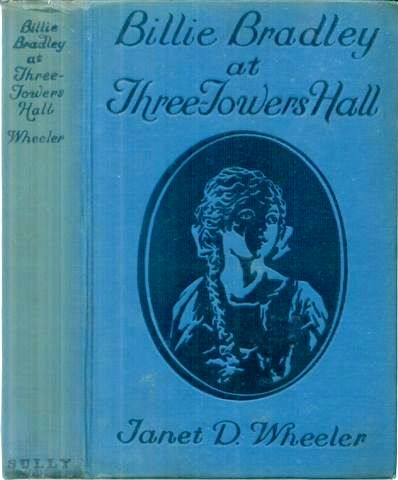

Title: Billie Bradley at Three Towers Hall; Or, Leading a Needed Rebellion

Author: Janet D. Wheeler

Release date: December 18, 2007 [eBook #23894]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Mary Meehan, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Mary Meehan,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

CHAPTER I Almost a Fortune

CHAPTER II The Wreck

CHAPTER III Recovered Treasure

CHAPTER IV The "Codfish"

CHAPTER V Amanda's Surprise

CHAPTER VI Off for Three Towers Hall

CHAPTER VII Miss Walters

CHAPTER VIII The Dill Pickles

CHAPTER IX A New Acquaintance

CHAPTER X Lake Molata

CHAPTER XI Lights Out

CHAPTER XII Too Much to Eat

CHAPTER XIII Four Enemies

CHAPTER XIV Billie Snores Successfully

CHAPTER XV A Plot Fails

CHAPTER XVI Mystery

CHAPTER XVII The Quarrel

CHAPTER XVIII The "Codfish" Again

CHAPTER XIX Robbed!

CHAPTER XX Chet Plays the Hero

CHAPTER XXI Raiding the Pantry

CHAPTER XXII A Challenge

CHAPTER XXIII A Prisoner of War

CHAPTER XXIV The Capture

CHAPTER XXV Happy Again

Other Books Published by GEORGE SULLY & COMPANY

"Oh, Dad, I can't believe it's true!"

In the rather dim light of the gloomy old room the boys and girls looked queer—almost ghostly. They were gathered about a shabby old trunk, and beside this trunk a man was kneeling. As Billie Bradley spoke, the man, who was her father, rose to his feet and thoughtfully brushed the dust from his clothes. Then he stood looking down at the hundreds and hundreds of postage stamps and old coins that filled the queer old trunk.

"Is it really true, Dad?" Billie continued, shaking her father's arm impatiently while the other young folks looked eagerly up at him.

Mr. Bradley nodded slowly.

"Yes, you really have made a find this time, Billie," he said. "Of course I'm not an expert, but I'm sure the coins in that old trunk are worth three thousand dollars, and the postage stamps ought to bring at least two thousand more——"

"At least two thousand more!" broke in Chet Bradley, excitedly. "Does that mean that Billie may get more for the postage stamps?"

"I shouldn't wonder," replied Mr. Bradley, nodding his head. "However," he added, smiling round at the girls and boys, "you'd better not count on anything over five thousand."

"But five thousand dollars!" interrupted Laura Jordon, in an awed voice. "Just think of it, Billie! And because your Aunt Beatrice left you this house and everything in it, every last cent of that five thousand belongs to you."

"Yes," said Teddy Jordon, turning to Billie with a chuckle. "I suppose you won't look at any of us now you've got this money. How does it feel, Billie?"

"I—I don't know, yet," stammered Billie, still staring at the wonderful trunk. "You'll just have to give me time to get used to it, that's all."

As those readers who have read the first book of this series, entitled "Billie Bradley and Her Inheritance," will probably have gathered, the girls, Billie Bradley, Laura Jordon and Violet Farrington, and their boy relatives and chums, Chet Bradley, Ferd Stowing and Teddy Jordon, were still at the old homestead at Cherry Corners where so many weird and mysterious experiences had befallen them.

For the benefit of those who are meeting the girls and boys for the first time, what had happened up to the time of this story will be sketched over briefly.

The young folks had grown up in North Bend, a town of perhaps twenty thousand people, and about forty miles by rail from New York City. The girls had seen the great metropolis several times, though their visits had been all too short to satisfy their eager curiosity.

Billie Bradley was called the most popular girl in North Bend, and, indeed, after one had been with Billie five minutes, one would never again wonder where she got the title.

Whether it was her sparkling brown eyes with the imp of mischief always lurking in them, or her merry laugh that made every one want to laugh with her, or the adventurous spirit that made her eager to embark on any kind of lark, it would be hard to tell—perhaps her popularity arose from a combination of all of these. But the fact remains that everybody loved her and she had not an enemy, except, perhaps, Amanda Peabody—but more of her later!

Then there was Laura Jordon, Billie's best chum, blue-eyed and golden-haired, who, despite the fact that her father was very wealthy and owned the thriving jewelry factory in North Bend, was not the slightest bit spoiled or conceited. She adored Billie, and although the two would sometimes enter into rather heated discussions, it was usually Laura who gave in to Billie in the end.

The last of the trio, but decidedly not the least, was Violet Farrington, who, tall and dark and less hasty and impetuous than the other two, often found the doubtfully blessed office of peacemaker thrust upon her. And though her slowness and tendency to hang back sometimes exasperated her chums, they nevertheless were very fond of her—and showed it.

Chetwood Bradley, known as Chet to his friends, was Billie's brother—and very proud of it. He was a splendid, fine looking, rather thoughtful boy whom everybody liked.

Ferd Stowing was a comical, jolly, all-around good fellow, who, though he was not related to any of the girls, had been drawn into the group through his friendship for the boys, Chet and Teddy.

And—Teddy! Teddy, who was the handsomest and gayest of all the boys, had been Billie's friend and playmate ever since they could remember. Either of them would have felt lost without the friendship of the other. Teddy was Laura's brother and had starred in almost all the sports in which the lads of North Bend had taken part—a fact which did not make Billie like him any the less.

Just the summer before this story opens, Billie, going back with Violet and Laura to the grammar school from which they had just graduated, had, in a moment of thoughtless skylarking, broken a handsome and expensive statue that belonged to her English teacher—Miss Martha Beggs.

The accident was nothing short of a tragedy to Billie, for her father, Martin Bradley, a real estate and insurance agent in North Bend, having most of his capital tied up in property and being at the time engaged in fighting a rather losing fight with the high cost of living was in no position to pay a hundred dollars—which was what the statue was worth.

Billie's worry was deepened by the fact that she would not be able to go with Laura and Violet to Three Towers Hall, a boarding school to which she had wanted to go all her life. The high school in North Bend was notoriously poor and inefficient, and the girls had set their hearts on attending Three Towers in the fall. And now, because of the broken statue, Billie could not go.

Then had come news of Beatrice Powerson's death. Beatrice Powerson was an aunt of Billie's mother for whom Billie had been named. Then came the strange inheritance which the queer old lady, who had spent her life traveling, had left to Billie—the old homestead at Cherry Corners which dated back to revolutionary times and had been the scene of more than one Indian attack.

Readers of the first book of this series will remember how the girls and boys had decided to spend their vacation there, the many queer and spooky experiences they had had, and finally the shabby old trunk which Billie had found stowed away in a corner of the attic—a shabby old trunk that contained riches; at least, so it now seemed to the boys and girls. Five thousand dollars in the shape of old coins and postage stamps.

Billie had sent the wonderful news post-haste to her family, and Mr. Bradley had hurried out to the old house to see if Billie's discovery was really worth anything.

And now he had just given the result of his investigation to six pairs of ears. To be exact it had better be made seven, for Mrs. Maria Gilligan, Mrs. Jordon's housekeeper and the girls' chaperone on this expedition, was looking on with interest from the doorway.

Five thousand dollars, perhaps more. This almost certainly meant that not only could Billie go to Three Towers Hall, but Chet would be able to go with the other boys to a military academy which was only a little over a mile from Three Towers.

"Oh, Daddy, I'm so glad you came!"

Billie squeezed her father's arm ecstatically.

"I'll say we are," said Ferd Stowing, staring down at the queer little trunk as though he already could see it full to the brim with shining new gold pieces from the mint instead of the old coins and rare postage stamps that were its present contents.

