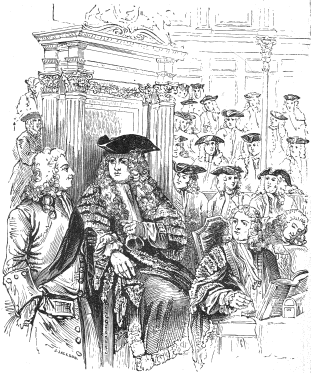

The House of Commons in the time of Sir Robert Walpole. Wigs in Parliament.

Title: At the Sign of the Barber's Pole: Studies In Hirsute History

Author: William Andrews

Release date: November 27, 2006 [eBook #19925]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ted Garvin, Karina Aleksandrova and the Online

Distributed Proofreaders Europe at http://dp.rastko.net

Transcriber's Notes:

Larger images may be viewed by clicking on any picture except the ornate letters.

onnected with the barber and his calling are many curiosities of history. In the following pages, an attempt has been made, and I trust not without success, to bring together notices of the more interesting matters that gather round the man and his trade.

In the compilation of this little book many works have been consulted, and among those which have yielded me the most information must be mentioned the following:—

"Annals of the Barber-Surgeons of London," by Sidney Young, London, 1890.

"An Apology for the Beard," by Artium Magister, London, 1862.

"Barbers' Company," by G. Lambert, F.S.A., London, 1881.

"Barber-Surgeons and Chandlers," by D. Embleton, M.D., Newcastle-on-Tyne, 1891.

"Barber's Shop," by R. W. Proctor, edited by W. E. A. Axon, Manchester, 1883.

"Philosophy of Beards," by T. S. Cowing, Ipswich.

"Some Account of the Beard and the Moustachio," by John Adey Repton, F.S.A., London, 1839.

"Why Shave?" by H. M., London.

Notes and Queries, and other periodicals, as well as encyclopædias, books on costume, and old plays, have been drawn upon, and numerous friends have supplied me with information. I must specially mention with gratitude Mr Everard Home Coleman, the well-known contributor to Notes and Queries.

Some of my chapters have been previously published in the magazines, but all have been carefully revised and additions have been made to them.

In conclusion, I hope this work will prove a welcome contribution to the byways of history.

WILLIAM ANDREWS.

Royal Institution, Hull,

August 11th, 1904.

| The Barber's Pole | 1 |

| The Barber's Shop | 8 |

| Sunday Shaving | 21 |

| From Barber to Surgeon | 26 |

| Bygone Beards | 33 |

| Taxing the Beard | 56 |

| Powdering the Hair | 59 |

| The Age of Wigs | 71 |

| Stealing Wigs | 93 |

| The Wig-Makers' Riot | 95 |

| The Moustache Movement | 96 |

| Index | 117 |

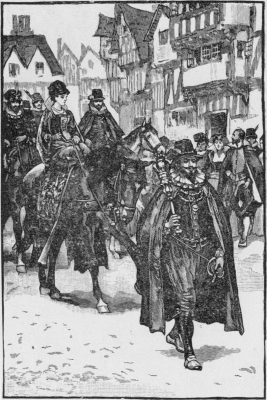

| The House of Commons in the time of Sir Robert Walpole. Wigs in Parliament | Frontispiece |

| The Barber's Shop, from "Orbis Pictus" | 3 |

| A Barber's Shop in the time of Queen Elizabeth | 10 |

| William Shakespeare (the Stratford Portrait) | 15 |

| Henry VIII. receiving the Barber-Surgeons | 29 |

| Bayeux Tapestry | 34 |

| John Knox, born 1505, died 1572 | 37 |

| John Taylor, the Water Poet, born 1580, died 1654 | 38 |

| The Lord Mayor of York escorting Princess Margaret through York in 1503. Shows the Beard of the Lord Mayor | 39 |

| Beards in the Olden Time | 42 |

| The Gunpowder Conspirators, from a print published immediately after the discovery. Shows the Beards in Fashion in 1605 | 45 |

| Geoffrey Chaucer, born about 1340, died 1400 | 52 |

| Russian Beard Token, A.D. 1705 | 58 |

| Egyptian Wig (probably for female), from the British Museum | 72 |

| The Earl of Albemarle | 78 |

| Man with Wig and Muff, 1693 (from a print of the period) | 80 |

| Campaign Wig | 81 |

| Periwig with Tail | 82 |

| Ramillie Wig | 83 |

| Pig-tail Wig | 84 |

| Bag-Wig | 84 |

| Heart-Breakers | 89 |

| With and Without a Wig | 90 |

| Lord Mansfield | 93 |

| Stealing a Wig | 94 |

| George Frederick Muntz, M.P. | 100 |

| Charles Dickens, born 1812, died 1870 | 106 |

n most instances the old signs which indicated the callings of shopkeepers have been swept away. Indeed, the three brass balls of the pawn-broker and the pole of the barber are all that are left of signs of the olden time. Round the barber's pole gather much curious fact and fiction. So many suggestions have been put forth as to its origin and meaning that the student of history is puzzled to give a correct solution. One circumstance is clear: its origin goes back to far distant times. An attempt is made in "The Athenian Oracle" (i. 334), to trace the remote origin of the pole. "The barber's art," says the book, "was so beneficial to the publick, that he who first brought it up in Rome had, as authors relate, a statue erected to his memory. In England they were in some sort the surgeons of old times, into whose art those beautiful leeches,[1] our fair virgins, were also accustomed to be initiated. In cities and corporate towns they still retain their name Barber-Chirurgions. They therefore used to hang their basons out upon poles to make known at a distance to the weary and wounded traveller where all might have recourse. They used poles, as some inns still gibbet their signs, across a town." It is a doubtful solution of the origin of the barber's sign.

[1]This is the old word for doctors or surgeons.

A more satisfactory explanation is given in the "Antiquarian Repertory." "The barber's pole," it is there stated, "has been the subject of many conjectures, some conceiving it to have originated from the word poll or head, with several other conceits far-fetched and as unmeaning; but the true intention of the party coloured staff was to show that the master of the shop practised surgery and could breathe a vein as well as mow a beard: such a staff being to this day by every village practitioner put in the hand of the patient undergoing the operation of phlebotomy. The white band, which encompasses the staff, was meant to represent the fillet thus elegantly twined about it." We reproduce a page from "Comenii Orbis Pictus," perhaps better known under its English title of the "Visible World." It is said to have been the first illustrated school-book printed, and was published in 1658. Comenius was born in 1592, was a Moravian bishop, a famous educational reformer, and the writer of many works, including the "Visible World: or a Nomenclature, and Pictures of all the chief things that are in the World, and of Men's Employments therein; in above an 150 Copper Cuts." Under each picture are explanatory sentences in two columns, one in Latin, and the other in English, and by this means the pupil in addition to learning Latin, was able to gain much useful knowledge respecting industries and other "chief things that are in the World." For a century this was the most popular text-book in Europe, and was translated into not fewer than fourteen languages. It has been described as a crude effort to interest the young, and it was more like an illustrated dictionary than a child's reading-book. In the picture of the interior of a barber's shop, a patient is undergoing the operation of phlebotomy (figure 11). He holds in his hand a pole or staff having a bandage twisted round it. It is stated in Brand's "Popular Antiquities" that an illustration in a missal of the time of Edward the First represents this ancient practice.

In a speech made in the House of Peers by Lord Thurlow, in support of postponing the further reading of the Surgeons' Incorporation Bill, from July 17th, 1797, to that day three months, the noble lord said that by a statute still in force, the barbers and surgeons were each to use a pole. The barbers were to have theirs blue and white, striped, with no other appendage; but the surgeon's pole, which was the same in other respects, was likewise to have a galley-pot and a red rag, to denote the particular nature of their vocation.

A question is put in the British Apollo (London, 1708):—

"... Why a barber at port-hole

Puts forth a party-coloured pole?"

This is the answer given:—

"In ancient Rome, when men lov'd fighting,

And wounds and scars took much delight in,

Man-menders then had noble pay,

Which we call surgeons to this day.

'Twas order'd that a hughe long pole,

With bason deck'd should grace the hole,

To guide the wounded, who unlopt

Could walk, on stumps the others hopt;

But, when they ended all their wars,

And men grew out of love with scars,

Their trade decaying; to keep swimming

They joyn'd the other trade of trimming,

And on their poles to publish either,

Thus twisted both their trades together."

