Title: The Fat of the Land: The Story of an American Farm

Author: John Williams Streeter

Release date: August 13, 2005 [eBook #16525]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bill Tozier, Barbara Tozier, Janet Blenkinship

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1904

All rights reserved

copyright, 1904.

by THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up, electrotyped, and published February, 1904. Reprinted March, April, May, 1904.

Norwood Press

J.S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

CONTENTS

THE FAT OF THE LAND

THE FAT OF THE LAND

CHAPTER I MY EXCUSE

CHAPTER II THE HUNTING OF THE LAND

CHAPTER III THE FIRST VISIT TO THE FARM

CHAPTER IV THE HIRED MAN

CHAPTER V BORING FOR WATER

CHAPTER VI WE TAKE POSSESSION

CHAPTER VII THE HORSE-AND-BUGGY MAN

CHAPTER VIII WE PLAT THE FARM

CHAPTER IX HOUSE-CLEANING

CHAPTER X FENCED IN

CHAPTER XI THE BUILDING LINE

CHAPTER XII CARPENTERS QUIT WORK

CHAPTER XIII PLANNING FOR THE TREES

CHAPTER XIV PLANTING OF THE TREES

CHAPTER XV POLLY'S JUDGMENT HALL

CHAPTER XVI WINTER WORK

CHAPTER XVII CARPENTERS QUIT WORK

CHAPTER XVIII WHITE WYANDOTTES

CHAPTER XIX FRIED PORK

CHAPTER XX A RATION FOR PRODUCT

CHAPTER XXI THE RAZORBACK

CHAPTER XXII THE OLD ORCHARD

CHAPTER XXIII THE FIRST HATCH

CHAPTER XXIV THE HOLSTEIN MILK MACHINE

CHAPTER XXV THE DAIRYMAID

CHAPTER XXVI LITTLE PIGS

CHAPTER XXVII WHAT SHALL WE ASK OF THE HEN?

CHAPTER XXVIII DISCOUNTING THE MARKET

CHAPTER XXIX FROM CITY TO COUNTRY

CHAPTER XXX AUTUMN RECKONING

CHAPTER XXXI THE CHILDREN

CHAPTER XXXII THE HOME-COMING

CHAPTER XXXIII CHRISTMAS EVE

CHAPTER XXXIV CHRISTMAS

CHAPTER XXXV WE CLOSE THE BOOKS FOR '96

CHAPTER XXXVI OUR FRIENDS

CHAPTER XXXVII THE HEADMAN'S JOB

CHAPTER XXXVIII SPRING OF '97

CHAPTER XXXIX THE YOUNG ORCHARD

CHAPTER XL THE TIMOTHY HARVEST

CHAPTER XLI STRIKE AT GORDON'S MINE

CHAPTER XLII THE RIOT

CHAPTER XLIII THE RESULT

CHAPTER XLIV DEEP WATERS

CHAPTER XLV DOGS AND HORSES

CHAPTER XLVI THE SKIM-MILK TRUST

CHAPTER XLVII NABOTH'S VINEYARD

CHAPTER XLVIII MAIDS AND MALLARDS

CHAPTER XLIX THE SUNKEN GARDEN

CHAPTER L THE HEADMAN GENERALIZES

CHAPTER LI THE GRAND-GIRLS

CHAPTER LII THE THIRD RECKONING

CHAPTER LIII THE MILK MACHINE

CHAPTER LIV DEEP WATERS

CHAPTER LV THE OLD TIME FARM-HAND

CHAPTER LVI THE SYNDICATE

CHAPTER LVII THE DEATH OF SIR TOM

CHAPTER LVIII BACTERIA

CHAPTER LIX COMFORT ME WITH APPLES

CHAPTER LX "I TOLD YOU SO"

CHAPTER LXI THE BELGIAN FARMER

CHAPTER LXII HOME-COMING

CHAPTER LXIII AN HUNDRED FOLD

CHAPTER LXIV COMFORT ME WITH APPLES

CHAPTER LXV THE END OF THE THIRD YEAR

CHAPTER LXVI LOOKING BACKWARD

CHAPTER LXVII LOOKING FORWARD

THE RURAL SCIENCE SERIES

My sixtieth birthday is a thing of yesterday, and I have, therefore, more than half descended the western slope. I have no quarrel with life or with time, for both have been polite to me; and I wish to give an account of the past seven years to prove the politeness of life, and to show how time has made amends to me for the forced resignation of my professional ambitions. For twenty-five years, up to 1895, I practised medicine and surgery in a large city. I loved my profession beyond the love of most men, and it loved me; at least, it gave me all that a reasonable man could desire in the way of honors and emoluments. The thought that I should ever drop out of this attractive, satisfying life, never seriously occurred to me, though I was conscious of a strong and persistent force that urged me toward the soil. By choice and by training I was a physician, and I gloried in my work; but by instinct I was, am, and always shall be, a farmer. All my life I have had visions of farms with flocks and herds, but I did not expect to realize my visions until I came on earth a second time.

I would never have given up my profession voluntarily; but when it gave me up, I had to accept the dismissal, surrender my ambitions, and fall back upon my primary instinct for diversion and happiness. The dismissal came without warning, like the fall of a tree when no wind shakes the forest, but it was imperative and peremptory. The doctors (and they were among the best in the land) said, "No more of this kind of work for years," and I had to accept their verdict, though I knew that "for years" meant forever.

My disappointment lasted longer than the acute attack; but, thanks to the cheerful spirit of my wife, by early summer of that year I was able to face the situation with courage that grew as strength increased. Fortunately we were well to do, and the loss of professional income was not a serious matter. We were not rich as wealth is counted nowadays; but we were more than comfortable for ourselves and our children, though I should never earn another dollar. This is not the common state of the physician, who gives more and gets less than most other men; it was simply a happy combination of circumstances. Polly was a small heiress when we married; I had some money from my maternal grandfather; our income was larger than our necessities, and our investments had been fortunate. Fate had set no wolf to howl at our door.

In June we decided to take to the woods, or rather to the country, to see what it had in store for us. The more we thought of it, the better I liked the plan, and Polly was no less happy over it. We talked of it morning, noon, and night, and my half-smothered instinct grew by what it fed on. Countless schemes at length resolved themselves into a factory farm, which should be a source of pleasure as well as of income. It was of all sizes, shapes, industries, and limits of expenditure, as the hours passed and enthusiasm waxed or waned. I finally compromised on from two hundred to three hundred acres of land, with a total expenditure of not more than $60,000 for the building of my factory. It was to produce butter, eggs, pork, and apples, all of best quality, and they were to be sold at best prices. I discoursed at some length on farms and farmers to Polly, who slept through most of the harangue. She afterward said that she enjoyed it, but I never knew whether she referred to my lecture or to her nap.

If farming be the art of elimination, I want it not. If the farmer and the farmer's family must, by the nature of the occupation, be deprived of reasonable leisure and luxury, if the conveniences and amenities must be shorn close, if comfort must be denied and life be reduced to the elemental necessities of food and shelter, I want it not. But I do not believe that this is the case. The wealth of the world comes from the land, which produces all the direct and immediate essentials for the preservation of life and the protection of the race. When people cease to look to the land for support, they lose their independence and fall under the tyranny of circumstances beyond their control. They are no longer producers, but consumers; and their prosperity is contingent upon the prosperity and good will of other people who are more or less alien. Only when a considerable percentage of a nation is living close to the land can the highest type of independence and prosperity be enjoyed. This law applies to the mass and also to the individual. The farmer, who produces all the necessities and many of the luxuries, and whose products are in constant demand and never out of vogue, should be independent in mode of life and prosperous in his fortunes. If this is not the condition of the average farmer (and I am sorry to say it is not), the fault is to be found, not in the land, but in the man who tills it.

Ninety-five per cent of those who engage in commercial and professional occupations fail of large success; more than fifty per cent fail utterly, and are doomed to miserable, dependent lives in the service of the more fortunate. That farmers do not fail nearly so often is due to the bounty of the land, the beneficence of Nature, and the ever-recurring seed-time and harvest, which even the most thoughtless cannot interrupt.

