Title: The Drama of the Forests: Romance and Adventure

Author: Arthur Heming

Release date: June 3, 2006 [eBook #18495]

Most recently updated: March 27, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

It was in childhood that the primitive spirit first came whispering to me. It was then that I had my first day-dreams of the Northland—of its forests, its rivers and lakes, its hunters and trappers and traders, its fur-runners and mounted police, its voyageurs and packeteers, its missionaries and Indians and prospectors, its animals, its birds and its fishes, its trees and its flowers, and its seasons.

Even in childhood I was for ever wondering … what is daily going on in the Great Northern Forest?… not just this week, this month, or this season, but what is actually occurring day by day, throughout the cycle of an entire year? It was that thought that fascinated me, and when I grew into boyhood, I began delving into books of northern travel, but I did not find the answer there. With the years this ever-present wonder grew, until it so possessed me that at last it spirited me away from the city, while I was still in my teens, and led me along a path of ever-changing and ever-increasing pleasure, showing me the world, not as men had mauled and marred it, but as the Master of Life had made it, in all its original beauty and splendour. Nor was this all. It led me to observe and ponder over the daily pages of the most profound and yet the most fascinating book that man has ever tried to read; and though, it seemed to me, my feeble attempts to decipher its text were always futile, it has, nevertheless, not only taught me to love Nature with an ever-increasing passion, but it has inspired in me an infinite homage toward the Almighty; for, as Emerson says: "In the woods we return to reason and faith. Then I feel that nothing can befall me in life—no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes)—which Nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground—my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space—all mean egoism vanishes.… I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty."

So, to make my life-dream come true, to contemplate in all its thrilling action and undying splendour the drama of the forests, I travelled twenty-three times through various parts of the vast northern woods, between Maine and Alaska, and covered thousands upon thousands of miles by canoe, pack-train, snowshoes, bateau, dog-train, buck-board, timber-raft, prairie-schooner, lumber-wagon, and "alligator." No one trip ever satisfied me, or afforded me the knowledge or the experience I sought, for traversing a single section of the forest was not unlike making one's way along a single street of a metropolis and then trying to persuade oneself that one knew all about the city's life. So back again I went at all seasons of the year to encamp in that great timber-land that sweeps from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Thus it has taken me thirty-three years to gather the information this volume contains, and my only hope in writing it is that perhaps others may have had the same day-dream, and that in this book they may find a reliable and satisfactory answer to all their wonderings. But making my dream come true—what delight it gave me! What sport and travel it afforded me! What toil and sweat it caused me! What food and rest it brought me! What charming places it led me through! What interesting people it ranged beside me! What romance it unfolded before me! and into what thrilling adventures it plunged me!

But before we paddle down the winding wilderness aisle toward the great stage upon which Diana and all her attendant huntsmen and forest creatures may appear, I wish to explain that in compliance with the wishes of the leading actors—who actually lived their parts of this story—fictitious names have been given to the principal characters and to the principal trading posts, lakes, and rivers herein depicted. Furthermore, in order to give the reader a more interesting, complete, and faithful description of the daily and the yearly life of the forest dwellers as I have observed it, I have taken the liberty of weaving together the more interesting facts I have gathered—both first- and second-hand—into one continuous narrative as though it all happened in a single year. And in order to retain all the primitive local colour, the unique costumes, and the fascinating romance of the fur-trade days as I witnessed them in my twenties—though much of the life has already passed away—the scene is set to represent a certain year in the early nineties.

ARTHUR HEMING.

It was September 9, 189-. From sunrise to sunset through mist, sunshine, shower, and shadow we travelled, and the nearer we drew to our first destination, the wilder the country became, the more water-fowl we saw, and the more the river banks were marked with traces of big game. Here signs told us that three caribou had crossed the stream, there muddy water was still trickling into the hoofprint of a moose, and yonder a bear had been fishing. Finally, the day of our arrival dawned, and as I paddled, I spent much of the time dreaming of the adventure before me. As our beautiful birchen craft still sped on her way, the handsome bow parted the shimmering waters, and a passing breeze sent little running waves gurgling along her sides, while the splendour of the autumn sun was reflected on a far-reaching row of dazzling ripples that danced upon the water, making our voyageurs lower their eyes and the trader doze again. There was no other sign of life except an eagle soaring in and out among the fleecy clouds slowly passing overhead. All around was a panorama of enchanting forest.

My travelling companion was a "Free Trader," whose name was Spear—a tall, stoop-shouldered man with heavy eyebrows and shaggy, drooping moustache. The way we met was amusing. It happened in a certain frontier town. His first question was as to whether I was single. His second, as to whether my time was my own. Then he slowly looked me over from head to foot. He seemed to be measuring my stature and strength and to be noting the colour of my eyes and hair.

Narrowing his vision, he scrutinized me more carefully than before, for now he seemed to be reading my character—if not my soul. Then, smiling, he blurted out:

"Come, be my guest for a couple of weeks. Will you?"

I laughed.

He frowned. But on realizing that my mirth was caused only by surprise, he smiled again and let flow a vivid description of a place he called Spearhead. It was the home of the northern fur trade. It was the centre of a great timber region. It was the heart of a vast fertile belt that was rapidly becoming the greatest of all farming districts. It was built on the fountain head of gigantic water power. It virtually stood over the very vault that contained the richest veins of mineral to be found in the whole Dominion—at least that's what he said—and he also assured me that the Government had realized it, too, for was it not going to hew a provincial highway clean through the forest to Spearhead? Was it not going to build a fleet of steamers to ply upon the lakes and rivers in that section? And was it not going to build a line of railroad to the town itself in order to connect it with the new transcontinental and thus put it in communication with the great commercial centres of the East and the West? In fact, he also impressed upon me that Spearhead was a town created for young men who were not averse to becoming wealthy in whatever line of business they might choose. It seemed that great riches were already there and had but to be lifted. Would I go?

But when I explained that although I was single, and quite free, I was not a business man, he became crestfallen, but presently revived enough to exclaim:

"Well, what the dickens are you?"

"An artist," I replied.

"Oh, I see! Well … we need an artist very badly. You'll have the field all to yourself in Spearhead. Besides, your pictures of the fur trade and of pioneer life would eventually become historical and bring you no end of wealth. You had better come. Better decide right away, or some other artist chap will get ahead of you."

But when I further explained that I was going to spend the winter in the wilderness, that I had already written to the Hudson's Bay Factor at Fort Consolation and that he was expecting me, Spear gloated:

"Bully boy!" and slapping me on the shoulder, he chuckled: "Why, my town is just across the lake from Fort Consolation. A mere five-mile paddle, old chap, and remember, I extend to you the freedom of Spearhead in the name of its future mayor. And, man alive, I'm leaving for there to-morrow morning in a big four-fathom birch bark, with four Indian canoe-men. Be my guest. It won't cost you a farthing, and we'll make the trip together."

I gladly accepted. The next morning we started. Free Trader Spear was a character, and I afterward learned that he was an Oxford University man, who, having been "ploughed," left for Canada, entered the service of the Hudson's Bay Company, and had finally been moved to Fort Consolation where he served seven years, learned the fur-trade business, and resigned to become a "free trader" as all fur traders are called who carry on business in opposition to "The Great Company." We were eight days upon the trip, but, strange to say, during each day's travel toward Spearhead, his conversation in reference to that thriving town made it appear to grow smaller and smaller, until at last it actually dwindled down to such a point, that, about sunset on the day we were to arrive, he turned to me and casually remarked:

"Presently you'll see Fort Consolation and the Indian village beyond. Spearhead is just across the lake, and by the bye, my boy, I forgot to tell you that Spearhead is just my log shack. But it's a nice little place, and you'll like it when you pay us a visit, for I want you to meet my wife."

Then our canoe passed a jutting point of land and in a moment the scene was changed—we were no longer on a river, but were now upon a lake, and the wilderness seemed suddenly left behind.

On the outer end of a distant point a cluster of poplars shaded a small, clapboarded log house. There, in charge of Fort Consolation, lived the Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company. Beyond a little lawn enclosed by a picket fence stood the large storehouse. The lower floor of this was used as a trading room; the upper story served for a fur loft. Behind were seen a number of shanties, then another large building in which dog-sleds and great birch-bark canoes were stored. Farther away was a long open shed, under which those big canoes were built, then a few small huts where the half-breeds lived. With the exception of the Factor's house, all the buildings were of rough-hewn logs plastered with clay. Around the sweeping bend of the bay was a village of tepees in which the Indian fur hunters and their families spend their midsummer. Crowning a knoll in the rear stood a quaint little church with a small tin spire glistening in the sun, and capped by a cross that spread its tiny arms to heaven. On the hill in the background the time-worn pines swayed their shaggy heads and softly whispered to that, the first gentle touch of civilization in the wilderness.

Presently, at irregular intervals, guns were discharged along the shore, beginning at the point nearest the canoe and running round the curve of the bay to the Indian camp, where a brisk fusillade took place. A moment later the Hudson's Bay Company's flag fluttered over Fort Consolation. Plainly, the arrival of our canoe was causing excitement at the Post. Trader Spear laughed aloud:

"That's one on old Mackenzie. He's taking my canoe for that of the Hudson's Bay Inspector. He's generally due about this time."

