[p9]

THE HEIRESS OF WYVERN COURT.

[Back to Contents]

CHAPTER I.

IN THE RAILWAY CARRIAGE—NEW FRIENDS.

“Well, little friend, and where do you hail from?”

The speaker was a merry-faced, brown-eyed boy of eleven, with curly brown hair—just the school-boy all over.

He had leaped into a railway carriage with cricket-bat, fishing-rod, and a knowing-looking little hamper, which he deposited on the seat beside him; then away went the snorting steam horse, train, people, and all, and out came this abrupt question. “Little friend” was a mite of a girl of nine, dressed in a homely blue serge frock and jacket, with blue velvet hat to match: a shy little midge of a grey-eyed maiden, with sunny brown curls twining about her forehead [p10] and rippling down upon her shoulders, nestling in one corner of the carriage—the sole occupant thereof until this merry questioner came to keep her company.

“I don’t quite know what you mean,” was the little girl’s reply—a sweet, refined way of speaking had she, and her eyes sparkled with shy merriment, although there was a startled look in them too.

“Well, where do you come from, my dear mademoiselle?” and now the merry speaker made a courtly bow.

“From London—but I’m not French, you know,” was the retort, with the demurest of demure smiles.

“No—just so; and where are you going?” One could but answer him, his questions came with such winning grace of manner.

“To Cherton—to uncle—to Mr. Jonathan Willett’s.”

“Cherton! why, that’s not far from my happy destination. I get out only one station before you.”

“Little friend” smiled her demure little smile again, as if she was glad to hear it.

[p11]

“So you’re going to Mr. Willett’s—Dr. Willett he’s generally called,

being a physician,” continued the boy, after glancing from the window a

second or two, as if to note how fast the landscape was rushing past the

train, or the train past the landscape.

“Yes; do you know him?” inquired the silvery tongue of the other.

“Oh yes; I know him!”—a short assent, comically spoken.

“I don’t,” sighed the little girl, as if the thought oppressed her.

“Then you’d like to know what he’s like,” spoke the boy, using the word like twice for want of another.

“Yes—only—only would it be nice to talk about a person—one’s uncle, one doesn’t know, be——” she did not like to say behind his back, but the faltering little tongue stuck fast, and the small sensitive face of the child looked a little confused.

“Ah! behind his back,” spoke the boy readily. “Well, perhaps not; but you’ll know him soon enough, I’m quite sure, and all about Peggy, too. Peggy is the best of the couple,” he added.

[p12]

“Do you mean Mrs. Grant, my uncle’s housekeeper?”

“Yes, that very lady—only, you see, I like to call her Peggy.”

“Yes,” returned the child, supposing she ought to say something.

“’Tis a farm, you know—jolly old place. Do you know that?”

“Yes—that is, I know ’tis a farm; mamma told me that. But I didn’t know ’twas jolly; mamma said ’twas very pretty, and home-like, and nice.”

“Ah, yes! just a lady’s view of the place,” nodded the boy approvingly. “The farm is the best part of it all, and so you’ll say when——”

“Perhaps we’ll not talk about it,” broke in “little friend” timidly.

“Well, you are a precise little lady not to talk about a farm, your uncle’s farm, behind its back,” laughed the boy.

“It’s mamma’s uncle,” corrected the little maiden.

“Ah, yes! and your great uncle. Well, I thought he was an old fogey to be your uncle—I beg your pardon—old gentleman I mean.” He [p13] laughed and made a low bow, but his cheeks took a rosier tint at that real slip of his tongue.

“Well, suppose we talk about ourselves; that wouldn’t be behind our own backs, would it?”

“Oh no!” came with a pretty jingle of laughter.

“Do you know my name? Dick.”

“I thought so,” replied the little girl.

“You did!—why?”

“You look like a Dick.”

“Well, that’s just like a girl’s bosh—but still, you’re right: I am Dick Gregory, son of George Gregory, surgeon, living at Lakely, next station to Cherton, where you get out, you know.”

The girl nodded.

“Now, mademoiselle, what may your name be?” he asked, as the train carried them into the station with a whiz.

“Inna Weston.”

“Inna: is that short for anything?”

“Yes—for Peninnah: papa’s mother’s name is Peninnah; and so, and so——”

“And so your father chose to let you play grandmother to yourself in the matter of names?”

[p14]

“Yes,” a little ripple of a word full of laughter—her companion was so

funny.

“Now guess what’s in this hamper?” was Dick’s next proposition; “that’s safe ground, you know, to guess over a hamper when the owner bids you,” he added, by way of encouragement.

“A kitten.” The train was carrying them on again, without any intruder to cut off the thread of their talk, except the guard, who put his head in at the window, and beamed a smile on Inna, as her caretaker; then he shut the door, and locked them in, and here was the train tearing on again.

“Well, now, you are a good guesser for a girl,” said Dick.

“I didn’t guess: I knew it. I heard her mew,” smiled Inna.

“Ah! Miss Inna is a little pitcher, pussy; she has sharp ears,” said pussy’s master, peering and speaking through the hamper.

“Me—e—e—w!” came like a prolonged protest against all the hurry-scurry and noise, so confusing to a kitten shut up in a hamper, not knowing why nor whither she was travelling.

[p15]

“Now, who am I taking her to? guess that; and if you guess right, I

should say you’re a seventh daughter of a seventh daughter, and of gipsy

origin”—so the merry boy challenged her.

“To your sister.”

“Right!” laughed Dick.

“But I’m not a seventh daughter—I’m only daughter to mamma, and so was mamma before me; and I’m not a gipsy.” Inna’s face was brimming over with shy merriment.

“Well, you ought to be, for you’re a clever guesser of dark secrets,” returned the boy. “Yes: I’m taking pussy home to my sister. Her name is—now, what is her name?”

Inna shook her head.

“Something pretty I should say, but I don’t know what.”

“Oh! you’re not much of a witch after all,” said Dick. “No, it isn’t anything pretty—it’s Jane.”

Inna smiled, and looked wise.

“Well, what is it, Miss Inna? Out with it!” cried Dick, watching her changeful little face.

“Mamma says, when one has an ugly name one must try to live a life to make it beautiful.”

[p16]

“Hum! Well, that isn’t bad. And when one has a beautiful name—like

Dick, for instance,” said he waggishly, “what then?”

“Then the name should help the life, and the life the name—so mamma said when I asked her.”

“Well, your mother must be good,” said Dick to this.

“Yes, she is.” Wistful lights were stealing into Inna’s eyes, and Dick had a suspicion that there were tears in them.

“I’m not blest with one,” spoke he, carelessly to all seeming.

“With no mother?” inquired his companion gently.

“I’m sort of foster-child to Meggy, our cook and housekeeper—ours is Meggy, you know, and yours is Peggy, at Willett’s Farm.”

“Yes,” smiled Inna, “yes.” She had tided over that tenderness of spirit caused by speaking of her mother.

The train was steaming into a station again, but no passenger intruded; only the guard peeped in, as caretaker, to see if she was safe, as Dick remarked, when they were moving on again.

[p17]

“Has he got you under his wing?” asked he.

“The guard has me under his care; ma—mamma asked him to see me safe.” The wistfulness was coming into her eyes again.

“So she has a mother; I thought perhaps she hadn’t,” thought Dick. Aloud he said bluffly, “’Tis well to be a girl, to have all made smooth for one. Now here am I, come all the way from Wenley, turned out of school because of the measles, and never a creature as much as to say, ‘Have you got a ticket, or money to buy one?’”

“Oh, but they’d not let you come without a ticket,” smiled Inna.

“I mean our chums at school, and father at home. Of course my father knew I was all right about money, because he’d just sent my quarter’s allowance.”

“And have they got the measles at your school?”

“Yes: are you afraid of me? Infection, you know.”

“Afraid? oh no!”

“Well, if you caught it you’d be all right, your uncle being a doctor. A doctor at a farm [p18] —queer, isn’t it, now?” So Dick went skimming from subject to subject, very like a swallow skimming over the surface of water after flies and gnats.

“Yes,” Inna could but confess it was—very guardedly, though, lest they might verge upon gossip again.

“But Peggy’s the farmer; your uncle has enough to do to look after his patients. He’s a clever fo—man—so clever that some say he’s got medicine on the brain.”

Inna’s lips were sealed conscientiously; but out of the brief silence that followed she put the safe question—

“What colour’s your kitten?”

“White. Wouldn’t you like to take a peep at her?” and good-natured Dick held the hamper so that she might catch a glimpse of the small four-legged traveller.

“She’s a beauty!”—such was Inna’s opinion of her.

“And, according to you, she ought to have a beautiful name. But what of my sister Jane? I call her Jenny, and Jin; and that reminds me of the other gin with a g, you know; and that [p19] carries me on to trap, and trapper. I sometimes call her Trapper. That sounds quite romantic, and carries one away into North American Indian story life. Have you ever read any North American Indian stories—about Indians, and scalps, and all that?”

“No,” was the decisive, though smiling, reply.

Ah! they were steaming into a station again.

“Lakely at last, and this is my station!” cried Dick, gathering his belongings together, so as to be ready to leap out when the train stopped, while a porter went shouting up and down the platform, “Lakely! Lakely!”

“Well, good-bye, little friend; mind, Cherton comes next, then ’twill be your turn to turn out.” He wrung her hand, and was out on the platform in a twinkle, loaded like a bee, happy as a boy.

“I say, Miss Inna, I should like you to come over to our place to see Jenny, or Trapper. I shall ask the doctor to give you a lift over in his gig,” he put his head back into the carriage to say.

Now he was scudding away down the platform, and claiming a trunk and portmanteau from a medley of luggage, had it set aside by the [p20] porter, who seemed to know him; this done, he darted back again, smiled in at the carriage window, where that sweet girlish face still watched him, and then vanished.

[Back to Contents]

[p21]

CHAPTER II.

WILLETT’S FARM—TEA IN THE DINING-ROOM.

“Cherton! Cherton! Cherton!”

Inna sprang from the corner of her lonely carriage, and stepped out upon the platform, helped by the kindly guard.

“Now, my dear, what’s to be done? There’s nobody here waiting for you, as I see,” said the man, looking up and down the small platform, where she seemed to be the only arrival—she and her neat little trunk, which a porter brought and set down at her feet.

“No, they don’t know I’m coming,” returned the child, with a sober shake of her head.

“Where for, miss?” inquired the porter, as the guard looked at him.

“My—Mr. Willett’s, at Willett’s Farm,” said Inna, in a sort of startled importance at having to speak for herself.

“Do you know the way?” asked the man.

[p22]

“No; but I should if you told me—I mean——”

“Yes, miss; I know what you mean,” replied the porter, noting her childish confusion. “I’ll see to her, and send her safely,” he promised the busy guard, and took her small gloved hand in his, and led her away out into the open road by the station, stretching away among fields, all bathed in crimson and golden sunshine.

“Now, miss,” said he, pointing with his finger, “you go along this road and turn to your right, and along a lane, turn to your right, and along another; don’t turn to your left at all; then turn to your right again, and there you are at Willett’s Farm. Do you understand?” he asked kindly, bending down to something like her height, so as to get her view of the way.

“Yes, thank you; I must keep to the right all the way, and turn three times—but I don’t think I quite know what a farm is like,” confessed she bravely.

“Oh, miss, that’s easy; there isn’t another house before you reach the farm—the village is above Willett’s Farm.”

“Thank you; then I’ll think I’ll go now.”

[p23]

“You’ll not lose yourself? I’d go with you, but I expect another train

in almost directly, and there isn’t a soul about here that I could send.

And about your box, miss: will you send for it?”

“Yes, I’ll send for it; and—and I don’t think I shall lose myself.”

“Then good evening, miss.” The porter touched his hat, and she bade him “good evening” in return; then the child went wandering down the road from the station—a blue dot in the evening sunshine.

Well, she took her three turnings to the right, and they brought her to the farm, lying not far up the last lane; the farm-buildings—barn, stable, and a whole clump of outbuildings—lying back from the road a little, and all lit up by the last rays of sunset. The house looked out upon the lane, where the shadows were gathering fast, under the many-tinted elm trees overshadowing it. Three spotlessly white steps led up to the front door, a strip of green turf lying each side, enclosed by green iron railings, and shut in by a little green gate. A quaint old house it was, with many crooks, corners, [p24] and gables, and small lattice diamond-paned windows, through one of which gleamed the ruddy glow of a fire. Ah! the air was crisp, the sun well-nigh gone, the evening creeping on. Inna sighed, and, tripping through the little green gate, mounted the three white steps, and, by dint of straining, reached up, and knocked with the knocker almost as loudly as a timid mouse. But it brought an answer, in the shape of a middle-aged woman, in a brown stuff gown, white apron and cap, dainty frillings of lace encircling her face. A sober face it was, yet kindly, peering down in astonishment at our small heroine, standing silent there among the deepening shadows in the crisp chilly air.

“Well, dearie, what is it?” she questioned, as the child opened her lips to speak, and said nothing.

“I’m Inna: please may I come in and tell you all about it?” asked the silvery tongue then.

“Yes, of course—that is, if you have anything to tell;” and with this the woman made way for the little girl to pass her, and shut the door.

“This way,” she said; and that was to the kitchen.

[p25]

Such a clean, cheery, comfortable place, with its wood fire filling it

with ruddy glow and warmth, which was like a silent welcome.

“Now, who’s ill and wants a doctor? Sick folks’ messengers shouldn’t lag,” said the woman, scanning her visitor as they both stood in the firelight glow.

“Oh, nobody is ill; and I only—I mean—I don’t know where to begin,” was the bewildering answer.

“Well, of course you know what brought you,” suggested the other.

“Oh, the train brought me; and I’ve come to stay here.”

“You have?” asked the woman.

“Yes; because Uncle Jonathan gave mamma a home once, when she was a little girl; and she said he would me, if she sent me.”

“And who are you? and who’s your mamma?”

“I’m Inna; and mamma is Uncle Jonathan’s niece.”

“You aren’t Miss Mercy’s daughter?” said the woman.

“Yes, I’m Miss Mercy’s daughter; and now, [p26] please, may I sit down?” asked the little tired voice.

“Yes, poor little unwelcome lamb; I’ll not be the one to deny that to Miss Mercy’s daughter. Come here;” and she set her own cushioned rocking-chair forward on the hearth. “But where is Miss Mercy? and why did she send you here?”

“Mamma is gone abroad with papa. Some people are afraid he’s dying; and”—Inna’s heart was full—“I’ve a letter in my pocket for Uncle Jonathan, to tell him all about it.”

“Well, well, this will be news for master—unwelcome news, I’m thinking,” muttered the woman as to herself, but speaking aloud.

“Do you mean I shan’t be welcome?” asked a strained little voice from the rocking-chair.

“Well, dearie, welcome or not, here you are, and here you must stay for to-night, at any rate. You see, Dr. Willett has one child on his hands already, and he’s a handful. I doubt if he’ll want another. But then, we must all have what we don’t want sometimes—eh, miss?”

To this Inna sighed a troubled little “Yes.”

Then Mrs. Grant—for she it was—bethought [p27] her to help her off with her jacket and hat, and inquired had she any belongings at the station? Yes, she had a trunk there; and an unknown Will—at least, unknown to Inna—was despatched for it.

“But maybe you’d like some tea?” suggested the housekeeper.

“Yes, I should, please,” the little lady assured her, folding her jacket neatly, as she had been taught.

“Well, they’re just having tea in the dining-room. Come along.”

No use for Inna to shrink or shiver, for Mrs. Grant was leading the way to those unknown tea-drinkers of whom she was to form one; the fire-light from the kitchen showing them the way along a passage. Then a door was opened, and the small shiverer thrust in, not unkindly, with the words—

“A little lady come for a bit and a sup with you, sir.”

Then the door closed, and she was in another fire-lit room. A lamp, too, burnt on a table in front of a wood fire, on which was laid a quaint old-fashioned tea equipage, with a hissing urn, [p28] and all complete. On the hearth knelt a lad, making toast; and by his side, leaning against the mantelpiece, was a tall man—red-haired, with streaks of grey in that of both head and closely-clipped beard. He had keen grey eyes, which seemed to scan Inna through; a small mouse-like figure by the door, afraid to advance.

“Oscar, where are your manners?” asked the gentleman, “to treat a lady in this way, when she’s thrust upon you?”

Thrust: here was another word which seemed to say she was not welcome.

“I beg your pardon,” lisped the child, thinking she ought to speak.

“No, no; a lady is very like a king—she never does wrong or needs pardon; ’tis this great lout of a boy here that is the aggressor.”

Whereupon the somewhat awkward, shy lad on the hearth laid down knife and toasting-fork, and came towards her.

“Well, whoever you are, will you please sit here?” said he, setting her a chair by the table, and taking another himself behind the urn.

“With a lady in the room, you’ll never do that,” said the gentleman, spying comically at [p29] him from where he still stood on the hearth, as the boy began to brew the tea.

“Oh no, thank you; I couldn’t manage the urn,” said Inna.

“I thought not,” growled Oscar, a big, handsome, fair-haired boy of eleven, with grey-blue eyes. “And now, here I am without a cup for you.”

Inna had not taken the seat he offered her by the table, but had glided round to the gentleman on the hearth. Oscar made a bolt from the room to fetch a cup and saucer.

“Won’t you say you will like to have me here, Uncle—Uncle Jonathan?” she asked hesitatingly. Such a mite she was, glancing up at the tall red-haired gentleman turning grey, such blushes coming and going in her cheeks.

“My dear little lady, I think you’re just the one element wanting in our male community: a little girl in our midst will save us from settling down into the savages we’re fast becoming,” replied the gentleman, glancing down in an amused way at her from his superior height.

“Well, isn’t that welcome enough?” he asked, still with that comical smile, as Inna gave a [p30] puzzled glance at him, as if not quite comprehending his high talk, and fumbling in her dress pocket.

“I have a letter that will tell you all about me—why I’ve come, you know,” said she.

“Ah yes, Dr. Willett’s letter,” he remarked, taking the missive from her and balancing it between his finger and thumb. Just then Oscar came back with a rush.

“I know all about you, and who you are,” said he, putting down the cup and saucer he had brought with a clatter. “You’re a sort of half-cousin of mine, and a great-niece of Uncle Jonathan’s,” he blurted out.

“Well, since you know so much, suppose you come here and enlighten your new half-cousin as to who I am. She has mistaken me for her uncle—and naturally too, since you, as host for the time being, were rude enough not to introduce us.”

At this reproach Oscar left his tea-making, and approached the two: Inna with burning cheeks, at her mistake about this unknown gentleman, not her uncle.

“Well, this is Mr. Barlow—Dr. Barlow, some [p31] people call him, but he’s no such thing; he’s a surgeon, and the one who plays David to Uncle Jonathan—you understand?” questioned the boy, with humour sparkling in his blue-grey eyes.

“Yes,” nodded Inna shyly; “his very dear friend, you mean.”

“Yes, that’s about the figure,” was the response, while the two bowed with ceremony.

“And now, I am—tell Mr. Barlow who I am, please,” pleaded the small maiden.

“Well, this is Miss Inna Weston, the daughter of a certain Mercy Willett, niece of Jonathan Willett, Doctor, who lived here years ago, before my time. Now, old man, come to tea.” With this, the boy slapped the other on the arm with pleasant familiarity, and went back to his tea-making.

Mr. Barlow led Inna to her seat, and saw her comfortable there, taking his own chair beside her, while Oscar sat with his back to the fire—like a cat on a frosty night, Mr. Barlow told him. Inna wondered where her uncle was, but asked no questions as yet—only munched away at her toast in her dainty way, and sipped her tea, [p32] trying hard to feel that she was at home. As for Oscar, he made such sloppy work with the urn, that Mr. Barlow had to say presently—

“Don’t make a sea of the table, boy. You see what incapable creatures we are, Miss Inna. I never could make tea, and your own eyes tell you what Oscar can do.”

“I suppose Uncle Jonathan makes tea when he is here,” was Inna’s reply.

At which the two gentlemen looked comically at each other.

“Well, I can’t say I ever saw the doctor come down from the clouds enough for that,” observed Mr. Barlow dryly; “but I hope his little great-niece—am I right in the pedigree, Oscar?—will set us to rights, and bring in the age of civilisation for us.”

Inna could but laugh a tinkling laugh at this, and asked timidly, “Do you live here, Mr. Barlow?”

“No, dear; but I’m here morning, noon, and night. My head-quarters are at Mrs. Tussell’s, whose name ought to be, now, guess what?”

People must suppose she had an aptitude for [p33] guessing, Inna thought, and asked with rosy cheeks was it “Fussy”?

“Just the word; only you mustn’t tell her so,” was the reply; at which Inna shook her head, and said she could not be so rude. Then came the sound of the doctor’s gig outside the house, a step and a voice in the passage.

“He’ll not come in here, dear,” Mr. Barlow told Inna, seeing her start and change colour; “he’ll have a cup of tea in his den, as we call it,” at which Oscar nodded, and said, “And a good name too!”

Tea over, Mr. Barlow rose, and said “Good-bye for to-night, Miss Inna; David is going to Jonathan,” patted her head, and was gone.

“Is his real name David?” she asked shyly of this cousin she had no idea of finding at Uncle Jonathan’s; nor had her mamma either, she decided in her own mind.

“No; William—Billy Barlow they call him in the village, only I didn’t say so just now,” returned Oscar drily.

“Mind your lessons, Master Oscar,” said Mrs. Grant, when she came in to fetch the tea equipage.

[p34]

“Fudge!” was the boy’s response, he and Inna established on the hearth,

roasting chestnuts; and they were still there when Dr. Willett surprised

them by a footfall close behind them.

Up sprang Inna, like a startled daisy.

“So you’re Mercy’s little daughter?” said he, by way of greeting.

[Back to Contents]

[p35]

CHAPTER III.

DR. WILLETT—THE NUTTING EXPEDITION—THE FIRE.

“So you’re Mercy’s little daughter?” said the doctor, by way of greeting.

“Yes,” faltered Inna; but she put her hand in his; this Uncle Jonathan, with whom she had come to live, was all she had in England now, except Oscar and Mr. Barlow, who was nobody as yet. The doctor pressed her small hand in his big strong one. Tall—taller than his friend David—was he, with dark hair and beard—at least, they had been dark, but were fast turning grey; his eyes were dark, piercing, and observant, full of fire; still, a kindly face, a kindly manner had he.

“Well, little woman, I’ve read your mother’s letter. I never intended to be troubled with any more children after Oscar fell to my lot; but for your mother’s sake, and her mother’s [p36] before her, I can’t shut my door against you. So now stay, and see if you can’t open another door on your own account.” This is what he said, still holding her hand in his.

“Do you know what door I mean?” he asked, as the child darted an upward glance at him.

“Yes,” she nodded, “yes.” She could not say more, her heart was thumping so, but her small twining fingers in the doctor’s palm told him a great deal.

He patted her on the head, and let her go; he did not kiss her. Inna wished he had when, later on, she was in bed, thinking of the many to-morrows she was to spend in this new uncle’s house. Her chamber was up in one of the gables of the quaint old house; the windows overlooked the garden and the home orchard, where, in the former, Michaelmas daisies and sunflowers flaunted in the sunshine when she looked out the next morning, and apples, rosy and golden, were waiting to be gathered in the latter. Birds were twittering and peeping at her through the ivy-wreathed window; away in the stubble fields, under the hills, sheep were straying, all in a glory of golden light; while rooks cawed [p37] and clamoured in the many-coloured elms by the house and garden, and all sweet morning freshness was everywhere. You may be sure she soon dressed, and tripped down the old-fashioned staircase—a dainty midge, in blue serge frock and white-bibbed apron. Below, she found Mary, the servant under the housekeeper, laying breakfast in the dining-room; and while the child stood shyly aloof by a window, in came Mrs. Grant with the urn, and her master behind her. Inna stepped forward, but her uncle took no notice of her; he only passed on to his seat at the table, took up his letters and newspaper, and, as it were, thus stepped into a world of his own. Oscar stole in like a thief, and began his usual tea-making—placing a cup by his uncle’s plate, upon which he laid slices of ham, carved as best he could; Inna, at a nod from him, cutting a piece of bread to keep company with the ham; while Mrs. Grant gave sundry nods, which the boy understood and returned, then she retired from the scene. Not a word was spoken during breakfast-time. Oscar helped himself and Inna to what the table afforded—ham, eggs, rolls, honey, golden butter—all so sweet and clean and homely.

[p38]

Before the young people had finished, the doctor rose and went tramping

out.

“Good morning,” said he at the door, breaking the spell of silence. Inna, rising, wished to spring toward him, but he was gone.

“There, he’s safe till two o’clock,” sighed Oscar.

“Safe?” said Inna.

“Yes; booked with his patients, you know. Some say he has patients on the brain. I wish them joy of him.”

“Don’t—don’t you like him?” she inquired falteringly.

“Do you?” asked the other, helping himself to an egg.

“I ought.”

“Ought! I can’t bear that word ought: ’tis dinned into my ears morning, noon, and night. Now, I tell you what we’ll do: we’ll fling ‘ought’ to the winds, and go a nutting expedition this morning.”

In came Mrs. Grant.

“Well, Master Oscar, I should hope you’d go down to Mr. Fane’s for lessons to-day,” said she.

[p39]

“I can’t; I’ve a prior engagement,” said he, as loftily as a mouth full

of bread and butter and egg could utter it.

“And what’s that, may I ask?”

“I’ve made a promise to a lady to go elsewhere.”

“Oh, Oscar! never mind me; you ought to do your lessons, you know.”

“I thought we flung that horrid word to the winds just now. There’s no ought in the case; I had a holiday yesterday, and I mean to to-day. I mean to take Inna to Black Hole, and round through the woods, on a nutting expedition—so there!”

This last to Mrs. Grant.

“Very well, Master Oscar; I shall have to set the doctor on to you again. I hope, Miss Inna, you’ll be a good little influence with him and teach him to obey his uncle.”

Oscar laughed, pushed back his plate, and left the table. “Now, Inna, run and put on your hat and jacket, and we’ll be off,” said he to the little girl.

“Go, dear,” said the housekeeper, as the child hesitated. “I suppose he means all right for [p40] this once, but he must take the consequence;” and away went Inna for hat and jacket, wondering if it was right to go.

When she came down, Oscar showed her a packet of sandwiches in the nutting basket, which Mrs. Grant had cut for them to eat if they were hungry.

“She isn’t a bad sort; her bark is worse than her bite,” said Oscar of her, when the two were well on their way.

On and on—over stubble fields they went, till by-and-by they were taking a short cut through a carriage drive in Owl’s Nest Park, as Oscar informed Inna. It was a pretty bowery walk, overarched with beeches and elms in all their autumn glory, and full of the clamour of rooks. Here they met an old lady in a wheel-chair, pushed by a page-boy—such a sweet sad-faced old lady was the occupant of the chair, with shining grey curls peeping out from beneath her black satin hood. She was wrapped in some sort of fur-lined cloak; and by her side walked two little dark-faced, shy-looking girls of seven, quaintly dressed in rich black velvet, very like two wee maidens stepped out of some old picture, [p41] and each wearing a hood similar to that worn by their aged companion.

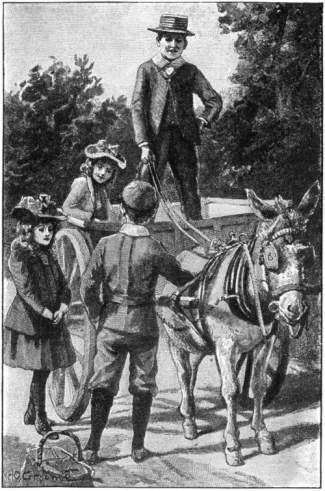

[p40a]

“A DONKEY AND CART CAME DRIVING UP.”

[Return to List of Illustrations]

“This is Madame Giche—spelt G-i-c-h-e—and her two grand-nieces; a queer party, all of them,” said Oscar, still leading on. “This isn’t her place: she can’t live at her own place, they say, all about some trouble she’s had; and so she took the Owl’s Nest of Sir Hubert Larch, who never lives there, on lease.”

“Are we intruding here?” inquired Inna.

“Oh, no; there is a right of way: that is, madame gives it, and people take it. Come on.”

He had the grace to raise his hat to the party as they passed them by, and anon they were out of the park, and on a well-worn road. Here the sound of wheels greeted them, and a donkey and cart came driving up—Dick Gregory charioteer, and a girl of about Inna’s age seated in the bed of the cart behind him.

“Why, little friend,” cried the boy, recognising Inna, “this is a happy meeting!” and down he sprang, and seized her hand with a boyish grip.

“How d’ye do, Willett?” this to Oscar, who returned the salutation.

[p42]

“Now you must be introduced to Trapper. Here, Trapper,” said Dick,

turning to the donkey-cart.

“Don’t be silly, Dick,” cried the pretty little maiden. “You know I’m not Trapper: at least, only to you, who call me Gin and then Trap and Trapper. My name is Jenny;” and down she sprang to Inna’s side.

“And I am Inna.”

“Yes; Dick has told me your name.”

“And how is your kitten?” Inna liked the pretty, free, fair-haired, fair-faced girl.

“Oh, first-rate, thank you, isn’t she, Dick?” said she, appealing to her brother, who was just settling with Oscar.

“Oh yes! We’ll just manage a morning of it in the woods; you can show your cousin Black Hole another time. Isn’t what?” he questioned of his sister.

“Isn’t Snowdrop first-rate?”

“Rather,” returned he, with a nod at Inna, which made her blush and laugh.

“I’m glad she’s well. And so you call her Snowdrop?”

“Yes; and what do you think of our donkey? [p43] We call him Rameses: that’s Dick’s choice of a name.”

“He’s a beautiful creature,” returned Inna, stroking the animal’s wise old head.

“Yes,” replied Dick, “I’m a lover of old names, so I thought I’d go back to the Pharaohs. Not a bad idea, was it? though no compliment, I daresay, to the old fogies.”

“No,” laughed Oscar; “but never mind about compliments for dead and gone fogies.”

“And what of the fogies of this generation?” inquired ready Dick.

“The same—never mind.”

“But come, we must make hay while the sun shines. In with you, you two girls, into the cart,” said Dick, which they did, Jenny helping Inna. Then up sprang the charioteer, Oscar beside him; crack went the whip, and off they drove like the wind.

That nutting expedition was like a fairy dream to London-reared Inna; the lads showed her a squirrel or two, a dormouse not yet gone to its winter snooze, in its mossy bed-chamber. A snake wriggled past them, which made her shudder; frogs and toads leaped here and there [p44] in dark places. Then, oh, the whir and whisper of the autumn wind among the trees! the lights and shadows! Oh, for the magic hand of her artist father to make them hers for ever in a picture for her bedroom! But the delight of a morning’s nutting must come to an end—so did theirs; the sandwiches demolished—share and share, as Oscar put it—they bethought themselves of dinner and the road leading thereto, so once more they were on their backward way, and parting company.

“Good-bye, mademoiselle!” cried Dick, as Inna stood at Oscar’s side, after she had kissed Jenny, and the two had vowed a girls’ eternal friendship. Then away went the donkey and cart, and our young people hastened home, just in time for dinner. A meal silent as breakfast was dinner, so far as they were concerned, for Mr. Barlow and the doctor kept a learned conversation high above their heads all the time—so Oscar said; and after it was over the boy vanished, nobody knew where. As for Inna, she roamed in the orchard all the afternoon in a dream of beauty, eating rosy apples, followed by tea—she and Mr. Barlow alone—she making [p45] the toast and managing the urn: a living proof of what can be done by trying, so the surgeon told her. Then he and the doctor went out, and Inna crept out to the kitchen, to wonder with Mrs. Grant where Oscar was, and what was keeping him.

“No good, Miss Inna; that boy’ll go to the dogs if somebody don’t take him in hand. You try, dearie, what you can do with him,” said the housekeeper.

“I!” cried astonished Inna. She try what she could do with a big boy like Oscar!

“But hark! that’s the fire-bell; there must be a fire somewhere,” said Mrs. Grant, and out she went, with her apron over her head, to listen at the back gates.

Inna, with no apron over her head, stole out to keep her company.

“Oh my!” said Mrs. Grant to shivering Inna. “I wish Master Oscar was at home. I’m thinking he’s a finger in the pie.”

Ah! there was the fire, sure enough; it was a flare and a flame against the darkening sky.

“What’s alight?” inquired Mrs. Grant of a man who went hurrying by.

[p46]

“Poor Jackson’s little farm; they say ’tis going like tinder, and he’s

half crazed,” came back to them as the man ran on.

“Oh dear! that boy, what he’ll have to answer for!” cried the housekeeper.

“But we’re not sure ’tis his work,” said sensible Inna.

“No, dear; but there’s seldom any mischief going that he don’t help in the brewing of.”

Inna was silent, watching the red glare of the fire mounting heavenwards.

[Back to Contents]

[p47]

CHAPTER IV.

OSCAR’S BURNT ARM—BLACK HOLE.

“You see, dearie,” went on the housekeeper, “he’s playing truant these two days, and I don’t like to bother the doctor, and get him into trouble. I hide what I can, in pity for his friendlessness.”

“Hasn’t he anybody but Uncle Jonathan?” inquired Inna.

“No, dearie; father and mother both dead, leaving him not a penny. ’Twould have been a sad life but for master, as I tell him; but I think that sets him more against the right than ever.”

“Suppose you weren’t to tell him, but ask him to do his studies, and—and right things, for love of duty and love of pleasing you?” suggested Inna.

“That’s where it is. I think if he had a sister—now, if you were to get him to love you, you’d be able to do anything with him. Love [p48] for anybody is a mighty power, though ’tis said to be like a silk thread—something not seen, but felt—you see, ’tis stronger than it seems.”

“Yes,” sighed Inna; “mamma says a loving heart will find work to do anywhere. Yes, mamma, I will try,” said she inwardly, thinking of her last talk with her dear mother, and that only on the evening before yesterday, so short, and yet so long a time ago.

Well, Oscar did not come, so the two went in, leaving the fire to flare itself out. Neither did Dr. Willett and Mr. Barlow return. It was quiet anxious work, sitting there by the log-fire, hearkening to the ticking of the old clock, waiting for someone who did not come—someone up to mischief, as Mrs. Grant said. Out she went again, with her apron over her head.

“Burnt to the ground, dearie—burnt to a tinder, is the farm: so Sam, our carter, says; and ’twas done by some idle boys lighting a bonfire of dry furze near.” This was her report when she returned to the kitchen.

Then they heard the master and Mr. Barlow come in, and the housekeeper went to carry them in supper. Ten o’clock, and they were [p49] going out again, Inna heard them say. The little girl now stole out herself to the back gates; there, in the shadow of the wall, she saw a moving shadow.

“Oscar!” She spoke his name; and Oscar stepped out into the moonlight beside her.

“Where have you been?” she ventured.

“Where I like.”

“Yes; but have you seen the fire?”

“Yes, I suppose I have.”

“Did you—did you have——”

“Did I have a hand in setting it alight? Ah yes! there you go—you’re all alike.”

“No, Oscar; no, but——” her small hands were clinging to his arm.

“Hands off!” cried he, shaking her off, as if he could not bear her even to touch him.

His sleeve was in tatters, she felt, before he shook himself free.

“I want you to do something for me,” said he, gloomily enough.

A startled “Yes,” was the reply.

“Go and get some oil and some flour, and come up to my room—you know your way in the dark, don’t you?”

“Think! be sure, and be quick!” With this grumpy injunction he swung himself away, hugging the shadows, and so into the house and upstairs.

Tap! tap! Gentle little Samaritan—she had the oil, if not the wine; and when he bade her enter, she saw that she had indeed to bind up his wounds. He stood with his arm bare to the elbow—a poor scorched arm, from which charred skin was hanging.

“Now, see here: mix some flour and oil into a paste in this pomatum-pot, and spread it on this handkerchief; then bind it on to my arm, and hold your tongue. Can you do it, do you think?”

“Yes;” and the small girlish hands soon had the plaster ready.

“Poor arm!” said she, as the boy winced at her kindly but bungling dressing.

“Fudge!” scoffed he.

“Oh, I wish you hadn’t had anything to do with it!” tearing a handkerchief into strips to bind it on with.

“Yes, that’s all you know about it. What [p51] has Mother Peggy been saying about me? I’m the dog with a bad name; I suppose she’s hanged me.”

“No; she said only kind words of you—at least, what she thought were kind.”

“Oh, ay! everybody is kind after that fashion, I suppose. Now, about holding your tongue?”

“Do you mean I mustn’t say anything about your burnt arm?”

“Yes.”

“I won’t, if I can help it.”

“We know you can help it. Good night.”

He let her go out, and she stole down to the kitchen, there to tell Mrs. Grant, when she came in from the dining-room, that Oscar was in, and gone to bed, without saying anything of what she had done.

“I say, come up here, and help me on with my jacket,” called Oscar, the next morning, from above stairs, to Inna below in the hall.

Up she ran, like a willing little friend in need, to the needy boy.

“This is my best jacket,” said he, when the injured arm was safe in its sleeve. “Now you [p52] hear what Mother Peggy will say when she sees me adorned with it.”

“Yes,” returned Inna; “has it pained you to-night?”

“Well, yes; I never slept a wink till ’twas almost get-up time.”

She looked at him; his face was worn, his eyes wild.

“Tell Uncle Jonathan, and let him see to it, or let me tell him.”

“At your peril, if you do!” said he, like a very despot. “And besides, ’tis more like Billy Barlow’s job than the doctor’s.”

“Let me tell Mr. Barlow, then,” she pleaded.

“I tell you, you shan’t. That’s the worst of having a girl in a mess—she won’t hold her tongue.”

“Yes, I will, if they don’t ask me about it,” said the child.

To which Oscar returned “Hum!” and ran downstairs, challenging her to catch him. Well-nigh over Mrs. Grant he went, she carrying in the urn, Inna like a dancing tom-tit behind.

“Have a care, Master Oscar,” said the house-[p53]keeper, coming to a full stop to let him pass. “And what’s that best jacket on for?”

“Because the one I wore yesterday is in holes,” was the moody reply; and he slipped away into the dining-room, to end the discussion.

There must be silence there, for the doctor was in his place at the table, buried in his papers, waiting for someone to minister to his wants.

“I can’t,” whispered Oscar, after a vain attempt to wield the carving-knife; and he and Inna changed places like two shadows. Well, trying generally brings some sort of success: it did to Inna. Carved very creditably were the slices of meat she laid on her uncle’s plate; and, fearing more of a deluge than usual at the urn, she took her seat at that, and presided over the meal with dainty dignity.

“I hope you’re going to lessons to-day,” said Mrs. Grant, as, the doctor gone, Oscar sauntered out into the passage.

“Yes, I am,” was the curt reply.

“And bring me that torn jacket to mend.”

“’Tis past mending,” was the reply, and, shouldering his book bag, the boy was gone.

“Do you think you could find your way down [p54] to the village, dearie, and inquire for Mrs. Jackson?” said the housekeeper to Inna. “I’ve known her from a girl, poor dear. Since she’s married she’s had losses, and now ’tis said she’s lost all by the fire.”

“I could find her by asking,” returned Inna.

“True, dearie; you have a tongue in your head.”

So a few minutes found Inna down in the heart of Cherton, asking for Mrs. Jackson. She found her in a neat cottage, and helping the mistress of the same to cook a monster dinner for two families. She looked pale and sad, but brightened at Inna’s kindly message, and the baskets of comforts she told her Mrs. Grant sent with her and the doctor’s compliments.

“Thank you, dear; and my compliments in return; and my heart’s best thanks to that brave boy, your—your—what is he to you, miss? I suppose he’s something?” said Mrs. Jackson.

“Do you mean Oscar?”

“Yes—he who saved my boy at the risk of his own young life.”

Inna’s cheeks flushed, and sweet lights stole into her eyes.

[p55]

“Do you mean——?” she faltered.

“I mean he rushed up the burning staircase, and brought down this little chap,” returned Mrs. Jackson, drawing a sunbeam of a boy of two to her side, “when strong men hesitated and stood back. Didn’t you know?”

“No; I know he burnt his arm.”

“Burnt, miss! ’Twas a wonder he wasn’t burnt to a cinder. Give him my blessing—a mother’s blessing—and tell him he ought to make a noble man.” This was Mrs. Jackson’s message to Oscar as she stood at the door, and watched the little girl away.

“Well, dear, that shows ’tisn’t wise to condemn people before they’re tried,” was Mrs. Grant’s comment when Inna told her of Oscar’s brave deed.

Dr. Willett and Mr. Barlow would dine late, and would be away all day. Oscar also failed to put in an appearance at dinner-time, so Inna dined in solitary state in the great dining-room, and had a pleasant afternoon in the orchard, where a man or two were gathering in apples. Still, she wished she knew why Oscar did not come to dinner, and where he was, for her heart [p56] was beginning to yearn already over the wilful, noble, undisciplined boy. It had always been her dream to have a brother—a big strong brother to lean upon, and here was one whom she would like to gather to her.

“I didn’t want any dinner, so saw no use in coming home,” was the account Oscar gave of himself that evening, when, at sundown, he came sauntering in. But he took his revenge by doing wonders at tea-time, sitting by the kitchen fire on a low stool, and eating his dinner, kept hot for him. Inna was in the dining-room, presiding at her uncle’s meal, like a small queen.

“Does it hurt, dear lad?” inquired Mrs. Grant of the boy.

“No; what good is it to make a fuss about a scratch like that?” returned he, wielding knife and fork as best he could, now one, now the other in his left hand.

But lo! to the astonishment of all, out came Dr. Willett and Mr. Barlow into the kitchen—who so seldom came there—followed by Inna.

“Oscar, let me see your arm,” said the doctor.

Ah! well the thing was out—so much for a girl.

[p57]

“I hardly know that I can, ’tis such a tight fit of a sleeve,” returned

the boy, with a reproachful look at Inna.

“Well, it went in, I suppose, and it must come out,” said Mr. Barlow, coming to his side.

“Oh, don’t, sir!” It was pitiful to hear the boy plead thus at the very thought.

“Cut the sleeve,” spoke the decisive doctor.

“Oh don’t, sir, do that!”—it was Mrs. Grant’s turn to plead now—“’tis his best jacket.”

“Yes, and his best arm, being the right; better sacrifice a jacket than an arm”; and Mr. Barlow’s scissors did the work, and laid bare Inna’s surgical dressing.

A nasty burn, but not unskilfully dressed for such young hands, they said; then they dressed it their own way, prescribed a sling for the arm, and a good night’s rest for the boy.

“And, my boy,” said the doctor impressively, “I’ve heard two reports of you in the village, both bad and good; and I will let the good plead with me against the bad this once, and prevail. But remember, one noble deed doesn’t make a life work: there’s the boy’s plodding on, learn-[p58]ing, and doing as you’re bid, and a hundred other things—the very foundation of a good useful life.”

“’Tis such humdrum work,” grumbled Oscar.

“And so is ours—noble art of healing, as it’s sometimes called—eh, Mr. Barlow?”

“Yes, it would be, if we weren’t applying a salve to somebody’s sore; and I suppose that’s what almost all work amounts to—salving somebody’s sore, easing the wheels of life somewhere,” was that gentleman’s reply. “And the humdrum drudging of a schoolboy, in learning and unlearning, is but the easing the wheels of his ignorant brain.”

Well, whether Oscar laid this new thought to heart or not, certain it is that he kept zealously to lessons and Mr. Fane, took kindly to Inna, and called her “a little brick,” and all the many flattering names found in a boy’s vocabulary. But his wound would not heal, for which the weather was blamed, and the constant friction he gave it, until his two doctors advised he should not race about so much; and so it came about that November was well on its way before the arm was well, and Inna saw that abyss of mystery, [p59] the Black Hole. Very like a lake, with an unfathomable hole in the centre—or said to be unfathomable, because it had been sounded by the villagers and no bottom found—over-spanned by a bridge, its water having some hidden outlet, and lying on the north side of Owl’s Nest Park, among tangled bushes and faded herbage: such was Black Hole. It was on a sunless hazy afternoon when they paid their visit to the gloomy place. Oscar betook himself with boy-like zest to testing the depth of the so-called unfathomable hole with a long pole he used for leaping with, Inna watching him, and wondering the while whether the hole, with its darkly swirling waters, were bottomless, as it was said to be.

“Have a care,” her companion had warned her. “Don’t lean against the rails of the bridge; the old thing is as crazy as crazy.”

But, like a girl, as he said afterwards, she must needs forget; and lo! as he poked and fathomed as he had often done before and made no new discovery, a scream rang out, and he looked up to find Inna and the rail had both vanished.

“I told you so,” said he, like a lad in a night-[p60]mare, his hair standing on end; and then in he sprang, with the forlorn hope of bringing her out. Ah! there was a dark story told of the victim once sucked in by that yawning mouth.

[Back to Contents]

[p61]

CHAPTER V.

INNA AT THE OWL’S NEST—MORE WRONG STEPS.

But that strong unseen Hand, so often stretched out in our great extremities, was stretched out now, although only for the saving of one little girl. It guided the boy to the spot where the poor little floundering bundle rose to the surface, helped him to play the hero, and to snatch her from those yawning watery jaws, that would fain have swallowed her—she was shudderingly near to her end, but after a time he grasped her tightly, and drew her to him.

At last he was landing after such a brief long struggle, his burden in his arms, on the dreary bank, little dreaming that any spectator was watching him play the man. Yet there were four—Madame Giche, her nieces, and Phil, her page; and all four came bearing down upon him, chair and all, as he laid Inna down among [p62] the rough grass a moment, to just take breath, shake himself, and then home, or the poor mite would die of cold. Her eyes were closed, and she looked very death-like, as it was.

“Take her to the house, to the Owl’s Nest,” came the command, with the tone of authority, from the depths of Madame Giche’s black hood.

“I thought of taking her home,” returned Oscar without ceremony.

“Yes, young people think a great many wrong thoughts; but if you take her to the house, you’ll be glad in an hour’s time you did an old woman’s bidding,” was the decisive reply.

Oscar caught up the insensible girl in his arms in moody silence; truth to tell, he would be glad to get her into something dry and warm; she certainly did look death-like.

“Do you know the short cut to the house?” inquired Madame Giche.

“Yes, thank you; I know.”

“Can you carry her, or shall Phil help you?”

At this, he might have been the giant-killer in the old nursery tale, carrying poor little Jack, by the way he took up his burden, and struck away for the boundary of the park; a curt [p63] “No, thank you,” ringing back over his shoulder in scant courtesy as he went.

Then Madame Giche’s party turned and went homeward by a less direct road, because of her chair, and Black Hole was again deserted. Madame Giche, however, despatched Phil to run forward with her message to the servants, that the child was to be taken in and attended to; her nieces propelling her along at a brisk canter, because she wished to be herself early on the spot. So Phil and Oscar mounted the north terrace together. Phil gave the alarm, the servants flocked out, and Long, Madame’s own maid, took possession of Inna, and bore her away to her own little room, next to her mistress’s bedchamber, on the first floor. Of course, Oscar loitered about outside, on the terrace, like a lad in a book, to wait for tidings; he was there when Madame arrived, and assisted her up the steps, he on one side, Phil on the other, because a trembling fit, brought on by the shock, was upon her. A frail little mite of a gentlewoman was she between the two sturdy lads, her nieces, like meek little handmaids, following behind them.

[p64]

“Now, boy, if you’re mad, I’m not. Come in and take off those wet

garments, and put on some of Phil’s.” So she half commanded half

persuaded him, still grasping his arm with her clinging fingers.

And for once the boy obeyed, and submitted to be so equipped, Phil taking him under his especial care and leading the way to his bedroom. Anon, when he descended the stairs, longing for tidings of Inna, Phil grinning slily behind him at his second self, out stepped Long from somewhere, and told him the little lady had come out of her swoon, and they had given her something comforting, and tucked her up in bed. “Madame Giche’s compliments to Dr. Willett, and they would take good care of her till to-morrow.” Then Phil appeared with a cup of steaming coffee, which Long made him drink before he left; then he set forth homeward.

Willett’s Farm was more dreary that evening than ever before, with little cheery Inna away, if she had only known it. But she was sweetly sleeping all the evening, in a bed hastily wheeled in to keep company with Long’s; and when, at midnight, she awoke to find herself there, [p65] Long bending over her, the fire-light rosy on the hearth, a shaded lamp somewhere behind her, you may be sure she felt like a story-book heroine, not herself. Still she was herself, and when she had taken some soup, been told that Oscar had gone home, and she was at the Owl’s Nest, she fell asleep, and woke the next morning to breakfast in bed. After this she dressed herself, and went down to form the acquaintance of Madame Giche and her grand-nieces.

“And so you’re none the worse for your wetting, my dear?” said her hostess, drawing her to her, and kissing her, after the little girl had gone up to her, as she sat by the log fire, and timidly said—

“Good morning, Madame Giche. Thank you for being so good to me.”

The child assured her that she was none the worse, her rosy face testifying to the same.

“Then, dear, don’t think about thanks. You are quite a pleasant surprise visitor to us—lonely people; to me and my two little shy nieces, who will be the better for having a little girl friend. Let me introduce you; they’re on the very tip-toe of waiting.”

[p66]

Then the two wee maidens came round from behind their aged relative’s

chair, and were introduced as Olive and Sybil. Two dark-haired,

brown-skinned damsels were they, in quaintly cut velvet frocks, with

frillings of lace at throat and wrists.

“Now see, dear, it’s pouring with rain. Do you think you could be happy as our guest to-day, or must I send you home in the carriage?” questioned Madame Giche.

They were in what was called the tapestried chamber, a room lined with needlework, done by dead fingers of long ago: those of some of the ladies whose portraits Inna was to see by-and-by in the grand staircase, and the gallery running round the hall.

“I should like—what would you like me to do, ma’am?” faltered Inna.

“We should much like you to stay, dear,” returned Madame Giche, still holding her hand.

“Then, thank you, I should like to stay.”

So it was decided, and Olive and Sybil, the twin sisters, drew away their guest to look at pretty foreign ornaments, in profusion all about the room.

[p67]

“All grand-auntie’s own,” as they told her, “which we brought from

abroad. You see, this isn’t our own home, but grand-auntie took it on

lease from a gentleman we met abroad. Grand-auntie has lived abroad for

years and years, ever since her heart was broken.” So they chatted, and

enlightened Inna.

This was in the afternoon, after they had lunched with Madame Giche in the tapestried room, and had wandered away up into the picture-gallery, to look at some of the pictures.

“There, that is grand-auntie; isn’t it like? That was done abroad,” said Sybil, who was the talker. Olive was sedate and somewhat silent.

There was no mistaking the sweet aged face peering down at them from the canvas, and Inna said so.

“And that is grand-auntie’s son—he who broke her heart, you know. He disappointed her, went abroad, married, and died,” whispered the child. “Ah! whisper it,” so she expressed it, “because it is all so sad. Grand-auntie was never reconciled to him, you see, and so can never make it up in this world. He had a wife [p68] and a little boy, and grand-auntie has searched Europe over, she says, and can’t find them.”

A dark, handsome, wilful young face had Madame Giche’s son, as seen in his portrait—a young man just on the threshold of manhood. Inna stood to gaze at it, wondering what it was stirring the depths of her sensitive little heart, and filling it with a lingering pain.

“Grand-auntie says these two pictures have no right here, and calls them alien pictures among aliens, because the house isn’t ours and the pictures don’t rightly belong here; but she took her son’s portrait with her in all her travels, and her own was done abroad, and of course she brought them here.”

“His wife wrote the letter telling of his death, and that he asked grand-auntie to forgive him—and that was all. She has never been able to find the wife nor the son.”

“’Tis sad,” sighed Inna; “because she might have been so fond of the son.”

“Papa’s portrait is at Wyvern Court—that’s grand-auntie’s own place, you know. Grand-auntie says we shall be twin heiresses by-and-by.”

[p69]

“And your papa is—” here Inna flushed at her inquisitive question.

“Dead; and mamma too,” said grave-browed Olive.

“Do you like living at the farm with your uncle?” inquired sprightly Sybil.

“Yes; only I haven’t been there long—and—and a grand-uncle isn’t like a grand-auntie,” said Inna.

“And Dr. Willett hasn’t got a broken heart,” returned Sybil; “I suppose doctors don’t have broken hearts.”

Well, the three dined in state at six with Madame Giche; the children were having a rather free-and-easy time of it, for their governess, Miss Gordon, was away nursing somebody ill, and so they did very much as they listed, so long as they did not weary their aged relative.

What a charmed life was that into which Inna took her one day’s peep, and the outcome of it all was that when Miss Gordon returned she was to go up to the Owl’s Nest, and have lessons with the twins. Meantime, she often spent a day there, and was brought home of an evening in the carriage; then Sybil and [p70] Olive came for tea at the farm, and, after a delightful evening spent in roasting chestnuts and the like, went back in their turn in the carriage, the happiest girls, perhaps, alive. Thus for a time all went merrily as Christmas bells; but one morning Oscar broke the pleasant spell by announcing, “I’m not going down to Mr. Fane’s to-day,” as Inna waited for him at the door to walk as far as the Rectory gates with him, on her way to the Owl’s Nest, her seat of learning.

“Oh! I wish you were,” said Inna.

“Why?” gruffly.

“Because you ought; because ’tis right.”

“Oh, bother right! I’m not going; in fact, I can’t. Dick Gregory’s coming over; there’s to be steam threshing in the yard, no end of fun, and I can’t disappoint him. Besides, it can’t be far wrong; doing it under uncle’s very nose;” and away went the boy, out of sight of his cousin’s reproachful eyes.

When Inna came home from the Owl’s Nest in the evening, a drizzling rain had come on. Oscar was absent somewhere with Dick Gregory, the two gentlemen still out; so after tea the little girl sat down with her knitting somewhat [p71] drearily by Mrs. Grant’s side, with tears not far from her eyes, because her cousin would persist in taking these sudden and backward steps.

“I know he’s to be a farmer, but there, even farmers mustn’t be blockheads of dunces, as Oscar’ll be if he don’t alter,” said Mrs. Grant.

“To be a farmer?” inquired Inna.

“Yes, dearie, that’s why his uncle is keeping on the farm. He talked of selling or letting it years ago, when it fell to him by heirship, but he didn’t, but kept it on and on; and when his brother’s orphan came to him, he said he’d keep it for him, if I didn’t mind seeing to it a few years longer; and I said I didn’t, being a farmer’s daughter. I think I’ve made a better farmer than—than your uncle,” laughed the good woman. “So the farm is for Master Oscar.”

“So Oscar is to be a farmer,” mused the little girl, hearkening for his coming, as she sat by the wood fire, while Mrs. Grant went presently to attend to the two hard-working doctors, just come in.

In he came at last.

“Well, Master Oscar, I hope you’ve had your [p72] swing,” said the housekeeper, meeting him in the passage.

“Yes, I have; and now I am going at once to make it straight with the doctor,” he peeped into the kitchen to say to Inna. “That’s a step in the right direction, you must confess;” and was gone.

[Back to Contents]

[p73]

CHAPTER VI.

INNA’S FIRSTFRUITS—ON THE TOR.

The going in to make confession of his neglect of his lessons by Oscar, that night, was like a very firstfruits to loving little Inna, in her endeavour to influence this big, strong, wilful cousin for good. Nay, she shamed him into industry and painstaking by her own application to studies, going to and from the Owl’s Nest, “like clockwork, you little grinder!” as the boy expressed it, making his awkward admission to her on Christmas Eve, the two wreathing the house with holly and evergreens. This was something which Carlo and Smut the black cat thought it their duty to look into, to judge from the way they pryingly inspected the monster heap of greenery in the wide passage, where the boy and girl worked, making Inna laugh and laugh again, till her uncle peeped out of his study door to inquire what was the matter.

[p74]

“I’m only laughing at Carlo and Smut, uncle,” was her shamefaced reply.

“Ah! laugh and grow fat.” With this, he went in and shut the door.

“Not at all a speech to address to a lady,” remarked Mr. Barlow, crossing the hall at the moment. “But Christmas is the time for liberties of all sorts and unheard-of requests—have you any of the latter, fair lady?” and the surgeon halted behind her.

“I have one little wish, and ’tis about uncle and his den,” ventured Inna, blushing a little.

“Well, suppose you tell me, and let me be the go-between—no enviable part to play, remember, to put a finger in anybody’s pie, much more in that of a doctor and a young lady combined.”

“May I put a bit of holly in uncle’s den?”

“Make Christmas in the lion’s den, eh, Oscar! Well, I’m off; but let me make sure of my errand. I go to prefer a petition from the lamb to the lion for permission to enter his den with a flag of truce.” In he went into the study.

“In the name of the lion, I say go in, little [p75] lamb, and at once,” he came out almost immediately to say, and he stood by Oscar and the holly heap, while Fairy Inna went on her magic mission.

After that evening the doctor’s study doors were open to Inna once and again; she tapped timidly for permission to go in and make up his fire on the cold evenings which came in with the new year, when snow lay upon the ground, and Mrs. Grant told her that most likely her studious, absorbed uncle was sitting with his fire gone out, and she herself dared not intrude to replenish it.

“Come in, dear,” he would say at such times. “You’ll not disturb me.” And before the winter was over he named her his “Little Salamander;” and once or twice peeped out and called for her when she did not come.

Well, winter was over at last, and March on its blustering way; the lambs in the fields, the colts in their paddock, and young exultant life everywhere. It was holiday time with Inna, for Miss Gordon was away with that invalid somebody again. Dick Gregory was still running wild in his happy banishment from school; [p76] Jenny, alias Trapper, was running wild with him whenever she could persuade the dear old lady who played the part of governess to her to forego her tales of ill-learnt lessons. A sad dunce was busy Mr. Gregory allowing his merry little daughter to grow up to be.

Well, with so many holiday keepers, Oscar dared to join hands, and to take French leave, as he called it, in plotting and planning an expedition to the Tor without asking permission of his uncle. Not that he anticipated a refusal, but just because young people will persist in thinking stolen waters are sweet—sweeter than any other waters. Ah, well! we know what the wise man says about the bread of deceit; it points out much the same moral.

But about the Tor. This was a high elevation—almost a mountain compared with the surrounding hills for miles—whence the sea could be descried, a misty mystery, not so far away; and around which sudden fogs wreathed themselves, shutting in those unfortunate enough to be on its heights in a rare tangle of perplexity when it thus chose to wrap itself up in this sullen mood. For there were ugly holes, pitfalls, and [p77] crevices in its ragged sides, making its descent a serious thing, except for adepts in climbing and scrambling down, even in the fair light of day. Moreover, there was on one side a disused flint-quarry, called by the ominous name of the Ugly Leap, because, once in the remote past, a shepherd boy, seeking a wandering lamb, had lost his way in the fog, having doubled and turned in his course unknowingly, and finally had fallen over the quarry side. Ah, well! he lost his life; and so his sad tale was told, and the Ugly Leap, with its suggestive name, bore witness to the same.

There were sea-fogs which swept up, and made the Tor so dangerous, Mrs. Grant affirmed; but Oscar always said “Fudge!” to this—a pet word of his, as he did on that fair March morning, when not a cloud or an atom of fog was to be seen anywhere, but all was cold and brilliant, as some March mornings are.

“Just the morning for the old Tor,” the lad said decisively: “the views splendid, sea and all.”

“But how about school and your uncle?” inquired Mrs. Grant.

[p78]

“Oh, they’ll do very well, if you don’t split upon me. I mean to go, and

Inna won’t be mean enough to go with me and play tell-tale-tit

afterwards; and besides, uncle wouldn’t refuse me this one day, just to

show Inna the Tor.”

“But suppose we were to wait and ask him?” suggested Inna.

“I can’t wait. Dick Gregory and his sister are coming over. We shall make such a jolly party, and there’ll be more fun to steal a march upon someone:” this was Oscar’s reasoning.

Perhaps Inna ought to have stood out against this stealing a march, as it was for her the expedition was said to be planned, but she said nothing; she had set her heart upon seeing the Tor, and realising somewhat of the thrilling sensation of an Alpine climber; and she was but nine—no great age for unerring wisdom. “Young people’s heads are renowned for folly.” Mrs. Grant said something like this when Dick and Jenny mustered at the gates, and the four set off, fortified with a good supply of sandwiches and other nice things in a satchel, which Oscar swung over his shoulder, traveller fashion; and so they started. The two little dwellers at the [p79] Owl’s Nest looked out at them longingly at the park gates, as they passed that way; not far from the Black Hole, with its thrilling memories, did their road lead them. Then away on through young corn, and other crops that dared put forth their greenness in the cold health-giving March air; and anon they had reached the Tor.

Up, up, still mounting up, they went, putting their best foot before, as their two guides admonished the girls, giving them many a tug and many a pull; and when they were half-way up, down they sat in the sunshine, and ate a lunch picnic, taking sundry sips of cold water from a bottle Oscar insisted on bringing, because he said climbing was such thirsty work in the clear cold air of the old Tor. Well, after this they went mounting up again, sometimes, like spiders, on all fours.

“It does take the breath out of one,” said Dick, tugging at Trapper, who, girl-like, kept slipping back, Oscar doing the same with Inna.

Inna, the Londoner, was a very poor climber; but once on the summit, what exultant delight was there!—the blue heavens above their heads; [p80] the sunny landscape, in its dainty spring dress, at their feet; the Owl’s Nest in the distance not nearly so imposing to look upon seen from that elevation; the sea—they could even discern somewhat of its shimmering upheaving, in this clearest of clear March mornings.

Dick, who was gifted with far-reaching sight, affirmed he could see the sails of the fishing-smacks, but none of the others could; still they all clapped their hands, and sang in a wild chorus:

“I mean to be a sailor,” said Oscar, when the singing ended. Silence reigned on the old Tor, save for the blustering wind, which played havoc with the girls’ hair, and clutched at all their hats.

“Oh, Oscar! and uncle intends you to be a farmer!” cried Inna, her tongue running away with her better judgment, which would have whispered her to think twice before she spoke once. But her heart was stirred with pity for Oscar, and for her uncle, knowing what Mrs. Grant had said about the boy’s future.

[p81]

“And so Mother Peggy has been whispering that into your ear,” was the

scoffing reply.

“Mrs. Grant told me so; but I don’t know that there was any whispering about it,” returned the little girl.

“Well, she told you what’ll never be. I mean to be a sailor, so there!”

“To be a farmer is no bad berth,” said sensible Dick.

“Oh yes, for them who take to it; but that’s not I. I mean to be a sailor, like my father before me.”

“Oh! but, Oscar, what will uncle say?” cried Inna.

“Oh, he’ll get over it. Every boy has a right to choose his own profession, and he knows it.”

“Yes; but ’tisn’t a right every boy goes in for. I meant to be a farmer, and my father set his heel upon that notion, and said I must be a doctor,” said Dick.

“Well?” and Oscar waited to hear more.

“I shall be a doctor; no good comes of a boy going on trying to go against his father’s way or will.”

[p82]

“No,” said the other, somewhat taken aback; “a father is different from

an uncle.”

“Yes,” was Dick’s retort. “I suppose an uncle would expect a little more yielding of number one to number two.”

“Why?” growled Oscar, not liking Dick’s views of the case.

“Because of gratitude. I suppose gratitude ought to have a voice with a fellow about his father’s wishes; but it ought to have two voices with those of an uncle playing a father’s part.”

“Well, an uncle’s wish ought not to make one wreck one’s life; and that’s what I shall do if I am a farmer.”

“Phew! you’d be more likely to be wrecked as a sailor now,” replied Dick loftily.

“Well, I mean to stand up for my rights,” contended Oscar.

“Better not, if you value your peace of mind. Since I’ve given up youth’s charming dream of farming—ha! how the words rhyme!—I’ve been as happy as a peg-top,” answered Dick.

The girls smiled.

“Oh yes,” grumbled Oscar, “well enough for you to laugh. You girls never have to [p83] choose or wish—you always have all you want.”

“Oh, come, Willett; little friend there could contradict that, I know,” said Dick. “But we didn’t come up here to discuss our wants and wishes. Suppose we look about a bit, and see the sights. Look, Miss Inna, that jutting rock yonder, by the sea, is Swallow’s Cliff, and behind it is a little bay;” and then he drew her away to look down the Ugly Leap. A dizzy height it was to gaze down from above, with a deep gorge at its foot, in which a stream of water gurgled, said by some to have a connection with Black Hole, the lad told her; over which Inna shuddered and turned away.

Then they all sat down, and lunched in earnest—a late lunch, for the afternoon was fast slipping away—and took more sips from Oscar’s water-bottle. And while they chatted, laughed, and loitered on foot, for it was becoming bitterly cold to sit down any longer, up came the enemy, from the sea it may be, behind their backs; at any rate, it was there with them—ere they realised it the mist was come. Surely the old Tor wasn’t going to turn nasty and ill-natured [p84] to-day, of all days! they said, in startled dismay; and Oscar affirmed he had seen the fog settle and rise, settle and rise, as fickle as any girl’s temper. “’Twas nothing,” he said; “it would lift.”

But it was something, and it did not lift; instead, it shut them in so that they could not see one another’s faces; and oh! the girls’ teeth chattered with cold. Worse, snow began to fall—blinding snow, which enveloped them quite. Well for them that they had put on fur-lined cloaks and overcoats, but——

“I say, we’re in for it!” cried Dick; that was when they stood deep in snow, and the cold was chilling them to the very bone.

“Don’t you think you could steer us down out of this, Willett? You know the old villain better than I do. We shall freeze!”

And Oscar said, “No; better freeze than lose one’s way, and——” They knew he was thinking of the shepherd lad and the Ugly Leap.

“Still, something must be done,” urged Dick; then the two lads made the shivering girls move and spring up and down, and hoped that the storm would clear. But it did not.

[p85]

Would anyone come to find them? they wondered.

“Well, I’ll make the attempt to go down and get a lantern, and bring back someone,” volunteered Oscar at last. “I don’t mind for myself, but I can’t play guide for——”

“Ay, I know,” agreed Dick; “to be hampered with other people’s lives is a great responsibility. Well, take your own life in your hands and go, and I’d take mine and go with you; but——”

“You stay there with the girls,” growled Oscar, and gripped their hands, as in parting, all the way round.

They let him go a few steps away, and his shadowy form was lost. The girls clung to Dick, too cold, too scared, too much as in a dreadful dream, to cry—ay, too much benumbed. The boy shouted, Oscar responded; once and again shouts were exchanged, then came a scream—a scream so shrill that it seemed to cleave their poor failing hearts in two—and then silence, blank silence, save for the howl of the wind as it whirled the snow. Dick shouted himself hoarse, but there came no answer. Something terrible must have happened to Oscar.

[Back to Contents]

[p86]

CHAPTER VII.

OSCAR LOST—A FRUITLESS SEARCH.

The dead silence that followed, save for the hooting of the storm, was more terrible, if that could be, than Oscar’s scream, for it told of what? They did not say, but their hearts throbbed out what they feared.

“Oh, Dick! what shall we do?” cried the little girls, clinging to him.

He was a boy so strong, so brave—surely he could think of something. Well, he did think of something, but that was after they had shouted “Oscar! Oscar!” till the storm itself seemed the name. This is what he thought of.

“There is nothing to be done but for me to go and look for him.”

It sounded like a miserably forlorn hope, and the girls thought so; for they clung to him, crying, “Oh, Dick, Dick!” and almost unnerved him.

[p87]

“Well, I can do no good up here, and it seems heartless to hear that

cry, and not to go a step to see what can be done. You know he ventured

his life for us.”

“Yes; but throwing away your life wouldn’t save his if—if it isn’t lost,” faltered fond little Jenny.

“No,” returned her brother; “and, God willing, I don’t mean to throw away my life.”

They were silent for a moment, while the storm raved on. I think they all breathed a sort of wordless prayer, then Dick spoke.

“Now, you girls must stand by each other, and comfort each other; and, whatever you do, don’t sit down and give in to sleep. Good-bye.”

There was no wringing of hands; the three could not bear it with that scream of Oscar ringing in their ears.

He went away, his shadowy figure vanishing in the obscurity almost immediately, as Oscar’s had done. Then the two girls were alone. Shout after shout rang reassuringly back to them, and they screamed back theirs in reply. True, Dick’s shouts were farther away each time, but no screams followed; then there came a [p88] break, and they heard nothing. Very, very much alone they were now.

Well, down in the village people were shutting doors, closing shutters, and heaping up fires, and saying what a cold snowy ending it was to such a fair day, as they made themselves cosy, little dreaming there were two small wanderers up on the old Tor in the storm. The two children could picture it all, and wondered what was doing at the farm: whether they were in a great fright about them—Mrs. Grant, Dr. Willett, and Mr. Barlow. Jenny thought too of what they were saying and doing at her home, but oh! where was Dick, where was Oscar? How the minutes lengthened into hours in the cold, the weariness, ay, even drowsiness. But they must not yield to sleep—Dick had warned them of this; they knew that sleep up there in that extreme cold meant death. What should they do?

Oh! what was that? An ugly shadow of some monster beast looming upon them from out that vast whirling waste of snow. This was when hope was very low in their hearts; it seemed that it was an hour or two since Dick [p89] had left them, and no help had come—nothing; and they had pictured themselves two little maidens, stiff, stark, dead, and cold, found by someone, at some time, up there all alone. Now here was this apparition bearing down upon them. They shrieked and clung to each other; they could not move; they had no boy to fight for them. Fight! Why, it was dear old Carlo from the farm. How he barked, and whined, and caressed them! They could but laugh and cry in the same breath at his funny antics. And this laughter and crying, and the efforts they made to keep on their feet under his wild hugs and leaps, stirred their blood; and with this, hope leaped up within them again.

“Oh, Carlo! where are they all? are they coming?” cried Inna, her arms about his neck.