THE HELPMATE.

Newly-wedded Husband (fresh from the altar). "Excuse me taking the liberty, Sir, but do you happen to know of any place where my wife could get a little charring to do?"

Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 146, February 4, 1914

Author: Various

Editor: Owen Seaman

Release date: January 12, 2008 [eBook #24265]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Matt Whittaker, Malcolm Farmer, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Matt Whittaker, Malcolm Farmer,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

The statement, made at the inquiry into the Dublin strike riots, that 245 policemen were injured during the disturbances has, we hear, done much to allay the prevailing discontent among the belabouring classes.

"Coaling the Stores" is a headline which caught our eye in a newspaper last week. To be followed, after the strike, we imagine, by "Storing the Coals."

A Russian officer, last week, shot the leader of a gipsy choir in a St. Petersburg restaurant, not because he sang out of tune but merely because he expressed resentment at the officer's conduct towards his daughter. It is thought that the incident may lead to an Entente between Germany and Russia.

Our Navy standard of 16 Dreadnoughts to 10 of the next most powerful Navy is, says Mr. C. P. Trevelyan, rough and ready. Well, in this matter our standards may or may not be rough, but let's hope they're ready, anyhow.

An organisation called "The Parents' League" has been formed in New York for the purpose of simplifying the lives of children. This has caused a considerable amount of uneasiness in juvenile circles, and it is said that a "Hands-off-our-jam" party has already been formed.

In a letter of Mrs. Carlyle's just published, the wife of the Chelsea sage describes a cat as "a selfish, immoral, improper beast." This has given no little satisfaction in canine circles, where the deceased lady is being hailed as a human being with the insight of a dog.

The Cambridge Review is talking of dropping the publication of the University sermon. It is possible, however, that the mere threat may have the effect of making the sermons more entertaining.

A volume entitled "The Great Scourge and How to End it" has made its appearance. We had imagined this to be a treatise on the anarchist activities of a certain section of the Suffragists until we discovered the name of Miss Christabel Pankhurst as its authoress.

Messrs. Hutchinson's interesting History of the Nations, the first part of which has just appeared, is something more than a mere compilation of facts already known to us. We had thought that both photography and limited companies were comparatively recent inventions. An illustration, however, in this new work, entitled "Charles I. going to execution," bears the description, "Photo by Henry J. Mullen, Ltd."

Councillor Sherlock has been elected Lord Mayor of Dublin for the third time in succession, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle will be interested to hear that there is some talk now of calling the local Mansion House "Sherlock's Home."

Belief in the innocence of the dove dies hard. At Driffield, last week, a Mr. Dove, who was charged with conducting a lottery, was acquitted in spite of his pleading guilty.

A music-hall performer gave a turn in a King's Bench court the other day. There was a time when a judge would have objected to his court being turned into a theatre, but since the advent of comic judges the line of demarcation has become blurred.

According to Dr. Frank E. Lakey, of the English High School, Boston, U.S.A., boys are at their naughtiest between 3 and 4 p.m.; and at their best at 10 a.m. But surely most boys are awake and out of bed at 10 a.m.?

"POPULAR MICROBES

Audience of 2,000 at a Blackpool Lecture."

Daily News.

One is so accustomed to think of the little chaps in millions that this seems rather a poor attendance.

Newly-wedded Husband (fresh from the altar). "Excuse me taking the liberty, Sir, but do you happen to know of any place where my wife could get a little charring to do?"

A cowardly hoax was recently perpetrated in Paris, where a number of politicians consented to assist in raising a statue to Hégésippe Simon, the educator of the Democracy and author of the famous epigram, "The darkness vanishes when the sun rises," only to discover later that Hégésippe Simon had never existed.

Needless to say, this has produced a profound impression upon public men in this country, who are regarding invitations of a similar character with the gravest suspicion.

For instance, Mr. William Archer, on receiving a request for his assistance in raising a monument to Ibsen, is reported to have replied cautiously that he would like to know more about this writer before giving an answer.

Mr. Clement Shorter, on being asked to join the committee of a Brontë memorial, replied suspiciously, "Why do you ask me of all people?"

Mr. J. L. Garvin, on being approached on the subject of a bust of Mr. Filson Young, is reported to have consulted his assistant-editor as to whether the name might not be a pure invention; while Mr. G. K. Chesterton remarked, when asked to assist in raising a bas-relief to Charles Dickens, that he didn't believe there was no such a person.

"Mr. M'Call, K.C., said Dr. Keats had charge of the boys in the infirmary, and for the purpose of maintaining order he was sometimes compelled to resort to corporal astonishment."—Glasgow Daily Record.

Billy Brown (surprised): "Ow!"

In our last issue, quoting from a Johannesburg telegram, we referred to The Evening Chronicle as a "Labour organ." Its London Manager writes protesting against this description; and we now offer our heartiest regrets for the grave injustice that we seem to have done to our South African contemporary.

I saw it on a map, most large and fine

(I saw it with the naked eye—no dream),

Showing how trains upon the Grand Trunk line,

Grand but Pacific, run along by steam

Right to Prince Rupert on the sea (a port)

And there are brought up short.

Smithers! I saw it on a map, I say,

A panoramic map in Cockspur Street.

And sudden in my heart began to play

Echoes of old romance, and all my feet

Fluttered responsive to the name's sheer beauty,

So rhythmical and fluty.

Smithers! The music of it filled my mouth.

I saw Provence and that enchanted shore,

And lotus-isles amid the dreamy South,

And champions out of mediæval lore

Looking at large for ladies in distress

Round storied Lyonnesse.

I was a trovatore (with guitar);

Venezia's airy domes above me shone;

I heard Alhambra's fountains, faint and far;

I broke the Kaliph's line at Carcassonne;

All kinds of lost chords latent in my withers

Woke at the name of Smithers.

Ah, if in Avalon's vale I may not rest

When envious Time has worn me to a thread,

Then let me go to Smithers in the West,

And on my gravestone let these words be read:

Attracted by its name to this fair scene,

He died a Smitherene.

O. S.

Now that the Headmaster of Bradfield has decided to start a "Commercial side," to enable boys to prepare at school for a business career, it may be of interest to publish these fragments from the diary of another Headmaster who has done pioneering work in a similar direction:—

January 20.—First day of term. This morning, in Hall, I made the momentous announcement that the School would shortly have a new "side"—devoted to Business. School-boys are usually so conservative that I had anticipated some signs of disapproval. Nothing of the sort. The speech was received with loud cheers, renewed when I prophesied that the Waterloo of the future would be won on the "Commercial side" of Fadfield. Truly a hopeful outlook.

January 21.—As I expected, the Commercial side has been the chief topic of conversation among boys and masters. The latter are, I fear, reactionary—realising, no doubt, their incompetence to deal with business subjects. The boys are enthusiastic. I am constantly approached in the corridors by lads who say it has always been their ambition to become a Tipton or a Whiteridge, or a Gilling and Warow, as the case may be. One little fellow quaintly confessed that he had always longed to be a "Mother Spiegel." Great Britain's future in trade is assured if this spirit continues.

January 22.—Even the Classical VI. seems interested in my new project, and questions proving a genuine keenness were asked me when I was taking Homer this morning. One boy propounded the doubtful but stimulating notion that Homer was really the name of some early Greek Co-operative Stores, and that the Iliad and Odyssey were parts of a gigantic scheme of advertisements. This is very illuminative and indicates that a real desire for efficiency exists in the most unlikely quarters.

January 23.—An example of the sort of prejudice one has to contend against occurred to-day. Henderson, one of the House masters, sent across a note asking what I should wish done in the following case. It appears that a boy in his House named Montague has by some form of bargaining already deprived three new boys of their pocket-money for the term. "Montague has exhibited such an extraordinary commercial aptitude in this matter," Henderson wrote, "that I propose to flog him. Before doing so however I thought I would ask for your assent, as you might prefer to make him a prefect."

January 24.—Brown Major, the Captain of Football, has been deputed to ask me if I could arrange a Jumble Sale match against Giggleswick. Have had to explain to a boy, Lipscombe, sent up for gambling, that the rule against this is inviolable, and that I could not accept as an excuse for his breaking it the fact that he intends, on leaving school, to adopt the business of a bookmaker. Specialisation at school in all branches of business is of course impossible.

