W.H.G. Kingston

"The Loss of the Royal George"

Chapter One.

My father, Richard Truscott, was boatswain of the Royal George, one of the finest ships in the navy. I lived with mother and several brothers and sisters at Gosport.

Father one day said to me, “Ben, you shall come with me, and we’ll make a sailor of you. Maybe you’ll some day walk the quarter-deck as an officer.”

I did not want to go to sea, and I did not care about being an officer; indeed I had never thought about the matter, but I had no choice in it. I was but a very little chap, and liked playing at marbles, or “chuck penny,” in our backyard, better than anything else.

“He is too small yet to be a sailor,” said mother.

“He is big enough to be a powder-monkey,” observed my father; and as he was not a man who chose to be contradicted, he the next day took me aboard his ship, then fitting out in Portsmouth harbour, to carry the flag of Admiral Sir Edward Hawke. She was indeed a proud ship, with the tautest masts and the squarest yards of any ship in the British navy. She carried one hundred and four guns, all of brass—forty-two pounders on the lower-deck; thirty-two on the middle deck; and twenty-four pounders on the quarter-deck, forecastle, poop, and main-deck. She had huge lanterns at her poop, into which four or five of us boys could stow ourselves away; and from the time she was first launched, in 1756, the flag of some great admiral always floated from the masthead. When my father left me, to attend to his duty, I thought I should have been lost in the big ship, with deck above deck, and guns all alike one another on either side; and hundreds of men bawling and shouting, and rushing about here and there and everywhere. Sitting down on a chest, outside his cabin,—my legs were not long enough to reach the deck,—I had a good cry; and a number of boys, some of them not much bigger than myself, came and had a look at me, but they did not jeer, or play me any tricks, for they had found out that I was the bo’sun’s son, and that they had better not. I soon, however, recovered, and learned to find my way, not only from one deck to another, but up aloft; and before many days were over, had been up to the main-truck; though when my father heard of it, for he was below at the time, he told me not to go again till I was bigger. As I was continually, from ignorance, getting into scrapes, and he could not keep an eye on me himself, he gave me in charge to Jerry Dix, the one-legged fiddler and cook’s mate. Jerry could take very good care of me, but was less able to take care of himself when he had got his grog aboard, and more than once when this happened I had to watch over him. This made us firm friends, and I am very sure that he had a sincere affection for me.

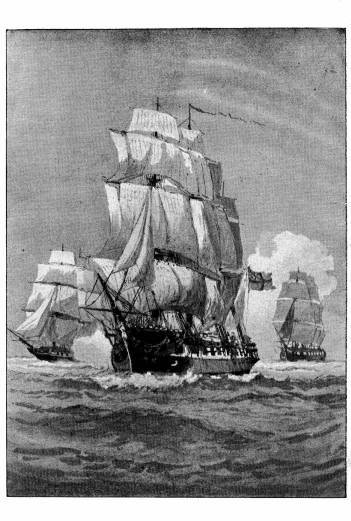

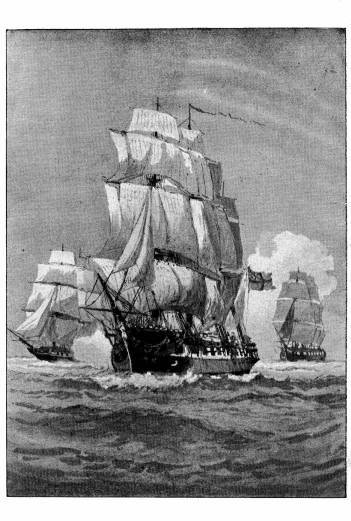

England was now engaged in what was known as the Seven Years’ War, which began in 1756, and had been going on for three years, the ships of England fighting those of France whenever they could find them, and generally giving them a drubbing. Our ship, which carried, as I have said, the flag of Admiral Sir Edward Hawke, had, with several other line-of-battle ships, been for some time watching the French fleet, under Admiral Conflans, shut up in Brest harbour, when, a heavy gale coming on, we were obliged to put into Torbay for shelter. We remained there for some time, while it blew great guns and small arms, which Jerry told me would keep the French ships shut up in harbour as securely as would our cannon. At length the weather moderated, and our admiral made the signal for the fleet to sail. It was a fine sight to see twenty-four line-of-battle ships, beside the Royal George, mostly seventy-four’s, some larger and some smaller, getting under way together, and standing over to the enemy’s coast. We were a few hours later than we should have been, however, for on our arrival we heard that Admiral Conflans had just before slipped out of Brest harbour, and sailed away for Quiberon Bay, hoping to cut off a small English squadron under Commodore Duff at anchor there.

We made all sail in chase, but a strong south-easterly wind blew in their teeth, and it was four days before we arrived off Belle Isle, when we were joined by Commodore Duff, with four fifty-gun ships and six frigates. Early in the morning, the Maidstone, one of our look-out frigates, made the signal that the enemy’s fleet was in sight! We, on this, threw out the signal for our ships to form in line, while the frigate was sent inshore to ascertain how far we were from it. You will understand that the fog prevented us from seeing the land or the enemy, and from the same cause it was no easy matter, as we all sailed close together, to prevent one ship from running into another.

We had not long to wait, however, before, the fog lifting, we caught sight of the French fleet, crowding all sail to get away from us, for their frigates had found out our fleet, while ours had discovered theirs. We made all sail in chase, both the enemy’s ships and ours having every stitch of canvas they could carry. In about three hours the van of our fleet got up with them.

I remember standing by my father’s side, in the forecastle, and thinking what a grand sight it was, as the Warspite and Dorchester gallantly commenced firing their broadsides into the enemy. The next ship that got into action was the Magnanime, commanded by the brave Lord Howe, followed quickly by the Revenge, Torbay, Montagu, and many others whose names are known to fame. There was a heavy sea running at the time, and, big as were our ships, they kept tumbling about so much that we were unable to fight our lower-deck guns. The captain of one of the French ships, the Thesée, engaged with the Torbay, thought that he could do so; and Captain Keppel,  who commanded the English seventy-four, unwisely followed his example. The two ships were thus hotly engaged, firing their broadsides into each other, when we saw the Frenchman give a lurch to starboard, and then down she went; out of all her gallant crew of eight hundred men, only twenty being saved by the British boats. The Torbay was very nearly following her, but by great exertions the guns were run in, and the ports closed, though not till she had shipped a good deal of water. Directly afterwards another Frenchman sank before our eyes, as we guessed, from the same cause.

who commanded the English seventy-four, unwisely followed his example. The two ships were thus hotly engaged, firing their broadsides into each other, when we saw the Frenchman give a lurch to starboard, and then down she went; out of all her gallant crew of eight hundred men, only twenty being saved by the British boats. The Torbay was very nearly following her, but by great exertions the guns were run in, and the ports closed, though not till she had shipped a good deal of water. Directly afterwards another Frenchman sank before our eyes, as we guessed, from the same cause.

I can’t say that I saw much more of what took place, for we were now going into action, and I was sent below to attend to my duty, which was to bring up ammunition in a tub, and to sit upon it on the main-deck, with the other ship’s boys, till it was wanted to load the guns. We were soon thundering away at the enemy, clouds of smoke filling the space between the decks, through which I could dimly see the crews of the guns, stripped to the waist, running them in to load, and running them out again as rapidly as they could. Shouts from the upper deck reached us, and we heard that one of the French ships had struck, but so heavy a sea was running, that no boat could be lowered to take possession of her; several others were also severely handled, and one completely dismasted. Night was coming on; and as we were but a short distance from the shore, the admiral made a signal for the fleet to anchor, and we, rounding-to, brought up. There we lay, the wind roaring and the sea foaming and tossing around us, anxiously waiting for daylight. I had not seen my father, who was, as I supposed, at his station on the upper deck, when the order came to secure the guns. I was still sitting on my tub joking with the other boys, who were congratulating themselves at not being killed, when Jerry Dix came stumping along the deck towards me; he took my hand kindly, and I thought I saw him wipe away a tear from his eye.

“What is the matter, Jerry?” I asked, seeing that something was wrong.