The waking dream of my life had been to own and to work land; to own it free of debt, and to work it with the same intelligence that has made me successful in my profession. Brains always seemed to me as necessary to success in farming as in law, or in medicine, or in business. I always felt that mind should control events in agriculture as in commercial life; that listlessness, carelessness, lack of thrift and energy, and waste, were the factors most potent in keeping the farmer poor and unreasonably harassed by the obligations of life. The men who cultivate the soil create incalculable wealth; by rights they should be the nation's healthiest, happiest, most comfortable, and most independent citizens. Their lives should be long, free from care and distress, and no more strenuous than is wholesome. That this condition is not general is due to the fact that the average farmer puts muscle before mind and brawn before brains, and follows, with unthinking persistence, the crude and careless traditions of his forefathers.

Conditions on the farm are gradually changing for the better. The agricultural colleges, the experiment stations, the lecture courses which are given all over the country, and the general diffusion of agricultural and horticultural knowledge, are introducing among farming communities a more intelligent and more liberal treatment of land. But these changes are so slow, and there is so much to be done before even a small percentage of our six millions of farmers begin to realize their opportunities, that even the weakest effort in this direction may be of use. This is my only excuse for going minutely into the details of my experiment in the cultivation of land. The plain and circumstantial narrative of how Four Oaks grew, in seven years, from a poor, ill-paying, sadly neglected farm, into a beautiful home and a profitable investment, must simply stand for what it is worth. It may give useful hints, to be followed on a smaller or a larger scale, or it may arouse criticisms which will work for good, both to the critic and to the author. I do not claim experience, excepting the most limited; I do not claim originality, except that most of this work was new to me; I do not claim hardships or difficulties, for I had none; but I do claim that I made good, that I arrived, that my experiment was physically and financially a success, and, as such, I am proud of it, and wish to give it to the world.

I was fifty-three years old when I began this experiment, and I was obliged to do quickly whatever I intended to do. I could devote any part of $60,000 to the experiment without inconvenience. My desire was to test the capacity of ordinary farm land, when properly treated, to support an average family in luxury, paying good wages to more than the usual number of people, keeping open house for many friends, and at the same time not depleting my bank account. I wished to experiment in intensive farming, using ordinary farm land as other men might do under similar or modified circumstances. I believed that if I fed the land, it would feed me. My plan was to sell nothing from the farm except finished products, such as butter, fruit, eggs, chickens, and hogs. I believed that best results would be attained by keeping only the best stock, and, after feeding it liberally, selling it in the most favorable market. To live on the fat of the land was what I proposed to do; and I ask your indulgence while I dip into the details of this seven years' experiment.

You may say that few persons have the time, inclination, taste, or money to carry out such an experiment; that the average farmer must make each year pay, and that the exploiting of this matter is therefore of interest to a very limited number. Admitting much of this, I still claim that there is a lesson to every struggling farmer in this narrative. It should teach the value of brain work on the farm, and the importance of intelligent cultivation; also the advantages of good seed, good tilth, good specimens of well-bred stock, good food, and good care. Feed the land liberally, and it will return you much. Permit no waste in space, product, time, tools, or strength. Do in a small way, if need be, what I have done on a large scale, and you will quickly commence to get good dividends. I have spent much more money than was really necessary on the place, and in the ornamentation of Four Oaks. This, however, was part of the experiment. I asked the land not only to supply immediate necessities, but to minister to my every want, to gratify the eye, and please the senses by a harmonious fusion of utility and beauty. I wanted a fine country home and a profitable investment within the same ring fence.

Will you follow me through the search for the land, the purchase, and the tremendous house-cleaning of the first year? After that we will take up the years as they come, finding something of special interest attaching naturally to each. I shall have to deal much with figures and statistics, in a small way, and my pages may look like a school book, but I cannot avoid this, for in these figures and statistics lies the practical lesson. Theory alone is of no value. Practical application of the theory is the test. I am not imaginative. I could not write a romance if I tried. My strength lies in special detail, and I am willing to spend a lot of time in working out a problem. I do not claim to have spent this time and money without making serious mistakes; I have made many, and I am willing to admit them, as you will see in the following pages. I do claim, however, that, in spite of mistakes, I have solved the problem, and have proved that an intelligent farmer can live in luxury on the fat of the land.

The location of the farm for this experiment was of the utmost importance. The land must be within reasonable distance of the city and near a railroad, consequently within easy touch of the market; and if possible it must be near a thriving village, to insure good train service. As to size, I was somewhat uncertain; my minimum limit was 150 acres and 400 the maximum. The land must be fertile, or capable of being made so.

I advertised for a farm of from two hundred to four hundred acres, within thirty-five miles of town, and convenient to a good line of transportation. Fifty-seven replies came, of which forty-six were impossible, eleven worth a second reading, and five worth investigating. My third trip carried me thirty miles southwest of the city, to a village almost wholly made up of wealthy people who did business in town, and who had their permanent or their summer homes in this village. There were probably twenty-seven or twenty-eight hundred people in the village, most of whom owned estates of from one to thirty acres, varying in value from $10,000 to $100,000. These seemed ideal surroundings. The farm was a trifle more than two miles from the station, and 320 acres in extent. It lay to the west of a north-and-south road, abutting on this road for half a mile, while on the south it was bordered for a mile by a gravelled road, and the west line was an ordinary country road. The lay of the land in general was a gentle slope to the west and south from a rather high knoll, the highest point of which was in the north half of the southeast forty. The land stretched away to the west, gradually sloping to its lowest point, which was about two-thirds of the distance to the western boundary. A straggling brook at its lowest point was more or less rampant in springtime, though during July and August it contained but little water.

Westward from the brook the land sloped gradually upward, terminating in a forest of forty to fifty acres. This forest was in good condition. The trees were mostly varieties of oak and hickory, with a scattering of wild cherry, a few maples, both hard and soft, and some lindens. It was much overgrown with underbrush, weeds, and wild flowers. The land was generally good, especially the lower parts of it. The soil of the higher ground was thin, but it lay on top of a friable clay which is fertile when properly worked and enriched.

The farm belonged to an unsettled estate, and was much run down, as little had been done to improve its fertility, and much to deplete it. There were two sets of buildings, including a house of goodly proportions, a cottage of no particular value, and some dilapidated barns. The property could be bought at a bargain. It had been held at $100 an acre; but as the estate was in process of settlement, and there was an urgent desire to force a sale, I finally secured it for $71 per acre. The two renters on the farm still had six months of occupancy before their leases expired. They were willing to resign their leases if I would pay a reasonable sum for the standing crops and their stock and equipments.

The crops comprised about forty acres of corn, fifty acres of oats, and five acres of potatoes. The stock was composed of two herds of cows (seven in one and nine in the other), eleven spring calves, about forty hogs, and the usual assortment of domestic fowls. The equipment of the farm in machinery and tools was meagre to the last degree. I offered the renters $700 and $600, respectively, for their leasehold and other property. This was more than their value, but I wanted to take possession at once.

It was the 8th of July, 1895, when I contracted for the farm; possession was to be given August 1st. On July 9th, Polly and I boarded an early train for Exeter, intending to make a day of it in every sense. We wished to go over the property thoroughly, and to decide on a general outline of treatment. Polly was as enthusiastic over the experiment as I, and she is energetic, quick to see, and prompt to perform. She was to have the planning of the home grounds—the house and the gardens; and not only the planning, but also the full control.

A ride of forty-five minutes brought us to Exeter. The service of this railroad, by the way, is of the best; there is hardly a half-hour in the day when one cannot make the trip either way, and the fare is moderate: $8.75 for twenty-five rides,—thirty-five cents a ride. We hired an open carriage and started for the farm. The first half-mile was over a well-kept macadam road through that part of the village which lies west of the railway. The homes bordering this street are of fine proportions, and beautifully kept. They are the country places of well-to-do people who love to get away from the noise and dirt of the city. Some of them have ten or fifteen acres of ground, but this land is for breathing space and beauty—not for serious cultivation. Beyond these homes we followed a well-gravelled road leading directly west. This road is bordered by small farms, most of them given over to dairying interests.