January 26.—M. Constantin, the French master, has come to me with a complaint. Two days ago, for trying to dazzle him during lessons with a sun-glass, he gave a boy named Dawkins 500 lines. To-day, instead of the usual Racine, Dawkins handed him lines copied from an advertisement in the daily press beginning:—"Perhaps you are suddenly becoming stout, or it may be that you have been putting on weight for years...." As Constantin is disposed to adiposity, he is convinced that Dawkins meant this for impertinence. Dawkins, however, has explained to me that he is profoundly interested in Patent Medicines, the sale of which he hopes to take up as soon as he has qualified on the Commercial side. Pardoned Dawkins and accepted M. Constantin's resignation.

January 27.—I fear the school is taking the Commercial side too literally—with unforeseen results. To-day there was a regrettable incident in the tuck-shop, outside the door of which, unknown to Mrs. Harrison, a placard was nailed up announcing "Harrison's Winter Sale. All goods at sacrificial prices. Must be cleared. No offer refused." As a consequence the boys burst into the place in a crowd, ate and drank everything they could lay hands on, and paid for nothing. I have undertaken to rectify this matter.

January 28.—Mutiny is rampant. The boys, inflated by their success in the tuck-shop, held "A Great White Sale" in most of the dormitories last night. As a consequence, all towels, sheets, pillows, flannels, etc., are inextricably mixed up, and a very large number can only be described as "remnants." Seven masters have resigned, including Herr Wolff, who was informed by a boy that he refused to handle the works of Schiller, because they were "made in Germany." Personally flogged the boy.

January 29.—Things are becoming intolerable. Three boys appeared in the lower Modern class this morning in frock coats and false waxed moustaches which they must have written to London for. They were sent up to me and had the audacity to explain that they hoped to be shop-walkers some day and wanted to practise. Another boy asked if a Hair Drill could be substituted for the ordinary drill. Verily the reformer's task is a thankless one.

January 30.—Actum est ... This morning I announced to assembled boys that I should not proceed with the Commercial side. The speech was received in silence, except that one boy (whom, I regret to say, I was unable to identify) called out, "And the next thing, Sir?" I fear there is no real commercial zeal as yet among boys.

The Spirit of Dancing (waking up). "WELL, THANK HEAVEN THAT'S OVER; ONE OF THE DULLEST NIGHTMARES I EVER MET."

The shopkeeper said he had not got it in stock, but he would get it for me.

"When?"

"By to-morrow morning."

"Before lunch?"

"Yes."

"For certain?"

"Yes."

Very well then, I would have it.

"Can I send it?" he asked.

"No, someone will call."

Very well. It should be ready for my man before lunch.

How did he know I had a man? I wondered. I had never been to the shop before. Do I look like a man who has a man? I suppose I must. Yet I always rather hoped that I didn't.

What had I said exactly? I had said, "someone will call."

Either, then, "someone" means, in such shops, a man-servant; or the fact that I am a man-keeping animal is visible all over me.

I went on to wonder if, should he see Lidbetter, he would know that he belonged to me. Did I not only betray the fact that I kept a man, but also what kind of a man I kept?

Good old Lidbetter—what should I do without him? I wondered. How get through the day at all? How, to begin with, get up?

The morning tea, the warmed copy of The Times and The Mail (only Lidbetter would ever have thought of warming them), the intimation that the bath (also of the right temperature) was ready—how should I be thus looked after without Lidbetter?

And then the careful stropping of my razors. Without Lidbetter how could I get that done for me?

Without him I am sure I should never change my neck-tie till it was worn out, or get new shirts until mustard and cress had begun to sprout on the cuffs of the old ones, or have a crease down my trousers like Mr. Gerald Du Maurier, or go out with anything but a dusty overcoat and dustier hat.

But with Lidbetter...!

How do people get on without Lidbetters? I wondered. I suppose there are men who do not keep men and yet exist—men who can't say, "My man"? An odd experience.

I wondered how old he was by now—Lidbetter. Difficult to tell the age of that type, so discreet and equable. He might be anything from thirty to fifty.

And what was his other name? Curious how I had never ascertained that. I must ask him, or, better still, get him to witness something and sign his full name. My will, say.

Talking of wills, perhaps I ought to leave Lidbetter something after such faithful service.

Good old Lidbetter!

Thus musing I walked home.

The next morning I went to the shop and asked for the parcel.

"You surely won't carry it yourself?" the shopkeeper said. "I would have sent it only I understood that your man would call."

"I haven't got a man," I said. "I've never had one."

"Pardon," he replied, and gave me the parcel.

"I assure you, Madam, these kitchen knives represent the greatest value ever offered at the price."

"They certainly look nice and seem very cheap. The only question is—will they cut?"

"Ah, Madam, if you ask me that, I'm bound to say they will not; but that is their one fault."

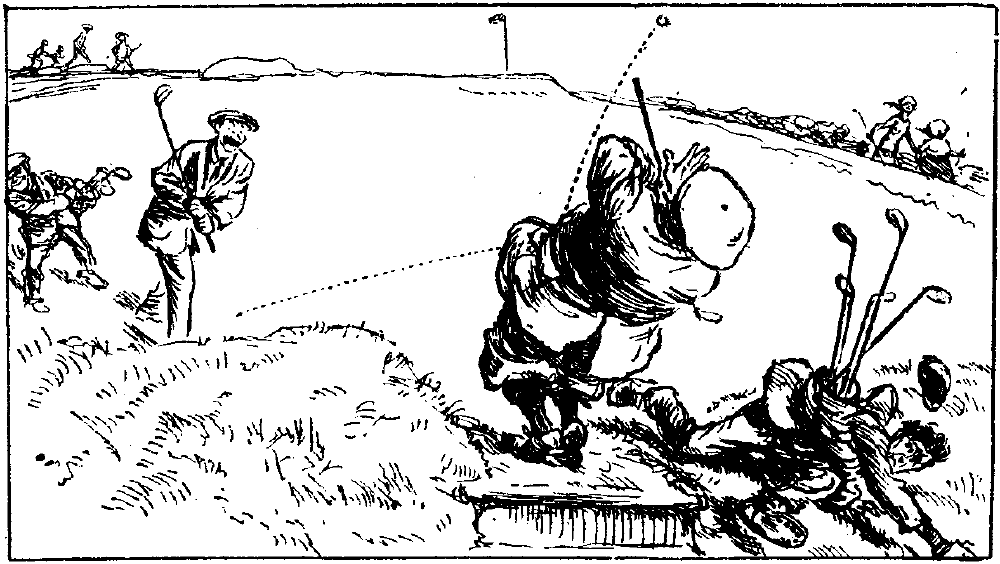

"Two quite unique golf performances have been made on the Lutterworth course. The Rev. W. C. Stocks and Mr. F. Marriott were playing a round of eighteen holes last Friday, and at the third hole, which is an iron shot (145 yards), Mr. Marriott surprised himself and amazed his opponent by holing out with an iron. Then when they came to the eighth hole, which is 188 yards distance, the rev. gentleman went one better. Taking his brassey, he had the delightful experience of seeing his ball roll into the hole. Both shots were magnificently directed."

Market Harborough Advertiser.

We guessed at once that they must have been fairly straight.

(A Tragedy in One Act, which may be played by the Abbey Theatre players without fee.)

Scene I.

[The kitchen in the M'Ganns' house. Mrs. M'Gann, Sheila M'Gann, Molly M'Gann, Aloysius Murphy, and Jeremiah Dunphy sit round the fire, top left centre. The door is top right centre. On the left side is a window. Four large grandfather clocks are standing here and there round the room. In front of the fire is seated a little wee bit of a pigeen. The Stranger is seated by the window, apart from the rest. As the curtain rises one of the clocks strikes two, another strikes eleven, while the others remain silent. It is thus impossible to tell what time it is. The Stranger gazes out of the window. No one speaks. The curtain falls.

Scene II.

[Much the same, except that the window is now on the right side. The women are engaged in peeling potatoes. The Stranger is obviously much embarrassed at the sudden change in the position of the window.

Jeremiah. 'Tis a terrible night—a terrible wet night.

Molly. Sure an' it's yourself that has no call to say the same, Jerry Dunphy, an' you saying a minute since that ye were as dry as ye could be!

[The rest break into a roar of laughter, with the exception of the Stranger and the pig.

Aloysius (slapping his knee). A good wan, that! It's yourself is the smart girl, Molly!

[The door is suddenly flung open with great violence and young Michael enters. He is carrying a number of hurls.

Jeremiah. Power to ye, Michael avick! And did ye win to-day?

Michael. Is it win? And will ye tell me why wouldn't we win?

[Sheila is about to speak, but checks herself as a thin piping voice is heard chanting outside.

The Voice.

"There is a little man

In a dirty wee shebeen,

And the spalpeens do be leppin' in the bog."

[The voice ends on a high note, which quavers away into silence.