From all directions men, women, and children were swarming toward the landing, and when our canoe arrived there must have been fully four hundred Indians present. The first to greet us was Factor Mackenzie—a gruff, bearded Scotsman with a clean-shaven upper lip, gray hair, and piercing gray eyes. When we entered the Factor's house we found it to be a typical wilderness home of an officer of the Hudson's Bay Company; and, therefore, as far unlike the interiors of furtraders' houses as shown upon the stage, movie screen, or in magazine illustration, as it is possible to imagine. Upon the walls we saw neither mounted heads nor skins of wild animals; nor were fur robes spread upon the floors, as one would expect to find after reading the average story of Hudson's Bay life. On the contrary, the well-scrubbed floors were perfectly bare, and the walls were papered from top to bottom with countless illustrations cut from the London Graphic and the Illustrated London News. The pictures not only took the place of wall paper, making the house more nearly wind-proof, but also afforded endless amusement to those who had to spend therein the long winter months. The house was furnished sparingly with simple, home-made furniture that had more the appearance of utility than of beauty.

At supper time we sat down with Mrs. Mackenzie, the Factor's half-breed wife, who took the head of the table. After the meal we gathered in the living room before an open fire, over the mantelpiece of which there were no guns, no powder horns, nor even a pair of snowshoes; for a fur trader would no more think of hanging his snowshoes there than a city dweller would think of hanging his overshoes over his drawing-room mantel. Upon the mantel shelf, however, stood a few unframed family photographs and some books, while above hung a rustic picture frame, the only frame to be seen in the room; it contained the motto, worked in coloured yarns: "God Bless Our Home." When pipes were lighted and we had drawn closer to the fire, the Factor occupied a quaint, home-made, rough-hewn affair known as the "Factor's chair." On the under side of the seat were inscribed the signatures and dates of accession to that throne of all the factors who had reigned at the Post during the past eighty-seven years.

After the two traders had finished "talking musquash"—fur-trade business—they began reminiscing on the more picturesque side of their work, and as I had come to spend the winter with the fur hunters on their hunting grounds, the subject naturally turned to that well-worn topic, the famous Nimrods of the North. It brought forth many an interesting tale, for both my companions were well versed in such lore, and in order to keep up my end I quoted from Warren's book on the Ojibways: "As an illustration of the kind and abundance of animals which then covered the country, it is stated that an Ojibway hunter named No-Ka, the grandfather of Chief White Fisher, killed in one day's hunt, starting from the mouth of Crow Wing River, sixteen elk, four buffalo, five deer, three bear, one lynx, and one porcupine. There was a trader wintering at the time at Crow Wing, and for his winter's supply of meat, No-Ka presented him with the fruits of his day's hunt."

My host granted that that was the biggest day's bag he had ever heard of, and Trader Spear, withdrawing his pipe from his mouth, remarked:

"No-Ka must have been a great hunter. I would like to have had his trade. But, nevertheless, I have heard of an Indian who might have been a match for him. He, too, was an Ojibway, and his name was Narphim. He lived somewhere out in the Peace River country, and I've heard it stated that he killed, in his lifetime, more than eighty thousand living things. Some bag for one hunter."

Since Trader Spear made that interesting remark I have had the pleasure of meeting a factor of the Hudson's Bay Company who knew Narphim from boyhood, and who was a personal friend of his, and who was actually in charge of a number of posts at which the Indian traded. Owing to their friendship for one another, the Factor took such a personal pride in the fame the hunter won, that he compiled, from the books of the Hudson's Bay Company, a complete record of all the fur-bearing animals the Indian killed between the time he began to trade as a hunter at the age of eleven, until his hunting days were ended. Furthermore, in discussing the subject with Narphim they together compiled an approximate list of the number of fish, wild fowl, and rabbits that the hunter must have secured each season, and thus Narphim's record stands as the following figures show. I would tell you the Factor's name but as he has written to me: "For many cogent reasons it is desirable that my name be not mentioned officially in your book," I must refrain. I shall, however, give you the history of Narphim in the Factor's own words:

"Narphim's proper name remains unknown as he was one of two children saved when a band of Ojibways were drowned in crossing a large lake that lies S. E. of Cat Lake and Island Lake, and S. E. of Norway House. He was called Narphim—Saved from the Waters. The other child that was rescued was a girl and she was called Neseemis—Our Little Sister. At first Narphim was adopted and lived with a Swampy Cree chief, the celebrated Keteche-ka-paness, who was a great medicine man. When Narphim grew to be eleven years old he became a hunter, and first traded his catch at Island Lake; then as the years went by, at Oxford House; then at Norway House, then at Fort Chepewyan, and then at Fort McMurray. After that he went to Lesser Slave Lake, then on to the Peace River at Dunvegan, then he showed up at Fort St. John, next at Battle River, and finally at Vermilion.

"The following is a list of the number of creatures Narphim killed, but of course he also killed a good deal of game that was never recorded in the Company's books, especially those animals whose skins were used for the clothing of the hunter's family.

"Bears 585, beaver 1,080, ermines 130, fishers 195, red foxes 362, cross foxes 78, silver and black foxes 6, lynxes 418, martens 1,078, minks 384, muskrats 900, porcupines 19, otters 194, wolves 112, wolverines 24, wood buffaloes 99, moose 396, caribou 196, jumping deer 72, wapiti 156, mountain sheep 60, mountain goats 29; and rabbits, approximately 8,000, wild fowl, approximately 23,800, and fish approximately 36,000. Total 74,573.

"Yes, Narphim was a great hunter and a good man," says the Factor in his last letter to me. "He was a fine, active, well-built Indian and a reliable and pleasant companion. In fact, he was one of Nature's gentlemen, whom we shall be, and well may be, proud to meet in the Great Beyond, known as the Happy Hunting Grounds."

Thus the evening drifted by. While the names of several of the best hunters had been mentioned as suitable men for me to accompany on their hunting trail, it was suggested that as the men themselves would probably visit the Post in the morning, I should have a chat with them before making my selection. Both Mackenzie and Spear, however, seemed much in favour of my going with an Indian called Oo-koo-hoo. Presently the clock struck ten and we turned in, the Free Trader sharing a big feather bed with me.

After breakfast next morning I strolled about the picturesque point. It was a windless, hazy day. An early frost had already clothed a number of the trees with their gorgeous autumnal mantles, the forerunners of Indian summer, the most glorious season of the Northern year.

When I turned down toward the wharf, I found a score of Indians and half-breed trippers unloading freight from a couple of six-fathom birch-bark canoes. Eager men and boys were good-naturedly loading themselves with packs and hurrying away with them to the storehouse, while others were lounging around or applauding the carriers with the heaviest loads. As the packers hurried by, Delaronde, the jovial, swarthy-faced, French-Canadian clerk, note-book in hand, checked the number of pieces. Over by the log huts a group of Indian women were sitting in the shade, talking to Delaronde's Indian wife. All about, and in and out of the Indian lodges, dirty, half-naked children romped together, and savage dogs prowled around seeking what they might devour. The deerskin or canvas covers of most of the tepees were raised a few feet to allow the breeze to pass under. Small groups of women and children squatted or reclined in the shade, smoking and chatting the hours away. Here and there women were cleaning fish, mending nets, weaving mats, making clothes, or standing over steaming kettles. Many of the men had joined the "goods brigade," and their return was hourly expected. Many canoes were resting upon the sandy beach, and many more were lying bottom up beneath the shade of trees.

The most important work undertaken by the Indians during the summer is canoe building. As some of the men are more expert at this than others, it often happens that the bulk of the work is done by a few who engage in it as a matter of business. Birch bark for canoe building is taken from the tree early in May. The chosen section, which may run from four to eight feet in length, is first cut at the top and bottom; then a two-inch strip is removed from top to bottom in order to make room for working a chisel-shaped wooden wedge—about two feet long—with which the bark is taken off. Where knots appear great care is exercised that the bark be not torn. To make it easier to pack, the sheet of bark is then rolled up the narrow way, and tied with willow. In this shape, it is transported to the summer camping grounds. Canoes range in size all the way from twelve feet to thirty-six feet in length. The smaller size, being more easily portaged, is used by hunters, and is known as a two-fathom canoe. For family use canoes are usually from two and a half to three and a half fathoms long. Canoes of the largest size, thirty-six feet, are called six-fathom or "North" canoes. With a crew of from eight to twelve, they have a carrying capacity of from three to four tons, and are used by the traders for transporting furs and supplies.

Some Indians engage in "voyaging" or "tripping" for the traders—taking out fur packs to the steamboats or railroads, by six-fathom canoe, York boat, or sturgeon-head scow brigades, and bringing in supplies. Others put in part of their time on an occasional hunt for moose or caribou, or in shooting wild fowl. On their return they potter around camp making paddles or snowshoe frames; or they give themselves up to gambling—a vice to which they are rather prone. Sometimes twenty men or more, divided into equal sides, will sit in the form of an oval, with their hair drawn over their faces that their expression may not easily be read, and with their knees covered with blankets. Leaders are chosen on either side, and each team is supplied with twelve small sticks. The game begins by one of the leaders placing his closed hands upon his blanket, and calling upon the other to match him. If the latter is holding his stick in the wrong hand, he loses; and so the game goes on. Two sets of drummers are playing continuously and all the while there is much chanting. In this simple wise they gamble away their belongings, even to their clothing, and, sometimes, their wives. When the wives are at stake, however, they have the privilege of taking a hand in the game.