Presently I called Polly's attention to the fact that the few apple trees we saw were healthy and well grown, though quite independent of the farmer's or the pruner's care. This thrifty condition of unkept apple orchards delighted me. I intended to make apple-growing a prominent feature in my experiment, and I reasoned that if these trees did fairly well without cultivation or care, others would do excellently well with both.

As we approached the second section line and climbed a rather steep hill, we got the first glimpse of our possession. At the bottom of the western slope of this hill we could see the crossing of the north-and-south road, which we knew to be the east boundary of our land; while, stretching straight away before us until lost in the distant wood, lay the well-kept road which for a good mile was our southern boundary. Descending the hill, we stopped at the crossing of the roads to take in the outline of the farm from this southeast corner. The north-and-south road ran level for 150 yards, gradually rose for the next 250, and then continued nearly level for a mile or more. We saw what Jane Austen calls "a happy fall of land," with a southern exposure, which included about two-thirds of the southeast forty, and high land beyond for the balance of this forty and the forty lying north of it. There was an irregular fringe of forest trees on this southern slope, especially well defined along the eastern border. I saw that Polly was pleased with the view.

"We must enter the home lot from this level at the foot of the hill," said she, "wind gracefully through the timber, and come out near those four large trees on the very highest ground. That will be effective and easily managed, and will give me a chance at landscape gardening, which I am just aching to try."

"All right," said I, "you shall have a free hand. Let's drive around the boundaries of our land and behold its magnitude before we make other plans."

We drove westward, my eyes intent upon the fields, the fences, the crops, and everything that pertained to the place. I had waited so many years for the sense of ownership of land that I could hardly realize that this was not another dream from which I would soon be awakened by something real. I noticed that the land was fairly smooth except where it was broken by half-rotted stumps or out-cropping boulders, that the corn looked well and the oats fair, but the pasture lands were too well seeded to dock, milkweed, and wild mustard to be attractive, and the fences were cheap and much broken.

The woodland near the western limit proved to be practically a virgin forest, in which oak trees predominated. The undergrowth was dense, except near the road; it was chiefly hazel, white thorn, dogwood, young cherry, and second growth hickory and oak. We turned the corner and followed the woods for half a mile to where a barbed wire fence separated our forest from the woodland adjoining it. Coming back to the starting-point we turned north and slowly climbed the hill to the east of our home lot, silently developing plans. We drove the full half-mile of our eastern boundary before turning back.

I looked with special interest at the orchard, which was on the northeast forty. I had seen it on my first visit, but had given it little attention, noting merely that the trees were well grown. I now counted the rows, and found that there were twelve; the trees in each row had originally been twenty, and as these trees were about thirty-five feet apart, it was easy to estimate that six acres had been given to this orchard. The vicissitudes of seventeen years had not been without effect, and there were irregular gaps in the rows,—here a sick tree, there a dead one. A careless estimate placed these casualties at fifty-five or sixty, which I later found was nearly correct. This left 180 trees in fair health; and in spite of the tight sod which covered their roots and a lamentable lack of pruning, they were well covered with young fruit. They had been headed high in the old-fashioned way, which made them look more like forest trees than a modern orchard. They had done well without a husbandman; what could not others do with one?

The group of farm buildings on the north forty consisted of a one-story cottage containing six rooms—sitting room, dining room, kitchen, and a bedroom opening off each—with a lean-to shed in the rear, and some woe-begone barns, sheds, and out-buildings that gave the impression of not caring how they looked. The second group was better. It was south of the orchard on the home forty, and quite near the road.

Why does the universal farm-house hang its gable over the public road, without tree or shrub to cover its boldness? It would look much better, and give greater comfort to its inmates, if it were more remote. A lawn leading up to a house, even though not beautiful or well kept, adds dignity and character to a place out of all proportion to its waste or expense. I know of nothing that would add so much to the beautification of the country-side as a building line prohibiting houses and barns within a hundred yards of a public road. A staring, glaring farm-house, flanked by a red barn and a pigsty, all crowding the public road as hard as the path-master will permit, is incongruous and unsightly. With all outdoors to choose from, why ape the crowded city streets? With much to apologize for in barn and pigsty, why place them in the seat of honor? Moreover, many things which take place on the farm gain enchantment from distance. It is best to leave some scope for the imagination of the passer-by. These and other things will change as farmers' lives grow more gracious, and more attention is given to beautifying country houses.

The house, whose gables looked up and down the street, was two stories in height, twenty-five feet by forty in the main, with a one-story ell running back. Without doubt there was a parlor, sitting room, and four chambers in the main, with dining room and kitchen in the ell.

"That will do for the head man's house, if we put it in the right place and fix it up," said Polly.

"My young lady, I propose to be the 'head man' on this farm, and I wish it spelled with a capital H, but I do not expect to live in that house. It will do first-rate for the farmer and his men, when you have placed it where you want it, but I intend to live in the big house with you."

"We'll not disagree about that, Mr. Headman."

The barns were fairly good, but badly placed. They were not worth the expense of moving, so I decided to let them stand as they were until we could build better ones, and then tear them down.

We drove in through a clump of trees behind the farm-house, and pushed on about three hundred yards to the crest of the knoll. Here we got out of the carriage and looked about, with keen interest, in every direction. The views were wide toward three points of the compass. North and northwest we could see pleasant lands for at least two miles; directly west, our eyes could not reach beyond our own forest; to the south and southwest, fruitful valleys stretched away to a range of wooded hills four miles distant; but on the east our view was limited by the fringe of woods which lay between us and the north-and-south road.

"This is the exact spot for the house," said Polly. "It must face to the south, with a broad piazza, and the chief entrance must be on the east. The kitchens and fussy things will be out of sight on the northwest corner; two stories, a high attic with rooms, and covered all over with yellow-brown shingles." She had it all settled in a minute.

"What will the paper on your bedroom wall be like?" I asked.

"I know perfectly well, but I shan't tell you."

Seating myself on an out-cropping boulder, I began to study the geography of the farm. In imagination I stripped it of stock, crops, buildings, and fences, and saw it as bald as the palm of my hand. I recited the table of long measure: Sixteen and a half feet, one rod, perch, or pole; forty rods, one furlong; eight furlongs, one mile. Eight times 40 is 320; there are 320 rods in a mile, but how much is 16-1/2. times 320? "Polly, how much is 16-1/2 times 320?"

"Don't bother me now; I'm busy."

(Just as if she could have told in her moment of greatest leisure!) I resorted to paper and pencil, and learned that there are 5280 feet in each and every mile. My land was, therefore, 5280 feet long and 2640 feet wide. I must split it in some way, by a road or a lane, to make all parts accessible. If I divided it by two lanes of twenty feet each, I could have on either side of these lanes lots 650 feet deep, and these would be quite manageable. I found that if these lots were 660 feet long, they would contain ten acres minus the ten feet used for the lane. This seemed a real discovery, as it simplified my calculations and relieved me of much mental effort.

"Polly, I am going to make a map of the place,—lay it out just as I want it."

"You may leave the home forty out of your map; I will look after that," said the lady.

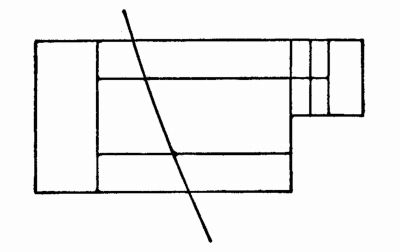

In my pocket I found three envelopes somewhat the worse for wear. This is how one of them looked when my map was finished.

I am not especially haughty about this map, but it settled a matter which had been chaotic in my mind. My plan was to make the farm a soiling one; to confine the stock within as limited a space as was consistent with good health, and to feed cultivated forage and crops. In drawing my map, the forty which Polly had segregated left the northeast forty standing alone, and I had to cast about for some good way of treating it. "Make it your feeding ground," said my good genius, and thus the wrath of Polly was made to glorify my plans.