Sheila. The blessed Saints preserve us! What was that?

Mrs. M'Gann. Musha, don't be frightened, child! Sure, it's only poor ould Blithero[1] Pat. (She goes to the door and opens it.) Come in, Pat, and have a bite an' a sup to warm ye this terrible night.

[The old man enters. He comes slowly over to the hearth, tapping with his stick, and seats himself in front of the fire. He seems to stare at the glowing turf. At last he speaks.

Blithero Pat. Comin' over the bog I met Black Finnegan. He had a powerful drop o' the drink on him.

Molly. The Saints preserve us from that man!

Blithero Pat (continuing in a dull monotone). And Shaun M'Gann was with him.

[Mrs. M'Gann sits back with a look of horror on her face.

Aloysius. Shaun does be a terrible man when he's on the drink.

[The pig rises and goes out by the door, which has been left open.

Sheila. The crathur! 'Tis himself can't bear to hear his master miscalled.

Blithero Pat (still continuing in the same tone). Shaun told me to tell ye, Mrs. M'Gann, that he was coming home the way he'd kill ye entirely.

Jeremiah (starting up quickly, as the others recoil in horror). We must stop him. He's coming by the bog, ye said, Pat?

Blithero Pat. Ay! Be the bog it is.

Aloysius. Come on, all of ye!

[Exeunt hastily all but Blithero Pat and the Stranger.

[Blithero Pat chuckles softly. He then addresses the Stranger in a hoarse whisper.

Blithero Pat. Divil the bit he's comin' be the bog. He's comin' be the cross-roads.

[The Stranger makes no reply. Blithero Pat laughs hideously and goes out.

Footnote 1: A Connemara word signifying blind.

Scene III.

[The same. The air is heavy with the scent of stout. Mrs. M'Gann sits before the fire. She still peels potatoes. The Stranger is almost concealed behind grandfather clock number four, from the shelter of which he peers nervously at the window, which has returned to its original position. A heavy step is heard outside.

Mrs. M'Gann (starting up in terror). That's Shaun's step!

[The door is kicked open and Shaun enters. He is fairly far gone in drink. As he looks at her she backs a step or two and stares at him wildly. He kicks over grandfather clock number one, which is evidently damaged by the fall, as it commences to strike wildly and insistently.

Mrs. M'Gann. Shaun!

[He staggers over and looks at her closely for a moment. Then he catches her by the throat, hurls her to the ground, and begins to kick her savagely. He laughs as he kicks her, for at heart he is not a bad-natured man. She gradually becomes still. At last he stops and looks at her.

Shaun. Mary! (A pause. Then in a louder tone, with a note of alarm in his voice) Mary!

[He looks at her for two minutes in a dazed way and then staggers out of the room. The Stranger, who until this moment has not said a word, does not speak now. Grandfather clock number one continues to strike insistently.

Curtain.

Scene—Village Concert—Squire's turn to sing.

Official. "'Ope you gets on all right, Sir. It's been fairly good oop t' now."

"The first brick of the structural work was laid on Tuesday, Jan. 6th, and is proceeding rapidly."—Clacton Times.

Destination unknown.

O, chiefly procured by a fate that is harshish

From ponderous pachyderms' innocent shapes!

O, shipped of old time by the navies of Tarshish

For Solomon's court and the wondering gapes

Of Jerusalem's Great Age,

The invoice for freightage

Including some items of peacocks and parcels of apes!

O exquisite surface of Orient idols!

O, hewn by the workmen of cunning Cathay

For the sword-hilts of kings and their saddles and bridles!

O, carved for Athene! O, chosen to-day

For the match now proceeding

Betwixt those two leading

And infantile billiard antagonists, Newman and Gray!

O, how shall I sing of thee, loved of immortals?

Remember what breaks of thy boon have been born?

Or describe how the dreams that go out at thy portals

Are true by the test of the amethyst morn,

Whilst the hopes that encumber

Our profitless slumber

Fare forth through the bonzoline exit—I should say the horn?

Shall I ask why it is that the sagest of mammals

Is toothed with such splendour, for woo or for weal,

As compared with giraffes or hyenas or camels

Or wombats? Why man, when he falls to a meal,

Can suffer no tusk-ache

From marmalade plus cake

To rival the infinite sorrows that Hathis may feel?

These things I might prate of and should do with pleasure

Except that they're far from the point of my song,

Which is aimed at a dental adornment, a treasure

Unheard of as yet by the ignorant throng,

But an ivory fairer,

More fleckless and rarer,

Than ever was looted by trader from elephant's prong.

For I care not for elephants, no, not a particle;

Sorrows they have, but they cause me no ruth;

And a fig for their tushes! I mentioned the article

Merely to lead you along to the truth,

To the fact of all wonder,

Our baby (no blunder—

You can not only feel, you can see it) has cut his first tooth.

Evoe.

"The doctors have stopped issuing bulletins regarding Sir Lionel Phillips whose condition continues to give satisfaction. He is able to lease his bed for a short time daily."—Natal Mercury.

"When Lord Kitchener arrived in Cairo very few people were aware that, travelling on the same train as his lordship, were a crocodile, two hyenas and two civet cats. These animals had been presented to Lord Kitchener when he was at Kosti."—Egyptian Gazette.

We wish we had had the luck to attend this levée.

[A fragment of a diary, signed H.H.A., which may be picked up in Bouverie Street some day.]

Monday.—Although I continue to wear an enigmatic smile in public, I may confess to myself that the situation causes me anxiety. The Home Rule Bill was passed five days ago, and already there are signs of military activity in Ireland. Anthony thinks I ought to proclaim martial law. In the course of a short lecture at breakfast this morning he referred to the historic case of South Africa, and reminded me of the enthusiasm with which the Unionist Party greeted this stirring exhibition of the strong hand. Martial law, he says, supersedes all other law, and the deportation of any person whose presence is not desired becomes——At this point I had him deported to the nursery, for I desired to be alone. All the same I feel that there is a good deal in what he says, and I shall think it over to-night.

Tuesday.—Martial law proclaimed. I have decided to be The Strong Man of England. Force may be no remedy, but it is much esteemed by the Unionist Party, and I don't see why Winston should be the only popular member of the Cabinet.

Wednesday.—Excellent. Carson has been safely smuggled out of the country. He travelled from Belfast to Liverpool in a packing-case labelled "Oranges," and was then embarked in a whaler for Greenland. The ship, I understand, has no wireless installation and will not stop at any port on the way. As he had to leave Belfast rather hurriedly, without packing, I have lent him a spare suit of Wedgwood Benn's clothes. The authorities have orders to deal with the other leading members of the Ulster Provisional Government in the same way.

Thursday.—The Ulster leaders have been safely deported. Unfortunately, there was no ship immediately available for them, and at the present moment they are in a pantechnicon labelled "Theatrical Troupe" (a tip from Botha) touring the Cromwell Road. They go up and down twice in a day, I am told, stopping nowhere on the way. Without their leaders the Ulstermen are weakening, and they may be expected to accept the Home Rule Act peaceably in the course of a few days. Martial law is certainly an extraordinary solvent of the most difficult situation, and I can only wonder that I never thought of it before.

Saturday.—However hard one tries one can never please everybody. In a fierce speech at Bootle last night, Bonar denounced me as (among other things) a Tyrant, a Dictator, and an Autocrat! (The other things were not so polite.) By an exhibition of the strong hand I have practically stifled the Ulster Revolution, and this is all the thanks I get from the Unionist Party. I have sent him a note, asking him to drop in in a friendly way and chat about it. We haven't had one of our little conversations for a long time.

Monday.—Bonar refused my invitation indignantly, and actually made another speech on the same lines at Pudsey. Even the Liberal papers confessed that it was enthusiastically received; in fact, P.W.W. in The Daily News went so far as to say that a staunch Radical in the gallery "paled suddenly" and later on "blenched." There was only one way of dealing with this situation. Bonar Law had become a serious danger to the State (me), he was fomenting rebellion against authority (mine), and he would have to go. I telegraphed instructions, and within half an hour Bonar had left Pudsey for Farnborough as a grand piano. To-night he is strapped on to an army aeroplane and launched into the Ewigkeit. The aeroplane has no wireless installation and will, I am informed, stop nowhere until it reaches its destination.

Tuesday.—Strict Press censorship ordered. Unionist Papers are forbidden to comment adversely on my operations. As a result, the first nineteen columns of The Pall Mall Gazette were blank this afternoon. In the evening edition, however, the editor could no longer restrain himself, and he is now waiting at the docks as a consignment of cocoa for Shackleton's South Pole party.

