Title: Happy Pollyooly: The Rich Little Poor Girl

Author: Edgar Jepson

Illustrator: Reginald B. Birch

Release date: September 17, 2006 [eBook #19310]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Al Haines

E-text prepared by Al Haines

The angel child looked at the letter from Buda-Pesth with lively interest, for she knew that it came from her friend and patroness Esmeralda, the dancer, who was engaged in a triumphant tour of the continent of Europe. She put it on the top of the pile of letters, mostly bills, which had come for her employer, the Honourable John Ruffin, set the pile beside his plate, and returned to the preparation of his breakfast.

She looked full young to hold the post of house-keeper to a barrister of the Inner Temple, for she was not yet thirteen; but there was an uncommonly capable intentness in her deep blue eyes as she watched the bacon, sizzling on the grill, for the right moment to turn the rashers. She never missed it. Now and again those deep blue eyes sparkled at the thought that the Honourable John Ruffin would presently give her news of her brilliant friend.

She heard him come out of his bedroom, and at once dished up his bacon, and carried it into his sitting-room. She found him already reading the letter, and saw that it was giving him no pleasure. His lips were set in a thin line; there was a frown on his brow and an angry gleam in his grey eyes. She knew that of all the emotions which moved him, anger was the rarest; indeed she could only remember having once seen him angry: on the occasion on which he had smitten Mr. Montague Fitzgerald on the head when that shining moneylender was trying to force from her the key of his chambers; and she wondered what had been happening to the Esmeralda to annoy him. She was too loyal to suppose that anything that the Esmeralda had herself done could be annoying him.

He ate his breakfast more slowly than usual, and with a brooding air. His eyes never once, as was their custom, rested with warm appreciation on Pollyooly's beautiful face, set in its aureole of red hair; he did not enliven his meal by talking to her about the affairs of the moment. She respected his musing, and waited on him in silence. She had cleared away the breakfast tray and was folding the table-cloth when, at last, he broke his thoughtful silence.

"There's nothing for it: I must go to Buda-Pesth," he said with a resolute air.

"There's nothing the matter with the Esmeralda, sir?" said Pollyooly with quick anxiety.

"There's something very much the matter with the Esmeralda—a Moldo-Wallachian," said the Honourable John Ruffin with stern coldness.

"Is it an illness, sir?" said Pollyooly yet more anxiously.

"No; it's a nobleman," said the Honourable John Ruffin with even colder sternness.

Pollyooly pondered the matter for a few seconds; then she said: "Is he—is he persecuting her, sir, like Senor Perez did when I was dancing with her in 'Titania's Awakening'?"

"It ought to be a persecution; but I fear it isn't," said the Honourable John Ruffin grimly. "I gather from this letter that she is regarding his attentions, which, I am sure, consist chiefly of fulsome flattery and uncouth gifts, with positive approbation."

Pollyooly pondered this information also; then she said:

"Is she going to marry him, sir?"

"She is not!" said the Honourable John Ruffin in a tone of the deepest conviction but rather loudly.

Pollyooly looked at him and waited for further information to throw light on his manifest disturbance of spirit.

He drummed a tattoo on the bare table with his fingers, frowning the while; then he said:

"Constancy to the ideal, though perhaps out of place in a man, is alike woman's privilege and her duty. I should be sorry—indeed I should be deeply shocked if the Esmeralda were to fail in that duty."

"Yes, sir," said Pollyooly in polite sympathy, though she had not the slightest notion what he meant.

"Especially since I took such pains to present to her the true ideal—the English ideal," he went on. "Whereas this Moldo-Wallachian—at least that's what I gather from this letter—is merely handsome in that cheap and obvious South-European way—that is to say he has big, black eyes, probably liquid, and a large, probably flowing, moustache. Therefore I go to Buda-Pesth."

"Yes, sir," said Pollyooly with the same politeness and in the same ignorance of his reason for going.

"I shall wire to her to-day—to give her pause—and to-morrow I shall start." He paused, looking at her thoughtfully for a moment, then went on: "I should like to take you with me, for I know how helpful you can be in the matter of these insolent and infatuated foreigners. But Buda-Pesth is too far away. And the question is what I am going to do with you while I'm away."

"We can stay here all right, sir—the Lump and me," said Pollyooly quickly, with a note of surprise in her voice.

Her little brother, Roger, who lived with her in the airy attic above the Honourable John Ruffin's chambers, had acquired the name of "The Lump" from his admirable placidity.

"I don't like the idea of your doing that," he said, shaking his head and frowning. "I don't know how long I may be away—the affirmation of the ideal is sometimes a lengthy process. Of course the Temple is a quiet place; but I don't like to leave two small children alone in it for a fortnight, or three weeks. It isn't as if Mr. Gedge-Tomkins were at home. If he were at hand—just across the landing, it would be a very different matter."

"But I'm sure we should be all right, sir," said Pollyooly with entire confidence.

"Oh, I'm bound to say that if any child in the world could take care of herself and a little brother, it's you," he said handsomely. "But I want to devote all my energies to the affirmation of the ideal; and I must not be troubled by anxiety about you. I shall have to dispose of you safely somehow."

With that he rose, lighted a cigar, and presently sallied forth into the world. The matter of learning the quickest way to Buda-Pesth and procuring a ticket for the morrow took him little more than half an hour. Then the matter of disposing safely of Pollyooly and the Lump during his absence rose again to his mind and he walked along pondering it. Presently there came to him a happy thought: there was their common friend, Hilary Vance, an artist who had employed Pollyooly as his model for a set of stories for The Blue Magazine. Hilary Vance was devoted to Pollyooly, and he had a spare bedroom. But for a while the Honourable John Ruffin hesitated; the artist was a man of an uncommonly mercurial, irresponsible temperament. Was it safe to entrust two small children to his care? Then he reflected that Pollyooly was a strong corrective of irresponsibility, and took a taxicab to Chelsea.

Hilary Vance, very broad, very thick, very round, with a fine, rebellious mop of tow-coloured hair, which had fallen forward so as nearly to hide his big, simple eyes, opened the door to him. At the sight of his visitor a spacious round smile spread over his spacious face; and he welcomed him with an effusive enthusiasm.

At his christening the good fairy had given to the Honourable John Ruffin a very lively interest in his fellow-creatures and a considerable power of observation with which to gratify it. He was used to the splendid expansiveness of Hilary Vance; but it seemed to him that to-day he was boiling with an added exuberance; and that curiosity was aroused. He took up a chair and hammered its back on the floor so that the dust fell off the seat, sat down astride it, and, bending forward a little, proceeded to observe the artist with very keen eyes. Hilary Vance, who was very busy, fell to work again, and after his manner, grew grandiloquent about the pleasures of the day before, which he had spent in the country.

Soon it grew clear to the Honourable John Ruffin that his friend had swollen with the insolent happiness so hateful to the Fates, and he said:

"You seem to be uncommonly cheerful, Vance. What's the matter?"

Hilary Vance looked at him gravely, drew himself upright in his chair, laid down his pencil, and said in a tone of solemnity calculated to awaken the deepest respect and awe:

"Ruffin, I have found a woman—a WOMAN!"

The quality of the Honourable John Ruffin's gaze changed; his eyes rested on the face of his friend with a caressing, almost cherishing, delight.

"Isn't it becoming rather a habit?" he said blandly.

"I don't know what you mean," said Hilary Vance with splendid dignity. "But this is different. This is a WOMAN!"

His face filled with an expression of the finest beatitude.

"They so often are," said the Honourable John Ruffin. "Does James know about her?"

At the sound of the name of the mentor and friend who had rescued him from so many difficulties, something of guilt mingled with the beatitude on Hilary Vance's face, and he said in a less assured tone:

"James is in Scotland."

The Honourable John Ruffin sprang from his chair with a briskness which made Hilary Vance himself jump, and cried in a tone of the liveliest commiseration and dismay:

"Good Heavens! Then you're lost—lost!"

"What do you mean?" said Hilary Vance quite sharply.

"I mean that your case is hopeless," said the Honourable John Ruffin in a less excited tone. "James is in Scotland; I'm off to Buda-Pesth; and you have found a WOMAN—probably THE WOMAN."

"I don't know what you mean," said Hilary Vance, frowning.

"That's the worst of it! That's why it's so hopeless!" said the Honourable John Ruffin in a tone of deep depression.

"What do you mean?" cried Hilary Vance in sudden bellow.

"Good-bye, old chap; good-bye," said the Honourable John Ruffin in the most mournful tone and with the most mournful air. "I can not save you. I've got to go to Buda-Pesth." He walked half-way to the door, turned sharply on his heel, clapped his hand to his head with the most dramatic gesture, and cried: "Stay! I'll wire to James!"