The women, in addition to their regular routine of summer camp duties, occupy themselves with fishing, moccasin making, and berry picking. The girls join their mothers in picking berries, which are plentiful and of great variety—raspberries, strawberries, cranberries, blueberries, gooseberries, swampberries, saskatoonberries, pembinaberries, pheasantberries, bearberries, and snakeberries. They gather also wild celery, the roots of rushes, and the inner bark of the poplar—all which they eat raw. In some parts, too, they gather wild rice. Before their summer holidays are over, they have usually secured a fair stock of dried berries, smoked meats and bladders and casings filled with fish oil or other soft grease, to help out their bill of fare during the winter. The women devote most of their spare moments to bead, hair, porcupine, or silk work which they use for the decoration of their clothing. They make mos-quil-moots, or hunting bags, of plaited babiche, or deerskin thongs, for the use of the men. The girl's first lesson in sewing is always upon the coarsest work; such as joining skins together for lodge coverings. The threads used are made from the sinews of the deer or the wolf. These sinews are first hung outside to dry a little, and are then split into the finest threads. The thread-maker passes each strand through her mouth to moisten it, then places it upon her bare thigh, and with a quick movement rolls it with the flat of her hand to twist it. Passing it again through her mouth, she ties a knot at one end, points the other, and puts it away to dry. The result is a thread like the finest hair-wire.

For colouring moose hair or porcupine quills for fancy work, the women obtain their dyes in the following ways: From the juice of boiled cranberries they derive a magenta dye. From alder bark, boiled, beaten, and strained, they get a dark, slate-coloured blue which is mixed with rabbits' gall to make it adhere. The juice of bearberries gives them a bright red. From gunpowder and water they obtain a fine black, and from coal tar a stain for work of the coarsest kind. They rely chiefly, however, upon the red, blue, green, and yellow ochres found in many parts of the country. These, when applied to the decoration of canoes, they mix with fish oil; but for general purposes the earths are baked and used in the form of powder.

From scenes such as I have described the summer traveller obtains his impression of the forest Indians. Too often their life and character are judged by such scenes, as if these truly represented their whole existence. In reality, this is but their holiday season which they are spending upon their tribal summer camping ground. It is only upon their hunting grounds that one may fairly study the Indians; so, presently, we shall follow them there. And when one experiences the wild, free life the Indian lives—hampered by no household goods or other property that he cannot at a moment's notice dump into his canoe and carry with him to the ends of the earth if he chooses—one not only envies him, but ceases to wonder which of the two is the greater philosopher—the white man or the red; for the poor old white man is so overwhelmed with absurd conventions and encumbering property that he can rarely do what his heart dictates.

Don't let us decide just yet, however, whether the Indian derives more pleasure from life than does the white man, at least, not until we return from our voyage of pleasure and investigation; but before we leave Fort Consolation it is well to know that the hunting grounds in possession of the Indian tribes that live in the Great Northern Forest have been for centuries divided and subdivided and allotted, either by bargain or by battle, to the main families of each band. In many cases the same hunting grounds have remained in the undisputed possession of the same families for generations. Family hunting grounds are usually delimited by natural boundaries, such as hills, valleys, rivers, and lakes. The allotments of land generally take the form of wedge-shaped tracts radiating from common centres. From the intersection of these converging boundary lines the common centres become the hubs of the various districts. These district centres mark convenient summer camping grounds for the reunion of families after their arduous labour during the long winter hunting season. The tribal summer camping grounds, therefore, are not only situated on the natural highways of the country—the principal rivers and lakes—but also indicate excellent fishing stations. There, too, the Indians have their burial grounds.

Often these camping grounds are the summer headquarters for from three to eight main families; and each main family may contain from five or six to fifty or sixty hunting men. Inter-marriage between families of two districts gives the man the right to hunt on the land of his wife's family as long as he "sits on the brush" with her—is wedded to her—but the children do not inherit that right; it dies with the father. An Indian usually lives upon his own land, but makes frequent excursions to the land of his wife's family.

In the past, the side boundaries of hunting grounds have been the cause of many family feuds, and the outer boundaries have furnished the occasion for many tribal wars. The past and the present headquarters camping grounds of the Strong Woods Indians—as the inhabitants of the Great Northern Forest are generally called—lie about one hundred and fifty miles apart.

The natural overland highways throughout the country, especially those intersecting the watercourses and now used as the roadbeds for our great transcontinental railways, were not originally discovered by man at all. The credit is due to the big game of the wilderness; for the animals were not only the first to find them, but also the first to use them. The Indian simply followed the animals, and the trader followed the Indian, and the official "explorer" followed the trader, and the engineer followed the "explorer," and the railroad contractor followed the engineer. It was the buffalo, the deer, the bear, and the wolf who were our original transcontinental path-finders, or rather pathmakers. Then, too, the praise bestowed upon the pioneer fur traders for the excellent judgment shown in choosing the sites upon which trading posts have been established throughout Canada, has not been deserved; the credit is really due to the Indians. The fur traders erected their posts or forts upon the tribal camping grounds simply because they found such spots to be the general meeting places of the Indians, and not only situated on the principal highways of the wilderness but accessible from all points of the surrounding country, and, moreover, the very centres of excellent fish and game regions. Thus in Canada many of the ancient tribal camping grounds are now known by the names of trading posts, of progressive frontier towns, or of important cities.

Now, as of old, the forest Indians after their winter's hunt return in the early summer to trade their catch of furs, to meet old friends, and to rest and gossip awhile before the turning leaf warns them to secure their next winter's "advances" from the trader, and once more paddle away to their distant hunting grounds.

The several zones of the Canadian wilderness are locally known as the Coast Country—the shores of the Arctic Ocean and Hudson Bay; the Barren Grounds—the treeless country between Hudson Bay and the Mackenzie River; the Strong Woods Country—the whole of that enormous belt of heavy timber that spans Canada from east to west; the Border Lands—the tracts of small, scattered timber that lie between the prairies and the northern forests; the Prairie Country; the Mountains; and the Big Lakes. These names have been adopted by the fur traders from the Indians. It is in the Strong Woods Country that most of the fur-bearing animals live.

About ten o'clock on the morning after our arrival at Fort Consolation, Free Trader Spear left for home with my promise to paddle over and dine at Spearhead next day.

At noon Factor Mackenzie informed me that he had received word that Oo-koo-hoo—The Owl—was coming to the Fort that afternoon and that, taking everything into consideration, he thought Oo-koo-hoo's hunting party the best for me to join. It consisted, he said, of Oo-koo-hoo and his wife, his daughter, and his son-in-law, Amik—The Beaver—and Amik's five children. The Factor further added that Oo-koo-hoo was not only one of the greatest hunters, and one of the best canoe-men in that district, but in his youth he had been a great traveller, as he had hunted with other Indian tribes, on Hudson Bay, on the Churchill, the Peace, the Athabasca, and the Slave rivers, and even on the far-away Mackenzie; and was a master at the game. His son-in-law, Amik, was his hunting partner. Though Amik would not be home until to-morrow, Oo-koo-hoo and his wife, their daughter and her children were coming that afternoon to get their "advances," as the party contemplated leaving for their hunting grounds on the second day. That I might look them over while they were getting their supplies in the Indian shop, and if I took a fancy to the old gentleman—who by the way was about sixty years of age—the trader would give me an introduction, and I could then make my arrangements with the hunter himself. So after dinner, when word came that they had landed, I left the living room for the Indian shop.

In the old days, in certain parts of the country, when the Indians came to the posts to get their "advances" or to barter their winter's catch of fur, the traders had to exercise constant caution to prevent them from looting the establishments. At some of the posts only a few Indians at a time were allowed within the fort, and even then trading was done through a wicket. But that applied only to the Plains Indians and to some of the natives of the Pacific Coast; for the Strong Woods people were remarkably honest. Even to-day this holds good notwithstanding the fact that they are now so much in contact with white men. Nowadays the Indians in any locality rarely cause trouble, and at the trading posts the business of the Indian shops is conducted in a quiet and orderly way.

The traders do most of their bartering with the Indians in the early summer when the hunters return laden with the spoils of their winter's hunt. In the early autumn, when the Indians are about to leave for their hunting grounds, much business is done, but little in the way of barter. At that season the Indians procure their outfit for the winter. Being usually insolvent, owing to the leisurely time spent upon the tribal camping grounds, they receive the necessary supplies on credit. The amount of credit, or "advances," given to each Indian seldom exceeds one third of the value of his average annual catch. That is the white man's way of securing, in advance, the bulk of the Indian's prospective hunt; yet, although a few of them are sometimes slow in settling their debts, they are never a match for the civilized white man.