Wednesday.—Overheard an unexpected compliment (paid me by a Unionist) in a District train this evening. This gentleman said, "After all, he's a strong man. One does know where one is with a man like that." He had to confess, however, that he didn't know where Bonar Law was. Neither do I. My new-found friend got out at the Temple, and I wish I could have followed him and asked him to tea one day, but the fact that I was disguised and on my way to Blackfriars Pier to see the Lord Mayor's departure in a submarine prevented me. I have always wanted to witness one of these deportations, and certainly the police were very nippy, if I may use the word. The Lord Mayor descended from a taxi in a straw-filled crate labelled "St. Bernard—fierce," and was in the submarine in no time. It was his own fault for summoning a non-party meeting of protest at the Guildhall. I hate these non-party meetings—they're always more insulting than the other sort.

Friday.—Anthony says that I shall have to get an Indemnity Bill through the Commons; otherwise, when martial law is over, I may get hanged or something. This is rather annoying. Deported Anthony to bed, but could not get rid of my anxiety so easily. The Unionists of course will vote against an Indemnity Bill, and so, I fear, will a good many Liberals and Labour men, who say that I am undemocratic. Awkward.

Saturday.—Still a little anxious about the I.B., but a great victory over the Chancellor of the Exchequer at golf in the afternoon has restored my spirits somewhat. We were square going to the eighteenth, and when I got into a nasty place in the bunker guarding the green it seemed all over; but with a sudden inspiration I proclaimed martial law (which, as Anthony says, supersedes the ordinary laws) and teed my ball up. Thence easily to the green and down in ten, David arriving in his usual mechanical eleven. He was a little silent at tea, I thought.

Wednesday.—Excellent. This martial law is a wonderful thing. On Monday I had the whole of the Opposition kidnapped and sent down by one of the special Saturday trains, well guarded and labelled "Football Party," to Twickenham. The train was guaranteed to stop for some hours at every station on the way, and is not due at Twickenham till to-morrow morning. Meanwhile my Indemnity Bill went triumphantly through the House this evening, and now all is well.

Thursday.—End of martial law. Rather a dull day on the whole.

A.A.M.

No, dear Sir, your high calling does not excuse you from observing the rules of civility common amongst laymen when writing to the Editor of a paper which has expressed views that do not happen to accord with your own.

"Dancing was engaged in around the bonfire to the skirl of the philabeg."—Glasgow Herald.

On reading this we immediately went round to our tailor and ordered a new pair of bagpipes.

"A change has come over the domestic habits of the French middle class. This means that the money that would have been accumulated for the girl's diary is now in some cases diverted into other channels."—T. P's Weekly.

Probably squandered on a packet of those useless New Year's cards.

Bosun (to new deck hand who has trodden on his toes while hauling on a rope). "'Beg your pardon,' indeed! That's bloomin' fine language to use to a ships bosun."

I.

From the Editor of "The Globe Fiction Magazine" to Aubrey Aston, Esq.

May 5th.

Dear Mr. Aston,—We are extremely sorry that we cannot see our way to using Red Shadows. The idea is an excellent one, if a trifle improbable. But you must be aware that West Africa has been worse handled by fiction-writers than any other locality, and we are afraid we dare not risk publishing a story in which the writer has drawn on his imagination for local colour, however vivid that imagination may be. The West African expert at our office assures us that Red Shadows contains some inaccuracies which would be bound to spring to the eye of any reader who had been near the West Coast. We cannot imperil the reputation of a magazine so widely circulated as ours, and we feel that in returning the MS. we are in some degree safeguarding your own. Thanking you for the many excellent stories you have let us have,

Yours very truly,

J. W. Ingleby, Editor.

II.

Aubrey Aston to the Editor.

Laburnam Rise, Hornsey.

May 8th.

Dear Mr. Editor,—Thanks for your note. I cannot help feeling that you were to some extent influenced by your knowledge of the fact that I had never been near the West Coast. I hope, however, to visit the White Man's Grave shortly and will possibly let you have some stuff from the spot.

Yours,

A. A.

III.

The Same to the Same.

From Sherbro, Sierra Leone.

June, 18th.

Mr. Aubrey Aston begs to enclose to the Editor of "The Globe Fiction Magazine" another West African effort, and hopes that it may pass his critic.

IV.

The Editor to Aubrey Aston.

July 31st.

Dear Mr. Aston,—Herewith proof of The Case of Mr. Everett. I trust you will be able to let us have some more West Coast tales while you are out. Stories with the true African ring about them, from such a practised pen as your own, are hard to come by. Our "critic" passed Mr. Everett with honours. You will no doubt see yourself by now how comparatively bald and unconvincing Red Shadows is, when set against a tale "hot from the oven."

Yours very truly,

J. W. I.

P.S.—Our West African expert asks me to thank you for information on several points on which he had been hazy. It is news to him that the Mendes have an Arabic strain in their blood; he had believed them to be pure Zishtis. He had also been in the dark as to the origin of the "leopard" murders.

V.

From Aubrey Aston to the Editor.

Hornsey, September 20th.

Dear Mr. Editor,—Many thanks for the proof (forwarded to me from Sierra Leone) of The Case of Mr. Everett—which I return corrected—and for your very gratifying note.

I'm afraid I have not yet found time to visit West Africa, but I still hope to. When I do, I will perhaps let you have some tales "hot from the oven." In the meantime I find the Travel section of our local library a more comfortable and probably a more accurate source of copy. But I still have to draw on my imagination to some extent. The Mendes may be pure Yanks for all I know to the contrary; but I hope for their own sakes they [pg 90]aren't Zishtis. It sounds such a horrible thing to be.

As for the "leopard" murders, I got my information from Major Kingsley, D.S.O., who has been a Government officer in Nigeria and Sierra Leone for fourteen years, so there may be something in it. As he is a close friend of mine I sent my story to him out there for him to look through before letting you have it, and he very kindly posted it direct to you. He has written to tell me that the ignorance shown in it was such as to preclude any possibility of improvement by revision.

By the way, Major Kingsley was the author of Red Shadows. He asked me as a special favour to godfather it, as he believed an unknown writer stood no chance. It is a perfectly true story. My kindest regards to your expert.

Yours very truly,

Aubrey Aston.

Wealthy American Westerner (anxious to show his great appreciation of the able and enthusiastic way in which the duchess has pleaded the cause of her pet charity). "Waal, good-bye, Duchess. I will send you a cheque, sure. I guess some of these charities wouldn't be so sick if they had crazy boomers like you to boost 'em along."

"Many correspondents have asked whether Mrs. Cornwallis received this compensation because her husband was a reader of this journal."—Daily Mail.

Could they have meant—correspondents being notoriously rude—that the husband deserved it more?

(whereby a modern male adult mortal may be pleasantly initiated into the fairy state).

O male adult, O male adult!

This is the way we make a fairy:—

Quicunque vult

Silvis terrisque imperare,

Think upon oaks and thorns and ashes,

On glow-worms and on fire-fly flashes,

On rooty loams and stony brashes!

Then upon thyme and tansy think,

On fields of sainfoin, ruddy pink,

On dells deep down and rocks upreared,

On lad's-love and on old-man's-beard,

On spearmint and on silver sages,

On colewort and on saxifrages!

Then think on pools in dimmest haunts,

Unwhipped of any wind that rages,

Where the lithe flag her purple flaunts,

Where frogs go plopping round the edge

And gnats are humming through the sedge,

And on the leaf of each wide lily

The scaly newts do lay their eggs

And the small people dip their legs

To shatter the moonshine floating stilly

O'er the pool's mystic weedy dregs!

Think yet again on rolling hills

Where little sleepy new-born rills

Are bedded deep in upland mosses,

Where tiny stars of tormentils

Peer skyward with their golden gaze,

Where lichened dikes and shallow fosses

Are signs of far-forgotten days—

Forgotten save by us who roam

Those uplands nightly after gloam,

And, linking in our magic rings,

Whirl in a dazzle of dancing wings—

Us only whose hot eyes beheld

Fordone delights of vanished eld!

Think on it! think on it!

And think no more on what you quit—

On hearth and home, on streets and shops,

On trousers, ties, and hunting-tops—

Think no more on City dinners,

On office hours and all the winners—

For you are fitted by field and dell

Us to follow, with us to dwell,

To be for ever free from harm,

A fairy changeling by this charm,

To be the lord of light and mirth,

To be the lord of all the earth.