"How soon," he asked, turning to Mr. Bradley, "will you be able to get real money for these?"

"Probably almost as soon as we can get the trunk to North Bend," said Mr. Bradley. "The bank——" But Billie would not let him finish.

"Oh, Daddy, let's hurry!" she cried; then as her chums stared at her in surprise she rushed over to the trunk and slammed the lid shut. "What are you waiting for?" she cried, stamping her foot impatiently as she turned to face them. "If you want to stand around looking foolish, all right. But I'm going home."

"Say! wait a minute," cried Teddy, stopping her as she started from the room. "Perhaps your father——"

"I was going to suggest," said Mr. Bradley, looking at his watch, "that we catch the eight o'clock train for North Bend. Is that at all possible, Mrs. Gilligan?" he asked, turning apologetically to Mrs. Gilligan.

However, before Mrs. Gilligan could reply, his daughter answered for her.

"Of course it is," she cried. "We girls were beginning to pack anyway. Come on, girls, what we need is action," and without giving them a chance to protest she fell upon the girls and dragged them from the room.

The boys looked after them with laughing eyes, and Mr. Bradley remarked with a smile: "My young daughter seems to be unusually happy about something."

"No wonder," said Chet, shaking his head ruefully. "I'd be happy, too, if anybody thought enough of me to give me five thousand dollars."

The rest of that afternoon was one wild scramble for the girls and boys, but at the end they made their train with, as the train was late, a few minutes to spare.

The boy who had driven them and their luggage to town was the same who had taken the girls and their chaperone to the old homestead at Cherry Corners upon their arrival over a month before.

As he turned away and went back to his antiquated wagon, he shook his head soberly.

"Gosh," he said, "I do be sorry to see 'em go. When they first came it sure did turn my heart cold to see three girls an' a woman goin' into that there haunted house. At night it was, too! But it seems they've come out all right, after all. Guess they must 'a' scared the ghosts away. Well, you've sure got to hand it to 'em." And he shook his head sagely as the springs of the old wagon creaked under him. "Giddap, Napoleon!" And a few minutes later wagon and driver were enveloped in the gray mist of the evening.

"If we only get the train!" Such had been Billie's thought throughout the drive to the station. Her mind was on getting home and turning the precious old coins and postage stamps into real money. Then she could arrange about going to Three Towers Hall and about sending her brother to Boxton Military Academy.

Fortunately the train was only ten minutes late, and presently they were safely aboard and on the way to North Bend.

Half an hour passed. Boys and girls were chatting gaily, the others congratulating Billie over and over again on her good fortune.

"Just like a page out of the Arabian Nights——" Teddy was saying when his words were cut short most unexpectedly.

There was a jar and a crash, a shock and another crash, and then the lights in the car went out, leaving the passengers in darkness.

What followed was like a terrible nightmare. Shaken and jolted badly, but not seriously hurt, it took the girls a horrible minute or two to realize what had happened. There had been an accident—a terrible accident. Then hands went out in the blackness and the girls called to each other in strangled whispers that could not be heard above the din and uproar outside.

They heard Mr. Bradley shouting above the noise, asking if any one of them was hurt and reassuring them. Gradually they managed to grope their way to his side, guided by his voice, and with an agony of relief in his heart he gathered the three girls to him and heard the voices of Mrs. Gilligan and the boys at his elbow.

"Let's get out of this," he cried, and began feeling his way cautiously toward what had been the front of the car.

He soon found the aisle blocked by what appeared to be the wreck of the forward end of the car and was forced to turn back and feel his way toward the rear platform.

Fortunately the train had not been crowded. There had been only three or four passengers in that car besides themselves, and so there was little danger of being trampled in the dark.

Fearfully, holding on to one another, the girls followed Mr. Bradley and the boys, stepping gingerly over broken glass and other débris and shivering with fear and excitement.

"I wonder if anybody was hurt," Laura cried into Billie's ear.

"Oh, I hope not," said Billie, her voice almost lost in the uproar. "I guess it must have been the forward cars that caught the worst of it. We just escaped." She shuddered and clasped Laura's hand more tightly.

It seemed ages before they finally reached the platform of the car. However, even nightmares come to an end, and they were suddenly startled by having a red light flashed in their faces. And then a friendly Irish voice accosted them in unmistakable brogue.

"So it's here you are!" cried the voice, the speaker swinging the lantern high so as to get a good look at them. "And it's glad Oi am to be seein' ye. Be there any more in the car wid yez?"

"I don't think so," replied Mr. Bradley, surprised to find that his voice was trembling and that the hand he raised to wipe his forehead shook like a leaf. If it had been himself alone who had been in danger—but the young folks!

As they descended to the platform the girls looked about them with wide, frightened eyes, while their hearts pounded suffocatingly.

The faces of the boys were white, but they plunged immediately into the work of rescue. Men came running from the farms about. All who could get lanterns had them, and the lights were seen swinging down the roadside or in the ruined cars, searching for any one who might be pinned under the wreckage.

Most of the passengers had already been accounted for, but there were one or two who must still be found. Mr. Bradley picked his way through the débris to the front of the train, while Mrs. Gilligan and the girls followed him slowly.

"I wonder how it happened," said Violet, and it was the first time she had spoken since the accident. "Oh, girls, I'm frightened to death!"

"I wonder if anybody was hurt," said Laura, her eyes dark with excitement.

"I don't think so," Billie answered. "The damage seems to be mostly at the front of the train. We may have run into another train. Oh, look!" she cried suddenly, pointing with trembling finger to the wreck of the car in front of them. "Fire, girls! The car's on fire!"

With horrified eyes the girls followed her pointing finger and saw a malignant tongue of flame shoot out—then another—and another.

"It's the baggage car!" screamed Laura, as men, attracted by the blaze, came running from all directions. "Billie, your trunk!"

"My trunk! my trunk!" wailed Billie distractedly. "Oh, it will be burnt up! All my money and everything!"

"Say, Chet, look! The baggage car's on fire!"

It was Teddy's voice, and Billie looked up to see him beside her staring unbelievingly at the burning car.

"Oh, Teddy," she cried, clutching his arm desperately, "my trunk's burning up! Can't you do something—can't you?"

Teddy gave a low whistle and kept on staring while Chet and Ferd came rushing up and joined him.

"The trunk——" Chet began, but Teddy clutched his arm excitedly.

"Look!" he cried. "It's the front end of the car that's on fire. If we climbed through the side door we'd have a chance to——"

He never finished the sentence, for the boys had caught the idea and were racing headlong for the burning car. Mr. Bradley, meeting them half way, literally had to drag them back.

"Don't be idiots!" he shouted to them. "Do you want to get burned up?"

"Let go, Dad!" gasped Chet, struggling to free himself. "Billie's trunk!"

"Billie's trunk will have to take its chance," Mr. Bradley yelled back at him. Then he added in a changed voice that made the boys stop struggling for a moment and follow the direction of his gaze. "Here come the fire engines. Maybe we'll save that trunk after all."

With a yell the boys dashed off down the platform to meet the engines, whether with a vague idea of helping the horses pull or just on general principles, no one will ever know.

The fire department was a country one, and there was not enough force of water; in fact, there seemed not to be enough of anything.

They did at last succeed in putting out the fire, however, while the girls stood by in an agony of suspense, and finally some of the train hands were allowed to climb into the sodden train and find what luggage, if any, could be saved.

Wildly hoping that their own particular little trunk with its precious contents would be among the saved, the girls and boys would have followed, but a guard politely but firmly held them back.

"Claim your baggage at the next town, please," he said, and, his hard heart softened perhaps by the sight of Billie's anxious face, added by way of explanation: "All the baggage will be sent to the next town to be claimed in the morning."

"In the morning!" gasped Billie in consternation. "Have we got to wait all night?"

"There won't be another train through till to-morrow," the guard explained, still patiently. "And it will save confusion to wait until morning to identify the baggage."

"How far is it to the next town?" inquired Mr. Bradley, and the guard turned to him with an air of relief that said as plainly as words, "Thank heaven, here's a man to talk to."

"Three miles, sir," he said. "I reckon you'll have to walk it, as they haven't taxi service around here." He grinned, but Mr. Bradley's face was sober. He was wondering how he was going to get his charges to the next town.