When I entered the trading room I saw that it was furnished with a U-shaped counter paralleling three sides of the room, and with a large box-stove in the middle of the intervening space. On the shelves and racks upon the walls and from hooks in the rafters rested or hung a conglomeration of goods to be offered in trade to the natives. There were copper pails and calico dresses, pain-killer bottles and Hudson's Bay blankets, sow-belly and chocolate drops, castor oil and gun worms, frying-pans and ladies' wire bustles, guns and corsets, axes and ribbons, shirts and hunting-knives, perfumes and bear traps. In a way, the Indian shop resembled a department store except that all the departments were jumbled together in a single room. At one post I visited years ago—that of Abitibi—they had a rather progressive addition in the way of a millinery department. It was contained in a large lidless packing case against the side of which stood a long steering paddle for the clerk's use in stirring about the varied assortment of white women's ancient headgear, should a fastidious Indian woman request to see more than the uppermost layer.

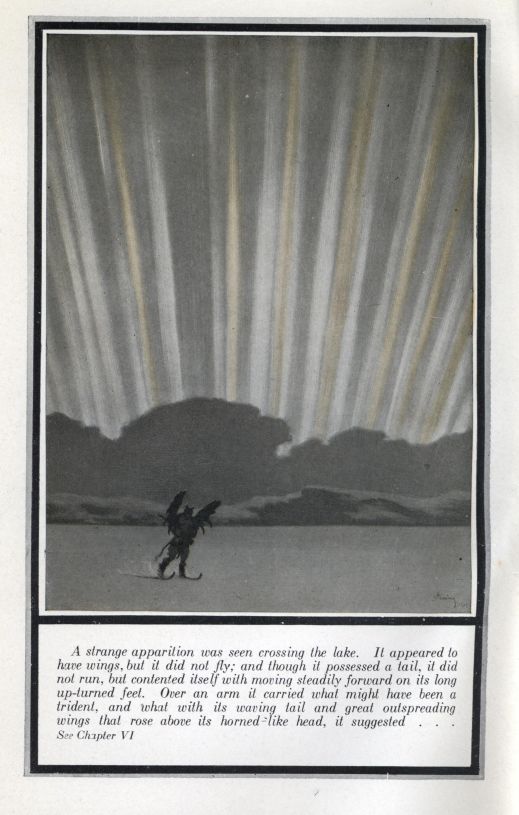

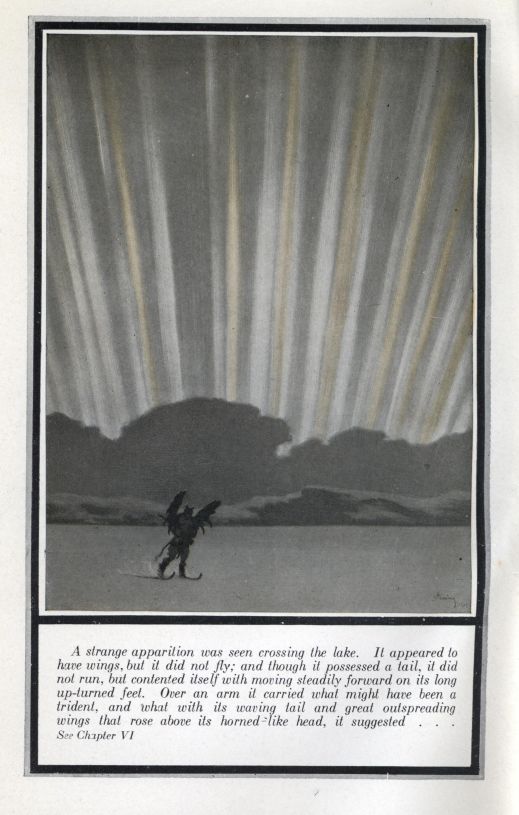

Already a number of Indians were being served by the Factor and Delaronde, the clerk, and I had not long to wait before Oo-koo-hoo appeared. I surmised at once who he was, for one could see by the merest glance at his remarkably pleasant yet thoroughly clever face, that he was all his name implied, a wise, dignified old gentleman, who was in the habit of observing much more than he gave tongue to—a rare quality in men—especially white men. Even before I heard him speak I liked Oo-koo-hoo—The Owl.

But before going any farther, I ought to explain that as I am endeavouring to render a faithful description of forest life, I am going to repeat in the next few paragraphs part of what once appeared in one of my fictitious stories of northern life. I then made use of the matter because it was the truth, and for that very reason I am now going to repeat it; also because this transaction as depicted is typical of what usually happens when the Indians try to secure their advances. Furthermore, I give the dialogue in detail, as perchance some reader may feel as Thoreau did, when he said: "It would be some advantage to live a primitive and frontier life, though in the midst of an outward civilization, if only to learn what are the gross necessaries of life and what methods have been taken to obtain them; or even to look over the old day-books of the merchants, to see what it was that men most commonly bought at the stores, what they stored, that is, what are the grossest groceries."

But while the following outfit might be considered the Indian's grossest groceries, the articles are not really necessaries at all for him; for, to go to the extreme, a good woodsman can hunt without even gun, axe, knife, or matches, and can live happily, absolutely independent of our civilization.

As the Factor was busy with another Indian when the Chief entered—for Oo-koo-hoo was the chief of the Ojibways of that district—he waited patiently, as he would not deign to do business with a clerk. When he saw the trader free, he greeted:

"Quay, quay, Hugemow!" (Good day, Master).

"Gude day, man Oo-koo-hoo, what can I do for ye the day?" amicably responded the Factor.

"Master, it is this way. I am about to leave for my hunting grounds; but this time I am going to spend the winter upon a new part of them, where I have not hunted for years, and where game of all kinds will be plentiful. Therefore, I want you to give me liberal advances so that my hunt will not be hindered."

"Pegs, Oo-koo-hoo, ma freen', yon's an auld, auld farrant. But ye're well kenn'd for a leal, honest man; an' sae, I'se no be unco haird upon ye."

So saying, the Factor made him a present of a couple of pounds of flour, half a pound of pork, half a pound of sugar, a quarter of a pound of tea, a plug of tobacco, and some matches. The Factor's generosity was prompted largely by his desire to keep the Indian in good humour. After a little friendly chaffing, the Factor promised to give the hunter advances to the extent of one hundred "skins."

A "skin," or, as it is often called, a "made beaver," is equivalent to one dollar in the Hudson Bay and the Mackenzie River districts, but only fifty cents in the region of the Athabasca.

Perhaps it should be explained here that while Oo-koo-hoo could speak broken English, he always preferred to use his own language when addressing the trader, whom he knew to be quite conversant with Ojibway, and so, throughout this book, I have chosen to render the Indian's speech as though it was translated from Ojibway into English, rather than at any time render it in broken English, as the former is not only easier to read, but is more expressive of the natural quality of the Indian's speech. In olden days some of the chiefs who could not speak English at all were, it is claimed, eloquent orators—far outclassing our greatest statesmen.

Oo-koo-hoo, having ascertained the amount of his credit, reckoned that he would use about fifty skins in buying traps and ammunition; the rest he would devote to the purchase of necessaries for himself and his party, as his son-in-law had arranged with him to look after his family's wants in his absence. So the old gentleman now asked for the promised skins. He was handed one hundred marked goose quills representing that number of skins. After checking them over in bunches of ten, he entrusted twenty to his eldest grandson, Ne-geek—The Otter—to be held in reserve for ammunition and tobacco, and ten to his eldest granddaughter, Neykia, with which to purchase an outfit for the rest of the party.

For a long time Oo-koo-hoo stood immersed in thought. At last his face brightened. He had reached a decision. For years he had coveted a new muzzle-loading gun, and he felt that the time had now arrived to get it. So he picked out one valued at forty skins and paid for it. Then, taking back the quills his grandson held, he bought twenty skins' worth of powder, caps, shot, and bullets. Then he selected for himself a couple of pairs of trousers, one pair made of moleskin and the other of tweed, costing ten skins; two shirts and a suit of underwear, ten skins; half a dozen assorted traps, ten skins. Finding that he had used up all his quills, he drew on those set aside for his wife and son-in-law's family and bought tobacco, five skins; files, one skin; an axe, two skins; a knife, one skin; matches, one half skin; and candy for his youngest grandchild, one half skin. On looking over his acquisitions he discovered that he must have at least ten skins' worth of twine for nets and snares, five skins' worth of tea, one skin worth of soap, one skin worth of needles and thread, as well as a tin pail and a new frying pan. After a good deal of haggling, the Factor threw him that number of quills, and Oo-koo-hoo's manifest contentment somewhat relieved the trader's anxiety.

A moment later, however, Oo-koo-hoo was reminded by his wife, Ojistoh, that there was nothing for her, so she determined to interview the Factor herself. She tried to persuade him to give her twenty skins in trade, and promised to pay for them in the spring with rat and ermine skins, or—should those fail her—with her dog, which was worth fully thirty skins. She had been counting on getting some cotton print for a dress, as well as thread and needles, to say nothing of extra tea, which in all would amount to at least thirty-five or forty skins. When, however, the Factor allowed her only ten skins, her disappointment was keen, and she ended by getting a shawl. Then she left the trading room to pay a visit to the Factor's wife, and confide to her the story of her expectations and of her disappointment so movingly that she would get a cup of tea, a word of sympathy, and perhaps even an old petticoat.

In the meantime, Oo-koo-hoo was catching it again. He had forgotten his daughter; so after more haggling the trader agreed to advance her ten skins. Her mind had long been made up. She bought a three-point blanket, a small head shawl, and a piece of cotton print. Then the grandsons crowded round and grumbled because there was nothing for them.