This feeding lot of forty acres is all high land, naturally drained. It was near the obvious building line, and it seemed suitable in every way. I drew a line from north to south, cutting it in the middle. The east twenty I devoted to cows and their belongings; the west twenty was divided by right lines into lots of five acres each, the southwest one for the hens and the other three for hogs.

Looking around for Polly to show her my work, I found she had disappeared; but soon I saw her white gown among the trees. Joining her, I said,—

"I have mapped seven forties; have you finished one?"

"I have not," she said. "Mine is of more importance than all of yours; I will give you a sketch this evening. This bit of woods is better than I thought. How much of it do you suppose there is?"

"About seven acres, I reckon, by hook and by crook; enough to amuse you and furnish a lot of wild-flower seed to be floated over the rest of the farm."

"You may plant what seeds you like on the rest of the farm, but I must have wild flowers. Do you know how long it is since I have had them? Not since I was a girl!"

"That is not very long, Polly. You don't look much more than a girl to-day. You shall have asters and goldenrod and black-eyed Susans to your heart's content if you will always be as young."

"I believe Time will turn backward for both of us out here, Mr. Headman. But I'm as hungry as a wolf. Do you think we can get a glass of milk of the 'farm lady'?"

We tried, succeeded, and then started for home. Neither of us had much to say on the return trip, for our minds were full of unsolved problems. That evening Polly showed me this plat of the home forty.

Modern farming is greatly handicapped by the difficulty of getting good help. I need not go into the causes which have operated to bring about this condition; it exists, and it has to be met. I cannot hope to solve the problem for others, but I can tell how I solved it for myself. I determined that the men who worked for me should find in me a considerate friend who would look after their interests in a reasonable and neighborly fashion. They should be well housed and well fed, and should have clean beds, clean table linen and an attractively set table, papers, magazines, and books, and a comfortable room in which to read them. There should be reasonable work hours and hours for recreation, and abundant bathing facilities; and everything at Four Oaks should proclaim the dignity of labor.

From the men I expected cleanliness, sobriety, uniform kindness to all animals, cheerful obedience, industry, and a disposition to save their wages. These demands seemed to me reasonable, and I made up my mind to adhere to them if I had to try a hundred men.

The best way to get good farm hands who would be happy and contented, I thought, was to go to the city and find men who had shot their bolts and failed of the mark; men who had come up from the farm hoping for easier or more ambitious lives, but who had failed to find what they sought and had experienced the unrest of a hand-to-mouth struggle for a living in a large city; men who were pining for the country, perhaps without knowing it, and who saw no way to get back to it. I advertised my wants in a morning paper, and asked my son, who was on vacation, to interview the applicants. From noon until six o'clock my ante-room was invaded by a motley procession—delicate boys of fifteen who wanted to go to the country, old men who thought they could do farm work, clerks and janitors out of employment, typical tramps and hoboes who diffused very naughty smells, and a few—a very few—who seemed to know what they could do and what they really wanted.

Jack took the names of five promising men, and asked them to come again the next day. In the morning I interviewed them, dismissed three, and accepted two on the condition that their references proved satisfactory. As these men are still at Four Oaks, after seven years of steady employment, and as I hope they will stay twenty years longer, I feel that the reader should know them. Much of the smooth sailing at the farm is due to their personal interest, steadiness of purpose, and cheerful optimism.

William Thompson, forty-six years of age, tall, lean, wiry, had been a farmer all his life. His wife had died three years before, and a year later, he had lost his farm through an imperfect title. Understanding machinery and being a fair carpenter, he then came to the city, with $200 in his pocket, joined the Carpenter's Union, and tried to make a living at that trade. Between dull business, lock-outs, tie-ups, and strikes, he was reduced to fifty cents, and owed three dollars for room rent. He was in dead earnest when he threw his union card on my table and said:—

"I would rather work for fifty cents a day on a farm than take my chances for six times as much in the union."

This was the sort of man I wanted: one who had tried other things and was glad of a chance to return to the land. Thompson said that after he had spent one lonesome year in the city, he had married a sensible woman of forty, who was now out at service on account of his hard luck. He also told of a husky son of two-and-twenty who was at work on a farm within fifty miles of the city. I liked the man from the first, for he seemed direct and earnest. I told him to eat up the fifty cents he had in his pocket and to see me at noon of the following day. Meantime I looked up one of his references; and when he came, I engaged him, with the understanding that his time should begin at once.

The wage agreed upon was $20 a month for the first half-year. If he proved satisfactory, he was to receive $21 a month for the next six months, and there was to be a raise of $1 a month for each half-year that he remained with me until his monthly wage should amount to $40,—each to give or take a month's notice to quit. This seemed fair to both. I would not pay more than $20 a month to an untried man, but a good man is worth more. As I wanted permanent, steady help, I proposed to offer a fair bonus to secure it. Other things being equal, the man who has "gotten the hang" of a farm can do better work and get better results than a stranger.

The transient farm-hand is a delusion and a snare. He has no interest except his wages, and he is a breeder of discontent. If the hundreds of thousands of able-bodied men who are working for scant wages in cities, or inanely tramping the country, could see the dignity of the labor which is directly productive, what a change would come over the face of the country! There are nearly six million farms in this nation, and four millions of them would be greatly benefited by the addition of another man to the working force. There is a comfortable living and a minimum of $180 a year for each of four million men, if they will only seek it and honestly earn it. Seven hundred millions in wages, and double or treble that in product and added values, is a consideration not unworthy the attention of social scientists. To favor an exodus to the land is, I believe, the highest type of benevolence, and the surest and safest solution of the labor problem.

Besides engaging Thompson, I tentatively bespoke the services of his wife and son. Mrs. Thompson was to come for $15 a month and a half-dollar raise for each six months, the son on the same terms as the father.

The other man whom I engaged that day was William Johnson, a tall, blond Swede about twenty-six years old. Johnson had learned gardening in the old country, and had followed it two years in the new. He was then employed in a market gardener's greenhouse; but he wanted to change from under glass to out of doors, and to have charge of a lawn, shrubs, flowers, and a kitchen garden. He spoke brokenly, but intelligently, had an honest eye, and looked to me like a real "find." Polly, who was to be his immediate boss, was pleased with him, and we took him with the understanding that he was to make himself generally useful until the time came for his special line of work. We now had two men engaged (with a possible third) and one woman, and my venire was exhausted.

Two days later I again advertised, and out of a number of applicants secured one man. Sam Jones was a sturdy-looking fellow of middle age, with a suspiciously red nose. He had been bred on a farm, had learned the carpenter's trade, and was especially good at taking care of chickens. His ambition was to own and run a chicken plant. I hired him on the same terms as the others, but with misgivings on account of the florid nose. This was on the 19th or 20th of July, and there were still ten days before I could enter into possession. The men were told to report for duty the last day of the month.

The water supply was the next problem. I determined to have an abundant and convenient supply of running water in the house, the barns, and the feeding grounds, and also on the lawn and gardens. I would have no carrying or hauling of water, and no lack of it. There were four wells on the place, two of them near the houses and two stock wells in the lower grounds. Near the well at the large house was a windmill that pumped water into a small tank, from which it was piped to the barn-yard and the lower story of the house. The supply was inadequate and not at all to my liking.

My plan involved not only finding, raising, and distributing water, but also the care of waste water and sewage. Inquiring among those who had deep wells in the village, I found that good water was usually reached at from 180 to 210 feet. As my well-site was high, I expected to have to bore deep. I contracted with a well man of good repute for a six-inch well of 250 feet (or less), piped and finished to the surface, for $2 a foot; any greater depth to be subject to further agreement.

