Title: Celebrated Travels and Travellers, Part 1.

Author: Jules Verne

Illustrator: Léon Benett

Paul Philippoteaux

Translator: Dora Leigh

Release date: March 7, 2008 [eBook #24777]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ron Swanson (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian

Libraries)

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||

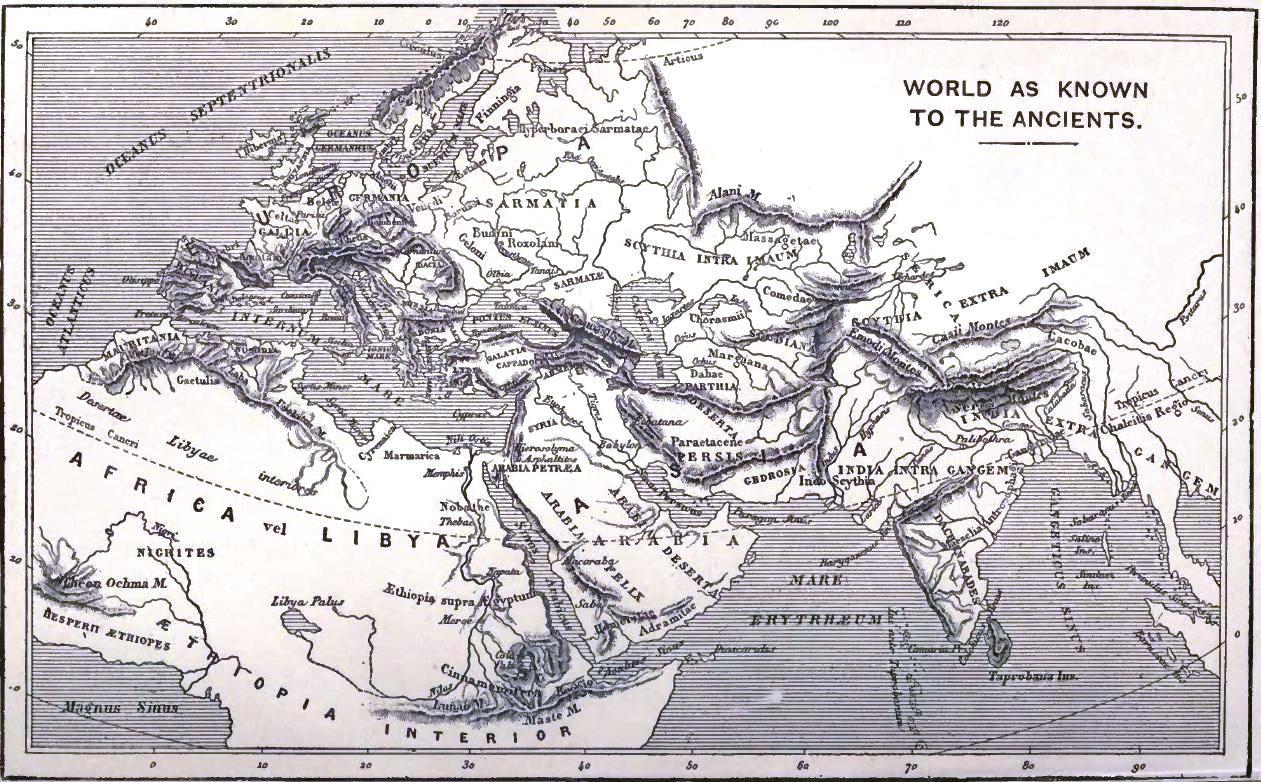

Map of the World as known to the Ancients.

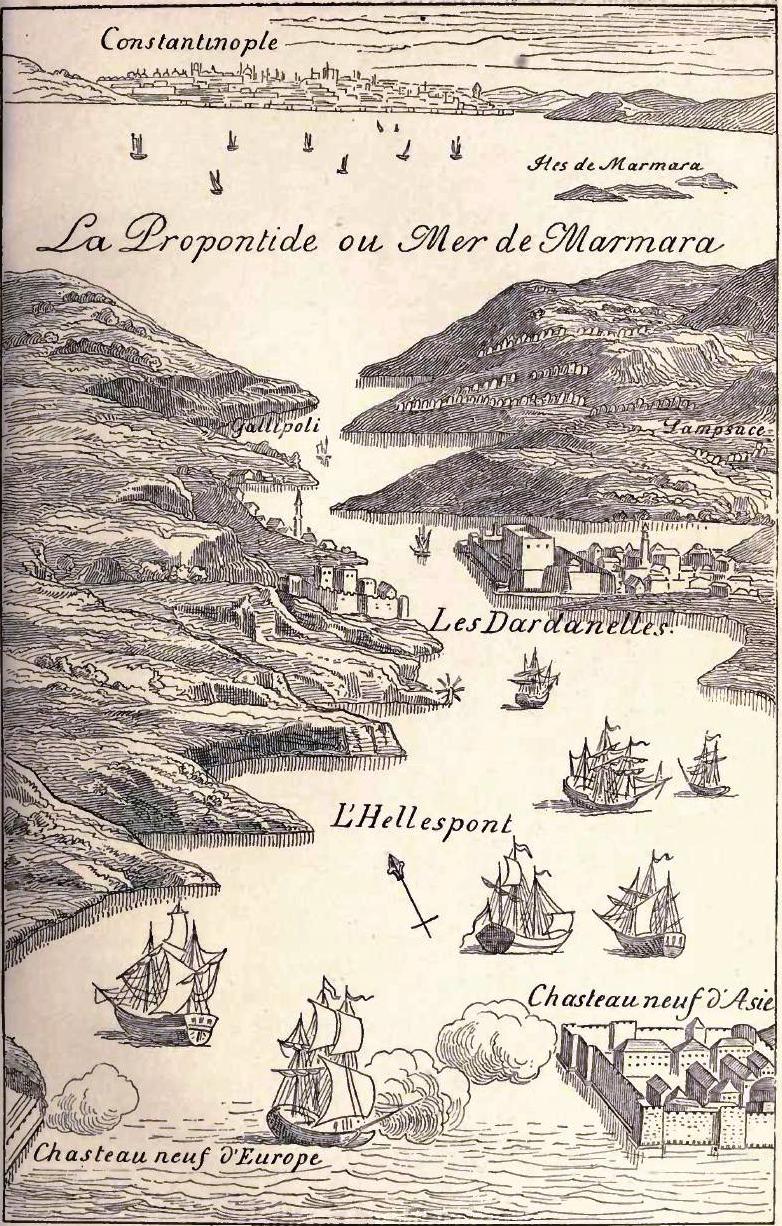

Approach to Constantinople. Anselmi Banduri Imperium orientale, tome II., p. 448. 2 vols. folio. Parisiis, 1711.

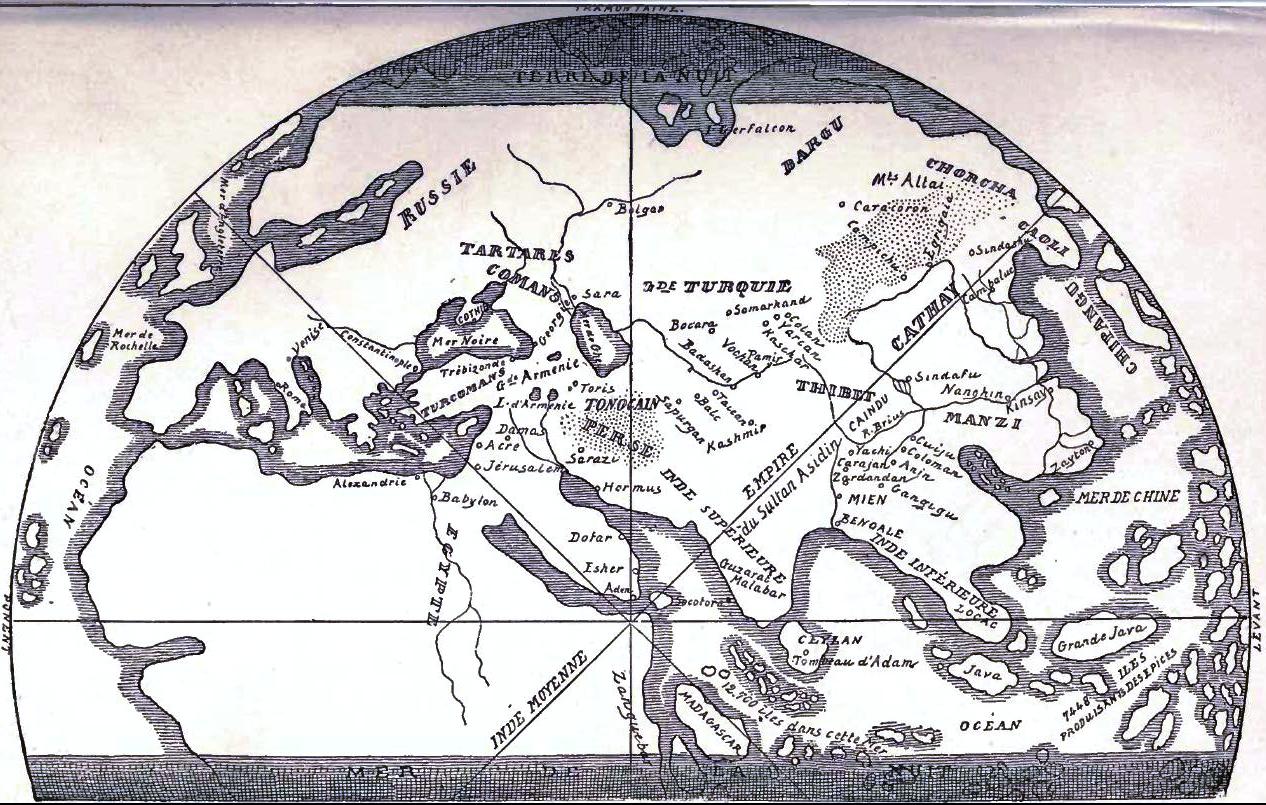

Map of the World according to Marco Polo's ideas. Vol. I., p. 134 of the edition of Marco Polo published in London by Colonel Yule, 2 vols. 8vo.

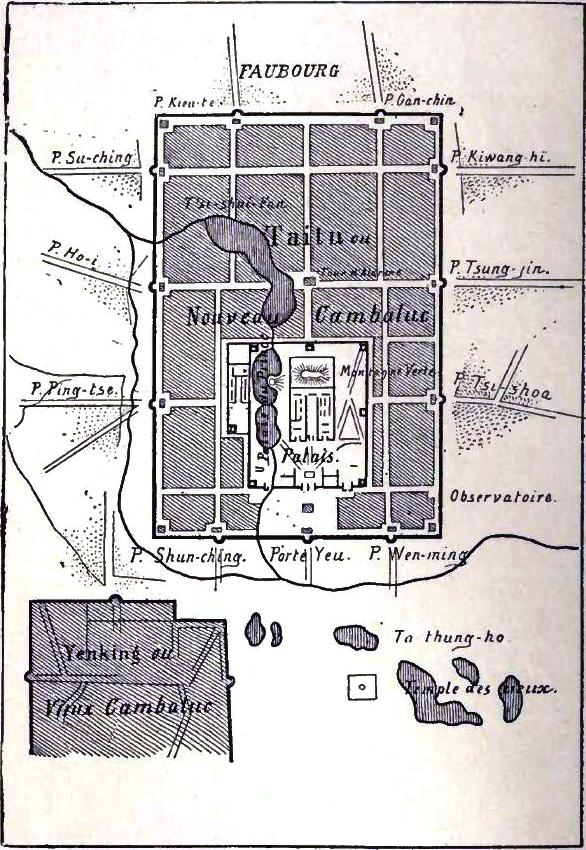

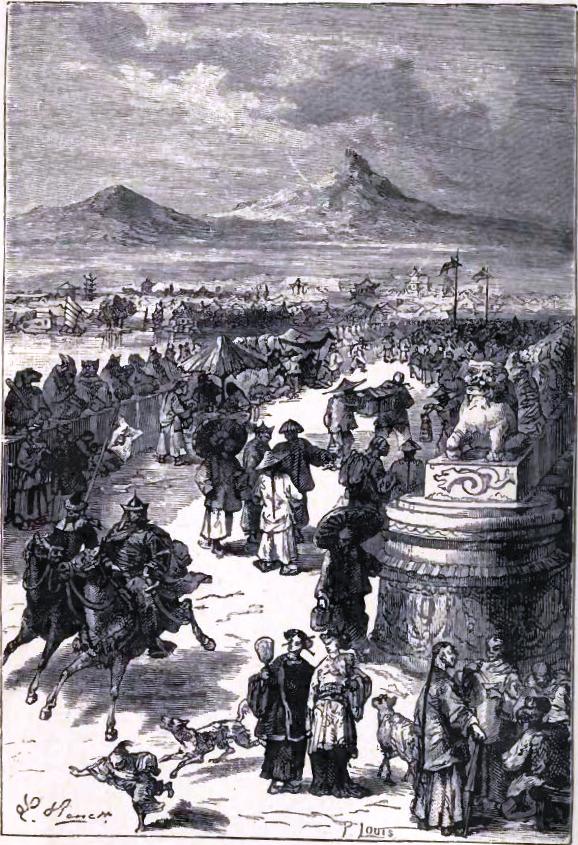

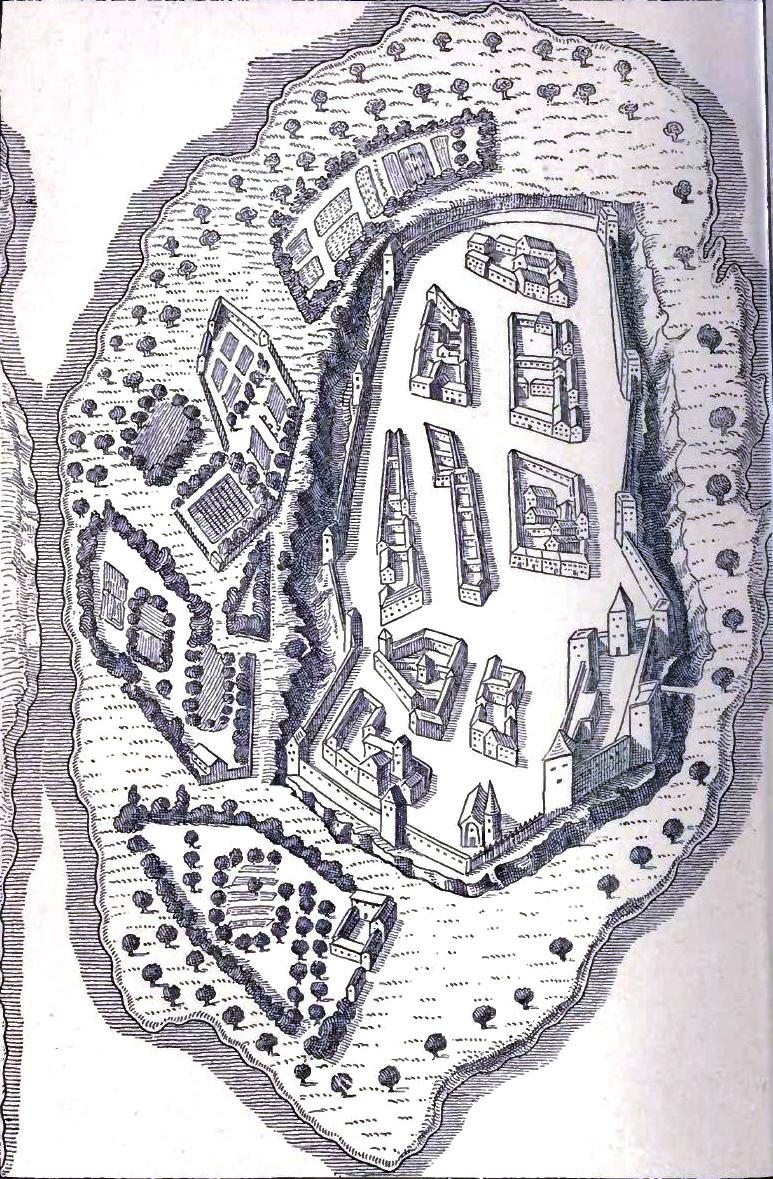

Plan of Pekin in 1290. Yule's edition. Vol. I., p. 332.

Portrait of Jean de Béthencourt. "The discovery and conquest of the Canaries." Page 1, 12mo. Paris, 1630.

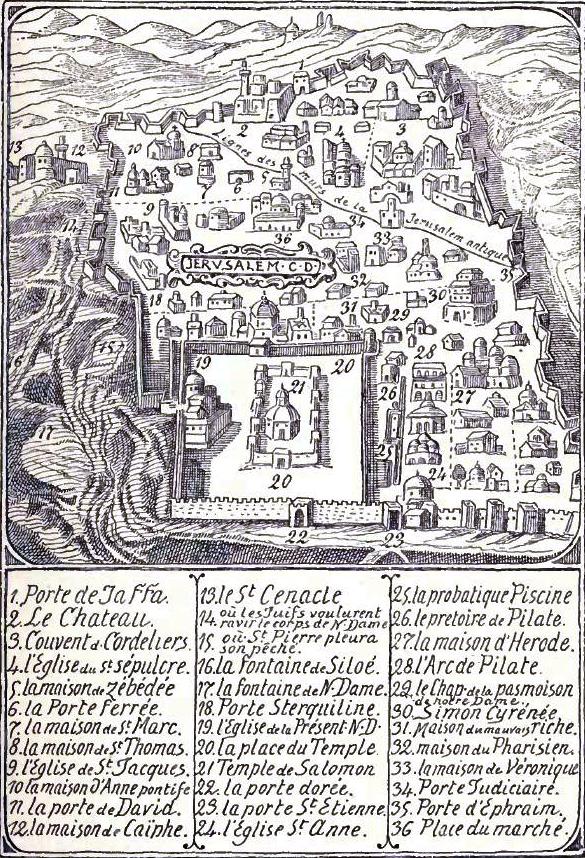

Plan of Jerusalem. "Narrative of the journey beyond seas to the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem," by Antoine Régnant, p. 229, 4to. Lyons, 1573.

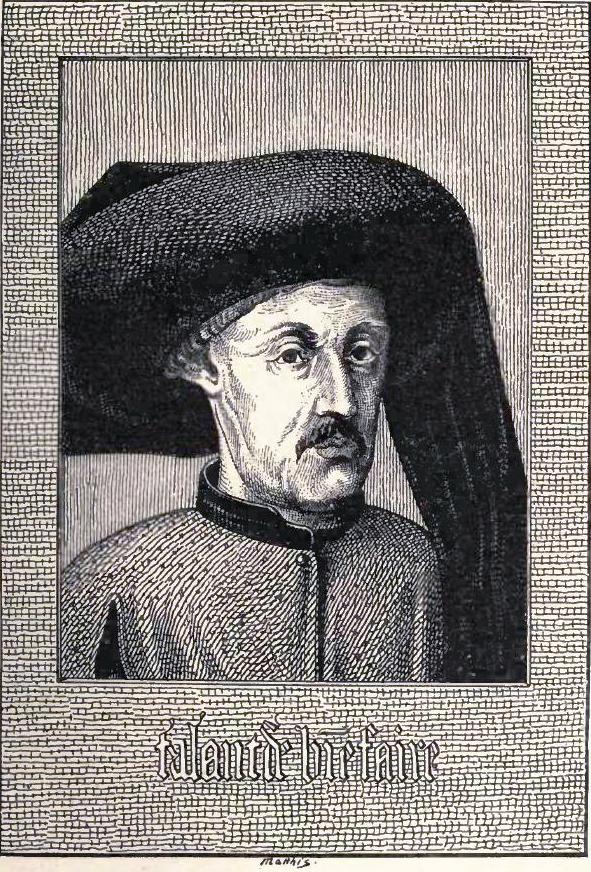

Prince Henry the Navigator. From a miniature engraved in "The Discoveries of Prince Henry the Navigator," by H. Major. 8vo. London, 1877.

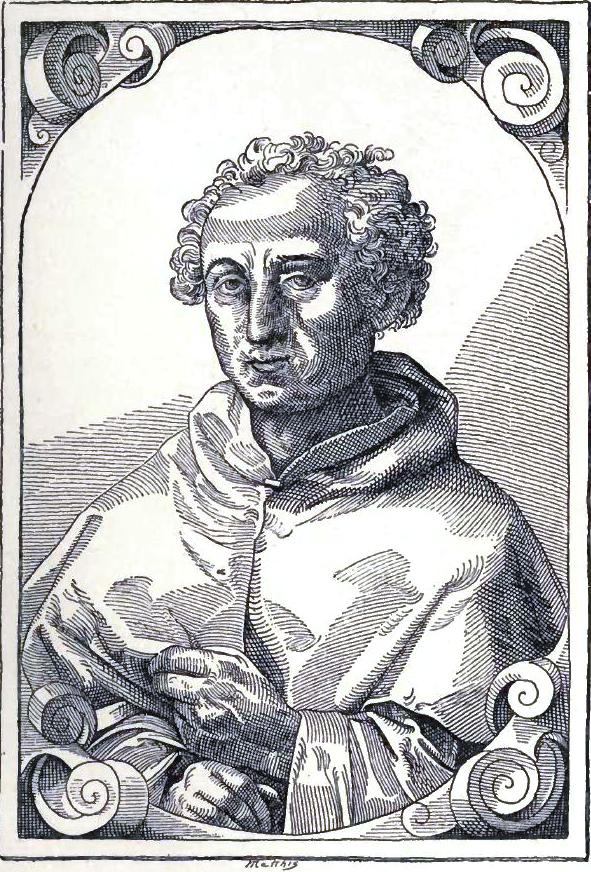

Christopher Columbus. Taken from "Vitæ illustrium virorum," by Paul Jove. Folio. Basileæ, Perna.

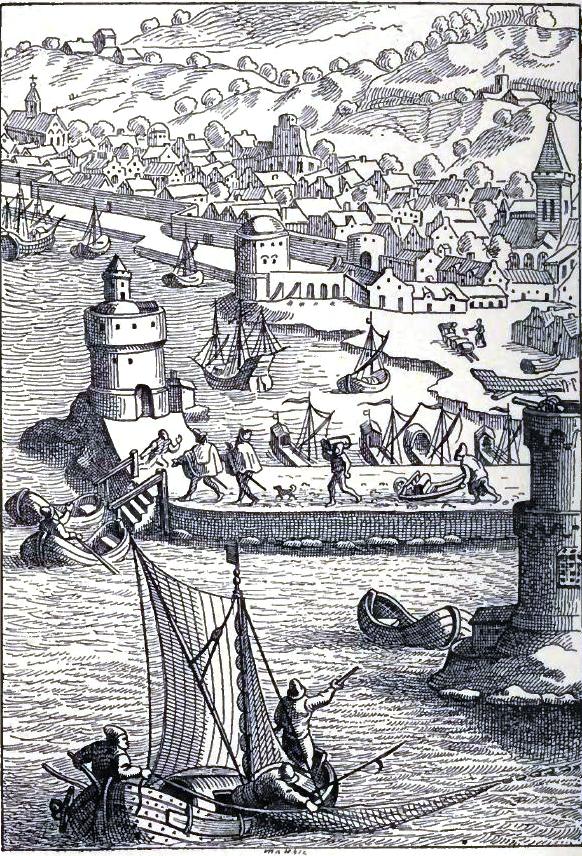

Imaginary view of Seville. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, pl. I., part IV.

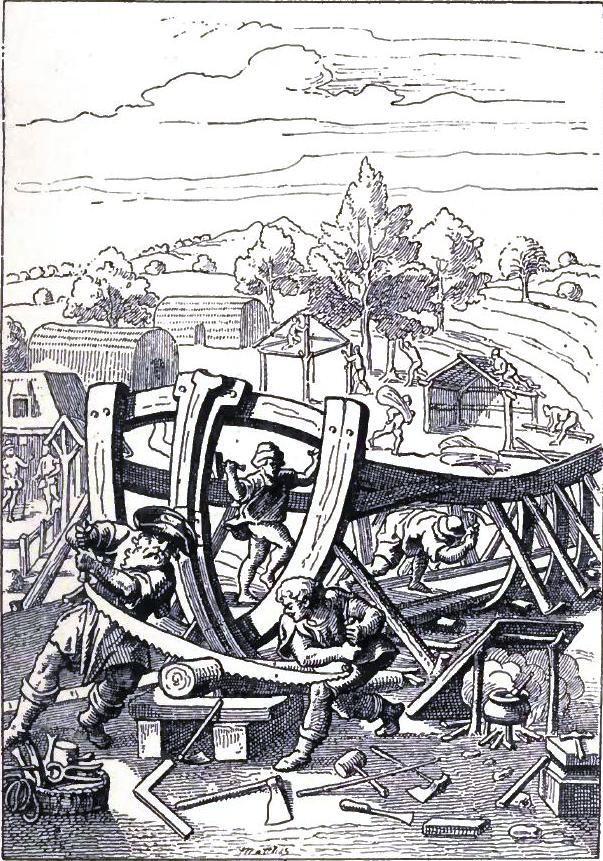

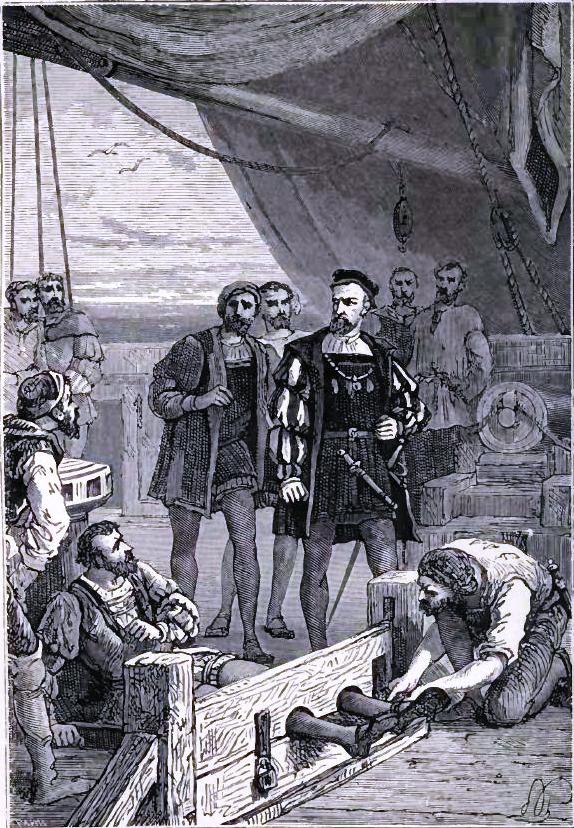

Building of a caravel. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part IV., plate XIX.

