Title: Vesty of the Basins

Author: Sarah Pratt McLean Greene

Release date: May 15, 2007 [eBook #21443]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | THE MEETIN' |

| II. | "SETTIN' ON THE LOG" |

| III. | "GETTIN' A NAIL PUT IN THE HOSS'S SHU" |

| IV. | LOVE, LOVE |

| V. | COLUMBUS AND THE EGG, AND LOT'S WIFE |

| VI. | THIS GREATER LOVE |

| VII. | "SETTIN' ON THE FENCE"—THE SHIFTY SPECTRE |

| VIII. | "VESTY'S MARRIED" |

| IX. | THE TALE or CAPTAIN LEEZUR'S SLY COURTSHIP |

| X. | A CALL FROM NOTELY'S YACHT |

| XI. | ANOTHER NAIL |

| XII. | THE MASTER REVELLER |

| XIII. | CAPTAIN LEEZUR RELATES HOW MIS' GARRISON ATE CROW |

| XIV. | "TAR-A-TA!" OF THE TRUMPET |

| XV. | THE BROTHERS |

| XVI. | THE POPLAR LEAVES TREMBLE |

| XVII. | GOIN' TO THE DAGARRIER'S |

| XVIII. | UNCLE BENNY SAILS AWAY TO GALILEE |

| XIX. | THE BASIN |

| XX. | SOCIAL DIVERSIONS AT THE "POST-OFFICE" |

| XXI. | BROKEN WINDOWS |

| XXII. | "NEIGHBORIN'" |

| XXIII. | THE "FLAG-RAISIN'," OR THE "OCCASION" |

| XXIV. | THE STORY OF THE SACRED COW |

| XXV. | IN THE LANE |

| XXVI. | JUST THE SCHOOL-HOUSE |

Now is it to be rain or a storm of wind at the Basin?

I love that foam out on the sea; those boulders, black and wet along the shore, they are a rest to me; the clouds chase one another; in this dim north country the wind is cool and strong, though it is now midsummer; at sunset you shall see such color!

From a little, low, storm-beaten building comes the sound of a fog-horn. That is the gift of Melchias Tibbitts, deceased, to the Basin school-house. Yonder is his schooner, the "Martha B. Fuller," long stranded, leaning seaward, down there in the cove.

It is Sunday afternoon; the fog-horn that Melchias Tibbitts gave—it serves as bell; the battered schoolhouse as church; and for Sunday raiment? some little reverent, aspiring compromise of an unwonted white collar, stretched stiff and holy and uncomfortable about the stalwart neck above a blue flannel shirt, or a new pair of rubber boots—the trousers much tucked in—worn with an air of conscious, deprecating pride.

But the women will be fine. God only knows how! but be sure, in some pitiful, sweet way they will be fine.

There are many panes of glass out of the windows, the panels of the doors are out; so better they can see the clouds pass: it is beautiful.

Oh, naught have I either, nor wisdom, nor fine speech—only a little knowledge of shipwreck out yonder, and mirth, and tears, and love. The windows and panels of my life are no strong plate, polished and glittering to all beholders; they are stained and broken through. Let me come in and sit with ye.

"We should like to open our meetin' with singin'," said Superintendent Skates; "will one of the Pointers lead us in singin'?"

The Pointers were the aristocrats of this region, living twelve miles away at the Point, in the midst of two grocery stores and a millinery establishment; there were two of them here for a Sunday drive and pastime. They were silent.

"I see," said Elder Skates patiently, "that a few of the Crooked Rivers have drove down to-day, too. Will one of the Crooked Rivers lead us in singin'?"

Lower down in the scale than the Pointers were they of Crooked River, but still far above the Basins; those present were not singers, they were silent.

"Then will one of the Capers lead us in singin'?" very meekly and patiently persisted Elder Skates.

Nearer, and of low degree, were they of the Cape, but still above the Basins. They were silent.

"I know," said Elder Skates, his subdued tone buoyant now with an undertone of hope, "that one of the Basins will lead us in singin'!"

For the Basins had reached those cheerful depths where there is no social or artistic status to maintain; so low as to be expected to do, or attempt to do, whatever might be asked of them, even though failure plunged them, if possible, in deeper depths of abasement. There was nothing beneath them except the Artichokes; and it was seldom, very seldom, an Artichoke was present.

But the Basins, though so low, were modest.

"Can't one of the Basins start, 'He will carry you through'?" said the enduring Brother Skates; "where is Vesty?"

"She 's a-helpin' Elvine with her baby," came now a prompt and ready reply: "she said she'd come along for social meetin', after you'd had Sunday-school, ef she could."

"How is Elvine's baby?" spoke up another voice.

"Wal', he 's poored away dreadful, but Aunt Lowize says he 's turned to git along all right now, and when Aunt Lowize gives hopes, it 's good hopes, she 's nachally so spleeny."

"Sure enough. Wal', I've raised six, and nary sick day, 'less it was a cat-bile or some sech little meachin' thing. I tell you there ain't no doctor's ructions like nine-tenths milk to two-tenths molasses, and sot 'em on the ground, and let 'em root."

At this simple and domestic throwing off of all social reserve, voices hitherto silent began to arise, numerous and cheerful.

"Is there any more rusticators come to board this summer?"

"There 's only four by and large," replied a male voice sadly. "These here liquor laws 't Washin'ton 's put onto nor'eastern Maine are a-killin' on us for a fash'nable summer resort. When folks finds out 't they've got to go to a doctor and swear 't there 's somethin' the matter with their insides, in order to git a little tod o' whiskey aboard, they turns and p'ints her direc' for Bar Harbor and Saratogy Springs; an' they not only p'ints her, they h'ists double-reef sails and sends her clippin'!"

"Lunette 's got two," came from the other side of the house.

"What do they pay?"

"Five dollars a week."

"Pshaw! what ructions! Three dollars a week had ought to pay the board of the fanciest human creetur 't God ever created yit. But some folks wants the 'arth, and'll take it too, if they can git it."

"Wal', I don' know; they're kind o' meachy, and allas souzlin' theirselves in hot water; it don't cost nothin', but it gives yer house a ridick'lous name. Then they told Lunette they wanted their lobsters br'iled alive. 'Thar,' says she, 'I sot my foot down. I told 'em I' wa'n't goin' to have no half-cooked lobsters hoppin' around in torments over my house. I calk'late to put my lobsters in the pot, and put the cover on and know where they be,' says she."

"I took a rusticator once 't was dietin' for dyspepsy—that's a state o' the stomick, ye know, kind o' between hay and grass—and if I didn't get tired o' makin' toast and droppin' eggs!"

"I never could see no fun in bein' a rusticator anyway, down there by the sea-wall on a hot day, settin' up agin' a spruce tree admirin' the lan'scape, with ants an' pitch ekally a-meanderin' over ye."

"Lunette's man-boarder there, the husban', he 's editor of a noos-sheet, and gits a thousand dollars a year—'tain't believable, but it's what they say—an' he thinks he knows it all. He got Fluke to take him out in his boat; he began to direc' Fluke how to do this, an' how to do that, and squallin' and flyin' at him. Fluke sailed back with him and sot him ashore. 'When I take a hen in a boat, I'll take a hen,' says he."

"Did ye hear about Fluke's tradin' cows?"

"No."——

Meanwhile Brother Skates had been standing listening, patient, interested, but now recovered himself, blushing, in his new rubber boots.

"Can't one of the Basins start 'He will carry you through'?" he entreated.

"I'd like to," said one sister, the string of her tongue having been unloosed in secular flights; "I've got all the dispersition in the world, Brother Skates, but I don't know the tune."

"It 's better to start her with only jest a good dispersition and no tune to speak of," said Brother Skates with gentle reproof, "than not to start her at all."

Thus encouraged the song burst forth, with tune enough and to spare.

It was this I heard—I, a happy adopted dweller, from the lowest handle-end of the Basin, while driving over through the woods with Captain Pharo Kobbe and his young third wife and children.

"Come, git up," said Captain Pharo, at the sound, applying the lap of the reins to the horse; "ye've never got us anywheres yet in time to hear 'Amen'! Thar 's no need o' yer shyin' at them spiles, ye darned old fool! Ye hauled 'em thar yourself, yesterday. Poo! poo! Hohum! Wal—wal—never mind—

Git up!"

As we alighted at the school-house, we listened through the open panel with comfort to the final but vociferous refrain of "He will carry you through," and entered in time to take our seats for the class.

Elder Skates stood with a lesson paper in his hand, from which he asked questions with painful literalness and adherence to the text.

The audience, having no lesson paper or previous preparation of the sort, and not daring to enter into these themes with that originality of thought and expression displayed in their former conversation, answered only now and then, with the pale air of hitting at a broad guess.

"Is sin the cause of sorrow?" said Elder Skates.

No reply.

"Is sin the cause of sorrow?" he repeated faithfully.

At this point, one of a row of small boys on the back seat, no more capable of appreciating this critical period of the Sunday-school than the broad-faced sculpin fish which he resembled, took an alder-leaf from his pocket and, lifting it to his mouth, popped it, with an explosion so successful and loud that it startled even himself.

His guardian (aunt), who sat directly in front of him, though deaf, heard some echo of this note; and seeing the sudden glances directed their way, she turned and, observing the look of frozen horror and surprise upon his features, said severely, "You stop that sithing" (sighing).

Delighted at this full and unexpected escape from guilt and its consequences, the sculpin embraced his fellow-sculpins with such ecstasy that he fell off from his seat, upon the floor.

His aunt, turning again, and having no doubt as to his position this time, lifted him and restored him to his place with a determination so pronounced that the act in itself was clearly audible.

"You set your spanker-beam down there now, and keep still!" she said.

Elber Skates took advantage of this providential disturbance to slide on to the next question:

"How can we escape trouble?"

No reply.

"How can we escape trouble?" he meekly and patiently repeated.

"Good Lord, Skates!" said Captain Pharo, and put his hand in his pocket for his pipe, but bethought himself, and withdrew it, with a deep sigh.

Elder Skates had looked at him with hope, but now again mechanically reiterated:

"How—can—we—escape—trouble?"

"We can't! we can't no way in this world!" said Captain Pharo. "Where in h—ll did you scrape up them questions, Skates? Escape trouble? Be you a married man, Skates? I'd always reckoned ye was! Poo! poo! Hohum! Wal—wal—never mind—

He bethought himself again of his surroundings, spat far out of the window as a melancholy resource, and was silent.

Elder Skates, alarmed and staggered, looked softly down his list of questions for something vaguely impersonal, widely abstract, and now lit upon it with a smile.

"What is the meaning of 'Alphy and Omegy'?" he said—and waited, weary but safe.

But at the second repetition of this inscrutable conundrum, a lank and tall girl of some fifteen summers, arose and said, not without something of the sublime air becoming a solitary intelligence: "It's the great and only Pot-entate."

Elder Skates showed no sign of having been hit to death, but gazed vaguely at each one of his audience in turn, and then turned with dazed approval to the girl.

"Very good. Very good indeed," said he. "How true that is! Let us try and act upon it during the week, according to our lights. Providence—nor nothin' else—preventin', we will have our Sunday-school here as usual next Sunday, and I hope we shall all try and keep up religion. Is there anybody willing to have the 'five-cent supper' this week, in order to raise funds for a united burying-ground? We have been long at work on this good cause, but, I'm sorry to say, interest seems to be flaggin'. Is there anybody willin' to have the five-cent supper this week?"

"I can, I suppose," said the woman who had been willing to sing without tune. "But I can't give beans no longer. I can give beet greens and duck."

"I don't think it was any wonder we was gettin' discouraged," said another now resuscitated voice. "Zely had the last one, and Fluke for devilment gets a lot of the Artichokes over early ter help the cause. Wal, you might know there wa'n't no beans left for the Capers and Basins, and Zely was dreadful mortified, for there was several Crooked Rivers."

"Cap'n Nason Teel says," continued that individual's wife, "that the treasury 's fell behind; he says there ain't nothin' made in five-cent suppers, Artichokes or no Artichokes—in beans and corn-beef; he says we've got to give somethin' that don't cost nothin'. Beet greens and duck don't cost nothin', and if that 's agreeable, I'm willin'."

"All the same, beet greens and duck is very good eatin', I think," proposed Elder Skates, and receiving no dissenting voice, continued:

"Providence—nor nothin' else—preventin', there will be a five-cent supper at Cap'n Nason Teel's, on Wednesday evenin'. Beet greens and duck. I will now close the Sunday-school, trusting we shall do all we can during the week to help the cause of the burying-ground and of religion. As soon as Brother Birds'll arrives, we can begin social meetin'."

"It 's natch'all he should be late; somebody said 't he was havin' pickled shad for dinner."

"Here he comes now, beatin' to wind'ard," said Captain Pharo from the window. "He'll make it! The wind 's pilin' in through this 'ere school-house on a clean sea-rake. I move 't we tack over to south'ard of her."

This nautical advice was being followed with some confusion; I did not see Vesty when she came in, but when the majority of us had tacked to south'ard, I, electing still to remain at the nor'east, saw her, not far in front of me, and knew it was she.

The wind was blowing the little scolding locks of dusky brown hair in her neck; her shoulders were broad to set against either wind or trouble; she was still and seemed to make stillness, and yet her breast was heaving under hard self-control, her cheeks were burning, her eyes downcast.

I looked. Nestled among those safe to the south'ard was a young man with very wide and beautiful blue eyes, that spoke for him without other utterance whatever he would. Of medium height and build, yet one only thought, somehow, how strong he was; clad meanly as the rest, even to the rubber storm-bonnet held in his tanned black hand, it was yet plain enough that he was rich, powerful, and at ease.

His wide eyes were on Vesty, and shot appealing mirth at her.

She never once glanced at him, her full young breast heaving.

"Can't some of the brothers fix this scuttle over my head?" said Elder Birds'll nervously, addressing the group of true and tried seamen, anchored cosily to south'ard.

One, Elder Cossey, arose, a Tartar, not much beloved, but prominent in these matters. In his endeavors he mounted the desk and disappeared, wrestling with the scuttle, all except his lower limbs and expansive boots.

"My Lord!" muttered one who had been long groaning under a Cossey mortgage; "ef I could only h'ist the rest of ye up there, and shet ye up!"

"I sh'd like to give him jest one jab with my hatpin," added a sister sufferer, under her breath.

"The scuttle is now closed," said Elder Birds'll gravely, as Elder Cossey descended, "and the social meetin' is now open."

Here the blow of silence again fell deeply.

The wide blue eyes gave Vesty a look, like the flying ripple on a deep lake.

She did not turn, but that ripple seemed to light upon her own sweet lips; they quivered with the temptation to laugh, the little scolding locks caressed her burning ears and tickled her neck, but she sat very still. I fancied there were tears of distress, almost, in her eyes. I wanted her to lift her eyes just once, that I might see what they were like.

"Hohum!" began Elder Cossey, with wholly devout intentions—"we thank Thee that another week has been wheeled along through the sand, about a foot deep between here and the woods, and over them rotten spiles on the way to the Point, and them four or five jaggedest boulders at the fork o' the woods—I wish there needn't be quite so much zigzagging and shuffling in their seats by them 't have come in barefoot afore the Throne o' Grace," said Elder Cossey, suddenly opening his eyes, and indicating the row of sculpins with distinct disfavor.

"Yes," he continued, "we've been a-straddlin' along through troublements and trialments and afflickaments, hanging out our phiols down by the cold streams o' Babylon, and not gittin' nothin' in 'em, hohum!"

Vibrating thus mysteriously, and free and unconfined, between exhortation and prayer, Elder Cossey finally merged into a recital of his own weakness and vileness as a miserable sinner.

And here a strange thing happened. A brother who had been noticing the winks and smiles cast broadly about, and thinking in all human justice that Elder Cossey was getting more than his share, got up and declared with emotion, that he'd "heered some say how folks was all'as talkin' about their sins for effex, and didn't mean nothin' by it, but I can say this much, thar ain't no talkin' for effex about Brother Cossey; he has been, and is, every bit jest as honest mean as what he 's been a-tellin' on!"

Elder Skates arose, trembling. "Vesty," said he, with unnatural quickness of tone; "will you start 'Rifted Rock'?"

The blue, handsome eyes were on her mercilessly—she was suffocating besides with a wild desire to laugh, her breath coming short and quick. She gave one agonized look at Brother Skates, and then, lifted her eyes to the window.

The clouds were sad and grand; there was a bird flying to them.

She fixed her eyes there, and her voice flowed out of her:

"'Softly through the storm of life,

Clear above the whirlwind's cry,

O'er the waves of sorrow, steals

The voice of Jesus, "It is I."'"

The music in her throat had trembled at first like the bird's flight, winging as it soared, but now all that was over; her uplifted face was holy, grave:

"'In the Rifted Rock I'm resting.'"

Elder Cossey forgot his wrath in mysterious deep movings of compunction. Fluke, who had entered, was soft, reverent, his fingers twitching for his violin. Even so, I thought, as I listened, it may be will sound to us some voice from the other shore, when we put out on the dark river.

"Vesty," said a mite of a girl, coming up to her after meeting, "Evelin wants to know if you can set up with Clarindy to-night. She 's been took again."

"Yes," said Vesty, the still look on her face, "I'll come."

"Vesty," said Elder Skates, "when can you haul over the organ and swipe her out? She 's full o' chalk."

"I'll try and do it to-morrow." Vesty looked at Elder Skates and smiled, showing her wholesome white teeth.

"Vesty," said Mrs. Nason Teel; "I want ye to set right down here, now I've got ye, and give me that resute for Mounting Dew pudding."

The blue eyes at the door gave Vesty an imperative, quick glance.

But she sat down by Mrs. Nason Teel; she sat there purposely until all the people were dispersed and the winding lanes were still outside.

Then she went her own way alone, something like tears veiled under those long, quiet lashes.

She saw first a muscular hand on the fence and dared not look up, until Notely Garrison had vaulted over at a bound and stood before her, his glad eyes flashing, his storm hat in his hand.

Then her look was wild reproach.

"Vesty!" he cried. "Is this the way, after all we have been to one another? Have you forgotten how we were like sister and brother, you and I? how Doctor Spearmint led us to school together?" he laughed eagerly. "How"——

"I haven't forgotten, Note. But it can't be the same again, as man and woman, with what you are, and what I am."

"Better! O Vesty!"—he stood quite on a level with her now; she was glad of that. She was a tall girl, taller than he when they parted. "O Vesty!" he drank in her beauty with an awe that uplifted her in his frank, bright gaze—"God was happy when He made you!"

But the girl's eyes only searched his with a Basin gravity, for faith.

A fatal step, searching in Notely's eyes! A beautiful pallor crept over her face, flushing into joy. She ran her hand through his rough, light hair in the old way.

"It has not changed you, being at the schools so long, as I thought it would," she said wistfully, stroking his hair with mature gentleness, though he was older than she. "Why, Note; you look just as brown, and hearty, and masterful as ever!"

"Oh, but it wasn't book-schools I went to, you know. It was rowing and foot-ball and taking six bars on the running leap, and swinging from the feet with the head downward, and all that. I can do it all."

He looked away from her with mischief in his eyes, and hummed a line through his fine Greek nose, as Captain Pharo might.

"I don't doubt it, but you were high in the college too—for Lunette saw it in a paper: so high it was spoken of!"

"I just asked them to do that, Vesty. People can't refuse me, you know. I get whatever I ask for."

He turned to her with a sort of childish pathos on his strong, handsome face.

She bit her lip for joy and pride in him, even his strange, gay ways.

"Come, Vesta!" he said, with an air of natural and graceful proprietorship; "a stolen meeting is nonsense between you and me. I shall see you home."

His face invited me, the skin drawn over it rather tightly, resembling a death's-head, yet beaming with immortal joy.

He was sitting on a log; his little granddaughter, on the other side of him, was as cheerfully diverted in falling off of it. He was picking his teeth with some mysterious talisman of a bone, selected from the forepaw of a deer, and gazing at the heavens as at a fond familiar brother.

"Won't you set down a spa-ll," he said, and the way he said spell suggested pleasing epochs of rest.

"Leezur's my name; and neow I'll tell ye how ye can all'as remember it; it's jest like all them great discoveries, it's dreadful easy when it's once been thought on. Leezur—leezure—see? Leezure means takin' things moderate, ye know, kind o' settin' areound in the shank o' the evenin'—Leezur—lee-zure—see!"

Oh, how he beamed! The systems of Newton and Copernicus seemed dwarfed in comparison. I sat down on the log; the little girl, gazing at me in astonishment, fell off.

"What's the marter, Dilly?" said her grandfather, in the same slow, mellow, jubilant tone with which he had propounded his discovery, and not withdrawing his fond smile from the heavens; "'s the log tew reoundin' for ye to set stiddy on?"

A rattling brown structure rose before us, surrounded by a somewhat firm staging; a skeleton roof, with a few shingles in one corner, twisted all ways by the wind. It told its own tale, of an interrupted vocation.

"I expect to git afoul of her agin to-morrer," continued Captain Leezur; "ef Pharo got my nails when he went up to the Point to-day. Some neow 's all'as dreadful oneasy when they gits to shinglin'; wants to drive the last shingle deown 'fore the first one's weather-shaped. Have ye ever noticed how some 's all'as shiftin' a chaw o' tobakker? Neow when I takes a chaw I wants ter let her lay off one side, and compeound with her own feelin's when she gits ready to melt away. Forced-to-go never gits far, ye know.

"Some 's that way," he resumed; "and some 's sarssy."

I looked up incredulously, but his fostering, abstracted smile was as serene as ever.

"Vesty, neow, stood down there in the lane this mornin', and sarssed me for a good ten minits; sarssed me abeout not havin' no nails, and sarssed me abeout settin' on the log a spall; stood there and sarssed and charffed."

"She is some relative—some grandniece of yours, Captain Leezur?"

"No, oh no. Vesty and me 's only jest mates; but we charff and sarss each other 'tell the ceows come home."

I thought of the tall girl with the holy eyelids and the brave resistance against mirth, and in spite of my predilection for Captain Leezur, his words seemed to me like sacrilege.

"I saw her, Sunday," I said.

"Wal, thar' neow! Vesty 's jest as pious lookin', Sundays, as Pharo's tew-seated kerridge. I tell her, I'm dreadful glad for her sake that there ain't but one Sunday tew a week, she couldn't hold out no longer. Still, she's vary partickeler, Vesty is, and she 's good for taking keer o' folks. Elder Birds'll says 't ef Vesty Kirtland ain't come under 'tonin' grace, then 'tonin' grace is mighty skeerce to the Basin."

"She is beautiful," I said.

"Oh, I don't know 'beout that. Vesty 's a little more hullsome lookin' sometimes 'long in the winter, when she gits bleached out and poored away a bit."

"People seem to depend on her a great deal."

"Sartin they dew. Wal, Vesty 's gittin' on. She 's nineteen year old. She can row a boat, or dew a washin', or help in a deliverunce case, and she 's r'al handy and comfortin' in death-damps."

"All that! Vesty—and nineteen!" I think I sighed.

"Ye mustn't let her kile herself reound ye," said Captain Leezur.

I looked up in dismay. Had he not seen my weakness of body, and my birth-scarred face?

No, apparently he had not; his benign blessed face uplifted, and his voice so glad:

"Ye know how 'tis with women folks; they don't give no warnin', but first ye know they're kilin' themselves all reound and reound yer h'art-strings. They don't know what it 's for and ye don't know what it 's for; but take a young man like you, and ef ye ain't keerful, Vesty'll jest as sartin git in a kile on you as the world."

"How about that strong-looking young man?" I said. "Very easy, swaggers gracefully—with the blue eyes."

"Neow I know jest who you mean! You mean Note Garrison. Sartin, Vesty 's done herself reound him from childhood to old age, as ye might say. I don't know whether he c'd ever unkile himself or not, but I shouldn't want to bet on no man's 'charnces with a woman like Vesty all weound areound and reound him that way. Some says 't he wouldn't look at a Basin when it comes to marryin'. But thar'! Note all'as kerries sail enough ter sink the boat—but what he says, he'll stick to."

"He is rich, then?"

"Wal, yes. They own teown prop'ty somewhars, and they own all the Neck here, and lays areound on her through the summer. Why, Note's father—he 's dead neow—he and I uster stand deown on the mud flats when we was boys, a-diggin' clarms tergether, barefoot; 'tell he cruised off somewhar's and made his fortin'.

"I might 'a' done jest the same thing," reflected Captain Leezur aloud, with a pensiveness that still had nothing of unavailing regret in it, "ef I'd been a mind tew; and had a monniment put up over me like one o' these here No. 10 Mornin' Glory coal stoves."

I too mused, deeply, sadly.

O placid, unconscious sarcasm! innocent as flowers: wise end, truly, of all earthly ambition! How much more distinguished, after all, Captain Leezur, the spireless grave waiting down there in the little home lot by the sea. Since five-cent suppers do not enrich the donor, and the treasury of the United Burying Ground is permanently low.

"Never mind, Dilly! crawl up agin. What ef ye did tunk onto yer little head; little gals' skulls is yieldin' and sof'."

"What is the weather going to be, Captain Leezur?" I said, following his gaze skyward.

"Wal, I put on my new felts," said he, indicating without any false assumption of modesty those chaste sepulchres enclosing his feet—"hopin' 'twould fetch a rain! said I didn't care ef I did spot my new felts ef 'twould only fetch a rain! One thing," he continued, scanning the dilatory sky with a look that was keen without being severe; "she'll rain arfter the moon fulls, ef she don't afore."

I reluctantly made some sign of going, but was restrained. "Wait a spall," he said; and ran his hand anticipatively into his pocket. He brought to light some lozenges that had evidently just been recovered from blushing intimacy with his "plug" of tobacco.

"Narvine lozenges," he explained; "they're dreadful moderatin' to the dispersition; quiet ye; take some.

"They come high," he confided to me, with the idea of enhancing, not begrudging the gift, as we sucked them luxuriously; "cent apiece, dollar a hunderd. Never mind, Dilly; here 's one o' Granpy's narvine lozenges; p'r'aps it'll help ye to set stiddier."

So, with a glad view to moderating my disposition, I sat with Captain Leezur and the little girl on the log, and ate soiled nervine lozenges, tinctured originally with such primal medicaments as catnip and thoroughwort; and whether from that source or not, yet peace did descend upon me like a river.

As I finally rose to go—

"D'ye ever have the toothache?" said Captain Leezur kindly; "ef ye do, come right straight deown to me, and ef she 's home you shall have her"—and he exhibited beamingly that talismanic little bone cleft from the forepaw of a deer, "Ye pick yer teeth with 'er and ye're sartin never to have the toothache, but ef you've got a toothache, she'll cure ye.

"Mine 's been lent a great deal," he continued proudly. "She 's been as far as 'Tit Menan Light, and one woman over to Sheep Island kep' her a week once. She 's been sent for sometimes right in the middle o' the night! When there ain't nobody else a-usin' of her, I takes the charnce to pick away with her a little myself. But ef you ever feel the toothache comin' on, come to me direc'—and ef she 's home, you shall have her."

I thanked him with a swelling heart. We shook hands affectionately, and I went on up the lane.

I turned the corner by the school-house. Away back there among the spruce trees, I saw moving figures, red, green, blue, and heard low voices and laughter.

Then I remembered how I had heard the orphan "help" of my hostess, Miss Pray, make a request that she might go "gumming" with the other girls that afternoon.

It was a long perspective to limp through alone, with all those bright, merry eyes peering from behind the spruce trees. But I had not labored over half the way, when I saw one, the tallest one, coming toward me.

Vesty.

"Won't you have some?" she said. "Strangers don't know how good it is; it is very good for you—a little." Yes, she was chewing the gum—a little—herself; but that wild pure resin from the trees, and with, oh, such teeth! such lips! a breath like the fragrant shades she had issued from.

She poured some of her spicy gleanings into my hand.

And now I could see her closely.

I do not know how she would have looked at other men, strong men; but at me she looked as the girl mother who bore me, untimely and in terror, might have done, had she been now in the flesh, mutely protective against all the world, without repugnance, infinitely tender.

"I am coming up to sit with you and Miss Pray, some evening," she said. Her warm brown fingers touched mine. She did not blush; she had her Sunday face—holy, grave.

"Come! God bless you, child!" I said, and limped on, strong against the world.

I sat by the fireplace that evening; not a night in all the year in this sweet north country but you shall find the fire welcome.

Miss Pray's fireplace stretched wide between door and door. Opposite it were the windows; you saw the water, the moon shone in.

Miss Pray did her own farming and was sleepy, yet sat by me with that religious awe of me as befitting one who had elected to pay seven dollars a week for board! I surprised a look of baffled wonder and curiosity on her face now and then, as well as of remorse at allowing me to attach such a mysterious value to my existence.

She did not know that her fire in itself was priceless.

It burned there—part of a lobster trap, washed ashore, three buoys, a section of a hen-coop, a bottomless chopping tray, a drift-wood stump with ten fantastic roots sending up blue and green flame, a portion of the wheel of an outworn cart, some lobster shells, the eyes glowing, some mussel shells, light green, and seaweed over all, shining, hissing, lisping.

Miss Pray snored gently. I put some of the spruce gum Vesty had given me into my mouth; well, yes, by birth I have very eminent right to aristocratic proclivities.

But the spruce woods came again before me with their balm, and her face. I dwelt upon it fondly, without that pang of hope which most men must endure, and smiled to think of Captain Leezur's dismay if he should know how Vesty had already coiled herself around my heart-strings!

They never noticed my physical misfortune except in this way: they invited me everywhere; to mill, to have the horse shod, all voyages by sea or land; my visiting and excursion list was a marvel of repletion.

Captain Pharo came down—my soul's brother—with more of "a h'tch and a go," than usual in his gait.

"My woman read in some fool-journal somewheres, lately," he explained, "about pourin' kerosene on yer corns and then takin' a match to her and lightin' of her off.

"Wal', I supposed she was a-dressin' my corns down in jest the old usual way, last Sunday mornin', when—by clam! ye don't want to splice onto too young a shipmate, major." (This last was a divinely Basin thought, treating me as a subject of the wars.)

"I've married all states but widders," said Captain Pharo, with a blasé air of conjugal experience; "but my advice above all things is," he murmured, lifting his maimed foot, "don't splice onto too young a shipmate. They're all'as a-tryin' some new ructions on ye. Now Vesty, even as stiddy as she is, she 's all'as gittin' the women folks crazy over some new patron for a apern, or some new resute for pudd'n' and pie. So," he added, "ef you sh'd come to me, intendin' to splice, all the advice 't I c'd give 'ud be, I don't know widders; poo! poo!—hohum! Wal, wal—

try widders."

As I stood speechless with conflicting emotions, he lit his pipe and continued, more hopefully:

"I've got to go up to the Point to git a nail put in the hoss's shu, so I come down to ask you to go up to the house and jine us."

Now I already knew that the Basin way of proceeding to get a nail put in the horse's shoe meant a day of widely excursive incident and pleasure, in which the main or stated object was cast far from our poetical vision. I accepted.

"My woman invited Miss Lester to go with us. The old double-decker rides easier for havin' consid'rable ballast, ye know—and Miss Lester tips her at nigh onto about two hunderd; she 's a widder too, ain't she, by the way? but she 's clost onto sixty-seven; hain't no thoughts o' splicin', in course. Miss Lester 's a vary sensible woman. But I thought cruisin' 'round with her kind o' frien'ly on the back seat, ye might git a sort of a token or a consute in general o' what widders is."

"True," said I gratefully, with flattered meditation.

"It 's a scand'lous windy kentry to keep anything on the clo's-line," said the captain, as we walked on together, sadly gathering up one of his stockings and a still more inseparable companion of his earthly pilgrimage from the path.

"What 's the time, major?" said he, as he led me into the kitchen, "or do you take her by the sun? I had Leezur up here a couple o' days to mend my clock. 'Pharo,' says he, 'thar 's too much friction in her.' So, by clam! he took out most of her insides and laid 'em by, and poured some ile over what they was left, and thar' she stands! She couldn't tick to save her void and 'tarnal emptiness. 'Forced-to-go never gits far,' says Leezur, he says—'ye know.'"

Captain Pharo and I, standing by the wood-box, nudged each other with delight over this conceit.

"'Forced-to-go never gets far, you know,'" said I.

"'Forced-to-go,'" began Captain Pharo, but was rudely haled away by Mrs. Pharo Kobbe, to dress.

That was another thing; apparently they could never get me to the house early enough, pleased that I should witness all their preparations. They led me to the sofa, and Mrs. Kobbe came and combed out her hair—pretty, long, woman's hair—in the looking-glass, over me; and then Captain Pharo came and parted his hair down the back and brushed it out rakishly both sides, over me. Usually I saw the children dressed; they were at school. It was too tender a thought for explanation, this way of taking me with brotherly fondness to the family bosom.

"How do you like Cap'n Pharo's new blouse?" said his wife.

In truth I hardly knew how to express my emotions; while he sniffed with affected disdain of his own brightness and beauty, I was so dim-looking, in comparison, sitting there!

"When I took up the old carpet this spring, I found sech a bright piece under the bed, that I jest took and made cap'n a blouse of her—and wal, thar? what do you think?"

I looked at him again. The hair of my soul's brother had ceased from the top of his head, but the long and scanty lower growth was brushed out several proud inches beyond his ears. He was not tall, and he was covered with sections of bloom; but as he turned he displayed one complete flower embracing his whole back, a tropical efflorescence, brilliant with many hues.

"She is beautiful," I murmured; "what sort of a flower is she?"

"Oh, I don' know," said Captain Pharo, with the same affected indifference to his charms, but there was—yes, there was—something jaunty in his gait now as he walked toward the barn; "they're rather skeerce in this kentry, I expect; some d—d arniky blossom or other! Poo! poo!

Come, wife, time ye was ready!"

I was not unprepared, on climbing to my seat in the carriage, to have to contest the occupancy of the cushions with a hen, who was accustomed to appropriate them for her maternal aspirations. I was in the midst of the battle, when Mrs. Kobbe coolly seized her and plunged her entire into a barrel of rain-water. She walked away, shaking her feathers, with an angry malediction of noise.

"Ef they're good eggs, we'll take 'em to Uncle Coffin Demmin' and Aunt Salomy," said Mrs. Kobbe.

She brought a bucket of fresh water, benevolently to test them, but left the enterprise half completed, reminded at the same time of a jug of buttermilk she had meant to put up.

She went into the house, and Captain Pharo, absorbed in lighting his pipe, and stepping about fussily and impatiently, had the misfortune to put a foot into two piles of eggs of contrasting qualities.

"By clam!" said he, white with dismay. "Ho-hum! oh dear! Wal, wal—

Guess, while she 's in the house, I'll go down to the herrin'-shed and git some lobsters to take 'em; they're very fond on 'em." He gave me an appealing, absolutely helpless smile of apology, and the arnica blossom faded rapidly from my vision.

Left in guardianship of the horse, I climbed again to my seat and covered myself with the star bed-quilt, which served as an only too beautiful carriage robe. Thus I, glowing behind that gorgeous, ever-radiating star, was taken by Mrs. Kobbe, I doubt not, for the culprit, as she finally emerged from the house and the captain was discovered innocently returning along the highway with the lobsters.

Let this literal history record of me that I said no word; nay, I was even happy in shielding my soul's brother.

"Now," said Mrs. Kobbe, as we set forth, "Miss Lester said not to come to her house for her, but wherever we saw the circle-basket settin' outside the door, there she'd be."

"I wish she'd made some different 'pointment," said the captain, with a sigh.

"Why?"

"Why! don't it strike ye, woman, 't they 's nothin' ondefinite 'n pokin' around over the 'nhabited 'arth, lookin' for the Widder Lester's circle-basket? I was hopin' widders was more definite, but it seems they're jest like all the rest on ye: poo! poo! hohum—jest like all the rest on ye."

"We've got to find her, cap'n; she sets sech store by talkin' along o' major."

"Major!" sniffed the captain; "she ain't worthy to ontie the major's shoe-lockets; they ain't none on 'em worthy, maids, widders—none on 'em!"

I knew to what he referred, what gratitude was moving in his breast.

"Wal, thar now, Cap'n Pharo Kobbe! ain't Vesty Kirtland worthy?"

"Vesty!" said the captain, undismayed—"Vesty 's an amazin' gal, but she ain't nowheres along o' major!"

"Wal, I must say! I wonder whatever put you in such a takin' to major."

He did not say.

We travelled vaguely, gazing from house to house, and then the road over again, without discovering any sign of the basket.

"By clam! it 's almost enough to make an infidel of a man," said the captain, furiously relighting his pipe.

"Cap'n Pharo Kobbe, you're all'as layin' everything either to women or religion."

"Don't mention on 'em in the same breath," said the captain; "don't. They hadn't never orter be classed together!"

Fortunately at this juncture we saw Mrs. Lester afar off at a fork of the roads standing and waving her arms to us, and we hastened to join her, but imagine the captain's feelings when from the circle-basket she took out a large, plump blueberry pie, or "turnover," for each of us, with a face all beaming with unconscious joy and good-will.

"How do you feel now, eatin' Miss Lester's turnover, after what you've been and said?" said his wife.

"What'd I say?" said the captain boldly, immersed in the joys of his blueberry pie; for a primitive, a generic appetite attaches to this region: one is always hungry; no sooner has one eaten than he is wholesomely hungry again.

"Do you want me to tell what you said, Cap'n Pharo Kobbe?"

"Poo! poo!" said the captain, wiping his mouth with a flourish.

"You'd ought to join a concert," said his wife, at the stinging height of sarcasm, for the captain's singing was generally regarded as a sacred subject.

But there was one calm spirit aboard, my companion, Mrs. Lester. Ah me! if I might but drive with her again! Her weight was such, settling the springs that side, that I, slender and uplifted, and tossed by the roughness of the road, had continually to cling to the side bars, in order to give a proper air of coolness to our relationship.

But when it came to the pie I had to give up the contest, and ate it reclining, literally, upon her bosom.

"I'm glad I didn't wear my dead-lustre silk," said she tenderly; "it might 'a' got spotted. I'm all'as a great hand to spot when I'm eatin' blueberry pie."

Blessed soul! it was not she; it was my arm that was scattering the contents of the pie.

"You know I board 'Blind Rodgers,'" she went on, still deeper to bury my regret and confusion. I had heard of him; his sightless, gentle ambition it was to live without making "spots."

"Wal, we had blueberry pie for dinner yesterday—and I wonder if them rich parents in New York 't left him with me jest because he was blind, and hain't for years took no notice of him 'cept to send his board—I wonder if they could 'a' done what he done? I made it with a lot o' sweet, rich juice, and I thought to myself, 'I know Blind Rodgers'll slop a little on the table-cloth to-day,' and I put on a clean table-cloth, jest hopin' he would. But where I set, with seein' eyes, there was two or three great spots on the cloth; and he et his pie, but on his place at table, when he got up, ye wouldn't 'a' known anybody'd been settin' there, it was so clean and white!"

Some tears coursed down her cheeks at the pure recollection—we, who have seeing eyes, make so many spots! I felt the tears coming to my own eyes, for we were as close in sympathy as in other respects.

Meanwhile the ancient horse was taking quite an unusual pace over the road.

"Another sail on ahead there somewhere," said Captain Pharo; "hoss is chasin' another hoss. It 's Mis' Garrison's imported coachman, takin' home some meal, 'cross kentry. He'll turn in to'ds the Neck by'n'by. Poo! poo! Mis' Garrison wanted Fluke to coach for her; he was so strong an' harnsome; an' she was tellin' him what she wanted him to do, curchy here, and curchy there. 'Mis' Garrison,' says Fluke, 'I'll drive ye 'round wherever ye wants me to, but I'll be d—d if I'll curchy to ye!' So she fetched along an imported one."

Whatever the obsequious conduct of this individual toward Mrs. Garrison, his manners to us were insolent to a degree. Having once turned to look at us, he composed his hat on one side, grinned, whistled, and would neither turn again nor give us room to pass, nor drive out of a walk, on our account.

"Either fly yer sails, or cl'ar the ship's channel there," cried Captain Pharo at last, snorting with indignation.

The wicked imported coachman continued the same.

It was now that our horse, who had been meanwhile going through what quiet mental processes we knew not, solved the apparent difficulty of the situation by a judicious selection of expedients. He lifted the bag of meal bodily from the coachman's wagon with his teeth, and, depositing it silently upon the ground by the roadside, paused of his own accord and gravely waited for us to do the rest.

The coachman was pursuing his way, unconscious, insolent, whistling.

"She'll take it out o' yer wages; she 's dreadful close," chuckled Captain Pharo, as we tucked the bag of meal away on the carriage floor. "See when ye'll scoff in my sails, and block up the ship's channel ag'in! Now then; touch and go is a good pilot," and we struck off on a divergent road at a rattling pace.

But these adventures had exhausted so much time, when we arrived at Crooked River it was high tide, and the bridge was already elevated for the passage of a schooner approaching in the distance.

"See, now, what ye done, don't ye?" said Captain Pharo—I must say it—with mean reproach, to his wife; "we've got to wait here an hour an' a half."

"Wal, thar, Cap'n Pharo Kobbe, seems to me I wouldn't say nothin' 'g'inst Providence nor nobody else, for once, ef I'd jest got two dollars' worth o' meal, jest for pickin' it up off'n the road."

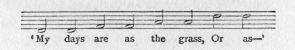

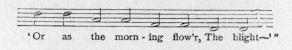

Touched by this view of the case, the captain sang with great cheerfulness that his days were as the grass or as the morning flower—when an inspiration struck him.

"I don' know," said he, "why we hadn't just as well turn here and go up Artichoke road, and git baited at Coffin's, 'stid er stoppin' to see 'em on the way home. I'm feelin' sharp as a meat-axe ag'in."

"I don' know whether the rest of ye are hungry or not," said plump little Mrs. Kobbe; "but I'm gittin as long-waisted as a knittin'-needle."

The language of vivid hyperbole being exhausted, Mrs. Lester and I expressed ourselves simply to the same effect. We turned, heedful no longer of the tides, and travelled delightfully along the Artichoke road until we reached a brown dwelling that I knew could be none other than theirs—Uncle Coffin's and Aunt Salomy's; they were in their sunny yard, and before I knew them, I loved them.

"Dodrabbit ye!" cried Uncle Coffin Demmin, springing out at us in hospitable ecstasy, Salomy beside him; "git out! git out quick! The sight on ye makes me sick, in there. Git out, I say!" he roared.

"No-o; guess not, Coffin," said Captain Pharo, with gloomy observance of formalities; "guess I ca-arnt; goin' up to the Point to git a nail put in my hoss's shu-u."

But Uncle Coffin was already leading the horse and carriage on to the barn floor.

"Dodrabbit ye!" he exclaimed, "git out, or I'll shute ye out."

At this invitation we began to descend with cheerful alacrity.

As the horse walked into an evidently familiar stall, Uncle Coffin seized Captain Pharo and whirled him about with admiring affection.

"Dodrabbit ye, Pharo!" he cried, struck with the new jacket; "ye've been to Boston!"

"I hain't; hain't been nigh her for forty year," said Captain Pharo, but he was unconscionably pleased.

"Dodrabbit ye, Pharo! ye've been a-junketin' around to Bar Harbor; that 's whar' ye been."

"I hain't, Coffin; honest I hain't been nigh her," chuckled Captain Pharo.

"Dodrabbit ye, Pharo!" said Uncle Coffin, seizing the hat from his head and regarding its bespattered surface with delight; "ye've been a-whitewashin'!"

This Captain Pharo proudly did not deny. "Dodrabbit ye, Pharo!" said our fond host, giving him another whirl, "yer hair 's pretty plumb 'fore, but she 's raked devilish well aft. Ye can't make no stand fer yerself! Ye're hungry, Pharo; ye're wastin'; come along!"

Uncle Coffin seized me on the way, but in voiceless appreciation of my physical meanness he supported me with one hand, while he affectionately mauled and whirled me with the other.

"Dodrabbit ye! you young spark, you! whar' ye been all this time?" he cried—though I had never gazed upon his face before!

His rough touch was a galvanic battery of human kindness. It thrilled and electrified me. No; he had not even seen my pitiful presence. I do not know where the people of the world get their manners; but these Artichokes got theirs, rough-coated though they were, straight from the blue above.

"Say! whar' ye been all this time? That 's what I want to know," sending a thrill of close human fellowship down my back. "Didn't ye reckon as Salomy and me 'ud miss ye, dodrabbit ye! you young lawn-tennis shu's, you!"

I glanced down at my feet. They were covered with a thick crust of buttermilk and meal. I remembered now to have experienced a pleasant sensation of coolness at my feet at one time, being too closely wedged in with Mrs. Lester and the meal, however, to investigate.

We found, on searching the carriage, that the jug had capsized, and one of the lobsters had extracted the cork, which he still grasped tightly in his claw.

"Look at that, Coffin," said Captain Pharo sadly; "even our lobsters is dry!"

"Wal, I'm cert'nly glad now," said Mrs. Lester, surveying the bottom of her gown, "'t I didn't wear my dead-lustre silk."

"Why so, Mis' Lester; why so?" said Uncle Coffin, performing a waltz with the small remaining contents of the buttermilk jug. "Ef it's a beauty in her to have her lustre dead, why wouldn't she be still harnsomer to have her lustre dedder!"

He drew me aside at this, and for some moments we stood helplessly doubled over with laughter. For the climate serves one the same in regard to jokes as in food. One is never satiated with them, and there are no morbid, worn distinctions of taste—an old one, an exceedingly mild one, have all the convulsive power of the keenest flash from less healthy and rubicund intellects.

When we had recovered ourselves sufficiently to walk, we went into the house, arm in arm. There Uncle Coffin seized Captain Pharo again and threw him delightedly several feet off into a chair.

"Ye're weary, Pharo, dodrabbit ye! Set thar'. Repose. Repose. Wait 'tell the flapjacks is ready. They're fryin'. Smell 'em?"

We perceived their odor, and that of the wild strawberries and coffee which Mrs. Lester had taken from her circle-basket.

"Why, father," said Aunt Salomy, as we sat at table, giving me a glance indicative of a beaming conversance with elegant conventionalities; "ye shouldn't set the surrup cup right atop o' the loaf o' bread.'

"Never mind whar' she sets, mother," said Uncle Coffin gayly, "so long as she 's squar' amidships."

He would pour out the treacle for us all—for that it was sweeter, sweeter than any refined juices I ever tasted. No denials, no protestations would avail to stay the utter generosity of his hand.

The griddle-cakes were of the apparent size of the moon when she is full in the heavens.

"Come, Pharo, brace up. Eat somethin', dodrabbit ye! Ye're poorin' away every minute ye're settin' there; ye hain't hauled yerself over but two yit."

"By clam! Coffin, sure as I'm a livin' man, I've hauled myself over fourteen," said Captain Pharo seriously.

"Come, come, major; ye're fadin' away to a shadder. Ye hain't hauled yerself over nothin' yet."

"Oh, I have," I rejoined, with urgent truth and unction. "I can't, honestly I can't, haul myself over anything more."

In spite of some suggestive winks directed on my behalf, not then understood, I remained innocently with Mrs. Lester and Aunt Salomy while they were doing the dishes. But presently through the open window where I sat I felt a bean take me sharply in the nape of the neck, and, turning, I discovered Captain Pharo outside. He winked at me. I naïvely winked back again. He coughed low and meaningly; I smiled and nodded.

He disappeared, and ere long I felt one of my ears tingling from the blow of another bean. It was Uncle Coffin this time; his wink was almost savage with excess of meaning. I returned it amiably. He coughed low and hopelessly, and disappeared.

But soon after he came walking nonchalantly into the room.

"Dodrabbit ye, major!" said he, punching me with a vigorous hand, "don't ye take no interest in a man's stock? Come along out and look at the stock."

At that I rose and followed him. Captain Pharo was waiting for us. They did not speak, but they led the way straight as the flight of an arrow to the barn, walked undeviatingly across the floor, lifted me solemnly ahead of them up the ladder to the hay-mow, stumbled across it to the farthest and darkest corner, dived down into it and brought up an ancient pea-jacket, unrolled it, and produced from the pocket a bottle, labelled with what I at once knew to be Uncle Coffin's own design:

"RAT PISON TO TOUCH HER IS DETH."

"Drink!" said Uncle Coffin.

All his former levity was gone. He had the look of bestowing, and Captain Pharo of witnessing bestowed, upon another, a boon inestimable, priceless, rare.

A temperate familiarity with the use of the cup informed me at once of the nature of this liquid. It was whiskey of a very vile quality.

But even had it contained something akin to the dark sequel on its label, I could not have refused it from Uncle Coffin's hand.

Slightly I drank. Captain Pharo drank. Uncle Coffin drank.

The bottle was replaced, and we as solemnly descended.

I had never been unwarily affected, even by a much larger quantity of the pure article; perhaps by way of compensation an electric spark from Uncle Coffin's own personality had entered into this compound. More likely still, it was the radiant atmosphere.

But I remembered standing out leaning against the pig-pen, with Captain Pharo and Uncle Coffin, of nudging and being nudged by them into frequent excess of laughter over some fondly rambling anecdote or confiding witticism, until Captain Pharo, "taking the sun," decided to put off until some other day going to the Point to get a nail put in the horse's shoe.

I remembered—well might I, for they were in my own too—the honest tears in the eyes of Uncle Coffin and Aunt Salomy as we parted; of being tucked in again under the Star, with new accessions to our store, of dried smelts and summer savory, and three newly born kittens in a bag, which I was instructed to hold so as to give them air without allowing them to escape. Yes, and of the dying splendor of the sun, the ineffable colors painting sea and sky; and of knowing that if I had not already become a Basin, I should inevitably have joined the Artichokes.

At Garrison's Neck was the old Garrison "shanty"—Notely's ideal; well preserved; built onto it a spacious dwelling, with stables attached, after Mrs. Garrison's idea.

Notely's shanty was a mixture of elegant easy-chairs and drying oil-skin raiment, black tobacco pipes, books, musical instruments, fishing-tackle, mirth and evening firelight; all the gravitation of the premises was toward it—the Garrison guests yearned for it.

His mother was with him now.

"You will drive down to the boat with me and meet them, Notely?"

Notely whistled with respectful concern, but his eyes were as happy as the dawn.

"Oh, well, ah—h—I'll have to ask you to let Tom drive you down to-day, mother. I've an engagement to sail over to Reef Island."

Mrs. Garrison did not condescend to look annoyed. She smiled, sweet and high.

"Considering the social position of Mrs. Langham and her daughter, and their wealth, Notely, you might postpone even that engagement. Possibly you could arrange to play with the fisher girl some other day."

When Notely was puzzled or provoked he felt for the pipe in his pocket, just like old Captain Pharo, laughed, and came straight again.

"Why, mother! you were a Basin girl yourself—the 'Beauty of the Basins,'" he said, with soft pride—he knew no better—and smiled as though he saw another face.

"Are you foolish?" said his mother, giving way sharply.

When one has come from such degree, has sought above all earthly good, and earned, a social eminence such as Mrs. Garrison had attained, it will leave some unbending lines on lip and brow; the eyes will not melt easily, although it wrings one's heart to find that one's only child is, after all, an ingrained Basin; yet their features were the same, only Notely's were simple, expressive Basin eyes—hers had become elevated.

"You! who have in you such success, if you only would!" she cried.

"'Success,' I'm afraid, mother," said Notely, with one of those sighs that was like a wayward note on his violin; "it 's a diviner thing, however, you know, to have in you the capacity for failure."

"You are as remarkable a mixture of barbarism and sentiment as your shanty," sneered Mrs. Garrison, looking about. "Do you speak in the Basin 'meetings'?"

"No," said Notely. "I ought to. Think of what I have had, and their deprivations. But there 's always something comes up so d—d funny!"

Mrs. Garrison smiled sympathetically now. "O Notely, think of the Langhams, and Grace even willing to show her preference for you, decorously, of course, but we all know."

Notely grabbed his pipe hard and shook his head.

"Why?" said his mother again, sharply. "I am sure Miss Langham is nearly as boisterous and in as rude health as the fisher girl. I have even known her to make important endearing lapses in grammar."

Notely was silent.

"Do you think, after a life-struggle to earn a place in society, it is filial and generous on your part, for the sake of a fisher sweetheart, to be willing to sink your family back again into skins and Gothicism?"

"Yes," said the young man, a hurricane in his blue eyes, which his strong hands gripped back.

"Very well; if you so elect, go back then, and be a common fisherman; but you shall have no countenance of mine."

"Shouldn't wonder if it would be a good thing. With the health I have, give me leisure and plenty of money, and I'm always certain to break the traces and make a run. Common fisherman it is." But he stood out bravely at the same time in an extravagant new yachting costume, for he was going by appointment to meet his sweetheart.

"You might help her up, mother—socially, that is; she needs no other help."

"Never!"

Notely lifted his cap to his mother—the reproach in his eyes was as dog-like as if he had not just graduated from the schools—and walked away.

She looked after him, a scornful sweet smile curving her lips. As the apple of her eye she loved him; it is necessary but hard to be elevated.

Notely put up sail and skirted the shore with his boat till he came to the waters of the Basin. Then he looked out eagerly, but Vesty was not on the banks waiting.

"Was there ever a Basin known to be on time?" he muttered, smiling and flushing too. He was always jealous of her.

He made fast his boat and sprang with light steps over the sea-wall.

Here was a good sign; so the Basins held. No sign so propitious to a love affair as meeting with one of God's innocent ones—a "natural." And here was Dr. Spearmint (Uncle Benny) leading the children to school—the very little ones. They clung to him, and one he carried.

And he was singing, in a sweet, high voice:

"We all have our trials here below,

Sail away to Galilee!

****

There's a tree I see in Paradise,

Sail away to Galilee!

****

Sail away to Galilee,

Sail away to Galilee,

Put on your long white robe of peace,

And sail away to Galilee!"

"Hello! Uncle Benny—'Dr. Spearmint'"—he liked that best. "Well, how are you? how are you? and have you seen Vesty this morning?"

"Fluke and Gurd 's keepin' company with her this mornin'," said Dr. Spearmint, in a voice softer than a woman's. "I jest stopped to sing a little with 'em on the way. I look dreadful," he added, rather ostentatiously fingering a light blue necktie.

"Oh, no, doctor; fine as usual," exclaimed Notely, anger in his soul, but with heart-broken eyes.

"I suppose," said the soft, sweet voice, "there 's a great deal o' passin' in New York, ain't there?"

"What, doctor?"

"A great deal o' passin' there, ain't there?"

"Oh, sights of it! Oh, my, yes! passing along the streets all the time."

"Some there 's worth four or five thousand dollars, ain't they?" said the sweet, incredulous voice.

"God bless you! yes, doctor! the more 's the pity," said Notely, with strange earnestness. "And how 's fruiting?"

"Dangleberries are quite plenty, thank you," the voice replied. When he had left the little ones at school he would go off and gather berries; but he would call for them without fail and lead them home. The little, tired, restless souls always found him out there in the sweet air and sunshine, waiting. Notely remembered; so he and Vesty had been led.

He passed, singing, out of sight with the children:

"Sail away to Galilee,

Sail away to Galilee,

Put on your long white robe of peace,

And sail away to Galilee!"

Notely felt a homesick pang. Vesty was his home; he walked on toward her threshold. Vesty's father had taken a new wife, and Vesty was almost always seen now with a baby in her arms.

So she was sitting as Notely drew near; and Fluke and Gurdon were there, with a pretence of fingering their violins. They looked up, as if expecting him.

"Why did you not come, Vesty?" said her lover. "You promised me."

"I've got something to say about that," said Fluke. "I sot Vesty down on that doorhold, and I threatened to shute her ef she moved off'n it. When she was tellin' Gurd' that you was 'round again wantin' to keep company with her jest the same, says I, 'We'll see about that.' Vesty hain't got no brothers, nor no mother, to look after her, and so Gurd' and me, which is twin brothers to each other, is also goin' to be brothers to her, and see that there ain't no harm done to Vesty."

"Well, then, Fluke, you are the best friends that either of us have," said Notely calmly.

"Why didn't ye let her alone in peace?" blurted out Fluke. "She was keepin' company contented enough along o' Gurd', ef you'd only left her alone. What'd ye come back a-makin' love to her for?"

"Because she is going to be my wife," said Notely. "We always kept company together; since we were that high! Belle Birds'll was Gurdon's company. Vesty was my company." His voice trembled. This was simple Basin parlance and unanswerable.

"Ye mean it?"

"If you want to fight, Fluke, come out and fight." Notely's eyes cut him.

"All the same," said he, "ef you sh'd happen to change your mind by 'n' by, as fash'nable fellers in women's light-colored clo's does sometimes, there 's a-goin' to be shutin'."

Notely grabbed his pipe, and his laugh rang out.

"Come," he said, "you know me! you know me! Confound the pretty clothes! I only put them on so as to try and have Vesty like me!"

"Wal' now, Vesty, make your choice. You'd ruther keep company along o' Note than Gurd', had ye?" But he could not restrain the severe contempt in his voice in making the comparison.

Vesty had been soothing her face in the baby's frowzled hair.

"I told you," she said. But she glanced up at Gurdon, and her face was piteous, his had turned so white.

"Come, Gurd'! What d'ye care? Go on, Vesty, ef ye want to. Gurd 'n' me'll tote the baby till Elvine gits back." He took the infant and began to toss it, to compensate it for Vesty's withdrawal. His thick black hair fell over his forehead, his nose was fine and straight. Gurdon came forward obediently to assist him. He had the same great bulk, and even handsomer features, only that his hair was smooth and parted.

Vesty and her lover passed on together. Her heart was leaping with joy and pride of him; still, she saw Gurdon's look.

"You have been so long at that great college, Notely."

"Yes."

"Why must some one always be hurt?"

"We go to school, but the schools can't teach us anything, Vesty.

"'Oh, sail away to Galilee,

Sail away to Galilee!'"

he hummed airily, gayly. "What was it you 'told them' back there, Vesty?"

Where now was Vesty's Sunday face? You would look far to find it.

"I told them you were a dude," said she.

"Did you, indeed! Girls who lead the singing in Sunday-school are not telling many very particular fibs this morning, are they? But you shall own up before night."

O Vesty!—the call of the "whistlers" down in the meadow by the sea-wall—"love! love! love!" No other note; it is that, too, breathing in the swift Bails and bounding the sea!

"You sail your boat as well as ever, Captain Notely."

"And why not—wife?"

These were the appellations of the old days, taken from their elders—"cap'n" and "wife."

Vesty did not think he would have dared that. Her dark eye chastised him. But he was not looking impudent; he was resolute and pale.

Vesty shivered. With all her earnest, sad experience of life, with her true love for Notely, she was yet in no haste to be bound. Wild, too, at heart; or else somehow the sea wind and the swift sails had freed her.

"Don't say that again. Come, catch the fish for our dinner, Note."

"I'm only a humble Basin, Miss Kirtland. I didn't think to fetch no bait."

Vesty took a parcel of six small herrings from her pocket, laughing.

"Yes, our women are smart," sighed Notely.

"Shall you catch, or will I?"

"You," said Notely, tossing out the anchor.

He watched her, strong and beautiful, her lips pursed with the feline pursuit of prey, as she baited her hook and threw out the line, quite oblivious now, apparently, of him.

He saw her thrill with excitement as the line stiffened and she began to haul in, hand over hand; it was a big cod too. Vesty always had the luck. There was glory in her cheeks when she brought the struggling, flopping fish over into the boat.

"Vesty," said Note mischievously, drawing near, "how would you feel to be caught like that on the end of somebody's line—struggling, flopping?"

His sentimental tone gave way in spite of himself. She turned and gave him a smart box on the ear.

"Very well, Miss Vesty Kirtland, very well. But there 's a marriage ceremony and a binding to 'love, honor and obey,' after which young women don't box their husbands' ears—aha!—at least, mine won't."

"Notely Garrison," said Vesty, with Basinly and womanly indignation, "I never fished for you in all my life—never!"

"Instinctive, darling; not your fault. Unconscious cerebration; do you understand?"

She did, a little, and she grievously disapproved of him.

"Kiss me, dearest," he pleaded. "You kissed me once, when I first came home."

"All the m-more reason why you ought not to ask me now. I w-wish you'd get your m-mind on something besides me."

Notely walked away, pulled up the anchor, and set sail again. Vesty composed herself at the end of the boat.

"Sweet-tempered child!" said he, regarding her from the helm.

She dipped her hand in the water and smoothed her stray locks; they curled up again. She was distressed, and Notely's mirthful eyes gave her no rest.

"My mind is still on you, Vesty—and will be for ever and aye, sweetheart."

With that he turned kindly and looked away, and Vesty bound up her hair.

Presently: "The tapestries are beautiful to-day, Note," she said.

They were sailing through the shallows near Reef Island, and they looked down through the green water. Gold, bronze and yellow, and dark velvet green, the tracings of broad sea-leaf and trailing vine on that floor.

"There isn't another house in any land tapestried like ours, Vesty. Say, wouldn't that be a charming place, after all, to rest, when——"

"You're getting aground, Note!"

"Thank you! How fortunate that you are aboard! I know how to steer a boat a little, of course, but nothing like——"

Vesty laughed, dazzled by this sarcasm. "But you didn't think of the bread or the salt or the pork for the chowder," said she triumphantly.

"Ah, I see you have them. You always think of those things. You were always my little woman, you know. You are my home."

As the boat touched the ledge she sprang out before him. By the time he had fastened his boat and clambered over the ledges with the kettle which he had brought from the crane in his shanty, Vesty had a fire of drift-wood burning.

She prepared the chowder, while he whittled out some forks of wood and gathered firm pieces of kelp for dishes.

They ate, with only the voice of the gulls, screaming, flying in disturbed, beautiful flight over the wide, lone island.

"Now for the gulls' eggs," said Vesty, rising, no dishes to put away.

"What a carnivorous little wild-cat it is—for one so necessary to the sick and afflicted!"

"Didn't you come to hunt gulls' eggs, Note?"

"You know that that is my sole aim and ambition in life. Come!"

Over ledges and salt marshes, at the feet of the thin, storm-broken trees, they found them, nestled there, three, four, eight in a nest, the birds flying, circling overhead. Vesty gathered them in her apron, eager, searching from tree to tree. Her hair came down. She looked up at Note, apologetic, humble, so eager she hardly minded.

"Hold my apron, Note."

This he did obediently.

With downcast eyes and a blush on her cheeks that would have exonerated Eve, she wound up her hair again, and restored her own hold on her apron.

"I did not kiss you then, Vesty."

"Well, of course."

"I'm good, but my mind is still on you."

Over ledges and salt marshes, and the thin, storm-broken trees, and out there on the water there 's a strange color growing. Even the Basins seldom fail to start, at least, for home by sunset.

So a little white sail puts out on the crimson sea. The breeze is dying out, the waters lap, subside. Notely takes down the sail and rows.

The sea fades to softer colors, hushed, wondrous, near the dim shore.

"It isn't ever known, in any place in all the world, that angels—no, I know—but look, Note!—they almost might."

"Only here at the Basin, Vesty; when that very last light fades. I saw two flying up—flying back again—just now. How many did you see?"

She turned her happy, awesome eyes on him, but his keen face, in that light, was as simple and pathetic as her own.

"But my mind is on you, Vesty. Now, before we touch the shore, when will you marry me?"

"I've been thinking. O Note, perhaps it isn't my place to marry you; perhaps I wouldn't do you any good to marry you, Note. They say you were first in your class, off there, and there are so many things for you, and your mother, and friends, will help you so much more—if I don't."

"I may as well tell you the truth, Vesty. I'm not that strong person that I look"—the angels that he saw, flying up, will forgive that sly smile on the boy's mouth—"I couldn't go away and leave you, and go into that false, feverish struggle out there, and live anything more than the wreck of a life, at least. I'm affected."

"Where is it that you have such trouble, Note?"

"It 's my heart, Vesty Kirtland. I must have a Basin for my wife, calm, strong, sweet; one who can see the 'angels' now and then—just you, in fact."

He handed her out of the boat and walked home with her. At the edge of the alders they stood. They could see the light in her father's house.

"When, Vesty?" he repeated.

"O Note, I love you!" she sobbed; "but I must have a little time to think. Every girl has that."

"Very well. You must keep your mind on me, however."

"Hark! hear the poplars tremble. You know what always makes them sigh and shiver that way, Note?"

"I've forgotten."

"They made the cross for Christ out of the poplars; they never got over it—see them shiver!—hush!"

"O my beautiful one!" He took her hands. "What was it you 'told them' back there this morning, Vesty, before we started?"

"You are cruel! O Note!"

He drew her to him. Her lips would not tell. Her Basin eyes, that he was gazing mercilessly into, betrayed her.

"Good child! sweet child! with my strong right arm, and a willingness for all toil and patience and endeavor, and all my soul's love, I thee endow." He kissed her solemnly.

"Love, love, love," chanted in ecstasy a thrush from the dim recesses of the wood.

"I often thinks o' Columbus and the egg. All them big folks in Spain was settin' areound, ye know, ta'ntin' of him, and sayin' as how an egg couldn't be made to sot.

"So Columbus, he took one up and give her a tunk, pretty solid, deown onto the table. 'There!' says he; 'you stay sot,' says he, 'and keep moderate a spall,' says he. 'Forced-to-go never gits far,' says he.

"Then there was Lot's wife.

"I don't remember jest the partickelers, nor what she was turnin' areound to look for; whether she was goin' to a sewin'-circle and lookin' back to see what Lot was dewin' to home, or whether she was jest strokin' deown her polonaise a little, the way women does; but anyway, she was one o' this 'ere kind that needed moderatin'.

"So she got turned into a pillar o' salt, and there she sot. But I've heerd lately that she 's got up and went?"

"I don't know," I murmured.

"Yes; Nason was tellin' me how 't, the last time he went cruisin', he met a man 't 'd jest come from Jaffy, 't told him how 't Lot's wife had got up and went.

"Wal, I was glad to hear on't. Moderation 's a virtu', even in all things. She must 'a' sot there some three or four hunderd pretty consid'rable number o' years, 's it was. Don't want to ride a free hoss to death, ye know. I wish 't this critter that's visitin' up to Garrison's Neck could be got sot a spall. She fa'rly w'ars me out."

Captain Leezur blinked at the sun, however, all heavenly placid and unworn.

"I happened to meet her in the lane," I said. "She had not seen me before. She screamed."

"Thar'! that 's jest her! Wal, neow, I hope ye didn't mind. Sech folks don't do no harm 'reound on the 'arth, no more'n lady-bugs, 'nd r'a'ly, they dew help to parss away the time.

"Neow this Langham girl, she driv up here with Note t'other day, to git some lobsters.

"'O Mr. Garrison,' says she, 'see that darlin' old aberiginile a-settin' out thar' on that log,' says she. 'Dew drive up; I want ter talk to him,' says she.

"Wal, I put in a chaw o' tobackker, and tucked her up comf'table one side, and there I sot, with my head straight for'ards, not lettin' on as I'd heered a word; t'wouldn't dew, ye know.

"So she came up with a yaller lace parasol, abeout twelve foot in c'cumf'rence, sorter makin' me think of a tud under a harrer; though, I sh'd have to say it afore the meetin'-house, she was dreadful purty-lookin', an' blamed ef she didn't know it.

"Wal, I see she'd made up her mind to kile herself 'reound me, ef she could. She kept a-arskin' questions, and everything she arsked I arnswered of her back dreadful moderate, and every time I arnswered of her back she'd give a little larff, endin' up on 'sol la ce do,' sorter highsteriky; so't I was kind o' feelin' areound in my pocket t' find her a narvine lozenger.

"And then I thought I wouldn't. All they want is the least little excuse and they'll begin to kile. When ye're in deoubt, ye know, stand well to leeward."

I looked at my friend with new gratitude, for the perils he had passed.

"She said she thought the folks to the Basin was so full of yewmer and pathers, 'don't yew?' says she.

"Wal, I told her I didn't know ars to that. 'Yewmer 's that 'ar' 'diction 't Job had, ain't it?' says I,' and pathers—thar' ye've kind o' got me,' says I, ''less maybe it 's some fancy New York way o' reelin' off pertaters,' says I.

"'Oh, dear!' says she, kind o' highsteriky ag'in, and Note driv off with her, she a-wavin' her hand to me: but I set straight for'ards, not lettin' on to take no notice of her. 'No, no, young woman,' thinks I to myself, 'ye don't git in no kile on me!'"

The nervine lozenge which my friend had cautiously refrained from giving Miss Langham he now bestowed upon me. I accepted it, for I was in sore need of it.

I could not refrain from asking him, however, if he had offered Miss Langham his deer-bone tooth-pick.

"No," said he, "she's lent neow, anyway. John Seabright 's got her over to Herrinport. I don't say but what if that 'ar' Langham girl sh'd have a r'al bad spall o' toothache come on, but what I'd let her take her, but I'd jest as soon she didn't know nothin' 'beout it. I'd ruther not make no openin' for a kile."

We sucked our nervine lozenges with mutual earnestness.

"You are getting on finely with the barn," I said, noticing several new rows of shingles on the roof.

"Yes, I sh'd be afoul of her ag'in to-day, only 't Nason come over yisterday and borrowed my lardder. I'm expectin' of him back with her along in the shank o' the evenin'. Preachin' ain't so bad," continued my friend, contemplatively, as the school-teacher passed by; "but I'd ruther be put to bone labor 'n school teachin'. Ye've all'as got to be thar', no marter heow many other 'ngagements——"

"Leezur!" called the soft voice of a Basin matron from the door. "Leezur, have ye fished the bucket out o' the well?"

"Jest baitin' my hook, mother," said my friend, his face breaking into the broadest human beam I ever saw.