It took nearly three months to finish the water system, but it has proved wonderfully convenient and satisfactory. During seven years I have not spent more than $50 for changes and repairs. We struck bed-rock at 197 feet, drilled 27 feet into this rock, and found water which rose to within 50 feet of the surface and which could not be materially lowered by the constant use of a three-inch power-pump. The water was milky white for three days, in spite of much pumping; and then, and ever after, it ran clear and sweet, with a temperature of 54° F. Well and water being satisfactory, I cheerfully paid the well man $448 for the job.

Meantime I contracted for a tank twelve by twelve feet, to be raised thirty feet above the well on eight timbers, each ten inches square, well bolted and braced, for $430,—I to put in the foundation. This consisted of eight concrete piers, each five feet deep in the clay, three feet square, and capped at the level of the ground with a limestone two feet square and eight inches thick. These piers were set in octagon form around the well, with their centres seven feet from the middle of the bore, making the spread of the framework fourteen feet at the ground and ten at the platform. The foundation cost $32. A Rider eight-inch, hot-air, wood-burning, pumping engine (with a two-inch pipe leading to the tank, and a four-inch pipe from it), filled the tank quickly; and it was surprising to see how little fuel it consumed. It cost $215.

I have now to confess to a small extravagance. I contracted with a carpenter to build an ornamental tower, fifty-five feet high, twenty feet across at the base, and fifteen feet at the top, sheeted and shingled, with a series of small windows in spiral and a narrow stairway leading to a balcony that surrounded the tower on a level with the top of the tank. This tower cost $425; but it was not all extravagance, because a third of the expense would have been incurred in protecting the engine and making the tank frost-proof.

To distribute the water, I had three lines of four-inch pipe leading from the tank's out-flow pipe. One of these went 250 feet to the house, with one-inch branches for the gardens and lawn; another led east 375 feet, past the proposed sites of the cottage, the farm-house, the dairy, and other buildings in that direction; while the third, about 400 feet long, led to the horse barn and the other projected buildings. From near the end of this west pipe a 1-1/2-inch pipe was carried due north through the centre of the five-acre lot set apart for the hennery, and into the fields beyond. This pipe was about 700 feet long. Altogether I used 1100 feet of four-inch, and about 2200 feet of smaller pipe, at a total cost of $803. All water pipes were placed 4-1/2 feet in the ground to be out of the reach of frost, and to this day they have received no further attention.

The trenches for the pipes were opened by a party of five Italians whom a railroad friend found for me. These men boarded themselves, slept in the barn, and did the work for seventy-five cents a rod, the job costing me $169.

Opening the sewer trenches cost a little more, for they were as deep as those for the water, and a little wider. Eight hundred feet of main sewer, a three-hundred-foot branch to the house, and short branches from barns, pens, and farm-houses, made in all about fourteen hundred feet, which cost $83 to open. The sewer ended in the stable yard back of the horse barn, in a ten-foot catch-basin near the manure pit. A few feet from this catch-basin was a second, and beyond this a third, all of the same size, with drain-pipes connecting them about two feet below the ground. These basins were closely covered at all times, and in winter they were protected from frost by a thick layer of coarse manure. They were placed near the site of the manure pit for convenience in cleaning, which had to be done every three months for the first one, once in six months for the second and rarely for the third; indeed, the water flowing from the third was always clear. This waste water was run through a drain-pipe diagonally across the northwest corner of the big orchard to an open ditch in the north lane. Opening this drain of forty rods cost $30. Later I carried this closed drain to the creek, at an additional expense of $67. The connecting of the water pipes and the laying of the sewer was done by a local plumber for $50; the drain-pipe and sewer-pipe cost $112; and the three catch-basins, bricked up and covered with two-inch plank, cost $63. The filling in of all these trenches was done by my own men with teams and scrapers, and should not be figured into this expense account. It must be borne in mind that while this elaborate water system was being installed, no buildings were completed and but few were even begun; the big house was not finished for more than a year. The sites of all the buildings had been decided on, and the farm-house and the cottage had been moved and remodelled, by the middle of October, at which date the water plant was completed. An abundant supply of good water is essential to the comfort of man and beast, and the money invested in securing it will pay a good interest in the long run. My water plant cost me a lot of money, $2758; but it hasn't cost me $10 a year since it was finished.

My barn was full of horses, but none of them was fit for farm work; so I engaged a veterinary surgeon to find three suitable teams. By the 25th of the month he had succeeded, and I inspected the animals and found them satisfactory, though not so smooth and smart-looking as I had pictured them. When I compared them, somewhat unfavorably, with the teams used for city trucks and delivery wagons, he retorted by saying: "I did not know that you wanted to pay $1200 a pair for your horses. These six horses will cost you $750, and they are worth it." They were a sturdy lot, young, well matched, not so large as to be unwieldy, but heavy enough for almost any work. The lightest was said to weigh 1375 pounds, and the heaviest not more than a hundred pounds more. Two of the teams were bay with a sprinkling of white feet, while the other pair was red roan, and, to my mind, the best looking.

Four of these horses are still doing service on the farm, after more than seven years. One of the bays died in the summer of '98, and one of the roans broke his stifle during the following winter and had to be shot. The bereaved relicts of these two pairs have taken kindly to each other, and now walk soberly side by side in double harness. I sometimes think, however, that I see a difference. The personal relation is not just as it was in the old union,—no bickerings or disagreements, but also no jokes and no caresses. The soft nose doesn't seek its neighbor's neck, there is no resting of chin on friendly withers while half-closed eyes see visions of cool shades, running brooks, and knee-deep clover; and the urgent whinney which called one to the other and told of loneliness when separated is no longer heard. It is pathetic to think that these good creatures have been robbed of the one thing which gave color to their lives and lifted them above the dreary treadmill of duty for duty's sake. The kindly friendship of each for his yoke-fellow is not the old sympathetic companionship, which will come again only when the cooling breezes, running brooks, and knee-deep pastures of the good horse's heaven are reached.

A horse is wonderfully sensitive for an animal of his size and strength. He is timid by nature and his courage comes only from his confidence in man. His speed, strength, and endurance he will willingly give, and give it to the utmost, if the hand that guides is strong and gentle, and the voice that controls is firm, confident, and friendly. Lack of courage in the master takes from the horse his only chance of being brave; lack of steadiness makes him indirect and futile; lack of kindness frightens him into actions which are the result of terror at first, and which become vices only by mismanagement. By nature the horse is good. If he learns bad manners by associating with bad men, we ought to lay the blame where it belongs. A kind master will make a kind horse; and I have no respect for a man who has had the privilege of training a horse from colt-hood and has failed to turn out a good one. Lack of good sense, or cruelty, is at the root of these failures. One can forgive lack of sense, for men are as God made them; but there is no forgiveness for the cruel: cooling shades and running brooks will not be prominent features in their ultimate landscapes.

For harness and farm equipments, tools and machinery, I went to a reliable firm which made most and handled the rest of the things that make a well-equipped farm. It is best to do much of one's business through one house, provided, of course, that the house is dependable. You become a valued customer whom it is important to please, you receive discounts, rebates, and concessions that are worth something, and a community of interest grows up that is worth much.

My first order to this house was for three heavy wagons with four-inch tires, three sets of heavy harness, two ploughs and a subsoiler, three harrows (disk, spring tooth, and flat), a steel land-roller, two wheelbarrows, an iron scraper, fly nets and other stable equipment, shovels, spades, hay forks, posthole tools, a hand seeder, a chest of tools, stock-pails, milk-pails and pans, axes, hatchets, saws of various kinds, a maul and wedges, six kegs of nails, and three lanterns. The total amount was $488; but as I received five per cent discount, I paid only $464. The goods, except the wagons and harnesses, were to go by freight to Exeter. Polly was to buy the necessary furnishings for the men's house, the only stipulation I made being that the beds should be good enough for me to sleep in. On the 25th of July she showed me a list of the things which she had purchased. It seemed interminable; but she assured me that she had bought nothing unnecessary, and that she had been very careful in all her purchases. As I knew that Polly was in the habit of getting the worth of her money, I paid the bills without more ado. The list footed up to $495.