By this time the trader was beginning to feel that he had done pretty well for the family already; but he kept up the appearance of bluff good humour, and asked:

"Well, Oo-koo-hoo, what wad ye be wantin' for the laddies?"

"My grandsons are no bunglers, as you know," said the proud old grandsire. "They can each kill at least twenty skins' worth of fur."

"Aye, aye!" rejoined the trader. "I shall e'en gi'e them twenty atween them."

In the goodness of his heart he offered the boys some advice as to what they should buy: "Ye'll be wantin' to buy traps, I'm jalousin', an' sure ye'll turn oot to be graun' hunters, Nimrods o' the North that men'll mak' sangs aboot i' the comin' years." He cautioned them to choose wisely, because from henceforth they would be personally responsible for everything they bought, and must pay, "skin for skin" (the motto of the Hudson's Bay Company).

The boys listened with gloomy civility, and then purchased an assortment of useless trifles such as ribbons, tobacco, buttons, candy, rings, pomatum, perfume, and Jew's harps.

The Factor's patience was now nearly exhausted. He picked up his account book, and strode to the door, and held it open as a hint to the Indians to leave. But they pretended to take no notice of his action.

The granddaughters, who had been growing more and more anxious lest they should be forgotten, now began to be voluble in complaint. Oo-koo-hoo called the trader aside and explained the trouble. The Factor realized that he was in a corner, and that if he now refused further supplies he would offend the old chief and drive him to sell his best furs to the opposition trader in revenge. He surrendered, and the girls received ten skins between them.

At long last everyone was pleased except the unhappy Factor. Gathering his purchases together, Oo-koo-hoo tied up the powder, shot, tea, and sugar in the legs of the trousers; placed the purchases for his wife, daughter, and granddaughters in the shawl, and the rest of the goods in the blanket.

Then he made the discovery that he had neither flour nor grease. He could not start without them. The Factor's blood was now almost at the boiling pitch, but he dared not betray his feelings; for the Indian was ready to take offence at the slightest word, so rich and independent did he feel. Angering him now would simply mean adding to the harvest of the opposition trader. He chewed his lower lip in the effort to smother his disgust, and growled out with an angry grin:

"Hoots, mon, ye ha'e gotten ower muckle already. It's fair redeeklus. I jist canna gi'e ye onythin' mair ava!"

"Ah, but, master, you have forgotten that I am a great hunter. And that my son-in-law is a great hunter, too. This is but the outfit for a lazy man! Besides, the Great Company is rich, and I am poor. If you will be stingy, I shall not trouble you more."

Once again the Factor gave way, and handed out the flour and grease. All filed out, and the Factor turned the key in the door. As he walked toward the house, his spirits began to rise, and he clapped the old Indian on the back good-naturedly. Presently Oo-koo-hoo halted in his tracks. He had forgotten something: he had nothing in case of sickness.

"Master, you know my voyage is long; my work is hard; the winter is severe. I am not very strong now: I may fall ill. My wife—she is not very strong—may fall ill also. My son-in-law is not very strong: he may fall ill too. My daughter is not.…"

"De'il ha'e ye!" roared the Factor, "what is't the noo?"

"Never mind, it will do to-morrow," muttered the hunter with an offended air.

"As I'm a leevin' sinner, it's noo or it's nivver," insisted the Factor, who had no desire to let the Indian have another day at it. "Come back this verra minnit, an' I'll gi'e ye a wheen poothers an' sic like, that'll keep ye a' hale and hearty, I houp, till ye win hame again."

The Factor took him back and gave him some salts, peppermint, pain-killer, and sticking-plaster to offset all the ills that might befall him and his party during the next ten months.

Once more they started for the house. The Factor was ready to put up with anything as long as he could get them away from the store. Oo-koo-hoo now told the trader not to charge anything against his wife as he would settle her account himself, and that as Amik would be back in the morning, he, too, would want his advances, and if they had forgotten anything, Amik could get it next day.

The Factor scowled again, but it was too late.

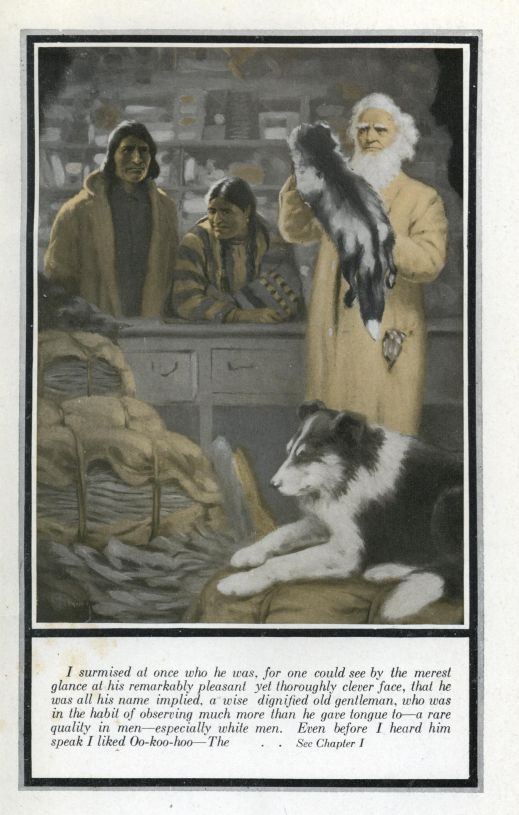

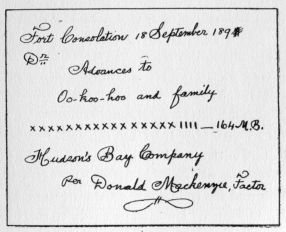

While the Indians lounged around the kitchen and talked to the Factor's wife and the half-breed servant girl, the Factor went to his office and made out Oo-koo-hoo's bill, which read:

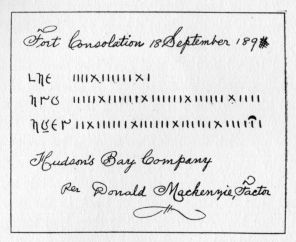

The Indian now told the trader that he wanted him to send the "Fur Runners" to him with supplies in ten weeks' time; and that he must have a "geese-wark," or measure of days, in order to know exactly when the Fur Runners would arrive at his camp. So the Factor made out the following calendar:

The above characters to the left are syllabic—a method of writing taught to the Indians by the missionaries. They spell the words September, October, and November. The 1's represent week days, and the X's Sundays. The calendar begins with the 18th of September, and the crescent marks the 29th of November, the date of the arrival of the Fur Runners. The Indian would keep track of the days by pricking a pin hole every day above the proper figure.

Presently the Factor and I were alone for a few moments and he growled:

"Whit d'ye think o' the auld de'il?"

"Fine, I'll go with him, if he will take me."

So I had a talk with the old Indian, and when he learned that I had no intention of killing game, but merely wanted to accompany him and his son-in-law on their hunts, he consented and we came to terms. I was to be ready to start early on the morning of the 20th. Then Oo-koo-hoo turned to the trader and said:

"Master, it is getting late and it will be later when I reach my lodge. I am hungry now, and I shall be hungrier still when I get home. I am growing …"

"Aye, aye, ma birkie," interrupted the Factor, "I un'erstaun' fine." He bestowed upon the confident petitioner a further gratuity of flour, tea, sugar, and tallow, a clay pipe, a plug of tobacco and some matches, so as to save him from having to break in upon his winter supplies before he started upon his journey to the hunting grounds. Oo-koo-hoo solemnly expressed his gratitude:

"Master, my heart is pleased. You are my father. I shall now hunt well, and you shall have all my fur."

To show his appreciation of the compliment, the Factor gave him an old shirt, and wished him good luck.

In the meantime, Oo-koo-hoo's wife had succeeded in obtaining from the Factor's wife old clothes for her grandchildren, needles and thread, and some food. Just as they got ready to go, the younger woman, Amik's wife, remembered that the baby had brought a duck as a present for the Factor's children so they had to give a present in return, worth at least twice as much as the duck.

The Factor and his family were by this time sufficiently weary. Right willingly did they go down to the landing to see the Indians off. No sooner had these taken their places in the canoes and paddled a few strokes away than the grandmother remembered that she had a present for the Factor and his wife. All paddled back again, and the Factor and his wife were each presented with a pair of moccasins. No, she would not take anything in return, at least, not just now. To-morrow, perhaps, when they came to say good-bye.

"Losh me! I thocht they were aff an' gane," exclaimed the trader as he turned and strode up the beach.

I inwardly laughed, for any man—red, white, black, or yellow—who could make such a hard-headed old Scotsman as Donald Mackenzie loosen up, was certainly clever; and the way old Oo-koo-hoo made off with such a lot of supplies proved him more than a match for the trader.

While we were at supper a perfect roar of gun shots ran around the bay and on our rushing to the doorway we saw the Inspector's big canoe coming. Up went the flag and more gun shots followed. Then we went down to the landing to meet Inspecting Chief Factor Bell.