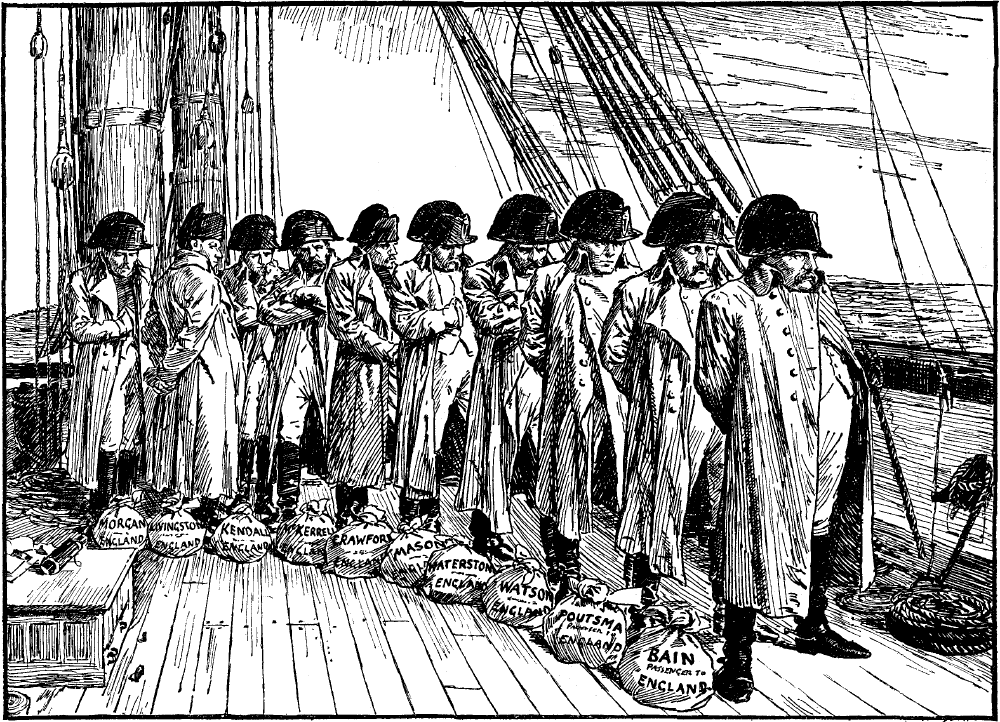

THE NEW BELLEROPHON:

or, BOTHA'S SURPRISE PACKET.

[The Government of S. Africa are sending, as a present to the Mother-country, the ten men whom they regard as their leading undesirables.]

The world-wide attention aroused by the recent correspondence about Rule 18, by which a player loses the hole if his opponent's ball strikes him, his caddie or his clubs, is already brightening golf. The doctor, who was playing "three more," got "dormy" at the seventeenth with a beautiful quarter brassie backhander, which took the colonel in the lower chest.

But the colonel saved the game on the last green. The doctor (whose caddie's play was beyond all praise) was caught napping, for he failed to avoid a stab to leg (the odd) which just found his putter.

(With acknowledgments to various distinguished writers in this vein.)

To me the robin is a peculiarly attractive bird. It bears itself with a sort of pompous pathos which moves me to a friendly tear and gentle laughter.

One came to the ledge of my parlour window the other morning, a not infrequent occurrence. "Good morning, Robin Red-breast," quoth I; and it acquiesced in an expressive silence. The conversation is generally one-sided on these occasions. "Bird," I continued, "it may interest you to know that I am writing a book. What about, you wonder? About any old thing that happens to crop up—yourself, for instance." The robin tripped hither and thither with vast self-importance. "Not so much of it," said I. "It isn't your intrinsic worth but the fact that you chanced to crop up first, that got you this publicity."

The robin flew away in high dudgeon as Martha entered the room bearing the boiled eggs and tea with which it is my custom to break my fast.

How long the greater tragedies of life lie hidden beneath the careless surface! From a chance remark of this excellent Martha's, I have but now discovered, after many years' experience of it, that what I have always fondly supposed to be tea, she, who makes it, equally fondly supposes to be coffee.

There is only one other thing worth mentioning about Martha, and I will mention it. For very many years, as she is in the habit of telling me once a week, she has been walking out with a policeman. This has suggested to me a quaint thought, that to marry a policeman is the cheapest and most effective way of insuring against burglary, but otherwise, I confess, I have shown and felt but little interest in this affaire de cœur.

A letter lay on the table beside my plate. It was addressed to me. I picked it up and, holding the envelope in my left hand, with the first finger of my right hand I tore open the flap. I then withdrew the enclosure and, standing with my back to the window so that the light fell on to the written sheet, I read it.

It was from my sister, my little sister Clare, and it told me that she was engaged to be married. My sister, my little sister Clare, engaged to be married, and to a partner in a firm of publishers of all people! Here was news indeed! I own that Clare's publisher interested me very much more than Martha's policeman.

I remember nothing more until I looked up a few moments later to see a robin once again upon my window-ledge. I would not swear that it was the same bird, but, feeling that one robin was as good as another, I told it all about Clare's publisher and what this might mean to all of us.

Some days later I came down to breakfast, to find another letter lying on the table beside my plate. This letter also was addressed to me. Having gone through much the same process as that used with regard to my earlier correspondence, I discovered that this was from Clare's fiancé. He thanked me for my very kind congratulations of the 13th ultimo, and went on to say that, with regard to the latter part of my letter, he was not quite sure exactly what an idyll might be, and so my interesting description of my embryo book conveyed little to him. Even so, he went on, he would have been honoured to publish any book written by any relative of his dear Clare, but that he dealt, to be candid, exclusively in legal text-books.

To Martha, entering at this moment, I confessed that there was at least this to be said for her and her man, that they had never concealed their connection with that odious thing, the Law.

Later, I read an extract from my manuscript aloud to the robin. He wore an air of abstraction and I could see that his thoughts were running on other matters more immediately concerned with his own interests.

To me the robin is a peculiarly human bird.

Revues and Things.

Park Lane.

January 31st.

Dearest Daphne,—I've been putting in quite a pleasant little time down at Much Gaddington with Bosh and Wee-Wee. Theatricals were the order of the night, and the best thing we did was a revue written for us by the Rector of Much Gaddington, who's a perfectly sweet man and immensely clever. It's a better revue than any of those at the theatres, and as that dreadful Censor had, of course, nothing to do with it the dear rector could make it as snappy as he liked. Wee-Wee and I were two "plume girls," Sal and Nan, in aprons, you know, and feathers and boots stitched with white; and our duet, "Biff along, Old Sport!" with a pavement dance between the verses, fairly brought down the house. The rector himself was impayable in his songs, "Wink to me only," and "Tango—Tangoing—Tangone!" But the outstanding feature of the whole affair was certainly Dick Flummery, who introduced his new and sensational Danse à trois Jambes, entirely his own invention!

What Dick doesn't know about dancing isn't worth knowing, and he says all the steps that can be done with two legs have been done, and for anything really novel another leg must be added. So he's had a clockwork leg made, and he winds it up before beginning and makes its movements blend in with the steps of his real legs, and the effect is simply enormous!

People wrote to Wee-Wee from far and near begging to come and see "Hold Tight, Please!"—that's the name of the rector's revue—so we decided to give it in the village school-room for charity. Since then Dick's been fairly snowed under with offers from London managers. They offer him big terms, and if his colonel decides that the prestige of the regiment won't suffer through one of its officers doing a three-legged dance at the Halls Dick will accept. If the colonel objects, Dick will still accept, for then he'll send in his papers, and go on the music-hall stage in earnest.

The rector has also had good offers for "Hold Tight, Please!" and he's busy toning it down before it's given in front of the dear old prudish public. He made us laugh one evening by telling us how he met his bishop lately at a Church Congress or something, and the bishop said, "There's a report that you've been seen once or twice lately at the Up-to-Date Variety Theatre, Piccadilly Square, London. You're able to contradict it, of course?" "Oh, that's quite all right, bishop," answered the dear rector; "I have run up to town several times in order to go to the Up-to-Date, but it was for business, not amusement. I'm responsible for the new ballet there, 'Fun, Frills and Frocks.'" So of course the bishop had no more to say.

I was talking to Norty yesterday about the state of Europe, and when we're to know who's who in the Near East, and which of the kingdoms out there are to be absorbed or abolished or allowed to go on; and he threw a new light on things by telling me that these matters are a good deal in the hands of the stamp-collectors—that when they agree among themselves as to what's to be done it will be done. A great many people who matter very much indeed are stamp-collectors, it seems, and it would make an immense difference in the value of their collections if certain countries were absorbed or abolished or allowed to go on. For instance, suppose anyone had a complete set of Albelian stamps, and Albelia wasn't allowed to go on, the set would become almost priceless. Norty says also that heaps of stamp-collectors who have been opposed tooth and nail to Home Rule on principle have been won over by the Coalition with the promise that an absolutely sweet set of Irish stamps would be issued as soon as H. R. became an accomplished fact. Ainsi va le monde.