During his residence at his living in the county of Meath, before he was advanced to the deanery of St Patrick's, Dean Swift was daily shaved by the village barber, who gained his esteem. The barber one morning, when busy lathering Swift, said he had a great favour to ask his reverence, adding that at the suggestion of his neighbours he had taken a small public-house at the corner of the churchyard. He hoped that with the two businesses he might make a better living for his family.

"Indeed," said the future Dean, "and what can I do to promote the happy union?"

"And please you," said the barber, "some of our customers have heard much about your reverence's poetry; so that, if you would but condescend to give me a smart little touch in that way to clap under my sign, it might be the making of me and mine for ever."

"But what do you intend for your sign?" inquired the cleric.

"The 'Jolly Barber,' if it please your reverence, with a razor in one hand and a full pot in the other."

"Well," rejoined Swift, "in that case there can be no great difficulty in supplying you with a suitable inscription." Taking up a pen he instantly wrote the following couplet, which was duly painted on the sign and remained there for many years:—

"Rove not from pole to pole, but step in here,

Where nought excels the shaving but—the beer."

Another barber headed his advertisement with a parody on a couplet from Goldsmith as follows:—

"Man wants but little beard below,

Nor wants that little long."

A witty Parisian hairdresser on one of the Boulevards put up a sign having on it a portrait of Absalom dangling by his hair from a tree, and Joab piercing his body with a spear. Under the painting was the following terse epigram:—

The lines lose some of their piquancy when rendered into English as follows:—

"The wretched Absalom behold,

Suspended by his flowing hair:

He might have 'scaped this hapless fate

Had he chosen a wig to wear."

he old-fashioned barber has passed away. In years agone he was a notable tradesman, and was a many-sided man of business, for he shaved, cut hair, made wigs, bled, dressed wounds, and performed other offices. When the daily papers were not in the hands of the people he retailed the current news, and usually managed to scent the latest scandal, which he was not slow to make known—in confidence, and in an undertone, of course. He was an intelligent fellow, with wit as keen as his razor; urbane, and having the best of tempers. It has been truthfully said of this old-time tradesman that one might travel from pole to pole and never encounter an ill-natured or stupid barber.

Long days are usually worked in the barber's shop, and many attempts have been made to reduce the hours of labour. We must not forget that compulsory early closing is by no means a new cry, as witness the following edict, issued in the reign of Henry VI., by the Reading Corporation: "Ordered that no barber open his shop to shave any man after 10 o'clock at night from Easter to Michaelmas, or 9 o'clock from Michaelmas to Easter, except it be any stranger or any worthy man of the town that hath need: whoever doeth to the contrary to pay one thousand tiles to the Guildhall."

In the reign of Queen Elizabeth the rich families from the country thought it no disgrace in that simple age to lodge in Fleet Street, or take rooms above some barber's shop. At this period, indeed, the barber-surgeon was a man of considerable importance. His shop was the gathering-place of idle gallants, who came to have their sword-wounds dressed after street frays. The gittern, or guitar, lay on the counter, and this was played by a customer to pass away the time until his turn came to have his hair trimmed, his beard starched, his mustachios curled, and his love-locks tied up. We give a picture of a barber's shop at this period; the place appears more like a museum than an establishment for conducting business. We get a word picture of a barber's shop in Greene's "Quip for an Upstart Courtier," published in 1592. It is related that the courtier sat down in the throne of a chair, and the barber, after saluting him with a low bow, would thus address him: "Sir, will you have your worship's hair cut after the Italian manner, short and round, and then frounst with the curling irons to make it look like a half-moon in a mist; or like a Spaniard, long at the ears and curled like to the two ends of an old cast periwig; or will you be Frenchified with a love-lock down to your shoulders, whereon you may wear your mistress's favour? The English cut is base, and gentlemen scorn it; novelty is dainty. Speak the word, sir, my scissors are ready to execute your worship's will." A couple of hours were spent in combing and dressing the ambrosial locks of the young Apollo; then the barber's basin was washed with camphor soap. At last the beard is reached, and with another congee the barber asks if his worship would wish it to be shaven; "whether he would have his peak cut short and sharp, and amiable like an inamorato, or broad pendent like a spade, to be amorous as a lover or terrible as a warrior and soldado; whether he will have his crates cut low like a juniper bush, or his subercles taken away with a razor; if it be his pleasure to have his appendices primed, or his moustachios fostered to turn about his ears like vine tendrils, fierce and curling, or cut down to the lip with the Italian lash?—and with every question a snip of the scissors and a bow." If a poor man entered the shop he was polled for twopence, and was soon trimmed around like a cheese, and dismissed with scarce a "God speed you."

The Puritans looked askance at the fashions introduced by the barbers. No wonder when the talk in the shop was about the French cut, the Spanish cut, the Dutch and the Italian mode; the bravado fashion, and the mean style. In addition to these were the gentleman's cut, the common cut, the Court cut, and county cut. "And," wrote Stubbes with indignation, "they have other kinds of cuts innumerable, and, therefore, when you come to be trimmed they will ask you whether you will be cut to look terrible to your enemy, or amiable to your friend; grim and stern in countenance, or pleasant and demure; for they have diverse kinds of cuts for all these purposes, or else they lie! Then when they have done all their feats, it is a world to consider how their mowchatows must be preserved and laid out from one cheek to another; yea, almost from one ear to another, and turned up like two horns towards the forehead. Besides that, when they come to the cutting of the hair, what tricking and trimming, what rubbing, what scratching, what combing and clawing, what trickling and toying, and all to tawe out money, you may be sure. And when they come to washing—oh, how gingerly they behave themselves therein! For then shall your mouth be bossed with the lather or foam that riseth of the balls (for they have their sweet balls wherewith they use to wash), your eyes closed must be anointed therewith also. Then snap go the fingers full bravely, God wot. Thus this tragedy ended, comes the warm clothes to wipe and dry him withall; next the ears must be picked, and closed together again, artificially, forsooth! The hair of the nostrils cut away, and everything done in order, comely to behold. The last action in the tragedy is the payment of money; and lest these cunning barbers might seem unconscionable in asking much for their pains, they are of such a shameful modesty as they will ask nothing at all, but, standing to the courtesy and liberality of the giver, they will receive all that comes, how much soever it be, not giving any again, I warrant you; for take a barber with that fault, and strike off his head. No, no; such fellows are rarae aves in terris, nigrisque simillimæ cygnis—rare birds on the earth, and as scarce as black swans. You shall have also your fragrant waters for your face, wherewith you shall be all besprinkled; your musick again, and pleasant harmony shall sound in your ears, and all to tickle the same with rare delight, and in the end your cloak shall be brushed, and 'God be with you, gentlemen!'"

John Gay issued in 1727 the first series of his "Fables," and in the one entitled "The Goat Without a Beard" we get a description of the barber's shop of the period:—

"His pole, with pewter basins hung,

Black, rotten teeth in order strung,

Rang'd cups that in the window stood,

Lin'd with red rags, to look like blood,

Did well his threefold trade explain,

Who shav'd, drew teeth, and breath'd a vein."

The wooden chair is next referred to, and then it is stated:—

"Mouth, nose, and cheeks, the lather hides:

Light, smooth, and swift, the razor glides."

Old barbers' shops had their regulations in poetry and prose. Forfeits used to be enforced for breaches of conduct as laid down in laws which were exhibited in a conspicuous manner, and might be read while the customer was awaiting his turn for attention at the hands of the knight of the razor. Forfeits had to be paid for such offences as the following:—

For handling the razors,

For talking of cutting throats,

For calling hair-powder flour,

For meddling with anything on the shop-board.

Shakespeare alludes to this custom in "Measure for Measure," Act v. sc. 1, as follows:—

"The strong statutes

Stand like the forfeits in a barber's shop,

As much in mock as mark."

Half a century ago there was hanging a code of laws in a barber's shop in Stratford-on-Avon, which the possessor mounted when he was an apprentice some fifty years previously. His master was in business as a barber at the time of the Garrick Jubilee in 1769, and he asserted that the list of forfeits was generally acknowledged by all the fraternity to have been in use for centuries. The following lines have found their way into several works, including Ingledew's "Ballads and Songs of Yorkshire" (1860). In some collections the lines are headed "Rules for Seemly Behaviour," and in others "The Barber of Thirsk's Forfeits." We draw upon Dr Ingledew for the following version, which is the best we have seen:—

"First come, first served—then come not late,

And when arrived keep your sate;

For he who from these rules shall swerve

Shall pay his forfeit—so observe.