"I'm damned if you do!" bellowed Hilary Vance.

"I must! I must!" cried the Honourable John Ruffin, still dramatic.

"You don't know his address, thank goodness!" growled Hilary Vance triumphantly. "And you won't get it from me."

"I shan't? Then it's hopeless indeed," said the Honourable John Ruffin with a gesture of despair. He stood and seemed to plunge into deep reflection, while Hilary Vance scowled an immense scowl at him.

The Honourable John Ruffin allowed a faint air of hope to lighten his gloom; then he said:

"There's a chance—there's yet a chance!"

"I don't want any chance!" cried Hilary Vance stormily. "You can jolly well mind your own business and leave me alone. I can look after myself without any help from you—or James either."

"Whom the gods wish to destroy they first madden young," said the Honourable John Ruffin sadly. "But there's always Pollyooly; she may save you yet. I came to suggest that while I'm away in Buda-Pesth you should let Pollyooly and the Lump occupy that spare bedroom of yours. I don't like leaving them alone in the Temple; and I thought that you might like to have them here for a while, though I fear Pollyooly will clean the place." He looked round the studio gloomily. "But you can stand that for once, I expect," he went on more cheerfully. "At any rate it would be worth your while, because you'd learn what grilled bacon really is."

At the mention of the name of Pollyooly the scowl on Hilary Vance's face began to smooth out; as the Honourable John Ruffin developed his suggestion it slowly disappeared.

"Oh, yes; I'll put them up. I shall be delighted to," he said eagerly. "Pollyooly gives more delight to my eye than any one I know. And there are so few people in town, and I'm lonely at times. I wish I liked bacon, since she is so good at grilling it; but I don't."

The Honourable John Ruffin came several steps down the room wearing an air of the wildest amazement:

"You don't like bacon?" he cried in astounded tones. "That explains everything. I've always wondered about you. Now I know. You are one of those whom the gods love; and I can't conceive why you didn't die younger."

"I don't know what you mean," said Hilary Vance, bristling and scowling again.

"You don't? Well, it doesn't matter. But I'm really very much obliged to you for relieving me of all anxiety about those children."

They discussed the hour at which Pollyooly and the Lump should come, and then the Honourable John Ruffin held out his hand.

But Hilary Vance rose and came to the front door with him. On the threshold he coughed gently and said:

"I should like you to see Flossie."

"Flossie?" said the Honourable John Ruffin. "Ah—the WOMAN." He looked at Hilary Vance very earnestly. "Yes, I see—I see—of course her name would be Flossie." Then he added sternly:

"No; if I saw her James might accuse me of having encouraged you. He would, in fact. He always does."

"She's only at the florist's just at the end of the street," said Hilary Vance in a persuasive tone.

"She would be," said the Honourable John Ruffin in a tone of extraordinary patience. "I don't know why it is that the WOMAN is so often at a florist's at the end of the street. It seems to be one of nature's strange whims." His face grew very gloomy again and in a very sad tone he added:

"Good-bye, poor old chap; good-bye!"

He shook hands firmly with his puzzled friend and started briskly up the street. Ten yards up it he paused, turned and called back:

"She's everything that's womanly, isn't she?"

"Yes—everything," cried Hilary Vance with fervour.

The Honourable John Ruffin shook his head sadly and without another word walked briskly on.

Hilary Vance, still looking puzzled, shut the door and went back to his studio. He failed, therefore, to perceive the Honourable John Ruffin enter the florist's shop at the end of the street. He did not come out of it for a quarter of an hour, and then he came out smiling. Seeing that he only brought with him a single rose, he had taken some time over its selection.

That afternoon, when Pollyooly was helping him pack his portmanteau for his journey to Buda-Pesth, the Honourable John Ruffin told her of the arrangement he had made with Hilary Vance, that she and the Lump should spend the time till his return at the studio at Chelsea.

Pollyooly's face brightened; and there was something of the joy which warriors feel in foemen worthy of their steel in the tone in which she said:

"Thank you, sir. I shall like that. It will be a change for the Lump; and I've always wanted to know what that studio would look like if once it were properly cleaned. That Mrs. Thomas who works for Mr. Vance does let it get so dirty."

"Yes; I told Mr. Vance that I was sure that you'd get the place really clean for him," said the Honourable John Ruffin with a chuckle.

"Oh, yes; I will," said Pollyooly firmly.

The Honourable John Ruffin chuckled again, and said:

"Mr. Vance is going to have the spring cleaning of a lifetime."

"Yes, sir. It's not quite summer-time yet," said Pollyooly.

The next morning before taking the train to Buda-Pesth, he despatched her, the Lump, and the brown tin box which contained their clothes, to Chelsea in a taxicab. Hilary Vance welcomed them with the most cordial exuberance, led the way to his spare bedroom, and with an entire unconsciousness of that bedroom's amazing resemblance to a long-forgotten dust-bin, invited Pollyooly to unpack the box and make herself at home.

Pollyooly gazed slowly round the room, and then she looked at her host in some discomfort. She was a well-mannered child, and careful of the feelings of a host. Then she said in a hesitating voice:

"I think I should like to—to—dust out the room before I unpack, please."

"By all means—by all means," said Hilary Vance cheerfully; and he went back to his work.

Owing to his absorption in it he failed to perceive the curious measures Pollyooly took to dust out the bedroom. She put on an apron, fastened up her hair and covered it with a large cotton handkerchief, rolled up her sleeves, and carried a broom, two pails of hot water from the kitchen, a scrubbing-brush, and a very large piece of soap into the room she proposed to dust. She shut herself in, took the counterpane off the bed, shook it with furious vigour, and even more vigourously still banged it against the end of the bedstead. When she had finished with it the counterpane was hardly white, but the room was dustier than ever. She covered up the bed again, took down the pictures and again made the room dustier. Then she swept the ceiling and the walls. After doing so she shook the counterpane again. And the room was still dusty; but the dust was nearly all on the floor, or on the black face of Pollyooly. She swept it up. Then she went quietly out into the street with the strips of carpet and banged them against the railings of the house; this time it was the street that was dustier than ever; and Pollyooly appeared to have come from the lower Congo. For the next half-hour, had he not been absorbed in his work, Hilary Vance might have heard a steady and sustained rasp of a scrubbing-brush.

Pollyooly came to the laying of the lunch with her angel face deeply flushed; but she wore a very cheerful air. Also she displayed an excellent appetite. In the middle of lunch she said in dreamy reminiscence, apropos of nothing in particular:

"I got this place clean once."

"Isn't it clean now?" said Hilary Vance in a tone of anxious surprise.

"It depends on what you call clean," said Pollyooly politely.

After lunch she brought the drawers from the chest of drawers in the bedroom into the kitchen and washed them and dried them in the sun. Then, at last, she unpacked the brown tin box and put away their clothes.

After that she took the Lump for an hour's walk on the embankment. She preferred it to the embankment below the Temple; it seemed to her airier. She returned to tea, and had a little struggle with the teaspoons. They enjoyed, after the lapse of months, the experience of shining. After tea Hilary Vance told her regretfully that he would not be able to come home to supper, but that she would find provisions in the cupboard, and advising them to go to bed early, bade them an affectionate good-night and went out in a northeasterly direction to talk about Art.

When the door closed behind him Pollyooly heaved a faint sigh of satisfaction and looked round the studio with the light of battle in her eye. Then she took the canvases, which were set against the wall three and four deep, into the street and brushed them. The dust in the street had been a tedious grey; in front of the house of Hilary Vance it became a warm black.

Then she put the Lump, with the toys she had brought with her, into the clean bedroom, and fell upon the studio. By the time she had brushed the pictures and the walls and the ceiling its floor had become very dusty indeed, and she was once more black. She swept it, and then she was an hour scrubbing it. When it was done she gave the Lump his supper and put him to bed. After supper she dealt faithfully with the windows. The skylight gave her trouble; it was so high. But she tied a wet cloth round the top of a broom, and by standing on the table reached it. It made her arms ache, but slowly the panes assumed a transparency to which they had long been unused. When she had cleaned them from the inside she considered thoughtfully the possibility of sitting astride the roof and cleaning their outside surfaces. But there was no way of getting on to the roof. Then she had a hot bath; she needed it.

Mrs. Thomas had been apprised of her coming and greeted her amiably. It is only fair to say that she gave the studio the cleaning it generally received without observing that anything whatever had happened to it.

Hilary Vance, who was of that rare, but happy, disposition, came to breakfast in splendid spirits. He also did not observe that anything had happened to the studio. But when he got to his work he kept looking up from it with a puzzled air.