After supper the newcomer and the Factor and I sat before the fire and discussed the fur trade. I liked to listen to the old trader, but the Inspector, being the greater traveller of the two, covering every year on the rounds of his regular work thousands upon thousands of miles, was the more interesting talker. Presently, when the subject turned to the distribution of the fur-bearing animals, Mr. Bell took a case from his bag and opening it, spread it out before us upon the Factor's desk. It was a map of the Dominion of Canada, on which the names of the principal posts of the Hudson's Bay Company were printed in red. Across it many irregular lines were drawn in different-coloured inks, and upon its margins were many written notes.

"This map, as you see," remarked the Inspector, "defines approximately the distribution of the fur-bearing animals of Canada, and I'll wager that you have never seen another like it; for if it were not for the records of the Hudson's Bay Company, no such map could have been compiled. How did I manage it? Well, to begin with, you must understand that the Indians invariably trade their winter's catch of fur at the trading post nearest their hunting grounds; so when the annual returns of all the posts are sent in to the Company's headquarters, those returns accurately define the distribution of the fur-bearing animals for that year. These irregular lines across the map were drawn after an examination of the annual returns from all the posts for the last forty years. Publish it? No, siree, that would never do!"

But the Inspector's remarks did not end the subject, as we began discussing the greatest breeding grounds of the various fur-bearers, and Mr. Bell presently continued:

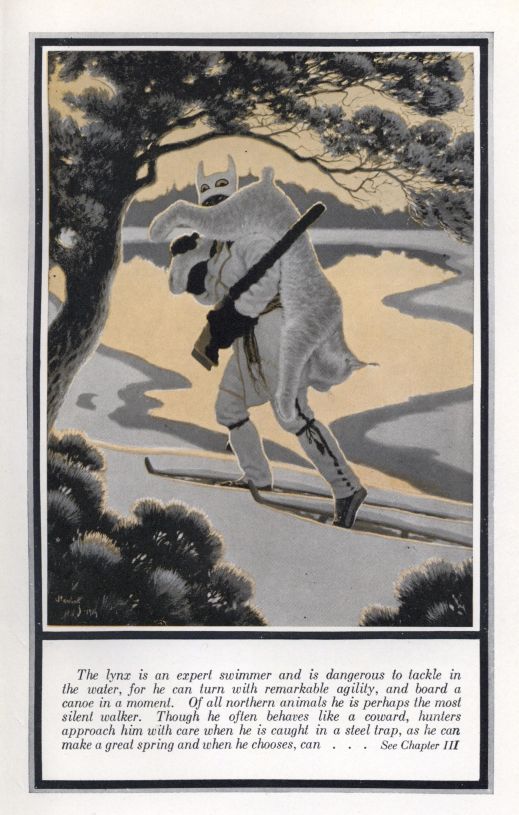

"The greatest centre for coloured foxes is near Salt River, which flows into Slave River at Fort Smith. There, too, most of the black foxes and silver foxes are trapped. The great otter and fisher centre is around Trout Lake, Island Lake, Sandy Lake, and God's Lake. Otter taken north of Lake Superior are found to be fully one third larger than those killed in any other region. Black bears and brown bears are most frequently to be met with between Fort Pelly and Portage La Loche. Cumberland House is the centre of the greatest breeding grounds for muskrat, mink, and ermine. Manitoba House is another great district for muskrat. Lynxes are found in greatest numbers in the Iroquois Valley, in the foothills on the eastern side of the Rockies. Coyote skins come chiefly from the district between Calgary and Qu'Appelle for a hundred miles both north and south. Skunks are most plentiful just south of Green Lake; formerly, they lived on the plains, but of late they have moved northward into the woods. Wolverines frequent most the timber country just south of the Barren Grounds, where they are often found travelling in bands. The home of the porcupine lies just north of Isle a la Crosse. Forty years ago the breeding grounds of the beaver were on the eastern side of the Rockies. Nowadays that region is hardly worth considering as a trapping ground for them. They have been steadily migrating eastward along the Churchill River, then by way of Cross Lake, Fort Hope, to Abitibi, thence north-easterly clean across the country to Labrador, where few were to be found twenty-five years ago. Don't misunderstand me. I'm not saying that beaver were not found in those parts years ago, but what I mean is that the source of the greatest harvest of beaver skins has moved steadily eastward during the last forty years. Strange to say, the finest marten skins secured in Canada are not those of the extreme northern limit, but those taken on the Parsnip River in British Columbia."

Next morning I busied myself making a few additions to my outfit for the winter. Then I borrowed a two-and-a-half fathom canoe and paddled across the lake to Spearhead. The town I had heard so much about from the Free Trader was just a little clearing of about three acres on the edge of the forest; in fact, it was really just a stump lot with a small one-and-a-half story log house standing in the middle. Where there was a rise in the field, a small log stable was set half underground, and upon its roof was stacked the winter's supply of hay for a team of horses, a cow, and a heifer.

At the front door Mr. and Mrs. Spear welcomed me. My hostess was a prepossessing Canadian woman of fair education, in fact, she had been a stenographer. On entering the house I found the trading room on the right of a tiny hall, on the left was the living room, which was also used to eat in, and the kitchen was, of course, in the rear. After being entertained for ten or fifteen minutes by my host and hostess, I heard light steps descending the stairs, and the next moment I beheld a charming girl. She was their only child. They called her Athabasca, after the beautiful lake of that name. She was sixteen years of age, tall, slender, and graceful, a brunette with large, soft eyes and long, flowing, wavy hair. She wore a simple little print dress that was becomingly short in the skirt, a pair of black stockings, and low, beaded moccasins. I admired her appearance, but regretted her shyness, for she was almost as bashful as I was. She bowed and blushed—so did I—and while her parents talked to me she sat demurely silent on the sofa. Occasionally, I caught from her with pleasant embarrassment a shy but fleeting glance.

Presently, dinner was announced by a half-breed maid, and we four took our places at the table, Athabasca opposite me. At first the talk was lively, though only three shared in it. Then, as the third seemed rather more interested in his silent partner, he would from time to time lose the thread of the discourse. By degrees the conversation died down into silence. A few minutes later Mrs. Spear suddenly remarked:

"Father … don't you think it would be a good thing if you took son-in-law into partnership?"

Father leaned back, scratched his head for a while, and then replied:

"Yes, Mother, I do, and I'll do it."

The silent though beautiful Athabasca, without even raising her eyes from her plate, blushed violently, and needless to say, I blushed, too, but, of course, only out of sympathy.

"The horses are too busy, just now, to haul the logs, but of course the young people could have our spare room until I could build them a log shack."

"Father, that's a capital idea. So there's no occasion for any delay whatever. Then, when their house is finished, we could spare them a bed, a table, a couple of chairs, and give them a new cooking stove."

Athabasca blushed deeper than ever, and studied her plate all the harder, and I began to show interest and prick up my ears, for I wondered who on earth son-in-law could be? I knew perfectly well there was no young white man in all that region, and that even if he lived in the nearest frontier town, it would take him, either by canoe or on snowshoes, at least two weeks to make the round trip to Spearhead, just to call on her. I couldn't fathom it at all.

"Besides, Mother, we might give them the heifer, as a starter, for she will be ready to milk in the spring. Then, too, we might give them a few ducks and geese and perhaps a pig."

"Excellent idea, Father; besides, I think I could spare enough cutlery, dishes, and cooking utensils to help out for a while."

"And I could lend them some blankets from the store," the trader returned.

But at that moment Athabasca miscalculated the distance to her mouth and dropped a bit of potato on the floor, and when she stooped to recover it, I caught a glance from the corner of her eye. It was one of those indescribable glances that girls give. I remember it made me perspire all over. Queer, isn't it, the way women sometimes affect one? I would have blushed more deeply, but by that time there was no possible chance of my face becoming any redder, notwithstanding the fact that I was a red-head. Ponder as I would, I couldn't fathom the mystery … who Son-in-law could be … though I had already begun to think him a lucky fellow—quite one to be envied.

Then Mrs. Spear exclaimed, as we rose from the table:

"Good!… Then that's settled … you'll take him into partnership, and I'm glad, for I like him, and I think he'll make an excellent trader."

Our getting away from the table rather relieved me, as I was dripping perspiration, and I wanted to fairly mop my face—of course, when they weren't looking.

Together they showed me over the establishment: the spare bedroom, the trading shop, the stable, the heifer, the ducks and geese, and even the pig—though it puzzled me why they singled out the very one they intended giving Son-in-law. The silent though beautiful Athabasca followed a few feet behind as we went the rounds, and inspected the wealth that was to be bestowed upon her lover. I was growing more inquisitive than ever as to who Son-in-law might be. Indeed, I felt like asking, but was really too shy, and besides, when I thought it over, I concluded it was none of my business.

When the time came for me to return to the Hudson's Bay Post, I shook hands with them all—Athabasca had nice hands and a good grip, too. Her parents gave me a pressing invitation to visit them again for a few days at New Year's, when everyone in the country would be going to the great winter festival that was always held at Fort Consolation. As I paddled away I mused:

"By George, Son-in-law is certainly a lucky dog, for Athabasca's a peach … but I don't see how in thunder her lover ever gets a chance to call."