However, even while he was wondering, the difficulty was being solved for him by some of the good-natured farmers who generously put their wagons at the disposal of the survivors of the wreck.

When they reached the village fate chose at last to smile upon them—a very little. They found a comfortable little cottage presided over by a comfortable little farmer's wife who first gave them supper and then led them to the best rooms in her house and tucked the girls in bed as if she had been their own mother.

Mrs. Jenkins, the farmer's wife, was as pretty and comely as a shining red apple—and just as neat. She said that her husband had gone to a neighboring town to sell some of their stock and would not be back for a week or two. She was so lonely that her guests were as welcome to her as she and her hospitality were welcome to them.

Yet in spite of comfortable beds and snowy sheets, the girls slept little. All night long they tossed and turned, and when occasionally, worn out, they would drop into an uncomfortable doze, they would always wake up with a start and a frightened cry.

Visions of crushed cars with flames shooting from the windows tormented them all night until at last, when it seemed they could stand it no longer, they opened their eyes upon the dawn.

"Oh, girls, it's morning!" cried Billie, jumping out of bed and beginning to drag her clothes on hastily.

"What are you going to do?" asked Violet, opening one sleepy eye.

"Do?" cried Billie, turning upon her like a little whirlwind. "What do you suppose I'm going to do? I'm going to find that trunk!"

To her great surprise Billie found that not only her father but the boys were up and had for the past half hour been busily engaged in eating a breakfast prepared for them by the rosy and good-natured farmer's wife.

They greeted the unexpected apparition of Billie with enthusiasm, and their impromptu hostess turned cheerfully back to the frying pan to fry another egg for the new arrival.

"I bet I know why you got up," said Ferd, his mouth full of biscuit and jam. "Come on over, Billie, and after you've daintily pecked at some food we're all going to look for your trunk."

"But I'm not hungry," protested Billie, as Teddy dragged a chair up to the table for her. "Don't you think we'd better get started right away?"

"Not before you've had some breakfast," said her father, and so she hurriedly ate—it might be said "gobbled," if it were not so unladylike—the breakfast that Mrs. Jenkins placed before her.

If it had not been for the real cause of her excitement the boys might have found amusing her effort to gulp down her whole breakfast in the time one usually takes to drink a cup of coffee. As it was, they sympathized, and once when she choked and became painfully red in the face, Ferd gravely handed her a glass of water and Teddy gallantly offered to pat her on the back.

When, contrary to everybody's expectations, the meal came to an end without any further mishap, Billie crumpled her napkin into a ball and threw it on the table.

"I won't eat another bite for anybody," she said, adding, as she started for the hall: "I'll put on my hat and be right with you."

In the bedroom she found that Laura and Violet had turned over for a nap and she stood for half a minute looking down at them reflectively and a little scornfully.

"Go ahead—sleep," she said under her breath. "It isn't your five thousand dollars." This was hardly fair, seeing that that five thousand dollars meant almost as much to Laura and Violet as to Billie herself in the happiness it would bring.

With one last disgusted look she fled from the room and joined the boys and Mr. Bradley in the hall. Mrs. Jenkins had directed them to the station, and, anxious to waste no further time, they set off at once.

"Daddy, do you suppose we'll find it?" asked Billie, her breath coming fast. "There were a good many trunks destroyed in the baggage car, weren't there?"

"It was hard to tell the extent of the damage," said Mr. Bradley, anxious to reassure her, yet afraid to raise her hopes too high. "However," he said, quickening his step a little, "there's the station right before us, so we ought to find out before long."

Early as they were, there was already a line of people on the rickety station platform and Billie was seized with a fresh spasm of dismay.

"Goodness! they couldn't possibly have saved trunks enough to go round," she cried, and Teddy, though he was feeling very anxious himself, laughed at her.

"There were two baggage cars, both loaded, you know," he reminded her. "And one of them wasn't touched by the fire. We'll hope yours was in that one."

"Oh, Teddy, you're such a comfort!" she cried, and squeezed his arm gratefully, at which Teddy flushed happily.

"Have we got to stand in line?" Billie whispered nervously to her father a minute later. "I know I can't stand still and behave myself, Daddy. Couldn't we go up and have a look around?"

"That wouldn't do any good," said her father, glancing at the piled-up baggage. "It would only make more confusion. And still——" He thought for a moment and then suddenly he strode off down the station and toward the guard who had been friendly the night before.

Billie could hear nothing, but she saw enough to make her heart beat faster. Mr. Bradley whispered a few words to the man who was at first inclined to be impatient and made a quick gesture as if to wave Mr. Bradley back to his place in the line.

However, Billie could see that whatever her father was saying was making an impression, for suddenly the guard straightened up and began to look interested.

"I wonder what Dad's handing him," said Chet slangily in her ear.

"Look!" cried Billie, clutching his arm. "They're going to look for something—probably our trunk. No, they're not. Look how excited he is! And Daddy, too! Oh, Chet, what in the world——" the last words were a wail, and Chet squeezed her hand warningly.

"Come on, let's find out," he said. "It looks as if something was up."

The four young people came within earshot just in time to hear the last part of Mr. Bradley's sentence.

"If it was only a few minutes ago, he hasn't had time to get far," her father was saying with a grim light in his eyes.

Billie could stand the suspense no longer, and she rushed forward, grasping her father's arm. The earnest conversation between the guard and Mr. Bradley and their evident excitement had already attracted the attention of the line of people, and now they watched Billie curiously.

"Daddy, what do you mean?" Billie cried in a voice tense with excitement. "Is the trunk safe? Have you found it?"

"Yes. But only to lose it again," said her father, and then went on hurriedly to explain. "The guard says he saw a trunk here only a little while ago that answers our description, but now it's gone. He remembers seeing a suspicious looking man hanging around, and it's barely possible that the man may have stolen it. He also remembers seeing this fellow drive off in a Ford car just a few minutes ago."

"O-oh!" cried Billie incredulously. "The trunk has been stolen!" Then she whirled around and faced the guard. "Are you sure it was our trunk? Could you describe it?"

"Yes," the guard answered, excited himself by this time. "I took special notice of it because it was so odd and shabby."

"That trunk was worth five thousand dollars!" wailed Billie, thereby causing another ripple of surprise among the onlookers. Then she turned pleadingly to her father.

"Daddy, we must find the trunk, we must!" she cried. "Just think what it means." She was on the verge of tears, and her father came suddenly to a decision. He turned quickly to the guard.

"Is it possible to get a machine around here—a fast one?" he asked.

"I don't know. But here's the man who keeps the livery stable."

Suddenly a well-dressed man, who had been watching the proceedings with lively interest, stepped forward and addressed Mr. Bradley courteously.

"I have my car here," he said, adding with a smile of pride: "And she's guaranteed to overtake anything that runs on four wheels. She's at your disposal, if you can run her. My man went on an errand."

"That's kind of you, sir," cried Mr. Bradley heartily. "If you will show me——"

"I'll say so," said the stranger boyishly, and led the way around the station to a car which, even in this minute of excitement, the boys eyed delightedly.

"I'll drive," announced Teddy; and before any one could have interfered if they had wanted to, he had jumped into the driver's seat and had thrown in the clutch. Teddy was young, but he knew all about cars.

Mr. Bradley took the seat beside him and the two boys and Billie scrambled into the tonneau. Mr. Bradley motioned to the owner of the car.

"Will you come?" he asked, but the man shook his head.

"No, thanks," he answered, "I'd rather stay here and watch for some other missing baggage. Good luck!" and he waved to them as the big car glided forward under Teddy's touch and shot around a turn in the road.

The wind roared in Billie's ears and whipped little strands of hair across her eyes, but she pushed them back impatiently and fixed her eyes upon the flying ribbon of road ahead.

"Faster, Teddy, faster!" she kept urging until even that young scatterbrain began to wonder at her.

"Can't be done, Billie!" he yelled back finally. "We're going about sixty now, and if we meet anything on the road, we'll have a smash-up."

"Be careful, Teddy," cautioned Mr. Bradley. "We don't want an accident."

"Oh, but we've got to catch that thief!" wailed Billie, hoping each time they rounded a bend in the road to see their quarry just ahead. "He may have got too much of a start——"

"Don't worry," Teddy shouted back. "No start will help a flivver against a car like this. Say, but she's a beauty! Just listen to that engine!" But Billie was in no mood to listen to anything except the jingle of queer old coins in a shabby old trunk. Then suddenly there came a yell from Teddy and an exclamation from Mr. Bradley.