At last he said:

"It's odd—very odd. Lately I've been thinking that my sight was beginning to weaken. But this morning I can see quite clearly. Yet it isn't a very bright morning."

"Perhaps if you had the skylight cleaned on the outside, too, you'd see clearer still," said Pollyooly in the tone of one throwing out a careless suggestion.

Hilary Vance looked round the studio more earnestly:

"By Jove! You've cleaned it again!" he cried. "You are a brick, Pollyooly. But all the same you're my guest here; and it's not the function of a guest to clean her host's house. I ought to have remembered it and had it cleaned before you came."

"But I liked doing it. I did, really," said Pollyooly.

"You are undoubtedly a brick—a splendid brick," he said enthusiastically.

Hilary Vance was one of those great-hearted men of thirty who crave for sympathy; he must unbosom himself. Pollyooly was not quite the confidante of his ideal; but his mentor, James, the novelist (not Henry), was in Scotland; and the salt sea flowed between him and the Honourable John Ruffin. Pollyooly was at hand, and she was intelligent. No later than the next morning he began to talk to her of Flossie—her beauty, her charm, her sympathetic nature, her womanliness, and her intelligence.

Pollyooly received his confidences with the utmost politeness. She could not, indeed, follow him in his higher, finer flights; but she succeeded in keeping on her angel face an expression of sufficient appreciation to satisfy his unexacting mind. It is to be feared that she did not really appreciate the splendour of the passion he displayed before her; it is even to be feared that she regarded it as no more than a further eccentricity in an eccentric nature. She grew curious, however, to see the lady who had so enthralled him, and was, therefore, pleased when she suggested that she should relieve Mrs. Thomas of the housekeeping, that he accepted the suggestion and told her to procure, among other things, some flowers for the studio.

She found Flossie to be a fair, fluffy-haired, plump and pretty girl of twenty, entirely pleased with herself and the world. It seemed to Pollyooly that she gave herself airs. She came away with the flowers, finding the ecstasies of Mr. Hilary Vance as inexplicable as ever. But she did not puzzle over the matter at all, for it was none of her business; Mr. Vance was like that.

Having once begun, Hilary Vance fell into the way of confiding to her from day to day his hopes and fears, the varying fortunes of his suit. Some days the skies of his heaven were fair and serene; some days they were livid with the darkest kind of cloud. Pollyooly, by dint of hearing so much about it, began to get some understanding of the matter, and consequently to take a greater interest in it. Always she made an excellent listener. Her intercourse with the Honourable John Ruffin had taught her that a comprehension of the matter under discussion was by no means a necessary qualification of the excellent listener; and Hilary Vance grew entirely satisfied with his confidante.

The affair was pursuing the usual course of his affairs of the heart: one day he was well up in the seventh heaven, talking joyfully of an early proposal and an immediate marriage; another he was well down in the seventh hell. Pollyooly was always ready with the kind of sympathy, chiefly facial, the changing occasion demanded.

Then one day her host had gone out to lunch with an editor and she was taking hers with the Lump, when there came a rather hurried knocking at the front door. She opened it, and to her surprise found Flossie standing without. She was at once stricken with admiration of Flossie's hat, which was very large and apparently loaded with the contents of several beds of flowers. But Flossie herself looked to be in a state of considerable perturbation.

"Is Mr. Vance in?" she said somewhat breathlessly.

She seemed to have been hurrying, and the hat was a little on one side.

Pollyooly eyed her with some disfavour, and said coldly: "No, he isn't."

"Will he be in soon?" said Flossie anxiously.

"I don't know," said Pollyooly yet more coldly.

Flossie gazed up and down the street with a helpless air; then she said:

"Then I'd better come In and write a note for him and leave it." And she walked down the passage and into the studio.

Still wearing an air of disapproval, Pollyooly found paper and pencil for her; and she sat down and began to write. She wrote a few words, stopped, and bit the end of the pencil.

"It's dreadful when gentlemen will quarrel about you," she said in a tone and with an air in which gratified vanity forced itself firmly through the affectation of distress.

"What gentlemen?" said Pollyooly.

"Mr. Vance and my fiongsay, Mr. Reginald Butterwick," said Flossie. "I don't know how he found out that Mr. Vance is friendly with me; and I'm sure there's nothing in it—I told him so. But he's that jealous when there's a gentleman in the case that he can't believe a word I say. It isn't that he doesn't try; but he can't. He says he can't. He's got a passionate nature; he says he has. And he can't do anything with it. It runs away with him; he says it does. And now it's Mr. Vance. How he found out I can't think—unless it was something I let slip by accident about his taking me to the Chelsea Empire. He's so quick at taking you up—Reginald is; and before you know where you are, there he is—making a fuss. And what's going to happen I don't know."

Her effort to look properly distressed failed.

Pollyooly was somewhat taken aback by the flood of information suddenly gushed upon her; but she said calmly:

"But what's he going to do?"

"He's going to knock the stuffing out of Mr. Vance—he said he would. And he'll do it, too—I know he will. He's done it before. There was a gentleman friend of mine who lives in the same street as me in Hammersmith; and he got to know about him—not that there was anything to know, mind you—but he thought there was. And he blacked his eyes and made his nose bleed. You see, Reginald's a splendid boxer; he boxes at the Chiswick Polytechnic. And if he goes for Mr. Vance he'll half kill him—I know he will. Reginald's simply a terror when his blood's up."

"But Mr. Vance is very big," said Pollyooly in a doubting tone.

"But that makes no difference; bigness is nothing to a good boxer," said Flossie with an air of superior knowledge. "Mr. Butterwick says he doesn't mind taking on the biggest man in England, if he's not a boxer. And he knows that Mr. Vance isn't a boxer, because I asked him about boxing—knowing Reginald put it into my head—and he told me he didn't know a thing about it. And he'd have no chance at all against Reginald. And I let it out when I was telling Reginald that Mr. Vance was a friend of mine—only just a friend of mine—and he mustn't hurt him, and there was nothing to make a fuss about."

"I don't see why you wanted to tell him about Mr. Vance at all for, if you knew he'd make a fuss," said Pollyooly in a tone of disapproval.

"I told you it slipped out when I wasn't thinking," said Flossie, in a tone which carried no conviction; and she bent hastily to the note and added a couple of lines.

Then she broke out again in the same high-pitched, excited tone:

"And I came round here as soon as I could get away, because there wasn't any time to be lost. Reginald says he doesn't believe in losing time in anything. And he's going to take an afternoon off and come round and knock the stuffing out of Mr. Vance this very day. He can always get an afternoon off, for he's with Messrs. Mercer & Topping, and the firm has the greatest confidence in him; he says they have."

She finished the note and folded it, saying with the air which Pollyooly found hypocritical:

"It's really dreadful when gentlemen will quarrel about one so. But what am I to do? There's no way of stopping them. You'll know what it is when you get to my age—at least you would if you hadn't got red hair."

With this almost brilliantly tactful remark, she rose, gave Pollyooly the note, and adjured her to give it to Mr. Hilary Vance the moment he came in.

"What time will Mr. Butterwick get here?" said Pollyooly anxiously.

"There's no saying," said Flossie cheerfully. "But he'll get here as soon as the firm can spare him. He never loses time—Reginald doesn't."

Again she adjured Pollyooly to give Hilary Vance the note as soon as he returned, and hurried down the street to the florist's shop.

Flossie's news filled Pollyooly with a considerable anxiety; but she was at a loss what to do. She knew that Hilary Vance was at the Savage Club, but she did not know whether she could reach it in time to find him there, for it was now a quarter of two. It did not seem to her a matter to be trusted to the electric telegraph; and living as she did in the old-time Temple, it never occurred to her to telephone.

There was nothing to do but await his return and give him Flossie's note of warning the moment he entered. She had been going to take the Lump for a walk on the embankment; she must postpone it. Then, unused to idleness, she cast about how she might fill up her time till his return.

She had swept and dusted the room that morning, after the departure of Mrs. Thomas, who had busied herself in them, for a short time, and ineffectually, with a dustpan, a brush, and a duster, so that there was no cleaning to be done. Presently it occurred to her that perhaps there might be some holes in the linen of her host which would be the better for her mending. A brief examination of his wardrobe showed her that her surmise was accurate: there was at least a month's hard mending to be done before that wardrobe would contain garments really worthy of the name of underclothing. She decided to begin by darning his socks, for she chanced to have some black darning wool in her workbox. She brought three pairs of them into the studio, and began to darn. Nature had been generous, even lavish, to Hilary Vance in the matter of feet; and his socks were enormous. So were the holes in them. But their magnitude did not shake Pollyooly's resolve to darn them.

