Rev Theodore P Wilson

"Nearly Lost but Dearly Won"

Chapter One.

Esau Tankardew.

Certainly, Mr Tankardew was not a pattern of cleanliness,

either in his house or his person. Someone had said of him

sarcastically, “that there was nothing clean in his house

but his towels;” and there was a great deal of truth

in the remark. He seemed to dwell in an element of cobwebs; the

atmosphere in which he lived, rather than breathed, was

apparently a mixture of fog and dust. Everything he had on was

faded—everything that he had about him was faded—the

only dew that seemed to visit the jaded-looking shrubs in the

approach to his dwelling was mildew. Dilapidation and

dinginess went hand-in-hand everywhere: the railings round the

house were dilapidated—some had lost there points, others

came to an abrupt conclusion a few inches above the stone-work

from which they sprang; the steps were dilapidated—one of

them rocked as you set your foot upon it, and the others sloped

inwards so as to hold treacherous puddles in wet weather to

entrap unwary visitors; the entrance hall was dilapidated; if

ever there had been a pattern to the paper, it had now retired

out of sight and given place to irregular stains, which looked

something like a vast map of a desolate country, all moors and

swamps; the doors were dilapidated, fitting so badly, that when

the front door opened a sympathetic clatter of all the lesser

ones rang through the house; the floors were dilapidated, and

afforded ample convenience for easy egress and ingress to the

flourishing colonies of rats and mice which had established

themselves on the premises; and above all, Mr Tankardew himself

was dilapidated in his dress, and in his whole appearance and

habits—his very voice was dilapidated, and his words

slipshod and slovenly.

And yet Mr Tankardew was a man of education and a gentleman,

and you knew it before you had been five minutes in his company.

He was the owner of the house he lived in, on the outskirts of

the small town of Hopeworth, and also of considerable property in

the neighbourhood. Amongst other possessions, he was the landlord

of two houses of some pretensions, a little out in the country,

which were prettily situated in the midst of shrubberies and

orchards. In one of these houses lived a Mr Rothwell, a gentleman

of independent means; in the other a Mrs Franklin, the widow of

an officer, with her daughter Mary, now about fifteen years of

age.

Mr Tankardew had settled in his present residence some ten

years since. Why he bought it nobody knew, nor was likely

to know; all that people were sure of was that he had

bought it, and pretty cheap too, for it was not a house likely to

attract any one who appreciated comfort or liveliness; moreover,

current report said that it was haunted. Still, it was for sale,

and it passed somehow or other into Mr Tankardew’s hands,

and Mr Tankardew’s hands and whole person passed into

it; and here he was now with his one old servant, Molly

Gilders, a shade more dingy and dilapidated than himself. Several

persons put questions to Molly about her master, but found it a

very discouraging business, so they gave up the attempt as

hopeless, and it remained an unexplained mystery why Mr Tankardew

came to Hopeworth, and where he came from. As for questioning the

old gentleman himself, no one had the hardihood to undertake it;

and indeed he gave them little opportunity, as he very rarely

showed his face out of his own door; so rumour had to say what it

pleased, and among other things, rumour said that the old

dressing-gown in which he was ordinarily seen was never off duty,

either day or night.

Mr Tankardew employed no agent, but collected his own rents;

which he required to be paid to himself half-yearly, in the

beginning of January and July, at his own residence.

It was on one crisp, frosty, cheery January morning that Mr

Rothwell, and his son Mark, a young lad of eighteen, were ushered

into Mr Tankardew’s sitting-room; if that could be properly

called a sitting-room, in which nobody seemed ever to sit, to

judge by the deep unruffled coating of dust which reposed on

every article, the chairs included. Respect for their own

garments caused father and son to stand while they waited for

their landlord; but, before he made his appearance, two more

visitors were introduced, or rather let into the room by old

Molly, who, considering her duty done when she had given them an

entrance into the apartment, never troubled herself as to their

further comfort and accommodation.

A strange contrast were these visitors to the old room and its

furniture. Mr Rothwell was a tall and rather portly man with a

pleasant countenance, a little flushed, indicating a somewhat

free indulgence in what is certainly miscalled “good

living.” The cast of his features was that of a person

easy-going, good-tempered, and happy; but a line or two of care

here and there, and an occasional wrinkling up of the forehead

showed that the surface was not to be trusted. Mark, his son, was

like him, and the very picture of good humour and

light-heartedness; so buoyant, indeed, that at times he seemed

indebted to spirits something more than “animal.” But

the brightness had not yet had any of the gilding rubbed

off—everyone liked him, no one could be dull where he was.

Mrs Franklin, how sweet and lovable her gentle face! You could

tell that, whatever she might have lost, she had gained

grace—a glow from the Better Land gave her a heavenly

cheerfulness. And Mary—she had all her mother’s

sweetness without the shadow from past sorrows, and her laugh was

as bright and joyous as the sunlit ripple on a lake in summer

time.

The Rothwells and Franklins, as old friends, exchanged a

hearty but whispered greeting.

“I daren’t speak out loud,” said Mark to

Mary, “for fear of raising the dust, for that’ll set

me sneezing, and then good-bye to one another; for the first

sneeze ’ll raise such a cloud that we shall never see each

other till we get out of doors again.”

“O Mark, don’t be foolish! You’ll make me

laugh, and we shall offend poor Mr Tankardew; but it is very odd.

I never was here before, but mamma wished me to come with her, as

a sort of protection, for she’s half afraid of the old

gentleman.”

“Your first visit to our landlord, I think?” said

Mr Rothwell.

“Yes,” replied Mrs Franklin. “I sent my last

half-year’s rent by Thomas, but as there are some little

alterations I want doing at the house, and Mr Tankardew,

I’m told, will never listen to anything on this subject

second-hand, I have come myself and brought Mary with

me.”

“Just exactly my own case,” said Mr Rothwell;

“and Mark has given me his company, just for the sake of

the walk. I think you have never met our landlord?”

“No, never!—and I must confess that I feel

considerably relieved that our interview will be less private

than I had anticipated.”

Further conversation was interrupted by the entrance of Mr

Tankardew himself. He was tall and very grey, with

strongly-marked features, and deeply-furrowed cheeks and

forehead. His eyes were piercing and restless, but there was a

strange gentleness of expression about the mouth, which might

lead one, when viewing his countenance as a whole, to gather that

he was one who, though often deceived, must still trust

and love. He had on slippers and worsted stockings, but neither

of them were pairs. He wore an old black handkerchief with the

tie half-way towards the back of his neck, while a very long and

discoloured dressing-gown happily shrouded from view a

considerable portion of his lower raiment.

The room in which he met his tenants was thoroughly in keeping

with its owner: old and dignified, panelled in dark wood, with a

curiously-carved chimneypiece, and a ceiling apparently adorned

with some historical or allegorical painting, if you could only

have seen it.

How Mr Tankardew got into the room on the present occasion was

by no means clear, for nobody saw him enter.

Mark suggested to Mary, in a whisper, that he had come up

through a trap door. At any rate he was there, and greeted his

visitors without embarrassment.

“Sorry to keep you waiting,” he muttered,

“sorry to see you standing. Ah! Dusty, I see;” and

with the long tail of his dressing-gown he proceeded to raise a

cloud of dust from four massive oak chairs, much to the

disturbance of Mark’s equanimity, who succeeded with some

difficulty in maintaining his gravity. “Sorry,” added

Mr Tankardew, “to appear in this dishabille, must

excuse and take me as I am.”

“Pray don’t mention it,” replied both his

tenants, and then proceeded to business.

The rent had been paid and receipts duly given, when the old

man raised his eyes and fixed them on Mary’s face. She had

been sitting back in the deep recess of a window, terribly afraid

of a mirthful explosion from Mark, and therefore drawing herself

as far out of sight as possible; but now a bright ray of sunshine

cast itself full on her sweet, loving features, and as Mr

Tankardew caught their expression he uttered a sudden

exclamation, and stood for a moment as if transfixed to the spot.

Mary felt and looked half-confused, half-frightened, but the next

moment Mr Tankardew turned away, muttered something to himself,

and then entered into the subject of requested alterations. His

visitors had anticipated some probable difficulties, if not a

refusal, on the part of their landlord; but to their surprise and

satisfaction he promised at once to do all that they required:

indeed he hardly seemed to take the matter in thoroughly, but to

have his mind occupied with something quite foreign to the

subject in hand. At last he said,—

“Well, well, get it all done—get it all done, Mr

Rothwell, Mrs Franklin—get it all done, and send in the

bills to me—there, there.”