Most of the housekeeping things were to be delivered at the station in Exeter; the rest were to go on the wagons. On the afternoon of the 30th the wagons and harnesses were sent to the stable where the horses had been kept, and the articles to go in these wagons were loaded for an early start the following morning. The distance from the station in the city to the station at Exeter is thirty miles, but the stable is three miles from the city station, the farm two and a half miles from Exeter station, and the wagon road not so direct as the railroad. The trip to the farm, therefore, could not be much less than forty miles, and would require the best part of two days. The three men whom I had engaged reported for duty, as also did Thompson's son, whom we are to know hereafter as Zeb.

Early on the last day of the month the men and teams were off, with cooked provisions for three days. They were to break the journey twenty-five miles out, and expected to reach the farm the next afternoon. Polly and I wished to see them arrive, so we took the train at 1 P.M. August 1st, and reached Four Oaks at 2.30, taking with us Mrs. Thompson, who was to cook for the men.

Before starting I had telephoned a local carpenter to meet me, and to bring a mason if possible. I found both men on the ground, and explained to them that there would be abundant work in their lines on the place for the next year or two, that I was perfectly willing to pay a reasonable profit on each job, but that I did not propose to make them rich out of any single contract.

The first thing to do, I told them, was to move the large farm-house to the site already chosen, about two hundred yards distant, enlarge it, and put a first-class cellar under the whole. The principal change needed in the house was an additional story on the ell, which would give a chamber eighteen by twenty-six, with closets five feet deep, to be used as a sleeping room for the men. I intended to change the sitting room, which ran across the main house, into a dining and reading room twenty feet by twenty-five, and to improve the shape and convenience of the kitchen by pantry and lavatory. There must also be a well-appointed bathroom on the upper floor, and set tubs in the kitchen. My men would dig the cellar, and the mason was to put in the foundation walls (twelve inches thick and two feet above ground), the cross or division walls, and the chimneys. He was also to put down a first-class cement floor over the whole cellar and approach. The house was to be heated by a hot-water system; and I afterward let this job to a city man, who put in a satisfactory plant for $500.

We had hardly finished with the carpenter and the mason when we saw our wagons turning into the grounds. We left the contractors to their measurements, plans, and figures, while we hastened to turn the teams back, as they must go to the cottage on the north forty. The horses looked a little done up by the heat and the unaccustomed journey, but Thompson said: "They're all right,—stood it first-rate."

The cottage and out-buildings furnished scanty accommodations for men and beasts, but they were all that we could provide. I told the men to make themselves and the horses as comfortable as they could, then to milk the cows and feed the hogs, and call it a day.

While the others were unloading and getting things into shape, I called Thompson off for a talk. "Thompson," I said, "you are to have the oversight of the work here for the present, and I want you to have some idea of my general plan. This experiment at farming is to last years. We won't look for results until we are ready to force them, but we are to get ready as soon as possible. In the meantime, we will have to do things in an awkward fashion, and not always for immediate effect. We must build the factory before we can turn out the finished product. The cows, for instance, must be cared for until we can dispose of them to advantage. Half of them, I fancy, are 'robber cows,' not worth their keep (if it costs anything to feed them), and we will certainly not winter them. Keep your eye on the herd, and be able to tell me if any of them will pay. Milk them carefully, and use what milk, cream, and butter you can, but don't waste useful time carting milk to market—feed it to the hogs rather. If a farmer or a milkman will call for it, sell what you have to spare for what he will give, and have done with it quickly. You are to manage the hogs on the same principle. Fatten those which are ready for it, with anything you find on the place. We will get rid of the whole bunch as soon as possible. You see, I must first clear the ground before I can build my factory. Let the hens alone for the present; you can eat them during the winter.

"Now, about the crops. The hay in barns and stacks is all right; the wheat is ready for threshing, but it can wait until the oats are also ready; the corn is weedy, but it is too late to help it, and the potatoes are probably covered with bugs. I will send out to-morrow some Paris green and a couple of blow-guns. There is not much real farm work to do just now, and you will have time for other things. The first and most important thing is to dig a cellar to put your house over; your comfort depends on that. Get the men and horses with plough and scraper out as early as you can to-morrow morning, and hustle. You have nothing to do but dig a big hole seven feet deep inside these lines. I count on you to keep things moving, and I will be out the day after to-morrow."

The mason had finished his estimate, which was $560. After some explanations, I concluded that it was a fair price, and agreed to it, provided the work could be done promptly. The carpenter was not ready to give me figures; he said, however, that he could get a man to move the house for $120, and that he would send me by mail that night an itemized estimate of costs, and also one from a plumber. This seemed like doing a lot of things in one afternoon, so Polly and I started for town content.

"Those people can't be very luxurious out there," said Polly, "but they can have good food and clean beds. They have all out-doors to breathe in, and I do not see what more one can ask on a fine August evening, do you, Mr. Headman?"

I could think of a few things, but I did not mention them, for her first words recalled some scenes of my early life on a backwoods farm: the log cabin, with hardly ten nails in it, the latch-string, the wide-mouthed stone-and-stick chimney, the spring-house with its deep crocks, the smoke-house made of a hollow gum-tree log, the ladder to the loft where I slept, and where the snows would drift on the floor through the rifts in the split clapboards that roofed me over. I wondered if to-day was so much better than yesterday as conditions would warrant us in expecting.

August 3 found me at Four Oaks in the early afternoon. A great hollow had been dug for the cellar, and Thompson said that it would take but one more full day to finish it. Piles of material gave evidence that the mason was alert, and the house-mover had already dropped his long timbers, winch, and chains by the side of the farm-house.

While I was discussing matters with Thompson, a smart trap turned into the lot, and a well-set-up young man sprang out of the stylish runabout and said,—

"Dr. Williams, I hear you want more help on your farm."

"I can use another man or two to advantage, if they are good ones."

"Well, I don't want to brag, but I guess I am a good one, all right. I ain't afraid of work, and there isn't much that I can't do on a farm. What wages do you pay?"

I told him my plan of an increasing wage scale, and he did not object. "That includes horse keep, I suppose?" said he.

"I do not know what you mean by 'horse keep.'"

"Why, most of the men on farms around here own a horse and buggy, to use nights, Sundays, and holidays, and we expect the boss to keep the horse. This is my rig. It is about the best in the township; cost me $280 for the outfit."

"See here, young man, this is another specimen of farm economics, and it is one of the worst in the lot. Let me do a small example in mental arithmetic for you. The interest on $280 is $14; the yearly depreciation of your property, without accidents, is at least $40; horse-shoeing and repairs, $20; loss of wages (for no man will keep your horse for less than $4 a month), $48. In addition to this, you will be tempted to spend at least $5 a month more with a horse than without one; that is $60 more. You are throwing away $182 every year without adding $1 to your value as an employee, one ounce of dignity to your employment, or one foot of gain in your social position, no matter from what point you view it.

"Taking it for granted that you receive $25 a month for every month of the year (and this is admitting too much), you waste more than half on that blessed rig, and you can make no provision for the future, for sickness, or for old age. No, I will not keep your horse, nor will I employ any man whose scheme of life doesn't run further than the ownership of a horse and buggy."

"But a fellow must keep up with the procession; he must have some recreation, and all the men around here have rigs."

"Not around Four Oaks. Recreation is all right, but find it in ways less expensive. Read, study, cultivate the best of your kind, plan for the future and save for it, and you will not lack for recreation. Sell your horse and buggy for $200, if you cannot get more, put the money at interest, save $200 out of your wages, and by the end of the year you will be worth over $400 in hard cash and much more in self-respect. You can easily add 1200 a year to your savings, without missing anything worth while; and it will not be long before you can buy a farm, marry a wife, and make an independent position. I will have no horse-and-buggy men on my farm. It's up to you."

"By Jove! I believe you may be right. It looks like a square deal, and I'll play it, if you'll give me time to sell the outfit."

"All right, come when you can. I'll find the work."