"Who enters here with boots and spurs

Must keep his nook, for if he stirs

And gives with arm'd heel a kick,

A pint he pays for every prick.

"Who rudely takes another's turn

By forfeit glass—may manners learn;

Who reverentless shall swear or curse

Must beg seven ha'pence from his purse.

"Who checks the barber in his tale,

Shall pay for that a gill of yale;

Who will or cannot miss his hat

Whilst trimming pays a pint for that.

"And he who can but will not pay

Shall hence be sent half-trimmed away;

For will he—nill he—if in fault,

He forfeit must in meal or malt.

"But mark, the man who is in drink

Must the cannikin, oh, never, never clink."

The foregoing table of forfeits was published by Dr Kenrick in his review of Dr Johnson's edition of Shakespeare in 1765, and it was stated that he had read them many years before in a Yorkshire town. This matter has been discussed at some length in Notes and Queries, and it is asserted that the foregoing is a forgery. Some interesting comments on the controversy appeared in the issue of March 20th, 1869.

Women barbers in the olden time were by no means uncommon in this country, and numerous accounts are given of the skilful manner they handled the razor. When railways were unknown and travellers went by stage-coach it took a considerable time to get from one important town to another, and shaving operations were often performed during the journey, and were usually done by women. In the byways of history we meet with allusions to "the five women barbers who lived in Drury-lane," who are said to have shamefully maltreated a woman in the days of Charles II. According to Aubrey, the Duchess of Albemarle was one of them.

At the commencement of the nineteenth century a street near the Strand was the haunt of black women who shaved with ease and dexterity. In St Giles'-in-the-Fields was another female shaver, and yet another woman wielder of the razor is mentioned in the "Topography of London," by J. T. Smith. "On one occasion," writes Smith, "that I might indulge the humour of being shaved by a woman, I repaired to the Seven Dials, where in Great St Andrew's Street a female performed the operations, whilst her husband, a strapping soldier in the Horse Guards, sat smoking his pipe." He mentions another woman barber in Swallow Street.

Two men from Hull some time ago went by an early morning trip to Scarborough, and getting up rather late the use of the razor was postponed until they arrived at the watering-place. Shortly after leaving the station they entered a barber's shop. A woman lathered their faces, which operation, although skilfully performed, caused surprise and gave rise to laughter. They fully expected a man would soon appear to complete the work, but they were mistaken. The female took a piece of brown paper from a shelf, and with this she held with her left hand the customer's nose, and in an artistic manner shaved him with her right hand. Some amusement was experienced, but the operation was finished without an accident. The gentlemen often told the story of their shave at Scarborough by a woman barber.

At Barnard Castle a wife frequently shaved the customers at the shop kept by her husband, who was often drunk and incapable of doing his work. Louth (Lincolnshire) boasted a female barber, who is said to have shaved lightly and neatly, and much better than most men.

Many stories, which are more or less true, are related respecting barbers. The following is said to be authentic, and we give it as related to us. The Duke of C—— upon one occasion entered a small barber's shop in Barnard Castle, and upon inquiring for the master was answered by an apprentice of fourteen that he was not at home. "Can you shave, then?" asked the duke. "Yes, sir, I always do," was the reply. "But can you shave without cutting?" "Yes, sir, I'll try," answered the youth. "Very well," said the duke, while seating himself, and loading his pistol; "but look here, if you let any blood, as true as I sit here I'll blow your brains out! Now consider well before you begin." After a moment's reflection, the boy began to make ready, and said, "I'm not afraid of cutting you, sir," and in a short time had completed the feat without a scratch, to the complete satisfaction of the duke. In gentle tones his grace asked, "Were you not afraid of having your brains blown out, when you might have cut me so easily?"

"No, sir, not at all; because I thought that as soon as I should happen to let any blood, before you could have time to fire I would cut your throat."

The smart reply won from the duke a handsome reward. It need scarcely to be added he never resumed his dangerous threats in a barber's shop. A lesson was taught him for life.

The barber of an English king boasted, says a story, that he must be the most loyal man in the realm, as he had every day the regal throat at his mercy. The king was startled at the observation, and concluded that the barbarous idea could never have entered an honest head, and for the future he resolved to grow a beard as a precautionary measure against summary execution.

With a barber's shop in Lichfield is associated an amusing story, in which the chief figure was Farquhar, a dramatist, who attained a measure of success in the eighteenth century. His manner was somewhat pompous, and he resented with a great show of indignation the dalliance of the master of the shop. Whilst he was fuming, a little deformed man came up to him and performed the operation satisfactorily. The same day Farquhar was dining at the table of Sir Theophilus Biddulph, when he noticed the dwarf there. Taking the opportunity of following his host out of the room, he asked for an explanation of his conduct, and said that he deemed it an insult to be seated in such inferior company. Amazed at the charge, Sir Theophilus assured the dramatist that every one of the guests was a gentleman, and that they were his particular friends. Farquhar was not satisfied. "I am certain," he said, "that the little humpbacked man who sat opposite me is a barber who shaved me this morning." The host returned to the room and related the story which he had just heard. "Ay, yes," replied the guest, who was a well-born gentleman, "I can make the matter clear. It was I who was in the barber's shop this morning, and as Farquhar seemed in such a hurry, and the barber was out, I shaved him."

The works of the old dramatists and other publications contain allusions to barbers' music. It was the practice, as we have said, when a customer was waiting for his turn in a barber's shop to pass his time playing on the gittern. Dekker mentions a "barber's cittern for every serving-man to play upon." Writing in 1583, Stubbes alludes to music at the barber's shop. In the "Diary of Samuel Pepys" we read: "After supper my Lord called for the lieutenant's cittern, and with two candlesticks with money in them for symballs, we made barber's music, with which my lord was well pleased." "My Lord was easily satisfied," says a well-known contributor to Punch, "and in our day would probably have enjoyed 'the horgans.'" We may rest assured that barber's music was of questionable melody.

n bygone England, the churchyard was a common place for holding fairs and the vending of merchandise, and it was also customary for barbers to shave their customers there. In 1422, by a particular prohibition of Richard Flemmyng, Bishop of Lincoln, the observance of the custom was restrained.

The regulations of the Gild of Barber-Surgeons of York deal with Lord's Day observance. In 1592 a rule was made, ordering, under a fine of ten shillings, "that none of the barbers shall work or keep open their shop on Sunday, except two Sundays next or before the assize weeks." Another law on the question was made in 1676 as follows:—"This court, taking notice of several irregular and unreasonable practices committed by the Company of Barber-Surgeons within this city in shaving, trimming, and cutting of several strangers' as well as citizens' hair and faces on the Lord's Day, which ought to be kept sacred, it is ordered by the whole consent of this court, and if any brother of the said Company shall at any time hereafter either by himself, servant, or substitute, tonse, barb, or trim any person on the Lord's Day, in any Inn or other public or private house or place, or shall go in or out of any such house or place on the said day with instruments used for that purpose, albeit the same cannot be positively proved, or made appear, but in case the Lord Mayor for the time being shall upon good circumstances consider and adjudge any such brother to have trimmed or barbed as is aforesaid, that then any such offender shall forfeit and pay for every such offence 10s., one half to the Lord Mayor, and the other to the use of the said Company, unless such brother shall voluntarily purge himself by oath to the contrary; and the searchers of the said Company for the time being are to make diligent search in all such as aforesaid public or private places for discovery of such offenders."

The following abstract of an order of the Barber-Surgeons of Chester shows that the members of the Company were strict Sabbatarians:—

"1680, seconde of July, ordered that no member of the Company or his servant or apprentice shall trim any person on the Lord's Day commonly called Sunday."

In the Corporation records of Pontefract under the year 1700 it is stated: "Whereas divers complaints have been made that the barbers of the said borough do frequently and openly use and exercise their respective trades upon the Lord's Day in profanation thereof, and to the high displeasure of Almighty God. To prevent such evil practices for the future it is therefore ordered that no barber shall ... use or exercise the trade of a barber within the borough of Pontefract upon the Lord's Day, commonly called Sunday, nor shall trim or shave any person upon that day, either publicly or privately." We have in the last clause an indication of public shaving performed in the churchyard or the market place.

The churchwardens of Worksop parish, Nottinghamshire, in 1729 paid half-a-crown for a bond in which the barbers bound themselves "not to shave on Sundays in the morning."