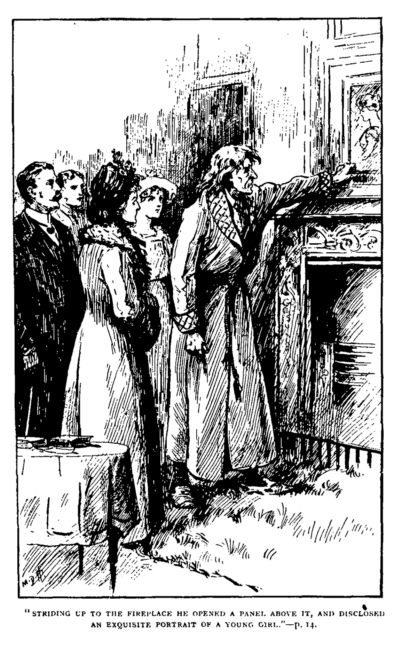

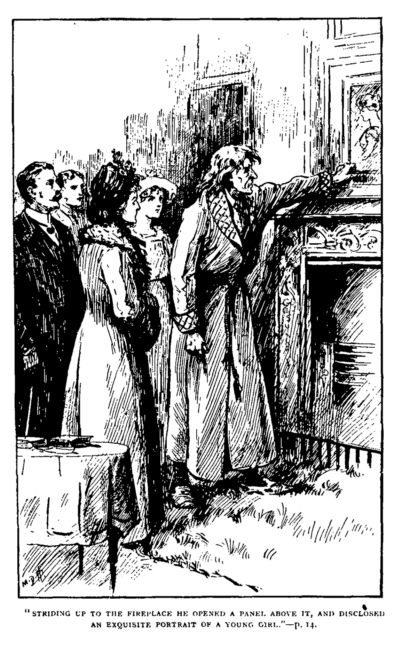

Again he fixed his eyes earnestly on Mary’s face, then

slowly withdrew  them,

and striding up to the fireplace opened a panel above it, and

disclosed an exquisite portrait of a young girl about

Mary’s age. Nothing could be more striking than the

contrast between the gloomy, dingy hue of the apartment, and the

vivid colouring of the picture, which beamed out upon them like a

rainbow spanning a storm-cloud. Then he closed the panel

abruptly, and turned towards the company with a deep sigh.

them,

and striding up to the fireplace opened a panel above it, and

disclosed an exquisite portrait of a young girl about

Mary’s age. Nothing could be more striking than the

contrast between the gloomy, dingy hue of the apartment, and the

vivid colouring of the picture, which beamed out upon them like a

rainbow spanning a storm-cloud. Then he closed the panel

abruptly, and turned towards the company with a deep sigh.

“Ah! Well, well,” he said, half aloud;

“well, good-morning, good-morning; when shall we meet

again?”

These last words were addressed to Mrs Franklin and her

daughter.

“Really,” replied the former, hardly knowing what

to say, “I’m sure, I—”

Mr Rothwell came to the rescue.

“My dear sir, I’m sure I shall be very glad to see

you at my house; you don’t go into society much;

it’ll do you good to come out a little; you’ll get

rid of a few of the cobwebs—from your mind”—he

added hastily, becoming painfully conscious that he was treading

on rather tender ground when he was talking about cobwebs.

“Wouldn’t Mr Tankardew like to come to our

juvenile party on Twelfth Night?” asked Mark with a little

dash of mischief in his voice, and a demure look at Mary.

Mrs Franklin bit her lips, and Mr Rothwell frowned.

“A juvenile party at your house?” asked Mr

Tankardew, very gravely.

“Only my son’s nonsense, you must pardon

him,” said Mr Rothwell; “we always have a young

people’s party that night, of course you would be heartily

welcome, only—”

“A juvenile party?” asked Mr Tankardew again, very

slowly.

“Yes, sir,” replied Mark, for the sake of saying

something, and feeling a little bit of a culprit; “twelfth

cake, crackers, negus, lots of fun, something like a breaking-up

at school. Miss Franklin will be there, and plenty more young

people too.”

“Something like a breaking-up,” muttered the old

man, “more like a breaking-down, I should

think—I’ll come.”

The effect of this announcement was perfectly overwhelming. Mr

Rothwell expressed his gratification with as much self-possession

as he could command, and named the hour. Mrs Franklin checked an

exclamation of astonishment with some difficulty. Poor Mary

coughed her suppressed laughter into her handkerchief; but as for

Mark, he was forced to beat a hasty retreat, and dashed down the

stairs like a whirlwind.

The way home lay first down a narrow lane, into which they

entered about a hundred yards from Mr Tankardew’s house.

Here the rest of the party found Mark behaving himself rather

like a recently-escaped lunatic: he was jumping up and down, then

tossing his cap into the air, then leaning back on the bank,

holding his sides, and every now and then crying out while the

tears rolled over his cheeks.

“Oh dear! Oh dear! What shall I do? Old

Tanky’s coming to our juvenile party.”

Chapter Two.

The Juvenile Party.

Let us look into two very different houses on the morning of

January 6th.

Mr Rothwell’s place is called “The Firs,”

from a belt of those trees which shelter the premises on the

north.

All is activity at “The Firs” on Twelfth-day

morning.

It is just noon, and Mrs Rothwell and her daughters are

assembled in the drawing-room making elaborate preparations for

the evening with holly, and artificial flowers and mottoes, and

various cunning and beautiful devices. On a little table by the

grand piano stands a tray with a decanter of sherry, a glass jug

filled (and likely to remain so) with water, and a few biscuits.

Mrs Rothwell is lying back in an elegant easy-chair, looking

flushed and languid. Her three daughters, Jane, Florence, and

Alice, are standing near her, all looking rather weary.

“What a bore these parties are!” exclaimed the

eldest. “I’m sick to death of them. I shall be tired

out before the evening begins.”

“So shall I,” chimes in her sister Florence.

“I hate having to be civil to those odious little frights,

the Graysons, and their cousins. Why can’t they stay at

home and knock one another’s heads about in the

nursery?”

“Very aimiable of you I must say, my dears,”

drawls out Mrs Rothwell. “Come, you must exert yourselves,

you know it only comes once a year.”

“Ay, once too often, mamma!”

“I’m sure,” cries little Alice, “I

shall enjoy the party very much: it’ll be jolly, as Mark

says, only I wish I wasn’t so tired just now: ah! Dear

me!”

“Oh! Child, don’t yawn!” says her mother;

“you’ll make me more fatigued than I am, and

I’m quite sinking now. Jane, do just pour me out another

glass of sherry. Thank you, I can sip a little as I want it. Take

some yourself, my dear, it’ll do you good.”

“And me too, mamma,” cries Alice, stretching out

her hand.

“Really, Alice, you’re too young; you

mustn’t be getting into wanting wine so early in the day,

it’ll spoil your digestion.”

“Oh! Nonsense, mamma! Everybody takes it now;

it’ll do me good, you’ll see. Mark often gives me

wine; he’s a dear good brother is Mark.”

Mrs Rothwell sighs, and takes a sip of sherry: she is

beginning to brighten up.

“What in the world did your father mean by asking old Mr

Tankardew to the party to-night?” she exclaims, turning to

her elder daughters.

“Mean! Mamma—you may well ask that: the old

scarecrow! They say he looks like a bag of dust and

rags.”

“Mark says,” cries her sister, “that

he’s just the image of a stuffed Guy Fawkes, which the boys

used to carry about London on a chair.”

“Well, my dears, we must make the best of matters, we

can’t help it now.”

“Oh! I daresay it’ll be capital fun,”

exclaims Alice; “I shall like to see Mark doing the polite

to ‘Old Tanky,’ as he calls him.”

“Come, Miss Pert, you must mind your behaviour,”

says Florence; “remember, Mr Tankardew is a gentleman and

an old man.”

“Indeed, Miss Gravity, but I’m not going to learn

manners of you; mamma pays Miss Craven to teach me that, so

good-bye;” and the child, with a mocking courtesy towards

her sister, runs out of the room laughing.

And now let us look into the breakfast-room of “The

Shrubbery,” as Mrs Franklin’s house is called.

Mary and her mother are sitting together, the former adding

some little adornments to her evening dress, and the latter

knitting.

“Don’t you like Mark Rothwell, mamma?”

“No, my child.”

“Oh! Mamma! What a cruelly direct answer!”

“Shouldn’t I speak the direct truth,

Mary?”

“Oh! Yes, certainly the truth, only you might have

softened it off a little, because I think you must like some

things in him.”

“Yes, he is cheerful and good-tempered.”

“And obliging, mamma?”

“I’m not so sure of that, Mary; self-indulgent

people are commonly selfish people, and selfish people are seldom

obliging: a really obliging person is one who will cross his own

inclination to gratify yours, without having any selfish end in

view.”

“And you don’t think Mark would do this,

mamma?”

“I almost think not. I like to see a person obliging

from principle, and not merely from impulse: not merely when his

being obliging is only another form of

self-gratification.”

“But why should not Mark Rothwell be obliging on

principle?”

“Well, Mary, you know my views. I can trust a person as

truly obliging who acts on Christian principle, who follows the

rule, ‘Look not everyone on his own things, but everyone

also on the things of others,’ because he loves Christ. I

am afraid poor Mark has never learned to love Christ.”

Mary sighs, and her mother looks anxiously at her.