She had been at work for about three-quarters of an hour when there came a knock at the door. She went to it in some trepidation, expecting to find a raging Butterwick on the threshold. She opened it gingerly, and to her relief looked into the friendly face of Mr. James, the novelist.

On that friendly face sat the expression of weary resignation with which he was wont to intervene in the affairs of his great-hearted, but impulsive, friend.

He greeted Pollyooly warmly, and asked if Hilary Vance were in. Pollyooly told him the artist was lunching at the Savage Club.

Mr. James hesitated; then walking down the passage into the studio, he said:

"Well, I expect that you'll be able to tell me the latest news of the affair. I've just got back from Scotland to find a letter from Mr. Ruffin to say that Mr. Vance has at last found the lady of his dreams and is engaged to be married to a florist's assistant of the name of Flossie. I expect Mr. Ruffin's rotting; he knows what a bother Mr. Vance is. But I thought I'd better come round and make sure. Do you know anything about it?"

"I don't think he's engaged to her quite. But he's expecting to be every day," said Pollyooly.

"Oh, he is, is he?" said Mr. James in a tone of some exasperation. "What's she like?"

"She's fair, with a lot of fair hair and a very large hat with lots of flowers in it," said Pollyooly.

"She would be!" broke in Mr. James with a groan.

"And she gives herself airs because of that hat."

"Just what I supposed," said Mr. James, fuming.

"But she's engaged to Mr. Reginald Butterwick," said Pollyooly.

"The deuce she is!" cried Mr. James; and a faint gleam of hope brightened his face. "And who is Mr. Reginald Butterwick?"

"He's with Messrs. Mercer & Topping; but he can always get an afternoon off to knock the stuffing out of any one, because he boxes at the Chiswick Polytechnic. And he's going to get his afternoon off to-day to knock the stuffing out of Mr. Vance."

"The deuce he is!" cried Mr. James. "Well, a good hiding would do Hilary a world of good," he added in a vengeful tone. "Teach him not to go spooning florists' assistants."

"Oh, no. He might get hurt ever so badly," said Pollyooly firmly.

Mr. James' face grew stubborn; then it softened, and he said:

"Well, there's always the danger of his getting a finger broken; and that wouldn't do. I suppose we must stop the affray—it might get into the papers too."

"Yes: we must stop it, if we can," said Pollyooly anxiously.

"Well, if he's lunching at the Savage he'll play Spelka after it; and I shall catch him there. I'll keep him out all the afternoon—till his rival has tired of waiting and gone."

"Oh, yes. That would be much the best," said Pollyooly gratefully.

Mr. James went briskly to the door. At it he stopped and said:

"There's a chance that I may miss him. There may not be a game of Spelka; and he may come straight home. Perhaps you'd better wait in till about five."

"Yes: I think I'd better. He'd be sure to come back and not know anything about Mr. Butterwick, if there weren't anybody here," said Pollyooly.

He bade her good-bye; and let himself out of the house. She returned to her darning.

It was as well that she had not left the house, for about twenty minutes later the front door was opened, and the passage and studio quivered gently to Hilary Vance's weight. Pollyooly sprang up and met him at the door of the studio with Flossie's note.

At the sight of the handwriting, a large, gratified smile covered all the round expanse of his face. But as he read, the smile faded, giving way to an expression of the liveliest surprise and consternation.

"What the deuce is this?" he cried loudly.

"She said he was going to knock the stuffing out of you, Mr. Vance, and he might be here any time this afternoon," said Pollyooly.

"And what the deuce for? What's it got to do with him?" cried Hilary Vance.

"She said he was her fiongsay," said Pollyooly, faithfully reproducing Flossie's pronunciation.

"Her fiancé?" roared Hilary Vance in accents of the liveliest surprise, dismay, and horror. "Oh, woman! Woman! The faithlessness! The treachery!"

With a vast, magnificent expression of despair he dropped heavily on to the nearest chair without pausing to select a strong one. Under the stress of his emotion and his weight the chair crumpled up; and he sat down on the floor with a violence which shook the house. He sprang up, smothered, out of regard for the age and sex of Pollyooly, some language suggested by the occurrence, and with a terrific kick sent the fragments of the chair flying across the studio. Then he howled, and holding his right toes in his left hand, hopped on his left leg. He had forgotten that he was wearing thin, but patent-leather, shoes.

Then he put his feet gingerly upon the floor, ground his teeth, and roared:

"Knock the stuffing out of me, will he? I'll tear him limb from limb! The insidious villain! I'll teach him to come between me and the woman I love!"

Sad to relate Pollyooly's heart, inured to violence by her battles with the young male inhabitants of the slum behind the Temple, where she had lodged before becoming the housekeeper of the Honourable John Ruffin, leapt joyfully at the thought of the fray, in spite of her friendship with Hilary Vance; and her quick mind grasped the fact that she might watch it in security from the door of her bedroom. Then her duty to her host came uppermost.

"But please, Mr. Vance: he's a boxer. He boxes at the Chiswick Polytechnic," she cried anxiously.

"Let him box! I'll tear him limb from limb!" roared Hilary Vance ferociously; and he strode up and down the studio, limping that he might not press heavily on his aching toes.

Pollyooly gazed at him doubtfully. Flossie's account of Mr. Butterwick's prowess had impressed her too deeply to permit her to believe that anything but painful ignominious defeat awaited Hilary Vance at his hands.

"But he blacks people's eyes and makes their noses bleed," protested Pollyooly.

"I'll tear him limb from limb!" roared Hilary Vance, still ferociously, but with less conviction in his tone.

"And he doesn't care how big anybody is, if they don't know how to box," Pollyooly insisted.

"No more do I!" roared Hilary Vance.

He stamped up and down the studio yet more vigorously since his aching toes were growing easier. Then he sank into a chair—a stronger chair—gingerly; and in a more moderate tone said:

"I'll have the scoundrel's blood. I'll teach him to cross my path."

He paused, considering the matter more coldly, and Pollyooly anxiously watched his working face. Little by little it grew calmer.

"After all it may not be the scoundrel's fault," he said in a tone of some magnanimity. "I know what women are—treachery for treachery's sake. Why should I destroy the poor wretch whose heart has probably been as scored as mine by the discovery of her treachery? He is a fellow victim."

"And perhaps you mightn't destroy him—if he's such a good boxer," said Pollyooly anxiously.

"I should certainly destroy him," said Hilary Vance with a dignified certainty. "But to what purpose? Would it give me back my unstained ideal? No. The ideal once tarnished never shines as bright again."

His face was now calm—calm and growing sorrowful. Then a sudden apprehension appeared on it:

"Besides—suppose I broke a finger—a finger of my right hand. Why should I give this blackguard a chance of maiming me?" he cried, and looked at Pollyooly earnestly.

"I don't know, Mr. Vance," said Pollyooly, answering the question in his urgent eyes.

"If I did break a finger, it might be weeks—months before I could work again. Why, I might never be able to work again!" he cried.

"That's just what Mr. James was afraid of," said Pollyooly.

"Mr. James! Has he been here?" cried Hilary Vance; and there was far more uneasiness than pleasure in his tone on thus hearing of his friend's return.

"Yes. He came to know if you were engaged yet," said Pollyooly.

"Oh, did he?" said Hilary Vance very glumly.

"Yes. And I told him you weren't."

"That's right," he said in a tone of relief.

"And he said we must stop the affray."

"He was right. It would be criminal," said Hilary Vance solemnly. "After all it isn't myself: I have to consider posterit—"

A sudden, very loud knocking on the front door cut short the word.

"That's him!" said Pollyooly in a hushed voice.

Hilary Vance rose, folded his two big arms, and faced the door of the studio, his brow knitted in a dreadful frown.

"Hadn't I better send him away?" said Pollyooly anxiously.

Hilary Vance ground his teeth and scowled steadily at the studio door for a good half-minute. Then he let his arms fall to his sides, walked with a very haughty air to his bedroom, opened the door, and from the threshold said:

"Yes: you'd better send him away—if you can."

As Pollyooly went to let the visitor in, she heard him (Mr. Vance) turn his key in the lock of his bedroom door.

It was perhaps as well that he did so; for as Pollyooly opened the front door a young man whose flashing eye proclaimed him Mr. Reginald Butterwick, pushed quickly past her and bounced into the studio.

Pollyooly followed him quickly, somewhat surprised by his size. He bounced well into the studio with an air of splendid intrepidity, which would have been more splendid had he been three or four inches higher and thicker, and uttered a snort of disappointment at its emptiness.