At a meeting of the barber-surgeons of Newcastle-on-Tyne held in 1742 it was ordered that no one should shave on a Sunday, and that "no brother should shave John Robinson till he pays what he owes to Robert Shafto."

The operation was in bygone Scotland pronounced sinful if performed on a Sunday. Members of congregations are entitled to object to the settlement of ministers, says the Rev. Dr Charles Rogers, provided they can substantiate any charge affecting their life or doctrine. Mr Davidson, presentee to Stenton in 1767, and Mr Edward Johnstone, presentee to Moffat in 1743, were objected to for desecrating the Sabbath by shaving on that day. The settlement of Mr Johnstone was delayed four years, so persistent were the objectors in maintaining what they regarded as the proper observance of the Sabbath.

The Rev. Patrick Brontë, father of the famous novelists, was Perpetual Curate of Thornton in Bradford Dale, from 1815 to 1820. Although a sense of decency was sadly deficient among the majority of the inhabitants of the district, they kept watch on the clergy, and were ever ready to make known to the world their presumed as well as their real offences and failings. The mistakes of some of them are well illustrated in an anecdote related by Mr Abraham Holroyd, a well-known collector of local lore. When Mr Brontë resided at Thornton it was rumoured in the village that he had been seen by a Dissenter, through a chamber window, shaving himself on a Sunday morning, which was considered to be a very serious disregard of the obligation of Sabbath observance on the part of a clergyman. Mrs Ackroyd, a lady residing in the parish, had an interview with Mr Brontë on the subject. On his hearing what she had to say, he observed: "I should like you to keep what I say in your family; but I never shaved myself in all my life, or was ever shaved by any one else. I have so little beard that a little clipping every three months is all that is necessary."

Occasionally, at the present day, barbers are brought before the magistrates for working on Sunday. They are summoned under an old Act of Charles II., for shaving on the Lord's Day. The maximum fine is five shillings, and the costs of a case cannot be recovered from the defendant. Generally the local hairdressers' association institutes the action.

rom the ancient but humble position of the barber is evolved the surgeon of modern times. Perhaps some members of the medical profession would like to ignore the connection, but it is too true to be omitted from the pages of history. The calling of a barber is of great antiquity. We find in the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel (v. 1) allusions to the Jewish custom of the barber shaving the head as a sign of mourning. In the remote past the art of surgery and the trade of barber were combined. It is clear that in all parts of the civilised world, in bygone times, the barber acted as a kind of surgeon, or, to state his position more precisely, he practised phlebotomy, the dressing of wounds, etc. Their shops were general in Greece about 420 B.C., and then, as now, were celebrated as places where the gossips met. Barbers settled in Rome from Sicily in B.C. 299.

The clergy up to about the twelfth century had the care of men's bodies as well as their souls, and practised surgery and medicine. Barbers gained much experience from the monks, whom they assisted in surgical operations. The practice of surgery involved the shedding of blood, and it was felt that this was incompatible with the functions of the clergy. After much consideration and discussion, in 1163, the Council of Tours, under Pope Alexander III., forbade the clergy to act as surgeons, but they were permitted to dispense medicine.

The Edict of Tours must have given satisfaction to the barbers, and they were not slow to avail themselves of the opportunities the change afforded them. In London, and it is to be feared in other places, the barbers advertised their blood-letting in a most objectionable manner. It was customary to put blood in their windows to attract the attention of the public. An ordinance was passed in 1307 directing the barbers in London to have the blood "privately carried into the Thames under the pain of paying two shillings to the use of the Sheriffs."

At an early period in London the barbers were banded together, and a gild was formed. In the first instance it seems that the chief object was the bringing together of the members at religious observances. They attended the funerals and obits of deceased members and their wives. Eventually it was transformed into a semi-social and religious gild, and subsequently became a trade gild. In 1308 Richard le Barber, the first master of the Barbers' Company, was sworn at the Guildhall, London. As time progressed the London Company of Barbers increased in importance. In the first year of the reign of Edward IV. (1462) the barbers were incorporated by a Royal Charter, and it was confirmed by succeeding monarchs.

A change of title occurred in 1540, and it was then named the Company of Barber-Surgeons. Holbein painted a picture of Henry VIII. and the Barber-Surgeons. The painting is still preserved, and may be seen at the Barber-Surgeons' Hall, Monkwell Street, London. Pepys pronounces this "not a pleasant though a good picture." It is the largest and last work of Holbein.

The date assigned for its commencement was 1541, and it was completed after the death of the artist in 1543. It is painted on vertical oak boards, 5 ft. 11 in. high, and 10 ft. 2 in. long. It has been slightly altered since it was delivered to the Barber-Surgeons. The figures represent notable men belonging to the company and leaders of the healing art of the period at which it was painted.

In the reign of Henry VIII., not a few disputes occurred between the barbers and the surgeons. The following enactment was in force: "No person using any shaving or barbery in London shall occupy any surgery, letting of blood, or other matter, except of drawing teeth." Laws were made, but they could not, or at all events were not, enforced. The barbers acted often as surgeons, and the surgeons increased their income by the use of the razor and shears. At this period, however, vigorous attempts were made to confine each to his legitimate work.

The Rev. J. L. Saywell has a note on bleeding in his "History and Annals of Northallerton" (1885). "Towards the early part of the nineteenth century," observes Mr Saywell, "a singular custom prevailed in the town and neighbourhood of Northallerton (Yorkshire). In the spring of the year nearly all the robust male adults, and occasionally females, repaired to a surgeon to be bled—a process which they considered essentially conduced to vigorous health." The charge for this operation was one shilling.

Parliament was petitioned, in 1542, praying that surgeons might be exempt from bearing arms and serving on juries, and thus be enabled without hindrance to attend to their professional duties. The request was granted, and to the present time medical men enjoy the privileges granted so long ago.

In 1745, the surgeons and the barbers were separated by Act of Parliament. The barber-surgeons lingered for a long time, the last in London, named Middleditch, of Great Suffolk Street, Southwark, only dying in 1821. Mr John Timbs, the popular writer, left on record that he had a vivid recollection of Middleditch's dentistry.

Over the last resting-places of some barber-surgeons are curious epitaphs. At Tewkesbury Abbey one in form of an acrostic is as follows:—

"Here lyeth the body of Thomas Merrett, of Tewkesbury, Barber-chirurgeon, who departed this life the 22nd day of October 1699.

Though only Stone Salutes the reader's eye,

Here (in deep silence) precious dust doth lye,

Obscurely Sleeping in Death's mighty store,

Mingled with common earth till time's no more.

Against Death's Stubborne laws, who dares repine,

Since So much Merrett did his life resigne.

Murmurs and Tears are useless in the grave,

Else hee whole Vollies at his Tomb might have.

Rest in Peace; who like a faithful steward,

Repair'd the Church, the Poore and needy cur'd;

Eternall mansions do attend the Just,

To clothe with Immortality their dust,

Tainted (whilst under ground) with wormes and rust."

Under the shadow of the ancient church of Bakewell, Derbyshire, is a stone containing a long inscription to the memory of John Dale, barber-surgeon, and his two wives, Elizabeth Foljambe and Sarah Bloodworth. It ends thus:—

"Know posterity, that on the 8th of April, in the year of grace 1757, the rambling remains of the above John Dale were, in the 86th yeare of his pilgrimage, laid upon his two wives.

This thing in life might raise some jealousy,

Here all three lie together lovingly,

But from embraces here no pleasure flows,

Alike are here all human joys and woes;

Here Sarah's chiding John no longer hears,

And old John's rambling Sarah no more fears;

A period's come to all their toylsome lives

The good man's quiet; still are both his wives."

he history of the beard presents many items of interest connected with our own and other countries. Its importance belongs more to the past than to the present, but even to-day its lore is of a curious character. We find in Leviticus xiii. 29, the earliest mention of our theme, where Moses gives directions for the treatment of a plague in the beard, and a little later he forbids the Israelites to "mar the corners" of it. David, himself bearded, tells us that Aaron possessed one going down to the skirts of his garments. In David's reign ambassadors were sent to the King of Ammon, who, treating them as spies, cut off half of each of their beards. We are told that they were greatly ashamed, and David sent out to meet them, saying, "Tarry at Jericho until your beards be grown, and then return." To shave off the beard was considered by the Jews as a mark of the deepest grief.