“My dearest child,” she says, earnestly, “I

don’t want you to get too intimate with the young

Rothwells. I am sure they are not such companions as your own

heart would approve of.”

“Why, no, mamma, I can’t say I admire the way in

which they have been brought up.”

“Admire it! Oh! Mary, this is one of the crying sins of

the day. I mean the utter selfishness and self-indulgence in

which so many young people are educated; they must eat, they must

drink, they must talk just like their elders; they acknowledge no

betters, they spurn all authority; the holy rule,

‘Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is

right,’ is quite out of date with too many of them

now.”

“I fear it is so, mamma. I don’t like the girls

much at ‘The Firs,’ but I cannot help liking Mark; I

mean,” she added, colouring, “as a light-hearted,

generous, pleasant boy.” A silence of a few moments, and

then she looks up and says, timidly and lovingly, “If you

think it better, dearest mamma, I won’t go to the party

to-night.”

“No, Mary, I would not advise that; I shall be

with you, and I should like you to see and judge for yourself. I

have every confidence in you. I do believe that you love your

Saviour, and loving Him, I feel sure that you will not knowingly

enter into any very intimate acquaintance with any one who has

not the same hope; without which hope, my precious child, there

may be much amiability and attractiveness, but can be no solid

and abiding happiness or peace.”

Mary’s reply is a child’s earnest embrace and a

whispered assurance of unchanging love to her mother, and trust

in her judgment.

Six o’clock.—Both drawing-rooms at “The

Firs” were thrown into one, and brilliantly lighted up.

Mysterious sounds in the dining-room below told of preparations

for that part of the evening’s proceedings, by no means the

least gratifying to the members of a juvenile party. Friends

began to assemble: young boys and girls in shoals, the former

dazzling in neckties and pins, the latter in brooches and

earrings: with a sprinkling of seniors. The host, hostess, and

her daughters were all smiles; the last-named especially, unable,

indeed, to give expression to their satisfaction at having the

happiness of receiving their dear young friends. Mark was there,

of course, full of fun, and really enjoying himself, the life and

soul of everything.

And now, when Mrs Franklin and Mary had just taken their seats

and had begun to look around them, the door was thrown widely

open, and the servant announced in a loud voice, “Mr Esau

Tankardew!”

Every sound was instantly hushed, every head bent forward,

every mouth parted in breathless expectation. Mark crept close up

to Mary and squeezed his white gloves into ropes; the next moment

Mr Tankardew entered.

Marvellous transformation! The faded garments had entirely

disappeared. Was this the man of dilapidation? Yes, it was Mr

Tankardew. He was habited in a suit of black, which, though not

new, had evidently not seen much service; his trousers ceased at

the knee, leaving his silk stockings and shoes conspicuous. No

reproach could be cast on the purity of his white neckcloth, nor

on the general cleanliness of his person. His greeting of the

host and hostess, though a little old-fashioned, was thoroughly

easy and courteous, after which he begged them to leave him to

himself, and to give their undivided attention to the young,

whose special evening it was. Curiosity once gratified, the

suspended buzz of eager talk broke out again, and allowed Mr

Tankardew to make his way to Mrs Franklin and her daughter. These

he saluted very heartily, and added, “Let an old man sit by

you awhile, and watch the proceedings of the young people, and

realise if he possibly can that he was once young

himself—ah yes! Once young,” and he sighed

deeply.

Fun and frolic were soon at their height. Merry music struck

up, and the larger of the two drawing-rooms was cleared for a

dance. Mark hurried up to Mary. “Come, Mary,” he

cried, “I want you for a partner; we shall have capital

fun; come along.”

“Thank you,” she replied; “I prefer to watch

the others—at present, at any rate.”

“Oh! Nonsense! You must come, there’ll be

no fun without you; it’s very hot though, but

there’ll be lots of negus presently.”

“Mary will do her part by trying to amuse some of the

very little ones,” said her mother; “I think that

will be more to her taste.”

“Oh! Yes, dear mamma, that it will. Thank you, Mark, all

the same.”

“Good, very good, very good,” cried Mr Tankardew,

in a low voice, and beating one hand gently on the other;

“keep to that, my child, keep to that.”

Mark retired with a very bad grace, and Mary, slipping away

from her mother’s side, gathered a company around her of

the tinier sort, with glowing cheeks and very wide eyes, who were

rather scared by the more boisterous proceedings of those

somewhat older; she amused them in a quiet way, raising many a

little happy laugh, and fairly winning their hearts.

“God bless her,” muttered Mr Tankardew, when he

had watched her for some time very attentively; “very good,

that will do, very good indeed; keep her to it, Mrs Franklin,

keep her to it.”

“She’s a dear, good child,” said her

mother.

“Very true, madam; yes, dear and good; some are dear and

bad—dear at any price. I see some now.”

Wine and negus were soon handed round; the tray was presented

to Mary. Mr Tankardew lent forward and bent a piercing look at

her. She declined, not at all knowing that he was watching

her.

“Good again; very good, good girl, wise girl, prudent

girl,” he murmured to himself.

The tray now came to Mrs Franklin. She took a glass of sherry.

Mr Tankardew’s brow clouded. “Ah!” he

exclaimed, and moved restlessly on his chair. The servant then

approached him and offered the contents of the tray, but he waved

it off with an imperious gesture of his hand, and did not

vouchsafe a word.

The more boisterous party in the other room now became

conscious of the presence of the wine and negus, and rushed in,

surrounding the maid who was bringing in a fresh supply. Mark was

at the head of them, and tossed down two glasses in rapid

succession. The rest clamoured for the strong drink with eager

hands and outstretched arms. “Give me some, give me

some,” was uttered on all sides. Self reigned

paramount.

Mr Tankardew’s tall form rose high above the edge of the

struggling crowd, which he had approached.

“Poor things, poor things, poor things!” he said

gloomily.

“A pleasant sight, these little ones enjoying

themselves,” said Mr Rothwell, coming up.

Mr Tankardew seemed scarcely to hear him, and returned to his

place by Mrs Franklin.

“Enjoying themselves!” he exclaimed, in an

undertone, “call it pampering the flesh, killing the soul,

and courting the devil.”

“Rather hard upon the poor dear children,”

laughingly remarked a lady, who overheard him: “why, surely

you wouldn’t deny them, their share of the enjoyment

of God’s good creatures?”

“God’s good creatures, madam! Are the wine and

negus God’s good creatures?”

“Certainly they are,” was the reply: “God

has permitted man to manufacture them out of the fruits of the

earth, and to make them the means of pleasurable excitement, and

therefore surely we may take them and give them as His good

creatures.”

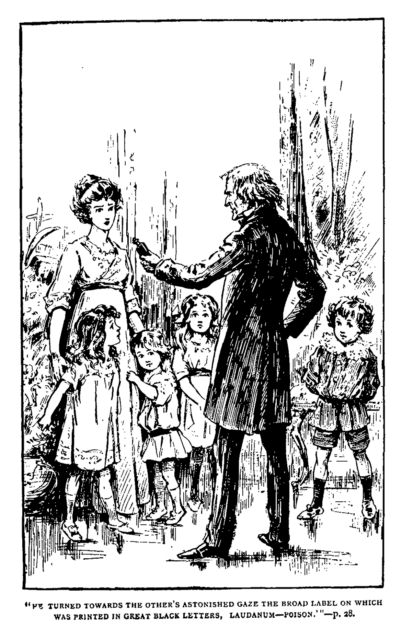

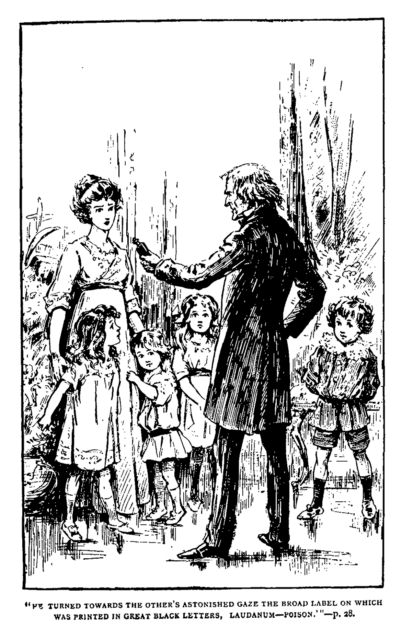

Mr Tankardew made no answer, but striding up to Mary, where

she sat with a circle of little interesting faces round her,

eagerly intent on some simple story she was telling them, he

said, “Miss Franklin, will you favour me by bringing me a

few of your young friends here. There, now, my dear,”

(speaking to one of the little girls), “just hand me that

empty negus glass.” The child did so, and Mr Tankardew,

producing from his coat pocket a considerable sized bottle,

turned to the lady who had addressed him, and said:

“Madam, will you help me to dispense some of the

contents of this bottle to these little children?”

“Gladly,” she replied. “I suppose it is

something very good, such as little folks like.”

“It is one of God’s good creatures, madam:”

saying which, he turned  towards the other’s astonished gaze the broad label on

which was printed in great black letters,

“Laudanum—Poison.”

towards the other’s astonished gaze the broad label on

which was printed in great black letters,

“Laudanum—Poison.”