The swing of the pendulum is going to make the coming season a stately one. It will be correct to be haughty and dignified. Features will be de rigueur, and aquiline noses will be very much worn. Dancing is to be deliberate and majestic, and partners will not touch each other; as Teddy Foljambe put it, "Soccer dancing will be in and Rugby dancing out." As far as one can see at present, the most popular dance at parties will be the war-dance of the Umgaroos, a tribe who live on the banks of some river at the back of beyond. I can't tell you anything about them except that they were found near this river doing this dance, and someone's brought it to Europe. It's very slow and impressive, and a native weapon, like a big egg-boiler with a long handle, is carried. The dance grows faster towards the end and the native weapon is twirled. In a crowded room there'd be a little danger here, and one would have to practise carefully beforehand. Already Popsy Lady Ramsgate's maid, has brought an action against her for "grievous bodily harm." In practising the war-dance of the Umgaroos, Popsy twirled her weapon too wide and struck the girl on the head.

What do you think of the New Music, my child? No answer is expected. It's a question few people dare to answer. Norty's definition of the New Humour—"the old Humour without the Humour"—won't do for the New Music. It's quite out by itself. But on the whole it's darling music, full of new paths to somewhere or other, and ideas and impressions of one doesn't know what, and sprinkled all over with delicious accidentals that seem to have been shaken out of a pepper-pot.

I've just got some piano studies of Schönvinsky's, to be played with the eyes shut and gloves on, and they're too wonderful for words!

Ever thine, Blanche.

(1) Snapshot, illustrating the coolness displayed by the intrepid mountain-climber, as sent to friends. (2) A full-sized unexpurgated edition of the same.

(Showing one of the reasons why the Tango is already démodé.)

(With apologies to Mr. Kipling.)

This is the sorrowful story told at the Tango Teas

Of the old folks dancing together, frivolous as you please:—

"Our mothers, came to the dances; dignified matrons, they,

They smilingly sat and watched us after we waltzed away.

"Our mothers looked on at the dancing—that was their business then;

Frowned on the detrimentals, smiled on the right young men.

"Then came this Tangomania, and when the fad was new

Badly it shocked the old folks—now they are doing it too!

"Now we may watch our mothers, smiling and flushed and gay,

Doing it, doing it, doing it, tangoing night and day,

"Stamping a Texas Tommy, wreathing a Grapevine Swirl,

Gleefully Gaby Gliding, young as the youngest girl.

"We may not laugh at our mothers, for (between me and you)

They can out-dance us often—get all our partners too!"

This is the sorrowful story told by a chastened lot

Of maidens sitting together, watching their mothers trot.

Nervous Lady (in whose street there have been several burglaries). "How often do you policemen come down this road? I'm constantly about, but I never see you."

Policeman. "Ah, very likely I sees you when you don't see me, Mum. It's a policeman's business to secrete 'isself!"

"I want to engage the next cook myself," I had said to my wife.

"Why?" she asked.

"Chiefly," I said, "because I am the only person in the house who minds what is placed on the table. If the food is distasteful I complain of it; you defend it; and we lose our tempers. Now it is perfectly clear that you cannot guard against certain culinary monstrosities when you engage a cook. I can. And coming from a man it will impress her more."

"Why can't I do it?"

"Because you haven't," I said. "You have engaged scores of cooks in your time and everyone does a certain thing which infuriates me."

"Have it your own way," she said.

I meant to.

In course of time the prospective cook was ushered into my study. If I liked her she was to stay.

"Good morning," I said. "There's only one thing I want to discuss with you. Apple tart. Can you cook apple tarts really well?"

She said it was her speciality, her forte.

"Yes, but can you do them as I like them, I wonder."

How did I like them?

"Well, my idea of an apple tart is that there should be so much lemon in it that it tastes of lemon rather than apple."

"Mine, too," she said. "I always put a lot of lemon in."

"And," I went on, "wherever the tart doesn't taste of lemon I like it to taste of cloves."

"I was just going to say the same. I always put in plenty of cloves."

"In short, the whole duty of a cook who is given an apple to cook is," I said, "to see that every scrap of the divine—of the flavour of the apple is smothered and killed."

She looked at me a little in perplexity.

"Isn't it?" I asked.

"Yes," she faltered.

"Well," I said, "I've recently been to see my doctor and he says that there are two things I must never touch again, at least in an apple tart: lemon and cloves. Otherwise he can't answer for the consequences. Will you help me to avoid them, at home at any rate? Will you?"

She was a good woman with a kind heart and she promised.

She has kept her promise.

Apple tarts in our house are worth eating.

"I am going to London," I said.

"Going to London?" said the lady of the house. "What for?"

"To live a double life," I said. "Many men do it and are never found out till they have been dead quite a long time. I'm going to begin to-day, and first I'm going to call on my tailor."

"But you can't call on your tailor in those clothes."

"Why not?" I said. "He made the clothes, and the least he can do is to look at them after I've worn them all these years."

"Dad's going to London in his old brown suit," said Helen to Rosie, who had just entered the room.

"Oh, but he simply can't," said Rosie in a shocked voice.

"I like the suit," said Peggy. "The trousers are so funny."

"They do bag at the knees," I admitted. "But then all sincere and honourable trousers do that. There is, of course, an unmanly variety that never bags and always keeps a crease down its middle, but you wouldn't have me wear those—now would you?"

"You can wear what you like," said the lady of the house, "so long as you don't wear what you've got on."

"Well," I said with dignity, "I'm not the man to insult an old friend. I shall wear this suit, and, what's more, I shall get my hair cut, too."

"That's right; get yourself cropped like a convict."

"You ought to be proud," I said, "to have a husband who's got any hair to crop. Some husbands are quite bald."

"And some want to look as if they were quite bald."

"Very well," I said, "I will give up the hair-cutting. Next week you shall see me in love-locks for the rest of my life."

I then went up-stairs and changed into patent leather boots, black tail coat and all that is necessarily associated with a black tail coat. This costume I completed with a top hat extracted from its dim and dusty lair, a dark overcoat, a walking-stick and a pair of gloves. Thus attired I set out for the station.

In the garden I found the junior members of the family gathered together to escort me. When they saw me they assumed an air of profound solemnity and doffed imaginary hats in my honour.

"He's got his Londons on after all," said Peggy, thus lightly alluding to my serious garments.

"Will his lordship deign to take my humble arm?" said Rosie.

"John," said Helen brightly, "run on, there's a good boy, and see if they've got out the red carpet. We must certainly knight the station-master."

They then formed up as a festal band—mostly big drums—and preceded me to the garden gate, where they scattered and left me with a final cheer.

At about 3 o'clock in the afternoon I found myself in the West-end—not, of course, in the whole of it, but in that particular part of it where my tailor has his establishment. Up to that moment I had been eager to see him, but now that I stood before his door all desire had vanished just as a toothache disappears when you get almost within forceps distance of a dentist. However I encouraged myself. "These clothes," I said, "have been waiting for months in a half-sewn state and with makeshift button-holes. They must be put out of their misery. It's to-day or never."

My entrance was warmly welcomed: "Try on? Yes, Sir. I'll call Mr. Thurgood. Will you step in here, Sir?"

I stepped in through a door in a glass partition and found myself in the familiar torture-chamber. The old coloured plates of distinguished gentlemen in dazzling uniforms still hung on the walls. Their trouser-knees didn't bulge an inch. They fitted into their suits as wine fits into a decanter. Why couldn't I be like that? Also there were the looking-glasses artfully arranged to show you your profile or your back, a morbid and detestable revelation of the unsuspected.

"You're quite a stranger, Sir," said Mr. Thurgood, coming briskly into the room, accompanied by a transitory acolyte bearing clothes. "Shall we try the blue serge first?"

"No, Mr. Thurgood," I said, "we will first talk about uniforms. Could you make me a uniform like that?" I pointed to an expressionless person tightly wedged into a dark blue dress.

"An Elder Brother of the Trinity House," said Mr. Thurgood. "I did not know—am I to congratulate? Of course we shall be proud to do it for you."

"Well, perhaps not yet, Mr. Thurgood. We must wait and see—ha-ha—wait and see, you know. Let us get on with the blue serge." I took off my coat and waistcoat.

"Let me help you with the trousers," said Mr. Thurgood. "They'll come off quite easily over the boots." They did, and I caught a glimpse of my undergarment as they came off, and clapped my hands on my knees. Why had I not noticed this before? Each knee was picturesquely darned in an elaborately cross-hatched pattern.

"I don't think," I said, "we'll worry about the trousers. I can take them on trust."

"Do you really think so, Sir? It's a difficult leg to fit, you know. Plenty of muscle here and there. Not like some. You set us a task. There's a good deal to contend against in a thigh like yours."

"That's it," I cried with enthusiasm. "You can't do yourself justice unless you've got lots to contend against. I shall make it harder for you if I don't try on, and your triumph will be all the more glorious."

"It's a curious thing," said Mr. Thurgood, looking meditatively at my hands; "I've got just such another patch of darning on my knee," and he pulled up his trouser. "It's funny how you forget to notice a little thing like that."

"In that case," I said, "we will proceed with the trying on," and I removed my hands. "I've got two of them, you see."

"So have I," said Mr. Thurgood. "They generally go together."

R. C. L.

From a story in The Pall Mall Gazette:—

"'Willie was right,' he muttered. 'The evil men do live after them. The good oft lies interred in their bones, but maybe it was only folly with me, not evil.'"

Willie was certainly right, but that's not exactly how (in Julius Cæsar) he put it.

"When the men went to the scale, the Welshman was found to be half-a-pound over the stipulated 8st., but he was allowed time to get this off, and just before three o'clock he passed the weight, while Ladbury weighed 7st. 14 1/4 lb."—Yorkshire Post.

Rather bad luck on the Welshman, who had been sprinting madly round the arena for some hours with eight ounces which nobody wanted, to find afterwards that Ladbury's extra four ounces were entirely ignored.

"Since tea the crowd had swelled considerably."

South African News.

An air of dough-nuts hangs over this sentence.

The Lady. "Hallo, Count! What's happened?"

The Count (who has come off at the third obstacle). "Once I jump and my horse he catch me; then I jump and he only catch me a little; anozer time I jump and he miss me altogezer."

(Suggested by a recent vindication of the "right but ruffling attitude" of the new and true artist.)

If you're anxious to acquire a reputation

For enlightened and emancipated views,

You must hold it as a duty to discard the cult of Beauty

And discourage all endeavours to amuse.

You must back the man who, obloquy enduring,

Subconsciousness determines to express;

Who, in short, is "elemental," "unalluring,"

But "arresting" in his Art—or in his dress.

Again, if you're desirous of attaining

Pre-eminence in places where they play,

Don't supply the smallest spoonful of the pleasing or the tuneful

Or you'll chuck your very finest chance away.

But be truculent, ferocious and ungentle

And the critics will infallibly acclaim

Your work as unalluring, elemental

But arresting and exalted in its aim.

Or is your cup habitually brimming

With water from the Heliconian fount?

Then remember the hubristic, the profane and pugilistic

Are the only kinds of poetry that count.

So select a tragic argument, ensuring

The maximum expenditure of gore,

And the epithets arresting, unalluring,

Elemental, will re-echo as before.

But if your bent propels you into fiction,

You should clearly and completely understand

That your duty in a novel is not to soar, but grovel,

If you want it to be profitably banned.

So be lavish and effusive in suggesting

A malignant and mephitic atmosphere,

And you're sure to be applauded as arresting,

Elemental, unalluring and sincere.

If you meditate a matrimonial venture

That will turn the cheek of Mrs. Grundy pale,

Don't be lured by pretty faces or by dainty airs and graces

That entrap the unsophisticated male.

No, look out for what is vital, transcendental,

And ask yourself, before you choose your wife,

"Is she wholly unalluring, elemental

But arresting in her attitude to life?"

In fine if you believe in self-expression

And disdain to be a law-abiding man,

You must cultivate a hobby of insulting ev'ry bobby

Whenever you conveniently can.

You'll find him quite impervious to jesting,

But he has another less attractive side,

Elemental, unalluring and arresting

When his patience is intolerably tried.

"It's got to be," I said.

I must have been thinking aloud, for Joyce said quickly—

"What's got to be?"

"The silver," I said.

"It doesn't sound sensible," said Joyce.

"It isn't," I said, "at all sensible, but it's inevitable."

"What's inevitable?"

"That about the silver," I said.

"But you didn't say anything about the silver, except that it's got to be."

"Well, it's got to be—hypothecated."

"What's that?"

"I mean," I said, "that I'm—er—temporarily embarrassed, and the silver has got to be made security for a loan—pawned, in fact—so that I can pay the balance of the rent and catch up with my outgoings. Is that clearly put?"

"Perfectly; but we can't spare the silver just now. The Armisteads are coming to tea on Friday."

"But," I protested, "you don't understand. We don't keep a valuable stud of silver tea-things for the Armisteads' amusement, but for our own, and as—er—collateral." I was sure this would be beyond Joyce.

"But what am I to do?"

"Call out the reserves," I said.

"But they're such a mixed lot," said Joyce. "I should be ashamed of having anyone to tea with them."

"Better," I said, "than having the bailiffs to dine and sleep."

"Ugh," said Joyce, "is it as bad as that?"

"It is," I said, "and all because Short won't send that cheque on account of royalties till I've made some alterations to the last chapter. Our landlord is becoming unmanageable. Besides," I said, "I hear there have been one or two burglaries in this road lately, so the silver will be safer."

"Look here," said Joyce, who declined to be scared by the idea of burglars. "To-day's Tuesday. Wait till Thursday. Something's sure to turn up."

"Yes," I said, "a bailiff. But I'll wait till to-morrow if you like."

"Good. And in the meantime we'll both think hard of some other way."

That evening at dinner Joyce said, "I have an idea, but I'm not going to tell you yet. Have you thought of anything?"

"Yes," I said. "I've got a brilliant scheme, but I'm going to keep it to myself for the present."

"I knew you'd think of a way out," Joyce said, "if you gave your mind to it."

My brilliant scheme was to pop the silver, and I managed to get away with it next morning (Wednesday) without arousing Joyce's suspicions. I got £20 on it at the local hypothecary's, squared the landlord, leaving a few pounds in hand, and hid the ticket in my writing-case. I spent the morning on the alterations for Short, and the afternoon on the links, and lost three good balls—curious coincidence, as I had found three such useful ones at the pawnbroker's in the morning.

The evening of Wednesday passed off quietly. Joyce looked very cheerful and didn't say a word about the silver, so I felt sure she hadn't missed it. Uncle Henry had called, she said, and wanted us both to go and dine with him at the Fitz on Saturday night, and she had accepted.

"Good," I said.

I suppose I looked very cheerful because Joyce said—

"Your scheme's come off, I suppose?"

"Oh, yes," I said, "it's come off—er—quite well. How's yours?"

"Mine was quite successful, thank you, and I shall get a new frock for dinner on Saturday."

As I didn't want to give my scheme away just then, I didn't press Joyce to reveal hers, and we retired for the night with honours easy.

When I got home on Thursday from a day in town, Joyce met me at the gate. She looked scared.

"We've had a burglar," she said. "The silver's gone. Oh, why didn't I take the warning?"

This was my big scene, but I never believe in rushing a good climax, so I simply said—

"The silver gone? Dear, dear. A burglar, did you say? I told you they were about."

"Really, I'm not joking," said Joyce. "Both Jessie and I were out this afternoon and he must have got in by the scullery window, which I'm afraid was unlatched."

I was enjoying her consternation immensely.

"A burglar?" I repeated. "How very interesting!"

"Oh," said Joyce, stamping her foot, "can't you do something?"

"My dear Joyce," I said, fixing her with my eleven-stone look, "let us stop this mummery. Behold the burglar!" and I struck the attitude that I thought would have done credit to Sir Herbert.

"You!" she said; "but——"

"Yes," I said. "Alone I did it. Aren't you glad? Come, do look glad and ring down the curtain. The play is over."

"But that was on Wednesday."

"Yes," I said, "it was. On Wednesday, at ten o'clock of the forenoon."

"Well, on Wednesday after lunch, I wanted an envelope and at last found one in your writing-case. I also found a ticket."

"Then you knew all the time?"

"Listen," said Joyce. "Uncle Henry called——"

"And asked us to dinner—good egg!"

"Well, I borrowed £25 from him and took the silver out of pawn."

[A housewife in a contemporary says:—"If my guests have friends in the neighbourhood they can ask them in without consulting my convenience at all, take them up to the bedroom, light the gasfire and make them quite comfortable there."]