That day being Saturday, I told Thompson that I would come out early Monday morning, bringing with me a rough map of the place as I had planned it, and we would go over it with a chain and drive some outlining stakes. I then returned to Exeter, found the carpenter and the plumber, and accepted their estimates,—$630 and $325, respectively. The farm-house moved, finished, furnished, and heated, but not painted or papered, would cost $2630. Painting, papering, window-shades, and odds and ends cost $275, making a total of $2905. It proved a good investment, for it was a comfortable and convenient home for the men and women who afterward occupied it. It has certainly been appreciated by its occupants, and few have left it without regret. We have always tried to make it an object lesson of cleanliness and cheerfulness, and I don't think a man has lived in it for six months without being bettered. It seemed a good deal of money to put on an old farm-house for farm-hands, but it proved one of the best investments at Four Oaks, for it kept the men contented and cheerful workers.

On Monday I was out by ten o'clock, armed with a surveyor's chain. Thompson had provided a lot of stakes, and we ran the lines, more or less straight, in general accord with my sketch plan. We walked, measured, estimated, and drove stakes until noon. At one o'clock we were at it again, and by four I was fit to drop from fatigue. Farm work was new to me, and I was soft as soft. I had, however, got the general lay of the land, and could, by the help of the plan, talk of its future subdivisions by numerals,—an arrangement that afterward proved definite and convenient. We adjourned to the shade of the big black oak on the knoll, and discussed the work in hand.

"You cannot finish the cellar before to-morrow night," I said, "because it grows slower as it grows deeper; but that will be doing well enough. I want you to start two teams ploughing Wednesday morning, and keep them going every day until the frost stops them. Let Sam take the plough, and have young Thompson follow with the subsoiler. Have them stick to this as a regular diet until I call them off. They are to commence in the wheat stubble where lots six and seven will be. I am going to try alfalfa in that ground, though I am not at all sure that it will do well, and the soil must be fitted as well as possible. After it has had deep ploughing it is to be crossed with the disk harrow; then have it rolled, disk it again, and then use the flat harrow until it feels as near like an ash heap as time will permit. We must get the seed in before September."

"We will need another team if you keep two ploughing and one on the harrow," said Thompson.

"You are right, and that means another $400, but you shall have it. We must not stop the ploughs for anything. Numbers 10, 11, 14, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and much of the home lot, ought to be ploughed before snow flies. That means about 160 acres,—80 odd days of steady work for the ploughmen and horses. You will probably find it best to change teams from time to time. A little variety will make it easier for them. As soon as 6 and 7 are finished, turn the ploughs into the 40 acres which make lots 1 to 5. All that must be seeded to pasture grass, for it will be our feeding-ground, and we'll be late with it if we don't look sharp.

"We must have more help, by the way. That horse-and-buggy man, Judson, is almost sure to come, and I will find another. Some of you will have to bunk in the hay for the present, for I am going to send out a woman to help your wife. Six men can do a lot of work, but there is a tremendous lot of work to do. We must fit the ground and plant at least three thousand apple trees before the end of November, and we ought to fence this whole plantation. Speaking of fences reminds me that I must order the cedar posts. Have you any idea how many posts it will take to fence this farm as we have platted it? I suppose not. Well, I can tell you. Twenty-two hundred and fifty at one rod apart, or 1850 at twenty feet apart. These posts must be six feet above and three feet below ground. They will cost eighteen cents each. That item will be $333, for there are seven miles of fence, including the line fence between me and my north neighbor. I am going to build that fence myself, and then I shall know whose fault it is if his stock breaks through. Of course some of the old posts are good, but I don't believe one in twenty is long enough for my purpose."

"What do you buy cedar posts for, when you have enough better ones on the place?" asked Thompson.

"I don't know what you mean."

"Well, down in the wood yonder there's enough dead white oak, standing or on the ground, to make three thousand, nine-foot posts, and one seasoned white oak will outlast two cedars, and it is twice as strong."

"Well, that's good! How much will it cost to get them out?"

"About five cents apiece. A couple of smart fellows can make good wages at that price."

"Good. We will save thirteen cents each. They will cost $93 instead of $333. I don't know everything yet, do I, Thompson?"

"You learn easy, I reckon."

"Keep your eyes and ears open, and if you find any one who can do this job, let him have it, for we are going to be too busy with other things at present. It's time for me to be off. I cannot be out again till Thursday, for I must find a man, a woman, and a team of horses and all that goes with them. I'll see you on the 8th at any rate."

I was dead tired when I reached home; but there wasn't a grain of depression in my fatigue,—rather a sense of elation. I felt that for the first time in thirty years real things were doing and I was having a hand in them. The fatigue was the same old tire that used to come after a hard day on my father's farm, and the sense was so suggestive of youth that I could not help feeling younger. I have never gotten away from the faith that the real seed of life lies hidden in the soil; that the man who gives it a chance to germinate is a benefactor, and that things done in connection with land are about the only real things. I have grown younger, stronger, happier, with each year of personal contact with the soil. I am thankful for seven years of it, and look forward to twice seven more. I have lost the softness which nearly wilted me that 5th day of August, and with the softness has gone twenty or thirty pounds of useless flesh. I am hard, active, and strong for a man of sixty, and I can do a fair day's work. To tell the truth, I prefer the moderate work that falls to the lot of the Headman, rather than the more strenuous life of the husbandman; but I find an infinite deal to thank the farm for in health and physical comfort.

After dinner I telephoned the veterinary surgeon that I wanted another team. He replied that he thought he knew of one that would suit, and that he would let me know the next day. I also telephoned two "want ads." to a morning paper, one for an experienced farm-hand, the other for a woman to do general housework in the country. Polly was to interview the women who applied, and I was to look after the men. That night I slept like a hired man.

Out of the dozen who applied the next day I accepted a Swede by the name of Anderson. He was about thirty, tall, thin, and nervous. He did not fit my idea of a stockman, but he looked like a worker, and as I could furnish the work we soon came to terms.

A few words more about Anderson. He proved a worker indeed. He had an insatiable appetite for work, and never knew when to quit. He was not popular at the farm, for he was too eager in the morning to start and too loath in the evening to stop. His unbridled passion for work was a thing to be deplored, as it kept him thin and nervous. I tried to moderate this propensity, but with no result. Anderson could not be trusted with horses, or, indeed, with animals of any kind, for he made them as nervous as himself; but in all other kinds of work he was the best man ever at Four Oaks. He worked for me nearly three years, and then suddenly gave out from a pain in his left chest and shortness of breath. I called a physician for poor Anderson, and the diagnosis was dilatation of the heart from over-exercise.

"A rare disease among farm-hands, Dr. Williams," said Dr. High, but my conscience did not fully forgive me. I asked Anderson to stay at the farm and see what could be done by rest and care. He declined this, as well as my offer to send him to a hospital. He expressed the liveliest gratitude for kindnesses received and others offered, but he said he must be independent and free. He had nearly $1200 in a savings bank in the city, and he proposed to use it, or such portion of it as was necessary. I saw him two months later. He was better, but not able to work. Hearing nothing from him for three years, a year ago I called at the bank where I knew he had kept his savings. They had sent sums of money to him, once to Rio Janeiro and once to Cape Town. For two years he had not been heard from. Whether he is living or dead I do not know. I only know that a valuable man and a unique farm-hand has disappeared. I never think of Anderson without wishing I had been more severe with him,—more persistent in my efforts to wean him from his real passion. Peace to his ashes, if he be ashes.

That same day I telephoned the Agricultural Implement Company to send me another wagon, with harness and equipment for the team. The veterinary surgeon reported that he had a span of mares for me to look at, but I was too much engaged that day to inspect the team, and promised to do so on the next.

When I reached home, Polly said she had found nothing in the way of a general housework girl for the country. She had seen nine women who wished to do all other kinds of work, but none to fit her wants.

"What do they come for if they don't want the place we described? Do they expect we are to change our plans of life to suit their personal notions?" she asked.

"It's hard to say what they came for or what they want. Their ways are past finding out. We will put in another 'ad.' and perhaps have better luck."