“Ben, my boy, he that’s gone told me to look after you, and so I will as long as I have a shot in the looker. You don’t hear his pipe, do you? and you never will no more. There’s the order to return powder to the magazine—as soon as you come up again, look out for me.”

The other boys and I hurried below to the magazine with our tubs; as soon as I came up I looked out for Jerry.

“What were you talking about?” I asked, having a feeling that something had happened to my father, though I scarcely dared to ask what.

“As I was saying, Ben, you have a friend in me if you have no other,” said Jerry, again taking my hand. “You will grieve, my boy, I know, but it can’t be helped; so I must out with it. We have not lost many men, but one has gone who was worth a dozen of the best; the Frenchman’s round shot coming aboard took off his head, and deprived you of your father and us of our bo’sun.”

“Do you mean to say that father’s killed?” I asked in a trembling voice, unable to believe the fact.

“Yes, boy, he has sounded his last pipe; we shall no more hear his voice rousing up all hands, or hailing the maintop; but he died doing his duty. We could have better spared a worse man, but there is no help for it and so, Ben, don’t pipe your eye.”

Notwithstanding Jerry’s exhortations, I did, however, cry heartily as I lay in my hammock; and even the other boys respected my sorrow, though it did not last long, I must confess.

The next day was an exciting one. As the morning broke, we saw our prize on shore, and another French ship at anchor dismasted; she, on seeing us, also ran on shore; when the Essex, a sixty-four, being sent in to take possession of her, was also wrecked; while another ship, the Resolution, seventy-four, was discovered on the rocks, the sea beating over her; and, before assistance could be sent, most of her gallant crew had perished. We succeeded, however, in burning the two French ships; but others, which were almost falling into our hands, by heaving their guns overboard, managed to escape up the river, where we could not follow.

“Although we have gained the victory, I do not see that we have gained much else for our trouble,” observed Jerry, who was a philosopher in his way. “We have, you see, destroyed four French ships, and sent well-nigh two thousand Frenchmen, more or less, out of the world, but then we have lost two of our own ships and some hundred British seamen; and, worse than all, our brave bo’sun, your father.”

The loss of my father was not to be repaired. I cannot say what might have happened had he lived, but losing him I grew up from boy to man, knocking about the world with many a chance of being knocked on the head, and yet with not the slightest hope of ever treading the quarter-deck as an officer—not that I ever thought about that. Jerry proved my firm friend. Though fond of his grog, for my sake he kept sober, that he might better look after me.

“Your father, Ben, lent me a helping hand when I had not a shot in the locker and was well-nigh starving, and it’s my duty to help you; and so I will, boy, as long as I can keep my fiddle-stick moving, and get a crust to put into my mouth.”

Jerry did me an essential service, for having seen better days he had got some learning, which was more than most men in the ship possessed, and he taught me to read and write, of which I knew nothing when I came to sea. Even my father, though boatswain of a line-of-battle ship, had not been much of a scholar. However, I am not now going to write about myself or my own adventures. When the ship was paid off, as my poor mother could not support me, and I had no fancy for any other calling, I went to sea again with Jerry, who got the rating of cook’s mate on board the Thunderer, seventy-four.

I was now a stout lad, and could stand to my gun or handle a cutlass as well as any man. We were stationed off Cadiz, with three other smaller vessels, looking out for a French squadron expected to sail for that port. Being driven off the coast by bad weather, on our return we found that the Frenchmen had slipped out, so away we went under all the canvas we could set in pursuit. We had come in sight of the Achille, a sixty-four gun ship, and, soon getting up with her, we opened our broadside, receiving a pretty hot fire from her in return. We were blazing away at each other, when a noise louder than all our guns together sounded in my ears, and I felt myself lifted off my legs and shot along the deck. For the moment I thought the world had come to an end, or that the ship had blown up. On opening my eyes, I caught sight of a number of dead and wounded men lying around me, and the after-part of the ship in flames. Among them, seeing Jerry, I picked myself up and ran to him.

“Are you killed, Jerry?” I asked.

“No, it’s only my wooden leg knocked away,” he answered. “Just get me a mop-stick, or bit of a broken pike, and I shall soon be on my pins again.”

Jerry having soon, spliced a piece of the mop-stick which I brought him to the stump of his leg, I set him on his pins. Meantime I found that one of the quarter-deck guns, having burst had created the havoc I have described and set the ship on fire. All hands labouring away with buckets, we got the flames extinguished, and stood after the enemy, who was trying to escape. We again, however, came up with her; and running alongside, the boarders were called away, headed by our first lieutenant, Mr Leslie, whom I followed closely. We had sprung on the deck of the enemy, and a big Frenchman was about to cut him down, when I caught the blow on my cutlass, and saved his life. One hundred and fifty gallant fellows coming on board after us, we quickly swept the Frenchmen from the deck, and they, crying out that they surrendered, we hauled down their flag. I did not think that Mr Leslie was aware of the service I had rendered him till he thanked me for it, and ever afterwards was my friend. I had the good chance, also, some time afterwards, of keeping his head above water, when our ship, the Laurel, was capsized in a hurricane in the West Indies; and though, of course, it was what I would have done for anyone, I was very thankful to have been the means of again saving his life, though I ran, he always declared, no little risk of losing my own. I served with him when he commanded the Favourite, sloop-of-war, and afterwards in the Active, frigate, when we captured a Spanish galleon, which put some hundred pounds into the pockets of each of the men, and a good many thousands into those of the captain. I was pretty fortunate on board other ships, in which I sailed to different parts of the world, getting back to old England safe at last.

Chapter Two.

Getting back safe home at last, like many another sailor, I might have sung—

“’Twas in the good ship Rover

I sail’d the world around,

For full ten years and over

I ne’er touch’d British ground.

And when at length I landed,

I could not long remain;

Found all my friends were stranded,

So went to sea again.”

Jerry, the truest of them, who had at the Peace gone on shore, I could nowhere hear of; my poor mother was dead, my brothers at sea, and my sisters either married or in service. One of the youngest, my sister Jane, I was told was living near Ryde with the family of a captain in the navy, and on inquiry I found he was no other than my old commander, Captain Leslie. I started at once with my pockets pretty well lined with gold, for I had just received a good lumping share of prize-money, which I was sorely puzzled to know what to do with. I was pleased at the thought of again seeing my old captain, though I scarcely fancied he would remember much about the little services I had done him. Who should open the door but Jane herself! She did not know me, but I knew her, though she had grown from a girl into a young woman, and I soon persuaded her who I was. She asked me down into the kitchen; and after we had had a talk, and she had told me all about those I cared for, she said she would go and tell Captain Leslie and his lady, who had often spoken to her about me, for they had found out that she was my sister. I was sent for into the drawing-room, when the captain welcomed me kindly, and told his wife and the young ladies—for there were two of them, besides a number of small children, boys and girls—how I had twice saved his life.

“I hope that you will stop as long as you like, and I will get you a lodging close at hand,” he said in his pleasant way. “I have often wished that I could have shown my gratitude more than I have been able to do.”

I told him not to trouble himself about that, as it was a pleasure to me to think that I had been of service; and as I had more money than I knew what to do with, and never wished to be anything but what I was, I didn’t see how he could have done more than he had done.

“I like your independent spirit, Ben,” he said, “but perhaps a time may come, when I may be able to serve you as I should wish.”

After a good talk of old times, I went back into the kitchen. I had been sitting there for some time, when a young woman came in with the sweetest face I ever set eyes on. I got up and made a sort of bow, with a scrape of my foot and a pull at a lovelock I wore in those days, for it was not for me, I felt, to sit in the presence of one like her; when Jane, laughing, said—

“Why, Ben, don’t you know Susan Willis?”

She was one of a lot of little girls I remember living next door to us, and I used to take her on my knee and sing to her, and tell her about Lord Hawke and the Royal George, when I was at home for the first time after going to sea. Susan smiled, and put out her hand, and that moment I felt I was not my own master; her voice was as sweet as her smile, and had the true ring of an honest heart in it.