He turned on Pollyooly and snapped out:

"Where's your guv'ner? Where's Hilary Vance?" Pollyooly hesitated; she was still taken aback by the young man's lack of the formidable largeness Flossie had led her to expect; and she was, besides, a very truthful child. Then she said:

"I expect he's somewhere in Chelsea."

"When'll he be back?" snapped the young man.

"He's generally in to tea," with less hesitation; and she looked at him with very limpid eyes.

"He is, is he? Then I'll wait for him," said the young man in as bloodcurdling a tone as his size would allow: he did not stand five feet three in his boots.

He stood still for a moment, scowling round the studio; then he said in a dreadful tone:

"There'll be plenty of room for us."

He fell into the position of a prizefighter on guard and danced two steps to the right, and two steps to the left.

Pollyooly gazed at him earnestly. Except for his flashing eye, he was not a figure to dread, for what he lost in height he gained in slenderness. He was indeed uncommonly slender. In fact, either he had forgotten to tell Flossie that he was a featherweight boxer, or she had forgotten to pass the information on. The most terrible thing about him was his fierce air, and the most dangerous-looking his sharp, tip-tilted nose.

Then Pollyooly sat down in considerable relief; she was quite sure now that did Mr. Reginald Butterwick discover that his rival was in his bedroom and hale him forth, the person who would suffer would be Mr. Reginald Butterwick. She took up again the gigantic sock she was mending; and she kept looking up from it to observe with an easy eye the pride of the Polytechnic as he walked round the studio examining the draperies, the pictures, and the drawings on the wall. Whenever his eye rested on one signed by Hilary Vance he sniffed a bitter, contemptuous sniff. For these he had but three words of criticism; they were: "Rot!" "Rubbish!" and "Piffle!"

Once he said in a bitterly scoffing tone:

"I suppose your precious guv'ner thinks he's got the artistic temperament."

"I don't know," said Pollyooly.

He squared briskly up to an easel, danced lightly on his toes before it, and said:

"I'll give him the artistic temperament all right."

At last he paused in his wanderings before the industrious Pollyooly, and his eyes fell on the gigantic sock she was darning. She saw his expression change; something of the fierce confidence of the intrepid boxer passed out of his face.

"I say, what's that you're darning?" he said quickly.

"It's a sock," said Pollyooly.

"It looks more like a sack than a sock. Whose sock is it?" said Mr. Reginald Butterwick; and there was a faint note of anxiety in his tone.

"It's Mr. Vance's sock," said Pollyooly; and with gentle pride she held it up in a fashion to display its full proportions.

Mr. Reginald Butterwick took two or three nervous steps to the right, looking askance at the sock as he moved. It was not really as large as a sack.

"Big man, your guv'ner? Eh?" he said in a finely careless tone.

"I should think he was!" cried Pollyooly with enthusiasm.

Mr. Reginald Butterwick looked still more earnestly at the sock and said:

"One of those tall lanky chaps—eh?"

"He's tall, but he isn't lanky—not a bit," said Pollyooly quickly. "He's tremendously big—broad and thick as well as tall, you know. He's more like a giant than a man."

"Oh, I know those giants—flabby—flabby," said Mr. Reginald Butterwick; and he laughed a short, scoffing laugh which rang uneasy.

"He's not flabby!" cried Pollyooly indignantly. "He's tremendously strong. Why—why—when he heard you were coming he smashed that chair and kicked it into the corner just because he was annoyed."

Mr. Reginald Butterwick looked at the smallish fragments of the chair in the corner; and his face became the face of a quiet, respectable clerk.

"He did, did he?" he said coldly.

"Yes, and he wanted to tear you limb from limb. He said so," said Pollyooly.

"That's a game two can play at," said Mr. Reginald Butterwick; but his tone lacked conviction.

"Oh, he'd do it—quite easily," said Pollyooly confidently.

Mr. Reginald Butterwick stared at her and then at the sock. He opened his mouth to speak and then shut it again. Then he whistled a short, defiant whistle which went out of tune toward the end. Then he walked the length of the studio and back. Then he stopped and said to Pollyooly very fiercely:

"Do you think I've got nothing else to do but wait here all the afternoon for your precious guv'ner to come home to tea?"

"I don't know," said Pollyooly politely.

"Well, I have—plenty," said Mr. Reginald Butterwick savagely.

Pollyooly said nothing.

"And what's more, I'm going to do it!" said Mr. Reginald Butterwick yet more savagely; and he strode firmly to the door. On the threshold he paused and added: "But you tell your guv'ner from me—Mr. Reginald Butterwick—that he hasn't seen the last of me—not by a long chalk. One of these fine nights when he's messing round with—well, you tell him what I've told you—that's all. He'll know."

With that he passed through the door and banged it heavily behind him. The front door was larger and heavier, so that he was able to bang it more loudly still.

Pollyooly heaved a sigh as the studio trembled to the shock of the banged front door, a sigh chiefly of relief, but tinged also with a faint regret that she had not seen Mr. Reginald Butterwick torn limb from limb. She knew that she would not really have enjoyed the sight; and the mess in the cleaned studio would have been exceedingly annoying; but there were primitive depths in her heart, and somewhere in them was the regret that she had missed the thrilling spectacle.

The studio still quivered to the bang, the sigh still trembled on Pollyooly's lip, when the bedroom door opened, and Hilary Vance came forth with an immense scowl on his spacious face and said fiercely:

"So the scoundrel's gone, has he?"

"Yes. When I told him how big you were, he didn't seem so eager to fight. And he went away," said Pollyooly quickly. "But he told me to tell you that you hadn't seen the last of him—not by a long chalk."

Her host's scowl lightened a little; there was almost a faint satisfaction on his face as he said:

"So he fears my rivalry still, does he?" Then his face grew gloomier than ever; and he added: "There's no need. I am not one to sit at the feet of a tarnished ideal. There will be a gap—there is a gap—but I have done with HER for good and all. I have—done—with—HER."

He had drawn himself up to utter the last words with a splendid air; then he said sadly:

"I think I should like my tea."

"I'll get it at once," said Pollyooly cheerfully.

She was not long about it. Hilary Vance took the Lump on his knee, gave him a lump of sugar, poured out the tea, and began to drink it with an air of gloomy resignation.

Presently he patted the Lump's bright red curls and said:

"Let this be a warning to you, red cherub, never to trust a woman—never as long as you live."

The Lump grunted peacefully.

"He's too young to understand, or it wouldn't be right to teach him such a thing as that," said Pollyooly in a tone of disapproval.

"Not right?" cried Hilary Vance stormily. "But you've seen for yourself! You've seen how that girl led me on to squander the treasure of a splendid passion on her unresponsive spirit while, all the time, she was abasing herself before a miserable, preposterous scoundrel like that ruffian Butterwick."

"He was rather small," said Pollyooly thoughtfully. "But I daresay he'd make her a good husband. He looked quite respectable."

"A good husband!" cried Hilary Vance with a dreadful sneer.

"But I expect she'll lead him a life. She looked like it," said Pollyooly, thoughtfully pursuing the subject.

"Serve him right!" cried Hilary Vance with terrible scorn. "He has learnt her treachery to me; and if he marries her after that, he deserves all he gets. If she betrays my trust, she'll betray his."

Pollyooly was silent, considering the matter. Then, summing it up, she said with conviction:

"I don't think she's the kind of girl to trust at all."

"I must have been blind—blind," said Hilary Vance.

Then came the sound of a taxicab drawing up before the house, and then a knocking at the front door. Pollyooly opened it, and found Mr. James on the threshold. He looked uncommonly anxious and said quickly:

"I missed him. Has he come back?"

"Yes; he's having his tea."

"And this fellow Butterwick?" said Mr. James.

"Oh, he came; and then, when he found how big Mr. Vance is, he went away. But he hasn't done with Mr. Vance—not by a long chalk. He told me to tell him so," said Pollyooly.

"Well, I'm glad they didn't scrap," said Mr. James in a tone of relief. "If they didn't at once, they're not very likely to later."

"Oh, no: they won't now," said Pollyooly confidently. "You see as soon as he heard that Mr. Butterwick was her—her fiongsay"—she hesitated over the word because Hilary Vance had shaken her original conception of its pronunciation—"he gave her up for good."

"That is a blessing," said the novelist in a tone of yet greater relief.

He had been looking forward to a disagreeable and very likely hopeless struggle with his friend's infatuation.

He walked down the passage and into the studio briskly. But not quickly enough to prevent an expression of funereal gloom flooding Hilary Vance's face.