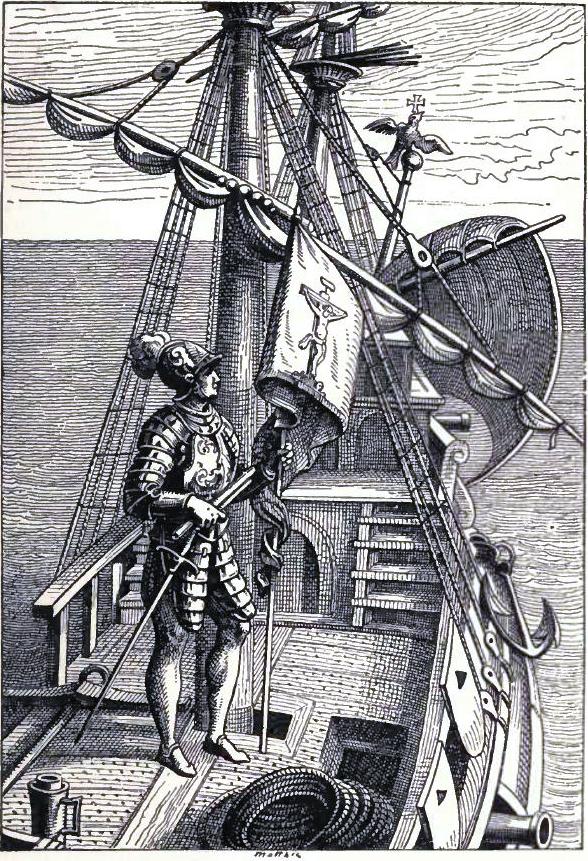

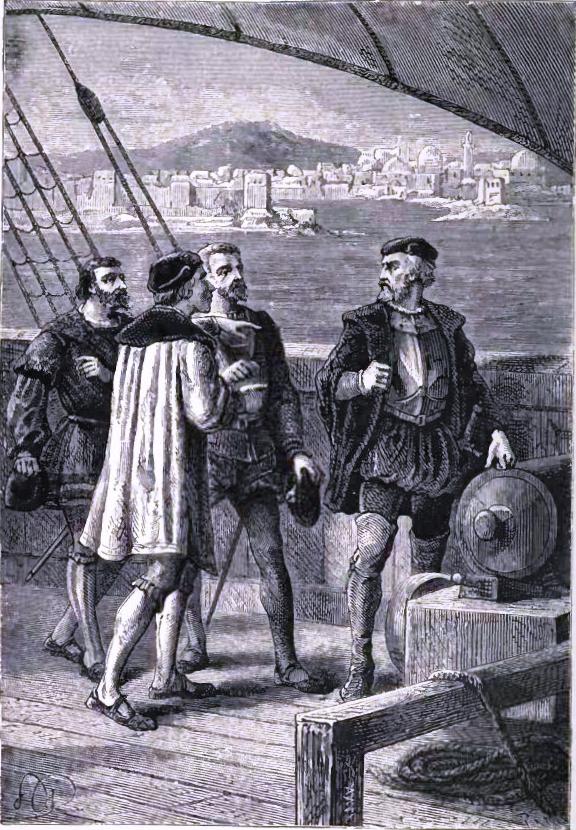

Christopher Columbus on board his caravel. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part IV., plate VI.

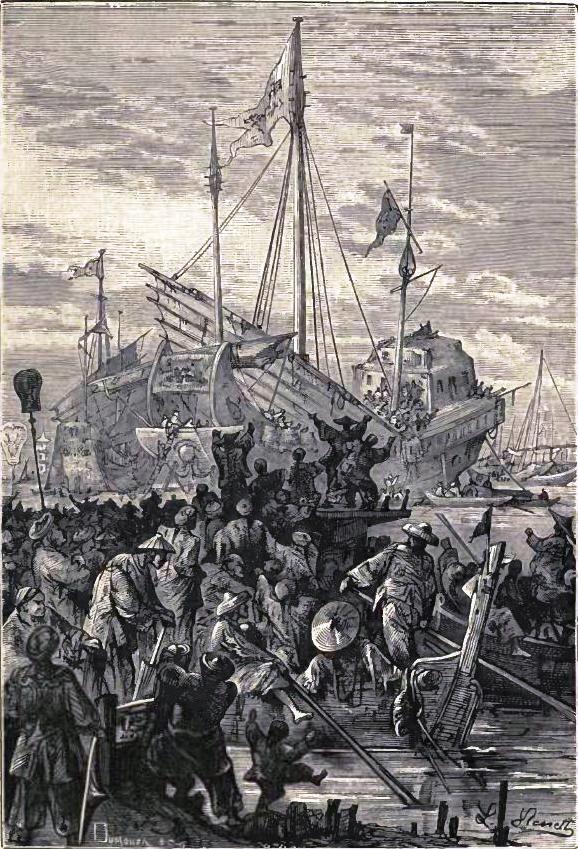

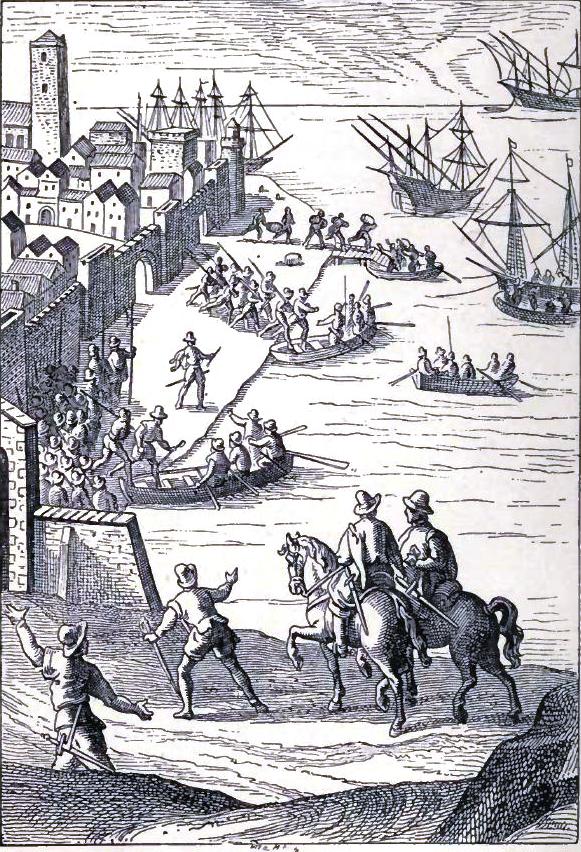

Embarkation of Christopher Columbus. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part IV., plate VIII.

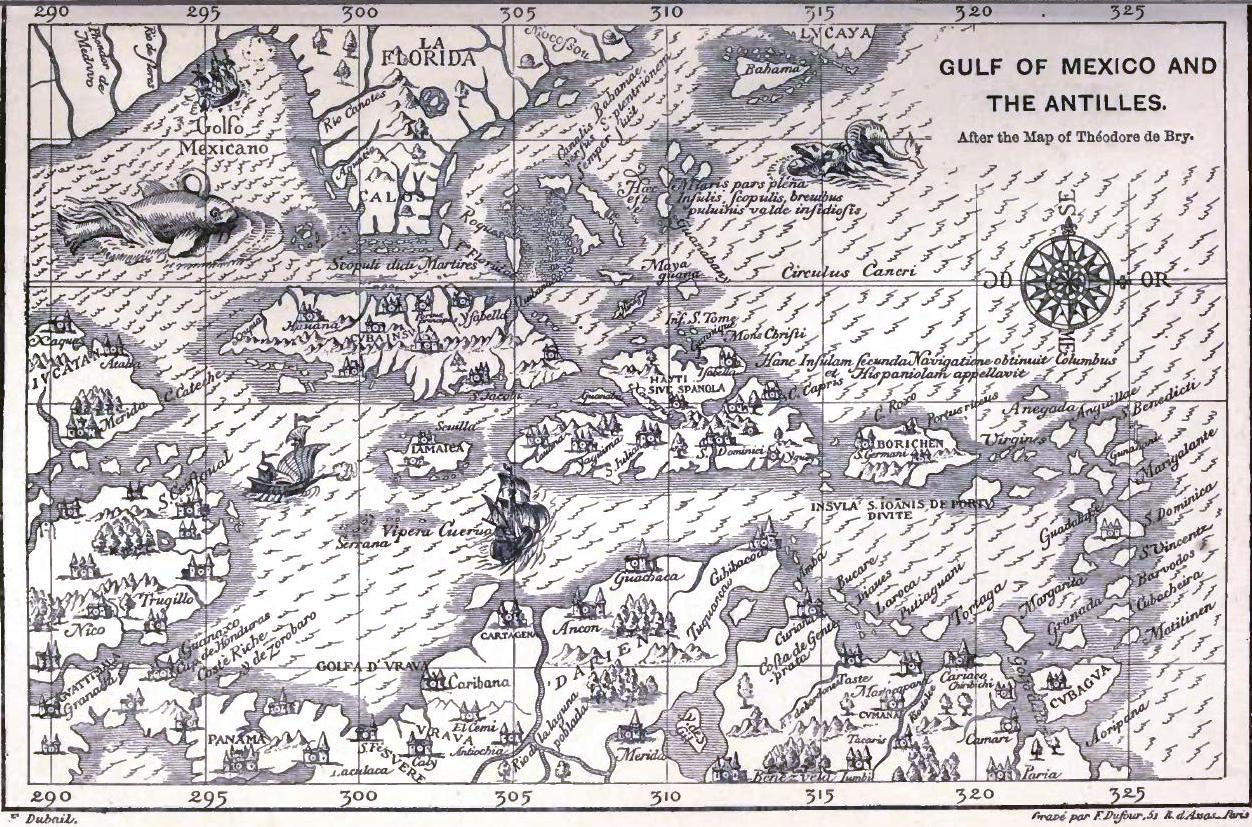

Map of the Antilles and the Gulf of Mexico. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part V.

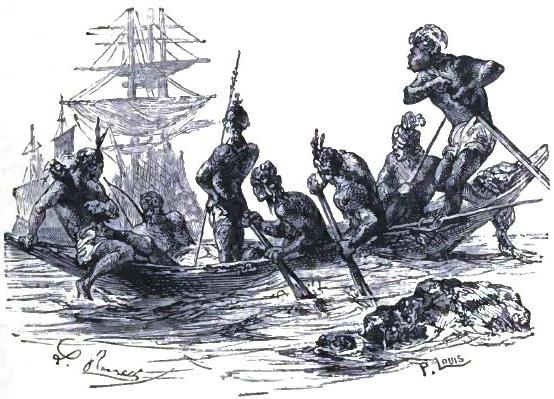

Fishing for Pearl oysters. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part IV., plate XII.

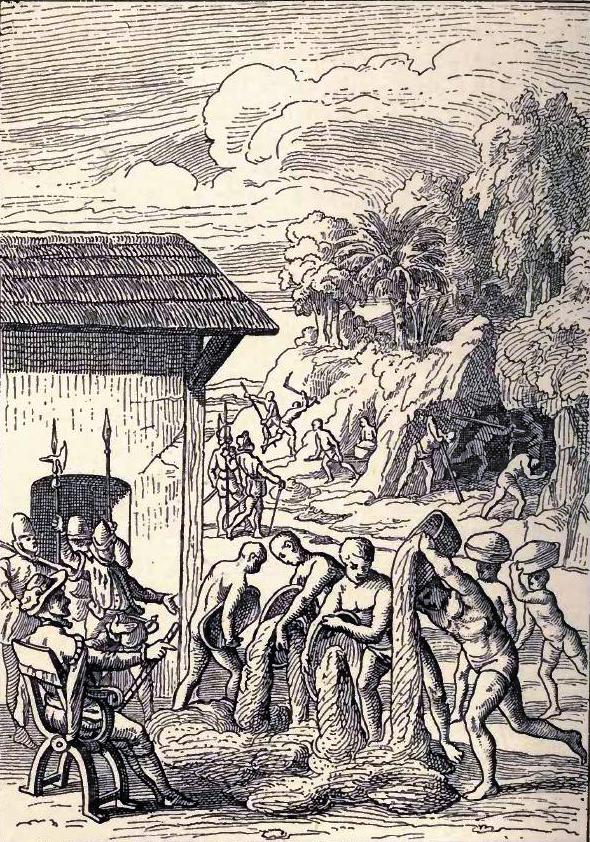

Gold-mines in Cuba. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part V., plate I.

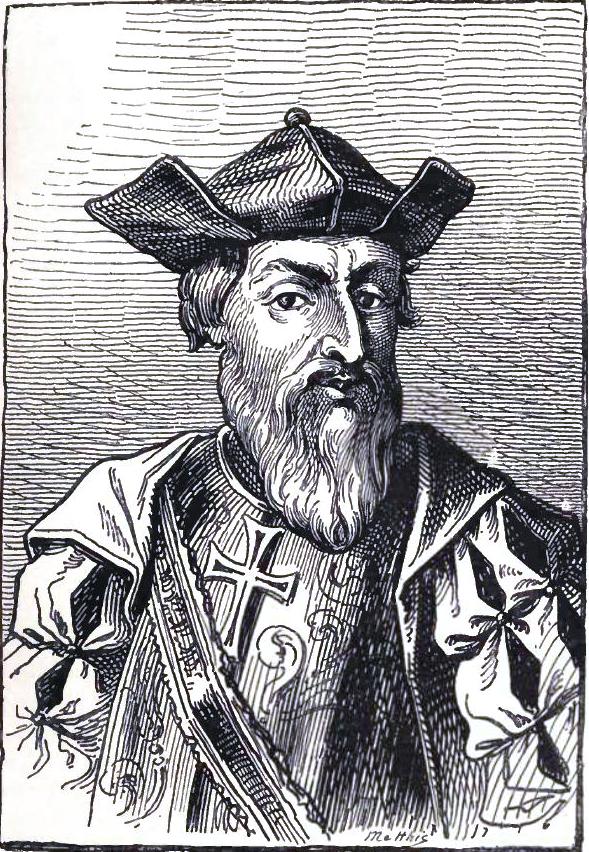

Vasco da Gama. From an engraving in the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibl. Nat.

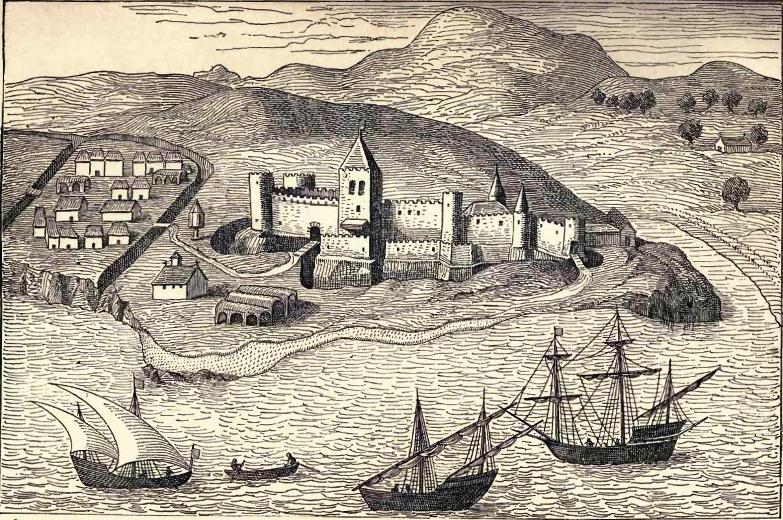

La Mina. "Histoire générale des Voyages," by the Abbé Prévost. Vol. III., p. 461, 4to. 20 vols. An X. 1746.

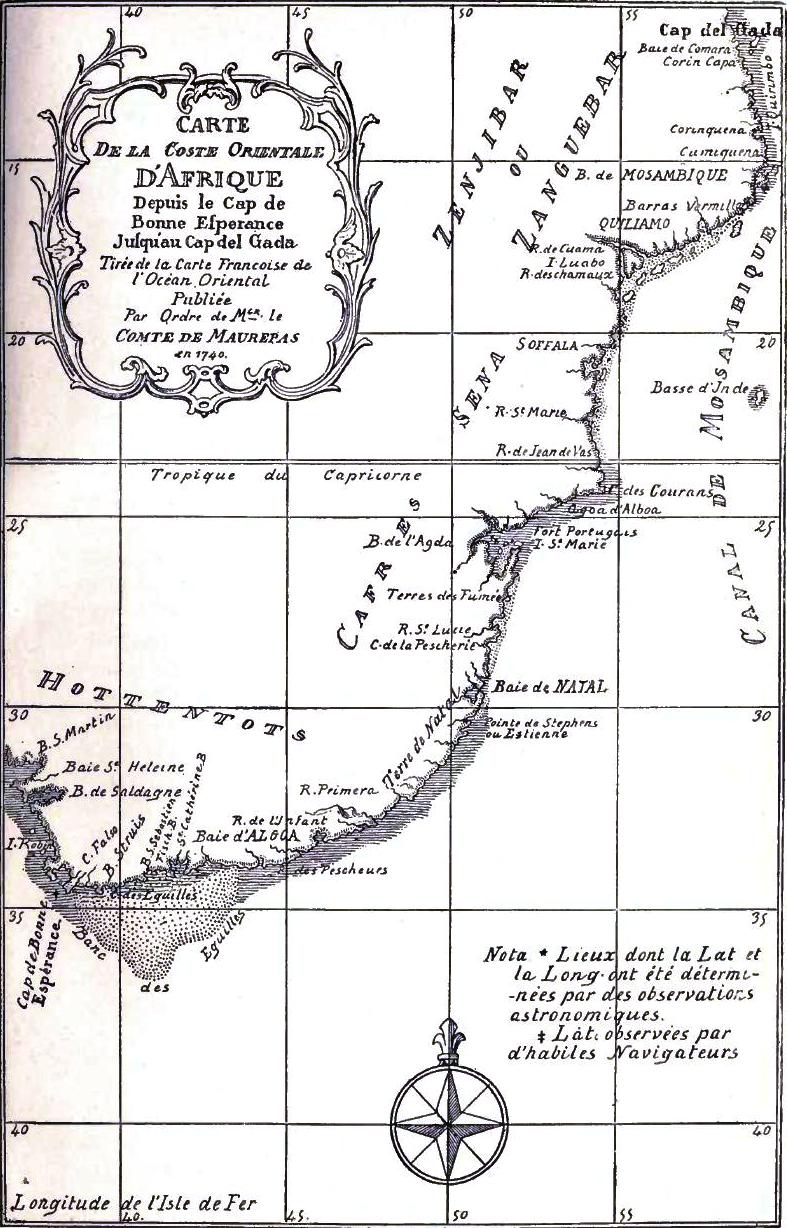

Map of the East Coast of Africa, from the Cape of Good Hope to the Cape del Gado. From the French map of the Eastern Ocean, published in 1740 by order of the Comte de Maurepas.

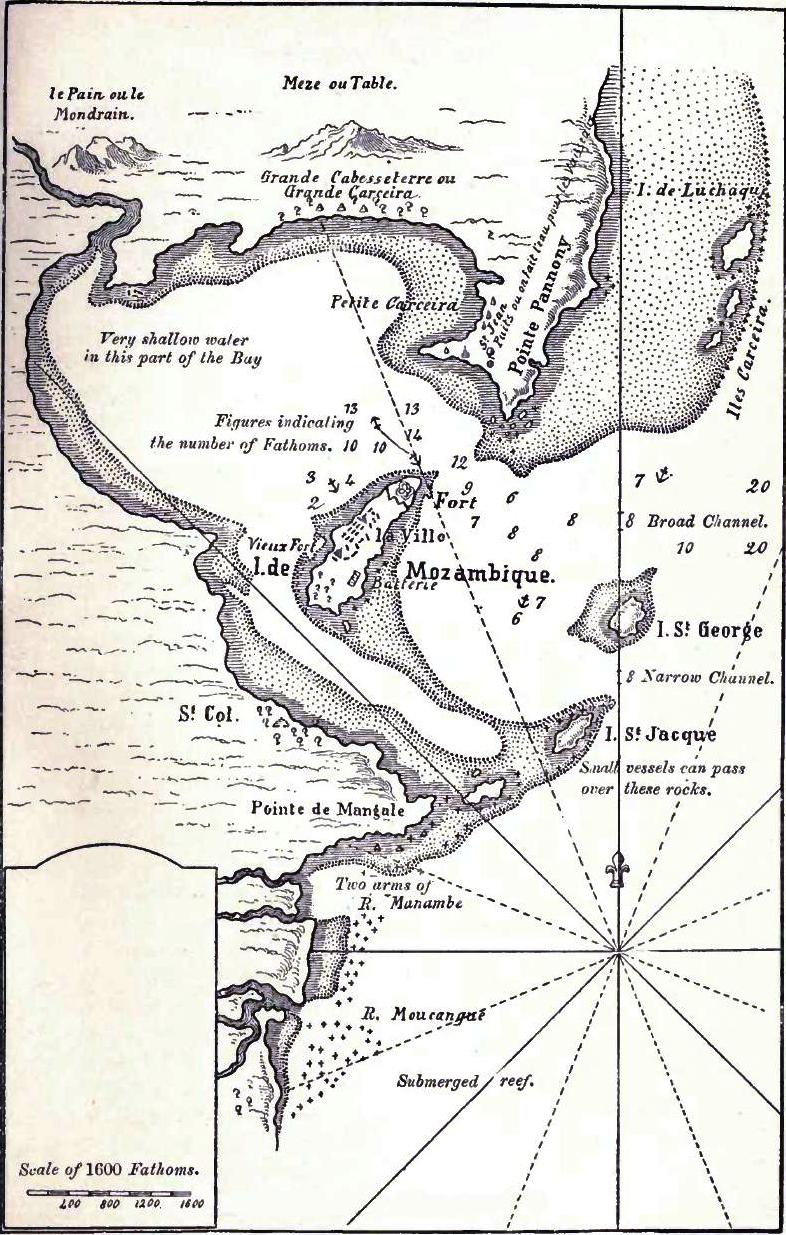

Map of Mozambique. Bibl. Nat. Estampes.