“She is the young ladies’ own maid,” said Jane; “and they are as fond of her as everyone is who knows her.”

“I am sure of it,” says I; “and I am thankful that I am among them.”

Susan looked down and blushed, and so I believe I did, though she could not see my blush through the brown skin of my face as well as I could see the rose on her lily cheeks.

Well, the long and the short of it is that day after day I went up to the house, and at last—I couldn’t help it—I knew that I should be miserable if Susan wouldn’t be mine, so I asked her to marry me. How my heart did beat when she said yes. The captain and his lady were agreeable, and when they heard that I had a matter of three hundred pounds prize-money, or more, they observed that it was a prudent match; and so I took a cottage and furnished it, not far off, that Susan might go up and see Mrs Leslie and the children whenever they wished, and we were married and were as happy as the day was long. I know I was, and Susan seemed contented with her lot.

Susan was a prudent young woman, and one day she says to me, “We must do something, Ben, to make a living.”

“Why do you think that, Susan?” I asked; “I have got no end of prize-money.”

“It’s just this,” says she; “you may think there is no end, but it will come to an end, notwithstanding: what with the rent, and furnishing the house, and the new clothes you got me, and the weekly bills, we have spent fifty pounds of it already. Now, if we could set up a shop, or you could turn carpenter or gardener, or go into service with someone living hereabouts, we could lay up the rest of the money till a rainy day; and as we have a pretty spare room, I might take in a lodger to help out the rent.”

I had never before thought of that sort of thing; but I was sure that Susan was right, and I began to turn in my mind what to do. I soon found that I was not fit for anything Susan proposed. I never was much of a carpenter, and I knew nothing about gardening. I tried my hand in my own garden, and had got everything shipshape as far as the palings, walks, and borders were concerned, but I could get nothing to come up. Still I kept thinking of Susan’s remark, and, seeing the wisdom of it, I knew that there was only one thing I was fit for, and that was to go to sea. I was loath to part from Susan, but there was no help for it. There came about this time a hot press at Portsmouth; and as more than once the pressgangs had landed in the Isle of Wight, I was very sure that unless I got stowed away securely I should be picked up. Now, thinks I, it’s better to enter as a free man; and hearing that my old ship, the Royal George, which was lying at Spithead, was in want of hands, after a talk with the captain and poor Susan, whose heart was well-nigh ready to break, though she could not help acknowledging that I was right, I went on board and entered. Captain Leslie had given me a note to Captain Waghorn, her commander, and I was at once rated as quartermaster. The flag of the brave Admiral Kempenfelt, who had a year before been appointed Admiral of the Blue, flew aboard her. We sailed shortly afterwards with a strong squadron for Brest, to look after a French fleet which had just left that port, conveying a large number of merchantmen bound for the East and West Indies. On the 12th of December we had the good fortune to discover the enemy’s fleet about thirty-five leagues to the westward of Ushant, we being a long way to leeward of the convoy. I heard the admiral talking to the captain.

“We will cut off the merchantmen first, and fight the enemy afterwards,” says he.

What he had determined on he was the man to carry out, and before evening we had picked up twenty merchantmen, laden with provisions and naval and military stores, two or three regiments of soldiers, and a large number of seamen. The Royal George had to heave-to for the rest of the squadron, which was a long way astern.

Next morning the French fleet was increased by a number of other ships appearing to leeward. The admiral was a prudent as well as a brave man, and considered that it would be wiser not to engage them, and so with our prizes we sailed back to Portsmouth. I could almost see my cottage from the maintop, but I could not get leave to go on shore; and as to having Susan off to see me, that I would not think of, for she would have had to see and hear things such as I did not wish my wife to witness. We again sailed for a cruise down Channel, and, after putting into Torbay, once more returned to Portsmouth. Admiral Kempenfelt, we had heard, had been appointed to the command of the fleet in the Mediterranean, and we expected to sail again in a week or less. This was in August 1782. Lord Howe’s fleet was also lying off Spithead, among them the Victory, Barfleur, Ocean, and Union, all three-deckers, close to us, and numerous other men-of-war and merchant vessels; indeed, the people who came off from Portsmouth declared they could hardly see the Isle of Wight on account of the masts and spars of the ships. In consequence of going foreign we had been paid in golden guineas. As soon as I had received my pay, I got leave to go on shore to spend a couple of days, to be off again on the evening of the 27th. I had no difficulty in getting a boat, for there were hundreds pulling backwards and forwards. I found Susan bright and well, and looking out for me, for I had written to say I hoped to come. We went up to see Captain Leslie and the ladies, who had sent word that they wished us to pay them a visit. They were as kind as ever. The hours went by a great deal too fast.

A sailor’s wife has a hard trial to bear, to have her husband at home for two or three days, and then away for as many years or more; however, I hoped to be at home again in less time than that, and so I cheered up Susan, and promised for her sake to take the best care of myself I could. She had not given up her notion of taking in a female lodger. We were standing in the porch of the cottage on the last day, when we saw a young lady in black, leading a little boy, coming along the road. The little chap had a sailor’s hat and jacket on, though he did not seem much more than three years old.

“She is some officer’s widow,” I remarked to Susan as we watched her.

“She seems almost too young to be the mother of that child; she is his sister, more likely,” answered Susan.

The young lady had stopped, and was looking about her; presently she came on to us.

“Can you tell me if I am likely to find a lodging hereabouts for a few days?” she asked in a sweet voice; “I have left my luggage at the inn in the village, but I do not wish to remain there, and I feel very tired with walking about.”

“Will you like to walk in, miss, and rest yourself?” said Susan, “for you do look tired and ill too.”

The young lady’s cheek was very pale.

“I shall indeed be thankful if you will let me do so,” she answered, and coming in she sank down in a chair.

Susan got tea ready; it seemed to revive her a little; the child, I observed, did not call her mother; and as I saw no wedding ring on her finger, I began to think that Susan was right about her not being the child’s mother. Susan was evidently taken with the young lady, and, calling me out, she said that she would ask her to stop, as she did not seem fit to walk back to the village. I offered to go to the inn and fetch her things, but she had a bag in her hand which she said contained sufficient for the night, and she would send for them the next morning. I soon afterwards had to go off to the ship, so I saw no more of the young lady, who had gone to her room with the little boy.

Chapter Three.

What a change it was from the quiet cottage, with my sweet Susan by my side, to the lower-deck of the big ship, crowded with people, not only her own seamen and marines, but some hundreds of visitors, women and children! some of them the honest wives of the men, but others drunken, swearing, loud-talking creatures—a disgrace to their sex. Quarrelling and fighting and the wildest uproar were taking place; and then there were a number of Jews with pinchbeck watches, and all sorts of trumpery wares, which they were eager to exchange for poor Jack’s golden guineas. Some of them went away in the evening, but many more came back the next morning to drive their trade, and would have come as long as coin was to be picked up.

I am not likely to forget that next morning, the 28th of August. It was a fine summer’s morning, and there was just a little sea on, with a strongish breeze blowing from the eastward, but not enough to prevent boats coming off from Portsmouth. I counted forty sail-of-the-line, a dozen frigates and smaller ships of war, and well-nigh three hundred merchant vessels, riding, as of course we were, to the flood with our heads towards Cowes.

You will understand that under the lower-deck was fitted a cistern, into which the sea-water was received and then pumped up by a hand pump, fixed in the middle of the gun-deck, for the purpose of washing the two lower gun-decks; the water was let into this cistern by a pipe which passed through the ship’s side, and which was secured by a stop-cock, on the inside. It had been found the morning before that this water-cock, which was about three feet below the water line, was out of order and must be repaired.

The foreman came off from the dockyard, and said that it was necessary to careen the ship over to port sufficiently to raise the mouth of the pipe, which went through the ship’s timbers below, clean out of the water, that he and his men might work at it. Between seven and eight o’clock the order was given to run the larboard guns out as far as they could go, the larboard ports being opened. The starboard guns were also run in amidships and secured by tackles, the moving over of this great weight of metal bringing the larboard lower-deck port-cills just level with the water. The men were then able to get at the mouth of the pipe. For an hour the ship remained in this position, while the carpenters were at work. We had been taking in ruin and shot in the previous day, and now a sloop called the Lark, which belonged to three brothers, came alongside with the last cargo of rum; she having been secured to the larboard side, the hands were piped to clear lighter.