Dear Tom, when your neighbours invited me first,

I made up mind to refuse,

But that was before I was properly versed

In the up-to-date hostess's views.

If I (like Achilles) remain in my room,

She'll never give vent to complaining.

Though she misses my jests, she will kindly presume

I am nevertheless entertaining.

And so, since I've many a friend on the spot,

I've quitted the comforts of town

In order to keep open house for the lot

In a chamber provided by Brown.

They shall come to my bedroom; I'll give them good cheer;

I'll ring for a handmaid and tell her

To serve us at once with a dinner up here,

Including the pick of the cellar.

And then in due course round the gas glowing red

Brown's choicest cigars shall be lit,

And, if we like resting our feet on the bed,

We may—it won't matter a bit.

Our talk of old times shall be joyous and bright,

Undisturbed we will gossip like billy-o,

And I shan't break away to bid Brown a good night;

'Twould savour of needless punctilio.

Dear Tom, since I love you the best of them all,

Call round here whenever you care,

And, if you should run against Brown in the hall,

Just give him an insolent stare.

And when, from rusticity taking a rest,

You come up to London and meet me,

Remember the evenings when you were my guest,

And take me out, Thomas, and treat me.

Zealous Boy Scout. "You can cross by this bridge, Sir. It will save you a long walk round."

Cautious Stout Party. "Thank you, my boy, but I'm afraid it would hardly bear me."

Zealous Boy Scout. "Oh, that's all right, Sir. We have first aid and ambulance on the other side!"

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

The author of Pantomime (Hutchinson) has placed me in something of a quandary. In an ordinary way, finding a story with this title, in which moreover the chief characters are spoken of as Princess and Principal Boy, and the narrative is broken every now and then by fantastical little dialogues with Fairies, I should have said at once that here was a clever young writer whom a natural admiration for the work of Mr. Dion Clayon Calthrop had betrayed into the sincerest form of flattery. But Mr. (or perhaps Miss) G. B. Stern has disarmed me by an open avowal of discipleship and a dedication of the tale to Mr. Calthrop himself. It is a quite pleasant tale. Personally I may confess to a preference, which I suspect most readers will share, for getting this precise form of whimsical romance from the original firm; but there is more than enough spirit in G. B. Stern's work to persuade me that he or she will one day be worth reading in an individual and unborrowed style. Two things in this story of Nan pleased me especially. One was the chapter relating her experiences at the Dramatic Academy, which is full of life and actuality, and should be read by all middle-aged supporters of that institution who wish to obtain a glimpse of its hard-working and high-spirited heart. The other is the episode of the muddled elopement, in which Nan and Tony, having got as far as Dover on their way to the Higher Liberty, severally——But I don't think I will spoil for you the delightful comedy of what happens at Dover by repeating it. This at least shows G. B. Stern as the owner of a happy gift of humour. Let us have some more of it soon, please, but if possible in a more original setting.

Mrs. Leverson is one of those authors who baffle criticism by sheer high spirits. She gives me first and last a prevailing impression that novel-writing must be tremendous fun; and this is so cheering that it is really impossible to be angry with her. Otherwise I might have some very sharp things to say about her light-hearted disregard of syntax and punctuation. Her pronouns, for example, are so elusive that not only am I frequently in doubt as to whom the heroine will marry in the end but as to which of the characters is speaking at any given moment. And not infrequently what can only be careless proofreading leaves sentences that contradict each other into an effect of nonsense. But just when I should be noting all these subjects for legitimate censure I am probably devouring page after page with giggles of delight for the wit and jollity of them. Bird of Paradise (Grant Richards) is in every respect a worthy companion to its predecessors. There are no very severe problems in this story of a group of Londoners, but plenty of the lightest, most airy dialogue, and some genuine character-drawing, conveyed so deftly that you only detect it afterwards by the way in which the persons remain in your memory. The whole thing, of course, is modern to the last moment; tango-teas and Russian ballets and picture-balls besprinkle the conversation. [pg 100]There is even a passage about a certain famous shop that made me wonder whether the New Advertising, familiar to readers of the afternoon journals had also invaded the realm of fiction. You will observe that I have made no effort to repeat the story; as it contains at least three heroines and five heroes the task would be too complicated. But you can take it on trust as a comedy of want of manners, brilliantly alive, exasperatingly careless, and altogether the greatest fun in the world.

Once upon a time there were two highwaymen, Charlie and Crabb Spring; two men, not highway, Saul Coplestone and John Cole; two marriageable sisters, Sarah and Christina Rowland. The highwaymen, being pestilential and murderous, badly wanted catching; of the two potential heroes, Saul was a stout enough fellow on the surface but a poltroon at bottom, while John, though less terrific in physique, was modest and courageous to a degree. Of the sisters, Sarah had most of the looks and Christina all the merits, so that at the beginning of things both Saul and John were concentrated upon the former, who, being a little fool, preferred Saul, but, being also a little vixen, encouraged both. The brothers Spring appearing Dartmoor way, Sarah promised, in an expansive moment, to marry whichever of her suitors caught them single-handed. This was apparently impossible, but nevertheless one of them did it. Need it be said which? Need it be said which of the two sisters the proved hero ultimately took to wife? No, this is one of those cases in which it is impossible for the reader, with the best intentions in the world, not to prophesy and prophesy accurately. None the less it is worth while to spend time and money on The Master of Merripit (Ward, Lock) for the following adequate reasons. It is from the pen of Mr. Eden Phillpotts; if the conclusions are foregone, the excitement throughout is intense; the local colour and the supernumerary characters are charming as usual, and the scheme by which the villains were entrapped is admirable in design and execution. This learned clerk, for all his expert knowledge of the art of catching highwaymen, neither anticipated it nor, upon the most critical reflection, is able to find a flaw in it.

I was discussing Mr. Gilbert Cannan with a friend, and he said, "I have read many reviews of his books, nearly all of them good reviews, but not one that made me want to read the book itself." Well, I am afraid this one won't make him want to read Old Mole (Martin Secker). The hero, Old Mole, otherwise H. J. Beenham, M.A., had himself written a book, and this is what Mr. Cannan says of it: "The essay was cool and deliberate, broken in its monotony by comical little stabs of malice. The writing was fastidious and competent. Panoukian thought the essay a masterpiece, and there crept a sort of reverence into his attitude towards its author.... Then, to complete his infatuation, he contrasted Old Mole with Harbottle." I am no Panoukian. Mr. Cannan's opinion of Old Mole's book may stand as mine of Mr. Cannan's book. But I can understand the Panoukian attitude; and when I read the Panoukian reviews—referring inevitably to the "damnable cleverness" of Mr. Cannan—then I suspect that they have been contrasting him with the Harbottles of the literary world, the gushers and the pushers and the slushers. After a month of these a fastidious writer may well infatuate a reviewer. For myself, who have not had to wade through Harbottles, I remain unstirred by Old Mole. Not a single character, male or female, moved me to the least interest; they were all cold, dead people, and Mr. Cannan talked over their bodies. Clever talk, certainly—he shall have that adjective again—but when it was over I had a wild mad longing to take to the Harbottle. Even Mr. Hall Caine ... but this is morbid talk.

In a preface to In the Cockpit of Europe (Smith, Elder) Lieut.-Colonel Alsager Pollock states that "the personal experiences of George Blagdon, in love and war, have been introduced solely in the hope of inducing some of my countrymen to read what I have to say about other important matters"—an ingenuous confession which deprives my sails of most of their wind. Otherwise I should have said that this book is not so much a novel as an airing-ground for grievances, adding for fairness that these grievances are national and not personal. A terrific war with Germany gives Blagdon opportunity to win various distinctions, and Marjory Corfe affords him ample justification for falling in love; but although I grant, even in the face of that preface, that Blagdon is not completely a puppet, he is used mainly to emphasize his creator's ideas. Officials at the War Office who read In the Cockpit of Europe may possibly require some artificial aids to digestion before they have finished it, but both they and the Parliamentary and Ministerial strategists will have to admit that their critic's honesty of purpose is beyond all manner of doubt.

The little jade Buddha (his favours increase!)—

He's soapy and bland,

And he sits on his stand

And he smiles, and he smiles in an infinite peace;

For he's old, and he knows that, whatever befall,

There is nothing that matters, no, nothing at all.

The little jade Buddha (on us be his balm!)—

The Wheel turneth just

As it must, as it must,

So he sits in an ageless, ineffable calm

Where apples and empires may ripen or fall,

But there's nothing that matters, no, nothing at all.

Transcriber's note:

The typographical error "sich" in the last paragraph of "Honorifics" on page 81 was replaced by "such".