they would hold. When he started for home, his cheeks sometimes looked as if he had a very severe case of the mumps.

One day in the autumn little Luke found out a queer thing about A-bal-ka. He was going up the trail with Old John. A-bal-ka started to cross the trail, but seeing the old Indian he became scared and ran up a tree. This was a thing which he seldom did; never unless he was obliged to, to escape from his enemies. He is a ground squirrel, and no tree climber, like his cousins the Red and the Gray Squirrels.

"Now," said Old John, "I'll show you something." So he got a stout stick and began to tap the tree. Tap, tap, tap, tap, as if he were beating time to music. This tapping had a strange effect upon A-bal-ka. At first he was greatly excited and tried to run farther up the tree. Soon he gave this up, turned around, and began to come down head foremost. He would lift his little feet and shake them as if something hurt them. Lower and lower he came, until the old Indian could easily have killed him with his club or caught him with his hand. He did neither. He just laughed and threw away his stick.

"There," said he, "that's the way to make a chipmunk come down out of a tree. They'll always do it, if you tap long enough,"

"That's queer," said the little boy; "what makes them come down? Why don't they run farther up?"

"I don't know," said Old John, "perhaps they think you are trying to cut down the tree, or maybe the jar hurts their feet. The Red Men used to think that there was some kind of a magic charm about it."

"I am glad you didn't hurt him," said the little boy, as they went on up the trail.

"Hurt him!" exclaimed the old Indian, "why, don't you know that no Indian ever hurts a chipmunk?"

"Why is that?" asked the little boy.

"It's an old, old story," said Old John, "but come, let us sit down on this log, and I'll tell it to you."

So when they were both comfortably seated, the old Indian began the tale which you will find in the next chapter.

"In the old days before winter had come into the land, the beasts and the birds, the fishes, and even the insects, all had one language. They could speak the speech of the Red Men and they all lived together in peace and friendship.

"In those days, there was no killing and no war. But after winter had come upon the land, the Red Men learned to kill the wild folk and to use their flesh for food and their skins for wigwams and for clothing.

"At first this was bad enough, but after men had learned to use bows and arrows, spears, knives, and hooks, it was still worse. They became more and more cruel. They delighted to slaughter even creatures for which they had no use. Out of heedlessness, they trod upon the worms and the frogs, and killed them without caring for the pain and suffering which they caused. At last the animals made up their minds to try to find out some means to check the slaughter of the wild kindreds.

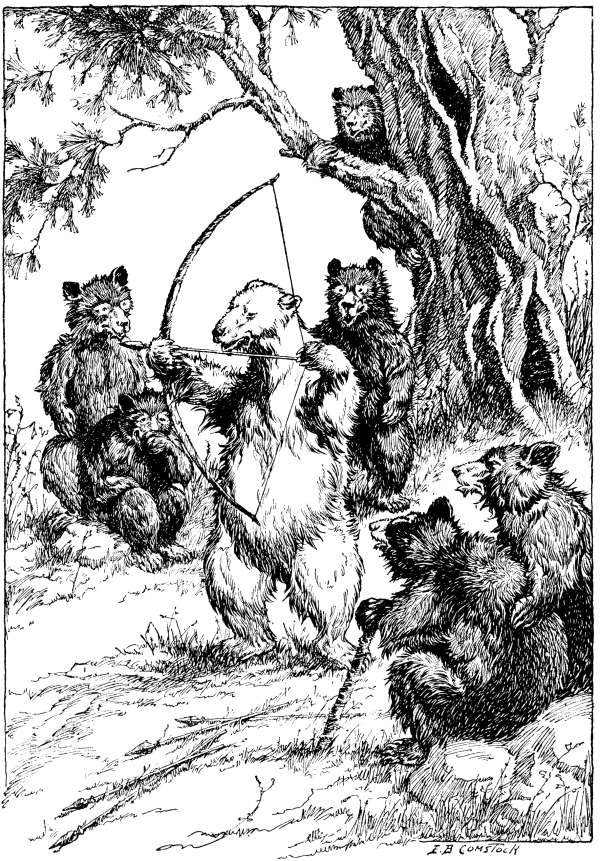

"The bears were the first to meet in council. After much talk, they decided to begin war at once against the human race.

"'What weapons shall we use against them?' asked one of the bears.

"'Why,' answered another, 'the same that they use; bows and arrows, of course.'

"'But how shall we make them?' asked one bear.

"'Oh, that is easy,' said another. 'I'll show you how to do it. You know I lived for a long time in one of their villages.'

"So this bear got a piece of ashwood and a string, some straight reeds and pieces of flint, and made a bow and some arrows.

"The White Bear, who was chief of the council, stepped out to make a trial of the bow. He pulled back the string and let the arrow fly, but his long claws caught the string and spoiled the shot.

"Seeing this, one of the bears proposed to cut off his own claws and make another trial. This was done and the arrow went straight to the mark.

"Now all the bears were ready to cut off their claws that they might practice with the bow and arrow. But their chief, the old White Bear, was wise.

"'No,' said he, 'let us not cut off our claws. If we do, we shall not be able to climb trees or to tear our food to pieces, and we shall all starve together. It is better to trust to the teeth and claws that the Master of Life has given us. Man's weapons are not for us.'

"All the bears agreed to this, and the council broke up without any plan for dealing with their cruel enemies.

"The deer were the next to hold a council. Each one had some story to tell about the cruelty of men. Each one had lost his father or his mother, his wife or his children, his brother or his sister.