I had been on duty on the main-deck; several ladies had come off early in the morning, friends and relations of the officers. Some of them were either in the ward-room or gun-room, and others were walking the quarter-deck with the help of their gentlemen friends, as it was no easy matter, the ship heeling over as much as she was then doing. They thought it very good fun, however, and were laughing and talking as they tried to keep their feet from slipping. I had been sent with a message to Mr Hollingbury, our third lieutenant, who was officer of the watch; he seemed out of temper, and gave me a rough answer, as he generally did. He was not a favourite indeed with us, and we used to call him “Jib-and-Foresail Jack”; for when he had the watch at night he was always singing out, “Up jib,” and “Down jib”; “Up foresail,” “Down foresail”; and from a habit he had of moving his fingers about when walking the quarter-deck, we used to say that he had been an organ-player in London. Just as I got back to the main-deck, I caught a glimpse of a young lady in black, leading a little boy; she turned her face towards me, and I saw that she was the very same who had come to my wife’s cottage the previous evening—indeed I should have known her by the little boy by her side. I had to return to the quarter-deck again, and when I once more came back to the main-deck I could nowhere see her; but whether she went into the ward-room, or had gone below, I could not learn. I asked several people, for I thought she might have brought me off a message from Susan, and I might, I fancied, have been of use to her in finding the person she wished to see. While I was looking about, Mr Webb, the purser’s clerk, who had received orders to go on shore in charge of a boat, came up and ordered me to call the crew away; a couple of midshipmen were going with him. This took up some time, and prevented me from finding the young lady. Just then, as I went up to report the boat gone to Mr Hollingbury, Mr Williams, the carpenter, came up from the lower-deck, and requested that he would be pleased to order the ship to be righted, as she was heeling over more than she could bear. The lieutenant gave one of his usual short answers to the carpenter, who went below, looking as if he did not at all like it. He was back again, however, before I had left the deck, when he said in a short quick way, as if there was not a moment to lose—

“If you please, sir, the ship is getting past her bearings; it’s my duty to tell you, she will no longer bear it.”

“If you think, sir, you can manage the ship better than I can, you had better take the command,” answered Mr Hollingbury in an angry tone, twitching his fingers and turning away.

About this time there were a good many men in the waist who heard what the carpenter had said, and what answer the lieutenant gave. They all knew, as I did, that the ship must be in great danger, or the carpenter would not have spoken so sharply as he had.

A large number of the crew, however, were below; some on board the lighter, others at the yard-tackles and stay-falls, hoisting in casks; some in the spirit-room stowing away, others bearing the casks down the hatchway, all busy clearing the lighter. The greater number, it will be understood, were on the larboard side, and that brought the ship down still more to larboard. There was a little more sea on than before, which had begun to wash into the lower-deck ports, and, having no escape, there was soon a good weight of water on the lower-deck. Several of the men, not dreaming of danger, were amusing themselves, laughing and shouting, catching mice, for there were a good many of them in the ship, which the water had driven out of their quarters. It’s my belief, however, that the casks of rum hoisted in, and lying on the larboard side, before they could be lowered into the hold, helped very much to bring the ship down.

There stood the lieutenant, fuming at the way the carpenter had spoken to him. Suddenly, however, it seemed to occur to him that the carpenter was right, and he ordered the drummer to beat to quarters, that the guns might be run into their places, and the ship righted.

“Dick Tattoo” was shouted quick enough along the deck, for everyone now saw that not a moment was to be lost, as the ship had just then heeled over still more. The moment the drummer was called, all hands began tumbling down the hatchways to their quarters, that they might run in their guns.

Just then I saw a young midshipman, whom I had observed going off with Mr Webb, standing at the entrance-port singing out for the boat; he had forgotten his dirk, he said, and had come back to fetch it. The boat, however, had got some distance off, and he was left behind. Poor fellow, it was a fatal piece of forgetfulness for him.

“Never mind, Jemmy Pish,” said little Crispo, one of the smallest midshipmen I ever saw, for he was only nine years old. “There is another boat going ashore directly, and you can go in her.”

He gave an angry answer, and went back into the gun-room, swearing at his ill-luck.

The men had just got hold of the gun-tackles, and were about to bowse out their guns, which had been run in amidship, some five hundred of them or more having for the purpose gone over to the larboard side, which caused the ship to heel still more, when the water made a rush into the larboard lower-deck ports, and, do all they could, the guns ran in again upon them. Feeling sure that the ship could not be righted, I, seizing little Crispo, made a rush to starboard, and, dashing through an open port, found myself outside the ship, which at that moment went completely over, her masts and spars sinking under the water. Somehow or other, the young midshipman broke from me and slipped over into the sea. I thought the poor little fellow would have been lost, but he struck out bravely, which was, as it turned out, the best thing he could have done, as he could swim well.

I had just before seen all the port-holes crowded with seamen, trying to escape, and jamming one another so that they could scarcely move one way or the other. The ship now lying down completely on her larboard broadside, suddenly the heads of most of the men disappeared, they having dropped back into the ship, many of those who were holding on being hauled down by others below them. It was, you see, as if they had been trying to get out of a number of chimneys, with nothing for their feet to rest upon. Directly afterwards there came such a rush of wind through the ports that my hat was blown off. It was the air from the hold, which, having no other vent, escaped as the water pouring in took up its space. The whole side of the ship was, I said, covered with seamen and marines, and here and there a Jew maybe, and a good many women and a few children shrieking and crying out for mercy. Never have I heard such a fearful wailing. One poor woman near me shrieked out for her husband, but he was nowhere to be seen, and she thought that he was below with those who by this time were drowned; for there were hundreds who had been on the lower-decks, and in the hold, who had never even reached the ports, and some who had fallen back into the sea as it rushed in at the larboard side. She implored me to help her, and I said I would if I could. We could see boats putting off from the ships all round us to our help, and here and there people swimming for their lives who had leaped from the stern-ports, or had been on the lower-deck. I could not help thinking of our fine old admiral, and wished that he might be among them; but he was not, for he was writing in his cabin at the time, and when the captain tried to let him know that the ship was sinking, he found the door so jammed by her heeling over that he could not open it, and was obliged to rush aft and make his escape through a stern-port to save his life. This I afterwards heard.

As the ship had floated for some minutes, I began to hope that she would continue in the same position, and that I and others around me on her side might be saved. I hoped this for my own sake, and still more for that of my dear wife. I had been thinking of her all the time, for I knew that it would go well-nigh to break her heart if I was taken from her, as it were, just before her eyes. Suddenly I found, to my horror, that the ship was settling down; the shrieks of despair which rent the air on every side, not only from women, but from many a man I had looked upon as a stout fellow, rang in my ears. Knowing that if I went down with the ship I should have a hard job to rise again, I seized the poor woman by the dress, and leaped off with her into the sea; but, to my horror, her dress tore, and before I could get hold of her again she was swept from me. I had struck out for some distance, when I felt myself, as it were, drawn back, and, on looking round, I saw the ship’s upper works disappear beneath the water, which was covered with a mass of human beings, shrieking and lifting up their hands in despair. Presently they all disappeared. Just then I felt myself drawn down by someone getting hold of my foot under the water, but, managing to kick off my shoe, I quickly rose again and struck out away from the spot, impelled by instinct rather than anything else, for I had no time for thought; then directly afterwards up came the masts almost with a bound, as it were, and stood out of the water, with a slight list only to starboard, with the fore, main, and mizzen tops all above water, as well as part of the bowsprit and ensign-staff, with the flag still hoisted to it. Many people were floating about, making for the tops and rigging, several of them terrorstricken, who could not swim, catching hold of those that could. I thought, on seeing this, that it would be wiser to keep clear of them, till I could reach a boat coming towards the wreck at no great distance off. I was pretty nigh exhausted when I reached the boat, in which were a waterman and two young gentlemen, who happened to be crossing from Ryde to Portsmouth at the time. They soon hauled me in, and I begged them to pull on and save some of the drowning people. As neither of them could row, quickly recovering I took one of the oars, and was about to sit down to help the waterman, when I saw, not far off, several sheep, pigs, and fowls swimming in all directions, while hencoops and all sorts of articles were floating about.