I was up early next morning and as I wished to see how Oo-koo-hoo and his party would pack up and board their canoes, I walked round the bay to the Indian village. After a hasty breakfast, the women pulled down the lodge coverings of sheets of birch bark and rolling them up placed them upon the star-chi-gan—the stage—along with other things which they intended leaving behind. The lodge poles were left standing in readiness for their return next summer, and it wasn't long before all their worldly goods—save their skin tepees and most of their traps, which had been left on their last winter's hunting grounds—were placed aboard their three canoes, and off they paddled to the Post, to say good-bye, while Amik secured his advances.

Just think of it, all you housekeepers—no gold plate or silverware to send to the vault, no bric-a-brac to pack, no furniture to cover, no bedding to put away, no rugs or furs or clothes to send to cold storage, no servants to wrangle with or discharge, no plumbers to swear over, no janitors to cuss at, no, not even any housecleaning to do before you depart—just move and nothing more. Just dump a little outfit into a canoe and then paddle away from all your tiresome environment, and travel wherever your heart dictates, and then settle down where not even an exasperating neighbour could find you. What would you give to live such a peaceful life?

"As I understand it," says Thoreau, "that was a valid objection urged by Momus against the house which Minerva made, that she had not made it movable, by which means a bad neighbourhood might be avoided; and it may still be urged, for our houses are such unwieldy property that we are often imprisoned rather than housed in them; and the bad neighbourhood to be avoided is our own scurvy selves."

On their arrival, Amik at once set about getting his advances. He was a stalwart, athletic-looking man of about thirty-five, but not the equal of his father-in-law in character. Oo-koo-hoo now told the Factor just where he intended to hunt, what fur he expected to get, and how the fur runners could best find his camp. As the price of fur had risen, the Factor told him what price he expected to pay. If, however, the price had dropped, the Factor would not have informed the hunter until his return next year. During the course of the conversation, the old hunter begged the loan of a second-hand gun and some traps for the use of his grandsons; and the Factor granted his request.

In the meantime, the women called upon the clergyman and the priest and the nuns to wish them farewell, and incidentally to do a little more begging. As they were not ready to go by noon, the Factor's wife spread a cloth upon the kitchen floor, and placed upon it some food for the party. After lunch they actually made ready to depart, and everybody came down to the landing to see us off. As the children and dogs scrambled aboard the canoes, the older woman remembered that she had not been paid for her gift of moccasins, and so another delay took place while the Factor selected a suitable present. It is always thus. Then, at last, the canoes push off. Amid the waving of hands, the shouting of farewells, and the shedding of a few tears even, the simple natives of the wilderness paddled away over the silent lake en route for their distant hunting grounds.

Thither the reader must follow, and there, amid the fastnesses of the Great Northern Forest, he must spend the winter if he would see the Indian at his best. There he is a beggar no longer. There, escaped from the civilization which the white man is ever forcing upon the red—a civilization which rarely fails to make a degenerate of him—he proves his manhood. There, contrary to the popular idea, he will be found to be a diligent and skilful worker and an affectionate husband and father. There, given health and game, no toil and no hardship will hinder him from procuring fur enough to pay off his indebtedness, and to lay up in store twice as much again with which to engage next spring in the delightful battle of wits between white man and red in the Great Company's trading room.

It was an ideal day and the season and the country were in keeping. Soon the trading posts faded from view, and when, after trolling around Fishing Point, we entered White River and went ashore for an early supper, everyone was smiling. I revelled over the prospect of work, freedom, contentment, and beauty before me; and over the thought of leaving behind me the last vestige of the white man's ugly, hypercritical, and oppressive civilization.

Was it any wonder I was happy? For me it was but the beginning of a never-to-be-forgotten journey in a land where man can be a man without the aid of money. Yes … without money. And that reminds me of a white man I knew who was born and bred in the Great Northern Forest, and who supported and educated a family of twelve, and yet he reached his sixtieth birthday without once having handled or ever having seen money. He was as generous, as refined, and as noble a man as one would desire to know; yet when he visited civilization for the first time—in his sixty-first year—he was reviled because he had a smile for all, he was swindled because he knew no guile, he was robbed because he trusted everyone, and he was arrested because he manifested brotherly love toward his fellow-creatures. Our vaunted civilization! It was the regret of his declining years that circumstances prevented him from leaving the enlightened Christians of the cities, and going back to live in peace among the honest, kindly hearted barbarians of the forest.

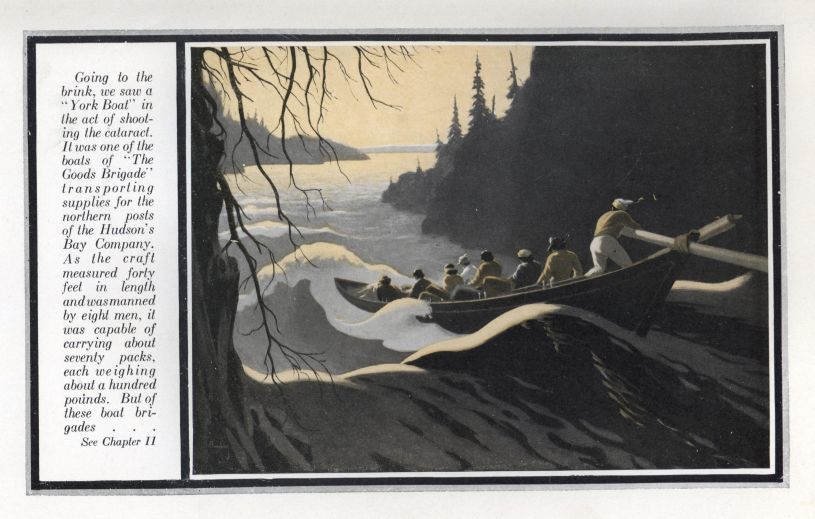

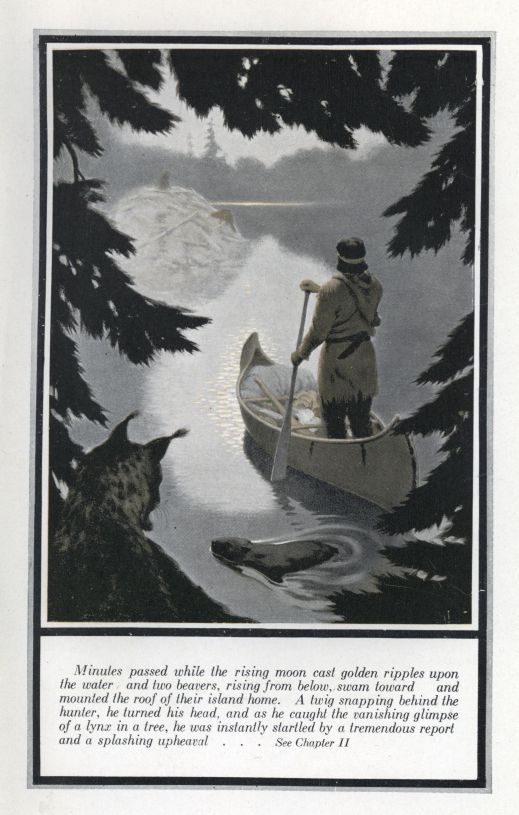

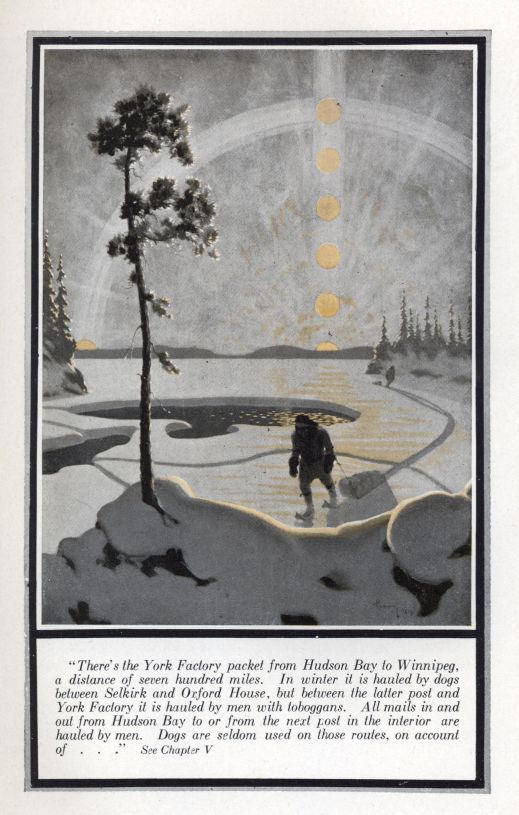

Soon there were salmon-trout—fried to a golden brown—crisp bannock, and tea for all; then a little re-adjusting of the packs, and we were again at the paddles. Oo-koo-hoo's wife, Ojistoh, along with her second granddaughter and her two grandsons, occupied one of the three-and-a-half fathom canoes; Amik, and his wife, Naudin, with her baby and eldest daughter, occupied the other; and Oo-koo-hoo and I paddled together in the two-and-a-half fathom canoe. One of the five dogs—Oo-koo-hoo's best hunter—travelled with us, while the other four took passage in the other canoes. Although the going was now up stream—the same river by which I had come—we made fair speed until Island Lake stretched before us, when we felt a southwest wind that threatened trouble; but by making a long detour about the bays of the southwestern shore the danger vanished. Arriving at the foot of the portage trail at Bear Rock Rapids, we carried our outfit to a cliff above, which afforded an excellent camping ground; and there arose the smoke of our evening fire. The cloudless sky giving no sign of rain, we contented ourselves with laying mattresses of balsam brush upon which to sleep. While the sunset glow still filled the western sky, we heard a man's voice shouting above the roar of the rapids, and on going to the brink, saw a "York boat" in the act of shooting the cataract. It was one of the boats of "The Goods Brigade" transporting supplies for the northern posts of the Hudson's Bay Company. As the craft measured forty feet in length and was manned by eight men, it was capable of carrying about seventy packs, each weighing about a hundred pounds. But of these boat brigades—more in due season.