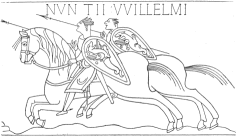

Bayeux Tapestry.

The above picture, showing two soldiers of William the Conqueror's army,

is taken from the celebrated Bayeux tapestry.

To turn to the annals of our own land, we find that the ancient Britons did not cultivate the beard. The Saxons wore the hair of the head long, and upon the upper lip, but the chin was clean shaven. Harold, in his progress towards the fateful field of Hastings, sent spies in advance to obtain an idea as to the strength of the enemy. On their return they stated among other things that "the host did almost seem to be priests, because they had all their face and both their lips shaven," a statement borne out by the representations of the Norman soldiers in the Bayeux tapestry. It is recorded that when the haughty victors had divided the broad lands of England among themselves, and when the Englishmen had been made to feel that they were a subdued and broken nation, the conquered people still kept up the old fashion of growing their hair long, so that they might resemble as little as possible their cropped and shaven masters.

Julius II., who ascended the Papal throne in 1503, was the first Pope to allow his beard to grow, "in order," as he said, "to inspire the greater respect among the faithful." A curious custom of the Middle Ages was that of imbedding three hairs from the king's beard in the wax of the seal, in order to give greater solemnity to the document. Another instance of the value placed on this adornment of nature by some nations comes to us in the story of the Eastern potentate to whom the King of England had sent a man without a beard as his ambassador. The Eastern monarch flew into a passion when the beardless visitor was presented. "Had my master measured wisdom by the beard," was the ready retort, "he would have sent a goat."

It is said that beards came into fashion in England in the thirteenth century, but by the nineteenth century they seem to have been given up by those holding leading positions in the land. Traces of beards do not appear on monumental brasses. A revival of the practice of wearing the beard occurred in the reign of Henry VIII., and in some quarters attempts were made to repress it. The authorities at Lincoln's Inn prohibited lawyers wearing beards from sitting at the great table, unless they paid double commons; but it is highly probable that this was before 1535, when the king ordered his courtiers to "poll their hair," and permit the crisp beard to grow. Taxing beards followed, and the amount was graduated according to the condition of the person wearing this hirsute adornment. An entry has often been reproduced from the Burghmote Book of Canterbury, made in the second year of the reign of Edward VI., to the effect that the Sheriff of Canterbury and another paid their dues for wearing beards, 3s. 4d. and 1s. 8d. During the next reign, Queen Mary does not appear to have meddled with the beard. She sent four agents to Moscow, and all were bearded; one of the number, George Killingworth, had an unusually long one, measureing 5ft. 2in. in length, the sight of which caused a smile to light up the face of Ivan the Terrible. It is described as a thick, broad, and yellow beard, and we are told that Ivan played with it after dinner as if it were a new toy. When Sir Thomas More laid his head on the block he carefully put his beard aside, saying, "It hath done no treason." John Knox (born 1505 and died 1572), the famous Scottish reformer, whose name figures so largely in the religious annals of his country, was remarkable for the length of his beard. The Rev. John More was a native of Yorkshire, and after being educated at Cambridge settled at Norwich. He was one of the worthiest clergymen in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, and gained the name of "the Apostle of Norwich." His beard was the largest and longest of any Englishman of his time. He used to give as his reason for wearing his beard of unusual size "that no act of his life might be unworthy of the gravity of his appearance." He died at Norwich in 1592.

In the first year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth an attempt was made to add to the revenue by taxing at the rate of 3s. 4d. every beard of above a fortnight's growth. It was an abortive measure, and was not taken seriously. It was never enforced, and people laughed at the Legislature for attempting to raise money by means of the beard. In Elizabeth's reign it was considered a mark of fashion to dye the beard and to cut it into a variety of shapes. In the reigns of the first James and the first Charles these forms attracted not a little attention from the poets of the period. The rugged lines of Taylor, "the Water Poet," are among the best known, and if not of great poetical merit, they show considerable descriptive skill, and enable us to realise the fashions of his day. In his "Superbiæ Flagellum," he describes a great variety of beards in his time, but omitted his own, which is that of a screw:—

"Now a few lines to paper I will put,

Of men's beards strange, and variable cut,

In which there's some that take as vain a pride

As almost in all other things beside;

Some are reap'd most substantial like a brush,

Which makes a nat'rel wit known by the bush;

And in my time of some men I have heard,

Whose wisdom have been only wealth and Beard;

Many of these the proverb well doth fit,

Which says, bush natural, more hair than wit:

Some seem, as they were starched stiff and fine,

Like to the bristles of some angry swine;

And some to set their love's desire on edge,

Are cut and prun'd like a quickset hedge;

Some like a spade, some like a fork, some square,

Some round, some mow'd like stubble, some stark bare;

Some sharp, stiletto fashion, dagger-like,

That may with whisp'ring, a man's eyes outpike;

Some with the hammer cut, or roman T,

Their Beards extravagant, reform'd must be;

Some with the quadrate, some triangle fashion,

Some circular, some oval in translation;

Some perpendicular in longitude;

Some like a thicket for their crassitude;

That heights, depths, breadths, triform, square, oval, round,

And rules geometrical in Beards are found."

Lord Mayor of York escorting Princess Margaret through York in 1503. Shows the Beard of the Lord Mayor.

Some curious lines appear in "Satirical Songs and Poems on Costume," edited by Frederick W. Fairholt, F.S.A., printed for the Percy Society, 1849. The piece which is entitled "The Ballad of the Beard," is reprinted from a collection of poems, entitled "Le Prince d'Amour," 1660, but it is evidently a production of the time of Charles I., if not earlier. "The varied form of the beard," says Fairholt, "which characterised the profession of each wearer, is amusingly descanted on, and is a curious fact in the chronicle of male fashions, during the first half of the seventeenth century." Taylor, the Water Poet, has alluded to the custom at some length; and other writers of the day have so frequently mentioned the same thing, as to furnish materials for a curious (privately-printed) pamphlet, by J. A. Repton, F.S.A., on the various forms of the beard and mustachio. The beard, like "the Roman T," mentioned in the following ballad, is exhibited in our cut—Fig. 1—from a portrait of G. Raigersperg, 1649, in Mr Repton's book.

The stiletto-beard, as worn by Sir Edward Coke, is seen in Fig. 2. The needle-beard was narrower and more pointed. The soldier's, or spade-beard, Fig. 3, is from a Dutch portrait, also in Mr Repton's book. The stubble, or close-cropped beard of a judge, requires no pictorial illustration. The bishop's-beard, Fig. 4, is given in Randle Holme's "Heraldry." He calls it "the broad, or cathedral-beard, because bishops, and grave men of the church, anciently did wear such beards." "The beard of King Harry may be seen in any portrait of Henry VIII. and the amusing accuracy of the description tested. The clown's beard, busy and not subject to any fashionable trimming, is sufficiently described in the words of the song." We quote nearly the whole of this old ballad, in fact all that has a real bearing on the subject of the beard:—

"The beard, thick or thin, on the lip or chin,

Doth dwell so near the tongue,

That her silence on the beard's defence

May do her neighbour wrong.

Now a beard is a thing that commands in a king,

Be his sceptres ne'er so fair:

Where the beard bears the sway, the people obey,

And are subject to a hair.

'Tis a princely sight, and a grave delight,

That adorns both young and old;

A well thatcht face is a comely grace,

And a shelter from the cold.

When the piercing north comes thundering forth,

Let barren face beware;

For a trick it will find, with a razor of wind,

To shave the face that's bare.

But there's many a nice and strange device,

That doth the beard disgrace;

But he that is in such a foolish sin,

Is a traitor to his face.

Now the beards there be of such a company,

And fashions such a throng,

That it is very hard to handle a beard,

Tho' it never be so long.

The Roman T, in its bravery,

Doth first itself disclose,

But so high it turns, that oft it burns

With the flames of a too red nose.

The stiletto-beard, oh! it makes me afeared,

It is so sharp beneath,

For he that doth place a dagger in 's face,

What wears he in his sheath?

But, methinks, I do itch to go thro' stich

The needle-beard to amend,

Which, without any wrong, I may call too long,

For man can see no end.

The soldier's-beard doth march in shear'd

In figure like a spade,

With which he'll make his enemies quake,

And think their graves are made.

The grim stubble eke on the judge's chin,

Shall not my verse despise;

It is more fit for a nutmeg, but yet

It grates poor prisoners' eyes.