“Let us save the poor beasts,” cried one of the young gentlemen thoughtlessly, just as young people are apt to speak sometimes. We, of course, took no heed of what he said, when our fellow-creatures had to be saved, and were pulling on when my eye fell on one of the sheep swimming away from us, which seemed to have someone holding on to its back. We put the boat round and followed, when, what was my surprise to see a child hanging on with both its hands to the sheep’s back! On a second look, it struck me that he was the very same little boy I had seen at my cottage, and who had come on board that morning with the young lady.

“Gently, now,” I cried out, afraid that the little fellow might let go his hold before we were up to him, but he held on bravely. In half a minute we were alongside the sheep, and I had the child safely in my arms. The young gentlemen hauled the poor sheep into the boat, for it would not have done to let it drown after having saved the child. I now saw that the little fellow was the same I had supposed, for he had his hat fastened on under his chin, and his sailor’s jacket and trousers on; he looked more astonished than frightened, and when I asked him how he had got into the water he could not tell me.

“Where is the young lady? is she your mother or aunt?” I asked.

He had no answer to give, but only gazed about with a startled look. He might have been younger than I had supposed; at all events, not a word could I get out of him to let me know who he was. One of the young gentlemen wished to hold him in his arms, so I gave the little fellow to him, and, taking the oar, we began to pull back towards the wreck to try and save any who might be still swimming about. The tops and rigging were by this time full of people who had managed to reach them, while several hanging on by ropes were still floating in the water. A number of boats from the men-of-war had, however, got up to the spot, and they were better able to go in among the spars and rigging than was our light wherry with the sea which was then running. Now that I was safe myself, I was anxious to learn who among my shipmates had escaped; but then I had the little boy to look after, who was all wet and shivering, and I knew too that the news of the accident would soon reach Susan, and that she would be in a fearful state of alarm if I did not let her know that I had been preserved. I told the young gentlemen this, and begged them to let the boatman put me and the child ashore at Ryde, promising him a guinea if he would do so. They were strangers who had been making a tour on the island, and, though they were in a hurry to get back to Portsmouth, they at once consented to do as I wished.

As we had a fair wind we hoisted the sail, and, soon getting away from the scene of the disaster, quickly reached the hard at Ryde. After thanking the young gentlemen and the waterman, I had jumped on shore with the child in my arms, and was stooping down to get hold of the sheep which I thought ought to be mine, or rather the little boy’s, when the waterman stopped me.

“No, no, master! you are not going to have that animal,” he said; “I want him.”

“We should not have stopped to pick up the sheep if it had not been for the little boy,” observed one of the young gentlemen; “and so, as the sheep’s life was saved on his account, the animal should go where he goes.”

The waterman, however, seemed determined to have the sheep.

“Come, master,” said I, “I will give you half a guinea, and that is as much as you will get for the animal.”

The waterman still held out.

“Come, you shall have a guinea,” said I, getting the money out of my pocket.

“And we will give five shillings apiece,” said one of the young gentlemen.

“Come, that must settle the matter,” said the other, giving the sheep a lift out of the boat.

Still the man grumbled, wanting to get more, but, handing the guinea to the young gentlemen, for the little boy being wet to the skin,—as of course I was, though that did not matter,—I wanted to be off home.  I got hold of the poor sheep and dragged it along, thinking thus to settle the matter. What had come over the waterman I do not know, but, springing out, he was going to catch hold of the sheep, when his foot slipped, and in he went between the boat and the hard.

I got hold of the poor sheep and dragged it along, thinking thus to settle the matter. What had come over the waterman I do not know, but, springing out, he was going to catch hold of the sheep, when his foot slipped, and in he went between the boat and the hard.

“Go on, sailor, go on,” cried the young gentlemen, laughing, while the waterman, now wet as I was, scrambled out, and, seeing that there was no use in following, got into his boat. Feeling very much obliged to the young gentlemen, and sorry I could not stop to thank them again, I hurried up as fast as I could to my home.

Chapter Four.

As I walked up the hill towards my cottage many people stopped, surprised at seeing me dripping wet, carrying a child and leading a sheep, and asked me all sorts of questions about the wreck; but I would not delay to answer them, except very briefly, or I should never have got home. I hoped that Susan would not have heard of the ship going down, still I half expected to meet her coming to learn if I had escaped; and I thought of the joy it would be to her to find that I was alive and well. As I drew near I saw that the cottage door was open; still Susan did not come out. My heart began to sink within me. I turned the sheep into the garden, and shut the wicket gate. I did not mind just then if the poor animal ate up all the flowers and vegetables; it deserved the best I could give it for the service it had rendered the little boy in my arms. No one was in the outer room, but I heard voices, and, opening the door of Susan’s room, I saw Mrs Leslie and the two young ladies, with my sister Jane, standing by Susan’s bed. Jane, catching sight of me, rushed out of the room and threw her arms round my neck.

“Thank Heaven, you are alive, Ben!” she exclaimed. “It will bring Susan to; don’t be afraid. The captain has gone off for the doctor. She saw the ship go down, and went off in a faint, thinking that all on board must be lost. I, fortunately, was with her. The captain, who was looking through his glass at the time, also saw the ship go over, and came down at once with the ladies to comfort her, he intending to go off to Spithead to learn all about the matter, and to hear if you had been saved. He, however, was first to go round to send up the doctor, and that was the reason he missed you.”

“But, Ben,” she asked, “is this the child Susan was telling me about? And the poor young lady, what has become of her?”

I just told Jane what had happened; but I could not say much, for all the time I was speaking I felt ready to drop, thinking that maybe Susan was gone altogether, but that she had not the heart to tell me so. I saw, however, that the ladies were burning feathers and holding salts to her; and at last Mrs Leslie came out, and after I had told her all I had said to Jane, with which she was much interested, she begged I would not be cast down, as she hoped my wife would soon again come round. She then went back to Susan’s room, but soon returned.

“You may go in,” she said, “and maybe, if she opens her eyes, the sight of you will do her more good than anything else.”

I did as she bid me, but as I leaned over Susan my heart sank, for she did not seem to breathe at all, and looked so pale that I thought she must really be dead. Still the young ladies kept applying the burnt feathers and salts, and then one of them held a small looking-glass for a moment over her mouth, and showed me that there was breath on it, and that made me feel a little less miserable. At last the doctor came; he felt her pulse, and looked very grave; then he opened her mouth, and, having given her something, stood watching its effects.

Soon I could see that she was beginning to breathe, a slight colour having come back to her cheeks, and then she opened her eyes, but she seemed not to be looking at anything. Presently, however, she began to move them, and uttering a faint cry she sat up, and, throwing her arms around my neck, burst into tears.

“She will do now very well,” said the doctor; and he and the ladies left the room. In a little time, however, they came back and called me out, telling Jane to go and sit with my wife. The doctor showed me some physic bottles on the mantelpiece, and, saying that Jane knew what to do with them, he began to make inquiries about the wreck and the little boy, and how I had saved him.

I found that the ladies had got off his wet clothes, which Jane had hung up to dry before the fire, while they had wrapped him up in their shawls. The only thing which the ladies found in his pockets was a little case. On opening it they saw that it contained a picture—a likeness of the child himself, just as he was then dressed. It was but slightly wet, as the water had not had time to soak it, so it was soon dried.

“It must be carefully preserved, as it may assist to prove who he is,” observed Mrs Leslie, though how that was to be was more than I could tell. “It is slightly done in water-colours, evidently by a lady,” observed Mrs Leslie.