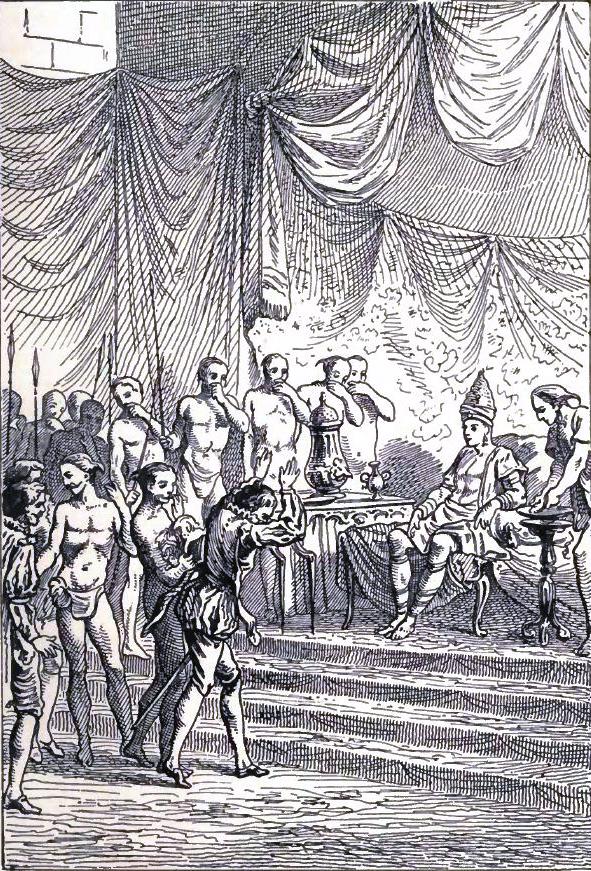

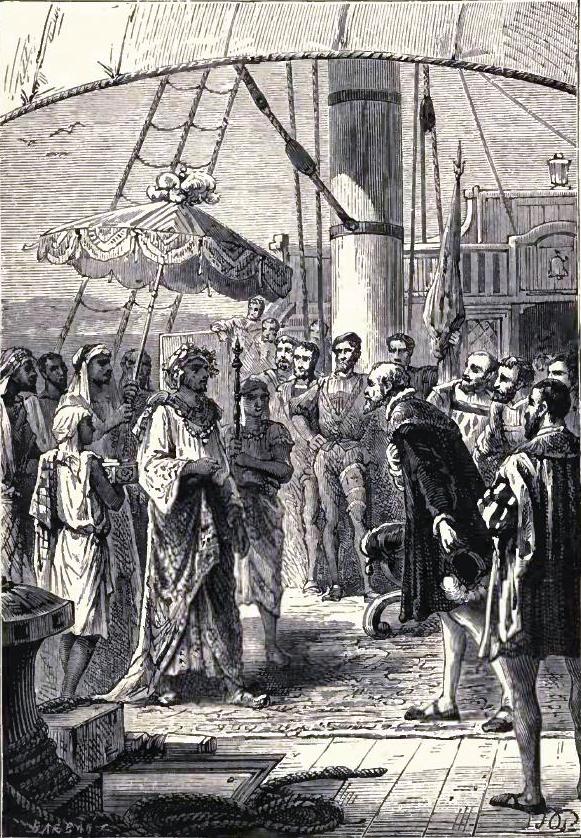

Interview with the Zamorin. "Hist. Gén. des Voyages," by Prévost. Vol. I., p. 39. 4to. An X. 20 vols. 1746.

View of Quiloa. From an engraving in the Cabinet des Estampes. Topography. (Africa).

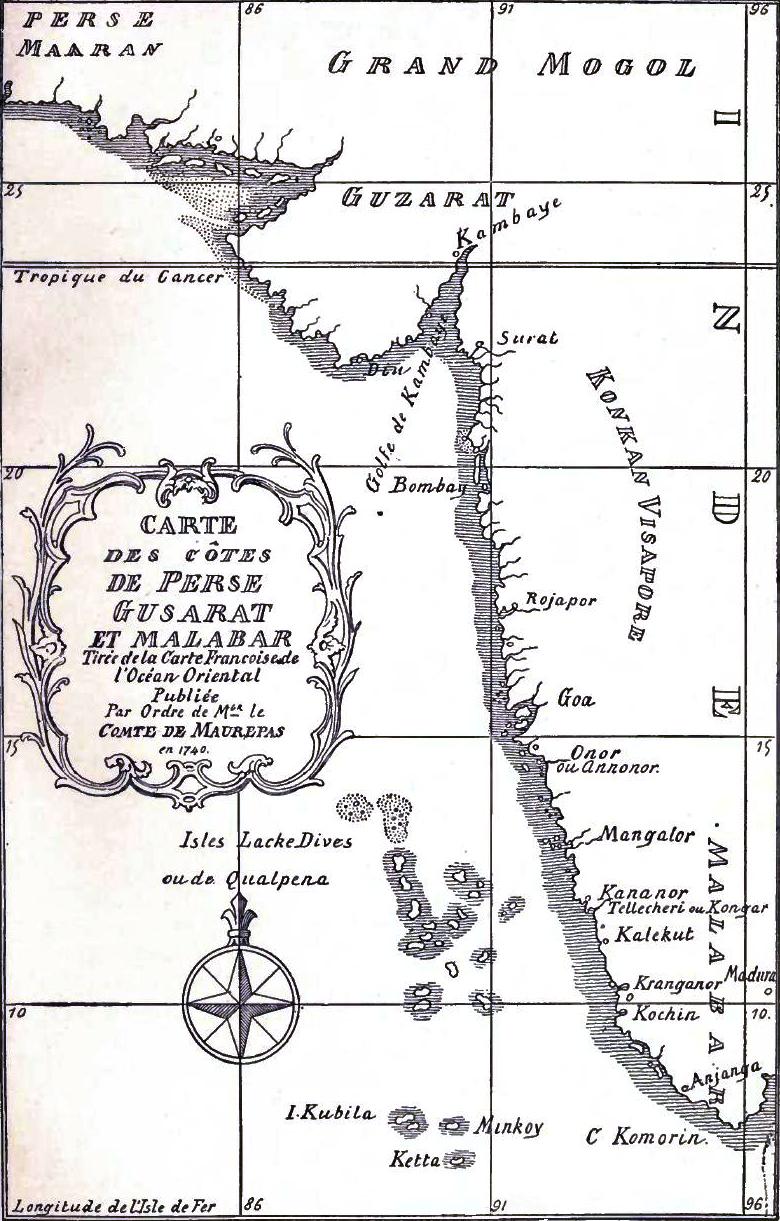

Map of the Coasts of Persia, Guzerat, and Malabar. From the French Map of the Eastern Ocean, pub. in 1740 by order of the Comte de Maurepas.

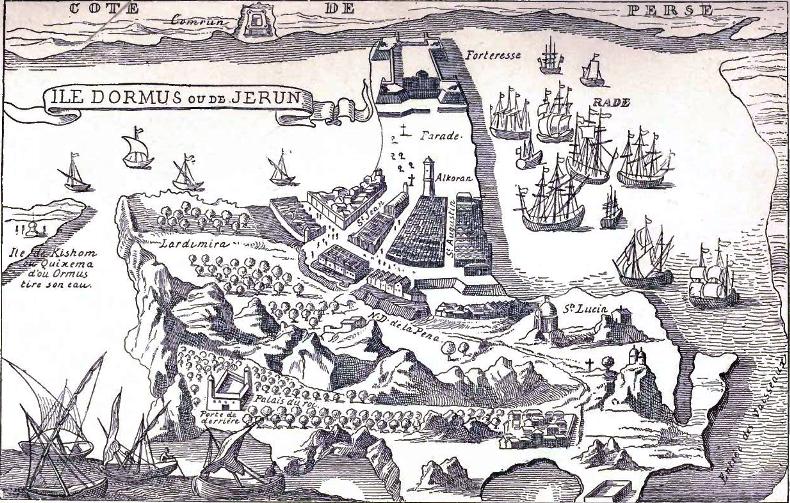

The Island of Ormuz. "Hist. Gén. des Voyages." Prévost. Vol. II., p. 98.

Americus Vespucius. From an engraving in the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

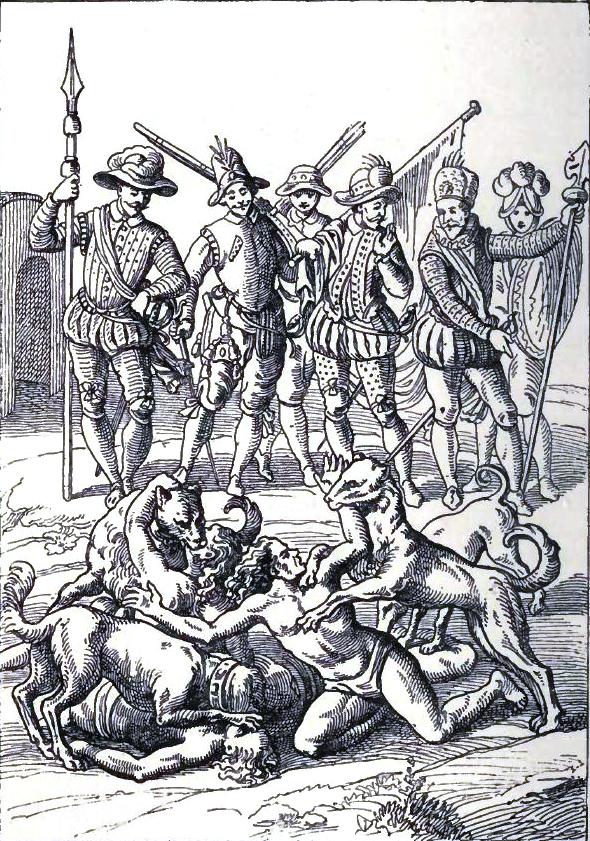

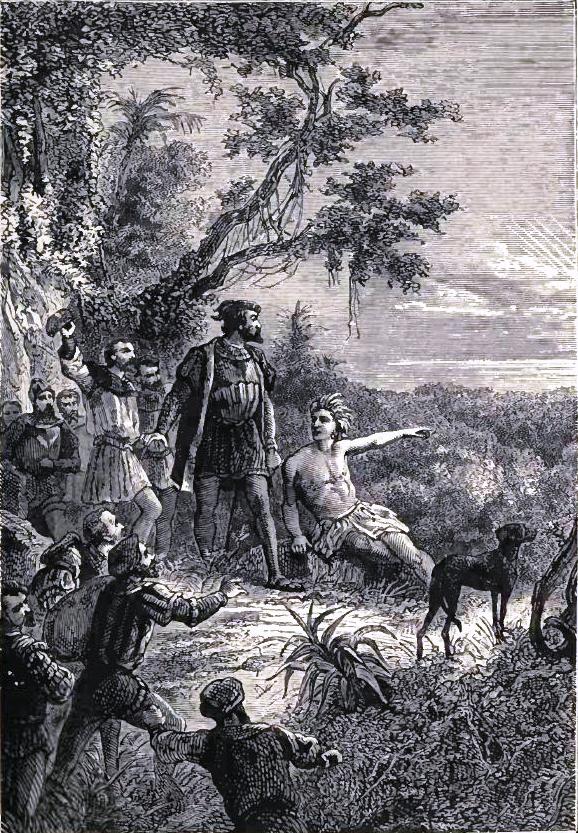

Indians devoured by dogs. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part IV., plate XXII.

Punishment of Indians. Page 17 of Las Casas' "Narratio regionum indicarum per Hispanos quosdam devastatarum," 4to. Francofurti, sumptibus Th. de Bry, 1698.

Portrait of F. Cortès. From an engraving after Velasquez in the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

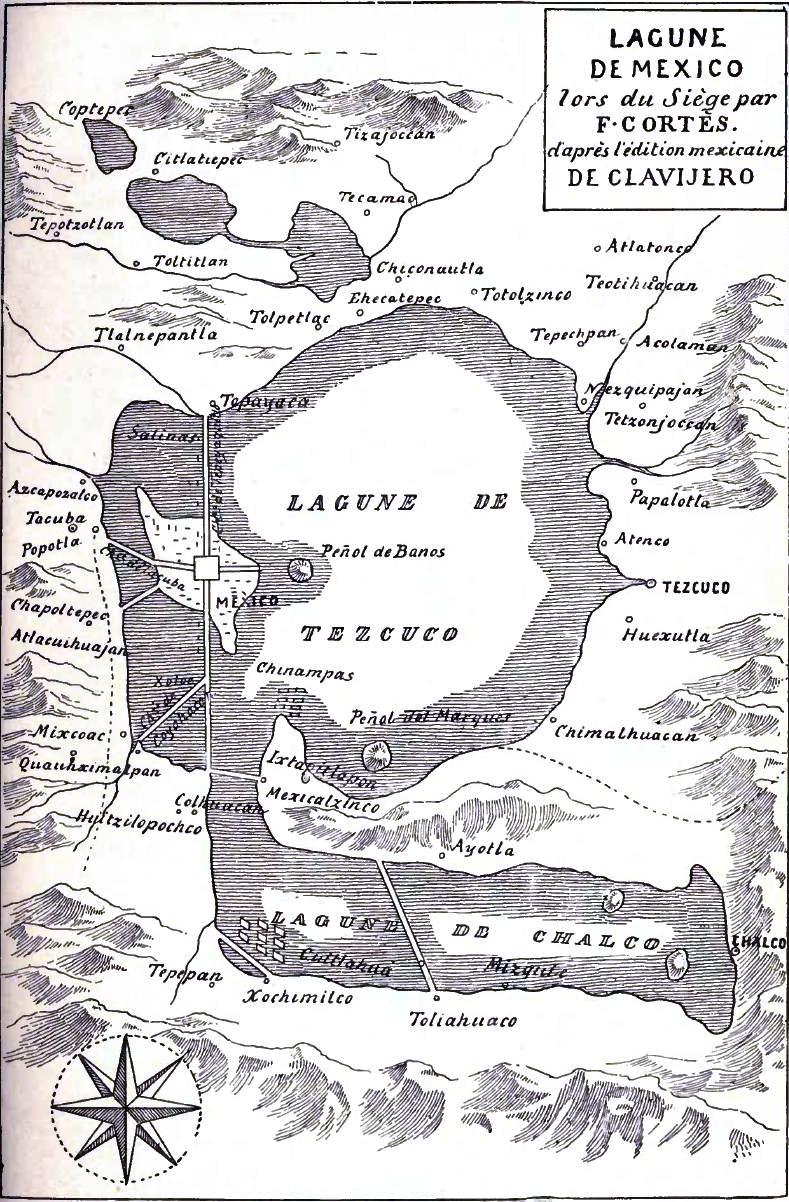

Plan of Mexico. From Clavigero and Bernal Diaz del Castillo. Jourdanet's translation, 2nd Edition.

Portrait of Pizarro. From an engraving in the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bib. Nat.

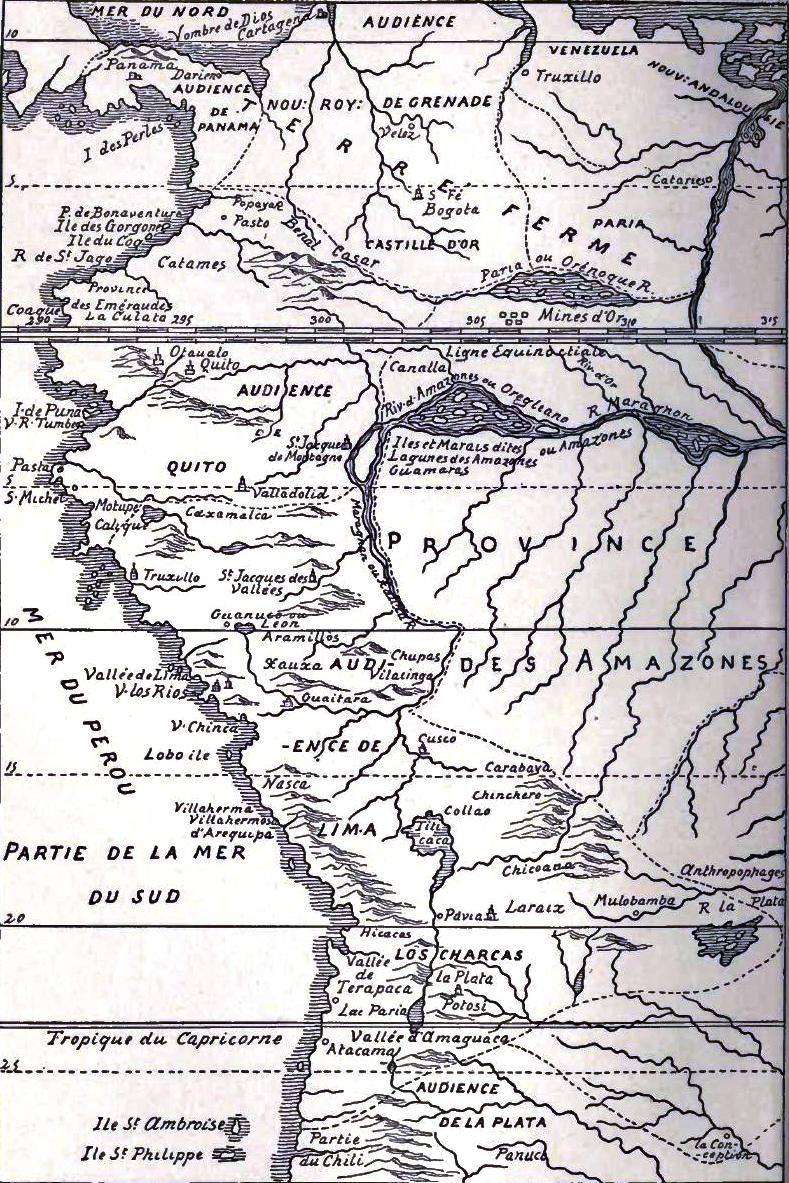

Map of Peru. From Garcilasso de la Vega. History of the Incas. 4to. Bernard, Amsterdam, 1738.

Atahualpa taken prisoner. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part VI., plate VII.

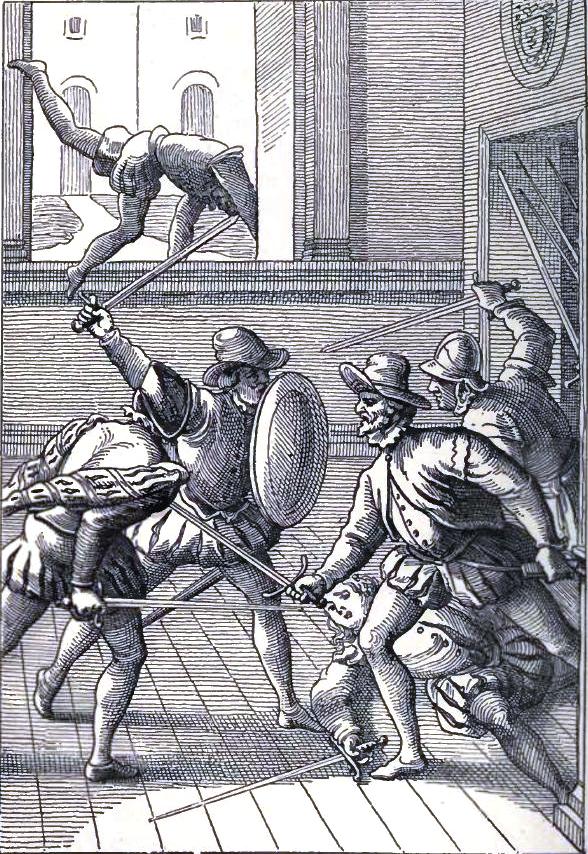

Assassination of Pizarro. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part VI., plate XV.

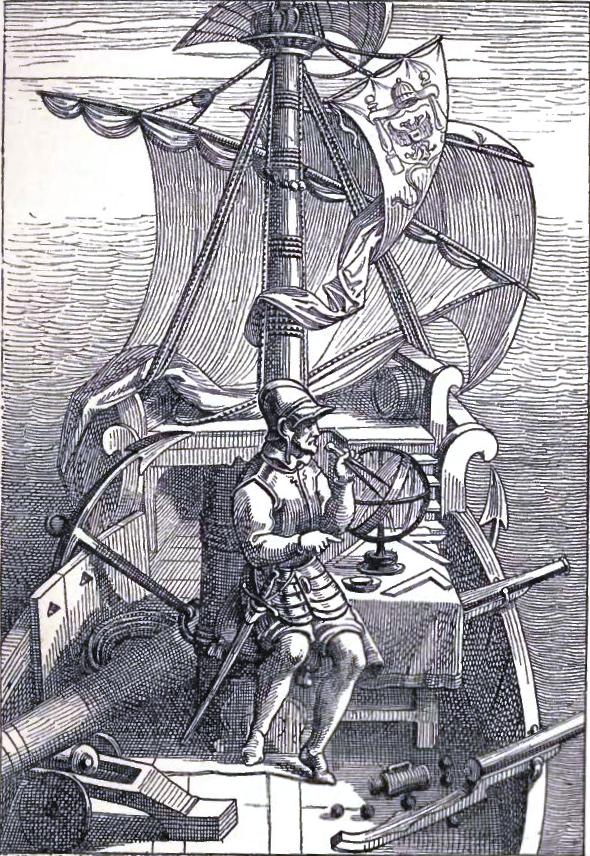

Magellan on board his caravel. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Americæ, part IV., plate XV.

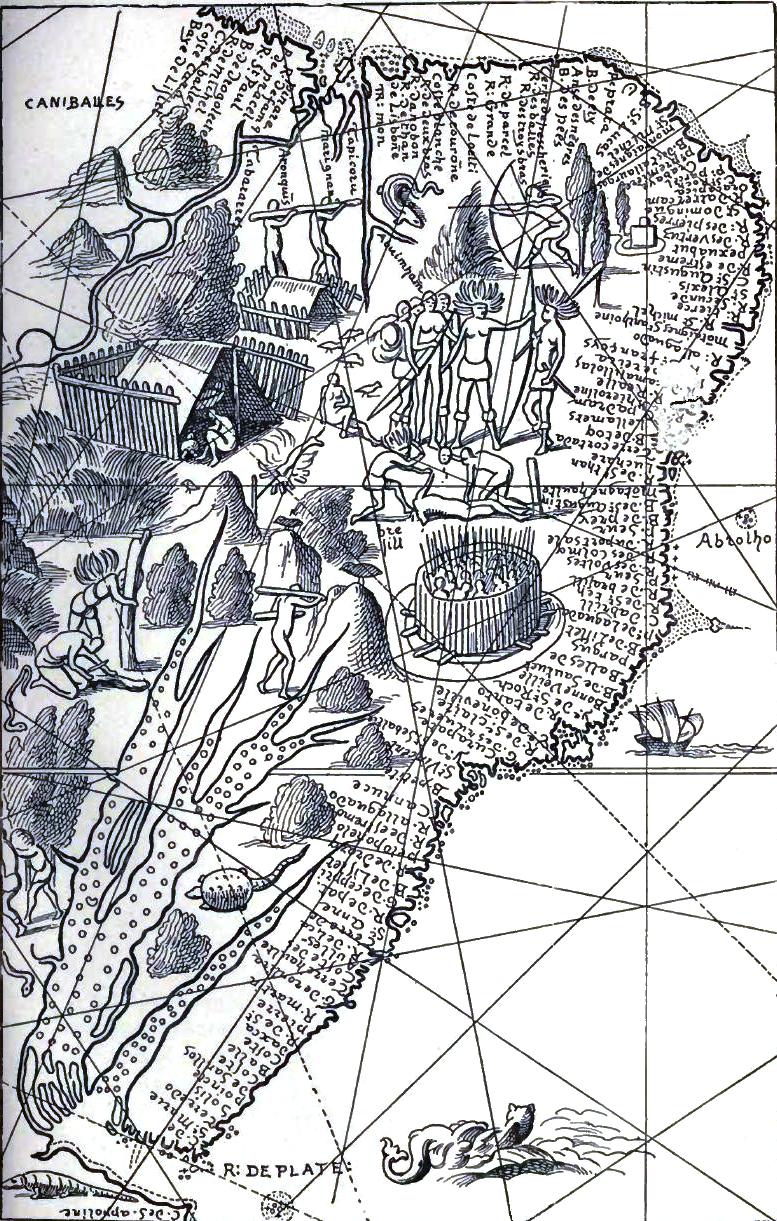

Map of the Coast of Brazil. From the map called Henry 2nd's. Bibl. Nat., Geographical collections.

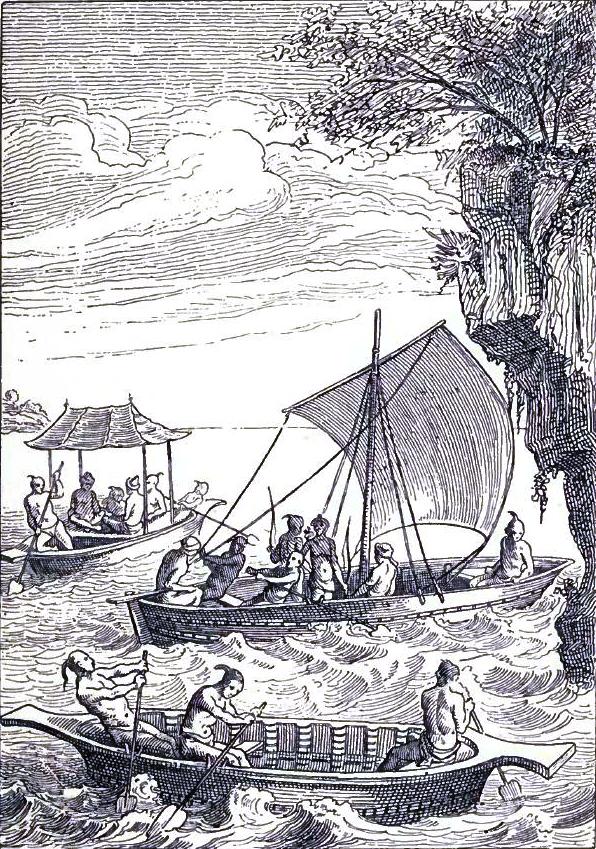

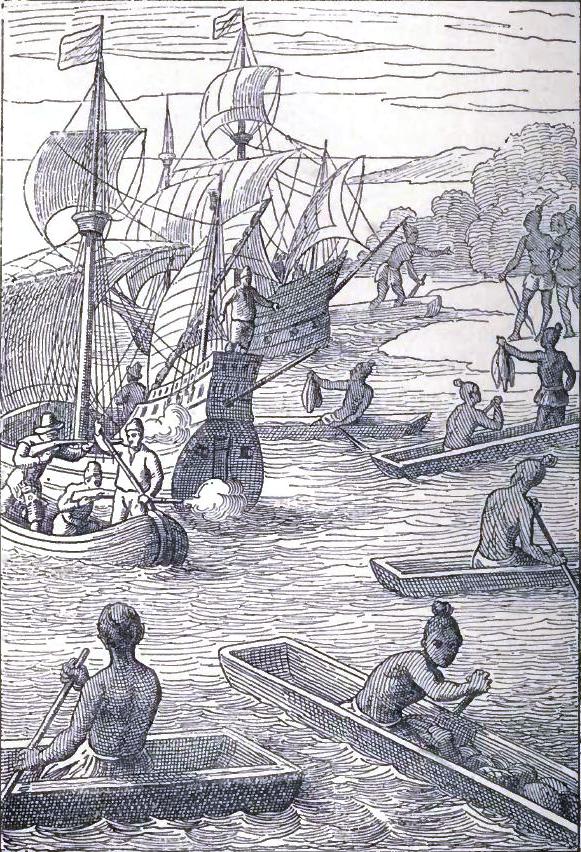

The Ladrone Islands. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Occidentalis Indiæ, pars VIII., p. 50.

Portrait of Sebastian Cabot. From a miniature engraved in "The remarkable Life, adventures, and discoveries of Sebastian Cabot," by Nicholls. 8vo. London, 1869.

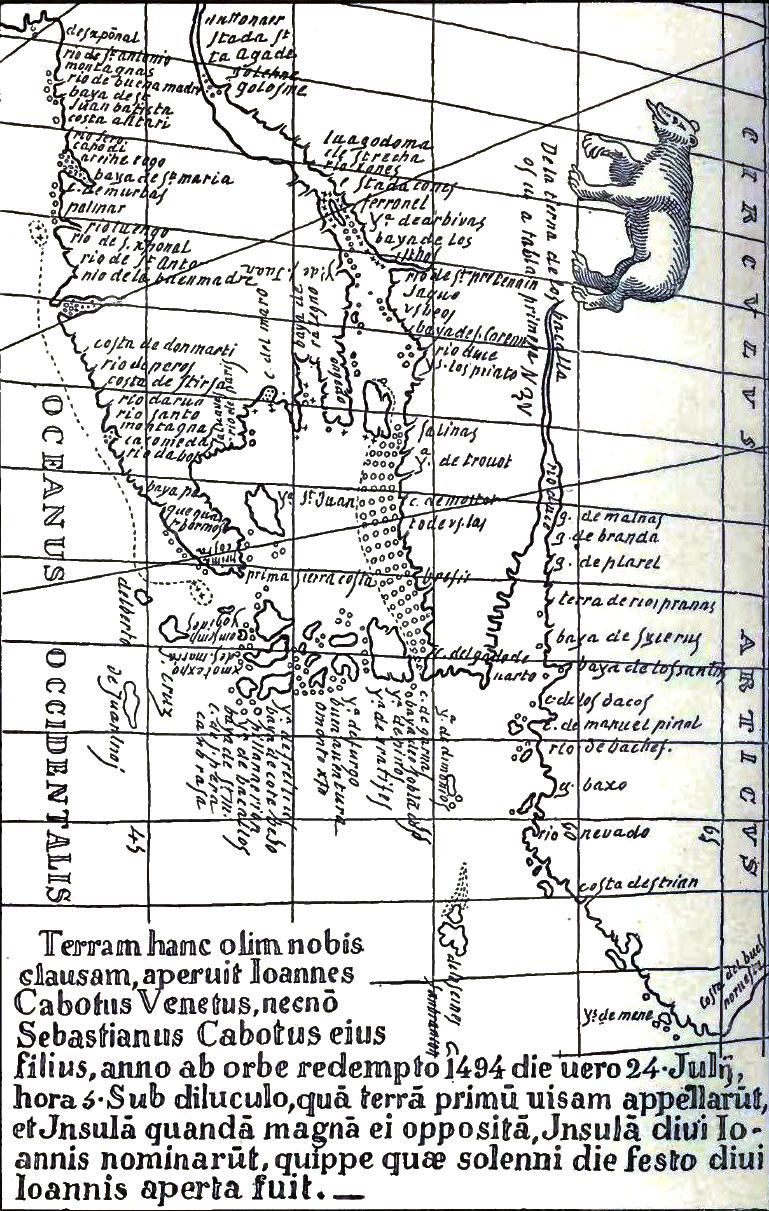

Fragment of Cabot's map. Bibl. Nat., Geographical collections.

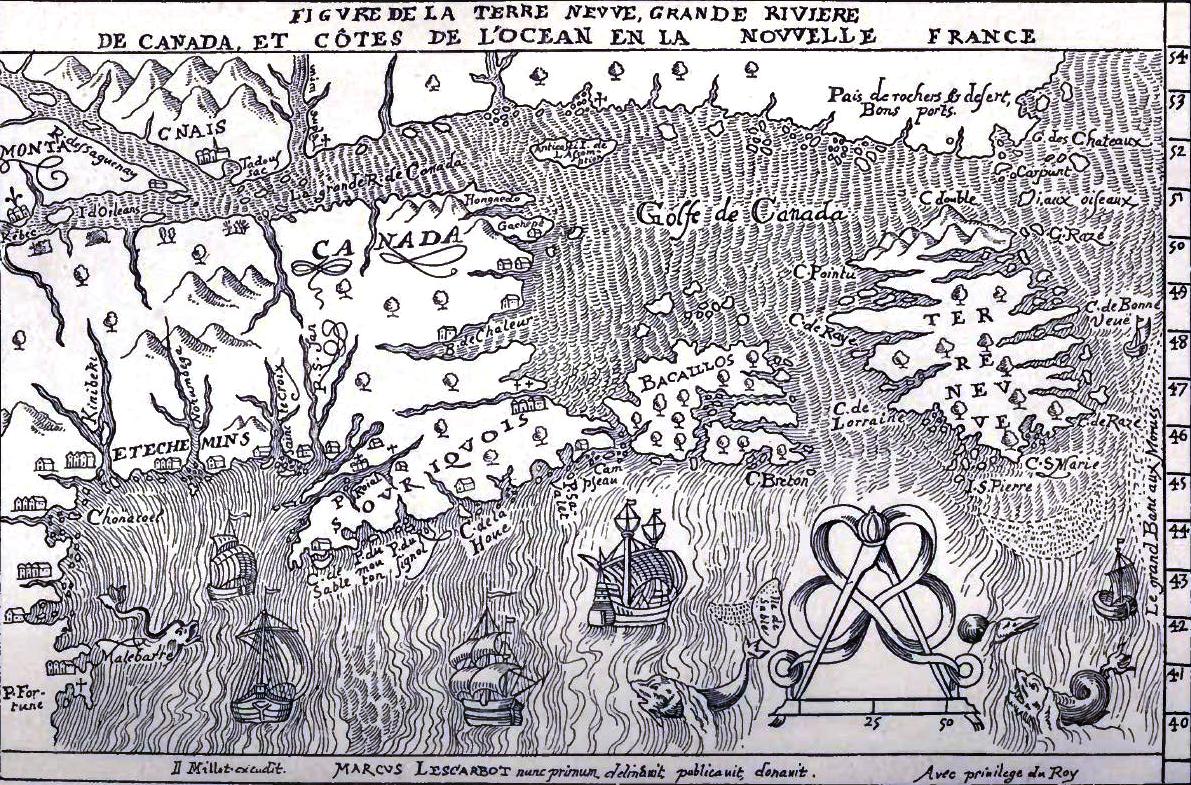

Map of Newfoundland and of the Mouth of the St. Lawrence. Lescarbot, "Histoire de la Nouvelle France." 12mo. Perier, Paris, 1617.

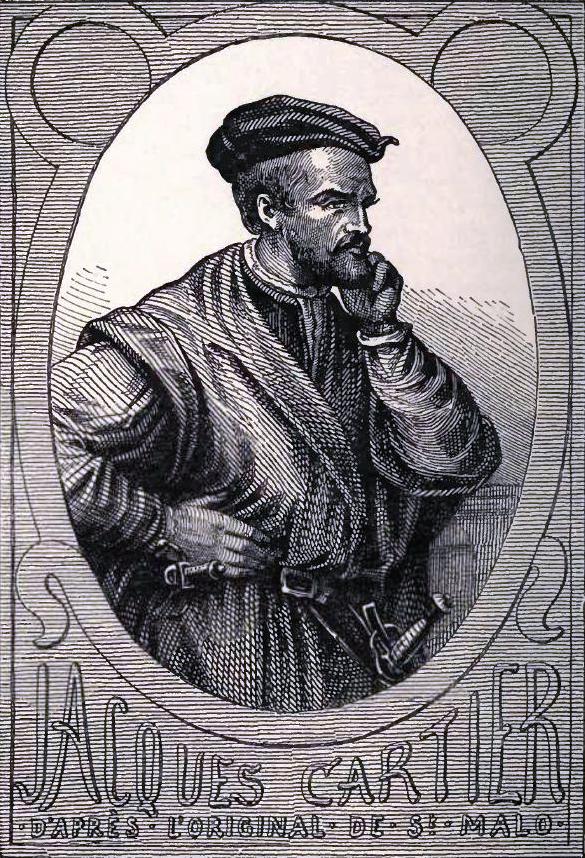

Portrait of Jacques Cartier. After Charlevoix. "History and general description of New France," translated by John Gilmary Shea, p. III. 6 vols. 4to. Shea, New York, 1866.

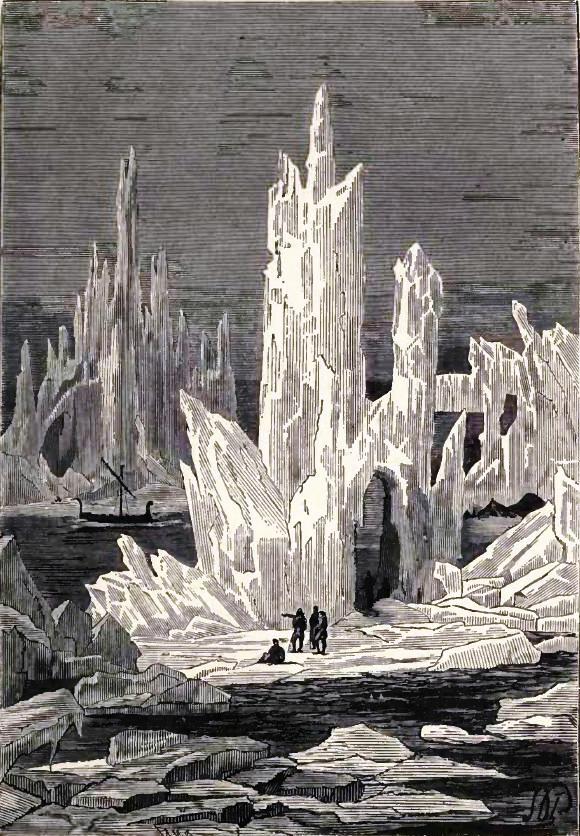

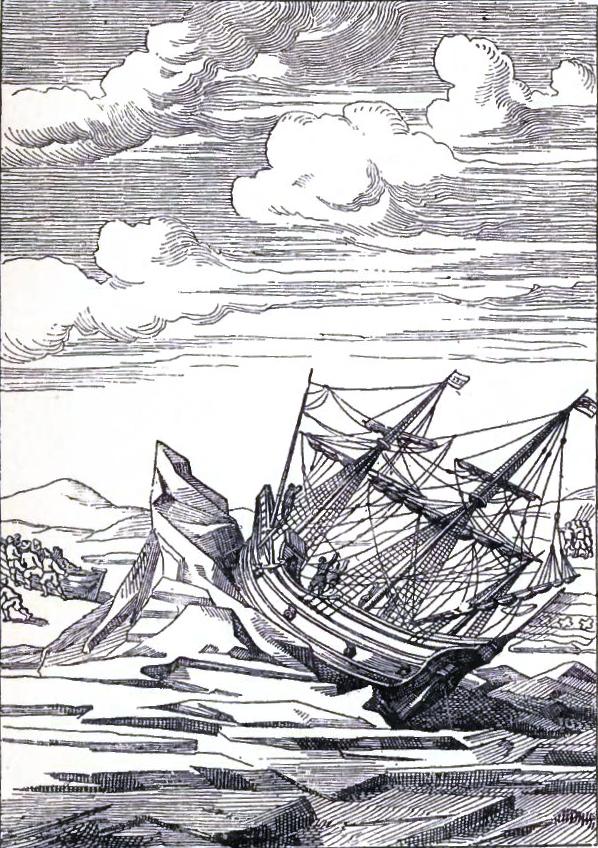

Barentz' ship fixed in the ice. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages. Tertia pars Indiæ Orientales, plate XLIV.

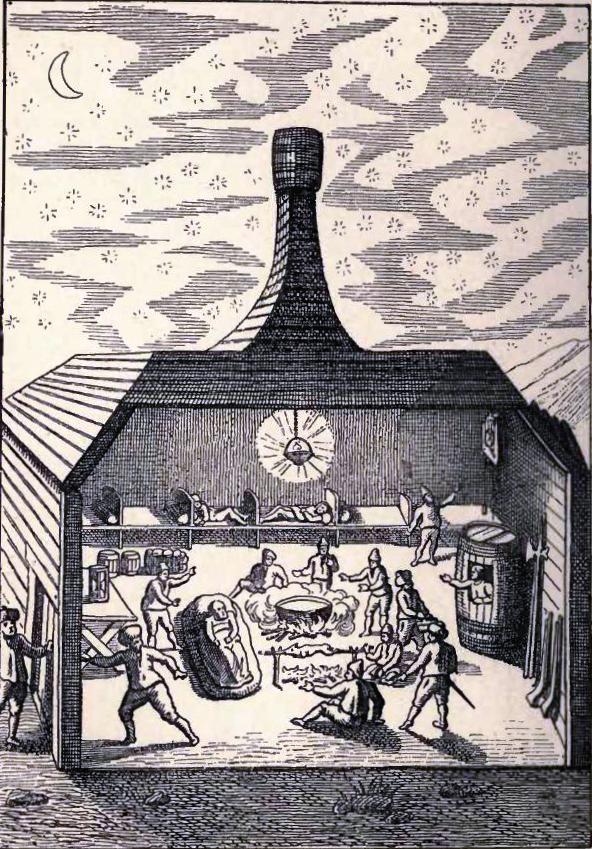

Interior of Barentz' house. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages. Tertia pars Indiæ Orientalis, plate XLVII.

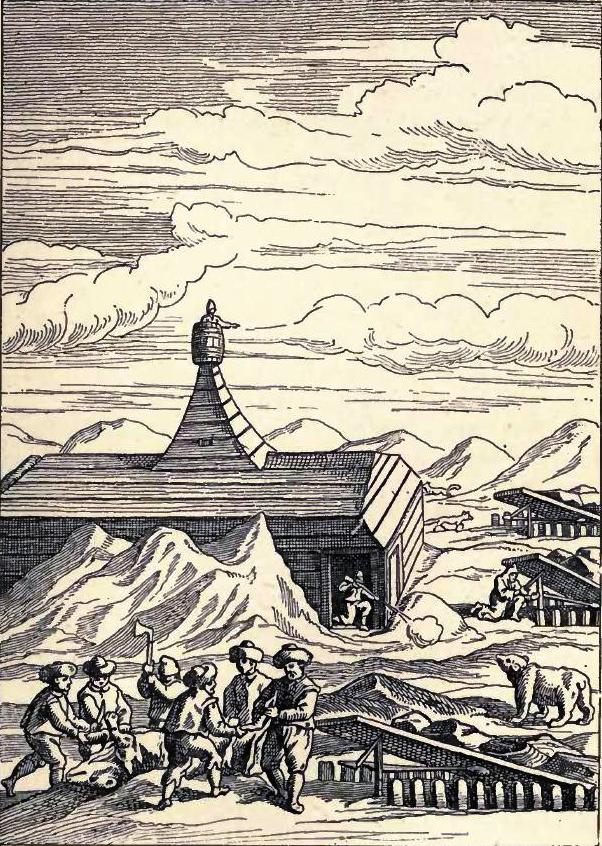

Exterior view of Barentz' house. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages. Tertia pars Indiæ Orientalis, plate XLVIII.

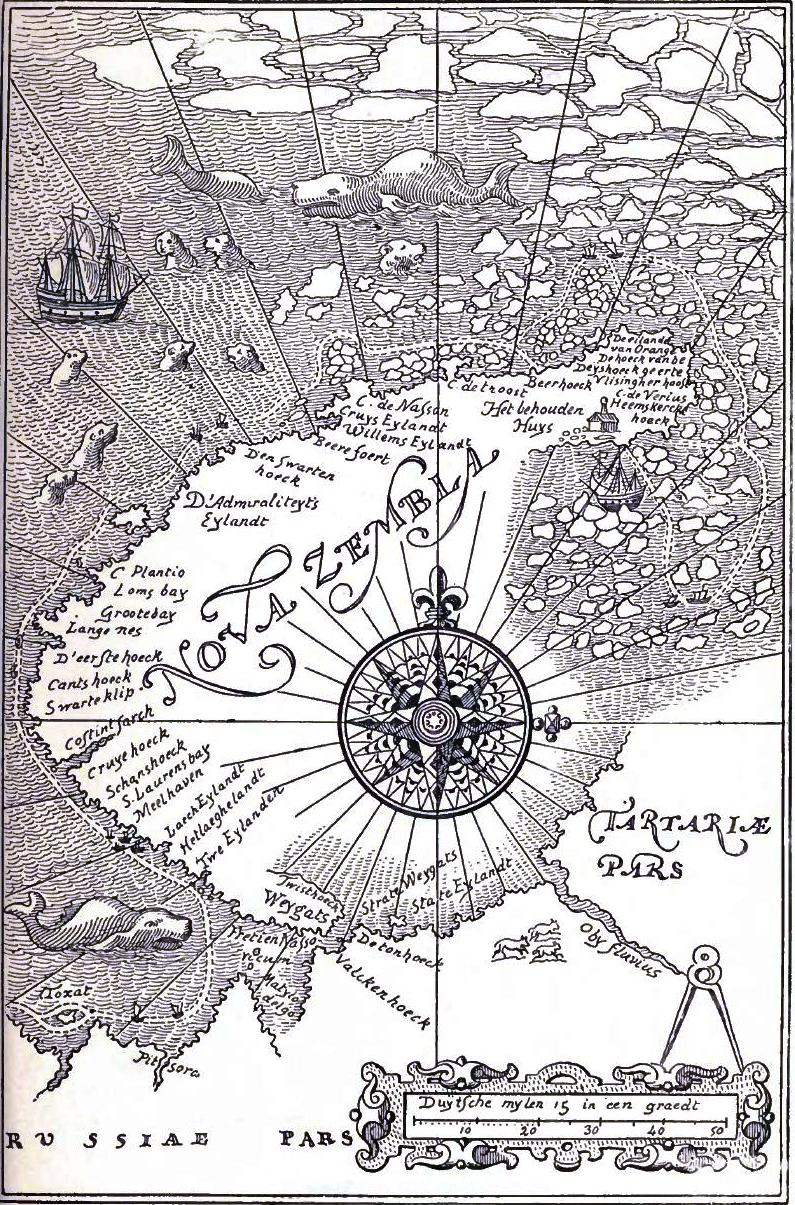

Map of Nova Zembla. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages. Tertia pars Indiæ Orientalis, plate LIX.

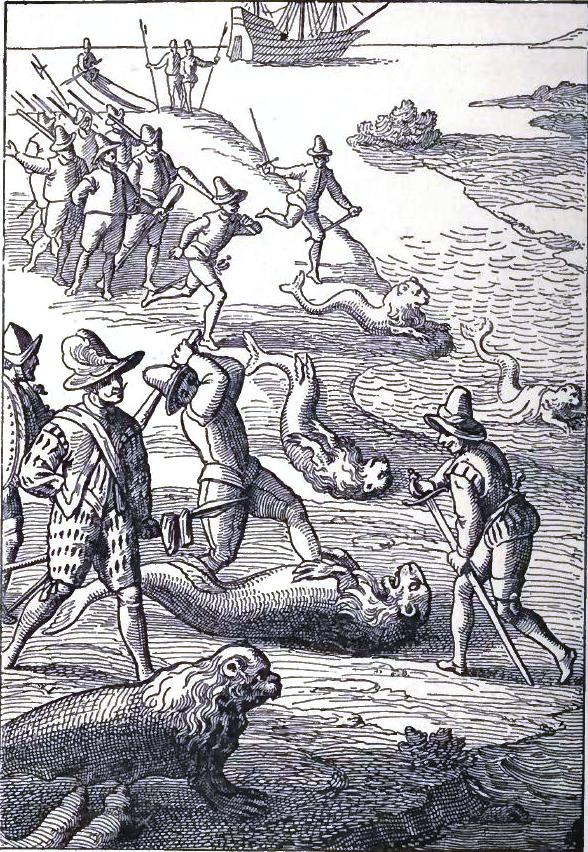

A sea-lion hunt. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, Occidentalis Indiæ, pars VIII., p. 37.

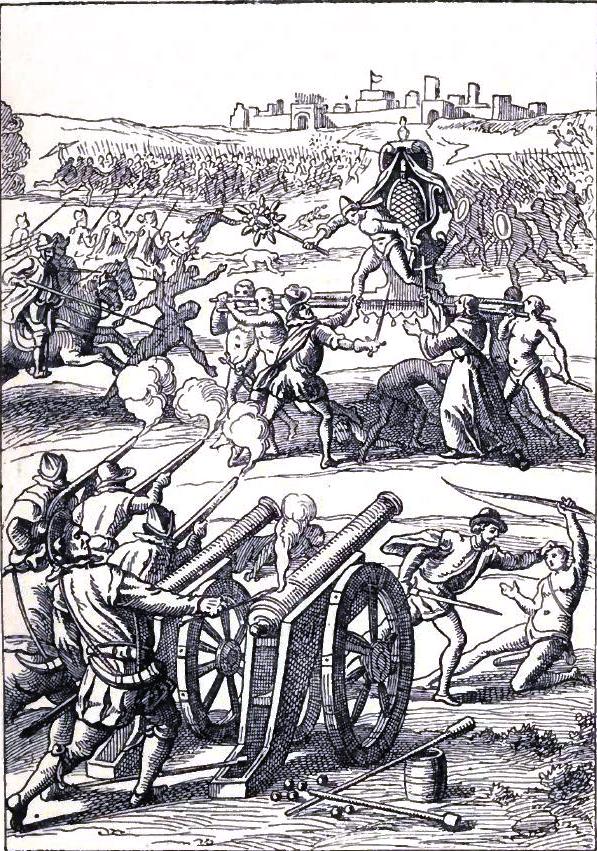

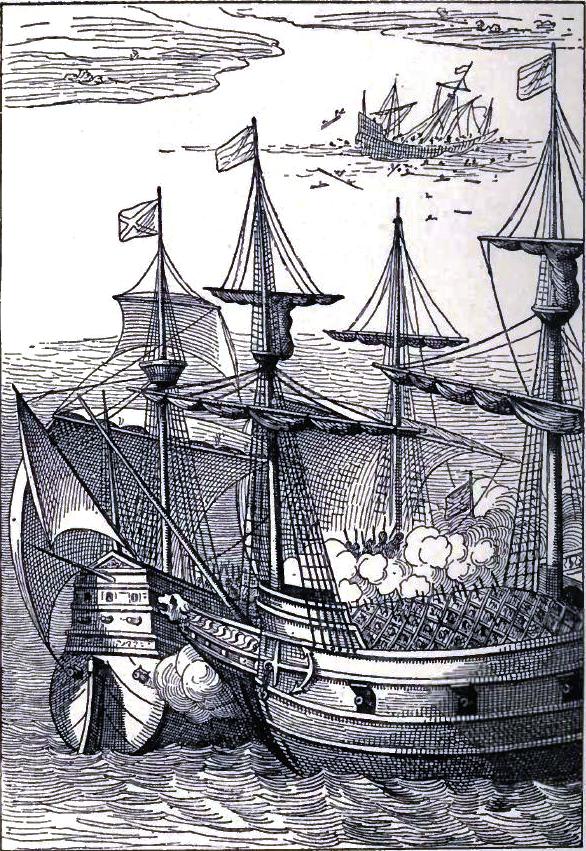

A fight between the Dutch and the Spaniards. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages, "Historiarum novi orbis;" part IX., book II., page 87.

Portrait of Raleigh. From an engraving in the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibl. Nat.

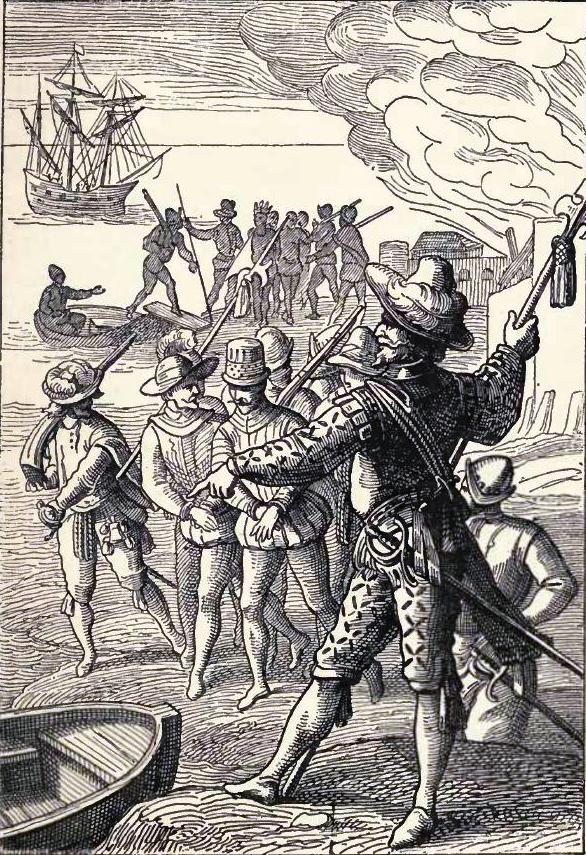

Berreo seized by Raleigh. Th. de Bry. Grands Voyages. Occid. Indiæ, part VIII., p. 64.

Portrait of Chardin. "Voyages de M. le Chevalier Chardin en Perse." Vol. I. 10 vols. 12mo. Ferrand, Rouen, 1723.

Japanese Archer. From a Japanese print engraved by Yule, vol. II., p. 206.

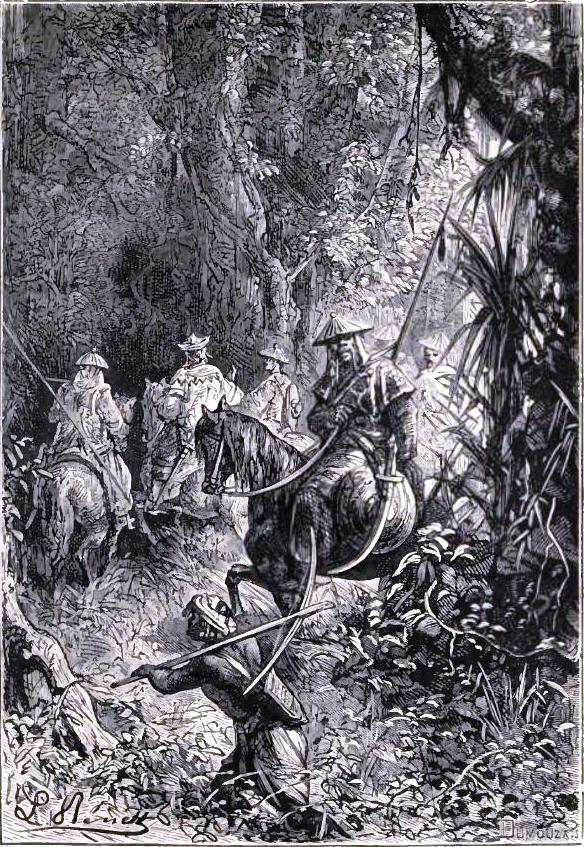

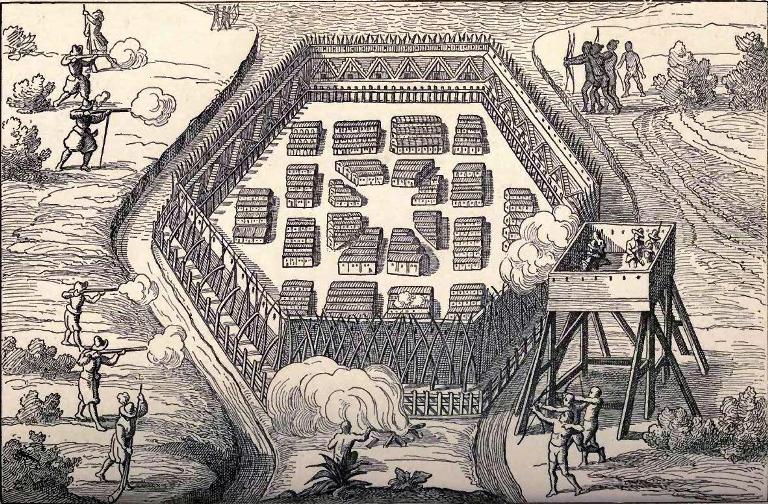

Attack upon an Indian Town. "Voyages du Sieur de Champlain," p. 44. 12mo. Collet, Paris, 1727.

HANNO—HERODOTUS—PYTHEAS—NEARCHUS—EUDOXUS—CÆSAR—STRABO—PAUSANIAS—FA-HIAN—COSMOS INDICOPLEUSTES—ARCULPHE—WILLIBALD—SOLEYMAN—BENJAMIN OF TUDELA—PLAN DE CARPIN—RUBRUQUIS—MARCO POLO—IBN BATUTA—JEAN DE BÉTHENCOURT—CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS—COVILHAM AND PAÏVA—VASCO DA GAMA—ALVARÈS CABRAL—JOAO DA NOVA—DA CUNHA—ALMEIDA—ALBUQUERQUE.

HOJEDA—AMERICUS VESPUCIUS—JUAN DE LA COSA—YAÑEZ PINZON—DIAZ DE SOLIS—PONCE DE LEON—BALBOA—GRIJALVA—CORTÈS—PIZARRO—ALMAGRO—ALVARADO—ORELLANA—MAGELLAN—ERIC THE RED—THE ZENI—THE CORTEREALS—THE CABOTS—WILLOUGHBY—CHANCELLOR—VERRAZZANO—JACQUES CARTIER—FROBISHER—JOHN DAVIS—BARENTZ AND HEEMSKERKE—DRAKE—CAVENDISH—DE NOORT—W. RALEIGH—LEMAIRE AND SCHOUTEN—TASMAN—MENDANA—QUIROS AND TORRÈS—PYRARD DE LAVAL—PIETRO DELLA VALLE—TAVERNIER—THÉVENOT—BERNIER—ROBERT KNOX—CHARDIN—DE BRUYN—KÆMPFER—WILLIAM DAMPIER—HUDSON AND BAFFIN—CHAMPLAIN AND LA SALE.

This narrative will comprehend not only all the explorations made in past ages, but also all the new discoveries which have of late years so greatly interested the scientific world. In order to give to this work—enlarged perforce by the recent labours of modern travellers,—all the accuracy possible, I have called in the aid of a man whom I with justice regard as one of the most competent geographers of the present day: M. Gabriel Marcel, attached to the Bibliothèque Nationale.

With the advantage of his acquaintance with several foreign languages which are unknown to me, we have been able to go to the fountain-head, and to derive all information from absolutely original documents. Our readers will, therefore, render to M. Marcel the credit due to him for his share in a work which will demonstrate what manner of men the great travellers have been, from the time of Hanno and Herodotus down to that of Livingstone and Stanley.

Hanno, the Carthaginian—Herodotus visits Egypt, Lybia, Ethiopia, Phoenicia, Arabia, Babylon, Persia, India, Media, Colchis, the Caspian Sea, Scythia, Thrace, and Greece—Pytheas explores the coasts of Iberia and Gaul, the English Channel, the Isle of Albion, the Orkney Islands, and the land of Thule—Nearchus visits the Asiatic coast, from the Indus to the Persian Gulf—Eudoxus reconnoitres the West Coast of Africa—Cæsar conquers Gaul and Great Britain—Strabo travels over the interior of Asia, and Egypt, Greece, and Italy

Pliny, Hippalus, Arian, and Ptolemy—Pausanias visits Attica, Corinth, Laconia, Messenia, Elis, Achaia, Arcadia, Boeotia, and Phocis—Fa-Hian explores Kan-tcheou, Tartary, Northern India, the Punjaub, Ceylon, and Java—Cosmos Indicopleustes, and the Christian Topography of the Universe—Arculphe describes Jerusalem, the valley of Jehoshaphat, the Mount of Olives, Bethlehem, Jericho, the river Jordan, Libanus, the Dead Sea, Capernaum, Nazareth, Mount Tabor, Damascus, Tyre, Alexandria, and Constantinople—Willibald and the Holy Land—Soleyman travels through Ceylon, and Sumatra, and crosses the Gulf of Siam and the China Sea

The Scandinavians in the North, Iceland and Greenland—Benjamin of Tudela visits Marseilles, Rome, Constantinople, the Archipelago, Palestine, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Damascus, Baalbec, Nineveh, Baghdad, Babylon, Bassorah, Ispahan, Shiraz, Samarcand, Thibet, Malabar, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Egypt, Sicily, Italy, Germany, and France—Carpini explores Turkestan—Manners and customs of the Tartars—Rubruquis and the Sea of Azov, the Volga, Karakorum, Astrakhan, and Derbend

The interest of the Genoese and Venetian merchants in encouraging the exploration of Central Asia—The family of Polo, and its position in Venice—Nicholas and Matteo Polo, the two brothers—They go from Constantinople to the Court of the Emperor of China—Their reception at the Court of Kublaï-Khan—The Emperor appoints them his ambassadors to the Pope—Their return to Venice—Marco Polo—He leaves his father Nicholas and his uncle Matteo for the residence of the King of Tartary—The new Pope Gregory X.—The narrative of Marco Polo is written in French from his dictation, by Rusticien of Pisa

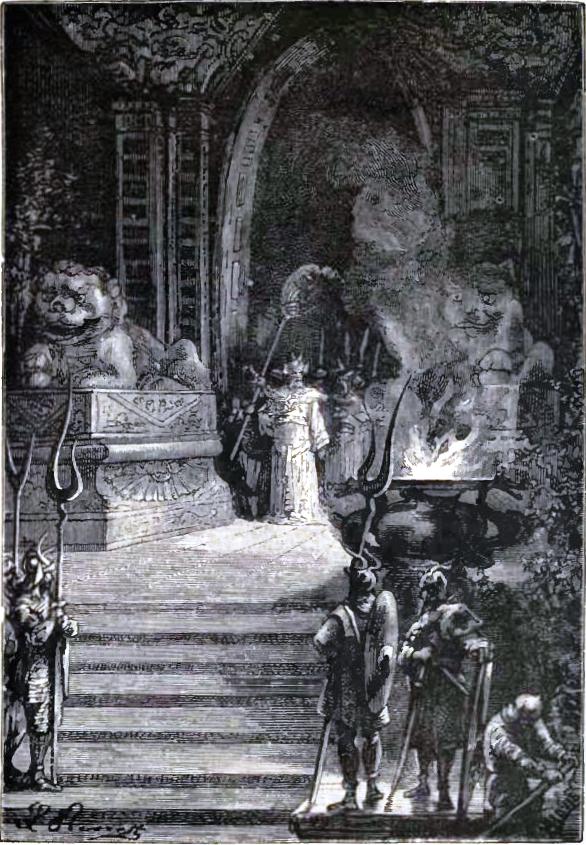

Armenia Minor—Armenia—Mount Ararat—Georgia—Mosul, Baghdad, Bussorah, Tauris—Persia—The Province of Kirman—Comadi—Ormuz—The Old Man of the Mountain—Cheburgan—Balkh—Cashmir—Kashgar—Samarcand—Kotan—The Desert—Tangun—Kara-Korum—Signan-fu—The Great Wall—Chang-tou—The residence of Kublaï-Khan—Cambaluc, now Pekin—The Emperor's fêtes—His hunting—Description of Pekin—Chinese Mint and bank-notes—The system of posts in the Empire

Tso-cheu—Tai-yen-fou—Pin-yang-fou—The Yellow River—Signan-fou—Szu-tchouan—Ching-tu-fou—Thibet—Li-kiang-fou—Carajan—Yung-tchang—Mien—Bengal—Annam—Tai-ping—Cintingui—Sindifoo—Té-cheu—Tsi-nan-fou—Lin-tsin-choo—Lin-sing—Mangi—Yang-tcheu-fou—Towns on the coast—Quin-say or Hang-tcheou-foo—Fo-kien

Japan—Departure of the three Venetians with the Emperor's daughter and the Persian ambassadors—Sai-gon—Java—Condor—Bintang—Sumatra—The Nicobar Islands—Ceylon—The Coromandel coast—The Malabar coast—The Sea of Oman—The island of Socotra—Madagascar—Zanzibar and the coast of Africa—Abyssinia—Yemen—Hadramaut and Oman—Ormuz—The return to Venice—A feast in the household of Polo—Marco Polo a Genoese prisoner—Death of Marco Polo about 1323

Ibn Batuta—The Nile—Gaza, Tyre, Tiberias, Libanus, Baalbec, Damascus, Meshid, Bussorah, Baghdad, Tabriz, Mecca and Medina—Yemen—Abyssinia—The country of the Berbers—Zanguebar—Ormuz—Syria—Anatolia—Asia Minor—Astrakhan—Constantinople—Turkestan—Herat—The Indus—Delhi—Malabar—The Maldives—Ceylon—The Coromandel coast—Bengal—The Nicobar Islands—Sumatra—China—Africa—The Niger—Timbuctoo

The Norman cavalier—His ideas of conquest—What was known of the Canary Islands—Cadiz—The Canary Archipelago—Graciosa—Lancerota—Fortaventura—Jean de Béthencourt returns to Spain—Revolt of Berneval—His interview with King Henry III.—Gadifer visits the Canary Archipelago—Canary Island or "Gran Canaria"—Ferro Island—Palma Island

The return of Jean de Béthencourt—Gadifer's jealousy—Béthencourt visits his archipelago—Gadifer goes to conquer Gran Canaria—Disagreement of the two commanders—Their return to Spain—Gadifer blamed by the King—Return of Béthencourt—The natives of Fortaventura are baptized—Béthencourt revisits Caux—Returns to Lancerota—Lands on the African coast—Conquest of Gran Canaria, Ferro, and Palma Islands—Maciot appointed Governor of the archipelago—Béthencourt obtains the Pope's consent to the Canary Islands being made an Episcopal See—His return to his country and his death

Discovery of Madeira, Cape de Verd Islands, the Azores, Congo, and Guinea—Bartholomew Diaz—Cabot and Labrador—The geographical and commercial tendencies of the middle ages—The erroneous idea of the distance between Europe and Asia—Birth of Christopher Columbus—His first voyages—His plans rejected—His sojourn at the Franciscan convent—His reception by Ferdinand and Isabella—Treaty of the 17th of April, 1492—The brothers Pinzon—Three armed caravels at the port of Palos—Departure on the 3rd of August, 1492

First voyage: The Great Canary—Gomera—Magnetic variation—Symptoms of revolt—Land, land—San Salvador—Taking possession—Conception—Fernandina or Great Exuma—Isabella, or Long Island—The Mucaras—Cuba—Description of the island—Archipelago of Notre-Dame—Hispaniola or San Domingo—Tortuga Island—The cacique on board the Santa-Maria—The caravel of Columbus goes aground and cannot be floated off—Island of Monte-Christi—Return—Tempest—Arrival in Spain—Homage rendered to Christopher Columbus

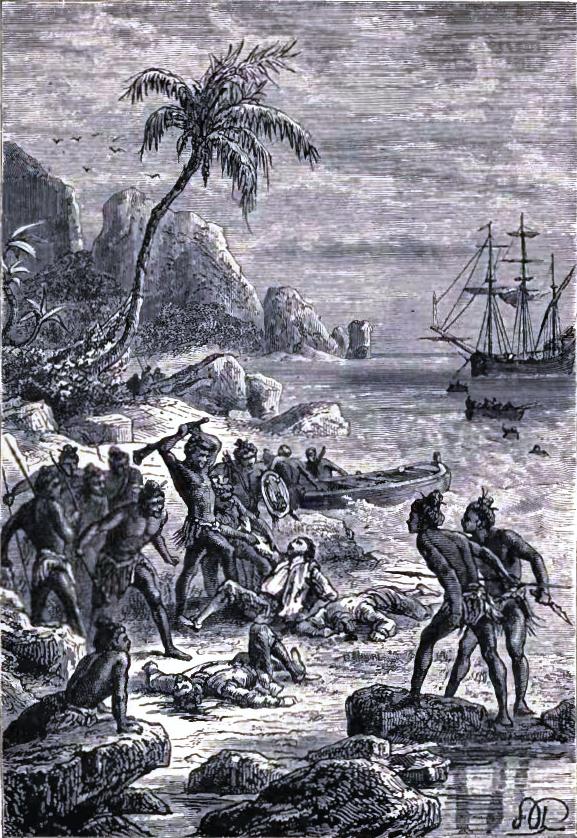

Second Voyage: Flotilla of seventeen vessels—Island of Ferro—Dominica—Marie-Galante—Guadaloupe—The Cannibals—Montserrat—Santa-Maria-la-Rodonda—St. Martin and Santa Cruz—Archipelago of the Eleven Thousand Virgins—The island of St. John Baptist, or Porto Rico—Hispaniola—The first Colonists massacred—Foundation of the town of Isabella—Twelve ships laden with treasure sent to Spain—Fort St. Thomas built in the Province of Cibao—Don Diego, Columbus' brother, named Governor of the Island—Jamaica—The Coast of Cuba—The Remora—Return to Isabella—The Cacique made prisoner—Revolt of the Natives—Famine—Columbus traduced in Spain—Juan Aguado sent as Commissary to Isabella—Gold-mines—Departure of Columbus—His arrival at Cadiz

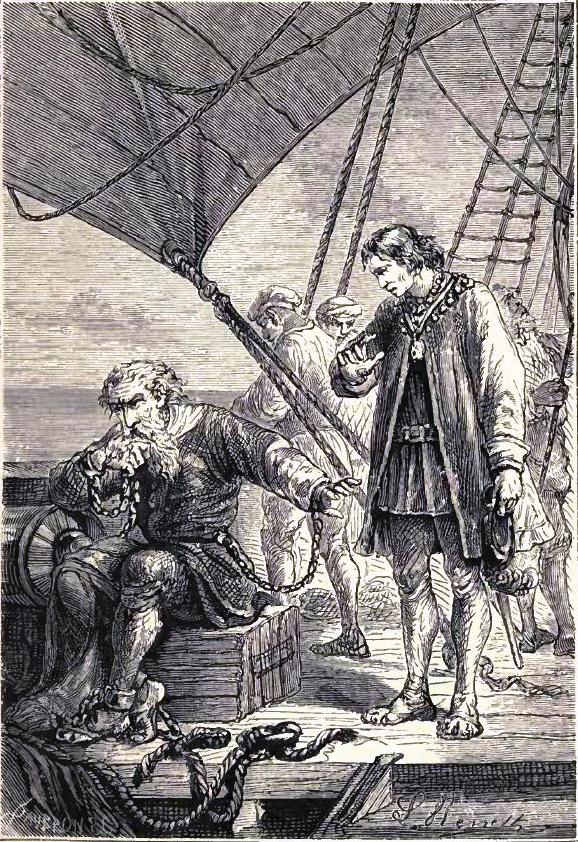

Third Voyage: Madeira—Santiago in the Cape Verd Archipelago—Trinidad—First sight of the American Coast in Venezuela, beyond the Orinoco, now the Province of Cumana—Gulf of Paria—The Gardens—Tobago—Grenada—Margarita—Cubaga—Hispaniola during the absence of Columbus—Foundation of the town of San Domingo—Arrival of Columbus—Insubordination in the Colony—Complaints in Spain—Bovadilla sent by the king to inquire into the conduct of Columbus—Columbus sent to Europe in fetters with his two brothers—His appearance before Ferdinand and Isabella—Renewal of royal favour

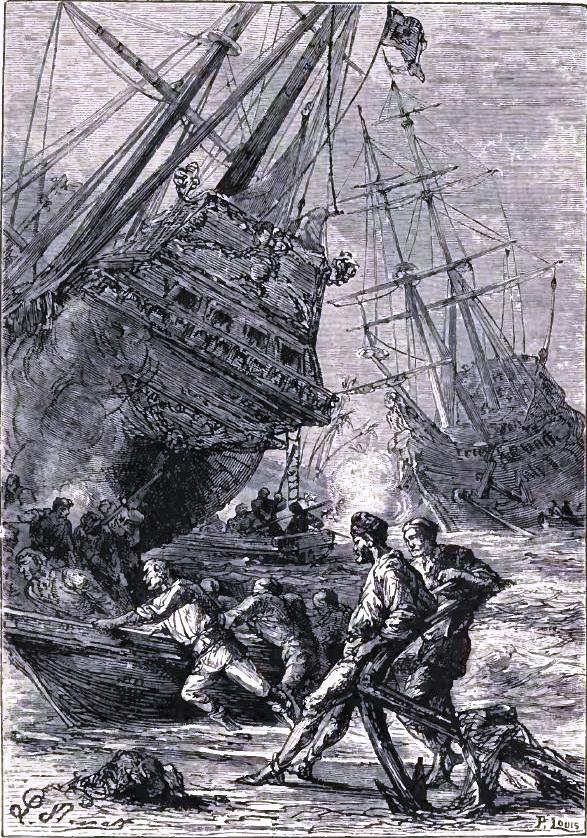

Fourth Voyage: A Flotilla of four vessels—Canary Islands—Martinique—Dominica—Santa-Cruz—Porto-Rico—Hispaniola—Jamaica—Cayman Island—Pinos Island—Island of Guanaja—Cape Honduras—The American Coast of Truxillo on the Gulf of Darien—The Limonare Islands—Huerta—The Coast of Veragua—Auriferous Strata—Revolt of the Natives—The Dream of Columbus—Porto-Bello—The Mulatas—Putting into port at Jamaica—Distress—Revolt of the Spaniards against Columbus—Lunar Eclipse—Arrival of Columbus at Hispaniola—Return of Columbus to Spain—His death, on the 20th of March, 1506

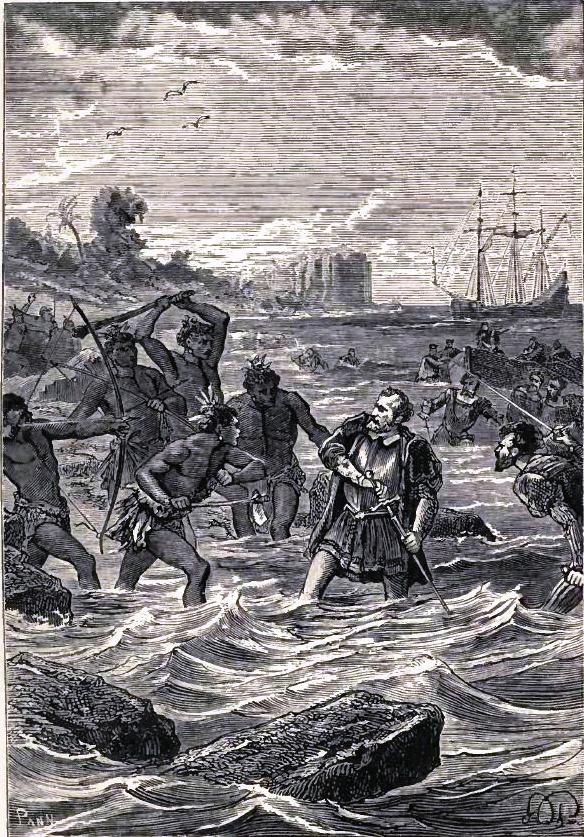

Covilham and Païva—Vasco da Gama—The Cape of Good Hope is doubled—Escalès at Sam-Braz—Mozambique, Mombaz, and Melinda—Arrival at Calicut—Treason of the Zamorin—Battles—Return to Europe—The scurvy—Death of Paul da Gama—Arrival at Lisbon

Alvarès Cabral—Discovery of Brazil—The coast of Africa—Arrival at Calicut, Cochin, Cananore—Joao da Nova—Gama's second expedition—The King of Cochin—The early life of Albuquerque—The taking of Goa—The siege and capture of Malacca—Second expedition against Ormuz—Ceylon—The Moluccas—Death of Albuquerque—Fate of the Portuguese empire of the Indies

Hojeda—Americus Vespucius—The New World named after him—Juan de la Cosa—Vincent Yañez Pinzon—Bastidas—Diego de Lepe—Diaz de Solis—Ponce de Leon and Florida—Balboa discovers the Pacific Ocean—Grijalva explores the coast of Mexico

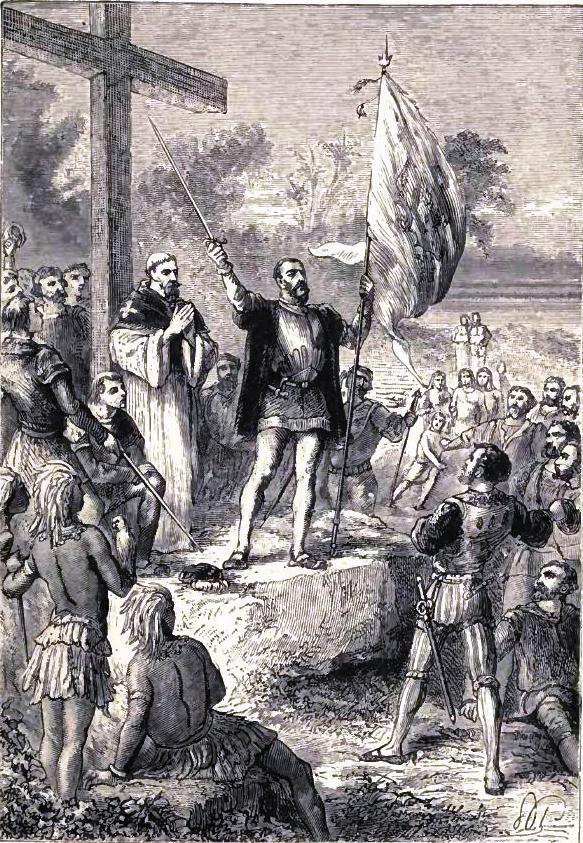

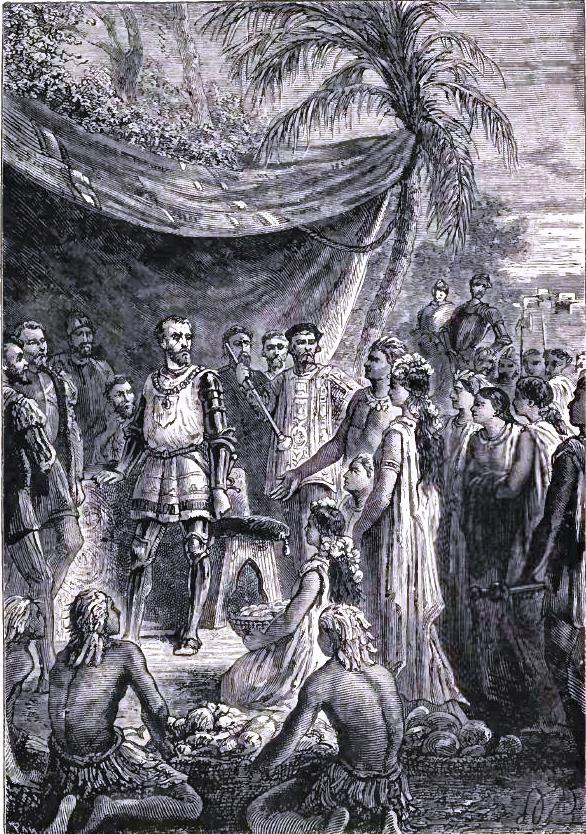

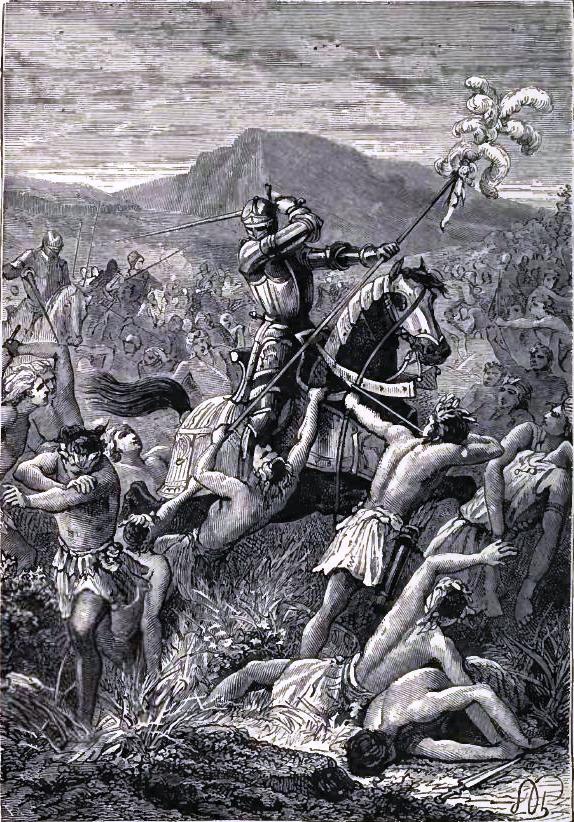

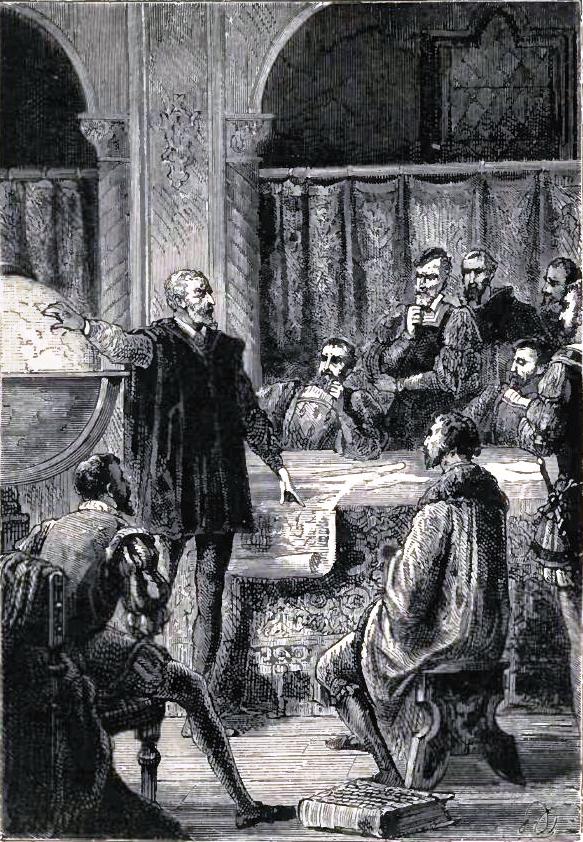

Ferdinand Cortès—His character—His appointment—Preparations for the expedition, and attempts of Velasquez to stop it—Landing at Vera-Cruz—Mexico and the Emperor Montezuma—The republic of Tlascala—March upon Mexico—The Emperor is made prisoner—Narvaez defeated—The Noche Triste—Battle of Otumba—The second siege and taking of Mexico—Expedition to Honduras—Voyage to Spain—Expeditions on the Pacific Ocean—Second Voyage of Cortès to Spain—His death

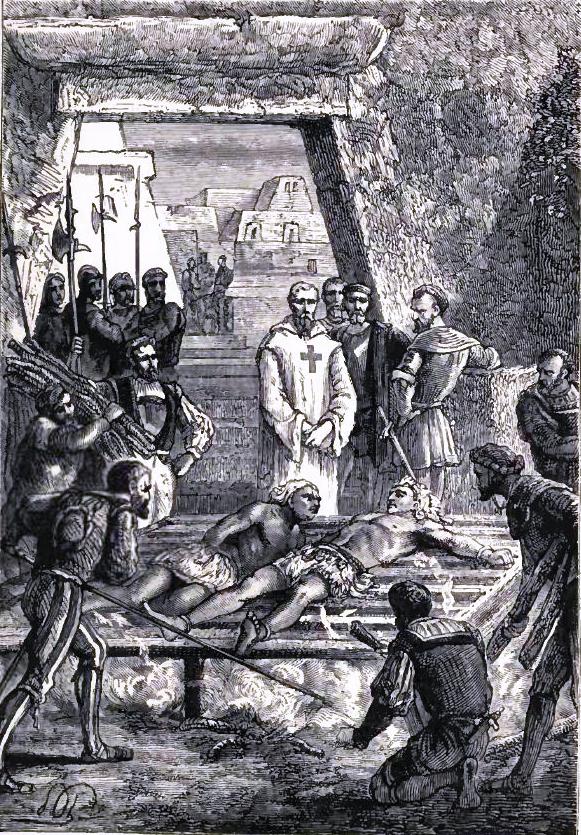

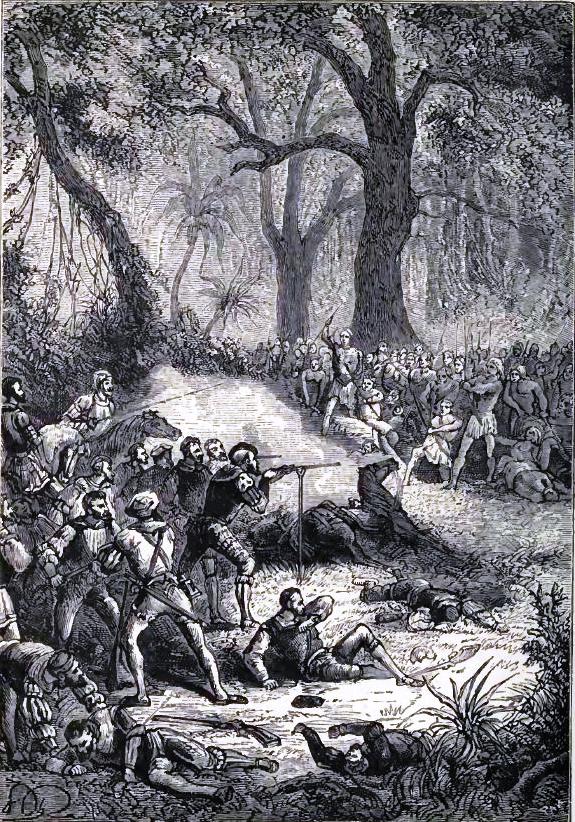

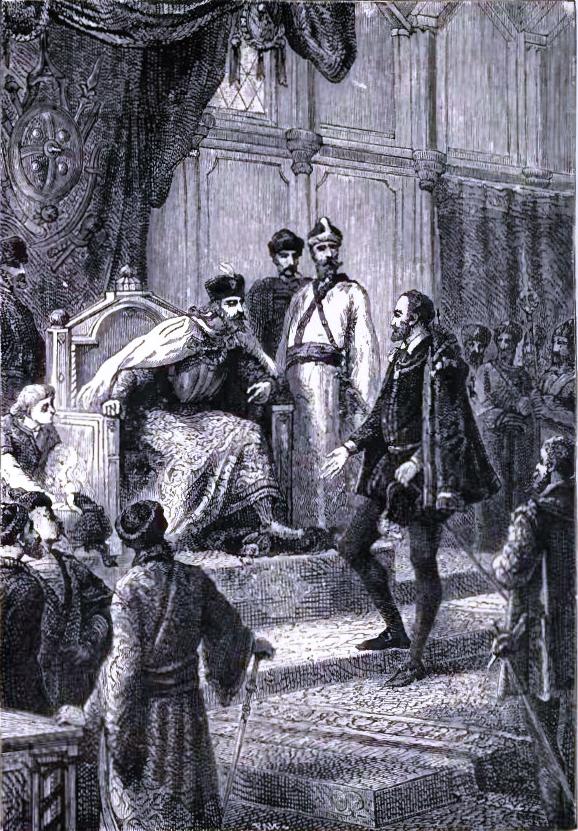

The triple alliance—Francisco Pizarro and his brothers—Don Diego d'Almagro—First attempts—Peru, its extent, people, and kings—Capture of Atahualpa, his ransom and death—Pedro d'Alvarado—Almagro in Chili—Strife among the conquerors—Trial and execution of Almagro—Expeditions of Gonzalo Pizarro and Orellana—Assassination of Francisco Pizarro—Rebellion and execution of his brother Gonzalo

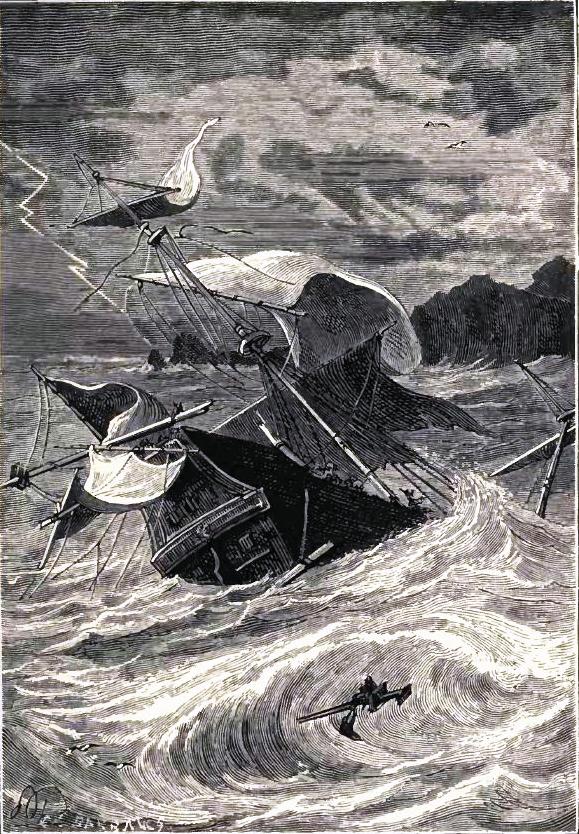

Magellan—His early history—His disappointment—His change of nationality—Preparations for the expedition—Rio de Janeiro— St. Julian's Bay—Revolt of a part of the squadron—Terrible punishment of the guilty—Magellan's Strait—Patagonia—The Pacific—The Ladrone Islands—Zebu and the Philippine Islands— Death of Magellan—Borneo—The Moluccas and their Productions— Separation of the Trinidad and Victoria—Return to Europe by the Cape of Good Hope—Last misadventures

The Northmen—Eric the Red—The Zenos—John Cabot—Cortereal—Sebastian Cabot—Willoughby—Chancellor

John Verrazzano—Jacques Cartier and his three voyages to Canada—The town of Hochelaga—Tobacco—The scurvy—Voyage of Roberval—Martin Frobisher and his voyages—John Davis—Barentz and Heemskerke—Spitzbergen—Winter season at Nova Zembla— Return to Europe—Relics of the Expedition

Drake—Cavendish—De Noort—Walter Raleigh

Distinguishing characteristics of the Seventeenth Century—The more thorough exploration of regions previously discovered—To the thirst for gold succeeds Apostolic zeal—Italian Missionaries in Congo—Portuguese Missionaries in Abyssinia—Brue in Senegal and Flacourt in Madagascar—The Apostles of India, of Indo-China, and of Japan

The Dutch in the Spice Islands—Lemaire and Schouten—Tasman—Mendana—Queiros and Torrès—Pyrard de Laval—Pietro della Valle—Tavernier—Thévenot—Bernier—Robert Knox—Chardin—De Bruyn—Kæmpfer

William Dampier; or a Sea-King of the Seventeenth Century

Hudson and Baffin—Champlain and La Sale—The English upon the coast of the Atlantic—The Spaniards in South America—Summary of the information acquired at the close of the 17th century—The measure of the terrestrial degree—Progress of cartography—Inauguration of Mathematical Geography

|

Hanno, the Carthaginian—Herodotus visits Egypt, Lybia, Ethiopia, Phoenicia, Arabia, Babylon, Persia, India, Media, Colchis, the Caspian Sea, Scythia, Thrace, and Greece—Pytheas explores the coasts of Iberia and Gaul, the English Channel, the Isle of Albion, the Orkney Islands, and the land of Thule—Nearchus visits the Asiatic coast, from the Indus to the Persian Gulf—Eudoxus reconnoitres the West Coast of Africa—Cæsar conquers Gaul and Great Britain—Strabo travels over the interior of Asia, and Egypt, Greece, and Italy.

The first traveller of whom we have any account in history, is Hanno, who was sent by the Carthaginian senate to colonize some parts of the Western coast of Africa. The account of this expedition was written in the Carthaginian language and afterwards translated into Greek. It is known to us now by the name of the "Periplus of Hanno." At what period this explorer lived, historians are not agreed, but the most probable account assigns the date B.C. 505 to his exploration of the African coast.

Hanno left Carthage with a fleet of sixty vessels of fifty oars each, carrying 30,000 persons, and provisions for a long voyage. These emigrants, for so we may call them, were destined to people the new towns that the Carthaginians hoped to found on the west coast of Libya, or as we now call it, Africa.

The fleet successfully passed the Pillars of Hercules, the rocks of Gibraltar and Ceuta which command the Strait, and ventured on the Atlantic, taking a southerly course. Two days after passing the Straits, Hanno anchored on the coast, and laid the foundation of the town of Thumiaterion.

Then he put to sea again, and doubling the cape of Soloïs, made fresh discoveries, and advanced to the mouth of a large African river, where he found a tribe of wandering shepherds camping on the banks. He only waited to conclude a treaty of alliance with them, before continuing his voyage southward. He next reached the Island of Cerne, situated in a bay, and measuring five stadia in circumference, or as we should say at the present day, nearly 925 yards. According to Hanno's own account, this island should be placed, with regard to the Pillars of Hercules, at an equal distance to that which separates these Pillars from Carthage.

They set sail again, and Hanno reached the mouth of the river Chretes, which forms a sort of natural harbour, but as they endeavoured to explore this river, they were assailed with showers of stones from the native negro race, inhabiting the surrounding country, and driven back, and after this inhospitable reception they returned to Cerne. We must not omit to add that Hanno mentions finding large numbers of crocodiles and hippopotami in this river. Twelve days after this unsuccessful expedition, the fleet reached a mountainous region, where fragrant trees and shrubs abounded, and it then entered a vast gulf which terminated in a plain. This region appeared quite calm during the day, but after nightfall it was illumined by tongues of flame, which might have proceeded from fires lighted by the natives, or from the natural ignition of the dry grass when the rainy season was over.

In five days, Hanno doubled the Cape, known as the Hespera Keras, there, according to his own account, "he heard the sound of fifes, cymbals, and tambourines, and the clamour of a multitude of people." The soothsayers, who accompanied the party of Carthaginian explorers, counselled flight from this land of terrors, and, in obedience to their advice, they set sail again, still taking a southerly course. They arrived at a cape, which, stretching southwards, formed a gulf, called Notu Keras, and, according to M. D'Avezac, this gulf must have been the mouth of the river Ouro, which falls into the Atlantic almost within the Tropic of Cancer. At the lower end of this gulf, they found an island inhabited by a vast number of gorillas, which the Carthaginians mistook for hairy savages. They contrived to get possession of three female gorillas, but were obliged to kill them on account of their great ferocity.

This Notu Keras must have been the extreme limit reached by the Carthaginian explorers, and though some historians incline to the belief that they only went to Bojador, which is two degrees North of the tropics, it is more probable that the former account is the true one, and that Hanno, finding himself short of provisions, returned northwards to Carthage, where he had the account of his voyage engraved in the temple of Baal Moloch.

After Hanno, the most illustrious of ancient travellers, was Herodotus, who has been called the "Father of History," and who was the nephew of the poet Panyasis, whose poems ranked with those of Homer and Hesiod. It will serve our purpose better if we only speak of Herodotus as a traveller, not an historian, as we wish to follow him so far as possible through the countries that he traversed.

Herodotus was born at Halicarnassus, a town in Asia Minor, in the year B.C. 484. His family were rich, and having large commercial transactions they were able to encourage the taste for explorations which he showed. At this time there were many different opinions as to the shape of the earth: the Pythagorean school having even then begun to teach that it must be round, but Herodotus took no part in this discussion, which was of the deepest interest to learned men of that time, and, still young, he left home with a view of exploring with great care all the then known world, and especially those parts of it of which there were but few and uncertain data.

He left Halicarnassus in 464, being then twenty years of age, and probably directed his steps first to Egypt, visiting Memphis, Heliopolis, and Thebes. He seems to have specially turned his attention to the overflow of the banks of the Nile, and he gives an account of the different opinions held as to the source of this river, which the Egyptians worshipped as one of their deities. "When the Nile overflows its banks," he says, "you can see nothing but the towns rising out of the water, and they appear like the islands in the Ægean Sea." He tells of the religious ceremonies among the Egyptians, their sacrifices, their ardour in celebrating the feasts in honour of their goddess Isis, which took place principally at Busiris (whose ruins may still be seen near Bushir), and of the veneration paid to both wild and tame animals, which were looked upon almost as sacred, and to whom they even rendered funeral honours at their death. He depicts in the most faithful colours, the Nile crocodile, its form, habits, and the way in which it is caught, and the hippopotamus, the momot, the phoenix, the ibis, and the serpents that were consecrated to the god Jupiter. Nothing can be more life-like than his accounts of Egyptian customs, and the notices of their habits, their games, and their way of embalming the dead, in which the chemists of that period seem to have excelled. Then we have the history of the country from Menes, its first king, downwards to Herodotus' time, and he describes the building of the Pyramids under Cheops, the Labyrinth that was built a little above the Lake Moeris (of which the remains were discovered in A.D. 1799), Lake Moeris itself, whose origin he ascribes to the hand of man, and the two Pyramids which are situated a little above the lake. He seems to have admired many of the Egyptian temples, and especially that of Minerva at Sais, and of Vulcan and Isis at Memphis, and the colossal monolith that was three years in course of transportation from Elephantina to Sais, though 2000 men were employed on the gigantic work.

After having carefully inspected everything of interest in Egypt, Herodotus went into Lybia, little thinking that the continent he was exploring, extended thence to the tropic of Cancer. He made special inquiries in Lybia as to the number of its inhabitants, who were a simple nomadic race principally living near the sea-coast, and he speaks of the Ammonians, who possessed the celebrated temple of Jupiter Ammon, the remains of which have been discovered on the north-east side of the Lybian desert, about 300 miles from Cairo. Herodotus furnishes us with some very valuable information on Lybian customs; he describes their habits; speaks of the animals that infest the country, serpents of a prodigious size, lions, elephants, bears, asps, horned asses (probably the rhinoceros of the present day), and cynocephali, "animals with no heads, and whose eyes are placed on their chest," to use his own expression; foxes, hyenas, porcupines, wild zarus, panthers, etc. He winds up his description by saying that the only two aboriginal nations that inhabit this region are the Lybians and Ethiopians.

According to Herodotus the Ethiopians were at that time to be found above Elephantina, but commentators are induced to doubt if this learned explorer ever really visited Ethiopia, and if he did not, he may easily have learnt from the Egyptians the details that he gives of its capital, Meroe, of the worship of Jupiter and Bacchus, and the longevity of the natives. There can be no doubt, however, that he set sail for Tyre in Phoenicia, and that he was much struck with the beauty of the two magnificent temples of Hercules. He next visited Tarsus and took advantage of the information gathered on the spot, to write a short history of Phoenicia, Syria, and Palestine.

We next find that he went southward to Arabia, and he calls it the Ethiopia of Asia, for he thought the southern parts of Arabia were the limits of human habitation. He tells us of the remarkable way in which the Arabs kept any vow that they might have made; that their two deities were Uranius and Bacchus, and of the abundant growth of myrrh, cinnamon and other spices, and he gives a very interesting account of their culture and preparation.

We cannot be quite sure which country he next visited, as he calls it both Assyria and Babylonia, but he gives a most minute account of the splendid city of Babylon (which was the home of the monarchs of that country, after the destruction of Nineveh), and whose ruins are now only in scattered heaps on either side of the Euphrates, which flowed a broad, deep, rapid river, dividing the city into two parts. On one side of the river the fortified palace of the king stood, and on the other the temple of Jupiter Belus, which may have been built on the site of the Tower of Babel. Herodotus next speaks of the two queens, Semiramis and Nitocris, telling us of all the means taken by the latter to increase the prosperity and safety of her capital, and passing on to speak of the natural products of the country, the wheat, barley, millet, sesame, the vine, fig-tree and palm-tree. He winds up with a description of the costume of the Babylonians, and their customs, especially that of celebrating their marriages by the public crier.

|

| The Marriage Ceremony. |

After exploring Babylonia he went to Persia, and as the express purpose of his travels was to collect all the information he could relating to the lengthy wars that had taken place between the Persians and Grecians, he was most anxious to visit the spots where the battles had been fought. He sets out by remarking upon the custom prevalent in Persia, of not clothing their deities in any human form, nor erecting temples nor altars where they might be worshipped, but contenting themselves with adoring them on the tops of the mountains. He notes their domestic habits, their disdain of animal food, their taste for delicacies, their passion for wine, and their custom of transacting business of the utmost importance when they had been drinking to excess; their curiosity as to the habits of other nations, their love of pleasure, their warlike qualities, their anxiety for the education of their children, their respect for the lives of all their fellow-creatures, even of their slaves, their horror both of debt and lying, and their repugnance to the disease of leprosy which they thought proved that the sufferer "had sinned in some way against the sun." The India of Herodotus, according to M. Vivien de St. Martin, only consisted of that part of the country that is watered by the five rivers of the Punjaub, adjoining Afghanistan, and this was the region where the young traveller turned his steps on leaving Persia. He thought that the population of India was larger than that of any other country, and he divided it into two classes, the first having settled habitations, the second leading a nomadic life. Those who lived in the eastern part of the country killed their sick and aged people, and ate them, while those in the north, who were a finer, braver, and more industrious race, employed themselves in collecting the auriferous sands. India was then the most easterly extremity of the inhabited world, as he thought, and he observes, "that the two extremities of the world seem to have shared nature's best gifts, as Greece enjoyed the most agreeable temperature possible," and that was his idea of the western limits of the world.

Media is the next country visited by this indefatigable traveller, and he gives the history of the Medes, the nation which was the first to shake off the Assyrian yoke. They founded the great city of Ecbatana, and surrounded it with seven concentric walls. They became a separate nation in the reign of Deioces. After crossing the mountains that separate Media from Colchis, the Greek traveller entered the country, made famous by the valour of Jason, and studied its manners and customs with the care and attention that were among his most striking characteristics.

Herodotus seems to have been well acquainted with the geography of the Caspian Sea, for he speaks of it as a Sea "quite by itself" and having no communication with any other. He considered that it was bounded on the west by the Caucasian Mountains and on the east by a great plain inhabited by the Massagetæ, who, both Arian and Diodorus Siculus think, may have been Scythians. These Massagetæ worshipped the Sun as their only deity, and sacrificed horses in its honour. He speaks here of two large rivers, one of which, the Araxes, would be the Volga, and the other, that he calls the Ista, must be the Danube. The traveller then went into Scythia, and he thought that the Scythians were the different tribes inhabiting the country that lay between the Danube and the Don, in fact a considerable portion of European Russia. He found the barbarous custom of putting out the eyes of their prisoners was practised among them, and he notices that they only wandered from place to place without caring to cultivate their land. Herodotus relates many of the fables that make the origin of the Scythian nation so obscure, and in which Hercules plays a prominent part. He adds a list of the different tribes that composed the Scythian nation, but he does not seem to have visited the country lying to the north of the Euxine, or Black Sea. He gives a minute description of the habits of these people, and expresses his admiration for the Pontus Euxinus. The dimensions that he gives of the Black Sea, the Bosphorus, of the Propontis, the Palus Mæotis and of the Ægean Sea, are almost exactly the same as those given by geographers of the present day. He also names the large rivers that flow into these seas. The Ister or Danube, the Borysthenes or Dnieper, the Tanais, or Don; and he finishes by relating how the alliance, and afterwards the union between the Scythians and Amazons took place, which explains the reason why the young women of that country are not allowed to marry before they have killed an enemy and established their character for valour.

After a short stay in Thrace, during which he was convinced that the Getæ were the bravest portion of this race, Herodotus arrived in Greece, which was to be the termination of his travels, to the country where he hoped to collect the only documents still wanting to complete his history, and he visited all the spots that had become illustrious by the great battles fought between the Greeks and Persians. He gives a minute description of the Pass of Thermopylæ, and of his visit to the plain of Marathon, the battlefield of Platæa, and his return to Asia Minor, whence he passed along the coast on which the Greeks had established several colonies. Herodotus can only have been twenty-eight years of age when he returned to Halicarnassus in Caria, for it was in B.C. 456 that he read the history of his travels at the Olympic Games. His country was at that time oppressed by Lygdamis, and he was exiled to Samos; but though he soon after rose in arms to overthrow the tyrant, the ingratitude of his fellow-citizens obliged him to return into exile. In 444 he took part in the games at the Pantheon, and there he read his completed work, which was received with enthusiasm, and towards the end of his life he retired to Thurium in Italy, where he died, B.C. 406, leaving behind him the reputation of being the greatest traveller and the most celebrated historian of antiquity.

After Herodotus we must pass over a century and a half, and only note, in passing, the Physician Ctesias, a contemporary of Xenophon, who published the account of a voyage to India that he really never made; and we shall come in chronological order to Pytheas, who was at once a traveller, geographer, and historian, one of the most celebrated men of his time. It was about the year B.C. 340 that Pytheas set out from the columns of Hercules with a single vessel, but instead of taking a southerly course like his Carthaginian predecessors, he went northwards, passing by the coasts of Iberia and Gaul to the furthest points which now form the Cape of Finisterre, and then he entered the English Channel and came upon the English coast—the British Isles—of which he was to be the first explorer. He disembarked at various points on the coast and made friends with the simple, honest, sober, industrious inhabitants, who traded largely in tin.

Pytheas ventured still further north, and went beyond the Orcades Islands to the furthest point of Scotland, and he must have reached a very high latitude, for during the summer the night only lasted two hours. After six days further sailing, he came to lands which he calls Thule, probably the Jutland or Norway of the present day, beyond which he could not pass, for he says, "there was neither land, sea, nor air there." He retraced his course, and changing it slightly, he came to the mouth of the Rhine, to the country of the Ostians, and, further inland, to Germany. Thence he visited the mouth of the Tanais, that is supposed to be the Elbe or the Oder, and he retuned to Marseilles, just a year after leaving his native town. Pytheas, besides being such a brave sailor, was a remarkably scientific man: he was the first to discover the influence that the moon exercises on the tides, and to notice that the polar star is not situated at the exact spot at which the axis of the globe is supposed to be. Some years after the time of Pytheas, about B.C. 326 a Greek traveller made his name famous. This was Nearchus, a native of Crete, one of Alexander's admirals, and he was charged to visit all the coast of Asia from the mouth of the Indus to that of the Euphrates. When Alexander first resolved that this expedition should take place, which had for its object the opening up of a communication between India and Egypt, he was at the upper part of the Indus. He furnished Nearchus with a fleet of thirty-three galleys, of some vessels with two decks, and a great number of transport ships, and 2000 men. Nearchus came down the Indus in about four months, escorted on either bank of the river by Alexander's armies, and after spending seven months in exploring the Delta, he set sail and followed the west line of what we call Beloochistan in the present day.

He put to sea on the second of October, a month before the winter storms had taken a direction that was favourable to his purpose, so that the commencement of his voyage was disastrous, and in forty days he had scarcely made eighty miles in a westerly direction. He touched first at Stura and at Corestis, which do not seem to answer to any of the now-existing villages on the coast; then at the Island of Crocala, which forms the bay of Caranthia. Beaten back by contrary winds, after doubling the cape of Monze, the fleet took refuge in a natural harbour that its commander thought that he could fortify as a defence against the attacks of the barbarous natives, who, even at the present day, keep up their character as pirates.

After spending twenty-four days in this harbour, Nearchus put to sea again on the 3rd of November. Severe gales often obliged him to keep very near the coast, and when this was the case he was obliged to take all possible precautions to defend himself from the attacks of the ferocious Beloochees, who are described by eastern historians "as a barbarous nation, with long dishevelled hair, and long flowing beards, who are more like bears or satyrs than human beings." Up to this time, however, no serious disaster had happened to the fleet, but on the 10th of November in a heavy gale two galleys and a ship sank. Nearchus then anchored at Crocala, and there he was met by a ship laden with corn that Alexander had sent out to him, and he was able to supply each vessel with provisions for ten days.

After many disasters and a skirmish with some of the natives, Nearchus reached the extreme point of the land of the Orites, which is marked in modern geography by Cape Morant. Here, he states in his narrative that the rays of the sun at mid-day are vertical, and therefore there are no shadows of any kind; but this is surely a mistake, for at this time in the Southern hemisphere the sun is in the Tropic of Capricorn; and, beyond this, his vessels were always some degrees distant from the Tropic of Cancer, therefore even in the height of summer this phenomenon could not have taken place, and we know that his voyage was in winter.

Circumstances seemed now rather more in his favour; for the time of the eastern monsoon was over, when he sailed along the coast which is inhabited by a tribe called Ichthyophagi, who subsist solely on fish, and from the failure of all vegetation are obliged to feed even their sheep upon the same food. The fleet was now becoming very short of provisions; so after doubling Cape Posmi Nearchus took a pilot from those shores on board his own vessel, and with the wind in their favour they made rapid progress, finding the country less bare as they advanced, a few scattered trees and shrubs being visible from the shore. They reached a little town, of the name of which we have no record, and as they were almost without food Nearchus surprised and took possession of it, the inhabitants making but little resistance. Canasida, or Churbar as we call it, was their next resting-place, and at the present day the ruins of a town are still visible in the bay. But their corn was now entirely exhausted, and though they tried successively at Canate, Trois, and Dagasira for further supplies, it was all in vain, these miserable little towns not being able to furnish more than enough for their own consumption. The fleet had neither corn nor meat, and they could not make up their minds to feed upon the tortoises that abound in that part of the coast.

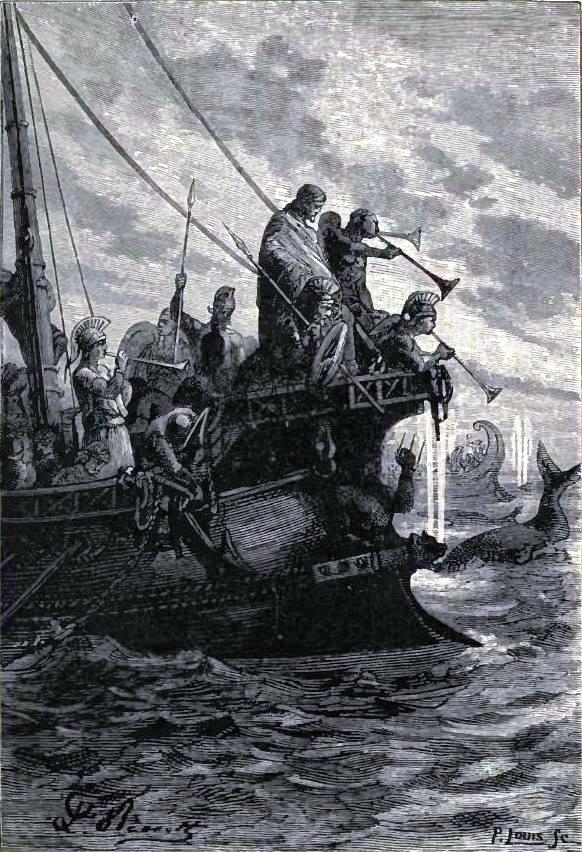

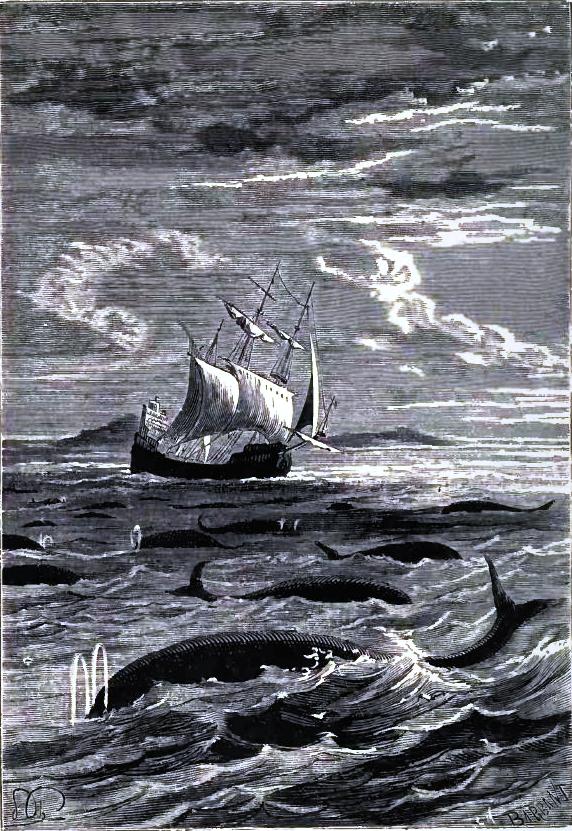

Just as they entered the Persian Gulf they encountered an immense number of whales, and the sailors were so terrified by their size and number, that they wished to fly; it was not without much difficulty that Nearchus at last prevailed upon them to advance boldly, and they soon scattered their formidable enemies.

|

| Nearchus leading on his followers against the monsters of the deep. |

Having changed their westerly course for a north-easterly one, they soon came upon fertile shores, and their eyes were refreshed by the sight of corn-fields and pasture-lands, interspersed with all kinds of fruit-trees except the olive. They put into Badis or Jask, and after leaving it and passing Maceta or Mussendon, they came in sight of the Persian Gulf, to which Nearchus, following the geography of the Arabs, gave the misnomer of the Red Sea.

They sailed up the gulf, and after one halt reached Harmozia, which has since given its name to the little island of Ormuz. There he learnt that Alexander's army was only five days' march from him, and he disembarked at once, and hastened to meet it. No news of the fleet having reached the army for twenty-one weeks, they had given up all hope of seeing it again, and great was Alexander's joy when Nearchus appeared before him, though the hardships he had endured had altered him almost beyond recognition. Alexander ordered games to be celebrated and sacrifices offered up to the gods; then Nearchus returned to Harmozia, as he wished to go as far as Susa with the fleet, and set sail again, having invoked Jupiter the Deliverer.

He touched at some of the neighbouring islands, probably those of Arek and Kismis, and soon afterwards the vessels ran aground, but the advancing tide floated them again, and after passing Bestion, they arrived at the island of Keish, that is sacred to Mercury and Venus. This was the boundary-line between Karmania and Persia. As they advanced along the Persian coast, they visited different places, Gillam, Indarabia, Shevou, &c., and at the last-named was found a quantity of wheat which Alexander had sent for the use of the explorers.

Some days after this they came to the mouth of the river Araxes, that separates Persia from Susiana, and thence they reached a large lake situated in the country now called Dorghestan, and finally anchored near the village of Degela, at the source of the Euphrates, having accomplished their project of visiting all the coast lying between the Euphrates and Indus. Nearchus returned a second time to Alexander, who rewarded him magnificently, and placed him in command of his fleet. Alexander's wish, that the whole of the Arabian coast should be explored as far as the Red Sea, was never fulfilled, as he died before the expedition was arranged.

It is said that Nearchus became governor of Lysia and Pamphylia, but in his leisure time he wrote an account of his travels, which has unfortunately perished, though not before Arian had made a complete analysis of it in his Historia Indica. It seems probable that Nearchus fell in the battle of Ipsu, leaving behind him the reputation of being a very able commander; his voyage may be looked upon as an event of no small importance in the history of navigation.

We must not omit to mention a most hazardous attempt made in B.C. 146, by Eudoxus of Cyzicus, a geographer living at the court of Euergetes II, to sail round Africa. He had visited Egypt and the coast of India, when this far greater project occurred to him, one which was only accomplished sixteen hundred years later by Vasco da Gama. Eudoxus fitted out a large vessel and two smaller ones, and set sail upon the unknown waters of the Atlantic. How far he took these vessels we do not know, but after having had communication with some natives, whom he thought were Ethiopians, he returned to Mauritania. Thence he went to Tiberia, and made preparations for another attempt to circumnavigate Africa, but whether he ever set out upon this voyage is not known; in fact some learned men are even inclined to consider Eudoxus an impostor.

We have still to mention two names of illustrious travellers, living before the Christian era; those of Cæsar and Strabo. Cæsar, born B.C. 100, was pre-eminently a conqueror, not an explorer, but we must remember, that in the year B.C. 58, he undertook the conquest of Gaul, and during the ten years that were occupied in this vast enterprise, he led his victorious Legions to the shores of Great Britain, where the inhabitants were of German extraction.

As to Strabo, who was born in Cappadocia B.C. 50, he distinguished himself more as a geographer than a traveller, but he travelled through the interior of Asia, and visited Egypt, Greece, and Italy, living many years in Rome, and dying there in the latter part of the reign of Tiberius. Strabo wrote a Geography in seventeen Books, of which the greater part has come down to us, and this work, with that of Ptolemy, are the two most valuable legacies of ancient to modern Geographers.

Pliny, Hippalus, Arian, and Ptolemy—Pausanias visits Attica, Corinth, Laconia, Messenia, Elis, Achaia, Arcadia, Boeotia, and Phocis—Fa-Hian explores Kan-tcheou, Tartary, Northern India, the Punjaub, Ceylon, and Java—Cosmos Indicopleustes, and the Christian Topography of the Universe—Arculphe describes Jerusalem, the valley of Jehoshaphat, the Mount of Olives, Bethlehem, Jericho, the river Jordan, Libanus, the Dead Sea, Capernaum, Nazareth, Mount Tabor, Damascus, Tyre, Alexandria, and Constantinople—Willibald and the Holy Land—Soleyman travels through Ceylon, and Sumatra, and crosses the Gulf of Siam and the China Sea.

In the first two centuries of the Christian era, the study of geography received a great stimulus from the advance of other branches of science, but travellers, or rather explorers of new countries were very few in number. Pliny in the year A.D. 23, devoted the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth books of his Natural History to geography, and in A.D. 50, Hippalus, a clever navigator, discovered the laws governing the monsoon in the Indian Ocean, and taught sailors how they might deviate from their usual course, so as to make these winds subservient to their being able to go to and return from India in one year. Arian, a Greek historian, born A.D. 105, wrote an account of the navigation of the Euxine or Black Sea, and pointed out as nearly as possible, the countries that had been discovered by explorers who had lived before his time; and Ptolemy the Egyptian, about A.D. 175, making use of the writings of his predecessors, published a celebrated geography, in which, for the first time, places and cities were marked in their relative latitude and longitude on a mathematical plan.

The first traveller of the Christian era, whose name has been handed down to us, was Pausanias, a Greek writer, living in Rome in the second century, and whose account of his travels bears the date of A.D. 175. Pausanias did for ancient Greece what Joanne, the industrious and clever Frenchman did for the other countries of Europe, in compiling the "Traveller's Guide." His account, a most reliable one on all points, and most exact even in details, was one upon which travellers of the second century might safely depend in their journeys through the different parts of Greece.

Pausanias gives a minute description of Attica, and especially of Athens and its monuments, tombs, temples, citadel, academy, columns, and of the Areopagus.

From Attica Pausanias went to Corinth, and then explored the Islands of Ægina and Methana, Sparta, the Island of Cerigo, Messene, Achaia, Arcadia, Boeotia, and Phocis. The roads in the provinces and even the streets in the towns, are mentioned in his narrative, as well as the general character of the country through which he passed; although we can scarcely say that he added any fresh discoveries to those already made, he was one of those careful travellers whose object was more to obtain exact information, than to make new discoveries. His narrative has been of the greatest use to all geographers and writers upon Greece and the Peloponnesus, and an author of the sixteenth century has truly said that this book is "a most ancient and rare specimen of erudition."

|

It was about a hundred and thirty years after the Greek historian, in the fourth century, that a Chinese monk undertook the exploration of the countries lying to the west of China. The account of his travels is still extant, and we may well agree with M. Charton when he says that "this is a most valuable work, carrying us beyond our ordinarily narrow view of western civilization."

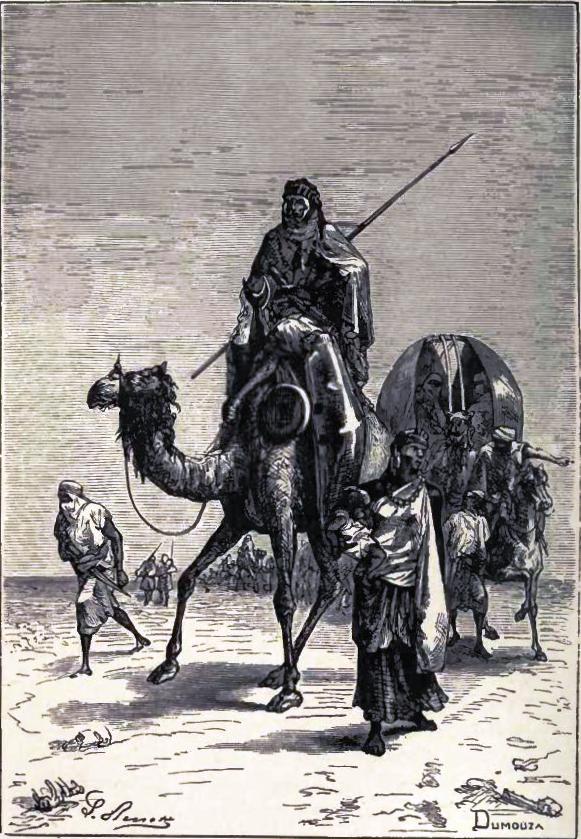

Fa-Hian, the traveller, was accompanied by several monks; wishing to leave China by the west, they crossed more than one chain of mountains, and reached the country now called Kan-tcheou, which is not far from the great wall. They crossed the river Cha-ho, and a desert that Marco Polo was to explore eight hundred years later. After seventeen days' march they reached the Lake of Lobnor in Turkestan. From this point all the countries that the monks visited were alike as to manners and customs, the languages alone differing. Being dissatisfied with the reception that they met with in the country of the Ourgas, who are not a hospitable people, they took a south-easterly course towards a desert country, where they had great difficulty in crossing the rivers; and, after a thirty-five days' march, the little caravan reached Tartary in the kingdom of Khotan, which contained, according to Fa-Hian, "Many times ten thousand holy men." Here they met with a cordial welcome, and after a residence of three months were allowed to assist at the "Procession of the Images," a great feast, in which both Brahmins and Buddhists join, when all the idols are placed upon magnificently decorated cars, and paraded through streets strewn with flowers, amid clouds of incense.

The feast over, the monks left Khotan for Koukonyar, and after resting there fifteen days, we find them further south in the Balistan country of the present day, a cold and mountainous district, where wheat was the only grain cultivated, and where Fa-Hian found in use the curious cylinders on which prayers are written, and which are turned by the faithful with the most extraordinary rapidity. Thence they went to the eastern part of Afghanistan; it took them four weeks to cross the mountains, in the midst of which, and the never-melting snow they are said to have found venomous dragons.

On the further side of this rocky chain the travellers found themselves in Northern India, where the country is watered by the streams which, further on, form the Sinde or Indus. After traversing the kingdoms of On-tchang, Su-ho-to, and Kian-tho-wei, they arrived at Fo-loo-cha, which must be the town of Peshawur, standing between Cabul and the Indus, and twenty-four leagues farther west, they came to the town of Hilo, built on the banks of a tributary of the river Kabout. In these towns Fa-Hian specially notices the feasts and religious ceremonies practised in the worship of Fo or Buddha.

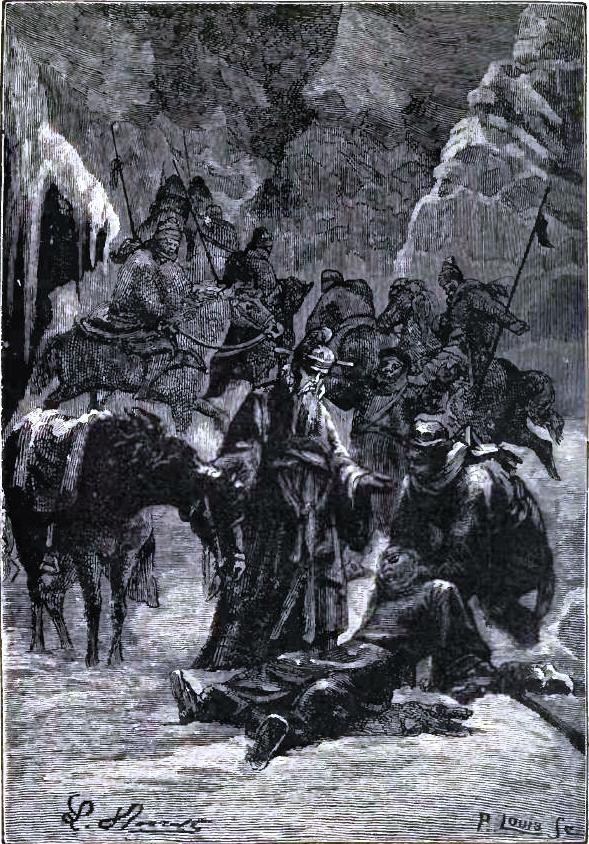

|

| One of Fa-Hian's companions falls. |

When the monks left Kito, they were obliged to cross the Hindoo-Koosh mountains, lying between Turkestan and the Gandhara, the cold being so intense that one of their party sank under it. After enduring great hardships they reached Banoo, a town that is still standing, and then, after again crossing the Indus, they entered the Punjaub. Thence, descending towards the south-east, with a view of crossing the northern part of the Indian Peninsula, they reached Mathura, a town in the province of Agra, and crossing the great salt desert which lies to the east of the Indus, travelled through a country that Fa-Hian calls "a happy kingdom, where the inhabitants are good and honest, needing neither laws nor magistrates, and indebted to none for their support; without markets or wine merchants, and living happily, with plenty of all that they required, where the temperature was neither hot nor cold." This happy kingdom was India. Fa-Hian followed a south-easterly route, and came to Feroukh-abad, where Buddha is said to have alighted as he came down from heaven, the Chinese traveller dwelling much upon the Buddhist Creed. Thence he visited the town of Kanoji, standing on the right bank of the Ganges, that he calls Heng, and this is the very centre of Buddhism. Wherever Buddha is supposed to have rested, his followers have erected high towers in his honour. The travellers visited the temple of Tchihouan, where for twenty-five years Fo practised the most severe mortifications, and where he is said to have given sight to five hundred blind men. They are said to have been much moved by the sight of this temple.

They set out again, passing Kapila and Goruckpoor, on the frontier of Nepaul, all made famous by Fo's miracles, and then reached the celebrated town of Palian-foo, in the delta of the Ganges, in the kingdom of Magadha. This was a fertile tract of country inhabited by a civilized, upright people, who loved all philosophic researches. After climbing the peak of Vautour, which stands at the source of the Dyardanes and Banourah rivers, Fa-Hian descended the Ganges, visited the temple of Issi-paten that was frequented by magicians and astrologers, reached Benares, "the kingdom of splendours," and a little lower down, the town of Tomo-li-ti, situated at the mouth of the river, a short distance from the site of Calcutta in the present day.

Fa-Hian found a party of merchants just preparing to put to sea with the intention of going to Ceylon; he sailed with them, and in fourteen days landed on the shores of the ancient Taprobana, of which the Greek merchant, Jamboulos, had given a curious account some centuries previously. Here the Chinese monk found all the traditions and legends regarding the god Fo, and passed two years in searching ancient manuscripts. He left Ceylon for Java, where he landed after a very rough voyage, in the course of which, when the sky was overclouded, he says, "we saw nothing but great waves dashing one against another, lightning, crocodiles, tortoises, and monsters of the deep."

He spent five months in Java, and then set sail for Canton; but the winds were again unfavourable, and after undergoing great hardships he landed at the town of Chantoung of the present day; then having spent some time at Nankin he returned to Fi-an-foo, his native town, after an absence of eighteen months. Such is the account of Fa-Hian's travels, which have been well translated by M. Abel de Rémusat, and which give very interesting details of Indian and Tartar customs, especially those relating to their religious ceremonies.

The next traveller to the Chinese monk, in chronological order, is an Egyptian called Cosmos Indicopleustes, a name that M. Charton renders as "Cosmographic traveller in India." He lived in the sixth century, and was a merchant of Alexandria, who, on his return from visiting Ethiopia and part of Asia, entered a monastery.

His narrative is called the "Christian Topography of the Universe." It gives no details of its author's voyages, but begins with cosmographic discussions, to prove that the world is square, and enclosed in a great oblong coffer with all the other planets. This is followed by some dissertations on the function of the angels, and a description of the dress of the Jewish Priests. Cosmos also gives the natural history of the animals of India and Ceylon, and notices the rhinoceros and buffalo, which can be made of use for domestic purposes, the giraffe, the wild ox, the musk that is hunted for its "perfumed blood," the unicorn, which he considers a real animal and not a myth, the wild boar, the hippopotamus, the phoca, the dolphin, and the tortoise. Afterwards, Cosmos describes the pepper-plant, as a frail and delicate shrub, like the smallest tendrils of the vine, and the cocoa-tree, whose fruit has a fragrance "equal to that of a nut."

From the earliest times of the Christian era there has been a great love for visiting the Holy Land, the cradle of the new religion. These pilgrimages became more and more frequent, and we have many names left to us of those who visited Palestine during the first centuries of Christianity.

One of these pilgrims, the French Bishop Arculphe, who lived towards the end of the seventh century, has left us an account of his travels.

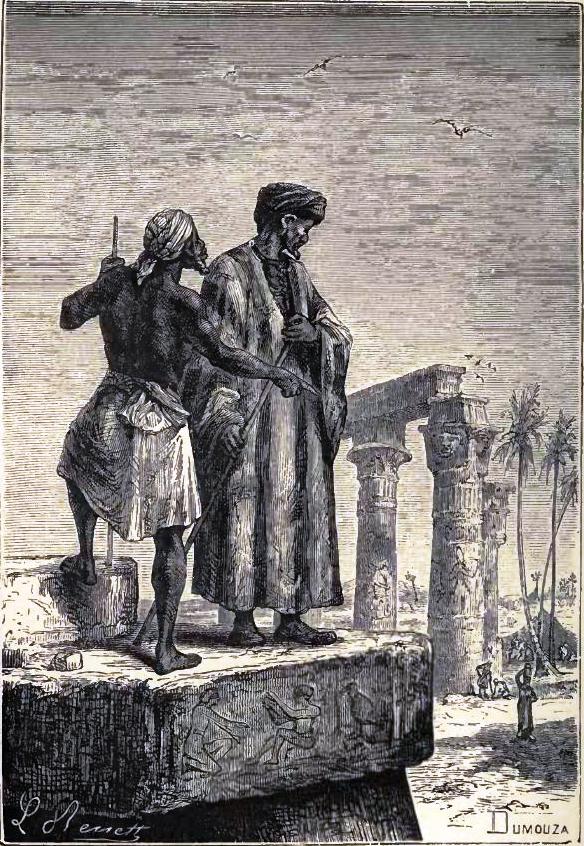

He sets out by giving a topographical description of the site of Jerusalem, and describes the wall that surrounds the holy city, then the circular church built over the Holy Sepulchre, the tomb of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the stone that closed it, the church dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the church built upon Calvary, and the basilica of Constantine on the site of the place where the real cross was found. These various churches are united in one building, which also encloses the Tomb of Christ, and Calvary, where our Lord was crucified.

Arculphe then descended into the Valley of Jehoshaphat, which is situated to the east of the city, and contains the church that covers the tomb of the Virgin; he also saw that of Absalom, which he calls the Tower of Jehoshaphat. He describes the Mount of Olives that faces the city beyond the valley, and he prayed in the cave where Jesus prayed. He also went to Mount Zion, which stands outside the town on the south side; he notices the gigantic fig-tree, on which, according to tradition, Judas Iscariot hanged himself, and he visited the church of the guest-chamber, now destroyed.

|

| Absalom's Tomb. |

After making the tour of the city by the Valley of Siloam, and ascending by the brook Cedron, the bishop returned to the Mount of Olives, which was covered with waving wheat and barley, grass and wild flowers, and he describes the place where Christ ascended from the summit of the mountain. On this spot a large church has been built, with three arched porticoes that are not roofed over or covered in any way, but are open to the sky. "They have not roofed in this church," says the bishop, "because it was the place whence our Saviour ascended upon a cloud, and the space open to heaven allows the prayers of the faithful to ascend thither. For when they paved this church they could not lay the pavement over the place where our Lord's feet had rested, as, when the stones were laid upon that spot, the earth, as though impatient of anything not divine resting upon it, threw them up again before the workmen. Beyond this, the dust bears the impress of the divine feet, and though, day by day, the faithful who visit the spot efface the marks, they immediately reappear and may be seen perpetually."

After having explored the neighbourhood of Bethany in the midst of the grove of olives, where the grave of Lazarus is said to be, and where the church, standing on the right hand is supposed to mark the spot where our Lord usually conversed with His disciples, Arculphe went to Bethlehem, which is a short distance from the holy city. He describes the birthplace of our Lord, a natural cave, hollowed out of the rock at the eastern end of the village, the church, built by St. Helena, the tombs of the three shepherds, upon whom the heavenly light shone at the birth of our Saviour, the burial-places of the patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and that of Rachel, and he visited the oak of Mamre, under which Abraham received the visit of the angels. Thence, Arculphe went to Jericho, or rather the place where the town once stood, whose walls fell at the sound of Joshua's trumpets. He explored the place where the children of Israel first rested in the land of Canaan after crossing the river Jordan, and he speaks of the church of Galgala, where the twelve stones are placed, which the children of Israel took from the river when they entered the promised land. He followed the course of the Jordan, and found near one of the bends of the river on the right bank, and among the most beautiful scenery, about an hour's walk from the Dead Sea, the place where our Lord was baptized by St. John the Baptist. A cross is placed to mark the spot, but when the river is swollen, it is covered by the water.

After examining the banks of the Dead Sea and tasting its brackish water, he viewed the source of the Jordan, at the foot of Libanus, and explored the greater part of the Lake of Tiberias, visiting the well where the woman of Samaria gave our Lord the water He so much needed, seeing the fountain in the desert of which St. John the Baptist drank, and the great plain of Gaza, where our Lord blessed the five loaves and two fishes, and fed the multitude. Next he went down to Capernaum, of which there are now no remains; then visited Nazareth, where our Lord spent His childhood, and ended his journey at Mount Tabor in Galilee.

The bishop's narrative contains both geographical and historical accounts of other places, beyond those immediately connected with our Lord's life on earth. He visited the royal city of Damascus, which is watered by four large rivers. Also Tyre, the chief town of Phoenicia, which, though once separated from the mainland, was joined to it again by the jetty or pier made by the orders of Nabuchodonosor. He speaks of Alexandria, once the capital of Egypt, which he reached forty days after leaving Jaffa, and lastly, of Constantinople, where he often visited the large church in which "the wood of the cross is preserved, upon which the Saviour suffered for the salvation of the human race."

The account of this journey was written by the Abbé de St. Columban at the dictation of the bishop, and not many years afterwards the same journey was undertaken by an English pilgrim, and accomplished in much the same way. The name of this pilgrim was Willibald, a member of a rich family living at Southampton, who, on his recovery from a long illness, dedicated him to God's service. All his early life was spent in holy exercises in the monastery of Woltheim; when he was grown up he had the most intense wish to see St. Peter's at Rome, and was so set upon this, that it induced his father, brother, and young sister to wish to go there also; they embarked at Southampton in the spring of 721, and making their way up the Seine, they landed at Rouen. We have but few details of the journey to Rome, but Willibald mentions that after passing through Cortona and Lucca, at which latter place his father sank under the fatigue of the journey and died, he reached Rome in safety with his brother and sister, and passed the winter there, but they were all in turn attacked with fever. When Willibald regained his health, he determined to continue his journey to the Holy Land. He sent his brother and sister back to England, while he joined some monks who were going in the same direction as himself. They went by Terracina and Gaeta to Naples, and set sail for Reggio in Calabria, and Catania and Syracuse in Sicily, whence they again embarked, and, after touching at Cos and Samos, landed at Ephesus in Asia Minor, where they visited the tombs of St. John the Evangelist, of Mary Magdalene, and of the seven sleepers of Ephesus, that is, seven Christians martyred in the time of the Emperor Decius.

They made some stay at Patara and at Mitylene, and then went to Cyprus and Paphos; we next find the party, seven in number, at Edessa, visiting the tomb of St. Thomas the Apostle. Here they were arrested as spies, and thrown into prison by the Saracens, but the king, on the petition of a Spaniard, set them at liberty. As soon as they were set free they left the town in great haste, and from that time their route is almost the same as that of the Bishop Arculphe; they visited Damascus, Nazareth, Cana, where they saw a wonderful amphora on Mount Tabor, where our Lord was transfigured, and the Lake of Tiberias, where St. Peter walked upon the water; Magdala, where Lazarus and his sister dwelt; Capernaum, where our Lord raised to life the son of the nobleman; Bethsaida in Galilee, the native place of St. Peter and St. Andrew; Chorazin, where our Lord cured those possessed with devils; Cæsarea, and the spot where our Lord was baptized, as well as Jericho and Jerusalem.

They also went to the Valley of Jehoshaphat, the Mount of Olives, and to Bethlehem, the scene of the murder of the Innocents by Herod, and Gaza. While they were at Gaza, Willibald tells us that he suddenly became blind, while he was in the church of St. Matthias, and only recovered his sight two months afterwards, as he entered the church of the Holy Cross at Jerusalem. He went through the valley of Diospolis or Lydda, ten miles from Jerusalem, and then went to Tyre and Sidon, and thence, by Libanus, Damascus, Cæsarea, and Emmaus, back to Jerusalem, where the travellers spent the winter.

This was not to be the limit of their exploration, for we hear of them at Ptolemais, Emesa, Jerusalem, Damascus, and Samaria, where St. John the Baptist is said to have been buried, and at Tyre, where it must be confessed that Willibald defrauded the revenue of that time by smuggling some balsam that was very celebrated, and on which a duty was levied. On quitting Tyre they went to Constantinople and lived there for two years before returning by Sicily, Calabria, Naples, and Capua. The English pilgrim reached the monastery of Monte Cassino, just ten years after his first setting out on his travels; but his time of rest had not yet come, as he was appointed to a bishopric in Franconia by Pope Gregory III. He was forty-one years of age when he was made bishop, and he lived forty years afterwards. In 938 he was canonized by Leo VII.

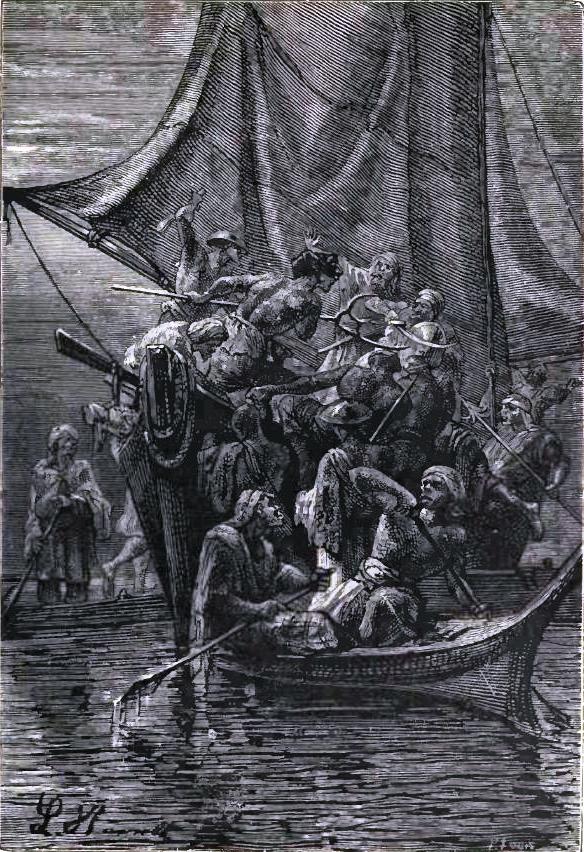

We will conclude the list of celebrated travellers living between the first and ninth centuries, by giving a short account of Soleyman, a merchant of Bassorah, who, starting from the Persian Gulf, arrived eventually on the shores of China. This narrative is in two distinct parts, one written in 851, by Soleyman himself, who was the traveller, and the other in 878 by a geographer named Abou-Zeyd Hassan with the view of completing the first. Renaud, the orientalist, is of opinion that this narrative "has thrown quite a new light on the commercial transactions that existed in the ninth century between Egypt, Arabia, and the countries bordering on the Persian Gulf on one side, and the vast provinces of India and China on the other."

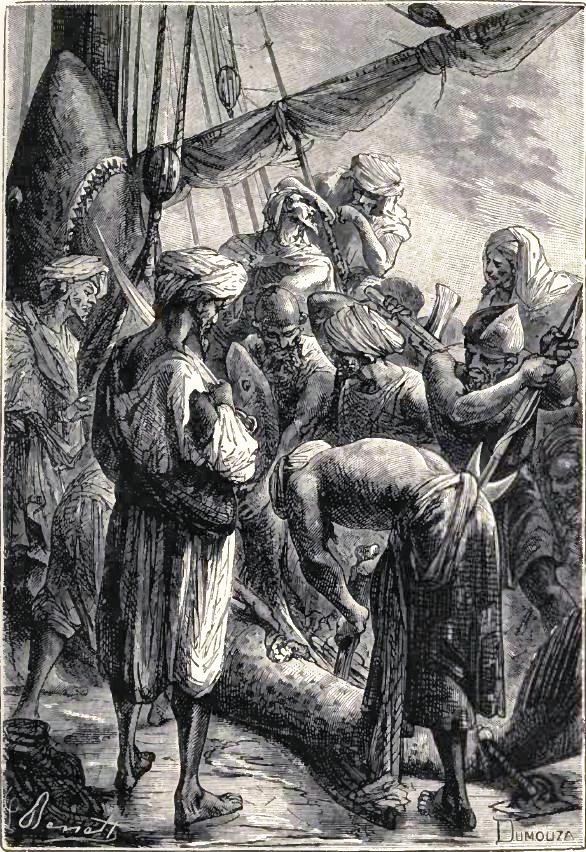

Soleyman, as we have said, started from the Persian Gulf after having taken in a good supply of fresh water at Muscat, and visited first, the second sea, or that of Oman. He noticed a fish of enormous size, probably a spermaceti whale, which the seamen endeavoured to frighten away by ringing a bell, then a shark, in whose stomach they found a smaller shark, enclosing in its turn one still smaller, "both alive," says the traveller, which is manifestly an exaggeration; then, after describing the remora, the dactyloptera, and the porpoise, he speaks of the sea near the Maldive Islands in which he counted an enormous number of islands, among them he mentions Ceylon by its Arabian name, with its pearl fisheries; Sumatra, inhabited by cannibals, and rich in gold-mines; Nicobar, and the Andaman Islands, where cannibalism still exists even at the present day. "This sea," he says, "is subject to fearful water-spouts which wreck the ships, and throw on its shores an immense number of dead fish and sometimes even large stones. When these tempests are at their height the sea seethes and boils." Soleyman imagined it to be infested by a sort of monster who preyed upon human beings; this is thought to have been a kind of dog-fish.

|

| Soleyman noticed a shark in whose stomach they found a smaller shark. |

Arrived at Nicobar, Soleyman traded with the inhabitants, bartering some iron for cocoa-nuts, sugar-cane, bananas, &c.; he then crossed the sea, and seems to have made for Singapore, and northwards by the Gulf of Siam. Soleyman put into a harbour, near Cape Varella, to revictual his ships, and thence he went by the China Sea to Jehan-fou the port of the present town of Tche-kiang. The remainder of the account of Soleyman's travels, written by Abou-Zeyd Hassan, contains a detailed account of the manners and customs of the Indians and Chinese; but it is not the traveller himself who is speaking, and we shall find the same subjects spoken of in a more interesting manner by later authors.

We must add, in reviewing the discoveries made by travellers sixteen centuries before, and nine centuries after, the Christian era, that from Norway to the extreme boundaries of China, taking a line through the Atlantic ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Sea of China, the immense extent of coast bordering these seas had been in a great measure visited. Some explorations had been attempted in the interior of these countries; for instance, in Egypt as far as Ethiopia, in Asia Minor to the Caucasus, in India and China; and if these old travellers may not have quite understood mathematical precision, as to some of the points they visited, at all events the manners and customs of the inhabitants, the productions of the different countries, the mode of trading with them, and their religious customs, were quite sufficiently understood. Ships could sail with more safety when the change of winds was no longer a subject of mere speculation, the caravans could take a more direct route in the interior of the countries, and the great increase of trade which took place in the middle ages is surely owing to the facilities afforded by the writings of travellers.

The Scandinavians in the North, Iceland and Greenland—Benjamin of Tudela visits Marseilles, Rome, Constantinople, the Archipelago, Palestine, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Damascus, Baalbec, Nineveh, Baghdad, Babylon, Bassorah, Ispahan, Shiraz, Samarcand, Thibet, Malabar, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Egypt, Sicily, Italy, Germany, and France—Carpini explores Turkestan—Manners and customs of the Tartars—Rubruquis and the Sea of Azov, the Volga, Karakorum, Astrakhan, and Derbend.

In the course of the tenth, and at the beginning of the eleventh century, a considerable amount of ardour for exploration had arisen in Northern Europe. Some Norwegians and adventurous Gauls had penetrated to the Northern seas, and, if we may trust to some accounts, they had gone as far as the White Sea and visited the country of the Samoyedes. Some documents say that Prince Madoc may have explored the American continent.

At all events we may be tolerably certain that Iceland was discovered about A.D. 861 by some Scandinavian adventurers, and that it was soon after colonized by Normans. About this same time a Norwegian had taken refuge on a newly discovered land, and surprised by its verdure he gave it the name of Greenland.

The communication with this portion of the American continent was difficult and uncertain, and one geographer says "it took five years for a vessel to go from Norway to Greenland, and to return from Greenland to Norway." Sometimes in severe winters the Northern Ocean was completely frozen over, and a certain Hollur-Geit, guided by a goat, was able to cross on foot from Norway to Greenland. We should keep in mind that the period of which we are speaking is the time when legends and traditions were very plentiful, and gained ready credence.

Let us return to well-authenticated facts, and relate the journey of a Spanish Jew, whose truthfulness is beyond question.

This Jew was the son of a rabbi of Tudela, a town in Navarre, and he was called Benjamin of Tudela. It seems probable that the object of his voyage was to make a census of his brother Jews scattered over the surface of the Globe, but whatever may have been his motive, he spent thirteen years, from 1160-1173, exploring nearly all the known world, and his narrative was considered the great authority on this subject up to the sixteenth century.

Benjamin of Tudela left Barcelona, and travelling by Tarragona, Gironde, Narbonne, Béziers, Montpellier, Sunel, Pousquiers, St. Gilles, and Arles, reached Marseilles. Here he visited the two synagogues in the town and the principal Jews, and then set sail for Genoa, arriving there in four days. The Genoese were masters of the sea at that time, and were at war with the people of Pisa, a brave people, who, like the Genoese, says the traveller, "owned neither kings nor princes, but only the judges whom they appointed at their own pleasure."

After visiting Lucca, Benjamin of Tudela went to Rome. Alexander III. was Pope at that time, and according to this traveller, he included some Jews among his ministers. Among the monuments of special interest in the eternal city, he mentions St. Peter's and St. John Lateran, but his descriptions are not interesting. From Rome by Capua, and Pozzuoli, then partly inundated, he went to Naples, where he seems to have seen nothing but the five hundred Jews living there; then by Salerno, Amalfi, Benevento, Ascoli, Trani, St. Nicholas of Bari, and Brindisi, he arrived at Otranto, having crossed Italy and yet found nothing interesting to relate of this splendid country.

The list of the places Benjamin of Tudela visited, is not interesting, but we must not omit to mention one of them, for his narrative is most precise, and it is useful to follow his route by the maps specially prepared for this purpose by Lelewel. From Otranto to Zeitun, his halting-places were Corfu, the Gulf of Arta, Achelous, an ancient town in Ætolia, Anatolia in Greece, on the Gulf of Patras, Patras, Lepanto, Crissa, at the foot of Mount Parnassus, Corinth, Thebes, whose two thousand Jewish inhabitants were the best makers of silk and purple in Greece, Negropont and Zeitoun. Here, according to the Spanish traveller, is the boundary-line of Wallachia; he says the Wallachians are as nimble as goats, and come down from the mountains to pillage the neighbouring Greek towns.

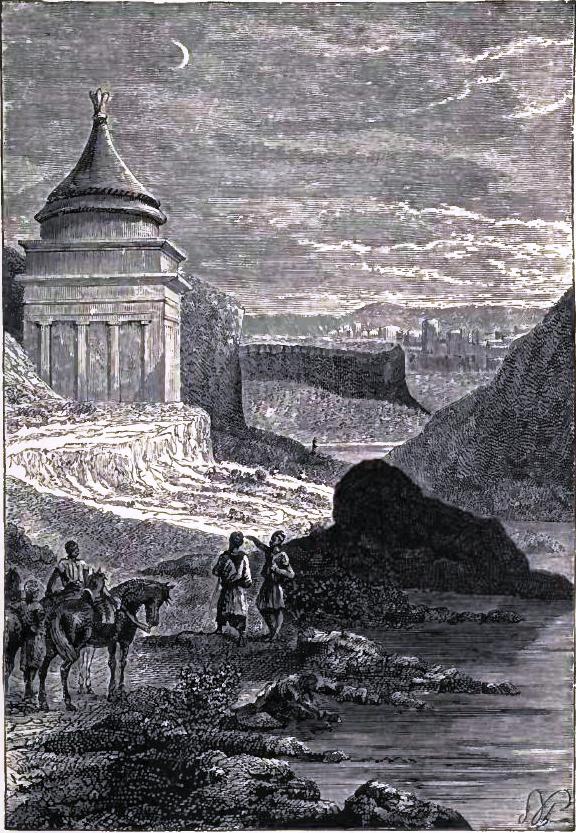

Benjamin of Tudela went on to Constantinople by way of Gardiki, a small township on the Gulf of Volo, Armyros, a port much frequented by the Venetians and Genoese, Bissina, a town of which no traces are left, Salonica, the ancient Thessalonica, and Abydos. He gives us some details of Constantinople; the Emperor Emmanuel Comnenus was reigning at that time and lived in a palace that he had built upon the sea-shore, containing columns of pure gold and silver, and "the golden throne studded with precious stones, above which a golden crown is suspended by a chain of the same precious metal, which rests upon the monarch's head as he sits upon the throne." In this crown are many precious stones, and one of priceless worth: "so brilliant are they," says this traveller, "that at night, there is no occasion for any further light than that thrown back by these jewels." He adds that there is a large population in the city, and for the number of merchants from all countries who assemble there, it can only be compared to Baghdad. The inhabitants are principally dressed in embroidered silk robes enriched with golden fringes, and to see them thus attired and mounted upon their horses, one would take them for princes, but they are not brave warriors, and they keep mercenaries from all nations to fight for them. One regret he expresses, and that is, that there are no Jews left in the City, and that they have all been transported to Galata, near the entrance of the port, where are nearly two thousand five hundred of the sects (Rabbinites and Caraites), and among them many rich merchants and silk manufacturers, but the Turks have a bitter hatred for them, and treat them with great severity. Only one of these rich Jews was allowed to ride on horseback, he was the Emperor's physician, Solomon, the Egyptian. As to the remarkable buildings of Constantinople, he mentions the Mosque of St. Sophia, in which the number of altars answers to the number of days in a year, and the columns and gold and silver candlesticks, are too numerous to be counted; also the Hippodrome, which at the present day is used as a horse-market, but was then the scene of combats between "lions, bears, tigers, other wild beasts, and even birds."

|

| The approach to Constantinople. |

When Benjamin of Tudela left Constantinople, he visited Gallipoli and Kilia, a port on the Eastern coast, and went to the islands in the Archipelago, Mitylene, Chios, whence there was much trade in the juice of the pistachio-tree, Samos, Rhodes, and Cyprus. As he sailed towards the land of Aram, he passed by Messis, by Antioch, where he admired the arrangements for supplying the city with water, and by Latakia on his way to Tripoli, which he found had been recently shaken by an earthquake, that had been felt for miles round. We next hear of him at Beyrout, at Sidon, and Tyre, celebrated for its glass manufactory, at Acre, at Jaffa near Mount Carmel, at Capernaum, at the beautiful town of Cæsarea, at Samaria, which is built in the midst of a fertile tract, where are vineyards, gardens, orchards, and olive-yards, at Nablous, at Gibeon, and then at Jerusalem.