After supper, when twilight was deepening, and tobacco—in the smoking of which the women conscientiously joined—was freely forthcoming, the subject of conversation turned to woodcraft. Since it fell to Oo-koo-hoo, as the principal hunter, to keep the party supplied with game while en route, I was wondering what he would do in case he saw a bear and went ashore to trail it. Would he himself skin and cut up the bear, or would he want the women to help him? If the latter, what sign or signal would he use so that they might keep in touch with him? But when I questioned Oo-koo-hoo, he replied:

"My white son"—for that is what he sometimes called me—"I see you are just like all white men, but if you are observant and listen to those who are wiser than you, you may some day rank almost the equal of an Indian."

Afterward, when I became better acquainted with him, I learned that with regard to white men in general, he held the same opinion that all Indians do, and that is, that they are perfect fools. When I agreed with the old gentleman, and assured him he was absolutely right, and that the biggest fool I ever knew was the one who was talking to him, he laughed outright, and replied that now he knew that I was quite different from most white men, and that he believed some day I would be the equal of an Indian. When I first heard his opinion of white men, I regarded him as a pretty sane man, but afterward, when I tried to get him to include not only his brother Indians, but also himself under the same definition, I could not get him to agree with me, therefore I was disappointed in him. He was not the philosopher I had at first taken him to be; for life has taught me that all men are fools—of one kind or another.

But to return to woodcraft. Emerson says: "Men are naturally hunters and inquisitive of woodcraft, and I suppose that such a gazetteer as wood-cutters and Indians should furnish facts for would take place in the most sumptuous drawing rooms of all the 'Wreaths' and 'Flora's Chaplets' of the bookshops" and believing that to be true, I shall therefore tell you not only how my Indian friends managed to keep their bearings while travelling without a compass, but how, without the aid of writing, they continued to leave various messages for their companions. When I asked Oo-koo-hoo how he would signal, in case he went ashore to trail game—when the other canoes were out of sight behind him—and he should want someone to follow him to help carry back the meat, he replied that he would cut a small bushy-topped sapling and plant it upright in the river near his landing place on the shore. That, he said, would signify that he wished his party to go ashore and camp on the first good camping ground; while, at the same time, it would warn them not to kindle a fire until they had first examined the tracks to make sure whether the smoke would frighten the game. Then someone would follow his trail to render him assistance, providing they saw that he had blazed a tree. If he did not want them to follow him, he would shove two sticks into the ground so that they would slant across the trail in the form of an X, but if he wanted them to follow he would blaze a tree. If he wanted them to hurry, he would blaze the same tree twice. If he wanted them to follow as fast as they could with caution, he would blaze the same tree three times, but if he desired them to abandon all caution and to follow with all speed, he would cut a long blaze and tear it off.

Then, again, if he were leaving the game trail to circle his quarry, and if he wished them to follow his tracks instead of those of the game, he would cut a long blaze on one tree and a small one on another tree, which would signify that he had left the game trail at a point between the two trees and that they were to follow his tracks instead of those of the game. But if he wished them to stop and come no farther, he would drop some article of his clothing on the trail. Should, however, the game trail happen to cross a muskeg where there were no trees to blaze, he would place moss upon the bushes to answer instead of blazes, and in case the ground was hard and left an invisible trail, he would cut a stick and shoving the small end into the trail, would slant the butt in the direction he had gone.

If traversing water where there were no saplings at hand, and he wished to let his followers know where he had left the water to cross a muskeg, he would try to secure a pole, which he would leave standing in the water, with grass protruding from the split upper end, and the pole slanting to show in which direction he had gone. If, on the arrival at the fork of a river, he wished to let his followers know up which fork he had paddled—say, for instance, if it were the right one—he would shove a long stick into either bank of the left fork in such a way that it would point straight across the channel of the left fork, to signify, as it were, that the channel was blocked. Then, a little farther up the right fork, he would plant a sapling or pole in the water, slanting in the direction he had gone—to prove to the follower that he was now on the right trail. Oo-koo-hoo further explained that if he were about to cross a lake and he wished to let his follower know the exact point upon which he intended to land, he would cut two poles, placing the larger nearest the woods and the smaller nearest the water, both in an upright position and in an exact line with the point to which he was going to head, so that the follower by taking sight from one pole to the other would learn the exact spot on the other shore where he should land—even though it were several miles away. But if he were not sure just where he intended to land, he would cut a willow branch and twist it into the form of a hoop and hang it upon the smaller pole—that would signify that he might land at any point of the surrounding shore of the lake.

If he wanted to signal his family to camp at any particular point along his trail, he would leave some article of his clothing and place near it a number of sticks standing in the form of the poles of a lodge, thus suggesting to them that they should erect their tepee upon that spot. If he had wounded big game and expected soon to overtake and kill it, and if he wanted help to carry back the meat, he would blaze a tree and upon that smooth surface would make a sketch, either with knife or charcoal, of the animal he was pursuing. If a full day had elapsed since the placing of crossed sticks over the trail, the follower would abandon all caution and follow at top speed, as he would realize that some misfortune had befallen the hunter. The second man, or follower, however, never blazes trees as he trails the first hunter, but simply breaks off twigs or bends branches in the direction in which he is going, so that should it be necessary that a third man should also follow, he could readily distinguish the difference between the two trails. If a hunter wishes to leave a good trail over a treeless district, he, as far as possible, chooses soft ground and treads upon his heels.

When a hunter is trailing an animal, he avoids stepping upon the animal's trail, so that should it be necessary for him to go back and re-trail his quarry, the animal's tracks shall not be obliterated. If, in circling about his quarry, the hunter should happen to cut his own trail, he takes great care to cut it at right angles, so that, should he have to circle several times, he may never be at a loss to know which was his original trail. If the hunter should wish to leave a danger signal behind him, he will take two saplings, one from either side of the trail, and twist them together in such a way that they shall block the passage of the follower, requiring him to pause in order to disentangle them or to pass around them; and if the hunter were to repeat such a signal two or three times, it would signify that the follower should use great caution and circle down wind in order to still-hunt the hunter's trail in exactly the same way he would still-hunt a moose. Then, again, if the hunter should wish to let the follower know the exact time of day he had passed a certain spot, he would draw on the earth or snow a bow with an arrow placed at right angles to the bow, but pointing straight in the direction where the sun had been at that precise moment.

Owing to their knowledge of wood-craft some Indians are very clever at deduction.

On Great Slave Lake near Fort Rae an Indian cripple, named Simpson's Brother, had joined a party of canoe-men for the purpose of hunting eggs. After paddling toward a group of islands, the party separated, finally landing on different isles. They had agreed, however, to meet at sunset on a certain island and there eat and sleep together. While at work several of the Indians saw Simpson's Brother alone on a little rocky islet, busily engaged in gathering eggs. Toward evening, the party met at their rendezvous and took supper together, but strange to say, Simpson's Brother did not appear. After smoking and talking for a while, some grew anxious about the cripple. The Bear began to fear lest some mishap had befallen him; but The Caribou scoffed at the idea: he was sure that Simpson's Brother was still working and that he would soon return with more eggs than any of them. The Bear, however, thought they ought to search for him, as his canoe might have drifted away. But The Mink replied that if anything like that had happened, the cripple would certainly have fired his gun. "But how could he fire his gun if his canoe had drifted away?" asked The Bear, "for would not his gun be in his canoe?" So they all paddled off to investigate the mystery. On nearing the island, they saw the Brother's canoe adrift. When they overhauled it, sure enough his gun was aboard. They then landed on the little isle where the cripple had been at work and began calling aloud for him. As they received no answer, some of the Indians claimed that he must be asleep. The Bear replied that if he was asleep their shouting would have awakened him and he would have answered, but that now they had best search the island.

So they divided into two parties and searched the shore in different directions until they finally met on the other side, then they scattered and examined every nook and corner of the place—but all in vain. Some now contended that the others were mistaken, and that that could not be the island on which the Brother had been working; but The Bear—though he had not seen the cripple there—insisted that it was. They asked him to prove it.

"The wind has been blowing steadily from the north," replied The Bear, "the other islands are all south of this one, and you know that we found his canoe adrift south of here and north of all the other islands. That is sufficient proof." Then he added: "The reason Simpson's Brother did not answer is because he is not on the island, but in the water."

Again they all clamoured for proof and The Bear answered: "But first I must find where he landed, and the quickest way to find that place is to remember that the wind was blowing too strong for him to land on the north shore, and that the running swells were too strong for him to land on either the east or west sides, therefore he landed on the south side—the sheltered side. Now let us go and see where he drew up his canoe."