“My dear sir, what do you mean?”

“I mean, madam, that the liquid in this bottle is made

from the poppy, which is one of the fruits of the earth;

therefore it is one of God’s good creatures, just as the

wine and negus are. It produces very pleasurable sensations, too,

if you take it, just as they do; therefore it is right to

indulge in it, and give it to others, just as it is right for the

same reasons to indulge in wine and negus and spirits, and to

give them to others.”

“I really don’t understand you, sir.”

“Don’t you, madam? I think you won’t be able

to pick a hole in my argument.”

“Ah! But this liquid is poison!”

“So is alcohol, madam, only it is not labelled so:

more’s the pity, for it has killed thousands and tens of

thousands, where laudanum has only killed units. There, my

child,” he added, turning to Mary, and taking an elegant

little packet from his pocket, “give these bonbons

to the little ones. I didn’t mean to disappoint

them.”

While this dialogue was going on, the rest of the party was

too full of noisy mirth to notice what was passing. Mark’s

voice was getting very wild and conspicuous; and now he made his

way with flushed face and sparkling eyes to Mary, who was sitting

quietly between her mother and Mr Tankardew. He carried a jug in

one hand, and a glass in the other, and, without noticing the

elder people, exclaimed, “It is an hour yet to supper time,

and you’ll be dead with thirst; I am sure I am. You must

take some of this, it is capital stuff; our butler made it: I

have just had a tumbler—it is punch. Come, Mary, you

must,” and he thrust the glass into her hand: “you

must, I say; you shall; never mind old Tanky,” he added, in

what he meant to be a whisper. Then he raised the jug with

unsteady fingers, but, before a drop could reach the tumbler, Mr

Tankardew had risen, and with one sweep of his hand dashed it out

of Mary’s grasp on the ground. Few heard the crash, amidst

the din of the general merriment, and those who noticed it

supposed it to be an accident. “Nearly lost!”

whispered Mr Tankardew in Mary’s ear; then he said, in a

louder voice, “Faugh! The atmosphere of this place does not

suit me. I must retire. Mrs Franklin, pray make an old

man’s excuses to our host and hostess.”

He was gone!

Chapter Three.

The Swollen Stream.

It is the morning after the juvenile party at “The

Firs.” A clear, bright frost still: everything

outside the house fresh and vigorous: half-a-dozen

labourers’ little children running to school with faces

like peonies; jumping, racing, sliding, puffing out clouds of

steaming breath as they shout out again and again for very excess

of health and spirits.

Everything inside the house limp, languid, and

lugubrious; the fires are sulky and won’t burn; the maids

are sulkier still. Mr Rothwell breakfasts alone, feeling warm in

nothing but his temper: the grate sends forth little white jets

of smoke from a wall of black coal, instead of presenting a

cheery surface of glowing heat: the toast is black at the corners

and white in the middle: the eggs look so truly new laid that

they seem to have come at once from the henhouse to the table,

without passing through the saucepan: the coffee is feeble and

the milk smoked: the news in the daily papers is flat, and the

state of affairs in country and county peculiarly depressing.

Upstairs, Mrs Rothwell tosses about with a sick headache, unable

to rest and unwilling to rise. The young ladies are dawdling in

dressing-gowns over a bedroom breakfast, and exchanging mutual

sarcasms and recriminations, blended with gall and bitterness

flung back on last night’s party. Poor Mark has the worst

of it, nausea and splitting headache, with a shameful sense of

having made both a fool and a beast of himself. So much for the

delights of “lots of negus, wine, and punch!” He has

also a humbling remembrance of having been rude to Mr Tankardew.

A knock at his door. “Come in.”

“Please, sir, there’s a hamper come for

you,” says the butler; “shall I bring it

in?”

“Yes, if you like.”

The hamper is brought in and opened; it is only a small one.

In the midst of a deep bed of straw lies a hard substance; it is

taken out and the paper wrapped round it unfolded; only a glass

tumbler! There is a paper in it on which is written, “To Mr

Mark Rothwell, from Mr Esau Tankardew, to replace what he broke

last night: keep it empty, my boy; keep it empty.”

Nine o’clock at “The Shrubbery.” Mary and

her mother are seated at breakfast, both a little dull and

disinclined to speak. At last Mary breaks the silence by a

profound sigh. Mrs Franklin smiles, and says:

“You seem rather burdened with care, my

child.”

“Well, I don’t know, dear mamma; I don’t

think it is exactly care, but I’m dissatisfied or

disappointed that I don’t feel happier for last

night’s party.”

“You don’t think there was much real enjoyment in

it?”

“Not to me, mamma; and I don’t imagine very

much to anybody—except, perhaps, to some of the very little

ones. There was a hollowness and emptiness about the whole thing;

plenty of excitement and a great deal of selfishness, but nothing

to make me feel really brighter and happier.”

“No, my child; I quite agree with you: and I was

specially sorry for old Mr Tankardew. I can’t quite

understand what induced him to come: his conduct was very

strange, and yet there is something very amiable about him in the

midst of his eccentricities.”

“What a horror he seems to have of wine and negus and

suchlike things, mamma.”

“Yes; and I’m sure what he saw last night would

not make him any fonder of them. Poor Mark Rothwell quite forgot

himself. I was truly glad to get away early.”

“Oh! So was I, mamma; it was terrible. I wish he

wouldn’t touch such things; I’m sure he’ll do

himself harm if he does.”

“Yes, indeed, Mary; harm in body, and character, and

soul. Those are fearful words, ‘No drunkard shall inherit

the kingdom of God.’”

“I wish I was like Mr Tankardew,” says Mary, after

a pause; “did you see, mamma, how he refused the negus? I

never saw such a frown.”

“Well, Mary, I’m not certain that total abstinence

would suit either of us, but it is better to be on the safe side.

I am sure, in these days of special self-indulgence, it would be

worth a little sacrifice if our example might do good; but

I’ll think about it.”

It was a lovely morning in the September after the juvenile

party, one of those mornings which combine the glow of summer

with the richness of autumn. A picnic had been arranged to a

celebrated hill about ten miles distant from Hopeworth. The

Rothwells had been the originators, and had pressed Mary Franklin

to join the party. Mrs Franklin had at first declined for her

daughter. She increasingly dreaded any intimacy between her and

Mark, whose habits she feared were getting more and more

self-indulgent; and Mary herself was by no means anxious to go,

but Mark’s father had been particularly pressing on the

subject, more so than Mrs Franklin could exactly understand, so

she yielded to the joint importunity of father and son, though

with much reluctance. Mary had seen Mark occasionally since the

night of the 6th of January, and still liked him, without a

thought of going beyond this; but she was grieved to see how

strongly her mother felt against him, and was inclined to think

her a little hard. True, he had been betrayed into an excess on

Twelfth night; but, then, he was no drunkard. So she argued to

herself, and so too many argue; but how strange it is that people

should argue so differently about the sin of drunkenness from

what they argue about other sins! If a man lies to us now and

then, do we call him habitually truthful? If a man

steals now and then, do we call him habitually

honest? Surely not; yet if a man is only now and then

drunken, his fault is winked at; he is considered by many as

habitually a sober man; and yet, assuredly, if there be

one sin more than another which from the guilt and misery that it

causes deserves little indulgence, it is the sin of drunkenness.

Mary took the common view, and could not think of Mark as being

otherwise than habitually sober, because he was only now and then

the worse for strong drink.

It was, as we have said, a lovely September morning, and all

the members of the picnic party were in high spirits. An omnibus

had been hired expressly for the occasion. Mark sat by the

driver, and acted as presiding genius. The common meeting-place

was an old oak, above a mile out of the town, and thither by ten

o’clock all the providers and their provisions had made

their way. No one could look more bright than Mark Rothwell, no

one more peacefully lovely than Mary Franklin. All being seated,

off they started at an uproarious signal from Mark. Away they

went, along level road, through pebbly lane, its banks gorgeous

with foxgloves and fragrant with honeysuckles, over wild heath,

and then up grassy slopes. There were fourteen in the party: Mr

Rothwell, Mark and his three sisters, and a lady neighbour; Mrs

Franklin and her daughter, with a female friend; and five young

gentlemen who were or seemed to be cousins, more or less, to

everybody. Five miles were soon passed, and then the road was

crossed by a little stream. Cautiously the lumbering vehicle made

its way down the shelving gravel, plunged into the sparkling

water, fouling it with thick eddies of liquid mud, and then, with

some slight prancings on the part of the willing horses, gained

the opposite bank. The other five miles were soon accomplished,

all feeling the exhilarating effect of drinking in copious

draughts of mountain air—God’s pure and unadulterated

stimulant to strengthen the nerves, string up the muscles, and

clear the brain, free from every drop of spirit except the

glowing spirit of health. And now the omnibus was abandoned by a

little roadside inn to the care of a hostler, who took the horses

(poor dumb brutes!) to feast on corn and water, God’s truly

“good creatures,” unspoilt by the perverse hand of

self-indulgent man!