"How are you?" said Mr. James cheerfully.

"In the depths—in the depths—my last illusion shattered," said the artist in the gloomiest kind of despairing croak.

"Oh, you never know," said Mr. James.

"I shall never trust a woman again—never," said the artist in an inexorable tone.

"But I thought you'd given up trusting them months ago," said Mr. James in considerable surprise.

"I was deceived—this one seemed so different. She was a serpent—a veritable serpent," said Hilary Vance in his deepest tone.

"Yes. They are apt to be like that," said Mr. James with some carelessness. "May I have some tea?"

Gloomily the artist poured him out a cup of tea; gloomily he watched him drink it. Heedless of his gloom, Mr. James plunged into an account of his stay in Scotland, telling of the country, the food, and the people with an agreeable, racy vivacity. Slowly the great cloud lifted from Hilary Vance's ample face. He grew interested; he asked questions; at last he said firmly:

"I must go to Scotland. Nature—Nature pure and undenied is what my seared soul needs."

"It wouldn't be a bad idea," said Mr. James.

"I shall wear a kilt," said Hilary Vance solemnly. "The winds of heaven playing round my legs would assist healing nature; and I must be in complete accord with the country."

"A kilt wouldn't be a bad idea," said Mr. James.

Hilary Vance paused and appeared to be thinking deeply; then he said:

"The Scotch peasant lassies, James—are they as attractive nowadays as they appear to have been in the days of Burns?"

"I thought you'd done with women!" cried Mr. James.

"I have done with women," said the poet with cold sternness. "I have done with the cold-hearted, treacherous, meretricious women of the town. But the simple, trusting and trustworthy country girl, the daughter of the soil, in perpetual touch with nature—surely communion with her would be healing too."

"Oh, hang it all!" said Mr. James quite despondently.

Hilary Vance plunged once more into deep thought; then he said:

"Where does one buy a kilt—and a sporran?"

"Whiteley's, I suppose," said Mr. James. Then he added hastily: "But I say, oughtn't we to do something to amuse these children?"

At once his friend forgot his seared heart; for the while the process of healing it did not exercise his wits. He flung himself heart and soul into the business of amusing Pollyooly and the Lump; and presently the studio rang with their screams of joy. There may have been some truth in the assertion of his detractors that Hilary Vance's drawing was facile and too far on the side of mere prettiness; but no one in the world could deny that he made a splendid elephant: his trumpeting was especially true to life.

Ten days passed pleasantly at his studio; and both Pollyooly and the Lump were the better for the change. Three times she went to the King's Bench Walk and cleaned the rooms against the Honourable John Ruffin's return; four times she went to the dancing class in Soho, where she was training for a career on the stage. On the evening of the tenth day came a letter to say that he would be back at noon on the morrow. After breakfast, therefore, Hilary Vance despatched the two children back to the King's Bench Walk in a taxicab, the Lump hugging a large box of chocolate creams, Pollyooly, in no less joy, clasping firmly her shabby little purse which contained, beyond the silver she carried to meet any natural expense, a golden sovereign, the artist's parting gift. Her sky was now serene; but she was still mindful of the days when the jaws of the workhouse had yawned for her and the Lump, and she lost no chance of adding to her hoard in the Post Office Savings Bank. Immediately on her arrival at the Temple she went to the post office and added the sovereign to it.

The Honourable John Ruffin arrived from Buda-Pesth, looking the browner for the change, and in very good spirits. He brought the friendliest messages and Hungarian gifts to Pollyooly and the Lump from the Esmeralda, and was able to assure them that she was in excellent health, and enjoying a genuine triumph.

When he had delivered the Esmeralda's gifts and assured Pollyooly of her prosperity, there came a short silence; then Pollyooly said:

"And the Moldo-Wallachian, sir?"

The fine grey eyes of the Honourable John Ruffin twinkled, as he said gravely:

"The Moldo-Wallachian has returned to Moldo-Wallachia. When the ideal was once more clearly presented to the Esmeralda, the attractions of the Moldo-Wallachian faded as flowers fade in a drought."

"I'm glad she isn't going to marry a foreigner," said Pollyooly with true patriotism.

"She would never be happy in Moldo-Wallachia," said the Honourable John Ruffin with conviction.

"Oh, no, sir," said Pollyooly.

There was a pause; then he said:

"And how did you leave Mr. Vance?"

"Oh, he was all right, sir," said Pollyooly.

"Oh, he was, was he? Did you by any chance come across a young lady of the name of Flossie while you were staying at Chelsea?"

"Yes, sir. But he doesn't have anything to do with her now, sir. He goes past the shop with an air of cold dignity—he says he does; and he's going to Scotland to wear a kilt to get quite cured—he says he is," said Pollyooly quickly.

"It sounds most efficacious," said the Honourable John Ruffin. "But how did it all happen?"

Pollyooly told the story of the intervention of Mr. Butterwick; and the Honourable John Ruffin chuckled freely, for no reason that she could see, as he listened to it. At the end of it he said sententiously:

"Well, all's well that ends well. These foreign countries are not suited to English girls: Miss Flossie would never be happy in Bohemia."

The next morning, when she brought in his grilled bacon, he said that they might now congratulate themselves on the prospect of leading their quiet, industrious lives in peace for a while.

These congratulations, however, were premature, for only three days later he was sitting in his rooms, having just come from the Law Courts, where he had been acting as junior counsel in an awkward case, and was bracing himself to the effort of getting himself his afternoon tea, since Pollyooly had gone with the Lump to take the air in Hyde Park.

Suddenly there came a sharp, hurried knocking on his outer door.

The Honourable John Ruffin raised his eyebrows, opened his eyes rather wide, and said to his cigarette:

"A woman in distress, evidently. Who on earth can it be?"

He did not spring to his feet and dash to the door to offer instant aid to the distressed one. He rose slowly and walked slowly to the door, assuming slowly as he went an air of deep, but patient, resignation.

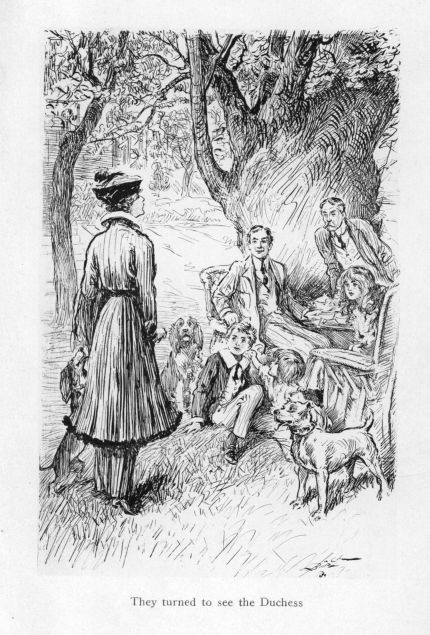

He opened the door gingerly. On the threshold stood the beautiful, high-spirited and wilful Duchess of Osterley.

"Caroline, by Jove! Why, I thought you were out of England, still hiding Marion from Osterley," he cried, and smiled with pleasure at the sight of her beautiful face.

The Duke and Duchess of Osterley had been at daggers drawn for nearly two years; and since both of them had sought to bring their feud forcibly to an end in the Law Courts, the Anglo-Saxon peoples had had no cause to complain of any lack of effort on their part to be entertaining. The upshot of the law proceedings had been that the Court, with a futility almost fatuous, had ordered the duchess to return to her husband, and, what was far more important, had given the custody of their little daughter of twelve, Lady Marion Ricksborough, to the duke.

The Anglo-Saxon peoples felt that the duke had scored heavily; and the duchess agreed with them. She was not one to sit submissive under defeat; and presently those peoples read with the liveliest interest and pleasure that she had carried off her daughter and hidden her with such skill that the detectives, official and unofficial, had failed utterly to find her.

In this carrying off and hiding Pollyooly had played the important part. It had been a freak of nature to make her and Lady Marion Ricksborough so closely alike, that even when they were together it was hard to tell which was which. The duchess had taken advantage of this likeness to substitute Pollyooly for Lady Marion at Ricksborough Court, the duke's chief country seat, for a fortnight.

The duke, Lady Marion's nurse, and her governess had believed Lady Marion Ricksborough to be still with them, and had given the duchess all the time she needed to hide her.

For a whole fortnight Pollyooly had played her part with such skill that only the duke's nephew and heir, Lord Ronald Ricksborough, had discovered that she was not Lady Marion. A most discreet boy of fourteen, and already Pollyooly's warm friend, he was the last person to spoil the sport; and at the end of the fortnight she had slipped away and returned by motor car to her post of housekeeper to the Honourable John Ruffin and Mr. Gedge-Tomkins in the King's Bench Walk.