She examined it carefully, but could find no name either on the picture or the case. It was placed on the mantelpiece to show to the captain as soon as he arrived. Jane then took the child in to see Susan, who kissed him again and again, as if he were her own child restored to her, and from that moment she felt towards him almost as if she was his mother. Of course I had to go over the whole story again, but I could only narrate what I knew.

“We must wait to hear more till the captain comes back,” said Mrs Leslie. “He will be truly thankful to find that you have escaped, Ben, and then we will consider what must be done with this little child. Perhaps his father or mother may have escaped and will claim him, or the poor young lady who you say took him on board, though you think she was not his mother.”

“Please, ma’am,” I said, “though I cannot claim any merit for saving the child—for it was the sheep saved him—I would like that my wife should have charge of him, and I am sure she would, for she said so just now. I say it at once for fear anybody else should ask to have him and I suspect that there will be a good many who will make the offer.”

“We will hear what the captain thinks,” said Mrs Leslie. “But you certainly have a better claim than anybody else, though, as I said before, probably some of his friends will come and claim him.”

I thought so too, but I knew in the meantime that it would please Susan greatly to have charge of the little fellow.

At last the ladies, leaving Jane with us, returned home; and the doctor went to visit his other patients, saying he would look in again during the evening.

By that time Susan was able to sit up and tell me more about the young lady. She had got up very early in the morning, and, begging to have some breakfast for herself and the little boy, said that she wanted to pay a visit to a ship at Spithead, and would be back in the evening. She had gone away, taking her bag with her, but left a letter with a sovereign in it, and a few words to the effect that she wished to pay her rent and board in advance. This, Susan thought, she did that it might not be supposed that she was going away without paying.

I went down to the inn, at which we understood the young lady had left her trunk, but I could hear nothing of it; the landlord said that no such person as I described had come there. I made inquiries at other public-houses, thinking that there might be some mistake, but I got the same answer.

Late in the evening Captain Leslie came back, and, shaking me by the hand, told me that he had been afraid I was lost, and how glad he was I had escaped. He had been over to Portsmouth, and had visited the Victory, and other ships on board which the people from the wreck had been carried, inquiring everywhere for me. He had heard a great deal about the wreck and the way in which many had been saved. I will mention what he then told me, and what I picked up from others.

Out of nearly a thousand souls who had been alive and well on board the ship in the morning, between seven and eight hundred were now lifeless. Besides our gallant admiral, who had been drowned while sitting writing in his cabin, three of the lieutenants, including the one whose obstinacy had produced the disaster, the larger number of the midshipmen, the surgeon, master, and the major and several other officers of marines, were drowned, as were some ladies who had just before come on board. Sixty of the marines had gone on shore in the morning, a considerable number of the rest who were on the upper deck were saved, but the greater number of the crew, many of whom were in the hold stowing away the rum casks, had perished; indeed, out of the ship’s whole complement, only seventy seamen escaped with their lives.

I was sorry to hear that Mr Williams, the carpenter, whose advice, had it been followed, would have saved the ship, was drowned; his body was picked up directly afterwards, and carried on board the Victory, where it was laid on the hearth before the galley-fire, in the hopes that he might recover, but life was extinct.

Captain Waghorn, though he could not swim, was saved. After trying to warn the admiral, he rushed across the deck and leaped into the sea, calling others to follow his example. A young gentleman, Mr Pierce, was near him.

“Can you swim?” he asked.

“No,” was the answer.

“Then you must try, my lad,” he said, and hurled him into the water.

Two men, fortunately good swimmers, followed. One of them getting hold of the captain, supported him, and swam away from the ship; the other fell upon Mr Pierce, of whom he got hold and supported above water till the ship settled, when he placed him on the maintop, and both were saved. The captain, in the meantime, was struggling in the water, and was with great difficulty kept afloat. A boat, with our seventh lieutenant, Mr Philip Durham, had on the very instant the ship went over come alongside, when she was drawn down, and all in her were thrown into the water. Mr Durham had just time to throw off his coat before the ship sank and left him floating among men and hammocks. A drowning marine caught hold of his waistcoat, and drew him several times under water. Finding that he could not free himself, and that both would be drowned, he threw his legs round a hammock, and, unbuttoning his waistcoat with one hand, he allowed it to be drawn off, and then swam for the main-shrouds. When there he caught sight of the captain struggling in the water, and a boat coming to take him off he refused assistance, till Captain Waghorn and the seaman supporting him were received on board. The captain’s son, poor lad, who had been below, lost his life.

I heard that the body of the marine was washed on shore ten days afterwards with the lieutenant’s waistcoat round his arm, and a pencil-case, having his initials on it, found safe in the pocket. There was only one woman saved out of the three hundred on board, and I believe she was the one I had helped out of the port; her name was Horn, and I was glad to find that her husband was saved also. It was curious that the youngest midshipman, Mr Crispo, and probably one of the smallest children, our little chap, should have been saved, while so many strong men were drowned.

I have known many a man come to grief through having too much grog aboard; but one of the midshipmen, who had taken more than was good for him, having overslept himself at the Star and Garter on the beach at Portsmouth, when he awoke in the morning found that his ship was at the bottom, and most of his messmates drowned.

Our first lieutenant, Mr Saunders, who had been busy in the wings, was drowned; his body, with his gold watch and some money in his pocket, was picked up, floating under the stern of an Indiaman off the Motherbank.

Of the three brothers who owned the sloop, two perished and one was saved. It was owing to her being lashed alongside that the ship righted, or she would have probably remained on her side. I was a good swimmer myself, and I should, had I not been, have lost my life long ago; and I have often thought what a pity it is that all seamen do not learn to swim. Many more might have been saved; but those who could not swim got hold of the men who could, and all were drowned together. If all had struck out from the ship when they found her going over, a greater number would have been picked up; instead of that, afraid to trust themselves in the water, they stuck by her, and they and a large number who got into the launch were drawn down with the ship, and all perished. The foreman of the plumbers, whose boat was lashed head and stern, was with all his men drawn into the vortex as the ship went down, and not one of them escaped. It was a sad sight, ten days or a fortnight afterwards, to see the bodies which were picked up; some were buried in Kingston churchyard, near Portsmouth, and a large number in an open spot to the east of Ryde. Some time afterwards a monument was put up in Kingston churchyard, to the memory of the brave Admiral Kempenfelt and his ship’s company. A court of inquiry was held, when Captain Waghorn was honourably acquitted, and it came out, that in so rotten a state was the side of the ship, that some large portion of her frame must have given way, and it is only a wonder that she did not go down before. When I come to think that she had upwards of one thousand tons of dead weight and spirits on board, it is surprising that she should have held together.

An attempt was made soon afterwards to raise the Royal George, and very nearly succeeded, as she was lifted up and moored some way from the spot where she went down; but a heavy gale coming on, some of the lighters sank, and the gear gave way, and she was again lost. It was whispered that on account of her rotten state the Admiralty had no wish to have her afloat, but that might have been scandal.

Having now said everything which people will care to hear about the fine old ship, I will go on with the history of the little boy saved from the wreck.

Chapter Five.

I must pass over the next seven years of my life and that of my young charge Harry, for that was the name Susan was certain the young lady called him. He sometimes spoke of himself as “Jack Tar,” but probably he had heard his friends call him so, because he was dressed like a little sailor. We were puzzled what surname to give him. The captain and Mrs Leslie and the young ladies and Susan and I talked it over, and at last settled to call him George, after the old ship; one of the young ladies thought Saint for saint would sound better, and so he went by the name of “Harry Saint George.”

I was at first greatly afraid that he would be taken from us, for a subscription was made for the families of those who perished when the ship foundered, and when his story was known a good share was given to him, besides other contributions, and many people wanted to have him. The captain stood my friend, as he did in all other matters, and insisted that as I pulled him out of the water, and the only friend of his we knew of had stopped at our house, Susan and I ought to have charge of him. He would have taken him himself, but he had a good many young children of his own, and thought that Harry would do better with us, and that he could still look after his education and interests as he grew older.