Wednesday, the 7th, I went to see the new team. I found a pair of flea-bitten gray Flemish mares, weighing about twenty-eight hundred pounds. They were four years old, short of leg and long of body, and looked fit. The surgeon passed them sound, and said he considered them well worth the price asked,—$300. I was pleased with the team, and remembered a remark I had heard as a boy from an itinerant Methodist minister at a time when the itinerant minister was supposed to know all there was to know about horse-flesh. This was his remark: "There was never a flea-bitten mare that was a poor horse." In spite of its ambiguity, the saying made an impression from which I never recovered. I always expected great things from flea-bitten grays.

The team, wagon, harness, etc., added $395 to the debit account against the farm. Polly secured her girl,—a green German who had not been long enough in America to despise the country.

"She doesn't know a thing about our ways," said Polly, "but Mrs. Thompson can train her as she likes. If you can spend time enough with green girls, they are apt to grow to your liking."

On Thursday I saw Anderson and the new team safely started for the farm. Then Polly, the new girl, and I took train for the most interesting spot on earth.

Soon after we arrived I lost sight of Polly, who seemed to have business of her own. I found the mason and his men at work on the cellar wall, which was almost to the top of the ground. The house was on wheels, and had made most of its journey. The house mover was in a rage because he had to put the house on a hole instead of on solid ground, as he had expected. "I have sent for every stick of timber and every cobbling block I own, to get this house over that hole; there's no money in this job for me; you ought to have dug the cellar after the house was placed," said he.

I made friends with him by agreeing to pay $30 more for the job. The house was safely placed, and by Saturday night the foundation walls were finished.

Sam and Zeb had made a good beginning on the ploughing, the teams were doing well for green ones, and the men seemed to understand what good ploughing meant. Thompson and Johnson had spent parts of two days in the potato patches in deadly conflict with the bugs.

"We've done for most of them this time," said Thompson, "but we'll have to go over the ground again by Monday."

The next piece of work was to clear the north forty (lots 1 to 5) of all fences, stumps, stones, and rubbish, and all buildings except the cottage. The barn was to be torn down, and the horses were to be temporarily stabled in the old barn on the home lot. Useful timbers and lumber were to be snugly piled, the manure around the barns was to be spread under the old apple trees, which were in lot No. 1, and everything not useful was to be burned. "Make a clean sweep, and leave it as bare as your hand," I told Thompson. "It must be ready for the plough as soon as possible."

Judson, the man with the buggy, reported at noon. He came with bag and baggage, but not with buggy, and said that he came to stay.

"Thompson," said I, "you are to put Judson in charge of the roan team to follow the boys when they are far enough ahead of him. In the meantime he and the team will be with you and Johnson in this house-cleaning. By to-morrow night Anderson and the new team will get in, and they, too, will help on this job. I want you to take personal charge of the gray team,—neither Johnson nor Anderson is the right sort to handle horses. The new team will do the trucking about and the regular farm work, while the other three are kept steadily at the ploughs and harrows."

The cleaning of the north forty proved a long job. Four men and two teams worked hard for ten days, and then it was not finished. By that time the ploughmen had finished 6 and 7, and were ready to begin on No. 1. Judson, with the roans and harrows, was sent to the twenty acres of ploughed ground, and Zeb and his team were put at the cleaning for three days, while Sam ploughed the six acres of old orchard with a shallow-set plough. The feeding roots of these trees would have been seriously injured if we had followed the deep ploughing practised in the open. By August 24 about two hundred loads of manure from the barn-yards, the accumulation of years, had been spread under the apple trees, and I felt sure it was well bestowed. Manuring, turning the sod, pruning, and spraying, ought to give a good crop of fruit next year.

We had several days of rain during this time, which interfered somewhat with the work, but the rains were gratefully received. I spent much of my time at Four Oaks, often going every day, and never let more than two days pass without spending some hours on the farm. To many of my friends this seemed a waste of time. They said, "Williams is carrying this fad too far,—spending too much time on it."

Polly did not agree with them, neither did I. Time is precious only as we make it so. To do the wholesome, satisfying thing, without direct or indirect injury to others, is the privilege of every man. To the charge of neglecting my profession I pleaded not guilty, for my profession had dismissed me without so much as saying "By your leave." I was obliged to change my mode of life, and I chose to be a producer rather than a consumer of things produced by others. I was conserving my health, pleasing my wife, and at the same time gratifying a desire which had long possessed me. I have neither apology to make nor regret to record; for as individuals and as a family we have lived healthier, happier, more wholesome, and more natural lives on the farm than we ever did in the city, and that is saying much.

On the 26th, when I reached the station at Exeter, I found Thompson and the gray team just starting for the farm with the second load of wire fencing. I had ordered fifty-six rolls of Page's woven wire fence, forty rods in each roll. This fence cost me seventy cents a rod, $224 a mile, or $1568 for the seven miles. Add to this $37 for freight, and the total amounted to $1605 for the wire to fence my land. I got this facer as I climbed to the seat beside Thompson. I did not blink, however, for I had resolved in the beginning to take no account of details until the 31st day of December, and to spend as much on the farm in that time as I could without being wasteful. I did not care much what others thought. I felt that at my age time was precious, and that things must be rushed as rapidly as possible.

I was glad of this slow ride with Thompson, for it gave me an opportunity to study him. I wondered then and afterward why a man of his general intelligence, industry, and special knowledge of the details of farming, should fail of success when working for himself. He knew ten times as much about the business as I did, and yet he had not succeeded in an independent position. Some quality, like broadness of mind or directness of purpose, was lacking, which made him incapable of carrying out a plan, no matter how well conceived. He was like Hooker at Chancellorsville, whose plan of campaign was perfect, whose orders were carried out with exactness, whose army fell into line as he wished, and whose enemy did the obvious thing, yet who failed terribly because the responsibility of the ultimate was greater than he could bear. As second in command, or as corps leader, he was superb; in independent command he was a disastrous failure.

Thompson, then, was a Joe Hooker on a reduced plane,—good only to execute another man's plans. Thompson might have rebutted this by saying that I too might prove a disastrous failure; that as yet I had shown only ability to spend,—perhaps not always wisely. Such rebuttal would have had weight seven years ago, but it would not be accepted to-day, for I have made my campaign and won my battle. The record of the past seven years shows that I can plan and also execute.

Thompson told me that he had found two woodsmen (by scouting around on Sunday) who were glad to take the job of cutting the white-oak posts at five cents each, and that they were even then at work; and that Nos. 6 and 7 would be fitted for alfalfa by the end of the week. He added that the seed ought to be sown as soon thereafter as possible and that a liberal dressing of commercial fertilizer should be sown before the seed was harrowed in.

"I have ordered five tons of fertilizer," I said, "and it ought to be here this week. Sow four bags to the acre."

"Four bags,—eight hundred pounds; that's pretty expensive. Costs, I suppose, $35 to $40 a ton."

"No; $24."

"How's that?"

"Friend at court; factory price; $120 for five tons; $5 freight, making in all $125. We must use at least eight hundred pounds this fall and five hundred in the spring. Alfalfa is an experiment, and we must give it a show."

"Never saw anything done with alfalfa in this region, but they never took no pains with it," said Thompson.

"I hope it will grow for us, for it is great forage if properly managed. The seed will be out this week, and you had best sow it on Monday, the 2d."

"How are you going to seed the north forty?"

"Timothy, red top, and blue grass; heavy seeding, to get rid of the weeds. These lots will all be used as stock lots. Small ones, you think, but we will depend almost entirely upon soiling. I hope to keep a fair sod on these lots, and they will be large enough to give the animals exercise and keep them healthy. I hope the carpenter is pushing things on the house. I want to get you into better quarters as soon as possible, and I want the cottage moved out of the way before we seed the lot."

"They're pushing things all right, I guess; that man Nelson is a hustler."

When I reached the farm I found Johnson and Anderson tearing down the old fence that was our eastern boundary. None of the posts were long enough for my purpose, so all were consigned to the woodpile.