What doth invest a bishop's breast

But a milk-white spreading hair?

Which an emblem may be of integrity,

Which doth inhabit there.

But, oh! let us tarry for the beard of King Harry,

That grows about the chin,

With his bushy pride, and a grove on each side,

And a champion ground between.

Last, the clown doth rush, with his beard like a bush,

Which may be well endur'd."

Charles I. wore the Vandyke-beard, made familiar to us by the great artist. This fashion, set by the king, was followed by nearly the whole of his Cavaliers. It has been thought by some students of this subject that with the tragic death of the king the beard disappeared, but if we are to put our faith in an old song, dated 1660, we must conclude that with the Restoration it once more came into fashion. It says:—

"Now of beards there be such company,

Of fashions such a throng,

That it is very hard to treat of the beard,

Tho' it be never so long."

It did not remain popular for any length of time, the razor everywhere keeping down its growth.

The Gunpowder Conspirators, from a print published immediately after the discovery. Shows the Beards in Fashion in 1605.

Sir Walter Scott's great grandsire was called "Beardie." He was an ardent Jacobite, and made a vow that he would never shave his beard until the Stuarts were restored. "It would have been well," said the novelist, "if his zeal for the vanished dynasty had stopped with letting his beard grow. But he took arms and intrigued in their cause, until he lost all he had in the world, and, as I have heard, ran a narrow risk of being hanged, had it not been for the interference of Anne, Duchess of Buccleuch and Monmouth." Sir Walter refers to him in the introduction to Canto VI. of "Marmion":—

"With amber beard and flaxen hair,

And reverend apostolic air.

Small thought was his, in after time

E'er to be pitched into a rhyme.

The simple sire could only boast

That he was loyal to his cost;

The banish'd race of kings revered,

And lost his land—but kept his beard."

He died in 1729 at Kelso. "Beardie's" second son, named Robert, was a farmer at Sandyknowe, and was Sir Walter Scott's grandfather.

A contributor to Notes and Queries, for October 1st, 1859, gives the following interesting particulars of a Shaving Statute relating to Ireland:—"In a parliament held at Trim by John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, then Lord-Lieutenant, anno 1447, 25 Henry VI., it was enacted 'That every Irishman must keep his upper lip shaved, or else be used as an Irish enemy.' The Irish at this time were much attached to the national foppery of wearing mustachios, the fashion then throughout Europe, and for more than two centuries after. The unfortunate Paddy who became an enemy for his beard, like an enemy was treated; for the treason could only be pardoned by the surrender of his land. Thus two benefits accrued to the king: his enemies were diminished, and his followers provided for; many of whose descendants enjoy the confiscated properties to this day, which may appropriately be designated Hair-breadth estates." The effects of this statute became so alarming that the people submitted to the English revolutionary razor, and found it more convenient to resign their beards than their lands. This agrarian law was repealed by Charles I., after existing two hundred years.

The Macedonian soldiers were ordered by Alexander to shave, lest their beards should be handles for the enemy to capture them by. The smooth chin was adopted in the Greek army. To pull a person's beard has from remote times been regarded as an act of most degrading insult. Dr Doran tells a tragic story bearing on this usage. "When the Jew," says the doctor, "who hated and feared the living Cid Rui Dios, heard that the great Spaniard was dead, he contrived to get into the room where the body lay, and he indulged his revengeful spirit by contemptuously plucking at the beard. But the 'son of somebody' (the hidalgo) was plucked temporarily into life and indignation by the outrage; and starting up, endeavoured to get his sword, an attempt which killed the Jew by mere fright which it caused." In Afghanistan "the system of administering justice was such," says the "Life of Abdur Rahman" (London, 1890) "that the humble were able to bring their claims before the sovereign by the simple process of getting hold of the sovereign's beard and turban, which meant to throw one's complaints on the shame of his beard, to which he was bound to listen. One day I was going to the Hum-hum (Turkish bath) when a man and his wife, running fast, rushed into the bathroom after me, and the husband, having got hold of my beard from the front, the wife was pulling me at the same time from behind. It was very painful, as he was pulling my beard rather hard. As there was no guard or sentry near to deliver me from their hands, I begged them to leave my beard alone, saying that I could listen without my beard being pulled, but all in vain. I was rather sorry that I had not adopted the fashion of the Europeans, whose faces are clean shaven. I ordered that in future a strong guard should be placed at the door of the Hum-hum."

Some of the ancient faiths regarded the beard as an appendage not to be touched with the razor, and a modern instance bearing on the old belief will be read with interest. Mr Edward Vizetelly, in his entertaining volume "From Cyprus to Zanzibar" (London, 1901), tells some good stories about the priests in Cyprus. Mr Vizetelly went to the island as soon as it passed into the hands of the British Government, and remained there a few years. "On one occasion," he says, "when I happened to be in the bazaar at Larnaca in the early afternoon, I was amazed to witness all the shopkeepers, apart from the Maltese, suddenly putting up their shutters, as if panic-stricken, but without any apparent cause. Inquiring the reason, it was only vouchsafed to me that someone had shaved off a priest's beard." The priest had been imprisoned for felling a tree in his own garden, which was against the laws of the land then in force. When in gaol the recalcitrant priest had his unclean hair and beard shorn off, in accordance with the prison regulations. The authorities were not aware that the hirsute adornments of the Orthodox Catholic faith were sacred. The act roused the Cyprist ire, and the High Commissioner had to issue orders that if any priest was locked up in future his hair and beard were to be left alone.

Respecting the beard are some popular sayings, and we deal with a few as follows.

A familiar example is "To pull the devil by the beard." When Archbishop Laud was advised to escape from this country he said, "If I should get into Holland, I should expose myself to the insults of those sectaries there, to whom my character is odious, and have every Anabaptist come to pull me by the beard." This insulting saying is by no means confined to England. To demand a person's beard was regarded as a still greater insult. King Ryons, when he sent a messenger to King Arthur to demand his beard, received the following answer:—

"Wel, sayd Arthur, thou hast said thy message, ye whiche is ye most vylaynous and lewdest message that ever man herd sent unto a kynge. Also thou mayst see, my berd is ful yong yet to make a purfyl of hit. But telle thou thy kynge this, I owe hym none homage, ne none of myn elders, but, or it be longe to, he shall do me homage on bothe his kneys, or else he shall lese his hede by ye feith of my body, for this is ye most shamefullest message that ever I herd speke of. I have aspyed, thy kyng met never yet with worshipful men; but tell hym, I wyll have his hede without he doo me homage. Thenne ye messager departed." ("The Byrth, Lyf and Actes of Kyng Arthur," edit, by Caxton, 1485, reprinted 1817.)

"To make any one's beard" is an old saying, which means "to cheat him," or "to deceive him." We read in Chaucer's Prologue to the Wife of Bath thus:—

"In faith he shal not kepe me, but me lest:

Yet coude I make his berd, so mete I the."

And again, in the "Reve's Tale," the Miller said:—

"I trow, the clerkes were aferde

Yet can a miller make a clerkes bearde,

For all his art."

A more familiar saying is "To beard a person," meaning to affront him, or to set him at defiance. Todd explains the allusion in a note in his edition of Spenser's Faerie Queene—"did beard affront him to his face"; so Shakespeare's King Henry IV., Part I. Act i.: "I beard thee to thy face"—Fr. "Faire la Barbe a quelqu'un." Ital. "Fa la barbe ad uno" (Upton.)

See Steevens's note on the use of the word Beard in King Henry IV., which is adopted, he says, "from romances, and originally signified to 'cut off the beard.'" Mr John Ady Repton, F.S.A., to whom we are mainly indebted for our illustrations of these popular sayings, directs attention to a specimen of defiance expressed in Agamemnon's speech to Achilles, as translated by Chapman:—

—"and so tell thy strength how eminent

My power is, being compared with thine;

all other making feare

To vaunt equality with me, or in this

proud kind beare

Their beards against me."

In Shirley's play, A Contention for Honour and Riches, 1633:—

"You have worn a sword thus long to show ye hilt,

Now let the blade appear.

Courtier.—Good Captain Voice,

It shall, and teach you manners; I have yet

No ague, I can look upon your buff,

And punto beard, and call for no strong waters."