As soon as Harry could speak, he said that he would be a sailor, that his father was one, and that he would be one too; but who his father had been was a puzzle, as about that, of course, he really knew nothing. He could not tell us either anything about those he had seen on board, or how he had got hold of the sheep, though it is my belief that someone must have placed him on the animal’s back, intending to lash him to it, but that the ship had gone down before there was time to do so. Perhaps it was the last act of the poor young lady, or maybe of his father, if his father, as seemed probable, was on board.

As may be supposed, that sheep was a great pet with us and the captain’s family as long as it lived. Harry was very fond of it, and would ride about on its back, holding on just as he had done when the creature saved him from drowning. People used to come and see him ride about, and the ladies made a gay silk collar for the sheep, and also a bridle, but Harry would not use it, and always held on by the wool, saying that the sheep always well knew where to go. I railed off a piece of the garden and laid it down in grass, and on one side I built a house for the animal; but as there was not food enough in the little plot, the captain had it up to a paddock near his house, where it used to scamper about with Harry on its back and enjoy itself.

“It’s an ill wind that blows no one good,” and people used to say that the foundering of the Royal George was a fortunate circumstance for the sheep, as it would long before have been under the butcher’s knife.

The captain, meantime, made all the inquiries he could to try and discover the friends of the little fellow, but in vain; none of those who were saved remembered to have seen the young lady talking to anyone, though two or three recollected seeing her, as I had, coming on board.

Susan, like a thoughtful woman as she was, would not let the little boy wear out his clothes, but at once set to work to make him a new suit, while she carefully laid up those he had had on, with his hat, and the little picture in the case, to assist, as she said, in proving who he was should any of his relatives appear. Still time went on, and there appeared less chance of that than ever.

I spent a very happy time on shore with Susan: as we had no children of our own, we loved Harry as much as if he was our own son. Still I could not be idle; had it not been, indeed, for the captain, I should have been pretty soon pressed and compelled to go to sea, whether I liked it or not. Susan would have gladly kept me at home, which was but natural; still, I was too young to settle down in idleness, and should have grown ashamed of myself; so, as seamen were badly wanted for the navy, I at last entered, with the captain’s advice, on board a fifty-gun ship, the Leander, he promising to use his influence to obtain a boatswain’s warrant for me. While I was serving on board her we had a desperate action with a French eighty-gun ship, the Couronne, when we lost thirteen killed, and many more wounded, but succeeded in beating her off and putting her to flight.

Peace came soon after this, and five years passed before I obtained my warrant as boatswain. The prize-money I had received enabled me in the meantime to keep Susan and Harry as I wished; and when I became boatswain she was able to draw a fair sum of money every year. During those years I spent five months at home, which was a pretty long time considering what generally falls to the lot of seamen.

Harry had grown into a fine manly boy, and the more I looked at him the more convinced I felt that he was of gentle birth; he called Susan mother, and me father, though he knew that we were not his parents. He had good manners, and, considering his age, a fair amount of learning, for he used to go up every day to the captain’s to receive instruction from the children’s governess. At last the captain considered that he ought to be sent to school, and arranged that he should go with his own son, Master Reginald, who was about his age, though Harry was the strongest, and, I may say, the most manly of the two.

While I was at home I taught Harry as much as he could learn of what I may call the first principles of seamanship,—to knot and splice, and box the compass. I also built and rigged a model ship, of which he was very fond.

“You will not forget all I have taught you, my boy,” I said, when I was going off to sea.

“No, indeed I will not, father,” he answered; “and when you come back I hope I shall have learnt more, for I will do my best to pick up information from everybody who will teach me. The captain, I know, will, when I come home for the holidays, and there is old Dick Wright, who has been at sea all his life, settled near us, and he will tell me anything I ask him; though there is no one teaches me so well as you do, father.”

In those piping times of peace the ships were not kept so long in commission as they were during the war, so after serving three years as boatswain of the Huzzar frigate, on the West India and North American station, I once more returned home. I found Harry more determined than ever to go to sea, and he told me that Reginald Leslie had made up his mind to go also.

“Does his father wish it?” I asked.

“Oh yes, he has no objection to his going; and do you know, father, the captain says that he will get him and me appointed to the same ship with you, provided she is sent to a healthy station,” was the answer.

“Well, Harry, I shall be very glad to have charge of you both, and I am pleased that the captain thinks so well of you; though, to be sure, he has always shown that,” said I.

Susan was much cast down at the thoughts of losing Harry, but she could not help acknowledging that it was time he should go to sea, if he was going at all.

“But a ship’s boy has a hard life of it, as you have often told me, Ben,” she said, “and he has been gently nurtured, and brought up, I may say, like a young gentleman.”

“And a young gentleman he will still remain; for, you may depend on it, the captain intends to get him placed on the quarter-deck; and, though he himself has retired from the service, he has interest enough to get me and the lads appointed to some ship commanded by a friend of his own; and I flatter myself that, from the certificate I got from my last captain, he will have no difficulty about that.”

We had almost given up any expectations of ever meeting Harry’s friends. I own that I did not care very much about this, for once on the quarter-deck I felt sure he would make his own way; and though it might be of advantage to him to find them out, it was possible that it might be very much to the contrary.

I was one day going up the street of Ryde with Harry, when we saw a crowd of women and children and a few men and boys standing round the model of a full-rigged ship, and we heard a loud voice singing out—

“Cease, rude Boreas, stormy railer;

List, ye landsmen all, to me;

Messmates, hear a brother sailor

Sing the dangers of the sea.”

Then came the sound of a fiddle, and the singer continued his song to his own accompaniment.

“Let us stop and hear the old sailor,” said Harry, drawing me towards the crowd.

We found room just opposite where the man was standing. I then saw that he had a timber leg, and that the ship was placed on a stand with a lump of lead fixed to the end of a bent iron rod at the bottom, which made it rock backwards and forwards.

“Oh yes! oh yes! all you good people, lend a ear to poor Jack’s yarn,” he continued; “and you pretty girls with the blue eyes and rosy cheeks, and you with the dark ones, who does more harm with your blinkers, when you’ve the mind, among the hearts of young fellows than ever our ships gets from the guns of the Frenchmen. There aren’t many men in the navy of Old England who has seen queerer sights, or gone through more ups and downs in life than the timber-toed old tar who stands afore you, and who lost his leg in action aboard the Thunderer, seventy-four, when we took a Frenchman and hauled down his colours afore he knew where he was. There aren’t many either, I’ve a notion, who’ve been worse rewarded, or more kicked about by cruel fate, or you wouldn’t find him playing the fiddle and singing songs for your amusement.  Howsomdever, that’s neither here nor there, and I daresay you wish to hear the end of his stave, and so you shall when each on you has helped to load this here craft with such coppers or sixpences or shillings as you may chance to have in your pockets, and I daresay now a golden guinea wouldn’t sink her. Just look at her, always a-tossing up and down on the salt sea; that’s what we poor sailors have to go through all our lives. She’s a correct model of the Royal George, that famous ship I once served aboard when she carried the flag of the great Admiral Lord Hawke; and which now lies out there at Spithead fathoms deep below the briny ocean, with all her drownded crew of gallant fellows, no more to hear the tempest howling, or fight the battles of their king and country!”

Howsomdever, that’s neither here nor there, and I daresay you wish to hear the end of his stave, and so you shall when each on you has helped to load this here craft with such coppers or sixpences or shillings as you may chance to have in your pockets, and I daresay now a golden guinea wouldn’t sink her. Just look at her, always a-tossing up and down on the salt sea; that’s what we poor sailors have to go through all our lives. She’s a correct model of the Royal George, that famous ship I once served aboard when she carried the flag of the great Admiral Lord Hawke; and which now lies out there at Spithead fathoms deep below the briny ocean, with all her drownded crew of gallant fellows, no more to hear the tempest howling, or fight the battles of their king and country!”

I had been looking hard at the old sailor, whose eye just then falling on me, he recognised me at once as a brother salt.

“What, Jerry Dix!” I exclaimed; he looked at me very hard. “Don’t you know me, old ship? have you forgotten little Ben Truscott?”

“What, Ben, my boy! Give us your flipper, old chum. I thought as how I had seen you afore when my blinkers first caught sight of you, but I didn’t like to make a wrong landfall,” he exclaimed.