The driver, with the rest of the party, toiled up the

hill-side, and all, on gaining the summit, gazed with admiration

across one of those lovely scenes which may well make us feel

that the stamp of God’s hand is there, however much man may

have marred what his Creator has made: wood and lane, cornfields

red-ripe, turnip fields in squares of dazzling green, were spread

out before them in rich embroidery with belts of silver stream

flashing like diamonds on the robe of beauty with which Almighty

love had clothed the earth. Oh! To think that sin should defile

so fair a prospect! Yet sin was there, though unseen by those

delighted gazers. Ay, and thickly sown among those sweet hills

and dales were drunkards’ houses, where hearts were

withering, and beings made for immortality were destroying body

and soul by a lingering suicide.

An hour passed quickly by, and there came a summons to

luncheon. Under a tall rock, affording an unbroken view of the

magnificent landscape outspread below, the tablecloth was laid

and secured at the corners by large stones. Pies both savoury and

sweet were abundant, bread sufficient, salt scanty, and water

absent altogether. Bottles were plentiful—bottles of ale,

of porter, of wines heavy and light. Corks popped, champagne

fizzed, ale sparkled. Mark surrendered the eatables into other

hands, and threw his whole energies into the joint consumption

and distribution of strong drink. He seemed in this matter, at

least, to act upon the rule that “Example is better than

precept”: if he pressed others to drink, he led the way by

taking copious draughts himself. The driver, too, was not

forgotten; the poor man was getting a chance of rising a little

above his daily plodding as he looked out on the lovely scenery

before him: but he was not to be left to God’s teachings;

ale, porter, champagne, he must taste them all. Mark insisted on

it; so the unfortunate man drank and drank, and then threw

himself down among some heath to sleep off, if he could, the

fumes of alcohol that were clouding his brains.

And what of Mrs Franklin and Mary? Both had declined all the

stimulants, and had asked for water.

“Nonsense,” cried Mark; “water! I’ve

taken very good care that there shall be no water drunk to-day;

you must take some wine or ale, you must indeed.”

“We will manage without it, if you please,” said

Mrs Franklin quietly.

Mark pressed the intoxicants upon them even to rudeness, but

without effect. Mr Rothwell was evidently annoyed at his

son’s pertinacity, and tried to check him; but all in vain,

for Mark had taken so much as just to make him obstinate and

unmanageable. But, finding that he could not prevail, the young

man hurried away in anger, and plied the other members of the

company with redoubled vigour.

So engrossing had been the luncheon that few of the party had

noticed a sudden lull in the atmosphere, and an oppressive calm

which had succeeded to the brisk and cheery breeze. But now, as

Mary rose from her seat on the grass, she said to her mother:

“Oh, mamma, how close it has become! And look there in

the distance: what a threatening bank of clouds! I fear we are

going to have a storm.”

“I fear so indeed, Mary; we must give our friends

warning, and seek out a shelter.”

All had now become conscious of the change. A stagnant heat

brooded over everything; not a breath of wind; huge banks of

magnificent storm-cloud came marching up majestically from the

horizon, throwing out little jets of lightning, with solemn

murmurs of thunder. Drop, drop, drop, tinkled on the gathered

leaves, now quicker, now quicker, and thicker. Under a huge roof

of overhanging rock the party cowered together. At last, down

came the storm with a blast like a hurricane, and deluges of

rain. On, on it poured relentlessly, with blinding lightning and

deafening peals of thunder. Hour after hour! Would it never

cease? At last a lull between four and five o’clock, and,

as the tempest rolled murmuring away, the dispirited friends

began their preparations for returning. Six o’clock before

all had reached the inn. Where were the driver and Mark? Another

tedious hour before they appeared, and each manifestly the worse

for liquor. Past seven by the time they had fairly started. And

now the clouds began to gather again. On they went, furiously at

first, and then in unsteady jerks, the omnibus swaying strangely.

It was getting dark, and the lowering clouds made it darker

still. Not a word was spoken by the passengers, but each was

secretly dreading the crossing of the stream. At last the bank

was gained—but what a change! The little brook had become a

torrent deep and strong.

“Oh! For goodness’ sake, stop! Stop! Let us get

out,” screamed the Misses Rothwell.

“In with it! In with it!” roared Mark to the

driver; “dash through like a trump.”

“Tchuck, tchuck,” was the half-drunken

driver’s reply, as he lashed his horses and urged them into

the stream.

Down they went: splash! Dash! Plunge! The water foaming

against the  wheels like

a millstream. Screams burst from all the terrified ladies except

Mary and her mother, who held each other’s hand tightly.

Mrs Franklin had taught her daughter presence of mind both by

example and precept. But now the water rushed into the vehicle

itself as the frightened horses struggled for the opposite bank.

Mark’s voice was now heard in curses, as he snatched the

whip from the driver and scourged the poor bewildered horses.

Another splash: the driver was gone: the poor animals pulled

nobly. Crash! Jerk! Bang! A trace had snapped: another jerk, a

fearful dashing and struggling, the omnibus was drawn half out of

the water, and lay partly over on its side: then all was still

except the wails and the shrieks of the ladies. Happily a lamp

had been lighted and still burned in the omnibus, which was now

above the full violence of the water. The door was opened and the

passengers released; but by whom?—certainly not by Mark. A

tall figure moved about in the dusk, and coming up to Mary threw

a large cloak over her shoulders, for it was now raining heavily,

and said in a voice whose tones she was sure she knew:

wheels like

a millstream. Screams burst from all the terrified ladies except

Mary and her mother, who held each other’s hand tightly.

Mrs Franklin had taught her daughter presence of mind both by

example and precept. But now the water rushed into the vehicle

itself as the frightened horses struggled for the opposite bank.

Mark’s voice was now heard in curses, as he snatched the

whip from the driver and scourged the poor bewildered horses.

Another splash: the driver was gone: the poor animals pulled

nobly. Crash! Jerk! Bang! A trace had snapped: another jerk, a

fearful dashing and struggling, the omnibus was drawn half out of

the water, and lay partly over on its side: then all was still

except the wails and the shrieks of the ladies. Happily a lamp

had been lighted and still burned in the omnibus, which was now

above the full violence of the water. The door was opened and the

passengers released; but by whom?—certainly not by Mark. A

tall figure moved about in the dusk, and coming up to Mary threw

a large cloak over her shoulders, for it was now raining heavily,

and said in a voice whose tones she was sure she knew:

“Come with me, my child, your mother is close at hand;

there, trust to me; take my other arm, Mrs Franklin: very

fortunate I was at hand to help. The drink, the drink,” he

muttered in a low voice; “if they’d stuck to the

water at the beginning they wouldn’t have stuck in

the water at the end.”

And now a light flashed on them: it was the ruddy glow from a

forge.

“Come in for a moment,” said their conductor,

“till I see what is to be done. Tom Flint, lend us a

lantern, and send your Jim to show some of these good people the

way to the inn; they’ll get no strong drink there,”

he said, half to himself.

And now several of the unlucky company had straggled into the

smithy, which was only a few yards from the swollen

stream. Among these was Mark, partially sobered by the accident,

and dripping from head to foot.

“Here’s some capital stuff to stave off a

cold,” he said, addressing Mrs Franklin and her daughter,

whose faces were visible in the forge light: at the same time he

rilled the cover of a small flask with spirits. “Come, let

us be as jolly as we can under the circumstances.”

“Thank you,” said Mrs Franklin; “perhaps a

very little mixed with water might be prudent, as Mary, I fear,

is very wet.”

Mark stretched out the cup towards her, but before a drop

could be taken the tall stranger had stepped forward, and

snatching it, had emptied its contents on the glowing coals. Up

there shot a brilliant dazzling flame to the smoky roof, and in

that vivid blaze Mrs Franklin and Mary both recognised in their

timely helper none other than Mr Esau Tankardew.

Chapter Four.

A Mysterious Stranger.

“This way, this way,” said Mr Tankardew, utterly

unmoved by the expression of angry astonishment on the face of

Mark Rothwell at the sudden conversion of his cup of liquid fire

into harmless flame—“Come this way, come this way,

Mrs and Miss Franklin: Tom, give me the lantern, I’ll take

the ladies to Sam Hodges’ farm, and do you be so good as to

see this young gentleman across to the ‘Wheatsheaf’;

Jones will look well after them all, I know.”

So saying, he offered his arm to Mrs Franklin, and bade Mary

follow close behind.

“It will be all right, madam,” he added, seeing a

little hesitation on the part of his companion; “you may

trust an old man to keep you out of harm’s way: there, let

me go first with the lantern; now, two steps and you are over the

stile: the path is rather narrow, you must keep close to the

hedge: just over three fields and we shall be there.”