"It is difficult to ascertain," says Repton, "when the custom of pulling the nose superseded that of pulling the beard, but most probably when the chin became naked and close shaven, affording no longer a handle for insult." In the reign of James II., William Cavendish, Earl of Devonshire, paid £30,000 for offering this insult to a person at Court. An earlier instance of pulling the nose may be found in Ben Jonson's Epicæne, or the Silent Woman, Act iv. sc. 5.

In "Aubrey's Letters" is an allusion to wiping the beard. "Ralph Kettle, D.D.," we read, "preached in St Mary's Church at Oxford, and, in conclusion of a sermon, said, 'But now I see it is time for me to shutt up my booke, for I see the doctors' men come in wiping their beards from the ale-house' (he could from the pulpit plainly see them, and 't was their custome to go there, and, about the end of the Sermon, to return to wayte on their masters)." An old play by Lyly, entitled Mother Bombie (1597-98), Act i. sc. 3, contains the following passage:—

"Tush, spit not you, and I'll warrant I, my beard is as good as a handkerchief."

Our quotations from old plays are mainly drawn from Repton's little book, "Some account of the Beard and Moustachio," of which one hundred copies were printed for private circulation in 1839.

The extracts which we have reproduced are not such as to cause the beard to find favour with the ladies. In Marston's Antonio and Melida, (1602), Act v., we read as follows:—

"Piero.—Faith, mad niece, I wonder when thou wilt marry?

"Rossaline.—Faith, kind Uncle, when men abandon jealousy, forsake taking tobacco, and cease to wear their beards so rudely long. Oh! to have a husband with a mouth continually smoking, with a bush of furze on the ridge of his chin, ready still to flop into his foaming chaps; ah! 't is more than most intolerable."

In another part of the same play are other objections to the mustachios. We find in other old plays allusions to women combing and stroking beards. "There is no accounting," says Repton, "for the taste of ladies. Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, with his large massive beard, won the heart of the fair sister of Henry VIII. Although the 'Cloth of friez may not be too bold,' the courtship was most probably begun by the lady (i.e. the Cloth of Gold). Although ladies do not speak out, they have a way of expressing their wishes by the 'eloquence of eyes.' That the fair princess ever amused herself in combing or brushing her husband's beard is not recorded in the history of England." Many references find a place in bygone plays relating to combs and brushes for the beard.

Starching the beard was an operation which occupied some time if carefully performed. It is stated in the "Life of Mrs Elizabeth Thomas," published in 1731, of Mr Richard Shute, her grandfather, a Turkey merchant, that he was very nice in the mode of that age, his valet being some hours every morning in starching his beard, and curling his whiskers, during which time a gentleman, whom he maintained as a companion, always read to him upon some useful subject. In closing, we have to state that cardboard boxes were worn at night in bed to protect the beard from being disarranged.

eards, in some instances, were taxed in bygone England, but not to the same extent as in Russia, which had numerous singular laws in force for nearly sixty years. In nearly all parts of Europe, by the commencement of the eighteenth century, the custom of wearing beards had been given up. Peter the Great was wishful that his subjects should conform to the prevailing fashion. In 1705 he imposed a tax upon all those who wore either a beard or a moustache, varying from thirty to one hundred roubles per annum. It was fixed according to the rank of the taxpayer. A peasant, for instance, was only required to pay two dengops, equal to one copeck, whenever he passed through the gate of a town. This tax gave rise to much discontent, and in enforcing it the utmost vigilance had to be exercised to prevent an outbreak in the country. Notwithstanding this, the law was, in 1714, put into operation in St Petersburg, which had previously been exempt. In 1722 it was ordered that all who retained their beards should wear a particular dress and pay fifty roubles annually. If a man would not shave, and was unable to pay, he was sentenced to hard labour. This law was extended to the provinces, but in 1723 peasants bringing produce into towns were wholly relieved from this tax. Peter passed away in 1725, and Catherine I. confirmed all the edicts relating to the beard in the ukase dated 4th August 1726.

A decree was issued by Peter II. in 1728 permitting peasants employed in agriculture to wear their beards. Fifty roubles had to be paid by all other persons, and the tax was rigidly enforced. The Empress Anne took a firm attitude against the beard. In 1731 she promulgated a ukase by which all persons not engaged in husbandry retaining their beards were entered in the class of Raskolnicks, in addition to paying the beard tax of fifty roubles, double the amount of all other taxes.

In 1743 the Empress Elizabeth confirmed the existing decrees in all their force. Peter III., on his accession to the throne in 1762, intended to strengthen the laws of his predecessors, and prepared some stringent measures; but his sudden death prevented them from being put into force. His widow, Catherine II. (1762), did not share his feelings in this matter, and immediately on obtaining sovereign power she removed every restriction relating to the beard. She invited the Raskolnicks, who had fled from the country to avoid the objectionable edicts, to return, and assigned land to them for their settlement.

During thirty-eight years in Russia, the beard-token or Borodoráia (the bearded), as it was called, was in use. As we write we have one of these tokens before us, and on one side are represented a nose, mouth, moustaches, and a large flowing beard, with the inscription "dinge vsatia," which means "money received"; the reverse bears the year in Russian characters (equivalent to "1705 year"), and the black eagle of the empire.

Our facts are mainly drawn from a paper by Mr Walter Hawkins in the "Numismatic Chronicle," volume vii., 1845. He says that beard-tokens are rare, and he thinks that the national aversion to their origin probably caused their destruction or dispersion after they had served their purpose for the year.

n the olden days hair-powder was largely used in this country, and many circumstances connected with its history are curious and interesting. We learn from Josephus that the Jews used hair-powder, and from the East it was no doubt imported into Rome. The history of the luxurious days of the later Roman Empire supplies some strange stories. At this period gold-dust was employed by several of the emperors. "The hair of Commodus," it is stated on the authority of Herodian, "glittered from its natural whiteness, and from the quantity of essences and gold-dust with which it was loaded, so that when the sun was shining it might have been thought that his head was on fire."

It is supposed, and not without a good show of reason, that the Saxons used coloured hair-powder, or perhaps they dyed their hair. In Saxon pictures the beard and hair are often painted blue. Strutt supplies interesting notes on the subject. "In some instances," he says, "which, indeed, are not so common, the hair is represented of a bright red colour, and in others it is of a green and orange hue. I have no doubt existing in my own mind, that arts of some kind were practised at this period to colour the hair; but whether it was done by tingeing or dyeing it with liquids prepared for that purpose according to the ancient Eastern custom, or by powders of different hues cast into it, agreeably to the modern practice, I shall not presume to determine."

It was customary among the Gauls to wash the hair with a lixivium made of chalk in order to increase its redness. The same custom was maintained in England for a long period, and was not given up until after the reign of Elizabeth. The sandy-coloured hair of the queen greatly increased the popularity of the practice.

The satirists have many allusions to this subject, more especially those of the reigns of James and Charles I. In a series of epigrams entitled "Wit's Recreations," 1640, the following appears under the heading of Our Monsieur Powder-wig:—

"Oh, doe but marke yon crisped sir, you meet!

How like a pageant he doth walk the street!

See how his perfumed head is powdered ore;

'Twou'd stink else, for it wanted salt before."

In "Musarum Deliciæ," 1655, we read:—

"At the devill's shopps you buy

A dresse of powdered hayre,

On which your feathers flaunt and fly;

But i'de wish you have a care,

Lest Lucifer's selfe, who is not prouder,

Do one day dresse up your haire with a powder."

From the pen of R. Younge, in 1656, appeared "The Impartial Monitor." The author closes with a tirade against female follies in these words: "It were a good deed to tell men also of mealing their heads and shoulders, of wearing fardingales about their legs, etc.; for these likewise deserve the rod, since all that are discreet do but hate and scorn them for it." A Loyal Litany against the Oliverians runs thus:—

"From a king-killing saint,

Patch, powder, and paint,

Libera nos, Domine."

Massinger, in the "City Madam," printed in 1679, describing the dress of a rich merchant's wife, mentions powder thus:—

"Since your husband was knighted, as I said,

The reverend hood cast off, your borrowed hair

Powdered and curled, was by your dresser's art,

Formed like a coronet, hanged with diamonds

And richest orient pearls."