We shook hands heartily. I was truly glad to see the old man again.

“I see that you have become a warrant officer,” he said, eyeing my uniform. “That’s better nor nothing, though I did think as how you’d have been higher up the ratlines. And are you at anchor hereabouts?”

I told him that I was living in the neighbourhood, and begged him to come at once to my cottage and see my missus, and have a talk about old times.

“In course I will, Ben,” he answered. Then recollecting his audience, he thought that some apology was necessary for leaving them so abruptly; turning round, therefore, and eyeing his model of the Royal George, as he called her, though she was more like a frigate than a line-of-battle ship, he said—

“You’ll excuse me, ladies and gentlemen, but you see as how I’ve fallen in with an old ship, who I’ve known as man and boy these twenty years, so I must just now keep him company; but I’ll come back to-morrow and finish that there stave I was a-singing, and spin you more of my wonderful yarns, if you’ll just be good enough to come here and meet me; now mind, my little dears, bring plenty of coppers; and you, my pretty girls, bring something in your purses for poor Jack; I never takes no money from ugly ones—it’s a rule of mine, it’s wonderful too how few I ever see’s; so good-bye, and blessings on all of you; and now, Ben, we’ll up anchor and make sail.”

Jerry on this unshipped his model from the stand, which he took under his arm, while he placed the vessel on his shoulder, and with a stout stick in his hand came stumping on alongside me.

“Well, Jerry, I am truly glad to see you,” I said; “what have you been doing with yourself since we parted?”

“That would be a hard matter to say, Ben, except as how I’ve been knocking about the country from east to west, and north to south, spinning yarns without end, and singing and fiddling, and doing all sorts of odd dodges to pick up a living. They were honest ones though, so don’t be afraid.”

“And the yarns were all quite true, Jerry, eh?” I could not help asking.

“As to that, maybe I have spun a tough one now and then,” answered Jerry, with a quizzical look.

“About losing your leg aboard the Thunderer, for instance,” I remarked.

“Well, I can’t say quite so true as that, for I did lose my leg aboard the Thunderer. To be sure, it was my wooden one. Why, don’t you mind, Ben, how you got a mop-stick and helped me to splice it? It sounds better too, do you see, to talk of the Thunderer. The name tickles the people’s ears, and it wouldn’t do to tell ’em I lost my leg by falling down the main hatchway when half-seas over; so, do you see, I generally sticks to the Thunderer story, as it’s nearer the truth than any other, and doesn’t so much hurt my conscience.”

I had till then forgotten the circumstance, and I felt that it would not do to press old Jerry too hard. I introduced him to Susan, who made him welcome, for she had often heard me speak about the old man; she soon got tea ready, and a few substantials; then I got out a bottle of rum and mixed some grog, which I knew would be more to his taste. He was very happy, and many a long yarn he spun. Harry listened to them eagerly, and seemed much taken with him. I must remark that, after Jerry had sat talking with us for some time, he completely changed his tone and style of speaking; and though he still used what may be called sailor’s language, it was such as an officer or any other educated man might have employed. Indeed, I remembered that in my early days, Jerry, when in a serious mood, often showed that he was much superior in mind to the generality of people in the position in which he was placed. He afforded a melancholy example of the condition to which drunkenness and idle habits may reduce a man, who, from birth and education, might have played a respectable part in life. “That’s a fine boy of yours,” observed Jerry when Harry had gone out of the room. “I don’t set up for a prophet, but this much I’m sure of, that if you get him placed on the quarter-deck, he will be a post-captain one of these days. Is he your only one?”

I of course told Jerry that he was not my son, and described how he was rescued from the Royal George.

“Well, that’s a surprising history,” said Jerry; “it’s a wonder I never heard of it. Do you see, I was at the time down in the West of England, where my family used to live; and I thought I would go and have a look at the old place and see if any of them were above-ground—not that I intended to make myself known. Few of my relatives would have wished to own a broken-down one-legged old tar like me. I found a brother a lawyer, and a cousin a parson, and two or three other relations; but, from what I heard, I thought I should ‘get more kicks than ha’pence’ if I troubled them, so I determined to ’bout ship and stand off again. I was, howsomdever, very nearly being found out. I had got this here craft, which I called the Conqueror in those days, and was showing her off and spinning one of my yarns, when who should appear at the door of a handsome house but a lady with several little girls like fairies, and two fine boys. She and the young ones came down the steps, and after listening for some time she said in a pleasant voice, taking one of the youngsters by the hand—

“‘This boy is going to sea some day, and we wish him to hear about sailors, and I know what you tell about them is true, for I once had a brother who went away to sea, and used to write to me and give me accounts of what happened. Poor fellow! he lost his leg just as you have done, and after that I heard no more from him, so that I fear he died.’

“‘That was very likely, marm,’ said I. ‘In case I might have fallen in with him, may I be so bold to ask his name?’

“The lady, as I had a curious feeling she would, told me my own name, and then I knew for certain that she was my youngest sister Mary, the only one of the family who pitied me when others had cast me off. I had a hard matter not to make myself known, but I thought to myself that it would do no good to those pretty young ladies and gentlemen to find out their weather-beaten, rough old uncle. Mary herself, too, I had a notion would not have been really pleased; though, bless her gentle heart, I was sure that she would have been kind to me; and so I gulped down my feelings, and declared that I remembered a man of that name, who was dead and gone long ago. The words stuck in my throat, howsomdever, as I spoke them; and I was obliged to wish her good-morning and stump off, or she would have found me out. I hadn’t got far before she called me back, and putting a five-shilling piece in my hand she said—

“‘Pray accept this trifle, my good man, for the sake of my lost brother, for I know what you tell me is true, and that you are a genuine sailor.’

“‘May Heaven bless you, my dear,’ says I—I was as near as possible popping out the word ‘Mary,’ but I checked myself in time, and said ‘lady’ instead. The tears came to my eyes, and my voice was as husky as a bear’s. She thought it was all from gratitude for her unexpected gift, and that I wasn’t accustomed to receive so much. To be sure, she did look at me rather curiously, and, as I was going away, on turning my head I saw that she was still standing on the doorsteps watching me.

“I stopped about the neighbourhood for better than a fortnight, for I could not tear myself away; it was a pleasure to get a sight of Mary driving about in her carriage with her little girls, and her fine boys on ponies trotting alongside. She was happily married, I found, to a man of good fortune.

“While I was putting up at ‘The Plough,’ which I had known well in my youth, I heard a number of things about the neighbouring families, for I was curious to learn what had become of all the people I had known. There were not many of those who frequented the house who could read, and there was no newspapers taken in, and that is how I did not come to hear about the Royal George till some time afterwards. It strikes me, though I may be wrong, that by a wonderful chance I got hold of something which has to do with this fine lad here, who you have been looking after. I will think the matter over, and try and rake up what I have heard; but I don’t want to disappoint you, and I may be altogether wrong.”

I was naturally curious, and tried to get more out of Jerry, but he would not say a word beyond repeating over again that he might be altogether out of his reckoning. I of course begged him to stop with us, promising him board and lodging as long as he liked to stay; for, as he was in no ways particular, I could easily manage to put him up. He thanked me heartily, and said he would stop a night or two at all events. In the evening he went back with me to the inn to get his traps, for he travelled with a sort of knapsack, which he left behind him when he went out for his day’s excursions.

The next morning he had a wash and shave, and turned out neat and trim, with a clean shirt and trousers, and altogether looked a different sort of person to what he had been the day before.

“You see, Ben, I have given up drinking, and like to keep a best suit of toggery, and to go to church on a Sunday in a decent fashion, which I used not to care about once upon a time. It’s little respect that I can pay to the day, but I don’t play my fiddle, nor sing songs, nor spin long yarns about things that never happened, as I think myself a more respectable sort of chap than I used to be.”

I was glad to hear Jerry say this of himself, though maybe his notion that it was allowable to spin long yarns which had, as he confessed, no foundation in truth, on other days in the week, was not a very correct one. I told him so.