Not a word was uttered as they followed their guide. Mrs

Franklin lifted up her heart in silent praise for their

preservation, and in prayer for present direction. Backward and

forward swayed the lantern, just revealing snatches of hedge and

miry path. At last the deep barking of a dog told that they were

not far off from a dwelling: the next minute Mr Tankardew

exclaimed, “Here we are;” and the light showed them

that they were come to a little gate in a paling fence.

“Hollo, Sam,” shouted out their guide: the

dog’s barking was instantly changed into a joyful whine. A

door opened a few yards in front of them, and a dark figure

appeared in the midst of a square opening all ablaze with

cheerful light.

“Hollo, Sam,” said Mr Tankardew again, in a more

subdued voice.

“Is that you, mayster? All right,” cried the

other.

“I’ve brought you some company, Sam, rather late

though.”

“You’re welcome, mayster, company and all,”

was the reply. In a few moments all three had entered, and found

themselves in an enormous kitchen, nearly large enough to

accommodate a village. Huge beams crossed the low white ceiling;

great massive doors opened in different directions rather on the

slant through age, and giving a liberal allowance of space at top

and bottom for ventilation. A small colony of hams and flitches

hung in view; and a monstrous chimney, with a fire in the centre,

invited a nearer approach, and seemed fashioned for a cozy

retiring place from the world of kitchen. Everything looked warm

and comfortable, from the farmer, his wife and daughter, to the

two cats dozing on the hearth. Vessels of copper, brass, and tin

shone so brightly that it seemed a shame to use them for anything

but looking-glasses; while tables and chairs glowed with the

results of perpetual friction.

“Come, sit ye down, sit ye down, ladies,” said Mrs

Hodges; “there, come into the chimney nook: eh! Deary me!

Ye’re quite wet.”

“Yes, Betty,” said Mr Tankardew, “these

ladies joined a party to the hills, and, coming back,

they’ve been nearly upset into the brook, which is running

now like a mill stream; they came in an omnibus, and very nearly

stuck fast in the middle; it is a mercy they were not all

drowned; no thanks to the driver, though.”

“Poor things,” exclaimed the farmer’s wife;

“come, I must help you to some dry things, such as they

are: and you must stay here to-night; it is not fit for you to go

home, indeed it is not,” she added, as Mrs Franklin

prepared to decline.

“I’ll make you as comfortable as ever I can. Jane,

go and put a fire in the Red-room.”

“Indeed,” said Mrs Franklin, “I can’t

think of allowing you to put yourself to all this trouble;

besides, our servants will be alarmed when they find us not

returning.”

“Leave that to me, madam,” said Mr Tankardew;

“I shall sleep at the ‘Wheatsheaf’ to-night,

and will take care to send a trusty messenger over to ‘The

Shrubbery’ to tell them how matters stand; and Mr Hodges

will, I am sure, drive you over in his gig in the morning. Hark

how the rain comes down! You really must stop: Mrs Hodges will

make you very comfortable.”

With many thanks, but still with considerable reluctance, Mrs

Franklin acquiesced in this arrangement. Their hostess then

accommodated them with such garments as they needed, and all

assembled round the blazing fire. Mr Tankardew had divested

himself of a rough top coat, and, looking like the gentleman he

was, begged Mrs Hodges to give them some tea.

What a tea that was! Mary, though delicately brought up,

thought she had never tasted anything like it, so delicious and

reviving: such ham! Such eggs! Such bread! Such cream! Really, it

was almost worth while getting the fright and the wetting to

enjoy such a meal with so keen a relish.

“They’ve got a famous distillery in this

house,” remarked Mr Tankardew when they had finished their

tea.

“A famous what?” asked Mrs Franklin, in great

surprise.

“Dear me,” said Mary aghast, “I really

thought I—”

“Oh! You thought they were teetotalers here: well, you

should know that it is a common custom in these parts to put rum

or other spirits into the tea, especially when people have

company. Now, Hodges and his wife are not content with putting

spirits into the tea, but they put them into everything: into

their bread, and their ham, and into their eggs.”

Mrs Franklin looked partly dismayed and partly puzzled.

“Yes, it is true, madam. The fact is simply this: the

spirits which my good tenants distil are made up of four

ingredients—diligence, good temper, honesty, and total

abstinence; and that is what makes everything they have to be so

good of its kind.”

“I wish we had more distilleries of this kind,”

said Mrs Franklin, smiling.

“So do I, madam; but it is a sadly dishonest,

unfaithful, and self-indulgent age, and the drink has very much

to do with it, directly or indirectly. Here, Sam,” to the

farmer and his wife who had just re-entered the kitchen,

“do you and your mistress come and draw up your chairs, and

give us a little of your thoughts on the subject; there’s

nothing, sometimes, so good as seeing with other people’s

eyes, specially when they are the eyes of persons who look on

things from a different level of life.”

“Why, Mayster Tankardew,” said the farmer,

“it isn’t for the likes of me to be giving my opinion

of things afore you and these ladies; but I has my

opinion, nevertheless.”

“Of course you have. Now, tell us what you think about

the young people of our day, and their self-indulgent

habits.”

“Ah! Mayster! You’re got upon a sore subject; it

is time summut was done, we’re losing all the girls and

boys, there’ll be none at all thirty years

hence.”

“Surely you don’t mean,” said Mrs Franklin

anxiously, “that there is any unusual mortality just now

among children.”

“No, no, ma’am, that’s not it,” cried

the farmer, laughing: “no, I mean that we shall have

nothing but babies and men and women; we shall skip the boys and

girls altogether.”

“How do you mean?”

“Why, just this way, ma’am: as soon as young

mayster and miss gets old enough to know how things is,

they’re too old for the nursery; they won’t go in

leading strings; they must be little men and women. Plain food

won’t do for ’em; they must have just what their pas

and mas has. They’ve no notion of holding their

tongues—not they; they must talk with the biggest; and I

blames their parents for it, I do. They never think of checking

them; they’re too much like old Eli. The good old-fashioned

rod’s gone to light the fire with.”

“Ay, and Sam,” broke in his wife,

“what’s almost worst of all—and oh! It is a sin

and a shame—they let ’em get to the beer and the wine

and the spirits: you mustn’t say them nay. Ay, it is sad,

it is for sure, to see how these little ones is brought up to

think of nothing but themselves; and then, when they goes wrong,

their fathers and mothers can’t think how it is.”

“You’re right, wife; they dress their bodies as

they like, and eat and drink what they like, and don’t see

how Christ bought their bodies for Himself, and they are not

their own. Ah! There’ll be an awful reckoning one day.

Young people can’t grow up as they’re doing and not

leave a mark on our country as it’ll take a big fire of the

Almighty’s chastisements to burn it out.”

Mrs Franklin sighed, and Mary looked very thoughtful.

Mr Tankardew was about to speak when a faint halloo was heard

above the noise of the storm, which was now again raging without.

All paused to listen. It was repeated again, and this time

nearer.

“Somebody missed his road, I should think,” said

Mr Tankardew.

“Maybe, sir; I’ll go out and see.”

So saying, Sam Hodges left the kitchen, and calling to quiet

his dog who was barking furiously, soon returned with a stranger

who was dressed in a long waterproof and felt hat, which he

doffed on seeing the ladies, disclosing a head of curling black

hair. He was rather tall, and apparently slightly made, as far as

could be judged; for the wrappings in which he was clothed from

head to foot concealed the build of his person.

“Sorry to disturb you,” he said, in a gentlemanly

voice. “It is a terrible night, and I’ve missed my

way. I ought to have been at Hopeworth by now, perhaps you can

kindly direct me.”

“Nay,” said the farmer, “you mustn’t

be off again to-night: we’ll manage to take you in:

we’ll find you a bed, and you’re welcome to such as

we have to eat and drink: it is plain, but it is

wholesome.”

“A thousand thanks, kind friends,” replied the

other; “but I feel sure that I am intruding. These

ladies—”

“We are driven in here like yourself by the

storm,” said Mrs Franklin. “I’m sure I should

be the very last to wish any one to expose himself again to such

a night on our account.”

Mr Tankardew had not spoken since the stranger’s

entrance; he was sitting rather in shadow and the new-comer had

scarcely noticed him. But now the old man leant forward, and

looked at the new guest as though his whole soul was going out of

his eyes; it was but for a moment, and then he leant back again.

The stranger glanced from one to another, and then his eyes

rested for a moment admiringly on Mary’s face—and who

could wonder! A sweeter picture and one more full of harmonious

contrast could hardly be seen than the young girl with her hair

somewhat negligently and yet neatly turned back from her

forehead, her dress partly her own and partly the coarser

garments of her hostess’s daughter, sitting in that plain

old massive kitchen, giving refinement and gaining simplicity,

with the mingled glow of health and bashfulness lending a special

brilliancy to her fair complexion. This was no ordinary

man’s child the stranger saw, and again he expressed his

willingness to retire and make his way to the town rather than

intrude his company on those who might prefer greater

privacy.

“Sit ye down, man, sit ye down,” said Hodges;

“the ladies ’ll do very well, the kitchen’s a

good big un, so there’s room for ye all. Have you crossed

the brook? You’d find it no easy matter unless you came

over the foot bridge.”