John Gay, in his poem, "Trivia, or the Art of Walking the Streets of London," published in 1716, advises in passing a coxcomb—

We learn from the "Annals of the Barber-Surgeons" some particulars respecting the taxing of powder. On 8th August 1751, "Mr John Brooks," it is stated, "attended and produced a deed to which he requested the subscription of the Court; this deed recited that by an Act of Parliament passed in the tenth year of Queen Anne, it was enacted that a duty of twopence per pound should be laid upon all starch imported, and of a penny per pound upon all starch made in Great Britain, that no perfumer, barber, or seller of hair-powder should mix any powder of alabaster, plaster of Paris, whiting, lime, etc. (sweet scents excepted), with any starch to be made use of for making hair-powder, under a pain of forfeiting the hair-powder and £50, and that any person who should expose the same for sale should forfeit it and £20." Other details were given in the deed, and the Barber-Surgeons gave it their support, and promised twenty guineas towards the cost of passing the Bill through Parliament.

A few years prior to the above proceeding we gather from the Gentleman's Magazine particulars of some convictions for using powder not made in accordance with the laws of the land. "On the 20th October, 1745," it is recorded, "fifty-one barbers were convicted before the commissioners of excise, and fined in the penalty of £20, for having in their custody hair-powder not made of starch, contrary to Act of Parliament: and on the 27th of the same month, forty-nine other barbers were convicted of the same offence, and fined in the like penalty."

Before powder was used, the hair was generally greased with pomade, and powdering operations were attended with some trouble. In houses of any pretension was a small room set apart for the purpose, and it was known as the powdering-room. Here were fixed two curtains, and the person went behind, exposing the head only, which received its proper supply of powder without any going on the clothes of the individual dressed. In the Rambler, No. 109, under date 1751, a young gentleman writes that his mother would rather follow him to his grave than see him sneak about with dirty shoes and blotted fingers, hair unpowdered, and a hat uncocked.

We have seen that hair-powder was taxed, and on the 5th of May, 1795, an Act of Parliament was passed taxing persons using it. Pitt was in power, and being sorely in need of money, hit upon the plan of a tax of a guinea per head on those who used hair powder. He was prepared to meet much ridicule by this movement, but he saw that it would yield a considerable revenue, estimating it at as much as £200,000 a year. Fox, with force, said that a fiscal arrangement dependent on a capricious fashion must be regarded as an absurdity, but the Opposition were unable to defeat the proposal, and the Act was passed. Pitt's powerful rival, Charles James Fox, in his early manhood, was one of the most fashionable men in London. Here are a few particulars of his "get up" about 1770, drawn from the Monthly Magazine: "He had his chapeau-bas, his red-heeled shoes, and his blue hair-powder." Later, when Pitt's tax was gathered, like other Whigs, he refused to use hair-powder. For more than a quarter of a century it had been customary for men to wear their hair long, tied in a pig-tail and powdered. Pitt's measure gave rise to a number of Crop Clubs. The Times for April 14th, 1795, contains particulars of one. "A numerous club," says the paragraph, "has been formed in Lambeth, called the Crop Club, every member of which, on his entrance, is obliged to have his head docked as close as the Duke of Bridgewater's old bay coach-horses. This assemblage is instituted for the purpose of opposing, or rather evading, the tax on powdered heads." Hair cropping was by no means confined to the humbler ranks of society. The Times of April 25th, 1795, reports that: "The following noblemen and gentlemen were at the party with the Duke of Bedford, at Woburn Abbey, when a general cropping and combing out of hair-powder took place: Lord W. Russell, Lord Villiers, Lord Paget, etc., etc. They entered into an engagement to forfeit a sum of money if any of them wore their hair tied, or powdered, within a certain period. Many noblemen and gentlemen in the county of Bedford have since followed the example: it has become general with the gentry in Hampshire, and the ladies have left off wearing powder." Hair powder did not long continue in use in the army, for in 1799 it was abolished on account of the high price of flour, caused through the bad harvests. Using flour for the hair instead of for food was an old grievance among the poor. In the "Art of Dressing the Hair," 1770, the author complains:—

"Their hoarded grain contractors spare,

And starve the poor to beautify the hair."

Pitt's estimates proved correct, for in the first year the tax produced £210,136. The tax was increased from a guinea to one pound three shillings and sixpence. Pitt's Tory friends gave him loyal support. The Whigs might taunt them by calling them "guinea-pigs," it mattered little, for they were not merely ready to pay the tax for themselves, but to pay patriotic guineas for their servants. A number of persons were exempt from paying the tax, including "the royal family and their servants, the clergy with an income of under £100 per annum, subalterns, non-commissioned officers and privates of the yeomanry and volunteers enrolled during the past year. A father having more than two unmarried daughters might obtain on payment for two, a licence for the remainder." A gentleman took out a licence for his butler, coachman, and footman, etc., and if he changed during the year it stood good for the newly engaged servants.

Powder was not wholly set aside by ladies until 1793, when with consideration Queen Charlotte abandoned its use, swayed no doubt by her desire to cheapen, in that time of dearth, the flour of which it was made. It has been said its disuse was attributable to Sir Joshua Reynolds, Angelica Kauffmann, and other painters of their day, but it is much more likely that the artists painted the hair "full and flowing" because they found it so, not that they as a class dictated to their patronesses in despite of fashion. The French Revolution had somewhat to do with the change; a powdered head or wig was a token of aristocracy, and as the fashion might lead to the guillotine, sensible people discarded it long before the English legislature put a tax upon its use. With reference to this Sir Walter Scott says, in the fifth chapter of "The Antiquary:" "Regular were the Antiquary's inquiries at an old-fashioned barber, who dressed the only three wigs in the parish, which, in defiance of taxes and times, were still subjected to the operation of powdering and frizzling, and who for that purpose divided his time among the three employers whom fashion had yet left him.

"'Fly with this letter, Caxon,' said the senior ('The Antiquary'), holding out his missive, 'fly to Knockwinnock, and bring me back an answer. Go as fast as if the town council were met and waiting for the provost, and the provost was waiting for his new powdered wig.' 'Ah, sir,' answered the messenger, with a deep sigh, 'thae days hae lang gane by. Deil a wig has a provost of Fairport worn sin' auld Provost Jervie's time—and he had a quean of a servant lass that dressed it hersel', wi' the doup o' a candle and a dredging box. But I hae seen the day, Monkbarns, when the town council of Fairport wad hae as soon wanted their town-clerk, or their gill of brandy owerhead after the haddies, as they wad hae wanted ilk ane a weel-favoured, sonsy, decent periwig on his pow. Hegh, sirs! nae wonder the commons will be discontent, and rise against the law, when they see magistrates, and bailies, and deacons, and the provost himsel', wi' heads as bald an' as bare as one o' my blocks.'" It was not in Scotland alone that the barber was peripatetic. "In the eighteenth century," says Mrs G. Linnæus Banks, author of the "Manchester Man" and other popular novels, "he waited on his chief customers or patrons at their own homes, not merely to shave, but to powder the hair or the wig, and he had to start on his round betimes. Where the patron was the owner of a spare periwig it might be dressed in advance, and sent home in a box or mounted on a stand, such as a barrister keeps handy at the present day. But when ladies had powdered top-knots, the hairdresser made his harvest, especially when a ball or a rout made the calls for his services many and imperative. When at least a couple of hours were required for the arrangement of a single toupée or tower, or commode, as the head-dress was called, it may be well understood that for two or three days prior to the ball the hairdresser was in demand, and as it was impossible to lie down without disarranging the structure he had raised on pads, or framework of wire, plastering with pomatum and disguising with powder, the belles so adorned or disfigured were compelled to sit up night and day, catching what sleep was possible in a chair. And when I add that a head so dressed was rarely disturbed for ten days or a fortnight, it needs no stretch of imagination to realise what a mass of loathsome nastiness the fine ladies of the last century carried about with them, or what strong stomachs the barbers must have had to deal with them."

When the eighteenth century was drawing to a close the cry for bread was heard in the land. In 1795 the price of grain rose very high on account of the small supplies coming into the market. Bakers in many instances sold bread deficient in weight, and to check the fraud many shopkeepers were fined sums from £64, 5s. to £106, 5s. The Privy Council gave the matter serious consideration, and strongly urged that families should refrain from having puddings, pies, and other articles made of flour. King George III. gave orders in 1795 for the bread used in his household to be made of meal and rye mixed. He would not permit any other sort to be baked, and the Royal Family partook of the same quality of bread as was eaten by the servants.

A great deal of flour was used as hair powder, and an attempt was made to check its use. The following is a copy of a municipal proclamation issued at Great Yarmouth, the original of which is preserved in the office of the Town Clerk:—

"Disuse of Hair Powder.