"There he is!" cried Teddy, leaning down over the wheel as though he would force even more speed out of the flying car. "See him, Billie? Didn't I tell you a flivver didn't have a chance?"

Even as Teddy spoke, the man in the machine ahead of them looked back. Then abruptly, and to the great surprise of Billie and the boys, he stopped his car and began groping wildly in the bottom of it for something.

Then, while every second brought them nearer, the man did an astonishing thing. He lifted a small object, which Billie excitedly recognized as the trunk, and with an effort succeeded in getting it over the side of the car.

Then he dropped it in the road and turned for a swift moment to look at his pursuers before he started his car again. It was only a moment, but those in the car behind were near enough to get a good look at his face.

It was a repulsive face topped with a mass of vivid red hair. But what the boys and Billie most noticed was his unusually wide, loose-lipped mouth.

So busy was Teddy in looking at the thief that, if it had not been for Billie, he would surely have run over the precious trunk in the road.

She stood up waving her arms excitedly.

"Teddy, look out! If you run over my trunk——" and Teddy swerved so suddenly that she was nearly thrown from the car. However, Chet caught her and put her safely back in the seat; and in another minute Teddy had brought the big car to a sliding standstill.

They tumbled to the roadside, and Billie, rushing over to the trunk, sank to her knees regardless of three inches of dust in the road, and encircled the shabby old thing with her arms.

And Teddy, watching her, said with a grin:

"Gosh! who wouldn't be a trunk?"

A few minutes later a very exultant crowd of young folks were starting back over the road they had just traveled so fast.

In the bottom of the tonneau,—Billie and the two boys were using it as a foot rest,—was safely stowed the shabby, but, oh! so precious old trunk, and on Billie's face was the "smile that wouldn't come off;" or at least that is what Ferd called it.

Teddy was the only member of the party who was not fully satisfied with the expedition.

"We should have followed and caught the thief," he was saying for the eleventh time—Billie had counted them. "It would have been like taking candy from a kid to have caught up with his old flivver, and then we could have landed him in jail, where he belongs."

"But we wouldn't have time, Teddy," Billie reminded him. "You know the train guard said there would be a train through about eleven o'clock. And we can't miss it. Besides," and she shifted her feet happily on her five thousand dollar footstool, "what do we care about that old man now that we've got the trunk?"

"Isn't that just like a girl," cried Teddy, almost running them into a ditch in his indignation. "I suppose you would be willing to let all the thieves in the world go free if you could only get back what they stole."

"I certainly would if we had a train to catch," agreed Billie, and Ferd chuckled.

"Good for you, Billie!" he cried approvingly. "Stick to your guns. I don't see any use of following up that old chap now that we've got the goods."

"He wasn't very handsome, was he?" asked Billie, remembering that one glimpse she had had of him.

"Maybe that's why you didn't want to follow him," chuckled Ferd, and Teddy scowled blackly at the wind shield.

"But wasn't he ugly?" Billie persisted. "I don't think I ever saw such red hair. And his mouth—ugh!" She paused reflectively.

"Yes, it looked just like the mouth of a codfish," said Chet.

"The poor fish," remarked Ferd jocularly, but be it said to their credit that no one laughed at this feeble attempt at a joke. They only stared.

As the car swept into the village again Billie had a sudden and rather conscience-stricken memory of her chums. For the first time in her life she had forgotten them completely. But then one doesn't lose five thousand dollars and recover it every day!

As the car stopped at the station it was surrounded by an eager crowd of people, among whom was the owner of the car. But for his generosity they would never have been able to recover the trunk.

"Did you get it?"

"Did you bring back the thief?"

"Say, you must have done some speeding!"

These and other like remarks greeted the adventurers as they climbed from the car, and under cover of the confusion Billie made her escape.

Teddy, looking around for her a moment later, missed her and started in pursuit.

"You're always running away," he protested plaintively, when he overtook her just a little way from the cottage, the owner of which had shown them such generous hospitality.

Billie wrinkled up her nose in surprise.

"Running away?" she repeated wonderingly. "Why, Teddy, sometimes I almost think you're foolish."

"That's what Mother says, only she's sure of it," said Teddy, with a wry little grimace that made Billie laugh.

"Well, she ought to know better than I," she said demurely. "She's known you longer."

"Not very much," Teddy retorted, opening the gate of the little picket fence for her. "And, anyway, you haven't answered my question. What did you run away for?"

"I didn't run away. I escaped," she explained, making a face at the memory of the crowd. "I wonder what makes people so curious. I do believe all a person would have to do to collect a crowd would be to stand on a soap box and say, 'Isn't this beautiful weather?'"

"You bet. Especially if that person were you," said Teddy, and Billie looked at him reproachfully.

As the two entered the hall they met the girls just coming down stairs.

They all went to the kitchen, where they found Mrs. Jenkins just finishing a batch of golden brown crullers. She greeted the girls with a beaming smile and insisted that Laura and Violet sit down while she got them some breakfast.

"Why, you must be nearly starved," she said.

The girls protested that they were making her too much trouble, but she gave them a cruller—"to stop their mouths," she said—and then set cheerily to work to fry some more bacon and eggs, putting in a word now and then and listening with a smile to the girls' merry chatter.

"You mustn't scold me when you're hungry," Billie said, and the gladness in her voice made the girls look at her eagerly. "No, I'm not going to tell you a word," she said firmly as they started to ply her with questions. "Not till you've had some breakfast, anyway. Eat, pretty creatures, eat."

Billie looked up at pretty Mrs. Jenkins and invitingly patted the empty chair beside her.

"Sit down here, please," she coaxed. "I want you to hear this too."

"Now tell us," Laura commanded impatiently. "Why did you leave us asleep and go out? And, oh, Billie! have you found your trunk?"

So Billie told the story while the girls listened open-eyed and open-mouthed, completely forgetting their breakfast, which lay untouched before them.

Mrs. Jenkins seemed almost as excited as they did, and leaned over the table, one hand clutching the bread knife, while her rosy face fairly beamed. Here was adventure such as rarely came to the village.

Billie had just come to the part where the thief dropped the trunk in the road when Mr. Bradley and the two other boys burst in upon them with the news that the train was due in about fifteen minutes.

Laura and Violet left their almost untouched breakfast, mumbled an excuse to Mrs. Jenkins, and rushed with Billie up to the bedroom they had occupied the night before to gather up their things and put on their hats and coats.

"Laura, you have my comb," said Violet accusingly, as Laura was stuffing that article hastily into her hand bag.

"Well, take your old comb," replied Laura, throwing it over to her. "It isn't as good as mine, anyway. It has a tooth out."

"Somebody will have more than one tooth out if she doesn't hurry," threatened Billie. "Girls, we mustn't lose that train. Listen! There's the whistle."

Thereupon the girls forgot to quarrel and combined forces for a rush to the train.

They rushed down the stairs, falling over their suitcases and each other, and found Mrs. Jenkins waiting for them at the bottom of the stairs.

Mr. Bradley had insisted upon paying her for her hospitality, but she had stubbornly refused to take a cent.

"No, sir," she had said, shaking her head decidedly. "Do you think I'm going to let you pay me for having a good time? I love the girls and boys, bless 'em, and I hate to see 'em go. Pay me—well, I guess not!"

So Mr. Bradley had shaken her hand and thanked her heartily, which was the best that he could do.

And now the girls even risked missing the train to give her the only kind of pay she wanted. Billie dropped her bag and impulsively threw her arms about the comely woman.

"You've just been sweet to us," she said, "and we'll never, never, never forget how kind you've been. I—I'd like to kiss you, if you don't mind."

Shyly she kissed Mrs. Jenkins' rosy cheek, and Violet and Laura followed suit. The boys and Mr. Bradley shook hands with her heartily, and then they picked up their belongings and fairly ran down the steps and out at the little white gate.

They turned to wave to Mrs. Jenkins, and she waved back at them until they disappeared around the corner; and when she started to go into the house she was surprised to find that there were tears in her eyes.

"The precious lambs," she said. "The precious little lambs! They kissed me, too, bless 'em!" and she put her hand up gently to her face.