“I’m sorry, my friend, to say,” was the

reply, “that I have both crossed the brook and been

in it. I was about to go over by a little bridge a mile or

so farther down, when I thought I saw some creature or other

struggling in the water. I stooped down, and to my surprise and

consternation found that it was a man. I plunged into the stream

and contrived to drag him to the bank, but he was evidently quite

dead. What I had taken for struggling was only the force of the

stream swaying him about against the supports of the bridge. His

dress was that of a coachman or driver of some public conveyance.

I got help from a neighbouring cottage, and we carried him in,

and I sent someone off for the nearest doctor, and then I thought

to take a short cut into the road, and I’ve been wandering

about for a long time now, and am very thankful to find any

shelter.”

During this account Mrs Franklin and her daughter turned

deadly pale, and then the former exclaimed:

“I fear it was our poor driver—I heard a splash

while our omnibus was struggling in the water. Oh! I fear, I fear

it must have been the unfortunate man; and oh! Poor man,

I’m afraid he wasn’t in a fit state to

die.”

“If he was like your young friend at the forge, I fear

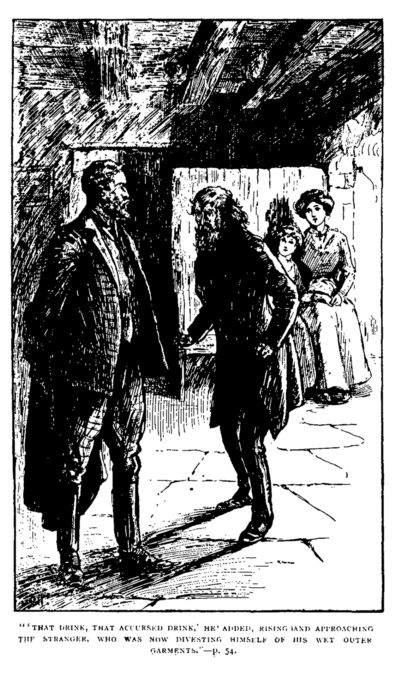

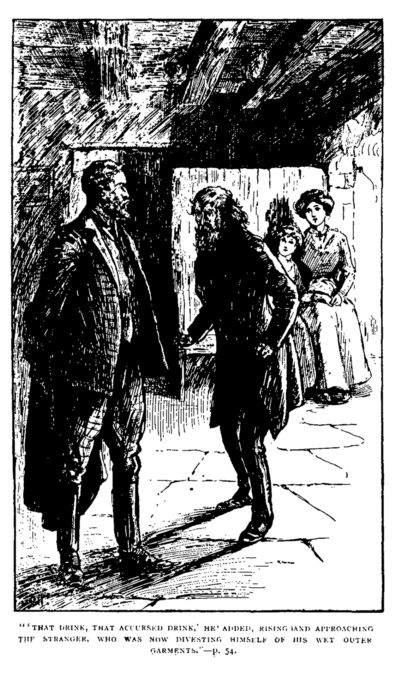

not indeed,” said Mr Tankardew.  “That drink that accursed

drink,” he added, rising and approaching the stranger, who

was now divesting himself of his wet outer garments. He was tall,

as we have said, and his figure was slight and graceful; he wore

a thick black beard and moustache, and had something of a

military air; his eyes were piercing and restless, and seemed to

take in at a glance and comprehend whatever they rested on.

“That drink that accursed

drink,” he added, rising and approaching the stranger, who

was now divesting himself of his wet outer garments. He was tall,

as we have said, and his figure was slight and graceful; he wore

a thick black beard and moustache, and had something of a

military air; his eyes were piercing and restless, and seemed to

take in at a glance and comprehend whatever they rested on.

But what was there in him that seemed familiar to Mrs Franklin

and Mary? Had they seen him elsewhere? They felt sure that they

had not, and yet his voice and face both reminded them of someone

they had seen and heard before. The same thing seemed to strike

Mr Tankardew, but, as he turned towards the young stranger, the

latter started back and uttered a confused exclamation of

astonishment. The old man also was now strangely moved, he

muttered aloud:

“It must be—no—it cannot be: yes, it surely

must be;” then he seemed to restrain himself by a sudden

effort, he paused for a moment, and then with two rapid strides

he reached the young man, placed his left hand upon the

other’s lips, and seizing him by the right hand hurried him

out of the kitchen before another word could be spoken.

Poor Mrs Franklin and her daughter looked on in astonishment,

hardly knowing what to say or think of this extraordinary

proceeding, but their host reassured them at once.

“Never fear, ma’am, the old mayster couldn’t

hurt a fly; it’ll be all right, take my word for it;

there’s summut strange as we can’t make out. I

think I sees a little into it, but it is not for me to speak if

the mayster wants to keep things secret. It’ll all turn out

right in the end, you may be sure. The old mayster’s been

getting a bit of a shake of late, but it is a shake of the right

sort. He’s been coming out of some of his odd ways and

giving his mind to better things. He’s had his heart broke

once, but it seems to me as he’s been getting it mended

again.”

For the next half hour, the farmer, his wife, and daughter

were busy about their home concerns, and their two guests were

left to their own meditations.

At last a distant door opened, and Mr Tankardew appeared

followed by the young stranger. By the flickering fire Mrs

Franklin thought she saw the traces of tears on both faces, and

there was a strange light in the old man’s eyes which she

had not seen there before.

“Let me introduce you to a young friend and an old

friend in one,” he said, addressing the ladies; “this

is Mr John Randolph, a great traveller.”

Mrs Franklin said some kind words expressive of her pleasure

in seeing the gratification Mr Tankardew felt in this renewal of

acquaintance.

“Ah! Yes,” said the old man; “you may well

say gratification. Why, I’ve known this young

gentleman’s father ever since I can remember. Sam,”

he added to the farmer, who had just come in, “I’m

going to run away with our young friend here, we shall both take

up our quarters at the inn for to-night. I see it is fairer now.

Mrs Franklin, pray make yourself quite easy. I shall despatch a

messenger at once to ‘The Shrubbery’ with full

particulars. Good-night! Good-night!”

And so Mary and her mother were left to their own musings and

conjectures, for the farmer and his family made no allusion

afterwards to the events of the evening.

Chapter Five.

The Young Musician.

A Grand piano being carried into Mr Esau Tankardew’s!

What next! What can the old gentleman want with a grand

piano? Most likely he has taken it for a bad debt—some

tenant sold up. But say what they may, the fact is the same. And,

stranger still, a tuner pays a visit to put the instrument in

tune. What can it all mean? Marvellous reports, too, tell of a

sudden domestic revolution. The dust and cobwebs have had notice

to quit, brooms and brushes have travelled into corners and

crevices hitherto unexplored, the piano rests in a parlour which

smiles in the gaiety of a new carpet and new curtains; prints

have come to light upon the walls, chairs and tables have taken

heart, and now wear an honest gloss upon their legs and faces;

ornaments, which had hitherto been too dirty to be ornamental,

now show themselves in their real colours. Outside the house,

also, wonderful things have come to pass; the rocking doorstep is

at rest, and its fellow has been adjusted to a proper level;

ever-greens have taken the place of the old

never-greens; knocker and door handle are not ashamed to

show their native brass; the missing rails have returned to their

duty in the ranks. The whole establishment, including its master,

has emerged out of a state of foggy dilapidation. Old Molly

Gilders has retired into the interior, and given place above

stairs to a dapper damsel. As for the ghosts, they could not be

expected to remain under such dispiriting circumstances,

and have had the good sense to resort to some more congenial

dwelling.

While gossip on this unlooked-for transformation was still

flying in hot haste about Hopeworth and the neighbourhood, the

families both at “The Firs” and “The

Shrubbery” were greatly astonished one morning by an

invitation to spend an evening at Mr Tankardew’s.

“Well,” said Mr Rothwell, “I suppose it

won’t do to decline; the old gentleman means it, no doubt,

as an attention, and it would not be politic to vex

him.”

“I am sure, my dear,” said his wife,

“I can’t think of going. I shall be bored to

death; you must make my excuses and accept the invitation for the

girls. I don’t suppose Mark will care to go; the old man

seems to have a spite against him—I can’t tell

why.”

“I’ll go,” interposed Mark, “if it be

only to see the fun. I’ll be on my good behaviour.

I’ll call for tea and toast-and-water at regular intervals

all through the evening, and then the old gentleman will be sure

to put me down for something handsome in his will.”

“You’d better take some music with you,”

said his mother, turning to her eldest daughter; “Mr

Tankardew has got his new piano on purpose, I suppose.”

“Ay, do,” cried Mark; “take something

lively, and you’ll fetch out the old spiders and

daddy-long-legs which have been sent into the corners like

naughty boys, and they’ll come out by millions and dance

for us.”

So it was settled that the invitation should be accepted. The

surprise at “The Shrubbery” was of a more agreeable

kind. Mrs Franklin and her daughter had learnt to love the old

man, in spite of his eccentricities; they saw the sterling

strength and consistency of his character. They had, however,

hardly expected such an invitation; but the reports of the

strange changes in progress in Mr Tankardew’s dwelling had

reached their ears, so that it was evident that he was intending,

for some unknown reasons, to break through the reserve and

retirement of years, and let a little more light and sociability

into the inner recesses of his establishment. That he had a

special object in doing this they felt assured; what that object

was they could not divine. Had Mrs Franklin known that the

Rothwells had been asked, she would have declined the invitation;

but she was unaware of this till she had agreed to go; it was

then too late to draw back.

All the guests were very punctual on the appointed evening,

curiosity having acted as a stimulant with the Rothwells of a

more wholesome kind than they were in the habit of imbibing. What

a change! It was now the end of October, and the evenings were

chilly, so that all were glad of the cheery fire, partly of wood

and partly of coal, which threw its brightness all abroad in

flashes of restless light. Old pictures, apparently family

portraits, adorned the walls, relieved by prints of a more modern

and lively appearance. One space was bare, where a portrait might

have been expected as a match to another on the other side of the

fireplace. The omission struck every one at once on entering. The

furniture, generally, was old-fashioned, and somewhat subdued in

its tints, as though it had long languished under the cold shade

of neglect, and had passed its best days in obscurity.

Not many minutes, however, were given to the guests for

observation, for Mr Tankardew soon appeared in evening costume,

accompanied by the young stranger who had taken refuge on the

night of the storm in Samuel Hodges’ farm kitchen. Mr

Tankardew introduced him to the Rothwells as Mr John Randolph, an

old-young friend. “I’ve known his father sixty years

and more,” he said; then he added, “my young friend

has travelled a good deal, and will have some curiosities to show

you by-and-by—but now let us have tea. Mrs Franklin, pray

do me the honour to preside.”

While tea was in progress, Mr Tankardew suddenly surprised his

guests by remarking dryly, and abruptly:

“You must know, ladies and gentlemen, that my mother was

a brewer.”

“Indeed!” exclaimed Mr Rothwell, in considerable

astonishment; and then asked, “was the business an

extensive one?”

“Pretty well, pretty well,” was the reply.

“She brewed every morning and night, but she’d only

one dray and that was a tray, and she’d a

famous large teapot for a vat; we never used hops nor sent our

barley to be malted, what little we used we gave to the fowls;

and we never felt the want of porter, or pale ale, or bitter

beer.”

“It is a pity that more people are not of your

mother’s mind,” said Mrs Franklin, laughing.

“So it is indeed; but I shouldn’t, perhaps, have

said anything about it, only the teapot you’ve got in your

hand now was my dear old mother’s brewery, and that set me

thinking and talking about it.”

It was not their host’s fault, nor Mr John

Randolph’s, who acted as joint entertainer, if their guests

did not make a hearty tea. The meal concluded, Mr Tankardew

requested his young friend to bring out some of his curiosities.

These greatly interested all the party—especially Mrs

Franklin and Mary, who were delighted with the traveller’s

liveliness and intelligence.

“Show our friends some of your sketches,” said the

old man. These were produced, and were principally in water

colours, evidently being the work of a master’s hand. As he

turned to a rather un-English scene, the young artist sighed and

said, “I have some very sad remembrances connected with

that sketch.”

“Pray let us have them,” said Mr Tankardew. Mr

Randolph complied, and proceeded: “This is an Australian

sketch: you see those curious-looking trees, they are blue and

red gums: there is the wattle, too, with its almond-scented

flowers, and the native lilac. That cottage in the foreground was

put up by an enterprising colonist, who went out from England

some fifteen years ago; you see how lovely its situation is with

its background of hills. I was out late one evening with a young

companion, and we were rather jaded with walking, when we came

upon this cottage. We stood upon no ceremony, but marched in and

craved hospitality, which no one in the bush ever dreamt of

refusing. We found the whole family at supper: the father had

died about a year before of consumption, after he had fenced in

his three acres and built his house, and planted vineyard and

peach orchard. There were sheep, too, with a black fellow for a

shepherd, and a stock yard with some fine bullocks in it;

altogether, it was a tidy little property, and a blooming family

to manage it. The widow sat at the head of the table, and her

son, a young man of two-and-twenty, next to her. There were three

younger children, two girls and a boy, all looking bright and

healthy. We had a hearty welcome, and poured out news while they

poured out tea, which with damper (an Australian cake baked on

the hearth), and mutton made an excellent meal. When tea was over

we had a good long talk, and found that the young farmer was an

excellent son, and in a fair way to establish the whole family in

prosperity. Well, the time came for parting, they pressed us to

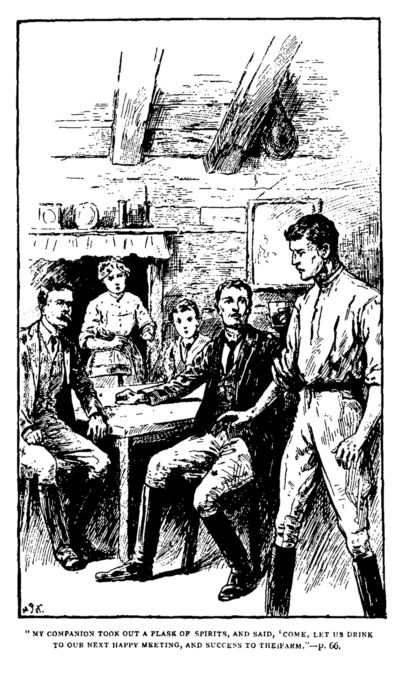

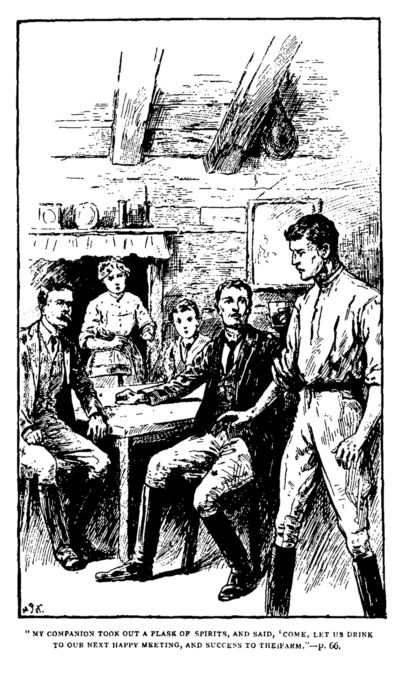

stay the night, but we could not.  Just as we were leaving, my companion took out a flask

of spirits, and said, ‘Come, let us drink to our next happy

meeting, and success to the farm.’ I shall never forget the

look of the poor mother, nor of the young man himself; the old

woman turned very pale, and the son very red, and said,

‘Thank you all the same, I’ve done with these things,

I’ve had too much of them.’ ‘Oh!

Nonsense,’ my friend said; ‘a little drop won’t

hurt you, perhaps we may never meet again.’ ‘Well, I

don’t know,’ said the other, in a sort of irresolute

way. I could see he was thirsting for the drink, for his eye

sparkled when the flask was produced. I whispered to my friend to

forbear, but he would not. ‘Nonsense,’ he said;

‘just a little can do them no harm, it is only friendly to

offer it.’ ‘Just a taste, then, merely a

taste,’ said our host, and produced glasses. The mother

tried to interfere, but her son frowned her into silence. So grog

was made, and the younger ones, too, must taste it, and before we

left the flask had been emptied. I took none myself, for never

has a drop of intoxicants passed my lips since I first left my

English home. I spoke strongly to my companion when we were on

our way again, but he only laughed at me, and said,

‘What’s the harm?’”

Just as we were leaving, my companion took out a flask

of spirits, and said, ‘Come, let us drink to our next happy

meeting, and success to the farm.’ I shall never forget the

look of the poor mother, nor of the young man himself; the old

woman turned very pale, and the son very red, and said,

‘Thank you all the same, I’ve done with these things,

I’ve had too much of them.’ ‘Oh!

Nonsense,’ my friend said; ‘a little drop won’t

hurt you, perhaps we may never meet again.’ ‘Well, I

don’t know,’ said the other, in a sort of irresolute

way. I could see he was thirsting for the drink, for his eye

sparkled when the flask was produced. I whispered to my friend to

forbear, but he would not. ‘Nonsense,’ he said;

‘just a little can do them no harm, it is only friendly to

offer it.’ ‘Just a taste, then, merely a

taste,’ said our host, and produced glasses. The mother

tried to interfere, but her son frowned her into silence. So grog

was made, and the younger ones, too, must taste it, and before we

left the flask had been emptied. I took none myself, for never

has a drop of intoxicants passed my lips since I first left my

English home. I spoke strongly to my companion when we were on

our way again, but he only laughed at me, and said,

‘What’s the harm?’”

“And what was the harm?” asked Mark, in a

rather sarcastic tone.

“I will tell you,” replied John Randolph, quietly.