Ignorant of the fact that Lady Marion Ricksborough had fled a fortnight previously, the detectives, both official and private, had taken up the search for her from the moment of Pollyooly's disappearance from the Court. It is hardly a matter for wonder that they did not go far along a trail which had been cold for a fortnight.

As he said, the Honourable John Ruffin had believed the duchess to be hiding out of England; and he showed himself unfeignedly pleased to see her. He put her in his most comfortable chair, made her take off her hat, and said:

"Now, I'll make you some tea."

The Honourable John Ruffin went to the kitchen; the duchess rose restlessly and followed him. As he made the tea he lectured her on the importance of making it not only with boiling water, but with water which had not been boiling for more than a quarter of a minute, and that poured on to a fine China tea in a warmed pot without taking the kettle right off the stove.

The rebellious duchess, impatient to tell him the object of her visit, made several faces at him; and twice she said contemptuously:

"You and your old tea!"

But when she came to drink it, she admitted handsomely that it was better than she could have made it herself.

She drank it; grew suddenly serious, and said:

"John, I'm in a mess, and I've come to you for help."

"It is yours to the half of my fortune—at present about fourteen shillings," said the Honourable John Ruffin warmly.

"Well, I didn't take Marion abroad," said the duchess. "They always look abroad for people who bolt. I borrowed Pinky Wallerton's car and drove her down, myself, to a cottage I bought in Devonshire—in the pinewoods above Budleigh Salterton."

"That sounds all right."

"It was—quite—till this morning. Then, without a word of warning, at eleven o'clock, one of Osterley's lawyers turned up with a detective."

"And got her?"

"No. Fortunately she was out in the wood with her nurse. I gave Eglantine, my maid, twenty pounds and told her to get quietly to Marion while I kept the brutes in play, rush her down to the station, and catch the London train. They'd just time if they ran most of the way."

"But the lawyer would only have to wire to Osterley to meet the train at Waterloo," said the Honourable John Ruffin.

"I thought of that," said the duchess quickly. "I told her to leave the express at Salisbury, go on to Woking by a slow train, take a taxi from there to my old nurse's, Mrs. Simpson's, in Camden Town, and leave Marion with her."

"Excellent," said the Honourable John Ruffin in warm approval.

"Then she's to come on here with Marion's clothes in time to catch the six o'clock to Exeter from Paddington."

"Here? With Marion's clothes? What for?" said the Honourable John Ruffin.

"Why, to put on Mary Bride—Pollyooly as you call her. I want to borrow her again, substitute her for Marion, and let her keep the brutes quiet while I carry Marion off to a cottage I have bought in the north of Scotland for just such an emergency as this."

The Honourable John Ruffin sprang to his feet with flashing eyes:

"What? Rob me of my bacon-griller again? The last time my breakfast was spoilt for a fortnight. You don't know what you ask!" he cried in tones in which indignation and horror were nicely blended.

"Oh, but this won't be for a fortnight—a couple of days at the outside. Surely you could eat fish for breakfast for a couple of mornings," pleaded the duchess.

"I never eat fish for breakfast," said the Honourable John Ruffin coldly. "I am an Englishman and a patriot—eggs and bacon."

"But just for once," said the duchess.

The hard expression faded slowly from his face; he took a turn up and down the room; then he said in a tone of infinite sadness:

"Well, well, I suppose I must sacrifice myself again. What a thing it is to be a cousin! But how are you going to work it? Surely you're being followed?"

"Rather," said the duchess cheerfully. "But I don't take Mary Bride with me. I go back to Budleigh Salterton by the four forty-five from Waterloo; and my follower will no doubt go with me. Eglantine and Mary Bride will go down to Exeter by the six o'clock from Paddington, motor over, and slip into the house late at night. There's sure to be some one watching it; and once they believe Marion to be in it, they'll go on watching it without bothering about me. I only want to be left alone for six hours, and I'll get Marion away without leaving a trace."

"Strategist," said the Honourable John Ruffin in a tone of admiring approval. "I hope you'll pull it off. You deserve to for having thought it out so thoroughly. Fortunately, Pollyooly is due home at a quarter of five, so there'll be no trouble there. She's the most punctual person in the Temple."

"That's lucky," said the duchess with a sigh of thankfulness.

There was nothing more to be arranged; and if she were going to catch her train comfortably, it was time that she started for Waterloo. He escorted her to Fleet Street, put her into a taxicab, and bade her good-bye.

The taxicab started; he turned to return to his rooms, stopped short, and said sharply:

"Bother! I forgot to arrange about Pollyooly's salary!"

On his way back to the King's Bench Walk the Honourable John Ruffin pondered this matter of salary and came to the conclusion that five pounds would not be too high a fee for the duchess to pay for skilled work of this kind. He must remember to tell Eglantine to tell her to give Pollyooly that sum.

Pollyooly was rather earlier than he had expected: at five and twenty minutes to five he heard her latchkey in the lock of his outer door, and when it opened he called to her to come to him.

She entered leading the Lump. His red hair was a rather brighter red than the hair of Pollyooly; but his eyes were of the same deep blue and his clear skin of the same paleness. They would have made a charming picture of Cupid led by an angel child.

"Ah, Pollyooly!" said the Honourable John Ruffin cheerfully. "You are about to realise the truth of those immortal lines:

"Oh, what a tangled web we weave

When first we practice to deceive!"

"Please, sir, I haven't been deceiving any one," said Pollyooly, knitting her brow in a faint anxiety.

"Not recently, perhaps. But you have deceived. You deceived the Duke of Osterley by taking the place of his daughter."

"Oh, him?" said Pollyooly in a very care-free tone; and her face grew serene.

"You don't seem to feel it much," said the Honourable John Ruffin sadly. "But now you are called on to deceive lawyers and detectives."

"Am I to be Lady Marion again?" said Pollyooly quickly.

"You are, indeed," said the Honourable John Ruffin.

"And shall I be paid again for doing it?"

Her angel face flushed, and her blue eyes danced.

"Certainly you will be paid. I am going to tell Eglantine, the duchess's maid, to see to it. She's coming for you, and you haven't any time to lose. She's going to take you down to Devonshire by the train which leaves Paddington at six," said the Honourable John Ruffin.

"Then I'd better take the Lump round to Mrs. Brown at once," said Pollyooly; and her eyes sparkled and danced.

"You had," said the Honourable John Ruffin. "It's only for a couple of nights at the outside, tell her."

"And that's quite as long as I like to leave him," she said in a tone of complete satisfaction; and she ran briskly up-stairs to their attic for the Lump's sleeping-suit.

She was not long taking him to Mrs. Brown, who lived in the little slum, the last remnant of Alsatia, behind the King's Bench Walk; and she welcomed him warmly. Pollyooly and he had lodged with her before they had gone to live in the King's Bench Walk, and Mrs. Brown had grown very fond of him. She had taken charge of him during the time Pollyooly had spent at Ricksborough Court and was delighted to have him with her again. Also she was disengaged for the next two days and was able to take charge of the housekeeping at number 75 the King's Bench Walk during Pollyooly's absence.

Pollyooly had not been gone five minutes, when there came a gentle knocking at the door of the Honourable John Ruffin's chambers. He opened it to find Eglantine, a pretty, dark, slim girl of twenty-two, standing on the doormat, carrying a small kitbag and wearing an air of deepest mystery.

"You're Mademoiselle Eglantine, I suppose?" he said.

"Ye—es. And you are Monsieur Ruffin," she whispered with an air of utter secrecy. "Ze duchess she 'av been 'ere?"

"She has. Come on in. Pollyooly is making preparations to go with you," said the Honourable John Ruffin briskly. "She'll be here in a few minutes."

He stepped aside for her to pass. She looked back down the staircase carefully and with the greatest caution; then she entered and went on tiptoe, noiselessly, down the passage into the sitting-room. There could be no doubt that she was thoroughly enjoying the part of a conspirator and resolved to play it to the limit.

The Honourable John Ruffin was the last man in the world to spoil her simple pleasure, and as they came into the sitting-room he suddenly gripped her arm.

Eglantine jumped and squeaked.

"Hist!" said the Honourable John Ruffin, laying a finger on his lips, frowning portentously, and rolling his eyes. Then he added in blank verse, as being appropriate to the conspiratorial attitude: "I thought I heard a footstep on the stairs."

They both listened intently—at least Eglantine did; she hardly breathed in her intentness. Then he said in a declamatory fashion:

"I was mistaken; we are saved again."