Meanwhile the train that was to carry the North Bend party back home had thundered into the station, and all the passengers who had been stranded in the place overnight were crowding on board.

As Billie was being hurried up the steps, she suddenly paused and looked back at her father.

"Where's the trunk?" she asked nervously.

"In the baggage car," Mr. Bradley assured her. "We'll get it safely to North Bend—unless we have another wreck."

As soon as he had made the speech he regretted it. Billie's face went white and Laura and Violet looked back at him with startled eyes, then went on more slowly into the car.

The luggage had been stowed away in the racks overhead and the girls were removing their hats when the train moved slowly from the station.

"You know, I'm terribly afraid," Violet confided in a whisper to Billie. "I—I won't feel safe for a minute until we reach North Bend."

Billie looked a little uncertain herself, but suddenly there floated across her vision a shabby, odd, little trunk, filled to the brim with old coins and postage stamps. Then she laughed.

"After this morning," she said, "I'm not afraid of anything. The luck's all on our side!"

Billie was right about their luck, for they reached home without further mishap. And it was with great relief the boys and girls later saw the precious trunk safely deposited in Billie's attic.

The next few days were mostly spent in telling wondering and interested home folks about the ghostly happenings at the old homestead that was Billie's inheritance and in recounting in detail the circumstances that led to the discovery of the treasure trunk.

And then one night Mr. Bradley came home with the wonderful news that he had sold most of the contents of the old trunk and had realized four thousand three hundred and fifty dollars—and every cent for Billie!

"Did you sell them all, Dad?" Billie inquired, her eyes shining.

"No, I kept out a few coins and stamps that were especially rare and I'll take them to another dealer. I think," and he looked at Billie thoughtfully, "they ought to bring in quite a little pile more."

"Oh, Daddy, it's like a fairy tale!" Billie cried, and then added, edging around to where her father stood and looking up at him appealingly: "You and Mother haven't really said it, Dad, but Chet and I will be able to go to boarding school, won't we?"

"I should think so—on four thousand dollars," her father answered dryly, and so Billie's cup of happiness was filled to the brim.

But Billie, young as she was, was beginning to learn that no matter how perfect a thing seems, there is almost sure to be a fly in the ointment somewhere; and it was not long before she discovered the fly in the present case.

It was one beautiful bright day, the kind that only early autumn knows, and the chums were walking down the main street of North Bend eagerly discussing plans and talking of the fun they would have at Three Towers Hall when suddenly Billie espied Miss Beggs, the English teacher whose statue she had broken, coming out of a drug store.

With a great wave of happiness that now she could pay for the statue, or at least replace the one she had broken, she hurried forward and spoke to the English teacher as she was about to enter another store.

"Why, how-do-you-do!" cried the latter, evidently surprised and very much pleased at the meeting. "I didn't know you were back yet."

"We left Cherry Corners on Monday," Billie replied, then added eagerly as Laura and Violet came hurrying up: "I'd like to tell you what happened to us there; that is, if you have time enough."

"Indeed I have," replied Miss Beggs heartily, and after she had greeted the other girls they all walked down the street together while Billie launched into the wonderful tale of her good fortune.

"Over four thousand dollars!" cried the teacher when Billie stopped for lack of breath. "Why, Billie, isn't that marvelous? It sounds like a story. What," she added, smiling down into the eager face, "do you intend to do with all that wealth?"

"Buy a statue for you, first of all," said Billie promptly, and Miss Beggs flushed.

"I had forgotten all about that statue," she said. "I told you it had already been broken, anyway."

"I know you did. But since you had mended it so it looked all right, it was almost as good as new, wasn't it? You mustn't say 'no,'" she added quickly, as she saw Miss Beggs was about to interrupt, "for it won't do the slightest bit of good. I'm not going to buy anything for myself till I replace that statue."

Miss Beggs gave a little helpless shrug of her shoulders.

"I can see that nobody has a chance to change your mind, Billie Bradley, when it's once made up," she said with a smile, then added as the girls turned toward home: "I know what I shall name my new statue. Her name shall be 'Billie.'"

"She's lovely, isn't she?" asked Violet, referring to Miss Beggs. "I wish she were going to be one of the instructors at Three Towers."

"I hope they're nice, for it's awful to live with people who aren't," sighed Laura.

"Well, we won't know very much about them till we get there."

"And then it may be too late," put in Violet dolefully.

"But Daddy says," Billie went on, "that Miss Walters, the head of the school, is just splendid."

"Well, that ought to help some," said Laura, adding with a quick change of tone that made the girls look up suddenly: "There's Amanda Peabody. Can't we hide or something?"

"I don't see where, and, besides, she won't bite you," said Billie.

Amanda Peabody was probably the most unpopular girl in North Bend. The girls disliked her as real girls always dislike a sneak and tattle-tale. Amanda was always spying around, minding everybody's business but her own, and making a general nuisance of herself.

And because Billie was so popular, Amanda seemed to have an especial grudge against her and was always trying to get her into trouble.

As Amanda came toward them on this beautiful afternoon she seemed more unpleasant than usual and there was a mean little smile at the corners of her thin-lipped mouth.

"Hello!" she accosted the girls, then turned to Billie with a more pronounced grin. "I've heard all about the money you found in that awful old house. You must feel like a regular Captain Kidd, don't you?"

"Since I never was sure how Captain Kidd felt, I don't know," said Billie coolly, although she could feel the blood slowly mounting into her face. Oh, if she could only do what she wanted to, Amanda Peabody wouldn't be smiling very long!

The girls made as if to go on, but with characteristic ill breeding, Amanda planted herself directly in front of Billie, still with that maddening grin on her face.

"I suppose now you'll be going to Three Towers Hall and your brother to Boxton Academy."

Billie did not say anything—she just looked. But that look must have been enough, for suddenly with a flirt of her dress and a toss of her head and an insolent look Amanda flung past them.

"Just the same you needn't think you're the only pebble on the beach," she called back. "I'm going to Three Towers, too."

For a minute the chums could not believe their ears. Then they looked at each other with horror written on their faces.

"Did you hear what I heard?" gasped Billie, when she could find her voice.

"Yes, I heard," said Laura faintly. "Girls, do you think she could have been telling the truth?"

"I don't see why she should want to fib about it," said Vi, feeling rather bewildered. "She'd know we would soon find it out."

"Oh, but it's too awful!" burst out Billie suddenly. "Why, girls, it's apt to spoil our whole year! Just think of having that sneak around, prying into all our affairs and reporting every little thing we do."

"I guess the only way out of that is not to do anything she can report," said Violet ruefully, and Laura caught her up quickly.

"There you go taking all the fun out of it before we start," she said, and in spite of their consternation the girls had to laugh.

"Why, you actually sound as if you intended to break the rules," said Billie, drolly adding, with a prim little pucker of her mouth: "Laura, I'm surprised at you."

"Listen to the good little girl talking," gibed Laura. "I never knew you to get into any mischief, Billie,—oh, no!"

"Well, I won't quarrel with you about it," said Billie, calmly adding with a little chuckle: "If we try to have any midnight feast at Three Towers with sweet Amanda wandering round loose we will have to appoint a guard to stand outside the door and warn us."

"I suppose that will be my job," said Violet plaintively. "It will be lots of fun standing out in a drafty hall looking for Amanda while you girls are having a feast."

"No, we'll fix it so it will be perfectly fair," said Billie soothingly. "We'll draw lots or something."

"But I don't know what good a guard would do anyway," said Laura dolefully. "There's something creepy about the way Amanda finds out things. You think she's miles away and the next day she tells you more about what you did than you know yourself."

"Maybe she has an accomplice," said Billie dramatically, and the girls giggled.

"Anybody'd think Amanda was a criminal or something," said Laura, but Billie shook her head decidedly.

"Uh-uh," she said. "I might like a good honest criminal but I'll be jiggered—scuse me, ladies—if I can like Amanda Peabody! She's too sly!"

It was just two weeks to the time when the girls were to leave for Three Towers Hall.

It seemed to them they would never get done all the things that they had to do, and they sewed and packed and planned until it seemed they must stop because of sheer exhaustion.

However, their parents sent them to bed early—and not without difficulty was this feat accomplished—on the night before the great day, and the morning found them refreshed and wildly eager for this new adventure.

As, in her own little room, Billie regarded her flushed reflection in the mirror it seemed impossible to make herself realize that she was really going to Three Towers Hall at last—Three Towers which had been the height of her ambition from the time she had entered the grammar school.

She was beginning to feel quite grown up—which was perhaps the reason she regarded her new and very pretty brown hat with a critical eye and smoothed down her new and very pretty brown dress with hands that trembled with excitement.

"Well, I think I'm all ready now," she said at last, and gave a little, half-frightened glance around the familiar room. She wondered how it would seem to sleep in a strange place with no mother or father near by.

Then she shook herself impatiently and picked up her bag—for was she not grown-up now?

However, she did not feel very grown-up when a moment later she met her mother in the hall and saw traces of tears on her face. For Mother had no new scenes to go to and the departure of her two noisy children would leave the house strangely quiet and subdued.

Billie flung herself upon her mother and hugged her tight.

"Mumsey, you've been crying!" she said to her accusingly. "And you know you mustn't."

Then to her great surprise she felt a peculiar lump in her own throat, and two tears forced themselves to her eyes.

She had never dreamt of crying, and for the first time she realized that leaving one's mother—even for Three Towers—was not easy, after all!

But it was Mrs. Bradley who came to the rescue and prevented a break down by asking:

"Isn't that Laura coming down the street? And the boy with her must be Teddy."

With a quick movement, Billie brushed her hand across her eyes, kissed her mother hard, and straightened the new brown hat.

"You're coming to the station, M—mother?" she asked, and Mrs. Bradley nodded.

After that Chet came in, wrestled with the same troublesome lump in his throat, told his mother, "Not to worry, Mumsey, he'd write every day, and she mustn't forget to write for he was going to miss her awfully," and then Mr. Bradley joined them and they all started for the station.

Mr. and Mrs. Jordon were with Teddy and Laura. Teddy said that Ferd was on his way, but had told them not to wait for him, he'd catch up to them later.

A little farther on they picked up Violet and Mr. and Mrs. Farrington, and after that there was no more time to think of being homesick.

There was something in the sunshine, the crisp air, the brilliant, changing colors of the leaves on the trees that went to Billie's head and made her feel as though she were walking on air.

"Do you suppose Ferd will catch up to us?" she asked of Teddy. Teddy was looking unusually handsome this morning—at least so Billie thought—and she was surprised to find that he was walking beside her. "It would be awful if he made us miss the train."

"You don't think we'd wait for him do you?" asked Teddy scornfully. "If Ferd's late he'll be the only one to miss the train!"

Both Teddy and Billie had always agreed that if you talked of an angel he or she was sure to turn up, and in this case their faith was justified.

For just as they reached the station platform a figure that looked very familiar turned the corner and came rushing down toward them as if bent on running a Marathon.

"There's Ferd—and here's the train," announced Teddy, as a shrill whistle made them jump and look eagerly down the track. "Not much time to waste at that."

The young folks were so taken up in the leave taking that they failed to notice two girls who got on the train just after them. Even if they had not been able to see the faces of these newcomers, an overheard sentence or two would have given them the clue to their identity.

"Isn't it just like them, the stuck up things," one of the girls said to the other, "to bring all their relations to see them off?"

"Never mind," said the other with a malicious grin. "I guess I gave them rather a jolt the other day when I told them I was going to Three Towers too. I guess they thought they owned the place and ought to have it all to themselves."

However, the boys and girls were perfectly unaware of this conversation concerning themselves; although it probably would not have bothered them very greatly if they had heard it.

They were still leaning out of the window, calling to those left on the platform and answering injunctions "not to get killed" from their mothers and to "please be careful and not get into any more scrapes than they could help" from their fathers, when the guard shouted a warning and the train started off.

They waved until the station and the people on it were out of sight, then settled back in their seats "to view the prospect o'er," Chet said.

For a moment they all felt a little lost and queer, though nothing in the world could have made them confess to the feeling. But the little wave of homesickness soon passed off, swallowed up by the vision of the amazing adventure ahead of them.

Before the little party had stowed away their baggage and taken off their wraps, several boys and girls they had known at school came over to greet them and talk things over, and Billie, leaning over to rescue a box of chocolates that had fallen at her feet, suddenly looked up and right into the beaming face of Nellie Bane.

Nellie was a friend of the chums who had rather expected to go to Three Towers Hall with them at first. But Mr. and Mrs. Bane had suddenly decided to go to Europe and take Nellie with them, which had rather upset Nellie's plans. And now here she was on the train with them.

"Why, Nellie!" Billie cried, almost dropping the chocolates again in her surprise and delight. "How did you get here——"

"Through the window," mocked Nellie, and dropped into a vacant seat beside Laura.

"But," stammered the latter, her eyes round and wide with wonder, "the last we heard of you you were going to England."

"Yes. But an aunt of Daddy's died and he decided we'd better postpone the voyage until next summer."

"Are you glad or sorry?" demanded Billie breathlessly.

"Glad," said Nellie without a moment's hesitation. "I want to go to Europe, of course. But I can go there any old time, and I was simply wild to go to Three Towers with you girls. You'll never know how jealous I was," she ended with a sigh.

"Isn't it funny?" marveled Violet. "And here we were envying you!"

They laughed, and thereupon entered into a spirited conversation that lasted until Ferd interrupted to inquire what they were keeping the chocolates to themselves for, anyway. Did they think they had a corner on the chocolate market? To this Billie answered by holding out the whole box, showing that they had been too busy talking even to open it.

This interruption led to others, however, and they found that nearly the whole car was occupied by girls and boys from North Bend who were going to Three Towers or the Boxton Military Academy.

At last, wearied with excitement and visiting, Billie sank into her own seat. A moment later Teddy came and sat down beside her.

"I see we have your friend with us," he said, handing over the candy box.

"My friend?" repeated Billie, bewildered.

"Amanda Peabody," he explained. "She is sitting with another girl who looks as if she might be a second edition of Amanda. There! Away at the end of the car! You surely missed a lot by not seeing them."

"Another girl," Billie repeated, looking worried. "Then there are two of them."

"Yes. But don't let it hurt your appetite. Have some more candy."

"Do you know her name—the other one?" asked Billie, ignoring the offered candy box.

"No, I didn't stop long enough to inquire. In fact," he chuckled and bit into a chocolate, "I gave them one look and beat it."

Billie dimpled, but the next moment her face was grave again.

"That's all right for you," she said. "But what would you do if you couldn't 'beat it'?"

It was Teddy's turn to be puzzled.

"What do you mean?" he asked.

"Only," said Billie, speaking very slowly and distinctly, "that Amanda and most likely that other girl, whoever she is, are both going to Three Towers Hall with us."

Teddy emitted a long whistle and looked sympathetic.

"Say, I'm sorry. That's tough luck."

"It's worse than that," wailed Billie. "It's—it's ruinous! I just know that Amanda Peabody will do her best to spoil the term for us girls!"

In spite of their eagerness to reach their destination, the ride seemed all too short to the boys and girls. They started when the guard called out, "Molata, next stop!"

Hardly knowing what she was doing, Billie found her hat and coat, put them on, and then sat on the very edge of her seat with her gladstone bag grasped tightly in one hand. Then she looked around at Laura who was sitting in the seat beside her.

It was then she got her surprise. For Laura was sitting in almost the same position as herself, perched on the edge of the seat, bag tightly gripped in one hand, pocketbook in the other and—this was the fact that made Billie chuckle—Laura's hat was very much over one eye.

Laura looked up at the sound of the chuckle and giggled as her eyes met Billie's.

"I'm so excited," she whispered in Billie's ear, "that my knees are trembling. I'm afraid I'll never be able to walk out."

"Well, you needn't expect me to carry you," said Billie, reaching up and putting Laura's hat on straight. "Because I'm going to have all I can do to manage myself. Goodness, what's that?"

It was merely the train stopping, but by the tone of Billie's voice one might have thought it was the end of the world.

"Say, are you girls all ready?" asked Ferd, leaning over the back of their seats.

The girls nodded nervously.

"Well, then let's go," Teddy chimed in, grabbing his suitcase and cap. "Come on, pick up your hats, girls, and don't forget your feet."

"Oh, isn't he funny?" gibed Laura making a face at him. Then she grabbed wildly at her bag as one of the excited girls seemed bent upon carrying it off with her. "Say, come back with that," she cried. "Isn't one enough for you?"

However, they did succeed at last in getting themselves safely on the station platform. It was a pretty station, and this being their first glimpse of the place where they were going to spend so much time, they looked about them with interest.

Molata was the nearest town to Three Towers Hall and Boxton Military Academy. Both of these schools were situated on Lake Molata, for which the town had been named. Most of the inhabitants of Molata were wealthy, and the estates in and about the town were magnificent. There was also a large hotel, filled during the summer season.

Even the station was in keeping with the general air of prosperity. In the minute the girls had to look about them, they saw a stone-built waiting room with a red-tiled roof. A beautiful green velvety lawn completely surrounded the station on three sides, while on one side a beautiful fountain sent its sparkling spray high into the clear air. And further back through the trees they caught glimpses of beautiful estates.

They found themselves being hustled toward the other end of the station where two conveyances, one from Three Towers Hall and the other from Boxton Military Academy, were waiting to take the girls and boys to their destination.

Two attendants tended to the trunks and deposited the luggage inside the cabs, while the girls and boys said excited good-byes to each other on the platform.

"We'll be only a little over a mile away from you," Chet called out. "And when we get an afternoon off we'll row down the lake and get you girls."

"Oh, won't that be fun!" cried Vi, her eyes dancing. "I'm just crazy to get out on the lake."

"Goodness, we haven't even seen it yet," Laura reminded her.

"Yes, and if we're going to," Billie added, "I guess we'd better get started. Come on, girls. Everybody's in but us. Good-bye, Chet! Good-bye, Ferd and Teddy! Please be good and don't get sent home the first week—we wouldn't have anybody to give us that row, you know. Good-bye—good-bye——"

Laura and Vi had already clambered into the long, car-like machine with Three Towers Hall painted in gold letters on the outside and were impatiently commanding Billie to follow them.

As soon as she was inside the boys rushed to the car with Boxton Military Academy painted in gold letters on the outside, and the good-byes were over.

As they left the station and swung into a wide smooth road on their way to Three Towers Hall the girls relaxed with a sigh of happiness.

"Isn't this a wonderful road?" said Billie, screwing her head around so that she could look out the window. The machine had two long seats on either side, running from the front to the back of it so that, in turning, Billie accidentally stuck her elbow into the girl next to her.

She had not noticed the girl, but now, when the latter spoke, Billie turned around quickly. The girl was Eliza Dilks, Amanda Peabody's chum, and beside her sat Amanda herself looking on with her usual sneering grin.

"Say, if you haven't got room enough," Eliza said in a thin high voice, "I can move over to the other side of the car."

For a minute Billie just stared, while several girls about them paused in their own conversations to listen. Vi was aghast and Laura was furious.

"Well," said Billie at last, letting her gaze travel from Eliza's mean face to her ill-fitting shoes—somewhere Billie had heard that people hate to have you look at their feet—"maybe you'd better move. There's lots more room on the other side."

The girls chuckled. Laura said: "Good for you, Billie," under her breath, and Eliza flushed angrily. She seemed about to speak, but as Billie was still gazing steadily at her feet she looked down at them herself and thereby lost the battle.

However, the incident had made them miss some of the prettiest scenery in Molata, and it was almost with a feeling of regret that the girls saw the majestic three towers of Three Towers Hall rise before them.

Their regret did not last long, however; and when the car started up the broad driveway the girls strained their eyes for a better view.

It was a beautiful place. The hall itself was built of rough, greenish-gray stone, and over the whole front of it, twining round the windows, hanging over the doors, grew clinging, bright green ivy.

A smooth velvety lawn sloped down straight to the water, and the girls cried out at this, their first glimpse of Lake Molata. Through the trees, the water of the lake glistened and shimmered and danced while the soft rippling sound of tiny wavelets lapping at the bank seemed to call to them invitingly.

"Oh, g-girls, it's lovelier even than we pictured it!" cried Laura, stammering in her eagerness. "Aren't you just c-crazy to get out on that water?"

"Yes. But look!" cried Billie, grasping her arm and pointing to the front door of Three Towers Hall. "There's the president, I suppose, waiting to welcome us."

For in the doorway was standing a slender figure in white, evidently waiting, as Billie had said, to welcome the girls to Three Towers Hall.

Other girls had noticed her, too, and as the attendant came around and opened the door, they all scrambled down in a flurry of excitement.

"It's Miss Walters," the whisper went around, and Billie felt a thrill of excitement.

"Miss Walters!" Always she had seemed to Billie a person to be looked up to—a sort of goddess set apart from ordinary mortals. For Miss Sara Walters had been head of Three Towers Hall for a number of years—always, it seemed to Billie. And now Billie was actually going to see her, talk to her, perhaps even make her take notice of her, Billie, above the others!

As she rather breathlessly ascended the steps to the entrance of Three Towers with the other girls she studied this slim, straight woman who had been the heroine of so many of her day dreams.

And what she saw satisfied even Billie.

Miss Walters was only thirty-five, but her hair was snow white and framed her face in thick wavy masses. Her complexion was pink and white, and her dark violet eyes looked almost black under their dark lashes. And her figure was that of a girl of twenty.

"Isn't she wonderful?" Vi whispered in her ear; but Billie squeezed her arm warningly.

"Sh-h," she said. "She might hear us."

"I wouldn't care if she did," said Violet with unusual spirit, and in her heart Billie could not blame her.

A moment more and Miss Walters was speaking to them, saying a few words to each of them, welcoming them to Three Towers Hall.

Then she turned and led the way into the building, the girls crowding after her eagerly.

"And her voice," said Billie, adoringly in Laura's ear, "is the very sweetest part of her!"

Miss Walters took the girls into her office, looked up the cards she had made out for them—for of course their names had been sent in some time before as prospective students at Three Towers Hall—and then called in another teacher, Miss Ada Dill, who had part charge of the dormitories.

Miss Dill was tall and thin with sharp black eyes and white hair drawn severely back from her forehead. She smiled when Miss Walters introduced her to the girls, but her smile reminded Billie of the smile on the face of a Chinese idol which she and her chums had come upon among the antiques of the old homestead at Cherry Corners. It was merely a crack in her face and the beady black eyes remained unsmiling.

"Miss Dill," Miss Walters told the girls, "will show you your places in the dormitories and will give you the hours for meals and such other information as you will need at first. Lunch will be served in half an hour, and after that you may have the rest of the day to yourselves to become acquainted with Three Towers Hall."

Then she dismissed them, and Billie and the other new arrivals found themselves following the stiff back of Miss Dill through the corridor and up a broad flight of steps.

They met several girls on their way to the dormitory, and the latter looked at them curiously. The girls learned a little later that these students had spent the summer at Three Towers, although most of the girls had gone home to relatives and friends and would not be back until the next day.

It was a rule at Three Towers Hall that the new students should report the day before the year formally opened for the purpose of becoming acquainted with the rules and regulations of the school.

"Wasn't that a pretty girl?" Vi whispered to Billie, as Miss Ada Dill opened the dormitory door and a lovely girl with very pink cheeks and very black hair stopped for a word with the teacher and then hurried past the girls on her way downstairs. "I wonder who she is."

"If she's as nice as she is pretty," Billie whispered back, "she'll be all right."

Then they stepped into the long, many-windowed room and looked about them curiously. There were beds, beds, beds and more beds. Everywhere the girls looked they seemed to see nothing but beds. As a matter of fact there were only ten of them, but the girls could have sworn there were at least twice that number.

"We can put five of you girls in here," Miss Dill said in a crisp, dry tone, almost as if she resented having to say it at all. "Are there any of you who would particularly like to be together?"

Of course Billie spoke up for herself and Laura and Vi, and after regarding her severely through her glasses for a moment, Miss Dill finally assigned three beds at the further end of the room to the chums.

"Then there is room for two more," Miss Dill said, and to the horror of the chums Amanda Peabody came forward, holding Eliza Dilks by the hand.

Laura uttered a little exclamation and seemed about to protest when Billie pinched her arm and made her say "ouch" instead.

"There's no use in saying anything," Billie whispered fiercely. "It wouldn't do any good, and we'd only make more of an enemy of that—those girls."

They were relieved a little when they saw that "those girls" were assigned to beds half way down the room so there would at least be a few neutral girls in the beds between.

"So if the rest of you will come with me," said Miss Dill, "I will give you places in the other dormitories."

Then she and the other girls went out into the hall, the door was shut, and the chums were left alone in the big room with Amanda Peabody and Eliza Dilks.

The girls sank down upon their beds and looked about them curiously. There was a little wash basin and a towel rack beside each snowy white bed and on the towel rack hung several small towels with blue and white borders.

The beds were set at regular intervals down the long room, and the spaces in between them were fitted out in such a manner as almost to make a separate little room for each girl.

Beside the wash basins, there was a dresser set at the foot of each white bed and under each bed was a hamper for soiled clothes. Each girl had a little table with a chair to match.

The woodwork had been painted white and the walls were a grayish blue color with several pretty pictures scattered about them to break the bareness.

"Why, the room's all blue and white," Billie suddenly discovered delightedly. "Isn't that a lovely blue they've painted the wall? And the snowy white woodwork! Oh, it's delicious!"

"And just look at the view from this window!" cried Vi, beckoning to them eagerly. As the girls looked over her shoulder they fairly gasped with delight.

Below them stretched the velvety lawn dotted with the darker green of shrubbery, while away through the trees glimmered and gleamed the water of Lake Molata. The day was warm for autumn, and a gentle breeze played among the leaves of the great trees bordering the lake, coming to the girls in a soft, rustling whisper. The picture was almost too perfect to be true.

"And she said," Billie murmured at last with a sigh of content, "that we could have all the afternoon to become acquainted with Three Towers."

"Yes," said Laura, turning from the window, "but I guess she meant only the inside of Three Towers. I don't believe they will allow us off the grounds so soon."

At that moment the door opened and the pretty girl that had passed them in the hall entered and shut the door softly behind her. In the bright light of the room she seemed even prettier than she had in the hall, but there was something about her—Billie could hardly have told what, perhaps it was the expression of her mouth—that made Billie instinctively dislike her.

The strange girl's eyes rested on Amanda and Eliza where they sat in their corner, talking in whispers, and her lips curled disdainfully. Then she came over to where Billie and her friends were standing.

"Hello!" she said with a quick smile. "You're the new girls, I suppose, and we might as well get acquainted right away. My name is Rose Belser, and I'm from Brighting," mentioning a town several miles the other side of North Bend.

"We're awfully glad to know you," Billie answered, with her own particular friendly smile. "I'm Beatrice Bradley, and these are my two chums, Violet Farrington and Laura Jordon. We're from North Bend."

"Glad to know you," said Rose Belser with a quick little nod of her black head. Then she curled herself on the foot of Billie's bed and proceeded to make herself at home.

"I've been staying here for the summer," she told them. "It's an awful place to spend the summer, you know. First time I ever did it, and I never was so lonesome in my life."

"Why, I'd love to spend the summer here," said Vi, thinking of the beautiful country they had glimpsed and the lovely lake where one might row or canoe to his heart's content. "The country's so pretty, and you have the lake——"

"Oh, the lake!" the girl interrupted impatiently. "And the country! I'm tired to death of the lake and the country. I want to go to the city where you can wear pretty clothes and go to parties and things."

"But I should think you could wear pretty clothes here," said Billie, wondering. "And as to parties—I thought you always could have parties at boarding school——"

"Maybe you can at some boarding schools," the girl interrupted again with that same impatient toss of her head. "But those schools don't have Dill Pickles for guardian angels."

The girls looked at her as though she had gone crazy, and indeed for a moment they thought she had. But Rose Belser gave a short little laugh and went on to explain.

"The Dill Pickles are two old-maid sisters. One of them brought you up here——"

"Miss Dill!" cried Billie, beginning to see light. "Oh, has she a sister?"

"Yes. And the sister is worse," said the girl, with a little grimace. "They are Miss Ada and Miss Cora, and Miss Cora is the terror of the Hall. If it weren't for Miss Walters——But say, you'd better hurry," she interrupted herself suddenly and jumped to her feet. "It's almost time for the lunch gong to ring, and if you're late for lunch, Miss Cora will be furious. She has charge of the dining hall, you know. You'd better wash and straighten your hair. Miss Cora looks you through with a gimlet eye."

She ran over to her wash basin, which happened to be the next one to Billie's, and began to wash her hands vigorously.

"Oh, dear, we forgot all about lunch, and we must be a sight!" cried Vi, pulling off her hat and excitedly patting her hair. "Girls, we haven't any combs—our trunks haven't come up yet. Give me a comb, somebody! Oh, here's one in my grip."

"How strange," mocked Billie, dashing cold water on her face till it shone rosily. "It almost seems to me I have one in mine also."

"Well, you'd better get busy and use it," Violet retorted, drawing her own comb through her heavy hair, "or you'll get in bad the very first day. Oh, dear! there's the gong." She stopped with her comb in the air and gazed in horror at the girls. As for Billie and Laura, they stood as if they had suddenly become paralyzed.

"If you'd start in time you'd be ready in time," said a nasal voice from the other end of the room, and the girls glanced around quickly. They had been so absorbed in their new experience that for a time they had completely forgotten Amanda and Eliza. But now they turned just in time to see the two girls leaving the room. As she shut the door behind her Amanda gave it a defiant little slam.

"Say, who's your friend?" asked Rose Belser, looking in astonishment at the closed door. "She's pleasant, isn't she?"

"They're neither of them friends of ours," said Billie, jerking her hair angrily as though she wished it had been Amanda's hair instead. "They just happen to come from the same town, that's all."

"Never mind about Amanda, Billie," pleaded Violet, looking uneasily at the door. "We're late——"

"Oh, don't worry," interrupted Rose, giving a final pat to her black hair. "That was only the first gong. The second one rings five minutes later. There it goes now. Are you ready?"

The girls were ready, and with quickly beating hearts they stepped out into the corridor.

"This way," said their new acquaintance, turning to the right and starting for the stairs. "Now for the second of the Dill Pickles. Long may she wave!" she added gaily.

It was a new experience for Billie Bradley and for Laura and Violet—that hour in the dining hall. The hall itself was an immense room and seemed at first glance to be made up almost entirely of windows. As Rose Belser afterward remarked to the girls, there was one thing that no one at Three Towers Hall had to complain of, and that was lack of light.

Three tables stretched almost the entire length of the hall, and although they all bore snowy cloths there was only one of them that was really "set for action," as Laura said.

Most of the girls had already assembled when the chums reached the dining hall. They were standing around in little groups of two or three, talking excitedly, and while the girls were hesitating which group to join Miss Cora Dill swept into the room.

"Now you'd better mind your Ps and Qs," Rose whispered to them, and the girls regarded with interest the second of the Dill twin sisters who had been called by the disrespectful name of the "Twin Dill Pickles."

Miss Cora Dill was indeed Miss Ada's counter-part. There was the same thin figure and straight back, the same black eyes and thin-lipped mouth, the only difference being that where Miss Ada's hair was white, Miss Cora's hair still retained some traces of its original brown color.

"Goodness, I'm glad there's some way we can tell them apart," said Billie to Laura in an under-tone. "If they were just exactly alike we'd have to do with them the way they do with twin babies—tie a blue ribbon on one and a pink ribbon on the other."

The idea of tying a pink ribbon or any other kind of ribbon on the "Twin Dill Pickles" was so ridiculous that the girls giggled aloud, thereby causing Vi to nudge Billie sharply.

"Sh-h," she whispered. "Her Highness is about to speak."

Miss Cora carried some cards in her hands, and as the girls gathered about her she asked them to answer when she called out their names.

Although there were a hundred students in Three Towers Hall, there were only half a dozen who, like pretty Rose Belser, had spent the summer at the school.

The rest of the girls were almost all from North Bend and the other surrounding towns, although a few had come from a distance.

When the girls had all reported present, Miss Cora gave them their seats at the table and took her own place at the head of it.

At first the girls were not at all sure whether they were supposed to talk or not, for the presence of thin-lipped Miss Cora at the head of the table threw rather a damper on both their enthusiasm and their appetites.

However, when Rose Belser leaned across several girls to say something to Billie the rest of the girls took courage and a little murmur of conversation traveled around the table.