He loosed her arm. She breathed more easily, tapped the kit-bag, and said:

"I 'av brought ze Lady Marion's clo'es."

"Good," said the Honourable John Ruffin. "Sit down."

She sat down, breathing quickly, gazing earnestly at the Honourable John Ruffin, who folded his arms and wore his best darkling air.

Presently Pollyooly's key grated in the lock.

"Hist! She comes!" said the Honourable John Ruffin.

Eglantine rose, quivering.

Pollyooly came in, shut the door sharply behind her, and came briskly down the passage into the sitting-room.

At the sight of her Eglantine forgot the whispering caution of the conspirator; she cried loudly:

"But ze likeness! Eet ees marvellous! Incredible! Eet ees 'er leetle ladyship exact!"

"Yes. And she'll be more like her than ever in her clothes. Hurry up and get her into them," said the Honourable John Ruffin briskly.

He bustled them up the stairs to Pollyooly's attic; and as Eglantine helped her into Lady Marion Ricksborough's clothes, she continued to express her lively wonder at the likeness. She was not long making the change, and they came quickly downstairs. But the Honourable John Ruffin would not let them start at once.

"It's no use your getting there too early and hanging about the station," he said firmly. "That's when you'd get spotted. You want to get there just about three minutes before the train starts. You've no luggage to bother you."

He made both of them eat some cake, and gave Eglantine a glass of wine with it, for he thought that she needed something to steady her excited nerves. Then he told her that the duchess was to pay Pollyooly a fee of five pounds, and bade Pollyooly be sure to wire to him the time of the train by which she was returning to London.

Then he decided that it was time for them to start, and wished them good luck. He did not go with them, for he did not wish to be seen by any one taking an active part in the affairs of the Duke and Duchess of Osterley.

In the taxicab Eglantine was eloquent on the matter of the charm and distinction of the Honourable John Ruffin: plainly he had made a deep impression on her. But when they reached the station she resumed the striking manners of a conspirator so admirably that in the three minutes she spent paying the taxi-driver and buying tickets she attracted the keen attention of two of the detectives of the railway. They followed her, as she tiptoed about with hunched shoulders, and watched her with the eyes of lynxes; but she puzzled them. They assured one another that she had some game on (their knowledge of fallen human nature was too exact for them to miss that fact) but for the life of them they could not discover, or guess, what it was.

On the platform she chose an empty compartment and stood before the door of it for a good half-minute, looking up and down the train with eyes even more lynxlike than those of the detectives. Then she almost flung Pollyooly into the carriage, hustled her into the farthest corner, and fairly sat on her in her effort to screen her from the eyes of the crowd.

"Do not stir!" she hissed. "Ze train veel soon start! Zen we are saved!"

Pollyooly could not have stirred, had she wished, so firmly did Eglantine crush her into the corner. One of the detectives came to the window and stared into the carriage gloomily. Eglantine met his gaze with steady eyes. The guard whistled and waved his flag; the detective fell back. He said to his colleague that it was a rum go. The train started.

As their carriage passed out of the station, with a deep sigh of relief Eglantine relaxed to an easier, less crushing posture, and at once took up the subject of the Honourable John Ruffin. She showed herself exceedingly curious about him, and Pollyooly's natural discretion was somewhat strained in answering her questions. It was difficult to convey as little information as possible.

But at the end of half an hour Eglantine had exhausted that subject; and she turned to the yet more interesting matter of her own affairs. She had much to tell Pollyooly about Devonshire, the wet garden of England. Its horticultural advantages seemed to weigh but lightly with her; she dwelt chiefly on the loneliness of the life she had been leading, and deplored bitterly the fact that its inglorious ease was spoiling her figure by increasing her girth.

Then, with an air of mystery and in deeper tones, she confided to Pollyooly that her lot in this wet desert was not without its alleviation. A wealthy landowner (he did own a part of the market-garden he so sedulously cultivated) had developed a grand—oh, but a grand!—passion for her, and was positively persecuting her with his honourable intentions.

Pollyooly was deeply interested by her tale, for her recent experience with Mr. Hilary Vance, Mr. Reginald Butterwick and Flossie had forced the tender passion on her attention. She was greatly puzzled by the reason which Eglantine gave for not making her landowner happy by marrying him, that he was bearded. Mrs. Brown's husband, a cheerful policeman, was bearded; but they were uncommonly happy together. In the end she made up her mind that Eglantine's feeling in the matter must be a French prejudice.

They reached Exeter at a few minutes past ten; and having no luggage but the little kit-bag, in a few minutes, in spite of the conspiratorial air and behaviour of Eglantine, they were speeding swiftly in the motor car toward Budleigh Salterton. It was a delightful, moonlit night, and Pollyooly enjoyed the drive greatly.

About forty minutes later the car stopped at a little gate leading into a pine wood, and they descended, bade the driver good night, and went through it. In the path through the dark wood Eglantine lost her air of competent and excited leadership. She was timorous, held Pollyooly tightly by the arm, and when a bird, or an animal, rustled in the bushes, she squeaked.

At last the path ended in a little gate opening into the garden of the lonely house. They came up to it very gently, and Eglantine peered round the garden, searching for the lawyer and the detective.

It seemed empty, and as she opened the gate she whispered:

"We must roon quick!"

They bolted across the garden to the back door, and as they reached it a man burst out of the bushes twenty yards on their left, and dashed at them. Eglantine screamed, but she opened the door, dragged Pollyooly through it, slammed the door in the pursuer's face, and shot the bolt. At the sound of the bang the duchess came flying through the lighted hall. At the sight of Pollyooly she cried:

"Thank goodness you've come!"

Eglantine burst into an excited narrative of their journey and narrow escape from the watcher in the garden.

"Then he actually saw Mary Bride come into the house?" cried the duchess joyfully, and she clapped her hands.

"But yes! Ever so plainly!" cried Eglantine.

"Good! Nothing could be better!" said the duchess. "They'll think that Marion is in the house, and that's all I want."

She kissed Pollyooly, thanked her for coming, asked if the journey had tired her very much, and led her into the dining-room, where a delicious supper awaited her. As she ate it the duchess, watching her with an air of lively satisfaction, matured her plans. At last she said:

"I was going to let them catch you to-morrow morning, and then I was going up to London with you. But you look like a clever little girl; do you think you could hide in the wood from them all the morning? If you could, I would go up to London first thing, and I should have lots of time to get away with Marion before they caught you and found out who you were."

"Oh, yes! I'm sure I could!" cried Pollyooly eagerly; and her eyes shone with a bright joy at the prospect of so excellent a game of hide-and-seek. "If once I got into that wood, they'd never find me unless I let them. Only it would be a good deal easier if I wore a dark frock."

"You shall!" cried the duchess. "It would be perfectly splendid! I know you're a clever little girl. Otherwise you couldn't have made them believe for so long at Ricksborough Court that you were Marion. Cook shall make you up a packet of sandwiches so that you won't starve; and if you can keep them busy till the afternoon, we shall have all the time we want to get comfortably away."

"I think I can," said Pollyooly with the confidence born of much experience in hide-and-seek. "But even if they do catch me, they won't know I'm not Lady Marion; I'm sure I can keep them from bothering you all day."

The duchess kissed her again, and said:

"I shall be ever so much obliged to you if you do. But half a day will be quite enough. And now you'd better go to bed; you must be sleepy, and the more sleep you get the fresher you'll be to-morrow. I shall be gone long before you're up."

She took her up-stairs to Marion's bedroom, a charming room on the first floor, and Pollyooly found the most comfortable spring bed so lulling that in spite of her expectation of an exciting morrow, she soon fell asleep.

The yet more excited duchess was longer falling asleep; but she rose at half-past five and dressed and breakfasted. It was a quarter past six when she came out into the garden, on her way to the station, and found the detective sunning himself, after the chill of his night-watch, on the garden fence at a point from which he had under observation both the path to the front door and that to the back. He had a rather heavy face, but he showed a proper sense of her rank and position, for he rose and raised his hat nearly three inches, respectfully.

A woman of the world, the duchess knew the advantage of his having a tale to think upon, for she said with a nice show of indignation:

"I'm going straight to my solicitor in town to take the final steps to have this persecution stopped! I'm going to have you removed by the police. You enter this house and touch my little girl at your own risk! I've warned you."

"Yes, your Grace. Quite so, your Grace. It'll be all right, your Grace," said the detective, sleepily vague, but anxious to propitiate.

The duchess walked briskly down to the station.

At half-past eight Eglantine, already bubbling, in spite of the earliness of the hour, with excited animation, awoke Pollyooly and pulled up the blind of the bedroom window.

Then she cried: